User login

GOC Discussions Among LTC Residents

Hospitalizations of long‐term care (LTC) residents are known to be frequent, costly, often preventable,[1, 2, 3] and potentially associated with negative health outcomes.[4] Often, an advance directive (AD) is made at LTC admission and updated annually when residents are in relatively stable health. An AD is a document that helps to inform a substitute decision maker (SDM) about the consent process for life‐sustaining treatments and is a resource that supports advance care planning (ACP). ACP is a process that allows individuals to consider, express, and plan for future healthcare in the event that they lack capacity to make their own decisions. When an LTC resident's health deteriorates and hospitalization is required, there is an opportunity to update prognosis, discuss risks and benefits of previously held treatment preferences, as well as reassess goals of care (GOC).

Engaging in ACP discussions during relatively stable health can help ensure patient preferences are followed.[5, 6] These discussions, however, are often insufficient, as they involve decision making for hypothetical situations that may not cover all potential scenarios, and may not reflect a patient's reality at the time of health status decline. Discussions held in the moment more authentically reflect the decisions of patients and/or SDM based on the specific needs and clinical realities particular to the patient at that time.[7] GOC discussions, defined in this context as ACP discussions occurring during hospitalization, have the potential to better align patient wishes with care received,[6] improve quality of life and satisfaction,[8, 9, 10] and reduce unwanted extra care.[11, 12] Although in‐the‐moment GOC discussions are recommended for all hospitalized patients who are seriously ill with a high risk of dying,[13] research suggests that this occurs infrequently for elderly patients. A recent multicenter survey of seriously ill hospitalized elderly patients found that only 25% of patients and 32% of family members reported that they had been asked about prior ACP or AD.[14] Another study of hospitalized LTC residents found that resuscitation status and family discussion was documented in only 55% and 42% of admissions, respectively.[15]

Further investigation is required to determine how often LTC patients have GOC discussions, what prompts these discussions, and what are the outcomes. Previous studies have focused on barriers to performing GOC discussions, rather than the factors that are associated with them.[16] By understanding why these discussions currently happen, we can potentially improve how often they occur and the quality of their outcomes.

The objectives of this study were to determine the rate of documented GOC discussions among hospitalized LTC residents, identify factors that were associated with documentation, and examine the association between documentation and outcomes of care.

METHODS

Study Population

We conducted a retrospective chart review of a random convenience sample of hospitalized patients admitted via the emergency department (ED) to the general internal medicine (GIM) service from January 1, 2012 through December 31, 2012, at 2 academic teaching hospitals in Toronto, Canada. Patients were identified through a search of each hospitals' electronic patient record (EPR). Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were (1) a LTC resident and (2) at least 65 years of age. For patients with multiple admissions to the GIM service during the specified 12‐month period, we only included data from the first hospitalization (index hospitalization). The hospital's research ethics board approved this study.

Our primary variable of interest was documentation in the hospital medical record of a discussion between physicians and the patient/family/SDM regarding GOC. A GOC discussion was considered to have taken place if there was documentation of (1) understanding/expectation of treatment options or (2) patient's preferences for life‐sustaining measures. Examples illustrating each criterion are provided in the Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article.

Factors Associated With GOC Documentation

From the EPR, we obtained visit‐level data including age, gender, Canadian Emergency Department Triage and Acuity Scale, vital signs at ED admission including temperature, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and shock index (defined as heart rate divided by systolic blood pressure), admission and discharge dates/times, discharge diagnosis, transfer to intensive care unit (ICU), and hospital use (number of ED visits and hospitalizations to the 2 study hospitals in the 1‐year period prior to index hospitalization).

Trained study personnel (J.W.) used a structured abstraction form to collect data from the hospital medical record that were not available through the EPR, including years living in LTC, contents of LTC AD forms, presence of SDM (identified as immediate family or surrogate with whom the care team communicated), dementia diagnosis (defined as documentation of dementia in the patient's past medical history and/or history of present illness), and measures of functional status. When available, we extracted the AD from LTC; they consisted of 4 levels (level 1: comfort careno transfer to hospital, no cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CPR]; level 2: supportive careadministration of antibiotics and/or other procedures that can be provided within LTC, no transfer to the hospital, no CPR; level 3: transfer to the hospitalno CPR; level 4: aggressive interventiontransfer to hospital for aggressive treatment, CPR).

GOC Documentation in the Discharge Summary

For the subset of patients who survived hospitalization and were discharged back to LTC, we examined whether the ADs ordered during hospitalization were communicated back to LTC via the discharge summary. We additionally assessed if the ADs determined during hospitalization differed from preferences documented prior to hospitalization. Physician orders for ADs were categorized as level 1: comfort measures only, level 3: no CPR, or level 4: full code. LTC level 2 was considered equivalent to physician‐ordered level 3 at admission; a patient with an LTC level 2 with no CPR (level 3) documented during hospitalized would be considered to have no change in the AD. An increase or decrease in the AD was determined by comparing LTC levels 1, 3, and 4 to physician‐ordered level 1, 3, and 4.

Outcomes of GOC Documentation

From the EPR, we obtained visit‐level outcome data including length of stay (LOS), resource intensity weight (RIW) (calculated based on patient case‐mix, severity, age, and procedures performed), visit disposition, number of ED visits and hospitalizations to the 2 study hospitals in the year following index hospitalization, in‐hospital death, and 1‐year mortality. We determined 1‐year mortality by following up with the LTC homes to determine whether the resident had died within the year following index hospitalization; only patients from LTC homes that responded to our request for data were included in 1‐year mortality analyses. We collected physician orders for the AD from chart review.

Statistical Analysis

Patients with and without documented GOC discussions were compared. Descriptive statistics including frequencies and percentages were used to characterize study variables. Differences between the study groups were assessed using Pearson 2/Fisher exact test. Multivariate logistic regression, which included variables that were significant in the bivariate analysis, was used to identify independent predictors of GOC discussion. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were presented for the logistic model. Patients with missing predictor data were excluded.

We also examined whether there was a correlation between GOC discussion and outcomes of care using Pearson 2/Fisher exact test. Outcomes included orders for the AD, LOS in days (stratified into quartiles), RIW (stratified into quartiles), visit disposition, hospital use in the year following index hospitalization, and 1‐year mortality following discharge back to LTC.

Lastly, to better understand the independent predictors of in‐hospital and 1‐year mortality, we used Pearson 2/Fisher exact test followed by logistic regression that included significant variables from the bivariate analyses.

All analyses were 2‐sided, and a P value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

We identified a total of 7084 hospitalizations to GIM between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2012, of which 665 (9.4%) met inclusion criteria of residence in LTC and age 65 years. Of these 665 hospitalizations, 512 were unique patients. We randomly selected a convenience sample of 200 index hospitalizations of the 512 eligible hospitalizations (39%) to perform the chart review.

Predictors of GOC Documentation

Of the 200 randomly sampled charts that were reviewed, 75 (37.5%) had a documented GOC discussion.

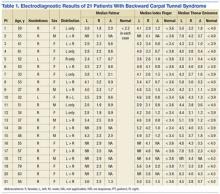

Characteristics of the study patients and results of bivariate analysis of the association between patient characteristics and GOC discussion are summarized in Table 1. No significant differences in demographic and baseline characteristics were seen between patients with and without discussion. However, a number of visit characteristics were found to be significantly associated with discussion. Forty percent of patients in the GOC discussion group had GCS scores 11 compared to 15.2% in the no‐discussion group. Higher respiratory rate, lower oxygen saturation, and ICU transfer were also significantly associated with discussions.

| Goals of Care Discussion Documented in Medical Chart | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, N = 125 | Yes, N = 75 | P Value | |||

| |||||

| Baseline characteristics | |||||

| Gender, n (%) | 0.88 | ||||

| Male | 48 | (38.4) | 30 | (40.0) | |

| Female | 77 | (61.6) | 45 | (60.0) | |

| Age, y, n (%) | 0.85 | ||||

| 6579 | 36 | (28.8) | 19 | (25.3) | |

| 8084 | 30 | (24.0) | 19 | (25.3) | |

| 8589 | 30 | (24.0) | 16 | (21.3) | |

| 90101 | 29 | (23.2) | 21 | (28.0) | |

| Years living in long‐term care, n (%)* | 0.65 | ||||

| [0, 1) | 28 | (22.4) | 12 | (16.0) | |

| [1, 3) | 31 | (24.8) | 22 | (29.3) | |

| [3, 6) | 33 | (26.4) | 22 | (29.3) | |

| [6, 22) | 25 | (20.0) | 13 | (17.3) | |

| Unknown | 8 | (6.4) | 6 | (8.0) | |

| AD from long‐term care, n (%) | 0.14 | ||||

| Comfort measures only | 2 | (1.6) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Supportive care with no transfer to hospital | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Supportive care with transfer to hospital | 70 | (56.0) | 44 | (58.7) | |

| Aggressive care | 53 | (42.4) | 27 | (36.0) | |

| Years since most recent AD signed, n (%)* | 0.12 | ||||

| [0, 1) | 79 | (63.2) | 48 | (64.0) | |

| [1, 2) | 21 | (16.8) | 6 | (8.0) | |

| [2, 6) | 9 | (7.2) | 10 | (13.3) | |

| Unknown | 16 | (12.8) | 11 | (14.7) | |

| Substitute decision maker, n (%) | 0.06 | ||||

| Child | 81 | (64.8) | 44 | (58.7) | |

| Spouse | 9 | (7.2) | 15 | (20.0) | |

| Other | 26 | (20.8) | 13 | (17.3) | |

| Public guardian trustee | 6 | (4.8) | 2 | (2.7) | |

| Unknown | 3 | (2.4) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Dementia, n (%) | 1.00 | ||||

| No | 47 | (37.6) | 28 | (37.3) | |

| Yes | 78 | (62.4) | 47 | (62.7) | |

| Mobility, n (%) | 0.26 | ||||

| Walk without assistance | 5 | (4.0) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Walker | 16 | (12.8) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Wheelchair | 43 | (34.4) | 29 | (38.7) | |

| Bedridden | 7 | (5.6) | 4 | (5.3) | |

| Unknown | 54 | (43.2) | 36 | (48.0) | |

| Continence, n (%) | 0.05 | ||||

| Mostly continent | 16 | (12.8) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Incontinent | 49 | (39.2) | 34 | (45.3) | |

| Catheter/stoma | 7 | (5.6) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Unknown | 53 | (42.4) | 37 | (49.3) | |

| Feeding, n (%) | 0.17 | ||||

| Mostly feeds self | 38 | (30.4) | 13 | (17.3) | |

| Needs to be fed | 17 | (13.6) | 14 | (18.7) | |

| Gastrostomy tube | 8 | (6.4) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| Unknown | 62 | (49.6) | 43 | (57.3) | |

| Diet, n (%) | 0.68 | ||||

| Normal | 43 | (34.4) | 16 | (21.3) | |

| Dysphagic | 32 | (25.6) | 15 | (20.0) | |

| Gastrostomy tube | 8 | (6.4) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| Unknown | 42 | (33.6) | 39 | (52.0) | |

| Previous ED visits in last year, n (%) | 0.43 | ||||

| 0 | 70 | (56.0) | 41 | (54.7) | |

| 1 | 35 | (28.0) | 17 | (22.7) | |

| 2+ | 20 | (16.0) | 17 | (22.7) | |

| Previous hospitalizations in last year, n (%) | 0.19 | ||||

| 0 | 98 | (78.4) | 54 | (72.0) | |

| 1 | 23 | (18.4) | 14 | (18.7) | |

| 2+ | 4 | (3.2) | 7 | (9.3) | |

| Visit characteristics | |||||

| Glasgow Coma Scale, n (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| 7 | 4 | (3.2) | 4 | (5.3) | |

| 711 | 15 | (12.0) | 26 | (34.7) | |

| 1213 | 7 | (5.6) | 8 | (10.7) | |

| 1415 | 85 | (68.0) | 32 | (42.7) | |

| Unknown | 14 | (11.2) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| Shock index, n (%) | 0.13 | ||||

| 1 | 105 | (84.0) | 54 | (72.0) | |

| >1 | 19 | (15.2) | 18 | (24.0) | |

| Unknown | 1 | (0.8) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Respiratory rate, n (%) | 0.02 | ||||

| 20 | 59 | (47.2) | 21 | (28.0) | |

| 20 | 66 | (52.8) | 52 | (69.3) | |

| Unknown | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (2.7) | |

| Oxygen saturation, n (%) | 0.03 | ||||

| 88 | 2 | (1.6) | 6 | (8.0) | |

| 88 | 122 | (97.6) | 65 | (86.7) | |

| Unknown | 1 | (0.8) | 4 | (5.3) | |

| Temperature, n (%) | 0.09 | ||||

| 38.0 | 100 | (80.0) | 51 | (68.0) | |

| 38.0 | 25 | (20.0) | 23 | (30.7) | |

| Unknown | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale, n (%) | 0.13 | ||||

| Resuscitation | 1 | (0.8) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Emergent | 70 | (56.0) | 49 | (65.3) | |

| Urgent | 52 | (41.6) | 22 | (29.3) | |

| Less urgent and nonurgent | 2 | (1.6) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Discharge diagnosis, n (%) | 0.29 | ||||

| Aspiration pneumonia | 12 | (9.6) | 12 | (16.0) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 15 | (12.0) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Dehydration/disorders fluid/electrolytes | 9 | (7.2) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 4 | (3.2) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Heart failure | 11 | (8.8) | 2 | (2.7) | |

| Infection (other or not identified) | 9 | (7.2) | 9 | (12.0) | |

| Influenza/pneumonia | 14 | (11.2) | 11 | (14.7) | |

| Lower urinary tract infection | 11 | (8.8) | 6 | (8.0) | |

| Other | 40 | (32.0) | 24 | (32.0) | |

| Hospitalization included ICU stay, n (%) | 0.01 | ||||

| No | 124 | (99.2) | 69 | (92.0) | |

| Yes | 1 | (0.8) | 6 | (8.0) | |

When these 4 significant clinical and visit characteristics were tested together in a logistic regression analysis, 2 remained statistically significant (Table 2). Patients with lower GCS scores (GCS 1213 and 711) were more likely to have discussions (AOR: 4.4 [95% CI: 1.4‐13.9] and AOR: 5.9 [95% CI: 2.6‐13.2], respectively) and patients with higher respiratory rates were also more likely to have discussions (AOR: 2.3 [95% CI: 1.1‐4.8]).

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 0.001 | ||

| 7 | 1.77 | 0.33‐9.58 | 0.51 |

| 711 | 5.90 | 2.64‐13.22 | 0.001 |

| 1213 | 4.43 | 1.41‐13.91 | 0.01 |

| 1415 | Reference | ||

| Respiration | |||

| 20 | Reference | ||

| 20 | 2.32 | 1.12‐4.78 | 0.02 |

| Oxygen saturation | |||

| 88 | 3.35 | 0.55‐20.56 | 0.19 |

| 88 | Reference | 0.05‐1.83 | |

| Hospitalization included ICU stay | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 7.87 | 0.83‐74.73 | 0.07 |

GOC Documentation in the Discharge Summary

For the subset of patients who survived index hospitalization and were discharged back to LTC (176 patients or 88%), we also investigated whether the ADs were documented in the discharge summary back to LTC (data not shown). Of the 42 patients (23.9%) who had a change in the AD (18 patients had an AD increase in care intensity due to hospitalization; 24 had a decrease), only 11 (26%) had this AD change documented in the discharge summary.

Outcomes of GOC Documentation

A number of outcomes differed significantly between patients with and without GOC discussions in unadjusted comparisons (Table 3). Patients with discussions had higher rates of orders for no CPR (80% vs 55%) and orders for comfort measures only (7% vs 0%). They also had higher rates of in‐hospital death (29% vs 1%), 1‐year mortality (63% vs 28%), and longer LOS. However, RIW and subsequent hospital use were not found to be significant.

| Variable | Goals of Care Discussion Documented in Medical Chart | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, N = 125 | Yes, N = 75 | P Value | |||

| |||||

| Physician orders, n (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| Comfort measures only | 0 | (0.0) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| No cardiopulmonary resuscitation | 69 | (55.2) | 60 | (80.0) | |

| Full code | 56 | (44.8) | 10 | (13.3) | |

| Visit disposition, n (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| Long‐term care home | 124 | (99.2) | 52 | (69.3) | |

| Died | 1 | (0.8) | 22 | (29.3) | |

| Transfer to palliative care facility | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Resource intensity weight, n (%) | 0.43 | ||||

| 0.250.75 | 35 | (28.0) | 19 | (25.3) | |

| 0.761.14 | 29 | (23.2) | 16 | (21.3) | |

| 1.151.60 | 34 | (27.2) | 16 | (21.3) | |

| 1.6125.5 | 27 | (21.6) | 24 | (32.0) | |

| Length of stay, d, n (%) | 0.01 | ||||

| 0.672.97 | 30 | (24.0) | 20 | (26.7) | |

| 2.984.60 | 40 | (32.0) | 10 | (13.3) | |

| 4.618.65 | 30 | (24.0) | 20 | (26.7) | |

| 8.66+ | 25 | (20.0) | 25 | (33.3) | |

| Subsequent emergency department visits in next year, n (% of applicable) | 0.38 | ||||

| 0 | 66 | (53.2) | 32 | (61.5) | |

| 1 | 30 | (24.2) | 13 | (25.0) | |

| 2+ | 28 | (22.6) | 7 | (13.5) | |

| Not applicable (died during index hospitalization or transfer to palliative care) | 1 | 23 | |||

| Subsequent hospitalizations in next year, n (% of applicable) | 0.87 | ||||

| 0 | 87 | (70.2) | 38 | (73.1) | |

| 1 | 24 | (19.4) | 10 | (19.2) | |

| 2+ | 13 | (10.5) | 4 | (7.7) | |

| Not applicable (died during index hospitalization or transfer to palliative care) | 1 | 23 | |||

| 1‐year mortality, n (% of applicable) | 0.001 | ||||

| Alive | 82 | (71.9) | 15 | (37.5) | |

| Dead | 32 | (28.1) | 25 | (62.5) | |

| Not applicable (died during index hospitalization or transfer to palliative care) | 1 | 23 | |||

| Not applicable (unsuccessful follow‐up with long‐term care home) | 10 | 12 | |||

Predictors of In‐hospital Death and 1‐Year Mortality

Given the significant positive associations between discussions and in‐hospital death and 1‐year mortality, we performed separate logistic regression analyses to test whether discussions independently predicted in‐hospital death and 1‐year mortality (Table 4). After adjusting for variables significant in their respective bivariate analyses, patients with discussions continued to have higher odds of in‐hospital death (AOR: 52.0 [95% CI: 6.2‐440.4]) and 1‐year mortality (AOR: 4.1 [95% CI: 1.7‐9.6]). Of note, the presence of dementia had significantly lower adjusted odds of in‐hospital death compared to the reference group of no dementia (AOR: 0.3 [95% CI: 0.1‐0.8]).

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| In‐hospital death odds ratios | |||

| Advance directives from long‐term care | 0.91 | ||

| Comfort measures only | Reference | ||

| Supportive care no transfer | 3.43E +18 | 0‐. | 1.00 |

| Transfer to hospital | 3.10E +8 | 0‐. | 1.00 |

| Aggressive care | 4.85E +8 | 0‐. | 1.00 |

| Dementia | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | .25 | 0.08‐0.79 | 0.02 |

| Previous hospitalizations in last year | 0.05 | ||

| 0 | Reference | ||

| 1 | 0.43 | 0.08‐2.38 | 0.34 |

| 2+ | 6.30 | 1.10‐36.06 | 0.04 |

| Respiration | |||

| 20 | Reference | ||

| 20 | 3.64 | 0.82‐16.24 | 0.09 |

| Documented goals of care discussion | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 52.04 | 6.15‐440.40 | 0.001 |

| 1‐year mortality odds ratios | |||

| Oxygen saturation, n (%) | |||

| 88 | 12.15 | 1.18‐124.97 | 0.04 |

| 88 | Reference | ||

| Previous ED visits in last year | 0.06 | ||

| 0 | Reference | ||

| 1 | 3.07 | 1.15‐8.17 | 0.03 |

| 2+ | 3.21 | 0.87‐11.81 | 0.08 |

| Previous hospitalizations in last year | 0.55 | ||

| 0 | Reference | ||

| 1 | 1.66 | 0.57‐4.86 | 0.36 |

| 2+ | 2.52 | 0.30‐20.89 | 0.39 |

| Documented goals of care discussion | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 4.07 | 1.73‐9.56 | 0.001 |

DISCUSSION

Our retrospective study of LTC residents admitted to the GIM service showed that these admissions comprised 9.4% of all admissions and that GOC discussions occurred infrequently (37.5%). Our study revealed no differences in baseline patient characteristics associated with discussions, whereas patient acuity at hospital presentation independently contributed to the likelihood of discussions. We found strong associations between documentation and certain outcomes of care, including orders for AD, LOS, in‐hospital death, and 1‐year mortality. No significant associations were found between documentation and subsequent hospital use. Lastly, we found that consistent communication back to the LTC home when there was a change in AD was very poor; only 26% of discharge summaries included this documentation.

Our finding of infrequent GOC discussions during hospitalization aligns with prior studies. A study that identified code status discussions in transcripts of audio‐recorded admission encounters found that code status was discussed in only 24% of seriously ill patient admissions.[17] Furthermore, in a study specific to LTC residents, only 42% of admissions longer than 48 hours had a documented GOC discussion.[15]

We found visit‐level, but not baseline, characteristics were associated with discussions. These findings are supported by a recent study that found that whether GOC discussions took place largely depended on the acute condition presented on admission.[15] Although these results suggest that clinicians are appropriately prioritizing sicker patients who might have the most pressing need for GOC discussions, they also highlight the gap in care for less‐sick patients and the need to broaden clinical practice and consider underlying conditions and functional status. Of note, although the GCS score was found to be significantly associated with discussions, patients in the lowest GCS range did not have significantly different odds of discussions compared to the reference level (highest GCS range). A recent study by You et al. may offer some insight into this finding. They found that patients lacking capacity to make GOC decisions was ranked fifth, whereas lack of SDM availability was eighth among 21 barriers to GOC discussions, as perceived by hospital‐based clinicians.[16]

A major finding of this study was that both in‐hospital and 1‐year mortality were strongly associated with having a GOC discussion, suggesting that patients at higher risk of dying are more likely to have discussions. This is reflected by illness severity measured at initial assessment and by persistence of the association between discussions and mortality after discharge back to LTC. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have reported these findings. There are likely some unmeasured clinical factors such as clinical deterioration during hospitalization that contributed to this strong association. Interestingly, in our logistic regression analysis for independent predictors of in‐hospital death, we found that having dementia was associated with lower odds of in‐hospital death. One interpretation of this finding is that perhaps only patients with mild dementia were hospitalized, and those with more advanced dementia had an AD established in LTC that allowed them to remain in their LTC home. This possibility is supported by a systematic review of factors associated with LTC home hospitalization, which found that dementia was shown to be associated with less hospitalization.[18]

For patients who survived hospitalization, we did not find an association between GOC discussions and hospital use in the year following index hospitalization. In both groups, nearly 30% of patients had 1 or more subsequent hospitalizations. This is relevant especially in light of the finding that among patients where GOC discussions resulted in an AD change, only 26% of discharge summaries back to LTC included this documentation. We can only speculate that had these discussions been properly documented, subsequent hospitalizations would have decreased in the GOC group. Previous research has found that omissions of critical information in discharge summaries were common. In a study of hip fracture and stroke patients discharged from a large Midwestern academic medical center in the United States, code status was included in the discharge summary only 7% of the time.[19] The discharge summary is the primary means of sharing patient information between the hospital and LTC home. If GOC discussions are not included in the discharge summary, it is very unlikely that this information will be subsequently updated in the LTC medical record and impact the care the patient receives. A key recommendation for hospital‐based providers is ensuring that GOC discussions are clearly, consistently, and completely documented in the discharge summary so that the care provided is based on the patients' wishes.

Our study has several limitations. Our analysis was based on chart review, and although our analyses take into account a number of patient characteristics, we did not capture other characteristics that might influence GOC discussions such as culture/religion, language barriers, SDM availability, or whether patients clinically deteriorated during the index admission. Additionally, provider‐level predictors, including seniority, previous GOC training, and time available to conduct these discussions, were not captured. We also did not capture the timing or number of occasions that GOC discussions took place during hospitalization. Due to the retrospective nature of our study, we were able to only look at documented GOC discussions. GOC discussions may have happened but were never documented. However, the standard of care is to document these discussions as part of the medical record, and if they are not documented, it can be considered not to have happened and indicates a lower quality of practice. A recent survey of Canadian hospital‐based healthcare providers identified standardized GOC documentation as an effective practice to improve GOC communication.[20] Finally, because our study was conducted in 2 academic hospitals, our results may be less generalizable to other community hospitals. However, our hospitals' catchment areas capture a diverse population, both culturally and in terms of their socioeconomic status.

CONCLUSION

GOC discussions occurred infrequently, appeared to be triggered by illness severity, and were poorly communicated back to LTC. Important outcomes of care, including in‐hospital death and 1‐year mortality, were associated with discussions. This study serves to identify gaps in who might benefit from GOC discussions and illustrates opportunities for improvement including implementing standardized documentation practices.

Disclosures

Hannah J. Wong, PhD, and Robert C. Wu, MD, had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Robert C. Wu, MD, Hannah J. Wong, PhD, and Michelle Grinman, MD, were responsible for the conception and design of the study. Robert C. Wu, MD, Hannah J. Wong, PhD, and Jamie Wang were responsible for the acquisition of the data. All of the authors were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and final approval of the manuscript. Hannah J. Wong, PhD obtained the funding. Hannah J. Wong, PhD, and Robert C. Wu, MD, supervised the study. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , , . Trends in emergency department visits for ambulatory care sensitive conditions by elderly nursing home residents, 2001 to 2010. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):156–158.

- , , , . Hospital transfers of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(5):905–909.

- , , , , . Potentially avoidable hospitalizations for elderly long‐stay residents in nursing homes. Med Care. 2013;51(8):673–681.

- , . Reducing unnecessary hospitalizations of nursing home residents. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):1165–1167.

- , , . Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1211–1218.

- , , , , , . The consistency between treatments provided to nursing facility residents and orders on the physician orders for life‐sustaining treatment form. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(11):2091–2099.

- , , . What should be the goal of advance care planning? JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1093–1094.

- , , , et al. Associations between end‐of‐life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–1673.

- , , , et al. Systematic implementation of an advance directive program in nursing homes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(11):1437–1444.

- , . Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1994–2003.

- , , . Predictors of nursing home residents' time to hospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(1 pt 1):82–104.

- , , , . Regional variation in the association between advance directives and end‐of‐life Medicare expenditures. JAMA. 2011;306(13):1447–1453.

- , , . Just ask: discussing goals of care with patients in hospital with serious illness. CMAJ. 2014;186(6):425–432.

- , , , et al. Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(9):778–787.

- , , , . Hospitalisation of high‐care residents of aged care facilities: are goals of care discussed? Intern Med J. 2013;43(2):144–149.

- , , , et al. Barriers to goals of care discussions with seriously ill hospitalized patients and their families: a multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):549–556.

- , , , , . Code status discussions between attending hospitalist physicians and medical patients at hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(4):359–366.

- , , , . Predictors of nursing home hospitalization: a review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65(1):3–39.

- , , , , . Provider characteristics, clinical‐work processes and their relationship to discharge summary quality for sub‐acute care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):78–84.

- , , , . Strategies for effective goals of care discussions and decision‐making: perspectives from a multi‐centre survey of Canadian hospital‐based healthcare providers. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:38.

Hospitalizations of long‐term care (LTC) residents are known to be frequent, costly, often preventable,[1, 2, 3] and potentially associated with negative health outcomes.[4] Often, an advance directive (AD) is made at LTC admission and updated annually when residents are in relatively stable health. An AD is a document that helps to inform a substitute decision maker (SDM) about the consent process for life‐sustaining treatments and is a resource that supports advance care planning (ACP). ACP is a process that allows individuals to consider, express, and plan for future healthcare in the event that they lack capacity to make their own decisions. When an LTC resident's health deteriorates and hospitalization is required, there is an opportunity to update prognosis, discuss risks and benefits of previously held treatment preferences, as well as reassess goals of care (GOC).

Engaging in ACP discussions during relatively stable health can help ensure patient preferences are followed.[5, 6] These discussions, however, are often insufficient, as they involve decision making for hypothetical situations that may not cover all potential scenarios, and may not reflect a patient's reality at the time of health status decline. Discussions held in the moment more authentically reflect the decisions of patients and/or SDM based on the specific needs and clinical realities particular to the patient at that time.[7] GOC discussions, defined in this context as ACP discussions occurring during hospitalization, have the potential to better align patient wishes with care received,[6] improve quality of life and satisfaction,[8, 9, 10] and reduce unwanted extra care.[11, 12] Although in‐the‐moment GOC discussions are recommended for all hospitalized patients who are seriously ill with a high risk of dying,[13] research suggests that this occurs infrequently for elderly patients. A recent multicenter survey of seriously ill hospitalized elderly patients found that only 25% of patients and 32% of family members reported that they had been asked about prior ACP or AD.[14] Another study of hospitalized LTC residents found that resuscitation status and family discussion was documented in only 55% and 42% of admissions, respectively.[15]

Further investigation is required to determine how often LTC patients have GOC discussions, what prompts these discussions, and what are the outcomes. Previous studies have focused on barriers to performing GOC discussions, rather than the factors that are associated with them.[16] By understanding why these discussions currently happen, we can potentially improve how often they occur and the quality of their outcomes.

The objectives of this study were to determine the rate of documented GOC discussions among hospitalized LTC residents, identify factors that were associated with documentation, and examine the association between documentation and outcomes of care.

METHODS

Study Population

We conducted a retrospective chart review of a random convenience sample of hospitalized patients admitted via the emergency department (ED) to the general internal medicine (GIM) service from January 1, 2012 through December 31, 2012, at 2 academic teaching hospitals in Toronto, Canada. Patients were identified through a search of each hospitals' electronic patient record (EPR). Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were (1) a LTC resident and (2) at least 65 years of age. For patients with multiple admissions to the GIM service during the specified 12‐month period, we only included data from the first hospitalization (index hospitalization). The hospital's research ethics board approved this study.

Our primary variable of interest was documentation in the hospital medical record of a discussion between physicians and the patient/family/SDM regarding GOC. A GOC discussion was considered to have taken place if there was documentation of (1) understanding/expectation of treatment options or (2) patient's preferences for life‐sustaining measures. Examples illustrating each criterion are provided in the Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article.

Factors Associated With GOC Documentation

From the EPR, we obtained visit‐level data including age, gender, Canadian Emergency Department Triage and Acuity Scale, vital signs at ED admission including temperature, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and shock index (defined as heart rate divided by systolic blood pressure), admission and discharge dates/times, discharge diagnosis, transfer to intensive care unit (ICU), and hospital use (number of ED visits and hospitalizations to the 2 study hospitals in the 1‐year period prior to index hospitalization).

Trained study personnel (J.W.) used a structured abstraction form to collect data from the hospital medical record that were not available through the EPR, including years living in LTC, contents of LTC AD forms, presence of SDM (identified as immediate family or surrogate with whom the care team communicated), dementia diagnosis (defined as documentation of dementia in the patient's past medical history and/or history of present illness), and measures of functional status. When available, we extracted the AD from LTC; they consisted of 4 levels (level 1: comfort careno transfer to hospital, no cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CPR]; level 2: supportive careadministration of antibiotics and/or other procedures that can be provided within LTC, no transfer to the hospital, no CPR; level 3: transfer to the hospitalno CPR; level 4: aggressive interventiontransfer to hospital for aggressive treatment, CPR).

GOC Documentation in the Discharge Summary

For the subset of patients who survived hospitalization and were discharged back to LTC, we examined whether the ADs ordered during hospitalization were communicated back to LTC via the discharge summary. We additionally assessed if the ADs determined during hospitalization differed from preferences documented prior to hospitalization. Physician orders for ADs were categorized as level 1: comfort measures only, level 3: no CPR, or level 4: full code. LTC level 2 was considered equivalent to physician‐ordered level 3 at admission; a patient with an LTC level 2 with no CPR (level 3) documented during hospitalized would be considered to have no change in the AD. An increase or decrease in the AD was determined by comparing LTC levels 1, 3, and 4 to physician‐ordered level 1, 3, and 4.

Outcomes of GOC Documentation

From the EPR, we obtained visit‐level outcome data including length of stay (LOS), resource intensity weight (RIW) (calculated based on patient case‐mix, severity, age, and procedures performed), visit disposition, number of ED visits and hospitalizations to the 2 study hospitals in the year following index hospitalization, in‐hospital death, and 1‐year mortality. We determined 1‐year mortality by following up with the LTC homes to determine whether the resident had died within the year following index hospitalization; only patients from LTC homes that responded to our request for data were included in 1‐year mortality analyses. We collected physician orders for the AD from chart review.

Statistical Analysis

Patients with and without documented GOC discussions were compared. Descriptive statistics including frequencies and percentages were used to characterize study variables. Differences between the study groups were assessed using Pearson 2/Fisher exact test. Multivariate logistic regression, which included variables that were significant in the bivariate analysis, was used to identify independent predictors of GOC discussion. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were presented for the logistic model. Patients with missing predictor data were excluded.

We also examined whether there was a correlation between GOC discussion and outcomes of care using Pearson 2/Fisher exact test. Outcomes included orders for the AD, LOS in days (stratified into quartiles), RIW (stratified into quartiles), visit disposition, hospital use in the year following index hospitalization, and 1‐year mortality following discharge back to LTC.

Lastly, to better understand the independent predictors of in‐hospital and 1‐year mortality, we used Pearson 2/Fisher exact test followed by logistic regression that included significant variables from the bivariate analyses.

All analyses were 2‐sided, and a P value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

We identified a total of 7084 hospitalizations to GIM between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2012, of which 665 (9.4%) met inclusion criteria of residence in LTC and age 65 years. Of these 665 hospitalizations, 512 were unique patients. We randomly selected a convenience sample of 200 index hospitalizations of the 512 eligible hospitalizations (39%) to perform the chart review.

Predictors of GOC Documentation

Of the 200 randomly sampled charts that were reviewed, 75 (37.5%) had a documented GOC discussion.

Characteristics of the study patients and results of bivariate analysis of the association between patient characteristics and GOC discussion are summarized in Table 1. No significant differences in demographic and baseline characteristics were seen between patients with and without discussion. However, a number of visit characteristics were found to be significantly associated with discussion. Forty percent of patients in the GOC discussion group had GCS scores 11 compared to 15.2% in the no‐discussion group. Higher respiratory rate, lower oxygen saturation, and ICU transfer were also significantly associated with discussions.

| Goals of Care Discussion Documented in Medical Chart | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, N = 125 | Yes, N = 75 | P Value | |||

| |||||

| Baseline characteristics | |||||

| Gender, n (%) | 0.88 | ||||

| Male | 48 | (38.4) | 30 | (40.0) | |

| Female | 77 | (61.6) | 45 | (60.0) | |

| Age, y, n (%) | 0.85 | ||||

| 6579 | 36 | (28.8) | 19 | (25.3) | |

| 8084 | 30 | (24.0) | 19 | (25.3) | |

| 8589 | 30 | (24.0) | 16 | (21.3) | |

| 90101 | 29 | (23.2) | 21 | (28.0) | |

| Years living in long‐term care, n (%)* | 0.65 | ||||

| [0, 1) | 28 | (22.4) | 12 | (16.0) | |

| [1, 3) | 31 | (24.8) | 22 | (29.3) | |

| [3, 6) | 33 | (26.4) | 22 | (29.3) | |

| [6, 22) | 25 | (20.0) | 13 | (17.3) | |

| Unknown | 8 | (6.4) | 6 | (8.0) | |

| AD from long‐term care, n (%) | 0.14 | ||||

| Comfort measures only | 2 | (1.6) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Supportive care with no transfer to hospital | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Supportive care with transfer to hospital | 70 | (56.0) | 44 | (58.7) | |

| Aggressive care | 53 | (42.4) | 27 | (36.0) | |

| Years since most recent AD signed, n (%)* | 0.12 | ||||

| [0, 1) | 79 | (63.2) | 48 | (64.0) | |

| [1, 2) | 21 | (16.8) | 6 | (8.0) | |

| [2, 6) | 9 | (7.2) | 10 | (13.3) | |

| Unknown | 16 | (12.8) | 11 | (14.7) | |

| Substitute decision maker, n (%) | 0.06 | ||||

| Child | 81 | (64.8) | 44 | (58.7) | |

| Spouse | 9 | (7.2) | 15 | (20.0) | |

| Other | 26 | (20.8) | 13 | (17.3) | |

| Public guardian trustee | 6 | (4.8) | 2 | (2.7) | |

| Unknown | 3 | (2.4) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Dementia, n (%) | 1.00 | ||||

| No | 47 | (37.6) | 28 | (37.3) | |

| Yes | 78 | (62.4) | 47 | (62.7) | |

| Mobility, n (%) | 0.26 | ||||

| Walk without assistance | 5 | (4.0) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Walker | 16 | (12.8) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Wheelchair | 43 | (34.4) | 29 | (38.7) | |

| Bedridden | 7 | (5.6) | 4 | (5.3) | |

| Unknown | 54 | (43.2) | 36 | (48.0) | |

| Continence, n (%) | 0.05 | ||||

| Mostly continent | 16 | (12.8) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Incontinent | 49 | (39.2) | 34 | (45.3) | |

| Catheter/stoma | 7 | (5.6) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Unknown | 53 | (42.4) | 37 | (49.3) | |

| Feeding, n (%) | 0.17 | ||||

| Mostly feeds self | 38 | (30.4) | 13 | (17.3) | |

| Needs to be fed | 17 | (13.6) | 14 | (18.7) | |

| Gastrostomy tube | 8 | (6.4) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| Unknown | 62 | (49.6) | 43 | (57.3) | |

| Diet, n (%) | 0.68 | ||||

| Normal | 43 | (34.4) | 16 | (21.3) | |

| Dysphagic | 32 | (25.6) | 15 | (20.0) | |

| Gastrostomy tube | 8 | (6.4) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| Unknown | 42 | (33.6) | 39 | (52.0) | |

| Previous ED visits in last year, n (%) | 0.43 | ||||

| 0 | 70 | (56.0) | 41 | (54.7) | |

| 1 | 35 | (28.0) | 17 | (22.7) | |

| 2+ | 20 | (16.0) | 17 | (22.7) | |

| Previous hospitalizations in last year, n (%) | 0.19 | ||||

| 0 | 98 | (78.4) | 54 | (72.0) | |

| 1 | 23 | (18.4) | 14 | (18.7) | |

| 2+ | 4 | (3.2) | 7 | (9.3) | |

| Visit characteristics | |||||

| Glasgow Coma Scale, n (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| 7 | 4 | (3.2) | 4 | (5.3) | |

| 711 | 15 | (12.0) | 26 | (34.7) | |

| 1213 | 7 | (5.6) | 8 | (10.7) | |

| 1415 | 85 | (68.0) | 32 | (42.7) | |

| Unknown | 14 | (11.2) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| Shock index, n (%) | 0.13 | ||||

| 1 | 105 | (84.0) | 54 | (72.0) | |

| >1 | 19 | (15.2) | 18 | (24.0) | |

| Unknown | 1 | (0.8) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Respiratory rate, n (%) | 0.02 | ||||

| 20 | 59 | (47.2) | 21 | (28.0) | |

| 20 | 66 | (52.8) | 52 | (69.3) | |

| Unknown | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (2.7) | |

| Oxygen saturation, n (%) | 0.03 | ||||

| 88 | 2 | (1.6) | 6 | (8.0) | |

| 88 | 122 | (97.6) | 65 | (86.7) | |

| Unknown | 1 | (0.8) | 4 | (5.3) | |

| Temperature, n (%) | 0.09 | ||||

| 38.0 | 100 | (80.0) | 51 | (68.0) | |

| 38.0 | 25 | (20.0) | 23 | (30.7) | |

| Unknown | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale, n (%) | 0.13 | ||||

| Resuscitation | 1 | (0.8) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Emergent | 70 | (56.0) | 49 | (65.3) | |

| Urgent | 52 | (41.6) | 22 | (29.3) | |

| Less urgent and nonurgent | 2 | (1.6) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Discharge diagnosis, n (%) | 0.29 | ||||

| Aspiration pneumonia | 12 | (9.6) | 12 | (16.0) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 15 | (12.0) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Dehydration/disorders fluid/electrolytes | 9 | (7.2) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 4 | (3.2) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Heart failure | 11 | (8.8) | 2 | (2.7) | |

| Infection (other or not identified) | 9 | (7.2) | 9 | (12.0) | |

| Influenza/pneumonia | 14 | (11.2) | 11 | (14.7) | |

| Lower urinary tract infection | 11 | (8.8) | 6 | (8.0) | |

| Other | 40 | (32.0) | 24 | (32.0) | |

| Hospitalization included ICU stay, n (%) | 0.01 | ||||

| No | 124 | (99.2) | 69 | (92.0) | |

| Yes | 1 | (0.8) | 6 | (8.0) | |

When these 4 significant clinical and visit characteristics were tested together in a logistic regression analysis, 2 remained statistically significant (Table 2). Patients with lower GCS scores (GCS 1213 and 711) were more likely to have discussions (AOR: 4.4 [95% CI: 1.4‐13.9] and AOR: 5.9 [95% CI: 2.6‐13.2], respectively) and patients with higher respiratory rates were also more likely to have discussions (AOR: 2.3 [95% CI: 1.1‐4.8]).

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 0.001 | ||

| 7 | 1.77 | 0.33‐9.58 | 0.51 |

| 711 | 5.90 | 2.64‐13.22 | 0.001 |

| 1213 | 4.43 | 1.41‐13.91 | 0.01 |

| 1415 | Reference | ||

| Respiration | |||

| 20 | Reference | ||

| 20 | 2.32 | 1.12‐4.78 | 0.02 |

| Oxygen saturation | |||

| 88 | 3.35 | 0.55‐20.56 | 0.19 |

| 88 | Reference | 0.05‐1.83 | |

| Hospitalization included ICU stay | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 7.87 | 0.83‐74.73 | 0.07 |

GOC Documentation in the Discharge Summary

For the subset of patients who survived index hospitalization and were discharged back to LTC (176 patients or 88%), we also investigated whether the ADs were documented in the discharge summary back to LTC (data not shown). Of the 42 patients (23.9%) who had a change in the AD (18 patients had an AD increase in care intensity due to hospitalization; 24 had a decrease), only 11 (26%) had this AD change documented in the discharge summary.

Outcomes of GOC Documentation

A number of outcomes differed significantly between patients with and without GOC discussions in unadjusted comparisons (Table 3). Patients with discussions had higher rates of orders for no CPR (80% vs 55%) and orders for comfort measures only (7% vs 0%). They also had higher rates of in‐hospital death (29% vs 1%), 1‐year mortality (63% vs 28%), and longer LOS. However, RIW and subsequent hospital use were not found to be significant.

| Variable | Goals of Care Discussion Documented in Medical Chart | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, N = 125 | Yes, N = 75 | P Value | |||

| |||||

| Physician orders, n (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| Comfort measures only | 0 | (0.0) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| No cardiopulmonary resuscitation | 69 | (55.2) | 60 | (80.0) | |

| Full code | 56 | (44.8) | 10 | (13.3) | |

| Visit disposition, n (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| Long‐term care home | 124 | (99.2) | 52 | (69.3) | |

| Died | 1 | (0.8) | 22 | (29.3) | |

| Transfer to palliative care facility | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Resource intensity weight, n (%) | 0.43 | ||||

| 0.250.75 | 35 | (28.0) | 19 | (25.3) | |

| 0.761.14 | 29 | (23.2) | 16 | (21.3) | |

| 1.151.60 | 34 | (27.2) | 16 | (21.3) | |

| 1.6125.5 | 27 | (21.6) | 24 | (32.0) | |

| Length of stay, d, n (%) | 0.01 | ||||

| 0.672.97 | 30 | (24.0) | 20 | (26.7) | |

| 2.984.60 | 40 | (32.0) | 10 | (13.3) | |

| 4.618.65 | 30 | (24.0) | 20 | (26.7) | |

| 8.66+ | 25 | (20.0) | 25 | (33.3) | |

| Subsequent emergency department visits in next year, n (% of applicable) | 0.38 | ||||

| 0 | 66 | (53.2) | 32 | (61.5) | |

| 1 | 30 | (24.2) | 13 | (25.0) | |

| 2+ | 28 | (22.6) | 7 | (13.5) | |

| Not applicable (died during index hospitalization or transfer to palliative care) | 1 | 23 | |||

| Subsequent hospitalizations in next year, n (% of applicable) | 0.87 | ||||

| 0 | 87 | (70.2) | 38 | (73.1) | |

| 1 | 24 | (19.4) | 10 | (19.2) | |

| 2+ | 13 | (10.5) | 4 | (7.7) | |

| Not applicable (died during index hospitalization or transfer to palliative care) | 1 | 23 | |||

| 1‐year mortality, n (% of applicable) | 0.001 | ||||

| Alive | 82 | (71.9) | 15 | (37.5) | |

| Dead | 32 | (28.1) | 25 | (62.5) | |

| Not applicable (died during index hospitalization or transfer to palliative care) | 1 | 23 | |||

| Not applicable (unsuccessful follow‐up with long‐term care home) | 10 | 12 | |||

Predictors of In‐hospital Death and 1‐Year Mortality

Given the significant positive associations between discussions and in‐hospital death and 1‐year mortality, we performed separate logistic regression analyses to test whether discussions independently predicted in‐hospital death and 1‐year mortality (Table 4). After adjusting for variables significant in their respective bivariate analyses, patients with discussions continued to have higher odds of in‐hospital death (AOR: 52.0 [95% CI: 6.2‐440.4]) and 1‐year mortality (AOR: 4.1 [95% CI: 1.7‐9.6]). Of note, the presence of dementia had significantly lower adjusted odds of in‐hospital death compared to the reference group of no dementia (AOR: 0.3 [95% CI: 0.1‐0.8]).

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| In‐hospital death odds ratios | |||

| Advance directives from long‐term care | 0.91 | ||

| Comfort measures only | Reference | ||

| Supportive care no transfer | 3.43E +18 | 0‐. | 1.00 |

| Transfer to hospital | 3.10E +8 | 0‐. | 1.00 |

| Aggressive care | 4.85E +8 | 0‐. | 1.00 |

| Dementia | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | .25 | 0.08‐0.79 | 0.02 |

| Previous hospitalizations in last year | 0.05 | ||

| 0 | Reference | ||

| 1 | 0.43 | 0.08‐2.38 | 0.34 |

| 2+ | 6.30 | 1.10‐36.06 | 0.04 |

| Respiration | |||

| 20 | Reference | ||

| 20 | 3.64 | 0.82‐16.24 | 0.09 |

| Documented goals of care discussion | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 52.04 | 6.15‐440.40 | 0.001 |

| 1‐year mortality odds ratios | |||

| Oxygen saturation, n (%) | |||

| 88 | 12.15 | 1.18‐124.97 | 0.04 |

| 88 | Reference | ||

| Previous ED visits in last year | 0.06 | ||

| 0 | Reference | ||

| 1 | 3.07 | 1.15‐8.17 | 0.03 |

| 2+ | 3.21 | 0.87‐11.81 | 0.08 |

| Previous hospitalizations in last year | 0.55 | ||

| 0 | Reference | ||

| 1 | 1.66 | 0.57‐4.86 | 0.36 |

| 2+ | 2.52 | 0.30‐20.89 | 0.39 |

| Documented goals of care discussion | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 4.07 | 1.73‐9.56 | 0.001 |

DISCUSSION

Our retrospective study of LTC residents admitted to the GIM service showed that these admissions comprised 9.4% of all admissions and that GOC discussions occurred infrequently (37.5%). Our study revealed no differences in baseline patient characteristics associated with discussions, whereas patient acuity at hospital presentation independently contributed to the likelihood of discussions. We found strong associations between documentation and certain outcomes of care, including orders for AD, LOS, in‐hospital death, and 1‐year mortality. No significant associations were found between documentation and subsequent hospital use. Lastly, we found that consistent communication back to the LTC home when there was a change in AD was very poor; only 26% of discharge summaries included this documentation.

Our finding of infrequent GOC discussions during hospitalization aligns with prior studies. A study that identified code status discussions in transcripts of audio‐recorded admission encounters found that code status was discussed in only 24% of seriously ill patient admissions.[17] Furthermore, in a study specific to LTC residents, only 42% of admissions longer than 48 hours had a documented GOC discussion.[15]

We found visit‐level, but not baseline, characteristics were associated with discussions. These findings are supported by a recent study that found that whether GOC discussions took place largely depended on the acute condition presented on admission.[15] Although these results suggest that clinicians are appropriately prioritizing sicker patients who might have the most pressing need for GOC discussions, they also highlight the gap in care for less‐sick patients and the need to broaden clinical practice and consider underlying conditions and functional status. Of note, although the GCS score was found to be significantly associated with discussions, patients in the lowest GCS range did not have significantly different odds of discussions compared to the reference level (highest GCS range). A recent study by You et al. may offer some insight into this finding. They found that patients lacking capacity to make GOC decisions was ranked fifth, whereas lack of SDM availability was eighth among 21 barriers to GOC discussions, as perceived by hospital‐based clinicians.[16]

A major finding of this study was that both in‐hospital and 1‐year mortality were strongly associated with having a GOC discussion, suggesting that patients at higher risk of dying are more likely to have discussions. This is reflected by illness severity measured at initial assessment and by persistence of the association between discussions and mortality after discharge back to LTC. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have reported these findings. There are likely some unmeasured clinical factors such as clinical deterioration during hospitalization that contributed to this strong association. Interestingly, in our logistic regression analysis for independent predictors of in‐hospital death, we found that having dementia was associated with lower odds of in‐hospital death. One interpretation of this finding is that perhaps only patients with mild dementia were hospitalized, and those with more advanced dementia had an AD established in LTC that allowed them to remain in their LTC home. This possibility is supported by a systematic review of factors associated with LTC home hospitalization, which found that dementia was shown to be associated with less hospitalization.[18]

For patients who survived hospitalization, we did not find an association between GOC discussions and hospital use in the year following index hospitalization. In both groups, nearly 30% of patients had 1 or more subsequent hospitalizations. This is relevant especially in light of the finding that among patients where GOC discussions resulted in an AD change, only 26% of discharge summaries back to LTC included this documentation. We can only speculate that had these discussions been properly documented, subsequent hospitalizations would have decreased in the GOC group. Previous research has found that omissions of critical information in discharge summaries were common. In a study of hip fracture and stroke patients discharged from a large Midwestern academic medical center in the United States, code status was included in the discharge summary only 7% of the time.[19] The discharge summary is the primary means of sharing patient information between the hospital and LTC home. If GOC discussions are not included in the discharge summary, it is very unlikely that this information will be subsequently updated in the LTC medical record and impact the care the patient receives. A key recommendation for hospital‐based providers is ensuring that GOC discussions are clearly, consistently, and completely documented in the discharge summary so that the care provided is based on the patients' wishes.

Our study has several limitations. Our analysis was based on chart review, and although our analyses take into account a number of patient characteristics, we did not capture other characteristics that might influence GOC discussions such as culture/religion, language barriers, SDM availability, or whether patients clinically deteriorated during the index admission. Additionally, provider‐level predictors, including seniority, previous GOC training, and time available to conduct these discussions, were not captured. We also did not capture the timing or number of occasions that GOC discussions took place during hospitalization. Due to the retrospective nature of our study, we were able to only look at documented GOC discussions. GOC discussions may have happened but were never documented. However, the standard of care is to document these discussions as part of the medical record, and if they are not documented, it can be considered not to have happened and indicates a lower quality of practice. A recent survey of Canadian hospital‐based healthcare providers identified standardized GOC documentation as an effective practice to improve GOC communication.[20] Finally, because our study was conducted in 2 academic hospitals, our results may be less generalizable to other community hospitals. However, our hospitals' catchment areas capture a diverse population, both culturally and in terms of their socioeconomic status.

CONCLUSION

GOC discussions occurred infrequently, appeared to be triggered by illness severity, and were poorly communicated back to LTC. Important outcomes of care, including in‐hospital death and 1‐year mortality, were associated with discussions. This study serves to identify gaps in who might benefit from GOC discussions and illustrates opportunities for improvement including implementing standardized documentation practices.

Disclosures

Hannah J. Wong, PhD, and Robert C. Wu, MD, had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Robert C. Wu, MD, Hannah J. Wong, PhD, and Michelle Grinman, MD, were responsible for the conception and design of the study. Robert C. Wu, MD, Hannah J. Wong, PhD, and Jamie Wang were responsible for the acquisition of the data. All of the authors were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and final approval of the manuscript. Hannah J. Wong, PhD obtained the funding. Hannah J. Wong, PhD, and Robert C. Wu, MD, supervised the study. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Hospitalizations of long‐term care (LTC) residents are known to be frequent, costly, often preventable,[1, 2, 3] and potentially associated with negative health outcomes.[4] Often, an advance directive (AD) is made at LTC admission and updated annually when residents are in relatively stable health. An AD is a document that helps to inform a substitute decision maker (SDM) about the consent process for life‐sustaining treatments and is a resource that supports advance care planning (ACP). ACP is a process that allows individuals to consider, express, and plan for future healthcare in the event that they lack capacity to make their own decisions. When an LTC resident's health deteriorates and hospitalization is required, there is an opportunity to update prognosis, discuss risks and benefits of previously held treatment preferences, as well as reassess goals of care (GOC).

Engaging in ACP discussions during relatively stable health can help ensure patient preferences are followed.[5, 6] These discussions, however, are often insufficient, as they involve decision making for hypothetical situations that may not cover all potential scenarios, and may not reflect a patient's reality at the time of health status decline. Discussions held in the moment more authentically reflect the decisions of patients and/or SDM based on the specific needs and clinical realities particular to the patient at that time.[7] GOC discussions, defined in this context as ACP discussions occurring during hospitalization, have the potential to better align patient wishes with care received,[6] improve quality of life and satisfaction,[8, 9, 10] and reduce unwanted extra care.[11, 12] Although in‐the‐moment GOC discussions are recommended for all hospitalized patients who are seriously ill with a high risk of dying,[13] research suggests that this occurs infrequently for elderly patients. A recent multicenter survey of seriously ill hospitalized elderly patients found that only 25% of patients and 32% of family members reported that they had been asked about prior ACP or AD.[14] Another study of hospitalized LTC residents found that resuscitation status and family discussion was documented in only 55% and 42% of admissions, respectively.[15]

Further investigation is required to determine how often LTC patients have GOC discussions, what prompts these discussions, and what are the outcomes. Previous studies have focused on barriers to performing GOC discussions, rather than the factors that are associated with them.[16] By understanding why these discussions currently happen, we can potentially improve how often they occur and the quality of their outcomes.

The objectives of this study were to determine the rate of documented GOC discussions among hospitalized LTC residents, identify factors that were associated with documentation, and examine the association between documentation and outcomes of care.

METHODS

Study Population

We conducted a retrospective chart review of a random convenience sample of hospitalized patients admitted via the emergency department (ED) to the general internal medicine (GIM) service from January 1, 2012 through December 31, 2012, at 2 academic teaching hospitals in Toronto, Canada. Patients were identified through a search of each hospitals' electronic patient record (EPR). Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were (1) a LTC resident and (2) at least 65 years of age. For patients with multiple admissions to the GIM service during the specified 12‐month period, we only included data from the first hospitalization (index hospitalization). The hospital's research ethics board approved this study.

Our primary variable of interest was documentation in the hospital medical record of a discussion between physicians and the patient/family/SDM regarding GOC. A GOC discussion was considered to have taken place if there was documentation of (1) understanding/expectation of treatment options or (2) patient's preferences for life‐sustaining measures. Examples illustrating each criterion are provided in the Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article.

Factors Associated With GOC Documentation

From the EPR, we obtained visit‐level data including age, gender, Canadian Emergency Department Triage and Acuity Scale, vital signs at ED admission including temperature, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and shock index (defined as heart rate divided by systolic blood pressure), admission and discharge dates/times, discharge diagnosis, transfer to intensive care unit (ICU), and hospital use (number of ED visits and hospitalizations to the 2 study hospitals in the 1‐year period prior to index hospitalization).

Trained study personnel (J.W.) used a structured abstraction form to collect data from the hospital medical record that were not available through the EPR, including years living in LTC, contents of LTC AD forms, presence of SDM (identified as immediate family or surrogate with whom the care team communicated), dementia diagnosis (defined as documentation of dementia in the patient's past medical history and/or history of present illness), and measures of functional status. When available, we extracted the AD from LTC; they consisted of 4 levels (level 1: comfort careno transfer to hospital, no cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CPR]; level 2: supportive careadministration of antibiotics and/or other procedures that can be provided within LTC, no transfer to the hospital, no CPR; level 3: transfer to the hospitalno CPR; level 4: aggressive interventiontransfer to hospital for aggressive treatment, CPR).

GOC Documentation in the Discharge Summary

For the subset of patients who survived hospitalization and were discharged back to LTC, we examined whether the ADs ordered during hospitalization were communicated back to LTC via the discharge summary. We additionally assessed if the ADs determined during hospitalization differed from preferences documented prior to hospitalization. Physician orders for ADs were categorized as level 1: comfort measures only, level 3: no CPR, or level 4: full code. LTC level 2 was considered equivalent to physician‐ordered level 3 at admission; a patient with an LTC level 2 with no CPR (level 3) documented during hospitalized would be considered to have no change in the AD. An increase or decrease in the AD was determined by comparing LTC levels 1, 3, and 4 to physician‐ordered level 1, 3, and 4.

Outcomes of GOC Documentation

From the EPR, we obtained visit‐level outcome data including length of stay (LOS), resource intensity weight (RIW) (calculated based on patient case‐mix, severity, age, and procedures performed), visit disposition, number of ED visits and hospitalizations to the 2 study hospitals in the year following index hospitalization, in‐hospital death, and 1‐year mortality. We determined 1‐year mortality by following up with the LTC homes to determine whether the resident had died within the year following index hospitalization; only patients from LTC homes that responded to our request for data were included in 1‐year mortality analyses. We collected physician orders for the AD from chart review.

Statistical Analysis

Patients with and without documented GOC discussions were compared. Descriptive statistics including frequencies and percentages were used to characterize study variables. Differences between the study groups were assessed using Pearson 2/Fisher exact test. Multivariate logistic regression, which included variables that were significant in the bivariate analysis, was used to identify independent predictors of GOC discussion. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were presented for the logistic model. Patients with missing predictor data were excluded.

We also examined whether there was a correlation between GOC discussion and outcomes of care using Pearson 2/Fisher exact test. Outcomes included orders for the AD, LOS in days (stratified into quartiles), RIW (stratified into quartiles), visit disposition, hospital use in the year following index hospitalization, and 1‐year mortality following discharge back to LTC.

Lastly, to better understand the independent predictors of in‐hospital and 1‐year mortality, we used Pearson 2/Fisher exact test followed by logistic regression that included significant variables from the bivariate analyses.

All analyses were 2‐sided, and a P value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

We identified a total of 7084 hospitalizations to GIM between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2012, of which 665 (9.4%) met inclusion criteria of residence in LTC and age 65 years. Of these 665 hospitalizations, 512 were unique patients. We randomly selected a convenience sample of 200 index hospitalizations of the 512 eligible hospitalizations (39%) to perform the chart review.

Predictors of GOC Documentation

Of the 200 randomly sampled charts that were reviewed, 75 (37.5%) had a documented GOC discussion.

Characteristics of the study patients and results of bivariate analysis of the association between patient characteristics and GOC discussion are summarized in Table 1. No significant differences in demographic and baseline characteristics were seen between patients with and without discussion. However, a number of visit characteristics were found to be significantly associated with discussion. Forty percent of patients in the GOC discussion group had GCS scores 11 compared to 15.2% in the no‐discussion group. Higher respiratory rate, lower oxygen saturation, and ICU transfer were also significantly associated with discussions.

| Goals of Care Discussion Documented in Medical Chart | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, N = 125 | Yes, N = 75 | P Value | |||

| |||||

| Baseline characteristics | |||||

| Gender, n (%) | 0.88 | ||||

| Male | 48 | (38.4) | 30 | (40.0) | |

| Female | 77 | (61.6) | 45 | (60.0) | |

| Age, y, n (%) | 0.85 | ||||

| 6579 | 36 | (28.8) | 19 | (25.3) | |

| 8084 | 30 | (24.0) | 19 | (25.3) | |

| 8589 | 30 | (24.0) | 16 | (21.3) | |

| 90101 | 29 | (23.2) | 21 | (28.0) | |

| Years living in long‐term care, n (%)* | 0.65 | ||||

| [0, 1) | 28 | (22.4) | 12 | (16.0) | |

| [1, 3) | 31 | (24.8) | 22 | (29.3) | |

| [3, 6) | 33 | (26.4) | 22 | (29.3) | |

| [6, 22) | 25 | (20.0) | 13 | (17.3) | |

| Unknown | 8 | (6.4) | 6 | (8.0) | |

| AD from long‐term care, n (%) | 0.14 | ||||

| Comfort measures only | 2 | (1.6) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Supportive care with no transfer to hospital | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Supportive care with transfer to hospital | 70 | (56.0) | 44 | (58.7) | |

| Aggressive care | 53 | (42.4) | 27 | (36.0) | |

| Years since most recent AD signed, n (%)* | 0.12 | ||||

| [0, 1) | 79 | (63.2) | 48 | (64.0) | |

| [1, 2) | 21 | (16.8) | 6 | (8.0) | |

| [2, 6) | 9 | (7.2) | 10 | (13.3) | |

| Unknown | 16 | (12.8) | 11 | (14.7) | |

| Substitute decision maker, n (%) | 0.06 | ||||

| Child | 81 | (64.8) | 44 | (58.7) | |

| Spouse | 9 | (7.2) | 15 | (20.0) | |

| Other | 26 | (20.8) | 13 | (17.3) | |

| Public guardian trustee | 6 | (4.8) | 2 | (2.7) | |

| Unknown | 3 | (2.4) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Dementia, n (%) | 1.00 | ||||

| No | 47 | (37.6) | 28 | (37.3) | |

| Yes | 78 | (62.4) | 47 | (62.7) | |

| Mobility, n (%) | 0.26 | ||||

| Walk without assistance | 5 | (4.0) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Walker | 16 | (12.8) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Wheelchair | 43 | (34.4) | 29 | (38.7) | |

| Bedridden | 7 | (5.6) | 4 | (5.3) | |

| Unknown | 54 | (43.2) | 36 | (48.0) | |

| Continence, n (%) | 0.05 | ||||

| Mostly continent | 16 | (12.8) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Incontinent | 49 | (39.2) | 34 | (45.3) | |

| Catheter/stoma | 7 | (5.6) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Unknown | 53 | (42.4) | 37 | (49.3) | |

| Feeding, n (%) | 0.17 | ||||

| Mostly feeds self | 38 | (30.4) | 13 | (17.3) | |

| Needs to be fed | 17 | (13.6) | 14 | (18.7) | |

| Gastrostomy tube | 8 | (6.4) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| Unknown | 62 | (49.6) | 43 | (57.3) | |

| Diet, n (%) | 0.68 | ||||

| Normal | 43 | (34.4) | 16 | (21.3) | |

| Dysphagic | 32 | (25.6) | 15 | (20.0) | |

| Gastrostomy tube | 8 | (6.4) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| Unknown | 42 | (33.6) | 39 | (52.0) | |

| Previous ED visits in last year, n (%) | 0.43 | ||||

| 0 | 70 | (56.0) | 41 | (54.7) | |

| 1 | 35 | (28.0) | 17 | (22.7) | |

| 2+ | 20 | (16.0) | 17 | (22.7) | |

| Previous hospitalizations in last year, n (%) | 0.19 | ||||

| 0 | 98 | (78.4) | 54 | (72.0) | |

| 1 | 23 | (18.4) | 14 | (18.7) | |

| 2+ | 4 | (3.2) | 7 | (9.3) | |

| Visit characteristics | |||||

| Glasgow Coma Scale, n (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| 7 | 4 | (3.2) | 4 | (5.3) | |

| 711 | 15 | (12.0) | 26 | (34.7) | |

| 1213 | 7 | (5.6) | 8 | (10.7) | |

| 1415 | 85 | (68.0) | 32 | (42.7) | |

| Unknown | 14 | (11.2) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| Shock index, n (%) | 0.13 | ||||

| 1 | 105 | (84.0) | 54 | (72.0) | |

| >1 | 19 | (15.2) | 18 | (24.0) | |

| Unknown | 1 | (0.8) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Respiratory rate, n (%) | 0.02 | ||||

| 20 | 59 | (47.2) | 21 | (28.0) | |

| 20 | 66 | (52.8) | 52 | (69.3) | |

| Unknown | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (2.7) | |

| Oxygen saturation, n (%) | 0.03 | ||||

| 88 | 2 | (1.6) | 6 | (8.0) | |

| 88 | 122 | (97.6) | 65 | (86.7) | |

| Unknown | 1 | (0.8) | 4 | (5.3) | |

| Temperature, n (%) | 0.09 | ||||

| 38.0 | 100 | (80.0) | 51 | (68.0) | |

| 38.0 | 25 | (20.0) | 23 | (30.7) | |

| Unknown | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale, n (%) | 0.13 | ||||

| Resuscitation | 1 | (0.8) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Emergent | 70 | (56.0) | 49 | (65.3) | |

| Urgent | 52 | (41.6) | 22 | (29.3) | |

| Less urgent and nonurgent | 2 | (1.6) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Discharge diagnosis, n (%) | 0.29 | ||||

| Aspiration pneumonia | 12 | (9.6) | 12 | (16.0) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 15 | (12.0) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Dehydration/disorders fluid/electrolytes | 9 | (7.2) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 4 | (3.2) | 3 | (4.0) | |

| Heart failure | 11 | (8.8) | 2 | (2.7) | |

| Infection (other or not identified) | 9 | (7.2) | 9 | (12.0) | |

| Influenza/pneumonia | 14 | (11.2) | 11 | (14.7) | |

| Lower urinary tract infection | 11 | (8.8) | 6 | (8.0) | |

| Other | 40 | (32.0) | 24 | (32.0) | |

| Hospitalization included ICU stay, n (%) | 0.01 | ||||

| No | 124 | (99.2) | 69 | (92.0) | |

| Yes | 1 | (0.8) | 6 | (8.0) | |

When these 4 significant clinical and visit characteristics were tested together in a logistic regression analysis, 2 remained statistically significant (Table 2). Patients with lower GCS scores (GCS 1213 and 711) were more likely to have discussions (AOR: 4.4 [95% CI: 1.4‐13.9] and AOR: 5.9 [95% CI: 2.6‐13.2], respectively) and patients with higher respiratory rates were also more likely to have discussions (AOR: 2.3 [95% CI: 1.1‐4.8]).

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 0.001 | ||

| 7 | 1.77 | 0.33‐9.58 | 0.51 |

| 711 | 5.90 | 2.64‐13.22 | 0.001 |

| 1213 | 4.43 | 1.41‐13.91 | 0.01 |

| 1415 | Reference | ||

| Respiration | |||

| 20 | Reference | ||

| 20 | 2.32 | 1.12‐4.78 | 0.02 |

| Oxygen saturation | |||

| 88 | 3.35 | 0.55‐20.56 | 0.19 |

| 88 | Reference | 0.05‐1.83 | |

| Hospitalization included ICU stay | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 7.87 | 0.83‐74.73 | 0.07 |

GOC Documentation in the Discharge Summary

For the subset of patients who survived index hospitalization and were discharged back to LTC (176 patients or 88%), we also investigated whether the ADs were documented in the discharge summary back to LTC (data not shown). Of the 42 patients (23.9%) who had a change in the AD (18 patients had an AD increase in care intensity due to hospitalization; 24 had a decrease), only 11 (26%) had this AD change documented in the discharge summary.

Outcomes of GOC Documentation

A number of outcomes differed significantly between patients with and without GOC discussions in unadjusted comparisons (Table 3). Patients with discussions had higher rates of orders for no CPR (80% vs 55%) and orders for comfort measures only (7% vs 0%). They also had higher rates of in‐hospital death (29% vs 1%), 1‐year mortality (63% vs 28%), and longer LOS. However, RIW and subsequent hospital use were not found to be significant.

| Variable | Goals of Care Discussion Documented in Medical Chart | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, N = 125 | Yes, N = 75 | P Value | |||

| |||||

| Physician orders, n (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| Comfort measures only | 0 | (0.0) | 5 | (6.7) | |

| No cardiopulmonary resuscitation | 69 | (55.2) | 60 | (80.0) | |

| Full code | 56 | (44.8) | 10 | (13.3) | |

| Visit disposition, n (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| Long‐term care home | 124 | (99.2) | 52 | (69.3) | |

| Died | 1 | (0.8) | 22 | (29.3) | |

| Transfer to palliative care facility | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.3) | |

| Resource intensity weight, n (%) | 0.43 | ||||

| 0.250.75 | 35 | (28.0) | 19 | (25.3) | |

| 0.761.14 | 29 | (23.2) | 16 | (21.3) | |

| 1.151.60 | 34 | (27.2) | 16 | (21.3) | |

| 1.6125.5 | 27 | (21.6) | 24 | (32.0) | |

| Length of stay, d, n (%) | 0.01 | ||||

| 0.672.97 | 30 | (24.0) | 20 | (26.7) | |

| 2.984.60 | 40 | (32.0) | 10 | (13.3) | |

| 4.618.65 | 30 | (24.0) | 20 | (26.7) | |

| 8.66+ | 25 | (20.0) | 25 | (33.3) | |

| Subsequent emergency department visits in next year, n (% of applicable) | 0.38 | ||||

| 0 | 66 | (53.2) | 32 | (61.5) | |

| 1 | 30 | (24.2) | 13 | (25.0) | |

| 2+ | 28 | (22.6) | 7 | (13.5) | |