User login

Grouped Erythematous Papules and Plaques on the Trunk

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma, Follicle Center Subtype

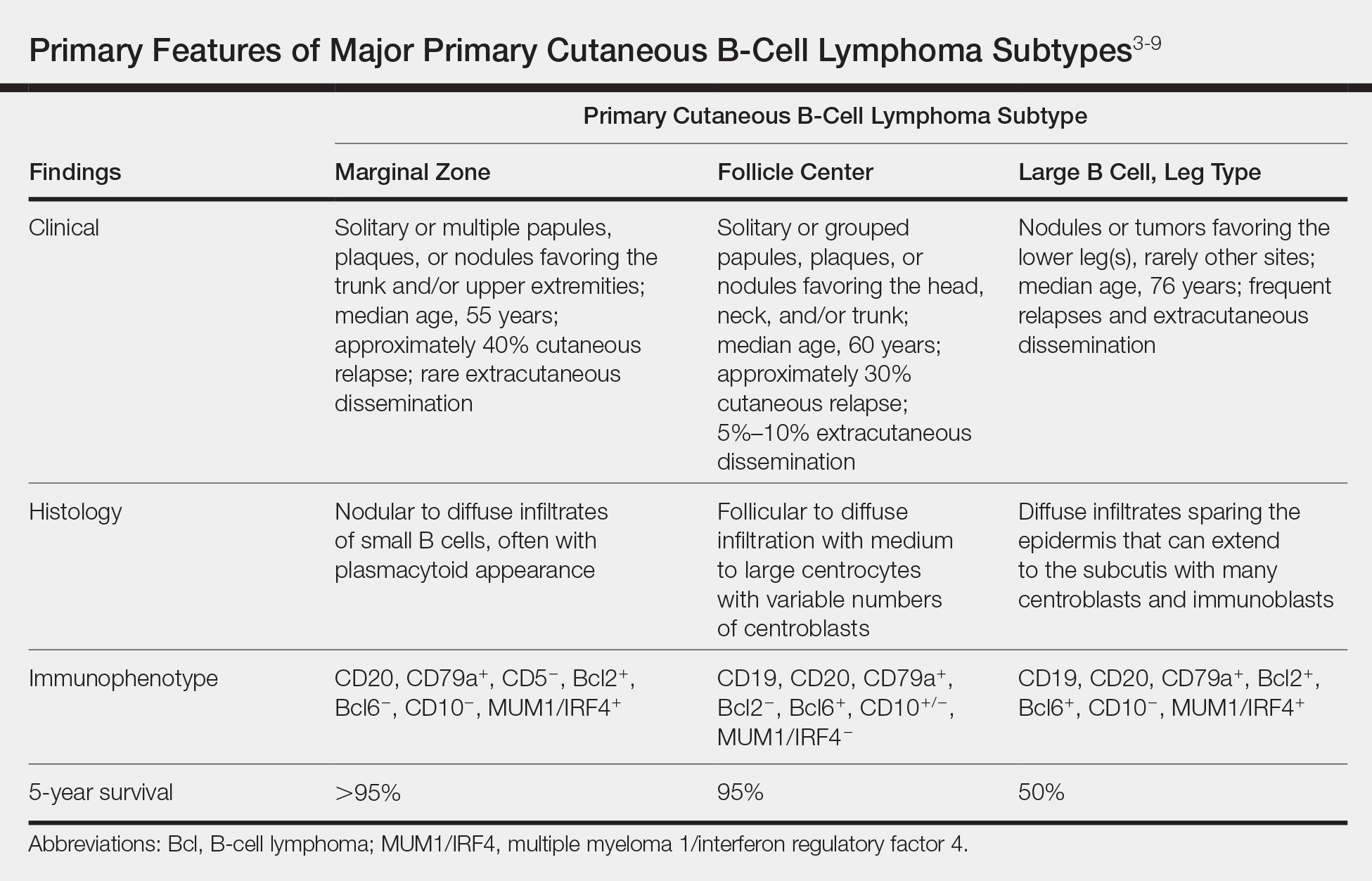

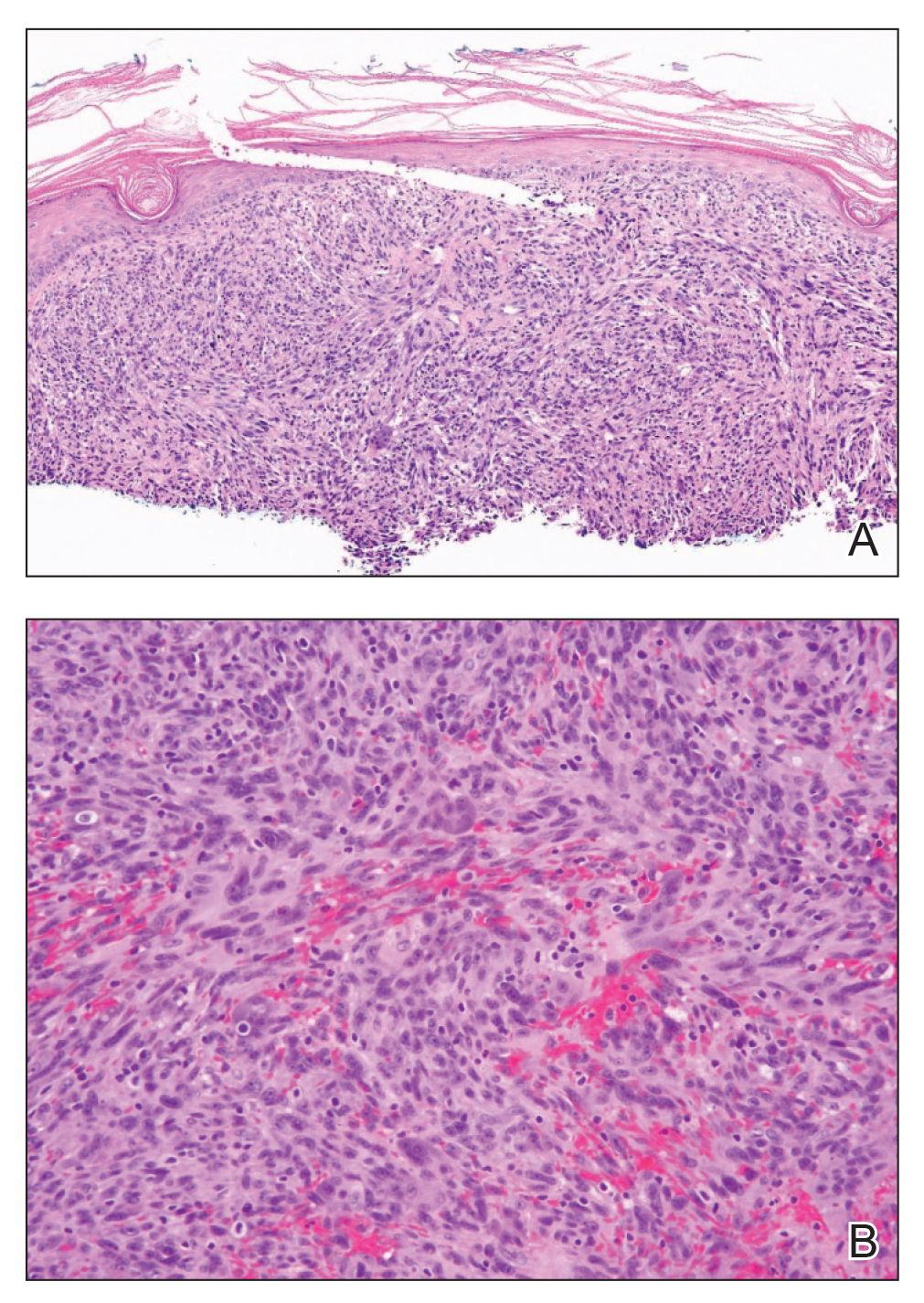

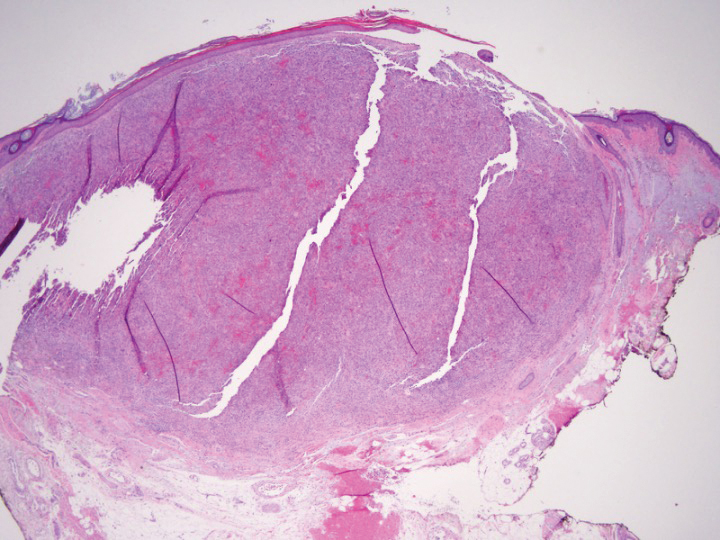

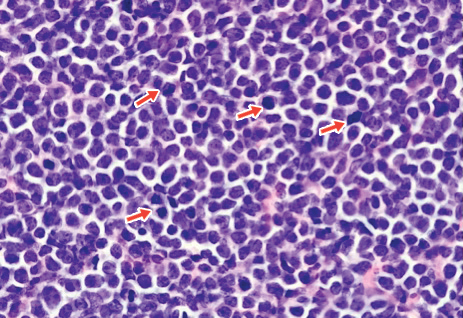

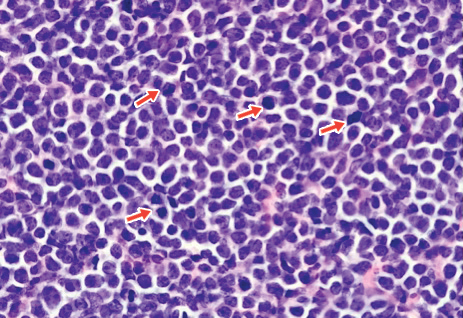

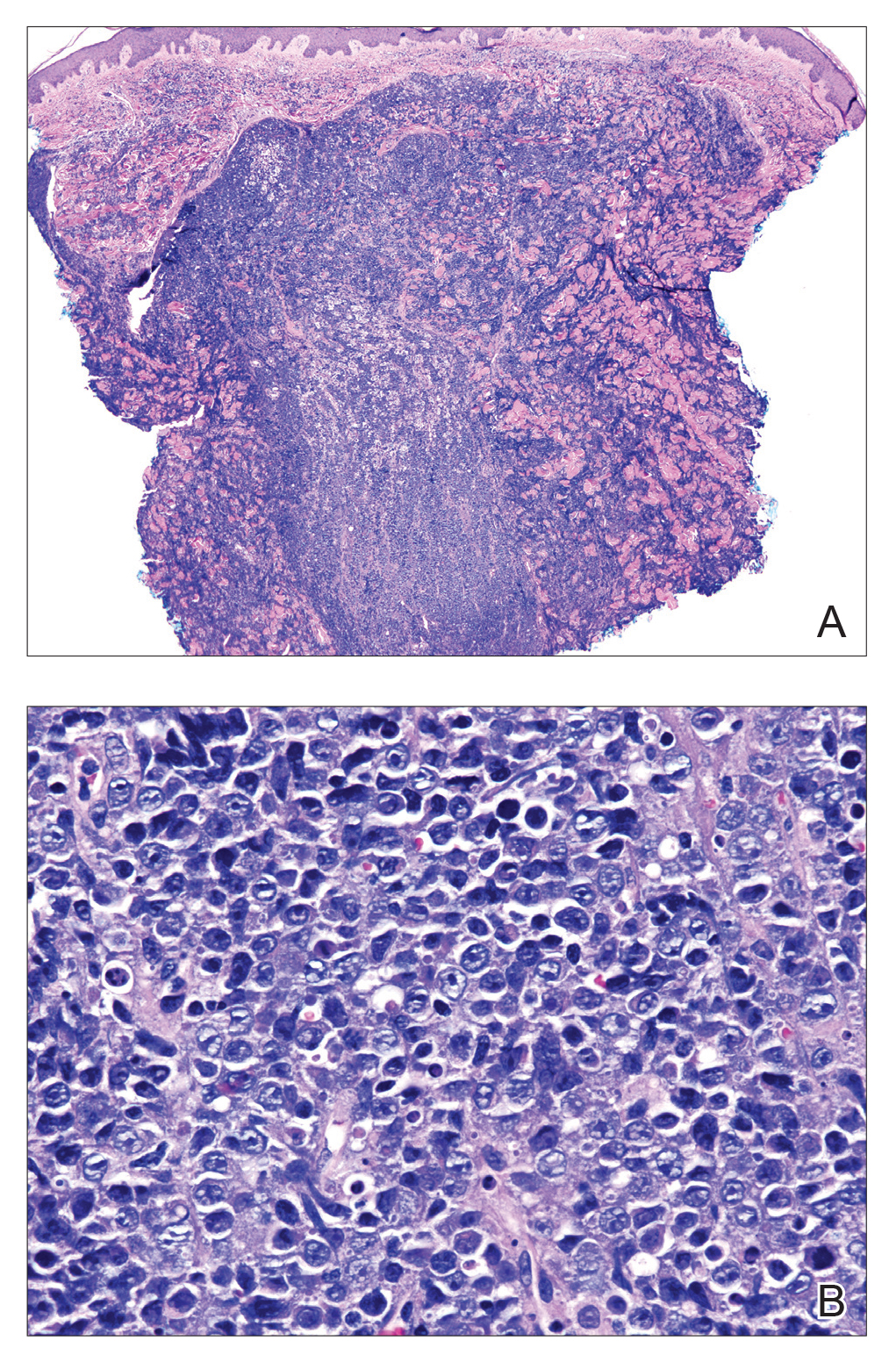

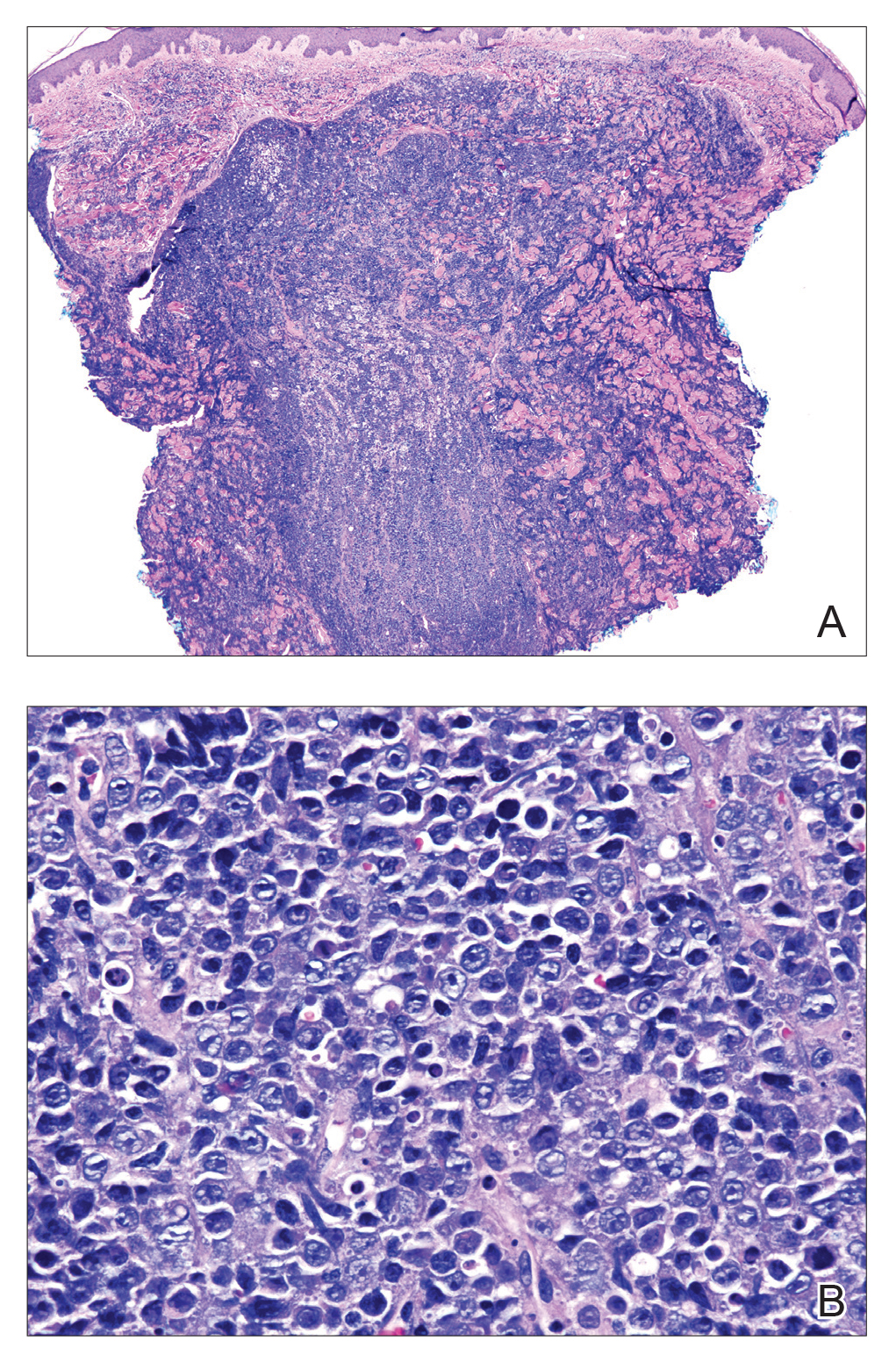

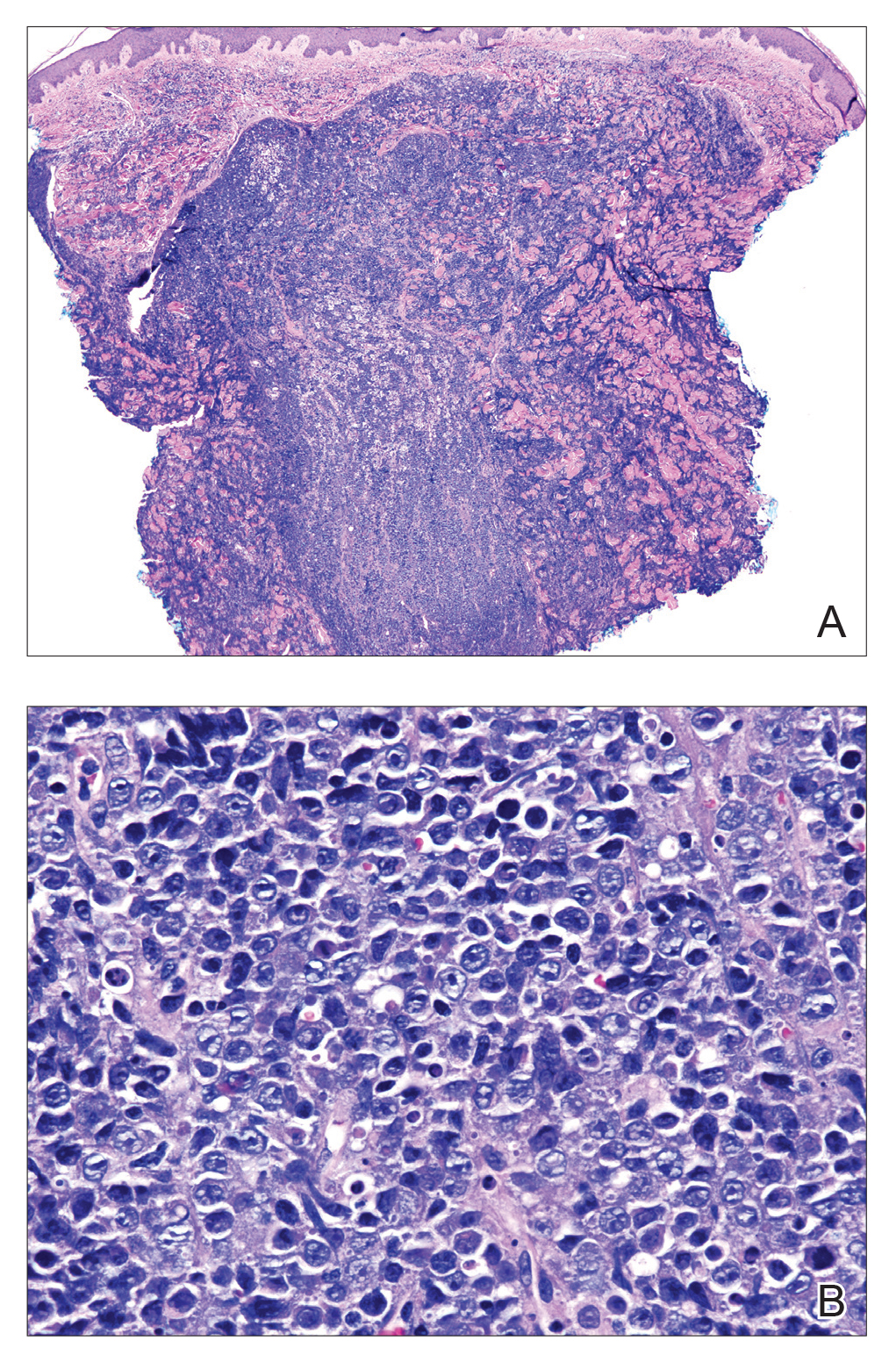

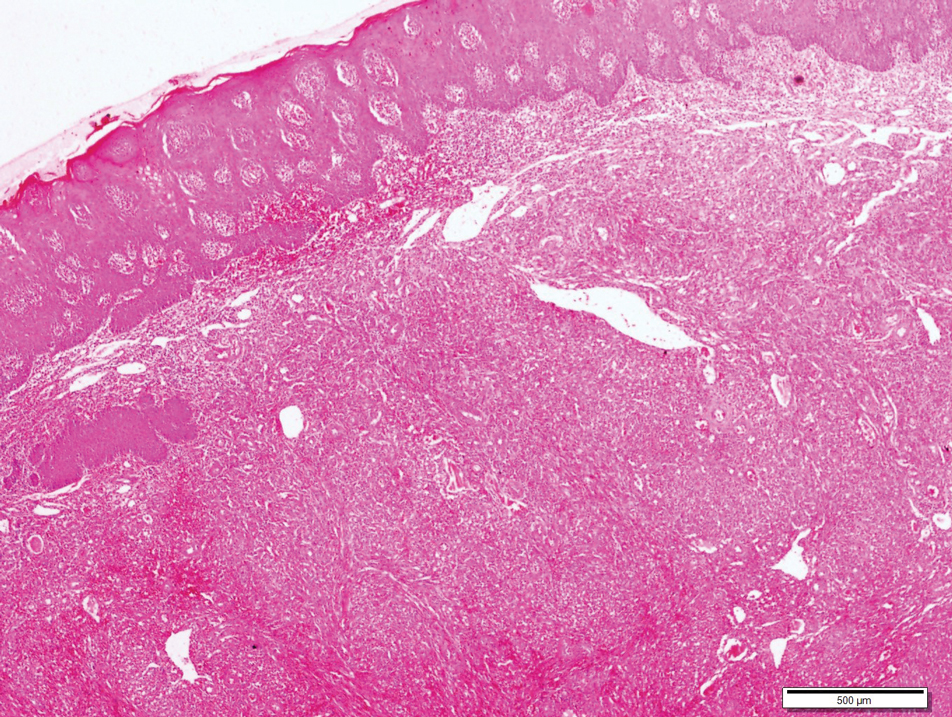

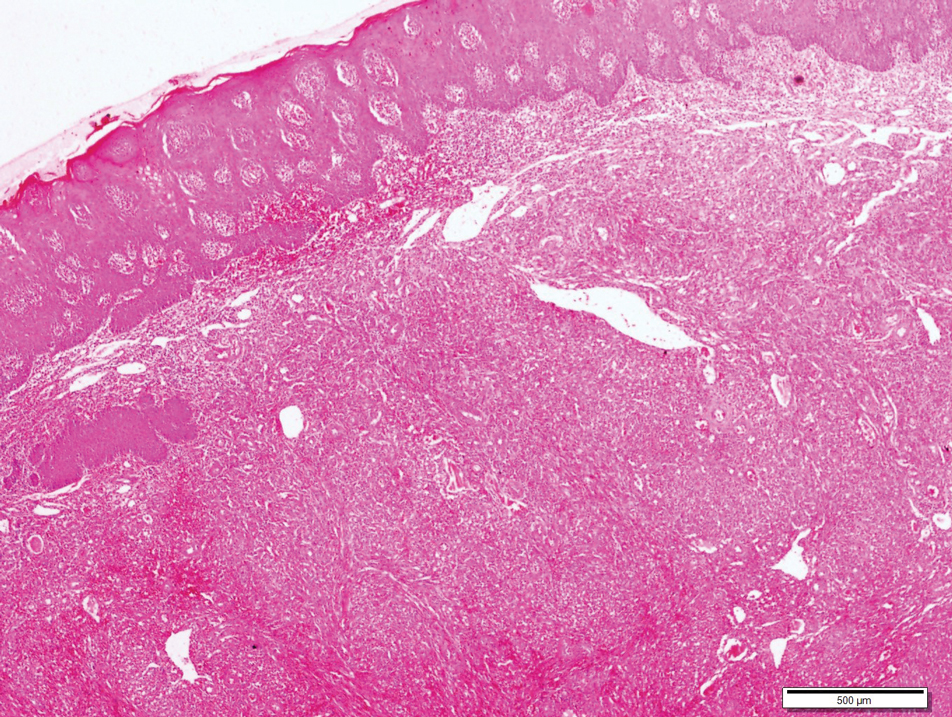

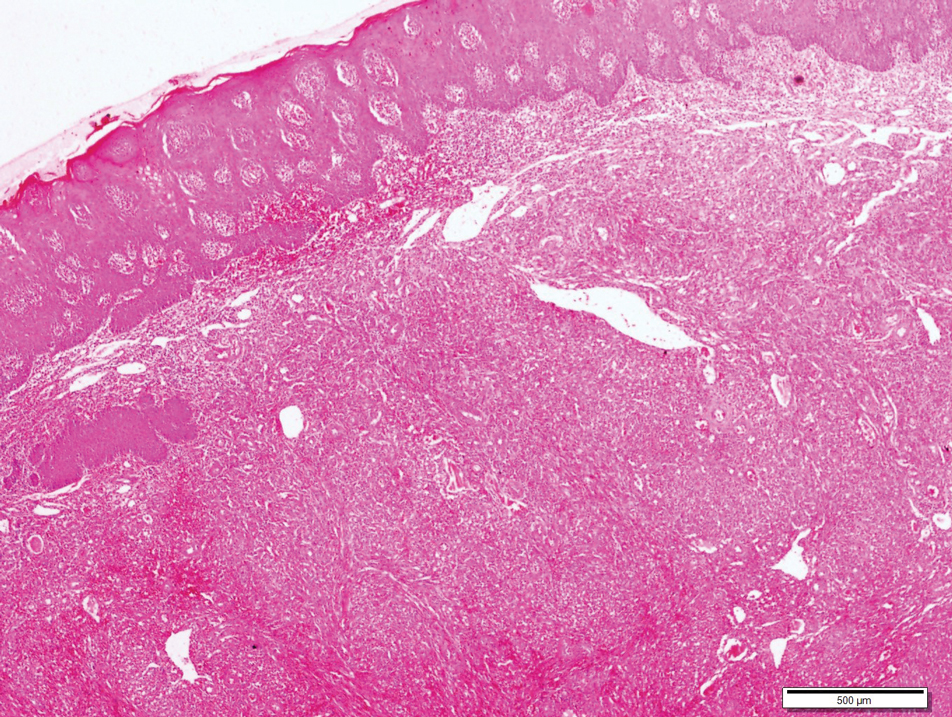

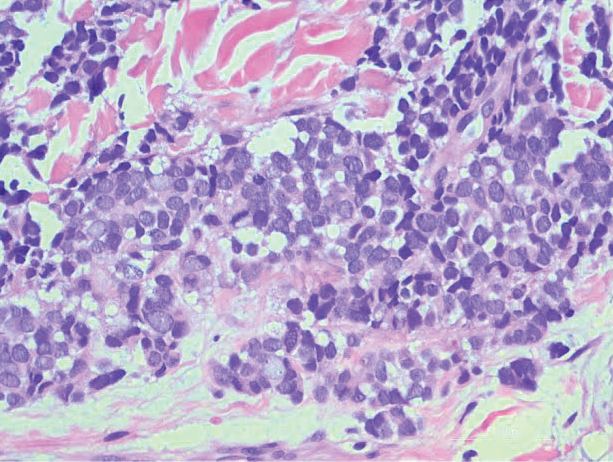

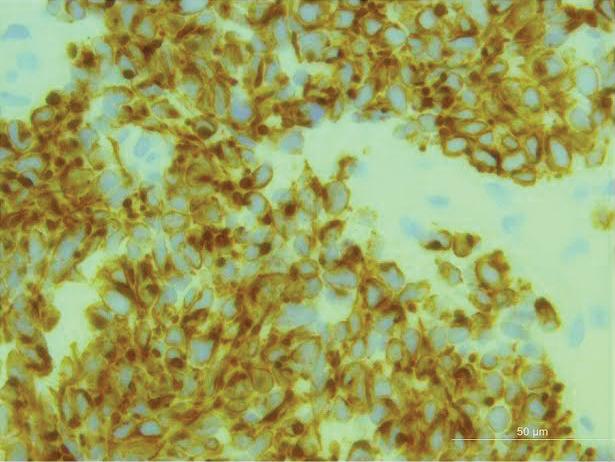

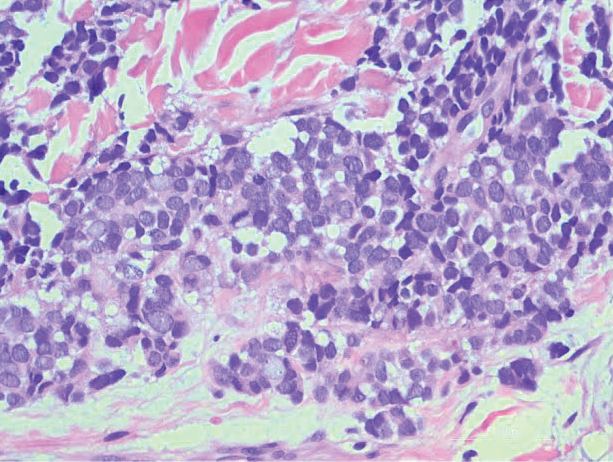

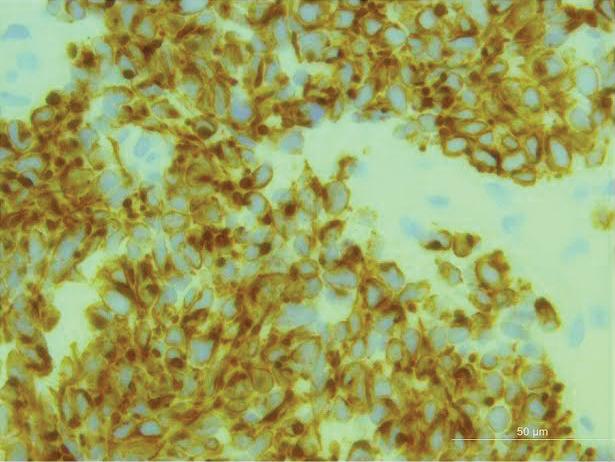

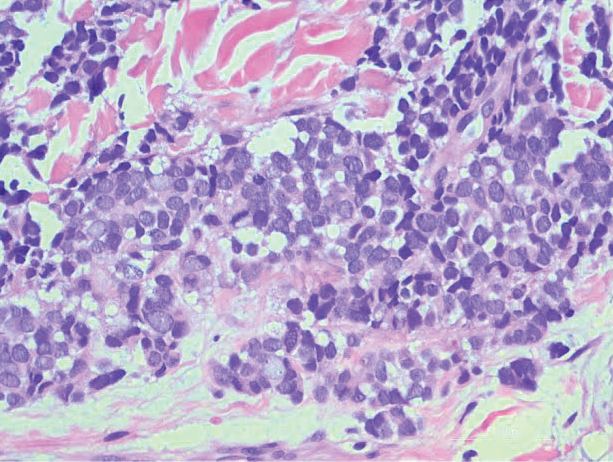

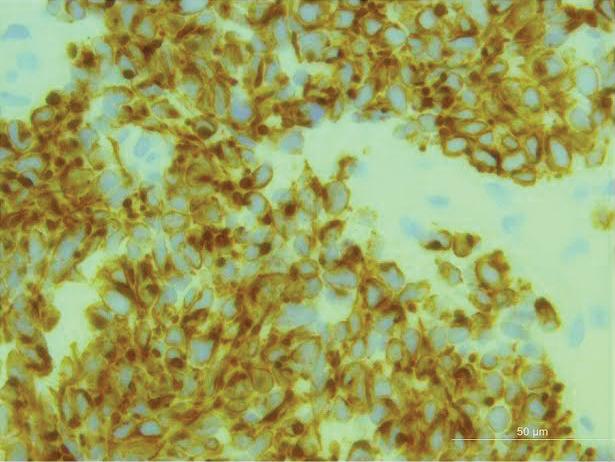

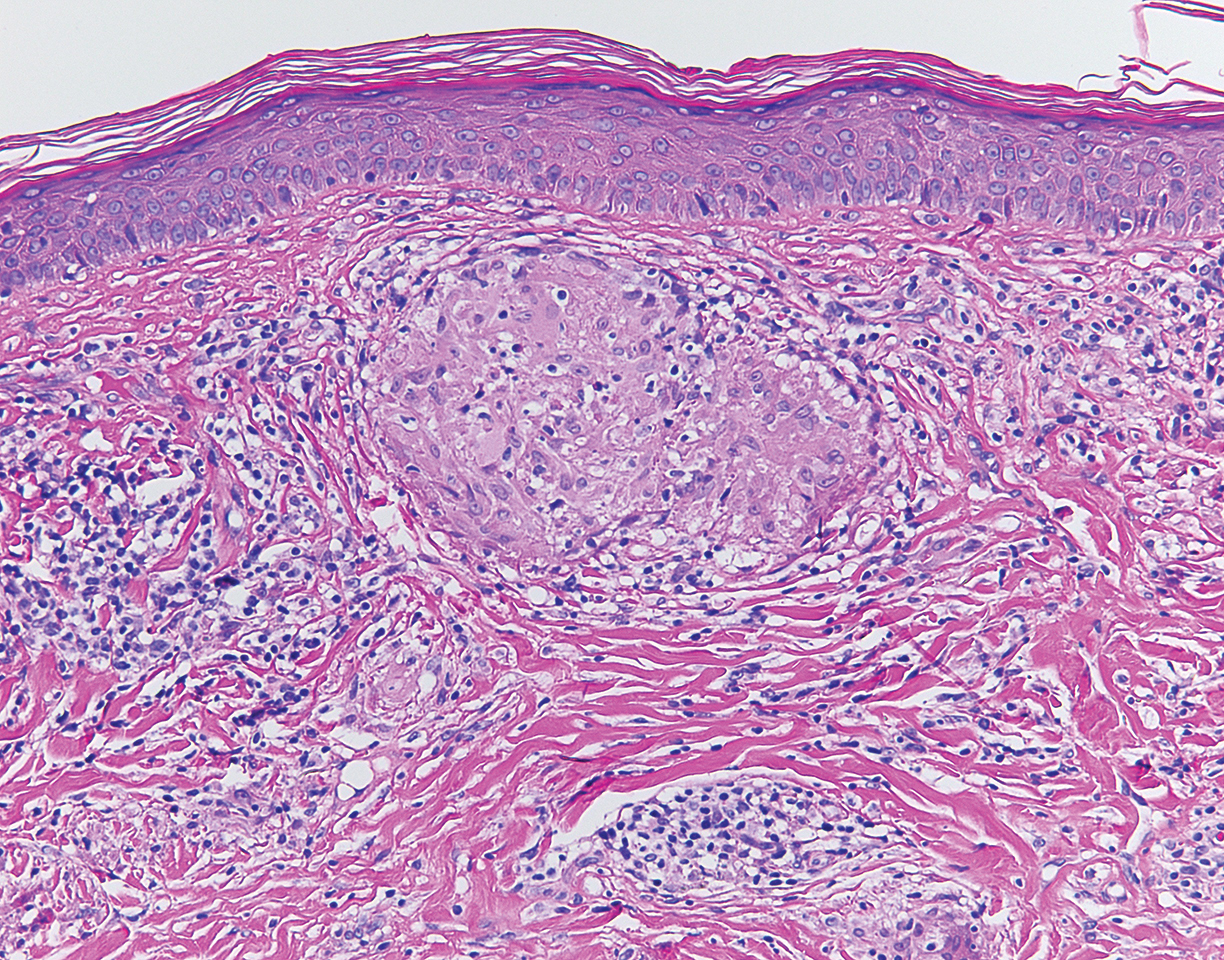

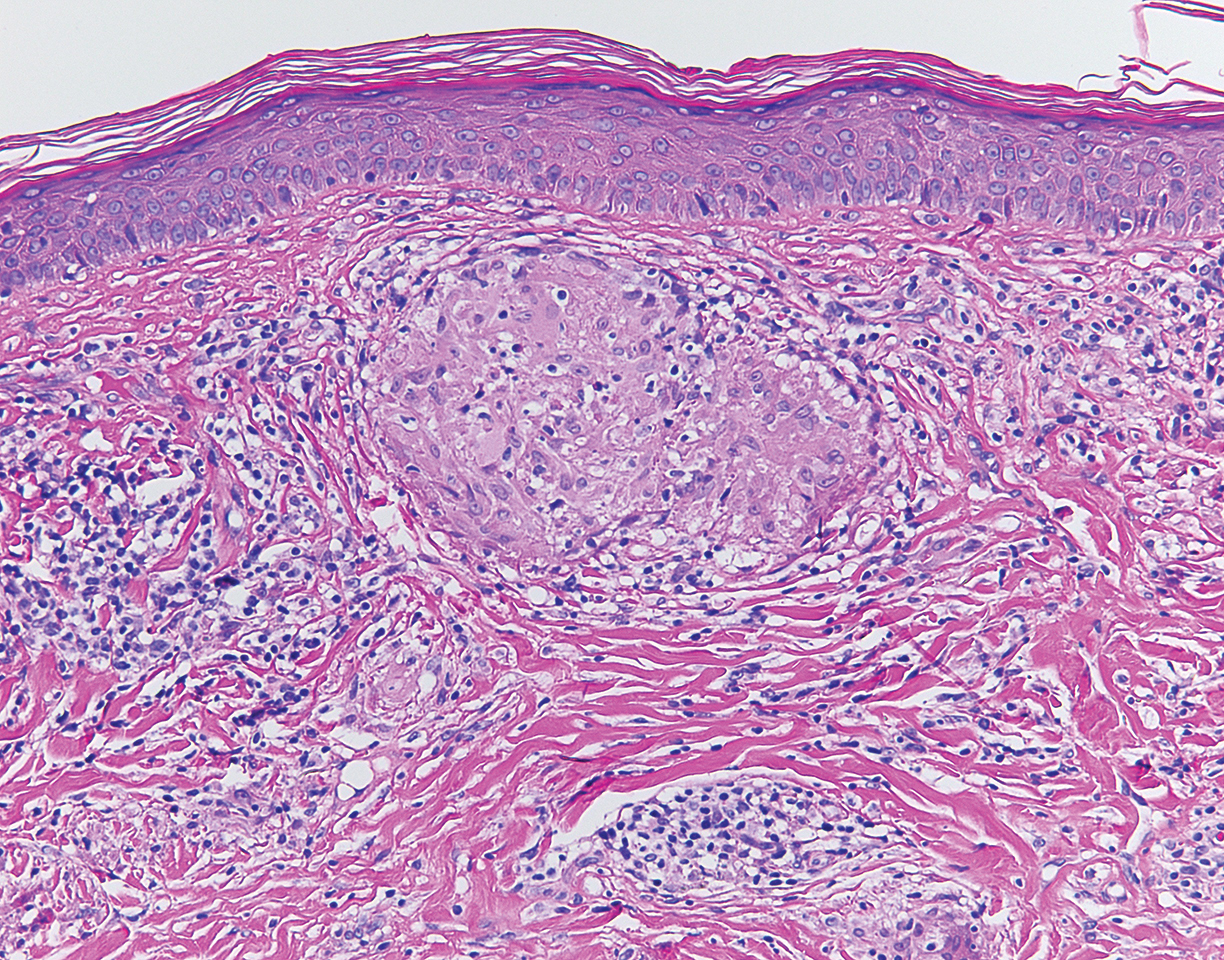

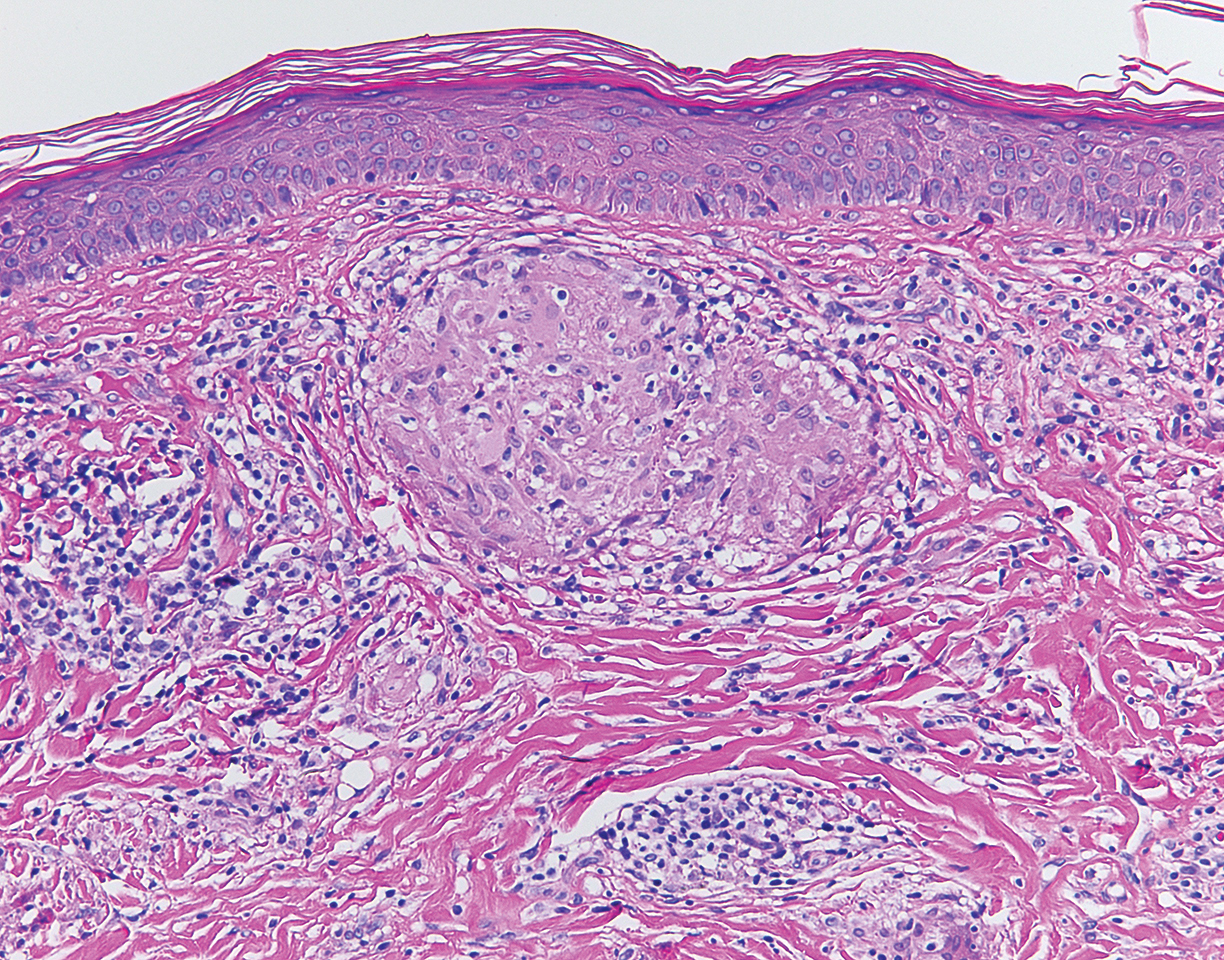

A 4-mm punch biopsy through the center of the largest lesion on the right posterior shoulder demonstrated a superficial and deep dermal atypical lymphoid infiltrate composed predominantly of small mature lymphocytes with interspersed intermediate-sized cells with irregular to cleaved nuclei, dispersed chromatin, one or more distinct nucleoli, occasional mitoses, and small amounts of cytoplasm (Figure, A). Immunoperoxidase studies showed the infiltrate to be a mixture of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (Figure, B). The B cells coexpressed B-cell lymphoma (Bcl) 6 protein (Figure, C) but were negative for multiple myeloma 1/interferon regulatory factor 4 and CD10; Bcl2 protein was positive in T cells but inconclusive for staining in B cells. Very few plasma cells were seen with CD138 stain. Fluorescence in situ hybridization studies were negative for IgH and BCL2 gene rearrangement. Molecular diagnostic studies for IgH and κ light chain gene rearrangement were positive for a clonal population. A clonal T-cell receptor γ chain gene rearrangement was not identified. The overall morphologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular findings were consistent with cutaneous involvement by a B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, favoring primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL).

The patient was referred to our cancer center for further workup consisting of a complete blood cell count with differential; comprehensive metabolic panel; lactate dehydrogenase; serum protein electrophoresis; peripheral blood flow cytometry; and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. The analysis was unremarkable, supporting primary cutaneous disease. Additional studies suggested in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines for primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas include hepatitis B testing if the patient is being considered for immunotherapy and/or chemotherapy due to risk of reactivation, pregnancy testing in women of childbearing age, and human immunodeficiency virus testing.1 These tests were not performed in our patient because he did not have any risk factors for hepatitis B or human immunodeficiency virus.

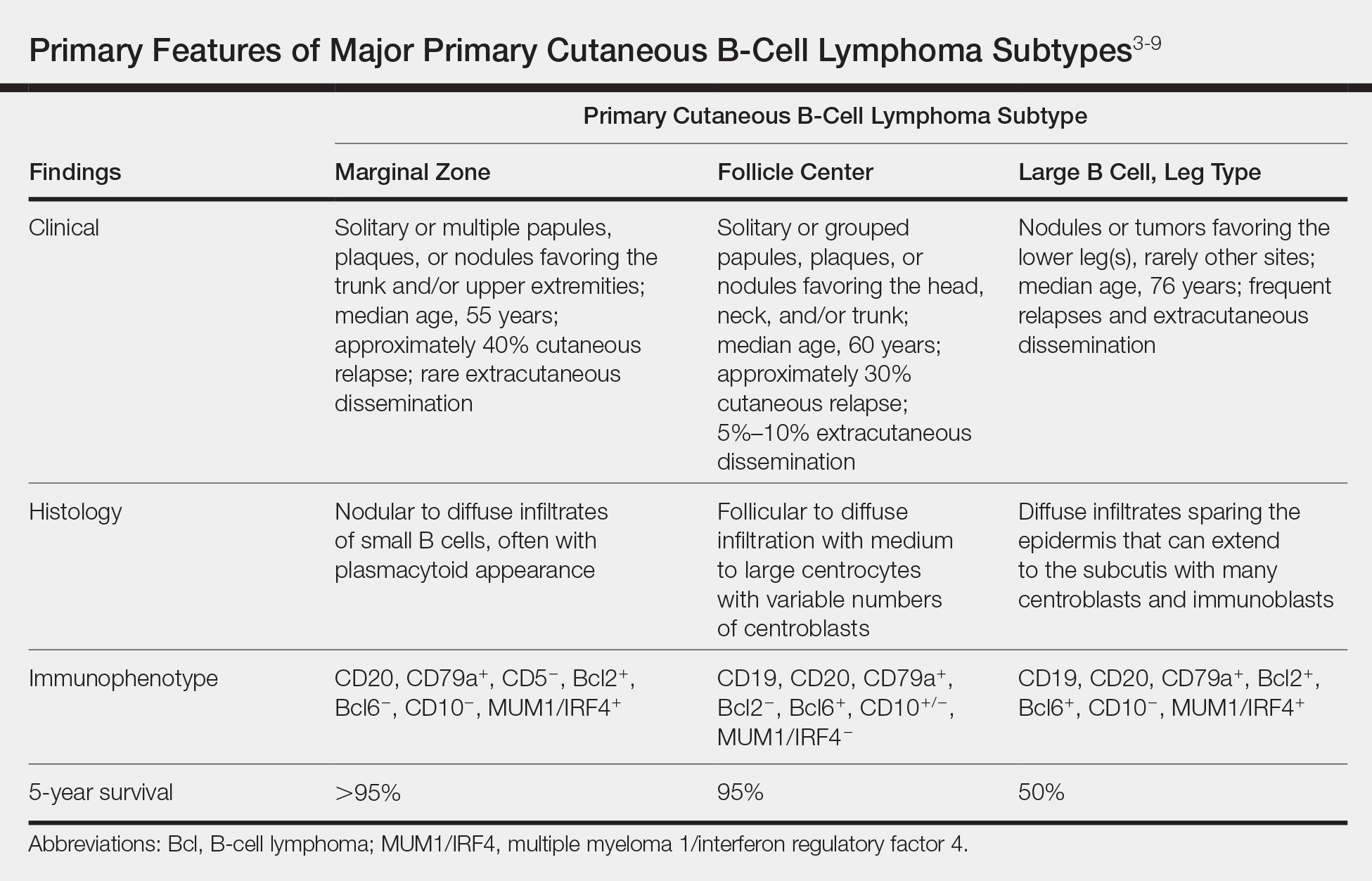

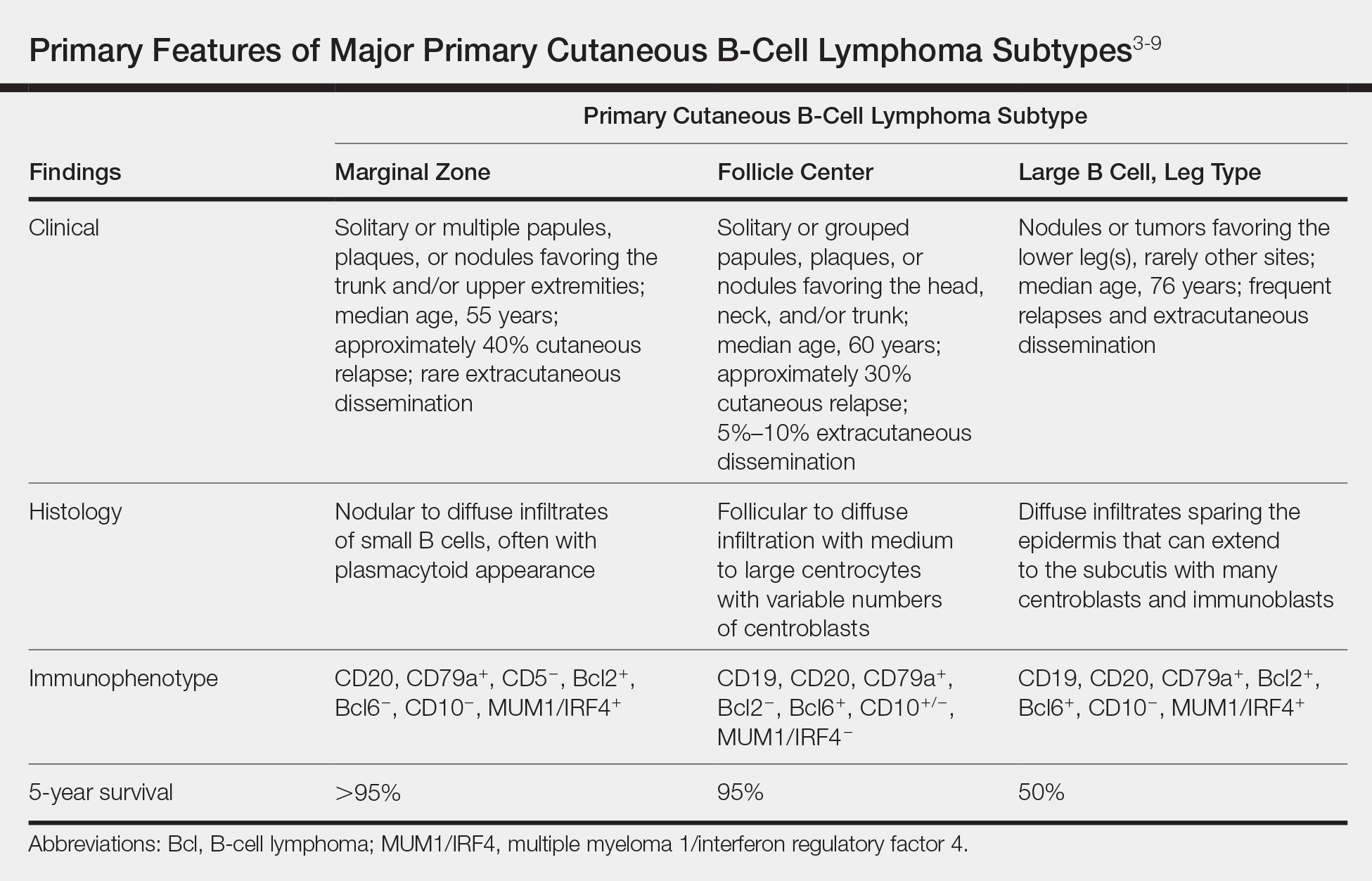

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas originate in the skin without evidence of extracutaneous disease at presentation. They account for approximately 25% of primary cutaneous lymphomas in the United States, with primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma being most common.2 The revised 2017 World Health Organization classification system defines 3 major subtypes of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (Table).3-9 Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is the most common subtype, accounting for approximately 60% of cases. In Europe, an association with Borrelia burgdorferi has been reported.10 The extent of skin involvement determines the T portion of TNM staging for PCFCL. It is based on the size and location of affected body regions that are delineated, such as the head and neck, chest, abdomen/genitalia, upper back, lower back/buttocks, each upper arm, each lower arm/hand, each upper leg, and each lower leg/foot. T1 is for solitary skin involvement in which the lesion is 5 cm or less in diameter (T1a) or greater than 5 cm (T1b). T2 is for regional skin involvement limited to 1 or 2 contiguous body regions, whereas T2a has all lesions confined to an area 15 cm or less in diameter, T2b has lesions confined to an area greater than 15 cm up to 30 cm in diameter, and the area for T2c is greater than 30 cm in diameter. Finally, T3 is generalized skin involvement, whereas T3a has multiple lesions in 2 noncontiguous body regions, and T3b has multiple lesions on 3 or more regions.11 At presentation, our patient was considered T2cN0M0, as his lesions were present on only 2 contiguous regions extending beyond 30 cm without any evidence of lymph node involvement or metastasis.

Treatment of PCFCL is tailored to each case, as there is a paucity of randomized data in this rare entity. It is guided by the number and location of cutaneous lesions, associated skin symptoms, age of the patient, and performance status. Local disease can be treated with intralesional corticosteroids, excision, or close monitoring if the patient is asymptomatic. Low-dose radiation therapy may be used as primary treatment or for local recurrence.12 Patients with more extensive skin lesions can relapse after clearing; those with refractory disease can be managed with single-agent rituximab.13 Our patient underwent low-dose radiation therapy with good response and has not experienced recurrence.

Lymphocytoma cutis, also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, can be idiopathic or can arise after arthropod assault, penetrative skin trauma, drugs, or infections. In granuloma annulare, small dermal papules may present in isolation or coalesce to form annular plaques. It is a benign inflammatory disorder of unknown cause, can have mild pruritus, and usually is self-limited. Pyogenic granuloma is a benign vascular proliferation of unknown etiology. Sarcoidosis is an immune-mediated systemic disorder with granuloma formation that has a predilection for the lungs and the skin.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphomas. Version 2.2018. https://oncolife.com.ua/doc/nccn/Primary_Cutaneous_B-Cell_Lymphomas.pdf. Published January 10, 2018. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- Dores GM, Anderson WF, Devesa SS. Cutaneous lymphomas reported to the National Cancer Institute's surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program: applying the new WHO-European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification system. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7246-7248.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC; 2017.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute website. https://seer.cancer.gov/. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Cerroni L. B-cell lymphomas of the skin. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:2113-2126.

- Jacobsen E, Freedman AS, Willemze R. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/primary-cutaneous-follicle-center-lymphoma. Updated February 7, 2018. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Jacobsen E, Freedman AS, Willemze R. Primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/primary-cutaneous-marginal-zone-lymphoma. Updated March 6, 2019. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Jacobsen E, Freedman AS, Willemze R. Primary cutaneous large B cell lymphoma, leg type. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/primary-cutaneous-large-b-cell-lymphoma-leg-type. Updated July 3, 2017. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 241-342.

- Goodlad JR, Davidson MM, Hollowood K, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma and Borrelia burgdorferi infection in patients from the Highlands of Scotand. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1279-1285.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- Wilcon RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:1052-1055.

- Morales AV, Advani R, Horwitz SM, et al. Indolent primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: experience using systemic rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:953-957.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma, Follicle Center Subtype

A 4-mm punch biopsy through the center of the largest lesion on the right posterior shoulder demonstrated a superficial and deep dermal atypical lymphoid infiltrate composed predominantly of small mature lymphocytes with interspersed intermediate-sized cells with irregular to cleaved nuclei, dispersed chromatin, one or more distinct nucleoli, occasional mitoses, and small amounts of cytoplasm (Figure, A). Immunoperoxidase studies showed the infiltrate to be a mixture of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (Figure, B). The B cells coexpressed B-cell lymphoma (Bcl) 6 protein (Figure, C) but were negative for multiple myeloma 1/interferon regulatory factor 4 and CD10; Bcl2 protein was positive in T cells but inconclusive for staining in B cells. Very few plasma cells were seen with CD138 stain. Fluorescence in situ hybridization studies were negative for IgH and BCL2 gene rearrangement. Molecular diagnostic studies for IgH and κ light chain gene rearrangement were positive for a clonal population. A clonal T-cell receptor γ chain gene rearrangement was not identified. The overall morphologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular findings were consistent with cutaneous involvement by a B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, favoring primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL).

The patient was referred to our cancer center for further workup consisting of a complete blood cell count with differential; comprehensive metabolic panel; lactate dehydrogenase; serum protein electrophoresis; peripheral blood flow cytometry; and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. The analysis was unremarkable, supporting primary cutaneous disease. Additional studies suggested in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines for primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas include hepatitis B testing if the patient is being considered for immunotherapy and/or chemotherapy due to risk of reactivation, pregnancy testing in women of childbearing age, and human immunodeficiency virus testing.1 These tests were not performed in our patient because he did not have any risk factors for hepatitis B or human immunodeficiency virus.

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas originate in the skin without evidence of extracutaneous disease at presentation. They account for approximately 25% of primary cutaneous lymphomas in the United States, with primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma being most common.2 The revised 2017 World Health Organization classification system defines 3 major subtypes of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (Table).3-9 Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is the most common subtype, accounting for approximately 60% of cases. In Europe, an association with Borrelia burgdorferi has been reported.10 The extent of skin involvement determines the T portion of TNM staging for PCFCL. It is based on the size and location of affected body regions that are delineated, such as the head and neck, chest, abdomen/genitalia, upper back, lower back/buttocks, each upper arm, each lower arm/hand, each upper leg, and each lower leg/foot. T1 is for solitary skin involvement in which the lesion is 5 cm or less in diameter (T1a) or greater than 5 cm (T1b). T2 is for regional skin involvement limited to 1 or 2 contiguous body regions, whereas T2a has all lesions confined to an area 15 cm or less in diameter, T2b has lesions confined to an area greater than 15 cm up to 30 cm in diameter, and the area for T2c is greater than 30 cm in diameter. Finally, T3 is generalized skin involvement, whereas T3a has multiple lesions in 2 noncontiguous body regions, and T3b has multiple lesions on 3 or more regions.11 At presentation, our patient was considered T2cN0M0, as his lesions were present on only 2 contiguous regions extending beyond 30 cm without any evidence of lymph node involvement or metastasis.

Treatment of PCFCL is tailored to each case, as there is a paucity of randomized data in this rare entity. It is guided by the number and location of cutaneous lesions, associated skin symptoms, age of the patient, and performance status. Local disease can be treated with intralesional corticosteroids, excision, or close monitoring if the patient is asymptomatic. Low-dose radiation therapy may be used as primary treatment or for local recurrence.12 Patients with more extensive skin lesions can relapse after clearing; those with refractory disease can be managed with single-agent rituximab.13 Our patient underwent low-dose radiation therapy with good response and has not experienced recurrence.

Lymphocytoma cutis, also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, can be idiopathic or can arise after arthropod assault, penetrative skin trauma, drugs, or infections. In granuloma annulare, small dermal papules may present in isolation or coalesce to form annular plaques. It is a benign inflammatory disorder of unknown cause, can have mild pruritus, and usually is self-limited. Pyogenic granuloma is a benign vascular proliferation of unknown etiology. Sarcoidosis is an immune-mediated systemic disorder with granuloma formation that has a predilection for the lungs and the skin.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma, Follicle Center Subtype

A 4-mm punch biopsy through the center of the largest lesion on the right posterior shoulder demonstrated a superficial and deep dermal atypical lymphoid infiltrate composed predominantly of small mature lymphocytes with interspersed intermediate-sized cells with irregular to cleaved nuclei, dispersed chromatin, one or more distinct nucleoli, occasional mitoses, and small amounts of cytoplasm (Figure, A). Immunoperoxidase studies showed the infiltrate to be a mixture of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (Figure, B). The B cells coexpressed B-cell lymphoma (Bcl) 6 protein (Figure, C) but were negative for multiple myeloma 1/interferon regulatory factor 4 and CD10; Bcl2 protein was positive in T cells but inconclusive for staining in B cells. Very few plasma cells were seen with CD138 stain. Fluorescence in situ hybridization studies were negative for IgH and BCL2 gene rearrangement. Molecular diagnostic studies for IgH and κ light chain gene rearrangement were positive for a clonal population. A clonal T-cell receptor γ chain gene rearrangement was not identified. The overall morphologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular findings were consistent with cutaneous involvement by a B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, favoring primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL).

The patient was referred to our cancer center for further workup consisting of a complete blood cell count with differential; comprehensive metabolic panel; lactate dehydrogenase; serum protein electrophoresis; peripheral blood flow cytometry; and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. The analysis was unremarkable, supporting primary cutaneous disease. Additional studies suggested in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines for primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas include hepatitis B testing if the patient is being considered for immunotherapy and/or chemotherapy due to risk of reactivation, pregnancy testing in women of childbearing age, and human immunodeficiency virus testing.1 These tests were not performed in our patient because he did not have any risk factors for hepatitis B or human immunodeficiency virus.

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas originate in the skin without evidence of extracutaneous disease at presentation. They account for approximately 25% of primary cutaneous lymphomas in the United States, with primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma being most common.2 The revised 2017 World Health Organization classification system defines 3 major subtypes of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (Table).3-9 Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is the most common subtype, accounting for approximately 60% of cases. In Europe, an association with Borrelia burgdorferi has been reported.10 The extent of skin involvement determines the T portion of TNM staging for PCFCL. It is based on the size and location of affected body regions that are delineated, such as the head and neck, chest, abdomen/genitalia, upper back, lower back/buttocks, each upper arm, each lower arm/hand, each upper leg, and each lower leg/foot. T1 is for solitary skin involvement in which the lesion is 5 cm or less in diameter (T1a) or greater than 5 cm (T1b). T2 is for regional skin involvement limited to 1 or 2 contiguous body regions, whereas T2a has all lesions confined to an area 15 cm or less in diameter, T2b has lesions confined to an area greater than 15 cm up to 30 cm in diameter, and the area for T2c is greater than 30 cm in diameter. Finally, T3 is generalized skin involvement, whereas T3a has multiple lesions in 2 noncontiguous body regions, and T3b has multiple lesions on 3 or more regions.11 At presentation, our patient was considered T2cN0M0, as his lesions were present on only 2 contiguous regions extending beyond 30 cm without any evidence of lymph node involvement or metastasis.

Treatment of PCFCL is tailored to each case, as there is a paucity of randomized data in this rare entity. It is guided by the number and location of cutaneous lesions, associated skin symptoms, age of the patient, and performance status. Local disease can be treated with intralesional corticosteroids, excision, or close monitoring if the patient is asymptomatic. Low-dose radiation therapy may be used as primary treatment or for local recurrence.12 Patients with more extensive skin lesions can relapse after clearing; those with refractory disease can be managed with single-agent rituximab.13 Our patient underwent low-dose radiation therapy with good response and has not experienced recurrence.

Lymphocytoma cutis, also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, can be idiopathic or can arise after arthropod assault, penetrative skin trauma, drugs, or infections. In granuloma annulare, small dermal papules may present in isolation or coalesce to form annular plaques. It is a benign inflammatory disorder of unknown cause, can have mild pruritus, and usually is self-limited. Pyogenic granuloma is a benign vascular proliferation of unknown etiology. Sarcoidosis is an immune-mediated systemic disorder with granuloma formation that has a predilection for the lungs and the skin.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphomas. Version 2.2018. https://oncolife.com.ua/doc/nccn/Primary_Cutaneous_B-Cell_Lymphomas.pdf. Published January 10, 2018. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- Dores GM, Anderson WF, Devesa SS. Cutaneous lymphomas reported to the National Cancer Institute's surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program: applying the new WHO-European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification system. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7246-7248.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC; 2017.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute website. https://seer.cancer.gov/. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Cerroni L. B-cell lymphomas of the skin. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:2113-2126.

- Jacobsen E, Freedman AS, Willemze R. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/primary-cutaneous-follicle-center-lymphoma. Updated February 7, 2018. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Jacobsen E, Freedman AS, Willemze R. Primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/primary-cutaneous-marginal-zone-lymphoma. Updated March 6, 2019. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Jacobsen E, Freedman AS, Willemze R. Primary cutaneous large B cell lymphoma, leg type. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/primary-cutaneous-large-b-cell-lymphoma-leg-type. Updated July 3, 2017. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 241-342.

- Goodlad JR, Davidson MM, Hollowood K, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma and Borrelia burgdorferi infection in patients from the Highlands of Scotand. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1279-1285.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- Wilcon RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:1052-1055.

- Morales AV, Advani R, Horwitz SM, et al. Indolent primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: experience using systemic rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:953-957.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphomas. Version 2.2018. https://oncolife.com.ua/doc/nccn/Primary_Cutaneous_B-Cell_Lymphomas.pdf. Published January 10, 2018. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- Dores GM, Anderson WF, Devesa SS. Cutaneous lymphomas reported to the National Cancer Institute's surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program: applying the new WHO-European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification system. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7246-7248.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC; 2017.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute website. https://seer.cancer.gov/. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Cerroni L. B-cell lymphomas of the skin. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:2113-2126.

- Jacobsen E, Freedman AS, Willemze R. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/primary-cutaneous-follicle-center-lymphoma. Updated February 7, 2018. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Jacobsen E, Freedman AS, Willemze R. Primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/primary-cutaneous-marginal-zone-lymphoma. Updated March 6, 2019. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Jacobsen E, Freedman AS, Willemze R. Primary cutaneous large B cell lymphoma, leg type. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/primary-cutaneous-large-b-cell-lymphoma-leg-type. Updated July 3, 2017. Accessed June 26, 2019.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 241-342.

- Goodlad JR, Davidson MM, Hollowood K, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma and Borrelia burgdorferi infection in patients from the Highlands of Scotand. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1279-1285.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- Wilcon RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:1052-1055.

- Morales AV, Advani R, Horwitz SM, et al. Indolent primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: experience using systemic rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:953-957.

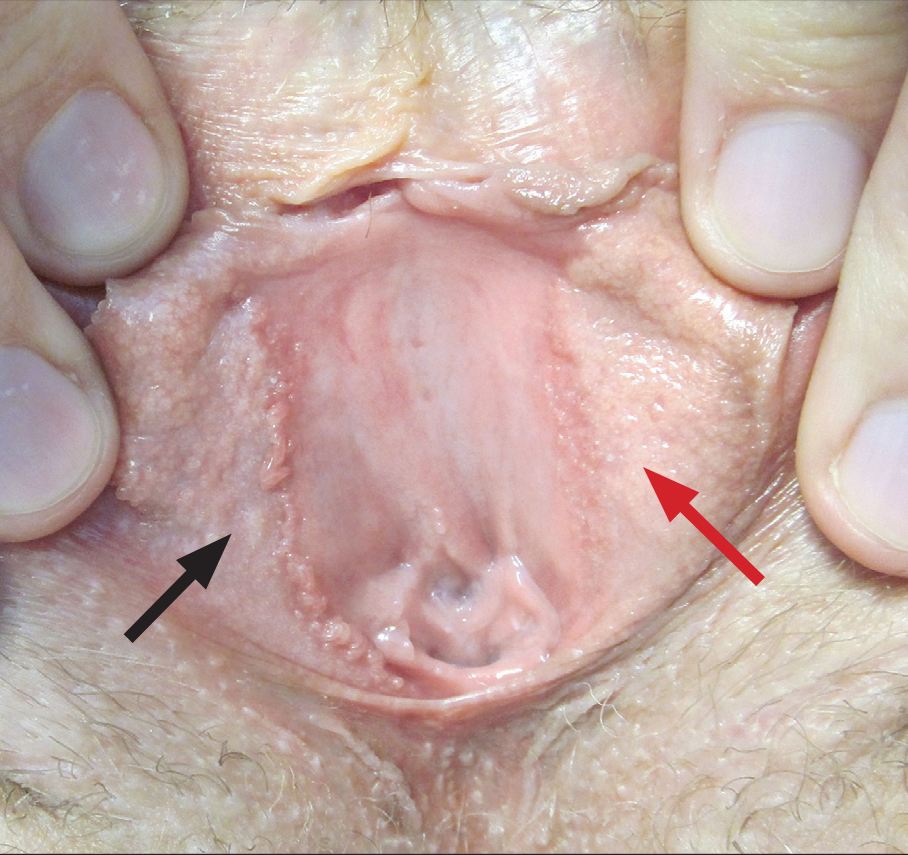

A 34-year-old man presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic with 3 groups of mildly pruritic, erythematous papules and plaques. The most prominent group appeared on the right posterior shoulder and had been slowly enlarging in size over the last 12 months (quiz image). A similar thinner group appeared on the left mid-back 6 months prior, and a third smaller group appeared over the left serratus anterior muscle 2 months prior. The patient reported having similar episodes dating back to his early 20s. In those instances, the lesions presented without an inciting incident, became more pronounced, and persisted for months to years before resolving. Previously affected areas included the upper and lateral back, flanks, and posterior upper arms. The patient used triamcinolone cream 0.1% up to 3 times daily on active lesions, which improved the pruritus and seemed to make the lesions resolve more quickly. He denied fever, chills, night sweats, anorexia, weight loss, fatigue, cough, and shortness of breath. His only medication was ranitidine 150 mg twice daily for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Physical examination revealed no palpable lymphadenopathy.

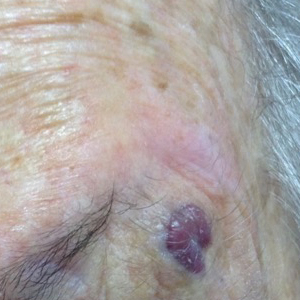

Rapidly Enlarging Neoplasm on the Face

The Diagnosis: Atypical Fibroxanthoma

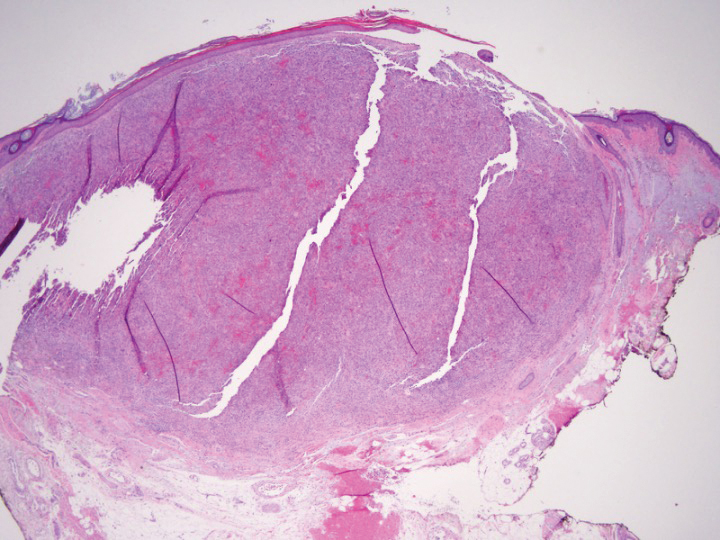

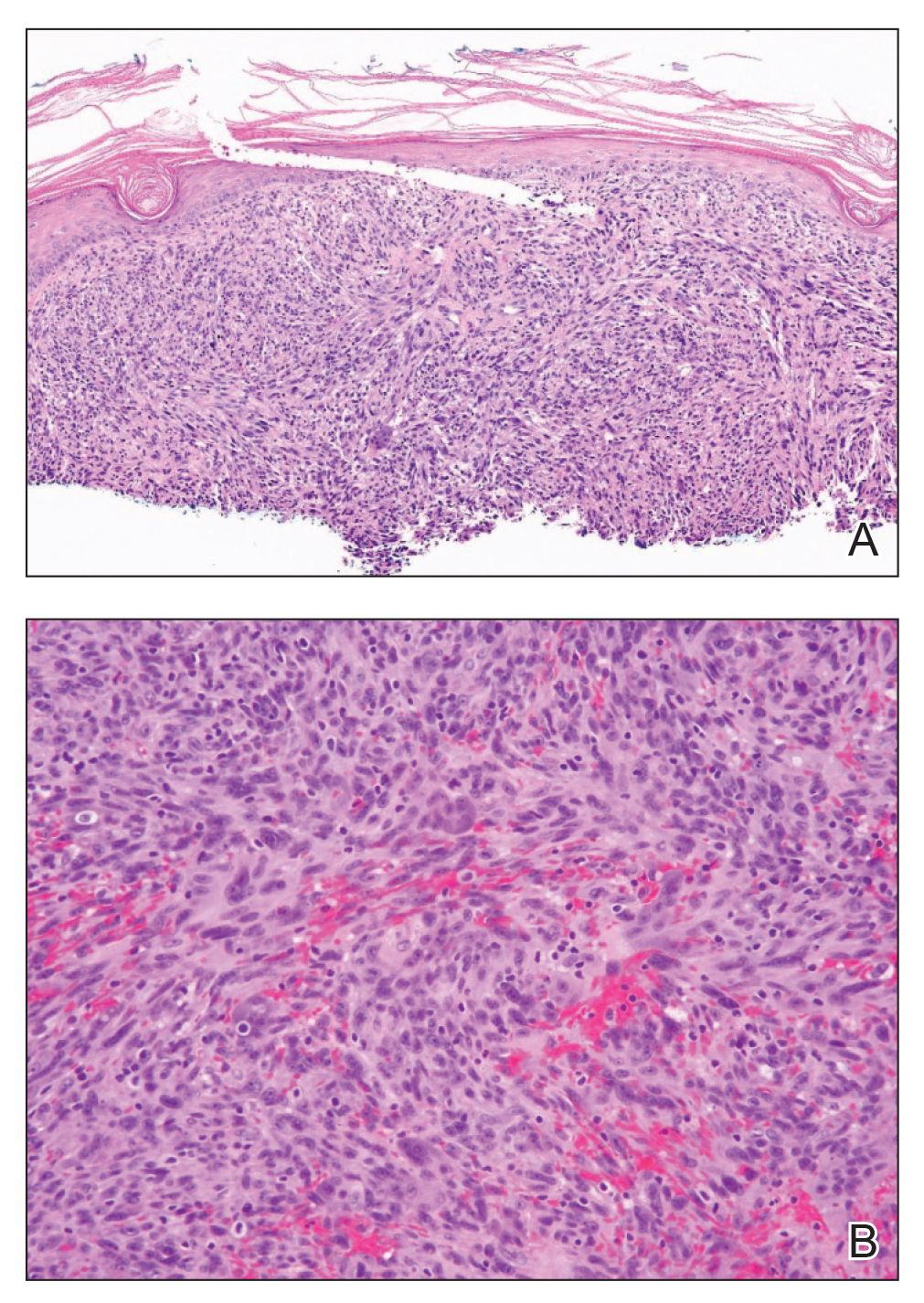

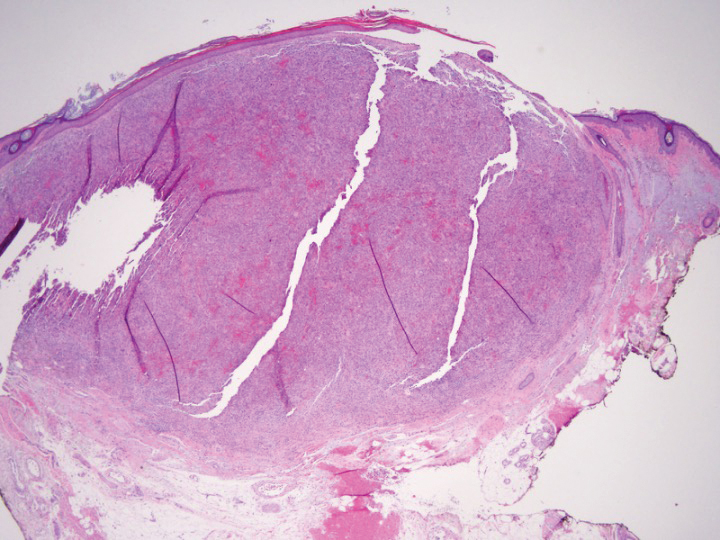

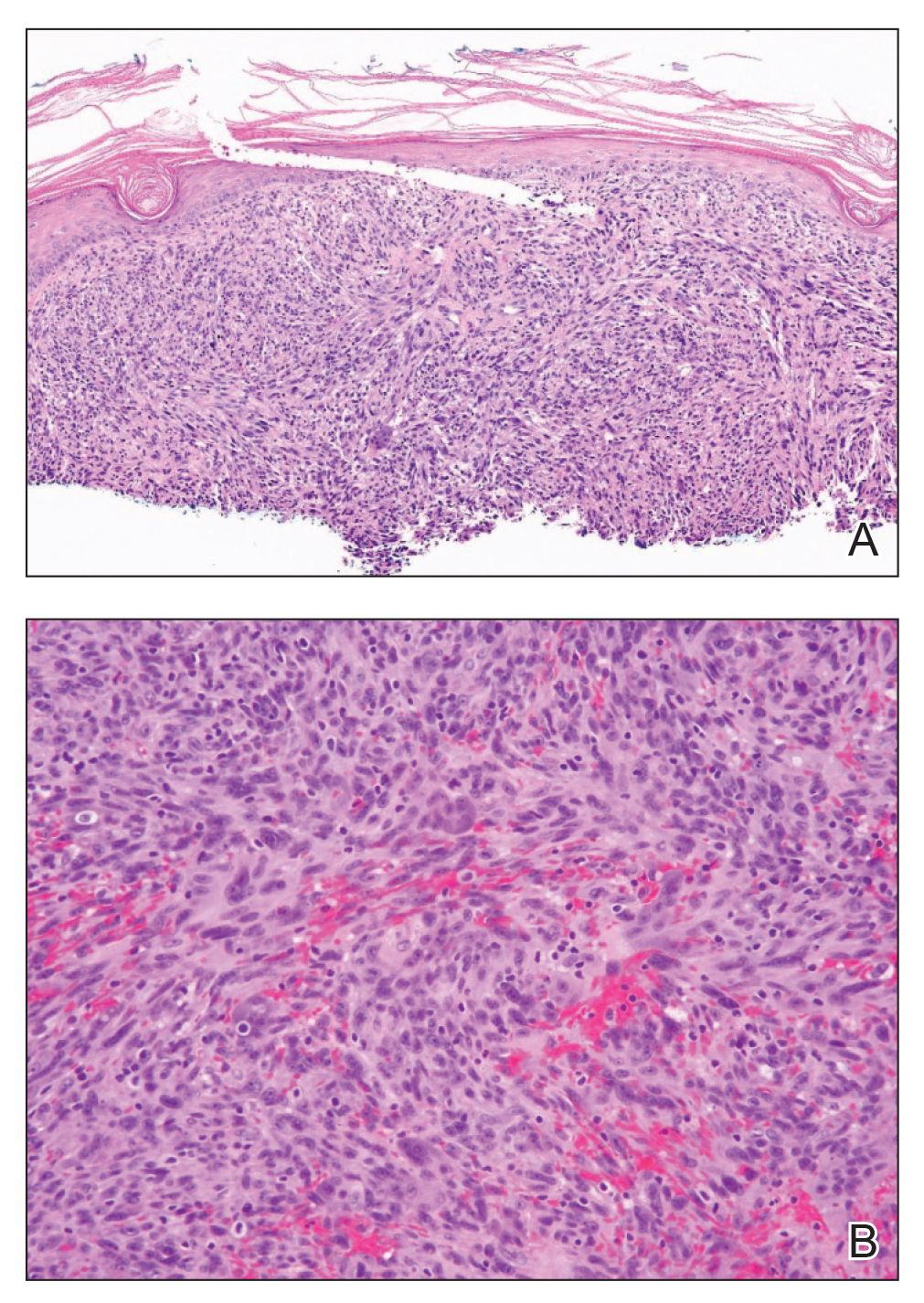

Shave biopsy showed the superficial aspect of a highly cellular tumor composed of pleomorphic spindle cells exhibiting storiform growth and increased mitotic activity (Figure 1). The tumor stained positive for factor XIIIa, CD163, CD68, and smooth muscle actin (mild), and negative for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (HMW-CK), p63, S-100, and melan-A. Subsequent excision with 0.5-cm margins was performed, and histopathology showed a well-circumscribed tumor contained within the dermis with a histologic scar at the outer margin (Figure 2). There was no lymphovascular or perineural invasion by tumor cells. Re-excision with 0.3-cm margins demonstrated no residual scar or tumor, and external radiation was deferred due to clear surgical margins.

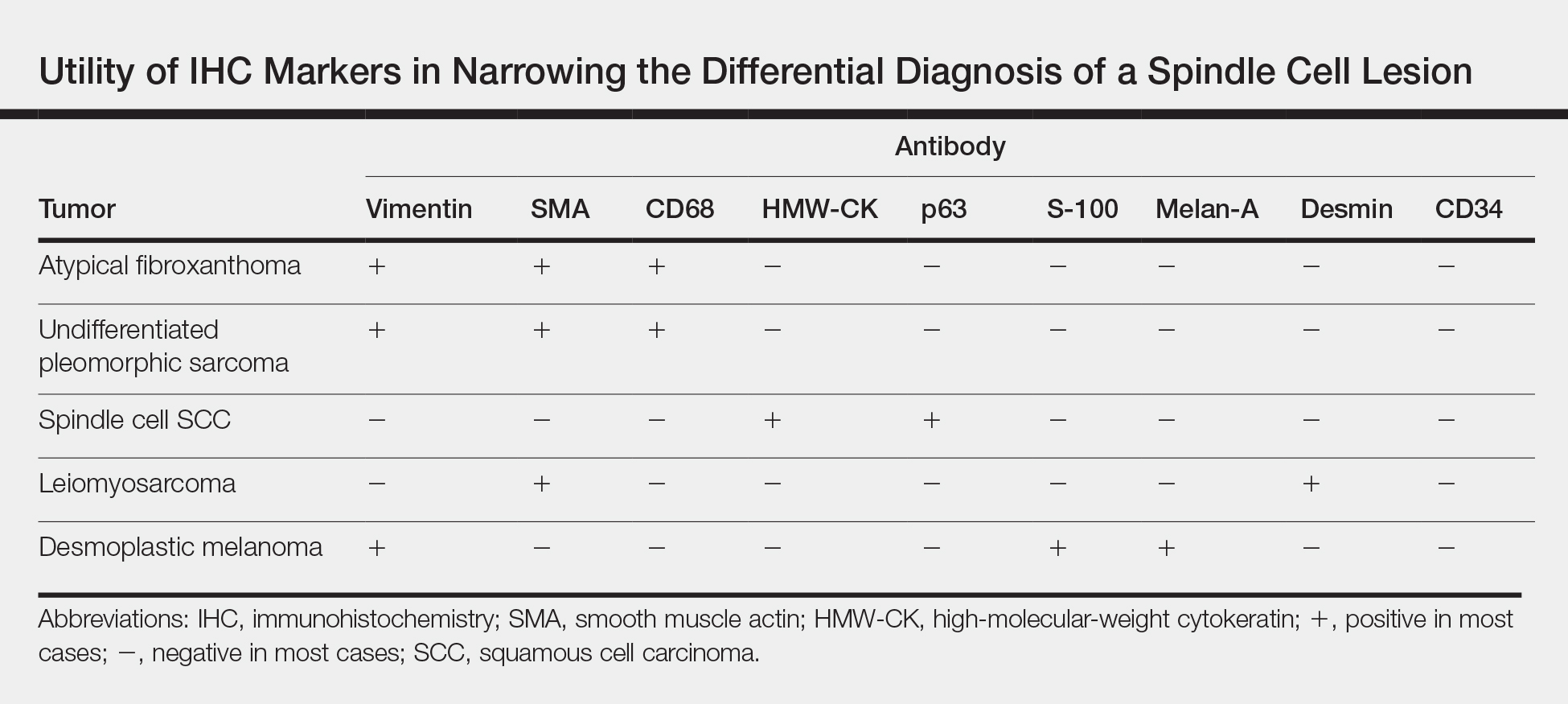

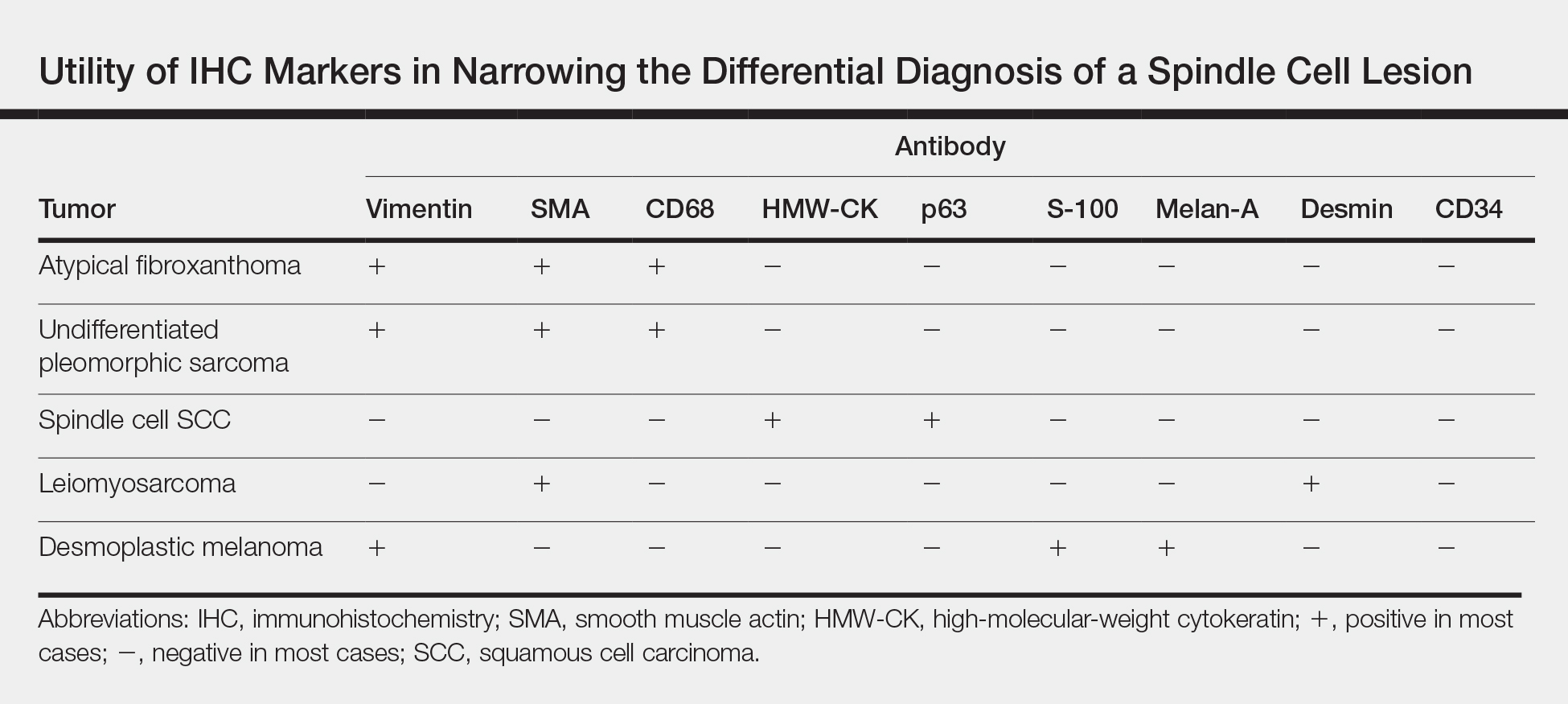

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) belongs to a group of spindle cell neoplasms that can be diagnostically challenging, as they often lack specific morphologic features on examination or routine histology. These neoplasms--of which the differential includes malignant fibrous histiocytoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), desmoplastic melanoma, and leiomyosarcoma--may each appear as a rapidly enlarging solitary plaque or nodule on sun-damaged skin on the head and neck or less commonly on the trunk, arms, or legs. Histologically, the cells of AFX exhibit notable pleomorphism with frequent atypical mitotic figures and nonspecific surrounding dermal changes. Subcutaneous and lymphovascular or perineural invasion of tumor cells can point away from the diagnosis of AFX; however, these features are likely to be missed in small superficial shave biopsies.1,2 Therefore, immunohistochemistry (IHC) and adequate tumor sampling are essential in the accurate diagnosis of AFX and other spindle cell neoplasms.

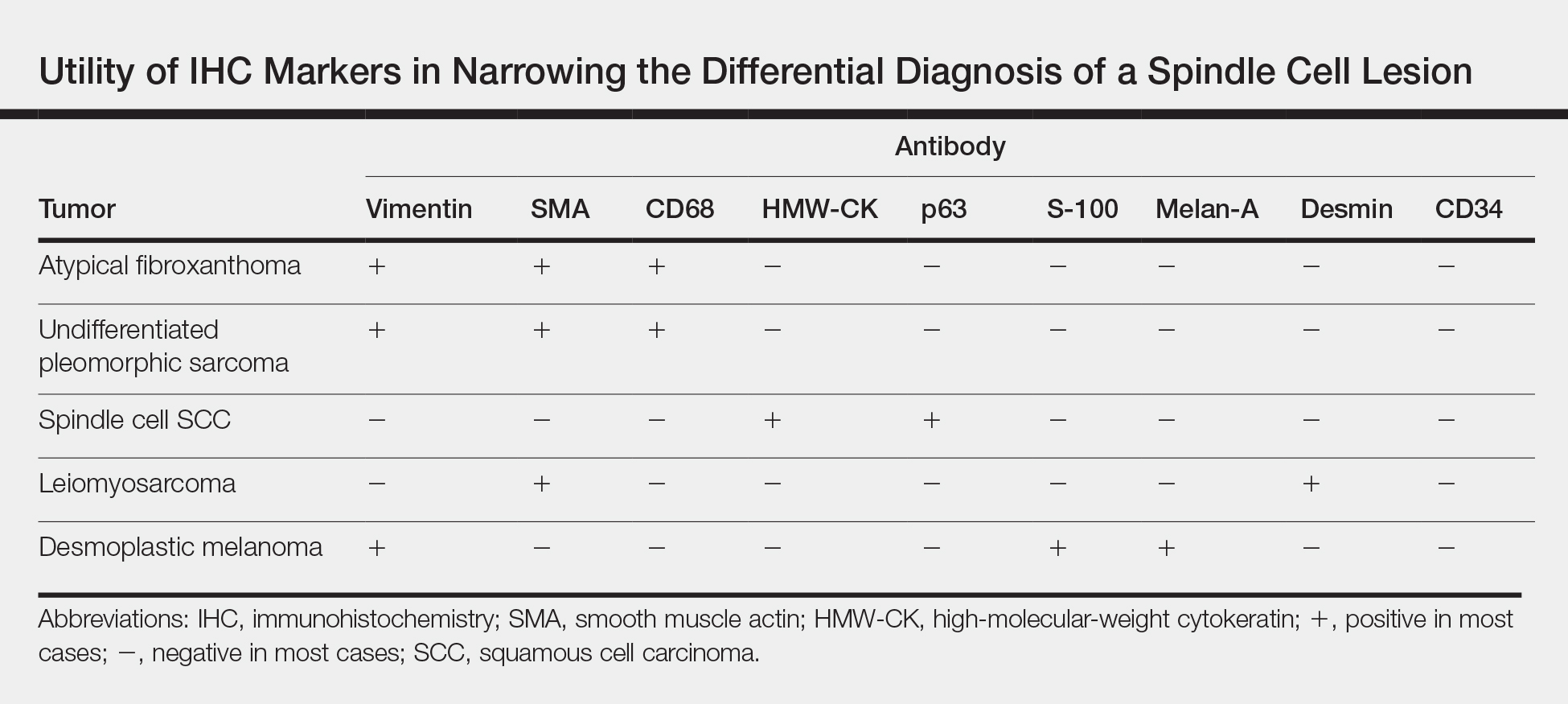

Several IHC markers have been employed in differentiating AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms.3-8 Positive stains for AFX include factor XIIIa (10%-25%), vimentin (>99%), CD10 (95%-100%), procollagen (87%), CD99 (35%-73%), CD163 (37%-79%), smooth muscle actin (50%), CD68 (>50%), and CD31 (43%). Other stains, such as HMW-CK, S-100, p63, desmin, CD34, and melan-A, typically are negative in AFX but are actively expressed in other pleomorphic spindle cell tumors. The Table summarizes the utility of these various markers in narrowing the differential diagnosis of a spindle cell lesion. Selection of an appropriate panel of IHC markers is critical for accurate diagnosis of AFX and exclusion of more aggressive, poorly differentiated spindle cell neoplasms. Key IHC markers include S-100 (negative in AFX; positive in desmoplastic melanoma), HMW-CK (negative in AFX; positive in spindle cell SCC), and p63 (negative in AFX; positive in spindle cell SCC). Benoit et al9 reported a case of a poorly differentiated spindle cell SCC misdiagnosed as AFX based on a limited IHC panel that was negative for pancytokeratin and S-100. Later, a more comprehensive IHC panel including HMW-CK and p63 confirmed spindle cell SCC, but by this time, a delay in therapy had allowed the tumor to metastasize, which ultimately proved fatal to the patient.9

In addition to incomplete IHC evaluation, accurate diagnosis of spindle cell tumors also may be obscured by inadequate tumor sampling. The cells of AFX tumors often are well circumscribed and dermally based, and an excisional biopsy is the preferred biopsy procedure for AFX. A tumor invading into subcutaneous tissue or into lymphovascular or perineural structures suggests a more aggressive, poorly differentiated spindle cell neoplasm.1,3 For example, the tumor cells of malignant fibrous histiocytoma, which belongs to the undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma group, may appear identical to those of AFX on histology, and the 2 tumors display similar IHC profiles.3 Malignant fibrous histiocytoma, however, extends into the subcutaneous space and portends a notably worse prognosis compared to AFX. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma tumors therefore require more aggressive treatment strategies such as external beam radiation therapy, whereas AFX can be safely treated with surgical removal alone. In our patient, complete visualization of tumor margins solidified the diagnosis of AFX and spared our patient from unnecessary radiation therapy. Overall, AFX has a good prognosis and metastasis is rare, particularly when good margin control is achieved.10

Our case highlights the importance of clinicopathologic correlation, including appropriate IHC analysis and adequate tumor sampling in the diagnostic workup of a pleomorphic spindle cell neoplasm. Although these tumors are well studied, their notable degree of clinical and histologic heterogeneity may pose a diagnostic challenge to even experienced dermatologists and require careful consideration of the potential pitfalls in diagnosis.

- Iorizzo LJ, Brown MD. Atypical fibroxanthoma: a review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:146-157.

- Lopez L, Velez R. Atypical fibroxanthoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:376-379.

- Hussein MR. Atypical fibroxanthoma: new insights. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2014;14:1075-1088.

- Gleason BC, Calder KB, Cibull TL, et al. Utility of p63 in the differential diagnosis of atypical fibroxanthoma and spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:543-547.

- Pouryazdanparast P, Yu L, Cutland JE, et al. Diagnostic value of CD163 in cutaneous spindle cell lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:859-864.

- Beer TW. CD163 is not a sensitive marker for identification of atypical fibroxanthoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:29-32.

- Longacre TA, Smoller BR, Rouse RV. Atypical fibroxanthoma. multiple immunohistologic profiles. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:1199-1209.

- Altman DA, Nickoloff BD, Fivenson DP. Differential expression of factor XIIa and CD34 in cutaneous mesenchymal tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 1993;20:154-158.

- Benoit A, Wisell J, Brown M. Cutaneous spindle cell carcinoma misdiagnosed as atypical fibroxanthoma based on immunohistochemical stains. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:392-394.

- New D, Bahrami S, Malone J, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma with regional lymph node metastasis: report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1399-1404.

The Diagnosis: Atypical Fibroxanthoma

Shave biopsy showed the superficial aspect of a highly cellular tumor composed of pleomorphic spindle cells exhibiting storiform growth and increased mitotic activity (Figure 1). The tumor stained positive for factor XIIIa, CD163, CD68, and smooth muscle actin (mild), and negative for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (HMW-CK), p63, S-100, and melan-A. Subsequent excision with 0.5-cm margins was performed, and histopathology showed a well-circumscribed tumor contained within the dermis with a histologic scar at the outer margin (Figure 2). There was no lymphovascular or perineural invasion by tumor cells. Re-excision with 0.3-cm margins demonstrated no residual scar or tumor, and external radiation was deferred due to clear surgical margins.

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) belongs to a group of spindle cell neoplasms that can be diagnostically challenging, as they often lack specific morphologic features on examination or routine histology. These neoplasms--of which the differential includes malignant fibrous histiocytoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), desmoplastic melanoma, and leiomyosarcoma--may each appear as a rapidly enlarging solitary plaque or nodule on sun-damaged skin on the head and neck or less commonly on the trunk, arms, or legs. Histologically, the cells of AFX exhibit notable pleomorphism with frequent atypical mitotic figures and nonspecific surrounding dermal changes. Subcutaneous and lymphovascular or perineural invasion of tumor cells can point away from the diagnosis of AFX; however, these features are likely to be missed in small superficial shave biopsies.1,2 Therefore, immunohistochemistry (IHC) and adequate tumor sampling are essential in the accurate diagnosis of AFX and other spindle cell neoplasms.

Several IHC markers have been employed in differentiating AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms.3-8 Positive stains for AFX include factor XIIIa (10%-25%), vimentin (>99%), CD10 (95%-100%), procollagen (87%), CD99 (35%-73%), CD163 (37%-79%), smooth muscle actin (50%), CD68 (>50%), and CD31 (43%). Other stains, such as HMW-CK, S-100, p63, desmin, CD34, and melan-A, typically are negative in AFX but are actively expressed in other pleomorphic spindle cell tumors. The Table summarizes the utility of these various markers in narrowing the differential diagnosis of a spindle cell lesion. Selection of an appropriate panel of IHC markers is critical for accurate diagnosis of AFX and exclusion of more aggressive, poorly differentiated spindle cell neoplasms. Key IHC markers include S-100 (negative in AFX; positive in desmoplastic melanoma), HMW-CK (negative in AFX; positive in spindle cell SCC), and p63 (negative in AFX; positive in spindle cell SCC). Benoit et al9 reported a case of a poorly differentiated spindle cell SCC misdiagnosed as AFX based on a limited IHC panel that was negative for pancytokeratin and S-100. Later, a more comprehensive IHC panel including HMW-CK and p63 confirmed spindle cell SCC, but by this time, a delay in therapy had allowed the tumor to metastasize, which ultimately proved fatal to the patient.9

In addition to incomplete IHC evaluation, accurate diagnosis of spindle cell tumors also may be obscured by inadequate tumor sampling. The cells of AFX tumors often are well circumscribed and dermally based, and an excisional biopsy is the preferred biopsy procedure for AFX. A tumor invading into subcutaneous tissue or into lymphovascular or perineural structures suggests a more aggressive, poorly differentiated spindle cell neoplasm.1,3 For example, the tumor cells of malignant fibrous histiocytoma, which belongs to the undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma group, may appear identical to those of AFX on histology, and the 2 tumors display similar IHC profiles.3 Malignant fibrous histiocytoma, however, extends into the subcutaneous space and portends a notably worse prognosis compared to AFX. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma tumors therefore require more aggressive treatment strategies such as external beam radiation therapy, whereas AFX can be safely treated with surgical removal alone. In our patient, complete visualization of tumor margins solidified the diagnosis of AFX and spared our patient from unnecessary radiation therapy. Overall, AFX has a good prognosis and metastasis is rare, particularly when good margin control is achieved.10

Our case highlights the importance of clinicopathologic correlation, including appropriate IHC analysis and adequate tumor sampling in the diagnostic workup of a pleomorphic spindle cell neoplasm. Although these tumors are well studied, their notable degree of clinical and histologic heterogeneity may pose a diagnostic challenge to even experienced dermatologists and require careful consideration of the potential pitfalls in diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Atypical Fibroxanthoma

Shave biopsy showed the superficial aspect of a highly cellular tumor composed of pleomorphic spindle cells exhibiting storiform growth and increased mitotic activity (Figure 1). The tumor stained positive for factor XIIIa, CD163, CD68, and smooth muscle actin (mild), and negative for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (HMW-CK), p63, S-100, and melan-A. Subsequent excision with 0.5-cm margins was performed, and histopathology showed a well-circumscribed tumor contained within the dermis with a histologic scar at the outer margin (Figure 2). There was no lymphovascular or perineural invasion by tumor cells. Re-excision with 0.3-cm margins demonstrated no residual scar or tumor, and external radiation was deferred due to clear surgical margins.

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) belongs to a group of spindle cell neoplasms that can be diagnostically challenging, as they often lack specific morphologic features on examination or routine histology. These neoplasms--of which the differential includes malignant fibrous histiocytoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), desmoplastic melanoma, and leiomyosarcoma--may each appear as a rapidly enlarging solitary plaque or nodule on sun-damaged skin on the head and neck or less commonly on the trunk, arms, or legs. Histologically, the cells of AFX exhibit notable pleomorphism with frequent atypical mitotic figures and nonspecific surrounding dermal changes. Subcutaneous and lymphovascular or perineural invasion of tumor cells can point away from the diagnosis of AFX; however, these features are likely to be missed in small superficial shave biopsies.1,2 Therefore, immunohistochemistry (IHC) and adequate tumor sampling are essential in the accurate diagnosis of AFX and other spindle cell neoplasms.

Several IHC markers have been employed in differentiating AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms.3-8 Positive stains for AFX include factor XIIIa (10%-25%), vimentin (>99%), CD10 (95%-100%), procollagen (87%), CD99 (35%-73%), CD163 (37%-79%), smooth muscle actin (50%), CD68 (>50%), and CD31 (43%). Other stains, such as HMW-CK, S-100, p63, desmin, CD34, and melan-A, typically are negative in AFX but are actively expressed in other pleomorphic spindle cell tumors. The Table summarizes the utility of these various markers in narrowing the differential diagnosis of a spindle cell lesion. Selection of an appropriate panel of IHC markers is critical for accurate diagnosis of AFX and exclusion of more aggressive, poorly differentiated spindle cell neoplasms. Key IHC markers include S-100 (negative in AFX; positive in desmoplastic melanoma), HMW-CK (negative in AFX; positive in spindle cell SCC), and p63 (negative in AFX; positive in spindle cell SCC). Benoit et al9 reported a case of a poorly differentiated spindle cell SCC misdiagnosed as AFX based on a limited IHC panel that was negative for pancytokeratin and S-100. Later, a more comprehensive IHC panel including HMW-CK and p63 confirmed spindle cell SCC, but by this time, a delay in therapy had allowed the tumor to metastasize, which ultimately proved fatal to the patient.9

In addition to incomplete IHC evaluation, accurate diagnosis of spindle cell tumors also may be obscured by inadequate tumor sampling. The cells of AFX tumors often are well circumscribed and dermally based, and an excisional biopsy is the preferred biopsy procedure for AFX. A tumor invading into subcutaneous tissue or into lymphovascular or perineural structures suggests a more aggressive, poorly differentiated spindle cell neoplasm.1,3 For example, the tumor cells of malignant fibrous histiocytoma, which belongs to the undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma group, may appear identical to those of AFX on histology, and the 2 tumors display similar IHC profiles.3 Malignant fibrous histiocytoma, however, extends into the subcutaneous space and portends a notably worse prognosis compared to AFX. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma tumors therefore require more aggressive treatment strategies such as external beam radiation therapy, whereas AFX can be safely treated with surgical removal alone. In our patient, complete visualization of tumor margins solidified the diagnosis of AFX and spared our patient from unnecessary radiation therapy. Overall, AFX has a good prognosis and metastasis is rare, particularly when good margin control is achieved.10

Our case highlights the importance of clinicopathologic correlation, including appropriate IHC analysis and adequate tumor sampling in the diagnostic workup of a pleomorphic spindle cell neoplasm. Although these tumors are well studied, their notable degree of clinical and histologic heterogeneity may pose a diagnostic challenge to even experienced dermatologists and require careful consideration of the potential pitfalls in diagnosis.

- Iorizzo LJ, Brown MD. Atypical fibroxanthoma: a review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:146-157.

- Lopez L, Velez R. Atypical fibroxanthoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:376-379.

- Hussein MR. Atypical fibroxanthoma: new insights. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2014;14:1075-1088.

- Gleason BC, Calder KB, Cibull TL, et al. Utility of p63 in the differential diagnosis of atypical fibroxanthoma and spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:543-547.

- Pouryazdanparast P, Yu L, Cutland JE, et al. Diagnostic value of CD163 in cutaneous spindle cell lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:859-864.

- Beer TW. CD163 is not a sensitive marker for identification of atypical fibroxanthoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:29-32.

- Longacre TA, Smoller BR, Rouse RV. Atypical fibroxanthoma. multiple immunohistologic profiles. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:1199-1209.

- Altman DA, Nickoloff BD, Fivenson DP. Differential expression of factor XIIa and CD34 in cutaneous mesenchymal tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 1993;20:154-158.

- Benoit A, Wisell J, Brown M. Cutaneous spindle cell carcinoma misdiagnosed as atypical fibroxanthoma based on immunohistochemical stains. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:392-394.

- New D, Bahrami S, Malone J, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma with regional lymph node metastasis: report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1399-1404.

- Iorizzo LJ, Brown MD. Atypical fibroxanthoma: a review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:146-157.

- Lopez L, Velez R. Atypical fibroxanthoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:376-379.

- Hussein MR. Atypical fibroxanthoma: new insights. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2014;14:1075-1088.

- Gleason BC, Calder KB, Cibull TL, et al. Utility of p63 in the differential diagnosis of atypical fibroxanthoma and spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:543-547.

- Pouryazdanparast P, Yu L, Cutland JE, et al. Diagnostic value of CD163 in cutaneous spindle cell lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:859-864.

- Beer TW. CD163 is not a sensitive marker for identification of atypical fibroxanthoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:29-32.

- Longacre TA, Smoller BR, Rouse RV. Atypical fibroxanthoma. multiple immunohistologic profiles. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:1199-1209.

- Altman DA, Nickoloff BD, Fivenson DP. Differential expression of factor XIIa and CD34 in cutaneous mesenchymal tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 1993;20:154-158.

- Benoit A, Wisell J, Brown M. Cutaneous spindle cell carcinoma misdiagnosed as atypical fibroxanthoma based on immunohistochemical stains. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:392-394.

- New D, Bahrami S, Malone J, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma with regional lymph node metastasis: report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1399-1404.

An 88-year-old woman presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic facial lesion that she first noticed 3 months prior, with rapid growth over the last month. Review of systems was negative, and she denied any history of connective tissue disease, skin cancer, or radiation to the head or neck area. Physical examination revealed a 1.5-cm, solitary, violaceous nodule on the left lateral eyebrow on a background of actinically damaged skin. The lesion was nontender and there were no similar lesions or palpable lymphadenopathy.

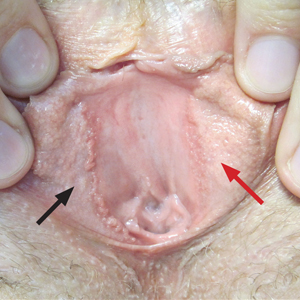

Recurrent Pruritic Multifocal Erythematous Rash

The Diagnosis: Wells Syndrome

Histopathologic examination of the biopsy demonstrated overlying acanthosis, focal spongiosis, and exocytosis. There also was proliferation and thickening of superficial capillaries and papillary fibrosis (Figure, A). There was a mixed interstitial and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils (Figure, A and B). Occasional flame figures were identified (Figure, C).

Wells syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, was first described in 1971 by Wells1 as a recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia. Rarely reported worldwide, this chronic relapsing condition is characterized by a pronounced eosinophilic infiltrate of the dermis resembling urticaria or cellulitis.2 The exact etiology has not been elucidated; however, links to certain medications, vaccines, exaggerated arthropod reactions, infections, and malignancies have been documented.3

Wells syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion and lacks a predictable dermatologic presentation, thereby mandating focused clinical follow-up as well as correlation with histopathology findings. Although the classic histologic hallmark of Wells syndrome is scattered flame figures, this finding is not specific and can be found in other hypereosinophilic conditions.2 Clinical manifestations most often consist of 2 distinct phases: an initial painful burning or pruritic sensation, followed by the development of erythematous and edematous dermal plaques that may heal with slight hyperpigmentation over 4 to 8 weeks. A case series of 19 patients demonstrated variants of Wells syndrome, with an annular granuloma-like appearance found primarily in adults and the signature plaque-type appearance predominating in children.4

Acute urticaria is characterized by pruritic erythematous wheals secondary to a histamine-mediated response brought on by a variety of triggers, typically allergic and self-resolving within 24 hours. When such lesions last longer than 24 hours, biopsy should be performed to exclude urticarial vasculitis, which is characterized by a burning or painful sensation rather than pruritis, in addition to dermal neutrophilia and perivascular infiltrate on histology. Erythema migrans of Lyme disease begins at the site of a tick bite, evolving from a red macule to an expanding targetoid lesion and typically is not pruritic. Infectious cellulitis presents with warm, tender, and poorly defined erythematous patches; can progress rapidly; and is accompanied by systemic symptoms such as fevers, malaise, and lymphadenopathy.

Best evidence favors the use of moderate- to high-dose corticosteroids as first-line treatment.5 The use of tumor necrosis factor blockers, various immunomodulating agents, and combination therapy with levocetirizine and hydroxyzine have demonstrated variable levels of efficacy, albeit often followed by high rates of relapse with drug discontinuation.6

- Wells GC. Recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:46-56.

- Aberer W, Konrad K, Wolff K. Wells' syndrome is a distinctive disease entity and not a histologic diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:105-114.

- Kaufmann D, Pichler W, Beer JH. Severe episode of high fever with rash, lymphadenopathy, neutropenia, and eosinophilia after minocycline therapy for acne. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1983-1984.

- Caputo R, Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Ferreli C, Pinna AL, Atzori L, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Well's syndrome): a new case description. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;13:41-45.

- Cormerais M, Poizeau F, Darrieux L, et al. Wells' syndrome mimicking facial cellulitis: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:117-122.

The Diagnosis: Wells Syndrome

Histopathologic examination of the biopsy demonstrated overlying acanthosis, focal spongiosis, and exocytosis. There also was proliferation and thickening of superficial capillaries and papillary fibrosis (Figure, A). There was a mixed interstitial and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils (Figure, A and B). Occasional flame figures were identified (Figure, C).

Wells syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, was first described in 1971 by Wells1 as a recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia. Rarely reported worldwide, this chronic relapsing condition is characterized by a pronounced eosinophilic infiltrate of the dermis resembling urticaria or cellulitis.2 The exact etiology has not been elucidated; however, links to certain medications, vaccines, exaggerated arthropod reactions, infections, and malignancies have been documented.3

Wells syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion and lacks a predictable dermatologic presentation, thereby mandating focused clinical follow-up as well as correlation with histopathology findings. Although the classic histologic hallmark of Wells syndrome is scattered flame figures, this finding is not specific and can be found in other hypereosinophilic conditions.2 Clinical manifestations most often consist of 2 distinct phases: an initial painful burning or pruritic sensation, followed by the development of erythematous and edematous dermal plaques that may heal with slight hyperpigmentation over 4 to 8 weeks. A case series of 19 patients demonstrated variants of Wells syndrome, with an annular granuloma-like appearance found primarily in adults and the signature plaque-type appearance predominating in children.4

Acute urticaria is characterized by pruritic erythematous wheals secondary to a histamine-mediated response brought on by a variety of triggers, typically allergic and self-resolving within 24 hours. When such lesions last longer than 24 hours, biopsy should be performed to exclude urticarial vasculitis, which is characterized by a burning or painful sensation rather than pruritis, in addition to dermal neutrophilia and perivascular infiltrate on histology. Erythema migrans of Lyme disease begins at the site of a tick bite, evolving from a red macule to an expanding targetoid lesion and typically is not pruritic. Infectious cellulitis presents with warm, tender, and poorly defined erythematous patches; can progress rapidly; and is accompanied by systemic symptoms such as fevers, malaise, and lymphadenopathy.

Best evidence favors the use of moderate- to high-dose corticosteroids as first-line treatment.5 The use of tumor necrosis factor blockers, various immunomodulating agents, and combination therapy with levocetirizine and hydroxyzine have demonstrated variable levels of efficacy, albeit often followed by high rates of relapse with drug discontinuation.6

The Diagnosis: Wells Syndrome

Histopathologic examination of the biopsy demonstrated overlying acanthosis, focal spongiosis, and exocytosis. There also was proliferation and thickening of superficial capillaries and papillary fibrosis (Figure, A). There was a mixed interstitial and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils (Figure, A and B). Occasional flame figures were identified (Figure, C).

Wells syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, was first described in 1971 by Wells1 as a recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia. Rarely reported worldwide, this chronic relapsing condition is characterized by a pronounced eosinophilic infiltrate of the dermis resembling urticaria or cellulitis.2 The exact etiology has not been elucidated; however, links to certain medications, vaccines, exaggerated arthropod reactions, infections, and malignancies have been documented.3

Wells syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion and lacks a predictable dermatologic presentation, thereby mandating focused clinical follow-up as well as correlation with histopathology findings. Although the classic histologic hallmark of Wells syndrome is scattered flame figures, this finding is not specific and can be found in other hypereosinophilic conditions.2 Clinical manifestations most often consist of 2 distinct phases: an initial painful burning or pruritic sensation, followed by the development of erythematous and edematous dermal plaques that may heal with slight hyperpigmentation over 4 to 8 weeks. A case series of 19 patients demonstrated variants of Wells syndrome, with an annular granuloma-like appearance found primarily in adults and the signature plaque-type appearance predominating in children.4

Acute urticaria is characterized by pruritic erythematous wheals secondary to a histamine-mediated response brought on by a variety of triggers, typically allergic and self-resolving within 24 hours. When such lesions last longer than 24 hours, biopsy should be performed to exclude urticarial vasculitis, which is characterized by a burning or painful sensation rather than pruritis, in addition to dermal neutrophilia and perivascular infiltrate on histology. Erythema migrans of Lyme disease begins at the site of a tick bite, evolving from a red macule to an expanding targetoid lesion and typically is not pruritic. Infectious cellulitis presents with warm, tender, and poorly defined erythematous patches; can progress rapidly; and is accompanied by systemic symptoms such as fevers, malaise, and lymphadenopathy.

Best evidence favors the use of moderate- to high-dose corticosteroids as first-line treatment.5 The use of tumor necrosis factor blockers, various immunomodulating agents, and combination therapy with levocetirizine and hydroxyzine have demonstrated variable levels of efficacy, albeit often followed by high rates of relapse with drug discontinuation.6

- Wells GC. Recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:46-56.

- Aberer W, Konrad K, Wolff K. Wells' syndrome is a distinctive disease entity and not a histologic diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:105-114.

- Kaufmann D, Pichler W, Beer JH. Severe episode of high fever with rash, lymphadenopathy, neutropenia, and eosinophilia after minocycline therapy for acne. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1983-1984.

- Caputo R, Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Ferreli C, Pinna AL, Atzori L, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Well's syndrome): a new case description. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;13:41-45.

- Cormerais M, Poizeau F, Darrieux L, et al. Wells' syndrome mimicking facial cellulitis: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:117-122.

- Wells GC. Recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:46-56.

- Aberer W, Konrad K, Wolff K. Wells' syndrome is a distinctive disease entity and not a histologic diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:105-114.

- Kaufmann D, Pichler W, Beer JH. Severe episode of high fever with rash, lymphadenopathy, neutropenia, and eosinophilia after minocycline therapy for acne. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1983-1984.

- Caputo R, Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Ferreli C, Pinna AL, Atzori L, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Well's syndrome): a new case description. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;13:41-45.

- Cormerais M, Poizeau F, Darrieux L, et al. Wells' syndrome mimicking facial cellulitis: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:117-122.

A 60-year-old man with a history of hyperlipidemia developed acute onset of an intensely pruritic and painful burning rash on the dorsal aspect of the left forearm of 8 days' duration. The patient described the rash as red and warm. It measured 2 cm at inception and peaked at 12 cm 6 months later when the patient presented. These symptoms resolved without therapeutic intervention.

Over the ensuing 6 months, he experienced 13 self-limited episodes of erythematous indurated cutaneous streaks, usually with proximal migration on the arms along with involvement of the posterior thorax and right leg. Five months prior to the onset of the initial rash, the patient had discontinued ezetimibe to treat hyperlipidemia due to swelling of the lips and tongue. He also reported that he regularly hunted in upstate Pennsylvania but reported no history of arthropod or animal bites. The patient did not take prescription or over-the-counter medications, and he denied the presence of fever, night sweats, fatigue, adenopathy, anorexia, weight loss, diarrhea, joint pain or swelling, or illicit drug use. Lyme titers, complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and comprehensive metabolic panel were within reference range. A punch biopsy was performed.

Rapidly Growing Cutaneous Nodules on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

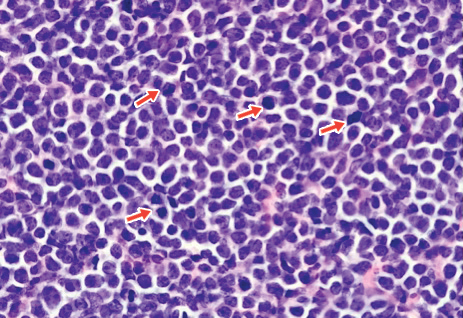

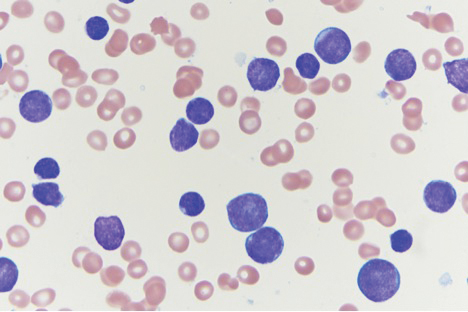

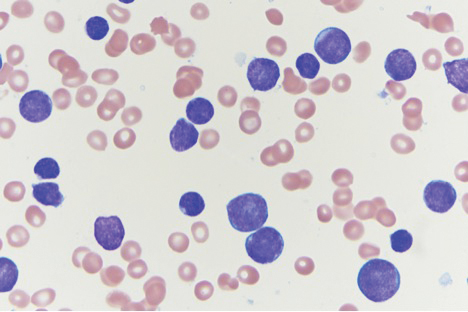

A 4-mm punch biopsy of one of the scalp lesions showed a diffuse infiltrate of intermediately sized cells with variably mature chromatin and irregular nuclear contours, consistent with a neoplastic process. Numerous mitotic figures were present, indicating a high proliferation rate (Figure 1). At that time there was no evidence of systemic involvement. A repeat biopsy with concurrent bone marrow biopsy was scheduled 10 days after the patient's initial presentation for further classification. Laboratory studies at that time revealed leukocytosis with elevated neutrophils and lymphocytes as well as a high absolute blast count.

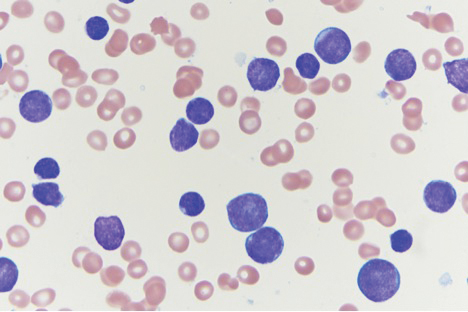

On immunohistochemical staining, the neoplastic cells were positive for CD45, which indicated the neoplasm was hematopoietic, as well as CD10 and the B-cell antigens PAX-5 and CD79a. The cells were negative for CD20, which also is a B-cell marker, but this marker is only expressed in approximately half of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cases with B-cell precursor origin.1 Markers that typically are expressed in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL)--CD34 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase--were both negative. These results were somewhat contradictory, and the differential remained open to both B-ALL and mature B-cell lymphoma. A bone marrow biopsy showed approximately 65% blasts or leukemic cells (Figure 2). Flow cytometry showed the cells were positive for CD10, CD19, weak CD79a, and variable lambda surface antigen expression. The cells were negative for expression of CD20, CD34, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, myeloid antigens, and CD3. Ultimately, the morphology and immunophenotype were most consistent with a diagnosis of B-ALL. Fluorescence in situ hybridization revealed mixed lineage leukemia, MLL, gene rearrangements.

In general, when considering the differential diagnosis of superficial nodules, 5 elements are helpful to consider: the number of nodules (single vs multiple); the location; and the presence or absence of tenderness, pigmentation or erythema, and firmness.2 Our patient had multiple nodules on the scalp, which were erythematous to slightly purple and firm. The differential diagnosis can be categorized into malignant; infectious; and benign inflammatory, vascular, and fibrous tumors.

Potential oncologic processes include leukemia cutis, lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Initial laboratory test results were reassuring. Infectious processes in the differential include deep fungal infections such as coccidioidomycosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Coccidioidomycosis was the most likely to cause skin lesions or masses in our patient; however, it was considered less likely because the patient's family had not traveled or been exposed to an endemic area.3

Benign tumors in the differential include deep hemangioma, which was deemed less likely in our patient because most hemangiomas reach 80% of their maximum size by 5 months of age.4 Another possible benign tumor is infantile myofibromatosis, which is rare but is the most common fibrous tumor of infancy.5

Early-onset childhood sarcoidosis also has been shown to produce multiple nontender firm nodules.2 This process was considered unlikely in our patient because not only is the disease relatively rare in the pediatric population, but most reported childhood cases have occurred in patients aged 13 to 15 years.6 Additionally, no uveitis or arthritis was observed in this case.

Ultimately, histopathology and bone marrow biopsy were necessary to determine the diagnosis of B-ALL. Although uncommon, cutaneous involvement can be an early sign of ALL in children.7 Thus, neoplastic etiologies should be considered in the workup of cutaneous nodules in children, especially when these nodules are hard, rapidly growing, ulcerated, fixed, and/or vascular.8 Once the diagnosis is established, initial workup of ALL in children should include complete blood cell count with manual differential, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, electrolytes, uric acid, and renal and liver function tests. Often, baseline viral titers such as cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and varicella-zoster virus also are included. Patients are risk stratified to the appropriate level of treatment based on tumor immunophenotype, cytogenetic findings, patient age, white blood cell count at the time of diagnosis, and response to initial therapy. Treatment typically is comprised of a multidrug regimen divided into several phases--induction, consolidation, and maintenance--as well as therapy directed to the central nervous system. Treatment protocols usually take 2 to 3 years to complete.

Our patient was treated with 1 dose of intrathecal methotrexate before starting the Interfant-06 protocol with a 7-day methylprednisolone prophase. The patient's nodules shrank over time and were no longer present after 14 days of treatment.

- Dworzak MN, Schumich A, Printz D, et al. CD20 up-regulation in pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia during induction treatment: setting the stage for anti-CD20 directed immunotherapy. Blood. 2008;112:3982-3988.

- Whelan JP, Zembowicz A. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. case 19-2006. a 22-month-old boy with the rapid growth of subcutaneous nodules. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2697-2704.

- Malo J, Luraschi-Monjagatta C, Wolk DM, et al. Update on the diagnosis of pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:243-253.

- Chang LC, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, et al. Growth characteristics of infantile hemangiomas: implications for management. Pediatrics. 2008;122:360-367.

- Schurr P, Moulsdale W. Infantile myofibroma. Adv Neonatal Care. 2008;8:13-20.

- Shetty AK, Gedalia A. Childhood sarcoidosis: a rare but fascinating disorder. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2008;6:16.

- Millot F, Robert A, Bertrand Y, et al. Cutaneous involvement in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia or lymphoblastic lymphoma. The Children's Leukemia Cooperative Group of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Pediatrics. 1997;100:60-64.

- Fogelson S, Dohil M. Papular and nodular skin lesions in children. Semin Plast Surg. 2006;20:180-191.

The Diagnosis: B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

A 4-mm punch biopsy of one of the scalp lesions showed a diffuse infiltrate of intermediately sized cells with variably mature chromatin and irregular nuclear contours, consistent with a neoplastic process. Numerous mitotic figures were present, indicating a high proliferation rate (Figure 1). At that time there was no evidence of systemic involvement. A repeat biopsy with concurrent bone marrow biopsy was scheduled 10 days after the patient's initial presentation for further classification. Laboratory studies at that time revealed leukocytosis with elevated neutrophils and lymphocytes as well as a high absolute blast count.

On immunohistochemical staining, the neoplastic cells were positive for CD45, which indicated the neoplasm was hematopoietic, as well as CD10 and the B-cell antigens PAX-5 and CD79a. The cells were negative for CD20, which also is a B-cell marker, but this marker is only expressed in approximately half of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cases with B-cell precursor origin.1 Markers that typically are expressed in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL)--CD34 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase--were both negative. These results were somewhat contradictory, and the differential remained open to both B-ALL and mature B-cell lymphoma. A bone marrow biopsy showed approximately 65% blasts or leukemic cells (Figure 2). Flow cytometry showed the cells were positive for CD10, CD19, weak CD79a, and variable lambda surface antigen expression. The cells were negative for expression of CD20, CD34, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, myeloid antigens, and CD3. Ultimately, the morphology and immunophenotype were most consistent with a diagnosis of B-ALL. Fluorescence in situ hybridization revealed mixed lineage leukemia, MLL, gene rearrangements.

In general, when considering the differential diagnosis of superficial nodules, 5 elements are helpful to consider: the number of nodules (single vs multiple); the location; and the presence or absence of tenderness, pigmentation or erythema, and firmness.2 Our patient had multiple nodules on the scalp, which were erythematous to slightly purple and firm. The differential diagnosis can be categorized into malignant; infectious; and benign inflammatory, vascular, and fibrous tumors.

Potential oncologic processes include leukemia cutis, lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Initial laboratory test results were reassuring. Infectious processes in the differential include deep fungal infections such as coccidioidomycosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Coccidioidomycosis was the most likely to cause skin lesions or masses in our patient; however, it was considered less likely because the patient's family had not traveled or been exposed to an endemic area.3

Benign tumors in the differential include deep hemangioma, which was deemed less likely in our patient because most hemangiomas reach 80% of their maximum size by 5 months of age.4 Another possible benign tumor is infantile myofibromatosis, which is rare but is the most common fibrous tumor of infancy.5

Early-onset childhood sarcoidosis also has been shown to produce multiple nontender firm nodules.2 This process was considered unlikely in our patient because not only is the disease relatively rare in the pediatric population, but most reported childhood cases have occurred in patients aged 13 to 15 years.6 Additionally, no uveitis or arthritis was observed in this case.

Ultimately, histopathology and bone marrow biopsy were necessary to determine the diagnosis of B-ALL. Although uncommon, cutaneous involvement can be an early sign of ALL in children.7 Thus, neoplastic etiologies should be considered in the workup of cutaneous nodules in children, especially when these nodules are hard, rapidly growing, ulcerated, fixed, and/or vascular.8 Once the diagnosis is established, initial workup of ALL in children should include complete blood cell count with manual differential, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, electrolytes, uric acid, and renal and liver function tests. Often, baseline viral titers such as cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and varicella-zoster virus also are included. Patients are risk stratified to the appropriate level of treatment based on tumor immunophenotype, cytogenetic findings, patient age, white blood cell count at the time of diagnosis, and response to initial therapy. Treatment typically is comprised of a multidrug regimen divided into several phases--induction, consolidation, and maintenance--as well as therapy directed to the central nervous system. Treatment protocols usually take 2 to 3 years to complete.

Our patient was treated with 1 dose of intrathecal methotrexate before starting the Interfant-06 protocol with a 7-day methylprednisolone prophase. The patient's nodules shrank over time and were no longer present after 14 days of treatment.

The Diagnosis: B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

A 4-mm punch biopsy of one of the scalp lesions showed a diffuse infiltrate of intermediately sized cells with variably mature chromatin and irregular nuclear contours, consistent with a neoplastic process. Numerous mitotic figures were present, indicating a high proliferation rate (Figure 1). At that time there was no evidence of systemic involvement. A repeat biopsy with concurrent bone marrow biopsy was scheduled 10 days after the patient's initial presentation for further classification. Laboratory studies at that time revealed leukocytosis with elevated neutrophils and lymphocytes as well as a high absolute blast count.

On immunohistochemical staining, the neoplastic cells were positive for CD45, which indicated the neoplasm was hematopoietic, as well as CD10 and the B-cell antigens PAX-5 and CD79a. The cells were negative for CD20, which also is a B-cell marker, but this marker is only expressed in approximately half of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cases with B-cell precursor origin.1 Markers that typically are expressed in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL)--CD34 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase--were both negative. These results were somewhat contradictory, and the differential remained open to both B-ALL and mature B-cell lymphoma. A bone marrow biopsy showed approximately 65% blasts or leukemic cells (Figure 2). Flow cytometry showed the cells were positive for CD10, CD19, weak CD79a, and variable lambda surface antigen expression. The cells were negative for expression of CD20, CD34, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, myeloid antigens, and CD3. Ultimately, the morphology and immunophenotype were most consistent with a diagnosis of B-ALL. Fluorescence in situ hybridization revealed mixed lineage leukemia, MLL, gene rearrangements.

In general, when considering the differential diagnosis of superficial nodules, 5 elements are helpful to consider: the number of nodules (single vs multiple); the location; and the presence or absence of tenderness, pigmentation or erythema, and firmness.2 Our patient had multiple nodules on the scalp, which were erythematous to slightly purple and firm. The differential diagnosis can be categorized into malignant; infectious; and benign inflammatory, vascular, and fibrous tumors.

Potential oncologic processes include leukemia cutis, lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Initial laboratory test results were reassuring. Infectious processes in the differential include deep fungal infections such as coccidioidomycosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Coccidioidomycosis was the most likely to cause skin lesions or masses in our patient; however, it was considered less likely because the patient's family had not traveled or been exposed to an endemic area.3

Benign tumors in the differential include deep hemangioma, which was deemed less likely in our patient because most hemangiomas reach 80% of their maximum size by 5 months of age.4 Another possible benign tumor is infantile myofibromatosis, which is rare but is the most common fibrous tumor of infancy.5

Early-onset childhood sarcoidosis also has been shown to produce multiple nontender firm nodules.2 This process was considered unlikely in our patient because not only is the disease relatively rare in the pediatric population, but most reported childhood cases have occurred in patients aged 13 to 15 years.6 Additionally, no uveitis or arthritis was observed in this case.

Ultimately, histopathology and bone marrow biopsy were necessary to determine the diagnosis of B-ALL. Although uncommon, cutaneous involvement can be an early sign of ALL in children.7 Thus, neoplastic etiologies should be considered in the workup of cutaneous nodules in children, especially when these nodules are hard, rapidly growing, ulcerated, fixed, and/or vascular.8 Once the diagnosis is established, initial workup of ALL in children should include complete blood cell count with manual differential, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, electrolytes, uric acid, and renal and liver function tests. Often, baseline viral titers such as cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and varicella-zoster virus also are included. Patients are risk stratified to the appropriate level of treatment based on tumor immunophenotype, cytogenetic findings, patient age, white blood cell count at the time of diagnosis, and response to initial therapy. Treatment typically is comprised of a multidrug regimen divided into several phases--induction, consolidation, and maintenance--as well as therapy directed to the central nervous system. Treatment protocols usually take 2 to 3 years to complete.

Our patient was treated with 1 dose of intrathecal methotrexate before starting the Interfant-06 protocol with a 7-day methylprednisolone prophase. The patient's nodules shrank over time and were no longer present after 14 days of treatment.

- Dworzak MN, Schumich A, Printz D, et al. CD20 up-regulation in pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia during induction treatment: setting the stage for anti-CD20 directed immunotherapy. Blood. 2008;112:3982-3988.

- Whelan JP, Zembowicz A. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. case 19-2006. a 22-month-old boy with the rapid growth of subcutaneous nodules. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2697-2704.

- Malo J, Luraschi-Monjagatta C, Wolk DM, et al. Update on the diagnosis of pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:243-253.

- Chang LC, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, et al. Growth characteristics of infantile hemangiomas: implications for management. Pediatrics. 2008;122:360-367.

- Schurr P, Moulsdale W. Infantile myofibroma. Adv Neonatal Care. 2008;8:13-20.

- Shetty AK, Gedalia A. Childhood sarcoidosis: a rare but fascinating disorder. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2008;6:16.

- Millot F, Robert A, Bertrand Y, et al. Cutaneous involvement in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia or lymphoblastic lymphoma. The Children's Leukemia Cooperative Group of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Pediatrics. 1997;100:60-64.

- Fogelson S, Dohil M. Papular and nodular skin lesions in children. Semin Plast Surg. 2006;20:180-191.

- Dworzak MN, Schumich A, Printz D, et al. CD20 up-regulation in pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia during induction treatment: setting the stage for anti-CD20 directed immunotherapy. Blood. 2008;112:3982-3988.

- Whelan JP, Zembowicz A. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. case 19-2006. a 22-month-old boy with the rapid growth of subcutaneous nodules. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2697-2704.

- Malo J, Luraschi-Monjagatta C, Wolk DM, et al. Update on the diagnosis of pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:243-253.

- Chang LC, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, et al. Growth characteristics of infantile hemangiomas: implications for management. Pediatrics. 2008;122:360-367.

- Schurr P, Moulsdale W. Infantile myofibroma. Adv Neonatal Care. 2008;8:13-20.

- Shetty AK, Gedalia A. Childhood sarcoidosis: a rare but fascinating disorder. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2008;6:16.

- Millot F, Robert A, Bertrand Y, et al. Cutaneous involvement in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia or lymphoblastic lymphoma. The Children's Leukemia Cooperative Group of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Pediatrics. 1997;100:60-64.

- Fogelson S, Dohil M. Papular and nodular skin lesions in children. Semin Plast Surg. 2006;20:180-191.

An 8-month-old infant girl presented with rapidly growing cutaneous nodules on the scalp of 1 month's duration. Her parents reported that she disliked lying flat but was otherwise growing and developing normally. Nondiagnostic ultrasonography of the head and brain had been performed as well as a skull radiograph, which found no evidence of lytic lesions. On physical examination, 3 erythematous to violaceous, subcutaneous, firm, fixed nodules were observed on the scalp. Notable cervical lymphadenopathy with several distinct, fixed, firm, subcutaneous nodules in the postauricular lymph chains also were noted. The patient had no pertinent medical history and was born via normal spontaneous vaginal delivery to healthy parents. The remainder of the physical examination and review of systems was negative.

Painless Nodule on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Plasmablastic Lymphoma

Histopathologic examination revealed a diffuse dense proliferation of large, atypical, and pleomorphic mononuclear cells with prominent nucleoli and many mitotic figures representing plasmacytoid cells in the dermis (Figure). Immunostaining was positive for MUM-1 (marker of late-stage plasma cells and activated T cells) and BCL-2 (antiapoptotic marker). Fluorescent polymerase chain reaction was positive for clonal IgH gene arrangement, and fluorescence in situ hybridization was positive for C-MYC rearrangement in 94% of cells. Epstein-Barr encoding region in situ hybridization also was positive. Rare cells stained positive for T-cell markers. CD20, BCL-6, and CD30 immunostains were negative, suggesting that these cells were not B or T cells, though terminally differentiated B cells also can lack these markers. Bone marrow biopsy showed a similar staining pattern to the skin with 10% atypical plasmacytoid cells. Computed tomography of the left leg showed an enlargement of the semimembranosus muscle with internal areas of high density and heterogeneous enhancement. The patient underwent decompression of the left peroneal nerve. Biopsy showed a staining pattern similar to the right skin nodule and bone marrow, consistent with lymphoma.