User login

Lesions on the Thigh After an Organ Transplant

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Lymphatic Malformation

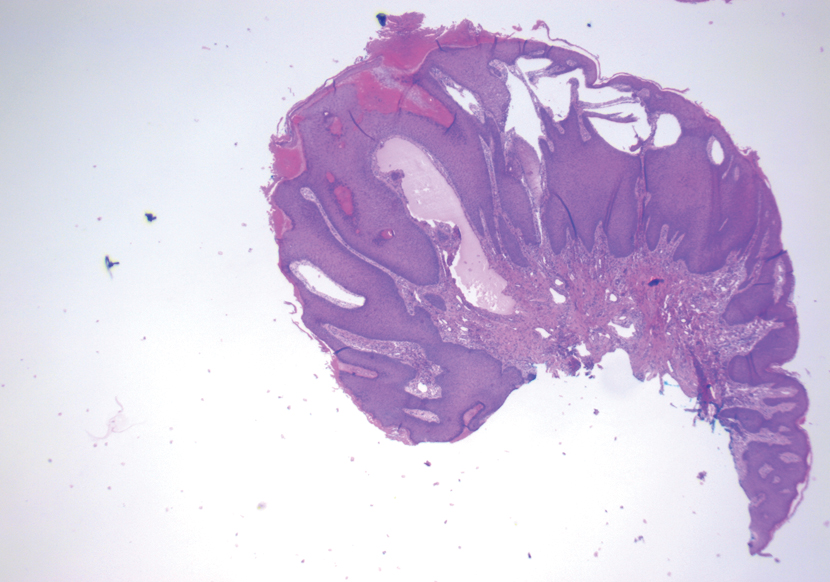

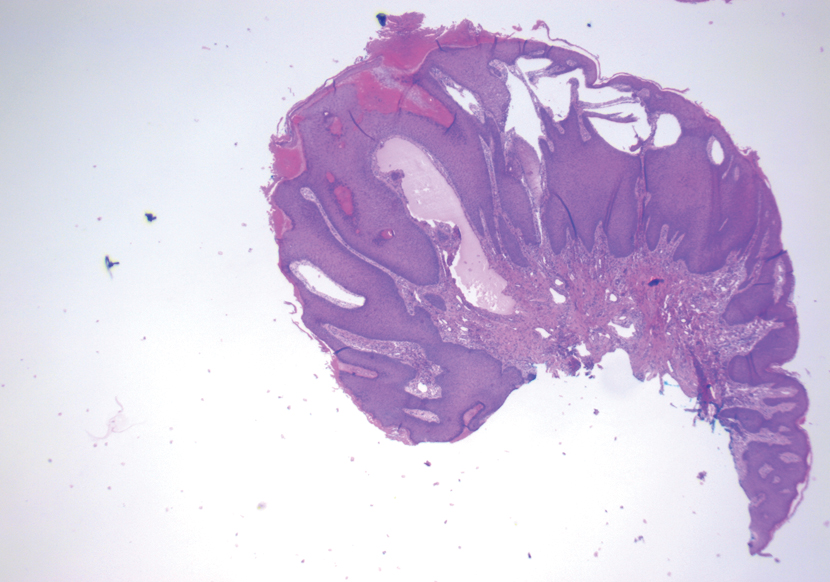

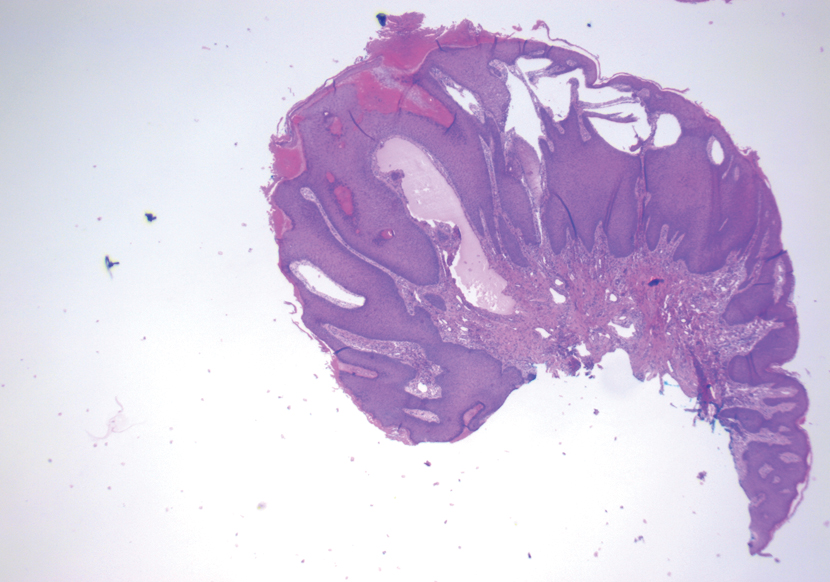

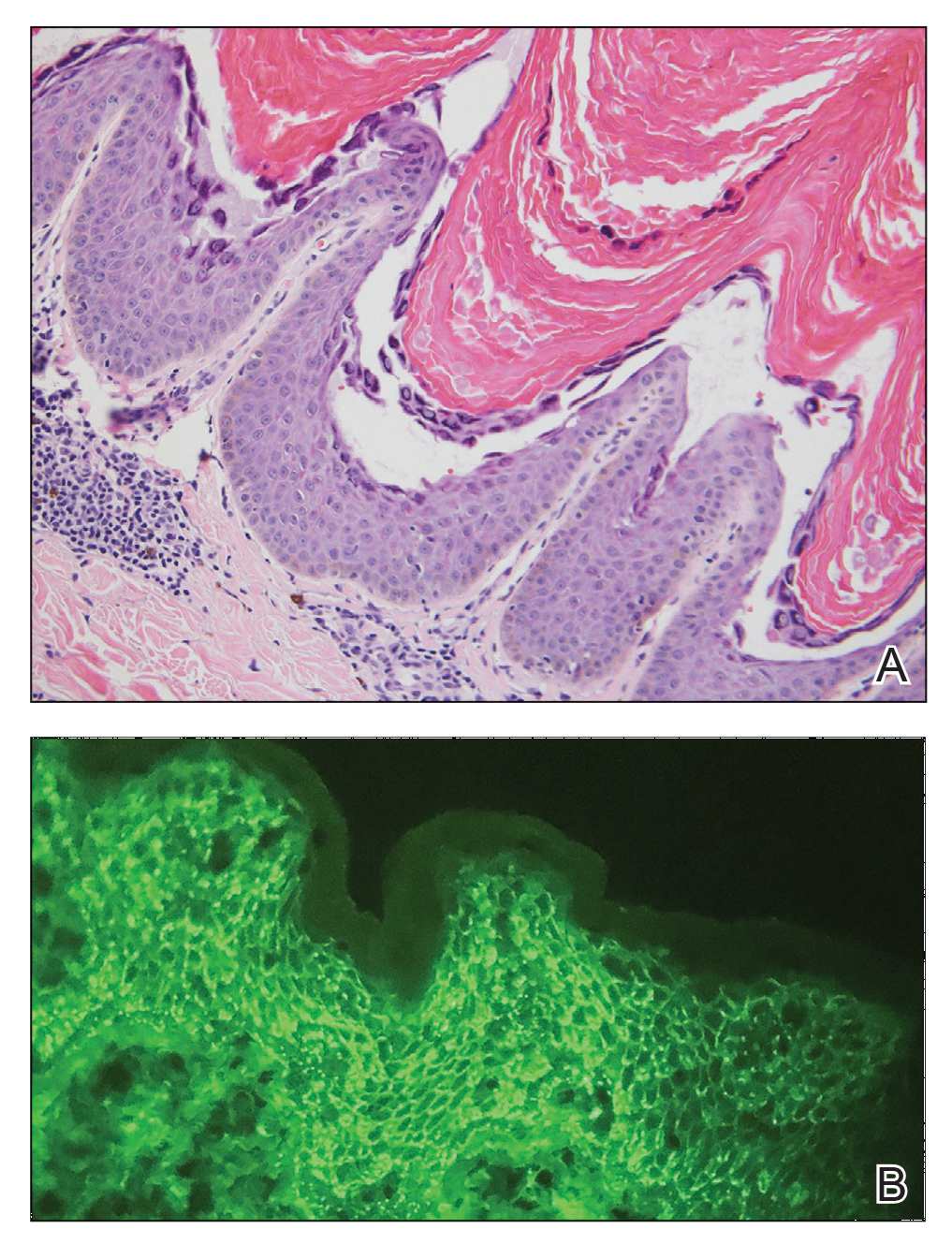

The shave biopsy demonstrated numerous thin-walled vascular spaces filled with lymphatic fluid within the dermis (Figure), consistent with a diagnosis of microcystic lymphatic malformation (LM). Lymphatic malformations represent a class of benign vascular lesions consisting of anomalous or dilated lymphatic vessels, which can be broadly categorized as macrocystic (formerly cavernous lymphangioma or cystic hygroma), microcystic (formerly lymphangioma circumscriptum), or mixed.1 Patients often will present with pruritus, crusting, secondary infection, edema, or oozing.2 The superficial blebs of microcystic LMs resemble frog spawn and range in color from clear to pink, brawny, or deep maroon.3 Although the lymphatic vessels involved in microcystic LMs appear disconnected from the major lymphatic circulation,3 systemic fluid overload could plausibly promote lesional swelling and tenderness; we attributed our patient's worsening symptoms to the cumulative 7.8 L of intravenous fluid he received intraoperatively during his cardiac transplant. The excess fluid allowed communication between lymphatic cisterns and thin-walled vesicles on the skin surface through dilated channels. Overall, LMs represent roughly 26% of pediatric benign vascular tumors and approximately 4% of all vascular tumors.4

Although microcystic LMs may appear especially vascular or verrucous, the differential diagnosis for our patient's LM included condyloma acuminatum,5,6 condyloma lata,7 epidermal nevus, and lymphangiosarcoma. Epidermal nevi are congenital lesions, varying in appearance from velvety to verrucous patches and plaques that often evolve during puberty and become thicker, more verrucous, and hyperpigmented. Keratinocytic epidermal nevus syndromes and other entities such as nevus sebaceous have been associated with somatic mutations affecting proteins in the fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling pathway (eg, FGFR3, HRAS).8 Although the clinical appearance alone may be similar, lymphangiosarcoma can be distinguished from LM via biopsy.

There are several methods to diagnose LM. Duplex sonography is possibly the best noninvasive method to identify the flow between venous valves. Magnetic resonance imaging can detect larger occurrences of LM, and lymphangiography can be utilized to confirm a normal or abnormal lymphatic network.4 Treatment options are broad, including surgical excision, laser ablation, and topical sirolimus. Hypertonic saline sclerotherapy can be injected into the afflicted lymphatic channels to decrease inflammation, erythema, and hyperpigmentation without further treatment or major side effects.4

However, the benefits of sclerotherapy alone in the treatment of LM often come gradually, and radiofrequency ablation may need to be utilized to achieve more immediate results.2 Overall, outcomes are highly variable, but favorable outcomes often can be difficult to obtain due to a high recurrence rate.2,8 Our patient's symptoms improved during his postoperative recovery, and he declined further intervention.

- Elluru RG, Balakrishnan K, Padua HM. Lymphatic malformations: diagnosis and management. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23:178-185. doi:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.07.002

- Niti K, Manish P. Microcystic lymphatic malformation (lymphangioma circumscriptum) treated using a minimally invasive technique of radiofrequency ablation and sclerotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1711-1717. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01723.x

- Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290-1295. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2009.04226.x

- Bikowski JB, Dumont AM. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: treatment with hypertonic saline sclerotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:442-444. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.04.086

- Costa-Silva M, Fernandes I, Rodrigues AG, et al. Anogenital warts in pediatric population. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:675-681. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.201756411

- Darmstadt GL. Perianal lymphangioma circumscriptum mistaken for genital warts. Pediatrics 1996;98;461.

- Bruins FG, van Deudekom FJA, de Vries HJC. Syphilitic condylomata lata mimicking anogenital warts. BMJ. 2015;350:h1259. doi:10.1136 /bmj.h1259

- Asch S, Sugarman JL. Epidermal nevus syndromes: new insights into whorls and swirls. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:21-29. doi:10.1111 /pde.13273

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Lymphatic Malformation

The shave biopsy demonstrated numerous thin-walled vascular spaces filled with lymphatic fluid within the dermis (Figure), consistent with a diagnosis of microcystic lymphatic malformation (LM). Lymphatic malformations represent a class of benign vascular lesions consisting of anomalous or dilated lymphatic vessels, which can be broadly categorized as macrocystic (formerly cavernous lymphangioma or cystic hygroma), microcystic (formerly lymphangioma circumscriptum), or mixed.1 Patients often will present with pruritus, crusting, secondary infection, edema, or oozing.2 The superficial blebs of microcystic LMs resemble frog spawn and range in color from clear to pink, brawny, or deep maroon.3 Although the lymphatic vessels involved in microcystic LMs appear disconnected from the major lymphatic circulation,3 systemic fluid overload could plausibly promote lesional swelling and tenderness; we attributed our patient's worsening symptoms to the cumulative 7.8 L of intravenous fluid he received intraoperatively during his cardiac transplant. The excess fluid allowed communication between lymphatic cisterns and thin-walled vesicles on the skin surface through dilated channels. Overall, LMs represent roughly 26% of pediatric benign vascular tumors and approximately 4% of all vascular tumors.4

Although microcystic LMs may appear especially vascular or verrucous, the differential diagnosis for our patient's LM included condyloma acuminatum,5,6 condyloma lata,7 epidermal nevus, and lymphangiosarcoma. Epidermal nevi are congenital lesions, varying in appearance from velvety to verrucous patches and plaques that often evolve during puberty and become thicker, more verrucous, and hyperpigmented. Keratinocytic epidermal nevus syndromes and other entities such as nevus sebaceous have been associated with somatic mutations affecting proteins in the fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling pathway (eg, FGFR3, HRAS).8 Although the clinical appearance alone may be similar, lymphangiosarcoma can be distinguished from LM via biopsy.

There are several methods to diagnose LM. Duplex sonography is possibly the best noninvasive method to identify the flow between venous valves. Magnetic resonance imaging can detect larger occurrences of LM, and lymphangiography can be utilized to confirm a normal or abnormal lymphatic network.4 Treatment options are broad, including surgical excision, laser ablation, and topical sirolimus. Hypertonic saline sclerotherapy can be injected into the afflicted lymphatic channels to decrease inflammation, erythema, and hyperpigmentation without further treatment or major side effects.4

However, the benefits of sclerotherapy alone in the treatment of LM often come gradually, and radiofrequency ablation may need to be utilized to achieve more immediate results.2 Overall, outcomes are highly variable, but favorable outcomes often can be difficult to obtain due to a high recurrence rate.2,8 Our patient's symptoms improved during his postoperative recovery, and he declined further intervention.

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Lymphatic Malformation

The shave biopsy demonstrated numerous thin-walled vascular spaces filled with lymphatic fluid within the dermis (Figure), consistent with a diagnosis of microcystic lymphatic malformation (LM). Lymphatic malformations represent a class of benign vascular lesions consisting of anomalous or dilated lymphatic vessels, which can be broadly categorized as macrocystic (formerly cavernous lymphangioma or cystic hygroma), microcystic (formerly lymphangioma circumscriptum), or mixed.1 Patients often will present with pruritus, crusting, secondary infection, edema, or oozing.2 The superficial blebs of microcystic LMs resemble frog spawn and range in color from clear to pink, brawny, or deep maroon.3 Although the lymphatic vessels involved in microcystic LMs appear disconnected from the major lymphatic circulation,3 systemic fluid overload could plausibly promote lesional swelling and tenderness; we attributed our patient's worsening symptoms to the cumulative 7.8 L of intravenous fluid he received intraoperatively during his cardiac transplant. The excess fluid allowed communication between lymphatic cisterns and thin-walled vesicles on the skin surface through dilated channels. Overall, LMs represent roughly 26% of pediatric benign vascular tumors and approximately 4% of all vascular tumors.4

Although microcystic LMs may appear especially vascular or verrucous, the differential diagnosis for our patient's LM included condyloma acuminatum,5,6 condyloma lata,7 epidermal nevus, and lymphangiosarcoma. Epidermal nevi are congenital lesions, varying in appearance from velvety to verrucous patches and plaques that often evolve during puberty and become thicker, more verrucous, and hyperpigmented. Keratinocytic epidermal nevus syndromes and other entities such as nevus sebaceous have been associated with somatic mutations affecting proteins in the fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling pathway (eg, FGFR3, HRAS).8 Although the clinical appearance alone may be similar, lymphangiosarcoma can be distinguished from LM via biopsy.

There are several methods to diagnose LM. Duplex sonography is possibly the best noninvasive method to identify the flow between venous valves. Magnetic resonance imaging can detect larger occurrences of LM, and lymphangiography can be utilized to confirm a normal or abnormal lymphatic network.4 Treatment options are broad, including surgical excision, laser ablation, and topical sirolimus. Hypertonic saline sclerotherapy can be injected into the afflicted lymphatic channels to decrease inflammation, erythema, and hyperpigmentation without further treatment or major side effects.4

However, the benefits of sclerotherapy alone in the treatment of LM often come gradually, and radiofrequency ablation may need to be utilized to achieve more immediate results.2 Overall, outcomes are highly variable, but favorable outcomes often can be difficult to obtain due to a high recurrence rate.2,8 Our patient's symptoms improved during his postoperative recovery, and he declined further intervention.

- Elluru RG, Balakrishnan K, Padua HM. Lymphatic malformations: diagnosis and management. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23:178-185. doi:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.07.002

- Niti K, Manish P. Microcystic lymphatic malformation (lymphangioma circumscriptum) treated using a minimally invasive technique of radiofrequency ablation and sclerotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1711-1717. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01723.x

- Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290-1295. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2009.04226.x

- Bikowski JB, Dumont AM. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: treatment with hypertonic saline sclerotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:442-444. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.04.086

- Costa-Silva M, Fernandes I, Rodrigues AG, et al. Anogenital warts in pediatric population. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:675-681. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.201756411

- Darmstadt GL. Perianal lymphangioma circumscriptum mistaken for genital warts. Pediatrics 1996;98;461.

- Bruins FG, van Deudekom FJA, de Vries HJC. Syphilitic condylomata lata mimicking anogenital warts. BMJ. 2015;350:h1259. doi:10.1136 /bmj.h1259

- Asch S, Sugarman JL. Epidermal nevus syndromes: new insights into whorls and swirls. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:21-29. doi:10.1111 /pde.13273

- Elluru RG, Balakrishnan K, Padua HM. Lymphatic malformations: diagnosis and management. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23:178-185. doi:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.07.002

- Niti K, Manish P. Microcystic lymphatic malformation (lymphangioma circumscriptum) treated using a minimally invasive technique of radiofrequency ablation and sclerotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1711-1717. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01723.x

- Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290-1295. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2009.04226.x

- Bikowski JB, Dumont AM. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: treatment with hypertonic saline sclerotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:442-444. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.04.086

- Costa-Silva M, Fernandes I, Rodrigues AG, et al. Anogenital warts in pediatric population. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:675-681. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.201756411

- Darmstadt GL. Perianal lymphangioma circumscriptum mistaken for genital warts. Pediatrics 1996;98;461.

- Bruins FG, van Deudekom FJA, de Vries HJC. Syphilitic condylomata lata mimicking anogenital warts. BMJ. 2015;350:h1259. doi:10.1136 /bmj.h1259

- Asch S, Sugarman JL. Epidermal nevus syndromes: new insights into whorls and swirls. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:21-29. doi:10.1111 /pde.13273

A 17-year-old adolescent boy presented with increasingly painful genital warts on the right thigh, groin, and scrotum that had been present since birth. The patient had a medical history of cardiac transplantation in the months prior to presentation and was on immunosuppressive therapy. The lesions had become more swollen and bothersome in the weeks following the transplantation and now prevented him from ambulating due to discomfort. He denied any history of sexual contact or oral lesions. Physical examination revealed numerous translucent and hemorrhagic vesicles clustered and linearly distributed on the right medial thigh. A shave biopsy of a vesicle was performed.

Verrucous Scalp Plaque and Widespread Eruption

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Foliaceous

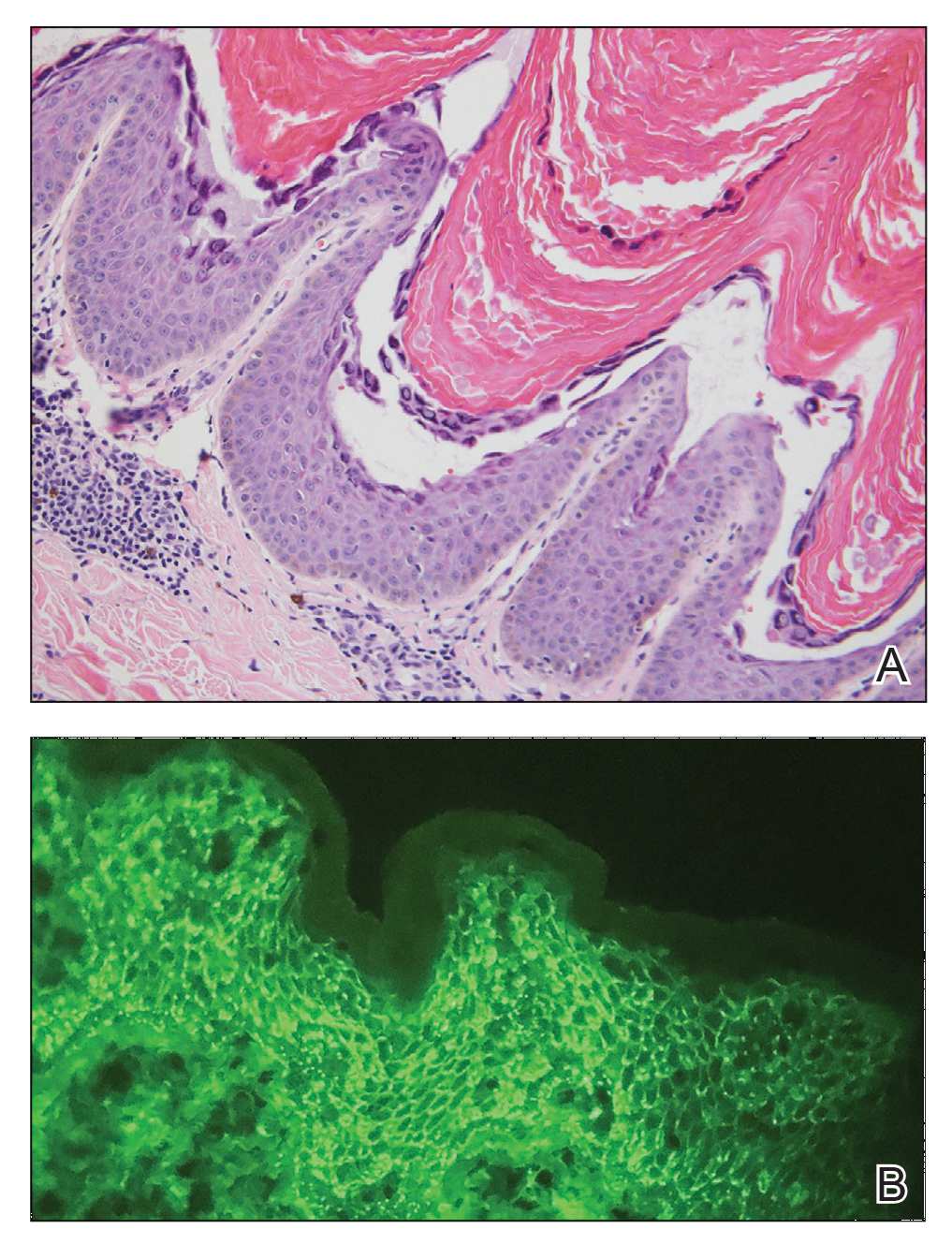

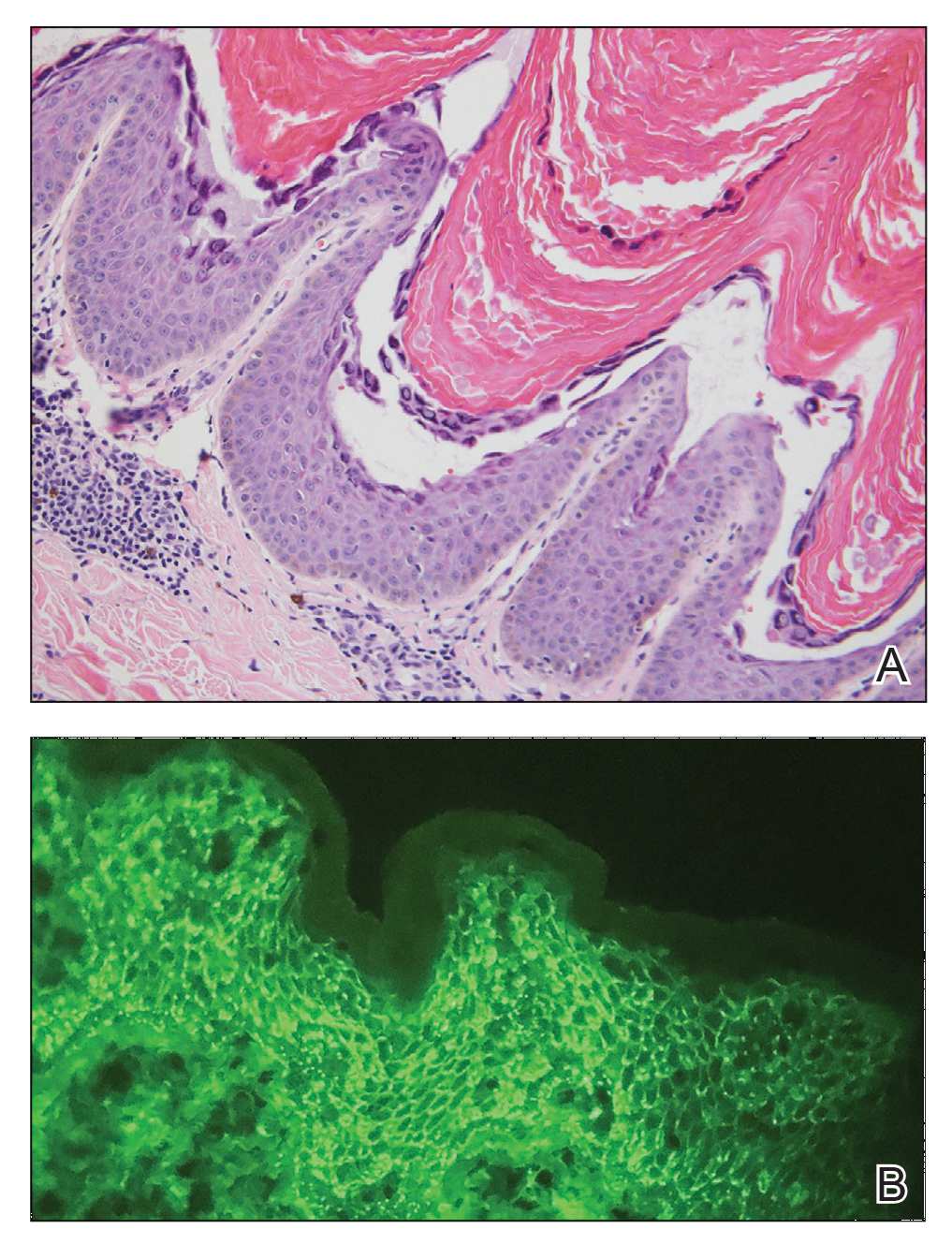

Laboratory workup including a complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, Sjögren syndrome A and B antibodies, hepatitis profile, rapid plasma reagin, HIV screen, aldolase, anti–Jo-1, T-Spot TB test (Quest Diagnostics), and tissue cultures was unremarkable. Two 4-mm punch biopsies were obtained from the left cheek and upper back, both of which demonstrated intragranular acantholysis suggestive of pemphigus foliaceous (Figure 1A). A subsequent punch biopsy from the right lower abdomen sent for direct immunofluorescence demonstrated netlike positivity of IgG and C3 in the upper epidermis (Figure 1B), and serum sent for indirect immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular IgG antibodies to desmoglein (Dsg) 1 on monkey esophagus and positive Dsg-1 antibodies on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, confirming the diagnosis.

The patient was started on a 60-mg prednisone taper as well as dapsone 50 mg daily; the dapsone was titrated up to 100 mg daily. After tapering down to 10 mg daily of prednisone over 2 months and continuing dapsone with minimal improvement, he was given 2 infusions of rituximab 1000 mg 2 weeks apart. The scalp plaque was dramatically improved at 3-month follow-up (Figure 2), with partial improvement of the cheek plaques (Figure 3). Dapsone was increased to 150 mg daily, and he was encouraged to use triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily, which led to further improvement.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune blistering disease that most commonly occurs in middle-aged adults. It generally is less common than pemphigus vulgaris, except in Finland, Tunisia, and Brazil, where there is an endemic condition with an identical clinical and histological presentation known as fogo selvagem.1

The pathogenesis of pemphigus foliaceous is characterized by IgG autoantibodies against Dsg-1, a transmembrane glycoprotein involved in the cellular adhesion of keratinocytes, which is preferentially expressed in the superficial epidermis.2-7 Dysfunction of Dsg-1 results in the separation of superficial epidermal cells, resulting in intraepidermal blisters.2,7 In contrast to pemphigus vulgaris, there typically is a lack of oral mucosal involvement due to compensation by Dsg-3 in the mucosa.4 Potential triggers for pemphigus foliaceous include exposure to UV radiation; radiotherapy; pregnancy; physiologic stress; and drugs, most commonly captopril, penicillamine, and thiols.8

Pemphigus foliaceous lesions clinically appear as eroded and crusted lesions on an erythematous base, commonly in a seborrheic distribution on the face, scalp, and trunk with sparing of the oral mucosa,2,6 but lesions can progress to a widespread and more severe exfoliative dermatitis.7 Lesions also can appear as psoriasiform plaques and often are initially misdiagnosed as psoriasis, particularly in patients with skin of color.9,10

Diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceous typically is made using a combination of histology as well as both direct and indirect immunofluorescence. Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus presents with subcorneal acantholysis, which is most prominent in the granular layer and occasionally the presence of neutrophils and eosinophils in the blister cavity.7 Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates netlike intercellular IgG and C3 in the upper portion of the epidermis.11 Indirect immunofluorescence can help detect circulating IgG antibodies to Dsg-1, with guinea pig esophagus being the ideal substrate.11,12

First-line treatment of pemphigus foliaceus consists of systemic glucocorticoid therapy, often administered with azathioprine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil.2,6,13 Although first-line treatment is effective in 60% to 80% of patients,2 relapsing cases can be treated with cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin, immunoadsorption, plasmapheresis, or rituximab.2

Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody targeting CD20+ B cells, leading to decreased antibody production, which has been shown to be effective in treating severe and refractory cases of pemphigus foliaceus.6,13Rituximab with short-course prednisone has been found to be more effective in achieving complete remission at 24 months than prednisone alone.14 In patients with contraindications to systemic glucocorticoid therapy, rituximab has been shown as an effective first-line therapy.15 One-quarter of patients treated with rituximab relapsed within 2 years of treatment6 (average time to relapse, 6–26 months).16 High-dose rituximab regimens, along with a higher number of rituximab treatment cycles, have been shown to prolong time to relapse.6 Further, higher baseline levels of Dsg-1 antibody have been correlated to earlier relapse and can be used following rituximab therapy to monitor disease progression.6,16

The differential diagnosis for pemphigus foliaceous includes disseminated blastomycosis, hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, sebopsoriasis, and secondary syphilis. Disseminated blastomycosis presents with cutaneous manifestations such as nodules, papules, or pustules evolving over weeks to months into ulcers with subsequent scarring.17 Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus presents with papules and nodules with associated keratotic scaling on the face, palms, and extensor surfaces of the limbs.18 Sebopsoriasis is characterized by well-defined lesions with an overlying scale distributed on the scalp, face, and chest.19 Secondary syphilis presents as early hyperpigmented macules transitioning to acral papulosquamous lesions involving the palms and soles.20

- Hans-Filho G, Aoki V, Hans Bittner NR, et al. Fogo selvagem: endemic pemphigus foliaceus. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:638-650.

- Jenson KK, Burr DM, Edwards BC. Case report: reatment of refractory pemphigus foliaceus with rituximab. Practical Dermatology. February 2016:33-36. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://practicaldermatology.com/articles/2016-feb/case-report -treatment-of-refractory-pemphigus-foliaceus-with-rituximab -financial-matters-aad-asds-resources

- Amagai M, Hashimoto T, Green KJ, et al. Antigen-specific immunoadsorption of pathogenic autoantibodies in pemphigus foliaceus. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:895-901.

- Mahoney MG, Wang Z, Rothenberger K, et al. Explanations for the clinical and microscopic localization of lesions in pemphigus foliaceus and vulgaris. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:461-468.

- Oktarina DAM, Sokol E, Kramer D, et al. Endocytosis of IgG, desmoglein 1, and plakoglobin in pemphigus foliaceus patient skin. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1-12.

- Kraft M, Worm M. Pemphigus foliaceus-repeated treatment with rituximab 7 years after initial response: a case report. Front Med. 2018;5:315.

- Hale EK. Pemphigus foliaceous. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8:9.

- Tavakolpour S. Pemphigus trigger factors: special focus on pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:95-106.

- A boobaker J, Morar N, Ramdial PK, et al. Pemphigus in South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:115-119.

- Austin E, Millsop JW, Ely H, et al. Psoriasiform pemphigus foliaceus in an African American female: an important clinical manifestation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:471.

- Arbache ST, Nogueira TG, Delgado L, et al. Immunofluorescence testing in the diagnosis of autoimmune blistering diseases: overview of 10-year experience. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:885-889.

- Sabolinski ML, Beutner EH, Krasny S, et al. Substrate specificity of antiepithelial antibodies of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus sera in immunofluorescence tests on monkey and guinea pig esophagus sections. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:545-549.

- Palacios-Álvarez I, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Curto-Barredo L, et al. Rituximab treatment of pemphigus foliaceus: a retrospective study of 12 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:484-486.

- Murrell DF, Sprecher E. Rituximab and short-course prednisone as the new gold standard for new-onset pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1143-1144.

- Gregoriou S, Efthymiou O, Stefanaki C, et al. Management of pemphigus vulgaris: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:521-527.

- Saleh MA. A prospective study comparing patients with early and late relapsing pemphigus treated with rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:97-103.

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264.

- Herzum A, Gasparini G, Emanuele C, et al. Atypical and rare forms of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the importance of the diagnosis for the best management of patients. Dermatology. 2013;1-10.

- Tull TJ, Noy M, Bunker CB, et al. Sebopsoriasis in patients with HIV: a case series of 20 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2016; 173:813-815.

- Balagula Y, Mattei P, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revised: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Foliaceous

Laboratory workup including a complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, Sjögren syndrome A and B antibodies, hepatitis profile, rapid plasma reagin, HIV screen, aldolase, anti–Jo-1, T-Spot TB test (Quest Diagnostics), and tissue cultures was unremarkable. Two 4-mm punch biopsies were obtained from the left cheek and upper back, both of which demonstrated intragranular acantholysis suggestive of pemphigus foliaceous (Figure 1A). A subsequent punch biopsy from the right lower abdomen sent for direct immunofluorescence demonstrated netlike positivity of IgG and C3 in the upper epidermis (Figure 1B), and serum sent for indirect immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular IgG antibodies to desmoglein (Dsg) 1 on monkey esophagus and positive Dsg-1 antibodies on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, confirming the diagnosis.

The patient was started on a 60-mg prednisone taper as well as dapsone 50 mg daily; the dapsone was titrated up to 100 mg daily. After tapering down to 10 mg daily of prednisone over 2 months and continuing dapsone with minimal improvement, he was given 2 infusions of rituximab 1000 mg 2 weeks apart. The scalp plaque was dramatically improved at 3-month follow-up (Figure 2), with partial improvement of the cheek plaques (Figure 3). Dapsone was increased to 150 mg daily, and he was encouraged to use triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily, which led to further improvement.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune blistering disease that most commonly occurs in middle-aged adults. It generally is less common than pemphigus vulgaris, except in Finland, Tunisia, and Brazil, where there is an endemic condition with an identical clinical and histological presentation known as fogo selvagem.1

The pathogenesis of pemphigus foliaceous is characterized by IgG autoantibodies against Dsg-1, a transmembrane glycoprotein involved in the cellular adhesion of keratinocytes, which is preferentially expressed in the superficial epidermis.2-7 Dysfunction of Dsg-1 results in the separation of superficial epidermal cells, resulting in intraepidermal blisters.2,7 In contrast to pemphigus vulgaris, there typically is a lack of oral mucosal involvement due to compensation by Dsg-3 in the mucosa.4 Potential triggers for pemphigus foliaceous include exposure to UV radiation; radiotherapy; pregnancy; physiologic stress; and drugs, most commonly captopril, penicillamine, and thiols.8

Pemphigus foliaceous lesions clinically appear as eroded and crusted lesions on an erythematous base, commonly in a seborrheic distribution on the face, scalp, and trunk with sparing of the oral mucosa,2,6 but lesions can progress to a widespread and more severe exfoliative dermatitis.7 Lesions also can appear as psoriasiform plaques and often are initially misdiagnosed as psoriasis, particularly in patients with skin of color.9,10

Diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceous typically is made using a combination of histology as well as both direct and indirect immunofluorescence. Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus presents with subcorneal acantholysis, which is most prominent in the granular layer and occasionally the presence of neutrophils and eosinophils in the blister cavity.7 Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates netlike intercellular IgG and C3 in the upper portion of the epidermis.11 Indirect immunofluorescence can help detect circulating IgG antibodies to Dsg-1, with guinea pig esophagus being the ideal substrate.11,12

First-line treatment of pemphigus foliaceus consists of systemic glucocorticoid therapy, often administered with azathioprine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil.2,6,13 Although first-line treatment is effective in 60% to 80% of patients,2 relapsing cases can be treated with cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin, immunoadsorption, plasmapheresis, or rituximab.2

Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody targeting CD20+ B cells, leading to decreased antibody production, which has been shown to be effective in treating severe and refractory cases of pemphigus foliaceus.6,13Rituximab with short-course prednisone has been found to be more effective in achieving complete remission at 24 months than prednisone alone.14 In patients with contraindications to systemic glucocorticoid therapy, rituximab has been shown as an effective first-line therapy.15 One-quarter of patients treated with rituximab relapsed within 2 years of treatment6 (average time to relapse, 6–26 months).16 High-dose rituximab regimens, along with a higher number of rituximab treatment cycles, have been shown to prolong time to relapse.6 Further, higher baseline levels of Dsg-1 antibody have been correlated to earlier relapse and can be used following rituximab therapy to monitor disease progression.6,16

The differential diagnosis for pemphigus foliaceous includes disseminated blastomycosis, hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, sebopsoriasis, and secondary syphilis. Disseminated blastomycosis presents with cutaneous manifestations such as nodules, papules, or pustules evolving over weeks to months into ulcers with subsequent scarring.17 Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus presents with papules and nodules with associated keratotic scaling on the face, palms, and extensor surfaces of the limbs.18 Sebopsoriasis is characterized by well-defined lesions with an overlying scale distributed on the scalp, face, and chest.19 Secondary syphilis presents as early hyperpigmented macules transitioning to acral papulosquamous lesions involving the palms and soles.20

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Foliaceous

Laboratory workup including a complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, Sjögren syndrome A and B antibodies, hepatitis profile, rapid plasma reagin, HIV screen, aldolase, anti–Jo-1, T-Spot TB test (Quest Diagnostics), and tissue cultures was unremarkable. Two 4-mm punch biopsies were obtained from the left cheek and upper back, both of which demonstrated intragranular acantholysis suggestive of pemphigus foliaceous (Figure 1A). A subsequent punch biopsy from the right lower abdomen sent for direct immunofluorescence demonstrated netlike positivity of IgG and C3 in the upper epidermis (Figure 1B), and serum sent for indirect immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular IgG antibodies to desmoglein (Dsg) 1 on monkey esophagus and positive Dsg-1 antibodies on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, confirming the diagnosis.

The patient was started on a 60-mg prednisone taper as well as dapsone 50 mg daily; the dapsone was titrated up to 100 mg daily. After tapering down to 10 mg daily of prednisone over 2 months and continuing dapsone with minimal improvement, he was given 2 infusions of rituximab 1000 mg 2 weeks apart. The scalp plaque was dramatically improved at 3-month follow-up (Figure 2), with partial improvement of the cheek plaques (Figure 3). Dapsone was increased to 150 mg daily, and he was encouraged to use triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily, which led to further improvement.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune blistering disease that most commonly occurs in middle-aged adults. It generally is less common than pemphigus vulgaris, except in Finland, Tunisia, and Brazil, where there is an endemic condition with an identical clinical and histological presentation known as fogo selvagem.1

The pathogenesis of pemphigus foliaceous is characterized by IgG autoantibodies against Dsg-1, a transmembrane glycoprotein involved in the cellular adhesion of keratinocytes, which is preferentially expressed in the superficial epidermis.2-7 Dysfunction of Dsg-1 results in the separation of superficial epidermal cells, resulting in intraepidermal blisters.2,7 In contrast to pemphigus vulgaris, there typically is a lack of oral mucosal involvement due to compensation by Dsg-3 in the mucosa.4 Potential triggers for pemphigus foliaceous include exposure to UV radiation; radiotherapy; pregnancy; physiologic stress; and drugs, most commonly captopril, penicillamine, and thiols.8

Pemphigus foliaceous lesions clinically appear as eroded and crusted lesions on an erythematous base, commonly in a seborrheic distribution on the face, scalp, and trunk with sparing of the oral mucosa,2,6 but lesions can progress to a widespread and more severe exfoliative dermatitis.7 Lesions also can appear as psoriasiform plaques and often are initially misdiagnosed as psoriasis, particularly in patients with skin of color.9,10

Diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceous typically is made using a combination of histology as well as both direct and indirect immunofluorescence. Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus presents with subcorneal acantholysis, which is most prominent in the granular layer and occasionally the presence of neutrophils and eosinophils in the blister cavity.7 Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates netlike intercellular IgG and C3 in the upper portion of the epidermis.11 Indirect immunofluorescence can help detect circulating IgG antibodies to Dsg-1, with guinea pig esophagus being the ideal substrate.11,12

First-line treatment of pemphigus foliaceus consists of systemic glucocorticoid therapy, often administered with azathioprine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil.2,6,13 Although first-line treatment is effective in 60% to 80% of patients,2 relapsing cases can be treated with cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin, immunoadsorption, plasmapheresis, or rituximab.2

Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody targeting CD20+ B cells, leading to decreased antibody production, which has been shown to be effective in treating severe and refractory cases of pemphigus foliaceus.6,13Rituximab with short-course prednisone has been found to be more effective in achieving complete remission at 24 months than prednisone alone.14 In patients with contraindications to systemic glucocorticoid therapy, rituximab has been shown as an effective first-line therapy.15 One-quarter of patients treated with rituximab relapsed within 2 years of treatment6 (average time to relapse, 6–26 months).16 High-dose rituximab regimens, along with a higher number of rituximab treatment cycles, have been shown to prolong time to relapse.6 Further, higher baseline levels of Dsg-1 antibody have been correlated to earlier relapse and can be used following rituximab therapy to monitor disease progression.6,16

The differential diagnosis for pemphigus foliaceous includes disseminated blastomycosis, hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, sebopsoriasis, and secondary syphilis. Disseminated blastomycosis presents with cutaneous manifestations such as nodules, papules, or pustules evolving over weeks to months into ulcers with subsequent scarring.17 Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus presents with papules and nodules with associated keratotic scaling on the face, palms, and extensor surfaces of the limbs.18 Sebopsoriasis is characterized by well-defined lesions with an overlying scale distributed on the scalp, face, and chest.19 Secondary syphilis presents as early hyperpigmented macules transitioning to acral papulosquamous lesions involving the palms and soles.20

- Hans-Filho G, Aoki V, Hans Bittner NR, et al. Fogo selvagem: endemic pemphigus foliaceus. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:638-650.

- Jenson KK, Burr DM, Edwards BC. Case report: reatment of refractory pemphigus foliaceus with rituximab. Practical Dermatology. February 2016:33-36. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://practicaldermatology.com/articles/2016-feb/case-report -treatment-of-refractory-pemphigus-foliaceus-with-rituximab -financial-matters-aad-asds-resources

- Amagai M, Hashimoto T, Green KJ, et al. Antigen-specific immunoadsorption of pathogenic autoantibodies in pemphigus foliaceus. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:895-901.

- Mahoney MG, Wang Z, Rothenberger K, et al. Explanations for the clinical and microscopic localization of lesions in pemphigus foliaceus and vulgaris. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:461-468.

- Oktarina DAM, Sokol E, Kramer D, et al. Endocytosis of IgG, desmoglein 1, and plakoglobin in pemphigus foliaceus patient skin. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1-12.

- Kraft M, Worm M. Pemphigus foliaceus-repeated treatment with rituximab 7 years after initial response: a case report. Front Med. 2018;5:315.

- Hale EK. Pemphigus foliaceous. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8:9.

- Tavakolpour S. Pemphigus trigger factors: special focus on pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:95-106.

- A boobaker J, Morar N, Ramdial PK, et al. Pemphigus in South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:115-119.

- Austin E, Millsop JW, Ely H, et al. Psoriasiform pemphigus foliaceus in an African American female: an important clinical manifestation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:471.

- Arbache ST, Nogueira TG, Delgado L, et al. Immunofluorescence testing in the diagnosis of autoimmune blistering diseases: overview of 10-year experience. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:885-889.

- Sabolinski ML, Beutner EH, Krasny S, et al. Substrate specificity of antiepithelial antibodies of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus sera in immunofluorescence tests on monkey and guinea pig esophagus sections. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:545-549.

- Palacios-Álvarez I, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Curto-Barredo L, et al. Rituximab treatment of pemphigus foliaceus: a retrospective study of 12 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:484-486.

- Murrell DF, Sprecher E. Rituximab and short-course prednisone as the new gold standard for new-onset pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1143-1144.

- Gregoriou S, Efthymiou O, Stefanaki C, et al. Management of pemphigus vulgaris: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:521-527.

- Saleh MA. A prospective study comparing patients with early and late relapsing pemphigus treated with rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:97-103.

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264.

- Herzum A, Gasparini G, Emanuele C, et al. Atypical and rare forms of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the importance of the diagnosis for the best management of patients. Dermatology. 2013;1-10.

- Tull TJ, Noy M, Bunker CB, et al. Sebopsoriasis in patients with HIV: a case series of 20 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2016; 173:813-815.

- Balagula Y, Mattei P, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revised: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

- Hans-Filho G, Aoki V, Hans Bittner NR, et al. Fogo selvagem: endemic pemphigus foliaceus. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:638-650.

- Jenson KK, Burr DM, Edwards BC. Case report: reatment of refractory pemphigus foliaceus with rituximab. Practical Dermatology. February 2016:33-36. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://practicaldermatology.com/articles/2016-feb/case-report -treatment-of-refractory-pemphigus-foliaceus-with-rituximab -financial-matters-aad-asds-resources

- Amagai M, Hashimoto T, Green KJ, et al. Antigen-specific immunoadsorption of pathogenic autoantibodies in pemphigus foliaceus. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:895-901.

- Mahoney MG, Wang Z, Rothenberger K, et al. Explanations for the clinical and microscopic localization of lesions in pemphigus foliaceus and vulgaris. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:461-468.

- Oktarina DAM, Sokol E, Kramer D, et al. Endocytosis of IgG, desmoglein 1, and plakoglobin in pemphigus foliaceus patient skin. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1-12.

- Kraft M, Worm M. Pemphigus foliaceus-repeated treatment with rituximab 7 years after initial response: a case report. Front Med. 2018;5:315.

- Hale EK. Pemphigus foliaceous. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8:9.

- Tavakolpour S. Pemphigus trigger factors: special focus on pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:95-106.

- A boobaker J, Morar N, Ramdial PK, et al. Pemphigus in South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:115-119.

- Austin E, Millsop JW, Ely H, et al. Psoriasiform pemphigus foliaceus in an African American female: an important clinical manifestation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:471.

- Arbache ST, Nogueira TG, Delgado L, et al. Immunofluorescence testing in the diagnosis of autoimmune blistering diseases: overview of 10-year experience. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:885-889.

- Sabolinski ML, Beutner EH, Krasny S, et al. Substrate specificity of antiepithelial antibodies of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus sera in immunofluorescence tests on monkey and guinea pig esophagus sections. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:545-549.

- Palacios-Álvarez I, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Curto-Barredo L, et al. Rituximab treatment of pemphigus foliaceus: a retrospective study of 12 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:484-486.

- Murrell DF, Sprecher E. Rituximab and short-course prednisone as the new gold standard for new-onset pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1143-1144.

- Gregoriou S, Efthymiou O, Stefanaki C, et al. Management of pemphigus vulgaris: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:521-527.

- Saleh MA. A prospective study comparing patients with early and late relapsing pemphigus treated with rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:97-103.

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:247-264.

- Herzum A, Gasparini G, Emanuele C, et al. Atypical and rare forms of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the importance of the diagnosis for the best management of patients. Dermatology. 2013;1-10.

- Tull TJ, Noy M, Bunker CB, et al. Sebopsoriasis in patients with HIV: a case series of 20 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2016; 173:813-815.

- Balagula Y, Mattei P, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revised: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

A 40-year-old Black man presented for evaluation of a thick plaque throughout the scalp (top), scaly plaques on the cheeks (bottom), and a spreading rash on the trunk that had progressed over the last few months. He had no relevant medical history, took no medications, and was in a monogamous relationship with a female partner. He previously saw an outside dermatologist who gave him triamcinolone cream, which was mildly helpful. Physical examination revealed a thick verrucous plaque throughout the scalp extending onto the forehead; thick plaques on the cheeks; and numerous, thinly eroded lesions on the trunk. Biopsies and a laboratory workup were performed.

Sudden-Onset Blistering Rash

The Diagnosis: Generalized Bullous Fixed Drug Eruption

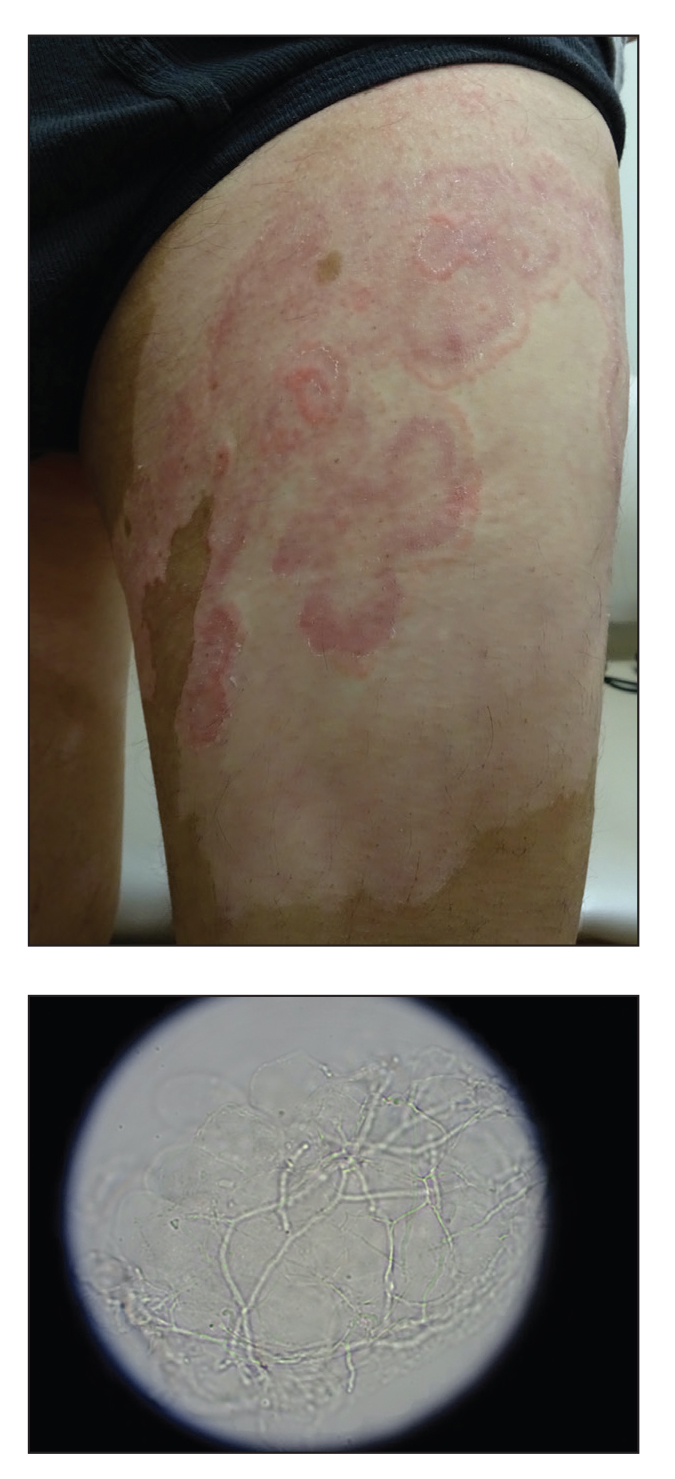

A punch biopsy from the left thigh revealed a vacuolar interface dermatitis with full-thickness necrosis of the epidermis and a patchy lichenoid inflammatory cell infiltrate in the superficial dermis consistent with a generalized bullous fixed drug eruption (GBFDE). The patient received supportive care and methylprednisolone with improvement of symptoms.

Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is a rare, potentially life-threatening form of a fixed drug eruption (FDE), a cutaneous drug reaction that occurs in response to a causative medication. It typically presents with welldemarcated, dusky, erythematous patches or plaques that recur in the same sites with repeat exposure.1 The pathogenesis of FDE has been hypothesized to involve epidermal CD8+ T cells, which are activated by drug exposure and release cytotoxic molecules including Fas, Fas ligand, perforin, and granzyme B, resulting in lysis of the surrounding keratinocytes.1-3 Common eliciting drugs include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibacterial agents (particularly trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole), barbiturates, acetaminophen, and antimalarials.1 In addition to the findings seen in FDE, GBFDE is characterized by widespread bullous skin lesions.1-4 Typical histologic patterns seen in GBFDE are dispersed epidermal apoptotic keratinocytes, prominent dermal eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltrates, and dermal melanophages.3 Discontinuing the causative agent and diligent prevention of re-exposure are the most important steps in management, as additional exposures can increase the number of lesions and overall severity. Symptoms typically resolve 7 to 14 days after drug discontinuation, often with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.3

Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption presents a diagnostic challenge, as it sometimes involves the oral mucosa and can exhibit the Nikolsky sign. Thus, it often is confused with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) or toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).1,4 Stevens-Johnson syndrome and TEN are severe cutaneous drug eruptions that also can present with diffuse bullous skin lesions. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and TEN are thought to be a spectrum of the same disease that initially presents with dusky red macules that can coalesce, develop central blistering, and lead to skin detachment.5 Stevens-Johnson syndrome is defined as skin detachment of less than 10% body surface area (BSA); TEN is defined as skin detachment of more than 30% BSA. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/TEN overlap syndrome includes skin detachment of 10% to 30% BSA.5

Causative medications overlap substantially with GBFDE and include anticonvulsants, sulfa-containing drugs, antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and uric acid–lowering agents. The histology of SJS/TEN also is quite similar to GBFDE, and these entities may be indistinguishable without clinical information.5 Lee et al1 found that absence of grouped necrotic keratinocytes (fire flag sign), deep inflammatory infiltrates, notable pigment incontinence, and higher eosinophil counts appear to be more common in GBFDE than SJS/TEN. Constitutional symptoms and mucosal involvement also were more frequent in SJS/TEN.

The timing of clinical presentation and medical history can be useful in differentiating between SJS/TEN and GBFDE. In SJS/TEN, drug exposure typically occurs 1 to 3 weeks before onset of symptoms vs 30 minutes to 24 hours in GBFDE.3 Additionally, a history of similar eruption in the same location is pathognomonic for GBFDE. Although GBFDE has been thought to have a better prognosis than SJS/TEN, more recent data suggest mortality rates may be similar.3 A case-control study found a mortality rate of 22% (13/58) in patients with GBFDE compared to 28% (n=170) in SJS/TEN patients.4

Erythema multiforme (EM) is an uncommon immunemediated disorder that typically presents as targetoid lesions with central epidermal necrosis in an acral distribution. Erythema multiforme can arise from a variety of factors, but up to 90% of cases are due to infection, most commonly herpes simplex virus; medications account for less than 10% of cases.6 Previously, EM has been thought to be on the same disease spectrum as SJS and TEN. It is now clear that EM is a separate entity with similar mucosal erosions but different cutaneous findings,6 mainly typical target lesions that differ from the atypical targets seen in SJS.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a blistering skin disorder associated with local Staphylococcus aureus infection. It most commonly is seen in children and rarely occurs in adults who are not on dialysis. Some Staphylococcus strains produce exfoliative toxins A and B, which are serine proteases that target and cleave desmoglein 1, a mediator of keratinocyte adhesion. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome initially presents with erythema accentuated in the skin folds that becomes generalized. The disruption of keratinocyte adhesion leads to bullae formation in areas of erythema and diffuse sheetlike desquamation. Pathology reveals subcorneal rather than subepidermal blistering, which is seen in GBFDE and SJS/TEN. Treatment involves antistaphylococcal antibiotics and supportive care. With proper treatment, most cases resolve within 2 to 3 weeks.7

Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis presents with prominent mucositis and can have cutaneous findings of sparse vesiculobullous or targetoid eruption.8 Mycoplasma pneumoniae typically infects the lungs and is a leading cause of community-acquired pneumonia. However, a subset of patients can have extrapulmonary disease presenting as mucocutaneous eruptions, which is preceded by an approximately weeklong prodrome of fever, cough, and malaise.7 Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis also affect children and young patients and is more common in males.8

- Lee CH, Chen YC, Cho YT, et al. Fixed-drug eruption: a retrospective study in a single referral center in northern Taiwan. Dermatologica Sinica. 2012;30:11-15. doi:10.1016/j.dsi.2012.02.002

- Cho Y-T, Lin J-W, Chen Y-C, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.015

- Mitre V, Applebaum DS, Albahrani Y, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption imitating toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case report and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23: 13030/qt25v009gs.

- Lipowicz S, Sekula P, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Prognosis of generalized bullous fixed drug eruption: comparison with StevensJohnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:726-732. doi:10.1111/bjd.12133

- Cho Y-T, Chu C-Y. Treatments for severe cutaneous adverse reactions [published online December 27, 2017]. J Immunol Res. doi:10.1155/2017/1503709

- Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05348.x

- Leung AKC, Barankin B, Leong KF. Staphylococcal-scalded skin syndrome: evaluation, diagnosis, and management. World J Pediatr. 2018;14:116-120.

- Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-245. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2014.06.026

The Diagnosis: Generalized Bullous Fixed Drug Eruption

A punch biopsy from the left thigh revealed a vacuolar interface dermatitis with full-thickness necrosis of the epidermis and a patchy lichenoid inflammatory cell infiltrate in the superficial dermis consistent with a generalized bullous fixed drug eruption (GBFDE). The patient received supportive care and methylprednisolone with improvement of symptoms.

Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is a rare, potentially life-threatening form of a fixed drug eruption (FDE), a cutaneous drug reaction that occurs in response to a causative medication. It typically presents with welldemarcated, dusky, erythematous patches or plaques that recur in the same sites with repeat exposure.1 The pathogenesis of FDE has been hypothesized to involve epidermal CD8+ T cells, which are activated by drug exposure and release cytotoxic molecules including Fas, Fas ligand, perforin, and granzyme B, resulting in lysis of the surrounding keratinocytes.1-3 Common eliciting drugs include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibacterial agents (particularly trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole), barbiturates, acetaminophen, and antimalarials.1 In addition to the findings seen in FDE, GBFDE is characterized by widespread bullous skin lesions.1-4 Typical histologic patterns seen in GBFDE are dispersed epidermal apoptotic keratinocytes, prominent dermal eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltrates, and dermal melanophages.3 Discontinuing the causative agent and diligent prevention of re-exposure are the most important steps in management, as additional exposures can increase the number of lesions and overall severity. Symptoms typically resolve 7 to 14 days after drug discontinuation, often with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.3

Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption presents a diagnostic challenge, as it sometimes involves the oral mucosa and can exhibit the Nikolsky sign. Thus, it often is confused with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) or toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).1,4 Stevens-Johnson syndrome and TEN are severe cutaneous drug eruptions that also can present with diffuse bullous skin lesions. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and TEN are thought to be a spectrum of the same disease that initially presents with dusky red macules that can coalesce, develop central blistering, and lead to skin detachment.5 Stevens-Johnson syndrome is defined as skin detachment of less than 10% body surface area (BSA); TEN is defined as skin detachment of more than 30% BSA. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/TEN overlap syndrome includes skin detachment of 10% to 30% BSA.5

Causative medications overlap substantially with GBFDE and include anticonvulsants, sulfa-containing drugs, antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and uric acid–lowering agents. The histology of SJS/TEN also is quite similar to GBFDE, and these entities may be indistinguishable without clinical information.5 Lee et al1 found that absence of grouped necrotic keratinocytes (fire flag sign), deep inflammatory infiltrates, notable pigment incontinence, and higher eosinophil counts appear to be more common in GBFDE than SJS/TEN. Constitutional symptoms and mucosal involvement also were more frequent in SJS/TEN.

The timing of clinical presentation and medical history can be useful in differentiating between SJS/TEN and GBFDE. In SJS/TEN, drug exposure typically occurs 1 to 3 weeks before onset of symptoms vs 30 minutes to 24 hours in GBFDE.3 Additionally, a history of similar eruption in the same location is pathognomonic for GBFDE. Although GBFDE has been thought to have a better prognosis than SJS/TEN, more recent data suggest mortality rates may be similar.3 A case-control study found a mortality rate of 22% (13/58) in patients with GBFDE compared to 28% (n=170) in SJS/TEN patients.4

Erythema multiforme (EM) is an uncommon immunemediated disorder that typically presents as targetoid lesions with central epidermal necrosis in an acral distribution. Erythema multiforme can arise from a variety of factors, but up to 90% of cases are due to infection, most commonly herpes simplex virus; medications account for less than 10% of cases.6 Previously, EM has been thought to be on the same disease spectrum as SJS and TEN. It is now clear that EM is a separate entity with similar mucosal erosions but different cutaneous findings,6 mainly typical target lesions that differ from the atypical targets seen in SJS.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a blistering skin disorder associated with local Staphylococcus aureus infection. It most commonly is seen in children and rarely occurs in adults who are not on dialysis. Some Staphylococcus strains produce exfoliative toxins A and B, which are serine proteases that target and cleave desmoglein 1, a mediator of keratinocyte adhesion. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome initially presents with erythema accentuated in the skin folds that becomes generalized. The disruption of keratinocyte adhesion leads to bullae formation in areas of erythema and diffuse sheetlike desquamation. Pathology reveals subcorneal rather than subepidermal blistering, which is seen in GBFDE and SJS/TEN. Treatment involves antistaphylococcal antibiotics and supportive care. With proper treatment, most cases resolve within 2 to 3 weeks.7

Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis presents with prominent mucositis and can have cutaneous findings of sparse vesiculobullous or targetoid eruption.8 Mycoplasma pneumoniae typically infects the lungs and is a leading cause of community-acquired pneumonia. However, a subset of patients can have extrapulmonary disease presenting as mucocutaneous eruptions, which is preceded by an approximately weeklong prodrome of fever, cough, and malaise.7 Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis also affect children and young patients and is more common in males.8

The Diagnosis: Generalized Bullous Fixed Drug Eruption

A punch biopsy from the left thigh revealed a vacuolar interface dermatitis with full-thickness necrosis of the epidermis and a patchy lichenoid inflammatory cell infiltrate in the superficial dermis consistent with a generalized bullous fixed drug eruption (GBFDE). The patient received supportive care and methylprednisolone with improvement of symptoms.

Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is a rare, potentially life-threatening form of a fixed drug eruption (FDE), a cutaneous drug reaction that occurs in response to a causative medication. It typically presents with welldemarcated, dusky, erythematous patches or plaques that recur in the same sites with repeat exposure.1 The pathogenesis of FDE has been hypothesized to involve epidermal CD8+ T cells, which are activated by drug exposure and release cytotoxic molecules including Fas, Fas ligand, perforin, and granzyme B, resulting in lysis of the surrounding keratinocytes.1-3 Common eliciting drugs include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibacterial agents (particularly trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole), barbiturates, acetaminophen, and antimalarials.1 In addition to the findings seen in FDE, GBFDE is characterized by widespread bullous skin lesions.1-4 Typical histologic patterns seen in GBFDE are dispersed epidermal apoptotic keratinocytes, prominent dermal eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltrates, and dermal melanophages.3 Discontinuing the causative agent and diligent prevention of re-exposure are the most important steps in management, as additional exposures can increase the number of lesions and overall severity. Symptoms typically resolve 7 to 14 days after drug discontinuation, often with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.3

Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption presents a diagnostic challenge, as it sometimes involves the oral mucosa and can exhibit the Nikolsky sign. Thus, it often is confused with Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) or toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).1,4 Stevens-Johnson syndrome and TEN are severe cutaneous drug eruptions that also can present with diffuse bullous skin lesions. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and TEN are thought to be a spectrum of the same disease that initially presents with dusky red macules that can coalesce, develop central blistering, and lead to skin detachment.5 Stevens-Johnson syndrome is defined as skin detachment of less than 10% body surface area (BSA); TEN is defined as skin detachment of more than 30% BSA. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/TEN overlap syndrome includes skin detachment of 10% to 30% BSA.5

Causative medications overlap substantially with GBFDE and include anticonvulsants, sulfa-containing drugs, antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and uric acid–lowering agents. The histology of SJS/TEN also is quite similar to GBFDE, and these entities may be indistinguishable without clinical information.5 Lee et al1 found that absence of grouped necrotic keratinocytes (fire flag sign), deep inflammatory infiltrates, notable pigment incontinence, and higher eosinophil counts appear to be more common in GBFDE than SJS/TEN. Constitutional symptoms and mucosal involvement also were more frequent in SJS/TEN.

The timing of clinical presentation and medical history can be useful in differentiating between SJS/TEN and GBFDE. In SJS/TEN, drug exposure typically occurs 1 to 3 weeks before onset of symptoms vs 30 minutes to 24 hours in GBFDE.3 Additionally, a history of similar eruption in the same location is pathognomonic for GBFDE. Although GBFDE has been thought to have a better prognosis than SJS/TEN, more recent data suggest mortality rates may be similar.3 A case-control study found a mortality rate of 22% (13/58) in patients with GBFDE compared to 28% (n=170) in SJS/TEN patients.4

Erythema multiforme (EM) is an uncommon immunemediated disorder that typically presents as targetoid lesions with central epidermal necrosis in an acral distribution. Erythema multiforme can arise from a variety of factors, but up to 90% of cases are due to infection, most commonly herpes simplex virus; medications account for less than 10% of cases.6 Previously, EM has been thought to be on the same disease spectrum as SJS and TEN. It is now clear that EM is a separate entity with similar mucosal erosions but different cutaneous findings,6 mainly typical target lesions that differ from the atypical targets seen in SJS.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a blistering skin disorder associated with local Staphylococcus aureus infection. It most commonly is seen in children and rarely occurs in adults who are not on dialysis. Some Staphylococcus strains produce exfoliative toxins A and B, which are serine proteases that target and cleave desmoglein 1, a mediator of keratinocyte adhesion. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome initially presents with erythema accentuated in the skin folds that becomes generalized. The disruption of keratinocyte adhesion leads to bullae formation in areas of erythema and diffuse sheetlike desquamation. Pathology reveals subcorneal rather than subepidermal blistering, which is seen in GBFDE and SJS/TEN. Treatment involves antistaphylococcal antibiotics and supportive care. With proper treatment, most cases resolve within 2 to 3 weeks.7

Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis presents with prominent mucositis and can have cutaneous findings of sparse vesiculobullous or targetoid eruption.8 Mycoplasma pneumoniae typically infects the lungs and is a leading cause of community-acquired pneumonia. However, a subset of patients can have extrapulmonary disease presenting as mucocutaneous eruptions, which is preceded by an approximately weeklong prodrome of fever, cough, and malaise.7 Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis also affect children and young patients and is more common in males.8

- Lee CH, Chen YC, Cho YT, et al. Fixed-drug eruption: a retrospective study in a single referral center in northern Taiwan. Dermatologica Sinica. 2012;30:11-15. doi:10.1016/j.dsi.2012.02.002

- Cho Y-T, Lin J-W, Chen Y-C, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.015

- Mitre V, Applebaum DS, Albahrani Y, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption imitating toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case report and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23: 13030/qt25v009gs.

- Lipowicz S, Sekula P, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Prognosis of generalized bullous fixed drug eruption: comparison with StevensJohnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:726-732. doi:10.1111/bjd.12133

- Cho Y-T, Chu C-Y. Treatments for severe cutaneous adverse reactions [published online December 27, 2017]. J Immunol Res. doi:10.1155/2017/1503709

- Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05348.x

- Leung AKC, Barankin B, Leong KF. Staphylococcal-scalded skin syndrome: evaluation, diagnosis, and management. World J Pediatr. 2018;14:116-120.

- Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-245. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2014.06.026

- Lee CH, Chen YC, Cho YT, et al. Fixed-drug eruption: a retrospective study in a single referral center in northern Taiwan. Dermatologica Sinica. 2012;30:11-15. doi:10.1016/j.dsi.2012.02.002

- Cho Y-T, Lin J-W, Chen Y-C, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.015

- Mitre V, Applebaum DS, Albahrani Y, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption imitating toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case report and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23: 13030/qt25v009gs.

- Lipowicz S, Sekula P, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Prognosis of generalized bullous fixed drug eruption: comparison with StevensJohnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:726-732. doi:10.1111/bjd.12133

- Cho Y-T, Chu C-Y. Treatments for severe cutaneous adverse reactions [published online December 27, 2017]. J Immunol Res. doi:10.1155/2017/1503709

- Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05348.x

- Leung AKC, Barankin B, Leong KF. Staphylococcal-scalded skin syndrome: evaluation, diagnosis, and management. World J Pediatr. 2018;14:116-120.

- Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-245. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2014.06.026

A 45-year-old woman presented with a diffuse rash 2 days after receiving ondansetron. She developed blisters on the arms, legs, trunk, and face 2 hours after exposure. There was no oral or vaginal involvement. She reported a history of leg blisters after prior exposure to ondansetron that were not as severe or numerous as the current episode. Physical examination revealed innumerable coalescing, ovoid and circular, dusky patches, some with central flaccid bullae, along with large areas of denuded skin on the trunk, arms, legs, and face. There were erosions on the lower eyelids without conjunctival or other mucosal involvement.

Ulcerated and Verrucous Plaque on the Chest

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Coccidioidomycosis

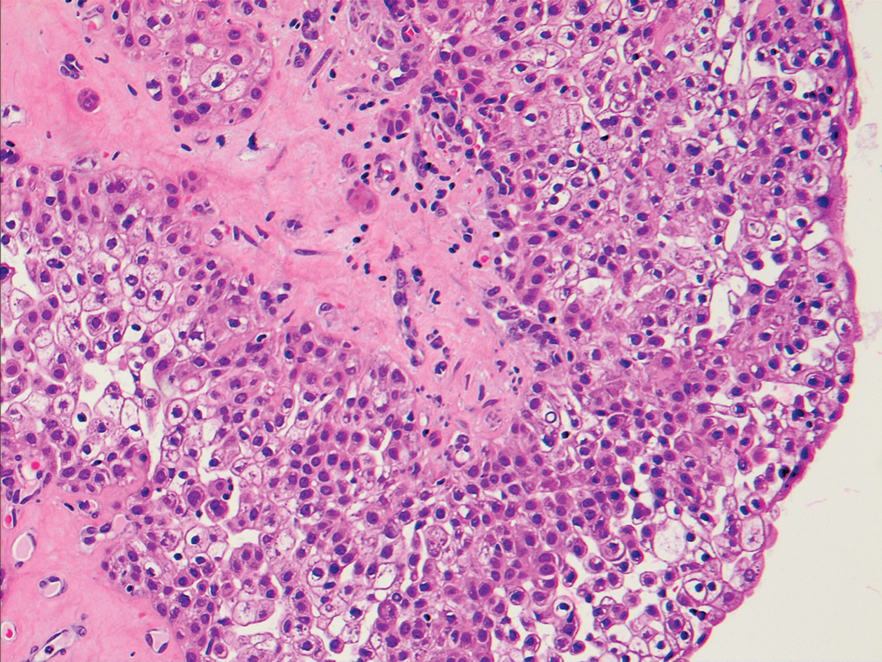

A6-mm punch biopsy was performed at the periphery of the ulcerated cutaneous lesion on the chest revealing extensive spherules. Serum antibody immunodiffusion for histoplasmosis and blastomycoses both were negative; however, B-D-glucan assay was positive at 364 pg/mL (reference range: <60 pg/mL, negative). Initial HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibody and antigen testing was negative as well as repeat testing at 3 weeks. Immunodiffusion for Coccidioides IgM and IgG was positive, and cocci antibody IgG complement fixation assays were positive at titers of 1:64 (reference range: <1:2, negative). A computed tomography needle-guided biopsy of the paravertebral soft tissue was performed. Gram stains and bacterial cultures of the biopsies were negative; however, fungal cultures were notable for growth of Coccidioides. Given the pertinent testing, a diagnosis of disseminated coccidioidomycosis was made.

Cutaneous coccidioidomycosis can occur in 3 situations: direct inoculation (primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis), disseminated infection (disseminated cutaneous coccidioidomycosis), or as a reactive component of pulmonary infection.1,2 Of them, primary and disseminated cutaneous coccidioidomycosis are organism specific and display characteristic spherules and fungus on histopathology and cultures, respectively. Reactive coccidioidomycosis differs from organism-specific disease, as it does not contain spherules in histopathologic sections of tissue biopsies.1 Reactive skin manifestations occur in 12% to 50% of patients with primary pulmonary infection and include erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, acute generalized exanthema, reactive interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, and Sweet syndrome.3

Organism-specific cutaneous coccidioidomycosis most often is correlated with hematogenous dissemination of primary pulmonary disease rather than direct inoculation of skin.1 The skin is the most common site of extrapulmonary involvement in disseminated coccidioidomycosis, and cutaneous lesions have been reported in 15% to 67% of cases of disseminated disease.1,4 In cutaneous disseminated disease, nodules, papules, macules, and verrucous plaques have been described. In a case series of disseminated cutaneous coccidioidomycosis, nodules were the most common cutaneous presentation and occurred in 39% (7/18) of patients, while verrucous plaques were the rarest and occurred in only 6% (1/18) of patients.5

The rate of coccidioidomycosis dissemination varies based on exposure and patient characteristics. Increased rates of dissemination have been reported in patients of African and Filipino descent, along with individuals that are immunosuppressed due to disease or medical therapy. Dissemination is clinically significant, as patients with multifocal dissemination have a greater than 50% risk for mortality.6

Disseminated coccidioidomycosis is a relatively rare manifestation of Coccidioides infection; approximately 1.6% of patients exposed to and infected with Coccidioides ultimately will develop systemic or disseminated disease.7,8 Although the rates of primary pulmonary infection are similar between patients of varying ethnicities, the rates of dissemination are higher in patients of African and Filipino ethnicity.8 In population studies of coccidioidomycosis (N=332), Black patients represented 33.3% (4/12) of disseminated cases but only 8.7% of Coccidioides cases overall.7

Population studies of Black patients with coccidioidomycosis have shown a 4-fold higher predisposition for severe disease compared to mild disease.9 Spondylitis and meningitis also are disproportionately more common in Black patients.8 Black patients comprised 75% of all spondylitis cases in a cohort where only 25% of patients were Black. Additionally, 33% of all meningitis cases occurred in Black patients in a cohort where 8% of total cases were Black patients.8 Within the United States, the highest rates of coccidioidomycosis meningitis are seen in Black patients.10

The pathophysiology underlying the increased susceptibility of individuals of African or Filipino descent to disseminated and severe coccidioidomycosis remains unknown.8 The level of vulnerability within this patient population has no association with increased environmental exposure or poor immunologic response to Coccidioides, as demonstrated by the ability of these populations to respond to experimental vaccination and skin testing (spherulin, coccidioidin) to a similar extent as other ethnicities.8 Class II HLA-DRB1*1301 alleles have been associated with an increased risk for severe disseminated Coccidioides infection regardless of ethnicity; however, these alleles are not overrepresented in these patient populations.8

In patients with primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis with no evidence of dissemination, guidelines generally recommend offering treatment to groups at high risk of dissemination, such as pregnant women and patients with diabetes mellitus. Given the high incidence of disseminated and severe disease in Black and Filipino patients, some guidelines endorse treatment of all cases of coccidioidomycosis in this patient population.8 No current data are available to help determine whether this broad treatment approach reduces the development of disseminated infection in these populations. Frequent monitoring for disease progression and/or dissemination involving clinical and laboratory reevaluation every 3 months for 2 years is highly recommended.8

Treatment generally is based on location and severity of infection, with disseminated nonmeningeal infection being treated with oral azole therapy (ketoconazole, itraconazole, or fluconazole).11 If there is involvement of the central nervous system structures or rapidly worsening disease despite azole therapy, amphotericin B is recommended at 0.5 to 0.7 mg/kg daily. In patients with disseminated meningeal infection, oral fluconazole (800–1000 mg/d) or a combination of an azole with intrathecal amphotericin B (0.01–1.5 mg/dose, interval ranging from daily to 1 week) is recommended to improve response.11

The differential diagnosis of cutaneous disseminated coccidioidomycosis is broad and includes other systemic endemic mycoses (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis) and infections (mycobacteria, leishmania). Lupus vulgaris, a form of cutaneous tuberculosis, presents as a palpable tubercular lesion that may coalesce into erythematous plaques, which may mimic endemic mycoses, especially in patients with risk factors for both infectious etiologies such as our patient.12 Disseminated histoplasmosis may present as polymorphic plaques, pustules, nodules, and ulcerated skin lesions, whereas disseminated blastomycosis characteristically presents as a crusted verrucous lesion with raised borders and painful ulcers, both of which may mimic coccidioidomycosis.13 Biopsy would reveal the characteristic intracellular yeast in Histoplasma capsulatum and broad-based budding yeast form of Blastomyces dermatitidis in histoplasmosis and blastomycosis, respectively, in contrast to the spherules seen in our patient’s biopsy.13 Localized cutaneous leishmaniasis initially develops as a nodular or papular lesion and can progress to open ulcerations with raised borders. Biopsy and histopathology would reveal round protozoal amastigotes.14 Other diagnoses that should be considered include mycetoma, nocardiosis, and sporotrichosis.15 As the cutaneous manifestations of Coccidioides infections are varied, a broad differential diagnosis should be maintained, and probable environmental and infectious exposures should be considered prior to ordering diagnostic studies.

- Garcia Garcia SC, Salas Alanis JC, Flores MG, et al. Coccidioidomycosis and the skin: a comprehensive review. An Bras Dermatol. 2015; 90:610-619.

- DiCaudo DJ. Coccidioidomycosis: a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:929-942; quiz 943-925.

- DiCaudo DJ, Yiannias JA, Laman SD, et al. The exanthem of acute pulmonary coccidioidomycosis: clinical and histopathologic features of 3 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:744-746.

- Blair JE. State-of-the-art treatment of coccidioidomycosis: skin and soft-tissue infections. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:411-421.

- Crum NF, Lederman ER, Stafford CM, et al. Coccidioidomycosis: a descriptive survey of a reemerging disease. clinical characteristics and current controversies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004;83:149-175.

- Borchers AT, Gershwin ME. The immune response in coccidioidomycosis. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;10:94-102.

- Smith CE, Beard RR. Varieties of coccidioidal infection in relation to the epidemiology and control of the diseases. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1946;36:1394-1402.

- Ruddy BE, Mayer AP, Ko MG, et al. Coccidioidomycosis in African Americans. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:63-69.

- Louie L, Ng S, Hajjeh R, et al. Influence of host genetics on the severity of coccidioidomycosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:672-680.

- McCotter OZ, Benedict K, Engelthaler DM, et al. Update on the epidemiology of coccidioidomycosis in the United States. Med Mycol. 2019;57(suppl 1):S30-S40.

- Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Catanzaro A, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:658-661.

- Khadka P, Koirala S, Thapaliya J. Cutaneous tuberculosis: clinicopathologic arrays and diagnostic challenges. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:7201973.

- Smith JA, Riddell JT, Kauffman CA. Cutaneous manifestations of endemic mycoses. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2013;15:440-449.

- Scorza BM, Carvalho EM, Wilson ME. Cutaneous manifestations of human and murine leishmaniasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1296.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Coccidioidomycosis

A6-mm punch biopsy was performed at the periphery of the ulcerated cutaneous lesion on the chest revealing extensive spherules. Serum antibody immunodiffusion for histoplasmosis and blastomycoses both were negative; however, B-D-glucan assay was positive at 364 pg/mL (reference range: <60 pg/mL, negative). Initial HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibody and antigen testing was negative as well as repeat testing at 3 weeks. Immunodiffusion for Coccidioides IgM and IgG was positive, and cocci antibody IgG complement fixation assays were positive at titers of 1:64 (reference range: <1:2, negative). A computed tomography needle-guided biopsy of the paravertebral soft tissue was performed. Gram stains and bacterial cultures of the biopsies were negative; however, fungal cultures were notable for growth of Coccidioides. Given the pertinent testing, a diagnosis of disseminated coccidioidomycosis was made.

Cutaneous coccidioidomycosis can occur in 3 situations: direct inoculation (primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis), disseminated infection (disseminated cutaneous coccidioidomycosis), or as a reactive component of pulmonary infection.1,2 Of them, primary and disseminated cutaneous coccidioidomycosis are organism specific and display characteristic spherules and fungus on histopathology and cultures, respectively. Reactive coccidioidomycosis differs from organism-specific disease, as it does not contain spherules in histopathologic sections of tissue biopsies.1 Reactive skin manifestations occur in 12% to 50% of patients with primary pulmonary infection and include erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, acute generalized exanthema, reactive interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, and Sweet syndrome.3

Organism-specific cutaneous coccidioidomycosis most often is correlated with hematogenous dissemination of primary pulmonary disease rather than direct inoculation of skin.1 The skin is the most common site of extrapulmonary involvement in disseminated coccidioidomycosis, and cutaneous lesions have been reported in 15% to 67% of cases of disseminated disease.1,4 In cutaneous disseminated disease, nodules, papules, macules, and verrucous plaques have been described. In a case series of disseminated cutaneous coccidioidomycosis, nodules were the most common cutaneous presentation and occurred in 39% (7/18) of patients, while verrucous plaques were the rarest and occurred in only 6% (1/18) of patients.5

The rate of coccidioidomycosis dissemination varies based on exposure and patient characteristics. Increased rates of dissemination have been reported in patients of African and Filipino descent, along with individuals that are immunosuppressed due to disease or medical therapy. Dissemination is clinically significant, as patients with multifocal dissemination have a greater than 50% risk for mortality.6

Disseminated coccidioidomycosis is a relatively rare manifestation of Coccidioides infection; approximately 1.6% of patients exposed to and infected with Coccidioides ultimately will develop systemic or disseminated disease.7,8 Although the rates of primary pulmonary infection are similar between patients of varying ethnicities, the rates of dissemination are higher in patients of African and Filipino ethnicity.8 In population studies of coccidioidomycosis (N=332), Black patients represented 33.3% (4/12) of disseminated cases but only 8.7% of Coccidioides cases overall.7

Population studies of Black patients with coccidioidomycosis have shown a 4-fold higher predisposition for severe disease compared to mild disease.9 Spondylitis and meningitis also are disproportionately more common in Black patients.8 Black patients comprised 75% of all spondylitis cases in a cohort where only 25% of patients were Black. Additionally, 33% of all meningitis cases occurred in Black patients in a cohort where 8% of total cases were Black patients.8 Within the United States, the highest rates of coccidioidomycosis meningitis are seen in Black patients.10