User login

YOU HAVE A NEW JOB: Monitor the lipid profile

Dr. Dayspring serves on the advisory board for LipoScience. Dr. Helmbold reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Add another item to your ever-growing list of responsibilities: monitoring your patients’ risk of atherosclerosis.

This task used to be the purview of internists and cardiologists but, because gynecologists are increasingly serving as a primary care provider, you need to learn to recognize and diagnose the many clinical expressions of atherosclerosis in your aging patients.

A crucial part of that knowledge is a thorough understanding of each and every lipid concentration parameter reported within the standard lipid profile. This article reviews those parameters, explains how to interpret them individually and in combination, and introduces a new paradigm: the analysis of lipoprotein particle concentrations as a more precise way to determine risk.

If used in its entirety, the lipid profile provides a significant amount of information about the presence or absence of pathologic lipoprotein concentrations. Far too many clinicians focus solely on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and ignore the rest of the profile. Failure to consider the other variables is one reason why atherosclerotic disease is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the United States in many patients—especially women.1

1. Look at the triglyceride (TG) level. If it is >500 mg/dL, treatment is indicated, and TG reduction takes precedence over all other lipid concentrations. If TG is <500 mg/dL, go to Step 2.

2. Look at the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level. If it is >190 mg/dL, drug therapy is indicated regardless of other findings. At lower levels, the need for therapy is based on the patient’s overall risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Therapeutic lifestyle recommendations are always indicated.

3. Look at high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). Increased risk is present if it is <50 mg/dL, the threshold for women. Do not assume that high HDL-C always means low CVD risk.

4. Calculate the total cholesterol (TC)/HDL-C ratio (a surrogate of apoB/apoA-I ratio). Increased risk is present if it is >4.0.

5. Calculate the non-HDL-C level (TC minus HDL-C). If it is >130 mg/dL (or >100 mg/dL in very-high-risk women), therapy is warranted. Newer data reveal that this calculation is always equal to, or better than, LDL-C at predicting CVD risk. Non-HDL-C is less valuable if TG is >500 mg/dL.

6. Calculate the TG/HDL-C ratio to estimate the size of LDL. If the ratio is >3.8, the likelihood of small LDL is 80%. (Small LDL usually has very high LDL-P.)

Why lipoproteins are important

There is only one absolute in atherosclerosis: Sterols—predominantly cholesterol—enter the artery wall, where they are oxidized, internalized by macrophages, and transformed into foam cells, the histologic hallmark of atherosclerosis. With the accumulation of foam cells, fatty streaks develop and, ultimately, so does complex plaque.

Lipids associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) include:

- cholesterol

- noncholesterol sterols such as sitosterol, campesterol, and others of mostly plant or shellfish origin

- triacylglycerol, or triglycerides (TG)

- phospholipids.

Because lipids are insoluble in aqueous solutions such as plasma, they must be “trafficked” within protein-enwrapped particles called lipoproteins. The surface proteins that provide structure and solubility to lipoproteins are called apolipoproteins. A key concept is that, with their surface apolipoproteins and cholesterol core, certain lipoproteins are potential agents of atherogenesis in that they transport sterols into the artery wall.2

Estimation of the risk of CVD involves careful analysis of all standard lipid concentrations and their various ratios, and prediction of the potential presence of atherogenic lipoproteins. Successful prevention or treatment of atherosclerosis entails limiting the presence of atherogenic lipoproteins.

A new paradigm is on its way

The atherogenicity of lipoprotein particles is determined by particle concentration as well as other variables, including particle size, lipid composition, and distinct surface apolipoproteins.

Lipoproteins smaller than 70 nm in diameter are driven into the arterial intima primarily by concentration gradients, regardless of lipid composition or particle size.3 A recent Consensus Statement from the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology observed that quantitative analysis of these potentially atherogenic lipoproteins is one of the best lipid/lipoprotein-related determinants of CVD risk.4 Lipoprotein particle concentrations have emerged not only as superb predictors of risk, but also as goals of therapy.5-7

Because of cost, third-party reimbursement, varying test availability, and lack of interpretive knowledge, few clinicians routinely order lipoprotein quantification. Historically, CVD risk and goals of therapy have been based on lipid concentrations (the amount of lipids trafficked within lipoprotein cores) reported in the lipid profile. Guidelines from the National Cholesterol Education Program, Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP-III)8,9 and the American Heart Association (AHA) CVD Prevention in Women10,11 use lipid concentrations such as total cholesterol (TC), LDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and TG as estimates or surrogates of lipoprotein concentrations ( TABLE 1 ).

The day is rapidly approaching, however, when lipoprotein concentrations may replace the lipid profile in clinical practice. It is critical that clinicians develop a solid understanding of lipoprotein physiology and pathology.7,12 It also is crucial that we be as skilled as possible in accurately predicting lipoprotein pathology using all of the lipid concentration parameters present in the lipid panel.

TABLE 1

Desirable lipid values for women

| Lipid | Level (mg/dL) |

|---|---|

| Total cholesterol | <200 |

| Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol | <100 |

| High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol | ≥50 |

| Triglycerides | <150 |

| Non-HDL-cholesterol | <130 |

| FOR VERY HIGH-RISK PATIENTS | |

| LDL-C | <70 |

| Non-HDL-C | <100 |

| Source: American Heart Association | |

How lipoproteins are analyzed

Lipoproteins can be separated into their components using any of several methodologies, including ultracentrifugation, electrophoresis, apolipoprotein content analysis, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Of these, only the last two provide information on particle concentrations.13,14

Apolipoprotein content analysis reveals two major categories of particles:

- alpha-lipoproteins, or HDL, which contain two to four molecules of apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I)

- beta-lipoproteins, a collective group of chylomicrons, very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL), and LDL, each containing a single molecule of apolipoprotein B (apoB). Because of very different half-lives (chylomicrons, 1 hour; VLDL, 2–6 hours; IDL, 1–2 hours; LDL, 2–3 days), the great majority (90% to 95%) of apoB-containing particles are LDL. Although apoB measurement yields quantification of all beta-lipoproteins, it is primarily a surrogate of LDL particle (LDL-P) concentration.15

Individual particle concentrations, determined by NMR spectroscopy, are reported as VLDL-P, IDL-P, LDL-P, and HDL-P (see the “Glossary”).14

Several epidemiologic studies that enrolled both genders found the best predictors of risk to be:

- elevated levels of apoB or LDL-P and reduced levels of apoA-I or HDL-P

- a high apoB/apoA-I ratio or LDL-P/HDL-P ratio.6,13,14

After adjustment for lipoprotein concentration data (apoB or LDL-P), other lipoprotein characteristics such as particle lipid content, size, or composition, for the most part, had no statistically significant relationship with the risk of cardiovascular disease.16,17

Lipids and lipoproteins: A glossary

| Variable | What is it? |

|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TG) | The triacylglycerol concentration within all of the TG-trafficking lipoproteins in 100 mL or 1 dL of plasma |

| Total cholesterol (TC) | Cholesterol content of all lipoproteins in 1 dL of plasma |

| Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol | Cholesterol content of all intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL) and LDL particles in 1 dL of plasma |

| High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol | Cholesterol content of all HDL particles in 1 dL of plasma |

| Very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol | Cholesterol content of all VLDL particles in 1 dL of plasma |

| Remnant-C | Cholesterol content of all remnants in 1 dL of plasma |

| Lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] cholesterol | Cholesterol content of LDL particles that have apo(a) attached |

| Lp(a) concentration | Concentration of apo(a) in 1 dL of plasma |

| Non-HDL cholesterol | Cholesterol within all apoB particles in 1 dL of plasma |

| LDL-P | Number of LDL particles in 1 L of plasma (expressed in nmol/L). This represents LDL particles of all sizes |

| Small LDL-P | Number of small and intermediate LDL particles in 1 L of plasma (nmol/L) |

| HDL-P | Number of HDL particles in 1 L of plasma (μmol/L). HDL-P is also reported as large, intermediate, and small HDL-P (μmol/L) |

| VLDL-P | Number of VLDL particles in 1 L of plasma (nmol/L) |

| IDL-P | Number of IDL particles in 1 L of plasma (nmol/L) |

| LDL size | Diameter of the predominant LDL species:

|

Using lipid measurements to estimate lipoproteins

Total cholesterol represents the cholesterol content within all lipoproteins in 1 dL of plasma. Because beta-lipoproteins are considerably larger than alpha-lipoproteins, approximately 75% of total cholesterol is carried in the apoB-containing particles, making TC an apoB surrogate.

VLDL-C, an often ignored variable, is not measured but calculated using the Friedewald formula, dividing TG by five. This calculation assumes—often erroneously as TG levels rise—that TG consists only of VLDL particles and that VLDL composition contains five times more TG than cholesterol molecules.

A desirable TG level is <150 mg/dL, so normal VLDL-C is 150/5 or <30 mg/dL.

LDL-C is also an apoB surrogate

Although VLDL-C is a weak apoB surrogate,15 data from the Framingham Heart Study showed it to be a good predictor of VLDL remnant particles.18 However, because the vast majority of beta-lipoproteins are LDL, LDL-C (especially if elevated) is a better apoB surrogate than VLDL-C and is the primary CVD risk factor and goal of therapy in every current guideline.

LDL-C is usually a calculated value using the formula:

LDL-C = TC – (HDL-C + VLDL-C)

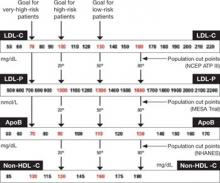

Upon special order, laboratories can directly measure LDL-C. This option is most useful when TG levels are high, rendering the Friedewald formula less accurate ( TABLE 2 ).19 For population cut points and desirable goals of therapy for lipid and lipoprotein concentrations, see the FIGURE .

TABLE 2

How lipid concentrations are determined

| TC = apoA-I-C + apoB-C |

| TC = HDL-C + LDL-C + VLDL-C + IDL-C + Chylomicron-C + Lp(a)-C + Remnant-C |

| In a fasting patient under normal circumstances, there are no chylomicrons and remnants (smaller chylomicrons or VLDL particles) and very few, if any, IDL particles. These are postprandial lipoproteins. Most patients do not have Lp(a) pathology. Therefore, the lipid concentration formula simplifies: |

| TC = HDL-C + LDL-C + VLDL-C |

| VLDL-C is estimated by TG/5 (assumes that all TG is in VLDL and that VLDL TG:cholesterol composition is 5:1). Therefore: |

| TC = HDL-C + LDL-C + TG/5 |

| LDL-C = TC – (HDL-C + TG/5) |

| Non-HDL-C = TC – HDL-C |

| In actuality, the calculated or directly measured LDL-C values in the standard lipid panel represent LDL-C + IDL-C + Lp(a)-C. However, because labs do not usually separate IDL and Lp(a) particles from LDL (without significant added expense), only total LDL-C is reported. |

FIGURE Population percentile cut points and goals for LDL-C, LDL-P, ApoB, and non-HDL-C

HDL-C, apoA-I are inversely related to cardiovascular risk

The epidemiologic data strongly indicate that both HDL-C and apoA-I are strongly and inversely related to CVD risk.6 HDL particles are a heterogenous collection of:

- unlipidated apoA-I

- very small pre-beta HDL

- more mature, lipidated HDL3 and HDL2 species (HDL3 smaller than HDL2).

NMR nomenclature identifies the smaller HDL species as H1 and H2 and the larger HDL species as H4 and H5.14 The smaller HDL species also contain apoA-II.

Although HDL can acquire cholesterol from any cell, including arterial-wall foam cells, the majority of HDL lipidation occurs in the liver or proximal small intestine, after which it is trafficked to steroidogenic tissue, adipocytes, or back to the liver. Normally, HDL carries little TG.20 The only lipid concentration that can serve as a surrogate of apoA-I or HDL-P is HDL-C, where the assumption is that higher HDL-C indicates higher apoA-I, and vice versa.

In reality, the correlation between apoA-I and HDL-C varies because each HDL particle can have from two to four apoA-I molecules, and the volume of cholesterol within the particle is a function of particle size and its TG content. For the most part, total HDL-C is indicative of the cholesterol carried in the larger, mature HDL2 (H4, H5) particles; patients with low HDL-C typically lack these mature, lipidated HDL particles.

Because HDL rapidly and repeatedly lipidates and then delipidates, there is no relationship between the HDL-C level and the complex dynamic process termed reverse cholesterol transport process. Neither HDL-C, nor apoA-I, nor HDL-P, nor HDL size is consistently related to HDL particle functionality—i.e., the ability of HDL to lipidate or delipidate, appropriately traffic cholesterol, or perform numerous other nonlipid antiatherogenic functions.20,21

Two premenopausal women undergo assessment of their basic lipid panel, with these results:

| LIPID | PATIENT 1 | PATIENT 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (TC) | 180 | 180 |

| LDL-C | 100 | 100 |

| HDL-C | 60 | 40 |

| VLDL-C | 20 | 40 |

| Triglycerides (TG) | 100 | 200 |

| Non-HDL-C | 120 | 160 |

| TC/HDL-C ratio | 3.0 | 4.5 |

| TG/HDL-C ratio | 1.6 | 5.0 |

| LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol | ||

| HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol | ||

| VLDL-C, very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol | ||

Both patients have the same desirable TC and LDL-C values. However, further analysis reveals an abnormal TC/HDL-C ratio and an abnormal non-HDL-C level in patient 2. This finding indicates a higher risk of CVD.

In addition, the TG/HDL-C ratio of 5.0 in patient 2 is highly suggestive of small-LDL phenotype B. That designation means that this patient will have 40% to 70% more LDL particles to traffic her LDL-C than patient 1, who appears to have LDL of normal size.27 The elevated VLDL-C of patient 2 indicates the presence of VLDL remnants, which predict risk above that conveyed by LDL-C.7

The typical clinician, looking only at TC or LDL-C, would miss the increased risk (high apoB) in patient 2. Obvious clues to her lipoprotein pathology are the elevated TG and reduced HDL-C (TG-HDL axis disorder). Beyond elevated TG and reduced HDL-C, patient 2 is also likely to have increased waist size, subtle hypertension, and possibly impaired fasting glucose—three additional parameters of metabolic syndrome.7,10,25

Focus on lipoprotein particle concentrations

To most accurately predict lipid-related CVD risk, you must determine which patients have elevated numbers of atherogenic lipoproteins using actual particle concentrations. In most practices, lipoprotein particle numbers must be estimated by scrutinizing all of the lipid concentrations and ratios (not simply LDL-C).

TC and, especially, LDL-C are apoB and LDL-P surrogates, but the best lipid concentration estimate of apoB is the calculated non-HDL-C value. By subtracting HDL-C from TC, it is possible to identify the cholesterol not in the HDL particles but in all of the potentially atherogenic apoB particles. In essence, non-HDL-C is VLDL-C plus LDL-C. This equation yields a better apoB or LDL-P proxy, compared with LDL-C alone.18 If a patient has reached her LDL-C goal but still has a high non-HDL-C level, we can assume that there are still too many apoB particles and that they are contributing to residual risk.

Because LDL is the predominant apoB species, non-HDL-C is the best lipid concentration predictor of LDL-P.15 Because neither TC nor HDL-C assays require a patient to fast, non-HDL-C is accurate in nonfasting patients, making it a very practical way to screen for CVD risk.8 In the Women’s Health Study, which involved mostly healthy women, non-HDL-C predicted the risk of coronary heart disease as well as apoB did, but not as well as LDL-P.22,23 In independent, separately published analyses from the Framingham Off-spring Study, LDL-P was a better predictor of risk than LDL-C and apoB.15,24

NCEP ATP-III guidelines introduced non-HDL-C as a secondary goal of therapy in patients with TG >200 mg/dL. Subsequent data indicate that non-HDL-C is always a better predictor of risk than LDL-C is, regardless of TG levels.18

The AHA Women’s Guideline was the first to set a desired non-HDL-C level (130 mg/dL) independent of the TG value.10 Because a normal VLDL-C concentration is 30 mg/dL, the non-HDL-C goal is 30 mg/dL above the desired LDL-C goal. For example, if the desired LDL-C value is 100 mg/dL, the non-HDL-C goal is 130 mg/dL. If the desired LDL-C goal is 70 mg/dL—as it is in a patient at very high risk—the non-HDL-C goal would be 100 mg/dL ( FIGURE ).9,11

Insulin resistance diminishes accuracy of lipid profile

The ability to predict lipoprotein particle concentrations using the lipid profile becomes far less accurate in situations associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in patients who have TG-HDL axis disorders. In women, these disorders are typified by an elevation of TG >150 mg/dL and a decrease in HDL-C <50 mg/dL, with borderline or normal LDL-C levels.25

As TG begins to rise above 120 mg/dL, hepatic secretion of TG-rich VLDL particles increases. As VLDL-TG is hydrolyzed by lipoprotein lipase in muscle and fat cells, in a process termed lipolysis, VLDL shrinks and transforms into IDL. Ultimately, unless it is cleared by hepatic LDL receptors, the IDL undergoes additional lipolysis by hepatic lipase and transforms into LDL particles. Because of their longer half-life, these LDL particles accumulate, further elevating apoB and LDL-P.

In the presence of TG-rich VLDL and chylomicrons, additional pathologic particle remodeling occurs. By way of a lipid transfer protein called cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), some of the TG molecules present in TG-rich lipoproteins are exchanged for cholesteryl esters in LDL and HDL. This lipid transfer creates LDL and HDL that are TG-rich and cholesterol-poor, enabling additional TG lipolysis by hepatic lipase to create smaller LDL and HDL. The latter is so small that it can pass through renal glomeruli and be excreted, leading to reductions of HDL-P, apoA-I, and HDL-C.

Also created in this process are smaller, atherogenic, cholesterol-rich VLDL and chylomicron remnants, diagnosable by an elevated VLDL-C. Patients who have this pathology typically have elevated TG, reduced HDL-C, variable LDL-C, and an increased TG/HDL-C ratio (>3.8), which are indicative of too many small LDL particles (high apoB, LDL-P) and reduced number of HDL particles (high apoB/A-I ratio).26,27

Such a scenario, typical of TG-HDL axis disorders, explains much of the risk associated with rising TG levels and is very common in premenopausal women who have insulin-resistant states such as type 2 diabetes or polycystic ovary syndrome and in menopausal women who have insulin resistance and coronary artery disease.1

LDL-C and LDL-P do not always correlate

Because the volume of a lipoprotein is a function of its radius cubed (V = 4/3πr3),14 a patient who has small LDL will require up to 40% to 70% more LDL particles to traffic a given amount of LDL-C. In such a patient, there is often little correlation between LDL-C and LDL-P or apoB values. Regardless of the LDL-C, the apoB, LDL-P, or non-HDL-C is often elevated.28 This risk, which cannot be predicted by looking only at LDL-C, is the main reason guidelines advocate the use of non-HDL-C or the TC/HDL-C ratio.8,11 (See the case studies.)

In summary, a large part of the risk of CVD seen in patients who have low HDL-C derives from the associated increase in the number of apoB particles, mostly composed of small LDL, as well as an increase in remnant particles.15,21,28 This crucial point explains why treatment of low HDL-C states should always first target apoB or LDL-P (LDL-C and non-HDL-C), rather than apoA-I or HDL-C ( TABLES 3 and 4 ).8,9

TABLE 3

Lipid markers of small low-density lipoproteins

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) <50 mg/dL |

| Triglyceride (TG) >130–150 mg/dL |

| Total cholesterol/HDL-C ratio >4.0 with normal low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) |

| TG/HDL-C ratio >3.8 in women |

| Unremarkable LDL-C but elevated non-HDL-C |

TABLE 4

Lipid markers of remnant lipoproteins

| Triglyceride (TG) >150–200 mg/dL |

| Very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >30 mg/dL |

| Unremarkable low-density lipoprotein cholesterol with elevated non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) |

| Low HDL-C in insulin-resistant patients |

| Elevated total cholesterol/HDL-C ratio and TG >150 mg/dL |

A few words of advice

The driving forces of atherogenesis are increased numbers of apoB-containing lipoproteins and impaired endothelial integrity. ApoB and LDL-P are the available lab assays that most accurately quantify atherogenic particle number.

The lipid-concentration surrogates that you should be using to better predict apoB and CVD risk are:

- TC (unless HDL-C is very high)

- LDL-C

- Non-HDL-C

- TC/HDL-C ratio

- TG/HDL-C ratio.

Because LDL is by far the most numerous of the apoB particles present in plasma, it is the primary agent of atherogenesis. However, apoB and LDL-P do not correlate with LDL-C when LDL particles are small, are TG-rich and cholesterol-poor, or simply cholesterol-poor (seen in some patients who have low LDL-C levels).7,15

Both NCEP ATP-III and AHA Women’s Guidelines use the TC/HDL ratio as a powerful risk predictor. However, as a goal of therapy, these guidelines recommend normalizing LDL-C and then non-HDL-C.8,11 In reality, normalization of non-HDL-C takes care of LDL-C as well. For example, say a patient has LDL-C <100 mg/dL, but non-HDL-C >130 mg/dL or TC/HDL-C ratio >4. These readings indicate residual risk and suggest that an elevated number of apoB particles is present. Therapy to normalize non-HDL-C or, better yet, apoB/LDL-P, is warranted. The clue that residual risk is present even when LDL-C is normal is the reduction of HDL-C and elevation of TG and non-HDL-C.

1. Lloyd-Jones DM, O’Donnell CJ, D’Agostino RB, et al. Applicability of cholesterol-lowering primary prevention trials to a general population. The Framingham Heart Study. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:949-954.

2. Biggerstaff KD, Wooten JS. Understanding lipoproteins as transporters of cholesterol and other lipids. Adv Physiol Educ. 2004;28:105-106.

3. Nordestgaard BG, Wooten R, Lewis B. Selective retention of VLDL, IDL and LDL in the arterial intima of genetically hyperlipidemic rabbits in vivo. Molecular size as a determinant of fractional loss from the intima-inner media. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:534-542.

4. Brunzell JD, Davidson M, Furberg CD, et al. Lipoprotein management in patients with cardiometabolic risk. Consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:811-822.

5. Barter PJ, Ballantyne CM, Carmena R, et al. ApoB versus cholesterol in estimating cardiovascular risk and in guiding therapy: report of the thirty-person/ten-country panel. J Intern Med. 2006;259:247-258.

6. Walldius G, Jungner I, Holme I, Aastveit AH, Kolar W, Steiner E. High apolipoprotein B, low apolipoprotein A-I, and improvement in the prediction of fatal myocardial infarction (AMORIS study): a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;358:2026-2033.

7. Mudd JO, Borlaug BA, Johnson PV, et al. Beyond low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: defining the role of low-density lipoprotein heterogeneity in coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1735-1741.

8. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486-2497.

9. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227-239.

10. Mosca L, Appel LJ, Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation. 2004;109:672-693.

11. Mosca L, Banka CL, Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: 2007 update. Circulation. 2007;115:1481.-

12. Sniderman AD. Apolipoprotein B versus non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. And the winner is… Circulation. 2005;112:3366-3367.

13. Sniderman AD, Marcovina SM. Apolipoprotein A-I and B. Clin Lab Med. 2006;26:733-750.

14. Jeyarajah EJ, Cromwell WC, Otvos JD. Lipoprotein particle analysis by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Clin Lab Med. 2006;26:847-870.

15. Cromwell WC, Otvos JD, Keyes MJ, et al. LDL particle number and risk of future cardiovascular disease in the Framingham Off spring Study—implications for LDL management. J Clin Lipidol. 2007;1:583-592.

16. El Harchaoui K, van der Steeg WA, Stroes ES, et al. Value of low-density lipoprotein particle number and size as predictors of coronary artery disease in apparently healthy men and women: the EPIC-Norfolk Prospective Population Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:547-553.

17. Mora S, Szklo M, Otvos JD, et al. LDL particle subclasses, LDL particle size, and carotid atherosclerosis in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Atherosclerosis. 2007;192:211-217.

18. Liu J, Sempos CT, Donahue RP, et al. Non-high-density lipoprotein and very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and their predictive risk values in coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1363-1368.

19. National Cholesterol Education Program. Recommendations on lipoprotein measurement from the Working Group on Lipoprotein Measurement. National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. NIH Publication No. 95-3044. Bethesda, Md: September 1995.

20. Dayspring T. High density lipoproteins: emerging knowledge. J Cardiometabol Syndr. 2007;2:59-62.

21. Cromwell WC. High-density lipoprotein associations with coronary heart disease: does measurement of cholesterol content give the best result? J Clin Lipidol. 2007;1:57-64.

22. Ridker PM, Rifai N, Cook NR, et al. Non-HDL cholesterol, apolipoproteins A-I and B100, standard lipid measures, lipid ratios, and CRP as risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women. JAMA. 2005;294:326.-

23. Blake GJ, Otvos JD, Rifai N, Ridker PM. Low-density lipoprotein particle concentration and size as determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy as predictors of cardiovascular disease in women. Circulation. 2002;106:1930-1937.

24. Ingelsson E, Schaefer EJ, Contois JH, et al. Clinical utility of different lipid measures for prediction of coronary heart disease in men and women. JAMA. 2007;298:776-785.

25. Szapary PO, Rader DJ. The triglyceride-high-density lipoprotein axis: an important target of therapy. Am Heart J. 2004;148:211-221.

26. Davidson MH, Yannicelli D. New concepts in dyslipidemia in the metabolic syndrome and diabetes. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2006;4:299-314.

27. Hanak V, Munoz J, Teague J, Stanley A, Jr, Bittner V. Accuracy of the triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio for prediction of the low-density lipoprotein phenotype B. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:219-222.

28. Kathiresan S, Otvos JD, Sullivan LM, et al. Increased small low-density lipoprotein particle number: a prominent feature of the metabolic syndrome in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2006;113:20-29.

Dr. Dayspring serves on the advisory board for LipoScience. Dr. Helmbold reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Add another item to your ever-growing list of responsibilities: monitoring your patients’ risk of atherosclerosis.

This task used to be the purview of internists and cardiologists but, because gynecologists are increasingly serving as a primary care provider, you need to learn to recognize and diagnose the many clinical expressions of atherosclerosis in your aging patients.

A crucial part of that knowledge is a thorough understanding of each and every lipid concentration parameter reported within the standard lipid profile. This article reviews those parameters, explains how to interpret them individually and in combination, and introduces a new paradigm: the analysis of lipoprotein particle concentrations as a more precise way to determine risk.

If used in its entirety, the lipid profile provides a significant amount of information about the presence or absence of pathologic lipoprotein concentrations. Far too many clinicians focus solely on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and ignore the rest of the profile. Failure to consider the other variables is one reason why atherosclerotic disease is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the United States in many patients—especially women.1

1. Look at the triglyceride (TG) level. If it is >500 mg/dL, treatment is indicated, and TG reduction takes precedence over all other lipid concentrations. If TG is <500 mg/dL, go to Step 2.

2. Look at the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level. If it is >190 mg/dL, drug therapy is indicated regardless of other findings. At lower levels, the need for therapy is based on the patient’s overall risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Therapeutic lifestyle recommendations are always indicated.

3. Look at high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). Increased risk is present if it is <50 mg/dL, the threshold for women. Do not assume that high HDL-C always means low CVD risk.

4. Calculate the total cholesterol (TC)/HDL-C ratio (a surrogate of apoB/apoA-I ratio). Increased risk is present if it is >4.0.

5. Calculate the non-HDL-C level (TC minus HDL-C). If it is >130 mg/dL (or >100 mg/dL in very-high-risk women), therapy is warranted. Newer data reveal that this calculation is always equal to, or better than, LDL-C at predicting CVD risk. Non-HDL-C is less valuable if TG is >500 mg/dL.

6. Calculate the TG/HDL-C ratio to estimate the size of LDL. If the ratio is >3.8, the likelihood of small LDL is 80%. (Small LDL usually has very high LDL-P.)

Why lipoproteins are important

There is only one absolute in atherosclerosis: Sterols—predominantly cholesterol—enter the artery wall, where they are oxidized, internalized by macrophages, and transformed into foam cells, the histologic hallmark of atherosclerosis. With the accumulation of foam cells, fatty streaks develop and, ultimately, so does complex plaque.

Lipids associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) include:

- cholesterol

- noncholesterol sterols such as sitosterol, campesterol, and others of mostly plant or shellfish origin

- triacylglycerol, or triglycerides (TG)

- phospholipids.

Because lipids are insoluble in aqueous solutions such as plasma, they must be “trafficked” within protein-enwrapped particles called lipoproteins. The surface proteins that provide structure and solubility to lipoproteins are called apolipoproteins. A key concept is that, with their surface apolipoproteins and cholesterol core, certain lipoproteins are potential agents of atherogenesis in that they transport sterols into the artery wall.2

Estimation of the risk of CVD involves careful analysis of all standard lipid concentrations and their various ratios, and prediction of the potential presence of atherogenic lipoproteins. Successful prevention or treatment of atherosclerosis entails limiting the presence of atherogenic lipoproteins.

A new paradigm is on its way

The atherogenicity of lipoprotein particles is determined by particle concentration as well as other variables, including particle size, lipid composition, and distinct surface apolipoproteins.

Lipoproteins smaller than 70 nm in diameter are driven into the arterial intima primarily by concentration gradients, regardless of lipid composition or particle size.3 A recent Consensus Statement from the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology observed that quantitative analysis of these potentially atherogenic lipoproteins is one of the best lipid/lipoprotein-related determinants of CVD risk.4 Lipoprotein particle concentrations have emerged not only as superb predictors of risk, but also as goals of therapy.5-7

Because of cost, third-party reimbursement, varying test availability, and lack of interpretive knowledge, few clinicians routinely order lipoprotein quantification. Historically, CVD risk and goals of therapy have been based on lipid concentrations (the amount of lipids trafficked within lipoprotein cores) reported in the lipid profile. Guidelines from the National Cholesterol Education Program, Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP-III)8,9 and the American Heart Association (AHA) CVD Prevention in Women10,11 use lipid concentrations such as total cholesterol (TC), LDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and TG as estimates or surrogates of lipoprotein concentrations ( TABLE 1 ).

The day is rapidly approaching, however, when lipoprotein concentrations may replace the lipid profile in clinical practice. It is critical that clinicians develop a solid understanding of lipoprotein physiology and pathology.7,12 It also is crucial that we be as skilled as possible in accurately predicting lipoprotein pathology using all of the lipid concentration parameters present in the lipid panel.

TABLE 1

Desirable lipid values for women

| Lipid | Level (mg/dL) |

|---|---|

| Total cholesterol | <200 |

| Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol | <100 |

| High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol | ≥50 |

| Triglycerides | <150 |

| Non-HDL-cholesterol | <130 |

| FOR VERY HIGH-RISK PATIENTS | |

| LDL-C | <70 |

| Non-HDL-C | <100 |

| Source: American Heart Association | |

How lipoproteins are analyzed

Lipoproteins can be separated into their components using any of several methodologies, including ultracentrifugation, electrophoresis, apolipoprotein content analysis, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Of these, only the last two provide information on particle concentrations.13,14

Apolipoprotein content analysis reveals two major categories of particles:

- alpha-lipoproteins, or HDL, which contain two to four molecules of apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I)

- beta-lipoproteins, a collective group of chylomicrons, very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL), and LDL, each containing a single molecule of apolipoprotein B (apoB). Because of very different half-lives (chylomicrons, 1 hour; VLDL, 2–6 hours; IDL, 1–2 hours; LDL, 2–3 days), the great majority (90% to 95%) of apoB-containing particles are LDL. Although apoB measurement yields quantification of all beta-lipoproteins, it is primarily a surrogate of LDL particle (LDL-P) concentration.15

Individual particle concentrations, determined by NMR spectroscopy, are reported as VLDL-P, IDL-P, LDL-P, and HDL-P (see the “Glossary”).14

Several epidemiologic studies that enrolled both genders found the best predictors of risk to be:

- elevated levels of apoB or LDL-P and reduced levels of apoA-I or HDL-P

- a high apoB/apoA-I ratio or LDL-P/HDL-P ratio.6,13,14

After adjustment for lipoprotein concentration data (apoB or LDL-P), other lipoprotein characteristics such as particle lipid content, size, or composition, for the most part, had no statistically significant relationship with the risk of cardiovascular disease.16,17

Lipids and lipoproteins: A glossary

| Variable | What is it? |

|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TG) | The triacylglycerol concentration within all of the TG-trafficking lipoproteins in 100 mL or 1 dL of plasma |

| Total cholesterol (TC) | Cholesterol content of all lipoproteins in 1 dL of plasma |

| Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol | Cholesterol content of all intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL) and LDL particles in 1 dL of plasma |

| High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol | Cholesterol content of all HDL particles in 1 dL of plasma |

| Very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol | Cholesterol content of all VLDL particles in 1 dL of plasma |

| Remnant-C | Cholesterol content of all remnants in 1 dL of plasma |

| Lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] cholesterol | Cholesterol content of LDL particles that have apo(a) attached |

| Lp(a) concentration | Concentration of apo(a) in 1 dL of plasma |

| Non-HDL cholesterol | Cholesterol within all apoB particles in 1 dL of plasma |

| LDL-P | Number of LDL particles in 1 L of plasma (expressed in nmol/L). This represents LDL particles of all sizes |

| Small LDL-P | Number of small and intermediate LDL particles in 1 L of plasma (nmol/L) |

| HDL-P | Number of HDL particles in 1 L of plasma (μmol/L). HDL-P is also reported as large, intermediate, and small HDL-P (μmol/L) |

| VLDL-P | Number of VLDL particles in 1 L of plasma (nmol/L) |

| IDL-P | Number of IDL particles in 1 L of plasma (nmol/L) |

| LDL size | Diameter of the predominant LDL species:

|

Using lipid measurements to estimate lipoproteins

Total cholesterol represents the cholesterol content within all lipoproteins in 1 dL of plasma. Because beta-lipoproteins are considerably larger than alpha-lipoproteins, approximately 75% of total cholesterol is carried in the apoB-containing particles, making TC an apoB surrogate.

VLDL-C, an often ignored variable, is not measured but calculated using the Friedewald formula, dividing TG by five. This calculation assumes—often erroneously as TG levels rise—that TG consists only of VLDL particles and that VLDL composition contains five times more TG than cholesterol molecules.

A desirable TG level is <150 mg/dL, so normal VLDL-C is 150/5 or <30 mg/dL.

LDL-C is also an apoB surrogate

Although VLDL-C is a weak apoB surrogate,15 data from the Framingham Heart Study showed it to be a good predictor of VLDL remnant particles.18 However, because the vast majority of beta-lipoproteins are LDL, LDL-C (especially if elevated) is a better apoB surrogate than VLDL-C and is the primary CVD risk factor and goal of therapy in every current guideline.

LDL-C is usually a calculated value using the formula:

LDL-C = TC – (HDL-C + VLDL-C)

Upon special order, laboratories can directly measure LDL-C. This option is most useful when TG levels are high, rendering the Friedewald formula less accurate ( TABLE 2 ).19 For population cut points and desirable goals of therapy for lipid and lipoprotein concentrations, see the FIGURE .

TABLE 2

How lipid concentrations are determined

| TC = apoA-I-C + apoB-C |

| TC = HDL-C + LDL-C + VLDL-C + IDL-C + Chylomicron-C + Lp(a)-C + Remnant-C |

| In a fasting patient under normal circumstances, there are no chylomicrons and remnants (smaller chylomicrons or VLDL particles) and very few, if any, IDL particles. These are postprandial lipoproteins. Most patients do not have Lp(a) pathology. Therefore, the lipid concentration formula simplifies: |

| TC = HDL-C + LDL-C + VLDL-C |

| VLDL-C is estimated by TG/5 (assumes that all TG is in VLDL and that VLDL TG:cholesterol composition is 5:1). Therefore: |

| TC = HDL-C + LDL-C + TG/5 |

| LDL-C = TC – (HDL-C + TG/5) |

| Non-HDL-C = TC – HDL-C |

| In actuality, the calculated or directly measured LDL-C values in the standard lipid panel represent LDL-C + IDL-C + Lp(a)-C. However, because labs do not usually separate IDL and Lp(a) particles from LDL (without significant added expense), only total LDL-C is reported. |

FIGURE Population percentile cut points and goals for LDL-C, LDL-P, ApoB, and non-HDL-C

HDL-C, apoA-I are inversely related to cardiovascular risk

The epidemiologic data strongly indicate that both HDL-C and apoA-I are strongly and inversely related to CVD risk.6 HDL particles are a heterogenous collection of:

- unlipidated apoA-I

- very small pre-beta HDL

- more mature, lipidated HDL3 and HDL2 species (HDL3 smaller than HDL2).

NMR nomenclature identifies the smaller HDL species as H1 and H2 and the larger HDL species as H4 and H5.14 The smaller HDL species also contain apoA-II.

Although HDL can acquire cholesterol from any cell, including arterial-wall foam cells, the majority of HDL lipidation occurs in the liver or proximal small intestine, after which it is trafficked to steroidogenic tissue, adipocytes, or back to the liver. Normally, HDL carries little TG.20 The only lipid concentration that can serve as a surrogate of apoA-I or HDL-P is HDL-C, where the assumption is that higher HDL-C indicates higher apoA-I, and vice versa.

In reality, the correlation between apoA-I and HDL-C varies because each HDL particle can have from two to four apoA-I molecules, and the volume of cholesterol within the particle is a function of particle size and its TG content. For the most part, total HDL-C is indicative of the cholesterol carried in the larger, mature HDL2 (H4, H5) particles; patients with low HDL-C typically lack these mature, lipidated HDL particles.

Because HDL rapidly and repeatedly lipidates and then delipidates, there is no relationship between the HDL-C level and the complex dynamic process termed reverse cholesterol transport process. Neither HDL-C, nor apoA-I, nor HDL-P, nor HDL size is consistently related to HDL particle functionality—i.e., the ability of HDL to lipidate or delipidate, appropriately traffic cholesterol, or perform numerous other nonlipid antiatherogenic functions.20,21

Two premenopausal women undergo assessment of their basic lipid panel, with these results:

| LIPID | PATIENT 1 | PATIENT 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (TC) | 180 | 180 |

| LDL-C | 100 | 100 |

| HDL-C | 60 | 40 |

| VLDL-C | 20 | 40 |

| Triglycerides (TG) | 100 | 200 |

| Non-HDL-C | 120 | 160 |

| TC/HDL-C ratio | 3.0 | 4.5 |

| TG/HDL-C ratio | 1.6 | 5.0 |

| LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol | ||

| HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol | ||

| VLDL-C, very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol | ||

Both patients have the same desirable TC and LDL-C values. However, further analysis reveals an abnormal TC/HDL-C ratio and an abnormal non-HDL-C level in patient 2. This finding indicates a higher risk of CVD.

In addition, the TG/HDL-C ratio of 5.0 in patient 2 is highly suggestive of small-LDL phenotype B. That designation means that this patient will have 40% to 70% more LDL particles to traffic her LDL-C than patient 1, who appears to have LDL of normal size.27 The elevated VLDL-C of patient 2 indicates the presence of VLDL remnants, which predict risk above that conveyed by LDL-C.7

The typical clinician, looking only at TC or LDL-C, would miss the increased risk (high apoB) in patient 2. Obvious clues to her lipoprotein pathology are the elevated TG and reduced HDL-C (TG-HDL axis disorder). Beyond elevated TG and reduced HDL-C, patient 2 is also likely to have increased waist size, subtle hypertension, and possibly impaired fasting glucose—three additional parameters of metabolic syndrome.7,10,25

Focus on lipoprotein particle concentrations

To most accurately predict lipid-related CVD risk, you must determine which patients have elevated numbers of atherogenic lipoproteins using actual particle concentrations. In most practices, lipoprotein particle numbers must be estimated by scrutinizing all of the lipid concentrations and ratios (not simply LDL-C).

TC and, especially, LDL-C are apoB and LDL-P surrogates, but the best lipid concentration estimate of apoB is the calculated non-HDL-C value. By subtracting HDL-C from TC, it is possible to identify the cholesterol not in the HDL particles but in all of the potentially atherogenic apoB particles. In essence, non-HDL-C is VLDL-C plus LDL-C. This equation yields a better apoB or LDL-P proxy, compared with LDL-C alone.18 If a patient has reached her LDL-C goal but still has a high non-HDL-C level, we can assume that there are still too many apoB particles and that they are contributing to residual risk.

Because LDL is the predominant apoB species, non-HDL-C is the best lipid concentration predictor of LDL-P.15 Because neither TC nor HDL-C assays require a patient to fast, non-HDL-C is accurate in nonfasting patients, making it a very practical way to screen for CVD risk.8 In the Women’s Health Study, which involved mostly healthy women, non-HDL-C predicted the risk of coronary heart disease as well as apoB did, but not as well as LDL-P.22,23 In independent, separately published analyses from the Framingham Off-spring Study, LDL-P was a better predictor of risk than LDL-C and apoB.15,24

NCEP ATP-III guidelines introduced non-HDL-C as a secondary goal of therapy in patients with TG >200 mg/dL. Subsequent data indicate that non-HDL-C is always a better predictor of risk than LDL-C is, regardless of TG levels.18

The AHA Women’s Guideline was the first to set a desired non-HDL-C level (130 mg/dL) independent of the TG value.10 Because a normal VLDL-C concentration is 30 mg/dL, the non-HDL-C goal is 30 mg/dL above the desired LDL-C goal. For example, if the desired LDL-C value is 100 mg/dL, the non-HDL-C goal is 130 mg/dL. If the desired LDL-C goal is 70 mg/dL—as it is in a patient at very high risk—the non-HDL-C goal would be 100 mg/dL ( FIGURE ).9,11

Insulin resistance diminishes accuracy of lipid profile

The ability to predict lipoprotein particle concentrations using the lipid profile becomes far less accurate in situations associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in patients who have TG-HDL axis disorders. In women, these disorders are typified by an elevation of TG >150 mg/dL and a decrease in HDL-C <50 mg/dL, with borderline or normal LDL-C levels.25

As TG begins to rise above 120 mg/dL, hepatic secretion of TG-rich VLDL particles increases. As VLDL-TG is hydrolyzed by lipoprotein lipase in muscle and fat cells, in a process termed lipolysis, VLDL shrinks and transforms into IDL. Ultimately, unless it is cleared by hepatic LDL receptors, the IDL undergoes additional lipolysis by hepatic lipase and transforms into LDL particles. Because of their longer half-life, these LDL particles accumulate, further elevating apoB and LDL-P.

In the presence of TG-rich VLDL and chylomicrons, additional pathologic particle remodeling occurs. By way of a lipid transfer protein called cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), some of the TG molecules present in TG-rich lipoproteins are exchanged for cholesteryl esters in LDL and HDL. This lipid transfer creates LDL and HDL that are TG-rich and cholesterol-poor, enabling additional TG lipolysis by hepatic lipase to create smaller LDL and HDL. The latter is so small that it can pass through renal glomeruli and be excreted, leading to reductions of HDL-P, apoA-I, and HDL-C.

Also created in this process are smaller, atherogenic, cholesterol-rich VLDL and chylomicron remnants, diagnosable by an elevated VLDL-C. Patients who have this pathology typically have elevated TG, reduced HDL-C, variable LDL-C, and an increased TG/HDL-C ratio (>3.8), which are indicative of too many small LDL particles (high apoB, LDL-P) and reduced number of HDL particles (high apoB/A-I ratio).26,27

Such a scenario, typical of TG-HDL axis disorders, explains much of the risk associated with rising TG levels and is very common in premenopausal women who have insulin-resistant states such as type 2 diabetes or polycystic ovary syndrome and in menopausal women who have insulin resistance and coronary artery disease.1

LDL-C and LDL-P do not always correlate

Because the volume of a lipoprotein is a function of its radius cubed (V = 4/3πr3),14 a patient who has small LDL will require up to 40% to 70% more LDL particles to traffic a given amount of LDL-C. In such a patient, there is often little correlation between LDL-C and LDL-P or apoB values. Regardless of the LDL-C, the apoB, LDL-P, or non-HDL-C is often elevated.28 This risk, which cannot be predicted by looking only at LDL-C, is the main reason guidelines advocate the use of non-HDL-C or the TC/HDL-C ratio.8,11 (See the case studies.)

In summary, a large part of the risk of CVD seen in patients who have low HDL-C derives from the associated increase in the number of apoB particles, mostly composed of small LDL, as well as an increase in remnant particles.15,21,28 This crucial point explains why treatment of low HDL-C states should always first target apoB or LDL-P (LDL-C and non-HDL-C), rather than apoA-I or HDL-C ( TABLES 3 and 4 ).8,9

TABLE 3

Lipid markers of small low-density lipoproteins

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) <50 mg/dL |

| Triglyceride (TG) >130–150 mg/dL |

| Total cholesterol/HDL-C ratio >4.0 with normal low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) |

| TG/HDL-C ratio >3.8 in women |

| Unremarkable LDL-C but elevated non-HDL-C |

TABLE 4

Lipid markers of remnant lipoproteins

| Triglyceride (TG) >150–200 mg/dL |

| Very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >30 mg/dL |

| Unremarkable low-density lipoprotein cholesterol with elevated non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) |

| Low HDL-C in insulin-resistant patients |

| Elevated total cholesterol/HDL-C ratio and TG >150 mg/dL |

A few words of advice

The driving forces of atherogenesis are increased numbers of apoB-containing lipoproteins and impaired endothelial integrity. ApoB and LDL-P are the available lab assays that most accurately quantify atherogenic particle number.

The lipid-concentration surrogates that you should be using to better predict apoB and CVD risk are:

- TC (unless HDL-C is very high)

- LDL-C

- Non-HDL-C

- TC/HDL-C ratio

- TG/HDL-C ratio.

Because LDL is by far the most numerous of the apoB particles present in plasma, it is the primary agent of atherogenesis. However, apoB and LDL-P do not correlate with LDL-C when LDL particles are small, are TG-rich and cholesterol-poor, or simply cholesterol-poor (seen in some patients who have low LDL-C levels).7,15

Both NCEP ATP-III and AHA Women’s Guidelines use the TC/HDL ratio as a powerful risk predictor. However, as a goal of therapy, these guidelines recommend normalizing LDL-C and then non-HDL-C.8,11 In reality, normalization of non-HDL-C takes care of LDL-C as well. For example, say a patient has LDL-C <100 mg/dL, but non-HDL-C >130 mg/dL or TC/HDL-C ratio >4. These readings indicate residual risk and suggest that an elevated number of apoB particles is present. Therapy to normalize non-HDL-C or, better yet, apoB/LDL-P, is warranted. The clue that residual risk is present even when LDL-C is normal is the reduction of HDL-C and elevation of TG and non-HDL-C.

Dr. Dayspring serves on the advisory board for LipoScience. Dr. Helmbold reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Add another item to your ever-growing list of responsibilities: monitoring your patients’ risk of atherosclerosis.

This task used to be the purview of internists and cardiologists but, because gynecologists are increasingly serving as a primary care provider, you need to learn to recognize and diagnose the many clinical expressions of atherosclerosis in your aging patients.

A crucial part of that knowledge is a thorough understanding of each and every lipid concentration parameter reported within the standard lipid profile. This article reviews those parameters, explains how to interpret them individually and in combination, and introduces a new paradigm: the analysis of lipoprotein particle concentrations as a more precise way to determine risk.

If used in its entirety, the lipid profile provides a significant amount of information about the presence or absence of pathologic lipoprotein concentrations. Far too many clinicians focus solely on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and ignore the rest of the profile. Failure to consider the other variables is one reason why atherosclerotic disease is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the United States in many patients—especially women.1

1. Look at the triglyceride (TG) level. If it is >500 mg/dL, treatment is indicated, and TG reduction takes precedence over all other lipid concentrations. If TG is <500 mg/dL, go to Step 2.

2. Look at the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level. If it is >190 mg/dL, drug therapy is indicated regardless of other findings. At lower levels, the need for therapy is based on the patient’s overall risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Therapeutic lifestyle recommendations are always indicated.

3. Look at high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). Increased risk is present if it is <50 mg/dL, the threshold for women. Do not assume that high HDL-C always means low CVD risk.

4. Calculate the total cholesterol (TC)/HDL-C ratio (a surrogate of apoB/apoA-I ratio). Increased risk is present if it is >4.0.

5. Calculate the non-HDL-C level (TC minus HDL-C). If it is >130 mg/dL (or >100 mg/dL in very-high-risk women), therapy is warranted. Newer data reveal that this calculation is always equal to, or better than, LDL-C at predicting CVD risk. Non-HDL-C is less valuable if TG is >500 mg/dL.

6. Calculate the TG/HDL-C ratio to estimate the size of LDL. If the ratio is >3.8, the likelihood of small LDL is 80%. (Small LDL usually has very high LDL-P.)

Why lipoproteins are important

There is only one absolute in atherosclerosis: Sterols—predominantly cholesterol—enter the artery wall, where they are oxidized, internalized by macrophages, and transformed into foam cells, the histologic hallmark of atherosclerosis. With the accumulation of foam cells, fatty streaks develop and, ultimately, so does complex plaque.

Lipids associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) include:

- cholesterol

- noncholesterol sterols such as sitosterol, campesterol, and others of mostly plant or shellfish origin

- triacylglycerol, or triglycerides (TG)

- phospholipids.

Because lipids are insoluble in aqueous solutions such as plasma, they must be “trafficked” within protein-enwrapped particles called lipoproteins. The surface proteins that provide structure and solubility to lipoproteins are called apolipoproteins. A key concept is that, with their surface apolipoproteins and cholesterol core, certain lipoproteins are potential agents of atherogenesis in that they transport sterols into the artery wall.2

Estimation of the risk of CVD involves careful analysis of all standard lipid concentrations and their various ratios, and prediction of the potential presence of atherogenic lipoproteins. Successful prevention or treatment of atherosclerosis entails limiting the presence of atherogenic lipoproteins.

A new paradigm is on its way

The atherogenicity of lipoprotein particles is determined by particle concentration as well as other variables, including particle size, lipid composition, and distinct surface apolipoproteins.

Lipoproteins smaller than 70 nm in diameter are driven into the arterial intima primarily by concentration gradients, regardless of lipid composition or particle size.3 A recent Consensus Statement from the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology observed that quantitative analysis of these potentially atherogenic lipoproteins is one of the best lipid/lipoprotein-related determinants of CVD risk.4 Lipoprotein particle concentrations have emerged not only as superb predictors of risk, but also as goals of therapy.5-7

Because of cost, third-party reimbursement, varying test availability, and lack of interpretive knowledge, few clinicians routinely order lipoprotein quantification. Historically, CVD risk and goals of therapy have been based on lipid concentrations (the amount of lipids trafficked within lipoprotein cores) reported in the lipid profile. Guidelines from the National Cholesterol Education Program, Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP-III)8,9 and the American Heart Association (AHA) CVD Prevention in Women10,11 use lipid concentrations such as total cholesterol (TC), LDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and TG as estimates or surrogates of lipoprotein concentrations ( TABLE 1 ).

The day is rapidly approaching, however, when lipoprotein concentrations may replace the lipid profile in clinical practice. It is critical that clinicians develop a solid understanding of lipoprotein physiology and pathology.7,12 It also is crucial that we be as skilled as possible in accurately predicting lipoprotein pathology using all of the lipid concentration parameters present in the lipid panel.

TABLE 1

Desirable lipid values for women

| Lipid | Level (mg/dL) |

|---|---|

| Total cholesterol | <200 |

| Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol | <100 |

| High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol | ≥50 |

| Triglycerides | <150 |

| Non-HDL-cholesterol | <130 |

| FOR VERY HIGH-RISK PATIENTS | |

| LDL-C | <70 |

| Non-HDL-C | <100 |

| Source: American Heart Association | |

How lipoproteins are analyzed

Lipoproteins can be separated into their components using any of several methodologies, including ultracentrifugation, electrophoresis, apolipoprotein content analysis, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Of these, only the last two provide information on particle concentrations.13,14

Apolipoprotein content analysis reveals two major categories of particles:

- alpha-lipoproteins, or HDL, which contain two to four molecules of apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I)

- beta-lipoproteins, a collective group of chylomicrons, very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL), and LDL, each containing a single molecule of apolipoprotein B (apoB). Because of very different half-lives (chylomicrons, 1 hour; VLDL, 2–6 hours; IDL, 1–2 hours; LDL, 2–3 days), the great majority (90% to 95%) of apoB-containing particles are LDL. Although apoB measurement yields quantification of all beta-lipoproteins, it is primarily a surrogate of LDL particle (LDL-P) concentration.15

Individual particle concentrations, determined by NMR spectroscopy, are reported as VLDL-P, IDL-P, LDL-P, and HDL-P (see the “Glossary”).14

Several epidemiologic studies that enrolled both genders found the best predictors of risk to be:

- elevated levels of apoB or LDL-P and reduced levels of apoA-I or HDL-P

- a high apoB/apoA-I ratio or LDL-P/HDL-P ratio.6,13,14

After adjustment for lipoprotein concentration data (apoB or LDL-P), other lipoprotein characteristics such as particle lipid content, size, or composition, for the most part, had no statistically significant relationship with the risk of cardiovascular disease.16,17

Lipids and lipoproteins: A glossary

| Variable | What is it? |

|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TG) | The triacylglycerol concentration within all of the TG-trafficking lipoproteins in 100 mL or 1 dL of plasma |

| Total cholesterol (TC) | Cholesterol content of all lipoproteins in 1 dL of plasma |

| Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol | Cholesterol content of all intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL) and LDL particles in 1 dL of plasma |

| High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol | Cholesterol content of all HDL particles in 1 dL of plasma |

| Very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol | Cholesterol content of all VLDL particles in 1 dL of plasma |

| Remnant-C | Cholesterol content of all remnants in 1 dL of plasma |

| Lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] cholesterol | Cholesterol content of LDL particles that have apo(a) attached |

| Lp(a) concentration | Concentration of apo(a) in 1 dL of plasma |

| Non-HDL cholesterol | Cholesterol within all apoB particles in 1 dL of plasma |

| LDL-P | Number of LDL particles in 1 L of plasma (expressed in nmol/L). This represents LDL particles of all sizes |

| Small LDL-P | Number of small and intermediate LDL particles in 1 L of plasma (nmol/L) |

| HDL-P | Number of HDL particles in 1 L of plasma (μmol/L). HDL-P is also reported as large, intermediate, and small HDL-P (μmol/L) |

| VLDL-P | Number of VLDL particles in 1 L of plasma (nmol/L) |

| IDL-P | Number of IDL particles in 1 L of plasma (nmol/L) |

| LDL size | Diameter of the predominant LDL species:

|

Using lipid measurements to estimate lipoproteins

Total cholesterol represents the cholesterol content within all lipoproteins in 1 dL of plasma. Because beta-lipoproteins are considerably larger than alpha-lipoproteins, approximately 75% of total cholesterol is carried in the apoB-containing particles, making TC an apoB surrogate.

VLDL-C, an often ignored variable, is not measured but calculated using the Friedewald formula, dividing TG by five. This calculation assumes—often erroneously as TG levels rise—that TG consists only of VLDL particles and that VLDL composition contains five times more TG than cholesterol molecules.

A desirable TG level is <150 mg/dL, so normal VLDL-C is 150/5 or <30 mg/dL.

LDL-C is also an apoB surrogate

Although VLDL-C is a weak apoB surrogate,15 data from the Framingham Heart Study showed it to be a good predictor of VLDL remnant particles.18 However, because the vast majority of beta-lipoproteins are LDL, LDL-C (especially if elevated) is a better apoB surrogate than VLDL-C and is the primary CVD risk factor and goal of therapy in every current guideline.

LDL-C is usually a calculated value using the formula:

LDL-C = TC – (HDL-C + VLDL-C)

Upon special order, laboratories can directly measure LDL-C. This option is most useful when TG levels are high, rendering the Friedewald formula less accurate ( TABLE 2 ).19 For population cut points and desirable goals of therapy for lipid and lipoprotein concentrations, see the FIGURE .

TABLE 2

How lipid concentrations are determined

| TC = apoA-I-C + apoB-C |

| TC = HDL-C + LDL-C + VLDL-C + IDL-C + Chylomicron-C + Lp(a)-C + Remnant-C |

| In a fasting patient under normal circumstances, there are no chylomicrons and remnants (smaller chylomicrons or VLDL particles) and very few, if any, IDL particles. These are postprandial lipoproteins. Most patients do not have Lp(a) pathology. Therefore, the lipid concentration formula simplifies: |

| TC = HDL-C + LDL-C + VLDL-C |

| VLDL-C is estimated by TG/5 (assumes that all TG is in VLDL and that VLDL TG:cholesterol composition is 5:1). Therefore: |

| TC = HDL-C + LDL-C + TG/5 |

| LDL-C = TC – (HDL-C + TG/5) |

| Non-HDL-C = TC – HDL-C |

| In actuality, the calculated or directly measured LDL-C values in the standard lipid panel represent LDL-C + IDL-C + Lp(a)-C. However, because labs do not usually separate IDL and Lp(a) particles from LDL (without significant added expense), only total LDL-C is reported. |

FIGURE Population percentile cut points and goals for LDL-C, LDL-P, ApoB, and non-HDL-C

HDL-C, apoA-I are inversely related to cardiovascular risk

The epidemiologic data strongly indicate that both HDL-C and apoA-I are strongly and inversely related to CVD risk.6 HDL particles are a heterogenous collection of:

- unlipidated apoA-I

- very small pre-beta HDL

- more mature, lipidated HDL3 and HDL2 species (HDL3 smaller than HDL2).

NMR nomenclature identifies the smaller HDL species as H1 and H2 and the larger HDL species as H4 and H5.14 The smaller HDL species also contain apoA-II.

Although HDL can acquire cholesterol from any cell, including arterial-wall foam cells, the majority of HDL lipidation occurs in the liver or proximal small intestine, after which it is trafficked to steroidogenic tissue, adipocytes, or back to the liver. Normally, HDL carries little TG.20 The only lipid concentration that can serve as a surrogate of apoA-I or HDL-P is HDL-C, where the assumption is that higher HDL-C indicates higher apoA-I, and vice versa.

In reality, the correlation between apoA-I and HDL-C varies because each HDL particle can have from two to four apoA-I molecules, and the volume of cholesterol within the particle is a function of particle size and its TG content. For the most part, total HDL-C is indicative of the cholesterol carried in the larger, mature HDL2 (H4, H5) particles; patients with low HDL-C typically lack these mature, lipidated HDL particles.

Because HDL rapidly and repeatedly lipidates and then delipidates, there is no relationship between the HDL-C level and the complex dynamic process termed reverse cholesterol transport process. Neither HDL-C, nor apoA-I, nor HDL-P, nor HDL size is consistently related to HDL particle functionality—i.e., the ability of HDL to lipidate or delipidate, appropriately traffic cholesterol, or perform numerous other nonlipid antiatherogenic functions.20,21

Two premenopausal women undergo assessment of their basic lipid panel, with these results:

| LIPID | PATIENT 1 | PATIENT 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (TC) | 180 | 180 |

| LDL-C | 100 | 100 |

| HDL-C | 60 | 40 |

| VLDL-C | 20 | 40 |

| Triglycerides (TG) | 100 | 200 |

| Non-HDL-C | 120 | 160 |

| TC/HDL-C ratio | 3.0 | 4.5 |

| TG/HDL-C ratio | 1.6 | 5.0 |

| LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol | ||

| HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol | ||

| VLDL-C, very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol | ||

Both patients have the same desirable TC and LDL-C values. However, further analysis reveals an abnormal TC/HDL-C ratio and an abnormal non-HDL-C level in patient 2. This finding indicates a higher risk of CVD.

In addition, the TG/HDL-C ratio of 5.0 in patient 2 is highly suggestive of small-LDL phenotype B. That designation means that this patient will have 40% to 70% more LDL particles to traffic her LDL-C than patient 1, who appears to have LDL of normal size.27 The elevated VLDL-C of patient 2 indicates the presence of VLDL remnants, which predict risk above that conveyed by LDL-C.7

The typical clinician, looking only at TC or LDL-C, would miss the increased risk (high apoB) in patient 2. Obvious clues to her lipoprotein pathology are the elevated TG and reduced HDL-C (TG-HDL axis disorder). Beyond elevated TG and reduced HDL-C, patient 2 is also likely to have increased waist size, subtle hypertension, and possibly impaired fasting glucose—three additional parameters of metabolic syndrome.7,10,25

Focus on lipoprotein particle concentrations

To most accurately predict lipid-related CVD risk, you must determine which patients have elevated numbers of atherogenic lipoproteins using actual particle concentrations. In most practices, lipoprotein particle numbers must be estimated by scrutinizing all of the lipid concentrations and ratios (not simply LDL-C).

TC and, especially, LDL-C are apoB and LDL-P surrogates, but the best lipid concentration estimate of apoB is the calculated non-HDL-C value. By subtracting HDL-C from TC, it is possible to identify the cholesterol not in the HDL particles but in all of the potentially atherogenic apoB particles. In essence, non-HDL-C is VLDL-C plus LDL-C. This equation yields a better apoB or LDL-P proxy, compared with LDL-C alone.18 If a patient has reached her LDL-C goal but still has a high non-HDL-C level, we can assume that there are still too many apoB particles and that they are contributing to residual risk.

Because LDL is the predominant apoB species, non-HDL-C is the best lipid concentration predictor of LDL-P.15 Because neither TC nor HDL-C assays require a patient to fast, non-HDL-C is accurate in nonfasting patients, making it a very practical way to screen for CVD risk.8 In the Women’s Health Study, which involved mostly healthy women, non-HDL-C predicted the risk of coronary heart disease as well as apoB did, but not as well as LDL-P.22,23 In independent, separately published analyses from the Framingham Off-spring Study, LDL-P was a better predictor of risk than LDL-C and apoB.15,24

NCEP ATP-III guidelines introduced non-HDL-C as a secondary goal of therapy in patients with TG >200 mg/dL. Subsequent data indicate that non-HDL-C is always a better predictor of risk than LDL-C is, regardless of TG levels.18

The AHA Women’s Guideline was the first to set a desired non-HDL-C level (130 mg/dL) independent of the TG value.10 Because a normal VLDL-C concentration is 30 mg/dL, the non-HDL-C goal is 30 mg/dL above the desired LDL-C goal. For example, if the desired LDL-C value is 100 mg/dL, the non-HDL-C goal is 130 mg/dL. If the desired LDL-C goal is 70 mg/dL—as it is in a patient at very high risk—the non-HDL-C goal would be 100 mg/dL ( FIGURE ).9,11

Insulin resistance diminishes accuracy of lipid profile

The ability to predict lipoprotein particle concentrations using the lipid profile becomes far less accurate in situations associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in patients who have TG-HDL axis disorders. In women, these disorders are typified by an elevation of TG >150 mg/dL and a decrease in HDL-C <50 mg/dL, with borderline or normal LDL-C levels.25

As TG begins to rise above 120 mg/dL, hepatic secretion of TG-rich VLDL particles increases. As VLDL-TG is hydrolyzed by lipoprotein lipase in muscle and fat cells, in a process termed lipolysis, VLDL shrinks and transforms into IDL. Ultimately, unless it is cleared by hepatic LDL receptors, the IDL undergoes additional lipolysis by hepatic lipase and transforms into LDL particles. Because of their longer half-life, these LDL particles accumulate, further elevating apoB and LDL-P.

In the presence of TG-rich VLDL and chylomicrons, additional pathologic particle remodeling occurs. By way of a lipid transfer protein called cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), some of the TG molecules present in TG-rich lipoproteins are exchanged for cholesteryl esters in LDL and HDL. This lipid transfer creates LDL and HDL that are TG-rich and cholesterol-poor, enabling additional TG lipolysis by hepatic lipase to create smaller LDL and HDL. The latter is so small that it can pass through renal glomeruli and be excreted, leading to reductions of HDL-P, apoA-I, and HDL-C.

Also created in this process are smaller, atherogenic, cholesterol-rich VLDL and chylomicron remnants, diagnosable by an elevated VLDL-C. Patients who have this pathology typically have elevated TG, reduced HDL-C, variable LDL-C, and an increased TG/HDL-C ratio (>3.8), which are indicative of too many small LDL particles (high apoB, LDL-P) and reduced number of HDL particles (high apoB/A-I ratio).26,27

Such a scenario, typical of TG-HDL axis disorders, explains much of the risk associated with rising TG levels and is very common in premenopausal women who have insulin-resistant states such as type 2 diabetes or polycystic ovary syndrome and in menopausal women who have insulin resistance and coronary artery disease.1

LDL-C and LDL-P do not always correlate

Because the volume of a lipoprotein is a function of its radius cubed (V = 4/3πr3),14 a patient who has small LDL will require up to 40% to 70% more LDL particles to traffic a given amount of LDL-C. In such a patient, there is often little correlation between LDL-C and LDL-P or apoB values. Regardless of the LDL-C, the apoB, LDL-P, or non-HDL-C is often elevated.28 This risk, which cannot be predicted by looking only at LDL-C, is the main reason guidelines advocate the use of non-HDL-C or the TC/HDL-C ratio.8,11 (See the case studies.)

In summary, a large part of the risk of CVD seen in patients who have low HDL-C derives from the associated increase in the number of apoB particles, mostly composed of small LDL, as well as an increase in remnant particles.15,21,28 This crucial point explains why treatment of low HDL-C states should always first target apoB or LDL-P (LDL-C and non-HDL-C), rather than apoA-I or HDL-C ( TABLES 3 and 4 ).8,9

TABLE 3

Lipid markers of small low-density lipoproteins

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) <50 mg/dL |

| Triglyceride (TG) >130–150 mg/dL |

| Total cholesterol/HDL-C ratio >4.0 with normal low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) |

| TG/HDL-C ratio >3.8 in women |

| Unremarkable LDL-C but elevated non-HDL-C |

TABLE 4

Lipid markers of remnant lipoproteins

| Triglyceride (TG) >150–200 mg/dL |

| Very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >30 mg/dL |

| Unremarkable low-density lipoprotein cholesterol with elevated non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) |

| Low HDL-C in insulin-resistant patients |

| Elevated total cholesterol/HDL-C ratio and TG >150 mg/dL |

A few words of advice

The driving forces of atherogenesis are increased numbers of apoB-containing lipoproteins and impaired endothelial integrity. ApoB and LDL-P are the available lab assays that most accurately quantify atherogenic particle number.

The lipid-concentration surrogates that you should be using to better predict apoB and CVD risk are:

- TC (unless HDL-C is very high)

- LDL-C

- Non-HDL-C

- TC/HDL-C ratio

- TG/HDL-C ratio.

Because LDL is by far the most numerous of the apoB particles present in plasma, it is the primary agent of atherogenesis. However, apoB and LDL-P do not correlate with LDL-C when LDL particles are small, are TG-rich and cholesterol-poor, or simply cholesterol-poor (seen in some patients who have low LDL-C levels).7,15

Both NCEP ATP-III and AHA Women’s Guidelines use the TC/HDL ratio as a powerful risk predictor. However, as a goal of therapy, these guidelines recommend normalizing LDL-C and then non-HDL-C.8,11 In reality, normalization of non-HDL-C takes care of LDL-C as well. For example, say a patient has LDL-C <100 mg/dL, but non-HDL-C >130 mg/dL or TC/HDL-C ratio >4. These readings indicate residual risk and suggest that an elevated number of apoB particles is present. Therapy to normalize non-HDL-C or, better yet, apoB/LDL-P, is warranted. The clue that residual risk is present even when LDL-C is normal is the reduction of HDL-C and elevation of TG and non-HDL-C.

1. Lloyd-Jones DM, O’Donnell CJ, D’Agostino RB, et al. Applicability of cholesterol-lowering primary prevention trials to a general population. The Framingham Heart Study. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:949-954.

2. Biggerstaff KD, Wooten JS. Understanding lipoproteins as transporters of cholesterol and other lipids. Adv Physiol Educ. 2004;28:105-106.

3. Nordestgaard BG, Wooten R, Lewis B. Selective retention of VLDL, IDL and LDL in the arterial intima of genetically hyperlipidemic rabbits in vivo. Molecular size as a determinant of fractional loss from the intima-inner media. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:534-542.

4. Brunzell JD, Davidson M, Furberg CD, et al. Lipoprotein management in patients with cardiometabolic risk. Consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:811-822.

5. Barter PJ, Ballantyne CM, Carmena R, et al. ApoB versus cholesterol in estimating cardiovascular risk and in guiding therapy: report of the thirty-person/ten-country panel. J Intern Med. 2006;259:247-258.

6. Walldius G, Jungner I, Holme I, Aastveit AH, Kolar W, Steiner E. High apolipoprotein B, low apolipoprotein A-I, and improvement in the prediction of fatal myocardial infarction (AMORIS study): a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;358:2026-2033.

7. Mudd JO, Borlaug BA, Johnson PV, et al. Beyond low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: defining the role of low-density lipoprotein heterogeneity in coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1735-1741.

8. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486-2497.

9. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227-239.

10. Mosca L, Appel LJ, Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation. 2004;109:672-693.

11. Mosca L, Banka CL, Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: 2007 update. Circulation. 2007;115:1481.-

12. Sniderman AD. Apolipoprotein B versus non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. And the winner is… Circulation. 2005;112:3366-3367.

13. Sniderman AD, Marcovina SM. Apolipoprotein A-I and B. Clin Lab Med. 2006;26:733-750.

14. Jeyarajah EJ, Cromwell WC, Otvos JD. Lipoprotein particle analysis by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Clin Lab Med. 2006;26:847-870.

15. Cromwell WC, Otvos JD, Keyes MJ, et al. LDL particle number and risk of future cardiovascular disease in the Framingham Off spring Study—implications for LDL management. J Clin Lipidol. 2007;1:583-592.