User login

Are Aspartame’s Benefits Sugarcoated?

Since my high school days, I have used some form of artificial sweetener in lieu of sugar. Long believing that sugar avoidance was the key to weight maintenance, I didn’t give much thought to the published ill effects of sugar substitutes—after all, I wasn’t a mouse, and I wasn’t consuming mass doses. Did the artificial sweeteners assist in controlling my weight? Quite honestly, I doubt it—but I was so used to being “sugar free” that I was habituated to using these products.

Several years ago at a luncheon, I was reaching for a packet of artificial sweetener to pour into my iced tea when an NP friend stopped me. She and her husband (a pharmacist) had sworn off these products after noting that he was having issues with his cognition and experiencing increased irritability. With no obvious cause for these symptoms, they investigated his diet. He had, over the previous year, increased his use of aspartame. They found research supporting an association between aspartame and changes in behavior and cognition. When he stopped using the product, they both noticed a return to his former jovial, intellectual self. I acknowledged their research conclusion as an “n = 1” but gave it no further credence.

More recently, friends who had adopted an “all-natural” diet chastised me for drinking sugar-free seltzer. I had switched years ago from diet sodas to this beverage as my primary source of hydration. What could be wrong? It had zero calories, no sodium, and no sugar. Ah, but it contained aspartame! Since switching to a food plan without aspartame, my friends had observed that they were feeling better and more alert. Hmm, sounded familiar … maybe there was something to these claims after all. I did a little research of my own, and was I surprised!

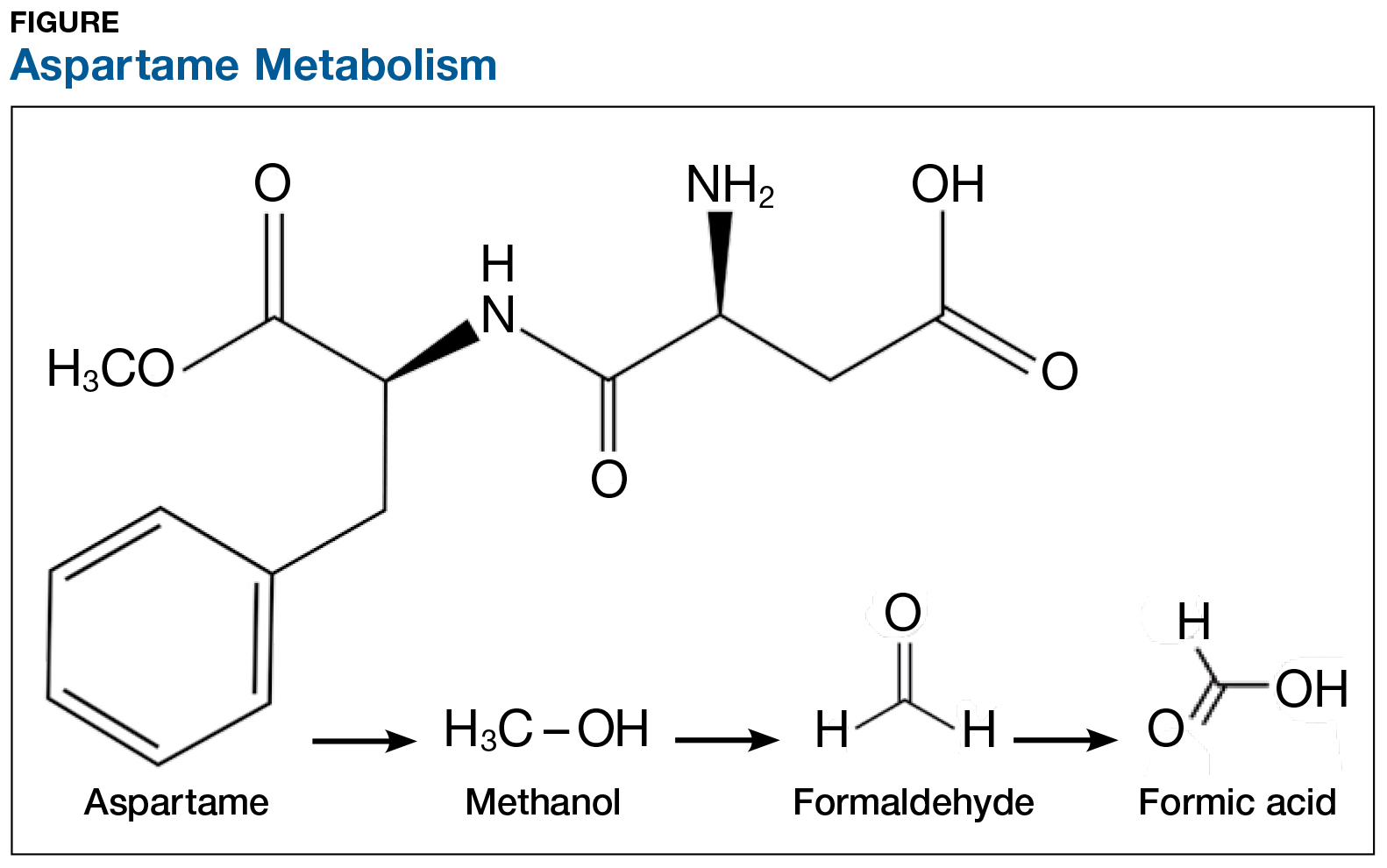

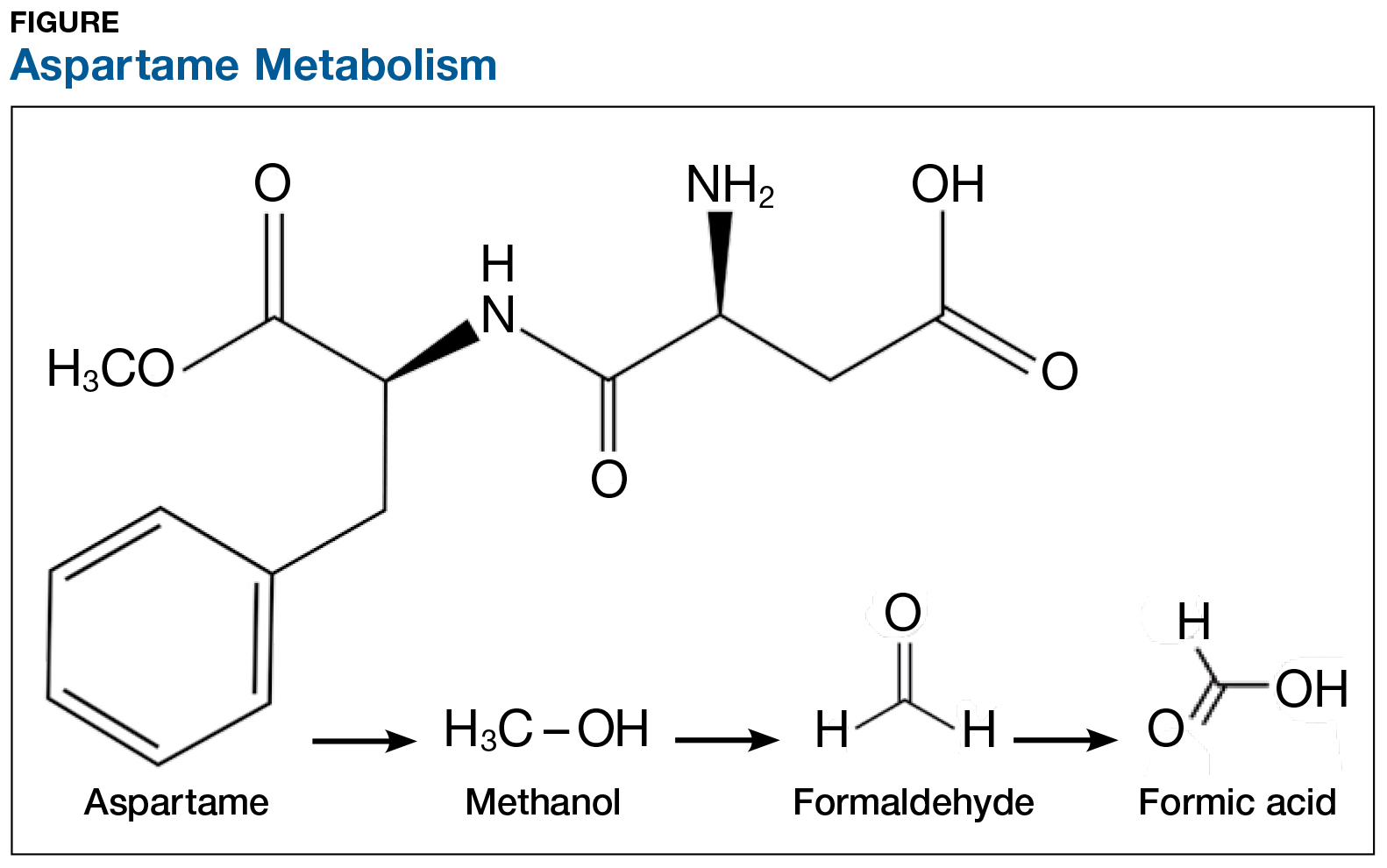

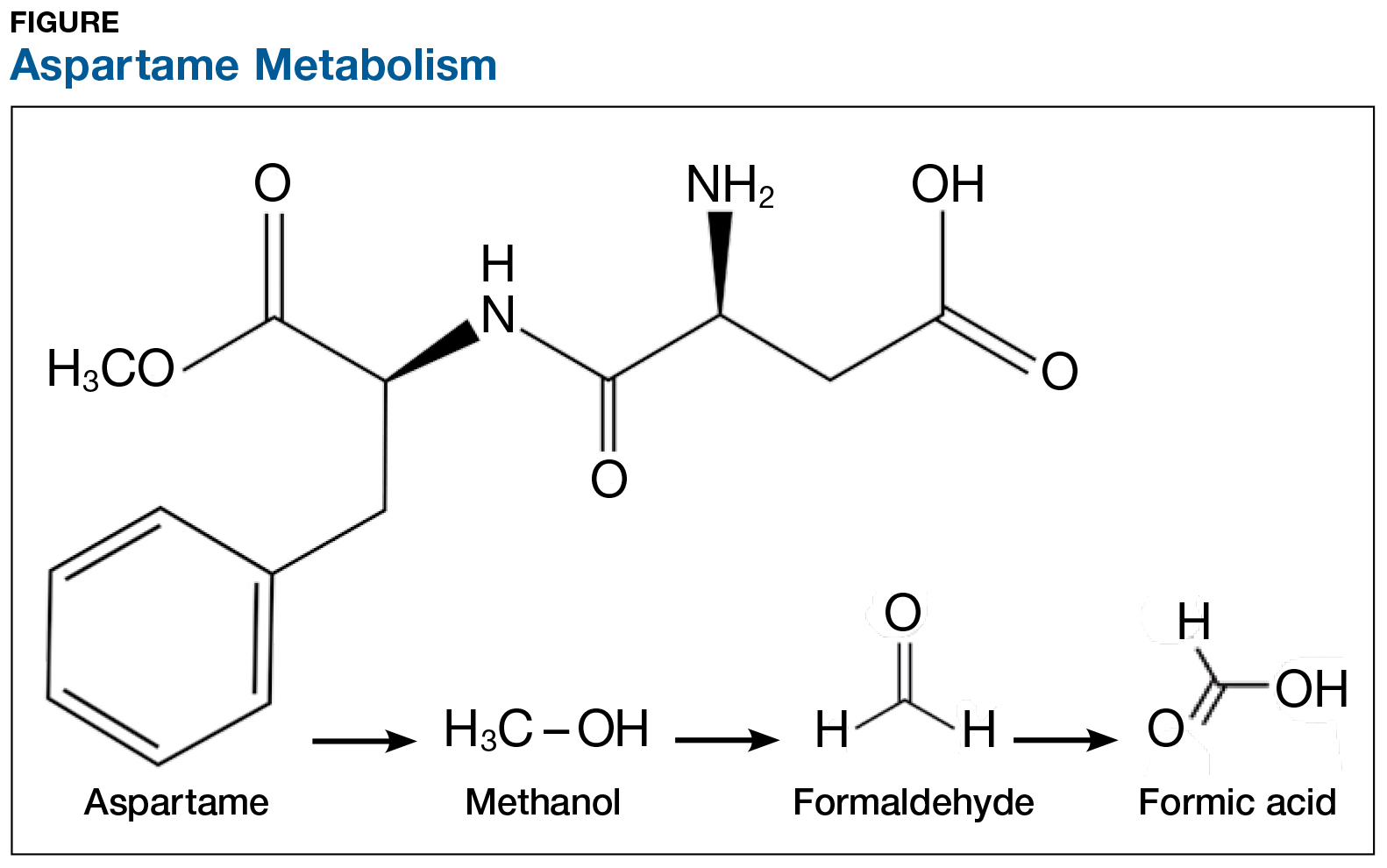

On the exterior, aspartame is a highly studied food additive with decades of research demonstrating its safety for human consumption.1 But what exactly happens when this sweetener is ingested? First, aspartame breaks down into amino acids and methanol (ie, wood alcohol). The methanol continues to break down into formaldehyde and formic acid, a substance commonly found in bee and ant venom (see Figure). And if that weren’t enough, a potential brain tumor agent (aspartylphenylalanine diketopiperazine) is also a residual byproduct.2,3 As you might expect, these components and byproducts come with varying adverse effects and potential health risks.

The majority of artificially sweetened beverages (ASBs) contain aspartame. As early as 1984—a mere six months after aspartame was approved for use in soft drinks—the FDA, with the assistance of the CDC, undertook an investigation of consumer complaints related to its use. The research team interviewed 517 complainants; 346 (67%) reported neurologic/behavioral symptoms, including headache, dizziness, and mood alteration.4 Despite that statistic, however, the researchers reported no evidence for the existence of serious, widespread, adverse health consequences resulting from aspartame consumption.4

Reading these reports reminded me of my friends’ comments and strongly suggested to me that soft drinks containing aspartame may be hard on the brain. Further to this point, a recent study found that ASB consumption is associated with an increased risk for stroke and dementia.5

Additional studies—including evaluations of possible associations between aspartame and headaches, seizures, behavior, cognition, and mood, as well as allergic-type reactions and use by potentially sensitive subpopulations—have been conducted. The verdict? Scientists maintain that aspartame is safe and that there are no unresolved questions regarding its safety when used as intended.6 Some researchers question the validity of the link between ASB consumption and negative health consequences, suggesting that individuals in worse health consume diet beverages in an effort to slow health deterioration or to lose weight.7 Yet, the debate about the effects of aspartame on our organs continues.

The number of epidemiologic studies that document strong associations between frequent ASB consumption and illness suggests that substituting or promoting artificial sweeteners as “healthy alternatives” to sugar may not be advisable.8 In fact, the most recent studies indicate that artificial sweeteners—the very compounds marketed to assist with weight control—can lead to weight gain, as they trick our brains into craving high-calorie foods. Moreover, ASB consumption is associated with a 21% increased risk for type 2 diabetes.9 Azad and colleagues found that evidence does not clearly support the use of nonnutritive sweeteners for weight management; they recommend using caution with these products until the long-term risks and benefits are fully understood.7

Is satisfying your sweet tooth with sugar alternatives worth the potential risk? Most of the studies conducted to support or refute aspartame-related health concerns prove correlation, not causality. A purist might point out that many of the studies have limitations that can lead to faulty conclusions. Be that as it may, it still gives one pause.

Small doses of aspartame each day might not be a tipping point toward the documented health complaints, but the consistent concerns about its effects were enough for me to make the switch to plain water, and sugar for my coffee. I do believe that Mary Poppins was correct—a spoonful of sugar does help—and I, for one, am following her lead.

What do you think? Are these concerns unfounded, or are we sweetening our road to poor health? Share your thoughts with me at [email protected].

1. Novella S. Aspartame: truth vs. fiction. https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/aspartame-truth-vs-fiction/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

2. Barua J, Bal A. Emerging facts about aspartame. www.manningsscience.com/uploads/8/6/8/1/8681125/article-on-aspartame.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

3. Supersweet blog. Learning about sweeteners. https://supersweetblog.wordpress.com/aspartame/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

4. CDC. Evaluation of consumer complaints related to aspartame use. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1984;33(43):605-607.

5. Pase MP, Himali JJ, Beiser AS, et al. Sugar- and artificially sweetened beverages and the risks of incident stroke and dementia: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2017;48(5): 1139-1146.

6. Butchko HH, Stargel WW, Comer CP, et al. Aspartame: review of safety. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2002;35(2):S1- S93.

7. Azad MB, Abou-Setta AM, Chauhan BF, et al. Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. CMAJ. 2017;189(28): E929-E939.

8. Wersching H, Gardener H, Sacco L. Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages in relation to stroke and dementia. Stroke. 2017;48(5):1129-1131.

9. Huang M, Quddus A, Stinson L, et al. Artificially sweetened beverages, sugar-sweetened beverages, plain water, and incident diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women: the prospective Women’s Health Initiative observational study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:614-622.

Since my high school days, I have used some form of artificial sweetener in lieu of sugar. Long believing that sugar avoidance was the key to weight maintenance, I didn’t give much thought to the published ill effects of sugar substitutes—after all, I wasn’t a mouse, and I wasn’t consuming mass doses. Did the artificial sweeteners assist in controlling my weight? Quite honestly, I doubt it—but I was so used to being “sugar free” that I was habituated to using these products.

Several years ago at a luncheon, I was reaching for a packet of artificial sweetener to pour into my iced tea when an NP friend stopped me. She and her husband (a pharmacist) had sworn off these products after noting that he was having issues with his cognition and experiencing increased irritability. With no obvious cause for these symptoms, they investigated his diet. He had, over the previous year, increased his use of aspartame. They found research supporting an association between aspartame and changes in behavior and cognition. When he stopped using the product, they both noticed a return to his former jovial, intellectual self. I acknowledged their research conclusion as an “n = 1” but gave it no further credence.

More recently, friends who had adopted an “all-natural” diet chastised me for drinking sugar-free seltzer. I had switched years ago from diet sodas to this beverage as my primary source of hydration. What could be wrong? It had zero calories, no sodium, and no sugar. Ah, but it contained aspartame! Since switching to a food plan without aspartame, my friends had observed that they were feeling better and more alert. Hmm, sounded familiar … maybe there was something to these claims after all. I did a little research of my own, and was I surprised!

On the exterior, aspartame is a highly studied food additive with decades of research demonstrating its safety for human consumption.1 But what exactly happens when this sweetener is ingested? First, aspartame breaks down into amino acids and methanol (ie, wood alcohol). The methanol continues to break down into formaldehyde and formic acid, a substance commonly found in bee and ant venom (see Figure). And if that weren’t enough, a potential brain tumor agent (aspartylphenylalanine diketopiperazine) is also a residual byproduct.2,3 As you might expect, these components and byproducts come with varying adverse effects and potential health risks.

The majority of artificially sweetened beverages (ASBs) contain aspartame. As early as 1984—a mere six months after aspartame was approved for use in soft drinks—the FDA, with the assistance of the CDC, undertook an investigation of consumer complaints related to its use. The research team interviewed 517 complainants; 346 (67%) reported neurologic/behavioral symptoms, including headache, dizziness, and mood alteration.4 Despite that statistic, however, the researchers reported no evidence for the existence of serious, widespread, adverse health consequences resulting from aspartame consumption.4

Reading these reports reminded me of my friends’ comments and strongly suggested to me that soft drinks containing aspartame may be hard on the brain. Further to this point, a recent study found that ASB consumption is associated with an increased risk for stroke and dementia.5

Additional studies—including evaluations of possible associations between aspartame and headaches, seizures, behavior, cognition, and mood, as well as allergic-type reactions and use by potentially sensitive subpopulations—have been conducted. The verdict? Scientists maintain that aspartame is safe and that there are no unresolved questions regarding its safety when used as intended.6 Some researchers question the validity of the link between ASB consumption and negative health consequences, suggesting that individuals in worse health consume diet beverages in an effort to slow health deterioration or to lose weight.7 Yet, the debate about the effects of aspartame on our organs continues.

The number of epidemiologic studies that document strong associations between frequent ASB consumption and illness suggests that substituting or promoting artificial sweeteners as “healthy alternatives” to sugar may not be advisable.8 In fact, the most recent studies indicate that artificial sweeteners—the very compounds marketed to assist with weight control—can lead to weight gain, as they trick our brains into craving high-calorie foods. Moreover, ASB consumption is associated with a 21% increased risk for type 2 diabetes.9 Azad and colleagues found that evidence does not clearly support the use of nonnutritive sweeteners for weight management; they recommend using caution with these products until the long-term risks and benefits are fully understood.7

Is satisfying your sweet tooth with sugar alternatives worth the potential risk? Most of the studies conducted to support or refute aspartame-related health concerns prove correlation, not causality. A purist might point out that many of the studies have limitations that can lead to faulty conclusions. Be that as it may, it still gives one pause.

Small doses of aspartame each day might not be a tipping point toward the documented health complaints, but the consistent concerns about its effects were enough for me to make the switch to plain water, and sugar for my coffee. I do believe that Mary Poppins was correct—a spoonful of sugar does help—and I, for one, am following her lead.

What do you think? Are these concerns unfounded, or are we sweetening our road to poor health? Share your thoughts with me at [email protected].

Since my high school days, I have used some form of artificial sweetener in lieu of sugar. Long believing that sugar avoidance was the key to weight maintenance, I didn’t give much thought to the published ill effects of sugar substitutes—after all, I wasn’t a mouse, and I wasn’t consuming mass doses. Did the artificial sweeteners assist in controlling my weight? Quite honestly, I doubt it—but I was so used to being “sugar free” that I was habituated to using these products.

Several years ago at a luncheon, I was reaching for a packet of artificial sweetener to pour into my iced tea when an NP friend stopped me. She and her husband (a pharmacist) had sworn off these products after noting that he was having issues with his cognition and experiencing increased irritability. With no obvious cause for these symptoms, they investigated his diet. He had, over the previous year, increased his use of aspartame. They found research supporting an association between aspartame and changes in behavior and cognition. When he stopped using the product, they both noticed a return to his former jovial, intellectual self. I acknowledged their research conclusion as an “n = 1” but gave it no further credence.

More recently, friends who had adopted an “all-natural” diet chastised me for drinking sugar-free seltzer. I had switched years ago from diet sodas to this beverage as my primary source of hydration. What could be wrong? It had zero calories, no sodium, and no sugar. Ah, but it contained aspartame! Since switching to a food plan without aspartame, my friends had observed that they were feeling better and more alert. Hmm, sounded familiar … maybe there was something to these claims after all. I did a little research of my own, and was I surprised!

On the exterior, aspartame is a highly studied food additive with decades of research demonstrating its safety for human consumption.1 But what exactly happens when this sweetener is ingested? First, aspartame breaks down into amino acids and methanol (ie, wood alcohol). The methanol continues to break down into formaldehyde and formic acid, a substance commonly found in bee and ant venom (see Figure). And if that weren’t enough, a potential brain tumor agent (aspartylphenylalanine diketopiperazine) is also a residual byproduct.2,3 As you might expect, these components and byproducts come with varying adverse effects and potential health risks.

The majority of artificially sweetened beverages (ASBs) contain aspartame. As early as 1984—a mere six months after aspartame was approved for use in soft drinks—the FDA, with the assistance of the CDC, undertook an investigation of consumer complaints related to its use. The research team interviewed 517 complainants; 346 (67%) reported neurologic/behavioral symptoms, including headache, dizziness, and mood alteration.4 Despite that statistic, however, the researchers reported no evidence for the existence of serious, widespread, adverse health consequences resulting from aspartame consumption.4

Reading these reports reminded me of my friends’ comments and strongly suggested to me that soft drinks containing aspartame may be hard on the brain. Further to this point, a recent study found that ASB consumption is associated with an increased risk for stroke and dementia.5

Additional studies—including evaluations of possible associations between aspartame and headaches, seizures, behavior, cognition, and mood, as well as allergic-type reactions and use by potentially sensitive subpopulations—have been conducted. The verdict? Scientists maintain that aspartame is safe and that there are no unresolved questions regarding its safety when used as intended.6 Some researchers question the validity of the link between ASB consumption and negative health consequences, suggesting that individuals in worse health consume diet beverages in an effort to slow health deterioration or to lose weight.7 Yet, the debate about the effects of aspartame on our organs continues.

The number of epidemiologic studies that document strong associations between frequent ASB consumption and illness suggests that substituting or promoting artificial sweeteners as “healthy alternatives” to sugar may not be advisable.8 In fact, the most recent studies indicate that artificial sweeteners—the very compounds marketed to assist with weight control—can lead to weight gain, as they trick our brains into craving high-calorie foods. Moreover, ASB consumption is associated with a 21% increased risk for type 2 diabetes.9 Azad and colleagues found that evidence does not clearly support the use of nonnutritive sweeteners for weight management; they recommend using caution with these products until the long-term risks and benefits are fully understood.7

Is satisfying your sweet tooth with sugar alternatives worth the potential risk? Most of the studies conducted to support or refute aspartame-related health concerns prove correlation, not causality. A purist might point out that many of the studies have limitations that can lead to faulty conclusions. Be that as it may, it still gives one pause.

Small doses of aspartame each day might not be a tipping point toward the documented health complaints, but the consistent concerns about its effects were enough for me to make the switch to plain water, and sugar for my coffee. I do believe that Mary Poppins was correct—a spoonful of sugar does help—and I, for one, am following her lead.

What do you think? Are these concerns unfounded, or are we sweetening our road to poor health? Share your thoughts with me at [email protected].

1. Novella S. Aspartame: truth vs. fiction. https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/aspartame-truth-vs-fiction/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

2. Barua J, Bal A. Emerging facts about aspartame. www.manningsscience.com/uploads/8/6/8/1/8681125/article-on-aspartame.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

3. Supersweet blog. Learning about sweeteners. https://supersweetblog.wordpress.com/aspartame/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

4. CDC. Evaluation of consumer complaints related to aspartame use. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1984;33(43):605-607.

5. Pase MP, Himali JJ, Beiser AS, et al. Sugar- and artificially sweetened beverages and the risks of incident stroke and dementia: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2017;48(5): 1139-1146.

6. Butchko HH, Stargel WW, Comer CP, et al. Aspartame: review of safety. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2002;35(2):S1- S93.

7. Azad MB, Abou-Setta AM, Chauhan BF, et al. Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. CMAJ. 2017;189(28): E929-E939.

8. Wersching H, Gardener H, Sacco L. Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages in relation to stroke and dementia. Stroke. 2017;48(5):1129-1131.

9. Huang M, Quddus A, Stinson L, et al. Artificially sweetened beverages, sugar-sweetened beverages, plain water, and incident diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women: the prospective Women’s Health Initiative observational study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:614-622.

1. Novella S. Aspartame: truth vs. fiction. https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/aspartame-truth-vs-fiction/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

2. Barua J, Bal A. Emerging facts about aspartame. www.manningsscience.com/uploads/8/6/8/1/8681125/article-on-aspartame.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2017.

3. Supersweet blog. Learning about sweeteners. https://supersweetblog.wordpress.com/aspartame/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

4. CDC. Evaluation of consumer complaints related to aspartame use. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1984;33(43):605-607.

5. Pase MP, Himali JJ, Beiser AS, et al. Sugar- and artificially sweetened beverages and the risks of incident stroke and dementia: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2017;48(5): 1139-1146.

6. Butchko HH, Stargel WW, Comer CP, et al. Aspartame: review of safety. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2002;35(2):S1- S93.

7. Azad MB, Abou-Setta AM, Chauhan BF, et al. Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. CMAJ. 2017;189(28): E929-E939.

8. Wersching H, Gardener H, Sacco L. Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages in relation to stroke and dementia. Stroke. 2017;48(5):1129-1131.

9. Huang M, Quddus A, Stinson L, et al. Artificially sweetened beverages, sugar-sweetened beverages, plain water, and incident diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women: the prospective Women’s Health Initiative observational study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:614-622.

Practice Makes Perfect?

It is human nature to practice things that we are already good at doing. If you’re a golfer, then you know what I’m talking about. I hit the driver over and over again on the range, but never practice hitting the bad lie in the bunker, or the half-swing wedge from a tight lie. I sink hundreds of 3 footers, but can’t putt into this range from 50 feet. I’ve gotten much better at golf since I started playing, but my scores have hardly gone down.

I think a similar thing happens in our orthopedic practices. I read everything I can on the anterior cruciate ligament, yet I already feel comfortable with my reconstruction technique. I skim, or avoid reading altogether, articles about topics I don’t like to treat, like the hand or spine. Yet, I still see these things every day in my practice and on call. If my depth of knowledge in these areas was as good as it is in sports medicine, I could provide better, more immediate care to my patients, rather than refer them to subspecialists.

A perfect orthopedic example would be the patellofemoral joint. One of the least enjoyable patient encounters for me is the young adult with normal alignment and intractable anterior knee pain that does not respond to nonoperative treatment. I’m concerned any surgical intervention may make them worse and I’m often left without much to offer the patient.

It’s for this reason AJO has partnered with Dr. Jack Farr to produce the patellofemoral issue; to provide a comprehensive guide to the latest thinking in the treatment of patellofemoral disorders (see the March/April 2017 issue). We solicited so much outstanding content, that a single issue could not hold all of the articles. In this issue, our patellofemoral series continues with 3 outstanding articles. Magnussen presents "Patella Alta Sees You, Do You See It?" and Hinckel and colleagues have authored a guide to patellofemoral cartilage restoration. Unal and colleagues follow-up with a review of the lateral retinaculum.

In our "Codes to Know" section, we reexamine diagnostic arthroscopy, a code most of us have billed infrequently. New technologies, however, have made it possible to peer into the joint in the office, and McMillan and colleagues teach us how to make it economically feasible, even for employed physicians.

Finally, we have a number of great articles on difficult problems—the stiff elbow, complex distal radius fractures, and intraoperative acetabular fractures during total hip arthroplasty.

Please enjoy this issue and think about what topics you tend to shy away from. I’m willing to bet you can add the most to your practice by studying up on these topics. As always, please provide your feedback to our editorial team so that we can continue to make improvements to our journal. We envision a change in the way orthopedists utilize a journal in their practice, and are continuously looking for ways to make AJO a more relevant tool for improving your patient care and workflow. We are working hard to give our readers the journal they deserve, but in my spare time, I’ll be brushing up on trochleoplasties and half-swing wedges.

It is human nature to practice things that we are already good at doing. If you’re a golfer, then you know what I’m talking about. I hit the driver over and over again on the range, but never practice hitting the bad lie in the bunker, or the half-swing wedge from a tight lie. I sink hundreds of 3 footers, but can’t putt into this range from 50 feet. I’ve gotten much better at golf since I started playing, but my scores have hardly gone down.

I think a similar thing happens in our orthopedic practices. I read everything I can on the anterior cruciate ligament, yet I already feel comfortable with my reconstruction technique. I skim, or avoid reading altogether, articles about topics I don’t like to treat, like the hand or spine. Yet, I still see these things every day in my practice and on call. If my depth of knowledge in these areas was as good as it is in sports medicine, I could provide better, more immediate care to my patients, rather than refer them to subspecialists.

A perfect orthopedic example would be the patellofemoral joint. One of the least enjoyable patient encounters for me is the young adult with normal alignment and intractable anterior knee pain that does not respond to nonoperative treatment. I’m concerned any surgical intervention may make them worse and I’m often left without much to offer the patient.

It’s for this reason AJO has partnered with Dr. Jack Farr to produce the patellofemoral issue; to provide a comprehensive guide to the latest thinking in the treatment of patellofemoral disorders (see the March/April 2017 issue). We solicited so much outstanding content, that a single issue could not hold all of the articles. In this issue, our patellofemoral series continues with 3 outstanding articles. Magnussen presents "Patella Alta Sees You, Do You See It?" and Hinckel and colleagues have authored a guide to patellofemoral cartilage restoration. Unal and colleagues follow-up with a review of the lateral retinaculum.

In our "Codes to Know" section, we reexamine diagnostic arthroscopy, a code most of us have billed infrequently. New technologies, however, have made it possible to peer into the joint in the office, and McMillan and colleagues teach us how to make it economically feasible, even for employed physicians.

Finally, we have a number of great articles on difficult problems—the stiff elbow, complex distal radius fractures, and intraoperative acetabular fractures during total hip arthroplasty.

Please enjoy this issue and think about what topics you tend to shy away from. I’m willing to bet you can add the most to your practice by studying up on these topics. As always, please provide your feedback to our editorial team so that we can continue to make improvements to our journal. We envision a change in the way orthopedists utilize a journal in their practice, and are continuously looking for ways to make AJO a more relevant tool for improving your patient care and workflow. We are working hard to give our readers the journal they deserve, but in my spare time, I’ll be brushing up on trochleoplasties and half-swing wedges.

It is human nature to practice things that we are already good at doing. If you’re a golfer, then you know what I’m talking about. I hit the driver over and over again on the range, but never practice hitting the bad lie in the bunker, or the half-swing wedge from a tight lie. I sink hundreds of 3 footers, but can’t putt into this range from 50 feet. I’ve gotten much better at golf since I started playing, but my scores have hardly gone down.

I think a similar thing happens in our orthopedic practices. I read everything I can on the anterior cruciate ligament, yet I already feel comfortable with my reconstruction technique. I skim, or avoid reading altogether, articles about topics I don’t like to treat, like the hand or spine. Yet, I still see these things every day in my practice and on call. If my depth of knowledge in these areas was as good as it is in sports medicine, I could provide better, more immediate care to my patients, rather than refer them to subspecialists.

A perfect orthopedic example would be the patellofemoral joint. One of the least enjoyable patient encounters for me is the young adult with normal alignment and intractable anterior knee pain that does not respond to nonoperative treatment. I’m concerned any surgical intervention may make them worse and I’m often left without much to offer the patient.

It’s for this reason AJO has partnered with Dr. Jack Farr to produce the patellofemoral issue; to provide a comprehensive guide to the latest thinking in the treatment of patellofemoral disorders (see the March/April 2017 issue). We solicited so much outstanding content, that a single issue could not hold all of the articles. In this issue, our patellofemoral series continues with 3 outstanding articles. Magnussen presents "Patella Alta Sees You, Do You See It?" and Hinckel and colleagues have authored a guide to patellofemoral cartilage restoration. Unal and colleagues follow-up with a review of the lateral retinaculum.

In our "Codes to Know" section, we reexamine diagnostic arthroscopy, a code most of us have billed infrequently. New technologies, however, have made it possible to peer into the joint in the office, and McMillan and colleagues teach us how to make it economically feasible, even for employed physicians.

Finally, we have a number of great articles on difficult problems—the stiff elbow, complex distal radius fractures, and intraoperative acetabular fractures during total hip arthroplasty.

Please enjoy this issue and think about what topics you tend to shy away from. I’m willing to bet you can add the most to your practice by studying up on these topics. As always, please provide your feedback to our editorial team so that we can continue to make improvements to our journal. We envision a change in the way orthopedists utilize a journal in their practice, and are continuously looking for ways to make AJO a more relevant tool for improving your patient care and workflow. We are working hard to give our readers the journal they deserve, but in my spare time, I’ll be brushing up on trochleoplasties and half-swing wedges.

Should psychologists be allowed to prescribe?

In response to Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial “Prescribing is the culmination of extensive medical training and psychologists don’t qualify” (From the Editor,

Tedd Judd, PhD, ABPP-CN

Diplomate in Clinical Neuropsychology

Certified Hispanic Mental Health Specialist

Cross-Cultural Specialist

Bellingham, Washington

I read Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial with a critical eye. As a psychologist in private clinical and forensic practice for more than 30 years, it is disheartening that you toe the politico-economic line proffered over the decades that establishes and buoys a clash between our helping professions in the hoary guise of protecting the consuming public.

It is disingenuous and misleading for you to cite “28,000 hours of training… 8 years of medical school” as a prerequisite for having adequate “psychopharmacological skills.”

Psychologists and psychiatrists can learn the same necessary and comprehensive skills to perform competent and equivalent prescription duties in succinct, operational ways.

It is about time the welfare of the consuming public be served instead of territorial profiteering. Perhaps you should focus more on the dwindling numbers of psychiatrists who perform psychotherapy in conjunction with psychopharmacology than on limiting the pool of providers who are qualified by training to do both. How many of those 28,000 hours are dedicated to training your psychiatrists in psychotherapy?

Norman R. Klein, PhD

Licensed Psychologist

Westport, Connecticut

Dr. Nasrallah wrote an unsurprisingly eloquent and passionate editorial and argues a cogent case for restricting prescription privileges to medically trained professionals. I wonder, though, if public health statistics of outcomes among mental health patients in states where clinical psychologists have been licensed to prescribe, such as New Mexico and Hawaii, bear out any of Dr. Nasrallah’s concerns.

Ole J. Thienhaus, MD, MBA

Department Head and Professor of Psychiatry

University of Arizona

College of Medicine-Tucson

Tucson, Arizona

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I am not surprised by Dr. Judd’s or Dr. Klein’s disagreement with my editorial asserting that psychologists do not receive the medical training that qualifies them to prescribe. They side with their fellow psychologists, just as psychiatrists agree with me. After all, those of us who have had the extensive training of psychiatric physicians know the abundance of medical skills needed for competent prescribing and find it preposterous that psychologists, who have a PhD and are acknowledged for their psychotherapy and psychometric skills, can take a drastic shortcut by getting politicians to give them the right to prescribe. Dr. Klein has no idea how much training it takes to become a competent prescriber, so his comments that both psychiatrists and psychologists can be similarly trained cannot be taken seriously. Even after 4 years of psychiatric residency with daily psychopharmacology teaching and training psychiatrists still feel they have much more to learn. It is dangerous hubris to think that even without the vital medical school foundation prior to psychiatric training that psychologists can

Here, I provide a description of one state’s proposed the training that psychologists would receive. I hope that Drs. Judd and Klein will recognize the dangerously inadequate training recently proposed for psychologists to become “prescribers.”

Proposed curriculum for psychologists

1. Online instruction, not face-to-face classroom experience

2. Many courses are prerecorded

3. Instructors are psychologists, not psychiatrists

4. Psychologists can complete the program at their own pace, which can be done in a few weeks

5. Hours of instruction range between 306 to 468 hours, compared with 500 hours required for massage therapists

6. A minimum of 40 hours of “basic training on clinical assessment” is required, compared with 60 hours for electrologists

7. The “graduate” must pass a test prepared by the American Psychological Association, which advocates for prescriptive authority and is not an independent testing organization

8. There is no minimum of requirements of an undergraduate biomedical prerequisite course—the work that is required for all medical students, physician assistants, and nursing students—which includes chemistry or biochemistry (with laboratory experience), human anatomy, physiology, general biology, microbiology (with laboratory experience), cell biology, and molecular biology

9. Recommended number of patient encounters is anemic: 600 encounters, which can be 10 encounters with 60 patients or 15 encounters with 40 patients. This is far below what is required of psychiatric residents

10. The proposed training requires treating a minimum of 75 patients over 2 years. A typical third-year psychiatric resident sees 75 patients every month. Each first- and second-year resident works up and treats >600 inpatients in <1 year

11. At the end of the practicum, applicants must demonstrate competency in 9 milestones, but competency is not defined. In contrast, psychiatric residency programs have mandates from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requiring that residents be graded every 6 months on 23 milestones, with specific anchor points provided

12. Only 25% of the practicum occurs on psychiatric inpatient wards or outpatient clinics. One wonders where the patients who need psychopharmacology would be

13. Supervision is inadequate. There is no requirement for supervision by psychiatrists, whose training and experience make them qualified psychopharmacologists

14. There is no guidance on the frequency or intensity of supervision. In psychiatry, residents are supervised with each patient encounter over 4 years. Should psychologists without medical training be held to a lesser standard?

15. There are no specifications of continuing medical education, ongoing supervision, or outcomes

16. The potential dangers of psychotropics are not emphasized. For example:

• permanent or life-threatening adverse effects, such as tardive dyskinesia or agranulocytosis

• addiction potential, such as with stimulants or benzodiazepines

• potentially fatal drug interactions with monoamine oxidase inhibitors and meperidine or serotonin syndrome, or cardiac arrests with overdoses of tricyclic antidepressants

17. Many medications require ongoing monitoring. Some involve physical examination (extrapyramidal side effects, metabolic syndrome) or laboratory tests (lithium, carbamazepine, clozapine, valproate, renal and hepatic functions, metabolic profile for all antipsychotics). Failure to monitor may lead to fatal outcomes. Some medications are considered unsafe during pregnancy or breast-feeding.

Psychologists do a great service for patients with mental illness by providing evidence-based psychotherapies, such as cognitive-behavioral, dialectical-behavioral, interpersonal, and behavioral therapy. They complement what psychiatrists and nurse practitioners do with pharmacotherapy. Many patients with mild or moderate psychiatric disorders improve significantly with psychotherapy without the use of psychotropics. Psychologists should focus on what they were trained to do because they can benefit numerous patients. That is much better than trying to become prescribers and practice mediocre psychopharmacology without the requisite medical training. Patients with mental illness deserve no less.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

In response to Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial “Prescribing is the culmination of extensive medical training and psychologists don’t qualify” (From the Editor,

Tedd Judd, PhD, ABPP-CN

Diplomate in Clinical Neuropsychology

Certified Hispanic Mental Health Specialist

Cross-Cultural Specialist

Bellingham, Washington

I read Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial with a critical eye. As a psychologist in private clinical and forensic practice for more than 30 years, it is disheartening that you toe the politico-economic line proffered over the decades that establishes and buoys a clash between our helping professions in the hoary guise of protecting the consuming public.

It is disingenuous and misleading for you to cite “28,000 hours of training… 8 years of medical school” as a prerequisite for having adequate “psychopharmacological skills.”

Psychologists and psychiatrists can learn the same necessary and comprehensive skills to perform competent and equivalent prescription duties in succinct, operational ways.

It is about time the welfare of the consuming public be served instead of territorial profiteering. Perhaps you should focus more on the dwindling numbers of psychiatrists who perform psychotherapy in conjunction with psychopharmacology than on limiting the pool of providers who are qualified by training to do both. How many of those 28,000 hours are dedicated to training your psychiatrists in psychotherapy?

Norman R. Klein, PhD

Licensed Psychologist

Westport, Connecticut

Dr. Nasrallah wrote an unsurprisingly eloquent and passionate editorial and argues a cogent case for restricting prescription privileges to medically trained professionals. I wonder, though, if public health statistics of outcomes among mental health patients in states where clinical psychologists have been licensed to prescribe, such as New Mexico and Hawaii, bear out any of Dr. Nasrallah’s concerns.

Ole J. Thienhaus, MD, MBA

Department Head and Professor of Psychiatry

University of Arizona

College of Medicine-Tucson

Tucson, Arizona

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I am not surprised by Dr. Judd’s or Dr. Klein’s disagreement with my editorial asserting that psychologists do not receive the medical training that qualifies them to prescribe. They side with their fellow psychologists, just as psychiatrists agree with me. After all, those of us who have had the extensive training of psychiatric physicians know the abundance of medical skills needed for competent prescribing and find it preposterous that psychologists, who have a PhD and are acknowledged for their psychotherapy and psychometric skills, can take a drastic shortcut by getting politicians to give them the right to prescribe. Dr. Klein has no idea how much training it takes to become a competent prescriber, so his comments that both psychiatrists and psychologists can be similarly trained cannot be taken seriously. Even after 4 years of psychiatric residency with daily psychopharmacology teaching and training psychiatrists still feel they have much more to learn. It is dangerous hubris to think that even without the vital medical school foundation prior to psychiatric training that psychologists can

Here, I provide a description of one state’s proposed the training that psychologists would receive. I hope that Drs. Judd and Klein will recognize the dangerously inadequate training recently proposed for psychologists to become “prescribers.”

Proposed curriculum for psychologists

1. Online instruction, not face-to-face classroom experience

2. Many courses are prerecorded

3. Instructors are psychologists, not psychiatrists

4. Psychologists can complete the program at their own pace, which can be done in a few weeks

5. Hours of instruction range between 306 to 468 hours, compared with 500 hours required for massage therapists

6. A minimum of 40 hours of “basic training on clinical assessment” is required, compared with 60 hours for electrologists

7. The “graduate” must pass a test prepared by the American Psychological Association, which advocates for prescriptive authority and is not an independent testing organization

8. There is no minimum of requirements of an undergraduate biomedical prerequisite course—the work that is required for all medical students, physician assistants, and nursing students—which includes chemistry or biochemistry (with laboratory experience), human anatomy, physiology, general biology, microbiology (with laboratory experience), cell biology, and molecular biology

9. Recommended number of patient encounters is anemic: 600 encounters, which can be 10 encounters with 60 patients or 15 encounters with 40 patients. This is far below what is required of psychiatric residents

10. The proposed training requires treating a minimum of 75 patients over 2 years. A typical third-year psychiatric resident sees 75 patients every month. Each first- and second-year resident works up and treats >600 inpatients in <1 year

11. At the end of the practicum, applicants must demonstrate competency in 9 milestones, but competency is not defined. In contrast, psychiatric residency programs have mandates from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requiring that residents be graded every 6 months on 23 milestones, with specific anchor points provided

12. Only 25% of the practicum occurs on psychiatric inpatient wards or outpatient clinics. One wonders where the patients who need psychopharmacology would be

13. Supervision is inadequate. There is no requirement for supervision by psychiatrists, whose training and experience make them qualified psychopharmacologists

14. There is no guidance on the frequency or intensity of supervision. In psychiatry, residents are supervised with each patient encounter over 4 years. Should psychologists without medical training be held to a lesser standard?

15. There are no specifications of continuing medical education, ongoing supervision, or outcomes

16. The potential dangers of psychotropics are not emphasized. For example:

• permanent or life-threatening adverse effects, such as tardive dyskinesia or agranulocytosis

• addiction potential, such as with stimulants or benzodiazepines

• potentially fatal drug interactions with monoamine oxidase inhibitors and meperidine or serotonin syndrome, or cardiac arrests with overdoses of tricyclic antidepressants

17. Many medications require ongoing monitoring. Some involve physical examination (extrapyramidal side effects, metabolic syndrome) or laboratory tests (lithium, carbamazepine, clozapine, valproate, renal and hepatic functions, metabolic profile for all antipsychotics). Failure to monitor may lead to fatal outcomes. Some medications are considered unsafe during pregnancy or breast-feeding.

Psychologists do a great service for patients with mental illness by providing evidence-based psychotherapies, such as cognitive-behavioral, dialectical-behavioral, interpersonal, and behavioral therapy. They complement what psychiatrists and nurse practitioners do with pharmacotherapy. Many patients with mild or moderate psychiatric disorders improve significantly with psychotherapy without the use of psychotropics. Psychologists should focus on what they were trained to do because they can benefit numerous patients. That is much better than trying to become prescribers and practice mediocre psychopharmacology without the requisite medical training. Patients with mental illness deserve no less.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

In response to Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial “Prescribing is the culmination of extensive medical training and psychologists don’t qualify” (From the Editor,

Tedd Judd, PhD, ABPP-CN

Diplomate in Clinical Neuropsychology

Certified Hispanic Mental Health Specialist

Cross-Cultural Specialist

Bellingham, Washington

I read Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial with a critical eye. As a psychologist in private clinical and forensic practice for more than 30 years, it is disheartening that you toe the politico-economic line proffered over the decades that establishes and buoys a clash between our helping professions in the hoary guise of protecting the consuming public.

It is disingenuous and misleading for you to cite “28,000 hours of training… 8 years of medical school” as a prerequisite for having adequate “psychopharmacological skills.”

Psychologists and psychiatrists can learn the same necessary and comprehensive skills to perform competent and equivalent prescription duties in succinct, operational ways.

It is about time the welfare of the consuming public be served instead of territorial profiteering. Perhaps you should focus more on the dwindling numbers of psychiatrists who perform psychotherapy in conjunction with psychopharmacology than on limiting the pool of providers who are qualified by training to do both. How many of those 28,000 hours are dedicated to training your psychiatrists in psychotherapy?

Norman R. Klein, PhD

Licensed Psychologist

Westport, Connecticut

Dr. Nasrallah wrote an unsurprisingly eloquent and passionate editorial and argues a cogent case for restricting prescription privileges to medically trained professionals. I wonder, though, if public health statistics of outcomes among mental health patients in states where clinical psychologists have been licensed to prescribe, such as New Mexico and Hawaii, bear out any of Dr. Nasrallah’s concerns.

Ole J. Thienhaus, MD, MBA

Department Head and Professor of Psychiatry

University of Arizona

College of Medicine-Tucson

Tucson, Arizona

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I am not surprised by Dr. Judd’s or Dr. Klein’s disagreement with my editorial asserting that psychologists do not receive the medical training that qualifies them to prescribe. They side with their fellow psychologists, just as psychiatrists agree with me. After all, those of us who have had the extensive training of psychiatric physicians know the abundance of medical skills needed for competent prescribing and find it preposterous that psychologists, who have a PhD and are acknowledged for their psychotherapy and psychometric skills, can take a drastic shortcut by getting politicians to give them the right to prescribe. Dr. Klein has no idea how much training it takes to become a competent prescriber, so his comments that both psychiatrists and psychologists can be similarly trained cannot be taken seriously. Even after 4 years of psychiatric residency with daily psychopharmacology teaching and training psychiatrists still feel they have much more to learn. It is dangerous hubris to think that even without the vital medical school foundation prior to psychiatric training that psychologists can

Here, I provide a description of one state’s proposed the training that psychologists would receive. I hope that Drs. Judd and Klein will recognize the dangerously inadequate training recently proposed for psychologists to become “prescribers.”

Proposed curriculum for psychologists

1. Online instruction, not face-to-face classroom experience

2. Many courses are prerecorded

3. Instructors are psychologists, not psychiatrists

4. Psychologists can complete the program at their own pace, which can be done in a few weeks

5. Hours of instruction range between 306 to 468 hours, compared with 500 hours required for massage therapists

6. A minimum of 40 hours of “basic training on clinical assessment” is required, compared with 60 hours for electrologists

7. The “graduate” must pass a test prepared by the American Psychological Association, which advocates for prescriptive authority and is not an independent testing organization

8. There is no minimum of requirements of an undergraduate biomedical prerequisite course—the work that is required for all medical students, physician assistants, and nursing students—which includes chemistry or biochemistry (with laboratory experience), human anatomy, physiology, general biology, microbiology (with laboratory experience), cell biology, and molecular biology

9. Recommended number of patient encounters is anemic: 600 encounters, which can be 10 encounters with 60 patients or 15 encounters with 40 patients. This is far below what is required of psychiatric residents

10. The proposed training requires treating a minimum of 75 patients over 2 years. A typical third-year psychiatric resident sees 75 patients every month. Each first- and second-year resident works up and treats >600 inpatients in <1 year

11. At the end of the practicum, applicants must demonstrate competency in 9 milestones, but competency is not defined. In contrast, psychiatric residency programs have mandates from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requiring that residents be graded every 6 months on 23 milestones, with specific anchor points provided

12. Only 25% of the practicum occurs on psychiatric inpatient wards or outpatient clinics. One wonders where the patients who need psychopharmacology would be

13. Supervision is inadequate. There is no requirement for supervision by psychiatrists, whose training and experience make them qualified psychopharmacologists

14. There is no guidance on the frequency or intensity of supervision. In psychiatry, residents are supervised with each patient encounter over 4 years. Should psychologists without medical training be held to a lesser standard?

15. There are no specifications of continuing medical education, ongoing supervision, or outcomes

16. The potential dangers of psychotropics are not emphasized. For example:

• permanent or life-threatening adverse effects, such as tardive dyskinesia or agranulocytosis

• addiction potential, such as with stimulants or benzodiazepines

• potentially fatal drug interactions with monoamine oxidase inhibitors and meperidine or serotonin syndrome, or cardiac arrests with overdoses of tricyclic antidepressants

17. Many medications require ongoing monitoring. Some involve physical examination (extrapyramidal side effects, metabolic syndrome) or laboratory tests (lithium, carbamazepine, clozapine, valproate, renal and hepatic functions, metabolic profile for all antipsychotics). Failure to monitor may lead to fatal outcomes. Some medications are considered unsafe during pregnancy or breast-feeding.

Psychologists do a great service for patients with mental illness by providing evidence-based psychotherapies, such as cognitive-behavioral, dialectical-behavioral, interpersonal, and behavioral therapy. They complement what psychiatrists and nurse practitioners do with pharmacotherapy. Many patients with mild or moderate psychiatric disorders improve significantly with psychotherapy without the use of psychotropics. Psychologists should focus on what they were trained to do because they can benefit numerous patients. That is much better than trying to become prescribers and practice mediocre psychopharmacology without the requisite medical training. Patients with mental illness deserve no less.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

Letters to the Editor: 'Endo hubris' - We got letters

[Editor’s Note: Dr. Russell Samson’s June editorial, “Endo hubris,” discussed the balance between open and endovascular surgery. His article garnered the most reader comment we have yet received. The letters that follow carry on this important discussion with a variety of voices from across the vascular community.]

To the Editor:

Thank you for your article, “Endo Hubris.” Your observations raise many deeper issues in our specialty of vascular surgery. It appears we vascular surgeons may be among a dwindling few that actually consider vascular surgery a specialty. With so many other specialists performing endovascular procedures, what is so “special” about our “specialty?” It is a keen observation and one made even more odious when one considers the fact that we do not even have our own board.

I also attended the last SVS meeting in San Diego and was happy to see it well attended and full of interesting presentations and discussion topics. However, one subject noticeably absent was having vascular surgery mature into a separate specialty with its own board. I don’t understand why we as a specialty group don’t discuss this. To me it is the most important issue facing our specialty as it relates to other specialties now and the future. Please let me explain.

Wouldn’t it be ideal if all surgeons could be equally competent at all types of operations, in all body regions? We could have one board which would certify all surgeons, certainly this would save money and be more efficient. Also, any boarded surgeon would be able to provide all surgical procedures in any part of the country, which would improve our nation’s access to subspecialty care. Sound good?

Yes, it does, but in reality, this is not reasonable nor feasible. Neurosurgeons take 6-7 years to train in brain and spine surgery. Orthopedic surgeons train as long to become the skeletal experts they are. Urologists also train many long years to become the masters of the genitourinary system. Combine all of these training programs together to make the ultimate surgeon and we would have surgeons in their 50’s or 60’s before being able to start practice. Then they would require adequate numbers of all cases to maintain proficiencies and maintenance of certification. That doesn’t sound good, that sounds absurd.

So goes my argument for having vascular surgery be an independent specialty. We have separate boards for neurosurgery, orthopedics, and urology because it is clearly safer for patients and allows for more advancement in each specialty. At present, we vascular surgeons are considered a subspecialty of general surgery, though we do have a “primary certificate” which allows for the independent attainment of vascular surgery board certification. So why don’t we just have a separate board? This question came up many years ago and caused a civil war in the world of vascular surgery.

A strong case for the independence of vascular surgery was put forth by Dr. Frank Veith et al. over a decade ago. The goal then was to form the American Board of Vascular Surgery (ABVS), independent from the American Board of Surgery. At that time there was already much progress in vascular surgery, including an official Certificate of Added Qualifications for Vascular Surgery by the American Board of Surgery. Also, there were existing accredited training programs for vascular surgery in the form of fellowships. To make a long story short, this motion was defeated after a bitter feud within the leadership of vascular surgery societies. The motion was defeated despite the endovascular revolution and the clear differentiation of vascular surgeons from their general surgery colleagues. Even more remarkable, the motion was defeated despite a 1997 survey showing that 91% of boarded vascular surgeons favored the formation of the ABVS.

So why does it matter? After all, patients are not routinely aware of the various boards and their purveys. They only want good outcomes from their operations. Well, I would argue that it probably doesn’t matter much on the national level, although an argument could be made about representation of specialties for Medicare reimbursement rates. I would argue, however, that the defeat of the ABVS in 2005 had significant effects down at the hospital and practice level. Vascular surgeons face severe challenges today with representation in hospital administration, equitable allocation of hospital resources, work-life balance, competition from interventional cardiology and radiology, to just mention a few. Even having adequate public awareness for peripheral vascular disease and our specialty has been lacking. These adverse forces can collectively, negatively impact our patient outcomes.

In summary, many challenges as such could have been averted with the formation of the ABVS, simply because our interests at the local level would have been addressed by an authoritative board of vascular surgeons answering only to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS). It stands to reason that hospitals organize service lines in at least some accordance with the ABMS represented specialties. Our defeat in 2005 was really a blow to our representation in local hospitals and multispecialty groups. Hopefully, we will rekindle this effort in the future for the sake of our specialty and the patients we serve.

Jeffrey H. Hsu, MD, FACS

Regional Chief of Vascular Surgery

Southern California Permanente Medical Group, Kaiser Permanente – Southern California

To the editor:

I always enjoy your editorials in Vascular Specialist, and I even agree with you, most of the time. But I think you hit a home run with the most recent editorial on endo hubris. I have long felt that the only thing that really separates us from the non-surgeon interventionists is that we can do the open surgical operations when they are either necessary or better. So thanks for bringing this issue to a broad audience.

Jerry Goldstone MD

Professor Emeritus, Surgery, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine; Past president, International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery, North American Chapter

To the Editor:

Your recent editorial “Endo hubris” is completely on point. While it is certainly important that vascular surgeons continue to be leaders in endovascular innovation, it would be a big mistake for us to marginalize open surgical skills. We wrote about such endo-exuberance in the early days of EVAR, realizing that some patients were (and still are) best served by an expertly performed open vascular procedure. Sadly, that skill set for performing larger open vascular procedures is waning as the volume for teaching continues to decline.

The ability to perform open vascular procedures is THE differentiator that sets us apart from all others providing vascular services. Let’s hope that our specialty does not let it wither away.

W. Charles Sternbergh III, MD

Professor and Chief, Vascular and Endovascular Surgery,

Vice-Chair for Research, Department of Surgery

Ochsner Health System

New Orleans, La.

To the Editor:

I read your commentary today regarding open surgery with interest (“Endo hubris”). Based on my recent involvement with the Vascular Annual Meeting (VAM) as well as the Vascular Surgery Board and Residency Review Committee for Surgery, I feel compelled to respond to some of the points you raised.

On behalf of my colleagues on the program and related SVS Committees, we are pleased to learn that you enjoyed the San Diego meeting, marijuana aromas and all! However, the implication that the program was imbalanced or biased towards endovascular presentations and solutions deserves comment. As you know, the plenary sessions are composed of investigator-submitted abstracts, all original content, and the Program Committee builds the plenaries based on the quality and diversity of the submitted abstracts. So as a first clarification, the content of the program largely reflects the interest of members and others who submit abstracts to the VAM.

I assure you that high-quality, compelling abstracts regarding open surgical procedures and outcomes are not disadvantaged in the selection process, and a number (including presentations on carotid body tumors, cervical ribs, pediatric renovascular hypertension, removal of infected endografts, carotid endarterectomy with proximal intervention, and open reconstruction of SVC syndrome, among others) were included within each plenary session. Additionally, the videos selected for the program included a large number of unusual and relevant open procedures, including the NAIS procedure from Johns Hopkins in the opening plenary, as well as a number of excellent open surgical videos on the “How I do it” video session on Saturday.

Secondly, your anecdote regarding the “excellent surgical resident” and his comfort with open pararenal AAA repair deserves comment as well. As you know, formal vascular training does not and cannot convey mastery in the practice of surgery. Rather, the training and fellowship process is intended to produce safe and competent surgeons, individuals who will continue to grow in their confidence and ability through their first several years in practice. In reality we’d expect any trainee today, let alone 10 or 20 years ago, to anticipate the need for assistance in safely exposing and repairing a pararenal aortic aneurysm early in their practice experience, particularly in today’s environment of registries, OPPE, FPPE, and hypersurveillance of surgical outcomes. The resident’s response (a first-year fellow, actually) was absolutely the right one under the circumstances, and I’d expect a different answer after his first few years in practice, if not by the end of his fellowship.

As you may also know, there are proposals under consideration to require open procedure case minimums for board eligibility and continuing program accreditation. This process is controversial, as no clear guidelines exist regarding “how much is enough,” but efforts are underway to ensure that each trainee performs sufficient numbers of the open arterial reconstructive procedures that define our specialty. In the process of preparing for these discussions, we were pleased to learn that, from ACGME case log data, the average numbers of open arterial operations (abdominal, peripheral and cerebrovascular reconstructive) performed by trainees have not declined over the last several years, despite perceptions to the contrary.

As a parting comment, you may have also noticed that the entire first plenary session at VAM was thematically focused on the limitations of endovascular aortic disease management, with a number of late complications considered, along with their potential solutions. This was not coincidental, as with any maturing technology, the long-term consequences of the endo-adventurism of the last 15 years are only now becoming apparent. Throughout the meeting, we took every opportunity to contrast the potential of new technology with the unknown and potentially deleterious consequences associated with early adoption.

Regarding the importance of highlighting the advantages of open surgery to our patients and colleagues when appropriate, I couldn’t agree with you more.

Despite our best efforts, however, patients will always be attracted to “minimally invasive” solutions regardless of their limitations. In my opinion, our specialty has managed this transition relatively well in the endovascular era, constantly benchmarking new techniques against old standards, and embracing the new when proven to be most advantageous to patients.

Regarding the range of commercial exhibitors participating in this year’s VAM, it is incumbent upon us as SVS members to emphasize to our local vendors and contractors that their presence at the VAM is a significant draw for attendance at the meeting, and that we appreciate their continued support.

Thanks for continuing to produce such spirited and inspiring commentaries for the Specialist, as well as your overall capable editorial stewardship of this important publication.

Ron Dalman, MD

Program Chair Emeritus, SVS Vascular Annual Meeting, 2015-2017

Member, Vascular Surgery Board, American Board of Surgery

Member Emeritus, Residency Review Committee for Surgery, 2010-2016

Dr. Samson replies:

At the outset I would like to thank Dr. Dalman for taking the time to write this letter and for his words of support for my other editorials.

I understand that some may take offense at some of the possible inferences in my editorial. However, it was certainly not my intention to malign the meeting. On the contrary, as I stated at the outset of my editorial, the meeting was outstanding in every aspect and I commend his committee on producing the finest, all-encompassing meeting I have ever attended. I was extremely proud to be a member of a Society that could create such an event. Nor did my editorial suggest that there was bias in selection of endovascular subjects instead of open procedures. Rather, as Dr. Dalman writes, “the content of the program largely reflects the interest of members and others who submit abstracts to the VAM.” In other words, a society of members whose interests now are largely directed towards endovascular procedures. Further, having run multiple meetings in the past, I am aware of the need to incorporate commercial exhibitors and their importance to the meeting. I used the fact that the majority of exhibitors displayed endovascular equipment as another example of the burgeoning influence of endovascular therapies.

I must admit that I thought long and hard before using the paragraph about the excellent vascular fellow. [See my editorial on page 3.] I was impressed by his talk and by the quality of his presentation. I was also very impressed by his candor in answering the question put to him from the audience. From Dr. Dalman’s letter it is apparent that he deserves praise, as does his fellowship training. However, multiple surgeons who were in the audience came up to me afterwards and that was partly the impetus for the editorial. The fact remains that we have an identity problem. I myself suffer from “Endo hubris” and waning surgical expertise. How we address this “malady” may be fundamental to the future of vascular surgery.

[Editor’s Note: Dr. Russell Samson’s June editorial, “Endo hubris,” discussed the balance between open and endovascular surgery. His article garnered the most reader comment we have yet received. The letters that follow carry on this important discussion with a variety of voices from across the vascular community.]

To the Editor:

Thank you for your article, “Endo Hubris.” Your observations raise many deeper issues in our specialty of vascular surgery. It appears we vascular surgeons may be among a dwindling few that actually consider vascular surgery a specialty. With so many other specialists performing endovascular procedures, what is so “special” about our “specialty?” It is a keen observation and one made even more odious when one considers the fact that we do not even have our own board.

I also attended the last SVS meeting in San Diego and was happy to see it well attended and full of interesting presentations and discussion topics. However, one subject noticeably absent was having vascular surgery mature into a separate specialty with its own board. I don’t understand why we as a specialty group don’t discuss this. To me it is the most important issue facing our specialty as it relates to other specialties now and the future. Please let me explain.

Wouldn’t it be ideal if all surgeons could be equally competent at all types of operations, in all body regions? We could have one board which would certify all surgeons, certainly this would save money and be more efficient. Also, any boarded surgeon would be able to provide all surgical procedures in any part of the country, which would improve our nation’s access to subspecialty care. Sound good?

Yes, it does, but in reality, this is not reasonable nor feasible. Neurosurgeons take 6-7 years to train in brain and spine surgery. Orthopedic surgeons train as long to become the skeletal experts they are. Urologists also train many long years to become the masters of the genitourinary system. Combine all of these training programs together to make the ultimate surgeon and we would have surgeons in their 50’s or 60’s before being able to start practice. Then they would require adequate numbers of all cases to maintain proficiencies and maintenance of certification. That doesn’t sound good, that sounds absurd.

So goes my argument for having vascular surgery be an independent specialty. We have separate boards for neurosurgery, orthopedics, and urology because it is clearly safer for patients and allows for more advancement in each specialty. At present, we vascular surgeons are considered a subspecialty of general surgery, though we do have a “primary certificate” which allows for the independent attainment of vascular surgery board certification. So why don’t we just have a separate board? This question came up many years ago and caused a civil war in the world of vascular surgery.

A strong case for the independence of vascular surgery was put forth by Dr. Frank Veith et al. over a decade ago. The goal then was to form the American Board of Vascular Surgery (ABVS), independent from the American Board of Surgery. At that time there was already much progress in vascular surgery, including an official Certificate of Added Qualifications for Vascular Surgery by the American Board of Surgery. Also, there were existing accredited training programs for vascular surgery in the form of fellowships. To make a long story short, this motion was defeated after a bitter feud within the leadership of vascular surgery societies. The motion was defeated despite the endovascular revolution and the clear differentiation of vascular surgeons from their general surgery colleagues. Even more remarkable, the motion was defeated despite a 1997 survey showing that 91% of boarded vascular surgeons favored the formation of the ABVS.

So why does it matter? After all, patients are not routinely aware of the various boards and their purveys. They only want good outcomes from their operations. Well, I would argue that it probably doesn’t matter much on the national level, although an argument could be made about representation of specialties for Medicare reimbursement rates. I would argue, however, that the defeat of the ABVS in 2005 had significant effects down at the hospital and practice level. Vascular surgeons face severe challenges today with representation in hospital administration, equitable allocation of hospital resources, work-life balance, competition from interventional cardiology and radiology, to just mention a few. Even having adequate public awareness for peripheral vascular disease and our specialty has been lacking. These adverse forces can collectively, negatively impact our patient outcomes.

In summary, many challenges as such could have been averted with the formation of the ABVS, simply because our interests at the local level would have been addressed by an authoritative board of vascular surgeons answering only to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS). It stands to reason that hospitals organize service lines in at least some accordance with the ABMS represented specialties. Our defeat in 2005 was really a blow to our representation in local hospitals and multispecialty groups. Hopefully, we will rekindle this effort in the future for the sake of our specialty and the patients we serve.

Jeffrey H. Hsu, MD, FACS

Regional Chief of Vascular Surgery

Southern California Permanente Medical Group, Kaiser Permanente – Southern California

To the editor:

I always enjoy your editorials in Vascular Specialist, and I even agree with you, most of the time. But I think you hit a home run with the most recent editorial on endo hubris. I have long felt that the only thing that really separates us from the non-surgeon interventionists is that we can do the open surgical operations when they are either necessary or better. So thanks for bringing this issue to a broad audience.

Jerry Goldstone MD

Professor Emeritus, Surgery, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine; Past president, International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery, North American Chapter

To the Editor:

Your recent editorial “Endo hubris” is completely on point. While it is certainly important that vascular surgeons continue to be leaders in endovascular innovation, it would be a big mistake for us to marginalize open surgical skills. We wrote about such endo-exuberance in the early days of EVAR, realizing that some patients were (and still are) best served by an expertly performed open vascular procedure. Sadly, that skill set for performing larger open vascular procedures is waning as the volume for teaching continues to decline.

The ability to perform open vascular procedures is THE differentiator that sets us apart from all others providing vascular services. Let’s hope that our specialty does not let it wither away.

W. Charles Sternbergh III, MD

Professor and Chief, Vascular and Endovascular Surgery,

Vice-Chair for Research, Department of Surgery

Ochsner Health System

New Orleans, La.

To the Editor:

I read your commentary today regarding open surgery with interest (“Endo hubris”). Based on my recent involvement with the Vascular Annual Meeting (VAM) as well as the Vascular Surgery Board and Residency Review Committee for Surgery, I feel compelled to respond to some of the points you raised.

On behalf of my colleagues on the program and related SVS Committees, we are pleased to learn that you enjoyed the San Diego meeting, marijuana aromas and all! However, the implication that the program was imbalanced or biased towards endovascular presentations and solutions deserves comment. As you know, the plenary sessions are composed of investigator-submitted abstracts, all original content, and the Program Committee builds the plenaries based on the quality and diversity of the submitted abstracts. So as a first clarification, the content of the program largely reflects the interest of members and others who submit abstracts to the VAM.

I assure you that high-quality, compelling abstracts regarding open surgical procedures and outcomes are not disadvantaged in the selection process, and a number (including presentations on carotid body tumors, cervical ribs, pediatric renovascular hypertension, removal of infected endografts, carotid endarterectomy with proximal intervention, and open reconstruction of SVC syndrome, among others) were included within each plenary session. Additionally, the videos selected for the program included a large number of unusual and relevant open procedures, including the NAIS procedure from Johns Hopkins in the opening plenary, as well as a number of excellent open surgical videos on the “How I do it” video session on Saturday.

Secondly, your anecdote regarding the “excellent surgical resident” and his comfort with open pararenal AAA repair deserves comment as well. As you know, formal vascular training does not and cannot convey mastery in the practice of surgery. Rather, the training and fellowship process is intended to produce safe and competent surgeons, individuals who will continue to grow in their confidence and ability through their first several years in practice. In reality we’d expect any trainee today, let alone 10 or 20 years ago, to anticipate the need for assistance in safely exposing and repairing a pararenal aortic aneurysm early in their practice experience, particularly in today’s environment of registries, OPPE, FPPE, and hypersurveillance of surgical outcomes. The resident’s response (a first-year fellow, actually) was absolutely the right one under the circumstances, and I’d expect a different answer after his first few years in practice, if not by the end of his fellowship.

As you may also know, there are proposals under consideration to require open procedure case minimums for board eligibility and continuing program accreditation. This process is controversial, as no clear guidelines exist regarding “how much is enough,” but efforts are underway to ensure that each trainee performs sufficient numbers of the open arterial reconstructive procedures that define our specialty. In the process of preparing for these discussions, we were pleased to learn that, from ACGME case log data, the average numbers of open arterial operations (abdominal, peripheral and cerebrovascular reconstructive) performed by trainees have not declined over the last several years, despite perceptions to the contrary.