User login

A dermatologist’s bad dream?

My plane doesn’t leave till 2:30. Glad I cut off seeing patients at 11, which should give me plenty of time. I’m getting smarter in my old age.

Smooth morning, paperwork pretty much done. Just one patient left. Look, a nice little old man. He has such a sweet smile.

“How can I help you, Mr. Goldfarb?”

“It’s complicated. This letter explains everything that’s happened the past 3 years,”

Oh-oh, that doesn’t sound good. “OK, let’s have a look.”

“My, you read fast, Doctor.”

When the first line says, ‘The lice all over my body don’t go away even after I apply bug shampoo every day,’ I’m pretty much done.

“Doctor, this bag has everything I’ve used: lice shampoo, insect spray, itch lotion. I forgot to bring in all the little bugs I collected from my combs and sheets.”

No! This can’t be happening! How do I negotiate with a delusion and still make my plane?

“Sometimes it feels like bugs are crawling on my skin.”

“Itching often feels that way ... ”

“I brought pictures. Want to see?”

No! Not an album! Snap after snap: scabs on the scalp, scaling at the corners of the mouth, linear scratches on the extremities.

“You know, Mr. Goldfarb – maybe firm confidence will let me regain control of this interview – what you’re describing does not sound like lice or bugs of any kind ... ”

“But Doctor, how do you explain this?” Another photo, this of a comb filled with brownish epidermal fragments. “I meant to bring some in, but I forgot.”

Enough. Time to look grim and speak briskly. “Mr. Goldfarb, this cannot be lice because ... ”

“I see them coming out of all my pores ... ”

“Mr. Goldfarb!” Now it’s my turn to interrupt. “I would appreciate it if you would let me finish my sentence.”

“Yes, Doctor. If it’s not lice, what do you think it is?”

Must think fast. “Sensitivity. Sensitive skin, especially if you’ve scratched it, can certainly feel as though there are things crawling on you. Patients often say that the skin feels this way. I will therefore treat this sensitivity with anti-inflammatory creams and lotion you will apply to the scalp, face, and the rest of your body respectively.”

Goldfarb is still listening. I’m almost there.

“I want you to use this medication for 2 weeks without stopping, and not use any more of the bug shampoos and creams because they can be irritating and increase itch and sensitivity. Please call me on my private extension at that point with your progress.” Easier to deny a delusion when not standing face to face.

“That’s good news, Doctor. I’ll pick up the medication and let you know.”

At most, he’ll stop scratching for a while. By the time he starts again, I’ll have made my plane and come back to the office. Meantime: Depart exam room briskly!

I can still make it if I leave right away. One last check of my office e-mail. There’s one from Zelda. She has a small scaly patch on one forearm. Claims it’s responded neither to topical antifungals nor steroids.

Here’s the text of her e-mail: “Doctor, I showed my rash to my neighbor Mary. She did some Internet research, and she’s convinced it’s chromoblastomycosis. I’m pretty sure she’s right. What do you think?”

I think I better leave right now.

My reply: “Dear Zelda, pretty unlikely. Try the new cream I’m going to prescribe for 2 weeks, and let me check on how you’re doing.”

How does evil dermatologic karma know that I’m trying to leave town? Parasitosis and chromoblastomycosis! Can this be a bad dream? If so, why don’t I wake up?

Mr. Goldfarb, still looking sweet and mild, sits in the waiting room, awaiting the elder shuttle to take him home.

Walk fast. Do not smile and meet his gaze. This is no time for politeness.

No, sir. I am outta here.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Write to him at [email protected].

My plane doesn’t leave till 2:30. Glad I cut off seeing patients at 11, which should give me plenty of time. I’m getting smarter in my old age.

Smooth morning, paperwork pretty much done. Just one patient left. Look, a nice little old man. He has such a sweet smile.

“How can I help you, Mr. Goldfarb?”

“It’s complicated. This letter explains everything that’s happened the past 3 years,”

Oh-oh, that doesn’t sound good. “OK, let’s have a look.”

“My, you read fast, Doctor.”

When the first line says, ‘The lice all over my body don’t go away even after I apply bug shampoo every day,’ I’m pretty much done.

“Doctor, this bag has everything I’ve used: lice shampoo, insect spray, itch lotion. I forgot to bring in all the little bugs I collected from my combs and sheets.”

No! This can’t be happening! How do I negotiate with a delusion and still make my plane?

“Sometimes it feels like bugs are crawling on my skin.”

“Itching often feels that way ... ”

“I brought pictures. Want to see?”

No! Not an album! Snap after snap: scabs on the scalp, scaling at the corners of the mouth, linear scratches on the extremities.

“You know, Mr. Goldfarb – maybe firm confidence will let me regain control of this interview – what you’re describing does not sound like lice or bugs of any kind ... ”

“But Doctor, how do you explain this?” Another photo, this of a comb filled with brownish epidermal fragments. “I meant to bring some in, but I forgot.”

Enough. Time to look grim and speak briskly. “Mr. Goldfarb, this cannot be lice because ... ”

“I see them coming out of all my pores ... ”

“Mr. Goldfarb!” Now it’s my turn to interrupt. “I would appreciate it if you would let me finish my sentence.”

“Yes, Doctor. If it’s not lice, what do you think it is?”

Must think fast. “Sensitivity. Sensitive skin, especially if you’ve scratched it, can certainly feel as though there are things crawling on you. Patients often say that the skin feels this way. I will therefore treat this sensitivity with anti-inflammatory creams and lotion you will apply to the scalp, face, and the rest of your body respectively.”

Goldfarb is still listening. I’m almost there.

“I want you to use this medication for 2 weeks without stopping, and not use any more of the bug shampoos and creams because they can be irritating and increase itch and sensitivity. Please call me on my private extension at that point with your progress.” Easier to deny a delusion when not standing face to face.

“That’s good news, Doctor. I’ll pick up the medication and let you know.”

At most, he’ll stop scratching for a while. By the time he starts again, I’ll have made my plane and come back to the office. Meantime: Depart exam room briskly!

I can still make it if I leave right away. One last check of my office e-mail. There’s one from Zelda. She has a small scaly patch on one forearm. Claims it’s responded neither to topical antifungals nor steroids.

Here’s the text of her e-mail: “Doctor, I showed my rash to my neighbor Mary. She did some Internet research, and she’s convinced it’s chromoblastomycosis. I’m pretty sure she’s right. What do you think?”

I think I better leave right now.

My reply: “Dear Zelda, pretty unlikely. Try the new cream I’m going to prescribe for 2 weeks, and let me check on how you’re doing.”

How does evil dermatologic karma know that I’m trying to leave town? Parasitosis and chromoblastomycosis! Can this be a bad dream? If so, why don’t I wake up?

Mr. Goldfarb, still looking sweet and mild, sits in the waiting room, awaiting the elder shuttle to take him home.

Walk fast. Do not smile and meet his gaze. This is no time for politeness.

No, sir. I am outta here.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Write to him at [email protected].

My plane doesn’t leave till 2:30. Glad I cut off seeing patients at 11, which should give me plenty of time. I’m getting smarter in my old age.

Smooth morning, paperwork pretty much done. Just one patient left. Look, a nice little old man. He has such a sweet smile.

“How can I help you, Mr. Goldfarb?”

“It’s complicated. This letter explains everything that’s happened the past 3 years,”

Oh-oh, that doesn’t sound good. “OK, let’s have a look.”

“My, you read fast, Doctor.”

When the first line says, ‘The lice all over my body don’t go away even after I apply bug shampoo every day,’ I’m pretty much done.

“Doctor, this bag has everything I’ve used: lice shampoo, insect spray, itch lotion. I forgot to bring in all the little bugs I collected from my combs and sheets.”

No! This can’t be happening! How do I negotiate with a delusion and still make my plane?

“Sometimes it feels like bugs are crawling on my skin.”

“Itching often feels that way ... ”

“I brought pictures. Want to see?”

No! Not an album! Snap after snap: scabs on the scalp, scaling at the corners of the mouth, linear scratches on the extremities.

“You know, Mr. Goldfarb – maybe firm confidence will let me regain control of this interview – what you’re describing does not sound like lice or bugs of any kind ... ”

“But Doctor, how do you explain this?” Another photo, this of a comb filled with brownish epidermal fragments. “I meant to bring some in, but I forgot.”

Enough. Time to look grim and speak briskly. “Mr. Goldfarb, this cannot be lice because ... ”

“I see them coming out of all my pores ... ”

“Mr. Goldfarb!” Now it’s my turn to interrupt. “I would appreciate it if you would let me finish my sentence.”

“Yes, Doctor. If it’s not lice, what do you think it is?”

Must think fast. “Sensitivity. Sensitive skin, especially if you’ve scratched it, can certainly feel as though there are things crawling on you. Patients often say that the skin feels this way. I will therefore treat this sensitivity with anti-inflammatory creams and lotion you will apply to the scalp, face, and the rest of your body respectively.”

Goldfarb is still listening. I’m almost there.

“I want you to use this medication for 2 weeks without stopping, and not use any more of the bug shampoos and creams because they can be irritating and increase itch and sensitivity. Please call me on my private extension at that point with your progress.” Easier to deny a delusion when not standing face to face.

“That’s good news, Doctor. I’ll pick up the medication and let you know.”

At most, he’ll stop scratching for a while. By the time he starts again, I’ll have made my plane and come back to the office. Meantime: Depart exam room briskly!

I can still make it if I leave right away. One last check of my office e-mail. There’s one from Zelda. She has a small scaly patch on one forearm. Claims it’s responded neither to topical antifungals nor steroids.

Here’s the text of her e-mail: “Doctor, I showed my rash to my neighbor Mary. She did some Internet research, and she’s convinced it’s chromoblastomycosis. I’m pretty sure she’s right. What do you think?”

I think I better leave right now.

My reply: “Dear Zelda, pretty unlikely. Try the new cream I’m going to prescribe for 2 weeks, and let me check on how you’re doing.”

How does evil dermatologic karma know that I’m trying to leave town? Parasitosis and chromoblastomycosis! Can this be a bad dream? If so, why don’t I wake up?

Mr. Goldfarb, still looking sweet and mild, sits in the waiting room, awaiting the elder shuttle to take him home.

Walk fast. Do not smile and meet his gaze. This is no time for politeness.

No, sir. I am outta here.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Write to him at [email protected].

Caring for gender-nonconforming youth in a primary care setting – Part 2

Gender identity typically develops in early childhood, and by age 4 years, most children consistently refer to themselves as a girl or a boy.1 For the majority of children, natal sex or sex assigned at birth, aligns with gender identity (a person’s innate sense of feeling male, female, or somewhere in between). However, this is not always the case. Gender identity can be understood as a spectrum with youth identifying as a gender that aligns with their natal sex (cisgender), is opposite of their natal sex (transgender), no gender (agender), or somewhere in between (genderqueer). The distress that can result from an incongruence between natal sex and gender identity is called gender dysphoria. Youth with gender dysphoria are at increased risk for a number of conditions, including suicide and self-harm. Early identification and appropriate care of these youth can reduce these risks. This month’s column will briefly review assessment of these youth in the pediatric setting.

Many youth who have a gender-nonconforming identity in childhood will not go on to have one in adulthood.2,3 Those who have a consistent, insistent, and persistent nonconforming identity are more likely to have this identity persist into adulthood. Youth who experience increased gender dysphoria with the onset of puberty rarely have this subside.

As it can be difficult to predict the trajectory of gender identity from childhood to adolescence, the approach to the prepubertal and pubertal gender nonconforming patient is different. It is important to note that research suggests that gender identity is innate and cannot be changed with interventions. The goals of care for gender-nonconforming (GN) youth include providing a safe environment where youth can explore their identities, and individualizing treatment to meet the needs of each patient and family.

Care for prepubertal GN youth

For parents:

Have you noticed, or are you concerned about your child’s:

• Preference or rejection of particular toys/games?

• Hair and clothing preferences or rejections?

• Preferred (if any) gender of playmates?

Has your child ever expressed:

• A desire to be or insistence that they are the other gender?

• A dislike of their sexual anatomy?

• A desire for primary (penis, vagina) or secondary (periods, facial hair) sex characteristics of the other gender?

Are you concerned about bullying ?

Do you have any concerns about your child’s mood or concerns for self-harm?

For children:

• Do you feel more like a girl, boy, neither, both?

• How would you like to play, cut your hair, dress?

• What name or pronoun (she for girl, he for boy) fits you?4

The goal for prepubertal youth with nonconforming identities is to ensure that they are safe at home, school, and at play. Some youth may express a desire to “transition” or live as their identified gender by changing their name and dressing as their identified gender. Some youth and families may choose to transition only in certain settings (at home, but not at school). Some youth and families may want a safe space where the child can grow, develop, and continue to explore their identity without transitioning. Mental health providers trained in the care of GN youth can help patients and families decide if transition is appropriate for them and support them with the process and timing of transitioning. For youth who experience depression, anxiety, bullying, or thoughts of self-harm related to their gender identity, care by an experienced mental health provider is essential. It is important to recognize that each patient and family will need an individualized approach based on their needs.

Care for pubertal GN youth

The development of secondary sex characteristics can be particularly distressing for GN youth. Some youth may first experience gender dysphoria at this time. This distress combined with the psychosocial stressors of adolescent development can lead to depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, self-harm, and other risk taking behaviors. Visits with pubertal GN youth, as with any adolescent, should include confidential time alone with the medical provider to discuss any concerns. Youth should be informed that information will be kept confidential, but parents will need to be notified of any safety concerns (such as suicidality or self-harm). As with prepubertal youth, a history related to hair and clothing preferences; distress related to genital anatomy; and the desire to be the other gender should be obtained. A pubertal history and any related symptoms of distress also should be obtained.

DO

• Ask preferred name and pronoun.

• Perform confidential strength and risk assessment.

• Assess for family and social support.

• Refer to appropriate mental health and transgender providers.

DON’T

• Assume names and pronouns.

• Interview patient only with parent in the room.

• Disclose identity without patient consent.

• Dismiss parents as sources of support.

• Refer for reparative therapy.4

Youth who are suspected to have a diagnosis of gender dysphoria should be referred to mental health and medical providers with experience caring for transgender youth. These specialists can work with patients and families, and determine when and if youth are eligible for puberty blocking therapy with GnRH analogues and/or hormone therapy. GnRH analogues, if appropriate, can be prescribed after patients have reached sexual maturity rating stage 2. The rationale for this treatment is to prevent the development of unwanted secondary sex characteristics while giving the youth a chance to continue with psychotherapy and explore their gender identity.5 Hormone therapy, if appropriate, can be prescribed a few years later under the care of a transgender specialist and mental health provider.

Summary

It is normal to experiment with gender roles and expression in childhood. Providing a safe space to do this is important.

Individuals who have a persistent, consistent, and insistent gender-nonconforming identification and who have increased distress with puberty are unlikely to have this subside.

Pediatricians can assess for gender dysphoria and screen for related mood disorders and behaviors in the primary care setting. Appropriate referral to trained professionals is important.

Care should be individualized and focused on the health and safety of the patient.

Resources

For health care professionals

• World Professional Association for Transgender Health: Standards of care on care of transgender patients and provider directory. www.wpath.org• Physicians for Reproductive Health’s adolescent reproductive and sexual health education program (ARSHEP): Best practices for adolescent and reproductive health: Module on caring for transgender adolescent patients. prh.org/teen-reproductive-health/arshep-downloads/

For patients and families

• Family Acceptance Project: familyproject.sfsu.edu/

• Healthychildren.org: Parenting website supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Links to articles on gender nonconforming and transgender children; gender identity development in children. www.healthychildren.org

References

1. Caring for Your School Age Child: Ages 5-12 by the American Academy of Pediatrics (New York: Bantam Books, 1995).

2. Dev Psychol. 2008 Jan;44(1):34-45.

3. J Am Acad Child and Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(12):1413-23

4. Caring for Transgender Adolescent Patients. Physicians for Reproductive Health’s Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health Education Program (ARSHEP): Best practices for adolescent and reproductive health: prh.org/teen-reproductive-health/arshep-downloads/

5. World Professional Association of Transgender Health, Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, 7th Edition (International Journal of Transgenderism. 2011;13:165-232)

Dr. Chelvakumar is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the Ohio State University, both in Columbus.

Gender identity typically develops in early childhood, and by age 4 years, most children consistently refer to themselves as a girl or a boy.1 For the majority of children, natal sex or sex assigned at birth, aligns with gender identity (a person’s innate sense of feeling male, female, or somewhere in between). However, this is not always the case. Gender identity can be understood as a spectrum with youth identifying as a gender that aligns with their natal sex (cisgender), is opposite of their natal sex (transgender), no gender (agender), or somewhere in between (genderqueer). The distress that can result from an incongruence between natal sex and gender identity is called gender dysphoria. Youth with gender dysphoria are at increased risk for a number of conditions, including suicide and self-harm. Early identification and appropriate care of these youth can reduce these risks. This month’s column will briefly review assessment of these youth in the pediatric setting.

Many youth who have a gender-nonconforming identity in childhood will not go on to have one in adulthood.2,3 Those who have a consistent, insistent, and persistent nonconforming identity are more likely to have this identity persist into adulthood. Youth who experience increased gender dysphoria with the onset of puberty rarely have this subside.

As it can be difficult to predict the trajectory of gender identity from childhood to adolescence, the approach to the prepubertal and pubertal gender nonconforming patient is different. It is important to note that research suggests that gender identity is innate and cannot be changed with interventions. The goals of care for gender-nonconforming (GN) youth include providing a safe environment where youth can explore their identities, and individualizing treatment to meet the needs of each patient and family.

Care for prepubertal GN youth

For parents:

Have you noticed, or are you concerned about your child’s:

• Preference or rejection of particular toys/games?

• Hair and clothing preferences or rejections?

• Preferred (if any) gender of playmates?

Has your child ever expressed:

• A desire to be or insistence that they are the other gender?

• A dislike of their sexual anatomy?

• A desire for primary (penis, vagina) or secondary (periods, facial hair) sex characteristics of the other gender?

Are you concerned about bullying ?

Do you have any concerns about your child’s mood or concerns for self-harm?

For children:

• Do you feel more like a girl, boy, neither, both?

• How would you like to play, cut your hair, dress?

• What name or pronoun (she for girl, he for boy) fits you?4

The goal for prepubertal youth with nonconforming identities is to ensure that they are safe at home, school, and at play. Some youth may express a desire to “transition” or live as their identified gender by changing their name and dressing as their identified gender. Some youth and families may choose to transition only in certain settings (at home, but not at school). Some youth and families may want a safe space where the child can grow, develop, and continue to explore their identity without transitioning. Mental health providers trained in the care of GN youth can help patients and families decide if transition is appropriate for them and support them with the process and timing of transitioning. For youth who experience depression, anxiety, bullying, or thoughts of self-harm related to their gender identity, care by an experienced mental health provider is essential. It is important to recognize that each patient and family will need an individualized approach based on their needs.

Care for pubertal GN youth

The development of secondary sex characteristics can be particularly distressing for GN youth. Some youth may first experience gender dysphoria at this time. This distress combined with the psychosocial stressors of adolescent development can lead to depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, self-harm, and other risk taking behaviors. Visits with pubertal GN youth, as with any adolescent, should include confidential time alone with the medical provider to discuss any concerns. Youth should be informed that information will be kept confidential, but parents will need to be notified of any safety concerns (such as suicidality or self-harm). As with prepubertal youth, a history related to hair and clothing preferences; distress related to genital anatomy; and the desire to be the other gender should be obtained. A pubertal history and any related symptoms of distress also should be obtained.

DO

• Ask preferred name and pronoun.

• Perform confidential strength and risk assessment.

• Assess for family and social support.

• Refer to appropriate mental health and transgender providers.

DON’T

• Assume names and pronouns.

• Interview patient only with parent in the room.

• Disclose identity without patient consent.

• Dismiss parents as sources of support.

• Refer for reparative therapy.4

Youth who are suspected to have a diagnosis of gender dysphoria should be referred to mental health and medical providers with experience caring for transgender youth. These specialists can work with patients and families, and determine when and if youth are eligible for puberty blocking therapy with GnRH analogues and/or hormone therapy. GnRH analogues, if appropriate, can be prescribed after patients have reached sexual maturity rating stage 2. The rationale for this treatment is to prevent the development of unwanted secondary sex characteristics while giving the youth a chance to continue with psychotherapy and explore their gender identity.5 Hormone therapy, if appropriate, can be prescribed a few years later under the care of a transgender specialist and mental health provider.

Summary

It is normal to experiment with gender roles and expression in childhood. Providing a safe space to do this is important.

Individuals who have a persistent, consistent, and insistent gender-nonconforming identification and who have increased distress with puberty are unlikely to have this subside.

Pediatricians can assess for gender dysphoria and screen for related mood disorders and behaviors in the primary care setting. Appropriate referral to trained professionals is important.

Care should be individualized and focused on the health and safety of the patient.

Resources

For health care professionals

• World Professional Association for Transgender Health: Standards of care on care of transgender patients and provider directory. www.wpath.org• Physicians for Reproductive Health’s adolescent reproductive and sexual health education program (ARSHEP): Best practices for adolescent and reproductive health: Module on caring for transgender adolescent patients. prh.org/teen-reproductive-health/arshep-downloads/

For patients and families

• Family Acceptance Project: familyproject.sfsu.edu/

• Healthychildren.org: Parenting website supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Links to articles on gender nonconforming and transgender children; gender identity development in children. www.healthychildren.org

References

1. Caring for Your School Age Child: Ages 5-12 by the American Academy of Pediatrics (New York: Bantam Books, 1995).

2. Dev Psychol. 2008 Jan;44(1):34-45.

3. J Am Acad Child and Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(12):1413-23

4. Caring for Transgender Adolescent Patients. Physicians for Reproductive Health’s Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health Education Program (ARSHEP): Best practices for adolescent and reproductive health: prh.org/teen-reproductive-health/arshep-downloads/

5. World Professional Association of Transgender Health, Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, 7th Edition (International Journal of Transgenderism. 2011;13:165-232)

Dr. Chelvakumar is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the Ohio State University, both in Columbus.

Gender identity typically develops in early childhood, and by age 4 years, most children consistently refer to themselves as a girl or a boy.1 For the majority of children, natal sex or sex assigned at birth, aligns with gender identity (a person’s innate sense of feeling male, female, or somewhere in between). However, this is not always the case. Gender identity can be understood as a spectrum with youth identifying as a gender that aligns with their natal sex (cisgender), is opposite of their natal sex (transgender), no gender (agender), or somewhere in between (genderqueer). The distress that can result from an incongruence between natal sex and gender identity is called gender dysphoria. Youth with gender dysphoria are at increased risk for a number of conditions, including suicide and self-harm. Early identification and appropriate care of these youth can reduce these risks. This month’s column will briefly review assessment of these youth in the pediatric setting.

Many youth who have a gender-nonconforming identity in childhood will not go on to have one in adulthood.2,3 Those who have a consistent, insistent, and persistent nonconforming identity are more likely to have this identity persist into adulthood. Youth who experience increased gender dysphoria with the onset of puberty rarely have this subside.

As it can be difficult to predict the trajectory of gender identity from childhood to adolescence, the approach to the prepubertal and pubertal gender nonconforming patient is different. It is important to note that research suggests that gender identity is innate and cannot be changed with interventions. The goals of care for gender-nonconforming (GN) youth include providing a safe environment where youth can explore their identities, and individualizing treatment to meet the needs of each patient and family.

Care for prepubertal GN youth

For parents:

Have you noticed, or are you concerned about your child’s:

• Preference or rejection of particular toys/games?

• Hair and clothing preferences or rejections?

• Preferred (if any) gender of playmates?

Has your child ever expressed:

• A desire to be or insistence that they are the other gender?

• A dislike of their sexual anatomy?

• A desire for primary (penis, vagina) or secondary (periods, facial hair) sex characteristics of the other gender?

Are you concerned about bullying ?

Do you have any concerns about your child’s mood or concerns for self-harm?

For children:

• Do you feel more like a girl, boy, neither, both?

• How would you like to play, cut your hair, dress?

• What name or pronoun (she for girl, he for boy) fits you?4

The goal for prepubertal youth with nonconforming identities is to ensure that they are safe at home, school, and at play. Some youth may express a desire to “transition” or live as their identified gender by changing their name and dressing as their identified gender. Some youth and families may choose to transition only in certain settings (at home, but not at school). Some youth and families may want a safe space where the child can grow, develop, and continue to explore their identity without transitioning. Mental health providers trained in the care of GN youth can help patients and families decide if transition is appropriate for them and support them with the process and timing of transitioning. For youth who experience depression, anxiety, bullying, or thoughts of self-harm related to their gender identity, care by an experienced mental health provider is essential. It is important to recognize that each patient and family will need an individualized approach based on their needs.

Care for pubertal GN youth

The development of secondary sex characteristics can be particularly distressing for GN youth. Some youth may first experience gender dysphoria at this time. This distress combined with the psychosocial stressors of adolescent development can lead to depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, self-harm, and other risk taking behaviors. Visits with pubertal GN youth, as with any adolescent, should include confidential time alone with the medical provider to discuss any concerns. Youth should be informed that information will be kept confidential, but parents will need to be notified of any safety concerns (such as suicidality or self-harm). As with prepubertal youth, a history related to hair and clothing preferences; distress related to genital anatomy; and the desire to be the other gender should be obtained. A pubertal history and any related symptoms of distress also should be obtained.

DO

• Ask preferred name and pronoun.

• Perform confidential strength and risk assessment.

• Assess for family and social support.

• Refer to appropriate mental health and transgender providers.

DON’T

• Assume names and pronouns.

• Interview patient only with parent in the room.

• Disclose identity without patient consent.

• Dismiss parents as sources of support.

• Refer for reparative therapy.4

Youth who are suspected to have a diagnosis of gender dysphoria should be referred to mental health and medical providers with experience caring for transgender youth. These specialists can work with patients and families, and determine when and if youth are eligible for puberty blocking therapy with GnRH analogues and/or hormone therapy. GnRH analogues, if appropriate, can be prescribed after patients have reached sexual maturity rating stage 2. The rationale for this treatment is to prevent the development of unwanted secondary sex characteristics while giving the youth a chance to continue with psychotherapy and explore their gender identity.5 Hormone therapy, if appropriate, can be prescribed a few years later under the care of a transgender specialist and mental health provider.

Summary

It is normal to experiment with gender roles and expression in childhood. Providing a safe space to do this is important.

Individuals who have a persistent, consistent, and insistent gender-nonconforming identification and who have increased distress with puberty are unlikely to have this subside.

Pediatricians can assess for gender dysphoria and screen for related mood disorders and behaviors in the primary care setting. Appropriate referral to trained professionals is important.

Care should be individualized and focused on the health and safety of the patient.

Resources

For health care professionals

• World Professional Association for Transgender Health: Standards of care on care of transgender patients and provider directory. www.wpath.org• Physicians for Reproductive Health’s adolescent reproductive and sexual health education program (ARSHEP): Best practices for adolescent and reproductive health: Module on caring for transgender adolescent patients. prh.org/teen-reproductive-health/arshep-downloads/

For patients and families

• Family Acceptance Project: familyproject.sfsu.edu/

• Healthychildren.org: Parenting website supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Links to articles on gender nonconforming and transgender children; gender identity development in children. www.healthychildren.org

References

1. Caring for Your School Age Child: Ages 5-12 by the American Academy of Pediatrics (New York: Bantam Books, 1995).

2. Dev Psychol. 2008 Jan;44(1):34-45.

3. J Am Acad Child and Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(12):1413-23

4. Caring for Transgender Adolescent Patients. Physicians for Reproductive Health’s Adolescent Reproductive and Sexual Health Education Program (ARSHEP): Best practices for adolescent and reproductive health: prh.org/teen-reproductive-health/arshep-downloads/

5. World Professional Association of Transgender Health, Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, 7th Edition (International Journal of Transgenderism. 2011;13:165-232)

Dr. Chelvakumar is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the Ohio State University, both in Columbus.

Examining the medical needs of military women

A supplement recently published in Military Medicine seeks to examine how the Defense Department meets the medical needs of its women warriors. Called “Combat: Framing the Issues of Health and Health Research for America’s Servicewomen,” the articles go a long way toward shining a light on an important issue.

Several of the articles in the supplement highlight mental health issues for women in the military. They include the pieces about sexual harassment, the many faces of military families, alcohol use, and the corrosive effects of ostracism.

One of the articles by Kate McGraw, Ph.D., of the Deployment Health Clinical Center, Silver Spring, Md., focuses on the mental well-being of servicewomen and sexual trauma. Underlying the supplement is the recognition that the most robust mental health research repeatedly conducted in Afghanistan, for example, did not include a single woman because of the sampling methodology. A dedicated group addressing service women’s health and inclusion in health research would have prevented this oversight.

The health of female service members has long been an interest of mine, partly because I was in the Army for 28 years and deployed to a lot of austere environments. They included the rice fields of Camp Edwards, near the DMZ in Korea; Mogadishu and other “cities” in Somalia; and various Forward Operating Bases in Iraq.

Many years ago, I published an article on health concerns of deployed women. That focused on concerns about how to avoid urinary tract infections (UTIs) while in the field – where bathrooms are often scarce and dirty – and other seemingly mundane issues.

Mundane unless you have a UTI, or are trying to figure out how to manage your menses with no tampons or places to wash your hands.

Since then the literature has grown. For example, I published a volume called “Women at War” (Oxford University Press, 2015) last spring. This recent supplement advances those discussions, including articles on avoiding anemia and stress fractures.

But the way forward has been spotty. Many political issues delay an open discussion, especially on reproductive concerns. Further, there is no driving function within the Department of Defense that focuses on funding research in support of service women and reporting back to the department and civilian leadership.

For example: Female service members have a rate of unintended pregnancy twice that of the civilian world. This leads to early attrition from the military, and in turn, to young female veterans with children who are homeless.

Some have said, highlighting these concerns, that females should not be in the military because our presence is a risk to operational readiness. However, this is not an issue without tested solutions.

Taking this one issue further, consider that all service women are included in the Military Health System and have access to a variety of forms of birth control. If female service members can be put on oral contraceptives, that would both suppress their menses and avoid unwanted pregnancies. However, longer lasting methods of birth control would enable service women to enjoy decreased menses, avoid unwanted pregnancies, and avoid access issues during deployment.

The supplement contains numerous health policy and research recommendations as well as a detailed look at the unique health and lifestyle challenges of service women. Other issues include: the reproductive health of women in austere environments, nutritional factors, avoiding musculoskeletal injuries, combat-related injuries, designing military equipment (including uniforms) for optimal performance, and the role of leadership. It concludes with 20 research gaps and accompanying recommendations.

The number of women serving in the military is increasing, while all jobs, particularly those in the ground combat element, are now open to women. The time is now to focus on establishing and tracking health and well-being issues to ensure the success of this population – and the Military Medicine special issue is just a first step.

Dr. Ritchie serves as professor of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Services in Bethesda, Md., and at Georgetown University in Washington. She helped write one of the articles in the supplement with Dr. McGraw and Tracey Perez Koehlmoos, Ph.D., an associate professor with the Uniformed Services University.

A supplement recently published in Military Medicine seeks to examine how the Defense Department meets the medical needs of its women warriors. Called “Combat: Framing the Issues of Health and Health Research for America’s Servicewomen,” the articles go a long way toward shining a light on an important issue.

Several of the articles in the supplement highlight mental health issues for women in the military. They include the pieces about sexual harassment, the many faces of military families, alcohol use, and the corrosive effects of ostracism.

One of the articles by Kate McGraw, Ph.D., of the Deployment Health Clinical Center, Silver Spring, Md., focuses on the mental well-being of servicewomen and sexual trauma. Underlying the supplement is the recognition that the most robust mental health research repeatedly conducted in Afghanistan, for example, did not include a single woman because of the sampling methodology. A dedicated group addressing service women’s health and inclusion in health research would have prevented this oversight.

The health of female service members has long been an interest of mine, partly because I was in the Army for 28 years and deployed to a lot of austere environments. They included the rice fields of Camp Edwards, near the DMZ in Korea; Mogadishu and other “cities” in Somalia; and various Forward Operating Bases in Iraq.

Many years ago, I published an article on health concerns of deployed women. That focused on concerns about how to avoid urinary tract infections (UTIs) while in the field – where bathrooms are often scarce and dirty – and other seemingly mundane issues.

Mundane unless you have a UTI, or are trying to figure out how to manage your menses with no tampons or places to wash your hands.

Since then the literature has grown. For example, I published a volume called “Women at War” (Oxford University Press, 2015) last spring. This recent supplement advances those discussions, including articles on avoiding anemia and stress fractures.

But the way forward has been spotty. Many political issues delay an open discussion, especially on reproductive concerns. Further, there is no driving function within the Department of Defense that focuses on funding research in support of service women and reporting back to the department and civilian leadership.

For example: Female service members have a rate of unintended pregnancy twice that of the civilian world. This leads to early attrition from the military, and in turn, to young female veterans with children who are homeless.

Some have said, highlighting these concerns, that females should not be in the military because our presence is a risk to operational readiness. However, this is not an issue without tested solutions.

Taking this one issue further, consider that all service women are included in the Military Health System and have access to a variety of forms of birth control. If female service members can be put on oral contraceptives, that would both suppress their menses and avoid unwanted pregnancies. However, longer lasting methods of birth control would enable service women to enjoy decreased menses, avoid unwanted pregnancies, and avoid access issues during deployment.

The supplement contains numerous health policy and research recommendations as well as a detailed look at the unique health and lifestyle challenges of service women. Other issues include: the reproductive health of women in austere environments, nutritional factors, avoiding musculoskeletal injuries, combat-related injuries, designing military equipment (including uniforms) for optimal performance, and the role of leadership. It concludes with 20 research gaps and accompanying recommendations.

The number of women serving in the military is increasing, while all jobs, particularly those in the ground combat element, are now open to women. The time is now to focus on establishing and tracking health and well-being issues to ensure the success of this population – and the Military Medicine special issue is just a first step.

Dr. Ritchie serves as professor of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Services in Bethesda, Md., and at Georgetown University in Washington. She helped write one of the articles in the supplement with Dr. McGraw and Tracey Perez Koehlmoos, Ph.D., an associate professor with the Uniformed Services University.

A supplement recently published in Military Medicine seeks to examine how the Defense Department meets the medical needs of its women warriors. Called “Combat: Framing the Issues of Health and Health Research for America’s Servicewomen,” the articles go a long way toward shining a light on an important issue.

Several of the articles in the supplement highlight mental health issues for women in the military. They include the pieces about sexual harassment, the many faces of military families, alcohol use, and the corrosive effects of ostracism.

One of the articles by Kate McGraw, Ph.D., of the Deployment Health Clinical Center, Silver Spring, Md., focuses on the mental well-being of servicewomen and sexual trauma. Underlying the supplement is the recognition that the most robust mental health research repeatedly conducted in Afghanistan, for example, did not include a single woman because of the sampling methodology. A dedicated group addressing service women’s health and inclusion in health research would have prevented this oversight.

The health of female service members has long been an interest of mine, partly because I was in the Army for 28 years and deployed to a lot of austere environments. They included the rice fields of Camp Edwards, near the DMZ in Korea; Mogadishu and other “cities” in Somalia; and various Forward Operating Bases in Iraq.

Many years ago, I published an article on health concerns of deployed women. That focused on concerns about how to avoid urinary tract infections (UTIs) while in the field – where bathrooms are often scarce and dirty – and other seemingly mundane issues.

Mundane unless you have a UTI, or are trying to figure out how to manage your menses with no tampons or places to wash your hands.

Since then the literature has grown. For example, I published a volume called “Women at War” (Oxford University Press, 2015) last spring. This recent supplement advances those discussions, including articles on avoiding anemia and stress fractures.

But the way forward has been spotty. Many political issues delay an open discussion, especially on reproductive concerns. Further, there is no driving function within the Department of Defense that focuses on funding research in support of service women and reporting back to the department and civilian leadership.

For example: Female service members have a rate of unintended pregnancy twice that of the civilian world. This leads to early attrition from the military, and in turn, to young female veterans with children who are homeless.

Some have said, highlighting these concerns, that females should not be in the military because our presence is a risk to operational readiness. However, this is not an issue without tested solutions.

Taking this one issue further, consider that all service women are included in the Military Health System and have access to a variety of forms of birth control. If female service members can be put on oral contraceptives, that would both suppress their menses and avoid unwanted pregnancies. However, longer lasting methods of birth control would enable service women to enjoy decreased menses, avoid unwanted pregnancies, and avoid access issues during deployment.

The supplement contains numerous health policy and research recommendations as well as a detailed look at the unique health and lifestyle challenges of service women. Other issues include: the reproductive health of women in austere environments, nutritional factors, avoiding musculoskeletal injuries, combat-related injuries, designing military equipment (including uniforms) for optimal performance, and the role of leadership. It concludes with 20 research gaps and accompanying recommendations.

The number of women serving in the military is increasing, while all jobs, particularly those in the ground combat element, are now open to women. The time is now to focus on establishing and tracking health and well-being issues to ensure the success of this population – and the Military Medicine special issue is just a first step.

Dr. Ritchie serves as professor of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Services in Bethesda, Md., and at Georgetown University in Washington. She helped write one of the articles in the supplement with Dr. McGraw and Tracey Perez Koehlmoos, Ph.D., an associate professor with the Uniformed Services University.

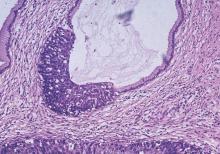

Fertility preservation in early cervical cancer

Historically, the standard of care for women diagnosed with early cervical cancer has been radical hysterectomy. Thus, young women are not only being confronted with a cancer diagnosis, but may also be forced to cope with the loss of their fertility.

As many young women with cervical cancer were not accepting of this treatment, Dr. Daniel Dargent pioneered the vaginal radical trachelectomy as a fertility-preserving treatment option for early cervical cancer in 1994. There have now been more than 900 vaginal radical trachelectomies performed and they have been shown to have oncologic outcomes similar to those of traditional radical hysterectomy, while sparing a woman’s fertility (Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013 Jul;23[6]:982-9).

Obstetric outcomes following vaginal radical trachelectomy are acceptable with 17% miscarriage rate in the first trimester (compared to 10%-20% in the general population) and 8% in the second trimester (compared to 1%-5% in the general population) (Am Fam Physician. 2007 Nov 1;76[9]:1341-6). Following vaginal radical trachelectomy, 64% of pregnancies deliver at term.

The usual criteria required to undergo radical trachelectomy include:

1) Reproductive age with desire for fertility.

2) Stage IA1 with LVSI (lymphovascular space invasion), IA2, or IB1 with tumor less than 2 cm.

3) Limited endocervical involvement via preoperative MRI.

4) Negative pelvic lymph nodes.

Preoperative PET scan can be used to evaluate nodal status, but suspicious lymph nodes should be evaluated on frozen section at the time of surgery. The presence of LVSI alone is not a contraindication to trachelectomy.

A key limitation of vaginal radical trachelectomy is the specialized training required to perform this technically challenging procedure. Few surgeons in the United States are trained to perform vaginal radical trachelectomy. In response to this limitation, surgeons began to attempt radical trachelectomy via laparotomy (Gynecol Oncol. 2006 Dec;103[3]:807-13). Oncologic outcomes following fertility-sparing abdominal radical trachelectomy have been reported to be equivalent to radical hysterectomy. Concerns regarding the abdominal approach to radical trachelectomy include higher rates of second trimester loss (19%) when compared to the vaginal approach (8%), higher rate of loss of fertility (30%), and risk of postoperative adhesions.

The advent of minimally invasive surgery, particularly robotic surgery, now offers surgeons the ability to perform a procedure technically similar to radical hysterectomy using a minimally invasive approach. Given the similarity of procedural steps of radical trachelectomy to radical hysterectomy using the robotic platform, this procedure is gaining acceptance in the United States with an associated improved surgeon learning curve (Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Nov;111[2]:255-60). In addition, the use of minimally invasive surgery should result in less adhesion formation facilitating natural fertility options postoperatively.

Obstetric and fertility outcomes are limited following minimally invasive radical trachelectomy via laparoscopy or robotic surgery given the novelty of this procedure. Emerging obstetric outcomes appear reassuring, but further data are needed to fully understand the effects of this procedure on pregnancy outcomes and the need for assisted reproductive techniques to achieve pregnancy.

The management of pregnancies following radical trachelectomy is also an area with limited data, which presents a clinical challenge to obstetricians. Many gynecologic oncologists perform a permanent cerclage at the time of trachelectomy and recommend delivery via scheduled cesarean at term for all subsequent pregnancies prior to labor (usually 37-38 weeks).

At our institution, we recommend the use of progesterone from 16 to 36 weeks despite no clear evidence on the role of progesterone in this setting. Maternal-fetal medicine consultation should be considered to either follow these patients during their pregnancies or to perform a single consultative visit to guide antepartum care.

Some have advocated for less radical surgery, such as simple trachelectomy or large cold knife conization, as the risk of parametrial extension in these patients is low (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Dec;123[3]:557-60). More data are needed to determine if this is a safe approach. Further, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by cold knife conization for fertility preservation in women with larger tumors has been proposed. This may be a feasible option in women with chemo-sensitive tumors, but progression on chemotherapy and increased recurrences have been reported with this approach (Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Dec;111[3]:438-43).

Women of reproductive age diagnosed with early cervical cancer now have multiple options for fertility preservation. Ongoing research regarding obstetric and fertility outcomes is needed; however, oncologic outcomes appear to be equivalent.

Dr. Clark is a fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics and gynecology, at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Boggess is an expert in robotic surgery in gynecologic oncology and is a professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at [email protected].

Historically, the standard of care for women diagnosed with early cervical cancer has been radical hysterectomy. Thus, young women are not only being confronted with a cancer diagnosis, but may also be forced to cope with the loss of their fertility.

As many young women with cervical cancer were not accepting of this treatment, Dr. Daniel Dargent pioneered the vaginal radical trachelectomy as a fertility-preserving treatment option for early cervical cancer in 1994. There have now been more than 900 vaginal radical trachelectomies performed and they have been shown to have oncologic outcomes similar to those of traditional radical hysterectomy, while sparing a woman’s fertility (Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013 Jul;23[6]:982-9).

Obstetric outcomes following vaginal radical trachelectomy are acceptable with 17% miscarriage rate in the first trimester (compared to 10%-20% in the general population) and 8% in the second trimester (compared to 1%-5% in the general population) (Am Fam Physician. 2007 Nov 1;76[9]:1341-6). Following vaginal radical trachelectomy, 64% of pregnancies deliver at term.

The usual criteria required to undergo radical trachelectomy include:

1) Reproductive age with desire for fertility.

2) Stage IA1 with LVSI (lymphovascular space invasion), IA2, or IB1 with tumor less than 2 cm.

3) Limited endocervical involvement via preoperative MRI.

4) Negative pelvic lymph nodes.

Preoperative PET scan can be used to evaluate nodal status, but suspicious lymph nodes should be evaluated on frozen section at the time of surgery. The presence of LVSI alone is not a contraindication to trachelectomy.

A key limitation of vaginal radical trachelectomy is the specialized training required to perform this technically challenging procedure. Few surgeons in the United States are trained to perform vaginal radical trachelectomy. In response to this limitation, surgeons began to attempt radical trachelectomy via laparotomy (Gynecol Oncol. 2006 Dec;103[3]:807-13). Oncologic outcomes following fertility-sparing abdominal radical trachelectomy have been reported to be equivalent to radical hysterectomy. Concerns regarding the abdominal approach to radical trachelectomy include higher rates of second trimester loss (19%) when compared to the vaginal approach (8%), higher rate of loss of fertility (30%), and risk of postoperative adhesions.

The advent of minimally invasive surgery, particularly robotic surgery, now offers surgeons the ability to perform a procedure technically similar to radical hysterectomy using a minimally invasive approach. Given the similarity of procedural steps of radical trachelectomy to radical hysterectomy using the robotic platform, this procedure is gaining acceptance in the United States with an associated improved surgeon learning curve (Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Nov;111[2]:255-60). In addition, the use of minimally invasive surgery should result in less adhesion formation facilitating natural fertility options postoperatively.

Obstetric and fertility outcomes are limited following minimally invasive radical trachelectomy via laparoscopy or robotic surgery given the novelty of this procedure. Emerging obstetric outcomes appear reassuring, but further data are needed to fully understand the effects of this procedure on pregnancy outcomes and the need for assisted reproductive techniques to achieve pregnancy.

The management of pregnancies following radical trachelectomy is also an area with limited data, which presents a clinical challenge to obstetricians. Many gynecologic oncologists perform a permanent cerclage at the time of trachelectomy and recommend delivery via scheduled cesarean at term for all subsequent pregnancies prior to labor (usually 37-38 weeks).

At our institution, we recommend the use of progesterone from 16 to 36 weeks despite no clear evidence on the role of progesterone in this setting. Maternal-fetal medicine consultation should be considered to either follow these patients during their pregnancies or to perform a single consultative visit to guide antepartum care.

Some have advocated for less radical surgery, such as simple trachelectomy or large cold knife conization, as the risk of parametrial extension in these patients is low (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Dec;123[3]:557-60). More data are needed to determine if this is a safe approach. Further, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by cold knife conization for fertility preservation in women with larger tumors has been proposed. This may be a feasible option in women with chemo-sensitive tumors, but progression on chemotherapy and increased recurrences have been reported with this approach (Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Dec;111[3]:438-43).

Women of reproductive age diagnosed with early cervical cancer now have multiple options for fertility preservation. Ongoing research regarding obstetric and fertility outcomes is needed; however, oncologic outcomes appear to be equivalent.

Dr. Clark is a fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics and gynecology, at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Boggess is an expert in robotic surgery in gynecologic oncology and is a professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at [email protected].

Historically, the standard of care for women diagnosed with early cervical cancer has been radical hysterectomy. Thus, young women are not only being confronted with a cancer diagnosis, but may also be forced to cope with the loss of their fertility.

As many young women with cervical cancer were not accepting of this treatment, Dr. Daniel Dargent pioneered the vaginal radical trachelectomy as a fertility-preserving treatment option for early cervical cancer in 1994. There have now been more than 900 vaginal radical trachelectomies performed and they have been shown to have oncologic outcomes similar to those of traditional radical hysterectomy, while sparing a woman’s fertility (Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013 Jul;23[6]:982-9).

Obstetric outcomes following vaginal radical trachelectomy are acceptable with 17% miscarriage rate in the first trimester (compared to 10%-20% in the general population) and 8% in the second trimester (compared to 1%-5% in the general population) (Am Fam Physician. 2007 Nov 1;76[9]:1341-6). Following vaginal radical trachelectomy, 64% of pregnancies deliver at term.

The usual criteria required to undergo radical trachelectomy include:

1) Reproductive age with desire for fertility.

2) Stage IA1 with LVSI (lymphovascular space invasion), IA2, or IB1 with tumor less than 2 cm.

3) Limited endocervical involvement via preoperative MRI.

4) Negative pelvic lymph nodes.

Preoperative PET scan can be used to evaluate nodal status, but suspicious lymph nodes should be evaluated on frozen section at the time of surgery. The presence of LVSI alone is not a contraindication to trachelectomy.

A key limitation of vaginal radical trachelectomy is the specialized training required to perform this technically challenging procedure. Few surgeons in the United States are trained to perform vaginal radical trachelectomy. In response to this limitation, surgeons began to attempt radical trachelectomy via laparotomy (Gynecol Oncol. 2006 Dec;103[3]:807-13). Oncologic outcomes following fertility-sparing abdominal radical trachelectomy have been reported to be equivalent to radical hysterectomy. Concerns regarding the abdominal approach to radical trachelectomy include higher rates of second trimester loss (19%) when compared to the vaginal approach (8%), higher rate of loss of fertility (30%), and risk of postoperative adhesions.

The advent of minimally invasive surgery, particularly robotic surgery, now offers surgeons the ability to perform a procedure technically similar to radical hysterectomy using a minimally invasive approach. Given the similarity of procedural steps of radical trachelectomy to radical hysterectomy using the robotic platform, this procedure is gaining acceptance in the United States with an associated improved surgeon learning curve (Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Nov;111[2]:255-60). In addition, the use of minimally invasive surgery should result in less adhesion formation facilitating natural fertility options postoperatively.

Obstetric and fertility outcomes are limited following minimally invasive radical trachelectomy via laparoscopy or robotic surgery given the novelty of this procedure. Emerging obstetric outcomes appear reassuring, but further data are needed to fully understand the effects of this procedure on pregnancy outcomes and the need for assisted reproductive techniques to achieve pregnancy.

The management of pregnancies following radical trachelectomy is also an area with limited data, which presents a clinical challenge to obstetricians. Many gynecologic oncologists perform a permanent cerclage at the time of trachelectomy and recommend delivery via scheduled cesarean at term for all subsequent pregnancies prior to labor (usually 37-38 weeks).

At our institution, we recommend the use of progesterone from 16 to 36 weeks despite no clear evidence on the role of progesterone in this setting. Maternal-fetal medicine consultation should be considered to either follow these patients during their pregnancies or to perform a single consultative visit to guide antepartum care.

Some have advocated for less radical surgery, such as simple trachelectomy or large cold knife conization, as the risk of parametrial extension in these patients is low (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Dec;123[3]:557-60). More data are needed to determine if this is a safe approach. Further, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by cold knife conization for fertility preservation in women with larger tumors has been proposed. This may be a feasible option in women with chemo-sensitive tumors, but progression on chemotherapy and increased recurrences have been reported with this approach (Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Dec;111[3]:438-43).

Women of reproductive age diagnosed with early cervical cancer now have multiple options for fertility preservation. Ongoing research regarding obstetric and fertility outcomes is needed; however, oncologic outcomes appear to be equivalent.

Dr. Clark is a fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics and gynecology, at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Boggess is an expert in robotic surgery in gynecologic oncology and is a professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at [email protected].

Understanding stillbirth

When a couple learns that “they are pregnant,” it is often one of the most joyous moments in their lives. However, despite the modern prenatal care available to women in the United States, pregnancy loss remains a real concern. Miscarriage is estimated to occur in 15%-20% of pregnancies; recurrent pregnancy loss in about 1%-2% of pregnancies; and stillbirth in as many as 1% of pregnancies. The causes of pregnancy loss can range from those we can diagnose, such as genetic factors, anatomic complications, and thrombophilia, to those that elude us completely.

In December 2015, investigators from Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm published a study indicating that women who gained weight between their first and second pregnancies, but who were a healthy weight prior to their first pregnancy, had an increased risk of experiencing a stillbirth (30%-50%), or having an infant who died within the first year (27%-60%) (Lancet 2015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00990-3). We have devoted a number of Master Class columns to the link between obesity and pregnancy complications, and this study further reinforces the influence of a healthy weight on pregnancy outcomes.

In addition to lifestyle modifications, evidence has suggested that low-molecular-weight heparin, aspirin, or vitamin supplements, in combination with appropriate surveillance and management, may reduce risk of pregnancy loss. However, more work is needed to fully understand why fetal death occurs if we are to better equip ourselves, and our patients, with all the information necessary to prevent loss from happening.

For this reason, we have invited Dr. Uma M. Reddy of the Pregnancy and Perinatology Branch of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health, to address one of the most devastating types of pregnancy losses: stillbirth. As a program scientist for large research studies, such as the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network, Dr. Reddy’s unique perspective will add greatly to our understanding of pregnancy loss.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece reported having no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column.

When a couple learns that “they are pregnant,” it is often one of the most joyous moments in their lives. However, despite the modern prenatal care available to women in the United States, pregnancy loss remains a real concern. Miscarriage is estimated to occur in 15%-20% of pregnancies; recurrent pregnancy loss in about 1%-2% of pregnancies; and stillbirth in as many as 1% of pregnancies. The causes of pregnancy loss can range from those we can diagnose, such as genetic factors, anatomic complications, and thrombophilia, to those that elude us completely.

In December 2015, investigators from Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm published a study indicating that women who gained weight between their first and second pregnancies, but who were a healthy weight prior to their first pregnancy, had an increased risk of experiencing a stillbirth (30%-50%), or having an infant who died within the first year (27%-60%) (Lancet 2015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00990-3). We have devoted a number of Master Class columns to the link between obesity and pregnancy complications, and this study further reinforces the influence of a healthy weight on pregnancy outcomes.

In addition to lifestyle modifications, evidence has suggested that low-molecular-weight heparin, aspirin, or vitamin supplements, in combination with appropriate surveillance and management, may reduce risk of pregnancy loss. However, more work is needed to fully understand why fetal death occurs if we are to better equip ourselves, and our patients, with all the information necessary to prevent loss from happening.

For this reason, we have invited Dr. Uma M. Reddy of the Pregnancy and Perinatology Branch of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health, to address one of the most devastating types of pregnancy losses: stillbirth. As a program scientist for large research studies, such as the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network, Dr. Reddy’s unique perspective will add greatly to our understanding of pregnancy loss.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece reported having no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column.

When a couple learns that “they are pregnant,” it is often one of the most joyous moments in their lives. However, despite the modern prenatal care available to women in the United States, pregnancy loss remains a real concern. Miscarriage is estimated to occur in 15%-20% of pregnancies; recurrent pregnancy loss in about 1%-2% of pregnancies; and stillbirth in as many as 1% of pregnancies. The causes of pregnancy loss can range from those we can diagnose, such as genetic factors, anatomic complications, and thrombophilia, to those that elude us completely.

In December 2015, investigators from Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm published a study indicating that women who gained weight between their first and second pregnancies, but who were a healthy weight prior to their first pregnancy, had an increased risk of experiencing a stillbirth (30%-50%), or having an infant who died within the first year (27%-60%) (Lancet 2015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00990-3). We have devoted a number of Master Class columns to the link between obesity and pregnancy complications, and this study further reinforces the influence of a healthy weight on pregnancy outcomes.

In addition to lifestyle modifications, evidence has suggested that low-molecular-weight heparin, aspirin, or vitamin supplements, in combination with appropriate surveillance and management, may reduce risk of pregnancy loss. However, more work is needed to fully understand why fetal death occurs if we are to better equip ourselves, and our patients, with all the information necessary to prevent loss from happening.

For this reason, we have invited Dr. Uma M. Reddy of the Pregnancy and Perinatology Branch of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health, to address one of the most devastating types of pregnancy losses: stillbirth. As a program scientist for large research studies, such as the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network, Dr. Reddy’s unique perspective will add greatly to our understanding of pregnancy loss.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece reported having no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column.

Research adds insight on stillbirth risk factors

Stillbirth is a major public health problem, occurring in approximately 1 of every 160 pregnancies in the United States. The rate has remained stagnant since 2006. Prior to that time, from 1990 to 2006, the rate declined somewhat, but only half as much as the decline in infant mortality during this time period. Racial disparities also have persisted, with non-Hispanic black women having more than a twofold increase in risk (Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;60:1-22).

Research conducted by the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network (SCRN) and others has provided us with insight on risk factors and on probable and possible causes of death among stillbirths, which are defined as fetal deaths at 20 or more weeks’ gestation. We know from SCRN data, for instance, that black women are more likely to have stillbirths associated with obstetric complications and infections than white and Hispanic women. However, we still cannot explain a substantial proportion of stillbirths, despite a complete evaluation, or predict who will have a stillbirth.

What we can do as obstetricians is be aware that stillbirth is one of the most common adverse pregnancy outcomes in the United States and counsel women regarding risk factors that are modifiable. Moreover, when stillbirth happens, a complete postmortem evaluation that includes autopsy, placental pathology, karyotype or microarray analysis, and fetal-maternal hemorrhage testing is recommended (Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113[3]:748-61). Recent data show that each of these four components is valuable and should be considered the basic work-up for stillbirth.

Risks and causes

Pregnancy history was the strongest baseline risk factor for stillbirth in an analysis of 614 stillbirths and 1,816 live births in the SCRN’s population-based, case-control study conducted between 2006 and 2008. The SCRN was initiated by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development in 2003. This critical population-based study was conducted at 59 U.S. tertiary care and community hospitals in five catchment areas and has been analyzed in more than 15 published reports.

Women with a previous stillbirth have been known to be at 5- to 10-fold increased risk of a recurrence of stillbirth, and the SCRN findings confirmed this. The study added to our knowledge, however, with the finding that even a prior pregnancy loss at less than 20 weeks’ gestation increased the risk for stillbirth.

Other risk factors identified in the study, in addition to race, included having a multifetal pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio of 4.59), diabetes (AOR of 2.50), maternal age of 40 years or older (AOR of 2.41), maternal AB blood type (AOR of 1.96, compared with type O), a history of drug addiction (AOR of 2.08), smoking during the 3 months prior to pregnancy (AOR of 1.55-1.57, depending on amount), and being unmarried and not cohabitating (AOR of 1.69). Regarding racial disparity, the study showed that elevated risk of stillbirth for non-Hispanic blacks occurred predominantly prior to 24 weeks of gestation.

As in prior research, overweight and obesity also conferred elevated risks in the SCRN study (AORs of 1.43 and 1.72, respectively), and these risks were not explained by either diabetes or hypertension (JAMA. 2011;306:2469-79).

The use of assisted reproductive technology was not included in the study’s multivariate model, but previous research has shown a fourfold increased risk of stillbirth for singleton IVF/ICSI pregnancies. The reason is unclear, but the risk appears to be more related to IVF/ICSI rather than the underlying infertility (Hum Reprod. 2010 May;25[5]:1312-6).

A previous preterm or small-for-gestational-age birth has also been shown in prior research to be a significant risk factor for stillbirth. Less clear is the role of previous cesarean delivery in stillbirth risk. An association has been demonstrated in several studies, however, including one involving about 180,000 singleton pregnancies of 23 or more weeks’ gestation. Women in this cohort who had a previous cesarean delivery had a 1.3-fold increased risk of antepartum stillbirth, after controlling for important factors such as race, body mass index (BMI), and maternal disease (Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Nov;116[5]:1119-26).

In another analysis of the SCRN study looking specifically at causes of stillbirth, a “probable” cause of death was found in 61% of cases and a “possible or probable” cause of death in more than 76% of cases. The most common causes were obstetric complications (29.3%), placental abnormalities (23.6%), fetal genetic/structural abnormalities (13.7%), infection (12.9%), umbilical cord abnormalities (10.4%), hypertensive disorders (9.2%), and other maternal medical conditions (7.8%).