User login

Symmetrical Pruriginous Nasal Rash

The Diagnosis: Irritant Contact Dermatitis

A slang term for volatile alkyl nitrites, poppers are inhaled for recreational purposes. They produce rapid-onset euphoria and sexual arousal, as well as relax anal and vaginal sphincters, facilitating sexual intercourse. Alkyl nitrites initially were developed to treat coronary disease and angina but were replaced by more potent drugs.1 Because of their psychoactive effects and smooth muscle relaxation properties, they are widely used by homosexual and bisexual men.1-3 The term poppers was originated by the sound generated when the glass vials are crushed; currently, they also may be found in other formats.1

Nausea, hypotension, and headache are mild common adverse effects of volatile alkyl nitrites1; cardiac arrhythmia, oxidative hemolysis,4 and poppers maculopathy5,6 with permanent eye damage also have been reported.7 On the skin, volatile alkyl nitrites induce irritant contact dermatitis that heals without scarring, characteristically involving the face and upper thoracic region, as they are volatile vapors.2 However, the reaction can occur elsewhere. There have been reports of contact dermatitis on other locations, such as the thigh or the ankle, due to vials broken while stored in pockets or on the cuff of the socks.1 There also is a report of irritant contact dermatitis manifesting as a penile ulcer.3 Albeit rare, allergic contact dermatitis to volatile alkyl nitrites and other nitrites also can occur.8

The abuse of alkyl nitrites may increase the risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), as they may decrease safer sexual practices and increase the propensity to engage in risky sexual behavior. It has been suggested to screen for STIs in patients with history of volatile alkyl nitrite use. In the past, volatile alkyl nitrites were believed to be a potential vector of human immunodeficiency virus.9 Other popular drugs used in social context or "club drugs," such as 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, gamma hydroxybutyrate, methamphetamine, and ketamine, do not produce irritant dermatitis as an adverse cutaneous reaction.10 The differential diagnosis in our patient included herpes simplex virus and contagious impetigo1 as well as bullous lupus erythematosus and periorificial dermatitis; however, the clinical picture, acute onset of the reaction, and the patient's medical history were critical in making the correct diagnosis.

The patient was treated with topical hydrocortisone and fusidic acid cream twice daily for 7 days with complete response. Sexually transmitted infection screening was unremarkable. We suggest performing an STI workup on patients with history of volatile alkyl nitrite use.

- Schauber J, Herzinger T. 'Poppers' dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:587-588.

- Foroozan M, Studer M, Splingard B, et al. Facial dermatitis due to inhalation of poppers [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:298-299.

- Latini A, Lora V, Zaccarelli M, et al. Unusual presentation of poppers dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:233-234.

- Shortt J, Polizzotto MN, Opat SS, et al. Oxidative haemolysis due to 'poppers'. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:328.

- Davies AJ, Kelly SP, Naylor SG, et al. Adverse ophthalmic reaction in poppers users: case series of 'poppers maculopathy'. Eye (Lond). 2012;26:1479-1486.

- Davies AJ, Kelly SP, Bhatt PR. 'Poppers maculopathy'--an emerging ophthalmic reaction to recreational substance abuse. Eye (Lond). 2012;26:888.

- Vignal-Clermont C, Audo I, Sahel JA, et al. Poppers-associated retinal toxicity. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1583-1585.

- Bos JD, Jansen FC, Timmer JG. Allergic contact dermatitis to amyl nitrite ('poppers'). Contact Dermatitis. 1985;12:109.

- Stratford M, Wilson PD. Agitation effects on microbial cell-cell interactions. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1990;11:1-6.

- Romanelli F, Smith KM, Thornton AC, et al. Poppers: epidemiology and clinical management of inhaled nitrite abuse. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:69-78.

The Diagnosis: Irritant Contact Dermatitis

A slang term for volatile alkyl nitrites, poppers are inhaled for recreational purposes. They produce rapid-onset euphoria and sexual arousal, as well as relax anal and vaginal sphincters, facilitating sexual intercourse. Alkyl nitrites initially were developed to treat coronary disease and angina but were replaced by more potent drugs.1 Because of their psychoactive effects and smooth muscle relaxation properties, they are widely used by homosexual and bisexual men.1-3 The term poppers was originated by the sound generated when the glass vials are crushed; currently, they also may be found in other formats.1

Nausea, hypotension, and headache are mild common adverse effects of volatile alkyl nitrites1; cardiac arrhythmia, oxidative hemolysis,4 and poppers maculopathy5,6 with permanent eye damage also have been reported.7 On the skin, volatile alkyl nitrites induce irritant contact dermatitis that heals without scarring, characteristically involving the face and upper thoracic region, as they are volatile vapors.2 However, the reaction can occur elsewhere. There have been reports of contact dermatitis on other locations, such as the thigh or the ankle, due to vials broken while stored in pockets or on the cuff of the socks.1 There also is a report of irritant contact dermatitis manifesting as a penile ulcer.3 Albeit rare, allergic contact dermatitis to volatile alkyl nitrites and other nitrites also can occur.8

The abuse of alkyl nitrites may increase the risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), as they may decrease safer sexual practices and increase the propensity to engage in risky sexual behavior. It has been suggested to screen for STIs in patients with history of volatile alkyl nitrite use. In the past, volatile alkyl nitrites were believed to be a potential vector of human immunodeficiency virus.9 Other popular drugs used in social context or "club drugs," such as 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, gamma hydroxybutyrate, methamphetamine, and ketamine, do not produce irritant dermatitis as an adverse cutaneous reaction.10 The differential diagnosis in our patient included herpes simplex virus and contagious impetigo1 as well as bullous lupus erythematosus and periorificial dermatitis; however, the clinical picture, acute onset of the reaction, and the patient's medical history were critical in making the correct diagnosis.

The patient was treated with topical hydrocortisone and fusidic acid cream twice daily for 7 days with complete response. Sexually transmitted infection screening was unremarkable. We suggest performing an STI workup on patients with history of volatile alkyl nitrite use.

The Diagnosis: Irritant Contact Dermatitis

A slang term for volatile alkyl nitrites, poppers are inhaled for recreational purposes. They produce rapid-onset euphoria and sexual arousal, as well as relax anal and vaginal sphincters, facilitating sexual intercourse. Alkyl nitrites initially were developed to treat coronary disease and angina but were replaced by more potent drugs.1 Because of their psychoactive effects and smooth muscle relaxation properties, they are widely used by homosexual and bisexual men.1-3 The term poppers was originated by the sound generated when the glass vials are crushed; currently, they also may be found in other formats.1

Nausea, hypotension, and headache are mild common adverse effects of volatile alkyl nitrites1; cardiac arrhythmia, oxidative hemolysis,4 and poppers maculopathy5,6 with permanent eye damage also have been reported.7 On the skin, volatile alkyl nitrites induce irritant contact dermatitis that heals without scarring, characteristically involving the face and upper thoracic region, as they are volatile vapors.2 However, the reaction can occur elsewhere. There have been reports of contact dermatitis on other locations, such as the thigh or the ankle, due to vials broken while stored in pockets or on the cuff of the socks.1 There also is a report of irritant contact dermatitis manifesting as a penile ulcer.3 Albeit rare, allergic contact dermatitis to volatile alkyl nitrites and other nitrites also can occur.8

The abuse of alkyl nitrites may increase the risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), as they may decrease safer sexual practices and increase the propensity to engage in risky sexual behavior. It has been suggested to screen for STIs in patients with history of volatile alkyl nitrite use. In the past, volatile alkyl nitrites were believed to be a potential vector of human immunodeficiency virus.9 Other popular drugs used in social context or "club drugs," such as 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, gamma hydroxybutyrate, methamphetamine, and ketamine, do not produce irritant dermatitis as an adverse cutaneous reaction.10 The differential diagnosis in our patient included herpes simplex virus and contagious impetigo1 as well as bullous lupus erythematosus and periorificial dermatitis; however, the clinical picture, acute onset of the reaction, and the patient's medical history were critical in making the correct diagnosis.

The patient was treated with topical hydrocortisone and fusidic acid cream twice daily for 7 days with complete response. Sexually transmitted infection screening was unremarkable. We suggest performing an STI workup on patients with history of volatile alkyl nitrite use.

- Schauber J, Herzinger T. 'Poppers' dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:587-588.

- Foroozan M, Studer M, Splingard B, et al. Facial dermatitis due to inhalation of poppers [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:298-299.

- Latini A, Lora V, Zaccarelli M, et al. Unusual presentation of poppers dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:233-234.

- Shortt J, Polizzotto MN, Opat SS, et al. Oxidative haemolysis due to 'poppers'. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:328.

- Davies AJ, Kelly SP, Naylor SG, et al. Adverse ophthalmic reaction in poppers users: case series of 'poppers maculopathy'. Eye (Lond). 2012;26:1479-1486.

- Davies AJ, Kelly SP, Bhatt PR. 'Poppers maculopathy'--an emerging ophthalmic reaction to recreational substance abuse. Eye (Lond). 2012;26:888.

- Vignal-Clermont C, Audo I, Sahel JA, et al. Poppers-associated retinal toxicity. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1583-1585.

- Bos JD, Jansen FC, Timmer JG. Allergic contact dermatitis to amyl nitrite ('poppers'). Contact Dermatitis. 1985;12:109.

- Stratford M, Wilson PD. Agitation effects on microbial cell-cell interactions. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1990;11:1-6.

- Romanelli F, Smith KM, Thornton AC, et al. Poppers: epidemiology and clinical management of inhaled nitrite abuse. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:69-78.

- Schauber J, Herzinger T. 'Poppers' dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:587-588.

- Foroozan M, Studer M, Splingard B, et al. Facial dermatitis due to inhalation of poppers [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:298-299.

- Latini A, Lora V, Zaccarelli M, et al. Unusual presentation of poppers dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:233-234.

- Shortt J, Polizzotto MN, Opat SS, et al. Oxidative haemolysis due to 'poppers'. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:328.

- Davies AJ, Kelly SP, Naylor SG, et al. Adverse ophthalmic reaction in poppers users: case series of 'poppers maculopathy'. Eye (Lond). 2012;26:1479-1486.

- Davies AJ, Kelly SP, Bhatt PR. 'Poppers maculopathy'--an emerging ophthalmic reaction to recreational substance abuse. Eye (Lond). 2012;26:888.

- Vignal-Clermont C, Audo I, Sahel JA, et al. Poppers-associated retinal toxicity. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1583-1585.

- Bos JD, Jansen FC, Timmer JG. Allergic contact dermatitis to amyl nitrite ('poppers'). Contact Dermatitis. 1985;12:109.

- Stratford M, Wilson PD. Agitation effects on microbial cell-cell interactions. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1990;11:1-6.

- Romanelli F, Smith KM, Thornton AC, et al. Poppers: epidemiology and clinical management of inhaled nitrite abuse. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:69-78.

A 44-year-old man was referred to the department of dermatology for a pruriginous nasal rash. Physical examination revealed vesicles with clear content and crusts symmetrically in both nostrils and philtra. The remainder of the examination was otherwise unremarkable. The patient reported inhalation of poppers the prior night during a party. No history of connective tissue diseases was present. The patient was in overall good health with no fever or chills.

Flesh-Colored Papules on the Scrotum

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Sarcoidosis

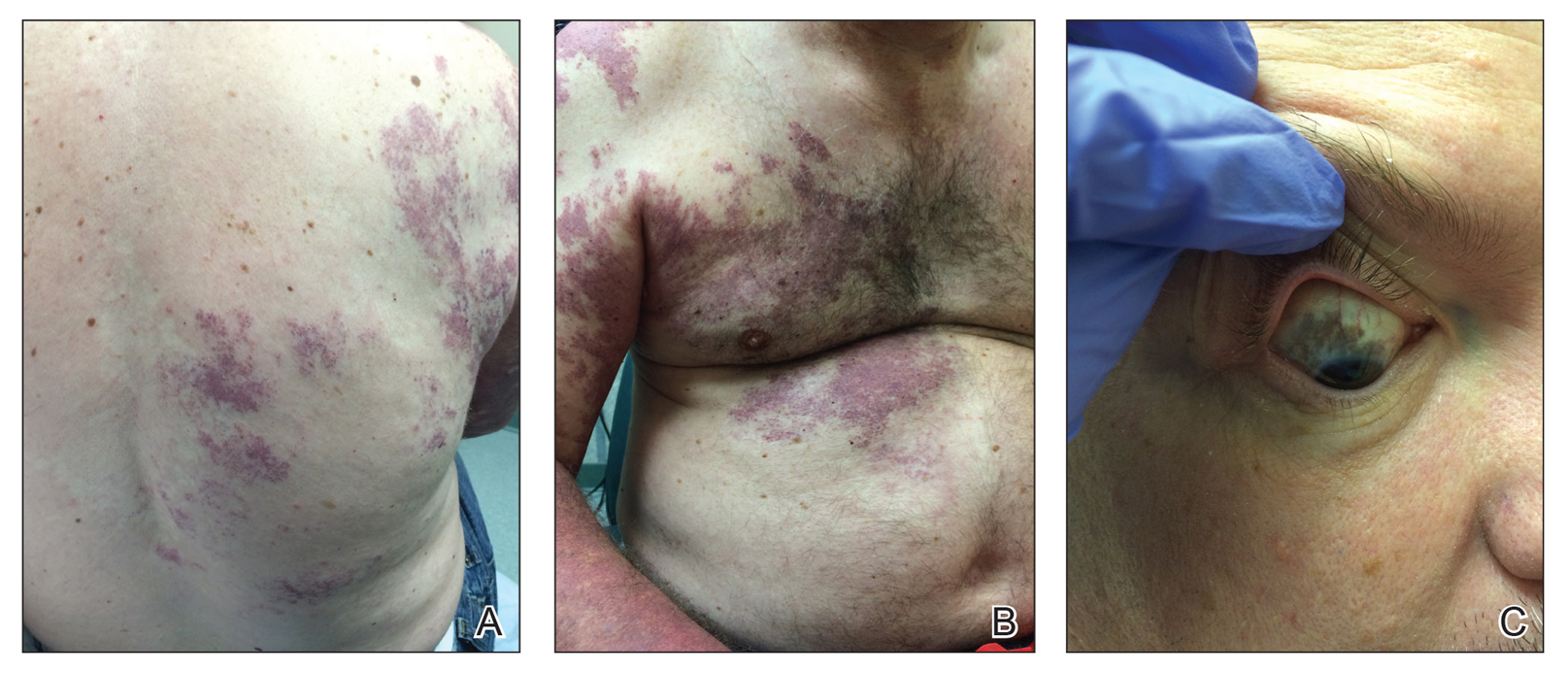

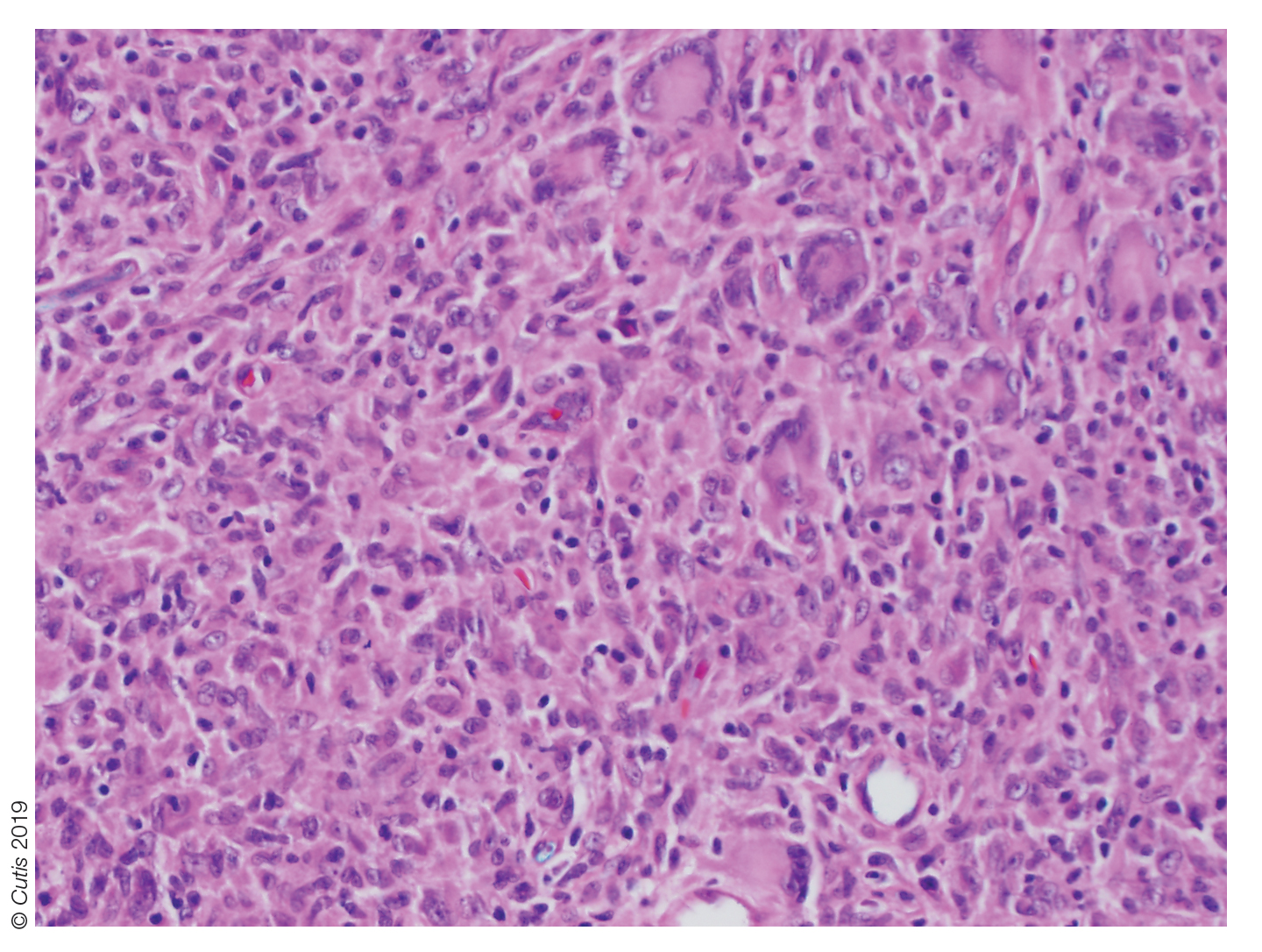

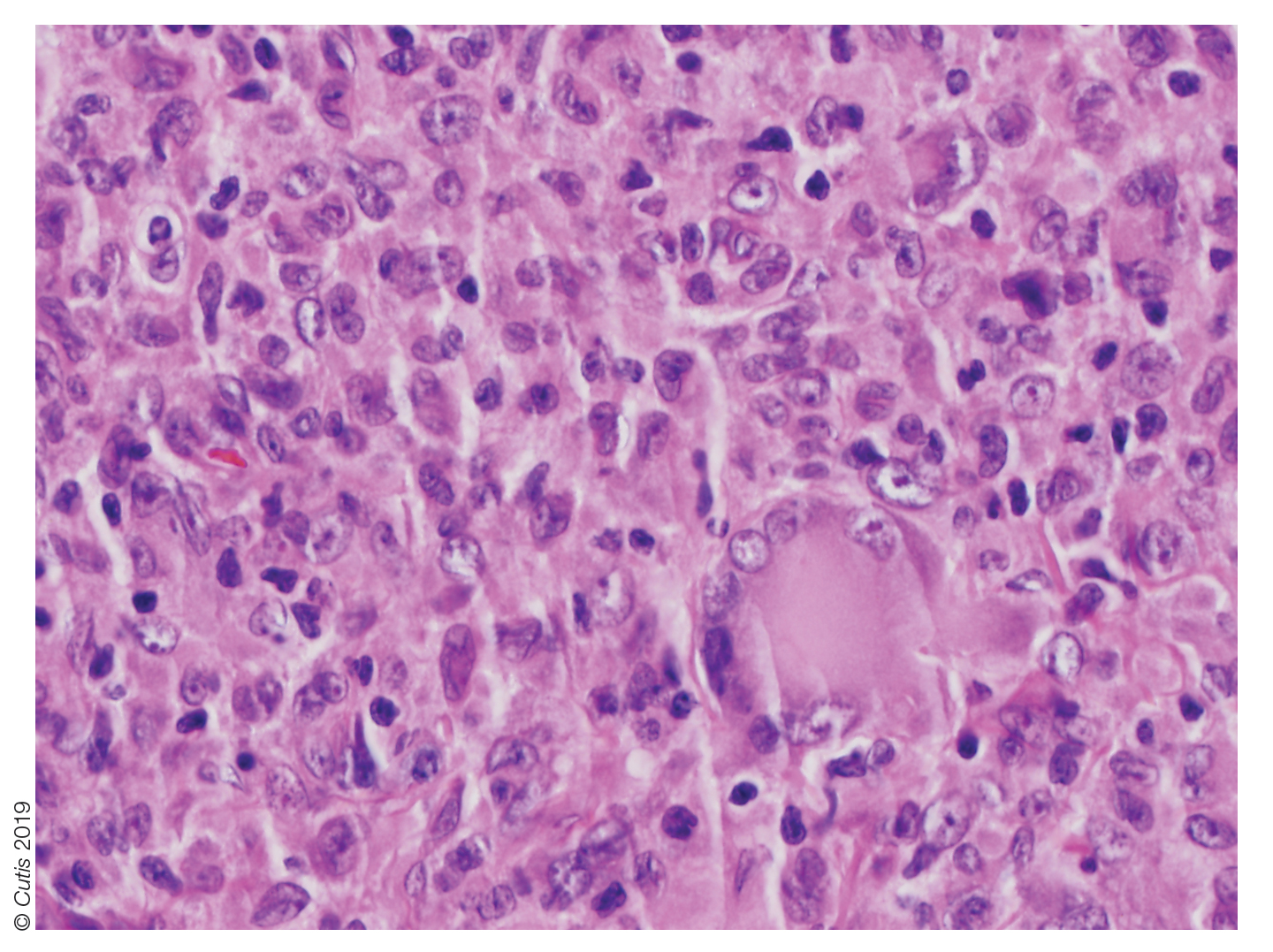

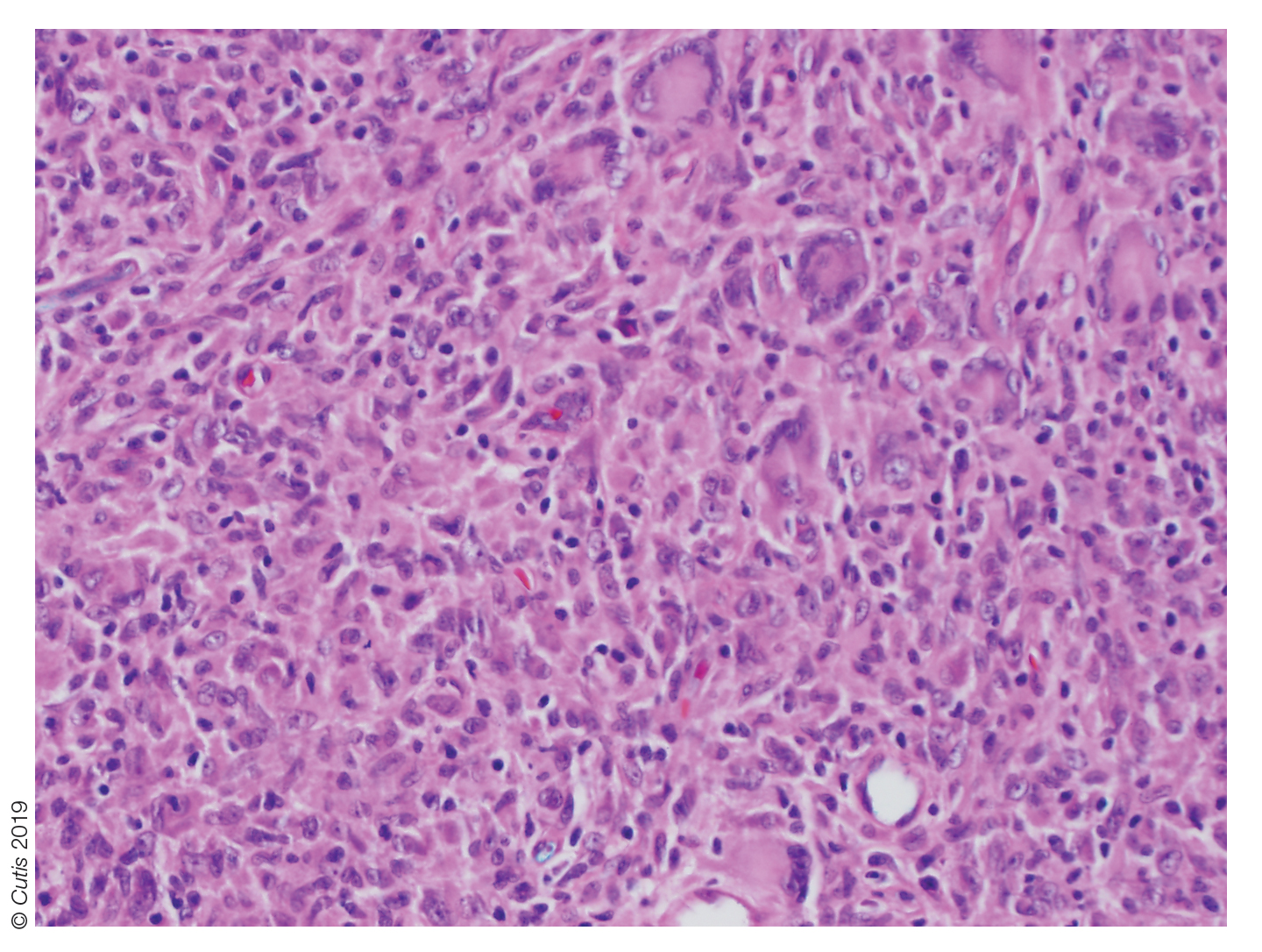

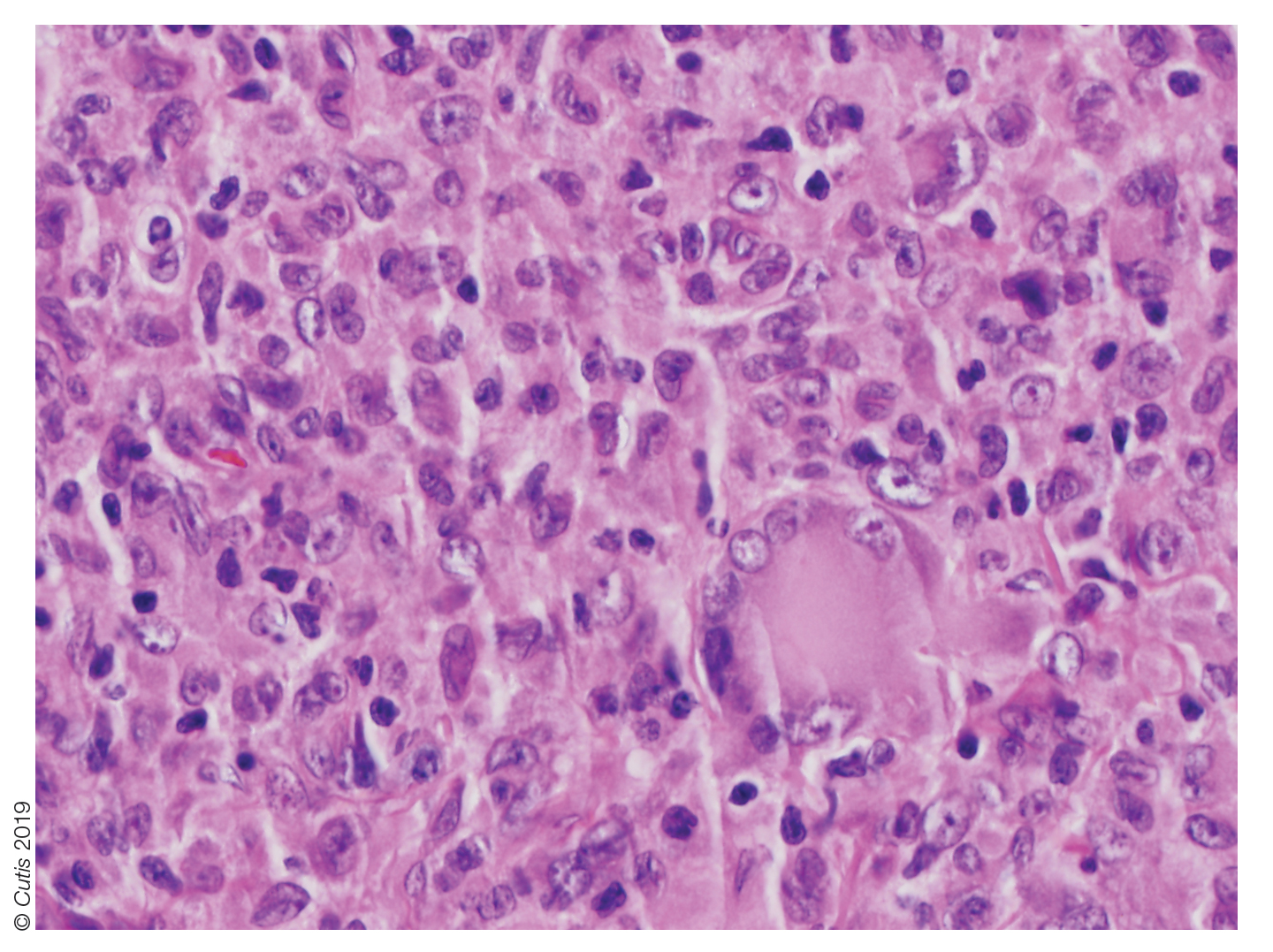

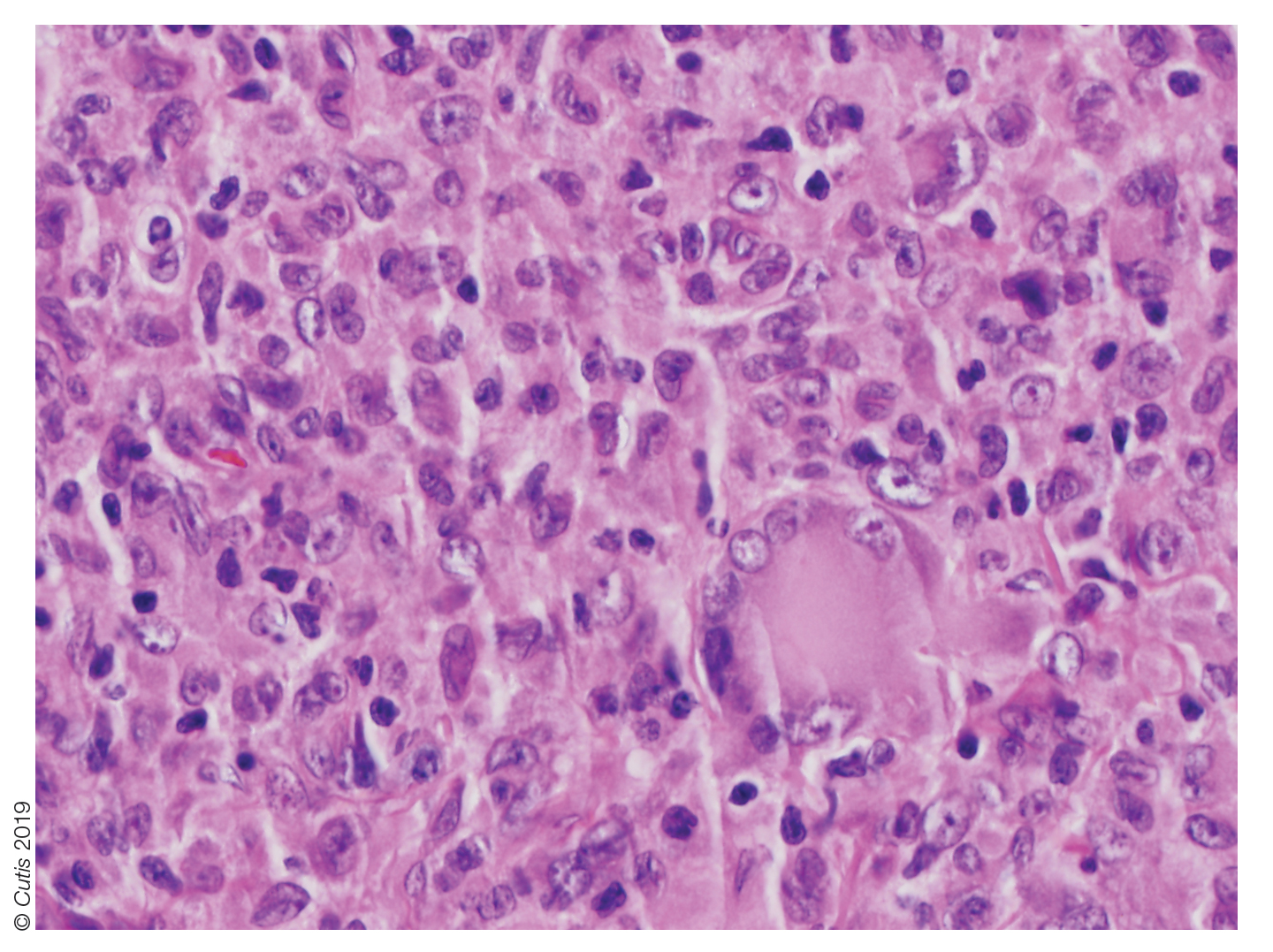

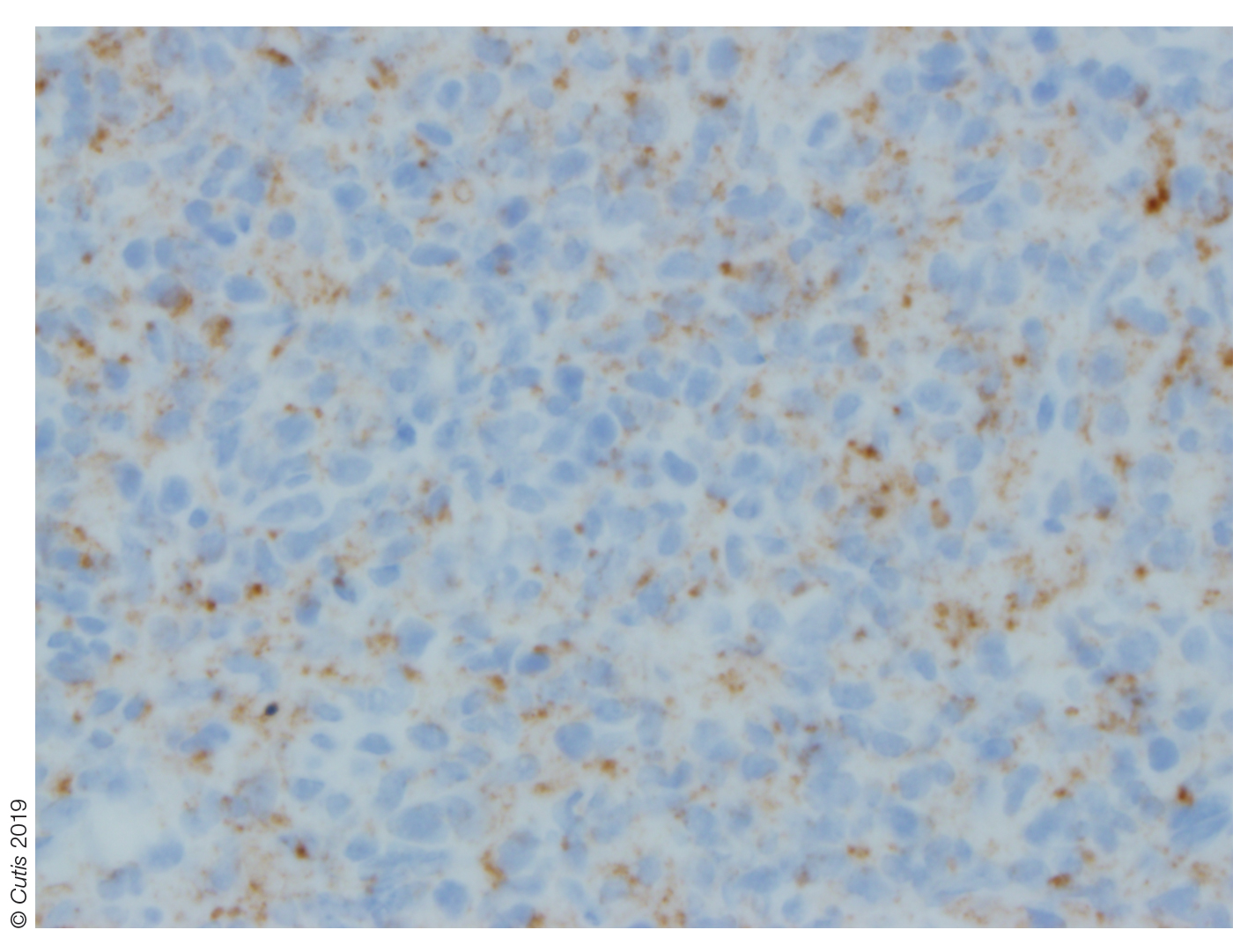

Histologic examination of the shave biopsy showed focal parakeratosis, irregular epidermal hyperplasia, and multiple noncaseating naked granulomas with occasional multinucleated giant cells in the dermis (Figure, A). The granulomas were surrounded by mild lymphocytic infiltration with rare eosinophils (Figure, B). Periodic acid-Schiff and Fite stains were negative for organisms, and polariscopic examination was negative; these findings confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. Topical or intralesional steroids were recommended, but our patient declined treatment given that the lesions were asymptomatic.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that affects the skin in approximately 25% of patients.1 Cutaneous lesions manifest in 2 forms: specific and nonspecific. Noncaseating granulomas are considered specific. Nonspecific lesions include erythema nodosum, calcinosis cutis, Sweet syndrome, and nail clubbing. The most common sites of specific sarcoidosis lesions include the face, lips, neck, upper trunk, and extremities. Few cases have reported cutaneous sarcoidosis involving the genitalia; most reports describe vulvar cutaneous sarcoidosis.2-4 Although there have been reports of sarcoidosis involving the epididymis and testes, which presented as scrotal masses, cutaneous scrotal involvement with the skin as the primary site of involvement is rare.5,6 McLaughlin et al5 reported an extensive, pruritic, and eczematous eruption of the scrotum with associated edema and tenderness. Wei et al6 reported cutaneous sarcoidosis in the form of multiple indurated papules involving the penis and scrotum, similar to our case.

Comparing our patient to the case reported by Wei et al,6 both patients had Fitzpatrick skin type V or VI and systemic involvement including pulmonary disease. However, Wei et al6 did not clearly mention if the cutaneous manifestations preceded the diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis or if they were present at the time of the diagnosis. Our patient developed cutaneous lesions 4 years after being diagnosed with systemic sarcoidosis from hilar lymphadenopathy. In addition to the scrotal lesions, he also had a lesion of lupus pernio presenting as a violaceous to brown plaque on the tip of the nose. Although both patients denied pruritus, the other patient's lesions were painful.6 Wei et al6 mentioned that treatment with topical, intralesional, and systemic steroids failed, and the patient's lesions continued to progress. Generally, topical and intralesional steroids are considered mainstay treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis despite insufficient data to support their efficacy.7

The differential diagnosis of papules on the scrotum can be broad. Our provisional diagnoses for this particular morphology of small, flesh-colored, shiny, polygonal, flat-topped papules included condyloma acuminatum; lichen planus; idiopathic scrotal calcinosis; steatocystoma multiplex; and sarcoidosis (although uncommon for the site), given the history of pulmonary involvement. We considered a diagnosis of condyloma acuminatum, but the lesions were too shiny and smooth. On histology, condyloma acuminatum shows a hyperkeratotic and parakeratotic stratum corneum, an exophytic growth with marked acanthosis, and superficially located koilocytes. Morphologically, our patient's lesions resembled genital lichen planus. However, Wickham striae were absent, and our patient's lesions were asymptomatic while lesions of lichen planus usually are pruritic. Histologically, lichen planus is characterized by hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth rete ridges, and lichenoid interface inflammation. Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis also could be included in the differential; however, the lesions would look whiter and firmer than those of our patient, and biopsy will clearly show calcium deposition. Steatocystoma multiplex is another condition that can affect the scrotum, along with the trunk, axillae, extremities, and neck. However, the lesions are expected to discharge oily material if squeezed and have a characteristic corrugated eosinophilic cuticle lining a cyst histologically.

Although it is undetermined if the risk for systemic involvement increases in patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis, evaluation for probable systemic involvement is necessary.1 Because cutaneous sarcoidosis generally can precede any systemic involvement, it would be reasonable to consider skin biopsies in patients who present with atypical wartlike lesions on the scrotum and penis to rule out sarcoidosis.

- Marcoval J, Mañá J, Rubio M. Specific cutaneous lesions in patients with systemic sarcoidosis: relationship to severity and chronicity of disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:739.

- Vera C, Funaro D, Bouffard D. Vulvar sarcoidosis: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:287-290.

- Watkins S, Ismail A, McKay K, et al. Systemic sarcoidosis with unique vulvar involvement. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:666-667.

- Pereira IB, Khan A. Sarcoidosis rare cutaneous manifestations: vulval and perianal involvement. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;6:1-2.

- McLaughlin SS, Linquist AM, Burnett JW. Cutaneous sarcoidosis of the scrotum: a rare manifestation of systemic disease. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:216-217.

- Wei H, Friedman KA, Rudikoff D. Multiple indurated papules on penis and scrotum. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:202-204.

- Doherty CB, Rosen T. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Drugs. 2008;68:1361.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Sarcoidosis

Histologic examination of the shave biopsy showed focal parakeratosis, irregular epidermal hyperplasia, and multiple noncaseating naked granulomas with occasional multinucleated giant cells in the dermis (Figure, A). The granulomas were surrounded by mild lymphocytic infiltration with rare eosinophils (Figure, B). Periodic acid-Schiff and Fite stains were negative for organisms, and polariscopic examination was negative; these findings confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. Topical or intralesional steroids were recommended, but our patient declined treatment given that the lesions were asymptomatic.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that affects the skin in approximately 25% of patients.1 Cutaneous lesions manifest in 2 forms: specific and nonspecific. Noncaseating granulomas are considered specific. Nonspecific lesions include erythema nodosum, calcinosis cutis, Sweet syndrome, and nail clubbing. The most common sites of specific sarcoidosis lesions include the face, lips, neck, upper trunk, and extremities. Few cases have reported cutaneous sarcoidosis involving the genitalia; most reports describe vulvar cutaneous sarcoidosis.2-4 Although there have been reports of sarcoidosis involving the epididymis and testes, which presented as scrotal masses, cutaneous scrotal involvement with the skin as the primary site of involvement is rare.5,6 McLaughlin et al5 reported an extensive, pruritic, and eczematous eruption of the scrotum with associated edema and tenderness. Wei et al6 reported cutaneous sarcoidosis in the form of multiple indurated papules involving the penis and scrotum, similar to our case.

Comparing our patient to the case reported by Wei et al,6 both patients had Fitzpatrick skin type V or VI and systemic involvement including pulmonary disease. However, Wei et al6 did not clearly mention if the cutaneous manifestations preceded the diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis or if they were present at the time of the diagnosis. Our patient developed cutaneous lesions 4 years after being diagnosed with systemic sarcoidosis from hilar lymphadenopathy. In addition to the scrotal lesions, he also had a lesion of lupus pernio presenting as a violaceous to brown plaque on the tip of the nose. Although both patients denied pruritus, the other patient's lesions were painful.6 Wei et al6 mentioned that treatment with topical, intralesional, and systemic steroids failed, and the patient's lesions continued to progress. Generally, topical and intralesional steroids are considered mainstay treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis despite insufficient data to support their efficacy.7

The differential diagnosis of papules on the scrotum can be broad. Our provisional diagnoses for this particular morphology of small, flesh-colored, shiny, polygonal, flat-topped papules included condyloma acuminatum; lichen planus; idiopathic scrotal calcinosis; steatocystoma multiplex; and sarcoidosis (although uncommon for the site), given the history of pulmonary involvement. We considered a diagnosis of condyloma acuminatum, but the lesions were too shiny and smooth. On histology, condyloma acuminatum shows a hyperkeratotic and parakeratotic stratum corneum, an exophytic growth with marked acanthosis, and superficially located koilocytes. Morphologically, our patient's lesions resembled genital lichen planus. However, Wickham striae were absent, and our patient's lesions were asymptomatic while lesions of lichen planus usually are pruritic. Histologically, lichen planus is characterized by hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth rete ridges, and lichenoid interface inflammation. Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis also could be included in the differential; however, the lesions would look whiter and firmer than those of our patient, and biopsy will clearly show calcium deposition. Steatocystoma multiplex is another condition that can affect the scrotum, along with the trunk, axillae, extremities, and neck. However, the lesions are expected to discharge oily material if squeezed and have a characteristic corrugated eosinophilic cuticle lining a cyst histologically.

Although it is undetermined if the risk for systemic involvement increases in patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis, evaluation for probable systemic involvement is necessary.1 Because cutaneous sarcoidosis generally can precede any systemic involvement, it would be reasonable to consider skin biopsies in patients who present with atypical wartlike lesions on the scrotum and penis to rule out sarcoidosis.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Sarcoidosis

Histologic examination of the shave biopsy showed focal parakeratosis, irregular epidermal hyperplasia, and multiple noncaseating naked granulomas with occasional multinucleated giant cells in the dermis (Figure, A). The granulomas were surrounded by mild lymphocytic infiltration with rare eosinophils (Figure, B). Periodic acid-Schiff and Fite stains were negative for organisms, and polariscopic examination was negative; these findings confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. Topical or intralesional steroids were recommended, but our patient declined treatment given that the lesions were asymptomatic.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that affects the skin in approximately 25% of patients.1 Cutaneous lesions manifest in 2 forms: specific and nonspecific. Noncaseating granulomas are considered specific. Nonspecific lesions include erythema nodosum, calcinosis cutis, Sweet syndrome, and nail clubbing. The most common sites of specific sarcoidosis lesions include the face, lips, neck, upper trunk, and extremities. Few cases have reported cutaneous sarcoidosis involving the genitalia; most reports describe vulvar cutaneous sarcoidosis.2-4 Although there have been reports of sarcoidosis involving the epididymis and testes, which presented as scrotal masses, cutaneous scrotal involvement with the skin as the primary site of involvement is rare.5,6 McLaughlin et al5 reported an extensive, pruritic, and eczematous eruption of the scrotum with associated edema and tenderness. Wei et al6 reported cutaneous sarcoidosis in the form of multiple indurated papules involving the penis and scrotum, similar to our case.

Comparing our patient to the case reported by Wei et al,6 both patients had Fitzpatrick skin type V or VI and systemic involvement including pulmonary disease. However, Wei et al6 did not clearly mention if the cutaneous manifestations preceded the diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis or if they were present at the time of the diagnosis. Our patient developed cutaneous lesions 4 years after being diagnosed with systemic sarcoidosis from hilar lymphadenopathy. In addition to the scrotal lesions, he also had a lesion of lupus pernio presenting as a violaceous to brown plaque on the tip of the nose. Although both patients denied pruritus, the other patient's lesions were painful.6 Wei et al6 mentioned that treatment with topical, intralesional, and systemic steroids failed, and the patient's lesions continued to progress. Generally, topical and intralesional steroids are considered mainstay treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis despite insufficient data to support their efficacy.7

The differential diagnosis of papules on the scrotum can be broad. Our provisional diagnoses for this particular morphology of small, flesh-colored, shiny, polygonal, flat-topped papules included condyloma acuminatum; lichen planus; idiopathic scrotal calcinosis; steatocystoma multiplex; and sarcoidosis (although uncommon for the site), given the history of pulmonary involvement. We considered a diagnosis of condyloma acuminatum, but the lesions were too shiny and smooth. On histology, condyloma acuminatum shows a hyperkeratotic and parakeratotic stratum corneum, an exophytic growth with marked acanthosis, and superficially located koilocytes. Morphologically, our patient's lesions resembled genital lichen planus. However, Wickham striae were absent, and our patient's lesions were asymptomatic while lesions of lichen planus usually are pruritic. Histologically, lichen planus is characterized by hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth rete ridges, and lichenoid interface inflammation. Idiopathic scrotal calcinosis also could be included in the differential; however, the lesions would look whiter and firmer than those of our patient, and biopsy will clearly show calcium deposition. Steatocystoma multiplex is another condition that can affect the scrotum, along with the trunk, axillae, extremities, and neck. However, the lesions are expected to discharge oily material if squeezed and have a characteristic corrugated eosinophilic cuticle lining a cyst histologically.

Although it is undetermined if the risk for systemic involvement increases in patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis, evaluation for probable systemic involvement is necessary.1 Because cutaneous sarcoidosis generally can precede any systemic involvement, it would be reasonable to consider skin biopsies in patients who present with atypical wartlike lesions on the scrotum and penis to rule out sarcoidosis.

- Marcoval J, Mañá J, Rubio M. Specific cutaneous lesions in patients with systemic sarcoidosis: relationship to severity and chronicity of disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:739.

- Vera C, Funaro D, Bouffard D. Vulvar sarcoidosis: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:287-290.

- Watkins S, Ismail A, McKay K, et al. Systemic sarcoidosis with unique vulvar involvement. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:666-667.

- Pereira IB, Khan A. Sarcoidosis rare cutaneous manifestations: vulval and perianal involvement. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;6:1-2.

- McLaughlin SS, Linquist AM, Burnett JW. Cutaneous sarcoidosis of the scrotum: a rare manifestation of systemic disease. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:216-217.

- Wei H, Friedman KA, Rudikoff D. Multiple indurated papules on penis and scrotum. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:202-204.

- Doherty CB, Rosen T. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Drugs. 2008;68:1361.

- Marcoval J, Mañá J, Rubio M. Specific cutaneous lesions in patients with systemic sarcoidosis: relationship to severity and chronicity of disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:739.

- Vera C, Funaro D, Bouffard D. Vulvar sarcoidosis: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:287-290.

- Watkins S, Ismail A, McKay K, et al. Systemic sarcoidosis with unique vulvar involvement. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:666-667.

- Pereira IB, Khan A. Sarcoidosis rare cutaneous manifestations: vulval and perianal involvement. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;6:1-2.

- McLaughlin SS, Linquist AM, Burnett JW. Cutaneous sarcoidosis of the scrotum: a rare manifestation of systemic disease. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:216-217.

- Wei H, Friedman KA, Rudikoff D. Multiple indurated papules on penis and scrotum. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:202-204.

- Doherty CB, Rosen T. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Drugs. 2008;68:1361.

A 44-year-old black man presented with "bumps on the scrotum" of approximately 4 months' duration. They were asymptomatic and untreated. The patient denied extramarital sexual contacts or a history of any sexually transmitted infection. His medical history was notable for sarcoidosis diagnosed 4 years prior to presentation when hilar lymphadenopathy was incidentally found on routine screening. His condition was managed with regular follow-up without treatment. He also had a positive tuberculosis skin test in the past without radiologic evidence of active pulmonary disease. Physical examination revealed multiple 2- to 5-mm, flesh-colored, shiny, polygonal, flat-topped papules spread diffusely over the scrotum. A 1-cm, barely palpable, nonscaly, violaceous to brown plaque also was seen on the tip of the nose. A punch biopsy was taken from a lesion on the scrotum.

Painful and Pruritic Erosions on the Back

The Diagnosis: Bullous Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE) is a rare blistering disease that affects patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Our patient had a several-year history of SLE and was being managed by a rheumatologist. She was taking hydroxychloroquine at the time of the flare. Although BSLE tends to present in those with SLE that has already been diagnosed, BSLE has been reported as a possible initial manifestation of SLE.1

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus is estimated to occur in less than 5% of patients with SLE and is more common in black women between the second and third decades of life,2 though it also can be seen in the pediatric population.3 The lesions of BSLE usually present as subepidermal blisters often located on the face, neck, and arms on an erythematous or possibly urticarial base. Although non-BSLE vesiculobullous eruptions may be seen in patients with SLE, BSLE is differentiated from these other eruptions by its appearance on sun-exposed and non-sun-exposed areas of the body, while other vesiculobullous eruptions associated with SLE typically are limited to sun-exposed sites.4

Due to its clinical presentation overlapping with several vesiculobullous conditions, a set of diagnostic criteria have been suggested for BSLE, including the following: (1) fulfillment of the American Rheumatism Association's criteria for SLE5; (2) a new-onset vesiculobullous eruption, primarily on sun-exposed skin; (3) histology showing a subepidermal blister with a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate; (4) presence of IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3 at the basement membrane zone; (5) evidence of antibodies to type VII collagen; and (6) immunoelectron microscopy showing codistribution of immunoglobulin deposits with anchoring fibrils/type VII collagen. To meet the diagnosis of type I BSLE, all 6 criteria must be satisfied. To meet the diagnosis of type II BSLE, only criteria 1 to 4 need to be satisfied.6

Patients with BSLE may be presumed to have a different but clinically similar vesiculobullous condition (eg, bullous pemphigoid, cutaneous manifestations of SLE) and may be started on systemic corticosteroids. However, BSLE patients often do not show great improvement while on corticosteroids and may even flare shortly after beginning systemic corticosteroid treatment. The current treatment of choice for BSLE is dapsone, a sulfa drug that is thought to exhibit its anti-inflammatory properties via the inhibition of the alternative pathway of the complement system and through the inhibition of polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions.7 A response to dapsone helps differentiate BSLE from histopathologically and immunopathologically identical conditions such as epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.4 Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus can be differentiated from dermatitis herpetiformis with the presence of antigliadin and antitissue transglutaminase antibodies, which are found in the latter. Additionally, BSLE may show the presence of IgG and IgM deposition in addition to IgA deposition, as opposed to dermatitis herpetiformis where only IgA is found.8 The presence of these additional antibody depositions also help differentiate BSLE from linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD), as LABD will only have IgA depositions and often presents with an annular, crown of jewels-like appearance. Finally, there is a well-described phenomenon of LABD being drug induced, particularly after a course of vancomycin,9 and such an association with vancomycin has not been documented for BSLE.

Our patient was diagnosed with BSLE following the flare approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation. She had been started on dapsone 75 mg daily at that time and was taking 75 mg at the time of presentation. She was admitted and treated as an inpatient with high-dose (1 mg/kg) intravenous prednisone due to the extensive current flare.

- Fujimoto W, Hamada T, Yamada J, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus as an initial manifestation of SLE. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1021-1027.

- Miziara ID, Mahmoud A, Chagury AA, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: case report. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;17:344-346.

- Tincopa M, Puttgen KB, Sule S, et al. Bullous lupus: an unusual initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in an adolescent girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:373-376.

- Grover C, Khurana A, Sharma S, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:492.

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of RheumatologyClassification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [published online August 6, 2019]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412.

- Gammon WR, Briggaman RA. Bullous SLE: a phenotypically distinctive but immunologically heterogeneous bullous disorder. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:28S-34S.

- Duan L, Chen L, Zhong S, et al. Treatment of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:6.

- Barbosa WS, Rodarte CM, Guerra JG, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: differential diagnosis with dermatitis herpetiformis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S92-S95.

- Yordanova I, Valtchev V, Gospodinov D, et al. IgA linear bullous dermatosis in childhood. J IMAB. 2015;21:1012-1014.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE) is a rare blistering disease that affects patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Our patient had a several-year history of SLE and was being managed by a rheumatologist. She was taking hydroxychloroquine at the time of the flare. Although BSLE tends to present in those with SLE that has already been diagnosed, BSLE has been reported as a possible initial manifestation of SLE.1

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus is estimated to occur in less than 5% of patients with SLE and is more common in black women between the second and third decades of life,2 though it also can be seen in the pediatric population.3 The lesions of BSLE usually present as subepidermal blisters often located on the face, neck, and arms on an erythematous or possibly urticarial base. Although non-BSLE vesiculobullous eruptions may be seen in patients with SLE, BSLE is differentiated from these other eruptions by its appearance on sun-exposed and non-sun-exposed areas of the body, while other vesiculobullous eruptions associated with SLE typically are limited to sun-exposed sites.4

Due to its clinical presentation overlapping with several vesiculobullous conditions, a set of diagnostic criteria have been suggested for BSLE, including the following: (1) fulfillment of the American Rheumatism Association's criteria for SLE5; (2) a new-onset vesiculobullous eruption, primarily on sun-exposed skin; (3) histology showing a subepidermal blister with a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate; (4) presence of IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3 at the basement membrane zone; (5) evidence of antibodies to type VII collagen; and (6) immunoelectron microscopy showing codistribution of immunoglobulin deposits with anchoring fibrils/type VII collagen. To meet the diagnosis of type I BSLE, all 6 criteria must be satisfied. To meet the diagnosis of type II BSLE, only criteria 1 to 4 need to be satisfied.6

Patients with BSLE may be presumed to have a different but clinically similar vesiculobullous condition (eg, bullous pemphigoid, cutaneous manifestations of SLE) and may be started on systemic corticosteroids. However, BSLE patients often do not show great improvement while on corticosteroids and may even flare shortly after beginning systemic corticosteroid treatment. The current treatment of choice for BSLE is dapsone, a sulfa drug that is thought to exhibit its anti-inflammatory properties via the inhibition of the alternative pathway of the complement system and through the inhibition of polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions.7 A response to dapsone helps differentiate BSLE from histopathologically and immunopathologically identical conditions such as epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.4 Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus can be differentiated from dermatitis herpetiformis with the presence of antigliadin and antitissue transglutaminase antibodies, which are found in the latter. Additionally, BSLE may show the presence of IgG and IgM deposition in addition to IgA deposition, as opposed to dermatitis herpetiformis where only IgA is found.8 The presence of these additional antibody depositions also help differentiate BSLE from linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD), as LABD will only have IgA depositions and often presents with an annular, crown of jewels-like appearance. Finally, there is a well-described phenomenon of LABD being drug induced, particularly after a course of vancomycin,9 and such an association with vancomycin has not been documented for BSLE.

Our patient was diagnosed with BSLE following the flare approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation. She had been started on dapsone 75 mg daily at that time and was taking 75 mg at the time of presentation. She was admitted and treated as an inpatient with high-dose (1 mg/kg) intravenous prednisone due to the extensive current flare.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE) is a rare blistering disease that affects patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Our patient had a several-year history of SLE and was being managed by a rheumatologist. She was taking hydroxychloroquine at the time of the flare. Although BSLE tends to present in those with SLE that has already been diagnosed, BSLE has been reported as a possible initial manifestation of SLE.1

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus is estimated to occur in less than 5% of patients with SLE and is more common in black women between the second and third decades of life,2 though it also can be seen in the pediatric population.3 The lesions of BSLE usually present as subepidermal blisters often located on the face, neck, and arms on an erythematous or possibly urticarial base. Although non-BSLE vesiculobullous eruptions may be seen in patients with SLE, BSLE is differentiated from these other eruptions by its appearance on sun-exposed and non-sun-exposed areas of the body, while other vesiculobullous eruptions associated with SLE typically are limited to sun-exposed sites.4

Due to its clinical presentation overlapping with several vesiculobullous conditions, a set of diagnostic criteria have been suggested for BSLE, including the following: (1) fulfillment of the American Rheumatism Association's criteria for SLE5; (2) a new-onset vesiculobullous eruption, primarily on sun-exposed skin; (3) histology showing a subepidermal blister with a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate; (4) presence of IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3 at the basement membrane zone; (5) evidence of antibodies to type VII collagen; and (6) immunoelectron microscopy showing codistribution of immunoglobulin deposits with anchoring fibrils/type VII collagen. To meet the diagnosis of type I BSLE, all 6 criteria must be satisfied. To meet the diagnosis of type II BSLE, only criteria 1 to 4 need to be satisfied.6

Patients with BSLE may be presumed to have a different but clinically similar vesiculobullous condition (eg, bullous pemphigoid, cutaneous manifestations of SLE) and may be started on systemic corticosteroids. However, BSLE patients often do not show great improvement while on corticosteroids and may even flare shortly after beginning systemic corticosteroid treatment. The current treatment of choice for BSLE is dapsone, a sulfa drug that is thought to exhibit its anti-inflammatory properties via the inhibition of the alternative pathway of the complement system and through the inhibition of polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions.7 A response to dapsone helps differentiate BSLE from histopathologically and immunopathologically identical conditions such as epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.4 Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus can be differentiated from dermatitis herpetiformis with the presence of antigliadin and antitissue transglutaminase antibodies, which are found in the latter. Additionally, BSLE may show the presence of IgG and IgM deposition in addition to IgA deposition, as opposed to dermatitis herpetiformis where only IgA is found.8 The presence of these additional antibody depositions also help differentiate BSLE from linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD), as LABD will only have IgA depositions and often presents with an annular, crown of jewels-like appearance. Finally, there is a well-described phenomenon of LABD being drug induced, particularly after a course of vancomycin,9 and such an association with vancomycin has not been documented for BSLE.

Our patient was diagnosed with BSLE following the flare approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation. She had been started on dapsone 75 mg daily at that time and was taking 75 mg at the time of presentation. She was admitted and treated as an inpatient with high-dose (1 mg/kg) intravenous prednisone due to the extensive current flare.

- Fujimoto W, Hamada T, Yamada J, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus as an initial manifestation of SLE. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1021-1027.

- Miziara ID, Mahmoud A, Chagury AA, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: case report. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;17:344-346.

- Tincopa M, Puttgen KB, Sule S, et al. Bullous lupus: an unusual initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in an adolescent girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:373-376.

- Grover C, Khurana A, Sharma S, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:492.

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of RheumatologyClassification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [published online August 6, 2019]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412.

- Gammon WR, Briggaman RA. Bullous SLE: a phenotypically distinctive but immunologically heterogeneous bullous disorder. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:28S-34S.

- Duan L, Chen L, Zhong S, et al. Treatment of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:6.

- Barbosa WS, Rodarte CM, Guerra JG, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: differential diagnosis with dermatitis herpetiformis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S92-S95.

- Yordanova I, Valtchev V, Gospodinov D, et al. IgA linear bullous dermatosis in childhood. J IMAB. 2015;21:1012-1014.

- Fujimoto W, Hamada T, Yamada J, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus as an initial manifestation of SLE. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1021-1027.

- Miziara ID, Mahmoud A, Chagury AA, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: case report. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;17:344-346.

- Tincopa M, Puttgen KB, Sule S, et al. Bullous lupus: an unusual initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in an adolescent girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:373-376.

- Grover C, Khurana A, Sharma S, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:492.

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of RheumatologyClassification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [published online August 6, 2019]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412.

- Gammon WR, Briggaman RA. Bullous SLE: a phenotypically distinctive but immunologically heterogeneous bullous disorder. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:28S-34S.

- Duan L, Chen L, Zhong S, et al. Treatment of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:6.

- Barbosa WS, Rodarte CM, Guerra JG, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: differential diagnosis with dermatitis herpetiformis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S92-S95.

- Yordanova I, Valtchev V, Gospodinov D, et al. IgA linear bullous dermatosis in childhood. J IMAB. 2015;21:1012-1014.

A 51-year-old black woman presented to the dermatology clinic with painful and pruritic erosions on the back, abdomen, neck, and arms of approximately 2 months' duration. The lesions started on the back and spread in a cephalocaudal manner. The patient denied any new changes in medication. Physical examination revealed large erosions with mild weeping of serosanguineous fluid on the back, abdomen, neck, and upper extremities. A few tense bullae were present on the dorsal aspect of the right hand. She had experienced a similar flare approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation. At that time, 2 shave biopsies from vesiculobullous lesions on the right side of the neck were sent for hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence. Biopsy results showed a subepidermal blister that extended along the course of the hair follicle and was associated with an infiltrate of neutrophilic granulocytes that also extended along the course of the hair follicle. Direct immunofluorescence showed IgG and C3 deposition in the basement membrane zone extending along the floor of the blister where the epidermis was separated from the dermis.

Enlarging Nodule on the Nipple

The Diagnosis: Nipple Adenoma (Florid Papillomatosis of the Nipple)

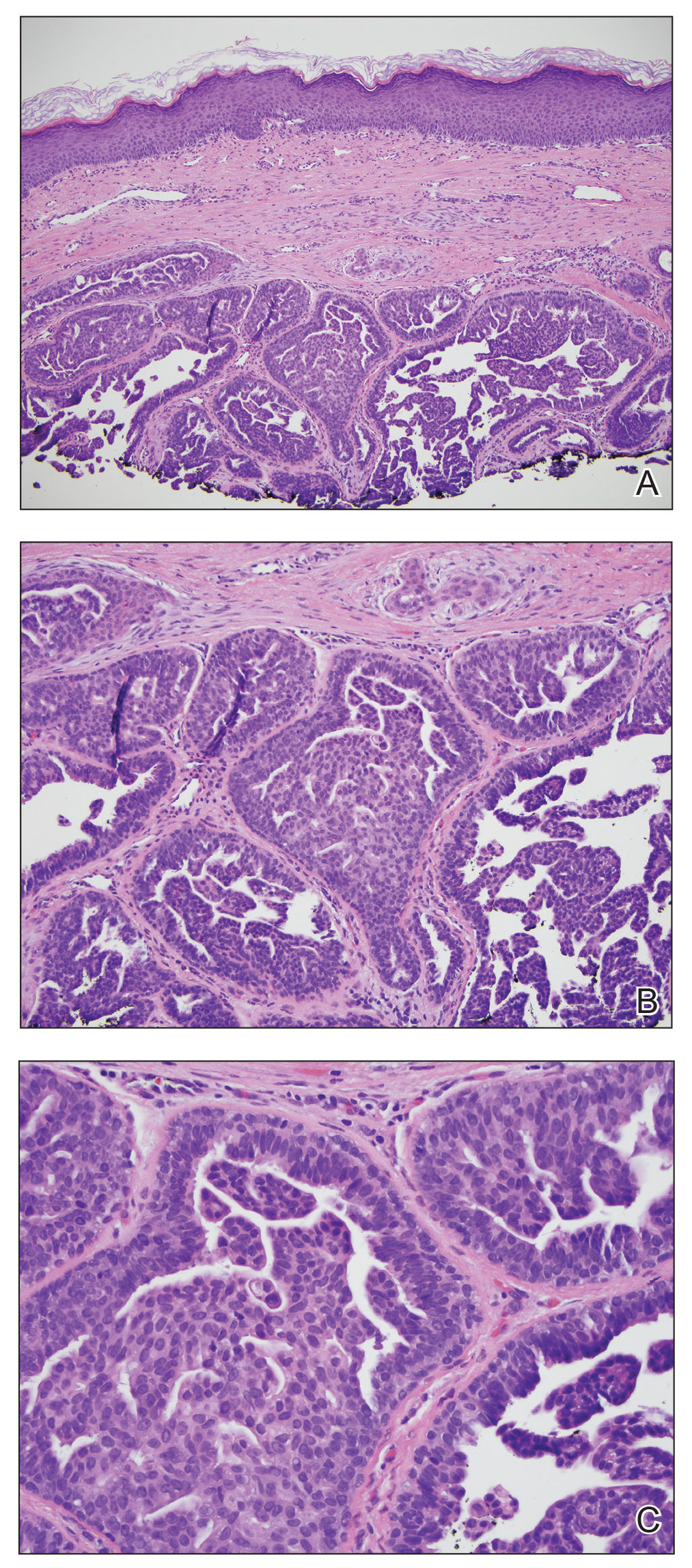

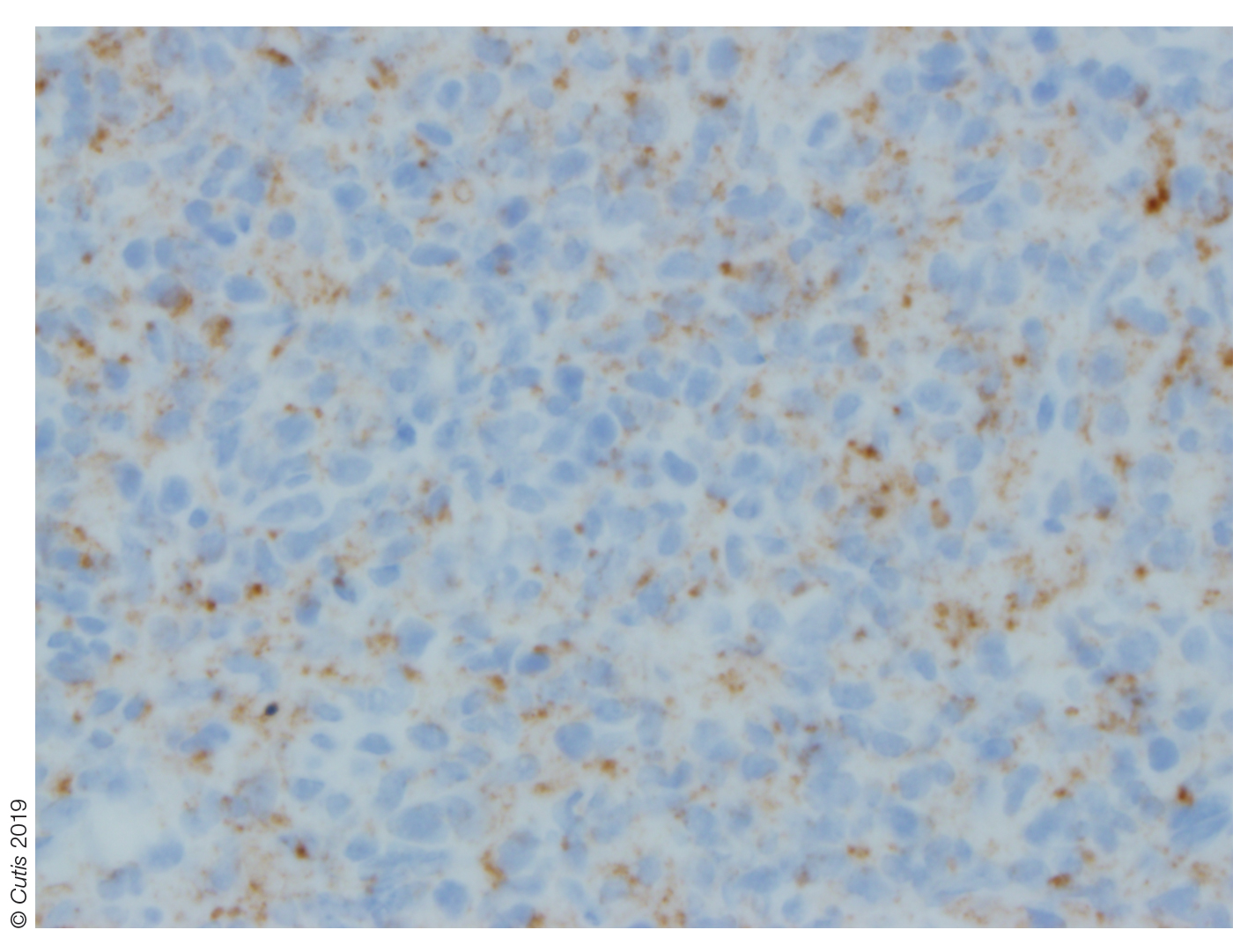

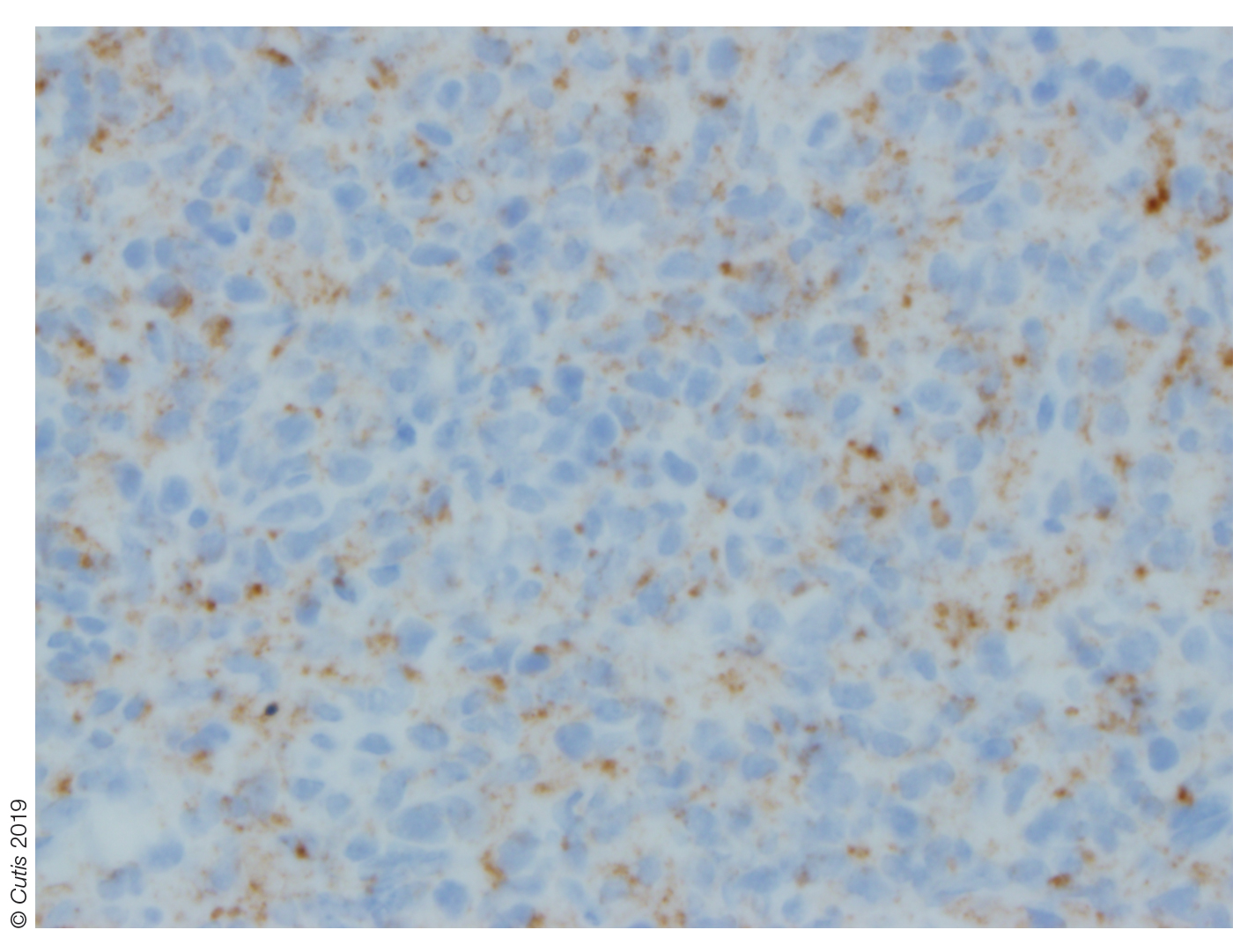

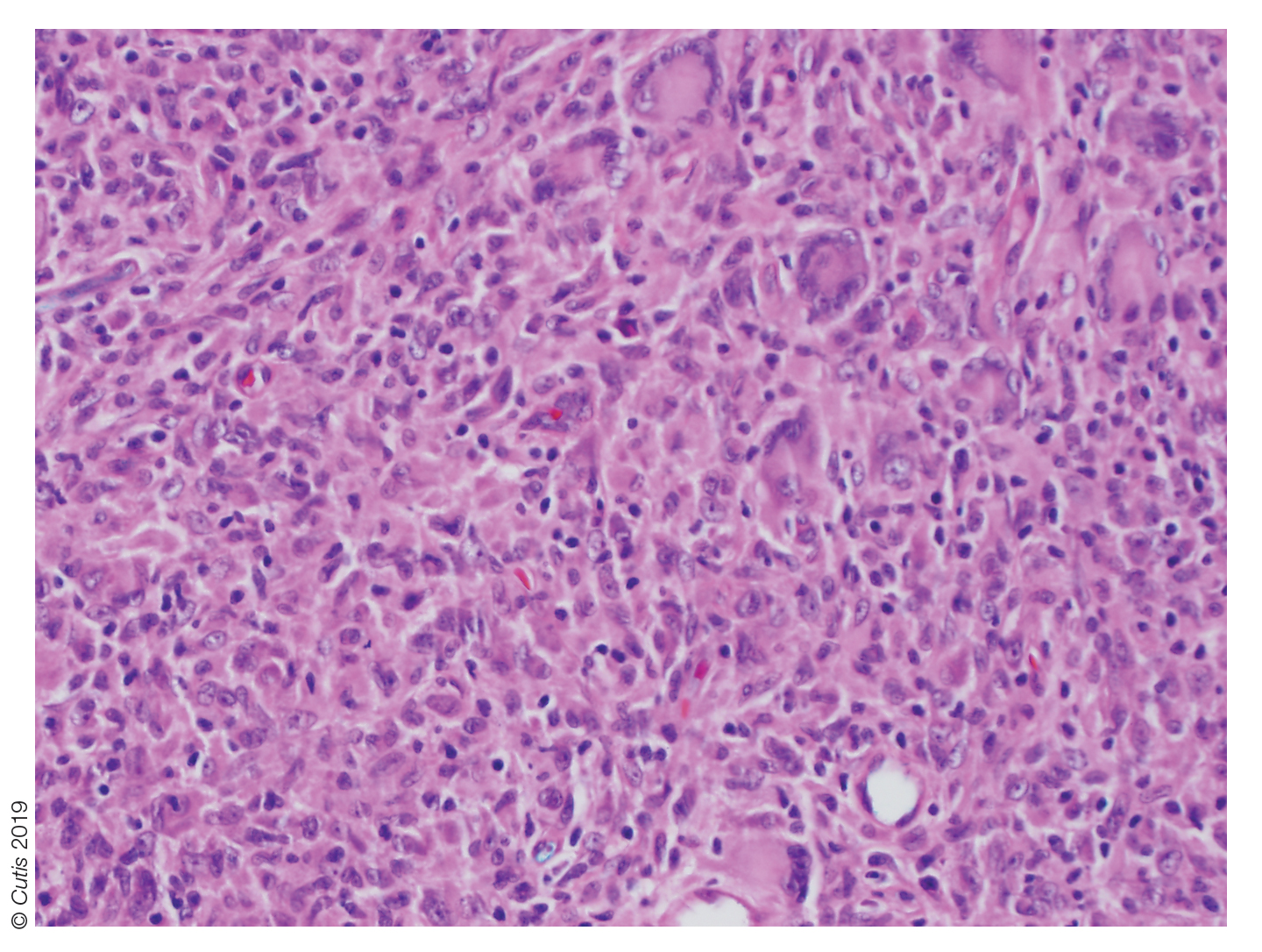

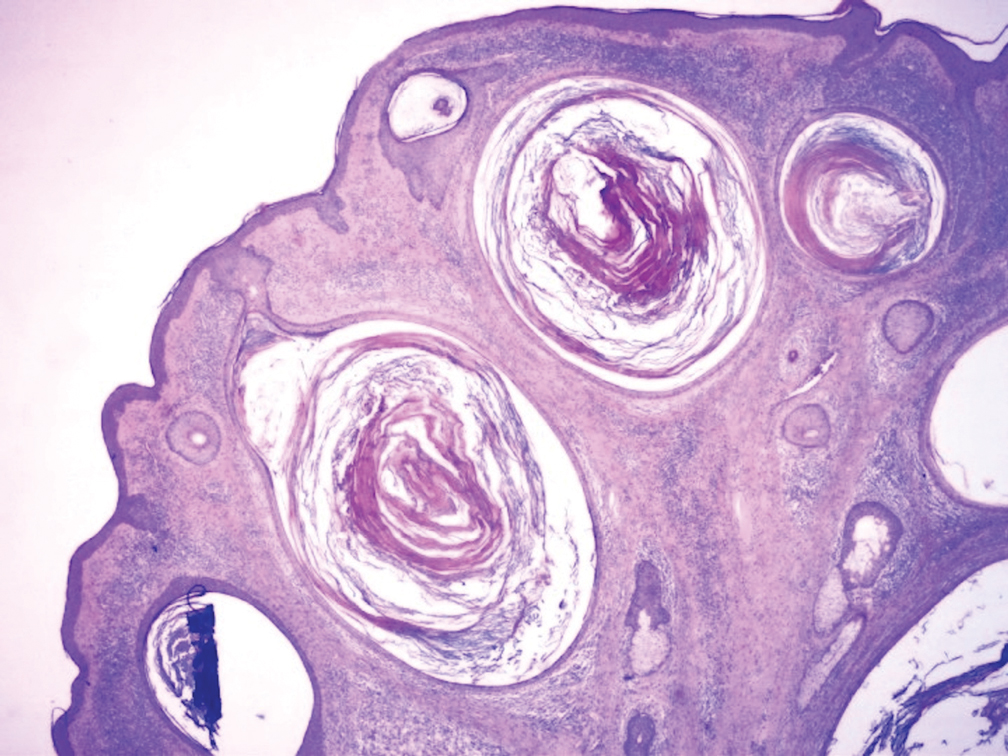

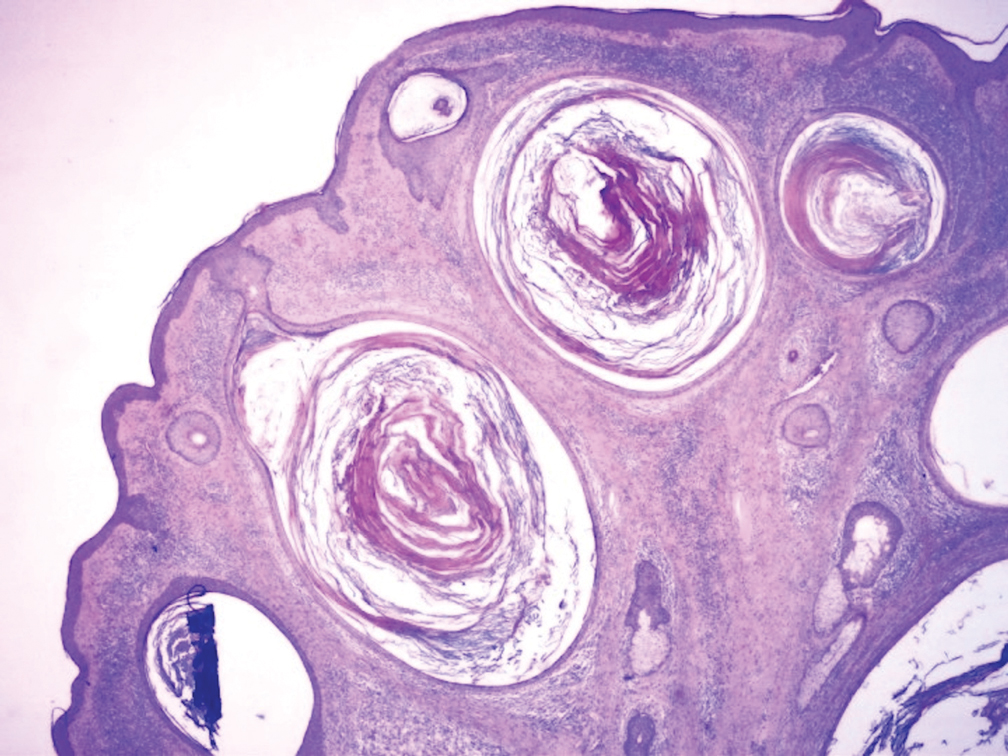

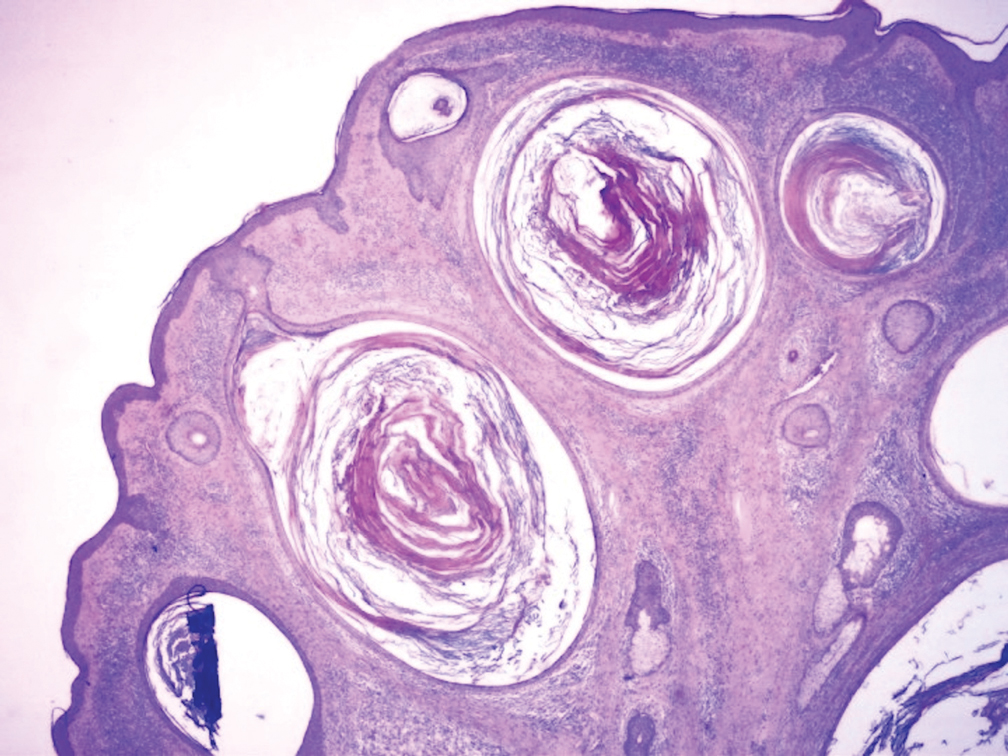

Biopsy of the nodule showed florid papillary hyperplasia of the ductal epithelium within the dermis that was sharply demarcated from the background stroma (Figure, A and B). Neither cytological nor architectural atypia were evident. There was no notable necrosis (Figure C). There was a background of fibrosis whereby the glandular ductal structures assumed a somewhat irregular growth pattern within the dermis with attendant hemorrhage. The patient underwent complete excision of the lesion. No evidence of carcinoma was seen on the final pathology, and the final margins were negative.

First described in 1923 and fully characterized in 1955, nipple adenoma (also known as florid papillomatosis of the nipple) is a benign proliferative neoplasm that originates in the lactiferous ducts of the nipple.1,2 It most commonly affects women aged 40 to 50 years (range, 0-89 years); less than 5% of cases are reported in men.3,4 It predominantly is unilateral, with only rare cases of bilateral papillomatosis reported. Patients often present with serous or serosanguineous discharge and an itching or burning sensation. Symptoms may worsen with the menstrual cycle.4 On physical examination, it presents as an ill-defined red nodule on the nipple with crusting, erosion, or erythema of the nipple surface. Although imaging generally is not used to confirm the diagnosis, mammography should be performed prior to biopsy to rule out underlying breast pathology. Dermoscopy may show linear cherry red structures or red serpiginous and annular structures.5,6 The differential diagnosis of nipple adenoma includes Paget disease of the breast, adenomyoepithelioma, subareolar subsclerosing duct hyperplasia, syringomatous adenoma, adenosis tumor, low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma, low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ, tubular carcinoma, and sweat gland tumors.3

Microscopic features of nipple adenoma have been categorized into 4 subtypes: sclerosing papillomatosis, papillomatosis, adenosis, and a mixed pattern.3,7 The tumors may have keratin cysts and focal necrosis but no atypia, and the myoepithelial cell layer is retained. Nipple adenomas show a glandular proliferation in the dermis that is relatively well circumscribed with glands that vary in appearance between a simple adenosislike pattern of growth to a papillary hyperplasia and/or usual ductal hyperplasia growth pattern. A pseudoinfiltrative pattern can occur when the glandular epithelium is entrapped within stromal fibrosis; however, the myoepithelial layer is retained. Occasionally, the glandular epithelium can grow in continuity with the surface squamous epithelium of the nipple, clinically simulating Paget disease of the breast.8 Immunohistochemical stains, specifically p63, p40, calponin 1, h-caldesmon, cytokeratin 5/6, CD10, and α; smooth muscle actin, highlight the myoepithelial cells, while cytokeratin 7 identifies the ductal epithelium, supporting the diagnosis.6 In addition to biopsy and microscopic tissue examination, touch preparation cytology, curettage cytology, and fine needle aspiration techniques have been used to perform cytologic examination of the lesions, aiding in identification of the benign or malignant nature of the neoplasm.6 Nipple adenoma also is referred to as florid papillomatosis of the nipple, papillary adenoma, erosive adenomatosis, and subareolar duct papillomatosis.7

Although nipple adenoma is a benign tumor, up to 16.5% of affected patients had an ipsilateral or contralateral mammary carcinoma.9 The majority arose coincidentally but separately in the same breast, and carcinoma arose directly from the nipple adenoma in 8 cases; 3 cases were carcinomas that arose in men.10 A definitive association or causal relationship between nipple adenoma and subsequent development of breast cancer has not been identified, and the incidence of nipple adenoma in patients with a positive family history of breast cancer has not been examined. Therefore, although various treatments including cryosurgery, nipple splitting enucleation, and Mohs micrographic surgery have been proposed, complete excision remains the gold standard of therapy. Regular breast examinations and digital mammography are necessary to screen for local recurrences.

- Miller E, Lewis D. The significance of serohemorrhagic or hemorrhagic discharge from the nipple. JAMA. 1923;81:1651-1657.

- Jones DB. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. Cancer. 1955;8:315-319.

- Rosen PP. Rosen's Breast Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:120-128.

- Brownstein MH, Phelps RG, Maqnin PH. Papillary adenoma of the nipple: analysis of fifteen new cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:707-715.

- Takashima S, Fujita Y, Miyauchi T, et al. Dermoscopic observation in adenoma of the nipple. J Dermatol. 2015;42:341-342.

- Spohn G, Trotter S, Tozbikian G, et al. Nipple adenoma in a female patient presenting with persistent erythema of the right nipple skin: case report, review of the literature, clinical implications, and relevancy to health care providers who evaluate and treat patients with dermatologic conditions of the breast skin. BMC Dermatol. 2016;16:4.

- Shin SJ. Nipple adenoma (florid papillomatosis of the nipple). In: Dabbs DJ, ed. Breast Pathology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:286-292.

- Schnitt SJ, Collins LC. Biopsy Interpretation of the Breast. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

- Salemis NS. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple: a rare presentation and review of the literature. Breast Dis. 2015;35:153-156.

- Di Bonito M, Cantile M, Collina F, et al. Adenoma of the nipple: a clinicopathological report of 13 cases. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1839-1842.

The Diagnosis: Nipple Adenoma (Florid Papillomatosis of the Nipple)

Biopsy of the nodule showed florid papillary hyperplasia of the ductal epithelium within the dermis that was sharply demarcated from the background stroma (Figure, A and B). Neither cytological nor architectural atypia were evident. There was no notable necrosis (Figure C). There was a background of fibrosis whereby the glandular ductal structures assumed a somewhat irregular growth pattern within the dermis with attendant hemorrhage. The patient underwent complete excision of the lesion. No evidence of carcinoma was seen on the final pathology, and the final margins were negative.

First described in 1923 and fully characterized in 1955, nipple adenoma (also known as florid papillomatosis of the nipple) is a benign proliferative neoplasm that originates in the lactiferous ducts of the nipple.1,2 It most commonly affects women aged 40 to 50 years (range, 0-89 years); less than 5% of cases are reported in men.3,4 It predominantly is unilateral, with only rare cases of bilateral papillomatosis reported. Patients often present with serous or serosanguineous discharge and an itching or burning sensation. Symptoms may worsen with the menstrual cycle.4 On physical examination, it presents as an ill-defined red nodule on the nipple with crusting, erosion, or erythema of the nipple surface. Although imaging generally is not used to confirm the diagnosis, mammography should be performed prior to biopsy to rule out underlying breast pathology. Dermoscopy may show linear cherry red structures or red serpiginous and annular structures.5,6 The differential diagnosis of nipple adenoma includes Paget disease of the breast, adenomyoepithelioma, subareolar subsclerosing duct hyperplasia, syringomatous adenoma, adenosis tumor, low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma, low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ, tubular carcinoma, and sweat gland tumors.3

Microscopic features of nipple adenoma have been categorized into 4 subtypes: sclerosing papillomatosis, papillomatosis, adenosis, and a mixed pattern.3,7 The tumors may have keratin cysts and focal necrosis but no atypia, and the myoepithelial cell layer is retained. Nipple adenomas show a glandular proliferation in the dermis that is relatively well circumscribed with glands that vary in appearance between a simple adenosislike pattern of growth to a papillary hyperplasia and/or usual ductal hyperplasia growth pattern. A pseudoinfiltrative pattern can occur when the glandular epithelium is entrapped within stromal fibrosis; however, the myoepithelial layer is retained. Occasionally, the glandular epithelium can grow in continuity with the surface squamous epithelium of the nipple, clinically simulating Paget disease of the breast.8 Immunohistochemical stains, specifically p63, p40, calponin 1, h-caldesmon, cytokeratin 5/6, CD10, and α; smooth muscle actin, highlight the myoepithelial cells, while cytokeratin 7 identifies the ductal epithelium, supporting the diagnosis.6 In addition to biopsy and microscopic tissue examination, touch preparation cytology, curettage cytology, and fine needle aspiration techniques have been used to perform cytologic examination of the lesions, aiding in identification of the benign or malignant nature of the neoplasm.6 Nipple adenoma also is referred to as florid papillomatosis of the nipple, papillary adenoma, erosive adenomatosis, and subareolar duct papillomatosis.7

Although nipple adenoma is a benign tumor, up to 16.5% of affected patients had an ipsilateral or contralateral mammary carcinoma.9 The majority arose coincidentally but separately in the same breast, and carcinoma arose directly from the nipple adenoma in 8 cases; 3 cases were carcinomas that arose in men.10 A definitive association or causal relationship between nipple adenoma and subsequent development of breast cancer has not been identified, and the incidence of nipple adenoma in patients with a positive family history of breast cancer has not been examined. Therefore, although various treatments including cryosurgery, nipple splitting enucleation, and Mohs micrographic surgery have been proposed, complete excision remains the gold standard of therapy. Regular breast examinations and digital mammography are necessary to screen for local recurrences.

The Diagnosis: Nipple Adenoma (Florid Papillomatosis of the Nipple)

Biopsy of the nodule showed florid papillary hyperplasia of the ductal epithelium within the dermis that was sharply demarcated from the background stroma (Figure, A and B). Neither cytological nor architectural atypia were evident. There was no notable necrosis (Figure C). There was a background of fibrosis whereby the glandular ductal structures assumed a somewhat irregular growth pattern within the dermis with attendant hemorrhage. The patient underwent complete excision of the lesion. No evidence of carcinoma was seen on the final pathology, and the final margins were negative.

First described in 1923 and fully characterized in 1955, nipple adenoma (also known as florid papillomatosis of the nipple) is a benign proliferative neoplasm that originates in the lactiferous ducts of the nipple.1,2 It most commonly affects women aged 40 to 50 years (range, 0-89 years); less than 5% of cases are reported in men.3,4 It predominantly is unilateral, with only rare cases of bilateral papillomatosis reported. Patients often present with serous or serosanguineous discharge and an itching or burning sensation. Symptoms may worsen with the menstrual cycle.4 On physical examination, it presents as an ill-defined red nodule on the nipple with crusting, erosion, or erythema of the nipple surface. Although imaging generally is not used to confirm the diagnosis, mammography should be performed prior to biopsy to rule out underlying breast pathology. Dermoscopy may show linear cherry red structures or red serpiginous and annular structures.5,6 The differential diagnosis of nipple adenoma includes Paget disease of the breast, adenomyoepithelioma, subareolar subsclerosing duct hyperplasia, syringomatous adenoma, adenosis tumor, low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma, low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ, tubular carcinoma, and sweat gland tumors.3

Microscopic features of nipple adenoma have been categorized into 4 subtypes: sclerosing papillomatosis, papillomatosis, adenosis, and a mixed pattern.3,7 The tumors may have keratin cysts and focal necrosis but no atypia, and the myoepithelial cell layer is retained. Nipple adenomas show a glandular proliferation in the dermis that is relatively well circumscribed with glands that vary in appearance between a simple adenosislike pattern of growth to a papillary hyperplasia and/or usual ductal hyperplasia growth pattern. A pseudoinfiltrative pattern can occur when the glandular epithelium is entrapped within stromal fibrosis; however, the myoepithelial layer is retained. Occasionally, the glandular epithelium can grow in continuity with the surface squamous epithelium of the nipple, clinically simulating Paget disease of the breast.8 Immunohistochemical stains, specifically p63, p40, calponin 1, h-caldesmon, cytokeratin 5/6, CD10, and α; smooth muscle actin, highlight the myoepithelial cells, while cytokeratin 7 identifies the ductal epithelium, supporting the diagnosis.6 In addition to biopsy and microscopic tissue examination, touch preparation cytology, curettage cytology, and fine needle aspiration techniques have been used to perform cytologic examination of the lesions, aiding in identification of the benign or malignant nature of the neoplasm.6 Nipple adenoma also is referred to as florid papillomatosis of the nipple, papillary adenoma, erosive adenomatosis, and subareolar duct papillomatosis.7

Although nipple adenoma is a benign tumor, up to 16.5% of affected patients had an ipsilateral or contralateral mammary carcinoma.9 The majority arose coincidentally but separately in the same breast, and carcinoma arose directly from the nipple adenoma in 8 cases; 3 cases were carcinomas that arose in men.10 A definitive association or causal relationship between nipple adenoma and subsequent development of breast cancer has not been identified, and the incidence of nipple adenoma in patients with a positive family history of breast cancer has not been examined. Therefore, although various treatments including cryosurgery, nipple splitting enucleation, and Mohs micrographic surgery have been proposed, complete excision remains the gold standard of therapy. Regular breast examinations and digital mammography are necessary to screen for local recurrences.

- Miller E, Lewis D. The significance of serohemorrhagic or hemorrhagic discharge from the nipple. JAMA. 1923;81:1651-1657.

- Jones DB. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. Cancer. 1955;8:315-319.

- Rosen PP. Rosen's Breast Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:120-128.

- Brownstein MH, Phelps RG, Maqnin PH. Papillary adenoma of the nipple: analysis of fifteen new cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:707-715.

- Takashima S, Fujita Y, Miyauchi T, et al. Dermoscopic observation in adenoma of the nipple. J Dermatol. 2015;42:341-342.

- Spohn G, Trotter S, Tozbikian G, et al. Nipple adenoma in a female patient presenting with persistent erythema of the right nipple skin: case report, review of the literature, clinical implications, and relevancy to health care providers who evaluate and treat patients with dermatologic conditions of the breast skin. BMC Dermatol. 2016;16:4.

- Shin SJ. Nipple adenoma (florid papillomatosis of the nipple). In: Dabbs DJ, ed. Breast Pathology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:286-292.

- Schnitt SJ, Collins LC. Biopsy Interpretation of the Breast. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

- Salemis NS. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple: a rare presentation and review of the literature. Breast Dis. 2015;35:153-156.

- Di Bonito M, Cantile M, Collina F, et al. Adenoma of the nipple: a clinicopathological report of 13 cases. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1839-1842.

- Miller E, Lewis D. The significance of serohemorrhagic or hemorrhagic discharge from the nipple. JAMA. 1923;81:1651-1657.

- Jones DB. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple ducts. Cancer. 1955;8:315-319.

- Rosen PP. Rosen's Breast Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:120-128.

- Brownstein MH, Phelps RG, Maqnin PH. Papillary adenoma of the nipple: analysis of fifteen new cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:707-715.

- Takashima S, Fujita Y, Miyauchi T, et al. Dermoscopic observation in adenoma of the nipple. J Dermatol. 2015;42:341-342.

- Spohn G, Trotter S, Tozbikian G, et al. Nipple adenoma in a female patient presenting with persistent erythema of the right nipple skin: case report, review of the literature, clinical implications, and relevancy to health care providers who evaluate and treat patients with dermatologic conditions of the breast skin. BMC Dermatol. 2016;16:4.

- Shin SJ. Nipple adenoma (florid papillomatosis of the nipple). In: Dabbs DJ, ed. Breast Pathology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:286-292.

- Schnitt SJ, Collins LC. Biopsy Interpretation of the Breast. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

- Salemis NS. Florid papillomatosis of the nipple: a rare presentation and review of the literature. Breast Dis. 2015;35:153-156.

- Di Bonito M, Cantile M, Collina F, et al. Adenoma of the nipple: a clinicopathological report of 13 cases. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1839-1842.

A healthy 48-year-old woman presented with a growth on the right nipple that had been slowly enlarging over the last few months. She initially noticed mild swelling in the area that persisted and formed a soft lump. She described mild pain with intermittent drainage but no bleeding. Her medical history was unremarkable, including a negative personal and family history of breast and skin cancer. She was taking no medications prior to development of the mass. She had no recent history of pregnancy or breastfeeding. A mammogram and breast ultrasound were not concerning for carcinoma. Physical examination showed a soft, exophytic, mildly tender, pink nodule on the right nipple that measured 12.2×7 mm; no drainage, bleeding, or ulceration was present. The surrounding skin of the areola and breast demonstrated no clinical changes. The contralateral breast, areola, and nipple were unaffected. The patient had no appreciable axillary or cervical lymphadenopathy. A deep shave biopsy of the nodule was performed and sent for histopathologic examination.

Violaceous Patches on the Arm

The Diagnosis: Phacomatosis Cesioflammea

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) encompasses a group of diseases that have a vascular nevus coupled with a pigmented nevus.1 It is divided into 5 types: Type I is defined by the presence of a vascular malformation and epidermal nevus; type II by a vascular malformation and dermal melanosis with or without nevus anemicus; type III by a vascular malformation and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; type IV by a vascular malformation, dermal melanosis, and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; and type V as cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and dermal melanosis.1

Happle2 proposed a descriptive classification system in 2005 that eliminated type I PPV because neither linear epidermal nevus nor Becker nevus are derived from pigmentary cells. An appended "a" denotes a subtype with isolated cutaneous findings, while "b" is associated with extracutaneous manifestations. Phacomatosis cesioflammea (type IIa/b) refers to blue-hued dermal melanocytosis and nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis spilorosea (type IIIa/b) refers to nevus spilus and rose-colored nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata (type Va/b) refers to dermal melanocytosis and cutis marmorata telangiectasia congenita. The last group (type IVa/b) is unclassifiable phacomatosis pigmentovascularis.2,3

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can be isolated to the skin or have associated extracutaneous findings, including ocular melanocytosis, seizures, or cognitive delay due to intracerebral vascular malformations. Patients also can develop limb and soft-tissue overgrowth.4 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been found to be associated with mutations in the GNA11 and GNAQ genes. The theory behind PPV is twin spotting, resulting from a somatic mutation that leads to mosaic proliferation of 2 different cell lines.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can occur in isolation or can demonstrate the phenotype of Sturge-Weber syndrome or Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. In Sturge-Weber syndrome, capillary malformations involve the face and underlying leptomeninges and cerebral cortex. Glaucoma and epilepsy also may be present. In Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, capillary malformations involve the extremities (usually the legs) in association with varicose veins, soft-tissue hypertrophy, and skeletal overgrowth.6-9 Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disease in which patients develop hamartomas throughout the body, including the brain, skin, eyes, kidneys, heart, and lungs. Cutaneous manifestations include facial angiofibromas, ungual fibromas, hypomelanotic macules (ash leaf spots, confetti-like lesions), shagreen patches or connective tissue hamartomas, and fibrous plaques on the forehead. Tuberous sclerosis does not include vascular malformations.10

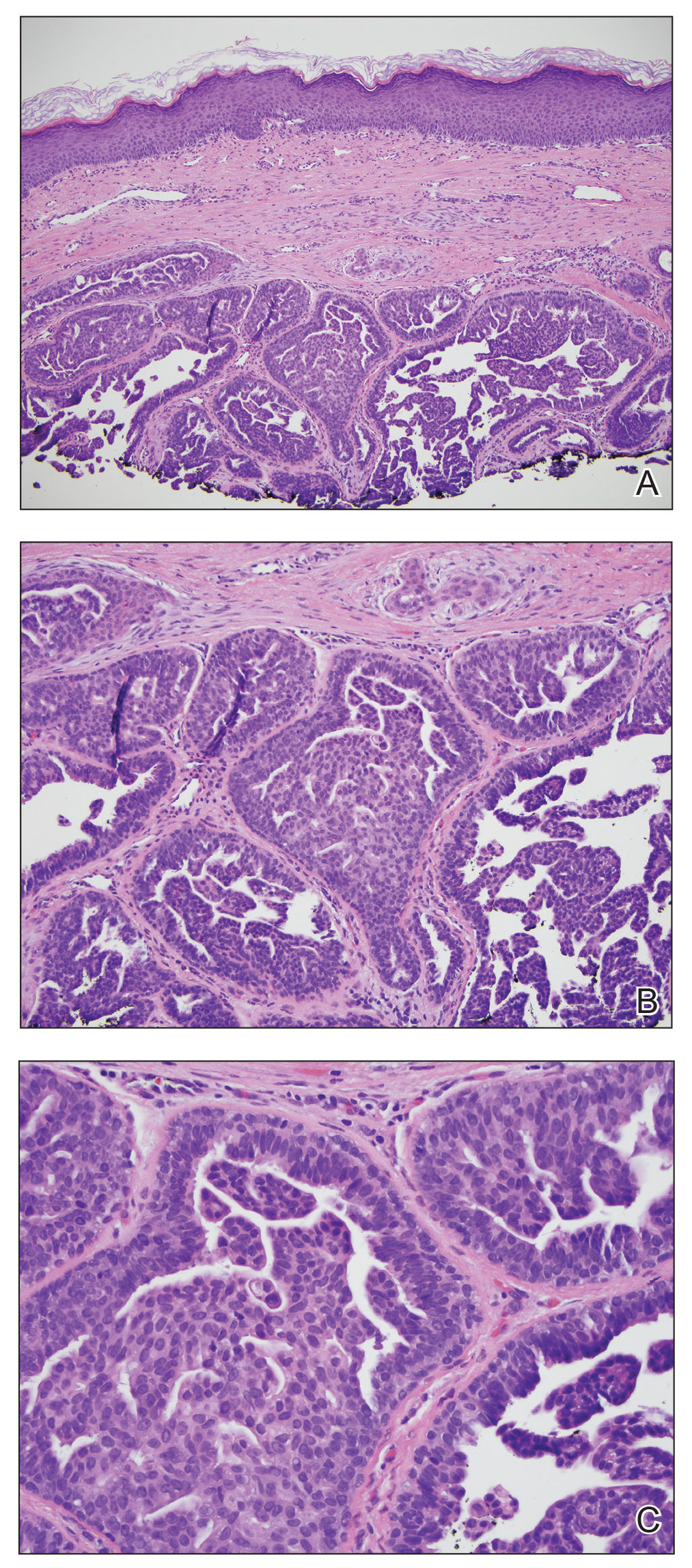

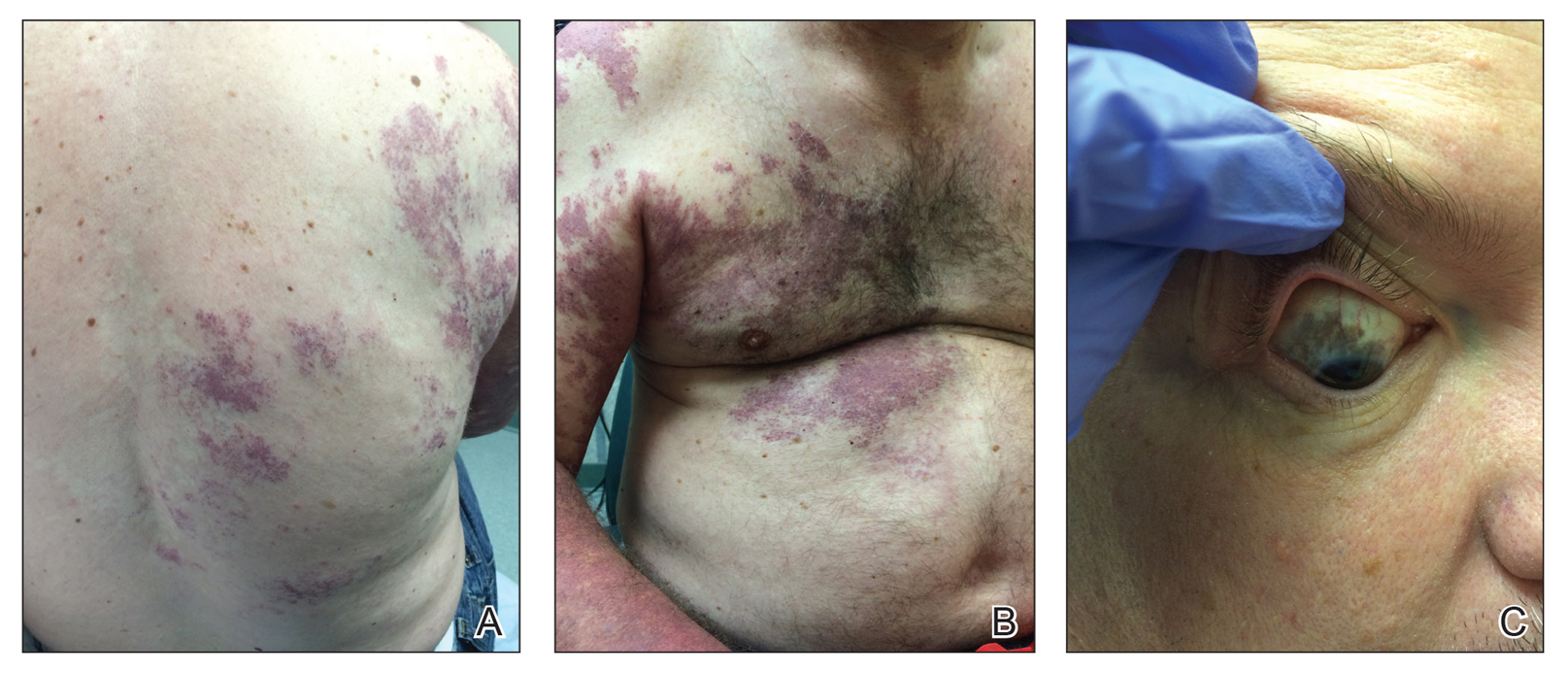

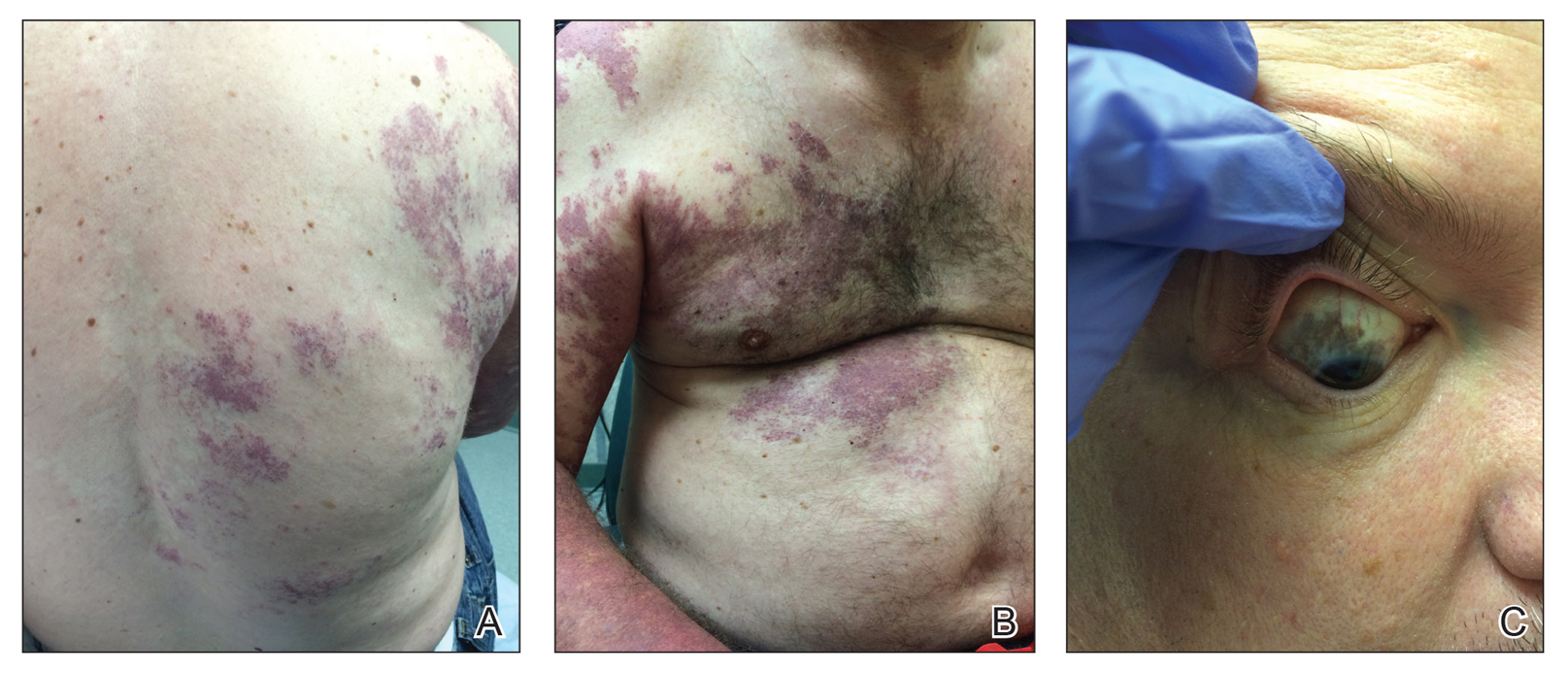

Our patient was diagnosed with PPV type IIb, or phacomatosis cesioflammea. He had a large port-wine stain involving the right upper arm, back (Figure, A), and chest (Figure, B) with involvement of the bilateral conjunctivae (Figure, C). Our case is unique because our patient did not have dermal melanocytosis, only ocular melanocytosis.

Once underlying neurologic and vascular anomalies have been ruled out, port-wine stains can be treated cosmetically. Pulsed dye laser is the gold standard therapy for capillary malformations, especially when instituted early. Follow-up with ophthalmology is advised to monitor ocular involvement. Shields et al11 suggested dilated fundoscopy for patients with port-wine stains because choroidal pigmentation often is the only ocular change seen. Ocular melanocytosis can progress to pigmented glaucoma or choroidal melanoma.

- Fernandez-Guarino M, Boixeda P, De las Heras E, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis: clinical findings in 15 patients and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:88-93.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Villarreal DJ, Leal F. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):54-56.

- Thomas AC, Zeng Z, Riviere JB, et al. Mosaic activating mutations in GNA11 and GNAQ are associated with phakomatosis pigmentovascularis and extensive dermal melanocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:770-778.

- Krema H, Simpson R, McGowan H. Choroidal melanoma in phacomatosis pigmentovascularis cesioflammea. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48:E41-E42.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:301-310.

- Pradhan S, Patnaik S, Padhi T, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIb, Sturge-Weber syndrome and cone shaped tongue: an unusual association. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:614-616.

- Turk BG, Turkmen M, Tuna A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIb associated with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and congenital triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E46-E49.

- Sen S, Bala S, Halder C, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis presenting with Sturge-Weber syndrome and Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:77-79.

- Schwartz RA, Fernandez G, Kotulska K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: advances in diagnosis, genetics, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:189-202.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

The Diagnosis: Phacomatosis Cesioflammea

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) encompasses a group of diseases that have a vascular nevus coupled with a pigmented nevus.1 It is divided into 5 types: Type I is defined by the presence of a vascular malformation and epidermal nevus; type II by a vascular malformation and dermal melanosis with or without nevus anemicus; type III by a vascular malformation and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; type IV by a vascular malformation, dermal melanosis, and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; and type V as cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and dermal melanosis.1

Happle2 proposed a descriptive classification system in 2005 that eliminated type I PPV because neither linear epidermal nevus nor Becker nevus are derived from pigmentary cells. An appended "a" denotes a subtype with isolated cutaneous findings, while "b" is associated with extracutaneous manifestations. Phacomatosis cesioflammea (type IIa/b) refers to blue-hued dermal melanocytosis and nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis spilorosea (type IIIa/b) refers to nevus spilus and rose-colored nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata (type Va/b) refers to dermal melanocytosis and cutis marmorata telangiectasia congenita. The last group (type IVa/b) is unclassifiable phacomatosis pigmentovascularis.2,3

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can be isolated to the skin or have associated extracutaneous findings, including ocular melanocytosis, seizures, or cognitive delay due to intracerebral vascular malformations. Patients also can develop limb and soft-tissue overgrowth.4 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been found to be associated with mutations in the GNA11 and GNAQ genes. The theory behind PPV is twin spotting, resulting from a somatic mutation that leads to mosaic proliferation of 2 different cell lines.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can occur in isolation or can demonstrate the phenotype of Sturge-Weber syndrome or Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. In Sturge-Weber syndrome, capillary malformations involve the face and underlying leptomeninges and cerebral cortex. Glaucoma and epilepsy also may be present. In Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, capillary malformations involve the extremities (usually the legs) in association with varicose veins, soft-tissue hypertrophy, and skeletal overgrowth.6-9 Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disease in which patients develop hamartomas throughout the body, including the brain, skin, eyes, kidneys, heart, and lungs. Cutaneous manifestations include facial angiofibromas, ungual fibromas, hypomelanotic macules (ash leaf spots, confetti-like lesions), shagreen patches or connective tissue hamartomas, and fibrous plaques on the forehead. Tuberous sclerosis does not include vascular malformations.10

Our patient was diagnosed with PPV type IIb, or phacomatosis cesioflammea. He had a large port-wine stain involving the right upper arm, back (Figure, A), and chest (Figure, B) with involvement of the bilateral conjunctivae (Figure, C). Our case is unique because our patient did not have dermal melanocytosis, only ocular melanocytosis.

Once underlying neurologic and vascular anomalies have been ruled out, port-wine stains can be treated cosmetically. Pulsed dye laser is the gold standard therapy for capillary malformations, especially when instituted early. Follow-up with ophthalmology is advised to monitor ocular involvement. Shields et al11 suggested dilated fundoscopy for patients with port-wine stains because choroidal pigmentation often is the only ocular change seen. Ocular melanocytosis can progress to pigmented glaucoma or choroidal melanoma.

The Diagnosis: Phacomatosis Cesioflammea

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) encompasses a group of diseases that have a vascular nevus coupled with a pigmented nevus.1 It is divided into 5 types: Type I is defined by the presence of a vascular malformation and epidermal nevus; type II by a vascular malformation and dermal melanosis with or without nevus anemicus; type III by a vascular malformation and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; type IV by a vascular malformation, dermal melanosis, and nevus spilus with or without nevus anemicus; and type V as cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and dermal melanosis.1

Happle2 proposed a descriptive classification system in 2005 that eliminated type I PPV because neither linear epidermal nevus nor Becker nevus are derived from pigmentary cells. An appended "a" denotes a subtype with isolated cutaneous findings, while "b" is associated with extracutaneous manifestations. Phacomatosis cesioflammea (type IIa/b) refers to blue-hued dermal melanocytosis and nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis spilorosea (type IIIa/b) refers to nevus spilus and rose-colored nevus flammeus. Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata (type Va/b) refers to dermal melanocytosis and cutis marmorata telangiectasia congenita. The last group (type IVa/b) is unclassifiable phacomatosis pigmentovascularis.2,3

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can be isolated to the skin or have associated extracutaneous findings, including ocular melanocytosis, seizures, or cognitive delay due to intracerebral vascular malformations. Patients also can develop limb and soft-tissue overgrowth.4 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been found to be associated with mutations in the GNA11 and GNAQ genes. The theory behind PPV is twin spotting, resulting from a somatic mutation that leads to mosaic proliferation of 2 different cell lines.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis can occur in isolation or can demonstrate the phenotype of Sturge-Weber syndrome or Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. In Sturge-Weber syndrome, capillary malformations involve the face and underlying leptomeninges and cerebral cortex. Glaucoma and epilepsy also may be present. In Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, capillary malformations involve the extremities (usually the legs) in association with varicose veins, soft-tissue hypertrophy, and skeletal overgrowth.6-9 Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disease in which patients develop hamartomas throughout the body, including the brain, skin, eyes, kidneys, heart, and lungs. Cutaneous manifestations include facial angiofibromas, ungual fibromas, hypomelanotic macules (ash leaf spots, confetti-like lesions), shagreen patches or connective tissue hamartomas, and fibrous plaques on the forehead. Tuberous sclerosis does not include vascular malformations.10

Our patient was diagnosed with PPV type IIb, or phacomatosis cesioflammea. He had a large port-wine stain involving the right upper arm, back (Figure, A), and chest (Figure, B) with involvement of the bilateral conjunctivae (Figure, C). Our case is unique because our patient did not have dermal melanocytosis, only ocular melanocytosis.

Once underlying neurologic and vascular anomalies have been ruled out, port-wine stains can be treated cosmetically. Pulsed dye laser is the gold standard therapy for capillary malformations, especially when instituted early. Follow-up with ophthalmology is advised to monitor ocular involvement. Shields et al11 suggested dilated fundoscopy for patients with port-wine stains because choroidal pigmentation often is the only ocular change seen. Ocular melanocytosis can progress to pigmented glaucoma or choroidal melanoma.

- Fernandez-Guarino M, Boixeda P, De las Heras E, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis: clinical findings in 15 patients and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:88-93.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.