User login

A guide to management: Adnexal masses in pregnancy

CASE 1 An enlarging cystic tumor

A 20-year-old gravida 3 para 1011 visits the emergency department with persistent right flank pain. Although ultrasonography (US) shows a 21-week gestation, the patient has had no prenatal care. Imaging also reveals a right-sided ovarian tumor, 14×11×8 cm, that is mainly cystic with some internal echogenicity.

At 30 weeks’ gestation, a gynecologic oncologist is consulted. Repeat US reveals the mass to be about 20 cm in diameter and cystic, without internal papillation. The patient’s CA-125 level is 12 U/mL. Based on this information, the physicians decide the likely finding is a benign ovarian cystadenoma.

How should they proceed?

The discovery of an adnexal mass during pregnancy isn’t as rare as you might think—depending on when and how closely you look, it occurs in about 1 in 100 gestations. In most cases, we have found, the mass is clearly benign (TABLE 1), warranting only observation.

TABLE 1

Adnexal masses removed during pregnancy: Histologic profile

| HISTOLOGIC TYPE | NUMBER (%) |

|---|---|

| Cystadenoma | 549 (33) |

| Dermoid | 451 (27) |

| Paraovarian/paratubal | 204 (12) |

| Functional | 237 (14) |

| Endometrioma | 55 (3) |

| Benign stromal | 28 (2) |

| Leiomyoma | 23 (1.5) |

| Luteoma | 8 (0.5) |

| Miscellaneous | 55 (3) |

| Malignant | 68 (4) |

| Total | 1,678 |

| Data supplied by the authors from surgical experience | |

In the case described above, the physicians followed the patient and removed the mass at term because it was cystic with no other indications of malignancy. At 37 weeks’ gestation, a cesarean section was performed through a midline laparotomy incision, followed by removal of the ovarian tumor, which was benign. The pathologist measured the tumor at 16×12×4 cm and determined that it was a corpus luteum cyst.

Presence of mass raises questions

Despite the rarity of malignancy, the discovery of an ovarian mass during pregnancy prompts several important questions:

How should the mass be assessed? How can the likelihood of malignancy be determined as quickly and efficiently as possible, without jeopardy to the pregnancy?

When is surgical intervention warranted? And when can it be postponed? Specifically, is elective operative intervention for a tumor that is probably benign appropriate during pregnancy?

When is the best time to operate? And what is the optimal surgical route?

In this article, we address these questions with a focus on intervention. As we’ll explain, only a small percentage of gravidas who have an adnexal mass require surgery during pregnancy. When surgery is necessary, it is usually indicated for an emergent problem or suspicion of malignancy. Even when ovarian cancer is confirmed, we have found that it is usually in its early stages and therefore has a favorable prognosis (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Malignant adnexal masses removed during pregnancy

| HISTOLOGIC TYPE | NUMBER (%) |

|---|---|

| Epithelial | 101 (28) |

| Borderline epithelial | 147 (40) |

| Germ-cell dysgerminoma | 47 (13) |

| Other | 34 (9) |

| Stromal | 24 (7) |

| Undifferentiated | 5 (1.4) |

| Sarcoma | 2 (0.5) |

| Metastatic | 4 (1.1) |

| Total | 364 |

| Data supplied by the authors from surgical experience | |

How should a mass be assessed?

Ultrasonography and other imaging often reveal the presence of a mass and help determine whether it is benign or malignant. In fact, most adnexal masses discovered during pregnancy are incidental findings at the time of routine prenatal US. (see the most commonly found tumors.) Operative intervention is required in 3 situations:

- malignancy is suspected

- an acute complication develops

- the sheer size of the tumor is likely to cause difficulty.

Corpus luteum

A persistent corpus luteum is a normal component of pregnancy. Although it usually appears as a small cystic structure on ultrasonographic imaging, the corpus luteum of pregnancy can reach 10 cm in size. Other types of “functional” ovarian cysts may also be found during pregnancy. Most functional cysts resolve by the early second trimester.4,6 In rare cases, a cyst may develop complications such as torsion or rupture, causing acute pain or hemorrhage. Otherwise, a cystic tumor identified in the first trimester should be characterized and followed using ultrasonography (US).

Benign neoplasm

An adnexal mass that persists beyond the first trimester is more likely to be a neoplasm.3-5,10,11,22 Such a mass is generally considered clinically significant if it exceeds 5 cm in diameter and has a complex sonographic appearance. Usually such a neoplasm will be a benign cystadenoma or cystic teratoma.5,10-13,19,23,24

Benign cystic teratoma

This tumor can be identified with a fairly high degree of specificity using a variety of imaging techniques, with management based on the presumptive diagnosis. This tumor is unlikely to grow substantially during pregnancy. When it is smaller than 6 cm, such a tumor can simply be observed.14 A larger tumor can occasionally rupture or lead to torsion or obstruction of labor, but such occurrences are rare.

Benign cystadenoma

In an asymptomatic patient with imaging that suggests a benign cystadenoma (see sonogram), benign cystic teratoma, or other benign tumor, observation is reasonable in most cases.4,6,7,9-11,14,19 Operative intervention is required when there is less certainty regarding the benign nature of the tumor, an acute complication develops, or the tumor is expected to pose problems because of its large size alone.

Uterine leiomyoma

It is rare for an ovarian tumor detected during pregnancy to have a solid appearance on US. When it does, it may be a uterine leiomyoma mimicking an adnexal tumor (see intraoperative photograph). It should be reevaluated with more detailed US or magnetic resonance imaging.25

Malignancy

About 10% of adnexal masses that persist during pregnancy are malignant, according to recent series.4,5,7-10,12,13,24,26

Most of the ovarian cancers diagnosed during pregnancy are epithelial, and a substantial portion of these are low-malignant-potential (LMP) tumors.5,10,11,13,19,23,24,26,27 This ratio is in keeping with the age of these women, which also explains the stage distribution (most are stage 1) and the large percentage of germ-cell tumors detected. The majority of ovarian cancers discovered in pregnant women have a favorable prognosis.

Benign-appearing cystadenoma

A morphologically benign-appearing, large, cystic adnexal mass can be seen in association with an 11-week gestation.

Leiomyoma mimics an ovarian tumor

This 17-week gestation was marked by a large pedunculated leiomyoma that at fist appeared to be a right adnexal tumor.

Appearance of adnexal masses on US

A functional cyst such as a follicular cyst, corpus luteum cyst, or theca lutein cyst usually has smooth borders and a fluid center. Other cysts may sometimes contain debris, such as clotted blood, that suggests endometriosis or a simple cyst with bleeding into it.

A benign cystic teratoma often has multiple tissue lines, evidence of calcification, and layering of fat and fluid contents.

A benign cystadenoma usually has the appearance of a simple cyst without large septates, whereas a cystadenocarcinoma often contains septates, abnormal blood flow, increased vascularity, or all of these. However, it is impossible to definitively distinguish a cystadenoma from a cystadenocarcinoma using US imaging alone.

Functional cysts usually resolve by the second trimester. A cyst warrants closer scrutiny when it persists, is larger than 5 cm in diameter, or has a complex appearance on US.

CA-125 may be useful after the first trimester

The serum CA-125 level is typically elevated during the first trimester, but may be useful during later assessment or for follow-up of a malignancy.1

A markedly elevated serum level of alpha-fetoprotein (fractionated in some cases) has been reported in some gravidas with an endodermal sinus or mixed germ-cell ovarian tumor.2 Alpha-fetoprotein should be measured when there is suspicion for a germ-cell tumor based on clinical or US findings.

When a mass is discovered during cesarean section

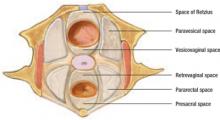

Occasionally, an adnexal mass is detected at the time of cesarean section (FIGURE 1).3 This phenomenon is increasingly common, given the large number of cesarean deliveries in the United States. To eliminate the need for future surgery and avoid a delay in the diagnosis of an ovarian malignancy, inspect the adnexa routinely after closing the uterine incision in all women who deliver by cesarean section.

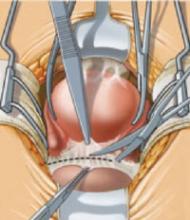

FIGURE 1 Mass discovered at cesarean section

This cystic tumor was discovered at cesarean section that was undertaken for obstetric indications.

CASE 2 LMP tumor is suspected

A 36-year-old gravida 3 para 1011 makes a prenatal visit during the first trimester. Her previous delivery was a cesarean section through a Pfannenstiel incision for a breech presentation. US imaging reveals a 6-week, 5-day fetus and a complex left adnexal mass, 4.5×3.9×4.1 cm. Imaging is repeated 1 month later at a tertiary-care center and shows an 11-week viable fetus, a right ovary with a corpus luteum cyst, and a left ovary with a 6.6×4 cm cystic mass with extensive vascular surface papillations that is suspicious for a low-malignant-potential (LMP) tumor. In several sonograms prior to the pregnancy, this mass appeared to be solid and was 3 cm in size.

When is surgery warranted?

Surgery is indicated when physical examination or imaging of a pregnant woman reveals an adnexal mass that is suspicious for malignancy, but the physician must weigh the benefit of prompt surgery against the risk to the pregnancy. This equation can be complicated in several ways. For example, surgical staging of clinically early ovarian cancer is more difficult due to the pregnant uterus, which is more extensively manipulated during these procedures. In addition, an optimal operation sometimes necessitates removal of the uterus.

At 13 weeks’ gestation, the patient described in case 2 underwent laparoscopy with peritoneal washings and left salpingo-oophorectomy, but the tumor ruptured during removal. Final pathology showed it to be a serous LMP tumor involving the surface of the left ovary. Washings were in line with this diagnosis.

The pregnancy continued uneventfully, and a repeat cesarean section was performed at 37 weeks through the Pfannenstiel scar, followed by limited surgical staging. Exploration and all biopsies were negative, and the final diagnosis was a stage 1C serous LMP tumor of the ovary.

The patient articulated a desire to preserve her fertility and was monitored with US imaging of the remaining ovary every 6 months.

Does ‘indolent’ behavior of malignancy justify watchful waiting?

LMP tumors comprise a relatively large percentage of ovarian “cancers” encountered during pregnancy. Some authors report the accurate identification of these tumors prospectively, based on ultrasonographic characteristics.4,5 When an LMP tumor is the likely diagnosis, serial observation during pregnancy may be appropriate because of the indolent nature of the tumor. Further studies are needed to refine preoperative diagnosis and determine the overall safety of this approach.

When the problem is acute

In rare cases, a pregnant patient will have (or develop during observation) an acute problem due to torsion or rupture of an adnexal mass. Some ovarian cancers may present acutely, such as a rapidly growing malignant germ-cell tumor or a ruptured and hemorrhaging granulosecell tumor. Emergent surgery is necessary to manage the acute adnexal disease and reduce the likelihood of pregnancy loss. These events are infrequent, occurring in less than 10% of women with a known, persistent adnexal mass during pregnancy.4-14 Furthermore, recent studies have not found a substantial pregnancy complication rate associated with such emergency surgeries.

CASE 3 Suspicious mass, ascites signal need for surgery

A 19-year-old gravida 1 para 0 seeks prenatal care at 17 weeks’ gestation, complaining of rapidly enlarging abdominal girth. The physical examination estimates gestational size to be considerably greater than dates, but US is consistent with a 17-week intrauterine pregnancy. Imaging also reveals a 12-cm heterogenous left adnexal mass and a large amount of ascites.

Surgery is clearly warranted, but how extensive should it be?

When a malignancy is detected, a thorough staging procedure may be justified, depending on gestational age, exposure, desires of the patient, and operative findings. A midline incision is preferred.

Pregnant and nonpregnant women with stage 1A or 1C epithelial ovarian cancer who undergo fertility-preserving surgery (with chemotherapy in selected patients) have a good prognosis and a high likelihood of achieving a subsequent normal pregnancy.15 The same is true for women with a malignant germ-cell tumor of the ovary, even when disease is advanced.16 However, careful surgical staging is necessary.

The most important consideration when deciding whether to continue the pregnancy is the need for adjuvant chemotherapy. Depending on the gestational age and diagnosis, a short delay (4 to 6 weeks) may be appropriate to allow the pregnancy to progress beyond the first trimester or to maturity.

In case 3, a laparotomy was performed at 19 weeks’ gestation via a midline incision, and approximately 5.3 L of ascites was evacuated. A large, nonadherent left ovarian tumor was removed. The right ovary appeared to be normal, as did the gravid uterus, which was minimally manipulated. The rest of the surgical exploration was normal, and the distal portion of the omentum was excised. The frozen-section diagnosis was a malignant stromal tumor. Final pathology showed an 18×13.5×8.8 cm, poorly differentiated, SertoliLeydig-cell tumor with heterologous elements in the form of mucinous epithelium. The omentum was negative for tumor.

Chemotherapy was initiated in the third trimester, based on the limited data available, with intravenous etoposide and platinum administered every 21 days. The patient received 3 cycles of chemotherapy prior to delivery.

At 37 weeks’ gestation, labor was successfully induced. After delivery, bleomycin was added to the chemotherapy regimen, and 3 additional courses with all 3 agents were administered. The patient was lost to follow-up shortly after completing chemotherapy.

Clearly, an informed discussion of the options with the patient is imperative before any surgery, especially when chemotherapy may be delayed. Pregnancy does not appear to alter the prognosis for the patient with an ovarian malignancy, and ovarian cancer has not been reported to metastasize to the fetus.

Pregnant women have a very low rate of ovarian cancer

Leiserowitz GS, Xing G, Cress R, Brahmbhatt B, Dalrymple JL, Smith LH. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: how often are they malignant? Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:315–321.

Ovarian malignancies are rare during pregnancy. When they do occur, they are likely to be early stage and to have a favorable outcome, according to this recent population-based study.

Using 3 large databases containing records on 4,846,505 California obstetric patients between 1991 and 1999, Leiserowitz and colleagues identified 9,375 women who had an ovarian mass associated with pregnancy. Of these, 87 had ovarian cancer and 115 had a low-malignant-potential (LMP) tumor, for a cancer occurrence rate of 0.93%, or 0.0179 per 1,000 deliveries. Thirty-four of the 87 cancers were germ-cell tumors.

Of the 87 ovarian cancers, 65.5% were localized, 6.9% regional, 23% remote, and 4.6% of unknown stage. The respective rates for LMP tumors were 81.7%, 7.8%, 4.4%, and 6.1%.

Women with malignant tumors were more likely than pregnant controls without cancer to undergo cesarean delivery, hysterectomy, transfusion, and prolonged hospitalization. These women did not, however, have a higher rate of adverse neonatal outcomes.

When cancer is advanced

Few data shed light on whether a pregnancy should continue when ovarian cancer is advanced.17 The definitive surgical approach must be highly individualized.

It is not always possible to make an accurate diagnosis based on a frozen section. In such a case, the pregnancy should be preserved until the time of definitive diagnosis. As always, the patient’s wishes and gestational age must be considered.

How factors besides malignancy can influence care

Most persistent adnexal masses move well out of the pelvis as pregnancy progresses. Occasionally, however, an ovarian tumor may be located in the posterior cul-de-sac even at term, a fact easily confirmed by examination or US.4,7 A tumor in the posterior cul-de-sac can obstruct delivery or rupture. When it has a benign cystic appearance on US, it may be decompressed via transvaginal aspiration. Otherwise, the best approach is cesarean section and concomitant management of the mass.

When size alone is the problem

Some ovarian tumors are so large they seem incompatible with an advancing pregnancy. Tumors up to 20 cm in diameter have been removed intact at the time of cesarean section (FIGURE 2).18 The tumor may accommodate in shape and become less problematic as it is gradually pushed into the upper abdomen (FIGURE 3).

The ability of the peritoneal cavity to accommodate a tumor varies greatly among women. As pregnancy advances, the likelihood that a large cystic mass will rupture tends to increase. Depending on the circumstances, percutaneous aspiration7,18 or removal of a benign-appearing cystic tumor may be appropriate.

FIGURE 2 Even a very large tumor may coexist with advancing pregnancy

This benign serous cystadenoma was exteriorized at the time of cesarean section at term.

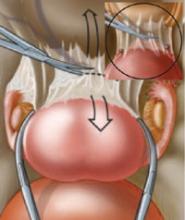

FIGURE 3 Large ovarian tumor has accommodated to the pregnancy

Laparotomy—performed at term for cesarean section and to manage this large tumor—revealed that the tumor had accommodated in shape between the enlarging pregnant uterus and the abdominal wall.

When is the best time to operate?

Surgery is generally not recommended during the first trimester.5-11 Among the reasons are the high likelihood of a corpus luteum cyst, the low likelihood of an invasive malignancy, the low risk of adnexal complications associated with observation, and the potential for pregnancy loss or teratogenicity. However, as pregnancy progresses beyond the first trimester, surgery poses other problems: Operative exposure diminishes and the need to manipulate the pregnant uterus increases.

Can surgery be delayed when a mass is detected?

Schmeler KM, Mayo-Smith WW, Peipert JF, Weitzen S, Manuel MD, Gordinier ME. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: surgery compared with observation. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1098–1103.

Close observation is a reasonable alternative to operative intervention during pregnancy, unless a malignancy is suspected.

Schmeler and colleagues reviewed the cases of 59 women who had an adnexal mass larger than 5 cm in diameter detected during pregnancy, out of a total of 127,177 deliveries at a single institution between 1990 and 2003. Antepartum surgery was performed in 17 women (29%). Of these, 13 cases had ultrasonographic findings suggesting malignancy, and 4 had ovarian torsion. The remaining women were observed, with surgery delayed until the time of cesarean section or later.

Twenty-five of the 59 masses (42%) were dermoid cysts. Cancer was diagnosed in 4 patients (6.8%), and 1 patient (1.7%) had an LMP tumor. All 5 cases (100%) involving a malignancy had a suspicious US appearance and were identified during antepartum surgery, whereas only 12 patients with a benign tumor (22%) underwent surgery prior to delivery.

Surgery poses risks to the pregnancy

Elective surgery for an adnexal mass any time during pregnancy increases the risk of pregnancy loss and the likelihood of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and preterm delivery.5,7,10,13,19 A 1989 study from Sweden20 defined a cohort of 5,405 women (from 720,000 births) who were known to have a nonobstetric operation while pregnant, with the following results:

- Congenital malformation and stillbirth were not increased in the women undergoing surgery

- The number of very-low- and low-birth-weight infants did rise, however—the result of both prematurity and IUGR

- Also elevated was the incidence of infants born alive but dying within 168 hours; these risks increased regardless of trimester

- No specific type of anesthesia or operation was associated with adverse reproductive outcomes, and the cause of those adverse outcomes was not determined.

Some recent data suggest that adnexal surgery during the late second or early third trimester poses the greatest risk of preterm delivery or IUGR, or both.13

Window of opportunity: early to mid- second trimester

During this time frame, elective surgery for an adnexal mass still affords some pelvic exposure without the need for significant uterine manipulation and has been associated with a lower risk of pregnancy complications.

The other window for operation is at the time of cesarean section. An elective cesarean section is sometimes performed specifically to manage a persistent adnexal mass. Among the factors that warrant consideration when contemplating this approach are the elective uterine incision (with its attendant implications for future pregnancies), the higher risks associated with cesarean delivery in general, the type of skin incision (a vertical incision is appropriate in the event of ovarian malignancy), the potential for better exposure or laparoscopy at a later date, the increased difficulty of ovarian cystectomy at the time of cesarean section, and the patient’s wishes.

The data on laparoscopy during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy indicate that it is as safe as laparotomy. A 1997 Swedish study21 identified cohorts of 2,181 women undergoing laparoscopy and 1,522 women undergoing laparotomy (from a total of 2,015,000 deliveries) between the fourth and 20th weeks of pregnancy. In both groups there was an increased risk for the infant to weigh less than 2,500 g, to be delivered before 37 weeks, and to have IUGR. There were no differences between the 2 groups for these and other adverse outcomes.

Small series of laparoscopic procedures to manage an adnexal mass during pregnancy suggest that this approach is most applicable during the first (for highly selected emergent cases) or early second trimester to manage masses less than 10 cm in diameter, particularly when adnexectomy is planned.

Laparoscopy may be considered “minimally invasive” because it reduces manipulation of the pregnant uterus during adnexal surgery. However, it is more difficult to assess and remove ovarian cysts laparoscopically, although an early ovarian malignancy could be staged via laparoscopy by an experienced surgeon.

Considerations during laparotomy

When performing a laparotomy or cesarean section for an adnexal mass, the surgeon must take into account a number of variables when selecting the type of incision (ie, vertical vs transverse). In general, if malignancy is suspected, or if uterine manipulation is to be minimized, a vertical incision is best. Other considerations include a prior scar, body habitus, obstetric issues, and the patient’s wishes.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Spitzer M, Kaushal N, Benjamin F. Maternal CA-125 levels in pregnancy and the puerperium. J Reprod Med. 1998;43:387-392.

2. Aoki Y, Higashino M, Ishii S, Tanaka K. Yolk sac tumor of the ovary during pregnancy: a case report. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:497-499.

3. Koonings PP, Platt LD, Wallace R. Incidental adnexal neoplasms at cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72:767-769.

4. Zanetta G, Mariani E, Lissoni A, et al. A prospective study of the role of ultrasound in the management of adnexal masses in pregnancy. BJOG. 2003;110:578-583.

5. Sherard GB, 3rd, Hodson CA, Williams HJ, et al. Adnexal masses and pregnancy: a 12 year experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:358-363.

6. Bernhard LM, Klebba PK, Gray DL, Mutch DG. Predictors of persistence of adnexal masses in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:585-589.

7. Platek DN, Henderson CE, Goldberg GL. The management of a persistent adnexal mass in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1236-1240.

8. Bromley B, Benacerraf B. Adnexal masses during pregnancy: accuracy of sonographic diagnosis and outcome. J Ultrasound Med. 1997;16:447-452.

9. Hill LM, Connors-Beatty DJ, Nowak A, Tush B. The role of ultrasonography in the detection and management of adnexal mass during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:703-707.

10. Agarwal N, Parul, Kriplani A, Bhatla N, Gupta A. Management and outcome of pregnancies complicated with adnexal masses. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;267:148-152.

11. Schmeler KM, Mayo-Smith WW, Peipert JF, Weitzen S, Manuel MD, Gordinier ME. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: surgery compared with observation. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1098-1103.

12. Coenen VH, Dunton C, Cardonick E, Berghella V. Persistent adnexal masses during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:66S.-

13. Whitecar P, Turner S, Higby K. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: a review of 130 cases undergoing surgical management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:19-24.

14. Caspi B, Levi R, Appelman Z, Rabinerson D, Goldman G, Hagay Z. Conservative management of ovarian cystic teratoma during pregnancy and labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:503-505.

15. Schilder JM, Thompson AM, DePriest PD, et al. Outcome of reproductive age women with stage IA or IC invasive epithelial ovarian cancer treated with fertility-sparing therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;87:1-7.

16. Tangir J, Zelterman D, Ma W, Schwartz PE. Reproductive function after conservative surgery and chemotherapy for malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:251-257.

17. Ferrandina G, Distefano M, Testa A, De Vincenzo R, Scambia G. Management of an advanced ovarian cancer at 15 weeks of gestation: case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:693-696.

18. Caspi B, Ben-Arie A, Appelman Z, Or Y, Hagay Z. Aspiration of simple pelvic cysts during pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2000;49:102-105.

19. Usui R, Minakami H, Kosuge S, et al. A retrospective survey of clinical, pathologic, and prognostic features of adnexal masses operated on during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2000;26(2):89-93.

20. Mazze RI, Källén B. Reproductive outcome after anesthesia and operation during pregnancy; a registry study of 5,405 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:1178-1185.

21. Reedy MB, Källén B, Kuehl TJ. Laparoscopy during pregnancy: a study of five fetal outcome parameters with use of the Swedish health registry. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:673-679.

22. Hermans RHM, Fischer D-C, van der Putten HWHM, et al. Adnexal masses in pregnancy. Onkologie. 2003;26:167-172.

23. Hoffman MS. Primary ovarian carcinoma during pregnancy. Clin Consul Obstet Gynecol. 1995;7:237-241.

24. Ueda M, Ueki M. Ovarian tumors associated with pregnancy. Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;55:59-65.

25. Curtis M, Hopkins MP, Zarlingo T, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging to avoid laparotomy in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:833-836.

26. Leiserowitz GS, Xing G, Cress R, et al. Adnexal masses in pregnancy; how often are they malignant? Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:315-321.

27. Rahman MS, Al-Sibai MH, Rahman J, et al. Ovarian carcinoma associated with pregnancy. A review of 9 cases. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:260-264.

CASE 1 An enlarging cystic tumor

A 20-year-old gravida 3 para 1011 visits the emergency department with persistent right flank pain. Although ultrasonography (US) shows a 21-week gestation, the patient has had no prenatal care. Imaging also reveals a right-sided ovarian tumor, 14×11×8 cm, that is mainly cystic with some internal echogenicity.

At 30 weeks’ gestation, a gynecologic oncologist is consulted. Repeat US reveals the mass to be about 20 cm in diameter and cystic, without internal papillation. The patient’s CA-125 level is 12 U/mL. Based on this information, the physicians decide the likely finding is a benign ovarian cystadenoma.

How should they proceed?

The discovery of an adnexal mass during pregnancy isn’t as rare as you might think—depending on when and how closely you look, it occurs in about 1 in 100 gestations. In most cases, we have found, the mass is clearly benign (TABLE 1), warranting only observation.

TABLE 1

Adnexal masses removed during pregnancy: Histologic profile

| HISTOLOGIC TYPE | NUMBER (%) |

|---|---|

| Cystadenoma | 549 (33) |

| Dermoid | 451 (27) |

| Paraovarian/paratubal | 204 (12) |

| Functional | 237 (14) |

| Endometrioma | 55 (3) |

| Benign stromal | 28 (2) |

| Leiomyoma | 23 (1.5) |

| Luteoma | 8 (0.5) |

| Miscellaneous | 55 (3) |

| Malignant | 68 (4) |

| Total | 1,678 |

| Data supplied by the authors from surgical experience | |

In the case described above, the physicians followed the patient and removed the mass at term because it was cystic with no other indications of malignancy. At 37 weeks’ gestation, a cesarean section was performed through a midline laparotomy incision, followed by removal of the ovarian tumor, which was benign. The pathologist measured the tumor at 16×12×4 cm and determined that it was a corpus luteum cyst.

Presence of mass raises questions

Despite the rarity of malignancy, the discovery of an ovarian mass during pregnancy prompts several important questions:

How should the mass be assessed? How can the likelihood of malignancy be determined as quickly and efficiently as possible, without jeopardy to the pregnancy?

When is surgical intervention warranted? And when can it be postponed? Specifically, is elective operative intervention for a tumor that is probably benign appropriate during pregnancy?

When is the best time to operate? And what is the optimal surgical route?

In this article, we address these questions with a focus on intervention. As we’ll explain, only a small percentage of gravidas who have an adnexal mass require surgery during pregnancy. When surgery is necessary, it is usually indicated for an emergent problem or suspicion of malignancy. Even when ovarian cancer is confirmed, we have found that it is usually in its early stages and therefore has a favorable prognosis (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Malignant adnexal masses removed during pregnancy

| HISTOLOGIC TYPE | NUMBER (%) |

|---|---|

| Epithelial | 101 (28) |

| Borderline epithelial | 147 (40) |

| Germ-cell dysgerminoma | 47 (13) |

| Other | 34 (9) |

| Stromal | 24 (7) |

| Undifferentiated | 5 (1.4) |

| Sarcoma | 2 (0.5) |

| Metastatic | 4 (1.1) |

| Total | 364 |

| Data supplied by the authors from surgical experience | |

How should a mass be assessed?

Ultrasonography and other imaging often reveal the presence of a mass and help determine whether it is benign or malignant. In fact, most adnexal masses discovered during pregnancy are incidental findings at the time of routine prenatal US. (see the most commonly found tumors.) Operative intervention is required in 3 situations:

- malignancy is suspected

- an acute complication develops

- the sheer size of the tumor is likely to cause difficulty.

Corpus luteum

A persistent corpus luteum is a normal component of pregnancy. Although it usually appears as a small cystic structure on ultrasonographic imaging, the corpus luteum of pregnancy can reach 10 cm in size. Other types of “functional” ovarian cysts may also be found during pregnancy. Most functional cysts resolve by the early second trimester.4,6 In rare cases, a cyst may develop complications such as torsion or rupture, causing acute pain or hemorrhage. Otherwise, a cystic tumor identified in the first trimester should be characterized and followed using ultrasonography (US).

Benign neoplasm

An adnexal mass that persists beyond the first trimester is more likely to be a neoplasm.3-5,10,11,22 Such a mass is generally considered clinically significant if it exceeds 5 cm in diameter and has a complex sonographic appearance. Usually such a neoplasm will be a benign cystadenoma or cystic teratoma.5,10-13,19,23,24

Benign cystic teratoma

This tumor can be identified with a fairly high degree of specificity using a variety of imaging techniques, with management based on the presumptive diagnosis. This tumor is unlikely to grow substantially during pregnancy. When it is smaller than 6 cm, such a tumor can simply be observed.14 A larger tumor can occasionally rupture or lead to torsion or obstruction of labor, but such occurrences are rare.

Benign cystadenoma

In an asymptomatic patient with imaging that suggests a benign cystadenoma (see sonogram), benign cystic teratoma, or other benign tumor, observation is reasonable in most cases.4,6,7,9-11,14,19 Operative intervention is required when there is less certainty regarding the benign nature of the tumor, an acute complication develops, or the tumor is expected to pose problems because of its large size alone.

Uterine leiomyoma

It is rare for an ovarian tumor detected during pregnancy to have a solid appearance on US. When it does, it may be a uterine leiomyoma mimicking an adnexal tumor (see intraoperative photograph). It should be reevaluated with more detailed US or magnetic resonance imaging.25

Malignancy

About 10% of adnexal masses that persist during pregnancy are malignant, according to recent series.4,5,7-10,12,13,24,26

Most of the ovarian cancers diagnosed during pregnancy are epithelial, and a substantial portion of these are low-malignant-potential (LMP) tumors.5,10,11,13,19,23,24,26,27 This ratio is in keeping with the age of these women, which also explains the stage distribution (most are stage 1) and the large percentage of germ-cell tumors detected. The majority of ovarian cancers discovered in pregnant women have a favorable prognosis.

Benign-appearing cystadenoma

A morphologically benign-appearing, large, cystic adnexal mass can be seen in association with an 11-week gestation.

Leiomyoma mimics an ovarian tumor

This 17-week gestation was marked by a large pedunculated leiomyoma that at fist appeared to be a right adnexal tumor.

Appearance of adnexal masses on US

A functional cyst such as a follicular cyst, corpus luteum cyst, or theca lutein cyst usually has smooth borders and a fluid center. Other cysts may sometimes contain debris, such as clotted blood, that suggests endometriosis or a simple cyst with bleeding into it.

A benign cystic teratoma often has multiple tissue lines, evidence of calcification, and layering of fat and fluid contents.

A benign cystadenoma usually has the appearance of a simple cyst without large septates, whereas a cystadenocarcinoma often contains septates, abnormal blood flow, increased vascularity, or all of these. However, it is impossible to definitively distinguish a cystadenoma from a cystadenocarcinoma using US imaging alone.

Functional cysts usually resolve by the second trimester. A cyst warrants closer scrutiny when it persists, is larger than 5 cm in diameter, or has a complex appearance on US.

CA-125 may be useful after the first trimester

The serum CA-125 level is typically elevated during the first trimester, but may be useful during later assessment or for follow-up of a malignancy.1

A markedly elevated serum level of alpha-fetoprotein (fractionated in some cases) has been reported in some gravidas with an endodermal sinus or mixed germ-cell ovarian tumor.2 Alpha-fetoprotein should be measured when there is suspicion for a germ-cell tumor based on clinical or US findings.

When a mass is discovered during cesarean section

Occasionally, an adnexal mass is detected at the time of cesarean section (FIGURE 1).3 This phenomenon is increasingly common, given the large number of cesarean deliveries in the United States. To eliminate the need for future surgery and avoid a delay in the diagnosis of an ovarian malignancy, inspect the adnexa routinely after closing the uterine incision in all women who deliver by cesarean section.

FIGURE 1 Mass discovered at cesarean section

This cystic tumor was discovered at cesarean section that was undertaken for obstetric indications.

CASE 2 LMP tumor is suspected

A 36-year-old gravida 3 para 1011 makes a prenatal visit during the first trimester. Her previous delivery was a cesarean section through a Pfannenstiel incision for a breech presentation. US imaging reveals a 6-week, 5-day fetus and a complex left adnexal mass, 4.5×3.9×4.1 cm. Imaging is repeated 1 month later at a tertiary-care center and shows an 11-week viable fetus, a right ovary with a corpus luteum cyst, and a left ovary with a 6.6×4 cm cystic mass with extensive vascular surface papillations that is suspicious for a low-malignant-potential (LMP) tumor. In several sonograms prior to the pregnancy, this mass appeared to be solid and was 3 cm in size.

When is surgery warranted?

Surgery is indicated when physical examination or imaging of a pregnant woman reveals an adnexal mass that is suspicious for malignancy, but the physician must weigh the benefit of prompt surgery against the risk to the pregnancy. This equation can be complicated in several ways. For example, surgical staging of clinically early ovarian cancer is more difficult due to the pregnant uterus, which is more extensively manipulated during these procedures. In addition, an optimal operation sometimes necessitates removal of the uterus.

At 13 weeks’ gestation, the patient described in case 2 underwent laparoscopy with peritoneal washings and left salpingo-oophorectomy, but the tumor ruptured during removal. Final pathology showed it to be a serous LMP tumor involving the surface of the left ovary. Washings were in line with this diagnosis.

The pregnancy continued uneventfully, and a repeat cesarean section was performed at 37 weeks through the Pfannenstiel scar, followed by limited surgical staging. Exploration and all biopsies were negative, and the final diagnosis was a stage 1C serous LMP tumor of the ovary.

The patient articulated a desire to preserve her fertility and was monitored with US imaging of the remaining ovary every 6 months.

Does ‘indolent’ behavior of malignancy justify watchful waiting?

LMP tumors comprise a relatively large percentage of ovarian “cancers” encountered during pregnancy. Some authors report the accurate identification of these tumors prospectively, based on ultrasonographic characteristics.4,5 When an LMP tumor is the likely diagnosis, serial observation during pregnancy may be appropriate because of the indolent nature of the tumor. Further studies are needed to refine preoperative diagnosis and determine the overall safety of this approach.

When the problem is acute

In rare cases, a pregnant patient will have (or develop during observation) an acute problem due to torsion or rupture of an adnexal mass. Some ovarian cancers may present acutely, such as a rapidly growing malignant germ-cell tumor or a ruptured and hemorrhaging granulosecell tumor. Emergent surgery is necessary to manage the acute adnexal disease and reduce the likelihood of pregnancy loss. These events are infrequent, occurring in less than 10% of women with a known, persistent adnexal mass during pregnancy.4-14 Furthermore, recent studies have not found a substantial pregnancy complication rate associated with such emergency surgeries.

CASE 3 Suspicious mass, ascites signal need for surgery

A 19-year-old gravida 1 para 0 seeks prenatal care at 17 weeks’ gestation, complaining of rapidly enlarging abdominal girth. The physical examination estimates gestational size to be considerably greater than dates, but US is consistent with a 17-week intrauterine pregnancy. Imaging also reveals a 12-cm heterogenous left adnexal mass and a large amount of ascites.

Surgery is clearly warranted, but how extensive should it be?

When a malignancy is detected, a thorough staging procedure may be justified, depending on gestational age, exposure, desires of the patient, and operative findings. A midline incision is preferred.

Pregnant and nonpregnant women with stage 1A or 1C epithelial ovarian cancer who undergo fertility-preserving surgery (with chemotherapy in selected patients) have a good prognosis and a high likelihood of achieving a subsequent normal pregnancy.15 The same is true for women with a malignant germ-cell tumor of the ovary, even when disease is advanced.16 However, careful surgical staging is necessary.

The most important consideration when deciding whether to continue the pregnancy is the need for adjuvant chemotherapy. Depending on the gestational age and diagnosis, a short delay (4 to 6 weeks) may be appropriate to allow the pregnancy to progress beyond the first trimester or to maturity.

In case 3, a laparotomy was performed at 19 weeks’ gestation via a midline incision, and approximately 5.3 L of ascites was evacuated. A large, nonadherent left ovarian tumor was removed. The right ovary appeared to be normal, as did the gravid uterus, which was minimally manipulated. The rest of the surgical exploration was normal, and the distal portion of the omentum was excised. The frozen-section diagnosis was a malignant stromal tumor. Final pathology showed an 18×13.5×8.8 cm, poorly differentiated, SertoliLeydig-cell tumor with heterologous elements in the form of mucinous epithelium. The omentum was negative for tumor.

Chemotherapy was initiated in the third trimester, based on the limited data available, with intravenous etoposide and platinum administered every 21 days. The patient received 3 cycles of chemotherapy prior to delivery.

At 37 weeks’ gestation, labor was successfully induced. After delivery, bleomycin was added to the chemotherapy regimen, and 3 additional courses with all 3 agents were administered. The patient was lost to follow-up shortly after completing chemotherapy.

Clearly, an informed discussion of the options with the patient is imperative before any surgery, especially when chemotherapy may be delayed. Pregnancy does not appear to alter the prognosis for the patient with an ovarian malignancy, and ovarian cancer has not been reported to metastasize to the fetus.

Pregnant women have a very low rate of ovarian cancer

Leiserowitz GS, Xing G, Cress R, Brahmbhatt B, Dalrymple JL, Smith LH. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: how often are they malignant? Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:315–321.

Ovarian malignancies are rare during pregnancy. When they do occur, they are likely to be early stage and to have a favorable outcome, according to this recent population-based study.

Using 3 large databases containing records on 4,846,505 California obstetric patients between 1991 and 1999, Leiserowitz and colleagues identified 9,375 women who had an ovarian mass associated with pregnancy. Of these, 87 had ovarian cancer and 115 had a low-malignant-potential (LMP) tumor, for a cancer occurrence rate of 0.93%, or 0.0179 per 1,000 deliveries. Thirty-four of the 87 cancers were germ-cell tumors.

Of the 87 ovarian cancers, 65.5% were localized, 6.9% regional, 23% remote, and 4.6% of unknown stage. The respective rates for LMP tumors were 81.7%, 7.8%, 4.4%, and 6.1%.

Women with malignant tumors were more likely than pregnant controls without cancer to undergo cesarean delivery, hysterectomy, transfusion, and prolonged hospitalization. These women did not, however, have a higher rate of adverse neonatal outcomes.

When cancer is advanced

Few data shed light on whether a pregnancy should continue when ovarian cancer is advanced.17 The definitive surgical approach must be highly individualized.

It is not always possible to make an accurate diagnosis based on a frozen section. In such a case, the pregnancy should be preserved until the time of definitive diagnosis. As always, the patient’s wishes and gestational age must be considered.

How factors besides malignancy can influence care

Most persistent adnexal masses move well out of the pelvis as pregnancy progresses. Occasionally, however, an ovarian tumor may be located in the posterior cul-de-sac even at term, a fact easily confirmed by examination or US.4,7 A tumor in the posterior cul-de-sac can obstruct delivery or rupture. When it has a benign cystic appearance on US, it may be decompressed via transvaginal aspiration. Otherwise, the best approach is cesarean section and concomitant management of the mass.

When size alone is the problem

Some ovarian tumors are so large they seem incompatible with an advancing pregnancy. Tumors up to 20 cm in diameter have been removed intact at the time of cesarean section (FIGURE 2).18 The tumor may accommodate in shape and become less problematic as it is gradually pushed into the upper abdomen (FIGURE 3).

The ability of the peritoneal cavity to accommodate a tumor varies greatly among women. As pregnancy advances, the likelihood that a large cystic mass will rupture tends to increase. Depending on the circumstances, percutaneous aspiration7,18 or removal of a benign-appearing cystic tumor may be appropriate.

FIGURE 2 Even a very large tumor may coexist with advancing pregnancy

This benign serous cystadenoma was exteriorized at the time of cesarean section at term.

FIGURE 3 Large ovarian tumor has accommodated to the pregnancy

Laparotomy—performed at term for cesarean section and to manage this large tumor—revealed that the tumor had accommodated in shape between the enlarging pregnant uterus and the abdominal wall.

When is the best time to operate?

Surgery is generally not recommended during the first trimester.5-11 Among the reasons are the high likelihood of a corpus luteum cyst, the low likelihood of an invasive malignancy, the low risk of adnexal complications associated with observation, and the potential for pregnancy loss or teratogenicity. However, as pregnancy progresses beyond the first trimester, surgery poses other problems: Operative exposure diminishes and the need to manipulate the pregnant uterus increases.

Can surgery be delayed when a mass is detected?

Schmeler KM, Mayo-Smith WW, Peipert JF, Weitzen S, Manuel MD, Gordinier ME. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: surgery compared with observation. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1098–1103.

Close observation is a reasonable alternative to operative intervention during pregnancy, unless a malignancy is suspected.

Schmeler and colleagues reviewed the cases of 59 women who had an adnexal mass larger than 5 cm in diameter detected during pregnancy, out of a total of 127,177 deliveries at a single institution between 1990 and 2003. Antepartum surgery was performed in 17 women (29%). Of these, 13 cases had ultrasonographic findings suggesting malignancy, and 4 had ovarian torsion. The remaining women were observed, with surgery delayed until the time of cesarean section or later.

Twenty-five of the 59 masses (42%) were dermoid cysts. Cancer was diagnosed in 4 patients (6.8%), and 1 patient (1.7%) had an LMP tumor. All 5 cases (100%) involving a malignancy had a suspicious US appearance and were identified during antepartum surgery, whereas only 12 patients with a benign tumor (22%) underwent surgery prior to delivery.

Surgery poses risks to the pregnancy

Elective surgery for an adnexal mass any time during pregnancy increases the risk of pregnancy loss and the likelihood of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and preterm delivery.5,7,10,13,19 A 1989 study from Sweden20 defined a cohort of 5,405 women (from 720,000 births) who were known to have a nonobstetric operation while pregnant, with the following results:

- Congenital malformation and stillbirth were not increased in the women undergoing surgery

- The number of very-low- and low-birth-weight infants did rise, however—the result of both prematurity and IUGR

- Also elevated was the incidence of infants born alive but dying within 168 hours; these risks increased regardless of trimester

- No specific type of anesthesia or operation was associated with adverse reproductive outcomes, and the cause of those adverse outcomes was not determined.

Some recent data suggest that adnexal surgery during the late second or early third trimester poses the greatest risk of preterm delivery or IUGR, or both.13

Window of opportunity: early to mid- second trimester

During this time frame, elective surgery for an adnexal mass still affords some pelvic exposure without the need for significant uterine manipulation and has been associated with a lower risk of pregnancy complications.

The other window for operation is at the time of cesarean section. An elective cesarean section is sometimes performed specifically to manage a persistent adnexal mass. Among the factors that warrant consideration when contemplating this approach are the elective uterine incision (with its attendant implications for future pregnancies), the higher risks associated with cesarean delivery in general, the type of skin incision (a vertical incision is appropriate in the event of ovarian malignancy), the potential for better exposure or laparoscopy at a later date, the increased difficulty of ovarian cystectomy at the time of cesarean section, and the patient’s wishes.

The data on laparoscopy during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy indicate that it is as safe as laparotomy. A 1997 Swedish study21 identified cohorts of 2,181 women undergoing laparoscopy and 1,522 women undergoing laparotomy (from a total of 2,015,000 deliveries) between the fourth and 20th weeks of pregnancy. In both groups there was an increased risk for the infant to weigh less than 2,500 g, to be delivered before 37 weeks, and to have IUGR. There were no differences between the 2 groups for these and other adverse outcomes.

Small series of laparoscopic procedures to manage an adnexal mass during pregnancy suggest that this approach is most applicable during the first (for highly selected emergent cases) or early second trimester to manage masses less than 10 cm in diameter, particularly when adnexectomy is planned.

Laparoscopy may be considered “minimally invasive” because it reduces manipulation of the pregnant uterus during adnexal surgery. However, it is more difficult to assess and remove ovarian cysts laparoscopically, although an early ovarian malignancy could be staged via laparoscopy by an experienced surgeon.

Considerations during laparotomy

When performing a laparotomy or cesarean section for an adnexal mass, the surgeon must take into account a number of variables when selecting the type of incision (ie, vertical vs transverse). In general, if malignancy is suspected, or if uterine manipulation is to be minimized, a vertical incision is best. Other considerations include a prior scar, body habitus, obstetric issues, and the patient’s wishes.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE 1 An enlarging cystic tumor

A 20-year-old gravida 3 para 1011 visits the emergency department with persistent right flank pain. Although ultrasonography (US) shows a 21-week gestation, the patient has had no prenatal care. Imaging also reveals a right-sided ovarian tumor, 14×11×8 cm, that is mainly cystic with some internal echogenicity.

At 30 weeks’ gestation, a gynecologic oncologist is consulted. Repeat US reveals the mass to be about 20 cm in diameter and cystic, without internal papillation. The patient’s CA-125 level is 12 U/mL. Based on this information, the physicians decide the likely finding is a benign ovarian cystadenoma.

How should they proceed?

The discovery of an adnexal mass during pregnancy isn’t as rare as you might think—depending on when and how closely you look, it occurs in about 1 in 100 gestations. In most cases, we have found, the mass is clearly benign (TABLE 1), warranting only observation.

TABLE 1

Adnexal masses removed during pregnancy: Histologic profile

| HISTOLOGIC TYPE | NUMBER (%) |

|---|---|

| Cystadenoma | 549 (33) |

| Dermoid | 451 (27) |

| Paraovarian/paratubal | 204 (12) |

| Functional | 237 (14) |

| Endometrioma | 55 (3) |

| Benign stromal | 28 (2) |

| Leiomyoma | 23 (1.5) |

| Luteoma | 8 (0.5) |

| Miscellaneous | 55 (3) |

| Malignant | 68 (4) |

| Total | 1,678 |

| Data supplied by the authors from surgical experience | |

In the case described above, the physicians followed the patient and removed the mass at term because it was cystic with no other indications of malignancy. At 37 weeks’ gestation, a cesarean section was performed through a midline laparotomy incision, followed by removal of the ovarian tumor, which was benign. The pathologist measured the tumor at 16×12×4 cm and determined that it was a corpus luteum cyst.

Presence of mass raises questions

Despite the rarity of malignancy, the discovery of an ovarian mass during pregnancy prompts several important questions:

How should the mass be assessed? How can the likelihood of malignancy be determined as quickly and efficiently as possible, without jeopardy to the pregnancy?

When is surgical intervention warranted? And when can it be postponed? Specifically, is elective operative intervention for a tumor that is probably benign appropriate during pregnancy?

When is the best time to operate? And what is the optimal surgical route?

In this article, we address these questions with a focus on intervention. As we’ll explain, only a small percentage of gravidas who have an adnexal mass require surgery during pregnancy. When surgery is necessary, it is usually indicated for an emergent problem or suspicion of malignancy. Even when ovarian cancer is confirmed, we have found that it is usually in its early stages and therefore has a favorable prognosis (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Malignant adnexal masses removed during pregnancy

| HISTOLOGIC TYPE | NUMBER (%) |

|---|---|

| Epithelial | 101 (28) |

| Borderline epithelial | 147 (40) |

| Germ-cell dysgerminoma | 47 (13) |

| Other | 34 (9) |

| Stromal | 24 (7) |

| Undifferentiated | 5 (1.4) |

| Sarcoma | 2 (0.5) |

| Metastatic | 4 (1.1) |

| Total | 364 |

| Data supplied by the authors from surgical experience | |

How should a mass be assessed?

Ultrasonography and other imaging often reveal the presence of a mass and help determine whether it is benign or malignant. In fact, most adnexal masses discovered during pregnancy are incidental findings at the time of routine prenatal US. (see the most commonly found tumors.) Operative intervention is required in 3 situations:

- malignancy is suspected

- an acute complication develops

- the sheer size of the tumor is likely to cause difficulty.

Corpus luteum

A persistent corpus luteum is a normal component of pregnancy. Although it usually appears as a small cystic structure on ultrasonographic imaging, the corpus luteum of pregnancy can reach 10 cm in size. Other types of “functional” ovarian cysts may also be found during pregnancy. Most functional cysts resolve by the early second trimester.4,6 In rare cases, a cyst may develop complications such as torsion or rupture, causing acute pain or hemorrhage. Otherwise, a cystic tumor identified in the first trimester should be characterized and followed using ultrasonography (US).

Benign neoplasm

An adnexal mass that persists beyond the first trimester is more likely to be a neoplasm.3-5,10,11,22 Such a mass is generally considered clinically significant if it exceeds 5 cm in diameter and has a complex sonographic appearance. Usually such a neoplasm will be a benign cystadenoma or cystic teratoma.5,10-13,19,23,24

Benign cystic teratoma

This tumor can be identified with a fairly high degree of specificity using a variety of imaging techniques, with management based on the presumptive diagnosis. This tumor is unlikely to grow substantially during pregnancy. When it is smaller than 6 cm, such a tumor can simply be observed.14 A larger tumor can occasionally rupture or lead to torsion or obstruction of labor, but such occurrences are rare.

Benign cystadenoma

In an asymptomatic patient with imaging that suggests a benign cystadenoma (see sonogram), benign cystic teratoma, or other benign tumor, observation is reasonable in most cases.4,6,7,9-11,14,19 Operative intervention is required when there is less certainty regarding the benign nature of the tumor, an acute complication develops, or the tumor is expected to pose problems because of its large size alone.

Uterine leiomyoma

It is rare for an ovarian tumor detected during pregnancy to have a solid appearance on US. When it does, it may be a uterine leiomyoma mimicking an adnexal tumor (see intraoperative photograph). It should be reevaluated with more detailed US or magnetic resonance imaging.25

Malignancy

About 10% of adnexal masses that persist during pregnancy are malignant, according to recent series.4,5,7-10,12,13,24,26

Most of the ovarian cancers diagnosed during pregnancy are epithelial, and a substantial portion of these are low-malignant-potential (LMP) tumors.5,10,11,13,19,23,24,26,27 This ratio is in keeping with the age of these women, which also explains the stage distribution (most are stage 1) and the large percentage of germ-cell tumors detected. The majority of ovarian cancers discovered in pregnant women have a favorable prognosis.

Benign-appearing cystadenoma

A morphologically benign-appearing, large, cystic adnexal mass can be seen in association with an 11-week gestation.

Leiomyoma mimics an ovarian tumor

This 17-week gestation was marked by a large pedunculated leiomyoma that at fist appeared to be a right adnexal tumor.

Appearance of adnexal masses on US

A functional cyst such as a follicular cyst, corpus luteum cyst, or theca lutein cyst usually has smooth borders and a fluid center. Other cysts may sometimes contain debris, such as clotted blood, that suggests endometriosis or a simple cyst with bleeding into it.

A benign cystic teratoma often has multiple tissue lines, evidence of calcification, and layering of fat and fluid contents.

A benign cystadenoma usually has the appearance of a simple cyst without large septates, whereas a cystadenocarcinoma often contains septates, abnormal blood flow, increased vascularity, or all of these. However, it is impossible to definitively distinguish a cystadenoma from a cystadenocarcinoma using US imaging alone.

Functional cysts usually resolve by the second trimester. A cyst warrants closer scrutiny when it persists, is larger than 5 cm in diameter, or has a complex appearance on US.

CA-125 may be useful after the first trimester

The serum CA-125 level is typically elevated during the first trimester, but may be useful during later assessment or for follow-up of a malignancy.1

A markedly elevated serum level of alpha-fetoprotein (fractionated in some cases) has been reported in some gravidas with an endodermal sinus or mixed germ-cell ovarian tumor.2 Alpha-fetoprotein should be measured when there is suspicion for a germ-cell tumor based on clinical or US findings.

When a mass is discovered during cesarean section

Occasionally, an adnexal mass is detected at the time of cesarean section (FIGURE 1).3 This phenomenon is increasingly common, given the large number of cesarean deliveries in the United States. To eliminate the need for future surgery and avoid a delay in the diagnosis of an ovarian malignancy, inspect the adnexa routinely after closing the uterine incision in all women who deliver by cesarean section.

FIGURE 1 Mass discovered at cesarean section

This cystic tumor was discovered at cesarean section that was undertaken for obstetric indications.

CASE 2 LMP tumor is suspected

A 36-year-old gravida 3 para 1011 makes a prenatal visit during the first trimester. Her previous delivery was a cesarean section through a Pfannenstiel incision for a breech presentation. US imaging reveals a 6-week, 5-day fetus and a complex left adnexal mass, 4.5×3.9×4.1 cm. Imaging is repeated 1 month later at a tertiary-care center and shows an 11-week viable fetus, a right ovary with a corpus luteum cyst, and a left ovary with a 6.6×4 cm cystic mass with extensive vascular surface papillations that is suspicious for a low-malignant-potential (LMP) tumor. In several sonograms prior to the pregnancy, this mass appeared to be solid and was 3 cm in size.

When is surgery warranted?

Surgery is indicated when physical examination or imaging of a pregnant woman reveals an adnexal mass that is suspicious for malignancy, but the physician must weigh the benefit of prompt surgery against the risk to the pregnancy. This equation can be complicated in several ways. For example, surgical staging of clinically early ovarian cancer is more difficult due to the pregnant uterus, which is more extensively manipulated during these procedures. In addition, an optimal operation sometimes necessitates removal of the uterus.

At 13 weeks’ gestation, the patient described in case 2 underwent laparoscopy with peritoneal washings and left salpingo-oophorectomy, but the tumor ruptured during removal. Final pathology showed it to be a serous LMP tumor involving the surface of the left ovary. Washings were in line with this diagnosis.

The pregnancy continued uneventfully, and a repeat cesarean section was performed at 37 weeks through the Pfannenstiel scar, followed by limited surgical staging. Exploration and all biopsies were negative, and the final diagnosis was a stage 1C serous LMP tumor of the ovary.

The patient articulated a desire to preserve her fertility and was monitored with US imaging of the remaining ovary every 6 months.

Does ‘indolent’ behavior of malignancy justify watchful waiting?

LMP tumors comprise a relatively large percentage of ovarian “cancers” encountered during pregnancy. Some authors report the accurate identification of these tumors prospectively, based on ultrasonographic characteristics.4,5 When an LMP tumor is the likely diagnosis, serial observation during pregnancy may be appropriate because of the indolent nature of the tumor. Further studies are needed to refine preoperative diagnosis and determine the overall safety of this approach.

When the problem is acute

In rare cases, a pregnant patient will have (or develop during observation) an acute problem due to torsion or rupture of an adnexal mass. Some ovarian cancers may present acutely, such as a rapidly growing malignant germ-cell tumor or a ruptured and hemorrhaging granulosecell tumor. Emergent surgery is necessary to manage the acute adnexal disease and reduce the likelihood of pregnancy loss. These events are infrequent, occurring in less than 10% of women with a known, persistent adnexal mass during pregnancy.4-14 Furthermore, recent studies have not found a substantial pregnancy complication rate associated with such emergency surgeries.

CASE 3 Suspicious mass, ascites signal need for surgery

A 19-year-old gravida 1 para 0 seeks prenatal care at 17 weeks’ gestation, complaining of rapidly enlarging abdominal girth. The physical examination estimates gestational size to be considerably greater than dates, but US is consistent with a 17-week intrauterine pregnancy. Imaging also reveals a 12-cm heterogenous left adnexal mass and a large amount of ascites.

Surgery is clearly warranted, but how extensive should it be?

When a malignancy is detected, a thorough staging procedure may be justified, depending on gestational age, exposure, desires of the patient, and operative findings. A midline incision is preferred.

Pregnant and nonpregnant women with stage 1A or 1C epithelial ovarian cancer who undergo fertility-preserving surgery (with chemotherapy in selected patients) have a good prognosis and a high likelihood of achieving a subsequent normal pregnancy.15 The same is true for women with a malignant germ-cell tumor of the ovary, even when disease is advanced.16 However, careful surgical staging is necessary.

The most important consideration when deciding whether to continue the pregnancy is the need for adjuvant chemotherapy. Depending on the gestational age and diagnosis, a short delay (4 to 6 weeks) may be appropriate to allow the pregnancy to progress beyond the first trimester or to maturity.

In case 3, a laparotomy was performed at 19 weeks’ gestation via a midline incision, and approximately 5.3 L of ascites was evacuated. A large, nonadherent left ovarian tumor was removed. The right ovary appeared to be normal, as did the gravid uterus, which was minimally manipulated. The rest of the surgical exploration was normal, and the distal portion of the omentum was excised. The frozen-section diagnosis was a malignant stromal tumor. Final pathology showed an 18×13.5×8.8 cm, poorly differentiated, SertoliLeydig-cell tumor with heterologous elements in the form of mucinous epithelium. The omentum was negative for tumor.

Chemotherapy was initiated in the third trimester, based on the limited data available, with intravenous etoposide and platinum administered every 21 days. The patient received 3 cycles of chemotherapy prior to delivery.

At 37 weeks’ gestation, labor was successfully induced. After delivery, bleomycin was added to the chemotherapy regimen, and 3 additional courses with all 3 agents were administered. The patient was lost to follow-up shortly after completing chemotherapy.

Clearly, an informed discussion of the options with the patient is imperative before any surgery, especially when chemotherapy may be delayed. Pregnancy does not appear to alter the prognosis for the patient with an ovarian malignancy, and ovarian cancer has not been reported to metastasize to the fetus.

Pregnant women have a very low rate of ovarian cancer

Leiserowitz GS, Xing G, Cress R, Brahmbhatt B, Dalrymple JL, Smith LH. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: how often are they malignant? Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:315–321.

Ovarian malignancies are rare during pregnancy. When they do occur, they are likely to be early stage and to have a favorable outcome, according to this recent population-based study.

Using 3 large databases containing records on 4,846,505 California obstetric patients between 1991 and 1999, Leiserowitz and colleagues identified 9,375 women who had an ovarian mass associated with pregnancy. Of these, 87 had ovarian cancer and 115 had a low-malignant-potential (LMP) tumor, for a cancer occurrence rate of 0.93%, or 0.0179 per 1,000 deliveries. Thirty-four of the 87 cancers were germ-cell tumors.

Of the 87 ovarian cancers, 65.5% were localized, 6.9% regional, 23% remote, and 4.6% of unknown stage. The respective rates for LMP tumors were 81.7%, 7.8%, 4.4%, and 6.1%.

Women with malignant tumors were more likely than pregnant controls without cancer to undergo cesarean delivery, hysterectomy, transfusion, and prolonged hospitalization. These women did not, however, have a higher rate of adverse neonatal outcomes.

When cancer is advanced

Few data shed light on whether a pregnancy should continue when ovarian cancer is advanced.17 The definitive surgical approach must be highly individualized.

It is not always possible to make an accurate diagnosis based on a frozen section. In such a case, the pregnancy should be preserved until the time of definitive diagnosis. As always, the patient’s wishes and gestational age must be considered.

How factors besides malignancy can influence care

Most persistent adnexal masses move well out of the pelvis as pregnancy progresses. Occasionally, however, an ovarian tumor may be located in the posterior cul-de-sac even at term, a fact easily confirmed by examination or US.4,7 A tumor in the posterior cul-de-sac can obstruct delivery or rupture. When it has a benign cystic appearance on US, it may be decompressed via transvaginal aspiration. Otherwise, the best approach is cesarean section and concomitant management of the mass.

When size alone is the problem

Some ovarian tumors are so large they seem incompatible with an advancing pregnancy. Tumors up to 20 cm in diameter have been removed intact at the time of cesarean section (FIGURE 2).18 The tumor may accommodate in shape and become less problematic as it is gradually pushed into the upper abdomen (FIGURE 3).

The ability of the peritoneal cavity to accommodate a tumor varies greatly among women. As pregnancy advances, the likelihood that a large cystic mass will rupture tends to increase. Depending on the circumstances, percutaneous aspiration7,18 or removal of a benign-appearing cystic tumor may be appropriate.

FIGURE 2 Even a very large tumor may coexist with advancing pregnancy

This benign serous cystadenoma was exteriorized at the time of cesarean section at term.

FIGURE 3 Large ovarian tumor has accommodated to the pregnancy

Laparotomy—performed at term for cesarean section and to manage this large tumor—revealed that the tumor had accommodated in shape between the enlarging pregnant uterus and the abdominal wall.

When is the best time to operate?

Surgery is generally not recommended during the first trimester.5-11 Among the reasons are the high likelihood of a corpus luteum cyst, the low likelihood of an invasive malignancy, the low risk of adnexal complications associated with observation, and the potential for pregnancy loss or teratogenicity. However, as pregnancy progresses beyond the first trimester, surgery poses other problems: Operative exposure diminishes and the need to manipulate the pregnant uterus increases.

Can surgery be delayed when a mass is detected?

Schmeler KM, Mayo-Smith WW, Peipert JF, Weitzen S, Manuel MD, Gordinier ME. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: surgery compared with observation. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1098–1103.

Close observation is a reasonable alternative to operative intervention during pregnancy, unless a malignancy is suspected.

Schmeler and colleagues reviewed the cases of 59 women who had an adnexal mass larger than 5 cm in diameter detected during pregnancy, out of a total of 127,177 deliveries at a single institution between 1990 and 2003. Antepartum surgery was performed in 17 women (29%). Of these, 13 cases had ultrasonographic findings suggesting malignancy, and 4 had ovarian torsion. The remaining women were observed, with surgery delayed until the time of cesarean section or later.

Twenty-five of the 59 masses (42%) were dermoid cysts. Cancer was diagnosed in 4 patients (6.8%), and 1 patient (1.7%) had an LMP tumor. All 5 cases (100%) involving a malignancy had a suspicious US appearance and were identified during antepartum surgery, whereas only 12 patients with a benign tumor (22%) underwent surgery prior to delivery.

Surgery poses risks to the pregnancy

Elective surgery for an adnexal mass any time during pregnancy increases the risk of pregnancy loss and the likelihood of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and preterm delivery.5,7,10,13,19 A 1989 study from Sweden20 defined a cohort of 5,405 women (from 720,000 births) who were known to have a nonobstetric operation while pregnant, with the following results:

- Congenital malformation and stillbirth were not increased in the women undergoing surgery

- The number of very-low- and low-birth-weight infants did rise, however—the result of both prematurity and IUGR

- Also elevated was the incidence of infants born alive but dying within 168 hours; these risks increased regardless of trimester

- No specific type of anesthesia or operation was associated with adverse reproductive outcomes, and the cause of those adverse outcomes was not determined.

Some recent data suggest that adnexal surgery during the late second or early third trimester poses the greatest risk of preterm delivery or IUGR, or both.13

Window of opportunity: early to mid- second trimester

During this time frame, elective surgery for an adnexal mass still affords some pelvic exposure without the need for significant uterine manipulation and has been associated with a lower risk of pregnancy complications.

The other window for operation is at the time of cesarean section. An elective cesarean section is sometimes performed specifically to manage a persistent adnexal mass. Among the factors that warrant consideration when contemplating this approach are the elective uterine incision (with its attendant implications for future pregnancies), the higher risks associated with cesarean delivery in general, the type of skin incision (a vertical incision is appropriate in the event of ovarian malignancy), the potential for better exposure or laparoscopy at a later date, the increased difficulty of ovarian cystectomy at the time of cesarean section, and the patient’s wishes.

The data on laparoscopy during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy indicate that it is as safe as laparotomy. A 1997 Swedish study21 identified cohorts of 2,181 women undergoing laparoscopy and 1,522 women undergoing laparotomy (from a total of 2,015,000 deliveries) between the fourth and 20th weeks of pregnancy. In both groups there was an increased risk for the infant to weigh less than 2,500 g, to be delivered before 37 weeks, and to have IUGR. There were no differences between the 2 groups for these and other adverse outcomes.

Small series of laparoscopic procedures to manage an adnexal mass during pregnancy suggest that this approach is most applicable during the first (for highly selected emergent cases) or early second trimester to manage masses less than 10 cm in diameter, particularly when adnexectomy is planned.

Laparoscopy may be considered “minimally invasive” because it reduces manipulation of the pregnant uterus during adnexal surgery. However, it is more difficult to assess and remove ovarian cysts laparoscopically, although an early ovarian malignancy could be staged via laparoscopy by an experienced surgeon.

Considerations during laparotomy

When performing a laparotomy or cesarean section for an adnexal mass, the surgeon must take into account a number of variables when selecting the type of incision (ie, vertical vs transverse). In general, if malignancy is suspected, or if uterine manipulation is to be minimized, a vertical incision is best. Other considerations include a prior scar, body habitus, obstetric issues, and the patient’s wishes.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Spitzer M, Kaushal N, Benjamin F. Maternal CA-125 levels in pregnancy and the puerperium. J Reprod Med. 1998;43:387-392.

2. Aoki Y, Higashino M, Ishii S, Tanaka K. Yolk sac tumor of the ovary during pregnancy: a case report. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:497-499.

3. Koonings PP, Platt LD, Wallace R. Incidental adnexal neoplasms at cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72:767-769.

4. Zanetta G, Mariani E, Lissoni A, et al. A prospective study of the role of ultrasound in the management of adnexal masses in pregnancy. BJOG. 2003;110:578-583.

5. Sherard GB, 3rd, Hodson CA, Williams HJ, et al. Adnexal masses and pregnancy: a 12 year experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:358-363.

6. Bernhard LM, Klebba PK, Gray DL, Mutch DG. Predictors of persistence of adnexal masses in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:585-589.

7. Platek DN, Henderson CE, Goldberg GL. The management of a persistent adnexal mass in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1236-1240.

8. Bromley B, Benacerraf B. Adnexal masses during pregnancy: accuracy of sonographic diagnosis and outcome. J Ultrasound Med. 1997;16:447-452.

9. Hill LM, Connors-Beatty DJ, Nowak A, Tush B. The role of ultrasonography in the detection and management of adnexal mass during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:703-707.

10. Agarwal N, Parul, Kriplani A, Bhatla N, Gupta A. Management and outcome of pregnancies complicated with adnexal masses. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;267:148-152.

11. Schmeler KM, Mayo-Smith WW, Peipert JF, Weitzen S, Manuel MD, Gordinier ME. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: surgery compared with observation. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1098-1103.

12. Coenen VH, Dunton C, Cardonick E, Berghella V. Persistent adnexal masses during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:66S.-

13. Whitecar P, Turner S, Higby K. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: a review of 130 cases undergoing surgical management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:19-24.

14. Caspi B, Levi R, Appelman Z, Rabinerson D, Goldman G, Hagay Z. Conservative management of ovarian cystic teratoma during pregnancy and labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:503-505.

15. Schilder JM, Thompson AM, DePriest PD, et al. Outcome of reproductive age women with stage IA or IC invasive epithelial ovarian cancer treated with fertility-sparing therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;87:1-7.

16. Tangir J, Zelterman D, Ma W, Schwartz PE. Reproductive function after conservative surgery and chemotherapy for malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:251-257.

17. Ferrandina G, Distefano M, Testa A, De Vincenzo R, Scambia G. Management of an advanced ovarian cancer at 15 weeks of gestation: case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:693-696.

18. Caspi B, Ben-Arie A, Appelman Z, Or Y, Hagay Z. Aspiration of simple pelvic cysts during pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2000;49:102-105.

19. Usui R, Minakami H, Kosuge S, et al. A retrospective survey of clinical, pathologic, and prognostic features of adnexal masses operated on during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2000;26(2):89-93.

20. Mazze RI, Källén B. Reproductive outcome after anesthesia and operation during pregnancy; a registry study of 5,405 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:1178-1185.