User login

Breaking the high-utilization cycle

Hospitalists know that a small percentage of patients account for a disproportionately large percentage of overall health care spending, much of which comes from inpatient admissions. Many programs have been developed around the country to work with this population, and most of these programs are – appropriately – outpatient based.

“However, a subset of frequently admitted patients either don’t make it to outpatient care or are unengaged with outpatient care and programs, for whom hospital stays can give us a unique opportunity to coordinate and streamline care, and to build trust that can then lead to increased patient engagement,” said Kirstin Knox, MD, PhD, of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and lead author of an abstract describing a method to address this challenge. “Our program works with these patients, the ‘outliers among the outliers’ to re-engage them in care, streamline admissions, coordinate inpatient and outpatient care, and address the underlying barriers/drivers that lead to frequent hospitalization.”

Their program designed and implemented a multidisciplinary intervention targeting the highest utilizers on their inpatient general medicine service. Each was assigned an inpatient continuity team, and the patient case was then presented to a multidisciplinary high-utilizer care committee that included physicians, nurses, and social workers, as well as representatives from a community health worker program, home care, and risk management to develop a care plan.

Analysis comparing the 6 months before and after intervention showed admissions and total hospital days were reduced by 55% and 47% respectively, and 30-day readmissions were reduced by 65%. Total direct costs were reduced from $2,923,000 to $1,284,000.

The top takeaway, Dr. Knox said, is that, through efforts to coordinate care and address underlying drivers of high utilization, hospital-based programs for the most frequently admitted patients can streamline inpatient care and decrease utilization for many high-risk, high-cost patients.

“I hope that hospitalists will consider starting inpatient-based high-utilizer programs at their own institutions, if they haven’t already,” she said. “Even starting with one or two of your most frequently admitted patients can be incredibly eye opening, and streamlining/coordinating care (as well as working overtime to address the underlying drivers/barriers that lead to high utilization) for these patients is incredibly rewarding.”

Reference

Knox K et al. Breaking the cycle: a successful inpatient based intervention for hospital high utilizers. Abstract published at Hospital Medicine 2018; Apr 8-11; Orlando, Fla., Abstract 319. Accessed 2018 Oct 2.

Hospitalists know that a small percentage of patients account for a disproportionately large percentage of overall health care spending, much of which comes from inpatient admissions. Many programs have been developed around the country to work with this population, and most of these programs are – appropriately – outpatient based.

“However, a subset of frequently admitted patients either don’t make it to outpatient care or are unengaged with outpatient care and programs, for whom hospital stays can give us a unique opportunity to coordinate and streamline care, and to build trust that can then lead to increased patient engagement,” said Kirstin Knox, MD, PhD, of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and lead author of an abstract describing a method to address this challenge. “Our program works with these patients, the ‘outliers among the outliers’ to re-engage them in care, streamline admissions, coordinate inpatient and outpatient care, and address the underlying barriers/drivers that lead to frequent hospitalization.”

Their program designed and implemented a multidisciplinary intervention targeting the highest utilizers on their inpatient general medicine service. Each was assigned an inpatient continuity team, and the patient case was then presented to a multidisciplinary high-utilizer care committee that included physicians, nurses, and social workers, as well as representatives from a community health worker program, home care, and risk management to develop a care plan.

Analysis comparing the 6 months before and after intervention showed admissions and total hospital days were reduced by 55% and 47% respectively, and 30-day readmissions were reduced by 65%. Total direct costs were reduced from $2,923,000 to $1,284,000.

The top takeaway, Dr. Knox said, is that, through efforts to coordinate care and address underlying drivers of high utilization, hospital-based programs for the most frequently admitted patients can streamline inpatient care and decrease utilization for many high-risk, high-cost patients.

“I hope that hospitalists will consider starting inpatient-based high-utilizer programs at their own institutions, if they haven’t already,” she said. “Even starting with one or two of your most frequently admitted patients can be incredibly eye opening, and streamlining/coordinating care (as well as working overtime to address the underlying drivers/barriers that lead to high utilization) for these patients is incredibly rewarding.”

Reference

Knox K et al. Breaking the cycle: a successful inpatient based intervention for hospital high utilizers. Abstract published at Hospital Medicine 2018; Apr 8-11; Orlando, Fla., Abstract 319. Accessed 2018 Oct 2.

Hospitalists know that a small percentage of patients account for a disproportionately large percentage of overall health care spending, much of which comes from inpatient admissions. Many programs have been developed around the country to work with this population, and most of these programs are – appropriately – outpatient based.

“However, a subset of frequently admitted patients either don’t make it to outpatient care or are unengaged with outpatient care and programs, for whom hospital stays can give us a unique opportunity to coordinate and streamline care, and to build trust that can then lead to increased patient engagement,” said Kirstin Knox, MD, PhD, of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and lead author of an abstract describing a method to address this challenge. “Our program works with these patients, the ‘outliers among the outliers’ to re-engage them in care, streamline admissions, coordinate inpatient and outpatient care, and address the underlying barriers/drivers that lead to frequent hospitalization.”

Their program designed and implemented a multidisciplinary intervention targeting the highest utilizers on their inpatient general medicine service. Each was assigned an inpatient continuity team, and the patient case was then presented to a multidisciplinary high-utilizer care committee that included physicians, nurses, and social workers, as well as representatives from a community health worker program, home care, and risk management to develop a care plan.

Analysis comparing the 6 months before and after intervention showed admissions and total hospital days were reduced by 55% and 47% respectively, and 30-day readmissions were reduced by 65%. Total direct costs were reduced from $2,923,000 to $1,284,000.

The top takeaway, Dr. Knox said, is that, through efforts to coordinate care and address underlying drivers of high utilization, hospital-based programs for the most frequently admitted patients can streamline inpatient care and decrease utilization for many high-risk, high-cost patients.

“I hope that hospitalists will consider starting inpatient-based high-utilizer programs at their own institutions, if they haven’t already,” she said. “Even starting with one or two of your most frequently admitted patients can be incredibly eye opening, and streamlining/coordinating care (as well as working overtime to address the underlying drivers/barriers that lead to high utilization) for these patients is incredibly rewarding.”

Reference

Knox K et al. Breaking the cycle: a successful inpatient based intervention for hospital high utilizers. Abstract published at Hospital Medicine 2018; Apr 8-11; Orlando, Fla., Abstract 319. Accessed 2018 Oct 2.

Bringing hospitalist coverage to critical access hospitals

“As a hospitalist, I believe that my specialty improves care for inpatients,” said Ethan Kuperman, MD, MS, FHM, clinical associate professor of medicine at University of Iowa Health Care in Iowa City. “I want hospitalists involved with as many hospitals as possible because I believe we will lead to better patient outcomes.”

But, he adds, it’s not feasible to place dedicated hospitalists in every rural hospital in the United States – especially those running far below the average hospitalist census. “As a university, academic hospitalist, I wanted to make sure that the innovations and knowledge of the University of Iowa could penetrate into the greater community, and I wanted to strengthen the continuity of care between our partners in rural Iowa and our physical location in Iowa City,” he said.

Enter the virtual hospitalist: A telemedicine “virtual hospitalist” may expand capabilities at a fractional cost of an on-site provider.

Dr. Kuperman’s 6-month pilot program provided “virtual hospitalist” coverage to patients at a critical access hospital in rural Iowa.

“Our rural partners want to ensure that they are providing high-quality care within their communities and aren’t transferring patients without a good indication to larger centers,” he said. “For patients, this program means more of them can remain in their communities, surrounded by their families. I don’t think the virtual hospitalist program delivers equivalent care to the university hospital – I think we deliver better care because of that continuity with local providers and the ability of patients to remain in contact with their support structures.”

The study concludes that the virtual hospitalist model increased the percentage of ED patients who could safely receive their care locally, and a single virtual hospitalist may be able to cover multiple critical access hospitals simultaneously.

“We have the technology to deliver hospitalist expertise to rural hospitals through telehealth in a way that benefits patients, rural hospitals, and academic hospitals,” he said.

Reference

Kuperman E et al. The Virtual Hospitalist: A single-site implementation bringing hospitalist coverage to critical access hospitals. Journal of Hospital Medicine. Published online first 2018 Sep 26. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3061. Accessed 2018 Oct 2.

“As a hospitalist, I believe that my specialty improves care for inpatients,” said Ethan Kuperman, MD, MS, FHM, clinical associate professor of medicine at University of Iowa Health Care in Iowa City. “I want hospitalists involved with as many hospitals as possible because I believe we will lead to better patient outcomes.”

But, he adds, it’s not feasible to place dedicated hospitalists in every rural hospital in the United States – especially those running far below the average hospitalist census. “As a university, academic hospitalist, I wanted to make sure that the innovations and knowledge of the University of Iowa could penetrate into the greater community, and I wanted to strengthen the continuity of care between our partners in rural Iowa and our physical location in Iowa City,” he said.

Enter the virtual hospitalist: A telemedicine “virtual hospitalist” may expand capabilities at a fractional cost of an on-site provider.

Dr. Kuperman’s 6-month pilot program provided “virtual hospitalist” coverage to patients at a critical access hospital in rural Iowa.

“Our rural partners want to ensure that they are providing high-quality care within their communities and aren’t transferring patients without a good indication to larger centers,” he said. “For patients, this program means more of them can remain in their communities, surrounded by their families. I don’t think the virtual hospitalist program delivers equivalent care to the university hospital – I think we deliver better care because of that continuity with local providers and the ability of patients to remain in contact with their support structures.”

The study concludes that the virtual hospitalist model increased the percentage of ED patients who could safely receive their care locally, and a single virtual hospitalist may be able to cover multiple critical access hospitals simultaneously.

“We have the technology to deliver hospitalist expertise to rural hospitals through telehealth in a way that benefits patients, rural hospitals, and academic hospitals,” he said.

Reference

Kuperman E et al. The Virtual Hospitalist: A single-site implementation bringing hospitalist coverage to critical access hospitals. Journal of Hospital Medicine. Published online first 2018 Sep 26. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3061. Accessed 2018 Oct 2.

“As a hospitalist, I believe that my specialty improves care for inpatients,” said Ethan Kuperman, MD, MS, FHM, clinical associate professor of medicine at University of Iowa Health Care in Iowa City. “I want hospitalists involved with as many hospitals as possible because I believe we will lead to better patient outcomes.”

But, he adds, it’s not feasible to place dedicated hospitalists in every rural hospital in the United States – especially those running far below the average hospitalist census. “As a university, academic hospitalist, I wanted to make sure that the innovations and knowledge of the University of Iowa could penetrate into the greater community, and I wanted to strengthen the continuity of care between our partners in rural Iowa and our physical location in Iowa City,” he said.

Enter the virtual hospitalist: A telemedicine “virtual hospitalist” may expand capabilities at a fractional cost of an on-site provider.

Dr. Kuperman’s 6-month pilot program provided “virtual hospitalist” coverage to patients at a critical access hospital in rural Iowa.

“Our rural partners want to ensure that they are providing high-quality care within their communities and aren’t transferring patients without a good indication to larger centers,” he said. “For patients, this program means more of them can remain in their communities, surrounded by their families. I don’t think the virtual hospitalist program delivers equivalent care to the university hospital – I think we deliver better care because of that continuity with local providers and the ability of patients to remain in contact with their support structures.”

The study concludes that the virtual hospitalist model increased the percentage of ED patients who could safely receive their care locally, and a single virtual hospitalist may be able to cover multiple critical access hospitals simultaneously.

“We have the technology to deliver hospitalist expertise to rural hospitals through telehealth in a way that benefits patients, rural hospitals, and academic hospitals,” he said.

Reference

Kuperman E et al. The Virtual Hospitalist: A single-site implementation bringing hospitalist coverage to critical access hospitals. Journal of Hospital Medicine. Published online first 2018 Sep 26. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3061. Accessed 2018 Oct 2.

Reducing sepsis mortality

The CDC estimates that 1.7 million people in the United States acquire sepsis annually; sepsis accounts for nearly 270,000 patient deaths per year.

Decreasing mortality and improving patient outcomes requires early detection and appropriate timely treatment. The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare’s recent sepsis project demonstrated this by analyzing root causes and reducing sepsis mortality with five leading hospitals by an aggregate of nearly 25%.

“Most organizations can tell you how they are doing with regard to whether or not they are ordering lactates or fluids, but many can’t tell you where in the process these elements are failing,” said Kelly Barnes, Black Belt III, Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. “For instance, is the issue in ordering lactates, drawing lactates, or getting the results of lactates in a timely manner? The key is to understand where in the process things are breaking down to identify what solutions an organization needs to put in place.”

During the Joint Commission project, one organization found that patients had inadequate fluid resuscitation due to staff fear of fluid overload, while another organization found they had issues with fluids being disconnected when patients were taken for tests and then not reconnected – different problems that needed different solutions.

The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare is currently developing a Targeted Solutions Tool® (TST®), scheduled for release in 2019, to help organizations determine their issues with sepsis recognition and barriers to meeting sepsis bundle element requirements and implement targeted solutions to address their specific issues. The tool will be available free of charge to all Joint Commission-accredited customers.

Reference

1. “Hospital-Wide Sepsis Project Reduces Mortality by Nearly 25 Percent,” Kelly Barnes, The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. 2018, Sep 25.

The CDC estimates that 1.7 million people in the United States acquire sepsis annually; sepsis accounts for nearly 270,000 patient deaths per year.

Decreasing mortality and improving patient outcomes requires early detection and appropriate timely treatment. The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare’s recent sepsis project demonstrated this by analyzing root causes and reducing sepsis mortality with five leading hospitals by an aggregate of nearly 25%.

“Most organizations can tell you how they are doing with regard to whether or not they are ordering lactates or fluids, but many can’t tell you where in the process these elements are failing,” said Kelly Barnes, Black Belt III, Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. “For instance, is the issue in ordering lactates, drawing lactates, or getting the results of lactates in a timely manner? The key is to understand where in the process things are breaking down to identify what solutions an organization needs to put in place.”

During the Joint Commission project, one organization found that patients had inadequate fluid resuscitation due to staff fear of fluid overload, while another organization found they had issues with fluids being disconnected when patients were taken for tests and then not reconnected – different problems that needed different solutions.

The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare is currently developing a Targeted Solutions Tool® (TST®), scheduled for release in 2019, to help organizations determine their issues with sepsis recognition and barriers to meeting sepsis bundle element requirements and implement targeted solutions to address their specific issues. The tool will be available free of charge to all Joint Commission-accredited customers.

Reference

1. “Hospital-Wide Sepsis Project Reduces Mortality by Nearly 25 Percent,” Kelly Barnes, The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. 2018, Sep 25.

The CDC estimates that 1.7 million people in the United States acquire sepsis annually; sepsis accounts for nearly 270,000 patient deaths per year.

Decreasing mortality and improving patient outcomes requires early detection and appropriate timely treatment. The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare’s recent sepsis project demonstrated this by analyzing root causes and reducing sepsis mortality with five leading hospitals by an aggregate of nearly 25%.

“Most organizations can tell you how they are doing with regard to whether or not they are ordering lactates or fluids, but many can’t tell you where in the process these elements are failing,” said Kelly Barnes, Black Belt III, Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. “For instance, is the issue in ordering lactates, drawing lactates, or getting the results of lactates in a timely manner? The key is to understand where in the process things are breaking down to identify what solutions an organization needs to put in place.”

During the Joint Commission project, one organization found that patients had inadequate fluid resuscitation due to staff fear of fluid overload, while another organization found they had issues with fluids being disconnected when patients were taken for tests and then not reconnected – different problems that needed different solutions.

The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare is currently developing a Targeted Solutions Tool® (TST®), scheduled for release in 2019, to help organizations determine their issues with sepsis recognition and barriers to meeting sepsis bundle element requirements and implement targeted solutions to address their specific issues. The tool will be available free of charge to all Joint Commission-accredited customers.

Reference

1. “Hospital-Wide Sepsis Project Reduces Mortality by Nearly 25 Percent,” Kelly Barnes, The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. 2018, Sep 25.

Just a series of fortunate events?

Building a career in hospital medicine

Residents and junior faculty have frequently asked me how they can attain a position similar to mine, focused on quality and leadership in a health care system. When I was first asked to offer advice on this topic, my response was generally something like, “Heck if I know! I just had a series of lucky accidents to get here!”

Back then, I would recount my career history. I established myself as a clinician educator and associate program director soon after Chief Residency. After that, I would explain, a series of fortunate events and health care trends shaped my career. Evidence-based medicine (EBM), the patient safety movement, a shift to incorporate value (as well as volume) into reimbursement models, and the hospital medicine movement all emerged in interesting and often synergistic ways.

A young SHM organization (then known as NAIP) grew rapidly even while the hospitalist programs I led in Phoenix, then at University of California, San Diego, grew in size and influence. Inevitably, it seemed, I was increasingly involved in quality improvement (QI) efforts, and began to publish and speak about them. Collaborative work with SHM and a number of hospital systems broadened my visibility regionally and nationally. Finally, in 2015, I was recruited away from UC San Diego into a new position, as chief quality officer at UC Davis.

On hearing this history, those seeking my sage advice would look a little confused, and then say something like, “So your advice is that I should get lucky??? Gee, thanks a lot! Really helpful!” (Insert sarcasm here).

The honor of being asked to contribute to the “Legacies” series in The Hospitalist gave me an opportunity to think about this a little differently. No one really wanted to know about how past changes in the health care environment led to my career success. They wanted advice on tools and strategies that will allow them to thrive in an environment of ongoing, disruptive change that is likely only going to accelerate. I now present my upgraded points of advice, intertwined with examples of how SHM positively influenced my career (and could assist yours):

Learn how your hospital works. Hospitalists obviously have an inside track on many aspects of hospital operations, but sometimes remain oblivious to the organizational and committee structure, priorities of hospital leadership, and the mechanism for implementing standardized care. Knowing where to go with new ideas, and the process of implementing protocols, will keep you from hitting political land mines and unintentionally encroaching on someone else’s turf, while aligning your efforts with institutional priorities improves the buy-in and resources available to do the work.

Start small, but think big. Don’t bite off more than you can chew, and make sure your ideas for change work on a small scale before trying to sell the world on them. On the other hand, think big! The care you and others provide is dependent on systems that go far beyond your immediate control. Policies, protocols, standardized order sets, checklists, and an array of other tools can be leveraged to influence care across an entire health system, and in the SHM Mentored Implementation programs, can impact hundreds of hospitals.

Broaden your skills. Commit to learning new skills that can increase your impact and career diversity. Procedural skills; information technology; and EMR, EBM, research, public health, QI, business, leadership, public speaking, advocacy, and telehealth, can all open up a whole world of possibilities when combined with a medical degree. These skills can move you into areas that keep you engaged and excited to go to work.

Engage in mentor/mentee relationships. As an associate program director and clinician-educator, I had a lot of opportunity to mentor residents and fellows. It is so rewarding to watch the mentee grow in experience and skills, and to eventually see many of them assume leadership and mentoring roles themselves. You don’t have to be in a teaching position to act as a mentor (my experience mentoring hospitalists and others in leadership and quality improvement now far surpasses my experience with house staff).

The mentor often benefits as much as the mentee from this relationship. I have been inspired by their passion and dedication, educated by their ideas and innovation, and frequently find I am learning more from them, than they are from me. I have had great experiences in the SHM Mentored Implementation program in the role of mentee and mentor.

Participate in a community. When I first joined NAIP, I was amazed that the giants (Wachter, Nelson, Whitcomb, Holman, Williams, Greeno, Howell, Huddleston, Wellikson, and on and on) were not only approachable, they were warm, friendly, interesting, and extraordinarily welcoming. The ever-expanding and evolving community at SHM continues that tradition and offers a forum to share innovative work, discuss common problems and solutions, contact world experts, or just find an empathetic ear. Working on toolkits and collaborative efforts with this community remains a real highlight of my career, and the source of several lasting friendships. So don’t be shy; step right up; and introduce yourself!

Avoid my past mistakes (this might be a long list). Random things you should try to avoid.

- Tribalism – It is natural to be protective of your hospitalist group, and to focus on the injustices heaped upon you from (insert favorite punching bag here, e.g., ED, orthopedists, cardiologists, nursing staff, evil administration penny pinchers, etc). While some of those injustices might be real, tribalism, defensiveness, and circling the wagons generally only makes things worse. Sit down face to face, learn a little bit about the opposing tribe (both about their work, and about them as people), and see how much more fun and productive work can be.

- Storming out of a meeting with the CMO and CEO, slamming the door, etc. – not productive. Administrative leaders are doing their own juggling act and are generally well intentioned and doing the best they can. Respect that, argue your case, but if things don’t pan out, shake their hand, and live to fight another day.

- Using e-mail (evil-mail) to resolve conflict – And if you’re a young whippersnapper, don’t use Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, or other social media to address conflict either!

- Forgetting to put patients first – Frame decisions for your group around what best serves your patients, not your doctors. Long term, this gives your group credibility and will serve the hospitalists better as well. SHM does this on a large scale with their advocacy efforts, resulting in more credibility and influence on Capitol Hill.

Make time for friends, family, fitness, fun, and reflection. A sense of humor and an occasional laugh when dealing with ill patients, hospital medicine politics, and the EMR all day provides resilience, as does taking the time to foster self-awareness and insight into your own weaknesses, strengths, and how you react to different stressors. A little bit of exercise and time with family and friends can go a long way towards improving your outlook, work, and life in general, while reducing burnout. Oh yeah, it’s also a good idea to choose a great life partner as well. Thanks Michelle!

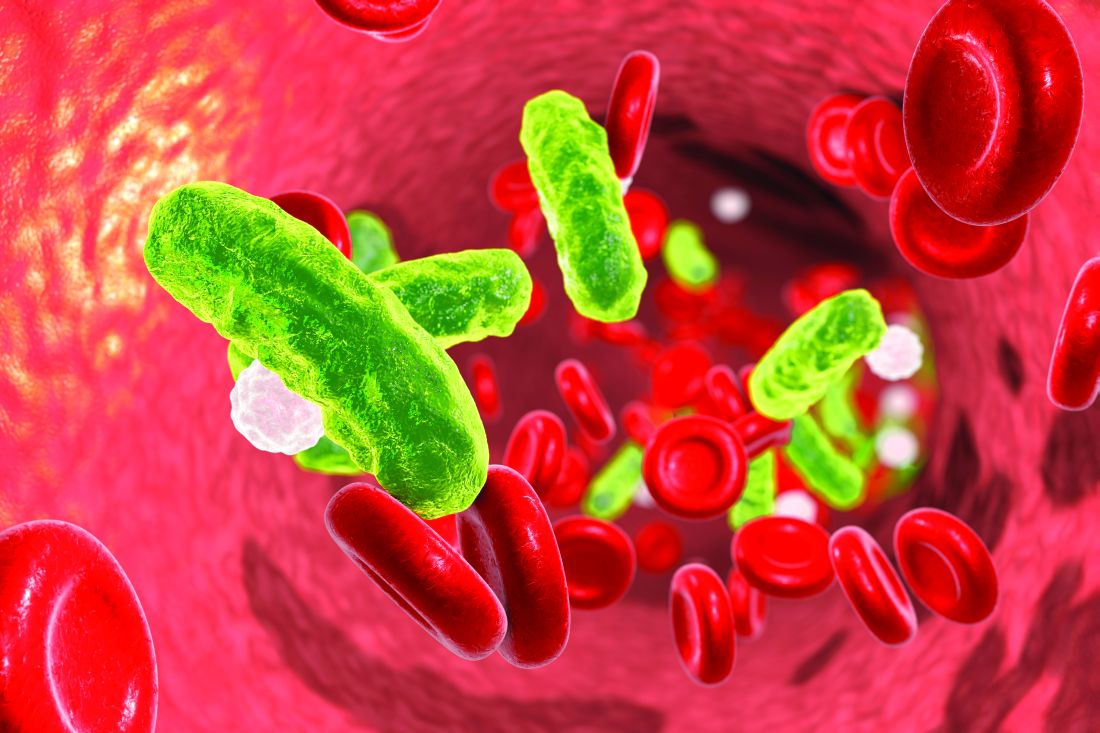

Dr. Maynard is chief quality officer, University of California Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, Calif.

Building a career in hospital medicine

Building a career in hospital medicine

Residents and junior faculty have frequently asked me how they can attain a position similar to mine, focused on quality and leadership in a health care system. When I was first asked to offer advice on this topic, my response was generally something like, “Heck if I know! I just had a series of lucky accidents to get here!”

Back then, I would recount my career history. I established myself as a clinician educator and associate program director soon after Chief Residency. After that, I would explain, a series of fortunate events and health care trends shaped my career. Evidence-based medicine (EBM), the patient safety movement, a shift to incorporate value (as well as volume) into reimbursement models, and the hospital medicine movement all emerged in interesting and often synergistic ways.

A young SHM organization (then known as NAIP) grew rapidly even while the hospitalist programs I led in Phoenix, then at University of California, San Diego, grew in size and influence. Inevitably, it seemed, I was increasingly involved in quality improvement (QI) efforts, and began to publish and speak about them. Collaborative work with SHM and a number of hospital systems broadened my visibility regionally and nationally. Finally, in 2015, I was recruited away from UC San Diego into a new position, as chief quality officer at UC Davis.

On hearing this history, those seeking my sage advice would look a little confused, and then say something like, “So your advice is that I should get lucky??? Gee, thanks a lot! Really helpful!” (Insert sarcasm here).

The honor of being asked to contribute to the “Legacies” series in The Hospitalist gave me an opportunity to think about this a little differently. No one really wanted to know about how past changes in the health care environment led to my career success. They wanted advice on tools and strategies that will allow them to thrive in an environment of ongoing, disruptive change that is likely only going to accelerate. I now present my upgraded points of advice, intertwined with examples of how SHM positively influenced my career (and could assist yours):

Learn how your hospital works. Hospitalists obviously have an inside track on many aspects of hospital operations, but sometimes remain oblivious to the organizational and committee structure, priorities of hospital leadership, and the mechanism for implementing standardized care. Knowing where to go with new ideas, and the process of implementing protocols, will keep you from hitting political land mines and unintentionally encroaching on someone else’s turf, while aligning your efforts with institutional priorities improves the buy-in and resources available to do the work.

Start small, but think big. Don’t bite off more than you can chew, and make sure your ideas for change work on a small scale before trying to sell the world on them. On the other hand, think big! The care you and others provide is dependent on systems that go far beyond your immediate control. Policies, protocols, standardized order sets, checklists, and an array of other tools can be leveraged to influence care across an entire health system, and in the SHM Mentored Implementation programs, can impact hundreds of hospitals.

Broaden your skills. Commit to learning new skills that can increase your impact and career diversity. Procedural skills; information technology; and EMR, EBM, research, public health, QI, business, leadership, public speaking, advocacy, and telehealth, can all open up a whole world of possibilities when combined with a medical degree. These skills can move you into areas that keep you engaged and excited to go to work.

Engage in mentor/mentee relationships. As an associate program director and clinician-educator, I had a lot of opportunity to mentor residents and fellows. It is so rewarding to watch the mentee grow in experience and skills, and to eventually see many of them assume leadership and mentoring roles themselves. You don’t have to be in a teaching position to act as a mentor (my experience mentoring hospitalists and others in leadership and quality improvement now far surpasses my experience with house staff).

The mentor often benefits as much as the mentee from this relationship. I have been inspired by their passion and dedication, educated by their ideas and innovation, and frequently find I am learning more from them, than they are from me. I have had great experiences in the SHM Mentored Implementation program in the role of mentee and mentor.

Participate in a community. When I first joined NAIP, I was amazed that the giants (Wachter, Nelson, Whitcomb, Holman, Williams, Greeno, Howell, Huddleston, Wellikson, and on and on) were not only approachable, they were warm, friendly, interesting, and extraordinarily welcoming. The ever-expanding and evolving community at SHM continues that tradition and offers a forum to share innovative work, discuss common problems and solutions, contact world experts, or just find an empathetic ear. Working on toolkits and collaborative efforts with this community remains a real highlight of my career, and the source of several lasting friendships. So don’t be shy; step right up; and introduce yourself!

Avoid my past mistakes (this might be a long list). Random things you should try to avoid.

- Tribalism – It is natural to be protective of your hospitalist group, and to focus on the injustices heaped upon you from (insert favorite punching bag here, e.g., ED, orthopedists, cardiologists, nursing staff, evil administration penny pinchers, etc). While some of those injustices might be real, tribalism, defensiveness, and circling the wagons generally only makes things worse. Sit down face to face, learn a little bit about the opposing tribe (both about their work, and about them as people), and see how much more fun and productive work can be.

- Storming out of a meeting with the CMO and CEO, slamming the door, etc. – not productive. Administrative leaders are doing their own juggling act and are generally well intentioned and doing the best they can. Respect that, argue your case, but if things don’t pan out, shake their hand, and live to fight another day.

- Using e-mail (evil-mail) to resolve conflict – And if you’re a young whippersnapper, don’t use Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, or other social media to address conflict either!

- Forgetting to put patients first – Frame decisions for your group around what best serves your patients, not your doctors. Long term, this gives your group credibility and will serve the hospitalists better as well. SHM does this on a large scale with their advocacy efforts, resulting in more credibility and influence on Capitol Hill.

Make time for friends, family, fitness, fun, and reflection. A sense of humor and an occasional laugh when dealing with ill patients, hospital medicine politics, and the EMR all day provides resilience, as does taking the time to foster self-awareness and insight into your own weaknesses, strengths, and how you react to different stressors. A little bit of exercise and time with family and friends can go a long way towards improving your outlook, work, and life in general, while reducing burnout. Oh yeah, it’s also a good idea to choose a great life partner as well. Thanks Michelle!

Dr. Maynard is chief quality officer, University of California Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, Calif.

Residents and junior faculty have frequently asked me how they can attain a position similar to mine, focused on quality and leadership in a health care system. When I was first asked to offer advice on this topic, my response was generally something like, “Heck if I know! I just had a series of lucky accidents to get here!”

Back then, I would recount my career history. I established myself as a clinician educator and associate program director soon after Chief Residency. After that, I would explain, a series of fortunate events and health care trends shaped my career. Evidence-based medicine (EBM), the patient safety movement, a shift to incorporate value (as well as volume) into reimbursement models, and the hospital medicine movement all emerged in interesting and often synergistic ways.

A young SHM organization (then known as NAIP) grew rapidly even while the hospitalist programs I led in Phoenix, then at University of California, San Diego, grew in size and influence. Inevitably, it seemed, I was increasingly involved in quality improvement (QI) efforts, and began to publish and speak about them. Collaborative work with SHM and a number of hospital systems broadened my visibility regionally and nationally. Finally, in 2015, I was recruited away from UC San Diego into a new position, as chief quality officer at UC Davis.

On hearing this history, those seeking my sage advice would look a little confused, and then say something like, “So your advice is that I should get lucky??? Gee, thanks a lot! Really helpful!” (Insert sarcasm here).

The honor of being asked to contribute to the “Legacies” series in The Hospitalist gave me an opportunity to think about this a little differently. No one really wanted to know about how past changes in the health care environment led to my career success. They wanted advice on tools and strategies that will allow them to thrive in an environment of ongoing, disruptive change that is likely only going to accelerate. I now present my upgraded points of advice, intertwined with examples of how SHM positively influenced my career (and could assist yours):

Learn how your hospital works. Hospitalists obviously have an inside track on many aspects of hospital operations, but sometimes remain oblivious to the organizational and committee structure, priorities of hospital leadership, and the mechanism for implementing standardized care. Knowing where to go with new ideas, and the process of implementing protocols, will keep you from hitting political land mines and unintentionally encroaching on someone else’s turf, while aligning your efforts with institutional priorities improves the buy-in and resources available to do the work.

Start small, but think big. Don’t bite off more than you can chew, and make sure your ideas for change work on a small scale before trying to sell the world on them. On the other hand, think big! The care you and others provide is dependent on systems that go far beyond your immediate control. Policies, protocols, standardized order sets, checklists, and an array of other tools can be leveraged to influence care across an entire health system, and in the SHM Mentored Implementation programs, can impact hundreds of hospitals.

Broaden your skills. Commit to learning new skills that can increase your impact and career diversity. Procedural skills; information technology; and EMR, EBM, research, public health, QI, business, leadership, public speaking, advocacy, and telehealth, can all open up a whole world of possibilities when combined with a medical degree. These skills can move you into areas that keep you engaged and excited to go to work.

Engage in mentor/mentee relationships. As an associate program director and clinician-educator, I had a lot of opportunity to mentor residents and fellows. It is so rewarding to watch the mentee grow in experience and skills, and to eventually see many of them assume leadership and mentoring roles themselves. You don’t have to be in a teaching position to act as a mentor (my experience mentoring hospitalists and others in leadership and quality improvement now far surpasses my experience with house staff).

The mentor often benefits as much as the mentee from this relationship. I have been inspired by their passion and dedication, educated by their ideas and innovation, and frequently find I am learning more from them, than they are from me. I have had great experiences in the SHM Mentored Implementation program in the role of mentee and mentor.

Participate in a community. When I first joined NAIP, I was amazed that the giants (Wachter, Nelson, Whitcomb, Holman, Williams, Greeno, Howell, Huddleston, Wellikson, and on and on) were not only approachable, they were warm, friendly, interesting, and extraordinarily welcoming. The ever-expanding and evolving community at SHM continues that tradition and offers a forum to share innovative work, discuss common problems and solutions, contact world experts, or just find an empathetic ear. Working on toolkits and collaborative efforts with this community remains a real highlight of my career, and the source of several lasting friendships. So don’t be shy; step right up; and introduce yourself!

Avoid my past mistakes (this might be a long list). Random things you should try to avoid.

- Tribalism – It is natural to be protective of your hospitalist group, and to focus on the injustices heaped upon you from (insert favorite punching bag here, e.g., ED, orthopedists, cardiologists, nursing staff, evil administration penny pinchers, etc). While some of those injustices might be real, tribalism, defensiveness, and circling the wagons generally only makes things worse. Sit down face to face, learn a little bit about the opposing tribe (both about their work, and about them as people), and see how much more fun and productive work can be.

- Storming out of a meeting with the CMO and CEO, slamming the door, etc. – not productive. Administrative leaders are doing their own juggling act and are generally well intentioned and doing the best they can. Respect that, argue your case, but if things don’t pan out, shake their hand, and live to fight another day.

- Using e-mail (evil-mail) to resolve conflict – And if you’re a young whippersnapper, don’t use Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, or other social media to address conflict either!

- Forgetting to put patients first – Frame decisions for your group around what best serves your patients, not your doctors. Long term, this gives your group credibility and will serve the hospitalists better as well. SHM does this on a large scale with their advocacy efforts, resulting in more credibility and influence on Capitol Hill.

Make time for friends, family, fitness, fun, and reflection. A sense of humor and an occasional laugh when dealing with ill patients, hospital medicine politics, and the EMR all day provides resilience, as does taking the time to foster self-awareness and insight into your own weaknesses, strengths, and how you react to different stressors. A little bit of exercise and time with family and friends can go a long way towards improving your outlook, work, and life in general, while reducing burnout. Oh yeah, it’s also a good idea to choose a great life partner as well. Thanks Michelle!

Dr. Maynard is chief quality officer, University of California Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, Calif.

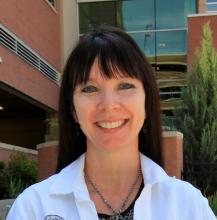

Most measles cases in 25 years prompts government pleas to vaccinate

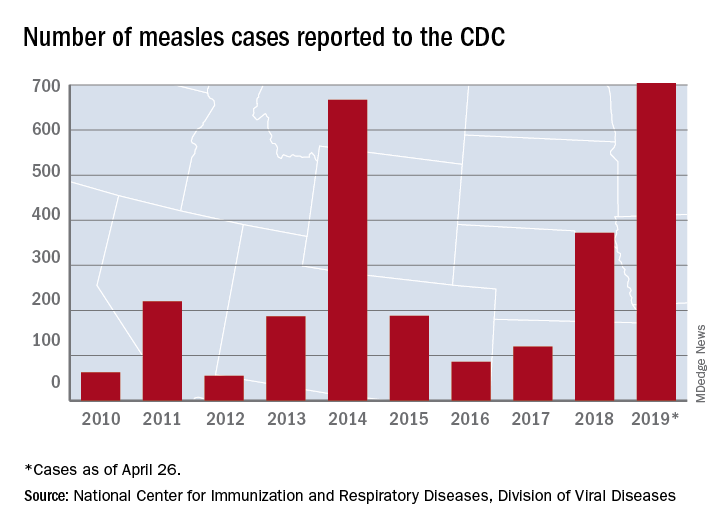

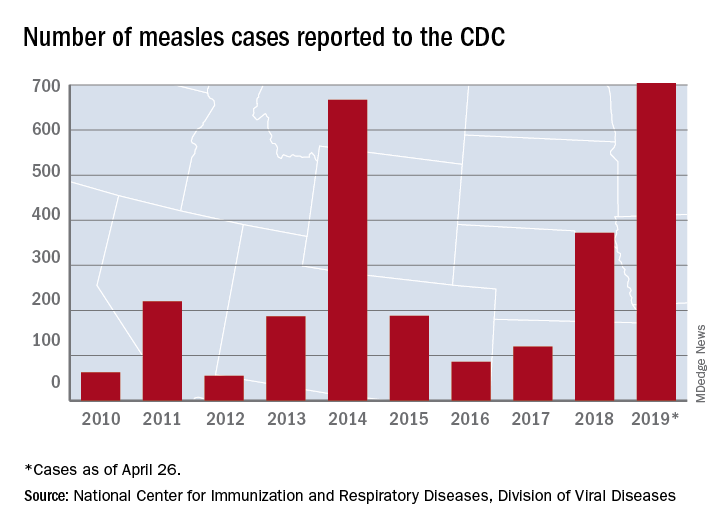

The updated figure adds 9 cases to the previous tally of 695 cases as of April 24, when the CDC announced that the number of cases in 2019 had surpassed the total for any year since the disease was considered effectively eliminated from the country in 2000.

Cases have been reported in 22 states, with the largest outbreaks in Washington and New York. The outbreak in Washington, which included 72 cases, was declared over last week. Two outbreaks in New York, however, are the largest and longest-lasting measles outbreaks since the disease was considered eliminated, said Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. The longer they continue, the “greater the chance that measles will again gain a foothold in the United States,” she said at CDC telebriefing on measles.

The outbreaks are linked to travelers who are exposed to measles abroad and bring it to the United States. The disease then may spread, especially in communities with high rates of unvaccinated people. “A significant factor contributing to the outbreaks in New York is misinformation in the communities about the safety of the measles/mumps/rubella vaccine,” according to the CDC.

National Infant Immunization Week

Until last week, 2014 – with 667 measles cases – had been the year with the most cases since the disease was effectively eliminated. The last time the United States had more measles cases was in 1994, when there were 963 cases for the year.

Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, also at the telebriefing, pointed out that 1994 also was the year that the United States first observed National Infant Immunization Week, which is April 27–May 4 this year. The CDC is marking the 25th anniversary of the annual observance, which highlights “the importance of protecting infants from vaccine-preventable diseases” and celebrates “the achievements of immunization programs in promoting healthy communities,” Secretary Azar said.

Message to health care providers

CDC director Robert Redfield Jr., MD, noted that measles has “no treatment, no cure, and no way to predict how bad a case will be.”

Some patients may have mild symptoms, whereas others may have serious complications such as pneumonia or encephalitis. In 2019, 3% of the patients with measles have developed pneumonia, he said. No patients have died.

Dr. Redfield, a virologist, noted that the CDC is recommending that children aged 6-12 months receive 1 dose of the measles vaccine if traveling abroad.

“As CDC director and as a physician, I have and continue to wholeheartedly advocate for infant immunization,” he said in a statement. “More importantly, as a father and grandfather I have ensured all of my children and grandchildren are vaccinated on the recommended schedule. Vaccines are safe. Vaccines do not cause autism. Vaccine-preventable diseases are dangerous.”

More than 94% of parents vaccinate their children, Dr. Redfield added. “CDC is working to reach the small percentage of vaccine-hesitant individuals so they too understand the importance of vaccines. It is imperative that we correct misinformation and reassure fearful parents so they protect their children from illnesses with long-lasting health impacts.”

About 1.3%, or 100,000 children, in the United States under 2 years old have not been vaccinated, he said.

“I call upon health care providers to encourage parents and expectant parents to vaccinate their children for their own protection and to avoid the spread of vaccine-preventable diseases within their families and communities,” he said. “We must join together as a nation to once again eliminate measles and prevent future disease outbreaks.”

The CDC has a complete list of clinical recommendations for health care providers on its website.

The president weighs in

President Donald Trump said that children should receive vaccinations – his first public comment about vaccines since his inauguration. Previously, he had questioned the safety of vaccines.

Asked by reporters about the measles outbreaks and his message for parents about having their kids vaccinated, he said: “They have to get the shot. The vaccinations are so important. This is really going around now. They have to get their shots.”

The updated figure adds 9 cases to the previous tally of 695 cases as of April 24, when the CDC announced that the number of cases in 2019 had surpassed the total for any year since the disease was considered effectively eliminated from the country in 2000.

Cases have been reported in 22 states, with the largest outbreaks in Washington and New York. The outbreak in Washington, which included 72 cases, was declared over last week. Two outbreaks in New York, however, are the largest and longest-lasting measles outbreaks since the disease was considered eliminated, said Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. The longer they continue, the “greater the chance that measles will again gain a foothold in the United States,” she said at CDC telebriefing on measles.

The outbreaks are linked to travelers who are exposed to measles abroad and bring it to the United States. The disease then may spread, especially in communities with high rates of unvaccinated people. “A significant factor contributing to the outbreaks in New York is misinformation in the communities about the safety of the measles/mumps/rubella vaccine,” according to the CDC.

National Infant Immunization Week

Until last week, 2014 – with 667 measles cases – had been the year with the most cases since the disease was effectively eliminated. The last time the United States had more measles cases was in 1994, when there were 963 cases for the year.

Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, also at the telebriefing, pointed out that 1994 also was the year that the United States first observed National Infant Immunization Week, which is April 27–May 4 this year. The CDC is marking the 25th anniversary of the annual observance, which highlights “the importance of protecting infants from vaccine-preventable diseases” and celebrates “the achievements of immunization programs in promoting healthy communities,” Secretary Azar said.

Message to health care providers

CDC director Robert Redfield Jr., MD, noted that measles has “no treatment, no cure, and no way to predict how bad a case will be.”

Some patients may have mild symptoms, whereas others may have serious complications such as pneumonia or encephalitis. In 2019, 3% of the patients with measles have developed pneumonia, he said. No patients have died.

Dr. Redfield, a virologist, noted that the CDC is recommending that children aged 6-12 months receive 1 dose of the measles vaccine if traveling abroad.

“As CDC director and as a physician, I have and continue to wholeheartedly advocate for infant immunization,” he said in a statement. “More importantly, as a father and grandfather I have ensured all of my children and grandchildren are vaccinated on the recommended schedule. Vaccines are safe. Vaccines do not cause autism. Vaccine-preventable diseases are dangerous.”

More than 94% of parents vaccinate their children, Dr. Redfield added. “CDC is working to reach the small percentage of vaccine-hesitant individuals so they too understand the importance of vaccines. It is imperative that we correct misinformation and reassure fearful parents so they protect their children from illnesses with long-lasting health impacts.”

About 1.3%, or 100,000 children, in the United States under 2 years old have not been vaccinated, he said.

“I call upon health care providers to encourage parents and expectant parents to vaccinate their children for their own protection and to avoid the spread of vaccine-preventable diseases within their families and communities,” he said. “We must join together as a nation to once again eliminate measles and prevent future disease outbreaks.”

The CDC has a complete list of clinical recommendations for health care providers on its website.

The president weighs in

President Donald Trump said that children should receive vaccinations – his first public comment about vaccines since his inauguration. Previously, he had questioned the safety of vaccines.

Asked by reporters about the measles outbreaks and his message for parents about having their kids vaccinated, he said: “They have to get the shot. The vaccinations are so important. This is really going around now. They have to get their shots.”

The updated figure adds 9 cases to the previous tally of 695 cases as of April 24, when the CDC announced that the number of cases in 2019 had surpassed the total for any year since the disease was considered effectively eliminated from the country in 2000.

Cases have been reported in 22 states, with the largest outbreaks in Washington and New York. The outbreak in Washington, which included 72 cases, was declared over last week. Two outbreaks in New York, however, are the largest and longest-lasting measles outbreaks since the disease was considered eliminated, said Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. The longer they continue, the “greater the chance that measles will again gain a foothold in the United States,” she said at CDC telebriefing on measles.

The outbreaks are linked to travelers who are exposed to measles abroad and bring it to the United States. The disease then may spread, especially in communities with high rates of unvaccinated people. “A significant factor contributing to the outbreaks in New York is misinformation in the communities about the safety of the measles/mumps/rubella vaccine,” according to the CDC.

National Infant Immunization Week

Until last week, 2014 – with 667 measles cases – had been the year with the most cases since the disease was effectively eliminated. The last time the United States had more measles cases was in 1994, when there were 963 cases for the year.

Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, also at the telebriefing, pointed out that 1994 also was the year that the United States first observed National Infant Immunization Week, which is April 27–May 4 this year. The CDC is marking the 25th anniversary of the annual observance, which highlights “the importance of protecting infants from vaccine-preventable diseases” and celebrates “the achievements of immunization programs in promoting healthy communities,” Secretary Azar said.

Message to health care providers

CDC director Robert Redfield Jr., MD, noted that measles has “no treatment, no cure, and no way to predict how bad a case will be.”

Some patients may have mild symptoms, whereas others may have serious complications such as pneumonia or encephalitis. In 2019, 3% of the patients with measles have developed pneumonia, he said. No patients have died.

Dr. Redfield, a virologist, noted that the CDC is recommending that children aged 6-12 months receive 1 dose of the measles vaccine if traveling abroad.

“As CDC director and as a physician, I have and continue to wholeheartedly advocate for infant immunization,” he said in a statement. “More importantly, as a father and grandfather I have ensured all of my children and grandchildren are vaccinated on the recommended schedule. Vaccines are safe. Vaccines do not cause autism. Vaccine-preventable diseases are dangerous.”

More than 94% of parents vaccinate their children, Dr. Redfield added. “CDC is working to reach the small percentage of vaccine-hesitant individuals so they too understand the importance of vaccines. It is imperative that we correct misinformation and reassure fearful parents so they protect their children from illnesses with long-lasting health impacts.”

About 1.3%, or 100,000 children, in the United States under 2 years old have not been vaccinated, he said.

“I call upon health care providers to encourage parents and expectant parents to vaccinate their children for their own protection and to avoid the spread of vaccine-preventable diseases within their families and communities,” he said. “We must join together as a nation to once again eliminate measles and prevent future disease outbreaks.”

The CDC has a complete list of clinical recommendations for health care providers on its website.

The president weighs in

President Donald Trump said that children should receive vaccinations – his first public comment about vaccines since his inauguration. Previously, he had questioned the safety of vaccines.

Asked by reporters about the measles outbreaks and his message for parents about having their kids vaccinated, he said: “They have to get the shot. The vaccinations are so important. This is really going around now. They have to get their shots.”

FROM A CDC TELEBRIEFING

Combo respiratory pathogen tests miss pertussis

BALTIMORE – Ann Arbor.

Respiratory pathogen panels are popular because they test for many things at once, but providers have to know their limits, said lead investigator Colleen Mayhew, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at the University of Michigan.

“Should RPAN be used to diagnosis pertussis? No,” she said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting. RPAN was negative for confirmed pertussis 44% of the time in the study.

“In our cohort, [it] was no better than a coin flip for detecting pertussis,” she said. Also, even when it missed pertussis, it still detected other pathogens, which raises the risk that symptoms might be attributed to a different infection. “This has serious public health implications.”

“The bottom line is, if you are concerned about pertussis, it’s important to use a dedicated pertussis PCR [polymerase chain reaction] assay, and to use comprehensive respiratory pathogen testing only if there are other, specific targets that will change your clinical management,” such as mycoplasma or the flu, Dr. Mayhew said.

In the study, 102 nasopharyngeal swabs positive for pertussis on standalone PCR testing – the university uses an assay from Focus Diagnostics – were thawed and tested with RPAN.

RPAN was negative for pertussis on 45 swabs (44%). “These are the potential missed pertussis cases if RPAN is used alone,” Dr. Mayhew said. RPAN detected other pathogens, such as coronavirus, about half the time, whether or not it tested positive for pertussis. “Those additional pathogens might represent coinfection, but might also represent asymptomatic carriage.” It’s impossible to differentiate between the two, she noted.

In short, “neither positive testing for other respiratory pathogens, nor negative testing for pertussis by RPAN, is reliable for excluding the diagnosis of pertussis. Dedicated pertussis PCR testing should be used for diagnosis,” she and her team concluded.

RPAN also is a PCR test, but with a different, perhaps less robust, genetic target.

The 102 positive swabs were from patients aged 1 month to 73 years, so “it’s important for all of us to keep pertussis on our differential diagnose” no matter how old patients are, Dr. Mayhew said.

Freezing and thawing the swabs shouldn’t have degraded the genetic material, but it might have; that was one of the limits of the study.

The team hopes to run a quality improvement project to encourage the use of standalone pertussis PCR in Ann Arbor.

There was no industry funding. Dr. Mayhew didn’t report any disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Ann Arbor.

Respiratory pathogen panels are popular because they test for many things at once, but providers have to know their limits, said lead investigator Colleen Mayhew, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at the University of Michigan.

“Should RPAN be used to diagnosis pertussis? No,” she said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting. RPAN was negative for confirmed pertussis 44% of the time in the study.

“In our cohort, [it] was no better than a coin flip for detecting pertussis,” she said. Also, even when it missed pertussis, it still detected other pathogens, which raises the risk that symptoms might be attributed to a different infection. “This has serious public health implications.”

“The bottom line is, if you are concerned about pertussis, it’s important to use a dedicated pertussis PCR [polymerase chain reaction] assay, and to use comprehensive respiratory pathogen testing only if there are other, specific targets that will change your clinical management,” such as mycoplasma or the flu, Dr. Mayhew said.

In the study, 102 nasopharyngeal swabs positive for pertussis on standalone PCR testing – the university uses an assay from Focus Diagnostics – were thawed and tested with RPAN.

RPAN was negative for pertussis on 45 swabs (44%). “These are the potential missed pertussis cases if RPAN is used alone,” Dr. Mayhew said. RPAN detected other pathogens, such as coronavirus, about half the time, whether or not it tested positive for pertussis. “Those additional pathogens might represent coinfection, but might also represent asymptomatic carriage.” It’s impossible to differentiate between the two, she noted.

In short, “neither positive testing for other respiratory pathogens, nor negative testing for pertussis by RPAN, is reliable for excluding the diagnosis of pertussis. Dedicated pertussis PCR testing should be used for diagnosis,” she and her team concluded.

RPAN also is a PCR test, but with a different, perhaps less robust, genetic target.

The 102 positive swabs were from patients aged 1 month to 73 years, so “it’s important for all of us to keep pertussis on our differential diagnose” no matter how old patients are, Dr. Mayhew said.

Freezing and thawing the swabs shouldn’t have degraded the genetic material, but it might have; that was one of the limits of the study.

The team hopes to run a quality improvement project to encourage the use of standalone pertussis PCR in Ann Arbor.

There was no industry funding. Dr. Mayhew didn’t report any disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Ann Arbor.

Respiratory pathogen panels are popular because they test for many things at once, but providers have to know their limits, said lead investigator Colleen Mayhew, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at the University of Michigan.

“Should RPAN be used to diagnosis pertussis? No,” she said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting. RPAN was negative for confirmed pertussis 44% of the time in the study.

“In our cohort, [it] was no better than a coin flip for detecting pertussis,” she said. Also, even when it missed pertussis, it still detected other pathogens, which raises the risk that symptoms might be attributed to a different infection. “This has serious public health implications.”

“The bottom line is, if you are concerned about pertussis, it’s important to use a dedicated pertussis PCR [polymerase chain reaction] assay, and to use comprehensive respiratory pathogen testing only if there are other, specific targets that will change your clinical management,” such as mycoplasma or the flu, Dr. Mayhew said.

In the study, 102 nasopharyngeal swabs positive for pertussis on standalone PCR testing – the university uses an assay from Focus Diagnostics – were thawed and tested with RPAN.

RPAN was negative for pertussis on 45 swabs (44%). “These are the potential missed pertussis cases if RPAN is used alone,” Dr. Mayhew said. RPAN detected other pathogens, such as coronavirus, about half the time, whether or not it tested positive for pertussis. “Those additional pathogens might represent coinfection, but might also represent asymptomatic carriage.” It’s impossible to differentiate between the two, she noted.

In short, “neither positive testing for other respiratory pathogens, nor negative testing for pertussis by RPAN, is reliable for excluding the diagnosis of pertussis. Dedicated pertussis PCR testing should be used for diagnosis,” she and her team concluded.

RPAN also is a PCR test, but with a different, perhaps less robust, genetic target.

The 102 positive swabs were from patients aged 1 month to 73 years, so “it’s important for all of us to keep pertussis on our differential diagnose” no matter how old patients are, Dr. Mayhew said.

Freezing and thawing the swabs shouldn’t have degraded the genetic material, but it might have; that was one of the limits of the study.

The team hopes to run a quality improvement project to encourage the use of standalone pertussis PCR in Ann Arbor.

There was no industry funding. Dr. Mayhew didn’t report any disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

Utilizing mentorship to achieve equity in leadership

Academic medicine and the health care industry

Achieving equity in leadership in academic medicine and the health care industry doesn’t have to be a pipe dream. There are clear, actionable steps that will lead us there.

The benefits of diversity are numerous and well documented. Diversity brings competitive advantage to organizations and strength to teams. With academic health centers (AHCs) facing continual stressors while at the same time being significant financial contributors to – and anchors in – their communities, ensuring their high performance is critical to society as a whole. To grow, thrive, and be ethical examples to their communities, health centers need the strongest and most innovative leaders who are reflective of the communities that they serve. This means more diversity in leadership positions.

When we look at the facts of the gender makeup of academic medicine and the health care industry, we can clearly see inequity – only 22% of medical school full professors, 18% of medical school department chairs, and 17% of medical school deans are women. Note that it has taken 50 years to get from 0 women deans to the 25 women deans who are now in this role. Only 28% of full and associate professors and 21% of department chairs are nonwhite. In the health care industry, only 13% of CEOs are women. The pace toward equity has been excruciatingly slow, and it’s not only women and underrepresented minorities who lose, but also the AHCs and their communities.

So how do we reach equity? Mentorship is a key pathway to this goal. In a session at Hospital Medicine 2019 (HM19), “What Mentorship Has Meant To Me (And What It Can Do For You): High Impact Stories from Leaders in Hospital Medicine,” fellow panelists and I outlined how mentorship can positively affect your career, define the qualities of effective mentors and mentees, describe the difference between mentorship and sponsorship, and explained how to navigate common pitfalls in mentor-mentee relationships.

We spoke about the responsibility the mentee has in the relationship and the need to “manage up,” a term borrowed from the corporate world, where the mentee takes responsibility for his or her part in the relationship and takes a leadership role in the relationship. The mentee must be an “active participant” in the relationship for the relationship to be successful. We hope that attendees at the session took some key points back to their institutions to open dialogue on strategies to achieve equity through building mentoring relationships.

When I look back on my time in residency and fellowship, I recognize that I was surrounded by people who offered guidance and advice. But once I became a faculty member, that guidance was less apparent, and I struggled in the first few years. It wasn’t until I attended a conference on peer mentoring that I recognized that I didn’t just need a didactic mentor, but that I needed a portfolio of mentors and that I had to take the initiative to actively engage mentorship. So I did, and its effects on my career have been powerful and numerous.

The evidence is there that mentorship can play a major role in advancing careers. Now it is up to the leadership of academic and nonacademic health centers to take the initiative and establish formalized programs in their institutions. We all benefit when we have diversity in leadership – so let’s get there together.

Dr. Spector is executive director, Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine, associate dean of faculty development, Drexel University, Philadelphia.

Academic medicine and the health care industry

Academic medicine and the health care industry

Achieving equity in leadership in academic medicine and the health care industry doesn’t have to be a pipe dream. There are clear, actionable steps that will lead us there.

The benefits of diversity are numerous and well documented. Diversity brings competitive advantage to organizations and strength to teams. With academic health centers (AHCs) facing continual stressors while at the same time being significant financial contributors to – and anchors in – their communities, ensuring their high performance is critical to society as a whole. To grow, thrive, and be ethical examples to their communities, health centers need the strongest and most innovative leaders who are reflective of the communities that they serve. This means more diversity in leadership positions.

When we look at the facts of the gender makeup of academic medicine and the health care industry, we can clearly see inequity – only 22% of medical school full professors, 18% of medical school department chairs, and 17% of medical school deans are women. Note that it has taken 50 years to get from 0 women deans to the 25 women deans who are now in this role. Only 28% of full and associate professors and 21% of department chairs are nonwhite. In the health care industry, only 13% of CEOs are women. The pace toward equity has been excruciatingly slow, and it’s not only women and underrepresented minorities who lose, but also the AHCs and their communities.

So how do we reach equity? Mentorship is a key pathway to this goal. In a session at Hospital Medicine 2019 (HM19), “What Mentorship Has Meant To Me (And What It Can Do For You): High Impact Stories from Leaders in Hospital Medicine,” fellow panelists and I outlined how mentorship can positively affect your career, define the qualities of effective mentors and mentees, describe the difference between mentorship and sponsorship, and explained how to navigate common pitfalls in mentor-mentee relationships.

We spoke about the responsibility the mentee has in the relationship and the need to “manage up,” a term borrowed from the corporate world, where the mentee takes responsibility for his or her part in the relationship and takes a leadership role in the relationship. The mentee must be an “active participant” in the relationship for the relationship to be successful. We hope that attendees at the session took some key points back to their institutions to open dialogue on strategies to achieve equity through building mentoring relationships.

When I look back on my time in residency and fellowship, I recognize that I was surrounded by people who offered guidance and advice. But once I became a faculty member, that guidance was less apparent, and I struggled in the first few years. It wasn’t until I attended a conference on peer mentoring that I recognized that I didn’t just need a didactic mentor, but that I needed a portfolio of mentors and that I had to take the initiative to actively engage mentorship. So I did, and its effects on my career have been powerful and numerous.

The evidence is there that mentorship can play a major role in advancing careers. Now it is up to the leadership of academic and nonacademic health centers to take the initiative and establish formalized programs in their institutions. We all benefit when we have diversity in leadership – so let’s get there together.

Dr. Spector is executive director, Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine, associate dean of faculty development, Drexel University, Philadelphia.

Achieving equity in leadership in academic medicine and the health care industry doesn’t have to be a pipe dream. There are clear, actionable steps that will lead us there.

The benefits of diversity are numerous and well documented. Diversity brings competitive advantage to organizations and strength to teams. With academic health centers (AHCs) facing continual stressors while at the same time being significant financial contributors to – and anchors in – their communities, ensuring their high performance is critical to society as a whole. To grow, thrive, and be ethical examples to their communities, health centers need the strongest and most innovative leaders who are reflective of the communities that they serve. This means more diversity in leadership positions.

When we look at the facts of the gender makeup of academic medicine and the health care industry, we can clearly see inequity – only 22% of medical school full professors, 18% of medical school department chairs, and 17% of medical school deans are women. Note that it has taken 50 years to get from 0 women deans to the 25 women deans who are now in this role. Only 28% of full and associate professors and 21% of department chairs are nonwhite. In the health care industry, only 13% of CEOs are women. The pace toward equity has been excruciatingly slow, and it’s not only women and underrepresented minorities who lose, but also the AHCs and their communities.

So how do we reach equity? Mentorship is a key pathway to this goal. In a session at Hospital Medicine 2019 (HM19), “What Mentorship Has Meant To Me (And What It Can Do For You): High Impact Stories from Leaders in Hospital Medicine,” fellow panelists and I outlined how mentorship can positively affect your career, define the qualities of effective mentors and mentees, describe the difference between mentorship and sponsorship, and explained how to navigate common pitfalls in mentor-mentee relationships.

We spoke about the responsibility the mentee has in the relationship and the need to “manage up,” a term borrowed from the corporate world, where the mentee takes responsibility for his or her part in the relationship and takes a leadership role in the relationship. The mentee must be an “active participant” in the relationship for the relationship to be successful. We hope that attendees at the session took some key points back to their institutions to open dialogue on strategies to achieve equity through building mentoring relationships.

When I look back on my time in residency and fellowship, I recognize that I was surrounded by people who offered guidance and advice. But once I became a faculty member, that guidance was less apparent, and I struggled in the first few years. It wasn’t until I attended a conference on peer mentoring that I recognized that I didn’t just need a didactic mentor, but that I needed a portfolio of mentors and that I had to take the initiative to actively engage mentorship. So I did, and its effects on my career have been powerful and numerous.

The evidence is there that mentorship can play a major role in advancing careers. Now it is up to the leadership of academic and nonacademic health centers to take the initiative and establish formalized programs in their institutions. We all benefit when we have diversity in leadership – so let’s get there together.

Dr. Spector is executive director, Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine, associate dean of faculty development, Drexel University, Philadelphia.

Speaking at a conference? Read these tips first

Recently, I was asked to present my top public speaking tips for a group of women leaders. This is a topic near and dear to my heart, and one that I teach a number of groups, from medical students to faculty.

I also benefited from just returning from the Harvard Macy Educators Course, where Victoria Brazil, MD, an experienced emergency medicine physician from Australia, provided her top tips. Here is a mash-up of the top tips to think about for any of the speakers out there among us – with a few shout-outs for the ladies out there. Please add your own!

The Dos

- Do project power: Stand tall with a relaxed stance and shoulders back – posture is everything. This is especially important for women, who may tend to shrink their bodies, or anyone who is short. A powerful messenger is just as important as the power of the message. The same also applies to sitting down, especially if you are on a panel. Do not look like you are falling into the table.

- Do look up: Think about addressing the people in the back, not in the front row. This looks better in photos as well since you are appealing to the large audience and not the front row. Dr. Brazil’s tip came from Cate Blanchett who said that before she gives talks, she literally and physically advises “picking up your crown and put it on your head.” Not only will you feel better, you will look it too.

- Do pause strategically: The human brain needs rest to process what you are about to say. You can ask people to “think of a time” and take a pause. Or “I want you to all think about what I just said for one moment.” And TAKE a moment. But think about Emma’s pause during the March For Your Lives. Pauses are powerful and serve as a way to cement what you are saying for even the most critical crowd. Think about when anyone on their phone pauses, even if you’re on a boring conference call others will wake up and wonder what is going on and are now engaged in the talk.

- Do strategically summarize: Before you end, or in between important sections, say the following: “There are three main things you can do.” Even if someone fell asleep, they will wake up to take note. It’s a way to get folks’ attention back. There is nothing like challenging others to do something.

The Don’ts

- Don’t start with an apology for “not being an expert”: Or whatever you are thinking about apologizing for. The voice in your head does not need to be broadcast to others. Just say thank you after you are introduced, and launch in. Someone has asked you to talk, so bring your own unique expertise and don’t start with undermining yourself!

- Don’t use your slides as a crutch: Make your audience look at you and not your slides. That means at times, you may be talking and your slides will not be moving. Other times, if you are starting with a story, maybe there is no slide behind you and the screen is blacked out. Some of the most powerful moments in a talk are when slides are not being used.

- Don’t stand behind the podium if you can help it. This means ask for a wireless microphone. Most podiums will overwhelm you. If you have to use a podium, go back to the posture in the “dos.” One year, I had a leg injury and definitely used the podium, so obviously there may be times you need to use a podium; even then, try as hard as possible to make sure you are seen.