User login

Terrorist Activity: Are You Ready?

I was relaxing after work in my local American Legion a few weeks ago when a quiet young man entered with a backpack. He set it down to use the restroom, and when he returned a few minutes later, he picked up the backpack and walked away. After he left, a group of us discussed how lax we were about this situation. Yes, it was probably innocent—but what if it wasn’t? A sign over the bar reads, “Don’t let anyone leave a stranger.” The purpose of that sign is, of course, to make everyone feel welcome, but these days I think it also means to be aware of your surroundings. I have seen too many American flags at half-staff this year to overlook a potential tragedy.

Today, clinicians must be prepared for all possible emergencies, including terrorism. Acts of terrorism (as the word implies) are designed to instill terror and panic, disrupt security and communication systems, destroy property, and kill or injure innocent civilians.

Recent terrorist attacks in 2016, while shocking in their brutality, were not inconceivable—public locations where large groups gather are logical targets. Terrorists often target high-traffic areas, such as airports or shopping malls, where they can quickly disappear into a crowd if necessary (hence the concern circling the Olympic Games to be held in Brazil this month).

Attacks at restaurants, airports, and other public “hot spots” are especially frightening. With terrorist attack locations in the past year ranging from nightclubs (the Pulse Nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida, left 49 dead) to restaurants (a bomb in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killed 20) to conference rooms (a shooting in San Bernardino, California, left 14 dead and 21 injured), it’s clear that the fundamental message terrorists want to send is: You are not safe—anywhere!

While organized events and big crowds are a bull’s-eye for terrorists, our personal surroundings have risk factors, too. Because a terrorist attack can happen anywhere at any time, you need to be prepared by knowing what to do and how to maximize your chances of survival.

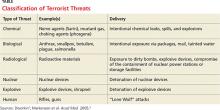

As this year’s attacks exemplify, we shouldn’t assume we understand the “logic” or thinking of terrorist organizations or individuals. Preparation for a terrorist attack boils down to being aware of the warning signs and being cautious and alert. Terrorists use a range of weapons and tactics, including bombs, arson, hijacking, and kidnapping (see Table).1,2

According to Dr. Howard Mell, an EMS director in North Carolina, the overwhelming majority of gunfire in the emergency department—or anywhere—is not the result of an active shooter. Most gunfire is targeted at a specific goal (ie, escaping or avoiding capture) or person. However, should there be an active shooter, he recommends three steps to take: Run (if the path is open), hide (if your exit is blocked), or fight (if there are no other alternatives).3

Wherever you are, always have multiple potential escape routes in mind. If you run, leave all belongings behind. Help others escape if possible, and take steps to prevent others from entering once you have left the area.

If you are unable to run, decide where to hide. If possible, barricade the area; if you are in a room, turn out the lights and stay away from the door. Be silent and put your cell phone on silent. While you are hiding, prepare to fight.

Fighting is the last resort. Act aggressively and improvise weapons to use against the assailant. If you have family, friends, or colleagues with you, put them to work!

When law enforcement officers arrive, understand that their job is to go right to the source and contain the danger. Keep your hands visible at all times, with fingers spread. Do not grab them for protection, and avoid yelling or pointing. Be prepared to give the authorities any pertinent information (eg, shooter description, last known location, direction of travel, or weapons seen).

Many health care facilities and organizations have valuable disaster and terrorism training programs, which include emergency evacuation procedures. I encourage you to take advantage of them, particularly if you travel internationally.4

Continue for personal preparedness >>

This is about personal preparedness. While I am not promoting paranoia, I do believe the risk for terrorist activity has increased in recent years.

I therefore urge you to have a healthy suspicion when you see or hear people

• Asking unusual questions about safety procedures at work

• Engaging in behaviors that provoke suspicion

• Loitering, parking, or standing in the same area over multiple days

• Attempting to disguise themselves from visit to visit

• Obtaining unusual quantities of weapons, ammunition, or explosive precursors

• Wearing clothing not appropriate for the season

• Leaving items, including backpacks or packages, unattended

• Leaving anonymous threats via telephone or e-mail

If after conducting a risk assessment of your surroundings, you believe you could (directly or indirectly) be impacted by terrorism, you must implement evacuation plans, notification of appropriate personnel, and personal safety measures.

In the event of a terrorist incident, remain calm, follow the advice of local emergency officials, and follow radio, television, and cell phone updates for news and instructions. 5

If an attack occurs near you or your home, here are practical steps you can take: Check for injuries. Give first aid and get help for seriously injured people. Check for damage using a flashlight—do not light matches or candles, or use electrical switches. Check for fires, fire hazards, and other household hazards. Sniff for gas leaks, starting at the water heater. If you smell gas or suspect a leak, turn off the main gas valve, open windows, and evacuate quickly. Shut off any damaged utilities, and confine or secure your pets. Call your family contact—but do not use the telephone again unless it is a life-threatening emergency. Cell phones may or may not be working. Check on your neighbors, especially those who are elderly or disabled.

Terrorist attacks leave citizens concerned about future incidents of terrorism in the United States and their potential impact. They raise ambiguity about what might happen next and increase stress levels. You can take steps to prepare for terrorist attacks and reduce the stress you may feel, now and later, should an emergency arise. Taking preparatory action can reassure you, your family, and your children that you have a measure of control—even in the face of terrorism. If you have additional suggestions for terrorist defense preparation, you can email your ideas to [email protected].

References

1. Dworkin RW. Preparing hospitals, doctors, and nurses for a terrorist attack. Hudson Institute. www.hudson.org/content/researchattach ments/attachment/291/dworkin_white_paper.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2016.

2. Markenson F, DiMaggio C, Redlener I. Preparing health professions students for terrorism, disaster, and public health emergencies: core competencies. Acad Med. 2005;80(6):517-526.

3. Mell HK. Run, hide, fight: how to react when there’s gunfire in the emergency department. ACEP NOW. June 21, 2016. www.acepnow.com/react-theres-gunfire-emergency-department/?elq_mid=10369&elq_cid=5274988. Accessed July 6, 2016.

4. Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress. Workplace preparedness for terrorism. www.cstsonline.org/assets/media/docu ments/CSTS_report_sloan_workplace_prepare_terrorism_preparedness.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2016.

5. American Red Cross. Terrorism Preparedness. www.redcross.org/prepare/disaster/terrorism. Accessed July 6, 2016.

I was relaxing after work in my local American Legion a few weeks ago when a quiet young man entered with a backpack. He set it down to use the restroom, and when he returned a few minutes later, he picked up the backpack and walked away. After he left, a group of us discussed how lax we were about this situation. Yes, it was probably innocent—but what if it wasn’t? A sign over the bar reads, “Don’t let anyone leave a stranger.” The purpose of that sign is, of course, to make everyone feel welcome, but these days I think it also means to be aware of your surroundings. I have seen too many American flags at half-staff this year to overlook a potential tragedy.

Today, clinicians must be prepared for all possible emergencies, including terrorism. Acts of terrorism (as the word implies) are designed to instill terror and panic, disrupt security and communication systems, destroy property, and kill or injure innocent civilians.

Recent terrorist attacks in 2016, while shocking in their brutality, were not inconceivable—public locations where large groups gather are logical targets. Terrorists often target high-traffic areas, such as airports or shopping malls, where they can quickly disappear into a crowd if necessary (hence the concern circling the Olympic Games to be held in Brazil this month).

Attacks at restaurants, airports, and other public “hot spots” are especially frightening. With terrorist attack locations in the past year ranging from nightclubs (the Pulse Nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida, left 49 dead) to restaurants (a bomb in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killed 20) to conference rooms (a shooting in San Bernardino, California, left 14 dead and 21 injured), it’s clear that the fundamental message terrorists want to send is: You are not safe—anywhere!

While organized events and big crowds are a bull’s-eye for terrorists, our personal surroundings have risk factors, too. Because a terrorist attack can happen anywhere at any time, you need to be prepared by knowing what to do and how to maximize your chances of survival.

As this year’s attacks exemplify, we shouldn’t assume we understand the “logic” or thinking of terrorist organizations or individuals. Preparation for a terrorist attack boils down to being aware of the warning signs and being cautious and alert. Terrorists use a range of weapons and tactics, including bombs, arson, hijacking, and kidnapping (see Table).1,2

According to Dr. Howard Mell, an EMS director in North Carolina, the overwhelming majority of gunfire in the emergency department—or anywhere—is not the result of an active shooter. Most gunfire is targeted at a specific goal (ie, escaping or avoiding capture) or person. However, should there be an active shooter, he recommends three steps to take: Run (if the path is open), hide (if your exit is blocked), or fight (if there are no other alternatives).3

Wherever you are, always have multiple potential escape routes in mind. If you run, leave all belongings behind. Help others escape if possible, and take steps to prevent others from entering once you have left the area.

If you are unable to run, decide where to hide. If possible, barricade the area; if you are in a room, turn out the lights and stay away from the door. Be silent and put your cell phone on silent. While you are hiding, prepare to fight.

Fighting is the last resort. Act aggressively and improvise weapons to use against the assailant. If you have family, friends, or colleagues with you, put them to work!

When law enforcement officers arrive, understand that their job is to go right to the source and contain the danger. Keep your hands visible at all times, with fingers spread. Do not grab them for protection, and avoid yelling or pointing. Be prepared to give the authorities any pertinent information (eg, shooter description, last known location, direction of travel, or weapons seen).

Many health care facilities and organizations have valuable disaster and terrorism training programs, which include emergency evacuation procedures. I encourage you to take advantage of them, particularly if you travel internationally.4

Continue for personal preparedness >>

This is about personal preparedness. While I am not promoting paranoia, I do believe the risk for terrorist activity has increased in recent years.

I therefore urge you to have a healthy suspicion when you see or hear people

• Asking unusual questions about safety procedures at work

• Engaging in behaviors that provoke suspicion

• Loitering, parking, or standing in the same area over multiple days

• Attempting to disguise themselves from visit to visit

• Obtaining unusual quantities of weapons, ammunition, or explosive precursors

• Wearing clothing not appropriate for the season

• Leaving items, including backpacks or packages, unattended

• Leaving anonymous threats via telephone or e-mail

If after conducting a risk assessment of your surroundings, you believe you could (directly or indirectly) be impacted by terrorism, you must implement evacuation plans, notification of appropriate personnel, and personal safety measures.

In the event of a terrorist incident, remain calm, follow the advice of local emergency officials, and follow radio, television, and cell phone updates for news and instructions. 5

If an attack occurs near you or your home, here are practical steps you can take: Check for injuries. Give first aid and get help for seriously injured people. Check for damage using a flashlight—do not light matches or candles, or use electrical switches. Check for fires, fire hazards, and other household hazards. Sniff for gas leaks, starting at the water heater. If you smell gas or suspect a leak, turn off the main gas valve, open windows, and evacuate quickly. Shut off any damaged utilities, and confine or secure your pets. Call your family contact—but do not use the telephone again unless it is a life-threatening emergency. Cell phones may or may not be working. Check on your neighbors, especially those who are elderly or disabled.

Terrorist attacks leave citizens concerned about future incidents of terrorism in the United States and their potential impact. They raise ambiguity about what might happen next and increase stress levels. You can take steps to prepare for terrorist attacks and reduce the stress you may feel, now and later, should an emergency arise. Taking preparatory action can reassure you, your family, and your children that you have a measure of control—even in the face of terrorism. If you have additional suggestions for terrorist defense preparation, you can email your ideas to [email protected].

References

1. Dworkin RW. Preparing hospitals, doctors, and nurses for a terrorist attack. Hudson Institute. www.hudson.org/content/researchattach ments/attachment/291/dworkin_white_paper.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2016.

2. Markenson F, DiMaggio C, Redlener I. Preparing health professions students for terrorism, disaster, and public health emergencies: core competencies. Acad Med. 2005;80(6):517-526.

3. Mell HK. Run, hide, fight: how to react when there’s gunfire in the emergency department. ACEP NOW. June 21, 2016. www.acepnow.com/react-theres-gunfire-emergency-department/?elq_mid=10369&elq_cid=5274988. Accessed July 6, 2016.

4. Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress. Workplace preparedness for terrorism. www.cstsonline.org/assets/media/docu ments/CSTS_report_sloan_workplace_prepare_terrorism_preparedness.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2016.

5. American Red Cross. Terrorism Preparedness. www.redcross.org/prepare/disaster/terrorism. Accessed July 6, 2016.

I was relaxing after work in my local American Legion a few weeks ago when a quiet young man entered with a backpack. He set it down to use the restroom, and when he returned a few minutes later, he picked up the backpack and walked away. After he left, a group of us discussed how lax we were about this situation. Yes, it was probably innocent—but what if it wasn’t? A sign over the bar reads, “Don’t let anyone leave a stranger.” The purpose of that sign is, of course, to make everyone feel welcome, but these days I think it also means to be aware of your surroundings. I have seen too many American flags at half-staff this year to overlook a potential tragedy.

Today, clinicians must be prepared for all possible emergencies, including terrorism. Acts of terrorism (as the word implies) are designed to instill terror and panic, disrupt security and communication systems, destroy property, and kill or injure innocent civilians.

Recent terrorist attacks in 2016, while shocking in their brutality, were not inconceivable—public locations where large groups gather are logical targets. Terrorists often target high-traffic areas, such as airports or shopping malls, where they can quickly disappear into a crowd if necessary (hence the concern circling the Olympic Games to be held in Brazil this month).

Attacks at restaurants, airports, and other public “hot spots” are especially frightening. With terrorist attack locations in the past year ranging from nightclubs (the Pulse Nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida, left 49 dead) to restaurants (a bomb in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killed 20) to conference rooms (a shooting in San Bernardino, California, left 14 dead and 21 injured), it’s clear that the fundamental message terrorists want to send is: You are not safe—anywhere!

While organized events and big crowds are a bull’s-eye for terrorists, our personal surroundings have risk factors, too. Because a terrorist attack can happen anywhere at any time, you need to be prepared by knowing what to do and how to maximize your chances of survival.

As this year’s attacks exemplify, we shouldn’t assume we understand the “logic” or thinking of terrorist organizations or individuals. Preparation for a terrorist attack boils down to being aware of the warning signs and being cautious and alert. Terrorists use a range of weapons and tactics, including bombs, arson, hijacking, and kidnapping (see Table).1,2

According to Dr. Howard Mell, an EMS director in North Carolina, the overwhelming majority of gunfire in the emergency department—or anywhere—is not the result of an active shooter. Most gunfire is targeted at a specific goal (ie, escaping or avoiding capture) or person. However, should there be an active shooter, he recommends three steps to take: Run (if the path is open), hide (if your exit is blocked), or fight (if there are no other alternatives).3

Wherever you are, always have multiple potential escape routes in mind. If you run, leave all belongings behind. Help others escape if possible, and take steps to prevent others from entering once you have left the area.

If you are unable to run, decide where to hide. If possible, barricade the area; if you are in a room, turn out the lights and stay away from the door. Be silent and put your cell phone on silent. While you are hiding, prepare to fight.

Fighting is the last resort. Act aggressively and improvise weapons to use against the assailant. If you have family, friends, or colleagues with you, put them to work!

When law enforcement officers arrive, understand that their job is to go right to the source and contain the danger. Keep your hands visible at all times, with fingers spread. Do not grab them for protection, and avoid yelling or pointing. Be prepared to give the authorities any pertinent information (eg, shooter description, last known location, direction of travel, or weapons seen).

Many health care facilities and organizations have valuable disaster and terrorism training programs, which include emergency evacuation procedures. I encourage you to take advantage of them, particularly if you travel internationally.4

Continue for personal preparedness >>

This is about personal preparedness. While I am not promoting paranoia, I do believe the risk for terrorist activity has increased in recent years.

I therefore urge you to have a healthy suspicion when you see or hear people

• Asking unusual questions about safety procedures at work

• Engaging in behaviors that provoke suspicion

• Loitering, parking, or standing in the same area over multiple days

• Attempting to disguise themselves from visit to visit

• Obtaining unusual quantities of weapons, ammunition, or explosive precursors

• Wearing clothing not appropriate for the season

• Leaving items, including backpacks or packages, unattended

• Leaving anonymous threats via telephone or e-mail

If after conducting a risk assessment of your surroundings, you believe you could (directly or indirectly) be impacted by terrorism, you must implement evacuation plans, notification of appropriate personnel, and personal safety measures.

In the event of a terrorist incident, remain calm, follow the advice of local emergency officials, and follow radio, television, and cell phone updates for news and instructions. 5

If an attack occurs near you or your home, here are practical steps you can take: Check for injuries. Give first aid and get help for seriously injured people. Check for damage using a flashlight—do not light matches or candles, or use electrical switches. Check for fires, fire hazards, and other household hazards. Sniff for gas leaks, starting at the water heater. If you smell gas or suspect a leak, turn off the main gas valve, open windows, and evacuate quickly. Shut off any damaged utilities, and confine or secure your pets. Call your family contact—but do not use the telephone again unless it is a life-threatening emergency. Cell phones may or may not be working. Check on your neighbors, especially those who are elderly or disabled.

Terrorist attacks leave citizens concerned about future incidents of terrorism in the United States and their potential impact. They raise ambiguity about what might happen next and increase stress levels. You can take steps to prepare for terrorist attacks and reduce the stress you may feel, now and later, should an emergency arise. Taking preparatory action can reassure you, your family, and your children that you have a measure of control—even in the face of terrorism. If you have additional suggestions for terrorist defense preparation, you can email your ideas to [email protected].

References

1. Dworkin RW. Preparing hospitals, doctors, and nurses for a terrorist attack. Hudson Institute. www.hudson.org/content/researchattach ments/attachment/291/dworkin_white_paper.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2016.

2. Markenson F, DiMaggio C, Redlener I. Preparing health professions students for terrorism, disaster, and public health emergencies: core competencies. Acad Med. 2005;80(6):517-526.

3. Mell HK. Run, hide, fight: how to react when there’s gunfire in the emergency department. ACEP NOW. June 21, 2016. www.acepnow.com/react-theres-gunfire-emergency-department/?elq_mid=10369&elq_cid=5274988. Accessed July 6, 2016.

4. Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress. Workplace preparedness for terrorism. www.cstsonline.org/assets/media/docu ments/CSTS_report_sloan_workplace_prepare_terrorism_preparedness.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2016.

5. American Red Cross. Terrorism Preparedness. www.redcross.org/prepare/disaster/terrorism. Accessed July 6, 2016.

Did Somebody Say “Precepting”?

But First, a Word About Vaping …

As advocates for tobacco control, my colleagues and I took great interest in Randy D. Danielsen’s editorial, “Vaping: Are Its ‘Benefits’ a Lot of Hot Air?” (Clinician Reviews. 2016;26[6]:15-16). Our practice offers evidence-based cessation treatment for individuals with nicotine addiction through counseling, pharmacotherapy, and the use of nicotine replacement products.

At our center, we often interact with clients who have had multiple quit attempts. Many of our clients state that they have been unsuccessful using an e-cigarette as a smoking cessation strategy. More often than not, they report smoking a cigarette “here and there” along with “vaping,” until they eventually relapse to their usual smoking pattern. Some report that they smoke even more than before they tried to quit. We have concerns about how vaping may renormalize the behaviors associated with smoking. Our clients say that when they vape, it reminds them of the “social” aspects of smoking— “being part of a group” and participating in an activity that keeps their hands busy.

Recent literature suggests that curiosity is the primary reason adolescents engage in e-cigarette use. While the newly implemented FDA regulations on e-cigarettes may keep these products out of the hands of some adolescents by prohibiting sales to those younger than 18, there is much more to consider. Along with exposure to nicotine, these devices offer a variety of kid-friendly flavorings that make these products attractive to middle and high school youth. Flavorings will not be regulated at this point in time.

According to researchers, this is a major concern. Findings from studies report that when inhaled, certain flavors are more harmful than others. For example, very high—even toxic—levels of benzaldehyde are inhaled by the user when cherry-flavored e-liquid is heated at high temperatures. The chemical diacetyl, a respiratory irritant known to be associated with bronchiolitis obliterans (popcorn lung), is produced by the aerosol vapors from buttered popcorn and certain fruit-flavored e-cigarette liquids.

As public health advocates, we must provide research to the FDA about the health hazards of the flavoring added to e-cigarettes and continue to fight for this regulation. We must support evidence-based tobacco control interventions, such as hard-hitting media campaigns and tobacco excise taxes, and promote access to cessation treatment, smoke-free policies, and statewide funding. Elimination of tobacco products will reduce the public health burden of tobacco-related illness.

Andrea Spatarella, DNP, RN, FNP-BC, Christine Fardellone, DNP, RN, Raisa Abramova, FNP-BC, RN

Great Neck, NY

Continue for Precepting & E-Quality of Care >>

Precepting & E-Quality of Care

As a woman of the baby-boomer generation, I was raised in an era when feminism was a focus for many. There was a great deal being written and discussed to encourage women to attain equal pay for equal work. Because nursing was (and still is) a profession dominated by women, this was a frequent topic in the classroom. We were repeatedly told, “Don’t give away your knowledge for free” and “You deserve to be paid what you’re worth, don’t discount yourself.”

I find it very telling that the same female-dominated academic programs that encouraged me to seek proper payment are now taking advantage of my free labor. I am somewhat offended by this attitude and consider it a step backward. Each time NPs are guilted or browbeaten into teaching without proper compensation, the profession is devalued. To continue to participate is to enable a problematic, if not broken, system.

NP education is in need of major reform. The precepting issue is the weak link in becoming a qualified professional who is able to meet the demands and responsibilities that academics and politicos are pushing harder and harder for. Our physician and PA colleagues can rightly argue that their clinical education is superior to ours—and I cannot fault our colleagues for expressing concern about quality of care. If nursing really wants an equal place at the table, this weakness must be improved, or the naysayers will have plenty of evidence that they were correct in the years to come.

Rebecca Shively, MSN, RN, FNP-BC

San Marcos, TX

Continue for NP Schools & Their Rigid Rules >>

NP Schools & Their Rigid Rules

I have been a preceptor for at least a dozen NP students and have yet to be offered compensation. Preceptors take the place of a paid instructor, giving away free advice and experiences. I don’t mind doing this, but at times it can be a struggle. Some students, for example, have never done a pelvic exam. Letting an inexperienced NP student practice a pelvic exam on a patient who made an appointment to see an experienced provider is unjust and unfair to the patient—I won’t do it. These schools need to provide practice sessions on paid patients so their students can learn these skills.

I have my beef with the institutes of higher learning, not the students. It feels like a one-way street. You fill out the forms they require in order to precept, which takes up valuable work time. You equip their students with the skills they need to practice safely and correctly, and then try to fill out their evaluation sheets on things that students are not licensed to do.

Schools present their contracts and won’t adapt them to match what your employer wants. We are doing them a service, yet they dictate how we do it. My practice no longer takes students from certain schools, simply because we do not agree with their contracts. These poor students are thrown out without a life raft to find their preceptors! Aren’t their schools getting paid to do something?

Carol Glascock, WHNP-BC

Columbia, MO

Continue for Teaching & Precepting: Two Sides of the Same Coin >>

Teaching & Precepting: Two Sides of the Same Coin

I am a 64-year-old NP who has been precepting in Montana for the past four years. The students I precept are responsible for finding their own preceptors, just as I was 20+ years ago. However, preceptors are hard to find here, as the population is widely scattered; this places an emotional burden on students. They cannot be picky in choosing where they go. Thus, students may not be familiar with the preceptor’s practice or ability to teach.

The students I precept are in doctorate programs. My experience has shown that these students have very little understanding of practical application and instead have an overabundance of theoretical knowledge that does not always apply to seeing and treating patients. I believe that this, and the suggested “lack of preparedness,” is the fault of the program—not of the student.

Regardless of program faults, students are looking to learn from our experience. Teaching is part of being a preceptor; if you do not want to teach, being a preceptor is not for you. If you want to share your experience and knowledge with those following you (mindful that they may treat you in the future), precepting is an enjoyable experience. But—a good practitioner does not always make a good teacher.

Before becoming a preceptor, you must consider your time constraints, as well as your staff’s. You also must consider how your patients will react to seeing a student in your place.

Preceptors need to have a relationship with the student’s university apart from signing a paper saying they, the NP, will be the student’s preceptor. The university needs to be more proactive, as medical schools are, when finding preceptors willing to take students.

Compensation is another consideration that is rarely mentioned or discussed. Compensation would eliminate some of the negative reactions and might get more preceptors to sign on.

Harold W. Bruce, MSN, FNP-BC

Butte, MT

Continue for Collision of Causes for Precepting Hurdles >>

Collision of Causes for Precepting Hurdles

I am a family NP practicing in a large internal medicine practice owned by a university-based health care system. I precept NP students because I feel an obligation to my profession. However, the stress and additional workload that precepting places on me will probably lead me to stop sooner than I would like.

The inability to locate enough quality preceptors is a multifaceted issue. Too many students in too many programs, as mentioned in the editorial, is one contributing problem. I have been told by nursing professors that universities profit from their NP programs. They have an incentive to admit a large quantity of students and push them through. We could learn from our MD colleagues, who recognize the value of limiting student numbers.

The rise in NP students has led to a high number of poorly prepared students who enter their programs with no experience as RNs. Preceptors should not teach the basics, and professors should not expect preceptors to do so. Likewise, professors should not expect employers to fill in the gaps for new NPs they hire.

Many NP students have no “real-life” clinical experience to supplement their knowledge and skills. A strong foundation that combines nursing and medical knowledge, clinical experiences, basic assessment skills, and an understanding of human nature and human responses is crucial to being a successful NP. The latter is only developed through experience with patients. Students cannot develop these skills when their professors push them to immediately enroll in NP or DNP programs upon graduation from their BSN or basic non-NP MSN programs.

Our programs would do well to provide all the didactic classroom hours prior to the start of clinical rotations. Thus, the limited clinical hours can be used to hone clinical skills, instead of the current practice of students learning basics while also trying to incorporate knowledge with practice. It is a disservice to our NP students not to have completed classroom learning before starting their limited clinical rotations.

Preceptor overload and “burnout” occurs when very busy NPs are expected to fit precepting into their usual clinical sessions. There are strict mandates that dictate the number of residents a physician can precept. Those rules also allot physicians time reserved just for precepting. Why are NPs expected to precept during their already overworked day? Why haven’t our Boards of Nursing and nursing educators demanded this?

Precepting puts us behind during our clinical sessions. In some cases, it can impact our relative value units or patient numbers and salaries. We are teaching on our own time, with no incentives or monetary gain, yet we are expected to devote time and resources to our students.

Most of us do not receive merit-based financial rewards for the extra work. When did it become wrong to expect to be paid for our work? No other profession has this sense of guilt or self-recrimination when asking to be paid for services.

Preceptor training is another issue. Unlike physicians, we are not acculturated in the “see one, do one, teach one” manner. In nursing, we are trained that we must be taught, observed, and tested before being allowed to do anything new. We have a need to be taught everything, including how to precept. That being said, precepting is both an art and a science that involves grasping the basic tenets of learning and mentoring. These are skills that should be taught through observation or in classes so that we can pass on our knowledge. If our NP programs were longer and more step-by-step—in terms of first acquiring knowledge, then incorporating clinical skills with practice—we might learn the skills of teaching and mentoring without feeling we need additional “education” in precepting.

I have been in nursing for more than 40 years and love my profession. There are challenges ahead of us that we can only meet if we are brave enough to look clearly at the way we teach younger nurses, create improved ways of teaching those who will replace us, and actually recognize the value and efforts of those we ask to precept the next generation.

Theresa Dippolito, MSN, NP-C, CRNP, APN, CCM

Levittown, PA

Continue for Raising the Bar >>

Raising the Bar

I no longer want to be involved in precepting. I, too, find the students to be poorly prepared, and I was flabbergasted when I read a recent post on Facebook—a student offered to pay her preceptor to sign off on her clinicals!

I graduated from an FNP program in 1998 and also felt unprepared at first. My class thought like nurses, in that we expected things to be presented to us. Very few of us were aware that we should prepare ourselves, and the program I went through did nothing to inform us of this. It was a rude awakening.

NP programs should have improved since then, but they certainly have not. I have precepted multiple students who did not know how to do a proper physical exam, despite having passed their related courses. I have also precepted students who thought they knew everything and felt I should let them practice solo. Sadly, the majority were simultaneously in both groups.

There is still the stigma that we should remain within a nursing philosophy when we practice, when the reality is that we practice side by side with the doctors. We need to think critically, as they do, and have our programs teach such thinking via competent instructors.

My suggestions include a competency exam for NP instructors so that we can assure a higher, more standardized level of teaching. There should also be a prep course for potential NP students on how to think, including an explanation that it will be their responsibility to go after knowledge as well. Finally, we need to stray from the nursing philosophy-type teaching in NP programs and instead focus on stronger clinical knowledge and competence.

Nikki Knight, MSN, FNP-C

San Francisco, CA

But First, a Word About Vaping …

As advocates for tobacco control, my colleagues and I took great interest in Randy D. Danielsen’s editorial, “Vaping: Are Its ‘Benefits’ a Lot of Hot Air?” (Clinician Reviews. 2016;26[6]:15-16). Our practice offers evidence-based cessation treatment for individuals with nicotine addiction through counseling, pharmacotherapy, and the use of nicotine replacement products.

At our center, we often interact with clients who have had multiple quit attempts. Many of our clients state that they have been unsuccessful using an e-cigarette as a smoking cessation strategy. More often than not, they report smoking a cigarette “here and there” along with “vaping,” until they eventually relapse to their usual smoking pattern. Some report that they smoke even more than before they tried to quit. We have concerns about how vaping may renormalize the behaviors associated with smoking. Our clients say that when they vape, it reminds them of the “social” aspects of smoking— “being part of a group” and participating in an activity that keeps their hands busy.

Recent literature suggests that curiosity is the primary reason adolescents engage in e-cigarette use. While the newly implemented FDA regulations on e-cigarettes may keep these products out of the hands of some adolescents by prohibiting sales to those younger than 18, there is much more to consider. Along with exposure to nicotine, these devices offer a variety of kid-friendly flavorings that make these products attractive to middle and high school youth. Flavorings will not be regulated at this point in time.

According to researchers, this is a major concern. Findings from studies report that when inhaled, certain flavors are more harmful than others. For example, very high—even toxic—levels of benzaldehyde are inhaled by the user when cherry-flavored e-liquid is heated at high temperatures. The chemical diacetyl, a respiratory irritant known to be associated with bronchiolitis obliterans (popcorn lung), is produced by the aerosol vapors from buttered popcorn and certain fruit-flavored e-cigarette liquids.

As public health advocates, we must provide research to the FDA about the health hazards of the flavoring added to e-cigarettes and continue to fight for this regulation. We must support evidence-based tobacco control interventions, such as hard-hitting media campaigns and tobacco excise taxes, and promote access to cessation treatment, smoke-free policies, and statewide funding. Elimination of tobacco products will reduce the public health burden of tobacco-related illness.

Andrea Spatarella, DNP, RN, FNP-BC, Christine Fardellone, DNP, RN, Raisa Abramova, FNP-BC, RN

Great Neck, NY

Continue for Precepting & E-Quality of Care >>

Precepting & E-Quality of Care

As a woman of the baby-boomer generation, I was raised in an era when feminism was a focus for many. There was a great deal being written and discussed to encourage women to attain equal pay for equal work. Because nursing was (and still is) a profession dominated by women, this was a frequent topic in the classroom. We were repeatedly told, “Don’t give away your knowledge for free” and “You deserve to be paid what you’re worth, don’t discount yourself.”

I find it very telling that the same female-dominated academic programs that encouraged me to seek proper payment are now taking advantage of my free labor. I am somewhat offended by this attitude and consider it a step backward. Each time NPs are guilted or browbeaten into teaching without proper compensation, the profession is devalued. To continue to participate is to enable a problematic, if not broken, system.

NP education is in need of major reform. The precepting issue is the weak link in becoming a qualified professional who is able to meet the demands and responsibilities that academics and politicos are pushing harder and harder for. Our physician and PA colleagues can rightly argue that their clinical education is superior to ours—and I cannot fault our colleagues for expressing concern about quality of care. If nursing really wants an equal place at the table, this weakness must be improved, or the naysayers will have plenty of evidence that they were correct in the years to come.

Rebecca Shively, MSN, RN, FNP-BC

San Marcos, TX

Continue for NP Schools & Their Rigid Rules >>

NP Schools & Their Rigid Rules

I have been a preceptor for at least a dozen NP students and have yet to be offered compensation. Preceptors take the place of a paid instructor, giving away free advice and experiences. I don’t mind doing this, but at times it can be a struggle. Some students, for example, have never done a pelvic exam. Letting an inexperienced NP student practice a pelvic exam on a patient who made an appointment to see an experienced provider is unjust and unfair to the patient—I won’t do it. These schools need to provide practice sessions on paid patients so their students can learn these skills.

I have my beef with the institutes of higher learning, not the students. It feels like a one-way street. You fill out the forms they require in order to precept, which takes up valuable work time. You equip their students with the skills they need to practice safely and correctly, and then try to fill out their evaluation sheets on things that students are not licensed to do.

Schools present their contracts and won’t adapt them to match what your employer wants. We are doing them a service, yet they dictate how we do it. My practice no longer takes students from certain schools, simply because we do not agree with their contracts. These poor students are thrown out without a life raft to find their preceptors! Aren’t their schools getting paid to do something?

Carol Glascock, WHNP-BC

Columbia, MO

Continue for Teaching & Precepting: Two Sides of the Same Coin >>

Teaching & Precepting: Two Sides of the Same Coin

I am a 64-year-old NP who has been precepting in Montana for the past four years. The students I precept are responsible for finding their own preceptors, just as I was 20+ years ago. However, preceptors are hard to find here, as the population is widely scattered; this places an emotional burden on students. They cannot be picky in choosing where they go. Thus, students may not be familiar with the preceptor’s practice or ability to teach.

The students I precept are in doctorate programs. My experience has shown that these students have very little understanding of practical application and instead have an overabundance of theoretical knowledge that does not always apply to seeing and treating patients. I believe that this, and the suggested “lack of preparedness,” is the fault of the program—not of the student.

Regardless of program faults, students are looking to learn from our experience. Teaching is part of being a preceptor; if you do not want to teach, being a preceptor is not for you. If you want to share your experience and knowledge with those following you (mindful that they may treat you in the future), precepting is an enjoyable experience. But—a good practitioner does not always make a good teacher.

Before becoming a preceptor, you must consider your time constraints, as well as your staff’s. You also must consider how your patients will react to seeing a student in your place.

Preceptors need to have a relationship with the student’s university apart from signing a paper saying they, the NP, will be the student’s preceptor. The university needs to be more proactive, as medical schools are, when finding preceptors willing to take students.

Compensation is another consideration that is rarely mentioned or discussed. Compensation would eliminate some of the negative reactions and might get more preceptors to sign on.

Harold W. Bruce, MSN, FNP-BC

Butte, MT

Continue for Collision of Causes for Precepting Hurdles >>

Collision of Causes for Precepting Hurdles

I am a family NP practicing in a large internal medicine practice owned by a university-based health care system. I precept NP students because I feel an obligation to my profession. However, the stress and additional workload that precepting places on me will probably lead me to stop sooner than I would like.

The inability to locate enough quality preceptors is a multifaceted issue. Too many students in too many programs, as mentioned in the editorial, is one contributing problem. I have been told by nursing professors that universities profit from their NP programs. They have an incentive to admit a large quantity of students and push them through. We could learn from our MD colleagues, who recognize the value of limiting student numbers.

The rise in NP students has led to a high number of poorly prepared students who enter their programs with no experience as RNs. Preceptors should not teach the basics, and professors should not expect preceptors to do so. Likewise, professors should not expect employers to fill in the gaps for new NPs they hire.

Many NP students have no “real-life” clinical experience to supplement their knowledge and skills. A strong foundation that combines nursing and medical knowledge, clinical experiences, basic assessment skills, and an understanding of human nature and human responses is crucial to being a successful NP. The latter is only developed through experience with patients. Students cannot develop these skills when their professors push them to immediately enroll in NP or DNP programs upon graduation from their BSN or basic non-NP MSN programs.

Our programs would do well to provide all the didactic classroom hours prior to the start of clinical rotations. Thus, the limited clinical hours can be used to hone clinical skills, instead of the current practice of students learning basics while also trying to incorporate knowledge with practice. It is a disservice to our NP students not to have completed classroom learning before starting their limited clinical rotations.

Preceptor overload and “burnout” occurs when very busy NPs are expected to fit precepting into their usual clinical sessions. There are strict mandates that dictate the number of residents a physician can precept. Those rules also allot physicians time reserved just for precepting. Why are NPs expected to precept during their already overworked day? Why haven’t our Boards of Nursing and nursing educators demanded this?

Precepting puts us behind during our clinical sessions. In some cases, it can impact our relative value units or patient numbers and salaries. We are teaching on our own time, with no incentives or monetary gain, yet we are expected to devote time and resources to our students.

Most of us do not receive merit-based financial rewards for the extra work. When did it become wrong to expect to be paid for our work? No other profession has this sense of guilt or self-recrimination when asking to be paid for services.

Preceptor training is another issue. Unlike physicians, we are not acculturated in the “see one, do one, teach one” manner. In nursing, we are trained that we must be taught, observed, and tested before being allowed to do anything new. We have a need to be taught everything, including how to precept. That being said, precepting is both an art and a science that involves grasping the basic tenets of learning and mentoring. These are skills that should be taught through observation or in classes so that we can pass on our knowledge. If our NP programs were longer and more step-by-step—in terms of first acquiring knowledge, then incorporating clinical skills with practice—we might learn the skills of teaching and mentoring without feeling we need additional “education” in precepting.

I have been in nursing for more than 40 years and love my profession. There are challenges ahead of us that we can only meet if we are brave enough to look clearly at the way we teach younger nurses, create improved ways of teaching those who will replace us, and actually recognize the value and efforts of those we ask to precept the next generation.

Theresa Dippolito, MSN, NP-C, CRNP, APN, CCM

Levittown, PA

Continue for Raising the Bar >>

Raising the Bar

I no longer want to be involved in precepting. I, too, find the students to be poorly prepared, and I was flabbergasted when I read a recent post on Facebook—a student offered to pay her preceptor to sign off on her clinicals!

I graduated from an FNP program in 1998 and also felt unprepared at first. My class thought like nurses, in that we expected things to be presented to us. Very few of us were aware that we should prepare ourselves, and the program I went through did nothing to inform us of this. It was a rude awakening.

NP programs should have improved since then, but they certainly have not. I have precepted multiple students who did not know how to do a proper physical exam, despite having passed their related courses. I have also precepted students who thought they knew everything and felt I should let them practice solo. Sadly, the majority were simultaneously in both groups.

There is still the stigma that we should remain within a nursing philosophy when we practice, when the reality is that we practice side by side with the doctors. We need to think critically, as they do, and have our programs teach such thinking via competent instructors.

My suggestions include a competency exam for NP instructors so that we can assure a higher, more standardized level of teaching. There should also be a prep course for potential NP students on how to think, including an explanation that it will be their responsibility to go after knowledge as well. Finally, we need to stray from the nursing philosophy-type teaching in NP programs and instead focus on stronger clinical knowledge and competence.

Nikki Knight, MSN, FNP-C

San Francisco, CA

But First, a Word About Vaping …

As advocates for tobacco control, my colleagues and I took great interest in Randy D. Danielsen’s editorial, “Vaping: Are Its ‘Benefits’ a Lot of Hot Air?” (Clinician Reviews. 2016;26[6]:15-16). Our practice offers evidence-based cessation treatment for individuals with nicotine addiction through counseling, pharmacotherapy, and the use of nicotine replacement products.

At our center, we often interact with clients who have had multiple quit attempts. Many of our clients state that they have been unsuccessful using an e-cigarette as a smoking cessation strategy. More often than not, they report smoking a cigarette “here and there” along with “vaping,” until they eventually relapse to their usual smoking pattern. Some report that they smoke even more than before they tried to quit. We have concerns about how vaping may renormalize the behaviors associated with smoking. Our clients say that when they vape, it reminds them of the “social” aspects of smoking— “being part of a group” and participating in an activity that keeps their hands busy.

Recent literature suggests that curiosity is the primary reason adolescents engage in e-cigarette use. While the newly implemented FDA regulations on e-cigarettes may keep these products out of the hands of some adolescents by prohibiting sales to those younger than 18, there is much more to consider. Along with exposure to nicotine, these devices offer a variety of kid-friendly flavorings that make these products attractive to middle and high school youth. Flavorings will not be regulated at this point in time.

According to researchers, this is a major concern. Findings from studies report that when inhaled, certain flavors are more harmful than others. For example, very high—even toxic—levels of benzaldehyde are inhaled by the user when cherry-flavored e-liquid is heated at high temperatures. The chemical diacetyl, a respiratory irritant known to be associated with bronchiolitis obliterans (popcorn lung), is produced by the aerosol vapors from buttered popcorn and certain fruit-flavored e-cigarette liquids.

As public health advocates, we must provide research to the FDA about the health hazards of the flavoring added to e-cigarettes and continue to fight for this regulation. We must support evidence-based tobacco control interventions, such as hard-hitting media campaigns and tobacco excise taxes, and promote access to cessation treatment, smoke-free policies, and statewide funding. Elimination of tobacco products will reduce the public health burden of tobacco-related illness.

Andrea Spatarella, DNP, RN, FNP-BC, Christine Fardellone, DNP, RN, Raisa Abramova, FNP-BC, RN

Great Neck, NY

Continue for Precepting & E-Quality of Care >>

Precepting & E-Quality of Care

As a woman of the baby-boomer generation, I was raised in an era when feminism was a focus for many. There was a great deal being written and discussed to encourage women to attain equal pay for equal work. Because nursing was (and still is) a profession dominated by women, this was a frequent topic in the classroom. We were repeatedly told, “Don’t give away your knowledge for free” and “You deserve to be paid what you’re worth, don’t discount yourself.”

I find it very telling that the same female-dominated academic programs that encouraged me to seek proper payment are now taking advantage of my free labor. I am somewhat offended by this attitude and consider it a step backward. Each time NPs are guilted or browbeaten into teaching without proper compensation, the profession is devalued. To continue to participate is to enable a problematic, if not broken, system.

NP education is in need of major reform. The precepting issue is the weak link in becoming a qualified professional who is able to meet the demands and responsibilities that academics and politicos are pushing harder and harder for. Our physician and PA colleagues can rightly argue that their clinical education is superior to ours—and I cannot fault our colleagues for expressing concern about quality of care. If nursing really wants an equal place at the table, this weakness must be improved, or the naysayers will have plenty of evidence that they were correct in the years to come.

Rebecca Shively, MSN, RN, FNP-BC

San Marcos, TX

Continue for NP Schools & Their Rigid Rules >>

NP Schools & Their Rigid Rules

I have been a preceptor for at least a dozen NP students and have yet to be offered compensation. Preceptors take the place of a paid instructor, giving away free advice and experiences. I don’t mind doing this, but at times it can be a struggle. Some students, for example, have never done a pelvic exam. Letting an inexperienced NP student practice a pelvic exam on a patient who made an appointment to see an experienced provider is unjust and unfair to the patient—I won’t do it. These schools need to provide practice sessions on paid patients so their students can learn these skills.

I have my beef with the institutes of higher learning, not the students. It feels like a one-way street. You fill out the forms they require in order to precept, which takes up valuable work time. You equip their students with the skills they need to practice safely and correctly, and then try to fill out their evaluation sheets on things that students are not licensed to do.

Schools present their contracts and won’t adapt them to match what your employer wants. We are doing them a service, yet they dictate how we do it. My practice no longer takes students from certain schools, simply because we do not agree with their contracts. These poor students are thrown out without a life raft to find their preceptors! Aren’t their schools getting paid to do something?

Carol Glascock, WHNP-BC

Columbia, MO

Continue for Teaching & Precepting: Two Sides of the Same Coin >>

Teaching & Precepting: Two Sides of the Same Coin

I am a 64-year-old NP who has been precepting in Montana for the past four years. The students I precept are responsible for finding their own preceptors, just as I was 20+ years ago. However, preceptors are hard to find here, as the population is widely scattered; this places an emotional burden on students. They cannot be picky in choosing where they go. Thus, students may not be familiar with the preceptor’s practice or ability to teach.

The students I precept are in doctorate programs. My experience has shown that these students have very little understanding of practical application and instead have an overabundance of theoretical knowledge that does not always apply to seeing and treating patients. I believe that this, and the suggested “lack of preparedness,” is the fault of the program—not of the student.

Regardless of program faults, students are looking to learn from our experience. Teaching is part of being a preceptor; if you do not want to teach, being a preceptor is not for you. If you want to share your experience and knowledge with those following you (mindful that they may treat you in the future), precepting is an enjoyable experience. But—a good practitioner does not always make a good teacher.

Before becoming a preceptor, you must consider your time constraints, as well as your staff’s. You also must consider how your patients will react to seeing a student in your place.

Preceptors need to have a relationship with the student’s university apart from signing a paper saying they, the NP, will be the student’s preceptor. The university needs to be more proactive, as medical schools are, when finding preceptors willing to take students.

Compensation is another consideration that is rarely mentioned or discussed. Compensation would eliminate some of the negative reactions and might get more preceptors to sign on.

Harold W. Bruce, MSN, FNP-BC

Butte, MT

Continue for Collision of Causes for Precepting Hurdles >>

Collision of Causes for Precepting Hurdles

I am a family NP practicing in a large internal medicine practice owned by a university-based health care system. I precept NP students because I feel an obligation to my profession. However, the stress and additional workload that precepting places on me will probably lead me to stop sooner than I would like.

The inability to locate enough quality preceptors is a multifaceted issue. Too many students in too many programs, as mentioned in the editorial, is one contributing problem. I have been told by nursing professors that universities profit from their NP programs. They have an incentive to admit a large quantity of students and push them through. We could learn from our MD colleagues, who recognize the value of limiting student numbers.

The rise in NP students has led to a high number of poorly prepared students who enter their programs with no experience as RNs. Preceptors should not teach the basics, and professors should not expect preceptors to do so. Likewise, professors should not expect employers to fill in the gaps for new NPs they hire.

Many NP students have no “real-life” clinical experience to supplement their knowledge and skills. A strong foundation that combines nursing and medical knowledge, clinical experiences, basic assessment skills, and an understanding of human nature and human responses is crucial to being a successful NP. The latter is only developed through experience with patients. Students cannot develop these skills when their professors push them to immediately enroll in NP or DNP programs upon graduation from their BSN or basic non-NP MSN programs.

Our programs would do well to provide all the didactic classroom hours prior to the start of clinical rotations. Thus, the limited clinical hours can be used to hone clinical skills, instead of the current practice of students learning basics while also trying to incorporate knowledge with practice. It is a disservice to our NP students not to have completed classroom learning before starting their limited clinical rotations.

Preceptor overload and “burnout” occurs when very busy NPs are expected to fit precepting into their usual clinical sessions. There are strict mandates that dictate the number of residents a physician can precept. Those rules also allot physicians time reserved just for precepting. Why are NPs expected to precept during their already overworked day? Why haven’t our Boards of Nursing and nursing educators demanded this?

Precepting puts us behind during our clinical sessions. In some cases, it can impact our relative value units or patient numbers and salaries. We are teaching on our own time, with no incentives or monetary gain, yet we are expected to devote time and resources to our students.

Most of us do not receive merit-based financial rewards for the extra work. When did it become wrong to expect to be paid for our work? No other profession has this sense of guilt or self-recrimination when asking to be paid for services.

Preceptor training is another issue. Unlike physicians, we are not acculturated in the “see one, do one, teach one” manner. In nursing, we are trained that we must be taught, observed, and tested before being allowed to do anything new. We have a need to be taught everything, including how to precept. That being said, precepting is both an art and a science that involves grasping the basic tenets of learning and mentoring. These are skills that should be taught through observation or in classes so that we can pass on our knowledge. If our NP programs were longer and more step-by-step—in terms of first acquiring knowledge, then incorporating clinical skills with practice—we might learn the skills of teaching and mentoring without feeling we need additional “education” in precepting.

I have been in nursing for more than 40 years and love my profession. There are challenges ahead of us that we can only meet if we are brave enough to look clearly at the way we teach younger nurses, create improved ways of teaching those who will replace us, and actually recognize the value and efforts of those we ask to precept the next generation.

Theresa Dippolito, MSN, NP-C, CRNP, APN, CCM

Levittown, PA

Continue for Raising the Bar >>

Raising the Bar

I no longer want to be involved in precepting. I, too, find the students to be poorly prepared, and I was flabbergasted when I read a recent post on Facebook—a student offered to pay her preceptor to sign off on her clinicals!

I graduated from an FNP program in 1998 and also felt unprepared at first. My class thought like nurses, in that we expected things to be presented to us. Very few of us were aware that we should prepare ourselves, and the program I went through did nothing to inform us of this. It was a rude awakening.

NP programs should have improved since then, but they certainly have not. I have precepted multiple students who did not know how to do a proper physical exam, despite having passed their related courses. I have also precepted students who thought they knew everything and felt I should let them practice solo. Sadly, the majority were simultaneously in both groups.

There is still the stigma that we should remain within a nursing philosophy when we practice, when the reality is that we practice side by side with the doctors. We need to think critically, as they do, and have our programs teach such thinking via competent instructors.

My suggestions include a competency exam for NP instructors so that we can assure a higher, more standardized level of teaching. There should also be a prep course for potential NP students on how to think, including an explanation that it will be their responsibility to go after knowledge as well. Finally, we need to stray from the nursing philosophy-type teaching in NP programs and instead focus on stronger clinical knowledge and competence.

Nikki Knight, MSN, FNP-C

San Francisco, CA

Madness and guns

“Bang, bang, you’re dead” has been uttered by millions of American children for generations. It is typical of the ordinary, angry, murderous thoughts of childhood; variations of it are universal. We expect children to learn to control their anger as they grow up and not to play out their angry wishes in reality. Unfortunately, this doesn’t always happen.

Following the many recent dramatic, crazed mass shootings, some commentators have called for restricting gun access for those with mental illness, but psychiatrists have rightly pointed out that murderers, including terror-inducing mass murderers, do not usually have a history of formally diagnosed mental illness. The psychiatrists are right for a reason: The potential for sudden, often unexpected, violence is widespread. This essay will employ a developmental perspective on how people handle anger, and on how we come to distinguish between fantasy and reality, to inform an understanding of gun violence.

Baby hyenas often try to kill their siblings shortly after birth. Human babies do not. They are not only motorically undeveloped, but their emotions appear to be mostly limited to the nonspecific states of distress and satisfaction. Distinct affects, such as anger, differentiate gradually. Babies smile by 2 months. Babies’ specific affection for and loyalty to their caregivers comes along a bit later, hence stranger anxiety commonly appears around 9 months. Facial expressions, sounds, and activity that look specifically like anger, and that occur when babies are frustrated or injured, are observed in the second half of the first year of human life. In the second year of life, feelings such as shame and guilt, which are dependent on the development of a distinct sense of self and other, appear. Shame and guilt, along with loving feelings, help form the basis for consideration of others and for the diminishment of young children’s omnipotence and egocentricity; they become a kind of social “glue,” tempering selfish, angry pursuits and tantrums.

There is a typical developmental sequence of how people come to handle their anger. Younger children express emotions directly, with little restraint; they hit, bite, and scream. Older children should be able to have more impulse control and be able to regulate the motor and verbal expression of their anger to a greater degree. At some point, most also become able to acknowledge their anger and not have to deny it. Adults, in principle, should be able both to inhibit the uncontrolled expression of anger and also, when appropriate, be able to use anger constructively. How tenuous this accomplishment is, and how often adults can function like overgrown children, can be readily observed at children’s sports matches, in which the children are often better behaved than their parents. In short, humans are endowed with the potential for enormous, destructive anger, but also, in our caring for others, a counterbalance to it.

The process of emotional development, and the regulation of anger, is intertwined with the development of the sense of self and of other. Evidence suggests that babies can start to distinguish self and other at birth, but that a full and reliable sense of self and other is a long, complicated developmental process.

The article by pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott, “Transitional Objects and Transitional Phenomena – A Study of the First Not-Me Possession,” one of the most frequently cited papers in the psychoanalytic literature, addresses this process (Int J Psychoanal. 1953;34[2]89-97). While transitional objects are not a human universal, the process of differentiating oneself from others, of finding out what is me and what is not-me, is. According to Dr. Winnicott, learning what is self and what is other assists babies in their related challenges of distinguishing animate from inanimate, wishes from causes, and fantasy from reality. Mother usually appears when I’m distressed – is she a part of me or a separate being? Does she appear because I wish, because I cry, or does she not appear despite my efforts? People never fully complete the developmental distinctions between self and other, and between wishes, fantasies, and magic, as opposed to reality.

Stressful events, such as a sudden loss, for example, commonly prompt a regressive denial of reality: “I don’t believe what I see” can be meant literally. When attending movies, we all “suspend disbelief” and participate, at least vicariously, in wishful magic. Further, although after early childhood, problems understanding material reality are characteristic of psychosis, all people are prone to at least occasional wishful or fearful errors in grasping social reality – we misperceive the meaning and intentions of others.

Combining the understanding of the development of how children handle anger and how they learn to differentiate self and other, and fantasy and reality, leads to an additional, important point. Suppose a person can’t tolerate his own angry wishes and he doesn’t distinguish well between self and other. He can easily attribute his own unwanted hatefulness to others, and he may then want to attack them for it. This process is extremely common, and we are all inclined to it to some degree. As childishly simplistic as it sounds, for humans, there is almost always an us and a them; we are good and they are bad. In addition to directing anger inappropriately at others, people can, of course, turn anger against themselves, and with just as much unreasonableness and venom. However much we grow up, development is never complete. We remain irrational, with a tenuous and incomplete perception of reality.

One would never give a weapon to an infant, but in light of these difficulties with respect to human development, should one give a weapon to an adult?

Whether or not humans have the self-control to possess weapons of great power and destructiveness, weapons are part of our evolution as a species. They have likely contributed to our remarkable success, protecting us from predators and enriching our diets. It is worth noting, however, that small-scale societies such as those we all evolved from often have high murder rates, and that lower rates of intra-societal violence tend to be found in larger, more highly regulated societies. People do not always adequately manage aggression themselves and benefit from external, societal assistance.

We humans all have the capacity to be mad: to be angry, to be crazy, to be crazed with anger. Fantasies of revenge are common when one is angry, and expectable when one has been hurt. Yet, expressions such as “blind with rage” and “seeing red” attest to the challenges to the sense of reality that rage can induce. The crucial distinction between having vengeful wishes and fantasies, and putting them into action, into reality, can crumble quickly. In addition to anger, fear is another emotion that can distort the perception of reality. Regular attention to the news suggests that police, whether they are aware of it or not, are more fearful of black men than of other people. They are more likely to perceive them as being armed and are quicker to shoot. For police and civilians alike, the presence of guns simultaneously requires greater impulse control and makes impulse control more difficult. The more guns, the more fear and anger, the more shootings – a vicious cycle.

Most people who commit crimes with guns, whether a singular “crime of passion” or a mass murder, have been crazed with anger. Some have been known to police as angry individuals with histories of getting into trouble, others not. But most have been angry, isolated individuals with problematic social relationships and little warm or respectful involvement with others to counterbalance their anger. Given the challenges inherent in human development, it is not surprising that in most societies there are a fair number of disaffected, angry, isolated individuals with inadequate realistic emotional regulation.

According to the anthropologist Scott Atran, who has studied both would-be and convicted terrorists, in addition to those individuals who are angry and disturbed, many recruits to terrorism are merely unsettled youth eager to find a sense of identity and belonging in a “band of brothers (and sisters).” He has described the “devoted actor,” who merges his identity with his combat unit and becomes willing to die for his comrades or their cause. These observations are consistent with both anthropological ideas about cultural influences on the sense of self in relation to groups, and with psychoanalytic emphasis on the difficulty of achieving a firm sense of self and other. In fusing with the group and its ideology, one gives up an independent self while feeling that one has gained a sense of self, belonging, and meaning. Whatever the psychological and social picture, it is obvious that the angry, isolated individuals who may regress and explode, and the countless unsettled youth of modern societies, cannot all be identified, tracked, and regulated by society, nor will they all seek help for their troubles. The United States’ decisions to allow massively destructive weapons to anyone and everyone are counter to everything we know about people.

Among many other things, Sigmund Freud is known for highlighting the comment that “The first man to hurl an insult rather than a spear was the founder of civilization.” Anger that is put into words is less destructive than anger put into violent action. From this point of view, the widespread presence of guns undermines civilization. Guns invite putting anger into action rather than conversation – they are a hindrance to impulse control and they shut down discussion. Democracy, a form of civilization contingent on impulse control, discussion, and voting, rather than submission to violent authority, is particularly undermined by guns. Congress should know: It has been so intimidated by the National Rifle Association that it has refused to outlaw private possession of military assault rifles and at the same time has submitted to outlawing the use of federal funds for research about gun violence. Despite this ban on research, there is overwhelming evidence that the presence of a gun in a home is associated not only with significantly increased murder rates, but also, as mental health professionals well know, greatly increased incidence of suicide.

As humans, we all have the ability to control ourselves to some degree. But, we all have the potential to become mad and to lose control. Our internal self-regulation is sometimes insufficient, and we need the restraining influence of our fellow humans. This can be in the form of a comforting word, a warning gesture, a carrot or a stick, or a law. The regulation of guns, assault rifles, and bomb-making materials is a mark of civilization.

Dr. Blum is a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst in private practice in Philadelphia. He teaches in the departments of anthropology and psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania and at the Psychoanalytic Center of Philadelphia.

“Bang, bang, you’re dead” has been uttered by millions of American children for generations. It is typical of the ordinary, angry, murderous thoughts of childhood; variations of it are universal. We expect children to learn to control their anger as they grow up and not to play out their angry wishes in reality. Unfortunately, this doesn’t always happen.

Following the many recent dramatic, crazed mass shootings, some commentators have called for restricting gun access for those with mental illness, but psychiatrists have rightly pointed out that murderers, including terror-inducing mass murderers, do not usually have a history of formally diagnosed mental illness. The psychiatrists are right for a reason: The potential for sudden, often unexpected, violence is widespread. This essay will employ a developmental perspective on how people handle anger, and on how we come to distinguish between fantasy and reality, to inform an understanding of gun violence.

Baby hyenas often try to kill their siblings shortly after birth. Human babies do not. They are not only motorically undeveloped, but their emotions appear to be mostly limited to the nonspecific states of distress and satisfaction. Distinct affects, such as anger, differentiate gradually. Babies smile by 2 months. Babies’ specific affection for and loyalty to their caregivers comes along a bit later, hence stranger anxiety commonly appears around 9 months. Facial expressions, sounds, and activity that look specifically like anger, and that occur when babies are frustrated or injured, are observed in the second half of the first year of human life. In the second year of life, feelings such as shame and guilt, which are dependent on the development of a distinct sense of self and other, appear. Shame and guilt, along with loving feelings, help form the basis for consideration of others and for the diminishment of young children’s omnipotence and egocentricity; they become a kind of social “glue,” tempering selfish, angry pursuits and tantrums.