User login

Sparing the rod

In the wake of the allegations that a star NFL running back abused his 4-year-old son by hitting him with a switch, the debate about spanking and other forms of corporal punishment has reignited. It’s not much of a debate. It’s really just a cacophony of “experts” condemning the act. There are a few dissenting voices who find fault with this particular high-profile event, but still hold the opinion that there are certain situations in which spanking may be an acceptable option. My mother taught me to never say never. But, the occasions in which an open-handed spank on a well-padded bottom are so rare that for all practical purposes, striking a child should not appear on any list of discipline strategies.

However, I’m not sure that spanking should automatically be equated with child abuse. It is seldom effective and should raise a red flag that we are dealing with a parent who needs help in managing his or her child’s behavior, but it’s generally not abuse.

In this recent case, the father has talked about the long lineage of corporal punishment that runs through his family. However, I think that most parents in this country instinctively know that hitting their child is not the best option. They may have learned from experience that it is ineffective and has a very narrow safety margin. But, parents aren’t sure what they should have done.

They may have read magazine articles or heard talking heads on television encouraging parents to engage their misbehaving children in a dialogue to explore their motives. Or, how to condemn the misdeeds without damaging the child’s self-image. To many parents, this kind of advice fells like just so much talk. They have already discovered that one can’t have a meaningful discussion with a child in the throes of a tantrum.

In many cases, the failure of words alone is the natural result of an uncountable number of threats that have never been followed by a consistent consequence. It’s not surprising that parents often fail to follow up on their threats because they lack even the smallest arsenal of safe and effective consequences. They know that corporal punishment is wrong. But, does that mean that discipline must be completely hands off? Is any physical restraint such as a bear hug of a toddler or preschooler in the throes of a tantrum so close to spanking that it could be interpreted as child abuse? Unfortunately, I suspect that there are a few child behavior experts who might say that it is.

What about putting a child in his room for time-out? If he won’t go willingly and has to be carried, is that corporal punishment? If he won’t stay in his room for even 30 seconds unless the door is held shut or latched, is that same as a penal institution’s use of solitary confinement? Although they have a physical component, these restrictions – if done sensibly – are far safer and more effective than hitting a child.

Of course, prevention should be the keystone of any behavior-management strategy. Does the parent understand the spectrum of age-appropriate behavior for his child? Does he accept that his child’s temperament may force him to modify his expectations? Have family dynamics and schedules created situations in which the child feels underappreciated? Is the parent himself in good physical and mental health?

As pediatricians, we must make it clear that we are prepared to help parents to deal with the challenges inherent in setting limits for their children and assist them in creating a strategies of safe consequences to assure that these limits are effective.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” E-mail him at [email protected].

In the wake of the allegations that a star NFL running back abused his 4-year-old son by hitting him with a switch, the debate about spanking and other forms of corporal punishment has reignited. It’s not much of a debate. It’s really just a cacophony of “experts” condemning the act. There are a few dissenting voices who find fault with this particular high-profile event, but still hold the opinion that there are certain situations in which spanking may be an acceptable option. My mother taught me to never say never. But, the occasions in which an open-handed spank on a well-padded bottom are so rare that for all practical purposes, striking a child should not appear on any list of discipline strategies.

However, I’m not sure that spanking should automatically be equated with child abuse. It is seldom effective and should raise a red flag that we are dealing with a parent who needs help in managing his or her child’s behavior, but it’s generally not abuse.

In this recent case, the father has talked about the long lineage of corporal punishment that runs through his family. However, I think that most parents in this country instinctively know that hitting their child is not the best option. They may have learned from experience that it is ineffective and has a very narrow safety margin. But, parents aren’t sure what they should have done.

They may have read magazine articles or heard talking heads on television encouraging parents to engage their misbehaving children in a dialogue to explore their motives. Or, how to condemn the misdeeds without damaging the child’s self-image. To many parents, this kind of advice fells like just so much talk. They have already discovered that one can’t have a meaningful discussion with a child in the throes of a tantrum.

In many cases, the failure of words alone is the natural result of an uncountable number of threats that have never been followed by a consistent consequence. It’s not surprising that parents often fail to follow up on their threats because they lack even the smallest arsenal of safe and effective consequences. They know that corporal punishment is wrong. But, does that mean that discipline must be completely hands off? Is any physical restraint such as a bear hug of a toddler or preschooler in the throes of a tantrum so close to spanking that it could be interpreted as child abuse? Unfortunately, I suspect that there are a few child behavior experts who might say that it is.

What about putting a child in his room for time-out? If he won’t go willingly and has to be carried, is that corporal punishment? If he won’t stay in his room for even 30 seconds unless the door is held shut or latched, is that same as a penal institution’s use of solitary confinement? Although they have a physical component, these restrictions – if done sensibly – are far safer and more effective than hitting a child.

Of course, prevention should be the keystone of any behavior-management strategy. Does the parent understand the spectrum of age-appropriate behavior for his child? Does he accept that his child’s temperament may force him to modify his expectations? Have family dynamics and schedules created situations in which the child feels underappreciated? Is the parent himself in good physical and mental health?

As pediatricians, we must make it clear that we are prepared to help parents to deal with the challenges inherent in setting limits for their children and assist them in creating a strategies of safe consequences to assure that these limits are effective.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” E-mail him at [email protected].

In the wake of the allegations that a star NFL running back abused his 4-year-old son by hitting him with a switch, the debate about spanking and other forms of corporal punishment has reignited. It’s not much of a debate. It’s really just a cacophony of “experts” condemning the act. There are a few dissenting voices who find fault with this particular high-profile event, but still hold the opinion that there are certain situations in which spanking may be an acceptable option. My mother taught me to never say never. But, the occasions in which an open-handed spank on a well-padded bottom are so rare that for all practical purposes, striking a child should not appear on any list of discipline strategies.

However, I’m not sure that spanking should automatically be equated with child abuse. It is seldom effective and should raise a red flag that we are dealing with a parent who needs help in managing his or her child’s behavior, but it’s generally not abuse.

In this recent case, the father has talked about the long lineage of corporal punishment that runs through his family. However, I think that most parents in this country instinctively know that hitting their child is not the best option. They may have learned from experience that it is ineffective and has a very narrow safety margin. But, parents aren’t sure what they should have done.

They may have read magazine articles or heard talking heads on television encouraging parents to engage their misbehaving children in a dialogue to explore their motives. Or, how to condemn the misdeeds without damaging the child’s self-image. To many parents, this kind of advice fells like just so much talk. They have already discovered that one can’t have a meaningful discussion with a child in the throes of a tantrum.

In many cases, the failure of words alone is the natural result of an uncountable number of threats that have never been followed by a consistent consequence. It’s not surprising that parents often fail to follow up on their threats because they lack even the smallest arsenal of safe and effective consequences. They know that corporal punishment is wrong. But, does that mean that discipline must be completely hands off? Is any physical restraint such as a bear hug of a toddler or preschooler in the throes of a tantrum so close to spanking that it could be interpreted as child abuse? Unfortunately, I suspect that there are a few child behavior experts who might say that it is.

What about putting a child in his room for time-out? If he won’t go willingly and has to be carried, is that corporal punishment? If he won’t stay in his room for even 30 seconds unless the door is held shut or latched, is that same as a penal institution’s use of solitary confinement? Although they have a physical component, these restrictions – if done sensibly – are far safer and more effective than hitting a child.

Of course, prevention should be the keystone of any behavior-management strategy. Does the parent understand the spectrum of age-appropriate behavior for his child? Does he accept that his child’s temperament may force him to modify his expectations? Have family dynamics and schedules created situations in which the child feels underappreciated? Is the parent himself in good physical and mental health?

As pediatricians, we must make it clear that we are prepared to help parents to deal with the challenges inherent in setting limits for their children and assist them in creating a strategies of safe consequences to assure that these limits are effective.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” E-mail him at [email protected].

Weighing self-determination against blissful ignorance at death’s door

I had a young cousin with thalassemia major. She had the textbook chipmunk facies, but you otherwise would not have known she was ill. Despite requiring blood transfusions every 3 weeks, she led a fairly normal life, graduating from college and holding down a good job.

In 2012, we found out that she had hepatitis C. She received treatment, but it did not succeed. By this point, she’d already developed cardiomyopathy, and she would later develop atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Earlier this year, Gilead was kind enough to give her its new drug sofosbuvir for free, but given her comorbidities, she could not tolerate it.

Recently, she was discharged after a protracted admission for heart failure. At that point, her hematologist, cardiologist, and hepatologist held a family meeting with her parents and siblings and pointed out the futility of her situation. Her family brought her home. They did what Filipino families in desperation do. They prayed and reached out to a “faith healer” – someone who uses poultices made from taro leaves, mutters incantations, and provides homemade remedies for any ailment. From a patient’s perspective, they provide hope where no one else will; from an outsider’s perspective, they are simply preying on the vulnerable.

Despite her family’s efforts, my cousin died about a month after coming home. She was only 27 years old. She woke up one morning feeling short of breath, weighed down by anasarca. She was brought to the hospital. Surrounded by her family, she asked her brother why he was crying. She asked her family not to bother calling her boyfriend; she’d talk to him when he came around. Then she fell asleep for the last time.

She did not know that she was dying. Her family had chosen to keep this from her.

When I learned about the circumstances of her passing I was angry and indignant at first. Why wouldn’t they tell her? What about patient self-determination and letting her be the judge of whether she wanted to be taken back to the hospital? Why would they deprive her of the opportunity to say goodbye? How is it that this sort of paternalistic, “I know what’s best for you” attitude still exists?

But I tried to put myself in her shoes, and it didn’t take long for me to question my certitude.

We romanticize the last moments of our lives. We imagine it to be filled with equanimity, a dignified acceptance of the inevitable. But that cannot always be the case. I can just as easily imagine myself to be angry, bitter, and, worst of all, fearful. Overwhelmed with sadness that it makes my last moments joyless rather than joyful.

Dying is intensely personal. Billions of people have led lives and reached endings unique to them. We may make noise about patient self-determination, but really, what is that if not just another manifestation of our arrogance that we know best? Is not insisting on patient self-determination just the other side of the same protect-the-patient-by-withholding-information coin?

I was humbled by my own ambivalence toward how her family handled her death, and a bit ashamed that I would be so quick to judge them. They did what they thought was best; who am I to question that? I may understand the science of life and death, but I cannot claim to understand living and dying.

Dr. Chan practices rheumatology in Pawtucket, R.I.

I had a young cousin with thalassemia major. She had the textbook chipmunk facies, but you otherwise would not have known she was ill. Despite requiring blood transfusions every 3 weeks, she led a fairly normal life, graduating from college and holding down a good job.

In 2012, we found out that she had hepatitis C. She received treatment, but it did not succeed. By this point, she’d already developed cardiomyopathy, and she would later develop atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Earlier this year, Gilead was kind enough to give her its new drug sofosbuvir for free, but given her comorbidities, she could not tolerate it.

Recently, she was discharged after a protracted admission for heart failure. At that point, her hematologist, cardiologist, and hepatologist held a family meeting with her parents and siblings and pointed out the futility of her situation. Her family brought her home. They did what Filipino families in desperation do. They prayed and reached out to a “faith healer” – someone who uses poultices made from taro leaves, mutters incantations, and provides homemade remedies for any ailment. From a patient’s perspective, they provide hope where no one else will; from an outsider’s perspective, they are simply preying on the vulnerable.

Despite her family’s efforts, my cousin died about a month after coming home. She was only 27 years old. She woke up one morning feeling short of breath, weighed down by anasarca. She was brought to the hospital. Surrounded by her family, she asked her brother why he was crying. She asked her family not to bother calling her boyfriend; she’d talk to him when he came around. Then she fell asleep for the last time.

She did not know that she was dying. Her family had chosen to keep this from her.

When I learned about the circumstances of her passing I was angry and indignant at first. Why wouldn’t they tell her? What about patient self-determination and letting her be the judge of whether she wanted to be taken back to the hospital? Why would they deprive her of the opportunity to say goodbye? How is it that this sort of paternalistic, “I know what’s best for you” attitude still exists?

But I tried to put myself in her shoes, and it didn’t take long for me to question my certitude.

We romanticize the last moments of our lives. We imagine it to be filled with equanimity, a dignified acceptance of the inevitable. But that cannot always be the case. I can just as easily imagine myself to be angry, bitter, and, worst of all, fearful. Overwhelmed with sadness that it makes my last moments joyless rather than joyful.

Dying is intensely personal. Billions of people have led lives and reached endings unique to them. We may make noise about patient self-determination, but really, what is that if not just another manifestation of our arrogance that we know best? Is not insisting on patient self-determination just the other side of the same protect-the-patient-by-withholding-information coin?

I was humbled by my own ambivalence toward how her family handled her death, and a bit ashamed that I would be so quick to judge them. They did what they thought was best; who am I to question that? I may understand the science of life and death, but I cannot claim to understand living and dying.

Dr. Chan practices rheumatology in Pawtucket, R.I.

I had a young cousin with thalassemia major. She had the textbook chipmunk facies, but you otherwise would not have known she was ill. Despite requiring blood transfusions every 3 weeks, she led a fairly normal life, graduating from college and holding down a good job.

In 2012, we found out that she had hepatitis C. She received treatment, but it did not succeed. By this point, she’d already developed cardiomyopathy, and she would later develop atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Earlier this year, Gilead was kind enough to give her its new drug sofosbuvir for free, but given her comorbidities, she could not tolerate it.

Recently, she was discharged after a protracted admission for heart failure. At that point, her hematologist, cardiologist, and hepatologist held a family meeting with her parents and siblings and pointed out the futility of her situation. Her family brought her home. They did what Filipino families in desperation do. They prayed and reached out to a “faith healer” – someone who uses poultices made from taro leaves, mutters incantations, and provides homemade remedies for any ailment. From a patient’s perspective, they provide hope where no one else will; from an outsider’s perspective, they are simply preying on the vulnerable.

Despite her family’s efforts, my cousin died about a month after coming home. She was only 27 years old. She woke up one morning feeling short of breath, weighed down by anasarca. She was brought to the hospital. Surrounded by her family, she asked her brother why he was crying. She asked her family not to bother calling her boyfriend; she’d talk to him when he came around. Then she fell asleep for the last time.

She did not know that she was dying. Her family had chosen to keep this from her.

When I learned about the circumstances of her passing I was angry and indignant at first. Why wouldn’t they tell her? What about patient self-determination and letting her be the judge of whether she wanted to be taken back to the hospital? Why would they deprive her of the opportunity to say goodbye? How is it that this sort of paternalistic, “I know what’s best for you” attitude still exists?

But I tried to put myself in her shoes, and it didn’t take long for me to question my certitude.

We romanticize the last moments of our lives. We imagine it to be filled with equanimity, a dignified acceptance of the inevitable. But that cannot always be the case. I can just as easily imagine myself to be angry, bitter, and, worst of all, fearful. Overwhelmed with sadness that it makes my last moments joyless rather than joyful.

Dying is intensely personal. Billions of people have led lives and reached endings unique to them. We may make noise about patient self-determination, but really, what is that if not just another manifestation of our arrogance that we know best? Is not insisting on patient self-determination just the other side of the same protect-the-patient-by-withholding-information coin?

I was humbled by my own ambivalence toward how her family handled her death, and a bit ashamed that I would be so quick to judge them. They did what they thought was best; who am I to question that? I may understand the science of life and death, but I cannot claim to understand living and dying.

Dr. Chan practices rheumatology in Pawtucket, R.I.

Meaningful Use – Stage 2 (Part 2 of 2)

In last month’s column, we began our discussion of Stage 2 of meaningful use. As a reminder, we noted that clinicians must meet or exceed the thresholds for the 17 core objectives and three of six menu objectives, as well as report on defined Clinical Quality Measures. We reviewed in detail the rationale for the program, as well as details of the core and menu measures.

For Stage 2 of meaningful use, the menu items and quality measures are aimed at enhancing actionable decision support to improve the quality of medical care and enable population management for patients who come into our office (and even for those who don’t). Stage 2 is also meant to facilitate physician-patient communication.

As a point of reminder and clarification, on August 29th the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services published a final rule allowing certain eligible providers the flexibility to continue using the Stage 1 criteria for the 2014 attestation year, even if they were due to start Stage 2. Unfortunately, this only applies to those who have been unable to obtain the 2014-certified software in time because of vendor delays. The reprieve does not extend to those who can’t meet Stage 2 due to measure difficulty or procrastination in purchasing software or adopting new work flow. As always, we recommend speaking with a meaningful use expert or consultant before attempting to take advantage of this flexibility. Either way, you’ll need to proceed with the 2014 Clinical Quality Measures, as these new definitions are now required by both the Stage 1 and Stage 2 goals. In this month’s EHR Report, we will highlight the most noteworthy 2014 Clinical Quality Measures.

Clinical Quality Measures are meant to measure and track the quality of health care services that are provided by the practitioner. Clinical Quality Measures are constructed to measure these aspects of care:

• Health outcomes

• Cinical processes

• Patient safety

• Efficient use of health care resources

• Care coordination

• Patient engagements

• Population and public health

• Adherence to clinical guidelines

Beginning in 2014, practitioners must select and report on 9 out of a list of 64 approved Clinical Quality Measures for the EHR Incentive Programs.

Clinical Quality Measures may be reported electronically through the EHR if this function is available through your EHR software. It can also be done through CMS’s Physician Quality Reporting System Portal. In order for a practice to report through the portal, the practice needs to sign up through CMS, which can be done through the CMS website. In addition, reporting can be done through a number of group reporting options if a practice is part of a large group of practices or an ACO, or via attestation as before. While the details go of how to report go beyond what we can cover in this column, your IT support person or consultant should be well acquainted with the process.

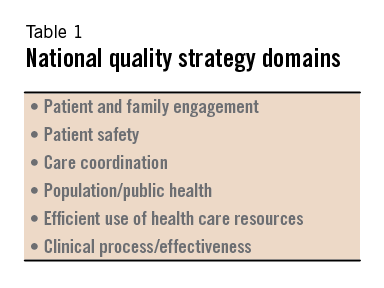

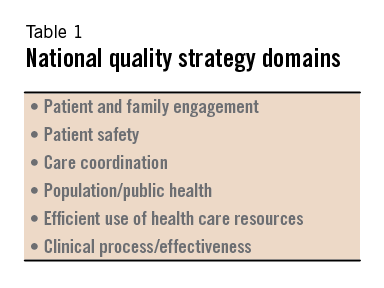

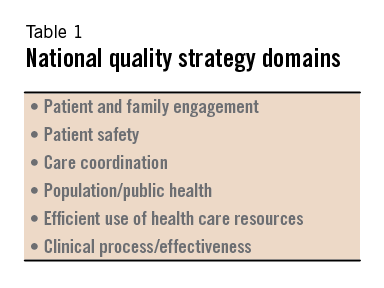

The Clinical Quality Measures are divided into six different domains of care, and providers must report on Clinical Quality Measures from at least three different domains (Table 1).

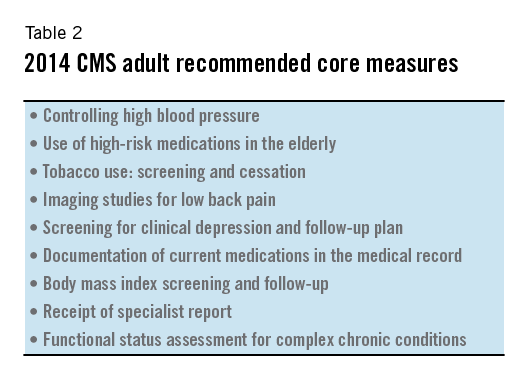

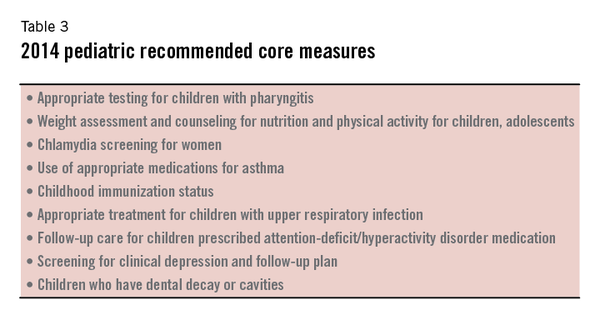

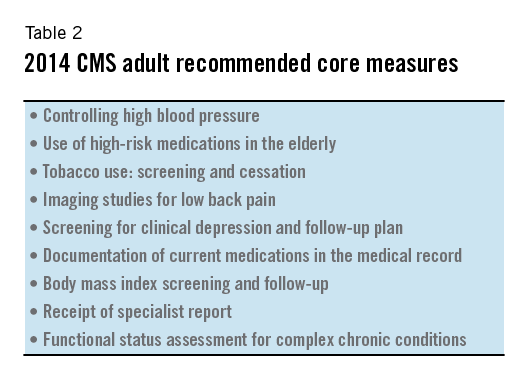

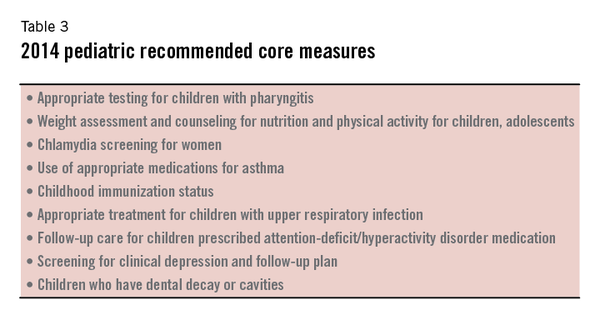

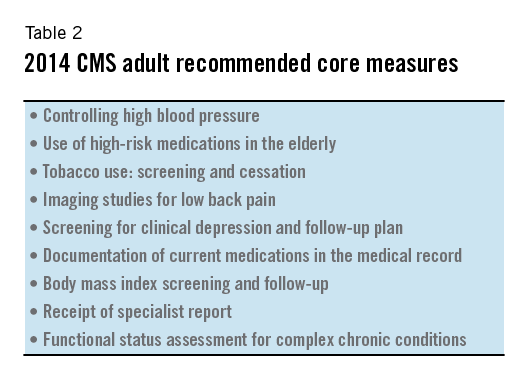

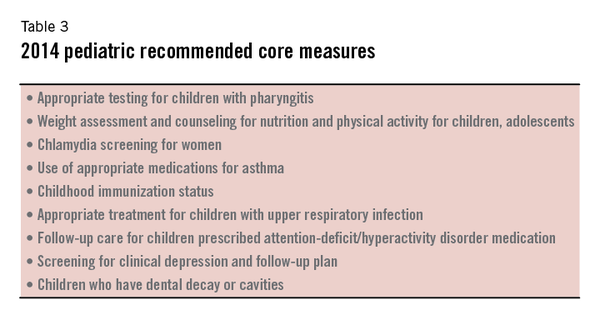

CMS encourages reporting on nine recommended core sets of Clinical Quality Measures, as long as those measures are relevant to a practitioner’s patient population. The recommended core measures focus on aspects of medical care that are felt to have the most significant effect on morbidity and mortality of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries.

They also focus on aspects of medical care that are consistent with national public health priorities or that particularly increase healthcare costs. The nine measures recommended by CMS for adult and pediatric populations are listed in Tables 2 and 3.

Between Core Objectives, Menu Objectives, and CQMs, the requirements for Stage 2 meaningful use have gotten more complicated and perhaps more confusing to track and implement than before. We recommend that every practice has an identified individual who will become a resource to help others both understand and implement Stage 2 meaningful use. We anticipate a range of opinion about the challenges of Stage 2 and are interested in your thoughts. Please email us, and we will try to publish some of the comments in upcoming columns.

References:

1. An Introduction to EHR Incentive Programs 2014 Clincial Quality Measure (CQM) Electronic Reporting Guide for Eligible Professionals.

http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/CQM2014_GuideEP.pdf.

2. Eligible Professionals Guide to Stage 2 of the EHR Incentive Programs http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/Stage2_Guide_EPs_9_23_13.pdf.

3. For a comprehensive list of the CQMs, see the 2014 CQMs for eligible professionals PDF (available at http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/EP_MeasuresTable_Posting_CQMs.pdf).

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

In last month’s column, we began our discussion of Stage 2 of meaningful use. As a reminder, we noted that clinicians must meet or exceed the thresholds for the 17 core objectives and three of six menu objectives, as well as report on defined Clinical Quality Measures. We reviewed in detail the rationale for the program, as well as details of the core and menu measures.

For Stage 2 of meaningful use, the menu items and quality measures are aimed at enhancing actionable decision support to improve the quality of medical care and enable population management for patients who come into our office (and even for those who don’t). Stage 2 is also meant to facilitate physician-patient communication.

As a point of reminder and clarification, on August 29th the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services published a final rule allowing certain eligible providers the flexibility to continue using the Stage 1 criteria for the 2014 attestation year, even if they were due to start Stage 2. Unfortunately, this only applies to those who have been unable to obtain the 2014-certified software in time because of vendor delays. The reprieve does not extend to those who can’t meet Stage 2 due to measure difficulty or procrastination in purchasing software or adopting new work flow. As always, we recommend speaking with a meaningful use expert or consultant before attempting to take advantage of this flexibility. Either way, you’ll need to proceed with the 2014 Clinical Quality Measures, as these new definitions are now required by both the Stage 1 and Stage 2 goals. In this month’s EHR Report, we will highlight the most noteworthy 2014 Clinical Quality Measures.

Clinical Quality Measures are meant to measure and track the quality of health care services that are provided by the practitioner. Clinical Quality Measures are constructed to measure these aspects of care:

• Health outcomes

• Cinical processes

• Patient safety

• Efficient use of health care resources

• Care coordination

• Patient engagements

• Population and public health

• Adherence to clinical guidelines

Beginning in 2014, practitioners must select and report on 9 out of a list of 64 approved Clinical Quality Measures for the EHR Incentive Programs.

Clinical Quality Measures may be reported electronically through the EHR if this function is available through your EHR software. It can also be done through CMS’s Physician Quality Reporting System Portal. In order for a practice to report through the portal, the practice needs to sign up through CMS, which can be done through the CMS website. In addition, reporting can be done through a number of group reporting options if a practice is part of a large group of practices or an ACO, or via attestation as before. While the details go of how to report go beyond what we can cover in this column, your IT support person or consultant should be well acquainted with the process.

The Clinical Quality Measures are divided into six different domains of care, and providers must report on Clinical Quality Measures from at least three different domains (Table 1).

CMS encourages reporting on nine recommended core sets of Clinical Quality Measures, as long as those measures are relevant to a practitioner’s patient population. The recommended core measures focus on aspects of medical care that are felt to have the most significant effect on morbidity and mortality of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries.

They also focus on aspects of medical care that are consistent with national public health priorities or that particularly increase healthcare costs. The nine measures recommended by CMS for adult and pediatric populations are listed in Tables 2 and 3.

Between Core Objectives, Menu Objectives, and CQMs, the requirements for Stage 2 meaningful use have gotten more complicated and perhaps more confusing to track and implement than before. We recommend that every practice has an identified individual who will become a resource to help others both understand and implement Stage 2 meaningful use. We anticipate a range of opinion about the challenges of Stage 2 and are interested in your thoughts. Please email us, and we will try to publish some of the comments in upcoming columns.

References:

1. An Introduction to EHR Incentive Programs 2014 Clincial Quality Measure (CQM) Electronic Reporting Guide for Eligible Professionals.

http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/CQM2014_GuideEP.pdf.

2. Eligible Professionals Guide to Stage 2 of the EHR Incentive Programs http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/Stage2_Guide_EPs_9_23_13.pdf.

3. For a comprehensive list of the CQMs, see the 2014 CQMs for eligible professionals PDF (available at http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/EP_MeasuresTable_Posting_CQMs.pdf).

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

In last month’s column, we began our discussion of Stage 2 of meaningful use. As a reminder, we noted that clinicians must meet or exceed the thresholds for the 17 core objectives and three of six menu objectives, as well as report on defined Clinical Quality Measures. We reviewed in detail the rationale for the program, as well as details of the core and menu measures.

For Stage 2 of meaningful use, the menu items and quality measures are aimed at enhancing actionable decision support to improve the quality of medical care and enable population management for patients who come into our office (and even for those who don’t). Stage 2 is also meant to facilitate physician-patient communication.

As a point of reminder and clarification, on August 29th the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services published a final rule allowing certain eligible providers the flexibility to continue using the Stage 1 criteria for the 2014 attestation year, even if they were due to start Stage 2. Unfortunately, this only applies to those who have been unable to obtain the 2014-certified software in time because of vendor delays. The reprieve does not extend to those who can’t meet Stage 2 due to measure difficulty or procrastination in purchasing software or adopting new work flow. As always, we recommend speaking with a meaningful use expert or consultant before attempting to take advantage of this flexibility. Either way, you’ll need to proceed with the 2014 Clinical Quality Measures, as these new definitions are now required by both the Stage 1 and Stage 2 goals. In this month’s EHR Report, we will highlight the most noteworthy 2014 Clinical Quality Measures.

Clinical Quality Measures are meant to measure and track the quality of health care services that are provided by the practitioner. Clinical Quality Measures are constructed to measure these aspects of care:

• Health outcomes

• Cinical processes

• Patient safety

• Efficient use of health care resources

• Care coordination

• Patient engagements

• Population and public health

• Adherence to clinical guidelines

Beginning in 2014, practitioners must select and report on 9 out of a list of 64 approved Clinical Quality Measures for the EHR Incentive Programs.

Clinical Quality Measures may be reported electronically through the EHR if this function is available through your EHR software. It can also be done through CMS’s Physician Quality Reporting System Portal. In order for a practice to report through the portal, the practice needs to sign up through CMS, which can be done through the CMS website. In addition, reporting can be done through a number of group reporting options if a practice is part of a large group of practices or an ACO, or via attestation as before. While the details go of how to report go beyond what we can cover in this column, your IT support person or consultant should be well acquainted with the process.

The Clinical Quality Measures are divided into six different domains of care, and providers must report on Clinical Quality Measures from at least three different domains (Table 1).

CMS encourages reporting on nine recommended core sets of Clinical Quality Measures, as long as those measures are relevant to a practitioner’s patient population. The recommended core measures focus on aspects of medical care that are felt to have the most significant effect on morbidity and mortality of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries.

They also focus on aspects of medical care that are consistent with national public health priorities or that particularly increase healthcare costs. The nine measures recommended by CMS for adult and pediatric populations are listed in Tables 2 and 3.

Between Core Objectives, Menu Objectives, and CQMs, the requirements for Stage 2 meaningful use have gotten more complicated and perhaps more confusing to track and implement than before. We recommend that every practice has an identified individual who will become a resource to help others both understand and implement Stage 2 meaningful use. We anticipate a range of opinion about the challenges of Stage 2 and are interested in your thoughts. Please email us, and we will try to publish some of the comments in upcoming columns.

References:

1. An Introduction to EHR Incentive Programs 2014 Clincial Quality Measure (CQM) Electronic Reporting Guide for Eligible Professionals.

http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/CQM2014_GuideEP.pdf.

2. Eligible Professionals Guide to Stage 2 of the EHR Incentive Programs http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/Stage2_Guide_EPs_9_23_13.pdf.

3. For a comprehensive list of the CQMs, see the 2014 CQMs for eligible professionals PDF (available at http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/EP_MeasuresTable_Posting_CQMs.pdf).

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Point/Counterpoint: Is TEVAR required for all Type B aortic dissections?

Yes, TEVAR is clearly indicated.

Aortic dissection is a devastating condition afflicting an estimated two to eight per 100,000 people annually and comprises a large portion of the clinical entity known as the acute aortic syndromes. Patients presenting with an uncomplicated type B acute aortic dissection (TBAD) generally have low in-hospital mortality rates (2.4%-9%) when managed appropriately with anti-impulse therapy. However, survival continues to decrease with follow-up, with survival ranging between 80% and more than 95% at 1 year, progressing to approximately 75% at 3-4 years, and 48%-65% at 10 years. In late follow-up, the development of a new dissection with complications is estimated to occur in 20%-50% of patients. Complicated aortic dissections affect between 22% and 47%, and when present, mortality reaches more than 50% within the first week. TEVAR in these patients has been shown to be clearly indicated in a variety of studies with marked improvements in early mortality and late survival. Thus, one can see that aortic dissection is a disease that needs to be managed lifelong, and is associated with a high risk of mortality for the next 10 years after the initial presentation.1,2,3

The long-term effects of a patent false lumen have been well documented. Several studies following patients with chronic TBAD have documented progressive enlargement in aortic diameter with a patent false lumen. The mean increase in maximum aortic diameter ranges from 3.8 to 7.1 mm annually with any flow in the false lumen (FL) versus 1-2 mm per year with a thrombosed FL. Patients with a patent FL had 7.5 times increased risk of a dissection-related death or need for surgery as compared to patients with thrombosis of the FL. Dissection-related death or need for surgery occurred at a significantly earlier follow-up period in the patients with a patent FL.1,2,3

The aortic diameter may also influence the patency of the FL at presentation. In a review of 110 patients presenting with acute uncomplicated TBAD, 44% were identified to have a patent FL on initial imaging. Thirty-one percent of these patients had a maximum aortic diameter of 45 mm or more versus 14% of patients with a thrombosed FL (P = .053). Incidentally, patients with FL patency were on average 4 years younger than their thrombosed counterparts (62 vs. 66 years, P = .009).

Moreover, it appears that the long-term risks associated with a patent FL are further augmented by aortic dilatation at presentation. When combining both risk factors (FL patency and aortic diameter of 40 mm or more), only 22% of patients are dissection-related event–free at 5-year follow-up.Onitsuka et al.4 substantiated this finding on multivariate analysis. Interestingly, 10 of the 76 patients included in that study met both conditions, and seven of those patients (70%) experienced a dissection-related death or surgical conversion. Certainly patients meeting both criteria merit close follow-up for the development of aortic enlargement or symptoms of impending rupture.

The natural history of TBAD lends itself to at least some thrombus formation within the FL and is a common finding as the dissection becomes chronic. But in fact, partial thrombosis of the FL is associated with higher mortality in patients discharged from the hospital with stable TBAD at 1- and 3-year follow-up (15.4% and 31.6%, respectively). Matched patients with a patent FL had a 5.4% and 13.7% rate of mortality at 1 and 3 years, and patients with complete FL thrombosis were found to have mortality rates of 0% and 22.6% at the same follow-up.

Aortic remodeling after TEVAR

Placement of a thoracic endograft under these acute circumstances can often significantly alter the preoperative morphology of the true and false lumen. Schoder and colleagues5 followed changes in the TL and FL diameter in 20 patients after TEVAR for acute complicated dissection. Ninety percent of patients were found to have complete FL thrombosis of the thoracic aorta at 1 year, with a mean decrease in FL diameter of 11.6 mm. Two patients with a patent FL showed a mean increase in the maximal aortic diameter of 4.5 mm. In a similar study, Conrad et al.6 documented aortic remodeling of 21 patients in the year following TEVAR, 88% of whom had thrombosis of the FL. Most often the mobile septum is easily displaced by the radial force of the stent graft, with minimal limitation of expansion to the design diameter. Thus, endograft selection should be directed by the diameter of the normal unaffected aorta with minimal oversizing commonly limited to 5%-10%. Balloon profiling is not typically necessary.

The INSTEAD trial7 evaluated the management of uncomplicated type B aortic dissection and compared optimum medical therapy (OMT) to OMT with TEVAR. A total of 140 subjects were enrolled at seven European sites with 68 patients enrolled in OMT and 72 in OMT with TEVAR. In patients treated with TEVAR there was 90.6% complete FL thrombosis with a maximum true lumen diameter of 32.6 mm as compared to 22% and 18.7 mm in those treated with medical therapy alone. Furthermore, there was a 12.4% absolute risk reduction in aortic specific mortality and a 19.1% absolute risk reduction in disease progression in patients treated with TEVAR.

It is clear that patients that present with complicated type B aortic dissections mandate intervention with TEVAR and potentially other interventions to alleviate the complications at presentation. INSTEAD demonstrates that elective TEVAR results in favorable aortic remodeling and long-term survival, reinterventions were low, and it prevents late expansion and malperfusion. TEVAR was also associated with improved 5-year aortic-specific survival. TEVAR appears to be beneficial in those patients who present initially with a false lumen diameter of greater than 22 mm and an aortic diameter of greater than 40 mm with a patent false lumen.

References

1. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013;4:407-16.

2. J. Vasc. Surg. 2012;55:641-51.

3. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;54:985-92

4. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2004;78:1268-73.

5. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2007;83:1059-66.

6. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009;50:510-17.

7. Circulation 2009;120:2519-28.

Dr. Arko is with the Aortic Institute, Sanger Heart & Vascular Institute, Charlotte, N.C. He reported no relevant conflicts.

No, evidence supports careful choice of patients.

While the role of TEVAR has been proven to treat complications of acute type B dissections,1 its value as a prophylactic treatment in uncomplicated cases remains controversial. Optimal medical treatment (OMT) with strict blood pressure (SBP less than 120 mm Hg) and heart rate control is associated with a low morbidity and mortality, despite the risk of progressive aortic dilation. On the other hand TEVAR can result in early death and significant neurologic complications; other devastating complications of TEVAR include retrograde aortic dissection and access vessel rupture with a high associated mortality.

A meta-analysis of the published literature reported a high technical success of TEVAR for uncomplicated type B dissection and a relatively high conversion rate (20%) for patient treated with OMT, however the results did not identify an advantage for TEVAR with respect to 30-day and 2-year mortality.2

An expert panel review of the world literature also did not find significant data to support use of TEVAR for uncomplicated type B dissection.3 In the only randomized prospective trial to examine the role of TEVAR for uncomplicated type B dissection, the INSTEAD trial randomized 140 patients to OMT vs. OMT and TEVAR.4 The study results also did not support the use of TEVAR for the treatment of uncomplicated type B dissection, there was no survival advantage at 2 years, while TEVAR was associated with a 11.1% overall mortality and 4.3% neurologic complication rate, compared with 4.4% and 1.4% in the OMT group. The initial study did however report improved aortic remodeling at 2 years with TEVAR. The results of INSTEAD have been challenged because critical analysis of the INSTEAD trial has determined that the results were underpowered and that there was a 21% crossover in the OMT group and four patients received TEVAR that should have been excluded.5

Subsequent long-term analysis of the INSTEAD XL data do demonstrate a significant survival benefit and freedom from aortic adverse events in the TEVAR group after the initial 2-year analysis.6 At the 5-year follow up only 27 patients remained without a TEVAR. Fortunately there were no adverse events in the patients that crossed over to TEVAR from the OMT group demonstrating the safety of delayed TEVAR in this group. The high rate of aortic associated adverse events may favor early TEVAR. The INSTEAD XL study did identify a large primary tear (more than 10 mm) and an initial aortic diameter of 40 mm as risk factors to crossover suggesting a more aggressive approach in this subset of patients.

So while the INSTEAD XL trial now supports the use of TEVAR for uncomplicated type B dissections this was a relatively small trial that was underpowered in its initial analysis. Expert review of the world literature still supports medical management in the initial phase of treatment. Obviously in cases of failure of medical management TEVAR provides an effective treatment to restore the true lumen and visceral perfusion with possible sustained remodeling of the false lumen.

Given the not insignificant morbidity associated with TEVAR placement, routine treatment of all acute, uncomplicated type B dissections cannot be supported with the current evidence. However, a strategy of selective treatment based on size of the entry tear, extent of dissection, false lumen diameter and extent of thrombosis, effectiveness of antihypertension medications, ability to comply with medical therapy, and surveillance may be implemented. Furthermore treatment at centers of excellence with extensive TEVAR experience based on established protocols favor improved patient outcomes.

References

1. N. Engl. J. Med. 199;340:1546-52

2. Vasc. Endovascular. Surg. 2013 Oct 12;47(7):497-501. Epub 2013 Jul 12.

3. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61(16):1661-78.

4. Circulation 2009;120:2519-28.

5. Circulation 2009;120:2513-14.

6. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013;6:407-16.

Dr. Shames is professor of surgery and radiology and program director of vascular surgery at the University of South Florida, Tampa. He reported no relevant conflicts.

Yes, TEVAR is clearly indicated.

Aortic dissection is a devastating condition afflicting an estimated two to eight per 100,000 people annually and comprises a large portion of the clinical entity known as the acute aortic syndromes. Patients presenting with an uncomplicated type B acute aortic dissection (TBAD) generally have low in-hospital mortality rates (2.4%-9%) when managed appropriately with anti-impulse therapy. However, survival continues to decrease with follow-up, with survival ranging between 80% and more than 95% at 1 year, progressing to approximately 75% at 3-4 years, and 48%-65% at 10 years. In late follow-up, the development of a new dissection with complications is estimated to occur in 20%-50% of patients. Complicated aortic dissections affect between 22% and 47%, and when present, mortality reaches more than 50% within the first week. TEVAR in these patients has been shown to be clearly indicated in a variety of studies with marked improvements in early mortality and late survival. Thus, one can see that aortic dissection is a disease that needs to be managed lifelong, and is associated with a high risk of mortality for the next 10 years after the initial presentation.1,2,3

The long-term effects of a patent false lumen have been well documented. Several studies following patients with chronic TBAD have documented progressive enlargement in aortic diameter with a patent false lumen. The mean increase in maximum aortic diameter ranges from 3.8 to 7.1 mm annually with any flow in the false lumen (FL) versus 1-2 mm per year with a thrombosed FL. Patients with a patent FL had 7.5 times increased risk of a dissection-related death or need for surgery as compared to patients with thrombosis of the FL. Dissection-related death or need for surgery occurred at a significantly earlier follow-up period in the patients with a patent FL.1,2,3

The aortic diameter may also influence the patency of the FL at presentation. In a review of 110 patients presenting with acute uncomplicated TBAD, 44% were identified to have a patent FL on initial imaging. Thirty-one percent of these patients had a maximum aortic diameter of 45 mm or more versus 14% of patients with a thrombosed FL (P = .053). Incidentally, patients with FL patency were on average 4 years younger than their thrombosed counterparts (62 vs. 66 years, P = .009).

Moreover, it appears that the long-term risks associated with a patent FL are further augmented by aortic dilatation at presentation. When combining both risk factors (FL patency and aortic diameter of 40 mm or more), only 22% of patients are dissection-related event–free at 5-year follow-up.Onitsuka et al.4 substantiated this finding on multivariate analysis. Interestingly, 10 of the 76 patients included in that study met both conditions, and seven of those patients (70%) experienced a dissection-related death or surgical conversion. Certainly patients meeting both criteria merit close follow-up for the development of aortic enlargement or symptoms of impending rupture.

The natural history of TBAD lends itself to at least some thrombus formation within the FL and is a common finding as the dissection becomes chronic. But in fact, partial thrombosis of the FL is associated with higher mortality in patients discharged from the hospital with stable TBAD at 1- and 3-year follow-up (15.4% and 31.6%, respectively). Matched patients with a patent FL had a 5.4% and 13.7% rate of mortality at 1 and 3 years, and patients with complete FL thrombosis were found to have mortality rates of 0% and 22.6% at the same follow-up.

Aortic remodeling after TEVAR

Placement of a thoracic endograft under these acute circumstances can often significantly alter the preoperative morphology of the true and false lumen. Schoder and colleagues5 followed changes in the TL and FL diameter in 20 patients after TEVAR for acute complicated dissection. Ninety percent of patients were found to have complete FL thrombosis of the thoracic aorta at 1 year, with a mean decrease in FL diameter of 11.6 mm. Two patients with a patent FL showed a mean increase in the maximal aortic diameter of 4.5 mm. In a similar study, Conrad et al.6 documented aortic remodeling of 21 patients in the year following TEVAR, 88% of whom had thrombosis of the FL. Most often the mobile septum is easily displaced by the radial force of the stent graft, with minimal limitation of expansion to the design diameter. Thus, endograft selection should be directed by the diameter of the normal unaffected aorta with minimal oversizing commonly limited to 5%-10%. Balloon profiling is not typically necessary.

The INSTEAD trial7 evaluated the management of uncomplicated type B aortic dissection and compared optimum medical therapy (OMT) to OMT with TEVAR. A total of 140 subjects were enrolled at seven European sites with 68 patients enrolled in OMT and 72 in OMT with TEVAR. In patients treated with TEVAR there was 90.6% complete FL thrombosis with a maximum true lumen diameter of 32.6 mm as compared to 22% and 18.7 mm in those treated with medical therapy alone. Furthermore, there was a 12.4% absolute risk reduction in aortic specific mortality and a 19.1% absolute risk reduction in disease progression in patients treated with TEVAR.

It is clear that patients that present with complicated type B aortic dissections mandate intervention with TEVAR and potentially other interventions to alleviate the complications at presentation. INSTEAD demonstrates that elective TEVAR results in favorable aortic remodeling and long-term survival, reinterventions were low, and it prevents late expansion and malperfusion. TEVAR was also associated with improved 5-year aortic-specific survival. TEVAR appears to be beneficial in those patients who present initially with a false lumen diameter of greater than 22 mm and an aortic diameter of greater than 40 mm with a patent false lumen.

References

1. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013;4:407-16.

2. J. Vasc. Surg. 2012;55:641-51.

3. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;54:985-92

4. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2004;78:1268-73.

5. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2007;83:1059-66.

6. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009;50:510-17.

7. Circulation 2009;120:2519-28.

Dr. Arko is with the Aortic Institute, Sanger Heart & Vascular Institute, Charlotte, N.C. He reported no relevant conflicts.

No, evidence supports careful choice of patients.

While the role of TEVAR has been proven to treat complications of acute type B dissections,1 its value as a prophylactic treatment in uncomplicated cases remains controversial. Optimal medical treatment (OMT) with strict blood pressure (SBP less than 120 mm Hg) and heart rate control is associated with a low morbidity and mortality, despite the risk of progressive aortic dilation. On the other hand TEVAR can result in early death and significant neurologic complications; other devastating complications of TEVAR include retrograde aortic dissection and access vessel rupture with a high associated mortality.

A meta-analysis of the published literature reported a high technical success of TEVAR for uncomplicated type B dissection and a relatively high conversion rate (20%) for patient treated with OMT, however the results did not identify an advantage for TEVAR with respect to 30-day and 2-year mortality.2

An expert panel review of the world literature also did not find significant data to support use of TEVAR for uncomplicated type B dissection.3 In the only randomized prospective trial to examine the role of TEVAR for uncomplicated type B dissection, the INSTEAD trial randomized 140 patients to OMT vs. OMT and TEVAR.4 The study results also did not support the use of TEVAR for the treatment of uncomplicated type B dissection, there was no survival advantage at 2 years, while TEVAR was associated with a 11.1% overall mortality and 4.3% neurologic complication rate, compared with 4.4% and 1.4% in the OMT group. The initial study did however report improved aortic remodeling at 2 years with TEVAR. The results of INSTEAD have been challenged because critical analysis of the INSTEAD trial has determined that the results were underpowered and that there was a 21% crossover in the OMT group and four patients received TEVAR that should have been excluded.5

Subsequent long-term analysis of the INSTEAD XL data do demonstrate a significant survival benefit and freedom from aortic adverse events in the TEVAR group after the initial 2-year analysis.6 At the 5-year follow up only 27 patients remained without a TEVAR. Fortunately there were no adverse events in the patients that crossed over to TEVAR from the OMT group demonstrating the safety of delayed TEVAR in this group. The high rate of aortic associated adverse events may favor early TEVAR. The INSTEAD XL study did identify a large primary tear (more than 10 mm) and an initial aortic diameter of 40 mm as risk factors to crossover suggesting a more aggressive approach in this subset of patients.

So while the INSTEAD XL trial now supports the use of TEVAR for uncomplicated type B dissections this was a relatively small trial that was underpowered in its initial analysis. Expert review of the world literature still supports medical management in the initial phase of treatment. Obviously in cases of failure of medical management TEVAR provides an effective treatment to restore the true lumen and visceral perfusion with possible sustained remodeling of the false lumen.

Given the not insignificant morbidity associated with TEVAR placement, routine treatment of all acute, uncomplicated type B dissections cannot be supported with the current evidence. However, a strategy of selective treatment based on size of the entry tear, extent of dissection, false lumen diameter and extent of thrombosis, effectiveness of antihypertension medications, ability to comply with medical therapy, and surveillance may be implemented. Furthermore treatment at centers of excellence with extensive TEVAR experience based on established protocols favor improved patient outcomes.

References

1. N. Engl. J. Med. 199;340:1546-52

2. Vasc. Endovascular. Surg. 2013 Oct 12;47(7):497-501. Epub 2013 Jul 12.

3. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61(16):1661-78.

4. Circulation 2009;120:2519-28.

5. Circulation 2009;120:2513-14.

6. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013;6:407-16.

Dr. Shames is professor of surgery and radiology and program director of vascular surgery at the University of South Florida, Tampa. He reported no relevant conflicts.

Yes, TEVAR is clearly indicated.

Aortic dissection is a devastating condition afflicting an estimated two to eight per 100,000 people annually and comprises a large portion of the clinical entity known as the acute aortic syndromes. Patients presenting with an uncomplicated type B acute aortic dissection (TBAD) generally have low in-hospital mortality rates (2.4%-9%) when managed appropriately with anti-impulse therapy. However, survival continues to decrease with follow-up, with survival ranging between 80% and more than 95% at 1 year, progressing to approximately 75% at 3-4 years, and 48%-65% at 10 years. In late follow-up, the development of a new dissection with complications is estimated to occur in 20%-50% of patients. Complicated aortic dissections affect between 22% and 47%, and when present, mortality reaches more than 50% within the first week. TEVAR in these patients has been shown to be clearly indicated in a variety of studies with marked improvements in early mortality and late survival. Thus, one can see that aortic dissection is a disease that needs to be managed lifelong, and is associated with a high risk of mortality for the next 10 years after the initial presentation.1,2,3

The long-term effects of a patent false lumen have been well documented. Several studies following patients with chronic TBAD have documented progressive enlargement in aortic diameter with a patent false lumen. The mean increase in maximum aortic diameter ranges from 3.8 to 7.1 mm annually with any flow in the false lumen (FL) versus 1-2 mm per year with a thrombosed FL. Patients with a patent FL had 7.5 times increased risk of a dissection-related death or need for surgery as compared to patients with thrombosis of the FL. Dissection-related death or need for surgery occurred at a significantly earlier follow-up period in the patients with a patent FL.1,2,3

The aortic diameter may also influence the patency of the FL at presentation. In a review of 110 patients presenting with acute uncomplicated TBAD, 44% were identified to have a patent FL on initial imaging. Thirty-one percent of these patients had a maximum aortic diameter of 45 mm or more versus 14% of patients with a thrombosed FL (P = .053). Incidentally, patients with FL patency were on average 4 years younger than their thrombosed counterparts (62 vs. 66 years, P = .009).

Moreover, it appears that the long-term risks associated with a patent FL are further augmented by aortic dilatation at presentation. When combining both risk factors (FL patency and aortic diameter of 40 mm or more), only 22% of patients are dissection-related event–free at 5-year follow-up.Onitsuka et al.4 substantiated this finding on multivariate analysis. Interestingly, 10 of the 76 patients included in that study met both conditions, and seven of those patients (70%) experienced a dissection-related death or surgical conversion. Certainly patients meeting both criteria merit close follow-up for the development of aortic enlargement or symptoms of impending rupture.

The natural history of TBAD lends itself to at least some thrombus formation within the FL and is a common finding as the dissection becomes chronic. But in fact, partial thrombosis of the FL is associated with higher mortality in patients discharged from the hospital with stable TBAD at 1- and 3-year follow-up (15.4% and 31.6%, respectively). Matched patients with a patent FL had a 5.4% and 13.7% rate of mortality at 1 and 3 years, and patients with complete FL thrombosis were found to have mortality rates of 0% and 22.6% at the same follow-up.

Aortic remodeling after TEVAR

Placement of a thoracic endograft under these acute circumstances can often significantly alter the preoperative morphology of the true and false lumen. Schoder and colleagues5 followed changes in the TL and FL diameter in 20 patients after TEVAR for acute complicated dissection. Ninety percent of patients were found to have complete FL thrombosis of the thoracic aorta at 1 year, with a mean decrease in FL diameter of 11.6 mm. Two patients with a patent FL showed a mean increase in the maximal aortic diameter of 4.5 mm. In a similar study, Conrad et al.6 documented aortic remodeling of 21 patients in the year following TEVAR, 88% of whom had thrombosis of the FL. Most often the mobile septum is easily displaced by the radial force of the stent graft, with minimal limitation of expansion to the design diameter. Thus, endograft selection should be directed by the diameter of the normal unaffected aorta with minimal oversizing commonly limited to 5%-10%. Balloon profiling is not typically necessary.

The INSTEAD trial7 evaluated the management of uncomplicated type B aortic dissection and compared optimum medical therapy (OMT) to OMT with TEVAR. A total of 140 subjects were enrolled at seven European sites with 68 patients enrolled in OMT and 72 in OMT with TEVAR. In patients treated with TEVAR there was 90.6% complete FL thrombosis with a maximum true lumen diameter of 32.6 mm as compared to 22% and 18.7 mm in those treated with medical therapy alone. Furthermore, there was a 12.4% absolute risk reduction in aortic specific mortality and a 19.1% absolute risk reduction in disease progression in patients treated with TEVAR.

It is clear that patients that present with complicated type B aortic dissections mandate intervention with TEVAR and potentially other interventions to alleviate the complications at presentation. INSTEAD demonstrates that elective TEVAR results in favorable aortic remodeling and long-term survival, reinterventions were low, and it prevents late expansion and malperfusion. TEVAR was also associated with improved 5-year aortic-specific survival. TEVAR appears to be beneficial in those patients who present initially with a false lumen diameter of greater than 22 mm and an aortic diameter of greater than 40 mm with a patent false lumen.

References

1. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013;4:407-16.

2. J. Vasc. Surg. 2012;55:641-51.

3. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;54:985-92

4. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2004;78:1268-73.

5. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2007;83:1059-66.

6. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009;50:510-17.

7. Circulation 2009;120:2519-28.

Dr. Arko is with the Aortic Institute, Sanger Heart & Vascular Institute, Charlotte, N.C. He reported no relevant conflicts.

No, evidence supports careful choice of patients.

While the role of TEVAR has been proven to treat complications of acute type B dissections,1 its value as a prophylactic treatment in uncomplicated cases remains controversial. Optimal medical treatment (OMT) with strict blood pressure (SBP less than 120 mm Hg) and heart rate control is associated with a low morbidity and mortality, despite the risk of progressive aortic dilation. On the other hand TEVAR can result in early death and significant neurologic complications; other devastating complications of TEVAR include retrograde aortic dissection and access vessel rupture with a high associated mortality.

A meta-analysis of the published literature reported a high technical success of TEVAR for uncomplicated type B dissection and a relatively high conversion rate (20%) for patient treated with OMT, however the results did not identify an advantage for TEVAR with respect to 30-day and 2-year mortality.2

An expert panel review of the world literature also did not find significant data to support use of TEVAR for uncomplicated type B dissection.3 In the only randomized prospective trial to examine the role of TEVAR for uncomplicated type B dissection, the INSTEAD trial randomized 140 patients to OMT vs. OMT and TEVAR.4 The study results also did not support the use of TEVAR for the treatment of uncomplicated type B dissection, there was no survival advantage at 2 years, while TEVAR was associated with a 11.1% overall mortality and 4.3% neurologic complication rate, compared with 4.4% and 1.4% in the OMT group. The initial study did however report improved aortic remodeling at 2 years with TEVAR. The results of INSTEAD have been challenged because critical analysis of the INSTEAD trial has determined that the results were underpowered and that there was a 21% crossover in the OMT group and four patients received TEVAR that should have been excluded.5

Subsequent long-term analysis of the INSTEAD XL data do demonstrate a significant survival benefit and freedom from aortic adverse events in the TEVAR group after the initial 2-year analysis.6 At the 5-year follow up only 27 patients remained without a TEVAR. Fortunately there were no adverse events in the patients that crossed over to TEVAR from the OMT group demonstrating the safety of delayed TEVAR in this group. The high rate of aortic associated adverse events may favor early TEVAR. The INSTEAD XL study did identify a large primary tear (more than 10 mm) and an initial aortic diameter of 40 mm as risk factors to crossover suggesting a more aggressive approach in this subset of patients.

So while the INSTEAD XL trial now supports the use of TEVAR for uncomplicated type B dissections this was a relatively small trial that was underpowered in its initial analysis. Expert review of the world literature still supports medical management in the initial phase of treatment. Obviously in cases of failure of medical management TEVAR provides an effective treatment to restore the true lumen and visceral perfusion with possible sustained remodeling of the false lumen.

Given the not insignificant morbidity associated with TEVAR placement, routine treatment of all acute, uncomplicated type B dissections cannot be supported with the current evidence. However, a strategy of selective treatment based on size of the entry tear, extent of dissection, false lumen diameter and extent of thrombosis, effectiveness of antihypertension medications, ability to comply with medical therapy, and surveillance may be implemented. Furthermore treatment at centers of excellence with extensive TEVAR experience based on established protocols favor improved patient outcomes.

References

1. N. Engl. J. Med. 199;340:1546-52

2. Vasc. Endovascular. Surg. 2013 Oct 12;47(7):497-501. Epub 2013 Jul 12.

3. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61(16):1661-78.

4. Circulation 2009;120:2519-28.

5. Circulation 2009;120:2513-14.

6. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013;6:407-16.

Dr. Shames is professor of surgery and radiology and program director of vascular surgery at the University of South Florida, Tampa. He reported no relevant conflicts.

COSMECEUTICAL CRITIQUE: Master formulators: The ‘Julia Childs’ of skin care

In the multibillion-dollar skin care industry, there are many well-recognized brands. However, we sometimes forget that behind these products were formulators who took their scientific ideas and turned them into recipes for cosmetically elegant active formulations.

I have spent the last 15 years researching the activity of cosmeceutical ingredients for my new textbook, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (McGraw Hill, 2014). Each ingredient has its own quirks, and they all do not “play well in the sandbox” together. Formulation knowledge (cosmetic chemistry) is required to take these ingredients and combine them in a way that enhances rather than hinders their activity, just as a chef combines ingredients and cooking techniques to enhance the flavor and presentation of food. When I discuss cosmeceutical products, I always stress the importance of the ingredients and understanding ingredient interactions, because they determine the end product – how effective it is and how elegant it feels. If a product works well but smells bad and feels unpleasant, consumers will not use it.

Whom are we trusting when it comes to this science? The formulators, also known as cosmetic chemists, who put their blood, sweat, and tears into years of work to develop products that yield efficacious results. They are often behind the scenes, and their contributions are not always recognized. I refer to them as the “Julia Childs” of skin care, because they remind me of how Julia Child combined her knowledge of ingredients and aesthetic sensibilities to change the world of cooking.

I’d like to shine the spotlight on several top skin care formulators that I have met. Their relentless desire to perfect skin care recipes has helped the industry boom and has improved skin health.

Richard Parker

Location: Melbourne

Richard Parker is the CEO/founder of the Australia-based company Rationale. When he was unable to find skin care products that worked with his skin type, he decided to study cosmetic chemistry and create his own skin care line. Today, Rationale can be found in dermatologists’ and plastic surgeons’ offices across Australia. Parker’s passion for cosmetic science is evident. Australia has a high incidence of melanoma, and sunscreens undergo greater scrutiny there compared with other countries. One of the things that Parker is most proud of is his creation of SPF products that are “as elegant as they are effective.” This is a difficult combination to achieve, because sunscreens tend to be too white or too greasy; formulating them properly requires a “master chef.”

In addition to formulating effective and elegant sun protection, he has developed Essential Six: a combination of six products that work in synergy, delivering the perfect combination of active ingredients at the correct concentration to be recognized and utilized by skin cells.

In order to succeed in the formulations industry, you must possess a desire to make it better; and Parker does just that. It’s his wish for the industry to have an increased awareness of a holistic approach to skin care that includes immune protection, antioxidants, sunscreens, gentle cleansing, alpha-hydroxy acids, and vitamin A.

If being at the forefront of this evolution isn’t enough, Parker is devoted to continue his mission for years to come, all the while helping younger chemists/formulators embrace the culture.

“For the past 25 years, I have had the privilege to work with Australia’s leading dermatologists to create the best possible products and procedures,” he said. “At this stage of my career, it is so gratifying to see the younger generation of skin specialists embrace medical skin care as a part of best clinical practice.”

Chuck Friedman

Location: Wendell, N.C.

Chuck Friedman is a man who prides himself on the use of natural products – not a small achievement for a man who has been in the industry for almost half a century. His work as a formulation chemist has spanned globally recognized companies such as Lanvin-Charles of the Ritz, Almay, Estée Lauder, Burt’s Bees, and Polysciences.

Friedman prides himself on his natural products. His product list includes hypoallergenic and natural versions of cleansers; toners; exfoliators; moisturizers and masks; shampoos; conditioners; dandruff treatments and hair sprays; antiperspirants and deodorants; lip balms; salves and cuticle treatments; shaving creams and aftershaves; over-the-counter analgesics; acne treatments and sunscreens; toothpastes; and liquid soap.

Friedman has said that he is most proud of his Burt’s Bees Orange Essence Cleansing Cream, which won Health Magazine’s Healthiest Cleanser of the Year in 1999. The product is an anhydrous, 100% natural, self-preserving translucent gel-emulsion of vegetable oil and vegetable glycerin stabilized by a proprietary protein.

During his tenure in the industry, Friedman has faced many hurdles in creating his natural formulations – achieving esthetics, efficacy, and physical stability at temperature extremes while maintaining microbiological integrity and using more green, renewable ingredients while formulating with fewer petrochemicals. His breakthrough natural formulations developed at Burt’s Bees are emulated and marketed widely today.

Sergio Nacht

Location: Las Vegas

Sergio Nacht is a biochemist, researcher, and product developer with 48 years of formulation experience. Currently, he is chief scientific officer/cofounder at resolutionMD and Riley-Nacht.

“A better understanding of the structure and function of the skin has resulted in the development of better functional products that deliver clinically demonstrable benefits and not only ‘hope in a jar,’ ” he has said.

Nacht has coauthored more than 50 scientific papers, and he holds 17 international and U.S. patents.

Possibly his most significant accomplishment followed the discovery of what he believes is one of the biggest challenges in skin care formulation. Microsponge Technology is the first – and still the only – U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved controlled-release technology for topical products that maximizes efficacy while minimizing side effects and optimizing cosmetic attributes by allowing slow release of ingredients. The microsponge is used to provide various therapeutic solutions for antiaging, acne treatment, skin firming, skin lightening, and mattifying – most notably as the lead technology behind Retin-A Micro.

Byeong-Deog Park

Location: Seoul, South Korea

Byeong-Deog Park holds a Ph.D. in industrial chemicals from Seoul National University, among his other achievements. Dr. Park’s company, Neopharm, is located in Seoul. He is a true scientist who has been awarded many patents in the areas of ceramides for the treatment of dry skin and atopic dermatitis; PPAR (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor)-alpha in the treatment of inflammatory disorders; and an antimicrobial peptide, Defensamide, which has been shown to prevent colonization of Staphylococcus aureus. His research led to the development of a proprietary MLE (multilamellar emulsion) technology in which lipids and ceramides form the identical Maltese cross structure that is seen in the natural lipid barrier of the skin, allowing effective skin barrier repair.

With MLE technology, the ceramides, fatty acids, and cholesterol required for an intact skin barrier are replaced in the proper ratio and three-dimensional structure needed to emulate the skin’s natural structure. This reforms the skin’s barrier and prevents water evaporation from the skin’s surface. Dr. Park has said that he is most proud of his patented MLE technology, found in the brands Atopalm and Zerafite. He also combined MLE technology and Defensamide in an atopic dermatitis treatment known as Zeroid.

Dr. Park never ceases to impress me with his scientific knowledge and dedication to the scientific method. In a field where many products are considered “hope in a jar,” his cosmetically elegant products stand out as “verified science in a jar.”

Gordon Dow

Location: Petaluma, Calif.

Gordon Dow started Dow Pharmaceutical Sciences in his garage. Today, Dow Pharmaceutical Sciences (recently acquired by Valeant Pharmaceuticals International) is a leading company in the formulation and manufacturing of dermatological products.

Over the past 25 years, Dow has commanded the company’s evolution by carefully balancing science and business. He previously served as vice president of research and development for Ingram Pharmaceuticals, where he developed seven commercially successful products, including four dermatologicals. He also served as the executive secretary of the research advisory panel for the State of California. A few of Dow’s best-known products include MetroGel, Ziana, and Acanya.

The passion for science and skin care of these individuals has shaped the dermatologic landscape for the best. They would probably agree with Julia Child, who once said, “Find something you’re passionate about and keep tremendously interested in it.”