User login

Improving sepsis-related outcomes

Early diagnosis a key goal

Sepsis is a leading cause of death and disease among patients in hospitals, and it’s the subject of a recent quality improvement study in the Journal for Healthcare Quality.

“The number of cases per year has been increasing in the U.S., and it is the most expensive condition treated in U.S. hospitals,” said lead author M. Courtney Hughes, PhD, of Northern Illinois University in DeKalb.

But early identification of symptoms can be complex and difficult for clinicians, meaning there’s a continuing need for research studies examining sepsis identification and prevention. “The purpose of this study was to examine a quality improvement project that consisted of clinical alerts, audit and feedback, and staff education at an integrated health care system in the Midwest,” she said.

In a retrospective analysis, the researchers examined data from three health systems to determine the impact of a 10-month sepsis quality improvement program that consisted of clinical alerts, audit and feedback, and staff education. The results showed that, compared with the control group, the intervention group significantly decreased length of stay and costs per stay.

“One way to improve sepsis health outcomes and decrease costs may be for hospitals to implement a sepsis quality improvement program,” Dr. Hughes said. “Also, providing sepsis performance data and education to hospital providers and administrators can arm staff with the knowledge and tools necessary for improving processes and performance related to sepsis.”

Dr. Hughes said that she hopes this work will encourage hospitalists to seek sepsis-related performance data and training. “By doing so, they may help achieve earlier diagnosis of sepsis cases and initiation of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle.”

Reference

Hughes MC et al. A quality improvement project to improve sepsis-related outcomes at an integrated healthcare system. J Healthc Qual. Published online 2019 Mar 14. doi: 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000193.

Early diagnosis a key goal

Early diagnosis a key goal

Sepsis is a leading cause of death and disease among patients in hospitals, and it’s the subject of a recent quality improvement study in the Journal for Healthcare Quality.

“The number of cases per year has been increasing in the U.S., and it is the most expensive condition treated in U.S. hospitals,” said lead author M. Courtney Hughes, PhD, of Northern Illinois University in DeKalb.

But early identification of symptoms can be complex and difficult for clinicians, meaning there’s a continuing need for research studies examining sepsis identification and prevention. “The purpose of this study was to examine a quality improvement project that consisted of clinical alerts, audit and feedback, and staff education at an integrated health care system in the Midwest,” she said.

In a retrospective analysis, the researchers examined data from three health systems to determine the impact of a 10-month sepsis quality improvement program that consisted of clinical alerts, audit and feedback, and staff education. The results showed that, compared with the control group, the intervention group significantly decreased length of stay and costs per stay.

“One way to improve sepsis health outcomes and decrease costs may be for hospitals to implement a sepsis quality improvement program,” Dr. Hughes said. “Also, providing sepsis performance data and education to hospital providers and administrators can arm staff with the knowledge and tools necessary for improving processes and performance related to sepsis.”

Dr. Hughes said that she hopes this work will encourage hospitalists to seek sepsis-related performance data and training. “By doing so, they may help achieve earlier diagnosis of sepsis cases and initiation of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle.”

Reference

Hughes MC et al. A quality improvement project to improve sepsis-related outcomes at an integrated healthcare system. J Healthc Qual. Published online 2019 Mar 14. doi: 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000193.

Sepsis is a leading cause of death and disease among patients in hospitals, and it’s the subject of a recent quality improvement study in the Journal for Healthcare Quality.

“The number of cases per year has been increasing in the U.S., and it is the most expensive condition treated in U.S. hospitals,” said lead author M. Courtney Hughes, PhD, of Northern Illinois University in DeKalb.

But early identification of symptoms can be complex and difficult for clinicians, meaning there’s a continuing need for research studies examining sepsis identification and prevention. “The purpose of this study was to examine a quality improvement project that consisted of clinical alerts, audit and feedback, and staff education at an integrated health care system in the Midwest,” she said.

In a retrospective analysis, the researchers examined data from three health systems to determine the impact of a 10-month sepsis quality improvement program that consisted of clinical alerts, audit and feedback, and staff education. The results showed that, compared with the control group, the intervention group significantly decreased length of stay and costs per stay.

“One way to improve sepsis health outcomes and decrease costs may be for hospitals to implement a sepsis quality improvement program,” Dr. Hughes said. “Also, providing sepsis performance data and education to hospital providers and administrators can arm staff with the knowledge and tools necessary for improving processes and performance related to sepsis.”

Dr. Hughes said that she hopes this work will encourage hospitalists to seek sepsis-related performance data and training. “By doing so, they may help achieve earlier diagnosis of sepsis cases and initiation of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle.”

Reference

Hughes MC et al. A quality improvement project to improve sepsis-related outcomes at an integrated healthcare system. J Healthc Qual. Published online 2019 Mar 14. doi: 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000193.

New ASH guideline: VTE prophylaxis after major surgery

ORLANDO – The latest American Society of Hematology guideline on venous thromboembolism (VTE) tackles 30 key questions regarding prophylaxis in hospitalized patients undergoing surgery, according to the chair of the guideline panel, who highlighted 9 of those questions during a special session at the society’s annual meeting.

The clinical practice guideline, published just about a week before the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, focuses mainly on pharmacologic prophylaxis in specific surgical settings, said David R. Anderson, MD, dean of the faculty of medicine of Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S.

“Our guidelines focused upon clinically important symptomatic outcomes, with less emphasis being placed on asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis detected by screening tests,” Dr. Anderson said.

At the special education session, Dr. Anderson highlighted several specific recommendations on prophylaxis in surgical patients.

Pharmacologic prophylaxis is not recommended for patients experiencing major trauma deemed to be at high risk of bleeding. Its use does reduce risk of symptomatic pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) by about 10 events per 1,000 patients treated; however, Dr. Anderson said, the panel’s opinion was that this benefit was outweighed by increased risk of major bleeding, at 24 events per 1,000 patients treated.

“We do recommend, however that this risk of bleeding must be reevaluated over the course of recovery of patients, and this may change the decision around this intervention over time,” Dr. Anderson told attendees at the special session.

That’s because pharmacologic prophylaxis is recommended in surgical patients at low to moderate risk of bleeding. In this scenario, the incremental risk of major bleeding (14 events per 1,000 patients treated) is outweighed by the benefit of the reduction of symptomatic VTE events, according to Dr. Anderson.

When pharmacologic prophylaxis is used, the panel recommends combined prophylaxis – mechanical prophylaxis in addition to pharmacologic prophylaxis – especially in those patients at high or very high risk of VTE. Evidence shows that the combination approach significantly reduces risk of PE, and strongly suggests it may also reduce risk of symptomatic proximal DVT, Dr. Anderson said.

In surgical patients not receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis, mechanical prophylaxis is recommended over no mechanical prophylaxis, he added. Moreover, in those patients receiving mechanical prophylaxis, the ASH panel recommends use of intermittent compression devices over graduated compression stockings.

The panel comes out against prophylactic inferior vena cava (IVC) filter insertion in the guidelines. Dr. Anderson said that the “small reduction” in PE risk seen in observational studies is outweighed by increased risk of DVT, and a resulting trend for increased mortality, associated with insertion of the devices.

“We did not consider other risks of IVC filters such as filter embolization or perforation, which again would be complications that would support our recommendation against routine use of these devices in patients undergoing major surgery,” he said.

In terms of the type of pharmacologic prophylaxis to use, the panel said low-molecular-weight heparin or unfractionated heparin would be reasonable choices in this setting. Available data do not demonstrate any significant differences between these choices for major clinical outcomes, Dr. Anderson added.

The guideline also addresses duration of pharmacologic prophylaxis, stating that extended prophylaxis – of at least 3 weeks – is favored over short-term prophylaxis, or up to 2 weeks of treatment. The extended approach significantly reduces risk of symptomatic PE and proximal DVT, though most of the supporting data come from studies of major joint arthroplasty and major general surgical procedures for patients with cancer. “We need more studies in other clinical areas to examine this particular question,” Dr. Anderson said.

The guideline on prophylaxis in surgical patients was published in Blood Advances (2019 Dec 3;3[23]:3898-944). Six other ASH VTE guidelines, all published in 2018, covered prophylaxis in medical patients, diagnosis, VTE in pregnancy, optimal anticoagulation, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and pediatric considerations. The guidelines are available on the ASH website.

Dr. Anderson reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – The latest American Society of Hematology guideline on venous thromboembolism (VTE) tackles 30 key questions regarding prophylaxis in hospitalized patients undergoing surgery, according to the chair of the guideline panel, who highlighted 9 of those questions during a special session at the society’s annual meeting.

The clinical practice guideline, published just about a week before the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, focuses mainly on pharmacologic prophylaxis in specific surgical settings, said David R. Anderson, MD, dean of the faculty of medicine of Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S.

“Our guidelines focused upon clinically important symptomatic outcomes, with less emphasis being placed on asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis detected by screening tests,” Dr. Anderson said.

At the special education session, Dr. Anderson highlighted several specific recommendations on prophylaxis in surgical patients.

Pharmacologic prophylaxis is not recommended for patients experiencing major trauma deemed to be at high risk of bleeding. Its use does reduce risk of symptomatic pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) by about 10 events per 1,000 patients treated; however, Dr. Anderson said, the panel’s opinion was that this benefit was outweighed by increased risk of major bleeding, at 24 events per 1,000 patients treated.

“We do recommend, however that this risk of bleeding must be reevaluated over the course of recovery of patients, and this may change the decision around this intervention over time,” Dr. Anderson told attendees at the special session.

That’s because pharmacologic prophylaxis is recommended in surgical patients at low to moderate risk of bleeding. In this scenario, the incremental risk of major bleeding (14 events per 1,000 patients treated) is outweighed by the benefit of the reduction of symptomatic VTE events, according to Dr. Anderson.

When pharmacologic prophylaxis is used, the panel recommends combined prophylaxis – mechanical prophylaxis in addition to pharmacologic prophylaxis – especially in those patients at high or very high risk of VTE. Evidence shows that the combination approach significantly reduces risk of PE, and strongly suggests it may also reduce risk of symptomatic proximal DVT, Dr. Anderson said.

In surgical patients not receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis, mechanical prophylaxis is recommended over no mechanical prophylaxis, he added. Moreover, in those patients receiving mechanical prophylaxis, the ASH panel recommends use of intermittent compression devices over graduated compression stockings.

The panel comes out against prophylactic inferior vena cava (IVC) filter insertion in the guidelines. Dr. Anderson said that the “small reduction” in PE risk seen in observational studies is outweighed by increased risk of DVT, and a resulting trend for increased mortality, associated with insertion of the devices.

“We did not consider other risks of IVC filters such as filter embolization or perforation, which again would be complications that would support our recommendation against routine use of these devices in patients undergoing major surgery,” he said.

In terms of the type of pharmacologic prophylaxis to use, the panel said low-molecular-weight heparin or unfractionated heparin would be reasonable choices in this setting. Available data do not demonstrate any significant differences between these choices for major clinical outcomes, Dr. Anderson added.

The guideline also addresses duration of pharmacologic prophylaxis, stating that extended prophylaxis – of at least 3 weeks – is favored over short-term prophylaxis, or up to 2 weeks of treatment. The extended approach significantly reduces risk of symptomatic PE and proximal DVT, though most of the supporting data come from studies of major joint arthroplasty and major general surgical procedures for patients with cancer. “We need more studies in other clinical areas to examine this particular question,” Dr. Anderson said.

The guideline on prophylaxis in surgical patients was published in Blood Advances (2019 Dec 3;3[23]:3898-944). Six other ASH VTE guidelines, all published in 2018, covered prophylaxis in medical patients, diagnosis, VTE in pregnancy, optimal anticoagulation, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and pediatric considerations. The guidelines are available on the ASH website.

Dr. Anderson reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – The latest American Society of Hematology guideline on venous thromboembolism (VTE) tackles 30 key questions regarding prophylaxis in hospitalized patients undergoing surgery, according to the chair of the guideline panel, who highlighted 9 of those questions during a special session at the society’s annual meeting.

The clinical practice guideline, published just about a week before the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, focuses mainly on pharmacologic prophylaxis in specific surgical settings, said David R. Anderson, MD, dean of the faculty of medicine of Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S.

“Our guidelines focused upon clinically important symptomatic outcomes, with less emphasis being placed on asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis detected by screening tests,” Dr. Anderson said.

At the special education session, Dr. Anderson highlighted several specific recommendations on prophylaxis in surgical patients.

Pharmacologic prophylaxis is not recommended for patients experiencing major trauma deemed to be at high risk of bleeding. Its use does reduce risk of symptomatic pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) by about 10 events per 1,000 patients treated; however, Dr. Anderson said, the panel’s opinion was that this benefit was outweighed by increased risk of major bleeding, at 24 events per 1,000 patients treated.

“We do recommend, however that this risk of bleeding must be reevaluated over the course of recovery of patients, and this may change the decision around this intervention over time,” Dr. Anderson told attendees at the special session.

That’s because pharmacologic prophylaxis is recommended in surgical patients at low to moderate risk of bleeding. In this scenario, the incremental risk of major bleeding (14 events per 1,000 patients treated) is outweighed by the benefit of the reduction of symptomatic VTE events, according to Dr. Anderson.

When pharmacologic prophylaxis is used, the panel recommends combined prophylaxis – mechanical prophylaxis in addition to pharmacologic prophylaxis – especially in those patients at high or very high risk of VTE. Evidence shows that the combination approach significantly reduces risk of PE, and strongly suggests it may also reduce risk of symptomatic proximal DVT, Dr. Anderson said.

In surgical patients not receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis, mechanical prophylaxis is recommended over no mechanical prophylaxis, he added. Moreover, in those patients receiving mechanical prophylaxis, the ASH panel recommends use of intermittent compression devices over graduated compression stockings.

The panel comes out against prophylactic inferior vena cava (IVC) filter insertion in the guidelines. Dr. Anderson said that the “small reduction” in PE risk seen in observational studies is outweighed by increased risk of DVT, and a resulting trend for increased mortality, associated with insertion of the devices.

“We did not consider other risks of IVC filters such as filter embolization or perforation, which again would be complications that would support our recommendation against routine use of these devices in patients undergoing major surgery,” he said.

In terms of the type of pharmacologic prophylaxis to use, the panel said low-molecular-weight heparin or unfractionated heparin would be reasonable choices in this setting. Available data do not demonstrate any significant differences between these choices for major clinical outcomes, Dr. Anderson added.

The guideline also addresses duration of pharmacologic prophylaxis, stating that extended prophylaxis – of at least 3 weeks – is favored over short-term prophylaxis, or up to 2 weeks of treatment. The extended approach significantly reduces risk of symptomatic PE and proximal DVT, though most of the supporting data come from studies of major joint arthroplasty and major general surgical procedures for patients with cancer. “We need more studies in other clinical areas to examine this particular question,” Dr. Anderson said.

The guideline on prophylaxis in surgical patients was published in Blood Advances (2019 Dec 3;3[23]:3898-944). Six other ASH VTE guidelines, all published in 2018, covered prophylaxis in medical patients, diagnosis, VTE in pregnancy, optimal anticoagulation, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and pediatric considerations. The guidelines are available on the ASH website.

Dr. Anderson reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ASH 2019

Unit-based rounding in the real world

Balance and flexibility are essential

Many hospitalists agree that their most productive and also sometimes least productive work can happen in the setting of interdisciplinary rounds. How can this paradox be true?

Most hospitals strive to assemble the health care team every day for a brief discussion of each patient’s needs as well as barriers to a safe/successful discharge. On most floors this requires a well-choreographed “dance” of nurses, case managers, social workers, physicians, and advanced practice providers coming together at agreed-upon times. All team members commit to efficient synchronized swimming through the most high-yield details for each patient in order to benefit the patients and families being served.

Of course, there are always challenges to this process in the unpredictable world of patients with acute needs. One variable that is at least partially controllable and tends to promote a more cohesive interdisciplinary experience is that of hospitalist unit-based rounding.

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) survey reveals that 68% of hospital medicine groups serving adults with greater than 30 physicians employ some degree of unit-based rounding; this trend decreases with smaller group size. About 54% of academic hospital medicine groups use some amount of unit-based rounding. Not surprisingly, smaller hospitals are less likely to have this routine, likely because of fewer total nursing units.

One of the most obvious benefits to unit-based rounding is that the physician or advanced practice provider is more reliably able to participate in the interdisciplinary discussions that day. When more of the team members are at the table each day, patients and families have the best chance of hearing a consistent message around the treatment and discharge plans.

There are challenges to unit-based rounding as well. If patients transfer to different floors for any variety of reasons, strict unit-based rounding may increase handoffs in care. If a hospital has times when it isn’t completely full and nursing units have a varying percentage of being occupied, strict unit-based rounding can cause significant workload inequities among physicians on different units, depending on numbers of patients on each unit.

If there is no attempt at unit-based rounding in larger hospitals, some physicians may be running among five or more units. They work to find different care managers, nurses, and pharmacists – not to mention the challenges of catching patients in their rooms between their departures for diagnostic studies and procedures.

It is often good to balance the benefit of promoting unit-based rounds with the reality of everyday patient care. Some groups maintain that the physician/patient relationship trumps the idea of perfect unit-based rounding. In other words, if a physician establishes a relationship with a patient while they are in the ED being admitted or boarding from overnight, that physician will continue seeing the patient regardless of the patient being assigned to a different unit. It can help for groups to agree that the pursuit of unit-based rounding may create some inequity in the numbers of patients seen each day because of these issues.

In a larger hospital, certain units are often dedicated to specialty care such as cardiac or stroke care. While most hospitalists want to maintain general medical knowledge, there are some who may enjoy having portions of their practice devoted to perioperative medicine or cardiac care, for instance. This promotes familiarity among hospitalists and groups of consultant physicians and nurse practitioners/physician assistants. Over time this allows for enhanced teamwork among those physicians, the nursing team, and the specialty physicians.

Depending on the group’s schedule, patients can be reassigned coinciding with the primary change of service day. This resets the physicians’ patients in the most ideal unit-based way on the evening prior to the first day of rounding for that week or group of shifts.

No matter how you do it, the goal of unit-based rounding is time efficiency for the care team and care coordination benefits for patients and families. If you have other suggestions or questions, go online to SHM HMX to join the discussion.

Take-home message: Unit-based rounding likely has its benefits. Don’t let the inability to achieve perfection in patient distribution to the physicians each day lead to abandonment of attempting these processes.

Dr. McNeal is the division director of inpatient medicine at Baylor Scott & White Medical Center in Temple, Tex.

Balance and flexibility are essential

Balance and flexibility are essential

Many hospitalists agree that their most productive and also sometimes least productive work can happen in the setting of interdisciplinary rounds. How can this paradox be true?

Most hospitals strive to assemble the health care team every day for a brief discussion of each patient’s needs as well as barriers to a safe/successful discharge. On most floors this requires a well-choreographed “dance” of nurses, case managers, social workers, physicians, and advanced practice providers coming together at agreed-upon times. All team members commit to efficient synchronized swimming through the most high-yield details for each patient in order to benefit the patients and families being served.

Of course, there are always challenges to this process in the unpredictable world of patients with acute needs. One variable that is at least partially controllable and tends to promote a more cohesive interdisciplinary experience is that of hospitalist unit-based rounding.

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) survey reveals that 68% of hospital medicine groups serving adults with greater than 30 physicians employ some degree of unit-based rounding; this trend decreases with smaller group size. About 54% of academic hospital medicine groups use some amount of unit-based rounding. Not surprisingly, smaller hospitals are less likely to have this routine, likely because of fewer total nursing units.

One of the most obvious benefits to unit-based rounding is that the physician or advanced practice provider is more reliably able to participate in the interdisciplinary discussions that day. When more of the team members are at the table each day, patients and families have the best chance of hearing a consistent message around the treatment and discharge plans.

There are challenges to unit-based rounding as well. If patients transfer to different floors for any variety of reasons, strict unit-based rounding may increase handoffs in care. If a hospital has times when it isn’t completely full and nursing units have a varying percentage of being occupied, strict unit-based rounding can cause significant workload inequities among physicians on different units, depending on numbers of patients on each unit.

If there is no attempt at unit-based rounding in larger hospitals, some physicians may be running among five or more units. They work to find different care managers, nurses, and pharmacists – not to mention the challenges of catching patients in their rooms between their departures for diagnostic studies and procedures.

It is often good to balance the benefit of promoting unit-based rounds with the reality of everyday patient care. Some groups maintain that the physician/patient relationship trumps the idea of perfect unit-based rounding. In other words, if a physician establishes a relationship with a patient while they are in the ED being admitted or boarding from overnight, that physician will continue seeing the patient regardless of the patient being assigned to a different unit. It can help for groups to agree that the pursuit of unit-based rounding may create some inequity in the numbers of patients seen each day because of these issues.

In a larger hospital, certain units are often dedicated to specialty care such as cardiac or stroke care. While most hospitalists want to maintain general medical knowledge, there are some who may enjoy having portions of their practice devoted to perioperative medicine or cardiac care, for instance. This promotes familiarity among hospitalists and groups of consultant physicians and nurse practitioners/physician assistants. Over time this allows for enhanced teamwork among those physicians, the nursing team, and the specialty physicians.

Depending on the group’s schedule, patients can be reassigned coinciding with the primary change of service day. This resets the physicians’ patients in the most ideal unit-based way on the evening prior to the first day of rounding for that week or group of shifts.

No matter how you do it, the goal of unit-based rounding is time efficiency for the care team and care coordination benefits for patients and families. If you have other suggestions or questions, go online to SHM HMX to join the discussion.

Take-home message: Unit-based rounding likely has its benefits. Don’t let the inability to achieve perfection in patient distribution to the physicians each day lead to abandonment of attempting these processes.

Dr. McNeal is the division director of inpatient medicine at Baylor Scott & White Medical Center in Temple, Tex.

Many hospitalists agree that their most productive and also sometimes least productive work can happen in the setting of interdisciplinary rounds. How can this paradox be true?

Most hospitals strive to assemble the health care team every day for a brief discussion of each patient’s needs as well as barriers to a safe/successful discharge. On most floors this requires a well-choreographed “dance” of nurses, case managers, social workers, physicians, and advanced practice providers coming together at agreed-upon times. All team members commit to efficient synchronized swimming through the most high-yield details for each patient in order to benefit the patients and families being served.

Of course, there are always challenges to this process in the unpredictable world of patients with acute needs. One variable that is at least partially controllable and tends to promote a more cohesive interdisciplinary experience is that of hospitalist unit-based rounding.

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) survey reveals that 68% of hospital medicine groups serving adults with greater than 30 physicians employ some degree of unit-based rounding; this trend decreases with smaller group size. About 54% of academic hospital medicine groups use some amount of unit-based rounding. Not surprisingly, smaller hospitals are less likely to have this routine, likely because of fewer total nursing units.

One of the most obvious benefits to unit-based rounding is that the physician or advanced practice provider is more reliably able to participate in the interdisciplinary discussions that day. When more of the team members are at the table each day, patients and families have the best chance of hearing a consistent message around the treatment and discharge plans.

There are challenges to unit-based rounding as well. If patients transfer to different floors for any variety of reasons, strict unit-based rounding may increase handoffs in care. If a hospital has times when it isn’t completely full and nursing units have a varying percentage of being occupied, strict unit-based rounding can cause significant workload inequities among physicians on different units, depending on numbers of patients on each unit.

If there is no attempt at unit-based rounding in larger hospitals, some physicians may be running among five or more units. They work to find different care managers, nurses, and pharmacists – not to mention the challenges of catching patients in their rooms between their departures for diagnostic studies and procedures.

It is often good to balance the benefit of promoting unit-based rounds with the reality of everyday patient care. Some groups maintain that the physician/patient relationship trumps the idea of perfect unit-based rounding. In other words, if a physician establishes a relationship with a patient while they are in the ED being admitted or boarding from overnight, that physician will continue seeing the patient regardless of the patient being assigned to a different unit. It can help for groups to agree that the pursuit of unit-based rounding may create some inequity in the numbers of patients seen each day because of these issues.

In a larger hospital, certain units are often dedicated to specialty care such as cardiac or stroke care. While most hospitalists want to maintain general medical knowledge, there are some who may enjoy having portions of their practice devoted to perioperative medicine or cardiac care, for instance. This promotes familiarity among hospitalists and groups of consultant physicians and nurse practitioners/physician assistants. Over time this allows for enhanced teamwork among those physicians, the nursing team, and the specialty physicians.

Depending on the group’s schedule, patients can be reassigned coinciding with the primary change of service day. This resets the physicians’ patients in the most ideal unit-based way on the evening prior to the first day of rounding for that week or group of shifts.

No matter how you do it, the goal of unit-based rounding is time efficiency for the care team and care coordination benefits for patients and families. If you have other suggestions or questions, go online to SHM HMX to join the discussion.

Take-home message: Unit-based rounding likely has its benefits. Don’t let the inability to achieve perfection in patient distribution to the physicians each day lead to abandonment of attempting these processes.

Dr. McNeal is the division director of inpatient medicine at Baylor Scott & White Medical Center in Temple, Tex.

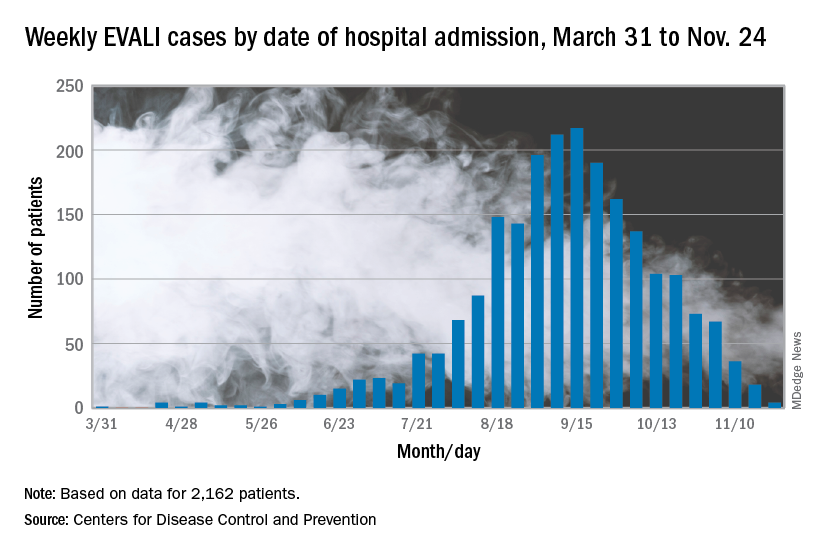

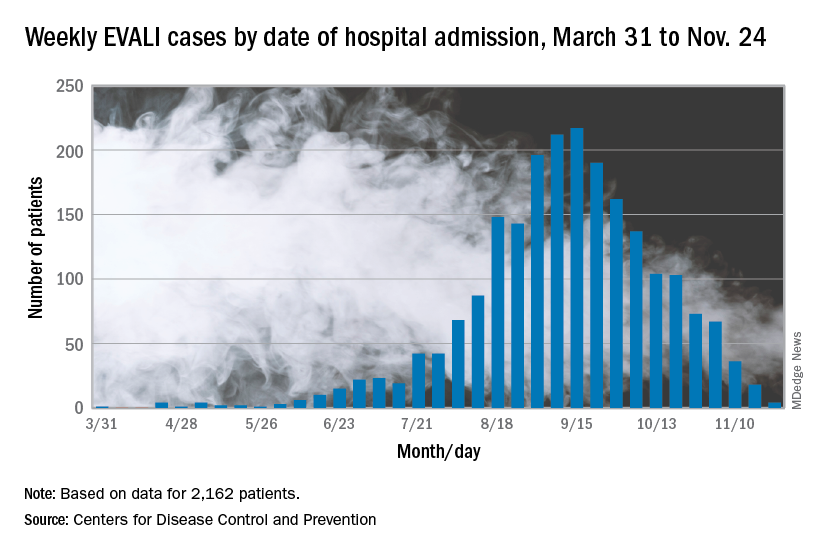

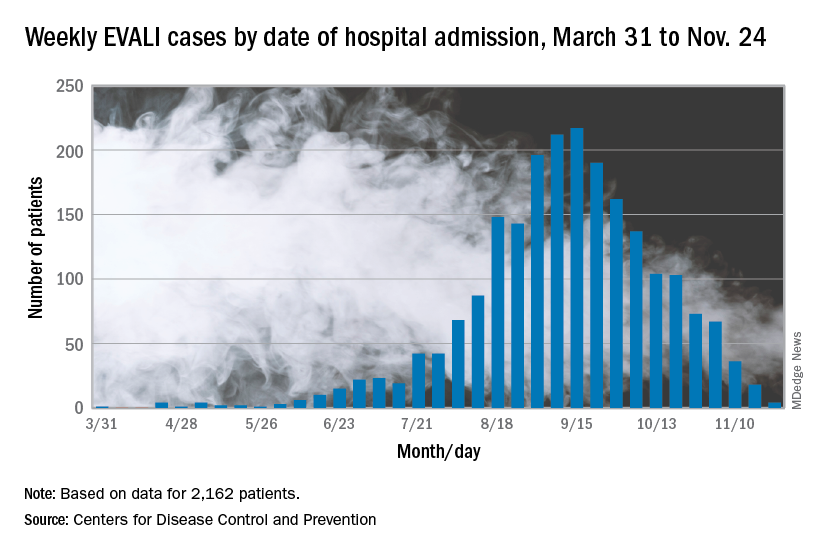

EVALI outbreak ongoing, but new cases decline

The vaping lung disease outbreak continues, but according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it may have peaked and the number of new hospitalized cases reported to the CDC may be decreasing.

In the Dec. 6, 2019, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the CDC has updated information about cases of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (EVALI): As of Dec. 3, there have been 2,291 cases reported from all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and two U.S. territories (Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands). A total of 48 deaths have been confirmed in 25 states and Washington, D.C., the CDC reported.

The largest number of weekly hospitalized cases occurred during the week of Sept. 15, 2019; since then, hospitalized cases have steadily declined. “Among all hospitalized EVALI patients reported to CDC weekly, the percentage of recent cases (patients hospitalized within the preceding 3 weeks) declined from 58% reported November 12 to 30% reported December 3,” the report stated.

About 80%of hospitalized EVALI patients reported using tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)–containing e-cigarette, or vaping, products. “Dank Vapes,” counterfeit THC-containing products of unknown origin, were the most commonly reported THC-containing branded products used. Dank Vapes were used by 56% of hospitalized EVALI patients nationwide, followed by TKO brand (15%), Smart Cart (13%), and Rove (12%).

Of EVALI patients for whom data were available, 67% were male, and the median age was 24 years (range, 13-77 years); 78% were aged under 35 years and 16% were under 18 years. About 75% of EVALI patients were non-Hispanic white and 16% were Hispanic. Among the 48 deaths, 54% of patients were male, and the median age was 52 years (range, 17-75 years).

CDC research on EVALI continues to be limited by the self-reported data, lack of data on substances used, missing data, loss to follow-up, and reporting lags, but the intensive investigation and data collection is ongoing.

The report concludes: “While the investigation continues, persons should consider refraining from the use of all e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Adults using e-cigarette, or vaping, products to quit smoking should not return to smoking cigarettes; they should weigh all risks and benefits and consider using [Food and Drug Administration]–approved cessation medications. Adults who continue to use e-cigarette, or vaping, products should carefully monitor themselves for symptoms and see a health care provider immediately if they develop symptoms similar to those reported in this outbreak. Irrespective of the ongoing investigation, e-cigarette, or vaping, products should never be used by youths, young adults or pregnant women.”

Information on the current investigation, reporting of cases, and other resources can be found on the CDC website.

SOURCE: Lozier MJ et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Dec 6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6849e1.

The vaping lung disease outbreak continues, but according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it may have peaked and the number of new hospitalized cases reported to the CDC may be decreasing.

In the Dec. 6, 2019, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the CDC has updated information about cases of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (EVALI): As of Dec. 3, there have been 2,291 cases reported from all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and two U.S. territories (Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands). A total of 48 deaths have been confirmed in 25 states and Washington, D.C., the CDC reported.

The largest number of weekly hospitalized cases occurred during the week of Sept. 15, 2019; since then, hospitalized cases have steadily declined. “Among all hospitalized EVALI patients reported to CDC weekly, the percentage of recent cases (patients hospitalized within the preceding 3 weeks) declined from 58% reported November 12 to 30% reported December 3,” the report stated.

About 80%of hospitalized EVALI patients reported using tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)–containing e-cigarette, or vaping, products. “Dank Vapes,” counterfeit THC-containing products of unknown origin, were the most commonly reported THC-containing branded products used. Dank Vapes were used by 56% of hospitalized EVALI patients nationwide, followed by TKO brand (15%), Smart Cart (13%), and Rove (12%).

Of EVALI patients for whom data were available, 67% were male, and the median age was 24 years (range, 13-77 years); 78% were aged under 35 years and 16% were under 18 years. About 75% of EVALI patients were non-Hispanic white and 16% were Hispanic. Among the 48 deaths, 54% of patients were male, and the median age was 52 years (range, 17-75 years).

CDC research on EVALI continues to be limited by the self-reported data, lack of data on substances used, missing data, loss to follow-up, and reporting lags, but the intensive investigation and data collection is ongoing.

The report concludes: “While the investigation continues, persons should consider refraining from the use of all e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Adults using e-cigarette, or vaping, products to quit smoking should not return to smoking cigarettes; they should weigh all risks and benefits and consider using [Food and Drug Administration]–approved cessation medications. Adults who continue to use e-cigarette, or vaping, products should carefully monitor themselves for symptoms and see a health care provider immediately if they develop symptoms similar to those reported in this outbreak. Irrespective of the ongoing investigation, e-cigarette, or vaping, products should never be used by youths, young adults or pregnant women.”

Information on the current investigation, reporting of cases, and other resources can be found on the CDC website.

SOURCE: Lozier MJ et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Dec 6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6849e1.

The vaping lung disease outbreak continues, but according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it may have peaked and the number of new hospitalized cases reported to the CDC may be decreasing.

In the Dec. 6, 2019, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the CDC has updated information about cases of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (EVALI): As of Dec. 3, there have been 2,291 cases reported from all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and two U.S. territories (Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands). A total of 48 deaths have been confirmed in 25 states and Washington, D.C., the CDC reported.

The largest number of weekly hospitalized cases occurred during the week of Sept. 15, 2019; since then, hospitalized cases have steadily declined. “Among all hospitalized EVALI patients reported to CDC weekly, the percentage of recent cases (patients hospitalized within the preceding 3 weeks) declined from 58% reported November 12 to 30% reported December 3,” the report stated.

About 80%of hospitalized EVALI patients reported using tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)–containing e-cigarette, or vaping, products. “Dank Vapes,” counterfeit THC-containing products of unknown origin, were the most commonly reported THC-containing branded products used. Dank Vapes were used by 56% of hospitalized EVALI patients nationwide, followed by TKO brand (15%), Smart Cart (13%), and Rove (12%).

Of EVALI patients for whom data were available, 67% were male, and the median age was 24 years (range, 13-77 years); 78% were aged under 35 years and 16% were under 18 years. About 75% of EVALI patients were non-Hispanic white and 16% were Hispanic. Among the 48 deaths, 54% of patients were male, and the median age was 52 years (range, 17-75 years).

CDC research on EVALI continues to be limited by the self-reported data, lack of data on substances used, missing data, loss to follow-up, and reporting lags, but the intensive investigation and data collection is ongoing.

The report concludes: “While the investigation continues, persons should consider refraining from the use of all e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Adults using e-cigarette, or vaping, products to quit smoking should not return to smoking cigarettes; they should weigh all risks and benefits and consider using [Food and Drug Administration]–approved cessation medications. Adults who continue to use e-cigarette, or vaping, products should carefully monitor themselves for symptoms and see a health care provider immediately if they develop symptoms similar to those reported in this outbreak. Irrespective of the ongoing investigation, e-cigarette, or vaping, products should never be used by youths, young adults or pregnant women.”

Information on the current investigation, reporting of cases, and other resources can be found on the CDC website.

SOURCE: Lozier MJ et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Dec 6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6849e1.

FROM THE MMWR

The QI pipeline supported by SHM’s Student Scholar Grant Program

As fall arrives, new interns are rapidly gaining clinical confidence, and residency recruitment season is ramping up. It’s also time to announce the opening of the SHM Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant Program applications; we are now recruiting our sixth group of scholars for the summer and longitudinal programs.

Since its creation in 2015, the grant has supported 23 students in this incredible opportunity to allow trainees to engage in scholarly work with guidance from a mentor to better understand the practice of hospital medicine and to further grow our robust pipeline.

The 2018-2019 cohort of scholars, Matthew Fallon, Philip Huang, and Erin Rainosek, just concluded their projects and are currently preparing their abstracts for submission for Hospital Medicine 2020, where there is a track for Early-Career Hospitalists. The projects targeted a diverse set of domains, including improving upon the patient experience, readmission quality metrics, geographic cohorting, and clinical documentation integrity – all highly relevant topics for a practicing hospitalist.

Matthew Fallon collaborated with his mentor, Dr. Venkata Andukuri, at Creighton University, to reduce the rate of hospital readmission for patients with heart failure, by analyzing retrospective data in a root cause analysis to identify factors that influence readmission rate, then targeting those directly. They also integrated the patient experience by seeking out patient input as to the challenges they face in the management of their heart failure.

Philip Huang worked with his mentor, Dr. Ethan Kuperman, at the Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, to improve geographic localization for hospitalized patients to improve care efficiency. They worked closely with an industrial engineering team to create a workflow model integrated into the hospital EHR to designate patient location and were able to better understand the role that other professions play in improving the health care delivery.

Finally, Erin Rainosek teamed up with her mentor, Dr. Luci Leykum, at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, to apply a design thinking strategy to redesign the health care experience for hospitalized patients. She engaged in over 120 hours of patient interviews and ultimately identified key themes that impact the experience of care, which will serve as target areas moving forward.

The student scholars in this cohort gained significant insight into the patient experience and quality issues relevant to the field of hospital medicine. We are proud of their accomplishments and look forward to their future successes and careers in hospital medicine. If you would like to learn more about the experience of our scholars this past summer, they have posted full write-ups on the Future Hospitalist RoundUp blog in HMX, SHM’s online community.

For students interested in becoming scholars, SHM offers two options to eligible medical students – the Summer Program and the Longitudinal Program. Both programs allow students to participate in projects related to quality improvement, patient safety, clinical research or hospital operations, in order to learn more about career paths in hospital medicine. Students will have the opportunity to conduct scholarly work with a mentor in these domains, with the option of participating over the summer during a 6-10-week period or longitudinally throughout the course of a year.

Discover additional benefits and how to apply on the SHM website. Applications will close in late January 2020.

Dr. Gottenborg is director of the Hospitalist Training Program within the Internal Medicine Residency Program at the University of Colorado. Dr. Duckett is assistant professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina.

As fall arrives, new interns are rapidly gaining clinical confidence, and residency recruitment season is ramping up. It’s also time to announce the opening of the SHM Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant Program applications; we are now recruiting our sixth group of scholars for the summer and longitudinal programs.

Since its creation in 2015, the grant has supported 23 students in this incredible opportunity to allow trainees to engage in scholarly work with guidance from a mentor to better understand the practice of hospital medicine and to further grow our robust pipeline.

The 2018-2019 cohort of scholars, Matthew Fallon, Philip Huang, and Erin Rainosek, just concluded their projects and are currently preparing their abstracts for submission for Hospital Medicine 2020, where there is a track for Early-Career Hospitalists. The projects targeted a diverse set of domains, including improving upon the patient experience, readmission quality metrics, geographic cohorting, and clinical documentation integrity – all highly relevant topics for a practicing hospitalist.

Matthew Fallon collaborated with his mentor, Dr. Venkata Andukuri, at Creighton University, to reduce the rate of hospital readmission for patients with heart failure, by analyzing retrospective data in a root cause analysis to identify factors that influence readmission rate, then targeting those directly. They also integrated the patient experience by seeking out patient input as to the challenges they face in the management of their heart failure.

Philip Huang worked with his mentor, Dr. Ethan Kuperman, at the Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, to improve geographic localization for hospitalized patients to improve care efficiency. They worked closely with an industrial engineering team to create a workflow model integrated into the hospital EHR to designate patient location and were able to better understand the role that other professions play in improving the health care delivery.

Finally, Erin Rainosek teamed up with her mentor, Dr. Luci Leykum, at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, to apply a design thinking strategy to redesign the health care experience for hospitalized patients. She engaged in over 120 hours of patient interviews and ultimately identified key themes that impact the experience of care, which will serve as target areas moving forward.

The student scholars in this cohort gained significant insight into the patient experience and quality issues relevant to the field of hospital medicine. We are proud of their accomplishments and look forward to their future successes and careers in hospital medicine. If you would like to learn more about the experience of our scholars this past summer, they have posted full write-ups on the Future Hospitalist RoundUp blog in HMX, SHM’s online community.

For students interested in becoming scholars, SHM offers two options to eligible medical students – the Summer Program and the Longitudinal Program. Both programs allow students to participate in projects related to quality improvement, patient safety, clinical research or hospital operations, in order to learn more about career paths in hospital medicine. Students will have the opportunity to conduct scholarly work with a mentor in these domains, with the option of participating over the summer during a 6-10-week period or longitudinally throughout the course of a year.

Discover additional benefits and how to apply on the SHM website. Applications will close in late January 2020.

Dr. Gottenborg is director of the Hospitalist Training Program within the Internal Medicine Residency Program at the University of Colorado. Dr. Duckett is assistant professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina.

As fall arrives, new interns are rapidly gaining clinical confidence, and residency recruitment season is ramping up. It’s also time to announce the opening of the SHM Student Hospitalist Scholar Grant Program applications; we are now recruiting our sixth group of scholars for the summer and longitudinal programs.

Since its creation in 2015, the grant has supported 23 students in this incredible opportunity to allow trainees to engage in scholarly work with guidance from a mentor to better understand the practice of hospital medicine and to further grow our robust pipeline.

The 2018-2019 cohort of scholars, Matthew Fallon, Philip Huang, and Erin Rainosek, just concluded their projects and are currently preparing their abstracts for submission for Hospital Medicine 2020, where there is a track for Early-Career Hospitalists. The projects targeted a diverse set of domains, including improving upon the patient experience, readmission quality metrics, geographic cohorting, and clinical documentation integrity – all highly relevant topics for a practicing hospitalist.

Matthew Fallon collaborated with his mentor, Dr. Venkata Andukuri, at Creighton University, to reduce the rate of hospital readmission for patients with heart failure, by analyzing retrospective data in a root cause analysis to identify factors that influence readmission rate, then targeting those directly. They also integrated the patient experience by seeking out patient input as to the challenges they face in the management of their heart failure.

Philip Huang worked with his mentor, Dr. Ethan Kuperman, at the Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, to improve geographic localization for hospitalized patients to improve care efficiency. They worked closely with an industrial engineering team to create a workflow model integrated into the hospital EHR to designate patient location and were able to better understand the role that other professions play in improving the health care delivery.

Finally, Erin Rainosek teamed up with her mentor, Dr. Luci Leykum, at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, to apply a design thinking strategy to redesign the health care experience for hospitalized patients. She engaged in over 120 hours of patient interviews and ultimately identified key themes that impact the experience of care, which will serve as target areas moving forward.

The student scholars in this cohort gained significant insight into the patient experience and quality issues relevant to the field of hospital medicine. We are proud of their accomplishments and look forward to their future successes and careers in hospital medicine. If you would like to learn more about the experience of our scholars this past summer, they have posted full write-ups on the Future Hospitalist RoundUp blog in HMX, SHM’s online community.

For students interested in becoming scholars, SHM offers two options to eligible medical students – the Summer Program and the Longitudinal Program. Both programs allow students to participate in projects related to quality improvement, patient safety, clinical research or hospital operations, in order to learn more about career paths in hospital medicine. Students will have the opportunity to conduct scholarly work with a mentor in these domains, with the option of participating over the summer during a 6-10-week period or longitudinally throughout the course of a year.

Discover additional benefits and how to apply on the SHM website. Applications will close in late January 2020.

Dr. Gottenborg is director of the Hospitalist Training Program within the Internal Medicine Residency Program at the University of Colorado. Dr. Duckett is assistant professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Quantifying the EHR connection to burnout

While plenty of anecdotal and other evidence exists to connect the use of electronic health records to physician burnout, new research puts a more standard, quantifiable measure to it in an effort to help measure progress in improving the usability of EHRs.

Researchers used the System Usability Scale (SUS), “favored as an industry standard as a short, simple, and reliable measurement of technology usability with solid benchmarks to easily interpret its results, as the measure in this research, Edward Melnick, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues wrote in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

“The previous studies have definitely hinted at [the link between EHRs and burnout], but never really quantified it,” Dr. Melnick said in an interview.

Among the 870 physicians evaluating their EHRs’ usability, the mean score on a scale of 0-100 (higher being more usable) was 45.9. As a point of comparison, Microsoft Excel has an SUS score of 57, digital video recorders score 74, Amazon scores 82, microwave ovens score 87, and Google search scores 93.

“A score of 45.9 is in the bottom 9% of usability scores across studies in other industries and is categorized as in the ‘not acceptable’ range with a grade of F,” the authors wrote. “In aggregate, 733 of 870 (84.2%) of respondents rated their EHR less than 68 on the SUS, the average score across industries.”

In tying the SUS results to burnout, which was measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, the authors noted that the scores “were strongly and independently associated with physician burnout in a dose-response relationship. The odds of burnout were lower for each 1 point more favorable SUS score, a finding that persisted after adjusting for an extensive array of other personal and professional characteristics. The relationship between SUS score and burnout also persisted when emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were treated as continuous variables.”

The authors did note that, despite the strong relationship, they could not determine a causation given the cross-sectional nature of the data.

“I’m hoping that this paper will spark conversation and drive change and be a way of tracking improvements,” Dr. Melnick said. “So, if you bring in something new and say this is going to be better, how do you know it is going to be better? Well maybe you measure it using the System Usability Scale” to give it a quantifiable measure of improvement. He said it is an advantage “of having a metric that has been standardized and used in other industries,” allowing EHR stakeholders to measure improvement. “Once you can measure it, you can manage it and make improvements faster.”

The findings “will not come as a surprise to anyone who practices medicine,” Patrice Harris, MD, president of the American Medical Association, said in a statement. “It is a national imperative to overhaul the design and use of EHRs and reframe the technology to focus primarily on its most critical function: helping physicians care for patients. Significantly enhancing EHR usability is key and the AMA is working to ensure a new generation of EHRs are designed to prioritize time with patients, rather than overload physicians with type-and-click tasks.”

Funding for the study was provided by the Stanford Medicine WebMD Center, AMA, and the Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine Program on Physician Well-Being. No conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

SOURCE: Melnick E et al. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2019 Nov 14. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.09.024.

While plenty of anecdotal and other evidence exists to connect the use of electronic health records to physician burnout, new research puts a more standard, quantifiable measure to it in an effort to help measure progress in improving the usability of EHRs.

Researchers used the System Usability Scale (SUS), “favored as an industry standard as a short, simple, and reliable measurement of technology usability with solid benchmarks to easily interpret its results, as the measure in this research, Edward Melnick, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues wrote in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

“The previous studies have definitely hinted at [the link between EHRs and burnout], but never really quantified it,” Dr. Melnick said in an interview.

Among the 870 physicians evaluating their EHRs’ usability, the mean score on a scale of 0-100 (higher being more usable) was 45.9. As a point of comparison, Microsoft Excel has an SUS score of 57, digital video recorders score 74, Amazon scores 82, microwave ovens score 87, and Google search scores 93.

“A score of 45.9 is in the bottom 9% of usability scores across studies in other industries and is categorized as in the ‘not acceptable’ range with a grade of F,” the authors wrote. “In aggregate, 733 of 870 (84.2%) of respondents rated their EHR less than 68 on the SUS, the average score across industries.”

In tying the SUS results to burnout, which was measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, the authors noted that the scores “were strongly and independently associated with physician burnout in a dose-response relationship. The odds of burnout were lower for each 1 point more favorable SUS score, a finding that persisted after adjusting for an extensive array of other personal and professional characteristics. The relationship between SUS score and burnout also persisted when emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were treated as continuous variables.”

The authors did note that, despite the strong relationship, they could not determine a causation given the cross-sectional nature of the data.

“I’m hoping that this paper will spark conversation and drive change and be a way of tracking improvements,” Dr. Melnick said. “So, if you bring in something new and say this is going to be better, how do you know it is going to be better? Well maybe you measure it using the System Usability Scale” to give it a quantifiable measure of improvement. He said it is an advantage “of having a metric that has been standardized and used in other industries,” allowing EHR stakeholders to measure improvement. “Once you can measure it, you can manage it and make improvements faster.”

The findings “will not come as a surprise to anyone who practices medicine,” Patrice Harris, MD, president of the American Medical Association, said in a statement. “It is a national imperative to overhaul the design and use of EHRs and reframe the technology to focus primarily on its most critical function: helping physicians care for patients. Significantly enhancing EHR usability is key and the AMA is working to ensure a new generation of EHRs are designed to prioritize time with patients, rather than overload physicians with type-and-click tasks.”

Funding for the study was provided by the Stanford Medicine WebMD Center, AMA, and the Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine Program on Physician Well-Being. No conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

SOURCE: Melnick E et al. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2019 Nov 14. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.09.024.

While plenty of anecdotal and other evidence exists to connect the use of electronic health records to physician burnout, new research puts a more standard, quantifiable measure to it in an effort to help measure progress in improving the usability of EHRs.

Researchers used the System Usability Scale (SUS), “favored as an industry standard as a short, simple, and reliable measurement of technology usability with solid benchmarks to easily interpret its results, as the measure in this research, Edward Melnick, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues wrote in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

“The previous studies have definitely hinted at [the link between EHRs and burnout], but never really quantified it,” Dr. Melnick said in an interview.

Among the 870 physicians evaluating their EHRs’ usability, the mean score on a scale of 0-100 (higher being more usable) was 45.9. As a point of comparison, Microsoft Excel has an SUS score of 57, digital video recorders score 74, Amazon scores 82, microwave ovens score 87, and Google search scores 93.

“A score of 45.9 is in the bottom 9% of usability scores across studies in other industries and is categorized as in the ‘not acceptable’ range with a grade of F,” the authors wrote. “In aggregate, 733 of 870 (84.2%) of respondents rated their EHR less than 68 on the SUS, the average score across industries.”

In tying the SUS results to burnout, which was measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, the authors noted that the scores “were strongly and independently associated with physician burnout in a dose-response relationship. The odds of burnout were lower for each 1 point more favorable SUS score, a finding that persisted after adjusting for an extensive array of other personal and professional characteristics. The relationship between SUS score and burnout also persisted when emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were treated as continuous variables.”

The authors did note that, despite the strong relationship, they could not determine a causation given the cross-sectional nature of the data.

“I’m hoping that this paper will spark conversation and drive change and be a way of tracking improvements,” Dr. Melnick said. “So, if you bring in something new and say this is going to be better, how do you know it is going to be better? Well maybe you measure it using the System Usability Scale” to give it a quantifiable measure of improvement. He said it is an advantage “of having a metric that has been standardized and used in other industries,” allowing EHR stakeholders to measure improvement. “Once you can measure it, you can manage it and make improvements faster.”

The findings “will not come as a surprise to anyone who practices medicine,” Patrice Harris, MD, president of the American Medical Association, said in a statement. “It is a national imperative to overhaul the design and use of EHRs and reframe the technology to focus primarily on its most critical function: helping physicians care for patients. Significantly enhancing EHR usability is key and the AMA is working to ensure a new generation of EHRs are designed to prioritize time with patients, rather than overload physicians with type-and-click tasks.”

Funding for the study was provided by the Stanford Medicine WebMD Center, AMA, and the Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine Program on Physician Well-Being. No conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

SOURCE: Melnick E et al. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2019 Nov 14. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.09.024.

FROM MAYO CLINIC PROCEEDINGS

Have lower readmission rates led to higher mortality for patients with COPD?

Be careful what you wish for

There is at least one aspect of “Obamacare” that my mother-in-law and I can firmly agree on: Hospitals should not get paid for frequent readmissions.

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP), enacted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in 2012 with the goal of penalizing hospitals for excessive readmissions, has great face validity – and noble intentions. Does it also have a potentially disastrous downside?

On one side of the coin, the HRRP has been a remarkable success. It moved the national needle significantly on readmission rates. Yes, there are some caveats about increases in observation status patients and other shifts that could account for some of the difference, but it is fairly uncontroversial that overall, there are fewer 30-day readmissions across the country following initiation of HRRP. That is perhaps encouraging evidence of the potential positive impact that policy can make to drive changes for specific targets.

However, there is also a murkier – and more controversial – side. There have been a number of studies that have suggested reductions in readmission rates may have been associated with an increase in mortality in some patient groups. You discharge a patient and hope they won’t return to the hospital, but perhaps you should be more careful what you actually wish for.

Overall, the evidence of an association between readmissions and mortality has been complicated and conflicting. Headlines have alternately raised alarm about increased deaths and then reassured that there has been no change or perhaps even some concordant improvements in mortality. Not necessarily surprising, considering that these studies are all unavoidably of observational design and use different criteria, datasets and analytic models, which then drive their seemingly conflicting results.

An article published recently in the Journal of Hospital Medicine enters into this fray. The researchers examined the potential association between changes in rates of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) readmissions and 30-day mortality following HRRP introduction. While the initial HRRP program and subsequent analyses included patients with heart failure, acute MI, and pneumonia, the program was extended in 2014 to include patients with COPD. So, what happened in this patient group?

Through a number of statistical gymnastics, which as a nonstatistician I am having difficulty truly wrapping my head around, the researchers seem to have found a number of important insights:

- The all-cause 30-day risk-standardized readmission rate declined from 2010 to 2017.

- The all-cause 30-day risk-standardized mortality rate increased from 2010 to 2017, and the rate of increase in mortality appears to be accelerating.

- Hospitals with higher readmission rates prior to COPD readmission penalties had a lower rate of increase in mortalities.

- Hospitals that had a larger decrease in readmission rates had a larger rate of increase in mortality.

These researchers could not evaluate data at the patient level and could not adjust for changes in disease severity. However, taken together, these findings suggest that something bad may be truly happening here.

The authors of this study also point out that the associations with increased mortality have largely been seen in patients with heart failure – and now in patients with COPD – which are both chronic diseases characterized by exacerbations, as opposed to acute MI and pneumonia, which are episodic and treatable. Perhaps in those types of disease, efforts to avoid readmissions may be more universally helpful. Maybe.

Even if it is challenging for me to adjudicate the complicated methods and results of this study, I find it concerning that there is “biological plausibility” for this association. Hospitalists know exactly how this might have happened. Have you heard of the pop-up alerts that fire in the emergency department to let the physicians know that this patient was discharged within the past 30 days? You know that alert is not meant to tell you what to do, but you just might want to consider trying to discharge them or at least place them in observation – use your clinical judgment, if you know what I mean.

Within the past decade, observation units quickly cropped up all over the country, often not staffed by hospitalists nor cardiologists, where patients with decompensated heart failure, chest pain, and/or COPD, can be given Lasix and/or nebulizer treatments – at least just enough to let them walk on back out that door without a hospital admission.

At the end of the day, whether mortality rates have truly increased in the real world, this well-intentioned program seems to have serious issues. As Ashish Jha, MD, wrote in 2018, “Right now, a high-readmission, low-mortality hospital will be penalized at 6-10 times the rate of a low-readmission, high-mortality hospital. The signal from policy makers is clear – readmissions matter a lot more than mortality – and this signal needs to stop.”

Dr. Moriates is a hospitalist, the assistant dean for health care value, and an associate professor of internal medicine at Dell Medical School at University of Texas, Austin. He is also director of implementation initiatives at Costs of Care. This article first appeared on the Hospital Leader, SHM’s official blog, at hospitalleader.org.

Be careful what you wish for

Be careful what you wish for

There is at least one aspect of “Obamacare” that my mother-in-law and I can firmly agree on: Hospitals should not get paid for frequent readmissions.

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP), enacted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in 2012 with the goal of penalizing hospitals for excessive readmissions, has great face validity – and noble intentions. Does it also have a potentially disastrous downside?

On one side of the coin, the HRRP has been a remarkable success. It moved the national needle significantly on readmission rates. Yes, there are some caveats about increases in observation status patients and other shifts that could account for some of the difference, but it is fairly uncontroversial that overall, there are fewer 30-day readmissions across the country following initiation of HRRP. That is perhaps encouraging evidence of the potential positive impact that policy can make to drive changes for specific targets.

However, there is also a murkier – and more controversial – side. There have been a number of studies that have suggested reductions in readmission rates may have been associated with an increase in mortality in some patient groups. You discharge a patient and hope they won’t return to the hospital, but perhaps you should be more careful what you actually wish for.

Overall, the evidence of an association between readmissions and mortality has been complicated and conflicting. Headlines have alternately raised alarm about increased deaths and then reassured that there has been no change or perhaps even some concordant improvements in mortality. Not necessarily surprising, considering that these studies are all unavoidably of observational design and use different criteria, datasets and analytic models, which then drive their seemingly conflicting results.

An article published recently in the Journal of Hospital Medicine enters into this fray. The researchers examined the potential association between changes in rates of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) readmissions and 30-day mortality following HRRP introduction. While the initial HRRP program and subsequent analyses included patients with heart failure, acute MI, and pneumonia, the program was extended in 2014 to include patients with COPD. So, what happened in this patient group?

Through a number of statistical gymnastics, which as a nonstatistician I am having difficulty truly wrapping my head around, the researchers seem to have found a number of important insights:

- The all-cause 30-day risk-standardized readmission rate declined from 2010 to 2017.

- The all-cause 30-day risk-standardized mortality rate increased from 2010 to 2017, and the rate of increase in mortality appears to be accelerating.

- Hospitals with higher readmission rates prior to COPD readmission penalties had a lower rate of increase in mortalities.

- Hospitals that had a larger decrease in readmission rates had a larger rate of increase in mortality.

These researchers could not evaluate data at the patient level and could not adjust for changes in disease severity. However, taken together, these findings suggest that something bad may be truly happening here.

The authors of this study also point out that the associations with increased mortality have largely been seen in patients with heart failure – and now in patients with COPD – which are both chronic diseases characterized by exacerbations, as opposed to acute MI and pneumonia, which are episodic and treatable. Perhaps in those types of disease, efforts to avoid readmissions may be more universally helpful. Maybe.

Even if it is challenging for me to adjudicate the complicated methods and results of this study, I find it concerning that there is “biological plausibility” for this association. Hospitalists know exactly how this might have happened. Have you heard of the pop-up alerts that fire in the emergency department to let the physicians know that this patient was discharged within the past 30 days? You know that alert is not meant to tell you what to do, but you just might want to consider trying to discharge them or at least place them in observation – use your clinical judgment, if you know what I mean.

Within the past decade, observation units quickly cropped up all over the country, often not staffed by hospitalists nor cardiologists, where patients with decompensated heart failure, chest pain, and/or COPD, can be given Lasix and/or nebulizer treatments – at least just enough to let them walk on back out that door without a hospital admission.

At the end of the day, whether mortality rates have truly increased in the real world, this well-intentioned program seems to have serious issues. As Ashish Jha, MD, wrote in 2018, “Right now, a high-readmission, low-mortality hospital will be penalized at 6-10 times the rate of a low-readmission, high-mortality hospital. The signal from policy makers is clear – readmissions matter a lot more than mortality – and this signal needs to stop.”

Dr. Moriates is a hospitalist, the assistant dean for health care value, and an associate professor of internal medicine at Dell Medical School at University of Texas, Austin. He is also director of implementation initiatives at Costs of Care. This article first appeared on the Hospital Leader, SHM’s official blog, at hospitalleader.org.

There is at least one aspect of “Obamacare” that my mother-in-law and I can firmly agree on: Hospitals should not get paid for frequent readmissions.

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP), enacted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in 2012 with the goal of penalizing hospitals for excessive readmissions, has great face validity – and noble intentions. Does it also have a potentially disastrous downside?

On one side of the coin, the HRRP has been a remarkable success. It moved the national needle significantly on readmission rates. Yes, there are some caveats about increases in observation status patients and other shifts that could account for some of the difference, but it is fairly uncontroversial that overall, there are fewer 30-day readmissions across the country following initiation of HRRP. That is perhaps encouraging evidence of the potential positive impact that policy can make to drive changes for specific targets.

However, there is also a murkier – and more controversial – side. There have been a number of studies that have suggested reductions in readmission rates may have been associated with an increase in mortality in some patient groups. You discharge a patient and hope they won’t return to the hospital, but perhaps you should be more careful what you actually wish for.

Overall, the evidence of an association between readmissions and mortality has been complicated and conflicting. Headlines have alternately raised alarm about increased deaths and then reassured that there has been no change or perhaps even some concordant improvements in mortality. Not necessarily surprising, considering that these studies are all unavoidably of observational design and use different criteria, datasets and analytic models, which then drive their seemingly conflicting results.

An article published recently in the Journal of Hospital Medicine enters into this fray. The researchers examined the potential association between changes in rates of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) readmissions and 30-day mortality following HRRP introduction. While the initial HRRP program and subsequent analyses included patients with heart failure, acute MI, and pneumonia, the program was extended in 2014 to include patients with COPD. So, what happened in this patient group?

Through a number of statistical gymnastics, which as a nonstatistician I am having difficulty truly wrapping my head around, the researchers seem to have found a number of important insights:

- The all-cause 30-day risk-standardized readmission rate declined from 2010 to 2017.

- The all-cause 30-day risk-standardized mortality rate increased from 2010 to 2017, and the rate of increase in mortality appears to be accelerating.

- Hospitals with higher readmission rates prior to COPD readmission penalties had a lower rate of increase in mortalities.

- Hospitals that had a larger decrease in readmission rates had a larger rate of increase in mortality.

These researchers could not evaluate data at the patient level and could not adjust for changes in disease severity. However, taken together, these findings suggest that something bad may be truly happening here.