User login

Delayed diagnosis of breast cancer: $15M award

Delayed diagnosis of breast cancer: $15M award

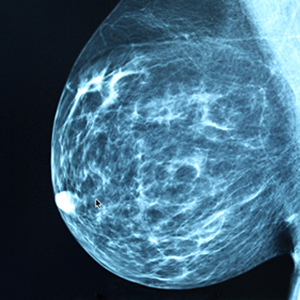

A woman in her mid-50s had been seen by a breast surgeon for 16 years for regular mammograms and sonograms. In May 2009, the breast surgeon misinterpreted a mammogram as negative, as did a radiologist who re-read the mammogram weeks later. In December 2010, the patient returned to the breast surgeon with nipple discharge. No further testing was conducted. In October 2011, the patient was found to have Stage IIIA breast cancer involving 4 lymph nodes. She underwent left radical mastectomy, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and breast reconstruction. At time of trial, the cancer had invaded her vertebrae, was Stage IV, and most likely incurable.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: Although the surgeon admittedly did not possess the qualifications required under the Mammography Quality Standards Act, he interpreted about 5,000 mammograms per year in his office. In this case, he failed to detect a small breast tumor in May 2009. He also failed to perform testing when the patient reported nipple discharge. A more timely diagnosis of breast cancer at Stage I would have provided a 90% chance of long-term survival.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The defense held the radiologist fully liable because the surgeon was not a qualified interpreter of mammography, therefore relying on the radiologist’s interpretation. The radiologist was legally responsible for the missed diagnosis.

VERDICT: A $15M New York verdict was reached, finding the breast surgeon 75% at fault and the radiologist 25%. The radiologist settled before the trial (the jury was not informed of this). The breast surgeon was responsible for $11.25M. The defense indicated intent to appeal.

Alleged failure to evacuate uterus after cesarean delivery

A 37-year-old woman underwent cesarean delivery (CD) performed by 2 ObGyns. After delivery, she began to hemorrhage and the uterus became atonic. Hysterectomy was performed but the bleeding did not stop. The ObGyns called in 3 other ObGyns. During exploratory laparotomy, the bleeding was halted.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: She and her husband had hoped to have more children but the hysterectomy precluded that. She sued all 5 ObGyns, alleging that the delivering ObGyns failed to properly perform the CD and that each physician failed to properly perform the laparotomy, causing a large scar. The claim was discontinued against the 3 surgical ObGyns; trial addressed the 2 delivering ObGyns.

The patient’s expert ObGyn remarked that the hemorrhage was caused by a small placental remnant that remained in the uterus as a result of inadequate evacuation following delivery. The presence of the remnant was indicated by the uterine atony and should have prompted immediate investigation. The physicians’ notes did not document exploration of the uterus prior to closure.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The defense’s expert contended that atony would not be a result of a small remnant of placenta. The patient’s uterus was properly evacuated, the hemorrhage was an unforeseeable complication, and the ObGyns properly addressed the hemorrhage.

VERDICT: A New York defense verdict was returned.

Alleged bowel injury during hysterectomy

Two days after a woman underwent a hysterectomy performed by her ObGyn, she went to the emergency department with increasing pain. Her ObGyn admitted her to the hospital. A general surgeon performed an exploratory laparotomy the next day that revealed an abscess; a 1-cm perforation of the patient’s bowel was surgically repaired. The patient had a difficult recovery. She developed pneumonia and respiratory failure. She underwent multiple repair surgeries for recurrent abscesses and fistulas because the wound was slow to heal.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The ObGyn’s surgical technique was negligent. He injured the bowel when inserting a trocar and did not identify the injury in a timely manner. The expert witness commented that such an injury can sometimes be a surgical complication, but not in this case: the ObGyn rushed the procedure because he had another patient waiting for CD at another hospital.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The ObGyn denied negligence and contended that the trocar used in surgery was too blunt to have caused a perforation. It would have been obvious to the ObGyn during surgery if a perforation had occurred. The perforation developed days after surgery within an abscess.

VERDICT: A Mississippi defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Delayed diagnosis of breast cancer: $15M award

A woman in her mid-50s had been seen by a breast surgeon for 16 years for regular mammograms and sonograms. In May 2009, the breast surgeon misinterpreted a mammogram as negative, as did a radiologist who re-read the mammogram weeks later. In December 2010, the patient returned to the breast surgeon with nipple discharge. No further testing was conducted. In October 2011, the patient was found to have Stage IIIA breast cancer involving 4 lymph nodes. She underwent left radical mastectomy, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and breast reconstruction. At time of trial, the cancer had invaded her vertebrae, was Stage IV, and most likely incurable.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: Although the surgeon admittedly did not possess the qualifications required under the Mammography Quality Standards Act, he interpreted about 5,000 mammograms per year in his office. In this case, he failed to detect a small breast tumor in May 2009. He also failed to perform testing when the patient reported nipple discharge. A more timely diagnosis of breast cancer at Stage I would have provided a 90% chance of long-term survival.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The defense held the radiologist fully liable because the surgeon was not a qualified interpreter of mammography, therefore relying on the radiologist’s interpretation. The radiologist was legally responsible for the missed diagnosis.

VERDICT: A $15M New York verdict was reached, finding the breast surgeon 75% at fault and the radiologist 25%. The radiologist settled before the trial (the jury was not informed of this). The breast surgeon was responsible for $11.25M. The defense indicated intent to appeal.

Alleged failure to evacuate uterus after cesarean delivery

A 37-year-old woman underwent cesarean delivery (CD) performed by 2 ObGyns. After delivery, she began to hemorrhage and the uterus became atonic. Hysterectomy was performed but the bleeding did not stop. The ObGyns called in 3 other ObGyns. During exploratory laparotomy, the bleeding was halted.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: She and her husband had hoped to have more children but the hysterectomy precluded that. She sued all 5 ObGyns, alleging that the delivering ObGyns failed to properly perform the CD and that each physician failed to properly perform the laparotomy, causing a large scar. The claim was discontinued against the 3 surgical ObGyns; trial addressed the 2 delivering ObGyns.

The patient’s expert ObGyn remarked that the hemorrhage was caused by a small placental remnant that remained in the uterus as a result of inadequate evacuation following delivery. The presence of the remnant was indicated by the uterine atony and should have prompted immediate investigation. The physicians’ notes did not document exploration of the uterus prior to closure.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The defense’s expert contended that atony would not be a result of a small remnant of placenta. The patient’s uterus was properly evacuated, the hemorrhage was an unforeseeable complication, and the ObGyns properly addressed the hemorrhage.

VERDICT: A New York defense verdict was returned.

Alleged bowel injury during hysterectomy

Two days after a woman underwent a hysterectomy performed by her ObGyn, she went to the emergency department with increasing pain. Her ObGyn admitted her to the hospital. A general surgeon performed an exploratory laparotomy the next day that revealed an abscess; a 1-cm perforation of the patient’s bowel was surgically repaired. The patient had a difficult recovery. She developed pneumonia and respiratory failure. She underwent multiple repair surgeries for recurrent abscesses and fistulas because the wound was slow to heal.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The ObGyn’s surgical technique was negligent. He injured the bowel when inserting a trocar and did not identify the injury in a timely manner. The expert witness commented that such an injury can sometimes be a surgical complication, but not in this case: the ObGyn rushed the procedure because he had another patient waiting for CD at another hospital.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The ObGyn denied negligence and contended that the trocar used in surgery was too blunt to have caused a perforation. It would have been obvious to the ObGyn during surgery if a perforation had occurred. The perforation developed days after surgery within an abscess.

VERDICT: A Mississippi defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Delayed diagnosis of breast cancer: $15M award

A woman in her mid-50s had been seen by a breast surgeon for 16 years for regular mammograms and sonograms. In May 2009, the breast surgeon misinterpreted a mammogram as negative, as did a radiologist who re-read the mammogram weeks later. In December 2010, the patient returned to the breast surgeon with nipple discharge. No further testing was conducted. In October 2011, the patient was found to have Stage IIIA breast cancer involving 4 lymph nodes. She underwent left radical mastectomy, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and breast reconstruction. At time of trial, the cancer had invaded her vertebrae, was Stage IV, and most likely incurable.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: Although the surgeon admittedly did not possess the qualifications required under the Mammography Quality Standards Act, he interpreted about 5,000 mammograms per year in his office. In this case, he failed to detect a small breast tumor in May 2009. He also failed to perform testing when the patient reported nipple discharge. A more timely diagnosis of breast cancer at Stage I would have provided a 90% chance of long-term survival.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The defense held the radiologist fully liable because the surgeon was not a qualified interpreter of mammography, therefore relying on the radiologist’s interpretation. The radiologist was legally responsible for the missed diagnosis.

VERDICT: A $15M New York verdict was reached, finding the breast surgeon 75% at fault and the radiologist 25%. The radiologist settled before the trial (the jury was not informed of this). The breast surgeon was responsible for $11.25M. The defense indicated intent to appeal.

Alleged failure to evacuate uterus after cesarean delivery

A 37-year-old woman underwent cesarean delivery (CD) performed by 2 ObGyns. After delivery, she began to hemorrhage and the uterus became atonic. Hysterectomy was performed but the bleeding did not stop. The ObGyns called in 3 other ObGyns. During exploratory laparotomy, the bleeding was halted.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: She and her husband had hoped to have more children but the hysterectomy precluded that. She sued all 5 ObGyns, alleging that the delivering ObGyns failed to properly perform the CD and that each physician failed to properly perform the laparotomy, causing a large scar. The claim was discontinued against the 3 surgical ObGyns; trial addressed the 2 delivering ObGyns.

The patient’s expert ObGyn remarked that the hemorrhage was caused by a small placental remnant that remained in the uterus as a result of inadequate evacuation following delivery. The presence of the remnant was indicated by the uterine atony and should have prompted immediate investigation. The physicians’ notes did not document exploration of the uterus prior to closure.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The defense’s expert contended that atony would not be a result of a small remnant of placenta. The patient’s uterus was properly evacuated, the hemorrhage was an unforeseeable complication, and the ObGyns properly addressed the hemorrhage.

VERDICT: A New York defense verdict was returned.

Alleged bowel injury during hysterectomy

Two days after a woman underwent a hysterectomy performed by her ObGyn, she went to the emergency department with increasing pain. Her ObGyn admitted her to the hospital. A general surgeon performed an exploratory laparotomy the next day that revealed an abscess; a 1-cm perforation of the patient’s bowel was surgically repaired. The patient had a difficult recovery. She developed pneumonia and respiratory failure. She underwent multiple repair surgeries for recurrent abscesses and fistulas because the wound was slow to heal.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The ObGyn’s surgical technique was negligent. He injured the bowel when inserting a trocar and did not identify the injury in a timely manner. The expert witness commented that such an injury can sometimes be a surgical complication, but not in this case: the ObGyn rushed the procedure because he had another patient waiting for CD at another hospital.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The ObGyn denied negligence and contended that the trocar used in surgery was too blunt to have caused a perforation. It would have been obvious to the ObGyn during surgery if a perforation had occurred. The perforation developed days after surgery within an abscess.

VERDICT: A Mississippi defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Sexual harassment and medicine

Sexual harassment hit a peak of cultural awareness over the past year. Will medicine be the next field to experience a reckoning?

In 2017, Time magazine’s Person of the Year Award went to the Silence Breakers who spoke out against sexual assault and harassment.1 The exposure of predatory behavior exhibited by once-celebrated movie producers, newscasters, and actors has given rise to a powerful change. The #MeToo movement has risen to support survivors and end sexual violence.

Just like show business, other industries have rich histories of discrimination and power. Think Wall Street, Silicon Valley, hospitality services, and the list goes on and on.2 But what about medicine? To answer this question, this article aims to:

- review the dilemma

- explore our duty to our patients and each other

- discuss solutions to address the problem.

Sexual harassment: A brief history

Decades ago, Anita Hill accused U.S. Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, her boss at the U.S. Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), of sexual harassment.3

The year was 1991, and President George H. W. Bush had nominated Thomas, a federal Circuit Judge, to succeed retiring Associate Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. With Thomas’s good character presented as a primary qualification, he appeared to be a sure thing.

Continue to: That was until an FBI interview...

That was until an FBI interview of Hill was leaked to the press. Hill asserted that Thomas had sexually harassed her while he was her supervisor at the Department of Education and the EEOC.4 Heavily scrutinized for her choice to follow Thomas to a second job after he had already allegedly harassed her, Hill was in a conundrum shared by many women—putting up with abuse in exchange for a reputable position and the opportunity to fulfill a career ambition.

Hill is a trailblazer for women yearning to speak the truth, and she brought national attention to sexual harassment in the early 1990s. On December 16, 2017, the Commission on Sexual Harassment and Advancing Equality in the Workplace was formed. Hill was selected to lead the charge against sexual harassment in the entertainment industry.5

A forensic assessment of harassment

Hill’s courageous story is one of many touched upon in the 2016 book Because of Sex.6 Author Gillian Thomas, a senior staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union’s Women’s Rights Project, explores how Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it illegal to discriminate “because of sex.”

The field of forensic psychiatry has long been attentive to themes of sexual harassment and discrimination. The American Academy of Psychiatry and Law has a robust list of landmark cases thought to be especially important and significant for forensic psychiatry.7 This list includes cases brought forth by tenacious, yet ordinary women who used the law to advocate, and some have taken their fight all the way to the Supreme Court. Let’s consider 2 such cases:

Meritor Savings Bank, FSB v Vinson (1986).8 This was a U.S. labor law case. Michelle Vinson rose through the ranks at Meritor Savings Bank, only to be fired for excessive sick leave. She filed a Title VII suit against the bank. Vinson alleged that the bank was liable for sexual harassment perpetrated by its employee and vice president, Sidney Taylor. Vinson claimed that there had been 40 to 50 sexual encounters over 4 years, ranging from fondling to indecent exposure to rape. Vinson asserted that she never reported these events for fear of losing her job. The Supreme Court, in a 9-to-0 decision, recognized sexual harassment as a violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Continue to: Harris v Forklift Systems, Inc. (1993)

Harris v Forklift Systems, Inc. (1993).9 Teresa Harris, a manager at Forklift Systems, Inc., claimed that the company’s president frequently directed offensive remarks at her that were sexual and discriminatory. The Supreme Court clarified the definition of a “hostile” or “abusive” work environment under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was joined by a unanimous majority opinion in agreement with Harris.

Physicians are not immune

Clinicians are affected by sexual harassment, too. We have a duty to protect our patients, colleagues, and ourselves. Psychiatrists in particular often are on the frontlines of helping victims process their trauma.10

But will the field of medicine also face a reckoning when it comes to perpetrating harassment? It seems likely that the medical field would be ripe with harassment when you consider its history of male domination and a hierarchical structure with strong power differentials—not to mention the late nights, exhaustion, easy access to beds, and late-night encounters where inhibitions may be lowered.11

A shocking number of female doctors are sexually harassed. Thirty percent of the top female clinician-researchers have experienced blatant sexual harassment on the job, according to a survey of 573 men and 493 women who received career development awards from the National Institutes of Health in 2006 to 2009.12 In this survey, harassment covered the scope of sexist remarks or behavior, unwanted sexual advances, bribery, threats, and coercion. The majority of those affected said the experience undermined their confidence as professionals, and many said the harassment negatively affected their career advancement.12

Continue to: But what about the progress women have made...

But what about the progress women have made in medicine? Women are surpassing men in terms of admittance to medical school. Last year, for the first time, women accounted for more than half of the enrollees in U.S. medical schools, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.13 Yet there has been a stalling in terms of change when it comes to harassment.12 Women may be more vulnerable to harassment, both when they’re perceived as weak and when they’re so strong that they challenge traditional hierarchies.

Perpetuating the problem is the trouble with reporting sexual harassment. Victims do not fare well in our society. Even in the #MeToo era, reporting such behavior is far from straightforward.11 Women fear that reporting any harassment will make them a target. Think of Anita Hill—her testimony against Clarence Thomas during his confirmation hearings for the Supreme Court showed that women who report sexual harassment experience marginalization, retaliation, stigmatization, and worse.

The result is that medical professionals tend to suppress the recognition of harassment. We make excuses for it, blame ourselves, or just take it on the chin and move on. There’s also confusion regarding what constitutes harassment. As doctors, especially psychiatrists, we hear harrowing stories. It’s reasonable to downplay our own experiences. Turning everyone into a victim of sexual harassment could detract from the stories of women who were raped, molested, and severely taken advantage of. There is a reasonable fear that diluting their message could be further damaging.14

Time for action

The field of medicine needs to do better in terms of education, support, anticipation, prevention, and reaction to harassment. We have the awareness. Now, we need action.

Continue to: One way to change any culture...

One way to change any culture of harassment or discrimination would be the advancement of more female physicians into leadership positions. The Association of American Medical Colleges has reported that fewer women than men hold faculty positions and full professorships.15,16 There’s also a striking imbalance among fields of medicine practiced by men and women, with more women seen in pediatrics, obstetrics, and gynecology as opposed to surgery. Advancement into policy-setting echelons of medicine is essential for change. Sexual harassment can be a silent problem that will be corrected only when institutions and leaders put it on the forefront of discussions.17

Another possible solution would be to shift problem-solving from punishment to prevention. Many institutions set expectations about intolerance of sexual harassment and conduct occasional lectures about it. However, enforcing protocols and safeguards that support and enforce policy are difficult on the ground level. In any event, punishment alone won’t change a culture.17

Working with students until they are comfortable disclosing details of incidents can be helpful. For example, the University of Wisconsin-Madison employs an ombuds to help with this process.18 All institutions should encourage reporting along confidential pathways and have multiple ways to report.17 Tracking complaints, even seemingly minor infractions, can help identify patterns of behavior and anticipate future incidents.

Some solutions seem obvious, such as informal and retaliation-free reporting that allows institutions to track perpetrators’ behavior; mandatory training that includes bystander training; and disciplining and monitoring transgressors and terminating their employment when appropriate—something along the lines of a zero-tolerance policy. There needs to be more research on the prevalence, severity, and outcomes of sexual harassment, and subsequent investigations, along with research into evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies.17

Continue to: Although this article focuses...

Although this article focuses on harassment of women, men are equally important to this conversation because they, too, can be victims. Men also can serve a pivotal role in mentoring and championing their female counterparts as they strive for advancement, equality, and respect.

The task ahead is large, and this discussion is not over.

1. Felsenthal E. TIME’s 2017 Person of the Year: the Silence Breakers. TIME. http://time.com/magazine/us/5055335/december-18th-2017-vol-190-no-25-u-s/. Published December 18, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018.

2. Hiltzik M. Los Angeles Times. Will medicine be the next field to face a sexual harassment reckoning? http://www.latimes.com/business/hiltzik/la-fi-hiltzik-medicine-harassment-20180110-story.html. Published January 10, 2018. Accessed April 23, 2018.

3. Thompson K. For Anita Hill, the Clarence Thomas hearings haven’t really ended. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/for-anita-hill-the-clarence-thomas-hearings-havent-really-ended/2011/10/05/gIQAy2b5QL_story.html. Published October 6, 2011. Accessed April 23, 2018.

4. Toobin J. Good versus evil. In: Toobin J. The nine: inside the secret world of the Supreme Court. New York, NY: Doubleday; 2007:30-32.

5. Barnes B. Motion picture academy finds no merit to accusations against its president. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/28/business/media/john-bailey-sexual-harassment-academy.html. The New York Times. Published March 28, 2018. Accessed April 23, 2018.

6. Thomas G. Because of sex: one law, ten cases, and fifty years that changed American women’s lives at work. New York, NY: Picador; 2016.

7. Landmark cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and Law. http://www.aapl.org/landmark_list.htm. 2014. Accessed April 22, 2018.

8. Meritor Savings Bank v Vinson, 477 US 57 (1986).

9. Harris v Forklift Systems, Inc., 114 S Ct 367 (1993).

10. Okwerekwu JA. #MeToo: so many of my patients have a story. And absorbing them is taking its toll. STAT. https://www.scribd.com/article/367482959/Me-Too-So-Many-Of-My-Patients-Have-A-Story-And-Absorbing-Them-Is-Taking-Its-Toll. Published December 18, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018.

11. Jagsi R. Sexual harassment in medicine—#MeToo. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:209-211.

12. Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones R. et al. Sexual harassment and discrimination experiences of academic medical faculty. JAMA. 2016;315(19):2120-2121.

13. AAMCNEWS. More women than men enrolled in U.S. medical schools in 2017. https://news.aamc.org/press-releases/article/applicant-enrollment-2017/. Published December 18, 2017. Accessed May 4, 2018.

14. Miller D. #MeToo: does it help? Clinical Psychiatry News. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/150148/depression/metoo-does-it-help. Published October 24, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018.

15. Chang S, Morahan PS, Magrane D, et al. Retaining faculty in academic medicine: the impact of career development programs for women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25(7):687-696.

16. Lautenberger DM, Dandar, VM, Raezer CL, et al. The state of women in academic medicine: the pipeline and pathways to leadership, 2013-2014. AAMC. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/The%20State%20of%20Women%20in%20Academic%20Medicine%202013-2014%20FINAL.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed May 4, 2018.

17. Jablow M. Zero tolerance: combating sexual harassment in academic medicine. AAMCNews. https://news.aamc.org/diversity/article/combating-sexual-harassment-academic-medicine. Published April 4, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018.

18. University of Wisconsin-Madison, the School of Medicine and Public Health. UW-Madison Policy on Sexual Harassment and Sexual Violence. https://compliance.wiscweb.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/102/2018/01/UW-Madison-Policy-on-Sexual-Harassment-And-Sexual-Violence-January-2018.pdf. Published January 2018. Accessed April 22, 2018.

Sexual harassment hit a peak of cultural awareness over the past year. Will medicine be the next field to experience a reckoning?

In 2017, Time magazine’s Person of the Year Award went to the Silence Breakers who spoke out against sexual assault and harassment.1 The exposure of predatory behavior exhibited by once-celebrated movie producers, newscasters, and actors has given rise to a powerful change. The #MeToo movement has risen to support survivors and end sexual violence.

Just like show business, other industries have rich histories of discrimination and power. Think Wall Street, Silicon Valley, hospitality services, and the list goes on and on.2 But what about medicine? To answer this question, this article aims to:

- review the dilemma

- explore our duty to our patients and each other

- discuss solutions to address the problem.

Sexual harassment: A brief history

Decades ago, Anita Hill accused U.S. Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, her boss at the U.S. Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), of sexual harassment.3

The year was 1991, and President George H. W. Bush had nominated Thomas, a federal Circuit Judge, to succeed retiring Associate Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. With Thomas’s good character presented as a primary qualification, he appeared to be a sure thing.

Continue to: That was until an FBI interview...

That was until an FBI interview of Hill was leaked to the press. Hill asserted that Thomas had sexually harassed her while he was her supervisor at the Department of Education and the EEOC.4 Heavily scrutinized for her choice to follow Thomas to a second job after he had already allegedly harassed her, Hill was in a conundrum shared by many women—putting up with abuse in exchange for a reputable position and the opportunity to fulfill a career ambition.

Hill is a trailblazer for women yearning to speak the truth, and she brought national attention to sexual harassment in the early 1990s. On December 16, 2017, the Commission on Sexual Harassment and Advancing Equality in the Workplace was formed. Hill was selected to lead the charge against sexual harassment in the entertainment industry.5

A forensic assessment of harassment

Hill’s courageous story is one of many touched upon in the 2016 book Because of Sex.6 Author Gillian Thomas, a senior staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union’s Women’s Rights Project, explores how Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it illegal to discriminate “because of sex.”

The field of forensic psychiatry has long been attentive to themes of sexual harassment and discrimination. The American Academy of Psychiatry and Law has a robust list of landmark cases thought to be especially important and significant for forensic psychiatry.7 This list includes cases brought forth by tenacious, yet ordinary women who used the law to advocate, and some have taken their fight all the way to the Supreme Court. Let’s consider 2 such cases:

Meritor Savings Bank, FSB v Vinson (1986).8 This was a U.S. labor law case. Michelle Vinson rose through the ranks at Meritor Savings Bank, only to be fired for excessive sick leave. She filed a Title VII suit against the bank. Vinson alleged that the bank was liable for sexual harassment perpetrated by its employee and vice president, Sidney Taylor. Vinson claimed that there had been 40 to 50 sexual encounters over 4 years, ranging from fondling to indecent exposure to rape. Vinson asserted that she never reported these events for fear of losing her job. The Supreme Court, in a 9-to-0 decision, recognized sexual harassment as a violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Continue to: Harris v Forklift Systems, Inc. (1993)

Harris v Forklift Systems, Inc. (1993).9 Teresa Harris, a manager at Forklift Systems, Inc., claimed that the company’s president frequently directed offensive remarks at her that were sexual and discriminatory. The Supreme Court clarified the definition of a “hostile” or “abusive” work environment under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was joined by a unanimous majority opinion in agreement with Harris.

Physicians are not immune

Clinicians are affected by sexual harassment, too. We have a duty to protect our patients, colleagues, and ourselves. Psychiatrists in particular often are on the frontlines of helping victims process their trauma.10

But will the field of medicine also face a reckoning when it comes to perpetrating harassment? It seems likely that the medical field would be ripe with harassment when you consider its history of male domination and a hierarchical structure with strong power differentials—not to mention the late nights, exhaustion, easy access to beds, and late-night encounters where inhibitions may be lowered.11

A shocking number of female doctors are sexually harassed. Thirty percent of the top female clinician-researchers have experienced blatant sexual harassment on the job, according to a survey of 573 men and 493 women who received career development awards from the National Institutes of Health in 2006 to 2009.12 In this survey, harassment covered the scope of sexist remarks or behavior, unwanted sexual advances, bribery, threats, and coercion. The majority of those affected said the experience undermined their confidence as professionals, and many said the harassment negatively affected their career advancement.12

Continue to: But what about the progress women have made...

But what about the progress women have made in medicine? Women are surpassing men in terms of admittance to medical school. Last year, for the first time, women accounted for more than half of the enrollees in U.S. medical schools, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.13 Yet there has been a stalling in terms of change when it comes to harassment.12 Women may be more vulnerable to harassment, both when they’re perceived as weak and when they’re so strong that they challenge traditional hierarchies.

Perpetuating the problem is the trouble with reporting sexual harassment. Victims do not fare well in our society. Even in the #MeToo era, reporting such behavior is far from straightforward.11 Women fear that reporting any harassment will make them a target. Think of Anita Hill—her testimony against Clarence Thomas during his confirmation hearings for the Supreme Court showed that women who report sexual harassment experience marginalization, retaliation, stigmatization, and worse.

The result is that medical professionals tend to suppress the recognition of harassment. We make excuses for it, blame ourselves, or just take it on the chin and move on. There’s also confusion regarding what constitutes harassment. As doctors, especially psychiatrists, we hear harrowing stories. It’s reasonable to downplay our own experiences. Turning everyone into a victim of sexual harassment could detract from the stories of women who were raped, molested, and severely taken advantage of. There is a reasonable fear that diluting their message could be further damaging.14

Time for action

The field of medicine needs to do better in terms of education, support, anticipation, prevention, and reaction to harassment. We have the awareness. Now, we need action.

Continue to: One way to change any culture...

One way to change any culture of harassment or discrimination would be the advancement of more female physicians into leadership positions. The Association of American Medical Colleges has reported that fewer women than men hold faculty positions and full professorships.15,16 There’s also a striking imbalance among fields of medicine practiced by men and women, with more women seen in pediatrics, obstetrics, and gynecology as opposed to surgery. Advancement into policy-setting echelons of medicine is essential for change. Sexual harassment can be a silent problem that will be corrected only when institutions and leaders put it on the forefront of discussions.17

Another possible solution would be to shift problem-solving from punishment to prevention. Many institutions set expectations about intolerance of sexual harassment and conduct occasional lectures about it. However, enforcing protocols and safeguards that support and enforce policy are difficult on the ground level. In any event, punishment alone won’t change a culture.17

Working with students until they are comfortable disclosing details of incidents can be helpful. For example, the University of Wisconsin-Madison employs an ombuds to help with this process.18 All institutions should encourage reporting along confidential pathways and have multiple ways to report.17 Tracking complaints, even seemingly minor infractions, can help identify patterns of behavior and anticipate future incidents.

Some solutions seem obvious, such as informal and retaliation-free reporting that allows institutions to track perpetrators’ behavior; mandatory training that includes bystander training; and disciplining and monitoring transgressors and terminating their employment when appropriate—something along the lines of a zero-tolerance policy. There needs to be more research on the prevalence, severity, and outcomes of sexual harassment, and subsequent investigations, along with research into evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies.17

Continue to: Although this article focuses...

Although this article focuses on harassment of women, men are equally important to this conversation because they, too, can be victims. Men also can serve a pivotal role in mentoring and championing their female counterparts as they strive for advancement, equality, and respect.

The task ahead is large, and this discussion is not over.

Sexual harassment hit a peak of cultural awareness over the past year. Will medicine be the next field to experience a reckoning?

In 2017, Time magazine’s Person of the Year Award went to the Silence Breakers who spoke out against sexual assault and harassment.1 The exposure of predatory behavior exhibited by once-celebrated movie producers, newscasters, and actors has given rise to a powerful change. The #MeToo movement has risen to support survivors and end sexual violence.

Just like show business, other industries have rich histories of discrimination and power. Think Wall Street, Silicon Valley, hospitality services, and the list goes on and on.2 But what about medicine? To answer this question, this article aims to:

- review the dilemma

- explore our duty to our patients and each other

- discuss solutions to address the problem.

Sexual harassment: A brief history

Decades ago, Anita Hill accused U.S. Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, her boss at the U.S. Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), of sexual harassment.3

The year was 1991, and President George H. W. Bush had nominated Thomas, a federal Circuit Judge, to succeed retiring Associate Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. With Thomas’s good character presented as a primary qualification, he appeared to be a sure thing.

Continue to: That was until an FBI interview...

That was until an FBI interview of Hill was leaked to the press. Hill asserted that Thomas had sexually harassed her while he was her supervisor at the Department of Education and the EEOC.4 Heavily scrutinized for her choice to follow Thomas to a second job after he had already allegedly harassed her, Hill was in a conundrum shared by many women—putting up with abuse in exchange for a reputable position and the opportunity to fulfill a career ambition.

Hill is a trailblazer for women yearning to speak the truth, and she brought national attention to sexual harassment in the early 1990s. On December 16, 2017, the Commission on Sexual Harassment and Advancing Equality in the Workplace was formed. Hill was selected to lead the charge against sexual harassment in the entertainment industry.5

A forensic assessment of harassment

Hill’s courageous story is one of many touched upon in the 2016 book Because of Sex.6 Author Gillian Thomas, a senior staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union’s Women’s Rights Project, explores how Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it illegal to discriminate “because of sex.”

The field of forensic psychiatry has long been attentive to themes of sexual harassment and discrimination. The American Academy of Psychiatry and Law has a robust list of landmark cases thought to be especially important and significant for forensic psychiatry.7 This list includes cases brought forth by tenacious, yet ordinary women who used the law to advocate, and some have taken their fight all the way to the Supreme Court. Let’s consider 2 such cases:

Meritor Savings Bank, FSB v Vinson (1986).8 This was a U.S. labor law case. Michelle Vinson rose through the ranks at Meritor Savings Bank, only to be fired for excessive sick leave. She filed a Title VII suit against the bank. Vinson alleged that the bank was liable for sexual harassment perpetrated by its employee and vice president, Sidney Taylor. Vinson claimed that there had been 40 to 50 sexual encounters over 4 years, ranging from fondling to indecent exposure to rape. Vinson asserted that she never reported these events for fear of losing her job. The Supreme Court, in a 9-to-0 decision, recognized sexual harassment as a violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Continue to: Harris v Forklift Systems, Inc. (1993)

Harris v Forklift Systems, Inc. (1993).9 Teresa Harris, a manager at Forklift Systems, Inc., claimed that the company’s president frequently directed offensive remarks at her that were sexual and discriminatory. The Supreme Court clarified the definition of a “hostile” or “abusive” work environment under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was joined by a unanimous majority opinion in agreement with Harris.

Physicians are not immune

Clinicians are affected by sexual harassment, too. We have a duty to protect our patients, colleagues, and ourselves. Psychiatrists in particular often are on the frontlines of helping victims process their trauma.10

But will the field of medicine also face a reckoning when it comes to perpetrating harassment? It seems likely that the medical field would be ripe with harassment when you consider its history of male domination and a hierarchical structure with strong power differentials—not to mention the late nights, exhaustion, easy access to beds, and late-night encounters where inhibitions may be lowered.11

A shocking number of female doctors are sexually harassed. Thirty percent of the top female clinician-researchers have experienced blatant sexual harassment on the job, according to a survey of 573 men and 493 women who received career development awards from the National Institutes of Health in 2006 to 2009.12 In this survey, harassment covered the scope of sexist remarks or behavior, unwanted sexual advances, bribery, threats, and coercion. The majority of those affected said the experience undermined their confidence as professionals, and many said the harassment negatively affected their career advancement.12

Continue to: But what about the progress women have made...

But what about the progress women have made in medicine? Women are surpassing men in terms of admittance to medical school. Last year, for the first time, women accounted for more than half of the enrollees in U.S. medical schools, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.13 Yet there has been a stalling in terms of change when it comes to harassment.12 Women may be more vulnerable to harassment, both when they’re perceived as weak and when they’re so strong that they challenge traditional hierarchies.

Perpetuating the problem is the trouble with reporting sexual harassment. Victims do not fare well in our society. Even in the #MeToo era, reporting such behavior is far from straightforward.11 Women fear that reporting any harassment will make them a target. Think of Anita Hill—her testimony against Clarence Thomas during his confirmation hearings for the Supreme Court showed that women who report sexual harassment experience marginalization, retaliation, stigmatization, and worse.

The result is that medical professionals tend to suppress the recognition of harassment. We make excuses for it, blame ourselves, or just take it on the chin and move on. There’s also confusion regarding what constitutes harassment. As doctors, especially psychiatrists, we hear harrowing stories. It’s reasonable to downplay our own experiences. Turning everyone into a victim of sexual harassment could detract from the stories of women who were raped, molested, and severely taken advantage of. There is a reasonable fear that diluting their message could be further damaging.14

Time for action

The field of medicine needs to do better in terms of education, support, anticipation, prevention, and reaction to harassment. We have the awareness. Now, we need action.

Continue to: One way to change any culture...

One way to change any culture of harassment or discrimination would be the advancement of more female physicians into leadership positions. The Association of American Medical Colleges has reported that fewer women than men hold faculty positions and full professorships.15,16 There’s also a striking imbalance among fields of medicine practiced by men and women, with more women seen in pediatrics, obstetrics, and gynecology as opposed to surgery. Advancement into policy-setting echelons of medicine is essential for change. Sexual harassment can be a silent problem that will be corrected only when institutions and leaders put it on the forefront of discussions.17

Another possible solution would be to shift problem-solving from punishment to prevention. Many institutions set expectations about intolerance of sexual harassment and conduct occasional lectures about it. However, enforcing protocols and safeguards that support and enforce policy are difficult on the ground level. In any event, punishment alone won’t change a culture.17

Working with students until they are comfortable disclosing details of incidents can be helpful. For example, the University of Wisconsin-Madison employs an ombuds to help with this process.18 All institutions should encourage reporting along confidential pathways and have multiple ways to report.17 Tracking complaints, even seemingly minor infractions, can help identify patterns of behavior and anticipate future incidents.

Some solutions seem obvious, such as informal and retaliation-free reporting that allows institutions to track perpetrators’ behavior; mandatory training that includes bystander training; and disciplining and monitoring transgressors and terminating their employment when appropriate—something along the lines of a zero-tolerance policy. There needs to be more research on the prevalence, severity, and outcomes of sexual harassment, and subsequent investigations, along with research into evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies.17

Continue to: Although this article focuses...

Although this article focuses on harassment of women, men are equally important to this conversation because they, too, can be victims. Men also can serve a pivotal role in mentoring and championing their female counterparts as they strive for advancement, equality, and respect.

The task ahead is large, and this discussion is not over.

1. Felsenthal E. TIME’s 2017 Person of the Year: the Silence Breakers. TIME. http://time.com/magazine/us/5055335/december-18th-2017-vol-190-no-25-u-s/. Published December 18, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018.

2. Hiltzik M. Los Angeles Times. Will medicine be the next field to face a sexual harassment reckoning? http://www.latimes.com/business/hiltzik/la-fi-hiltzik-medicine-harassment-20180110-story.html. Published January 10, 2018. Accessed April 23, 2018.

3. Thompson K. For Anita Hill, the Clarence Thomas hearings haven’t really ended. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/for-anita-hill-the-clarence-thomas-hearings-havent-really-ended/2011/10/05/gIQAy2b5QL_story.html. Published October 6, 2011. Accessed April 23, 2018.

4. Toobin J. Good versus evil. In: Toobin J. The nine: inside the secret world of the Supreme Court. New York, NY: Doubleday; 2007:30-32.

5. Barnes B. Motion picture academy finds no merit to accusations against its president. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/28/business/media/john-bailey-sexual-harassment-academy.html. The New York Times. Published March 28, 2018. Accessed April 23, 2018.

6. Thomas G. Because of sex: one law, ten cases, and fifty years that changed American women’s lives at work. New York, NY: Picador; 2016.

7. Landmark cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and Law. http://www.aapl.org/landmark_list.htm. 2014. Accessed April 22, 2018.

8. Meritor Savings Bank v Vinson, 477 US 57 (1986).

9. Harris v Forklift Systems, Inc., 114 S Ct 367 (1993).

10. Okwerekwu JA. #MeToo: so many of my patients have a story. And absorbing them is taking its toll. STAT. https://www.scribd.com/article/367482959/Me-Too-So-Many-Of-My-Patients-Have-A-Story-And-Absorbing-Them-Is-Taking-Its-Toll. Published December 18, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018.

11. Jagsi R. Sexual harassment in medicine—#MeToo. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:209-211.

12. Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones R. et al. Sexual harassment and discrimination experiences of academic medical faculty. JAMA. 2016;315(19):2120-2121.

13. AAMCNEWS. More women than men enrolled in U.S. medical schools in 2017. https://news.aamc.org/press-releases/article/applicant-enrollment-2017/. Published December 18, 2017. Accessed May 4, 2018.

14. Miller D. #MeToo: does it help? Clinical Psychiatry News. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/150148/depression/metoo-does-it-help. Published October 24, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018.

15. Chang S, Morahan PS, Magrane D, et al. Retaining faculty in academic medicine: the impact of career development programs for women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25(7):687-696.

16. Lautenberger DM, Dandar, VM, Raezer CL, et al. The state of women in academic medicine: the pipeline and pathways to leadership, 2013-2014. AAMC. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/The%20State%20of%20Women%20in%20Academic%20Medicine%202013-2014%20FINAL.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed May 4, 2018.

17. Jablow M. Zero tolerance: combating sexual harassment in academic medicine. AAMCNews. https://news.aamc.org/diversity/article/combating-sexual-harassment-academic-medicine. Published April 4, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018.

18. University of Wisconsin-Madison, the School of Medicine and Public Health. UW-Madison Policy on Sexual Harassment and Sexual Violence. https://compliance.wiscweb.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/102/2018/01/UW-Madison-Policy-on-Sexual-Harassment-And-Sexual-Violence-January-2018.pdf. Published January 2018. Accessed April 22, 2018.

1. Felsenthal E. TIME’s 2017 Person of the Year: the Silence Breakers. TIME. http://time.com/magazine/us/5055335/december-18th-2017-vol-190-no-25-u-s/. Published December 18, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018.

2. Hiltzik M. Los Angeles Times. Will medicine be the next field to face a sexual harassment reckoning? http://www.latimes.com/business/hiltzik/la-fi-hiltzik-medicine-harassment-20180110-story.html. Published January 10, 2018. Accessed April 23, 2018.

3. Thompson K. For Anita Hill, the Clarence Thomas hearings haven’t really ended. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/for-anita-hill-the-clarence-thomas-hearings-havent-really-ended/2011/10/05/gIQAy2b5QL_story.html. Published October 6, 2011. Accessed April 23, 2018.

4. Toobin J. Good versus evil. In: Toobin J. The nine: inside the secret world of the Supreme Court. New York, NY: Doubleday; 2007:30-32.

5. Barnes B. Motion picture academy finds no merit to accusations against its president. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/28/business/media/john-bailey-sexual-harassment-academy.html. The New York Times. Published March 28, 2018. Accessed April 23, 2018.

6. Thomas G. Because of sex: one law, ten cases, and fifty years that changed American women’s lives at work. New York, NY: Picador; 2016.

7. Landmark cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and Law. http://www.aapl.org/landmark_list.htm. 2014. Accessed April 22, 2018.

8. Meritor Savings Bank v Vinson, 477 US 57 (1986).

9. Harris v Forklift Systems, Inc., 114 S Ct 367 (1993).

10. Okwerekwu JA. #MeToo: so many of my patients have a story. And absorbing them is taking its toll. STAT. https://www.scribd.com/article/367482959/Me-Too-So-Many-Of-My-Patients-Have-A-Story-And-Absorbing-Them-Is-Taking-Its-Toll. Published December 18, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018.

11. Jagsi R. Sexual harassment in medicine—#MeToo. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:209-211.

12. Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones R. et al. Sexual harassment and discrimination experiences of academic medical faculty. JAMA. 2016;315(19):2120-2121.

13. AAMCNEWS. More women than men enrolled in U.S. medical schools in 2017. https://news.aamc.org/press-releases/article/applicant-enrollment-2017/. Published December 18, 2017. Accessed May 4, 2018.

14. Miller D. #MeToo: does it help? Clinical Psychiatry News. https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/150148/depression/metoo-does-it-help. Published October 24, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018.

15. Chang S, Morahan PS, Magrane D, et al. Retaining faculty in academic medicine: the impact of career development programs for women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25(7):687-696.

16. Lautenberger DM, Dandar, VM, Raezer CL, et al. The state of women in academic medicine: the pipeline and pathways to leadership, 2013-2014. AAMC. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/The%20State%20of%20Women%20in%20Academic%20Medicine%202013-2014%20FINAL.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed May 4, 2018.

17. Jablow M. Zero tolerance: combating sexual harassment in academic medicine. AAMCNews. https://news.aamc.org/diversity/article/combating-sexual-harassment-academic-medicine. Published April 4, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018.

18. University of Wisconsin-Madison, the School of Medicine and Public Health. UW-Madison Policy on Sexual Harassment and Sexual Violence. https://compliance.wiscweb.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/102/2018/01/UW-Madison-Policy-on-Sexual-Harassment-And-Sexual-Violence-January-2018.pdf. Published January 2018. Accessed April 22, 2018.

Lessons from a daunting malpractice event

CASE Failure to perform cesarean delivery1–4

A 19-year-old woman (G1P0) received prenatal care at a federally funded health center. Her pregnancy was normal without complications. She presented to the hospital after spontaneous rupture of membranes (SROM). The on-call ObGyn employed by the clinic was offsite when the mother was admitted.

The mother signed a standard consent form for vaginal and cesarean deliveries and any other surgical procedure required during the course of giving birth.

The ObGyn ordered low-dose oxytocin to augment labor in light of her SROM. Oxytocin was started at 9:46

Upon delivery, the infant was flaccid and not breathing. His Apgar scores were 2, 3, and 6 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively, and the cord pH was 7. The neonatal intensive care (NICU) team provided aggressive resuscitation.

At the time of trial, the 18-month-old boy was being fed through a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube and had a tracheostomy that required periodic suctioning. The child was not able to stand, crawl, or support himself, and will require 24-hour nursing care for the rest of his life.

LAWSUIT. The parents filed a lawsuit in federal court for damages under the Federal Tort Claims Act (see “Notes about this case,”). The mother claimed that she had requested a cesarean delivery early in labor when FHR tracings showed fetal distress, and again prior to vacuum extraction; the ObGyn refused both times.

The ObGyn claimed that when he noted a category III tracing, he recommended cesarean delivery, but the patient refused. He recorded the refusal in the chart some time later, after he had noted the neonate’s appearance.

The parents’ expert testified that restarting oxytocin and using vacuum extraction multiple times were dangerous and gross deviations from acceptable practice. Prolonged and repetitive use of the vacuum extractor caused a large subgaleal hematoma that decreased blood flow to the fetal brain, resulting in irreversible central nervous system (CNS) damage secondary to hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. An emergency cesarean delivery should have been performed at the first sign of fetal distress.

The defense expert pointed out that the ObGyn discussed the need for cesarean delivery with the patient when fetal distress occurred and that the ObGyn was bedside and monitoring the fetus and the mother. Although the mother consented to a cesarean delivery at time of admission, she refused to allow the procedure.

The labor and delivery (L&D) nurse corroborated the mother’s story that a cesarean delivery was not offered by the ObGyn, and when the patient asked for a cesarean delivery, he refused. The nurse stated that the note added to the records by the ObGyn about the mother’s refusal was a lie. If the mother had refused a cesarean, the nurse would have documented the refusal by completing a Refusal of Treatment form that would have been faxed to the risk manager. No such form was required because nothing was ever offered that the mother refused.

The nurse also testified that during the course of the latter part of labor, the ObGyn left the room several times to assist other patients, deliver another baby, and make an 8-minute phone call to his stockbroker. She reported that the ObGyn was out of the room when delivery occurred.

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

Read about the verdict and medical considerations.

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

The medical care and the federal-court bench trial held in front of a judge (not a jury) occurred in Florida. The verdict suggests that the ObGyn breached the standard of care by not offering or proceeding with a cesarean delivery and this management resulted in the child’s injuries. The court awarded damages in the amount of $33,813,495.91, including $29,413,495.91 for the infant; $3,300,000.00 for the plaintiff; and $1,100,000.00 for her spouse.4

Medical considerations

Refusal of medical care

Although it appears that in this case the patient did not actually refuse medical care (cesarean delivery), the case does raise the question of refusal. Refusal of medical care has been addressed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) predicated upon care that supports maternal and fetal wellbeing.5 There may be a fine balance between safeguarding the pregnant woman’s autonomy and optimization of fetal wellbeing. “Forced compliance,” on the other hand, is the alternative to respecting refusal of treatment. Ethical issues come into play: patient rights; respect for autonomy; violations of bodily integrity; power differentials; and gender equality.5 The use of coercion is “not only ethically impermissible but also medically inadvisable secondary to the realities of prognostic uncertainty and the limitations of medical knowledge.”5 There is an obligation to elicit the patient’s reasoning and lived experience. Perhaps most importantly, as clinicians working to achieve a resolution, consideration of the following is appropriate5:

- reliability and validity of evidence-based medicine

- severity of the prospective outcome

- degree of risk or burden placed on the patient

- patient understanding of the gravity of the situation and risks

- degree of urgency.

Much of this boils down to the obligation to discuss “risks and benefits of treatment, alternatives and consequences of refusing treatment.”6

Complications from vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery

Ghidini and associates, in a multicenter retrospective study, evaluated complications relating to vacuum-assisted delivery. They listed major primary outcomes of subgaleal hemorrhage, skull fracture, and intracranial bleeding, and minor primary outcomes of cephalohematoma, scalp laceration, and extensive skin abrasions. Secondary outcomes included a 5-minute Apgar score of <7, umbilical artery pH of <7.10, shoulder dystocia, and NICU admission.7

A retrospective study from Sweden assessing all vacuum deliveries over a 2-year period compared the use of the Kiwi OmniCup (Clinical Innovations) to use of the Malmström metal cup (Medela). No statistical differences in maternal or neonatal outcomes as well as failure rates were noted. However, the duration of the procedure was longer and the requirement for fundal pressure was higher with the Malmström device.8

Subgaleal hemorrhage. Ghidini and colleagues reported a heightened incidence of head injury related to the duration of vacuum application and birth weight.7 Specifically, vacuum delivery devices increase the risk of subgaleal hemorrhage. Blood can accumulate between the scalp’s epicranial aponeurosis and the periosteum and potentially can extend forward to the orbital margins, backward to the nuchal ridge, and laterally to the temporal fascia. As much as 260 mL of blood can get into this subaponeurotic space in term babies.9 Up to one-quarter of babies who require NICU admission for this condition die.10 This injury seldom occurs with forceps.

Shoulder dystocia. In a meta-analysisfrom Italy, the vacuum extractor was associated with increased risk of shoulder dystocia compared with spontaneous vaginal delivery.11

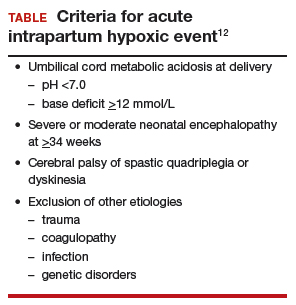

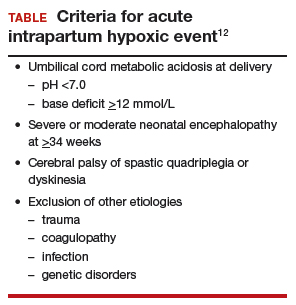

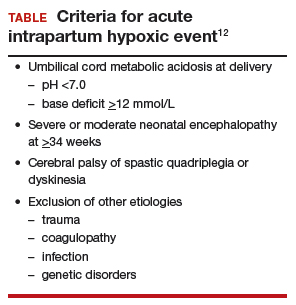

Intrapartum hypoxia. In 2003, the ACOG Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy defined an acute intrapartum hypoxic event (TABLE).12

Cerebral palsy (CP) is defined as “a chronic neuromuscular disability characterized by aberrant control of movement or posture appearing early in life and not the result of recognized progressive disease.”13,14

The Collaborative Perinatal Project concluded that birth trauma plays a minimal role in development of CP.15 Arrested labor, use of oxytocin, or prolonged labor did not play a role. CP can develop following significant cerebral or posterior fossa hemorrhage in term infants.16

Perinatal asphyxia is a poor and imprecise term and use of the expression should be abandoned. Overall, 90% of children with CP do not have birth asphyxia as the underlying etiology.14

Prognostic assessment can be made, in part, by using the Sarnat classification system (classification scale for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy of the newborn) or an electroencephalogram to stratify the severity of neonatal encephalopathy.12 Such tests are not stand-alone but a segment of assessment. At this point “a better understanding of the processes leading to neonatal encephalopathy and associated outcomes” appear to be required to understand and associate outcomes.12 “More accurate and reliable tools (are required) for prognostic forecasting.”12

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy involves multisystem organ failure including renal, hepatic, hematologic, cardiac, gastrointestinal, and metabolic abnormalities. There is no correlation between the degree of CNS injury and level of other organ abnormalities.12

Differential diagnosis

When events such as those described in this case occur, develop a differential diagnosis by considering the following12:

- uterine rupture

- severe placental abruption

- umbilical cord prolapse

- amniotic fluid embolus

- maternal cardiovascular collapse

- fetal exsanguination.

Read about the legal considerations.

Legal considerations

Although ObGyns are among the specialties most likely to experience malpractice claims,17 a verdict of more than $33 million is unusual.18 Despite the failure of adequate care, and the enormous damages, the ObGyn involved probably will not be responsible for paying the verdict (see “Notes about this case”). The case presents a number of important lessons and reminders for anyone practicing obstetrics.

A procedural comment

The case in this article arose under the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA).1 Most government entities have sovereign immunity, meaning that they can be sued only with their consent. In the FTCA, the federal government consented to being sued for the acts of its employees. This right has a number of limitations and some technical procedures, but at its core, it permits the United States to be sued as though it was a private individual.2 Private individuals can be sued for the acts of the agents (including employees).

Although the FTCA is a federal law, and these cases are tried in federal court, the substantive law of the state applies. This case occurred in Florida, so Florida tort law, defenses, and limitation on claims applied here also. Had the events occurred in Iowa, Iowa law would have applied.

In FTCA cases, the United States is the defendant (generally it is the government, not the employee who is the defendant).3 In this case, the ObGyn was employed by a federal government entity to provide delivery services. As a result, the United States was the primary defendant, had the obligation to defend the suit, and will almost certainly be obligated to pay the verdict.

The case facts

Although this description is based on an actual case, the facts were taken from the opinion of the trial court, legal summaries and press reports and not from the full case documents.4-7 We could not independently assess the accuracy of the facts, but for the purpose of this discussion, we have assumed the facts to be correct. The government has apparently filed an appeal in the Eleventh Circuit.

References

- Federal Tort Claims Act. Vol 28 U.S.C. Pt.VI Ch.171 and 28 U.S.C. § 1346(b).

- About the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA). Health Resources & Services Administration: Health Center Program. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/ftca/about/index.html. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Dowell MA, Scott CD. Federally Qualified Health Center Federal Tort Claims Act Insurance Coverage. Health Law. 2015;5:31-43.

- Chang D. Miami doctor's call to broker during baby's delivery leads to $33.8 million judgment. Miami Herald. http://www.miamiherald.com/news/health-care/article147506019.html. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed January 11, 2018.

- Teller SE. $33.8 Million judgment reached in malpractice lawsuit. Legal Reader. https://www.legalreader.com/33-8-million-judgment-reached/. Published May 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Laska L. Medical Malpractice: Verdicts, Settlements, & Experts. 2017;33(11):17-18.

- Dixon v. U.S. Civil Action No. 15-23502-Civ-Scola. LEAGLE.com. https://www.leagle.com/decision/infdco20170501s18. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed May 8, 2018.

Very large verdict

The extraordinary size of this verdict ($33 million without any punitive damages) is a reminder that in obstetrics, mistakes can have catastrophic consequences and very high costs.19 This fact is reflected in malpractice insurance rates.

A substantial amount of this case’s award will provide around-the-clock care for the child. This verdict was not the result of a runaway jury—it was a judge’s decision. It is also noteworthy to report that a small percentage of physicians (1%) appear responsible for a significant number (about one-third) of paid claims.20

Although the size of the verdict is unusual, the case is a fairly straightforward negligence tort. The judge found that the ObGyn had breached the duty of care for his patient. The actions that fell below the standard of care included restarting the oxytocin, using the Kiwi vacuum device 3 times, and failing to perform a cesarean delivery in light of obvious fetal distress. That negligence caused injury to the infant (and his parents).21 The judge determined that the 4 elements of negligence were present: 1) duty of care, 2) breach of that duty, 3) injury, and 4) a causal link between the breach of duty and the injury. The failure to adhere to good practice standards practically defines breach of duty.22

Multitasking

One important lesson is that multitasking, absence, and inattention can look terrible when things go wrong. Known as “hindsight bias,” the awareness that there was a disastrous result makes it easier to attribute the outcome to small mistakes that otherwise might seem trivial. This ObGyn was in and out of the room during a difficult labor. Perhaps that was understandable if it were unavoidable because of another delivery, but being absent frequently and not present for the delivery now looks very significant.23 And, of course, the 8-minute phone call to the stockbroker shines as a heartless, self-centered act of inattention.

Manipulating the record

Another lesson of this case: Do not manipulate the record. The ObGyn recorded that the patient had refused the cesarean delivery he recommended. Had that been the truth, it would have substantially improved his case. But apparently it was not the truth. Although there was circumstantial evidence (the charting of the patient’s refusal only after the newborn’s condition was obvious, failure to complete appropriate hospital forms), the most damning evidence was the direct testimony of the L&D nurse. She reported that, contrary to what the ObGyn put in the chart, the patient requested a cesarean delivery. In truth, it was the ObGyn who had refused.

A physician who is dishonest with charting—making false statements or going back or “correcting” a chart later—loses credibility and the presumption of acting in good faith. That is disastrous for the physician.24

A hidden lesson

Another lesson, more human than legal, is that it matters how patients are treated when things go wrong. According to press reports, the parents felt that the ObGyn had not recognized that he had made any errors, did not apologize, and had even blamed the mother for the outcome. It does not require graduate work in psychology to expect that this approach would make the parents angry enough to pursue legal action. True regret, respect, and apologies are not panaceas, but they are important.25 Who gets sued and why is a key question that is part of a larger risk management plan. In this case, the magnitude of the injuries made a suit very likely, which is not the case with all bad outcomes.26 Honest communication with patients in the face of bad results remains the goal.27

Pulling it all together

Clinicians must always remain cognizant that the patient comes first and of the importance of working as a team with nursing staff and other allied health professionals. Excellent communication and support staff interaction in good times and bad can make a difference in patient outcomes and, indeed, in medical malpractice verdicts.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Chang D. Miami doctor’s call to broker during baby’s delivery leads to $33.8 million judgment. Miami Herald. http://www.miamiherald.com/news/health-care/article147506019.html. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Teller SE. $33.8 Million judgment reached in malpractice lawsuit. Legal Reader. https://www.legalreader.com/33-8-million-judgment-reached/. Published May 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Laska L. Medical Malpractice: Verdicts, Settlements, & Experts. 2017;33(11):17−18.

- Dixon v. U.S. Civil Action No. 15-23502-Civ-Scola. LEAGLE.com. https://www.leagle.com/decision/infdco20170501s18. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. Committee Opinion No. 664: Refusal of medically recommended treatment during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;126(6):e175−e182.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Professional liability and risk management an essential guide for obstetrician-gynecologist. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: 2014.

- Ghidini A, Stewart D, Pezzullo J, Locatelli A. Neonatal complications in vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery: are they associated with number of pulls, cup detachments, and duration of vacuum application? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295(1):67−73.

- Turkmen S. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in vacuum-assisted delivery with the Kiwi OmniCup and Malmstrom metal cup. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(2):207−213.

- Davis DJ. Neonatal subgaleal hemorrhage: diagnosis and management. CMAJ. 2001;164(10):1452−1453.

- Chadwick LM, Pemberton PJ, Kurinczuk JJ. Neonatal subgaleal haematoma: associated risk factors, complications and outcome. J Paediatr Child Health. 1996;32(3):228−232.

- Dall’Asta A, Ghi T, Pedrazzi G, Frusca T. Does vacuum delivery carry a higher risk of shoulder dystocia? Review and metanalysis of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;201:62−68.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy. Neonatal Encephalopathy and Neurologic Outcomes. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: 2014.

- Nelson K, Ellenberg J. Apgar scores as predictors of chronic neurologic disability. Pediatrics. 1981;68:36−44.

- ACOG Technical Bulletin No. 163: Fetal and neonatal neurologic injury. Int J. Gynaecol Obstet. 1993;41(1):97−101.

- Nelson K, Ellenberg J. Antecedents of cerebral palsy. I. Univariate analysis of risks. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139(10):1031−1038.

- Fenichel GM, Webster D, Wong WK. Intracranial hemorrhage in the term newborn. Arch Neurol. 1984;41(1):30−34.

- Peckham C. Medscape Malpractice Report 2015: Why Ob/Gyns Get Sued. Medscape. https://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/malpractice-report-2015/obgyn#page=1. Published January 2016. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Bixenstine PJ, Shore AD, Mehtsun WT, Ibrahim AM, Freischlag JA, Makary MA. Catastrophic medical malpractice payouts in the United States. J Healthc Qual. 2014;36(4):43−53.

- Santos P, Ritter GA, Hefele JL, Hendrich A, McCoy CK. Decreasing intrapartum malpractice: Targeting the most injurious neonatal adverse events. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2015;34(4):20−27.

- Studdert DM, Bismark MM, Mello MM, Singh H, Spittal MJ. Prevalence and characteristics of physicians prone to malpractice claims. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):354−362.

- Levine AS. Legal 101: Tort law and medical malpractice for physicians. Contemp OBGYN. http://www.contem poraryobgyn.net/obstetrics-gynecology-womens-health/legal-101-tort-law-and-medical-malpractice-physicians. Published July 17, 2015. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Smith SR, Sanfilippo JS. Applied Business Law. In: Sanfilippo JS, Bieber EJ, Javitch DG, Siegrist RB, eds. MBA for Healthcare. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2016:91−126.

- Glaser LM, Alvi FA, Milad MP. Trends in malpractice claims for obstetric and gynecologic procedures, 2005 through 2014. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(3):340.e1–e6.

- Seegert L. Malpractice pitfalls: 5 strategies to reduce lawsuit threats. Medical Econ. http://www.medicaleconomics.com/medical-economics-blog/5-strategies-reduce-malpractice-lawsuit-threats. Published November 10, 2016. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Peckham C. Malpractice and medicine: who gets sued and why? Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/855229. Published December 8, 2015. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- McMichael B. The failure of ‘sorry’: an empirical evaluation of apology laws, health care, and medical malpractice. Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3020352. Published August 16, 2017. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- Carranza L, Lyerly AD, Lipira L, Prouty CD, Loren D, Gallagher TH. Delivering the truth: challenges and opportunities for error disclosure in obstetrics. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(3):656−659.

CASE Failure to perform cesarean delivery1–4

A 19-year-old woman (G1P0) received prenatal care at a federally funded health center. Her pregnancy was normal without complications. She presented to the hospital after spontaneous rupture of membranes (SROM). The on-call ObGyn employed by the clinic was offsite when the mother was admitted.

The mother signed a standard consent form for vaginal and cesarean deliveries and any other surgical procedure required during the course of giving birth.

The ObGyn ordered low-dose oxytocin to augment labor in light of her SROM. Oxytocin was started at 9:46

Upon delivery, the infant was flaccid and not breathing. His Apgar scores were 2, 3, and 6 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively, and the cord pH was 7. The neonatal intensive care (NICU) team provided aggressive resuscitation.

At the time of trial, the 18-month-old boy was being fed through a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube and had a tracheostomy that required periodic suctioning. The child was not able to stand, crawl, or support himself, and will require 24-hour nursing care for the rest of his life.

LAWSUIT. The parents filed a lawsuit in federal court for damages under the Federal Tort Claims Act (see “Notes about this case,”). The mother claimed that she had requested a cesarean delivery early in labor when FHR tracings showed fetal distress, and again prior to vacuum extraction; the ObGyn refused both times.

The ObGyn claimed that when he noted a category III tracing, he recommended cesarean delivery, but the patient refused. He recorded the refusal in the chart some time later, after he had noted the neonate’s appearance.