User login

How Many Patients Have Benign MS?

Patients and physicians interpret the term differently, thus making its use in the clinical setting problematic.

An estimated 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) have a benign course of disease, according to findings from a population-based UK study published online ahead of print September 3 in Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. The term “benign MS” remains problematic, however.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” said Emma Clare Tallantyre, BMBS, PhD, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Neurosciences at Cardiff University in the UK, and her colleagues.

The investigators found that of 1,049 patients with a disease duration of longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those patients, 60 were clinically assessed, and nine (15%) had benign MS, which was defined as an EDSS score less than 3.0 and lack of significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, and disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at at least 15 years after symptom onset.

Extrapolating these data, the investigators estimated that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had benign MS, yielding a prevalence of 2.9%. Of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS, based on the following definition: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications, and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” said the investigators.

—Jeff Evans

Suggested Reading

Tallantyre EC, Major PC, Atherton MJ, et al. How common is truly benign MS in a UK population? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3 [Epub ahead of print].

Patients and physicians interpret the term differently, thus making its use in the clinical setting problematic.

Patients and physicians interpret the term differently, thus making its use in the clinical setting problematic.

An estimated 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) have a benign course of disease, according to findings from a population-based UK study published online ahead of print September 3 in Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. The term “benign MS” remains problematic, however.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” said Emma Clare Tallantyre, BMBS, PhD, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Neurosciences at Cardiff University in the UK, and her colleagues.

The investigators found that of 1,049 patients with a disease duration of longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those patients, 60 were clinically assessed, and nine (15%) had benign MS, which was defined as an EDSS score less than 3.0 and lack of significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, and disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at at least 15 years after symptom onset.

Extrapolating these data, the investigators estimated that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had benign MS, yielding a prevalence of 2.9%. Of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS, based on the following definition: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications, and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” said the investigators.

—Jeff Evans

Suggested Reading

Tallantyre EC, Major PC, Atherton MJ, et al. How common is truly benign MS in a UK population? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3 [Epub ahead of print].

An estimated 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) have a benign course of disease, according to findings from a population-based UK study published online ahead of print September 3 in Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. The term “benign MS” remains problematic, however.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” said Emma Clare Tallantyre, BMBS, PhD, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Neurosciences at Cardiff University in the UK, and her colleagues.

The investigators found that of 1,049 patients with a disease duration of longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those patients, 60 were clinically assessed, and nine (15%) had benign MS, which was defined as an EDSS score less than 3.0 and lack of significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, and disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at at least 15 years after symptom onset.

Extrapolating these data, the investigators estimated that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had benign MS, yielding a prevalence of 2.9%. Of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS, based on the following definition: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications, and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” said the investigators.

—Jeff Evans

Suggested Reading

Tallantyre EC, Major PC, Atherton MJ, et al. How common is truly benign MS in a UK population? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3 [Epub ahead of print].

Teva Announces FDA Approval of Ajovy (fremanezumab-vfrm)

Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. announced that the FDA approved Ajovy (fremanezumab-vfrm) injection for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults. Ajovy, a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) ligand and blocks its binding to the receptor, is the first and only anti-CGRP treatment for the prevention of migraine with quarterly (675 mg) and monthly (225 mg) dosing options.

“Migraine is a disabling neurological disease that affects more than 36 million people in the United States,” said Stephen Silberstein

Ajovy was evaluated in two Phase III, placebo-controlled clinical trials that enrolled patients with disabling migraine and was studied as both a stand-alone preventive treatment and in combination with oral preventive treatments. In these trials, patients experienced a reduction in monthly migraine days during a 12-week period. The most common adverse reactions (≥ 5% and greater than placebo) were injection site reactions.

Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. announced that the FDA approved Ajovy (fremanezumab-vfrm) injection for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults. Ajovy, a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) ligand and blocks its binding to the receptor, is the first and only anti-CGRP treatment for the prevention of migraine with quarterly (675 mg) and monthly (225 mg) dosing options.

“Migraine is a disabling neurological disease that affects more than 36 million people in the United States,” said Stephen Silberstein

Ajovy was evaluated in two Phase III, placebo-controlled clinical trials that enrolled patients with disabling migraine and was studied as both a stand-alone preventive treatment and in combination with oral preventive treatments. In these trials, patients experienced a reduction in monthly migraine days during a 12-week period. The most common adverse reactions (≥ 5% and greater than placebo) were injection site reactions.

Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. announced that the FDA approved Ajovy (fremanezumab-vfrm) injection for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults. Ajovy, a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) ligand and blocks its binding to the receptor, is the first and only anti-CGRP treatment for the prevention of migraine with quarterly (675 mg) and monthly (225 mg) dosing options.

“Migraine is a disabling neurological disease that affects more than 36 million people in the United States,” said Stephen Silberstein

Ajovy was evaluated in two Phase III, placebo-controlled clinical trials that enrolled patients with disabling migraine and was studied as both a stand-alone preventive treatment and in combination with oral preventive treatments. In these trials, patients experienced a reduction in monthly migraine days during a 12-week period. The most common adverse reactions (≥ 5% and greater than placebo) were injection site reactions.

Benign MS is real in small minority of patients

Nearly 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are estimated to have a truly benign course of disease over at least 15 years without the use of disease-modifying therapy, based on findings from a U.K. population-based study that also showed how poorly benign disease tracks with disability measures and lacks agreement between patients and physicians.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of EDSS [Expanded Disability Status Scale]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” Emma Clare Tallantyre, MD, of Cardiff (Wales) University, and her colleagues wrote in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Dr. Tallantyre and her colleagues found that, of 1,049 patients with disease duration longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those 200, 60 were clinically assessed and 9 (15%) were found to have truly benign MS, defined as having an EDSS less than 3.0 and having no significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, or disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at least 15 years after symptom onset.

The investigators extrapolated these data to estimate that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had truly benign MS, for a prevalence of 2.9%. However, of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS based on the lay definition provided: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Tallantyre EC et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318802.

Nearly 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are estimated to have a truly benign course of disease over at least 15 years without the use of disease-modifying therapy, based on findings from a U.K. population-based study that also showed how poorly benign disease tracks with disability measures and lacks agreement between patients and physicians.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of EDSS [Expanded Disability Status Scale]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” Emma Clare Tallantyre, MD, of Cardiff (Wales) University, and her colleagues wrote in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Dr. Tallantyre and her colleagues found that, of 1,049 patients with disease duration longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those 200, 60 were clinically assessed and 9 (15%) were found to have truly benign MS, defined as having an EDSS less than 3.0 and having no significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, or disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at least 15 years after symptom onset.

The investigators extrapolated these data to estimate that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had truly benign MS, for a prevalence of 2.9%. However, of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS based on the lay definition provided: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Tallantyre EC et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318802.

Nearly 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are estimated to have a truly benign course of disease over at least 15 years without the use of disease-modifying therapy, based on findings from a U.K. population-based study that also showed how poorly benign disease tracks with disability measures and lacks agreement between patients and physicians.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of EDSS [Expanded Disability Status Scale]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” Emma Clare Tallantyre, MD, of Cardiff (Wales) University, and her colleagues wrote in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Dr. Tallantyre and her colleagues found that, of 1,049 patients with disease duration longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those 200, 60 were clinically assessed and 9 (15%) were found to have truly benign MS, defined as having an EDSS less than 3.0 and having no significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, or disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at least 15 years after symptom onset.

The investigators extrapolated these data to estimate that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had truly benign MS, for a prevalence of 2.9%. However, of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS based on the lay definition provided: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Tallantyre EC et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318802.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGY, NEUROSURGERY & PSYCHIATRY

Serum Nf-L shows promise as biomarker for BMT response in MS

LOS ANGELES – Serum neurofilament light chain shows promise as a biomarker for disease severity and response to treatment with autologous bone marrow transplant in patients with multiple sclerosis, according to findings from an analysis of paired samples.

Serum neurofilament light chain (Nf-L) levels were found to be significantly elevated in both the serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of 23 patients with aggressive multiple sclerosis (MS), compared with samples from 5 controls with noninflammatory neurologic conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome or migraine. The levels in the patients with MS were significantly reduced following autologous bone marrow transplant (BMT), Simon Thebault, MD, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Nf-L has been shown to be a biomarker for neuronal damage and to have potential for denoting disease severity and treatment response in MS; for this analysis, samples from patients were collected at baseline and annually for 3 years after transplant. Samples from controls were obtained for comparison.

“Our objective, really, was [to determine if we could] detect a treatment response in neurofilament light chain, and secondly, did the degree of neurofilament light chain being high at baseline predict anything about subsequent disease outcome?” Dr. Thebault, a third-year resident at the University of Ottawa, reported in the poster.

Indeed, a treatment response was detected; baseline levels were high, and levels in both serum and CSF were down significantly (P = .05) at both 1 and 3 years following bone marrow transplant, and they stayed down. “In fact, they were so low, they were not significantly different from [the levels] in noninflammatory controls,” he said, noting that serum and CSF NfL levels were highly correlated (r = .833; P less than .001).

Study subjects were patients with aggressive MS, characterized by early disease onset, rapid progression, frequent relapses, and poor treatment responses. Such patients who have received autologous BMT represent an interesting group for examining treatment responses, he said.

At baseline, these patients presumably have a high burden of tissue injury, which would be representative of high levels of Nf-L; good, prospective data show these patients have no evidence of ongoing inflammatory disease following an intensive regimen that includes chemoablation and reinfusion of autologous stem cells, which is representative of a significant reduction of neurofilament levels, he explained.

Importantly, serum and CSF levels were correlated in this study, he said, noting that most prior work has involved CSF, but “the real clinical utility in neurofilament light chain is probably in the serum, because patients don’t like having lumbar punctures too often.”

With respect to the second question pertaining to disease outcomes, the study did show that patients with baseline Nf-L levels above the median for the group had worse T1 lesion volumes at baseline and after transplant (P = .0021 at 36 months), and also had worsening brain atrophy even after transplant (P = .0389 at 60 months).

The curves appeared to be diverging, suggesting that, in the absence of inflammatory disease activity, patients with high Nf-L levels at baseline continue to have ongoing atrophy at a differential rate, compared with those with low baseline levels, Dr. Thebault said.

Other findings included better Expanded Disability Status Scale outcomes after transplant in patients with lower baseline Nf-L, and a trend toward worsening outcomes among those with higher baseline Nf-L levels, although the study may have been underpowered for this. Additionally, lower baseline Nf-L predicted significantly lower T1 and T2 lesion volume, number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions, and a reduction in brain atrophy, whereas higher baseline Nf-L predicted the opposite, he noted, adding that N-acetylaspartate-to-creatinine ratios also tended to vary inversely with Nf-L levels.

The most important findings of the study are “the sustained reduction in Nf-L levels after BMT, and that higher baseline levels predicted worse MRI outcomes,” Dr. Thebault noted. “Together these data add to a growing body of evidence that suggests that serum Nf-L has a role in monitoring treatment responses and even a predictive value in determining disease severity.”

This study was supported by Quanterix, which provided Nf-L assay kits. Dr. Thebault reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Thebault S et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr;90(15 Suppl.):P5.036.

LOS ANGELES – Serum neurofilament light chain shows promise as a biomarker for disease severity and response to treatment with autologous bone marrow transplant in patients with multiple sclerosis, according to findings from an analysis of paired samples.

Serum neurofilament light chain (Nf-L) levels were found to be significantly elevated in both the serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of 23 patients with aggressive multiple sclerosis (MS), compared with samples from 5 controls with noninflammatory neurologic conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome or migraine. The levels in the patients with MS were significantly reduced following autologous bone marrow transplant (BMT), Simon Thebault, MD, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Nf-L has been shown to be a biomarker for neuronal damage and to have potential for denoting disease severity and treatment response in MS; for this analysis, samples from patients were collected at baseline and annually for 3 years after transplant. Samples from controls were obtained for comparison.

“Our objective, really, was [to determine if we could] detect a treatment response in neurofilament light chain, and secondly, did the degree of neurofilament light chain being high at baseline predict anything about subsequent disease outcome?” Dr. Thebault, a third-year resident at the University of Ottawa, reported in the poster.

Indeed, a treatment response was detected; baseline levels were high, and levels in both serum and CSF were down significantly (P = .05) at both 1 and 3 years following bone marrow transplant, and they stayed down. “In fact, they were so low, they were not significantly different from [the levels] in noninflammatory controls,” he said, noting that serum and CSF NfL levels were highly correlated (r = .833; P less than .001).

Study subjects were patients with aggressive MS, characterized by early disease onset, rapid progression, frequent relapses, and poor treatment responses. Such patients who have received autologous BMT represent an interesting group for examining treatment responses, he said.

At baseline, these patients presumably have a high burden of tissue injury, which would be representative of high levels of Nf-L; good, prospective data show these patients have no evidence of ongoing inflammatory disease following an intensive regimen that includes chemoablation and reinfusion of autologous stem cells, which is representative of a significant reduction of neurofilament levels, he explained.

Importantly, serum and CSF levels were correlated in this study, he said, noting that most prior work has involved CSF, but “the real clinical utility in neurofilament light chain is probably in the serum, because patients don’t like having lumbar punctures too often.”

With respect to the second question pertaining to disease outcomes, the study did show that patients with baseline Nf-L levels above the median for the group had worse T1 lesion volumes at baseline and after transplant (P = .0021 at 36 months), and also had worsening brain atrophy even after transplant (P = .0389 at 60 months).

The curves appeared to be diverging, suggesting that, in the absence of inflammatory disease activity, patients with high Nf-L levels at baseline continue to have ongoing atrophy at a differential rate, compared with those with low baseline levels, Dr. Thebault said.

Other findings included better Expanded Disability Status Scale outcomes after transplant in patients with lower baseline Nf-L, and a trend toward worsening outcomes among those with higher baseline Nf-L levels, although the study may have been underpowered for this. Additionally, lower baseline Nf-L predicted significantly lower T1 and T2 lesion volume, number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions, and a reduction in brain atrophy, whereas higher baseline Nf-L predicted the opposite, he noted, adding that N-acetylaspartate-to-creatinine ratios also tended to vary inversely with Nf-L levels.

The most important findings of the study are “the sustained reduction in Nf-L levels after BMT, and that higher baseline levels predicted worse MRI outcomes,” Dr. Thebault noted. “Together these data add to a growing body of evidence that suggests that serum Nf-L has a role in monitoring treatment responses and even a predictive value in determining disease severity.”

This study was supported by Quanterix, which provided Nf-L assay kits. Dr. Thebault reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Thebault S et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr;90(15 Suppl.):P5.036.

LOS ANGELES – Serum neurofilament light chain shows promise as a biomarker for disease severity and response to treatment with autologous bone marrow transplant in patients with multiple sclerosis, according to findings from an analysis of paired samples.

Serum neurofilament light chain (Nf-L) levels were found to be significantly elevated in both the serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of 23 patients with aggressive multiple sclerosis (MS), compared with samples from 5 controls with noninflammatory neurologic conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome or migraine. The levels in the patients with MS were significantly reduced following autologous bone marrow transplant (BMT), Simon Thebault, MD, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Nf-L has been shown to be a biomarker for neuronal damage and to have potential for denoting disease severity and treatment response in MS; for this analysis, samples from patients were collected at baseline and annually for 3 years after transplant. Samples from controls were obtained for comparison.

“Our objective, really, was [to determine if we could] detect a treatment response in neurofilament light chain, and secondly, did the degree of neurofilament light chain being high at baseline predict anything about subsequent disease outcome?” Dr. Thebault, a third-year resident at the University of Ottawa, reported in the poster.

Indeed, a treatment response was detected; baseline levels were high, and levels in both serum and CSF were down significantly (P = .05) at both 1 and 3 years following bone marrow transplant, and they stayed down. “In fact, they were so low, they were not significantly different from [the levels] in noninflammatory controls,” he said, noting that serum and CSF NfL levels were highly correlated (r = .833; P less than .001).

Study subjects were patients with aggressive MS, characterized by early disease onset, rapid progression, frequent relapses, and poor treatment responses. Such patients who have received autologous BMT represent an interesting group for examining treatment responses, he said.

At baseline, these patients presumably have a high burden of tissue injury, which would be representative of high levels of Nf-L; good, prospective data show these patients have no evidence of ongoing inflammatory disease following an intensive regimen that includes chemoablation and reinfusion of autologous stem cells, which is representative of a significant reduction of neurofilament levels, he explained.

Importantly, serum and CSF levels were correlated in this study, he said, noting that most prior work has involved CSF, but “the real clinical utility in neurofilament light chain is probably in the serum, because patients don’t like having lumbar punctures too often.”

With respect to the second question pertaining to disease outcomes, the study did show that patients with baseline Nf-L levels above the median for the group had worse T1 lesion volumes at baseline and after transplant (P = .0021 at 36 months), and also had worsening brain atrophy even after transplant (P = .0389 at 60 months).

The curves appeared to be diverging, suggesting that, in the absence of inflammatory disease activity, patients with high Nf-L levels at baseline continue to have ongoing atrophy at a differential rate, compared with those with low baseline levels, Dr. Thebault said.

Other findings included better Expanded Disability Status Scale outcomes after transplant in patients with lower baseline Nf-L, and a trend toward worsening outcomes among those with higher baseline Nf-L levels, although the study may have been underpowered for this. Additionally, lower baseline Nf-L predicted significantly lower T1 and T2 lesion volume, number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions, and a reduction in brain atrophy, whereas higher baseline Nf-L predicted the opposite, he noted, adding that N-acetylaspartate-to-creatinine ratios also tended to vary inversely with Nf-L levels.

The most important findings of the study are “the sustained reduction in Nf-L levels after BMT, and that higher baseline levels predicted worse MRI outcomes,” Dr. Thebault noted. “Together these data add to a growing body of evidence that suggests that serum Nf-L has a role in monitoring treatment responses and even a predictive value in determining disease severity.”

This study was supported by Quanterix, which provided Nf-L assay kits. Dr. Thebault reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Thebault S et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr;90(15 Suppl.):P5.036.

REPORTING FROM AAN 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Serum and cerebrospinal fluid Nf-L levels declines significantly after bone marrow transplant (P less than .05) and did not differ from the levels in controls.

Study details: An analysis of paired samples from 23 patients with multiple sclerosis and 5 controls.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Quanterix, which provided Nf-L assay kits. Dr. Thebault reported having no disclosures.

Source: Thebault S et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr;90(15 Suppl.):P5.036.

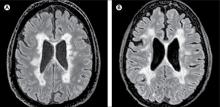

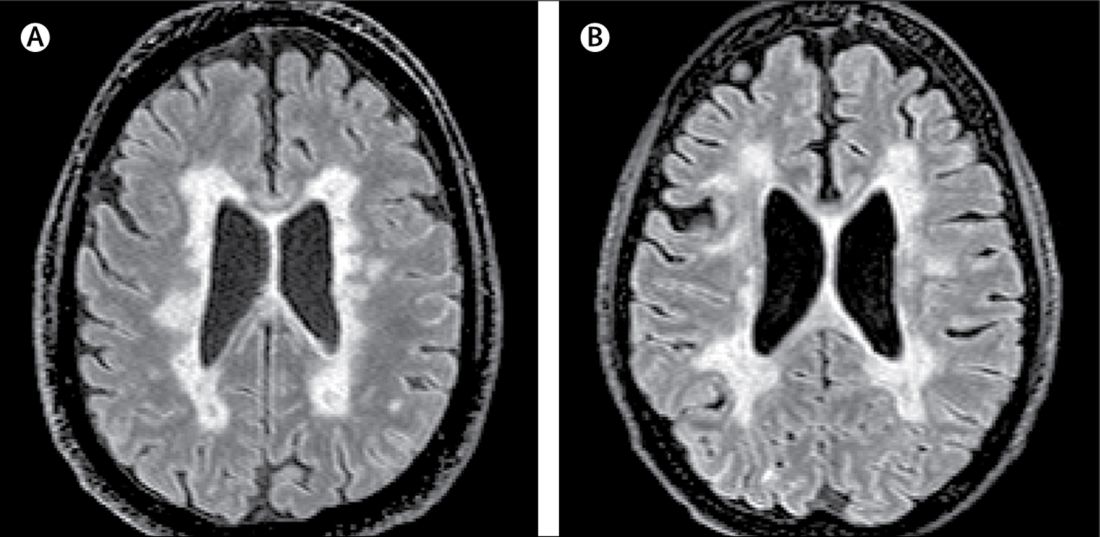

New MS subtype shows absence of cerebral white matter demyelination

A new subtype of multiple sclerosis called myelocortical multiple sclerosis is characterized by demyelination only in the spinal cord and cerebral cortex and not in the cerebral white matter.

A paper published online Aug. 21 in Lancet Neurology presents the results of a study of the brains and spinal cords of 100 patients who died of multiple sclerosis.

Bruce D. Trapp, PhD, of the Lerner Research Institute at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and his coauthors wrote that while the demyelination of cerebral white matter is a pathologic hallmark of multiple sclerosis, previous research has found only around half of cerebral T2-weighted hyperintense white matter lesions are demyelinated, and these lesions account for less than a third of variance in the rate of brain atrophy.

“In the absence of specific MRI metrics for demyelination, the relationship between cerebral white-matter demyelination and neurodegeneration remains speculative,” they wrote.

In this study, researchers scanned the brains with MRI before autopsy, then took centimeter-thick hemispheric slices to study the white-matter lesions. They identified 12 individuals as having what they describe as ‘myelocortical multiple sclerosis,’ characterized by the absence of areas of cerebral white-matter discoloration indicative of demyelinated lesions.

The authors then compared these individuals to 12 individuals with typical multiple sclerosis matched by age, sex, MRI protocol, multiple sclerosis disease subtype, disease duration, and Expanded Disability Status Scale.

They found that while individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis did not have demyelinated lesions in the cerebral white matter, they had similar areas of demyelinated lesions in the cerebral cortex to individuals with typical multiple sclerosis (median 4.45% vs. 9.74% respectively, P = .5512).

However, the individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis had a significantly smaller area of spinal cord demyelination (median 3.81% vs. 13.81%, P = .0083).

Individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis also had significantly lower mean cortical neuronal densities, compared with healthy control brains in layer III, layer V, and layer VI. But individuals with typical multiple sclerosis only had a lower cortical neuronal density in layer V when compared with controls.

Researchers also saw that in typical multiple sclerosis, neuronal density decreased as the area of brain white-matter demyelination increased. However, this negative linear correlation was not seen in myelocortical multiple sclerosis.

On MRI, researchers were still able to see abnormalities in the cerebral white matter in individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis, in T2-weighted, T1-weighted and magnetization transfer ratios (MTR) images.

They also found similar total T2-weighted and T1-weighted lesion volumes in individuals with myelocortical and with typical multiple sclerosis, although individuals with typical multiple sclerosis had significantly greater MTR lesion volumes.

“We propose that myelocortical multiple sclerosis is characterized by spinal cord demyelination, subpial cortical demyelination, and an absence of cerebral white-matter demyelination,” the authors wrote. “Our findings indicate that abnormal cerebral white-matter T2-T1-MTR regions of interest are not always demyelinated, and this pathological evidence suggests that cerebral white-matter demyelination and cortical neuronal degeneration can be independent events in myelocortical multiple sclerosis.”

The authors noted that their study may have been affected by selection bias, as all the patients in the study had died from complications of advanced multiple sclerosis. They suggested that it was therefore not appropriate to conclude that the prevalence of myelocortical multiple sclerosis seen in their sample would be similar across the multiple sclerosis population, nor were the findings likely to apply to people with earlier stage disease.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and National Multiple Sclerosis Society. One author was an employee of Renovo Neural, and three authors were employees of Biogen. One author declared a pending patent related to automated lesion segmentation from MRI images, and four authors declared funding, fees, and non-financial support from pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Trapp B et al. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1016/ S1474-4422(18)30245-X.

A new subtype of multiple sclerosis called myelocortical multiple sclerosis is characterized by demyelination only in the spinal cord and cerebral cortex and not in the cerebral white matter.

A paper published online Aug. 21 in Lancet Neurology presents the results of a study of the brains and spinal cords of 100 patients who died of multiple sclerosis.

Bruce D. Trapp, PhD, of the Lerner Research Institute at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and his coauthors wrote that while the demyelination of cerebral white matter is a pathologic hallmark of multiple sclerosis, previous research has found only around half of cerebral T2-weighted hyperintense white matter lesions are demyelinated, and these lesions account for less than a third of variance in the rate of brain atrophy.

“In the absence of specific MRI metrics for demyelination, the relationship between cerebral white-matter demyelination and neurodegeneration remains speculative,” they wrote.

In this study, researchers scanned the brains with MRI before autopsy, then took centimeter-thick hemispheric slices to study the white-matter lesions. They identified 12 individuals as having what they describe as ‘myelocortical multiple sclerosis,’ characterized by the absence of areas of cerebral white-matter discoloration indicative of demyelinated lesions.

The authors then compared these individuals to 12 individuals with typical multiple sclerosis matched by age, sex, MRI protocol, multiple sclerosis disease subtype, disease duration, and Expanded Disability Status Scale.

They found that while individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis did not have demyelinated lesions in the cerebral white matter, they had similar areas of demyelinated lesions in the cerebral cortex to individuals with typical multiple sclerosis (median 4.45% vs. 9.74% respectively, P = .5512).

However, the individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis had a significantly smaller area of spinal cord demyelination (median 3.81% vs. 13.81%, P = .0083).

Individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis also had significantly lower mean cortical neuronal densities, compared with healthy control brains in layer III, layer V, and layer VI. But individuals with typical multiple sclerosis only had a lower cortical neuronal density in layer V when compared with controls.

Researchers also saw that in typical multiple sclerosis, neuronal density decreased as the area of brain white-matter demyelination increased. However, this negative linear correlation was not seen in myelocortical multiple sclerosis.

On MRI, researchers were still able to see abnormalities in the cerebral white matter in individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis, in T2-weighted, T1-weighted and magnetization transfer ratios (MTR) images.

They also found similar total T2-weighted and T1-weighted lesion volumes in individuals with myelocortical and with typical multiple sclerosis, although individuals with typical multiple sclerosis had significantly greater MTR lesion volumes.

“We propose that myelocortical multiple sclerosis is characterized by spinal cord demyelination, subpial cortical demyelination, and an absence of cerebral white-matter demyelination,” the authors wrote. “Our findings indicate that abnormal cerebral white-matter T2-T1-MTR regions of interest are not always demyelinated, and this pathological evidence suggests that cerebral white-matter demyelination and cortical neuronal degeneration can be independent events in myelocortical multiple sclerosis.”

The authors noted that their study may have been affected by selection bias, as all the patients in the study had died from complications of advanced multiple sclerosis. They suggested that it was therefore not appropriate to conclude that the prevalence of myelocortical multiple sclerosis seen in their sample would be similar across the multiple sclerosis population, nor were the findings likely to apply to people with earlier stage disease.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and National Multiple Sclerosis Society. One author was an employee of Renovo Neural, and three authors were employees of Biogen. One author declared a pending patent related to automated lesion segmentation from MRI images, and four authors declared funding, fees, and non-financial support from pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Trapp B et al. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1016/ S1474-4422(18)30245-X.

A new subtype of multiple sclerosis called myelocortical multiple sclerosis is characterized by demyelination only in the spinal cord and cerebral cortex and not in the cerebral white matter.

A paper published online Aug. 21 in Lancet Neurology presents the results of a study of the brains and spinal cords of 100 patients who died of multiple sclerosis.

Bruce D. Trapp, PhD, of the Lerner Research Institute at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and his coauthors wrote that while the demyelination of cerebral white matter is a pathologic hallmark of multiple sclerosis, previous research has found only around half of cerebral T2-weighted hyperintense white matter lesions are demyelinated, and these lesions account for less than a third of variance in the rate of brain atrophy.

“In the absence of specific MRI metrics for demyelination, the relationship between cerebral white-matter demyelination and neurodegeneration remains speculative,” they wrote.

In this study, researchers scanned the brains with MRI before autopsy, then took centimeter-thick hemispheric slices to study the white-matter lesions. They identified 12 individuals as having what they describe as ‘myelocortical multiple sclerosis,’ characterized by the absence of areas of cerebral white-matter discoloration indicative of demyelinated lesions.

The authors then compared these individuals to 12 individuals with typical multiple sclerosis matched by age, sex, MRI protocol, multiple sclerosis disease subtype, disease duration, and Expanded Disability Status Scale.

They found that while individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis did not have demyelinated lesions in the cerebral white matter, they had similar areas of demyelinated lesions in the cerebral cortex to individuals with typical multiple sclerosis (median 4.45% vs. 9.74% respectively, P = .5512).

However, the individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis had a significantly smaller area of spinal cord demyelination (median 3.81% vs. 13.81%, P = .0083).

Individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis also had significantly lower mean cortical neuronal densities, compared with healthy control brains in layer III, layer V, and layer VI. But individuals with typical multiple sclerosis only had a lower cortical neuronal density in layer V when compared with controls.

Researchers also saw that in typical multiple sclerosis, neuronal density decreased as the area of brain white-matter demyelination increased. However, this negative linear correlation was not seen in myelocortical multiple sclerosis.

On MRI, researchers were still able to see abnormalities in the cerebral white matter in individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis, in T2-weighted, T1-weighted and magnetization transfer ratios (MTR) images.

They also found similar total T2-weighted and T1-weighted lesion volumes in individuals with myelocortical and with typical multiple sclerosis, although individuals with typical multiple sclerosis had significantly greater MTR lesion volumes.

“We propose that myelocortical multiple sclerosis is characterized by spinal cord demyelination, subpial cortical demyelination, and an absence of cerebral white-matter demyelination,” the authors wrote. “Our findings indicate that abnormal cerebral white-matter T2-T1-MTR regions of interest are not always demyelinated, and this pathological evidence suggests that cerebral white-matter demyelination and cortical neuronal degeneration can be independent events in myelocortical multiple sclerosis.”

The authors noted that their study may have been affected by selection bias, as all the patients in the study had died from complications of advanced multiple sclerosis. They suggested that it was therefore not appropriate to conclude that the prevalence of myelocortical multiple sclerosis seen in their sample would be similar across the multiple sclerosis population, nor were the findings likely to apply to people with earlier stage disease.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and National Multiple Sclerosis Society. One author was an employee of Renovo Neural, and three authors were employees of Biogen. One author declared a pending patent related to automated lesion segmentation from MRI images, and four authors declared funding, fees, and non-financial support from pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Trapp B et al. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1016/ S1474-4422(18)30245-X.

FROM LANCET NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Researchers have identified a new subtype of multiple sclerosis.

Major finding: Individuals with myelocortical multiple sclerosis show demyelination in the spinal cord and cortex only.

Study details: Post-mortem study of brains and spinal cords of 100 individuals with multiple sclerosis.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and National Multiple Sclerosis Society. One author was an employee of Renovo Neural, three authors were employees of Biogen. One author declared a pending patent related to automated lesion segmentation from MRI images, and four authors declared funding, fees and non-financial support from pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Trapp B et al. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1016/ S1474-4422(18)30245-X.

Latex Allergy From Biologic Injectable Devices

Innovations Lead to More Targeted Prostate Cancer Treatments (FULL)

The main treatment for prostate cancer—the third leading cause of cancer death in American men—often is “watchful waiting.” But what happens before, during, and after that waiting period has changed tremendously in recent years. Innovative and improved methods and drugs allow for a more precise diagnosis, better risk stratification, targeted treatment options, and longer survival.

Innovations in diagnosis include a revised histologic grading system, which was incorporated into the 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors. The new grading system ranks prostate cancer on a 1-to-5 scale, making it more discriminating, as validated in a study of more than 25,000 men.

The use of new prognostic biomarkers has advanced risk stratification. According to a recent review, biopsy guided by ultrasound misses between 21% and 28% of prostate cancers and undergrades between 14% and 17%.1 But new serum-, tissue-, and image-based biomarkers may help identify potential false negatives. The prostate cancer antigen 3 test, for example, has an 88% negative predictive value for subsequent biopsy. Molecular biomarkers also can predict clinical progression, risk of adverse pathology, and metastatic risk.

Fortunately, biopsy guided by ultrasound is getting more precise. Advances in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) now allow for “targeted biopsies.” The enhanced MRI has 89% sensitivity and 73% specificity for identifying prostate cancer. According to one study of 1,003 men, targeted prostate biopsy using MRI-ultrasound fusion identified 30% more cases of Gleason score ≥ 4 + 3 than did systematic prostate biopsy.1 Updates in positron emission tomography are garnering interest for improved staging because this technology allows for better detection of local recurrence, regional lymph node metastases, and distant metastases.

Once a prostate cancer diagnosis has been confirmed, the decision of what to do next may be watchful waiting (treating symptoms palliatively), but recent research suggests that active surveillance that includes regular prostate-specific antigen testing, physical examinations, and prostate biopsies may be a better choice, particularly for men with less aggressive cancer. One study of 1,298 men with mostly very low-risk disease followed for up to 60 months found metastasis in only 5; only 2 died. The Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) trial found that the number of deaths in the active monitoring group did not differ significantly from those in the surgery or radiation groups.

What should be the contemporary standard of care? Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is still the go-to treatment for men with metastatic prostate cancer. Although ADT has been associated with toxicity, a meta-analysis found continuous ADT was better than intermittent in terms of disease progression and survival.1

Other research has focused on which types of prostate cancer respond best to specific therapies. Molecular subtyping (already available in bladder and breast cancer) is gaining popularity. Prostate cancer was thought to derive from glandular luminal cells, but recent evidence supports the idea that basal cells play a role as well. Researchers who analyzed nearly 4,000 samples suggest that luminal B tumors respond better to postoperative ADT than do nonluminal B cancers. These findings suggest that “personalized” ADT treatment may be possible.2

Several drugs have been shown to improve survival: Among them, docetaxel, abiraterone acetate, enzalutamide, and cabazitaxel. In the STAMPEDE trial, men with locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer who received ADT plus abiraterone and prednisolone had significantly higher rates of overall and failure-free survival.3

Docetaxel, which can extend survival by 10 to 13 months compared with standard ADT, is taking on a bigger role for its ability to delay progression and recurrence while being well tolerated. Options for men whose cancer does not respond to ADT include abiraterone and enzalutamide. Both act on the androgen axis to slow progression and improve survival.

More than 30% of patients treated with radical prostatectomy will have recurrent cancer as will 50% of those treated with salvage radiation therapy. Bicalutamide has shown extremely promising action against recurrent cancer. In one study, the cumulative incidence of metastatic prostate cancer at 12 years was 14.5% in the bicalutamide group, compared with 23.0% in the placebo group.4

But while that study was going on, it was superseded by injectable gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists as first-choice hormonal therapy with radiation. However, the researchers say that does not

Multimodal therapy and precision medicine are becoming bywords in prostate cancer treatment. Drugs on the horizon likely will be tailored to tumor molecular biology, with genetic information used to specifically guide diagnosis and treatment. Prostate cancer may still be a slow killer, but immunotherapies (like sipuleucel-T, the first FDA-approved cancer vaccine), hormonal therapies, and bone-targeting agents enable men with prostate cancer to not only live longer but also with a better quality of life.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Litwin MS, Tan HJ. The diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer: a review. JAMA. 2017;317(24):2532-2542.

2. Zhao SG, Chang SL, Erho N, et al. Associations of luminal and basal subtyping of prostate cancer with prognosis and response to androgen deprivation therapy. JAMA Oncol. 2017. [Epub ahead of print.]

3. James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, et al; for the STAMPEDE Investigators. Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017. [Epub ahead of print.]

4. Shipley WU, Seiferheld W, Lukka HR, et al; NRG Oncology RTOG. Radiation with or without antiandrogen therapy in recurrent prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(5):417-428.

The main treatment for prostate cancer—the third leading cause of cancer death in American men—often is “watchful waiting.” But what happens before, during, and after that waiting period has changed tremendously in recent years. Innovative and improved methods and drugs allow for a more precise diagnosis, better risk stratification, targeted treatment options, and longer survival.

Innovations in diagnosis include a revised histologic grading system, which was incorporated into the 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors. The new grading system ranks prostate cancer on a 1-to-5 scale, making it more discriminating, as validated in a study of more than 25,000 men.

The use of new prognostic biomarkers has advanced risk stratification. According to a recent review, biopsy guided by ultrasound misses between 21% and 28% of prostate cancers and undergrades between 14% and 17%.1 But new serum-, tissue-, and image-based biomarkers may help identify potential false negatives. The prostate cancer antigen 3 test, for example, has an 88% negative predictive value for subsequent biopsy. Molecular biomarkers also can predict clinical progression, risk of adverse pathology, and metastatic risk.

Fortunately, biopsy guided by ultrasound is getting more precise. Advances in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) now allow for “targeted biopsies.” The enhanced MRI has 89% sensitivity and 73% specificity for identifying prostate cancer. According to one study of 1,003 men, targeted prostate biopsy using MRI-ultrasound fusion identified 30% more cases of Gleason score ≥ 4 + 3 than did systematic prostate biopsy.1 Updates in positron emission tomography are garnering interest for improved staging because this technology allows for better detection of local recurrence, regional lymph node metastases, and distant metastases.

Once a prostate cancer diagnosis has been confirmed, the decision of what to do next may be watchful waiting (treating symptoms palliatively), but recent research suggests that active surveillance that includes regular prostate-specific antigen testing, physical examinations, and prostate biopsies may be a better choice, particularly for men with less aggressive cancer. One study of 1,298 men with mostly very low-risk disease followed for up to 60 months found metastasis in only 5; only 2 died. The Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) trial found that the number of deaths in the active monitoring group did not differ significantly from those in the surgery or radiation groups.

What should be the contemporary standard of care? Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is still the go-to treatment for men with metastatic prostate cancer. Although ADT has been associated with toxicity, a meta-analysis found continuous ADT was better than intermittent in terms of disease progression and survival.1

Other research has focused on which types of prostate cancer respond best to specific therapies. Molecular subtyping (already available in bladder and breast cancer) is gaining popularity. Prostate cancer was thought to derive from glandular luminal cells, but recent evidence supports the idea that basal cells play a role as well. Researchers who analyzed nearly 4,000 samples suggest that luminal B tumors respond better to postoperative ADT than do nonluminal B cancers. These findings suggest that “personalized” ADT treatment may be possible.2

Several drugs have been shown to improve survival: Among them, docetaxel, abiraterone acetate, enzalutamide, and cabazitaxel. In the STAMPEDE trial, men with locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer who received ADT plus abiraterone and prednisolone had significantly higher rates of overall and failure-free survival.3

Docetaxel, which can extend survival by 10 to 13 months compared with standard ADT, is taking on a bigger role for its ability to delay progression and recurrence while being well tolerated. Options for men whose cancer does not respond to ADT include abiraterone and enzalutamide. Both act on the androgen axis to slow progression and improve survival.

More than 30% of patients treated with radical prostatectomy will have recurrent cancer as will 50% of those treated with salvage radiation therapy. Bicalutamide has shown extremely promising action against recurrent cancer. In one study, the cumulative incidence of metastatic prostate cancer at 12 years was 14.5% in the bicalutamide group, compared with 23.0% in the placebo group.4

But while that study was going on, it was superseded by injectable gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists as first-choice hormonal therapy with radiation. However, the researchers say that does not

Multimodal therapy and precision medicine are becoming bywords in prostate cancer treatment. Drugs on the horizon likely will be tailored to tumor molecular biology, with genetic information used to specifically guide diagnosis and treatment. Prostate cancer may still be a slow killer, but immunotherapies (like sipuleucel-T, the first FDA-approved cancer vaccine), hormonal therapies, and bone-targeting agents enable men with prostate cancer to not only live longer but also with a better quality of life.

Click here to read the digital edition.

The main treatment for prostate cancer—the third leading cause of cancer death in American men—often is “watchful waiting.” But what happens before, during, and after that waiting period has changed tremendously in recent years. Innovative and improved methods and drugs allow for a more precise diagnosis, better risk stratification, targeted treatment options, and longer survival.

Innovations in diagnosis include a revised histologic grading system, which was incorporated into the 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors. The new grading system ranks prostate cancer on a 1-to-5 scale, making it more discriminating, as validated in a study of more than 25,000 men.

The use of new prognostic biomarkers has advanced risk stratification. According to a recent review, biopsy guided by ultrasound misses between 21% and 28% of prostate cancers and undergrades between 14% and 17%.1 But new serum-, tissue-, and image-based biomarkers may help identify potential false negatives. The prostate cancer antigen 3 test, for example, has an 88% negative predictive value for subsequent biopsy. Molecular biomarkers also can predict clinical progression, risk of adverse pathology, and metastatic risk.

Fortunately, biopsy guided by ultrasound is getting more precise. Advances in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) now allow for “targeted biopsies.” The enhanced MRI has 89% sensitivity and 73% specificity for identifying prostate cancer. According to one study of 1,003 men, targeted prostate biopsy using MRI-ultrasound fusion identified 30% more cases of Gleason score ≥ 4 + 3 than did systematic prostate biopsy.1 Updates in positron emission tomography are garnering interest for improved staging because this technology allows for better detection of local recurrence, regional lymph node metastases, and distant metastases.

Once a prostate cancer diagnosis has been confirmed, the decision of what to do next may be watchful waiting (treating symptoms palliatively), but recent research suggests that active surveillance that includes regular prostate-specific antigen testing, physical examinations, and prostate biopsies may be a better choice, particularly for men with less aggressive cancer. One study of 1,298 men with mostly very low-risk disease followed for up to 60 months found metastasis in only 5; only 2 died. The Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) trial found that the number of deaths in the active monitoring group did not differ significantly from those in the surgery or radiation groups.

What should be the contemporary standard of care? Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is still the go-to treatment for men with metastatic prostate cancer. Although ADT has been associated with toxicity, a meta-analysis found continuous ADT was better than intermittent in terms of disease progression and survival.1

Other research has focused on which types of prostate cancer respond best to specific therapies. Molecular subtyping (already available in bladder and breast cancer) is gaining popularity. Prostate cancer was thought to derive from glandular luminal cells, but recent evidence supports the idea that basal cells play a role as well. Researchers who analyzed nearly 4,000 samples suggest that luminal B tumors respond better to postoperative ADT than do nonluminal B cancers. These findings suggest that “personalized” ADT treatment may be possible.2

Several drugs have been shown to improve survival: Among them, docetaxel, abiraterone acetate, enzalutamide, and cabazitaxel. In the STAMPEDE trial, men with locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer who received ADT plus abiraterone and prednisolone had significantly higher rates of overall and failure-free survival.3

Docetaxel, which can extend survival by 10 to 13 months compared with standard ADT, is taking on a bigger role for its ability to delay progression and recurrence while being well tolerated. Options for men whose cancer does not respond to ADT include abiraterone and enzalutamide. Both act on the androgen axis to slow progression and improve survival.

More than 30% of patients treated with radical prostatectomy will have recurrent cancer as will 50% of those treated with salvage radiation therapy. Bicalutamide has shown extremely promising action against recurrent cancer. In one study, the cumulative incidence of metastatic prostate cancer at 12 years was 14.5% in the bicalutamide group, compared with 23.0% in the placebo group.4

But while that study was going on, it was superseded by injectable gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists as first-choice hormonal therapy with radiation. However, the researchers say that does not

Multimodal therapy and precision medicine are becoming bywords in prostate cancer treatment. Drugs on the horizon likely will be tailored to tumor molecular biology, with genetic information used to specifically guide diagnosis and treatment. Prostate cancer may still be a slow killer, but immunotherapies (like sipuleucel-T, the first FDA-approved cancer vaccine), hormonal therapies, and bone-targeting agents enable men with prostate cancer to not only live longer but also with a better quality of life.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Litwin MS, Tan HJ. The diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer: a review. JAMA. 2017;317(24):2532-2542.

2. Zhao SG, Chang SL, Erho N, et al. Associations of luminal and basal subtyping of prostate cancer with prognosis and response to androgen deprivation therapy. JAMA Oncol. 2017. [Epub ahead of print.]

3. James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, et al; for the STAMPEDE Investigators. Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017. [Epub ahead of print.]

4. Shipley WU, Seiferheld W, Lukka HR, et al; NRG Oncology RTOG. Radiation with or without antiandrogen therapy in recurrent prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(5):417-428.

1. Litwin MS, Tan HJ. The diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer: a review. JAMA. 2017;317(24):2532-2542.

2. Zhao SG, Chang SL, Erho N, et al. Associations of luminal and basal subtyping of prostate cancer with prognosis and response to androgen deprivation therapy. JAMA Oncol. 2017. [Epub ahead of print.]

3. James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, et al; for the STAMPEDE Investigators. Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017. [Epub ahead of print.]

4. Shipley WU, Seiferheld W, Lukka HR, et al; NRG Oncology RTOG. Radiation with or without antiandrogen therapy in recurrent prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(5):417-428.

Acute Leukemia of Ambiguous Lineage in Elderly Patients: A SEER-Medicare Database Analysis (FULL)

About Research in Context

In this article, the authors of recent scholarship have been asked to discuss the implications of their research on federal health care providers and specifically the veteran and active-duty service member patient populations. Because the article does not include new research and cannot be blinded, it has undergone an abbreviated peer review process. The original article can be found at Guru Murthy GS, Dhakal I, Lee JY, Mehta P. Acute leukemia of ambiguous lineage in elderly patients - analysis of survival using surveillance epidemiology and end results-Medicare database. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17(2):100-107.

Acute leukemia of ambiguous lineage (ALAL) is a rare disorder in adults, constituting about 3% to 5% of acute leukemia cases. Unlike acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), ALAL cannot be clearly differentiated into a single subtype based on immunophenotyping. The diagnostic criteria for accurately identifying ALAL has evolved over time. There is paucity of information regarding the outcomes and management of this rare leukemia especially in elderly patients, and it is unclear whether treatment improves survival in these patients.

We performed a retrospective analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare linked database to describe the outcomes of ALAL in the elderly population in U.S.1 Patients included in the analysis were aged > 65 years, with a pathologically confirmed diagnosis of ALAL, diagnosed between 1992-2010, and on active follow-up. Information on patient demographics, treatment, chemotherapeutic agents used in treatment, and survival was obtained and analyzed using appropriate statistical methods. A total of 705 patients with a median age of 80 years were included. There was a higher proportion of males than females and a higher proportion of white patients compared with African Americans and other races. We found that the overall survival (OS) declined significantly with increasing age, and treatment with chemotherapy improved the survival. However, factors such as gender, race, or type of chemotherapy received (ALL based, AML based, or other regimens) did not significantly influence the survival.

Even in the current era, the optimal therapy for ALAL is not well established. Although options such as AML-based or ALL-based chemotherapy are available, the best chemotherapy regimen and its sequence is unknown as prior studies have demonstrated varying results.2-5 Among elderly patients, numerous factors such as performance status, comorbidities, and ability to tolerate therapy influence the treatment decision. In light of the poor prognosis in elderly patients, a question often arises in the clinician’s mind about whether chemotherapy would provide any benefit for the patient.

Our study results showed that chemotherapy likely improves survival in these patients. However, due to the smaller number of patients, caution is needed in interpreting the result that there was no significant difference between AML-directed or ALL-directed chemotherapy. Another factor highlighted in the study was that only about 21.5% of patients had been treated with chemotherapy. Due to the inherent nature of the database, we could not identify the factors that may have influenced treatment decisions in these patients. Additionally, patients with stem cell transplantation-related claims could not be included in the analysis due to noncontinuous Medicare coverage during the study period. Hence, the role of stem cell transplantation in these patients could not be determined.

Implications Among Veterans

Actual incidence of ALAL among veterans is not known. Whether the incidence of ALAL relates to exposures to chemicals or toxins during military training and service also is unknown. However, ALAL is likely to be at least as prevalent as it is in the nonveteran population and perhaps more so because of exposures and stresses during military training and service.

It is unclear whether veterans attending VA hospitals receive less or different treatment given the higher comorbidities. Finally, it also is not known whether the outcomes for veterans would be different with or without treatment.

Our findings suggest that treatment should be seriously considered in all patients (veterans or not) who are healthy enough to receive chemotherapy regardless of their age. More research is needed to determine the disease incidence and prevalence among veterans and to evaluate whether there are specific etiologic correlations between ALAL and military exposures, whether the natural history is similar to other populations, and to delineate responsiveness to treatment.

Conclusion

This study suggests a poor survival for elderly patients with ALAL in the U.S. Although treatment is associated with an improvement in survival, only 21.5% of patients have received therapy. The optimal choice of chemotherapy for this disease is still not known and warrants prospective studies.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Guru Murthy GS, Dhakal I, Lee JY, Mehta P. Acute leukemia of ambiguous lineage in elderly patients—analysis of survival using surveillance epidemiology and end results—Medicare database. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17(2):100-107.

2. Rubnitz JE, Onciu M, Pounds S, et al. Acute mixed lineage leukemia in children: the experience of St Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Blood. 2009;113(21):5083-5089.

3. Matutes E, Pickl WF, Van’t Veer M, et al. Mixed phenotype acute leukemia: clinical and laboratory features and out-come in 100 patients defined according to the WHO classification. Blood. 2011;117(11):3163-3171.

4. Wolach O, Stone RM. How I treat mixed-phenotype acute leukemia. Blood. 2015;125(16):2477-2485.

5. Lee JH, Min YH, Chung CW, et al; Korean Society of Hematology AML/MDS Working Party. Prognostic implications of the immunophenotype in biphenotypic acute leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(4):700-709.

About Research in Context

In this article, the authors of recent scholarship have been asked to discuss the implications of their research on federal health care providers and specifically the veteran and active-duty service member patient populations. Because the article does not include new research and cannot be blinded, it has undergone an abbreviated peer review process. The original article can be found at Guru Murthy GS, Dhakal I, Lee JY, Mehta P. Acute leukemia of ambiguous lineage in elderly patients - analysis of survival using surveillance epidemiology and end results-Medicare database. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17(2):100-107.

Acute leukemia of ambiguous lineage (ALAL) is a rare disorder in adults, constituting about 3% to 5% of acute leukemia cases. Unlike acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), ALAL cannot be clearly differentiated into a single subtype based on immunophenotyping. The diagnostic criteria for accurately identifying ALAL has evolved over time. There is paucity of information regarding the outcomes and management of this rare leukemia especially in elderly patients, and it is unclear whether treatment improves survival in these patients.

We performed a retrospective analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare linked database to describe the outcomes of ALAL in the elderly population in U.S.1 Patients included in the analysis were aged > 65 years, with a pathologically confirmed diagnosis of ALAL, diagnosed between 1992-2010, and on active follow-up. Information on patient demographics, treatment, chemotherapeutic agents used in treatment, and survival was obtained and analyzed using appropriate statistical methods. A total of 705 patients with a median age of 80 years were included. There was a higher proportion of males than females and a higher proportion of white patients compared with African Americans and other races. We found that the overall survival (OS) declined significantly with increasing age, and treatment with chemotherapy improved the survival. However, factors such as gender, race, or type of chemotherapy received (ALL based, AML based, or other regimens) did not significantly influence the survival.

Even in the current era, the optimal therapy for ALAL is not well established. Although options such as AML-based or ALL-based chemotherapy are available, the best chemotherapy regimen and its sequence is unknown as prior studies have demonstrated varying results.2-5 Among elderly patients, numerous factors such as performance status, comorbidities, and ability to tolerate therapy influence the treatment decision. In light of the poor prognosis in elderly patients, a question often arises in the clinician’s mind about whether chemotherapy would provide any benefit for the patient.

Our study results showed that chemotherapy likely improves survival in these patients. However, due to the smaller number of patients, caution is needed in interpreting the result that there was no significant difference between AML-directed or ALL-directed chemotherapy. Another factor highlighted in the study was that only about 21.5% of patients had been treated with chemotherapy. Due to the inherent nature of the database, we could not identify the factors that may have influenced treatment decisions in these patients. Additionally, patients with stem cell transplantation-related claims could not be included in the analysis due to noncontinuous Medicare coverage during the study period. Hence, the role of stem cell transplantation in these patients could not be determined.

Implications Among Veterans

Actual incidence of ALAL among veterans is not known. Whether the incidence of ALAL relates to exposures to chemicals or toxins during military training and service also is unknown. However, ALAL is likely to be at least as prevalent as it is in the nonveteran population and perhaps more so because of exposures and stresses during military training and service.

It is unclear whether veterans attending VA hospitals receive less or different treatment given the higher comorbidities. Finally, it also is not known whether the outcomes for veterans would be different with or without treatment.

Our findings suggest that treatment should be seriously considered in all patients (veterans or not) who are healthy enough to receive chemotherapy regardless of their age. More research is needed to determine the disease incidence and prevalence among veterans and to evaluate whether there are specific etiologic correlations between ALAL and military exposures, whether the natural history is similar to other populations, and to delineate responsiveness to treatment.

Conclusion

This study suggests a poor survival for elderly patients with ALAL in the U.S. Although treatment is associated with an improvement in survival, only 21.5% of patients have received therapy. The optimal choice of chemotherapy for this disease is still not known and warrants prospective studies.

Click here to read the digital edition.

About Research in Context

In this article, the authors of recent scholarship have been asked to discuss the implications of their research on federal health care providers and specifically the veteran and active-duty service member patient populations. Because the article does not include new research and cannot be blinded, it has undergone an abbreviated peer review process. The original article can be found at Guru Murthy GS, Dhakal I, Lee JY, Mehta P. Acute leukemia of ambiguous lineage in elderly patients - analysis of survival using surveillance epidemiology and end results-Medicare database. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17(2):100-107.

Acute leukemia of ambiguous lineage (ALAL) is a rare disorder in adults, constituting about 3% to 5% of acute leukemia cases. Unlike acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), ALAL cannot be clearly differentiated into a single subtype based on immunophenotyping. The diagnostic criteria for accurately identifying ALAL has evolved over time. There is paucity of information regarding the outcomes and management of this rare leukemia especially in elderly patients, and it is unclear whether treatment improves survival in these patients.

We performed a retrospective analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare linked database to describe the outcomes of ALAL in the elderly population in U.S.1 Patients included in the analysis were aged > 65 years, with a pathologically confirmed diagnosis of ALAL, diagnosed between 1992-2010, and on active follow-up. Information on patient demographics, treatment, chemotherapeutic agents used in treatment, and survival was obtained and analyzed using appropriate statistical methods. A total of 705 patients with a median age of 80 years were included. There was a higher proportion of males than females and a higher proportion of white patients compared with African Americans and other races. We found that the overall survival (OS) declined significantly with increasing age, and treatment with chemotherapy improved the survival. However, factors such as gender, race, or type of chemotherapy received (ALL based, AML based, or other regimens) did not significantly influence the survival.

Even in the current era, the optimal therapy for ALAL is not well established. Although options such as AML-based or ALL-based chemotherapy are available, the best chemotherapy regimen and its sequence is unknown as prior studies have demonstrated varying results.2-5 Among elderly patients, numerous factors such as performance status, comorbidities, and ability to tolerate therapy influence the treatment decision. In light of the poor prognosis in elderly patients, a question often arises in the clinician’s mind about whether chemotherapy would provide any benefit for the patient.

Our study results showed that chemotherapy likely improves survival in these patients. However, due to the smaller number of patients, caution is needed in interpreting the result that there was no significant difference between AML-directed or ALL-directed chemotherapy. Another factor highlighted in the study was that only about 21.5% of patients had been treated with chemotherapy. Due to the inherent nature of the database, we could not identify the factors that may have influenced treatment decisions in these patients. Additionally, patients with stem cell transplantation-related claims could not be included in the analysis due to noncontinuous Medicare coverage during the study period. Hence, the role of stem cell transplantation in these patients could not be determined.

Implications Among Veterans