User login

Updated gout guidelines: Don’t let kidney function dictate allopurinol dosing

ATLANTA – Soon-to-be-published gout guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology will recommend dosing allopurinol above 300 mg/day to get serum urate below 6 mg/dL, even in people with renal impairment.

It’s the same strong treat-to-target recommendation the group made in its last outing in 2012, but “we now have more evidence to support it,” said co–lead author, rheumatologist, and epidemiologist Tuhina Neogi, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine at Boston University.

She gave a sneak preview of the new guidelines, which will be published in 2020, at the ACR annual meeting. They are under review, but she said the “major recommendations will remain the same.”

“There will still be controversy that we have not yet proven that a threshold of 6 mg/dL is better than a threshold of 7 mg/dL, but we know that” at physiologic pH and temperature, monosodium urate starts to crystallize out at 6.8 mg/dL. “Serum urate is not a perfect measure or total body urate, so we need to get urate to below at least 6 mg/dL,” she said, and perhaps lower in some.

A popular alternative in primary care – where most gout is managed – is to treat to avoid symptoms. It “has no evidence,” and people “end up getting tophaceous gout with joint destruction. Suppressive colchicine therapy does not manage underlying hyperuricemia,” Dr. Neogi said.

With the symptom approach, “patients are often [profoundly] dismayed” when they find out they have large tophi and joint damage because they weren’t managed properly. “Primary care physicians [don’t often] see that because those patients don’t go back to them,” she said.

Dr. Neogi suspects that, for rheumatologists, the biggest surprise in the new guidelines will be a deemphasis on lifestyle and dietary factors. They can be triggers, but “gout is increasingly recognized as largely genetically determined,” and the impact of other factors on serum urate is low. Plus, “patients are embarrassed” by gout, and even less comfortable being honest with physicians “if they think we are blaming them,” she said.

The new document will recommend allopurinol as the definitive first-line option for hyperuricemia. Febuxostat (Uloric) was put on pretty much equal footing in 2012, but now “we acknowledge” that allopurinol dosing in head-to-head trials – 300 mg/day or 200 mg/day with renal impairment – was too low for most people, “so to say febuxostat is equivalent or superior isn’t really fair.” The substantially higher cost of febuxostat was also taken into consideration, she said.

The ACR will broaden the indications for urate lowering beyond frequent flares, tophi, and radiologic joint damage to include conditional, shared decision-making recommendations for people who have less than two flares per year, those with kidney stones, and people with a first flare if they are particularly susceptible to a second – namely those with serum urate at or above 9 mg/dL and people with stage 3 or worse chronic kidney disease, who are less able to tolerate NSAIDs and colchicine for symptom treatment.

The group will also relax its advice against treating asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Febuxostat trials have shown a reduction in incident gout, but the number needed to treat was large, so the ACR will recommend shared decision making.

Inadequate allopurinol dosing, meanwhile, has been the bête noire of rheumatology for years, but there is still reluctance among many to go above 300 mg/day. Dr. Neogi said it’s because of a decades-old concern, “unsupported by any evidence, that higher doses may be detrimental in people with renal insufficiency.” It’s frustrating, she said, because “there is good data supporting the safety of increasing the dose above 300 mg/day even in those with renal impairment,” and not doing so opens the door to entirely preventable complications.

As for allopurinol hypersensitivity – another reason people shy away from higher dosing, especially in the renally impaired – the trick is to start low and slowly titrate allopurinol up to the target urate range. Asian and black people, especially, should be screened beforehand for the HLA-B*58:01 genetic variant that increases the risk of severe reactions. Both will be strong recommendations in the new guidelines.

Dr. Neogi didn’t have any relevant industry disclosures.

ATLANTA – Soon-to-be-published gout guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology will recommend dosing allopurinol above 300 mg/day to get serum urate below 6 mg/dL, even in people with renal impairment.

It’s the same strong treat-to-target recommendation the group made in its last outing in 2012, but “we now have more evidence to support it,” said co–lead author, rheumatologist, and epidemiologist Tuhina Neogi, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine at Boston University.

She gave a sneak preview of the new guidelines, which will be published in 2020, at the ACR annual meeting. They are under review, but she said the “major recommendations will remain the same.”

“There will still be controversy that we have not yet proven that a threshold of 6 mg/dL is better than a threshold of 7 mg/dL, but we know that” at physiologic pH and temperature, monosodium urate starts to crystallize out at 6.8 mg/dL. “Serum urate is not a perfect measure or total body urate, so we need to get urate to below at least 6 mg/dL,” she said, and perhaps lower in some.

A popular alternative in primary care – where most gout is managed – is to treat to avoid symptoms. It “has no evidence,” and people “end up getting tophaceous gout with joint destruction. Suppressive colchicine therapy does not manage underlying hyperuricemia,” Dr. Neogi said.

With the symptom approach, “patients are often [profoundly] dismayed” when they find out they have large tophi and joint damage because they weren’t managed properly. “Primary care physicians [don’t often] see that because those patients don’t go back to them,” she said.

Dr. Neogi suspects that, for rheumatologists, the biggest surprise in the new guidelines will be a deemphasis on lifestyle and dietary factors. They can be triggers, but “gout is increasingly recognized as largely genetically determined,” and the impact of other factors on serum urate is low. Plus, “patients are embarrassed” by gout, and even less comfortable being honest with physicians “if they think we are blaming them,” she said.

The new document will recommend allopurinol as the definitive first-line option for hyperuricemia. Febuxostat (Uloric) was put on pretty much equal footing in 2012, but now “we acknowledge” that allopurinol dosing in head-to-head trials – 300 mg/day or 200 mg/day with renal impairment – was too low for most people, “so to say febuxostat is equivalent or superior isn’t really fair.” The substantially higher cost of febuxostat was also taken into consideration, she said.

The ACR will broaden the indications for urate lowering beyond frequent flares, tophi, and radiologic joint damage to include conditional, shared decision-making recommendations for people who have less than two flares per year, those with kidney stones, and people with a first flare if they are particularly susceptible to a second – namely those with serum urate at or above 9 mg/dL and people with stage 3 or worse chronic kidney disease, who are less able to tolerate NSAIDs and colchicine for symptom treatment.

The group will also relax its advice against treating asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Febuxostat trials have shown a reduction in incident gout, but the number needed to treat was large, so the ACR will recommend shared decision making.

Inadequate allopurinol dosing, meanwhile, has been the bête noire of rheumatology for years, but there is still reluctance among many to go above 300 mg/day. Dr. Neogi said it’s because of a decades-old concern, “unsupported by any evidence, that higher doses may be detrimental in people with renal insufficiency.” It’s frustrating, she said, because “there is good data supporting the safety of increasing the dose above 300 mg/day even in those with renal impairment,” and not doing so opens the door to entirely preventable complications.

As for allopurinol hypersensitivity – another reason people shy away from higher dosing, especially in the renally impaired – the trick is to start low and slowly titrate allopurinol up to the target urate range. Asian and black people, especially, should be screened beforehand for the HLA-B*58:01 genetic variant that increases the risk of severe reactions. Both will be strong recommendations in the new guidelines.

Dr. Neogi didn’t have any relevant industry disclosures.

ATLANTA – Soon-to-be-published gout guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology will recommend dosing allopurinol above 300 mg/day to get serum urate below 6 mg/dL, even in people with renal impairment.

It’s the same strong treat-to-target recommendation the group made in its last outing in 2012, but “we now have more evidence to support it,” said co–lead author, rheumatologist, and epidemiologist Tuhina Neogi, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine at Boston University.

She gave a sneak preview of the new guidelines, which will be published in 2020, at the ACR annual meeting. They are under review, but she said the “major recommendations will remain the same.”

“There will still be controversy that we have not yet proven that a threshold of 6 mg/dL is better than a threshold of 7 mg/dL, but we know that” at physiologic pH and temperature, monosodium urate starts to crystallize out at 6.8 mg/dL. “Serum urate is not a perfect measure or total body urate, so we need to get urate to below at least 6 mg/dL,” she said, and perhaps lower in some.

A popular alternative in primary care – where most gout is managed – is to treat to avoid symptoms. It “has no evidence,” and people “end up getting tophaceous gout with joint destruction. Suppressive colchicine therapy does not manage underlying hyperuricemia,” Dr. Neogi said.

With the symptom approach, “patients are often [profoundly] dismayed” when they find out they have large tophi and joint damage because they weren’t managed properly. “Primary care physicians [don’t often] see that because those patients don’t go back to them,” she said.

Dr. Neogi suspects that, for rheumatologists, the biggest surprise in the new guidelines will be a deemphasis on lifestyle and dietary factors. They can be triggers, but “gout is increasingly recognized as largely genetically determined,” and the impact of other factors on serum urate is low. Plus, “patients are embarrassed” by gout, and even less comfortable being honest with physicians “if they think we are blaming them,” she said.

The new document will recommend allopurinol as the definitive first-line option for hyperuricemia. Febuxostat (Uloric) was put on pretty much equal footing in 2012, but now “we acknowledge” that allopurinol dosing in head-to-head trials – 300 mg/day or 200 mg/day with renal impairment – was too low for most people, “so to say febuxostat is equivalent or superior isn’t really fair.” The substantially higher cost of febuxostat was also taken into consideration, she said.

The ACR will broaden the indications for urate lowering beyond frequent flares, tophi, and radiologic joint damage to include conditional, shared decision-making recommendations for people who have less than two flares per year, those with kidney stones, and people with a first flare if they are particularly susceptible to a second – namely those with serum urate at or above 9 mg/dL and people with stage 3 or worse chronic kidney disease, who are less able to tolerate NSAIDs and colchicine for symptom treatment.

The group will also relax its advice against treating asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Febuxostat trials have shown a reduction in incident gout, but the number needed to treat was large, so the ACR will recommend shared decision making.

Inadequate allopurinol dosing, meanwhile, has been the bête noire of rheumatology for years, but there is still reluctance among many to go above 300 mg/day. Dr. Neogi said it’s because of a decades-old concern, “unsupported by any evidence, that higher doses may be detrimental in people with renal insufficiency.” It’s frustrating, she said, because “there is good data supporting the safety of increasing the dose above 300 mg/day even in those with renal impairment,” and not doing so opens the door to entirely preventable complications.

As for allopurinol hypersensitivity – another reason people shy away from higher dosing, especially in the renally impaired – the trick is to start low and slowly titrate allopurinol up to the target urate range. Asian and black people, especially, should be screened beforehand for the HLA-B*58:01 genetic variant that increases the risk of severe reactions. Both will be strong recommendations in the new guidelines.

Dr. Neogi didn’t have any relevant industry disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ACR 2019

Bile acid diarrhea guideline highlights data shortage

The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) recently co-published a clinical practice guideline for the management of bile acid diarrhea (BAD) in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology and the Journal of the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology.

Given a minimal evidence base, 16 out of the 17 guideline recommendations are conditional, according to lead author Daniel C. Sadowski, MD, of Royal Alexandra Hospital, Edmonton, Alta., and colleagues. Considering the shortage of high-quality evidence, the panel called for more randomized clinical trials to address current knowledge gaps.

“BAD is an understudied, often underappreciated condition, and questions remain regarding its diagnosis and treatment,” the panelists wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “There have been guidelines on the management of chronic diarrhea from the American Gastroenterological Association, and the British Society of Gastroenterology, but diagnosis and management of BAD was not assessed extensively in these publications. The British Society of Gastroenterology updated guidelines on the investigation of chronic diarrhea in adults, published after the consensus meeting, addressed some issues related to BAD.”

For the current guideline, using available evidence and clinical experience, expert panelists from Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom aimed to “provide a reasonable and practical approach to care for specialists.” The guideline was further reviewed by the CAG Practice Affairs and Clinical Affairs Committees and the CAG Board of Directors.

The guideline first puts BAD in clinical context, noting a chronic diarrhea prevalence rate of approximately 5%. According to the guideline, approximately 1 out of 4 of these patients with chronic diarrhea may have BAD and prevalence of BAD is likely higher among those with other conditions, such as terminal ileal disease.

While BAD may be relatively common, it isn’t necessarily easy to diagnose, the panelists noted.

“The diagnosis of BAD continues to be a challenge, although this may be improved in the future with the general availability of screening serologic tests and other diagnostic tests,” the panelists wrote. “Although a treatment trial with bile acid sequestrants therapy (BAST) often is used, this approach has not been studied adequately, and likely is imprecise, and may lead to both undertreatment and overtreatment.”

Instead, the panelists recommended testing for BAD with 75-selenium homocholic acid taurine (SeHCAT) or 7-alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one.

After addressing treatable causes of BAD, the guideline recommends initial therapy with cholestyramine or, if this is poorly tolerated, switching to BAST. However, the panelists advised against BAST for patients with resection or ileal Crohn’s disease, for whom other antidiarrheal agents are more suitable. When appropriate, BAST should be given at the lowest effective dose, with periodic trials of on-demand, intermittent administration, the panelists recommended. When BAST is ineffective, the guideline recommends that clinicians review concurrent medications as a possible cause of BAD or reinvestigate.

Concluding the guideline, the panelists emphasized the need for more high-quality research.

“The group recognized that specific, high-certainty evidence was lacking in many areas and recommended further studies that would improve the data available in future methodologic evaluations,” the panelists wrote.

While improving diagnostic accuracy of BAD should be a major goal of such research, progress is currently limited by an integral shortcoming of diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) studies, the panelists wrote.

“The main challenge in conducting DTA studies for BAD is the lack of a widely accepted or universally agreed-upon reference standard because the condition is defined and classified based on pathophysiologic mechanisms and its response to treatment (BAST),” the panelists wrote. “In addition, the index tests (SeHCAT, C4, FGF19, fecal bile acid assay) provide a continuous measure of metabolic function. Hence, DTA studies are not the most appropriate study design.”

“Therefore, one of the research priorities in BAD is for the scientific and clinical communities to agree on a reference standard that best represents BAD (e.g., response to BAST), with full understanding that the reference standard is and likely will be imperfect.”

The guideline was funded by unrestricted grants from Pendopharm and GE Healthcare Canada. The panelists disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

Review the AGA clinical practice guideline on the laboratory evaluation of functional diarrhea and diarrhea-predominan irritable bowel syndrome in adults at https:/www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(19)41083-4/fulltext.

SOURCE: Sadowski DC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.062.

The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) recently co-published a clinical practice guideline for the management of bile acid diarrhea (BAD) in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology and the Journal of the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology.

Given a minimal evidence base, 16 out of the 17 guideline recommendations are conditional, according to lead author Daniel C. Sadowski, MD, of Royal Alexandra Hospital, Edmonton, Alta., and colleagues. Considering the shortage of high-quality evidence, the panel called for more randomized clinical trials to address current knowledge gaps.

“BAD is an understudied, often underappreciated condition, and questions remain regarding its diagnosis and treatment,” the panelists wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “There have been guidelines on the management of chronic diarrhea from the American Gastroenterological Association, and the British Society of Gastroenterology, but diagnosis and management of BAD was not assessed extensively in these publications. The British Society of Gastroenterology updated guidelines on the investigation of chronic diarrhea in adults, published after the consensus meeting, addressed some issues related to BAD.”

For the current guideline, using available evidence and clinical experience, expert panelists from Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom aimed to “provide a reasonable and practical approach to care for specialists.” The guideline was further reviewed by the CAG Practice Affairs and Clinical Affairs Committees and the CAG Board of Directors.

The guideline first puts BAD in clinical context, noting a chronic diarrhea prevalence rate of approximately 5%. According to the guideline, approximately 1 out of 4 of these patients with chronic diarrhea may have BAD and prevalence of BAD is likely higher among those with other conditions, such as terminal ileal disease.

While BAD may be relatively common, it isn’t necessarily easy to diagnose, the panelists noted.

“The diagnosis of BAD continues to be a challenge, although this may be improved in the future with the general availability of screening serologic tests and other diagnostic tests,” the panelists wrote. “Although a treatment trial with bile acid sequestrants therapy (BAST) often is used, this approach has not been studied adequately, and likely is imprecise, and may lead to both undertreatment and overtreatment.”

Instead, the panelists recommended testing for BAD with 75-selenium homocholic acid taurine (SeHCAT) or 7-alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one.

After addressing treatable causes of BAD, the guideline recommends initial therapy with cholestyramine or, if this is poorly tolerated, switching to BAST. However, the panelists advised against BAST for patients with resection or ileal Crohn’s disease, for whom other antidiarrheal agents are more suitable. When appropriate, BAST should be given at the lowest effective dose, with periodic trials of on-demand, intermittent administration, the panelists recommended. When BAST is ineffective, the guideline recommends that clinicians review concurrent medications as a possible cause of BAD or reinvestigate.

Concluding the guideline, the panelists emphasized the need for more high-quality research.

“The group recognized that specific, high-certainty evidence was lacking in many areas and recommended further studies that would improve the data available in future methodologic evaluations,” the panelists wrote.

While improving diagnostic accuracy of BAD should be a major goal of such research, progress is currently limited by an integral shortcoming of diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) studies, the panelists wrote.

“The main challenge in conducting DTA studies for BAD is the lack of a widely accepted or universally agreed-upon reference standard because the condition is defined and classified based on pathophysiologic mechanisms and its response to treatment (BAST),” the panelists wrote. “In addition, the index tests (SeHCAT, C4, FGF19, fecal bile acid assay) provide a continuous measure of metabolic function. Hence, DTA studies are not the most appropriate study design.”

“Therefore, one of the research priorities in BAD is for the scientific and clinical communities to agree on a reference standard that best represents BAD (e.g., response to BAST), with full understanding that the reference standard is and likely will be imperfect.”

The guideline was funded by unrestricted grants from Pendopharm and GE Healthcare Canada. The panelists disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

Review the AGA clinical practice guideline on the laboratory evaluation of functional diarrhea and diarrhea-predominan irritable bowel syndrome in adults at https:/www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(19)41083-4/fulltext.

SOURCE: Sadowski DC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.062.

The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) recently co-published a clinical practice guideline for the management of bile acid diarrhea (BAD) in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology and the Journal of the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology.

Given a minimal evidence base, 16 out of the 17 guideline recommendations are conditional, according to lead author Daniel C. Sadowski, MD, of Royal Alexandra Hospital, Edmonton, Alta., and colleagues. Considering the shortage of high-quality evidence, the panel called for more randomized clinical trials to address current knowledge gaps.

“BAD is an understudied, often underappreciated condition, and questions remain regarding its diagnosis and treatment,” the panelists wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “There have been guidelines on the management of chronic diarrhea from the American Gastroenterological Association, and the British Society of Gastroenterology, but diagnosis and management of BAD was not assessed extensively in these publications. The British Society of Gastroenterology updated guidelines on the investigation of chronic diarrhea in adults, published after the consensus meeting, addressed some issues related to BAD.”

For the current guideline, using available evidence and clinical experience, expert panelists from Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom aimed to “provide a reasonable and practical approach to care for specialists.” The guideline was further reviewed by the CAG Practice Affairs and Clinical Affairs Committees and the CAG Board of Directors.

The guideline first puts BAD in clinical context, noting a chronic diarrhea prevalence rate of approximately 5%. According to the guideline, approximately 1 out of 4 of these patients with chronic diarrhea may have BAD and prevalence of BAD is likely higher among those with other conditions, such as terminal ileal disease.

While BAD may be relatively common, it isn’t necessarily easy to diagnose, the panelists noted.

“The diagnosis of BAD continues to be a challenge, although this may be improved in the future with the general availability of screening serologic tests and other diagnostic tests,” the panelists wrote. “Although a treatment trial with bile acid sequestrants therapy (BAST) often is used, this approach has not been studied adequately, and likely is imprecise, and may lead to both undertreatment and overtreatment.”

Instead, the panelists recommended testing for BAD with 75-selenium homocholic acid taurine (SeHCAT) or 7-alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one.

After addressing treatable causes of BAD, the guideline recommends initial therapy with cholestyramine or, if this is poorly tolerated, switching to BAST. However, the panelists advised against BAST for patients with resection or ileal Crohn’s disease, for whom other antidiarrheal agents are more suitable. When appropriate, BAST should be given at the lowest effective dose, with periodic trials of on-demand, intermittent administration, the panelists recommended. When BAST is ineffective, the guideline recommends that clinicians review concurrent medications as a possible cause of BAD or reinvestigate.

Concluding the guideline, the panelists emphasized the need for more high-quality research.

“The group recognized that specific, high-certainty evidence was lacking in many areas and recommended further studies that would improve the data available in future methodologic evaluations,” the panelists wrote.

While improving diagnostic accuracy of BAD should be a major goal of such research, progress is currently limited by an integral shortcoming of diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) studies, the panelists wrote.

“The main challenge in conducting DTA studies for BAD is the lack of a widely accepted or universally agreed-upon reference standard because the condition is defined and classified based on pathophysiologic mechanisms and its response to treatment (BAST),” the panelists wrote. “In addition, the index tests (SeHCAT, C4, FGF19, fecal bile acid assay) provide a continuous measure of metabolic function. Hence, DTA studies are not the most appropriate study design.”

“Therefore, one of the research priorities in BAD is for the scientific and clinical communities to agree on a reference standard that best represents BAD (e.g., response to BAST), with full understanding that the reference standard is and likely will be imperfect.”

The guideline was funded by unrestricted grants from Pendopharm and GE Healthcare Canada. The panelists disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

Review the AGA clinical practice guideline on the laboratory evaluation of functional diarrhea and diarrhea-predominan irritable bowel syndrome in adults at https:/www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(19)41083-4/fulltext.

SOURCE: Sadowski DC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.062.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology recently published a clinical practice guideline for the management of bile acid diarrhea (BAD).

Major finding: BAD occurs in up to 35% of patients with chronic diarrhea or diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome.

Study details: A clinical practice guideline for the management of BAD.

Disclosures: The guideline was funded by unrestricted grants from Pendopharm and GE Healthcare Canada. The panelists disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

Source: Sadowski DC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.062.

AGA releases clinical practice update for pancreatic necrosis

The American Gastroenterological Association recently issued a clinical practice update for the management of pancreatic necrosis, including 15 recommendations based on a comprehensive literature review and the experiences of leading experts.

Recommendations range from the general, such as the need for a multidisciplinary approach, to the specific, such as the superiority of metal over plastic stents for endoscopic transmural drainage.

The expert review, which was conducted by lead author Todd H. Baron, MD, of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and three other colleagues, was vetted by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee (CPUC) and the AGA Governing Board. In addition, the update underwent external peer review prior to publication in Gastroenterology.

In the update, the authors outlined the clinical landscape for pancreatic necrosis, including challenges posed by complex cases and a mortality rate as high as 30%.

“Successful management of these patients requires expert multidisciplinary care by gastroenterologists, surgeons, interventional radiologists, and specialists in critical care medicine, infectious disease, and nutrition,” the investigators wrote.

They went on to explain how management has evolved over the past 10 years.

“Whereby major surgical intervention and debridement was once the mainstay of therapy for patients with symptomatic necrotic collections, a minimally invasive approach focusing on percutaneous drainage and/or endoscopic drainage or debridement is now favored,” they wrote. They added that debridement is still generally agreed to be the best choice for cases of infected necrosis or patients with sterile necrosis “marked by abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and nutritional failure or with associated complications including gastrointestinal luminal obstruction, biliary obstruction, recurrent acute pancreatitis, fistulas, or persistent systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).”

Other elements of care, however, remain debated, the investigators noted, which has led to variations in multiple aspects of care, such as interventional timing, intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and nutrition. Within this framework, the present practice update is aimed at offering “concise best practice advice for the optimal management of patients with this highly morbid condition.”

Among these pieces of advice, the authors emphasized that routine prophylactic antibiotics and/or antifungals to prevent infected necrosis are unsupported by multiple clinical trials. When infection is suspected, the update recommends broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics, noting that, in most cases, it is unnecessary to perform CT-guided fine-needle aspiration for cultures and gram stain.

Regarding nutrition, the update recommends against “pancreatic rest”; instead, it calls for early oral intake and, if this is not possible, then initiation of total enteral nutrition. Although the authors deemed multiple routes of enteral feeding acceptable, they favored nasogastric or nasoduodenal tubes, when appropriate, because of ease of placement and maintenance. For prolonged total enteral nutrition or patients unable to tolerate nasoenteric feeding, the authors recommended endoscopic feeding tube placement with a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube for those who can tolerate gastric feeding or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy tube for those who cannot or have a high risk of aspiration.

As described above, the update recommends debridement for cases of infected pancreatic necrosis. Ideally, this should be performed at least 4 weeks after onset, and avoided altogether within the first 2 weeks, because of associated risks of morbidity and mortality; instead, during this acute phase, percutaneous drainage may be considered.

For walled-off pancreatic necrosis, the authors recommended transmural drainage via endoscopic therapy because this mitigates risk of pancreatocutaneous fistula. Percutaneous drainage may be considered in addition to, or in absence of, endoscopic drainage, depending on clinical status.

The remainder of the update covers decisions related to stents, other minimally invasive techniques, open operative debridement, and disconnected left pancreatic remnants, along with discussions of key supporting clinical trials.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Cook Endoscopy, Boston Scientific, Olympus, and others.

SOURCE: Baron TH et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Aug 31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.064.

The American Gastroenterological Association recently issued a clinical practice update for the management of pancreatic necrosis, including 15 recommendations based on a comprehensive literature review and the experiences of leading experts.

Recommendations range from the general, such as the need for a multidisciplinary approach, to the specific, such as the superiority of metal over plastic stents for endoscopic transmural drainage.

The expert review, which was conducted by lead author Todd H. Baron, MD, of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and three other colleagues, was vetted by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee (CPUC) and the AGA Governing Board. In addition, the update underwent external peer review prior to publication in Gastroenterology.

In the update, the authors outlined the clinical landscape for pancreatic necrosis, including challenges posed by complex cases and a mortality rate as high as 30%.

“Successful management of these patients requires expert multidisciplinary care by gastroenterologists, surgeons, interventional radiologists, and specialists in critical care medicine, infectious disease, and nutrition,” the investigators wrote.

They went on to explain how management has evolved over the past 10 years.

“Whereby major surgical intervention and debridement was once the mainstay of therapy for patients with symptomatic necrotic collections, a minimally invasive approach focusing on percutaneous drainage and/or endoscopic drainage or debridement is now favored,” they wrote. They added that debridement is still generally agreed to be the best choice for cases of infected necrosis or patients with sterile necrosis “marked by abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and nutritional failure or with associated complications including gastrointestinal luminal obstruction, biliary obstruction, recurrent acute pancreatitis, fistulas, or persistent systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).”

Other elements of care, however, remain debated, the investigators noted, which has led to variations in multiple aspects of care, such as interventional timing, intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and nutrition. Within this framework, the present practice update is aimed at offering “concise best practice advice for the optimal management of patients with this highly morbid condition.”

Among these pieces of advice, the authors emphasized that routine prophylactic antibiotics and/or antifungals to prevent infected necrosis are unsupported by multiple clinical trials. When infection is suspected, the update recommends broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics, noting that, in most cases, it is unnecessary to perform CT-guided fine-needle aspiration for cultures and gram stain.

Regarding nutrition, the update recommends against “pancreatic rest”; instead, it calls for early oral intake and, if this is not possible, then initiation of total enteral nutrition. Although the authors deemed multiple routes of enteral feeding acceptable, they favored nasogastric or nasoduodenal tubes, when appropriate, because of ease of placement and maintenance. For prolonged total enteral nutrition or patients unable to tolerate nasoenteric feeding, the authors recommended endoscopic feeding tube placement with a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube for those who can tolerate gastric feeding or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy tube for those who cannot or have a high risk of aspiration.

As described above, the update recommends debridement for cases of infected pancreatic necrosis. Ideally, this should be performed at least 4 weeks after onset, and avoided altogether within the first 2 weeks, because of associated risks of morbidity and mortality; instead, during this acute phase, percutaneous drainage may be considered.

For walled-off pancreatic necrosis, the authors recommended transmural drainage via endoscopic therapy because this mitigates risk of pancreatocutaneous fistula. Percutaneous drainage may be considered in addition to, or in absence of, endoscopic drainage, depending on clinical status.

The remainder of the update covers decisions related to stents, other minimally invasive techniques, open operative debridement, and disconnected left pancreatic remnants, along with discussions of key supporting clinical trials.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Cook Endoscopy, Boston Scientific, Olympus, and others.

SOURCE: Baron TH et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Aug 31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.064.

The American Gastroenterological Association recently issued a clinical practice update for the management of pancreatic necrosis, including 15 recommendations based on a comprehensive literature review and the experiences of leading experts.

Recommendations range from the general, such as the need for a multidisciplinary approach, to the specific, such as the superiority of metal over plastic stents for endoscopic transmural drainage.

The expert review, which was conducted by lead author Todd H. Baron, MD, of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and three other colleagues, was vetted by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee (CPUC) and the AGA Governing Board. In addition, the update underwent external peer review prior to publication in Gastroenterology.

In the update, the authors outlined the clinical landscape for pancreatic necrosis, including challenges posed by complex cases and a mortality rate as high as 30%.

“Successful management of these patients requires expert multidisciplinary care by gastroenterologists, surgeons, interventional radiologists, and specialists in critical care medicine, infectious disease, and nutrition,” the investigators wrote.

They went on to explain how management has evolved over the past 10 years.

“Whereby major surgical intervention and debridement was once the mainstay of therapy for patients with symptomatic necrotic collections, a minimally invasive approach focusing on percutaneous drainage and/or endoscopic drainage or debridement is now favored,” they wrote. They added that debridement is still generally agreed to be the best choice for cases of infected necrosis or patients with sterile necrosis “marked by abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and nutritional failure or with associated complications including gastrointestinal luminal obstruction, biliary obstruction, recurrent acute pancreatitis, fistulas, or persistent systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).”

Other elements of care, however, remain debated, the investigators noted, which has led to variations in multiple aspects of care, such as interventional timing, intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and nutrition. Within this framework, the present practice update is aimed at offering “concise best practice advice for the optimal management of patients with this highly morbid condition.”

Among these pieces of advice, the authors emphasized that routine prophylactic antibiotics and/or antifungals to prevent infected necrosis are unsupported by multiple clinical trials. When infection is suspected, the update recommends broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics, noting that, in most cases, it is unnecessary to perform CT-guided fine-needle aspiration for cultures and gram stain.

Regarding nutrition, the update recommends against “pancreatic rest”; instead, it calls for early oral intake and, if this is not possible, then initiation of total enteral nutrition. Although the authors deemed multiple routes of enteral feeding acceptable, they favored nasogastric or nasoduodenal tubes, when appropriate, because of ease of placement and maintenance. For prolonged total enteral nutrition or patients unable to tolerate nasoenteric feeding, the authors recommended endoscopic feeding tube placement with a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube for those who can tolerate gastric feeding or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy tube for those who cannot or have a high risk of aspiration.

As described above, the update recommends debridement for cases of infected pancreatic necrosis. Ideally, this should be performed at least 4 weeks after onset, and avoided altogether within the first 2 weeks, because of associated risks of morbidity and mortality; instead, during this acute phase, percutaneous drainage may be considered.

For walled-off pancreatic necrosis, the authors recommended transmural drainage via endoscopic therapy because this mitigates risk of pancreatocutaneous fistula. Percutaneous drainage may be considered in addition to, or in absence of, endoscopic drainage, depending on clinical status.

The remainder of the update covers decisions related to stents, other minimally invasive techniques, open operative debridement, and disconnected left pancreatic remnants, along with discussions of key supporting clinical trials.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Cook Endoscopy, Boston Scientific, Olympus, and others.

SOURCE: Baron TH et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Aug 31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.064.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: The American Gastroenterological Association has issued a clinical practice update for the management of pancreatic necrosis.

Major finding: N/A

Study details: A clinical practice update for the management of pancreatic necrosis.

Disclosures: The investigators disclosed relationships with Cook Endoscopy, Boston Scientific, Olympus, and others.

Source: Baron TH et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Aug 31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.064.

Guideline: Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia

A new guideline has been published to update the 2007 guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

The practice guideline was jointly written by an ad hoc committee of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. CAP refers to a pneumonia infection that was acquired by a patient in his or her community. Decisions about which antibiotics to use to treat this kind of infection are based on risk factors for resistant organisms and the severity of illness.

Pathogens

Traditionally, CAP is caused by common bacterial pathogens that include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella species, Chlamydia pneumonia, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Risk factors for multidrug resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa include previous infection with MRSA or P. aeruginosa, recent hospitalization, and requiring parenteral antibiotics in the last 90 days.

Defining severe community-acquired pneumonia

The health care–associated pneumonia, or HCAP, classification should no longer be used to determine empiric treatment. The recommendations for which antibiotics to use are linked to the severity of illness. Previously the site of treatment drove antibiotic selection, but since decision about the site of care can be affected by many considerations, the guidelines recommend using the CAP severity criteria. Severe CAP includes either one major or at least three minor criteria.

Major criteria are:

- Septic shock requiring vasopressors.

- Respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

Minor criteria are:

- Respiratory rate greater than or equal to 30 breaths/min.

- Ratio of arterial O2 partial pressure to fractional inspired O2 less than or equal to 250.

- Multilobar infiltrates.

- Confusion/disorientation.

- Uremia (blood urea nitrogen level greater than or equal to 20 mg/dL).

- Leukopenia (white blood cell count less than 4,000 cells/mcL).

- Thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 100,000 mcL)

- Hypothermia (core temperature less than 36º C).

- Hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation.

Management and diagnostic testing

Clinicians should use the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and clinical judgment to guide the site of treatment for patients. Gram stain, sputum, and blood culture should not be routinely obtained in an outpatient setting. Legionella antigen should not be routinely obtained unless indicated by epidemiological factors. During influenza season, a rapid influenza assay, preferably a nucleic acid amplification test, should be obtained to help guide treatment.

For patients with severe CAP or risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa, gram stain and culture and Legionella antigen should be obtained to manage antibiotic choices. Also, blood cultures should be obtained for these patients.

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated based on clinical judgment and radiographic confirmation of CAP. Serum procalcitonin should not be used to assess initiation of antibiotic therapy.

Empiric antibiotic therapy

Healthy adults without comorbidities should be treated with monotherapy of either:

- Amoxicillin 1 g three times daily.

- OR doxycycline 100 mg twice daily.

- OR a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily or clarithromycin extended release 1,000 mg daily) only in areas with pneumococcal resistance to macrolides less than 25%.

Adults with comorbidities such as chronic heart, lung, liver, or renal disease; diabetes mellitus; alcoholism; malignancy; or asplenia should be treated with:

- Amoxicillin/clavulanate 500 mg/125 mg three times daily, or amoxicillin/ clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg twice daily, or 2,000 mg/125 mg twice daily, or a cephalosporin (cefpodoxime 200 mg twice daily or cefuroxime 500 mg twice daily); and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily, clarithromycin [500 mg twice daily or extended release 1,000 mg once daily]), or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. (Some experts recommend that the first dose of doxycycline should be 200 mg.)

- OR monotherapy with respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily, or gemifloxacin 320 mg daily).

Inpatient pneumonia that is not severe, without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with:

- Beta-lactam (ampicillin 1 sulbactam 1.5-3 g every 6 h, cefotaxime 1-2 g every 8 h, ceftriaxone 1-2 g daily, or ceftaroline 600 mg every 12 h) and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily).

- OR monotherapy with a respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily).

If there is a contraindication for the use of both a macrolide and a fluoroquinolone, then doxycycline can be used instead.

Severe inpatient pneumonia without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with combination therapy of either (agents and doses the same as above):

- Beta-lactam and macrolide.

- OR fluoroquinolone and beta-lactam.

It is recommended to not routinely add anaerobic coverage for suspected aspiration pneumonia unless lung abscess or empyema is suspected. Clinicians should identify risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa before adding additional agents.

Duration of antibiotic therapy is determined by the patient achieving clinical stability with no less than 5 days of antibiotics. In adults with symptom resolution within 5-7 days, no additional follow-up chest imaging is recommended. If patients test positive for influenza, then anti-influenza treatment such as oseltamivir should be used in addition to antibiotics regardless of length of influenza symptoms before presentation.

The bottom line

CAP treatment should be based on severity of illness and risk factors for resistant organisms. Blood and sputum cultures are recommended only for patients with severe pneumonia. There have been important changes in the recommendations for antibiotic treatment of CAP, with high-dose amoxicillin recommended for most patients with CAP who are treated as outpatients. Patients who exhibit clinical stability should be treated for at least 5 days and do not require follow up imaging studies.

For a podcast of this guideline, go to iTunes and download the Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline podcast.

Reference

Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Oct 1;200(7):e45-e67.

Tina Chuong, DO, is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

A new guideline has been published to update the 2007 guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

The practice guideline was jointly written by an ad hoc committee of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. CAP refers to a pneumonia infection that was acquired by a patient in his or her community. Decisions about which antibiotics to use to treat this kind of infection are based on risk factors for resistant organisms and the severity of illness.

Pathogens

Traditionally, CAP is caused by common bacterial pathogens that include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella species, Chlamydia pneumonia, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Risk factors for multidrug resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa include previous infection with MRSA or P. aeruginosa, recent hospitalization, and requiring parenteral antibiotics in the last 90 days.

Defining severe community-acquired pneumonia

The health care–associated pneumonia, or HCAP, classification should no longer be used to determine empiric treatment. The recommendations for which antibiotics to use are linked to the severity of illness. Previously the site of treatment drove antibiotic selection, but since decision about the site of care can be affected by many considerations, the guidelines recommend using the CAP severity criteria. Severe CAP includes either one major or at least three minor criteria.

Major criteria are:

- Septic shock requiring vasopressors.

- Respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

Minor criteria are:

- Respiratory rate greater than or equal to 30 breaths/min.

- Ratio of arterial O2 partial pressure to fractional inspired O2 less than or equal to 250.

- Multilobar infiltrates.

- Confusion/disorientation.

- Uremia (blood urea nitrogen level greater than or equal to 20 mg/dL).

- Leukopenia (white blood cell count less than 4,000 cells/mcL).

- Thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 100,000 mcL)

- Hypothermia (core temperature less than 36º C).

- Hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation.

Management and diagnostic testing

Clinicians should use the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and clinical judgment to guide the site of treatment for patients. Gram stain, sputum, and blood culture should not be routinely obtained in an outpatient setting. Legionella antigen should not be routinely obtained unless indicated by epidemiological factors. During influenza season, a rapid influenza assay, preferably a nucleic acid amplification test, should be obtained to help guide treatment.

For patients with severe CAP or risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa, gram stain and culture and Legionella antigen should be obtained to manage antibiotic choices. Also, blood cultures should be obtained for these patients.

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated based on clinical judgment and radiographic confirmation of CAP. Serum procalcitonin should not be used to assess initiation of antibiotic therapy.

Empiric antibiotic therapy

Healthy adults without comorbidities should be treated with monotherapy of either:

- Amoxicillin 1 g three times daily.

- OR doxycycline 100 mg twice daily.

- OR a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily or clarithromycin extended release 1,000 mg daily) only in areas with pneumococcal resistance to macrolides less than 25%.

Adults with comorbidities such as chronic heart, lung, liver, or renal disease; diabetes mellitus; alcoholism; malignancy; or asplenia should be treated with:

- Amoxicillin/clavulanate 500 mg/125 mg three times daily, or amoxicillin/ clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg twice daily, or 2,000 mg/125 mg twice daily, or a cephalosporin (cefpodoxime 200 mg twice daily or cefuroxime 500 mg twice daily); and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily, clarithromycin [500 mg twice daily or extended release 1,000 mg once daily]), or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. (Some experts recommend that the first dose of doxycycline should be 200 mg.)

- OR monotherapy with respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily, or gemifloxacin 320 mg daily).

Inpatient pneumonia that is not severe, without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with:

- Beta-lactam (ampicillin 1 sulbactam 1.5-3 g every 6 h, cefotaxime 1-2 g every 8 h, ceftriaxone 1-2 g daily, or ceftaroline 600 mg every 12 h) and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily).

- OR monotherapy with a respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily).

If there is a contraindication for the use of both a macrolide and a fluoroquinolone, then doxycycline can be used instead.

Severe inpatient pneumonia without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with combination therapy of either (agents and doses the same as above):

- Beta-lactam and macrolide.

- OR fluoroquinolone and beta-lactam.

It is recommended to not routinely add anaerobic coverage for suspected aspiration pneumonia unless lung abscess or empyema is suspected. Clinicians should identify risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa before adding additional agents.

Duration of antibiotic therapy is determined by the patient achieving clinical stability with no less than 5 days of antibiotics. In adults with symptom resolution within 5-7 days, no additional follow-up chest imaging is recommended. If patients test positive for influenza, then anti-influenza treatment such as oseltamivir should be used in addition to antibiotics regardless of length of influenza symptoms before presentation.

The bottom line

CAP treatment should be based on severity of illness and risk factors for resistant organisms. Blood and sputum cultures are recommended only for patients with severe pneumonia. There have been important changes in the recommendations for antibiotic treatment of CAP, with high-dose amoxicillin recommended for most patients with CAP who are treated as outpatients. Patients who exhibit clinical stability should be treated for at least 5 days and do not require follow up imaging studies.

For a podcast of this guideline, go to iTunes and download the Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline podcast.

Reference

Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Oct 1;200(7):e45-e67.

Tina Chuong, DO, is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

A new guideline has been published to update the 2007 guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

The practice guideline was jointly written by an ad hoc committee of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. CAP refers to a pneumonia infection that was acquired by a patient in his or her community. Decisions about which antibiotics to use to treat this kind of infection are based on risk factors for resistant organisms and the severity of illness.

Pathogens

Traditionally, CAP is caused by common bacterial pathogens that include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella species, Chlamydia pneumonia, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Risk factors for multidrug resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa include previous infection with MRSA or P. aeruginosa, recent hospitalization, and requiring parenteral antibiotics in the last 90 days.

Defining severe community-acquired pneumonia

The health care–associated pneumonia, or HCAP, classification should no longer be used to determine empiric treatment. The recommendations for which antibiotics to use are linked to the severity of illness. Previously the site of treatment drove antibiotic selection, but since decision about the site of care can be affected by many considerations, the guidelines recommend using the CAP severity criteria. Severe CAP includes either one major or at least three minor criteria.

Major criteria are:

- Septic shock requiring vasopressors.

- Respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

Minor criteria are:

- Respiratory rate greater than or equal to 30 breaths/min.

- Ratio of arterial O2 partial pressure to fractional inspired O2 less than or equal to 250.

- Multilobar infiltrates.

- Confusion/disorientation.

- Uremia (blood urea nitrogen level greater than or equal to 20 mg/dL).

- Leukopenia (white blood cell count less than 4,000 cells/mcL).

- Thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 100,000 mcL)

- Hypothermia (core temperature less than 36º C).

- Hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation.

Management and diagnostic testing

Clinicians should use the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and clinical judgment to guide the site of treatment for patients. Gram stain, sputum, and blood culture should not be routinely obtained in an outpatient setting. Legionella antigen should not be routinely obtained unless indicated by epidemiological factors. During influenza season, a rapid influenza assay, preferably a nucleic acid amplification test, should be obtained to help guide treatment.

For patients with severe CAP or risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa, gram stain and culture and Legionella antigen should be obtained to manage antibiotic choices. Also, blood cultures should be obtained for these patients.

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated based on clinical judgment and radiographic confirmation of CAP. Serum procalcitonin should not be used to assess initiation of antibiotic therapy.

Empiric antibiotic therapy

Healthy adults without comorbidities should be treated with monotherapy of either:

- Amoxicillin 1 g three times daily.

- OR doxycycline 100 mg twice daily.

- OR a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily or clarithromycin extended release 1,000 mg daily) only in areas with pneumococcal resistance to macrolides less than 25%.

Adults with comorbidities such as chronic heart, lung, liver, or renal disease; diabetes mellitus; alcoholism; malignancy; or asplenia should be treated with:

- Amoxicillin/clavulanate 500 mg/125 mg three times daily, or amoxicillin/ clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg twice daily, or 2,000 mg/125 mg twice daily, or a cephalosporin (cefpodoxime 200 mg twice daily or cefuroxime 500 mg twice daily); and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily, clarithromycin [500 mg twice daily or extended release 1,000 mg once daily]), or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. (Some experts recommend that the first dose of doxycycline should be 200 mg.)

- OR monotherapy with respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily, or gemifloxacin 320 mg daily).

Inpatient pneumonia that is not severe, without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with:

- Beta-lactam (ampicillin 1 sulbactam 1.5-3 g every 6 h, cefotaxime 1-2 g every 8 h, ceftriaxone 1-2 g daily, or ceftaroline 600 mg every 12 h) and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily).

- OR monotherapy with a respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily).

If there is a contraindication for the use of both a macrolide and a fluoroquinolone, then doxycycline can be used instead.

Severe inpatient pneumonia without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with combination therapy of either (agents and doses the same as above):

- Beta-lactam and macrolide.

- OR fluoroquinolone and beta-lactam.

It is recommended to not routinely add anaerobic coverage for suspected aspiration pneumonia unless lung abscess or empyema is suspected. Clinicians should identify risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa before adding additional agents.

Duration of antibiotic therapy is determined by the patient achieving clinical stability with no less than 5 days of antibiotics. In adults with symptom resolution within 5-7 days, no additional follow-up chest imaging is recommended. If patients test positive for influenza, then anti-influenza treatment such as oseltamivir should be used in addition to antibiotics regardless of length of influenza symptoms before presentation.

The bottom line

CAP treatment should be based on severity of illness and risk factors for resistant organisms. Blood and sputum cultures are recommended only for patients with severe pneumonia. There have been important changes in the recommendations for antibiotic treatment of CAP, with high-dose amoxicillin recommended for most patients with CAP who are treated as outpatients. Patients who exhibit clinical stability should be treated for at least 5 days and do not require follow up imaging studies.

For a podcast of this guideline, go to iTunes and download the Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline podcast.

Reference

Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Oct 1;200(7):e45-e67.

Tina Chuong, DO, is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

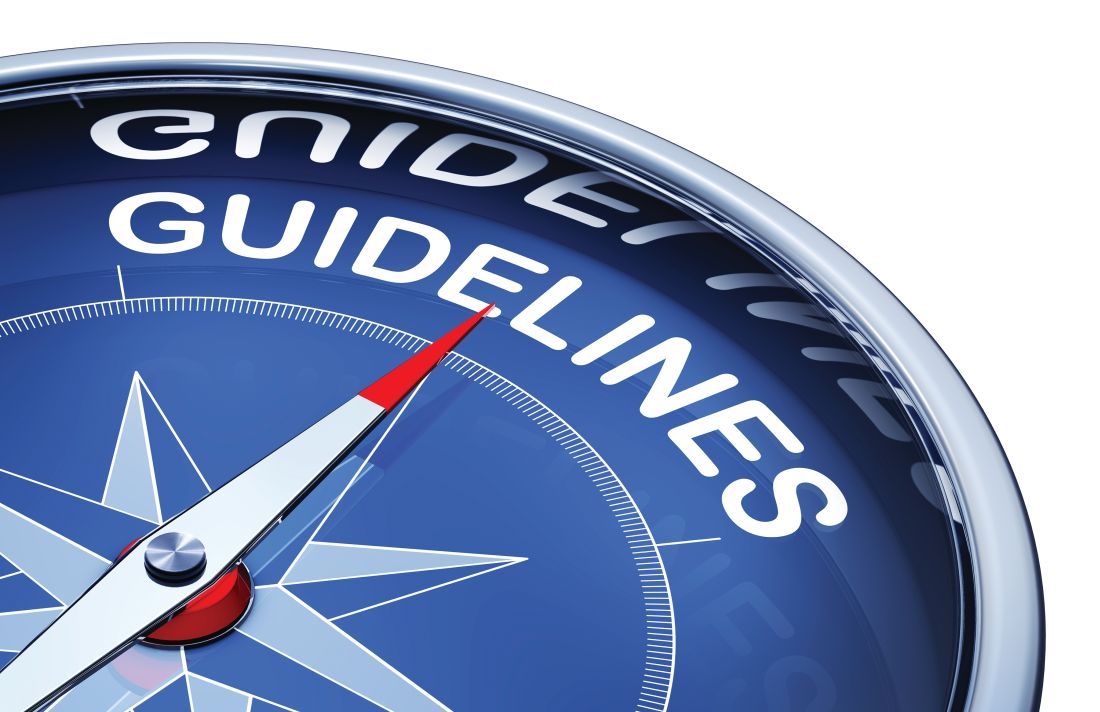

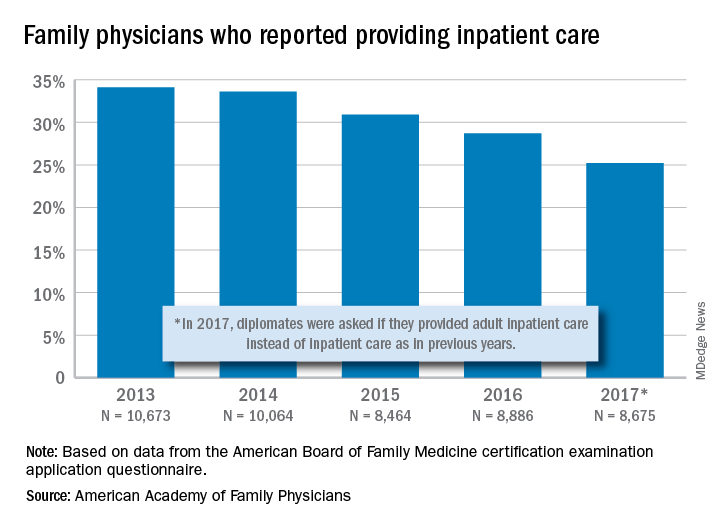

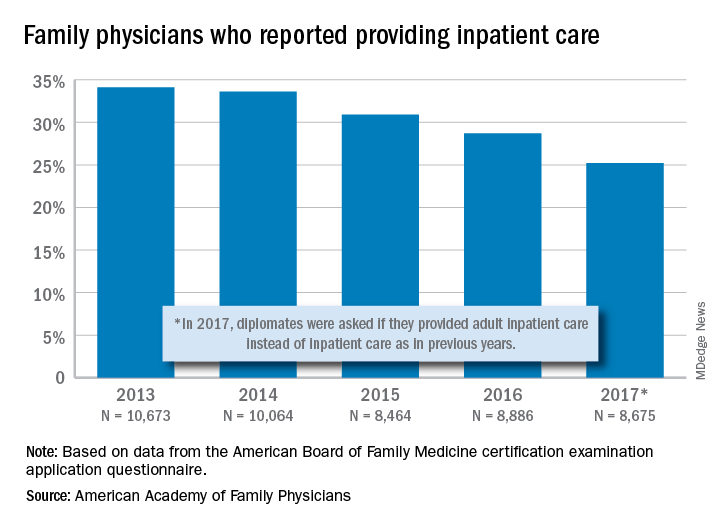

Inpatient care declining among family physicians

and by 2017, only one of four FPs was practicing hospital medicine, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians.

The share of family physicians who provided hospital care went from 34.1% in 2013 to 25.2% in 2017, for a relative decrease of 26% that left only a quarter of FPs seeing inpatients, based on data from the annual American Board of Family Medicine certification exam application questionnaire. For the 5-year period, 46,762 individuals were included in the study sample of FPs in direct patient care.

“As observed in other domains (prenatal care, home visits, nursing home care, and obstetric care), this study adds to the evidence demonstrating contracting scope of practice among FPs,” Anuradha Jetty, MPH, of the AAFP’s Robert Graham Center in Washington, D.C., and associates said in a recent Policy Brief published in the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine.

Much of that contraction is occurring among new family physicians who can’t “find positions that allow them to use all their expertise,” the investigators said in a separate statement. The AAFP had previously reported that about 40% of family physicians had full hospital privileges in 2018, compared with 56% in 2012.

Many new FPs now work in large multispecialty practices or hospital systems, and “[some] of these employers dictate scope of practice, limiting family physicians to coordinating outpatient care and relying on subspecialists or hospitalists to provide inpatient care,” they noted.

and by 2017, only one of four FPs was practicing hospital medicine, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians.

The share of family physicians who provided hospital care went from 34.1% in 2013 to 25.2% in 2017, for a relative decrease of 26% that left only a quarter of FPs seeing inpatients, based on data from the annual American Board of Family Medicine certification exam application questionnaire. For the 5-year period, 46,762 individuals were included in the study sample of FPs in direct patient care.

“As observed in other domains (prenatal care, home visits, nursing home care, and obstetric care), this study adds to the evidence demonstrating contracting scope of practice among FPs,” Anuradha Jetty, MPH, of the AAFP’s Robert Graham Center in Washington, D.C., and associates said in a recent Policy Brief published in the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine.

Much of that contraction is occurring among new family physicians who can’t “find positions that allow them to use all their expertise,” the investigators said in a separate statement. The AAFP had previously reported that about 40% of family physicians had full hospital privileges in 2018, compared with 56% in 2012.

Many new FPs now work in large multispecialty practices or hospital systems, and “[some] of these employers dictate scope of practice, limiting family physicians to coordinating outpatient care and relying on subspecialists or hospitalists to provide inpatient care,” they noted.

and by 2017, only one of four FPs was practicing hospital medicine, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians.

The share of family physicians who provided hospital care went from 34.1% in 2013 to 25.2% in 2017, for a relative decrease of 26% that left only a quarter of FPs seeing inpatients, based on data from the annual American Board of Family Medicine certification exam application questionnaire. For the 5-year period, 46,762 individuals were included in the study sample of FPs in direct patient care.

“As observed in other domains (prenatal care, home visits, nursing home care, and obstetric care), this study adds to the evidence demonstrating contracting scope of practice among FPs,” Anuradha Jetty, MPH, of the AAFP’s Robert Graham Center in Washington, D.C., and associates said in a recent Policy Brief published in the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine.

Much of that contraction is occurring among new family physicians who can’t “find positions that allow them to use all their expertise,” the investigators said in a separate statement. The AAFP had previously reported that about 40% of family physicians had full hospital privileges in 2018, compared with 56% in 2012.

Many new FPs now work in large multispecialty practices or hospital systems, and “[some] of these employers dictate scope of practice, limiting family physicians to coordinating outpatient care and relying on subspecialists or hospitalists to provide inpatient care,” they noted.

AAD-NPF Pediatric psoriasis guideline advises on physical and mental care

Psoriasis management in children involves attention not only to treatment of the physical condition but also psychosocial wellness and quality of life, according to

Psoriasis affects approximately 1% of children, either alone or associated with comorbid conditions such as psoriatic arthritis (PsA), wrote Alan Menter, MD, of Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, and coauthors of the guideline.

In the guideline, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the multidisciplinary work group identified screening tools to measure disease severity, strategies for management of comorbidities, and the safety and effectiveness of topical, systemic, and phototherapy treatments.

To assess disease severity, the work group recommended not only the use of body surface area (BSA), similar to measurement of severity in adults, but also the use of the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, a 10-question quality of life survey, as BSA alone does not account for the potential negative impact of the disease on quality of life in terms of physical, emotional, social, and psychological function.

“For example, a child with psoriasis limited to the face or the entire scalp does not have severe disease based on BSA definitions, but if this involvement causes shame, social withdrawal, or bullying, it satisfies criteria for severe disease based on impact beyond the skin,” they said.

The work group stated that a variety of conditions may trigger or exacerbate psoriasis in children, including infections, cutaneous trauma, or physiological, emotional, and environmental stressors.

The majority of children with PsA develop joint inflammation before skin disease, the work group wrote. In addition, children with psoriasis are at increased risk for rheumatoid arthritis, so clinicians may need to distinguish between a combination of psoriasis and musculoskeletal issues and cases of either psoriatic or rheumatoid arthritis in young patients.

The cardiovascular risk factors associated with metabolic syndrome are greater in children with psoriasis, compared with children without psoriasis, the work group noted. In addition, pediatric psoriasis patients have a higher prevalence of obesity than children without psoriasis, and they recommended that children with psoriasis be monitored for the development of obesity, and that obese children with psoriasis should be referred for weight management.

The work group noted that data are insufficient in children to support the link between psoriasis and cardiovascular disease that has been documented in adults with psoriasis. However, “patients with pediatric psoriasis should have American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)–recommended age-related cardiovascular screening regardless of the presence of signs or symptoms,” they said.

The guideline also recommends screening for dyslipidemia and hypertension according to AAP guidelines and educating pediatric psoriasis patients about the risk of diabetes and regularly screening for diabetes and insulin resistance in those who are obese. Overweight children with psoriasis may be screened at the provider’s discretion, they wrote. Patients with signs of inflammatory bowel disease, which also is associated with psoriasis in adults, should be considered for referral to a gastroenterologist, they noted.

Children with psoriasis should be screened regularly for mental health conditions regardless of age, and they should be asked about substance abuse, according to the guideline, and those with concerns should be referred for additional assessment and management.

The guideline divides treatment of psoriasis in children into three categories: topical, phototherapy and photochemotherapy, and systemic treatments (nonbiologic or biologic).

For topicals, the guideline recommendations include corticosteroids as an off-label therapy, as well as ultra-high-potency topical corticosteroids as monotherapy. Overall, “selection of a therapeutic routine (potency, delivery vehicle, frequency of application) should take into account sites of involvement, type and thickness of psoriasis, age of the patient, total BSA of application, anticipated occlusion, and disease acuity, among other patient-, disease-, and drug-related factors,” the authors wrote. Other topical options included in the recommendations: calcineurin inhibitors, topical vitamin D analogues, tazarotene (off label), anthralin, and coal tar.

Phototherapy has a history of use in psoriasis treatment and remains part of the current recommendations, although data in children are limited, and data on the use of phototherapy for pustular psoriasis in children are insufficient to make specific treatment and dosing recommendations, the work group noted. The researchers also noted that in-office phototherapy may not be feasible for many patients, but that in-home ultraviolet light equipment or natural sunlight in moderation could be recommended as an alternative.

The use of systemic, nonbiologic treatments for pediatric psoriasis should be “based on baseline severity of disease, subtype of psoriasis, speed of disease progression, lack of response to more conservative therapies such as topical agents and phototherapy (when appropriate), impaired physical or psychological functioning or [quality of life] due to disease extent, and the presence of comorbidities such as PsA,” the workgroup said.

Options for systemic treatment include methotrexate, cyclosporine (notably for pustular as well as plaque and erythrodermic psoriasis), and systemic retinoids. In addition, fumaric acid esters may be an option for children with moderate to severe psoriasis, with recommended clinical and laboratory monitoring.

The increasing safety and efficacy data on biologics in pediatric psoriasis patients support their consideration among first-line systemic treatments, the work group suggested. “Etanercept and ustekinumab are now [Food and Drug Administration] approved for patients with psoriasis 4 years and older and 12 years and older, respectively,” they said, and infliximab and adalimumab have been used off label in children.

The work group concluded that research and knowledge gaps about pediatric psoriasis persist and include mechanism of disease onset, development of comorbidities, and identification of ideal dosing for various treatments.

Finally, the work group emphasized the importance of collaboration between dermatologists and primary care providers for managing psoriasis in children, as well as the importance of patient education.

“Dermatologists should be mindful of the unique aspects of the emotional development of children and the social dynamics of having a visible difference,” they wrote. “Shared decision making with the patient (if age appropriate) and the caregivers is a useful approach, particularly as related to the use of off-label medications to treat severe disease,” they said.

“This is the first time that pediatric psoriasis has been discussed as an independent topic within the guideline,” said one of the guideline authors, Dawn M.R. Davis, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., in an interview. “Children have unique physiology and psychosocial aspects to their care relative to adults. In addition, psoriasis has some clinical manifestations that are oftentimes distinctly seen in children,” she commented. “Creation of a guideline specific to children allows us to summarize the similarities and differences of disease presentation and management. It also allows an opportunity to clarify what research data (especially therapeutics) have been studied in children and their uses, safety profiles, and dosing,” she noted.

Psoriasis can be a psychosocially debilitating disease, she emphasized. “In children, for example, isolated or prominent facial involvement is common, which can be embarrassing and impact relationships.”

The take-home message for clinicians, Dr. Davis said, is to keep in mind the multisystemic nature of psoriasis. “It is not limited to the skin,” she said. “Treating a patient with psoriasis necessitates practicing whole-person care” and considering the multiple comorbidities that impact quality of life and overall health in children, as well as adults with psoriasis, she commented. “Dermatologists can empower patients and their caregivers by educating them on the multifocal, complex nature of the disease.” She added, “We have much to learn regarding psoriasis in the pediatric population. More research into therapeutics, topical and systemic, is necessary to optimize patient care.”

The guideline was based on studies published in the PubMed and MEDLINE databases from January 2011 through December 31, 2017.

Dr. Menter and Craig A. Elmets, MD, professor of dermatology, at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, were cochairs of the work group. The pediatric guideline is the latest in a multipart series of AAD-NPF guidelines on psoriasis being published this year in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Many of the guideline authors, including lead author Dr. Menter, disclosed relationships with multiple companies; however, a minimum 51% of workgroup members had no relevant conflicts of interest in accordance with AAD policy. There was no funding source. Dr. Davis disclosed serving as an investigator for Regeneron, with no compensation.

SOURCE: Menter et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.049.

Psoriasis management in children involves attention not only to treatment of the physical condition but also psychosocial wellness and quality of life, according to