User login

Circumscribed Nodule in a Renal Transplant Patient

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Phaeohyphomycosis

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (SP), also called mycotic cyst, is characterized by a painless, nodular lesion that develops in response to traumatic implantation of dematiaceous, pigment-forming fungi.1 Similar to other fungal infections, SP can arise opportunistically in immunocompromised patients.2,3 More than 60 genera (and more than 100 species) are known etiologic agents of phaeohyphomycosis; the 2 main causes of infection are Bipolaris spicifera and Exophiala jeanselmei.4,5 Given this variety, phaeohyphomycosis can present superficially as black piedra or tinea nigra, cutaneously as scytalidiosis, subcutaneously as SP, or disseminated as sinusitis or systemic phaeohyphomycosis.

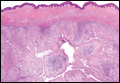

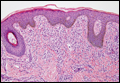

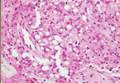

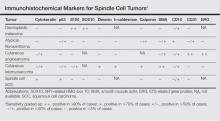

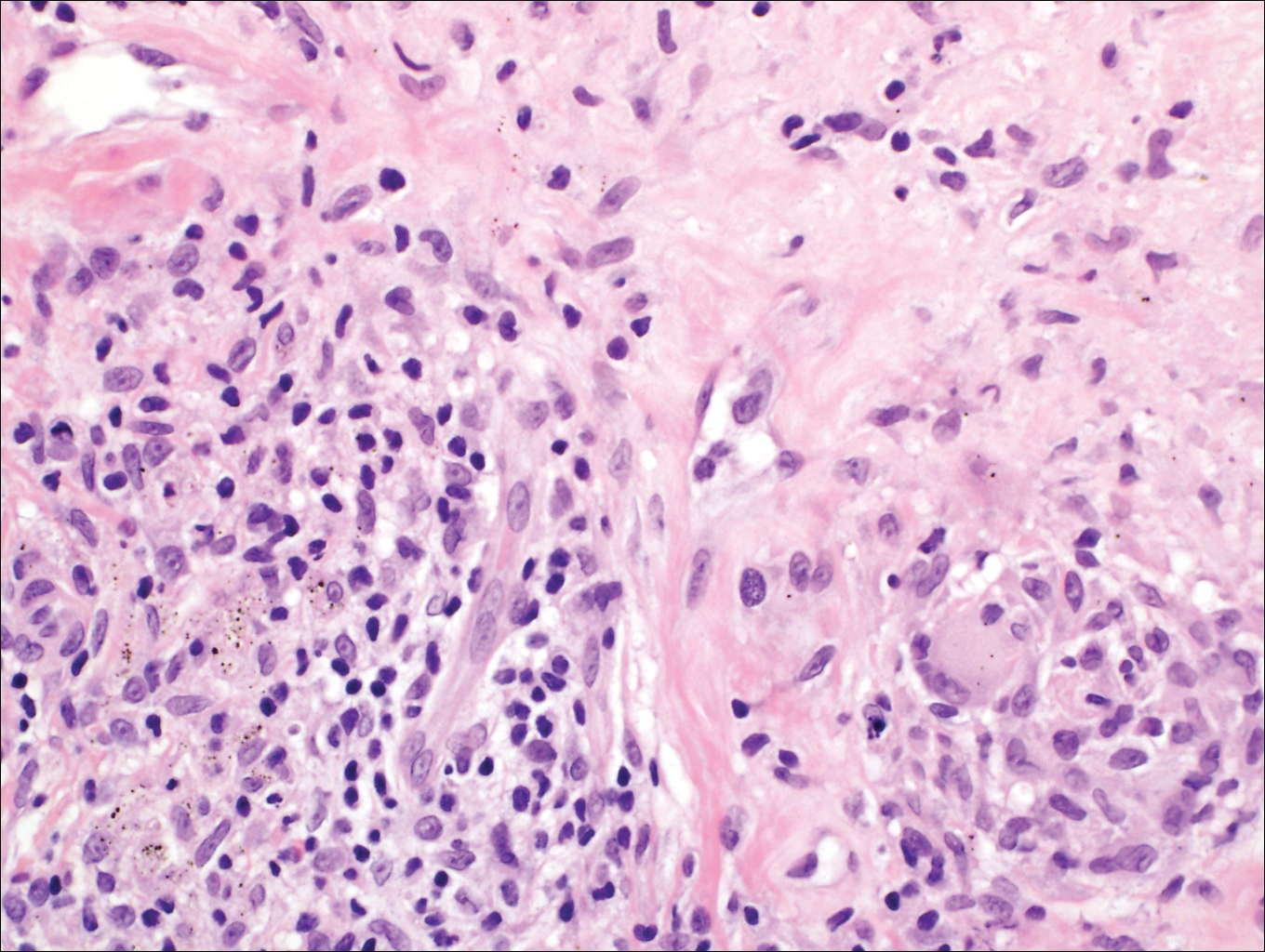

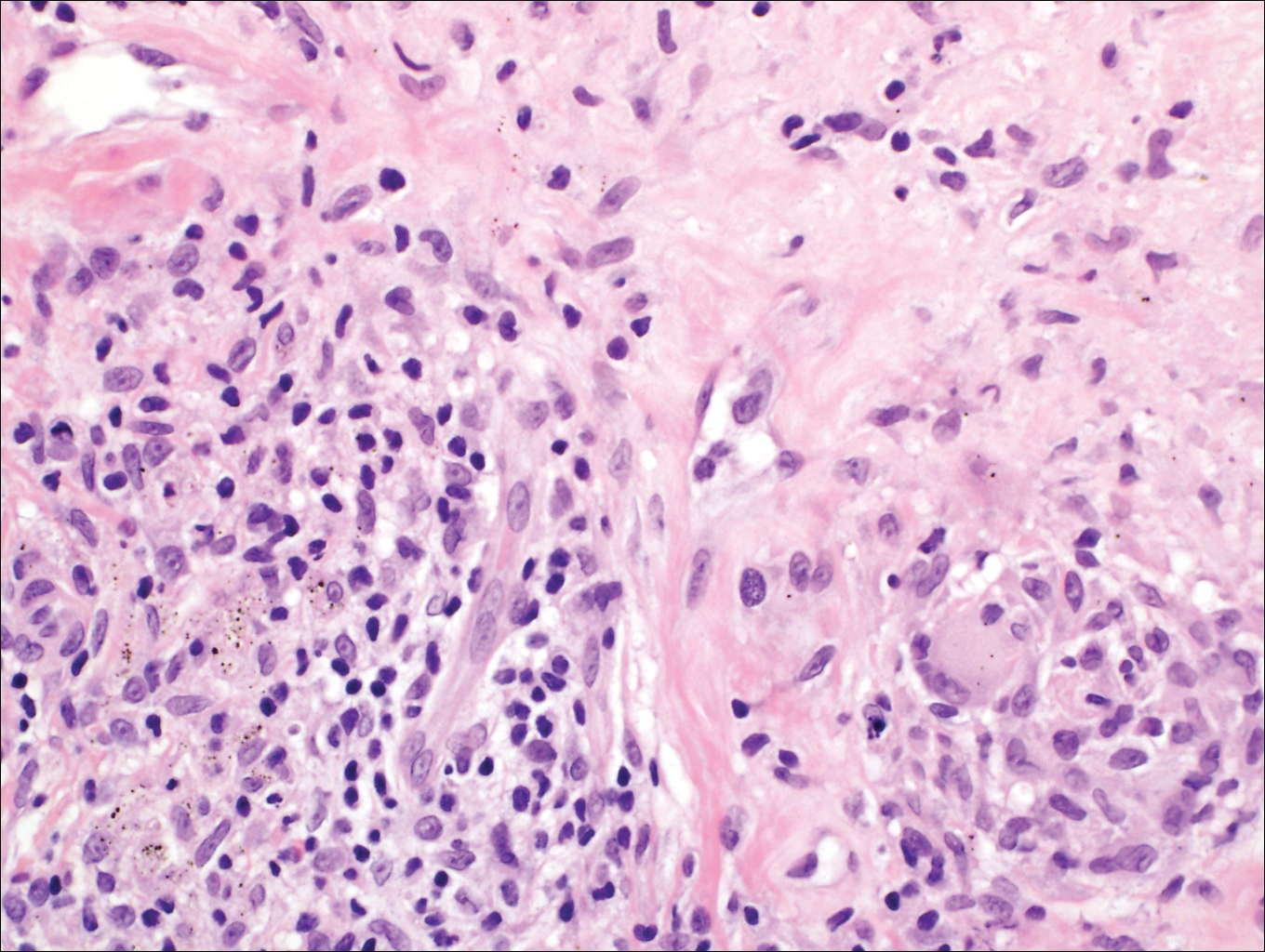

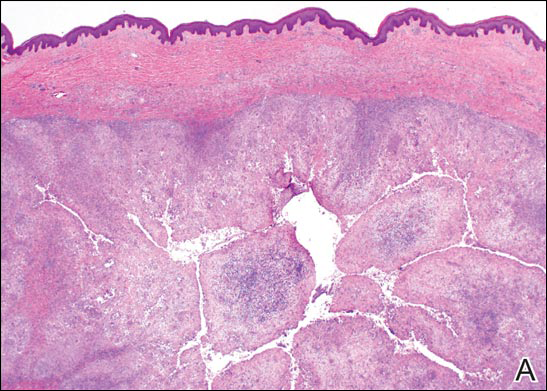

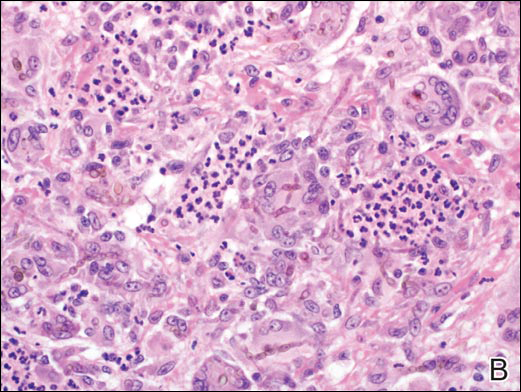

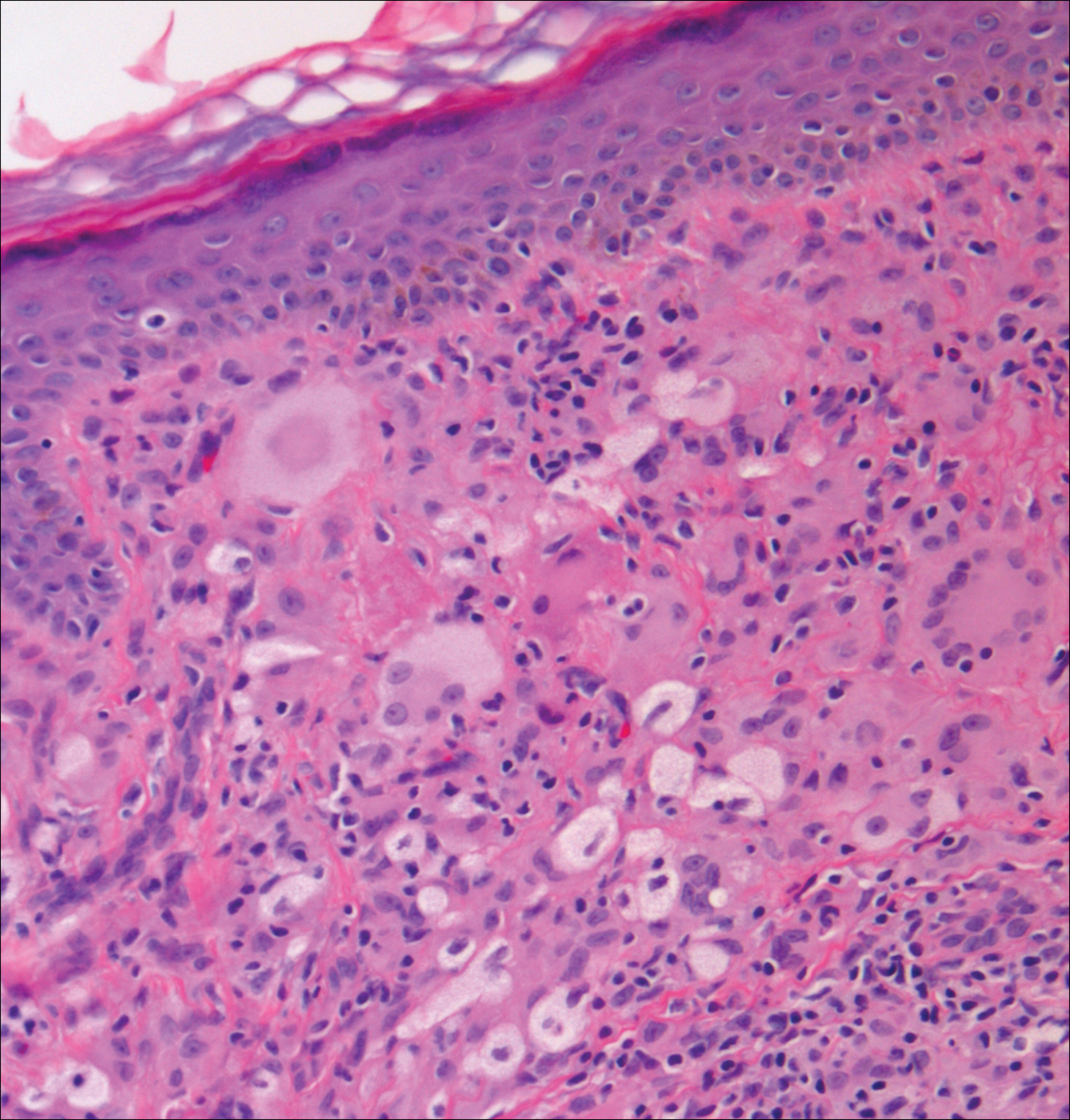

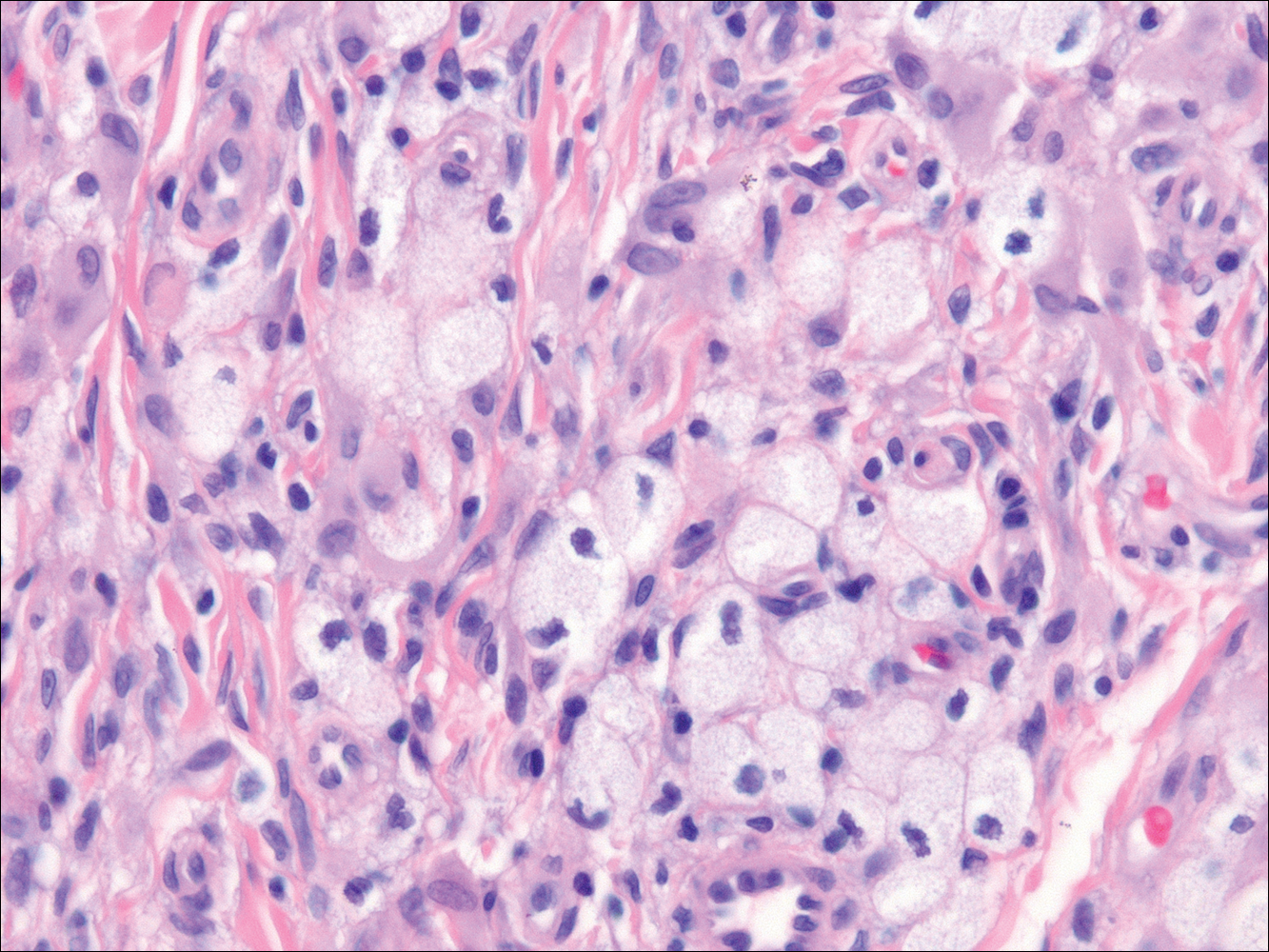

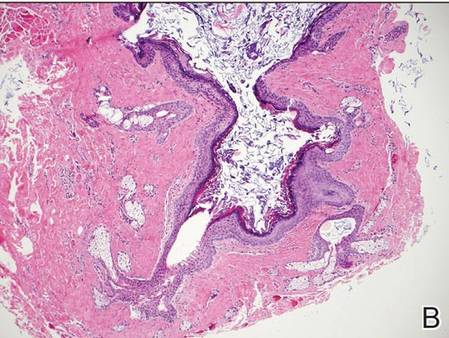

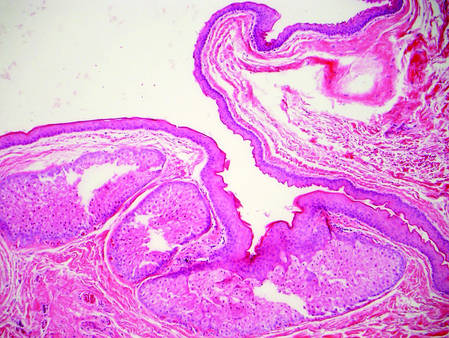

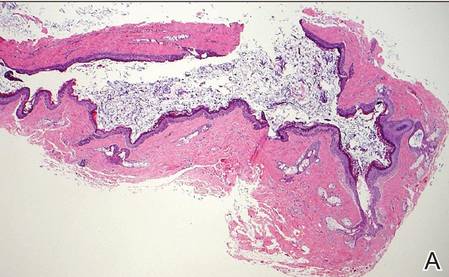

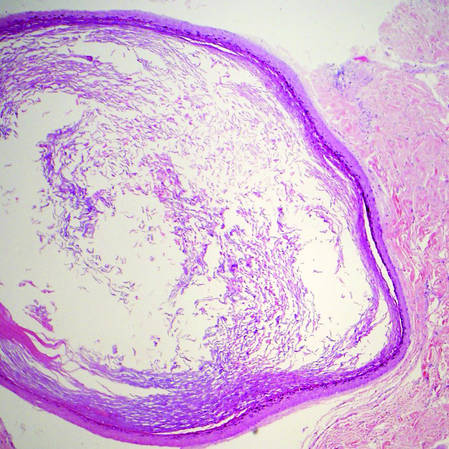

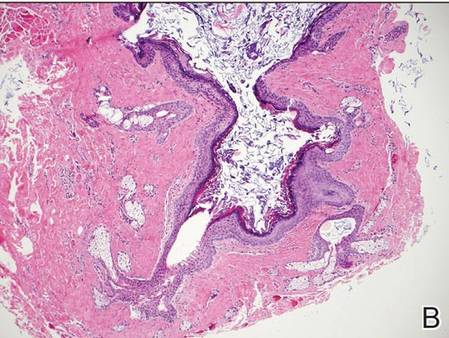

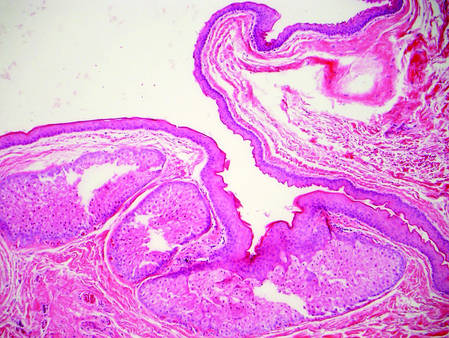

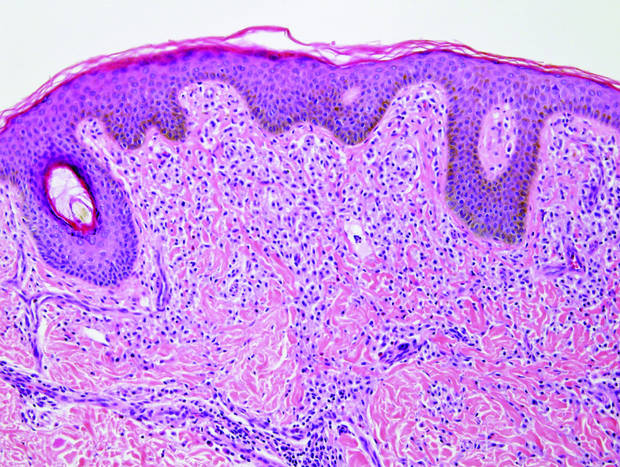

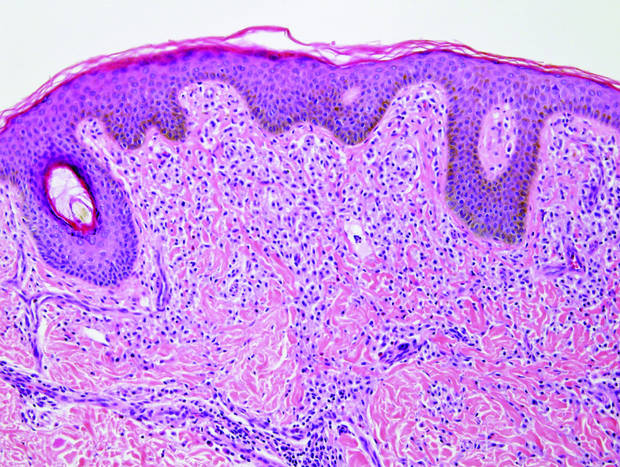

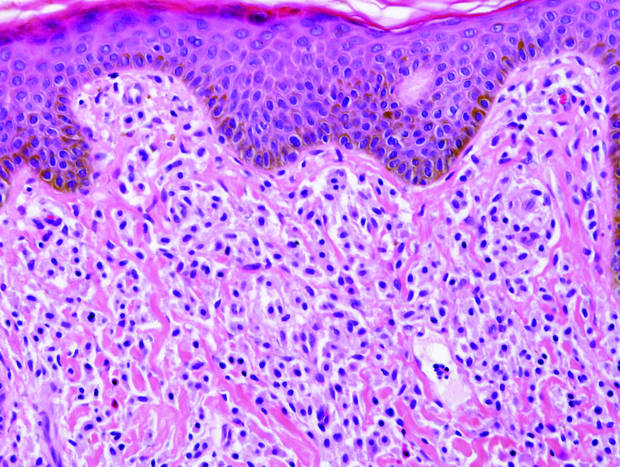

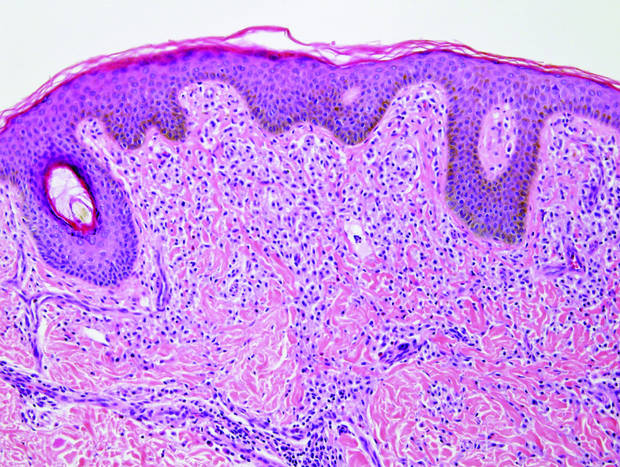

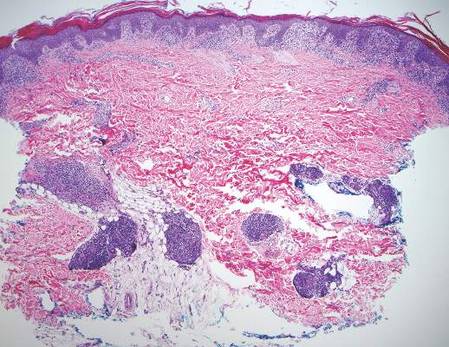

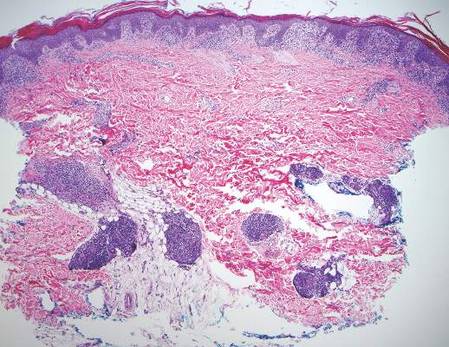

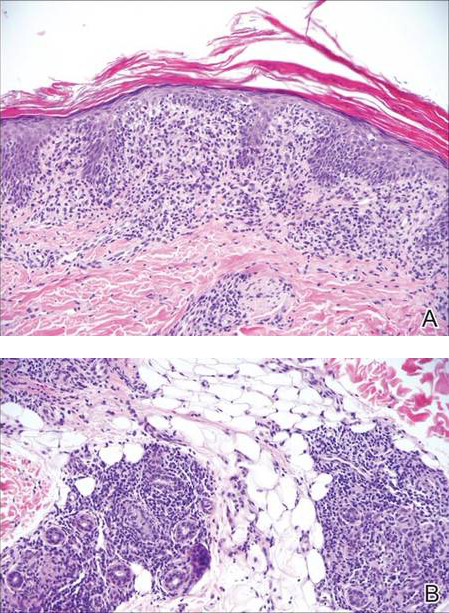

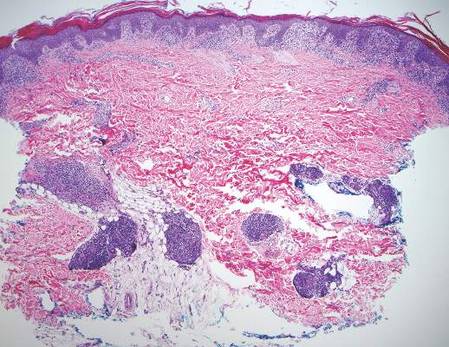

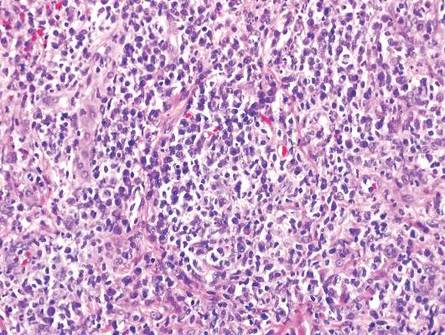

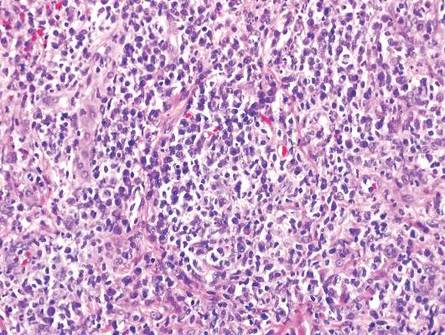

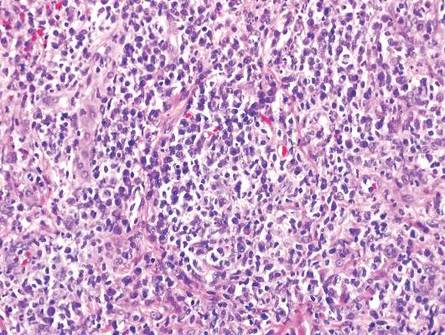

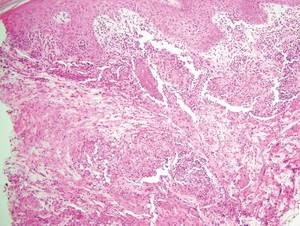

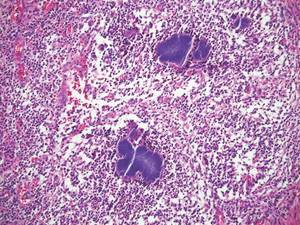

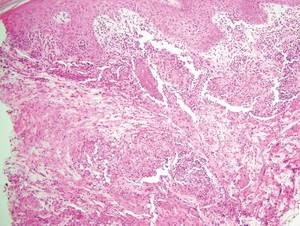

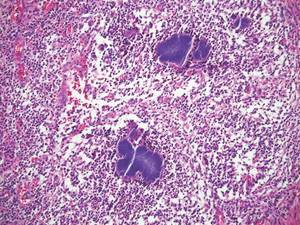

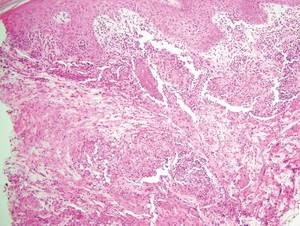

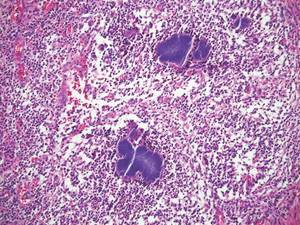

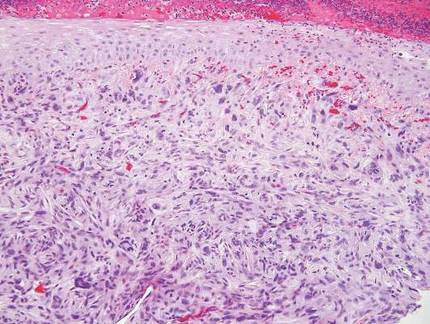

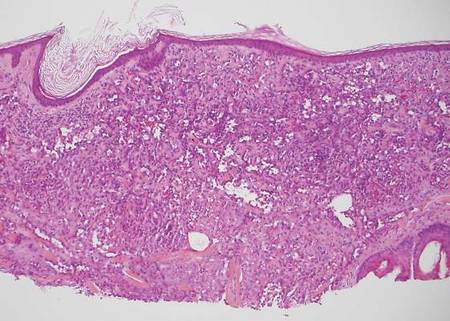

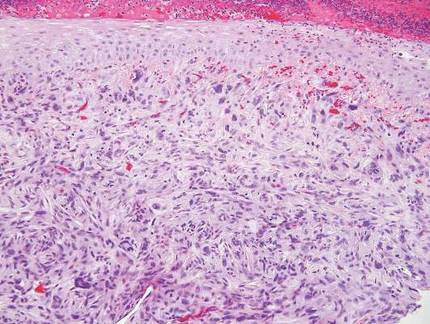

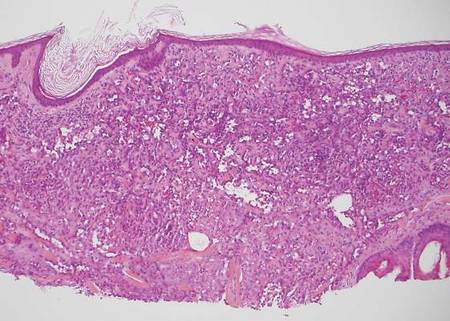

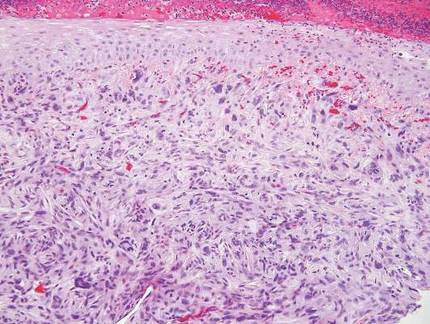

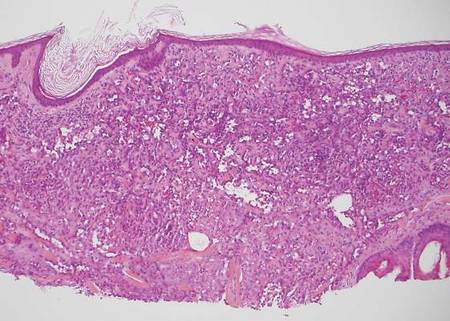

Coined in 1974 by Ajello et al,6 the term phaeohyphomycosis translates to “condition of dark hyphal fungus,” a term used to designate mycoses caused by fungi with melanized hyphae. Histologically, SP demonstrates a circumscribed chronic cyst or abscess with a dense fibrous wall (quiz image A). At high power, the wall is composed of chronic granulomatous inflammation with foamy macrophages, and the cystic cavity contains necrotic debris admixed with neutrophils. Pigmented filamentous hyphae and yeastlike entities can be seen in the cyst wall, in multinucleated giant cells, in the necrotic debris, or directly attached to the implanted foreign material (quiz image B).7 The first-line treatment of SP is wide local excision and oral itraconazole. It often requires adjustments to dosage or change to antifungal due to recurrence and etiologic variation.8 Furthermore, if SP is not definitively treated, immunocompromised patients are at an increased risk for developing potentially fatal systemic phaeohyphomycosis.3

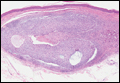

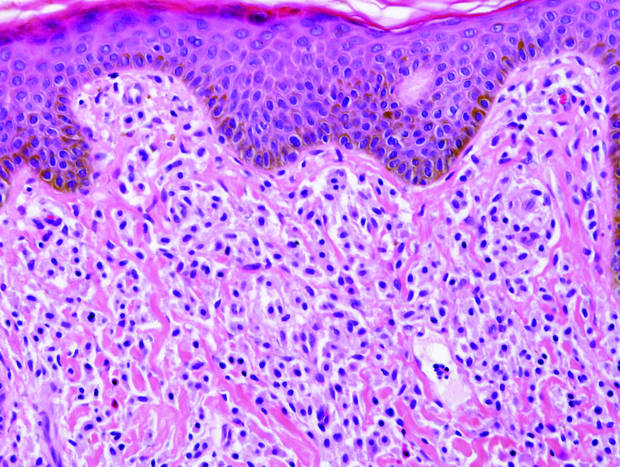

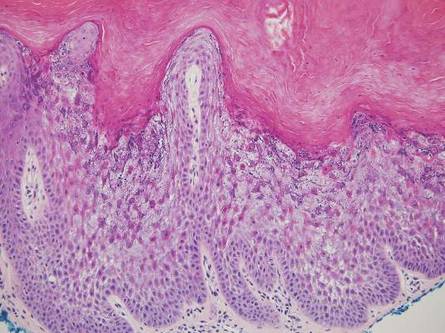

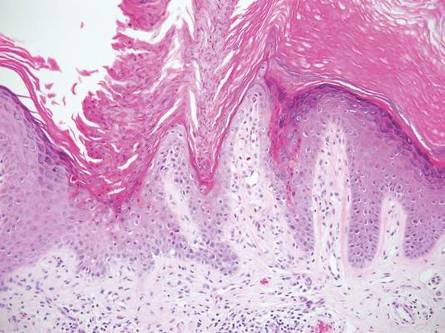

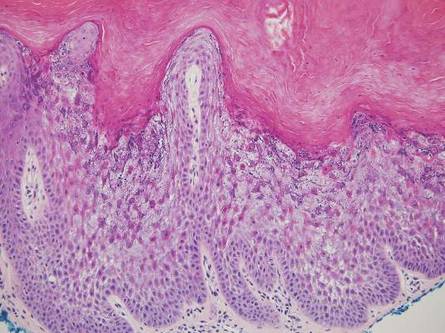

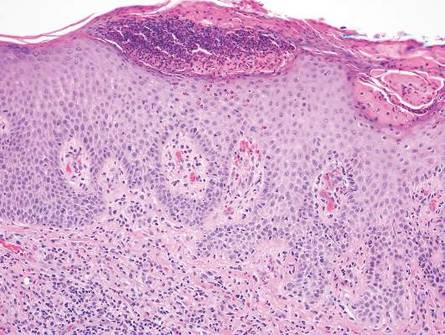

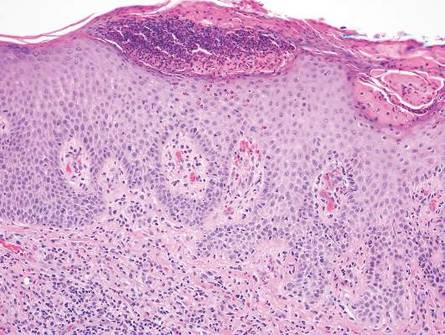

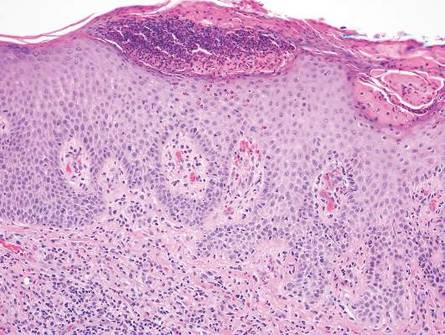

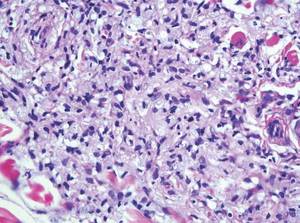

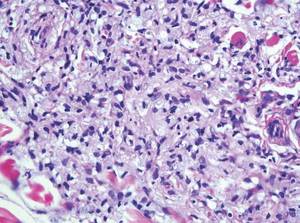

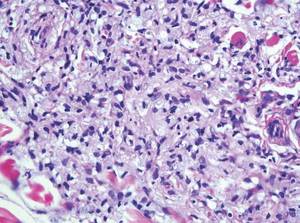

Chromoblastomycosis (CBM), also caused by dematiaceous fungi, is characterized by an initially indolent clinical presentation. Typically found on the legs and lower thighs of agricultural workers, the lesion begins as a slow-growing, nodular papule with subsequent transformation into an edematous verrucous plaque with peripheral erythema.9 Lesions can be annular with central clearing, and lymphedema with elephantiasis may be present.10 Histologically, CBM shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and intraepidermal pustules as the host rids the infection via transepithelial elimination. Dematiaceous fungi often are seen in the dermis, either freestanding or attached to foreign plant material. Medlar bodies, also called copper penny spores or sclerotic bodies, are the most defining histologic finding and are characterized by groups of brown, thick-walled cells found in giant cells or neutrophil abscesses (Figure 1). Hyphae are not typically found in this type of infection.11

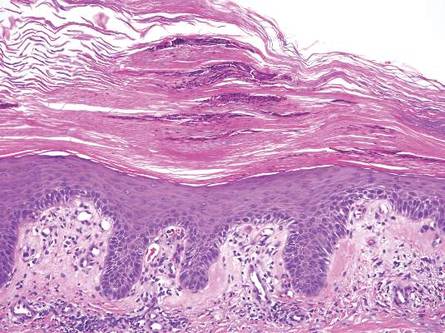

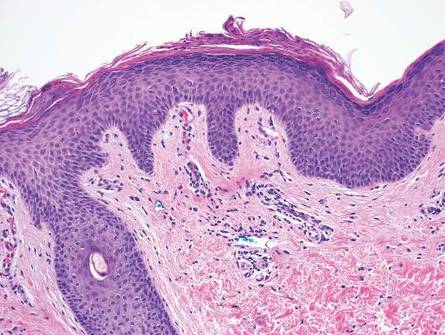

Granulomatous foreign body reactions occur in response to the inoculation of nonhuman material and are characterized by dermal or subcutaneous nodules. Tissue macrophages phagocytize material not removed shortly after implantation, which initiates an inflammatory response that attempts to isolate the material from the uninvolved surrounding tissue. Vegetative foreign bodies will cause the most severe inflammatory reactions.12 Histologically, foreign body granulomas are noncaseating with epithelioid histiocytes surrounding a central foreign body (Figure 2). Occasionally, foreign bodies may be difficult to detect; some are birefringent to polarized light.13 Additionally, inoculation injuries can predispose patients to SP, CBM, and other fungal infections.

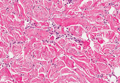

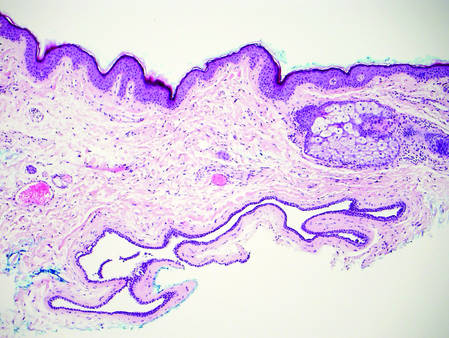

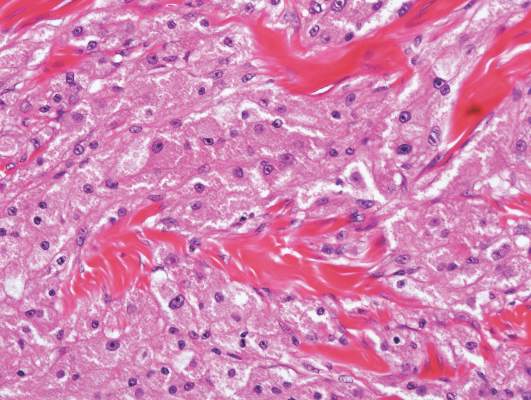

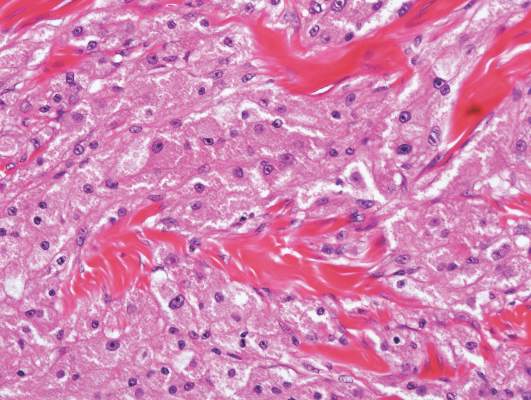

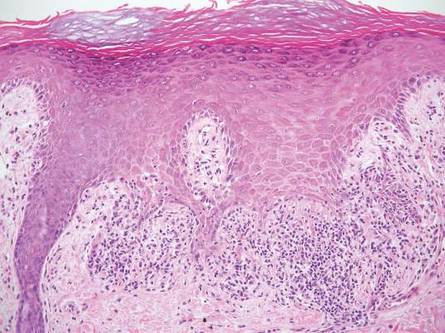

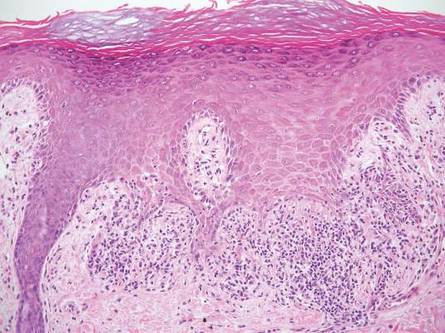

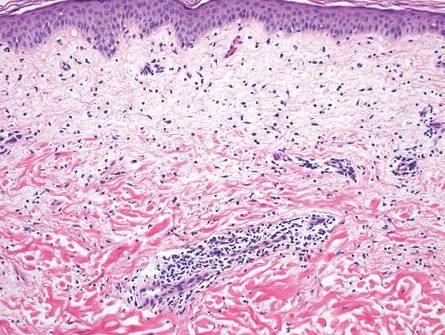

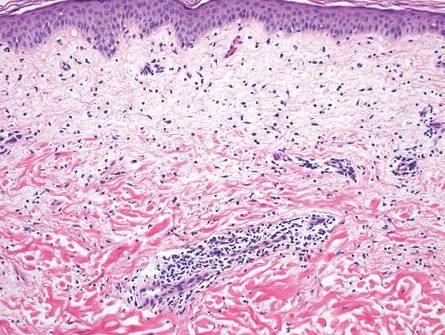

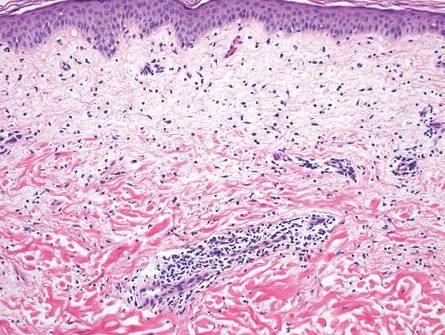

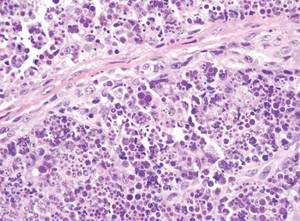

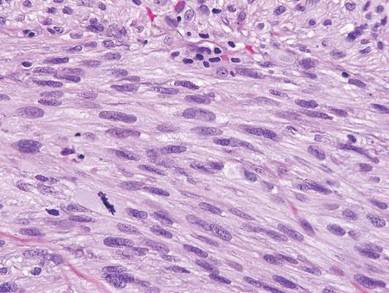

Tattoos are characterized by exogenous pigment deposition into the dermis.14 Histologically, tattoos display exogenous pigment deposited throughout the reticular dermis, attached to collagen bundles, within macrophages, or adjacent to adnexal structures (eg, pilosebaceous units or eccrine glands). Although all tattoo pigments can cause adverse reactions, hypersensitivity reactions occur most commonly in response to red pigment, resulting in discrete areas of spongiosis and granulomatous or lichenoid inflammation. Occasionally, hypersensitivity reactions can induce necrobiotic granulomatous reactions characterized by collagen alteration surrounded by palisaded histiocytes and lymphocytes (Figure 3).15,16 There also may be focally dense areas of superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Clinical context is important, as brown tattoo pigment (Figure 3) can be easily confused with the pigmented hyphae of phaeohyphomycosis, melanin, or hemosiderin.

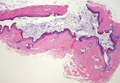

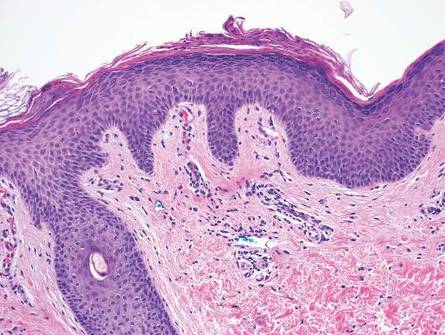

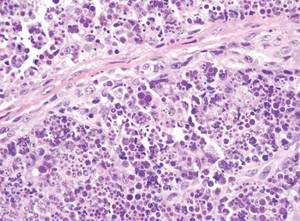

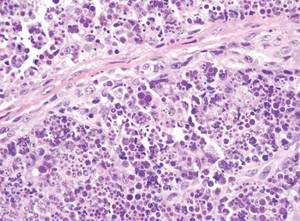

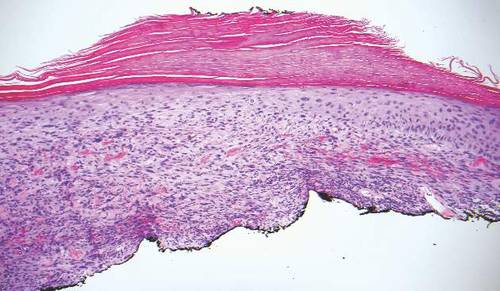

Subcutaneous hyalohyphomycosis is a nondemat-iaceous (nonpigmented) infection that is caused by hyaline septate hyphal cells.17 Hyalohyphomycosis skin lesions can present as painful erythematous nodules that evolve into excoriated pustules.18 Hyalohyphomycosis most often arises in immunocompromised patients. Causative organisms are ubiquitous soil saprophytes and plant pathogens, most often Aspergillus and Fusarium species, with a predilection for affecting severely immunocompromised hosts, particularly children.19 These species tend to be vasculotropic, which can result in tissue necrosis and systemic dissemination. Histologically, fungi are dispersed within tissue. They have a bright, bubbly, mildly basophilic cytoplasm and are nonpigmented, branching, and septate (Figure 4).11

- Isa-Isa R, García C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Rubin RH. Infectious disease complications of renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 1993;44:221-236.

- Ogawa MM, Galante NZ, Godoy P, et al. Treatment of subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis and prospective follow-up of 17 kidney transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:977-985.

- Matsumoto T, Ajello L, Matsuda T, et al. Developments in hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32(suppl 1):329-349.

- Rinaldi MG. Phaeohyphomycosis. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:147-153.

- Ajello L, Georg LK, Steigbigel RT, et al. A case of phaeohyphomycosis caused by a new species of Phialophora. Mycologia. 1974;66:490-498.

- Patterson J. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2014.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Bonifaz A, Carrasco-Gerard E, Saúl A. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical and mycologic experience of 51 cases. Mycoses. 2001;44:1-7.

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

- Elston D, Ferringer T, Peckham S, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

- Lammers RL. Soft tissue foreign bodies. In: Tintinalli J, Stapczynski S, Ma O, et al, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Professional; 2011.

- Murphy GF, Saavedra AP, Mihm MC. Nodular/interstitial dermatitis. In: Murphy GF, Saavedra AP, Mihm MC, eds. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology: Inflammatory Disorders of the Skin. Vol 10. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology; 2012:337-395.

- Laumann A. Body art. In: Goldsmith L, Katz S, Gilchrest B, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012. http://access medicine.mhmedical.com.proxy.lib.uiowa.edu/content.aspx?bookid=392&Sectionid=41138811. Accessed July 17,2016.

- Wood A, Hamilton SA, Wallace WA, et al. Necrobiotic granulomatous tattoo reaction: report of an unusual case showing features of both necrobiosis lipoidica and granuloma annulare patterns. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:e152-e155.

- Mortimer N, Chave T, Johnston G. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Ajello L. Hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis: two global disease entities of public health importance. Eur J Epidemiol. 1986;2:243-251.

- Safdar A. Progressive cutaneous hyalohyphomycosis due to Paecilomyces lilacinus: rapid response to treatment with caspofungin and itraconazole. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1415-1417.

- Marcoux D, Jafarian F, Joncas V, et al. Deep cutaneous fungal infections in immunocompromised children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:857-864.

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Phaeohyphomycosis

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (SP), also called mycotic cyst, is characterized by a painless, nodular lesion that develops in response to traumatic implantation of dematiaceous, pigment-forming fungi.1 Similar to other fungal infections, SP can arise opportunistically in immunocompromised patients.2,3 More than 60 genera (and more than 100 species) are known etiologic agents of phaeohyphomycosis; the 2 main causes of infection are Bipolaris spicifera and Exophiala jeanselmei.4,5 Given this variety, phaeohyphomycosis can present superficially as black piedra or tinea nigra, cutaneously as scytalidiosis, subcutaneously as SP, or disseminated as sinusitis or systemic phaeohyphomycosis.

Coined in 1974 by Ajello et al,6 the term phaeohyphomycosis translates to “condition of dark hyphal fungus,” a term used to designate mycoses caused by fungi with melanized hyphae. Histologically, SP demonstrates a circumscribed chronic cyst or abscess with a dense fibrous wall (quiz image A). At high power, the wall is composed of chronic granulomatous inflammation with foamy macrophages, and the cystic cavity contains necrotic debris admixed with neutrophils. Pigmented filamentous hyphae and yeastlike entities can be seen in the cyst wall, in multinucleated giant cells, in the necrotic debris, or directly attached to the implanted foreign material (quiz image B).7 The first-line treatment of SP is wide local excision and oral itraconazole. It often requires adjustments to dosage or change to antifungal due to recurrence and etiologic variation.8 Furthermore, if SP is not definitively treated, immunocompromised patients are at an increased risk for developing potentially fatal systemic phaeohyphomycosis.3

Chromoblastomycosis (CBM), also caused by dematiaceous fungi, is characterized by an initially indolent clinical presentation. Typically found on the legs and lower thighs of agricultural workers, the lesion begins as a slow-growing, nodular papule with subsequent transformation into an edematous verrucous plaque with peripheral erythema.9 Lesions can be annular with central clearing, and lymphedema with elephantiasis may be present.10 Histologically, CBM shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and intraepidermal pustules as the host rids the infection via transepithelial elimination. Dematiaceous fungi often are seen in the dermis, either freestanding or attached to foreign plant material. Medlar bodies, also called copper penny spores or sclerotic bodies, are the most defining histologic finding and are characterized by groups of brown, thick-walled cells found in giant cells or neutrophil abscesses (Figure 1). Hyphae are not typically found in this type of infection.11

Granulomatous foreign body reactions occur in response to the inoculation of nonhuman material and are characterized by dermal or subcutaneous nodules. Tissue macrophages phagocytize material not removed shortly after implantation, which initiates an inflammatory response that attempts to isolate the material from the uninvolved surrounding tissue. Vegetative foreign bodies will cause the most severe inflammatory reactions.12 Histologically, foreign body granulomas are noncaseating with epithelioid histiocytes surrounding a central foreign body (Figure 2). Occasionally, foreign bodies may be difficult to detect; some are birefringent to polarized light.13 Additionally, inoculation injuries can predispose patients to SP, CBM, and other fungal infections.

Tattoos are characterized by exogenous pigment deposition into the dermis.14 Histologically, tattoos display exogenous pigment deposited throughout the reticular dermis, attached to collagen bundles, within macrophages, or adjacent to adnexal structures (eg, pilosebaceous units or eccrine glands). Although all tattoo pigments can cause adverse reactions, hypersensitivity reactions occur most commonly in response to red pigment, resulting in discrete areas of spongiosis and granulomatous or lichenoid inflammation. Occasionally, hypersensitivity reactions can induce necrobiotic granulomatous reactions characterized by collagen alteration surrounded by palisaded histiocytes and lymphocytes (Figure 3).15,16 There also may be focally dense areas of superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Clinical context is important, as brown tattoo pigment (Figure 3) can be easily confused with the pigmented hyphae of phaeohyphomycosis, melanin, or hemosiderin.

Subcutaneous hyalohyphomycosis is a nondemat-iaceous (nonpigmented) infection that is caused by hyaline septate hyphal cells.17 Hyalohyphomycosis skin lesions can present as painful erythematous nodules that evolve into excoriated pustules.18 Hyalohyphomycosis most often arises in immunocompromised patients. Causative organisms are ubiquitous soil saprophytes and plant pathogens, most often Aspergillus and Fusarium species, with a predilection for affecting severely immunocompromised hosts, particularly children.19 These species tend to be vasculotropic, which can result in tissue necrosis and systemic dissemination. Histologically, fungi are dispersed within tissue. They have a bright, bubbly, mildly basophilic cytoplasm and are nonpigmented, branching, and septate (Figure 4).11

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Phaeohyphomycosis

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (SP), also called mycotic cyst, is characterized by a painless, nodular lesion that develops in response to traumatic implantation of dematiaceous, pigment-forming fungi.1 Similar to other fungal infections, SP can arise opportunistically in immunocompromised patients.2,3 More than 60 genera (and more than 100 species) are known etiologic agents of phaeohyphomycosis; the 2 main causes of infection are Bipolaris spicifera and Exophiala jeanselmei.4,5 Given this variety, phaeohyphomycosis can present superficially as black piedra or tinea nigra, cutaneously as scytalidiosis, subcutaneously as SP, or disseminated as sinusitis or systemic phaeohyphomycosis.

Coined in 1974 by Ajello et al,6 the term phaeohyphomycosis translates to “condition of dark hyphal fungus,” a term used to designate mycoses caused by fungi with melanized hyphae. Histologically, SP demonstrates a circumscribed chronic cyst or abscess with a dense fibrous wall (quiz image A). At high power, the wall is composed of chronic granulomatous inflammation with foamy macrophages, and the cystic cavity contains necrotic debris admixed with neutrophils. Pigmented filamentous hyphae and yeastlike entities can be seen in the cyst wall, in multinucleated giant cells, in the necrotic debris, or directly attached to the implanted foreign material (quiz image B).7 The first-line treatment of SP is wide local excision and oral itraconazole. It often requires adjustments to dosage or change to antifungal due to recurrence and etiologic variation.8 Furthermore, if SP is not definitively treated, immunocompromised patients are at an increased risk for developing potentially fatal systemic phaeohyphomycosis.3

Chromoblastomycosis (CBM), also caused by dematiaceous fungi, is characterized by an initially indolent clinical presentation. Typically found on the legs and lower thighs of agricultural workers, the lesion begins as a slow-growing, nodular papule with subsequent transformation into an edematous verrucous plaque with peripheral erythema.9 Lesions can be annular with central clearing, and lymphedema with elephantiasis may be present.10 Histologically, CBM shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and intraepidermal pustules as the host rids the infection via transepithelial elimination. Dematiaceous fungi often are seen in the dermis, either freestanding or attached to foreign plant material. Medlar bodies, also called copper penny spores or sclerotic bodies, are the most defining histologic finding and are characterized by groups of brown, thick-walled cells found in giant cells or neutrophil abscesses (Figure 1). Hyphae are not typically found in this type of infection.11

Granulomatous foreign body reactions occur in response to the inoculation of nonhuman material and are characterized by dermal or subcutaneous nodules. Tissue macrophages phagocytize material not removed shortly after implantation, which initiates an inflammatory response that attempts to isolate the material from the uninvolved surrounding tissue. Vegetative foreign bodies will cause the most severe inflammatory reactions.12 Histologically, foreign body granulomas are noncaseating with epithelioid histiocytes surrounding a central foreign body (Figure 2). Occasionally, foreign bodies may be difficult to detect; some are birefringent to polarized light.13 Additionally, inoculation injuries can predispose patients to SP, CBM, and other fungal infections.

Tattoos are characterized by exogenous pigment deposition into the dermis.14 Histologically, tattoos display exogenous pigment deposited throughout the reticular dermis, attached to collagen bundles, within macrophages, or adjacent to adnexal structures (eg, pilosebaceous units or eccrine glands). Although all tattoo pigments can cause adverse reactions, hypersensitivity reactions occur most commonly in response to red pigment, resulting in discrete areas of spongiosis and granulomatous or lichenoid inflammation. Occasionally, hypersensitivity reactions can induce necrobiotic granulomatous reactions characterized by collagen alteration surrounded by palisaded histiocytes and lymphocytes (Figure 3).15,16 There also may be focally dense areas of superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Clinical context is important, as brown tattoo pigment (Figure 3) can be easily confused with the pigmented hyphae of phaeohyphomycosis, melanin, or hemosiderin.

Subcutaneous hyalohyphomycosis is a nondemat-iaceous (nonpigmented) infection that is caused by hyaline septate hyphal cells.17 Hyalohyphomycosis skin lesions can present as painful erythematous nodules that evolve into excoriated pustules.18 Hyalohyphomycosis most often arises in immunocompromised patients. Causative organisms are ubiquitous soil saprophytes and plant pathogens, most often Aspergillus and Fusarium species, with a predilection for affecting severely immunocompromised hosts, particularly children.19 These species tend to be vasculotropic, which can result in tissue necrosis and systemic dissemination. Histologically, fungi are dispersed within tissue. They have a bright, bubbly, mildly basophilic cytoplasm and are nonpigmented, branching, and septate (Figure 4).11

- Isa-Isa R, García C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Rubin RH. Infectious disease complications of renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 1993;44:221-236.

- Ogawa MM, Galante NZ, Godoy P, et al. Treatment of subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis and prospective follow-up of 17 kidney transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:977-985.

- Matsumoto T, Ajello L, Matsuda T, et al. Developments in hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32(suppl 1):329-349.

- Rinaldi MG. Phaeohyphomycosis. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:147-153.

- Ajello L, Georg LK, Steigbigel RT, et al. A case of phaeohyphomycosis caused by a new species of Phialophora. Mycologia. 1974;66:490-498.

- Patterson J. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2014.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Bonifaz A, Carrasco-Gerard E, Saúl A. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical and mycologic experience of 51 cases. Mycoses. 2001;44:1-7.

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

- Elston D, Ferringer T, Peckham S, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

- Lammers RL. Soft tissue foreign bodies. In: Tintinalli J, Stapczynski S, Ma O, et al, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Professional; 2011.

- Murphy GF, Saavedra AP, Mihm MC. Nodular/interstitial dermatitis. In: Murphy GF, Saavedra AP, Mihm MC, eds. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology: Inflammatory Disorders of the Skin. Vol 10. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology; 2012:337-395.

- Laumann A. Body art. In: Goldsmith L, Katz S, Gilchrest B, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012. http://access medicine.mhmedical.com.proxy.lib.uiowa.edu/content.aspx?bookid=392&Sectionid=41138811. Accessed July 17,2016.

- Wood A, Hamilton SA, Wallace WA, et al. Necrobiotic granulomatous tattoo reaction: report of an unusual case showing features of both necrobiosis lipoidica and granuloma annulare patterns. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:e152-e155.

- Mortimer N, Chave T, Johnston G. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Ajello L. Hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis: two global disease entities of public health importance. Eur J Epidemiol. 1986;2:243-251.

- Safdar A. Progressive cutaneous hyalohyphomycosis due to Paecilomyces lilacinus: rapid response to treatment with caspofungin and itraconazole. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1415-1417.

- Marcoux D, Jafarian F, Joncas V, et al. Deep cutaneous fungal infections in immunocompromised children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:857-864.

- Isa-Isa R, García C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Rubin RH. Infectious disease complications of renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 1993;44:221-236.

- Ogawa MM, Galante NZ, Godoy P, et al. Treatment of subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis and prospective follow-up of 17 kidney transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:977-985.

- Matsumoto T, Ajello L, Matsuda T, et al. Developments in hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32(suppl 1):329-349.

- Rinaldi MG. Phaeohyphomycosis. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:147-153.

- Ajello L, Georg LK, Steigbigel RT, et al. A case of phaeohyphomycosis caused by a new species of Phialophora. Mycologia. 1974;66:490-498.

- Patterson J. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2014.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Bonifaz A, Carrasco-Gerard E, Saúl A. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical and mycologic experience of 51 cases. Mycoses. 2001;44:1-7.

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

- Elston D, Ferringer T, Peckham S, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

- Lammers RL. Soft tissue foreign bodies. In: Tintinalli J, Stapczynski S, Ma O, et al, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Professional; 2011.

- Murphy GF, Saavedra AP, Mihm MC. Nodular/interstitial dermatitis. In: Murphy GF, Saavedra AP, Mihm MC, eds. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology: Inflammatory Disorders of the Skin. Vol 10. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology; 2012:337-395.

- Laumann A. Body art. In: Goldsmith L, Katz S, Gilchrest B, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012. http://access medicine.mhmedical.com.proxy.lib.uiowa.edu/content.aspx?bookid=392&Sectionid=41138811. Accessed July 17,2016.

- Wood A, Hamilton SA, Wallace WA, et al. Necrobiotic granulomatous tattoo reaction: report of an unusual case showing features of both necrobiosis lipoidica and granuloma annulare patterns. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:e152-e155.

- Mortimer N, Chave T, Johnston G. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Ajello L. Hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis: two global disease entities of public health importance. Eur J Epidemiol. 1986;2:243-251.

- Safdar A. Progressive cutaneous hyalohyphomycosis due to Paecilomyces lilacinus: rapid response to treatment with caspofungin and itraconazole. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1415-1417.

- Marcoux D, Jafarian F, Joncas V, et al. Deep cutaneous fungal infections in immunocompromised children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:857-864.

A 63-year-old man on immunosuppressive therapy following renal transplantation 5 years prior presented with a nontender circumscribed nodule above the left knee of 6 months’ duration. The patient denied any trauma or injury to the site.

Erythema and Induration on the Right Ear and Maxilla

Lepromatous Leprosy

Lepromatous leprosy (LL) is a chronic, cutaneous, granulomatous infection caused by Mycobacterium leprae or the newly discovered Mycobacterium lepromatosis, both acid-fast, intracellular, bacillus bacterium.1 Although decreasing in prevalence due to effective treatment with antimicrobials, LL continues to be endemic in warm tropical or subtropical areas in Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and South America.1 The mode of transmission of infection is not well established.

The cutaneous manifestation of leprosy was previously classified based on the cell-mediated immune response of the patient, as described by Ridley and Jopling,2 ranging from tuberculoid leprosy (TT) to LL. In this spectrum of leprosy are the borderline lesions including borderline tuberculoid, borderline, and borderline lepromatous.2,3 Although this classification is popular, in 2012 the World Health Organization implemented a new 2-category classification system to standardize treatment regimens: paucibacillary (2–5 lesions or 1 nerve involvement) and multibacillary (>5 lesions or multiple nerve involvement).4

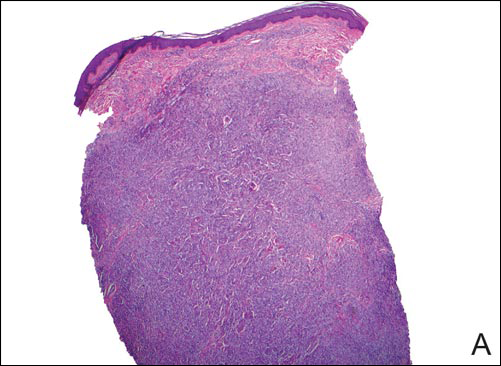

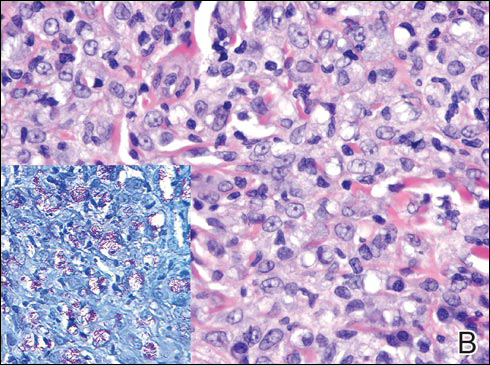

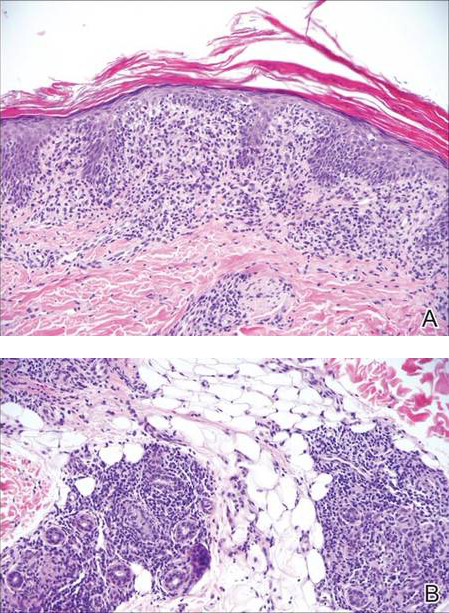

In LL, a cell-mediated immune response is not mounted against the infection in the patient. Clinically, the disease can manifest as macular and nodular erythematous cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders that are preferentially located on the face, earlobes, and nasal mucosa. Chronic infections are associated with sensory loss. Histologically, the dermis is densely infiltrated by foamy macrophages (Virchow cells or lepra cells), which do not form granulomas (quiz image A). The infiltrate may have varying accompanying lymphocytes and plasma cells, which can extend deep into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Between the dermal infiltrate and epidermis is an uninvolved band of superficial dermis called the Grenz zone. The epidermis is flattened and atrophic. Nerves often are surrounded by macrophages with degrees of hyalinization but rarely are swollen. On acid-fast staining (Wade-Fite or Ziehl-Neelsen), numerous acid-fast bacilli are present within dermal cells in densely packed, intracellular collections called globi (quiz image B).2,3,5

In TT, the robust immune response causes epithelioid granuloma formation, similar to cutaneous sarcoidosis, and few, if any, organisms can be found on special stains. The remaining borderline lesions have varying numbers of bacilli and varying amounts of granuloma formation.3,6,7 Many cases of TT resolve without specific treatment. For most leprous diseases, the World Health Organization currently recommends a regimen of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine combination treatments for 6 to 12 months depending on the type of leprosy.8

Cutaneous leishmaniasis should be included in the differential diagnosis for patients from LL endemic areas. Early lesions can have a histiocytic infiltration with associated mixed inflammation and prominent epidermal hyperplasia. These early lesions usually have parasitic organisms located within the periphery of the cytoplasm of macrophages (“marquee sign”) to help differentiate it from leprous diseases (Figure 1).9

In nonendemic areas, leprous diseases often are mistaken for sarcoidosis, xanthomas, granular cell tumors, paraffinomas, or other histiocytic-rich lesions.10 Cutaneous sarcoidosis may be difficult to distinguish from TT, as both have noncaseating granulomas (Figure 2). Rare acid-fast bacilli may aid in the diagnosis, and sarcoid granulomas are not typically associated with cutaneous nerve involvement. New diagnostic tools such as polymerase chain reaction or genome sequencing can pick up rare organisms.

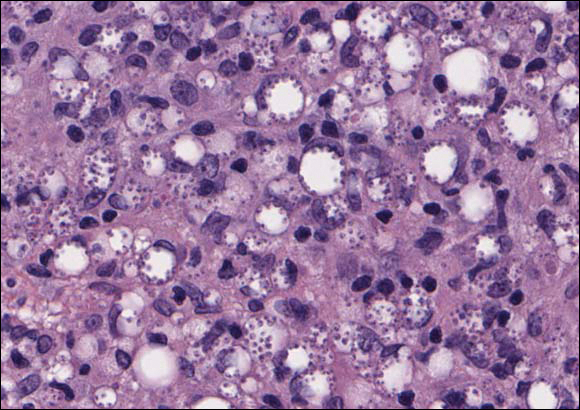

Xanthogranuolomas and xanthomas may histologically resemble LL with a dense dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes. No organisms are found in the infiltrate. Histologically, xanthogranulomas (juvenile or adult) will be a mixed infiltrate with foamy histiocytes; giant cell formation, especially Touton giant cells; lymphocytes; and granulocytes (Figure 3). Touton giant cells have a wreathlike formation of nuclei and an outer vacuolated cytoplasm. Xanthomas have sheets of large histiocytes with a foamy, lipid-filled interior and mild lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4).

- Han XY, Seo YH, Sizer KC, et al. A new Mycobacterium species causing diffuse lepromatous leprosy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;130:856-864.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. a five-group system. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1966;34:255-273.

- Ridley DS. Histological classification and the immunological spectrum of leprosy. Bull World Health Organ. 1974;51:451-465.

- World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2012;968:1-61.

- Massone C, Belachew WA, Schettini A. Histopathology of the lepromatous skin biopsy. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:38-45.

- Britton WJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Lancet. 2004;363:1209-1219.

- Crowson AN, Magro C, Mihm M Jr. Treponemal diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson Jr BL, et al. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:540-579.

- Dacso MM, Jacobson RR, Scollard DM, et al. Evaluation of multi-drug therapy for leprosy in the United States using daily rifampin. South Med J. 2011;104:689-694.

- Handler MZ, Patel PA, Kapila R, et al. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: differential diagnosis, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:911-926.

- Massone C, Nunzi E, Cerroni L. Histopathologic diagnosis of leprosy in a nonendemic area. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:417-419.

Lepromatous Leprosy

Lepromatous leprosy (LL) is a chronic, cutaneous, granulomatous infection caused by Mycobacterium leprae or the newly discovered Mycobacterium lepromatosis, both acid-fast, intracellular, bacillus bacterium.1 Although decreasing in prevalence due to effective treatment with antimicrobials, LL continues to be endemic in warm tropical or subtropical areas in Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and South America.1 The mode of transmission of infection is not well established.

The cutaneous manifestation of leprosy was previously classified based on the cell-mediated immune response of the patient, as described by Ridley and Jopling,2 ranging from tuberculoid leprosy (TT) to LL. In this spectrum of leprosy are the borderline lesions including borderline tuberculoid, borderline, and borderline lepromatous.2,3 Although this classification is popular, in 2012 the World Health Organization implemented a new 2-category classification system to standardize treatment regimens: paucibacillary (2–5 lesions or 1 nerve involvement) and multibacillary (>5 lesions or multiple nerve involvement).4

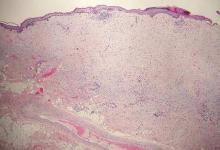

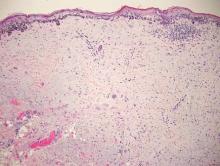

In LL, a cell-mediated immune response is not mounted against the infection in the patient. Clinically, the disease can manifest as macular and nodular erythematous cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders that are preferentially located on the face, earlobes, and nasal mucosa. Chronic infections are associated with sensory loss. Histologically, the dermis is densely infiltrated by foamy macrophages (Virchow cells or lepra cells), which do not form granulomas (quiz image A). The infiltrate may have varying accompanying lymphocytes and plasma cells, which can extend deep into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Between the dermal infiltrate and epidermis is an uninvolved band of superficial dermis called the Grenz zone. The epidermis is flattened and atrophic. Nerves often are surrounded by macrophages with degrees of hyalinization but rarely are swollen. On acid-fast staining (Wade-Fite or Ziehl-Neelsen), numerous acid-fast bacilli are present within dermal cells in densely packed, intracellular collections called globi (quiz image B).2,3,5

In TT, the robust immune response causes epithelioid granuloma formation, similar to cutaneous sarcoidosis, and few, if any, organisms can be found on special stains. The remaining borderline lesions have varying numbers of bacilli and varying amounts of granuloma formation.3,6,7 Many cases of TT resolve without specific treatment. For most leprous diseases, the World Health Organization currently recommends a regimen of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine combination treatments for 6 to 12 months depending on the type of leprosy.8

Cutaneous leishmaniasis should be included in the differential diagnosis for patients from LL endemic areas. Early lesions can have a histiocytic infiltration with associated mixed inflammation and prominent epidermal hyperplasia. These early lesions usually have parasitic organisms located within the periphery of the cytoplasm of macrophages (“marquee sign”) to help differentiate it from leprous diseases (Figure 1).9

In nonendemic areas, leprous diseases often are mistaken for sarcoidosis, xanthomas, granular cell tumors, paraffinomas, or other histiocytic-rich lesions.10 Cutaneous sarcoidosis may be difficult to distinguish from TT, as both have noncaseating granulomas (Figure 2). Rare acid-fast bacilli may aid in the diagnosis, and sarcoid granulomas are not typically associated with cutaneous nerve involvement. New diagnostic tools such as polymerase chain reaction or genome sequencing can pick up rare organisms.

Xanthogranuolomas and xanthomas may histologically resemble LL with a dense dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes. No organisms are found in the infiltrate. Histologically, xanthogranulomas (juvenile or adult) will be a mixed infiltrate with foamy histiocytes; giant cell formation, especially Touton giant cells; lymphocytes; and granulocytes (Figure 3). Touton giant cells have a wreathlike formation of nuclei and an outer vacuolated cytoplasm. Xanthomas have sheets of large histiocytes with a foamy, lipid-filled interior and mild lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4).

Lepromatous Leprosy

Lepromatous leprosy (LL) is a chronic, cutaneous, granulomatous infection caused by Mycobacterium leprae or the newly discovered Mycobacterium lepromatosis, both acid-fast, intracellular, bacillus bacterium.1 Although decreasing in prevalence due to effective treatment with antimicrobials, LL continues to be endemic in warm tropical or subtropical areas in Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and South America.1 The mode of transmission of infection is not well established.

The cutaneous manifestation of leprosy was previously classified based on the cell-mediated immune response of the patient, as described by Ridley and Jopling,2 ranging from tuberculoid leprosy (TT) to LL. In this spectrum of leprosy are the borderline lesions including borderline tuberculoid, borderline, and borderline lepromatous.2,3 Although this classification is popular, in 2012 the World Health Organization implemented a new 2-category classification system to standardize treatment regimens: paucibacillary (2–5 lesions or 1 nerve involvement) and multibacillary (>5 lesions or multiple nerve involvement).4

In LL, a cell-mediated immune response is not mounted against the infection in the patient. Clinically, the disease can manifest as macular and nodular erythematous cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders that are preferentially located on the face, earlobes, and nasal mucosa. Chronic infections are associated with sensory loss. Histologically, the dermis is densely infiltrated by foamy macrophages (Virchow cells or lepra cells), which do not form granulomas (quiz image A). The infiltrate may have varying accompanying lymphocytes and plasma cells, which can extend deep into the subcutaneous adipose tissue. Between the dermal infiltrate and epidermis is an uninvolved band of superficial dermis called the Grenz zone. The epidermis is flattened and atrophic. Nerves often are surrounded by macrophages with degrees of hyalinization but rarely are swollen. On acid-fast staining (Wade-Fite or Ziehl-Neelsen), numerous acid-fast bacilli are present within dermal cells in densely packed, intracellular collections called globi (quiz image B).2,3,5

In TT, the robust immune response causes epithelioid granuloma formation, similar to cutaneous sarcoidosis, and few, if any, organisms can be found on special stains. The remaining borderline lesions have varying numbers of bacilli and varying amounts of granuloma formation.3,6,7 Many cases of TT resolve without specific treatment. For most leprous diseases, the World Health Organization currently recommends a regimen of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine combination treatments for 6 to 12 months depending on the type of leprosy.8

Cutaneous leishmaniasis should be included in the differential diagnosis for patients from LL endemic areas. Early lesions can have a histiocytic infiltration with associated mixed inflammation and prominent epidermal hyperplasia. These early lesions usually have parasitic organisms located within the periphery of the cytoplasm of macrophages (“marquee sign”) to help differentiate it from leprous diseases (Figure 1).9

In nonendemic areas, leprous diseases often are mistaken for sarcoidosis, xanthomas, granular cell tumors, paraffinomas, or other histiocytic-rich lesions.10 Cutaneous sarcoidosis may be difficult to distinguish from TT, as both have noncaseating granulomas (Figure 2). Rare acid-fast bacilli may aid in the diagnosis, and sarcoid granulomas are not typically associated with cutaneous nerve involvement. New diagnostic tools such as polymerase chain reaction or genome sequencing can pick up rare organisms.

Xanthogranuolomas and xanthomas may histologically resemble LL with a dense dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes. No organisms are found in the infiltrate. Histologically, xanthogranulomas (juvenile or adult) will be a mixed infiltrate with foamy histiocytes; giant cell formation, especially Touton giant cells; lymphocytes; and granulocytes (Figure 3). Touton giant cells have a wreathlike formation of nuclei and an outer vacuolated cytoplasm. Xanthomas have sheets of large histiocytes with a foamy, lipid-filled interior and mild lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4).

- Han XY, Seo YH, Sizer KC, et al. A new Mycobacterium species causing diffuse lepromatous leprosy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;130:856-864.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. a five-group system. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1966;34:255-273.

- Ridley DS. Histological classification and the immunological spectrum of leprosy. Bull World Health Organ. 1974;51:451-465.

- World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2012;968:1-61.

- Massone C, Belachew WA, Schettini A. Histopathology of the lepromatous skin biopsy. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:38-45.

- Britton WJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Lancet. 2004;363:1209-1219.

- Crowson AN, Magro C, Mihm M Jr. Treponemal diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson Jr BL, et al. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:540-579.

- Dacso MM, Jacobson RR, Scollard DM, et al. Evaluation of multi-drug therapy for leprosy in the United States using daily rifampin. South Med J. 2011;104:689-694.

- Handler MZ, Patel PA, Kapila R, et al. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: differential diagnosis, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:911-926.

- Massone C, Nunzi E, Cerroni L. Histopathologic diagnosis of leprosy in a nonendemic area. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:417-419.

- Han XY, Seo YH, Sizer KC, et al. A new Mycobacterium species causing diffuse lepromatous leprosy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;130:856-864.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. a five-group system. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1966;34:255-273.

- Ridley DS. Histological classification and the immunological spectrum of leprosy. Bull World Health Organ. 1974;51:451-465.

- World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2012;968:1-61.

- Massone C, Belachew WA, Schettini A. Histopathology of the lepromatous skin biopsy. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:38-45.

- Britton WJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Lancet. 2004;363:1209-1219.

- Crowson AN, Magro C, Mihm M Jr. Treponemal diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson Jr BL, et al. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:540-579.

- Dacso MM, Jacobson RR, Scollard DM, et al. Evaluation of multi-drug therapy for leprosy in the United States using daily rifampin. South Med J. 2011;104:689-694.

- Handler MZ, Patel PA, Kapila R, et al. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: differential diagnosis, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:911-926.

- Massone C, Nunzi E, Cerroni L. Histopathologic diagnosis of leprosy in a nonendemic area. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:417-419.

A 43-year-old man from Ghana presented with erythema and induration on the skin of the right maxillary region and right ear of several weeks’ duration.

The best diagnosis is:

a. cutaneous leishmaniasis

b. lepromatous leprosy

c. sarcoidosis

d. xanthogranuloma

e. xanthoma

Growing Papule on the Right Shoulder of an Elderly Man

Granular Cell Basal Cell Carcinoma

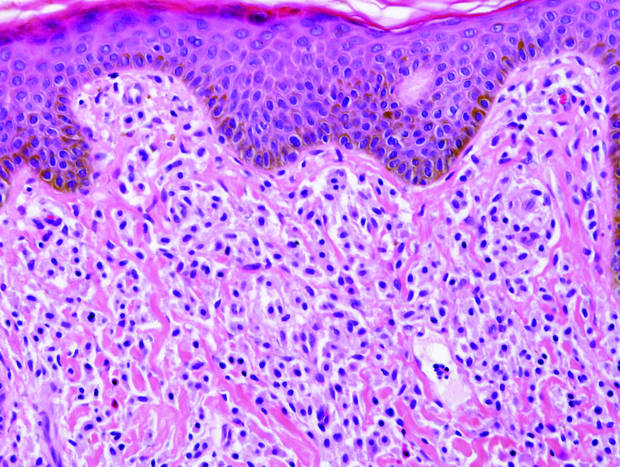

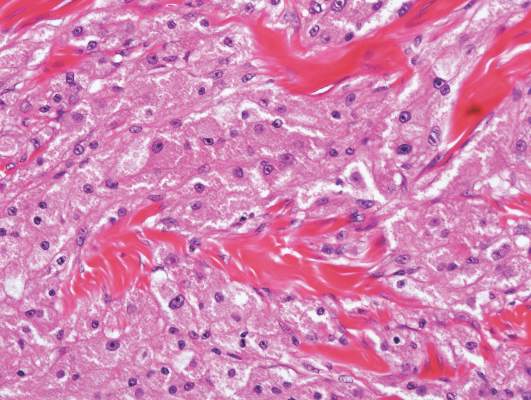

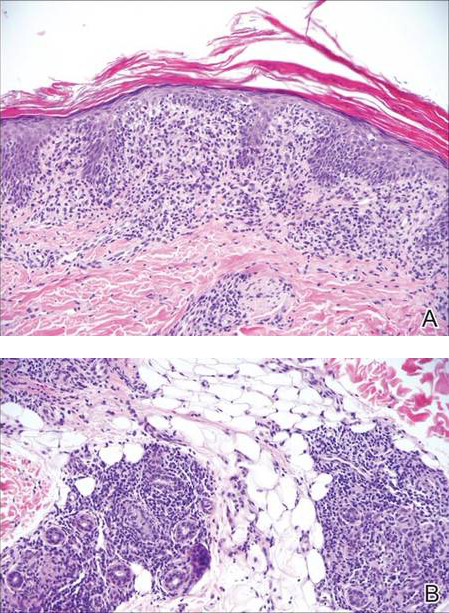

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common human epithelial malignancy. There are several histologic variants, the rarest being granular cell BCC (GBCC).1 Granular cell BCC is reported most commonly in men with a mean age of 63 years. Sixty-four percent of cases develop on the face, with the remainder arising on the chest or trunk. Granular cell BCC has distinct histologic features but has no specific epidemiologic or clinical features that differentiate it from more common forms of BCC. Treatment of GBCC is identical to BCC and demonstrates similar outcomes. The presence of granular cells can make GBCC difficult to differentiate from other benign and malignant lesions that display similar granular histologic changes.1,2 Rarely, tumors that are histologically similar to human GBCC have been reported in animals.1

Histologically, GBCC commonly demonstrates the architecture of a nodular BCC or may extend from an existing nodular BCC (quiz images A and B). Granular cell BCC is comprised of large islands of basaloid cells extending from the epidermis with rare mitotic activity. Certain variants showing no epidermal attachments have been described,1,3 as in the current case. Classically, BCC and GBCC both demonstrate a peripheral palisade of blue basal cells; however, GBCC may lack this palisading feature in some cases. Therefore, GBCC may be comprised of granular cells only, which may be more easily confused with other tumors with granular cell differentiation. Even when GBCC retains the traditional peripheral palisade of blue basal cells, the central cells are filled with eosinophilic granules.1,2

Electron microscopy of GBCC usually reveals bundles of cytoplasmic tonofilaments and desmosomes in both granular cells and the peripherally palisaded cells. Electron microscopy imaging also demonstrates 0.1- to 0.5-µm membrane-bound lysosomelike structures. In certain reports, these structures show focal positivity for lysozymes.1,2 The etiology of the granules is unclear; however, they are thought to represent degenerative changes related to metabolic alteration and accumulation of lysosomelike structures. These lysosomelike structures have been highlighted with CD68 staining, which was negative in our case.1,2 The lesional cells in GBCC stain positively for cytokeratins, p63, and Ber-EP4, and negatively for S-100 protein, epithelial membrane antigen, and carcinoembryonic antigen. The granules in GBCC generally are positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining.1-4

The histologic differential diagnosis for GBCC includes granular cell tumor as well as other tumors that can present with granular cell changes such as ameloblastoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, and granular cell trichoblastoma. Granular cell ameloblastomas have histologic features and staining patterns that are identical to GBCC; however, ameloblastomas are distinguished by their location within the oral cavity. Granular cell tumors and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors stain positive for S-100 protein, and angiosarcomas stain positive for D2-40 and CD31. Leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas can be differentiated by staining with smooth muscle actin or desmin.1 Granular cell trichoblastomas can be differentiated by the follicular stem cell marker protein PHLDA1 positivity.5

Desmoplastic trichilemmoma is difficult to distinguish from BCC. These tumors are comprised of superficial lobules of basaloid cells with a perilobular hyaline mantel surrounding a central desmoplastic stroma (Figure 1). The basaloid cells in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma demonstrate clear cell change; however, granular features are not seen. The cells within the desmoplastic areas are arranged haphazardly in cords and nests and can mimic an invasive carcinoma; however, nuclear atypia and mitotic activity generally are absent in desmoplastic trichilemmoma.6

Granular cell tumors generally are poorly circumscribed dermal nodules comprised of large polygonal cells with an eosinophilic granular cytoplasm (Figure 2). The nuclei are generally small and round, and cytological atypia, necrosis, and mitotic activity are uncommon. The cells are positive for S-100 protein and neuron-specific enolase but negative for CD68. The granules are positive for periodic acid–Schiff stain and are diastase resistant. Rarely, these tumors can be malignant.7

Sebaceous adenoma is a well-circumscribed tumor comprised of lobules of characteristic mature sebocytes with bubbly or multivacuolated cytoplasm and crenated nuclei (Figure 3). There is an expansion and increased prominence of the peripherally located basaloid cells; however, in contrast to sebaceous epithelioma, less than 50% of the tumor usually is comprised of these basaloid cells.8

Xanthogranuloma demonstrates a dense collection of histiocytes in the dermis, commonly with Touton giant cell formation (Figure 4). The cells often have a foamy cytoplasm and cytoplasmic vacuoles are observed. The histiocytes are positive for factor XIIIa and CD68, and generally negative for S-100 protein and CD1a, which allows for differentiation from Langerhans cells.9

- Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Granular-cell basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:301-303.

- Dundr P, Stork J, Povysil C, et al. Granular cell basal cell carcinoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:70-72.

- Hayden AA, Shamma HN. Ber-EP4 and MNF-116 in a previously undescribed morphologic pattern of granular basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:530-532.

- Ansai S, Takayama R, Kimura T, et al. Ber-EP4 is a useful marker for follicular germinative cell differentiation of cutaneous epithelial neoplasms. J Dermatol. 2012;39:688-692.

- Battistella M, Peltre B, Cribier B. PHLDA1, a follicular stem cell marker, differentiates clear-cell/granular-cell trichoblastoma and clear-cell/granular cell basal cell carcinoma: a case-control study, with first description of granular-cell trichoblastoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:643-650.

- Tellechea O, Reis JP, Baptista AP. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:107-114.

- Battistella M, Cribier B, Feugeas JP, et al. Vascular invasion and other invasive features in granular cell tumours of the skin: a multicentre study of 119 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:19-25.

- Shalin SC, Lyle S, Calonje E, et al. Sebaceous neoplasia and the Muir-Torre syndrome: important connections with clinical implications. Histopathology. 2010;56:133-147.

- Janssen D, Harms D. Juvenile xanthogranuloma in childhood and adolescence: a clinicopathologic study of 129 patients from the kiel pediatric tumor registry. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:21-28.

Granular Cell Basal Cell Carcinoma

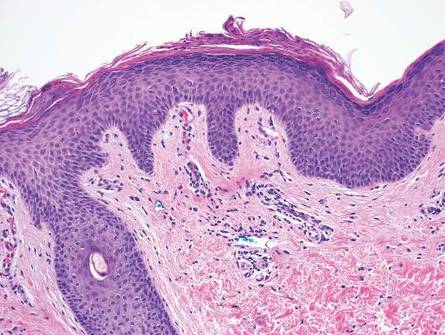

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common human epithelial malignancy. There are several histologic variants, the rarest being granular cell BCC (GBCC).1 Granular cell BCC is reported most commonly in men with a mean age of 63 years. Sixty-four percent of cases develop on the face, with the remainder arising on the chest or trunk. Granular cell BCC has distinct histologic features but has no specific epidemiologic or clinical features that differentiate it from more common forms of BCC. Treatment of GBCC is identical to BCC and demonstrates similar outcomes. The presence of granular cells can make GBCC difficult to differentiate from other benign and malignant lesions that display similar granular histologic changes.1,2 Rarely, tumors that are histologically similar to human GBCC have been reported in animals.1

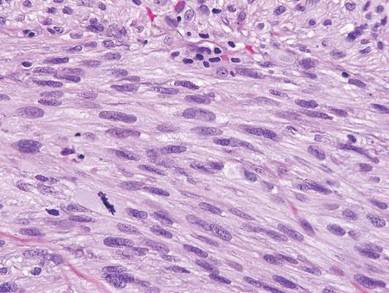

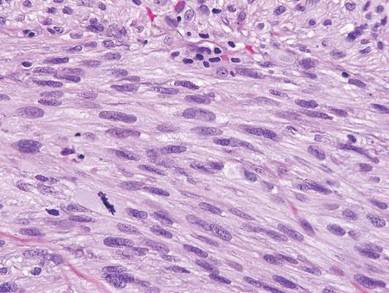

Histologically, GBCC commonly demonstrates the architecture of a nodular BCC or may extend from an existing nodular BCC (quiz images A and B). Granular cell BCC is comprised of large islands of basaloid cells extending from the epidermis with rare mitotic activity. Certain variants showing no epidermal attachments have been described,1,3 as in the current case. Classically, BCC and GBCC both demonstrate a peripheral palisade of blue basal cells; however, GBCC may lack this palisading feature in some cases. Therefore, GBCC may be comprised of granular cells only, which may be more easily confused with other tumors with granular cell differentiation. Even when GBCC retains the traditional peripheral palisade of blue basal cells, the central cells are filled with eosinophilic granules.1,2

Electron microscopy of GBCC usually reveals bundles of cytoplasmic tonofilaments and desmosomes in both granular cells and the peripherally palisaded cells. Electron microscopy imaging also demonstrates 0.1- to 0.5-µm membrane-bound lysosomelike structures. In certain reports, these structures show focal positivity for lysozymes.1,2 The etiology of the granules is unclear; however, they are thought to represent degenerative changes related to metabolic alteration and accumulation of lysosomelike structures. These lysosomelike structures have been highlighted with CD68 staining, which was negative in our case.1,2 The lesional cells in GBCC stain positively for cytokeratins, p63, and Ber-EP4, and negatively for S-100 protein, epithelial membrane antigen, and carcinoembryonic antigen. The granules in GBCC generally are positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining.1-4

The histologic differential diagnosis for GBCC includes granular cell tumor as well as other tumors that can present with granular cell changes such as ameloblastoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, and granular cell trichoblastoma. Granular cell ameloblastomas have histologic features and staining patterns that are identical to GBCC; however, ameloblastomas are distinguished by their location within the oral cavity. Granular cell tumors and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors stain positive for S-100 protein, and angiosarcomas stain positive for D2-40 and CD31. Leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas can be differentiated by staining with smooth muscle actin or desmin.1 Granular cell trichoblastomas can be differentiated by the follicular stem cell marker protein PHLDA1 positivity.5

Desmoplastic trichilemmoma is difficult to distinguish from BCC. These tumors are comprised of superficial lobules of basaloid cells with a perilobular hyaline mantel surrounding a central desmoplastic stroma (Figure 1). The basaloid cells in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma demonstrate clear cell change; however, granular features are not seen. The cells within the desmoplastic areas are arranged haphazardly in cords and nests and can mimic an invasive carcinoma; however, nuclear atypia and mitotic activity generally are absent in desmoplastic trichilemmoma.6

Granular cell tumors generally are poorly circumscribed dermal nodules comprised of large polygonal cells with an eosinophilic granular cytoplasm (Figure 2). The nuclei are generally small and round, and cytological atypia, necrosis, and mitotic activity are uncommon. The cells are positive for S-100 protein and neuron-specific enolase but negative for CD68. The granules are positive for periodic acid–Schiff stain and are diastase resistant. Rarely, these tumors can be malignant.7

Sebaceous adenoma is a well-circumscribed tumor comprised of lobules of characteristic mature sebocytes with bubbly or multivacuolated cytoplasm and crenated nuclei (Figure 3). There is an expansion and increased prominence of the peripherally located basaloid cells; however, in contrast to sebaceous epithelioma, less than 50% of the tumor usually is comprised of these basaloid cells.8

Xanthogranuloma demonstrates a dense collection of histiocytes in the dermis, commonly with Touton giant cell formation (Figure 4). The cells often have a foamy cytoplasm and cytoplasmic vacuoles are observed. The histiocytes are positive for factor XIIIa and CD68, and generally negative for S-100 protein and CD1a, which allows for differentiation from Langerhans cells.9

Granular Cell Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common human epithelial malignancy. There are several histologic variants, the rarest being granular cell BCC (GBCC).1 Granular cell BCC is reported most commonly in men with a mean age of 63 years. Sixty-four percent of cases develop on the face, with the remainder arising on the chest or trunk. Granular cell BCC has distinct histologic features but has no specific epidemiologic or clinical features that differentiate it from more common forms of BCC. Treatment of GBCC is identical to BCC and demonstrates similar outcomes. The presence of granular cells can make GBCC difficult to differentiate from other benign and malignant lesions that display similar granular histologic changes.1,2 Rarely, tumors that are histologically similar to human GBCC have been reported in animals.1

Histologically, GBCC commonly demonstrates the architecture of a nodular BCC or may extend from an existing nodular BCC (quiz images A and B). Granular cell BCC is comprised of large islands of basaloid cells extending from the epidermis with rare mitotic activity. Certain variants showing no epidermal attachments have been described,1,3 as in the current case. Classically, BCC and GBCC both demonstrate a peripheral palisade of blue basal cells; however, GBCC may lack this palisading feature in some cases. Therefore, GBCC may be comprised of granular cells only, which may be more easily confused with other tumors with granular cell differentiation. Even when GBCC retains the traditional peripheral palisade of blue basal cells, the central cells are filled with eosinophilic granules.1,2

Electron microscopy of GBCC usually reveals bundles of cytoplasmic tonofilaments and desmosomes in both granular cells and the peripherally palisaded cells. Electron microscopy imaging also demonstrates 0.1- to 0.5-µm membrane-bound lysosomelike structures. In certain reports, these structures show focal positivity for lysozymes.1,2 The etiology of the granules is unclear; however, they are thought to represent degenerative changes related to metabolic alteration and accumulation of lysosomelike structures. These lysosomelike structures have been highlighted with CD68 staining, which was negative in our case.1,2 The lesional cells in GBCC stain positively for cytokeratins, p63, and Ber-EP4, and negatively for S-100 protein, epithelial membrane antigen, and carcinoembryonic antigen. The granules in GBCC generally are positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining.1-4

The histologic differential diagnosis for GBCC includes granular cell tumor as well as other tumors that can present with granular cell changes such as ameloblastoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, and granular cell trichoblastoma. Granular cell ameloblastomas have histologic features and staining patterns that are identical to GBCC; however, ameloblastomas are distinguished by their location within the oral cavity. Granular cell tumors and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors stain positive for S-100 protein, and angiosarcomas stain positive for D2-40 and CD31. Leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas can be differentiated by staining with smooth muscle actin or desmin.1 Granular cell trichoblastomas can be differentiated by the follicular stem cell marker protein PHLDA1 positivity.5

Desmoplastic trichilemmoma is difficult to distinguish from BCC. These tumors are comprised of superficial lobules of basaloid cells with a perilobular hyaline mantel surrounding a central desmoplastic stroma (Figure 1). The basaloid cells in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma demonstrate clear cell change; however, granular features are not seen. The cells within the desmoplastic areas are arranged haphazardly in cords and nests and can mimic an invasive carcinoma; however, nuclear atypia and mitotic activity generally are absent in desmoplastic trichilemmoma.6

Granular cell tumors generally are poorly circumscribed dermal nodules comprised of large polygonal cells with an eosinophilic granular cytoplasm (Figure 2). The nuclei are generally small and round, and cytological atypia, necrosis, and mitotic activity are uncommon. The cells are positive for S-100 protein and neuron-specific enolase but negative for CD68. The granules are positive for periodic acid–Schiff stain and are diastase resistant. Rarely, these tumors can be malignant.7

Sebaceous adenoma is a well-circumscribed tumor comprised of lobules of characteristic mature sebocytes with bubbly or multivacuolated cytoplasm and crenated nuclei (Figure 3). There is an expansion and increased prominence of the peripherally located basaloid cells; however, in contrast to sebaceous epithelioma, less than 50% of the tumor usually is comprised of these basaloid cells.8

Xanthogranuloma demonstrates a dense collection of histiocytes in the dermis, commonly with Touton giant cell formation (Figure 4). The cells often have a foamy cytoplasm and cytoplasmic vacuoles are observed. The histiocytes are positive for factor XIIIa and CD68, and generally negative for S-100 protein and CD1a, which allows for differentiation from Langerhans cells.9

- Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Granular-cell basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:301-303.

- Dundr P, Stork J, Povysil C, et al. Granular cell basal cell carcinoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:70-72.

- Hayden AA, Shamma HN. Ber-EP4 and MNF-116 in a previously undescribed morphologic pattern of granular basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:530-532.

- Ansai S, Takayama R, Kimura T, et al. Ber-EP4 is a useful marker for follicular germinative cell differentiation of cutaneous epithelial neoplasms. J Dermatol. 2012;39:688-692.

- Battistella M, Peltre B, Cribier B. PHLDA1, a follicular stem cell marker, differentiates clear-cell/granular-cell trichoblastoma and clear-cell/granular cell basal cell carcinoma: a case-control study, with first description of granular-cell trichoblastoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:643-650.

- Tellechea O, Reis JP, Baptista AP. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:107-114.

- Battistella M, Cribier B, Feugeas JP, et al. Vascular invasion and other invasive features in granular cell tumours of the skin: a multicentre study of 119 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:19-25.

- Shalin SC, Lyle S, Calonje E, et al. Sebaceous neoplasia and the Muir-Torre syndrome: important connections with clinical implications. Histopathology. 2010;56:133-147.

- Janssen D, Harms D. Juvenile xanthogranuloma in childhood and adolescence: a clinicopathologic study of 129 patients from the kiel pediatric tumor registry. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:21-28.

- Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Granular-cell basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:301-303.

- Dundr P, Stork J, Povysil C, et al. Granular cell basal cell carcinoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:70-72.

- Hayden AA, Shamma HN. Ber-EP4 and MNF-116 in a previously undescribed morphologic pattern of granular basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:530-532.

- Ansai S, Takayama R, Kimura T, et al. Ber-EP4 is a useful marker for follicular germinative cell differentiation of cutaneous epithelial neoplasms. J Dermatol. 2012;39:688-692.

- Battistella M, Peltre B, Cribier B. PHLDA1, a follicular stem cell marker, differentiates clear-cell/granular-cell trichoblastoma and clear-cell/granular cell basal cell carcinoma: a case-control study, with first description of granular-cell trichoblastoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:643-650.

- Tellechea O, Reis JP, Baptista AP. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:107-114.

- Battistella M, Cribier B, Feugeas JP, et al. Vascular invasion and other invasive features in granular cell tumours of the skin: a multicentre study of 119 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:19-25.

- Shalin SC, Lyle S, Calonje E, et al. Sebaceous neoplasia and the Muir-Torre syndrome: important connections with clinical implications. Histopathology. 2010;56:133-147.

- Janssen D, Harms D. Juvenile xanthogranuloma in childhood and adolescence: a clinicopathologic study of 129 patients from the kiel pediatric tumor registry. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:21-28.

The best diagnosis is:

a. desmoplastic trichilemmoma

b. granular cell basal cell carcinoma

c. granular cell tumor

d. sebaceous adenoma

e. xanthogranuloma

Continue to the next page for the diagnosis >>

Benign Lesion on the Posterior Aspect of the Neck

Nuchal-Type Fibroma

Nuchal-type fibroma (NTF) is a rare benign proliferation of the dermis and subcutis associated with diabetes mellitus and Gardner syndrome.1,2 Forty-four percent of patients with NTF have diabetes mellitus.2 The posterior aspect of the neck is the most frequently affected site, but lesions also may present on the upper back, lumbosacral area, buttocks, and face. Physical examination generally reveals an indurated, asymptomatic, ill-defined, 3-cm or smaller nodule that is hard and white, unencapsulated, and poorly circumscribed.

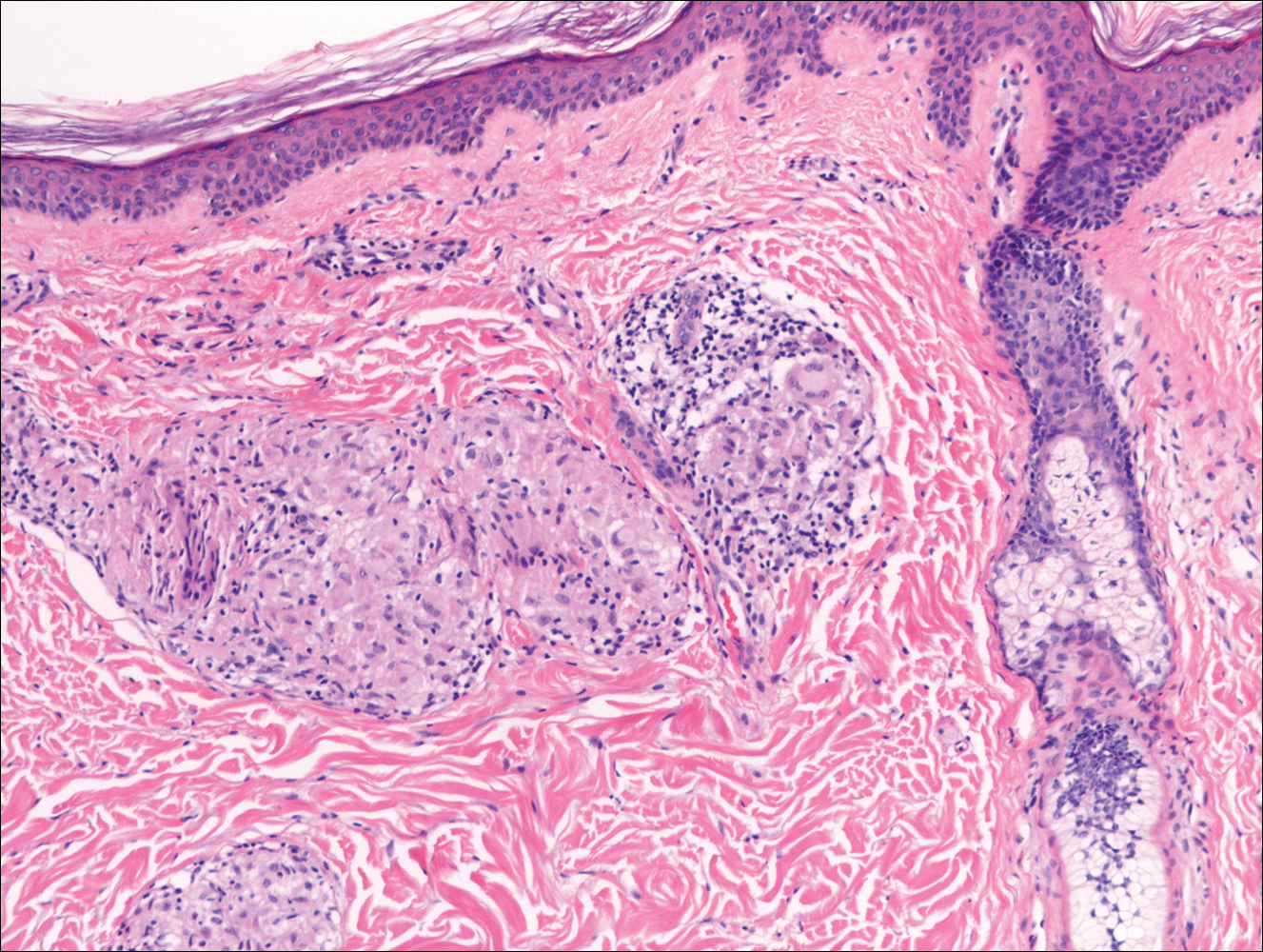

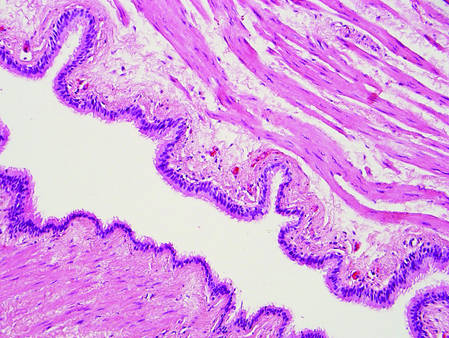

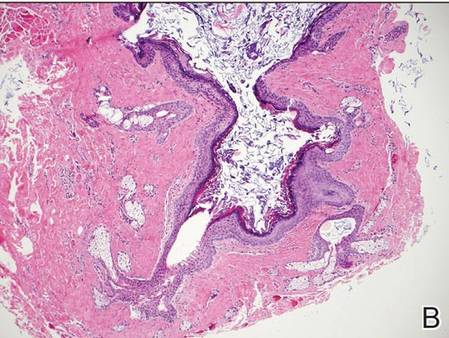

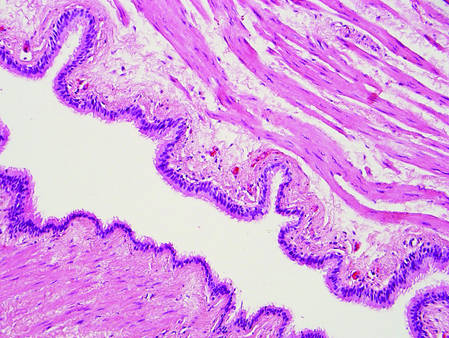

Histopathologic examination of NTF typically reveals a nodular paucicellular proliferation of thick collagen bundles with inconspicuous fibroblasts, radiation of collagenous septa into the subcutaneous fat, and entrapment of mature adipose tissue and small nerves (quiz image A). Collagen bundles are thickened with entrapment of adipose tissue without increased cellularity (quiz image B). S-100 staining can show the entrapped nerves.

Similar to NTF, sclerotic fibroma is a firm dermal nodule with histologic examination usually demonstrating a paucicellular collagenous tumor. In sclerotic fibromas, the collagen pattern resembles Vincent van Gogh’s painting “The Starry Night” and may be a marker for Cowden disease (Figure 1).3 Solitary fibrous tumors are distinguished by more hypercellular areas, patternless pattern, and staghorn-shaped blood vessels (Figure 2).4 Spindle cell lipoma classically demonstrates a mixture of mature adipocytes and bland spindle cells in a mucinous or fibrous background with thick collagen bundles with no storiform pattern (Figure 3). Some variants of spindle cell lipoma have minimal or no fat.5 All of these conditions have positive immunohistochemical staining for CD34.

However, dermatofibroma is CD34‒. Dermatofibroma is characterized by an interstitial spindle cell proliferation with a loose storiform pattern, collagen trapping at the outer edges of the tumor, overlying platelike acanthosis, and sometimes follicular induction (Figure 4).

Nuchal-type fibroma also can resemble scleredema. Both lesions can show increased and thickened collagen bundles without notable fibroblast proliferation; the difference is the occurrence of mucin in scleredema. However, incases of late-stage scleredema, mucin is not always demonstrated. Therefore, one can conclude that histologically NTF is closely associated with late-stage scleredema.6

- Dawes LC, La Hei ER, Tobias V, et al. Nuchal fibroma should be recognized as a new extracolonic manifestation of Gardner-variant familial adenomatous polyposis. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70:824-826.

- Michal M, Fetsch JF, Hes O, et al. Nuchal-type fibroma: a clinicopathologic study of 52 cases. Cancer. 1999;85:156-163.

- Pernet C, Durand L, Bessis D, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a possible clue for Cowden syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:278-279.

- Omori Y, Saeki H, Ito K, et al. Solitary fibrous tumour of the scalp. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:539-541.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL. Diagnostically challenging spindle cell lipomas: a report of 34 “low-fat” and “fat-free” variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:437-442.

- Banney LA, Weedon D, Muir JB. Nuchal fibroma associated with scleredema, diabetes mellitus and organic solvent exposure. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:39-41.

Nuchal-Type Fibroma

Nuchal-type fibroma (NTF) is a rare benign proliferation of the dermis and subcutis associated with diabetes mellitus and Gardner syndrome.1,2 Forty-four percent of patients with NTF have diabetes mellitus.2 The posterior aspect of the neck is the most frequently affected site, but lesions also may present on the upper back, lumbosacral area, buttocks, and face. Physical examination generally reveals an indurated, asymptomatic, ill-defined, 3-cm or smaller nodule that is hard and white, unencapsulated, and poorly circumscribed.

Histopathologic examination of NTF typically reveals a nodular paucicellular proliferation of thick collagen bundles with inconspicuous fibroblasts, radiation of collagenous septa into the subcutaneous fat, and entrapment of mature adipose tissue and small nerves (quiz image A). Collagen bundles are thickened with entrapment of adipose tissue without increased cellularity (quiz image B). S-100 staining can show the entrapped nerves.

Similar to NTF, sclerotic fibroma is a firm dermal nodule with histologic examination usually demonstrating a paucicellular collagenous tumor. In sclerotic fibromas, the collagen pattern resembles Vincent van Gogh’s painting “The Starry Night” and may be a marker for Cowden disease (Figure 1).3 Solitary fibrous tumors are distinguished by more hypercellular areas, patternless pattern, and staghorn-shaped blood vessels (Figure 2).4 Spindle cell lipoma classically demonstrates a mixture of mature adipocytes and bland spindle cells in a mucinous or fibrous background with thick collagen bundles with no storiform pattern (Figure 3). Some variants of spindle cell lipoma have minimal or no fat.5 All of these conditions have positive immunohistochemical staining for CD34.

However, dermatofibroma is CD34‒. Dermatofibroma is characterized by an interstitial spindle cell proliferation with a loose storiform pattern, collagen trapping at the outer edges of the tumor, overlying platelike acanthosis, and sometimes follicular induction (Figure 4).

Nuchal-type fibroma also can resemble scleredema. Both lesions can show increased and thickened collagen bundles without notable fibroblast proliferation; the difference is the occurrence of mucin in scleredema. However, incases of late-stage scleredema, mucin is not always demonstrated. Therefore, one can conclude that histologically NTF is closely associated with late-stage scleredema.6

Nuchal-Type Fibroma

Nuchal-type fibroma (NTF) is a rare benign proliferation of the dermis and subcutis associated with diabetes mellitus and Gardner syndrome.1,2 Forty-four percent of patients with NTF have diabetes mellitus.2 The posterior aspect of the neck is the most frequently affected site, but lesions also may present on the upper back, lumbosacral area, buttocks, and face. Physical examination generally reveals an indurated, asymptomatic, ill-defined, 3-cm or smaller nodule that is hard and white, unencapsulated, and poorly circumscribed.

Histopathologic examination of NTF typically reveals a nodular paucicellular proliferation of thick collagen bundles with inconspicuous fibroblasts, radiation of collagenous septa into the subcutaneous fat, and entrapment of mature adipose tissue and small nerves (quiz image A). Collagen bundles are thickened with entrapment of adipose tissue without increased cellularity (quiz image B). S-100 staining can show the entrapped nerves.

Similar to NTF, sclerotic fibroma is a firm dermal nodule with histologic examination usually demonstrating a paucicellular collagenous tumor. In sclerotic fibromas, the collagen pattern resembles Vincent van Gogh’s painting “The Starry Night” and may be a marker for Cowden disease (Figure 1).3 Solitary fibrous tumors are distinguished by more hypercellular areas, patternless pattern, and staghorn-shaped blood vessels (Figure 2).4 Spindle cell lipoma classically demonstrates a mixture of mature adipocytes and bland spindle cells in a mucinous or fibrous background with thick collagen bundles with no storiform pattern (Figure 3). Some variants of spindle cell lipoma have minimal or no fat.5 All of these conditions have positive immunohistochemical staining for CD34.

However, dermatofibroma is CD34‒. Dermatofibroma is characterized by an interstitial spindle cell proliferation with a loose storiform pattern, collagen trapping at the outer edges of the tumor, overlying platelike acanthosis, and sometimes follicular induction (Figure 4).

Nuchal-type fibroma also can resemble scleredema. Both lesions can show increased and thickened collagen bundles without notable fibroblast proliferation; the difference is the occurrence of mucin in scleredema. However, incases of late-stage scleredema, mucin is not always demonstrated. Therefore, one can conclude that histologically NTF is closely associated with late-stage scleredema.6

- Dawes LC, La Hei ER, Tobias V, et al. Nuchal fibroma should be recognized as a new extracolonic manifestation of Gardner-variant familial adenomatous polyposis. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70:824-826.

- Michal M, Fetsch JF, Hes O, et al. Nuchal-type fibroma: a clinicopathologic study of 52 cases. Cancer. 1999;85:156-163.

- Pernet C, Durand L, Bessis D, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a possible clue for Cowden syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:278-279.

- Omori Y, Saeki H, Ito K, et al. Solitary fibrous tumour of the scalp. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:539-541.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL. Diagnostically challenging spindle cell lipomas: a report of 34 “low-fat” and “fat-free” variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:437-442.

- Banney LA, Weedon D, Muir JB. Nuchal fibroma associated with scleredema, diabetes mellitus and organic solvent exposure. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:39-41.

- Dawes LC, La Hei ER, Tobias V, et al. Nuchal fibroma should be recognized as a new extracolonic manifestation of Gardner-variant familial adenomatous polyposis. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70:824-826.

- Michal M, Fetsch JF, Hes O, et al. Nuchal-type fibroma: a clinicopathologic study of 52 cases. Cancer. 1999;85:156-163.

- Pernet C, Durand L, Bessis D, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a possible clue for Cowden syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:278-279.

- Omori Y, Saeki H, Ito K, et al. Solitary fibrous tumour of the scalp. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:539-541.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL. Diagnostically challenging spindle cell lipomas: a report of 34 “low-fat” and “fat-free” variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:437-442.

- Banney LA, Weedon D, Muir JB. Nuchal fibroma associated with scleredema, diabetes mellitus and organic solvent exposure. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:39-41.

The best diagnosis is:

a. dermatofibroma

b. nuchal-type fibroma

c. sclerotic fibroma

d. solitary fibrous tumor

e. spindle cell lipoma

Continue to the next page for the diagnosis >>

Cyst on the Eyebrow

The best diagnosis is:

a. bronchogenic cyst

b. dermoid cyst

c. epidermal inclusion cyst

d. hidrocystoma

e. steatocystoma

|

|

| H&E, original magnification ×40. |

|

| H&E, original magnification ×100. |

Continue to the next page for the diagnosis >>

Dermoid Cyst

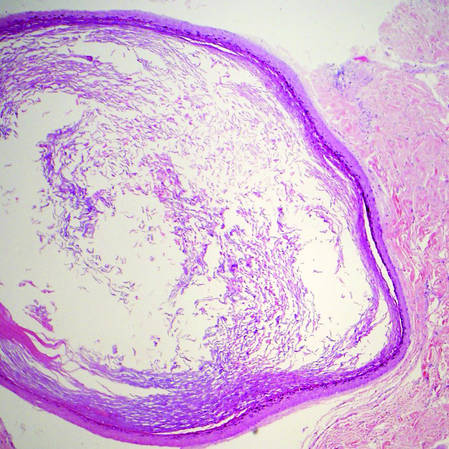

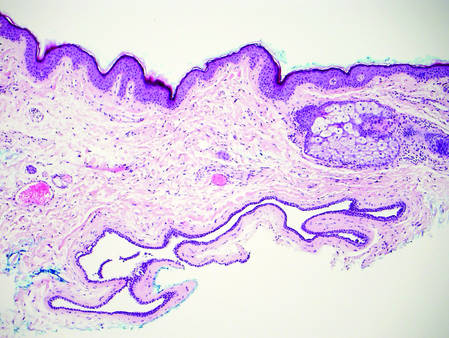

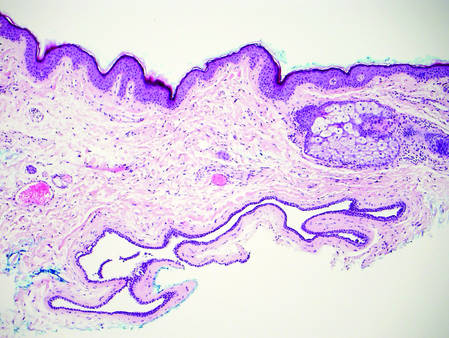

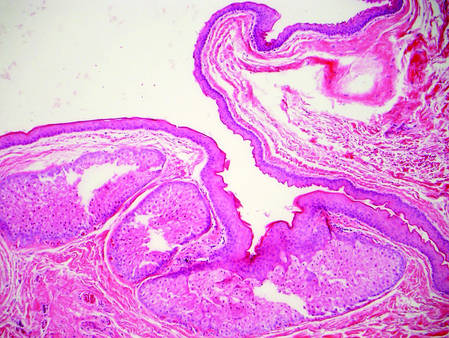

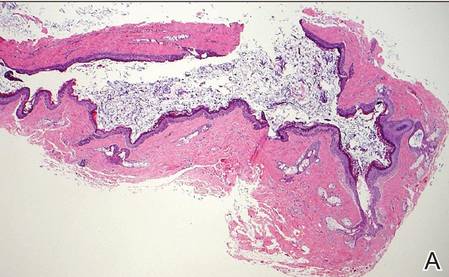

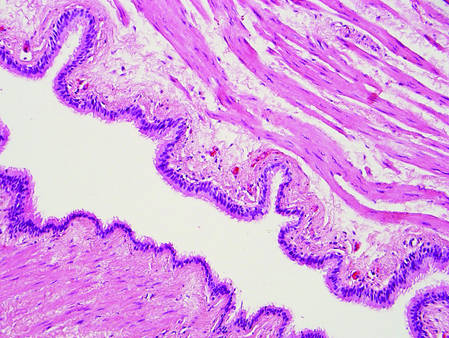

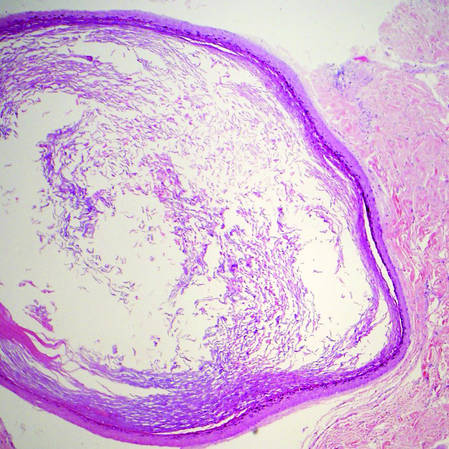

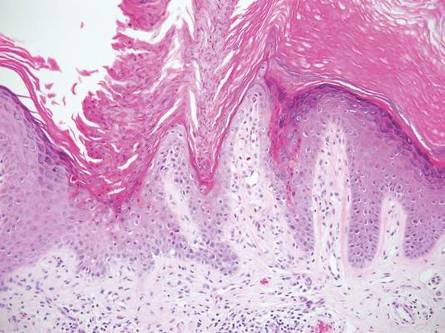

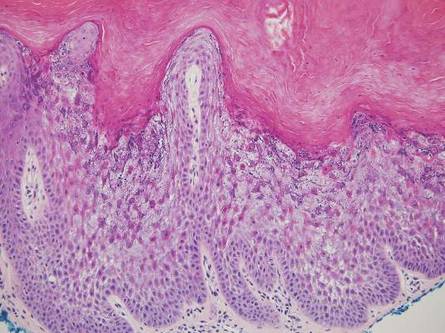

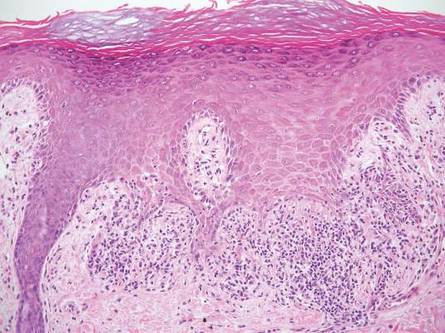

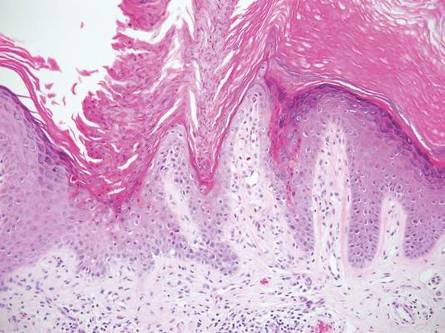

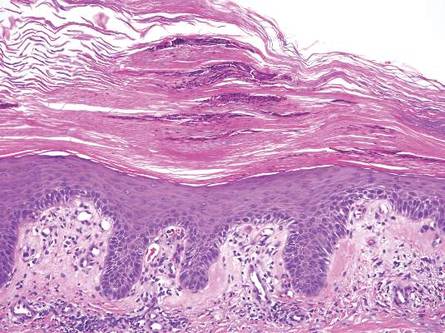

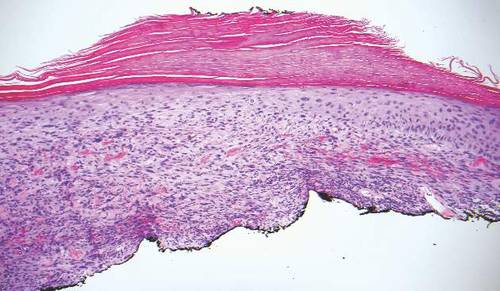

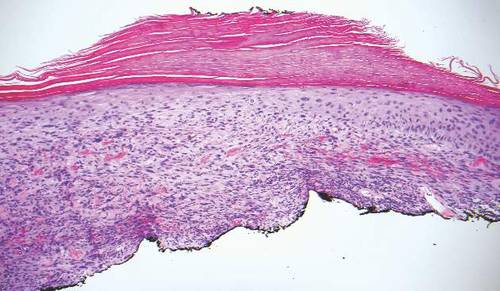

Dermoid cysts often present clinically as firm subcutaneous nodules on the head or neck in young children. They tend to arise along the lateral aspect of the eyebrow but also can occur on the nose, forehead, neck, chest, or scalp.1 Dermoid cysts are thought to arise from the sequestration of ectodermal tissues along the embryonic fusion planes during development.2 As such, they represent congenital defects and often are identified at birth; however, some are not noticed until much later when they enlarge or become inflamed or infected. Midline dermoid cysts may be associated with underlying dysraphism or intracranial extension.3,4 Thus, any midline lesion warrants evaluation that incorporates imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.4,5 Histologically, dermoid cysts are lined by a keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium (quiz image A), but the lining may be brightly eosinophilic and wavy resembling shark teeth.1,3 The wall of a dermoid cyst commonly contains mature adnexal structures such as terminal hair follicles, sebaceous glands, apocrine glands, and/or eccrine glands (quiz image B).1 Smooth muscle also may be seen within the lining; however, bone and cartilage are not commonly reported in dermoid cysts.2 Lamellar keratin is typical of the cyst contents, and terminal hair shafts also are sometimes noted within the cystic space (quiz image B).1,2 Treatment options include excision at the time of diagnosis or close clinical monitoring with subsequent excision if the lesion grows or becomes symptomatic.4,5 Many practitioners opt to excise these cysts at diagnosis, as untreated lesions are at risk for infection and/or inflammation or may be cosmetically deforming.6,7 Surgical resection, including removal of the wall of the cyst, is curative and reoccurrence is rare.5

| |

Figure 1. Bronchogenic cyst demonstrating a ciliated pseudostratified epithelial lining encircled by smooth muscle (H&E, original magnification ×200). | |

| |

| Figure 2. Epidermal inclusion cyst containing loose lamellar keratin and a lining that closely resembles the surface epidermis (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

Bronchogenic cysts demonstrate an epithelial lining that often is pseudostratified cuboidal or columnar as well as ciliated (Figure 1). Goblet cells are present in the lining in approximately 50% of cases. Smooth muscle may be seen circumferentially surrounding the cyst lining, and rare cases also contain cartilage.1 In contrast to dermoid cysts, other types of adnexal structures are not found within the lining. Bronchogenic cysts that arise in the skin are extremely rare.2 These cysts are thought to arise from respiratory epithelium that has been sequestered during embryologic formation of the tracheobronchial tree. They often are seen overlying the suprasternal notch and occasionally are found on the anterior aspect of the neck or chin. These cysts also are present at birth, similar to dermoid cysts.3

Epidermal inclusion cysts have a lining that histologically bears close resemblance to the surface epidermis. These cysts contain loose lamellar keratin, similar to a dermoid cyst. In contrast, the lining of an epidermal inclusion cyst will lack adnexal structures (Figure 2).1 Clinically, epidermal inclusion cysts often present as smooth, dome-shaped papules and nodules with a central punctum. They are classically found on the face, neck, and trunk. These cysts are thought to arise after a traumatic insult to the pilosebaceous unit.2

Hidrocystomas can be apocrine or eccrine.3 Eccrine hidrocystomas are unilocular cysts that are lined by 2 layers of flattened to cuboidal epithelial cells (Figure 3). The cysts are filled with clear fluid and often are found adjacent to normal eccrine glands.1 Apocrine hidrocystomas are unilocular or multilocular cysts that are lined by 1 to several layers of epithelial cells. The lining of an apocrine hidrocystoma will often exhibit luminal decapitation secretion.3 Apocrine and eccrine hidrocystomas are clinically identical and appear as blue translucent papules on the cheeks or eyelids of adults.1-3 They usually occur periorbitally but also can be seen on the trunk, popliteal fossa, external ears, or vulva. Eccrine hidrocystomas can wax and wane in accordance with the amount of sweat produced; thus, they often expand in size during the summer months.2

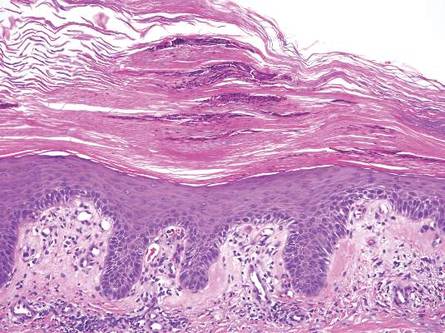

Steatocystomas, or simple sebaceous duct cysts, histologically demonstrate a characteristically wavy and eosinophilic cuticle resembling shark teeth (Figure 4) similar to the lining of the sebaceous duct where it enters the follicle.1 Sebaceous glands are an almost invariable feature, either present within the lining of the cyst (Figure 4) or in the adjacent tissue.2 In comparison, dermoid cysts may have a red wavy cuticle but also will usually have terminal hair follicles or eccrine or apocrine glands within the wall of the cyst. Steatocystomas typically are collapsed and empty or only contain sebaceous debris (Figure 4) rather than the lamellar keratin seen in dermoid and epidermoid inclusion cysts. Steatocystomas can occur as solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple (steatocystoma multiplex) lesions.1,3 They are clinically comprised of small dome-shaped papules that often are translucent and yellow. These cysts are commonly found on the sternum of males and the axillae or groin of females.2

|

| |

Figure 3. Eccrine hidrocystoma with clear contents and lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelial cells (H&E, original magnification ×100). | Figure 4. Steatocystoma with a red wavy cuticle, sparse sebaceous contents, and sebaceous glands within the lining (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

|