User login

It Is What It Is…. For Now.

This issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine addresses an emerging trend in internal medicine graduate medical education: the hospitalist rotation.

In the article, Training Residents in Hospital Medicine: The Hospitalist Elective National Survey (HENS). by Ludwin et al., the authors present a descriptive overview of the composition of hospital medicine rotations, as described by program directors from some of the largest training programs. 1 It can be said for sure that hospital medicine rotations exist: half of the 82 programs that replied to the survey noted that a hospital medicine rotation was already in place. That is where the certainty ends. Although there are common themes across these rotations, there is no one clear definition of such a rotation. Like all good contributions to the medical literature, this study inspires more questions than it answers.

The Mark Twain-inspired cynic would be quick to make an interpretation of the hospital medicine rotation: Is this not just a clever way to coax residents into using their elective time to cover the service needs left over from Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)-mandated shift limits and admission caps? Seventy-one percent of these rotations were involved in “admitting new patients.” And since forty-six percent were tasked with taking hold-over admissions, it is reasonable to surmise that these rotations are playing a role in covering patient care duties left over from traditional ward services.

But is there anything wrong with that? Within the confines of reasonable intensity, caring for more patients usually benefits a resident’s education. And if the resident is learning knowledge, skills and attitudes that are unique from those that are acquired on a traditional ward service, painting the fence for free might not be that bad. The question is: “Does the hospitalist rotation help in the acquisition of those unique knowledge, skills and attitudes?” Although this study alludes to such unique components via its qualitative analysis (ie, more autonomy, co-management of non-medicine services, etc.), it does not fully answer that question. It does, however, inspire the next study: How do residents perceive the unique and additional value (if any) of the hospital medicine rotation?

For the sake of argument, let’s say that residents’ perception of the hospital medicine rotation is one of meaning and value. Does that matter? It is great if they do, but equally important is the question of whether or not hospital medicine rotations are effective in preparing resident graduates for a career in hospital medicine. This study suggests that those who have designed these rotations have tried to anticipate and address this need. Components such as quality, patient safety, co-management, and billing and compliance are all clearly a part of a hospitalist’s practice, and all are elements that have not been traditionally emphasized in residency training. The question is: ”Are these elements the knowledge, skills and attitudes that are most lacking in the residency graduate as he/she enters the practice of hospital medicine?” The unfortunate answer is that we do not know for sure, and this uncertainty has been the Achilles heel of our current residency-training infrastructure. Not unique to hospital medicine, there is simply not a well-defined feedback loop between practice requirements and residency training requirements. A structured and regular gap analysis comparing the residents’ areas of competence at the end of training to what they need in practice, would go a long way in answering questions such as this one, and would most certainly inform the components of a hospital medicine elective going forward.

Even if the components of a hospital medicine rotation are valuable, and even if they do align with what the practice needs, there is still the question of whether a month-long hospital medicine rotation can even come close to closing the gap of what is needed versus what is delivered. One can surmise that the answer to that question is what has extended the “hospital medicine rotation” to the “hospital medicine track,” comprised of a multiple of such rotations. Like all discussions on time-constrained medical education curricula, what will be discarded to make room for these rotations? In thirty-six months of training, there is opportunity cost: every month spent on a hospital medicine elective is a month that could have been spent on something else (rheumatology, nephrology, etc.). Again, this is not unique to hospital medicine; the same could be said of the resident who does too many cardiology electives at the exclusion of learning about endocrinology. It would be overly dramatic to say that devoting a month to a hospital medicine rotation, or any elective for that matter, meaningfully compromises the resident’s overall competence as an internist. It is, instead, a question of degree: an excessive number of these electives would likely compromise the resident’s overall competence. The likelihood of this happening is proportional to the size of the gap between what is required to effectively enter hospital medicine practice and what can be delivered in a month-long hospital medicine rotation. We return, then, to the question: How much hospital medicine training in residency would be required to fully prepare a resident for the current practice of a hospitalist?

Whatever the answer might be, that question takes us to a difficult dilemma that has lurked in the background of residency training for some time now; one that is not at all unique to hospital medicine. Should residency training be “voc-tech” or “liberal arts”? A purist would argue that an understanding and appreciation of all things not hospital medicine is what truly makes for the great hospitalist. An understanding of primary care, for example, would seem to optimize a hospitalist’s performance with respect to transitions of care. Adding to the gravity of such an argument is that residency might be the last time to acquire such “non-hospital-medicine” experiences.

Noting that the practice of hospital medicine being so dynamic and heterogeneous, the realist might pile on by saying that it is simply impossible to fully prepare a resident for the actual practice of hospital medicine. Further, many of these skills might be impossible to fully master outside of being fully immersed in the practice of hospital medicine (i.e., billing and coding). The best that can be done is to set a solid foundation that would enable them to learn further as they practice; there will be opportunities to learn the specific components of the field later on.

On the other hand, it is hard to justify residency training if the graduate is unprepared to practice, and without the fundamental knowledge, skills and attitudes specific to their career as they practice. For example, it is reasonable to suspect that a new hospitalist who has had no prior training in quality improvement will, because of the inertia that comes with engaging in any new and foreign skill, find it much harder to engage in quality improvement as a part of her career. It is also worth considering the role that mastery, autonomy and purpose have upon the overall residency experience. Engaging in electives that have a palpable purpose for the resident’s eventual career, and engender an opportunity to begin developing a sense of mastery in that field, could be an effective antidote in mitigating the burn-out that is far too common in residency training today.

For residents engaged in a future practice of hospital medicine, the hospital medicine rotation seems like a promising way out of this dilemma. An effectively designed elective approach could enable maintaining a core foundational education, while getting an early start on the specific components necessary for a promising career in hospital medicine. The operative words, of course, are “effectively designed.” What exactly does that entail? That is why this study is so important; even if we do not fully know what it should look like, we now have our first glimpse of what it is.

Disclosures

The author has nothing to disclose.

1. Ludwin S, Harrison J, Ranji S, et al. Training Residents in Hospital Medicine: The Hospitalist Elective National Survey (HENS). J Hosp Med. 2018;13(9):623-625. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2952. PubMed

This issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine addresses an emerging trend in internal medicine graduate medical education: the hospitalist rotation.

In the article, Training Residents in Hospital Medicine: The Hospitalist Elective National Survey (HENS). by Ludwin et al., the authors present a descriptive overview of the composition of hospital medicine rotations, as described by program directors from some of the largest training programs. 1 It can be said for sure that hospital medicine rotations exist: half of the 82 programs that replied to the survey noted that a hospital medicine rotation was already in place. That is where the certainty ends. Although there are common themes across these rotations, there is no one clear definition of such a rotation. Like all good contributions to the medical literature, this study inspires more questions than it answers.

The Mark Twain-inspired cynic would be quick to make an interpretation of the hospital medicine rotation: Is this not just a clever way to coax residents into using their elective time to cover the service needs left over from Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)-mandated shift limits and admission caps? Seventy-one percent of these rotations were involved in “admitting new patients.” And since forty-six percent were tasked with taking hold-over admissions, it is reasonable to surmise that these rotations are playing a role in covering patient care duties left over from traditional ward services.

But is there anything wrong with that? Within the confines of reasonable intensity, caring for more patients usually benefits a resident’s education. And if the resident is learning knowledge, skills and attitudes that are unique from those that are acquired on a traditional ward service, painting the fence for free might not be that bad. The question is: “Does the hospitalist rotation help in the acquisition of those unique knowledge, skills and attitudes?” Although this study alludes to such unique components via its qualitative analysis (ie, more autonomy, co-management of non-medicine services, etc.), it does not fully answer that question. It does, however, inspire the next study: How do residents perceive the unique and additional value (if any) of the hospital medicine rotation?

For the sake of argument, let’s say that residents’ perception of the hospital medicine rotation is one of meaning and value. Does that matter? It is great if they do, but equally important is the question of whether or not hospital medicine rotations are effective in preparing resident graduates for a career in hospital medicine. This study suggests that those who have designed these rotations have tried to anticipate and address this need. Components such as quality, patient safety, co-management, and billing and compliance are all clearly a part of a hospitalist’s practice, and all are elements that have not been traditionally emphasized in residency training. The question is: ”Are these elements the knowledge, skills and attitudes that are most lacking in the residency graduate as he/she enters the practice of hospital medicine?” The unfortunate answer is that we do not know for sure, and this uncertainty has been the Achilles heel of our current residency-training infrastructure. Not unique to hospital medicine, there is simply not a well-defined feedback loop between practice requirements and residency training requirements. A structured and regular gap analysis comparing the residents’ areas of competence at the end of training to what they need in practice, would go a long way in answering questions such as this one, and would most certainly inform the components of a hospital medicine elective going forward.

Even if the components of a hospital medicine rotation are valuable, and even if they do align with what the practice needs, there is still the question of whether a month-long hospital medicine rotation can even come close to closing the gap of what is needed versus what is delivered. One can surmise that the answer to that question is what has extended the “hospital medicine rotation” to the “hospital medicine track,” comprised of a multiple of such rotations. Like all discussions on time-constrained medical education curricula, what will be discarded to make room for these rotations? In thirty-six months of training, there is opportunity cost: every month spent on a hospital medicine elective is a month that could have been spent on something else (rheumatology, nephrology, etc.). Again, this is not unique to hospital medicine; the same could be said of the resident who does too many cardiology electives at the exclusion of learning about endocrinology. It would be overly dramatic to say that devoting a month to a hospital medicine rotation, or any elective for that matter, meaningfully compromises the resident’s overall competence as an internist. It is, instead, a question of degree: an excessive number of these electives would likely compromise the resident’s overall competence. The likelihood of this happening is proportional to the size of the gap between what is required to effectively enter hospital medicine practice and what can be delivered in a month-long hospital medicine rotation. We return, then, to the question: How much hospital medicine training in residency would be required to fully prepare a resident for the current practice of a hospitalist?

Whatever the answer might be, that question takes us to a difficult dilemma that has lurked in the background of residency training for some time now; one that is not at all unique to hospital medicine. Should residency training be “voc-tech” or “liberal arts”? A purist would argue that an understanding and appreciation of all things not hospital medicine is what truly makes for the great hospitalist. An understanding of primary care, for example, would seem to optimize a hospitalist’s performance with respect to transitions of care. Adding to the gravity of such an argument is that residency might be the last time to acquire such “non-hospital-medicine” experiences.

Noting that the practice of hospital medicine being so dynamic and heterogeneous, the realist might pile on by saying that it is simply impossible to fully prepare a resident for the actual practice of hospital medicine. Further, many of these skills might be impossible to fully master outside of being fully immersed in the practice of hospital medicine (i.e., billing and coding). The best that can be done is to set a solid foundation that would enable them to learn further as they practice; there will be opportunities to learn the specific components of the field later on.

On the other hand, it is hard to justify residency training if the graduate is unprepared to practice, and without the fundamental knowledge, skills and attitudes specific to their career as they practice. For example, it is reasonable to suspect that a new hospitalist who has had no prior training in quality improvement will, because of the inertia that comes with engaging in any new and foreign skill, find it much harder to engage in quality improvement as a part of her career. It is also worth considering the role that mastery, autonomy and purpose have upon the overall residency experience. Engaging in electives that have a palpable purpose for the resident’s eventual career, and engender an opportunity to begin developing a sense of mastery in that field, could be an effective antidote in mitigating the burn-out that is far too common in residency training today.

For residents engaged in a future practice of hospital medicine, the hospital medicine rotation seems like a promising way out of this dilemma. An effectively designed elective approach could enable maintaining a core foundational education, while getting an early start on the specific components necessary for a promising career in hospital medicine. The operative words, of course, are “effectively designed.” What exactly does that entail? That is why this study is so important; even if we do not fully know what it should look like, we now have our first glimpse of what it is.

Disclosures

The author has nothing to disclose.

This issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine addresses an emerging trend in internal medicine graduate medical education: the hospitalist rotation.

In the article, Training Residents in Hospital Medicine: The Hospitalist Elective National Survey (HENS). by Ludwin et al., the authors present a descriptive overview of the composition of hospital medicine rotations, as described by program directors from some of the largest training programs. 1 It can be said for sure that hospital medicine rotations exist: half of the 82 programs that replied to the survey noted that a hospital medicine rotation was already in place. That is where the certainty ends. Although there are common themes across these rotations, there is no one clear definition of such a rotation. Like all good contributions to the medical literature, this study inspires more questions than it answers.

The Mark Twain-inspired cynic would be quick to make an interpretation of the hospital medicine rotation: Is this not just a clever way to coax residents into using their elective time to cover the service needs left over from Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)-mandated shift limits and admission caps? Seventy-one percent of these rotations were involved in “admitting new patients.” And since forty-six percent were tasked with taking hold-over admissions, it is reasonable to surmise that these rotations are playing a role in covering patient care duties left over from traditional ward services.

But is there anything wrong with that? Within the confines of reasonable intensity, caring for more patients usually benefits a resident’s education. And if the resident is learning knowledge, skills and attitudes that are unique from those that are acquired on a traditional ward service, painting the fence for free might not be that bad. The question is: “Does the hospitalist rotation help in the acquisition of those unique knowledge, skills and attitudes?” Although this study alludes to such unique components via its qualitative analysis (ie, more autonomy, co-management of non-medicine services, etc.), it does not fully answer that question. It does, however, inspire the next study: How do residents perceive the unique and additional value (if any) of the hospital medicine rotation?

For the sake of argument, let’s say that residents’ perception of the hospital medicine rotation is one of meaning and value. Does that matter? It is great if they do, but equally important is the question of whether or not hospital medicine rotations are effective in preparing resident graduates for a career in hospital medicine. This study suggests that those who have designed these rotations have tried to anticipate and address this need. Components such as quality, patient safety, co-management, and billing and compliance are all clearly a part of a hospitalist’s practice, and all are elements that have not been traditionally emphasized in residency training. The question is: ”Are these elements the knowledge, skills and attitudes that are most lacking in the residency graduate as he/she enters the practice of hospital medicine?” The unfortunate answer is that we do not know for sure, and this uncertainty has been the Achilles heel of our current residency-training infrastructure. Not unique to hospital medicine, there is simply not a well-defined feedback loop between practice requirements and residency training requirements. A structured and regular gap analysis comparing the residents’ areas of competence at the end of training to what they need in practice, would go a long way in answering questions such as this one, and would most certainly inform the components of a hospital medicine elective going forward.

Even if the components of a hospital medicine rotation are valuable, and even if they do align with what the practice needs, there is still the question of whether a month-long hospital medicine rotation can even come close to closing the gap of what is needed versus what is delivered. One can surmise that the answer to that question is what has extended the “hospital medicine rotation” to the “hospital medicine track,” comprised of a multiple of such rotations. Like all discussions on time-constrained medical education curricula, what will be discarded to make room for these rotations? In thirty-six months of training, there is opportunity cost: every month spent on a hospital medicine elective is a month that could have been spent on something else (rheumatology, nephrology, etc.). Again, this is not unique to hospital medicine; the same could be said of the resident who does too many cardiology electives at the exclusion of learning about endocrinology. It would be overly dramatic to say that devoting a month to a hospital medicine rotation, or any elective for that matter, meaningfully compromises the resident’s overall competence as an internist. It is, instead, a question of degree: an excessive number of these electives would likely compromise the resident’s overall competence. The likelihood of this happening is proportional to the size of the gap between what is required to effectively enter hospital medicine practice and what can be delivered in a month-long hospital medicine rotation. We return, then, to the question: How much hospital medicine training in residency would be required to fully prepare a resident for the current practice of a hospitalist?

Whatever the answer might be, that question takes us to a difficult dilemma that has lurked in the background of residency training for some time now; one that is not at all unique to hospital medicine. Should residency training be “voc-tech” or “liberal arts”? A purist would argue that an understanding and appreciation of all things not hospital medicine is what truly makes for the great hospitalist. An understanding of primary care, for example, would seem to optimize a hospitalist’s performance with respect to transitions of care. Adding to the gravity of such an argument is that residency might be the last time to acquire such “non-hospital-medicine” experiences.

Noting that the practice of hospital medicine being so dynamic and heterogeneous, the realist might pile on by saying that it is simply impossible to fully prepare a resident for the actual practice of hospital medicine. Further, many of these skills might be impossible to fully master outside of being fully immersed in the practice of hospital medicine (i.e., billing and coding). The best that can be done is to set a solid foundation that would enable them to learn further as they practice; there will be opportunities to learn the specific components of the field later on.

On the other hand, it is hard to justify residency training if the graduate is unprepared to practice, and without the fundamental knowledge, skills and attitudes specific to their career as they practice. For example, it is reasonable to suspect that a new hospitalist who has had no prior training in quality improvement will, because of the inertia that comes with engaging in any new and foreign skill, find it much harder to engage in quality improvement as a part of her career. It is also worth considering the role that mastery, autonomy and purpose have upon the overall residency experience. Engaging in electives that have a palpable purpose for the resident’s eventual career, and engender an opportunity to begin developing a sense of mastery in that field, could be an effective antidote in mitigating the burn-out that is far too common in residency training today.

For residents engaged in a future practice of hospital medicine, the hospital medicine rotation seems like a promising way out of this dilemma. An effectively designed elective approach could enable maintaining a core foundational education, while getting an early start on the specific components necessary for a promising career in hospital medicine. The operative words, of course, are “effectively designed.” What exactly does that entail? That is why this study is so important; even if we do not fully know what it should look like, we now have our first glimpse of what it is.

Disclosures

The author has nothing to disclose.

1. Ludwin S, Harrison J, Ranji S, et al. Training Residents in Hospital Medicine: The Hospitalist Elective National Survey (HENS). J Hosp Med. 2018;13(9):623-625. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2952. PubMed

1. Ludwin S, Harrison J, Ranji S, et al. Training Residents in Hospital Medicine: The Hospitalist Elective National Survey (HENS). J Hosp Med. 2018;13(9):623-625. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2952. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Healthy Skepticism and Due Process

For more than 75 years, pediatrics has sought sound guidelines for prescribing maintenance intravenous fluid (mIVF) for children. In 1957, Holliday and Segar (H&S)1 introduced a breakthrough method for estimating mIVF needs. Their guidelines for calculating free-water and electrolyte needs for mIVF gained wide-spread acceptance and became the standard of care for decades.

Over the last two decades, awareness has grown around the occurrence of rare, life-threatening hyponatremic conditions, especially hyponatremic encephalopathy, in hospitalized children. Concomitantly, an increasing awareness shows that serum levels of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) are often elevated in sick children and triggered by nonosmotic conditions (pain, vomiting, perioperative state, meningitis, and pulmonary disease). This situation led to heightened concern of clinicians and investigators who assumed that hospitalized patients would exhibit reduced tolerance for hypotonic mIVF the mainstay of the H&S method. The possibility that the H&S method could be a significant contributing factor to the development of hyponatremic encephalopathy in hospitalized children became a research topic. This research speculated that even mildly reduced serum sodium levels might be a marker for the much rarer condition of hyponatremic encephalopathy. A number of hospitalists also switched from quarter-normal to half-normal saline in mIVF.

The substitution of hypotonic fluids with isotonic fluids (eg, 0.9% normal saline or lactated Ringer’s) is the current front-runner alternative to increase sodium delivery. The hypothesis is that the delivery of additional sodium, while maintaining the same H&S method volume/rate of fluid delivery, will protect against life-threatening hyponatremic events.

The challenge we face is whether we are moving from mIVF therapy, which features a long track record of success and an excellent safety profile, to a safer or more effective therapeutic approach. We should consider the burden of proof which should be satisfied to support creating new guidelines which center on changing from hypotonic mIVF to isotonic mIVF.

Is there sufficient scientific proof that isotonic mIVF is safer and/or more effective than hypotonic mIVF in preventing life-threatening hyponatremic events?

Is there compelling biologic plausibility for this change for patients with risk factors that are associated with elevated serum ADH levels?

What is the magnitude of the benefit?

What is the magnitude of unintended harms?

We offer our perspective on each of these questions.

The primary difficulty with addressing the adverse events of catastrophic hyponatremia (encephalopathy, seizures, cerebral edema, and death) is their rarity. The events stand out when they occur, prompting mortality and morbidity (M&M) conferences to blunder into action. But that action is not evidence-based, even if a rationale mentions a meta-analysis, because the rationales lack estimates of the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one catastrophic event. Estimates of the NNT to prevent mild hypernatremia are not useful. Furthermore, estimates of the number needed to harm (NNH) via unintended consequences of infusing extra sodium chloride are unavailable. True evidence-based medicine (EBM) is rigorous in requiring NNT and NNH. Anything less is considered M&M-based medicine masquerading as EBM.

No technical jargon distinguishes the profound and catastrophic events from the common, mild hyponatremia frequently observed in ill toddlers upon admission. As an analogy, in dealing with fever, astute pediatricians recognize that a moderate fever of 103.4 °F is not halfway to a heatstroke of 108 °F. Fever is not a near miss for heatstroke. Physicians do not recommend acetaminophen to prevent heatstroke, although many parents act that way.

No published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed the incidence of these catastrophic hyponatremic events. In the meta-analysis of 10 disparate and uncoordinated trials in 2014,2 no serious adverse events were noted among the 1,000 patients involved. Since then, newer RCTs have added another 1,000 patients to the meta-analysis pool, but still no serious adverse event has been observed.

The H&S method features 60 years of proven safety and remains the appropriate estimate when composing long-term parenteral nutrition. No recommendation is perfect for all situations. Many hospitalized children will exhibit an increased level of ADH. A very small fraction of those children will present a sufficiently elevated ADH level long enough to risk creating profound hyponatremia. An approximation is in the order of magnitude of 1 per 100,000 pediatric medical admissions and 1 per 10,000 postoperative patients. With 3 million pediatric admissions yearly in the United States, such numbers mean that large children’s hospitals might see one or two catastrophic adverse events each decade due to mIVF in previously healthy children. The risk in chronically ill children and in the ICU will be higher. The potential for causing unintended greater harm amongst the other millions of patients is high, requiring application of the precautionary principle.

Thus, EBM and RCTs are poor methodologies for quality improvement of this issue. Assigning surrogate measures, such as moderate hyponatremia or even mild hyponatremia, to increase sensitivity and incidence for research purposes lacks a validated scientific link to the much rarer profound hyponatremic events. The resulting nonvalid extrapolation is precisely what true EBM seeks to avoid. A serum sodium of 132 mEq/L is not a near miss. The NNT to prevent the catastrophic events is unknown. Indeed, no paper advocating adoption of isotonic mIVF has even ventured an approximation.

The RCTs are also, therefore, underpowered to identify harms from using normal saline as a maintenance fluid. A few studies mention hypernatremia, but serum sodium is not a statistical variable. Renal physiology predicts that kidneys can easily handle excess infused sodium and can protect against hypernatremia. However, the extra chloride load risks creating hyperchloremic acidosis, particularly when a patient with respiratory insufficiency cannot compensate by lowering pCO2 through increased minute ventilation. Edema is another risk. Both respiratory insufficiency and edema already occur more frequently (by orders of magnitude) in hospitalized patients on any mIVF than the profound hyponatremia events in hospitalized patients on hypotonic mIVF. For instance, about 1% of hospitalized infants with bronchiolitis are ventilated for respiratory failure. If hyperchloremic acidosis unintentionally caused by isotonic mIVF slightly increases the frequency of intubation, then such result far outweighs any benefit from reducing catastrophic hyponatremic events. Difficulty will also arise in detecting this unintended increase in the rate of intubation compared with the current background frequency. Detecting these unintended harms becomes impossible if the RCT is underpowered by 100-fold due to utilizing a surrogate measure, such as serum sodium <135 mEq/L, as the dependent variable instead of measuring serious hyponatremic adverse events.

All claims that “no evidence of harm” was found from using normal saline as mIVF are type II statistical errors. There is little chance of detecting any harm with a grossly underpowered study or a meta-analysis of 10 such studies. Simply put, EBM is impossible to use for events that occur less than 1 per 10,000 patients using RCTs with 1,000 patients. No usable safety data are available for normal saline as mIVF in any published RCT. As the RCTs are underpowered, one should rely on science to guide therapy, rather than on invalid statistics.

Using the precautionary principle, hypothetically, adding extra sodium chloride to maintenance fluids should be considered in the same manner as adding any other drug. Based on the current evidence, would the Food and Drug Administration approve the drug intravenous sodium chloride for the prevention of hyponatremia induced by maintenance fluids? An increasing evidence of a minimal beneficial effect is observed, but no evidence of safety nor physiology is available. A new drug application for using normal saline as a default maintenance fluid would be soundly rejected by an FDA panel, just as it has been rejected by the majority of pediatric hospitalists throughout the past 15 years since the idea was proposed in 2003.

With the lack of compelling statistical evidence to guide practice, clinicians often rely on biologic plausibility. Relatively recent studies have revealed that many sick children develop elevated blood levels of ADH due to nonosmotic and nonhemodynamic triggers. Fortunately, we also possess a strong body of knowledge around management of children with syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH). We understand that elevated levels of ADH in the blood causes an increase in the resorption of free water from the renal collecting tubules. No increase in loss of renal sodium nor chloride is associated with this hormonal influence. The resultant hyponatremia is due to excess free-water retention and not the excess loss of sodium or chloride. To manage this condition, patients are not given a salt shaker and then allowed to drink ad libitum. The standard and well-accepted management of patients with SIADH is the restriction of free-water intake because this step addresses the dysfunctional renal process. Administering sodium chloride to a child with SIADH might possibly slow down the progression of hyponatremia but would also expand the total fluid volumes of the patient and would indirectly deal with a problem that could be addressed directly.

Understandably, in an intensive care setting, when hemodynamics is dicey, and when fluid-restriction could risk hypovolemia, employing a volume-expanding solution for mIVF therapy might be reasonable. However, in an ICU setting, SIADH is routinely treated with free-water restriction, and careful calculations of an individual patient’s fluid and electrolyte losses and needs are made.

In conclusion, we recognize the motivation for questioning the H&S method for mIVF as our field surveilles more than a half-century of accumulated experience with this method and the advances in our understanding of physiology and pathophysiology. However, we believe that the current body of evidence fails to substantiate the proposed recommendations.3 The avoidance of laboratory-detectable decreases in serum sodium levels is an unproven marker for the development of life-threatening hyponatremic events. Concerns for untoward effects (eg, excessive volume expansion and effects of hyperchloremia toward acidosis) and the exploration of alternative approaches (eg, modifications in volumes/rates of fluid delivery) have been inadequately explored. The proposed changes in practice may provide no mitigation in the rare events we hope to avoid, may fail to serve all subpopulations within the proposed scope of patients, and will likely

Disclosures

Dr. Powell and Dr. Zaoutis have nothing to disclose.

1. Holliday MA, Segar WE. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics 1957;19(5):823-832. PubMed

2. Wang J, Xu E, Xiao Y. Isotonic versus hypotonic maintenance IV fluids in hospitalized children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2014;133(1):105-113. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2041. PubMed

3. Hall AM, Ayus JC, Moritz ML. The default use of hypotonic maintenance intravenous fluids in pediatrics. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(9)637-640. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3040. PubMed

For more than 75 years, pediatrics has sought sound guidelines for prescribing maintenance intravenous fluid (mIVF) for children. In 1957, Holliday and Segar (H&S)1 introduced a breakthrough method for estimating mIVF needs. Their guidelines for calculating free-water and electrolyte needs for mIVF gained wide-spread acceptance and became the standard of care for decades.

Over the last two decades, awareness has grown around the occurrence of rare, life-threatening hyponatremic conditions, especially hyponatremic encephalopathy, in hospitalized children. Concomitantly, an increasing awareness shows that serum levels of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) are often elevated in sick children and triggered by nonosmotic conditions (pain, vomiting, perioperative state, meningitis, and pulmonary disease). This situation led to heightened concern of clinicians and investigators who assumed that hospitalized patients would exhibit reduced tolerance for hypotonic mIVF the mainstay of the H&S method. The possibility that the H&S method could be a significant contributing factor to the development of hyponatremic encephalopathy in hospitalized children became a research topic. This research speculated that even mildly reduced serum sodium levels might be a marker for the much rarer condition of hyponatremic encephalopathy. A number of hospitalists also switched from quarter-normal to half-normal saline in mIVF.

The substitution of hypotonic fluids with isotonic fluids (eg, 0.9% normal saline or lactated Ringer’s) is the current front-runner alternative to increase sodium delivery. The hypothesis is that the delivery of additional sodium, while maintaining the same H&S method volume/rate of fluid delivery, will protect against life-threatening hyponatremic events.

The challenge we face is whether we are moving from mIVF therapy, which features a long track record of success and an excellent safety profile, to a safer or more effective therapeutic approach. We should consider the burden of proof which should be satisfied to support creating new guidelines which center on changing from hypotonic mIVF to isotonic mIVF.

Is there sufficient scientific proof that isotonic mIVF is safer and/or more effective than hypotonic mIVF in preventing life-threatening hyponatremic events?

Is there compelling biologic plausibility for this change for patients with risk factors that are associated with elevated serum ADH levels?

What is the magnitude of the benefit?

What is the magnitude of unintended harms?

We offer our perspective on each of these questions.

The primary difficulty with addressing the adverse events of catastrophic hyponatremia (encephalopathy, seizures, cerebral edema, and death) is their rarity. The events stand out when they occur, prompting mortality and morbidity (M&M) conferences to blunder into action. But that action is not evidence-based, even if a rationale mentions a meta-analysis, because the rationales lack estimates of the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one catastrophic event. Estimates of the NNT to prevent mild hypernatremia are not useful. Furthermore, estimates of the number needed to harm (NNH) via unintended consequences of infusing extra sodium chloride are unavailable. True evidence-based medicine (EBM) is rigorous in requiring NNT and NNH. Anything less is considered M&M-based medicine masquerading as EBM.

No technical jargon distinguishes the profound and catastrophic events from the common, mild hyponatremia frequently observed in ill toddlers upon admission. As an analogy, in dealing with fever, astute pediatricians recognize that a moderate fever of 103.4 °F is not halfway to a heatstroke of 108 °F. Fever is not a near miss for heatstroke. Physicians do not recommend acetaminophen to prevent heatstroke, although many parents act that way.

No published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed the incidence of these catastrophic hyponatremic events. In the meta-analysis of 10 disparate and uncoordinated trials in 2014,2 no serious adverse events were noted among the 1,000 patients involved. Since then, newer RCTs have added another 1,000 patients to the meta-analysis pool, but still no serious adverse event has been observed.

The H&S method features 60 years of proven safety and remains the appropriate estimate when composing long-term parenteral nutrition. No recommendation is perfect for all situations. Many hospitalized children will exhibit an increased level of ADH. A very small fraction of those children will present a sufficiently elevated ADH level long enough to risk creating profound hyponatremia. An approximation is in the order of magnitude of 1 per 100,000 pediatric medical admissions and 1 per 10,000 postoperative patients. With 3 million pediatric admissions yearly in the United States, such numbers mean that large children’s hospitals might see one or two catastrophic adverse events each decade due to mIVF in previously healthy children. The risk in chronically ill children and in the ICU will be higher. The potential for causing unintended greater harm amongst the other millions of patients is high, requiring application of the precautionary principle.

Thus, EBM and RCTs are poor methodologies for quality improvement of this issue. Assigning surrogate measures, such as moderate hyponatremia or even mild hyponatremia, to increase sensitivity and incidence for research purposes lacks a validated scientific link to the much rarer profound hyponatremic events. The resulting nonvalid extrapolation is precisely what true EBM seeks to avoid. A serum sodium of 132 mEq/L is not a near miss. The NNT to prevent the catastrophic events is unknown. Indeed, no paper advocating adoption of isotonic mIVF has even ventured an approximation.

The RCTs are also, therefore, underpowered to identify harms from using normal saline as a maintenance fluid. A few studies mention hypernatremia, but serum sodium is not a statistical variable. Renal physiology predicts that kidneys can easily handle excess infused sodium and can protect against hypernatremia. However, the extra chloride load risks creating hyperchloremic acidosis, particularly when a patient with respiratory insufficiency cannot compensate by lowering pCO2 through increased minute ventilation. Edema is another risk. Both respiratory insufficiency and edema already occur more frequently (by orders of magnitude) in hospitalized patients on any mIVF than the profound hyponatremia events in hospitalized patients on hypotonic mIVF. For instance, about 1% of hospitalized infants with bronchiolitis are ventilated for respiratory failure. If hyperchloremic acidosis unintentionally caused by isotonic mIVF slightly increases the frequency of intubation, then such result far outweighs any benefit from reducing catastrophic hyponatremic events. Difficulty will also arise in detecting this unintended increase in the rate of intubation compared with the current background frequency. Detecting these unintended harms becomes impossible if the RCT is underpowered by 100-fold due to utilizing a surrogate measure, such as serum sodium <135 mEq/L, as the dependent variable instead of measuring serious hyponatremic adverse events.

All claims that “no evidence of harm” was found from using normal saline as mIVF are type II statistical errors. There is little chance of detecting any harm with a grossly underpowered study or a meta-analysis of 10 such studies. Simply put, EBM is impossible to use for events that occur less than 1 per 10,000 patients using RCTs with 1,000 patients. No usable safety data are available for normal saline as mIVF in any published RCT. As the RCTs are underpowered, one should rely on science to guide therapy, rather than on invalid statistics.

Using the precautionary principle, hypothetically, adding extra sodium chloride to maintenance fluids should be considered in the same manner as adding any other drug. Based on the current evidence, would the Food and Drug Administration approve the drug intravenous sodium chloride for the prevention of hyponatremia induced by maintenance fluids? An increasing evidence of a minimal beneficial effect is observed, but no evidence of safety nor physiology is available. A new drug application for using normal saline as a default maintenance fluid would be soundly rejected by an FDA panel, just as it has been rejected by the majority of pediatric hospitalists throughout the past 15 years since the idea was proposed in 2003.

With the lack of compelling statistical evidence to guide practice, clinicians often rely on biologic plausibility. Relatively recent studies have revealed that many sick children develop elevated blood levels of ADH due to nonosmotic and nonhemodynamic triggers. Fortunately, we also possess a strong body of knowledge around management of children with syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH). We understand that elevated levels of ADH in the blood causes an increase in the resorption of free water from the renal collecting tubules. No increase in loss of renal sodium nor chloride is associated with this hormonal influence. The resultant hyponatremia is due to excess free-water retention and not the excess loss of sodium or chloride. To manage this condition, patients are not given a salt shaker and then allowed to drink ad libitum. The standard and well-accepted management of patients with SIADH is the restriction of free-water intake because this step addresses the dysfunctional renal process. Administering sodium chloride to a child with SIADH might possibly slow down the progression of hyponatremia but would also expand the total fluid volumes of the patient and would indirectly deal with a problem that could be addressed directly.

Understandably, in an intensive care setting, when hemodynamics is dicey, and when fluid-restriction could risk hypovolemia, employing a volume-expanding solution for mIVF therapy might be reasonable. However, in an ICU setting, SIADH is routinely treated with free-water restriction, and careful calculations of an individual patient’s fluid and electrolyte losses and needs are made.

In conclusion, we recognize the motivation for questioning the H&S method for mIVF as our field surveilles more than a half-century of accumulated experience with this method and the advances in our understanding of physiology and pathophysiology. However, we believe that the current body of evidence fails to substantiate the proposed recommendations.3 The avoidance of laboratory-detectable decreases in serum sodium levels is an unproven marker for the development of life-threatening hyponatremic events. Concerns for untoward effects (eg, excessive volume expansion and effects of hyperchloremia toward acidosis) and the exploration of alternative approaches (eg, modifications in volumes/rates of fluid delivery) have been inadequately explored. The proposed changes in practice may provide no mitigation in the rare events we hope to avoid, may fail to serve all subpopulations within the proposed scope of patients, and will likely

Disclosures

Dr. Powell and Dr. Zaoutis have nothing to disclose.

For more than 75 years, pediatrics has sought sound guidelines for prescribing maintenance intravenous fluid (mIVF) for children. In 1957, Holliday and Segar (H&S)1 introduced a breakthrough method for estimating mIVF needs. Their guidelines for calculating free-water and electrolyte needs for mIVF gained wide-spread acceptance and became the standard of care for decades.

Over the last two decades, awareness has grown around the occurrence of rare, life-threatening hyponatremic conditions, especially hyponatremic encephalopathy, in hospitalized children. Concomitantly, an increasing awareness shows that serum levels of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) are often elevated in sick children and triggered by nonosmotic conditions (pain, vomiting, perioperative state, meningitis, and pulmonary disease). This situation led to heightened concern of clinicians and investigators who assumed that hospitalized patients would exhibit reduced tolerance for hypotonic mIVF the mainstay of the H&S method. The possibility that the H&S method could be a significant contributing factor to the development of hyponatremic encephalopathy in hospitalized children became a research topic. This research speculated that even mildly reduced serum sodium levels might be a marker for the much rarer condition of hyponatremic encephalopathy. A number of hospitalists also switched from quarter-normal to half-normal saline in mIVF.

The substitution of hypotonic fluids with isotonic fluids (eg, 0.9% normal saline or lactated Ringer’s) is the current front-runner alternative to increase sodium delivery. The hypothesis is that the delivery of additional sodium, while maintaining the same H&S method volume/rate of fluid delivery, will protect against life-threatening hyponatremic events.

The challenge we face is whether we are moving from mIVF therapy, which features a long track record of success and an excellent safety profile, to a safer or more effective therapeutic approach. We should consider the burden of proof which should be satisfied to support creating new guidelines which center on changing from hypotonic mIVF to isotonic mIVF.

Is there sufficient scientific proof that isotonic mIVF is safer and/or more effective than hypotonic mIVF in preventing life-threatening hyponatremic events?

Is there compelling biologic plausibility for this change for patients with risk factors that are associated with elevated serum ADH levels?

What is the magnitude of the benefit?

What is the magnitude of unintended harms?

We offer our perspective on each of these questions.

The primary difficulty with addressing the adverse events of catastrophic hyponatremia (encephalopathy, seizures, cerebral edema, and death) is their rarity. The events stand out when they occur, prompting mortality and morbidity (M&M) conferences to blunder into action. But that action is not evidence-based, even if a rationale mentions a meta-analysis, because the rationales lack estimates of the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one catastrophic event. Estimates of the NNT to prevent mild hypernatremia are not useful. Furthermore, estimates of the number needed to harm (NNH) via unintended consequences of infusing extra sodium chloride are unavailable. True evidence-based medicine (EBM) is rigorous in requiring NNT and NNH. Anything less is considered M&M-based medicine masquerading as EBM.

No technical jargon distinguishes the profound and catastrophic events from the common, mild hyponatremia frequently observed in ill toddlers upon admission. As an analogy, in dealing with fever, astute pediatricians recognize that a moderate fever of 103.4 °F is not halfway to a heatstroke of 108 °F. Fever is not a near miss for heatstroke. Physicians do not recommend acetaminophen to prevent heatstroke, although many parents act that way.

No published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed the incidence of these catastrophic hyponatremic events. In the meta-analysis of 10 disparate and uncoordinated trials in 2014,2 no serious adverse events were noted among the 1,000 patients involved. Since then, newer RCTs have added another 1,000 patients to the meta-analysis pool, but still no serious adverse event has been observed.

The H&S method features 60 years of proven safety and remains the appropriate estimate when composing long-term parenteral nutrition. No recommendation is perfect for all situations. Many hospitalized children will exhibit an increased level of ADH. A very small fraction of those children will present a sufficiently elevated ADH level long enough to risk creating profound hyponatremia. An approximation is in the order of magnitude of 1 per 100,000 pediatric medical admissions and 1 per 10,000 postoperative patients. With 3 million pediatric admissions yearly in the United States, such numbers mean that large children’s hospitals might see one or two catastrophic adverse events each decade due to mIVF in previously healthy children. The risk in chronically ill children and in the ICU will be higher. The potential for causing unintended greater harm amongst the other millions of patients is high, requiring application of the precautionary principle.

Thus, EBM and RCTs are poor methodologies for quality improvement of this issue. Assigning surrogate measures, such as moderate hyponatremia or even mild hyponatremia, to increase sensitivity and incidence for research purposes lacks a validated scientific link to the much rarer profound hyponatremic events. The resulting nonvalid extrapolation is precisely what true EBM seeks to avoid. A serum sodium of 132 mEq/L is not a near miss. The NNT to prevent the catastrophic events is unknown. Indeed, no paper advocating adoption of isotonic mIVF has even ventured an approximation.

The RCTs are also, therefore, underpowered to identify harms from using normal saline as a maintenance fluid. A few studies mention hypernatremia, but serum sodium is not a statistical variable. Renal physiology predicts that kidneys can easily handle excess infused sodium and can protect against hypernatremia. However, the extra chloride load risks creating hyperchloremic acidosis, particularly when a patient with respiratory insufficiency cannot compensate by lowering pCO2 through increased minute ventilation. Edema is another risk. Both respiratory insufficiency and edema already occur more frequently (by orders of magnitude) in hospitalized patients on any mIVF than the profound hyponatremia events in hospitalized patients on hypotonic mIVF. For instance, about 1% of hospitalized infants with bronchiolitis are ventilated for respiratory failure. If hyperchloremic acidosis unintentionally caused by isotonic mIVF slightly increases the frequency of intubation, then such result far outweighs any benefit from reducing catastrophic hyponatremic events. Difficulty will also arise in detecting this unintended increase in the rate of intubation compared with the current background frequency. Detecting these unintended harms becomes impossible if the RCT is underpowered by 100-fold due to utilizing a surrogate measure, such as serum sodium <135 mEq/L, as the dependent variable instead of measuring serious hyponatremic adverse events.

All claims that “no evidence of harm” was found from using normal saline as mIVF are type II statistical errors. There is little chance of detecting any harm with a grossly underpowered study or a meta-analysis of 10 such studies. Simply put, EBM is impossible to use for events that occur less than 1 per 10,000 patients using RCTs with 1,000 patients. No usable safety data are available for normal saline as mIVF in any published RCT. As the RCTs are underpowered, one should rely on science to guide therapy, rather than on invalid statistics.

Using the precautionary principle, hypothetically, adding extra sodium chloride to maintenance fluids should be considered in the same manner as adding any other drug. Based on the current evidence, would the Food and Drug Administration approve the drug intravenous sodium chloride for the prevention of hyponatremia induced by maintenance fluids? An increasing evidence of a minimal beneficial effect is observed, but no evidence of safety nor physiology is available. A new drug application for using normal saline as a default maintenance fluid would be soundly rejected by an FDA panel, just as it has been rejected by the majority of pediatric hospitalists throughout the past 15 years since the idea was proposed in 2003.

With the lack of compelling statistical evidence to guide practice, clinicians often rely on biologic plausibility. Relatively recent studies have revealed that many sick children develop elevated blood levels of ADH due to nonosmotic and nonhemodynamic triggers. Fortunately, we also possess a strong body of knowledge around management of children with syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH). We understand that elevated levels of ADH in the blood causes an increase in the resorption of free water from the renal collecting tubules. No increase in loss of renal sodium nor chloride is associated with this hormonal influence. The resultant hyponatremia is due to excess free-water retention and not the excess loss of sodium or chloride. To manage this condition, patients are not given a salt shaker and then allowed to drink ad libitum. The standard and well-accepted management of patients with SIADH is the restriction of free-water intake because this step addresses the dysfunctional renal process. Administering sodium chloride to a child with SIADH might possibly slow down the progression of hyponatremia but would also expand the total fluid volumes of the patient and would indirectly deal with a problem that could be addressed directly.

Understandably, in an intensive care setting, when hemodynamics is dicey, and when fluid-restriction could risk hypovolemia, employing a volume-expanding solution for mIVF therapy might be reasonable. However, in an ICU setting, SIADH is routinely treated with free-water restriction, and careful calculations of an individual patient’s fluid and electrolyte losses and needs are made.

In conclusion, we recognize the motivation for questioning the H&S method for mIVF as our field surveilles more than a half-century of accumulated experience with this method and the advances in our understanding of physiology and pathophysiology. However, we believe that the current body of evidence fails to substantiate the proposed recommendations.3 The avoidance of laboratory-detectable decreases in serum sodium levels is an unproven marker for the development of life-threatening hyponatremic events. Concerns for untoward effects (eg, excessive volume expansion and effects of hyperchloremia toward acidosis) and the exploration of alternative approaches (eg, modifications in volumes/rates of fluid delivery) have been inadequately explored. The proposed changes in practice may provide no mitigation in the rare events we hope to avoid, may fail to serve all subpopulations within the proposed scope of patients, and will likely

Disclosures

Dr. Powell and Dr. Zaoutis have nothing to disclose.

1. Holliday MA, Segar WE. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics 1957;19(5):823-832. PubMed

2. Wang J, Xu E, Xiao Y. Isotonic versus hypotonic maintenance IV fluids in hospitalized children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2014;133(1):105-113. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2041. PubMed

3. Hall AM, Ayus JC, Moritz ML. The default use of hypotonic maintenance intravenous fluids in pediatrics. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(9)637-640. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3040. PubMed

1. Holliday MA, Segar WE. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics 1957;19(5):823-832. PubMed

2. Wang J, Xu E, Xiao Y. Isotonic versus hypotonic maintenance IV fluids in hospitalized children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2014;133(1):105-113. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2041. PubMed

3. Hall AM, Ayus JC, Moritz ML. The default use of hypotonic maintenance intravenous fluids in pediatrics. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(9)637-640. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3040. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Phosphorus in kidney disease: Culprit or bystander?

Phosphorus is essential for life. However, both low and high levels of phosphorus in the body have consequences, and its concentration in the blood is tightly regulated through dietary absorption, bone flux, and renal excretion and is influenced by calcitriol (1,25 hydroxyvitamin D3), parathyroid hormone, and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23).

See related articles by M. Shetty and A. Sekar

Sekar et al,1 in this issue of the Journal, provide an extensive review of the pathophysiology of phosphorus metabolism and strategies to control phosphorus levels in patients with hyperphosphatemia and end-stage kidney disease.

PHOSPHORUS OR PHOSPHATE?

What's in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other word would smell as sweet.

—Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

The terms phosphate and phosphorus are often used interchangeably, though most writers still prefer phosphate over phosphorus.

The serum concentrations of phosphate and phosphorus are the same when expressed in millimoles per liter, as every mole of phosphate contains 1 mole of phosphorus, but not the same when expressed in milligrams per deciliter.2 The molecular weight of phosphorus is 30.97, whereas the molecular weight of the phosphate ion (PO43–) is 94.97—more than 3 times higher. Therefore, using these terms interchangeably in this context can lead to numerical error.3

Phosphorus, being highly reactive, does not exist by itself in nature and is typically present as phosphates in biologic systems. When describing phosphorus metabolism, the term phosphates should ideally be used because phosphates are the actual participants in the bodily processes. But in the clinical laboratory, all methods that measure serum phosphorus in fact measure inorganic phosphate and are expressed in terms of milligrams of phosphorus per deciliter rather than milligrams of phosphate per deciliter, and using these 2 terms interchangeably in clinical practice should not be of concern.4

THE PROBLEM

US adults typically ingest 1,200 mg of phosphorus each day, and about 60% to 70% of the ingested phosphorus is absorbed both by passive paracellular diffusion via tight junctions and by active transcellular transport via sodium-phosphate cotransport. The kidneys must excrete the same amount daily to maintain a steady state. As kidney function declines, phosphorus accumulates in the blood, leading to hyperphosphatemia.

Hyperphosphatemia is often asymptomatic, but it can cause generalized itching, red eyes, and adverse effects on the bone and parathyroid glands. Higher serum phosphorus levels have been shown to be associated with vascular calcification,5 cardiovascular events, and higher all-cause mortality rates in the general population,6 in patients with diabetes,7 and in those with chronic kidney disease.8 This association between higher serum phosphorus levels and the all-cause mortality rate led to the assumption that lowering serum phosphorus levels in these patients could reduce the rates of cardiovascular events and death, and to efforts to correct hyperphosphatemia.

Research into FGF23 continues, especially its role in cardiovascular complications of chronic kidney disease, as both phosphorus and FGF23 levels are elevated in chronic kidney disease and are implicated in poor clinical outcomes in these patients. However, both FGF23 and parathyroid hormone levels rise early in the course of kidney disease, long before overt hyperphosphatemia develops. Further, FGF23 rises earlier than parathyroid hormone and has been found to be an independent risk factor for cardiovascular events and death from any cause in end-stage kidney disease.9

Whether hyperphosphatemia is the culprit or merely an epiphenomenon of metabolic complications of chronic kidney disease is still unclear, as more molecules are being identified in the complex process of cardiovascular calcification.10

However, one thing is clear: vascular calcification is not just a simple precipitation of calcium and phosphorus. Instead, it is an active process that involves many regulators of mineral metabolism.10 The complex nature of this process is likely one of the reasons that evidence is conflicting11 about the benefits of phosphorus binders in terms of cardiovascular events or all-cause mortality in these patients.

STRATEGIES TO CONTROL HYPERPHOSPHATEMIA

Reducing intake

Dietary phosphorus restriction is the first step in controlling serum phosphorus. But reducing phosphorus intake while otherwise trying to optimize the nutritional status can be challenging.

The recommended daily protein intake is 1.0 to 1.2 g/kg. But phosphorus is typically found in foods rich in proteins, and restricting protein severely can compromise nutritional status and may be as bad as elevated phosphate levels in terms of outcomes.

Although plant-based foods contain more phosphate per gram of protein (ie, they have a higher ratio of phosphorus to protein) than animal-based foods, the bioavailability of phosphorus from plant foods is lower. Phosphorus in plant-based foods is mainly in the form of phytate. Humans cannot hydrolyze phytate because we lack the phytase enzyme; hence, the phosphorus in plant-based foods is not well absorbed. Therefore, a vegetarian diet may be preferable and beneficial in patients with chronic kidney disease. A small study in humans showed that a vegetarian diet resulted in lower serum phosphorus and FGF23 levels, but the study was limited by its small sample size.12

Patients should be advised to avoid foods that have a high phosphate content, such as processed foods, fast foods, and cola beverages, which often have phosphate-based food additives.

Further, one should be cautious about using supplements with healthy-sounding names. A case in point is “vitamin water”: 12 oz of this fruit punch-flavored beverage contains 392 mg of phosphorus,13 and this alone would require 12 to 15 phosphate binder tablets to bind its phosphorus content.

In addition, many prescription drugs have significant amounts of phosphorus, and this is often unrecognized.

Sherman et al14 reviewed 200 of the most commonly prescribed drugs in dialysis patients and found that 23 (11.5%) of the drug labels listed phosphorus-containing ingredients, but the actual amount of phosphorus was not listed. The phosphorus content ranged from 1.4 mg (clonidine 0.2 mg, Blue Point Laboratories, Dublin, Ireland) to 111.5 mg (paroxetine 40 mg, GlaxoSmith Kline, Philadelphia, PA). The phosphorus content was inconsistent and varied with the dose of the agent, type of formulation (tablet or syrup), branded or generic formulation, and manufacturer.

Branded lisinopril (Merck, Kenilworth, NJ) had 21.4 mg of phosphorus per 10-mg dose, while a generic product (Blue Point Laboratories, Dublin, Ireland) had 32.6 mg. Different brands of generic amlodipine 10 mg varied in their phosphorus content from 8.6 mg (Lupin Pharmaceuticals, Mumbai, India) to 27.8 mg (Greenstone LLC, Peapack, NJ) to 40.1 mg (Qualitest Pharmaceuticals, Huntsville, AL. Rena-Vite (Cypress Pharmaceuticals, Madison, MS), a multivitamin marketed to patients with kidney disease, had 37.7 mg of phosphorus per tablet. Thus, just to bind the phosphorus content of these 3 tablets (lisinopril, amlodipine, and Rena-Vite), a patient could need at least 3 to 4 extra doses of phosphate binder.

The phosphate content of medications should be considered when prescribing. For example, Reno Caps (Nnodum Pharmaceuticals, Cincinnati, OH), another vitamin supplement, has only 1.7 mg of phosphorus per tablet and should be considered, especially in patients with poorly controlled serum phosphorus levels. However, the challenge is that medication labels do not provide the phosphorus content.

Reducing phosphorus absorption

Although these agents reduce serum phosphorus and help reduce symptoms, an important quality-of-life measure, it is uncertain whether they improve clinical outcomes.11 To date, no specific phosphorus binder offers a survival benefit over placebo.11

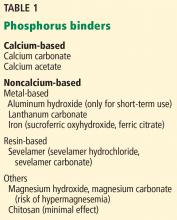

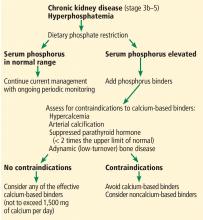

Based on the limited and conflicting evidence, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines, recently updated, suggest that oral phosphorus binders should be used in patients with hyperphosphatemia to lower serum phosphorus levels toward the normal range.15 They further recommend not exceeding 1,500 mg of elemental calcium per day if a calcium-based binder is used, and they recommend avoiding calcium-based binders in patients with hypercalcemia, adynamic bone disease, or vascular calcification.

Phosphorus binders may account for up to 50% of the daily pill burden and may contribute to poor medication adherence.16 Dialysis patients need to take a lot of these drugs: by weight, 5 to 6 pounds per year.

These drugs can bind and interfere with the absorption of other vital medications and so should be taken with meals and separately from other medications.

Removing phosphorus

Removal of phosphorus by adequate dialysis or kidney transplant is the final strategy.

New agents under study

To improve phosphorus control, other agents that inhibit absorption of phosphate are being investigated.

Nicotinamide reduces expression of the sodium-phosphorus cotransporter NTP2b. Its use in combination with a low-phosphorus diet and phosphorus binders may maximize reductions in phosphorus absorption and is being studied in the CKD Optimal Management With Binders and Nicotinamide (COMBINE) study.

Tenapanor, an inhibitor of the sodium-hydrogen transporter NHE3, has been shown in animal studies to increase fecal phosphate excretion and decrease urinary phosphate excretion17 but requires further evaluation.

- Sekar A, Kaur T, Nally JV Jr, Rincon-Choles H, Jolly S, Nakhoul G. Phosphorus binders: the new and the old, and how to choose. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(8):629–638. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17054

- Young DS. "Phosphorus" or "phosphate." Ann Intern Med 1980; 93(4):631. pmid:7436198

- Bartter FC. Reporting of phosphate and phosphorus plasma values. Am J Med 1981; 71(5):848. pmid:7304659.

- Iheagwara OS, Ing TS, Kjellstrand CM, Lew SQ. Phosphorus, phosphorous, and phosphate. Hemodial Int 2013; 17(4):479–482. doi:10.1111/hdi.12010

- Adeney KL, Siscovick DS, Ix JH, et al. Association of serum phosphate with vascular and valvular calcification in moderate CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20(2):381–387. doi:10.1681/ASN.2008040349

- Dhingra R, Sullivan LM, Fox CS, et al. Relations of serum phosphorus and calcium levels to the incidence of cardiovascular disease in the community. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167(9):879–885. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.9.879

- Chonchol M, Dale R, Schrier RW, Estacio R. Serum phosphorus and cardiovascular mortality in type 2 diabetes. Am J Med 2009; 122(4):380–386. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.039

- Covic A, Kothawala P, Bernal M, Robbins S, Chalian A, Goldsmith D. Systematic review of the evidence underlying the association between mineral metabolism disturbances and risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and cardiovascular events in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009; 24(5):1506–1523. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn613

- Gutiérrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 2008; 359(6):584–592. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0706130

- Lullo LD, Barbera V, Bellasi A, et al. Vascular and valvular calcifications in chronic kidney disease: an update. EMJ Nephrol 2016; 4(1):84–91. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/150f/c7b5dfe671c9b61e4c76d54b7d713b60ba6a.pdf. Accesssed June 5, 2018.

- Palmer SC, Gardner S, Tonelli M, et al. Phosphate-binding agents in adults with CKD: a network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Kidney Dis 2016; 68(5):691–702. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.05.015

- Moe SM, Zidehsarai MP, Chambers MA, et al. Vegetarian compared with meat dietary protein source and phosphorus homeostasis in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6(2):257–264. doi:10.2215/CJN.05040610

- Moser M, White K, Henry B, et al. Phosphorus content of popular beverages. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 65(6):969–971. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.02.330

- Sherman RA, Ravella S, Kapoian T. A dearth of data: the problem of phosphorus in prescription medications. Kidney Int 2015; 87(6):1097–1099. doi:10.1038/ki.2015.67

- KDIGO 2017 clinical practice guideline update for diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Supplements 2017; 7(1 suppl): 1–59. www.kisupplements.org/article/S2157-1716(17)30001-1/pdf. Accessed June 5, 2018.

- Fissell RB, Karaboyas A, Bieber BA, et al. Phosphate binder pill burden, patient-reported non-adherence, and mineral bone disorder markers: findings from the DOPPS. Hemodial Int 2016; 20(1):38–49. doi:10.1111/hdi.12315

- Labonté ED, Carreras CW, Leadbetter MR, et al. Gastrointestinal inhibition of sodium-hydrogen exchanger 3 reduces phosphorus absorption and protects against vascular calcification in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 26(5):1138–1149. doi:10.1681/ASN.2014030317

Phosphorus is essential for life. However, both low and high levels of phosphorus in the body have consequences, and its concentration in the blood is tightly regulated through dietary absorption, bone flux, and renal excretion and is influenced by calcitriol (1,25 hydroxyvitamin D3), parathyroid hormone, and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23).

See related articles by M. Shetty and A. Sekar

Sekar et al,1 in this issue of the Journal, provide an extensive review of the pathophysiology of phosphorus metabolism and strategies to control phosphorus levels in patients with hyperphosphatemia and end-stage kidney disease.

PHOSPHORUS OR PHOSPHATE?

What's in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other word would smell as sweet.

—Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

The terms phosphate and phosphorus are often used interchangeably, though most writers still prefer phosphate over phosphorus.

The serum concentrations of phosphate and phosphorus are the same when expressed in millimoles per liter, as every mole of phosphate contains 1 mole of phosphorus, but not the same when expressed in milligrams per deciliter.2 The molecular weight of phosphorus is 30.97, whereas the molecular weight of the phosphate ion (PO43–) is 94.97—more than 3 times higher. Therefore, using these terms interchangeably in this context can lead to numerical error.3

Phosphorus, being highly reactive, does not exist by itself in nature and is typically present as phosphates in biologic systems. When describing phosphorus metabolism, the term phosphates should ideally be used because phosphates are the actual participants in the bodily processes. But in the clinical laboratory, all methods that measure serum phosphorus in fact measure inorganic phosphate and are expressed in terms of milligrams of phosphorus per deciliter rather than milligrams of phosphate per deciliter, and using these 2 terms interchangeably in clinical practice should not be of concern.4

THE PROBLEM

US adults typically ingest 1,200 mg of phosphorus each day, and about 60% to 70% of the ingested phosphorus is absorbed both by passive paracellular diffusion via tight junctions and by active transcellular transport via sodium-phosphate cotransport. The kidneys must excrete the same amount daily to maintain a steady state. As kidney function declines, phosphorus accumulates in the blood, leading to hyperphosphatemia.

Hyperphosphatemia is often asymptomatic, but it can cause generalized itching, red eyes, and adverse effects on the bone and parathyroid glands. Higher serum phosphorus levels have been shown to be associated with vascular calcification,5 cardiovascular events, and higher all-cause mortality rates in the general population,6 in patients with diabetes,7 and in those with chronic kidney disease.8 This association between higher serum phosphorus levels and the all-cause mortality rate led to the assumption that lowering serum phosphorus levels in these patients could reduce the rates of cardiovascular events and death, and to efforts to correct hyperphosphatemia.

Research into FGF23 continues, especially its role in cardiovascular complications of chronic kidney disease, as both phosphorus and FGF23 levels are elevated in chronic kidney disease and are implicated in poor clinical outcomes in these patients. However, both FGF23 and parathyroid hormone levels rise early in the course of kidney disease, long before overt hyperphosphatemia develops. Further, FGF23 rises earlier than parathyroid hormone and has been found to be an independent risk factor for cardiovascular events and death from any cause in end-stage kidney disease.9

Whether hyperphosphatemia is the culprit or merely an epiphenomenon of metabolic complications of chronic kidney disease is still unclear, as more molecules are being identified in the complex process of cardiovascular calcification.10

However, one thing is clear: vascular calcification is not just a simple precipitation of calcium and phosphorus. Instead, it is an active process that involves many regulators of mineral metabolism.10 The complex nature of this process is likely one of the reasons that evidence is conflicting11 about the benefits of phosphorus binders in terms of cardiovascular events or all-cause mortality in these patients.

STRATEGIES TO CONTROL HYPERPHOSPHATEMIA

Reducing intake

Dietary phosphorus restriction is the first step in controlling serum phosphorus. But reducing phosphorus intake while otherwise trying to optimize the nutritional status can be challenging.

The recommended daily protein intake is 1.0 to 1.2 g/kg. But phosphorus is typically found in foods rich in proteins, and restricting protein severely can compromise nutritional status and may be as bad as elevated phosphate levels in terms of outcomes.

Although plant-based foods contain more phosphate per gram of protein (ie, they have a higher ratio of phosphorus to protein) than animal-based foods, the bioavailability of phosphorus from plant foods is lower. Phosphorus in plant-based foods is mainly in the form of phytate. Humans cannot hydrolyze phytate because we lack the phytase enzyme; hence, the phosphorus in plant-based foods is not well absorbed. Therefore, a vegetarian diet may be preferable and beneficial in patients with chronic kidney disease. A small study in humans showed that a vegetarian diet resulted in lower serum phosphorus and FGF23 levels, but the study was limited by its small sample size.12