User login

Finding meaning in ‘Lean’?

Using systems improvement strategies to support the Quadruple Aim

General background on well-being and burnout

With burnout increasingly recognized as a shared responsibility that requires addressing organizational drivers while supporting individuals to be well,1-4 practical strategies and examples of successful implementation of systems interventions to address burnout will be helpful for service directors to support their staff. The Charter on Physician Well-being, recently developed through collaborative input from multiple organizations, defines guiding principles and key commitments at the societal, organizational, interpersonal, and individual levels and may be a useful framework for organizations that are developing well-being initiatives.5

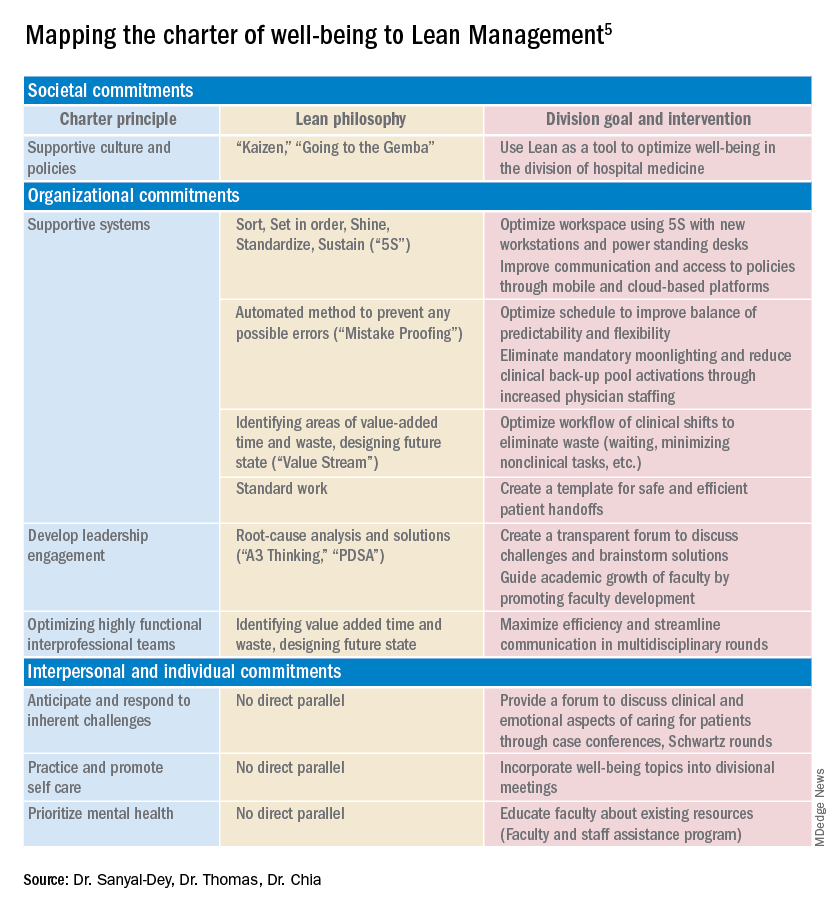

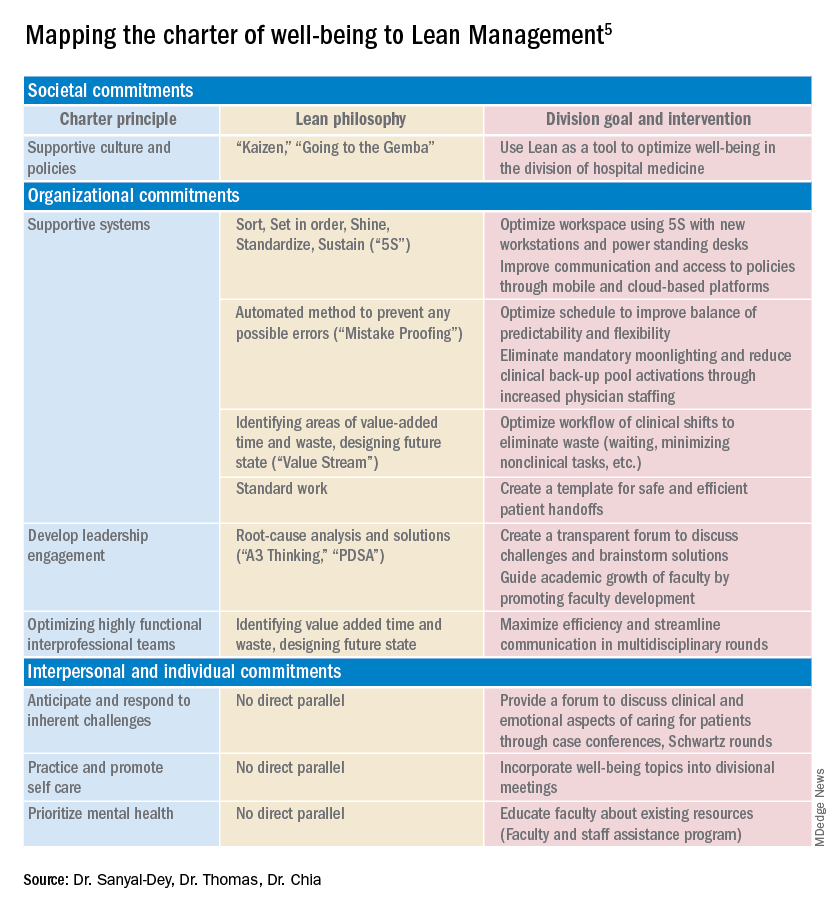

The charter advocates including physician well-being as a quality improvement metric for health systems, aligned with the concept of the Quadruple Aim of optimizing patient care by enhancing provider experience, promoting high-value care, and improving population health.6 Identifying areas of alignment between the charter’s recommendations and systems improvement strategies that seek to optimize efficiency and reduce waste, such as Lean Management, may help physician leaders to contextualize well-being initiatives more easily within ongoing systems improvement efforts. In this perspective, we provide one division’s experience using the Charter to assess successes and identify additional areas of improvement for well-being initiatives developed using Lean Management methodology.

Past and current state of affairs

In 2011, the division of hospital medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital was established and has seen continual expansion in terms of direct patient care, medical education, and hospital leadership.

In 2015, the division of hospital medicine experienced leadership transitions, faculty attrition, and insufficient recruitment resulting in staffing shortages, service line closure, schedule instability, and ultimately, low morale. A baseline survey conducted using the 2-Item Maslach Burnout Inventory. This survey, which uses one item in the domain of emotional exhaustion and one item in the domain of depersonalization, has shown good correlation with the full Maslach Burnout Inventory.7 At baseline, approximately one-third of the division’s physicians experienced burnout.

In response, a subsequent retreat focused on the three greatest areas of concern identified by the survey: scheduling, faculty development, and well-being.

Like many health systems, the hospital has adopted Lean as its preferred systems-improvement framework. The retreat was structured around the principles of Lean philosophy, and was designed to emulate that of a consolidated Kaizen workshop.

“Kaizen” in Japanese means “change for the better.” A typical Kaizen workshop revolves around rapid problem-solving over the course of 3-5 days, in which a team of people come together to identify and implement significant improvements for a selected process. To this end, the retreat was divided into subgroups for each area of concern. In turn, each subgroup mapped out existing workflows (“value stream”), identified areas of waste and non–value added time, and generated ideas of what an idealized process would be. Next, a root-cause analysis was performed and subsequent interventions (“countermeasures”) developed to address each problem. At the conclusion of the retreat, each subgroup shared a summary of their findings with the larger group.

Moving forward, this information served as a guiding framework for service and division leadership to run small tests of change. We enacted a series of countermeasures over the course of several years, and multiple cycles of improvement work addressed the three areas of concern. We developed an A3 report (a Lean project management tool that incorporates the plan-do-study-act cycle, organizes strategic efforts, and tracks progress on a single page) to summarize and present these initiatives to the Performance Improvement and Patient Safety Committee of the hospital executive leadership team. This structure illustrated alignment with the hospital’s core values (“true north”) of “developing people” and “care experience.”

In 2018, interval surveys demonstrated a gradual reduction of burnout to approximately one-fifth of division physicians as measured by the 2-item Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Initiatives in faculty well-being

The Charter of Physician Well-being outlines a framework to promote well-being among doctors by maximizing a sense of fulfillment and minimizing the harms of burnout. It shares this responsibility among societal, organizational, and interpersonal and individual commitments.5

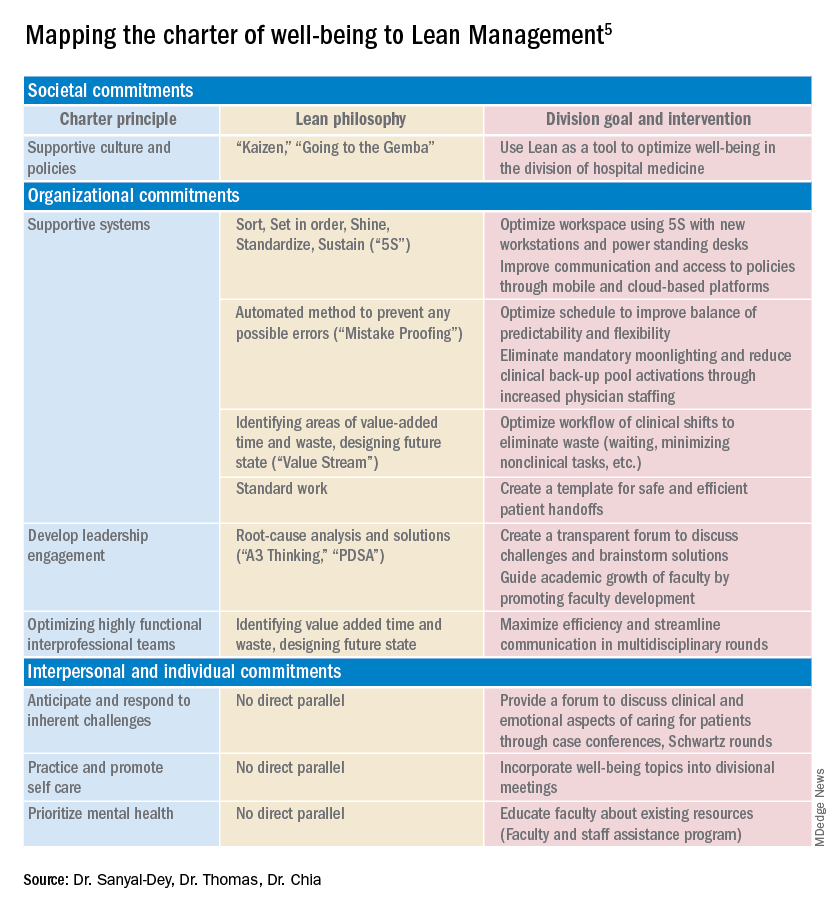

As illustrated above, we used principles of Lean Management to prospectively create initiatives to improve well-being in our division. Lean in health care is designed to optimize primarily the patient experience; its implementation has subsequently demonstrated mixed provider and staff experiences,8,9 and many providers are skeptical of Lean’s potential to improve their own well-being. If, however, Lean is aligned with best practice frameworks for well-being such as those outline in the charter, it may also help to meet the Quadruple Aim of optimizing both provider well-being and patient experience. To further test this hypothesis, we retrospectively categorized our Lean-based interventions into the commitments described by the charter to identify areas of alignment and gaps that were not initially addressed using Lean Management (Table).

Organizational commitments5Supportive systems

We optimized scheduling and enhanced physician staffing by budgeting for a physician staffing buffer each academic year in order to minimize mandatory moonlighting and jeopardy pool activations that result from operating on a thin staffing margin when expected personal leave and reductions in clinical effort occur. Furthermore, we revised scheduling principles to balance patient continuity and individual time off requests while setting limits on the maximum duration of clinical stretches and instituting mandatory minimum time off between them.

Leadership engagement

We initiated monthly operations meetings as a forum to discuss challenges, brainstorm solutions, and message new initiatives with group input. For example, as a result of these meetings, we designed and implemented an additional service line to address the high census, revised the distribution of new patient admissions to level-load clinical shifts, and established a maximum number of weekends worked per month and year. This approach aligns with recommendations to use participatory leadership strategies to enhance physician well-being.10 Engaging both executive level and service level management to focus on burnout and other related well-being metrics is necessary for sustaining such work.

Interprofessional teamwork

We revised multidisciplinary rounds with social work, utilization management, and physical therapy to maximize efficiency and streamline communication by developing standard approaches for each patient presentation.

Interpersonal and individual commitments5Address emotional challenges of physician work

Although these commitments did not have a direct corollary with Lean philosophy, some of these needs were identified by our physician group at our annual retreats. As a result, we initiated a monthly faculty-led noon conference series focused on the clinical challenges of caring for vulnerable populations, a particular source of distress in our practice setting, and revised the division schedule to encourage attendance at the hospital’s Schwartz rounds.

Mental health and self-care

We organized focus groups and faculty development sessions on provider well-being and burnout and dealing with challenging patients and invited the Faculty and Staff Assistance Program, our institution’s mental health service provider, to our weekly division meeting.

Future directions

After using Lean Management as an approach to prospectively improve physician well-being, we were able to use the Charter on Physician Well-being retrospectively as a “checklist” to identify additional gaps for targeted intervention to ensure all commitments are sufficiently addressed.

Overall, we found that, not surprisingly, Lean Management aligned best with the organizational commitments in the charter. Reviewing the organizational commitments, we found our biggest remaining challenges are in building supportive systems, namely ensuring sustainable workloads, offloading and delegating nonphysician tasks, and minimizing the burden of documentation and administration.

Reviewing the societal commitments helped us to identify opportunities for future directions that we may not have otherwise considered. As a safety-net institution, we benefit from a strong sense of mission and shared values within our hospital and division. However, we recognize the need to continue to be vigilant to ensure that our physicians perceive that their own values are aligned with the division’s stated mission. Devoting a Kaizen-style retreat to well-being likely helped, and allocating divisional resources to a well-being committee indirectly helped, to foster a culture of well-being; however, we could more deliberately identify local policies that may benefit from advocacy or revision. Although our faculty identified interventions to improve interpersonal and individual drivers of well-being, these charter commitments did not have direct parallels in Lean philosophy, and organizations may need to deliberately seek to address these commitments outside of a Lean approach. Specifically, by reviewing the charter, we identified opportunities to provide additional resources for peer support and protected time for mental health care and self-care.

Conclusion

Lean Management can be an effective strategy to address many of the organizational commitments outlined in the Charter on Physician Well-being. This approach may be particularly effective for solving local challenges with systems and workflows. Those who use Lean as a primary method to approach systems improvement in support of the Quadruple Aim may need to use additional strategies to address societal and interpersonal and individual commitments outlined in the charter.

Dr. Sanyal-Dey is visiting associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and director of client services, LeanTaaS. Dr. Thomas is associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Chia is associate professor of clinical medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

References

1. West CP et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-81.

2. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-46.

3. Shanafelt T et al. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-32.

4. Shanafelt T et al. Building a program on well-being: Key design considerations to meet the unique needs of each organization. Acad Med. 2019 Feb;94(2):156-161.

5. Thomas LR et al. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-42.

6. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-6.

7. West CP et al. Concurrent Validity of Single-Item Measures of Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization in Burnout Assessment. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1445-52.

8. Hung DY et al. Experiences of primary care physicians and staff following lean workflow redesign. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Apr 10;18(1):274.

9. Zibrowski E et al. Easier and faster is not always better: Grounded theory of the impact of large-scale system transformation on the clinical work of emergency medicine nurses and physicians. JMIR Hum Factors. 2018. doi: 10.2196/11013.

10. Shanafelt TD et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(4):432-40.

Using systems improvement strategies to support the Quadruple Aim

Using systems improvement strategies to support the Quadruple Aim

General background on well-being and burnout

With burnout increasingly recognized as a shared responsibility that requires addressing organizational drivers while supporting individuals to be well,1-4 practical strategies and examples of successful implementation of systems interventions to address burnout will be helpful for service directors to support their staff. The Charter on Physician Well-being, recently developed through collaborative input from multiple organizations, defines guiding principles and key commitments at the societal, organizational, interpersonal, and individual levels and may be a useful framework for organizations that are developing well-being initiatives.5

The charter advocates including physician well-being as a quality improvement metric for health systems, aligned with the concept of the Quadruple Aim of optimizing patient care by enhancing provider experience, promoting high-value care, and improving population health.6 Identifying areas of alignment between the charter’s recommendations and systems improvement strategies that seek to optimize efficiency and reduce waste, such as Lean Management, may help physician leaders to contextualize well-being initiatives more easily within ongoing systems improvement efforts. In this perspective, we provide one division’s experience using the Charter to assess successes and identify additional areas of improvement for well-being initiatives developed using Lean Management methodology.

Past and current state of affairs

In 2011, the division of hospital medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital was established and has seen continual expansion in terms of direct patient care, medical education, and hospital leadership.

In 2015, the division of hospital medicine experienced leadership transitions, faculty attrition, and insufficient recruitment resulting in staffing shortages, service line closure, schedule instability, and ultimately, low morale. A baseline survey conducted using the 2-Item Maslach Burnout Inventory. This survey, which uses one item in the domain of emotional exhaustion and one item in the domain of depersonalization, has shown good correlation with the full Maslach Burnout Inventory.7 At baseline, approximately one-third of the division’s physicians experienced burnout.

In response, a subsequent retreat focused on the three greatest areas of concern identified by the survey: scheduling, faculty development, and well-being.

Like many health systems, the hospital has adopted Lean as its preferred systems-improvement framework. The retreat was structured around the principles of Lean philosophy, and was designed to emulate that of a consolidated Kaizen workshop.

“Kaizen” in Japanese means “change for the better.” A typical Kaizen workshop revolves around rapid problem-solving over the course of 3-5 days, in which a team of people come together to identify and implement significant improvements for a selected process. To this end, the retreat was divided into subgroups for each area of concern. In turn, each subgroup mapped out existing workflows (“value stream”), identified areas of waste and non–value added time, and generated ideas of what an idealized process would be. Next, a root-cause analysis was performed and subsequent interventions (“countermeasures”) developed to address each problem. At the conclusion of the retreat, each subgroup shared a summary of their findings with the larger group.

Moving forward, this information served as a guiding framework for service and division leadership to run small tests of change. We enacted a series of countermeasures over the course of several years, and multiple cycles of improvement work addressed the three areas of concern. We developed an A3 report (a Lean project management tool that incorporates the plan-do-study-act cycle, organizes strategic efforts, and tracks progress on a single page) to summarize and present these initiatives to the Performance Improvement and Patient Safety Committee of the hospital executive leadership team. This structure illustrated alignment with the hospital’s core values (“true north”) of “developing people” and “care experience.”

In 2018, interval surveys demonstrated a gradual reduction of burnout to approximately one-fifth of division physicians as measured by the 2-item Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Initiatives in faculty well-being

The Charter of Physician Well-being outlines a framework to promote well-being among doctors by maximizing a sense of fulfillment and minimizing the harms of burnout. It shares this responsibility among societal, organizational, and interpersonal and individual commitments.5

As illustrated above, we used principles of Lean Management to prospectively create initiatives to improve well-being in our division. Lean in health care is designed to optimize primarily the patient experience; its implementation has subsequently demonstrated mixed provider and staff experiences,8,9 and many providers are skeptical of Lean’s potential to improve their own well-being. If, however, Lean is aligned with best practice frameworks for well-being such as those outline in the charter, it may also help to meet the Quadruple Aim of optimizing both provider well-being and patient experience. To further test this hypothesis, we retrospectively categorized our Lean-based interventions into the commitments described by the charter to identify areas of alignment and gaps that were not initially addressed using Lean Management (Table).

Organizational commitments5Supportive systems

We optimized scheduling and enhanced physician staffing by budgeting for a physician staffing buffer each academic year in order to minimize mandatory moonlighting and jeopardy pool activations that result from operating on a thin staffing margin when expected personal leave and reductions in clinical effort occur. Furthermore, we revised scheduling principles to balance patient continuity and individual time off requests while setting limits on the maximum duration of clinical stretches and instituting mandatory minimum time off between them.

Leadership engagement

We initiated monthly operations meetings as a forum to discuss challenges, brainstorm solutions, and message new initiatives with group input. For example, as a result of these meetings, we designed and implemented an additional service line to address the high census, revised the distribution of new patient admissions to level-load clinical shifts, and established a maximum number of weekends worked per month and year. This approach aligns with recommendations to use participatory leadership strategies to enhance physician well-being.10 Engaging both executive level and service level management to focus on burnout and other related well-being metrics is necessary for sustaining such work.

Interprofessional teamwork

We revised multidisciplinary rounds with social work, utilization management, and physical therapy to maximize efficiency and streamline communication by developing standard approaches for each patient presentation.

Interpersonal and individual commitments5Address emotional challenges of physician work

Although these commitments did not have a direct corollary with Lean philosophy, some of these needs were identified by our physician group at our annual retreats. As a result, we initiated a monthly faculty-led noon conference series focused on the clinical challenges of caring for vulnerable populations, a particular source of distress in our practice setting, and revised the division schedule to encourage attendance at the hospital’s Schwartz rounds.

Mental health and self-care

We organized focus groups and faculty development sessions on provider well-being and burnout and dealing with challenging patients and invited the Faculty and Staff Assistance Program, our institution’s mental health service provider, to our weekly division meeting.

Future directions

After using Lean Management as an approach to prospectively improve physician well-being, we were able to use the Charter on Physician Well-being retrospectively as a “checklist” to identify additional gaps for targeted intervention to ensure all commitments are sufficiently addressed.

Overall, we found that, not surprisingly, Lean Management aligned best with the organizational commitments in the charter. Reviewing the organizational commitments, we found our biggest remaining challenges are in building supportive systems, namely ensuring sustainable workloads, offloading and delegating nonphysician tasks, and minimizing the burden of documentation and administration.

Reviewing the societal commitments helped us to identify opportunities for future directions that we may not have otherwise considered. As a safety-net institution, we benefit from a strong sense of mission and shared values within our hospital and division. However, we recognize the need to continue to be vigilant to ensure that our physicians perceive that their own values are aligned with the division’s stated mission. Devoting a Kaizen-style retreat to well-being likely helped, and allocating divisional resources to a well-being committee indirectly helped, to foster a culture of well-being; however, we could more deliberately identify local policies that may benefit from advocacy or revision. Although our faculty identified interventions to improve interpersonal and individual drivers of well-being, these charter commitments did not have direct parallels in Lean philosophy, and organizations may need to deliberately seek to address these commitments outside of a Lean approach. Specifically, by reviewing the charter, we identified opportunities to provide additional resources for peer support and protected time for mental health care and self-care.

Conclusion

Lean Management can be an effective strategy to address many of the organizational commitments outlined in the Charter on Physician Well-being. This approach may be particularly effective for solving local challenges with systems and workflows. Those who use Lean as a primary method to approach systems improvement in support of the Quadruple Aim may need to use additional strategies to address societal and interpersonal and individual commitments outlined in the charter.

Dr. Sanyal-Dey is visiting associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and director of client services, LeanTaaS. Dr. Thomas is associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Chia is associate professor of clinical medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

References

1. West CP et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-81.

2. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-46.

3. Shanafelt T et al. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-32.

4. Shanafelt T et al. Building a program on well-being: Key design considerations to meet the unique needs of each organization. Acad Med. 2019 Feb;94(2):156-161.

5. Thomas LR et al. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-42.

6. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-6.

7. West CP et al. Concurrent Validity of Single-Item Measures of Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization in Burnout Assessment. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1445-52.

8. Hung DY et al. Experiences of primary care physicians and staff following lean workflow redesign. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Apr 10;18(1):274.

9. Zibrowski E et al. Easier and faster is not always better: Grounded theory of the impact of large-scale system transformation on the clinical work of emergency medicine nurses and physicians. JMIR Hum Factors. 2018. doi: 10.2196/11013.

10. Shanafelt TD et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(4):432-40.

General background on well-being and burnout

With burnout increasingly recognized as a shared responsibility that requires addressing organizational drivers while supporting individuals to be well,1-4 practical strategies and examples of successful implementation of systems interventions to address burnout will be helpful for service directors to support their staff. The Charter on Physician Well-being, recently developed through collaborative input from multiple organizations, defines guiding principles and key commitments at the societal, organizational, interpersonal, and individual levels and may be a useful framework for organizations that are developing well-being initiatives.5

The charter advocates including physician well-being as a quality improvement metric for health systems, aligned with the concept of the Quadruple Aim of optimizing patient care by enhancing provider experience, promoting high-value care, and improving population health.6 Identifying areas of alignment between the charter’s recommendations and systems improvement strategies that seek to optimize efficiency and reduce waste, such as Lean Management, may help physician leaders to contextualize well-being initiatives more easily within ongoing systems improvement efforts. In this perspective, we provide one division’s experience using the Charter to assess successes and identify additional areas of improvement for well-being initiatives developed using Lean Management methodology.

Past and current state of affairs

In 2011, the division of hospital medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital was established and has seen continual expansion in terms of direct patient care, medical education, and hospital leadership.

In 2015, the division of hospital medicine experienced leadership transitions, faculty attrition, and insufficient recruitment resulting in staffing shortages, service line closure, schedule instability, and ultimately, low morale. A baseline survey conducted using the 2-Item Maslach Burnout Inventory. This survey, which uses one item in the domain of emotional exhaustion and one item in the domain of depersonalization, has shown good correlation with the full Maslach Burnout Inventory.7 At baseline, approximately one-third of the division’s physicians experienced burnout.

In response, a subsequent retreat focused on the three greatest areas of concern identified by the survey: scheduling, faculty development, and well-being.

Like many health systems, the hospital has adopted Lean as its preferred systems-improvement framework. The retreat was structured around the principles of Lean philosophy, and was designed to emulate that of a consolidated Kaizen workshop.

“Kaizen” in Japanese means “change for the better.” A typical Kaizen workshop revolves around rapid problem-solving over the course of 3-5 days, in which a team of people come together to identify and implement significant improvements for a selected process. To this end, the retreat was divided into subgroups for each area of concern. In turn, each subgroup mapped out existing workflows (“value stream”), identified areas of waste and non–value added time, and generated ideas of what an idealized process would be. Next, a root-cause analysis was performed and subsequent interventions (“countermeasures”) developed to address each problem. At the conclusion of the retreat, each subgroup shared a summary of their findings with the larger group.

Moving forward, this information served as a guiding framework for service and division leadership to run small tests of change. We enacted a series of countermeasures over the course of several years, and multiple cycles of improvement work addressed the three areas of concern. We developed an A3 report (a Lean project management tool that incorporates the plan-do-study-act cycle, organizes strategic efforts, and tracks progress on a single page) to summarize and present these initiatives to the Performance Improvement and Patient Safety Committee of the hospital executive leadership team. This structure illustrated alignment with the hospital’s core values (“true north”) of “developing people” and “care experience.”

In 2018, interval surveys demonstrated a gradual reduction of burnout to approximately one-fifth of division physicians as measured by the 2-item Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Initiatives in faculty well-being

The Charter of Physician Well-being outlines a framework to promote well-being among doctors by maximizing a sense of fulfillment and minimizing the harms of burnout. It shares this responsibility among societal, organizational, and interpersonal and individual commitments.5

As illustrated above, we used principles of Lean Management to prospectively create initiatives to improve well-being in our division. Lean in health care is designed to optimize primarily the patient experience; its implementation has subsequently demonstrated mixed provider and staff experiences,8,9 and many providers are skeptical of Lean’s potential to improve their own well-being. If, however, Lean is aligned with best practice frameworks for well-being such as those outline in the charter, it may also help to meet the Quadruple Aim of optimizing both provider well-being and patient experience. To further test this hypothesis, we retrospectively categorized our Lean-based interventions into the commitments described by the charter to identify areas of alignment and gaps that were not initially addressed using Lean Management (Table).

Organizational commitments5Supportive systems

We optimized scheduling and enhanced physician staffing by budgeting for a physician staffing buffer each academic year in order to minimize mandatory moonlighting and jeopardy pool activations that result from operating on a thin staffing margin when expected personal leave and reductions in clinical effort occur. Furthermore, we revised scheduling principles to balance patient continuity and individual time off requests while setting limits on the maximum duration of clinical stretches and instituting mandatory minimum time off between them.

Leadership engagement

We initiated monthly operations meetings as a forum to discuss challenges, brainstorm solutions, and message new initiatives with group input. For example, as a result of these meetings, we designed and implemented an additional service line to address the high census, revised the distribution of new patient admissions to level-load clinical shifts, and established a maximum number of weekends worked per month and year. This approach aligns with recommendations to use participatory leadership strategies to enhance physician well-being.10 Engaging both executive level and service level management to focus on burnout and other related well-being metrics is necessary for sustaining such work.

Interprofessional teamwork

We revised multidisciplinary rounds with social work, utilization management, and physical therapy to maximize efficiency and streamline communication by developing standard approaches for each patient presentation.

Interpersonal and individual commitments5Address emotional challenges of physician work

Although these commitments did not have a direct corollary with Lean philosophy, some of these needs were identified by our physician group at our annual retreats. As a result, we initiated a monthly faculty-led noon conference series focused on the clinical challenges of caring for vulnerable populations, a particular source of distress in our practice setting, and revised the division schedule to encourage attendance at the hospital’s Schwartz rounds.

Mental health and self-care

We organized focus groups and faculty development sessions on provider well-being and burnout and dealing with challenging patients and invited the Faculty and Staff Assistance Program, our institution’s mental health service provider, to our weekly division meeting.

Future directions

After using Lean Management as an approach to prospectively improve physician well-being, we were able to use the Charter on Physician Well-being retrospectively as a “checklist” to identify additional gaps for targeted intervention to ensure all commitments are sufficiently addressed.

Overall, we found that, not surprisingly, Lean Management aligned best with the organizational commitments in the charter. Reviewing the organizational commitments, we found our biggest remaining challenges are in building supportive systems, namely ensuring sustainable workloads, offloading and delegating nonphysician tasks, and minimizing the burden of documentation and administration.

Reviewing the societal commitments helped us to identify opportunities for future directions that we may not have otherwise considered. As a safety-net institution, we benefit from a strong sense of mission and shared values within our hospital and division. However, we recognize the need to continue to be vigilant to ensure that our physicians perceive that their own values are aligned with the division’s stated mission. Devoting a Kaizen-style retreat to well-being likely helped, and allocating divisional resources to a well-being committee indirectly helped, to foster a culture of well-being; however, we could more deliberately identify local policies that may benefit from advocacy or revision. Although our faculty identified interventions to improve interpersonal and individual drivers of well-being, these charter commitments did not have direct parallels in Lean philosophy, and organizations may need to deliberately seek to address these commitments outside of a Lean approach. Specifically, by reviewing the charter, we identified opportunities to provide additional resources for peer support and protected time for mental health care and self-care.

Conclusion

Lean Management can be an effective strategy to address many of the organizational commitments outlined in the Charter on Physician Well-being. This approach may be particularly effective for solving local challenges with systems and workflows. Those who use Lean as a primary method to approach systems improvement in support of the Quadruple Aim may need to use additional strategies to address societal and interpersonal and individual commitments outlined in the charter.

Dr. Sanyal-Dey is visiting associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and director of client services, LeanTaaS. Dr. Thomas is associate clinical professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Chia is associate professor of clinical medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

References

1. West CP et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-81.

2. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-46.

3. Shanafelt T et al. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-32.

4. Shanafelt T et al. Building a program on well-being: Key design considerations to meet the unique needs of each organization. Acad Med. 2019 Feb;94(2):156-161.

5. Thomas LR et al. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-42.

6. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-6.

7. West CP et al. Concurrent Validity of Single-Item Measures of Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization in Burnout Assessment. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1445-52.

8. Hung DY et al. Experiences of primary care physicians and staff following lean workflow redesign. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Apr 10;18(1):274.

9. Zibrowski E et al. Easier and faster is not always better: Grounded theory of the impact of large-scale system transformation on the clinical work of emergency medicine nurses and physicians. JMIR Hum Factors. 2018. doi: 10.2196/11013.

10. Shanafelt TD et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(4):432-40.

DOACs show safety benefit in early stages of CKD

Background: Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is both a prothrombotic state and a condition with an elevated bleeding risk that increases in a linear fashion as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decreases. These features of the disease along with the exclusion of patients with CKD from most anticoagulation trials have resulted in uncertainty about overall risks and benefits of anticoagulant use in this population.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Variable across included trials.

Synopsis: Forty-five randomized, controlled trials of anticoagulation covering a broad range of anticoagulants, doses, indications, and methodologies were included in this meta-analysis, representing 34,082 patients with CKD or end-stage kidney disease.

The most compelling data were seen in the management of atrial fibrillation in early-stage CKD (five studies representing 11,332 patients) in which high-dose DOACs were associated with a lower risk for stroke or systemic embolism (risk ratio, 0.79; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.92), hemorrhagic stroke (RR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.30-0.76), and all-cause death (RR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.78-0.99). Overall stroke reduction was primarily hemorrhagic, and DOACs were equivalent to vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) for ischemic stroke risk.

The analysis also suggests that, in CKD, DOACs may reduce major bleeding when compared with VKAs across a variety of indications, though that finding was not statistically significant.

Efficacy of DOACs, compared with VKAs, in treatment of venous thromboembolism was uncertain, and patients with end-stage kidney disease and advanced CKD (creatinine clearance, less than 25 mL/min) were excluded from all trials comparing DOACs with VKAs, with limited overall data in these populations.

Bottom line: For patients with atrial fibrillation and early-stage CKD, direct oral anticoagulants show a promising risk-benefit profile when compared with vitamin K antagonists. Very few data are available on the safety and efficacy of anticoagulants in patients with advanced CKD and end-stage kidney disease.

Citation: Ha JT et al. Benefits and harms of oral anticoagulant therapy in chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 6;171(3):181-9.

Dr. Herrle is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland and at Stephens Memorial Hospital in Norway, Maine.

Background: Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is both a prothrombotic state and a condition with an elevated bleeding risk that increases in a linear fashion as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decreases. These features of the disease along with the exclusion of patients with CKD from most anticoagulation trials have resulted in uncertainty about overall risks and benefits of anticoagulant use in this population.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Variable across included trials.

Synopsis: Forty-five randomized, controlled trials of anticoagulation covering a broad range of anticoagulants, doses, indications, and methodologies were included in this meta-analysis, representing 34,082 patients with CKD or end-stage kidney disease.

The most compelling data were seen in the management of atrial fibrillation in early-stage CKD (five studies representing 11,332 patients) in which high-dose DOACs were associated with a lower risk for stroke or systemic embolism (risk ratio, 0.79; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.92), hemorrhagic stroke (RR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.30-0.76), and all-cause death (RR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.78-0.99). Overall stroke reduction was primarily hemorrhagic, and DOACs were equivalent to vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) for ischemic stroke risk.

The analysis also suggests that, in CKD, DOACs may reduce major bleeding when compared with VKAs across a variety of indications, though that finding was not statistically significant.

Efficacy of DOACs, compared with VKAs, in treatment of venous thromboembolism was uncertain, and patients with end-stage kidney disease and advanced CKD (creatinine clearance, less than 25 mL/min) were excluded from all trials comparing DOACs with VKAs, with limited overall data in these populations.

Bottom line: For patients with atrial fibrillation and early-stage CKD, direct oral anticoagulants show a promising risk-benefit profile when compared with vitamin K antagonists. Very few data are available on the safety and efficacy of anticoagulants in patients with advanced CKD and end-stage kidney disease.

Citation: Ha JT et al. Benefits and harms of oral anticoagulant therapy in chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 6;171(3):181-9.

Dr. Herrle is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland and at Stephens Memorial Hospital in Norway, Maine.

Background: Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is both a prothrombotic state and a condition with an elevated bleeding risk that increases in a linear fashion as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decreases. These features of the disease along with the exclusion of patients with CKD from most anticoagulation trials have resulted in uncertainty about overall risks and benefits of anticoagulant use in this population.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Variable across included trials.

Synopsis: Forty-five randomized, controlled trials of anticoagulation covering a broad range of anticoagulants, doses, indications, and methodologies were included in this meta-analysis, representing 34,082 patients with CKD or end-stage kidney disease.

The most compelling data were seen in the management of atrial fibrillation in early-stage CKD (five studies representing 11,332 patients) in which high-dose DOACs were associated with a lower risk for stroke or systemic embolism (risk ratio, 0.79; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.92), hemorrhagic stroke (RR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.30-0.76), and all-cause death (RR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.78-0.99). Overall stroke reduction was primarily hemorrhagic, and DOACs were equivalent to vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) for ischemic stroke risk.

The analysis also suggests that, in CKD, DOACs may reduce major bleeding when compared with VKAs across a variety of indications, though that finding was not statistically significant.

Efficacy of DOACs, compared with VKAs, in treatment of venous thromboembolism was uncertain, and patients with end-stage kidney disease and advanced CKD (creatinine clearance, less than 25 mL/min) were excluded from all trials comparing DOACs with VKAs, with limited overall data in these populations.

Bottom line: For patients with atrial fibrillation and early-stage CKD, direct oral anticoagulants show a promising risk-benefit profile when compared with vitamin K antagonists. Very few data are available on the safety and efficacy of anticoagulants in patients with advanced CKD and end-stage kidney disease.

Citation: Ha JT et al. Benefits and harms of oral anticoagulant therapy in chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 6;171(3):181-9.

Dr. Herrle is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland and at Stephens Memorial Hospital in Norway, Maine.

Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of COPD appears rampant

Background: COPD is a highly morbid disease, and there is a need for a better understanding of the true prevalence. Little is known regarding overdiagnosis of COPD. According to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), airflow limitation by spirometry is a key criteria for diagnosis.

Study design: Population-based survey.

Setting: Altogether, 23 sites in 20 countries worldwide were included.

Synopsis: The Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study recruited community-dwelling adults who underwent questionnaires, as well as spirometry. Of the 16,717 participants, 919 self-reported a COPD diagnosis. Of these, more than half were found to not meet obstructive lung disease criteria on spirometry, and therefore were misdiagnosed: 62% when defined as forced expiratory volume in 1 second to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) ratio less than the lower limit of normal and 55% when using the GOLD definition of FEV1/FVC less than 0.7. After patients with reported asthma were excluded, 34% of participants with false-positive COPD were found to be treated with respiratory medications as outpatients.

Overdiagnosis of COPD was noted to be more prevalent in high-income countries than they were in low- to middle-income countries (4.9% versus 1.9% of the participants sampled).

The self-reporting of the diagnosis of COPD is a limitation of the study because it may have artificially inflated the rate of false positives.

Bottom line: Patient-reported diagnoses of COPD should be taken with a degree of caution because of high rates of overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

Citation: Sator L et al. Overdiagnosis of COPD in subjects with unobstructed spirometry. Chest. 2019 Aug;156(2):277-88.

Dr. Gordon is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland.

Background: COPD is a highly morbid disease, and there is a need for a better understanding of the true prevalence. Little is known regarding overdiagnosis of COPD. According to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), airflow limitation by spirometry is a key criteria for diagnosis.

Study design: Population-based survey.

Setting: Altogether, 23 sites in 20 countries worldwide were included.

Synopsis: The Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study recruited community-dwelling adults who underwent questionnaires, as well as spirometry. Of the 16,717 participants, 919 self-reported a COPD diagnosis. Of these, more than half were found to not meet obstructive lung disease criteria on spirometry, and therefore were misdiagnosed: 62% when defined as forced expiratory volume in 1 second to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) ratio less than the lower limit of normal and 55% when using the GOLD definition of FEV1/FVC less than 0.7. After patients with reported asthma were excluded, 34% of participants with false-positive COPD were found to be treated with respiratory medications as outpatients.

Overdiagnosis of COPD was noted to be more prevalent in high-income countries than they were in low- to middle-income countries (4.9% versus 1.9% of the participants sampled).

The self-reporting of the diagnosis of COPD is a limitation of the study because it may have artificially inflated the rate of false positives.

Bottom line: Patient-reported diagnoses of COPD should be taken with a degree of caution because of high rates of overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

Citation: Sator L et al. Overdiagnosis of COPD in subjects with unobstructed spirometry. Chest. 2019 Aug;156(2):277-88.

Dr. Gordon is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland.

Background: COPD is a highly morbid disease, and there is a need for a better understanding of the true prevalence. Little is known regarding overdiagnosis of COPD. According to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), airflow limitation by spirometry is a key criteria for diagnosis.

Study design: Population-based survey.

Setting: Altogether, 23 sites in 20 countries worldwide were included.

Synopsis: The Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study recruited community-dwelling adults who underwent questionnaires, as well as spirometry. Of the 16,717 participants, 919 self-reported a COPD diagnosis. Of these, more than half were found to not meet obstructive lung disease criteria on spirometry, and therefore were misdiagnosed: 62% when defined as forced expiratory volume in 1 second to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) ratio less than the lower limit of normal and 55% when using the GOLD definition of FEV1/FVC less than 0.7. After patients with reported asthma were excluded, 34% of participants with false-positive COPD were found to be treated with respiratory medications as outpatients.

Overdiagnosis of COPD was noted to be more prevalent in high-income countries than they were in low- to middle-income countries (4.9% versus 1.9% of the participants sampled).

The self-reporting of the diagnosis of COPD is a limitation of the study because it may have artificially inflated the rate of false positives.

Bottom line: Patient-reported diagnoses of COPD should be taken with a degree of caution because of high rates of overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

Citation: Sator L et al. Overdiagnosis of COPD in subjects with unobstructed spirometry. Chest. 2019 Aug;156(2):277-88.

Dr. Gordon is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland.

A standardized approach to postop management of DOACs in AFib

Clinical question: Is it safe to adopt a standardized approach to direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) interruption for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) who are undergoing elective surgeries/procedures?

Background: At present, perioperative management of DOACs for patients with AFib has significant variation, and robust data are absent. Points of controversy include: The length of time to hold DOACs before and after the procedure, whether to bridge with heparin, and whether to measure coagulation function studies prior to the procedure.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Conducted in Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Synopsis: The PAUSE study included adults with atrial fibrillation who were long-term users of either apixaban, dabigatran, or rivaroxaban and were scheduled for an elective procedure (n = 3,007). Patients were placed on a standardized DOAC interruption schedule based on whether their procedure had high bleeding risk (held for 2 days prior; resumed 2-3 days after) or low bleeding risk (held for 1 day prior; resumed 1 day after).

The primary clinical outcomes were major bleeding and arterial thromboembolism. Authors determined safety by comparing to expected outcome rates derived from research on perioperative warfarin management.

They found that all three drugs were associated with acceptable rates of arterial thromboembolism (apixaban 0.2%, dabigatran 0.6%, rivaroxaban 0.4%). The rates of major bleeding observed with each drug (apixaban 0.6% low-risk procedures, 3% high-risk procedures; dabigatran 0.9% both low- and high-risk procedures; and rivaroxaban 1.3% low-risk procedures, 3% high-risk procedures) were similar to those in the BRIDGE trial (patients on warfarin who were not bridged perioperatively). However, it must still be noted that only dabigatran met the authors’ predetermined definition of safety for major bleeding.

Limitations include the lack of true control rates for major bleeding and stroke, the relatively low mean CHADS2-Va2Sc of 3.3-3.5, and that greater than 95% of patients were white.

Bottom line: For patients with moderate-risk atrial fibrillation, a standardized approach to DOAC interruption in the perioperative period that omits bridging along with coagulation function testing appears safe in this preliminary study.

Citation: Douketis JD et al. Perioperative management of patients with atrial fibrillation receiving a direct oral anticoagulant. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2431.

Dr. Gordon is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland.

Clinical question: Is it safe to adopt a standardized approach to direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) interruption for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) who are undergoing elective surgeries/procedures?

Background: At present, perioperative management of DOACs for patients with AFib has significant variation, and robust data are absent. Points of controversy include: The length of time to hold DOACs before and after the procedure, whether to bridge with heparin, and whether to measure coagulation function studies prior to the procedure.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Conducted in Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Synopsis: The PAUSE study included adults with atrial fibrillation who were long-term users of either apixaban, dabigatran, or rivaroxaban and were scheduled for an elective procedure (n = 3,007). Patients were placed on a standardized DOAC interruption schedule based on whether their procedure had high bleeding risk (held for 2 days prior; resumed 2-3 days after) or low bleeding risk (held for 1 day prior; resumed 1 day after).

The primary clinical outcomes were major bleeding and arterial thromboembolism. Authors determined safety by comparing to expected outcome rates derived from research on perioperative warfarin management.

They found that all three drugs were associated with acceptable rates of arterial thromboembolism (apixaban 0.2%, dabigatran 0.6%, rivaroxaban 0.4%). The rates of major bleeding observed with each drug (apixaban 0.6% low-risk procedures, 3% high-risk procedures; dabigatran 0.9% both low- and high-risk procedures; and rivaroxaban 1.3% low-risk procedures, 3% high-risk procedures) were similar to those in the BRIDGE trial (patients on warfarin who were not bridged perioperatively). However, it must still be noted that only dabigatran met the authors’ predetermined definition of safety for major bleeding.

Limitations include the lack of true control rates for major bleeding and stroke, the relatively low mean CHADS2-Va2Sc of 3.3-3.5, and that greater than 95% of patients were white.

Bottom line: For patients with moderate-risk atrial fibrillation, a standardized approach to DOAC interruption in the perioperative period that omits bridging along with coagulation function testing appears safe in this preliminary study.

Citation: Douketis JD et al. Perioperative management of patients with atrial fibrillation receiving a direct oral anticoagulant. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2431.

Dr. Gordon is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland.

Clinical question: Is it safe to adopt a standardized approach to direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) interruption for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) who are undergoing elective surgeries/procedures?

Background: At present, perioperative management of DOACs for patients with AFib has significant variation, and robust data are absent. Points of controversy include: The length of time to hold DOACs before and after the procedure, whether to bridge with heparin, and whether to measure coagulation function studies prior to the procedure.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Conducted in Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Synopsis: The PAUSE study included adults with atrial fibrillation who were long-term users of either apixaban, dabigatran, or rivaroxaban and were scheduled for an elective procedure (n = 3,007). Patients were placed on a standardized DOAC interruption schedule based on whether their procedure had high bleeding risk (held for 2 days prior; resumed 2-3 days after) or low bleeding risk (held for 1 day prior; resumed 1 day after).

The primary clinical outcomes were major bleeding and arterial thromboembolism. Authors determined safety by comparing to expected outcome rates derived from research on perioperative warfarin management.

They found that all three drugs were associated with acceptable rates of arterial thromboembolism (apixaban 0.2%, dabigatran 0.6%, rivaroxaban 0.4%). The rates of major bleeding observed with each drug (apixaban 0.6% low-risk procedures, 3% high-risk procedures; dabigatran 0.9% both low- and high-risk procedures; and rivaroxaban 1.3% low-risk procedures, 3% high-risk procedures) were similar to those in the BRIDGE trial (patients on warfarin who were not bridged perioperatively). However, it must still be noted that only dabigatran met the authors’ predetermined definition of safety for major bleeding.

Limitations include the lack of true control rates for major bleeding and stroke, the relatively low mean CHADS2-Va2Sc of 3.3-3.5, and that greater than 95% of patients were white.

Bottom line: For patients with moderate-risk atrial fibrillation, a standardized approach to DOAC interruption in the perioperative period that omits bridging along with coagulation function testing appears safe in this preliminary study.

Citation: Douketis JD et al. Perioperative management of patients with atrial fibrillation receiving a direct oral anticoagulant. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2431.

Dr. Gordon is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland.

How can hospitalists change the status quo?

Lean framework for efficiency and empathy of care

“My census is too high.”

“I don’t have enough time to talk to patients.”

“These are outside our scope of practice.”

These are statements that I have heard from colleagues over the last fourteen years as a hospitalist. Back in 1996, when Dr. Bob Wachter coined the term ‘hospitalist,’ we were still in our infancy – the scope of what we could do had yet to be fully realized. Our focus was on providing care for hospitalized patients and improving quality of clinical care and patient safety. As health care organizations began to see the potential for our field, the demands on our services grew. We grew to comanage patients with our surgical colleagues, worked on patient satisfaction, facilitated transitions of care, and attempted to reduce readmissions – all of which improved patient care and the bottom line for our organizations.

Somewhere along the way, we were expected to staff high patient volumes to add more value, but this always seemed to come with compromise in another aspect of care or our own well-being. After all, there are only so many hours in the day and a limit on what one individual can accomplish in that time.

One of the reasons I love hospital medicine is the novelty of what we do – we are creative thinkers. We have the capacity to innovate solutions to hospital problems based on our expertise as frontline providers for our patients. Hospitalists of every discipline staff a large majority of inpatients, which makes our collective experience significant to the management of inpatient health care. We are often the ones tasked with executing improvement projects, but how often are we involved in their design? I know that we collectively have an enormous opportunity to improve our health care practice, both for ourselves, our patients, and the institutions we work for. But more than just being a voice of advocacy, we need to understand how to positively influence the health care structures that allow us to deliver quality patient care.

It is no surprise that the inefficiencies we deal with in our hospitals are many – daily workflow interruptions, delays in results, scheduling issues, communication difficulties. These are not unique to any one institution. The pandemic added more to that plate – PPE deficiencies, patient volume triage, and resource management are examples. Hospitals often contract consultants to help solve these problems, and many utilize a variety of frameworks to improve these system processes. The Lean framework is one of these, and it originated in the manufacturing industry to eliminate waste in systems in the pursuit of efficiency.

In my business training and prior hospital medicine leadership roles, I was educated in Lean thinking and methodologies for improving quality and applied its principles to projects for improving workflow. Last year I attended a virtual conference on ‘Lean Innovation during the pandemic’ for New York region hospitals, and it again highlighted how the Lean management methodology can help improve patient care but importantly, our workflow as clinicians. This got me thinking. Why is Lean well accepted in business and manufacturing circles, but less so in health care?

I think the answer is twofold – knowledge and people.

What is Lean and how can it help us?

The ‘Toyota Production System’-based philosophy has 14 core principles that help eliminate waste in systems in pursuit of efficiency. These principles are the “Toyota Way.” They center around two pillars: continuous improvement and respect for people. The cornerstone of this management methodology is based on efficient processes, developing employees to add value to the organization and continuous improvement through problem-solving and organizational learning.

Lean is often implemented with Six Sigma methodology. Six Sigma has its origins in Motorola. While Lean cuts waste in our systems to provide value, Six Sigma uses DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) to reduce variation in our processes. When done in its entirety, Lean Six Sigma methodology adds value by increasing efficiency, reducing cost, and improving our everyday work.

Statistical principles suggest that 80% of consequences comes from 20% of causes. Lean methodology and tools allow us to systematically identify root causes for the problems we face and help narrow it down to the ‘vital few.’ In other words, fixing these would give us the most bang for our buck. As hospitalists, we are able to do this better than most because we work in these hospital processes everyday – we truly know the strengths and weaknesses of our systems.

As a hospitalist, I would love for the process of seeing patients in hospitals to be more efficient, less variable, and be more cost-effective for my institution. By eliminating the time wasted performing unnecessary and redundant tasks in my everyday work, I can reallocate that time to patient care – the very reason I chose a career in medicine.

We, the people

There are two common rebuttals I hear for adopting Lean Six Sigma methodology in health care. A frequent misconception is that Lean is all about reducing staff or time with patients. The second is that manufacturing methodologies do not work for a service profession. For instance, an article published on Reuters Events (www.reutersevents.com/supplychain/supply-chain/end-just-time) talks about Lean JIT (Just In Time) inventory as a culprit for creating a supply chain deficit during COVID-19. It is not entirely without merit. However, if done the correct way, Lean is all about involving the frontline worker to create a workflow that would work best for them.

Reducing the waste in our processes and empowering our frontline doctors to be creative in finding solutions naturally leads to cost reduction. The cornerstone of Lean is creating a continuously learning organization and putting your employees at the forefront. I think it is important that Lean principles be utilized within health care – but we cannot push to fix every problem in our systems to perfection at a significant expense to the physician and other health care staff.

Why HM can benefit from Lean

There is no hard and fast rule about the way health care should adopt Lean thinking. It is a way of thinking that aims to balance purpose, people, and process – extremes of inventory management may not be necessary to be successful in health care. Lean tools alone would not create results. John Shook, chairman of Lean Global Network, has said that the social side of Lean needs to be in balance with the technical side. In other words, rigidity and efficiency is good, but so is encouraging creativity and flexibility in thinking within the workforce.

In the crisis created by the novel coronavirus, many hospitals in New York state, including my own, turned to Lean to respond quickly and effectively to the challenges. Lean principles helped them problem-solve and develop strategies to both recover from the pandemic surge and adapt to future problems that could occur. Geographic clustering of patients, PPE supply, OR shut down and ramp up, emergency management offices at the peak of the pandemic, telehealth streamlining, and post-COVID-19 care planning are some areas where the application of Lean resulted in successful responses to the challenges that 2020 brought to our work.

As Warren Bennis said, ‘The manager accepts the status quo; the leader challenges it.’ As hospitalists, we can lead the way our hospitals provide care. Lean is not just a way for hospitals to cut costs (although it helps quite a bit there). Its processes and philosophies could enable hospitalists to maximize potential, efficiency, quality of care, and allow for a balanced work environment. When applied in a manner that focuses on continuous improvement (and is cognizant of its limitations), it has the potential to increase the capability of our service lines and streamline our processes and workday for greater efficiency. As a specialty, we stand to benefit by taking the lead role in choosing how best to improve how we work. We should think outside the box. What better time to do this than now?

Dr. Kanikkannan is a practicing hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at Albany (N.Y) Medical College. She is a former hospitalist medical director and has served on SHM’s national committees, and is a certified Lean Six Sigma black belt and MBA candidate.

Lean framework for efficiency and empathy of care

Lean framework for efficiency and empathy of care

“My census is too high.”

“I don’t have enough time to talk to patients.”

“These are outside our scope of practice.”

These are statements that I have heard from colleagues over the last fourteen years as a hospitalist. Back in 1996, when Dr. Bob Wachter coined the term ‘hospitalist,’ we were still in our infancy – the scope of what we could do had yet to be fully realized. Our focus was on providing care for hospitalized patients and improving quality of clinical care and patient safety. As health care organizations began to see the potential for our field, the demands on our services grew. We grew to comanage patients with our surgical colleagues, worked on patient satisfaction, facilitated transitions of care, and attempted to reduce readmissions – all of which improved patient care and the bottom line for our organizations.

Somewhere along the way, we were expected to staff high patient volumes to add more value, but this always seemed to come with compromise in another aspect of care or our own well-being. After all, there are only so many hours in the day and a limit on what one individual can accomplish in that time.

One of the reasons I love hospital medicine is the novelty of what we do – we are creative thinkers. We have the capacity to innovate solutions to hospital problems based on our expertise as frontline providers for our patients. Hospitalists of every discipline staff a large majority of inpatients, which makes our collective experience significant to the management of inpatient health care. We are often the ones tasked with executing improvement projects, but how often are we involved in their design? I know that we collectively have an enormous opportunity to improve our health care practice, both for ourselves, our patients, and the institutions we work for. But more than just being a voice of advocacy, we need to understand how to positively influence the health care structures that allow us to deliver quality patient care.

It is no surprise that the inefficiencies we deal with in our hospitals are many – daily workflow interruptions, delays in results, scheduling issues, communication difficulties. These are not unique to any one institution. The pandemic added more to that plate – PPE deficiencies, patient volume triage, and resource management are examples. Hospitals often contract consultants to help solve these problems, and many utilize a variety of frameworks to improve these system processes. The Lean framework is one of these, and it originated in the manufacturing industry to eliminate waste in systems in the pursuit of efficiency.

In my business training and prior hospital medicine leadership roles, I was educated in Lean thinking and methodologies for improving quality and applied its principles to projects for improving workflow. Last year I attended a virtual conference on ‘Lean Innovation during the pandemic’ for New York region hospitals, and it again highlighted how the Lean management methodology can help improve patient care but importantly, our workflow as clinicians. This got me thinking. Why is Lean well accepted in business and manufacturing circles, but less so in health care?

I think the answer is twofold – knowledge and people.

What is Lean and how can it help us?

The ‘Toyota Production System’-based philosophy has 14 core principles that help eliminate waste in systems in pursuit of efficiency. These principles are the “Toyota Way.” They center around two pillars: continuous improvement and respect for people. The cornerstone of this management methodology is based on efficient processes, developing employees to add value to the organization and continuous improvement through problem-solving and organizational learning.

Lean is often implemented with Six Sigma methodology. Six Sigma has its origins in Motorola. While Lean cuts waste in our systems to provide value, Six Sigma uses DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) to reduce variation in our processes. When done in its entirety, Lean Six Sigma methodology adds value by increasing efficiency, reducing cost, and improving our everyday work.

Statistical principles suggest that 80% of consequences comes from 20% of causes. Lean methodology and tools allow us to systematically identify root causes for the problems we face and help narrow it down to the ‘vital few.’ In other words, fixing these would give us the most bang for our buck. As hospitalists, we are able to do this better than most because we work in these hospital processes everyday – we truly know the strengths and weaknesses of our systems.

As a hospitalist, I would love for the process of seeing patients in hospitals to be more efficient, less variable, and be more cost-effective for my institution. By eliminating the time wasted performing unnecessary and redundant tasks in my everyday work, I can reallocate that time to patient care – the very reason I chose a career in medicine.

We, the people

There are two common rebuttals I hear for adopting Lean Six Sigma methodology in health care. A frequent misconception is that Lean is all about reducing staff or time with patients. The second is that manufacturing methodologies do not work for a service profession. For instance, an article published on Reuters Events (www.reutersevents.com/supplychain/supply-chain/end-just-time) talks about Lean JIT (Just In Time) inventory as a culprit for creating a supply chain deficit during COVID-19. It is not entirely without merit. However, if done the correct way, Lean is all about involving the frontline worker to create a workflow that would work best for them.

Reducing the waste in our processes and empowering our frontline doctors to be creative in finding solutions naturally leads to cost reduction. The cornerstone of Lean is creating a continuously learning organization and putting your employees at the forefront. I think it is important that Lean principles be utilized within health care – but we cannot push to fix every problem in our systems to perfection at a significant expense to the physician and other health care staff.

Why HM can benefit from Lean

There is no hard and fast rule about the way health care should adopt Lean thinking. It is a way of thinking that aims to balance purpose, people, and process – extremes of inventory management may not be necessary to be successful in health care. Lean tools alone would not create results. John Shook, chairman of Lean Global Network, has said that the social side of Lean needs to be in balance with the technical side. In other words, rigidity and efficiency is good, but so is encouraging creativity and flexibility in thinking within the workforce.

In the crisis created by the novel coronavirus, many hospitals in New York state, including my own, turned to Lean to respond quickly and effectively to the challenges. Lean principles helped them problem-solve and develop strategies to both recover from the pandemic surge and adapt to future problems that could occur. Geographic clustering of patients, PPE supply, OR shut down and ramp up, emergency management offices at the peak of the pandemic, telehealth streamlining, and post-COVID-19 care planning are some areas where the application of Lean resulted in successful responses to the challenges that 2020 brought to our work.

As Warren Bennis said, ‘The manager accepts the status quo; the leader challenges it.’ As hospitalists, we can lead the way our hospitals provide care. Lean is not just a way for hospitals to cut costs (although it helps quite a bit there). Its processes and philosophies could enable hospitalists to maximize potential, efficiency, quality of care, and allow for a balanced work environment. When applied in a manner that focuses on continuous improvement (and is cognizant of its limitations), it has the potential to increase the capability of our service lines and streamline our processes and workday for greater efficiency. As a specialty, we stand to benefit by taking the lead role in choosing how best to improve how we work. We should think outside the box. What better time to do this than now?

Dr. Kanikkannan is a practicing hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at Albany (N.Y) Medical College. She is a former hospitalist medical director and has served on SHM’s national committees, and is a certified Lean Six Sigma black belt and MBA candidate.

“My census is too high.”

“I don’t have enough time to talk to patients.”

“These are outside our scope of practice.”

These are statements that I have heard from colleagues over the last fourteen years as a hospitalist. Back in 1996, when Dr. Bob Wachter coined the term ‘hospitalist,’ we were still in our infancy – the scope of what we could do had yet to be fully realized. Our focus was on providing care for hospitalized patients and improving quality of clinical care and patient safety. As health care organizations began to see the potential for our field, the demands on our services grew. We grew to comanage patients with our surgical colleagues, worked on patient satisfaction, facilitated transitions of care, and attempted to reduce readmissions – all of which improved patient care and the bottom line for our organizations.

Somewhere along the way, we were expected to staff high patient volumes to add more value, but this always seemed to come with compromise in another aspect of care or our own well-being. After all, there are only so many hours in the day and a limit on what one individual can accomplish in that time.

One of the reasons I love hospital medicine is the novelty of what we do – we are creative thinkers. We have the capacity to innovate solutions to hospital problems based on our expertise as frontline providers for our patients. Hospitalists of every discipline staff a large majority of inpatients, which makes our collective experience significant to the management of inpatient health care. We are often the ones tasked with executing improvement projects, but how often are we involved in their design? I know that we collectively have an enormous opportunity to improve our health care practice, both for ourselves, our patients, and the institutions we work for. But more than just being a voice of advocacy, we need to understand how to positively influence the health care structures that allow us to deliver quality patient care.

It is no surprise that the inefficiencies we deal with in our hospitals are many – daily workflow interruptions, delays in results, scheduling issues, communication difficulties. These are not unique to any one institution. The pandemic added more to that plate – PPE deficiencies, patient volume triage, and resource management are examples. Hospitals often contract consultants to help solve these problems, and many utilize a variety of frameworks to improve these system processes. The Lean framework is one of these, and it originated in the manufacturing industry to eliminate waste in systems in the pursuit of efficiency.

In my business training and prior hospital medicine leadership roles, I was educated in Lean thinking and methodologies for improving quality and applied its principles to projects for improving workflow. Last year I attended a virtual conference on ‘Lean Innovation during the pandemic’ for New York region hospitals, and it again highlighted how the Lean management methodology can help improve patient care but importantly, our workflow as clinicians. This got me thinking. Why is Lean well accepted in business and manufacturing circles, but less so in health care?

I think the answer is twofold – knowledge and people.

What is Lean and how can it help us?

The ‘Toyota Production System’-based philosophy has 14 core principles that help eliminate waste in systems in pursuit of efficiency. These principles are the “Toyota Way.” They center around two pillars: continuous improvement and respect for people. The cornerstone of this management methodology is based on efficient processes, developing employees to add value to the organization and continuous improvement through problem-solving and organizational learning.

Lean is often implemented with Six Sigma methodology. Six Sigma has its origins in Motorola. While Lean cuts waste in our systems to provide value, Six Sigma uses DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) to reduce variation in our processes. When done in its entirety, Lean Six Sigma methodology adds value by increasing efficiency, reducing cost, and improving our everyday work.