User login

Treating pain with virtual reality

Pilot studies are underway

Physicians may soon have another tool to help patients deal with pain: virtual reality (VR) therapy. A New York Times article earlier this year described this new treatment option and the way immersive VR experiences seem to crowd pain sensations out of the brain.

Jeffrey I. Gold, PhD, director of the Children’s Outcomes, Research, and Evaluation program at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, told the newspaper that VR was “like an endogenous narcotic providing a physiological and chemical burst that causes you to feel good.”

So far, VR has been most successfully used in cases of acute pain. “But it can also enhance the effectiveness of established techniques like physical therapy, hypnosis and cognitive behavioral therapy to treat debilitating chronic pain,” the New York Times reported.

“Using VR as an adjunct, we can teach coping skills, techniques patients can use on their own that will help diminish chronic pain,” said Hunter Hoffman, PhD, principal investigator at the Human Photonics Laboratory of the University of Washington, Seattle. “Learning changes the brain and gives patients something that continues to work when they take the helmet off. When patients realize their pain isn’t inevitable, they’re more receptive to doing physical therapy exercises and more likely to move on their own.”

Others with experience in VR say the technique can foster mindfulness, which teaches the mind how to quiet the body and nervous system through breathing.

Pilot studies of VR and pain management are underway, and software companies are developing programs that create therapeutic VR environments.

Reference

1. “Virtual Reality as Therapy for Pain.” Jane E. Brody, New York Times. 2019 Apr 29. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/29/well/live/virtual-reality-as-therapy-for-pain.html.

Pilot studies are underway

Pilot studies are underway

Physicians may soon have another tool to help patients deal with pain: virtual reality (VR) therapy. A New York Times article earlier this year described this new treatment option and the way immersive VR experiences seem to crowd pain sensations out of the brain.

Jeffrey I. Gold, PhD, director of the Children’s Outcomes, Research, and Evaluation program at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, told the newspaper that VR was “like an endogenous narcotic providing a physiological and chemical burst that causes you to feel good.”

So far, VR has been most successfully used in cases of acute pain. “But it can also enhance the effectiveness of established techniques like physical therapy, hypnosis and cognitive behavioral therapy to treat debilitating chronic pain,” the New York Times reported.

“Using VR as an adjunct, we can teach coping skills, techniques patients can use on their own that will help diminish chronic pain,” said Hunter Hoffman, PhD, principal investigator at the Human Photonics Laboratory of the University of Washington, Seattle. “Learning changes the brain and gives patients something that continues to work when they take the helmet off. When patients realize their pain isn’t inevitable, they’re more receptive to doing physical therapy exercises and more likely to move on their own.”

Others with experience in VR say the technique can foster mindfulness, which teaches the mind how to quiet the body and nervous system through breathing.

Pilot studies of VR and pain management are underway, and software companies are developing programs that create therapeutic VR environments.

Reference

1. “Virtual Reality as Therapy for Pain.” Jane E. Brody, New York Times. 2019 Apr 29. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/29/well/live/virtual-reality-as-therapy-for-pain.html.

Physicians may soon have another tool to help patients deal with pain: virtual reality (VR) therapy. A New York Times article earlier this year described this new treatment option and the way immersive VR experiences seem to crowd pain sensations out of the brain.

Jeffrey I. Gold, PhD, director of the Children’s Outcomes, Research, and Evaluation program at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, told the newspaper that VR was “like an endogenous narcotic providing a physiological and chemical burst that causes you to feel good.”

So far, VR has been most successfully used in cases of acute pain. “But it can also enhance the effectiveness of established techniques like physical therapy, hypnosis and cognitive behavioral therapy to treat debilitating chronic pain,” the New York Times reported.

“Using VR as an adjunct, we can teach coping skills, techniques patients can use on their own that will help diminish chronic pain,” said Hunter Hoffman, PhD, principal investigator at the Human Photonics Laboratory of the University of Washington, Seattle. “Learning changes the brain and gives patients something that continues to work when they take the helmet off. When patients realize their pain isn’t inevitable, they’re more receptive to doing physical therapy exercises and more likely to move on their own.”

Others with experience in VR say the technique can foster mindfulness, which teaches the mind how to quiet the body and nervous system through breathing.

Pilot studies of VR and pain management are underway, and software companies are developing programs that create therapeutic VR environments.

Reference

1. “Virtual Reality as Therapy for Pain.” Jane E. Brody, New York Times. 2019 Apr 29. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/29/well/live/virtual-reality-as-therapy-for-pain.html.

Cultivating patient activation through technology

Tech alone is not enough

Patient activation refers to an individual’s knowledge, skill, and confidence in managing their health and health care, according to a recent BMJ editorial. It’s recognized as a critical aspect of high-quality, patient-centered health care – patient activation has the potential to improve patient outcomes while reducing costs.

Total knee replacement offers a great opportunity to study patient activation, said editorial lead author Jesse I. Wolfstadt, MD, MS, FRCSC, of the University of Toronto. “It may help address the one in five patients who are unsatisfied with their knee replacement despite an otherwise technically sound procedure.”

The authors considered some patient activation studies that have shown positive results for cultivating activation through technology. In one, patients engaging with a bedside multimedia intervention on a tablet after undergoing knee replacement reported better pain scores, length of stay, knee function, and satisfaction with care. Another study showed patients who received automated text messages after joint replacement improved time spent on home exercises, decreased their use of narcotics, and had fewer calls to the surgeon’s office.

But “negative mobile app studies seem to suggest that when technologies are used as a passive educational intervention, patient activation may suffer,” according to the editorial. “One possible key ingredient to successful patient activation is the engagement of the health care team that is facilitated through mobile technology. ... Mobile apps and other technological interventions also must have clear goals if they are to be used successfully; and these goals are likely to differ for different patient populations and disease processes.”

Technology alone is not enough to affect patient activation, Dr. Wolfstadt said. “The key to success will likely involve tailoring interventions to individual patients and facilitating increased engagement with the health care team. You can’t just give a patient an app or other form of technology and expect it to replace the function of patient-clinician communication/interaction.”

Reference

1. Wolfstadt JI et ak. Improving patient outcomes following total joint arthroplasty: Is there an app for that? BMJ Qual Saf. 2019 May 2019. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009571.

Tech alone is not enough

Tech alone is not enough

Patient activation refers to an individual’s knowledge, skill, and confidence in managing their health and health care, according to a recent BMJ editorial. It’s recognized as a critical aspect of high-quality, patient-centered health care – patient activation has the potential to improve patient outcomes while reducing costs.

Total knee replacement offers a great opportunity to study patient activation, said editorial lead author Jesse I. Wolfstadt, MD, MS, FRCSC, of the University of Toronto. “It may help address the one in five patients who are unsatisfied with their knee replacement despite an otherwise technically sound procedure.”

The authors considered some patient activation studies that have shown positive results for cultivating activation through technology. In one, patients engaging with a bedside multimedia intervention on a tablet after undergoing knee replacement reported better pain scores, length of stay, knee function, and satisfaction with care. Another study showed patients who received automated text messages after joint replacement improved time spent on home exercises, decreased their use of narcotics, and had fewer calls to the surgeon’s office.

But “negative mobile app studies seem to suggest that when technologies are used as a passive educational intervention, patient activation may suffer,” according to the editorial. “One possible key ingredient to successful patient activation is the engagement of the health care team that is facilitated through mobile technology. ... Mobile apps and other technological interventions also must have clear goals if they are to be used successfully; and these goals are likely to differ for different patient populations and disease processes.”

Technology alone is not enough to affect patient activation, Dr. Wolfstadt said. “The key to success will likely involve tailoring interventions to individual patients and facilitating increased engagement with the health care team. You can’t just give a patient an app or other form of technology and expect it to replace the function of patient-clinician communication/interaction.”

Reference

1. Wolfstadt JI et ak. Improving patient outcomes following total joint arthroplasty: Is there an app for that? BMJ Qual Saf. 2019 May 2019. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009571.

Patient activation refers to an individual’s knowledge, skill, and confidence in managing their health and health care, according to a recent BMJ editorial. It’s recognized as a critical aspect of high-quality, patient-centered health care – patient activation has the potential to improve patient outcomes while reducing costs.

Total knee replacement offers a great opportunity to study patient activation, said editorial lead author Jesse I. Wolfstadt, MD, MS, FRCSC, of the University of Toronto. “It may help address the one in five patients who are unsatisfied with their knee replacement despite an otherwise technically sound procedure.”

The authors considered some patient activation studies that have shown positive results for cultivating activation through technology. In one, patients engaging with a bedside multimedia intervention on a tablet after undergoing knee replacement reported better pain scores, length of stay, knee function, and satisfaction with care. Another study showed patients who received automated text messages after joint replacement improved time spent on home exercises, decreased their use of narcotics, and had fewer calls to the surgeon’s office.

But “negative mobile app studies seem to suggest that when technologies are used as a passive educational intervention, patient activation may suffer,” according to the editorial. “One possible key ingredient to successful patient activation is the engagement of the health care team that is facilitated through mobile technology. ... Mobile apps and other technological interventions also must have clear goals if they are to be used successfully; and these goals are likely to differ for different patient populations and disease processes.”

Technology alone is not enough to affect patient activation, Dr. Wolfstadt said. “The key to success will likely involve tailoring interventions to individual patients and facilitating increased engagement with the health care team. You can’t just give a patient an app or other form of technology and expect it to replace the function of patient-clinician communication/interaction.”

Reference

1. Wolfstadt JI et ak. Improving patient outcomes following total joint arthroplasty: Is there an app for that? BMJ Qual Saf. 2019 May 2019. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009571.

Experts call to revise the Uniform Determination of Death Act

, according to an editorial published online Dec. 24, 2019, in Annals of Internal Medicine. Proposed revisions would identify the standards for determining death by neurologic criteria and address the question of whether consent is required to make this determination. If accepted, the revisions would enhance public trust in the determination of death by neurologic criteria, the authors said.

“There is a disconnect between the medical and legal standards for brain death,” said Ariane K. Lewis, MD, associate professor of neurology and neurosurgery at New York University and lead author of the editorial. The discrepancy must be remedied because it has led to lawsuits and has proved to be problematic from a societal standpoint, she added.

“We defend changing the law to match medical practice, rather than changing medical practice to match the law,” said Thaddeus Mason Pope, JD, PhD, director of the Health Law Institute at Mitchell Hamline School of Law in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and an author of the editorial.

Accepted medical standards are unclear

The UDDA was drafted in 1981 to establish a uniform legal standard for death by neurologic criteria. A person with “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem,” is dead, according to the statute. A determination of death, it adds, “must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.”

But the medical standards used to determine death by neurologic cause have not been uniform. In 2015, the Supreme Court of Nevada ruled that it was not clear that the standard published by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), which had been used in the case at issue, was the “accepted medical standard.” An AAN summit later affirmed that the accepted medical standards for determination of death by neurologic cause are the 2010 AAN standard for determination of brain death in adults and the 2011 Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and Child Neurology Society (CNS) standard for determination of brain death in children. The Nevada legislature amended the state UDDA to identify these standards as the accepted standards. A revised UDDA also should identify these standards and grant an administrative agency (i.e., the board of medicine) the power to review and update the accepted medical standards as needed, according to the editorial.

To the extent that hospitals are not following the AAN or SCCM/AAP/CNS standards for determining death by neurologic cause, “enshrining” these standards in a revised UDDA “should increase uniformity and consistency” in hospitals’ policies on brain death, Dr. Pope said.

The question of hormonal function

Lawsuits in California and Nevada raised the question of whether the pituitary gland and hypothalamus are parts of the brain. If so, then the accepted medical standards for death by neurologic cause are not consistent with the statutory requirements for the determination of death, since the former do not test for cessation of hormonal function.

The current edition of the adult standards for determining death by neurologic cause were published in 2010. “Whenever we measure brain death, we’re not measuring the cessation of all functions of the entire brain,” Dr. Pope said. “That’s not a new thing; that’s been the case for a long time.”

To address the discrepancy between medical practice and the legal statute, Dr. Lewis and colleagues proposed that the UDDA’s reference to “irreversible cessation of functions of the entire brain” be followed by the following clause: “including the brainstem, leading to unresponsive coma with loss of capacity for consciousness, brainstem areflexia, and the inability to breathe spontaneously.” An alternative revision would be to add the briefer phrase “... with the exception of hormonal function.”

Authors say consent is not required for testing

Other complications have arisen from the UDDA’s failure to specify whether consent is required for a determination of death by neurologic cause. Court rulings on this question have not been consistent. Dr. Lewis and colleagues propose adding the following text to the UDDA: “Reasonable efforts should be made to notify a patient’s legally authorized decision-maker before performing a determination of death by neurologic criteria, but consent is not required to initiate such an evaluation.”

The proposed revisions to the UDDA “might give [clinicians] more confidence to proceed with brain death testing, because it would clarify that they don’t need the parents’ [or the patient’s legally authorized decision-maker] consent to do the tests,” said Dr. Pope. “If anything, they might even have a duty to do the tests.”

The final problem with the UDDA that Dr. Lewis and colleagues cited is that it does not provide clear guidance about how to respond to religious objections to discontinuation of organ support after a determination of death by neurologic cause. “Because the issue is rather complicated, we have not advocated for a singular position related to this [question] in our revised UDDA,” Dr. Lewis said. “Rather, we recommended the need for a multidisciplinary group to come together to determine what is the best approach. In an ideal world, this [approach] would be universal throughout the country.”

Although a revised UDDA would provide greater clarity to physicians and promote uniformity of practice, it would not resolve ongoing theological and philosophical debates about whether brain death is biological death, Dr. Pope said. “The key thing is that it would give clinicians a green light or certainty and clarity that they may proceed to do the test in the first place. If the tests are positive and the patient really is dead, then they could proceed to organ procurement or to move to the morgue.”

Dr. Lewis is a member of various AAN committees and working groups but receives no compensation for her role. A coauthor received personal fees from the AAN that were unrelated to the editorial.

SOURCE: Lewis A et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Dec 24. doi: 10.7326/M19-2731.

, according to an editorial published online Dec. 24, 2019, in Annals of Internal Medicine. Proposed revisions would identify the standards for determining death by neurologic criteria and address the question of whether consent is required to make this determination. If accepted, the revisions would enhance public trust in the determination of death by neurologic criteria, the authors said.

“There is a disconnect between the medical and legal standards for brain death,” said Ariane K. Lewis, MD, associate professor of neurology and neurosurgery at New York University and lead author of the editorial. The discrepancy must be remedied because it has led to lawsuits and has proved to be problematic from a societal standpoint, she added.

“We defend changing the law to match medical practice, rather than changing medical practice to match the law,” said Thaddeus Mason Pope, JD, PhD, director of the Health Law Institute at Mitchell Hamline School of Law in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and an author of the editorial.

Accepted medical standards are unclear

The UDDA was drafted in 1981 to establish a uniform legal standard for death by neurologic criteria. A person with “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem,” is dead, according to the statute. A determination of death, it adds, “must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.”

But the medical standards used to determine death by neurologic cause have not been uniform. In 2015, the Supreme Court of Nevada ruled that it was not clear that the standard published by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), which had been used in the case at issue, was the “accepted medical standard.” An AAN summit later affirmed that the accepted medical standards for determination of death by neurologic cause are the 2010 AAN standard for determination of brain death in adults and the 2011 Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and Child Neurology Society (CNS) standard for determination of brain death in children. The Nevada legislature amended the state UDDA to identify these standards as the accepted standards. A revised UDDA also should identify these standards and grant an administrative agency (i.e., the board of medicine) the power to review and update the accepted medical standards as needed, according to the editorial.

To the extent that hospitals are not following the AAN or SCCM/AAP/CNS standards for determining death by neurologic cause, “enshrining” these standards in a revised UDDA “should increase uniformity and consistency” in hospitals’ policies on brain death, Dr. Pope said.

The question of hormonal function

Lawsuits in California and Nevada raised the question of whether the pituitary gland and hypothalamus are parts of the brain. If so, then the accepted medical standards for death by neurologic cause are not consistent with the statutory requirements for the determination of death, since the former do not test for cessation of hormonal function.

The current edition of the adult standards for determining death by neurologic cause were published in 2010. “Whenever we measure brain death, we’re not measuring the cessation of all functions of the entire brain,” Dr. Pope said. “That’s not a new thing; that’s been the case for a long time.”

To address the discrepancy between medical practice and the legal statute, Dr. Lewis and colleagues proposed that the UDDA’s reference to “irreversible cessation of functions of the entire brain” be followed by the following clause: “including the brainstem, leading to unresponsive coma with loss of capacity for consciousness, brainstem areflexia, and the inability to breathe spontaneously.” An alternative revision would be to add the briefer phrase “... with the exception of hormonal function.”

Authors say consent is not required for testing

Other complications have arisen from the UDDA’s failure to specify whether consent is required for a determination of death by neurologic cause. Court rulings on this question have not been consistent. Dr. Lewis and colleagues propose adding the following text to the UDDA: “Reasonable efforts should be made to notify a patient’s legally authorized decision-maker before performing a determination of death by neurologic criteria, but consent is not required to initiate such an evaluation.”

The proposed revisions to the UDDA “might give [clinicians] more confidence to proceed with brain death testing, because it would clarify that they don’t need the parents’ [or the patient’s legally authorized decision-maker] consent to do the tests,” said Dr. Pope. “If anything, they might even have a duty to do the tests.”

The final problem with the UDDA that Dr. Lewis and colleagues cited is that it does not provide clear guidance about how to respond to religious objections to discontinuation of organ support after a determination of death by neurologic cause. “Because the issue is rather complicated, we have not advocated for a singular position related to this [question] in our revised UDDA,” Dr. Lewis said. “Rather, we recommended the need for a multidisciplinary group to come together to determine what is the best approach. In an ideal world, this [approach] would be universal throughout the country.”

Although a revised UDDA would provide greater clarity to physicians and promote uniformity of practice, it would not resolve ongoing theological and philosophical debates about whether brain death is biological death, Dr. Pope said. “The key thing is that it would give clinicians a green light or certainty and clarity that they may proceed to do the test in the first place. If the tests are positive and the patient really is dead, then they could proceed to organ procurement or to move to the morgue.”

Dr. Lewis is a member of various AAN committees and working groups but receives no compensation for her role. A coauthor received personal fees from the AAN that were unrelated to the editorial.

SOURCE: Lewis A et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Dec 24. doi: 10.7326/M19-2731.

, according to an editorial published online Dec. 24, 2019, in Annals of Internal Medicine. Proposed revisions would identify the standards for determining death by neurologic criteria and address the question of whether consent is required to make this determination. If accepted, the revisions would enhance public trust in the determination of death by neurologic criteria, the authors said.

“There is a disconnect between the medical and legal standards for brain death,” said Ariane K. Lewis, MD, associate professor of neurology and neurosurgery at New York University and lead author of the editorial. The discrepancy must be remedied because it has led to lawsuits and has proved to be problematic from a societal standpoint, she added.

“We defend changing the law to match medical practice, rather than changing medical practice to match the law,” said Thaddeus Mason Pope, JD, PhD, director of the Health Law Institute at Mitchell Hamline School of Law in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and an author of the editorial.

Accepted medical standards are unclear

The UDDA was drafted in 1981 to establish a uniform legal standard for death by neurologic criteria. A person with “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem,” is dead, according to the statute. A determination of death, it adds, “must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.”

But the medical standards used to determine death by neurologic cause have not been uniform. In 2015, the Supreme Court of Nevada ruled that it was not clear that the standard published by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), which had been used in the case at issue, was the “accepted medical standard.” An AAN summit later affirmed that the accepted medical standards for determination of death by neurologic cause are the 2010 AAN standard for determination of brain death in adults and the 2011 Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and Child Neurology Society (CNS) standard for determination of brain death in children. The Nevada legislature amended the state UDDA to identify these standards as the accepted standards. A revised UDDA also should identify these standards and grant an administrative agency (i.e., the board of medicine) the power to review and update the accepted medical standards as needed, according to the editorial.

To the extent that hospitals are not following the AAN or SCCM/AAP/CNS standards for determining death by neurologic cause, “enshrining” these standards in a revised UDDA “should increase uniformity and consistency” in hospitals’ policies on brain death, Dr. Pope said.

The question of hormonal function

Lawsuits in California and Nevada raised the question of whether the pituitary gland and hypothalamus are parts of the brain. If so, then the accepted medical standards for death by neurologic cause are not consistent with the statutory requirements for the determination of death, since the former do not test for cessation of hormonal function.

The current edition of the adult standards for determining death by neurologic cause were published in 2010. “Whenever we measure brain death, we’re not measuring the cessation of all functions of the entire brain,” Dr. Pope said. “That’s not a new thing; that’s been the case for a long time.”

To address the discrepancy between medical practice and the legal statute, Dr. Lewis and colleagues proposed that the UDDA’s reference to “irreversible cessation of functions of the entire brain” be followed by the following clause: “including the brainstem, leading to unresponsive coma with loss of capacity for consciousness, brainstem areflexia, and the inability to breathe spontaneously.” An alternative revision would be to add the briefer phrase “... with the exception of hormonal function.”

Authors say consent is not required for testing

Other complications have arisen from the UDDA’s failure to specify whether consent is required for a determination of death by neurologic cause. Court rulings on this question have not been consistent. Dr. Lewis and colleagues propose adding the following text to the UDDA: “Reasonable efforts should be made to notify a patient’s legally authorized decision-maker before performing a determination of death by neurologic criteria, but consent is not required to initiate such an evaluation.”

The proposed revisions to the UDDA “might give [clinicians] more confidence to proceed with brain death testing, because it would clarify that they don’t need the parents’ [or the patient’s legally authorized decision-maker] consent to do the tests,” said Dr. Pope. “If anything, they might even have a duty to do the tests.”

The final problem with the UDDA that Dr. Lewis and colleagues cited is that it does not provide clear guidance about how to respond to religious objections to discontinuation of organ support after a determination of death by neurologic cause. “Because the issue is rather complicated, we have not advocated for a singular position related to this [question] in our revised UDDA,” Dr. Lewis said. “Rather, we recommended the need for a multidisciplinary group to come together to determine what is the best approach. In an ideal world, this [approach] would be universal throughout the country.”

Although a revised UDDA would provide greater clarity to physicians and promote uniformity of practice, it would not resolve ongoing theological and philosophical debates about whether brain death is biological death, Dr. Pope said. “The key thing is that it would give clinicians a green light or certainty and clarity that they may proceed to do the test in the first place. If the tests are positive and the patient really is dead, then they could proceed to organ procurement or to move to the morgue.”

Dr. Lewis is a member of various AAN committees and working groups but receives no compensation for her role. A coauthor received personal fees from the AAN that were unrelated to the editorial.

SOURCE: Lewis A et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Dec 24. doi: 10.7326/M19-2731.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Aligning scheduling and satisfaction

Research reveals counterintuitive results

Hospitalist work schedules have been the subject of much reporting – and recent research. Studies have shown that control over work hours and schedule flexibility are predictors of clinicians’ career satisfaction and burnout, factors linked to quality of patient care and retention.

Starting in January 2017, an academic hospital medicine group at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, undertook a scheduling redesign using improvement methodology, combined with purchased scheduling software. Tyler Anstett, DO, a hospitalist and assistant professor at the university, and colleagues presented the results in an abstract published during the SHM 2019 annual conference last March.

“We wrote this abstract as a report of the work that we did over several years in our hospital medicine group to improve hospitalist satisfaction with their schedules,” said Dr. Anstett. “We identified that, despite not following the traditional seven-on, seven-off model and 100% fulfillment of individual schedule requests, the majority of clinicians were dissatisfied with the scheduling process and their overall clinical schedules. Further, building these complex, individualized schedules resulted in a heavy administrative burden. We strove to provide better alignment of schedule satisfaction and the administrative burden of incorporating individualized schedule requests.”

Prior to January 2017, service stretches had ranged from 5 to 9 days, and there were few limits on time-off requests.

“Through sequential interventions, we standardized service stretches to 7 days (Tuesday-Monday), introduced a limited number of guaranteed 7-day time-off requests (Tuesday-Monday), and added a limited number of nonguaranteed 3-day flexible time-off requests,” according to the authors. “This simplification improved the automation of the scheduling software, which increased the schedule release lead time to an average of 16 weeks. Further, despite standardizing service stretches to 7 days and limiting time-off requests, physicians surveyed reported improved satisfaction with both their scheduling process (34% of participants ‘satisfied’ in 2017 to 67% in 2018) and their overall clinical schedules (50% of participants ‘satisfied’ in 2017 to 75% in 2018).”So counterintuitively, creating individualized schedules may not result in improved satisfaction and likely results in heavy administrative burden, Dr. Anstett said. “Standardization of schedule creation with allowance of a ‘free-market’ system, allowing clinicians to self-individualize their schedules may also result in less administrative burden and improved satisfaction.”

Reference

1. Anstett T et al. K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple … Schedules): How Standardization and Simplification Can Improve Scheduling and Physician Satisfaction. SHM 2019, Abstract 112. Accessed June 4, 2019.

Research reveals counterintuitive results

Research reveals counterintuitive results

Hospitalist work schedules have been the subject of much reporting – and recent research. Studies have shown that control over work hours and schedule flexibility are predictors of clinicians’ career satisfaction and burnout, factors linked to quality of patient care and retention.

Starting in January 2017, an academic hospital medicine group at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, undertook a scheduling redesign using improvement methodology, combined with purchased scheduling software. Tyler Anstett, DO, a hospitalist and assistant professor at the university, and colleagues presented the results in an abstract published during the SHM 2019 annual conference last March.

“We wrote this abstract as a report of the work that we did over several years in our hospital medicine group to improve hospitalist satisfaction with their schedules,” said Dr. Anstett. “We identified that, despite not following the traditional seven-on, seven-off model and 100% fulfillment of individual schedule requests, the majority of clinicians were dissatisfied with the scheduling process and their overall clinical schedules. Further, building these complex, individualized schedules resulted in a heavy administrative burden. We strove to provide better alignment of schedule satisfaction and the administrative burden of incorporating individualized schedule requests.”

Prior to January 2017, service stretches had ranged from 5 to 9 days, and there were few limits on time-off requests.

“Through sequential interventions, we standardized service stretches to 7 days (Tuesday-Monday), introduced a limited number of guaranteed 7-day time-off requests (Tuesday-Monday), and added a limited number of nonguaranteed 3-day flexible time-off requests,” according to the authors. “This simplification improved the automation of the scheduling software, which increased the schedule release lead time to an average of 16 weeks. Further, despite standardizing service stretches to 7 days and limiting time-off requests, physicians surveyed reported improved satisfaction with both their scheduling process (34% of participants ‘satisfied’ in 2017 to 67% in 2018) and their overall clinical schedules (50% of participants ‘satisfied’ in 2017 to 75% in 2018).”So counterintuitively, creating individualized schedules may not result in improved satisfaction and likely results in heavy administrative burden, Dr. Anstett said. “Standardization of schedule creation with allowance of a ‘free-market’ system, allowing clinicians to self-individualize their schedules may also result in less administrative burden and improved satisfaction.”

Reference

1. Anstett T et al. K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple … Schedules): How Standardization and Simplification Can Improve Scheduling and Physician Satisfaction. SHM 2019, Abstract 112. Accessed June 4, 2019.

Hospitalist work schedules have been the subject of much reporting – and recent research. Studies have shown that control over work hours and schedule flexibility are predictors of clinicians’ career satisfaction and burnout, factors linked to quality of patient care and retention.

Starting in January 2017, an academic hospital medicine group at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, undertook a scheduling redesign using improvement methodology, combined with purchased scheduling software. Tyler Anstett, DO, a hospitalist and assistant professor at the university, and colleagues presented the results in an abstract published during the SHM 2019 annual conference last March.

“We wrote this abstract as a report of the work that we did over several years in our hospital medicine group to improve hospitalist satisfaction with their schedules,” said Dr. Anstett. “We identified that, despite not following the traditional seven-on, seven-off model and 100% fulfillment of individual schedule requests, the majority of clinicians were dissatisfied with the scheduling process and their overall clinical schedules. Further, building these complex, individualized schedules resulted in a heavy administrative burden. We strove to provide better alignment of schedule satisfaction and the administrative burden of incorporating individualized schedule requests.”

Prior to January 2017, service stretches had ranged from 5 to 9 days, and there were few limits on time-off requests.

“Through sequential interventions, we standardized service stretches to 7 days (Tuesday-Monday), introduced a limited number of guaranteed 7-day time-off requests (Tuesday-Monday), and added a limited number of nonguaranteed 3-day flexible time-off requests,” according to the authors. “This simplification improved the automation of the scheduling software, which increased the schedule release lead time to an average of 16 weeks. Further, despite standardizing service stretches to 7 days and limiting time-off requests, physicians surveyed reported improved satisfaction with both their scheduling process (34% of participants ‘satisfied’ in 2017 to 67% in 2018) and their overall clinical schedules (50% of participants ‘satisfied’ in 2017 to 75% in 2018).”So counterintuitively, creating individualized schedules may not result in improved satisfaction and likely results in heavy administrative burden, Dr. Anstett said. “Standardization of schedule creation with allowance of a ‘free-market’ system, allowing clinicians to self-individualize their schedules may also result in less administrative burden and improved satisfaction.”

Reference

1. Anstett T et al. K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple … Schedules): How Standardization and Simplification Can Improve Scheduling and Physician Satisfaction. SHM 2019, Abstract 112. Accessed June 4, 2019.

The measles comeback of 2019

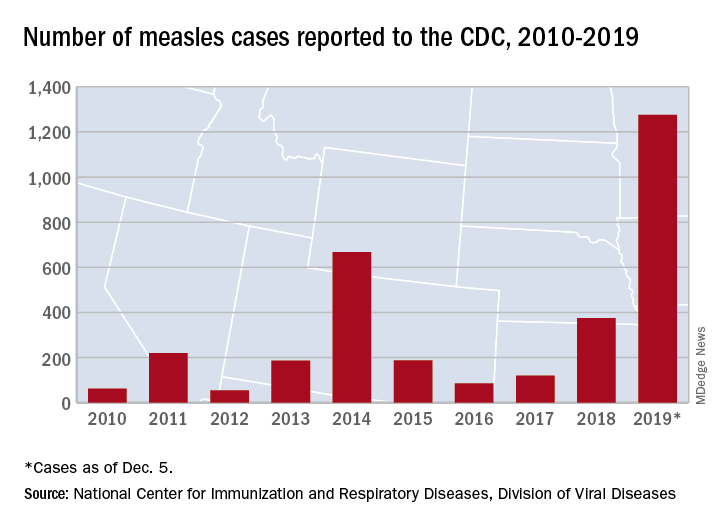

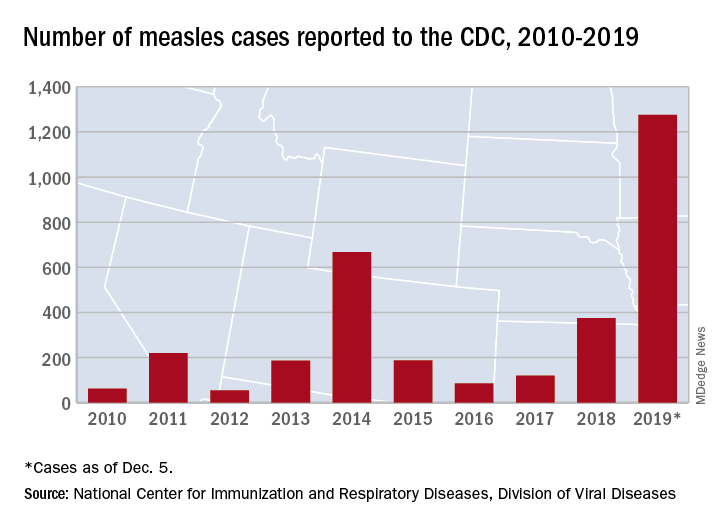

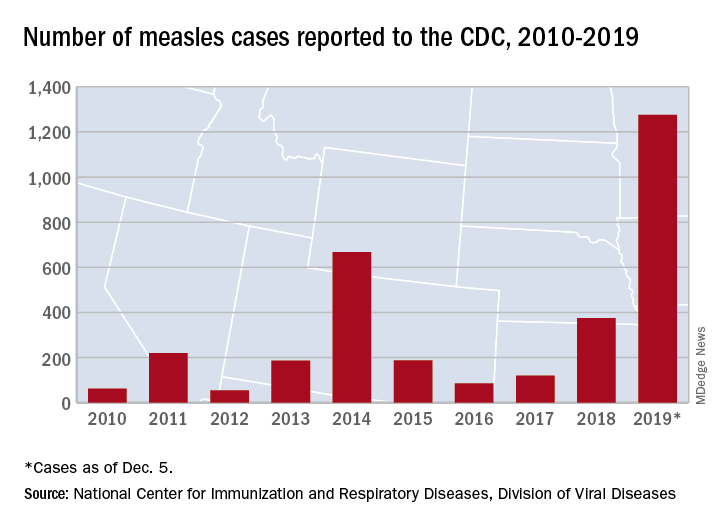

Measles made a comeback in 2019.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that, as of Dec. 5, 2019, 1,276 individual cases of measles of measles were confirmed in 31 states, the largest number since 1992. This number is a major uptick in cases, compared with previous years since 2000 when the CDC declared measles eliminated from the United States. No deaths have been reported for 2019.

Three-quarters of these cases in 2019 were linked to recent outbreaks in New York and occurred in primarily in underimmunized, close-knit communities and in patients with links to international travel. A total of 124 of the people who got measles this year were hospitalized, and 61 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis. The overall median patient age was 6 years (31% aged 1-4 years, 27% aged 5-17 years, and 29% aged at least 18 years).

The good news is that most of these cases occurred in unvaccinated patients. The national vaccination rate for the almost 4 million kindergartners reported as enrolled in 2018-2019 was 94.7% for two doses of the MMR vaccine, falling just short of the CDC recommended 95% vaccination rate threshold. The CDC reported an approximate 2.5% rate of vaccination exemptions among school-age children.

The bad news is that, despite the high rate of MMR vaccination rates among U.S. children, there are gaps in measles protection in the U.S. population because of factors leaving patients immunocompromised and antivaccination sentiment that has led some parents to defer or refuse the MMR.

In addition, adults who were vaccinated prior to 1968 with either inactivated measles vaccine or measles vaccine of unknown type may have limited immunity. The inactivated measles vaccine, which was available in 1963-1967, did not achieve effective measles protection.

A global measles surge

While antivaccination sentiment contributed to the 2019 measles cases, a more significant factor may be the global surge of measles. More than 140,000 people worldwide died from measles in 2018, according to the World Health Organization and the CDC.

“[Recent data on measles] indicates that during the first 6 months of the year there have been more measles cases reported worldwide than in any year since 2006. From Jan. 1 to July 31, 2019, 182 countries reported 364,808 measles cases to the WHO. This surpasses the 129,239 reported during the same time period in 2018. WHO regions with the biggest increases in cases include the African region (900%), the Western Pacific region (230%), and the European region (150%),” according to a CDC report.

Studies on hospitalization and complications linked to measles in the United States are scarce, but two outbreaks in Minnesota (2011 and 2017) provided some data on what to expect if the measles surge continues into 2020. The investigators found that poor feeding was a primary reason for admission (97%); additional complications included otitis media (42%), pneumonia (30%), and tracheitis (6%). Three-quarters received antibiotics, 30% required oxygen, and 21% received vitamin A. Median length of stay was 3.7 days (range, 1.1-26.2 days) (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019 Jun;38[6]:547-52. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002221).

‘Immunological amnesia’

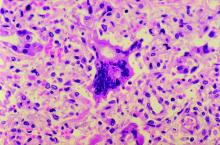

Infection with the measles virus appears to reduce immunity to other pathogens, according to a paper published in Science (2019 Nov 1;366[6465]599-606).

The hypothesis that the measles virus could cause “immunological amnesia” by impairing immune memory is supported by early research showing children with measles had negative cutaneous tuberculin reactions after having previously tested positive.

“Subsequent studies have shown decreased interferon signaling, skewed cytokine responses, lymphopenia, and suppression of lymphocyte proliferation shortly after infection,” wrote Michael Mina, MD, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and coauthors.

“Given the variation in the degree of immune repertoire modulation we observed, we anticipate that future risk of morbidity and mortality after measles would not be homogeneous but would be skewed toward individuals with the most severe elimination of immunological memory,” they wrote. “These findings underscore the crucial need for continued widespread vaccination.”

In this study, researchers compared the levels of around 400 pathogen-specific antibodies in blood samples from 77 unvaccinated children, taken before and 2 months after natural measles infection, with 5 unvaccinated children who did not contract measles. A total of 34 children experienced mild measles, and 43 had severe measles.

They found that the samples taken after measles infection showed “substantial” reductions in the number of pathogen epitopes, compared with the samples from children who did not get infected with measles.

This amounted to approximately a 20% mean reduction in overall diversity or size of the antibody repertoire. However, in children who experienced severe measles, there was a median loss of 40% (range, 11%-62%) of antibody repertoire, compared with a median of 33% (range, 12%-73%) range in children who experienced mild infection. Meanwhile, the control subjects retained approximately 90% of their antibody repertoire over a similar or longer time period. Some children lost up to 70% of antibodies for specific pathogens.

Maternal-acquired immunity fades

In another study of measles immunity, maternal antibodies were found to be insufficient to provide immunity to infants after 6 months.

The study of 196 infants showed that maternal measles antibodies had dropped below the protective threshold by 3 months of age – well before the recommended age of 12-15 months for the first dose of MMR vaccine.

The odds of inadequate protection doubled for each additional month of age, Michelle Science, MD, of the University of Toronto and associates reported in Pediatrics (2019 Dec 1. doi 10.1542/peds.2019-0630).

“The widening gap between loss of maternal antibodies and measles vaccination described in our study leaves infants vulnerable to measles for much of their infancy and highlights the need for further research to support public health policy,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote.

The researchers randomly selected 25 samples for each of eight different age groups: up to 30 days old; 1 month (31-60 days), 2 months (61-89 days), 3 months (90-119 days), 4 months, 5 months, 6-9 months, and 9-11 months.

Just over half the babies (56%) were male, and 35% had an underlying condition, but none had conditions that might affect antibody levels. The conditions were primarily a developmental delay or otherwise affecting the central nervous system, liver, or gastrointestinal function. Mean maternal age was 32 years.

To ensure high test sensitivity, the researchers used the plaque-reduction neutralization test to test for measles-neutralizing antibodies instead of using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, because “ELISA sensitivity decreases as antibody titers decrease,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote. They used a neutralization titer of less than 192 mIU/mL as the threshold for protection against measles.

When the researchers calculated the predicted standardized mean antibody titer for infants with a mother aged 32 years, they determined their mean to be 541 mIU/mL at 1 month, 142 mIU/mL at 3 months (below the measles threshold of susceptibility of 192 mIU/mL), and 64 mIU/mL at 6 months. None of the infants had measles antibodies above the protective threshold at 6 months old, the authors noted.

Children’s odds of susceptibility to measles doubled for each additional month of age, after adjustment for infant sex and maternal age (odds ratio, 2.13). Children’s likelihood of susceptibility to measles modestly increased as maternal age increased in 5-year increments from 25 to 40 years.

Children with an underlying conditions had greater susceptibility to measles (83%), compared with those without a comorbidity (68%, P = .03). No difference in susceptibility existed between males and females or based on gestational age at birth (ranging from 37 to 41 weeks).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices permits measles vaccination “as early as 6 months for infants who plan to travel internationally, infants with ongoing risk for exposure during measles outbreaks and as postexposure prophylaxis,” Huong Q. McLean, PhD, of Marshfield (Wisc.) Clinic Research Institute, and Walter A. Orenstein, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, noted in an editorial.

The research was funded by the Public Health Ontario Project Initiation Fund. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Bianca Nogrady and Tara Haelle contributed to this story.

Measles made a comeback in 2019.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that, as of Dec. 5, 2019, 1,276 individual cases of measles of measles were confirmed in 31 states, the largest number since 1992. This number is a major uptick in cases, compared with previous years since 2000 when the CDC declared measles eliminated from the United States. No deaths have been reported for 2019.

Three-quarters of these cases in 2019 were linked to recent outbreaks in New York and occurred in primarily in underimmunized, close-knit communities and in patients with links to international travel. A total of 124 of the people who got measles this year were hospitalized, and 61 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis. The overall median patient age was 6 years (31% aged 1-4 years, 27% aged 5-17 years, and 29% aged at least 18 years).

The good news is that most of these cases occurred in unvaccinated patients. The national vaccination rate for the almost 4 million kindergartners reported as enrolled in 2018-2019 was 94.7% for two doses of the MMR vaccine, falling just short of the CDC recommended 95% vaccination rate threshold. The CDC reported an approximate 2.5% rate of vaccination exemptions among school-age children.

The bad news is that, despite the high rate of MMR vaccination rates among U.S. children, there are gaps in measles protection in the U.S. population because of factors leaving patients immunocompromised and antivaccination sentiment that has led some parents to defer or refuse the MMR.

In addition, adults who were vaccinated prior to 1968 with either inactivated measles vaccine or measles vaccine of unknown type may have limited immunity. The inactivated measles vaccine, which was available in 1963-1967, did not achieve effective measles protection.

A global measles surge

While antivaccination sentiment contributed to the 2019 measles cases, a more significant factor may be the global surge of measles. More than 140,000 people worldwide died from measles in 2018, according to the World Health Organization and the CDC.

“[Recent data on measles] indicates that during the first 6 months of the year there have been more measles cases reported worldwide than in any year since 2006. From Jan. 1 to July 31, 2019, 182 countries reported 364,808 measles cases to the WHO. This surpasses the 129,239 reported during the same time period in 2018. WHO regions with the biggest increases in cases include the African region (900%), the Western Pacific region (230%), and the European region (150%),” according to a CDC report.

Studies on hospitalization and complications linked to measles in the United States are scarce, but two outbreaks in Minnesota (2011 and 2017) provided some data on what to expect if the measles surge continues into 2020. The investigators found that poor feeding was a primary reason for admission (97%); additional complications included otitis media (42%), pneumonia (30%), and tracheitis (6%). Three-quarters received antibiotics, 30% required oxygen, and 21% received vitamin A. Median length of stay was 3.7 days (range, 1.1-26.2 days) (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019 Jun;38[6]:547-52. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002221).

‘Immunological amnesia’

Infection with the measles virus appears to reduce immunity to other pathogens, according to a paper published in Science (2019 Nov 1;366[6465]599-606).

The hypothesis that the measles virus could cause “immunological amnesia” by impairing immune memory is supported by early research showing children with measles had negative cutaneous tuberculin reactions after having previously tested positive.

“Subsequent studies have shown decreased interferon signaling, skewed cytokine responses, lymphopenia, and suppression of lymphocyte proliferation shortly after infection,” wrote Michael Mina, MD, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and coauthors.

“Given the variation in the degree of immune repertoire modulation we observed, we anticipate that future risk of morbidity and mortality after measles would not be homogeneous but would be skewed toward individuals with the most severe elimination of immunological memory,” they wrote. “These findings underscore the crucial need for continued widespread vaccination.”

In this study, researchers compared the levels of around 400 pathogen-specific antibodies in blood samples from 77 unvaccinated children, taken before and 2 months after natural measles infection, with 5 unvaccinated children who did not contract measles. A total of 34 children experienced mild measles, and 43 had severe measles.

They found that the samples taken after measles infection showed “substantial” reductions in the number of pathogen epitopes, compared with the samples from children who did not get infected with measles.

This amounted to approximately a 20% mean reduction in overall diversity or size of the antibody repertoire. However, in children who experienced severe measles, there was a median loss of 40% (range, 11%-62%) of antibody repertoire, compared with a median of 33% (range, 12%-73%) range in children who experienced mild infection. Meanwhile, the control subjects retained approximately 90% of their antibody repertoire over a similar or longer time period. Some children lost up to 70% of antibodies for specific pathogens.

Maternal-acquired immunity fades

In another study of measles immunity, maternal antibodies were found to be insufficient to provide immunity to infants after 6 months.

The study of 196 infants showed that maternal measles antibodies had dropped below the protective threshold by 3 months of age – well before the recommended age of 12-15 months for the first dose of MMR vaccine.

The odds of inadequate protection doubled for each additional month of age, Michelle Science, MD, of the University of Toronto and associates reported in Pediatrics (2019 Dec 1. doi 10.1542/peds.2019-0630).

“The widening gap between loss of maternal antibodies and measles vaccination described in our study leaves infants vulnerable to measles for much of their infancy and highlights the need for further research to support public health policy,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote.

The researchers randomly selected 25 samples for each of eight different age groups: up to 30 days old; 1 month (31-60 days), 2 months (61-89 days), 3 months (90-119 days), 4 months, 5 months, 6-9 months, and 9-11 months.

Just over half the babies (56%) were male, and 35% had an underlying condition, but none had conditions that might affect antibody levels. The conditions were primarily a developmental delay or otherwise affecting the central nervous system, liver, or gastrointestinal function. Mean maternal age was 32 years.

To ensure high test sensitivity, the researchers used the plaque-reduction neutralization test to test for measles-neutralizing antibodies instead of using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, because “ELISA sensitivity decreases as antibody titers decrease,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote. They used a neutralization titer of less than 192 mIU/mL as the threshold for protection against measles.

When the researchers calculated the predicted standardized mean antibody titer for infants with a mother aged 32 years, they determined their mean to be 541 mIU/mL at 1 month, 142 mIU/mL at 3 months (below the measles threshold of susceptibility of 192 mIU/mL), and 64 mIU/mL at 6 months. None of the infants had measles antibodies above the protective threshold at 6 months old, the authors noted.

Children’s odds of susceptibility to measles doubled for each additional month of age, after adjustment for infant sex and maternal age (odds ratio, 2.13). Children’s likelihood of susceptibility to measles modestly increased as maternal age increased in 5-year increments from 25 to 40 years.

Children with an underlying conditions had greater susceptibility to measles (83%), compared with those without a comorbidity (68%, P = .03). No difference in susceptibility existed between males and females or based on gestational age at birth (ranging from 37 to 41 weeks).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices permits measles vaccination “as early as 6 months for infants who plan to travel internationally, infants with ongoing risk for exposure during measles outbreaks and as postexposure prophylaxis,” Huong Q. McLean, PhD, of Marshfield (Wisc.) Clinic Research Institute, and Walter A. Orenstein, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, noted in an editorial.

The research was funded by the Public Health Ontario Project Initiation Fund. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Bianca Nogrady and Tara Haelle contributed to this story.

Measles made a comeback in 2019.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that, as of Dec. 5, 2019, 1,276 individual cases of measles of measles were confirmed in 31 states, the largest number since 1992. This number is a major uptick in cases, compared with previous years since 2000 when the CDC declared measles eliminated from the United States. No deaths have been reported for 2019.

Three-quarters of these cases in 2019 were linked to recent outbreaks in New York and occurred in primarily in underimmunized, close-knit communities and in patients with links to international travel. A total of 124 of the people who got measles this year were hospitalized, and 61 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis. The overall median patient age was 6 years (31% aged 1-4 years, 27% aged 5-17 years, and 29% aged at least 18 years).

The good news is that most of these cases occurred in unvaccinated patients. The national vaccination rate for the almost 4 million kindergartners reported as enrolled in 2018-2019 was 94.7% for two doses of the MMR vaccine, falling just short of the CDC recommended 95% vaccination rate threshold. The CDC reported an approximate 2.5% rate of vaccination exemptions among school-age children.

The bad news is that, despite the high rate of MMR vaccination rates among U.S. children, there are gaps in measles protection in the U.S. population because of factors leaving patients immunocompromised and antivaccination sentiment that has led some parents to defer or refuse the MMR.

In addition, adults who were vaccinated prior to 1968 with either inactivated measles vaccine or measles vaccine of unknown type may have limited immunity. The inactivated measles vaccine, which was available in 1963-1967, did not achieve effective measles protection.

A global measles surge

While antivaccination sentiment contributed to the 2019 measles cases, a more significant factor may be the global surge of measles. More than 140,000 people worldwide died from measles in 2018, according to the World Health Organization and the CDC.

“[Recent data on measles] indicates that during the first 6 months of the year there have been more measles cases reported worldwide than in any year since 2006. From Jan. 1 to July 31, 2019, 182 countries reported 364,808 measles cases to the WHO. This surpasses the 129,239 reported during the same time period in 2018. WHO regions with the biggest increases in cases include the African region (900%), the Western Pacific region (230%), and the European region (150%),” according to a CDC report.

Studies on hospitalization and complications linked to measles in the United States are scarce, but two outbreaks in Minnesota (2011 and 2017) provided some data on what to expect if the measles surge continues into 2020. The investigators found that poor feeding was a primary reason for admission (97%); additional complications included otitis media (42%), pneumonia (30%), and tracheitis (6%). Three-quarters received antibiotics, 30% required oxygen, and 21% received vitamin A. Median length of stay was 3.7 days (range, 1.1-26.2 days) (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019 Jun;38[6]:547-52. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002221).

‘Immunological amnesia’

Infection with the measles virus appears to reduce immunity to other pathogens, according to a paper published in Science (2019 Nov 1;366[6465]599-606).

The hypothesis that the measles virus could cause “immunological amnesia” by impairing immune memory is supported by early research showing children with measles had negative cutaneous tuberculin reactions after having previously tested positive.

“Subsequent studies have shown decreased interferon signaling, skewed cytokine responses, lymphopenia, and suppression of lymphocyte proliferation shortly after infection,” wrote Michael Mina, MD, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and coauthors.

“Given the variation in the degree of immune repertoire modulation we observed, we anticipate that future risk of morbidity and mortality after measles would not be homogeneous but would be skewed toward individuals with the most severe elimination of immunological memory,” they wrote. “These findings underscore the crucial need for continued widespread vaccination.”

In this study, researchers compared the levels of around 400 pathogen-specific antibodies in blood samples from 77 unvaccinated children, taken before and 2 months after natural measles infection, with 5 unvaccinated children who did not contract measles. A total of 34 children experienced mild measles, and 43 had severe measles.

They found that the samples taken after measles infection showed “substantial” reductions in the number of pathogen epitopes, compared with the samples from children who did not get infected with measles.

This amounted to approximately a 20% mean reduction in overall diversity or size of the antibody repertoire. However, in children who experienced severe measles, there was a median loss of 40% (range, 11%-62%) of antibody repertoire, compared with a median of 33% (range, 12%-73%) range in children who experienced mild infection. Meanwhile, the control subjects retained approximately 90% of their antibody repertoire over a similar or longer time period. Some children lost up to 70% of antibodies for specific pathogens.

Maternal-acquired immunity fades

In another study of measles immunity, maternal antibodies were found to be insufficient to provide immunity to infants after 6 months.

The study of 196 infants showed that maternal measles antibodies had dropped below the protective threshold by 3 months of age – well before the recommended age of 12-15 months for the first dose of MMR vaccine.

The odds of inadequate protection doubled for each additional month of age, Michelle Science, MD, of the University of Toronto and associates reported in Pediatrics (2019 Dec 1. doi 10.1542/peds.2019-0630).

“The widening gap between loss of maternal antibodies and measles vaccination described in our study leaves infants vulnerable to measles for much of their infancy and highlights the need for further research to support public health policy,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote.

The researchers randomly selected 25 samples for each of eight different age groups: up to 30 days old; 1 month (31-60 days), 2 months (61-89 days), 3 months (90-119 days), 4 months, 5 months, 6-9 months, and 9-11 months.

Just over half the babies (56%) were male, and 35% had an underlying condition, but none had conditions that might affect antibody levels. The conditions were primarily a developmental delay or otherwise affecting the central nervous system, liver, or gastrointestinal function. Mean maternal age was 32 years.

To ensure high test sensitivity, the researchers used the plaque-reduction neutralization test to test for measles-neutralizing antibodies instead of using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, because “ELISA sensitivity decreases as antibody titers decrease,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote. They used a neutralization titer of less than 192 mIU/mL as the threshold for protection against measles.

When the researchers calculated the predicted standardized mean antibody titer for infants with a mother aged 32 years, they determined their mean to be 541 mIU/mL at 1 month, 142 mIU/mL at 3 months (below the measles threshold of susceptibility of 192 mIU/mL), and 64 mIU/mL at 6 months. None of the infants had measles antibodies above the protective threshold at 6 months old, the authors noted.

Children’s odds of susceptibility to measles doubled for each additional month of age, after adjustment for infant sex and maternal age (odds ratio, 2.13). Children’s likelihood of susceptibility to measles modestly increased as maternal age increased in 5-year increments from 25 to 40 years.

Children with an underlying conditions had greater susceptibility to measles (83%), compared with those without a comorbidity (68%, P = .03). No difference in susceptibility existed between males and females or based on gestational age at birth (ranging from 37 to 41 weeks).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices permits measles vaccination “as early as 6 months for infants who plan to travel internationally, infants with ongoing risk for exposure during measles outbreaks and as postexposure prophylaxis,” Huong Q. McLean, PhD, of Marshfield (Wisc.) Clinic Research Institute, and Walter A. Orenstein, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, noted in an editorial.

The research was funded by the Public Health Ontario Project Initiation Fund. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Bianca Nogrady and Tara Haelle contributed to this story.

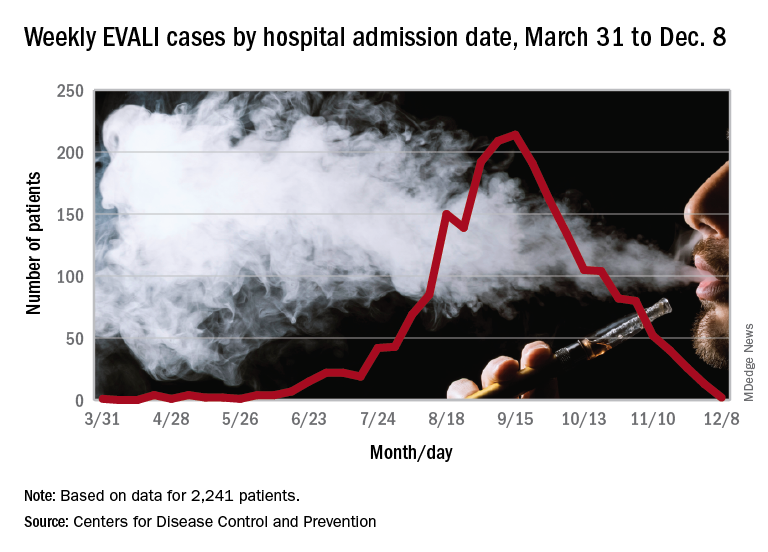

EVALI readmissions and deaths prompt guideline change

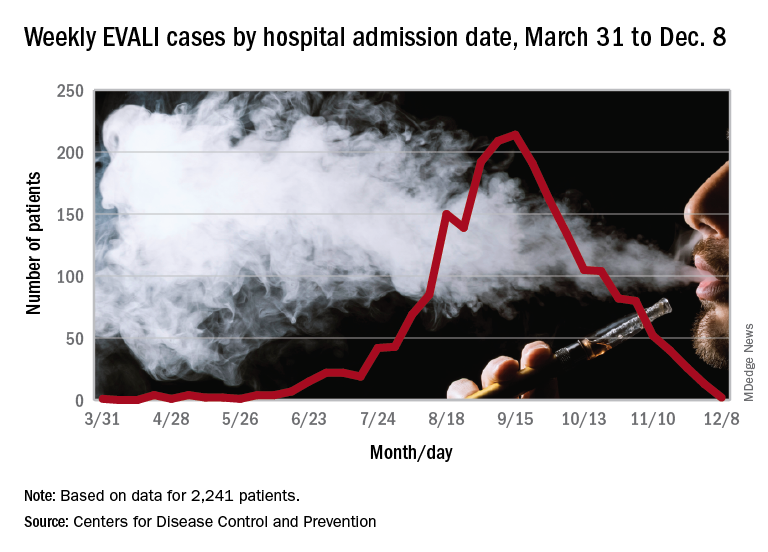

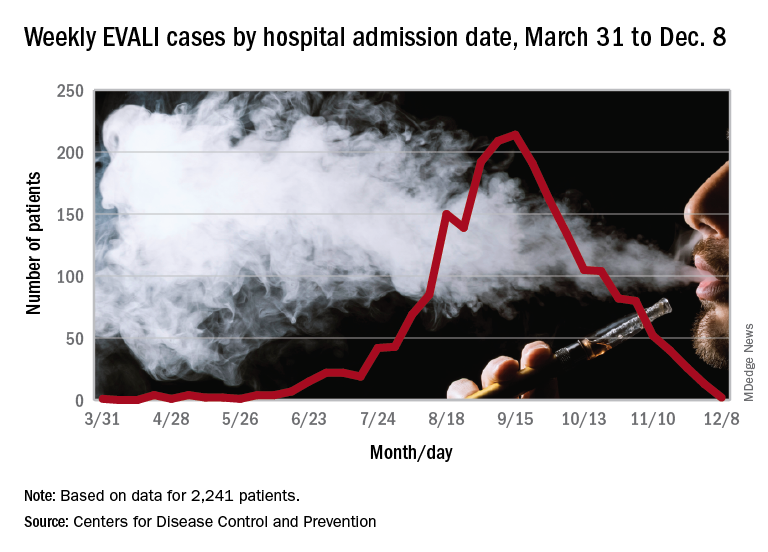

Those who required rehospitalization for e-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) and those who died after discharge were more likely to have one or more chronic conditions than were other EVALI patients, and those “who died also were more likely to have been admitted to an intensive care unit, experienced respiratory failure necessitating intubation and mechanical ventilation, and were significantly older,” Christina A. Mikosz, MD, and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Their analysis included the 1,139 EVALI patients who were discharged on or after Oct. 31, 2019. Of that group, 31 (2.7%) patients were rehospitalized and subsequently discharged and another 7 died after the initial discharge. The median age was 54 years for those who died, 27 years for those who were rehospitalized, and 23 for those who survived without rehospitalization, said Dr. Mikosz of the CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Atlanta, and associates.

Those findings, along with the rates of one or more comorbidities – 83% for those who died, 71% for those who were rehospitalized, and 26% for those who did not die or get readmitted – prompted the CDC to update its guidance for postdischarge follow-up of EVALI patients.

That update involves six specific recommendations to determine readiness for discharge, which include “confirming no clinically significant fluctuations in vital signs for at least 24-48 hours before discharge [and] preparation for hospital discharge and postdischarge care coordination to reduce risk of rehospitalization and death,” Mary E. Evans, MD, and associates said in a separate CDC communication (MMWR. 2019 Dec. 20. 68[early release]:1-6).

As of Dec. 17, the CDC reports that 2,506 patients have been hospitalized with EVALI since March 31, 2019, and 54 deaths have been confirmed in 27 states and the District of Columbia. The outbreak appears to have peaked in September, but cases are still being reported: 13 during the week of Dec. 1-7 and one case for the week of Dec. 8-14.

SOURCE: Mikosz CA et al. MMWR. 2019 Dec. 20. 68[early release]:1-7.

Those who required rehospitalization for e-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) and those who died after discharge were more likely to have one or more chronic conditions than were other EVALI patients, and those “who died also were more likely to have been admitted to an intensive care unit, experienced respiratory failure necessitating intubation and mechanical ventilation, and were significantly older,” Christina A. Mikosz, MD, and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Their analysis included the 1,139 EVALI patients who were discharged on or after Oct. 31, 2019. Of that group, 31 (2.7%) patients were rehospitalized and subsequently discharged and another 7 died after the initial discharge. The median age was 54 years for those who died, 27 years for those who were rehospitalized, and 23 for those who survived without rehospitalization, said Dr. Mikosz of the CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Atlanta, and associates.

Those findings, along with the rates of one or more comorbidities – 83% for those who died, 71% for those who were rehospitalized, and 26% for those who did not die or get readmitted – prompted the CDC to update its guidance for postdischarge follow-up of EVALI patients.

That update involves six specific recommendations to determine readiness for discharge, which include “confirming no clinically significant fluctuations in vital signs for at least 24-48 hours before discharge [and] preparation for hospital discharge and postdischarge care coordination to reduce risk of rehospitalization and death,” Mary E. Evans, MD, and associates said in a separate CDC communication (MMWR. 2019 Dec. 20. 68[early release]:1-6).

As of Dec. 17, the CDC reports that 2,506 patients have been hospitalized with EVALI since March 31, 2019, and 54 deaths have been confirmed in 27 states and the District of Columbia. The outbreak appears to have peaked in September, but cases are still being reported: 13 during the week of Dec. 1-7 and one case for the week of Dec. 8-14.

SOURCE: Mikosz CA et al. MMWR. 2019 Dec. 20. 68[early release]:1-7.

Those who required rehospitalization for e-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) and those who died after discharge were more likely to have one or more chronic conditions than were other EVALI patients, and those “who died also were more likely to have been admitted to an intensive care unit, experienced respiratory failure necessitating intubation and mechanical ventilation, and were significantly older,” Christina A. Mikosz, MD, and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Their analysis included the 1,139 EVALI patients who were discharged on or after Oct. 31, 2019. Of that group, 31 (2.7%) patients were rehospitalized and subsequently discharged and another 7 died after the initial discharge. The median age was 54 years for those who died, 27 years for those who were rehospitalized, and 23 for those who survived without rehospitalization, said Dr. Mikosz of the CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Atlanta, and associates.

Those findings, along with the rates of one or more comorbidities – 83% for those who died, 71% for those who were rehospitalized, and 26% for those who did not die or get readmitted – prompted the CDC to update its guidance for postdischarge follow-up of EVALI patients.

That update involves six specific recommendations to determine readiness for discharge, which include “confirming no clinically significant fluctuations in vital signs for at least 24-48 hours before discharge [and] preparation for hospital discharge and postdischarge care coordination to reduce risk of rehospitalization and death,” Mary E. Evans, MD, and associates said in a separate CDC communication (MMWR. 2019 Dec. 20. 68[early release]:1-6).

As of Dec. 17, the CDC reports that 2,506 patients have been hospitalized with EVALI since March 31, 2019, and 54 deaths have been confirmed in 27 states and the District of Columbia. The outbreak appears to have peaked in September, but cases are still being reported: 13 during the week of Dec. 1-7 and one case for the week of Dec. 8-14.

SOURCE: Mikosz CA et al. MMWR. 2019 Dec. 20. 68[early release]:1-7.

FROM MMWR

Envisioning the future of hospital medicine

I have written frequently over the last few years on topics related to the sustainability of the hospital medicine practice model. I continue to be concerned by what I see as a confluence of significant trends that are conspiring to challenge hospital medicine’s status quo.

On one hand, the financial pressures on U.S. hospitals are unrelenting, and their willingness or even ability to continue providing significant funding to support their hospital medicine groups is in question. Combine this with hospitalists’ rapidly evolving clinical scope and the ever-increasing demands of physicians in other specialties for hospitalist support, and the result is hospital medicine groups that will continue to grow in size, complexity, and the demand for ever more financial support.

On the other hand, the hospitalists I interact with in my work all over the country seem more stressed out than ever, and many are questioning whether this is a job that can be satisfying and sustainable for a career. Increasing patient complexity, productivity pressures, a lack of resources to address patients’ social issues, a systole-diastole schedule, the frustration of EHRs and other documentation responsibilities, and feeling “dumped on” by physicians in other specialties all contribute to hospitalist job stress.

A quick look at the literature confirms that in 2019 hospitalist burnout is definitely “a thing.” Interestingly, it’s been a thing for a while; the risk of hospitalist burnout was first identified by Hoff, et al., in 2002 (doi: 10.2307/30902462002). My colleague, John Nelson, MD, MHM, has written a number of times about strategies for preventing or mitigating hospitalist burnout.

As these trends converge, the hospital medicine practice model as we know it may be facing an existential crisis. If that sounds overly dramatic, let me say instead that the hospital medicine practice model will need to evolve significantly over the next decade in order to continue to meet patient and institutional needs while remaining both affordable and sustainable for the clinicians who work in it.

In September 2019, SHM’s Multi-Site Leaders Special Interest Group met in Chicago for their second annual Multi-Site Leaders Summit to explore the theme of sustainability in hospital medicine. The participants held robust discussions about coping with our changing practice environment, issues relating to hospitalist burnout and resiliency, innovative staffing models, the role of technology in HM sustainability, and financial sustainability

At the end of the meeting, the group engaged in a visioning exercise designed to move beyond what we are doing today by envisioning what the future of hospital medicine will look like and what interventions will be necessary for us to get from here to there. I’d like to share this visioning exercise with you and encourage you to “play along” by thinking seriously about the questions it poses.

Visioning exercise

Feel free to jot down some thoughts as we go through this exercise. But otherwise, just close your eyes and come along for the ride. Imagine yourself sitting at your desk looking at a desk calendar showing today’s date. Watch the pages flip from today, to tomorrow, to the next day, then to next month, and the next, and then to the next year and so on, until we arrive at December 2029.

Imagine that you look up from your desk, and suddenly realize that you aren’t in your office at all, but instead in a huge auditorium where someone is speaking about an award that is going to be announced. It’s crowded and a little stuffy in the auditorium, but people around you are whispering to each other with an air of eager anticipation, their eyes glued to the stage. You realize that the person being introduced up on the podium is the President of the United States, and the award is the Presidential Medal of Freedom, which is only awarded to people or groups who have made “an especially meritorious contribution to the security or national interests of the United States, world peace, cultural, or other significant public or private endeavors.”

Today, the Medal is being awarded to the Society of Hospital Medicine on behalf of all hospital medicine leaders nationally, for their collective accomplishments in saving the specialty of hospital medicine and, by doing so, ensuring that sick people are able to continue receiving the care they need in our nation’s hospitals – and that the hospitals themselves have become reliably safe, efficient, and effective in achieving high quality outcomes.

The President says, “At no time in the history of this award until now have we given this, the highest civilian award in the land, to a whole group of physician leaders across an entire specialty. But the achievements of this group of people in preserving and even enhancing the presence of highly energized, dedicated, capable clinicians in our nation’s hospitals against the significant odds they have faced over the last 10 years is nothing short of extraordinary.” There is a standing ovation, as people jump up out of their chairs to cheer and applaud. When the applause finally dies down, the President goes on to list all the accomplishments that made this group of leaders deserving. Listen to what she is saying. Fill it in in your own mind. What is it that this group has accomplished?

[Brief silence]

Up on a huge screen beside the stage, a video starts. In it, there are several hospital and physician executives in a focus group, and one exec says, “The thing that is great about what these leaders have accomplished in the field of hospital medicine is…” Fill it in – what did that executive say? Another leader jumps in: “That’s all fine and wonderful, but the thing that really makes hospital medicine stand out today compared to where they were 10 years ago is…” Listen to what these executives are saying. What accomplishments are they praising?