User login

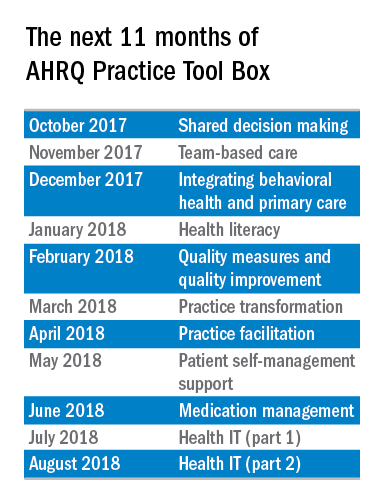

The AHRQ Practice Tool Box

This is the first in a series of articles from the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research (NCEPCR) in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). This series introduces sets of tools and resources designed to help your practice.

Primary care providers deal with a multitude of challenging clinical issues (e.g., providing first contact and preventive care, diagnosis in the undifferentiated patient, care of patients with chronic illness and multiple chronic conditions, keeping up with the literature) while managing a rapidly changing and often difficult health care environment. Despite this complexity and these challenges, primary care clinicians and health care systems strive to provide high-quality health care – i.e., care that is safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), a subdivision of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, recognizes that revitalizing this nation’s primary care system is critical to achieving quality health care. To that end, the agency is committed to helping you improve the care you deliver by offering the latest information, providing evidence syntheses, developing tools for improving primary care practice, and generating data and measures to track and improve performance in primary care.

AHRQ established the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research (NCEPCR) to be its intellectual home for primary care research. It is the agency’s vehicle for communicating the evidence from AHRQ’s research – and information about how this evidence can be used to improve health and primary health care – to researchers, primary care professionals, health care decision makers, patients, and families.

Electronic resources for daily practice

Every day you rely on guidelines for handling issues that range from prevention to caring for those with multiple chronic conditions. Two of AHRQ’s tools make the use of these guidelines easier.

First, the Electronic Prevention Services Selector (ePSS) is a free application that allows you to search or browse U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations on the Web, a PDA, or a mobile device. You can enter patient-specific information (for example, age, sex, smoking status) to get customized information for your patient. The ePSS brings information on clinical preventive services – recommendations, clinical considerations, and selected practice tools – to the point of care. You can sign up for notifications when there are updates.

The National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) provides health professionals with a tool for obtaining objective, detailed information on evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. After you enter a condition onto the webpage, the site offers key information on guidelines related to that condition – including relevant FDA drug safety alerts – and flags guidelines addressing multiple chronic conditions. The site lets you readily compare different guidelines on the same topic.

Like all of AHRQ’s tools and resources, the ePSS and NGC are freely available. These and other tools can be found at the NCEPCR website.

Dr. Bierman is the director of the Center for Evidence and Practice Improvement at AHRQ. Dr. Ganiats is the director for the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research at AHRQ.

This is the first in a series of articles from the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research (NCEPCR) in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). This series introduces sets of tools and resources designed to help your practice.

Primary care providers deal with a multitude of challenging clinical issues (e.g., providing first contact and preventive care, diagnosis in the undifferentiated patient, care of patients with chronic illness and multiple chronic conditions, keeping up with the literature) while managing a rapidly changing and often difficult health care environment. Despite this complexity and these challenges, primary care clinicians and health care systems strive to provide high-quality health care – i.e., care that is safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), a subdivision of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, recognizes that revitalizing this nation’s primary care system is critical to achieving quality health care. To that end, the agency is committed to helping you improve the care you deliver by offering the latest information, providing evidence syntheses, developing tools for improving primary care practice, and generating data and measures to track and improve performance in primary care.

AHRQ established the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research (NCEPCR) to be its intellectual home for primary care research. It is the agency’s vehicle for communicating the evidence from AHRQ’s research – and information about how this evidence can be used to improve health and primary health care – to researchers, primary care professionals, health care decision makers, patients, and families.

Electronic resources for daily practice

Every day you rely on guidelines for handling issues that range from prevention to caring for those with multiple chronic conditions. Two of AHRQ’s tools make the use of these guidelines easier.

First, the Electronic Prevention Services Selector (ePSS) is a free application that allows you to search or browse U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations on the Web, a PDA, or a mobile device. You can enter patient-specific information (for example, age, sex, smoking status) to get customized information for your patient. The ePSS brings information on clinical preventive services – recommendations, clinical considerations, and selected practice tools – to the point of care. You can sign up for notifications when there are updates.

The National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) provides health professionals with a tool for obtaining objective, detailed information on evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. After you enter a condition onto the webpage, the site offers key information on guidelines related to that condition – including relevant FDA drug safety alerts – and flags guidelines addressing multiple chronic conditions. The site lets you readily compare different guidelines on the same topic.

Like all of AHRQ’s tools and resources, the ePSS and NGC are freely available. These and other tools can be found at the NCEPCR website.

Dr. Bierman is the director of the Center for Evidence and Practice Improvement at AHRQ. Dr. Ganiats is the director for the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research at AHRQ.

This is the first in a series of articles from the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research (NCEPCR) in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). This series introduces sets of tools and resources designed to help your practice.

Primary care providers deal with a multitude of challenging clinical issues (e.g., providing first contact and preventive care, diagnosis in the undifferentiated patient, care of patients with chronic illness and multiple chronic conditions, keeping up with the literature) while managing a rapidly changing and often difficult health care environment. Despite this complexity and these challenges, primary care clinicians and health care systems strive to provide high-quality health care – i.e., care that is safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), a subdivision of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, recognizes that revitalizing this nation’s primary care system is critical to achieving quality health care. To that end, the agency is committed to helping you improve the care you deliver by offering the latest information, providing evidence syntheses, developing tools for improving primary care practice, and generating data and measures to track and improve performance in primary care.

AHRQ established the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research (NCEPCR) to be its intellectual home for primary care research. It is the agency’s vehicle for communicating the evidence from AHRQ’s research – and information about how this evidence can be used to improve health and primary health care – to researchers, primary care professionals, health care decision makers, patients, and families.

Electronic resources for daily practice

Every day you rely on guidelines for handling issues that range from prevention to caring for those with multiple chronic conditions. Two of AHRQ’s tools make the use of these guidelines easier.

First, the Electronic Prevention Services Selector (ePSS) is a free application that allows you to search or browse U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations on the Web, a PDA, or a mobile device. You can enter patient-specific information (for example, age, sex, smoking status) to get customized information for your patient. The ePSS brings information on clinical preventive services – recommendations, clinical considerations, and selected practice tools – to the point of care. You can sign up for notifications when there are updates.

The National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) provides health professionals with a tool for obtaining objective, detailed information on evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. After you enter a condition onto the webpage, the site offers key information on guidelines related to that condition – including relevant FDA drug safety alerts – and flags guidelines addressing multiple chronic conditions. The site lets you readily compare different guidelines on the same topic.

Like all of AHRQ’s tools and resources, the ePSS and NGC are freely available. These and other tools can be found at the NCEPCR website.

Dr. Bierman is the director of the Center for Evidence and Practice Improvement at AHRQ. Dr. Ganiats is the director for the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research at AHRQ.

The Inflection Point

In the early 1600s, the French playwright Molière wrote one of the great satires of all time, “The Doctor in Spite of Himself.” In that play the main character, Sganarelle, is a woodcutter who wastes all his money on alcohol, so his wife Martine decides she will teach him a lesson. As she is plotting her revenge, Martine overhears two peasants discussing how they have been trying to find a doctor for their rich employer’s daughter, who has become suddenly mute. Martine seizes the opportunity to tell the peasants that her husband is a brilliant – though eccentric – doctor who usually hides his identity. Learning this, the peasants find Sganarelle and beg him to see their master’s daughter. Though he initially refuses, they berate him until he can take it no more, and he finally says that he is a doctor and agrees to assess the ill young woman.

Sganarelle does his best to impersonate a doctor while examining the young woman, and as he is doing so it becomes apparent even to him that she is not truly ill. She is pretending to be mute because she’s being forced to marry a wealthy man she does not love. Sganarelle discusses the diagnosis with her father, stating, “this impediment to the action of the tongue is caused by certain humors.” He goes on to say that her muteness was triggered by, “the vapors that pass from the left side, where the liver resides, to the right side, where the heart dwells.” The rich aristocrat listens intently and accepts the diagnosis, though he seems puzzled about one thing. “Isn’t the heart on the left side of the chest?” he asks. To this insightful and obvious question Sganarelle replies, “Yes, that used to be true; but we’ve changed all that, and we practice medicine now according to a whole new method.”

It is astonishing that Molière, in a farcical comedy written in the 1600s, could have anticipated the dizzying rate of change in modern medicine. While the heart and liver have not changed sides, the ways we are practicing medicine have undergone landmark shifts over the past 10 years. Just look at the new ways in which we record documentation, learn new information, send in prescriptions, manage populations in addition to individual patients, and so many other aspects of care. At times this evolution has its own satirical feel to it. For example, the notion that refusing to refill an opioid prescription for a patient that broke their opioid contract could lead to a bad review on Yelp or points off on a Press Ganey satisfaction survey does not seem reasonable, but it is real.

When we started this column about 10 years ago, we regularly received emails (and even letters written in fine penmanship and mailed in envelopes) from physicians who felt that the EHR was ruining their practice and their lives. Many of the letters talked about early retirement. Some physicians ended up retiring early. Many of these physicians were smart, able people who we believe took great care of patients. But as Leon C. Megginson, interpreting the work of Darwin, observed, “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.” Adaptability favors the young; the young have fewer habits to break, few preconceived ideas of how things should be, and perhaps more energy to give to new tasks.

We believe we have now reached the inflection point – a time in the history of an industry where an event (in this case the advent of the EHR) so fundamentally impacts the industry that the industry is changed from that point forward. The industry, and more importantly those who work in the industry, must adopt new approaches and attitudes in order to survive in the changed environment. Andrew Grove, the former CEO of Intel, talked about Strategic Inflection Points in a keynote address to the Academy of Management: “…what is common to [inflection points] and what is key is that they require a fundamental change in business strategy.” Grove also said, “That change can mean an opportunity to rise to new heights. But it may just as likely signal the beginning of the end.”

Up until recently, the introduction of the EHR lead to discussions about what was good and what was bad about the advent of EHRs. That time is past. We no longer receive letters from physicians expressing their concerns about the EHR, as many of those physicians have taken the change as a signal of the end of their careers, and chosen to retire. The rest have adapted to a new world. And in this new world we are certainly rising to new heights. We are forward-focused and looking at the multi-fold ways that our new technologies can accomplish their many missions – to improve the health of the population, to serve as a source of data to assess the real-world effectiveness of novel therapies, to evaluate and affect the quality of care given by practices and individual physicians, and to take excellent personalized care of individual patients. While we are physicians, not wood cutters as in Molière’s play, it remains incumbent upon us never to stop listening to our patients’ hearts, and to interpret their symptoms and signs with common sense, empathy and even humor when appropriate, all the while embracing approaches that move the health care of our patients forward to new heights.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health. Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is also a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records.

In the early 1600s, the French playwright Molière wrote one of the great satires of all time, “The Doctor in Spite of Himself.” In that play the main character, Sganarelle, is a woodcutter who wastes all his money on alcohol, so his wife Martine decides she will teach him a lesson. As she is plotting her revenge, Martine overhears two peasants discussing how they have been trying to find a doctor for their rich employer’s daughter, who has become suddenly mute. Martine seizes the opportunity to tell the peasants that her husband is a brilliant – though eccentric – doctor who usually hides his identity. Learning this, the peasants find Sganarelle and beg him to see their master’s daughter. Though he initially refuses, they berate him until he can take it no more, and he finally says that he is a doctor and agrees to assess the ill young woman.

Sganarelle does his best to impersonate a doctor while examining the young woman, and as he is doing so it becomes apparent even to him that she is not truly ill. She is pretending to be mute because she’s being forced to marry a wealthy man she does not love. Sganarelle discusses the diagnosis with her father, stating, “this impediment to the action of the tongue is caused by certain humors.” He goes on to say that her muteness was triggered by, “the vapors that pass from the left side, where the liver resides, to the right side, where the heart dwells.” The rich aristocrat listens intently and accepts the diagnosis, though he seems puzzled about one thing. “Isn’t the heart on the left side of the chest?” he asks. To this insightful and obvious question Sganarelle replies, “Yes, that used to be true; but we’ve changed all that, and we practice medicine now according to a whole new method.”

It is astonishing that Molière, in a farcical comedy written in the 1600s, could have anticipated the dizzying rate of change in modern medicine. While the heart and liver have not changed sides, the ways we are practicing medicine have undergone landmark shifts over the past 10 years. Just look at the new ways in which we record documentation, learn new information, send in prescriptions, manage populations in addition to individual patients, and so many other aspects of care. At times this evolution has its own satirical feel to it. For example, the notion that refusing to refill an opioid prescription for a patient that broke their opioid contract could lead to a bad review on Yelp or points off on a Press Ganey satisfaction survey does not seem reasonable, but it is real.

When we started this column about 10 years ago, we regularly received emails (and even letters written in fine penmanship and mailed in envelopes) from physicians who felt that the EHR was ruining their practice and their lives. Many of the letters talked about early retirement. Some physicians ended up retiring early. Many of these physicians were smart, able people who we believe took great care of patients. But as Leon C. Megginson, interpreting the work of Darwin, observed, “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.” Adaptability favors the young; the young have fewer habits to break, few preconceived ideas of how things should be, and perhaps more energy to give to new tasks.

We believe we have now reached the inflection point – a time in the history of an industry where an event (in this case the advent of the EHR) so fundamentally impacts the industry that the industry is changed from that point forward. The industry, and more importantly those who work in the industry, must adopt new approaches and attitudes in order to survive in the changed environment. Andrew Grove, the former CEO of Intel, talked about Strategic Inflection Points in a keynote address to the Academy of Management: “…what is common to [inflection points] and what is key is that they require a fundamental change in business strategy.” Grove also said, “That change can mean an opportunity to rise to new heights. But it may just as likely signal the beginning of the end.”

Up until recently, the introduction of the EHR lead to discussions about what was good and what was bad about the advent of EHRs. That time is past. We no longer receive letters from physicians expressing their concerns about the EHR, as many of those physicians have taken the change as a signal of the end of their careers, and chosen to retire. The rest have adapted to a new world. And in this new world we are certainly rising to new heights. We are forward-focused and looking at the multi-fold ways that our new technologies can accomplish their many missions – to improve the health of the population, to serve as a source of data to assess the real-world effectiveness of novel therapies, to evaluate and affect the quality of care given by practices and individual physicians, and to take excellent personalized care of individual patients. While we are physicians, not wood cutters as in Molière’s play, it remains incumbent upon us never to stop listening to our patients’ hearts, and to interpret their symptoms and signs with common sense, empathy and even humor when appropriate, all the while embracing approaches that move the health care of our patients forward to new heights.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health. Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is also a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records.

In the early 1600s, the French playwright Molière wrote one of the great satires of all time, “The Doctor in Spite of Himself.” In that play the main character, Sganarelle, is a woodcutter who wastes all his money on alcohol, so his wife Martine decides she will teach him a lesson. As she is plotting her revenge, Martine overhears two peasants discussing how they have been trying to find a doctor for their rich employer’s daughter, who has become suddenly mute. Martine seizes the opportunity to tell the peasants that her husband is a brilliant – though eccentric – doctor who usually hides his identity. Learning this, the peasants find Sganarelle and beg him to see their master’s daughter. Though he initially refuses, they berate him until he can take it no more, and he finally says that he is a doctor and agrees to assess the ill young woman.

Sganarelle does his best to impersonate a doctor while examining the young woman, and as he is doing so it becomes apparent even to him that she is not truly ill. She is pretending to be mute because she’s being forced to marry a wealthy man she does not love. Sganarelle discusses the diagnosis with her father, stating, “this impediment to the action of the tongue is caused by certain humors.” He goes on to say that her muteness was triggered by, “the vapors that pass from the left side, where the liver resides, to the right side, where the heart dwells.” The rich aristocrat listens intently and accepts the diagnosis, though he seems puzzled about one thing. “Isn’t the heart on the left side of the chest?” he asks. To this insightful and obvious question Sganarelle replies, “Yes, that used to be true; but we’ve changed all that, and we practice medicine now according to a whole new method.”

It is astonishing that Molière, in a farcical comedy written in the 1600s, could have anticipated the dizzying rate of change in modern medicine. While the heart and liver have not changed sides, the ways we are practicing medicine have undergone landmark shifts over the past 10 years. Just look at the new ways in which we record documentation, learn new information, send in prescriptions, manage populations in addition to individual patients, and so many other aspects of care. At times this evolution has its own satirical feel to it. For example, the notion that refusing to refill an opioid prescription for a patient that broke their opioid contract could lead to a bad review on Yelp or points off on a Press Ganey satisfaction survey does not seem reasonable, but it is real.

When we started this column about 10 years ago, we regularly received emails (and even letters written in fine penmanship and mailed in envelopes) from physicians who felt that the EHR was ruining their practice and their lives. Many of the letters talked about early retirement. Some physicians ended up retiring early. Many of these physicians were smart, able people who we believe took great care of patients. But as Leon C. Megginson, interpreting the work of Darwin, observed, “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.” Adaptability favors the young; the young have fewer habits to break, few preconceived ideas of how things should be, and perhaps more energy to give to new tasks.

We believe we have now reached the inflection point – a time in the history of an industry where an event (in this case the advent of the EHR) so fundamentally impacts the industry that the industry is changed from that point forward. The industry, and more importantly those who work in the industry, must adopt new approaches and attitudes in order to survive in the changed environment. Andrew Grove, the former CEO of Intel, talked about Strategic Inflection Points in a keynote address to the Academy of Management: “…what is common to [inflection points] and what is key is that they require a fundamental change in business strategy.” Grove also said, “That change can mean an opportunity to rise to new heights. But it may just as likely signal the beginning of the end.”

Up until recently, the introduction of the EHR lead to discussions about what was good and what was bad about the advent of EHRs. That time is past. We no longer receive letters from physicians expressing their concerns about the EHR, as many of those physicians have taken the change as a signal of the end of their careers, and chosen to retire. The rest have adapted to a new world. And in this new world we are certainly rising to new heights. We are forward-focused and looking at the multi-fold ways that our new technologies can accomplish their many missions – to improve the health of the population, to serve as a source of data to assess the real-world effectiveness of novel therapies, to evaluate and affect the quality of care given by practices and individual physicians, and to take excellent personalized care of individual patients. While we are physicians, not wood cutters as in Molière’s play, it remains incumbent upon us never to stop listening to our patients’ hearts, and to interpret their symptoms and signs with common sense, empathy and even humor when appropriate, all the while embracing approaches that move the health care of our patients forward to new heights.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health. Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is also a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records.

Climate change may lead to more cellulitis

As a follow-up to our previous column on the effects of climate change on the skin (Dermatology News, June 2016, p. 28), this month’s column will focus on a study recently published in Clinical Infectious Diseases that explores warmer weather as a possible risk factor for cellulitis.1 As the summer continues with sweltering weather, humidity, and the recent spate of hurricanes in North America, it’s interesting to think about how the climate affects our patients and puts them at risk.

Much attention has been given to global warming and climate change over the past several years. The results of this study demonstrate that, if temperatures consistently increase, the odds of cellulitis also may increase in regions exposed to warmer temperatures.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Reference

1. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Jul 31. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix487.

As a follow-up to our previous column on the effects of climate change on the skin (Dermatology News, June 2016, p. 28), this month’s column will focus on a study recently published in Clinical Infectious Diseases that explores warmer weather as a possible risk factor for cellulitis.1 As the summer continues with sweltering weather, humidity, and the recent spate of hurricanes in North America, it’s interesting to think about how the climate affects our patients and puts them at risk.

Much attention has been given to global warming and climate change over the past several years. The results of this study demonstrate that, if temperatures consistently increase, the odds of cellulitis also may increase in regions exposed to warmer temperatures.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Reference

1. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Jul 31. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix487.

As a follow-up to our previous column on the effects of climate change on the skin (Dermatology News, June 2016, p. 28), this month’s column will focus on a study recently published in Clinical Infectious Diseases that explores warmer weather as a possible risk factor for cellulitis.1 As the summer continues with sweltering weather, humidity, and the recent spate of hurricanes in North America, it’s interesting to think about how the climate affects our patients and puts them at risk.

Much attention has been given to global warming and climate change over the past several years. The results of this study demonstrate that, if temperatures consistently increase, the odds of cellulitis also may increase in regions exposed to warmer temperatures.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Reference

1. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Jul 31. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix487.

Ethics in compulsory treatment of patients with severe mental illness

“Ethics is knowing the difference between what you have a right to do and what is right to do.”

– Potter Stewart, U.S. Supreme Court Justice

An understanding of the difference between what is allowed or even recommended and what is ethical often is contemplated in the treatment of mental illness. Mental illnesses can impair judgment in patients confronted with complex decisions about their treatment. A provider, therefore, has to make a decision between respecting autonomy and/or engaging in what may be considered beneficent. While the line separating beneficent care and the respect for the autonomy of a patient may not be present, the question often arises – especially in inpatient care of patients with severe mental illness.

In the inpatient units, I was taught to justify and be mindful of any removal of someone’s right. I learned the responsibility of stripping someone’s freedom. Not only would I find myself preventing someone from going where they wanted or from talking to whomever they wanted, but frequently, we involuntary injected patients with neuroactive chemicals. Those measures are used only in extreme circumstances: In most states, one has to be unable to provide themselves with food, clothing, or shelter secondary to mental illness to be subjected to such aggressive treatment.

Currently, the United States is seeing an increase in the focus on providing more treatment: an emphasis on beneficence over autonomy. This change can be witnessed in the passage of compulsory outpatient treatment laws. Those rulings, such as Laura’s Law in California and Kendra’s Law in New York, have been promoted in response to an increased concern over the consequences of untreated mental illness in crime. In this commentary, I present a case where I felt that despite being given the right and expectation to involuntary treat someone, I did not feel that it was ethical to involuntarily medicate him. (I have made appropriate changes to the patient’s case to maintain confidentiality.)

Our facility

The Psychiatric Stabilization Unit (PSU) of the San Diego Jails is a 30-bed acute psychiatric unit. We serve the 4,500 male inmates and one of the largest mental health systems in the county. The vast majority (from 70% to 90% at any one time) of patients suffer from a psychotic illness, and more than 50% have a comorbid substance use disorder. Contrary to most inpatient units, we do not have pressure from insurance or utilization review to regularly change dosages or medications, and we do not have significant pressure to discharge patients within a certain time frame. The unit serves very disenfranchised patients with most being homeless prior to their arrest and many having no emergency contact or social support of any sort. The unit is staffed by one attending psychiatrist and two therapists. We are subjected to the same involuntary commitment and involuntary medication laws as are community psychiatric hospitals, but we get a significant number of patients under court orders.

The patient presented in this case came under such court order for restoration of his competency to stand trial. In the United States, one cannot stand trial unless competent. Competency is defined as one’s ability to take a meaningful or active part in a trial, the capacity to understand laws, the capacity to understand personal responsibility, the ability to express a plea, and the capability to instruct legal counsel. When patients are found incompetent, they commonly get court ordered to an unit like the PSU with a court order that they cannot understand the risk, benefits, and alternatives of psychotropic treatment and thus can be involuntarily medicated. Often, including in this case, the court order will mention that the patient will not become competent without treatment, including involuntary antipsychotics.

Overview of the case

George is a 50-year-old white male without psychiatric history. He had never been hospitalized psychiatrically voluntarily or involuntarily. He has never engaged in outpatient psychiatric care, has never taken psychotropic medication, and has never been diagnosed with mental illness. He mentions no prior episode of self-harm, suicidality, or suicide attempt. He occasionally drinks alcohol and has smoked marijuana on a few occasions. He despises other drugs, saying that they are “dangerous.” He mentions that his parents had “difficult personalities” but denies any knowledge of them having formal mental illness.

He was born in rural Louisiana to a British mother and an American father. His parents divorced while he was in preschool. His mother remarried, to a salesman, which required them to move frequently to different states for his work. He mentions having performed moderately in school, but poor grades were secondary to his “boredom.” He graduated high school and went to vocational school in technological manufacturing but was unable to graduate. He has since held a series of low-level jobs in retail and janitorial services. He mentions having been in romantic relationships, but when asked to elaborate, he is unable to name any past girlfriends or describe any past relationships. Nonetheless, he describes a wide array of social supports with many friends, though it must be noted that all of his friends have some form of mental illness or intellectual disability.

At this time, he lives with his friend Harry. Harry has a moderate form of autism. George helps him with everything from grocery shopping to financial matters to assistance in personal hygiene. In exchange, Harry provides him with housing that he inherited and financial assistance from his disability benefits. They have lived in the same home for 2 years, since Harry asked George to move in because of concern that he would lose his home over the unsanitary conditions that were present at that time.

George had never been arrested prior to this incarceration. The circumstances of his arrest are unusual. After a neighbor had made complaints that Harry and George were illegally lodging in Harry’s home, the city investigated the matter. George’s report was that Harry was unable to fill out the forms appropriately and was asked to present himself in court. George came along for moral support but became extremely upset when lawyers and judges asked his friend to answer questions he did not have the cognitive ability to answer. Without second thought, George voiced his anger but was asked to remain quiet while not on the stand. He was asked to remain seated and was demanded to follow orders. A few moments later, George was arrested for contempt of court and obstruction to an officer.

Once incarcerated, he declined having any mental illness or needing any treatment during the customary triage visit. He had no problem as an inmate and was never referred to psychiatric services. However, when meeting with his public defender, George derailed into delusions. He talked about how the cops had been conspiring against him all of his life, with his current incarceration as a culmination. He mentioned how the judge was purposely trying to get them evicted so that he could own the house himself. He asked his lawyer to countersue the judge for a violation of his rights. The public defender filed for a competency evaluation of his client.

The forensic psychiatrist evaluated the patient and had a similar interpretation. This was a patient who had delusions and was perseverating on them to the point of being unable to engage in meaningful work with his attorney. The psychiatrist recommended involuntary treatment with an antipsychotic after diagnosing the patient with a psychotic illness.

My interactions with George

George is a loud and bucolic man with an usual mix of Southern idioms, a slightly British accent, and East Coast humor. He insisted on telling me why he wanted the staff to refer to him by his Native American nickname prior to the start our interview. He then asked me to listen to his life story to understand why Harry meant so much to him. Despite recounting their truly meaningful relationship, his affect was odd with poor reactivity; he had an incongruent and somewhat ungenuine joyfulness.

Once I heard his account of their friendship, I asked him about his charges and the incident in the courtroom. His answer was a long diatribe about the wrongs that had been done to him, but most of his speech was a series of illogical delusions. I informed him of my thoughts about his fixed and false beliefs, but he was not able to understand my comments. Nonetheless, I felt that he related to me well and that we had established good rapport.

As I was informing him about the antipsychotic I had chosen for his involuntary treatment, he asked me to hold off. He asked me to consider working with him for some time without medications. After all, he did not believe that he had a mental illness and wanted to attempt to engage in the competency training with our therapist without being medicated.

My conceptualization of him

George is a peculiar case. Practically all patients who are committed to my unit for competency restoration are psychotic, and their psychosis prevents their engagement with their attorneys. They have poor insight into their illness, which leads to their commitment. On admission, I confirm the assessment of the forensic psychiatrist and start the ordered involuntary treatment on patients. Many of them are gravely disabled – making the ethical dilemma easier to navigate. For other patients, the idea that they will be kept incarcerated until found competent also makes the forced treatment a simpler decision.

George was different – his impeccable grooming, his dislike of jail food, and his request for appropriately fitting jail clothes were far from disorganized. More importantly, however, he had adequate shelter outside of jail, income for assisting Harry, and a rich network of friends. Despite being riddled with delusions, his thought process was linear, and he was redirectable – even when discussing his delusions. I conceptualized the ethical conflict as such: Not treating him might lead to a longer period of incompetence and a longer incarceration; treating him would go against his desire to remain untreated.

After contacting Harry, I was fairly certain that George had suffered from his delusions for at least a significant part of his adult life, if not in its entirety. However, Harry was infinitely thankful for George’s assistance and felt that George had a good life. This added another fundamental question: Would forcing George to engage in formal mental health treatment lead him to have a better life? He was happy, had meaningful relationships, and contributed to his life as well as his friends’ lives in a deep way.

I diagnosed him as having an unspecified psychotic disorder, likely schizophrenia; he had delusions and negative symptoms, like his impaired affect. Despite this diagnosis, I decided to hold off from using involuntary treatment. I met with him daily for more than 2 weeks, and we discussed his story, his feelings, and his beliefs. On occasion, it was hard to separate the delusions from justifiable anger at the system. He had felt that he and Harry had been wronged, when society should have protected their vulnerability. He learned to trust me, and his therapist taught him competency training. Despite a possible 1-year commitment, we declared him competent to stand trial in 2 weeks. He had learned and excelled in all facets of the training.

George still had delusions, but he understood his charges, that he had acted inappropriately in the courtroom, and how to discuss his case with his legal counsel. Harry found George to be at his baseline during visits. George acted appropriately; he followed the complex rules set on inmates and engaged in all groups that are held on the unit.

Discussion

I certainly do not question the value of involuntary psychiatric treatment for many patients with grave disabilities, violent tendencies, or incompetence. However, George’s case makes me wonder if many people living with schizophrenia can have rich and meaningful lives without ever being in contact with a mental health provider. I wonder if our almost-obsessive attention to antipsychotics makes us lose sight. Our biological reductionism may lead us to see patients such as George as someone with overactive dopaminergic pathways in need of antidopaminergic antipsychotic. Unfortunately for many, biological reductionism often is based on unsubstantiated evidence.

George reminds me that life, including schizophrenia, is more interesting and complicated than a set of genes, pathways, neurons, or neurotransmitters. Our patients’ lives may be convoluted with delusions, often stemming from truth or impaired affects, which are nonetheless genuine. I don’t know what will happen to George, but his past 50 years suggest that he will continue to have friends, and he will continue to live without being impaired by his delusions. Strangely, I worry less about him than many of my other patients.

Many mental health providers have advocated for a wider and easier access to involuntarily medicate our patients. I think that there is a misguided belief that involuntary antipsychotic treatment will lead to a rise in their use. However, if Carl Rogers, PhD, and others were right in stating that our relationship with our patients was the ultimate factor in their recovery, at what cost are we willing to jeopardize this? My fear is that this cost will be the loss of trust, which is so necessary in treatment. I hope that my short relationship with George did not scare him from ever seeing a psychiatrist again. In some ways, I suspect that by simply listening to George and withholding forced treatment, he will be more inclined to seek treatment in the future.

Take-home points

- Certain patients with psychosis have fairly high functioning.

- Milieu therapy is, in certain cases, able to assuage some symptoms of psychosis.

- Compulsory antipsychotic administration may not be ethical in certain cases of acute psychosis.

- Biological reductionism may undermine a complete ethical understanding of psychosis.

- Psychiatric disorders are etiologically complex and multifactorial.

- Involuntary treatment may provide short-term gains, but prevent long-term trust between patient and provider.

Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre also mentors several residents on projects, including reduction in the use of solitary confinement of patients with mental illness, reduction in the use of involuntary treatment of the mentally ill, and examination of the mentally ill offender.

“Ethics is knowing the difference between what you have a right to do and what is right to do.”

– Potter Stewart, U.S. Supreme Court Justice

An understanding of the difference between what is allowed or even recommended and what is ethical often is contemplated in the treatment of mental illness. Mental illnesses can impair judgment in patients confronted with complex decisions about their treatment. A provider, therefore, has to make a decision between respecting autonomy and/or engaging in what may be considered beneficent. While the line separating beneficent care and the respect for the autonomy of a patient may not be present, the question often arises – especially in inpatient care of patients with severe mental illness.

In the inpatient units, I was taught to justify and be mindful of any removal of someone’s right. I learned the responsibility of stripping someone’s freedom. Not only would I find myself preventing someone from going where they wanted or from talking to whomever they wanted, but frequently, we involuntary injected patients with neuroactive chemicals. Those measures are used only in extreme circumstances: In most states, one has to be unable to provide themselves with food, clothing, or shelter secondary to mental illness to be subjected to such aggressive treatment.

Currently, the United States is seeing an increase in the focus on providing more treatment: an emphasis on beneficence over autonomy. This change can be witnessed in the passage of compulsory outpatient treatment laws. Those rulings, such as Laura’s Law in California and Kendra’s Law in New York, have been promoted in response to an increased concern over the consequences of untreated mental illness in crime. In this commentary, I present a case where I felt that despite being given the right and expectation to involuntary treat someone, I did not feel that it was ethical to involuntarily medicate him. (I have made appropriate changes to the patient’s case to maintain confidentiality.)

Our facility

The Psychiatric Stabilization Unit (PSU) of the San Diego Jails is a 30-bed acute psychiatric unit. We serve the 4,500 male inmates and one of the largest mental health systems in the county. The vast majority (from 70% to 90% at any one time) of patients suffer from a psychotic illness, and more than 50% have a comorbid substance use disorder. Contrary to most inpatient units, we do not have pressure from insurance or utilization review to regularly change dosages or medications, and we do not have significant pressure to discharge patients within a certain time frame. The unit serves very disenfranchised patients with most being homeless prior to their arrest and many having no emergency contact or social support of any sort. The unit is staffed by one attending psychiatrist and two therapists. We are subjected to the same involuntary commitment and involuntary medication laws as are community psychiatric hospitals, but we get a significant number of patients under court orders.

The patient presented in this case came under such court order for restoration of his competency to stand trial. In the United States, one cannot stand trial unless competent. Competency is defined as one’s ability to take a meaningful or active part in a trial, the capacity to understand laws, the capacity to understand personal responsibility, the ability to express a plea, and the capability to instruct legal counsel. When patients are found incompetent, they commonly get court ordered to an unit like the PSU with a court order that they cannot understand the risk, benefits, and alternatives of psychotropic treatment and thus can be involuntarily medicated. Often, including in this case, the court order will mention that the patient will not become competent without treatment, including involuntary antipsychotics.

Overview of the case

George is a 50-year-old white male without psychiatric history. He had never been hospitalized psychiatrically voluntarily or involuntarily. He has never engaged in outpatient psychiatric care, has never taken psychotropic medication, and has never been diagnosed with mental illness. He mentions no prior episode of self-harm, suicidality, or suicide attempt. He occasionally drinks alcohol and has smoked marijuana on a few occasions. He despises other drugs, saying that they are “dangerous.” He mentions that his parents had “difficult personalities” but denies any knowledge of them having formal mental illness.

He was born in rural Louisiana to a British mother and an American father. His parents divorced while he was in preschool. His mother remarried, to a salesman, which required them to move frequently to different states for his work. He mentions having performed moderately in school, but poor grades were secondary to his “boredom.” He graduated high school and went to vocational school in technological manufacturing but was unable to graduate. He has since held a series of low-level jobs in retail and janitorial services. He mentions having been in romantic relationships, but when asked to elaborate, he is unable to name any past girlfriends or describe any past relationships. Nonetheless, he describes a wide array of social supports with many friends, though it must be noted that all of his friends have some form of mental illness or intellectual disability.

At this time, he lives with his friend Harry. Harry has a moderate form of autism. George helps him with everything from grocery shopping to financial matters to assistance in personal hygiene. In exchange, Harry provides him with housing that he inherited and financial assistance from his disability benefits. They have lived in the same home for 2 years, since Harry asked George to move in because of concern that he would lose his home over the unsanitary conditions that were present at that time.

George had never been arrested prior to this incarceration. The circumstances of his arrest are unusual. After a neighbor had made complaints that Harry and George were illegally lodging in Harry’s home, the city investigated the matter. George’s report was that Harry was unable to fill out the forms appropriately and was asked to present himself in court. George came along for moral support but became extremely upset when lawyers and judges asked his friend to answer questions he did not have the cognitive ability to answer. Without second thought, George voiced his anger but was asked to remain quiet while not on the stand. He was asked to remain seated and was demanded to follow orders. A few moments later, George was arrested for contempt of court and obstruction to an officer.

Once incarcerated, he declined having any mental illness or needing any treatment during the customary triage visit. He had no problem as an inmate and was never referred to psychiatric services. However, when meeting with his public defender, George derailed into delusions. He talked about how the cops had been conspiring against him all of his life, with his current incarceration as a culmination. He mentioned how the judge was purposely trying to get them evicted so that he could own the house himself. He asked his lawyer to countersue the judge for a violation of his rights. The public defender filed for a competency evaluation of his client.

The forensic psychiatrist evaluated the patient and had a similar interpretation. This was a patient who had delusions and was perseverating on them to the point of being unable to engage in meaningful work with his attorney. The psychiatrist recommended involuntary treatment with an antipsychotic after diagnosing the patient with a psychotic illness.

My interactions with George

George is a loud and bucolic man with an usual mix of Southern idioms, a slightly British accent, and East Coast humor. He insisted on telling me why he wanted the staff to refer to him by his Native American nickname prior to the start our interview. He then asked me to listen to his life story to understand why Harry meant so much to him. Despite recounting their truly meaningful relationship, his affect was odd with poor reactivity; he had an incongruent and somewhat ungenuine joyfulness.

Once I heard his account of their friendship, I asked him about his charges and the incident in the courtroom. His answer was a long diatribe about the wrongs that had been done to him, but most of his speech was a series of illogical delusions. I informed him of my thoughts about his fixed and false beliefs, but he was not able to understand my comments. Nonetheless, I felt that he related to me well and that we had established good rapport.

As I was informing him about the antipsychotic I had chosen for his involuntary treatment, he asked me to hold off. He asked me to consider working with him for some time without medications. After all, he did not believe that he had a mental illness and wanted to attempt to engage in the competency training with our therapist without being medicated.

My conceptualization of him

George is a peculiar case. Practically all patients who are committed to my unit for competency restoration are psychotic, and their psychosis prevents their engagement with their attorneys. They have poor insight into their illness, which leads to their commitment. On admission, I confirm the assessment of the forensic psychiatrist and start the ordered involuntary treatment on patients. Many of them are gravely disabled – making the ethical dilemma easier to navigate. For other patients, the idea that they will be kept incarcerated until found competent also makes the forced treatment a simpler decision.

George was different – his impeccable grooming, his dislike of jail food, and his request for appropriately fitting jail clothes were far from disorganized. More importantly, however, he had adequate shelter outside of jail, income for assisting Harry, and a rich network of friends. Despite being riddled with delusions, his thought process was linear, and he was redirectable – even when discussing his delusions. I conceptualized the ethical conflict as such: Not treating him might lead to a longer period of incompetence and a longer incarceration; treating him would go against his desire to remain untreated.

After contacting Harry, I was fairly certain that George had suffered from his delusions for at least a significant part of his adult life, if not in its entirety. However, Harry was infinitely thankful for George’s assistance and felt that George had a good life. This added another fundamental question: Would forcing George to engage in formal mental health treatment lead him to have a better life? He was happy, had meaningful relationships, and contributed to his life as well as his friends’ lives in a deep way.

I diagnosed him as having an unspecified psychotic disorder, likely schizophrenia; he had delusions and negative symptoms, like his impaired affect. Despite this diagnosis, I decided to hold off from using involuntary treatment. I met with him daily for more than 2 weeks, and we discussed his story, his feelings, and his beliefs. On occasion, it was hard to separate the delusions from justifiable anger at the system. He had felt that he and Harry had been wronged, when society should have protected their vulnerability. He learned to trust me, and his therapist taught him competency training. Despite a possible 1-year commitment, we declared him competent to stand trial in 2 weeks. He had learned and excelled in all facets of the training.

George still had delusions, but he understood his charges, that he had acted inappropriately in the courtroom, and how to discuss his case with his legal counsel. Harry found George to be at his baseline during visits. George acted appropriately; he followed the complex rules set on inmates and engaged in all groups that are held on the unit.

Discussion

I certainly do not question the value of involuntary psychiatric treatment for many patients with grave disabilities, violent tendencies, or incompetence. However, George’s case makes me wonder if many people living with schizophrenia can have rich and meaningful lives without ever being in contact with a mental health provider. I wonder if our almost-obsessive attention to antipsychotics makes us lose sight. Our biological reductionism may lead us to see patients such as George as someone with overactive dopaminergic pathways in need of antidopaminergic antipsychotic. Unfortunately for many, biological reductionism often is based on unsubstantiated evidence.

George reminds me that life, including schizophrenia, is more interesting and complicated than a set of genes, pathways, neurons, or neurotransmitters. Our patients’ lives may be convoluted with delusions, often stemming from truth or impaired affects, which are nonetheless genuine. I don’t know what will happen to George, but his past 50 years suggest that he will continue to have friends, and he will continue to live without being impaired by his delusions. Strangely, I worry less about him than many of my other patients.

Many mental health providers have advocated for a wider and easier access to involuntarily medicate our patients. I think that there is a misguided belief that involuntary antipsychotic treatment will lead to a rise in their use. However, if Carl Rogers, PhD, and others were right in stating that our relationship with our patients was the ultimate factor in their recovery, at what cost are we willing to jeopardize this? My fear is that this cost will be the loss of trust, which is so necessary in treatment. I hope that my short relationship with George did not scare him from ever seeing a psychiatrist again. In some ways, I suspect that by simply listening to George and withholding forced treatment, he will be more inclined to seek treatment in the future.

Take-home points

- Certain patients with psychosis have fairly high functioning.

- Milieu therapy is, in certain cases, able to assuage some symptoms of psychosis.

- Compulsory antipsychotic administration may not be ethical in certain cases of acute psychosis.

- Biological reductionism may undermine a complete ethical understanding of psychosis.

- Psychiatric disorders are etiologically complex and multifactorial.

- Involuntary treatment may provide short-term gains, but prevent long-term trust between patient and provider.

Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre also mentors several residents on projects, including reduction in the use of solitary confinement of patients with mental illness, reduction in the use of involuntary treatment of the mentally ill, and examination of the mentally ill offender.

“Ethics is knowing the difference between what you have a right to do and what is right to do.”

– Potter Stewart, U.S. Supreme Court Justice

An understanding of the difference between what is allowed or even recommended and what is ethical often is contemplated in the treatment of mental illness. Mental illnesses can impair judgment in patients confronted with complex decisions about their treatment. A provider, therefore, has to make a decision between respecting autonomy and/or engaging in what may be considered beneficent. While the line separating beneficent care and the respect for the autonomy of a patient may not be present, the question often arises – especially in inpatient care of patients with severe mental illness.

In the inpatient units, I was taught to justify and be mindful of any removal of someone’s right. I learned the responsibility of stripping someone’s freedom. Not only would I find myself preventing someone from going where they wanted or from talking to whomever they wanted, but frequently, we involuntary injected patients with neuroactive chemicals. Those measures are used only in extreme circumstances: In most states, one has to be unable to provide themselves with food, clothing, or shelter secondary to mental illness to be subjected to such aggressive treatment.

Currently, the United States is seeing an increase in the focus on providing more treatment: an emphasis on beneficence over autonomy. This change can be witnessed in the passage of compulsory outpatient treatment laws. Those rulings, such as Laura’s Law in California and Kendra’s Law in New York, have been promoted in response to an increased concern over the consequences of untreated mental illness in crime. In this commentary, I present a case where I felt that despite being given the right and expectation to involuntary treat someone, I did not feel that it was ethical to involuntarily medicate him. (I have made appropriate changes to the patient’s case to maintain confidentiality.)

Our facility

The Psychiatric Stabilization Unit (PSU) of the San Diego Jails is a 30-bed acute psychiatric unit. We serve the 4,500 male inmates and one of the largest mental health systems in the county. The vast majority (from 70% to 90% at any one time) of patients suffer from a psychotic illness, and more than 50% have a comorbid substance use disorder. Contrary to most inpatient units, we do not have pressure from insurance or utilization review to regularly change dosages or medications, and we do not have significant pressure to discharge patients within a certain time frame. The unit serves very disenfranchised patients with most being homeless prior to their arrest and many having no emergency contact or social support of any sort. The unit is staffed by one attending psychiatrist and two therapists. We are subjected to the same involuntary commitment and involuntary medication laws as are community psychiatric hospitals, but we get a significant number of patients under court orders.

The patient presented in this case came under such court order for restoration of his competency to stand trial. In the United States, one cannot stand trial unless competent. Competency is defined as one’s ability to take a meaningful or active part in a trial, the capacity to understand laws, the capacity to understand personal responsibility, the ability to express a plea, and the capability to instruct legal counsel. When patients are found incompetent, they commonly get court ordered to an unit like the PSU with a court order that they cannot understand the risk, benefits, and alternatives of psychotropic treatment and thus can be involuntarily medicated. Often, including in this case, the court order will mention that the patient will not become competent without treatment, including involuntary antipsychotics.

Overview of the case

George is a 50-year-old white male without psychiatric history. He had never been hospitalized psychiatrically voluntarily or involuntarily. He has never engaged in outpatient psychiatric care, has never taken psychotropic medication, and has never been diagnosed with mental illness. He mentions no prior episode of self-harm, suicidality, or suicide attempt. He occasionally drinks alcohol and has smoked marijuana on a few occasions. He despises other drugs, saying that they are “dangerous.” He mentions that his parents had “difficult personalities” but denies any knowledge of them having formal mental illness.

He was born in rural Louisiana to a British mother and an American father. His parents divorced while he was in preschool. His mother remarried, to a salesman, which required them to move frequently to different states for his work. He mentions having performed moderately in school, but poor grades were secondary to his “boredom.” He graduated high school and went to vocational school in technological manufacturing but was unable to graduate. He has since held a series of low-level jobs in retail and janitorial services. He mentions having been in romantic relationships, but when asked to elaborate, he is unable to name any past girlfriends or describe any past relationships. Nonetheless, he describes a wide array of social supports with many friends, though it must be noted that all of his friends have some form of mental illness or intellectual disability.

At this time, he lives with his friend Harry. Harry has a moderate form of autism. George helps him with everything from grocery shopping to financial matters to assistance in personal hygiene. In exchange, Harry provides him with housing that he inherited and financial assistance from his disability benefits. They have lived in the same home for 2 years, since Harry asked George to move in because of concern that he would lose his home over the unsanitary conditions that were present at that time.

George had never been arrested prior to this incarceration. The circumstances of his arrest are unusual. After a neighbor had made complaints that Harry and George were illegally lodging in Harry’s home, the city investigated the matter. George’s report was that Harry was unable to fill out the forms appropriately and was asked to present himself in court. George came along for moral support but became extremely upset when lawyers and judges asked his friend to answer questions he did not have the cognitive ability to answer. Without second thought, George voiced his anger but was asked to remain quiet while not on the stand. He was asked to remain seated and was demanded to follow orders. A few moments later, George was arrested for contempt of court and obstruction to an officer.

Once incarcerated, he declined having any mental illness or needing any treatment during the customary triage visit. He had no problem as an inmate and was never referred to psychiatric services. However, when meeting with his public defender, George derailed into delusions. He talked about how the cops had been conspiring against him all of his life, with his current incarceration as a culmination. He mentioned how the judge was purposely trying to get them evicted so that he could own the house himself. He asked his lawyer to countersue the judge for a violation of his rights. The public defender filed for a competency evaluation of his client.

The forensic psychiatrist evaluated the patient and had a similar interpretation. This was a patient who had delusions and was perseverating on them to the point of being unable to engage in meaningful work with his attorney. The psychiatrist recommended involuntary treatment with an antipsychotic after diagnosing the patient with a psychotic illness.

My interactions with George

George is a loud and bucolic man with an usual mix of Southern idioms, a slightly British accent, and East Coast humor. He insisted on telling me why he wanted the staff to refer to him by his Native American nickname prior to the start our interview. He then asked me to listen to his life story to understand why Harry meant so much to him. Despite recounting their truly meaningful relationship, his affect was odd with poor reactivity; he had an incongruent and somewhat ungenuine joyfulness.

Once I heard his account of their friendship, I asked him about his charges and the incident in the courtroom. His answer was a long diatribe about the wrongs that had been done to him, but most of his speech was a series of illogical delusions. I informed him of my thoughts about his fixed and false beliefs, but he was not able to understand my comments. Nonetheless, I felt that he related to me well and that we had established good rapport.

As I was informing him about the antipsychotic I had chosen for his involuntary treatment, he asked me to hold off. He asked me to consider working with him for some time without medications. After all, he did not believe that he had a mental illness and wanted to attempt to engage in the competency training with our therapist without being medicated.

My conceptualization of him

George is a peculiar case. Practically all patients who are committed to my unit for competency restoration are psychotic, and their psychosis prevents their engagement with their attorneys. They have poor insight into their illness, which leads to their commitment. On admission, I confirm the assessment of the forensic psychiatrist and start the ordered involuntary treatment on patients. Many of them are gravely disabled – making the ethical dilemma easier to navigate. For other patients, the idea that they will be kept incarcerated until found competent also makes the forced treatment a simpler decision.

George was different – his impeccable grooming, his dislike of jail food, and his request for appropriately fitting jail clothes were far from disorganized. More importantly, however, he had adequate shelter outside of jail, income for assisting Harry, and a rich network of friends. Despite being riddled with delusions, his thought process was linear, and he was redirectable – even when discussing his delusions. I conceptualized the ethical conflict as such: Not treating him might lead to a longer period of incompetence and a longer incarceration; treating him would go against his desire to remain untreated.

After contacting Harry, I was fairly certain that George had suffered from his delusions for at least a significant part of his adult life, if not in its entirety. However, Harry was infinitely thankful for George’s assistance and felt that George had a good life. This added another fundamental question: Would forcing George to engage in formal mental health treatment lead him to have a better life? He was happy, had meaningful relationships, and contributed to his life as well as his friends’ lives in a deep way.

I diagnosed him as having an unspecified psychotic disorder, likely schizophrenia; he had delusions and negative symptoms, like his impaired affect. Despite this diagnosis, I decided to hold off from using involuntary treatment. I met with him daily for more than 2 weeks, and we discussed his story, his feelings, and his beliefs. On occasion, it was hard to separate the delusions from justifiable anger at the system. He had felt that he and Harry had been wronged, when society should have protected their vulnerability. He learned to trust me, and his therapist taught him competency training. Despite a possible 1-year commitment, we declared him competent to stand trial in 2 weeks. He had learned and excelled in all facets of the training.

George still had delusions, but he understood his charges, that he had acted inappropriately in the courtroom, and how to discuss his case with his legal counsel. Harry found George to be at his baseline during visits. George acted appropriately; he followed the complex rules set on inmates and engaged in all groups that are held on the unit.

Discussion

I certainly do not question the value of involuntary psychiatric treatment for many patients with grave disabilities, violent tendencies, or incompetence. However, George’s case makes me wonder if many people living with schizophrenia can have rich and meaningful lives without ever being in contact with a mental health provider. I wonder if our almost-obsessive attention to antipsychotics makes us lose sight. Our biological reductionism may lead us to see patients such as George as someone with overactive dopaminergic pathways in need of antidopaminergic antipsychotic. Unfortunately for many, biological reductionism often is based on unsubstantiated evidence.

George reminds me that life, including schizophrenia, is more interesting and complicated than a set of genes, pathways, neurons, or neurotransmitters. Our patients’ lives may be convoluted with delusions, often stemming from truth or impaired affects, which are nonetheless genuine. I don’t know what will happen to George, but his past 50 years suggest that he will continue to have friends, and he will continue to live without being impaired by his delusions. Strangely, I worry less about him than many of my other patients.

Many mental health providers have advocated for a wider and easier access to involuntarily medicate our patients. I think that there is a misguided belief that involuntary antipsychotic treatment will lead to a rise in their use. However, if Carl Rogers, PhD, and others were right in stating that our relationship with our patients was the ultimate factor in their recovery, at what cost are we willing to jeopardize this? My fear is that this cost will be the loss of trust, which is so necessary in treatment. I hope that my short relationship with George did not scare him from ever seeing a psychiatrist again. In some ways, I suspect that by simply listening to George and withholding forced treatment, he will be more inclined to seek treatment in the future.

Take-home points

- Certain patients with psychosis have fairly high functioning.

- Milieu therapy is, in certain cases, able to assuage some symptoms of psychosis.

- Compulsory antipsychotic administration may not be ethical in certain cases of acute psychosis.

- Biological reductionism may undermine a complete ethical understanding of psychosis.

- Psychiatric disorders are etiologically complex and multifactorial.

- Involuntary treatment may provide short-term gains, but prevent long-term trust between patient and provider.

Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre also mentors several residents on projects, including reduction in the use of solitary confinement of patients with mental illness, reduction in the use of involuntary treatment of the mentally ill, and examination of the mentally ill offender.

Shinal v. Toms: It’s Now Harder to Get Informed Consent

Question: Which of the following statements regarding Shinal v. Toms, a recent landmark decision on informed consent, is correct?:

A. The case was heard in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and its decision is binding only in that state.

B. It held that obtaining informed consent is a doctor’s duty that is non-delegable.

C. The decision reversed the lower courts, which had held that the defendant’s qualified assistant could obtain consent.

D. An earlier case heard by the same court had ruled that doctors, not hospitals, owe the legal duty to obtain informed consent.

E. All are correct.

Answer: E.

On Nov. 26, 2007, Megan Shinal and Dr. Steven Toms met for a 20-minute initial consultation to discuss removing a recurrent craniopharyngioma.1 Years earlier, a surgeon had performed a transsphenoidal resection, but was unable to remove all of it. The residual portion of the tumor had increased in size and extended into vital structures of the brain, jeopardizing Mrs. Shinal’s eyesight and her carotid artery, causing headaches, and threatening to impact her pituitary function.

Dr. Toms testified that he reviewed with Mrs. Shinal the alternatives, risks, and benefits of total versus subtotal resection, and shared his opinion that, although a less aggressive approach to removing the tumor was safer in the short term, such an approach would increase the likelihood that the tumor would regrow. Dr. Toms was unable to recall many of the specifics, but he testified that he advised Mrs. Shinal that total surgical resection offered the highest chance for long-term survival. By the end of the visit, Mrs. Shinal had decided to undergo surgery. However, the type of surgery had not yet been determined.

Shortly thereafter, on Dec. 19, 2007, Mrs. Shinal had a telephone conversation with Dr. Toms’ physician assistant. Mrs. Shinal later testified that she asked the physician assistant about scarring that would likely result from surgery, whether radiation would be necessary, and about the date of surgery. The medical record of this telephone call indicated that Dr. Toms’ physician assistant also answered questions about the craniotomy incision. On Jan. 17, 2008, Mrs. Shinal met with the physician assistant at the Geisinger Medical Center’s neurosurgery clinic. The assistant obtained Mrs. Shinal’s medical history, conducted a physical, and provided Mrs. Shinal with information relating to the surgery. Mrs. Shinal signed an informed consent form.

On Jan. 31, 2008, Mrs. Shinal underwent an open craniotomy for a total resection of the pituitary tumor at Geisinger Medical Center. During the operation, Dr. Toms perforated Mrs. Shinal’s carotid artery, which resulted in hemorrhage, stroke, brain injury, and partial blindness.

According to the Shinals’ complaint, Dr. Toms failed to explain the risks of surgery to Mrs. Shinal or to offer her the lower-risk surgical alternative of subtotal resection of the benign tumor, followed by radiation. At trial, Mrs. Shinal was unable to recall being informed of the relative risks of the surgery, other than coma and death. She testified that, had she known the alternative approaches to surgery, i.e., total versus subtotal resection, she would have chosen subtotal resection as the safer, less aggressive alternative.