User login

‘The kids will be all right,’ won’t they?

Pediatric patients and COVID-19

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic affects us in many ways. Pediatric patients, interestingly, are largely unaffected clinically by this disease. Less than 1% of documented infections occur in children under 10 years old, according to a review of over 72,000 cases from China.1 In that review, most children were asymptomatic or had mild illness, only three required intensive care, and only one death had been reported as of March 10, 2020. This is in stark contrast to the shocking morbidity and mortality statistics we are becoming all too familiar with on the adult side.

From a social standpoint, however, our pediatric patients’ lives have been turned upside down. Their schedules and routines upended, their education and friendships interrupted, and many are likely experiencing real anxiety and fear.2 For countless children, school is a major source of social, emotional, and nutritional support that has been cut off. Some will lose parents, grandparents, or other loved ones to this disease. Parents will lose jobs and will be unable to afford necessities. Pediatric patients will experience delays of procedures or treatments because of the pandemic. Some have projected that rates of child abuse will increase as has been reported during natural disasters.3

Pediatricians around the country are coming together to tackle these issues in creative ways, including the rapid expansion of virtual/telehealth programs. The school systems are developing strategies to deliver online content, and even food, to their students’ homes. Hopefully these tactics will mitigate some of the potential effects on the mental and physical well-being of these patients.

How about my kids? Will they be all right? I am lucky that my husband and I will have jobs throughout this ordeal. Unfortunately, given my role as a hospitalist and my husband’s as a pulmonary/critical care physician, these same jobs that will keep our kids nourished and supported pose the greatest threat to them. As health care workers, we are worried about protecting our families, which may include vulnerable members. The Spanish health ministry announced that medical professionals account for approximately one in eight documented COVID-19 infections in Spain.4 With inadequate supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) in our own nation, we are concerned that our statistics could be similar.

There are multiple strategies to protect ourselves and our families during this difficult time. First, appropriate PPE is essential and integrity with the process must be maintained always. Hospital leaders can protect us by tirelessly working to acquire PPE. In Grand Rapids, Mich., our health system has partnered with multiple local manufacturing companies, including Steelcase, who are producing PPE for our workforce.5 Leaders can diligently update their system’s PPE recommendations to be in line with the latest CDC recommendations and disseminate the information regularly. Hospitalists should frequently check with their Infection Prevention department to make sure they understand if there have been any changes to the recommendations. Innovative solutions for sterilization of PPE, stethoscopes, badges and other equipment, such as with the use of UV boxes or hydrogen peroxide vapor,6 should be explored to minimize contamination. Hospitalists should bring a set of clothes and shoes to change into upon arrival to work and to change out of prior to leaving the hospital.

We must also keep our heads strong. Currently the anxiety amongst physicians is palpable but there is solidarity. Hospital leaders must ensure that hospitalists have easy access to free mental health resources, such as virtual counseling. Wellness teams must rise to the occasion with innovative tactics to support us. For example, Spectrum Health’s wellness team is sponsoring a blog where physicians can discuss COVID-19–related challenges openly. Hospitalist leaders should ensure that there is a structure for debriefing after critical incidents, which are sure to increase in frequency. Email lists and discussion boards sponsored by professional society also provide a collaborative venue for some of these discussions. We must take advantage of these resources and communicate with each other.

For me, in the end it comes back to the kids. My kids and most pediatric patients are not likely to be hospitalized from COVID-19, but they are also not immune to the toll that fighting this pandemic will take on our families. We took an oath to protect our patients, but what do we owe to our own children? At a minimum we can optimize how we protect ourselves every day, both physically and mentally. As we come together as a strong community to fight this pandemic, in addition to saving lives, we are working to ensure that, in the end, the kids will be all right.

Dr. Hadley is chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Spectrum Health/Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich., and clinical assistant professor at Michigan State University, East Lansing.

References

1. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

2. Hagan JF Jr; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Task Force on Terrorism. Psychosocial implications of disaster or terrorism on children: A guide for the pediatrician. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):787-795.

3. Gearhart S et al. The impact of natural disasters on domestic violence: An analysis of reports of simple assault in Florida (1997-2007). Violence Gend. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1089/vio.2017.0077.

4. Minder R, Peltier E. Virus knocks thousands of health workers out of action in Europe. The New York Times. March 24, 2020.

5. McVicar B. West Michigan businesses hustle to produce medical supplies amid coronavirus pandemic. MLive. March 25, 2020.

6. Kenney PA et al. Hydrogen Peroxide Vapor sterilization of N95 respirators for reuse. medRxiv preprint. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.24.20041087.

Pediatric patients and COVID-19

Pediatric patients and COVID-19

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic affects us in many ways. Pediatric patients, interestingly, are largely unaffected clinically by this disease. Less than 1% of documented infections occur in children under 10 years old, according to a review of over 72,000 cases from China.1 In that review, most children were asymptomatic or had mild illness, only three required intensive care, and only one death had been reported as of March 10, 2020. This is in stark contrast to the shocking morbidity and mortality statistics we are becoming all too familiar with on the adult side.

From a social standpoint, however, our pediatric patients’ lives have been turned upside down. Their schedules and routines upended, their education and friendships interrupted, and many are likely experiencing real anxiety and fear.2 For countless children, school is a major source of social, emotional, and nutritional support that has been cut off. Some will lose parents, grandparents, or other loved ones to this disease. Parents will lose jobs and will be unable to afford necessities. Pediatric patients will experience delays of procedures or treatments because of the pandemic. Some have projected that rates of child abuse will increase as has been reported during natural disasters.3

Pediatricians around the country are coming together to tackle these issues in creative ways, including the rapid expansion of virtual/telehealth programs. The school systems are developing strategies to deliver online content, and even food, to their students’ homes. Hopefully these tactics will mitigate some of the potential effects on the mental and physical well-being of these patients.

How about my kids? Will they be all right? I am lucky that my husband and I will have jobs throughout this ordeal. Unfortunately, given my role as a hospitalist and my husband’s as a pulmonary/critical care physician, these same jobs that will keep our kids nourished and supported pose the greatest threat to them. As health care workers, we are worried about protecting our families, which may include vulnerable members. The Spanish health ministry announced that medical professionals account for approximately one in eight documented COVID-19 infections in Spain.4 With inadequate supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) in our own nation, we are concerned that our statistics could be similar.

There are multiple strategies to protect ourselves and our families during this difficult time. First, appropriate PPE is essential and integrity with the process must be maintained always. Hospital leaders can protect us by tirelessly working to acquire PPE. In Grand Rapids, Mich., our health system has partnered with multiple local manufacturing companies, including Steelcase, who are producing PPE for our workforce.5 Leaders can diligently update their system’s PPE recommendations to be in line with the latest CDC recommendations and disseminate the information regularly. Hospitalists should frequently check with their Infection Prevention department to make sure they understand if there have been any changes to the recommendations. Innovative solutions for sterilization of PPE, stethoscopes, badges and other equipment, such as with the use of UV boxes or hydrogen peroxide vapor,6 should be explored to minimize contamination. Hospitalists should bring a set of clothes and shoes to change into upon arrival to work and to change out of prior to leaving the hospital.

We must also keep our heads strong. Currently the anxiety amongst physicians is palpable but there is solidarity. Hospital leaders must ensure that hospitalists have easy access to free mental health resources, such as virtual counseling. Wellness teams must rise to the occasion with innovative tactics to support us. For example, Spectrum Health’s wellness team is sponsoring a blog where physicians can discuss COVID-19–related challenges openly. Hospitalist leaders should ensure that there is a structure for debriefing after critical incidents, which are sure to increase in frequency. Email lists and discussion boards sponsored by professional society also provide a collaborative venue for some of these discussions. We must take advantage of these resources and communicate with each other.

For me, in the end it comes back to the kids. My kids and most pediatric patients are not likely to be hospitalized from COVID-19, but they are also not immune to the toll that fighting this pandemic will take on our families. We took an oath to protect our patients, but what do we owe to our own children? At a minimum we can optimize how we protect ourselves every day, both physically and mentally. As we come together as a strong community to fight this pandemic, in addition to saving lives, we are working to ensure that, in the end, the kids will be all right.

Dr. Hadley is chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Spectrum Health/Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich., and clinical assistant professor at Michigan State University, East Lansing.

References

1. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

2. Hagan JF Jr; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Task Force on Terrorism. Psychosocial implications of disaster or terrorism on children: A guide for the pediatrician. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):787-795.

3. Gearhart S et al. The impact of natural disasters on domestic violence: An analysis of reports of simple assault in Florida (1997-2007). Violence Gend. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1089/vio.2017.0077.

4. Minder R, Peltier E. Virus knocks thousands of health workers out of action in Europe. The New York Times. March 24, 2020.

5. McVicar B. West Michigan businesses hustle to produce medical supplies amid coronavirus pandemic. MLive. March 25, 2020.

6. Kenney PA et al. Hydrogen Peroxide Vapor sterilization of N95 respirators for reuse. medRxiv preprint. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.24.20041087.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic affects us in many ways. Pediatric patients, interestingly, are largely unaffected clinically by this disease. Less than 1% of documented infections occur in children under 10 years old, according to a review of over 72,000 cases from China.1 In that review, most children were asymptomatic or had mild illness, only three required intensive care, and only one death had been reported as of March 10, 2020. This is in stark contrast to the shocking morbidity and mortality statistics we are becoming all too familiar with on the adult side.

From a social standpoint, however, our pediatric patients’ lives have been turned upside down. Their schedules and routines upended, their education and friendships interrupted, and many are likely experiencing real anxiety and fear.2 For countless children, school is a major source of social, emotional, and nutritional support that has been cut off. Some will lose parents, grandparents, or other loved ones to this disease. Parents will lose jobs and will be unable to afford necessities. Pediatric patients will experience delays of procedures or treatments because of the pandemic. Some have projected that rates of child abuse will increase as has been reported during natural disasters.3

Pediatricians around the country are coming together to tackle these issues in creative ways, including the rapid expansion of virtual/telehealth programs. The school systems are developing strategies to deliver online content, and even food, to their students’ homes. Hopefully these tactics will mitigate some of the potential effects on the mental and physical well-being of these patients.

How about my kids? Will they be all right? I am lucky that my husband and I will have jobs throughout this ordeal. Unfortunately, given my role as a hospitalist and my husband’s as a pulmonary/critical care physician, these same jobs that will keep our kids nourished and supported pose the greatest threat to them. As health care workers, we are worried about protecting our families, which may include vulnerable members. The Spanish health ministry announced that medical professionals account for approximately one in eight documented COVID-19 infections in Spain.4 With inadequate supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) in our own nation, we are concerned that our statistics could be similar.

There are multiple strategies to protect ourselves and our families during this difficult time. First, appropriate PPE is essential and integrity with the process must be maintained always. Hospital leaders can protect us by tirelessly working to acquire PPE. In Grand Rapids, Mich., our health system has partnered with multiple local manufacturing companies, including Steelcase, who are producing PPE for our workforce.5 Leaders can diligently update their system’s PPE recommendations to be in line with the latest CDC recommendations and disseminate the information regularly. Hospitalists should frequently check with their Infection Prevention department to make sure they understand if there have been any changes to the recommendations. Innovative solutions for sterilization of PPE, stethoscopes, badges and other equipment, such as with the use of UV boxes or hydrogen peroxide vapor,6 should be explored to minimize contamination. Hospitalists should bring a set of clothes and shoes to change into upon arrival to work and to change out of prior to leaving the hospital.

We must also keep our heads strong. Currently the anxiety amongst physicians is palpable but there is solidarity. Hospital leaders must ensure that hospitalists have easy access to free mental health resources, such as virtual counseling. Wellness teams must rise to the occasion with innovative tactics to support us. For example, Spectrum Health’s wellness team is sponsoring a blog where physicians can discuss COVID-19–related challenges openly. Hospitalist leaders should ensure that there is a structure for debriefing after critical incidents, which are sure to increase in frequency. Email lists and discussion boards sponsored by professional society also provide a collaborative venue for some of these discussions. We must take advantage of these resources and communicate with each other.

For me, in the end it comes back to the kids. My kids and most pediatric patients are not likely to be hospitalized from COVID-19, but they are also not immune to the toll that fighting this pandemic will take on our families. We took an oath to protect our patients, but what do we owe to our own children? At a minimum we can optimize how we protect ourselves every day, both physically and mentally. As we come together as a strong community to fight this pandemic, in addition to saving lives, we are working to ensure that, in the end, the kids will be all right.

Dr. Hadley is chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Spectrum Health/Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich., and clinical assistant professor at Michigan State University, East Lansing.

References

1. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

2. Hagan JF Jr; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Task Force on Terrorism. Psychosocial implications of disaster or terrorism on children: A guide for the pediatrician. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):787-795.

3. Gearhart S et al. The impact of natural disasters on domestic violence: An analysis of reports of simple assault in Florida (1997-2007). Violence Gend. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1089/vio.2017.0077.

4. Minder R, Peltier E. Virus knocks thousands of health workers out of action in Europe. The New York Times. March 24, 2020.

5. McVicar B. West Michigan businesses hustle to produce medical supplies amid coronavirus pandemic. MLive. March 25, 2020.

6. Kenney PA et al. Hydrogen Peroxide Vapor sterilization of N95 respirators for reuse. medRxiv preprint. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.24.20041087.

The future of hospital medicine

Assured? Or a definite maybe?

When I started at SHM in 2000, there were fewer than 1,000 hospitalists in the US, and now there are more than 60,000. SHM (back then, we were the National Association of Inpatient Physicians) had about 300 members; now, we have more than 20,000.

Today, hospitalists are part of the medical staff at virtually every hospital in the country, and hospital medicine is recognized as a unique medical specialty with our own knowledge base, textbooks, competencies, meetings, and medical professional society. In a health care environment swirling with change, we are one of the few specialties forged with the ability to adapt and, at times, lead this change. Yet there is so much disruption and instability that there are still many twists and turns in the road that will affect hospitalists’ ability to carve out an even brighter future.

Consolidation has come to health care on a large scale. Hospitals are merging. Health insurers are combining, and even large hospital medicine companies like TeamHealth, Sound, Envision, and others are merging, growing, and acquiring.

At the same time, outside forces from industries not usually associated with health care or inpatient care are swarming into our world: CVS acquires Aetna and aims to reshape primary care; Amazon dominates health care supply chains and moves into pharmacy benefits, and even gets into health care delivery via their partnership with Berkshire Hathaway and JP Morgan; Walmart merges with Humana to create one of the biggest players in Medicare; and Apple expands their inroads into wearables and chronic disease management.

Employment of clinicians has grown logarithmically, especially with inpatient physicians, reshaping the medical staff compensation and accountability. At the same time, payers, both government and private, are evolving into population health with an emphasis not so much on transactions (visits and procedures), but more aligned with outcomes, effectiveness, and efficiency.

All of this leads to a new paradigm of what is important and a new set of values that seems at times more like corporate America where the loyalty of employees can be torn between their employer and the patient. This is especially troublesome in a field traditionally based on the primacy of the doctor-patient relationship. This can put the hospitalist right in the middle at the time when the patient can be most vulnerable.

This has led to new ways to deliver the care that hospitalists provide. First as a pilot and now moving more mainstream, patients with several diagnoses (e.g., heart failure, dehydration, or pneumonia) are now managed not in bricks and mortar hospitals, but in “hospitals at home.” The last few days of a typical hospitalization now take place outside the hospital in a skilled nursing facility (SNF). Fear of uncompensated and unnecessary readmissions leads hospitals to engage hospitalists to handle the first few post-discharge outpatient visits.

This is just a small part of the expanding scope for hospitalists. In addition to managing SNFs and the discharge clinic, hospitalists are now the major providers of perioperative care and play a growing role in palliative care, especially for inpatients. As other specialties that abut hospital medicine have increasing demands and yet fewer new specialists, hospitalists are taking on more critical care and geriatrics, providing procedures, and occupy an evolving role in the emergency room.

There is a lot of work coming towards hospital medicine, and to expand our workforce, hospital medicine groups have incorporated advanced practice providers, including nurse practitioners and physician assistants. But building a true team of health professionals is not seamless or easy with each constituency having a unique scope of practice, limits on their licensure, their own culture, and a distinct training background.

But wait. There will be more new players on the hospital medicine team going forward – some we cannot even anticipate at the present time. In the future, the hospitalist may not even touch the electronic health record (EHR). Clinicians have never excelled at data entry or analysis, and it is time to use a combination of artificial intelligence (AI), voice-activated gathering of history into the record, and staff trained to manage the EHR on both the input and the output sides.

While there may be cheering for this new approach to the EHR – especially because it is a major factor in hospitalist burnout – this will refocus the role and work of the hospitalist to be more of a reviewer and integrator of data, and a strategist and decision-maker overseeing 30 or more patients. As Amazon, CVS, and Walmart move into health care, they will look for the best way to utilize the $300-400/hour hospitalist to the top of our skill level.

In the end, this all comes back to how hospitalists add value, how we can create a career that is rewarding, and how we can help hospitalists be resilient and avoid burnout.

The good news is that hospitalists will not be replaced by AI, nor should we expect to have our incomes cut as less well-trained alternatives replace highly compensated physicians in other specialties. This is a real prospect for many other specialties like dermatology, radiology, pathology, anesthesiology, and even cardiology. But hospitalists will need to adapt to changes in what is valued (i.e., how you can be the most effective and efficient) and to a new job description (i.e., overseeing more patients and managing a team that does more of the H&P, data collecting, and bedside work).

After 20 years of coming out of nowhere to being in the middle of everything in health care, I am confident that hospitalists, with the help of SHM, can continue to forge a path where we can be key difference makers and where we can create a rewarding and sustainable career. It won’t “just happen.” It is not inevitable. But if the past 20 years is any example, we are well-positioned to make the adaptation to succeed in the next 20 years. It is up to all of us to make it happen.

Dr. Wellikson is the CEO of SHM and is retiring from his role in 2020. This article is the second in a series celebrating Dr. Wellikson’s tenure as CEO.

Assured? Or a definite maybe?

Assured? Or a definite maybe?

When I started at SHM in 2000, there were fewer than 1,000 hospitalists in the US, and now there are more than 60,000. SHM (back then, we were the National Association of Inpatient Physicians) had about 300 members; now, we have more than 20,000.

Today, hospitalists are part of the medical staff at virtually every hospital in the country, and hospital medicine is recognized as a unique medical specialty with our own knowledge base, textbooks, competencies, meetings, and medical professional society. In a health care environment swirling with change, we are one of the few specialties forged with the ability to adapt and, at times, lead this change. Yet there is so much disruption and instability that there are still many twists and turns in the road that will affect hospitalists’ ability to carve out an even brighter future.

Consolidation has come to health care on a large scale. Hospitals are merging. Health insurers are combining, and even large hospital medicine companies like TeamHealth, Sound, Envision, and others are merging, growing, and acquiring.

At the same time, outside forces from industries not usually associated with health care or inpatient care are swarming into our world: CVS acquires Aetna and aims to reshape primary care; Amazon dominates health care supply chains and moves into pharmacy benefits, and even gets into health care delivery via their partnership with Berkshire Hathaway and JP Morgan; Walmart merges with Humana to create one of the biggest players in Medicare; and Apple expands their inroads into wearables and chronic disease management.

Employment of clinicians has grown logarithmically, especially with inpatient physicians, reshaping the medical staff compensation and accountability. At the same time, payers, both government and private, are evolving into population health with an emphasis not so much on transactions (visits and procedures), but more aligned with outcomes, effectiveness, and efficiency.

All of this leads to a new paradigm of what is important and a new set of values that seems at times more like corporate America where the loyalty of employees can be torn between their employer and the patient. This is especially troublesome in a field traditionally based on the primacy of the doctor-patient relationship. This can put the hospitalist right in the middle at the time when the patient can be most vulnerable.

This has led to new ways to deliver the care that hospitalists provide. First as a pilot and now moving more mainstream, patients with several diagnoses (e.g., heart failure, dehydration, or pneumonia) are now managed not in bricks and mortar hospitals, but in “hospitals at home.” The last few days of a typical hospitalization now take place outside the hospital in a skilled nursing facility (SNF). Fear of uncompensated and unnecessary readmissions leads hospitals to engage hospitalists to handle the first few post-discharge outpatient visits.

This is just a small part of the expanding scope for hospitalists. In addition to managing SNFs and the discharge clinic, hospitalists are now the major providers of perioperative care and play a growing role in palliative care, especially for inpatients. As other specialties that abut hospital medicine have increasing demands and yet fewer new specialists, hospitalists are taking on more critical care and geriatrics, providing procedures, and occupy an evolving role in the emergency room.

There is a lot of work coming towards hospital medicine, and to expand our workforce, hospital medicine groups have incorporated advanced practice providers, including nurse practitioners and physician assistants. But building a true team of health professionals is not seamless or easy with each constituency having a unique scope of practice, limits on their licensure, their own culture, and a distinct training background.

But wait. There will be more new players on the hospital medicine team going forward – some we cannot even anticipate at the present time. In the future, the hospitalist may not even touch the electronic health record (EHR). Clinicians have never excelled at data entry or analysis, and it is time to use a combination of artificial intelligence (AI), voice-activated gathering of history into the record, and staff trained to manage the EHR on both the input and the output sides.

While there may be cheering for this new approach to the EHR – especially because it is a major factor in hospitalist burnout – this will refocus the role and work of the hospitalist to be more of a reviewer and integrator of data, and a strategist and decision-maker overseeing 30 or more patients. As Amazon, CVS, and Walmart move into health care, they will look for the best way to utilize the $300-400/hour hospitalist to the top of our skill level.

In the end, this all comes back to how hospitalists add value, how we can create a career that is rewarding, and how we can help hospitalists be resilient and avoid burnout.

The good news is that hospitalists will not be replaced by AI, nor should we expect to have our incomes cut as less well-trained alternatives replace highly compensated physicians in other specialties. This is a real prospect for many other specialties like dermatology, radiology, pathology, anesthesiology, and even cardiology. But hospitalists will need to adapt to changes in what is valued (i.e., how you can be the most effective and efficient) and to a new job description (i.e., overseeing more patients and managing a team that does more of the H&P, data collecting, and bedside work).

After 20 years of coming out of nowhere to being in the middle of everything in health care, I am confident that hospitalists, with the help of SHM, can continue to forge a path where we can be key difference makers and where we can create a rewarding and sustainable career. It won’t “just happen.” It is not inevitable. But if the past 20 years is any example, we are well-positioned to make the adaptation to succeed in the next 20 years. It is up to all of us to make it happen.

Dr. Wellikson is the CEO of SHM and is retiring from his role in 2020. This article is the second in a series celebrating Dr. Wellikson’s tenure as CEO.

When I started at SHM in 2000, there were fewer than 1,000 hospitalists in the US, and now there are more than 60,000. SHM (back then, we were the National Association of Inpatient Physicians) had about 300 members; now, we have more than 20,000.

Today, hospitalists are part of the medical staff at virtually every hospital in the country, and hospital medicine is recognized as a unique medical specialty with our own knowledge base, textbooks, competencies, meetings, and medical professional society. In a health care environment swirling with change, we are one of the few specialties forged with the ability to adapt and, at times, lead this change. Yet there is so much disruption and instability that there are still many twists and turns in the road that will affect hospitalists’ ability to carve out an even brighter future.

Consolidation has come to health care on a large scale. Hospitals are merging. Health insurers are combining, and even large hospital medicine companies like TeamHealth, Sound, Envision, and others are merging, growing, and acquiring.

At the same time, outside forces from industries not usually associated with health care or inpatient care are swarming into our world: CVS acquires Aetna and aims to reshape primary care; Amazon dominates health care supply chains and moves into pharmacy benefits, and even gets into health care delivery via their partnership with Berkshire Hathaway and JP Morgan; Walmart merges with Humana to create one of the biggest players in Medicare; and Apple expands their inroads into wearables and chronic disease management.

Employment of clinicians has grown logarithmically, especially with inpatient physicians, reshaping the medical staff compensation and accountability. At the same time, payers, both government and private, are evolving into population health with an emphasis not so much on transactions (visits and procedures), but more aligned with outcomes, effectiveness, and efficiency.

All of this leads to a new paradigm of what is important and a new set of values that seems at times more like corporate America where the loyalty of employees can be torn between their employer and the patient. This is especially troublesome in a field traditionally based on the primacy of the doctor-patient relationship. This can put the hospitalist right in the middle at the time when the patient can be most vulnerable.

This has led to new ways to deliver the care that hospitalists provide. First as a pilot and now moving more mainstream, patients with several diagnoses (e.g., heart failure, dehydration, or pneumonia) are now managed not in bricks and mortar hospitals, but in “hospitals at home.” The last few days of a typical hospitalization now take place outside the hospital in a skilled nursing facility (SNF). Fear of uncompensated and unnecessary readmissions leads hospitals to engage hospitalists to handle the first few post-discharge outpatient visits.

This is just a small part of the expanding scope for hospitalists. In addition to managing SNFs and the discharge clinic, hospitalists are now the major providers of perioperative care and play a growing role in palliative care, especially for inpatients. As other specialties that abut hospital medicine have increasing demands and yet fewer new specialists, hospitalists are taking on more critical care and geriatrics, providing procedures, and occupy an evolving role in the emergency room.

There is a lot of work coming towards hospital medicine, and to expand our workforce, hospital medicine groups have incorporated advanced practice providers, including nurse practitioners and physician assistants. But building a true team of health professionals is not seamless or easy with each constituency having a unique scope of practice, limits on their licensure, their own culture, and a distinct training background.

But wait. There will be more new players on the hospital medicine team going forward – some we cannot even anticipate at the present time. In the future, the hospitalist may not even touch the electronic health record (EHR). Clinicians have never excelled at data entry or analysis, and it is time to use a combination of artificial intelligence (AI), voice-activated gathering of history into the record, and staff trained to manage the EHR on both the input and the output sides.

While there may be cheering for this new approach to the EHR – especially because it is a major factor in hospitalist burnout – this will refocus the role and work of the hospitalist to be more of a reviewer and integrator of data, and a strategist and decision-maker overseeing 30 or more patients. As Amazon, CVS, and Walmart move into health care, they will look for the best way to utilize the $300-400/hour hospitalist to the top of our skill level.

In the end, this all comes back to how hospitalists add value, how we can create a career that is rewarding, and how we can help hospitalists be resilient and avoid burnout.

The good news is that hospitalists will not be replaced by AI, nor should we expect to have our incomes cut as less well-trained alternatives replace highly compensated physicians in other specialties. This is a real prospect for many other specialties like dermatology, radiology, pathology, anesthesiology, and even cardiology. But hospitalists will need to adapt to changes in what is valued (i.e., how you can be the most effective and efficient) and to a new job description (i.e., overseeing more patients and managing a team that does more of the H&P, data collecting, and bedside work).

After 20 years of coming out of nowhere to being in the middle of everything in health care, I am confident that hospitalists, with the help of SHM, can continue to forge a path where we can be key difference makers and where we can create a rewarding and sustainable career. It won’t “just happen.” It is not inevitable. But if the past 20 years is any example, we are well-positioned to make the adaptation to succeed in the next 20 years. It is up to all of us to make it happen.

Dr. Wellikson is the CEO of SHM and is retiring from his role in 2020. This article is the second in a series celebrating Dr. Wellikson’s tenure as CEO.

Meet the new SHM president: Dr. Danielle Scheurer

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSRC, SFHM, is the chief quality officer and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is the outgoing medical editor of The Hospitalist, and the new president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. She assumes the role from immediate past-president Christopher Frost, MD, SFHM.

As a hospitalist for 17 years, Dr. Scheurer has practiced in both academic tertiary care, as well as community hospital settings. As a chief quality officer, she has worked to improve quality and safety in all health care settings, including ambulatory care, nursing homes, home health, and surgical centers. She brings a broad experience in the medical industry to the SHM presidency.

At what point in your education/training did you decide to practice hospital medicine?

I always loved inpatient medicine throughout my entire meds-peds residency training at Duke University in Durham, N.C. I honestly never had a doubt that hospital medicine was going to be my career. What appeals to me is that each hour and each day is different, which is invigorating.

What are your favorite aspects of clinical practice and of your administrative duties?

I like doing both administrative work and clinical work because I believe having a view of both worlds helps me to be a better physician and a better administrator. It greatly helps me bring realistic solutions to the front lines since I have a good understanding of what needs to be done, but also what is likely to actually work.

As president of SHM over the next year, what are your primary goals?

My primary goal is to deeply connect with the SHM membership and understand what their needs are. There is enormous change happening in the medical industry, and SHM should be a conduit for information sharing, resources, and most importantly, answers to all our difficult problems. Hospitalists are critical to success for our hospitals and our communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. We must be able to give and receive information quickly and seamlessly to effectively help each other across the country and the world. SHM must be seen as a critical convener, especially in times of crisis.

Additionally, SHM has always fostered a “big tent” philosophy, so we will continue to explore ways to expand membership beyond “the core” of internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics and reach a better understanding of what our constituents need and how we can add value to their work lives and careers. In addition to expanding membership within our borders, other expansions already include working with international chapters and members with an “all teach, all learn” attitude to better understand mutually beneficial partnerships with international members. Through all these expansions, we will come closer to truly realizing our mission at SHM, which is to “promote exceptional care for hospitalized patients.”

You mention COVID-19. What resources is SHM offering to members?

We have opened up the SHM Learning Portal to help members and non-members address upcoming challenges, such as expanding ICU coverage or cross-training providers for hospital medicine. Several modules in SHM’s “Critical Care for the Hospitalist” series may be especially relevant during the COVID-19 crisis:

- Fluid Resuscitation in the Critically Ill

- Mechanical Ventilation Part I – The Basics

- Mechanical Ventilation Part II – Beyond the Basics

- Mechanical Ventilation Part III – ARDS

Finally, in this time when so many hospitalists are busy dealing with COVID-19, SHM is committed to offering valuable resources and is in the process of offering new material, including Twitter chats, webinars, blogs, and podcasts to help hospitalists share best practices. Please bookmark SHM’s compilation of COVID-19 resources at hospitalmedicine.org/coronavirus.

We also continue to forge ahead with our publications, The Hospitalist and the Journal of Hospital Medicine, by adding online content as it becomes available. Visit the COVID-19 news feed on The Hospitalist website at www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/coronavirus-updates.

In this trying time, we can still connect as a community and continue to learn from each other. We encourage you to use SHM’s online community, HMX, to share resources and crowd-source solutions. Ideas for SHM resources can be submitted via email at [email protected].

What are some of the current challenges for hospital medicine?

The demands placed on hospitalists are greater than ever. With shortening length of stay, rising acuity and complexity, increasing administrative burdens, and high emphasis on care transitions, our skills (and our patience) need to rise to these increasing demands. As a member-based society, SHM (and the board of directors) seeks to ensure we are helping hospitalists be the very best they can be, regardless of hospitalist type or practice setting.

The good news is that we are still in high demand. Within the medical industry, there has been an explosive growth in the need for hospitalists, and we can now be found in almost every hospital setting in the United States. But as a current commodity, it is imperative that we continue to prove the value we are adding to our patients and their families, the systems in which we work, and the industry as a whole.

How will hospital medicine change in the next decade?

I believe one of the biggest changes we will see is the shift to ambulatory settings and the use of telehealth, and we all need to gain significant comfort with both to be effective.

Do you have any advice for students and residents interested in hospital medicine?

It is an incredibly dynamic and invigorating career; I can’t imagine doing anything else.

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSRC, SFHM, is the chief quality officer and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is the outgoing medical editor of The Hospitalist, and the new president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. She assumes the role from immediate past-president Christopher Frost, MD, SFHM.

As a hospitalist for 17 years, Dr. Scheurer has practiced in both academic tertiary care, as well as community hospital settings. As a chief quality officer, she has worked to improve quality and safety in all health care settings, including ambulatory care, nursing homes, home health, and surgical centers. She brings a broad experience in the medical industry to the SHM presidency.

At what point in your education/training did you decide to practice hospital medicine?

I always loved inpatient medicine throughout my entire meds-peds residency training at Duke University in Durham, N.C. I honestly never had a doubt that hospital medicine was going to be my career. What appeals to me is that each hour and each day is different, which is invigorating.

What are your favorite aspects of clinical practice and of your administrative duties?

I like doing both administrative work and clinical work because I believe having a view of both worlds helps me to be a better physician and a better administrator. It greatly helps me bring realistic solutions to the front lines since I have a good understanding of what needs to be done, but also what is likely to actually work.

As president of SHM over the next year, what are your primary goals?

My primary goal is to deeply connect with the SHM membership and understand what their needs are. There is enormous change happening in the medical industry, and SHM should be a conduit for information sharing, resources, and most importantly, answers to all our difficult problems. Hospitalists are critical to success for our hospitals and our communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. We must be able to give and receive information quickly and seamlessly to effectively help each other across the country and the world. SHM must be seen as a critical convener, especially in times of crisis.

Additionally, SHM has always fostered a “big tent” philosophy, so we will continue to explore ways to expand membership beyond “the core” of internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics and reach a better understanding of what our constituents need and how we can add value to their work lives and careers. In addition to expanding membership within our borders, other expansions already include working with international chapters and members with an “all teach, all learn” attitude to better understand mutually beneficial partnerships with international members. Through all these expansions, we will come closer to truly realizing our mission at SHM, which is to “promote exceptional care for hospitalized patients.”

You mention COVID-19. What resources is SHM offering to members?

We have opened up the SHM Learning Portal to help members and non-members address upcoming challenges, such as expanding ICU coverage or cross-training providers for hospital medicine. Several modules in SHM’s “Critical Care for the Hospitalist” series may be especially relevant during the COVID-19 crisis:

- Fluid Resuscitation in the Critically Ill

- Mechanical Ventilation Part I – The Basics

- Mechanical Ventilation Part II – Beyond the Basics

- Mechanical Ventilation Part III – ARDS

Finally, in this time when so many hospitalists are busy dealing with COVID-19, SHM is committed to offering valuable resources and is in the process of offering new material, including Twitter chats, webinars, blogs, and podcasts to help hospitalists share best practices. Please bookmark SHM’s compilation of COVID-19 resources at hospitalmedicine.org/coronavirus.

We also continue to forge ahead with our publications, The Hospitalist and the Journal of Hospital Medicine, by adding online content as it becomes available. Visit the COVID-19 news feed on The Hospitalist website at www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/coronavirus-updates.

In this trying time, we can still connect as a community and continue to learn from each other. We encourage you to use SHM’s online community, HMX, to share resources and crowd-source solutions. Ideas for SHM resources can be submitted via email at [email protected].

What are some of the current challenges for hospital medicine?

The demands placed on hospitalists are greater than ever. With shortening length of stay, rising acuity and complexity, increasing administrative burdens, and high emphasis on care transitions, our skills (and our patience) need to rise to these increasing demands. As a member-based society, SHM (and the board of directors) seeks to ensure we are helping hospitalists be the very best they can be, regardless of hospitalist type or practice setting.

The good news is that we are still in high demand. Within the medical industry, there has been an explosive growth in the need for hospitalists, and we can now be found in almost every hospital setting in the United States. But as a current commodity, it is imperative that we continue to prove the value we are adding to our patients and their families, the systems in which we work, and the industry as a whole.

How will hospital medicine change in the next decade?

I believe one of the biggest changes we will see is the shift to ambulatory settings and the use of telehealth, and we all need to gain significant comfort with both to be effective.

Do you have any advice for students and residents interested in hospital medicine?

It is an incredibly dynamic and invigorating career; I can’t imagine doing anything else.

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSRC, SFHM, is the chief quality officer and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is the outgoing medical editor of The Hospitalist, and the new president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. She assumes the role from immediate past-president Christopher Frost, MD, SFHM.

As a hospitalist for 17 years, Dr. Scheurer has practiced in both academic tertiary care, as well as community hospital settings. As a chief quality officer, she has worked to improve quality and safety in all health care settings, including ambulatory care, nursing homes, home health, and surgical centers. She brings a broad experience in the medical industry to the SHM presidency.

At what point in your education/training did you decide to practice hospital medicine?

I always loved inpatient medicine throughout my entire meds-peds residency training at Duke University in Durham, N.C. I honestly never had a doubt that hospital medicine was going to be my career. What appeals to me is that each hour and each day is different, which is invigorating.

What are your favorite aspects of clinical practice and of your administrative duties?

I like doing both administrative work and clinical work because I believe having a view of both worlds helps me to be a better physician and a better administrator. It greatly helps me bring realistic solutions to the front lines since I have a good understanding of what needs to be done, but also what is likely to actually work.

As president of SHM over the next year, what are your primary goals?

My primary goal is to deeply connect with the SHM membership and understand what their needs are. There is enormous change happening in the medical industry, and SHM should be a conduit for information sharing, resources, and most importantly, answers to all our difficult problems. Hospitalists are critical to success for our hospitals and our communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. We must be able to give and receive information quickly and seamlessly to effectively help each other across the country and the world. SHM must be seen as a critical convener, especially in times of crisis.

Additionally, SHM has always fostered a “big tent” philosophy, so we will continue to explore ways to expand membership beyond “the core” of internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics and reach a better understanding of what our constituents need and how we can add value to their work lives and careers. In addition to expanding membership within our borders, other expansions already include working with international chapters and members with an “all teach, all learn” attitude to better understand mutually beneficial partnerships with international members. Through all these expansions, we will come closer to truly realizing our mission at SHM, which is to “promote exceptional care for hospitalized patients.”

You mention COVID-19. What resources is SHM offering to members?

We have opened up the SHM Learning Portal to help members and non-members address upcoming challenges, such as expanding ICU coverage or cross-training providers for hospital medicine. Several modules in SHM’s “Critical Care for the Hospitalist” series may be especially relevant during the COVID-19 crisis:

- Fluid Resuscitation in the Critically Ill

- Mechanical Ventilation Part I – The Basics

- Mechanical Ventilation Part II – Beyond the Basics

- Mechanical Ventilation Part III – ARDS

Finally, in this time when so many hospitalists are busy dealing with COVID-19, SHM is committed to offering valuable resources and is in the process of offering new material, including Twitter chats, webinars, blogs, and podcasts to help hospitalists share best practices. Please bookmark SHM’s compilation of COVID-19 resources at hospitalmedicine.org/coronavirus.

We also continue to forge ahead with our publications, The Hospitalist and the Journal of Hospital Medicine, by adding online content as it becomes available. Visit the COVID-19 news feed on The Hospitalist website at www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/coronavirus-updates.

In this trying time, we can still connect as a community and continue to learn from each other. We encourage you to use SHM’s online community, HMX, to share resources and crowd-source solutions. Ideas for SHM resources can be submitted via email at [email protected].

What are some of the current challenges for hospital medicine?

The demands placed on hospitalists are greater than ever. With shortening length of stay, rising acuity and complexity, increasing administrative burdens, and high emphasis on care transitions, our skills (and our patience) need to rise to these increasing demands. As a member-based society, SHM (and the board of directors) seeks to ensure we are helping hospitalists be the very best they can be, regardless of hospitalist type or practice setting.

The good news is that we are still in high demand. Within the medical industry, there has been an explosive growth in the need for hospitalists, and we can now be found in almost every hospital setting in the United States. But as a current commodity, it is imperative that we continue to prove the value we are adding to our patients and their families, the systems in which we work, and the industry as a whole.

How will hospital medicine change in the next decade?

I believe one of the biggest changes we will see is the shift to ambulatory settings and the use of telehealth, and we all need to gain significant comfort with both to be effective.

Do you have any advice for students and residents interested in hospital medicine?

It is an incredibly dynamic and invigorating career; I can’t imagine doing anything else.

HM20 canceled: SHM explains why

COVID-19 made holding meeting impossible

In mid-March, the Society of Hospital Medicine board of directors concluded that it was impossible for SHM to move forward with Hospital Medicine 2020 because of the continued spread of virus that causes Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Given the most recent information available from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and the World Health Organization about the evolving global pandemic and the number of institutions that had travel bans in place, SHM leadership concluded that canceling the Annual Conference was the only path forward.

“Canceling the conference during this unprecedented time is the right thing to do,” said Benji K. Mathews, MD, SFHM, CLHM, course director for HM20. “With the evolving circumstances out of our control, there were risks to our community as it would have gathered, communities we connect with on our travels, and our home communities and hospitals – canceling was the best way to mitigate these risks. Through it all, I couldn’t have asked for a better leadership team and the larger SHM community for their support.”

Because hospitalists are on the front lines of patient care at their institutions, they will be needed more than ever as the pandemic continues to grow in order to manage care of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and other illnesses. As the only medical society dedicated to hospital medicine, SHM will continue to support hospitalists with resources and research specific to COVID-19 and its impact on the practice of hospital medicine.

SHM is aware that this necessary cancellation impacts many from both a financial and logistical perspective. As such, SHM will refund all conference registration fees for HM20 in full. SHM is also providing the opportunity to defer your HM20 registration to HM21, taking place May 4-7, 2021 in Las Vegas, or Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2020, taking place July 23-26, 2020 in Lake Buena Vista, Fla.

For accommodation or travel cancellations, SHM requests that individuals please refer to their respective hotel or carrier’s customer service team and related cancellation policies.

To provide the world-class education that conference attendees have come to expect from SHM over the years, the SHM team is exploring virtual options to offer select content originally anticipated at HM20. SHM also offers online education via the SHM Learning Portal and the new SHM Education app.

Visit shmannualconference.org/faqs for a full list of FAQs. For additional questions, please contact [email protected].

SHM will continue to monitor the COVID-19 pandemic and provide hospitalists with useful resources in this time of need at hospitalmedicine.org/coronavirus. For news coverage of COVID-19, visit https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/coronavirus-updates.

COVID-19 made holding meeting impossible

COVID-19 made holding meeting impossible

In mid-March, the Society of Hospital Medicine board of directors concluded that it was impossible for SHM to move forward with Hospital Medicine 2020 because of the continued spread of virus that causes Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Given the most recent information available from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and the World Health Organization about the evolving global pandemic and the number of institutions that had travel bans in place, SHM leadership concluded that canceling the Annual Conference was the only path forward.

“Canceling the conference during this unprecedented time is the right thing to do,” said Benji K. Mathews, MD, SFHM, CLHM, course director for HM20. “With the evolving circumstances out of our control, there were risks to our community as it would have gathered, communities we connect with on our travels, and our home communities and hospitals – canceling was the best way to mitigate these risks. Through it all, I couldn’t have asked for a better leadership team and the larger SHM community for their support.”

Because hospitalists are on the front lines of patient care at their institutions, they will be needed more than ever as the pandemic continues to grow in order to manage care of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and other illnesses. As the only medical society dedicated to hospital medicine, SHM will continue to support hospitalists with resources and research specific to COVID-19 and its impact on the practice of hospital medicine.

SHM is aware that this necessary cancellation impacts many from both a financial and logistical perspective. As such, SHM will refund all conference registration fees for HM20 in full. SHM is also providing the opportunity to defer your HM20 registration to HM21, taking place May 4-7, 2021 in Las Vegas, or Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2020, taking place July 23-26, 2020 in Lake Buena Vista, Fla.

For accommodation or travel cancellations, SHM requests that individuals please refer to their respective hotel or carrier’s customer service team and related cancellation policies.

To provide the world-class education that conference attendees have come to expect from SHM over the years, the SHM team is exploring virtual options to offer select content originally anticipated at HM20. SHM also offers online education via the SHM Learning Portal and the new SHM Education app.

Visit shmannualconference.org/faqs for a full list of FAQs. For additional questions, please contact [email protected].

SHM will continue to monitor the COVID-19 pandemic and provide hospitalists with useful resources in this time of need at hospitalmedicine.org/coronavirus. For news coverage of COVID-19, visit https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/coronavirus-updates.

In mid-March, the Society of Hospital Medicine board of directors concluded that it was impossible for SHM to move forward with Hospital Medicine 2020 because of the continued spread of virus that causes Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Given the most recent information available from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and the World Health Organization about the evolving global pandemic and the number of institutions that had travel bans in place, SHM leadership concluded that canceling the Annual Conference was the only path forward.

“Canceling the conference during this unprecedented time is the right thing to do,” said Benji K. Mathews, MD, SFHM, CLHM, course director for HM20. “With the evolving circumstances out of our control, there were risks to our community as it would have gathered, communities we connect with on our travels, and our home communities and hospitals – canceling was the best way to mitigate these risks. Through it all, I couldn’t have asked for a better leadership team and the larger SHM community for their support.”

Because hospitalists are on the front lines of patient care at their institutions, they will be needed more than ever as the pandemic continues to grow in order to manage care of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and other illnesses. As the only medical society dedicated to hospital medicine, SHM will continue to support hospitalists with resources and research specific to COVID-19 and its impact on the practice of hospital medicine.

SHM is aware that this necessary cancellation impacts many from both a financial and logistical perspective. As such, SHM will refund all conference registration fees for HM20 in full. SHM is also providing the opportunity to defer your HM20 registration to HM21, taking place May 4-7, 2021 in Las Vegas, or Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2020, taking place July 23-26, 2020 in Lake Buena Vista, Fla.

For accommodation or travel cancellations, SHM requests that individuals please refer to their respective hotel or carrier’s customer service team and related cancellation policies.

To provide the world-class education that conference attendees have come to expect from SHM over the years, the SHM team is exploring virtual options to offer select content originally anticipated at HM20. SHM also offers online education via the SHM Learning Portal and the new SHM Education app.

Visit shmannualconference.org/faqs for a full list of FAQs. For additional questions, please contact [email protected].

SHM will continue to monitor the COVID-19 pandemic and provide hospitalists with useful resources in this time of need at hospitalmedicine.org/coronavirus. For news coverage of COVID-19, visit https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/coronavirus-updates.

Comorbidities more common in hospitalized COVID-19 patients

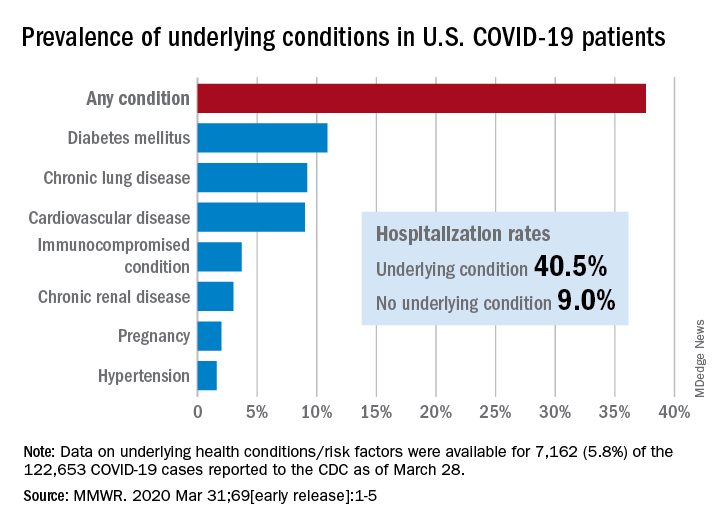

Greater prevalence of underlying health conditions such as diabetes and chronic lung disease was seen among nearly 7,200 Americans hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Of the 122,653 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases reported to the CDC as of March 28, the COVID-19 Response Team had access to data on the presence or absence of underlying health conditions and other recognized risk factors for severe outcomes from respiratory infections for 7,162 (5.8%) patients.

“Among these patients, higher percentages of patients with underlying conditions were admitted to the hospital and to an ICU than patients without reported underlying conditions. These results are consistent with findings from China and Italy,” Katherine Fleming-Dutra, MD, and associates said in the MMWR.

Individuals with underlying health conditions/risk factors made up 37.6% of all COVID-19 patients in the study but represented a majority of ICU (78%) and non-ICU (71%) hospital admissions. In contrast, 73% of COVID-19 patients who were not hospitalized had no underlying conditions, Dr. Fleming-Dutra and the CDC COVID-19 Response Team reported.

With a prevalence of 10.9%, diabetes mellitus was the most common condition reported among all COVID-19 patients, followed by chronic lung disease (9.2%) and cardiovascular disease (9.0%), the investigators said.

Another look at the data shows that 40.5% of those with underlying conditions were hospitalized, compared with 9.0% of the 4,470 COVID-19 patients without any risk factors.

“Strategies to protect all persons and especially those with underlying health conditions, including social distancing and handwashing, should be implemented by all communities and all persons to help slow the spread of COVID-19,” the response team wrote.

SOURCE: Fleming-Dutra K et al. MMWR. 2020 Mar 31;69 (early release):1-5.

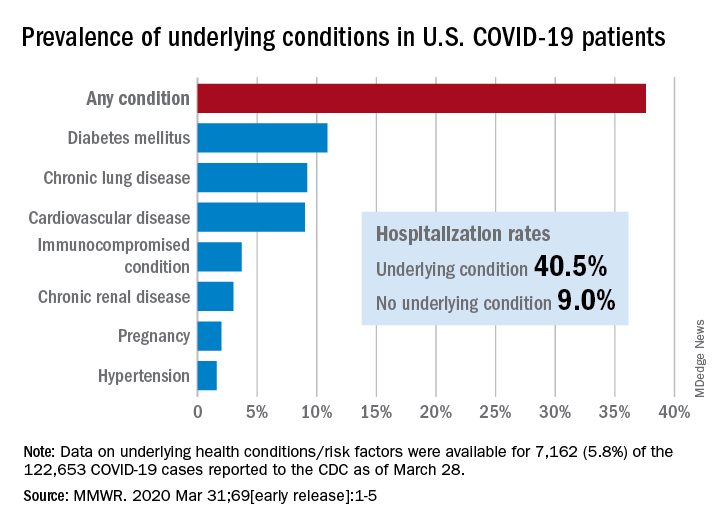

Greater prevalence of underlying health conditions such as diabetes and chronic lung disease was seen among nearly 7,200 Americans hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Of the 122,653 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases reported to the CDC as of March 28, the COVID-19 Response Team had access to data on the presence or absence of underlying health conditions and other recognized risk factors for severe outcomes from respiratory infections for 7,162 (5.8%) patients.

“Among these patients, higher percentages of patients with underlying conditions were admitted to the hospital and to an ICU than patients without reported underlying conditions. These results are consistent with findings from China and Italy,” Katherine Fleming-Dutra, MD, and associates said in the MMWR.

Individuals with underlying health conditions/risk factors made up 37.6% of all COVID-19 patients in the study but represented a majority of ICU (78%) and non-ICU (71%) hospital admissions. In contrast, 73% of COVID-19 patients who were not hospitalized had no underlying conditions, Dr. Fleming-Dutra and the CDC COVID-19 Response Team reported.

With a prevalence of 10.9%, diabetes mellitus was the most common condition reported among all COVID-19 patients, followed by chronic lung disease (9.2%) and cardiovascular disease (9.0%), the investigators said.

Another look at the data shows that 40.5% of those with underlying conditions were hospitalized, compared with 9.0% of the 4,470 COVID-19 patients without any risk factors.

“Strategies to protect all persons and especially those with underlying health conditions, including social distancing and handwashing, should be implemented by all communities and all persons to help slow the spread of COVID-19,” the response team wrote.

SOURCE: Fleming-Dutra K et al. MMWR. 2020 Mar 31;69 (early release):1-5.

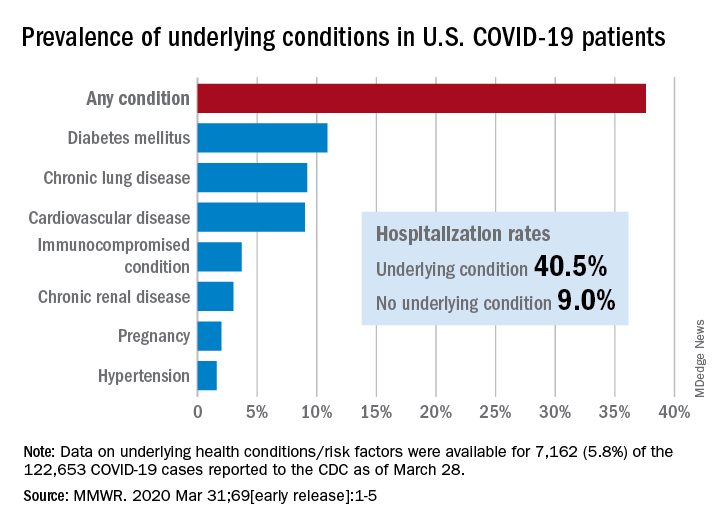

Greater prevalence of underlying health conditions such as diabetes and chronic lung disease was seen among nearly 7,200 Americans hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Of the 122,653 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases reported to the CDC as of March 28, the COVID-19 Response Team had access to data on the presence or absence of underlying health conditions and other recognized risk factors for severe outcomes from respiratory infections for 7,162 (5.8%) patients.

“Among these patients, higher percentages of patients with underlying conditions were admitted to the hospital and to an ICU than patients without reported underlying conditions. These results are consistent with findings from China and Italy,” Katherine Fleming-Dutra, MD, and associates said in the MMWR.

Individuals with underlying health conditions/risk factors made up 37.6% of all COVID-19 patients in the study but represented a majority of ICU (78%) and non-ICU (71%) hospital admissions. In contrast, 73% of COVID-19 patients who were not hospitalized had no underlying conditions, Dr. Fleming-Dutra and the CDC COVID-19 Response Team reported.

With a prevalence of 10.9%, diabetes mellitus was the most common condition reported among all COVID-19 patients, followed by chronic lung disease (9.2%) and cardiovascular disease (9.0%), the investigators said.

Another look at the data shows that 40.5% of those with underlying conditions were hospitalized, compared with 9.0% of the 4,470 COVID-19 patients without any risk factors.

“Strategies to protect all persons and especially those with underlying health conditions, including social distancing and handwashing, should be implemented by all communities and all persons to help slow the spread of COVID-19,” the response team wrote.

SOURCE: Fleming-Dutra K et al. MMWR. 2020 Mar 31;69 (early release):1-5.

FROM MMWR

Which tube placement is best for a patient requiring enteral nutrition?

Comparative advantages of EN tubes

Case

A 68-year-old diabetic nonverbal female presents to the ED because of “seizure” 1 hour ago. On exam, her blood glucose is 200. She is unable to speak and has dysphagia because of a stroke she sustained last month. The patient’s husband adds that she hasn’t been eating and drinking sufficiently in the past couple of days. Imaging was negative for any acute intracranial bleeds or lesions. Labs showed a serum sodium level of 150 milliequivalents/L. D5W is started, and the following day, the patient has a sodium level of 154 milliequivalents/L.

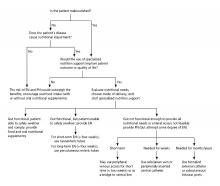

Brief overview

Many hospitalized patients are unable to maintain hydration and/or nutritional status by mouth and will need enteral nutrition. Variables such as past medical history, swallowing ability, history of aspiration, prognosis, and functional capacity of each gastrointestinal segment will determine the best option for enteral nutrition for each patient. Each type of enteral tube feeding has advantages, disadvantages, and complications.

Overview of the data

Enteral nutrition should be started within 24-48 hours in a critically ill patient who is unable to maintain intake according to the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.1 This can be provided through a nasogastric (NG) tube, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, PEG tube with jejunal extension (PEG-J), or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunal (PEJ) tube.1

NG tubes are often the first method deployed because of their low cost and convenience. They are also suitable for the patient who requires this type of feeding for less than 4 weeks. However, NG tubes do require some patient cooperation (to place and maintain)and are contraindicated in some patients with orofacial trauma, upper GI tumors, inadequate lower esophageal sphincter tone, and gastroparesis.2

Another option is a PEG tube, which is a good alternative for patients who are sedated; ventilated; or have neurodegenerative processes, stroke with dysphagia, or head and neck cancers. These are typically recommended when enteral nutrition will be needed for more than 4 weeks. Disadvantages of PEG tubes include tube obstruction or displacement, gastroesophageal reflux, and leakage of gastric content around the percutaneous site or into the peritoneum.

PEG-J tubes, PEJ tubes, or jejunostomy tubes are best suited for patients with GI dysmotility, patients who have unsuccessfully undergone the aforementioned methods, patients with histories of partial gastrectomies, or patients with gastric or pancreatic cancers/multiple traumas. The PEG-J tube extends into the distal duodenum; because it is longer and more narrow, it is more likely to coil and occlude the flow of nutrients during feedings.2,3 Jejunal feeding methods incorporate a continuous pump controlled infusion; if set too rapidly, this could cause dumping syndrome. A benefit of jejunal nutrition is a lower risk of aspiration, compared with other enteral tubes.4

It is best to appraise the selected method for its efficacy and patient preference. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends starting with orogastric or nasogastric feeds, and switching to postpyloric or jejunal feeds for those intolerant to or at high risk for aspiration.5 The most important aspect is early enteral nutrition in hospitalized patients unable to maintain oral nutrition.

Application of the data to the original case

This is a severely hypernatremic diabetic patient unable to swallow. On day 2 of her hospitalization, the clinical team provided the patient with an NG tube for increased free-water intake to gradually decrease her serum sodium. By hospital day 4, the patient’s sodium had normalized. Considering the patient’s long-term prognosis and dysphagia, discussions were held with the patient and husband for PEG tube placement. The patient received a PEG tube and was subsequently discharged 2 days later.

Bottom line

Enteral nutrition is a common need among hospitalized patients. Modality of enteral nutrition will depend on the patient’s past medical history, anticipated duration, and preferences.

Dr. Basnet is the hospitalist program director for Apogee Physicians Group at Eastern New Mexico Medical Center in Roswell. Ms. Tayes is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine in Las Cruces, N.M., with interests in surgery, internal medicine, and emergency medicine. Ms. Gallivan is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine, with interests in cardiothoracic surgery, general surgery, and internal medicine.

References

1. Boullata JI et al. ASPEN Safe Practices for Enteral Nutrition Therapy. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;1-89.

2. Kirby DF et al. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on tube feeding for enteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1282.

3. Lazarus BA et al. Aspiration associated with long-term gastric versus jejunal feeding: A critical analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:46.

4. Alkhawaja S et al. Postpyloric versus gastric tube feeding for preventing pneumonia and improving nutritional outcomes in critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 4;(8):CD008875.

5. McCalve SA et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition therapy in the hospitalized patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:315-34. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.28.

Additional reading

Bellini LM. Nutrition Support in Advanced Lung Disease. UptoDate. https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.ad.bcomnm.org/contents/nutritional-support-in-advanced-lung-disease?. Published April 20, 2018.

Commercial Formulas for the Feeding Tube. The Oral Cancer Foundation. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/nutrition/commercial-formulas-feeding-tube/. Published June 5, 2018.

Marik Z. Immunonutrition in critically ill patients: A systematic review and analysis of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(11). doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1213-6.

Wischmeyer PE. Enteral nutrition can be given to patients on vasopressors. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(1):122-5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003965.

Comparative advantages of EN tubes

Comparative advantages of EN tubes

Case

A 68-year-old diabetic nonverbal female presents to the ED because of “seizure” 1 hour ago. On exam, her blood glucose is 200. She is unable to speak and has dysphagia because of a stroke she sustained last month. The patient’s husband adds that she hasn’t been eating and drinking sufficiently in the past couple of days. Imaging was negative for any acute intracranial bleeds or lesions. Labs showed a serum sodium level of 150 milliequivalents/L. D5W is started, and the following day, the patient has a sodium level of 154 milliequivalents/L.

Brief overview

Many hospitalized patients are unable to maintain hydration and/or nutritional status by mouth and will need enteral nutrition. Variables such as past medical history, swallowing ability, history of aspiration, prognosis, and functional capacity of each gastrointestinal segment will determine the best option for enteral nutrition for each patient. Each type of enteral tube feeding has advantages, disadvantages, and complications.

Overview of the data

Enteral nutrition should be started within 24-48 hours in a critically ill patient who is unable to maintain intake according to the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.1 This can be provided through a nasogastric (NG) tube, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, PEG tube with jejunal extension (PEG-J), or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunal (PEJ) tube.1

NG tubes are often the first method deployed because of their low cost and convenience. They are also suitable for the patient who requires this type of feeding for less than 4 weeks. However, NG tubes do require some patient cooperation (to place and maintain)and are contraindicated in some patients with orofacial trauma, upper GI tumors, inadequate lower esophageal sphincter tone, and gastroparesis.2

Another option is a PEG tube, which is a good alternative for patients who are sedated; ventilated; or have neurodegenerative processes, stroke with dysphagia, or head and neck cancers. These are typically recommended when enteral nutrition will be needed for more than 4 weeks. Disadvantages of PEG tubes include tube obstruction or displacement, gastroesophageal reflux, and leakage of gastric content around the percutaneous site or into the peritoneum.

PEG-J tubes, PEJ tubes, or jejunostomy tubes are best suited for patients with GI dysmotility, patients who have unsuccessfully undergone the aforementioned methods, patients with histories of partial gastrectomies, or patients with gastric or pancreatic cancers/multiple traumas. The PEG-J tube extends into the distal duodenum; because it is longer and more narrow, it is more likely to coil and occlude the flow of nutrients during feedings.2,3 Jejunal feeding methods incorporate a continuous pump controlled infusion; if set too rapidly, this could cause dumping syndrome. A benefit of jejunal nutrition is a lower risk of aspiration, compared with other enteral tubes.4

It is best to appraise the selected method for its efficacy and patient preference. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends starting with orogastric or nasogastric feeds, and switching to postpyloric or jejunal feeds for those intolerant to or at high risk for aspiration.5 The most important aspect is early enteral nutrition in hospitalized patients unable to maintain oral nutrition.