User login

Smartphone device detects atrial fibrillation

The Food and Drug Administration cleared an algorithm for use by patients on a device that attaches to a smartphone to screen for atrial fibrillation instantly.

The AliveCor Heart Monitor attaches to the back of iPhones or Android-based smartphones. Users place fingers on the device and see information on the phone’s screen. They can log their symptoms, and the ECG reading is sent to the company’s server, so data can be accessed later.

The FDA approved the AliveCor Heart Monitor in 2013, and patients have used it since March 2014, with the device sending the ECG reading to a cardiologist or cardiac technician who would send a reply within 24 hours. In August 2014, the FDA cleared an algorithm to be used in a new, free app on the device that allows patients to get an immediate result showing whether or not they are likely to have atrial fibrillation. The company launched the app on the marketplace at the Health 2.0 fall conference in Santa Clara, Calif.

Validation trials have shown that the single-lead AliveCor Heart Monitor system is comparable to a conventional 12-lead ECG, Dr. Omar Dawood said in an interview at the conference. He is a clinical adviser to AliveCor, a surgeon by training who now works with technology companies. And results of two small Australian trials in clinical settings suggest that the AliveCor system is easily used on patients by pharmacists or nurses and is cost-effective.

In one study, pharmacists screened 1,000 pharmacy customers aged 65 years or older using the AliveCor system. A cardiologist read the results, and patients with suspected new atrial fibrillation were referred to general practitioners for conventional 12-lead ECG.

The AliveCor screening identified new cases of atrial fibrillation in 1.5% of patients and a 6.7% prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the cohort. The automated AliveCor algorithm was 98.5% sensitive and 91.4% specific for atrial fibrillation, reported Nicole Lowres of the University of Sydney, and her associates (Thromb. Haemost. 2014;111:1167-76). The investigators also estimated the incremental cost-effectiveness if AliveCor screening were extended into the community, with some patients receiving prescriptions for warfarin and 55% of those adhering to the medication regimen. They calculated a cost in U.S. dollars of $4,066 per quality-adjusted life-year gained and $20,695 to prevent one stroke.

Screening with the AliveCor Heart Monitor “in pharmacies with an automated algorithm is both feasible and cost-effective,” the investigators concluded.

In a separate pilot study, 88 patients seen in three general practices in Sydney were screened by a receptionist or a nurse using AliveCor before seeing the physician. The AliveCor results were transmitted to a secure website where the physician could see them during the patient’s consultation during the same visit.

The device found active atrial fibrillation in 17 patients (19%), all previously diagnosed. The general practitioners and nurses liked the system and its immediate results, but the receptionists felt uneasy doing the screening, reported Jessica Orchard, also of the university, and her associates.

“Atrial fibrillation screening in general practice is feasible,” the investigators concluded (Aust. Fam. Physician 2014;43:315-9). The AliveCor sells for $60-$199, depending on the model of smartphone.

For more on AliveCor, see our video interview with Dr. Dawood at the Health 2.0 fall conference.

AliveCor provided free devices for the studies, which were funded by scholarships from the National Heart Foundation of Australia. The investigators reported having no other financial associations with AliveCor. Some reported financial associations with BMS/Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Servier, and AstraZeneca.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

The Food and Drug Administration cleared an algorithm for use by patients on a device that attaches to a smartphone to screen for atrial fibrillation instantly.

The AliveCor Heart Monitor attaches to the back of iPhones or Android-based smartphones. Users place fingers on the device and see information on the phone’s screen. They can log their symptoms, and the ECG reading is sent to the company’s server, so data can be accessed later.

The FDA approved the AliveCor Heart Monitor in 2013, and patients have used it since March 2014, with the device sending the ECG reading to a cardiologist or cardiac technician who would send a reply within 24 hours. In August 2014, the FDA cleared an algorithm to be used in a new, free app on the device that allows patients to get an immediate result showing whether or not they are likely to have atrial fibrillation. The company launched the app on the marketplace at the Health 2.0 fall conference in Santa Clara, Calif.

Validation trials have shown that the single-lead AliveCor Heart Monitor system is comparable to a conventional 12-lead ECG, Dr. Omar Dawood said in an interview at the conference. He is a clinical adviser to AliveCor, a surgeon by training who now works with technology companies. And results of two small Australian trials in clinical settings suggest that the AliveCor system is easily used on patients by pharmacists or nurses and is cost-effective.

In one study, pharmacists screened 1,000 pharmacy customers aged 65 years or older using the AliveCor system. A cardiologist read the results, and patients with suspected new atrial fibrillation were referred to general practitioners for conventional 12-lead ECG.

The AliveCor screening identified new cases of atrial fibrillation in 1.5% of patients and a 6.7% prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the cohort. The automated AliveCor algorithm was 98.5% sensitive and 91.4% specific for atrial fibrillation, reported Nicole Lowres of the University of Sydney, and her associates (Thromb. Haemost. 2014;111:1167-76). The investigators also estimated the incremental cost-effectiveness if AliveCor screening were extended into the community, with some patients receiving prescriptions for warfarin and 55% of those adhering to the medication regimen. They calculated a cost in U.S. dollars of $4,066 per quality-adjusted life-year gained and $20,695 to prevent one stroke.

Screening with the AliveCor Heart Monitor “in pharmacies with an automated algorithm is both feasible and cost-effective,” the investigators concluded.

In a separate pilot study, 88 patients seen in three general practices in Sydney were screened by a receptionist or a nurse using AliveCor before seeing the physician. The AliveCor results were transmitted to a secure website where the physician could see them during the patient’s consultation during the same visit.

The device found active atrial fibrillation in 17 patients (19%), all previously diagnosed. The general practitioners and nurses liked the system and its immediate results, but the receptionists felt uneasy doing the screening, reported Jessica Orchard, also of the university, and her associates.

“Atrial fibrillation screening in general practice is feasible,” the investigators concluded (Aust. Fam. Physician 2014;43:315-9). The AliveCor sells for $60-$199, depending on the model of smartphone.

For more on AliveCor, see our video interview with Dr. Dawood at the Health 2.0 fall conference.

AliveCor provided free devices for the studies, which were funded by scholarships from the National Heart Foundation of Australia. The investigators reported having no other financial associations with AliveCor. Some reported financial associations with BMS/Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Servier, and AstraZeneca.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

The Food and Drug Administration cleared an algorithm for use by patients on a device that attaches to a smartphone to screen for atrial fibrillation instantly.

The AliveCor Heart Monitor attaches to the back of iPhones or Android-based smartphones. Users place fingers on the device and see information on the phone’s screen. They can log their symptoms, and the ECG reading is sent to the company’s server, so data can be accessed later.

The FDA approved the AliveCor Heart Monitor in 2013, and patients have used it since March 2014, with the device sending the ECG reading to a cardiologist or cardiac technician who would send a reply within 24 hours. In August 2014, the FDA cleared an algorithm to be used in a new, free app on the device that allows patients to get an immediate result showing whether or not they are likely to have atrial fibrillation. The company launched the app on the marketplace at the Health 2.0 fall conference in Santa Clara, Calif.

Validation trials have shown that the single-lead AliveCor Heart Monitor system is comparable to a conventional 12-lead ECG, Dr. Omar Dawood said in an interview at the conference. He is a clinical adviser to AliveCor, a surgeon by training who now works with technology companies. And results of two small Australian trials in clinical settings suggest that the AliveCor system is easily used on patients by pharmacists or nurses and is cost-effective.

In one study, pharmacists screened 1,000 pharmacy customers aged 65 years or older using the AliveCor system. A cardiologist read the results, and patients with suspected new atrial fibrillation were referred to general practitioners for conventional 12-lead ECG.

The AliveCor screening identified new cases of atrial fibrillation in 1.5% of patients and a 6.7% prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the cohort. The automated AliveCor algorithm was 98.5% sensitive and 91.4% specific for atrial fibrillation, reported Nicole Lowres of the University of Sydney, and her associates (Thromb. Haemost. 2014;111:1167-76). The investigators also estimated the incremental cost-effectiveness if AliveCor screening were extended into the community, with some patients receiving prescriptions for warfarin and 55% of those adhering to the medication regimen. They calculated a cost in U.S. dollars of $4,066 per quality-adjusted life-year gained and $20,695 to prevent one stroke.

Screening with the AliveCor Heart Monitor “in pharmacies with an automated algorithm is both feasible and cost-effective,” the investigators concluded.

In a separate pilot study, 88 patients seen in three general practices in Sydney were screened by a receptionist or a nurse using AliveCor before seeing the physician. The AliveCor results were transmitted to a secure website where the physician could see them during the patient’s consultation during the same visit.

The device found active atrial fibrillation in 17 patients (19%), all previously diagnosed. The general practitioners and nurses liked the system and its immediate results, but the receptionists felt uneasy doing the screening, reported Jessica Orchard, also of the university, and her associates.

“Atrial fibrillation screening in general practice is feasible,” the investigators concluded (Aust. Fam. Physician 2014;43:315-9). The AliveCor sells for $60-$199, depending on the model of smartphone.

For more on AliveCor, see our video interview with Dr. Dawood at the Health 2.0 fall conference.

AliveCor provided free devices for the studies, which were funded by scholarships from the National Heart Foundation of Australia. The investigators reported having no other financial associations with AliveCor. Some reported financial associations with BMS/Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Servier, and AstraZeneca.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

VIDEO: Smartphone ECG detects atrial fibrillation

SANTA CLARA, CALIF. – When Dr. Omar Dawood demonstrated the AliveCor Heart Monitor with a new app and algorithm for detecting atrial fibrillation on stage at the Health 2.0 fall conference 2014, it showed that his heart was in normal sinus rhythm – but he had a heart rate of 135 beats per minute.

Chalk it up to the excitement of speaking before an audience of physicians and technologists about this new mobile ECG tool, Dr. Dawood said. “I’m not always that anxious.”

The AliveCor device attaches to the back of iPhones or Android-based smartphones and sells for $60-$199, depending on the model of smartphone. The Food and Drug Administration approved it in 2013, and patients have used it since March 2014. The device sends an ECG reading to a cardiologist or cardiac technician, who sends a reply within 24 hours.

With the new, free app, however, patients get an immediate result from the device showing whether or not they are likely to have atrial fibrillation. The FDA cleared the algorithm for the app in August 2014, and the company launched it on the marketplace at the Health 2.0 conference.

Validation studies have shown that the AliveCor system performs comparably to a traditional 12-lead ECG, Dr. Dawood said in a video interview.

For other recent news on studies of AliveCor in clinical settings, see our Evidence-Based Apps column.

Dr. Dawood, a surgeon by training, is a clinical adviser at AliveCor and also works for a separate technology company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SANTA CLARA, CALIF. – When Dr. Omar Dawood demonstrated the AliveCor Heart Monitor with a new app and algorithm for detecting atrial fibrillation on stage at the Health 2.0 fall conference 2014, it showed that his heart was in normal sinus rhythm – but he had a heart rate of 135 beats per minute.

Chalk it up to the excitement of speaking before an audience of physicians and technologists about this new mobile ECG tool, Dr. Dawood said. “I’m not always that anxious.”

The AliveCor device attaches to the back of iPhones or Android-based smartphones and sells for $60-$199, depending on the model of smartphone. The Food and Drug Administration approved it in 2013, and patients have used it since March 2014. The device sends an ECG reading to a cardiologist or cardiac technician, who sends a reply within 24 hours.

With the new, free app, however, patients get an immediate result from the device showing whether or not they are likely to have atrial fibrillation. The FDA cleared the algorithm for the app in August 2014, and the company launched it on the marketplace at the Health 2.0 conference.

Validation studies have shown that the AliveCor system performs comparably to a traditional 12-lead ECG, Dr. Dawood said in a video interview.

For other recent news on studies of AliveCor in clinical settings, see our Evidence-Based Apps column.

Dr. Dawood, a surgeon by training, is a clinical adviser at AliveCor and also works for a separate technology company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SANTA CLARA, CALIF. – When Dr. Omar Dawood demonstrated the AliveCor Heart Monitor with a new app and algorithm for detecting atrial fibrillation on stage at the Health 2.0 fall conference 2014, it showed that his heart was in normal sinus rhythm – but he had a heart rate of 135 beats per minute.

Chalk it up to the excitement of speaking before an audience of physicians and technologists about this new mobile ECG tool, Dr. Dawood said. “I’m not always that anxious.”

The AliveCor device attaches to the back of iPhones or Android-based smartphones and sells for $60-$199, depending on the model of smartphone. The Food and Drug Administration approved it in 2013, and patients have used it since March 2014. The device sends an ECG reading to a cardiologist or cardiac technician, who sends a reply within 24 hours.

With the new, free app, however, patients get an immediate result from the device showing whether or not they are likely to have atrial fibrillation. The FDA cleared the algorithm for the app in August 2014, and the company launched it on the marketplace at the Health 2.0 conference.

Validation studies have shown that the AliveCor system performs comparably to a traditional 12-lead ECG, Dr. Dawood said in a video interview.

For other recent news on studies of AliveCor in clinical settings, see our Evidence-Based Apps column.

Dr. Dawood, a surgeon by training, is a clinical adviser at AliveCor and also works for a separate technology company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @sherryboschert

New business model puts dermatology ‘back in the hands of the dermatologist’

Dermatology has yet to conquer the cosmetic corner of the specialty. That’s according to Dr. Leslie S. Baumann, of the Miami-based, Skin Type Solutions, who explains a new franchise model she says will help “put dermatology back in the hands of dermatologists.”

In this interview, Dr. Baumann, who writes the Cosmeceutical Critique column for Skin & Allergy News, explains her new franchise method for selling skin care products in the dermatologist’s office, and why she thinks it will “disrupt” business as usual in the retail skin care marketplace, including for online retailers.

The following is an edited transcript of the interview, which you can hear in its entirety here.

SAN: Welcome, Dr. Baumann. You recently wrote that you were helping to “put dermatology back in the hands of dermatologists.” Can you expand on that?

Dr. Baumann: I find that most patients really don’t buy their products from dermatologists. They buy them from Sephora, CVS, or the department store, but it’s dermatologists who have years of training about skin, and consumers don’t realize that the dermatologist’s office is the natural choice for where to buy their skin care products. I know that in some parts of the country, access to dermatologists is limited. I think that if a person can see a dermatologist, then that should be where they go for products as well, but that’s not happening. I think dermatologists have done a poor job in getting the word out that we’re the complete skin care experts.

SAN: So, you’ve created a business model to help with this. Please explain how it works.

Dr. Baumann: I love the science of skin care ingredients, and I want to prescribe the right skin care products to my patients. I was at the University of Miami for about 15 years. We didn’t have a huge staff, and I went through the whole skin care evaluation process and created the correct regimen myself. The original evaluation regimen took about 45 minutes, and I realized that patients would probably purchase products from me at first, but the next time, they would buy them somewhere else.

So, I streamlined my approach to make it faster and not require a lot of staff. I determined that I needed to divide patients into skin types. I came up with 16 main skin types, based on four issues: oily vs. dry; sensitive vs. resistant; pigmented vs. unpigmented; and whether the skin is wrinkle-prone. This was the basis of my book, “The Skin Type Solution,” which was a New York Times Bestseller. This showed me that consumers really care about skin products.

The biggest challenge was to get my staff to be able to correctly diagnose the skin type. It took me years to develop my questionnaire, and we have done all kinds of clinical trials to validate it. Now my staff can administer that questionnaire on an iPad, and it automatically calculates the skin type.

The next step was figuring out which products work for each skin type, and then presetting regimens. I found the best products from the companies that had the best technology, and then I tested those on different skin types. I might have five or six products from four or five different brands for one skin type.

SAN: And you are confident that mixing products from the different brands and all the different ingredients won’t somehow irritate the patient’s skin?

Dr. Baumann: I have done a lot of research on cosmetic ingredients; that’s really my core competency. One company might have the best sunscreen technology, but that doesn’t mean they have the best retinol technology, yet every brand feels that pressure to have lots of different products. However, because I do the research trials for the companies, I know each one’s best technology. So, I find the best technology and apply it like a Rubik’s Cube to each skin type’s need, so they always get the best product, and then I test the product. I have been testing this method since 2005.

SAN: What about eponymous skin care lines?

Dr. Baumann: When you go private label, you hire a formulator the way you’d hire a personal chef. That person may not be the scientist who invented that technology. When you have a private label, there is no way you can achieve the same results as you can when you are sourcing products from the best scientists in the world. I know who these people are because I do the research trials. I also know the ingredient supply companies who have the basic scientists in the lab, tinkering with the cell cultures and looking at the mitochondria, so I know where those basic ingredients go. Because I have a large following after the sale of my book and my online blog, I can get volume discounts from the companies. I created a store in the office, and each shelf is color-coded by skin type so it’s easy to know what products to buy,

My friend, who franchised Blimpie’s sandwich shops, was in my office one day watching customers take everything off the shelf and purchase all of it, and he convinced me to franchise it.

It’s important to understand why we chose this model. If you are a cosmetics company, you are not allowed to tell doctors how much to charge for the products because it violates antitrust laws. This allows some people to buy products and then dump them cheaply on the Internet. We control that by having the doctors sign an agreement that they will not sell the products online, and if they do, we cut them off.

SAN: How do you ensure that the products in your franchises aren’t elsewhere on the Internet?

Dr. Baumann: The plan is that once we have enough doctors in the program, we will negotiate with the manufacturers to create products that are exclusive to us.

SAN: Is this a revolution?

Dr. Baumann: That’s the point. It’s putting the power back in the hands of the dermatologist because we are the authorities on skin care. We need to be the ones that people get all the best news and products from first. Just imagine a world where a great new skin care technology comes out, and the only place you can get it is from the dermatologists. That’s going to drive so much business into the dermatologist’s office, and will help dermatologists build their general and cosmetic practice. The beauty of my system is that it trains your staff to identify the most appropriate products for each patient, but I have selected those products. I tested this method in six dermatologists’ offices, and we found that the product exchange rate went from about 35% to 3%. So, when your patient has a better outcome, they are more likely to trust you, and more likely to refer friends to you.

SAN: But what if a patient doesn’t have access to a dermatologist and the model for purchasing skin care products does change? It sounds like it will be harder for them to get the skin care they need.

Dr. Baumann: That is a great question. It’s a problem I have to figure out how to solve. Right now we’re considering Skype consults. This is not considered practicing medicine, so you can do it across state lines.

SAN: Do you plan to franchise dermatologists only or would you also sell the franchise rights to medical spas and physicians other than dermatologists?

Dr. Baumann: That’s really against my philosophy. I want to bring skin care back to the dermatologist. Did you know that only 15 percent of dermatologists sell skin care products in their practice? It’s difficult for them to set the system up and buy products from the different companies. My company streamlines that process. Another reason many dermatologists don’t sell products is because of ethical concerns. I believe if you are offering patients the best products for their skin types, products they can’t get somewhere else, and at the best price, then that is ethical. When you’re just selling things to make money by taking advantage of the patient-doctor relationship, then I am absolutely against it.

SAN: Why might a dermatologist turn away from this franchise model?

Dr. Baumann: There is no reason not to do it, because the startup costs are minimal. The only reason they might not want to do it is if they have their own skin care brand. A doctor could still sell his or her own brand, but they wouldn’t be able to have it on the Skin Type Solutions shelves, and that gets complicated. Based on patient surveys I’ve done, people don’t really want private skin care labels. I think they feel very suspicious of them. My system solves that problem by helping consumers realize the doctor isn’t pretending they invented these products. This is a more honest approach, in my opinion. That might be controversial, but that’s how I feel.

SAN: It sounds like the cosmetic manufacturers would favor this if you like their line.

Dr. Baumann: My system favors good technology. So the charlatans who are trying to sell stem cell therapies or peptides that don’t work aren’t going to like my system. My system favors the geniuses in the lab who don’t know how to get their technology out there, and I know a lot of them. We’ll be able to find that technology and then launch it through dermatology practices. This helps the genius underdogs who don’t know what to do with what they’ve discovered.

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in the Design District in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (McGraw-Hill, New York 2002) , and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2001. Her latest book, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” will be published in November 2014. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Evolus, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kythera, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy,Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Dermatology has yet to conquer the cosmetic corner of the specialty. That’s according to Dr. Leslie S. Baumann, of the Miami-based, Skin Type Solutions, who explains a new franchise model she says will help “put dermatology back in the hands of dermatologists.”

In this interview, Dr. Baumann, who writes the Cosmeceutical Critique column for Skin & Allergy News, explains her new franchise method for selling skin care products in the dermatologist’s office, and why she thinks it will “disrupt” business as usual in the retail skin care marketplace, including for online retailers.

The following is an edited transcript of the interview, which you can hear in its entirety here.

SAN: Welcome, Dr. Baumann. You recently wrote that you were helping to “put dermatology back in the hands of dermatologists.” Can you expand on that?

Dr. Baumann: I find that most patients really don’t buy their products from dermatologists. They buy them from Sephora, CVS, or the department store, but it’s dermatologists who have years of training about skin, and consumers don’t realize that the dermatologist’s office is the natural choice for where to buy their skin care products. I know that in some parts of the country, access to dermatologists is limited. I think that if a person can see a dermatologist, then that should be where they go for products as well, but that’s not happening. I think dermatologists have done a poor job in getting the word out that we’re the complete skin care experts.

SAN: So, you’ve created a business model to help with this. Please explain how it works.

Dr. Baumann: I love the science of skin care ingredients, and I want to prescribe the right skin care products to my patients. I was at the University of Miami for about 15 years. We didn’t have a huge staff, and I went through the whole skin care evaluation process and created the correct regimen myself. The original evaluation regimen took about 45 minutes, and I realized that patients would probably purchase products from me at first, but the next time, they would buy them somewhere else.

So, I streamlined my approach to make it faster and not require a lot of staff. I determined that I needed to divide patients into skin types. I came up with 16 main skin types, based on four issues: oily vs. dry; sensitive vs. resistant; pigmented vs. unpigmented; and whether the skin is wrinkle-prone. This was the basis of my book, “The Skin Type Solution,” which was a New York Times Bestseller. This showed me that consumers really care about skin products.

The biggest challenge was to get my staff to be able to correctly diagnose the skin type. It took me years to develop my questionnaire, and we have done all kinds of clinical trials to validate it. Now my staff can administer that questionnaire on an iPad, and it automatically calculates the skin type.

The next step was figuring out which products work for each skin type, and then presetting regimens. I found the best products from the companies that had the best technology, and then I tested those on different skin types. I might have five or six products from four or five different brands for one skin type.

SAN: And you are confident that mixing products from the different brands and all the different ingredients won’t somehow irritate the patient’s skin?

Dr. Baumann: I have done a lot of research on cosmetic ingredients; that’s really my core competency. One company might have the best sunscreen technology, but that doesn’t mean they have the best retinol technology, yet every brand feels that pressure to have lots of different products. However, because I do the research trials for the companies, I know each one’s best technology. So, I find the best technology and apply it like a Rubik’s Cube to each skin type’s need, so they always get the best product, and then I test the product. I have been testing this method since 2005.

SAN: What about eponymous skin care lines?

Dr. Baumann: When you go private label, you hire a formulator the way you’d hire a personal chef. That person may not be the scientist who invented that technology. When you have a private label, there is no way you can achieve the same results as you can when you are sourcing products from the best scientists in the world. I know who these people are because I do the research trials. I also know the ingredient supply companies who have the basic scientists in the lab, tinkering with the cell cultures and looking at the mitochondria, so I know where those basic ingredients go. Because I have a large following after the sale of my book and my online blog, I can get volume discounts from the companies. I created a store in the office, and each shelf is color-coded by skin type so it’s easy to know what products to buy,

My friend, who franchised Blimpie’s sandwich shops, was in my office one day watching customers take everything off the shelf and purchase all of it, and he convinced me to franchise it.

It’s important to understand why we chose this model. If you are a cosmetics company, you are not allowed to tell doctors how much to charge for the products because it violates antitrust laws. This allows some people to buy products and then dump them cheaply on the Internet. We control that by having the doctors sign an agreement that they will not sell the products online, and if they do, we cut them off.

SAN: How do you ensure that the products in your franchises aren’t elsewhere on the Internet?

Dr. Baumann: The plan is that once we have enough doctors in the program, we will negotiate with the manufacturers to create products that are exclusive to us.

SAN: Is this a revolution?

Dr. Baumann: That’s the point. It’s putting the power back in the hands of the dermatologist because we are the authorities on skin care. We need to be the ones that people get all the best news and products from first. Just imagine a world where a great new skin care technology comes out, and the only place you can get it is from the dermatologists. That’s going to drive so much business into the dermatologist’s office, and will help dermatologists build their general and cosmetic practice. The beauty of my system is that it trains your staff to identify the most appropriate products for each patient, but I have selected those products. I tested this method in six dermatologists’ offices, and we found that the product exchange rate went from about 35% to 3%. So, when your patient has a better outcome, they are more likely to trust you, and more likely to refer friends to you.

SAN: But what if a patient doesn’t have access to a dermatologist and the model for purchasing skin care products does change? It sounds like it will be harder for them to get the skin care they need.

Dr. Baumann: That is a great question. It’s a problem I have to figure out how to solve. Right now we’re considering Skype consults. This is not considered practicing medicine, so you can do it across state lines.

SAN: Do you plan to franchise dermatologists only or would you also sell the franchise rights to medical spas and physicians other than dermatologists?

Dr. Baumann: That’s really against my philosophy. I want to bring skin care back to the dermatologist. Did you know that only 15 percent of dermatologists sell skin care products in their practice? It’s difficult for them to set the system up and buy products from the different companies. My company streamlines that process. Another reason many dermatologists don’t sell products is because of ethical concerns. I believe if you are offering patients the best products for their skin types, products they can’t get somewhere else, and at the best price, then that is ethical. When you’re just selling things to make money by taking advantage of the patient-doctor relationship, then I am absolutely against it.

SAN: Why might a dermatologist turn away from this franchise model?

Dr. Baumann: There is no reason not to do it, because the startup costs are minimal. The only reason they might not want to do it is if they have their own skin care brand. A doctor could still sell his or her own brand, but they wouldn’t be able to have it on the Skin Type Solutions shelves, and that gets complicated. Based on patient surveys I’ve done, people don’t really want private skin care labels. I think they feel very suspicious of them. My system solves that problem by helping consumers realize the doctor isn’t pretending they invented these products. This is a more honest approach, in my opinion. That might be controversial, but that’s how I feel.

SAN: It sounds like the cosmetic manufacturers would favor this if you like their line.

Dr. Baumann: My system favors good technology. So the charlatans who are trying to sell stem cell therapies or peptides that don’t work aren’t going to like my system. My system favors the geniuses in the lab who don’t know how to get their technology out there, and I know a lot of them. We’ll be able to find that technology and then launch it through dermatology practices. This helps the genius underdogs who don’t know what to do with what they’ve discovered.

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in the Design District in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (McGraw-Hill, New York 2002) , and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2001. Her latest book, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” will be published in November 2014. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Evolus, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kythera, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy,Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Dermatology has yet to conquer the cosmetic corner of the specialty. That’s according to Dr. Leslie S. Baumann, of the Miami-based, Skin Type Solutions, who explains a new franchise model she says will help “put dermatology back in the hands of dermatologists.”

In this interview, Dr. Baumann, who writes the Cosmeceutical Critique column for Skin & Allergy News, explains her new franchise method for selling skin care products in the dermatologist’s office, and why she thinks it will “disrupt” business as usual in the retail skin care marketplace, including for online retailers.

The following is an edited transcript of the interview, which you can hear in its entirety here.

SAN: Welcome, Dr. Baumann. You recently wrote that you were helping to “put dermatology back in the hands of dermatologists.” Can you expand on that?

Dr. Baumann: I find that most patients really don’t buy their products from dermatologists. They buy them from Sephora, CVS, or the department store, but it’s dermatologists who have years of training about skin, and consumers don’t realize that the dermatologist’s office is the natural choice for where to buy their skin care products. I know that in some parts of the country, access to dermatologists is limited. I think that if a person can see a dermatologist, then that should be where they go for products as well, but that’s not happening. I think dermatologists have done a poor job in getting the word out that we’re the complete skin care experts.

SAN: So, you’ve created a business model to help with this. Please explain how it works.

Dr. Baumann: I love the science of skin care ingredients, and I want to prescribe the right skin care products to my patients. I was at the University of Miami for about 15 years. We didn’t have a huge staff, and I went through the whole skin care evaluation process and created the correct regimen myself. The original evaluation regimen took about 45 minutes, and I realized that patients would probably purchase products from me at first, but the next time, they would buy them somewhere else.

So, I streamlined my approach to make it faster and not require a lot of staff. I determined that I needed to divide patients into skin types. I came up with 16 main skin types, based on four issues: oily vs. dry; sensitive vs. resistant; pigmented vs. unpigmented; and whether the skin is wrinkle-prone. This was the basis of my book, “The Skin Type Solution,” which was a New York Times Bestseller. This showed me that consumers really care about skin products.

The biggest challenge was to get my staff to be able to correctly diagnose the skin type. It took me years to develop my questionnaire, and we have done all kinds of clinical trials to validate it. Now my staff can administer that questionnaire on an iPad, and it automatically calculates the skin type.

The next step was figuring out which products work for each skin type, and then presetting regimens. I found the best products from the companies that had the best technology, and then I tested those on different skin types. I might have five or six products from four or five different brands for one skin type.

SAN: And you are confident that mixing products from the different brands and all the different ingredients won’t somehow irritate the patient’s skin?

Dr. Baumann: I have done a lot of research on cosmetic ingredients; that’s really my core competency. One company might have the best sunscreen technology, but that doesn’t mean they have the best retinol technology, yet every brand feels that pressure to have lots of different products. However, because I do the research trials for the companies, I know each one’s best technology. So, I find the best technology and apply it like a Rubik’s Cube to each skin type’s need, so they always get the best product, and then I test the product. I have been testing this method since 2005.

SAN: What about eponymous skin care lines?

Dr. Baumann: When you go private label, you hire a formulator the way you’d hire a personal chef. That person may not be the scientist who invented that technology. When you have a private label, there is no way you can achieve the same results as you can when you are sourcing products from the best scientists in the world. I know who these people are because I do the research trials. I also know the ingredient supply companies who have the basic scientists in the lab, tinkering with the cell cultures and looking at the mitochondria, so I know where those basic ingredients go. Because I have a large following after the sale of my book and my online blog, I can get volume discounts from the companies. I created a store in the office, and each shelf is color-coded by skin type so it’s easy to know what products to buy,

My friend, who franchised Blimpie’s sandwich shops, was in my office one day watching customers take everything off the shelf and purchase all of it, and he convinced me to franchise it.

It’s important to understand why we chose this model. If you are a cosmetics company, you are not allowed to tell doctors how much to charge for the products because it violates antitrust laws. This allows some people to buy products and then dump them cheaply on the Internet. We control that by having the doctors sign an agreement that they will not sell the products online, and if they do, we cut them off.

SAN: How do you ensure that the products in your franchises aren’t elsewhere on the Internet?

Dr. Baumann: The plan is that once we have enough doctors in the program, we will negotiate with the manufacturers to create products that are exclusive to us.

SAN: Is this a revolution?

Dr. Baumann: That’s the point. It’s putting the power back in the hands of the dermatologist because we are the authorities on skin care. We need to be the ones that people get all the best news and products from first. Just imagine a world where a great new skin care technology comes out, and the only place you can get it is from the dermatologists. That’s going to drive so much business into the dermatologist’s office, and will help dermatologists build their general and cosmetic practice. The beauty of my system is that it trains your staff to identify the most appropriate products for each patient, but I have selected those products. I tested this method in six dermatologists’ offices, and we found that the product exchange rate went from about 35% to 3%. So, when your patient has a better outcome, they are more likely to trust you, and more likely to refer friends to you.

SAN: But what if a patient doesn’t have access to a dermatologist and the model for purchasing skin care products does change? It sounds like it will be harder for them to get the skin care they need.

Dr. Baumann: That is a great question. It’s a problem I have to figure out how to solve. Right now we’re considering Skype consults. This is not considered practicing medicine, so you can do it across state lines.

SAN: Do you plan to franchise dermatologists only or would you also sell the franchise rights to medical spas and physicians other than dermatologists?

Dr. Baumann: That’s really against my philosophy. I want to bring skin care back to the dermatologist. Did you know that only 15 percent of dermatologists sell skin care products in their practice? It’s difficult for them to set the system up and buy products from the different companies. My company streamlines that process. Another reason many dermatologists don’t sell products is because of ethical concerns. I believe if you are offering patients the best products for their skin types, products they can’t get somewhere else, and at the best price, then that is ethical. When you’re just selling things to make money by taking advantage of the patient-doctor relationship, then I am absolutely against it.

SAN: Why might a dermatologist turn away from this franchise model?

Dr. Baumann: There is no reason not to do it, because the startup costs are minimal. The only reason they might not want to do it is if they have their own skin care brand. A doctor could still sell his or her own brand, but they wouldn’t be able to have it on the Skin Type Solutions shelves, and that gets complicated. Based on patient surveys I’ve done, people don’t really want private skin care labels. I think they feel very suspicious of them. My system solves that problem by helping consumers realize the doctor isn’t pretending they invented these products. This is a more honest approach, in my opinion. That might be controversial, but that’s how I feel.

SAN: It sounds like the cosmetic manufacturers would favor this if you like their line.

Dr. Baumann: My system favors good technology. So the charlatans who are trying to sell stem cell therapies or peptides that don’t work aren’t going to like my system. My system favors the geniuses in the lab who don’t know how to get their technology out there, and I know a lot of them. We’ll be able to find that technology and then launch it through dermatology practices. This helps the genius underdogs who don’t know what to do with what they’ve discovered.

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in the Design District in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (McGraw-Hill, New York 2002) , and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2001. Her latest book, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” will be published in November 2014. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Evolus, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kythera, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy,Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Is Gustav next?

Thursday was a rough day. Not for me, but for my front-desk personnel. I wouldn’t even have known about it, if Nilda hadn’t clued me in.

“I’m a preschool teacher,” she said, after asking about Botox for underarm sweating. “So I have a lot of patience. But your front-desk people are amazing.”

“What do you mean?” I asked her.

“This lady walks in without an appointment,” she said. “Several people are trying to check in, and she just waltzes over and says, ‘The doctor said I could come in whenever I wanted.’”

I smiled. “That’s Harriet. She’s worried that she has an infection. We make allowances for people over 90.”

“And then there was a woman who didn’t even want to be seen,” Nilda went on. “She’d gotten a bill she didn’t approve of, and she kept going on and on.

“Your secretary said she would call the insurance company to look into it, but the woman kept saying, ‘I’ve been a patient here for 20 years, and there’s never been a problem with the insurance.’

“It would have been fine for your secretary to politely tell the woman she’d take care of it, but now she had to get back to patients trying to register. But she didn’t lose her cool, just kept repeating that she would call the patient’s insurer and let her know.”

I thanked Nilda very much for the feedback. “Most people don’t bother to comment unless they have a complaint,” I said, “so I appreciate your taking the time to say something positive. I’ll be sure to pass it on.”

“And I thought preschool children were tough,” said Nilda.

At lunch, I asked the staff what had been going on.

“Must be a full moon,” said Irma, her eyes twinkling. “The registration desk was like a zoo, what with all the new patients and the old ones who hadn’t been here in years re-registering. And in the middle of it all, a lady whose husband had already checked in and sat down kept calling out, ‘Is Gustav next’?”

“The man sitting next to her – must have been Gustav himself – grumbled at her to please keep quiet, but she kept calling out, ‘Is Gustav next?’

“Then Dorit comes in, complaining about her bill. It turns out that her insurance changed in May, but she had forgotten about it, and she didn’t understand what the change would mean for payment. I told her I would call her insurer and find out.

“ ‘I’ve been a patient here for 20 years,’ she kept saying. ‘So don’t overcharge me!’

“I told her I would let her know what her insurer said and promised that we wouldn’t overcharge her on the copay.

“In the meantime, Harriet, the walk-in, kept standing in front of the window saying, ‘Doctor Rockoff said I could come in whenever I want, and my son-in-law took off work to bring me in and he’s waiting outside.’

“And while Harriet was saying that, the lady in the chair kept calling out, ‘Is Gustav next? Is Gustav next?’ ”

I smiled to myself, trying to think of which absurdist playwright could do justice to what went on that morning in my waiting room, and maybe on lots of mornings and afternoons in waiting rooms everywhere.

“You should know,” I told Irma and the rest of the staff, “that one of the patients commented on how well you all did. You handled all that insanity while staying cool and polite. Great job!”

Of course, we have to stay vigilant for rude or discourteous behavior on the part of our staff. But that same staff often protects us from some pretty unreasonable behavior that patients sometimes can throw at them. It makes sense to make a point of telling our front-desk representatives from time to time how much we appreciate the graceful way they handle the guff and allow us to focus on each patient in the exam room.

Meantime, I am working on my new drama, a sequel to Waiting for Godot. I will call it, Is Gustav Next?

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Skin & Allergy News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years.

Thursday was a rough day. Not for me, but for my front-desk personnel. I wouldn’t even have known about it, if Nilda hadn’t clued me in.

“I’m a preschool teacher,” she said, after asking about Botox for underarm sweating. “So I have a lot of patience. But your front-desk people are amazing.”

“What do you mean?” I asked her.

“This lady walks in without an appointment,” she said. “Several people are trying to check in, and she just waltzes over and says, ‘The doctor said I could come in whenever I wanted.’”

I smiled. “That’s Harriet. She’s worried that she has an infection. We make allowances for people over 90.”

“And then there was a woman who didn’t even want to be seen,” Nilda went on. “She’d gotten a bill she didn’t approve of, and she kept going on and on.

“Your secretary said she would call the insurance company to look into it, but the woman kept saying, ‘I’ve been a patient here for 20 years, and there’s never been a problem with the insurance.’

“It would have been fine for your secretary to politely tell the woman she’d take care of it, but now she had to get back to patients trying to register. But she didn’t lose her cool, just kept repeating that she would call the patient’s insurer and let her know.”

I thanked Nilda very much for the feedback. “Most people don’t bother to comment unless they have a complaint,” I said, “so I appreciate your taking the time to say something positive. I’ll be sure to pass it on.”

“And I thought preschool children were tough,” said Nilda.

At lunch, I asked the staff what had been going on.

“Must be a full moon,” said Irma, her eyes twinkling. “The registration desk was like a zoo, what with all the new patients and the old ones who hadn’t been here in years re-registering. And in the middle of it all, a lady whose husband had already checked in and sat down kept calling out, ‘Is Gustav next’?”

“The man sitting next to her – must have been Gustav himself – grumbled at her to please keep quiet, but she kept calling out, ‘Is Gustav next?’

“Then Dorit comes in, complaining about her bill. It turns out that her insurance changed in May, but she had forgotten about it, and she didn’t understand what the change would mean for payment. I told her I would call her insurer and find out.

“ ‘I’ve been a patient here for 20 years,’ she kept saying. ‘So don’t overcharge me!’

“I told her I would let her know what her insurer said and promised that we wouldn’t overcharge her on the copay.

“In the meantime, Harriet, the walk-in, kept standing in front of the window saying, ‘Doctor Rockoff said I could come in whenever I want, and my son-in-law took off work to bring me in and he’s waiting outside.’

“And while Harriet was saying that, the lady in the chair kept calling out, ‘Is Gustav next? Is Gustav next?’ ”

I smiled to myself, trying to think of which absurdist playwright could do justice to what went on that morning in my waiting room, and maybe on lots of mornings and afternoons in waiting rooms everywhere.

“You should know,” I told Irma and the rest of the staff, “that one of the patients commented on how well you all did. You handled all that insanity while staying cool and polite. Great job!”

Of course, we have to stay vigilant for rude or discourteous behavior on the part of our staff. But that same staff often protects us from some pretty unreasonable behavior that patients sometimes can throw at them. It makes sense to make a point of telling our front-desk representatives from time to time how much we appreciate the graceful way they handle the guff and allow us to focus on each patient in the exam room.

Meantime, I am working on my new drama, a sequel to Waiting for Godot. I will call it, Is Gustav Next?

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Skin & Allergy News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years.

Thursday was a rough day. Not for me, but for my front-desk personnel. I wouldn’t even have known about it, if Nilda hadn’t clued me in.

“I’m a preschool teacher,” she said, after asking about Botox for underarm sweating. “So I have a lot of patience. But your front-desk people are amazing.”

“What do you mean?” I asked her.

“This lady walks in without an appointment,” she said. “Several people are trying to check in, and she just waltzes over and says, ‘The doctor said I could come in whenever I wanted.’”

I smiled. “That’s Harriet. She’s worried that she has an infection. We make allowances for people over 90.”

“And then there was a woman who didn’t even want to be seen,” Nilda went on. “She’d gotten a bill she didn’t approve of, and she kept going on and on.

“Your secretary said she would call the insurance company to look into it, but the woman kept saying, ‘I’ve been a patient here for 20 years, and there’s never been a problem with the insurance.’

“It would have been fine for your secretary to politely tell the woman she’d take care of it, but now she had to get back to patients trying to register. But she didn’t lose her cool, just kept repeating that she would call the patient’s insurer and let her know.”

I thanked Nilda very much for the feedback. “Most people don’t bother to comment unless they have a complaint,” I said, “so I appreciate your taking the time to say something positive. I’ll be sure to pass it on.”

“And I thought preschool children were tough,” said Nilda.

At lunch, I asked the staff what had been going on.

“Must be a full moon,” said Irma, her eyes twinkling. “The registration desk was like a zoo, what with all the new patients and the old ones who hadn’t been here in years re-registering. And in the middle of it all, a lady whose husband had already checked in and sat down kept calling out, ‘Is Gustav next’?”

“The man sitting next to her – must have been Gustav himself – grumbled at her to please keep quiet, but she kept calling out, ‘Is Gustav next?’

“Then Dorit comes in, complaining about her bill. It turns out that her insurance changed in May, but she had forgotten about it, and she didn’t understand what the change would mean for payment. I told her I would call her insurer and find out.

“ ‘I’ve been a patient here for 20 years,’ she kept saying. ‘So don’t overcharge me!’

“I told her I would let her know what her insurer said and promised that we wouldn’t overcharge her on the copay.

“In the meantime, Harriet, the walk-in, kept standing in front of the window saying, ‘Doctor Rockoff said I could come in whenever I want, and my son-in-law took off work to bring me in and he’s waiting outside.’

“And while Harriet was saying that, the lady in the chair kept calling out, ‘Is Gustav next? Is Gustav next?’ ”

I smiled to myself, trying to think of which absurdist playwright could do justice to what went on that morning in my waiting room, and maybe on lots of mornings and afternoons in waiting rooms everywhere.

“You should know,” I told Irma and the rest of the staff, “that one of the patients commented on how well you all did. You handled all that insanity while staying cool and polite. Great job!”

Of course, we have to stay vigilant for rude or discourteous behavior on the part of our staff. But that same staff often protects us from some pretty unreasonable behavior that patients sometimes can throw at them. It makes sense to make a point of telling our front-desk representatives from time to time how much we appreciate the graceful way they handle the guff and allow us to focus on each patient in the exam room.

Meantime, I am working on my new drama, a sequel to Waiting for Godot. I will call it, Is Gustav Next?

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Skin & Allergy News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years.

Urinary incontinence – An individual and societal ill

Urinary incontinence is a major health care concern, both in terms of the numbers of women who are suffering and with respect to societal costs and the impact on health care spending. Approximately 15 years ago, an international group reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association that 200 million people worldwide – 75%-80% of them women – were suffering from urinary incontinence (JAMA 1998;280:951-3).

Since then, a high prevalence of urinary incontinence has been documented in various studies and reports. Experts have estimated, for instance, that between 13 million and 25 million adult Americans experience transient or chronic symptoms, and that approximately half of these patients suffer from severe or bothersome symptoms. Again, the majority of these individuals are women.

Consumer-based research suggests that 25% of women over the age of 18 years experience episodes of urinary incontinence, according to prevalence data collected by the National Association for Continence. In 2001, 10% of women under the age of 65 years and 35% of women over 65 had symptoms of involuntary leakage, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Despite this, nearly two-thirds of patients never discussed bladder health with their health care provider and on average, women wait over 6 years from symptom onset before a diagnosis is established. Moreover, the costs are significant; in 2001, the cost for urinary incontinence in the United States was $16.3 billion (Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;98:398-406).

There are four types of urinary incontinence – urge, stress, mixed, and overflow. Urge incontinence typically is accompanied by urgency. Stress incontinence occurs with the increased abdominal pressure that accompanies effort, exertion, laughing, coughing, and sneezing. Overflow incontinence generally involves continuous urinary loss and incomplete bladder emptying.

Over the next four installments of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have chosen to feature the workup and treatment of urinary incontinence. For our first installment, I have asked my former resident Dr. Sandra Culbertson, who is now a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago, to share her knowledge of the optimal approach for evaluating urinary incontinence in the office. As she explains, it is critical to discern the uncomplicated cases of stress urinary incontinence from possibly complicated cases that require more assessment.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller had no relevant financial disclosures.

Urinary incontinence is a major health care concern, both in terms of the numbers of women who are suffering and with respect to societal costs and the impact on health care spending. Approximately 15 years ago, an international group reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association that 200 million people worldwide – 75%-80% of them women – were suffering from urinary incontinence (JAMA 1998;280:951-3).

Since then, a high prevalence of urinary incontinence has been documented in various studies and reports. Experts have estimated, for instance, that between 13 million and 25 million adult Americans experience transient or chronic symptoms, and that approximately half of these patients suffer from severe or bothersome symptoms. Again, the majority of these individuals are women.

Consumer-based research suggests that 25% of women over the age of 18 years experience episodes of urinary incontinence, according to prevalence data collected by the National Association for Continence. In 2001, 10% of women under the age of 65 years and 35% of women over 65 had symptoms of involuntary leakage, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Despite this, nearly two-thirds of patients never discussed bladder health with their health care provider and on average, women wait over 6 years from symptom onset before a diagnosis is established. Moreover, the costs are significant; in 2001, the cost for urinary incontinence in the United States was $16.3 billion (Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;98:398-406).

There are four types of urinary incontinence – urge, stress, mixed, and overflow. Urge incontinence typically is accompanied by urgency. Stress incontinence occurs with the increased abdominal pressure that accompanies effort, exertion, laughing, coughing, and sneezing. Overflow incontinence generally involves continuous urinary loss and incomplete bladder emptying.

Over the next four installments of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have chosen to feature the workup and treatment of urinary incontinence. For our first installment, I have asked my former resident Dr. Sandra Culbertson, who is now a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago, to share her knowledge of the optimal approach for evaluating urinary incontinence in the office. As she explains, it is critical to discern the uncomplicated cases of stress urinary incontinence from possibly complicated cases that require more assessment.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller had no relevant financial disclosures.

Urinary incontinence is a major health care concern, both in terms of the numbers of women who are suffering and with respect to societal costs and the impact on health care spending. Approximately 15 years ago, an international group reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association that 200 million people worldwide – 75%-80% of them women – were suffering from urinary incontinence (JAMA 1998;280:951-3).

Since then, a high prevalence of urinary incontinence has been documented in various studies and reports. Experts have estimated, for instance, that between 13 million and 25 million adult Americans experience transient or chronic symptoms, and that approximately half of these patients suffer from severe or bothersome symptoms. Again, the majority of these individuals are women.

Consumer-based research suggests that 25% of women over the age of 18 years experience episodes of urinary incontinence, according to prevalence data collected by the National Association for Continence. In 2001, 10% of women under the age of 65 years and 35% of women over 65 had symptoms of involuntary leakage, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Despite this, nearly two-thirds of patients never discussed bladder health with their health care provider and on average, women wait over 6 years from symptom onset before a diagnosis is established. Moreover, the costs are significant; in 2001, the cost for urinary incontinence in the United States was $16.3 billion (Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;98:398-406).

There are four types of urinary incontinence – urge, stress, mixed, and overflow. Urge incontinence typically is accompanied by urgency. Stress incontinence occurs with the increased abdominal pressure that accompanies effort, exertion, laughing, coughing, and sneezing. Overflow incontinence generally involves continuous urinary loss and incomplete bladder emptying.

Over the next four installments of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have chosen to feature the workup and treatment of urinary incontinence. For our first installment, I have asked my former resident Dr. Sandra Culbertson, who is now a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago, to share her knowledge of the optimal approach for evaluating urinary incontinence in the office. As she explains, it is critical to discern the uncomplicated cases of stress urinary incontinence from possibly complicated cases that require more assessment.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller had no relevant financial disclosures.

AUDIO: Franchiser hopes to put dermatology ‘back in the hands of the dermatologist’

Dermatology has yet to conquer the cosmetic corner of the specialty. That’s according to Dr. Leslie S. Baumann of the Miami-based Skin Type Solutions, who explains a new franchise model she says will help “put dermatology back in the hands of dermatologists.”

In this interview, Dr. Baumann, who writes the Cosmeceutical Critique column for Skin & Allergy News, explains her new franchise method for selling skin care products in the dermatologist’s office, and why she thinks it will “disrupt” business as usual in the retail skin care marketplace, including for online retailers.

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in the Design District in Miami. She founded the cosmetic dermatology center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (McGraw-Hill, April 2002), and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (Bantam, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2001. Her latest book, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” will be published in November 2014. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Evolus, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kythera, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy,Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Dermatology has yet to conquer the cosmetic corner of the specialty. That’s according to Dr. Leslie S. Baumann of the Miami-based Skin Type Solutions, who explains a new franchise model she says will help “put dermatology back in the hands of dermatologists.”

In this interview, Dr. Baumann, who writes the Cosmeceutical Critique column for Skin & Allergy News, explains her new franchise method for selling skin care products in the dermatologist’s office, and why she thinks it will “disrupt” business as usual in the retail skin care marketplace, including for online retailers.

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in the Design District in Miami. She founded the cosmetic dermatology center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (McGraw-Hill, April 2002), and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (Bantam, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2001. Her latest book, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” will be published in November 2014. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Evolus, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kythera, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy,Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Dermatology has yet to conquer the cosmetic corner of the specialty. That’s according to Dr. Leslie S. Baumann of the Miami-based Skin Type Solutions, who explains a new franchise model she says will help “put dermatology back in the hands of dermatologists.”

In this interview, Dr. Baumann, who writes the Cosmeceutical Critique column for Skin & Allergy News, explains her new franchise method for selling skin care products in the dermatologist’s office, and why she thinks it will “disrupt” business as usual in the retail skin care marketplace, including for online retailers.

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in the Design District in Miami. She founded the cosmetic dermatology center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (McGraw-Hill, April 2002), and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (Bantam, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2001. Her latest book, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” will be published in November 2014. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Evolus, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kythera, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy,Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Master Class: Office evaluation for incontinence

Ten years ago, urodynamics were widely viewed as the gold standard for evaluating urinary incontinence. We often turned to such testing to confirm or reject the findings of our basic evaluation before determining the best type of treatment – especially before proceeding with primary anti-incontinence surgery.

What has emerged in recent years is a body of evidence that tells us otherwise. We now know that urodynamics do not give us all the answers, and that we can be much more judicious with its use.

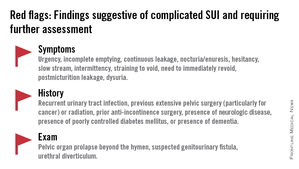

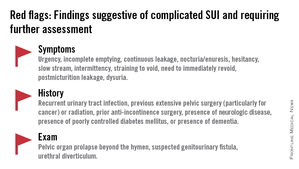

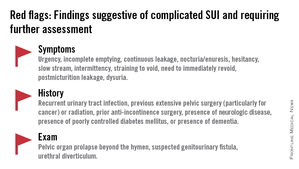

A good history followed by a thorough physical examination and some office tests often enables us to make sound treatment recommendations without costly and potentially uncomfortable urodynamic testing. The key lies in discerning complicated and uncomplicated cases. For patients deemed to have uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence (SUI) – especially those who have failed conservative management – we can comfortably recommend surgical repair without urodynamic testing.

Identifying uncomplicated SUI

The history is the most important part of the evaluation for incontinence. Every patient who answers “yes” to a basic opening question about whether she has any concerns about bladder control should be asked a series of questions that will enable the physician to fully understand her symptoms, their severity, and their impact on her life and daily activities.

It is critical to determine whether you are dealing with pure SUI, pure urge incontinence (UI), or SUI with a component of UI. Mixed incontinence is quite prevalent. An analysis of recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data showed that of those women reporting incontinence symptoms, almost 50% reported pure SUI, and 34% reported mixed incontinence (J. Urol. 2008;179: 656-61). Other studies similarly have shown prevalence rates of mixed incontinence above 30%.

The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) recommends the use of validated questionnaires to assess incontinence and the relative contribution of UI and SUI symptoms. Some physicians do find the organized and structured format of questionnaires helpful in their practices. Others have incorporated questions from various tools into history-taking templates on their electronic medical records. Still others have made them part of a mental checklist for history taking.

The short-form version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), for instance, asks the patient whether she experiences – and how much she is bothered by – the following: frequent urination; leakage related to a feeling of urgency; leakage related to activity, coughing, or sneezing; small amount of leakage; difficulty emptying the bladder; and pain or discomfort in the lower abdominal or genital area.

The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire can be used to further assess the impact of symptoms. The short-form IIQ (the IIQ-7) asks, for instance, about the extent to which urine leakage has affected household chores, physical recreation, social activities, or emotional health.

Since the UDI and IIQ were developed about 20 years ago, at least several other urinary incontinence questionnaires have been developed and validated. Whether or not questionnaires are utilized as official tools, history taking should capture their essence and provide you with enough information to ascertain the type of incontinence, frequency of occurrence, severity, and effect on daily life.

The history also must assess the possibility of voiding dysfunction. Positive responses to questions about nocturia, hesitancy, and the need to immediately revoid, for instance, point toward complicated SUI and the need for further assessment before embarking on surgical treatment for SUI.

Patients who have uncomplicated SUI, on the other hand, will answer negatively to questions about symptoms of predominant urgency, functional impairment, continuous leakage, and/or incomplete emptying. They also will not have had recurrent urinary tract infections or medical conditions that can affect lower urinary tract function (such as neurologic disease and poorly controlled diabetes).

The physical exam

Along with the history, the physical exam is important for identifying complicated SUI and confirming which cases of SUI are truly uncomplicated. Evaluation should include a cough stress test to confirm leakage from the urethra under stress, an assessment of urethral mobility, and an assessment for pelvic organ prolapse.

The cough stress test is usually done with the patient in the supine or semirecumbent lithotomy position. If you strongly suspect stress incontinence but have a negative result, consider the following:

• Make sure the patient has a comfortably full bladder.

• Many women will contract their pelvic floor muscles when coughing to try to avoid leaking. You can apply pressure against the posterior vaginal wall either digitally or with half of the bivalve speculum to keep the patient from activating her muscles.

• The cough test can be performed in the standing position.

Assessing urethral mobility similarly involves simple observation while the patient is in a supine lithotomy position and straining. A Q-tip test or the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system may be used, but visualization and palpation also are completely acceptable.

Just as the absence of urethral mobility is a red flag, so is prolapse beyond the hymen. This patient could potentially have urethral kinking, which can mask the severity of SUI or be a source of retention. Either finding the absence of urethral mobility or the presence of POP beyond the hymen moves the case from the uncomplicated to complicated category and signals the need for further evaluation with urodynamics or other tests.

These and other findings for uncomplicated versus complicated SUI are outlined in a committee opinion issued recently by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society (Committee Opinion No. 603, Obstet .Gynecol. 2014;123:1403-7).