User login

COVID-19 in pediatric patients: What the hospitalist needs to know

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11. This rapidly spreading disease is caused by the novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The infection has spread to more than 140 countries, including the United States. As of March 16, more than 170,400 people had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and more than 6,619 people have died across the globe.

The number of new COVID-19 cases appears to be decreasing in China, but the number of cases are rapidly increasing worldwide. Based on available data, primarily from China, children (aged 0-19 years) account for only about 2% of all cases. Despite the probable low virulence and incidence of infection in children, they could act as potential vectors and transmit infection to more vulnerable populations. As of March 16, approximately 3,823 cases and more than 67 deaths had been reported in the United States with few pediatric patients testing positive for the disease.

SARS-CoV2 transmission mainly occurs via respiratory route through close contact with infected individuals and through fomites. The incubation period ranges from 2-14 days with an average of about 5 days. Adult patients present with cough and fever, which may progress to lower respiratory tract symptoms, including shortness of breath. Approximately 10% of all patients develop severe disease and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), requiring mechanical ventilation.

COVID-19 carries a mortality rate of up to 3%, but has been significantly higher in the elderly population, and those with chronic health conditions. Available data so far shows that children are at lower risk and the severity of the disease has been milder compared to adults. The reasons for this are not clear at this time. As of March 16, there were no reported COVID-19 related deaths in children under age 9 years.

The pediatric population: Disease patterns and transmission

The epidemiology and spectrum of disease for COVID-19 is poorly understood in pediatrics because of the low number of reported pediatric cases and limited data available from these patients. Small numbers of reported cases in children has led some to believe that children are relatively immune to the infection by SARS-CoV-2. However, Oifang et al. found that children are equally as likely as adults to be infected.1

Liu et al. found that of 366 children admitted to a hospital in Wuhan with respiratory infections in January 2020, 1.6% (six patients) cases were positive for SARS-CoV-2.2 These six children were aged 1-7 years and had all been previously healthy; all six presented with cough and fever of 102.2° F or greater. Four of the children also had vomiting. Laboratory findings were notable for lymphopenia (six of six), leukopenia (four of six), and neutropenia (3/6) with mild to moderate elevation in C-reactive protein (6.8-58.8 mg/L). Five of six children had chest CT scans. One child’s CT scan showed “bilateral ground-glass opacities” (similar to what is reported in adults), three showed “bilateral patchy shadows,” and one was normal. One child (aged 3 years) was admitted to the ICU. All of the children were treated with supportive measures, empiric antibiotics, and antivirals (six of six received oseltamivir and four of six received ribavirin). All six children recovered completely and their median hospital stay was 7.5 days with a range of 5-13 days.

Xia et al. reviewed 20 children (aged 1 day to 14 years) admitted to a hospital in Wuhan during Jan. 23–Feb. 8.3 The study reported that fever and cough were the most common presenting symptoms (approximately 65%). Less common symptoms included rhinorrhea (15%), diarrhea (15%), vomiting (10%), and sore throat (5%). WBC count was normal in majority of children (70%) with leukopenia in 20% and leukocytosis in 10%. Lymphopenia was noted to be 35%. Elevated procalcitonin was noted in 80% of children, although the degree of elevation is unclear. In this study, 8 of 20 children were coinfected with other respiratory pathogens such as influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, mycoplasma, and cytomegalovirus. All children had chest CT scans. Ten of 20 children had bilateral pulmonary lesions, 6 of 20 had unilateral pulmonary lesions, 12 of 20 had ground-glass opacities and 10 of 20 had lung consolidations with halo signs.

Wei et al., retrospective chart review of nine infants admitted for COVID-19 found that all nine had at least one infected family member.4 This study reported that seven of nine were female infants, four of nine had fever, two had mild upper respiratory infection symptoms, and one had no symptoms. The study did report that two infants did not have any information available related to symptoms. None of the infants developed severe symptoms or required ICU admission.

The youngest patient to be diagnosed with COVID-19 was a newborn of less than 24 hours old from England, whose mother also tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. However, Chen et al. found no evidence of vertical transmission of the virus from infected pregnant women to their newborns.5

Although the risk of infection in children has been reported to be low, the infection has been shown to be particularly severe in adults with compromised immune systems and chronic health conditions. Thus immunocompromised children and those with chronic health conditions are thought to be at a higher risk for contracting the infection, with the probability for increased morbidity and mortality. Some of these risk groups include premature infants, young infants, immunocompromised children, and children with chronic health conditions like asthma, diabetes, and others. It is essential that caregivers, healthy siblings, and other family members are protected from contracting the infection in order to protect these vulnerable children. Given the high infectivity of SARS-CoV-2, the implications of infected children attending schools and daycares may be far reaching if there is delayed identification of the infection. For these reasons, it is important to closely monitor and promptly test children living with infected adults to prevent the spread. It may become necessary to close schools to mitigate transmission.

Schools and daycares should work with their local health departments and physicians in case of infected individuals in their community. In China, authorities closed schools and allowed students to receive virtual education from home, which may be a reasonable choice depending on resources.

Current challenges

Given the aggressive transmission of COVID-19, these numbers seem to be increasing exponentially with a significant impact on the life of the entire country. Therefore, we must focus on containing the spread and mitigating the transmission with a multimodality approach.

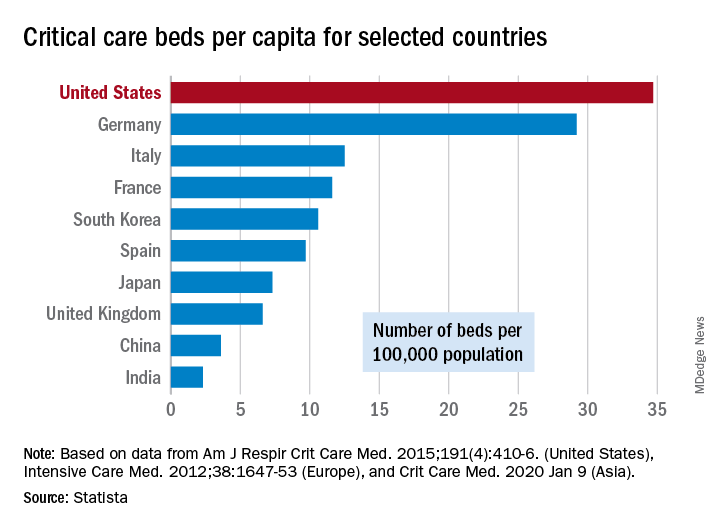

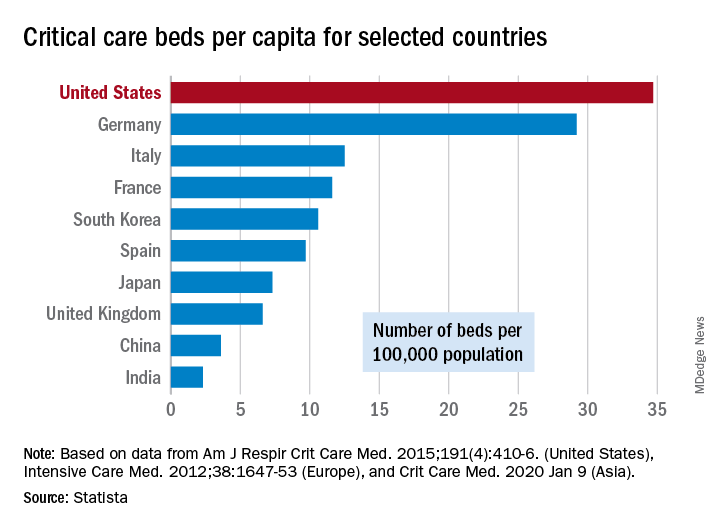

Some of the initial challenges faced by physicians in the United States were related to difficulty in access to testing in persons under investigation (PUI), which in turn resulted in a delay in diagnosis and infection control. At this time, the need is to increase surge testing capabilities across the country through a variety of innovative approaches including public-private partnerships with commercial labs through Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Department of Health and Human Services. To minimize exposure to health care professionals, telemedicine and telehealth capabilities should be exploited. This will minimize the exposure to infected patients and reduce the need for already limited personal protective equipment (PPE). As the number of cases rise, hospitals should expect and prepare for a surge in COVID-19–related hospitalizations and health care utilization.

Conclusion

Various theories are being proposed as to why children are not experiencing severe disease with COVID-19. Children may have cross-protective immunity from infection with other coronaviruses. Children may not have the same exposures from work, travel, and caregiving that adults experience as they are typically exposed by someone in their home. At this time, not enough is known about clinical presentations in children as the situation continues to evolve across the globe.

Respiratory infections in children pose unique infection control challenges with respect to compliant hand hygiene, cough etiquette, and the use of PPE when indicated. There is also concern for persistent fecal shedding of virus in infected pediatric patients, which could be another mode of transmission.6 Children could, however, be very efficient vectors of COVID-19, similar to flu, and potentially spread the pathogen to very vulnerable populations leading to high morbidity and mortality. School closures are an effective social distancing measure needed to flatten the curve and avoid overwhelming the health care structure of the United States.

Dr. Konanki is a board-certified pediatrician doing inpatient work at Wellspan Chambersburg Hospital and outpatient work at Keystone Pediatrics in Chambersburg, Pa. He also serves as the physician member of the hospital’s Code Blue Jr. committee and as a member of Quality Metrics committee at Keystone Health. Dr. Tirupathi is the medical director of Keystone Infectious Diseases/HIV in Chambersburg, Pa., and currently chair of infection prevention at Wellspan Chambersburg and Waynesboro (Pa.) Hospitals. He also is the lead physician for antibiotic stewardship at these hospitals. Dr. Palabindala is hospital medicine division chief at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson.

References

1. Bi Q et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in Shenzhen China: Analysis of 391 cases and 1,286 of their close contacts. medRxiv 2020.03.03.20028423.

2. Liu W et al. Detection of Covid-19 in children in early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717.

3. Xia W et al. Clinical and CT features in pediatric patients with COVID‐19 infection: Different points from adults. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020 Mar 5. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24718.

4. Wei M et al. Novel Coronavirus infection in hospitalized infants under 1 year of age in China. JAMA. 2020 Feb. 14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2131.

5. Huijun C et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: A retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020 Mar 7 395;10226:809-15.

6. Xu Y et al. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat Med. 2020 Mar 13. doi. org/10.1038/s41591-020-0817-4.

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11. This rapidly spreading disease is caused by the novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The infection has spread to more than 140 countries, including the United States. As of March 16, more than 170,400 people had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and more than 6,619 people have died across the globe.

The number of new COVID-19 cases appears to be decreasing in China, but the number of cases are rapidly increasing worldwide. Based on available data, primarily from China, children (aged 0-19 years) account for only about 2% of all cases. Despite the probable low virulence and incidence of infection in children, they could act as potential vectors and transmit infection to more vulnerable populations. As of March 16, approximately 3,823 cases and more than 67 deaths had been reported in the United States with few pediatric patients testing positive for the disease.

SARS-CoV2 transmission mainly occurs via respiratory route through close contact with infected individuals and through fomites. The incubation period ranges from 2-14 days with an average of about 5 days. Adult patients present with cough and fever, which may progress to lower respiratory tract symptoms, including shortness of breath. Approximately 10% of all patients develop severe disease and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), requiring mechanical ventilation.

COVID-19 carries a mortality rate of up to 3%, but has been significantly higher in the elderly population, and those with chronic health conditions. Available data so far shows that children are at lower risk and the severity of the disease has been milder compared to adults. The reasons for this are not clear at this time. As of March 16, there were no reported COVID-19 related deaths in children under age 9 years.

The pediatric population: Disease patterns and transmission

The epidemiology and spectrum of disease for COVID-19 is poorly understood in pediatrics because of the low number of reported pediatric cases and limited data available from these patients. Small numbers of reported cases in children has led some to believe that children are relatively immune to the infection by SARS-CoV-2. However, Oifang et al. found that children are equally as likely as adults to be infected.1

Liu et al. found that of 366 children admitted to a hospital in Wuhan with respiratory infections in January 2020, 1.6% (six patients) cases were positive for SARS-CoV-2.2 These six children were aged 1-7 years and had all been previously healthy; all six presented with cough and fever of 102.2° F or greater. Four of the children also had vomiting. Laboratory findings were notable for lymphopenia (six of six), leukopenia (four of six), and neutropenia (3/6) with mild to moderate elevation in C-reactive protein (6.8-58.8 mg/L). Five of six children had chest CT scans. One child’s CT scan showed “bilateral ground-glass opacities” (similar to what is reported in adults), three showed “bilateral patchy shadows,” and one was normal. One child (aged 3 years) was admitted to the ICU. All of the children were treated with supportive measures, empiric antibiotics, and antivirals (six of six received oseltamivir and four of six received ribavirin). All six children recovered completely and their median hospital stay was 7.5 days with a range of 5-13 days.

Xia et al. reviewed 20 children (aged 1 day to 14 years) admitted to a hospital in Wuhan during Jan. 23–Feb. 8.3 The study reported that fever and cough were the most common presenting symptoms (approximately 65%). Less common symptoms included rhinorrhea (15%), diarrhea (15%), vomiting (10%), and sore throat (5%). WBC count was normal in majority of children (70%) with leukopenia in 20% and leukocytosis in 10%. Lymphopenia was noted to be 35%. Elevated procalcitonin was noted in 80% of children, although the degree of elevation is unclear. In this study, 8 of 20 children were coinfected with other respiratory pathogens such as influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, mycoplasma, and cytomegalovirus. All children had chest CT scans. Ten of 20 children had bilateral pulmonary lesions, 6 of 20 had unilateral pulmonary lesions, 12 of 20 had ground-glass opacities and 10 of 20 had lung consolidations with halo signs.

Wei et al., retrospective chart review of nine infants admitted for COVID-19 found that all nine had at least one infected family member.4 This study reported that seven of nine were female infants, four of nine had fever, two had mild upper respiratory infection symptoms, and one had no symptoms. The study did report that two infants did not have any information available related to symptoms. None of the infants developed severe symptoms or required ICU admission.

The youngest patient to be diagnosed with COVID-19 was a newborn of less than 24 hours old from England, whose mother also tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. However, Chen et al. found no evidence of vertical transmission of the virus from infected pregnant women to their newborns.5

Although the risk of infection in children has been reported to be low, the infection has been shown to be particularly severe in adults with compromised immune systems and chronic health conditions. Thus immunocompromised children and those with chronic health conditions are thought to be at a higher risk for contracting the infection, with the probability for increased morbidity and mortality. Some of these risk groups include premature infants, young infants, immunocompromised children, and children with chronic health conditions like asthma, diabetes, and others. It is essential that caregivers, healthy siblings, and other family members are protected from contracting the infection in order to protect these vulnerable children. Given the high infectivity of SARS-CoV-2, the implications of infected children attending schools and daycares may be far reaching if there is delayed identification of the infection. For these reasons, it is important to closely monitor and promptly test children living with infected adults to prevent the spread. It may become necessary to close schools to mitigate transmission.

Schools and daycares should work with their local health departments and physicians in case of infected individuals in their community. In China, authorities closed schools and allowed students to receive virtual education from home, which may be a reasonable choice depending on resources.

Current challenges

Given the aggressive transmission of COVID-19, these numbers seem to be increasing exponentially with a significant impact on the life of the entire country. Therefore, we must focus on containing the spread and mitigating the transmission with a multimodality approach.

Some of the initial challenges faced by physicians in the United States were related to difficulty in access to testing in persons under investigation (PUI), which in turn resulted in a delay in diagnosis and infection control. At this time, the need is to increase surge testing capabilities across the country through a variety of innovative approaches including public-private partnerships with commercial labs through Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Department of Health and Human Services. To minimize exposure to health care professionals, telemedicine and telehealth capabilities should be exploited. This will minimize the exposure to infected patients and reduce the need for already limited personal protective equipment (PPE). As the number of cases rise, hospitals should expect and prepare for a surge in COVID-19–related hospitalizations and health care utilization.

Conclusion

Various theories are being proposed as to why children are not experiencing severe disease with COVID-19. Children may have cross-protective immunity from infection with other coronaviruses. Children may not have the same exposures from work, travel, and caregiving that adults experience as they are typically exposed by someone in their home. At this time, not enough is known about clinical presentations in children as the situation continues to evolve across the globe.

Respiratory infections in children pose unique infection control challenges with respect to compliant hand hygiene, cough etiquette, and the use of PPE when indicated. There is also concern for persistent fecal shedding of virus in infected pediatric patients, which could be another mode of transmission.6 Children could, however, be very efficient vectors of COVID-19, similar to flu, and potentially spread the pathogen to very vulnerable populations leading to high morbidity and mortality. School closures are an effective social distancing measure needed to flatten the curve and avoid overwhelming the health care structure of the United States.

Dr. Konanki is a board-certified pediatrician doing inpatient work at Wellspan Chambersburg Hospital and outpatient work at Keystone Pediatrics in Chambersburg, Pa. He also serves as the physician member of the hospital’s Code Blue Jr. committee and as a member of Quality Metrics committee at Keystone Health. Dr. Tirupathi is the medical director of Keystone Infectious Diseases/HIV in Chambersburg, Pa., and currently chair of infection prevention at Wellspan Chambersburg and Waynesboro (Pa.) Hospitals. He also is the lead physician for antibiotic stewardship at these hospitals. Dr. Palabindala is hospital medicine division chief at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson.

References

1. Bi Q et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in Shenzhen China: Analysis of 391 cases and 1,286 of their close contacts. medRxiv 2020.03.03.20028423.

2. Liu W et al. Detection of Covid-19 in children in early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717.

3. Xia W et al. Clinical and CT features in pediatric patients with COVID‐19 infection: Different points from adults. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020 Mar 5. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24718.

4. Wei M et al. Novel Coronavirus infection in hospitalized infants under 1 year of age in China. JAMA. 2020 Feb. 14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2131.

5. Huijun C et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: A retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020 Mar 7 395;10226:809-15.

6. Xu Y et al. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat Med. 2020 Mar 13. doi. org/10.1038/s41591-020-0817-4.

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11. This rapidly spreading disease is caused by the novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The infection has spread to more than 140 countries, including the United States. As of March 16, more than 170,400 people had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and more than 6,619 people have died across the globe.

The number of new COVID-19 cases appears to be decreasing in China, but the number of cases are rapidly increasing worldwide. Based on available data, primarily from China, children (aged 0-19 years) account for only about 2% of all cases. Despite the probable low virulence and incidence of infection in children, they could act as potential vectors and transmit infection to more vulnerable populations. As of March 16, approximately 3,823 cases and more than 67 deaths had been reported in the United States with few pediatric patients testing positive for the disease.

SARS-CoV2 transmission mainly occurs via respiratory route through close contact with infected individuals and through fomites. The incubation period ranges from 2-14 days with an average of about 5 days. Adult patients present with cough and fever, which may progress to lower respiratory tract symptoms, including shortness of breath. Approximately 10% of all patients develop severe disease and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), requiring mechanical ventilation.

COVID-19 carries a mortality rate of up to 3%, but has been significantly higher in the elderly population, and those with chronic health conditions. Available data so far shows that children are at lower risk and the severity of the disease has been milder compared to adults. The reasons for this are not clear at this time. As of March 16, there were no reported COVID-19 related deaths in children under age 9 years.

The pediatric population: Disease patterns and transmission

The epidemiology and spectrum of disease for COVID-19 is poorly understood in pediatrics because of the low number of reported pediatric cases and limited data available from these patients. Small numbers of reported cases in children has led some to believe that children are relatively immune to the infection by SARS-CoV-2. However, Oifang et al. found that children are equally as likely as adults to be infected.1

Liu et al. found that of 366 children admitted to a hospital in Wuhan with respiratory infections in January 2020, 1.6% (six patients) cases were positive for SARS-CoV-2.2 These six children were aged 1-7 years and had all been previously healthy; all six presented with cough and fever of 102.2° F or greater. Four of the children also had vomiting. Laboratory findings were notable for lymphopenia (six of six), leukopenia (four of six), and neutropenia (3/6) with mild to moderate elevation in C-reactive protein (6.8-58.8 mg/L). Five of six children had chest CT scans. One child’s CT scan showed “bilateral ground-glass opacities” (similar to what is reported in adults), three showed “bilateral patchy shadows,” and one was normal. One child (aged 3 years) was admitted to the ICU. All of the children were treated with supportive measures, empiric antibiotics, and antivirals (six of six received oseltamivir and four of six received ribavirin). All six children recovered completely and their median hospital stay was 7.5 days with a range of 5-13 days.

Xia et al. reviewed 20 children (aged 1 day to 14 years) admitted to a hospital in Wuhan during Jan. 23–Feb. 8.3 The study reported that fever and cough were the most common presenting symptoms (approximately 65%). Less common symptoms included rhinorrhea (15%), diarrhea (15%), vomiting (10%), and sore throat (5%). WBC count was normal in majority of children (70%) with leukopenia in 20% and leukocytosis in 10%. Lymphopenia was noted to be 35%. Elevated procalcitonin was noted in 80% of children, although the degree of elevation is unclear. In this study, 8 of 20 children were coinfected with other respiratory pathogens such as influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, mycoplasma, and cytomegalovirus. All children had chest CT scans. Ten of 20 children had bilateral pulmonary lesions, 6 of 20 had unilateral pulmonary lesions, 12 of 20 had ground-glass opacities and 10 of 20 had lung consolidations with halo signs.

Wei et al., retrospective chart review of nine infants admitted for COVID-19 found that all nine had at least one infected family member.4 This study reported that seven of nine were female infants, four of nine had fever, two had mild upper respiratory infection symptoms, and one had no symptoms. The study did report that two infants did not have any information available related to symptoms. None of the infants developed severe symptoms or required ICU admission.

The youngest patient to be diagnosed with COVID-19 was a newborn of less than 24 hours old from England, whose mother also tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. However, Chen et al. found no evidence of vertical transmission of the virus from infected pregnant women to their newborns.5

Although the risk of infection in children has been reported to be low, the infection has been shown to be particularly severe in adults with compromised immune systems and chronic health conditions. Thus immunocompromised children and those with chronic health conditions are thought to be at a higher risk for contracting the infection, with the probability for increased morbidity and mortality. Some of these risk groups include premature infants, young infants, immunocompromised children, and children with chronic health conditions like asthma, diabetes, and others. It is essential that caregivers, healthy siblings, and other family members are protected from contracting the infection in order to protect these vulnerable children. Given the high infectivity of SARS-CoV-2, the implications of infected children attending schools and daycares may be far reaching if there is delayed identification of the infection. For these reasons, it is important to closely monitor and promptly test children living with infected adults to prevent the spread. It may become necessary to close schools to mitigate transmission.

Schools and daycares should work with their local health departments and physicians in case of infected individuals in their community. In China, authorities closed schools and allowed students to receive virtual education from home, which may be a reasonable choice depending on resources.

Current challenges

Given the aggressive transmission of COVID-19, these numbers seem to be increasing exponentially with a significant impact on the life of the entire country. Therefore, we must focus on containing the spread and mitigating the transmission with a multimodality approach.

Some of the initial challenges faced by physicians in the United States were related to difficulty in access to testing in persons under investigation (PUI), which in turn resulted in a delay in diagnosis and infection control. At this time, the need is to increase surge testing capabilities across the country through a variety of innovative approaches including public-private partnerships with commercial labs through Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Department of Health and Human Services. To minimize exposure to health care professionals, telemedicine and telehealth capabilities should be exploited. This will minimize the exposure to infected patients and reduce the need for already limited personal protective equipment (PPE). As the number of cases rise, hospitals should expect and prepare for a surge in COVID-19–related hospitalizations and health care utilization.

Conclusion

Various theories are being proposed as to why children are not experiencing severe disease with COVID-19. Children may have cross-protective immunity from infection with other coronaviruses. Children may not have the same exposures from work, travel, and caregiving that adults experience as they are typically exposed by someone in their home. At this time, not enough is known about clinical presentations in children as the situation continues to evolve across the globe.

Respiratory infections in children pose unique infection control challenges with respect to compliant hand hygiene, cough etiquette, and the use of PPE when indicated. There is also concern for persistent fecal shedding of virus in infected pediatric patients, which could be another mode of transmission.6 Children could, however, be very efficient vectors of COVID-19, similar to flu, and potentially spread the pathogen to very vulnerable populations leading to high morbidity and mortality. School closures are an effective social distancing measure needed to flatten the curve and avoid overwhelming the health care structure of the United States.

Dr. Konanki is a board-certified pediatrician doing inpatient work at Wellspan Chambersburg Hospital and outpatient work at Keystone Pediatrics in Chambersburg, Pa. He also serves as the physician member of the hospital’s Code Blue Jr. committee and as a member of Quality Metrics committee at Keystone Health. Dr. Tirupathi is the medical director of Keystone Infectious Diseases/HIV in Chambersburg, Pa., and currently chair of infection prevention at Wellspan Chambersburg and Waynesboro (Pa.) Hospitals. He also is the lead physician for antibiotic stewardship at these hospitals. Dr. Palabindala is hospital medicine division chief at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson.

References

1. Bi Q et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in Shenzhen China: Analysis of 391 cases and 1,286 of their close contacts. medRxiv 2020.03.03.20028423.

2. Liu W et al. Detection of Covid-19 in children in early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717.

3. Xia W et al. Clinical and CT features in pediatric patients with COVID‐19 infection: Different points from adults. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020 Mar 5. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24718.

4. Wei M et al. Novel Coronavirus infection in hospitalized infants under 1 year of age in China. JAMA. 2020 Feb. 14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2131.

5. Huijun C et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: A retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020 Mar 7 395;10226:809-15.

6. Xu Y et al. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat Med. 2020 Mar 13. doi. org/10.1038/s41591-020-0817-4.

Coronavirus stays in aerosols for hours, on surfaces for days

according to a new study.

The data indicate that the stability of the new virus is similar to that of SARS-CoV-1, which caused the SARS epidemic, researchers report in an article published on the medRxivpreprint server. (The posted article has been submitted for journal publication but has not been peer reviewed.)

Transmission of SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, has quickly outstripped the pace of the 2003 SARS epidemic. “Superspread” of the earlier disease arose from infection during medical procedures, in which a single infected individual seeded many secondary cases. In contrast, the novel coronavirus appears to be spread more through human-to-human transmission in a variety of settings.

However, it’s not yet known the extent to which asymptomatic or presymptomatic individuals spread the new virus through daily routine.

To investigate how long SARS-CoV-2 remains infective in the environment, Neeltje van Doremalen, PhD, of the Laboratory of Virology, Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in Hamilton, Montana, and colleagues conducted simulation experiments in which they compared the viability of SARS-CoV-2 with that of SARS-CoV-1 in aerosols and on surfaces.

Among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, viral loads in the upper respiratory tract are high; as a consequence, respiratory secretion in the form of aerosols (<5 μm) or droplets (>5 mcm) is likely, the authors note.

van Doremalen and colleagues used nebulizers to generate aerosols. Samples of SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 were collecting at 0, 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes on a gelatin filter. The researchers then tested the infectivity of the viruses on Vero cells grown in culture.

They found that SARS-CoV-2 was largely stable through the full 180-minute test, with only a slight decline at 3 hours. This time course is similar to that of SARS-CoV-1; both viruses have a median half-life in aerosols of 2.7 hours (range, 1.65 hr for SARS-CoV-1, vs 7.24 hr for SARS-CoV-2).

The researchers then tested the viruses on a variety of surfaces for up to 7 days, using humidity values and temperatures designed to mimic “a variety of household and hospital situations.” The volumes of viral exposures that the team used were consistent with amounts found in the human upper and lower respiratory tracts.

For example, they applied 50 mcL of virus-containing solution to a piece of cardboard and then swabbed the surface, at different times, with an additional 1 mcL of medium. Each surface assay was replicated three times.

The novel coronavirus was most stable on plastic and stainless steel, with some virus remaining viable up to 72 hours. However, by that time the viral load had fallen by about three orders of magnitude, indicating exponential decay. This profile was remarkably similar to that of SARS-CoV-1, according to the authors.

However, the two viruses differed in staying power on copper and cardboard. No viable SARS-CoV-2 was detectable on copper after 4 hours or on cardboard after 24 hours. In contrast, SARS-CoV-1 was not viable beyond 8 hours for either copper or cardboard.

“Taken together, our results indicate that aerosol and fomite transmission of HCoV-19 [SARS-CoV-2] are plausible, as the virus can remain viable in aerosols for multiple hours and on surfaces up to days,” the authors conclude.

Andrew Pekosz, PhD, codirector of the Center of Excellence in Influenza Research and Surveillance and director of the Center for Emerging Viruses and Infectious Diseases at the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health, Baltimore, Maryland, applauds the real-world value of the experiments.

“The PCR [polymerase chain reaction] test used [in other studies] to detect SARS-CoV-2 just detects the virus genome. It doesn’t tell you if the virus was still infectious, or ‘viable.’ That’s why this study is interesting,” Pekosz said. “It focuses on infectious virus, which is the virus that has the potential to transmit and infect another person. What we don’t know yet is how much infectious (viable) virus is needed to initiate infection in another person.”

He suggests that further investigations evaluate other types of environmental surfaces, including lacquered wood that is made into desks and ceramic tiles found in bathrooms and kitchens.

One limitation of the study is that the data for experiments on cardboard were more variable than the data for other surfaces tested.

The investigators and Pekosz have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new study.

The data indicate that the stability of the new virus is similar to that of SARS-CoV-1, which caused the SARS epidemic, researchers report in an article published on the medRxivpreprint server. (The posted article has been submitted for journal publication but has not been peer reviewed.)

Transmission of SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, has quickly outstripped the pace of the 2003 SARS epidemic. “Superspread” of the earlier disease arose from infection during medical procedures, in which a single infected individual seeded many secondary cases. In contrast, the novel coronavirus appears to be spread more through human-to-human transmission in a variety of settings.

However, it’s not yet known the extent to which asymptomatic or presymptomatic individuals spread the new virus through daily routine.

To investigate how long SARS-CoV-2 remains infective in the environment, Neeltje van Doremalen, PhD, of the Laboratory of Virology, Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in Hamilton, Montana, and colleagues conducted simulation experiments in which they compared the viability of SARS-CoV-2 with that of SARS-CoV-1 in aerosols and on surfaces.

Among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, viral loads in the upper respiratory tract are high; as a consequence, respiratory secretion in the form of aerosols (<5 μm) or droplets (>5 mcm) is likely, the authors note.

van Doremalen and colleagues used nebulizers to generate aerosols. Samples of SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 were collecting at 0, 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes on a gelatin filter. The researchers then tested the infectivity of the viruses on Vero cells grown in culture.

They found that SARS-CoV-2 was largely stable through the full 180-minute test, with only a slight decline at 3 hours. This time course is similar to that of SARS-CoV-1; both viruses have a median half-life in aerosols of 2.7 hours (range, 1.65 hr for SARS-CoV-1, vs 7.24 hr for SARS-CoV-2).

The researchers then tested the viruses on a variety of surfaces for up to 7 days, using humidity values and temperatures designed to mimic “a variety of household and hospital situations.” The volumes of viral exposures that the team used were consistent with amounts found in the human upper and lower respiratory tracts.

For example, they applied 50 mcL of virus-containing solution to a piece of cardboard and then swabbed the surface, at different times, with an additional 1 mcL of medium. Each surface assay was replicated three times.

The novel coronavirus was most stable on plastic and stainless steel, with some virus remaining viable up to 72 hours. However, by that time the viral load had fallen by about three orders of magnitude, indicating exponential decay. This profile was remarkably similar to that of SARS-CoV-1, according to the authors.

However, the two viruses differed in staying power on copper and cardboard. No viable SARS-CoV-2 was detectable on copper after 4 hours or on cardboard after 24 hours. In contrast, SARS-CoV-1 was not viable beyond 8 hours for either copper or cardboard.

“Taken together, our results indicate that aerosol and fomite transmission of HCoV-19 [SARS-CoV-2] are plausible, as the virus can remain viable in aerosols for multiple hours and on surfaces up to days,” the authors conclude.

Andrew Pekosz, PhD, codirector of the Center of Excellence in Influenza Research and Surveillance and director of the Center for Emerging Viruses and Infectious Diseases at the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health, Baltimore, Maryland, applauds the real-world value of the experiments.

“The PCR [polymerase chain reaction] test used [in other studies] to detect SARS-CoV-2 just detects the virus genome. It doesn’t tell you if the virus was still infectious, or ‘viable.’ That’s why this study is interesting,” Pekosz said. “It focuses on infectious virus, which is the virus that has the potential to transmit and infect another person. What we don’t know yet is how much infectious (viable) virus is needed to initiate infection in another person.”

He suggests that further investigations evaluate other types of environmental surfaces, including lacquered wood that is made into desks and ceramic tiles found in bathrooms and kitchens.

One limitation of the study is that the data for experiments on cardboard were more variable than the data for other surfaces tested.

The investigators and Pekosz have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new study.

The data indicate that the stability of the new virus is similar to that of SARS-CoV-1, which caused the SARS epidemic, researchers report in an article published on the medRxivpreprint server. (The posted article has been submitted for journal publication but has not been peer reviewed.)

Transmission of SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, has quickly outstripped the pace of the 2003 SARS epidemic. “Superspread” of the earlier disease arose from infection during medical procedures, in which a single infected individual seeded many secondary cases. In contrast, the novel coronavirus appears to be spread more through human-to-human transmission in a variety of settings.

However, it’s not yet known the extent to which asymptomatic or presymptomatic individuals spread the new virus through daily routine.

To investigate how long SARS-CoV-2 remains infective in the environment, Neeltje van Doremalen, PhD, of the Laboratory of Virology, Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in Hamilton, Montana, and colleagues conducted simulation experiments in which they compared the viability of SARS-CoV-2 with that of SARS-CoV-1 in aerosols and on surfaces.

Among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, viral loads in the upper respiratory tract are high; as a consequence, respiratory secretion in the form of aerosols (<5 μm) or droplets (>5 mcm) is likely, the authors note.

van Doremalen and colleagues used nebulizers to generate aerosols. Samples of SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 were collecting at 0, 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes on a gelatin filter. The researchers then tested the infectivity of the viruses on Vero cells grown in culture.

They found that SARS-CoV-2 was largely stable through the full 180-minute test, with only a slight decline at 3 hours. This time course is similar to that of SARS-CoV-1; both viruses have a median half-life in aerosols of 2.7 hours (range, 1.65 hr for SARS-CoV-1, vs 7.24 hr for SARS-CoV-2).

The researchers then tested the viruses on a variety of surfaces for up to 7 days, using humidity values and temperatures designed to mimic “a variety of household and hospital situations.” The volumes of viral exposures that the team used were consistent with amounts found in the human upper and lower respiratory tracts.

For example, they applied 50 mcL of virus-containing solution to a piece of cardboard and then swabbed the surface, at different times, with an additional 1 mcL of medium. Each surface assay was replicated three times.

The novel coronavirus was most stable on plastic and stainless steel, with some virus remaining viable up to 72 hours. However, by that time the viral load had fallen by about three orders of magnitude, indicating exponential decay. This profile was remarkably similar to that of SARS-CoV-1, according to the authors.

However, the two viruses differed in staying power on copper and cardboard. No viable SARS-CoV-2 was detectable on copper after 4 hours or on cardboard after 24 hours. In contrast, SARS-CoV-1 was not viable beyond 8 hours for either copper or cardboard.

“Taken together, our results indicate that aerosol and fomite transmission of HCoV-19 [SARS-CoV-2] are plausible, as the virus can remain viable in aerosols for multiple hours and on surfaces up to days,” the authors conclude.

Andrew Pekosz, PhD, codirector of the Center of Excellence in Influenza Research and Surveillance and director of the Center for Emerging Viruses and Infectious Diseases at the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health, Baltimore, Maryland, applauds the real-world value of the experiments.

“The PCR [polymerase chain reaction] test used [in other studies] to detect SARS-CoV-2 just detects the virus genome. It doesn’t tell you if the virus was still infectious, or ‘viable.’ That’s why this study is interesting,” Pekosz said. “It focuses on infectious virus, which is the virus that has the potential to transmit and infect another person. What we don’t know yet is how much infectious (viable) virus is needed to initiate infection in another person.”

He suggests that further investigations evaluate other types of environmental surfaces, including lacquered wood that is made into desks and ceramic tiles found in bathrooms and kitchens.

One limitation of the study is that the data for experiments on cardboard were more variable than the data for other surfaces tested.

The investigators and Pekosz have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Treating COVID-19 in patients with diabetes

Patients with diabetes may be at extra risk for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) mortality, and doctors treating them need to keep up with the latest guidelines and expert advice.

Most health advisories about COVID-19 mention diabetes as one of the high-risk categories for the disease, likely because early data coming out of China, where the disease was first reported, indicated an elevated case-fatality rate for COVID-19 patients who also had diabetes.

In an article published in JAMA, Zunyou Wu, MD, and Jennifer M. McGoogan, PhD, summarized the findings from a February report on 44,672 confirmed cases of the disease from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The overall case-fatality rate (CFR) at that stage was 2.3% (1,023 deaths of the 44,672 confirmed cases). The data indicated that the CFR was elevated among COVID-19 patients with preexisting comorbid conditions, specifically, cardiovascular disease (CFR, 10.5%), diabetes (7.3%), chronic respiratory disease (6.3%), hypertension (6%), and cancer (5.6%).

The data also showed an aged-related trend in the CFR, with patients aged 80 years or older having a CFR of 14.8% and those aged 70-79 years, a rate of 8.0%, while there were no fatal cases reported in patients aged 9 years or younger (JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648).

Those findings have been echoed by the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. The American Diabetes Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists have in turn referenced the CDC in their COVID-19 guidance recommendations for patients with diabetes.

Guidelines were already in place for treatment of infections in patients with diabetes, and

In general, patients with diabetes – especially those whose disease is not controlled, or not well controlled – can be more susceptible to more common infections, such as influenza and pneumonia, possibly because hyperglycemia can subdue immunity by disrupting function of the white blood cells.

Glucose control is key

An important factor in any form of infection control in patients with diabetes seems to be whether or not a patient’s glucose levels are well controlled, according to comments from members of the editorial advisory board for Clinical Endocrinology News. Good glucose control, therefore, could be instrumental in reducing both the risk for and severity of infection.

Paul Jellinger, MD, of the Center for Diabetes & Endocrine Care, Hollywood, Fla., said that, over the years, he had not observed higher infection rates in general in patients with hemoglobin A1c levels below 7, or even higher. However, “a bigger question for me, given the broad category of ‘diabetes’ listed as a risk for serious coronavirus complications by the CDC, has been: Just which individuals with diabetes are really at risk? Are patients with well-controlled diabetes at increased risk as much as those with significant hyperglycemia and uncontrolled diabetes? In my view, not likely.”

Alan Jay Cohen, MD, agreed with Dr. Jellinger. “Many patients have called the office in the last 10 days to ask if there are special precautions they should take because they are reading that they are in the high-risk group because they have diabetes. Many of them are in superb, or at least pretty good, control. I have not seen where they have had a higher incidence of infection than the general population, and I have not seen data with COVID-19 that specifically demonstrates that a person with diabetes in good control has an increased risk,” he said.

“My recommendations to these patients have been the same as those given to the general population,” added Dr. Cohen, medical director at Baptist Medical Group: The Endocrine Clinic, Memphis.

Herbert I. Rettinger, MD, also conceded that poorly controlled blood sugars and confounding illnesses, such as renal and cardiac conditions, are common in patients with long-standing diabetes, but “there is a huge population of patients with type 1 diabetes, and very few seem to be more susceptible to infection. Perhaps I am missing those with poor diet and glucose control.”

Philip Levy, MD, picked up on that latter point, emphasizing that “endocrinologists take care of fewer patients with diabetes than do primary care physicians. Most patients with type 2 diabetes are not seen by us unless the PCP has problems [treating them],” so it could be that PCPs may see a higher number of patients who are at a greater risk for infections.

Ultimately, “good glucose control is very helpful in avoiding infections,” said Dr. Levy, of the Banner University Medical Group Endocrinology & Diabetes, Phoenix.

For sick patients

Guidelines for patients at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston advise patients who are feeling sick to continue taking their diabetes medications, unless instructed otherwise by their providers, and to monitor their glucose more frequently because it can spike suddenly.

Patients with type 1 diabetes should check for ketones if their glucose passes 250 mg/dL, according to the guidelines, and patients should remain hydrated at all times and get plenty of rest.

“Sick-day guidelines definitely apply, but patients should be advised to get tested if they have any symptoms they are concerned about,” said Dr. Rettinger, of the Endocrinology Medical Group of Orange County, Orange, Calif.

If patients with diabetes develop COVID-19, then home management may still be possible, according to Ritesh Gupta, MD, of Fortis C-DOC Hospital, New Delhi, and colleagues (Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020 Mar 10;14[3]:211-2. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.002).

Dr. Rettinger agreed, noting that home management would be feasible as long as “everything is going well, that is, the patient is not experiencing respiratory problems or difficulties in controlling glucose levels. Consider patients with type 1 diabetes who have COVID-19 as you would a nursing home patient – ever vigilant.”

Dr. Gupta and coauthors also recommended basic treatment measures such as maintaining hydration and managing symptoms with acetaminophen and steam inhalation, and home isolation for 14 days or until the symptoms resolve. However, the ADA warns in its guidelines that patients should “be aware that some constant glucose monitoring sensors (Dexcom G5, Medtronic Enlite, and Guardian) are impacted by acetaminophen (Tylenol), and that patients should check with finger sticks to ensure accuracy [if they are taking acetaminophen].”

In the event of hyperglycemia with fever in patients with type 1 diabetes, blood glucose and urinary ketones should be monitored often, the authors wrote, cautioning that “frequent changes in dosage and correctional bolus may be required to maintain normoglycemia.” Dr Rettinger emphasized that “hyperglycemia, as always, is best treated with fluids and insulin and frequent checks of sugars to be sure the treatment regimen is successful.”

In regard to diabetic drug regimens, patients with type 1 or 2 disease should continue on their current medications, advised Yehuda Handelsman, MD. “Some, especially those on insulin, may require more of it. And the patient should increase fluid intake to prevent fluid depletion. We do not reduce antihyperglycemic medication to preserve fluids.

“As for hypoglycemia, we always aim for less to no hypoglycemia,” he continued. “Monitoring glucose and appropriate dosage is the way to go. In other words, do not reduce medications in sick patients who typically need more medication.”

Dr. Handelsman, medical director and principal investigator at Metabolic Institute of America, Tarzana, Calif., added that very sick patients who are hospitalized should be managed with insulin and that oral agents – particularly metformin and sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitors – should be stopped.

“Once the patient has recovered and stabilized, you can return to the prior regimen, and, even if the patient is still in hospital, noninsulin therapy can be reintroduced,” he said.

“This is standard procedure in very sick patients, especially those in critical care. Metformin may raise lactic acid levels, and the SGLT2 inhibitors cause volume contraction, fat metabolism, and acidosis,” he explained. “We also stop the glucagon-like peptide receptor–1 analogues, which can cause nausea and vomiting, and pioglitazone because it causes fluid overload.

“Only insulin can be used for acutely sick patients – those with sepsis, for example. The same would apply if they have severe breathing disorders, and definitely, if they are on a ventilator. This is also the time we stop aromatase inhibitor orals and we use insulin.”

Preventive measures

In the interest of maintaining good glucose control, patients also should monitor their glucose levels more frequently so that fluctuations can be detected early and quickly addressed with the appropriate medication adjustments, according to guidelines from the ADA and AACE. They should continue to follow a healthy diet that includes adequate protein and they should exercise regularly.

Patients should ensure that they have enough medication and testing supplies – for at least 14 days, and longer, if costs permit – in case they have to go into quarantine.

General preventive measures, such as frequent hand washing with soap and water, practicing good respiratory hygiene by sneezing or coughing into a facial tissue or bent elbow, also apply for reducing the risk of infection. Touching of the face should be avoided, as should nonessential travel and contact with infected individuals.

Patients with diabetes should always be current with their influenza and pneumonia shots.

Dr. Rettinger said that he always recommends the following preventative measures to his patients and he is using the current health crisis to reinforce them:

- Eat lots of multicolored fruits and vegetables.

- Eat yogurt and take probiotics to keep the intestinal biome strong and functional.

- Be extra vigilant regarding sugars and sugar control to avoid peaks and valleys wherever possible.

- Keep the immune system strong with at least 7-8 hours sleep and reduce stress levels whenever possible.

- Avoid crowds and handshaking.

- Wash hands regularly.

Possible therapies

There are currently no drugs that have been approved specifically for the treatment of COVID-19, although a vaccine against the disease is currently under development.

Dr. Gupta and his colleagues noted in their article that there have been reports of the anecdotal use of antiviral drugs such as lopinavir, ritonavir, interferon-beta, the RNA polymerase inhibitor remdesivir, and chloroquine.

However, Dr. Handelsman said that, as far as he knows, none of these drugs has been shown to be beneficial for COVID-19. “Some [providers] have tried Tamiflu, but with no clear outcomes, and for severely sick patients, they tried medications for anti-HIV, hepatitis C, and malaria, but so far, there has been no breakthrough.”

Dr. Cohen, Dr. Handelsman, Dr. Jellinger, Dr. Levy, and Dr. Rettinger are members of the editorial advisory board of Clinical Endocrinology News. Dr. Gupta and Dr. Wu, and their colleagues, reported no conflicts of interest.

Patients with diabetes may be at extra risk for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) mortality, and doctors treating them need to keep up with the latest guidelines and expert advice.

Most health advisories about COVID-19 mention diabetes as one of the high-risk categories for the disease, likely because early data coming out of China, where the disease was first reported, indicated an elevated case-fatality rate for COVID-19 patients who also had diabetes.

In an article published in JAMA, Zunyou Wu, MD, and Jennifer M. McGoogan, PhD, summarized the findings from a February report on 44,672 confirmed cases of the disease from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The overall case-fatality rate (CFR) at that stage was 2.3% (1,023 deaths of the 44,672 confirmed cases). The data indicated that the CFR was elevated among COVID-19 patients with preexisting comorbid conditions, specifically, cardiovascular disease (CFR, 10.5%), diabetes (7.3%), chronic respiratory disease (6.3%), hypertension (6%), and cancer (5.6%).

The data also showed an aged-related trend in the CFR, with patients aged 80 years or older having a CFR of 14.8% and those aged 70-79 years, a rate of 8.0%, while there were no fatal cases reported in patients aged 9 years or younger (JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648).

Those findings have been echoed by the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. The American Diabetes Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists have in turn referenced the CDC in their COVID-19 guidance recommendations for patients with diabetes.

Guidelines were already in place for treatment of infections in patients with diabetes, and

In general, patients with diabetes – especially those whose disease is not controlled, or not well controlled – can be more susceptible to more common infections, such as influenza and pneumonia, possibly because hyperglycemia can subdue immunity by disrupting function of the white blood cells.

Glucose control is key

An important factor in any form of infection control in patients with diabetes seems to be whether or not a patient’s glucose levels are well controlled, according to comments from members of the editorial advisory board for Clinical Endocrinology News. Good glucose control, therefore, could be instrumental in reducing both the risk for and severity of infection.

Paul Jellinger, MD, of the Center for Diabetes & Endocrine Care, Hollywood, Fla., said that, over the years, he had not observed higher infection rates in general in patients with hemoglobin A1c levels below 7, or even higher. However, “a bigger question for me, given the broad category of ‘diabetes’ listed as a risk for serious coronavirus complications by the CDC, has been: Just which individuals with diabetes are really at risk? Are patients with well-controlled diabetes at increased risk as much as those with significant hyperglycemia and uncontrolled diabetes? In my view, not likely.”

Alan Jay Cohen, MD, agreed with Dr. Jellinger. “Many patients have called the office in the last 10 days to ask if there are special precautions they should take because they are reading that they are in the high-risk group because they have diabetes. Many of them are in superb, or at least pretty good, control. I have not seen where they have had a higher incidence of infection than the general population, and I have not seen data with COVID-19 that specifically demonstrates that a person with diabetes in good control has an increased risk,” he said.

“My recommendations to these patients have been the same as those given to the general population,” added Dr. Cohen, medical director at Baptist Medical Group: The Endocrine Clinic, Memphis.

Herbert I. Rettinger, MD, also conceded that poorly controlled blood sugars and confounding illnesses, such as renal and cardiac conditions, are common in patients with long-standing diabetes, but “there is a huge population of patients with type 1 diabetes, and very few seem to be more susceptible to infection. Perhaps I am missing those with poor diet and glucose control.”

Philip Levy, MD, picked up on that latter point, emphasizing that “endocrinologists take care of fewer patients with diabetes than do primary care physicians. Most patients with type 2 diabetes are not seen by us unless the PCP has problems [treating them],” so it could be that PCPs may see a higher number of patients who are at a greater risk for infections.

Ultimately, “good glucose control is very helpful in avoiding infections,” said Dr. Levy, of the Banner University Medical Group Endocrinology & Diabetes, Phoenix.

For sick patients

Guidelines for patients at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston advise patients who are feeling sick to continue taking their diabetes medications, unless instructed otherwise by their providers, and to monitor their glucose more frequently because it can spike suddenly.

Patients with type 1 diabetes should check for ketones if their glucose passes 250 mg/dL, according to the guidelines, and patients should remain hydrated at all times and get plenty of rest.

“Sick-day guidelines definitely apply, but patients should be advised to get tested if they have any symptoms they are concerned about,” said Dr. Rettinger, of the Endocrinology Medical Group of Orange County, Orange, Calif.

If patients with diabetes develop COVID-19, then home management may still be possible, according to Ritesh Gupta, MD, of Fortis C-DOC Hospital, New Delhi, and colleagues (Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020 Mar 10;14[3]:211-2. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.002).

Dr. Rettinger agreed, noting that home management would be feasible as long as “everything is going well, that is, the patient is not experiencing respiratory problems or difficulties in controlling glucose levels. Consider patients with type 1 diabetes who have COVID-19 as you would a nursing home patient – ever vigilant.”

Dr. Gupta and coauthors also recommended basic treatment measures such as maintaining hydration and managing symptoms with acetaminophen and steam inhalation, and home isolation for 14 days or until the symptoms resolve. However, the ADA warns in its guidelines that patients should “be aware that some constant glucose monitoring sensors (Dexcom G5, Medtronic Enlite, and Guardian) are impacted by acetaminophen (Tylenol), and that patients should check with finger sticks to ensure accuracy [if they are taking acetaminophen].”

In the event of hyperglycemia with fever in patients with type 1 diabetes, blood glucose and urinary ketones should be monitored often, the authors wrote, cautioning that “frequent changes in dosage and correctional bolus may be required to maintain normoglycemia.” Dr Rettinger emphasized that “hyperglycemia, as always, is best treated with fluids and insulin and frequent checks of sugars to be sure the treatment regimen is successful.”

In regard to diabetic drug regimens, patients with type 1 or 2 disease should continue on their current medications, advised Yehuda Handelsman, MD. “Some, especially those on insulin, may require more of it. And the patient should increase fluid intake to prevent fluid depletion. We do not reduce antihyperglycemic medication to preserve fluids.

“As for hypoglycemia, we always aim for less to no hypoglycemia,” he continued. “Monitoring glucose and appropriate dosage is the way to go. In other words, do not reduce medications in sick patients who typically need more medication.”

Dr. Handelsman, medical director and principal investigator at Metabolic Institute of America, Tarzana, Calif., added that very sick patients who are hospitalized should be managed with insulin and that oral agents – particularly metformin and sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitors – should be stopped.

“Once the patient has recovered and stabilized, you can return to the prior regimen, and, even if the patient is still in hospital, noninsulin therapy can be reintroduced,” he said.

“This is standard procedure in very sick patients, especially those in critical care. Metformin may raise lactic acid levels, and the SGLT2 inhibitors cause volume contraction, fat metabolism, and acidosis,” he explained. “We also stop the glucagon-like peptide receptor–1 analogues, which can cause nausea and vomiting, and pioglitazone because it causes fluid overload.

“Only insulin can be used for acutely sick patients – those with sepsis, for example. The same would apply if they have severe breathing disorders, and definitely, if they are on a ventilator. This is also the time we stop aromatase inhibitor orals and we use insulin.”

Preventive measures

In the interest of maintaining good glucose control, patients also should monitor their glucose levels more frequently so that fluctuations can be detected early and quickly addressed with the appropriate medication adjustments, according to guidelines from the ADA and AACE. They should continue to follow a healthy diet that includes adequate protein and they should exercise regularly.

Patients should ensure that they have enough medication and testing supplies – for at least 14 days, and longer, if costs permit – in case they have to go into quarantine.

General preventive measures, such as frequent hand washing with soap and water, practicing good respiratory hygiene by sneezing or coughing into a facial tissue or bent elbow, also apply for reducing the risk of infection. Touching of the face should be avoided, as should nonessential travel and contact with infected individuals.

Patients with diabetes should always be current with their influenza and pneumonia shots.

Dr. Rettinger said that he always recommends the following preventative measures to his patients and he is using the current health crisis to reinforce them:

- Eat lots of multicolored fruits and vegetables.

- Eat yogurt and take probiotics to keep the intestinal biome strong and functional.

- Be extra vigilant regarding sugars and sugar control to avoid peaks and valleys wherever possible.

- Keep the immune system strong with at least 7-8 hours sleep and reduce stress levels whenever possible.

- Avoid crowds and handshaking.

- Wash hands regularly.

Possible therapies

There are currently no drugs that have been approved specifically for the treatment of COVID-19, although a vaccine against the disease is currently under development.

Dr. Gupta and his colleagues noted in their article that there have been reports of the anecdotal use of antiviral drugs such as lopinavir, ritonavir, interferon-beta, the RNA polymerase inhibitor remdesivir, and chloroquine.

However, Dr. Handelsman said that, as far as he knows, none of these drugs has been shown to be beneficial for COVID-19. “Some [providers] have tried Tamiflu, but with no clear outcomes, and for severely sick patients, they tried medications for anti-HIV, hepatitis C, and malaria, but so far, there has been no breakthrough.”

Dr. Cohen, Dr. Handelsman, Dr. Jellinger, Dr. Levy, and Dr. Rettinger are members of the editorial advisory board of Clinical Endocrinology News. Dr. Gupta and Dr. Wu, and their colleagues, reported no conflicts of interest.

Patients with diabetes may be at extra risk for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) mortality, and doctors treating them need to keep up with the latest guidelines and expert advice.

Most health advisories about COVID-19 mention diabetes as one of the high-risk categories for the disease, likely because early data coming out of China, where the disease was first reported, indicated an elevated case-fatality rate for COVID-19 patients who also had diabetes.

In an article published in JAMA, Zunyou Wu, MD, and Jennifer M. McGoogan, PhD, summarized the findings from a February report on 44,672 confirmed cases of the disease from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The overall case-fatality rate (CFR) at that stage was 2.3% (1,023 deaths of the 44,672 confirmed cases). The data indicated that the CFR was elevated among COVID-19 patients with preexisting comorbid conditions, specifically, cardiovascular disease (CFR, 10.5%), diabetes (7.3%), chronic respiratory disease (6.3%), hypertension (6%), and cancer (5.6%).

The data also showed an aged-related trend in the CFR, with patients aged 80 years or older having a CFR of 14.8% and those aged 70-79 years, a rate of 8.0%, while there were no fatal cases reported in patients aged 9 years or younger (JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648).

Those findings have been echoed by the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. The American Diabetes Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists have in turn referenced the CDC in their COVID-19 guidance recommendations for patients with diabetes.

Guidelines were already in place for treatment of infections in patients with diabetes, and

In general, patients with diabetes – especially those whose disease is not controlled, or not well controlled – can be more susceptible to more common infections, such as influenza and pneumonia, possibly because hyperglycemia can subdue immunity by disrupting function of the white blood cells.

Glucose control is key

An important factor in any form of infection control in patients with diabetes seems to be whether or not a patient’s glucose levels are well controlled, according to comments from members of the editorial advisory board for Clinical Endocrinology News. Good glucose control, therefore, could be instrumental in reducing both the risk for and severity of infection.

Paul Jellinger, MD, of the Center for Diabetes & Endocrine Care, Hollywood, Fla., said that, over the years, he had not observed higher infection rates in general in patients with hemoglobin A1c levels below 7, or even higher. However, “a bigger question for me, given the broad category of ‘diabetes’ listed as a risk for serious coronavirus complications by the CDC, has been: Just which individuals with diabetes are really at risk? Are patients with well-controlled diabetes at increased risk as much as those with significant hyperglycemia and uncontrolled diabetes? In my view, not likely.”

Alan Jay Cohen, MD, agreed with Dr. Jellinger. “Many patients have called the office in the last 10 days to ask if there are special precautions they should take because they are reading that they are in the high-risk group because they have diabetes. Many of them are in superb, or at least pretty good, control. I have not seen where they have had a higher incidence of infection than the general population, and I have not seen data with COVID-19 that specifically demonstrates that a person with diabetes in good control has an increased risk,” he said.

“My recommendations to these patients have been the same as those given to the general population,” added Dr. Cohen, medical director at Baptist Medical Group: The Endocrine Clinic, Memphis.

Herbert I. Rettinger, MD, also conceded that poorly controlled blood sugars and confounding illnesses, such as renal and cardiac conditions, are common in patients with long-standing diabetes, but “there is a huge population of patients with type 1 diabetes, and very few seem to be more susceptible to infection. Perhaps I am missing those with poor diet and glucose control.”

Philip Levy, MD, picked up on that latter point, emphasizing that “endocrinologists take care of fewer patients with diabetes than do primary care physicians. Most patients with type 2 diabetes are not seen by us unless the PCP has problems [treating them],” so it could be that PCPs may see a higher number of patients who are at a greater risk for infections.

Ultimately, “good glucose control is very helpful in avoiding infections,” said Dr. Levy, of the Banner University Medical Group Endocrinology & Diabetes, Phoenix.

For sick patients

Guidelines for patients at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston advise patients who are feeling sick to continue taking their diabetes medications, unless instructed otherwise by their providers, and to monitor their glucose more frequently because it can spike suddenly.

Patients with type 1 diabetes should check for ketones if their glucose passes 250 mg/dL, according to the guidelines, and patients should remain hydrated at all times and get plenty of rest.

“Sick-day guidelines definitely apply, but patients should be advised to get tested if they have any symptoms they are concerned about,” said Dr. Rettinger, of the Endocrinology Medical Group of Orange County, Orange, Calif.

If patients with diabetes develop COVID-19, then home management may still be possible, according to Ritesh Gupta, MD, of Fortis C-DOC Hospital, New Delhi, and colleagues (Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020 Mar 10;14[3]:211-2. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.002).

Dr. Rettinger agreed, noting that home management would be feasible as long as “everything is going well, that is, the patient is not experiencing respiratory problems or difficulties in controlling glucose levels. Consider patients with type 1 diabetes who have COVID-19 as you would a nursing home patient – ever vigilant.”

Dr. Gupta and coauthors also recommended basic treatment measures such as maintaining hydration and managing symptoms with acetaminophen and steam inhalation, and home isolation for 14 days or until the symptoms resolve. However, the ADA warns in its guidelines that patients should “be aware that some constant glucose monitoring sensors (Dexcom G5, Medtronic Enlite, and Guardian) are impacted by acetaminophen (Tylenol), and that patients should check with finger sticks to ensure accuracy [if they are taking acetaminophen].”

In the event of hyperglycemia with fever in patients with type 1 diabetes, blood glucose and urinary ketones should be monitored often, the authors wrote, cautioning that “frequent changes in dosage and correctional bolus may be required to maintain normoglycemia.” Dr Rettinger emphasized that “hyperglycemia, as always, is best treated with fluids and insulin and frequent checks of sugars to be sure the treatment regimen is successful.”

In regard to diabetic drug regimens, patients with type 1 or 2 disease should continue on their current medications, advised Yehuda Handelsman, MD. “Some, especially those on insulin, may require more of it. And the patient should increase fluid intake to prevent fluid depletion. We do not reduce antihyperglycemic medication to preserve fluids.

“As for hypoglycemia, we always aim for less to no hypoglycemia,” he continued. “Monitoring glucose and appropriate dosage is the way to go. In other words, do not reduce medications in sick patients who typically need more medication.”

Dr. Handelsman, medical director and principal investigator at Metabolic Institute of America, Tarzana, Calif., added that very sick patients who are hospitalized should be managed with insulin and that oral agents – particularly metformin and sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitors – should be stopped.

“Once the patient has recovered and stabilized, you can return to the prior regimen, and, even if the patient is still in hospital, noninsulin therapy can be reintroduced,” he said.

“This is standard procedure in very sick patients, especially those in critical care. Metformin may raise lactic acid levels, and the SGLT2 inhibitors cause volume contraction, fat metabolism, and acidosis,” he explained. “We also stop the glucagon-like peptide receptor–1 analogues, which can cause nausea and vomiting, and pioglitazone because it causes fluid overload.

“Only insulin can be used for acutely sick patients – those with sepsis, for example. The same would apply if they have severe breathing disorders, and definitely, if they are on a ventilator. This is also the time we stop aromatase inhibitor orals and we use insulin.”

Preventive measures

In the interest of maintaining good glucose control, patients also should monitor their glucose levels more frequently so that fluctuations can be detected early and quickly addressed with the appropriate medication adjustments, according to guidelines from the ADA and AACE. They should continue to follow a healthy diet that includes adequate protein and they should exercise regularly.

Patients should ensure that they have enough medication and testing supplies – for at least 14 days, and longer, if costs permit – in case they have to go into quarantine.

General preventive measures, such as frequent hand washing with soap and water, practicing good respiratory hygiene by sneezing or coughing into a facial tissue or bent elbow, also apply for reducing the risk of infection. Touching of the face should be avoided, as should nonessential travel and contact with infected individuals.

Patients with diabetes should always be current with their influenza and pneumonia shots.

Dr. Rettinger said that he always recommends the following preventative measures to his patients and he is using the current health crisis to reinforce them:

- Eat lots of multicolored fruits and vegetables.

- Eat yogurt and take probiotics to keep the intestinal biome strong and functional.

- Be extra vigilant regarding sugars and sugar control to avoid peaks and valleys wherever possible.

- Keep the immune system strong with at least 7-8 hours sleep and reduce stress levels whenever possible.

- Avoid crowds and handshaking.

- Wash hands regularly.

Possible therapies

There are currently no drugs that have been approved specifically for the treatment of COVID-19, although a vaccine against the disease is currently under development.