User login

Reactivation of a BCG Vaccination Scar Following the First Dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in notable morbidity and mortality worldwide. In December 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization for 2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines—produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna—for the prevention of COVID-19. Phase 3 trials of the vaccine developed by Moderna showed 94.1% efficacy at preventing COVID-19 after 2 doses.1

Common cutaneous adverse effects of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine include injection-site reactions, such as pain, induration, and erythema. Less frequently reported dermatologic adverse effects include diffuse bullous rash and hypersensitivity reactions.1 We report a case of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar after the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine.

Case Report

A 48-year-old Asian man who was otherwise healthy presented with erythema, induration, and mild pruritus on the deltoid muscle of the left arm, near the scar from an earlier BCG vaccine, which he received at approximately 5 years of age when living in Taiwan. The patient received the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine approximately 5 to 7 cm distant from the BCG vaccination scar. One to 2 days after inoculation, the patient endorsed tenderness at the site of COVID-19 vaccination but denied systemic symptoms. He had never been given a diagnosis of COVID-19. His SARS-CoV-2 antibody status was unknown.

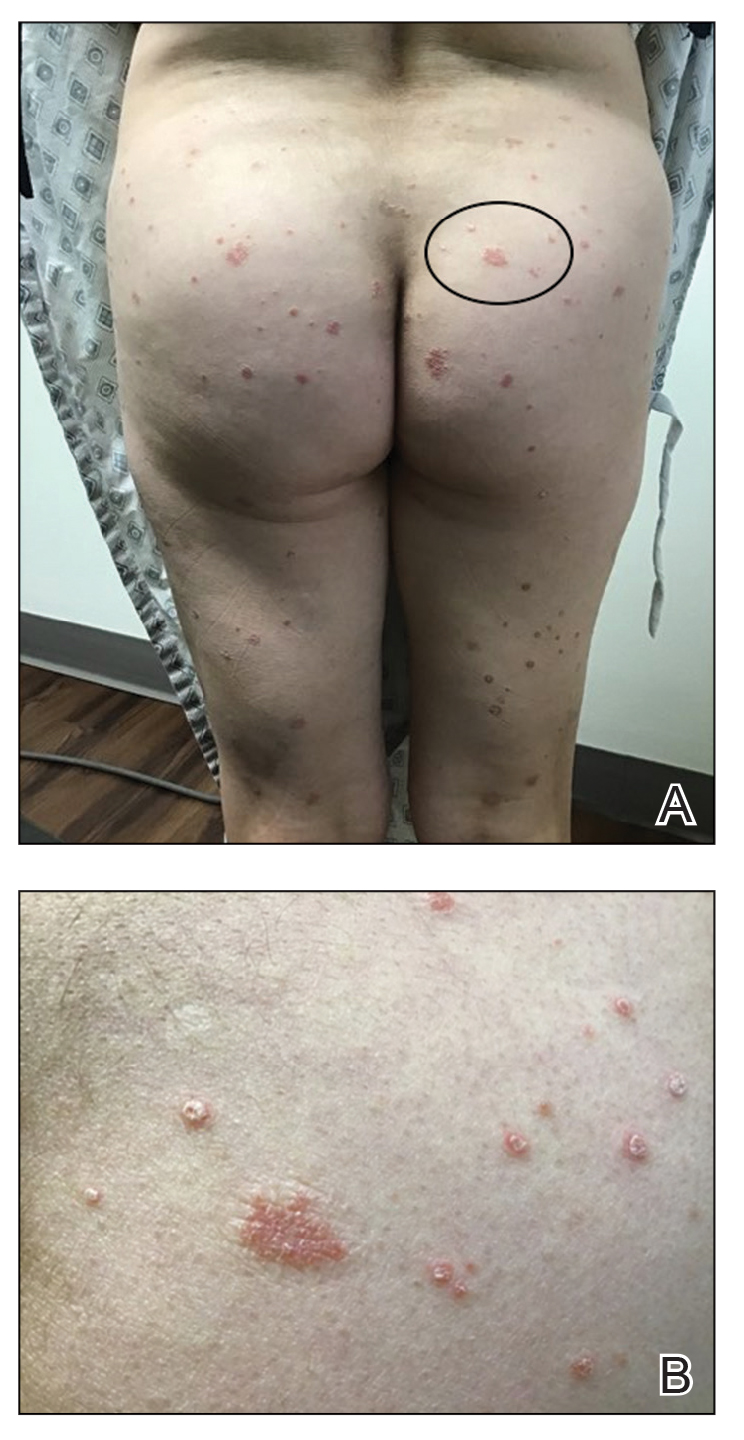

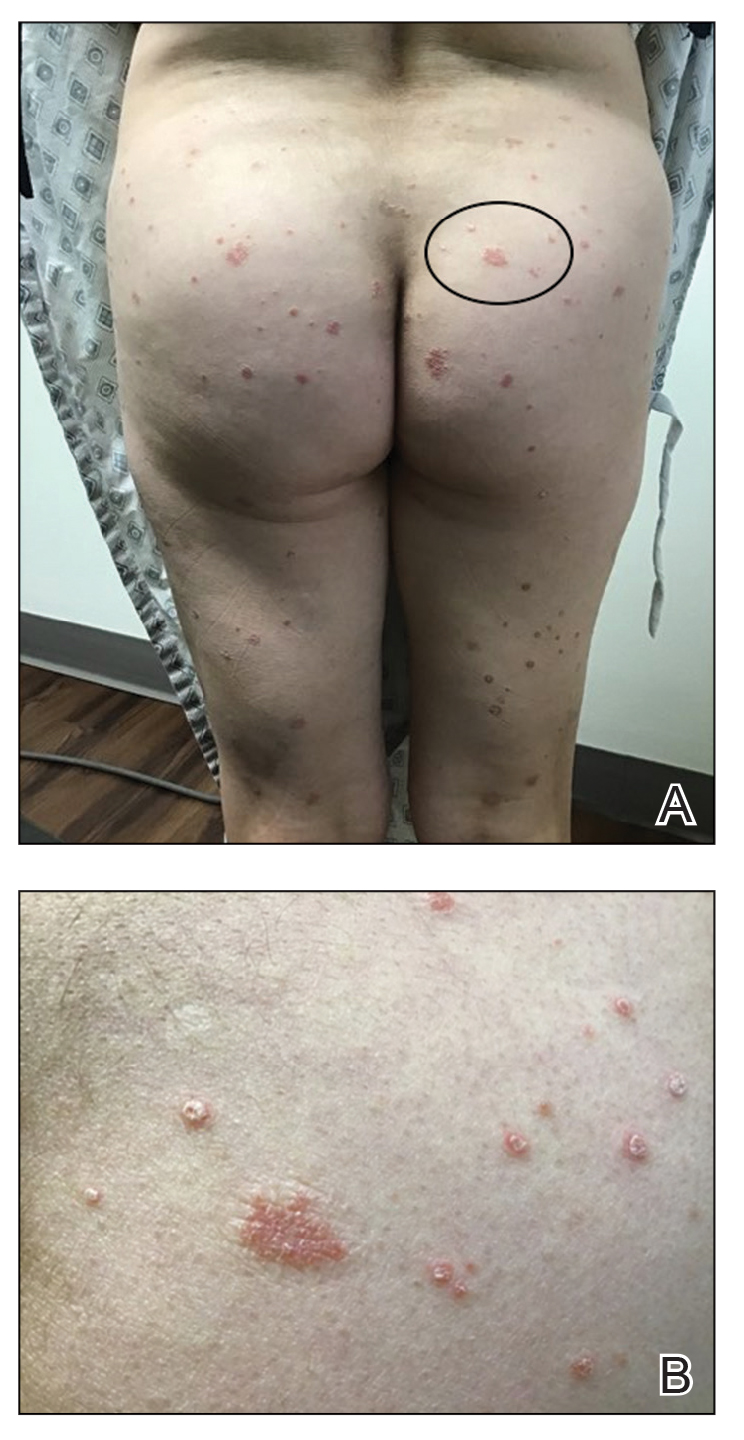

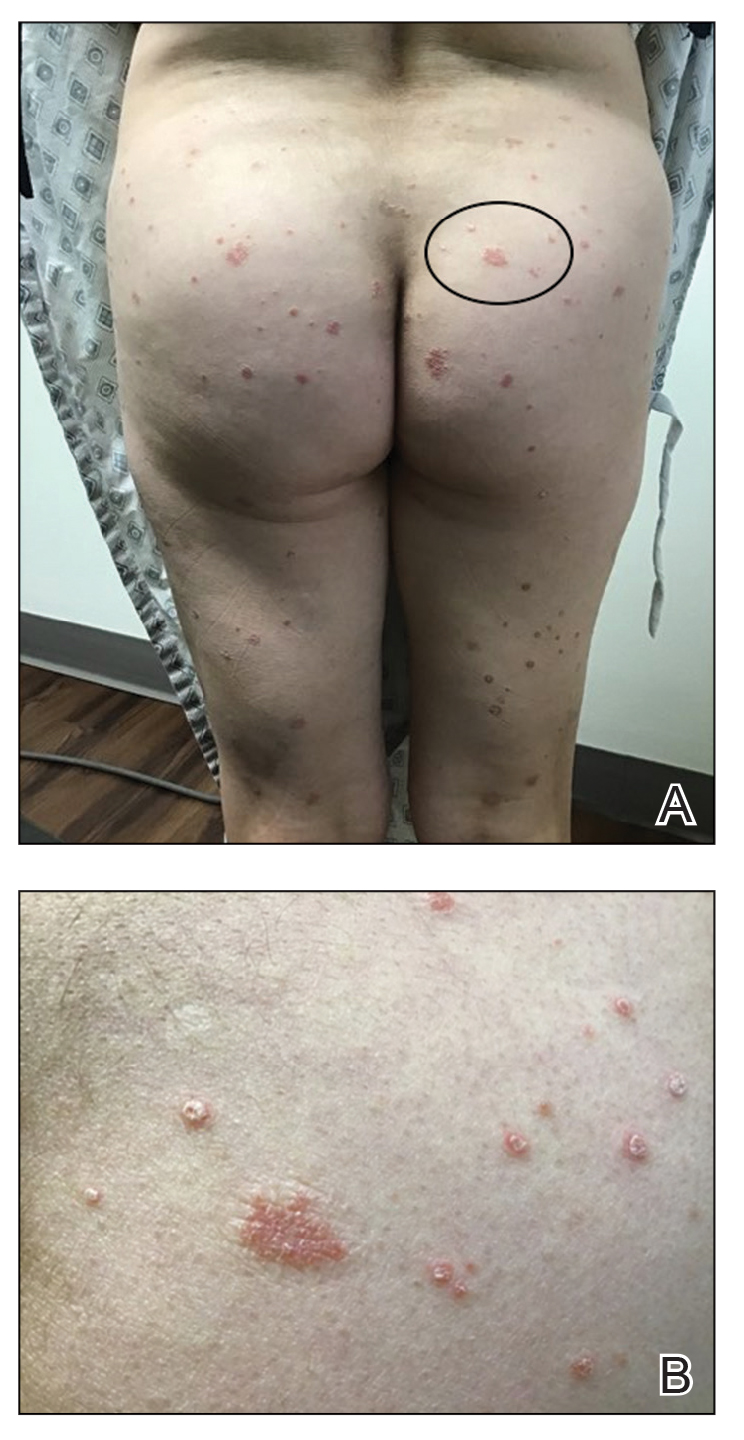

Eight days later, the patient noticed a well-defined, erythematous, indurated plaque with mild itchiness overlying and around the BCG vaccination scar that did not involve the COVID-19 vaccination site. The following day, the redness and induration became worse (Figure).

The patient was otherwise well. Vital signs were normal; there was no lymphadenopathy. The rash resolved without treatment over the next 4 days.

Comment

The BCG vaccine is an intradermal live attenuated virus vaccine used to prevent certain forms of tuberculosis and potentially other Mycobacterium infections. Although the vaccine is not routinely administered in the United States, it is part of the vaccination schedule in most countries, administered most often to newborns and infants. Administration of the BCG vaccine commonly results in mild localized erythema, swelling, and pain at the injection site. Most inoculated patients also develop an ulcer that heals with the characteristic BCG vaccination scar.2,3

There is evidence that the BCG vaccine can enhance the innate immune system response and might decrease the rate of infection by unrelated pathogens, including viruses.4 Several epidemiologic studies have suggested that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19, possibly due to a resemblance of the amino acid sequences of BCG and SARS-CoV-2, which might provoke cross-reactive T cells.5,6 Further studies are underway to determine whether the BCG vaccine is truly protective against COVID-19.

BCG vaccination scar reactivation presents as redness, swelling, or ulceration at the BCG injection site months to years after inoculation. Although erythema and induration of the BCG scar are not included in the diagnostic criteria of Kawasaki disease, likely due to variable vaccine requirements in different countries, these findings are largely recognized as specific for Kawasaki disease and present in approximately half of affected patients who received the BCG vaccine.2

Heat Shock Proteins—Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are produced by cells in response to stressors. The proposed mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation is a cross-reaction between human homologue HSP 63 and Mycobacterium HSP 65, leading to hyperactivity of the immune system against BCG.7 There also are reports of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar from measles infection and influenza vaccination.2,8,9 Most prior reports of BCG vaccination scar reactivation have been in pediatric patients; our patient is an adult who received the BCG vaccine more than 40 years ago.

Mechanism of Reactivation—The mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation in our patient, who received the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, is unclear. Possible mechanisms include (1) release of HSP mediated by the COVID-19 vaccine, leading to an immune response at the BCG vaccine scar, or (2) another immune-mediated cross-reaction between BCG and the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine mRNA nanoparticle or encoded spike protein antigen. It has been hypothesized that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19; this remains uncertain and is under further investigation.10 A recent retrospective cohort study showed that a BCG vaccination booster may decrease COVID-19 infection rates in higher-risk populations.11

Conclusion

We present a case of BCG vaccine scar reactivation occurring after a dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, a likely underreported, self-limiting, cutaneous adverse effect of this mRNA vaccine.

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:403-416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

- Muthuvelu S, Lim KS, Huang L-Y, et al. Measles infection causing bacillus Calmette-Guérin reactivation: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:251. doi:10.1186/s12887-019-1635-z

- Fatima S, Kumari A, Das G, et al. Tuberculosis vaccine: a journey from BCG to present. Life Sci. 2020;252:117594. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117594

- O’Neill LAJ, Netea MG. BCG-induced trained immunity: can it offer protection against COVID-19? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:335-337. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-0337-y

- Brooks NA, Puri A, Garg S, et al. The association of coronavirus disease-19 mortality and prior bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination: a robust ecological analysis using unsupervised machine learning. Sci Rep. 2021;11:774. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80787-z

- Tomita Y, Sato R, Ikeda T, et al. BCG vaccine may generate cross-reactive T-cells against SARS-CoV-2: in silico analyses and a hypothesis. Vaccine. 2020;38:6352-6356. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.045

- Lim KYY, Chua MC, Tan NWH, et al. Reactivation of BCG inoculation site in a child with febrile exanthema of 3 days duration: an early indicator of incomplete Kawasaki disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:E239648. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-239648

- Kondo M, Goto H, Yamamoto S. First case of redness and erosion at bacillus Calmette-Guérin inoculation site after vaccination against influenza. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1229-1231. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13365

- Chavarri-Guerra Y, Soto-Pérez-de-Celis E. Erythema at the bacillus Calmette-Guerin scar after influenza vaccination. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2019;53:E20190390. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0390-2019

- Fu W, Ho P-C, Liu C-L, et al. Reconcile the debate over protective effects of BCG vaccine against COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8356. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-87731-9

- Amirlak L, Haddad R, Hardy JD, et al. Effectiveness of booster BCG vaccination in preventing COVID-19 infection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:3913-3915. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1956228

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in notable morbidity and mortality worldwide. In December 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization for 2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines—produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna—for the prevention of COVID-19. Phase 3 trials of the vaccine developed by Moderna showed 94.1% efficacy at preventing COVID-19 after 2 doses.1

Common cutaneous adverse effects of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine include injection-site reactions, such as pain, induration, and erythema. Less frequently reported dermatologic adverse effects include diffuse bullous rash and hypersensitivity reactions.1 We report a case of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar after the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine.

Case Report

A 48-year-old Asian man who was otherwise healthy presented with erythema, induration, and mild pruritus on the deltoid muscle of the left arm, near the scar from an earlier BCG vaccine, which he received at approximately 5 years of age when living in Taiwan. The patient received the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine approximately 5 to 7 cm distant from the BCG vaccination scar. One to 2 days after inoculation, the patient endorsed tenderness at the site of COVID-19 vaccination but denied systemic symptoms. He had never been given a diagnosis of COVID-19. His SARS-CoV-2 antibody status was unknown.

Eight days later, the patient noticed a well-defined, erythematous, indurated plaque with mild itchiness overlying and around the BCG vaccination scar that did not involve the COVID-19 vaccination site. The following day, the redness and induration became worse (Figure).

The patient was otherwise well. Vital signs were normal; there was no lymphadenopathy. The rash resolved without treatment over the next 4 days.

Comment

The BCG vaccine is an intradermal live attenuated virus vaccine used to prevent certain forms of tuberculosis and potentially other Mycobacterium infections. Although the vaccine is not routinely administered in the United States, it is part of the vaccination schedule in most countries, administered most often to newborns and infants. Administration of the BCG vaccine commonly results in mild localized erythema, swelling, and pain at the injection site. Most inoculated patients also develop an ulcer that heals with the characteristic BCG vaccination scar.2,3

There is evidence that the BCG vaccine can enhance the innate immune system response and might decrease the rate of infection by unrelated pathogens, including viruses.4 Several epidemiologic studies have suggested that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19, possibly due to a resemblance of the amino acid sequences of BCG and SARS-CoV-2, which might provoke cross-reactive T cells.5,6 Further studies are underway to determine whether the BCG vaccine is truly protective against COVID-19.

BCG vaccination scar reactivation presents as redness, swelling, or ulceration at the BCG injection site months to years after inoculation. Although erythema and induration of the BCG scar are not included in the diagnostic criteria of Kawasaki disease, likely due to variable vaccine requirements in different countries, these findings are largely recognized as specific for Kawasaki disease and present in approximately half of affected patients who received the BCG vaccine.2

Heat Shock Proteins—Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are produced by cells in response to stressors. The proposed mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation is a cross-reaction between human homologue HSP 63 and Mycobacterium HSP 65, leading to hyperactivity of the immune system against BCG.7 There also are reports of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar from measles infection and influenza vaccination.2,8,9 Most prior reports of BCG vaccination scar reactivation have been in pediatric patients; our patient is an adult who received the BCG vaccine more than 40 years ago.

Mechanism of Reactivation—The mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation in our patient, who received the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, is unclear. Possible mechanisms include (1) release of HSP mediated by the COVID-19 vaccine, leading to an immune response at the BCG vaccine scar, or (2) another immune-mediated cross-reaction between BCG and the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine mRNA nanoparticle or encoded spike protein antigen. It has been hypothesized that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19; this remains uncertain and is under further investigation.10 A recent retrospective cohort study showed that a BCG vaccination booster may decrease COVID-19 infection rates in higher-risk populations.11

Conclusion

We present a case of BCG vaccine scar reactivation occurring after a dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, a likely underreported, self-limiting, cutaneous adverse effect of this mRNA vaccine.

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in notable morbidity and mortality worldwide. In December 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization for 2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines—produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna—for the prevention of COVID-19. Phase 3 trials of the vaccine developed by Moderna showed 94.1% efficacy at preventing COVID-19 after 2 doses.1

Common cutaneous adverse effects of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine include injection-site reactions, such as pain, induration, and erythema. Less frequently reported dermatologic adverse effects include diffuse bullous rash and hypersensitivity reactions.1 We report a case of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar after the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine.

Case Report

A 48-year-old Asian man who was otherwise healthy presented with erythema, induration, and mild pruritus on the deltoid muscle of the left arm, near the scar from an earlier BCG vaccine, which he received at approximately 5 years of age when living in Taiwan. The patient received the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine approximately 5 to 7 cm distant from the BCG vaccination scar. One to 2 days after inoculation, the patient endorsed tenderness at the site of COVID-19 vaccination but denied systemic symptoms. He had never been given a diagnosis of COVID-19. His SARS-CoV-2 antibody status was unknown.

Eight days later, the patient noticed a well-defined, erythematous, indurated plaque with mild itchiness overlying and around the BCG vaccination scar that did not involve the COVID-19 vaccination site. The following day, the redness and induration became worse (Figure).

The patient was otherwise well. Vital signs were normal; there was no lymphadenopathy. The rash resolved without treatment over the next 4 days.

Comment

The BCG vaccine is an intradermal live attenuated virus vaccine used to prevent certain forms of tuberculosis and potentially other Mycobacterium infections. Although the vaccine is not routinely administered in the United States, it is part of the vaccination schedule in most countries, administered most often to newborns and infants. Administration of the BCG vaccine commonly results in mild localized erythema, swelling, and pain at the injection site. Most inoculated patients also develop an ulcer that heals with the characteristic BCG vaccination scar.2,3

There is evidence that the BCG vaccine can enhance the innate immune system response and might decrease the rate of infection by unrelated pathogens, including viruses.4 Several epidemiologic studies have suggested that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19, possibly due to a resemblance of the amino acid sequences of BCG and SARS-CoV-2, which might provoke cross-reactive T cells.5,6 Further studies are underway to determine whether the BCG vaccine is truly protective against COVID-19.

BCG vaccination scar reactivation presents as redness, swelling, or ulceration at the BCG injection site months to years after inoculation. Although erythema and induration of the BCG scar are not included in the diagnostic criteria of Kawasaki disease, likely due to variable vaccine requirements in different countries, these findings are largely recognized as specific for Kawasaki disease and present in approximately half of affected patients who received the BCG vaccine.2

Heat Shock Proteins—Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are produced by cells in response to stressors. The proposed mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation is a cross-reaction between human homologue HSP 63 and Mycobacterium HSP 65, leading to hyperactivity of the immune system against BCG.7 There also are reports of reactivation of a BCG vaccination scar from measles infection and influenza vaccination.2,8,9 Most prior reports of BCG vaccination scar reactivation have been in pediatric patients; our patient is an adult who received the BCG vaccine more than 40 years ago.

Mechanism of Reactivation—The mechanism of BCG vaccination scar reactivation in our patient, who received the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, is unclear. Possible mechanisms include (1) release of HSP mediated by the COVID-19 vaccine, leading to an immune response at the BCG vaccine scar, or (2) another immune-mediated cross-reaction between BCG and the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine mRNA nanoparticle or encoded spike protein antigen. It has been hypothesized that the BCG vaccine might offer some protection against COVID-19; this remains uncertain and is under further investigation.10 A recent retrospective cohort study showed that a BCG vaccination booster may decrease COVID-19 infection rates in higher-risk populations.11

Conclusion

We present a case of BCG vaccine scar reactivation occurring after a dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine, a likely underreported, self-limiting, cutaneous adverse effect of this mRNA vaccine.

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:403-416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

- Muthuvelu S, Lim KS, Huang L-Y, et al. Measles infection causing bacillus Calmette-Guérin reactivation: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:251. doi:10.1186/s12887-019-1635-z

- Fatima S, Kumari A, Das G, et al. Tuberculosis vaccine: a journey from BCG to present. Life Sci. 2020;252:117594. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117594

- O’Neill LAJ, Netea MG. BCG-induced trained immunity: can it offer protection against COVID-19? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:335-337. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-0337-y

- Brooks NA, Puri A, Garg S, et al. The association of coronavirus disease-19 mortality and prior bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination: a robust ecological analysis using unsupervised machine learning. Sci Rep. 2021;11:774. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80787-z

- Tomita Y, Sato R, Ikeda T, et al. BCG vaccine may generate cross-reactive T-cells against SARS-CoV-2: in silico analyses and a hypothesis. Vaccine. 2020;38:6352-6356. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.045

- Lim KYY, Chua MC, Tan NWH, et al. Reactivation of BCG inoculation site in a child with febrile exanthema of 3 days duration: an early indicator of incomplete Kawasaki disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:E239648. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-239648

- Kondo M, Goto H, Yamamoto S. First case of redness and erosion at bacillus Calmette-Guérin inoculation site after vaccination against influenza. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1229-1231. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13365

- Chavarri-Guerra Y, Soto-Pérez-de-Celis E. Erythema at the bacillus Calmette-Guerin scar after influenza vaccination. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2019;53:E20190390. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0390-2019

- Fu W, Ho P-C, Liu C-L, et al. Reconcile the debate over protective effects of BCG vaccine against COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8356. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-87731-9

- Amirlak L, Haddad R, Hardy JD, et al. Effectiveness of booster BCG vaccination in preventing COVID-19 infection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:3913-3915. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1956228

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:403-416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

- Muthuvelu S, Lim KS, Huang L-Y, et al. Measles infection causing bacillus Calmette-Guérin reactivation: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:251. doi:10.1186/s12887-019-1635-z

- Fatima S, Kumari A, Das G, et al. Tuberculosis vaccine: a journey from BCG to present. Life Sci. 2020;252:117594. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117594

- O’Neill LAJ, Netea MG. BCG-induced trained immunity: can it offer protection against COVID-19? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:335-337. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-0337-y

- Brooks NA, Puri A, Garg S, et al. The association of coronavirus disease-19 mortality and prior bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination: a robust ecological analysis using unsupervised machine learning. Sci Rep. 2021;11:774. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80787-z

- Tomita Y, Sato R, Ikeda T, et al. BCG vaccine may generate cross-reactive T-cells against SARS-CoV-2: in silico analyses and a hypothesis. Vaccine. 2020;38:6352-6356. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.045

- Lim KYY, Chua MC, Tan NWH, et al. Reactivation of BCG inoculation site in a child with febrile exanthema of 3 days duration: an early indicator of incomplete Kawasaki disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:E239648. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-239648

- Kondo M, Goto H, Yamamoto S. First case of redness and erosion at bacillus Calmette-Guérin inoculation site after vaccination against influenza. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1229-1231. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13365

- Chavarri-Guerra Y, Soto-Pérez-de-Celis E. Erythema at the bacillus Calmette-Guerin scar after influenza vaccination. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2019;53:E20190390. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0390-2019

- Fu W, Ho P-C, Liu C-L, et al. Reconcile the debate over protective effects of BCG vaccine against COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8356. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-87731-9

- Amirlak L, Haddad R, Hardy JD, et al. Effectiveness of booster BCG vaccination in preventing COVID-19 infection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:3913-3915. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1956228

Practice Points

- BCG vaccination scar reactivation is a potential benign, self-limited reaction in patients who receive the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine.

- Symptoms of BCG vaccination scar reactivation, which is seen more commonly in children with Kawasaki disease, include redness, swelling, and ulceration.

NY radiation oncologist loses license, poses ‘potential danger’

The state Board for Professional Medical Conduct has revoked the medical license of Won Sam Yi, MD, following a lengthy review of the care he provided to seven cancer patients; six of them died.

“He is a danger to potential new patients should he be reinstated as a radiation oncologist,” board members wrote, according to a news report in the Buffalo News.

Dr. Yi’s lawyer said that he is appealing the decision.

Dr. Yi was the former CEO of the now-defunct private cancer practice CCS Oncology, located in western New York.

In 2018, the state health department brought numerous charges of professional misconduct against Dr. Yi, including charges that he had failed to “account for prior doses of radiotherapy” as well as exceeding “appropriate tissue tolerances” during the treatment.

Now, the state’s Board for Professional Medical Conduct has upheld nearly all of the departmental charges that had been levied against him, and also found that Dr. Yi failed to take responsibility or show contrition for his treatment decisions.

However, whistleblower claims from a former CSS Oncology employee were dismissed.

Troubled history

CCS Oncology was once one of the largest private cancer practices in Erie and Niagara counties, both in the Buffalo metropolitan area.

Dr. Yi purchased CCS Oncology in 2008 and was its sole shareholder, and in 2012 he also acquired CCS Medical. As of 2016, the practices provided care to about 30% of cancer patients in the region. CCS also began acquiring other practices as it expanded into noncancer specialties, including primary care.

However, CCS began to struggle financially in late 2016, when health insurance provider Independent Health announced it was removing CCS Oncology from its network, and several vendors and lenders subsequently sued CCS and Dr. Yi for nonpayment.

The announcement from Independent Health was “financially devastating to CCS,” and also was “the direct cause” of the practice defaulting on its Bank of America loan and of the practice’s inability to pay not only its vendors but state and federal tax agencies, the Buffalo News reported. As a result, several vendors and lenders had sued CCS and Dr. Yi for nonpayment.

The FBI raided numerous CCS locations in March 2018, seizing financial and other data as part of an investigation into possible Medicare billing fraud. The following month, CCS filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, citing it owed millions of dollars to Bank of America and other creditors. Shortly afterward, the practice closed.

Medical misconduct

The state’s charges of professional misconduct accused Dr. Yi of “gross negligence,” “gross incompetence,” and several other cases of misconduct in treating seven patients between 2009 and 2013 at various CCS locations. The patients ranged in age from 27 to 72. Six of the seven patients died.

In one case, Dr. Yi was accused of providing whole-brain radiation therapy to a 43-year-old woman for about 6 weeks in 2012, but the treatment was “contrary to medical indications” and did not take into account prior doses of such treatment. The patient died in December of that year, and the board concluded that Dr. Yi had improperly treated her with a high dose of radiation that was intended to cure her cancer even though she was at a stage where her disease was incurable.

The state board eventually concluded that for all but one of the patients in question, Dr. Yi was guilty of misconduct in his treatment decisions. They wrote that Dr. Yi had frequently administered radiation doses without taking into account how much radiation therapy the patients had received previously and without considering the risk of serious complications for them.

Dr. Yi plans to appeal the board’s decision in state court, according to his attorney, Anthony Scher.

“Dr Yi has treated over 10,000 patients in his career,” Mr. Scher told the Buffalo News. “These handful of cases don’t represent the thousands of success stories that he’s had.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The state Board for Professional Medical Conduct has revoked the medical license of Won Sam Yi, MD, following a lengthy review of the care he provided to seven cancer patients; six of them died.

“He is a danger to potential new patients should he be reinstated as a radiation oncologist,” board members wrote, according to a news report in the Buffalo News.

Dr. Yi’s lawyer said that he is appealing the decision.

Dr. Yi was the former CEO of the now-defunct private cancer practice CCS Oncology, located in western New York.

In 2018, the state health department brought numerous charges of professional misconduct against Dr. Yi, including charges that he had failed to “account for prior doses of radiotherapy” as well as exceeding “appropriate tissue tolerances” during the treatment.

Now, the state’s Board for Professional Medical Conduct has upheld nearly all of the departmental charges that had been levied against him, and also found that Dr. Yi failed to take responsibility or show contrition for his treatment decisions.

However, whistleblower claims from a former CSS Oncology employee were dismissed.

Troubled history

CCS Oncology was once one of the largest private cancer practices in Erie and Niagara counties, both in the Buffalo metropolitan area.

Dr. Yi purchased CCS Oncology in 2008 and was its sole shareholder, and in 2012 he also acquired CCS Medical. As of 2016, the practices provided care to about 30% of cancer patients in the region. CCS also began acquiring other practices as it expanded into noncancer specialties, including primary care.

However, CCS began to struggle financially in late 2016, when health insurance provider Independent Health announced it was removing CCS Oncology from its network, and several vendors and lenders subsequently sued CCS and Dr. Yi for nonpayment.

The announcement from Independent Health was “financially devastating to CCS,” and also was “the direct cause” of the practice defaulting on its Bank of America loan and of the practice’s inability to pay not only its vendors but state and federal tax agencies, the Buffalo News reported. As a result, several vendors and lenders had sued CCS and Dr. Yi for nonpayment.

The FBI raided numerous CCS locations in March 2018, seizing financial and other data as part of an investigation into possible Medicare billing fraud. The following month, CCS filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, citing it owed millions of dollars to Bank of America and other creditors. Shortly afterward, the practice closed.

Medical misconduct

The state’s charges of professional misconduct accused Dr. Yi of “gross negligence,” “gross incompetence,” and several other cases of misconduct in treating seven patients between 2009 and 2013 at various CCS locations. The patients ranged in age from 27 to 72. Six of the seven patients died.

In one case, Dr. Yi was accused of providing whole-brain radiation therapy to a 43-year-old woman for about 6 weeks in 2012, but the treatment was “contrary to medical indications” and did not take into account prior doses of such treatment. The patient died in December of that year, and the board concluded that Dr. Yi had improperly treated her with a high dose of radiation that was intended to cure her cancer even though she was at a stage where her disease was incurable.

The state board eventually concluded that for all but one of the patients in question, Dr. Yi was guilty of misconduct in his treatment decisions. They wrote that Dr. Yi had frequently administered radiation doses without taking into account how much radiation therapy the patients had received previously and without considering the risk of serious complications for them.

Dr. Yi plans to appeal the board’s decision in state court, according to his attorney, Anthony Scher.

“Dr Yi has treated over 10,000 patients in his career,” Mr. Scher told the Buffalo News. “These handful of cases don’t represent the thousands of success stories that he’s had.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The state Board for Professional Medical Conduct has revoked the medical license of Won Sam Yi, MD, following a lengthy review of the care he provided to seven cancer patients; six of them died.

“He is a danger to potential new patients should he be reinstated as a radiation oncologist,” board members wrote, according to a news report in the Buffalo News.

Dr. Yi’s lawyer said that he is appealing the decision.

Dr. Yi was the former CEO of the now-defunct private cancer practice CCS Oncology, located in western New York.

In 2018, the state health department brought numerous charges of professional misconduct against Dr. Yi, including charges that he had failed to “account for prior doses of radiotherapy” as well as exceeding “appropriate tissue tolerances” during the treatment.

Now, the state’s Board for Professional Medical Conduct has upheld nearly all of the departmental charges that had been levied against him, and also found that Dr. Yi failed to take responsibility or show contrition for his treatment decisions.

However, whistleblower claims from a former CSS Oncology employee were dismissed.

Troubled history

CCS Oncology was once one of the largest private cancer practices in Erie and Niagara counties, both in the Buffalo metropolitan area.

Dr. Yi purchased CCS Oncology in 2008 and was its sole shareholder, and in 2012 he also acquired CCS Medical. As of 2016, the practices provided care to about 30% of cancer patients in the region. CCS also began acquiring other practices as it expanded into noncancer specialties, including primary care.

However, CCS began to struggle financially in late 2016, when health insurance provider Independent Health announced it was removing CCS Oncology from its network, and several vendors and lenders subsequently sued CCS and Dr. Yi for nonpayment.

The announcement from Independent Health was “financially devastating to CCS,” and also was “the direct cause” of the practice defaulting on its Bank of America loan and of the practice’s inability to pay not only its vendors but state and federal tax agencies, the Buffalo News reported. As a result, several vendors and lenders had sued CCS and Dr. Yi for nonpayment.

The FBI raided numerous CCS locations in March 2018, seizing financial and other data as part of an investigation into possible Medicare billing fraud. The following month, CCS filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, citing it owed millions of dollars to Bank of America and other creditors. Shortly afterward, the practice closed.

Medical misconduct

The state’s charges of professional misconduct accused Dr. Yi of “gross negligence,” “gross incompetence,” and several other cases of misconduct in treating seven patients between 2009 and 2013 at various CCS locations. The patients ranged in age from 27 to 72. Six of the seven patients died.

In one case, Dr. Yi was accused of providing whole-brain radiation therapy to a 43-year-old woman for about 6 weeks in 2012, but the treatment was “contrary to medical indications” and did not take into account prior doses of such treatment. The patient died in December of that year, and the board concluded that Dr. Yi had improperly treated her with a high dose of radiation that was intended to cure her cancer even though she was at a stage where her disease was incurable.

The state board eventually concluded that for all but one of the patients in question, Dr. Yi was guilty of misconduct in his treatment decisions. They wrote that Dr. Yi had frequently administered radiation doses without taking into account how much radiation therapy the patients had received previously and without considering the risk of serious complications for them.

Dr. Yi plans to appeal the board’s decision in state court, according to his attorney, Anthony Scher.

“Dr Yi has treated over 10,000 patients in his career,” Mr. Scher told the Buffalo News. “These handful of cases don’t represent the thousands of success stories that he’s had.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Why pregnant people were left behind while vaccines moved at ‘warp speed’ to help the masses

Kia Slade was 7 months pregnant, unvaccinated, and fighting for breath, her oxygen levels plummeting, when her son came into the world last May.

A severe case of COVID-19 pneumonia had left Ms. Slade delirious. When the intensive care team tried to place an oxygen mask on her face, she snatched it away, she recalled. Her baby’s heart rate began to drop.

Ms. Slade’s doctor performed an emergency cesarean section at her bedside in the intensive care unit, delivering baby Tristan 10 weeks early. He weighed just 2 pounds, 14 ounces, about half the size of small full-term baby.

But Ms. Slade wouldn’t meet him until July. She was on a ventilator in a medically-induced coma for 8 weeks, and she developed a serious infection and blood clot while unconscious. It was only after a perilous 2½ months in the hospital, during which her heart stopped twice, that Ms. Slade was vaccinated against COVID-19.

“I wish I had gotten the vaccine earlier,” said Ms. Slade, 42, who remains too sick to return to work as a special education teacher in Baltimore. Doctors “kept pushing me to get vaccinated, but there just wasn’t enough information out there for me to do it.”

A year ago, there was little to no vaccine safety data for pregnant people like Ms. Slade, because they had been excluded from clinical trials run by Pfizer, Moderna, and other vaccine makers.

Lacking data, health experts were unsure and divided about how to advise expectant parents. Although U.S. health officials permitted pregnant people to be vaccinated, the World Health Organization in January 2021 actually discouraged them from doing so; it later reversed that recommendation.

The uncertainty led many women to delay vaccination, and only about two-thirds of the pregnant people who have been tracked by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were fully vaccinated as of Feb. 5, 2022, leaving many expectant moms at a high risk of infection and life-threatening complications.

More than 29,000 pregnant people have been hospitalized with COVID-19 and 274 have died, according to the CDC.

“There were surely women who were hospitalized because there wasn’t information available to them,” said Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Vaccine developers say that pregnant people – who have special health needs and risks – were excluded from clinical trials to protect them from potential side effects of novel technologies, including the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines and formulations made with cold viruses, such as the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

But a KHN analysis also shows that pregnant people were left behind because including them in vaccine studies would have complicated and potentially delayed the delivery of COVID-19 vaccines to the broader population.

A growing number of women’s health researchers and advocates say that excluding pregnant people – and the months-long delay in recommending that they be immunized – helped fuel widespread vaccine hesitancy in this vulnerable group.

“Women and their unborn fetuses are dying of COVID infection,” said Jane Van Dis, MD, an ob.gyn. at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center who has treated many patients like Ms. Slade. “Our failure as a society to vaccinate women in pregnancy will be remembered by the children and families who lost their mothers to this disease.”

New technology, uncertain risks

At the time COVID-19 vaccines were being developed, scientists had very little experience using mRNA vaccines in pregnant women, said Jacqueline Miller, MD, a senior vice president involved in vaccine research at Moderna.

“When you study anything in pregnant women, you have two patients, the mom and the unborn child,” Dr. Miller said. “Until we had more safety data on the platform, it wasn’t something we wanted to undertake.”

But Dr. Offit noted that vaccines have a strong record of safety in pregnancy and he sees no reason to have excluded pregnant people. None of the vaccines currently in use – including the chickenpox and rubella vaccines, which contain live viruses – have been shown to harm fetuses, he said. Doctors routinely recommend that pregnant people receive pertussis and flu vaccinations.

Dr. Offit, the coinventor of a rotavirus vaccine, said that some concerns about vaccines stem from commercial, not medical, interests. Drug makers don’t want to risk that their product will be blamed for any problems occurring in pregnant people, even if coincidental, he said.

“These companies don’t want bad news,” Dr. Offit said.

In the United States, health officials typically would have told expectant mothers not to take a vaccine that was untested during pregnancy, said Dr. Offit, a member of a committee that advises the Food and Drug Administration on vaccines.

Due to the urgency of the pandemic, health agencies instead permitted pregnant people to make up their own minds about vaccines without recommending them.

Women’s medical associations were also hampered by the lack of data. Neither the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists nor the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine actively encouraged pregnant people to be vaccinated until July 30, 2021, after the first real-world vaccine studies had been published. The CDC followed suit in August of 2021.

“If we had had this data in the beginning, we would have been able to vaccinate more women,” said Kelli Burroughs, MD, the department chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Memorial Hermann Sugar Land Hospital near Houston.

Yet anti-vaccine groups wasted no time in scaring pregnant people, flooding social media with misinformation about impaired fertility and harm to the fetus.

In the first few months after the COVID-19 vaccines were approved, some doctors were ambivalent about recommending them, and some still advise pregnant patients against vaccination.

An estimated 67% of pregnant people today are fully vaccinated, compared with about 89% of people 65 and older, another high-risk group, and 65% of Americans overall. Vaccination rates are lower among minorities, with 65% of expectant Hispanic mothers and 53% of pregnant African Americans fully vaccinated, according to the CDC.

Vaccination is especially important during pregnancy, because of increased risks of hospitalization, ICU admission, and mechanical ventilation, Dr. Burroughs said. A study released in February from the National Institutes of Health found that pregnant people with a moderate to severe COVID-19 infection also were more likely to have a C-section, deliver preterm, or develop a postpartum hemorrhage.

Black moms such as Ms. Slade were already at higher risk of maternal and infant mortality before the pandemic, because of higher underlying risks, unequal access to health care, and other factors. COVID-19 has magnified those risks, said Dr. Burroughs, who has persuaded reluctant patients by revealing that she had a healthy pregnancy and child after being vaccinated.

Ms. Slade said she has never opposed vaccines and had no hesitation about receiving other vaccines while pregnant. But she said she “just wasn’t comfortable” with COVID-19 shots.

“If there had been data out there saying the COVID shot was safe, and that nothing would happen to my baby and there was no risk of birth defects, I would have taken it,” said Ms. Slade, who has had type 2 diabetes for 12 years.

Working at warp speed

Government scientists at the NIH were concerned about the risk of COVID-19 to pregnant people from the very beginning and knew that expectant moms needed vaccines as much or more than anyone else, said Larry Corey, MD, a leader of the COVID-19 Prevention Network, which coordinated COVID-19 vaccine trials for the federal government.

But including pregnant volunteers in the larger vaccine trials could have led to interruptions and delays, Dr. Corey said. Researchers would have had to enroll thousands of pregnant volunteers to achieve statistically robust results that weren’t due to chance, he said.

Pregnancy can bring on a wide range of complications: gestational diabetes, hypertension, anemia, bleeding, blood clots, or problems with the placenta, for example. Up to 20% of people who know they’re pregnant miscarry. Because researchers would have been obliged to investigate any medical problem to make sure it wasn’t caused by one of the COVID-19 vaccines, including pregnant people might have meant having to hit pause on those trials, Dr. Corey said.

With death tolls from the pandemic mounting, “we had a mission to do this as quickly and as thoroughly as possible,” Dr. Corey said. Making COVID-19 vaccines available within a year “saved hundreds of thousands of lives.”

The first data on COVID-19 vaccine safety in pregnancy was published in April of 2021 when the CDC released an analysis of nearly 36,000 vaccinated pregnant people who had enrolled in a registry called V-safe, which allows users to log the dates of their vaccinations and any subsequent symptoms.

Later research showed that COVID-19 vaccines weren’t associated with increased risk of miscarriage or premature delivery.

Brenna Hughes, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist and member of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ COVID-19 expert group, agrees that adding pregnant people to large-scale COVID-19 vaccine and drug trials may have been impractical. But researchers could have launched parallel trials of pregnant women, once early studies showed the vaccines were safe in humans, she said.

“Would it have been hard? Everything with COVID is hard,” Dr. Hughes said. “But it would have been feasible.”

The FDA requires that researchers perform additional animal studies – called developmental and reproductive toxicity studies – before testing vaccines in pregnant people. Although these studies are essential, they take 5-6 months, and weren’t completed until late 2020, around the time the first COVID-19 vaccines were authorized for adults, said Emily Erbelding, MD, director of microbiology and infectious diseases at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the NIH.

Pregnancy studies “were an afterthought,” said Irina Burd, MD, director of Johns Hopkins’ Integrated Research Center for Fetal Medicine and a professor of gynecology and obstetrics. “They should have been done sooner.”

The NIH is conducting a study of pregnant and postpartum people who decided on their own to be vaccinated, Dr. Erbelding said. The study is due to be completed by July 2023.

Janssen and Moderna are also conducting studies in pregnant people, both due to be completed in 2024.

Pfizer scientists encountered problems when they initiated a clinical trial, which would have randomly assigned pregnant people to receive either a vaccine or placebo. Once vaccines were widely available, many patients weren’t willing to take a chance on being unvaccinated until after delivery.

Pfizer has stopped recruiting patients and has not said whether it will publicly report any data from the trial.

Dr. Hughes said vaccine developers need to include pregnant people from the very beginning.

“There is this notion of protecting pregnant people from research,” Dr. Hughes said. “But we should be protecting patients through research, not from research.”

Recovering physically and emotionally

Ms. Slade still regrets being deprived of time with her children while she fought the disease.

Being on a ventilator kept her from spending those early weeks with her newborn, or from seeing her 9-year-old daughter, Zoe.

Even when Ms. Slade was finally able to see her son, she wasn’t able to tell him she loved him or sing a lullaby, or even talk at all, because of a breathing tube in her throat.

Today, Ms. Slade is a strong advocate of COVID-19 vaccinations, urging her friends and family to get their shots to avoid suffering the way she has.

Ms. Slade had to relearn to walk after being bedridden for weeks. Her many weeks on a ventilator may have contributed to her stomach paralysis, which often causes intense pain, nausea, and even vomiting when she eats or drinks. Ms. Slade weighs 50 pounds less today than before she became pregnant and has resorted to going to the emergency department when the pain is unbearable. “Most days, I’m just miserable,” she said.

Her family suffered as well. Like many babies born prematurely, Tristan, now nearly 9 months old and crawling, receives physical therapy to strengthen his muscles. At 15 pounds, Tristan is largely healthy, although his doctor said he has symptoms of asthma.

Ms. Slade said she would like to attend family counseling with Zoe, who rarely complains and tends to keep her feelings to herself. Ms. Slade said she knows her illness must have been terrifying for her little girl.

“The other day she was talking to me,” Ms. Slade said, “and she said, ‘You know, I almost had to bury you.’ ”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Kia Slade was 7 months pregnant, unvaccinated, and fighting for breath, her oxygen levels plummeting, when her son came into the world last May.

A severe case of COVID-19 pneumonia had left Ms. Slade delirious. When the intensive care team tried to place an oxygen mask on her face, she snatched it away, she recalled. Her baby’s heart rate began to drop.

Ms. Slade’s doctor performed an emergency cesarean section at her bedside in the intensive care unit, delivering baby Tristan 10 weeks early. He weighed just 2 pounds, 14 ounces, about half the size of small full-term baby.

But Ms. Slade wouldn’t meet him until July. She was on a ventilator in a medically-induced coma for 8 weeks, and she developed a serious infection and blood clot while unconscious. It was only after a perilous 2½ months in the hospital, during which her heart stopped twice, that Ms. Slade was vaccinated against COVID-19.

“I wish I had gotten the vaccine earlier,” said Ms. Slade, 42, who remains too sick to return to work as a special education teacher in Baltimore. Doctors “kept pushing me to get vaccinated, but there just wasn’t enough information out there for me to do it.”

A year ago, there was little to no vaccine safety data for pregnant people like Ms. Slade, because they had been excluded from clinical trials run by Pfizer, Moderna, and other vaccine makers.

Lacking data, health experts were unsure and divided about how to advise expectant parents. Although U.S. health officials permitted pregnant people to be vaccinated, the World Health Organization in January 2021 actually discouraged them from doing so; it later reversed that recommendation.

The uncertainty led many women to delay vaccination, and only about two-thirds of the pregnant people who have been tracked by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were fully vaccinated as of Feb. 5, 2022, leaving many expectant moms at a high risk of infection and life-threatening complications.

More than 29,000 pregnant people have been hospitalized with COVID-19 and 274 have died, according to the CDC.

“There were surely women who were hospitalized because there wasn’t information available to them,” said Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Vaccine developers say that pregnant people – who have special health needs and risks – were excluded from clinical trials to protect them from potential side effects of novel technologies, including the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines and formulations made with cold viruses, such as the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

But a KHN analysis also shows that pregnant people were left behind because including them in vaccine studies would have complicated and potentially delayed the delivery of COVID-19 vaccines to the broader population.

A growing number of women’s health researchers and advocates say that excluding pregnant people – and the months-long delay in recommending that they be immunized – helped fuel widespread vaccine hesitancy in this vulnerable group.

“Women and their unborn fetuses are dying of COVID infection,” said Jane Van Dis, MD, an ob.gyn. at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center who has treated many patients like Ms. Slade. “Our failure as a society to vaccinate women in pregnancy will be remembered by the children and families who lost their mothers to this disease.”

New technology, uncertain risks

At the time COVID-19 vaccines were being developed, scientists had very little experience using mRNA vaccines in pregnant women, said Jacqueline Miller, MD, a senior vice president involved in vaccine research at Moderna.

“When you study anything in pregnant women, you have two patients, the mom and the unborn child,” Dr. Miller said. “Until we had more safety data on the platform, it wasn’t something we wanted to undertake.”

But Dr. Offit noted that vaccines have a strong record of safety in pregnancy and he sees no reason to have excluded pregnant people. None of the vaccines currently in use – including the chickenpox and rubella vaccines, which contain live viruses – have been shown to harm fetuses, he said. Doctors routinely recommend that pregnant people receive pertussis and flu vaccinations.

Dr. Offit, the coinventor of a rotavirus vaccine, said that some concerns about vaccines stem from commercial, not medical, interests. Drug makers don’t want to risk that their product will be blamed for any problems occurring in pregnant people, even if coincidental, he said.

“These companies don’t want bad news,” Dr. Offit said.

In the United States, health officials typically would have told expectant mothers not to take a vaccine that was untested during pregnancy, said Dr. Offit, a member of a committee that advises the Food and Drug Administration on vaccines.

Due to the urgency of the pandemic, health agencies instead permitted pregnant people to make up their own minds about vaccines without recommending them.

Women’s medical associations were also hampered by the lack of data. Neither the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists nor the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine actively encouraged pregnant people to be vaccinated until July 30, 2021, after the first real-world vaccine studies had been published. The CDC followed suit in August of 2021.

“If we had had this data in the beginning, we would have been able to vaccinate more women,” said Kelli Burroughs, MD, the department chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Memorial Hermann Sugar Land Hospital near Houston.

Yet anti-vaccine groups wasted no time in scaring pregnant people, flooding social media with misinformation about impaired fertility and harm to the fetus.

In the first few months after the COVID-19 vaccines were approved, some doctors were ambivalent about recommending them, and some still advise pregnant patients against vaccination.

An estimated 67% of pregnant people today are fully vaccinated, compared with about 89% of people 65 and older, another high-risk group, and 65% of Americans overall. Vaccination rates are lower among minorities, with 65% of expectant Hispanic mothers and 53% of pregnant African Americans fully vaccinated, according to the CDC.

Vaccination is especially important during pregnancy, because of increased risks of hospitalization, ICU admission, and mechanical ventilation, Dr. Burroughs said. A study released in February from the National Institutes of Health found that pregnant people with a moderate to severe COVID-19 infection also were more likely to have a C-section, deliver preterm, or develop a postpartum hemorrhage.

Black moms such as Ms. Slade were already at higher risk of maternal and infant mortality before the pandemic, because of higher underlying risks, unequal access to health care, and other factors. COVID-19 has magnified those risks, said Dr. Burroughs, who has persuaded reluctant patients by revealing that she had a healthy pregnancy and child after being vaccinated.

Ms. Slade said she has never opposed vaccines and had no hesitation about receiving other vaccines while pregnant. But she said she “just wasn’t comfortable” with COVID-19 shots.

“If there had been data out there saying the COVID shot was safe, and that nothing would happen to my baby and there was no risk of birth defects, I would have taken it,” said Ms. Slade, who has had type 2 diabetes for 12 years.

Working at warp speed

Government scientists at the NIH were concerned about the risk of COVID-19 to pregnant people from the very beginning and knew that expectant moms needed vaccines as much or more than anyone else, said Larry Corey, MD, a leader of the COVID-19 Prevention Network, which coordinated COVID-19 vaccine trials for the federal government.

But including pregnant volunteers in the larger vaccine trials could have led to interruptions and delays, Dr. Corey said. Researchers would have had to enroll thousands of pregnant volunteers to achieve statistically robust results that weren’t due to chance, he said.

Pregnancy can bring on a wide range of complications: gestational diabetes, hypertension, anemia, bleeding, blood clots, or problems with the placenta, for example. Up to 20% of people who know they’re pregnant miscarry. Because researchers would have been obliged to investigate any medical problem to make sure it wasn’t caused by one of the COVID-19 vaccines, including pregnant people might have meant having to hit pause on those trials, Dr. Corey said.

With death tolls from the pandemic mounting, “we had a mission to do this as quickly and as thoroughly as possible,” Dr. Corey said. Making COVID-19 vaccines available within a year “saved hundreds of thousands of lives.”

The first data on COVID-19 vaccine safety in pregnancy was published in April of 2021 when the CDC released an analysis of nearly 36,000 vaccinated pregnant people who had enrolled in a registry called V-safe, which allows users to log the dates of their vaccinations and any subsequent symptoms.

Later research showed that COVID-19 vaccines weren’t associated with increased risk of miscarriage or premature delivery.

Brenna Hughes, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist and member of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ COVID-19 expert group, agrees that adding pregnant people to large-scale COVID-19 vaccine and drug trials may have been impractical. But researchers could have launched parallel trials of pregnant women, once early studies showed the vaccines were safe in humans, she said.

“Would it have been hard? Everything with COVID is hard,” Dr. Hughes said. “But it would have been feasible.”

The FDA requires that researchers perform additional animal studies – called developmental and reproductive toxicity studies – before testing vaccines in pregnant people. Although these studies are essential, they take 5-6 months, and weren’t completed until late 2020, around the time the first COVID-19 vaccines were authorized for adults, said Emily Erbelding, MD, director of microbiology and infectious diseases at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the NIH.

Pregnancy studies “were an afterthought,” said Irina Burd, MD, director of Johns Hopkins’ Integrated Research Center for Fetal Medicine and a professor of gynecology and obstetrics. “They should have been done sooner.”

The NIH is conducting a study of pregnant and postpartum people who decided on their own to be vaccinated, Dr. Erbelding said. The study is due to be completed by July 2023.

Janssen and Moderna are also conducting studies in pregnant people, both due to be completed in 2024.

Pfizer scientists encountered problems when they initiated a clinical trial, which would have randomly assigned pregnant people to receive either a vaccine or placebo. Once vaccines were widely available, many patients weren’t willing to take a chance on being unvaccinated until after delivery.

Pfizer has stopped recruiting patients and has not said whether it will publicly report any data from the trial.

Dr. Hughes said vaccine developers need to include pregnant people from the very beginning.

“There is this notion of protecting pregnant people from research,” Dr. Hughes said. “But we should be protecting patients through research, not from research.”

Recovering physically and emotionally

Ms. Slade still regrets being deprived of time with her children while she fought the disease.

Being on a ventilator kept her from spending those early weeks with her newborn, or from seeing her 9-year-old daughter, Zoe.

Even when Ms. Slade was finally able to see her son, she wasn’t able to tell him she loved him or sing a lullaby, or even talk at all, because of a breathing tube in her throat.

Today, Ms. Slade is a strong advocate of COVID-19 vaccinations, urging her friends and family to get their shots to avoid suffering the way she has.

Ms. Slade had to relearn to walk after being bedridden for weeks. Her many weeks on a ventilator may have contributed to her stomach paralysis, which often causes intense pain, nausea, and even vomiting when she eats or drinks. Ms. Slade weighs 50 pounds less today than before she became pregnant and has resorted to going to the emergency department when the pain is unbearable. “Most days, I’m just miserable,” she said.

Her family suffered as well. Like many babies born prematurely, Tristan, now nearly 9 months old and crawling, receives physical therapy to strengthen his muscles. At 15 pounds, Tristan is largely healthy, although his doctor said he has symptoms of asthma.

Ms. Slade said she would like to attend family counseling with Zoe, who rarely complains and tends to keep her feelings to herself. Ms. Slade said she knows her illness must have been terrifying for her little girl.

“The other day she was talking to me,” Ms. Slade said, “and she said, ‘You know, I almost had to bury you.’ ”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Kia Slade was 7 months pregnant, unvaccinated, and fighting for breath, her oxygen levels plummeting, when her son came into the world last May.

A severe case of COVID-19 pneumonia had left Ms. Slade delirious. When the intensive care team tried to place an oxygen mask on her face, she snatched it away, she recalled. Her baby’s heart rate began to drop.

Ms. Slade’s doctor performed an emergency cesarean section at her bedside in the intensive care unit, delivering baby Tristan 10 weeks early. He weighed just 2 pounds, 14 ounces, about half the size of small full-term baby.

But Ms. Slade wouldn’t meet him until July. She was on a ventilator in a medically-induced coma for 8 weeks, and she developed a serious infection and blood clot while unconscious. It was only after a perilous 2½ months in the hospital, during which her heart stopped twice, that Ms. Slade was vaccinated against COVID-19.

“I wish I had gotten the vaccine earlier,” said Ms. Slade, 42, who remains too sick to return to work as a special education teacher in Baltimore. Doctors “kept pushing me to get vaccinated, but there just wasn’t enough information out there for me to do it.”

A year ago, there was little to no vaccine safety data for pregnant people like Ms. Slade, because they had been excluded from clinical trials run by Pfizer, Moderna, and other vaccine makers.

Lacking data, health experts were unsure and divided about how to advise expectant parents. Although U.S. health officials permitted pregnant people to be vaccinated, the World Health Organization in January 2021 actually discouraged them from doing so; it later reversed that recommendation.

The uncertainty led many women to delay vaccination, and only about two-thirds of the pregnant people who have been tracked by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were fully vaccinated as of Feb. 5, 2022, leaving many expectant moms at a high risk of infection and life-threatening complications.

More than 29,000 pregnant people have been hospitalized with COVID-19 and 274 have died, according to the CDC.

“There were surely women who were hospitalized because there wasn’t information available to them,” said Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Vaccine developers say that pregnant people – who have special health needs and risks – were excluded from clinical trials to protect them from potential side effects of novel technologies, including the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines and formulations made with cold viruses, such as the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

But a KHN analysis also shows that pregnant people were left behind because including them in vaccine studies would have complicated and potentially delayed the delivery of COVID-19 vaccines to the broader population.

A growing number of women’s health researchers and advocates say that excluding pregnant people – and the months-long delay in recommending that they be immunized – helped fuel widespread vaccine hesitancy in this vulnerable group.

“Women and their unborn fetuses are dying of COVID infection,” said Jane Van Dis, MD, an ob.gyn. at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center who has treated many patients like Ms. Slade. “Our failure as a society to vaccinate women in pregnancy will be remembered by the children and families who lost their mothers to this disease.”

New technology, uncertain risks

At the time COVID-19 vaccines were being developed, scientists had very little experience using mRNA vaccines in pregnant women, said Jacqueline Miller, MD, a senior vice president involved in vaccine research at Moderna.

“When you study anything in pregnant women, you have two patients, the mom and the unborn child,” Dr. Miller said. “Until we had more safety data on the platform, it wasn’t something we wanted to undertake.”

But Dr. Offit noted that vaccines have a strong record of safety in pregnancy and he sees no reason to have excluded pregnant people. None of the vaccines currently in use – including the chickenpox and rubella vaccines, which contain live viruses – have been shown to harm fetuses, he said. Doctors routinely recommend that pregnant people receive pertussis and flu vaccinations.

Dr. Offit, the coinventor of a rotavirus vaccine, said that some concerns about vaccines stem from commercial, not medical, interests. Drug makers don’t want to risk that their product will be blamed for any problems occurring in pregnant people, even if coincidental, he said.

“These companies don’t want bad news,” Dr. Offit said.

In the United States, health officials typically would have told expectant mothers not to take a vaccine that was untested during pregnancy, said Dr. Offit, a member of a committee that advises the Food and Drug Administration on vaccines.

Due to the urgency of the pandemic, health agencies instead permitted pregnant people to make up their own minds about vaccines without recommending them.

Women’s medical associations were also hampered by the lack of data. Neither the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists nor the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine actively encouraged pregnant people to be vaccinated until July 30, 2021, after the first real-world vaccine studies had been published. The CDC followed suit in August of 2021.

“If we had had this data in the beginning, we would have been able to vaccinate more women,” said Kelli Burroughs, MD, the department chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Memorial Hermann Sugar Land Hospital near Houston.

Yet anti-vaccine groups wasted no time in scaring pregnant people, flooding social media with misinformation about impaired fertility and harm to the fetus.

In the first few months after the COVID-19 vaccines were approved, some doctors were ambivalent about recommending them, and some still advise pregnant patients against vaccination.

An estimated 67% of pregnant people today are fully vaccinated, compared with about 89% of people 65 and older, another high-risk group, and 65% of Americans overall. Vaccination rates are lower among minorities, with 65% of expectant Hispanic mothers and 53% of pregnant African Americans fully vaccinated, according to the CDC.

Vaccination is especially important during pregnancy, because of increased risks of hospitalization, ICU admission, and mechanical ventilation, Dr. Burroughs said. A study released in February from the National Institutes of Health found that pregnant people with a moderate to severe COVID-19 infection also were more likely to have a C-section, deliver preterm, or develop a postpartum hemorrhage.

Black moms such as Ms. Slade were already at higher risk of maternal and infant mortality before the pandemic, because of higher underlying risks, unequal access to health care, and other factors. COVID-19 has magnified those risks, said Dr. Burroughs, who has persuaded reluctant patients by revealing that she had a healthy pregnancy and child after being vaccinated.

Ms. Slade said she has never opposed vaccines and had no hesitation about receiving other vaccines while pregnant. But she said she “just wasn’t comfortable” with COVID-19 shots.

“If there had been data out there saying the COVID shot was safe, and that nothing would happen to my baby and there was no risk of birth defects, I would have taken it,” said Ms. Slade, who has had type 2 diabetes for 12 years.

Working at warp speed

Government scientists at the NIH were concerned about the risk of COVID-19 to pregnant people from the very beginning and knew that expectant moms needed vaccines as much or more than anyone else, said Larry Corey, MD, a leader of the COVID-19 Prevention Network, which coordinated COVID-19 vaccine trials for the federal government.

But including pregnant volunteers in the larger vaccine trials could have led to interruptions and delays, Dr. Corey said. Researchers would have had to enroll thousands of pregnant volunteers to achieve statistically robust results that weren’t due to chance, he said.

Pregnancy can bring on a wide range of complications: gestational diabetes, hypertension, anemia, bleeding, blood clots, or problems with the placenta, for example. Up to 20% of people who know they’re pregnant miscarry. Because researchers would have been obliged to investigate any medical problem to make sure it wasn’t caused by one of the COVID-19 vaccines, including pregnant people might have meant having to hit pause on those trials, Dr. Corey said.

With death tolls from the pandemic mounting, “we had a mission to do this as quickly and as thoroughly as possible,” Dr. Corey said. Making COVID-19 vaccines available within a year “saved hundreds of thousands of lives.”

The first data on COVID-19 vaccine safety in pregnancy was published in April of 2021 when the CDC released an analysis of nearly 36,000 vaccinated pregnant people who had enrolled in a registry called V-safe, which allows users to log the dates of their vaccinations and any subsequent symptoms.

Later research showed that COVID-19 vaccines weren’t associated with increased risk of miscarriage or premature delivery.

Brenna Hughes, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist and member of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ COVID-19 expert group, agrees that adding pregnant people to large-scale COVID-19 vaccine and drug trials may have been impractical. But researchers could have launched parallel trials of pregnant women, once early studies showed the vaccines were safe in humans, she said.

“Would it have been hard? Everything with COVID is hard,” Dr. Hughes said. “But it would have been feasible.”

The FDA requires that researchers perform additional animal studies – called developmental and reproductive toxicity studies – before testing vaccines in pregnant people. Although these studies are essential, they take 5-6 months, and weren’t completed until late 2020, around the time the first COVID-19 vaccines were authorized for adults, said Emily Erbelding, MD, director of microbiology and infectious diseases at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the NIH.

Pregnancy studies “were an afterthought,” said Irina Burd, MD, director of Johns Hopkins’ Integrated Research Center for Fetal Medicine and a professor of gynecology and obstetrics. “They should have been done sooner.”

The NIH is conducting a study of pregnant and postpartum people who decided on their own to be vaccinated, Dr. Erbelding said. The study is due to be completed by July 2023.

Janssen and Moderna are also conducting studies in pregnant people, both due to be completed in 2024.

Pfizer scientists encountered problems when they initiated a clinical trial, which would have randomly assigned pregnant people to receive either a vaccine or placebo. Once vaccines were widely available, many patients weren’t willing to take a chance on being unvaccinated until after delivery.

Pfizer has stopped recruiting patients and has not said whether it will publicly report any data from the trial.

Dr. Hughes said vaccine developers need to include pregnant people from the very beginning.

“There is this notion of protecting pregnant people from research,” Dr. Hughes said. “But we should be protecting patients through research, not from research.”

Recovering physically and emotionally

Ms. Slade still regrets being deprived of time with her children while she fought the disease.

Being on a ventilator kept her from spending those early weeks with her newborn, or from seeing her 9-year-old daughter, Zoe.

Even when Ms. Slade was finally able to see her son, she wasn’t able to tell him she loved him or sing a lullaby, or even talk at all, because of a breathing tube in her throat.

Today, Ms. Slade is a strong advocate of COVID-19 vaccinations, urging her friends and family to get their shots to avoid suffering the way she has.

Ms. Slade had to relearn to walk after being bedridden for weeks. Her many weeks on a ventilator may have contributed to her stomach paralysis, which often causes intense pain, nausea, and even vomiting when she eats or drinks. Ms. Slade weighs 50 pounds less today than before she became pregnant and has resorted to going to the emergency department when the pain is unbearable. “Most days, I’m just miserable,” she said.

Her family suffered as well. Like many babies born prematurely, Tristan, now nearly 9 months old and crawling, receives physical therapy to strengthen his muscles. At 15 pounds, Tristan is largely healthy, although his doctor said he has symptoms of asthma.

Ms. Slade said she would like to attend family counseling with Zoe, who rarely complains and tends to keep her feelings to herself. Ms. Slade said she knows her illness must have been terrifying for her little girl.

“The other day she was talking to me,” Ms. Slade said, “and she said, ‘You know, I almost had to bury you.’ ”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Most Americans unaware alcohol can cause cancer

The majority of Americans are not aware that alcohol consumption causes a variety of cancers and especially do not consider wine and beer to have a link with cancer, suggest the results from a national survey.

write lead author Andrew Seidenberg, PhD, MPH, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, Md., and colleagues.

“Increasing awareness of the alcohol-cancer link, such as through multimedia campaigns and patient-provider communication, may be an important new strategy for health advocates working to implement preventive alcohol policies,” they add.

The findings were published in the February issue of the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

“This is the first study to examine the relationship between alcohol control policy support and awareness of the alcohol-cancer link among a national U.S. sample,” the authors write.

The results show that there is some public support for the idea of adding written warnings about the alcohol-cancer risk to alcoholic beverages, which is something that a number of cancer organizations have been petitioning for.

A petition filed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American Institute for Cancer Research, and Breast Cancer Prevention Partners, all in collaboration with several public health organizations, proposes labeling that would read: “WARNING: According to the Surgeon General, consumption of alcoholic beverages can cause cancer, including breast and colon cancers.”

Such labeling has “the potential to save lives by ensuring that consumers have a more accurate understanding of the link between alcohol and cancer, which will empower them to better protect their health,” the groups said in the petition.

Public support

The findings come from an analysis of the 2020 Health Information National Trends Survey 5 Cycle 4. A total of 3,865 adults participated in the survey, approximately half of whom were nondrinkers.

As well as investigating how aware people were of the alcohol-cancer link, the investigators looked at how prevalent public support might be for the following three communication-focused alcohol policies:

- Banning outdoor alcohol-related advertising

- Requiring health warnings on alcohol beverage containers

- Requiring recommended drinking guidelines on alcoholic beverage containers

“Awareness of the alcohol-cancer link was measured separately for wine, beer, and liquor by asking: In your opinion, how much does drinking the following types of alcohol affect the risk of getting cancer?” the authors explain.

“Awareness of the alcohol-cancer link was low,” the investigators comment; only about one-third (31.8%) of participants were aware that alcohol increases the risk of cancer. The figures were even lower for individual beverage type, at 20.3% for wine, 24.9% for beer, and 31.2% for liquor. Furthermore, approximately half of participants responded with “don’t know” to the three awareness items, investigators noted.

On the other hand, more than half of the Americans surveyed supported adding both health warning labels (65.1%) and information on recommended drinking guidelines (63.9%) to alcoholic beverage containers. Support was lower (34.4% of respondents) for banning outdoor alcohol advertising.

Among Americans who were aware that alcohol increased cancer risk, support was also higher for all three policies.

For example, about 75% of respondents who were aware that alcohol increases cancer risk supported adding health warnings and drinking guidelines to beverage containers, compared with about half of Americans who felt that alcohol consumption had either no effect on or decreased cancer risk.

Even among those who were aware of the alcohol-cancer link, public support for outdoor advertising was not high (37.8%), but it was even lower (23.6%) among respondents who felt alcohol had no effect on or decreased the risk of cancer.

“Policy support was highest among nondrinkers, followed by drinkers, and was lowest among heavier drinkers,” the authors report.

For example, almost 43% of nondrinkers supported restrictions on outdoor alcohol advertising, compared with only about 28.6% of drinkers and 22% of heavier drinkers. More respondents supported adding health warning labels on alcoholic beverages – 70% of nondrinkers, 65% of drinkers, and 57% of heavier drinkers, investigators observe.

The study had no specific funding. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The majority of Americans are not aware that alcohol consumption causes a variety of cancers and especially do not consider wine and beer to have a link with cancer, suggest the results from a national survey.

write lead author Andrew Seidenberg, PhD, MPH, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, Md., and colleagues.