User login

Gestational diabetes and the Barker Hypothesis

Although there are some glimmers of hope that U.S. birthweights may be declining, the average infant birthweight has remained significantly tilted toward obesity. Moreover, and alarming number of infants, children, and adolescents are obese.

In 2007-2008, 9.5% of infants and toddlers were at or above the 95th percentile of the weight-for-recumbent-length growth charts. Among children and adolescents aged 2-19 years, 11.9% were at or above the 97th percentile of the body-mass-index-for-age growth charts; 16.9% were at or above the 95th percentile; and 31.7% were at or above the 85th percentile of BMI for age (JAMA 2010;303:242-9).

While more recent reports of obesity in children indicate a modest decline in obesity among 2- to 5-year-olds (JAMA 2014;311:806-14), an alarming number of infants and children have excess adiposity (roughly twice what is expected). In addition, cardiovascular mortality later in life continues to rise.

The question arises, have childhood and adult obesity rates remained high because mothers are feeding their children the wrong foods or because these children were born obese? One also wonders, with respect to cardiovascular mortality in adulthood, is the in utero environment playing a role?

Old lessons, growing relevance

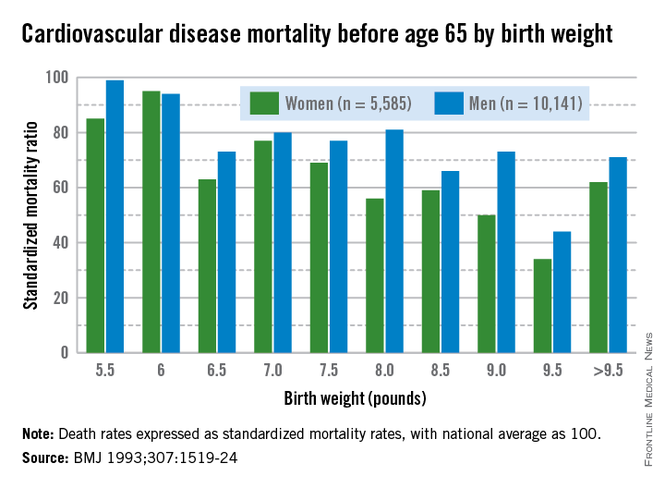

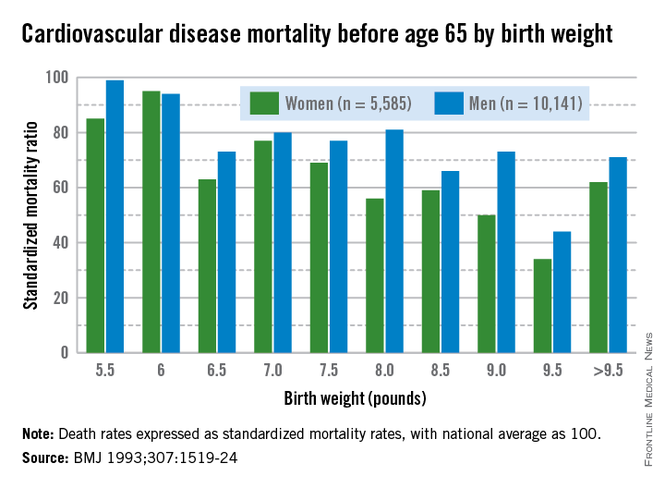

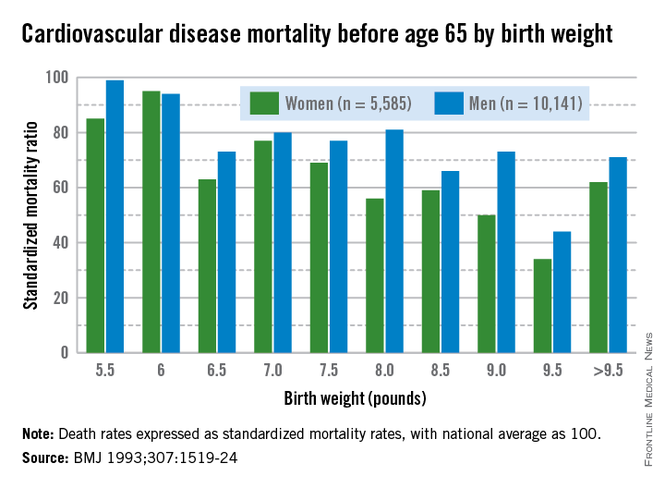

More than 3 decades ago, the late British physician Dr. David Barker got us thinking about how a challenging life in the womb can set us up for downstream ill health. He studied births from 1910 to 1945 and found that the cardiovascular mortality of individuals born during that time was inversely related to birthweight. Smaller babies, he found, could have cardiovascular mortality risks that were double or even quadruple the risks of larger babies.

Dr. Barker theorized that, when faced with undernutrition, the fetus adapts by sending more blood to the brain and sacrificing blood flow to less essential tissues. His theory about how growth and nutrition before birth may affect the heart became known as the "Barker Hypothesis." It was initially controversial, but it led to an explosion of research – especially since 2000 – on various downstream effects of the intrauterine environment.

Investigators have learned that it is not only cardiovascular mortality that is affected by low birthweight, but also the risk of developing diabetes and being overweight. This is because the fetus makes less essential systems insulin resistant. Insulin resistance persists in the womb and after birth as well, predisposing individuals to insulin resistance and obesity, both of which are closely linked to the risk of metabolic syndrome – a group of risk factors that raises the likelihood of developing heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.

In fact, further research on cohorts of Barker children – individuals who had low birthweights – has shown that not only have they had higher rates of cardiovascular disease, but they have had higher blood sugars and higher rates of insulin resistance as well.

Today, we appreciate a fuller picture of the Barker data, one that shows a reversal of this trend when birthweights reach 4,000-4,500 grams. At this point, what was a progressively downward slope of cardiovascular mortality rates with increasing birthweight suddenly shoots upward again when birthweight exceeds 4,000 g.

It is this end of the curve that is most relevant – and most concerning – for ob.gyns. today. Our problem in the United States is not so much one of starving or growth-restricted newborns, as these babies account for 5% or less of all births. It is one of overweight and obese newborns who now represent as many as 1 in 7 births. Just like the Barker babies who were growth restricted, these newborns have high insulin levels and increased risk of cardiovascular disease as adults.

Changing the trajectory

Both maternal obesity and gestational diabetes get at the heart of the Barker Hypothesis, albeit a twist, in that excessive maternal adiposity and associated insulin resistance results in high maternal blood glucose, transferring excessive nutrients to the fetus. This causes accumulation of fat in the fetus and programs the fetus for an increased and persistent risk of adiposity after birth, early-onset metabolic syndrome, and downstream cardiovascular disease in adulthood.

Dr. Dana Dabelea’s sibling study of almost 15 years ago demonstrated the long-term impact of the adverse intrauterine environment associated with maternal diabetes. Matched siblings who were born after their mothers had developed diabetes had almost double the rate of obesity as adolescents, compared with the siblings born before their mothers were diagnosed with diabetes. In childhood, these siblings ate at the same table and came from the same gene pools (with the same fathers), but they experienced dramatically different health outcomes (Diabetes 2000:49:2208-11).

This landmark study has been reproduced by other investigators who have compared children of mothers who had gestational diabetes and/or were overweight, with children whose mothers did not have gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) or were of normal weight. Such studies have consistently shown that, faced with either or both maternal obesity and diabetes in utero, offspring were significantly more likely to become overweight children and adults with insulin resistance and other components of the metabolic syndrome.

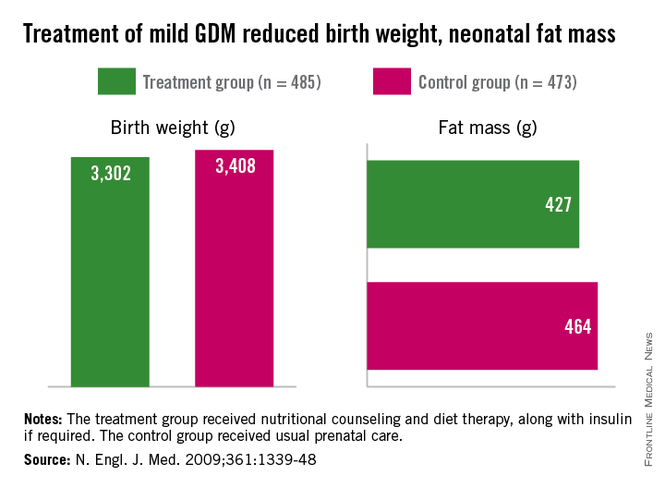

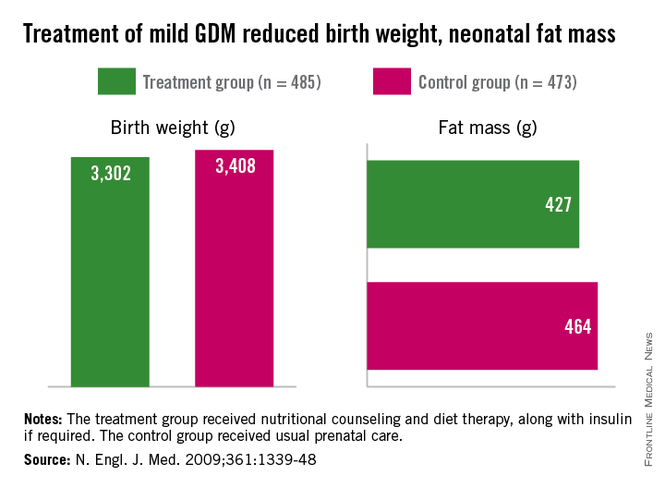

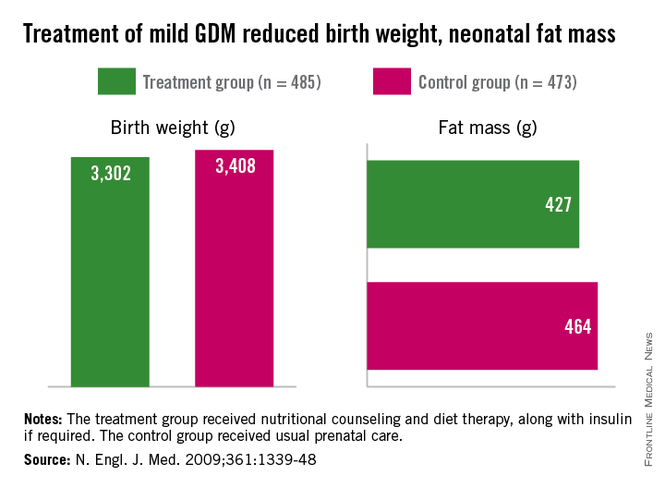

Importantly, we have evidence from randomized trials that interventions to treat GDM can effectively reduce rates of newborn obesity. While differences in birthweight between treatment and no-treatment arms have been modest, reductions in neonatal body fat, as measured by skin-fold thickness, the ponderal index, and birthweight percentile, have been highly significant.

The offspring of mothers who were treated in these trials, the Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women (N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:2477-86), and a study by Dr. Mark B. Landon and his colleagues (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1339-48), had approximately half of the newborn adiposity than did offspring of mothers who were not treated. In the latter study, maternal dietary measures alone were successful in reducing neonatal adiposity in over 80% of infants.

While published follow-up data of the offspring in these cohorts have covered only 5-8 years (showing persistently less adiposity in the treated groups), the offspring in the Australian cohort are still being monitored. Based on the cohort and case-control studies summarized above, it seems fair to expect that the children of mothers who were treated for GDM will have significantly better health profiles into and through adulthood.

We know from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study that what were formerly considered mild and inconsequential maternal blood glucose levels are instead potentially quite harmful. The study showed a clear linear relationship between maternal fasting blood glucose levels, fetal cord blood insulin concentrations (a reflection of fetal glucose levels), and newborn body fat percentage (N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:1991-2002).

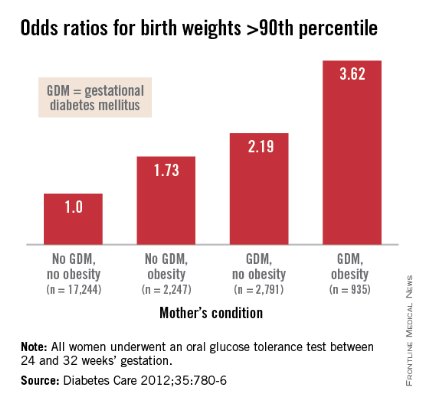

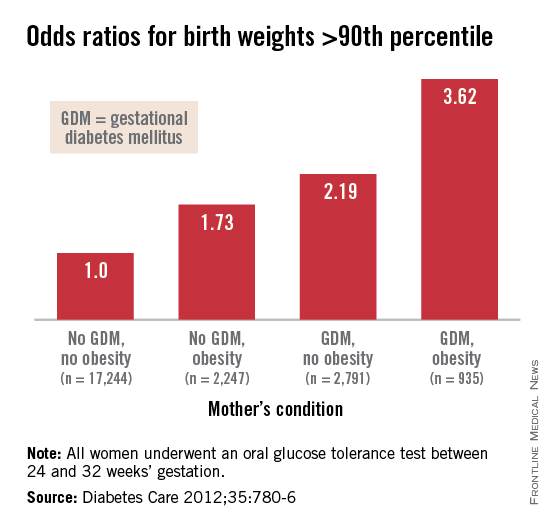

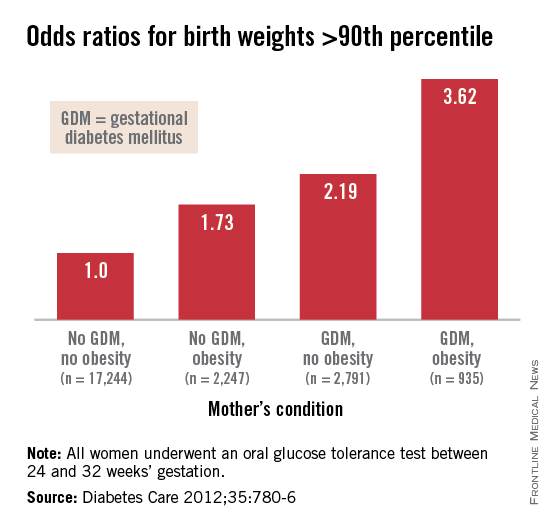

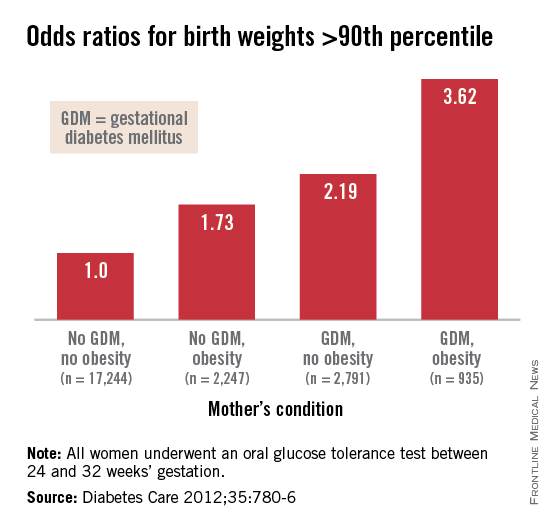

Interestingly, Dr. Patrick Catalano’s analysis of data from the HAPO study (Diabetes Care 2012;35:780-6) shows us more: Maternal obesity is almost as strong a driver of newborn obesity as is GDM. Compared with GDM (which increased the percentage of infant birthweights to greater than the 90th percentile by a factor of 2.19), maternal obesity alone increased the frequency of LGA by a factor of 1.73, and maternal obesity and GDM together increased LGA newborns by 3.62-fold.

In light of these recent findings, it is critical that we not only treat our patients who have GDM, but that we attempt to interrupt the chain of obesity that passes from mother to fetus, and from obese newborns onto their subsequent offspring.

A growing proportion of women across all race and ethnicity groups gain more than 40 pounds during pregnancy for singleton births, and many of them do not lose the weight between pregnancies. Increasingly, we have patients whose first child may not have been exposed to obesity in utero, but whose second child is exposed to overweight or obesity and higher levels of insulin resistance and glycemia.

The Institute of Medicine documented these issues in its 2009 report, "Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines." Data on maternal postpartum weights are not widely available, but data that have been collected suggest that gaining above recommended ranges is associated with excess maternal weight retention post partum, regardless of prepregnancy BMI. Women who gained above the range recommended by the IOM in 1990 had postpartum weight retention of 15-20 pounds. Among women who gained excessive amounts of weight, moreover, more than 40% retained more than 20 pounds, according to the report.

We must break the intergenerational transfer of obesity and insulin resistance by liberally treating GDM and optimizing glucose control during pregnancy. More importantly, we must emphasize to women the importance of having healthy weights at the time of conception. Recent research affirms that moderately simple interventions, such as dietary improvements and exercise can go a long way to achieving these goals. If we don’t – in keeping with the knowledge spurred on by Dr. Barker – we will be programming more newborns for life with insulin resistance, obesity, and disease.

Dr. Moore is a perinatologist who is chair of the department of reproductive medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Although there are some glimmers of hope that U.S. birthweights may be declining, the average infant birthweight has remained significantly tilted toward obesity. Moreover, and alarming number of infants, children, and adolescents are obese.

In 2007-2008, 9.5% of infants and toddlers were at or above the 95th percentile of the weight-for-recumbent-length growth charts. Among children and adolescents aged 2-19 years, 11.9% were at or above the 97th percentile of the body-mass-index-for-age growth charts; 16.9% were at or above the 95th percentile; and 31.7% were at or above the 85th percentile of BMI for age (JAMA 2010;303:242-9).

While more recent reports of obesity in children indicate a modest decline in obesity among 2- to 5-year-olds (JAMA 2014;311:806-14), an alarming number of infants and children have excess adiposity (roughly twice what is expected). In addition, cardiovascular mortality later in life continues to rise.

The question arises, have childhood and adult obesity rates remained high because mothers are feeding their children the wrong foods or because these children were born obese? One also wonders, with respect to cardiovascular mortality in adulthood, is the in utero environment playing a role?

Old lessons, growing relevance

More than 3 decades ago, the late British physician Dr. David Barker got us thinking about how a challenging life in the womb can set us up for downstream ill health. He studied births from 1910 to 1945 and found that the cardiovascular mortality of individuals born during that time was inversely related to birthweight. Smaller babies, he found, could have cardiovascular mortality risks that were double or even quadruple the risks of larger babies.

Dr. Barker theorized that, when faced with undernutrition, the fetus adapts by sending more blood to the brain and sacrificing blood flow to less essential tissues. His theory about how growth and nutrition before birth may affect the heart became known as the "Barker Hypothesis." It was initially controversial, but it led to an explosion of research – especially since 2000 – on various downstream effects of the intrauterine environment.

Investigators have learned that it is not only cardiovascular mortality that is affected by low birthweight, but also the risk of developing diabetes and being overweight. This is because the fetus makes less essential systems insulin resistant. Insulin resistance persists in the womb and after birth as well, predisposing individuals to insulin resistance and obesity, both of which are closely linked to the risk of metabolic syndrome – a group of risk factors that raises the likelihood of developing heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.

In fact, further research on cohorts of Barker children – individuals who had low birthweights – has shown that not only have they had higher rates of cardiovascular disease, but they have had higher blood sugars and higher rates of insulin resistance as well.

Today, we appreciate a fuller picture of the Barker data, one that shows a reversal of this trend when birthweights reach 4,000-4,500 grams. At this point, what was a progressively downward slope of cardiovascular mortality rates with increasing birthweight suddenly shoots upward again when birthweight exceeds 4,000 g.

It is this end of the curve that is most relevant – and most concerning – for ob.gyns. today. Our problem in the United States is not so much one of starving or growth-restricted newborns, as these babies account for 5% or less of all births. It is one of overweight and obese newborns who now represent as many as 1 in 7 births. Just like the Barker babies who were growth restricted, these newborns have high insulin levels and increased risk of cardiovascular disease as adults.

Changing the trajectory

Both maternal obesity and gestational diabetes get at the heart of the Barker Hypothesis, albeit a twist, in that excessive maternal adiposity and associated insulin resistance results in high maternal blood glucose, transferring excessive nutrients to the fetus. This causes accumulation of fat in the fetus and programs the fetus for an increased and persistent risk of adiposity after birth, early-onset metabolic syndrome, and downstream cardiovascular disease in adulthood.

Dr. Dana Dabelea’s sibling study of almost 15 years ago demonstrated the long-term impact of the adverse intrauterine environment associated with maternal diabetes. Matched siblings who were born after their mothers had developed diabetes had almost double the rate of obesity as adolescents, compared with the siblings born before their mothers were diagnosed with diabetes. In childhood, these siblings ate at the same table and came from the same gene pools (with the same fathers), but they experienced dramatically different health outcomes (Diabetes 2000:49:2208-11).

This landmark study has been reproduced by other investigators who have compared children of mothers who had gestational diabetes and/or were overweight, with children whose mothers did not have gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) or were of normal weight. Such studies have consistently shown that, faced with either or both maternal obesity and diabetes in utero, offspring were significantly more likely to become overweight children and adults with insulin resistance and other components of the metabolic syndrome.

Importantly, we have evidence from randomized trials that interventions to treat GDM can effectively reduce rates of newborn obesity. While differences in birthweight between treatment and no-treatment arms have been modest, reductions in neonatal body fat, as measured by skin-fold thickness, the ponderal index, and birthweight percentile, have been highly significant.

The offspring of mothers who were treated in these trials, the Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women (N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:2477-86), and a study by Dr. Mark B. Landon and his colleagues (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1339-48), had approximately half of the newborn adiposity than did offspring of mothers who were not treated. In the latter study, maternal dietary measures alone were successful in reducing neonatal adiposity in over 80% of infants.

While published follow-up data of the offspring in these cohorts have covered only 5-8 years (showing persistently less adiposity in the treated groups), the offspring in the Australian cohort are still being monitored. Based on the cohort and case-control studies summarized above, it seems fair to expect that the children of mothers who were treated for GDM will have significantly better health profiles into and through adulthood.

We know from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study that what were formerly considered mild and inconsequential maternal blood glucose levels are instead potentially quite harmful. The study showed a clear linear relationship between maternal fasting blood glucose levels, fetal cord blood insulin concentrations (a reflection of fetal glucose levels), and newborn body fat percentage (N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:1991-2002).

Interestingly, Dr. Patrick Catalano’s analysis of data from the HAPO study (Diabetes Care 2012;35:780-6) shows us more: Maternal obesity is almost as strong a driver of newborn obesity as is GDM. Compared with GDM (which increased the percentage of infant birthweights to greater than the 90th percentile by a factor of 2.19), maternal obesity alone increased the frequency of LGA by a factor of 1.73, and maternal obesity and GDM together increased LGA newborns by 3.62-fold.

In light of these recent findings, it is critical that we not only treat our patients who have GDM, but that we attempt to interrupt the chain of obesity that passes from mother to fetus, and from obese newborns onto their subsequent offspring.

A growing proportion of women across all race and ethnicity groups gain more than 40 pounds during pregnancy for singleton births, and many of them do not lose the weight between pregnancies. Increasingly, we have patients whose first child may not have been exposed to obesity in utero, but whose second child is exposed to overweight or obesity and higher levels of insulin resistance and glycemia.

The Institute of Medicine documented these issues in its 2009 report, "Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines." Data on maternal postpartum weights are not widely available, but data that have been collected suggest that gaining above recommended ranges is associated with excess maternal weight retention post partum, regardless of prepregnancy BMI. Women who gained above the range recommended by the IOM in 1990 had postpartum weight retention of 15-20 pounds. Among women who gained excessive amounts of weight, moreover, more than 40% retained more than 20 pounds, according to the report.

We must break the intergenerational transfer of obesity and insulin resistance by liberally treating GDM and optimizing glucose control during pregnancy. More importantly, we must emphasize to women the importance of having healthy weights at the time of conception. Recent research affirms that moderately simple interventions, such as dietary improvements and exercise can go a long way to achieving these goals. If we don’t – in keeping with the knowledge spurred on by Dr. Barker – we will be programming more newborns for life with insulin resistance, obesity, and disease.

Dr. Moore is a perinatologist who is chair of the department of reproductive medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Although there are some glimmers of hope that U.S. birthweights may be declining, the average infant birthweight has remained significantly tilted toward obesity. Moreover, and alarming number of infants, children, and adolescents are obese.

In 2007-2008, 9.5% of infants and toddlers were at or above the 95th percentile of the weight-for-recumbent-length growth charts. Among children and adolescents aged 2-19 years, 11.9% were at or above the 97th percentile of the body-mass-index-for-age growth charts; 16.9% were at or above the 95th percentile; and 31.7% were at or above the 85th percentile of BMI for age (JAMA 2010;303:242-9).

While more recent reports of obesity in children indicate a modest decline in obesity among 2- to 5-year-olds (JAMA 2014;311:806-14), an alarming number of infants and children have excess adiposity (roughly twice what is expected). In addition, cardiovascular mortality later in life continues to rise.

The question arises, have childhood and adult obesity rates remained high because mothers are feeding their children the wrong foods or because these children were born obese? One also wonders, with respect to cardiovascular mortality in adulthood, is the in utero environment playing a role?

Old lessons, growing relevance

More than 3 decades ago, the late British physician Dr. David Barker got us thinking about how a challenging life in the womb can set us up for downstream ill health. He studied births from 1910 to 1945 and found that the cardiovascular mortality of individuals born during that time was inversely related to birthweight. Smaller babies, he found, could have cardiovascular mortality risks that were double or even quadruple the risks of larger babies.

Dr. Barker theorized that, when faced with undernutrition, the fetus adapts by sending more blood to the brain and sacrificing blood flow to less essential tissues. His theory about how growth and nutrition before birth may affect the heart became known as the "Barker Hypothesis." It was initially controversial, but it led to an explosion of research – especially since 2000 – on various downstream effects of the intrauterine environment.

Investigators have learned that it is not only cardiovascular mortality that is affected by low birthweight, but also the risk of developing diabetes and being overweight. This is because the fetus makes less essential systems insulin resistant. Insulin resistance persists in the womb and after birth as well, predisposing individuals to insulin resistance and obesity, both of which are closely linked to the risk of metabolic syndrome – a group of risk factors that raises the likelihood of developing heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.

In fact, further research on cohorts of Barker children – individuals who had low birthweights – has shown that not only have they had higher rates of cardiovascular disease, but they have had higher blood sugars and higher rates of insulin resistance as well.

Today, we appreciate a fuller picture of the Barker data, one that shows a reversal of this trend when birthweights reach 4,000-4,500 grams. At this point, what was a progressively downward slope of cardiovascular mortality rates with increasing birthweight suddenly shoots upward again when birthweight exceeds 4,000 g.

It is this end of the curve that is most relevant – and most concerning – for ob.gyns. today. Our problem in the United States is not so much one of starving or growth-restricted newborns, as these babies account for 5% or less of all births. It is one of overweight and obese newborns who now represent as many as 1 in 7 births. Just like the Barker babies who were growth restricted, these newborns have high insulin levels and increased risk of cardiovascular disease as adults.

Changing the trajectory

Both maternal obesity and gestational diabetes get at the heart of the Barker Hypothesis, albeit a twist, in that excessive maternal adiposity and associated insulin resistance results in high maternal blood glucose, transferring excessive nutrients to the fetus. This causes accumulation of fat in the fetus and programs the fetus for an increased and persistent risk of adiposity after birth, early-onset metabolic syndrome, and downstream cardiovascular disease in adulthood.

Dr. Dana Dabelea’s sibling study of almost 15 years ago demonstrated the long-term impact of the adverse intrauterine environment associated with maternal diabetes. Matched siblings who were born after their mothers had developed diabetes had almost double the rate of obesity as adolescents, compared with the siblings born before their mothers were diagnosed with diabetes. In childhood, these siblings ate at the same table and came from the same gene pools (with the same fathers), but they experienced dramatically different health outcomes (Diabetes 2000:49:2208-11).

This landmark study has been reproduced by other investigators who have compared children of mothers who had gestational diabetes and/or were overweight, with children whose mothers did not have gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) or were of normal weight. Such studies have consistently shown that, faced with either or both maternal obesity and diabetes in utero, offspring were significantly more likely to become overweight children and adults with insulin resistance and other components of the metabolic syndrome.

Importantly, we have evidence from randomized trials that interventions to treat GDM can effectively reduce rates of newborn obesity. While differences in birthweight between treatment and no-treatment arms have been modest, reductions in neonatal body fat, as measured by skin-fold thickness, the ponderal index, and birthweight percentile, have been highly significant.

The offspring of mothers who were treated in these trials, the Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women (N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:2477-86), and a study by Dr. Mark B. Landon and his colleagues (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1339-48), had approximately half of the newborn adiposity than did offspring of mothers who were not treated. In the latter study, maternal dietary measures alone were successful in reducing neonatal adiposity in over 80% of infants.

While published follow-up data of the offspring in these cohorts have covered only 5-8 years (showing persistently less adiposity in the treated groups), the offspring in the Australian cohort are still being monitored. Based on the cohort and case-control studies summarized above, it seems fair to expect that the children of mothers who were treated for GDM will have significantly better health profiles into and through adulthood.

We know from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study that what were formerly considered mild and inconsequential maternal blood glucose levels are instead potentially quite harmful. The study showed a clear linear relationship between maternal fasting blood glucose levels, fetal cord blood insulin concentrations (a reflection of fetal glucose levels), and newborn body fat percentage (N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:1991-2002).

Interestingly, Dr. Patrick Catalano’s analysis of data from the HAPO study (Diabetes Care 2012;35:780-6) shows us more: Maternal obesity is almost as strong a driver of newborn obesity as is GDM. Compared with GDM (which increased the percentage of infant birthweights to greater than the 90th percentile by a factor of 2.19), maternal obesity alone increased the frequency of LGA by a factor of 1.73, and maternal obesity and GDM together increased LGA newborns by 3.62-fold.

In light of these recent findings, it is critical that we not only treat our patients who have GDM, but that we attempt to interrupt the chain of obesity that passes from mother to fetus, and from obese newborns onto their subsequent offspring.

A growing proportion of women across all race and ethnicity groups gain more than 40 pounds during pregnancy for singleton births, and many of them do not lose the weight between pregnancies. Increasingly, we have patients whose first child may not have been exposed to obesity in utero, but whose second child is exposed to overweight or obesity and higher levels of insulin resistance and glycemia.

The Institute of Medicine documented these issues in its 2009 report, "Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines." Data on maternal postpartum weights are not widely available, but data that have been collected suggest that gaining above recommended ranges is associated with excess maternal weight retention post partum, regardless of prepregnancy BMI. Women who gained above the range recommended by the IOM in 1990 had postpartum weight retention of 15-20 pounds. Among women who gained excessive amounts of weight, moreover, more than 40% retained more than 20 pounds, according to the report.

We must break the intergenerational transfer of obesity and insulin resistance by liberally treating GDM and optimizing glucose control during pregnancy. More importantly, we must emphasize to women the importance of having healthy weights at the time of conception. Recent research affirms that moderately simple interventions, such as dietary improvements and exercise can go a long way to achieving these goals. If we don’t – in keeping with the knowledge spurred on by Dr. Barker – we will be programming more newborns for life with insulin resistance, obesity, and disease.

Dr. Moore is a perinatologist who is chair of the department of reproductive medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

The fetal origins hypothesis

On Aug. 27, 2013, the field of obstetrics and gynecology suffered a great loss: the passing of Dr. David J.P. Barker. Dr. Barker was a visionary and leader whose hypothesis about the links between a mother’s health and the long-term health of her children was controversial when he first posed it in the late 1980s. However, after subsequent decades of maternal-fetal practice and research, his idea that preventing chronic disease starts with a healthy mother and baby, is embraced by the medical and science communities today.

I was just starting my career when Dr. Barker’s hypothesis, known then as the "fetal origins hypothesis" but subsequently referred to as the "Barker Hypothesis," was published. During my fellowship in maternal-fetal medicine at Yale University, I had the privilege of attending one of Dr. Barker’s lectures and meeting him. While my colleagues and I thought him an eloquent and impassioned speaker, Dr. Barker’s theory – that there was a relationship between a person’s birth weight and his or her lifetime risk for chronic disease – was highly contentious. He had based his hypothesis on large epidemiological studies conducted in Finland, India, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States – all of which revealed that the lower a person’s birth weight, the higher his or her risk for developing coronary heart disease. In addition, he concluded that the lower a person’s birth weight, but the faster the weight gain after age 2 years, the higher a person’s risk for hypertension, stroke, and type 2 diabetes.

At that time, we did not fully realize the significance, gravity, and enormity of Dr. Barker’s contribution to the ob.gyn. field. I could not imagine the impact that his work would have on my professional path. Dr. Barker’s early papers often concluded with a section looking to the future, and in one of them he stated that "we now need to progress beyond epidemiologic associations [between in utero conditions and health later in life] to greater understanding of the cellular and molecular processes that underlie them"(Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000;71:1344s-52s). From my work as a physician with diabetic pregnant women to my scientific research devoted to understanding how, at the molecular level, maternal diabetes affects the developing fetus, I have a great appreciation and respect for Dr. Barker’s work.

Therefore, I am very pleased that this month’s Master Class is devoted to a discussion of how the Barker Hypothesis applies today. We have invited Dr. Thomas R. Moore, a perinatologist who is chair of the department of reproductive medicine at the University of California, San Diego, to give his reflection on how Dr. Barker’s once radical ideas revolutionized our field.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of the Master Class column. Contact him at [email protected].

On Aug. 27, 2013, the field of obstetrics and gynecology suffered a great loss: the passing of Dr. David J.P. Barker. Dr. Barker was a visionary and leader whose hypothesis about the links between a mother’s health and the long-term health of her children was controversial when he first posed it in the late 1980s. However, after subsequent decades of maternal-fetal practice and research, his idea that preventing chronic disease starts with a healthy mother and baby, is embraced by the medical and science communities today.

I was just starting my career when Dr. Barker’s hypothesis, known then as the "fetal origins hypothesis" but subsequently referred to as the "Barker Hypothesis," was published. During my fellowship in maternal-fetal medicine at Yale University, I had the privilege of attending one of Dr. Barker’s lectures and meeting him. While my colleagues and I thought him an eloquent and impassioned speaker, Dr. Barker’s theory – that there was a relationship between a person’s birth weight and his or her lifetime risk for chronic disease – was highly contentious. He had based his hypothesis on large epidemiological studies conducted in Finland, India, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States – all of which revealed that the lower a person’s birth weight, the higher his or her risk for developing coronary heart disease. In addition, he concluded that the lower a person’s birth weight, but the faster the weight gain after age 2 years, the higher a person’s risk for hypertension, stroke, and type 2 diabetes.

At that time, we did not fully realize the significance, gravity, and enormity of Dr. Barker’s contribution to the ob.gyn. field. I could not imagine the impact that his work would have on my professional path. Dr. Barker’s early papers often concluded with a section looking to the future, and in one of them he stated that "we now need to progress beyond epidemiologic associations [between in utero conditions and health later in life] to greater understanding of the cellular and molecular processes that underlie them"(Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000;71:1344s-52s). From my work as a physician with diabetic pregnant women to my scientific research devoted to understanding how, at the molecular level, maternal diabetes affects the developing fetus, I have a great appreciation and respect for Dr. Barker’s work.

Therefore, I am very pleased that this month’s Master Class is devoted to a discussion of how the Barker Hypothesis applies today. We have invited Dr. Thomas R. Moore, a perinatologist who is chair of the department of reproductive medicine at the University of California, San Diego, to give his reflection on how Dr. Barker’s once radical ideas revolutionized our field.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of the Master Class column. Contact him at [email protected].

On Aug. 27, 2013, the field of obstetrics and gynecology suffered a great loss: the passing of Dr. David J.P. Barker. Dr. Barker was a visionary and leader whose hypothesis about the links between a mother’s health and the long-term health of her children was controversial when he first posed it in the late 1980s. However, after subsequent decades of maternal-fetal practice and research, his idea that preventing chronic disease starts with a healthy mother and baby, is embraced by the medical and science communities today.

I was just starting my career when Dr. Barker’s hypothesis, known then as the "fetal origins hypothesis" but subsequently referred to as the "Barker Hypothesis," was published. During my fellowship in maternal-fetal medicine at Yale University, I had the privilege of attending one of Dr. Barker’s lectures and meeting him. While my colleagues and I thought him an eloquent and impassioned speaker, Dr. Barker’s theory – that there was a relationship between a person’s birth weight and his or her lifetime risk for chronic disease – was highly contentious. He had based his hypothesis on large epidemiological studies conducted in Finland, India, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States – all of which revealed that the lower a person’s birth weight, the higher his or her risk for developing coronary heart disease. In addition, he concluded that the lower a person’s birth weight, but the faster the weight gain after age 2 years, the higher a person’s risk for hypertension, stroke, and type 2 diabetes.

At that time, we did not fully realize the significance, gravity, and enormity of Dr. Barker’s contribution to the ob.gyn. field. I could not imagine the impact that his work would have on my professional path. Dr. Barker’s early papers often concluded with a section looking to the future, and in one of them he stated that "we now need to progress beyond epidemiologic associations [between in utero conditions and health later in life] to greater understanding of the cellular and molecular processes that underlie them"(Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000;71:1344s-52s). From my work as a physician with diabetic pregnant women to my scientific research devoted to understanding how, at the molecular level, maternal diabetes affects the developing fetus, I have a great appreciation and respect for Dr. Barker’s work.

Therefore, I am very pleased that this month’s Master Class is devoted to a discussion of how the Barker Hypothesis applies today. We have invited Dr. Thomas R. Moore, a perinatologist who is chair of the department of reproductive medicine at the University of California, San Diego, to give his reflection on how Dr. Barker’s once radical ideas revolutionized our field.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of the Master Class column. Contact him at [email protected].

Need for more data

The need for more and better quality data on medication safety in human pregnancy has been in the public and regulatory spotlight for decades. The issue is becoming even more urgent with the impending revisions to the product label format that will eliminate the traditional A, B, C, D, X pregnancy categories, and substitute more data-driven narratives.

In response to this need, over the last several years there has been a steady increase in the number of regulatory requests/requirements for postmarketing surveillance studies for new medications likely to be used by women of reproductive age or by pregnant women. These requests most often have been fulfilled by the initiation of pregnancy registries. However, concern has been raised that pregnancy registries by and large have been challenged to recruit sufficient numbers of study subjects, and the time to completion of these studies is typically longer than desirable. Other questions have been raised about the adequacy of pregnancy registries alone (especially those with small sample sizes and no internal comparison groups) to test hypotheses related to birth outcomes.

In May 2014, the Food and Drug Administration hosted a public meeting to highlight some of these issues and to seek advice and solutions, titled "Study Approaches and Methods to Evaluate the Safety of Drugs and Biological Products During Pregnancy in the Post-Approval Setting." Panelists included representation from federal agencies including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Defense Naval Health Research Center, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Food and Drug Administration. Other panelists represented academic and HMO-based research networks, contract research organizations, the pharmaceutical industry, obstetric providers, and patients. Comments also were provided by audience members who represented a variety of entities including academic societies, professional associations, and advocacy groups.

Specific strategies for obtaining better data in a more timely fashion were presented by the panelists. These included the value and efficiency of utilizing large administrative claims databases or systemwide electronic capture of pregnancy exposure and outcome data. Using this approach, representative samples of patients can be accrued while not requiring individual active informed consent. Limitations of such sources of data also were mentioned, including inability to validate that the pregnant woman actually took a medication of interest, when, and at what dose, and the usual absence of information in claims data on some important confounders such as alcohol use and folic acid supplementation.

Panelists representing various pregnancy registry study designs described approaches to addressing some of the limitations of these studies. For example, some panelists emphasized that "disease-based" registries that involve examination of birth outcomes for several medications used for the treatment of one or more similar maternal conditions have several distinct advantages. These include a more streamlined referral process, whereby clinicians can more easily identify and refer all pregnant patients who have the same underlying condition, irrespective of treatment with any specific medication under study. Examples of successful disease-based approaches that were highlighted by panelists included the Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnancy Registry, the North American Antiepileptic Drug Pregnancy Registry, and the OTIS/MotherToBaby Autoimmune Diseases in Pregnancy Project. Each of these studies allows for comparison of outcomes across various treatments, while accounting for the possible contribution of the underlying maternal condition to adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Panelists also emphasized that more effective methods are needed for raising awareness of the existence and value of pregnancy registries for providers and consumers alike, including more efficient and extensive use of social media. Panelists, and in particular obstetric providers, indicated a need for better methods of identifying women who are eligible for participation in a pregnancy study, and facilitating the referral process. The obstetric provider panelist suggested that existing electronic medical records systems could be adapted to generate automated alerts to providers regarding patients who qualify for referral to a registry.

The patient representative panelist emphasized the need to engage the pregnant woman in the research process. This was confirmed by research groups whose primary interaction in pregnancy studies is with the pregnant woman herself, resulting in minimal loss-to-follow-up and high participant satisfaction.

Last, there was extensive discussion about the use of other alternative study designs, such as case-control studies, that could help address the limitations of pregnancy registries, especially in terms of statistical power for evaluating rare outcomes such as specific birth defects. The Vaccines and Medications in Pregnancy Surveillance System (VAMPSS) was described as one such alternative, combining the benefits of a cohort (registry-type) study with a concurrent case-control study to address the same exposures in pregnancy.

There was general consensus among panel members that no single approach to postmarketing safety studies would likely be sufficient to evaluate new or existing products, and that complementary approaches are needed.

A complete set of the panelists’ slide presentations from the public meeting as well as webcasts of the 2-day proceedings in their entirety are available for viewing here.

Dr. Chambers is a professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital, and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is director of MotherToBaby California, a past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society. She said that she had no relevant financial disclosures. To comment, e-mail her at [email protected].

The need for more and better quality data on medication safety in human pregnancy has been in the public and regulatory spotlight for decades. The issue is becoming even more urgent with the impending revisions to the product label format that will eliminate the traditional A, B, C, D, X pregnancy categories, and substitute more data-driven narratives.

In response to this need, over the last several years there has been a steady increase in the number of regulatory requests/requirements for postmarketing surveillance studies for new medications likely to be used by women of reproductive age or by pregnant women. These requests most often have been fulfilled by the initiation of pregnancy registries. However, concern has been raised that pregnancy registries by and large have been challenged to recruit sufficient numbers of study subjects, and the time to completion of these studies is typically longer than desirable. Other questions have been raised about the adequacy of pregnancy registries alone (especially those with small sample sizes and no internal comparison groups) to test hypotheses related to birth outcomes.

In May 2014, the Food and Drug Administration hosted a public meeting to highlight some of these issues and to seek advice and solutions, titled "Study Approaches and Methods to Evaluate the Safety of Drugs and Biological Products During Pregnancy in the Post-Approval Setting." Panelists included representation from federal agencies including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Defense Naval Health Research Center, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Food and Drug Administration. Other panelists represented academic and HMO-based research networks, contract research organizations, the pharmaceutical industry, obstetric providers, and patients. Comments also were provided by audience members who represented a variety of entities including academic societies, professional associations, and advocacy groups.

Specific strategies for obtaining better data in a more timely fashion were presented by the panelists. These included the value and efficiency of utilizing large administrative claims databases or systemwide electronic capture of pregnancy exposure and outcome data. Using this approach, representative samples of patients can be accrued while not requiring individual active informed consent. Limitations of such sources of data also were mentioned, including inability to validate that the pregnant woman actually took a medication of interest, when, and at what dose, and the usual absence of information in claims data on some important confounders such as alcohol use and folic acid supplementation.

Panelists representing various pregnancy registry study designs described approaches to addressing some of the limitations of these studies. For example, some panelists emphasized that "disease-based" registries that involve examination of birth outcomes for several medications used for the treatment of one or more similar maternal conditions have several distinct advantages. These include a more streamlined referral process, whereby clinicians can more easily identify and refer all pregnant patients who have the same underlying condition, irrespective of treatment with any specific medication under study. Examples of successful disease-based approaches that were highlighted by panelists included the Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnancy Registry, the North American Antiepileptic Drug Pregnancy Registry, and the OTIS/MotherToBaby Autoimmune Diseases in Pregnancy Project. Each of these studies allows for comparison of outcomes across various treatments, while accounting for the possible contribution of the underlying maternal condition to adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Panelists also emphasized that more effective methods are needed for raising awareness of the existence and value of pregnancy registries for providers and consumers alike, including more efficient and extensive use of social media. Panelists, and in particular obstetric providers, indicated a need for better methods of identifying women who are eligible for participation in a pregnancy study, and facilitating the referral process. The obstetric provider panelist suggested that existing electronic medical records systems could be adapted to generate automated alerts to providers regarding patients who qualify for referral to a registry.

The patient representative panelist emphasized the need to engage the pregnant woman in the research process. This was confirmed by research groups whose primary interaction in pregnancy studies is with the pregnant woman herself, resulting in minimal loss-to-follow-up and high participant satisfaction.

Last, there was extensive discussion about the use of other alternative study designs, such as case-control studies, that could help address the limitations of pregnancy registries, especially in terms of statistical power for evaluating rare outcomes such as specific birth defects. The Vaccines and Medications in Pregnancy Surveillance System (VAMPSS) was described as one such alternative, combining the benefits of a cohort (registry-type) study with a concurrent case-control study to address the same exposures in pregnancy.

There was general consensus among panel members that no single approach to postmarketing safety studies would likely be sufficient to evaluate new or existing products, and that complementary approaches are needed.

A complete set of the panelists’ slide presentations from the public meeting as well as webcasts of the 2-day proceedings in their entirety are available for viewing here.

Dr. Chambers is a professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital, and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is director of MotherToBaby California, a past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society. She said that she had no relevant financial disclosures. To comment, e-mail her at [email protected].

The need for more and better quality data on medication safety in human pregnancy has been in the public and regulatory spotlight for decades. The issue is becoming even more urgent with the impending revisions to the product label format that will eliminate the traditional A, B, C, D, X pregnancy categories, and substitute more data-driven narratives.

In response to this need, over the last several years there has been a steady increase in the number of regulatory requests/requirements for postmarketing surveillance studies for new medications likely to be used by women of reproductive age or by pregnant women. These requests most often have been fulfilled by the initiation of pregnancy registries. However, concern has been raised that pregnancy registries by and large have been challenged to recruit sufficient numbers of study subjects, and the time to completion of these studies is typically longer than desirable. Other questions have been raised about the adequacy of pregnancy registries alone (especially those with small sample sizes and no internal comparison groups) to test hypotheses related to birth outcomes.

In May 2014, the Food and Drug Administration hosted a public meeting to highlight some of these issues and to seek advice and solutions, titled "Study Approaches and Methods to Evaluate the Safety of Drugs and Biological Products During Pregnancy in the Post-Approval Setting." Panelists included representation from federal agencies including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Defense Naval Health Research Center, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Food and Drug Administration. Other panelists represented academic and HMO-based research networks, contract research organizations, the pharmaceutical industry, obstetric providers, and patients. Comments also were provided by audience members who represented a variety of entities including academic societies, professional associations, and advocacy groups.

Specific strategies for obtaining better data in a more timely fashion were presented by the panelists. These included the value and efficiency of utilizing large administrative claims databases or systemwide electronic capture of pregnancy exposure and outcome data. Using this approach, representative samples of patients can be accrued while not requiring individual active informed consent. Limitations of such sources of data also were mentioned, including inability to validate that the pregnant woman actually took a medication of interest, when, and at what dose, and the usual absence of information in claims data on some important confounders such as alcohol use and folic acid supplementation.

Panelists representing various pregnancy registry study designs described approaches to addressing some of the limitations of these studies. For example, some panelists emphasized that "disease-based" registries that involve examination of birth outcomes for several medications used for the treatment of one or more similar maternal conditions have several distinct advantages. These include a more streamlined referral process, whereby clinicians can more easily identify and refer all pregnant patients who have the same underlying condition, irrespective of treatment with any specific medication under study. Examples of successful disease-based approaches that were highlighted by panelists included the Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnancy Registry, the North American Antiepileptic Drug Pregnancy Registry, and the OTIS/MotherToBaby Autoimmune Diseases in Pregnancy Project. Each of these studies allows for comparison of outcomes across various treatments, while accounting for the possible contribution of the underlying maternal condition to adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Panelists also emphasized that more effective methods are needed for raising awareness of the existence and value of pregnancy registries for providers and consumers alike, including more efficient and extensive use of social media. Panelists, and in particular obstetric providers, indicated a need for better methods of identifying women who are eligible for participation in a pregnancy study, and facilitating the referral process. The obstetric provider panelist suggested that existing electronic medical records systems could be adapted to generate automated alerts to providers regarding patients who qualify for referral to a registry.

The patient representative panelist emphasized the need to engage the pregnant woman in the research process. This was confirmed by research groups whose primary interaction in pregnancy studies is with the pregnant woman herself, resulting in minimal loss-to-follow-up and high participant satisfaction.

Last, there was extensive discussion about the use of other alternative study designs, such as case-control studies, that could help address the limitations of pregnancy registries, especially in terms of statistical power for evaluating rare outcomes such as specific birth defects. The Vaccines and Medications in Pregnancy Surveillance System (VAMPSS) was described as one such alternative, combining the benefits of a cohort (registry-type) study with a concurrent case-control study to address the same exposures in pregnancy.

There was general consensus among panel members that no single approach to postmarketing safety studies would likely be sufficient to evaluate new or existing products, and that complementary approaches are needed.

A complete set of the panelists’ slide presentations from the public meeting as well as webcasts of the 2-day proceedings in their entirety are available for viewing here.

Dr. Chambers is a professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital, and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is director of MotherToBaby California, a past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society. She said that she had no relevant financial disclosures. To comment, e-mail her at [email protected].

The Medical Roundtable: Heart Disease in Women

We're going to discuss an issue that has been in the headlines for more than a decade: heart disease in women. We’ll discuss what we know about it, where we've been in terms of problems that have been elucidated, and how we've addressed those problems. We all know that heart disease is the chief cause of mortality in women over their lifetime. Heart disease is actually the second highest cause of mortality in women until the age of 75; it is second to cancer until that age. But it is so great after the age of 75 that when averaged over the lifetime, heart disease becomes the chief cause of mortality in women. I think that may provide some perspective. Heart disease, particularly coronary heart disease, which is the major cause of mortality in women among the cardiovascular diseases, rises sharply after menopause. Coronary heart disease is unusual in women prior to menopause, unless there are outstanding risk factors such as familial hypercholesterolemia or diabetes. Finally, the risk of heart disease in women is always less than men throughout the lifetime.

Kristin, you authored the chapter with Pamela Douglas on heart disease in women in the latest edition of the Braunwald text on heart disease.1 Can you tell us about the situation as you see it now in terms of what we recognize as previous underdiagnosis and undertreatment of heart disease in women with a focus on coronary heart disease.

Dr. Newby: Thank you. I think that's an important question. We can look at a number of sources and I think most of them suggest that we have underappreciated the risk of heart disease in women. In part that's because women develop coronary artery disease later in life or the consequences of coronary artery disease are manifest later in life. I think every signal tells us that we are doing better, including physicians’ perception of risk and treatment. There was a recent study by Lori Mosca published maybe a couple of years ago that shows that women are increasingly aware of heart disease as a major risk factor.2 That said, however, only about half of women think that heart disease is their leading lifetime risk; many still believe it is cancer. So it's about 50/50 now, where it was about 30/70 maybe 5 to 10 years ago. We're making progress, and I think the Red Dress3 campaign and other awareness campaigns have been effective.

We still see gaps in treatment; use of evidence-based therapy in women is lower than it is in men, although it has improved. I think importantly on the side of clinical trials and testing new therapies we're seeing a better balance. But there is still underrepresentation of women in clinical trials that establish evidence for treatment.

Dr. Amsterdam: Your last point is key, and leads me to note that an age cutoff of 75 for enrollment in many clinical trials may be partly responsible for female under-representation, because it’s after 75 that cardiac disease really proliferates in women.

Jeff, what are your views on how much progress we’ve made?

Dr. Borer: Of course, I agree with everything Kristin said. I would emphasize something that we don't talk about so often, and that is that when women do manifest evidence of coronary disease, and particularly when they have a myocardial infarction (MI), they’re about twice as likely as men to die within a year of that first infarction. If only we were more attentive we would do something to modulate that bad outcome. Women are much less likely to get the needed drugs such as beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, aspirin, and other therapies known to improve survival after MI than are men. If we were more aggressive about that, maybe the outcome would be better. However, the problem is that men who have prognostically important coronary disease, which may be heralded by a first infarction, actually are best treated, or I should say their outcome is best improved, if they undergo coronary artery bypass grafting. One might think, therefore, that this strategy should then be applied to women. However, women are much more likely to die during a bypass grafting procedure than men.

Therefore, the appropriate therapy for women to reduce this extraordinarily higher risk after MI is not clear. I don't think we’re as good at giving medicines as we ought to be, but going the next step and using invasive therapy, that’s something else again. It’s not clear whether women benefit sufficiently to warrant that approach, and that's something we have to think about. We need a great deal more data on that subject.

Dr. Amsterdam: I would add a couple of short points. Kristin indicated that things have gotten better. In fact, in the past 10 years there's been a sharp decrease in the rate of death from cardiovascular disease in women. If you look at the curve of the decrease in mortality from heart disease for the past 50 years in this country, there is a steady downtrend. But when we break up the data, the curve for women was pretty flat, indicating that they did not share in this benefit until recently. It was mostly men until the past decade, when we saw a sharp drop in mortality in women. The death rate in women has fallen almost to that of men. This is attributable to programs such as the Red Dress campaign, as Kristin mentioned, and the “Get with the Guidelines” campaign. When women and men are risk-adjusted after an MI, the outlook is similar—women are older and have more comorbidities when they have their MI. So the question is, is there something intrinsic that puts women at higher risk, or are they just older, sicker, and with more comorbidities, which leads to a different outcome? Jeff?

Dr. Borer: I think it's a good point and I don't really know the answer, but the fact is that the disease is different in women than in men, whether that accounts for some of the difference in outcomes that we see or not. Typically, atherosclerosis in the coronary artery is much more diffuse in women than it is in men, so that angiographic findings often suggest narrow normal arteries when in fact they’re loaded with plaque. In contrast, men’s obstructions tend to be relatively discrete. That difference in the manifestations of atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries in women and in men may well have an important impact on outcome.So while it may be that risk adjustment makes things look more similar among men and women, the fact is the disease is different.

Dr. Amsterdam: Important point. Kristin, would you like to add something on that topic?

Dr. Newby: I think the points that you both have made are good in that looking at risk-adjusted outcomes is important and it gives us an idea of one group relative to another. Unfortunately, sometimes that masks the issue, which is that women are dying at a pretty high rate. Whether it's because they're older or not, it suggests that we've got a high-risk population in which we need to figure out what is different in the way they respond to therapy or whether there are other interventions that could be applied that might improve outcome.

Risk adjustment is important, but I don't think it is the whole answer and it doesn't do away with the challenge of the high event rates in women.

Dr. Borer: I agree with that and if you just look at patients younger than 50, just under age 50, a MI in a woman is twice as likely to be fatal as it is in a man.4

Dr. Amsterdam: On the other hand, of women under 35 who come to the emergency department (ED) with chest pain, only about 1 in 1000 turn out to have an MI. So there's a high frequency of chest pain in women and they generally tend to use the ED and medical system more than men for symptoms. This may be because there’s less denial in women, but there are lots of negative tests in women for symptoms like chest pain or chest discomfort. Would you agree with that, Kristin?

Dr. Newby: It is true. I think there are a number of other features, unfortunately, that may lead, perhaps not in young women but in older women, to missed or delayed diagnosis that may also contribute to their worse prognosis. That may explain some of the difference as well. I would just throw that out for discussion.

Dr. Amsterdam: A lot of the data that we’re talking about in underdiagnosis and undertreatment come from papers, many of which are 10 years and 20 years old. In your own institutions, are you seeing a persistence of these issues, because I'm not aware of any recent studies indicating that there's been an improvement in these trends, other than that we know that cardiovascular disease leading to mortality is decreasing in women.

In your own institutions, do you see a persistence of the woman who sits in the ED with chest pain and doesn't get an electrocardiogram (ECG) within 10 minutes, or a good workup, or a referral from a clinic or office for chest pain? Jeff, what’s your experience?

Dr. Borer: The issue, I suppose, is, what does the cardiologist do? I think over the past decade or more, maybe 2 decades, there's been a heightened sensitivity among cardiologists of the fact that women do in fact have atherosclerosis, they do have coronary disease, they do have MIs, and they do die from it. But I think the problem is a little bit different.

It's not so much now, I think, allowing a woman to sit in the ED with chest pain for too long. I don't think that happens terribly often, at least not from what I've seen. It's that the symptom pattern is different in women than in men, and while a lot of women have chest discomfort and often the chest discomfort isn't associated with coronary disease, a lot of women have coronary disease with symptoms that don't include chest discomfort. The difficulty in the sensitivity to that possibility is something that we still have to improve.

Dr. Amsterdam: Kristin, Jeff raised an important point about the difference of symptoms in women and men when they present with coronary disease. We know that symptoms in the elderly are different than those who are younger when presenting with ischemic heart disease. So is it that the symptoms are different in women per se, or is it that they comprise a large part of the elderly population with coronary artery disease, and if you compare elderly men with elderly women, would there be a difference in symptom presentation?

Dr. Newby: That's a good question. You know one of the better studies that's been done on this actually revealed that the majority of patients who were having an acute MI presented with some type of chest-related symptoms, such as tightness and pressure.1

My personal experience, and again I don't think this has been well studied specifically in the elderly, is that the issue with atypical symptoms is in part a phenomenon of age, where the elderly tend to present more frequently with just dyspnea or fatigue. One really has to be paying attention to that. That disproportionately affects women who present later in life with acute ischemic syndromes.

I want to move to the risk factors for coronary disease in men and women. Jeff, any differences or similarities—I will tell you my view right off the bat that the risk factors for coronary artery disease other than pregnancy and menopause, which act through the traditional risk factors, are the same in men and women. There are some differences, and in her chapter in Braunwald, Kristin pointed them out nicely with regard to diabetes from the INTERHEART study.5 What's your view on the risk factors in women? Do we need preventive cardiology clinics for women and for women with heart disease; or can women come to a good preventive cardiology clinic that men also attend?

Dr. Borer: I think the risk factors are pretty much the same. You know there may be some difference in outcomes associated with them, depending on age, with diabetes being the major issue. I think it has more of an impact on the risk of second MI in women than in men, so you have to be more cognizant of that particular risk factor in women.

But I think the risk factors are the same and the outcomes are qualitatively the same and so managing patients by trying to modulate risk factors could be done in a preventive cardiology unit. I don't think you need a separate one for women because I don't think we have sufficient data to suggest a different strategy for men and for women.

Dr. Amsterdam: Kristin?

Dr. Newby: I fully agree. I think that the risk factors, with the possible exception that diabetes may be a bit more potent in women, are still the same risk factors and we know the same treatments work in both groups. What I think is probably more interesting that came out of INTERHEART is the differential strength (stronger in women) of protective factors in women, such as exercise, eating a diet high in fruits and vegetables, and stress management. I found that to be interesting and potentially more informative than focusing on the proven risk factors.

Dr. Amsterdam: I think INTERHEART was a very good confirmation of what the Framingham Heart Study showed of the traditional risk factors.6

Would you agree, Kristin, that there is more stress in general, more psychosocial stress, in women than in men? Women work and take care of the kids—men do better now, but we don't do an equal share, and that seems to be having an impact on women and disease.

Dr. Newby: Yes, I think that's an interesting topic, and I think women's response to stress and the stress that they're dealing with may be different from that of men. I think there’s an interesting analysis that’s been done several times about support systems and how men do better when they have a spouse who’s taking care of them. Women on the other hand who have an MI who have a spouse actually do worse. So I'm not sure what that tells us, but I do think there's either some disproportionate amount of reaction to or ability to cope with stress among women. That is important for us to understand and work through.

Dr. Amsterdam: It's too bad we can't measure that the way we measure other data. Now let’s consider a stable patient who comes to the physician’s office with chest pain; it may be typical or atypical, but it's suspicious enough for the patient to require a careful evaluation.

Jeff, which tests do you use to detect objective evidence of myocardial ischemia and, by that factor, the likelihood of coronary disease? Exercise treadmill test has really been criticized for its value in women because of its repute for false-positive results. Some experts have advised going straight to a stress imaging study rather than a plain treadmill test.

Dr. Borer: Yes, well that's what I do, actually. The fact is that the specificity of every noninvasive test for coronary disease is lower in women than in men. The positive predictive value is less in women than in men, whether it be a radionuclide test, an echocardiography-based test, it's not just the exercise ECG. On the other hand, it seems to me that radionuclide based studies do provide greater accuracy in women than the exercise ECG, and that's what I use.

Dr. Amsterdam: This is good because thus far we’ve had little divergence of opinion and it’s good to have some differences. Thus, I am a strong proponent of the standard treadmill exercise test without imaging if the patient has a normal baseline ECG and the history indicates adequate exercise capacity, which is what the guidelines have advocated since 1998. So in these circumstances, my first test is always a plain treadmill study, and we train our fellows to follow this approach. Kristin, your method?

Dr. Newby: Yes, I think I fall a little bit more to Jeff's side of things. So there are two things I think about: one is if I see someone in the clinic who gives me a very good story for symptoms and they can't exercise and can’t do their usual activities. I either move to treat them with medicines and cardiac rehabilitation or with catheterization if I have a high index of suspicion that I'm dealing with coronary disease. So I think that's the first thing. Then the question is, how do we think about the individuals who aren't clear-cut? We want to rule out the group that has the highest likelihood to have a false positive—the ones with very atypical symptoms, which I know we all see in our clinics—and try to work with them without doing any kind of further workup if at all possible. But if I do a stress test in the clinic and I'm on the fence, I, like Jeff, add imaging.7 We tend to use more stress echocardiography than stress nuclear testing, but I don't think there's any evidence that one or the other, if you're adding an imaging study, is of a major advantage given the certain limitations of each study in terms of acquiring the images.

Dr. Amsterdam: I agree. They're very similar. Perhaps nuclear is a little more sensitive but less specific than echocardiography.

So I will say quickly, I think we all know the guidelines of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC)8—that I just referred to. They’re very clear in stating that the first test, even in a stable female patient with a normal ECG who is able to exercise should be a plain old treadmill test. I'll make a couple of points; one, we have in press a paper on how to improve the positive predictive value of the exercise ECG in women. The more risk factors the patient has, the deeper the ST depression, the longer the persistence of ST depression post-exercise—these factors can increase the positive predictive value up to about 80% in women. These ECG factors and non-ECG factors can help. We have also shown that if the patient, man or woman, has a positive treadmill ECG and can exercise to 10 metabolic equivalents (METs) (Stage III of the Bruce test),9,10 and then is referred for a stress imaging test, about a 94% likelihood that the stress imaging test will be negative.

So the key point for me is that assessment of the exercise test by ECG criteria alone is really obsolete. The poor positive predictive value and the high rate of false-positives are based solely on the ST segment when we know that the best prognostic indicator is functional capacity. So that's why we always do the treadmill test as the initial assessment unless there's a baseline abnormality or the patient can't exercise.

Do you have any comments on any of that, Jeff?

Dr. Borer: I would like to pick up on two things that Kristin said. She talked about symptoms, and I would say that if a person, and it doesn't matter whether it's a man or a woman, has typical symptoms, when you take a history and you put that person on a treadmill and you reproduce the symptoms and you do an ECG alone, the concordance of the ECG criteria and the symptoms has a very high predictive value. But that presumes that the person is going to get symptoms on the treadmill, and that may not happen.

The other point that Kristin made was that in certain patients with a compelling clinical presentation, she might go right to a catheterization. I would have to say that I don't do that. I guess it depends on how you define “compelling.” If somebody has a history that is consistent with crescendo angina, yes, I would send him or her to catheterization. But absent that, I would not because I believe that the noninvasive testing provides prognostic information even in the presence of true coronary disease.

The problem that I fear in sending someone to catheterization is that, in the absence of prognostically important disease, they'll come away with an angioplasty with no evidence at all that anything will be done to their natural history, only that their symptoms will be relieved and that could probably have been done with medication. So I'm a little more wary about sending people directly to catheterization. There really has to be what I would call a “compelling” history, and it may be the same that Kristin would call “compelling” or it may not.

Dr. Amsterdam: We’re into the art of medicine, and it’s legitimate to differ if we have good reasons to go down different paths. Kristin, your comments on this?

Dr. Newby: When I'm thinking of somebody whose symptoms are compelling enough that I would send them to catheterization, it's the woman who was active, doing her gardening, mowing her yard, whatever last summer, and has over the past several months progressively deteriorated in terms of activity levels. So you already know their functional capacity has declined by what they're telling you through their history. In those individuals, I don't think you gain a lot more information by documenting that on a treadmill.

You're right, maybe you take that person and you try medication or maybe you commit that they have coronary disease, you're going to take care of their angina, get them immediately back to functional capacity. I think those are style points, as you said, the art of medicine. To some extent it's driven by patient preferences and I think that's the thing that sometimes we also forget.

There are patients who, once they know what you're thinking, don't want to deal with multiple steps to get to an answer—they want to know. Maybe that's right, maybe that's wrong, maybe that's part of what's wrong with our healthcare system. We could debate those points for another hour probably, but I think those factors all play into how we manage patients.

Then you think about taking somebody when you're pretty sure you know what the diagnosis is, or maybe you're pretty sure you don't think it's the diagnosis, but you put them on a treadmill or a treadmill with imaging and it's positive, and now you've got them worried. They want to know what's going on, and they may or not may not tolerate medicines.

These are some practical issues in medicine, as well, that we have to think about, and again, as you said, that's the art of medicine.

Dr. Amsterdam: Kristin, can you tell us a little about the Duke treadmill score? Because it's a very good prognostic indicator.