User login

At U.S. Ground Zero for coronavirus, a hospital is transformed

David Baker, MD, a hospitalist at EvergreenHealth in Kirkland, Wash., had just come off a 7-day stretch of work and was early into his usual 7 days off. He’d helped care for some patients from a nearby assisted living facility who had been admitted with puzzlingly severe viral pneumonia that wasn’t influenza.

Though COVID-19, the novel coronavirus that was sickening tens of thousands in the Chinese province of Hubei, was in the back of everyone’s mind in late February, he said he wasn’t really expecting the call notifying him that two of the patients with pneumonia had tested positive for COVID-19.

Michael Chu, MD, was coming onto EvergreenHealth’s hospitalist service at about the time Dr. Baker was rotating off. He recalled learning of the first two positive COVID-19 tests on the evening of Feb. 28 – a Friday. He and his colleagues took in this information, coming to the realization that they were seeing other patients from the same facility who had viral pneumonia and negative influenza tests. “The first cohort of coronavirus patients all came from Life Care,” the Kirkland assisted living facility that was the epicenter of the first identified U.S. outbreak of community-transmitted coronavirus, said Dr. Chu. “They all fit a clinical syndrome” and many of them were critically ill or failing fast, since they were aged and with multiple risk factors, he said during the interviews he and his colleagues participated in.

As he processed the news of the positive tests and his inadvertent exposure to COVID-19, Dr. Baker realized that his duty schedule worked in his favor, since he wasn’t expected back for several more days. When he did come back to work after remaining asymptomatic, he found a much-changed environment as the coronavirus cases poured in and continual adaptations were made to accommodate these patients – and to keep staff and other patients safe.

The hospital adapts to a new normal

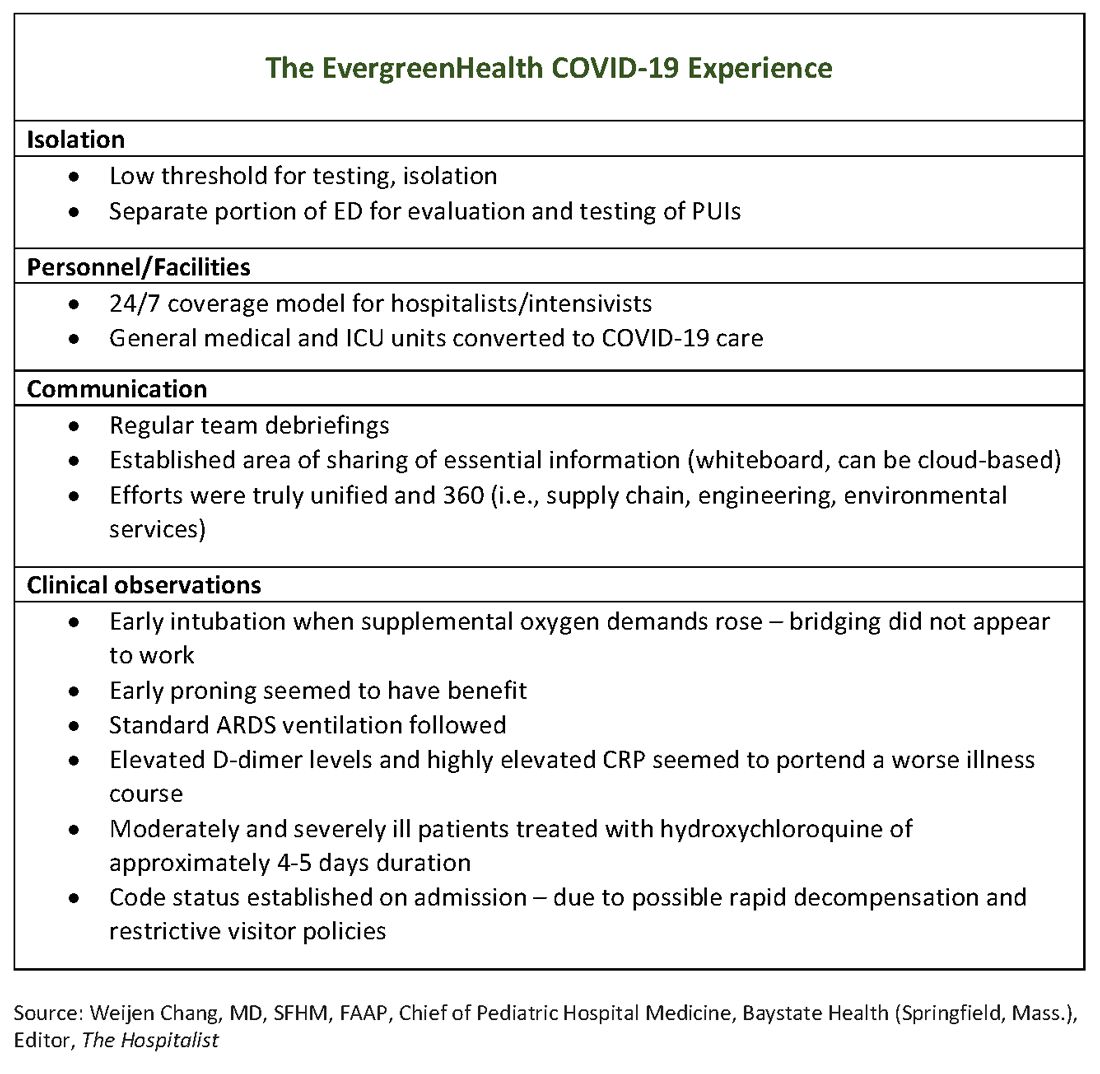

The usual protocol in EvergreenHealth’s ICU is for the nocturnist hospitalists, such as Dr. Baker, to staff that unit, with intensivists readily available for phone consultation. However, as the numbers of critically ill, ventilated COVID-19 patients climbed, the facility switched to 24/7 staffing with intensivists to augment the hospitalist team, said Nancy Marshall, MD, the director of EvergreenHealth’s hospitalist service.

Dr. Marshall related how the entire hospital rallied to create appropriate – but flexible – staffing and environmental adaptations to the influx of coronavirus patients. “Early on, we established a separate portion of the emergency department to evaluate and test persons under investigation,” for COVID-19, she said. When they realized that they were seeing the nation’s first cluster of community coronavirus transmission, they used “appropriate isolation precautions” when indicated. Triggers for clinical suspicion included not just fever or cough, but also a new requirement for supplemental oxygen and new abnormal findings on chest radiographs.

Patients with confirmed or suspected coronavirus, once admitted, were placed in negative-pressure rooms, and droplet precautions were used with these patients. In the absence of aerosol-generating procedures, those caring for these patients used a standard surgical mask, goggles or face shield, an isolation gown, and gloves. For intubations, bronchoscopies, and other aerosol-generating procedures, N95 masks were used; the facility also has some powered and controlled air-purifying respirators.

In short order, once the size of the outbreak was appreciated, said Dr. Marshall, the entire ICU and half of another general medical floor in the hospital were converted to negative-pressure rooms.

Dr. Marshall said that having daily team debriefings has been essential. The hospitalist team room has a big whiteboard where essential information can be put up and shared. Frequent video conferencing has allowed physicians and advanced practice clinicians on the hospitalist team to ask questions, share concerns, and develop a shared knowledge base and vocabulary as they confronted this novel illness.

The rapid adaptations that EvergreenHealth successfully made depended on a responsive administration, good communication among physician services and with nursing staff, and the active participation of engineering and environmental services teams in adjusting to shifting patient needs, said Dr. Marshall.

“Preparedness is key,” Dr. Chu noted. “Managing this has required a unified effort” that addresses everything from the supply chain for personal protective equipment, to cleaning procedures, to engineering fixes that quickly added negative-pressure rooms.

“I can’t emphasize enough that this is a team sport,” said Dr. Marshall.

The unpredictable clinical course of COVID-19

The chimeric clinical course of COVID-19 means clinicians need to keep an open mind and be ready to act nimbly, said the EvergreenHealth hospitalists. Pattern recognition is a key to competent clinical management of hospitalized patients, but the course of coronavirus thus far defies any convenient application of heuristics.

Those first two patients had some characteristics in common, aside from their arrival from the same long-term care facility They each had unexplained acute respiratory distress syndrome and ground-glass opacities seen on chest CT, said Dr. Marshall. But all agreed it is still not clear who will fare well, and who will do poorly once they are admitted with coronavirus.

“We have noticed that these patients tend to have a rough course,” said Dr. Marshall. The “brisk inflammatory response” seen in some patients manifests in persistent fevers, big C-reactive protein (CRP) elevations, and likely is part of the picture of yet-unknown host factors that contribute to a worse disease course for some, she said. “These patients look toxic for a long time.”

Dr. Chu said that he’s seen even younger, healthier-looking patients admitted from the emergency department who are already quite dyspneic and may be headed for ventilation. These patients may have a low procalcitonin, and will often turn out to have an “impressive-looking” chest x-ray or CT that will show prominent bilateral infiltrates.

On the other hand, said Dr. Marshall, she and her colleagues have admitted frail-appearing nonagenarians who “just kind of sleep it off,” with little more than a cough and intermittent fevers.

Dr. Chu concurred: “So many of these patients had risk factors for severe disease and only had mild illness. Many were really quite stable.”

In terms of managing respiratory status, Dr. Baker said that the time to start planning for intubation is when the supplemental oxygen demands of COVID-19 patients start to go up. Unlike with patients who may be in some respiratory distress from other causes, once these patients have increased Fi02 needs, bridging “doesn’t work. ... They need to be intubated. Early intubation is important.” Clinicians’ level of concern should spike when they see increased work of breathing in a coronavirus patient, regardless of what the numbers are saying, he added.

For coronavirus patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), early proning also seems to provide some benefit, he said. At EvergreenHealth, standard ARDS ventilation protocols are being followed, including low tidal volume ventilation and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) ladders. Coronavirus ventilation management has thus far been “pretty similar to standard practice with ARDS patients,” he said.

The hospitalist team was able to tap into the building knowledge base in China: Two of the EvergreenHealth hospitalists spoke fluent Mandarin, and one had contacts in China that allowed her to connect with Chinese physicians who had been treating COVID-19 patients since that outbreak had started. They established regular communication on WeChat, checking in frequently for updates on therapies and diagnostics being used in China as well.

One benefit of being in communication with colleagues in China, said Dr. Baker, was that they were able to get anecdotal evidence that elevated D-dimer levels and highly elevated CRP levels can portend a worse illness course. These findings seem to have held generally true for EvergreenHealth patients, he said. Dr. Marshall also spoke to the value of early communication with Chinese teams, who confirmed that the picture of a febrile illness with elevated CRP and leukopenia should raise the index of suspicion for coronavirus.

“Patients might improve over a few days, and then in the final 24 hours of their lives, we see changes in hemodynamics,” including reduced ejection fraction consistent with cardiogenic shock, as well as arrhythmias, said Dr. Baker. Some of the early patient deaths at EvergreenHealth followed this pattern, he said, noting that others have called for investigation into whether viral myocarditis is at play in some coronavirus deaths.

Moderately and severely ill coronavirus patients at EvergreenHealth currently receive a course of hydroxychloroquine of approximately 4-5 days’ duration. The hospital obtained remdesivir from Gilead through its compassionate-use program early on, and now is participating in a clinical trial for COVID-19 patients in the ICU.

By March 23, the facility had seen 162 confirmed COVID-19 cases, and 30 patients had died. Twenty-two inpatients had been discharged, and an additional 58 who were seen in the emergency department had been discharged home without admission.

Be suspicious – and prepared

When asked what he’d like his colleagues around the country to know as they diagnose and admit their first patients who are ill with coronavirus, Dr. Baker advised maintaining a high index of suspicion and a low threshold for testing. “I’ve given some thought to this,” he said. “From our reading and what information is out there, we are geared to pick up on the classic symptoms of coronavirus – cough, fever, some gastrointestinal symptoms.” However, many elderly patients “are not good historians. Some may have advanced dementia. ... When patients arrive with no history, we do our best to gather information,” but sometimes a case can still take clinicians by surprise, he said.

Dr. Baker told a cautionary tale of one of his patients, a woman who was admitted for a hip fracture after a fall at an assisted living facility. The patient was mildly hypoxic, but had an unremarkable physical exam, no fever, and a clear chest x-ray. She went to surgery and then to a postoperative floor with no isolation measures. When her respiratory status unexpectedly deteriorated, she was tested for COVID-19 – and was positive.

“When in doubt, isolate,” said Dr. Baker.

Dr. Chu concurred: “As soon as you suspect, move them, rather than testing first.”

Dr. Baker acknowledged, though, that when testing criteria and availability of personal protective equipment and test materials may vary by region, “it’s a challenge, especially with limited resources.”

Dr. Chu said that stringent isolation, though necessary, creates great hardship for patients and families. “It’s really important for us to check in with family members,” he said; patients are alone and afraid, and family members feel cut off – and also afraid on behalf of their ill loved ones. Workflow planning should acknowledge this and allocate extra time for patient connection and a little more time on the phone with families.

Dr. Chu offered a sobering final word. Make sure family members know their ill loved one’s wishes for care, he said: “There’s never been a better time to clarify code status on admission.”

Physicians at EvergreenHealth have created a document that contains consolidated information on what to anticipate and how to prepare for the arrival of COVID-19+ patients, recommendations on maximizing safety in the hospital environment, and key clinical management considerations. The document will be updated as new information arises.

Correction, 3/27/20: An earlier version of this article referenced white blood counts, presence of lymphopenia, and elevated hepatic enzymes for patients at EvergreenHealth when in fact that information pertained to patients in China. That paragraph has been deleted.

David Baker, MD, a hospitalist at EvergreenHealth in Kirkland, Wash., had just come off a 7-day stretch of work and was early into his usual 7 days off. He’d helped care for some patients from a nearby assisted living facility who had been admitted with puzzlingly severe viral pneumonia that wasn’t influenza.

Though COVID-19, the novel coronavirus that was sickening tens of thousands in the Chinese province of Hubei, was in the back of everyone’s mind in late February, he said he wasn’t really expecting the call notifying him that two of the patients with pneumonia had tested positive for COVID-19.

Michael Chu, MD, was coming onto EvergreenHealth’s hospitalist service at about the time Dr. Baker was rotating off. He recalled learning of the first two positive COVID-19 tests on the evening of Feb. 28 – a Friday. He and his colleagues took in this information, coming to the realization that they were seeing other patients from the same facility who had viral pneumonia and negative influenza tests. “The first cohort of coronavirus patients all came from Life Care,” the Kirkland assisted living facility that was the epicenter of the first identified U.S. outbreak of community-transmitted coronavirus, said Dr. Chu. “They all fit a clinical syndrome” and many of them were critically ill or failing fast, since they were aged and with multiple risk factors, he said during the interviews he and his colleagues participated in.

As he processed the news of the positive tests and his inadvertent exposure to COVID-19, Dr. Baker realized that his duty schedule worked in his favor, since he wasn’t expected back for several more days. When he did come back to work after remaining asymptomatic, he found a much-changed environment as the coronavirus cases poured in and continual adaptations were made to accommodate these patients – and to keep staff and other patients safe.

The hospital adapts to a new normal

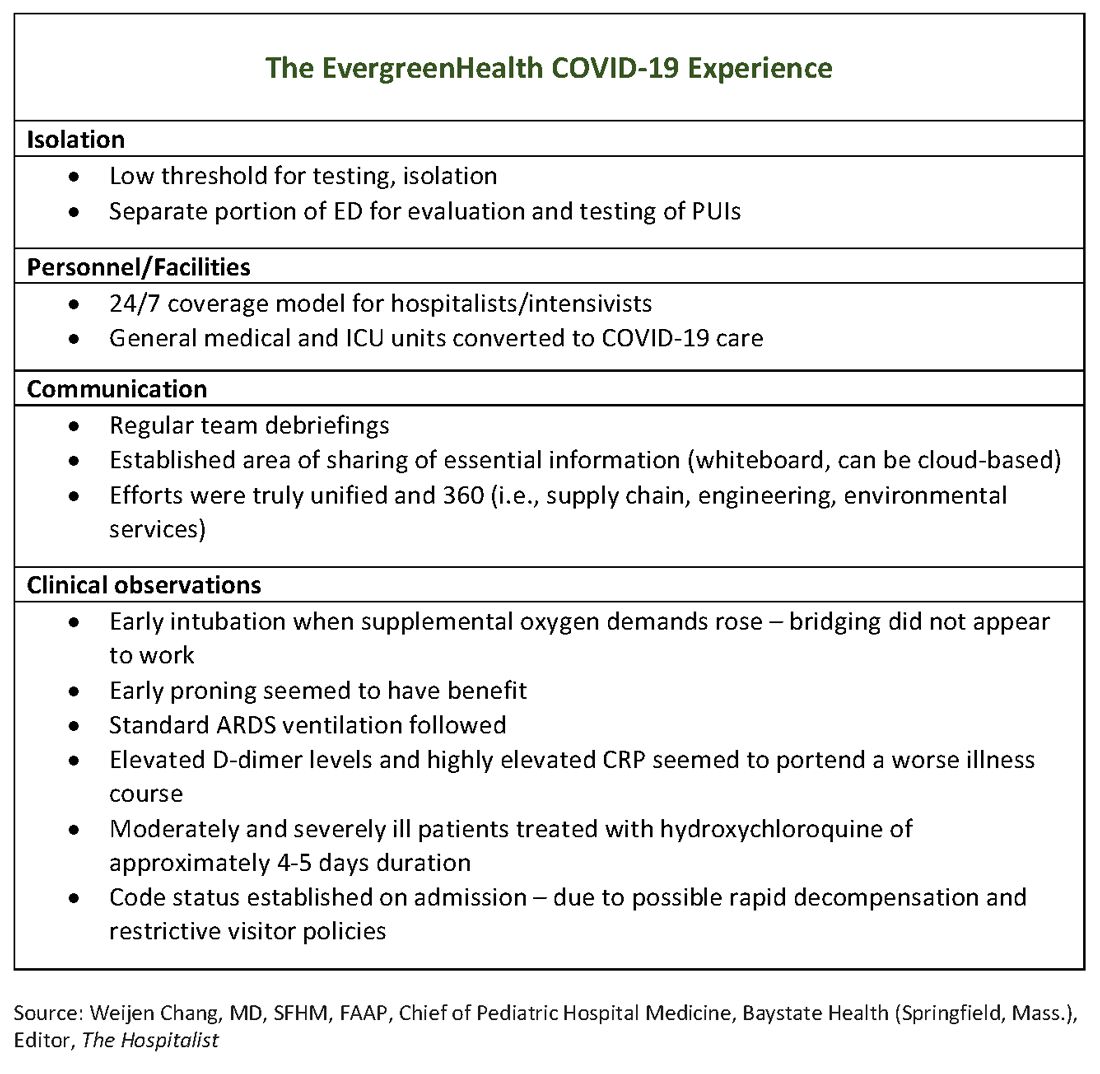

The usual protocol in EvergreenHealth’s ICU is for the nocturnist hospitalists, such as Dr. Baker, to staff that unit, with intensivists readily available for phone consultation. However, as the numbers of critically ill, ventilated COVID-19 patients climbed, the facility switched to 24/7 staffing with intensivists to augment the hospitalist team, said Nancy Marshall, MD, the director of EvergreenHealth’s hospitalist service.

Dr. Marshall related how the entire hospital rallied to create appropriate – but flexible – staffing and environmental adaptations to the influx of coronavirus patients. “Early on, we established a separate portion of the emergency department to evaluate and test persons under investigation,” for COVID-19, she said. When they realized that they were seeing the nation’s first cluster of community coronavirus transmission, they used “appropriate isolation precautions” when indicated. Triggers for clinical suspicion included not just fever or cough, but also a new requirement for supplemental oxygen and new abnormal findings on chest radiographs.

Patients with confirmed or suspected coronavirus, once admitted, were placed in negative-pressure rooms, and droplet precautions were used with these patients. In the absence of aerosol-generating procedures, those caring for these patients used a standard surgical mask, goggles or face shield, an isolation gown, and gloves. For intubations, bronchoscopies, and other aerosol-generating procedures, N95 masks were used; the facility also has some powered and controlled air-purifying respirators.

In short order, once the size of the outbreak was appreciated, said Dr. Marshall, the entire ICU and half of another general medical floor in the hospital were converted to negative-pressure rooms.

Dr. Marshall said that having daily team debriefings has been essential. The hospitalist team room has a big whiteboard where essential information can be put up and shared. Frequent video conferencing has allowed physicians and advanced practice clinicians on the hospitalist team to ask questions, share concerns, and develop a shared knowledge base and vocabulary as they confronted this novel illness.

The rapid adaptations that EvergreenHealth successfully made depended on a responsive administration, good communication among physician services and with nursing staff, and the active participation of engineering and environmental services teams in adjusting to shifting patient needs, said Dr. Marshall.

“Preparedness is key,” Dr. Chu noted. “Managing this has required a unified effort” that addresses everything from the supply chain for personal protective equipment, to cleaning procedures, to engineering fixes that quickly added negative-pressure rooms.

“I can’t emphasize enough that this is a team sport,” said Dr. Marshall.

The unpredictable clinical course of COVID-19

The chimeric clinical course of COVID-19 means clinicians need to keep an open mind and be ready to act nimbly, said the EvergreenHealth hospitalists. Pattern recognition is a key to competent clinical management of hospitalized patients, but the course of coronavirus thus far defies any convenient application of heuristics.

Those first two patients had some characteristics in common, aside from their arrival from the same long-term care facility They each had unexplained acute respiratory distress syndrome and ground-glass opacities seen on chest CT, said Dr. Marshall. But all agreed it is still not clear who will fare well, and who will do poorly once they are admitted with coronavirus.

“We have noticed that these patients tend to have a rough course,” said Dr. Marshall. The “brisk inflammatory response” seen in some patients manifests in persistent fevers, big C-reactive protein (CRP) elevations, and likely is part of the picture of yet-unknown host factors that contribute to a worse disease course for some, she said. “These patients look toxic for a long time.”

Dr. Chu said that he’s seen even younger, healthier-looking patients admitted from the emergency department who are already quite dyspneic and may be headed for ventilation. These patients may have a low procalcitonin, and will often turn out to have an “impressive-looking” chest x-ray or CT that will show prominent bilateral infiltrates.

On the other hand, said Dr. Marshall, she and her colleagues have admitted frail-appearing nonagenarians who “just kind of sleep it off,” with little more than a cough and intermittent fevers.

Dr. Chu concurred: “So many of these patients had risk factors for severe disease and only had mild illness. Many were really quite stable.”

In terms of managing respiratory status, Dr. Baker said that the time to start planning for intubation is when the supplemental oxygen demands of COVID-19 patients start to go up. Unlike with patients who may be in some respiratory distress from other causes, once these patients have increased Fi02 needs, bridging “doesn’t work. ... They need to be intubated. Early intubation is important.” Clinicians’ level of concern should spike when they see increased work of breathing in a coronavirus patient, regardless of what the numbers are saying, he added.

For coronavirus patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), early proning also seems to provide some benefit, he said. At EvergreenHealth, standard ARDS ventilation protocols are being followed, including low tidal volume ventilation and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) ladders. Coronavirus ventilation management has thus far been “pretty similar to standard practice with ARDS patients,” he said.

The hospitalist team was able to tap into the building knowledge base in China: Two of the EvergreenHealth hospitalists spoke fluent Mandarin, and one had contacts in China that allowed her to connect with Chinese physicians who had been treating COVID-19 patients since that outbreak had started. They established regular communication on WeChat, checking in frequently for updates on therapies and diagnostics being used in China as well.

One benefit of being in communication with colleagues in China, said Dr. Baker, was that they were able to get anecdotal evidence that elevated D-dimer levels and highly elevated CRP levels can portend a worse illness course. These findings seem to have held generally true for EvergreenHealth patients, he said. Dr. Marshall also spoke to the value of early communication with Chinese teams, who confirmed that the picture of a febrile illness with elevated CRP and leukopenia should raise the index of suspicion for coronavirus.

“Patients might improve over a few days, and then in the final 24 hours of their lives, we see changes in hemodynamics,” including reduced ejection fraction consistent with cardiogenic shock, as well as arrhythmias, said Dr. Baker. Some of the early patient deaths at EvergreenHealth followed this pattern, he said, noting that others have called for investigation into whether viral myocarditis is at play in some coronavirus deaths.

Moderately and severely ill coronavirus patients at EvergreenHealth currently receive a course of hydroxychloroquine of approximately 4-5 days’ duration. The hospital obtained remdesivir from Gilead through its compassionate-use program early on, and now is participating in a clinical trial for COVID-19 patients in the ICU.

By March 23, the facility had seen 162 confirmed COVID-19 cases, and 30 patients had died. Twenty-two inpatients had been discharged, and an additional 58 who were seen in the emergency department had been discharged home without admission.

Be suspicious – and prepared

When asked what he’d like his colleagues around the country to know as they diagnose and admit their first patients who are ill with coronavirus, Dr. Baker advised maintaining a high index of suspicion and a low threshold for testing. “I’ve given some thought to this,” he said. “From our reading and what information is out there, we are geared to pick up on the classic symptoms of coronavirus – cough, fever, some gastrointestinal symptoms.” However, many elderly patients “are not good historians. Some may have advanced dementia. ... When patients arrive with no history, we do our best to gather information,” but sometimes a case can still take clinicians by surprise, he said.

Dr. Baker told a cautionary tale of one of his patients, a woman who was admitted for a hip fracture after a fall at an assisted living facility. The patient was mildly hypoxic, but had an unremarkable physical exam, no fever, and a clear chest x-ray. She went to surgery and then to a postoperative floor with no isolation measures. When her respiratory status unexpectedly deteriorated, she was tested for COVID-19 – and was positive.

“When in doubt, isolate,” said Dr. Baker.

Dr. Chu concurred: “As soon as you suspect, move them, rather than testing first.”

Dr. Baker acknowledged, though, that when testing criteria and availability of personal protective equipment and test materials may vary by region, “it’s a challenge, especially with limited resources.”

Dr. Chu said that stringent isolation, though necessary, creates great hardship for patients and families. “It’s really important for us to check in with family members,” he said; patients are alone and afraid, and family members feel cut off – and also afraid on behalf of their ill loved ones. Workflow planning should acknowledge this and allocate extra time for patient connection and a little more time on the phone with families.

Dr. Chu offered a sobering final word. Make sure family members know their ill loved one’s wishes for care, he said: “There’s never been a better time to clarify code status on admission.”

Physicians at EvergreenHealth have created a document that contains consolidated information on what to anticipate and how to prepare for the arrival of COVID-19+ patients, recommendations on maximizing safety in the hospital environment, and key clinical management considerations. The document will be updated as new information arises.

Correction, 3/27/20: An earlier version of this article referenced white blood counts, presence of lymphopenia, and elevated hepatic enzymes for patients at EvergreenHealth when in fact that information pertained to patients in China. That paragraph has been deleted.

David Baker, MD, a hospitalist at EvergreenHealth in Kirkland, Wash., had just come off a 7-day stretch of work and was early into his usual 7 days off. He’d helped care for some patients from a nearby assisted living facility who had been admitted with puzzlingly severe viral pneumonia that wasn’t influenza.

Though COVID-19, the novel coronavirus that was sickening tens of thousands in the Chinese province of Hubei, was in the back of everyone’s mind in late February, he said he wasn’t really expecting the call notifying him that two of the patients with pneumonia had tested positive for COVID-19.

Michael Chu, MD, was coming onto EvergreenHealth’s hospitalist service at about the time Dr. Baker was rotating off. He recalled learning of the first two positive COVID-19 tests on the evening of Feb. 28 – a Friday. He and his colleagues took in this information, coming to the realization that they were seeing other patients from the same facility who had viral pneumonia and negative influenza tests. “The first cohort of coronavirus patients all came from Life Care,” the Kirkland assisted living facility that was the epicenter of the first identified U.S. outbreak of community-transmitted coronavirus, said Dr. Chu. “They all fit a clinical syndrome” and many of them were critically ill or failing fast, since they were aged and with multiple risk factors, he said during the interviews he and his colleagues participated in.

As he processed the news of the positive tests and his inadvertent exposure to COVID-19, Dr. Baker realized that his duty schedule worked in his favor, since he wasn’t expected back for several more days. When he did come back to work after remaining asymptomatic, he found a much-changed environment as the coronavirus cases poured in and continual adaptations were made to accommodate these patients – and to keep staff and other patients safe.

The hospital adapts to a new normal

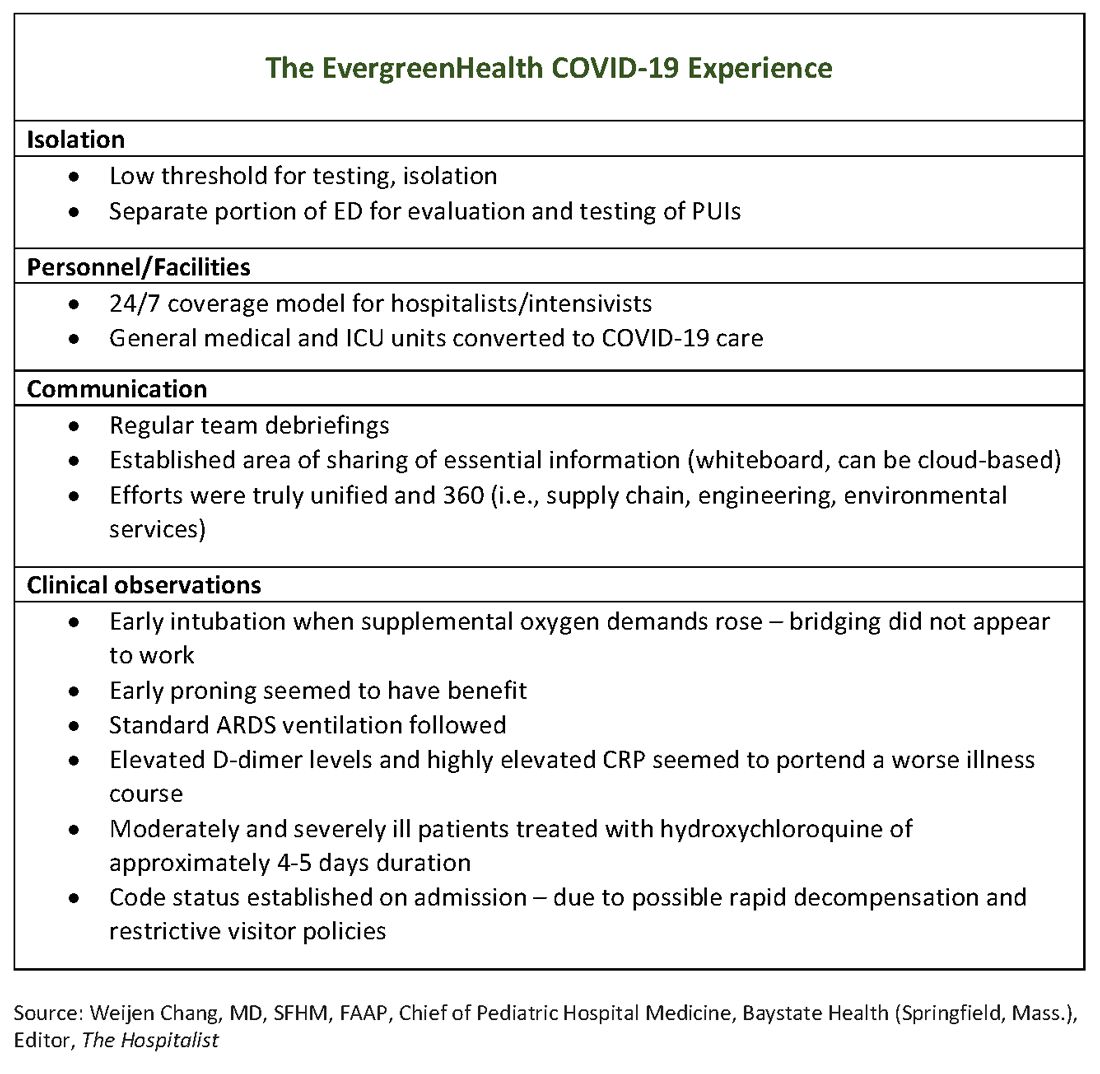

The usual protocol in EvergreenHealth’s ICU is for the nocturnist hospitalists, such as Dr. Baker, to staff that unit, with intensivists readily available for phone consultation. However, as the numbers of critically ill, ventilated COVID-19 patients climbed, the facility switched to 24/7 staffing with intensivists to augment the hospitalist team, said Nancy Marshall, MD, the director of EvergreenHealth’s hospitalist service.

Dr. Marshall related how the entire hospital rallied to create appropriate – but flexible – staffing and environmental adaptations to the influx of coronavirus patients. “Early on, we established a separate portion of the emergency department to evaluate and test persons under investigation,” for COVID-19, she said. When they realized that they were seeing the nation’s first cluster of community coronavirus transmission, they used “appropriate isolation precautions” when indicated. Triggers for clinical suspicion included not just fever or cough, but also a new requirement for supplemental oxygen and new abnormal findings on chest radiographs.

Patients with confirmed or suspected coronavirus, once admitted, were placed in negative-pressure rooms, and droplet precautions were used with these patients. In the absence of aerosol-generating procedures, those caring for these patients used a standard surgical mask, goggles or face shield, an isolation gown, and gloves. For intubations, bronchoscopies, and other aerosol-generating procedures, N95 masks were used; the facility also has some powered and controlled air-purifying respirators.

In short order, once the size of the outbreak was appreciated, said Dr. Marshall, the entire ICU and half of another general medical floor in the hospital were converted to negative-pressure rooms.

Dr. Marshall said that having daily team debriefings has been essential. The hospitalist team room has a big whiteboard where essential information can be put up and shared. Frequent video conferencing has allowed physicians and advanced practice clinicians on the hospitalist team to ask questions, share concerns, and develop a shared knowledge base and vocabulary as they confronted this novel illness.

The rapid adaptations that EvergreenHealth successfully made depended on a responsive administration, good communication among physician services and with nursing staff, and the active participation of engineering and environmental services teams in adjusting to shifting patient needs, said Dr. Marshall.

“Preparedness is key,” Dr. Chu noted. “Managing this has required a unified effort” that addresses everything from the supply chain for personal protective equipment, to cleaning procedures, to engineering fixes that quickly added negative-pressure rooms.

“I can’t emphasize enough that this is a team sport,” said Dr. Marshall.

The unpredictable clinical course of COVID-19

The chimeric clinical course of COVID-19 means clinicians need to keep an open mind and be ready to act nimbly, said the EvergreenHealth hospitalists. Pattern recognition is a key to competent clinical management of hospitalized patients, but the course of coronavirus thus far defies any convenient application of heuristics.

Those first two patients had some characteristics in common, aside from their arrival from the same long-term care facility They each had unexplained acute respiratory distress syndrome and ground-glass opacities seen on chest CT, said Dr. Marshall. But all agreed it is still not clear who will fare well, and who will do poorly once they are admitted with coronavirus.

“We have noticed that these patients tend to have a rough course,” said Dr. Marshall. The “brisk inflammatory response” seen in some patients manifests in persistent fevers, big C-reactive protein (CRP) elevations, and likely is part of the picture of yet-unknown host factors that contribute to a worse disease course for some, she said. “These patients look toxic for a long time.”

Dr. Chu said that he’s seen even younger, healthier-looking patients admitted from the emergency department who are already quite dyspneic and may be headed for ventilation. These patients may have a low procalcitonin, and will often turn out to have an “impressive-looking” chest x-ray or CT that will show prominent bilateral infiltrates.

On the other hand, said Dr. Marshall, she and her colleagues have admitted frail-appearing nonagenarians who “just kind of sleep it off,” with little more than a cough and intermittent fevers.

Dr. Chu concurred: “So many of these patients had risk factors for severe disease and only had mild illness. Many were really quite stable.”

In terms of managing respiratory status, Dr. Baker said that the time to start planning for intubation is when the supplemental oxygen demands of COVID-19 patients start to go up. Unlike with patients who may be in some respiratory distress from other causes, once these patients have increased Fi02 needs, bridging “doesn’t work. ... They need to be intubated. Early intubation is important.” Clinicians’ level of concern should spike when they see increased work of breathing in a coronavirus patient, regardless of what the numbers are saying, he added.

For coronavirus patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), early proning also seems to provide some benefit, he said. At EvergreenHealth, standard ARDS ventilation protocols are being followed, including low tidal volume ventilation and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) ladders. Coronavirus ventilation management has thus far been “pretty similar to standard practice with ARDS patients,” he said.

The hospitalist team was able to tap into the building knowledge base in China: Two of the EvergreenHealth hospitalists spoke fluent Mandarin, and one had contacts in China that allowed her to connect with Chinese physicians who had been treating COVID-19 patients since that outbreak had started. They established regular communication on WeChat, checking in frequently for updates on therapies and diagnostics being used in China as well.

One benefit of being in communication with colleagues in China, said Dr. Baker, was that they were able to get anecdotal evidence that elevated D-dimer levels and highly elevated CRP levels can portend a worse illness course. These findings seem to have held generally true for EvergreenHealth patients, he said. Dr. Marshall also spoke to the value of early communication with Chinese teams, who confirmed that the picture of a febrile illness with elevated CRP and leukopenia should raise the index of suspicion for coronavirus.

“Patients might improve over a few days, and then in the final 24 hours of their lives, we see changes in hemodynamics,” including reduced ejection fraction consistent with cardiogenic shock, as well as arrhythmias, said Dr. Baker. Some of the early patient deaths at EvergreenHealth followed this pattern, he said, noting that others have called for investigation into whether viral myocarditis is at play in some coronavirus deaths.

Moderately and severely ill coronavirus patients at EvergreenHealth currently receive a course of hydroxychloroquine of approximately 4-5 days’ duration. The hospital obtained remdesivir from Gilead through its compassionate-use program early on, and now is participating in a clinical trial for COVID-19 patients in the ICU.

By March 23, the facility had seen 162 confirmed COVID-19 cases, and 30 patients had died. Twenty-two inpatients had been discharged, and an additional 58 who were seen in the emergency department had been discharged home without admission.

Be suspicious – and prepared

When asked what he’d like his colleagues around the country to know as they diagnose and admit their first patients who are ill with coronavirus, Dr. Baker advised maintaining a high index of suspicion and a low threshold for testing. “I’ve given some thought to this,” he said. “From our reading and what information is out there, we are geared to pick up on the classic symptoms of coronavirus – cough, fever, some gastrointestinal symptoms.” However, many elderly patients “are not good historians. Some may have advanced dementia. ... When patients arrive with no history, we do our best to gather information,” but sometimes a case can still take clinicians by surprise, he said.

Dr. Baker told a cautionary tale of one of his patients, a woman who was admitted for a hip fracture after a fall at an assisted living facility. The patient was mildly hypoxic, but had an unremarkable physical exam, no fever, and a clear chest x-ray. She went to surgery and then to a postoperative floor with no isolation measures. When her respiratory status unexpectedly deteriorated, she was tested for COVID-19 – and was positive.

“When in doubt, isolate,” said Dr. Baker.

Dr. Chu concurred: “As soon as you suspect, move them, rather than testing first.”

Dr. Baker acknowledged, though, that when testing criteria and availability of personal protective equipment and test materials may vary by region, “it’s a challenge, especially with limited resources.”

Dr. Chu said that stringent isolation, though necessary, creates great hardship for patients and families. “It’s really important for us to check in with family members,” he said; patients are alone and afraid, and family members feel cut off – and also afraid on behalf of their ill loved ones. Workflow planning should acknowledge this and allocate extra time for patient connection and a little more time on the phone with families.

Dr. Chu offered a sobering final word. Make sure family members know their ill loved one’s wishes for care, he said: “There’s never been a better time to clarify code status on admission.”

Physicians at EvergreenHealth have created a document that contains consolidated information on what to anticipate and how to prepare for the arrival of COVID-19+ patients, recommendations on maximizing safety in the hospital environment, and key clinical management considerations. The document will be updated as new information arises.

Correction, 3/27/20: An earlier version of this article referenced white blood counts, presence of lymphopenia, and elevated hepatic enzymes for patients at EvergreenHealth when in fact that information pertained to patients in China. That paragraph has been deleted.

Step 1 scoring moves to pass/fail: Hospitalists’ role and unintended consequences

The National Board of Medical Examiners recently announced a change in the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score reporting from a 3-digit score to a pass/fail score beginning in 2022.1 Endorsed by a broad coalition of organizations involved in undergraduate (UME) and graduate medical education (GME), this change is intended as a first step toward systemic improvements in the UME-GME transition to residency by promoting holistic reviews of applicants. Additionally, it is meant to tackle widespread concerns about medical student distress brought about by the residency selection process. For example, switching to pass/fail preclinical curricula has resulted in an improvement in medical student well-being at many medical schools.2 It is the hope that a mirrored change in Step 1 may similarly improve mental health and encourage a growth mindset towards learning.

On the other hand, many residency programs rely on USMLE scores for screening potential candidates, especially as application inflation has burdened programs with thousands of applications.3 The change to a pass/fail Step 1 score will likely shift emphasis and stress to the Step 2 CK Exam, essentially negating the intended effect. Furthermore, for schools still reporting NBME Subject (shelf) Exam scores and Clerkship grades, there will likely be a greater emphasis placed on these metrics as well. The need for objective assessment methods are seen by many as so critical that some GME leaders have advocated for instituting entrance exams or requiring a Standardized Letter of Evaluation as a prerequisite to residency application. Finally, medical students jockeying for competitive residency positions may also feel pressured to distinguish themselves by boosting other aspects of their portfolio by taking a research year or applying for away electives, which risks marginalizing students of lesser means or with family responsibilities.

Ultimately, the change to a pass/fail Step 1 exam will likely do little to address the expanding gulf between the UME and GME communities. Residency program directors are searching for students with qualities of a good physician, such as interpersonal skills, “teamsmanship,” compassion, and professionalism, but reliable, objective, and standardized assessment tools are not available. Currently our best tools are clinical evaluations which are subject to grade inflation and implicit racial and gender biases. Furthermore, other components of a residency application, such as letters of recommendation, Chair’s letters, and the Medical Student Performance Evaluation (Dean’s letter), are regarded to be less informative as schools move toward no student rankings, pass/fail grading schemes, and nonstandardized summative adjectives to describe medical students overall medical school performance.

Finally, medical student distress in the residency application process may stem from the perpetuation of elitism that extends from medical school to fellowship training and academic hospital medicine. Rankings of medical schools, residencies, fellowships, and hospitals serve to create a hierarchical system. Competitive residency applicants see admittance into the best training programs as opening doors to opportunities, while not getting into these programs is seen as closing doors to career paths and opportunities.

With this change in Step 1 score reporting, where do we as hospitalists fit in? Hospitalists are at the forefront of educating and evaluating medical students in academic medical centers, and we are often asked to write letters of recommendation and serve as mentors. If done well, these activities can have a positive impact on medical student applications to residency by alleviating some of the stresses and mitigating the downsides to the new Step 1 scoring system. Writing impactful letters and thoughtful evaluations are all skills that should be incorporated in hospitalist faculty development programs. Moreover, in order to serve as better advocates for our students, it is important that academic hospitalists understand the evolving landscape of the residency application process and are mindful of the stresses that medical students face. Changing Step 1 scoring to pass/fail will likely have unintended consequences for our medical students, and we as hospitalists must be ready to improve our knowledge and skills in order to continue to support and advocate for our medical students.

Dr. Esquivel is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York; Dr. Chang is associate professor and interprofessional education thread director (MD curriculum) at Washington University, St. Louis; Dr. Ricotta is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School; Dr. Rendon is a hospitalist at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque; Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and associate professor at the University of California, San Diego. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee.

References

1. United States Medical Licensing Examination (2020 Feb). Change to pass/fail score reporting for Step 1.

2. Slavin SJ and Chibnall JT. Finding the why, changing the how: Improving the mental health of medical students, residents, and physicians. Academic Medicine. 2016;91(9):1194‐6.

3. Pereira AG, Chelminski PR, et al. Application inflation for internal medicine applicants in the Match: Drivers, consequences, and potential solutions. Am J Med. 2016 Aug;129(8): 885-91.

The National Board of Medical Examiners recently announced a change in the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score reporting from a 3-digit score to a pass/fail score beginning in 2022.1 Endorsed by a broad coalition of organizations involved in undergraduate (UME) and graduate medical education (GME), this change is intended as a first step toward systemic improvements in the UME-GME transition to residency by promoting holistic reviews of applicants. Additionally, it is meant to tackle widespread concerns about medical student distress brought about by the residency selection process. For example, switching to pass/fail preclinical curricula has resulted in an improvement in medical student well-being at many medical schools.2 It is the hope that a mirrored change in Step 1 may similarly improve mental health and encourage a growth mindset towards learning.

On the other hand, many residency programs rely on USMLE scores for screening potential candidates, especially as application inflation has burdened programs with thousands of applications.3 The change to a pass/fail Step 1 score will likely shift emphasis and stress to the Step 2 CK Exam, essentially negating the intended effect. Furthermore, for schools still reporting NBME Subject (shelf) Exam scores and Clerkship grades, there will likely be a greater emphasis placed on these metrics as well. The need for objective assessment methods are seen by many as so critical that some GME leaders have advocated for instituting entrance exams or requiring a Standardized Letter of Evaluation as a prerequisite to residency application. Finally, medical students jockeying for competitive residency positions may also feel pressured to distinguish themselves by boosting other aspects of their portfolio by taking a research year or applying for away electives, which risks marginalizing students of lesser means or with family responsibilities.

Ultimately, the change to a pass/fail Step 1 exam will likely do little to address the expanding gulf between the UME and GME communities. Residency program directors are searching for students with qualities of a good physician, such as interpersonal skills, “teamsmanship,” compassion, and professionalism, but reliable, objective, and standardized assessment tools are not available. Currently our best tools are clinical evaluations which are subject to grade inflation and implicit racial and gender biases. Furthermore, other components of a residency application, such as letters of recommendation, Chair’s letters, and the Medical Student Performance Evaluation (Dean’s letter), are regarded to be less informative as schools move toward no student rankings, pass/fail grading schemes, and nonstandardized summative adjectives to describe medical students overall medical school performance.

Finally, medical student distress in the residency application process may stem from the perpetuation of elitism that extends from medical school to fellowship training and academic hospital medicine. Rankings of medical schools, residencies, fellowships, and hospitals serve to create a hierarchical system. Competitive residency applicants see admittance into the best training programs as opening doors to opportunities, while not getting into these programs is seen as closing doors to career paths and opportunities.

With this change in Step 1 score reporting, where do we as hospitalists fit in? Hospitalists are at the forefront of educating and evaluating medical students in academic medical centers, and we are often asked to write letters of recommendation and serve as mentors. If done well, these activities can have a positive impact on medical student applications to residency by alleviating some of the stresses and mitigating the downsides to the new Step 1 scoring system. Writing impactful letters and thoughtful evaluations are all skills that should be incorporated in hospitalist faculty development programs. Moreover, in order to serve as better advocates for our students, it is important that academic hospitalists understand the evolving landscape of the residency application process and are mindful of the stresses that medical students face. Changing Step 1 scoring to pass/fail will likely have unintended consequences for our medical students, and we as hospitalists must be ready to improve our knowledge and skills in order to continue to support and advocate for our medical students.

Dr. Esquivel is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York; Dr. Chang is associate professor and interprofessional education thread director (MD curriculum) at Washington University, St. Louis; Dr. Ricotta is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School; Dr. Rendon is a hospitalist at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque; Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and associate professor at the University of California, San Diego. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee.

References

1. United States Medical Licensing Examination (2020 Feb). Change to pass/fail score reporting for Step 1.

2. Slavin SJ and Chibnall JT. Finding the why, changing the how: Improving the mental health of medical students, residents, and physicians. Academic Medicine. 2016;91(9):1194‐6.

3. Pereira AG, Chelminski PR, et al. Application inflation for internal medicine applicants in the Match: Drivers, consequences, and potential solutions. Am J Med. 2016 Aug;129(8): 885-91.

The National Board of Medical Examiners recently announced a change in the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score reporting from a 3-digit score to a pass/fail score beginning in 2022.1 Endorsed by a broad coalition of organizations involved in undergraduate (UME) and graduate medical education (GME), this change is intended as a first step toward systemic improvements in the UME-GME transition to residency by promoting holistic reviews of applicants. Additionally, it is meant to tackle widespread concerns about medical student distress brought about by the residency selection process. For example, switching to pass/fail preclinical curricula has resulted in an improvement in medical student well-being at many medical schools.2 It is the hope that a mirrored change in Step 1 may similarly improve mental health and encourage a growth mindset towards learning.

On the other hand, many residency programs rely on USMLE scores for screening potential candidates, especially as application inflation has burdened programs with thousands of applications.3 The change to a pass/fail Step 1 score will likely shift emphasis and stress to the Step 2 CK Exam, essentially negating the intended effect. Furthermore, for schools still reporting NBME Subject (shelf) Exam scores and Clerkship grades, there will likely be a greater emphasis placed on these metrics as well. The need for objective assessment methods are seen by many as so critical that some GME leaders have advocated for instituting entrance exams or requiring a Standardized Letter of Evaluation as a prerequisite to residency application. Finally, medical students jockeying for competitive residency positions may also feel pressured to distinguish themselves by boosting other aspects of their portfolio by taking a research year or applying for away electives, which risks marginalizing students of lesser means or with family responsibilities.

Ultimately, the change to a pass/fail Step 1 exam will likely do little to address the expanding gulf between the UME and GME communities. Residency program directors are searching for students with qualities of a good physician, such as interpersonal skills, “teamsmanship,” compassion, and professionalism, but reliable, objective, and standardized assessment tools are not available. Currently our best tools are clinical evaluations which are subject to grade inflation and implicit racial and gender biases. Furthermore, other components of a residency application, such as letters of recommendation, Chair’s letters, and the Medical Student Performance Evaluation (Dean’s letter), are regarded to be less informative as schools move toward no student rankings, pass/fail grading schemes, and nonstandardized summative adjectives to describe medical students overall medical school performance.

Finally, medical student distress in the residency application process may stem from the perpetuation of elitism that extends from medical school to fellowship training and academic hospital medicine. Rankings of medical schools, residencies, fellowships, and hospitals serve to create a hierarchical system. Competitive residency applicants see admittance into the best training programs as opening doors to opportunities, while not getting into these programs is seen as closing doors to career paths and opportunities.

With this change in Step 1 score reporting, where do we as hospitalists fit in? Hospitalists are at the forefront of educating and evaluating medical students in academic medical centers, and we are often asked to write letters of recommendation and serve as mentors. If done well, these activities can have a positive impact on medical student applications to residency by alleviating some of the stresses and mitigating the downsides to the new Step 1 scoring system. Writing impactful letters and thoughtful evaluations are all skills that should be incorporated in hospitalist faculty development programs. Moreover, in order to serve as better advocates for our students, it is important that academic hospitalists understand the evolving landscape of the residency application process and are mindful of the stresses that medical students face. Changing Step 1 scoring to pass/fail will likely have unintended consequences for our medical students, and we as hospitalists must be ready to improve our knowledge and skills in order to continue to support and advocate for our medical students.

Dr. Esquivel is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York; Dr. Chang is associate professor and interprofessional education thread director (MD curriculum) at Washington University, St. Louis; Dr. Ricotta is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School; Dr. Rendon is a hospitalist at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque; Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and associate professor at the University of California, San Diego. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee.

References

1. United States Medical Licensing Examination (2020 Feb). Change to pass/fail score reporting for Step 1.

2. Slavin SJ and Chibnall JT. Finding the why, changing the how: Improving the mental health of medical students, residents, and physicians. Academic Medicine. 2016;91(9):1194‐6.

3. Pereira AG, Chelminski PR, et al. Application inflation for internal medicine applicants in the Match: Drivers, consequences, and potential solutions. Am J Med. 2016 Aug;129(8): 885-91.

Treatment options for COVID-19: Dr. Annie Luetkemeyer

Annie Luetkemeyer, MD, professor of infectious diseases at UCSF, is an expert on the treatment of viral infections. Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, chair of the UCSF Department of Medicine, interviewed her about the evidence behind potential treatments for COVID-19 (including chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, and others), as well as how to assess new and existing drugs in a pandemic.

Annie Luetkemeyer, MD, professor of infectious diseases at UCSF, is an expert on the treatment of viral infections. Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, chair of the UCSF Department of Medicine, interviewed her about the evidence behind potential treatments for COVID-19 (including chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, and others), as well as how to assess new and existing drugs in a pandemic.

Annie Luetkemeyer, MD, professor of infectious diseases at UCSF, is an expert on the treatment of viral infections. Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, chair of the UCSF Department of Medicine, interviewed her about the evidence behind potential treatments for COVID-19 (including chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, and others), as well as how to assess new and existing drugs in a pandemic.

Get out the inpatient vote

Disenfranchisement undeniably remains a major problem across the United States. While it is challenging for health care providers to find time to vote, hospitalized patients are an underrecognized vulnerable group, often unable to exercise this constitutional right. With the 2020 election approaching, voting is as important as ever.

On morning rounds after the 2018 election, we discussed the impact of a changing majority in the House of Representatives and its potential impact on health care in America. We discussed where, when, and how we voted, and then suddenly considered a question that we were unable to answer: How do our hospitalized patients vote and did any of them vote in this important election?

Inpatients rarely know when or how long they will be hospitalized. They often have no chance to prepare by paying bills, arranging care for loved ones, or finding coverage for employment responsibilities. The sickest patients can do little more than wonder about anything other than their short-term health. As a result of restricted voting laws, they, like too many others, are effectively disenfranchised.

We asked administrators in multiple hospitals across New York City how to help our patients vote. Unfortunately, the process is overwhelmingly complex and varies by state. Absentee ballots, which are easily accessible in New York if it they are requested no later than 7 days before the election, are harder to come by on the same day. Most people struggle to vote in general – with only 61% voting in the 2016 election.1 To combat this, individual hospitals have created initiatives such as Penn Votes, which has helped 65 hospitalized Pennsylvania residents vote in the last three elections2 – a success, but still leaving so many without a voice.

With health care being a major policy issue for the 2020 election, voting has never been more important for patients. With nearly 1 million hospital beds in America,3 hospitalized patients represent a significant number of potential voters who are functionally disenfranchised. Most importantly, these patients are directly under our care, and we are their strongest advocates. Therefore, we ask our fellow health care providers to start planning today how we will help our patients exercise their voices, participate in our health care policy debate, and choose the future leaders of our country.

Dr. Rosenblatt is assistant professor of medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. Dr. Verna is assistant professor of medicine, Department of Surgery, at Columbia University Irving Medical School, New York. Dr. Rosenblatt and Dr. Verna reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1. File T. Voting in America: A Look at the 2016 Presidential Election [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 7];Available from: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2017/05/voting_in_america.html.

2. Vigodner S. Penn students are helping hospitalized patients cast emergency ballots for Tuesday’s election [Internet]. Dly. Pennsylvanian. 2018;Available from: https://www.thedp.com/article/2018/11/penn-med-votes-emergency-hospital-patients-upenn-philadelphia-elections.

3. Association AH. Fast facts on US hospitals [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 7];Available from: https://www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals.

Disenfranchisement undeniably remains a major problem across the United States. While it is challenging for health care providers to find time to vote, hospitalized patients are an underrecognized vulnerable group, often unable to exercise this constitutional right. With the 2020 election approaching, voting is as important as ever.

On morning rounds after the 2018 election, we discussed the impact of a changing majority in the House of Representatives and its potential impact on health care in America. We discussed where, when, and how we voted, and then suddenly considered a question that we were unable to answer: How do our hospitalized patients vote and did any of them vote in this important election?

Inpatients rarely know when or how long they will be hospitalized. They often have no chance to prepare by paying bills, arranging care for loved ones, or finding coverage for employment responsibilities. The sickest patients can do little more than wonder about anything other than their short-term health. As a result of restricted voting laws, they, like too many others, are effectively disenfranchised.

We asked administrators in multiple hospitals across New York City how to help our patients vote. Unfortunately, the process is overwhelmingly complex and varies by state. Absentee ballots, which are easily accessible in New York if it they are requested no later than 7 days before the election, are harder to come by on the same day. Most people struggle to vote in general – with only 61% voting in the 2016 election.1 To combat this, individual hospitals have created initiatives such as Penn Votes, which has helped 65 hospitalized Pennsylvania residents vote in the last three elections2 – a success, but still leaving so many without a voice.

With health care being a major policy issue for the 2020 election, voting has never been more important for patients. With nearly 1 million hospital beds in America,3 hospitalized patients represent a significant number of potential voters who are functionally disenfranchised. Most importantly, these patients are directly under our care, and we are their strongest advocates. Therefore, we ask our fellow health care providers to start planning today how we will help our patients exercise their voices, participate in our health care policy debate, and choose the future leaders of our country.

Dr. Rosenblatt is assistant professor of medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. Dr. Verna is assistant professor of medicine, Department of Surgery, at Columbia University Irving Medical School, New York. Dr. Rosenblatt and Dr. Verna reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1. File T. Voting in America: A Look at the 2016 Presidential Election [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 7];Available from: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2017/05/voting_in_america.html.

2. Vigodner S. Penn students are helping hospitalized patients cast emergency ballots for Tuesday’s election [Internet]. Dly. Pennsylvanian. 2018;Available from: https://www.thedp.com/article/2018/11/penn-med-votes-emergency-hospital-patients-upenn-philadelphia-elections.

3. Association AH. Fast facts on US hospitals [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 7];Available from: https://www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals.

Disenfranchisement undeniably remains a major problem across the United States. While it is challenging for health care providers to find time to vote, hospitalized patients are an underrecognized vulnerable group, often unable to exercise this constitutional right. With the 2020 election approaching, voting is as important as ever.

On morning rounds after the 2018 election, we discussed the impact of a changing majority in the House of Representatives and its potential impact on health care in America. We discussed where, when, and how we voted, and then suddenly considered a question that we were unable to answer: How do our hospitalized patients vote and did any of them vote in this important election?

Inpatients rarely know when or how long they will be hospitalized. They often have no chance to prepare by paying bills, arranging care for loved ones, or finding coverage for employment responsibilities. The sickest patients can do little more than wonder about anything other than their short-term health. As a result of restricted voting laws, they, like too many others, are effectively disenfranchised.

We asked administrators in multiple hospitals across New York City how to help our patients vote. Unfortunately, the process is overwhelmingly complex and varies by state. Absentee ballots, which are easily accessible in New York if it they are requested no later than 7 days before the election, are harder to come by on the same day. Most people struggle to vote in general – with only 61% voting in the 2016 election.1 To combat this, individual hospitals have created initiatives such as Penn Votes, which has helped 65 hospitalized Pennsylvania residents vote in the last three elections2 – a success, but still leaving so many without a voice.

With health care being a major policy issue for the 2020 election, voting has never been more important for patients. With nearly 1 million hospital beds in America,3 hospitalized patients represent a significant number of potential voters who are functionally disenfranchised. Most importantly, these patients are directly under our care, and we are their strongest advocates. Therefore, we ask our fellow health care providers to start planning today how we will help our patients exercise their voices, participate in our health care policy debate, and choose the future leaders of our country.

Dr. Rosenblatt is assistant professor of medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. Dr. Verna is assistant professor of medicine, Department of Surgery, at Columbia University Irving Medical School, New York. Dr. Rosenblatt and Dr. Verna reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1. File T. Voting in America: A Look at the 2016 Presidential Election [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 7];Available from: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2017/05/voting_in_america.html.

2. Vigodner S. Penn students are helping hospitalized patients cast emergency ballots for Tuesday’s election [Internet]. Dly. Pennsylvanian. 2018;Available from: https://www.thedp.com/article/2018/11/penn-med-votes-emergency-hospital-patients-upenn-philadelphia-elections.

3. Association AH. Fast facts on US hospitals [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 7];Available from: https://www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals.

Managing the COVID-19 isolation floor at UCSF Medical Center

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, chair of the department of medicine at UCSF, interviewed Armond Esmaili, MD, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UCSF, who is the leader of the Respiratory Isolation Unit at UCSF Medical Center, where the institution's COVID-19 and rule-out COVID-19 patients are being cohorted.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, chair of the department of medicine at UCSF, interviewed Armond Esmaili, MD, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UCSF, who is the leader of the Respiratory Isolation Unit at UCSF Medical Center, where the institution's COVID-19 and rule-out COVID-19 patients are being cohorted.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, chair of the department of medicine at UCSF, interviewed Armond Esmaili, MD, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UCSF, who is the leader of the Respiratory Isolation Unit at UCSF Medical Center, where the institution's COVID-19 and rule-out COVID-19 patients are being cohorted.

Dramatic rise in hypertension-related deaths in the United States

There has been a dramatic rise in hypertension-related deaths in the United States between 2007 and 2017, a new study shows. The authors, led by Lakshmi Nambiar, MD, Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont, Burlington, analyzed data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which collates information from every death certificate in the country, amounting to more than 10 million deaths.

They found that age-adjusted hypertension-related deaths had increased from 18.3 per 100,000 in 2007 to 23.0 per 100,000 in 2017 (P < .001 for decade-long temporal trend).

Nambiar reported results of the study at an American College of Cardiology 2020/World Congress of Cardiology press conference on March 19. It was also published online on the same day in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

She noted that death rates due to cardiovascular disease have been falling over the past 20 years largely attributable to statins to treat high cholesterol and stents to treat coronary artery disease. But since 2011, the rate of decline in cardiovascular deaths has slowed. One contributing factor is an increase in heart failure-related deaths but there hasn’t been any data in recent years on hypertension-related deaths.

“Our data show an increase in hypertension-related deaths in all age groups, in all regions of the United States, and in both sexes. These findings are alarming and warrant further investigation, as well as preventative efforts,” Nambiar said. “This is a public health emergency that has not been fully recognized,” she added.

“We were surprised to see how dramatically these deaths were increasing, and we think this is related to the rise in diabetes, obesity, and the aging of the population. We need targeted public health measures to address some of those factors,” Nambiar told Medscape Medical News.

“We are winning the battle against coronary artery disease with statins and stents but we are not winning the battle against hypertension,” she added.

Worst Figures in Rural South

Results showed that hypertension-related deaths increased in both rural and urban regions, but the increase was much steeper in rural areas — a 72% increase over the decade compared with a 20% increase in urban areas.

The highest death risk was identified in the rural South, which demonstrated an age-adjusted 2.5-fold higher death rate compared with other regions (P < .001).

The urban South also demonstrated increasing hypertension-related cardiovascular death rates over time: age-adjusted death rates in the urban South increased by 27% compared with all other urban regions (P < .001).

But the absolute mortality rates and slope of the curves demonstrate the highest risk in patients in the rural South, the researchers report. Age-adjusted hypertension-related death rates increased in the rural South from 23.9 deaths per 100,000 in 2007 to 39.5 deaths per 100,000 in 2017.

Nambiar said the trends in the rural South could be related to social factors and lack of access to healthcare in the area, which has been exacerbated by failure to adopt Medicaid expansion in many of the states in this region.

“When it comes to the management of hypertension you need to be seen regularly by a primary care doctor to get the best treatment and regular assessments,” she stressed.

Chair of the ACC press conference at which the data were presented, Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona School of Medicine, Phoenix, said: “In this day and time, there is less smoking, which should translate into lower rates of hypertension, but these trends reported here are very different from what we would expect and are probably associated with the rise in other risk factors such as diabetes and obesity, especially in the rural South.”

Nambiar praised the new ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines that recommend a lower diagnostic threshold, “so more people now fit the criteria for raised blood pressure and need treatment.”

“It is important for all primary care physicians and cardiologists to recognize the new threshold and treat people accordingly,” she said. “High blood pressure is the leading cause of cardiovascular disease. If we can control it better, we may be able to control some of this increased mortality we are seeing.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There has been a dramatic rise in hypertension-related deaths in the United States between 2007 and 2017, a new study shows. The authors, led by Lakshmi Nambiar, MD, Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont, Burlington, analyzed data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which collates information from every death certificate in the country, amounting to more than 10 million deaths.

They found that age-adjusted hypertension-related deaths had increased from 18.3 per 100,000 in 2007 to 23.0 per 100,000 in 2017 (P < .001 for decade-long temporal trend).

Nambiar reported results of the study at an American College of Cardiology 2020/World Congress of Cardiology press conference on March 19. It was also published online on the same day in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

She noted that death rates due to cardiovascular disease have been falling over the past 20 years largely attributable to statins to treat high cholesterol and stents to treat coronary artery disease. But since 2011, the rate of decline in cardiovascular deaths has slowed. One contributing factor is an increase in heart failure-related deaths but there hasn’t been any data in recent years on hypertension-related deaths.

“Our data show an increase in hypertension-related deaths in all age groups, in all regions of the United States, and in both sexes. These findings are alarming and warrant further investigation, as well as preventative efforts,” Nambiar said. “This is a public health emergency that has not been fully recognized,” she added.

“We were surprised to see how dramatically these deaths were increasing, and we think this is related to the rise in diabetes, obesity, and the aging of the population. We need targeted public health measures to address some of those factors,” Nambiar told Medscape Medical News.

“We are winning the battle against coronary artery disease with statins and stents but we are not winning the battle against hypertension,” she added.

Worst Figures in Rural South

Results showed that hypertension-related deaths increased in both rural and urban regions, but the increase was much steeper in rural areas — a 72% increase over the decade compared with a 20% increase in urban areas.

The highest death risk was identified in the rural South, which demonstrated an age-adjusted 2.5-fold higher death rate compared with other regions (P < .001).

The urban South also demonstrated increasing hypertension-related cardiovascular death rates over time: age-adjusted death rates in the urban South increased by 27% compared with all other urban regions (P < .001).

But the absolute mortality rates and slope of the curves demonstrate the highest risk in patients in the rural South, the researchers report. Age-adjusted hypertension-related death rates increased in the rural South from 23.9 deaths per 100,000 in 2007 to 39.5 deaths per 100,000 in 2017.

Nambiar said the trends in the rural South could be related to social factors and lack of access to healthcare in the area, which has been exacerbated by failure to adopt Medicaid expansion in many of the states in this region.

“When it comes to the management of hypertension you need to be seen regularly by a primary care doctor to get the best treatment and regular assessments,” she stressed.

Chair of the ACC press conference at which the data were presented, Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona School of Medicine, Phoenix, said: “In this day and time, there is less smoking, which should translate into lower rates of hypertension, but these trends reported here are very different from what we would expect and are probably associated with the rise in other risk factors such as diabetes and obesity, especially in the rural South.”

Nambiar praised the new ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines that recommend a lower diagnostic threshold, “so more people now fit the criteria for raised blood pressure and need treatment.”

“It is important for all primary care physicians and cardiologists to recognize the new threshold and treat people accordingly,” she said. “High blood pressure is the leading cause of cardiovascular disease. If we can control it better, we may be able to control some of this increased mortality we are seeing.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There has been a dramatic rise in hypertension-related deaths in the United States between 2007 and 2017, a new study shows. The authors, led by Lakshmi Nambiar, MD, Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont, Burlington, analyzed data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which collates information from every death certificate in the country, amounting to more than 10 million deaths.

They found that age-adjusted hypertension-related deaths had increased from 18.3 per 100,000 in 2007 to 23.0 per 100,000 in 2017 (P < .001 for decade-long temporal trend).

Nambiar reported results of the study at an American College of Cardiology 2020/World Congress of Cardiology press conference on March 19. It was also published online on the same day in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

She noted that death rates due to cardiovascular disease have been falling over the past 20 years largely attributable to statins to treat high cholesterol and stents to treat coronary artery disease. But since 2011, the rate of decline in cardiovascular deaths has slowed. One contributing factor is an increase in heart failure-related deaths but there hasn’t been any data in recent years on hypertension-related deaths.

“Our data show an increase in hypertension-related deaths in all age groups, in all regions of the United States, and in both sexes. These findings are alarming and warrant further investigation, as well as preventative efforts,” Nambiar said. “This is a public health emergency that has not been fully recognized,” she added.

“We were surprised to see how dramatically these deaths were increasing, and we think this is related to the rise in diabetes, obesity, and the aging of the population. We need targeted public health measures to address some of those factors,” Nambiar told Medscape Medical News.

“We are winning the battle against coronary artery disease with statins and stents but we are not winning the battle against hypertension,” she added.

Worst Figures in Rural South

Results showed that hypertension-related deaths increased in both rural and urban regions, but the increase was much steeper in rural areas — a 72% increase over the decade compared with a 20% increase in urban areas.

The highest death risk was identified in the rural South, which demonstrated an age-adjusted 2.5-fold higher death rate compared with other regions (P < .001).

The urban South also demonstrated increasing hypertension-related cardiovascular death rates over time: age-adjusted death rates in the urban South increased by 27% compared with all other urban regions (P < .001).

But the absolute mortality rates and slope of the curves demonstrate the highest risk in patients in the rural South, the researchers report. Age-adjusted hypertension-related death rates increased in the rural South from 23.9 deaths per 100,000 in 2007 to 39.5 deaths per 100,000 in 2017.

Nambiar said the trends in the rural South could be related to social factors and lack of access to healthcare in the area, which has been exacerbated by failure to adopt Medicaid expansion in many of the states in this region.

“When it comes to the management of hypertension you need to be seen regularly by a primary care doctor to get the best treatment and regular assessments,” she stressed.

Chair of the ACC press conference at which the data were presented, Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona School of Medicine, Phoenix, said: “In this day and time, there is less smoking, which should translate into lower rates of hypertension, but these trends reported here are very different from what we would expect and are probably associated with the rise in other risk factors such as diabetes and obesity, especially in the rural South.”

Nambiar praised the new ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines that recommend a lower diagnostic threshold, “so more people now fit the criteria for raised blood pressure and need treatment.”