User login

Q&A with Hospitalist Administrator Amit Prachand

Amit Prachand, MEng

Division Administrator, Hospital Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Feinberg School of Medicine,

Northwestern University, Chicago

Question: What motivated you to join SHM’s Administrators Task Force (ATF)?

A: I wanted to be able to directly interface with the community of leaders in similar administrator roles in order to obtain a stronger perspective of the role, its rewards and challenges, and of the creative solutions different practices have implemented to address issues relevant to hospital medicine and the overall healthcare delivery model. I was also relatively new to hospital medicine practice management, and even healthcare, so I wanted to put myself in the best position to soak in as much as possible as well as help facilitate the sharing of ideas amongst my new group of peers.

Q: How is the Administrators Task Force moving HM forward?

A: One of our main thrusts in the task force is to help expand the administrative membership in SHM. As hospitalist programs mature and the environment in which hospital medicine is practiced evolves, it is imperative that we develop the community, the infrastructure, and the tools required to partner with our stakeholders—both internal and external—to help lead hospital medicine forward.

Q: Has your participation in the Administrators Task Force helped your group?

A: The ATF has helped develop direct lines of communication with peers. This helps when it come to issues for which we are finding the best solutions for; areas such as on-boarding of new physicians, negotiations with hospitals, coding and billing improvement, and meaningful performance reporting.

Q: How is the task force helping hospitals improve patient care?

A: By having a peer group on the administrative side, I believe we are now able to more readily share ideas that support the ideas around patient-care improvement that are being shared amongst the physician membership.

One of the key roles we play as an administrator is to help develop the systems and structures that help improve patient care. That may range from advocating for physician representation on certain hospital committees to facilitating a process/QI project that involves hospitalists and other members of the extended patient-care team, such as physicians from other medical specialties, nursing, pharmacists, case management, bed management, environmental services, and information technology.

Q: How is the task force helping hospitals improve healthcare overall?

A: We are continually improving the infrastructure for administrators to share ideas and solutions to address overall healthcare issues (payment reform, readmissions, compliance, cost). It is through this infrastructure that we can identify best implementation practices of ideas. The webinar series (www.hospitalmedicine.org/roundtables) that we’ve developed addresses many of the issues that healthcare in general is facing. This series has exceeded expectations for participation and interest.

Q: What do you like most about your job as an administrator?

A: It is never dull, always exciting. From the firefighting to the long-term planning, the role keeps me on my toes. I enjoy being in a position that is so tightly intertwined with so many critical functions and disciplines across the medical center in a profession—hospital medicine—that is continuing to lead advances in healthcare delivery.

—Brendon Shank

Amit Prachand, MEng

Division Administrator, Hospital Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Feinberg School of Medicine,

Northwestern University, Chicago

Question: What motivated you to join SHM’s Administrators Task Force (ATF)?

A: I wanted to be able to directly interface with the community of leaders in similar administrator roles in order to obtain a stronger perspective of the role, its rewards and challenges, and of the creative solutions different practices have implemented to address issues relevant to hospital medicine and the overall healthcare delivery model. I was also relatively new to hospital medicine practice management, and even healthcare, so I wanted to put myself in the best position to soak in as much as possible as well as help facilitate the sharing of ideas amongst my new group of peers.

Q: How is the Administrators Task Force moving HM forward?

A: One of our main thrusts in the task force is to help expand the administrative membership in SHM. As hospitalist programs mature and the environment in which hospital medicine is practiced evolves, it is imperative that we develop the community, the infrastructure, and the tools required to partner with our stakeholders—both internal and external—to help lead hospital medicine forward.

Q: Has your participation in the Administrators Task Force helped your group?

A: The ATF has helped develop direct lines of communication with peers. This helps when it come to issues for which we are finding the best solutions for; areas such as on-boarding of new physicians, negotiations with hospitals, coding and billing improvement, and meaningful performance reporting.

Q: How is the task force helping hospitals improve patient care?

A: By having a peer group on the administrative side, I believe we are now able to more readily share ideas that support the ideas around patient-care improvement that are being shared amongst the physician membership.

One of the key roles we play as an administrator is to help develop the systems and structures that help improve patient care. That may range from advocating for physician representation on certain hospital committees to facilitating a process/QI project that involves hospitalists and other members of the extended patient-care team, such as physicians from other medical specialties, nursing, pharmacists, case management, bed management, environmental services, and information technology.

Q: How is the task force helping hospitals improve healthcare overall?

A: We are continually improving the infrastructure for administrators to share ideas and solutions to address overall healthcare issues (payment reform, readmissions, compliance, cost). It is through this infrastructure that we can identify best implementation practices of ideas. The webinar series (www.hospitalmedicine.org/roundtables) that we’ve developed addresses many of the issues that healthcare in general is facing. This series has exceeded expectations for participation and interest.

Q: What do you like most about your job as an administrator?

A: It is never dull, always exciting. From the firefighting to the long-term planning, the role keeps me on my toes. I enjoy being in a position that is so tightly intertwined with so many critical functions and disciplines across the medical center in a profession—hospital medicine—that is continuing to lead advances in healthcare delivery.

—Brendon Shank

Amit Prachand, MEng

Division Administrator, Hospital Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Feinberg School of Medicine,

Northwestern University, Chicago

Question: What motivated you to join SHM’s Administrators Task Force (ATF)?

A: I wanted to be able to directly interface with the community of leaders in similar administrator roles in order to obtain a stronger perspective of the role, its rewards and challenges, and of the creative solutions different practices have implemented to address issues relevant to hospital medicine and the overall healthcare delivery model. I was also relatively new to hospital medicine practice management, and even healthcare, so I wanted to put myself in the best position to soak in as much as possible as well as help facilitate the sharing of ideas amongst my new group of peers.

Q: How is the Administrators Task Force moving HM forward?

A: One of our main thrusts in the task force is to help expand the administrative membership in SHM. As hospitalist programs mature and the environment in which hospital medicine is practiced evolves, it is imperative that we develop the community, the infrastructure, and the tools required to partner with our stakeholders—both internal and external—to help lead hospital medicine forward.

Q: Has your participation in the Administrators Task Force helped your group?

A: The ATF has helped develop direct lines of communication with peers. This helps when it come to issues for which we are finding the best solutions for; areas such as on-boarding of new physicians, negotiations with hospitals, coding and billing improvement, and meaningful performance reporting.

Q: How is the task force helping hospitals improve patient care?

A: By having a peer group on the administrative side, I believe we are now able to more readily share ideas that support the ideas around patient-care improvement that are being shared amongst the physician membership.

One of the key roles we play as an administrator is to help develop the systems and structures that help improve patient care. That may range from advocating for physician representation on certain hospital committees to facilitating a process/QI project that involves hospitalists and other members of the extended patient-care team, such as physicians from other medical specialties, nursing, pharmacists, case management, bed management, environmental services, and information technology.

Q: How is the task force helping hospitals improve healthcare overall?

A: We are continually improving the infrastructure for administrators to share ideas and solutions to address overall healthcare issues (payment reform, readmissions, compliance, cost). It is through this infrastructure that we can identify best implementation practices of ideas. The webinar series (www.hospitalmedicine.org/roundtables) that we’ve developed addresses many of the issues that healthcare in general is facing. This series has exceeded expectations for participation and interest.

Q: What do you like most about your job as an administrator?

A: It is never dull, always exciting. From the firefighting to the long-term planning, the role keeps me on my toes. I enjoy being in a position that is so tightly intertwined with so many critical functions and disciplines across the medical center in a profession—hospital medicine—that is continuing to lead advances in healthcare delivery.

—Brendon Shank

Q&A with Hospitalist Administrator Kristi Gylten

Kristi Gylten, MBA

Director, Hospitalist Service,

Rapid City (S.D.) Regional Hospital

Question: What motivated you to join the Administrators Task Force (ATF)?

Answer: I wanted to have the opportunity to meet and network with my peers, and to be a part of developing resources and a place “on the map” for hospitalist administrators. The Administrators Task Force is bringing awareness to the administrative and business side of hospital medicine through the eyes of the hospitalist administrators.

Q: Has your participation on the task force helped out your group?

A: My group has benefited through the access and utilization of the available tools and resources to evaluate my own program, including tools like dashboards, job descriptions, patient communication, and marketing materials. The ATF has increased my awareness of the resources available, clinical and operational, to hospitalist groups, including my own.

Q: How is the ATF helping hospitals improve healthcare overall?

A: I believe the task force has its pulse on how healthcare could ideally be provided in the future. And, to me, it is extremely exciting to be part of the team that will help design the future of inpatient medicine and, in part, the continuum of care.

As hospitalist administrators, you have a close and collaborative relationship with the inpatient providers. And I think that because of that relationship and the fact that they live and breathe inpatient medicine, you are able to engage your team in improving many aspects of healthcare.

Q: What do you like most about your job as an administrator?

A: I like the wide variety of opportunities and challenges the role presents: human resources, contracting, recruitment, marketing and public relations, customer satisfaction, quality, and financials. The list goes on. No one day is like the previous, and it’s never dull. And most of all, I enjoy the challenge of strategizing and planning for the future of providing healthcare.

—Brendon Shank

Kristi Gylten, MBA

Director, Hospitalist Service,

Rapid City (S.D.) Regional Hospital

Question: What motivated you to join the Administrators Task Force (ATF)?

Answer: I wanted to have the opportunity to meet and network with my peers, and to be a part of developing resources and a place “on the map” for hospitalist administrators. The Administrators Task Force is bringing awareness to the administrative and business side of hospital medicine through the eyes of the hospitalist administrators.

Q: Has your participation on the task force helped out your group?

A: My group has benefited through the access and utilization of the available tools and resources to evaluate my own program, including tools like dashboards, job descriptions, patient communication, and marketing materials. The ATF has increased my awareness of the resources available, clinical and operational, to hospitalist groups, including my own.

Q: How is the ATF helping hospitals improve healthcare overall?

A: I believe the task force has its pulse on how healthcare could ideally be provided in the future. And, to me, it is extremely exciting to be part of the team that will help design the future of inpatient medicine and, in part, the continuum of care.

As hospitalist administrators, you have a close and collaborative relationship with the inpatient providers. And I think that because of that relationship and the fact that they live and breathe inpatient medicine, you are able to engage your team in improving many aspects of healthcare.

Q: What do you like most about your job as an administrator?

A: I like the wide variety of opportunities and challenges the role presents: human resources, contracting, recruitment, marketing and public relations, customer satisfaction, quality, and financials. The list goes on. No one day is like the previous, and it’s never dull. And most of all, I enjoy the challenge of strategizing and planning for the future of providing healthcare.

—Brendon Shank

Kristi Gylten, MBA

Director, Hospitalist Service,

Rapid City (S.D.) Regional Hospital

Question: What motivated you to join the Administrators Task Force (ATF)?

Answer: I wanted to have the opportunity to meet and network with my peers, and to be a part of developing resources and a place “on the map” for hospitalist administrators. The Administrators Task Force is bringing awareness to the administrative and business side of hospital medicine through the eyes of the hospitalist administrators.

Q: Has your participation on the task force helped out your group?

A: My group has benefited through the access and utilization of the available tools and resources to evaluate my own program, including tools like dashboards, job descriptions, patient communication, and marketing materials. The ATF has increased my awareness of the resources available, clinical and operational, to hospitalist groups, including my own.

Q: How is the ATF helping hospitals improve healthcare overall?

A: I believe the task force has its pulse on how healthcare could ideally be provided in the future. And, to me, it is extremely exciting to be part of the team that will help design the future of inpatient medicine and, in part, the continuum of care.

As hospitalist administrators, you have a close and collaborative relationship with the inpatient providers. And I think that because of that relationship and the fact that they live and breathe inpatient medicine, you are able to engage your team in improving many aspects of healthcare.

Q: What do you like most about your job as an administrator?

A: I like the wide variety of opportunities and challenges the role presents: human resources, contracting, recruitment, marketing and public relations, customer satisfaction, quality, and financials. The list goes on. No one day is like the previous, and it’s never dull. And most of all, I enjoy the challenge of strategizing and planning for the future of providing healthcare.

—Brendon Shank

CPT 2011 Update

In the past, observation services typically did not exceed 24 hours or two calendar days. However, changes in healthcare policy coupled with the impetus to reduce wasteful spending have spurred an atmosphere of scrutiny over hospital admissions. Sometimes there are discrepancies between a hospital’s utilization review committee and a payor’s utilization review committee in determining the appropriateness of healthcare services and supplies, in accordance with each party’s definition of medical necessity. This situation has caused an increase in both the number and cost of observation stays.

In response, subsequent observation-care codes (99224-99226) were developed and published in the 2011 edition of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT).1

Codes and Their Uses

CPT outlines three subsequent observation care codes:

- 99224: Subsequent observation care, per day, for the evaluation and management (E/M) of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: problem-focused interval history; problem-focused examination; and medical decision-making that is straightforward or of low complexity. Counseling and/or coordination of care with other providers or agencies are provided consistent with the nature of the problem(s) and the patient’s and/or family’s needs. Usually, the patient is stable, recovering, or improving. Physicians typically spend 15 minutes at the bedside and on the patient’s hospital floor or unit.

- 99225: Subsequent observation care, per day, for the E/M of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: expanded problem focused interval history; expanded problem focused examination; and medical decision-making of moderate complexity. Counseling and/or coordination of care with other providers or agencies are provided consistent with the nature of the problem(s) and the patient’s and/or family’s needs. Usually, the patient is responding inadequately to therapy or has developed a minor complication. Physicians typically spend 25 minutes at the bedside and on the patient’s hospital floor or unit.

- 99226: Subsequent observation care, per day, for the E/M of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: detailed interval history; detailed examination; and medical decision-making of high complexity. Counseling and/or coordination of care with other providers or agencies are provided consistent with the nature of the problem(s) and the patient’s and/or family’s needs. Usually, the patient is unstable or has developed a significant complication or a significant new problem. Physicians typically spend 35 minutes at the bedside and on the patient’s hospital floor or unit.

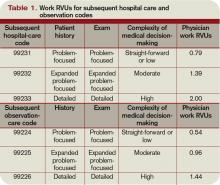

Subsequent observation-care codes replicate the key components and time requirements established for subsequent hospital care services (99231-99233). However, the relative value units (RVUs) of physician work associated with subsequent observation care are not weighted equally (see Table 1, below). Subsequent observation care is a less-intense service, and therefore is valued at a lesser rate.

The attending of record writes the orders to admit the patient to observation (OBS); indicates the reason for the stay; outlines the plan of care; and manages the patient during the stay. Specialists typically are called onto an OBS case for their opinion/advice (i.e. consultants) but do not function as the attending of record.

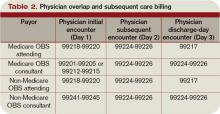

According to CPT 2011, subsequent OBS care codes can be reported by both the attending physician of record and specialists who provide medically necessary, nonoverlapping care to patients on any day other than the admission or discharge day (see Table 2, above). At press time, CMS and private payors had not provided written clarification on the use of subsequent observation-care codes. Therefore, it is imperative to monitor payments, denials, and policy clarifications providing further billing instruction.

On the Horizon

Prior reporting guidelines required the reporting of subsequent observation-care days with established outpatient codes (99212-99215). Some member plans insisted on referrals for all outpatient visits regardless nature of the service. Without the mandated referral for established patient visits performed in the observation setting, physician services were denied for coverage.

The creation of subsequent observation codes might play a role in decreasing these denials. Be sure to review the private payors’ fee schedules for inclusion of 99224-99226 codes. If missing, contact the payor or include it as an agenda item during your contract negotiations.

For more information on observation care services, check out “Observation Care” in the July 2010 issue of The Hospitalist. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Evans D. Current Procedural Terminology: Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 16, 2011.

In the past, observation services typically did not exceed 24 hours or two calendar days. However, changes in healthcare policy coupled with the impetus to reduce wasteful spending have spurred an atmosphere of scrutiny over hospital admissions. Sometimes there are discrepancies between a hospital’s utilization review committee and a payor’s utilization review committee in determining the appropriateness of healthcare services and supplies, in accordance with each party’s definition of medical necessity. This situation has caused an increase in both the number and cost of observation stays.

In response, subsequent observation-care codes (99224-99226) were developed and published in the 2011 edition of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT).1

Codes and Their Uses

CPT outlines three subsequent observation care codes:

- 99224: Subsequent observation care, per day, for the evaluation and management (E/M) of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: problem-focused interval history; problem-focused examination; and medical decision-making that is straightforward or of low complexity. Counseling and/or coordination of care with other providers or agencies are provided consistent with the nature of the problem(s) and the patient’s and/or family’s needs. Usually, the patient is stable, recovering, or improving. Physicians typically spend 15 minutes at the bedside and on the patient’s hospital floor or unit.

- 99225: Subsequent observation care, per day, for the E/M of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: expanded problem focused interval history; expanded problem focused examination; and medical decision-making of moderate complexity. Counseling and/or coordination of care with other providers or agencies are provided consistent with the nature of the problem(s) and the patient’s and/or family’s needs. Usually, the patient is responding inadequately to therapy or has developed a minor complication. Physicians typically spend 25 minutes at the bedside and on the patient’s hospital floor or unit.

- 99226: Subsequent observation care, per day, for the E/M of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: detailed interval history; detailed examination; and medical decision-making of high complexity. Counseling and/or coordination of care with other providers or agencies are provided consistent with the nature of the problem(s) and the patient’s and/or family’s needs. Usually, the patient is unstable or has developed a significant complication or a significant new problem. Physicians typically spend 35 minutes at the bedside and on the patient’s hospital floor or unit.

Subsequent observation-care codes replicate the key components and time requirements established for subsequent hospital care services (99231-99233). However, the relative value units (RVUs) of physician work associated with subsequent observation care are not weighted equally (see Table 1, below). Subsequent observation care is a less-intense service, and therefore is valued at a lesser rate.

The attending of record writes the orders to admit the patient to observation (OBS); indicates the reason for the stay; outlines the plan of care; and manages the patient during the stay. Specialists typically are called onto an OBS case for their opinion/advice (i.e. consultants) but do not function as the attending of record.

According to CPT 2011, subsequent OBS care codes can be reported by both the attending physician of record and specialists who provide medically necessary, nonoverlapping care to patients on any day other than the admission or discharge day (see Table 2, above). At press time, CMS and private payors had not provided written clarification on the use of subsequent observation-care codes. Therefore, it is imperative to monitor payments, denials, and policy clarifications providing further billing instruction.

On the Horizon

Prior reporting guidelines required the reporting of subsequent observation-care days with established outpatient codes (99212-99215). Some member plans insisted on referrals for all outpatient visits regardless nature of the service. Without the mandated referral for established patient visits performed in the observation setting, physician services were denied for coverage.

The creation of subsequent observation codes might play a role in decreasing these denials. Be sure to review the private payors’ fee schedules for inclusion of 99224-99226 codes. If missing, contact the payor or include it as an agenda item during your contract negotiations.

For more information on observation care services, check out “Observation Care” in the July 2010 issue of The Hospitalist. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Evans D. Current Procedural Terminology: Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 16, 2011.

In the past, observation services typically did not exceed 24 hours or two calendar days. However, changes in healthcare policy coupled with the impetus to reduce wasteful spending have spurred an atmosphere of scrutiny over hospital admissions. Sometimes there are discrepancies between a hospital’s utilization review committee and a payor’s utilization review committee in determining the appropriateness of healthcare services and supplies, in accordance with each party’s definition of medical necessity. This situation has caused an increase in both the number and cost of observation stays.

In response, subsequent observation-care codes (99224-99226) were developed and published in the 2011 edition of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT).1

Codes and Their Uses

CPT outlines three subsequent observation care codes:

- 99224: Subsequent observation care, per day, for the evaluation and management (E/M) of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: problem-focused interval history; problem-focused examination; and medical decision-making that is straightforward or of low complexity. Counseling and/or coordination of care with other providers or agencies are provided consistent with the nature of the problem(s) and the patient’s and/or family’s needs. Usually, the patient is stable, recovering, or improving. Physicians typically spend 15 minutes at the bedside and on the patient’s hospital floor or unit.

- 99225: Subsequent observation care, per day, for the E/M of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: expanded problem focused interval history; expanded problem focused examination; and medical decision-making of moderate complexity. Counseling and/or coordination of care with other providers or agencies are provided consistent with the nature of the problem(s) and the patient’s and/or family’s needs. Usually, the patient is responding inadequately to therapy or has developed a minor complication. Physicians typically spend 25 minutes at the bedside and on the patient’s hospital floor or unit.

- 99226: Subsequent observation care, per day, for the E/M of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: detailed interval history; detailed examination; and medical decision-making of high complexity. Counseling and/or coordination of care with other providers or agencies are provided consistent with the nature of the problem(s) and the patient’s and/or family’s needs. Usually, the patient is unstable or has developed a significant complication or a significant new problem. Physicians typically spend 35 minutes at the bedside and on the patient’s hospital floor or unit.

Subsequent observation-care codes replicate the key components and time requirements established for subsequent hospital care services (99231-99233). However, the relative value units (RVUs) of physician work associated with subsequent observation care are not weighted equally (see Table 1, below). Subsequent observation care is a less-intense service, and therefore is valued at a lesser rate.

The attending of record writes the orders to admit the patient to observation (OBS); indicates the reason for the stay; outlines the plan of care; and manages the patient during the stay. Specialists typically are called onto an OBS case for their opinion/advice (i.e. consultants) but do not function as the attending of record.

According to CPT 2011, subsequent OBS care codes can be reported by both the attending physician of record and specialists who provide medically necessary, nonoverlapping care to patients on any day other than the admission or discharge day (see Table 2, above). At press time, CMS and private payors had not provided written clarification on the use of subsequent observation-care codes. Therefore, it is imperative to monitor payments, denials, and policy clarifications providing further billing instruction.

On the Horizon

Prior reporting guidelines required the reporting of subsequent observation-care days with established outpatient codes (99212-99215). Some member plans insisted on referrals for all outpatient visits regardless nature of the service. Without the mandated referral for established patient visits performed in the observation setting, physician services were denied for coverage.

The creation of subsequent observation codes might play a role in decreasing these denials. Be sure to review the private payors’ fee schedules for inclusion of 99224-99226 codes. If missing, contact the payor or include it as an agenda item during your contract negotiations.

For more information on observation care services, check out “Observation Care” in the July 2010 issue of The Hospitalist. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Evans D. Current Procedural Terminology: Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 16, 2011.

Shared/Split Service

In response to internal and external pressures to minimize length of stay, adhere to limitations on the maximum number of admitted patients, focus on evidence-based care, and improve outcomes of care, hospitalists have incorporated nonphysician providers (NPPs), such as acute-care nurse practitioners (ACNPs), into their group practices.1 HM groups employing these practitioners must be aware of state and federal regulations, as well as billing and documentation standards surrounding NPP services.

Consider the following common hospitalist scenario: A nurse practitioner evaluates a 67-year-old patient admitted for chronic obstructive bronchitis and progressing shortness of breath. The nurse practitioner documents the service and provides the attending physician with an update on the patient’s status. Later in the day, the physician makes rounds and concurs with the patient’s current plan of care.

The above scenario represents a shared/split service in which two providers from the same group perform a service for the same patient on the same calendar day. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) allows these visits to be combined and reported under a single provider’s name if the shared/split billing criteria are met and appropriately documented.

Eligible Providers

The shared/split billing option only applies to services rendered by the attending physician and specified NPPs: nurse practitioners, physician assistants, clinical nurse specialists, and certified nurse-midwives. Both the attending physician and the NPP must be part of the same group practice, either through direct employment or a leased arrangement that contractually links the two individuals. The “leased” relationship often occurs when the facility directly employs the NPP but arranges for the NPP to provide services exclusively for the physician group. It is imperative that the bills for the NPP services are captured and reported by one entity—the hospitalist group.

Several other NPPs (e.g. clinical psychologists or certified registered nurse anesthetists) are recognized by CMS but are ineligible for shared/split billing and must report their services under a different Medicare billing option. Additionally, shared/split services do not apply to physicians in training (interns, residents, fellows) or students.

Qualifying Services

Medicare reimburses services that are considered reasonable and necessary and not otherwise excluded from coverage. From a clinical perspective, NPPs might provide any service permitted by the state scope of practice and performed under the appropriate level of supervision or collaboration as depicted in licensure requirements. These typically comprise visits or procedures rendered by ancillary staff or considered a “physician” service.

Alternatively, shared/split billing regulations limit the types of services that can be reported under this methodology, recognizing only evaluation and management (E/M) services provided in explicit facility-based settings: EDs, outpatient hospital clinics, or inpatient hospitals. Critical-care services and procedures are excluded.

Physician Involvement

The NPP and the physician must have a face-to-face encounter with the same patient on the same calendar day, and there are no constraints on which provider should perform the initial encounter of the day.2

The extent of each provider’s involvement is left to provider discretion and/or local Medicare contractor requirements. Some contractors refer to the physician performing a “substantive” service but do not elaborate with specific service parameters, leaving the physician to determine the critical or key portion of his/her service. A corresponding, detailed notation alleviates any misconceptions of physician involvement.

Documentation by the attending physician should include an attestation that unequivocally demonstrates their personal encounter with the patient—for example, “Patient seen and examined by me.” Additionally, both the NPP and the physician should document the name of the individual with whom the service is shared/split—for example, “Agree with note by ____.” This allows for better charge capture; alerts coders, auditors, and payor representatives to consider both notes in support of the billed service; and ensures that the correct notes are sent to the payor in the event of claim denial and subsequent appeal.

Each provider must document their portion of the rendered service, date and legibly sign their corresponding note, and select the visit level supported by the cumulative encounter—for example, “Pulse oximetry 94% on room air. Audible rhonchi at bilateral lung bases. Start O2 2L nasal cannula. Obtain CXR.”

Only one claim can be submitted for a shared/split service. The services might either be reported with the physician’s NPI or the NPP’s NPI. Reimbursement is dependent upon this designation. The physician NPI generates 100% of the Medicare allowable rate; the NPP NPI limits reimbursement to 85% of the allowable physician rate.

Non-Medicare Claims

The shared/split billing policy only applies to Medicare beneficiaries. Due to excessive costs of NPP credentialing and enrollment, most non-Medicare insurers do not issue NPP provider numbers.

Effective June 1, 2010, Aetna began to enroll and reimburse NPP services, but it has not yet outlined a policy that parallels Medicare’s shared/split billing policy. However, lack of payor policy does not preclude payment for shared NPP services; it necessitates additional—and initial—efforts to obtain recognition and corresponding reimbursement.

After determining which insurers have applicable shared/split billing policies, develop a reasonable guideline to offer those payors who do not recognize the billing option. Alert the payor, in writing, that policy implementation will take place in a predetermined timeframe unless the payor can provide an alternate billing option. Some experts suggest physician groups outline the following key issues when structuring a billing option:

- Types of NPP involved in patient care;

- Category of services provided (e.g. E/M, procedures);

- Service location(s) (ED, inpatient, or outpatient hospital);

- Physician involvement;

- Mechanism for reporting services; and

- Documentation requirements.

This can be performed for any of the NPP billing options and is not limited to shared/split billing. Be sure to obtain payor response before initiating the shared/split billing process.

Summary

NPPs are involved in numerous services within the hospital, and often share/split services with hospitalists. Successful reporting requires understanding of and adherence to federal, state, and billing guidelines.

It is important to identify NPP employment relationships, the NPP’s role in the provision of services, the state supervisory or collaborative rules, and local payor interpretations to prevent misrepresentations, misunderstandings, or erroneous reporting. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Howie JN, Erickson M. Acute care nurse practitioners: creating and implementing a model of care for an inpatient general medical service. Am J Crit Care. 2002; 11(5):448-458.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1B. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2010.

- Pohlig, C. Nonphysician providers in your practice. In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2009. Northbrook, Ill.: American College of Chest Physicians; 2010.

- Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15, Section 190-200. CMS website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c15.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2010.

In response to internal and external pressures to minimize length of stay, adhere to limitations on the maximum number of admitted patients, focus on evidence-based care, and improve outcomes of care, hospitalists have incorporated nonphysician providers (NPPs), such as acute-care nurse practitioners (ACNPs), into their group practices.1 HM groups employing these practitioners must be aware of state and federal regulations, as well as billing and documentation standards surrounding NPP services.

Consider the following common hospitalist scenario: A nurse practitioner evaluates a 67-year-old patient admitted for chronic obstructive bronchitis and progressing shortness of breath. The nurse practitioner documents the service and provides the attending physician with an update on the patient’s status. Later in the day, the physician makes rounds and concurs with the patient’s current plan of care.

The above scenario represents a shared/split service in which two providers from the same group perform a service for the same patient on the same calendar day. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) allows these visits to be combined and reported under a single provider’s name if the shared/split billing criteria are met and appropriately documented.

Eligible Providers

The shared/split billing option only applies to services rendered by the attending physician and specified NPPs: nurse practitioners, physician assistants, clinical nurse specialists, and certified nurse-midwives. Both the attending physician and the NPP must be part of the same group practice, either through direct employment or a leased arrangement that contractually links the two individuals. The “leased” relationship often occurs when the facility directly employs the NPP but arranges for the NPP to provide services exclusively for the physician group. It is imperative that the bills for the NPP services are captured and reported by one entity—the hospitalist group.

Several other NPPs (e.g. clinical psychologists or certified registered nurse anesthetists) are recognized by CMS but are ineligible for shared/split billing and must report their services under a different Medicare billing option. Additionally, shared/split services do not apply to physicians in training (interns, residents, fellows) or students.

Qualifying Services

Medicare reimburses services that are considered reasonable and necessary and not otherwise excluded from coverage. From a clinical perspective, NPPs might provide any service permitted by the state scope of practice and performed under the appropriate level of supervision or collaboration as depicted in licensure requirements. These typically comprise visits or procedures rendered by ancillary staff or considered a “physician” service.

Alternatively, shared/split billing regulations limit the types of services that can be reported under this methodology, recognizing only evaluation and management (E/M) services provided in explicit facility-based settings: EDs, outpatient hospital clinics, or inpatient hospitals. Critical-care services and procedures are excluded.

Physician Involvement

The NPP and the physician must have a face-to-face encounter with the same patient on the same calendar day, and there are no constraints on which provider should perform the initial encounter of the day.2

The extent of each provider’s involvement is left to provider discretion and/or local Medicare contractor requirements. Some contractors refer to the physician performing a “substantive” service but do not elaborate with specific service parameters, leaving the physician to determine the critical or key portion of his/her service. A corresponding, detailed notation alleviates any misconceptions of physician involvement.

Documentation by the attending physician should include an attestation that unequivocally demonstrates their personal encounter with the patient—for example, “Patient seen and examined by me.” Additionally, both the NPP and the physician should document the name of the individual with whom the service is shared/split—for example, “Agree with note by ____.” This allows for better charge capture; alerts coders, auditors, and payor representatives to consider both notes in support of the billed service; and ensures that the correct notes are sent to the payor in the event of claim denial and subsequent appeal.

Each provider must document their portion of the rendered service, date and legibly sign their corresponding note, and select the visit level supported by the cumulative encounter—for example, “Pulse oximetry 94% on room air. Audible rhonchi at bilateral lung bases. Start O2 2L nasal cannula. Obtain CXR.”

Only one claim can be submitted for a shared/split service. The services might either be reported with the physician’s NPI or the NPP’s NPI. Reimbursement is dependent upon this designation. The physician NPI generates 100% of the Medicare allowable rate; the NPP NPI limits reimbursement to 85% of the allowable physician rate.

Non-Medicare Claims

The shared/split billing policy only applies to Medicare beneficiaries. Due to excessive costs of NPP credentialing and enrollment, most non-Medicare insurers do not issue NPP provider numbers.

Effective June 1, 2010, Aetna began to enroll and reimburse NPP services, but it has not yet outlined a policy that parallels Medicare’s shared/split billing policy. However, lack of payor policy does not preclude payment for shared NPP services; it necessitates additional—and initial—efforts to obtain recognition and corresponding reimbursement.

After determining which insurers have applicable shared/split billing policies, develop a reasonable guideline to offer those payors who do not recognize the billing option. Alert the payor, in writing, that policy implementation will take place in a predetermined timeframe unless the payor can provide an alternate billing option. Some experts suggest physician groups outline the following key issues when structuring a billing option:

- Types of NPP involved in patient care;

- Category of services provided (e.g. E/M, procedures);

- Service location(s) (ED, inpatient, or outpatient hospital);

- Physician involvement;

- Mechanism for reporting services; and

- Documentation requirements.

This can be performed for any of the NPP billing options and is not limited to shared/split billing. Be sure to obtain payor response before initiating the shared/split billing process.

Summary

NPPs are involved in numerous services within the hospital, and often share/split services with hospitalists. Successful reporting requires understanding of and adherence to federal, state, and billing guidelines.

It is important to identify NPP employment relationships, the NPP’s role in the provision of services, the state supervisory or collaborative rules, and local payor interpretations to prevent misrepresentations, misunderstandings, or erroneous reporting. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Howie JN, Erickson M. Acute care nurse practitioners: creating and implementing a model of care for an inpatient general medical service. Am J Crit Care. 2002; 11(5):448-458.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1B. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2010.

- Pohlig, C. Nonphysician providers in your practice. In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2009. Northbrook, Ill.: American College of Chest Physicians; 2010.

- Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15, Section 190-200. CMS website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c15.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2010.

In response to internal and external pressures to minimize length of stay, adhere to limitations on the maximum number of admitted patients, focus on evidence-based care, and improve outcomes of care, hospitalists have incorporated nonphysician providers (NPPs), such as acute-care nurse practitioners (ACNPs), into their group practices.1 HM groups employing these practitioners must be aware of state and federal regulations, as well as billing and documentation standards surrounding NPP services.

Consider the following common hospitalist scenario: A nurse practitioner evaluates a 67-year-old patient admitted for chronic obstructive bronchitis and progressing shortness of breath. The nurse practitioner documents the service and provides the attending physician with an update on the patient’s status. Later in the day, the physician makes rounds and concurs with the patient’s current plan of care.

The above scenario represents a shared/split service in which two providers from the same group perform a service for the same patient on the same calendar day. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) allows these visits to be combined and reported under a single provider’s name if the shared/split billing criteria are met and appropriately documented.

Eligible Providers

The shared/split billing option only applies to services rendered by the attending physician and specified NPPs: nurse practitioners, physician assistants, clinical nurse specialists, and certified nurse-midwives. Both the attending physician and the NPP must be part of the same group practice, either through direct employment or a leased arrangement that contractually links the two individuals. The “leased” relationship often occurs when the facility directly employs the NPP but arranges for the NPP to provide services exclusively for the physician group. It is imperative that the bills for the NPP services are captured and reported by one entity—the hospitalist group.

Several other NPPs (e.g. clinical psychologists or certified registered nurse anesthetists) are recognized by CMS but are ineligible for shared/split billing and must report their services under a different Medicare billing option. Additionally, shared/split services do not apply to physicians in training (interns, residents, fellows) or students.

Qualifying Services

Medicare reimburses services that are considered reasonable and necessary and not otherwise excluded from coverage. From a clinical perspective, NPPs might provide any service permitted by the state scope of practice and performed under the appropriate level of supervision or collaboration as depicted in licensure requirements. These typically comprise visits or procedures rendered by ancillary staff or considered a “physician” service.

Alternatively, shared/split billing regulations limit the types of services that can be reported under this methodology, recognizing only evaluation and management (E/M) services provided in explicit facility-based settings: EDs, outpatient hospital clinics, or inpatient hospitals. Critical-care services and procedures are excluded.

Physician Involvement

The NPP and the physician must have a face-to-face encounter with the same patient on the same calendar day, and there are no constraints on which provider should perform the initial encounter of the day.2

The extent of each provider’s involvement is left to provider discretion and/or local Medicare contractor requirements. Some contractors refer to the physician performing a “substantive” service but do not elaborate with specific service parameters, leaving the physician to determine the critical or key portion of his/her service. A corresponding, detailed notation alleviates any misconceptions of physician involvement.

Documentation by the attending physician should include an attestation that unequivocally demonstrates their personal encounter with the patient—for example, “Patient seen and examined by me.” Additionally, both the NPP and the physician should document the name of the individual with whom the service is shared/split—for example, “Agree with note by ____.” This allows for better charge capture; alerts coders, auditors, and payor representatives to consider both notes in support of the billed service; and ensures that the correct notes are sent to the payor in the event of claim denial and subsequent appeal.

Each provider must document their portion of the rendered service, date and legibly sign their corresponding note, and select the visit level supported by the cumulative encounter—for example, “Pulse oximetry 94% on room air. Audible rhonchi at bilateral lung bases. Start O2 2L nasal cannula. Obtain CXR.”

Only one claim can be submitted for a shared/split service. The services might either be reported with the physician’s NPI or the NPP’s NPI. Reimbursement is dependent upon this designation. The physician NPI generates 100% of the Medicare allowable rate; the NPP NPI limits reimbursement to 85% of the allowable physician rate.

Non-Medicare Claims

The shared/split billing policy only applies to Medicare beneficiaries. Due to excessive costs of NPP credentialing and enrollment, most non-Medicare insurers do not issue NPP provider numbers.

Effective June 1, 2010, Aetna began to enroll and reimburse NPP services, but it has not yet outlined a policy that parallels Medicare’s shared/split billing policy. However, lack of payor policy does not preclude payment for shared NPP services; it necessitates additional—and initial—efforts to obtain recognition and corresponding reimbursement.

After determining which insurers have applicable shared/split billing policies, develop a reasonable guideline to offer those payors who do not recognize the billing option. Alert the payor, in writing, that policy implementation will take place in a predetermined timeframe unless the payor can provide an alternate billing option. Some experts suggest physician groups outline the following key issues when structuring a billing option:

- Types of NPP involved in patient care;

- Category of services provided (e.g. E/M, procedures);

- Service location(s) (ED, inpatient, or outpatient hospital);

- Physician involvement;

- Mechanism for reporting services; and

- Documentation requirements.

This can be performed for any of the NPP billing options and is not limited to shared/split billing. Be sure to obtain payor response before initiating the shared/split billing process.

Summary

NPPs are involved in numerous services within the hospital, and often share/split services with hospitalists. Successful reporting requires understanding of and adherence to federal, state, and billing guidelines.

It is important to identify NPP employment relationships, the NPP’s role in the provision of services, the state supervisory or collaborative rules, and local payor interpretations to prevent misrepresentations, misunderstandings, or erroneous reporting. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Howie JN, Erickson M. Acute care nurse practitioners: creating and implementing a model of care for an inpatient general medical service. Am J Crit Care. 2002; 11(5):448-458.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1B. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2010.

- Pohlig, C. Nonphysician providers in your practice. In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2009. Northbrook, Ill.: American College of Chest Physicians; 2010.

- Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15, Section 190-200. CMS website. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c15.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2010.

New Resources, Opportunities for Practice Administrators

Every clinician in HM depends on a smooth-running hospitalist program to ensure the best possible patient care and efficiency. Even though they might not be visible to hospitalized patients, practice administration issues (e.g. compensation and incentives, reporting return on investment, or the Physician’s Quality Reporting System) are vital components to effectively running an HM group. And that’s what explains the growing popularity of SHM’s new resources for administrators.

In 2010, SHM presented five free online discussions for hospitalist practice leaders. Each session in the Practice Administrators’ Roundtable Series began with a formal presentation and was followed with open discussion from administrators and leaders from around the country.

SHM will continue the program in 2011 with such topics as Hospitalist Recruitment, Retention, & Orientation (Feb. 24) and Patient Satisfaction (May 26).

“The response to new programs for hospitalist administrators has been very positive,” says Kim Dickinson, MA, regional COO for Cogent Healthcare and a member of SHM’s Administrators’ Task Force, which has taken the lead on planning the roundtables. “As hospital medicine programs continue to evolve, there will be a growing need to address their administrative issues, too.”

The program will break new ground in 2011 with the first SHM Award for Excellence in Hospital Medicine. The new award, to be presented at HM11, will recognize a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, RN, pharmacist, administrator, case manager, or a nonphysician member of SHM.

“Hospital medicine groups depend on effective leadership, communication and administration,” says SHM president Jeff Wiese, MD, SFHM. “That’s why these new programs are so critical to improving quality, safety, and efficiency in hospital care. It is appropriate then that the best of the best should be recognized in this regard. I am personally excited to present the first SHM Award for Excellence in Hospital Medicine at the SHM annual meeting in Dallas.”

All of the roundtable discussions are archived in SHM’s Practice Management Institute (www.hospitalmedicine.org/practiceresources).

Every clinician in HM depends on a smooth-running hospitalist program to ensure the best possible patient care and efficiency. Even though they might not be visible to hospitalized patients, practice administration issues (e.g. compensation and incentives, reporting return on investment, or the Physician’s Quality Reporting System) are vital components to effectively running an HM group. And that’s what explains the growing popularity of SHM’s new resources for administrators.

In 2010, SHM presented five free online discussions for hospitalist practice leaders. Each session in the Practice Administrators’ Roundtable Series began with a formal presentation and was followed with open discussion from administrators and leaders from around the country.

SHM will continue the program in 2011 with such topics as Hospitalist Recruitment, Retention, & Orientation (Feb. 24) and Patient Satisfaction (May 26).

“The response to new programs for hospitalist administrators has been very positive,” says Kim Dickinson, MA, regional COO for Cogent Healthcare and a member of SHM’s Administrators’ Task Force, which has taken the lead on planning the roundtables. “As hospital medicine programs continue to evolve, there will be a growing need to address their administrative issues, too.”

The program will break new ground in 2011 with the first SHM Award for Excellence in Hospital Medicine. The new award, to be presented at HM11, will recognize a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, RN, pharmacist, administrator, case manager, or a nonphysician member of SHM.

“Hospital medicine groups depend on effective leadership, communication and administration,” says SHM president Jeff Wiese, MD, SFHM. “That’s why these new programs are so critical to improving quality, safety, and efficiency in hospital care. It is appropriate then that the best of the best should be recognized in this regard. I am personally excited to present the first SHM Award for Excellence in Hospital Medicine at the SHM annual meeting in Dallas.”

All of the roundtable discussions are archived in SHM’s Practice Management Institute (www.hospitalmedicine.org/practiceresources).

Every clinician in HM depends on a smooth-running hospitalist program to ensure the best possible patient care and efficiency. Even though they might not be visible to hospitalized patients, practice administration issues (e.g. compensation and incentives, reporting return on investment, or the Physician’s Quality Reporting System) are vital components to effectively running an HM group. And that’s what explains the growing popularity of SHM’s new resources for administrators.

In 2010, SHM presented five free online discussions for hospitalist practice leaders. Each session in the Practice Administrators’ Roundtable Series began with a formal presentation and was followed with open discussion from administrators and leaders from around the country.

SHM will continue the program in 2011 with such topics as Hospitalist Recruitment, Retention, & Orientation (Feb. 24) and Patient Satisfaction (May 26).

“The response to new programs for hospitalist administrators has been very positive,” says Kim Dickinson, MA, regional COO for Cogent Healthcare and a member of SHM’s Administrators’ Task Force, which has taken the lead on planning the roundtables. “As hospital medicine programs continue to evolve, there will be a growing need to address their administrative issues, too.”

The program will break new ground in 2011 with the first SHM Award for Excellence in Hospital Medicine. The new award, to be presented at HM11, will recognize a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, RN, pharmacist, administrator, case manager, or a nonphysician member of SHM.

“Hospital medicine groups depend on effective leadership, communication and administration,” says SHM president Jeff Wiese, MD, SFHM. “That’s why these new programs are so critical to improving quality, safety, and efficiency in hospital care. It is appropriate then that the best of the best should be recognized in this regard. I am personally excited to present the first SHM Award for Excellence in Hospital Medicine at the SHM annual meeting in Dallas.”

All of the roundtable discussions are archived in SHM’s Practice Management Institute (www.hospitalmedicine.org/practiceresources).

Concurrent Care

Let’s examine a documentation case for hospitalists providing daily care: A 65-year-old male patient is admitted with a left hip fracture. The patient also has hypertension and Type 2 diabetes, which might complicate his care. The orthopedic surgeon manages the patient’s perioperative course for the fracture while the hospitalist provides daily post-op care for hypertension and diabetes.

A common scenario is the hospitalist will provide concurrent care, along with a varying number of specialists, depending on the complexity of the patient’s presenting problems and existing comorbidities. Payors define concurrent care as more than one physician providing care to the same patient on the same date, or during the same hospitalization. Payors often consider two key principles before reimbursing concurrent care:

- Does the patient’s condition warrant more than one physician? and

- Are the services provided by each physician reasonable and necessary?1

When more than one medical condition exists and each physician actively treats the condition related to their expertise, each physician can demonstrate medical necessity. As in the above example, the orthopedic surgeon cares for the patient’s fracture while the hospitalist oversees diabetes and hypertension management. Claim submission follows the same logic. Report each subsequent hospital care code (99231-99233) with the corresponding diagnosis each physician primarily manages (i.e., orthopedic surgeon: 9923x with 820.8; hospitalist: 9923x with 250.00, 401.1).

When each physician assigns a different primary diagnosis code to the visit code, each is more likely to receive payment. Because each of these physicians are in different specialties and different provider groups, most payors do not require modifier 25 (separately identifiable E/M service on the same day as a procedure or other service) appended to the visit code. However, some managed-care payors require each physician to append modifier 25 to the concurrent E/M visit code (i.e., 99232-25) despite claim submission under different tax identification numbers.

Unfortunately, the physicians might not realize this until a claim rejection has been issued. Furthermore, payors might want to see the proof before rendering payment. In other words, they pay the first claim received and deny any subsequent claim in order to confirm medical necessity of the concurrent visit. Appeal denied such claims rejections with supporting documentation that distinguishes each physician visit, if possible. This assists the payors in understanding each physician’s contribution to care.

Reasons for Denial

Concurrent care services are more easily distinguished when separate diagnoses are reported with each service. Conversely, payors are likely to deny services that are hard to differentiate. Furthermore, payors frequently deny concurrent care services for the following reasons:

- Services exceed normal frequency or duration for a given condition without documented circumstances requiring additional care; or

- Services by one physician duplicate or overlap those of another provider without recognizable distinction.2

For example, a hospitalist might be involved in the post-op care of patients with fractures and no other identifiable chronic or acute conditions or complications. In these cases, the hospitalist’s continued involvement might constitute a facility policy (e.g., quality of care, risk reduction, etc.) rather than active clinical management. Claim submission could erroneously occur with each physician reporting 9923x for 820.8. Payors deny medically unnecessary services, or request refunds for inappropriate payments.

Hospitalists might attempt to negotiate other terms with the facility to account for the unpaid time and effort directed toward these types of cases.

Group Practice

Physicians in the same group practice with the same specialty designation must report, and are paid, as a single physician. Multiple visits to the same patient can occur on the same day by members of the same group (e.g., hospitalist A evaluates the patient in the morning, and hospitalist B reviews test results and the resulting course of treatment in the afternoon). However, only one subsequent hospital care service can be reported for the day.

The hospitalists should select the visit level representative of the combined services and submit one appropriately determined code (e.g., 99233), thereby capturing the medically necessary efforts of each physician. To complicate matters, the hospitalists must determine which name to report on the claim: the physician who provided the first encounter, or the physician who provided the most extensive or best-documented encounter.

Tracking productivity for these cases proves challenging. Some practices develop an internal accounting system and credit each physician for their medically necessary efforts (a labor-intensive task for administrators and physicians). TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Concurrent Care. Chapter 15, Section 30.E. CMS website. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c15.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Physicians in Group Practice. Chapter 12, Section 30.6.5. CMS website. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2010.

- Pohlig, C. Daily care conundrums. The Hospitalist website. Available at: www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/188735/Daily_Care_Conundrums_.html. Accessed July 9, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Hospital Visits Same Day But by Different Physicians. Chapter 12, Section 30.6.9.C. CMS website. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2010.

- Abraham M, Beebe M, Dalton J, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2010:15.

Let’s examine a documentation case for hospitalists providing daily care: A 65-year-old male patient is admitted with a left hip fracture. The patient also has hypertension and Type 2 diabetes, which might complicate his care. The orthopedic surgeon manages the patient’s perioperative course for the fracture while the hospitalist provides daily post-op care for hypertension and diabetes.

A common scenario is the hospitalist will provide concurrent care, along with a varying number of specialists, depending on the complexity of the patient’s presenting problems and existing comorbidities. Payors define concurrent care as more than one physician providing care to the same patient on the same date, or during the same hospitalization. Payors often consider two key principles before reimbursing concurrent care:

- Does the patient’s condition warrant more than one physician? and

- Are the services provided by each physician reasonable and necessary?1

When more than one medical condition exists and each physician actively treats the condition related to their expertise, each physician can demonstrate medical necessity. As in the above example, the orthopedic surgeon cares for the patient’s fracture while the hospitalist oversees diabetes and hypertension management. Claim submission follows the same logic. Report each subsequent hospital care code (99231-99233) with the corresponding diagnosis each physician primarily manages (i.e., orthopedic surgeon: 9923x with 820.8; hospitalist: 9923x with 250.00, 401.1).

When each physician assigns a different primary diagnosis code to the visit code, each is more likely to receive payment. Because each of these physicians are in different specialties and different provider groups, most payors do not require modifier 25 (separately identifiable E/M service on the same day as a procedure or other service) appended to the visit code. However, some managed-care payors require each physician to append modifier 25 to the concurrent E/M visit code (i.e., 99232-25) despite claim submission under different tax identification numbers.

Unfortunately, the physicians might not realize this until a claim rejection has been issued. Furthermore, payors might want to see the proof before rendering payment. In other words, they pay the first claim received and deny any subsequent claim in order to confirm medical necessity of the concurrent visit. Appeal denied such claims rejections with supporting documentation that distinguishes each physician visit, if possible. This assists the payors in understanding each physician’s contribution to care.

Reasons for Denial

Concurrent care services are more easily distinguished when separate diagnoses are reported with each service. Conversely, payors are likely to deny services that are hard to differentiate. Furthermore, payors frequently deny concurrent care services for the following reasons:

- Services exceed normal frequency or duration for a given condition without documented circumstances requiring additional care; or

- Services by one physician duplicate or overlap those of another provider without recognizable distinction.2

For example, a hospitalist might be involved in the post-op care of patients with fractures and no other identifiable chronic or acute conditions or complications. In these cases, the hospitalist’s continued involvement might constitute a facility policy (e.g., quality of care, risk reduction, etc.) rather than active clinical management. Claim submission could erroneously occur with each physician reporting 9923x for 820.8. Payors deny medically unnecessary services, or request refunds for inappropriate payments.

Hospitalists might attempt to negotiate other terms with the facility to account for the unpaid time and effort directed toward these types of cases.

Group Practice

Physicians in the same group practice with the same specialty designation must report, and are paid, as a single physician. Multiple visits to the same patient can occur on the same day by members of the same group (e.g., hospitalist A evaluates the patient in the morning, and hospitalist B reviews test results and the resulting course of treatment in the afternoon). However, only one subsequent hospital care service can be reported for the day.

The hospitalists should select the visit level representative of the combined services and submit one appropriately determined code (e.g., 99233), thereby capturing the medically necessary efforts of each physician. To complicate matters, the hospitalists must determine which name to report on the claim: the physician who provided the first encounter, or the physician who provided the most extensive or best-documented encounter.

Tracking productivity for these cases proves challenging. Some practices develop an internal accounting system and credit each physician for their medically necessary efforts (a labor-intensive task for administrators and physicians). TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Concurrent Care. Chapter 15, Section 30.E. CMS website. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c15.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Physicians in Group Practice. Chapter 12, Section 30.6.5. CMS website. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2010.

- Pohlig, C. Daily care conundrums. The Hospitalist website. Available at: www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/188735/Daily_Care_Conundrums_.html. Accessed July 9, 2010.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Hospital Visits Same Day But by Different Physicians. Chapter 12, Section 30.6.9.C. CMS website. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2010.

- Abraham M, Beebe M, Dalton J, Evans D, Glenn R. Current Procedural Terminology Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2010:15.

Let’s examine a documentation case for hospitalists providing daily care: A 65-year-old male patient is admitted with a left hip fracture. The patient also has hypertension and Type 2 diabetes, which might complicate his care. The orthopedic surgeon manages the patient’s perioperative course for the fracture while the hospitalist provides daily post-op care for hypertension and diabetes.

A common scenario is the hospitalist will provide concurrent care, along with a varying number of specialists, depending on the complexity of the patient’s presenting problems and existing comorbidities. Payors define concurrent care as more than one physician providing care to the same patient on the same date, or during the same hospitalization. Payors often consider two key principles before reimbursing concurrent care:

- Does the patient’s condition warrant more than one physician? and

- Are the services provided by each physician reasonable and necessary?1

When more than one medical condition exists and each physician actively treats the condition related to their expertise, each physician can demonstrate medical necessity. As in the above example, the orthopedic surgeon cares for the patient’s fracture while the hospitalist oversees diabetes and hypertension management. Claim submission follows the same logic. Report each subsequent hospital care code (99231-99233) with the corresponding diagnosis each physician primarily manages (i.e., orthopedic surgeon: 9923x with 820.8; hospitalist: 9923x with 250.00, 401.1).

When each physician assigns a different primary diagnosis code to the visit code, each is more likely to receive payment. Because each of these physicians are in different specialties and different provider groups, most payors do not require modifier 25 (separately identifiable E/M service on the same day as a procedure or other service) appended to the visit code. However, some managed-care payors require each physician to append modifier 25 to the concurrent E/M visit code (i.e., 99232-25) despite claim submission under different tax identification numbers.

Unfortunately, the physicians might not realize this until a claim rejection has been issued. Furthermore, payors might want to see the proof before rendering payment. In other words, they pay the first claim received and deny any subsequent claim in order to confirm medical necessity of the concurrent visit. Appeal denied such claims rejections with supporting documentation that distinguishes each physician visit, if possible. This assists the payors in understanding each physician’s contribution to care.

Reasons for Denial

Concurrent care services are more easily distinguished when separate diagnoses are reported with each service. Conversely, payors are likely to deny services that are hard to differentiate. Furthermore, payors frequently deny concurrent care services for the following reasons:

- Services exceed normal frequency or duration for a given condition without documented circumstances requiring additional care; or

- Services by one physician duplicate or overlap those of another provider without recognizable distinction.2

For example, a hospitalist might be involved in the post-op care of patients with fractures and no other identifiable chronic or acute conditions or complications. In these cases, the hospitalist’s continued involvement might constitute a facility policy (e.g., quality of care, risk reduction, etc.) rather than active clinical management. Claim submission could erroneously occur with each physician reporting 9923x for 820.8. Payors deny medically unnecessary services, or request refunds for inappropriate payments.

Hospitalists might attempt to negotiate other terms with the facility to account for the unpaid time and effort directed toward these types of cases.

Group Practice