User login

What Matters: Probiotics for colds

In the midst of the cold and flu season, we should reflect on the fact that our patients are laying down billions of dollars annually on preventions and cures for respiratory tract infections.

An aside: I am frequently turned down on my offer of the influenza vaccine, for which we probably have the best evidence. But $60 per month for a completely unproven preventive/curative agent made in some random factory in some random foreign land with no guarantee of good manufacturing practices (never mind the lack of active ingredients)? Stores can’t keep it in stock.

But I digress.

Our patients may lack the awareness of where to access evidence-based information when seeking answers about efficacy for cold remedies. So, it’s up to us to have at least some sense of where to get reliable information.

Truth be told, I am an enormous fan of safe and effective nonmedication therapies for the treatment and prevention of disease. So, when time permits, I will do a quick PubMed.gov search limiting my articles to randomized trials or systematic reviews on the latest and greatest home remedy.

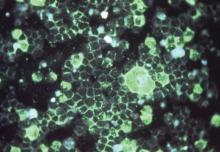

Probiotics have been around for a while, and I think of them as a cure in search of a disease. The Cochrane Collaboration conducted a systematic review evaluating probiotics for the prevention of upper respiratory tract infection. In this review, 13 randomized, controlled trials were included (Explore [NY]. 2015 Sep-Oct;11[5]:418-20).

Probiotics were observed to be significantly better than placebo for reducing episodes of upper respiratory tract infection, the mean duration of episodes, antibiotic prescription rates, and cold-related absences. The evidence was of moderate to low quality.

Some may wonder how an ingested probiotic helps the respiratory tract stave off or fight infection. The prevailing theory appears to be that probiotics may function by mobilizing cells from the intestine to immunomodulate respiratory mucosa.

As for what probiotic/organism to prescribe? On this issue, there is a lot of smoke and not a lot of heat.

In general, the product should be encapsulated, and the label should include the genus and species of the strains (e.g., Lactobacillus acidophilus), the number of organisms (e.g., 5 billion), storage conditions (e.g., refrigerated or room temperature), and the shelf life. Pharmacy chain house brands may be cheaper. Gummy and chewable products tend to have 92% fewer beneficial bacteria than standard formulations.

How can we ensure purity?

That is tough, because supplements like probiotics are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration above and beyond the agency’s trying to ensure good manufacturing practices. However, companies such as LabDoor (which generates revenue through affiliate links) test and grade supplements for label accuracy and purity. Websites like this might be the best place to start.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

In the midst of the cold and flu season, we should reflect on the fact that our patients are laying down billions of dollars annually on preventions and cures for respiratory tract infections.

An aside: I am frequently turned down on my offer of the influenza vaccine, for which we probably have the best evidence. But $60 per month for a completely unproven preventive/curative agent made in some random factory in some random foreign land with no guarantee of good manufacturing practices (never mind the lack of active ingredients)? Stores can’t keep it in stock.

But I digress.

Our patients may lack the awareness of where to access evidence-based information when seeking answers about efficacy for cold remedies. So, it’s up to us to have at least some sense of where to get reliable information.

Truth be told, I am an enormous fan of safe and effective nonmedication therapies for the treatment and prevention of disease. So, when time permits, I will do a quick PubMed.gov search limiting my articles to randomized trials or systematic reviews on the latest and greatest home remedy.

Probiotics have been around for a while, and I think of them as a cure in search of a disease. The Cochrane Collaboration conducted a systematic review evaluating probiotics for the prevention of upper respiratory tract infection. In this review, 13 randomized, controlled trials were included (Explore [NY]. 2015 Sep-Oct;11[5]:418-20).

Probiotics were observed to be significantly better than placebo for reducing episodes of upper respiratory tract infection, the mean duration of episodes, antibiotic prescription rates, and cold-related absences. The evidence was of moderate to low quality.

Some may wonder how an ingested probiotic helps the respiratory tract stave off or fight infection. The prevailing theory appears to be that probiotics may function by mobilizing cells from the intestine to immunomodulate respiratory mucosa.

As for what probiotic/organism to prescribe? On this issue, there is a lot of smoke and not a lot of heat.

In general, the product should be encapsulated, and the label should include the genus and species of the strains (e.g., Lactobacillus acidophilus), the number of organisms (e.g., 5 billion), storage conditions (e.g., refrigerated or room temperature), and the shelf life. Pharmacy chain house brands may be cheaper. Gummy and chewable products tend to have 92% fewer beneficial bacteria than standard formulations.

How can we ensure purity?

That is tough, because supplements like probiotics are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration above and beyond the agency’s trying to ensure good manufacturing practices. However, companies such as LabDoor (which generates revenue through affiliate links) test and grade supplements for label accuracy and purity. Websites like this might be the best place to start.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

In the midst of the cold and flu season, we should reflect on the fact that our patients are laying down billions of dollars annually on preventions and cures for respiratory tract infections.

An aside: I am frequently turned down on my offer of the influenza vaccine, for which we probably have the best evidence. But $60 per month for a completely unproven preventive/curative agent made in some random factory in some random foreign land with no guarantee of good manufacturing practices (never mind the lack of active ingredients)? Stores can’t keep it in stock.

But I digress.

Our patients may lack the awareness of where to access evidence-based information when seeking answers about efficacy for cold remedies. So, it’s up to us to have at least some sense of where to get reliable information.

Truth be told, I am an enormous fan of safe and effective nonmedication therapies for the treatment and prevention of disease. So, when time permits, I will do a quick PubMed.gov search limiting my articles to randomized trials or systematic reviews on the latest and greatest home remedy.

Probiotics have been around for a while, and I think of them as a cure in search of a disease. The Cochrane Collaboration conducted a systematic review evaluating probiotics for the prevention of upper respiratory tract infection. In this review, 13 randomized, controlled trials were included (Explore [NY]. 2015 Sep-Oct;11[5]:418-20).

Probiotics were observed to be significantly better than placebo for reducing episodes of upper respiratory tract infection, the mean duration of episodes, antibiotic prescription rates, and cold-related absences. The evidence was of moderate to low quality.

Some may wonder how an ingested probiotic helps the respiratory tract stave off or fight infection. The prevailing theory appears to be that probiotics may function by mobilizing cells from the intestine to immunomodulate respiratory mucosa.

As for what probiotic/organism to prescribe? On this issue, there is a lot of smoke and not a lot of heat.

In general, the product should be encapsulated, and the label should include the genus and species of the strains (e.g., Lactobacillus acidophilus), the number of organisms (e.g., 5 billion), storage conditions (e.g., refrigerated or room temperature), and the shelf life. Pharmacy chain house brands may be cheaper. Gummy and chewable products tend to have 92% fewer beneficial bacteria than standard formulations.

How can we ensure purity?

That is tough, because supplements like probiotics are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration above and beyond the agency’s trying to ensure good manufacturing practices. However, companies such as LabDoor (which generates revenue through affiliate links) test and grade supplements for label accuracy and purity. Websites like this might be the best place to start.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

Vascular surgery – it’s personal

Let’s get personal for a moment. The next time you walk past your local cancer center, pay attention to the signs, the branding, and the message. I’ll bet you won’t have to look too hard to see reference to personalized or precision medicine. Our oncology colleagues have completely invested in these principles and it’s easy to see why.

The concept of personalized medicine involves therapeutic strategies that take individual variability into account. Along with advances in patient care this strategy has resonated with patients, funding agencies, philanthropists, and governments. Most recently, President Obama announced a new precision medicine initiative in his State of the Union Address, and this month we’ve seen these ideas reflected in Vice President Biden’s “moonshot” to cure cancer.

All well and good, but what about vascular surgery? Let’s see – making therapeutic decisions at the individual patient level, taking patient variability into account, whether its anatomy, comorbidities, genetic profile – isn’t this what we do every day? Of course, it is! We just haven’t been as forthright in owning it or broadcasting it.

If we think about it, we are further along the path to personalized vascular therapy than we think (Vascular. 2016 Jan 13. pii:1708538115624810). In a practical sense, we do it every day, whether its custom devices for aortic therapy, applying data from registries and randomized, controlled trials to individual patients, or using genetic information to make recommendations regarding medical, surgical, or endovascular therapy, we regularly make recommendations “taking individual patient variability into account.”

There are ongoing advances in all of these areas by our innovative vascular surgery colleagues. Dr. Benjamin W. Starnes is using 3-D printing to develop custom templates for personalized “point of care” aortic endograft fenestration (J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:1637-41). Genetic variability is being considered when applying medical therapy, known as pharmacogenetics, but also when applying surgical therapy, as “surgicogenetics.”

A prime example is the pioneering work led by Dr. Michael S. Conte and the late Dr. Alexander Clowes, who are attempting to explain some of the variability in outcomes following infrainguinal bypass surgery by differences in a single nucleotide polymorphism (J Vasc Surg. 2013 May;57:1179-85). Genetics drives surgical outcomes, surgicogenetics indeed!

These are just some of the examples of “Personalized Vascular Therapy” that all vascular surgeons practice to a certain extent and where there are lively areas of investigation.

So the time has come for us to not only practice personalized medicine, but to own it, to broadcast it, to leverage it, as well. Personalized Vascular Therapy has a nice ring to it, don’t you think? We do it, let’s not by shy about it.

Dr. Forbes is professor and chair of the division of vascular surgery at the University of Toronto.

Let’s get personal for a moment. The next time you walk past your local cancer center, pay attention to the signs, the branding, and the message. I’ll bet you won’t have to look too hard to see reference to personalized or precision medicine. Our oncology colleagues have completely invested in these principles and it’s easy to see why.

The concept of personalized medicine involves therapeutic strategies that take individual variability into account. Along with advances in patient care this strategy has resonated with patients, funding agencies, philanthropists, and governments. Most recently, President Obama announced a new precision medicine initiative in his State of the Union Address, and this month we’ve seen these ideas reflected in Vice President Biden’s “moonshot” to cure cancer.

All well and good, but what about vascular surgery? Let’s see – making therapeutic decisions at the individual patient level, taking patient variability into account, whether its anatomy, comorbidities, genetic profile – isn’t this what we do every day? Of course, it is! We just haven’t been as forthright in owning it or broadcasting it.

If we think about it, we are further along the path to personalized vascular therapy than we think (Vascular. 2016 Jan 13. pii:1708538115624810). In a practical sense, we do it every day, whether its custom devices for aortic therapy, applying data from registries and randomized, controlled trials to individual patients, or using genetic information to make recommendations regarding medical, surgical, or endovascular therapy, we regularly make recommendations “taking individual patient variability into account.”

There are ongoing advances in all of these areas by our innovative vascular surgery colleagues. Dr. Benjamin W. Starnes is using 3-D printing to develop custom templates for personalized “point of care” aortic endograft fenestration (J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:1637-41). Genetic variability is being considered when applying medical therapy, known as pharmacogenetics, but also when applying surgical therapy, as “surgicogenetics.”

A prime example is the pioneering work led by Dr. Michael S. Conte and the late Dr. Alexander Clowes, who are attempting to explain some of the variability in outcomes following infrainguinal bypass surgery by differences in a single nucleotide polymorphism (J Vasc Surg. 2013 May;57:1179-85). Genetics drives surgical outcomes, surgicogenetics indeed!

These are just some of the examples of “Personalized Vascular Therapy” that all vascular surgeons practice to a certain extent and where there are lively areas of investigation.

So the time has come for us to not only practice personalized medicine, but to own it, to broadcast it, to leverage it, as well. Personalized Vascular Therapy has a nice ring to it, don’t you think? We do it, let’s not by shy about it.

Dr. Forbes is professor and chair of the division of vascular surgery at the University of Toronto.

Let’s get personal for a moment. The next time you walk past your local cancer center, pay attention to the signs, the branding, and the message. I’ll bet you won’t have to look too hard to see reference to personalized or precision medicine. Our oncology colleagues have completely invested in these principles and it’s easy to see why.

The concept of personalized medicine involves therapeutic strategies that take individual variability into account. Along with advances in patient care this strategy has resonated with patients, funding agencies, philanthropists, and governments. Most recently, President Obama announced a new precision medicine initiative in his State of the Union Address, and this month we’ve seen these ideas reflected in Vice President Biden’s “moonshot” to cure cancer.

All well and good, but what about vascular surgery? Let’s see – making therapeutic decisions at the individual patient level, taking patient variability into account, whether its anatomy, comorbidities, genetic profile – isn’t this what we do every day? Of course, it is! We just haven’t been as forthright in owning it or broadcasting it.

If we think about it, we are further along the path to personalized vascular therapy than we think (Vascular. 2016 Jan 13. pii:1708538115624810). In a practical sense, we do it every day, whether its custom devices for aortic therapy, applying data from registries and randomized, controlled trials to individual patients, or using genetic information to make recommendations regarding medical, surgical, or endovascular therapy, we regularly make recommendations “taking individual patient variability into account.”

There are ongoing advances in all of these areas by our innovative vascular surgery colleagues. Dr. Benjamin W. Starnes is using 3-D printing to develop custom templates for personalized “point of care” aortic endograft fenestration (J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:1637-41). Genetic variability is being considered when applying medical therapy, known as pharmacogenetics, but also when applying surgical therapy, as “surgicogenetics.”

A prime example is the pioneering work led by Dr. Michael S. Conte and the late Dr. Alexander Clowes, who are attempting to explain some of the variability in outcomes following infrainguinal bypass surgery by differences in a single nucleotide polymorphism (J Vasc Surg. 2013 May;57:1179-85). Genetics drives surgical outcomes, surgicogenetics indeed!

These are just some of the examples of “Personalized Vascular Therapy” that all vascular surgeons practice to a certain extent and where there are lively areas of investigation.

So the time has come for us to not only practice personalized medicine, but to own it, to broadcast it, to leverage it, as well. Personalized Vascular Therapy has a nice ring to it, don’t you think? We do it, let’s not by shy about it.

Dr. Forbes is professor and chair of the division of vascular surgery at the University of Toronto.

On my own during an employee’s maternity leave

Recently, my secretary was out on maternity leave for 6 weeks.

I run a small practice, and my medical assistant works from home on the far side of town. So I was on my own at the office. My MA and I split things up, and since I was the only one physically in the building, I took over all the front office stuff and she took the back office.

I ran the front desk for the whole time – checking people in and out, taking copays, copying insurance cards, giving referrals to therapy places, sending logs to the billing company, and doing other everyday stuff.

Plenty of people asked why I didn’t hire a temp, obviously not knowing how close to the edge a modern solo practice runs. If I hire a temp, that’s another salary to pay, meaning one of the other three of us here would have to skip a few paychecks. I’m not going to put my secretary on unpaid leave for that time. She’s awesome, has been with me since 2004, and has stuck with me through good and bad years. If I don’t pay her that time, she can’t pay her rent, and I don’t have the heart to do that to her. Maybe a big corporate person wouldn’t lose any sleep about it, but I would. Great people are hard to find, and I want to keep the ones I have.

Besides, if I hired a temp, I’d have to train them from the beginning. I don’t use off-the-shelf medical software, just a system I designed myself. It would take time out of my day to teach them how to use it, where I send patients for tests and referrals, and how to sort documents accurately into the correct e-charts. So, for 6 weeks it just seemed easier to do it myself. I know how I like it done.

It wasn’t easy for my MA as well. She had to take over scheduling appointments, handling billing questions, making reminder calls, and doing other miscellaneous stuff. Even after work was over, I’d be at home catching up on all the dictations I hadn’t had time to do, and we’d be going back and forth by phone and email to settle different issues until 8:00 at night or so. By the end of the 6 weeks, we were both pretty burned out and exhausted.

I’m sure the patients weren’t thrilled, either. During that time, they could only reach a voice mail box telling them to leave a message and we’d get back to them as quickly as possible.

I assumed my practice was the only one dinky (or poor, by medical standards) enough to have to resort to this – until I had a chance conversation with a local family practice doctor, when he mentioned he’d had to do something similar when his secretary retired and he didn’t find a replacement for several weeks. A cardiologist mentioned doing the same thing while we were chatting at the hospital. Like me, they were both in solo practice.

This is, apparently, the nature of a modern small practice. The revenue and expense streams are too tight to allow for an extra salary, so even the doctor pitches in to cover. I’m sure my colleagues in large groups will laugh at the thought, but I don’t care. I have to do what’s right for my practice and to survive in the modern medical climate. And if working the front desk for a few weeks is what’s needed to stay independent, so be it.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently, my secretary was out on maternity leave for 6 weeks.

I run a small practice, and my medical assistant works from home on the far side of town. So I was on my own at the office. My MA and I split things up, and since I was the only one physically in the building, I took over all the front office stuff and she took the back office.

I ran the front desk for the whole time – checking people in and out, taking copays, copying insurance cards, giving referrals to therapy places, sending logs to the billing company, and doing other everyday stuff.

Plenty of people asked why I didn’t hire a temp, obviously not knowing how close to the edge a modern solo practice runs. If I hire a temp, that’s another salary to pay, meaning one of the other three of us here would have to skip a few paychecks. I’m not going to put my secretary on unpaid leave for that time. She’s awesome, has been with me since 2004, and has stuck with me through good and bad years. If I don’t pay her that time, she can’t pay her rent, and I don’t have the heart to do that to her. Maybe a big corporate person wouldn’t lose any sleep about it, but I would. Great people are hard to find, and I want to keep the ones I have.

Besides, if I hired a temp, I’d have to train them from the beginning. I don’t use off-the-shelf medical software, just a system I designed myself. It would take time out of my day to teach them how to use it, where I send patients for tests and referrals, and how to sort documents accurately into the correct e-charts. So, for 6 weeks it just seemed easier to do it myself. I know how I like it done.

It wasn’t easy for my MA as well. She had to take over scheduling appointments, handling billing questions, making reminder calls, and doing other miscellaneous stuff. Even after work was over, I’d be at home catching up on all the dictations I hadn’t had time to do, and we’d be going back and forth by phone and email to settle different issues until 8:00 at night or so. By the end of the 6 weeks, we were both pretty burned out and exhausted.

I’m sure the patients weren’t thrilled, either. During that time, they could only reach a voice mail box telling them to leave a message and we’d get back to them as quickly as possible.

I assumed my practice was the only one dinky (or poor, by medical standards) enough to have to resort to this – until I had a chance conversation with a local family practice doctor, when he mentioned he’d had to do something similar when his secretary retired and he didn’t find a replacement for several weeks. A cardiologist mentioned doing the same thing while we were chatting at the hospital. Like me, they were both in solo practice.

This is, apparently, the nature of a modern small practice. The revenue and expense streams are too tight to allow for an extra salary, so even the doctor pitches in to cover. I’m sure my colleagues in large groups will laugh at the thought, but I don’t care. I have to do what’s right for my practice and to survive in the modern medical climate. And if working the front desk for a few weeks is what’s needed to stay independent, so be it.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently, my secretary was out on maternity leave for 6 weeks.

I run a small practice, and my medical assistant works from home on the far side of town. So I was on my own at the office. My MA and I split things up, and since I was the only one physically in the building, I took over all the front office stuff and she took the back office.

I ran the front desk for the whole time – checking people in and out, taking copays, copying insurance cards, giving referrals to therapy places, sending logs to the billing company, and doing other everyday stuff.

Plenty of people asked why I didn’t hire a temp, obviously not knowing how close to the edge a modern solo practice runs. If I hire a temp, that’s another salary to pay, meaning one of the other three of us here would have to skip a few paychecks. I’m not going to put my secretary on unpaid leave for that time. She’s awesome, has been with me since 2004, and has stuck with me through good and bad years. If I don’t pay her that time, she can’t pay her rent, and I don’t have the heart to do that to her. Maybe a big corporate person wouldn’t lose any sleep about it, but I would. Great people are hard to find, and I want to keep the ones I have.

Besides, if I hired a temp, I’d have to train them from the beginning. I don’t use off-the-shelf medical software, just a system I designed myself. It would take time out of my day to teach them how to use it, where I send patients for tests and referrals, and how to sort documents accurately into the correct e-charts. So, for 6 weeks it just seemed easier to do it myself. I know how I like it done.

It wasn’t easy for my MA as well. She had to take over scheduling appointments, handling billing questions, making reminder calls, and doing other miscellaneous stuff. Even after work was over, I’d be at home catching up on all the dictations I hadn’t had time to do, and we’d be going back and forth by phone and email to settle different issues until 8:00 at night or so. By the end of the 6 weeks, we were both pretty burned out and exhausted.

I’m sure the patients weren’t thrilled, either. During that time, they could only reach a voice mail box telling them to leave a message and we’d get back to them as quickly as possible.

I assumed my practice was the only one dinky (or poor, by medical standards) enough to have to resort to this – until I had a chance conversation with a local family practice doctor, when he mentioned he’d had to do something similar when his secretary retired and he didn’t find a replacement for several weeks. A cardiologist mentioned doing the same thing while we were chatting at the hospital. Like me, they were both in solo practice.

This is, apparently, the nature of a modern small practice. The revenue and expense streams are too tight to allow for an extra salary, so even the doctor pitches in to cover. I’m sure my colleagues in large groups will laugh at the thought, but I don’t care. I have to do what’s right for my practice and to survive in the modern medical climate. And if working the front desk for a few weeks is what’s needed to stay independent, so be it.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Quo vadis, Psychiatry?

Psychiatrists frequently complain about their lack of recognition by other specialties, stigmatization of mental illness and the practice of psychiatry, and diminishing sense of identity as a specialty. Although I share these concerns, there is another trend that worries me perhaps more: the deliberate abandonment of more and more areas of what has traditionally been and should be psychiatry’s area of expertise and skills. Not all of this is our own doing; the fact is that other clinicians would like to get “a piece of our pie”—a trend seen in other specialties as well (eg, parts of radiology taken over by cardiologists). However, I view our role in this process as larger than other specialties’ or disciplines’ efforts.

Many of us choose not to treat substance abuse patients and instead refer them to “specialists”; yet, don’t we have enough of our own trained specialists and don’t we fill our addiction psychiatry fellowship training positions? Similarly, many do not like to treat patients with comorbid psychiatric illness and substance abuse, although this occurs frequently in our practice. Cognitive disorders often are left to neurologists and our role in managing these patients is diminishing. Pulmonologists gradually are taking over sleep disorders; one wonders why. We do not like to ask our patients about their sexual history, not even talking about treating their sexual problems! Most psychiatrists are afraid of prescribing phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors. We are leaving the entire field of human sexuality to gynecologists, urologists, and other specialists. Paraphilic disorders are something we do not want to manage and we would rather get the whole area out of our classification systems, with the implication that these are not really mental health problems.

Many of us prefer not to treat personality disorder patients—especially those with borderline personality disorder—because they are “difficult.” Some do not even feel comfortable managing adverse effects of psychotropics such as the metabolic syndrome, or use “unusual” augmentations such as thyroid hormone. We prescribe fewer and fewer older, yet efficacious, psychotropic medications; only a small fraction of psychiatrists still prescribes monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Other disciplines, eg, primary care and pain medicine, prescribe some tricyclic antidepressants more than we do. We irrationally avoid benzodiazepines and do not like prescribing lithium, because it requires ordering blood levels and lab tests. We seem comfortable only with newer antidepressants and antipsychotics. How is this way of prescribing different from what is done in primary care? Some of our leaders sneer at the idea of psychiatrists practicing psychotherapy, perhaps feeling that such a “lowly art” should be provided by psychologists and social workers. We do not address relational issues. Last but not least, I hear colleagues saying that they do not like to treat “difficult” patients.

What are we aspiring to be and to do? To treat schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and maybe depression, with a limited medication armamentarium we feel comfortable with and no psychotherapy? I am sure that many will say I am exaggerating, but I think not. We have, as Pogo said, met the enemy and he is us. We should get off the slippery slope of selling out psychiatry piece-by-piece, and fully embrace—clinically and research-wise (funding!)—all of what has been part of psychiatry.

Psychiatrists frequently complain about their lack of recognition by other specialties, stigmatization of mental illness and the practice of psychiatry, and diminishing sense of identity as a specialty. Although I share these concerns, there is another trend that worries me perhaps more: the deliberate abandonment of more and more areas of what has traditionally been and should be psychiatry’s area of expertise and skills. Not all of this is our own doing; the fact is that other clinicians would like to get “a piece of our pie”—a trend seen in other specialties as well (eg, parts of radiology taken over by cardiologists). However, I view our role in this process as larger than other specialties’ or disciplines’ efforts.

Many of us choose not to treat substance abuse patients and instead refer them to “specialists”; yet, don’t we have enough of our own trained specialists and don’t we fill our addiction psychiatry fellowship training positions? Similarly, many do not like to treat patients with comorbid psychiatric illness and substance abuse, although this occurs frequently in our practice. Cognitive disorders often are left to neurologists and our role in managing these patients is diminishing. Pulmonologists gradually are taking over sleep disorders; one wonders why. We do not like to ask our patients about their sexual history, not even talking about treating their sexual problems! Most psychiatrists are afraid of prescribing phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors. We are leaving the entire field of human sexuality to gynecologists, urologists, and other specialists. Paraphilic disorders are something we do not want to manage and we would rather get the whole area out of our classification systems, with the implication that these are not really mental health problems.

Many of us prefer not to treat personality disorder patients—especially those with borderline personality disorder—because they are “difficult.” Some do not even feel comfortable managing adverse effects of psychotropics such as the metabolic syndrome, or use “unusual” augmentations such as thyroid hormone. We prescribe fewer and fewer older, yet efficacious, psychotropic medications; only a small fraction of psychiatrists still prescribes monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Other disciplines, eg, primary care and pain medicine, prescribe some tricyclic antidepressants more than we do. We irrationally avoid benzodiazepines and do not like prescribing lithium, because it requires ordering blood levels and lab tests. We seem comfortable only with newer antidepressants and antipsychotics. How is this way of prescribing different from what is done in primary care? Some of our leaders sneer at the idea of psychiatrists practicing psychotherapy, perhaps feeling that such a “lowly art” should be provided by psychologists and social workers. We do not address relational issues. Last but not least, I hear colleagues saying that they do not like to treat “difficult” patients.

What are we aspiring to be and to do? To treat schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and maybe depression, with a limited medication armamentarium we feel comfortable with and no psychotherapy? I am sure that many will say I am exaggerating, but I think not. We have, as Pogo said, met the enemy and he is us. We should get off the slippery slope of selling out psychiatry piece-by-piece, and fully embrace—clinically and research-wise (funding!)—all of what has been part of psychiatry.

Psychiatrists frequently complain about their lack of recognition by other specialties, stigmatization of mental illness and the practice of psychiatry, and diminishing sense of identity as a specialty. Although I share these concerns, there is another trend that worries me perhaps more: the deliberate abandonment of more and more areas of what has traditionally been and should be psychiatry’s area of expertise and skills. Not all of this is our own doing; the fact is that other clinicians would like to get “a piece of our pie”—a trend seen in other specialties as well (eg, parts of radiology taken over by cardiologists). However, I view our role in this process as larger than other specialties’ or disciplines’ efforts.

Many of us choose not to treat substance abuse patients and instead refer them to “specialists”; yet, don’t we have enough of our own trained specialists and don’t we fill our addiction psychiatry fellowship training positions? Similarly, many do not like to treat patients with comorbid psychiatric illness and substance abuse, although this occurs frequently in our practice. Cognitive disorders often are left to neurologists and our role in managing these patients is diminishing. Pulmonologists gradually are taking over sleep disorders; one wonders why. We do not like to ask our patients about their sexual history, not even talking about treating their sexual problems! Most psychiatrists are afraid of prescribing phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors. We are leaving the entire field of human sexuality to gynecologists, urologists, and other specialists. Paraphilic disorders are something we do not want to manage and we would rather get the whole area out of our classification systems, with the implication that these are not really mental health problems.

Many of us prefer not to treat personality disorder patients—especially those with borderline personality disorder—because they are “difficult.” Some do not even feel comfortable managing adverse effects of psychotropics such as the metabolic syndrome, or use “unusual” augmentations such as thyroid hormone. We prescribe fewer and fewer older, yet efficacious, psychotropic medications; only a small fraction of psychiatrists still prescribes monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Other disciplines, eg, primary care and pain medicine, prescribe some tricyclic antidepressants more than we do. We irrationally avoid benzodiazepines and do not like prescribing lithium, because it requires ordering blood levels and lab tests. We seem comfortable only with newer antidepressants and antipsychotics. How is this way of prescribing different from what is done in primary care? Some of our leaders sneer at the idea of psychiatrists practicing psychotherapy, perhaps feeling that such a “lowly art” should be provided by psychologists and social workers. We do not address relational issues. Last but not least, I hear colleagues saying that they do not like to treat “difficult” patients.

What are we aspiring to be and to do? To treat schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and maybe depression, with a limited medication armamentarium we feel comfortable with and no psychotherapy? I am sure that many will say I am exaggerating, but I think not. We have, as Pogo said, met the enemy and he is us. We should get off the slippery slope of selling out psychiatry piece-by-piece, and fully embrace—clinically and research-wise (funding!)—all of what has been part of psychiatry.

The newest ‘rage’: disruptive mood dysregulation disorder

Outbursts by children when frustrated or when asked to “do something they don’t want to do” are among the most common behavioral complaints voiced by parents. But behavioral outbursts, beyond the typical tantrums of children up to age 4 years, can be signs of very severe mental health disorders and are the most common reason for psychiatric admission (50%-60%).

While behavioral dysregulation is undeniably a huge problem for families, there has been an unreasonable 40-fold rise in diagnosis of bipolar disorder from 1994 to 2003, and 48% were prescribed atypical neuroleptics – medications with serious side effects. In response to this overdiagnosis as bipolar disorder, in 2013 the DSM-5 created a new diagnosis called disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) to differentiate children who experience explosive outbursts who have a different outcome. This new classification includes children aged 6-12 years with persistent irritability most of the time, nearly every day, lasting at least 12 months and starting before age 10 years. DMDD diagnosis is not used after age 18 years.

To be diagnosed, the child has to have frequent, severe temper outbursts “grossly out of proportion” to the situation, averaging at least three times per week. The outbursts can be verbal or physical aggression to people, things, or themselves. While tantrums can be severe in children with delayed development, for the DMDD diagnosis these behaviors must be inconsistent with developmental level and must occur in at least two settings, and in one setting it must be severe. While outbursts are common, only half of children in one study of severe tantrum behavior in 5- to 9-year-olds also had the required persistent irritability.

If this does sound a lot like bipolar disorder so far, you are right. So what is different? DMDD has a prevalence of 2%-5% and occurs mostly in boys, whereas bipolar disorder affects boys and girls equally and affects less than 1% prior to adolescence.

The key features distinguishing DMDD from bipolar disorder are lack of an episodic nature to the irritability and lack of mania. Irritability in DMDD has to be persistently present with breaks of no more than 3 consecutive months in the defining 12-month period. There also cannot be any more than 1 day of the elevated mood features of mania or hypomania. Identifying mania is the hardest part, even in diagnosing adult bipolar, where it occurs only 1% of the year, much less in children who are generally lively! Hypomania, while less intense than mania, is when the person is energetic, talkative, and confident to an extreme extent, often with a flight of creative ideas. Excitement over birthdays or Christmas specifically does not count! So getting this history has to be done carefully, generally by a mental health professional, to make the distinction.

Interestingly, DMDD is not diagnosed when outbursts and irritability are better explained by autism spectrum disorder, separation anxiety disorder, or PTSD. To me, these exclusions point out the importance of sorting out the “set conditions” for all problematic behaviors, not always an easy task. Symptoms of autism in high functioning individuals can be quite subtle. Was the upset from change in a rigid routine known only to the child? Were sensory stimuli such as loud noises intolerable to this child? Was a nonverbal signal of a peer mistaken as a threat? While violent outbursts precipitated by these factors would still be considered “grossly out of proportion to the situation” for a typical child, they are not uncommon in atypical children. Similarly, children with separation anxiety disorder experience a high level of threat from even thinking about being apart from their caregivers, setting them up for alarm by situations other children would not find difficult.

The American Academy of Pediatrics emphasizes the need to assess all children for a history of psychological trauma. Traumas are quite common, and their sequelae affect many aspects of the child’s life; in the case of outbursts, it is emotional resilience that is impaired. As for all DSM-5 diagnoses, DMDD is not diagnosed when the irritability is due to physiological effects of a substance (e.g. steroids) or another medical or neurological disorder. Children with chronic pain conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or sickle cell usually cope remarkably well, but when they don’t, their irritability should not be considered a mental health disorder. More commonly, sleep debt can produce chronic irritability and always should be assessed.

When coaching families about outbursts, I work to help them recognize that the child is not just angry, but very distressed. While “typical” tantrums last 1-5 minutes and show a rise then decline in intensity of the anger and distress, anger outbursts are longer and have an initial short and rapid burst of anger that then declines over the duration of the outburst, and with a steady but lower level of distress throughout.

The option to hug and verbally console the child’s distress is sometimes effective and does not reinforce the behavior unless the parent also yields to demands. But once outbursts begin, I liken them to a bomb going off – there is no intervention possible then. Instead, the task of the family, and over time that of the child, is to recognize and better manage the triggers.

Dr. Ross Greene, in his book, “The Explosive Child: A New Approach for Understanding and Parenting Easily Frustrated, Chronically Inflexible Children,” asserts that the child’s anger and distress can be interpreted as frustration from a gap in skills. This has treatment implications for identifying, educating about, and ameliorating the child’s weaknesses (deficits in understanding, communication, emotion regulation, flexibility or performance; or excess jealousy or hypersensitivity), and coaching parents to recognize, acknowledge, and avoid stressing these areas, if possible. I coach families to give points to the child for progressive little steps toward being able to recognize, verbalize, and inhibit outbursts with a reward system for the points. This helps put the parents and child “on the same team” in working on improving these skills.

Research on children with DMDD indicates that they show less positive affect when winning a “fixed” video game and are less able to suppress negative affect when losing. (Don’t forget to examine the role of real video games as precipitants of tantrums and contingently remove them!) Threshold for upset is lower and the degree of the upsets less well handled by children with DMDD.

In another study, when presented with a series of ambiguous facial expressions, children with DMDD were more likely to see anger in the faces than were controls. One hopeful result was that they could be taught to shift their perceptions significantly away from seeing anger, also reducing irritability and resulting in functional MRI changes. Such hostile bias attribution (tending to see threat) is well known to predispose to aggression. Cognitive behavioral therapy, the most effective counseling intervention, similarly teaches children to rethink their own negative thoughts before acting.

If irritability and rages were not enough, most children with DMDD have other psychiatric disorders; 39% having two, and 51% three or more (J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2013 Nov;23[9]:588-96). If not for the DMDD diagnosis, 82% would meet criteria for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). The other common comorbidities are attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (74.5%), anxiety disorders (49.0%), and depression that is not major depressive disorder (MDD)(33.3%). When MDD is present, that diagnosis takes precedence. One cannot diagnose ODD, intermittent explosive disorder, or bipolar disorder along with DMDD, conditions from which it is intended to differentiate. Each of these comorbid disorders can be difficult to manage alone much less in combination, making DMDD a disorder deserving diagnosis and treatment by a mental health professional.

One of the main reasons DMDD was created is that children with these features go on to depressive or anxiety disorder in adolescence, not bipolar disorder.

While there is no treatment specific to DMDD, the depression component and prognosis suggest use of SSRIs, in addition to psychosocial therapies, and stimulants for the comorbid ADHD. Unfortunately, these two classes of medication are relatively contraindicated in bipolar disorder because they can lead to treatment-induced episodic mania (TEM). TEM occurs twice as often with antidepressants compared with stimulants (44% vs. 18%) in children with bipolar disorder (J Affect Disord. 2004 Oct 1;82[1]:149-58). Getting the diagnosis correct is, therefore, of great importance when medication is considered.

Approaches such as behavior modification, family therapy, and inpatient treatment can be effective for chronic irritability and aggression. Stimulant treatment of comorbid ADHD can decrease aggression and irritability. Alpha agonists such as guanfacine or clonidine also can help. In cases of partial improvement, adding either risperidone or divalproex may further decrease aggression in ADHD. In refractory aggression, risperidone has the best evidence. The Affective Reactivity Index or Outburst Monitoring Scale can be helpful in assessing severity and monitoring outcomes.

While a prognosis for depression rather than bipolar disorder sounds like a plus, in a longitudinal study, adults who had DMDD as children had worse outcomes, including being more likely to have adverse health outcomes (smoking, sexually transmitted infection), police contact, and low educational attainment, and being more likely to live in poverty, compared with controls who had other psychiatric disorders. While DMDD is a new and different diagnosis, it is similar to bipolar in having a potential course of life disruption, dangerous behaviors, suicide risk, and hospitalization.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline. E-mail her at [email protected].

Outbursts by children when frustrated or when asked to “do something they don’t want to do” are among the most common behavioral complaints voiced by parents. But behavioral outbursts, beyond the typical tantrums of children up to age 4 years, can be signs of very severe mental health disorders and are the most common reason for psychiatric admission (50%-60%).

While behavioral dysregulation is undeniably a huge problem for families, there has been an unreasonable 40-fold rise in diagnosis of bipolar disorder from 1994 to 2003, and 48% were prescribed atypical neuroleptics – medications with serious side effects. In response to this overdiagnosis as bipolar disorder, in 2013 the DSM-5 created a new diagnosis called disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) to differentiate children who experience explosive outbursts who have a different outcome. This new classification includes children aged 6-12 years with persistent irritability most of the time, nearly every day, lasting at least 12 months and starting before age 10 years. DMDD diagnosis is not used after age 18 years.

To be diagnosed, the child has to have frequent, severe temper outbursts “grossly out of proportion” to the situation, averaging at least three times per week. The outbursts can be verbal or physical aggression to people, things, or themselves. While tantrums can be severe in children with delayed development, for the DMDD diagnosis these behaviors must be inconsistent with developmental level and must occur in at least two settings, and in one setting it must be severe. While outbursts are common, only half of children in one study of severe tantrum behavior in 5- to 9-year-olds also had the required persistent irritability.

If this does sound a lot like bipolar disorder so far, you are right. So what is different? DMDD has a prevalence of 2%-5% and occurs mostly in boys, whereas bipolar disorder affects boys and girls equally and affects less than 1% prior to adolescence.

The key features distinguishing DMDD from bipolar disorder are lack of an episodic nature to the irritability and lack of mania. Irritability in DMDD has to be persistently present with breaks of no more than 3 consecutive months in the defining 12-month period. There also cannot be any more than 1 day of the elevated mood features of mania or hypomania. Identifying mania is the hardest part, even in diagnosing adult bipolar, where it occurs only 1% of the year, much less in children who are generally lively! Hypomania, while less intense than mania, is when the person is energetic, talkative, and confident to an extreme extent, often with a flight of creative ideas. Excitement over birthdays or Christmas specifically does not count! So getting this history has to be done carefully, generally by a mental health professional, to make the distinction.

Interestingly, DMDD is not diagnosed when outbursts and irritability are better explained by autism spectrum disorder, separation anxiety disorder, or PTSD. To me, these exclusions point out the importance of sorting out the “set conditions” for all problematic behaviors, not always an easy task. Symptoms of autism in high functioning individuals can be quite subtle. Was the upset from change in a rigid routine known only to the child? Were sensory stimuli such as loud noises intolerable to this child? Was a nonverbal signal of a peer mistaken as a threat? While violent outbursts precipitated by these factors would still be considered “grossly out of proportion to the situation” for a typical child, they are not uncommon in atypical children. Similarly, children with separation anxiety disorder experience a high level of threat from even thinking about being apart from their caregivers, setting them up for alarm by situations other children would not find difficult.

The American Academy of Pediatrics emphasizes the need to assess all children for a history of psychological trauma. Traumas are quite common, and their sequelae affect many aspects of the child’s life; in the case of outbursts, it is emotional resilience that is impaired. As for all DSM-5 diagnoses, DMDD is not diagnosed when the irritability is due to physiological effects of a substance (e.g. steroids) or another medical or neurological disorder. Children with chronic pain conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or sickle cell usually cope remarkably well, but when they don’t, their irritability should not be considered a mental health disorder. More commonly, sleep debt can produce chronic irritability and always should be assessed.

When coaching families about outbursts, I work to help them recognize that the child is not just angry, but very distressed. While “typical” tantrums last 1-5 minutes and show a rise then decline in intensity of the anger and distress, anger outbursts are longer and have an initial short and rapid burst of anger that then declines over the duration of the outburst, and with a steady but lower level of distress throughout.

The option to hug and verbally console the child’s distress is sometimes effective and does not reinforce the behavior unless the parent also yields to demands. But once outbursts begin, I liken them to a bomb going off – there is no intervention possible then. Instead, the task of the family, and over time that of the child, is to recognize and better manage the triggers.

Dr. Ross Greene, in his book, “The Explosive Child: A New Approach for Understanding and Parenting Easily Frustrated, Chronically Inflexible Children,” asserts that the child’s anger and distress can be interpreted as frustration from a gap in skills. This has treatment implications for identifying, educating about, and ameliorating the child’s weaknesses (deficits in understanding, communication, emotion regulation, flexibility or performance; or excess jealousy or hypersensitivity), and coaching parents to recognize, acknowledge, and avoid stressing these areas, if possible. I coach families to give points to the child for progressive little steps toward being able to recognize, verbalize, and inhibit outbursts with a reward system for the points. This helps put the parents and child “on the same team” in working on improving these skills.

Research on children with DMDD indicates that they show less positive affect when winning a “fixed” video game and are less able to suppress negative affect when losing. (Don’t forget to examine the role of real video games as precipitants of tantrums and contingently remove them!) Threshold for upset is lower and the degree of the upsets less well handled by children with DMDD.

In another study, when presented with a series of ambiguous facial expressions, children with DMDD were more likely to see anger in the faces than were controls. One hopeful result was that they could be taught to shift their perceptions significantly away from seeing anger, also reducing irritability and resulting in functional MRI changes. Such hostile bias attribution (tending to see threat) is well known to predispose to aggression. Cognitive behavioral therapy, the most effective counseling intervention, similarly teaches children to rethink their own negative thoughts before acting.

If irritability and rages were not enough, most children with DMDD have other psychiatric disorders; 39% having two, and 51% three or more (J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2013 Nov;23[9]:588-96). If not for the DMDD diagnosis, 82% would meet criteria for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). The other common comorbidities are attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (74.5%), anxiety disorders (49.0%), and depression that is not major depressive disorder (MDD)(33.3%). When MDD is present, that diagnosis takes precedence. One cannot diagnose ODD, intermittent explosive disorder, or bipolar disorder along with DMDD, conditions from which it is intended to differentiate. Each of these comorbid disorders can be difficult to manage alone much less in combination, making DMDD a disorder deserving diagnosis and treatment by a mental health professional.

One of the main reasons DMDD was created is that children with these features go on to depressive or anxiety disorder in adolescence, not bipolar disorder.

While there is no treatment specific to DMDD, the depression component and prognosis suggest use of SSRIs, in addition to psychosocial therapies, and stimulants for the comorbid ADHD. Unfortunately, these two classes of medication are relatively contraindicated in bipolar disorder because they can lead to treatment-induced episodic mania (TEM). TEM occurs twice as often with antidepressants compared with stimulants (44% vs. 18%) in children with bipolar disorder (J Affect Disord. 2004 Oct 1;82[1]:149-58). Getting the diagnosis correct is, therefore, of great importance when medication is considered.

Approaches such as behavior modification, family therapy, and inpatient treatment can be effective for chronic irritability and aggression. Stimulant treatment of comorbid ADHD can decrease aggression and irritability. Alpha agonists such as guanfacine or clonidine also can help. In cases of partial improvement, adding either risperidone or divalproex may further decrease aggression in ADHD. In refractory aggression, risperidone has the best evidence. The Affective Reactivity Index or Outburst Monitoring Scale can be helpful in assessing severity and monitoring outcomes.

While a prognosis for depression rather than bipolar disorder sounds like a plus, in a longitudinal study, adults who had DMDD as children had worse outcomes, including being more likely to have adverse health outcomes (smoking, sexually transmitted infection), police contact, and low educational attainment, and being more likely to live in poverty, compared with controls who had other psychiatric disorders. While DMDD is a new and different diagnosis, it is similar to bipolar in having a potential course of life disruption, dangerous behaviors, suicide risk, and hospitalization.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline. E-mail her at [email protected].

Outbursts by children when frustrated or when asked to “do something they don’t want to do” are among the most common behavioral complaints voiced by parents. But behavioral outbursts, beyond the typical tantrums of children up to age 4 years, can be signs of very severe mental health disorders and are the most common reason for psychiatric admission (50%-60%).

While behavioral dysregulation is undeniably a huge problem for families, there has been an unreasonable 40-fold rise in diagnosis of bipolar disorder from 1994 to 2003, and 48% were prescribed atypical neuroleptics – medications with serious side effects. In response to this overdiagnosis as bipolar disorder, in 2013 the DSM-5 created a new diagnosis called disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) to differentiate children who experience explosive outbursts who have a different outcome. This new classification includes children aged 6-12 years with persistent irritability most of the time, nearly every day, lasting at least 12 months and starting before age 10 years. DMDD diagnosis is not used after age 18 years.

To be diagnosed, the child has to have frequent, severe temper outbursts “grossly out of proportion” to the situation, averaging at least three times per week. The outbursts can be verbal or physical aggression to people, things, or themselves. While tantrums can be severe in children with delayed development, for the DMDD diagnosis these behaviors must be inconsistent with developmental level and must occur in at least two settings, and in one setting it must be severe. While outbursts are common, only half of children in one study of severe tantrum behavior in 5- to 9-year-olds also had the required persistent irritability.

If this does sound a lot like bipolar disorder so far, you are right. So what is different? DMDD has a prevalence of 2%-5% and occurs mostly in boys, whereas bipolar disorder affects boys and girls equally and affects less than 1% prior to adolescence.

The key features distinguishing DMDD from bipolar disorder are lack of an episodic nature to the irritability and lack of mania. Irritability in DMDD has to be persistently present with breaks of no more than 3 consecutive months in the defining 12-month period. There also cannot be any more than 1 day of the elevated mood features of mania or hypomania. Identifying mania is the hardest part, even in diagnosing adult bipolar, where it occurs only 1% of the year, much less in children who are generally lively! Hypomania, while less intense than mania, is when the person is energetic, talkative, and confident to an extreme extent, often with a flight of creative ideas. Excitement over birthdays or Christmas specifically does not count! So getting this history has to be done carefully, generally by a mental health professional, to make the distinction.

Interestingly, DMDD is not diagnosed when outbursts and irritability are better explained by autism spectrum disorder, separation anxiety disorder, or PTSD. To me, these exclusions point out the importance of sorting out the “set conditions” for all problematic behaviors, not always an easy task. Symptoms of autism in high functioning individuals can be quite subtle. Was the upset from change in a rigid routine known only to the child? Were sensory stimuli such as loud noises intolerable to this child? Was a nonverbal signal of a peer mistaken as a threat? While violent outbursts precipitated by these factors would still be considered “grossly out of proportion to the situation” for a typical child, they are not uncommon in atypical children. Similarly, children with separation anxiety disorder experience a high level of threat from even thinking about being apart from their caregivers, setting them up for alarm by situations other children would not find difficult.

The American Academy of Pediatrics emphasizes the need to assess all children for a history of psychological trauma. Traumas are quite common, and their sequelae affect many aspects of the child’s life; in the case of outbursts, it is emotional resilience that is impaired. As for all DSM-5 diagnoses, DMDD is not diagnosed when the irritability is due to physiological effects of a substance (e.g. steroids) or another medical or neurological disorder. Children with chronic pain conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or sickle cell usually cope remarkably well, but when they don’t, their irritability should not be considered a mental health disorder. More commonly, sleep debt can produce chronic irritability and always should be assessed.

When coaching families about outbursts, I work to help them recognize that the child is not just angry, but very distressed. While “typical” tantrums last 1-5 minutes and show a rise then decline in intensity of the anger and distress, anger outbursts are longer and have an initial short and rapid burst of anger that then declines over the duration of the outburst, and with a steady but lower level of distress throughout.

The option to hug and verbally console the child’s distress is sometimes effective and does not reinforce the behavior unless the parent also yields to demands. But once outbursts begin, I liken them to a bomb going off – there is no intervention possible then. Instead, the task of the family, and over time that of the child, is to recognize and better manage the triggers.

Dr. Ross Greene, in his book, “The Explosive Child: A New Approach for Understanding and Parenting Easily Frustrated, Chronically Inflexible Children,” asserts that the child’s anger and distress can be interpreted as frustration from a gap in skills. This has treatment implications for identifying, educating about, and ameliorating the child’s weaknesses (deficits in understanding, communication, emotion regulation, flexibility or performance; or excess jealousy or hypersensitivity), and coaching parents to recognize, acknowledge, and avoid stressing these areas, if possible. I coach families to give points to the child for progressive little steps toward being able to recognize, verbalize, and inhibit outbursts with a reward system for the points. This helps put the parents and child “on the same team” in working on improving these skills.

Research on children with DMDD indicates that they show less positive affect when winning a “fixed” video game and are less able to suppress negative affect when losing. (Don’t forget to examine the role of real video games as precipitants of tantrums and contingently remove them!) Threshold for upset is lower and the degree of the upsets less well handled by children with DMDD.

In another study, when presented with a series of ambiguous facial expressions, children with DMDD were more likely to see anger in the faces than were controls. One hopeful result was that they could be taught to shift their perceptions significantly away from seeing anger, also reducing irritability and resulting in functional MRI changes. Such hostile bias attribution (tending to see threat) is well known to predispose to aggression. Cognitive behavioral therapy, the most effective counseling intervention, similarly teaches children to rethink their own negative thoughts before acting.

If irritability and rages were not enough, most children with DMDD have other psychiatric disorders; 39% having two, and 51% three or more (J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2013 Nov;23[9]:588-96). If not for the DMDD diagnosis, 82% would meet criteria for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). The other common comorbidities are attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (74.5%), anxiety disorders (49.0%), and depression that is not major depressive disorder (MDD)(33.3%). When MDD is present, that diagnosis takes precedence. One cannot diagnose ODD, intermittent explosive disorder, or bipolar disorder along with DMDD, conditions from which it is intended to differentiate. Each of these comorbid disorders can be difficult to manage alone much less in combination, making DMDD a disorder deserving diagnosis and treatment by a mental health professional.

One of the main reasons DMDD was created is that children with these features go on to depressive or anxiety disorder in adolescence, not bipolar disorder.

While there is no treatment specific to DMDD, the depression component and prognosis suggest use of SSRIs, in addition to psychosocial therapies, and stimulants for the comorbid ADHD. Unfortunately, these two classes of medication are relatively contraindicated in bipolar disorder because they can lead to treatment-induced episodic mania (TEM). TEM occurs twice as often with antidepressants compared with stimulants (44% vs. 18%) in children with bipolar disorder (J Affect Disord. 2004 Oct 1;82[1]:149-58). Getting the diagnosis correct is, therefore, of great importance when medication is considered.

Approaches such as behavior modification, family therapy, and inpatient treatment can be effective for chronic irritability and aggression. Stimulant treatment of comorbid ADHD can decrease aggression and irritability. Alpha agonists such as guanfacine or clonidine also can help. In cases of partial improvement, adding either risperidone or divalproex may further decrease aggression in ADHD. In refractory aggression, risperidone has the best evidence. The Affective Reactivity Index or Outburst Monitoring Scale can be helpful in assessing severity and monitoring outcomes.

While a prognosis for depression rather than bipolar disorder sounds like a plus, in a longitudinal study, adults who had DMDD as children had worse outcomes, including being more likely to have adverse health outcomes (smoking, sexually transmitted infection), police contact, and low educational attainment, and being more likely to live in poverty, compared with controls who had other psychiatric disorders. While DMDD is a new and different diagnosis, it is similar to bipolar in having a potential course of life disruption, dangerous behaviors, suicide risk, and hospitalization.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline. E-mail her at [email protected].

The Starbucks generation

Iced, Half-Caff, Ristretto, Venti, 4-Pump, Sugar Free, Cinnamon, Dolce Soy Skinny Latte. Or Non-Fat Frappuccino with Extra Whipped Cream and Chocolate Sauce. Sorry, let me simplify: Triple, Venti, Soy, No Foam Latte. If you’re thinking I am speaking a foreign language, just ask a teen and they likely will be able to translate for you. This is normal Starbucks lingo. If you’re not a coffee drinker, you’re likely completely lost, but for those of us who live by the bean, it’s the language of love, caffeine love.

Twenty years ago, the thought of a teen drinking coffee was unheard of. Sure, soda has been there for decades, and in many cultures tea is a common drink, but today many kids are lining up at Starbucks for the caffeine jolt, and the new drinks such as 5-Hour Energy, Jolt, and Red Bull are making this generation the most sleep-deprived ever.

But how bad is caffeine for teens? The average adult consumes approximately 300 mg of caffeine per day,1 which is equivalent to 2-4 cups of coffee; this is considered to be a moderate intake. But the average teen intake of caffeine is not limited to just coffee. Many are consuming their favorite drink from Starbucks, then a few cans of soda, chocolate candy, and maybe even an energy drink – all before the school day is over. When we consider the content of caffeine in these products, the intake of caffeine is staggering.

For example, the average soda contains 35-55 mg of caffeine. Energy drinks such as Red Bull, Amp, and Monster contain approximately 150 mg of caffeine. A tall (small) Starbucks coffee also contains about 150 mg of caffeine, and when we increase the size to a grande, then we are looking at 320 mg.2,4 Simple math will show that the average teen likely has excessive intake of caffeine, resulting in adverse health effects.

The most concerning adverse effect is sleep deprivation.5 Physiologically, the circadian rhythm of adolescents changes and decreases the secretion of melatonin naturally, making it more difficult for them to fall asleep. With the addition of caffeine in high amounts, this is making falling asleep a greater challenge. Sleep deprivation leads to daytime sleepiness and inattention, resulting in learning issues.

Other ill effects found in some studies is that consumption of more than 220 mg of caffeine per day is associated with increased impulsivity, sensation seeking, and risk-taking behaviors.2 In people who are predisposed to arrhythmias, excessive intake can result in the onset of arrhythmias. Nervousness and jitteriness are other common effects.

Another consideration beyond the direct effects of caffeine is that it is usually coupled with sugary substances like those found in syrups used in Starbucks drinks, chocolate candy, and energy drinks. This has led to concerns of obesity as well as dental decay.

Now, when caffeine is taken in small to moderate amounts, less than 300 mg, there are health benefits. It certainly does improve concentration by attaching to the adenosine receptors that block the adenosine effect of sedation on the brain. This leads to improved concentration, memory retention, auditory vigilance, and reaction time.

Recent studies have shown that caffeine in moderate amounts can protect against Alzheimer’s, and is linked to a small decreased risk of cancer and liver disease. Coffee drinkers have also shown a moderate decrease in Parkinson’s disease and stroke.3,6

Regardless of the benefits of caffeine, the American Academy of Pediatrics has been very clear that it does not recommend caffeine in children. In its 2011 guideline,7 the extra calories, the risk of impulsive behavior, and sleep deprivation far outweighed any benefit that caffeine would have. It is critical that physicians educate their patients about foods that contain caffeine and the cumulative effect these foods have on their well-being, now and in the future.

References

1. “Trends in Caffeine Intake Among US Children and Adolescents” (Pediatrics 2014;133:386-93).

2. Caffeine Consumption Among Children and Adolescents. National Council on Strength and Fitness.

3. What is it about coffee? Harvard Health Letter (www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/what-is-it-about-coffee).

4. Caffeine counts. American Physiological Association (Monitor on Psychology. 2001 June;32[6]).

5. J Pediatrics. 2011 March;158(3):508-9.

6. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(suppl 1):s167-74.

7. Pediatrics 2011 June;127(6):1182-9

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill.

Iced, Half-Caff, Ristretto, Venti, 4-Pump, Sugar Free, Cinnamon, Dolce Soy Skinny Latte. Or Non-Fat Frappuccino with Extra Whipped Cream and Chocolate Sauce. Sorry, let me simplify: Triple, Venti, Soy, No Foam Latte. If you’re thinking I am speaking a foreign language, just ask a teen and they likely will be able to translate for you. This is normal Starbucks lingo. If you’re not a coffee drinker, you’re likely completely lost, but for those of us who live by the bean, it’s the language of love, caffeine love.

Twenty years ago, the thought of a teen drinking coffee was unheard of. Sure, soda has been there for decades, and in many cultures tea is a common drink, but today many kids are lining up at Starbucks for the caffeine jolt, and the new drinks such as 5-Hour Energy, Jolt, and Red Bull are making this generation the most sleep-deprived ever.

But how bad is caffeine for teens? The average adult consumes approximately 300 mg of caffeine per day,1 which is equivalent to 2-4 cups of coffee; this is considered to be a moderate intake. But the average teen intake of caffeine is not limited to just coffee. Many are consuming their favorite drink from Starbucks, then a few cans of soda, chocolate candy, and maybe even an energy drink – all before the school day is over. When we consider the content of caffeine in these products, the intake of caffeine is staggering.

For example, the average soda contains 35-55 mg of caffeine. Energy drinks such as Red Bull, Amp, and Monster contain approximately 150 mg of caffeine. A tall (small) Starbucks coffee also contains about 150 mg of caffeine, and when we increase the size to a grande, then we are looking at 320 mg.2,4 Simple math will show that the average teen likely has excessive intake of caffeine, resulting in adverse health effects.

The most concerning adverse effect is sleep deprivation.5 Physiologically, the circadian rhythm of adolescents changes and decreases the secretion of melatonin naturally, making it more difficult for them to fall asleep. With the addition of caffeine in high amounts, this is making falling asleep a greater challenge. Sleep deprivation leads to daytime sleepiness and inattention, resulting in learning issues.

Other ill effects found in some studies is that consumption of more than 220 mg of caffeine per day is associated with increased impulsivity, sensation seeking, and risk-taking behaviors.2 In people who are predisposed to arrhythmias, excessive intake can result in the onset of arrhythmias. Nervousness and jitteriness are other common effects.

Another consideration beyond the direct effects of caffeine is that it is usually coupled with sugary substances like those found in syrups used in Starbucks drinks, chocolate candy, and energy drinks. This has led to concerns of obesity as well as dental decay.

Now, when caffeine is taken in small to moderate amounts, less than 300 mg, there are health benefits. It certainly does improve concentration by attaching to the adenosine receptors that block the adenosine effect of sedation on the brain. This leads to improved concentration, memory retention, auditory vigilance, and reaction time.

Recent studies have shown that caffeine in moderate amounts can protect against Alzheimer’s, and is linked to a small decreased risk of cancer and liver disease. Coffee drinkers have also shown a moderate decrease in Parkinson’s disease and stroke.3,6

Regardless of the benefits of caffeine, the American Academy of Pediatrics has been very clear that it does not recommend caffeine in children. In its 2011 guideline,7 the extra calories, the risk of impulsive behavior, and sleep deprivation far outweighed any benefit that caffeine would have. It is critical that physicians educate their patients about foods that contain caffeine and the cumulative effect these foods have on their well-being, now and in the future.

References

1. “Trends in Caffeine Intake Among US Children and Adolescents” (Pediatrics 2014;133:386-93).

2. Caffeine Consumption Among Children and Adolescents. National Council on Strength and Fitness.

3. What is it about coffee? Harvard Health Letter (www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/what-is-it-about-coffee).