User login

Times change, but children still come first

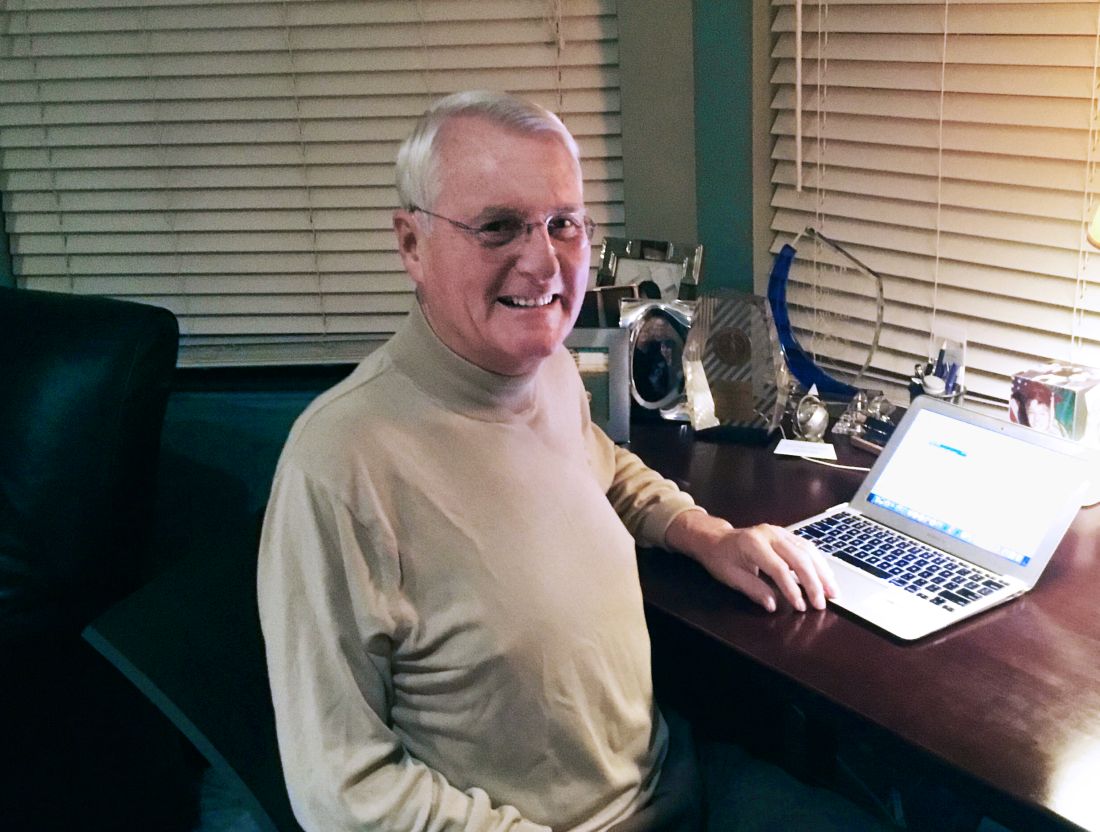

After decades of pediatric practice, Thomas K. McInerny, MD, still accentuates the positive. “I decided to become a pediatrician in my third year of medical school after my pediatrics rotation. I loved working with the children and their families so full of joy and hope,” he said. “I still feel that pediatrics is the greatest profession despite some frustrations with rules, regulations, and computer work.”

Many childhood diseases, including birth defects and forms of cancer that were fatal 50 years ago, now can be treated successfully, he noted. “However, there are more children with emotional, behavioral, and school problems, which pediatricians are now treating as there is a great shortage of mental health professionals for children.”

Although the dedication of pediatricians to their specialty has remained strong over the past 50 years, their work environment has evolved in many ways.

David T. Tayloe Jr., MD, also a past president of the AAP, currently practices in Goldsboro, N.C. When he established a solo community practice in 1977, he was one of a few pediatricians in the area, and he was busy. “I was the only pediatrician who could take care of really sick newborns and hospital patients, so I basically was available 24-7 for those first 2 years; there were two older pediatricians in town, and they took routine night call with me, giving me some time with my family,” he said. “With 1,500 deliveries a year at our hospital, there were always sick babies who needed my services. My office hours were 9 a.m. until 5 p.m. but often, in the cooler months, we saw patients until 8 p.m.” These days, Dr. Tayloe said he works 3-4 days in the office, and “my practice is largely behavioral health, school problems, obesity, asthma, and well-baby/child care.”

“In the last 20 years, my typical work day has changed in many ways,” said Julia Richerson, MD, who practices at the Family Health Center Iroquois office in South Louisville, Ky.

“I use electronic resources to find patient education, to look up current treatments, and research complicated diagnosis,” she noted.

“I feel that having the computer in the room isn’t a barrier to communication with my patients and families. Using the EHR doesn’t take me more time to see a patient,” she said. “However, the review of consult and ER records is harder and takes longer to complete. Consult, ER, and other outside records are much larger with the key clinical data more disorganized and harder to find among the pages and pages of nonrelevant content. This makes the workday much longer.”

The conditions that take up most of a pediatric office visit have changed as well, and include more complex medical, behavioral, and social issues, Dr. Richerson observed. “Obesity, ADHD, autism, complications of prematurity, behavioral health issues, developmental delays, and asthma are commonly seen in practice now. One in five children nationally have a chronic illness or special health care need. And we strive to help ease the challenges for families struggling with economic insecurity, and children growing up experiencing significant adversities.”

The office and the EHR

EHRs are a fact of life in all specialties today, but should not get in the way of interacting with patients, Dr. McInerny said. Many pediatricians complete their medical records after hours at home because they don’t have time to complete them in the office.

“I would advise the younger pediatricians to be sure to look at and interact with their families as much as possible while working on the computer, and showing the families entries and graphs from the computer. We were able to interact with families much more easily when writing out notes with pen and paper,” he said.

In his early years of practice, Dr. Tayloe recalled, “I spent less time with each patient; my focus was infectious disease, and I treated many patients with what today are vaccine-preventable diseases. I could see patients much faster with paper charts, but my documentation left much to be desired,” he said. “With the electronic record, I spend more time with each patient, but I type really fast and finish my charts in the exam rooms with the patients.”

“EHRs have made daily practice easier and more complicated for pediatricians,” said Dr. Richerson. “In the moment-to-moment use of EHRs while seeing patients, we can fairly quickly document the information we need to for patient care.” However, she said, “It takes some additional time to document all the data points required for quality- and value-based reimbursement programs, and it takes a significant amount of additional time in most EHRs to retrieve relevant information because you cannot query the system for clinical content on a patient. Also, reviewing incoming records is difficult because the information is voluminous and poorly organized,” she noted. “There are so many opportunities for improvement, and hopefully 20 years from now we will have EHRs that significantly improve quality and safety of patient care.”

Money and malpractice

The Vaccines for Children program led to an increase in incomes for pediatricians in the United States after 1994, according to Dr. Tayloe. “We began to be paid by insurance companies for most of what we do during the mid-90s and that boosted revenues,” he said. However, “On the flip side, we are now at the mercy of private payers, and must participate in all their very burdensome quality improvement/assurance programs if we are to be paid fairly. Our incomes were pretty flat over the last 5-10 years, especially for practices that participate fully in Medicaid/CHIP.”

Over the past 50 years, malpractice claims against pediatricians have remained consistently among the lowest for any medical specialty, according to Paul Greve, JD, a registered professional liability underwriter and executive vice president and senior consultant at Willis Towers Watson Health Care Practice.

The impact of EHRs on pediatric practice from a legal standpoint depends on the format of the EHR itself, Mr. Greve said. “Many of the EHRs that are designed for physicians, particularly the ones used in acute care settings, don’t allow the doctor to really highlight their thinking as they work through the diagnostic process, and that is very important in the defense of a malpractice case against a pediatrician,” he said.

“The pediatrician doesn’t have to be correct all the time, but it is important for the lawyers defending the case to see what the pediatrician’s thought process was. If the EHR allows for capturing the doctor’s thought process, that’s a well-designed EHR, and that’s critical,” he emphasized.

Diagnostic error is one of the most entrenched problems in medical malpractice, said Mr. Greve. Failure to diagnose and delay in diagnosis remain the most common allegations against pediatricians, he noted. Also, being aware of the environment is important to risk management in the office.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics has excellent publications on safety and risk management that all pediatricians should be aware of,” he said.

Inspiration and intangibles

“I think the changes that we are starting to see will continue to evolve over the next 50 years,” said Dr. Richerson. “Increased medical and social complexity of patients, changes in health technology, EHRs, personal health data monitoring, and continued changes in value based payment methods will be key.

“I hope that we gain, as a health delivery system, an appreciation of the impact of child health on adult health. Long-term adult health outcomes depend on improved child health outcomes. Investing in diseases like childhood obesity, mental health, and developmental issues, to name a few, will have a bigger impact on adult disease than any adult interventions,” she said. And really dealing with the impact of childhood adversity in health care and in the community and nationally in general is critical. This requires grassroots interventions to support families as well as local, state, and national policy. It also requires payment for health care services for the needed interventions in the office and hospital. Providing comprehensive medical care and addressing the medical and social complexities of child health in an effective, compassionate, and family-centered way takes time. It’s not easy, but it’s not impossible. But it requires more resources than are currently given to child health care. Adult medicine is accustomed to paying for disease managers for diabetes or care coordinators for heart failure. This is not the current state of delivery for children’s care and it should be. These are some of the major issues confronting pediatricians.

What has remained the same in pediatrics is the love the doctors have for their work, and the reflections of veteran clinicians on the intangible rewards of the practice may inspire the next generation.

Dr. Tayloe said that he chose pediatrics because “I was really intrigued by the skills necessary to care for sick newborns, including premature babies. I wanted to practice in a remote location where I could use all the skills I developed during residency, and be of significant value to the community.” Two of his four adult children were similarly inspired and followed in his footsteps.

“For pediatricians, helping families raise healthy children is a real privilege and very satisfying,” Dr. McInerny said.

After decades of pediatric practice, Thomas K. McInerny, MD, still accentuates the positive. “I decided to become a pediatrician in my third year of medical school after my pediatrics rotation. I loved working with the children and their families so full of joy and hope,” he said. “I still feel that pediatrics is the greatest profession despite some frustrations with rules, regulations, and computer work.”

Many childhood diseases, including birth defects and forms of cancer that were fatal 50 years ago, now can be treated successfully, he noted. “However, there are more children with emotional, behavioral, and school problems, which pediatricians are now treating as there is a great shortage of mental health professionals for children.”

Although the dedication of pediatricians to their specialty has remained strong over the past 50 years, their work environment has evolved in many ways.

David T. Tayloe Jr., MD, also a past president of the AAP, currently practices in Goldsboro, N.C. When he established a solo community practice in 1977, he was one of a few pediatricians in the area, and he was busy. “I was the only pediatrician who could take care of really sick newborns and hospital patients, so I basically was available 24-7 for those first 2 years; there were two older pediatricians in town, and they took routine night call with me, giving me some time with my family,” he said. “With 1,500 deliveries a year at our hospital, there were always sick babies who needed my services. My office hours were 9 a.m. until 5 p.m. but often, in the cooler months, we saw patients until 8 p.m.” These days, Dr. Tayloe said he works 3-4 days in the office, and “my practice is largely behavioral health, school problems, obesity, asthma, and well-baby/child care.”

“In the last 20 years, my typical work day has changed in many ways,” said Julia Richerson, MD, who practices at the Family Health Center Iroquois office in South Louisville, Ky.

“I use electronic resources to find patient education, to look up current treatments, and research complicated diagnosis,” she noted.

“I feel that having the computer in the room isn’t a barrier to communication with my patients and families. Using the EHR doesn’t take me more time to see a patient,” she said. “However, the review of consult and ER records is harder and takes longer to complete. Consult, ER, and other outside records are much larger with the key clinical data more disorganized and harder to find among the pages and pages of nonrelevant content. This makes the workday much longer.”

The conditions that take up most of a pediatric office visit have changed as well, and include more complex medical, behavioral, and social issues, Dr. Richerson observed. “Obesity, ADHD, autism, complications of prematurity, behavioral health issues, developmental delays, and asthma are commonly seen in practice now. One in five children nationally have a chronic illness or special health care need. And we strive to help ease the challenges for families struggling with economic insecurity, and children growing up experiencing significant adversities.”

The office and the EHR

EHRs are a fact of life in all specialties today, but should not get in the way of interacting with patients, Dr. McInerny said. Many pediatricians complete their medical records after hours at home because they don’t have time to complete them in the office.

“I would advise the younger pediatricians to be sure to look at and interact with their families as much as possible while working on the computer, and showing the families entries and graphs from the computer. We were able to interact with families much more easily when writing out notes with pen and paper,” he said.

In his early years of practice, Dr. Tayloe recalled, “I spent less time with each patient; my focus was infectious disease, and I treated many patients with what today are vaccine-preventable diseases. I could see patients much faster with paper charts, but my documentation left much to be desired,” he said. “With the electronic record, I spend more time with each patient, but I type really fast and finish my charts in the exam rooms with the patients.”

“EHRs have made daily practice easier and more complicated for pediatricians,” said Dr. Richerson. “In the moment-to-moment use of EHRs while seeing patients, we can fairly quickly document the information we need to for patient care.” However, she said, “It takes some additional time to document all the data points required for quality- and value-based reimbursement programs, and it takes a significant amount of additional time in most EHRs to retrieve relevant information because you cannot query the system for clinical content on a patient. Also, reviewing incoming records is difficult because the information is voluminous and poorly organized,” she noted. “There are so many opportunities for improvement, and hopefully 20 years from now we will have EHRs that significantly improve quality and safety of patient care.”

Money and malpractice

The Vaccines for Children program led to an increase in incomes for pediatricians in the United States after 1994, according to Dr. Tayloe. “We began to be paid by insurance companies for most of what we do during the mid-90s and that boosted revenues,” he said. However, “On the flip side, we are now at the mercy of private payers, and must participate in all their very burdensome quality improvement/assurance programs if we are to be paid fairly. Our incomes were pretty flat over the last 5-10 years, especially for practices that participate fully in Medicaid/CHIP.”

Over the past 50 years, malpractice claims against pediatricians have remained consistently among the lowest for any medical specialty, according to Paul Greve, JD, a registered professional liability underwriter and executive vice president and senior consultant at Willis Towers Watson Health Care Practice.

The impact of EHRs on pediatric practice from a legal standpoint depends on the format of the EHR itself, Mr. Greve said. “Many of the EHRs that are designed for physicians, particularly the ones used in acute care settings, don’t allow the doctor to really highlight their thinking as they work through the diagnostic process, and that is very important in the defense of a malpractice case against a pediatrician,” he said.

“The pediatrician doesn’t have to be correct all the time, but it is important for the lawyers defending the case to see what the pediatrician’s thought process was. If the EHR allows for capturing the doctor’s thought process, that’s a well-designed EHR, and that’s critical,” he emphasized.

Diagnostic error is one of the most entrenched problems in medical malpractice, said Mr. Greve. Failure to diagnose and delay in diagnosis remain the most common allegations against pediatricians, he noted. Also, being aware of the environment is important to risk management in the office.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics has excellent publications on safety and risk management that all pediatricians should be aware of,” he said.

Inspiration and intangibles

“I think the changes that we are starting to see will continue to evolve over the next 50 years,” said Dr. Richerson. “Increased medical and social complexity of patients, changes in health technology, EHRs, personal health data monitoring, and continued changes in value based payment methods will be key.

“I hope that we gain, as a health delivery system, an appreciation of the impact of child health on adult health. Long-term adult health outcomes depend on improved child health outcomes. Investing in diseases like childhood obesity, mental health, and developmental issues, to name a few, will have a bigger impact on adult disease than any adult interventions,” she said. And really dealing with the impact of childhood adversity in health care and in the community and nationally in general is critical. This requires grassroots interventions to support families as well as local, state, and national policy. It also requires payment for health care services for the needed interventions in the office and hospital. Providing comprehensive medical care and addressing the medical and social complexities of child health in an effective, compassionate, and family-centered way takes time. It’s not easy, but it’s not impossible. But it requires more resources than are currently given to child health care. Adult medicine is accustomed to paying for disease managers for diabetes or care coordinators for heart failure. This is not the current state of delivery for children’s care and it should be. These are some of the major issues confronting pediatricians.

What has remained the same in pediatrics is the love the doctors have for their work, and the reflections of veteran clinicians on the intangible rewards of the practice may inspire the next generation.

Dr. Tayloe said that he chose pediatrics because “I was really intrigued by the skills necessary to care for sick newborns, including premature babies. I wanted to practice in a remote location where I could use all the skills I developed during residency, and be of significant value to the community.” Two of his four adult children were similarly inspired and followed in his footsteps.

“For pediatricians, helping families raise healthy children is a real privilege and very satisfying,” Dr. McInerny said.

After decades of pediatric practice, Thomas K. McInerny, MD, still accentuates the positive. “I decided to become a pediatrician in my third year of medical school after my pediatrics rotation. I loved working with the children and their families so full of joy and hope,” he said. “I still feel that pediatrics is the greatest profession despite some frustrations with rules, regulations, and computer work.”

Many childhood diseases, including birth defects and forms of cancer that were fatal 50 years ago, now can be treated successfully, he noted. “However, there are more children with emotional, behavioral, and school problems, which pediatricians are now treating as there is a great shortage of mental health professionals for children.”

Although the dedication of pediatricians to their specialty has remained strong over the past 50 years, their work environment has evolved in many ways.

David T. Tayloe Jr., MD, also a past president of the AAP, currently practices in Goldsboro, N.C. When he established a solo community practice in 1977, he was one of a few pediatricians in the area, and he was busy. “I was the only pediatrician who could take care of really sick newborns and hospital patients, so I basically was available 24-7 for those first 2 years; there were two older pediatricians in town, and they took routine night call with me, giving me some time with my family,” he said. “With 1,500 deliveries a year at our hospital, there were always sick babies who needed my services. My office hours were 9 a.m. until 5 p.m. but often, in the cooler months, we saw patients until 8 p.m.” These days, Dr. Tayloe said he works 3-4 days in the office, and “my practice is largely behavioral health, school problems, obesity, asthma, and well-baby/child care.”

“In the last 20 years, my typical work day has changed in many ways,” said Julia Richerson, MD, who practices at the Family Health Center Iroquois office in South Louisville, Ky.

“I use electronic resources to find patient education, to look up current treatments, and research complicated diagnosis,” she noted.

“I feel that having the computer in the room isn’t a barrier to communication with my patients and families. Using the EHR doesn’t take me more time to see a patient,” she said. “However, the review of consult and ER records is harder and takes longer to complete. Consult, ER, and other outside records are much larger with the key clinical data more disorganized and harder to find among the pages and pages of nonrelevant content. This makes the workday much longer.”

The conditions that take up most of a pediatric office visit have changed as well, and include more complex medical, behavioral, and social issues, Dr. Richerson observed. “Obesity, ADHD, autism, complications of prematurity, behavioral health issues, developmental delays, and asthma are commonly seen in practice now. One in five children nationally have a chronic illness or special health care need. And we strive to help ease the challenges for families struggling with economic insecurity, and children growing up experiencing significant adversities.”

The office and the EHR

EHRs are a fact of life in all specialties today, but should not get in the way of interacting with patients, Dr. McInerny said. Many pediatricians complete their medical records after hours at home because they don’t have time to complete them in the office.

“I would advise the younger pediatricians to be sure to look at and interact with their families as much as possible while working on the computer, and showing the families entries and graphs from the computer. We were able to interact with families much more easily when writing out notes with pen and paper,” he said.

In his early years of practice, Dr. Tayloe recalled, “I spent less time with each patient; my focus was infectious disease, and I treated many patients with what today are vaccine-preventable diseases. I could see patients much faster with paper charts, but my documentation left much to be desired,” he said. “With the electronic record, I spend more time with each patient, but I type really fast and finish my charts in the exam rooms with the patients.”

“EHRs have made daily practice easier and more complicated for pediatricians,” said Dr. Richerson. “In the moment-to-moment use of EHRs while seeing patients, we can fairly quickly document the information we need to for patient care.” However, she said, “It takes some additional time to document all the data points required for quality- and value-based reimbursement programs, and it takes a significant amount of additional time in most EHRs to retrieve relevant information because you cannot query the system for clinical content on a patient. Also, reviewing incoming records is difficult because the information is voluminous and poorly organized,” she noted. “There are so many opportunities for improvement, and hopefully 20 years from now we will have EHRs that significantly improve quality and safety of patient care.”

Money and malpractice

The Vaccines for Children program led to an increase in incomes for pediatricians in the United States after 1994, according to Dr. Tayloe. “We began to be paid by insurance companies for most of what we do during the mid-90s and that boosted revenues,” he said. However, “On the flip side, we are now at the mercy of private payers, and must participate in all their very burdensome quality improvement/assurance programs if we are to be paid fairly. Our incomes were pretty flat over the last 5-10 years, especially for practices that participate fully in Medicaid/CHIP.”

Over the past 50 years, malpractice claims against pediatricians have remained consistently among the lowest for any medical specialty, according to Paul Greve, JD, a registered professional liability underwriter and executive vice president and senior consultant at Willis Towers Watson Health Care Practice.

The impact of EHRs on pediatric practice from a legal standpoint depends on the format of the EHR itself, Mr. Greve said. “Many of the EHRs that are designed for physicians, particularly the ones used in acute care settings, don’t allow the doctor to really highlight their thinking as they work through the diagnostic process, and that is very important in the defense of a malpractice case against a pediatrician,” he said.

“The pediatrician doesn’t have to be correct all the time, but it is important for the lawyers defending the case to see what the pediatrician’s thought process was. If the EHR allows for capturing the doctor’s thought process, that’s a well-designed EHR, and that’s critical,” he emphasized.

Diagnostic error is one of the most entrenched problems in medical malpractice, said Mr. Greve. Failure to diagnose and delay in diagnosis remain the most common allegations against pediatricians, he noted. Also, being aware of the environment is important to risk management in the office.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics has excellent publications on safety and risk management that all pediatricians should be aware of,” he said.

Inspiration and intangibles

“I think the changes that we are starting to see will continue to evolve over the next 50 years,” said Dr. Richerson. “Increased medical and social complexity of patients, changes in health technology, EHRs, personal health data monitoring, and continued changes in value based payment methods will be key.

“I hope that we gain, as a health delivery system, an appreciation of the impact of child health on adult health. Long-term adult health outcomes depend on improved child health outcomes. Investing in diseases like childhood obesity, mental health, and developmental issues, to name a few, will have a bigger impact on adult disease than any adult interventions,” she said. And really dealing with the impact of childhood adversity in health care and in the community and nationally in general is critical. This requires grassroots interventions to support families as well as local, state, and national policy. It also requires payment for health care services for the needed interventions in the office and hospital. Providing comprehensive medical care and addressing the medical and social complexities of child health in an effective, compassionate, and family-centered way takes time. It’s not easy, but it’s not impossible. But it requires more resources than are currently given to child health care. Adult medicine is accustomed to paying for disease managers for diabetes or care coordinators for heart failure. This is not the current state of delivery for children’s care and it should be. These are some of the major issues confronting pediatricians.

What has remained the same in pediatrics is the love the doctors have for their work, and the reflections of veteran clinicians on the intangible rewards of the practice may inspire the next generation.

Dr. Tayloe said that he chose pediatrics because “I was really intrigued by the skills necessary to care for sick newborns, including premature babies. I wanted to practice in a remote location where I could use all the skills I developed during residency, and be of significant value to the community.” Two of his four adult children were similarly inspired and followed in his footsteps.

“For pediatricians, helping families raise healthy children is a real privilege and very satisfying,” Dr. McInerny said.

Group B streptococcus

It once was a very a common scenario. A baby born at term looks fine for the first 24 hours of life. Without much warning, the infant develops grunting, tachypnea, and tachycardia. Sepsis is suspected, and within a few hours, group B streptococcus (GBS) is isolated from a blood culture.

According to the CDC, a woman colonized with Group B strep at the time of delivery has a 1 in 200 chance of delivering a baby who will develop GBS disease. Antibiotics during labor drop that risk to 1 in 4,000. It’s not perfect – there are still about 1,000 cases annually in the United States – but is has been a major step forward. In recent years, the incidence of early-onset GBS disease has fallen to just under 0.3 cases per 1,000 live births, and some experts think rates could go even lower with improved adherence to current guidelines.

Reducing late-onset GBS disease requires a different strategy. Efforts to develop a GBS vaccine that could be given to pregnant women continue, and recent phase 2 trials of a trivalent polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine looked promising. Fingers crossed that we won’t have to wait until we celebrate the 75th anniversary of Pediatric News to tout the impact of maternal immunization on reducing GBS disease in infants.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

It once was a very a common scenario. A baby born at term looks fine for the first 24 hours of life. Without much warning, the infant develops grunting, tachypnea, and tachycardia. Sepsis is suspected, and within a few hours, group B streptococcus (GBS) is isolated from a blood culture.

According to the CDC, a woman colonized with Group B strep at the time of delivery has a 1 in 200 chance of delivering a baby who will develop GBS disease. Antibiotics during labor drop that risk to 1 in 4,000. It’s not perfect – there are still about 1,000 cases annually in the United States – but is has been a major step forward. In recent years, the incidence of early-onset GBS disease has fallen to just under 0.3 cases per 1,000 live births, and some experts think rates could go even lower with improved adherence to current guidelines.

Reducing late-onset GBS disease requires a different strategy. Efforts to develop a GBS vaccine that could be given to pregnant women continue, and recent phase 2 trials of a trivalent polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine looked promising. Fingers crossed that we won’t have to wait until we celebrate the 75th anniversary of Pediatric News to tout the impact of maternal immunization on reducing GBS disease in infants.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

It once was a very a common scenario. A baby born at term looks fine for the first 24 hours of life. Without much warning, the infant develops grunting, tachypnea, and tachycardia. Sepsis is suspected, and within a few hours, group B streptococcus (GBS) is isolated from a blood culture.

According to the CDC, a woman colonized with Group B strep at the time of delivery has a 1 in 200 chance of delivering a baby who will develop GBS disease. Antibiotics during labor drop that risk to 1 in 4,000. It’s not perfect – there are still about 1,000 cases annually in the United States – but is has been a major step forward. In recent years, the incidence of early-onset GBS disease has fallen to just under 0.3 cases per 1,000 live births, and some experts think rates could go even lower with improved adherence to current guidelines.

Reducing late-onset GBS disease requires a different strategy. Efforts to develop a GBS vaccine that could be given to pregnant women continue, and recent phase 2 trials of a trivalent polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine looked promising. Fingers crossed that we won’t have to wait until we celebrate the 75th anniversary of Pediatric News to tout the impact of maternal immunization on reducing GBS disease in infants.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Vaccine renaissance

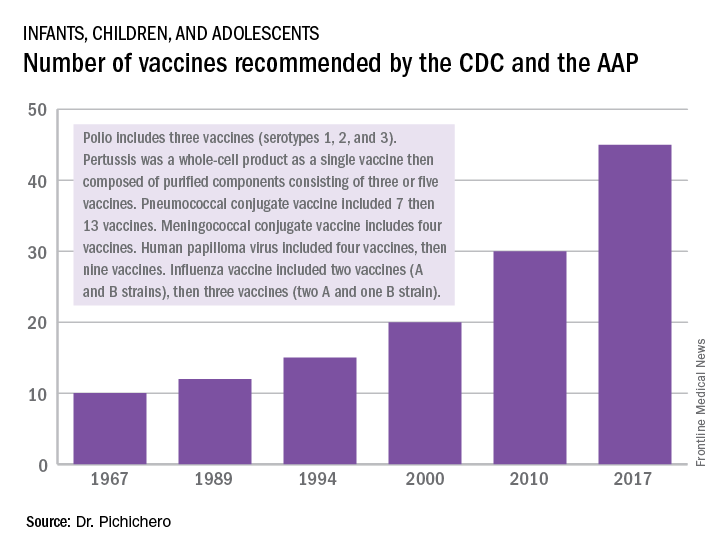

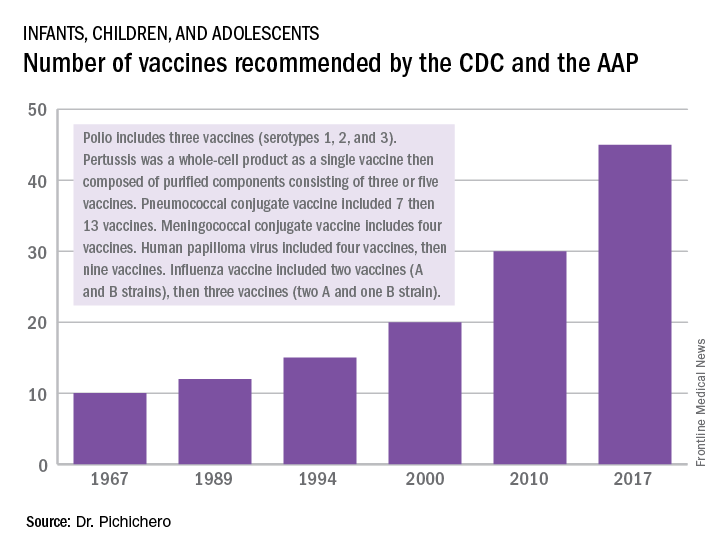

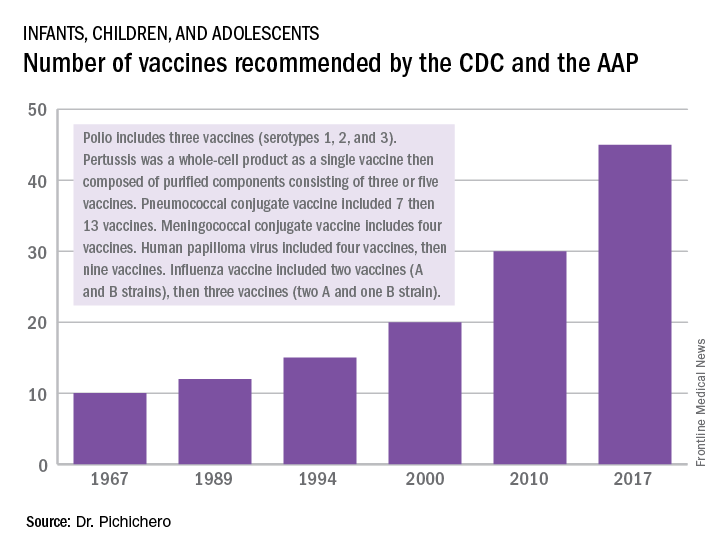

In 1967, pediatric patients were vaccinated routinely against eight diseases with 10 vaccines: smallpox; diphtheria; tetanus and pertussis; polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3; measles; rubella; and mumps. Then in 1989, vaccine discovery took a dramatic upward trend. For the physicians and scientists involved in vaccine discovery, the driving force may have been a passion for scientific discovery and a humanitarian motivation, but what drove this major change in pediatric infectious diseases was economics.

I believe The hiatus of more than 20 years between the introduction of the mumps vaccine in 1967 and that of the Hib vaccine in 1989 in my view was because the economic incentives to develop vaccines were absent. In fact, in the 1970s and early 1980s, vaccine manufacturers were drawing back from making vaccines because they were losing money selling them at a few dollars per dose.

A trailblazing path had been created, and more and more vaccines have been discovered and come to market since then. Combination vaccines and vaccines for adolescents and adults have followed. The biggest blockbuster is Prevnar13 (actually 13 vaccines contained in a single combination), now with annual sales in excess of $7 billion worldwide and growing. Other vaccines with sales of a billion dollars or more are also on the market; anything in excess of $1 billion is considered a blockbuster in the pharmaceutical industry and gets the attention of CEOs (and investors) in a big way.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has received funding awarded to his institution for vaccine research from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur. Email him at [email protected].

In 1967, pediatric patients were vaccinated routinely against eight diseases with 10 vaccines: smallpox; diphtheria; tetanus and pertussis; polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3; measles; rubella; and mumps. Then in 1989, vaccine discovery took a dramatic upward trend. For the physicians and scientists involved in vaccine discovery, the driving force may have been a passion for scientific discovery and a humanitarian motivation, but what drove this major change in pediatric infectious diseases was economics.

I believe The hiatus of more than 20 years between the introduction of the mumps vaccine in 1967 and that of the Hib vaccine in 1989 in my view was because the economic incentives to develop vaccines were absent. In fact, in the 1970s and early 1980s, vaccine manufacturers were drawing back from making vaccines because they were losing money selling them at a few dollars per dose.

A trailblazing path had been created, and more and more vaccines have been discovered and come to market since then. Combination vaccines and vaccines for adolescents and adults have followed. The biggest blockbuster is Prevnar13 (actually 13 vaccines contained in a single combination), now with annual sales in excess of $7 billion worldwide and growing. Other vaccines with sales of a billion dollars or more are also on the market; anything in excess of $1 billion is considered a blockbuster in the pharmaceutical industry and gets the attention of CEOs (and investors) in a big way.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has received funding awarded to his institution for vaccine research from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur. Email him at [email protected].

In 1967, pediatric patients were vaccinated routinely against eight diseases with 10 vaccines: smallpox; diphtheria; tetanus and pertussis; polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3; measles; rubella; and mumps. Then in 1989, vaccine discovery took a dramatic upward trend. For the physicians and scientists involved in vaccine discovery, the driving force may have been a passion for scientific discovery and a humanitarian motivation, but what drove this major change in pediatric infectious diseases was economics.

I believe The hiatus of more than 20 years between the introduction of the mumps vaccine in 1967 and that of the Hib vaccine in 1989 in my view was because the economic incentives to develop vaccines were absent. In fact, in the 1970s and early 1980s, vaccine manufacturers were drawing back from making vaccines because they were losing money selling them at a few dollars per dose.

A trailblazing path had been created, and more and more vaccines have been discovered and come to market since then. Combination vaccines and vaccines for adolescents and adults have followed. The biggest blockbuster is Prevnar13 (actually 13 vaccines contained in a single combination), now with annual sales in excess of $7 billion worldwide and growing. Other vaccines with sales of a billion dollars or more are also on the market; anything in excess of $1 billion is considered a blockbuster in the pharmaceutical industry and gets the attention of CEOs (and investors) in a big way.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has received funding awarded to his institution for vaccine research from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur. Email him at [email protected].

Artemisinin: Its global impact on the treatment of malaria

Malaria remains a major international public health concern. In 2015, the World Health Organization estimated that 212 million individuals were infected and that there were 429,000 deaths. This represents a 21% decline in incidence globally and a 29% decline in global mortality between 2010 and 2015. In 2016, malaria was endemic in 91 countries and territories, down from 108 in 2000. Although malaria has been eliminated from the United States since the early 1950s, approximately 1,700 cases are reported annually, most of which occur in returned travelers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Five species of Plasmodium (P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and, more recently, P. knowelsi) account for most of the infections in humans and are transmitted by the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. The disease is rarely acquired by blood transfusion, by needle sharing, by organ transplantation, or congenitally. Once diagnosed, malaria can be treated; however, delay in initiating therapy can lead to both serious and fatal outcomes.

Treatment

Historically, drug development was driven by the need to protect the military. While quinine was isolated from the bark of the cinchona tree in 1820, chloroquine, proguanil, mefloquine, and atovaquone each were developed during or after a military conflict during 1945-1985. Tetracycline/doxycycline and clindamycin also have antimalarial activity. Use of any of these agents as monotherapy has led to drug resistance and treatment failure.

Artemisinin

Artemisinin (also known as qinghao su) and its derivatives are a new class of antimalarials derived from the sweet wormwood plant Artemisia annua. Initially developed in China in the 1970s, this class gained global attention in the 1990s. and have the fastest parasite clearance time, rapid resolution of symptoms, and an excellent safety profile. They have activity against all Plasmodium species.

Because of artemisinins’ rapid elimination, they are used in combination with an agent that also kills blood parasites but has a slower elimination rate and a different mechanism of action. The goal is to prevent and delay the development of resistance and reduce recrudescence. The superiority of artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) over monotherapies has been documented.

Resistance, always a concern, has remained limited to specific areas in Southeast Asia since reported in 2008. Monitoring drug efficacy, safety, quality of antimalarials is ongoing, as is discouraging monotherapy use of these agents. Globally, artemisinins are the mainstay of treatment. Spread of resistance would be a major setback for both malaria control and elimination.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Malaria remains a major international public health concern. In 2015, the World Health Organization estimated that 212 million individuals were infected and that there were 429,000 deaths. This represents a 21% decline in incidence globally and a 29% decline in global mortality between 2010 and 2015. In 2016, malaria was endemic in 91 countries and territories, down from 108 in 2000. Although malaria has been eliminated from the United States since the early 1950s, approximately 1,700 cases are reported annually, most of which occur in returned travelers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Five species of Plasmodium (P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and, more recently, P. knowelsi) account for most of the infections in humans and are transmitted by the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. The disease is rarely acquired by blood transfusion, by needle sharing, by organ transplantation, or congenitally. Once diagnosed, malaria can be treated; however, delay in initiating therapy can lead to both serious and fatal outcomes.

Treatment

Historically, drug development was driven by the need to protect the military. While quinine was isolated from the bark of the cinchona tree in 1820, chloroquine, proguanil, mefloquine, and atovaquone each were developed during or after a military conflict during 1945-1985. Tetracycline/doxycycline and clindamycin also have antimalarial activity. Use of any of these agents as monotherapy has led to drug resistance and treatment failure.

Artemisinin

Artemisinin (also known as qinghao su) and its derivatives are a new class of antimalarials derived from the sweet wormwood plant Artemisia annua. Initially developed in China in the 1970s, this class gained global attention in the 1990s. and have the fastest parasite clearance time, rapid resolution of symptoms, and an excellent safety profile. They have activity against all Plasmodium species.

Because of artemisinins’ rapid elimination, they are used in combination with an agent that also kills blood parasites but has a slower elimination rate and a different mechanism of action. The goal is to prevent and delay the development of resistance and reduce recrudescence. The superiority of artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) over monotherapies has been documented.

Resistance, always a concern, has remained limited to specific areas in Southeast Asia since reported in 2008. Monitoring drug efficacy, safety, quality of antimalarials is ongoing, as is discouraging monotherapy use of these agents. Globally, artemisinins are the mainstay of treatment. Spread of resistance would be a major setback for both malaria control and elimination.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Malaria remains a major international public health concern. In 2015, the World Health Organization estimated that 212 million individuals were infected and that there were 429,000 deaths. This represents a 21% decline in incidence globally and a 29% decline in global mortality between 2010 and 2015. In 2016, malaria was endemic in 91 countries and territories, down from 108 in 2000. Although malaria has been eliminated from the United States since the early 1950s, approximately 1,700 cases are reported annually, most of which occur in returned travelers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Five species of Plasmodium (P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and, more recently, P. knowelsi) account for most of the infections in humans and are transmitted by the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. The disease is rarely acquired by blood transfusion, by needle sharing, by organ transplantation, or congenitally. Once diagnosed, malaria can be treated; however, delay in initiating therapy can lead to both serious and fatal outcomes.

Treatment

Historically, drug development was driven by the need to protect the military. While quinine was isolated from the bark of the cinchona tree in 1820, chloroquine, proguanil, mefloquine, and atovaquone each were developed during or after a military conflict during 1945-1985. Tetracycline/doxycycline and clindamycin also have antimalarial activity. Use of any of these agents as monotherapy has led to drug resistance and treatment failure.

Artemisinin

Artemisinin (also known as qinghao su) and its derivatives are a new class of antimalarials derived from the sweet wormwood plant Artemisia annua. Initially developed in China in the 1970s, this class gained global attention in the 1990s. and have the fastest parasite clearance time, rapid resolution of symptoms, and an excellent safety profile. They have activity against all Plasmodium species.

Because of artemisinins’ rapid elimination, they are used in combination with an agent that also kills blood parasites but has a slower elimination rate and a different mechanism of action. The goal is to prevent and delay the development of resistance and reduce recrudescence. The superiority of artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) over monotherapies has been documented.

Resistance, always a concern, has remained limited to specific areas in Southeast Asia since reported in 2008. Monitoring drug efficacy, safety, quality of antimalarials is ongoing, as is discouraging monotherapy use of these agents. Globally, artemisinins are the mainstay of treatment. Spread of resistance would be a major setback for both malaria control and elimination.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

A ‘game changer’ for pediatric HIV

In memory of Anne Marie Regan, CPNP, senior research coordinator, Pediatric HIV Program, Boston City Hospital

Our first child with perinatal HIV presented in 1985 at age 4 weeks with failure to thrive, vomiting, diarrhea, and thrush. Over the next several years, the number of HIV-infected infants grew exponentially, and by 1991, we were caring for more than 50 infants and children at Boston City Hospital.

Antiretrovirals were marginally effective for HIV-infected infants and children at this time. Subsequently, we embarked on a national effort to prevent vertical transmission. We participated first in the study of pharmacokinetics of zidovudine (AZT) in newborns. We enrolled patients in ACTG 076 to test the hypothesis that treatment with AZT during pregnancy and labor, and in the infant, would reduce the risk of vertical transmission. Fifty U.S. and nine French sites enrolled 473 women between April 1991 and December 20, 1993. The results were spectacular; 8 of 100 infants in the AZT treatment group, compared with 25 out of 100 infants in the control group, developed HIV. By 1995, HIV testing was offered to all women at Boston Medical Center (formerly Boston City Hospital), and the promise of prevention of vertical transmission was reaching fruition. Between 1996 and 2016, approximately 500 HIV-infected women delivered at Boston Medical Center with vertical transmission identified in only 6 (1.2%) infants; without ACTG 076, we would have expected 125! In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 70% of pregnant HIV-infected women received the complete 076 regimen, and 93% of mothers or infants received some part of the regimen. In 1992, 900 HIV-infected infants were diagnosed in the United States, and as many as 2,000 newborns were estimated to have been born infected with HIV; in 2015, 86 vertical transmissions were identified. This was, and remains, a remarkable accomplishment.

Dr. Pelton is chief of pediatric infectious diseases and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. Ms. Moloney is a certified pediatric nurse practitioner in the division of pediatric infectious diseases. Dr. Pelton said he had no relevant financial disclosures, and Ms. Moloney is a speaker (on vaccines) for Sanofi Pasteur. Email them at [email protected].

In memory of Anne Marie Regan, CPNP, senior research coordinator, Pediatric HIV Program, Boston City Hospital

Our first child with perinatal HIV presented in 1985 at age 4 weeks with failure to thrive, vomiting, diarrhea, and thrush. Over the next several years, the number of HIV-infected infants grew exponentially, and by 1991, we were caring for more than 50 infants and children at Boston City Hospital.

Antiretrovirals were marginally effective for HIV-infected infants and children at this time. Subsequently, we embarked on a national effort to prevent vertical transmission. We participated first in the study of pharmacokinetics of zidovudine (AZT) in newborns. We enrolled patients in ACTG 076 to test the hypothesis that treatment with AZT during pregnancy and labor, and in the infant, would reduce the risk of vertical transmission. Fifty U.S. and nine French sites enrolled 473 women between April 1991 and December 20, 1993. The results were spectacular; 8 of 100 infants in the AZT treatment group, compared with 25 out of 100 infants in the control group, developed HIV. By 1995, HIV testing was offered to all women at Boston Medical Center (formerly Boston City Hospital), and the promise of prevention of vertical transmission was reaching fruition. Between 1996 and 2016, approximately 500 HIV-infected women delivered at Boston Medical Center with vertical transmission identified in only 6 (1.2%) infants; without ACTG 076, we would have expected 125! In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 70% of pregnant HIV-infected women received the complete 076 regimen, and 93% of mothers or infants received some part of the regimen. In 1992, 900 HIV-infected infants were diagnosed in the United States, and as many as 2,000 newborns were estimated to have been born infected with HIV; in 2015, 86 vertical transmissions were identified. This was, and remains, a remarkable accomplishment.

Dr. Pelton is chief of pediatric infectious diseases and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. Ms. Moloney is a certified pediatric nurse practitioner in the division of pediatric infectious diseases. Dr. Pelton said he had no relevant financial disclosures, and Ms. Moloney is a speaker (on vaccines) for Sanofi Pasteur. Email them at [email protected].

In memory of Anne Marie Regan, CPNP, senior research coordinator, Pediatric HIV Program, Boston City Hospital

Our first child with perinatal HIV presented in 1985 at age 4 weeks with failure to thrive, vomiting, diarrhea, and thrush. Over the next several years, the number of HIV-infected infants grew exponentially, and by 1991, we were caring for more than 50 infants and children at Boston City Hospital.

Antiretrovirals were marginally effective for HIV-infected infants and children at this time. Subsequently, we embarked on a national effort to prevent vertical transmission. We participated first in the study of pharmacokinetics of zidovudine (AZT) in newborns. We enrolled patients in ACTG 076 to test the hypothesis that treatment with AZT during pregnancy and labor, and in the infant, would reduce the risk of vertical transmission. Fifty U.S. and nine French sites enrolled 473 women between April 1991 and December 20, 1993. The results were spectacular; 8 of 100 infants in the AZT treatment group, compared with 25 out of 100 infants in the control group, developed HIV. By 1995, HIV testing was offered to all women at Boston Medical Center (formerly Boston City Hospital), and the promise of prevention of vertical transmission was reaching fruition. Between 1996 and 2016, approximately 500 HIV-infected women delivered at Boston Medical Center with vertical transmission identified in only 6 (1.2%) infants; without ACTG 076, we would have expected 125! In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 70% of pregnant HIV-infected women received the complete 076 regimen, and 93% of mothers or infants received some part of the regimen. In 1992, 900 HIV-infected infants were diagnosed in the United States, and as many as 2,000 newborns were estimated to have been born infected with HIV; in 2015, 86 vertical transmissions were identified. This was, and remains, a remarkable accomplishment.

Dr. Pelton is chief of pediatric infectious diseases and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. Ms. Moloney is a certified pediatric nurse practitioner in the division of pediatric infectious diseases. Dr. Pelton said he had no relevant financial disclosures, and Ms. Moloney is a speaker (on vaccines) for Sanofi Pasteur. Email them at [email protected].

50 years of pediatric dermatology

The world in pediatric dermatology has changed in incredible ways since 1967. In fact, pediatric dermatology was not an organized specialty until years later! This article will look back at some of the history of pediatric dermatology, exploring how different the field was 50 years ago, and how it has evolved into the vibrant field that it is. By looking at some disease states, and differences in practice in relation to the care of dermatologic conditions in children both by pediatricians and dermatologists, we can see the tremendous evolution in our understanding and management of pediatric skin conditions, and perhaps gain insight into the future.

Pediatric dermatology was fairly “neonatal” 50 years ago, with only a few practitioners in the field. Recognizing that up to 30% of pediatric primary care visits include a skin-related problem, and that there was limited training about skin diseases among primary care practitioners and inconsistent training amongst dermatologists, there was a clinical need for establishing the subspecialty of pediatric dermatology. The first international symposium was held in Mexico City in October 1972, and with this meeting the International Society of Pediatric Dermatology was founded. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) began in 1973, with Alvin Jacobs, MD, Samuel Weinberg, MD, Nancy Esterly, MD, Sidney Hurwitz, MD, William Weston, MD, and Coleman Jacobson, MD, as some of the initial “founding mothers and fathers.” The journal Pediatric Dermatology released its first issue in 1982 (35 years ago), and the American Academy of Pediatrics did not have a section of dermatology until 1986.

Pediatrics and dermatology: The interface

Many of the first generation of pediatric dermatologists trained as pediatricians prior to pursuing their dermatology work, with some being “assigned” dermatology as pediatric experts, while others did formal residencies in dermatology. This history is important, as pediatric dermatology was, and remains, integrated with pediatrics, even while training in dermatology residencies became standard practice. An important part of the development of the field has been the education of pediatricians and dermatologists by pediatric dermatologists, with a strong sensibility that improved training for both generalists and specialists about pediatric skin disease would yield better care for patients and families.

Initially, there were very few pediatric or dermatology programs in the United States that had pediatric dermatologists. Over the succeeding decades, this is now less common, although even now there are still dermatology and pediatric residency programs that do not have a pediatric dermatologist for either training or to serve their patients. The founding leaders of the SPD set a tone of collaboration nationally and internationally, reaching out to pediatric colleagues and dermatology associates from around the world, and establishing superb educational programs for the exchange of ideas, presentation of challenging cases, and promoting state of the art knowledge of the field. Through annual meetings of the SPD, conferences immediately preceding the American Academy of Dermatology annual meetings, the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology, and other regional and international meetings, the field developed as the number of practitioners grew, and as the specialized published literature reflected new knowledge in diagnosis and therapy.

Building upon the history of collaboration and reflecting the maturation of the field with a desire to influence the breadth and quantity of research in pediatric dermatology, the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA) was formed in 2012. This organization was formed to promote and facilitate high quality collaborative clinical, translational, educational, and basic science research in pediatric dermatology with a vision to create sustainable, collaborative networks to better understand, prevent, treat, and cure dermatologic diseases in children. This network is now composed of over 230 members representing over 68 institutions from the United States and Canada, but including involvement globally from Mexico, Europe, and the Middle East.

Examples of changing perspectives: hemangiomas

A good way to look at evolution of the field is take a look at some of the similarities and differences in clinical practice in relation to common and uncommon disease states.

A great example is hemangiomas. Some of the first natural history studies on hemangiomas were done in the early 1960s, establishing that many lesions had a typical clinical course of fairly rapid growth, plateau, and involution over time. Of course, the identification of hemangiomas of infancy (or “HOI” in the trade), was confused with vascular malformations, and no one had recognized variant tumors that were distinct, such as rapidly involuting and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (RICHs or NICHs), tufted angiomas, and hemangioendotheliomas. PHACE syndrome (posterior fossa brain malformations) had yet to be described (that was done in 1996 by Ilona Frieden and her colleagues). For a time period, hemangiomas were treated with X-rays, before the negative impact of such radiation was acknowledged. For many years after that, even deforming and functionally significant lesions were “followed clinically” for natural involution, presumably a backlash from the radiation therapy interventions.

This story also reflects how organized research efforts helped with the evolution of knowledge and clinical care. The Hemangioma of Infancy Group was formed to take a collaborative approach to characterize and study hemangiomas and related tumors. Beginning with energetic, insightful pediatric dermatologists, and little funding, they changed our knowledge base of how hemangiomas present, the risk factors for their development and the characteristics and multiple organ findings associated with PHACE and other syndromic hemangiomas.

Procedural pediatric dermatology: Tremendous revolution in surgery and laser

The first generation of pediatric dermatologists were considered medical dermatologist specialists. And how important this specialty work was! Acne, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, diaper and seborrheic dermatitis, and rare genetic syndromes, these conditions were a major part of the work of early pediatric dermatologists (and remain so now). What was not common was for pediatric dermatologists to have procedural or surgical practices, while this now is routinely part of the work of specialists in the field. How did this shift occur?

The fundamental shift began to occur with the introduction of the pulsed dye laser in 1989 and the publication of a seminal article in the New England Journal of Medicine (1989 Feb 16;320[7]:416-21) on its utility in treating port-wine stains in children with minimal scarring. Vascular lesions including port-wine stains were common, and pediatric dermatologists managed these patients for both diagnosis and medical management. Also, dermatology residencies at this time offered training in cutaneous surgery, excisions (including Mohs surgery) and repairs, and trainees in pediatric dermatology were “trained up” to high levels of expertise. As lasers were incorporated into dermatology residency work and practices, pediatric dermatologists had the exposure and skill to do this work. An added advantage was having the pediatric knowledge of how to handle children and adolescents in an age appropriate manner, and consideration of methods to minimize the pain and anxiety of procedures. Within a few years, pediatric dermatologists were at the forefront of the use of topical anesthetics (EMLA and liposomal lidocaine) and had general anesthesia privileges for laser and excisional surgery.

So while pediatric dermatologists still do “small procedures” every hour in most practices (cryotherapy for warts, cantharidin for molluscum, shave and punch biopsies), a subset now have extensive procedural practices, which in recent years has extended to pigment lesion lasers (to treat nevus of Ota), hair lasers (to treat perineal areas to prevent pilonidal cyst recurrence or to treat hirsutism), and combinations of lasers to treat hypertrophic, constrictive, and/or deforming scars).

Inflammatory skin disorders: Bread and butter ... and peanut butter?

The care of pediatric inflammatory skin disorders has evolved, but more slowly for some diseases than others. Acne vulgaris now is recognized as much more common under age 12 years than previously, presumably reflecting earlier pubertal changes in our preteens. Over the past 30 years, therapy has evolved with the use of topical retinoids (still underused by pediatricians, considered a “practice gap”), hormonal therapy with combined oral contraceptives, and oral isotretinoin, a powerful but highly effective systemic agent for severe and refractory acne. Specific pediatric guidelines came much later. Pediatric acne expert recommendations were formulated by the American Acne and Rosacea Society and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2013 (Pediatrics. 2013;131:S163-86). Over the past few years, there is a push by experts for more judicious use of antibiotics for acne (oral and topical) to minimize the emergence of bacterial resistance.

Psoriasis has been a condition that has been “behind the revolution,” in that no biologic agent was approved for pediatric psoriasis in the United States until several months ago, lagging behind Europe and elsewhere in the world by almost a decade. Adult psoriasis has been recognized to be associated with a broad set of comorbidities, including obesity and early heart disease, and there is now research on how children are at risk as well, and new recommendations on how to screen children with psoriasis. Moderate to severe psoriasis in adults is now tremendously controllable with biologic agents targeting TNF-alpha, IL 12/23, and IL-17. Etanercept has been approved for children with psoriasis aged 4 years and older, and other biologic agents are under study.

Atopic dermatitis now is ready for its revolution! AD has increased in prevalence from around 5% of the pediatric population 30-plus years ago to 10%-15%. Treatment of most individuals has remained the same over the decades: Good skin care, frequent moisturizers, topical corticosteroids for flares, management of infection if noted. The topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) broadened the therapeutic approach when introduced in 2000 and 2001, but the boxed warning resulted in some practitioners minimizing their utilization of these useful agents.

It has been recognized for years that children with AD have higher risk of developing food allergies than children without AD. A changing understanding of how early food exposure may induce tolerance is changing the world of allergy and influencing the care of children with AD. This is where the peanut butter (or other processed peanut, such as “Bamba”) may be life saving. New guidelines have come from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases recommending that infants with severe eczema (or egg allergy, or both) have introduction of age-appropriate peanut-containing food as early as 4-6 months of age to reduce the risk of development of peanut allergy. It is recommended that these infants undergo early evaluation for possible sensitization to peanut protein, with referral to allergists for skin prick tests or serum IgE screens (though if positive, referral to allergists is appropriate), and assess the safety of going ahead with early feeding. It is hoped that following these new guidelines can minimize the development of peanut allergy.

The future

Where will pediatric skin disease, or more importantly, skin health over a lifetime be in 50 years? Can we cure or prevent the consequences of our lethal and life altering genetic diseases such as epidermolysis bullosa or our neurocutaneous disorders? Will our new insights into birthmarks (they are mostly somatic mutations) allow us to form specific, personalized therapies to minimize their impact? Will we be using computers equipped with imaging devices and algorithms to assess our patients’ moles, papules, and nodules? Will our vaccines have wiped out warts, molluscum, and perhaps, acne? Will we have cured our inflammatory skin disorders, or perhaps prevented them by interventions in the neonatal period? No predictions will be offered here, other than that we can look forward to incredible changes for our future generations of health care practitioners, patients, and families.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield has served as a consultant for Anacor/Pfizer and Regeneron/Sanofi. Email him at [email protected].

The world in pediatric dermatology has changed in incredible ways since 1967. In fact, pediatric dermatology was not an organized specialty until years later! This article will look back at some of the history of pediatric dermatology, exploring how different the field was 50 years ago, and how it has evolved into the vibrant field that it is. By looking at some disease states, and differences in practice in relation to the care of dermatologic conditions in children both by pediatricians and dermatologists, we can see the tremendous evolution in our understanding and management of pediatric skin conditions, and perhaps gain insight into the future.

Pediatric dermatology was fairly “neonatal” 50 years ago, with only a few practitioners in the field. Recognizing that up to 30% of pediatric primary care visits include a skin-related problem, and that there was limited training about skin diseases among primary care practitioners and inconsistent training amongst dermatologists, there was a clinical need for establishing the subspecialty of pediatric dermatology. The first international symposium was held in Mexico City in October 1972, and with this meeting the International Society of Pediatric Dermatology was founded. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) began in 1973, with Alvin Jacobs, MD, Samuel Weinberg, MD, Nancy Esterly, MD, Sidney Hurwitz, MD, William Weston, MD, and Coleman Jacobson, MD, as some of the initial “founding mothers and fathers.” The journal Pediatric Dermatology released its first issue in 1982 (35 years ago), and the American Academy of Pediatrics did not have a section of dermatology until 1986.

Pediatrics and dermatology: The interface

Many of the first generation of pediatric dermatologists trained as pediatricians prior to pursuing their dermatology work, with some being “assigned” dermatology as pediatric experts, while others did formal residencies in dermatology. This history is important, as pediatric dermatology was, and remains, integrated with pediatrics, even while training in dermatology residencies became standard practice. An important part of the development of the field has been the education of pediatricians and dermatologists by pediatric dermatologists, with a strong sensibility that improved training for both generalists and specialists about pediatric skin disease would yield better care for patients and families.

Initially, there were very few pediatric or dermatology programs in the United States that had pediatric dermatologists. Over the succeeding decades, this is now less common, although even now there are still dermatology and pediatric residency programs that do not have a pediatric dermatologist for either training or to serve their patients. The founding leaders of the SPD set a tone of collaboration nationally and internationally, reaching out to pediatric colleagues and dermatology associates from around the world, and establishing superb educational programs for the exchange of ideas, presentation of challenging cases, and promoting state of the art knowledge of the field. Through annual meetings of the SPD, conferences immediately preceding the American Academy of Dermatology annual meetings, the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology, and other regional and international meetings, the field developed as the number of practitioners grew, and as the specialized published literature reflected new knowledge in diagnosis and therapy.

Building upon the history of collaboration and reflecting the maturation of the field with a desire to influence the breadth and quantity of research in pediatric dermatology, the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA) was formed in 2012. This organization was formed to promote and facilitate high quality collaborative clinical, translational, educational, and basic science research in pediatric dermatology with a vision to create sustainable, collaborative networks to better understand, prevent, treat, and cure dermatologic diseases in children. This network is now composed of over 230 members representing over 68 institutions from the United States and Canada, but including involvement globally from Mexico, Europe, and the Middle East.

Examples of changing perspectives: hemangiomas

A good way to look at evolution of the field is take a look at some of the similarities and differences in clinical practice in relation to common and uncommon disease states.

A great example is hemangiomas. Some of the first natural history studies on hemangiomas were done in the early 1960s, establishing that many lesions had a typical clinical course of fairly rapid growth, plateau, and involution over time. Of course, the identification of hemangiomas of infancy (or “HOI” in the trade), was confused with vascular malformations, and no one had recognized variant tumors that were distinct, such as rapidly involuting and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (RICHs or NICHs), tufted angiomas, and hemangioendotheliomas. PHACE syndrome (posterior fossa brain malformations) had yet to be described (that was done in 1996 by Ilona Frieden and her colleagues). For a time period, hemangiomas were treated with X-rays, before the negative impact of such radiation was acknowledged. For many years after that, even deforming and functionally significant lesions were “followed clinically” for natural involution, presumably a backlash from the radiation therapy interventions.

This story also reflects how organized research efforts helped with the evolution of knowledge and clinical care. The Hemangioma of Infancy Group was formed to take a collaborative approach to characterize and study hemangiomas and related tumors. Beginning with energetic, insightful pediatric dermatologists, and little funding, they changed our knowledge base of how hemangiomas present, the risk factors for their development and the characteristics and multiple organ findings associated with PHACE and other syndromic hemangiomas.

Procedural pediatric dermatology: Tremendous revolution in surgery and laser

The first generation of pediatric dermatologists were considered medical dermatologist specialists. And how important this specialty work was! Acne, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, diaper and seborrheic dermatitis, and rare genetic syndromes, these conditions were a major part of the work of early pediatric dermatologists (and remain so now). What was not common was for pediatric dermatologists to have procedural or surgical practices, while this now is routinely part of the work of specialists in the field. How did this shift occur?

The fundamental shift began to occur with the introduction of the pulsed dye laser in 1989 and the publication of a seminal article in the New England Journal of Medicine (1989 Feb 16;320[7]:416-21) on its utility in treating port-wine stains in children with minimal scarring. Vascular lesions including port-wine stains were common, and pediatric dermatologists managed these patients for both diagnosis and medical management. Also, dermatology residencies at this time offered training in cutaneous surgery, excisions (including Mohs surgery) and repairs, and trainees in pediatric dermatology were “trained up” to high levels of expertise. As lasers were incorporated into dermatology residency work and practices, pediatric dermatologists had the exposure and skill to do this work. An added advantage was having the pediatric knowledge of how to handle children and adolescents in an age appropriate manner, and consideration of methods to minimize the pain and anxiety of procedures. Within a few years, pediatric dermatologists were at the forefront of the use of topical anesthetics (EMLA and liposomal lidocaine) and had general anesthesia privileges for laser and excisional surgery.

So while pediatric dermatologists still do “small procedures” every hour in most practices (cryotherapy for warts, cantharidin for molluscum, shave and punch biopsies), a subset now have extensive procedural practices, which in recent years has extended to pigment lesion lasers (to treat nevus of Ota), hair lasers (to treat perineal areas to prevent pilonidal cyst recurrence or to treat hirsutism), and combinations of lasers to treat hypertrophic, constrictive, and/or deforming scars).

Inflammatory skin disorders: Bread and butter ... and peanut butter?

The care of pediatric inflammatory skin disorders has evolved, but more slowly for some diseases than others. Acne vulgaris now is recognized as much more common under age 12 years than previously, presumably reflecting earlier pubertal changes in our preteens. Over the past 30 years, therapy has evolved with the use of topical retinoids (still underused by pediatricians, considered a “practice gap”), hormonal therapy with combined oral contraceptives, and oral isotretinoin, a powerful but highly effective systemic agent for severe and refractory acne. Specific pediatric guidelines came much later. Pediatric acne expert recommendations were formulated by the American Acne and Rosacea Society and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2013 (Pediatrics. 2013;131:S163-86). Over the past few years, there is a push by experts for more judicious use of antibiotics for acne (oral and topical) to minimize the emergence of bacterial resistance.

Psoriasis has been a condition that has been “behind the revolution,” in that no biologic agent was approved for pediatric psoriasis in the United States until several months ago, lagging behind Europe and elsewhere in the world by almost a decade. Adult psoriasis has been recognized to be associated with a broad set of comorbidities, including obesity and early heart disease, and there is now research on how children are at risk as well, and new recommendations on how to screen children with psoriasis. Moderate to severe psoriasis in adults is now tremendously controllable with biologic agents targeting TNF-alpha, IL 12/23, and IL-17. Etanercept has been approved for children with psoriasis aged 4 years and older, and other biologic agents are under study.

Atopic dermatitis now is ready for its revolution! AD has increased in prevalence from around 5% of the pediatric population 30-plus years ago to 10%-15%. Treatment of most individuals has remained the same over the decades: Good skin care, frequent moisturizers, topical corticosteroids for flares, management of infection if noted. The topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) broadened the therapeutic approach when introduced in 2000 and 2001, but the boxed warning resulted in some practitioners minimizing their utilization of these useful agents.

It has been recognized for years that children with AD have higher risk of developing food allergies than children without AD. A changing understanding of how early food exposure may induce tolerance is changing the world of allergy and influencing the care of children with AD. This is where the peanut butter (or other processed peanut, such as “Bamba”) may be life saving. New guidelines have come from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases recommending that infants with severe eczema (or egg allergy, or both) have introduction of age-appropriate peanut-containing food as early as 4-6 months of age to reduce the risk of development of peanut allergy. It is recommended that these infants undergo early evaluation for possible sensitization to peanut protein, with referral to allergists for skin prick tests or serum IgE screens (though if positive, referral to allergists is appropriate), and assess the safety of going ahead with early feeding. It is hoped that following these new guidelines can minimize the development of peanut allergy.

The future