User login

Lung Cancer Screening: Translating Research Into Practice (FULL)

According to the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), use of low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) reduced lung cancer deaths by 20%. That finding led the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) to recommend screening for high-risk individuals (current and former heavy smokers). And that, in turn, led to hospitals nationwide setting up lung cancer screening programs—a number that rose “dramatically,” according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), after the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services decided to cover LDCT screening for high-risk Medicare beneficiaries.

But how does the screening recommendation pan out in real life? Primary care physicians and pulmonologists alike were concerned about the workability of putting LDCT into real-life practice. And not without basis: Published experience with implementation of lung cancer screening (LCS) is limited, say VHA researchers. Their 3-year demonstration project bears out the concerns, they add.

When they designed the study, the researchers wanted to see how feasible LCS would be in terms of resources and effort, whether patients would take part, what their clinical experience might be, and what type of findings the screenings might produce. The researchers found that establishing and sustaining a screening program requires “significant clinical effort for as-yet uncertain patient benefit.” They also found “wide variation” in both processes and patient experiences among the 8 VA hospitals in the study. Moreover, they found that, although most patients had findings that required follow-up, few had early-stage lung cancers.

Of the 2,106 screened patients in a JAMA Internal Medicine study, 1,257 had nodules. More than half of those required tracking, and 2% required further evaluation, but the findings were not cancer. Just 1.5% had lung cancer. Scans of 857 patients (40.7%) also revealed a variety of incidental findings, such as emphysema, other pulmonary abnormalities, and coronary artery calcification.

The researchers say that implementing a comprehensive program that followed recommendations was “challenging and complex,” requiring new tools and processes for staff as well as for dedicated patient coordination. As an example, they say creating electronic tools to capture the necessary clinical data in real time that met the needs of the screening coordinators proved to be difficult, “even with the VHA’s highly regarded electronic medical record.”

Also, finding out who actually had a smoking history of > 30 pack-years of smoking per the USPSTF recommendation was not easy. Lead investigator Linda Kinsinger, MD, MPH, points out, “People who smoke don’t track that sort of thing as closely as you think they would, and they don’t smoke at the same level for years and years.”

The researchers estimate that nearly 900,000 veterans meet the initial screening criteria for age, smoking history, and medical history, but they caution that accurately identifying the patients and discussing risks and benefits will take “significant effort” for primary care teams. Even if that number were reduced by 16% to account for longer medical contraindications, the number of veterans who might be candidates for annual LCS would be “substantial.” And based on the researchers’ experience, a bit more than half the candidates will agree to be screened.

Although screening programs are a complex endeavor, the researchers say, the results of their study can help the VHA plan for broader implementation of comprehensive screening programs.

“What [the VHA] is reporting is the initial experience for almost everybody,” said Lynn Tanoue, MD, director of the Lung Screening and Nodule Program at Yale Cancer Center in New Haven, Connecticut, in an interview with the NCI. “Until people really started doing lung cancer screening and began to understand the challenges of doing it properly, you couldn’t have known what it was going to be like.” But she adds, “The data from NLST were very clear. We should accept that there is benefit and choose the right population to screen.”

However, although the LDCT screening can find signs of early lung cancer, a biopsy is often necessary. Researchers from Boston University suggest an effective, much less invasive approach: analyzing gene expression in nasal cell samples.

The researchers collected and analyzed nasal cell samples from 505 current and former smokers for gene expression. They found 535 genes that were expressed differently between patients who were diagnosed with lung cancer and those whose lesions were benign.

Comparing those data with data from bronchial airway samples from the same patients, the researchers found changes that were similar between the nose and lung samples of patients with lung cancer, suggesting that smoking might cause similar genetic changes throughout the entire airway.

The researchers used the 30 most prominent changes to create a biomarker panel and tested it in 130 other patients. Compared with a clinical risk factor model that considered age, smoking status, and other factors, the biomarker panel was better at predicting lung cancer. Combining the 2 models further improved detection. “We find that nasal gene expression contains information about the presence of cancer that is independent of standard clinical risk factors,” said one of the co-lead investigators.

Lung cancer screening is still experiencing “growing pains,” the NCI says. And the need for screening is both acute and chronic: A 2015 study found that only 4% of people who meet the criteria for screening actually undergo screening.

These studies not only open avenues for better screening and diagnosis, but also highlight the need for better patient education.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Kinsinger LS, Anderson C, Kim J, et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):399-406.

National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/research/nlst. Updated September 8, 2014. Accessed April 25, 2017.

National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/noninvasive-strategies-lung-cancer-testing. Published March 7, 2017. Accessed April

25, 2017.

AEGIS Study Team. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(7).

National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2017/lung-cancer-screening-challenges. Published February 27, 2017. Accessed April

25, 2017.

According to the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), use of low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) reduced lung cancer deaths by 20%. That finding led the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) to recommend screening for high-risk individuals (current and former heavy smokers). And that, in turn, led to hospitals nationwide setting up lung cancer screening programs—a number that rose “dramatically,” according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), after the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services decided to cover LDCT screening for high-risk Medicare beneficiaries.

But how does the screening recommendation pan out in real life? Primary care physicians and pulmonologists alike were concerned about the workability of putting LDCT into real-life practice. And not without basis: Published experience with implementation of lung cancer screening (LCS) is limited, say VHA researchers. Their 3-year demonstration project bears out the concerns, they add.

When they designed the study, the researchers wanted to see how feasible LCS would be in terms of resources and effort, whether patients would take part, what their clinical experience might be, and what type of findings the screenings might produce. The researchers found that establishing and sustaining a screening program requires “significant clinical effort for as-yet uncertain patient benefit.” They also found “wide variation” in both processes and patient experiences among the 8 VA hospitals in the study. Moreover, they found that, although most patients had findings that required follow-up, few had early-stage lung cancers.

Of the 2,106 screened patients in a JAMA Internal Medicine study, 1,257 had nodules. More than half of those required tracking, and 2% required further evaluation, but the findings were not cancer. Just 1.5% had lung cancer. Scans of 857 patients (40.7%) also revealed a variety of incidental findings, such as emphysema, other pulmonary abnormalities, and coronary artery calcification.

The researchers say that implementing a comprehensive program that followed recommendations was “challenging and complex,” requiring new tools and processes for staff as well as for dedicated patient coordination. As an example, they say creating electronic tools to capture the necessary clinical data in real time that met the needs of the screening coordinators proved to be difficult, “even with the VHA’s highly regarded electronic medical record.”

Also, finding out who actually had a smoking history of > 30 pack-years of smoking per the USPSTF recommendation was not easy. Lead investigator Linda Kinsinger, MD, MPH, points out, “People who smoke don’t track that sort of thing as closely as you think they would, and they don’t smoke at the same level for years and years.”

The researchers estimate that nearly 900,000 veterans meet the initial screening criteria for age, smoking history, and medical history, but they caution that accurately identifying the patients and discussing risks and benefits will take “significant effort” for primary care teams. Even if that number were reduced by 16% to account for longer medical contraindications, the number of veterans who might be candidates for annual LCS would be “substantial.” And based on the researchers’ experience, a bit more than half the candidates will agree to be screened.

Although screening programs are a complex endeavor, the researchers say, the results of their study can help the VHA plan for broader implementation of comprehensive screening programs.

“What [the VHA] is reporting is the initial experience for almost everybody,” said Lynn Tanoue, MD, director of the Lung Screening and Nodule Program at Yale Cancer Center in New Haven, Connecticut, in an interview with the NCI. “Until people really started doing lung cancer screening and began to understand the challenges of doing it properly, you couldn’t have known what it was going to be like.” But she adds, “The data from NLST were very clear. We should accept that there is benefit and choose the right population to screen.”

However, although the LDCT screening can find signs of early lung cancer, a biopsy is often necessary. Researchers from Boston University suggest an effective, much less invasive approach: analyzing gene expression in nasal cell samples.

The researchers collected and analyzed nasal cell samples from 505 current and former smokers for gene expression. They found 535 genes that were expressed differently between patients who were diagnosed with lung cancer and those whose lesions were benign.

Comparing those data with data from bronchial airway samples from the same patients, the researchers found changes that were similar between the nose and lung samples of patients with lung cancer, suggesting that smoking might cause similar genetic changes throughout the entire airway.

The researchers used the 30 most prominent changes to create a biomarker panel and tested it in 130 other patients. Compared with a clinical risk factor model that considered age, smoking status, and other factors, the biomarker panel was better at predicting lung cancer. Combining the 2 models further improved detection. “We find that nasal gene expression contains information about the presence of cancer that is independent of standard clinical risk factors,” said one of the co-lead investigators.

Lung cancer screening is still experiencing “growing pains,” the NCI says. And the need for screening is both acute and chronic: A 2015 study found that only 4% of people who meet the criteria for screening actually undergo screening.

These studies not only open avenues for better screening and diagnosis, but also highlight the need for better patient education.

Click here to read the digital edition.

According to the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), use of low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) reduced lung cancer deaths by 20%. That finding led the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) to recommend screening for high-risk individuals (current and former heavy smokers). And that, in turn, led to hospitals nationwide setting up lung cancer screening programs—a number that rose “dramatically,” according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), after the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services decided to cover LDCT screening for high-risk Medicare beneficiaries.

But how does the screening recommendation pan out in real life? Primary care physicians and pulmonologists alike were concerned about the workability of putting LDCT into real-life practice. And not without basis: Published experience with implementation of lung cancer screening (LCS) is limited, say VHA researchers. Their 3-year demonstration project bears out the concerns, they add.

When they designed the study, the researchers wanted to see how feasible LCS would be in terms of resources and effort, whether patients would take part, what their clinical experience might be, and what type of findings the screenings might produce. The researchers found that establishing and sustaining a screening program requires “significant clinical effort for as-yet uncertain patient benefit.” They also found “wide variation” in both processes and patient experiences among the 8 VA hospitals in the study. Moreover, they found that, although most patients had findings that required follow-up, few had early-stage lung cancers.

Of the 2,106 screened patients in a JAMA Internal Medicine study, 1,257 had nodules. More than half of those required tracking, and 2% required further evaluation, but the findings were not cancer. Just 1.5% had lung cancer. Scans of 857 patients (40.7%) also revealed a variety of incidental findings, such as emphysema, other pulmonary abnormalities, and coronary artery calcification.

The researchers say that implementing a comprehensive program that followed recommendations was “challenging and complex,” requiring new tools and processes for staff as well as for dedicated patient coordination. As an example, they say creating electronic tools to capture the necessary clinical data in real time that met the needs of the screening coordinators proved to be difficult, “even with the VHA’s highly regarded electronic medical record.”

Also, finding out who actually had a smoking history of > 30 pack-years of smoking per the USPSTF recommendation was not easy. Lead investigator Linda Kinsinger, MD, MPH, points out, “People who smoke don’t track that sort of thing as closely as you think they would, and they don’t smoke at the same level for years and years.”

The researchers estimate that nearly 900,000 veterans meet the initial screening criteria for age, smoking history, and medical history, but they caution that accurately identifying the patients and discussing risks and benefits will take “significant effort” for primary care teams. Even if that number were reduced by 16% to account for longer medical contraindications, the number of veterans who might be candidates for annual LCS would be “substantial.” And based on the researchers’ experience, a bit more than half the candidates will agree to be screened.

Although screening programs are a complex endeavor, the researchers say, the results of their study can help the VHA plan for broader implementation of comprehensive screening programs.

“What [the VHA] is reporting is the initial experience for almost everybody,” said Lynn Tanoue, MD, director of the Lung Screening and Nodule Program at Yale Cancer Center in New Haven, Connecticut, in an interview with the NCI. “Until people really started doing lung cancer screening and began to understand the challenges of doing it properly, you couldn’t have known what it was going to be like.” But she adds, “The data from NLST were very clear. We should accept that there is benefit and choose the right population to screen.”

However, although the LDCT screening can find signs of early lung cancer, a biopsy is often necessary. Researchers from Boston University suggest an effective, much less invasive approach: analyzing gene expression in nasal cell samples.

The researchers collected and analyzed nasal cell samples from 505 current and former smokers for gene expression. They found 535 genes that were expressed differently between patients who were diagnosed with lung cancer and those whose lesions were benign.

Comparing those data with data from bronchial airway samples from the same patients, the researchers found changes that were similar between the nose and lung samples of patients with lung cancer, suggesting that smoking might cause similar genetic changes throughout the entire airway.

The researchers used the 30 most prominent changes to create a biomarker panel and tested it in 130 other patients. Compared with a clinical risk factor model that considered age, smoking status, and other factors, the biomarker panel was better at predicting lung cancer. Combining the 2 models further improved detection. “We find that nasal gene expression contains information about the presence of cancer that is independent of standard clinical risk factors,” said one of the co-lead investigators.

Lung cancer screening is still experiencing “growing pains,” the NCI says. And the need for screening is both acute and chronic: A 2015 study found that only 4% of people who meet the criteria for screening actually undergo screening.

These studies not only open avenues for better screening and diagnosis, but also highlight the need for better patient education.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Kinsinger LS, Anderson C, Kim J, et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):399-406.

National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/research/nlst. Updated September 8, 2014. Accessed April 25, 2017.

National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/noninvasive-strategies-lung-cancer-testing. Published March 7, 2017. Accessed April

25, 2017.

AEGIS Study Team. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(7).

National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2017/lung-cancer-screening-challenges. Published February 27, 2017. Accessed April

25, 2017.

Kinsinger LS, Anderson C, Kim J, et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):399-406.

National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/research/nlst. Updated September 8, 2014. Accessed April 25, 2017.

National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/noninvasive-strategies-lung-cancer-testing. Published March 7, 2017. Accessed April

25, 2017.

AEGIS Study Team. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(7).

National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2017/lung-cancer-screening-challenges. Published February 27, 2017. Accessed April

25, 2017.

Enhanced Melanoma Diagnosis With Multispectral Digital Skin Lesion Analysis

Early detection of melanoma, which is known to improve survival rates, remains a challenge for dermatologists. Suspicious pigmented lesions typically are evaluated via clinical examination and dermoscopy; however, new technologies are being developed to provide additional objective information for clinicians to incorporate into their biopsy decisions.

Multispectral digital skin lesion analysis (MSDSLA) uses 10 bands of visible and near-infrared light (430–950 nm) to image and analyze pigmented skin lesions (PSLs) down to 2.5 mm below the skin surface and measures the distribution of melanin using 75 unique algorithms to determine the degree of the morphologic disorder. Using a logical regression model previously validated on a set of 1632 PSLs, the probability of melanoma and probability of being a melanoma/PSL of high-risk malignant potential are then provided to the clinician.1

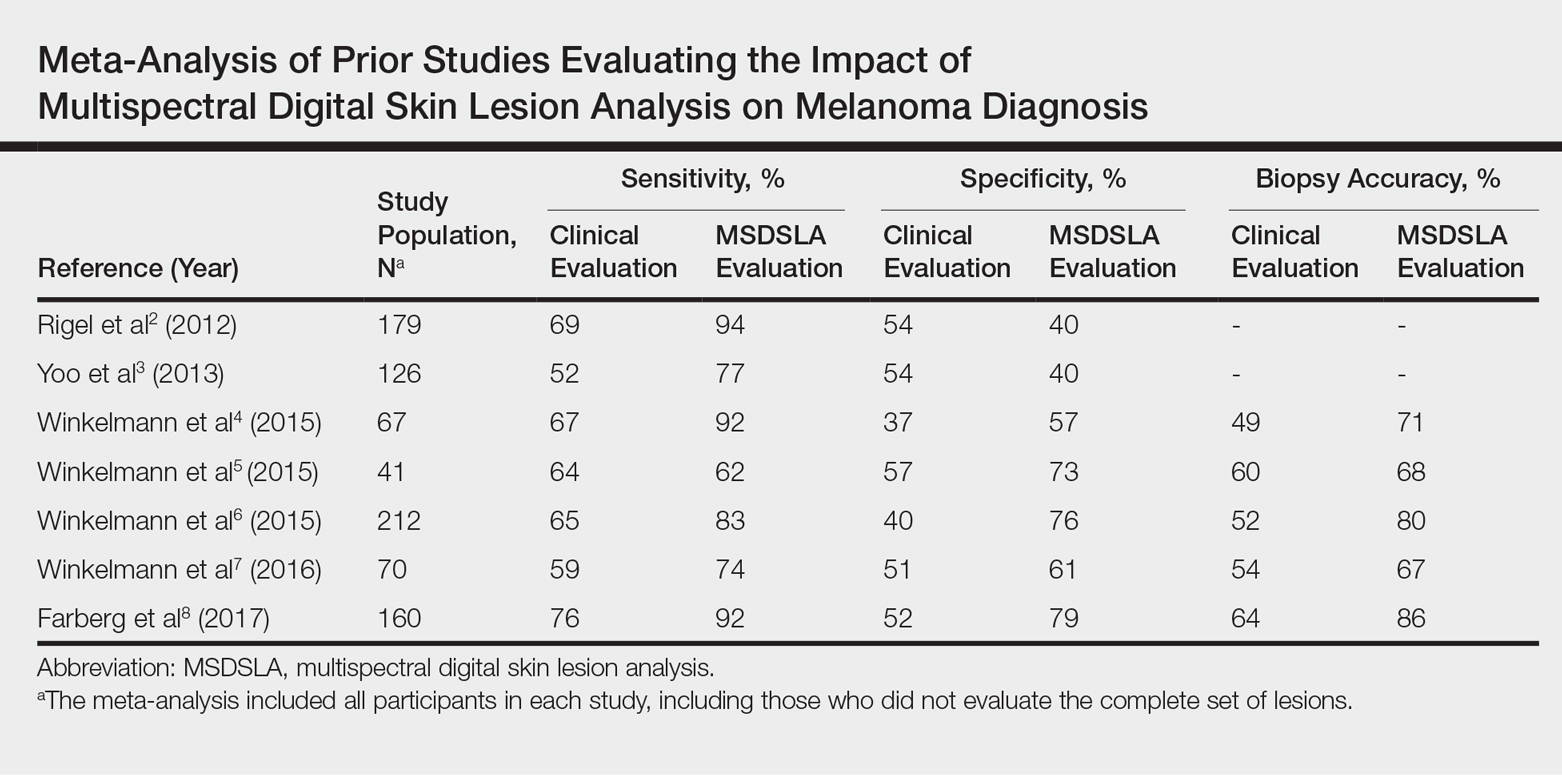

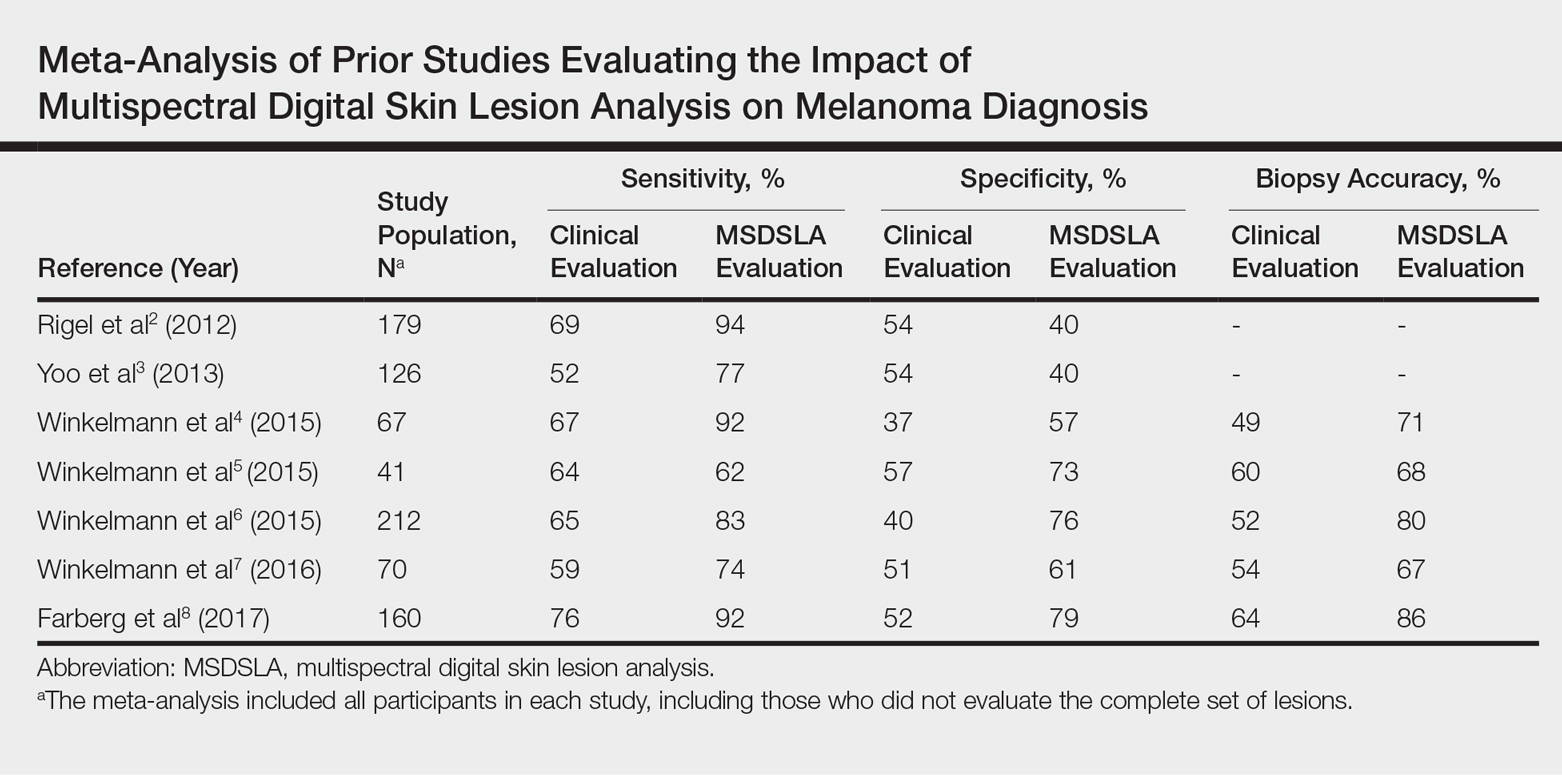

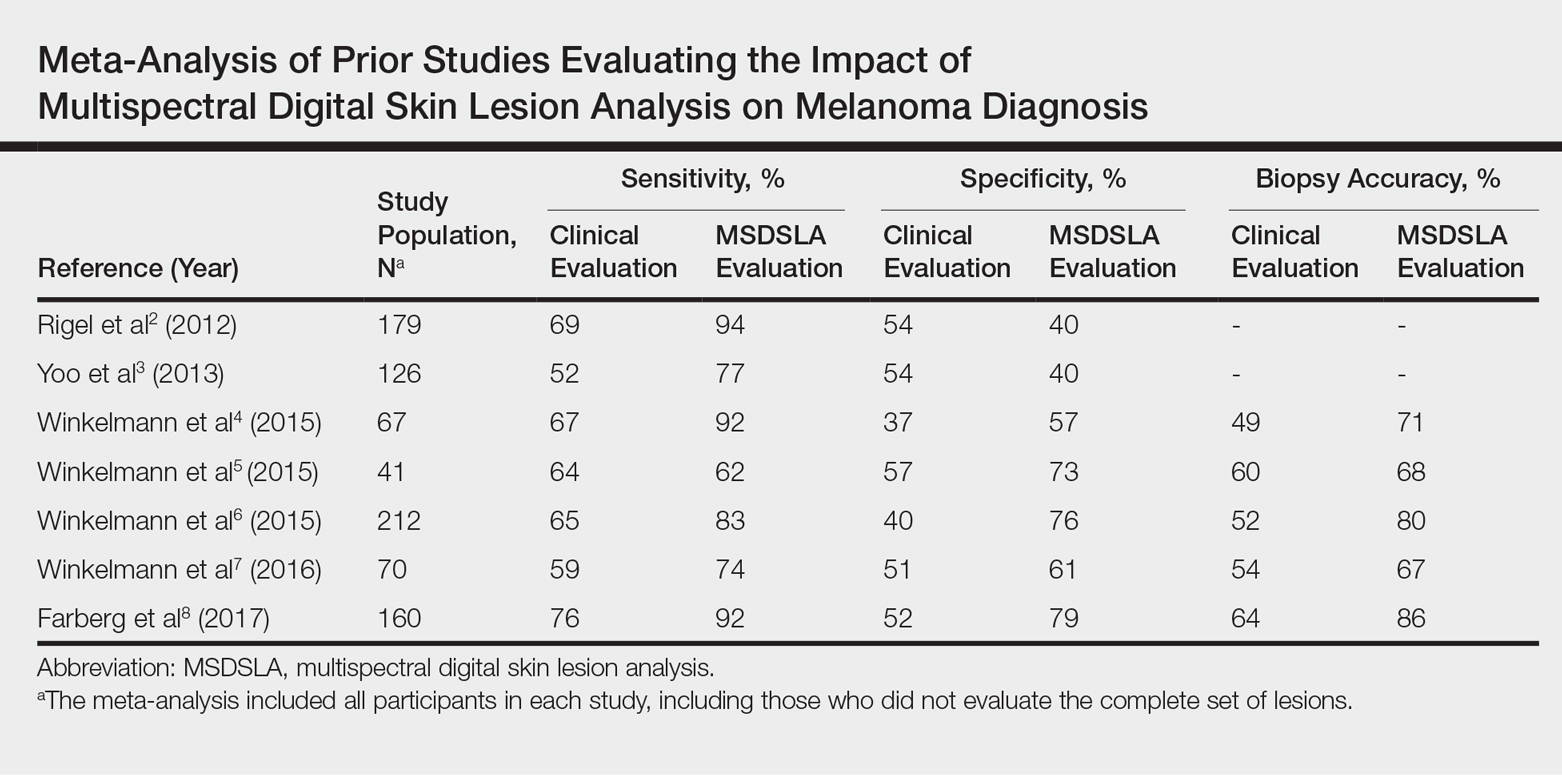

In this study, we analyzed aggregate data from 7 prior studies2-8 to better determine how MSDSLA impacts the biopsy decisions of dermatologists and nondermatologists following clinical examination and dermoscopic evaluation of PSLs.

Methods

Results

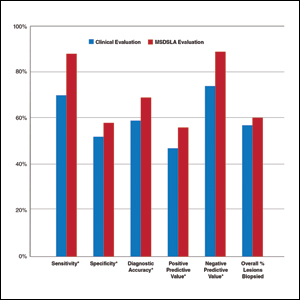

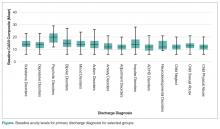

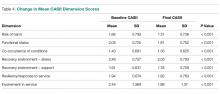

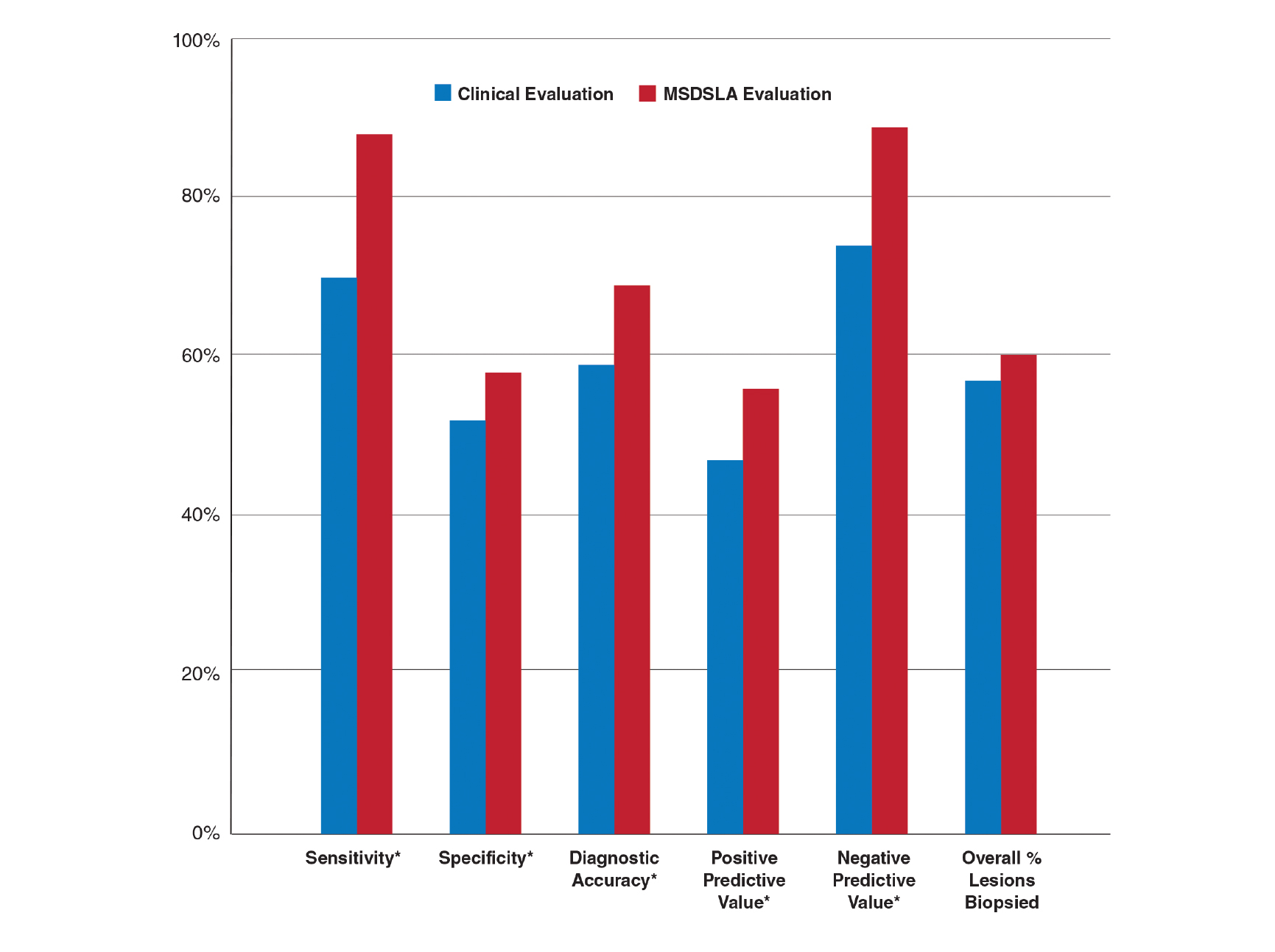

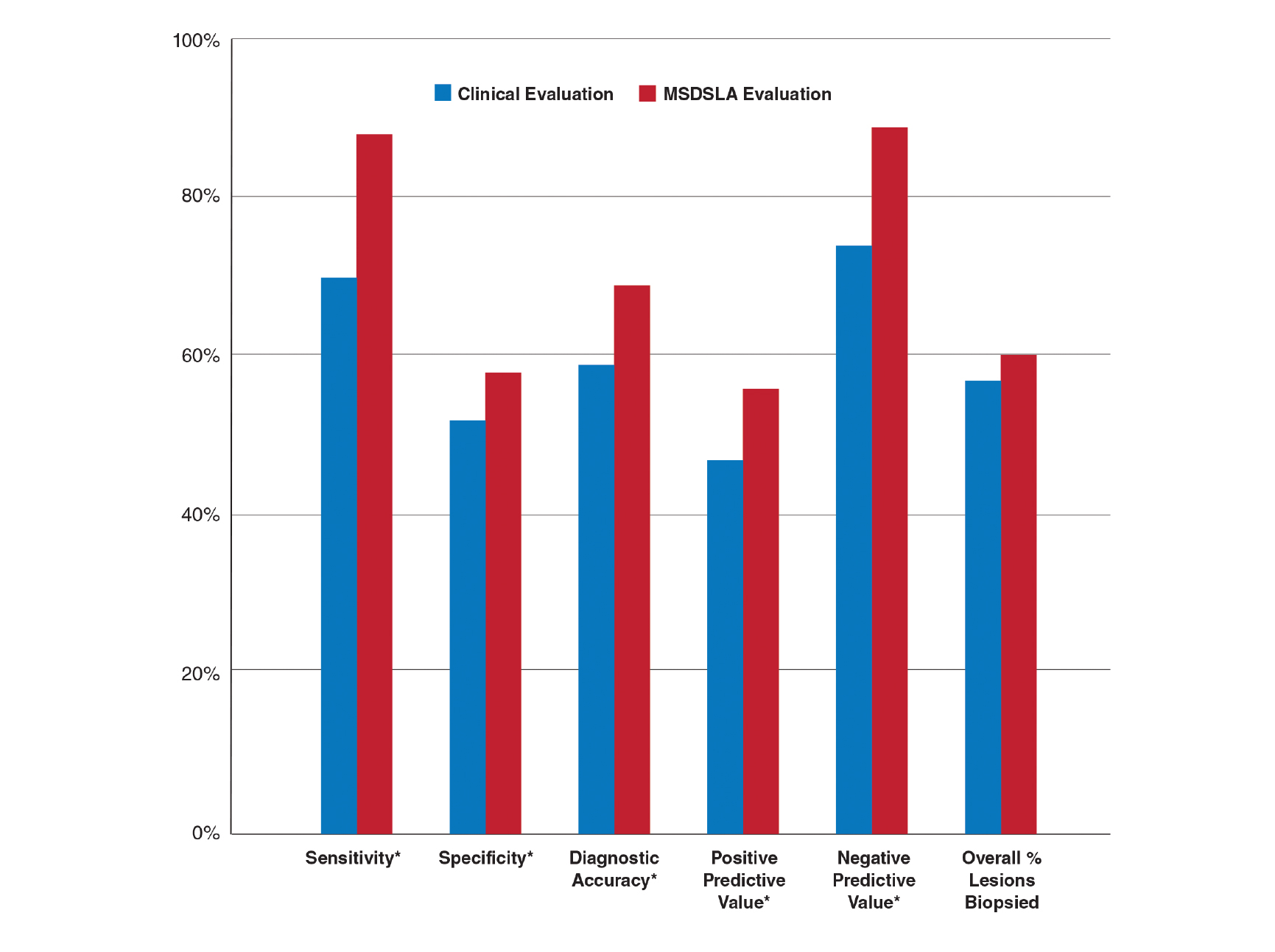

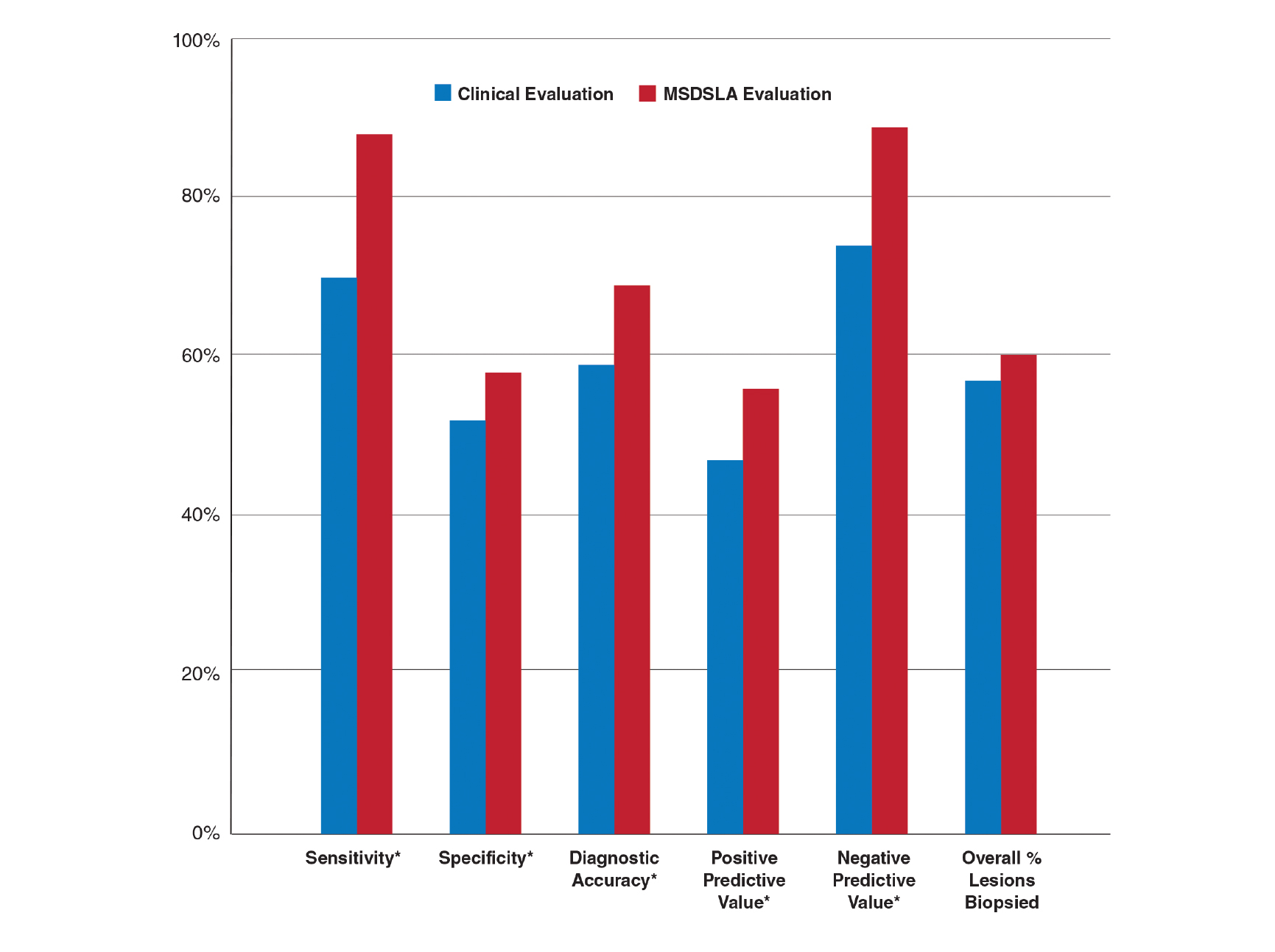

Overall sensitivity for the detection of melanoma or other high-grade PSLs improved from 70% on clinical and dermoscopic evaluation to 88% after MSDSLA information was provided (P<.0001), and specificity increased from 52% to 58% (P<.001). Diagnostic accuracy also improved from 59% on clinical evaluation to 69% after review of MSDSLA findings (P<.0001). The positive predictive value of biopsy decisions was 47% following clinical evaluation, which improved to 56% after evaluation of MSDSLA findings (P<.001), and the negative predictive value increased from 74% to 89% (P<.0001). The overall percentage of lesions selected for biopsy did not significantly change following MSDSLA data integration (57% vs 60%)(Figure). Given that similar numbers of lesions were biopsied with improved sensitivity and specificity, the integration of MSDSLA data into the biopsy decision led to an improved biopsy ratio (ratio of melanomas biopsied to total biopsies) and fewer unnecessary biopsies.

Comment

Our broad analysis further supported the findings of prior studies that decisions to biopsy clinically suspicious PSLs are more sensitive, specific, and accurate when practitioners are provided MSDSLA information following clinical examination.2-8

Given the evolution in health care economics, it is clear that greater emphasis will continue to be placed on superior, evidence-based, effective care. The reported diagnostic sensitivities and specificities of clinical evaluation and dermoscopy for melanoma detection vary widely throughout the literature, with sensitivities ranging from 58% to over 90% and specificities ranging from 77% to 99%.9-11

Our study had several limitations. For this analysis to be more representative of lesion biopsy selection in the clinical setting, biopsy sensitivity (correctly identifying lesions appropriate for biopsy) vs melanoma sensitivity (identifying a lesion as melanoma) was used.13 The overall sensitivity found was within the range of prior studies,2-8 but this approach may have potentially led to a lower specificity due to an increased number of lesions biopsied. Additionally, the melanomas selected for these studies were early (malignant melanoma in situ or mean thickness of invasive malignant melanoma of 0.3 mm), and the nonmelanomas (including low-grade dysplastic nevi) were not necessarily diagnostically straightforward. This may have led to the clinical and dermoscopic sensitivity and specificity noted being lower than in some prior studies.9-11

The risk of missing a melanoma with MSDSLA devices has led manufacturers to strive for a high sensitivity for their devices, leading to lower specificity as a consequence. For this reason and other ambiguous practical considerations (eg, device and patient costs, difficulty with insurance reimbursement), the adoption of this technology into routine clinical practice has remained relatively static; however, using enhanced diagnostic technologies such as MSDSLA may help with more accurate identification of high-risk PSLs, thereby leading to earlier detection and overall less expensive, more cost-effective treatment of melanoma.

- Monheit G, Cognetta AB, Ferris L, et al. The performance of MelaFind: a prospective multicenter study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:188-194.

- Rigel DS, Roy M, Yoo J, et al. Impact of guidance from a computer-aided multispectral digital skin lesion analysis device on decision to biopsy lesions clinically suggestive of melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:541-543.

- Yoo J, Rigel DS, Roy M, et al. Impact of guidance from a multispectral digital skin lesion analysis device on dermatology residents decisions to biopsy lesions clinically suggestive of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB152.

- Winkelmann RR, Yoo J, Tucker N, et al. Impact of guidance provided by a multispectral digital skin lesion analysis device following dermoscopy on decisions to biopsy atypical melanocytic lesions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:21-24.

- Winkelmann RR, Hauschild A, Tucker N, et al. The impact of multispectral digital skin lesion analysis on German dermatologist decisions to biopsy atypical pigmented lesions with clinical characteristics of melanoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:27-29.

- Winkelmann RR, Tucker N, White R, et al. Pigmented skin lesion biopsies after computer-aided multispectral digital skin lesion analysis. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2015;115:666-669.

- Winkelmann RR, Farberg AS, Tucker N, et al. Enhancement of international dermatologists’ pigmented skin lesion biopsy decisions following dermoscopy with subsequent integration of multispectral digital skin lesion analysis [published online July 1, 2016]. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:53-55.

- Farberg AS, Winkelmann RR, Tucker N, et al. The impact of quantitative data provided by a multi-spectral digital skin lesion analysis device on dermatologists’ decisions to biopsy pigmented lesions [published online September 1, 2017]. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:24-26.

- Wolf IH, Smolle J, Soyer HP, et al. Sensitivity in the clinical diagnosis of malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res. 1998;8:425-429.

- Kittler H, Pehamberger H, Wolff K, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:159-165.

- Ascierto PA, Palmieri G, Celentano E, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of epiluminescence microscopy: evaluation on a sample of 2731 excised cutaneous pigmented lesions: the Melanoma Cooperative Study. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:893-898.

- Carli P, Nardini P, Crocetti E, et al. Frequency and characteristics of melanomas missed at a pigmented lesion clinic: a registry-based study. Melanoma Res. 2004;14:403-407.

- Friedman RJ, Gutkowicz-Krusin D, Farber MJ, et al. The diagnostic performance of expert dermoscopists vs a computer-vision system on small-diameter melanomas. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:476-482.

Early detection of melanoma, which is known to improve survival rates, remains a challenge for dermatologists. Suspicious pigmented lesions typically are evaluated via clinical examination and dermoscopy; however, new technologies are being developed to provide additional objective information for clinicians to incorporate into their biopsy decisions.

Multispectral digital skin lesion analysis (MSDSLA) uses 10 bands of visible and near-infrared light (430–950 nm) to image and analyze pigmented skin lesions (PSLs) down to 2.5 mm below the skin surface and measures the distribution of melanin using 75 unique algorithms to determine the degree of the morphologic disorder. Using a logical regression model previously validated on a set of 1632 PSLs, the probability of melanoma and probability of being a melanoma/PSL of high-risk malignant potential are then provided to the clinician.1

In this study, we analyzed aggregate data from 7 prior studies2-8 to better determine how MSDSLA impacts the biopsy decisions of dermatologists and nondermatologists following clinical examination and dermoscopic evaluation of PSLs.

Methods

Results

Overall sensitivity for the detection of melanoma or other high-grade PSLs improved from 70% on clinical and dermoscopic evaluation to 88% after MSDSLA information was provided (P<.0001), and specificity increased from 52% to 58% (P<.001). Diagnostic accuracy also improved from 59% on clinical evaluation to 69% after review of MSDSLA findings (P<.0001). The positive predictive value of biopsy decisions was 47% following clinical evaluation, which improved to 56% after evaluation of MSDSLA findings (P<.001), and the negative predictive value increased from 74% to 89% (P<.0001). The overall percentage of lesions selected for biopsy did not significantly change following MSDSLA data integration (57% vs 60%)(Figure). Given that similar numbers of lesions were biopsied with improved sensitivity and specificity, the integration of MSDSLA data into the biopsy decision led to an improved biopsy ratio (ratio of melanomas biopsied to total biopsies) and fewer unnecessary biopsies.

Comment

Our broad analysis further supported the findings of prior studies that decisions to biopsy clinically suspicious PSLs are more sensitive, specific, and accurate when practitioners are provided MSDSLA information following clinical examination.2-8

Given the evolution in health care economics, it is clear that greater emphasis will continue to be placed on superior, evidence-based, effective care. The reported diagnostic sensitivities and specificities of clinical evaluation and dermoscopy for melanoma detection vary widely throughout the literature, with sensitivities ranging from 58% to over 90% and specificities ranging from 77% to 99%.9-11

Our study had several limitations. For this analysis to be more representative of lesion biopsy selection in the clinical setting, biopsy sensitivity (correctly identifying lesions appropriate for biopsy) vs melanoma sensitivity (identifying a lesion as melanoma) was used.13 The overall sensitivity found was within the range of prior studies,2-8 but this approach may have potentially led to a lower specificity due to an increased number of lesions biopsied. Additionally, the melanomas selected for these studies were early (malignant melanoma in situ or mean thickness of invasive malignant melanoma of 0.3 mm), and the nonmelanomas (including low-grade dysplastic nevi) were not necessarily diagnostically straightforward. This may have led to the clinical and dermoscopic sensitivity and specificity noted being lower than in some prior studies.9-11

The risk of missing a melanoma with MSDSLA devices has led manufacturers to strive for a high sensitivity for their devices, leading to lower specificity as a consequence. For this reason and other ambiguous practical considerations (eg, device and patient costs, difficulty with insurance reimbursement), the adoption of this technology into routine clinical practice has remained relatively static; however, using enhanced diagnostic technologies such as MSDSLA may help with more accurate identification of high-risk PSLs, thereby leading to earlier detection and overall less expensive, more cost-effective treatment of melanoma.

Early detection of melanoma, which is known to improve survival rates, remains a challenge for dermatologists. Suspicious pigmented lesions typically are evaluated via clinical examination and dermoscopy; however, new technologies are being developed to provide additional objective information for clinicians to incorporate into their biopsy decisions.

Multispectral digital skin lesion analysis (MSDSLA) uses 10 bands of visible and near-infrared light (430–950 nm) to image and analyze pigmented skin lesions (PSLs) down to 2.5 mm below the skin surface and measures the distribution of melanin using 75 unique algorithms to determine the degree of the morphologic disorder. Using a logical regression model previously validated on a set of 1632 PSLs, the probability of melanoma and probability of being a melanoma/PSL of high-risk malignant potential are then provided to the clinician.1

In this study, we analyzed aggregate data from 7 prior studies2-8 to better determine how MSDSLA impacts the biopsy decisions of dermatologists and nondermatologists following clinical examination and dermoscopic evaluation of PSLs.

Methods

Results

Overall sensitivity for the detection of melanoma or other high-grade PSLs improved from 70% on clinical and dermoscopic evaluation to 88% after MSDSLA information was provided (P<.0001), and specificity increased from 52% to 58% (P<.001). Diagnostic accuracy also improved from 59% on clinical evaluation to 69% after review of MSDSLA findings (P<.0001). The positive predictive value of biopsy decisions was 47% following clinical evaluation, which improved to 56% after evaluation of MSDSLA findings (P<.001), and the negative predictive value increased from 74% to 89% (P<.0001). The overall percentage of lesions selected for biopsy did not significantly change following MSDSLA data integration (57% vs 60%)(Figure). Given that similar numbers of lesions were biopsied with improved sensitivity and specificity, the integration of MSDSLA data into the biopsy decision led to an improved biopsy ratio (ratio of melanomas biopsied to total biopsies) and fewer unnecessary biopsies.

Comment

Our broad analysis further supported the findings of prior studies that decisions to biopsy clinically suspicious PSLs are more sensitive, specific, and accurate when practitioners are provided MSDSLA information following clinical examination.2-8

Given the evolution in health care economics, it is clear that greater emphasis will continue to be placed on superior, evidence-based, effective care. The reported diagnostic sensitivities and specificities of clinical evaluation and dermoscopy for melanoma detection vary widely throughout the literature, with sensitivities ranging from 58% to over 90% and specificities ranging from 77% to 99%.9-11

Our study had several limitations. For this analysis to be more representative of lesion biopsy selection in the clinical setting, biopsy sensitivity (correctly identifying lesions appropriate for biopsy) vs melanoma sensitivity (identifying a lesion as melanoma) was used.13 The overall sensitivity found was within the range of prior studies,2-8 but this approach may have potentially led to a lower specificity due to an increased number of lesions biopsied. Additionally, the melanomas selected for these studies were early (malignant melanoma in situ or mean thickness of invasive malignant melanoma of 0.3 mm), and the nonmelanomas (including low-grade dysplastic nevi) were not necessarily diagnostically straightforward. This may have led to the clinical and dermoscopic sensitivity and specificity noted being lower than in some prior studies.9-11

The risk of missing a melanoma with MSDSLA devices has led manufacturers to strive for a high sensitivity for their devices, leading to lower specificity as a consequence. For this reason and other ambiguous practical considerations (eg, device and patient costs, difficulty with insurance reimbursement), the adoption of this technology into routine clinical practice has remained relatively static; however, using enhanced diagnostic technologies such as MSDSLA may help with more accurate identification of high-risk PSLs, thereby leading to earlier detection and overall less expensive, more cost-effective treatment of melanoma.

- Monheit G, Cognetta AB, Ferris L, et al. The performance of MelaFind: a prospective multicenter study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:188-194.

- Rigel DS, Roy M, Yoo J, et al. Impact of guidance from a computer-aided multispectral digital skin lesion analysis device on decision to biopsy lesions clinically suggestive of melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:541-543.

- Yoo J, Rigel DS, Roy M, et al. Impact of guidance from a multispectral digital skin lesion analysis device on dermatology residents decisions to biopsy lesions clinically suggestive of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB152.

- Winkelmann RR, Yoo J, Tucker N, et al. Impact of guidance provided by a multispectral digital skin lesion analysis device following dermoscopy on decisions to biopsy atypical melanocytic lesions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:21-24.

- Winkelmann RR, Hauschild A, Tucker N, et al. The impact of multispectral digital skin lesion analysis on German dermatologist decisions to biopsy atypical pigmented lesions with clinical characteristics of melanoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:27-29.

- Winkelmann RR, Tucker N, White R, et al. Pigmented skin lesion biopsies after computer-aided multispectral digital skin lesion analysis. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2015;115:666-669.

- Winkelmann RR, Farberg AS, Tucker N, et al. Enhancement of international dermatologists’ pigmented skin lesion biopsy decisions following dermoscopy with subsequent integration of multispectral digital skin lesion analysis [published online July 1, 2016]. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:53-55.

- Farberg AS, Winkelmann RR, Tucker N, et al. The impact of quantitative data provided by a multi-spectral digital skin lesion analysis device on dermatologists’ decisions to biopsy pigmented lesions [published online September 1, 2017]. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:24-26.

- Wolf IH, Smolle J, Soyer HP, et al. Sensitivity in the clinical diagnosis of malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res. 1998;8:425-429.

- Kittler H, Pehamberger H, Wolff K, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:159-165.

- Ascierto PA, Palmieri G, Celentano E, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of epiluminescence microscopy: evaluation on a sample of 2731 excised cutaneous pigmented lesions: the Melanoma Cooperative Study. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:893-898.

- Carli P, Nardini P, Crocetti E, et al. Frequency and characteristics of melanomas missed at a pigmented lesion clinic: a registry-based study. Melanoma Res. 2004;14:403-407.

- Friedman RJ, Gutkowicz-Krusin D, Farber MJ, et al. The diagnostic performance of expert dermoscopists vs a computer-vision system on small-diameter melanomas. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:476-482.

- Monheit G, Cognetta AB, Ferris L, et al. The performance of MelaFind: a prospective multicenter study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:188-194.

- Rigel DS, Roy M, Yoo J, et al. Impact of guidance from a computer-aided multispectral digital skin lesion analysis device on decision to biopsy lesions clinically suggestive of melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:541-543.

- Yoo J, Rigel DS, Roy M, et al. Impact of guidance from a multispectral digital skin lesion analysis device on dermatology residents decisions to biopsy lesions clinically suggestive of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB152.

- Winkelmann RR, Yoo J, Tucker N, et al. Impact of guidance provided by a multispectral digital skin lesion analysis device following dermoscopy on decisions to biopsy atypical melanocytic lesions. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:21-24.

- Winkelmann RR, Hauschild A, Tucker N, et al. The impact of multispectral digital skin lesion analysis on German dermatologist decisions to biopsy atypical pigmented lesions with clinical characteristics of melanoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:27-29.

- Winkelmann RR, Tucker N, White R, et al. Pigmented skin lesion biopsies after computer-aided multispectral digital skin lesion analysis. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2015;115:666-669.

- Winkelmann RR, Farberg AS, Tucker N, et al. Enhancement of international dermatologists’ pigmented skin lesion biopsy decisions following dermoscopy with subsequent integration of multispectral digital skin lesion analysis [published online July 1, 2016]. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:53-55.

- Farberg AS, Winkelmann RR, Tucker N, et al. The impact of quantitative data provided by a multi-spectral digital skin lesion analysis device on dermatologists’ decisions to biopsy pigmented lesions [published online September 1, 2017]. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:24-26.

- Wolf IH, Smolle J, Soyer HP, et al. Sensitivity in the clinical diagnosis of malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res. 1998;8:425-429.

- Kittler H, Pehamberger H, Wolff K, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:159-165.

- Ascierto PA, Palmieri G, Celentano E, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of epiluminescence microscopy: evaluation on a sample of 2731 excised cutaneous pigmented lesions: the Melanoma Cooperative Study. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:893-898.

- Carli P, Nardini P, Crocetti E, et al. Frequency and characteristics of melanomas missed at a pigmented lesion clinic: a registry-based study. Melanoma Res. 2004;14:403-407.

- Friedman RJ, Gutkowicz-Krusin D, Farber MJ, et al. The diagnostic performance of expert dermoscopists vs a computer-vision system on small-diameter melanomas. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:476-482.

Practice Points

- Multispectral digital skin lesion analysis (MSDSLA) can be a valuable tool in the evaluation of pigmented skin lesions (PSLs).

- MSDSLA may help to better identify high-risk PSLs and improve cost of care.

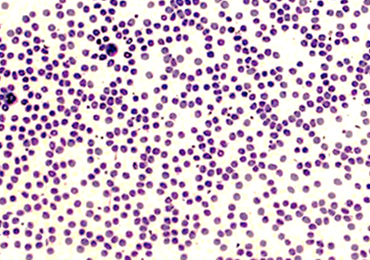

Mohs Micrographic Surgery for Digital Melanoma and Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers

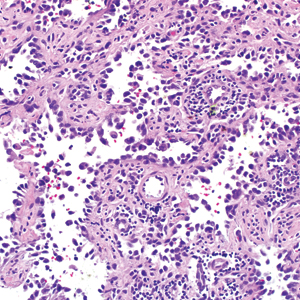

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a specialized surgical technique for the treatment of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs).1-3 The procedure involves surgical excision, histopathologic examination, precise mapping of malignant tissue, and wound management. Indications for MMS in skin cancer patients include recurring lesions, lesions in high-risk anatomic locations, aggressive histologic subtypes (ie, morpheaform, micronodular, infiltrative, high-grade, poorly differentiated), perineural invasion, large lesion size (>2 cm in diameter), poorly defined lateral or vertical clinical borders, rapid growth of the lesion, immunocompromised status, and sites of positive margins on prior excision. The therapeutic advantages of MMS include tissue conservation and optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas, such as acral sites (eg, hands, feet, digits).1,3

The intricacies of the nail apparatus complicate diagnostic biopsy and precise delineation of peripheral margins in digital skin cancers; thus, early diagnosis and intraoperative histologic examination of the margins are essential. Traditionally, the surgical approach to subungual cutaneous tumors such as melanoma has included digital amputation4; however, a study of the treatment of subungual melanoma revealed no difference in survival based on the level of amputation, therefore advocating for less radical treatment.4

Interestingly, MMS for cutaneous tumors localized to the digits is not frequently reviewed in the dermatologic literature. We present a retrospective case series evaluating the clinical outcomes of digital melanoma and NMSCs treated with MMS.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed at a private dermatology practice to identify patients who underwent MMS for melanoma or NMSC localized to the digits from January 2009 to December 2014. All patients were treated in the office by 1 Mohs surgeon (A.H.) and were evaluated before and after MMS. Data were collected from the electronic medical record of the practice, including patient demographics, histopathologic diagnosis, tumor status (primary or recurrent lesion), anatomic site of the tumor, preoperative and postoperative size of the lesion, number of MMS stages, surgical repair technique, postoperative complications, and follow-up period.

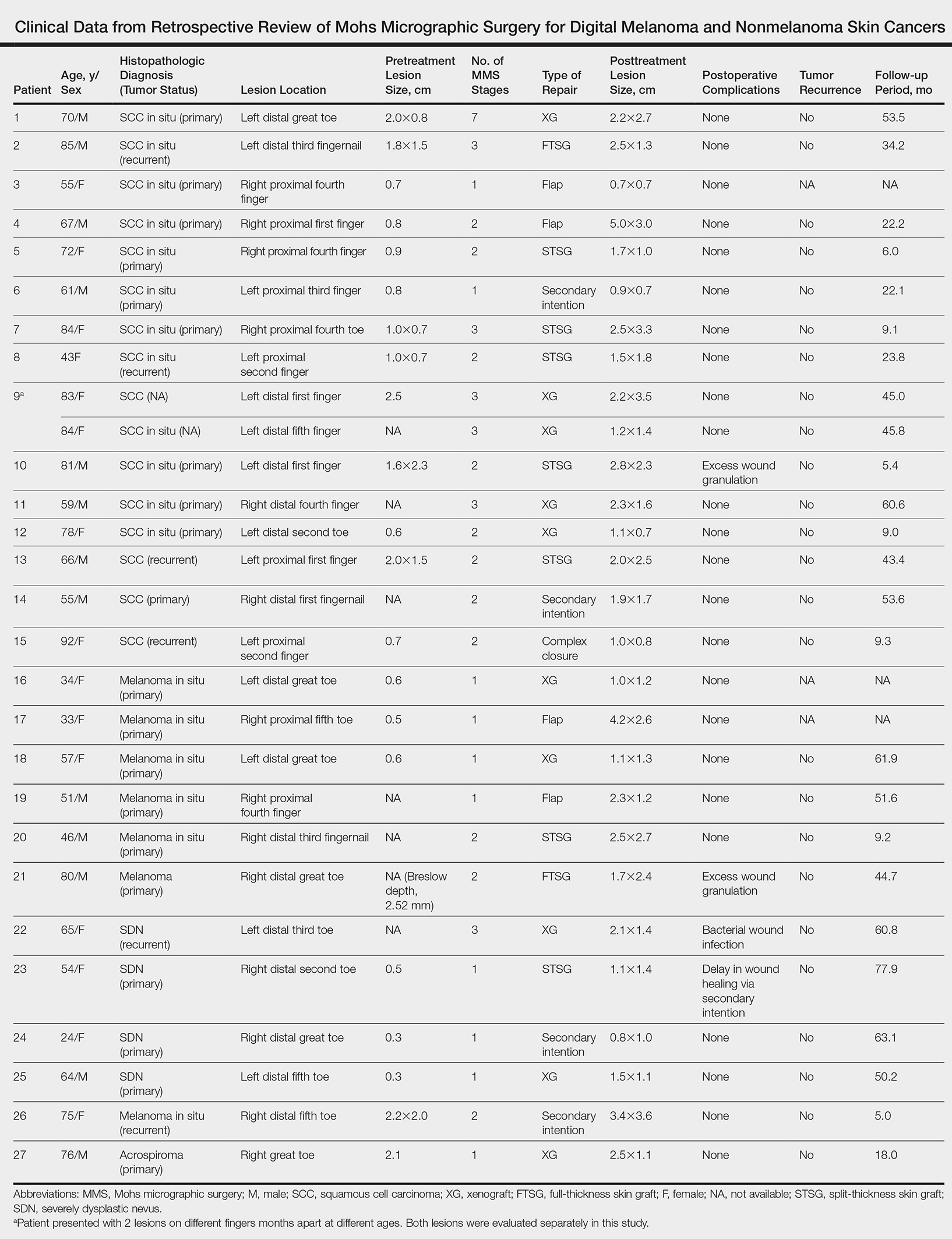

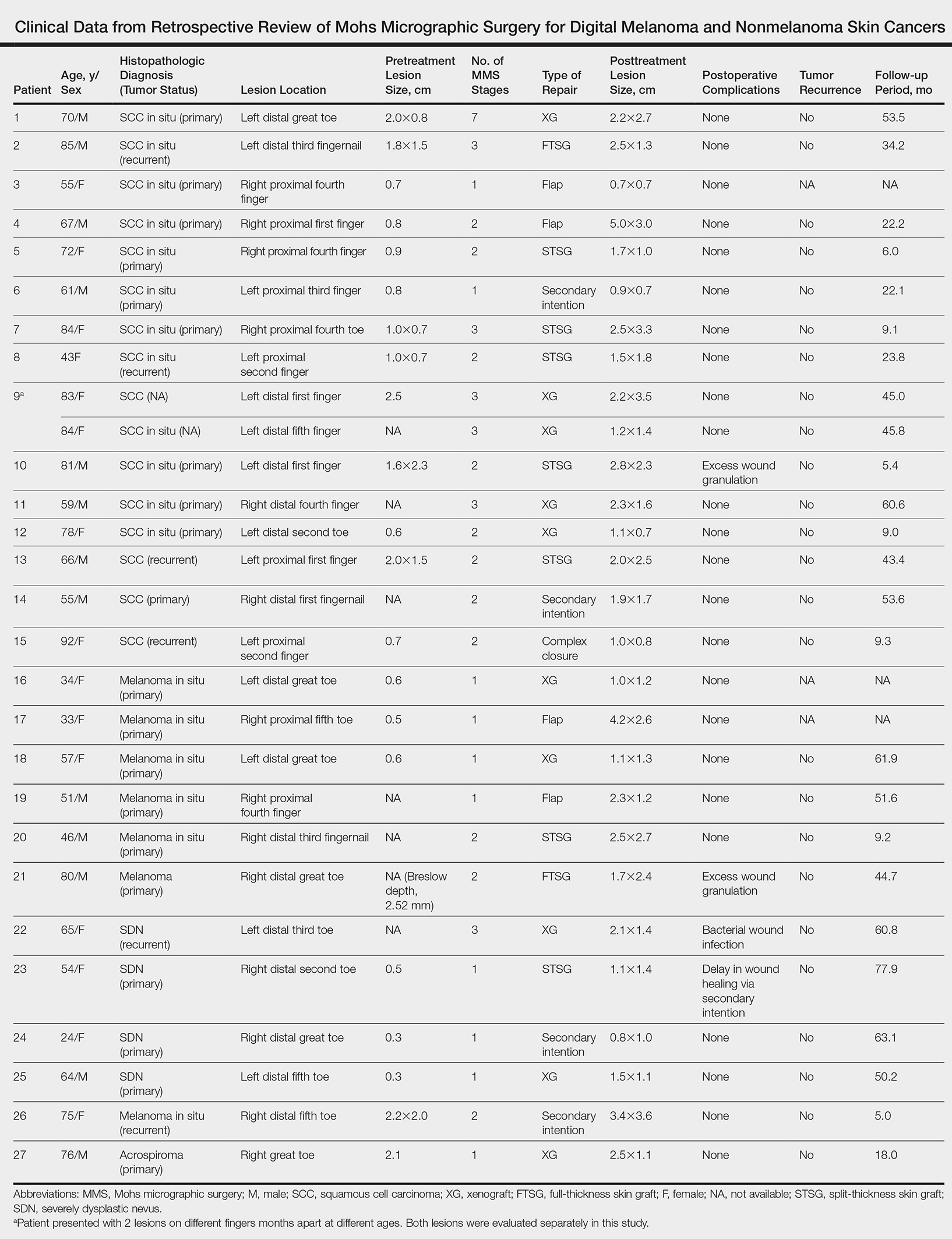

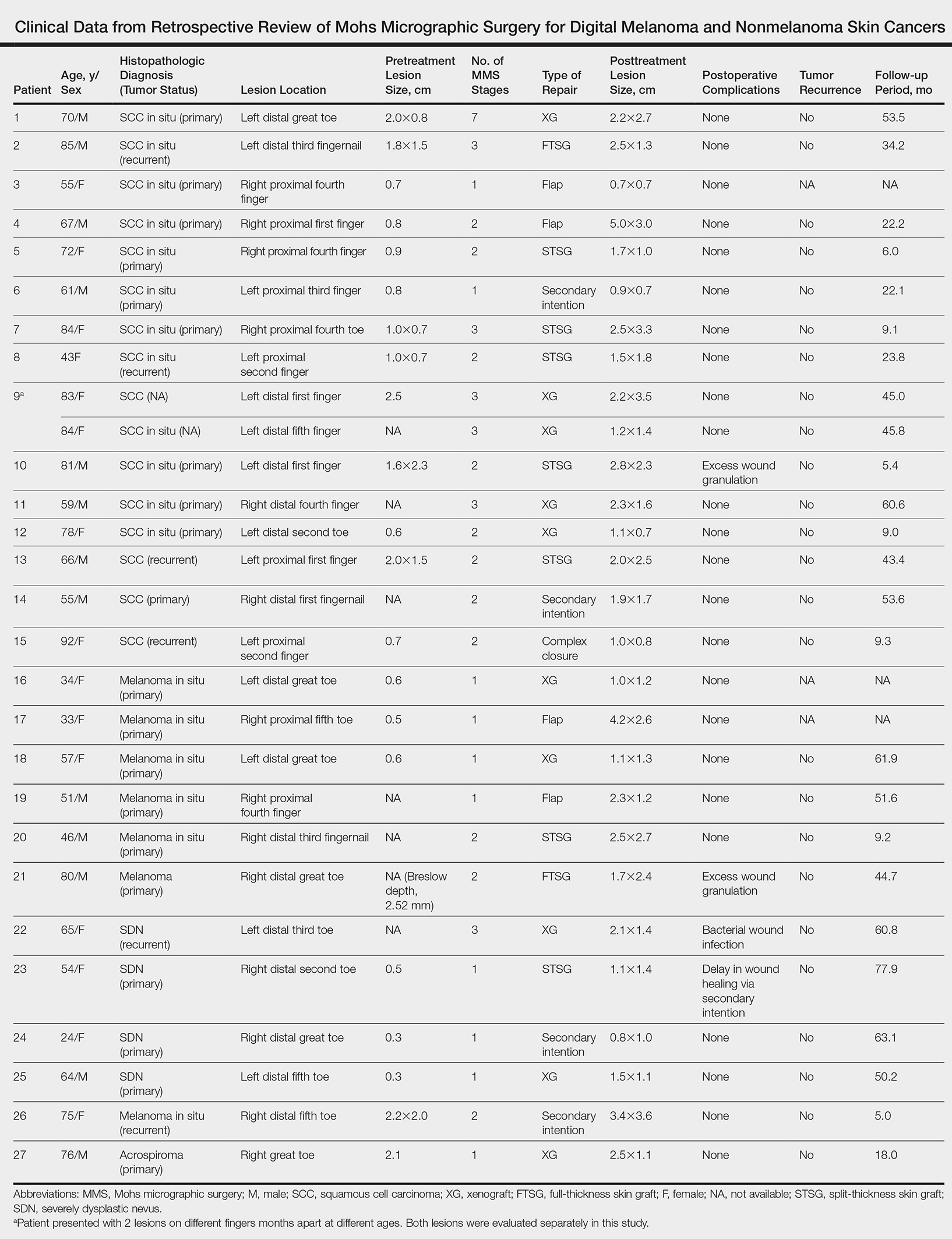

Results

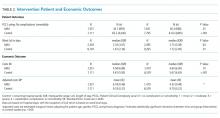

Twenty-seven patients (13 male, 14 female) with a total of 28 lesions (malignant melanoma or NMSC) localized to the digits were identified (Table). The mean age at the time of MMS was 64.07 years.

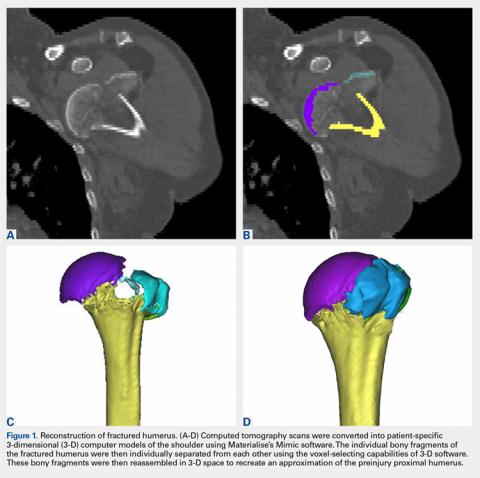

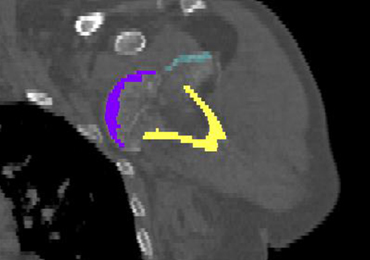

Surgical techniques used for repair following MMS included xenograft (10/28 [35.71%]); split-thickness skin graft (7/28 [25.0%]); secondary intention (4/28 [14.29%]); flap (4/28 [14.29%]); full-thickness skin graft (2/28 [7.14%]); and complex closure (1/28 [3.57%]). Clinical preoperative, operative, and postoperative photos from Patient 21 in this series are shown here (Figure). Two patients required bony phalanx resection due to invasion of the tumor into the periosteum: 1 had a malignant melanoma (Breslow depth, 2.52 mm); the other had an SCC. In addition, following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus, debulked tissue revealed melanoma in 1 patient.

Postoperative complications were noted in 4 (14.29%) of 28 MMS procedures, including bacterial wound infection (3.57%), excess granulation tissue that required wound debridement (7.14%), and delay in wound healing (3.57%). Follow-up data were available for 25 of the 28 MMS procedures (mean follow-up, 35.4 months), during which no recurrences were observed.

Comment

Mohs micrographic surgery is a specialized technique used in the treatment of cutaneous tumors, including basal cell carcinoma, SCC, melanoma in situ, atypical fibroxanthoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma, among other cutaneous tumors.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery provides the advantage of tissue conservation as well as optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas while providing a higher cure rate than surgical excision. During the procedure, the surgical margin is examined histologically, thus ensuring definitive removal of the tumor but minimal loss of surrounding normal tissue.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery is particularly useful for treating lesions on acral sites (eg, hands, feet, and digits).3-5

The treatment of digital skin cancers has evolved over the past 50 years with advancements resulting in more precise, tissue-sparing methods, in contrast to previous treatments such as amputation and wide local excision.6 More specifically, traditional digital amputation for the treatment of subungual melanoma has been reevaluated in multiple studies, which did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in survival based on the level of amputation, thereby favoring less radical treatment.4,6 Moehrle et al7 found no statistical difference in recurrence rate when comparing patients with digital melanomas treated with partial amputation and those treated with digit-sparing surgery with limited excision and histologic evaluation of margins. Additionally, in a study conducted by Lazar et al,8 no recurrence of 13 subungual malignancies treated with MMS that utilized a full-thickness graft was reported at 4-year follow-up. In a large retrospective series of digital melanomas treated with MMS, Terushkin et al5 reported that 96.5% (55/57) of patients with primary melanomas that were treated with MMS avoided amputation, and the 5- and 10-year melanoma-specific survival rates for all patients treated with MMS were 95.0% and 82.6%, respectively.

In our study, cutaneous malignancies were located most often on the fingers, and the most common skin cancer identified was SCC in situ. The literature has shown that SCC in situ and SCC are the most common cutaneous neoplasms of the digits and nail unit.9 The most common specific anatomic site of cutaneous malignancy in our study was the great toe, followed by the fourth finger. A study conducted by Tan et al9 revealed that the great toe was the most common location of melanoma of the nail bed and subungual region, followed by the thumb. In contrast, primary subungual SCCs occur most frequently on the finger, with rare cases involving the toes.10

The etiology of digital SCC may involve extensive sun exposure, chronic trauma and wounds, and viral infection.9,11 More specifically, the dermatologic literature provides evidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 involvement in the pathogenesis of digital and periungual SCC. A genital-digital mechanism of spread has been implicated.11,12 An increased recurrence rate of HPV-associated digital SCCs has been reported following MMS, likely secondary to residual postsurgical HPV infection.11,12

Maintaining function and cosmesis of the hands, feet, and digits following MMS can be challenging, sometimes requiring skin grafts and flaps to close the defect. In the 28 MMS procedures evaluated in our study, 19 (67.9%) surgical defects were repaired with a graft (ie, split-thickness skin graft, full-thickness skin graft, xenograft), 4 (14.3%) with a flap (advancement and rotation), 4 (14.3%) by secondary intention, and 1 (3.6%) with primary complex closure.

Surgical grafts can be categorized based on the origin of the graft.2,13 Autografts, derived from the patient’s skin, are the most frequently used dermatologic graft and can be further categorized as full-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and the entire dermis, thus preserving adnexal structures, and split-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and partial dermis.2,13

A cross-sectional survey of fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons revealed that more than two-thirds of repairs for cutaneous acral cancers were performed using a primary closure technique, and one-fourth of closures were performed using secondary intention.15 Of the less frequently utilized skin-graft repairs, more were for acral lesions on the legs than on the arms.14 The type of procedure and graft used is dependent on multiple variables, including the anatomic location of the lesion and final size of the defect following MMS.2 Similarly, the use of specific types of sutures depends on the anatomic location of the lesion, relative thickness of the skin, degree of tension, and desired cosmetic result.15 The expertise of a hand surgeon may be required, particularly in cases in which the extensor tendon of the distal interphalangeal joint is compromised, manifested by a droopy fingertip when the hand is held horizontally. Additionally, special attention should be paid to removing the entire nail matrix before skin grafting for subungual tumors to avoid nail growth under the skin graft.

Evaluation of debulked tissue from digital skin cancers proved to be important in our study. In Patient 21, debulked tissue revealed melanoma following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus. This finding emphasizes the importance of complete excision of such lesions, as remaining underlying portions of the lesion can reveal residual tumor of the same or different histopathology.

In a prospective study, MMS was shown to have a low rate (0.91%; 95% confidence interval, 0.38%-1.45%) of surgical site infection in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics.16 The highest rates of surgical site infection were closely associated with flap closure. In our study, most patients had an uncomplicated and successful postoperative recovery. Only 1 (3.57%) of the 28 MMS procedures (Patient 22) was complicated by a bacterial wound infection postoperatively. The lesion removed in this case was a severely dysplastic melanocytic nevus on the toe. Infection resolved after a course of oral antibiotics, but the underlying cause of the wound infection in the patient was unclear. Other postoperative complications in our study included delayed wound healing and excess granulation tissue requiring wound debridement.

There are limited data in the dermatologic literature regarding outcomes following MMS for the treatment of cutaneous malignancies localized to the digits.

Additional limitations of this case review include its single-center and retrospective design, the small sample size, and 1 Mohs surgeon having performed all surgeries.

Conclusion

This study provides further evidence of the benefit of MMS for the treatment of malignant melanoma and NMSCs of the digits. This procedure provides margin-controlled excision of these malignant neoplasms while preserving maximal normal tissue, thereby providing patients with improved postoperative function and cosmesis. Long-term follow-up data demonstrating a lack of tumor recurrence underscores the assertion that MMS is safe and effective for the treatment of skin cancer of the digits.

- Dim-Jamora KC, Perone JB. Management of cutaneous tumors with mohs micrographic surgery. Semin Plast Surg. 2008;22:247-256.

- McLeod MP, Choudhary S, Alqubaisy YA, et al. Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery. In: Nouri K, ed. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:5-13.

- Loosemore MP, Morales-Burgos A, Goldberg LH. Acral lentiginous melanoma of the toe treated using Mohs surgery with sparing of the digit and subsequent reconstruction using split-thickness skin graft. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:136-138.

- Rayatt SS, Dancey AL, Davison PM. Thumb subungual melanoma: is amputation necessary? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:635-638.

- Terushkin V, Brodland DG, Sharon DJ, et al. Digit-sparing Mohs surgery for melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:83-93.

- Viola KV, Jhaveri MB, Soulos PR, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment in the Medicare population. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:473-477.

- Moehrle M, Metzger S, Schippert W. “Functional” surgery in subungual melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:366-374.

- Lazar A, Abimelec P, Dumontier C, et al. Full thickness skin graft from nail unit reconstruction. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30:194-198.

- Tan KB, Moncrieff M, Thompson JF, et al. Subungual melanoma: a study of 124 cases highlighting features of early lesions, potential for histologic reports. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1902-1912.

- Nasca MR, Innocenzi D, Micali G. Subungual squamous cell carcinoma of the toe: report on three cases. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:345-348.

- Dika E, Piraccini BM, Balestri RR, et al. Mohs surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the nail: report of 15 cases. our experience and a long-term follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1310-1314.

- Alam M, Caldwell JB, Eliezri YD. Human papillomavirus-associated digital squamous cell carcinoma: literature review and report of 21 new cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:385-393.

- Filho L, Anselmo J, Dadalti P, et al. Skin grafts in cutaneous oncology. Braz Ann Dermatol. 2006;81:465-472.

- Raimer DW, Group AR, Petitt MS, et al. Porcine xenograft biosynthetic wound dressings for the management of postoperative Mohs wounds. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Alam M, Helenowksi IB, Cohen JL, et al. Association between type of reconstruction after Mohs micrographic surgery and surgeon-, patient-, and tumor-specific features: a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:51-55.

- Rogers HD, Desciak EB, Marcus RP, et al. Prospective study of wound infections in Mohs micrographic surgery using clean surgical technique in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:842-851.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a specialized surgical technique for the treatment of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs).1-3 The procedure involves surgical excision, histopathologic examination, precise mapping of malignant tissue, and wound management. Indications for MMS in skin cancer patients include recurring lesions, lesions in high-risk anatomic locations, aggressive histologic subtypes (ie, morpheaform, micronodular, infiltrative, high-grade, poorly differentiated), perineural invasion, large lesion size (>2 cm in diameter), poorly defined lateral or vertical clinical borders, rapid growth of the lesion, immunocompromised status, and sites of positive margins on prior excision. The therapeutic advantages of MMS include tissue conservation and optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas, such as acral sites (eg, hands, feet, digits).1,3

The intricacies of the nail apparatus complicate diagnostic biopsy and precise delineation of peripheral margins in digital skin cancers; thus, early diagnosis and intraoperative histologic examination of the margins are essential. Traditionally, the surgical approach to subungual cutaneous tumors such as melanoma has included digital amputation4; however, a study of the treatment of subungual melanoma revealed no difference in survival based on the level of amputation, therefore advocating for less radical treatment.4

Interestingly, MMS for cutaneous tumors localized to the digits is not frequently reviewed in the dermatologic literature. We present a retrospective case series evaluating the clinical outcomes of digital melanoma and NMSCs treated with MMS.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed at a private dermatology practice to identify patients who underwent MMS for melanoma or NMSC localized to the digits from January 2009 to December 2014. All patients were treated in the office by 1 Mohs surgeon (A.H.) and were evaluated before and after MMS. Data were collected from the electronic medical record of the practice, including patient demographics, histopathologic diagnosis, tumor status (primary or recurrent lesion), anatomic site of the tumor, preoperative and postoperative size of the lesion, number of MMS stages, surgical repair technique, postoperative complications, and follow-up period.

Results

Twenty-seven patients (13 male, 14 female) with a total of 28 lesions (malignant melanoma or NMSC) localized to the digits were identified (Table). The mean age at the time of MMS was 64.07 years.

Surgical techniques used for repair following MMS included xenograft (10/28 [35.71%]); split-thickness skin graft (7/28 [25.0%]); secondary intention (4/28 [14.29%]); flap (4/28 [14.29%]); full-thickness skin graft (2/28 [7.14%]); and complex closure (1/28 [3.57%]). Clinical preoperative, operative, and postoperative photos from Patient 21 in this series are shown here (Figure). Two patients required bony phalanx resection due to invasion of the tumor into the periosteum: 1 had a malignant melanoma (Breslow depth, 2.52 mm); the other had an SCC. In addition, following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus, debulked tissue revealed melanoma in 1 patient.

Postoperative complications were noted in 4 (14.29%) of 28 MMS procedures, including bacterial wound infection (3.57%), excess granulation tissue that required wound debridement (7.14%), and delay in wound healing (3.57%). Follow-up data were available for 25 of the 28 MMS procedures (mean follow-up, 35.4 months), during which no recurrences were observed.

Comment

Mohs micrographic surgery is a specialized technique used in the treatment of cutaneous tumors, including basal cell carcinoma, SCC, melanoma in situ, atypical fibroxanthoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma, among other cutaneous tumors.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery provides the advantage of tissue conservation as well as optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas while providing a higher cure rate than surgical excision. During the procedure, the surgical margin is examined histologically, thus ensuring definitive removal of the tumor but minimal loss of surrounding normal tissue.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery is particularly useful for treating lesions on acral sites (eg, hands, feet, and digits).3-5

The treatment of digital skin cancers has evolved over the past 50 years with advancements resulting in more precise, tissue-sparing methods, in contrast to previous treatments such as amputation and wide local excision.6 More specifically, traditional digital amputation for the treatment of subungual melanoma has been reevaluated in multiple studies, which did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in survival based on the level of amputation, thereby favoring less radical treatment.4,6 Moehrle et al7 found no statistical difference in recurrence rate when comparing patients with digital melanomas treated with partial amputation and those treated with digit-sparing surgery with limited excision and histologic evaluation of margins. Additionally, in a study conducted by Lazar et al,8 no recurrence of 13 subungual malignancies treated with MMS that utilized a full-thickness graft was reported at 4-year follow-up. In a large retrospective series of digital melanomas treated with MMS, Terushkin et al5 reported that 96.5% (55/57) of patients with primary melanomas that were treated with MMS avoided amputation, and the 5- and 10-year melanoma-specific survival rates for all patients treated with MMS were 95.0% and 82.6%, respectively.

In our study, cutaneous malignancies were located most often on the fingers, and the most common skin cancer identified was SCC in situ. The literature has shown that SCC in situ and SCC are the most common cutaneous neoplasms of the digits and nail unit.9 The most common specific anatomic site of cutaneous malignancy in our study was the great toe, followed by the fourth finger. A study conducted by Tan et al9 revealed that the great toe was the most common location of melanoma of the nail bed and subungual region, followed by the thumb. In contrast, primary subungual SCCs occur most frequently on the finger, with rare cases involving the toes.10

The etiology of digital SCC may involve extensive sun exposure, chronic trauma and wounds, and viral infection.9,11 More specifically, the dermatologic literature provides evidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 involvement in the pathogenesis of digital and periungual SCC. A genital-digital mechanism of spread has been implicated.11,12 An increased recurrence rate of HPV-associated digital SCCs has been reported following MMS, likely secondary to residual postsurgical HPV infection.11,12

Maintaining function and cosmesis of the hands, feet, and digits following MMS can be challenging, sometimes requiring skin grafts and flaps to close the defect. In the 28 MMS procedures evaluated in our study, 19 (67.9%) surgical defects were repaired with a graft (ie, split-thickness skin graft, full-thickness skin graft, xenograft), 4 (14.3%) with a flap (advancement and rotation), 4 (14.3%) by secondary intention, and 1 (3.6%) with primary complex closure.

Surgical grafts can be categorized based on the origin of the graft.2,13 Autografts, derived from the patient’s skin, are the most frequently used dermatologic graft and can be further categorized as full-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and the entire dermis, thus preserving adnexal structures, and split-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and partial dermis.2,13

A cross-sectional survey of fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons revealed that more than two-thirds of repairs for cutaneous acral cancers were performed using a primary closure technique, and one-fourth of closures were performed using secondary intention.15 Of the less frequently utilized skin-graft repairs, more were for acral lesions on the legs than on the arms.14 The type of procedure and graft used is dependent on multiple variables, including the anatomic location of the lesion and final size of the defect following MMS.2 Similarly, the use of specific types of sutures depends on the anatomic location of the lesion, relative thickness of the skin, degree of tension, and desired cosmetic result.15 The expertise of a hand surgeon may be required, particularly in cases in which the extensor tendon of the distal interphalangeal joint is compromised, manifested by a droopy fingertip when the hand is held horizontally. Additionally, special attention should be paid to removing the entire nail matrix before skin grafting for subungual tumors to avoid nail growth under the skin graft.

Evaluation of debulked tissue from digital skin cancers proved to be important in our study. In Patient 21, debulked tissue revealed melanoma following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus. This finding emphasizes the importance of complete excision of such lesions, as remaining underlying portions of the lesion can reveal residual tumor of the same or different histopathology.

In a prospective study, MMS was shown to have a low rate (0.91%; 95% confidence interval, 0.38%-1.45%) of surgical site infection in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics.16 The highest rates of surgical site infection were closely associated with flap closure. In our study, most patients had an uncomplicated and successful postoperative recovery. Only 1 (3.57%) of the 28 MMS procedures (Patient 22) was complicated by a bacterial wound infection postoperatively. The lesion removed in this case was a severely dysplastic melanocytic nevus on the toe. Infection resolved after a course of oral antibiotics, but the underlying cause of the wound infection in the patient was unclear. Other postoperative complications in our study included delayed wound healing and excess granulation tissue requiring wound debridement.

There are limited data in the dermatologic literature regarding outcomes following MMS for the treatment of cutaneous malignancies localized to the digits.

Additional limitations of this case review include its single-center and retrospective design, the small sample size, and 1 Mohs surgeon having performed all surgeries.

Conclusion

This study provides further evidence of the benefit of MMS for the treatment of malignant melanoma and NMSCs of the digits. This procedure provides margin-controlled excision of these malignant neoplasms while preserving maximal normal tissue, thereby providing patients with improved postoperative function and cosmesis. Long-term follow-up data demonstrating a lack of tumor recurrence underscores the assertion that MMS is safe and effective for the treatment of skin cancer of the digits.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a specialized surgical technique for the treatment of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs).1-3 The procedure involves surgical excision, histopathologic examination, precise mapping of malignant tissue, and wound management. Indications for MMS in skin cancer patients include recurring lesions, lesions in high-risk anatomic locations, aggressive histologic subtypes (ie, morpheaform, micronodular, infiltrative, high-grade, poorly differentiated), perineural invasion, large lesion size (>2 cm in diameter), poorly defined lateral or vertical clinical borders, rapid growth of the lesion, immunocompromised status, and sites of positive margins on prior excision. The therapeutic advantages of MMS include tissue conservation and optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas, such as acral sites (eg, hands, feet, digits).1,3

The intricacies of the nail apparatus complicate diagnostic biopsy and precise delineation of peripheral margins in digital skin cancers; thus, early diagnosis and intraoperative histologic examination of the margins are essential. Traditionally, the surgical approach to subungual cutaneous tumors such as melanoma has included digital amputation4; however, a study of the treatment of subungual melanoma revealed no difference in survival based on the level of amputation, therefore advocating for less radical treatment.4

Interestingly, MMS for cutaneous tumors localized to the digits is not frequently reviewed in the dermatologic literature. We present a retrospective case series evaluating the clinical outcomes of digital melanoma and NMSCs treated with MMS.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed at a private dermatology practice to identify patients who underwent MMS for melanoma or NMSC localized to the digits from January 2009 to December 2014. All patients were treated in the office by 1 Mohs surgeon (A.H.) and were evaluated before and after MMS. Data were collected from the electronic medical record of the practice, including patient demographics, histopathologic diagnosis, tumor status (primary or recurrent lesion), anatomic site of the tumor, preoperative and postoperative size of the lesion, number of MMS stages, surgical repair technique, postoperative complications, and follow-up period.

Results

Twenty-seven patients (13 male, 14 female) with a total of 28 lesions (malignant melanoma or NMSC) localized to the digits were identified (Table). The mean age at the time of MMS was 64.07 years.

Surgical techniques used for repair following MMS included xenograft (10/28 [35.71%]); split-thickness skin graft (7/28 [25.0%]); secondary intention (4/28 [14.29%]); flap (4/28 [14.29%]); full-thickness skin graft (2/28 [7.14%]); and complex closure (1/28 [3.57%]). Clinical preoperative, operative, and postoperative photos from Patient 21 in this series are shown here (Figure). Two patients required bony phalanx resection due to invasion of the tumor into the periosteum: 1 had a malignant melanoma (Breslow depth, 2.52 mm); the other had an SCC. In addition, following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus, debulked tissue revealed melanoma in 1 patient.

Postoperative complications were noted in 4 (14.29%) of 28 MMS procedures, including bacterial wound infection (3.57%), excess granulation tissue that required wound debridement (7.14%), and delay in wound healing (3.57%). Follow-up data were available for 25 of the 28 MMS procedures (mean follow-up, 35.4 months), during which no recurrences were observed.

Comment

Mohs micrographic surgery is a specialized technique used in the treatment of cutaneous tumors, including basal cell carcinoma, SCC, melanoma in situ, atypical fibroxanthoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma, among other cutaneous tumors.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery provides the advantage of tissue conservation as well as optimal margin control in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas while providing a higher cure rate than surgical excision. During the procedure, the surgical margin is examined histologically, thus ensuring definitive removal of the tumor but minimal loss of surrounding normal tissue.1-3 Mohs micrographic surgery is particularly useful for treating lesions on acral sites (eg, hands, feet, and digits).3-5

The treatment of digital skin cancers has evolved over the past 50 years with advancements resulting in more precise, tissue-sparing methods, in contrast to previous treatments such as amputation and wide local excision.6 More specifically, traditional digital amputation for the treatment of subungual melanoma has been reevaluated in multiple studies, which did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in survival based on the level of amputation, thereby favoring less radical treatment.4,6 Moehrle et al7 found no statistical difference in recurrence rate when comparing patients with digital melanomas treated with partial amputation and those treated with digit-sparing surgery with limited excision and histologic evaluation of margins. Additionally, in a study conducted by Lazar et al,8 no recurrence of 13 subungual malignancies treated with MMS that utilized a full-thickness graft was reported at 4-year follow-up. In a large retrospective series of digital melanomas treated with MMS, Terushkin et al5 reported that 96.5% (55/57) of patients with primary melanomas that were treated with MMS avoided amputation, and the 5- and 10-year melanoma-specific survival rates for all patients treated with MMS were 95.0% and 82.6%, respectively.

In our study, cutaneous malignancies were located most often on the fingers, and the most common skin cancer identified was SCC in situ. The literature has shown that SCC in situ and SCC are the most common cutaneous neoplasms of the digits and nail unit.9 The most common specific anatomic site of cutaneous malignancy in our study was the great toe, followed by the fourth finger. A study conducted by Tan et al9 revealed that the great toe was the most common location of melanoma of the nail bed and subungual region, followed by the thumb. In contrast, primary subungual SCCs occur most frequently on the finger, with rare cases involving the toes.10

The etiology of digital SCC may involve extensive sun exposure, chronic trauma and wounds, and viral infection.9,11 More specifically, the dermatologic literature provides evidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 involvement in the pathogenesis of digital and periungual SCC. A genital-digital mechanism of spread has been implicated.11,12 An increased recurrence rate of HPV-associated digital SCCs has been reported following MMS, likely secondary to residual postsurgical HPV infection.11,12

Maintaining function and cosmesis of the hands, feet, and digits following MMS can be challenging, sometimes requiring skin grafts and flaps to close the defect. In the 28 MMS procedures evaluated in our study, 19 (67.9%) surgical defects were repaired with a graft (ie, split-thickness skin graft, full-thickness skin graft, xenograft), 4 (14.3%) with a flap (advancement and rotation), 4 (14.3%) by secondary intention, and 1 (3.6%) with primary complex closure.

Surgical grafts can be categorized based on the origin of the graft.2,13 Autografts, derived from the patient’s skin, are the most frequently used dermatologic graft and can be further categorized as full-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and the entire dermis, thus preserving adnexal structures, and split-thickness skin grafts, which include the epidermis and partial dermis.2,13

A cross-sectional survey of fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons revealed that more than two-thirds of repairs for cutaneous acral cancers were performed using a primary closure technique, and one-fourth of closures were performed using secondary intention.15 Of the less frequently utilized skin-graft repairs, more were for acral lesions on the legs than on the arms.14 The type of procedure and graft used is dependent on multiple variables, including the anatomic location of the lesion and final size of the defect following MMS.2 Similarly, the use of specific types of sutures depends on the anatomic location of the lesion, relative thickness of the skin, degree of tension, and desired cosmetic result.15 The expertise of a hand surgeon may be required, particularly in cases in which the extensor tendon of the distal interphalangeal joint is compromised, manifested by a droopy fingertip when the hand is held horizontally. Additionally, special attention should be paid to removing the entire nail matrix before skin grafting for subungual tumors to avoid nail growth under the skin graft.

Evaluation of debulked tissue from digital skin cancers proved to be important in our study. In Patient 21, debulked tissue revealed melanoma following removal of a severely dysplastic nevus. This finding emphasizes the importance of complete excision of such lesions, as remaining underlying portions of the lesion can reveal residual tumor of the same or different histopathology.

In a prospective study, MMS was shown to have a low rate (0.91%; 95% confidence interval, 0.38%-1.45%) of surgical site infection in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics.16 The highest rates of surgical site infection were closely associated with flap closure. In our study, most patients had an uncomplicated and successful postoperative recovery. Only 1 (3.57%) of the 28 MMS procedures (Patient 22) was complicated by a bacterial wound infection postoperatively. The lesion removed in this case was a severely dysplastic melanocytic nevus on the toe. Infection resolved after a course of oral antibiotics, but the underlying cause of the wound infection in the patient was unclear. Other postoperative complications in our study included delayed wound healing and excess granulation tissue requiring wound debridement.

There are limited data in the dermatologic literature regarding outcomes following MMS for the treatment of cutaneous malignancies localized to the digits.

Additional limitations of this case review include its single-center and retrospective design, the small sample size, and 1 Mohs surgeon having performed all surgeries.

Conclusion

This study provides further evidence of the benefit of MMS for the treatment of malignant melanoma and NMSCs of the digits. This procedure provides margin-controlled excision of these malignant neoplasms while preserving maximal normal tissue, thereby providing patients with improved postoperative function and cosmesis. Long-term follow-up data demonstrating a lack of tumor recurrence underscores the assertion that MMS is safe and effective for the treatment of skin cancer of the digits.

- Dim-Jamora KC, Perone JB. Management of cutaneous tumors with mohs micrographic surgery. Semin Plast Surg. 2008;22:247-256.

- McLeod MP, Choudhary S, Alqubaisy YA, et al. Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery. In: Nouri K, ed. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:5-13.

- Loosemore MP, Morales-Burgos A, Goldberg LH. Acral lentiginous melanoma of the toe treated using Mohs surgery with sparing of the digit and subsequent reconstruction using split-thickness skin graft. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:136-138.

- Rayatt SS, Dancey AL, Davison PM. Thumb subungual melanoma: is amputation necessary? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:635-638.

- Terushkin V, Brodland DG, Sharon DJ, et al. Digit-sparing Mohs surgery for melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:83-93.

- Viola KV, Jhaveri MB, Soulos PR, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment in the Medicare population. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:473-477.

- Moehrle M, Metzger S, Schippert W. “Functional” surgery in subungual melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:366-374.

- Lazar A, Abimelec P, Dumontier C, et al. Full thickness skin graft from nail unit reconstruction. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30:194-198.

- Tan KB, Moncrieff M, Thompson JF, et al. Subungual melanoma: a study of 124 cases highlighting features of early lesions, potential for histologic reports. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1902-1912.

- Nasca MR, Innocenzi D, Micali G. Subungual squamous cell carcinoma of the toe: report on three cases. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:345-348.

- Dika E, Piraccini BM, Balestri RR, et al. Mohs surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the nail: report of 15 cases. our experience and a long-term follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1310-1314.

- Alam M, Caldwell JB, Eliezri YD. Human papillomavirus-associated digital squamous cell carcinoma: literature review and report of 21 new cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:385-393.

- Filho L, Anselmo J, Dadalti P, et al. Skin grafts in cutaneous oncology. Braz Ann Dermatol. 2006;81:465-472.

- Raimer DW, Group AR, Petitt MS, et al. Porcine xenograft biosynthetic wound dressings for the management of postoperative Mohs wounds. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Alam M, Helenowksi IB, Cohen JL, et al. Association between type of reconstruction after Mohs micrographic surgery and surgeon-, patient-, and tumor-specific features: a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:51-55.

- Rogers HD, Desciak EB, Marcus RP, et al. Prospective study of wound infections in Mohs micrographic surgery using clean surgical technique in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:842-851.

- Dim-Jamora KC, Perone JB. Management of cutaneous tumors with mohs micrographic surgery. Semin Plast Surg. 2008;22:247-256.

- McLeod MP, Choudhary S, Alqubaisy YA, et al. Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery. In: Nouri K, ed. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:5-13.