User login

VIDEO: How should you respond to a possible privacy breach?

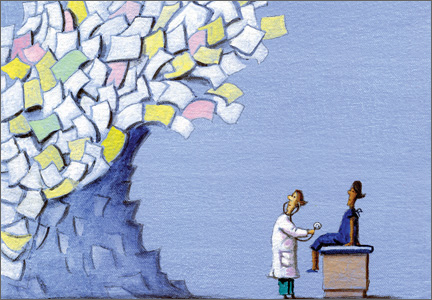

CHICAGO – Overreact, don’t underreact, when it comes to possible health care privacy breaches, attorney Clinton Mikel advised at a conference held by the American Bar Association.

The actions that physicians take immediately following a potential data exposure will significantly impact how the Health and Human Services Department’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) responds to the incident and whether physicians face penalties, said Mr. Mikel, who specializes in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and state privacy laws.

In an interview at the conference, Mr. Mikel, who practices law in Southfield, Mich., discussed common misconceptions that physicians have about privacy breaches and the best ways in which to respond internally to possible exposures. He also offered guidance on the top mistakes to avoid when confronted with possible security breaches and shared perspective on how the OCR might address such issues in the future.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @legal_med

CHICAGO – Overreact, don’t underreact, when it comes to possible health care privacy breaches, attorney Clinton Mikel advised at a conference held by the American Bar Association.

The actions that physicians take immediately following a potential data exposure will significantly impact how the Health and Human Services Department’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) responds to the incident and whether physicians face penalties, said Mr. Mikel, who specializes in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and state privacy laws.

In an interview at the conference, Mr. Mikel, who practices law in Southfield, Mich., discussed common misconceptions that physicians have about privacy breaches and the best ways in which to respond internally to possible exposures. He also offered guidance on the top mistakes to avoid when confronted with possible security breaches and shared perspective on how the OCR might address such issues in the future.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @legal_med

CHICAGO – Overreact, don’t underreact, when it comes to possible health care privacy breaches, attorney Clinton Mikel advised at a conference held by the American Bar Association.

The actions that physicians take immediately following a potential data exposure will significantly impact how the Health and Human Services Department’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) responds to the incident and whether physicians face penalties, said Mr. Mikel, who specializes in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and state privacy laws.

In an interview at the conference, Mr. Mikel, who practices law in Southfield, Mich., discussed common misconceptions that physicians have about privacy breaches and the best ways in which to respond internally to possible exposures. He also offered guidance on the top mistakes to avoid when confronted with possible security breaches and shared perspective on how the OCR might address such issues in the future.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @legal_med

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE PHYSICIANS LEGAL ISSUES CONFERENCE

The SGR is abolished! What comes next?

Congratulations, OBG Management readers! After years of hard work and collective advocacy on your part, the US Congress finally passed, and President Barack Obama quickly signed into law, a permanent repeal of the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) physician payment system. Yes, celebrations are in order.

The US House of Representatives passed the bill, HR 2, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), sponsored by American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Fellow and US Rep. Michael Burgess (R-TX), on March 26, with 382 Republicans and Democrats voting “Yes.” The Senate followed, on April 14, and agreed with the House to repeal, forever, the Medicare SGR, passing the Burgess bill without amendment, on a bipartisan vote of 92–8. With only hours to go before the scheduled 21.2% cut took effect, the President signed the bill, now Public Law (PL) 114-10, on April 16. The President noted that he was “proud to sign the bill into law.” ACOG is proud to have been such an important part of this landmark moment.

SGR: the perennial nemesis of physicians

The SGR has wreaked havoc on medicine and patient care for 15 years or more. Approximately 30,000 ObGyns participate in Medicare, and many private health insurers use Medicare payment policies, as does TriCare, the nation’s health care coverage for military members and their families. The SGR’s effect was felt widely across medicine, making it nearly impossible for physician practices to invest in health information technology and other patient safety advances, or even to plan for the next year or continue accepting Medicare patients.

When it was introduced last year, HR 2 was supported by more than 600 national and state medical societies and specialty organizations, plus patient and provider organizations, policy think tanks, and advocacy groups across the political spectrum.

ACOG Fellows petitioned their members of Congress with incredible passion, perseverance, and commitment to put an end to the SGR wrecking ball. Hundreds flew into Washington, DC, sent thousands of emails, made phone calls, wrote letters, and personally lobbied at home and in the halls of Congress.

Special kudos, too, to our champions in Congress, and there are many, led by ACOG Fellows and US Reps. Dr. Burgess and Phil Roe, MD (R-TN). Burgess wrote the House bill and, together with Roe, pushed nonstop to get this bill over the finish line. It wouldn’t have happened without them.

ACOG worked tirelessly on its own and in coalition with the American Medical Association, surgical groups, and many other partners. We were able to win important provisions in the statute that we anticipate will greatly help ObGyns successfully transition to this new payment system.

PL114-10 replaces the SGR with a new payment system intended to promote care coordination and quality improvement and lead to better health for our nation’s seniors. Congress developed this new payment plan with the physician community, rather than imposing it on us. That’s why throughout the statute, we see repeated requirements that the Secretary of Health and Human Services must develop quality measures, alternative payment models, and a host of key aspects with input from and in consultation with physicians and the relevant medical specialties, ensuring that physicians retain their preeminent roles in these areas. Funding is provided for quality measure development at $15 million per year from 2015 to 2019.

This law will likely change physician practices more than the ACA ever will, and Congress agreed that physicians should be integral to its development to ensure that they can continue to thrive and provide high-quality care and access for their patients.

Let’s take a closer look at the new Medicare payment system—especially what it will mean for your practice.

What the new law does

Important provisions

- MACRA retains the fee-for-service payment model, now called the Merit-based Incentive Payment System, or MIPS. Physician participation in the Advanced Payment Models (APMs) is entirely voluntary. But physicians who participate in APMs and who score better each year will earn more.

- All physician types are treated equally. Congress didn’t pick specialty winners and losers.

- The new payment system rewards physicians for continuous improvement. You can determine how financially well you do.

- Beginning in 2019, Medicare physician payments will reflect each individual physician’s performance, based on a range of measures developed by the relevant medical specialty that will give individuals options that best reflect their practices.

- Individual physicians will receive confidential quarterly feedback on their performance.

- Technical support is provided for smaller practices, funded at $20 million per year from 2016 to 2020, to help them transition to MIPS and APMs. And physicians in small practices can opt to join a “virtual MIPS group,” associating with other practices or hospitals in the same geographic region or by specialty types.

- The law protects physicians from liability from federal or state standards of care. No health care guideline or other standard developed under federal or state requirements associated with this law may be used as a standard of care or duty of care owed by a health care professional to a patient in a medical liability lawsuit.

MACRA stabilizes the Medicare payment system by permanently repealing the SGR and scheduling payments into the future:

- through June 2015: Stable payments with no cuts

- July 2015–2019: 0.5% annual payment increases to all Medicare physicians

- 2020–2025: No automatic annual payment changes but opportunities for payment increases based on individual performance

- 2026 and beyond: 0.75% annual payment increases for qualifying APMs, 0.25% for MIPS providers, with opportunities in both systems for higher payments based on individual performance.

Top ACOG wins

Among the most meaningful accomplishments achieved by ACOG in its work to repeal the sustainable growth rate are:

- Reliable payment increases for the first 5 years. The law ensures a period of stability with modest Medicare payment in-

creases for 5 years and no cuts, with opportunity for payment increases for the next 5 years. This 5-year period gives physicians time to get ready for the new payment systems. - Protection for low-Medicare–volume physician practices. ObGyns and other physicians with a small Medicare patient population are exempt from many program requirements and penalties.

- Stops the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) policy on global surgical codes, reinstating 10-day and 90-day global payment bundles for surgical services. This directly helps ObGyn subspecialists, including urogynecologists and gynecologic oncologists.

- Physician liability protections. The law ensures that federal quality measurements cannot be used to imply medical negligence and generate lawsuits.

- Protection for ultrasound. There are no cuts to ultrasound reimbursement.

- An end, in 2018, to penalties related to electronic health record (EHR) meaningful use, Physician Quality Reporting Systems, and the use of the value-based modifier.

- APM bonus payments. Bonus eligibility for Alternative Payment Model (APM) participation is based on patient volume, not just revenue, to make it easier for ObGyns to qualify.

- 2-year extension of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which provides comprehensive coverage to 8 million children, adolescents, and pregnant women across the country.

- Quality-measure development. The law helps professional organizations, such as ACOG, develop quality measures for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) rather than allow these measures to be developed by a federal agency, ensuring that this new program works for physicians and our patients.

Two payment system options reward continuous quality improvement

Option 1: MIPS. MACRA consolidates and expands pay-for-performance incentives within the old SGR fee-for-service system, creating the new MIPS. Under MIPS, the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), electronic health record (EHR) meaningful use incentive program, and physician value-based modifiers (VBMs) become a single program. In 2019, a physician’s individual score on these measures will be used to adjust his or her Medicare payments, and the penalties previously associated with these programs come to an end.

MACRA creates 4 categories of measures that are weighted to calculate an individual physician’s MIPS score:

- Quality (50% of total adjustment in 2019, shrinking to 30% of total adjustment in 2021). Quality measures currently in use in the PQRS, VBM, and EHR meaningful use programs will continue to be used. The Secretary of Health and Human Services must fund and work with specialty societies to develop any additional measures, and measures utilized in clinical data registries can be used for this category as well. Measures will be updated annually, and ACOG and other specialties can submit measures directly for approval, rather than rely on an outside entity.

- Resource use (10% of total adjustment in 2019, growing to 30% of total adjustment by 2021). Resource use measures are risk-adjusted and include those already used in the VBM program; others must be developed with physicians, reflecting both the physician’s role in treating the patient (eg, primary or specialty care) and the type of treatment (eg, chronic or acute).

- EHR use (25% of total adjustment). Current meaningful use systems will qualify for this category. The law also requires EHR interoperability by 2018 and prohibits the blocking of information sharing between EHR vendors.

- Clinical improvement (15% of total adjustment). This is a new component of physician measurement, intended to give physicians credit for working to improve their practices and help them participate in APMs, which have higher reimbursement potential. This menu of qualifying activities—including 24-hour availability, safety, and patient satisfaction—must be developed with physicians and must be attainable by all specialties and practice types, including small practices and those in rural and underserved areas. Maintenance of certification can be used to qual-ify for a high score.

Physicians will only be assessed on the categories, measures, and activities that apply to them. A physician’s composite score (0–100) will be compared with a performance threshold that reflects all physicians. Those who score above the threshold will receive increased payments; those who score below the threshold will receive reduced payments. Physicians will know these thresholds in advance and will know the score they must reach to avoid penalties and win higher reimbursements in each performance period.

As physicians as a whole improve their performance, the threshold will move with them. So each year, physicians will have the incentive to keep improving their quality, resource use, clinical improvement, and EHR use. A physician’s payment adjustment in one year will not affect his or her payment adjustment in the next year.

The range of potential payment adjustments based on MIPS performance measures increases each year through 2022. Providers who have high scores are rewarded with a 4% increase in 2019. By 2022, the reward is 9%. The program is budget-neutral, so total positive adjustments across all providers will equal total negative adjustments across all providers to poor performers. Separate funds are set aside to reward the highest performers, who will earn bonuses of up to 10% of their fee-for-service payment rate from 2019 through 2024, as well as to help low performers improve and qualify for increased payments from 2016 through 2020.

Help for physicians includes:

- flexibility to participate in a way that best reflects their practice, using risk-adjusted clinical outcome measures

- option to participate in a virtual MIPS group rather than go it alone

- technical assistance to practices with 15 or fewer professionals, $20 million annually from 2016 through 2020, with preference to practices with low MIPS scores and those in rural and underserved areas

- quarterly confidential feedback on performance in the quality and resource use categories

- advance notification to each physician of the score needed to reach higher payment levels

- exclusion from MIPS of physicians who treat few Medicare patients, as well as those who receive a significant portion of their revenues from APMs.

Option 2: APMs. Physicians can earn higher fees by opting out of MIPS fee for service and participating in APMs. The law defines qualifying APMs as those that require participating providers to take on “more than nominal” financial risk, report quality measures, and use certified EHR technology.

APMs will cover multiple services, show that they can limit the growth of spending, and use performance-based methods of compensation. These and other provisions will likely continue the trend away from physicians practicing in solo or small-group fee-for-service practices into risk-based multispecialty settings that are subject to increased management and oversight.

From 2019 to 2024, qualified APM physicians will receive a 5% annual lump sum bonus based on their prior year’s physician fee-schedule payments plus shared savings from participation. This bonus is based on patient volume, not just revenue, to make it easier for ObGyns to qualify. To make the bonus widely available, the Secretary of Health and Human Services must test APMs designed for specific specialties and physicians in small practices. As in MIPS, top APM performers will also receive an additional bonus.

To qualify, physicians must meet increasing thresholds for the percentage of their revenue that they receive through APMs. Those who are below but near the required level of APM revenue can be exempted from MIPS adjustments.

- 2019–2020: 25% of Medicare revenue must be received through APMs.

- 2021–2022: 50% of Medicare revenue or 50% of all-payer revenue along with 25% of Medicare revenue must be received through APMs.

- 2023 and beyond: 75% of Medicare revenue or 75% of all-payer revenue along with 25% of Medicare revenue must be received through APMs.

Who pays the bill?

Medicare beneficiaries pay more

The new law increases the percentage of Medicare Parts B and D premiums that high-income beneficiaries must pay beginning in 2018:

- Single seniors reporting income of more than $133,500 and married couples with income of more than $267,000 will see their share of premiums rise from 50% to 65%.

- Single seniors reporting income above $160,000 and married couples with income above $320,000 will see their premium share rise from 65% to 80%.

This change will affect about 2% of Medicare beneficiaries; half of all Medicare beneficiaries currently have annual incomes below $26,000.1

Medigap “first-dollar coverage” will end

Many Medigap plans on the market today provide “first-dollar coverage” for beneficiaries, which means that the plans pay the deductibles and copayments so that the beneficiaries have no out-of-pocket costs. Beginning in 2020, Medigap plans will only be available to cover costs above the Medicare Part B deductible, currently $147 per year, for new Medigap enrollees. Many lawmakers thought it was important for Medicare beneficiaries to have “skin in the game.”

The law cuts payments for some providers

To partially offset the cost of repealing the SGR, MACRA cuts Medicare payments to hospitals and postacute providers. It:

- delays Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) cuts scheduled to begin in 2017 by a year and extends them through 2025

- requires an increase in payments to hospitals scheduled for 2018 to instead be phased in over 6 years

- limits the 2018 payment update for post-acute providers to 1%.

The law extends many programs

These programs are vital to support the future ObGyn workforce and access to health care. Among these programs are:

- a halt to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) policy on global surgical codes. The law reinstates 10-day and 90-day global payment bundles for surgical services. This directly helps ObGyn subspecialists, such as urogynecologists and gynecologic oncologists.

- renewal of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which provides comprehensive coverage to 8 million children, adolescents, and pregnant women across the country

- establishment of a Medicaid/CHIP Pediatric Quality Measures Program, supporting the development and physician adoption of quality measures, including for prenatal and preconception care

- funding for the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program, helping at-risk pregnant women and their families to promote healthy births and early childhood development

- funding for community health centers, an important source of care for 13 million women and girls in all 50 states and the District of Columbia

- funding for the National Health Service Corps, bringing ObGyns and other primary care providers to underserved rural and urban areas through scholarships and loan repayment programs

- funding for the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education Payment Program, enhancing training for ObGyns and other primary care providers in community-based settings

- extending the Medicare Geographic Practice Cost Index floor, helping ensure access to care for women in rural areas

- extending the Personal Responsibility Education Program to help prevent teen pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections.

Next steps

It’s very important that ObGyns and other physicians use these early years to understand and get ready for the new payment systems. ACOG is developing educational material for our members, and will work closely with our colleague medical organizations and the Department of Health and Human Services to develop key aspects of the law and ensure that it is properly implemented to work for physicians and patients.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

1. Aaron HJ. Three cheers for log-rolling: The demise of the SGR. Brookings Health360. http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/health360/posts/2015/04/22-medicare-sgr-repeal-doc-fix-aaron. Published April 22, 2015. Accessed May 12, 2015.

Congratulations, OBG Management readers! After years of hard work and collective advocacy on your part, the US Congress finally passed, and President Barack Obama quickly signed into law, a permanent repeal of the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) physician payment system. Yes, celebrations are in order.

The US House of Representatives passed the bill, HR 2, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), sponsored by American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Fellow and US Rep. Michael Burgess (R-TX), on March 26, with 382 Republicans and Democrats voting “Yes.” The Senate followed, on April 14, and agreed with the House to repeal, forever, the Medicare SGR, passing the Burgess bill without amendment, on a bipartisan vote of 92–8. With only hours to go before the scheduled 21.2% cut took effect, the President signed the bill, now Public Law (PL) 114-10, on April 16. The President noted that he was “proud to sign the bill into law.” ACOG is proud to have been such an important part of this landmark moment.

SGR: the perennial nemesis of physicians

The SGR has wreaked havoc on medicine and patient care for 15 years or more. Approximately 30,000 ObGyns participate in Medicare, and many private health insurers use Medicare payment policies, as does TriCare, the nation’s health care coverage for military members and their families. The SGR’s effect was felt widely across medicine, making it nearly impossible for physician practices to invest in health information technology and other patient safety advances, or even to plan for the next year or continue accepting Medicare patients.

When it was introduced last year, HR 2 was supported by more than 600 national and state medical societies and specialty organizations, plus patient and provider organizations, policy think tanks, and advocacy groups across the political spectrum.

ACOG Fellows petitioned their members of Congress with incredible passion, perseverance, and commitment to put an end to the SGR wrecking ball. Hundreds flew into Washington, DC, sent thousands of emails, made phone calls, wrote letters, and personally lobbied at home and in the halls of Congress.

Special kudos, too, to our champions in Congress, and there are many, led by ACOG Fellows and US Reps. Dr. Burgess and Phil Roe, MD (R-TN). Burgess wrote the House bill and, together with Roe, pushed nonstop to get this bill over the finish line. It wouldn’t have happened without them.

ACOG worked tirelessly on its own and in coalition with the American Medical Association, surgical groups, and many other partners. We were able to win important provisions in the statute that we anticipate will greatly help ObGyns successfully transition to this new payment system.

PL114-10 replaces the SGR with a new payment system intended to promote care coordination and quality improvement and lead to better health for our nation’s seniors. Congress developed this new payment plan with the physician community, rather than imposing it on us. That’s why throughout the statute, we see repeated requirements that the Secretary of Health and Human Services must develop quality measures, alternative payment models, and a host of key aspects with input from and in consultation with physicians and the relevant medical specialties, ensuring that physicians retain their preeminent roles in these areas. Funding is provided for quality measure development at $15 million per year from 2015 to 2019.

This law will likely change physician practices more than the ACA ever will, and Congress agreed that physicians should be integral to its development to ensure that they can continue to thrive and provide high-quality care and access for their patients.

Let’s take a closer look at the new Medicare payment system—especially what it will mean for your practice.

What the new law does

Important provisions

- MACRA retains the fee-for-service payment model, now called the Merit-based Incentive Payment System, or MIPS. Physician participation in the Advanced Payment Models (APMs) is entirely voluntary. But physicians who participate in APMs and who score better each year will earn more.

- All physician types are treated equally. Congress didn’t pick specialty winners and losers.

- The new payment system rewards physicians for continuous improvement. You can determine how financially well you do.

- Beginning in 2019, Medicare physician payments will reflect each individual physician’s performance, based on a range of measures developed by the relevant medical specialty that will give individuals options that best reflect their practices.

- Individual physicians will receive confidential quarterly feedback on their performance.

- Technical support is provided for smaller practices, funded at $20 million per year from 2016 to 2020, to help them transition to MIPS and APMs. And physicians in small practices can opt to join a “virtual MIPS group,” associating with other practices or hospitals in the same geographic region or by specialty types.

- The law protects physicians from liability from federal or state standards of care. No health care guideline or other standard developed under federal or state requirements associated with this law may be used as a standard of care or duty of care owed by a health care professional to a patient in a medical liability lawsuit.

MACRA stabilizes the Medicare payment system by permanently repealing the SGR and scheduling payments into the future:

- through June 2015: Stable payments with no cuts

- July 2015–2019: 0.5% annual payment increases to all Medicare physicians

- 2020–2025: No automatic annual payment changes but opportunities for payment increases based on individual performance

- 2026 and beyond: 0.75% annual payment increases for qualifying APMs, 0.25% for MIPS providers, with opportunities in both systems for higher payments based on individual performance.

Top ACOG wins

Among the most meaningful accomplishments achieved by ACOG in its work to repeal the sustainable growth rate are:

- Reliable payment increases for the first 5 years. The law ensures a period of stability with modest Medicare payment in-

creases for 5 years and no cuts, with opportunity for payment increases for the next 5 years. This 5-year period gives physicians time to get ready for the new payment systems. - Protection for low-Medicare–volume physician practices. ObGyns and other physicians with a small Medicare patient population are exempt from many program requirements and penalties.

- Stops the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) policy on global surgical codes, reinstating 10-day and 90-day global payment bundles for surgical services. This directly helps ObGyn subspecialists, including urogynecologists and gynecologic oncologists.

- Physician liability protections. The law ensures that federal quality measurements cannot be used to imply medical negligence and generate lawsuits.

- Protection for ultrasound. There are no cuts to ultrasound reimbursement.

- An end, in 2018, to penalties related to electronic health record (EHR) meaningful use, Physician Quality Reporting Systems, and the use of the value-based modifier.

- APM bonus payments. Bonus eligibility for Alternative Payment Model (APM) participation is based on patient volume, not just revenue, to make it easier for ObGyns to qualify.

- 2-year extension of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which provides comprehensive coverage to 8 million children, adolescents, and pregnant women across the country.

- Quality-measure development. The law helps professional organizations, such as ACOG, develop quality measures for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) rather than allow these measures to be developed by a federal agency, ensuring that this new program works for physicians and our patients.

Two payment system options reward continuous quality improvement

Option 1: MIPS. MACRA consolidates and expands pay-for-performance incentives within the old SGR fee-for-service system, creating the new MIPS. Under MIPS, the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), electronic health record (EHR) meaningful use incentive program, and physician value-based modifiers (VBMs) become a single program. In 2019, a physician’s individual score on these measures will be used to adjust his or her Medicare payments, and the penalties previously associated with these programs come to an end.

MACRA creates 4 categories of measures that are weighted to calculate an individual physician’s MIPS score:

- Quality (50% of total adjustment in 2019, shrinking to 30% of total adjustment in 2021). Quality measures currently in use in the PQRS, VBM, and EHR meaningful use programs will continue to be used. The Secretary of Health and Human Services must fund and work with specialty societies to develop any additional measures, and measures utilized in clinical data registries can be used for this category as well. Measures will be updated annually, and ACOG and other specialties can submit measures directly for approval, rather than rely on an outside entity.

- Resource use (10% of total adjustment in 2019, growing to 30% of total adjustment by 2021). Resource use measures are risk-adjusted and include those already used in the VBM program; others must be developed with physicians, reflecting both the physician’s role in treating the patient (eg, primary or specialty care) and the type of treatment (eg, chronic or acute).

- EHR use (25% of total adjustment). Current meaningful use systems will qualify for this category. The law also requires EHR interoperability by 2018 and prohibits the blocking of information sharing between EHR vendors.

- Clinical improvement (15% of total adjustment). This is a new component of physician measurement, intended to give physicians credit for working to improve their practices and help them participate in APMs, which have higher reimbursement potential. This menu of qualifying activities—including 24-hour availability, safety, and patient satisfaction—must be developed with physicians and must be attainable by all specialties and practice types, including small practices and those in rural and underserved areas. Maintenance of certification can be used to qual-ify for a high score.

Physicians will only be assessed on the categories, measures, and activities that apply to them. A physician’s composite score (0–100) will be compared with a performance threshold that reflects all physicians. Those who score above the threshold will receive increased payments; those who score below the threshold will receive reduced payments. Physicians will know these thresholds in advance and will know the score they must reach to avoid penalties and win higher reimbursements in each performance period.

As physicians as a whole improve their performance, the threshold will move with them. So each year, physicians will have the incentive to keep improving their quality, resource use, clinical improvement, and EHR use. A physician’s payment adjustment in one year will not affect his or her payment adjustment in the next year.

The range of potential payment adjustments based on MIPS performance measures increases each year through 2022. Providers who have high scores are rewarded with a 4% increase in 2019. By 2022, the reward is 9%. The program is budget-neutral, so total positive adjustments across all providers will equal total negative adjustments across all providers to poor performers. Separate funds are set aside to reward the highest performers, who will earn bonuses of up to 10% of their fee-for-service payment rate from 2019 through 2024, as well as to help low performers improve and qualify for increased payments from 2016 through 2020.

Help for physicians includes:

- flexibility to participate in a way that best reflects their practice, using risk-adjusted clinical outcome measures

- option to participate in a virtual MIPS group rather than go it alone

- technical assistance to practices with 15 or fewer professionals, $20 million annually from 2016 through 2020, with preference to practices with low MIPS scores and those in rural and underserved areas

- quarterly confidential feedback on performance in the quality and resource use categories

- advance notification to each physician of the score needed to reach higher payment levels

- exclusion from MIPS of physicians who treat few Medicare patients, as well as those who receive a significant portion of their revenues from APMs.

Option 2: APMs. Physicians can earn higher fees by opting out of MIPS fee for service and participating in APMs. The law defines qualifying APMs as those that require participating providers to take on “more than nominal” financial risk, report quality measures, and use certified EHR technology.

APMs will cover multiple services, show that they can limit the growth of spending, and use performance-based methods of compensation. These and other provisions will likely continue the trend away from physicians practicing in solo or small-group fee-for-service practices into risk-based multispecialty settings that are subject to increased management and oversight.

From 2019 to 2024, qualified APM physicians will receive a 5% annual lump sum bonus based on their prior year’s physician fee-schedule payments plus shared savings from participation. This bonus is based on patient volume, not just revenue, to make it easier for ObGyns to qualify. To make the bonus widely available, the Secretary of Health and Human Services must test APMs designed for specific specialties and physicians in small practices. As in MIPS, top APM performers will also receive an additional bonus.

To qualify, physicians must meet increasing thresholds for the percentage of their revenue that they receive through APMs. Those who are below but near the required level of APM revenue can be exempted from MIPS adjustments.

- 2019–2020: 25% of Medicare revenue must be received through APMs.

- 2021–2022: 50% of Medicare revenue or 50% of all-payer revenue along with 25% of Medicare revenue must be received through APMs.

- 2023 and beyond: 75% of Medicare revenue or 75% of all-payer revenue along with 25% of Medicare revenue must be received through APMs.

Who pays the bill?

Medicare beneficiaries pay more

The new law increases the percentage of Medicare Parts B and D premiums that high-income beneficiaries must pay beginning in 2018:

- Single seniors reporting income of more than $133,500 and married couples with income of more than $267,000 will see their share of premiums rise from 50% to 65%.

- Single seniors reporting income above $160,000 and married couples with income above $320,000 will see their premium share rise from 65% to 80%.

This change will affect about 2% of Medicare beneficiaries; half of all Medicare beneficiaries currently have annual incomes below $26,000.1

Medigap “first-dollar coverage” will end

Many Medigap plans on the market today provide “first-dollar coverage” for beneficiaries, which means that the plans pay the deductibles and copayments so that the beneficiaries have no out-of-pocket costs. Beginning in 2020, Medigap plans will only be available to cover costs above the Medicare Part B deductible, currently $147 per year, for new Medigap enrollees. Many lawmakers thought it was important for Medicare beneficiaries to have “skin in the game.”

The law cuts payments for some providers

To partially offset the cost of repealing the SGR, MACRA cuts Medicare payments to hospitals and postacute providers. It:

- delays Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) cuts scheduled to begin in 2017 by a year and extends them through 2025

- requires an increase in payments to hospitals scheduled for 2018 to instead be phased in over 6 years

- limits the 2018 payment update for post-acute providers to 1%.

The law extends many programs

These programs are vital to support the future ObGyn workforce and access to health care. Among these programs are:

- a halt to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) policy on global surgical codes. The law reinstates 10-day and 90-day global payment bundles for surgical services. This directly helps ObGyn subspecialists, such as urogynecologists and gynecologic oncologists.

- renewal of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which provides comprehensive coverage to 8 million children, adolescents, and pregnant women across the country

- establishment of a Medicaid/CHIP Pediatric Quality Measures Program, supporting the development and physician adoption of quality measures, including for prenatal and preconception care

- funding for the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program, helping at-risk pregnant women and their families to promote healthy births and early childhood development

- funding for community health centers, an important source of care for 13 million women and girls in all 50 states and the District of Columbia

- funding for the National Health Service Corps, bringing ObGyns and other primary care providers to underserved rural and urban areas through scholarships and loan repayment programs

- funding for the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education Payment Program, enhancing training for ObGyns and other primary care providers in community-based settings

- extending the Medicare Geographic Practice Cost Index floor, helping ensure access to care for women in rural areas

- extending the Personal Responsibility Education Program to help prevent teen pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections.

Next steps

It’s very important that ObGyns and other physicians use these early years to understand and get ready for the new payment systems. ACOG is developing educational material for our members, and will work closely with our colleague medical organizations and the Department of Health and Human Services to develop key aspects of the law and ensure that it is properly implemented to work for physicians and patients.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Congratulations, OBG Management readers! After years of hard work and collective advocacy on your part, the US Congress finally passed, and President Barack Obama quickly signed into law, a permanent repeal of the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) physician payment system. Yes, celebrations are in order.

The US House of Representatives passed the bill, HR 2, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), sponsored by American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Fellow and US Rep. Michael Burgess (R-TX), on March 26, with 382 Republicans and Democrats voting “Yes.” The Senate followed, on April 14, and agreed with the House to repeal, forever, the Medicare SGR, passing the Burgess bill without amendment, on a bipartisan vote of 92–8. With only hours to go before the scheduled 21.2% cut took effect, the President signed the bill, now Public Law (PL) 114-10, on April 16. The President noted that he was “proud to sign the bill into law.” ACOG is proud to have been such an important part of this landmark moment.

SGR: the perennial nemesis of physicians

The SGR has wreaked havoc on medicine and patient care for 15 years or more. Approximately 30,000 ObGyns participate in Medicare, and many private health insurers use Medicare payment policies, as does TriCare, the nation’s health care coverage for military members and their families. The SGR’s effect was felt widely across medicine, making it nearly impossible for physician practices to invest in health information technology and other patient safety advances, or even to plan for the next year or continue accepting Medicare patients.

When it was introduced last year, HR 2 was supported by more than 600 national and state medical societies and specialty organizations, plus patient and provider organizations, policy think tanks, and advocacy groups across the political spectrum.

ACOG Fellows petitioned their members of Congress with incredible passion, perseverance, and commitment to put an end to the SGR wrecking ball. Hundreds flew into Washington, DC, sent thousands of emails, made phone calls, wrote letters, and personally lobbied at home and in the halls of Congress.

Special kudos, too, to our champions in Congress, and there are many, led by ACOG Fellows and US Reps. Dr. Burgess and Phil Roe, MD (R-TN). Burgess wrote the House bill and, together with Roe, pushed nonstop to get this bill over the finish line. It wouldn’t have happened without them.

ACOG worked tirelessly on its own and in coalition with the American Medical Association, surgical groups, and many other partners. We were able to win important provisions in the statute that we anticipate will greatly help ObGyns successfully transition to this new payment system.

PL114-10 replaces the SGR with a new payment system intended to promote care coordination and quality improvement and lead to better health for our nation’s seniors. Congress developed this new payment plan with the physician community, rather than imposing it on us. That’s why throughout the statute, we see repeated requirements that the Secretary of Health and Human Services must develop quality measures, alternative payment models, and a host of key aspects with input from and in consultation with physicians and the relevant medical specialties, ensuring that physicians retain their preeminent roles in these areas. Funding is provided for quality measure development at $15 million per year from 2015 to 2019.

This law will likely change physician practices more than the ACA ever will, and Congress agreed that physicians should be integral to its development to ensure that they can continue to thrive and provide high-quality care and access for their patients.

Let’s take a closer look at the new Medicare payment system—especially what it will mean for your practice.

What the new law does

Important provisions

- MACRA retains the fee-for-service payment model, now called the Merit-based Incentive Payment System, or MIPS. Physician participation in the Advanced Payment Models (APMs) is entirely voluntary. But physicians who participate in APMs and who score better each year will earn more.

- All physician types are treated equally. Congress didn’t pick specialty winners and losers.

- The new payment system rewards physicians for continuous improvement. You can determine how financially well you do.

- Beginning in 2019, Medicare physician payments will reflect each individual physician’s performance, based on a range of measures developed by the relevant medical specialty that will give individuals options that best reflect their practices.

- Individual physicians will receive confidential quarterly feedback on their performance.

- Technical support is provided for smaller practices, funded at $20 million per year from 2016 to 2020, to help them transition to MIPS and APMs. And physicians in small practices can opt to join a “virtual MIPS group,” associating with other practices or hospitals in the same geographic region or by specialty types.

- The law protects physicians from liability from federal or state standards of care. No health care guideline or other standard developed under federal or state requirements associated with this law may be used as a standard of care or duty of care owed by a health care professional to a patient in a medical liability lawsuit.

MACRA stabilizes the Medicare payment system by permanently repealing the SGR and scheduling payments into the future:

- through June 2015: Stable payments with no cuts

- July 2015–2019: 0.5% annual payment increases to all Medicare physicians

- 2020–2025: No automatic annual payment changes but opportunities for payment increases based on individual performance

- 2026 and beyond: 0.75% annual payment increases for qualifying APMs, 0.25% for MIPS providers, with opportunities in both systems for higher payments based on individual performance.

Top ACOG wins

Among the most meaningful accomplishments achieved by ACOG in its work to repeal the sustainable growth rate are:

- Reliable payment increases for the first 5 years. The law ensures a period of stability with modest Medicare payment in-

creases for 5 years and no cuts, with opportunity for payment increases for the next 5 years. This 5-year period gives physicians time to get ready for the new payment systems. - Protection for low-Medicare–volume physician practices. ObGyns and other physicians with a small Medicare patient population are exempt from many program requirements and penalties.

- Stops the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) policy on global surgical codes, reinstating 10-day and 90-day global payment bundles for surgical services. This directly helps ObGyn subspecialists, including urogynecologists and gynecologic oncologists.

- Physician liability protections. The law ensures that federal quality measurements cannot be used to imply medical negligence and generate lawsuits.

- Protection for ultrasound. There are no cuts to ultrasound reimbursement.

- An end, in 2018, to penalties related to electronic health record (EHR) meaningful use, Physician Quality Reporting Systems, and the use of the value-based modifier.

- APM bonus payments. Bonus eligibility for Alternative Payment Model (APM) participation is based on patient volume, not just revenue, to make it easier for ObGyns to qualify.

- 2-year extension of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which provides comprehensive coverage to 8 million children, adolescents, and pregnant women across the country.

- Quality-measure development. The law helps professional organizations, such as ACOG, develop quality measures for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) rather than allow these measures to be developed by a federal agency, ensuring that this new program works for physicians and our patients.

Two payment system options reward continuous quality improvement

Option 1: MIPS. MACRA consolidates and expands pay-for-performance incentives within the old SGR fee-for-service system, creating the new MIPS. Under MIPS, the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), electronic health record (EHR) meaningful use incentive program, and physician value-based modifiers (VBMs) become a single program. In 2019, a physician’s individual score on these measures will be used to adjust his or her Medicare payments, and the penalties previously associated with these programs come to an end.

MACRA creates 4 categories of measures that are weighted to calculate an individual physician’s MIPS score:

- Quality (50% of total adjustment in 2019, shrinking to 30% of total adjustment in 2021). Quality measures currently in use in the PQRS, VBM, and EHR meaningful use programs will continue to be used. The Secretary of Health and Human Services must fund and work with specialty societies to develop any additional measures, and measures utilized in clinical data registries can be used for this category as well. Measures will be updated annually, and ACOG and other specialties can submit measures directly for approval, rather than rely on an outside entity.

- Resource use (10% of total adjustment in 2019, growing to 30% of total adjustment by 2021). Resource use measures are risk-adjusted and include those already used in the VBM program; others must be developed with physicians, reflecting both the physician’s role in treating the patient (eg, primary or specialty care) and the type of treatment (eg, chronic or acute).

- EHR use (25% of total adjustment). Current meaningful use systems will qualify for this category. The law also requires EHR interoperability by 2018 and prohibits the blocking of information sharing between EHR vendors.

- Clinical improvement (15% of total adjustment). This is a new component of physician measurement, intended to give physicians credit for working to improve their practices and help them participate in APMs, which have higher reimbursement potential. This menu of qualifying activities—including 24-hour availability, safety, and patient satisfaction—must be developed with physicians and must be attainable by all specialties and practice types, including small practices and those in rural and underserved areas. Maintenance of certification can be used to qual-ify for a high score.

Physicians will only be assessed on the categories, measures, and activities that apply to them. A physician’s composite score (0–100) will be compared with a performance threshold that reflects all physicians. Those who score above the threshold will receive increased payments; those who score below the threshold will receive reduced payments. Physicians will know these thresholds in advance and will know the score they must reach to avoid penalties and win higher reimbursements in each performance period.

As physicians as a whole improve their performance, the threshold will move with them. So each year, physicians will have the incentive to keep improving their quality, resource use, clinical improvement, and EHR use. A physician’s payment adjustment in one year will not affect his or her payment adjustment in the next year.

The range of potential payment adjustments based on MIPS performance measures increases each year through 2022. Providers who have high scores are rewarded with a 4% increase in 2019. By 2022, the reward is 9%. The program is budget-neutral, so total positive adjustments across all providers will equal total negative adjustments across all providers to poor performers. Separate funds are set aside to reward the highest performers, who will earn bonuses of up to 10% of their fee-for-service payment rate from 2019 through 2024, as well as to help low performers improve and qualify for increased payments from 2016 through 2020.

Help for physicians includes:

- flexibility to participate in a way that best reflects their practice, using risk-adjusted clinical outcome measures

- option to participate in a virtual MIPS group rather than go it alone

- technical assistance to practices with 15 or fewer professionals, $20 million annually from 2016 through 2020, with preference to practices with low MIPS scores and those in rural and underserved areas

- quarterly confidential feedback on performance in the quality and resource use categories

- advance notification to each physician of the score needed to reach higher payment levels

- exclusion from MIPS of physicians who treat few Medicare patients, as well as those who receive a significant portion of their revenues from APMs.

Option 2: APMs. Physicians can earn higher fees by opting out of MIPS fee for service and participating in APMs. The law defines qualifying APMs as those that require participating providers to take on “more than nominal” financial risk, report quality measures, and use certified EHR technology.

APMs will cover multiple services, show that they can limit the growth of spending, and use performance-based methods of compensation. These and other provisions will likely continue the trend away from physicians practicing in solo or small-group fee-for-service practices into risk-based multispecialty settings that are subject to increased management and oversight.

From 2019 to 2024, qualified APM physicians will receive a 5% annual lump sum bonus based on their prior year’s physician fee-schedule payments plus shared savings from participation. This bonus is based on patient volume, not just revenue, to make it easier for ObGyns to qualify. To make the bonus widely available, the Secretary of Health and Human Services must test APMs designed for specific specialties and physicians in small practices. As in MIPS, top APM performers will also receive an additional bonus.

To qualify, physicians must meet increasing thresholds for the percentage of their revenue that they receive through APMs. Those who are below but near the required level of APM revenue can be exempted from MIPS adjustments.

- 2019–2020: 25% of Medicare revenue must be received through APMs.

- 2021–2022: 50% of Medicare revenue or 50% of all-payer revenue along with 25% of Medicare revenue must be received through APMs.

- 2023 and beyond: 75% of Medicare revenue or 75% of all-payer revenue along with 25% of Medicare revenue must be received through APMs.

Who pays the bill?

Medicare beneficiaries pay more

The new law increases the percentage of Medicare Parts B and D premiums that high-income beneficiaries must pay beginning in 2018:

- Single seniors reporting income of more than $133,500 and married couples with income of more than $267,000 will see their share of premiums rise from 50% to 65%.

- Single seniors reporting income above $160,000 and married couples with income above $320,000 will see their premium share rise from 65% to 80%.

This change will affect about 2% of Medicare beneficiaries; half of all Medicare beneficiaries currently have annual incomes below $26,000.1

Medigap “first-dollar coverage” will end

Many Medigap plans on the market today provide “first-dollar coverage” for beneficiaries, which means that the plans pay the deductibles and copayments so that the beneficiaries have no out-of-pocket costs. Beginning in 2020, Medigap plans will only be available to cover costs above the Medicare Part B deductible, currently $147 per year, for new Medigap enrollees. Many lawmakers thought it was important for Medicare beneficiaries to have “skin in the game.”

The law cuts payments for some providers

To partially offset the cost of repealing the SGR, MACRA cuts Medicare payments to hospitals and postacute providers. It:

- delays Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) cuts scheduled to begin in 2017 by a year and extends them through 2025

- requires an increase in payments to hospitals scheduled for 2018 to instead be phased in over 6 years

- limits the 2018 payment update for post-acute providers to 1%.

The law extends many programs

These programs are vital to support the future ObGyn workforce and access to health care. Among these programs are:

- a halt to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) policy on global surgical codes. The law reinstates 10-day and 90-day global payment bundles for surgical services. This directly helps ObGyn subspecialists, such as urogynecologists and gynecologic oncologists.

- renewal of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which provides comprehensive coverage to 8 million children, adolescents, and pregnant women across the country

- establishment of a Medicaid/CHIP Pediatric Quality Measures Program, supporting the development and physician adoption of quality measures, including for prenatal and preconception care

- funding for the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program, helping at-risk pregnant women and their families to promote healthy births and early childhood development

- funding for community health centers, an important source of care for 13 million women and girls in all 50 states and the District of Columbia

- funding for the National Health Service Corps, bringing ObGyns and other primary care providers to underserved rural and urban areas through scholarships and loan repayment programs

- funding for the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education Payment Program, enhancing training for ObGyns and other primary care providers in community-based settings

- extending the Medicare Geographic Practice Cost Index floor, helping ensure access to care for women in rural areas

- extending the Personal Responsibility Education Program to help prevent teen pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections.

Next steps

It’s very important that ObGyns and other physicians use these early years to understand and get ready for the new payment systems. ACOG is developing educational material for our members, and will work closely with our colleague medical organizations and the Department of Health and Human Services to develop key aspects of the law and ensure that it is properly implemented to work for physicians and patients.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

1. Aaron HJ. Three cheers for log-rolling: The demise of the SGR. Brookings Health360. http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/health360/posts/2015/04/22-medicare-sgr-repeal-doc-fix-aaron. Published April 22, 2015. Accessed May 12, 2015.

Reference

1. Aaron HJ. Three cheers for log-rolling: The demise of the SGR. Brookings Health360. http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/health360/posts/2015/04/22-medicare-sgr-repeal-doc-fix-aaron. Published April 22, 2015. Accessed May 12, 2015.

Sunshine Act – another reminder

I’ve written about the Physician Payment Sunshine Act several times since it became law in 2013. My basic opinion – that it is a tempest in a teapot – has not changed. Nonetheless, now is the time to review the 2014 data reported under your name – and if necessary, initiate a dispute – before the information is posted publicly on June 30.

A quick review: The Sunshine Act, known officially as the “Open Payments Program,” requires all manufacturers of drugs, devices, and medical supplies covered by federal health care programs to report to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services any financial interactions with physicians and teaching hospitals.

Reportable interactions include consulting, food, ownership or investment interest, direct compensation for speakers at education programs, and research. Compensation for clinical trials must be reported but is not made public until the product receives FDA approval, or until 4 years after the payment, whichever is earlier. Payments for trials involving a new indication for an approved drug are posted the following year.

Exemptions include CME activities funded by manufacturers and product samples for patient use. Medical students and residents are exempted entirely.

You are allowed to review your data and request corrections before information is posted publicly. You will have an additional 2 years to pursue corrections after the content goes live at the end of June, but any erroneous information will remain online until the next scheduled update, so you should find and fix errors as promptly as possible.

If you don’t see drug reps, accept sponsored lunches, or give sponsored talks, don’t assume that you won’t be on the website. Check anyway: You might be indirectly involved in a compensation that you were not aware of, or you might have been reported in error.

To review your data, register at the CMS Enterprise Portal (https://portal.cms.gov/wps/portal/unauthportal/home/) and request access to the Open Payments system.

The question remains as to what effect the law might be having on research, continuing education, or physicians’ relationships with the pharmaceutical industry. The short answer is that no one knows. The first data posting this past September came and went with little fanfare, and no repercussions directly attributable to the program have been reported as of this writing.

Sunshine laws have been in effect for several years in six states: California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Vermont, and West Virginia, plus the District of Columbia. (Maine repealed its law in 2011.) Observers disagree on their impact. Studies in Maine and West Virginia showed no significant public reaction or changes in prescribing patterns, according to a 2012 article in the Archives of Internal Medicine (now JAMA Internal Medicine).

Reactions from the public are equally inscrutable. Do citizens think less of doctors who accept the occasional industry-sponsored lunch for their employees? Do they think more of doctors who speak at meetings, or conduct industry-sponsored clinical research? There are no objective data. Anecdotally, I haven’t heard a peep – positive, negative, or indifferent – from any of my patients, nor have any other physicians that I’ve asked.

As of now, I stand by my initial prediction that attorneys, activists, and the occasional reporter will data-mine the information for various purposes, but few patients will bother to visit. Of course, that doesn’t mean you should ignore it as well. As always, I suggest you review the accuracy of anything posted about you, in any form or context, on any venue. This year’s data (reflecting all 2014 reports) have been available for review since April 6. You can initiate a dispute at any time over the next 2 years, before or after public release on June 30, but the sooner the better. Corrections are made each time CMS updates the system.

Maintaining accurate financial records has always been important, but it will be even more important now to support your disputes. CMS won’t simply take your word for it. A free app is available to help you track payments and other reportable industry interactions; search for “Open Payments” at your favorite app store.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News.

I’ve written about the Physician Payment Sunshine Act several times since it became law in 2013. My basic opinion – that it is a tempest in a teapot – has not changed. Nonetheless, now is the time to review the 2014 data reported under your name – and if necessary, initiate a dispute – before the information is posted publicly on June 30.

A quick review: The Sunshine Act, known officially as the “Open Payments Program,” requires all manufacturers of drugs, devices, and medical supplies covered by federal health care programs to report to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services any financial interactions with physicians and teaching hospitals.

Reportable interactions include consulting, food, ownership or investment interest, direct compensation for speakers at education programs, and research. Compensation for clinical trials must be reported but is not made public until the product receives FDA approval, or until 4 years after the payment, whichever is earlier. Payments for trials involving a new indication for an approved drug are posted the following year.

Exemptions include CME activities funded by manufacturers and product samples for patient use. Medical students and residents are exempted entirely.

You are allowed to review your data and request corrections before information is posted publicly. You will have an additional 2 years to pursue corrections after the content goes live at the end of June, but any erroneous information will remain online until the next scheduled update, so you should find and fix errors as promptly as possible.

If you don’t see drug reps, accept sponsored lunches, or give sponsored talks, don’t assume that you won’t be on the website. Check anyway: You might be indirectly involved in a compensation that you were not aware of, or you might have been reported in error.

To review your data, register at the CMS Enterprise Portal (https://portal.cms.gov/wps/portal/unauthportal/home/) and request access to the Open Payments system.

The question remains as to what effect the law might be having on research, continuing education, or physicians’ relationships with the pharmaceutical industry. The short answer is that no one knows. The first data posting this past September came and went with little fanfare, and no repercussions directly attributable to the program have been reported as of this writing.

Sunshine laws have been in effect for several years in six states: California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Vermont, and West Virginia, plus the District of Columbia. (Maine repealed its law in 2011.) Observers disagree on their impact. Studies in Maine and West Virginia showed no significant public reaction or changes in prescribing patterns, according to a 2012 article in the Archives of Internal Medicine (now JAMA Internal Medicine).

Reactions from the public are equally inscrutable. Do citizens think less of doctors who accept the occasional industry-sponsored lunch for their employees? Do they think more of doctors who speak at meetings, or conduct industry-sponsored clinical research? There are no objective data. Anecdotally, I haven’t heard a peep – positive, negative, or indifferent – from any of my patients, nor have any other physicians that I’ve asked.

As of now, I stand by my initial prediction that attorneys, activists, and the occasional reporter will data-mine the information for various purposes, but few patients will bother to visit. Of course, that doesn’t mean you should ignore it as well. As always, I suggest you review the accuracy of anything posted about you, in any form or context, on any venue. This year’s data (reflecting all 2014 reports) have been available for review since April 6. You can initiate a dispute at any time over the next 2 years, before or after public release on June 30, but the sooner the better. Corrections are made each time CMS updates the system.

Maintaining accurate financial records has always been important, but it will be even more important now to support your disputes. CMS won’t simply take your word for it. A free app is available to help you track payments and other reportable industry interactions; search for “Open Payments” at your favorite app store.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News.

I’ve written about the Physician Payment Sunshine Act several times since it became law in 2013. My basic opinion – that it is a tempest in a teapot – has not changed. Nonetheless, now is the time to review the 2014 data reported under your name – and if necessary, initiate a dispute – before the information is posted publicly on June 30.

A quick review: The Sunshine Act, known officially as the “Open Payments Program,” requires all manufacturers of drugs, devices, and medical supplies covered by federal health care programs to report to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services any financial interactions with physicians and teaching hospitals.

Reportable interactions include consulting, food, ownership or investment interest, direct compensation for speakers at education programs, and research. Compensation for clinical trials must be reported but is not made public until the product receives FDA approval, or until 4 years after the payment, whichever is earlier. Payments for trials involving a new indication for an approved drug are posted the following year.

Exemptions include CME activities funded by manufacturers and product samples for patient use. Medical students and residents are exempted entirely.

You are allowed to review your data and request corrections before information is posted publicly. You will have an additional 2 years to pursue corrections after the content goes live at the end of June, but any erroneous information will remain online until the next scheduled update, so you should find and fix errors as promptly as possible.

If you don’t see drug reps, accept sponsored lunches, or give sponsored talks, don’t assume that you won’t be on the website. Check anyway: You might be indirectly involved in a compensation that you were not aware of, or you might have been reported in error.

To review your data, register at the CMS Enterprise Portal (https://portal.cms.gov/wps/portal/unauthportal/home/) and request access to the Open Payments system.

The question remains as to what effect the law might be having on research, continuing education, or physicians’ relationships with the pharmaceutical industry. The short answer is that no one knows. The first data posting this past September came and went with little fanfare, and no repercussions directly attributable to the program have been reported as of this writing.

Sunshine laws have been in effect for several years in six states: California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Vermont, and West Virginia, plus the District of Columbia. (Maine repealed its law in 2011.) Observers disagree on their impact. Studies in Maine and West Virginia showed no significant public reaction or changes in prescribing patterns, according to a 2012 article in the Archives of Internal Medicine (now JAMA Internal Medicine).

Reactions from the public are equally inscrutable. Do citizens think less of doctors who accept the occasional industry-sponsored lunch for their employees? Do they think more of doctors who speak at meetings, or conduct industry-sponsored clinical research? There are no objective data. Anecdotally, I haven’t heard a peep – positive, negative, or indifferent – from any of my patients, nor have any other physicians that I’ve asked.

As of now, I stand by my initial prediction that attorneys, activists, and the occasional reporter will data-mine the information for various purposes, but few patients will bother to visit. Of course, that doesn’t mean you should ignore it as well. As always, I suggest you review the accuracy of anything posted about you, in any form or context, on any venue. This year’s data (reflecting all 2014 reports) have been available for review since April 6. You can initiate a dispute at any time over the next 2 years, before or after public release on June 30, but the sooner the better. Corrections are made each time CMS updates the system.

Maintaining accurate financial records has always been important, but it will be even more important now to support your disputes. CMS won’t simply take your word for it. A free app is available to help you track payments and other reportable industry interactions; search for “Open Payments” at your favorite app store.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News.

Family Medicine’s Increasing Presence in Hospital Medicine

Years ago, I struggled with a difficult decision. Given the fact that the military disallowed dual training tracks, such as internal medicine/pediatrics (med/peds), I had to choose from internal medicine (IM), pediatrics (Peds), or family practice (FP) residencies. My personal history and experiential data remained incomplete and the view ahead blurry; still, the choice remained.

Over time, I’ve embraced the uncertainty inherent in most analyses. Such is the case with the current composition of specialties that make up hospital medicine nationwide. Available data remains in flux, yet I see apparent trends.

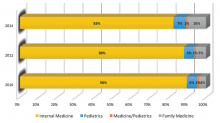

A new question in the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) report asked, “Did your hospital medicine group employ hospitalist physicians trained and certified in the following specialties…?” Strikingly, a full 59% of groups serving adult patients only reported having at least one family medicine-trained provider in their midst! And in these adult-only practices, 98% of groups utilized at least one internal medicine physician, 24% reported a med/peds doc, and none reported pediatricians.

Meanwhile, of 40 groups caring for children only, 95% reported using pediatrics, 2.5% internal medicine (huh?), 22.5% med/peds, and zero FPs. The 19 groups serving both adults and children revealed participation from all four nonsurgical hospitalist specialties (IM, peds, FP, med/peds).

So what is the specialty distribution of medical hospitalists overall? There’s no good data about this.

The 2014 Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) sample, licensed for use in SOHM, reported data for roughly 4,200 community hospital medicine providers: 82% were internal medicine, 10% family medicine, 7% pediatrics, and <1% med/peds. MGMA, however, cautions against assuming that this represents the entire population of hospitalists and their training. Although representative of the groups who participated in the survey, it may not be representative of groups that didn’t participate, and thus it would be misleading to suggest that this distribution holds true nationally.

In an effort to corroborate the MGMA distribution, I reviewed other compensation and productivity surveys; one such survey, conducted by the American Medical Group Association, reported hospitalists by training program. It contained over 3,700 community hospital providers—89% internal medicine, 6% family medicine, 5% pediatrics—but did not inquire about medicine/pediatrics.

Finally, if one combines the academic and community provider samples from MGMA (n=4,867), the distribution is 80% IM, 8.5% FP, 10% peds, and <1% med/peds.

Which of these, if any, is the actual distribution of nonprocedural hospitalists? Although we cannot know exactly, I believe something close to the following to be current state: internal medicine 80%, family medicine 10%, pediatrics 10%, and medicine/pediatrics <1%.

It is clear from survey trends that the proportion of family medicine providers is growing, while the internal medicine super-majority is shrinking somewhat. Pediatrics appears to remain stable as a proportion of the total, as does med/peds, with the latter unable to grow in numbers proportionally given the small number of providers nationally compared to the other three fields.

The growth of family medicine-trained hospitalists relates to the continued high demand for the profession, with such residents comprising the largest pool of available providers, second only to internal medicine.

Based on the SHM survey, family medicine hospitalists seem to practice similarly to IM; they generally see adults only. It appears that they are accepted into traditional adult hospitalist practices, readily contrasting with groups serving children, which report no FP participation. Meanwhile, med/peds hospitalists provide care across the spectrum of hospitalist groups, though they often report splitting their duties between adults-only services and pediatric services.

As for me, a generation removed from my election of a family practice internship and subsequent transition to internal medicine residency, I should not have worried so. Both paths can lead to hospital medicine.

Dr. Ahlstrom is a hospitalist at Indigo Health Partners in Traverse City, Mich., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Years ago, I struggled with a difficult decision. Given the fact that the military disallowed dual training tracks, such as internal medicine/pediatrics (med/peds), I had to choose from internal medicine (IM), pediatrics (Peds), or family practice (FP) residencies. My personal history and experiential data remained incomplete and the view ahead blurry; still, the choice remained.

Over time, I’ve embraced the uncertainty inherent in most analyses. Such is the case with the current composition of specialties that make up hospital medicine nationwide. Available data remains in flux, yet I see apparent trends.

A new question in the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) report asked, “Did your hospital medicine group employ hospitalist physicians trained and certified in the following specialties…?” Strikingly, a full 59% of groups serving adult patients only reported having at least one family medicine-trained provider in their midst! And in these adult-only practices, 98% of groups utilized at least one internal medicine physician, 24% reported a med/peds doc, and none reported pediatricians.

Meanwhile, of 40 groups caring for children only, 95% reported using pediatrics, 2.5% internal medicine (huh?), 22.5% med/peds, and zero FPs. The 19 groups serving both adults and children revealed participation from all four nonsurgical hospitalist specialties (IM, peds, FP, med/peds).

So what is the specialty distribution of medical hospitalists overall? There’s no good data about this.