User login

Large Hyperpigmented Nodule on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibroma

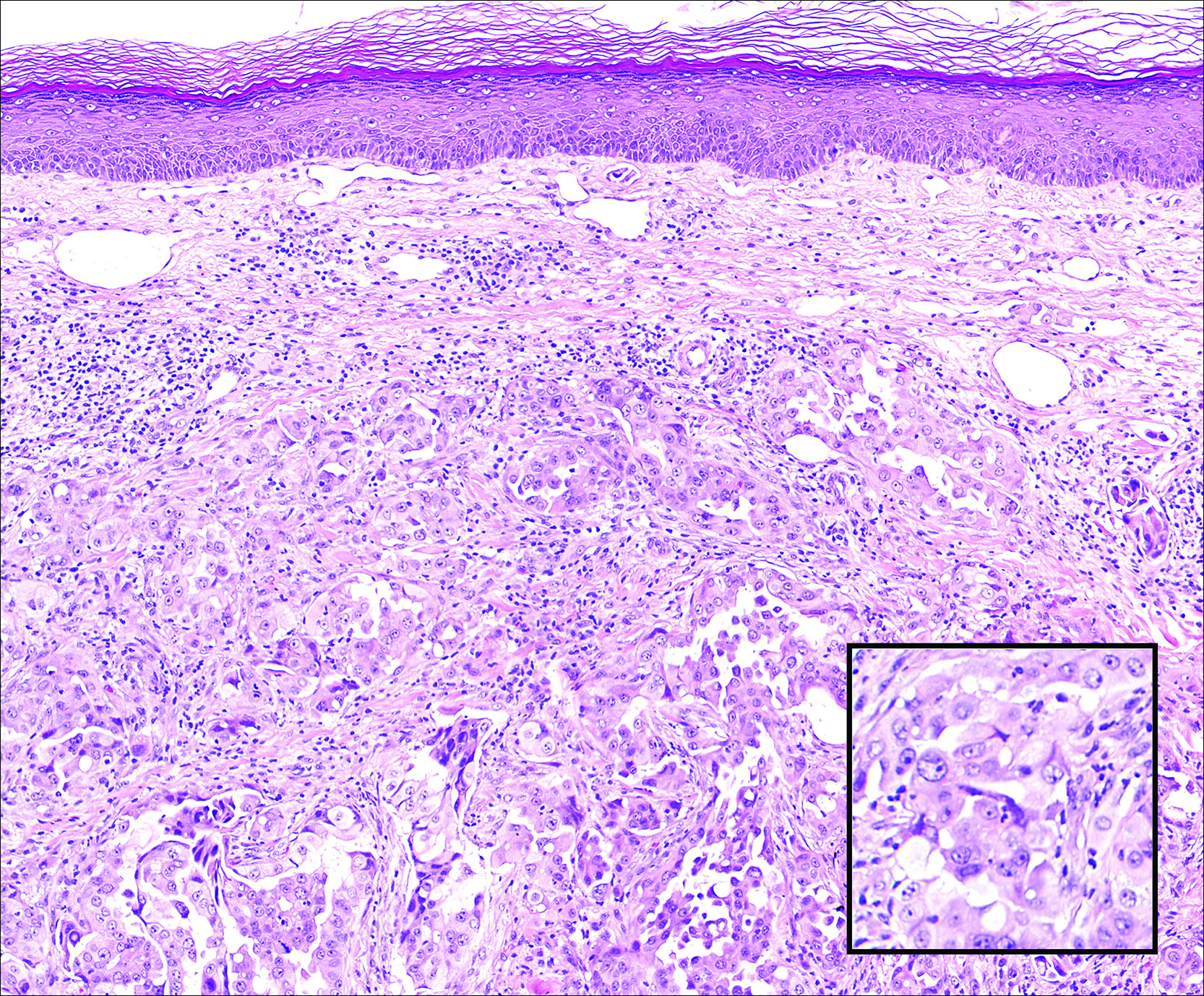

Dermatofibroma (DF) is a commonly encountered lesion. Although usually a straightforward clinical diagnosis, histopathological diagnosis is sometimes required. Conventional histologic findings of DF are hyperkeratosis, induction of the epidermis with acanthosis, and basal layer hyperpigmentation.1,2 Within the dermis there usually is proliferation of fibroblasts, histiocytes, and blood vessels that sometimes spares the overlying papillary dermis. Nomenclature of specific variants may be assigned based on the predominant component (eg, nodular subepidermal fibrosis, histiocytoma, sclerosing hemangioma) or histologic findings (eg, fibrocollagenous, sclerotic, cellular, histiocytic, lipidized, angiomatous, aneurysmal, clear cell, monster cell, myxoid, keloidal, palisading, osteoclastic, epithelioid).3-5 Of the histologic variants, fibrocollagenous is most common, but knowledge of other variants is important for accurate diagnosis, especially to exclude malignancy.

The sclerosing hemangioma variant of DF may pre-sent a diagnostic dilemma. In addition to typical features of DF, pseudovascular spaces, abundant hemosiderin, and reactive-appearing spindled cells are histologically demonstrated. The marked sclerosis and pigment deposition may mimic a blue nevus, and the dilated pseudovascular spaces may be reminiscent of a vascular neoplasm such as angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma. However, the presence of characteristic features such as peripheral collagen trapping and overlying epidermal hyperplasia provide important clues for correct diagnosis.

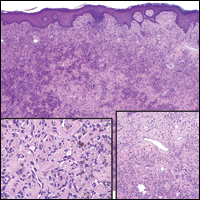

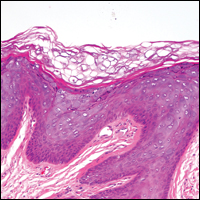

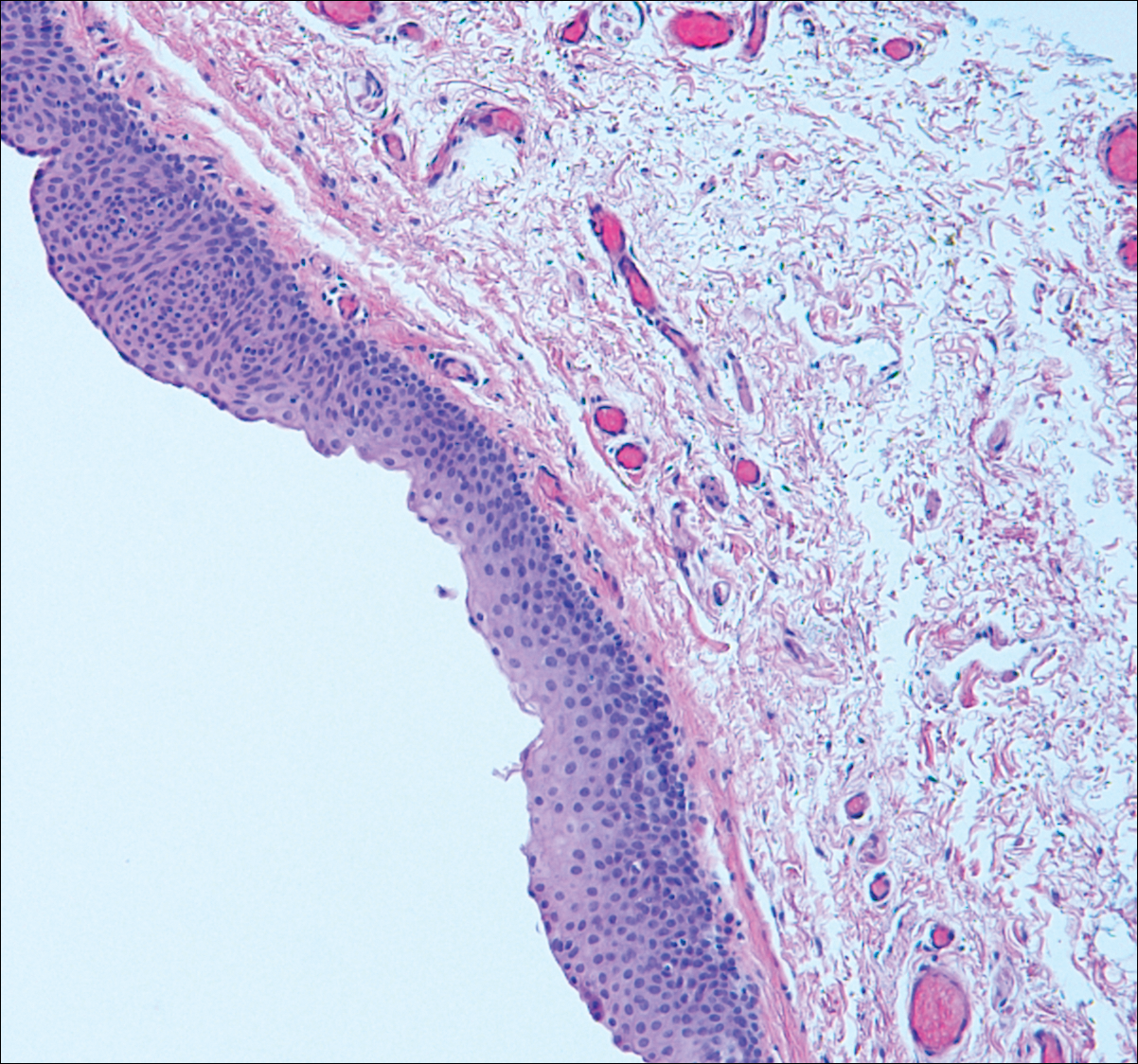

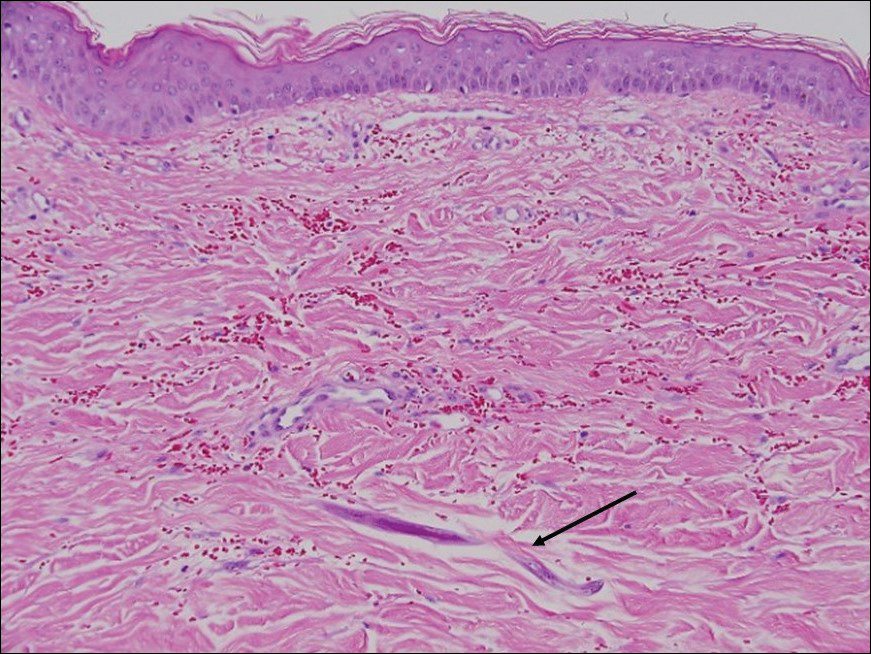

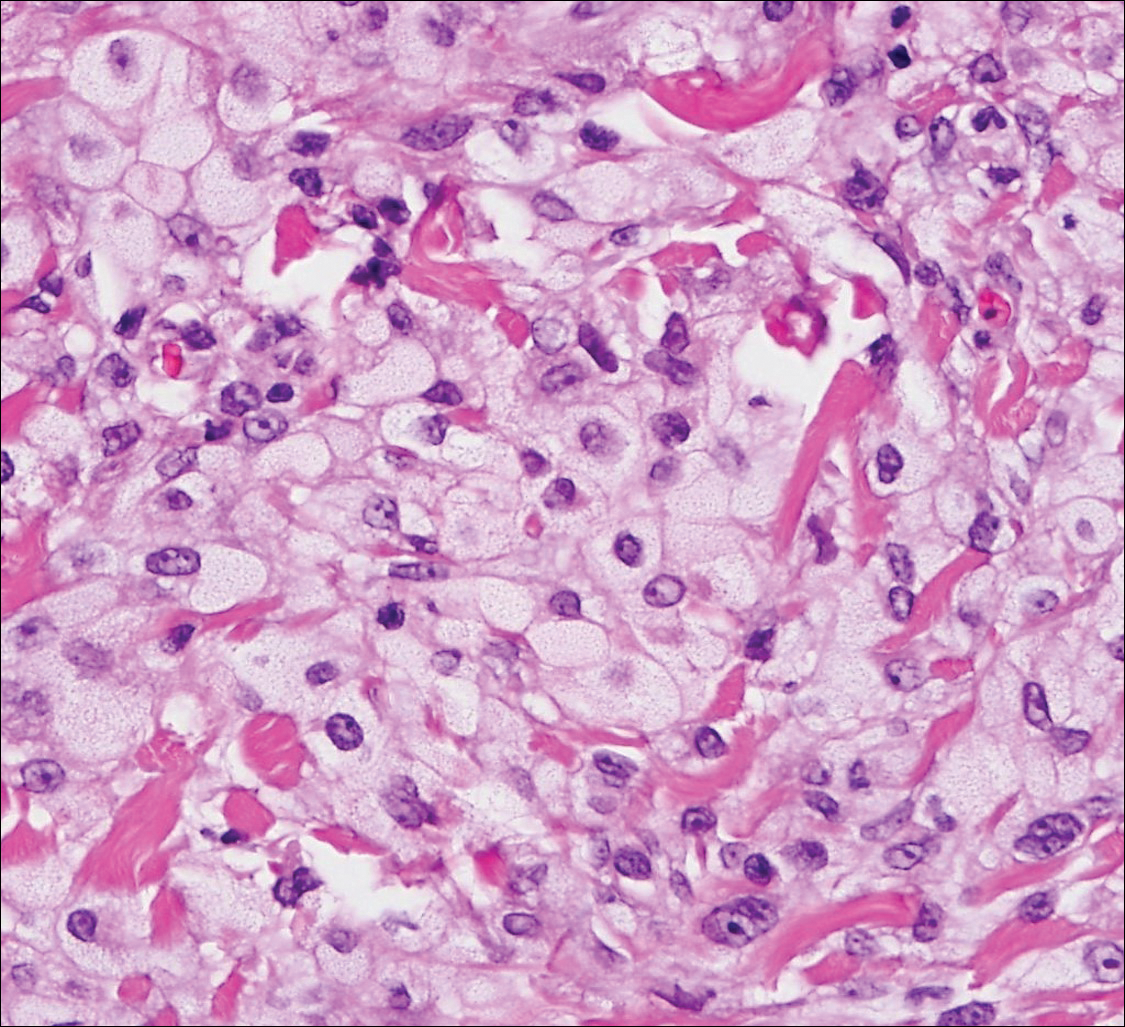

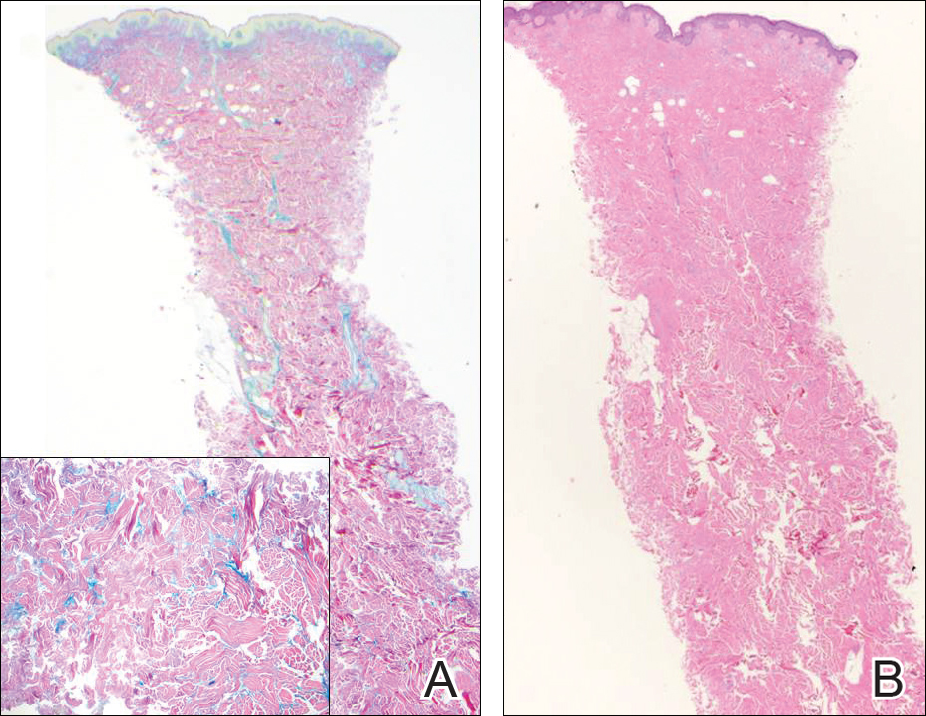

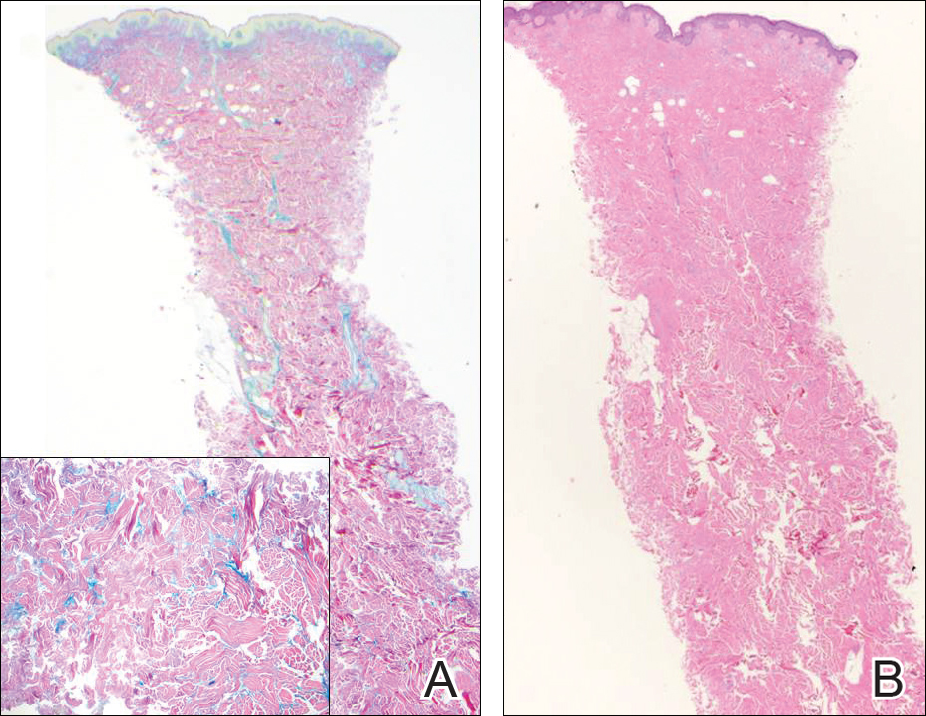

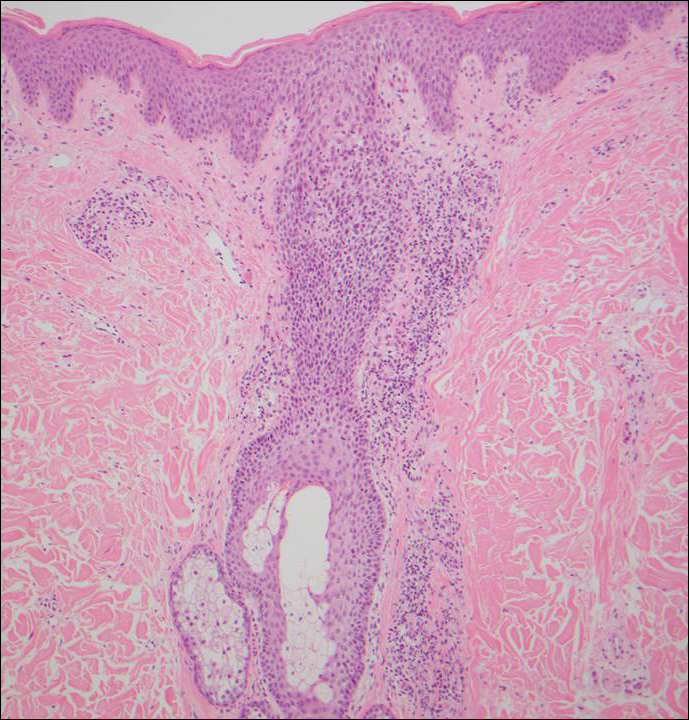

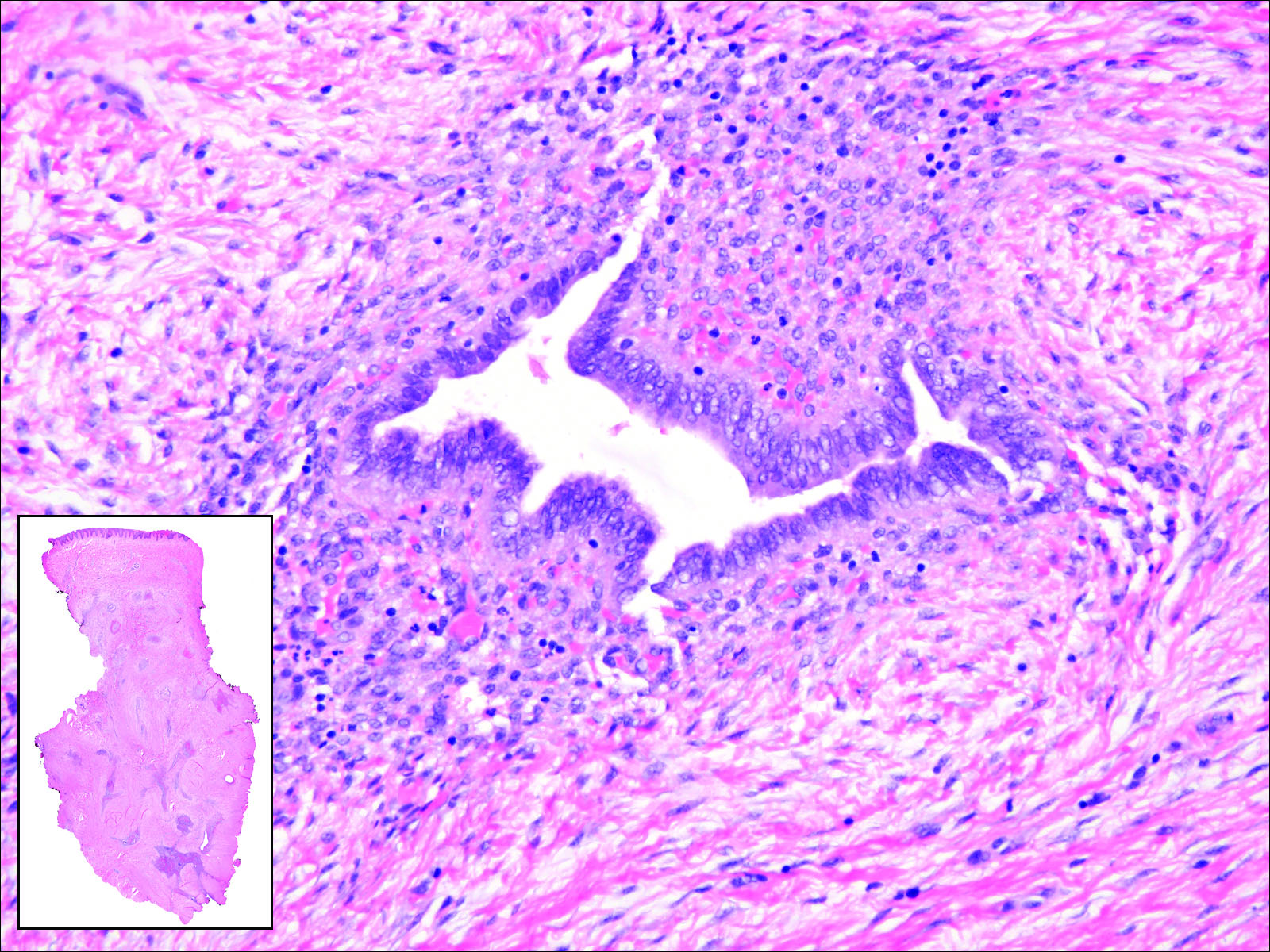

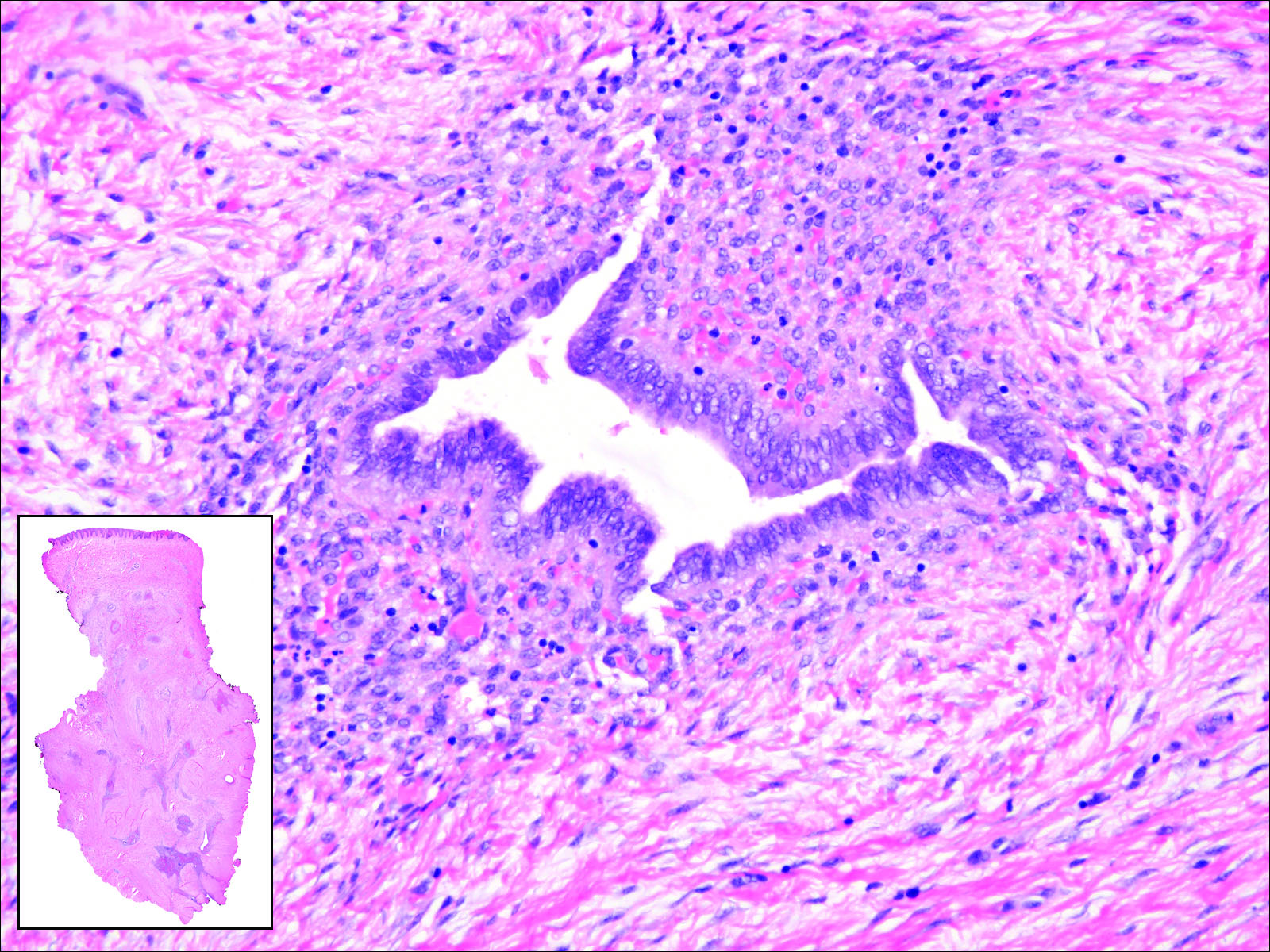

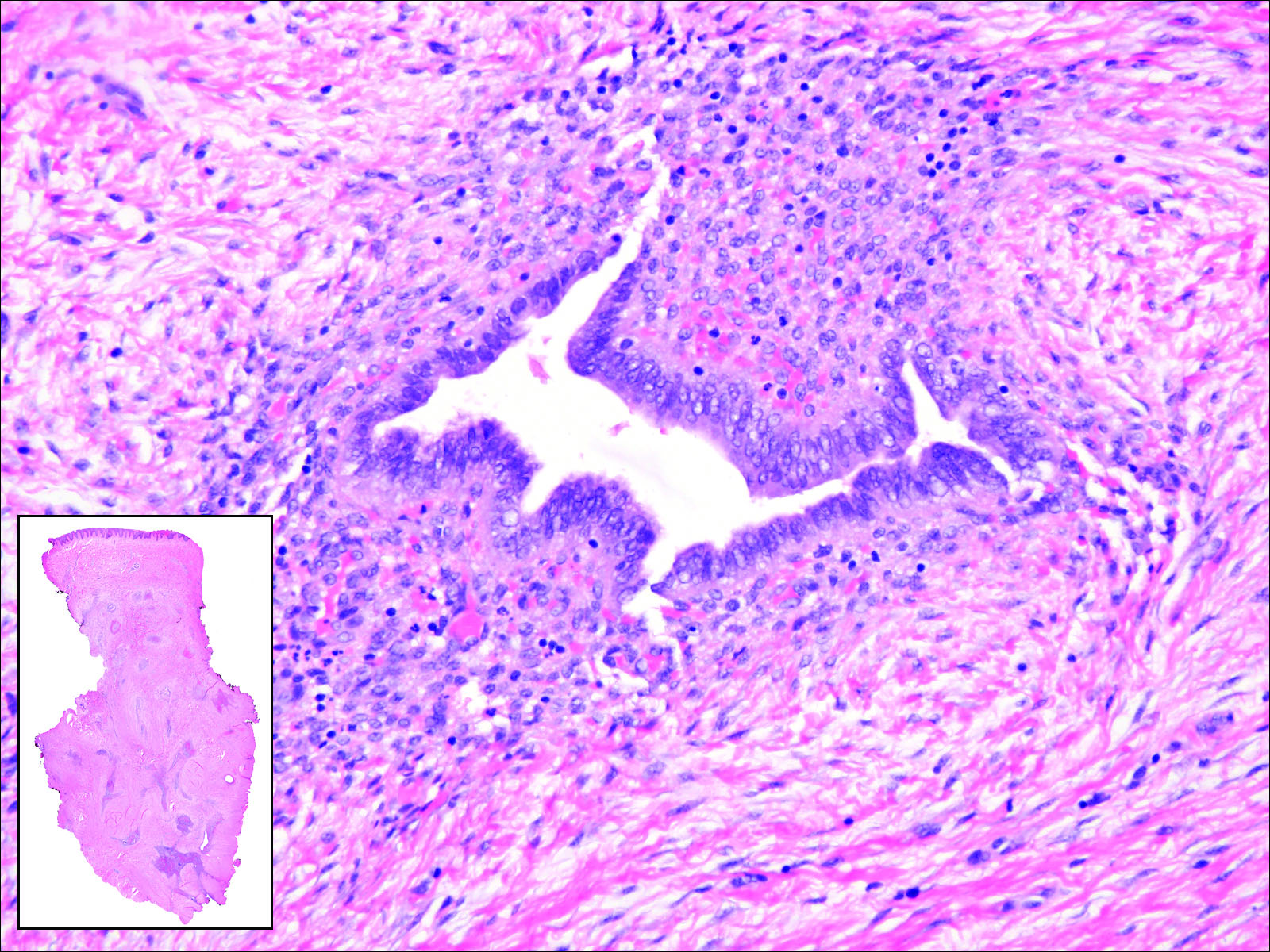

Angiosarcomas (Figure 1) are malignant neoplasms with vascular differentiation. Cutaneous angiosarcomas present as purple plaques or nodules on the head and/or neck in elderly individuals as well as in patients with chronic lymphedema or prior radiation exposure.6-9 They are aggressive neoplasms with high rates of recurrence and metastases. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of anastomosing vascular channels lined by atypical endothelial cells with a multilayered appearance. There is frequent red blood cell extravasation, and substantial hemosiderin deposition may be noted in long-standing lesions. Neoplastic cells are positive for vascular markers (CD34, CD31, ETS-related gene transcription factor). Notably, cases associated with radiation exposure and chronic lymphedema are positive for MYC.10

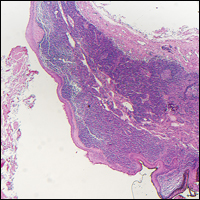

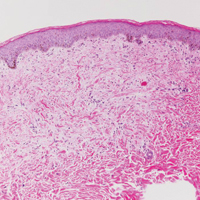

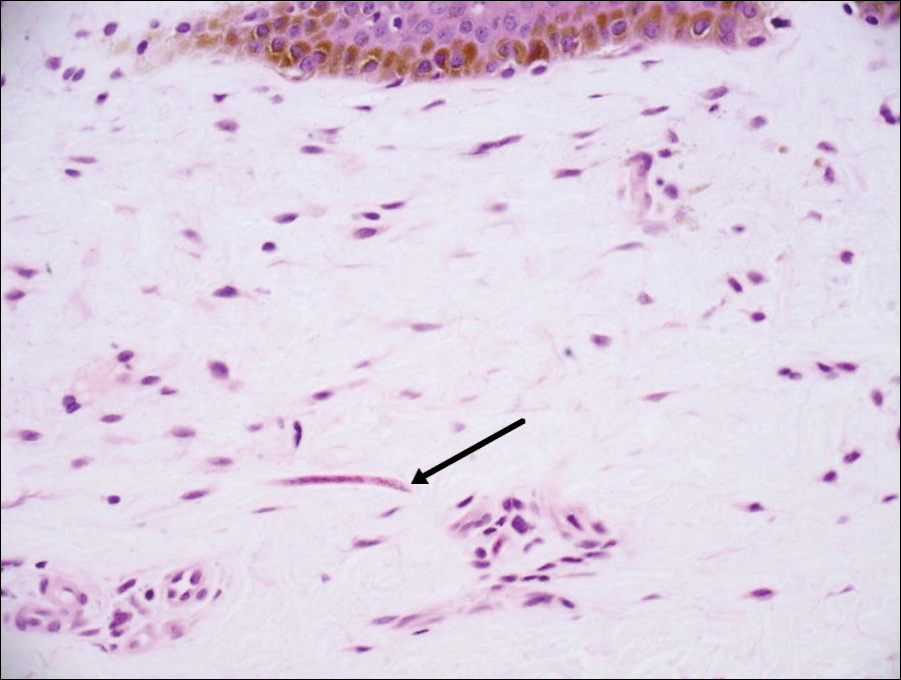

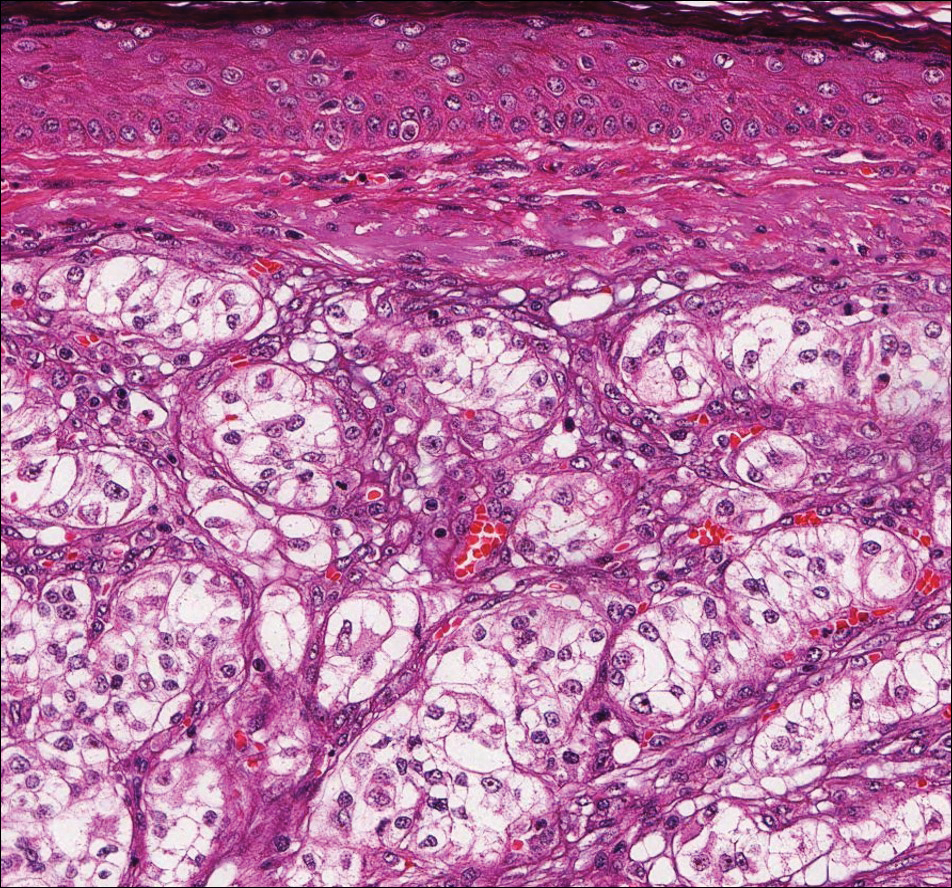

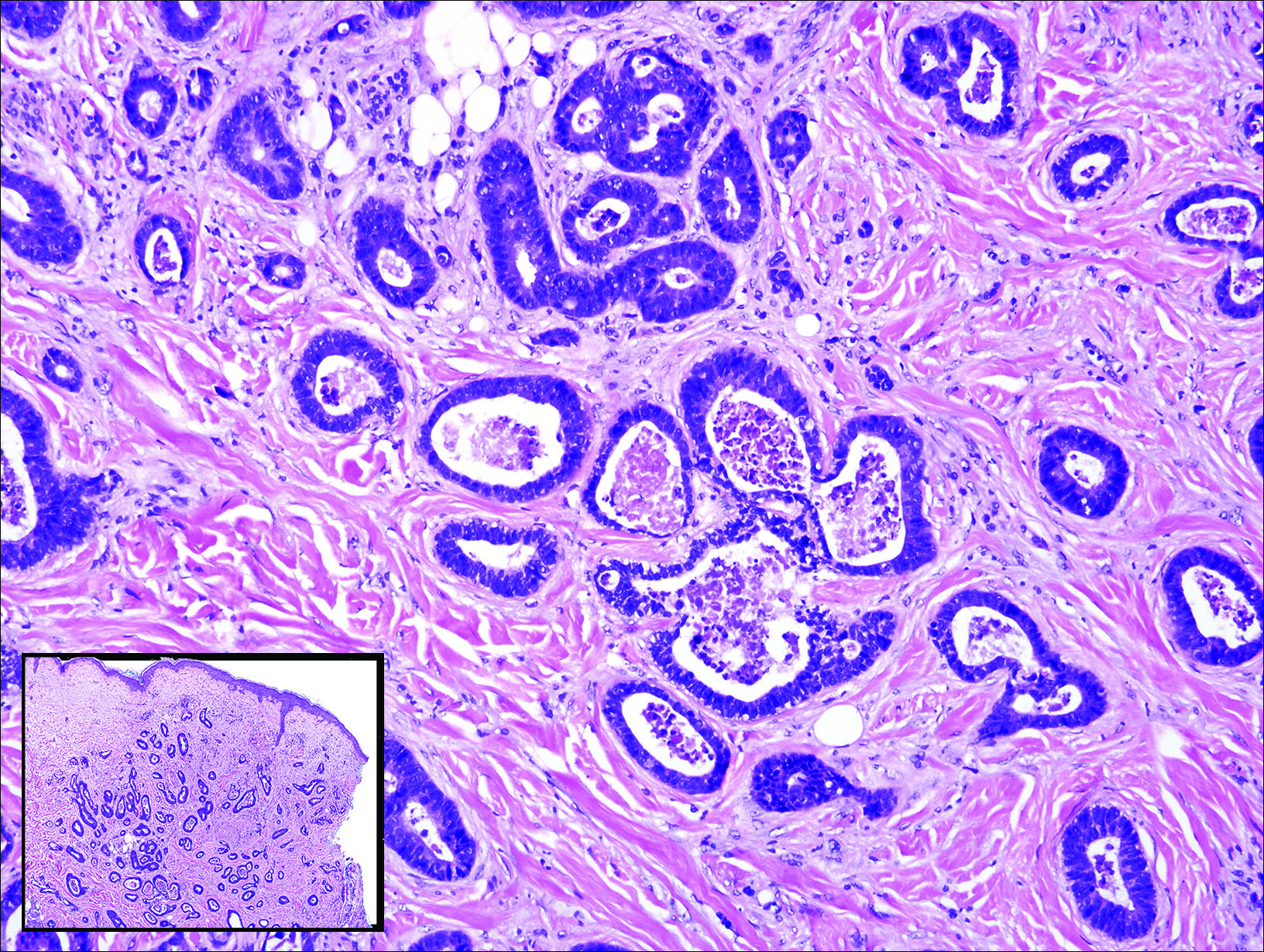

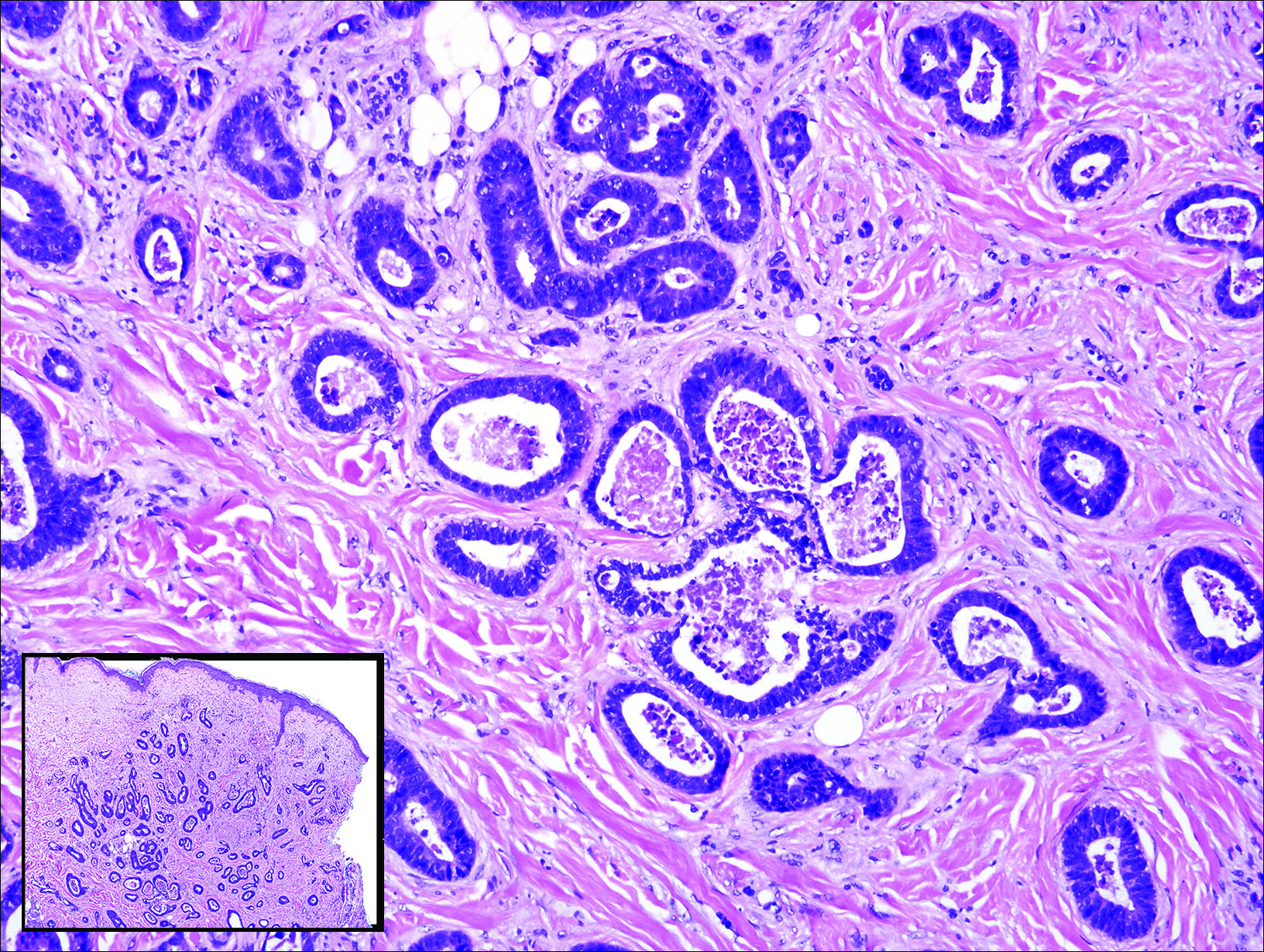

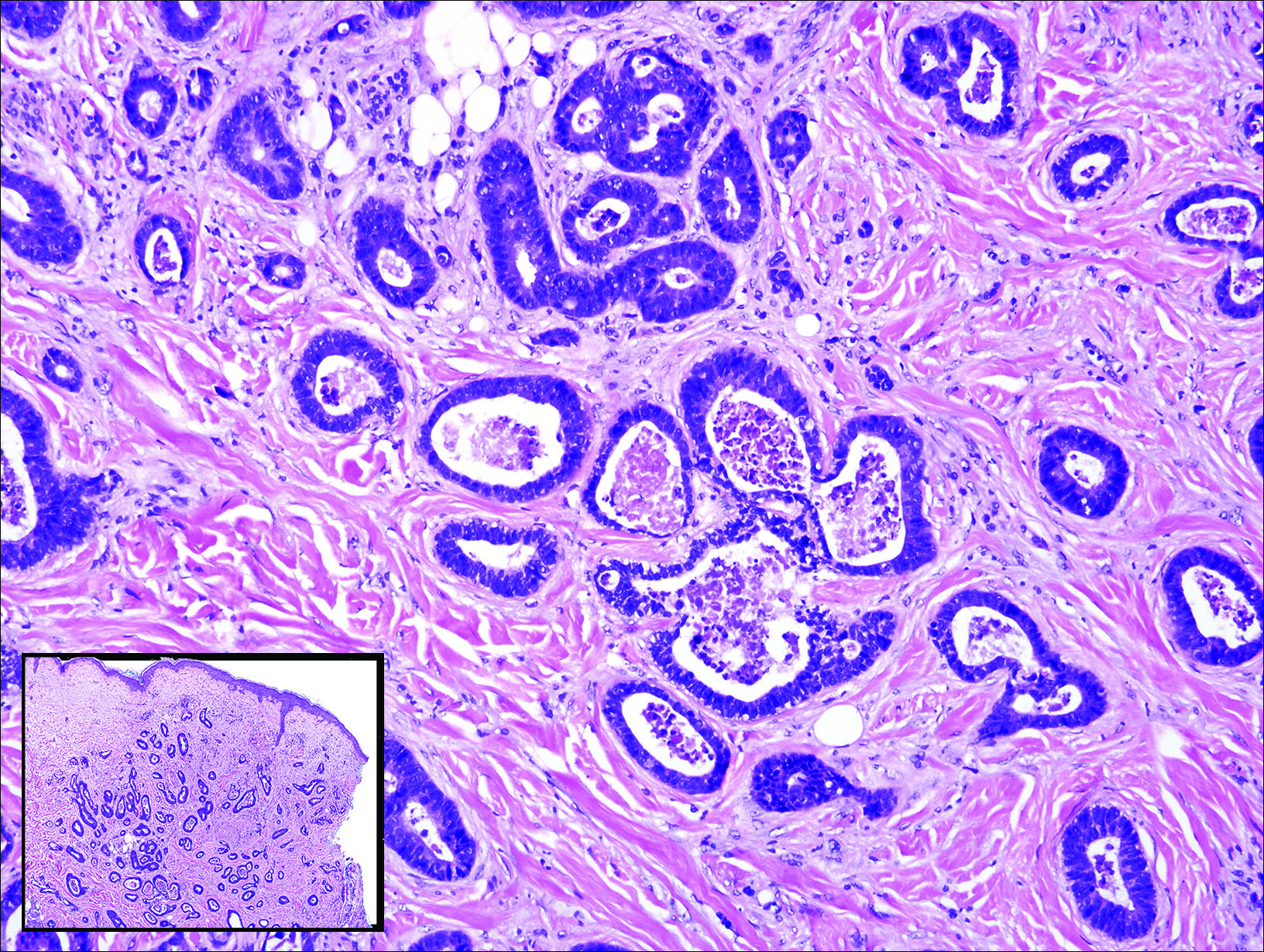

Blue nevi (Figure 2) are benign melanocytic tumors that occur most frequently in children but may pre-sent in any age group. Clinical presentation is a blue to black, slightly raised papule that may be found on any site of the body. Biopsy typically shows a wedge-shaped infiltrate of spindled melanocytes with elongated dendritic processes in a sclerotic collagenous stroma. There frequently is a striking population of heavily pigmented melanophages. The melanocytes are positive for melanoma antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1)/melan-A, S-100, and transcription factor SOX-10. In contrast to other benign nevi, human melanoma black-45 will be positive in the dermal component.

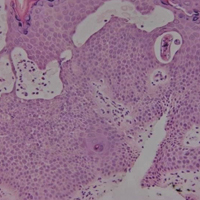

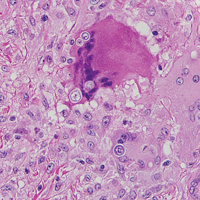

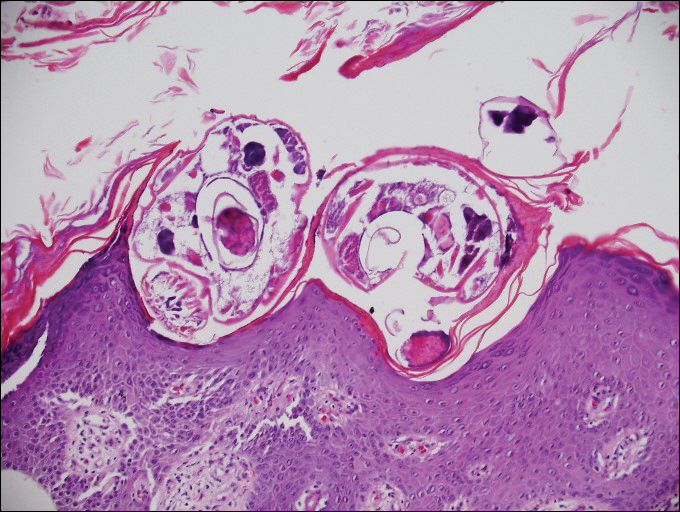

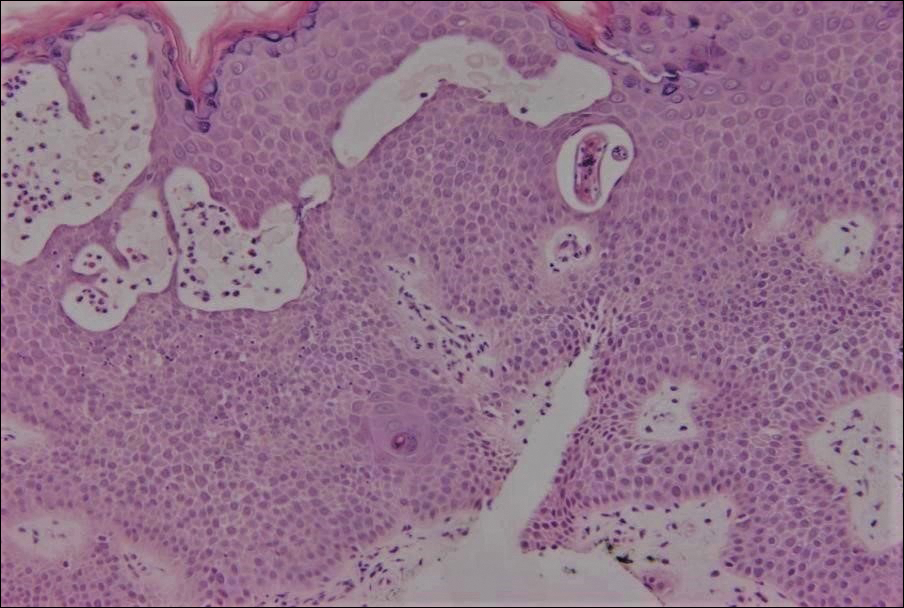

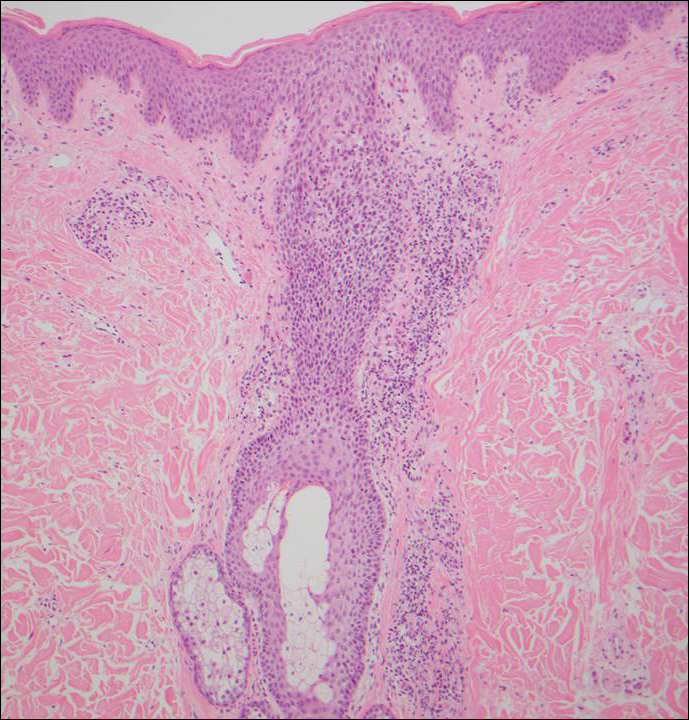

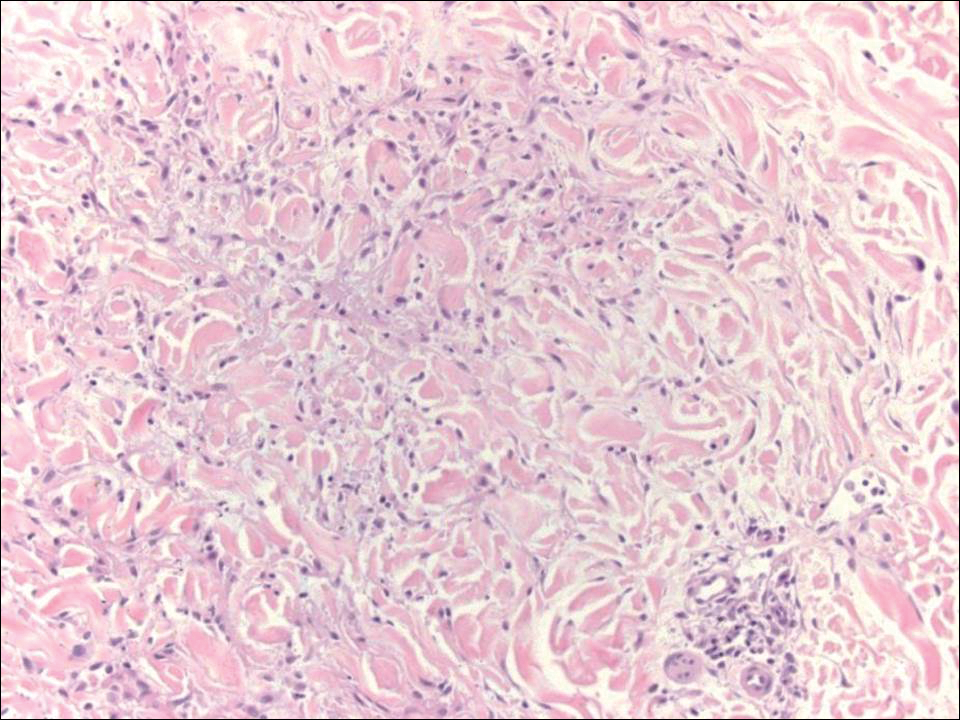

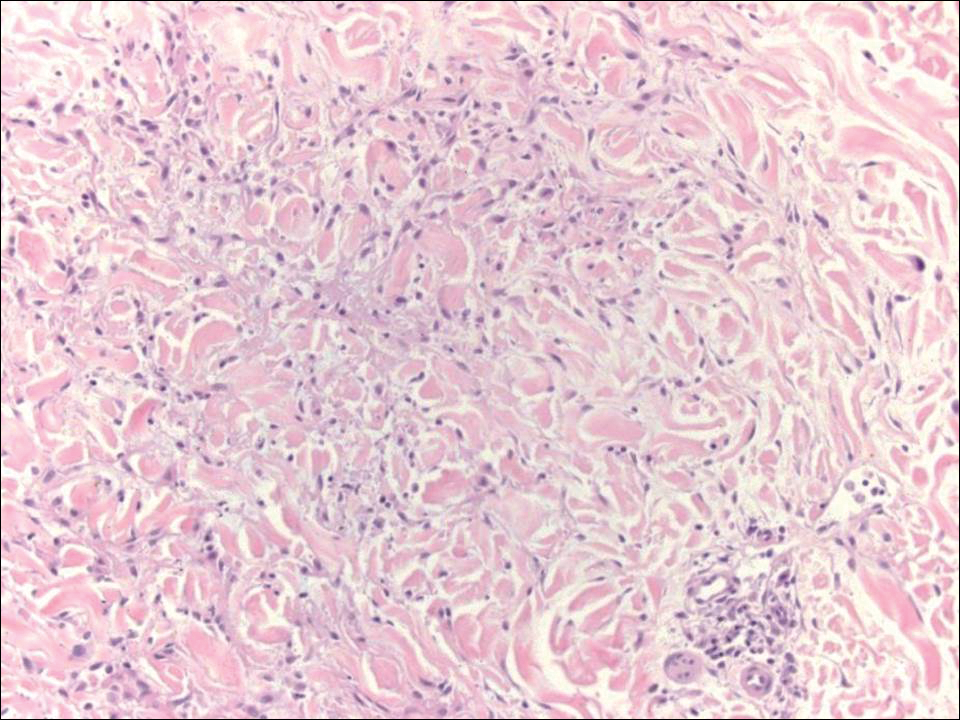

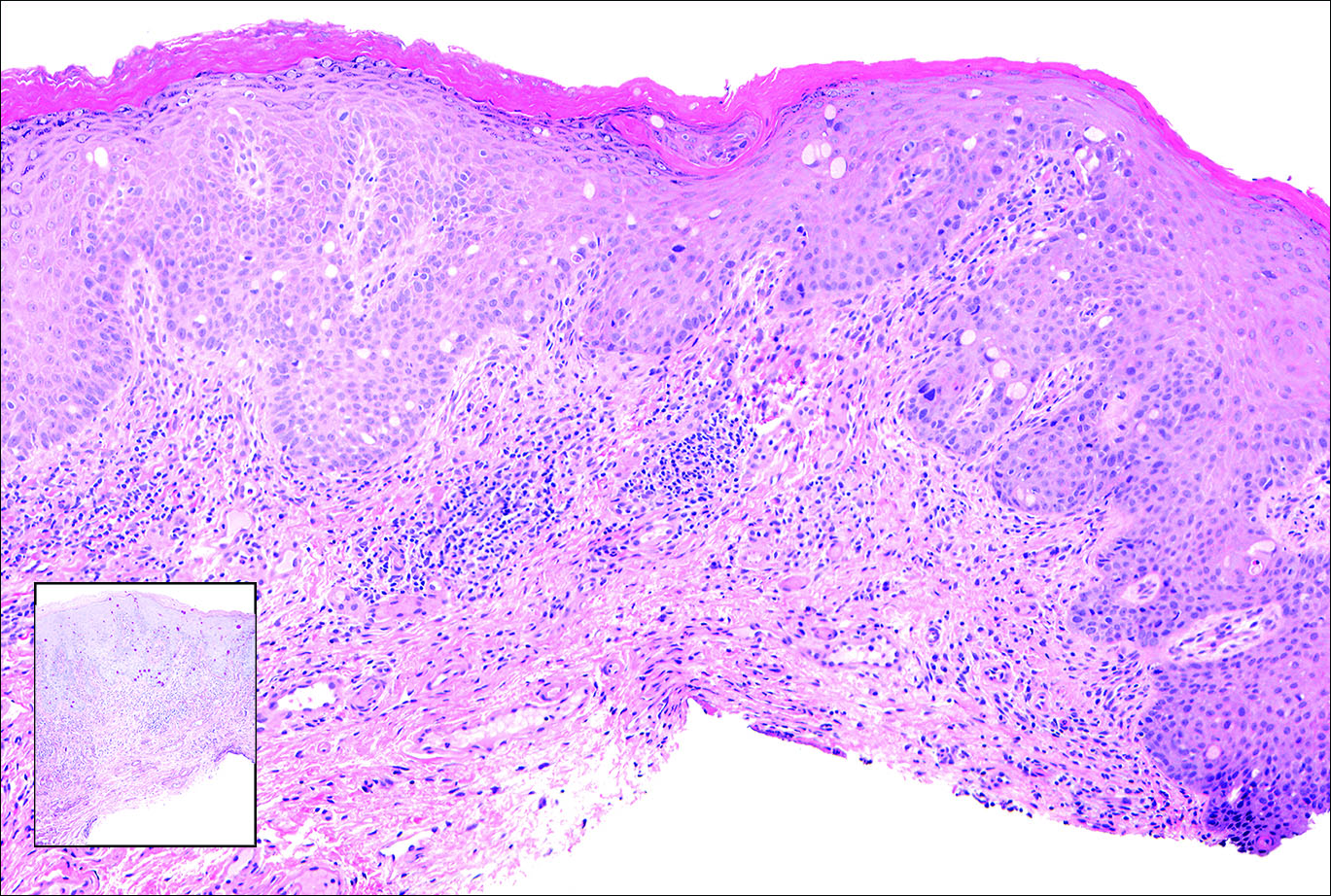

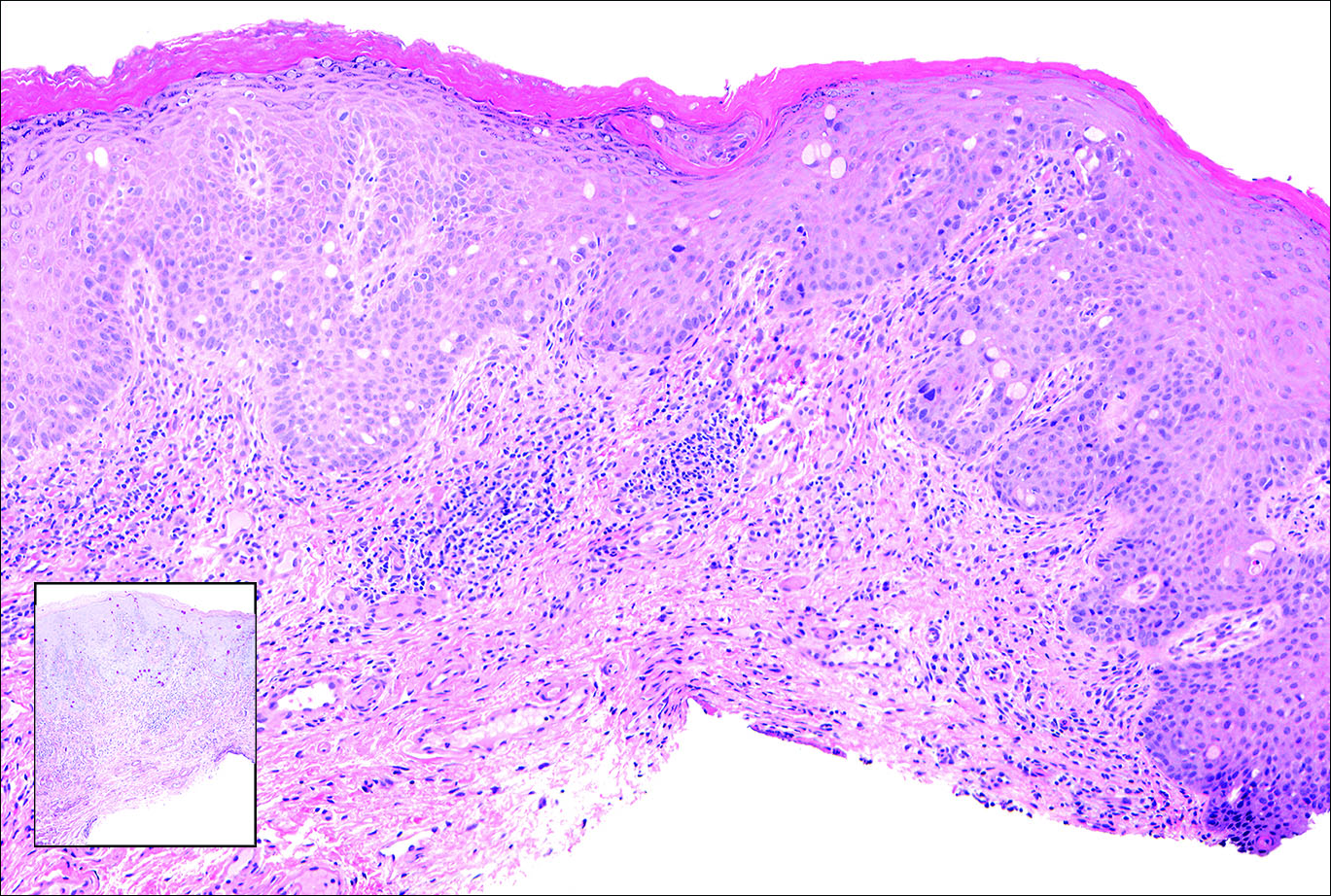

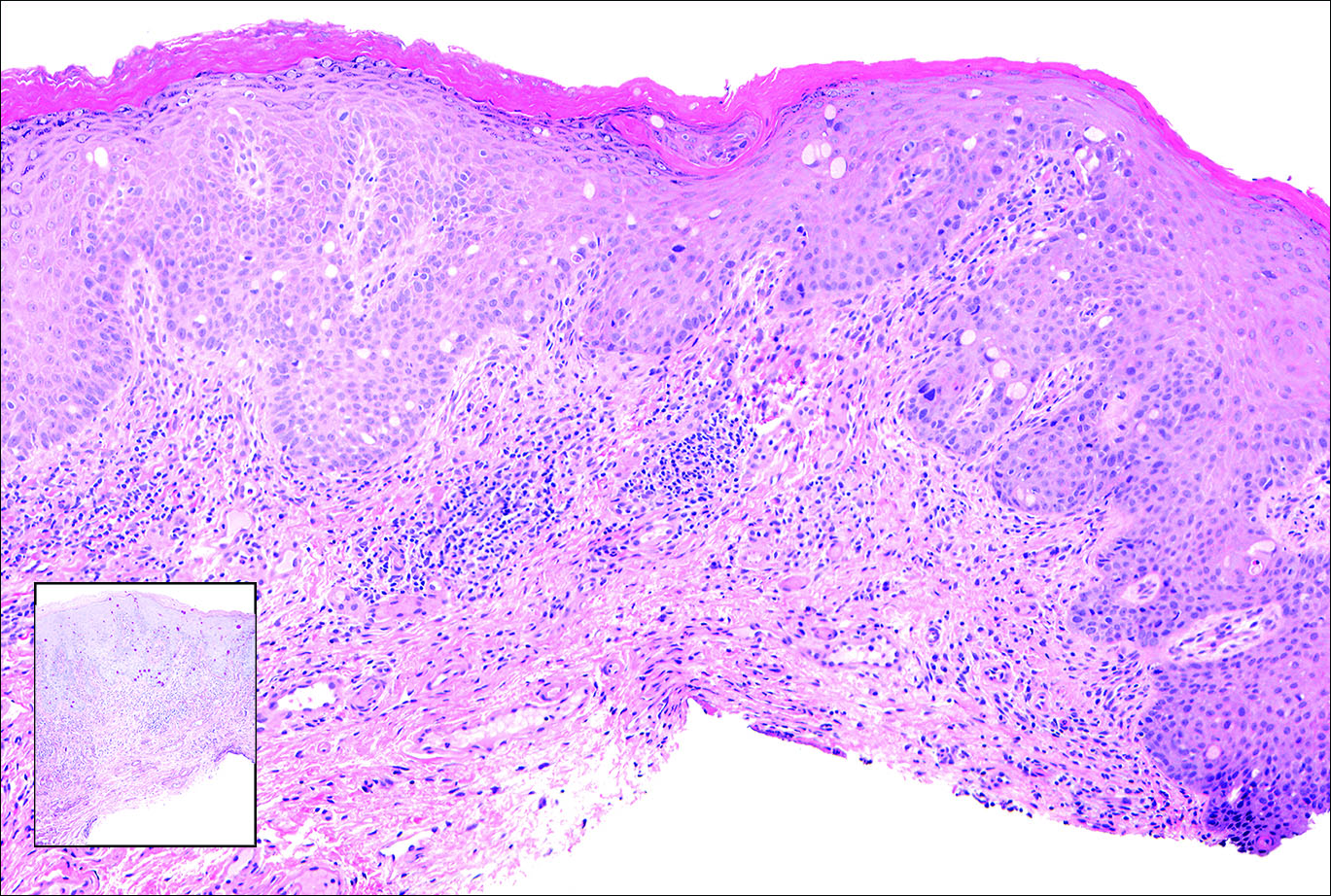

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (Figure 3) is a dermal-based tumor of intermediate malignant potential with a high rate of local recurrence and potential for sarcomatous transformation. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans most commonly presents in young adults as firm, pink to brown plaques and can occur on any site of the body. Histologically, they show a dermal proliferation of spindled cells that infiltrate in a storiform fashion into the subcutaneous adipose tissue,11 which imparts a honeycomb or Swiss cheese pattern. The tumor characteristically demonstrates positive staining for CD34. Loss of CD34 staining, increased mitoses, nuclear atypia, and fascicular growth are features suggestive of sarcomatous transformation.11,12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is associated with chromosomal abnormalities of chromosomes 17 and 22, resulting in COL1A1 (collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain) and PDGF-β (platelet-derived growth factor subunit B) gene fusion.13

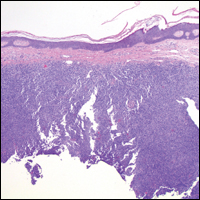

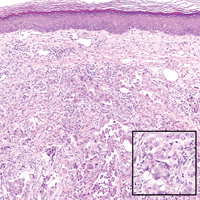

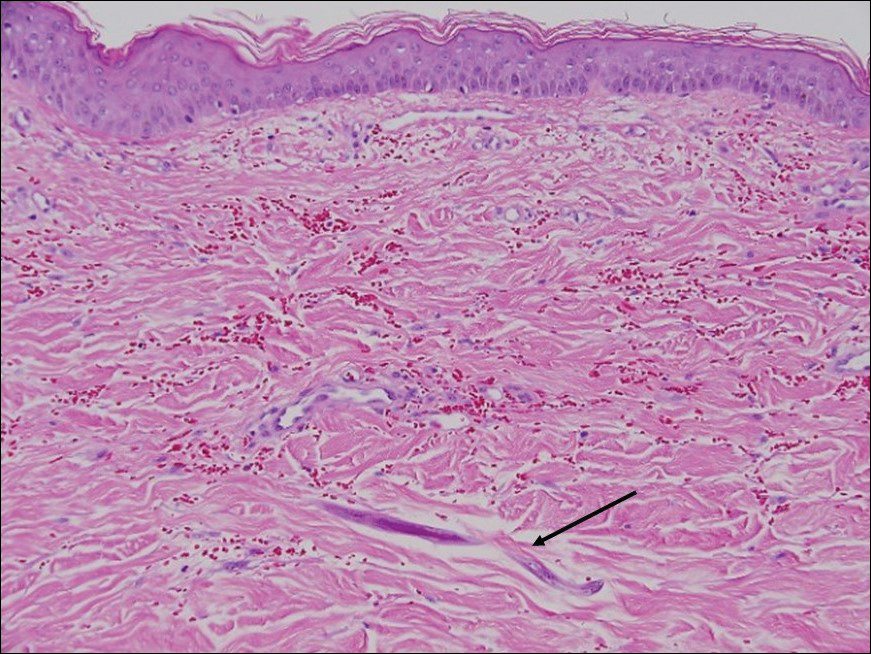

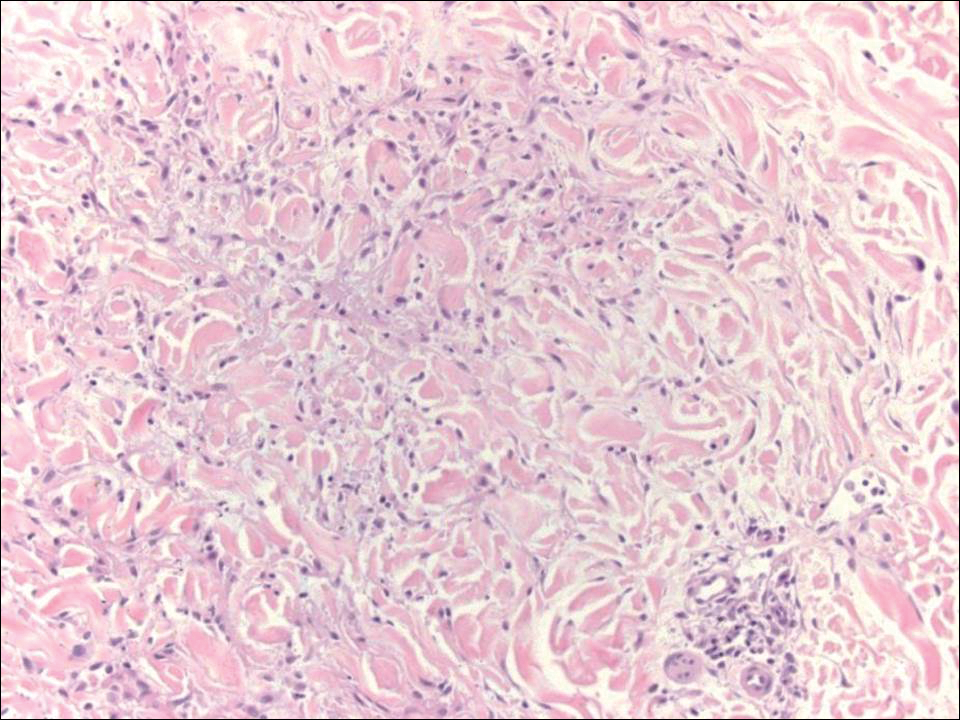

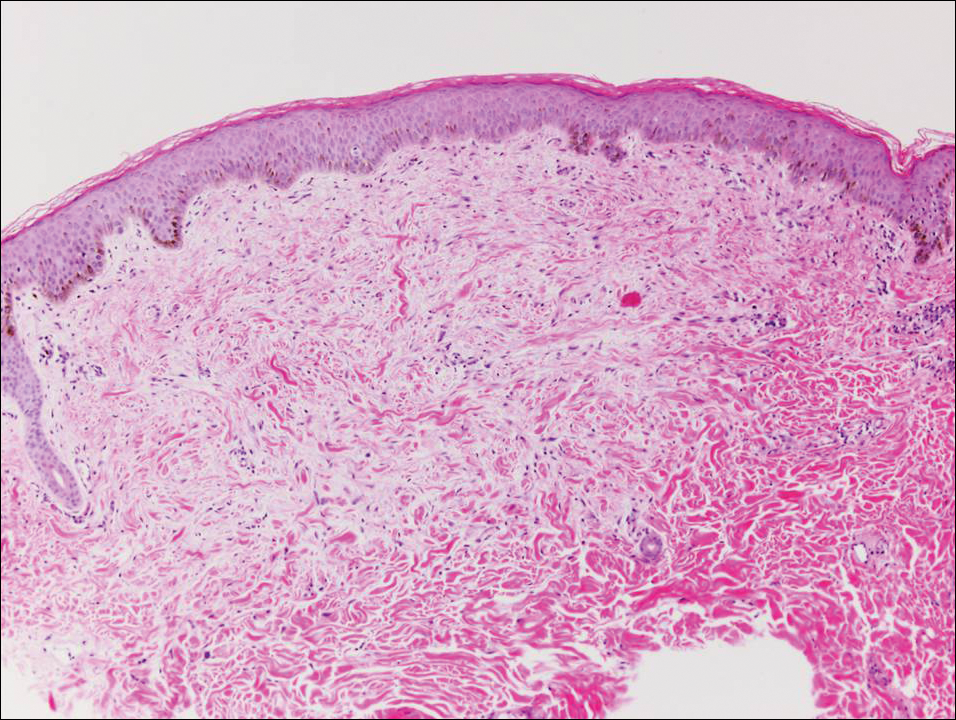

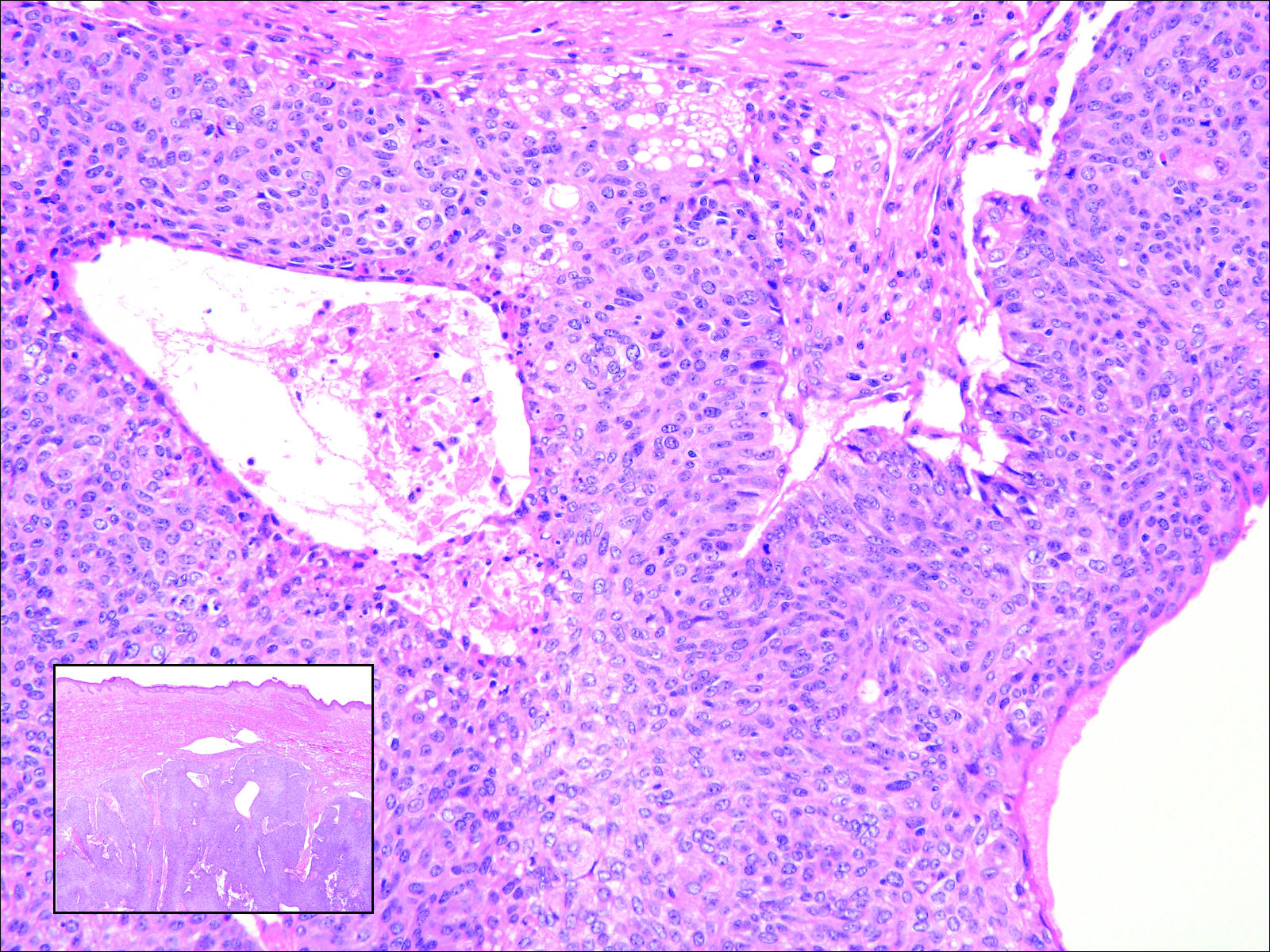

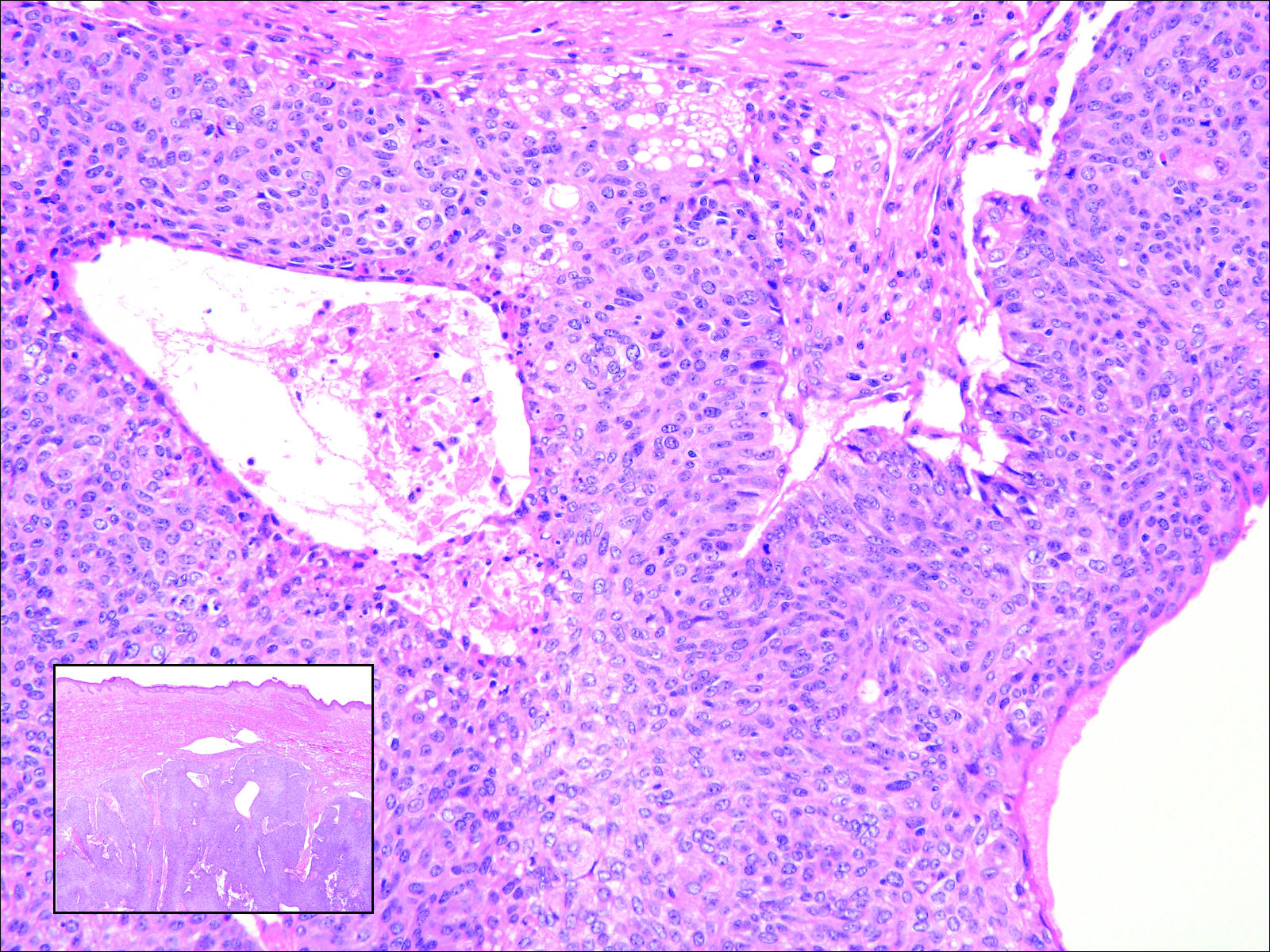

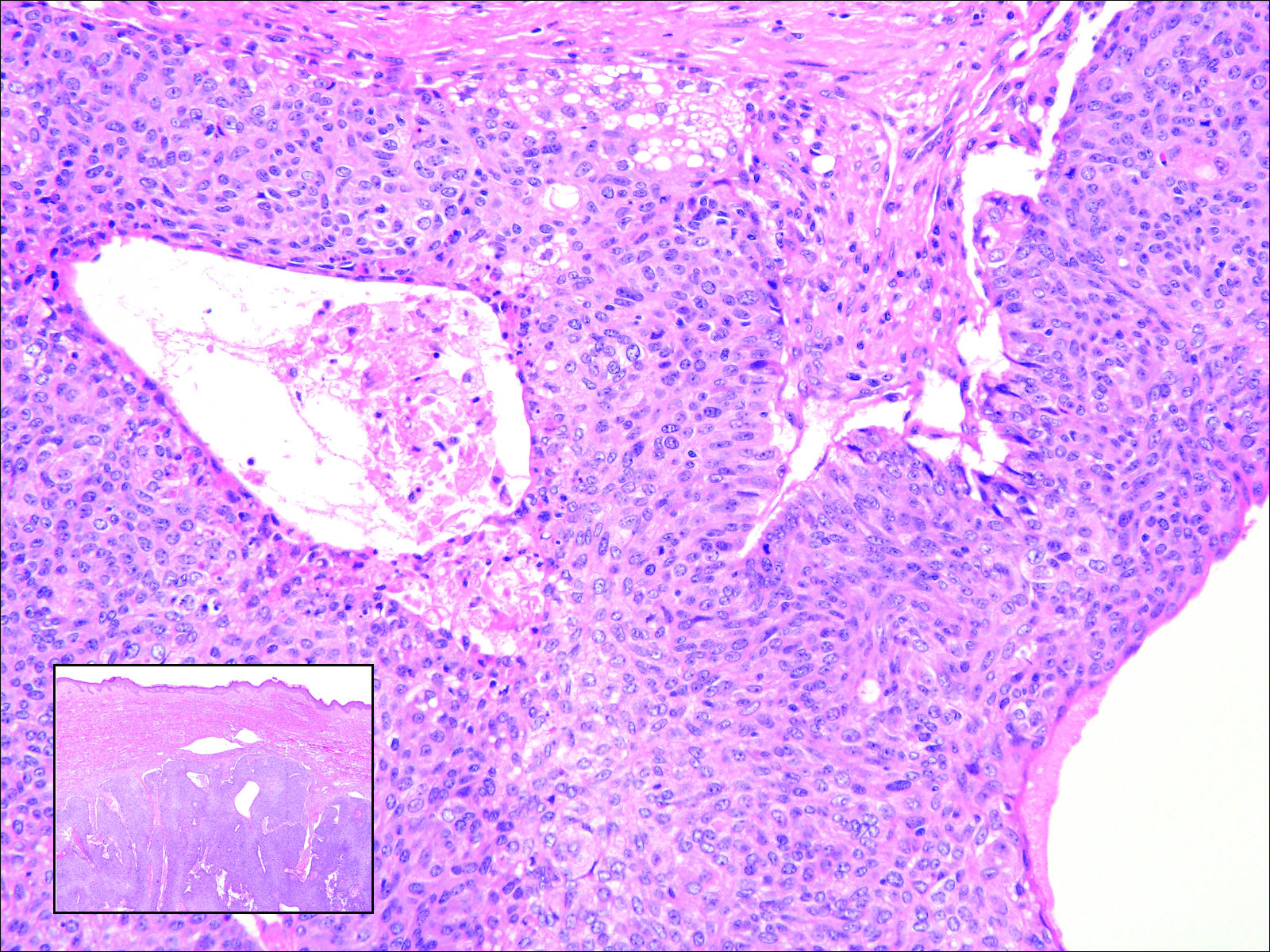

Sclerotic fibromas (also known as storiform collagenomas)(Figure 4) may represent regressed DFs and are frequently associated with prior trauma to the affected area.14,15 They usually appear as flesh-colored papules or nodules on the face and trunk. The presence of multiple sclerotic fibromas is associated with Cowden syndrome.16,17 Histologically, the lesions present as well-demarcated, nonencapsulated, dermal nodules composed of a storiform or whorled arrangement of collagen with spindled fibroblasts. The sclerotic collagen bundles often are separated by small clefts imparting a plywoodlike pattern.16

The differential diagnosis for DF expands once atypical clinical and histopathological findings are present. In this case, the nodule was much larger and darker than the usual appearance of DF (3-10 mm).2,4 Given the lesion's nodularity, the clinical dimple sign on lateral compression could not be seen. On biopsy, the predominance of blood vessels and sclerosis further complicated the diagnostic picture. In unusual cases such as this one, correlation of clinical history, histology, and immunophenotype is ever important.

- Zeidi M, North JP. Sebaceous induction in dermatofibroma: a common feature of dermatofibromas on the shoulder. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:400-405.

- Şenel E, Yuyucu Karabulut Y, Doğruer S¸enel S. Clinical, histopathological, dermatoscopic and digital microscopic features of dermatofibroma: a retrospective analysis of 200 lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1958-1966.

- Vilanova JR, Flint A. The morphological variations of fibrous histiocytomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1974;1:155-164.

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JH, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma)[published online May 27, 2011]. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Alves JVP, Matos DM, Barreiros HF, et al. Variants of dermatofibroma--a histopathological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:472-477.

- Rosai J, Sumner HW, Major MC, et al. Angiosarcoma of the skin: a clinicopathologic and fine structural study. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:83-109.

- Haustein UF. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:851-856.

- Stewart FW, Treves N. Lymphangiosarcoma in postmastectomy lymphedema: a report of six cases in elephantiasis chirurgica. Cancer. 1948;1:64-81.

- Goette DK, Detlefs RL. Postirradiation angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(5 pt 2):922-926.

- Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:34-39.

- Voth H, Landsberg J, Hinz T, et al. Management of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with fibrosarcomatous transformation: an evidence-based review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1385-1391.

- Goldblum JR. CD34 positivity in fibrosarcomas which arise in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:238-241.

- Patel KU, Szabo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- Sohn IB, Hwang SM, Lee SH, et al. Dermatofibroma with sclerotic areas resembling a sclerotic fibroma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:44-47.

- Pujol RM, de Castro F, Schroeter AL, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a sclerotic dermatofibroma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:620-624.

- Requena L, Gutiérrez J, Sánchez Yus E. Multiple sclerotic fibromas of the skin: a cutaneous marker of Cowden's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:346-351.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibroma

Dermatofibroma (DF) is a commonly encountered lesion. Although usually a straightforward clinical diagnosis, histopathological diagnosis is sometimes required. Conventional histologic findings of DF are hyperkeratosis, induction of the epidermis with acanthosis, and basal layer hyperpigmentation.1,2 Within the dermis there usually is proliferation of fibroblasts, histiocytes, and blood vessels that sometimes spares the overlying papillary dermis. Nomenclature of specific variants may be assigned based on the predominant component (eg, nodular subepidermal fibrosis, histiocytoma, sclerosing hemangioma) or histologic findings (eg, fibrocollagenous, sclerotic, cellular, histiocytic, lipidized, angiomatous, aneurysmal, clear cell, monster cell, myxoid, keloidal, palisading, osteoclastic, epithelioid).3-5 Of the histologic variants, fibrocollagenous is most common, but knowledge of other variants is important for accurate diagnosis, especially to exclude malignancy.

The sclerosing hemangioma variant of DF may pre-sent a diagnostic dilemma. In addition to typical features of DF, pseudovascular spaces, abundant hemosiderin, and reactive-appearing spindled cells are histologically demonstrated. The marked sclerosis and pigment deposition may mimic a blue nevus, and the dilated pseudovascular spaces may be reminiscent of a vascular neoplasm such as angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma. However, the presence of characteristic features such as peripheral collagen trapping and overlying epidermal hyperplasia provide important clues for correct diagnosis.

Angiosarcomas (Figure 1) are malignant neoplasms with vascular differentiation. Cutaneous angiosarcomas present as purple plaques or nodules on the head and/or neck in elderly individuals as well as in patients with chronic lymphedema or prior radiation exposure.6-9 They are aggressive neoplasms with high rates of recurrence and metastases. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of anastomosing vascular channels lined by atypical endothelial cells with a multilayered appearance. There is frequent red blood cell extravasation, and substantial hemosiderin deposition may be noted in long-standing lesions. Neoplastic cells are positive for vascular markers (CD34, CD31, ETS-related gene transcription factor). Notably, cases associated with radiation exposure and chronic lymphedema are positive for MYC.10

Blue nevi (Figure 2) are benign melanocytic tumors that occur most frequently in children but may pre-sent in any age group. Clinical presentation is a blue to black, slightly raised papule that may be found on any site of the body. Biopsy typically shows a wedge-shaped infiltrate of spindled melanocytes with elongated dendritic processes in a sclerotic collagenous stroma. There frequently is a striking population of heavily pigmented melanophages. The melanocytes are positive for melanoma antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1)/melan-A, S-100, and transcription factor SOX-10. In contrast to other benign nevi, human melanoma black-45 will be positive in the dermal component.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (Figure 3) is a dermal-based tumor of intermediate malignant potential with a high rate of local recurrence and potential for sarcomatous transformation. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans most commonly presents in young adults as firm, pink to brown plaques and can occur on any site of the body. Histologically, they show a dermal proliferation of spindled cells that infiltrate in a storiform fashion into the subcutaneous adipose tissue,11 which imparts a honeycomb or Swiss cheese pattern. The tumor characteristically demonstrates positive staining for CD34. Loss of CD34 staining, increased mitoses, nuclear atypia, and fascicular growth are features suggestive of sarcomatous transformation.11,12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is associated with chromosomal abnormalities of chromosomes 17 and 22, resulting in COL1A1 (collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain) and PDGF-β (platelet-derived growth factor subunit B) gene fusion.13

Sclerotic fibromas (also known as storiform collagenomas)(Figure 4) may represent regressed DFs and are frequently associated with prior trauma to the affected area.14,15 They usually appear as flesh-colored papules or nodules on the face and trunk. The presence of multiple sclerotic fibromas is associated with Cowden syndrome.16,17 Histologically, the lesions present as well-demarcated, nonencapsulated, dermal nodules composed of a storiform or whorled arrangement of collagen with spindled fibroblasts. The sclerotic collagen bundles often are separated by small clefts imparting a plywoodlike pattern.16

The differential diagnosis for DF expands once atypical clinical and histopathological findings are present. In this case, the nodule was much larger and darker than the usual appearance of DF (3-10 mm).2,4 Given the lesion's nodularity, the clinical dimple sign on lateral compression could not be seen. On biopsy, the predominance of blood vessels and sclerosis further complicated the diagnostic picture. In unusual cases such as this one, correlation of clinical history, histology, and immunophenotype is ever important.

The Diagnosis: Dermatofibroma

Dermatofibroma (DF) is a commonly encountered lesion. Although usually a straightforward clinical diagnosis, histopathological diagnosis is sometimes required. Conventional histologic findings of DF are hyperkeratosis, induction of the epidermis with acanthosis, and basal layer hyperpigmentation.1,2 Within the dermis there usually is proliferation of fibroblasts, histiocytes, and blood vessels that sometimes spares the overlying papillary dermis. Nomenclature of specific variants may be assigned based on the predominant component (eg, nodular subepidermal fibrosis, histiocytoma, sclerosing hemangioma) or histologic findings (eg, fibrocollagenous, sclerotic, cellular, histiocytic, lipidized, angiomatous, aneurysmal, clear cell, monster cell, myxoid, keloidal, palisading, osteoclastic, epithelioid).3-5 Of the histologic variants, fibrocollagenous is most common, but knowledge of other variants is important for accurate diagnosis, especially to exclude malignancy.

The sclerosing hemangioma variant of DF may pre-sent a diagnostic dilemma. In addition to typical features of DF, pseudovascular spaces, abundant hemosiderin, and reactive-appearing spindled cells are histologically demonstrated. The marked sclerosis and pigment deposition may mimic a blue nevus, and the dilated pseudovascular spaces may be reminiscent of a vascular neoplasm such as angiosarcoma or Kaposi sarcoma. However, the presence of characteristic features such as peripheral collagen trapping and overlying epidermal hyperplasia provide important clues for correct diagnosis.

Angiosarcomas (Figure 1) are malignant neoplasms with vascular differentiation. Cutaneous angiosarcomas present as purple plaques or nodules on the head and/or neck in elderly individuals as well as in patients with chronic lymphedema or prior radiation exposure.6-9 They are aggressive neoplasms with high rates of recurrence and metastases. Microscopically, the tumor is composed of anastomosing vascular channels lined by atypical endothelial cells with a multilayered appearance. There is frequent red blood cell extravasation, and substantial hemosiderin deposition may be noted in long-standing lesions. Neoplastic cells are positive for vascular markers (CD34, CD31, ETS-related gene transcription factor). Notably, cases associated with radiation exposure and chronic lymphedema are positive for MYC.10

Blue nevi (Figure 2) are benign melanocytic tumors that occur most frequently in children but may pre-sent in any age group. Clinical presentation is a blue to black, slightly raised papule that may be found on any site of the body. Biopsy typically shows a wedge-shaped infiltrate of spindled melanocytes with elongated dendritic processes in a sclerotic collagenous stroma. There frequently is a striking population of heavily pigmented melanophages. The melanocytes are positive for melanoma antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1)/melan-A, S-100, and transcription factor SOX-10. In contrast to other benign nevi, human melanoma black-45 will be positive in the dermal component.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (Figure 3) is a dermal-based tumor of intermediate malignant potential with a high rate of local recurrence and potential for sarcomatous transformation. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans most commonly presents in young adults as firm, pink to brown plaques and can occur on any site of the body. Histologically, they show a dermal proliferation of spindled cells that infiltrate in a storiform fashion into the subcutaneous adipose tissue,11 which imparts a honeycomb or Swiss cheese pattern. The tumor characteristically demonstrates positive staining for CD34. Loss of CD34 staining, increased mitoses, nuclear atypia, and fascicular growth are features suggestive of sarcomatous transformation.11,12 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is associated with chromosomal abnormalities of chromosomes 17 and 22, resulting in COL1A1 (collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain) and PDGF-β (platelet-derived growth factor subunit B) gene fusion.13

Sclerotic fibromas (also known as storiform collagenomas)(Figure 4) may represent regressed DFs and are frequently associated with prior trauma to the affected area.14,15 They usually appear as flesh-colored papules or nodules on the face and trunk. The presence of multiple sclerotic fibromas is associated with Cowden syndrome.16,17 Histologically, the lesions present as well-demarcated, nonencapsulated, dermal nodules composed of a storiform or whorled arrangement of collagen with spindled fibroblasts. The sclerotic collagen bundles often are separated by small clefts imparting a plywoodlike pattern.16

The differential diagnosis for DF expands once atypical clinical and histopathological findings are present. In this case, the nodule was much larger and darker than the usual appearance of DF (3-10 mm).2,4 Given the lesion's nodularity, the clinical dimple sign on lateral compression could not be seen. On biopsy, the predominance of blood vessels and sclerosis further complicated the diagnostic picture. In unusual cases such as this one, correlation of clinical history, histology, and immunophenotype is ever important.

- Zeidi M, North JP. Sebaceous induction in dermatofibroma: a common feature of dermatofibromas on the shoulder. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:400-405.

- Şenel E, Yuyucu Karabulut Y, Doğruer S¸enel S. Clinical, histopathological, dermatoscopic and digital microscopic features of dermatofibroma: a retrospective analysis of 200 lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1958-1966.

- Vilanova JR, Flint A. The morphological variations of fibrous histiocytomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1974;1:155-164.

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JH, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma)[published online May 27, 2011]. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Alves JVP, Matos DM, Barreiros HF, et al. Variants of dermatofibroma--a histopathological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:472-477.

- Rosai J, Sumner HW, Major MC, et al. Angiosarcoma of the skin: a clinicopathologic and fine structural study. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:83-109.

- Haustein UF. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:851-856.

- Stewart FW, Treves N. Lymphangiosarcoma in postmastectomy lymphedema: a report of six cases in elephantiasis chirurgica. Cancer. 1948;1:64-81.

- Goette DK, Detlefs RL. Postirradiation angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(5 pt 2):922-926.

- Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:34-39.

- Voth H, Landsberg J, Hinz T, et al. Management of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with fibrosarcomatous transformation: an evidence-based review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1385-1391.

- Goldblum JR. CD34 positivity in fibrosarcomas which arise in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:238-241.

- Patel KU, Szabo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- Sohn IB, Hwang SM, Lee SH, et al. Dermatofibroma with sclerotic areas resembling a sclerotic fibroma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:44-47.

- Pujol RM, de Castro F, Schroeter AL, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a sclerotic dermatofibroma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:620-624.

- Requena L, Gutiérrez J, Sánchez Yus E. Multiple sclerotic fibromas of the skin: a cutaneous marker of Cowden's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:346-351.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Zeidi M, North JP. Sebaceous induction in dermatofibroma: a common feature of dermatofibromas on the shoulder. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:400-405.

- Şenel E, Yuyucu Karabulut Y, Doğruer S¸enel S. Clinical, histopathological, dermatoscopic and digital microscopic features of dermatofibroma: a retrospective analysis of 200 lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1958-1966.

- Vilanova JR, Flint A. The morphological variations of fibrous histiocytomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1974;1:155-164.

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JH, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma)[published online May 27, 2011]. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Alves JVP, Matos DM, Barreiros HF, et al. Variants of dermatofibroma--a histopathological study. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:472-477.

- Rosai J, Sumner HW, Major MC, et al. Angiosarcoma of the skin: a clinicopathologic and fine structural study. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:83-109.

- Haustein UF. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:851-856.

- Stewart FW, Treves N. Lymphangiosarcoma in postmastectomy lymphedema: a report of six cases in elephantiasis chirurgica. Cancer. 1948;1:64-81.

- Goette DK, Detlefs RL. Postirradiation angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(5 pt 2):922-926.

- Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:34-39.

- Voth H, Landsberg J, Hinz T, et al. Management of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with fibrosarcomatous transformation: an evidence-based review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1385-1391.

- Goldblum JR. CD34 positivity in fibrosarcomas which arise in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:238-241.

- Patel KU, Szabo SS, Hernandez VS, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans COL1A1-PDGFB fusion is identified in virtually all dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans cases when investigated by newly developed multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization assays. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:184-193.

- Sohn IB, Hwang SM, Lee SH, et al. Dermatofibroma with sclerotic areas resembling a sclerotic fibroma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:44-47.

- Pujol RM, de Castro F, Schroeter AL, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a sclerotic dermatofibroma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:620-624.

- Requena L, Gutiérrez J, Sánchez Yus E. Multiple sclerotic fibromas of the skin: a cutaneous marker of Cowden's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:346-351.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

A 61-year-old woman presented with a 2.5-cm hyperpigmented exophytic nodule on the anterior aspect of the left shin of approximately 2 years' duration. The patient initially noticed a small lesion following a bee sting, but it subsequently grew over the ensuing 2 years. A shave biopsy was obtained.

Enlarging Mass on the Lateral Neck

Branchial Cleft Cyst

Cystic lesions present in a myriad of ways and often require histopathologic examination for definitive diagnosis. Correct identification of the cells comprising the lining of the cyst and the composition of the surrounding tissue are utilized to classify these lesions.

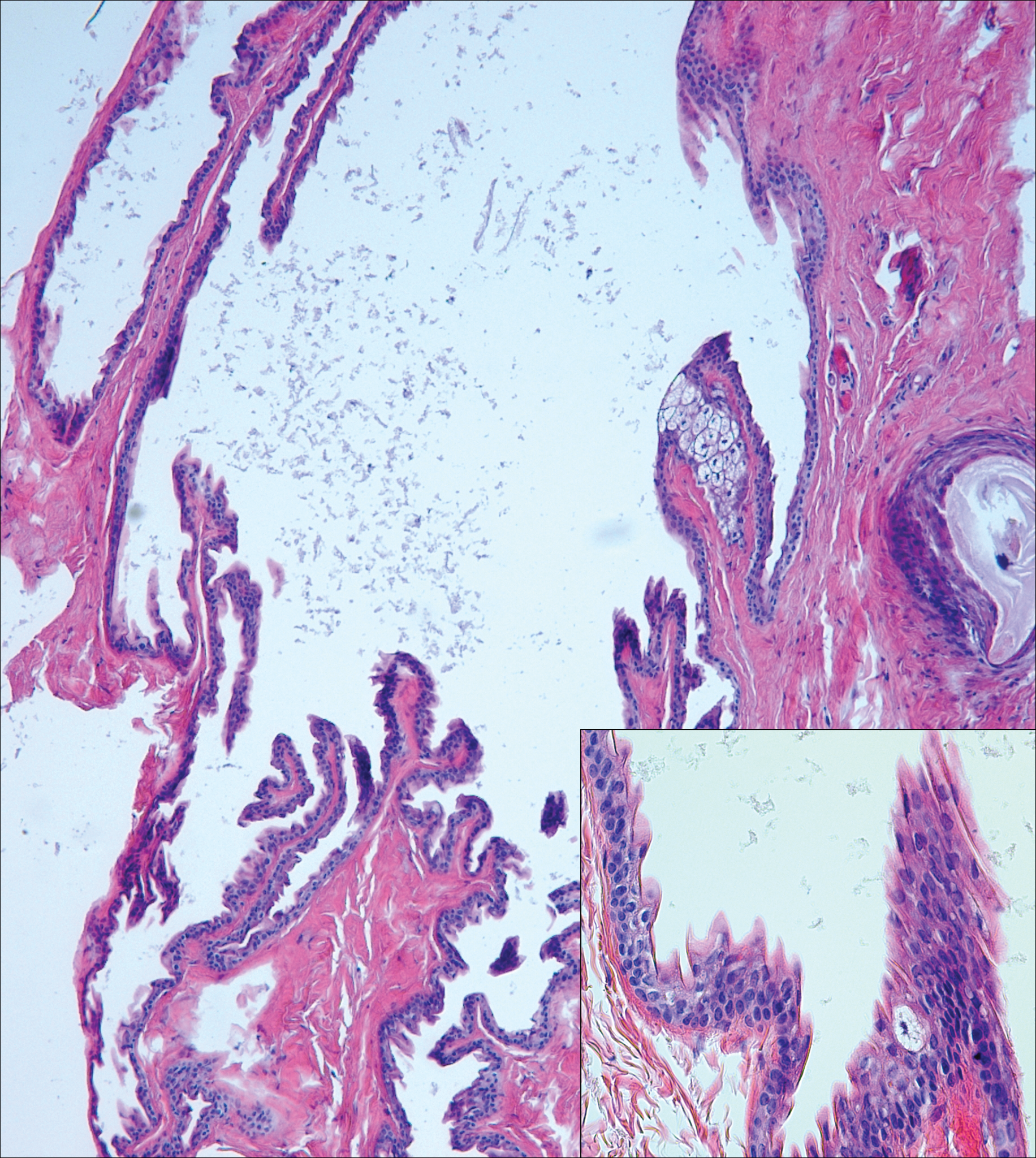

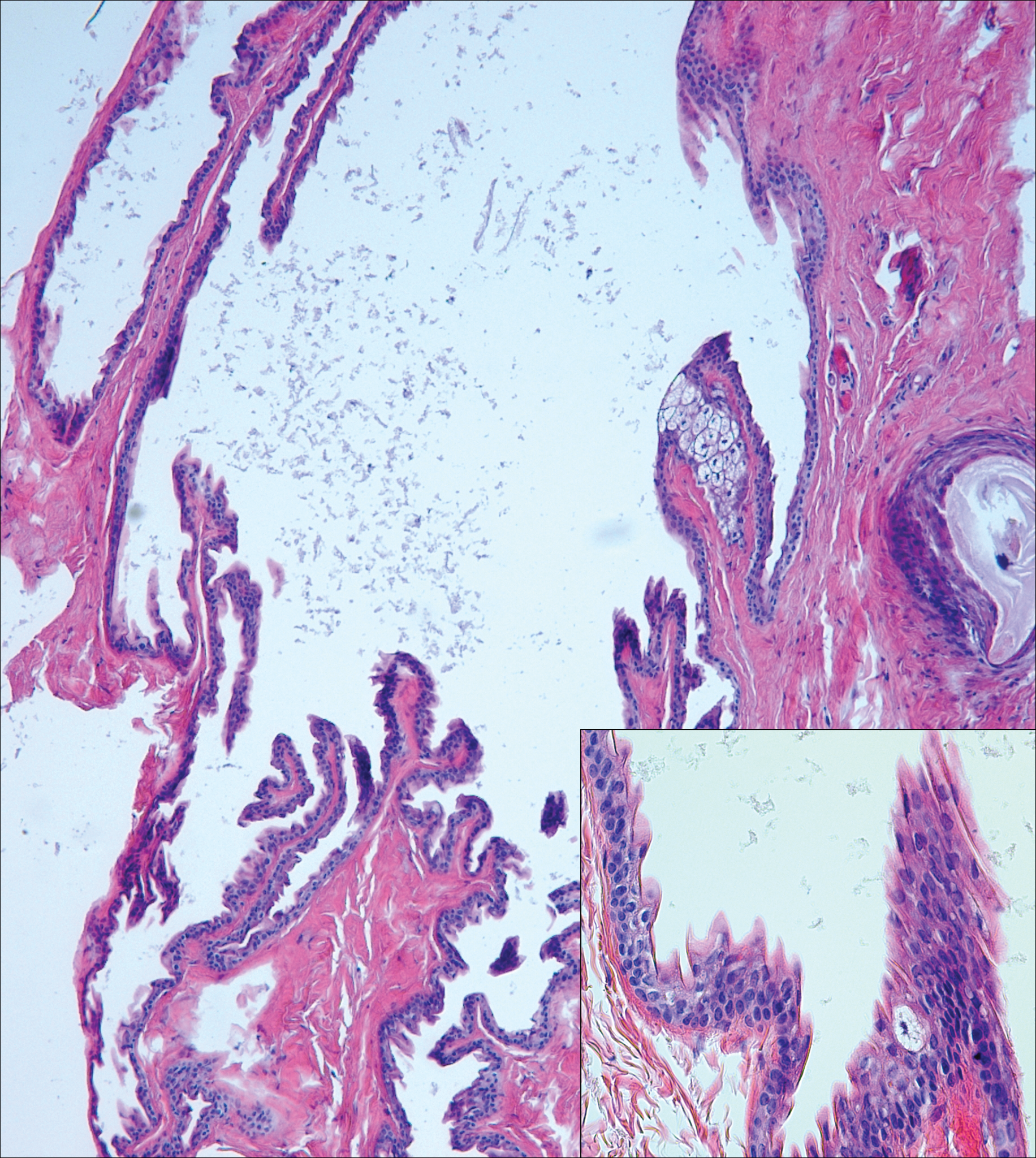

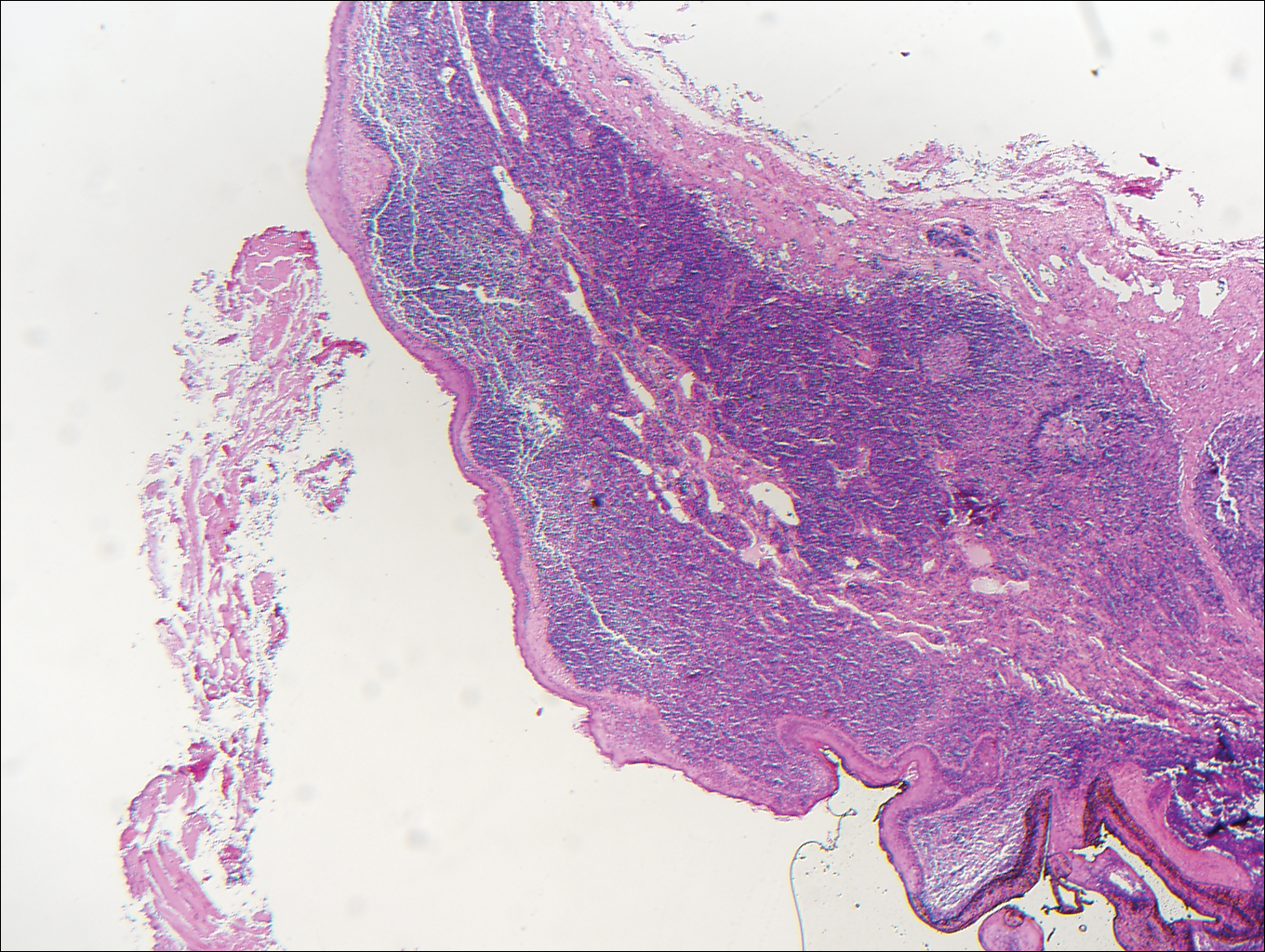

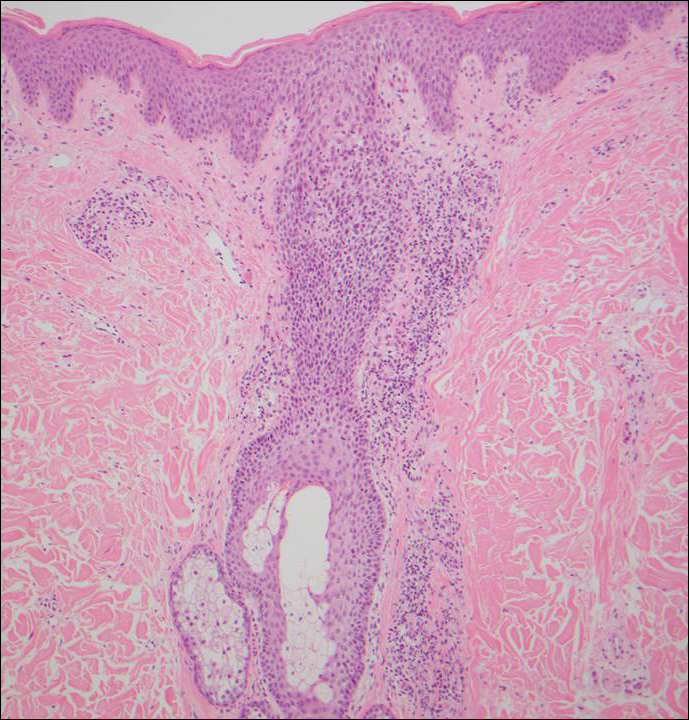

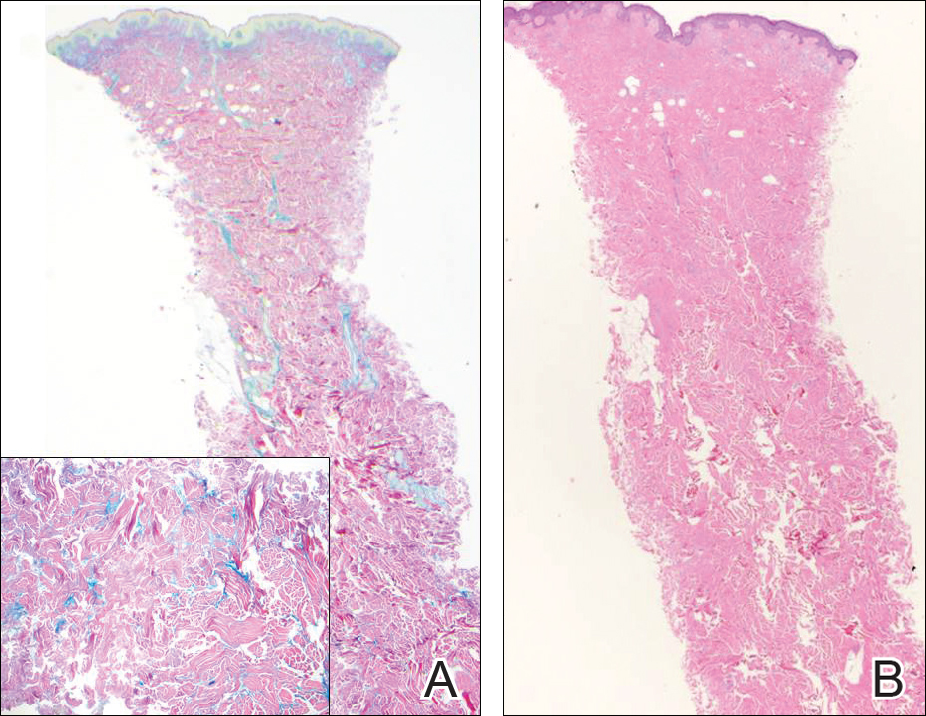

Branchial cleft cysts (quiz image, Figure 1) most commonly present as a soft tissue swelling of the lateral neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid; they also can present in the preauricular or mandibular region.1,2 Although the cyst is present at birth, it typically is not clinically apparent until the second or third decades of life. The origin of branchial cleft cysts is subject to some debate; however, the prevailing theory is that they result from failure of obliteration of the second branchial arch during development.1 Histopathologically, branchial cleft cysts are characterized by a stratified squamous epithelial lining and abundant lymphoid tissue with germinal centers.3,4 Infection is a common reason for presentation and excision is curative.

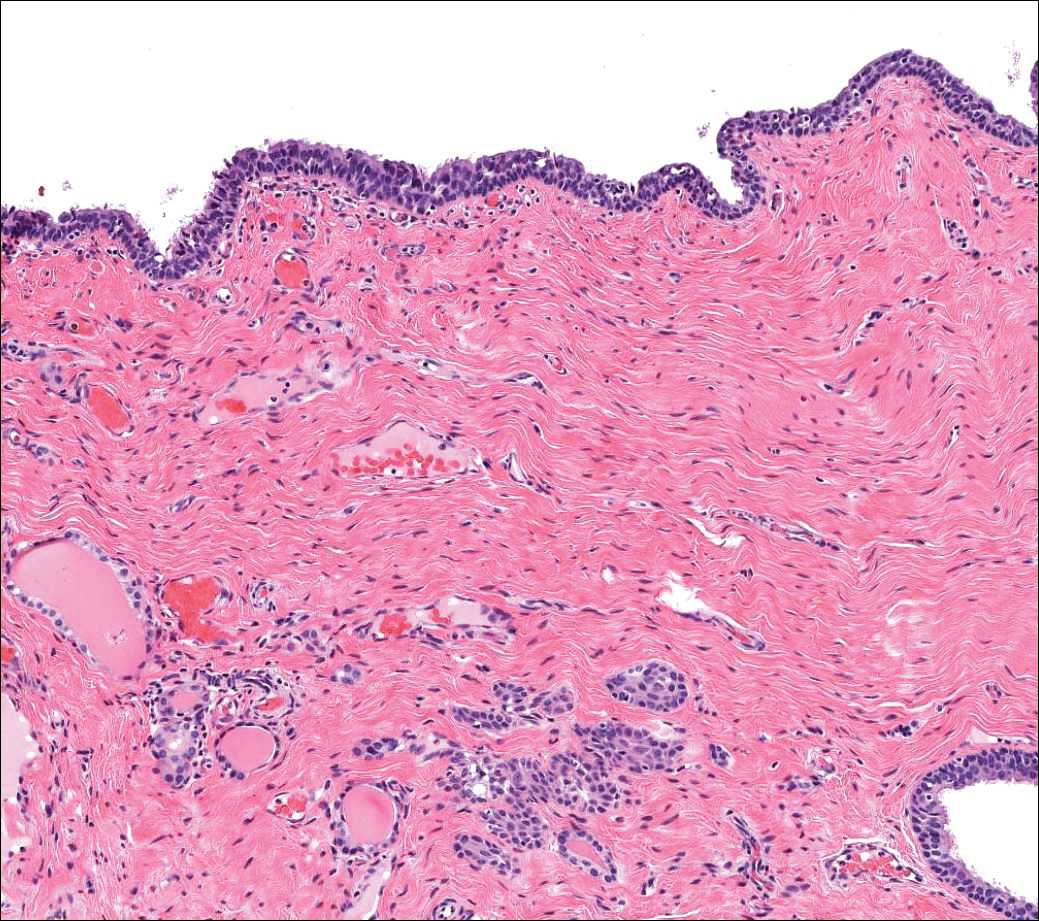

Bronchogenic cysts (Figure 2) present as midline lesions in the suprasternal notch and can present clinically due to compression of the airway.5 They develop as anomalies of the primitive foregut, budding off of the tracheobronchial tree. Similar to respiratory tissue, they are lined with a ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium and contain goblet cells. Concentric smooth muscle often surrounds the cyst and cartilage may be present.4 Excision is curative and recommended if the cyst encroaches on vital structures.

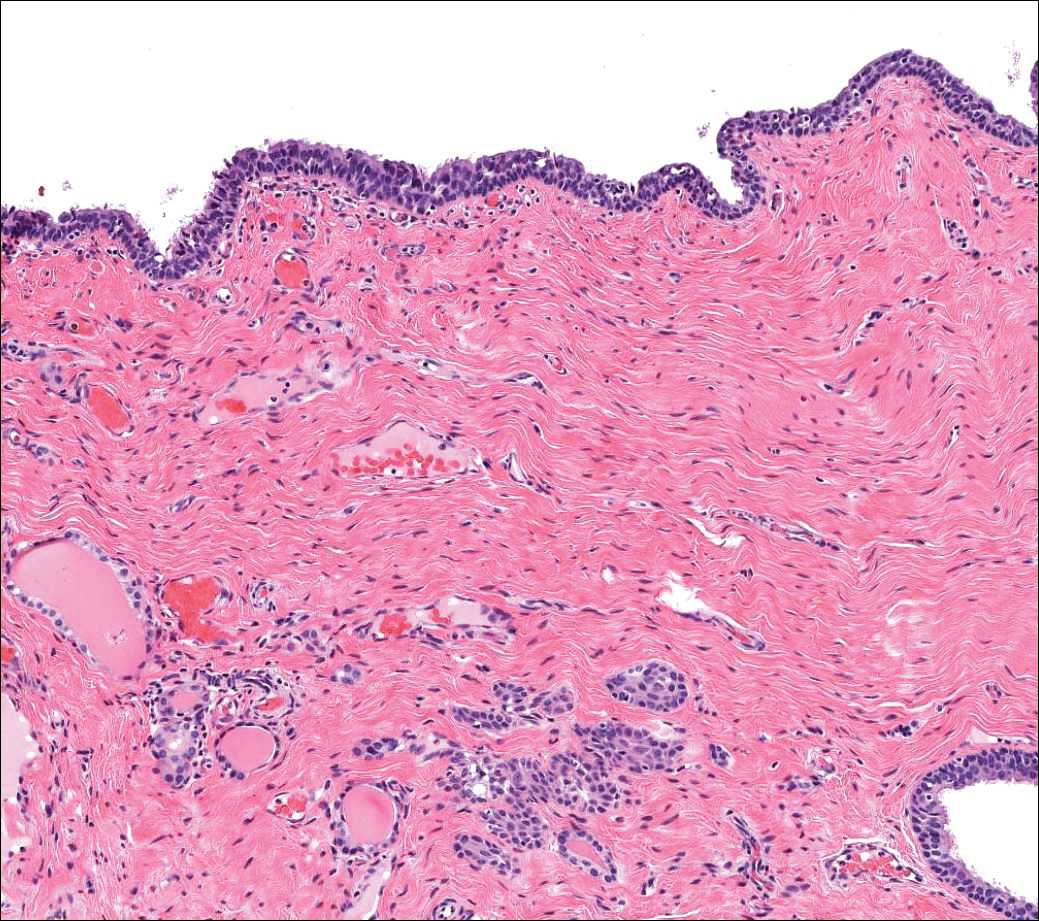

Median raphe cysts occur most commonly on the ventral surface of the penis on or near the glans (Figure 3). These cysts are thought to result from anomalous budding from the urethral epithelium, though they do not maintain contact with the urethra.3 The lining varies in thickness from 1 to 4 cell layers and mimics the transitional epithelium of the urethra. Amorphous debris often is seen within the cyst, and surrounding genital tissue can be appreciated by identification of delicate collagen, smooth muscle, and numerous small nerves and vessels.3,4 Excision is curative and often is sought when the cyst becomes irritated or cosmetically bothersome.

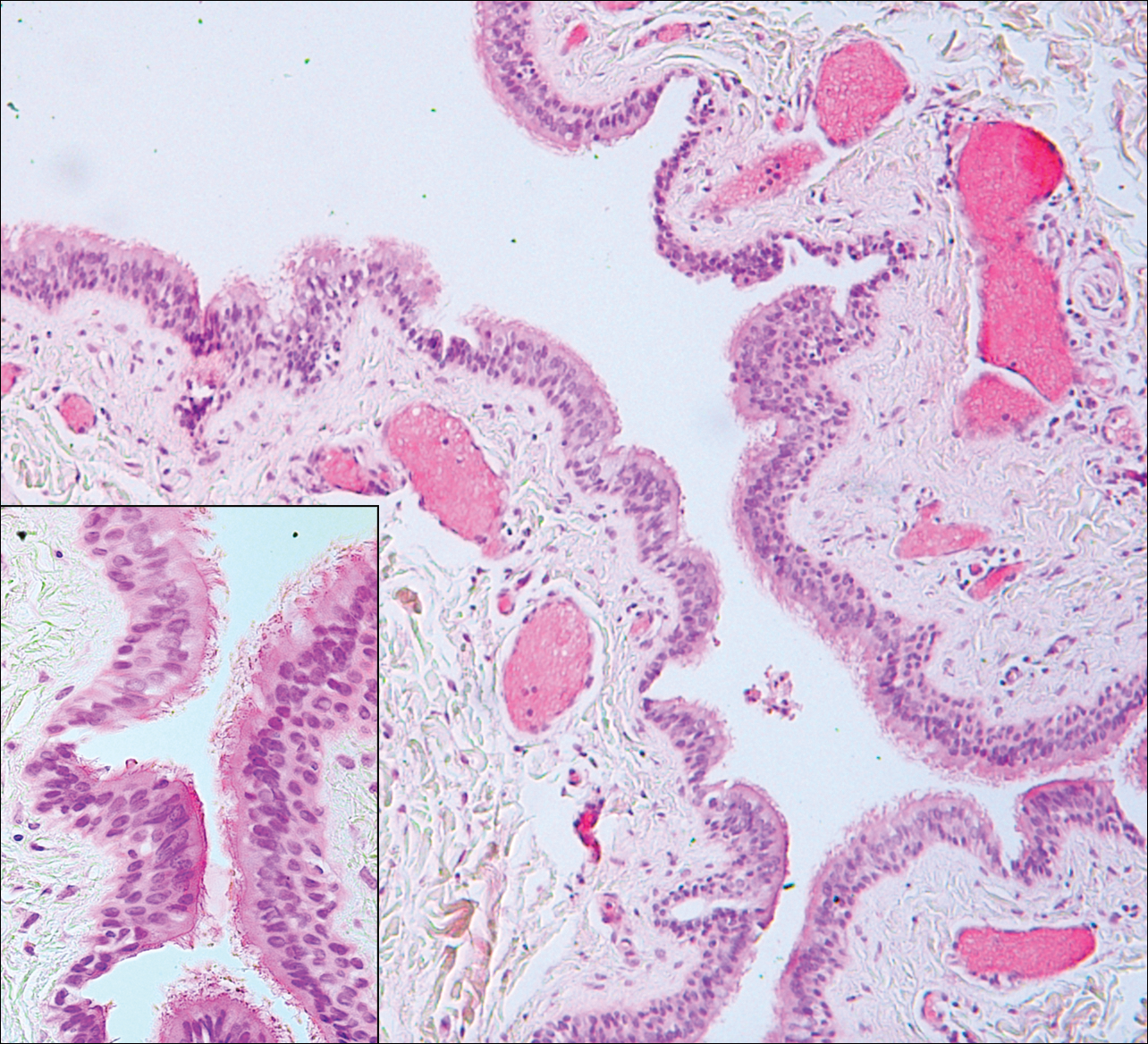

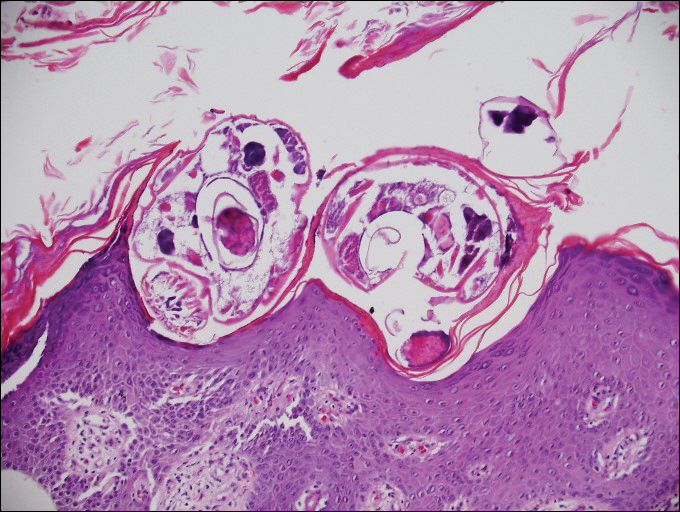

Steatocystomas can present as solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple lesions (steatocystoma multiplex)(Figure 4). They present as small, well-defined, yellow cystic papules most commonly on the chest, axilla, or groin.2 Their lining is composed of a stratified squamous epithelium that lacks a granular layer and contains a distinct overlying corrugated "shark tooth" eosinophilic cuticle. Sebaceous lobules are characteristically present along or within the cyst wall.3,4 Excision is curative and treatment often is sought for cosmetic purposes.

Similar to bronchogenic cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts (Figure 5) present on the midline neck, though they characteristically move with swallowing. The thyroglossal duct develops as the thyroid migrates from the floor of the pharynx to the anterior neck. Remnants of this duct result in the thyroglossal duct cyst.2 These cysts contain a respiratory-type epithelial lining and are distinguished by distinct thyroid follicles and lymphoid aggregates surrounding the cyst wall. Unlike bronchogenic cysts, they do not contain smooth muscle.3,4 Excision is curative.

- Chavan S, Deshmukh R, Karande P, et al. Branchial cleft cyst: a case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:150.

- Stone MS. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1817-1828.

- Kirkham N, Aljefri K. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Rosenbach M, et al, eds. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:969-1024.

- Elston DM. Benign tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2014:49-55.

- Hsu CG, Heller M, Johnston GS, et al. An unusual cause of airway compromise in the emergency department: mediastinal bronchogenic cyst [published online December 13, 2016]. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:E91-E93.

Branchial Cleft Cyst

Cystic lesions present in a myriad of ways and often require histopathologic examination for definitive diagnosis. Correct identification of the cells comprising the lining of the cyst and the composition of the surrounding tissue are utilized to classify these lesions.

Branchial cleft cysts (quiz image, Figure 1) most commonly present as a soft tissue swelling of the lateral neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid; they also can present in the preauricular or mandibular region.1,2 Although the cyst is present at birth, it typically is not clinically apparent until the second or third decades of life. The origin of branchial cleft cysts is subject to some debate; however, the prevailing theory is that they result from failure of obliteration of the second branchial arch during development.1 Histopathologically, branchial cleft cysts are characterized by a stratified squamous epithelial lining and abundant lymphoid tissue with germinal centers.3,4 Infection is a common reason for presentation and excision is curative.

Bronchogenic cysts (Figure 2) present as midline lesions in the suprasternal notch and can present clinically due to compression of the airway.5 They develop as anomalies of the primitive foregut, budding off of the tracheobronchial tree. Similar to respiratory tissue, they are lined with a ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium and contain goblet cells. Concentric smooth muscle often surrounds the cyst and cartilage may be present.4 Excision is curative and recommended if the cyst encroaches on vital structures.

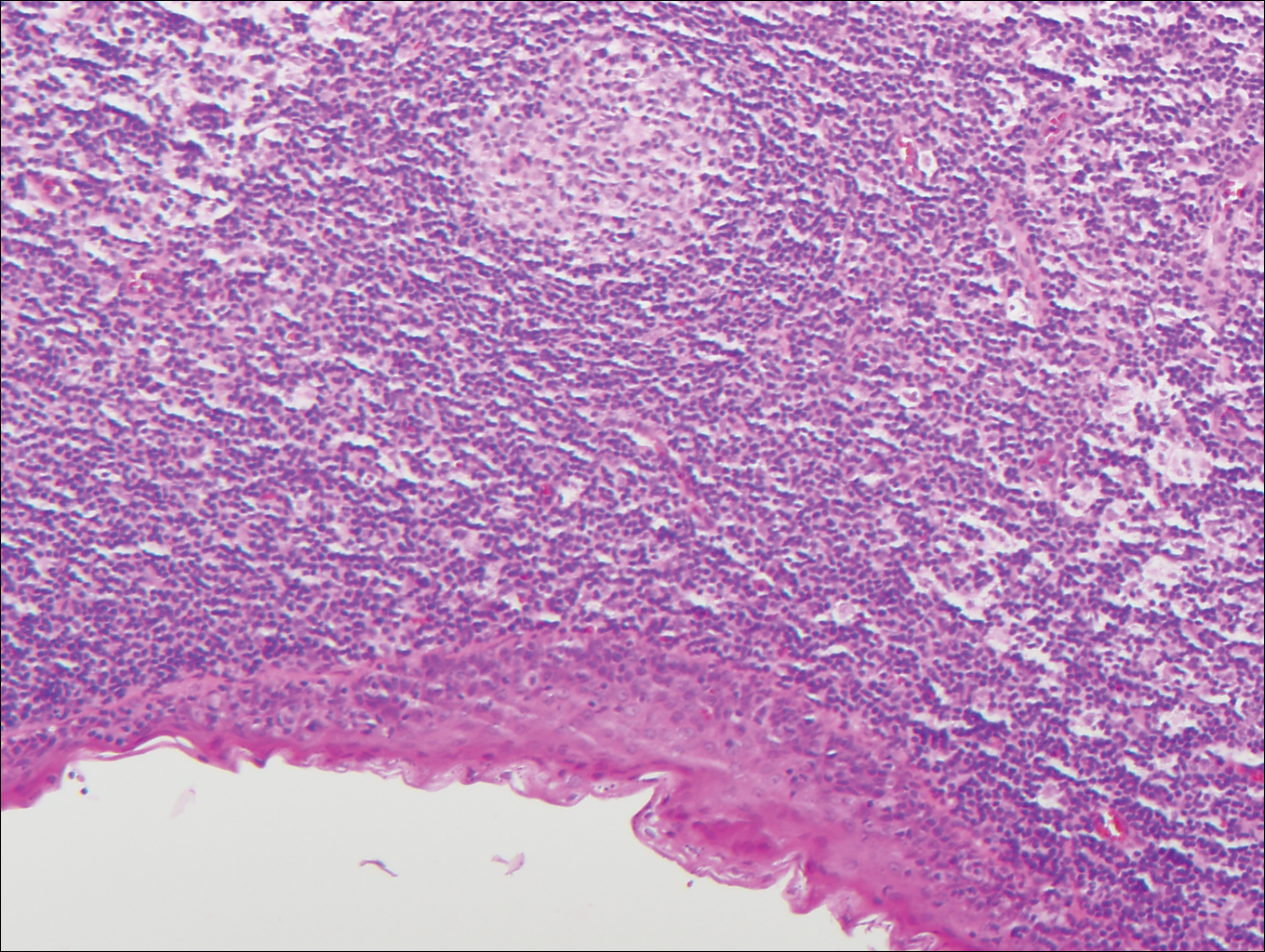

Median raphe cysts occur most commonly on the ventral surface of the penis on or near the glans (Figure 3). These cysts are thought to result from anomalous budding from the urethral epithelium, though they do not maintain contact with the urethra.3 The lining varies in thickness from 1 to 4 cell layers and mimics the transitional epithelium of the urethra. Amorphous debris often is seen within the cyst, and surrounding genital tissue can be appreciated by identification of delicate collagen, smooth muscle, and numerous small nerves and vessels.3,4 Excision is curative and often is sought when the cyst becomes irritated or cosmetically bothersome.

Steatocystomas can present as solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple lesions (steatocystoma multiplex)(Figure 4). They present as small, well-defined, yellow cystic papules most commonly on the chest, axilla, or groin.2 Their lining is composed of a stratified squamous epithelium that lacks a granular layer and contains a distinct overlying corrugated "shark tooth" eosinophilic cuticle. Sebaceous lobules are characteristically present along or within the cyst wall.3,4 Excision is curative and treatment often is sought for cosmetic purposes.

Similar to bronchogenic cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts (Figure 5) present on the midline neck, though they characteristically move with swallowing. The thyroglossal duct develops as the thyroid migrates from the floor of the pharynx to the anterior neck. Remnants of this duct result in the thyroglossal duct cyst.2 These cysts contain a respiratory-type epithelial lining and are distinguished by distinct thyroid follicles and lymphoid aggregates surrounding the cyst wall. Unlike bronchogenic cysts, they do not contain smooth muscle.3,4 Excision is curative.

Branchial Cleft Cyst

Cystic lesions present in a myriad of ways and often require histopathologic examination for definitive diagnosis. Correct identification of the cells comprising the lining of the cyst and the composition of the surrounding tissue are utilized to classify these lesions.

Branchial cleft cysts (quiz image, Figure 1) most commonly present as a soft tissue swelling of the lateral neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid; they also can present in the preauricular or mandibular region.1,2 Although the cyst is present at birth, it typically is not clinically apparent until the second or third decades of life. The origin of branchial cleft cysts is subject to some debate; however, the prevailing theory is that they result from failure of obliteration of the second branchial arch during development.1 Histopathologically, branchial cleft cysts are characterized by a stratified squamous epithelial lining and abundant lymphoid tissue with germinal centers.3,4 Infection is a common reason for presentation and excision is curative.

Bronchogenic cysts (Figure 2) present as midline lesions in the suprasternal notch and can present clinically due to compression of the airway.5 They develop as anomalies of the primitive foregut, budding off of the tracheobronchial tree. Similar to respiratory tissue, they are lined with a ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium and contain goblet cells. Concentric smooth muscle often surrounds the cyst and cartilage may be present.4 Excision is curative and recommended if the cyst encroaches on vital structures.

Median raphe cysts occur most commonly on the ventral surface of the penis on or near the glans (Figure 3). These cysts are thought to result from anomalous budding from the urethral epithelium, though they do not maintain contact with the urethra.3 The lining varies in thickness from 1 to 4 cell layers and mimics the transitional epithelium of the urethra. Amorphous debris often is seen within the cyst, and surrounding genital tissue can be appreciated by identification of delicate collagen, smooth muscle, and numerous small nerves and vessels.3,4 Excision is curative and often is sought when the cyst becomes irritated or cosmetically bothersome.

Steatocystomas can present as solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple lesions (steatocystoma multiplex)(Figure 4). They present as small, well-defined, yellow cystic papules most commonly on the chest, axilla, or groin.2 Their lining is composed of a stratified squamous epithelium that lacks a granular layer and contains a distinct overlying corrugated "shark tooth" eosinophilic cuticle. Sebaceous lobules are characteristically present along or within the cyst wall.3,4 Excision is curative and treatment often is sought for cosmetic purposes.

Similar to bronchogenic cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts (Figure 5) present on the midline neck, though they characteristically move with swallowing. The thyroglossal duct develops as the thyroid migrates from the floor of the pharynx to the anterior neck. Remnants of this duct result in the thyroglossal duct cyst.2 These cysts contain a respiratory-type epithelial lining and are distinguished by distinct thyroid follicles and lymphoid aggregates surrounding the cyst wall. Unlike bronchogenic cysts, they do not contain smooth muscle.3,4 Excision is curative.

- Chavan S, Deshmukh R, Karande P, et al. Branchial cleft cyst: a case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:150.

- Stone MS. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1817-1828.

- Kirkham N, Aljefri K. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Rosenbach M, et al, eds. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:969-1024.

- Elston DM. Benign tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2014:49-55.

- Hsu CG, Heller M, Johnston GS, et al. An unusual cause of airway compromise in the emergency department: mediastinal bronchogenic cyst [published online December 13, 2016]. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:E91-E93.

- Chavan S, Deshmukh R, Karande P, et al. Branchial cleft cyst: a case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:150.

- Stone MS. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1817-1828.

- Kirkham N, Aljefri K. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Rosenbach M, et al, eds. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:969-1024.

- Elston DM. Benign tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2014:49-55.

- Hsu CG, Heller M, Johnston GS, et al. An unusual cause of airway compromise in the emergency department: mediastinal bronchogenic cyst [published online December 13, 2016]. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:E91-E93.

A 14-year-old adolescent boy presented with a nontender mass on the left lateral neck. The mass had been present since birth but had recently grown in size.

Pruritic Rash on the Buttock

Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) is caused by the larval migration of animal hookworms. Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma ceylanicum, and Ancylostoma caninum are the species most commonly associated with the disease. The hookworm is endemic to tropical and subtropical climates in areas such as Africa, Southeast Asia, South America, and the southeastern United States.1 Although cats and dogs are most commonly affected, humans can be infected if they are exposed to sand or soil containing hookworm larvae, often due to contamination from animal feces.2 Cutaneous larva migrans is characterized by pruritic erythematous papules and linear or serpiginous, reddish brown, elevated tracks most commonly appearing on the feet, buttocks, thighs, and lower legs; however, lesions can appear anywhere. In human hosts, the larvae travel in the epidermis and are unable to invade the dermis; it is speculated that they lack the collagenase enzymes required to penetrate the basement membrane before invading the dermis.2

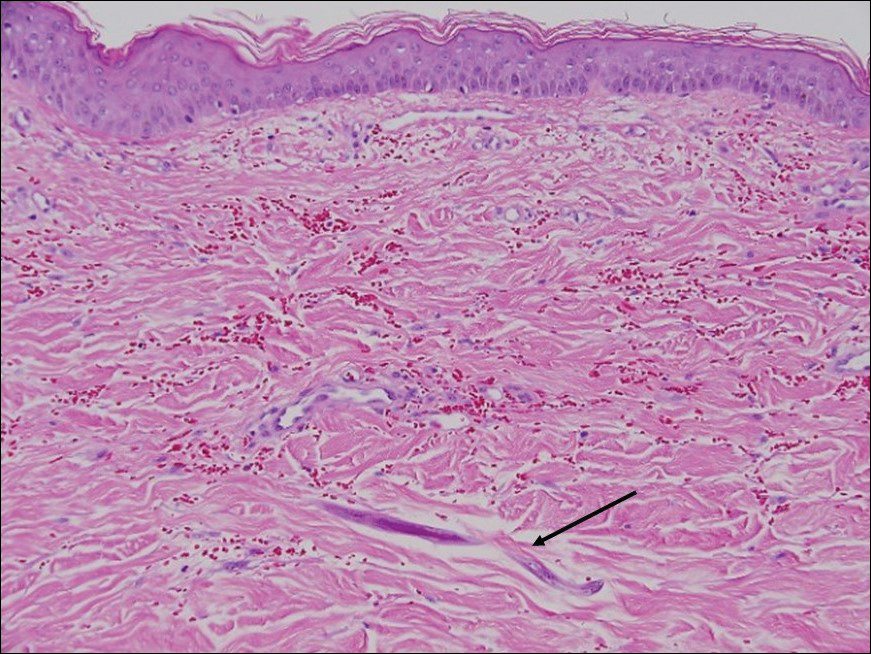

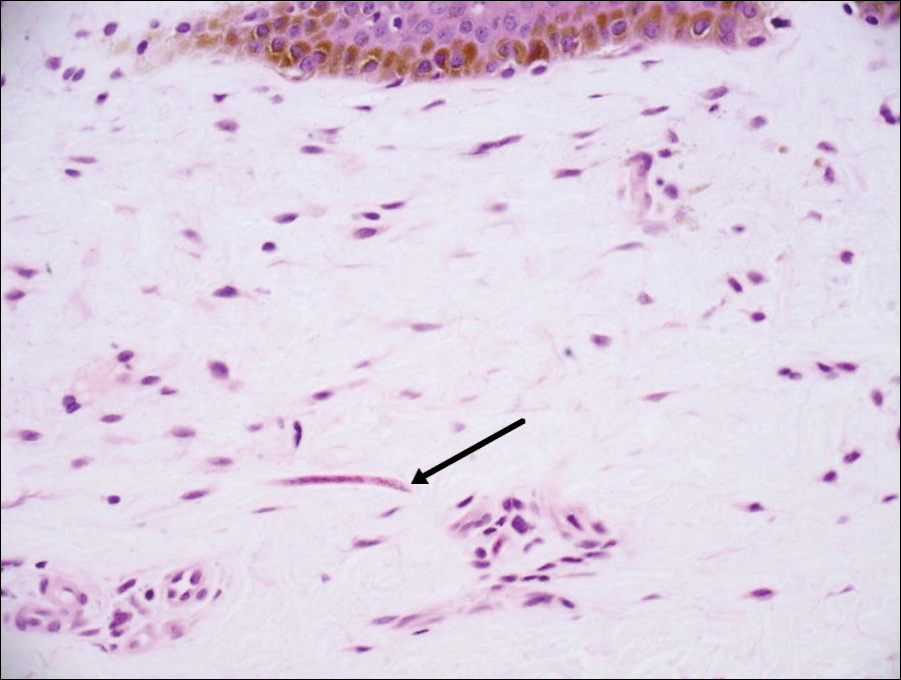

On histopathology, there typically are small cavities in the epidermis corresponding to the track of the larvae.3 There often is a spongiotic dermatitis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate following the larvae with scattered eosinophils. The migrating larvae may be up to 1 mm in size and have bilateral double alae, or winglike projections, on the side of the body (Figure 1).4 The larvae are difficult to find on histopathology because they often travel beyond the areas that demonstrate clinical findings. The diagnosis of CLM is mostly clinical, but if a biopsy is performed, the specimen should be taken ahead of the track.

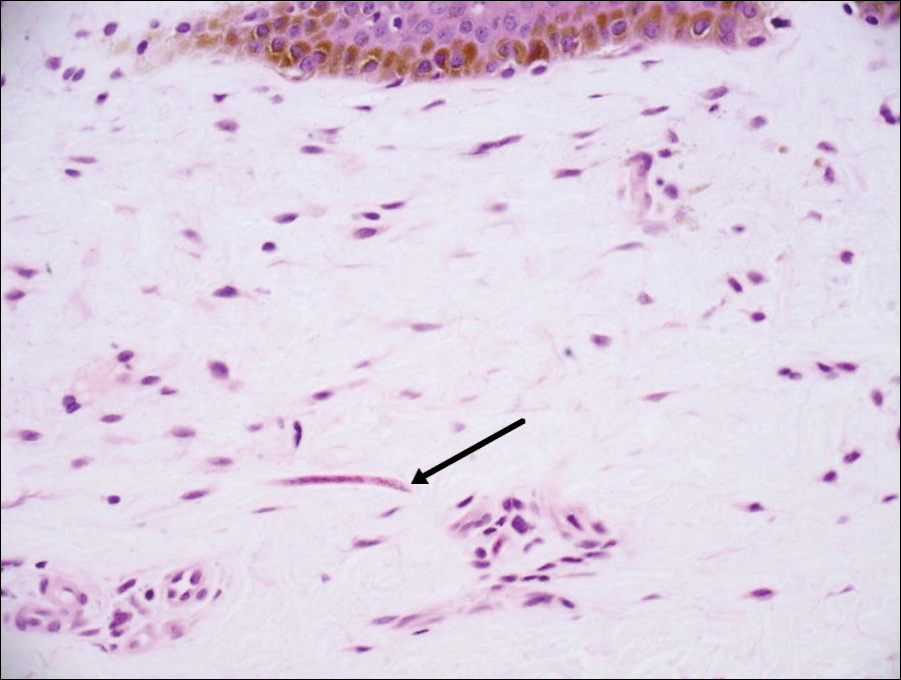

Disseminated strongyloidiasis is caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. When filariform larvae migrate out of the intestinal tract into the skin, they can cause an urticarial rash and serpiginous patterns on the skin that can move 5 to 15 cm per hour, a clinical condition known as larva currens. In immunocompromised individuals, there can be hyperinfection with diffuse petechial thumbprint purpura seen clinically, which characteristically radiate from the periumbilical area.1 On pathology, there may be numerous larvae found between the dermal collagen bundles, measuring 9 to 15 µm in diameter. Rarely, they also can be found in small blood vessels.3 They often are accompanied by extravasated red blood cells in the tissues (Figure 2).

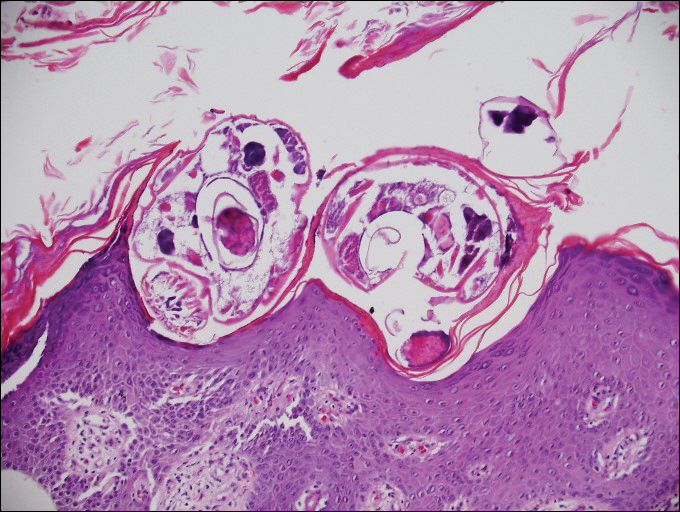

Myiasis represents the largest pathogen in the differential diagnosis for CLM. In myiasis, fly larvae will infest human tissue, usually by forming a small cavity in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. The larvae are visible to the human eye and can be up to several centimeters in length. In the skin, the histology of myiasis usually is accompanied by a heavy mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with many eosinophils. Fragments of the larvae are seen encased by a thick chitinous cuticle with widely spaced spines or pigmented setae (Figure 3) on the surface of the cuticle.5 Layers of striated muscle and internal organs may be seen beneath the cuticle.3

Onchocerciasis, or river blindness, is a parasitic disease caused by Onchocerca volvulus that is most often seen in sub-Saharan Africa. It may cause the skin finding of an onchocercoma, a subcutaneous nodule made up of Onchocerca nematodes. However, when the filaria disseminate, it may cause onchocerciasis with cutaneous findings of an eczematous dermatitis with itching and lichenification.1 In onchocercal dermatitis, microfilariae may be found in the dermis and there may be a mild dermal chronic inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils.3 These microfilariae are smaller than Strongyloides larvae (Figure 4).

Sarcoptes scabiei are mites that are pathologically found limited to the stratum corneum. There often is a spongiotic dermatitis as the mite travels with an accompanying mixed cell inflammatory infiltrate with many eosinophils. One or more mites may be seen with or without eggs and excreta or scybala (Figure 5). Pink pigtails may be seen connected to the stratum corneum, representing egg fragments or casings left behind after the mite hatches.3 The female mite measures up to 0.4 mm in length.3

- Lupi O, Downing C, Lee M, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations of helminth infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:929-944.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Patterson J. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Milner D. Diagnostic Pathology: Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Ferringer T, Peckham S, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) is caused by the larval migration of animal hookworms. Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma ceylanicum, and Ancylostoma caninum are the species most commonly associated with the disease. The hookworm is endemic to tropical and subtropical climates in areas such as Africa, Southeast Asia, South America, and the southeastern United States.1 Although cats and dogs are most commonly affected, humans can be infected if they are exposed to sand or soil containing hookworm larvae, often due to contamination from animal feces.2 Cutaneous larva migrans is characterized by pruritic erythematous papules and linear or serpiginous, reddish brown, elevated tracks most commonly appearing on the feet, buttocks, thighs, and lower legs; however, lesions can appear anywhere. In human hosts, the larvae travel in the epidermis and are unable to invade the dermis; it is speculated that they lack the collagenase enzymes required to penetrate the basement membrane before invading the dermis.2

On histopathology, there typically are small cavities in the epidermis corresponding to the track of the larvae.3 There often is a spongiotic dermatitis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate following the larvae with scattered eosinophils. The migrating larvae may be up to 1 mm in size and have bilateral double alae, or winglike projections, on the side of the body (Figure 1).4 The larvae are difficult to find on histopathology because they often travel beyond the areas that demonstrate clinical findings. The diagnosis of CLM is mostly clinical, but if a biopsy is performed, the specimen should be taken ahead of the track.

Disseminated strongyloidiasis is caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. When filariform larvae migrate out of the intestinal tract into the skin, they can cause an urticarial rash and serpiginous patterns on the skin that can move 5 to 15 cm per hour, a clinical condition known as larva currens. In immunocompromised individuals, there can be hyperinfection with diffuse petechial thumbprint purpura seen clinically, which characteristically radiate from the periumbilical area.1 On pathology, there may be numerous larvae found between the dermal collagen bundles, measuring 9 to 15 µm in diameter. Rarely, they also can be found in small blood vessels.3 They often are accompanied by extravasated red blood cells in the tissues (Figure 2).

Myiasis represents the largest pathogen in the differential diagnosis for CLM. In myiasis, fly larvae will infest human tissue, usually by forming a small cavity in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. The larvae are visible to the human eye and can be up to several centimeters in length. In the skin, the histology of myiasis usually is accompanied by a heavy mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with many eosinophils. Fragments of the larvae are seen encased by a thick chitinous cuticle with widely spaced spines or pigmented setae (Figure 3) on the surface of the cuticle.5 Layers of striated muscle and internal organs may be seen beneath the cuticle.3

Onchocerciasis, or river blindness, is a parasitic disease caused by Onchocerca volvulus that is most often seen in sub-Saharan Africa. It may cause the skin finding of an onchocercoma, a subcutaneous nodule made up of Onchocerca nematodes. However, when the filaria disseminate, it may cause onchocerciasis with cutaneous findings of an eczematous dermatitis with itching and lichenification.1 In onchocercal dermatitis, microfilariae may be found in the dermis and there may be a mild dermal chronic inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils.3 These microfilariae are smaller than Strongyloides larvae (Figure 4).

Sarcoptes scabiei are mites that are pathologically found limited to the stratum corneum. There often is a spongiotic dermatitis as the mite travels with an accompanying mixed cell inflammatory infiltrate with many eosinophils. One or more mites may be seen with or without eggs and excreta or scybala (Figure 5). Pink pigtails may be seen connected to the stratum corneum, representing egg fragments or casings left behind after the mite hatches.3 The female mite measures up to 0.4 mm in length.3

Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) is caused by the larval migration of animal hookworms. Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma ceylanicum, and Ancylostoma caninum are the species most commonly associated with the disease. The hookworm is endemic to tropical and subtropical climates in areas such as Africa, Southeast Asia, South America, and the southeastern United States.1 Although cats and dogs are most commonly affected, humans can be infected if they are exposed to sand or soil containing hookworm larvae, often due to contamination from animal feces.2 Cutaneous larva migrans is characterized by pruritic erythematous papules and linear or serpiginous, reddish brown, elevated tracks most commonly appearing on the feet, buttocks, thighs, and lower legs; however, lesions can appear anywhere. In human hosts, the larvae travel in the epidermis and are unable to invade the dermis; it is speculated that they lack the collagenase enzymes required to penetrate the basement membrane before invading the dermis.2

On histopathology, there typically are small cavities in the epidermis corresponding to the track of the larvae.3 There often is a spongiotic dermatitis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate following the larvae with scattered eosinophils. The migrating larvae may be up to 1 mm in size and have bilateral double alae, or winglike projections, on the side of the body (Figure 1).4 The larvae are difficult to find on histopathology because they often travel beyond the areas that demonstrate clinical findings. The diagnosis of CLM is mostly clinical, but if a biopsy is performed, the specimen should be taken ahead of the track.

Disseminated strongyloidiasis is caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. When filariform larvae migrate out of the intestinal tract into the skin, they can cause an urticarial rash and serpiginous patterns on the skin that can move 5 to 15 cm per hour, a clinical condition known as larva currens. In immunocompromised individuals, there can be hyperinfection with diffuse petechial thumbprint purpura seen clinically, which characteristically radiate from the periumbilical area.1 On pathology, there may be numerous larvae found between the dermal collagen bundles, measuring 9 to 15 µm in diameter. Rarely, they also can be found in small blood vessels.3 They often are accompanied by extravasated red blood cells in the tissues (Figure 2).

Myiasis represents the largest pathogen in the differential diagnosis for CLM. In myiasis, fly larvae will infest human tissue, usually by forming a small cavity in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. The larvae are visible to the human eye and can be up to several centimeters in length. In the skin, the histology of myiasis usually is accompanied by a heavy mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with many eosinophils. Fragments of the larvae are seen encased by a thick chitinous cuticle with widely spaced spines or pigmented setae (Figure 3) on the surface of the cuticle.5 Layers of striated muscle and internal organs may be seen beneath the cuticle.3

Onchocerciasis, or river blindness, is a parasitic disease caused by Onchocerca volvulus that is most often seen in sub-Saharan Africa. It may cause the skin finding of an onchocercoma, a subcutaneous nodule made up of Onchocerca nematodes. However, when the filaria disseminate, it may cause onchocerciasis with cutaneous findings of an eczematous dermatitis with itching and lichenification.1 In onchocercal dermatitis, microfilariae may be found in the dermis and there may be a mild dermal chronic inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils.3 These microfilariae are smaller than Strongyloides larvae (Figure 4).

Sarcoptes scabiei are mites that are pathologically found limited to the stratum corneum. There often is a spongiotic dermatitis as the mite travels with an accompanying mixed cell inflammatory infiltrate with many eosinophils. One or more mites may be seen with or without eggs and excreta or scybala (Figure 5). Pink pigtails may be seen connected to the stratum corneum, representing egg fragments or casings left behind after the mite hatches.3 The female mite measures up to 0.4 mm in length.3

- Lupi O, Downing C, Lee M, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations of helminth infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:929-944.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Patterson J. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Milner D. Diagnostic Pathology: Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Ferringer T, Peckham S, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

- Lupi O, Downing C, Lee M, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations of helminth infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:929-944.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Patterson J. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Milner D. Diagnostic Pathology: Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Ferringer T, Peckham S, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

An 18-year-old man presented with a several-week history of an expanding pruritic serpiginous and linear eruption on the buttock. The patient recently had spent some time vacationing at the beach in the southeastern United States. Physical examination revealed erythematous linear papules and serpiginous raised tracks on the buttock. A biopsy of the lesion was performed.

Erythematous Pearly Papule on the Chest

Primary Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (CBCLs) are a diverse but rare group of cutaneous lymphoproliferative neoplasms that make up approximately 20% of the total number of hematolymphoid neoplasms primary to the skin.1 These lymphomas are comprised of neoplastic B cells in various stages of differentiation. As a whole, they are rare neoplasms that primarily involve the head, neck, trunk, arms, or legs.1 Clinically, patients present with nontender, compressible, solitary, red to violaceous papules or nodules. Most CBCLs are considered low-grade malignancies with nonaggressive behavior and excellent prognosis; however, the diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, including but not limited to intravascular and leg type; lymphomatoid granulomatosis; and B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma can act more aggressively.1

Histopathologic examination of primary CBCL generally reveals a relatively normal epidermis accompanied by a nodular to diffuse monomorphic lymphocytic cellular infiltrate in the dermis that can occasionally extend into the subcutaneous tissue (quiz image). Although not specific for CBCLs, oftentimes there is an acellular portion of the superficial papillary dermis known as a grenz zone that can serve as a histopathologic clue to the diagnosis of a cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. The list of malignant B-cell neoplasms is extensive (eg, cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, intravascular large B-cell lymphoma), and few are seen in the skin.

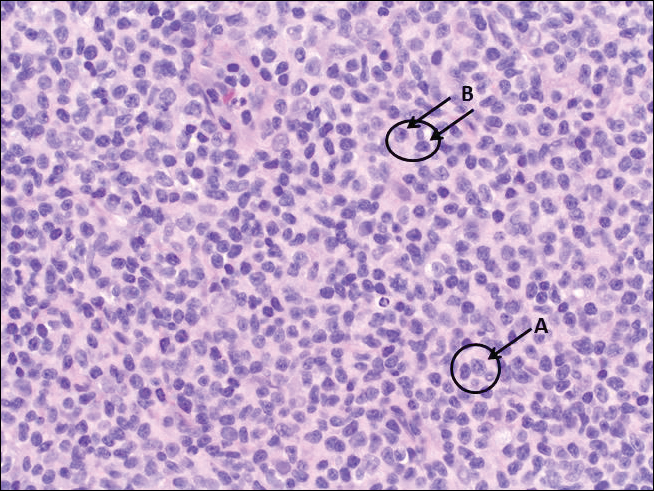

The most common type of CBCL is marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, which is considered to be a tumor of mucosa-associated (or skin-associated) lymphoid tissue. It is characterized by a monomorphous population of small mature lymphocytes showing characteristics of the B cells of the marginal zone of the lymph node. Some cells have the features of centrocytes/centroblasts (Figure 1) demonstrated by slightly irregular or indented nuclei and generous amounts of cytoplasm. Larger and more pleomorphic cells such as immunoblasts are similarly noted (Figure 1). The quiz image and Figure 1 demonstrate a cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. A histomorphologic clue supporting a diagnosis of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma over reactive lymphoid hyperplasia is a B-cell predominate (B- to T-cell ratio of at least 3 to 1) infiltrate that is comprised of marginal zone-type cells. Immunohistochemistry demonstrating fewer differentiated B cells with light chain restriction may provide additional evidence that supports a clonal and potentially malignant process.

Erythematous to violaceous nodules on the head and neck of older individuals are characteristic of both granuloma faciale and CBCL. Histologically, granuloma faciale is characterized by a dense cellular infiltrate, often with a nodular outline, occupying the mid dermis.2 Granuloma faciale typically spares the immediate subepidermis and hair follicles, forming a grenz zone. The cellular infiltrate is polymorphic and consists of eosinophils and neutrophils with scattered plasma cells, mast cells, and lymphocytes in a vasculocentric distribution, eventually with chronic concentric fibrosis (Figure 2).

Leukemia cutis demonstrates a dermal infiltrate that contains atypical mononuclear cells (myeloblasts and myelocytes)(Figure 3).3 These markedly atypical mononuclear cells can have kidney bean-shaped nuclei and percolate through the dermal collagen, resembling single-file cells. They have increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios and occasionally have prominent nucleoli. Correlation with immunophenotypic and cytochemical studies is required for specific typing of the leukemic infiltrate.

Similar to primary CBCL, lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) consists of erythematous papules or nodules that can occur anywhere on the body. In contrast to CBCL, the lesions of LyP classically self-resolve. However, approximately 10% to 20% of patients develop a malignant lymphoma, with mycosis fungoides, Hodgkin disease, and anaplastic large cell lymphoma being the most commonly associated.

Histologic examination of lesions of LyP classically demonstrates a wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate with variable epidermal changes (Figure 4). The wedge-shaped infiltrate is composed of large atypical cells. Three main types of lesions have been delineated: types A, B, and C. Type A is characterized by an increased number of cells with large vesicular nuclei with clumped chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and pronounced cytoplasm. Reed-Sternberg-like cells with an admixture of inflammatory cells including small lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and eosinophils also are present. Type B neoplastic cells vary in size and feature hyperchromatic, convoluted, or cerebriform nuclei. The infiltrate can be dense and bandlike with fewer cells resembling mycosis fungoides; type B LyP has neoplastic cells, not inflammatory cells. Finally, type C demonstrates solid sheets of large atypical cells resembling anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Immunohistochemically, the atypical cells often are CD4+ and CD8- with variable loss of pan-T-cell antigens. The atypical cells of types A and C express CD30 reactivity.4

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin that usually arises on sun-exposed skin in elderly patients with lesions that histologically and clinically resemble cutaneous lymphoma.5 It classically is composed of small, round to oval, basophilic cells with a vesicular nucleus and multiple small nucleoli. Apoptotic cells and mitoses often are present.6 One key finding that helps to differentiate MCC from lymphoma is the presence of finely dispersed salt-and-pepper chromatin and molded nuclear contour in MCC (Figure 5).

Immunophenotyping is important in the differentiation of these diagnoses. The atypical cells of LyP are positive for CD3, CD4, and CD30 but are negative for CD8. However, in type B LyP, the large CD30+ cells seen in the other types are not commonly seen. In contrast, MCC expresses reactivity with cytokeratins, in particular cytokeratin 20 and CAM5.2, classically in a paranuclear dotlike pattern. In keeping with MCC's neuroendocrine differentiation, the tumor cells will demonstrate reactivity with synaptophysin, chromogranin, and CD56. The immunohistochemistry for leukemia cutis varies depending on the type of leukemia. Acute myelomonocytic leukemia is positive for myeloperoxidase, CD13, CD33, and CD68. The immunophenotype of these marginal zone lymphoma cells is as follows: positive for CD20, CD79a, and Bcl-2; negative for Bcl-6, CD5, CD10, CD23, and cyclin D1 (Bcl-1).7

- Olsen EA. Evaluation, diagnosis, and staging of cutaneous lymphoma. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:643-654.

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Wieser I, Wohlmuth C, Nunez CA, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:319-327.

- Sibley RK, Dehner LP, Rosai J. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell?) carcinoma of the skin: I. a clinicopathologic and ultrastructural study of 43 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:95-108.

- Frigerio B, Capella C, Eusebi V, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: the structure and origin of normal Merkel cells. Histopathology. 1983;7:229-249.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

Primary Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (CBCLs) are a diverse but rare group of cutaneous lymphoproliferative neoplasms that make up approximately 20% of the total number of hematolymphoid neoplasms primary to the skin.1 These lymphomas are comprised of neoplastic B cells in various stages of differentiation. As a whole, they are rare neoplasms that primarily involve the head, neck, trunk, arms, or legs.1 Clinically, patients present with nontender, compressible, solitary, red to violaceous papules or nodules. Most CBCLs are considered low-grade malignancies with nonaggressive behavior and excellent prognosis; however, the diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, including but not limited to intravascular and leg type; lymphomatoid granulomatosis; and B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma can act more aggressively.1

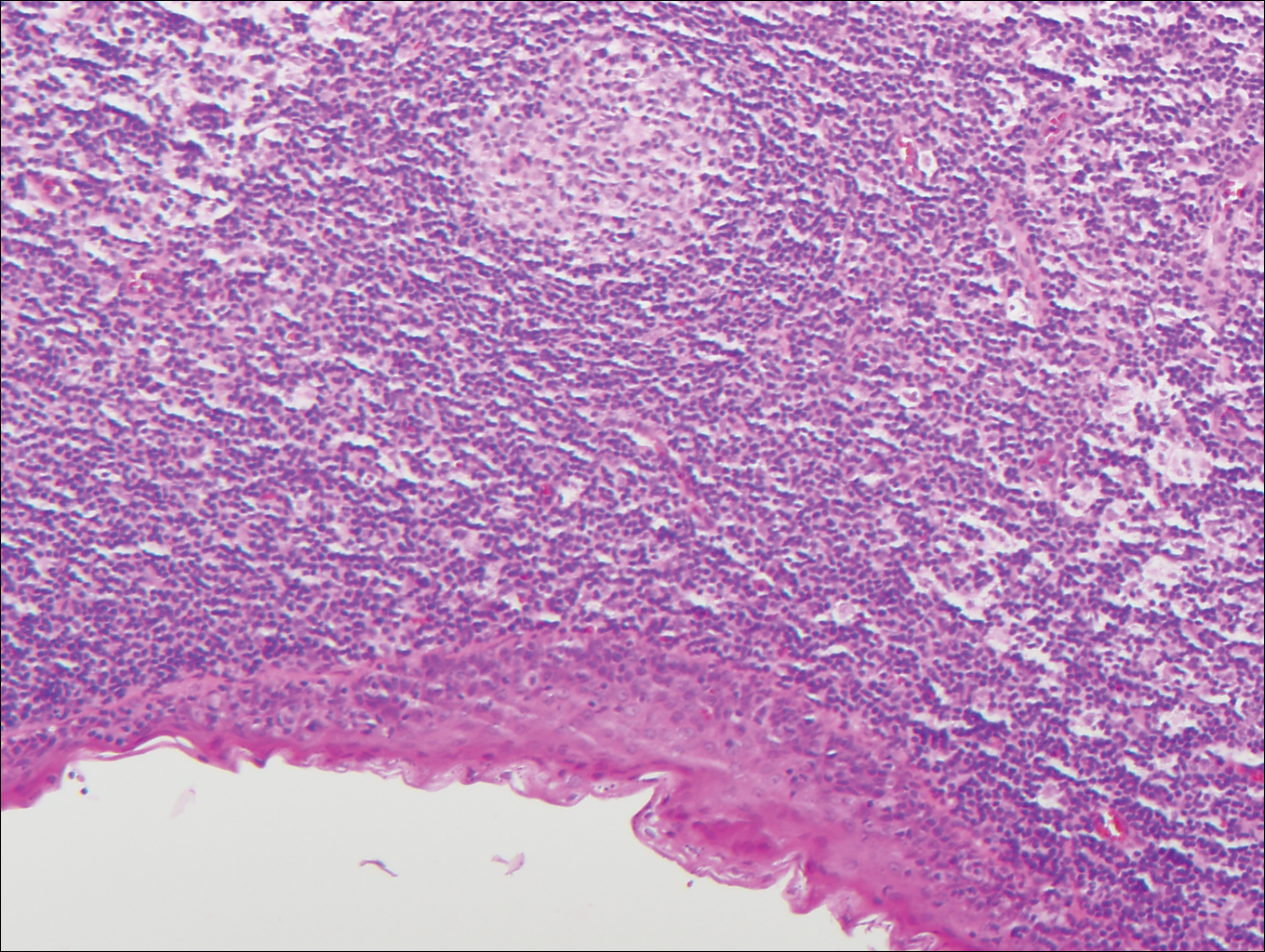

Histopathologic examination of primary CBCL generally reveals a relatively normal epidermis accompanied by a nodular to diffuse monomorphic lymphocytic cellular infiltrate in the dermis that can occasionally extend into the subcutaneous tissue (quiz image). Although not specific for CBCLs, oftentimes there is an acellular portion of the superficial papillary dermis known as a grenz zone that can serve as a histopathologic clue to the diagnosis of a cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. The list of malignant B-cell neoplasms is extensive (eg, cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, intravascular large B-cell lymphoma), and few are seen in the skin.

The most common type of CBCL is marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, which is considered to be a tumor of mucosa-associated (or skin-associated) lymphoid tissue. It is characterized by a monomorphous population of small mature lymphocytes showing characteristics of the B cells of the marginal zone of the lymph node. Some cells have the features of centrocytes/centroblasts (Figure 1) demonstrated by slightly irregular or indented nuclei and generous amounts of cytoplasm. Larger and more pleomorphic cells such as immunoblasts are similarly noted (Figure 1). The quiz image and Figure 1 demonstrate a cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. A histomorphologic clue supporting a diagnosis of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma over reactive lymphoid hyperplasia is a B-cell predominate (B- to T-cell ratio of at least 3 to 1) infiltrate that is comprised of marginal zone-type cells. Immunohistochemistry demonstrating fewer differentiated B cells with light chain restriction may provide additional evidence that supports a clonal and potentially malignant process.

Erythematous to violaceous nodules on the head and neck of older individuals are characteristic of both granuloma faciale and CBCL. Histologically, granuloma faciale is characterized by a dense cellular infiltrate, often with a nodular outline, occupying the mid dermis.2 Granuloma faciale typically spares the immediate subepidermis and hair follicles, forming a grenz zone. The cellular infiltrate is polymorphic and consists of eosinophils and neutrophils with scattered plasma cells, mast cells, and lymphocytes in a vasculocentric distribution, eventually with chronic concentric fibrosis (Figure 2).

Leukemia cutis demonstrates a dermal infiltrate that contains atypical mononuclear cells (myeloblasts and myelocytes)(Figure 3).3 These markedly atypical mononuclear cells can have kidney bean-shaped nuclei and percolate through the dermal collagen, resembling single-file cells. They have increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios and occasionally have prominent nucleoli. Correlation with immunophenotypic and cytochemical studies is required for specific typing of the leukemic infiltrate.

Similar to primary CBCL, lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) consists of erythematous papules or nodules that can occur anywhere on the body. In contrast to CBCL, the lesions of LyP classically self-resolve. However, approximately 10% to 20% of patients develop a malignant lymphoma, with mycosis fungoides, Hodgkin disease, and anaplastic large cell lymphoma being the most commonly associated.

Histologic examination of lesions of LyP classically demonstrates a wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate with variable epidermal changes (Figure 4). The wedge-shaped infiltrate is composed of large atypical cells. Three main types of lesions have been delineated: types A, B, and C. Type A is characterized by an increased number of cells with large vesicular nuclei with clumped chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and pronounced cytoplasm. Reed-Sternberg-like cells with an admixture of inflammatory cells including small lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and eosinophils also are present. Type B neoplastic cells vary in size and feature hyperchromatic, convoluted, or cerebriform nuclei. The infiltrate can be dense and bandlike with fewer cells resembling mycosis fungoides; type B LyP has neoplastic cells, not inflammatory cells. Finally, type C demonstrates solid sheets of large atypical cells resembling anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Immunohistochemically, the atypical cells often are CD4+ and CD8- with variable loss of pan-T-cell antigens. The atypical cells of types A and C express CD30 reactivity.4

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin that usually arises on sun-exposed skin in elderly patients with lesions that histologically and clinically resemble cutaneous lymphoma.5 It classically is composed of small, round to oval, basophilic cells with a vesicular nucleus and multiple small nucleoli. Apoptotic cells and mitoses often are present.6 One key finding that helps to differentiate MCC from lymphoma is the presence of finely dispersed salt-and-pepper chromatin and molded nuclear contour in MCC (Figure 5).

Immunophenotyping is important in the differentiation of these diagnoses. The atypical cells of LyP are positive for CD3, CD4, and CD30 but are negative for CD8. However, in type B LyP, the large CD30+ cells seen in the other types are not commonly seen. In contrast, MCC expresses reactivity with cytokeratins, in particular cytokeratin 20 and CAM5.2, classically in a paranuclear dotlike pattern. In keeping with MCC's neuroendocrine differentiation, the tumor cells will demonstrate reactivity with synaptophysin, chromogranin, and CD56. The immunohistochemistry for leukemia cutis varies depending on the type of leukemia. Acute myelomonocytic leukemia is positive for myeloperoxidase, CD13, CD33, and CD68. The immunophenotype of these marginal zone lymphoma cells is as follows: positive for CD20, CD79a, and Bcl-2; negative for Bcl-6, CD5, CD10, CD23, and cyclin D1 (Bcl-1).7

Primary Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (CBCLs) are a diverse but rare group of cutaneous lymphoproliferative neoplasms that make up approximately 20% of the total number of hematolymphoid neoplasms primary to the skin.1 These lymphomas are comprised of neoplastic B cells in various stages of differentiation. As a whole, they are rare neoplasms that primarily involve the head, neck, trunk, arms, or legs.1 Clinically, patients present with nontender, compressible, solitary, red to violaceous papules or nodules. Most CBCLs are considered low-grade malignancies with nonaggressive behavior and excellent prognosis; however, the diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, including but not limited to intravascular and leg type; lymphomatoid granulomatosis; and B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma can act more aggressively.1

Histopathologic examination of primary CBCL generally reveals a relatively normal epidermis accompanied by a nodular to diffuse monomorphic lymphocytic cellular infiltrate in the dermis that can occasionally extend into the subcutaneous tissue (quiz image). Although not specific for CBCLs, oftentimes there is an acellular portion of the superficial papillary dermis known as a grenz zone that can serve as a histopathologic clue to the diagnosis of a cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. The list of malignant B-cell neoplasms is extensive (eg, cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, intravascular large B-cell lymphoma), and few are seen in the skin.

The most common type of CBCL is marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, which is considered to be a tumor of mucosa-associated (or skin-associated) lymphoid tissue. It is characterized by a monomorphous population of small mature lymphocytes showing characteristics of the B cells of the marginal zone of the lymph node. Some cells have the features of centrocytes/centroblasts (Figure 1) demonstrated by slightly irregular or indented nuclei and generous amounts of cytoplasm. Larger and more pleomorphic cells such as immunoblasts are similarly noted (Figure 1). The quiz image and Figure 1 demonstrate a cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. A histomorphologic clue supporting a diagnosis of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma over reactive lymphoid hyperplasia is a B-cell predominate (B- to T-cell ratio of at least 3 to 1) infiltrate that is comprised of marginal zone-type cells. Immunohistochemistry demonstrating fewer differentiated B cells with light chain restriction may provide additional evidence that supports a clonal and potentially malignant process.

Erythematous to violaceous nodules on the head and neck of older individuals are characteristic of both granuloma faciale and CBCL. Histologically, granuloma faciale is characterized by a dense cellular infiltrate, often with a nodular outline, occupying the mid dermis.2 Granuloma faciale typically spares the immediate subepidermis and hair follicles, forming a grenz zone. The cellular infiltrate is polymorphic and consists of eosinophils and neutrophils with scattered plasma cells, mast cells, and lymphocytes in a vasculocentric distribution, eventually with chronic concentric fibrosis (Figure 2).

Leukemia cutis demonstrates a dermal infiltrate that contains atypical mononuclear cells (myeloblasts and myelocytes)(Figure 3).3 These markedly atypical mononuclear cells can have kidney bean-shaped nuclei and percolate through the dermal collagen, resembling single-file cells. They have increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios and occasionally have prominent nucleoli. Correlation with immunophenotypic and cytochemical studies is required for specific typing of the leukemic infiltrate.

Similar to primary CBCL, lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) consists of erythematous papules or nodules that can occur anywhere on the body. In contrast to CBCL, the lesions of LyP classically self-resolve. However, approximately 10% to 20% of patients develop a malignant lymphoma, with mycosis fungoides, Hodgkin disease, and anaplastic large cell lymphoma being the most commonly associated.

Histologic examination of lesions of LyP classically demonstrates a wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate with variable epidermal changes (Figure 4). The wedge-shaped infiltrate is composed of large atypical cells. Three main types of lesions have been delineated: types A, B, and C. Type A is characterized by an increased number of cells with large vesicular nuclei with clumped chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and pronounced cytoplasm. Reed-Sternberg-like cells with an admixture of inflammatory cells including small lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and eosinophils also are present. Type B neoplastic cells vary in size and feature hyperchromatic, convoluted, or cerebriform nuclei. The infiltrate can be dense and bandlike with fewer cells resembling mycosis fungoides; type B LyP has neoplastic cells, not inflammatory cells. Finally, type C demonstrates solid sheets of large atypical cells resembling anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Immunohistochemically, the atypical cells often are CD4+ and CD8- with variable loss of pan-T-cell antigens. The atypical cells of types A and C express CD30 reactivity.4

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin that usually arises on sun-exposed skin in elderly patients with lesions that histologically and clinically resemble cutaneous lymphoma.5 It classically is composed of small, round to oval, basophilic cells with a vesicular nucleus and multiple small nucleoli. Apoptotic cells and mitoses often are present.6 One key finding that helps to differentiate MCC from lymphoma is the presence of finely dispersed salt-and-pepper chromatin and molded nuclear contour in MCC (Figure 5).

Immunophenotyping is important in the differentiation of these diagnoses. The atypical cells of LyP are positive for CD3, CD4, and CD30 but are negative for CD8. However, in type B LyP, the large CD30+ cells seen in the other types are not commonly seen. In contrast, MCC expresses reactivity with cytokeratins, in particular cytokeratin 20 and CAM5.2, classically in a paranuclear dotlike pattern. In keeping with MCC's neuroendocrine differentiation, the tumor cells will demonstrate reactivity with synaptophysin, chromogranin, and CD56. The immunohistochemistry for leukemia cutis varies depending on the type of leukemia. Acute myelomonocytic leukemia is positive for myeloperoxidase, CD13, CD33, and CD68. The immunophenotype of these marginal zone lymphoma cells is as follows: positive for CD20, CD79a, and Bcl-2; negative for Bcl-6, CD5, CD10, CD23, and cyclin D1 (Bcl-1).7

- Olsen EA. Evaluation, diagnosis, and staging of cutaneous lymphoma. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:643-654.

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Wieser I, Wohlmuth C, Nunez CA, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:319-327.

- Sibley RK, Dehner LP, Rosai J. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell?) carcinoma of the skin: I. a clinicopathologic and ultrastructural study of 43 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:95-108.

- Frigerio B, Capella C, Eusebi V, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: the structure and origin of normal Merkel cells. Histopathology. 1983;7:229-249.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Olsen EA. Evaluation, diagnosis, and staging of cutaneous lymphoma. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:643-654.

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Wieser I, Wohlmuth C, Nunez CA, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:319-327.

- Sibley RK, Dehner LP, Rosai J. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell?) carcinoma of the skin: I. a clinicopathologic and ultrastructural study of 43 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:95-108.

- Frigerio B, Capella C, Eusebi V, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: the structure and origin of normal Merkel cells. Histopathology. 1983;7:229-249.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

An 81-year-old man with a history of hyperthyroidism, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and nonmelanoma skin cancer presented with an erythematous pearly papule on the right lateral chest of 1 year's duration. The patient reported no symptoms of pruritus, bleeding, or burning. He was otherwise asymptomatic, and a review of systems revealed no abnormalities. His current medications included aspirin, benazepril, finasteride, levothyroxine, tamsulosin, warfarin, and alprazolam. He denied any new medications, recent travel, or preceding trauma. He had a history of Agent Orange exposure. Physical examination revealed a 0.4-cm erythematous pearly papule on the right lateral chest. A shave biopsy was obtained.

Progressive Widespread Warty Skin Growths

Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV) is a rare hereditary disorder that predisposes affected individuals to widespread infection with various forms of human papillomavirus (HPV). It is inherited in an autosomal-recessive pattern.1 The first manifestations generally are seen in childhood. The clinical appearance of lesions can vary, at times mimicking other disease processes. Patients can present with flat wartlike papules resembling verruca plana distributed in sun-exposed areas. Another distinct presentation is multiple salmon-colored, hyperpigmented, or hypopigmented macules, papules, or plaques with overlying scale that can resemble tinea versicolor.1,2 A large percentage of patients will go on to develop actinic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma by 40 years of age.2 The malignancies most commonly develop in sun-exposed areas, suggesting UV radiation as an important contributor to development along with HPV infection. Mutations in the EVER1 and EVER2 genes that code for transmembrane proteins on the endoplasmic reticulum that are involved in zinc transport lead to EV. The mutations lead to decreased zinc movement into the cytoplasm, which is thought to play a role in preventing HPV infection. The decreased protection against HPV leads to infections from both common subtypes and those that immunocompetent individuals would be resistant to, namely the β-genus HPV-5, -8, -9 and -20.1,2 Immunosuppressed individuals, such as those with human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS, also are at an increased risk for infection with these HPV subtypes and generally have similar clinical and histological presentations.1 It is important to promote sunscreen use for preventive care in patients with EV due to the increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.

Histologically, the lesions in EV are composed of acanthosis and hyperkeratosis with keratinocytes arranged in clusters.1,3 There is orthokeratosis and parakeratosis.1 Scattered or clustered keratinocytes in the granular layer or upper stratum spinosum appear swollen with foamy blue-gray cytoplasm (quiz image and Figure 1).1,4 The keratinocytes may become atypical and progress to squamous cell carcinoma, particularly in sun-exposed regions. Cell differentiation becomes disorganized and nuclei become enlarged and hyperchromatic.1

Condyloma acuminatum will have pronounced acanthosis and hyperkeratosis with exophytic growth. Rounded parakeratosis is visible. The characteristic cell is the koilocyte, a keratinocyte that has an enlarged nucleus with areas of surrounding clearing, increased dark color in the nucleus, and wrinkled nuclear membrane (Figure 2).1,3 True koilocytes may be rare in condyloma acuminatum.4 Other distinct features include coarse hypergranulosis and a compact stratum corneum.

Herpesvirus lesions typically demonstrate ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes.1 They will become pale and fuse to form multinucleated giant cells, a feature not found in verruca. The nuclei will be slate gray with margination of the chromatin, which can be identified due to its increased basophilic appearance (Figure 3).1,4 Inclusion bodies can be found, but unlike molluscum contagiosum (MC), these bodies are intranuclear as opposed to cytoplasmic.1