User login

An MRI Analysis of the Pelvis to Determine the Ideal Method for Ultrasound-Guided Bone Marrow Aspiration from the Iliac Crest

ABSTRACT

Use of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow has gained significant popularity. The iliac crest has been determined to be an effective site for harvesting mesenchymal stem cells. Review of the literature reveals that multiple techniques are used to harvest bone marrow aspirate from the iliac crest, but the descriptions are based on the experience of various authors as opposed to studied anatomy. A safe, reliable, and reproducible method for aspiration has yet to be studied and described. We hypothesized that there would be an ideal angle and distance for aspiration that would be the safest, most consistent, and most reliable. Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), we reviewed 26 total lumbar spine MRI scans (13 males, 13 females) and found that an angle of 24° should be used when entering the most medial aspect of the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) and that this angle did not differ between the sexes. The distance that the trocar can advance after entry before hitting the anterior ilium wall varied significantly between males and females, being 7.53 cm in males and 6.74 cm in females. In addition, the size of the PSIS table was significantly different between males and females (1.20 cm and 0.96 cm, respectively). No other significant differences in the measurements gathered were found. Using the data gleaned from this study, we developed an aspiration technique. This method uses ultrasound to determine the location of the PSIS and the entry point on the PSIS. This contrasts with most techniques that use landmark palpation, which is known to be unreliable and inaccurate. The described technique for aspiration from the PSIS is safe, reliable, reproducible, and substantiated by data.

The iliac crest is an effective site for harvesting bone marrow stem cells. It allows for easy access and is superficial in most individuals, allowing for a relatively quick and simple procedure. Use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for treatment of orthopedic injuries has grown recently. Whereas overall use has increased, review of the literature reveals very few techniques for iliac crest aspiration,1 but these are not based on anatomic relationships or studies. Hernigou and colleagues2,3 attempted to quantitatively evaluate potential “sectors” allowing for safe aspiration using cadaver and computed tomographic reconstruction imaging. We used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to analyze aspiration parameters. Owing to the ilium’s anatomy, improper positioning or aspiration technique during aspiration can result in serious injury.2,4-6 We hypothesized that there is an ideal angle and positioning for bone marrow aspiration from the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) that is safe, consistent, and reproducible. Although most aspiration techniques use landmark palpation, this is unreliable and inaccurate, especially when compared with ultrasound-guided injections7-16 and procedures.9,12,17-19 We describe our technique using ultrasound to visualize patient anatomy and accurately determine anatomic entry with the trocar.

METHODS

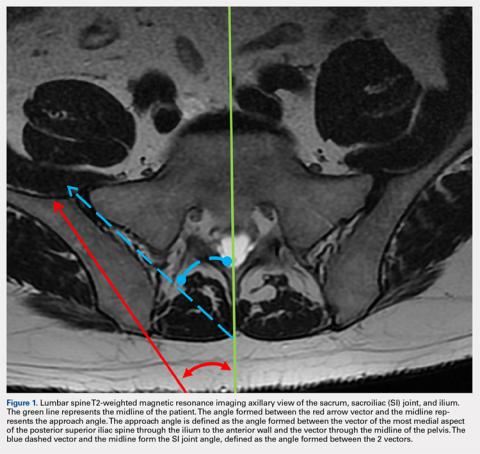

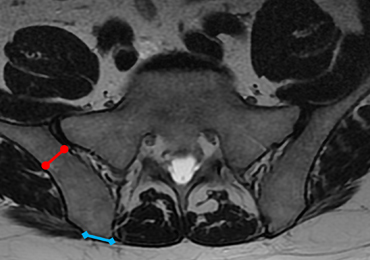

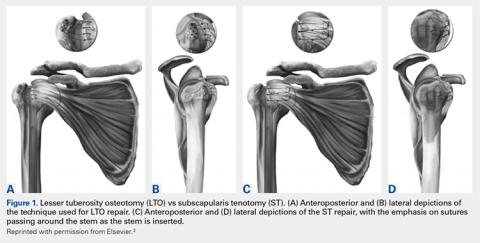

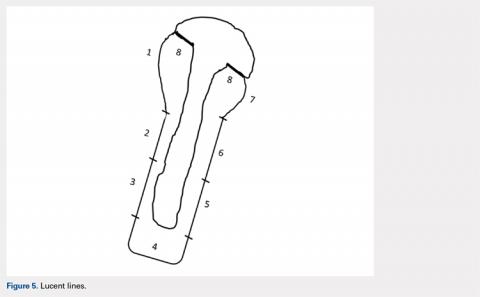

MRI scans of 26 patients (13 males, 13 females) were reviewed to determine average angles and distances. Axial T2-weighted views of the lumbar spine were used in all analyses. The sacroiliac (SI) joint angle was defined as the angle formed between the vector through the midline of the pelvis and the vector that is parallel to the SI joint. The approach angle was defined as the angle formed between the vector of the most medial aspect of the PSIS through the ilium to the anterior wall and the vector through the midline of the pelvis (Figure 1).

Continue to: For the 13 males, the mean SI joint...

RESULTS

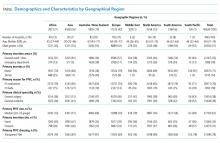

The results are reported in the Table.

Table. Measurements of Patients Taken on Axial T2-Weighted Views of Lumbosacral MRI Scansa

Patient | SI Joint Angle (°) | Approach Angle (°) | PSIS Table Width (cm) | PSIS to Anterior Ilium Wall (cm) | Perpendicular Distance PSIS to Anterior Joint (cm) | Post Ilium Wall to SI Joint Width (cm) |

Males | ||||||

1 | 28.80 | 19.50 | 1.24 | 8.80 | 4.16 | 1.52 |

2 | 31.80 | 27.60 | 1.70 | 7.89 | 3.49 | 1.02 |

3 | 33.70 | 27.70 | 1.12 | 8.14 | 3.15 | 1.28 |

4 | 23.70 | 26.40 | 0.95 | 6.66 | 3.22 | 0.65 |

5 | 35.90 | 28.40 | 0.84 | 7.60 | 2.57 | 0.95 |

6 | 33.80 | 29.30 | 1.20 | 7.73 | 2.34 | 0.90 |

7 | 30.30 | 21.20 | 1.36 | 8.44 | 3.95 | 1.18 |

8 | 34.50 | 20.40 | 1.53 | 7.08 | 3.98 | 1.56 |

9 | 28.70 | 24.00 | 1.34 | 8.19 | 3.51 | 1.31 |

10 | 22.40 | 20.10 | 1.37 | 7.30 | 3.87 | 1.28 |

11 | 33.60 | 20.80 | 0.88 | 6.43 | 3.26 | 0.94 |

12 | 48.50 | 31.00 | 1.15 | 6.69 | 2.97 | 1.38 |

13 | 20.20 | 20.90 | 0.94 | 6.95 | 3.79 | 1.05 |

Averages | 31.22 | 24.41 | 1.20 | 7.53 | 3.40 | 1.16 |

Standard Deviation | 7.18 | 4.11 | 0.26 | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.26 |

Females | ||||||

14 | 22.80 | 23.20 | 1.54 | 7.21 | 3.45 | 1.39 |

15 | 33.30 | 21.40 | 1.09 | 7.26 | 3.57 | 0.98 |

16 | 19.70 | 15.60 | 0.78 | 8.32 | 3.76 | 0.86 |

17 | 17.50 | 15.60 | 0.61 | 7.57 | 3.37 | 1.03 |

18 | 48.20 | 26.60 | 0.94 | 6.62 | 3.16 | 0.71 |

19 | 38.20 | 28.30 | 0.90 | 6.32 | 2.23 | 0.91 |

20 | 44.50 | 31.70 | 0.99 | 6.19 | 3.06 | 0.76 |

21 | 24.10 | 18.00 | 0.92 | 6.99 | 3.23 | 0.71 |

22 | 17.20 | 14.80 | 0.81 | 6.00 | 2.81 | 1.13 |

23 | 42.00 | 38.50 | 1.00 | 5.33 | 2.47 | 1.42 |

24 | 32.00 | 25.50 | 0.98 | 6.01 | 2.79 | 1.21 |

25 | 24.70 | 24.80 | 0.87 | 6.09 | 2.79 | 1.02 |

26 | 19.80 | 22.30 | 1.04 | 7.71 | 2.37 | 1.36 |

Averages | 29.54 | 23.56 | 0.96 | 6.74 | 3.00 | 1.04 |

Standard Deviation | 10.84 | 6.88 | 0.21 | 0.85 | 0.48 | 0.25 |

All patients Averages | 30.38 | 23.98 | 1.08 | 7.14 | 3.20 | 1.10 |

Standard Deviation | 9.05 | 5.57 | 0.26 | 0.88 | 0.55 | 0.26 |

aStatistical significance is denoted as P < .02.

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PSIS, posterior iliac spine; SI, sacroiliac.

For the 13 males, the mean SI joint angle was 31.22° ± 7.18° (range, 20.20° to 48.50°). The mean approach angle was 24.41° ± 4.11° (range, 19.50° to 31.00°). The mean PSIS table width was 1.20 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.84 cm to 1.70 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 7.53 cm ± 0.75 cm (range, 6.43 cm to 8.80 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.40 cm ± 0.56 cm (range, 2.34 cm to 4.16 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.16 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.65 cm to 1.56 cm).

For the 13 females, the mean SI joint angle was 29.54° ± 10.84° (range, 17.20° to 48.20°). The mean approach angle was 23.56° ± 6.88° (range, 14.80° to 38.50°). The mean PSIS table width was 0.96 cm ± 0.21 cm (range, 0.61 cm to 1.54 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 6.74 cm ± 0.85 cm (range, 5.33 cm to 8.32 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.00 cm ± 0.48 cm (range, 2.23 cm to 3.76 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.04 cm ± 0.25 cm (range, 0.71 cm to 1.42 cm).

For the 26 total patients, the mean SI joint angle was 30.38° ± 9.05° (range, 17.20° to 48.50°). The mean approach angle was 23.98° ± 5.57° (range, 14.80° to 38.50°). The mean PSIS table width was 1.08 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.61 cm to 1.70 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 7.14 cm ± 0.88 cm (range, 5.33 cm to 8.80 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.20 cm ± 0.55 cm (range, 2.23 cm to 4.16 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.10 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.65 cm to 1.56 cm).

There was a statistically significant difference between the male and female groups for the maximum distance the trocar can be advanced from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall (P < .02), and a statistically significant difference for the PSIS table width (P < .02). There were no significant differences between the male and female groups for the approach angle, the SI joint angle, the perpendicular distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium, and the minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint.

Continue to: The patient is brought to the procedure...

TECHNIQUE: ILIAC CREST (PSIS) BONE MARROW ASPIRATION

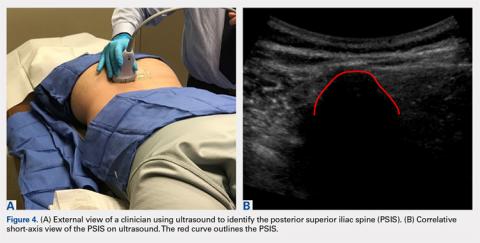

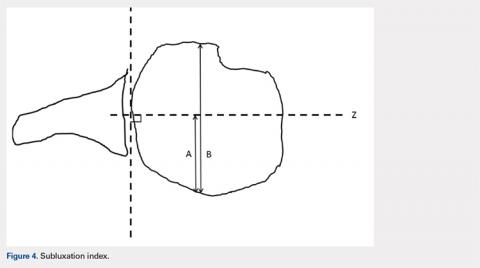

The patient is brought to the procedure room and placed in a prone position. The donor site is prepared and draped in the usual sterile manner. Ultrasound is used to identify the median sacral crest in a short-axis view. The probe is then moved laterally to identify the PSIS (Figures 4A, 4B).

The crosshairs on the ultrasound probe are used to mark the center lines of each plane. The central point marks the location of the PSIS. Alternatively, an in-plane technique can be used to place a spinal needle on the exact entry point on the PSIS. Once the PSIS and entry point are identified, the site is blocked with 10 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine.

Prior to introduction of the trocar, all instrumentation is primed with heparin and syringes are prepped with anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution, solution A. A stab incision is made at the site. The trocar is placed at the entry point, which should be centered in a superior-inferior plane and at the most medial point of the PSIS. Starting with the trocar vertical, the trocar is angled laterally 24° by dropping the hand medially toward the midline. No angulation cephalad or caudad is necessary, but cephalad must be avoided so as not to skive superiorly. This angle, which is recommended for both males and females, allows for the greatest distance the trocar can travel in bone before hitting the anterior ilium wall. A standard deviation of 5.57° is present, which should be considered. Steady pressure should be applied with a slight twisting motion on the PSIS. If advancement of the trocar is too difficult, a mallet or drill can be used to assist in penetration.

With the trocar advanced into the bone 1 cm, the trocar needle is removed while the cannula remains in place. The syringe is attached to the top of the cannula. The syringe plunger is pulled back to aspirate 20 mL of bone marrow. The cannula and syringe assembly are advanced 2 cm farther into the bone to allow for aspiration of a new location within the bone marrow cavity, and 20 mL of bone marrow are again aspirated. This is done a final time, advancing the trocar another 2 cm and aspirating a final 20 mL of bone marrow. The entire process should yield roughly 60 mL of bone marrow from one side. If desired, the same process can be repeated for the contralateral PSIS to yield a total of 120 mL of bone marrow from the 2 sites.

Based on our data, the average distance to the anterior ilium wall was 7 cm, but the shortest distance noted in this study was 5 cm. On the basis of the data presented, this technique allows for safe advancement based on even the shortest measured distance, without fear of puncturing the anterior ilium wall. Perforation could damage the femoral nerve and the internal or external iliac artery or vein that lie anterior to the ilium.

Continue to: We hypothesized that there...

DISCUSSION

We hypothesized that there would be an optimal angle of entry and maximal safe distance the trocar could advance through the ilium when aspirating. Because male and female pelvic anatomy differs, we also hypothesized that there would be differences in distance and size measurements for males and females. Our results supported our hypothesis that there is an ideal approach angle. The results also showed that the maximum distance the trocar can advance and the width of the PSIS table differ significantly between males and females.

Although pelvic anatomy differs between males and females, there should be an ideal entry angle that would allow maximum advancement into the ilium without perforating the anterior wall, which we defined as the approach angle. In our comparison of 26 MRI scans, we found that the approach angle did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (13 males, 13 females). This allows clinicians to enter the PSIS at roughly 24° medial to the parasagittal line, maximizing the space before puncturing into the anterior pelvis in either males or females.

If clinicians were to enter perpendicular to the patient’s PSIS, they would, on average, be able to advance only 3.20 cm before encountering the SI joint. When entering at 24° as we recommend, the average distance increases to 7.14 cm. Although the angle did not differ significantly, there was a significant difference between males and females in the length from the PSIS to the anterior wall, with males having 7.53 cm distance and females 6.74 cm. This is an important measurement because if the anterior ilium wall is punctured, the femoral nerve and the common, internal and external iliac arteries and veins could be damaged, resulting in retroperitoneal hemorrhage.

A fatality in 2001 in the United Kingdom led to a national audit of bone marrow aspiration and biopsies.4-6 Although these procedures were done primarily for patients with cancer, hemorrhagic events were the most frequent and serious events. This audit led to the identification of many risk factors. Bain4-6 conducted reviews of bone marrow aspirations and biopsies in the United Kingdom from 2002 to 2004. Of a total of 53,088 procedures conducted during that time frame, 48 (0.09%) adverse events occurred, with 29 (0.05%) being hemorrhagic events. Although infrequent, hemorrhagic adverse events represent significant morbidity. Reviews such as those conducted by Bain4-6 highlight the importance of a study that helps determine the optimal parameters for aspiration to ensure safety and reliability.

Hernigou and colleagues2,3 conducted studies analyzing different “sectors” in an attempt to develop a safe aspiration technique. They found that obese patients were at higher risk, and some sites of aspiration (sectors 1, 4, 5) had increased risk for perforation and damage to surrounding structures. Their sector 6, which incorporated the entirety of the PSIS table, was considered the safest, most reliable site for trocar introduction.2,3 Hernigou and colleagues,2 in comparing the bone mass of the sectors, also noted that sector 6 has the greatest bone thickness close to the entry point, making it the most favorable site. The PSIS is not just a point; it is more a “table.” The PSIS can be palpated posteriorly, but this is inaccurate and unreliable, particularly in larger individuals. The PSIS table can be identified on ultrasound before introducing the trocar, which is a more reliable method of landmark identification than palpation guidance, just as in ultrasound-guided injections7-16 and procedures.9,12,17-19

Continue to: If the PSIS is not accurately...

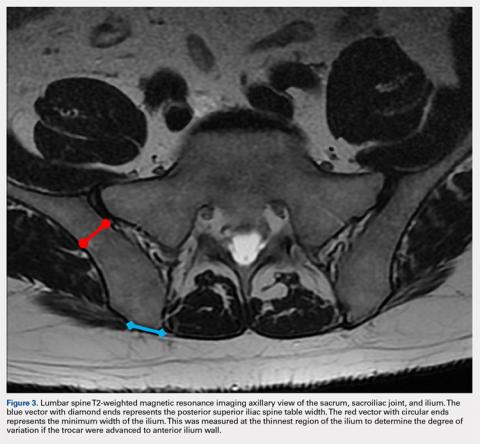

If the PSIS is not accurately identified, penetration laterally will result in entering the ilium wing, where it is quite narrow. We found the distance between the posterior ilium wall and the SI joint to be only 1.10 cm wide (Figure 3); we defined this area as the narrow corridor. Superior and lateral entry could damage the superior cluneal nerves coming over the iliac crest, which are located 6 cm lateral to the SI joint. Inferior and lateral entry 6 cm below the PSIS could reach the greater sciatic foramen, damaging the sacral plexus and superior gluteal artery and vein. If the entry slips above the PSIS over the pelvis, the trocar could enter the retroperitoneal space and damage the femoral nerve and common iliac artery and vein, leading to a retroperitoneal hemorrhage.4-6,20

MSCs are found as perivascular cells and lie in the cortices of bones.21 Following the approach angle and directed line from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall described in this study (Figures 1 and 2), the trocar would pass through the narrow corridor as it advances farther into the ilium. The minimum width of this corridor was measured in this study and, on average, was 1.10 cm wide from cortex to cortex (Figure 3). As the bone marrow is aspirated from this narrow corridor, the clinician is gathering MSCs from both the lateral and medial cortices of the ilium. By aspirating from a greater surface area of the cortices, it is believed that this will increase the total collection of MSCs.

CONCLUSION

Although there are reports in the literature that describe techniques for bone marrow aspiration from the iliac crest, the techniques are very general and vague regarding the ideal angles and methods. Studies have attempted to quantify the safest entry sites for aspiration but have not detailed ideal parameters for collection. Blind aspiration from the iliac crest can have serious implications if adverse events occur, and thus there is a need for a safe and reliable method of aspiration from the iliac crest. Ultrasound guidance to identify anatomy, as opposed to palpation guidance, ensures anatomic placement of the trocar while minimizing the risk of aspiration. Based on the measurements gathered in this study, an optimal angle of entry and safe distance of penetration have been identified. Using our data and relevant literature, we developed a technique for a safe, consistent, and reliable method of bone marrow aspiration out of the iliac crest.

1. Chahla J, Mannava S, Cinque ME, Geeslin AG, Codina D, LaPrade RF. Bone marrow aspirate concentrate harvesting and processing technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6(2):e441-e445. doi:10.1016/j.eats.2016.10.024.

2. Hernigou J, Alves A, Homma Y, Guissou I, Hernigou P. Anatomy of the ilium for bone marrow aspiration: map of sectors and implication for safe trocar placement. Int Orthop. 2014;38(12):2585-2590. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2353-7.

3. Hernigou J, Picard L, Alves A, Silvera J, Homma Y, Hernigou P. Understanding bone safety zones during bone marrow aspiration from the iliac crest: the sector rule. Int Orthop. 2014;38(11):2377-2384. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2343-9.

4. Bain BJ. Bone marrow biopsy morbidity: review of 2003. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(4):406-408. doi:10.1136/jcp.2004.022178.

5. Bain BJ. Bone marrow biopsy morbidity and mortality: 2002 data. Clin Lab Haematol. 2004;26(5):315-318. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2257.2004.00630.x.

6. Bain BJ. Morbidity associated with bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy - a review of UK data for 2004. Haematologica. 2006;91(9):1293-1294.

7. Berkoff DJ, Miller LE, Block JE. Clinical utility of ultrasound guidance for intra-articular knee injections: a review. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:89-95. doi:10.2147/CIA.S29265.

8. Henkus HE, Cobben LP, Coerkamp EG, Nelissen RG, van Arkel ER. The accuracy of subacromial injections: a prospective randomized magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(3):277-282. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2005.12.019.

9. Hirahara AM, Panero AJ. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 3: interventional and procedural uses. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):440-445.

10. Jackson DW, Evans NA, Thomas BM. Accuracy of needle placement into the intra-articular space of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A(9):1522-1527.

11. Naredo E, Cabero F, Beneyto P, et al. A randomized comparative study of short term response to blind versus sonographic-guided injection of local corticosteroids in patients with painful shoulder. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):308-314.

12. Panero AJ, Hirahara AM. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 2: the diagnostic evaluation. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(4):233-238.

13. Sethi PM, El Attrache N. Accuracy of intra-articular injection of the glenohumeral joint: a cadaveric study. Orthopedics. 2006;29(2):149-152.

14. Sibbit WL Jr, Peisajovich A, Michael AA, et al. Does sonographic needle guidance affect the clinical outcome of intraarticular injections? J Rheumatol. 2009;36(9):1892-1902. doi:10.3899/jrheum.090013.

15. Smith J, Brault JS, Rizzo M, Sayeed YA, Finnoff JT. Accuracy of sonographically guided and palpation guided scaphotrapeziotrapezoid joint injections. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30(11):1509-1515. doi:10.7863/jum.2011.30.11.1509.

16. Yamakado K. The targeting accuracy of subacromial injection to the shoulder: an arthrographic evaluation. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(8):887-891.

17. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous reconstruction of the anterolateral ligament: surgical technique and case report. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):418-422, 460.

18. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous repair of medial patellofemoral ligament: surgical technique and outcomes. Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):152-157.

19. Hirahara AM, Mackay G, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided InternalBrace of the medial collateral ligament. Arthrosc Tech. Submitted.

20. Jamaludin WFW, Mukari SAM, Wahid SFA. Retroperitoneal hemorrhage associated with bone marrow trephine biopsy. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:489-493. doi:10.12659/AJCR.889274.

21. Bianco P, Cao X, Frenette PS, et al. The meaning, the sense and the significance: translating the science of mesenchymal stem cells into medicine. Nat Med. 2013;19(1):35-42. doi:10.1038/nm.3028.

ABSTRACT

Use of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow has gained significant popularity. The iliac crest has been determined to be an effective site for harvesting mesenchymal stem cells. Review of the literature reveals that multiple techniques are used to harvest bone marrow aspirate from the iliac crest, but the descriptions are based on the experience of various authors as opposed to studied anatomy. A safe, reliable, and reproducible method for aspiration has yet to be studied and described. We hypothesized that there would be an ideal angle and distance for aspiration that would be the safest, most consistent, and most reliable. Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), we reviewed 26 total lumbar spine MRI scans (13 males, 13 females) and found that an angle of 24° should be used when entering the most medial aspect of the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) and that this angle did not differ between the sexes. The distance that the trocar can advance after entry before hitting the anterior ilium wall varied significantly between males and females, being 7.53 cm in males and 6.74 cm in females. In addition, the size of the PSIS table was significantly different between males and females (1.20 cm and 0.96 cm, respectively). No other significant differences in the measurements gathered were found. Using the data gleaned from this study, we developed an aspiration technique. This method uses ultrasound to determine the location of the PSIS and the entry point on the PSIS. This contrasts with most techniques that use landmark palpation, which is known to be unreliable and inaccurate. The described technique for aspiration from the PSIS is safe, reliable, reproducible, and substantiated by data.

The iliac crest is an effective site for harvesting bone marrow stem cells. It allows for easy access and is superficial in most individuals, allowing for a relatively quick and simple procedure. Use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for treatment of orthopedic injuries has grown recently. Whereas overall use has increased, review of the literature reveals very few techniques for iliac crest aspiration,1 but these are not based on anatomic relationships or studies. Hernigou and colleagues2,3 attempted to quantitatively evaluate potential “sectors” allowing for safe aspiration using cadaver and computed tomographic reconstruction imaging. We used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to analyze aspiration parameters. Owing to the ilium’s anatomy, improper positioning or aspiration technique during aspiration can result in serious injury.2,4-6 We hypothesized that there is an ideal angle and positioning for bone marrow aspiration from the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) that is safe, consistent, and reproducible. Although most aspiration techniques use landmark palpation, this is unreliable and inaccurate, especially when compared with ultrasound-guided injections7-16 and procedures.9,12,17-19 We describe our technique using ultrasound to visualize patient anatomy and accurately determine anatomic entry with the trocar.

METHODS

MRI scans of 26 patients (13 males, 13 females) were reviewed to determine average angles and distances. Axial T2-weighted views of the lumbar spine were used in all analyses. The sacroiliac (SI) joint angle was defined as the angle formed between the vector through the midline of the pelvis and the vector that is parallel to the SI joint. The approach angle was defined as the angle formed between the vector of the most medial aspect of the PSIS through the ilium to the anterior wall and the vector through the midline of the pelvis (Figure 1).

Continue to: For the 13 males, the mean SI joint...

RESULTS

The results are reported in the Table.

Table. Measurements of Patients Taken on Axial T2-Weighted Views of Lumbosacral MRI Scansa

Patient | SI Joint Angle (°) | Approach Angle (°) | PSIS Table Width (cm) | PSIS to Anterior Ilium Wall (cm) | Perpendicular Distance PSIS to Anterior Joint (cm) | Post Ilium Wall to SI Joint Width (cm) |

Males | ||||||

1 | 28.80 | 19.50 | 1.24 | 8.80 | 4.16 | 1.52 |

2 | 31.80 | 27.60 | 1.70 | 7.89 | 3.49 | 1.02 |

3 | 33.70 | 27.70 | 1.12 | 8.14 | 3.15 | 1.28 |

4 | 23.70 | 26.40 | 0.95 | 6.66 | 3.22 | 0.65 |

5 | 35.90 | 28.40 | 0.84 | 7.60 | 2.57 | 0.95 |

6 | 33.80 | 29.30 | 1.20 | 7.73 | 2.34 | 0.90 |

7 | 30.30 | 21.20 | 1.36 | 8.44 | 3.95 | 1.18 |

8 | 34.50 | 20.40 | 1.53 | 7.08 | 3.98 | 1.56 |

9 | 28.70 | 24.00 | 1.34 | 8.19 | 3.51 | 1.31 |

10 | 22.40 | 20.10 | 1.37 | 7.30 | 3.87 | 1.28 |

11 | 33.60 | 20.80 | 0.88 | 6.43 | 3.26 | 0.94 |

12 | 48.50 | 31.00 | 1.15 | 6.69 | 2.97 | 1.38 |

13 | 20.20 | 20.90 | 0.94 | 6.95 | 3.79 | 1.05 |

Averages | 31.22 | 24.41 | 1.20 | 7.53 | 3.40 | 1.16 |

Standard Deviation | 7.18 | 4.11 | 0.26 | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.26 |

Females | ||||||

14 | 22.80 | 23.20 | 1.54 | 7.21 | 3.45 | 1.39 |

15 | 33.30 | 21.40 | 1.09 | 7.26 | 3.57 | 0.98 |

16 | 19.70 | 15.60 | 0.78 | 8.32 | 3.76 | 0.86 |

17 | 17.50 | 15.60 | 0.61 | 7.57 | 3.37 | 1.03 |

18 | 48.20 | 26.60 | 0.94 | 6.62 | 3.16 | 0.71 |

19 | 38.20 | 28.30 | 0.90 | 6.32 | 2.23 | 0.91 |

20 | 44.50 | 31.70 | 0.99 | 6.19 | 3.06 | 0.76 |

21 | 24.10 | 18.00 | 0.92 | 6.99 | 3.23 | 0.71 |

22 | 17.20 | 14.80 | 0.81 | 6.00 | 2.81 | 1.13 |

23 | 42.00 | 38.50 | 1.00 | 5.33 | 2.47 | 1.42 |

24 | 32.00 | 25.50 | 0.98 | 6.01 | 2.79 | 1.21 |

25 | 24.70 | 24.80 | 0.87 | 6.09 | 2.79 | 1.02 |

26 | 19.80 | 22.30 | 1.04 | 7.71 | 2.37 | 1.36 |

Averages | 29.54 | 23.56 | 0.96 | 6.74 | 3.00 | 1.04 |

Standard Deviation | 10.84 | 6.88 | 0.21 | 0.85 | 0.48 | 0.25 |

All patients Averages | 30.38 | 23.98 | 1.08 | 7.14 | 3.20 | 1.10 |

Standard Deviation | 9.05 | 5.57 | 0.26 | 0.88 | 0.55 | 0.26 |

aStatistical significance is denoted as P < .02.

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PSIS, posterior iliac spine; SI, sacroiliac.

For the 13 males, the mean SI joint angle was 31.22° ± 7.18° (range, 20.20° to 48.50°). The mean approach angle was 24.41° ± 4.11° (range, 19.50° to 31.00°). The mean PSIS table width was 1.20 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.84 cm to 1.70 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 7.53 cm ± 0.75 cm (range, 6.43 cm to 8.80 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.40 cm ± 0.56 cm (range, 2.34 cm to 4.16 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.16 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.65 cm to 1.56 cm).

For the 13 females, the mean SI joint angle was 29.54° ± 10.84° (range, 17.20° to 48.20°). The mean approach angle was 23.56° ± 6.88° (range, 14.80° to 38.50°). The mean PSIS table width was 0.96 cm ± 0.21 cm (range, 0.61 cm to 1.54 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 6.74 cm ± 0.85 cm (range, 5.33 cm to 8.32 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.00 cm ± 0.48 cm (range, 2.23 cm to 3.76 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.04 cm ± 0.25 cm (range, 0.71 cm to 1.42 cm).

For the 26 total patients, the mean SI joint angle was 30.38° ± 9.05° (range, 17.20° to 48.50°). The mean approach angle was 23.98° ± 5.57° (range, 14.80° to 38.50°). The mean PSIS table width was 1.08 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.61 cm to 1.70 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 7.14 cm ± 0.88 cm (range, 5.33 cm to 8.80 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.20 cm ± 0.55 cm (range, 2.23 cm to 4.16 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.10 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.65 cm to 1.56 cm).

There was a statistically significant difference between the male and female groups for the maximum distance the trocar can be advanced from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall (P < .02), and a statistically significant difference for the PSIS table width (P < .02). There were no significant differences between the male and female groups for the approach angle, the SI joint angle, the perpendicular distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium, and the minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint.

Continue to: The patient is brought to the procedure...

TECHNIQUE: ILIAC CREST (PSIS) BONE MARROW ASPIRATION

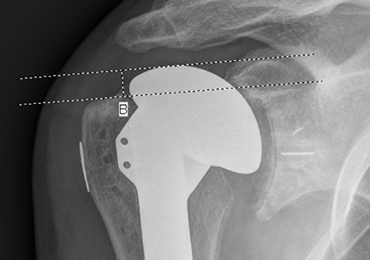

The patient is brought to the procedure room and placed in a prone position. The donor site is prepared and draped in the usual sterile manner. Ultrasound is used to identify the median sacral crest in a short-axis view. The probe is then moved laterally to identify the PSIS (Figures 4A, 4B).

The crosshairs on the ultrasound probe are used to mark the center lines of each plane. The central point marks the location of the PSIS. Alternatively, an in-plane technique can be used to place a spinal needle on the exact entry point on the PSIS. Once the PSIS and entry point are identified, the site is blocked with 10 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine.

Prior to introduction of the trocar, all instrumentation is primed with heparin and syringes are prepped with anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution, solution A. A stab incision is made at the site. The trocar is placed at the entry point, which should be centered in a superior-inferior plane and at the most medial point of the PSIS. Starting with the trocar vertical, the trocar is angled laterally 24° by dropping the hand medially toward the midline. No angulation cephalad or caudad is necessary, but cephalad must be avoided so as not to skive superiorly. This angle, which is recommended for both males and females, allows for the greatest distance the trocar can travel in bone before hitting the anterior ilium wall. A standard deviation of 5.57° is present, which should be considered. Steady pressure should be applied with a slight twisting motion on the PSIS. If advancement of the trocar is too difficult, a mallet or drill can be used to assist in penetration.

With the trocar advanced into the bone 1 cm, the trocar needle is removed while the cannula remains in place. The syringe is attached to the top of the cannula. The syringe plunger is pulled back to aspirate 20 mL of bone marrow. The cannula and syringe assembly are advanced 2 cm farther into the bone to allow for aspiration of a new location within the bone marrow cavity, and 20 mL of bone marrow are again aspirated. This is done a final time, advancing the trocar another 2 cm and aspirating a final 20 mL of bone marrow. The entire process should yield roughly 60 mL of bone marrow from one side. If desired, the same process can be repeated for the contralateral PSIS to yield a total of 120 mL of bone marrow from the 2 sites.

Based on our data, the average distance to the anterior ilium wall was 7 cm, but the shortest distance noted in this study was 5 cm. On the basis of the data presented, this technique allows for safe advancement based on even the shortest measured distance, without fear of puncturing the anterior ilium wall. Perforation could damage the femoral nerve and the internal or external iliac artery or vein that lie anterior to the ilium.

Continue to: We hypothesized that there...

DISCUSSION

We hypothesized that there would be an optimal angle of entry and maximal safe distance the trocar could advance through the ilium when aspirating. Because male and female pelvic anatomy differs, we also hypothesized that there would be differences in distance and size measurements for males and females. Our results supported our hypothesis that there is an ideal approach angle. The results also showed that the maximum distance the trocar can advance and the width of the PSIS table differ significantly between males and females.

Although pelvic anatomy differs between males and females, there should be an ideal entry angle that would allow maximum advancement into the ilium without perforating the anterior wall, which we defined as the approach angle. In our comparison of 26 MRI scans, we found that the approach angle did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (13 males, 13 females). This allows clinicians to enter the PSIS at roughly 24° medial to the parasagittal line, maximizing the space before puncturing into the anterior pelvis in either males or females.

If clinicians were to enter perpendicular to the patient’s PSIS, they would, on average, be able to advance only 3.20 cm before encountering the SI joint. When entering at 24° as we recommend, the average distance increases to 7.14 cm. Although the angle did not differ significantly, there was a significant difference between males and females in the length from the PSIS to the anterior wall, with males having 7.53 cm distance and females 6.74 cm. This is an important measurement because if the anterior ilium wall is punctured, the femoral nerve and the common, internal and external iliac arteries and veins could be damaged, resulting in retroperitoneal hemorrhage.

A fatality in 2001 in the United Kingdom led to a national audit of bone marrow aspiration and biopsies.4-6 Although these procedures were done primarily for patients with cancer, hemorrhagic events were the most frequent and serious events. This audit led to the identification of many risk factors. Bain4-6 conducted reviews of bone marrow aspirations and biopsies in the United Kingdom from 2002 to 2004. Of a total of 53,088 procedures conducted during that time frame, 48 (0.09%) adverse events occurred, with 29 (0.05%) being hemorrhagic events. Although infrequent, hemorrhagic adverse events represent significant morbidity. Reviews such as those conducted by Bain4-6 highlight the importance of a study that helps determine the optimal parameters for aspiration to ensure safety and reliability.

Hernigou and colleagues2,3 conducted studies analyzing different “sectors” in an attempt to develop a safe aspiration technique. They found that obese patients were at higher risk, and some sites of aspiration (sectors 1, 4, 5) had increased risk for perforation and damage to surrounding structures. Their sector 6, which incorporated the entirety of the PSIS table, was considered the safest, most reliable site for trocar introduction.2,3 Hernigou and colleagues,2 in comparing the bone mass of the sectors, also noted that sector 6 has the greatest bone thickness close to the entry point, making it the most favorable site. The PSIS is not just a point; it is more a “table.” The PSIS can be palpated posteriorly, but this is inaccurate and unreliable, particularly in larger individuals. The PSIS table can be identified on ultrasound before introducing the trocar, which is a more reliable method of landmark identification than palpation guidance, just as in ultrasound-guided injections7-16 and procedures.9,12,17-19

Continue to: If the PSIS is not accurately...

If the PSIS is not accurately identified, penetration laterally will result in entering the ilium wing, where it is quite narrow. We found the distance between the posterior ilium wall and the SI joint to be only 1.10 cm wide (Figure 3); we defined this area as the narrow corridor. Superior and lateral entry could damage the superior cluneal nerves coming over the iliac crest, which are located 6 cm lateral to the SI joint. Inferior and lateral entry 6 cm below the PSIS could reach the greater sciatic foramen, damaging the sacral plexus and superior gluteal artery and vein. If the entry slips above the PSIS over the pelvis, the trocar could enter the retroperitoneal space and damage the femoral nerve and common iliac artery and vein, leading to a retroperitoneal hemorrhage.4-6,20

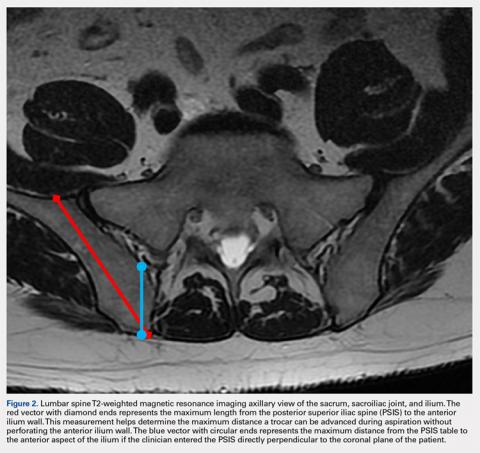

MSCs are found as perivascular cells and lie in the cortices of bones.21 Following the approach angle and directed line from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall described in this study (Figures 1 and 2), the trocar would pass through the narrow corridor as it advances farther into the ilium. The minimum width of this corridor was measured in this study and, on average, was 1.10 cm wide from cortex to cortex (Figure 3). As the bone marrow is aspirated from this narrow corridor, the clinician is gathering MSCs from both the lateral and medial cortices of the ilium. By aspirating from a greater surface area of the cortices, it is believed that this will increase the total collection of MSCs.

CONCLUSION

Although there are reports in the literature that describe techniques for bone marrow aspiration from the iliac crest, the techniques are very general and vague regarding the ideal angles and methods. Studies have attempted to quantify the safest entry sites for aspiration but have not detailed ideal parameters for collection. Blind aspiration from the iliac crest can have serious implications if adverse events occur, and thus there is a need for a safe and reliable method of aspiration from the iliac crest. Ultrasound guidance to identify anatomy, as opposed to palpation guidance, ensures anatomic placement of the trocar while minimizing the risk of aspiration. Based on the measurements gathered in this study, an optimal angle of entry and safe distance of penetration have been identified. Using our data and relevant literature, we developed a technique for a safe, consistent, and reliable method of bone marrow aspiration out of the iliac crest.

ABSTRACT

Use of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow has gained significant popularity. The iliac crest has been determined to be an effective site for harvesting mesenchymal stem cells. Review of the literature reveals that multiple techniques are used to harvest bone marrow aspirate from the iliac crest, but the descriptions are based on the experience of various authors as opposed to studied anatomy. A safe, reliable, and reproducible method for aspiration has yet to be studied and described. We hypothesized that there would be an ideal angle and distance for aspiration that would be the safest, most consistent, and most reliable. Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), we reviewed 26 total lumbar spine MRI scans (13 males, 13 females) and found that an angle of 24° should be used when entering the most medial aspect of the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) and that this angle did not differ between the sexes. The distance that the trocar can advance after entry before hitting the anterior ilium wall varied significantly between males and females, being 7.53 cm in males and 6.74 cm in females. In addition, the size of the PSIS table was significantly different between males and females (1.20 cm and 0.96 cm, respectively). No other significant differences in the measurements gathered were found. Using the data gleaned from this study, we developed an aspiration technique. This method uses ultrasound to determine the location of the PSIS and the entry point on the PSIS. This contrasts with most techniques that use landmark palpation, which is known to be unreliable and inaccurate. The described technique for aspiration from the PSIS is safe, reliable, reproducible, and substantiated by data.

The iliac crest is an effective site for harvesting bone marrow stem cells. It allows for easy access and is superficial in most individuals, allowing for a relatively quick and simple procedure. Use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for treatment of orthopedic injuries has grown recently. Whereas overall use has increased, review of the literature reveals very few techniques for iliac crest aspiration,1 but these are not based on anatomic relationships or studies. Hernigou and colleagues2,3 attempted to quantitatively evaluate potential “sectors” allowing for safe aspiration using cadaver and computed tomographic reconstruction imaging. We used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to analyze aspiration parameters. Owing to the ilium’s anatomy, improper positioning or aspiration technique during aspiration can result in serious injury.2,4-6 We hypothesized that there is an ideal angle and positioning for bone marrow aspiration from the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) that is safe, consistent, and reproducible. Although most aspiration techniques use landmark palpation, this is unreliable and inaccurate, especially when compared with ultrasound-guided injections7-16 and procedures.9,12,17-19 We describe our technique using ultrasound to visualize patient anatomy and accurately determine anatomic entry with the trocar.

METHODS

MRI scans of 26 patients (13 males, 13 females) were reviewed to determine average angles and distances. Axial T2-weighted views of the lumbar spine were used in all analyses. The sacroiliac (SI) joint angle was defined as the angle formed between the vector through the midline of the pelvis and the vector that is parallel to the SI joint. The approach angle was defined as the angle formed between the vector of the most medial aspect of the PSIS through the ilium to the anterior wall and the vector through the midline of the pelvis (Figure 1).

Continue to: For the 13 males, the mean SI joint...

RESULTS

The results are reported in the Table.

Table. Measurements of Patients Taken on Axial T2-Weighted Views of Lumbosacral MRI Scansa

Patient | SI Joint Angle (°) | Approach Angle (°) | PSIS Table Width (cm) | PSIS to Anterior Ilium Wall (cm) | Perpendicular Distance PSIS to Anterior Joint (cm) | Post Ilium Wall to SI Joint Width (cm) |

Males | ||||||

1 | 28.80 | 19.50 | 1.24 | 8.80 | 4.16 | 1.52 |

2 | 31.80 | 27.60 | 1.70 | 7.89 | 3.49 | 1.02 |

3 | 33.70 | 27.70 | 1.12 | 8.14 | 3.15 | 1.28 |

4 | 23.70 | 26.40 | 0.95 | 6.66 | 3.22 | 0.65 |

5 | 35.90 | 28.40 | 0.84 | 7.60 | 2.57 | 0.95 |

6 | 33.80 | 29.30 | 1.20 | 7.73 | 2.34 | 0.90 |

7 | 30.30 | 21.20 | 1.36 | 8.44 | 3.95 | 1.18 |

8 | 34.50 | 20.40 | 1.53 | 7.08 | 3.98 | 1.56 |

9 | 28.70 | 24.00 | 1.34 | 8.19 | 3.51 | 1.31 |

10 | 22.40 | 20.10 | 1.37 | 7.30 | 3.87 | 1.28 |

11 | 33.60 | 20.80 | 0.88 | 6.43 | 3.26 | 0.94 |

12 | 48.50 | 31.00 | 1.15 | 6.69 | 2.97 | 1.38 |

13 | 20.20 | 20.90 | 0.94 | 6.95 | 3.79 | 1.05 |

Averages | 31.22 | 24.41 | 1.20 | 7.53 | 3.40 | 1.16 |

Standard Deviation | 7.18 | 4.11 | 0.26 | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.26 |

Females | ||||||

14 | 22.80 | 23.20 | 1.54 | 7.21 | 3.45 | 1.39 |

15 | 33.30 | 21.40 | 1.09 | 7.26 | 3.57 | 0.98 |

16 | 19.70 | 15.60 | 0.78 | 8.32 | 3.76 | 0.86 |

17 | 17.50 | 15.60 | 0.61 | 7.57 | 3.37 | 1.03 |

18 | 48.20 | 26.60 | 0.94 | 6.62 | 3.16 | 0.71 |

19 | 38.20 | 28.30 | 0.90 | 6.32 | 2.23 | 0.91 |

20 | 44.50 | 31.70 | 0.99 | 6.19 | 3.06 | 0.76 |

21 | 24.10 | 18.00 | 0.92 | 6.99 | 3.23 | 0.71 |

22 | 17.20 | 14.80 | 0.81 | 6.00 | 2.81 | 1.13 |

23 | 42.00 | 38.50 | 1.00 | 5.33 | 2.47 | 1.42 |

24 | 32.00 | 25.50 | 0.98 | 6.01 | 2.79 | 1.21 |

25 | 24.70 | 24.80 | 0.87 | 6.09 | 2.79 | 1.02 |

26 | 19.80 | 22.30 | 1.04 | 7.71 | 2.37 | 1.36 |

Averages | 29.54 | 23.56 | 0.96 | 6.74 | 3.00 | 1.04 |

Standard Deviation | 10.84 | 6.88 | 0.21 | 0.85 | 0.48 | 0.25 |

All patients Averages | 30.38 | 23.98 | 1.08 | 7.14 | 3.20 | 1.10 |

Standard Deviation | 9.05 | 5.57 | 0.26 | 0.88 | 0.55 | 0.26 |

aStatistical significance is denoted as P < .02.

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PSIS, posterior iliac spine; SI, sacroiliac.

For the 13 males, the mean SI joint angle was 31.22° ± 7.18° (range, 20.20° to 48.50°). The mean approach angle was 24.41° ± 4.11° (range, 19.50° to 31.00°). The mean PSIS table width was 1.20 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.84 cm to 1.70 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 7.53 cm ± 0.75 cm (range, 6.43 cm to 8.80 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.40 cm ± 0.56 cm (range, 2.34 cm to 4.16 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.16 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.65 cm to 1.56 cm).

For the 13 females, the mean SI joint angle was 29.54° ± 10.84° (range, 17.20° to 48.20°). The mean approach angle was 23.56° ± 6.88° (range, 14.80° to 38.50°). The mean PSIS table width was 0.96 cm ± 0.21 cm (range, 0.61 cm to 1.54 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 6.74 cm ± 0.85 cm (range, 5.33 cm to 8.32 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.00 cm ± 0.48 cm (range, 2.23 cm to 3.76 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.04 cm ± 0.25 cm (range, 0.71 cm to 1.42 cm).

For the 26 total patients, the mean SI joint angle was 30.38° ± 9.05° (range, 17.20° to 48.50°). The mean approach angle was 23.98° ± 5.57° (range, 14.80° to 38.50°). The mean PSIS table width was 1.08 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.61 cm to 1.70 cm). The mean distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall was 7.14 cm ± 0.88 cm (range, 5.33 cm to 8.80 cm). The mean perpendicular distance from the PSIS table to the anterior ilium was 3.20 cm ± 0.55 cm (range, 2.23 cm to 4.16 cm). The mean minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint was 1.10 cm ± 0.26 cm (range, 0.65 cm to 1.56 cm).

There was a statistically significant difference between the male and female groups for the maximum distance the trocar can be advanced from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall (P < .02), and a statistically significant difference for the PSIS table width (P < .02). There were no significant differences between the male and female groups for the approach angle, the SI joint angle, the perpendicular distance from the PSIS to the anterior ilium, and the minimum width of the ilium to the SI joint.

Continue to: The patient is brought to the procedure...

TECHNIQUE: ILIAC CREST (PSIS) BONE MARROW ASPIRATION

The patient is brought to the procedure room and placed in a prone position. The donor site is prepared and draped in the usual sterile manner. Ultrasound is used to identify the median sacral crest in a short-axis view. The probe is then moved laterally to identify the PSIS (Figures 4A, 4B).

The crosshairs on the ultrasound probe are used to mark the center lines of each plane. The central point marks the location of the PSIS. Alternatively, an in-plane technique can be used to place a spinal needle on the exact entry point on the PSIS. Once the PSIS and entry point are identified, the site is blocked with 10 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine.

Prior to introduction of the trocar, all instrumentation is primed with heparin and syringes are prepped with anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution, solution A. A stab incision is made at the site. The trocar is placed at the entry point, which should be centered in a superior-inferior plane and at the most medial point of the PSIS. Starting with the trocar vertical, the trocar is angled laterally 24° by dropping the hand medially toward the midline. No angulation cephalad or caudad is necessary, but cephalad must be avoided so as not to skive superiorly. This angle, which is recommended for both males and females, allows for the greatest distance the trocar can travel in bone before hitting the anterior ilium wall. A standard deviation of 5.57° is present, which should be considered. Steady pressure should be applied with a slight twisting motion on the PSIS. If advancement of the trocar is too difficult, a mallet or drill can be used to assist in penetration.

With the trocar advanced into the bone 1 cm, the trocar needle is removed while the cannula remains in place. The syringe is attached to the top of the cannula. The syringe plunger is pulled back to aspirate 20 mL of bone marrow. The cannula and syringe assembly are advanced 2 cm farther into the bone to allow for aspiration of a new location within the bone marrow cavity, and 20 mL of bone marrow are again aspirated. This is done a final time, advancing the trocar another 2 cm and aspirating a final 20 mL of bone marrow. The entire process should yield roughly 60 mL of bone marrow from one side. If desired, the same process can be repeated for the contralateral PSIS to yield a total of 120 mL of bone marrow from the 2 sites.

Based on our data, the average distance to the anterior ilium wall was 7 cm, but the shortest distance noted in this study was 5 cm. On the basis of the data presented, this technique allows for safe advancement based on even the shortest measured distance, without fear of puncturing the anterior ilium wall. Perforation could damage the femoral nerve and the internal or external iliac artery or vein that lie anterior to the ilium.

Continue to: We hypothesized that there...

DISCUSSION

We hypothesized that there would be an optimal angle of entry and maximal safe distance the trocar could advance through the ilium when aspirating. Because male and female pelvic anatomy differs, we also hypothesized that there would be differences in distance and size measurements for males and females. Our results supported our hypothesis that there is an ideal approach angle. The results also showed that the maximum distance the trocar can advance and the width of the PSIS table differ significantly between males and females.

Although pelvic anatomy differs between males and females, there should be an ideal entry angle that would allow maximum advancement into the ilium without perforating the anterior wall, which we defined as the approach angle. In our comparison of 26 MRI scans, we found that the approach angle did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (13 males, 13 females). This allows clinicians to enter the PSIS at roughly 24° medial to the parasagittal line, maximizing the space before puncturing into the anterior pelvis in either males or females.

If clinicians were to enter perpendicular to the patient’s PSIS, they would, on average, be able to advance only 3.20 cm before encountering the SI joint. When entering at 24° as we recommend, the average distance increases to 7.14 cm. Although the angle did not differ significantly, there was a significant difference between males and females in the length from the PSIS to the anterior wall, with males having 7.53 cm distance and females 6.74 cm. This is an important measurement because if the anterior ilium wall is punctured, the femoral nerve and the common, internal and external iliac arteries and veins could be damaged, resulting in retroperitoneal hemorrhage.

A fatality in 2001 in the United Kingdom led to a national audit of bone marrow aspiration and biopsies.4-6 Although these procedures were done primarily for patients with cancer, hemorrhagic events were the most frequent and serious events. This audit led to the identification of many risk factors. Bain4-6 conducted reviews of bone marrow aspirations and biopsies in the United Kingdom from 2002 to 2004. Of a total of 53,088 procedures conducted during that time frame, 48 (0.09%) adverse events occurred, with 29 (0.05%) being hemorrhagic events. Although infrequent, hemorrhagic adverse events represent significant morbidity. Reviews such as those conducted by Bain4-6 highlight the importance of a study that helps determine the optimal parameters for aspiration to ensure safety and reliability.

Hernigou and colleagues2,3 conducted studies analyzing different “sectors” in an attempt to develop a safe aspiration technique. They found that obese patients were at higher risk, and some sites of aspiration (sectors 1, 4, 5) had increased risk for perforation and damage to surrounding structures. Their sector 6, which incorporated the entirety of the PSIS table, was considered the safest, most reliable site for trocar introduction.2,3 Hernigou and colleagues,2 in comparing the bone mass of the sectors, also noted that sector 6 has the greatest bone thickness close to the entry point, making it the most favorable site. The PSIS is not just a point; it is more a “table.” The PSIS can be palpated posteriorly, but this is inaccurate and unreliable, particularly in larger individuals. The PSIS table can be identified on ultrasound before introducing the trocar, which is a more reliable method of landmark identification than palpation guidance, just as in ultrasound-guided injections7-16 and procedures.9,12,17-19

Continue to: If the PSIS is not accurately...

If the PSIS is not accurately identified, penetration laterally will result in entering the ilium wing, where it is quite narrow. We found the distance between the posterior ilium wall and the SI joint to be only 1.10 cm wide (Figure 3); we defined this area as the narrow corridor. Superior and lateral entry could damage the superior cluneal nerves coming over the iliac crest, which are located 6 cm lateral to the SI joint. Inferior and lateral entry 6 cm below the PSIS could reach the greater sciatic foramen, damaging the sacral plexus and superior gluteal artery and vein. If the entry slips above the PSIS over the pelvis, the trocar could enter the retroperitoneal space and damage the femoral nerve and common iliac artery and vein, leading to a retroperitoneal hemorrhage.4-6,20

MSCs are found as perivascular cells and lie in the cortices of bones.21 Following the approach angle and directed line from the PSIS to the anterior ilium wall described in this study (Figures 1 and 2), the trocar would pass through the narrow corridor as it advances farther into the ilium. The minimum width of this corridor was measured in this study and, on average, was 1.10 cm wide from cortex to cortex (Figure 3). As the bone marrow is aspirated from this narrow corridor, the clinician is gathering MSCs from both the lateral and medial cortices of the ilium. By aspirating from a greater surface area of the cortices, it is believed that this will increase the total collection of MSCs.

CONCLUSION

Although there are reports in the literature that describe techniques for bone marrow aspiration from the iliac crest, the techniques are very general and vague regarding the ideal angles and methods. Studies have attempted to quantify the safest entry sites for aspiration but have not detailed ideal parameters for collection. Blind aspiration from the iliac crest can have serious implications if adverse events occur, and thus there is a need for a safe and reliable method of aspiration from the iliac crest. Ultrasound guidance to identify anatomy, as opposed to palpation guidance, ensures anatomic placement of the trocar while minimizing the risk of aspiration. Based on the measurements gathered in this study, an optimal angle of entry and safe distance of penetration have been identified. Using our data and relevant literature, we developed a technique for a safe, consistent, and reliable method of bone marrow aspiration out of the iliac crest.

1. Chahla J, Mannava S, Cinque ME, Geeslin AG, Codina D, LaPrade RF. Bone marrow aspirate concentrate harvesting and processing technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6(2):e441-e445. doi:10.1016/j.eats.2016.10.024.

2. Hernigou J, Alves A, Homma Y, Guissou I, Hernigou P. Anatomy of the ilium for bone marrow aspiration: map of sectors and implication for safe trocar placement. Int Orthop. 2014;38(12):2585-2590. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2353-7.

3. Hernigou J, Picard L, Alves A, Silvera J, Homma Y, Hernigou P. Understanding bone safety zones during bone marrow aspiration from the iliac crest: the sector rule. Int Orthop. 2014;38(11):2377-2384. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2343-9.

4. Bain BJ. Bone marrow biopsy morbidity: review of 2003. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(4):406-408. doi:10.1136/jcp.2004.022178.

5. Bain BJ. Bone marrow biopsy morbidity and mortality: 2002 data. Clin Lab Haematol. 2004;26(5):315-318. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2257.2004.00630.x.

6. Bain BJ. Morbidity associated with bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy - a review of UK data for 2004. Haematologica. 2006;91(9):1293-1294.

7. Berkoff DJ, Miller LE, Block JE. Clinical utility of ultrasound guidance for intra-articular knee injections: a review. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:89-95. doi:10.2147/CIA.S29265.

8. Henkus HE, Cobben LP, Coerkamp EG, Nelissen RG, van Arkel ER. The accuracy of subacromial injections: a prospective randomized magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(3):277-282. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2005.12.019.

9. Hirahara AM, Panero AJ. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 3: interventional and procedural uses. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):440-445.

10. Jackson DW, Evans NA, Thomas BM. Accuracy of needle placement into the intra-articular space of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A(9):1522-1527.

11. Naredo E, Cabero F, Beneyto P, et al. A randomized comparative study of short term response to blind versus sonographic-guided injection of local corticosteroids in patients with painful shoulder. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):308-314.

12. Panero AJ, Hirahara AM. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 2: the diagnostic evaluation. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(4):233-238.

13. Sethi PM, El Attrache N. Accuracy of intra-articular injection of the glenohumeral joint: a cadaveric study. Orthopedics. 2006;29(2):149-152.

14. Sibbit WL Jr, Peisajovich A, Michael AA, et al. Does sonographic needle guidance affect the clinical outcome of intraarticular injections? J Rheumatol. 2009;36(9):1892-1902. doi:10.3899/jrheum.090013.

15. Smith J, Brault JS, Rizzo M, Sayeed YA, Finnoff JT. Accuracy of sonographically guided and palpation guided scaphotrapeziotrapezoid joint injections. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30(11):1509-1515. doi:10.7863/jum.2011.30.11.1509.

16. Yamakado K. The targeting accuracy of subacromial injection to the shoulder: an arthrographic evaluation. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(8):887-891.

17. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous reconstruction of the anterolateral ligament: surgical technique and case report. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):418-422, 460.

18. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous repair of medial patellofemoral ligament: surgical technique and outcomes. Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):152-157.

19. Hirahara AM, Mackay G, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided InternalBrace of the medial collateral ligament. Arthrosc Tech. Submitted.

20. Jamaludin WFW, Mukari SAM, Wahid SFA. Retroperitoneal hemorrhage associated with bone marrow trephine biopsy. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:489-493. doi:10.12659/AJCR.889274.

21. Bianco P, Cao X, Frenette PS, et al. The meaning, the sense and the significance: translating the science of mesenchymal stem cells into medicine. Nat Med. 2013;19(1):35-42. doi:10.1038/nm.3028.

1. Chahla J, Mannava S, Cinque ME, Geeslin AG, Codina D, LaPrade RF. Bone marrow aspirate concentrate harvesting and processing technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6(2):e441-e445. doi:10.1016/j.eats.2016.10.024.

2. Hernigou J, Alves A, Homma Y, Guissou I, Hernigou P. Anatomy of the ilium for bone marrow aspiration: map of sectors and implication for safe trocar placement. Int Orthop. 2014;38(12):2585-2590. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2353-7.

3. Hernigou J, Picard L, Alves A, Silvera J, Homma Y, Hernigou P. Understanding bone safety zones during bone marrow aspiration from the iliac crest: the sector rule. Int Orthop. 2014;38(11):2377-2384. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2343-9.

4. Bain BJ. Bone marrow biopsy morbidity: review of 2003. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(4):406-408. doi:10.1136/jcp.2004.022178.

5. Bain BJ. Bone marrow biopsy morbidity and mortality: 2002 data. Clin Lab Haematol. 2004;26(5):315-318. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2257.2004.00630.x.

6. Bain BJ. Morbidity associated with bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy - a review of UK data for 2004. Haematologica. 2006;91(9):1293-1294.

7. Berkoff DJ, Miller LE, Block JE. Clinical utility of ultrasound guidance for intra-articular knee injections: a review. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:89-95. doi:10.2147/CIA.S29265.

8. Henkus HE, Cobben LP, Coerkamp EG, Nelissen RG, van Arkel ER. The accuracy of subacromial injections: a prospective randomized magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(3):277-282. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2005.12.019.

9. Hirahara AM, Panero AJ. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 3: interventional and procedural uses. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):440-445.

10. Jackson DW, Evans NA, Thomas BM. Accuracy of needle placement into the intra-articular space of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A(9):1522-1527.

11. Naredo E, Cabero F, Beneyto P, et al. A randomized comparative study of short term response to blind versus sonographic-guided injection of local corticosteroids in patients with painful shoulder. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):308-314.

12. Panero AJ, Hirahara AM. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 2: the diagnostic evaluation. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(4):233-238.

13. Sethi PM, El Attrache N. Accuracy of intra-articular injection of the glenohumeral joint: a cadaveric study. Orthopedics. 2006;29(2):149-152.

14. Sibbit WL Jr, Peisajovich A, Michael AA, et al. Does sonographic needle guidance affect the clinical outcome of intraarticular injections? J Rheumatol. 2009;36(9):1892-1902. doi:10.3899/jrheum.090013.

15. Smith J, Brault JS, Rizzo M, Sayeed YA, Finnoff JT. Accuracy of sonographically guided and palpation guided scaphotrapeziotrapezoid joint injections. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30(11):1509-1515. doi:10.7863/jum.2011.30.11.1509.

16. Yamakado K. The targeting accuracy of subacromial injection to the shoulder: an arthrographic evaluation. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(8):887-891.

17. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous reconstruction of the anterolateral ligament: surgical technique and case report. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):418-422, 460.

18. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous repair of medial patellofemoral ligament: surgical technique and outcomes. Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):152-157.

19. Hirahara AM, Mackay G, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided InternalBrace of the medial collateral ligament. Arthrosc Tech. Submitted.

20. Jamaludin WFW, Mukari SAM, Wahid SFA. Retroperitoneal hemorrhage associated with bone marrow trephine biopsy. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:489-493. doi:10.12659/AJCR.889274.

21. Bianco P, Cao X, Frenette PS, et al. The meaning, the sense and the significance: translating the science of mesenchymal stem cells into medicine. Nat Med. 2013;19(1):35-42. doi:10.1038/nm.3028.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- There is an ideal angle and distance for optimization of a bone marrow harvest from the iliac crest.

- Ultrasound is a reliable technology that allows clinicians to accurately and consistently identify the PSIS and avoid neurovascular structures.

- This safe, reliable bone marrow aspiration technique can lower the risk of serious potential complications.

- The ideal angle does not differ significantly between sexes, but the safe distance a clinician can advance does.

- The PSIS should be considered a “table” as opposed to a protuberance.

Use of Short Peripheral Intravenous Catheters: Characteristics, Management, and Outcomes Worldwide

The majority of hospitalized patients worldwide have at least one peripheral intravenous catheter (PIVC),1 making PIVC insertion one of the most common clinical procedures. In the United States, physicians, advanced practitioners, and nurses insert over 300 million of these devices in hospitalized patients annually.2 Despite their prevalence, PIVCs are associated with high rates of complications, including insertion difficulty, phlebitis, infiltration, occlusion, dislodgment, and catheter-associated bloodstream infection (CABSI), known to increase morbidity and mortality risk.2-9 Up to 90% of PIVCs are prematurely removed owing to failure before planned replacement or before intravenous (IV) therapy completion.3-6,10-12

PIVC complication and failure commonly triggers insertion of a replacement device and can entail significant costs.2-4 One example is PIVC-related CABSI, where treatment costs have been estimated to be between US$35,000 and US$56,000 per patient.6,13 Another important consideration is the pain and anxiety experienced by patients who need a replacement device, particularly those with difficult vascular access, who may require multiple cannulation attempts to replace a PIVC.12,14-16 In developing nations, serious adverse events related to PIVCs are even more concerning, because hospital acquired infection rates and associated mortality are nearly 20 times greater than in developed nations.17

A number of evidence-based interventions have been suggested to reduce PIVC failure rates. In addition to optimal hand hygiene when inserting or accessing a PIVC to prevent infection,18 recommended interventions include placement of the PIVC in an area of non-flexion such as the forearm to provide stability for the device and to reduce patient discomfort, securing the PIVC to reduce movement of the catheter at the insertion site and within the blood vessel, and use of occlusive dressings that reduce the risk of external contamination of the PIVC site.11,19,20 Best practice guidelines also recommend the prompt removal of devices that are symptomatic (when phlebitis or other complications are suspected) and when the catheter is no longer required.21,22

Recent evidence has demonstrated that catheter size can have an impact on device survival rates. In adults, large-bore catheters of 18 gauge (G) or higher were found to have an increased rate of thrombosis, and smaller-bore catheters of 22G or lower (in adults) were found to have higher rates of dislodgment and occlusion/infiltration. The catheter size recommended for adults based on the latest evidence for most clinical applications is 20G.3,20,23,24 In addition, the documentation of insertion, maintenance, and removal of PIVCs in the medical record is a requirement in most healthcare facilities worldwide and is recommended by best practice guidelines; however, adherence remains a challenge.1,19

The concerning prevalence of PIVC-related complications and the lack of comparative data internationally on organizational compliance with best practice guidelines formed the rationale for this study. Our study aim was to describe the insertion characteristics, management practices, and outcomes of PIVCs internationally and to compare these variables to recommended best practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Participants

In this international cross-sectional study, we recruited hospitals through professional networks, including vascular access, infection prevention, safety and quality, nursing, and hospital associations (Appendix 2). Healthcare organizations, government health departments, and intravascular device suppliers were informed of the study and requested to further disseminate information through their networks. A study website was developed,25 and social media outlets, including Twitter®, LinkedIn®, and Facebook®, were used to promote the study.

Approval was granted by the Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee in Australia (reference number NRS/34/13/HREC). In addition, evidence of study site and local institutional review board/ethics committee approval was required prior to study commencement. Each participating site agreed to follow the study protocol and signed an authorship agreement form. No financial support was provided to any site.

Hospitalized adult and pediatric patients with a PIVC in situ on the day of the study were eligible for inclusion. Sample size was determined by local capacity. Hospitals were encouraged to audit their entire institution if possible; however, data were accepted from as little as one ward. Data collectors comprised nurses and doctors with experience in PIVC assessment. They were briefed on the study protocol and data collection forms by the local site coordinator, and they were supported by an overall global coordinator. Clinicians assessed the PIVC insertion site and accessed hospital records to collect data related to PIVC insertion, concurrent medications, and IV fluid orders. Further clarification of data was obtained if necessary by the clinicians from the patients and treating staff. No identifiable patient information was collected.

Data Collection

To assess whether clinical facilities were following best practice recommendations, the study team developed three data collection forms to collect information regarding site characteristics (site questionnaire), track participant recruitment (screening log), and collect data regarding PIVC characteristics and management practices (case report form [CRF]). All forms were internally and externally validated following a pilot study involving 14 sites in 13 countries.1

The CRF included variables used to assess best practice interventions, such as catheter insertion characteristics (date and time, reason, location, profession of inserter, anatomical site of placement), catheter type (gauge, brand, and product), insertion site assessment (adverse symptoms, dressing type and integrity), and information related to the IV therapy (types of IV fluids and medications, flushing solutions). Idle PIVCs were defined as not being used for blood sampling or IV therapy in the preceding 24 h.

Data collection forms were translated into 15 languages by professional translators and back-translated for validity. Translation of some languages included additional rigor. For example, Spanish-speaking members from the Spanish mainland as well as from South America were employed so that appropriate synonyms were used to capture local terms and practice. Three options were provided for data entry: directly into a purpose-developed electronic database (Lime Survey® Project, Hamburg, Germany); on paper, then transcribed into the survey database at a later time by the hospital site; or paper entry then sent (via email or post) to the coordinating center for data entry. Once cleaned and collated, all data were provided to each participating hospital to confirm accuracy and for site use in local quality improvement processes. Data were collected between June 1, 2014 and July 31, 2015.

Statistical Analysis

All data management was undertaken using SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC, USA). Results are presented for eight geographical regions using descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, and 95% CIs) for the variables of interest. To assess trends in catheter dwell time and rates of phlebitis, Poisson regression was used. All analyses were undertaken using the R language for statistical analysis (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). The (STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement) guidelines for cross-sectional studies were followed, and results are presented according to these recommendations.26

RESULTS

Of the 415 hospitals that participated in this study, 406 had patients with PIVCs on the day of the study (the others being small rural centers). Thus, a total of 40,620 PIVCs in 38,161 patients from 406 hospitals in 51 countries were assessed, with no more than 5% missing data for any CRF question. There were 2459 patients (6.1%) with two or more PIVCs concurrently in situ. The median patient age was 59 y (interquartile range [IQR], 37–74 y), and just over half were male (n = 20,550, 51%). Hospital size ranged from fewer than 10 beds to over 1,000 beds, and hospitals were located in rural, regional, and metropolitan districts. The majority of countries (n = 31, 61%) contributed multiple sites, the highest being Australia with 79 hospitals. Countries with the most PIVCs studied were Spain (n = 5,553, 14%) and the United States (n = 5,048, 12%).

General surgical (n = 15,616, 39%) and medical (n = 15,448, 38%) patients represented most of the population observed. PIVCs were inserted primarily in general wards or clinics (n = 22,167, 55%) or in emergency departments (n = 7,388, 18%; Table) and for the administration of IV medication (n = 28,571, 70%) and IV fluids (n = 7,093, 18%; Table).

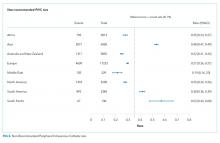

Globally, nurses were the primary PIVC inserters (n = 28,575, 71%); however, Australia/New Zealand had only 26% (n = 1,518) of PIVCs inserted by this group (Table). Only about one-third of PIVCs were placed in an area of non-flexion (forearm, n = 12,675, 31%, Table) the majority (n = 27,856, 69%) were placed in non-recommended anatomical sites (Figure 1). Most PIVCs were placed in the hand (n = 13,265, 32.7%) followed by the antecubital veins (n = 6176, 15.2%) and the wrist (n = 5,465, 13.5%). Site selection varied widely across the regions; 29% (n = 1686) of PIVCs in Australia/New Zealand were inserted into the antecubital veins, twice the study group average. Over half of the PIVCs inserted in the Middle East were placed in the hand (n = 295, 56%). This region also had the highest prevalence of devices placed in nonrecommended sites (n = 416, 79%; Figure 1).

The majority of PIVCs (n = 27,192, 67%; Table) were of recommended size (20–22G); however, some devices were observed to be large (14–18G; n = 6,802, 17%) or small (24-26g; n = 4,869, 12%) in adults. In Asia, 41% (n = 2,617) of devices inserted were 24-26G, more than three times the global rate. Half of all devices in Asia (n = 3,077, 48%) and the South Pacific (n = 67, 52%) were of a size not recommended for routine IV therapy (Figure 2).

The primary dressing material used was a transparent dressing (n = 31,596, 77.8%; Table); however, nearly 1 in 5 dressings used had either nonsterile tape alone (n = 5,169, 13%; Appendix 4), or a sterile gauze and tape (n = 2,592, 6%; Appendix 4.1). We found a wide variation in the use of nonsterile tape, including 1 in every 3 devices in South America dressed with nonsterile tape (n = 714, 30%) and a larger proportion in Africa (n = 543, 19%) and Europe (n = 3,056, 18%). Nonsterile tape was rarely used in North America and Australia/New Zealand. Although most PIVC dressings were clean, dry, and intact (n = 31,786, 79%; Table), one-fifth overall were compromised (moist, soiled, and/or lifting off the skin). Compromised dressings (Appendix 4.2) were more prevalent in Australia/New Zealand (n = 1,448; 25%) and in Africa (n = 707, 25%) than elsewhere.

Ten percent of PIVCs (n = 4,204) had signs and/or symptoms suggestive of phlebitis (characterized by pain, redness and/or swelling at the insertion site; Appendix 4.3). The highest prevalence of phlebitis occurred in Asia (n = 1,021, 16%), Africa (n = 360, 13%), and South America (n = 284, 12%). Pain and/or redness were the most common phlebitis symptoms. We found no association between dwell time of PIVCs and phlebitis rates (P = .085). Phlebitis rates were 12% (Days 1-3; n = 15,625), 16% (Days 4-7; n = 3,348), 10% (Days 8-21; n = 457), and 13% (Day21+; n = 174). Nearly 10% (n = 3,879) of catheters were observed to have signs of malfunction such as blood in the infusion tubing, leaking at the insertion site, or dislodgment (Appendix 4.4).

We observed 14% (n = 5,796) of PIVCs to be idle (Appendix 4.5), defined as not used in the preceding 24 h. Nearly one-fourth of all devices in North America (n = 1,230, 23%) and Australia/New Zealand (n = 1,335, 23%) were idle. PIVC documentation in hospital records was also poor, nearly half of all PIVCs (n = 19,768, 49%) had no documented date and time of insertion. The poorest compliance was in Australia/New Zealand (n = 3,428, 59%; Appendix 4.6). We also observed that 1 in 10 PIVCs had no documentation regarding who inserted the PIVC (n = 3,905). Thirty-six percent of PIVCs (n = 14,787) had no documented assessment of the PIVC site on the day of review (Appendix 4.7), including over half of all PIVCs in Asia (n = 3,364, 52%). Overall, the median dwell at the time of assessment for PIVCs with insertion date/time documented was 1.5 d (IQR, 1.0–2.5 d).

DISCUSSION

This international assessment of more than 40,000 PIVCs in 51 countries provides great insight into device characteristics and variation in management practices. Predominantly, PIVCs were inserted by nurses in the general ward environment for IV medication. One in ten PIVCs had at least one symptom of phlebitis, one in ten were dysfunctional, one in five PIVC dressings were compromised, and one in six PIVCs had not been used in the preceding 24 h. Nearly half of the PIVCs audited had the insertion date and time missing.

Regional variation was found in the professions inserting PIVCs, as well as in anatomical placement. In Australia/New Zealand, the proportion of nurses inserting PIVCs was much lower than the study group average (26% vs 71%). Because these countries contributed a substantial number of hospitals to the study, this seems a representative finding and suggests a need for education targeted at nurses for PIVC insertion in this region. The veins in the forearm are recommended as optimal for PIVC insertion in adults, rather than areas of high flexion, because the forearm provides a wide surface area to secure and dress PIVCs. Forearm placement can reduce pain during catheter dwell as well as decrease the risk of accidental removal or occlusion.3,19,27 We found only one-third of PIVCs were placed in the forearm, with most placed in the hand, antecubital veins, or wrist. This highlights an inconsistency with published recommendations and suggests that additional training and technology are required so that staff can better identify and insert PIVCs in the forearm for other than very short-term (procedural) PIVCp;s.19