User login

Vulvovaginal disorders: 4 challenging conditions

The symptoms are recited every day in gynecologists’ offices around the world: itching, irritation, burning, rawness, pain, dyspareunia. The challenge is tracing these general symptoms to a specific pathology, a task harder than one might expect, because vulvovaginal conditions often represent a complex mix of several problems. Candida and bacterial invasion frequently complicate genital dermatologic conditions. Atrophy and loss of the epithelial barrier worsen the problem. Over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription remedies can lead to contact dermatitis. Vulvodynia may be the ultimate outcome, possibly from central sensitization after chronic inflammation, which in turn can mislead the clinician into thinking appropriate therapy “doesn’t work.” And it is important to remember that any genital complaint has the potential to dampen a woman’s self-esteem and hamper sexual function.

This article covers the fine points of diagnosis and treatment of 4 common vulvovaginal problems:

- Candidiasis

- Contact dermatitis

- Lichen sclerosus

- Vestibulodynia

Could all 4 problems coexist in 1 patient? They frequently do. As always, a careful history and physical examination with appropriate use of yeast cultures make it possible to manage the complexity.

1. CandidiasisTelephone and self-diagnosis are a waste of time

In vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), symptoms can range from none to recurrent. VVC can complicate genital dermatologic conditions and interfere with the treatment of illnesses that call for steroids or antibiotics. Because the symptoms of VVC are nonspecific, diagnosis necessitates consideration of a long list of other potential causes, both infectious and noninfectious.

Candida albicans predominates in 85% to 90% of positive vaginal yeast cultures. Non-albicans species such as C glabrata, parapsilosis, krusei, lusitaniae, and tropicalis are more difficult to treat.

Not all episodes are the same

VVC is uncomplicated when it occurs sporadically or infrequently in a woman in good overall health and involves mild to moderate symptoms; albicans species are likely. VVC is complicated when it is severe or recurrent or occurs in a debilitated, unhealthy, or pregnant woman; non-albicans species often are involved. Proper classification is essential to successful treatment.1

Phone diagnosis is usually inaccurate

Although phone diagnosis is unreliable,2 it is still fairly common, and fewer offices use microscopy and vaginal pH to diagnose vaginal infections because of the tightened (though still simple) requirements of the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment. (Clinicians who do wet mounts and KOH are required to pass a simple test each year to continue the practice.)

Women are poor self-diagnosticians when it comes to Candida infection; only one third of a group purchasing OTC antifungals had accurately identified their condition.3

Clinicians are not exempt from error, either. About 50% of the time, Candida is misdiagnosed,4 largely because of the assumption that the wet mount is more specific than it actually is (it is only 40% specific for Candida).

Ask about sex habits, douching, drugs, and diseases

Accurate diagnosis requires a careful history, focusing on risk factors for Candida: a new sexual partner; oral sex; douching; use of antibiotics, steroids, or exogenous estrogen; and uncontrolled diabetes.

Look for signs of vulvar and vaginal erythema, edema, and excoriation.

Classic “cottage cheese” discharge may not be present, and the amount has no correlation with symptom severity.

Vaginal pH of less than 4.5 excludes bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis, atrophic vaginitis, desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, and vaginal lichen planus.

Blastospores or pseudohyphae are diagnostic (on 10% KOH microscopy). If they are absent, a yeast culture is essential and will allow speciation. A vaginal culture is especially important in women with recurrent or refractory symptoms.

Always consider testing for sexually transmitted diseases.

Azole antifungals are usual treatment

For uncomplicated VVC, azole antifungals are best (TABLE 1). For complicated VVC, follow this therapy with maintenance fluconazole (150 mg weekly for 6 months), which clears Candida in 90.8% of cases.5

Non-albicans infection can be treated with boric acid capsules (inserted vaginally at bedtime for 14 days) or terconazole cream (7 days) or suppositories (3 days). A culture to confirm cure is essential, since non-albicans infection can be difficult to eradicate.

Note that boric acid is not approved for pregnancy.

TABLE 1

CDC guidelines for treatment of candidiasis

Any of these intravaginal or oral regimens may be used

| DOSE (NUMBER OF DAYS) | |

|---|---|

| INTRAVAGINAL AGENTS | |

| Butoconazole | |

| 2% cream* | 5 g (3) |

| Butoconazole-1 sustained-release cream | 5 g (1) |

| Clotrimazole | |

| 1% cream* | 5 g (7–14) |

| 100 mg | 1 tablet (7) |

| 2 tablets (3) | |

| 500 mg | 1 tablet (1) |

| Miconazole | |

| 2% cream* | 5 g (7) |

| 100 mg* | 1 suppository (7) |

| 200 mg* | 1 suppository (3) |

| Nystatin | |

| 100,000 U | 1 tablet (14) |

| Tioconazole | |

| 6.5% ointment* | 5 g (1) |

| Terconazole | |

| 0.4% cream | 5 g (7) |

| 0.8% cream | 5 g (3) |

| 80 mg | 1 suppository (3) |

| ORAL AGENT | |

| Fluconazole | |

| 150 mg | 1 tablet (1) |

| * Over-the-counter | |

2. Contact DermatitisNine essentials of treatment

Contact dermatitis, the most common form of vulvar dermatitis, is inflammation of the skin caused by an external agent that acts as an irritant or allergen. The skin reaction may escape notice because changes ranging from minor to extreme are often superimposed on complex preexisting conditions such as lichen simplex chronicus, lichen planus, and lichen sclerosus.6

Contact dermatitis occurs readily in the vulvar area because the skin of the vulva reacts more intensely to irritants than other skin, and its barrier function is easily weakened by moisture, friction, urine, and vaginal discharge. The 3 main types of irritant dermatitis are7:

- A potent irritant, which may produce the equivalent of a chemical burn.

- A weaker irritant, which may be applied repeatedly before inflammation manifests.

- Stinging and burning, which can occur without detectable skin change, due to chemical exposure.

Many products can cause dermatitis. Even typically harmless products can cause dermatitis if combined with lack of estrogen or use of pads, panty hose, or girdles.

No typical pattern

Patients complain of varying degrees of itching, burning, and irritation. Depending on the agent involved, onset may be sudden or gradual, and the woman may be aware or oblivious of the cause. New reactions to “old” practices or products are also possible.

Ask about personal hygiene, care during menses and after intercourse, and about soap, cleansers, and any product applied to the genital skin, as well as clothing types and exercise habits. Review prescription and OTC products, including topicals, and note which products or actions improve or aggravate symptoms. A history of allergy and atopy should heighten suspicion.

The physical exam may reveal erythema and edema; scaling is possible. Severe cases manifest as erosion, ulceration, or pigment changes. Secondary infection, if any, may involve pustules, crusting, and fissuring. The dermatitis may be localized, but often extends over the area of product spread to the mons, labiocrural folds, and anus. C albicans often complicates genital dermatologic conditions.

9-step treatment

- Stop the offending product and/or practices.

- Restore the skin barrier with sitz baths in plain lukewarm water for 5 to 10 minutes twice daily. Compresses or a handheld shower are alternatives.

- Provide moisture. After hydration, have the patient pat dry and apply a thin film of plain petrolatum.

- Replace local estrogen if necessary.

- Control any concomitant Candida with oral fluconazole 150 mg weekly, avoiding the potential irritation caused by topical antifungals.

- Treat itching and scratching with cool gel packs from the refrigerator, not the freezer (frozen packs can burn). Stop involuntary nighttime scratching with sedation: doxepin or hydroxyzine (10–75 mg at 6 PM).

- Use topical steroids for dermatitis:

- Moderate: Triamcinolone, 0.1% ointment twice daily.

- Severe: A super-potent steroid such as clobetasol, 0.05% ointment, twice daily for 1 to 3 weeks.

- Extreme: Burst and taper prednisone (0.5–1 mg/kg/day decreased over 14–21 days) or a single dose of intramuscular triamcinolone (1 mg/kg).

- Order patch testing to rule out or define allergens.

- Educate the patient about the many potential causes of dermatitis, to prevent recurrence.

CAUSTIC AGENTS

Bichloracetic acid

Trichloroacetic acid

5-Fluorouracil

Lye (in soap)

Phenol

Podophyllin

Sodium hypochlorite

Solvents

WEAK CUMULATIVE IRRITANTS

Alcohol

Deodorants

Diapers

Feces

Feminine spray

Pads

Perfume

Povidone iodine

Powders

Propylene glycol

Semen

Soap

Sweat

Urine

Vaginal secretions

Water

Wipes

PHYSICALLY ABRASIVE CONTACTANTS

Face cloths

Sponges

THERMAL IRRITANTS

Hot water bottles

Hair dryers

Source: Lynette Margesson,MD26

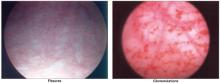

FIGURE 1 A mutilating disease of mysterious origin

Though lichen sclerosus is a disfiguring disease, the intensity of symptoms does not necessarily correlate with clinical appearance. Generally, the first change is (A) whitening of an irregular area on the labia, near the clitoris, on the perineum, and/or other vulvar areas. In some cases (A and B), inflammation can alter the anatomy of the vulva by flattening the labia minora, fusing the hood over the clitoris, effectively burying it beneath the skin, and shrinking the skin around the vaginal opening. Images courtesy Lynette Margesson, MD

3. Lichen SclerosusLifelong follow-up is a must

Although it has long been described in medical journals and textbooks, information on lichen sclerosus was often unreliable until recently, and adequate treatment guidelines were lacking. The cause still has not been fully elucidated, but a wealth of information now allows for considerable expertise in the management of this disease.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory and scarring disease that preferentially affects the anogenital area and is 6 to 10 times more prevalent in women than men.8 Any cutaneous site may also be affected, but the vagina is never involved.

Infection? Autoimmunity? An infectious cause has been proposed but never proven. In some women, an autoimmune component is recognized: Immunoglobulin G antibodies to extracellular matrix protein I have been found in 67% of patients with lichen sclerosus, but whether these antibodies are secondary or pathogenic is unclear.9 A genetic component is suggested by the association with autoimmunity and by the link with human leukocyte antigen DQ7 in women10 and girls.11

Affects 1.7%, or 1 in 60 women.12 In females, lichen sclerosus peaks in 2 populations: prepubertal girls and postmenopausal women.

No remission after age 70. Although remission of the disease has been reported, a recent study concluded that lichen sclerosus never remits after the age of 70; the average length of remission is 4.7 years, although this figure is still in question.13 Only close follow-up can determine if disease is in remission.

Main symptom is itching

Pruritus is the most common symptom, but dysuria and a sore or burning sensation have also been reported. Some women have no symptoms. When erosions, fissures, or introital narrowing are present, dyspareunia may also occur.

Typical lesions are porcelain-white papules and plaques, often with areas of fissuring or ecchymosis on the vulva or extending around the anus in a figure-of-8 pattern.

Both lichen sclerosus and lichen planus may be seen on the same vulva.

Squamous cell carcinoma can arise in anogenital lichen sclerosus; risk is thought to be 5%. Instruct women in regular self-examination because carcinoma can arise between annual or semiannual visits.

Ultrapotent steroids: Good control, but risk of malignancy persists

Renaud-Vilmer C, Cavalier-Balloy B, Porcher R, Dubertret L. Vulvar lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:709-712.

If we gynecologists have been assuming that lichen sclerosus is one of those nebulous, little-explored diseases out there, we need to think again. Lichen sclerosus is a chronic and mutilating condition, an obstacle to quality of life, a threat to body image, a destroyer of sexual function, and a risk for malignancy.

Cancer developed only in untreated or irregularly treated lesions

In a key study, Renaud-Vilmer and colleagues13 explored remission and recurrence rates after treatment with 0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment, as well as whether the treatment reduces risk of malignant evolution. They determined that the rate of clinical and histologic remission is related to age. Although 72% of women under age 50 had complete remission, only 23% of women between 50 and 70 years of age had complete remission, and none of the women older than 70 did. Relapse was noted in most women over time (50% by 18 months), and 9.6% of women were later diagnosed with invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

Although we have known since 1988 that ultrapotent steroids offer outstanding relief of symptoms and some control over the disease, the optimal length of treatment has never been clear. The prospective study by Renaud-Vilmer et al has impressive power that derives from its 20-year duration. They demonstrated that ultrapotent steroids do not cure lichen sclerosus in women over 70. Complete remission in younger women is only temporary, and steroid therapy offers no significant reduction in the risk of vulvar cancer—although carcinoma developed only in untreated or irregularly treated lesions.

Histologic and clinical findings were used to judge efficacy. Because only 83 women were studied, the cohort is too small for the findings on carcinoma to be significant, but the authors emphasized that lifelong follow-up is necessary in all cases.

Lichen sclerosus never backs down after menopause

In more than 15 years of vulvovaginal specialization, I have found similar results. Older women detest the need to apply topicals to the genital area, but they are the ones who need ongoing use, because the disease never backs down after menopause.

I follow a cohort of young women in whom I detected early disease. Their clinical signs regressed and scarring was prevented by steroid treatment, but disease recurrence appears to be inevitable: The longest remission has been just over 4 years.

I have seen cancer arise quickly even in closely supervised patients, although many cases of squamous cell carcinoma have occurred in women with undetected or poorly treated disease.

Use tacrolimus with caution

Although small trials have produced some enthusiasm for therapeutic use of tacrolimus, treatment should proceed with extreme caution, as the drug inhibits an arm of the immune system and women with lichen sclerosus are at risk for malignancy. The agent now carries a warning based on the development of malignancy in animals.

Consider treatment even without biopsy proof

Although a biopsy generally makes the diagnosis, treatment should be considered even in the face of an inconclusive or negative finding if the clinician suspects that lichen sclerosus is present. The reason treatment should proceed in these cases: Loss of the labia or fusion over the clitoris can occur if the disease progresses, as shown in the photos on page.

Powerful corticosteroids are treatment of choice

Treatment can control lichen sclerosus, relieve symptoms, and prevent further anatomical changes. Potent or ultrapotent topical corticosteroids in an ointment base are preferred. These drugs are now widely recognized for their efficacy and minimal adverse effects, although no regimen is universally advocated.14 The patient applies ointment once daily for 1 to 3 months, depending on severity, and then once or twice a week.

Ointments are preferred over creams for vulvar treatment, because creams frequently contain allergens or irritants such as fragrance and propylene glycol preservative.

I continue once-weekly therapy indefinitely in postmenopausal women. If a premenopausal woman is not comfortable using the ointment indefinitely, I will allow her to discontinue treatment but follow her every 3 to 6 months.

Treatment also requires educating the patient about the disease, instructing her in gentle local care, and showing her exactly where to apply the ointment.

In all cases, lifelong follow-up is necessary. Hyperkeratosis, ecchymoses, fissuring, and erosions resolve, but atrophy and color change remain. Scarring usually remains unchanged, but may resolve if treated early in the course of the disease.15

Testosterone is not as effective as an ultrapotent steroid,16 and is no more effective than an emollient.17

Estrogen is valuable for skin integrity, but has no role in the treatment of lichen sclerosus.

Dilator work may be necessary for dyspareunia, once the disease is controlled.

Refer for help with depression and/or negative body image, if present.

4. VestibulodyniaEight treatment options to try

The prevalence of pain in an ethnically diverse population is 16%, and approximately half of this figure (8%) represents vulvodynia.18 The International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease now classifies vulvar pain in 3 categories:

- vulvar pain with a known cause, including infection, trauma, and systemic disease (TABLE 2),

- generalized vulvodynia, also known as dysesthetic vulvodynia, essential vulvodynia, or pudendal neuralgia, and

- localized vulvodynia or vestibulodynia, formerly called vestibulitis, vulvar vestibulitis syndrome, and vestibular adenitis.

Terminology is likely to evolve with further study.

Vestibulodynia, the leading cause of dyspareunia in women under age 50,19 refers to pain on touch within the vestibule. It is primary pain if it has been present since the first tampon use or sexual experience, and it is secondary if it arises after a period of comfortable sexual function.

TABLE 2

Rule out these known causes of vulvar pain

| INFECTIONS |

|

| TRAUMA |

|

| SYSTEMIC DISEASE |

|

| CANCER AND PRE-CANCER |

|

| IRRITANTS |

|

| SKIN CONDITIONS |

|

| Source: Haefner and Pearlman27 |

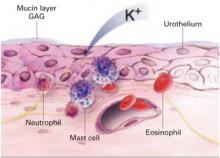

Inflammation starts the cascade

Current theory suggests that inflammatory events such as yeast infection, seminal plasma allergy, and local chemical application release a cascade of cytokines that sensitizes nociceptors in the vestibular epithelium. Prolonged neural firing in turn alters neurons in the dorsal horn, allowing sensitization of mechanoreceptive fibers in the vestibule with sensory allodynia (pain on touch). The proliferation of introital nociceptive fibers is well documented.20

Diagnosis: Report of pain and a positive Q-tip test

When a woman reports superficial dyspareunia with introital contact and clinical examination reveals pain on touch in the vestibule (using a cotton swab), vestibulodynia is diagnosed, provided no other known causes of the vulvar pain are detected during a careful history and examination or after pH measurement, a wet mount, and any indicated cultures.

A careful psychosexual history can help the clinician identify current sexual practices, prior sexual issues, and the impact of the current sexual dysfunction with an eye toward guiding support and counseling.

Multifactorial treatment: 8 options

Because the cause of vestibulodynia is unclear, a multifactorial approach generally is accepted and involves the following:

- Patient education about the problem and instruction in gentle local care and the elimination of contactants.

- Referral for support, counseling, and treatment of depression, as indicated.

- Elimination of any known trigger such as C albicans, although this generally does not lead to remission unless the pain is also treated.

- Suppression of nociceptor afferent input using topical lidocaine hydrochloride, for which good results have been reported.21

- Systemic oral analgesia with a tricyclic antidepressant modulates the serotonin and epinephrine imbalance associated with persistent pain (TABLE 3).22

- Use of anticonvulsants such as gabapentin to increase the amount of stimuli needed for nerves to fire and elevate the central pain threshold.23

- Reduction of muscle tension and spasm in the pelvic floor, using physical therapy and biofeedback.24

- When medical management fails, vulvar vestibulectomy with vaginal advancement yields excellent long-term results,25 but should be a last resort.

TABLE 3

Tricyclic antidepressants modify chemical imbalance associated with persistent pain of vestibulodynia

| Names of standard agents used | Amitriptyline (Elavil) |

| Nortriptyline (Aventyl, Pamelor) | |

| Desipramine (Norpramin) | |

| Imipramine (Tofranil) | |

| Standard dosing | Start with 10 mg; increase by 10 mg weekly to 100–150 mg |

| Side effects | Sedation, often transient |

| Constipation, must be actively managed | |

| Dry mouth | |

| Palpitations, tachycardia | |

| Sun sensitivity | |

| Cautions | Obtain EKG over 50 years or with cardiac history |

| Contraindicated in glaucoma | |

| Levels must be monitored if combined with SSRI | |

| Success | Slow change over 6–12 months in sensitivity to touch; ability to use tampon. Minimal pain with dilator use, penetration |

| Failure | Over 3 months at max dose without any improvement |

1. Sobel JD, Faro S, Force RW, et al. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: epidemiologic, diagnostic, and therapeutic considerations. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:203-211.

2. Spinollo A, Pizzoli G, Colonna L, Nicola S, DeSeta F, Guashino S. Epidemiologic characteristics of women with idiopathic recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:14-17.

3. Ferris DG, Nyirjesy P, Sobel JD, Soper D, Pavletic A, Litaker MS. Over-the-counter antifungal drug misuse associated with patient-diagnosed vulvovaginal candidiasis. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:419-425.

4. Ledger WJ, Polaneczky MM, Yih MC. Difficulties in the diagnosis of Candida vaginitis. Inf Dis Clin Pract. 2000;9:66-69.

5. Sobel JD, Wiesenfeld HC, Martens M, et al. Maintenance fluconazole therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2004;35:876-883.

6. Margesson LJ. Contact dermatitis of the vulva. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:20-27.

7. Kamarashev JA, Vassileva SG. Dermatologic diseases of the vulva. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:53-65.

8. Powell J, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

9. Oyama N, Chan I, Neill SM, et al. Autoantibodies to extracellular matrix protein 1 in lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 2003;362:118-213.

10. Marren P, Yell J, Charnock FM, Bunce M, Welsh K, Wojnarowska F. The association between lichen sclerosus and antigens of the HLA system. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:197-203.

11. Powell J, Wojnarowska F, Winsey S, Marren P, Welsh K. Lichen sclerosus premenarche: autoimmunity and immunogenetics. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:481-484.

12. Goldstein AT, Marinoff SC, Cristopher K, Srodon M. Prevalence of vulvar lichen sclerosus in a general gynecology practice. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:477-480.

13. Renaud-Vilmer C, Cavalier-Balloy B, Porcher R, Dubertret L. Vulvar lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:709-712.

14. Dalziel KL, Millard PR, Wojnarowska F. The treatment of vulval lichen sclerosus with a very potent topical steroid (clobetasol propionate 0.05%) cream. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:461-464.

15. Cooper SM, Gao XH, Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Does treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus influence its prognosis? Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:702-706.

16. Bornstein J, Heifetz S, Kellner Y, et al. Clobetasol dipropionate 0.05% versus 2% testosterone application for severe vulvar lichen sclerosus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:80-84.

17. Sideri M, Origoni M, Spinaci L, Ferrari A. Topical testosterone in the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1994;46:53-56.

18. Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58:82-88.

19. Meana M, Binik YM, Khalife S, et al. Biopsychosocial profile of women with dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:583-589.

20. Bohm-Starke N, Hilliges M, Falconer C, Rylander E. Neurochemical characterization of the vestibular nerves in women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1999;48:270-275.

21. Zolnoun DA, Hartmann KE, Steege JF. Overnight 5% lidocaine ointment for treatment of vulvar vestibulitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:84-87.

22. Mariani L. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: an overview of nonsurgical treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;101:109-112.

23. Graziottin A, Vincenti E. Analgesic treatment of intractable pain due to vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: preliminary results with oral gabapentin and anesthetic block of ganglion impar. Poster presented at: International Meeting of the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health; 2002; Vancouver, Canada.

24. Glazer HI, Rodke G, Swencionis C, Hertz R, Young AW. Treatment of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome with electromyographic biofeedback of pelvic floor musculature. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:283-290.

25. Haefner HK, Collins ME, Davis GD, et al. The vulvodynia guideline. J Lower Gen Tract Dis. 2005;9:40-45.

26. Margesson LJ. Inflammatory disorders of the vulva. In: Fisher BK, Margesson LJ, eds. Genital Skin Disorders Diagnosis and Treatment. St Louis: Mosby; 1998:155-157.

27. Haefner HK, Pearlman MD. Diagnosing and managing vulvodynia. Contemp ObGyn. 1999;2:110.-

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

The symptoms are recited every day in gynecologists’ offices around the world: itching, irritation, burning, rawness, pain, dyspareunia. The challenge is tracing these general symptoms to a specific pathology, a task harder than one might expect, because vulvovaginal conditions often represent a complex mix of several problems. Candida and bacterial invasion frequently complicate genital dermatologic conditions. Atrophy and loss of the epithelial barrier worsen the problem. Over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription remedies can lead to contact dermatitis. Vulvodynia may be the ultimate outcome, possibly from central sensitization after chronic inflammation, which in turn can mislead the clinician into thinking appropriate therapy “doesn’t work.” And it is important to remember that any genital complaint has the potential to dampen a woman’s self-esteem and hamper sexual function.

This article covers the fine points of diagnosis and treatment of 4 common vulvovaginal problems:

- Candidiasis

- Contact dermatitis

- Lichen sclerosus

- Vestibulodynia

Could all 4 problems coexist in 1 patient? They frequently do. As always, a careful history and physical examination with appropriate use of yeast cultures make it possible to manage the complexity.

1. CandidiasisTelephone and self-diagnosis are a waste of time

In vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), symptoms can range from none to recurrent. VVC can complicate genital dermatologic conditions and interfere with the treatment of illnesses that call for steroids or antibiotics. Because the symptoms of VVC are nonspecific, diagnosis necessitates consideration of a long list of other potential causes, both infectious and noninfectious.

Candida albicans predominates in 85% to 90% of positive vaginal yeast cultures. Non-albicans species such as C glabrata, parapsilosis, krusei, lusitaniae, and tropicalis are more difficult to treat.

Not all episodes are the same

VVC is uncomplicated when it occurs sporadically or infrequently in a woman in good overall health and involves mild to moderate symptoms; albicans species are likely. VVC is complicated when it is severe or recurrent or occurs in a debilitated, unhealthy, or pregnant woman; non-albicans species often are involved. Proper classification is essential to successful treatment.1

Phone diagnosis is usually inaccurate

Although phone diagnosis is unreliable,2 it is still fairly common, and fewer offices use microscopy and vaginal pH to diagnose vaginal infections because of the tightened (though still simple) requirements of the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment. (Clinicians who do wet mounts and KOH are required to pass a simple test each year to continue the practice.)

Women are poor self-diagnosticians when it comes to Candida infection; only one third of a group purchasing OTC antifungals had accurately identified their condition.3

Clinicians are not exempt from error, either. About 50% of the time, Candida is misdiagnosed,4 largely because of the assumption that the wet mount is more specific than it actually is (it is only 40% specific for Candida).

Ask about sex habits, douching, drugs, and diseases

Accurate diagnosis requires a careful history, focusing on risk factors for Candida: a new sexual partner; oral sex; douching; use of antibiotics, steroids, or exogenous estrogen; and uncontrolled diabetes.

Look for signs of vulvar and vaginal erythema, edema, and excoriation.

Classic “cottage cheese” discharge may not be present, and the amount has no correlation with symptom severity.

Vaginal pH of less than 4.5 excludes bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis, atrophic vaginitis, desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, and vaginal lichen planus.

Blastospores or pseudohyphae are diagnostic (on 10% KOH microscopy). If they are absent, a yeast culture is essential and will allow speciation. A vaginal culture is especially important in women with recurrent or refractory symptoms.

Always consider testing for sexually transmitted diseases.

Azole antifungals are usual treatment

For uncomplicated VVC, azole antifungals are best (TABLE 1). For complicated VVC, follow this therapy with maintenance fluconazole (150 mg weekly for 6 months), which clears Candida in 90.8% of cases.5

Non-albicans infection can be treated with boric acid capsules (inserted vaginally at bedtime for 14 days) or terconazole cream (7 days) or suppositories (3 days). A culture to confirm cure is essential, since non-albicans infection can be difficult to eradicate.

Note that boric acid is not approved for pregnancy.

TABLE 1

CDC guidelines for treatment of candidiasis

Any of these intravaginal or oral regimens may be used

| DOSE (NUMBER OF DAYS) | |

|---|---|

| INTRAVAGINAL AGENTS | |

| Butoconazole | |

| 2% cream* | 5 g (3) |

| Butoconazole-1 sustained-release cream | 5 g (1) |

| Clotrimazole | |

| 1% cream* | 5 g (7–14) |

| 100 mg | 1 tablet (7) |

| 2 tablets (3) | |

| 500 mg | 1 tablet (1) |

| Miconazole | |

| 2% cream* | 5 g (7) |

| 100 mg* | 1 suppository (7) |

| 200 mg* | 1 suppository (3) |

| Nystatin | |

| 100,000 U | 1 tablet (14) |

| Tioconazole | |

| 6.5% ointment* | 5 g (1) |

| Terconazole | |

| 0.4% cream | 5 g (7) |

| 0.8% cream | 5 g (3) |

| 80 mg | 1 suppository (3) |

| ORAL AGENT | |

| Fluconazole | |

| 150 mg | 1 tablet (1) |

| * Over-the-counter | |

2. Contact DermatitisNine essentials of treatment

Contact dermatitis, the most common form of vulvar dermatitis, is inflammation of the skin caused by an external agent that acts as an irritant or allergen. The skin reaction may escape notice because changes ranging from minor to extreme are often superimposed on complex preexisting conditions such as lichen simplex chronicus, lichen planus, and lichen sclerosus.6

Contact dermatitis occurs readily in the vulvar area because the skin of the vulva reacts more intensely to irritants than other skin, and its barrier function is easily weakened by moisture, friction, urine, and vaginal discharge. The 3 main types of irritant dermatitis are7:

- A potent irritant, which may produce the equivalent of a chemical burn.

- A weaker irritant, which may be applied repeatedly before inflammation manifests.

- Stinging and burning, which can occur without detectable skin change, due to chemical exposure.

Many products can cause dermatitis. Even typically harmless products can cause dermatitis if combined with lack of estrogen or use of pads, panty hose, or girdles.

No typical pattern

Patients complain of varying degrees of itching, burning, and irritation. Depending on the agent involved, onset may be sudden or gradual, and the woman may be aware or oblivious of the cause. New reactions to “old” practices or products are also possible.

Ask about personal hygiene, care during menses and after intercourse, and about soap, cleansers, and any product applied to the genital skin, as well as clothing types and exercise habits. Review prescription and OTC products, including topicals, and note which products or actions improve or aggravate symptoms. A history of allergy and atopy should heighten suspicion.

The physical exam may reveal erythema and edema; scaling is possible. Severe cases manifest as erosion, ulceration, or pigment changes. Secondary infection, if any, may involve pustules, crusting, and fissuring. The dermatitis may be localized, but often extends over the area of product spread to the mons, labiocrural folds, and anus. C albicans often complicates genital dermatologic conditions.

9-step treatment

- Stop the offending product and/or practices.

- Restore the skin barrier with sitz baths in plain lukewarm water for 5 to 10 minutes twice daily. Compresses or a handheld shower are alternatives.

- Provide moisture. After hydration, have the patient pat dry and apply a thin film of plain petrolatum.

- Replace local estrogen if necessary.

- Control any concomitant Candida with oral fluconazole 150 mg weekly, avoiding the potential irritation caused by topical antifungals.

- Treat itching and scratching with cool gel packs from the refrigerator, not the freezer (frozen packs can burn). Stop involuntary nighttime scratching with sedation: doxepin or hydroxyzine (10–75 mg at 6 PM).

- Use topical steroids for dermatitis:

- Moderate: Triamcinolone, 0.1% ointment twice daily.

- Severe: A super-potent steroid such as clobetasol, 0.05% ointment, twice daily for 1 to 3 weeks.

- Extreme: Burst and taper prednisone (0.5–1 mg/kg/day decreased over 14–21 days) or a single dose of intramuscular triamcinolone (1 mg/kg).

- Order patch testing to rule out or define allergens.

- Educate the patient about the many potential causes of dermatitis, to prevent recurrence.

CAUSTIC AGENTS

Bichloracetic acid

Trichloroacetic acid

5-Fluorouracil

Lye (in soap)

Phenol

Podophyllin

Sodium hypochlorite

Solvents

WEAK CUMULATIVE IRRITANTS

Alcohol

Deodorants

Diapers

Feces

Feminine spray

Pads

Perfume

Povidone iodine

Powders

Propylene glycol

Semen

Soap

Sweat

Urine

Vaginal secretions

Water

Wipes

PHYSICALLY ABRASIVE CONTACTANTS

Face cloths

Sponges

THERMAL IRRITANTS

Hot water bottles

Hair dryers

Source: Lynette Margesson,MD26

FIGURE 1 A mutilating disease of mysterious origin

Though lichen sclerosus is a disfiguring disease, the intensity of symptoms does not necessarily correlate with clinical appearance. Generally, the first change is (A) whitening of an irregular area on the labia, near the clitoris, on the perineum, and/or other vulvar areas. In some cases (A and B), inflammation can alter the anatomy of the vulva by flattening the labia minora, fusing the hood over the clitoris, effectively burying it beneath the skin, and shrinking the skin around the vaginal opening. Images courtesy Lynette Margesson, MD

3. Lichen SclerosusLifelong follow-up is a must

Although it has long been described in medical journals and textbooks, information on lichen sclerosus was often unreliable until recently, and adequate treatment guidelines were lacking. The cause still has not been fully elucidated, but a wealth of information now allows for considerable expertise in the management of this disease.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory and scarring disease that preferentially affects the anogenital area and is 6 to 10 times more prevalent in women than men.8 Any cutaneous site may also be affected, but the vagina is never involved.

Infection? Autoimmunity? An infectious cause has been proposed but never proven. In some women, an autoimmune component is recognized: Immunoglobulin G antibodies to extracellular matrix protein I have been found in 67% of patients with lichen sclerosus, but whether these antibodies are secondary or pathogenic is unclear.9 A genetic component is suggested by the association with autoimmunity and by the link with human leukocyte antigen DQ7 in women10 and girls.11

Affects 1.7%, or 1 in 60 women.12 In females, lichen sclerosus peaks in 2 populations: prepubertal girls and postmenopausal women.

No remission after age 70. Although remission of the disease has been reported, a recent study concluded that lichen sclerosus never remits after the age of 70; the average length of remission is 4.7 years, although this figure is still in question.13 Only close follow-up can determine if disease is in remission.

Main symptom is itching

Pruritus is the most common symptom, but dysuria and a sore or burning sensation have also been reported. Some women have no symptoms. When erosions, fissures, or introital narrowing are present, dyspareunia may also occur.

Typical lesions are porcelain-white papules and plaques, often with areas of fissuring or ecchymosis on the vulva or extending around the anus in a figure-of-8 pattern.

Both lichen sclerosus and lichen planus may be seen on the same vulva.

Squamous cell carcinoma can arise in anogenital lichen sclerosus; risk is thought to be 5%. Instruct women in regular self-examination because carcinoma can arise between annual or semiannual visits.

Ultrapotent steroids: Good control, but risk of malignancy persists

Renaud-Vilmer C, Cavalier-Balloy B, Porcher R, Dubertret L. Vulvar lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:709-712.

If we gynecologists have been assuming that lichen sclerosus is one of those nebulous, little-explored diseases out there, we need to think again. Lichen sclerosus is a chronic and mutilating condition, an obstacle to quality of life, a threat to body image, a destroyer of sexual function, and a risk for malignancy.

Cancer developed only in untreated or irregularly treated lesions

In a key study, Renaud-Vilmer and colleagues13 explored remission and recurrence rates after treatment with 0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment, as well as whether the treatment reduces risk of malignant evolution. They determined that the rate of clinical and histologic remission is related to age. Although 72% of women under age 50 had complete remission, only 23% of women between 50 and 70 years of age had complete remission, and none of the women older than 70 did. Relapse was noted in most women over time (50% by 18 months), and 9.6% of women were later diagnosed with invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

Although we have known since 1988 that ultrapotent steroids offer outstanding relief of symptoms and some control over the disease, the optimal length of treatment has never been clear. The prospective study by Renaud-Vilmer et al has impressive power that derives from its 20-year duration. They demonstrated that ultrapotent steroids do not cure lichen sclerosus in women over 70. Complete remission in younger women is only temporary, and steroid therapy offers no significant reduction in the risk of vulvar cancer—although carcinoma developed only in untreated or irregularly treated lesions.

Histologic and clinical findings were used to judge efficacy. Because only 83 women were studied, the cohort is too small for the findings on carcinoma to be significant, but the authors emphasized that lifelong follow-up is necessary in all cases.

Lichen sclerosus never backs down after menopause

In more than 15 years of vulvovaginal specialization, I have found similar results. Older women detest the need to apply topicals to the genital area, but they are the ones who need ongoing use, because the disease never backs down after menopause.

I follow a cohort of young women in whom I detected early disease. Their clinical signs regressed and scarring was prevented by steroid treatment, but disease recurrence appears to be inevitable: The longest remission has been just over 4 years.

I have seen cancer arise quickly even in closely supervised patients, although many cases of squamous cell carcinoma have occurred in women with undetected or poorly treated disease.

Use tacrolimus with caution

Although small trials have produced some enthusiasm for therapeutic use of tacrolimus, treatment should proceed with extreme caution, as the drug inhibits an arm of the immune system and women with lichen sclerosus are at risk for malignancy. The agent now carries a warning based on the development of malignancy in animals.

Consider treatment even without biopsy proof

Although a biopsy generally makes the diagnosis, treatment should be considered even in the face of an inconclusive or negative finding if the clinician suspects that lichen sclerosus is present. The reason treatment should proceed in these cases: Loss of the labia or fusion over the clitoris can occur if the disease progresses, as shown in the photos on page.

Powerful corticosteroids are treatment of choice

Treatment can control lichen sclerosus, relieve symptoms, and prevent further anatomical changes. Potent or ultrapotent topical corticosteroids in an ointment base are preferred. These drugs are now widely recognized for their efficacy and minimal adverse effects, although no regimen is universally advocated.14 The patient applies ointment once daily for 1 to 3 months, depending on severity, and then once or twice a week.

Ointments are preferred over creams for vulvar treatment, because creams frequently contain allergens or irritants such as fragrance and propylene glycol preservative.

I continue once-weekly therapy indefinitely in postmenopausal women. If a premenopausal woman is not comfortable using the ointment indefinitely, I will allow her to discontinue treatment but follow her every 3 to 6 months.

Treatment also requires educating the patient about the disease, instructing her in gentle local care, and showing her exactly where to apply the ointment.

In all cases, lifelong follow-up is necessary. Hyperkeratosis, ecchymoses, fissuring, and erosions resolve, but atrophy and color change remain. Scarring usually remains unchanged, but may resolve if treated early in the course of the disease.15

Testosterone is not as effective as an ultrapotent steroid,16 and is no more effective than an emollient.17

Estrogen is valuable for skin integrity, but has no role in the treatment of lichen sclerosus.

Dilator work may be necessary for dyspareunia, once the disease is controlled.

Refer for help with depression and/or negative body image, if present.

4. VestibulodyniaEight treatment options to try

The prevalence of pain in an ethnically diverse population is 16%, and approximately half of this figure (8%) represents vulvodynia.18 The International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease now classifies vulvar pain in 3 categories:

- vulvar pain with a known cause, including infection, trauma, and systemic disease (TABLE 2),

- generalized vulvodynia, also known as dysesthetic vulvodynia, essential vulvodynia, or pudendal neuralgia, and

- localized vulvodynia or vestibulodynia, formerly called vestibulitis, vulvar vestibulitis syndrome, and vestibular adenitis.

Terminology is likely to evolve with further study.

Vestibulodynia, the leading cause of dyspareunia in women under age 50,19 refers to pain on touch within the vestibule. It is primary pain if it has been present since the first tampon use or sexual experience, and it is secondary if it arises after a period of comfortable sexual function.

TABLE 2

Rule out these known causes of vulvar pain

| INFECTIONS |

|

| TRAUMA |

|

| SYSTEMIC DISEASE |

|

| CANCER AND PRE-CANCER |

|

| IRRITANTS |

|

| SKIN CONDITIONS |

|

| Source: Haefner and Pearlman27 |

Inflammation starts the cascade

Current theory suggests that inflammatory events such as yeast infection, seminal plasma allergy, and local chemical application release a cascade of cytokines that sensitizes nociceptors in the vestibular epithelium. Prolonged neural firing in turn alters neurons in the dorsal horn, allowing sensitization of mechanoreceptive fibers in the vestibule with sensory allodynia (pain on touch). The proliferation of introital nociceptive fibers is well documented.20

Diagnosis: Report of pain and a positive Q-tip test

When a woman reports superficial dyspareunia with introital contact and clinical examination reveals pain on touch in the vestibule (using a cotton swab), vestibulodynia is diagnosed, provided no other known causes of the vulvar pain are detected during a careful history and examination or after pH measurement, a wet mount, and any indicated cultures.

A careful psychosexual history can help the clinician identify current sexual practices, prior sexual issues, and the impact of the current sexual dysfunction with an eye toward guiding support and counseling.

Multifactorial treatment: 8 options

Because the cause of vestibulodynia is unclear, a multifactorial approach generally is accepted and involves the following:

- Patient education about the problem and instruction in gentle local care and the elimination of contactants.

- Referral for support, counseling, and treatment of depression, as indicated.

- Elimination of any known trigger such as C albicans, although this generally does not lead to remission unless the pain is also treated.

- Suppression of nociceptor afferent input using topical lidocaine hydrochloride, for which good results have been reported.21

- Systemic oral analgesia with a tricyclic antidepressant modulates the serotonin and epinephrine imbalance associated with persistent pain (TABLE 3).22

- Use of anticonvulsants such as gabapentin to increase the amount of stimuli needed for nerves to fire and elevate the central pain threshold.23

- Reduction of muscle tension and spasm in the pelvic floor, using physical therapy and biofeedback.24

- When medical management fails, vulvar vestibulectomy with vaginal advancement yields excellent long-term results,25 but should be a last resort.

TABLE 3

Tricyclic antidepressants modify chemical imbalance associated with persistent pain of vestibulodynia

| Names of standard agents used | Amitriptyline (Elavil) |

| Nortriptyline (Aventyl, Pamelor) | |

| Desipramine (Norpramin) | |

| Imipramine (Tofranil) | |

| Standard dosing | Start with 10 mg; increase by 10 mg weekly to 100–150 mg |

| Side effects | Sedation, often transient |

| Constipation, must be actively managed | |

| Dry mouth | |

| Palpitations, tachycardia | |

| Sun sensitivity | |

| Cautions | Obtain EKG over 50 years or with cardiac history |

| Contraindicated in glaucoma | |

| Levels must be monitored if combined with SSRI | |

| Success | Slow change over 6–12 months in sensitivity to touch; ability to use tampon. Minimal pain with dilator use, penetration |

| Failure | Over 3 months at max dose without any improvement |

The symptoms are recited every day in gynecologists’ offices around the world: itching, irritation, burning, rawness, pain, dyspareunia. The challenge is tracing these general symptoms to a specific pathology, a task harder than one might expect, because vulvovaginal conditions often represent a complex mix of several problems. Candida and bacterial invasion frequently complicate genital dermatologic conditions. Atrophy and loss of the epithelial barrier worsen the problem. Over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription remedies can lead to contact dermatitis. Vulvodynia may be the ultimate outcome, possibly from central sensitization after chronic inflammation, which in turn can mislead the clinician into thinking appropriate therapy “doesn’t work.” And it is important to remember that any genital complaint has the potential to dampen a woman’s self-esteem and hamper sexual function.

This article covers the fine points of diagnosis and treatment of 4 common vulvovaginal problems:

- Candidiasis

- Contact dermatitis

- Lichen sclerosus

- Vestibulodynia

Could all 4 problems coexist in 1 patient? They frequently do. As always, a careful history and physical examination with appropriate use of yeast cultures make it possible to manage the complexity.

1. CandidiasisTelephone and self-diagnosis are a waste of time

In vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), symptoms can range from none to recurrent. VVC can complicate genital dermatologic conditions and interfere with the treatment of illnesses that call for steroids or antibiotics. Because the symptoms of VVC are nonspecific, diagnosis necessitates consideration of a long list of other potential causes, both infectious and noninfectious.

Candida albicans predominates in 85% to 90% of positive vaginal yeast cultures. Non-albicans species such as C glabrata, parapsilosis, krusei, lusitaniae, and tropicalis are more difficult to treat.

Not all episodes are the same

VVC is uncomplicated when it occurs sporadically or infrequently in a woman in good overall health and involves mild to moderate symptoms; albicans species are likely. VVC is complicated when it is severe or recurrent or occurs in a debilitated, unhealthy, or pregnant woman; non-albicans species often are involved. Proper classification is essential to successful treatment.1

Phone diagnosis is usually inaccurate

Although phone diagnosis is unreliable,2 it is still fairly common, and fewer offices use microscopy and vaginal pH to diagnose vaginal infections because of the tightened (though still simple) requirements of the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment. (Clinicians who do wet mounts and KOH are required to pass a simple test each year to continue the practice.)

Women are poor self-diagnosticians when it comes to Candida infection; only one third of a group purchasing OTC antifungals had accurately identified their condition.3

Clinicians are not exempt from error, either. About 50% of the time, Candida is misdiagnosed,4 largely because of the assumption that the wet mount is more specific than it actually is (it is only 40% specific for Candida).

Ask about sex habits, douching, drugs, and diseases

Accurate diagnosis requires a careful history, focusing on risk factors for Candida: a new sexual partner; oral sex; douching; use of antibiotics, steroids, or exogenous estrogen; and uncontrolled diabetes.

Look for signs of vulvar and vaginal erythema, edema, and excoriation.

Classic “cottage cheese” discharge may not be present, and the amount has no correlation with symptom severity.

Vaginal pH of less than 4.5 excludes bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis, atrophic vaginitis, desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, and vaginal lichen planus.

Blastospores or pseudohyphae are diagnostic (on 10% KOH microscopy). If they are absent, a yeast culture is essential and will allow speciation. A vaginal culture is especially important in women with recurrent or refractory symptoms.

Always consider testing for sexually transmitted diseases.

Azole antifungals are usual treatment

For uncomplicated VVC, azole antifungals are best (TABLE 1). For complicated VVC, follow this therapy with maintenance fluconazole (150 mg weekly for 6 months), which clears Candida in 90.8% of cases.5

Non-albicans infection can be treated with boric acid capsules (inserted vaginally at bedtime for 14 days) or terconazole cream (7 days) or suppositories (3 days). A culture to confirm cure is essential, since non-albicans infection can be difficult to eradicate.

Note that boric acid is not approved for pregnancy.

TABLE 1

CDC guidelines for treatment of candidiasis

Any of these intravaginal or oral regimens may be used

| DOSE (NUMBER OF DAYS) | |

|---|---|

| INTRAVAGINAL AGENTS | |

| Butoconazole | |

| 2% cream* | 5 g (3) |

| Butoconazole-1 sustained-release cream | 5 g (1) |

| Clotrimazole | |

| 1% cream* | 5 g (7–14) |

| 100 mg | 1 tablet (7) |

| 2 tablets (3) | |

| 500 mg | 1 tablet (1) |

| Miconazole | |

| 2% cream* | 5 g (7) |

| 100 mg* | 1 suppository (7) |

| 200 mg* | 1 suppository (3) |

| Nystatin | |

| 100,000 U | 1 tablet (14) |

| Tioconazole | |

| 6.5% ointment* | 5 g (1) |

| Terconazole | |

| 0.4% cream | 5 g (7) |

| 0.8% cream | 5 g (3) |

| 80 mg | 1 suppository (3) |

| ORAL AGENT | |

| Fluconazole | |

| 150 mg | 1 tablet (1) |

| * Over-the-counter | |

2. Contact DermatitisNine essentials of treatment

Contact dermatitis, the most common form of vulvar dermatitis, is inflammation of the skin caused by an external agent that acts as an irritant or allergen. The skin reaction may escape notice because changes ranging from minor to extreme are often superimposed on complex preexisting conditions such as lichen simplex chronicus, lichen planus, and lichen sclerosus.6

Contact dermatitis occurs readily in the vulvar area because the skin of the vulva reacts more intensely to irritants than other skin, and its barrier function is easily weakened by moisture, friction, urine, and vaginal discharge. The 3 main types of irritant dermatitis are7:

- A potent irritant, which may produce the equivalent of a chemical burn.

- A weaker irritant, which may be applied repeatedly before inflammation manifests.

- Stinging and burning, which can occur without detectable skin change, due to chemical exposure.

Many products can cause dermatitis. Even typically harmless products can cause dermatitis if combined with lack of estrogen or use of pads, panty hose, or girdles.

No typical pattern

Patients complain of varying degrees of itching, burning, and irritation. Depending on the agent involved, onset may be sudden or gradual, and the woman may be aware or oblivious of the cause. New reactions to “old” practices or products are also possible.

Ask about personal hygiene, care during menses and after intercourse, and about soap, cleansers, and any product applied to the genital skin, as well as clothing types and exercise habits. Review prescription and OTC products, including topicals, and note which products or actions improve or aggravate symptoms. A history of allergy and atopy should heighten suspicion.

The physical exam may reveal erythema and edema; scaling is possible. Severe cases manifest as erosion, ulceration, or pigment changes. Secondary infection, if any, may involve pustules, crusting, and fissuring. The dermatitis may be localized, but often extends over the area of product spread to the mons, labiocrural folds, and anus. C albicans often complicates genital dermatologic conditions.

9-step treatment

- Stop the offending product and/or practices.

- Restore the skin barrier with sitz baths in plain lukewarm water for 5 to 10 minutes twice daily. Compresses or a handheld shower are alternatives.

- Provide moisture. After hydration, have the patient pat dry and apply a thin film of plain petrolatum.

- Replace local estrogen if necessary.

- Control any concomitant Candida with oral fluconazole 150 mg weekly, avoiding the potential irritation caused by topical antifungals.

- Treat itching and scratching with cool gel packs from the refrigerator, not the freezer (frozen packs can burn). Stop involuntary nighttime scratching with sedation: doxepin or hydroxyzine (10–75 mg at 6 PM).

- Use topical steroids for dermatitis:

- Moderate: Triamcinolone, 0.1% ointment twice daily.

- Severe: A super-potent steroid such as clobetasol, 0.05% ointment, twice daily for 1 to 3 weeks.

- Extreme: Burst and taper prednisone (0.5–1 mg/kg/day decreased over 14–21 days) or a single dose of intramuscular triamcinolone (1 mg/kg).

- Order patch testing to rule out or define allergens.

- Educate the patient about the many potential causes of dermatitis, to prevent recurrence.

CAUSTIC AGENTS

Bichloracetic acid

Trichloroacetic acid

5-Fluorouracil

Lye (in soap)

Phenol

Podophyllin

Sodium hypochlorite

Solvents

WEAK CUMULATIVE IRRITANTS

Alcohol

Deodorants

Diapers

Feces

Feminine spray

Pads

Perfume

Povidone iodine

Powders

Propylene glycol

Semen

Soap

Sweat

Urine

Vaginal secretions

Water

Wipes

PHYSICALLY ABRASIVE CONTACTANTS

Face cloths

Sponges

THERMAL IRRITANTS

Hot water bottles

Hair dryers

Source: Lynette Margesson,MD26

FIGURE 1 A mutilating disease of mysterious origin

Though lichen sclerosus is a disfiguring disease, the intensity of symptoms does not necessarily correlate with clinical appearance. Generally, the first change is (A) whitening of an irregular area on the labia, near the clitoris, on the perineum, and/or other vulvar areas. In some cases (A and B), inflammation can alter the anatomy of the vulva by flattening the labia minora, fusing the hood over the clitoris, effectively burying it beneath the skin, and shrinking the skin around the vaginal opening. Images courtesy Lynette Margesson, MD

3. Lichen SclerosusLifelong follow-up is a must

Although it has long been described in medical journals and textbooks, information on lichen sclerosus was often unreliable until recently, and adequate treatment guidelines were lacking. The cause still has not been fully elucidated, but a wealth of information now allows for considerable expertise in the management of this disease.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory and scarring disease that preferentially affects the anogenital area and is 6 to 10 times more prevalent in women than men.8 Any cutaneous site may also be affected, but the vagina is never involved.

Infection? Autoimmunity? An infectious cause has been proposed but never proven. In some women, an autoimmune component is recognized: Immunoglobulin G antibodies to extracellular matrix protein I have been found in 67% of patients with lichen sclerosus, but whether these antibodies are secondary or pathogenic is unclear.9 A genetic component is suggested by the association with autoimmunity and by the link with human leukocyte antigen DQ7 in women10 and girls.11

Affects 1.7%, or 1 in 60 women.12 In females, lichen sclerosus peaks in 2 populations: prepubertal girls and postmenopausal women.

No remission after age 70. Although remission of the disease has been reported, a recent study concluded that lichen sclerosus never remits after the age of 70; the average length of remission is 4.7 years, although this figure is still in question.13 Only close follow-up can determine if disease is in remission.

Main symptom is itching

Pruritus is the most common symptom, but dysuria and a sore or burning sensation have also been reported. Some women have no symptoms. When erosions, fissures, or introital narrowing are present, dyspareunia may also occur.

Typical lesions are porcelain-white papules and plaques, often with areas of fissuring or ecchymosis on the vulva or extending around the anus in a figure-of-8 pattern.

Both lichen sclerosus and lichen planus may be seen on the same vulva.

Squamous cell carcinoma can arise in anogenital lichen sclerosus; risk is thought to be 5%. Instruct women in regular self-examination because carcinoma can arise between annual or semiannual visits.

Ultrapotent steroids: Good control, but risk of malignancy persists

Renaud-Vilmer C, Cavalier-Balloy B, Porcher R, Dubertret L. Vulvar lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:709-712.

If we gynecologists have been assuming that lichen sclerosus is one of those nebulous, little-explored diseases out there, we need to think again. Lichen sclerosus is a chronic and mutilating condition, an obstacle to quality of life, a threat to body image, a destroyer of sexual function, and a risk for malignancy.

Cancer developed only in untreated or irregularly treated lesions

In a key study, Renaud-Vilmer and colleagues13 explored remission and recurrence rates after treatment with 0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment, as well as whether the treatment reduces risk of malignant evolution. They determined that the rate of clinical and histologic remission is related to age. Although 72% of women under age 50 had complete remission, only 23% of women between 50 and 70 years of age had complete remission, and none of the women older than 70 did. Relapse was noted in most women over time (50% by 18 months), and 9.6% of women were later diagnosed with invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

Although we have known since 1988 that ultrapotent steroids offer outstanding relief of symptoms and some control over the disease, the optimal length of treatment has never been clear. The prospective study by Renaud-Vilmer et al has impressive power that derives from its 20-year duration. They demonstrated that ultrapotent steroids do not cure lichen sclerosus in women over 70. Complete remission in younger women is only temporary, and steroid therapy offers no significant reduction in the risk of vulvar cancer—although carcinoma developed only in untreated or irregularly treated lesions.

Histologic and clinical findings were used to judge efficacy. Because only 83 women were studied, the cohort is too small for the findings on carcinoma to be significant, but the authors emphasized that lifelong follow-up is necessary in all cases.

Lichen sclerosus never backs down after menopause

In more than 15 years of vulvovaginal specialization, I have found similar results. Older women detest the need to apply topicals to the genital area, but they are the ones who need ongoing use, because the disease never backs down after menopause.

I follow a cohort of young women in whom I detected early disease. Their clinical signs regressed and scarring was prevented by steroid treatment, but disease recurrence appears to be inevitable: The longest remission has been just over 4 years.

I have seen cancer arise quickly even in closely supervised patients, although many cases of squamous cell carcinoma have occurred in women with undetected or poorly treated disease.

Use tacrolimus with caution

Although small trials have produced some enthusiasm for therapeutic use of tacrolimus, treatment should proceed with extreme caution, as the drug inhibits an arm of the immune system and women with lichen sclerosus are at risk for malignancy. The agent now carries a warning based on the development of malignancy in animals.

Consider treatment even without biopsy proof

Although a biopsy generally makes the diagnosis, treatment should be considered even in the face of an inconclusive or negative finding if the clinician suspects that lichen sclerosus is present. The reason treatment should proceed in these cases: Loss of the labia or fusion over the clitoris can occur if the disease progresses, as shown in the photos on page.

Powerful corticosteroids are treatment of choice

Treatment can control lichen sclerosus, relieve symptoms, and prevent further anatomical changes. Potent or ultrapotent topical corticosteroids in an ointment base are preferred. These drugs are now widely recognized for their efficacy and minimal adverse effects, although no regimen is universally advocated.14 The patient applies ointment once daily for 1 to 3 months, depending on severity, and then once or twice a week.

Ointments are preferred over creams for vulvar treatment, because creams frequently contain allergens or irritants such as fragrance and propylene glycol preservative.

I continue once-weekly therapy indefinitely in postmenopausal women. If a premenopausal woman is not comfortable using the ointment indefinitely, I will allow her to discontinue treatment but follow her every 3 to 6 months.

Treatment also requires educating the patient about the disease, instructing her in gentle local care, and showing her exactly where to apply the ointment.

In all cases, lifelong follow-up is necessary. Hyperkeratosis, ecchymoses, fissuring, and erosions resolve, but atrophy and color change remain. Scarring usually remains unchanged, but may resolve if treated early in the course of the disease.15

Testosterone is not as effective as an ultrapotent steroid,16 and is no more effective than an emollient.17

Estrogen is valuable for skin integrity, but has no role in the treatment of lichen sclerosus.

Dilator work may be necessary for dyspareunia, once the disease is controlled.

Refer for help with depression and/or negative body image, if present.

4. VestibulodyniaEight treatment options to try

The prevalence of pain in an ethnically diverse population is 16%, and approximately half of this figure (8%) represents vulvodynia.18 The International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease now classifies vulvar pain in 3 categories:

- vulvar pain with a known cause, including infection, trauma, and systemic disease (TABLE 2),

- generalized vulvodynia, also known as dysesthetic vulvodynia, essential vulvodynia, or pudendal neuralgia, and

- localized vulvodynia or vestibulodynia, formerly called vestibulitis, vulvar vestibulitis syndrome, and vestibular adenitis.

Terminology is likely to evolve with further study.

Vestibulodynia, the leading cause of dyspareunia in women under age 50,19 refers to pain on touch within the vestibule. It is primary pain if it has been present since the first tampon use or sexual experience, and it is secondary if it arises after a period of comfortable sexual function.

TABLE 2

Rule out these known causes of vulvar pain

| INFECTIONS |

|

| TRAUMA |

|

| SYSTEMIC DISEASE |

|

| CANCER AND PRE-CANCER |

|

| IRRITANTS |

|

| SKIN CONDITIONS |

|

| Source: Haefner and Pearlman27 |

Inflammation starts the cascade

Current theory suggests that inflammatory events such as yeast infection, seminal plasma allergy, and local chemical application release a cascade of cytokines that sensitizes nociceptors in the vestibular epithelium. Prolonged neural firing in turn alters neurons in the dorsal horn, allowing sensitization of mechanoreceptive fibers in the vestibule with sensory allodynia (pain on touch). The proliferation of introital nociceptive fibers is well documented.20

Diagnosis: Report of pain and a positive Q-tip test

When a woman reports superficial dyspareunia with introital contact and clinical examination reveals pain on touch in the vestibule (using a cotton swab), vestibulodynia is diagnosed, provided no other known causes of the vulvar pain are detected during a careful history and examination or after pH measurement, a wet mount, and any indicated cultures.

A careful psychosexual history can help the clinician identify current sexual practices, prior sexual issues, and the impact of the current sexual dysfunction with an eye toward guiding support and counseling.

Multifactorial treatment: 8 options

Because the cause of vestibulodynia is unclear, a multifactorial approach generally is accepted and involves the following:

- Patient education about the problem and instruction in gentle local care and the elimination of contactants.

- Referral for support, counseling, and treatment of depression, as indicated.

- Elimination of any known trigger such as C albicans, although this generally does not lead to remission unless the pain is also treated.

- Suppression of nociceptor afferent input using topical lidocaine hydrochloride, for which good results have been reported.21

- Systemic oral analgesia with a tricyclic antidepressant modulates the serotonin and epinephrine imbalance associated with persistent pain (TABLE 3).22

- Use of anticonvulsants such as gabapentin to increase the amount of stimuli needed for nerves to fire and elevate the central pain threshold.23

- Reduction of muscle tension and spasm in the pelvic floor, using physical therapy and biofeedback.24

- When medical management fails, vulvar vestibulectomy with vaginal advancement yields excellent long-term results,25 but should be a last resort.

TABLE 3

Tricyclic antidepressants modify chemical imbalance associated with persistent pain of vestibulodynia

| Names of standard agents used | Amitriptyline (Elavil) |

| Nortriptyline (Aventyl, Pamelor) | |

| Desipramine (Norpramin) | |

| Imipramine (Tofranil) | |

| Standard dosing | Start with 10 mg; increase by 10 mg weekly to 100–150 mg |

| Side effects | Sedation, often transient |

| Constipation, must be actively managed | |

| Dry mouth | |

| Palpitations, tachycardia | |

| Sun sensitivity | |

| Cautions | Obtain EKG over 50 years or with cardiac history |

| Contraindicated in glaucoma | |

| Levels must be monitored if combined with SSRI | |

| Success | Slow change over 6–12 months in sensitivity to touch; ability to use tampon. Minimal pain with dilator use, penetration |

| Failure | Over 3 months at max dose without any improvement |

1. Sobel JD, Faro S, Force RW, et al. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: epidemiologic, diagnostic, and therapeutic considerations. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:203-211.

2. Spinollo A, Pizzoli G, Colonna L, Nicola S, DeSeta F, Guashino S. Epidemiologic characteristics of women with idiopathic recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:14-17.

3. Ferris DG, Nyirjesy P, Sobel JD, Soper D, Pavletic A, Litaker MS. Over-the-counter antifungal drug misuse associated with patient-diagnosed vulvovaginal candidiasis. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:419-425.

4. Ledger WJ, Polaneczky MM, Yih MC. Difficulties in the diagnosis of Candida vaginitis. Inf Dis Clin Pract. 2000;9:66-69.

5. Sobel JD, Wiesenfeld HC, Martens M, et al. Maintenance fluconazole therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2004;35:876-883.

6. Margesson LJ. Contact dermatitis of the vulva. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:20-27.

7. Kamarashev JA, Vassileva SG. Dermatologic diseases of the vulva. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:53-65.

8. Powell J, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

9. Oyama N, Chan I, Neill SM, et al. Autoantibodies to extracellular matrix protein 1 in lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 2003;362:118-213.

10. Marren P, Yell J, Charnock FM, Bunce M, Welsh K, Wojnarowska F. The association between lichen sclerosus and antigens of the HLA system. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:197-203.

11. Powell J, Wojnarowska F, Winsey S, Marren P, Welsh K. Lichen sclerosus premenarche: autoimmunity and immunogenetics. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:481-484.

12. Goldstein AT, Marinoff SC, Cristopher K, Srodon M. Prevalence of vulvar lichen sclerosus in a general gynecology practice. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:477-480.

13. Renaud-Vilmer C, Cavalier-Balloy B, Porcher R, Dubertret L. Vulvar lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:709-712.

14. Dalziel KL, Millard PR, Wojnarowska F. The treatment of vulval lichen sclerosus with a very potent topical steroid (clobetasol propionate 0.05%) cream. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:461-464.

15. Cooper SM, Gao XH, Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Does treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus influence its prognosis? Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:702-706.

16. Bornstein J, Heifetz S, Kellner Y, et al. Clobetasol dipropionate 0.05% versus 2% testosterone application for severe vulvar lichen sclerosus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:80-84.

17. Sideri M, Origoni M, Spinaci L, Ferrari A. Topical testosterone in the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1994;46:53-56.

18. Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58:82-88.

19. Meana M, Binik YM, Khalife S, et al. Biopsychosocial profile of women with dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:583-589.

20. Bohm-Starke N, Hilliges M, Falconer C, Rylander E. Neurochemical characterization of the vestibular nerves in women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1999;48:270-275.

21. Zolnoun DA, Hartmann KE, Steege JF. Overnight 5% lidocaine ointment for treatment of vulvar vestibulitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:84-87.

22. Mariani L. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: an overview of nonsurgical treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;101:109-112.

23. Graziottin A, Vincenti E. Analgesic treatment of intractable pain due to vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: preliminary results with oral gabapentin and anesthetic block of ganglion impar. Poster presented at: International Meeting of the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health; 2002; Vancouver, Canada.

24. Glazer HI, Rodke G, Swencionis C, Hertz R, Young AW. Treatment of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome with electromyographic biofeedback of pelvic floor musculature. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:283-290.

25. Haefner HK, Collins ME, Davis GD, et al. The vulvodynia guideline. J Lower Gen Tract Dis. 2005;9:40-45.

26. Margesson LJ. Inflammatory disorders of the vulva. In: Fisher BK, Margesson LJ, eds. Genital Skin Disorders Diagnosis and Treatment. St Louis: Mosby; 1998:155-157.

27. Haefner HK, Pearlman MD. Diagnosing and managing vulvodynia. Contemp ObGyn. 1999;2:110.-

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Sobel JD, Faro S, Force RW, et al. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: epidemiologic, diagnostic, and therapeutic considerations. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:203-211.

2. Spinollo A, Pizzoli G, Colonna L, Nicola S, DeSeta F, Guashino S. Epidemiologic characteristics of women with idiopathic recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:14-17.

3. Ferris DG, Nyirjesy P, Sobel JD, Soper D, Pavletic A, Litaker MS. Over-the-counter antifungal drug misuse associated with patient-diagnosed vulvovaginal candidiasis. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:419-425.

4. Ledger WJ, Polaneczky MM, Yih MC. Difficulties in the diagnosis of Candida vaginitis. Inf Dis Clin Pract. 2000;9:66-69.

5. Sobel JD, Wiesenfeld HC, Martens M, et al. Maintenance fluconazole therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2004;35:876-883.

6. Margesson LJ. Contact dermatitis of the vulva. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:20-27.

7. Kamarashev JA, Vassileva SG. Dermatologic diseases of the vulva. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:53-65.

8. Powell J, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

9. Oyama N, Chan I, Neill SM, et al. Autoantibodies to extracellular matrix protein 1 in lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 2003;362:118-213.

10. Marren P, Yell J, Charnock FM, Bunce M, Welsh K, Wojnarowska F. The association between lichen sclerosus and antigens of the HLA system. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:197-203.

11. Powell J, Wojnarowska F, Winsey S, Marren P, Welsh K. Lichen sclerosus premenarche: autoimmunity and immunogenetics. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:481-484.

12. Goldstein AT, Marinoff SC, Cristopher K, Srodon M. Prevalence of vulvar lichen sclerosus in a general gynecology practice. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:477-480.

13. Renaud-Vilmer C, Cavalier-Balloy B, Porcher R, Dubertret L. Vulvar lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:709-712.

14. Dalziel KL, Millard PR, Wojnarowska F. The treatment of vulval lichen sclerosus with a very potent topical steroid (clobetasol propionate 0.05%) cream. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:461-464.

15. Cooper SM, Gao XH, Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Does treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus influence its prognosis? Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:702-706.

16. Bornstein J, Heifetz S, Kellner Y, et al. Clobetasol dipropionate 0.05% versus 2% testosterone application for severe vulvar lichen sclerosus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:80-84.

17. Sideri M, Origoni M, Spinaci L, Ferrari A. Topical testosterone in the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1994;46:53-56.

18. Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58:82-88.

19. Meana M, Binik YM, Khalife S, et al. Biopsychosocial profile of women with dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:583-589.

20. Bohm-Starke N, Hilliges M, Falconer C, Rylander E. Neurochemical characterization of the vestibular nerves in women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1999;48:270-275.

21. Zolnoun DA, Hartmann KE, Steege JF. Overnight 5% lidocaine ointment for treatment of vulvar vestibulitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:84-87.

22. Mariani L. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: an overview of nonsurgical treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;101:109-112.