User login

What Is Your Diagnosis? New World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

A 40-year-old man presented with a nonhealing ulcer on the right hand of 2 months’ duration. The lesion had started as a pruritic papule while he was visiting Guyana 2 months prior. The area had slowly enlarged with progressive ulceration. He denied any systemic signs including fever, chills, or weight loss, and his medical history was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed a 4-cm fungating ulceration with heaped-up borders on the dorsal aspect of the right hand.

The Diagnosis: New World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

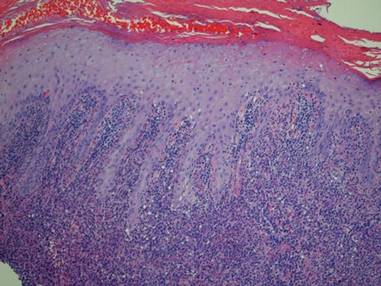

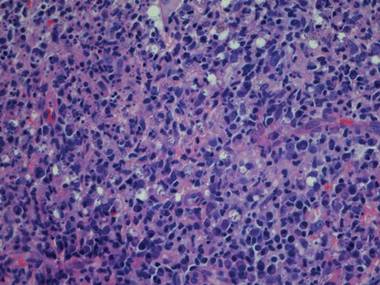

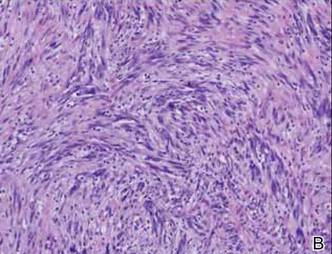

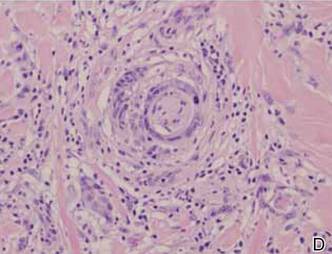

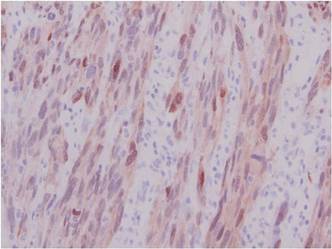

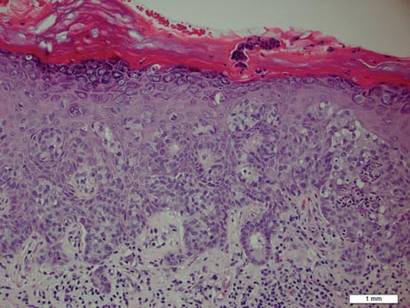

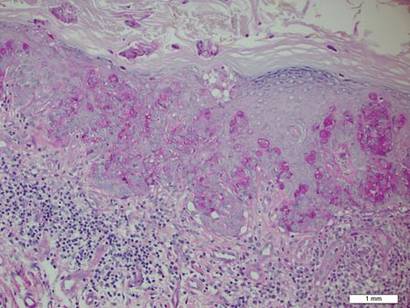

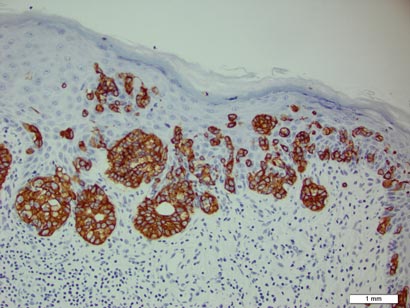

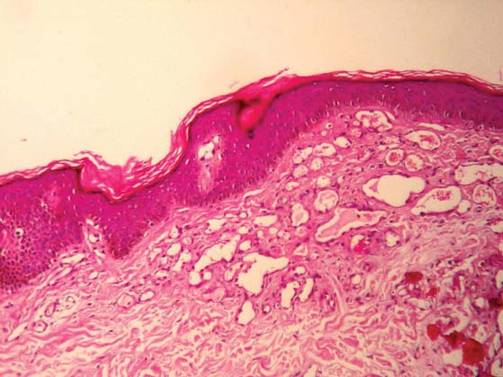

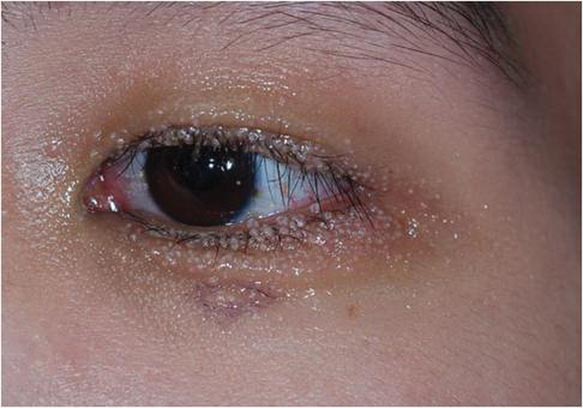

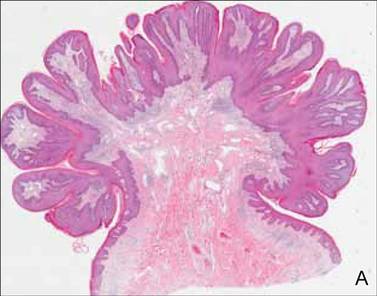

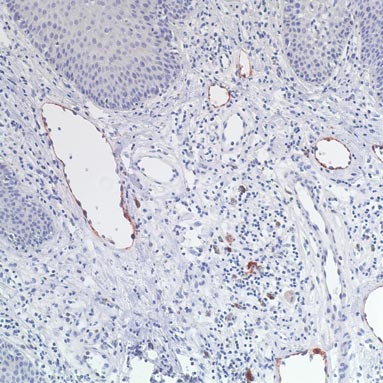

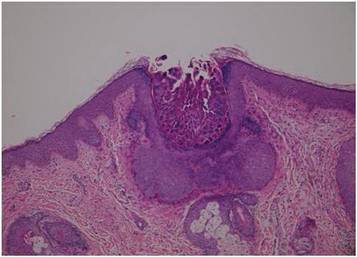

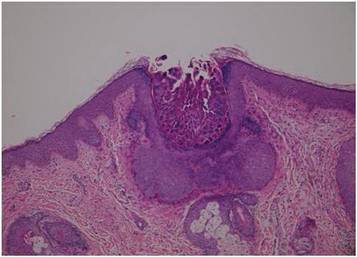

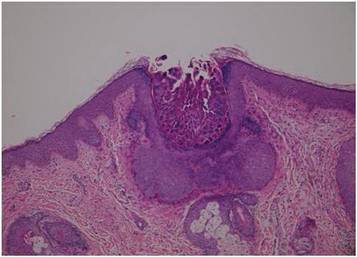

In addition to the ulceration on the right hand, a 2-cm ulcerated plaque also had developed on the right side of the chin a few days later (Figure 1). A biopsy was obtained from the lesion on the hand. Histopathologic examination revealed granulomatous inflammation with numerous histiocytes containing intracellular organisms (Figure 2). The microorganisms had pale pink nuclei with basophilic kinetoplasts (Figure 3). Tissue culture showed a mixed growth of gram-positive and gram-negative organisms but no predominant organism. Fungal and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of New World cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) was made due to visualization of intracellular microorganisms containing basophilic kinetoplasts. Polymerase chain reaction on the tissue block confirmed the presence of Leishmania guyanensis.

|

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is caused by protozoa from the Leishmania species and is transmitted by the bite of the female sandfly. There are 2 classifications for the disease: Old World and New World. Old World CL is transmitted by the sandfly of the genus Phlebotomus, which is endemic in Asia, Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East. New World CL is transmitted by the sandflies of the genus Lutzomyia, which are endemic in Mexico, Central America, and South America. There have been occasional cases of autochthonous transmission reported in Texas and Oklahoma,1 but there has been no known transmission of CL in Australia or the Pacific Islands.2 Human infection can be transmitted by 21 species of Leishmania and can be speciated by designated laboratories such as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (Silver Spring, Maryland) using tissue culture and polymerase chain reaction.1 The CDC can assist with the collection of specimens and supply of culture medium for cases occurring in the United States. Identification of the species is important because there are associated implications for treatment and prognosis.

There are 3 major forms of leishmaniasis: cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral. Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common form. There are approximately 1.5 million new cases of CL each year worldwide,3 and more than 90% of these cases occur in Afghanistan, Algeria, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Brazil, and Peru.1 New World CL is caused by 2 species complexes: Leishmania mexicana and Leishmania viannia, including the subspecies L guyanensis, which was seen in our patient.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis usually begins as a small, well-defined papule at the site of the insect bite that then enlarges and becomes a nodule or plaque. Next, the lesion becomes ulcerated with raised borders (Figure 1). The ulcer typically is painless unless there is secondary bacterial or fungal infection.3,4 The incubation period usually is 2 to 8 weeks and multiple lesions may be present, as seen in our patient.4

Old World CL can resolve without treatment, but New World CL is less likely to spontaneously resolve. Additionally, there is a greater risk for spread of the infection to mucous membranes or for systemic dissemination if New World CL is left untreated.2,5 Patients with multiple lesions (ie, ≥3); large lesions (ie, >2.5 cm); lesions on the face, hands, feet, or joints; and those who are immunocompromised should be treated promptly.2 Pentavalent antimonials (eg, meglumine antimoniate, sodium stibogluconate) are the treatment of choice for New World CL, except for infections caused by L guyanensis. The most common pentavalent antimonial agent used in the United States is sodium stibogluconate and is given at a standard intravenous dose of 20 mg antimony/kg daily for 20 days.2 The drug is only available through the CDC’s Drug Service under an Investigational New Drug protocol.1

Intramuscular pentamidine (3 mg/kg daily every other day for 4 doses) is the first-line treatment of CL caused by L guyanensis because systemic antimony usually is not effective.2,6,7 Intralesional injection with pentavalent antimonials usually is not recommended for treatment of New World CL because of the possibility of disseminated disease.2 Liposomal amphotericin B has mainly been used to treat visceral and mucosal leishmaniasis, but there have been some small studies and case reports that have showed it to be successful in treating CL.8-10 Larger controlled studies need to be performed. Oral antifungal drugs (eg, fluconazole, ketoconazole, itraconazole) also have been used to treat CL with variable results depending on the Leishmania species.11

There currently are no vaccines or drugs available to prevent against leishmaniasis. Preventive measures such as avoiding outdoor activities from dusk to dawn when sandflies are the most active, wearing protective clothing, and applying insect repellent that contains DEET (diethyltoluamide) can help reduce a traveler’s risk for becoming infected. Mosquito nets also should be treated with permethrin, which acts as an insect repellent, as sandflies are so small that they can penetrate mosquito nets.1,3,11

Acknowledgements—We would like to thank Francis Steurer, MS, and Barbara Herwaldt, MD, MPH, at the CDC in Atlanta, Georgia, for their help with the identification of the Leishmania species.

1. Herwaldt BL, Magill AJ. Infectious diseases related to travel: leishmaniasis, cutaneous. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2010/chapter-5/cutaneous-leish maniasis.htm. Published August 1, 2013. Accessed March 5, 2015.

2. Mitropolos P, Konidas P, Durkin-Konidas M. New World cutaneous leishmaniasis: updated review of current and future diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:309-322.

3. Hepburn NC. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an overview. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:50-54.

4. Markle WH, Makhoul K. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: recognition and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1455-1460.

5. Couppié P, Clyti E, Sainte Marie D, et al. Disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania guyanensis: case of a patient with 425 lesions. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:558-560.

6. Nacher M, Carme B, Sainte Marie D, et al. Influence of clinical presentation on the efficacy of a short course of pentamidine in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in French Guiana. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2001;95:331-336.

7. Minodier P, Parola P. Cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment. Trav Med Inf Dis. 2007;5:150-158.

8. Solomon M, Baum S, Barzilai A, et al. Liposomal amphotericin B in comparison to sodium stibogluconate for cutaneous infection due to Leishmania braziliensis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:612-616.

9. Konecny P, Stark DJ. An Australian case of New World cutaneous leishmaniasis. Med J Aust. 2007;186:315-317.

10. Brown M, Noursadeghi M, Boyle J, et al. Successful liposomal amphotericin B treatment of Leishmania braziliensis cutaneous leishmaniasis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:203-205.

11. Parasites: leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/index.html. Updated January 10, 2013. Accessed March 5, 2015.

A 40-year-old man presented with a nonhealing ulcer on the right hand of 2 months’ duration. The lesion had started as a pruritic papule while he was visiting Guyana 2 months prior. The area had slowly enlarged with progressive ulceration. He denied any systemic signs including fever, chills, or weight loss, and his medical history was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed a 4-cm fungating ulceration with heaped-up borders on the dorsal aspect of the right hand.

The Diagnosis: New World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

In addition to the ulceration on the right hand, a 2-cm ulcerated plaque also had developed on the right side of the chin a few days later (Figure 1). A biopsy was obtained from the lesion on the hand. Histopathologic examination revealed granulomatous inflammation with numerous histiocytes containing intracellular organisms (Figure 2). The microorganisms had pale pink nuclei with basophilic kinetoplasts (Figure 3). Tissue culture showed a mixed growth of gram-positive and gram-negative organisms but no predominant organism. Fungal and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of New World cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) was made due to visualization of intracellular microorganisms containing basophilic kinetoplasts. Polymerase chain reaction on the tissue block confirmed the presence of Leishmania guyanensis.

|

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is caused by protozoa from the Leishmania species and is transmitted by the bite of the female sandfly. There are 2 classifications for the disease: Old World and New World. Old World CL is transmitted by the sandfly of the genus Phlebotomus, which is endemic in Asia, Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East. New World CL is transmitted by the sandflies of the genus Lutzomyia, which are endemic in Mexico, Central America, and South America. There have been occasional cases of autochthonous transmission reported in Texas and Oklahoma,1 but there has been no known transmission of CL in Australia or the Pacific Islands.2 Human infection can be transmitted by 21 species of Leishmania and can be speciated by designated laboratories such as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (Silver Spring, Maryland) using tissue culture and polymerase chain reaction.1 The CDC can assist with the collection of specimens and supply of culture medium for cases occurring in the United States. Identification of the species is important because there are associated implications for treatment and prognosis.

There are 3 major forms of leishmaniasis: cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral. Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common form. There are approximately 1.5 million new cases of CL each year worldwide,3 and more than 90% of these cases occur in Afghanistan, Algeria, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Brazil, and Peru.1 New World CL is caused by 2 species complexes: Leishmania mexicana and Leishmania viannia, including the subspecies L guyanensis, which was seen in our patient.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis usually begins as a small, well-defined papule at the site of the insect bite that then enlarges and becomes a nodule or plaque. Next, the lesion becomes ulcerated with raised borders (Figure 1). The ulcer typically is painless unless there is secondary bacterial or fungal infection.3,4 The incubation period usually is 2 to 8 weeks and multiple lesions may be present, as seen in our patient.4

Old World CL can resolve without treatment, but New World CL is less likely to spontaneously resolve. Additionally, there is a greater risk for spread of the infection to mucous membranes or for systemic dissemination if New World CL is left untreated.2,5 Patients with multiple lesions (ie, ≥3); large lesions (ie, >2.5 cm); lesions on the face, hands, feet, or joints; and those who are immunocompromised should be treated promptly.2 Pentavalent antimonials (eg, meglumine antimoniate, sodium stibogluconate) are the treatment of choice for New World CL, except for infections caused by L guyanensis. The most common pentavalent antimonial agent used in the United States is sodium stibogluconate and is given at a standard intravenous dose of 20 mg antimony/kg daily for 20 days.2 The drug is only available through the CDC’s Drug Service under an Investigational New Drug protocol.1

Intramuscular pentamidine (3 mg/kg daily every other day for 4 doses) is the first-line treatment of CL caused by L guyanensis because systemic antimony usually is not effective.2,6,7 Intralesional injection with pentavalent antimonials usually is not recommended for treatment of New World CL because of the possibility of disseminated disease.2 Liposomal amphotericin B has mainly been used to treat visceral and mucosal leishmaniasis, but there have been some small studies and case reports that have showed it to be successful in treating CL.8-10 Larger controlled studies need to be performed. Oral antifungal drugs (eg, fluconazole, ketoconazole, itraconazole) also have been used to treat CL with variable results depending on the Leishmania species.11

There currently are no vaccines or drugs available to prevent against leishmaniasis. Preventive measures such as avoiding outdoor activities from dusk to dawn when sandflies are the most active, wearing protective clothing, and applying insect repellent that contains DEET (diethyltoluamide) can help reduce a traveler’s risk for becoming infected. Mosquito nets also should be treated with permethrin, which acts as an insect repellent, as sandflies are so small that they can penetrate mosquito nets.1,3,11

Acknowledgements—We would like to thank Francis Steurer, MS, and Barbara Herwaldt, MD, MPH, at the CDC in Atlanta, Georgia, for their help with the identification of the Leishmania species.

A 40-year-old man presented with a nonhealing ulcer on the right hand of 2 months’ duration. The lesion had started as a pruritic papule while he was visiting Guyana 2 months prior. The area had slowly enlarged with progressive ulceration. He denied any systemic signs including fever, chills, or weight loss, and his medical history was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed a 4-cm fungating ulceration with heaped-up borders on the dorsal aspect of the right hand.

The Diagnosis: New World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

In addition to the ulceration on the right hand, a 2-cm ulcerated plaque also had developed on the right side of the chin a few days later (Figure 1). A biopsy was obtained from the lesion on the hand. Histopathologic examination revealed granulomatous inflammation with numerous histiocytes containing intracellular organisms (Figure 2). The microorganisms had pale pink nuclei with basophilic kinetoplasts (Figure 3). Tissue culture showed a mixed growth of gram-positive and gram-negative organisms but no predominant organism. Fungal and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of New World cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) was made due to visualization of intracellular microorganisms containing basophilic kinetoplasts. Polymerase chain reaction on the tissue block confirmed the presence of Leishmania guyanensis.

|

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is caused by protozoa from the Leishmania species and is transmitted by the bite of the female sandfly. There are 2 classifications for the disease: Old World and New World. Old World CL is transmitted by the sandfly of the genus Phlebotomus, which is endemic in Asia, Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East. New World CL is transmitted by the sandflies of the genus Lutzomyia, which are endemic in Mexico, Central America, and South America. There have been occasional cases of autochthonous transmission reported in Texas and Oklahoma,1 but there has been no known transmission of CL in Australia or the Pacific Islands.2 Human infection can be transmitted by 21 species of Leishmania and can be speciated by designated laboratories such as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (Silver Spring, Maryland) using tissue culture and polymerase chain reaction.1 The CDC can assist with the collection of specimens and supply of culture medium for cases occurring in the United States. Identification of the species is important because there are associated implications for treatment and prognosis.

There are 3 major forms of leishmaniasis: cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral. Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common form. There are approximately 1.5 million new cases of CL each year worldwide,3 and more than 90% of these cases occur in Afghanistan, Algeria, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Brazil, and Peru.1 New World CL is caused by 2 species complexes: Leishmania mexicana and Leishmania viannia, including the subspecies L guyanensis, which was seen in our patient.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis usually begins as a small, well-defined papule at the site of the insect bite that then enlarges and becomes a nodule or plaque. Next, the lesion becomes ulcerated with raised borders (Figure 1). The ulcer typically is painless unless there is secondary bacterial or fungal infection.3,4 The incubation period usually is 2 to 8 weeks and multiple lesions may be present, as seen in our patient.4

Old World CL can resolve without treatment, but New World CL is less likely to spontaneously resolve. Additionally, there is a greater risk for spread of the infection to mucous membranes or for systemic dissemination if New World CL is left untreated.2,5 Patients with multiple lesions (ie, ≥3); large lesions (ie, >2.5 cm); lesions on the face, hands, feet, or joints; and those who are immunocompromised should be treated promptly.2 Pentavalent antimonials (eg, meglumine antimoniate, sodium stibogluconate) are the treatment of choice for New World CL, except for infections caused by L guyanensis. The most common pentavalent antimonial agent used in the United States is sodium stibogluconate and is given at a standard intravenous dose of 20 mg antimony/kg daily for 20 days.2 The drug is only available through the CDC’s Drug Service under an Investigational New Drug protocol.1

Intramuscular pentamidine (3 mg/kg daily every other day for 4 doses) is the first-line treatment of CL caused by L guyanensis because systemic antimony usually is not effective.2,6,7 Intralesional injection with pentavalent antimonials usually is not recommended for treatment of New World CL because of the possibility of disseminated disease.2 Liposomal amphotericin B has mainly been used to treat visceral and mucosal leishmaniasis, but there have been some small studies and case reports that have showed it to be successful in treating CL.8-10 Larger controlled studies need to be performed. Oral antifungal drugs (eg, fluconazole, ketoconazole, itraconazole) also have been used to treat CL with variable results depending on the Leishmania species.11

There currently are no vaccines or drugs available to prevent against leishmaniasis. Preventive measures such as avoiding outdoor activities from dusk to dawn when sandflies are the most active, wearing protective clothing, and applying insect repellent that contains DEET (diethyltoluamide) can help reduce a traveler’s risk for becoming infected. Mosquito nets also should be treated with permethrin, which acts as an insect repellent, as sandflies are so small that they can penetrate mosquito nets.1,3,11

Acknowledgements—We would like to thank Francis Steurer, MS, and Barbara Herwaldt, MD, MPH, at the CDC in Atlanta, Georgia, for their help with the identification of the Leishmania species.

1. Herwaldt BL, Magill AJ. Infectious diseases related to travel: leishmaniasis, cutaneous. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2010/chapter-5/cutaneous-leish maniasis.htm. Published August 1, 2013. Accessed March 5, 2015.

2. Mitropolos P, Konidas P, Durkin-Konidas M. New World cutaneous leishmaniasis: updated review of current and future diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:309-322.

3. Hepburn NC. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an overview. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:50-54.

4. Markle WH, Makhoul K. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: recognition and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1455-1460.

5. Couppié P, Clyti E, Sainte Marie D, et al. Disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania guyanensis: case of a patient with 425 lesions. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:558-560.

6. Nacher M, Carme B, Sainte Marie D, et al. Influence of clinical presentation on the efficacy of a short course of pentamidine in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in French Guiana. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2001;95:331-336.

7. Minodier P, Parola P. Cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment. Trav Med Inf Dis. 2007;5:150-158.

8. Solomon M, Baum S, Barzilai A, et al. Liposomal amphotericin B in comparison to sodium stibogluconate for cutaneous infection due to Leishmania braziliensis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:612-616.

9. Konecny P, Stark DJ. An Australian case of New World cutaneous leishmaniasis. Med J Aust. 2007;186:315-317.

10. Brown M, Noursadeghi M, Boyle J, et al. Successful liposomal amphotericin B treatment of Leishmania braziliensis cutaneous leishmaniasis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:203-205.

11. Parasites: leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/index.html. Updated January 10, 2013. Accessed March 5, 2015.

1. Herwaldt BL, Magill AJ. Infectious diseases related to travel: leishmaniasis, cutaneous. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2010/chapter-5/cutaneous-leish maniasis.htm. Published August 1, 2013. Accessed March 5, 2015.

2. Mitropolos P, Konidas P, Durkin-Konidas M. New World cutaneous leishmaniasis: updated review of current and future diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:309-322.

3. Hepburn NC. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an overview. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:50-54.

4. Markle WH, Makhoul K. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: recognition and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1455-1460.

5. Couppié P, Clyti E, Sainte Marie D, et al. Disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania guyanensis: case of a patient with 425 lesions. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:558-560.

6. Nacher M, Carme B, Sainte Marie D, et al. Influence of clinical presentation on the efficacy of a short course of pentamidine in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in French Guiana. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2001;95:331-336.

7. Minodier P, Parola P. Cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment. Trav Med Inf Dis. 2007;5:150-158.

8. Solomon M, Baum S, Barzilai A, et al. Liposomal amphotericin B in comparison to sodium stibogluconate for cutaneous infection due to Leishmania braziliensis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:612-616.

9. Konecny P, Stark DJ. An Australian case of New World cutaneous leishmaniasis. Med J Aust. 2007;186:315-317.

10. Brown M, Noursadeghi M, Boyle J, et al. Successful liposomal amphotericin B treatment of Leishmania braziliensis cutaneous leishmaniasis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:203-205.

11. Parasites: leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/index.html. Updated January 10, 2013. Accessed March 5, 2015.

Fibrous Forehead Plaque

The Diagnosis: Tuberous Sclerosis Complex

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous syndrome characterized by multiple hamartomas distributed in multiple organs of the body, most commonly the skin, brain, eyes, heart, kidneys, liver, and lungs. In 1908, Vogt1 elucidated the classic diagnostic triad of seizures, mental retardation, and facial angiofibromas (formerly termed adenoma sebaceum). However, the full triad is evident in only 29% of cases; 6% of TSC patients have none of these 3 findings.2 The disease is caused by alterations in 2 TSC genes, TSC1 and TSC2, on chromosomes 9 and 16, respectively. Both are tumor suppressor genes and mutations in either can be responsible for all the complications seen in the disease.3 The gene products of the 2 genes, hamartin and tuberin, appear to act together in the regulation of cell growth by inhibiting a substance known as the mechanistic target of rapamycin.4,5 Up to two-thirds of cases may occur from spontaneous mutations.2,6 The disease is extremely variable in its manifestations, particularly the skin manifestations. This discussion will review the many cutaneous manifestations of TSC, most of them documented in our patient, and their frequency of occurrence.

Early recognition of TSC is vital because prompt implementation of the recommended diagnostic evaluation (eg, neuroimaging studies, electroencephalogram, electrocardiography, renal ultrasonography, chest computed tomography) may prevent serious clinical consequences.7 Neurologic manifestations are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with TSC.2,8,9 Brain hamartomas in the form of cortical tubers, subependymal nodules, and subependymal giant cell astrocytomas often are responsible for intractable seizures, most commonly as infantile spasms. Approximately 90% to 96% of TSC patients have seizures.6 Renal manifestations are strongly associated with TSC. Angiomyolipoma is the most common renal lesion found in TSC patients.4,9,10 Up to 80% of patients have renal angiomyolipomas. Their incidence increases with age.4,11,12 Tuberous sclerosis complex is known as a cause of epilepsy and mental retardation, but renal disease is a major cause of morbidity.13 Cardiovascular manifestations often are the earliest diagnostic findings in patients with TSC. Rhabdomyoma is the most common primary cardiac tumor in infants and children.11,13,14 The most common ocular findings in TSC are retinal hamartomas, appearing in 40% to 50% of patients.15

Cutaneous features frequently occur and are the most clinically apparent findings of TSC; if overlooked, diagnosis could be delayed, which ultimately increases mortality. The diagnosis of TSC continues to be based primarily on clinical grounds because most patients older than 5 years demonstrate multiple skin lesions.6 In 1992, specific diagnostic clinical criteria were created for TSC, which stratified the clinical features of TSC into 3 tiers—primary, secondary, and tertiary—based on their specificity.16 In subsequent years, some of the classic clinical signs once regarded as pathognomonic for TSC, such as single ungual fibroma or multiple renal angiomyolipomas, were questioned. New modifications to the original diagnostic criteria were necessary given the advances in both TSC clinical information and molecular genetics. In the summer of 1998, a consensus conference held in Annapolis, Maryland, was assembled by the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance for the purpose of reevaluating and updating the clinical diagnostic criteria.7 The revised criteria were simplified into 2 main categories—major and minor features—based on the diagnostic importance and degree of specificity for TSC of each clinical and radiographic feature (Table 1). There are a number of considerations that merit close attention when applying these clinical criteria. Despite the large number of clinical features delineated, the diagnosis of TSC may be challenging early in life, particularly in patients younger than 2 years. The value of the clinical criteria for early diagnosis and prompt management of TSC is limited by the fact that many stigmata become apparent only in late childhood or adulthood. The lack of pathognomonic signs of TSC can add to the challenge of diagnosing subtle or atypical cases.6

A careful skin examination of individuals at risk for TSC is the best and the easiest method of establishing the diagnosis in most cases. According to Gomez,17 96% of patients with TSC have one or more main skin lesions of the disease, including facial angiofibromas, ungual fibromas, shagreen patches, or hypomelanotic macules. However, the diagnosis is more difficult in small children because many skin lesions become obvious with age; in fact, the full dermatological spectrum may never develop.17

Facial angiofibromas, also known as sebaceous adenomas, are the most visible and unsightly cutaneous manifestations of TSC, often resulting in stigmatization for both the affected individuals and their family members. These facial lesions often do not appear until late childhood or adulthood. In this case, the initial diagnosis often is made by the dermatologist who appreciates the significance of the white macules in a neonate. However, these hypomelanotic macules cannot be detected by the unaided eye, thus a physician would be wise to examine an infant with infantile spasms or mental retardation with a Wood lamp, which accentuates the lesions.2

Hypomelanotic macules were the overwhelmingly most common early findings in TSC. Infants with seizures or other possible stigmata of TSC should be carefully evaluated for these hypomelanotic macules as well as for other associated findings. Hypomelanotic macules can appear anywhere on the body, except the hands, feet, and genitalia; they are most commonly found on the lower extremities. Wood lamp examination reveals an accentuation of the hypopigmentation, which is a decrease in but not an absence of pigmentation. Lance ovate hypomelanotic macules are pathognomonic for TSC, thus the presence of 3 or more macules in an infant seriously suggests the diagnosis of TSC and echocardiography should be performed. The combination of white macules and seizures also increases the likelihood of TSC.18

Angiofibromas typically are found in the butterfly region of the face. Nico et al19 reported 2 patients with the complete syndrome of TSC who had multiple papules on the genital area in addition to classic facial lesions. Thus, it is important to examine the genital region of TSC patients and not misdiagnose these lesions as genital warts.

Jóźwiak et al18 screened 106 children with TSC and listed the prevalence of the most common cutaneous lesions. The results are presented in Table 2.

In a study by Webb et al,2 131 patients with TSC were examined and 126 (96%) exhibited skin signs. Although there was considerable variation in the age of expression of all the skin lesions, there was a trend toward the earlier expression of hypomelanotic macules and forehead fibrous plaques compared with facial angiofibromas and ungual fibromas. Shagreen patches usually were present by puberty. Ungual fibromas appeared for the first time as late as the fifth decade of life and were the only clinical feature in 3 patients. Ungual fibromas were present in 36% (47/131). Ten patients (8%) presented because of the skin manifestations and 21% (28/131) received treatment of symptomatic skin lesions. Two patients had large hamartomas at unusual sites, the occiput and forearm.2

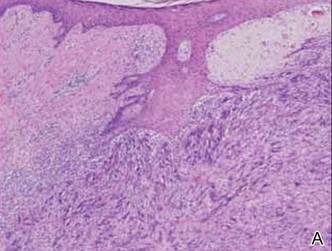

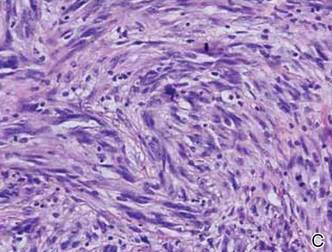

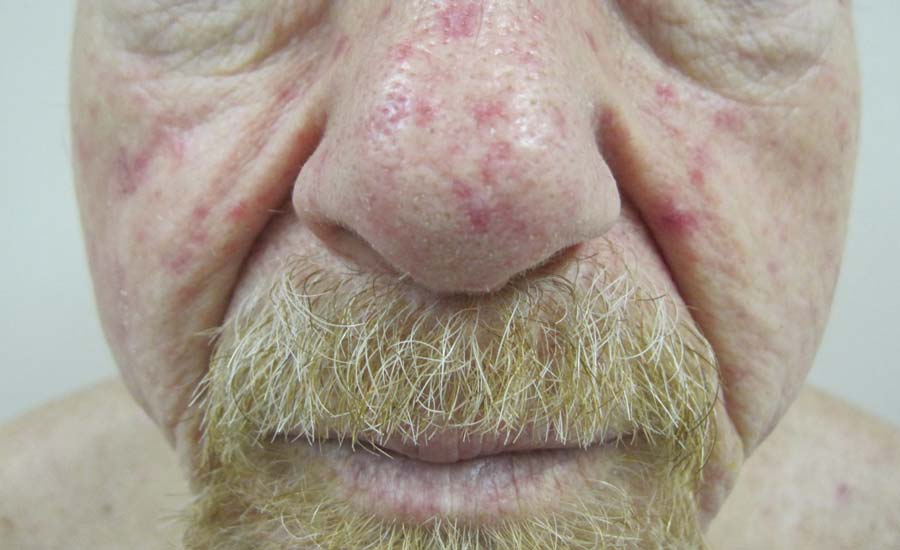

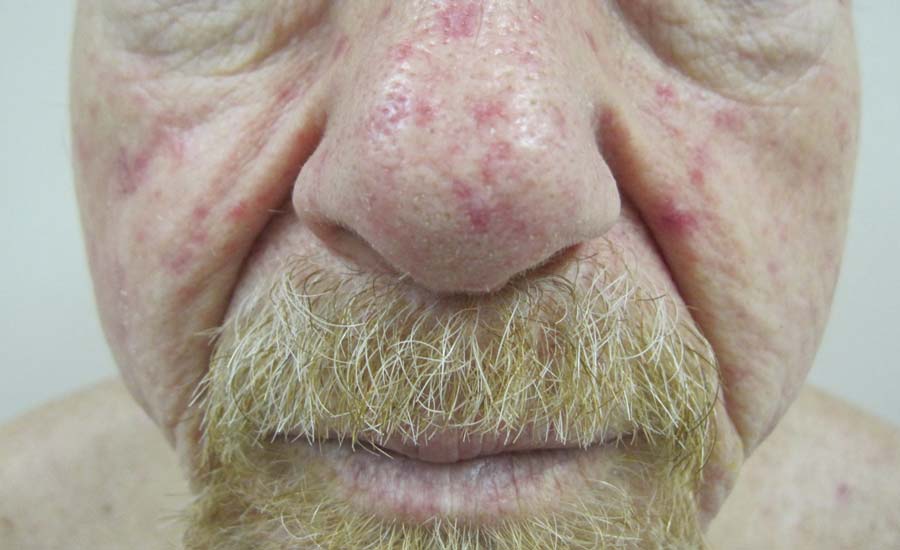

Our 30-year-old patient presented to our clinic accompanied by her grandmother who served as legal guardian and historian for the patient. The patient experienced her first seizure at 15 months of age. She was evaluated by the neurology department at that time and was diagnosed with epilepsy. In the months following, she developed strabismus of the eyes and was examined by the ophthalmology department. Retinal hamartomas were discovered and she was diagnosed with TSC. Her seizure disorder was managed by a neurologist with the use of topiramate. In her 20s, she had renal and cardiac workups, which were negative, and she continued to be free of any genitourinary or cardiac concerns. One year prior to presentation she underwent a brain computed tomography scan after a bicycle accident and was informed that she had “scarlike” lesions within the cerebral cortex. There was no known history of TSC in other family members. On physical examination, she was noted to be delayed in mental development and intelligence. She stated her first notable skin lesions appeared at 10 years of age and were skin tags of the upper back and neck and over the face. Soon after, the cheeks and nose developed numerous shiny brownish pink papules (Figure 1). Over the course of the next 20 years she developed other skin findings noted on our present skin examination. The superior aspect of the mid forehead revealed a 4×2-cm, raised, flesh-colored, firm tumorous plaque. The neck and upper back had multiple 2- to 5-mm, soft, pedunculated, polypoid, brownish pink papules. Her mid back revealed ill-defined, slightly elevated, rosy plaques and macules with a roughened speckled appearance (Figure 2). Several of the toenails and fingernails showed firm, fleshy, spiculelike papules around and under the nail bed (Figure 3). The lower anterior tibia revealed several oval-shaped, flat, well-demarcated, hypopigmented macules (Figure 4). Lesions on the face and mid back were biopsied and histopathology confirmed angiofibroma and shagreen patch, or connective tissue nevus, respectively. Our patient did not undergo treatment of any of these skin lesions, particularly the facial angiofibromas. Cosmetic treatment options such as laser or surgical removal were presented to her, but she declined.

|

|

A brief review of the literature for treatment options of facial angiofibromas and the fibrous forehead plaque indicated that current treatments include but are not limited to cryotherapy, electrocautery, electrosurgery, shave excision, chemical peels, argon laser, CO2 laser, and radiofrequency equipment.20 For the best outcome, these treatments have to be repeated throughout childhood and teenage years. Rapamycin, also known as sirolimus, and its analogs are new therapeutic options for TSC. Rapamycin is an inhibitor of the mechanistic target of rapamycin and can normalize this unregulated pathway in a TSC patient. Various preclinical models have shown that rapamycin treatment reduces TSC-related tumors, including brain, skin, and kidney tumors.21 A pilot study by Foster et al22 revealed improvement in the facial angiofibromas of 4 children treated with 2 topical preparations of rapamycin. The study revealed that younger patients with smaller angiofibromas had the best response with near-complete clearance. Rapamycin topical preparations were more cost effective than pulsed dye laser under general anesthesia.22

|

|

Tuberous sclerosis complex is not the only syndrome that can present with facial angiofibromas or numerous skin tag–type lesions such as those in our patient. It is important to also consider Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 in the differential diagnosis of multiple facial angiofibromas, particularly with adult onset.23

Our case was presented to review the cutaneous manifestations of TSC and their presentation frequency, with the intent to enable the dermatologist to make a more accurate and earlier diagnosis of TSC. In doing so, morbidity of TSC patients could be decreased and quality of life increased.

1. Vogt H. Zur Diagnostik der tuberosen sklerose. Z Erforsch Behandl Jugeudl Schwachsinns. 1908;2:1-6.

2. Webb DW, Clarke A, Fryer A, et al. The cutaneous features of tuberous sclerosis: a population study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:1-5.

3. van Slegtenhorst M, de Hoogt R, Hermans C, et al. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science. 1997;277:805-808.

4. O’Callaghan F. Tuberous sclerosis complex: from basic science to clinical phenotypes. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:985.

5. Kwiatkowski DJ. Tuberous sclerosis: from tubers to mTOR. Ann Hum Genet. 2003;67:87-96.

6. Schwartz RA. Tuberous sclerosis complex: advances in diagnosis, genetics, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:189-202.

7. Roach ES, Gomez MR, Northrup H. Tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference: revised clinical diagnostic criteria. J Child Neurol. 1998;13:624-628.

8. Tworetzky W, McElhinney DB, Margossian R, et al. Association between cardiac tumors and tuberous sclerosis in the fetus and neonate. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:487-489.

9. Casper KA, Donnelly LF, Chen B, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: renal imaging findings. Radiology. 2002;225:451-456.

10. El-Hashemite N, Zhang H, Henske EP, et al. Mutation in TSC2 and activation of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway in renal angiomyolipoma. Lancet. 2003;361:1348-1349.

11. Jóźwiak S, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK, et al. Usefulness of diagnostic criteria of tuberous sclerosis complex in pediatric patients. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:652-659.

12. Ewalt DH, Sheffield E, Sparagana SP, et al. Renal lesion growth in children with tuberous sclerosis complex. J Urol. 1998;160:141-145.

13. Webb DW, Thomas RD, Osborne JP. Cardiac rhabdomyomas and their association with tuberous sclerosis. Arch Dis Child. 1993;68:367-370.

14. Holley DG, Martin GR, Brenner JI, et al. Diagnosis and management of fetal cardiac tumors: a multicenter experience and review of published reports. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:516-520.

15. Robertson DM. Ophthalmic manifestations of tuberous sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615:17-25.

16. Roach ES, Smith M, Huttenlocher P, et al. Diagnostic criteria: tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 1992;7:221-224.

17. Gomez MR. Tuberous sclerosis. In: Gomez MR, ed. Neurocutaneous Diseases. A Practical Approach. Boston, MA: Butterworth; 1987:30-52.

18. Jóźwiak S, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK, et al. Skin lesions in children with tuberous sclerosis complex: their prevalence, natural course, and diagnostic significance. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:911-917.

19. Nico MM, Ito LM, Valente NY. Genital angiofibromas in tuberous sclerosis: two cases. J Dermatol. 1999;26:111-114.

20. Gomes AA, Gomes YV, Lima FB, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas treated with high frequency equipment. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:186-189.

21. Borkowska J, Schwartz RA, Kotulska K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: tumors and tumorigenesis. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:13-20.

22. Foster RS, Bint LJ, Halbert AR. Topical 0.1% rapamycin for angiofibromas in paediatric patients with tuberous sclerosis: a pilot study of four patients. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:52-56.

23. Schaffer JV, Gohara MA, McNiff JM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas: a cutaneous manifestation of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:108-111.

The Diagnosis: Tuberous Sclerosis Complex

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous syndrome characterized by multiple hamartomas distributed in multiple organs of the body, most commonly the skin, brain, eyes, heart, kidneys, liver, and lungs. In 1908, Vogt1 elucidated the classic diagnostic triad of seizures, mental retardation, and facial angiofibromas (formerly termed adenoma sebaceum). However, the full triad is evident in only 29% of cases; 6% of TSC patients have none of these 3 findings.2 The disease is caused by alterations in 2 TSC genes, TSC1 and TSC2, on chromosomes 9 and 16, respectively. Both are tumor suppressor genes and mutations in either can be responsible for all the complications seen in the disease.3 The gene products of the 2 genes, hamartin and tuberin, appear to act together in the regulation of cell growth by inhibiting a substance known as the mechanistic target of rapamycin.4,5 Up to two-thirds of cases may occur from spontaneous mutations.2,6 The disease is extremely variable in its manifestations, particularly the skin manifestations. This discussion will review the many cutaneous manifestations of TSC, most of them documented in our patient, and their frequency of occurrence.

Early recognition of TSC is vital because prompt implementation of the recommended diagnostic evaluation (eg, neuroimaging studies, electroencephalogram, electrocardiography, renal ultrasonography, chest computed tomography) may prevent serious clinical consequences.7 Neurologic manifestations are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with TSC.2,8,9 Brain hamartomas in the form of cortical tubers, subependymal nodules, and subependymal giant cell astrocytomas often are responsible for intractable seizures, most commonly as infantile spasms. Approximately 90% to 96% of TSC patients have seizures.6 Renal manifestations are strongly associated with TSC. Angiomyolipoma is the most common renal lesion found in TSC patients.4,9,10 Up to 80% of patients have renal angiomyolipomas. Their incidence increases with age.4,11,12 Tuberous sclerosis complex is known as a cause of epilepsy and mental retardation, but renal disease is a major cause of morbidity.13 Cardiovascular manifestations often are the earliest diagnostic findings in patients with TSC. Rhabdomyoma is the most common primary cardiac tumor in infants and children.11,13,14 The most common ocular findings in TSC are retinal hamartomas, appearing in 40% to 50% of patients.15

Cutaneous features frequently occur and are the most clinically apparent findings of TSC; if overlooked, diagnosis could be delayed, which ultimately increases mortality. The diagnosis of TSC continues to be based primarily on clinical grounds because most patients older than 5 years demonstrate multiple skin lesions.6 In 1992, specific diagnostic clinical criteria were created for TSC, which stratified the clinical features of TSC into 3 tiers—primary, secondary, and tertiary—based on their specificity.16 In subsequent years, some of the classic clinical signs once regarded as pathognomonic for TSC, such as single ungual fibroma or multiple renal angiomyolipomas, were questioned. New modifications to the original diagnostic criteria were necessary given the advances in both TSC clinical information and molecular genetics. In the summer of 1998, a consensus conference held in Annapolis, Maryland, was assembled by the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance for the purpose of reevaluating and updating the clinical diagnostic criteria.7 The revised criteria were simplified into 2 main categories—major and minor features—based on the diagnostic importance and degree of specificity for TSC of each clinical and radiographic feature (Table 1). There are a number of considerations that merit close attention when applying these clinical criteria. Despite the large number of clinical features delineated, the diagnosis of TSC may be challenging early in life, particularly in patients younger than 2 years. The value of the clinical criteria for early diagnosis and prompt management of TSC is limited by the fact that many stigmata become apparent only in late childhood or adulthood. The lack of pathognomonic signs of TSC can add to the challenge of diagnosing subtle or atypical cases.6

A careful skin examination of individuals at risk for TSC is the best and the easiest method of establishing the diagnosis in most cases. According to Gomez,17 96% of patients with TSC have one or more main skin lesions of the disease, including facial angiofibromas, ungual fibromas, shagreen patches, or hypomelanotic macules. However, the diagnosis is more difficult in small children because many skin lesions become obvious with age; in fact, the full dermatological spectrum may never develop.17

Facial angiofibromas, also known as sebaceous adenomas, are the most visible and unsightly cutaneous manifestations of TSC, often resulting in stigmatization for both the affected individuals and their family members. These facial lesions often do not appear until late childhood or adulthood. In this case, the initial diagnosis often is made by the dermatologist who appreciates the significance of the white macules in a neonate. However, these hypomelanotic macules cannot be detected by the unaided eye, thus a physician would be wise to examine an infant with infantile spasms or mental retardation with a Wood lamp, which accentuates the lesions.2

Hypomelanotic macules were the overwhelmingly most common early findings in TSC. Infants with seizures or other possible stigmata of TSC should be carefully evaluated for these hypomelanotic macules as well as for other associated findings. Hypomelanotic macules can appear anywhere on the body, except the hands, feet, and genitalia; they are most commonly found on the lower extremities. Wood lamp examination reveals an accentuation of the hypopigmentation, which is a decrease in but not an absence of pigmentation. Lance ovate hypomelanotic macules are pathognomonic for TSC, thus the presence of 3 or more macules in an infant seriously suggests the diagnosis of TSC and echocardiography should be performed. The combination of white macules and seizures also increases the likelihood of TSC.18

Angiofibromas typically are found in the butterfly region of the face. Nico et al19 reported 2 patients with the complete syndrome of TSC who had multiple papules on the genital area in addition to classic facial lesions. Thus, it is important to examine the genital region of TSC patients and not misdiagnose these lesions as genital warts.

Jóźwiak et al18 screened 106 children with TSC and listed the prevalence of the most common cutaneous lesions. The results are presented in Table 2.

In a study by Webb et al,2 131 patients with TSC were examined and 126 (96%) exhibited skin signs. Although there was considerable variation in the age of expression of all the skin lesions, there was a trend toward the earlier expression of hypomelanotic macules and forehead fibrous plaques compared with facial angiofibromas and ungual fibromas. Shagreen patches usually were present by puberty. Ungual fibromas appeared for the first time as late as the fifth decade of life and were the only clinical feature in 3 patients. Ungual fibromas were present in 36% (47/131). Ten patients (8%) presented because of the skin manifestations and 21% (28/131) received treatment of symptomatic skin lesions. Two patients had large hamartomas at unusual sites, the occiput and forearm.2

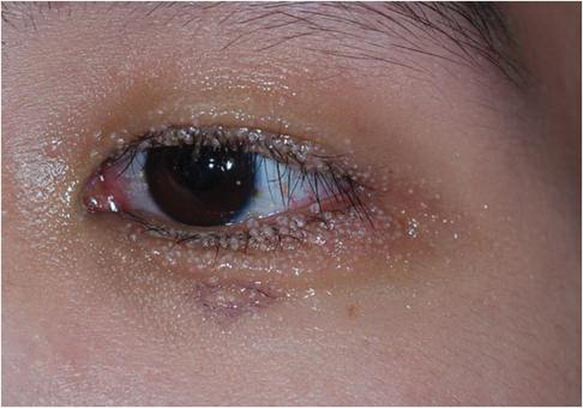

Our 30-year-old patient presented to our clinic accompanied by her grandmother who served as legal guardian and historian for the patient. The patient experienced her first seizure at 15 months of age. She was evaluated by the neurology department at that time and was diagnosed with epilepsy. In the months following, she developed strabismus of the eyes and was examined by the ophthalmology department. Retinal hamartomas were discovered and she was diagnosed with TSC. Her seizure disorder was managed by a neurologist with the use of topiramate. In her 20s, she had renal and cardiac workups, which were negative, and she continued to be free of any genitourinary or cardiac concerns. One year prior to presentation she underwent a brain computed tomography scan after a bicycle accident and was informed that she had “scarlike” lesions within the cerebral cortex. There was no known history of TSC in other family members. On physical examination, she was noted to be delayed in mental development and intelligence. She stated her first notable skin lesions appeared at 10 years of age and were skin tags of the upper back and neck and over the face. Soon after, the cheeks and nose developed numerous shiny brownish pink papules (Figure 1). Over the course of the next 20 years she developed other skin findings noted on our present skin examination. The superior aspect of the mid forehead revealed a 4×2-cm, raised, flesh-colored, firm tumorous plaque. The neck and upper back had multiple 2- to 5-mm, soft, pedunculated, polypoid, brownish pink papules. Her mid back revealed ill-defined, slightly elevated, rosy plaques and macules with a roughened speckled appearance (Figure 2). Several of the toenails and fingernails showed firm, fleshy, spiculelike papules around and under the nail bed (Figure 3). The lower anterior tibia revealed several oval-shaped, flat, well-demarcated, hypopigmented macules (Figure 4). Lesions on the face and mid back were biopsied and histopathology confirmed angiofibroma and shagreen patch, or connective tissue nevus, respectively. Our patient did not undergo treatment of any of these skin lesions, particularly the facial angiofibromas. Cosmetic treatment options such as laser or surgical removal were presented to her, but she declined.

|

|

A brief review of the literature for treatment options of facial angiofibromas and the fibrous forehead plaque indicated that current treatments include but are not limited to cryotherapy, electrocautery, electrosurgery, shave excision, chemical peels, argon laser, CO2 laser, and radiofrequency equipment.20 For the best outcome, these treatments have to be repeated throughout childhood and teenage years. Rapamycin, also known as sirolimus, and its analogs are new therapeutic options for TSC. Rapamycin is an inhibitor of the mechanistic target of rapamycin and can normalize this unregulated pathway in a TSC patient. Various preclinical models have shown that rapamycin treatment reduces TSC-related tumors, including brain, skin, and kidney tumors.21 A pilot study by Foster et al22 revealed improvement in the facial angiofibromas of 4 children treated with 2 topical preparations of rapamycin. The study revealed that younger patients with smaller angiofibromas had the best response with near-complete clearance. Rapamycin topical preparations were more cost effective than pulsed dye laser under general anesthesia.22

|

|

Tuberous sclerosis complex is not the only syndrome that can present with facial angiofibromas or numerous skin tag–type lesions such as those in our patient. It is important to also consider Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 in the differential diagnosis of multiple facial angiofibromas, particularly with adult onset.23

Our case was presented to review the cutaneous manifestations of TSC and their presentation frequency, with the intent to enable the dermatologist to make a more accurate and earlier diagnosis of TSC. In doing so, morbidity of TSC patients could be decreased and quality of life increased.

The Diagnosis: Tuberous Sclerosis Complex

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous syndrome characterized by multiple hamartomas distributed in multiple organs of the body, most commonly the skin, brain, eyes, heart, kidneys, liver, and lungs. In 1908, Vogt1 elucidated the classic diagnostic triad of seizures, mental retardation, and facial angiofibromas (formerly termed adenoma sebaceum). However, the full triad is evident in only 29% of cases; 6% of TSC patients have none of these 3 findings.2 The disease is caused by alterations in 2 TSC genes, TSC1 and TSC2, on chromosomes 9 and 16, respectively. Both are tumor suppressor genes and mutations in either can be responsible for all the complications seen in the disease.3 The gene products of the 2 genes, hamartin and tuberin, appear to act together in the regulation of cell growth by inhibiting a substance known as the mechanistic target of rapamycin.4,5 Up to two-thirds of cases may occur from spontaneous mutations.2,6 The disease is extremely variable in its manifestations, particularly the skin manifestations. This discussion will review the many cutaneous manifestations of TSC, most of them documented in our patient, and their frequency of occurrence.

Early recognition of TSC is vital because prompt implementation of the recommended diagnostic evaluation (eg, neuroimaging studies, electroencephalogram, electrocardiography, renal ultrasonography, chest computed tomography) may prevent serious clinical consequences.7 Neurologic manifestations are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with TSC.2,8,9 Brain hamartomas in the form of cortical tubers, subependymal nodules, and subependymal giant cell astrocytomas often are responsible for intractable seizures, most commonly as infantile spasms. Approximately 90% to 96% of TSC patients have seizures.6 Renal manifestations are strongly associated with TSC. Angiomyolipoma is the most common renal lesion found in TSC patients.4,9,10 Up to 80% of patients have renal angiomyolipomas. Their incidence increases with age.4,11,12 Tuberous sclerosis complex is known as a cause of epilepsy and mental retardation, but renal disease is a major cause of morbidity.13 Cardiovascular manifestations often are the earliest diagnostic findings in patients with TSC. Rhabdomyoma is the most common primary cardiac tumor in infants and children.11,13,14 The most common ocular findings in TSC are retinal hamartomas, appearing in 40% to 50% of patients.15

Cutaneous features frequently occur and are the most clinically apparent findings of TSC; if overlooked, diagnosis could be delayed, which ultimately increases mortality. The diagnosis of TSC continues to be based primarily on clinical grounds because most patients older than 5 years demonstrate multiple skin lesions.6 In 1992, specific diagnostic clinical criteria were created for TSC, which stratified the clinical features of TSC into 3 tiers—primary, secondary, and tertiary—based on their specificity.16 In subsequent years, some of the classic clinical signs once regarded as pathognomonic for TSC, such as single ungual fibroma or multiple renal angiomyolipomas, were questioned. New modifications to the original diagnostic criteria were necessary given the advances in both TSC clinical information and molecular genetics. In the summer of 1998, a consensus conference held in Annapolis, Maryland, was assembled by the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance for the purpose of reevaluating and updating the clinical diagnostic criteria.7 The revised criteria were simplified into 2 main categories—major and minor features—based on the diagnostic importance and degree of specificity for TSC of each clinical and radiographic feature (Table 1). There are a number of considerations that merit close attention when applying these clinical criteria. Despite the large number of clinical features delineated, the diagnosis of TSC may be challenging early in life, particularly in patients younger than 2 years. The value of the clinical criteria for early diagnosis and prompt management of TSC is limited by the fact that many stigmata become apparent only in late childhood or adulthood. The lack of pathognomonic signs of TSC can add to the challenge of diagnosing subtle or atypical cases.6

A careful skin examination of individuals at risk for TSC is the best and the easiest method of establishing the diagnosis in most cases. According to Gomez,17 96% of patients with TSC have one or more main skin lesions of the disease, including facial angiofibromas, ungual fibromas, shagreen patches, or hypomelanotic macules. However, the diagnosis is more difficult in small children because many skin lesions become obvious with age; in fact, the full dermatological spectrum may never develop.17

Facial angiofibromas, also known as sebaceous adenomas, are the most visible and unsightly cutaneous manifestations of TSC, often resulting in stigmatization for both the affected individuals and their family members. These facial lesions often do not appear until late childhood or adulthood. In this case, the initial diagnosis often is made by the dermatologist who appreciates the significance of the white macules in a neonate. However, these hypomelanotic macules cannot be detected by the unaided eye, thus a physician would be wise to examine an infant with infantile spasms or mental retardation with a Wood lamp, which accentuates the lesions.2

Hypomelanotic macules were the overwhelmingly most common early findings in TSC. Infants with seizures or other possible stigmata of TSC should be carefully evaluated for these hypomelanotic macules as well as for other associated findings. Hypomelanotic macules can appear anywhere on the body, except the hands, feet, and genitalia; they are most commonly found on the lower extremities. Wood lamp examination reveals an accentuation of the hypopigmentation, which is a decrease in but not an absence of pigmentation. Lance ovate hypomelanotic macules are pathognomonic for TSC, thus the presence of 3 or more macules in an infant seriously suggests the diagnosis of TSC and echocardiography should be performed. The combination of white macules and seizures also increases the likelihood of TSC.18

Angiofibromas typically are found in the butterfly region of the face. Nico et al19 reported 2 patients with the complete syndrome of TSC who had multiple papules on the genital area in addition to classic facial lesions. Thus, it is important to examine the genital region of TSC patients and not misdiagnose these lesions as genital warts.

Jóźwiak et al18 screened 106 children with TSC and listed the prevalence of the most common cutaneous lesions. The results are presented in Table 2.

In a study by Webb et al,2 131 patients with TSC were examined and 126 (96%) exhibited skin signs. Although there was considerable variation in the age of expression of all the skin lesions, there was a trend toward the earlier expression of hypomelanotic macules and forehead fibrous plaques compared with facial angiofibromas and ungual fibromas. Shagreen patches usually were present by puberty. Ungual fibromas appeared for the first time as late as the fifth decade of life and were the only clinical feature in 3 patients. Ungual fibromas were present in 36% (47/131). Ten patients (8%) presented because of the skin manifestations and 21% (28/131) received treatment of symptomatic skin lesions. Two patients had large hamartomas at unusual sites, the occiput and forearm.2

Our 30-year-old patient presented to our clinic accompanied by her grandmother who served as legal guardian and historian for the patient. The patient experienced her first seizure at 15 months of age. She was evaluated by the neurology department at that time and was diagnosed with epilepsy. In the months following, she developed strabismus of the eyes and was examined by the ophthalmology department. Retinal hamartomas were discovered and she was diagnosed with TSC. Her seizure disorder was managed by a neurologist with the use of topiramate. In her 20s, she had renal and cardiac workups, which were negative, and she continued to be free of any genitourinary or cardiac concerns. One year prior to presentation she underwent a brain computed tomography scan after a bicycle accident and was informed that she had “scarlike” lesions within the cerebral cortex. There was no known history of TSC in other family members. On physical examination, she was noted to be delayed in mental development and intelligence. She stated her first notable skin lesions appeared at 10 years of age and were skin tags of the upper back and neck and over the face. Soon after, the cheeks and nose developed numerous shiny brownish pink papules (Figure 1). Over the course of the next 20 years she developed other skin findings noted on our present skin examination. The superior aspect of the mid forehead revealed a 4×2-cm, raised, flesh-colored, firm tumorous plaque. The neck and upper back had multiple 2- to 5-mm, soft, pedunculated, polypoid, brownish pink papules. Her mid back revealed ill-defined, slightly elevated, rosy plaques and macules with a roughened speckled appearance (Figure 2). Several of the toenails and fingernails showed firm, fleshy, spiculelike papules around and under the nail bed (Figure 3). The lower anterior tibia revealed several oval-shaped, flat, well-demarcated, hypopigmented macules (Figure 4). Lesions on the face and mid back were biopsied and histopathology confirmed angiofibroma and shagreen patch, or connective tissue nevus, respectively. Our patient did not undergo treatment of any of these skin lesions, particularly the facial angiofibromas. Cosmetic treatment options such as laser or surgical removal were presented to her, but she declined.

|

|

A brief review of the literature for treatment options of facial angiofibromas and the fibrous forehead plaque indicated that current treatments include but are not limited to cryotherapy, electrocautery, electrosurgery, shave excision, chemical peels, argon laser, CO2 laser, and radiofrequency equipment.20 For the best outcome, these treatments have to be repeated throughout childhood and teenage years. Rapamycin, also known as sirolimus, and its analogs are new therapeutic options for TSC. Rapamycin is an inhibitor of the mechanistic target of rapamycin and can normalize this unregulated pathway in a TSC patient. Various preclinical models have shown that rapamycin treatment reduces TSC-related tumors, including brain, skin, and kidney tumors.21 A pilot study by Foster et al22 revealed improvement in the facial angiofibromas of 4 children treated with 2 topical preparations of rapamycin. The study revealed that younger patients with smaller angiofibromas had the best response with near-complete clearance. Rapamycin topical preparations were more cost effective than pulsed dye laser under general anesthesia.22

|

|

Tuberous sclerosis complex is not the only syndrome that can present with facial angiofibromas or numerous skin tag–type lesions such as those in our patient. It is important to also consider Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 in the differential diagnosis of multiple facial angiofibromas, particularly with adult onset.23

Our case was presented to review the cutaneous manifestations of TSC and their presentation frequency, with the intent to enable the dermatologist to make a more accurate and earlier diagnosis of TSC. In doing so, morbidity of TSC patients could be decreased and quality of life increased.

1. Vogt H. Zur Diagnostik der tuberosen sklerose. Z Erforsch Behandl Jugeudl Schwachsinns. 1908;2:1-6.

2. Webb DW, Clarke A, Fryer A, et al. The cutaneous features of tuberous sclerosis: a population study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:1-5.

3. van Slegtenhorst M, de Hoogt R, Hermans C, et al. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science. 1997;277:805-808.

4. O’Callaghan F. Tuberous sclerosis complex: from basic science to clinical phenotypes. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:985.

5. Kwiatkowski DJ. Tuberous sclerosis: from tubers to mTOR. Ann Hum Genet. 2003;67:87-96.

6. Schwartz RA. Tuberous sclerosis complex: advances in diagnosis, genetics, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:189-202.

7. Roach ES, Gomez MR, Northrup H. Tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference: revised clinical diagnostic criteria. J Child Neurol. 1998;13:624-628.

8. Tworetzky W, McElhinney DB, Margossian R, et al. Association between cardiac tumors and tuberous sclerosis in the fetus and neonate. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:487-489.

9. Casper KA, Donnelly LF, Chen B, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: renal imaging findings. Radiology. 2002;225:451-456.

10. El-Hashemite N, Zhang H, Henske EP, et al. Mutation in TSC2 and activation of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway in renal angiomyolipoma. Lancet. 2003;361:1348-1349.

11. Jóźwiak S, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK, et al. Usefulness of diagnostic criteria of tuberous sclerosis complex in pediatric patients. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:652-659.

12. Ewalt DH, Sheffield E, Sparagana SP, et al. Renal lesion growth in children with tuberous sclerosis complex. J Urol. 1998;160:141-145.

13. Webb DW, Thomas RD, Osborne JP. Cardiac rhabdomyomas and their association with tuberous sclerosis. Arch Dis Child. 1993;68:367-370.

14. Holley DG, Martin GR, Brenner JI, et al. Diagnosis and management of fetal cardiac tumors: a multicenter experience and review of published reports. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:516-520.

15. Robertson DM. Ophthalmic manifestations of tuberous sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615:17-25.

16. Roach ES, Smith M, Huttenlocher P, et al. Diagnostic criteria: tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 1992;7:221-224.

17. Gomez MR. Tuberous sclerosis. In: Gomez MR, ed. Neurocutaneous Diseases. A Practical Approach. Boston, MA: Butterworth; 1987:30-52.

18. Jóźwiak S, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK, et al. Skin lesions in children with tuberous sclerosis complex: their prevalence, natural course, and diagnostic significance. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:911-917.

19. Nico MM, Ito LM, Valente NY. Genital angiofibromas in tuberous sclerosis: two cases. J Dermatol. 1999;26:111-114.

20. Gomes AA, Gomes YV, Lima FB, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas treated with high frequency equipment. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:186-189.

21. Borkowska J, Schwartz RA, Kotulska K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: tumors and tumorigenesis. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:13-20.

22. Foster RS, Bint LJ, Halbert AR. Topical 0.1% rapamycin for angiofibromas in paediatric patients with tuberous sclerosis: a pilot study of four patients. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:52-56.

23. Schaffer JV, Gohara MA, McNiff JM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas: a cutaneous manifestation of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:108-111.

1. Vogt H. Zur Diagnostik der tuberosen sklerose. Z Erforsch Behandl Jugeudl Schwachsinns. 1908;2:1-6.

2. Webb DW, Clarke A, Fryer A, et al. The cutaneous features of tuberous sclerosis: a population study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:1-5.

3. van Slegtenhorst M, de Hoogt R, Hermans C, et al. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science. 1997;277:805-808.

4. O’Callaghan F. Tuberous sclerosis complex: from basic science to clinical phenotypes. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:985.

5. Kwiatkowski DJ. Tuberous sclerosis: from tubers to mTOR. Ann Hum Genet. 2003;67:87-96.

6. Schwartz RA. Tuberous sclerosis complex: advances in diagnosis, genetics, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:189-202.

7. Roach ES, Gomez MR, Northrup H. Tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference: revised clinical diagnostic criteria. J Child Neurol. 1998;13:624-628.

8. Tworetzky W, McElhinney DB, Margossian R, et al. Association between cardiac tumors and tuberous sclerosis in the fetus and neonate. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:487-489.

9. Casper KA, Donnelly LF, Chen B, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: renal imaging findings. Radiology. 2002;225:451-456.

10. El-Hashemite N, Zhang H, Henske EP, et al. Mutation in TSC2 and activation of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway in renal angiomyolipoma. Lancet. 2003;361:1348-1349.

11. Jóźwiak S, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK, et al. Usefulness of diagnostic criteria of tuberous sclerosis complex in pediatric patients. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:652-659.

12. Ewalt DH, Sheffield E, Sparagana SP, et al. Renal lesion growth in children with tuberous sclerosis complex. J Urol. 1998;160:141-145.

13. Webb DW, Thomas RD, Osborne JP. Cardiac rhabdomyomas and their association with tuberous sclerosis. Arch Dis Child. 1993;68:367-370.

14. Holley DG, Martin GR, Brenner JI, et al. Diagnosis and management of fetal cardiac tumors: a multicenter experience and review of published reports. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:516-520.

15. Robertson DM. Ophthalmic manifestations of tuberous sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615:17-25.

16. Roach ES, Smith M, Huttenlocher P, et al. Diagnostic criteria: tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 1992;7:221-224.

17. Gomez MR. Tuberous sclerosis. In: Gomez MR, ed. Neurocutaneous Diseases. A Practical Approach. Boston, MA: Butterworth; 1987:30-52.

18. Jóźwiak S, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK, et al. Skin lesions in children with tuberous sclerosis complex: their prevalence, natural course, and diagnostic significance. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:911-917.

19. Nico MM, Ito LM, Valente NY. Genital angiofibromas in tuberous sclerosis: two cases. J Dermatol. 1999;26:111-114.

20. Gomes AA, Gomes YV, Lima FB, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas treated with high frequency equipment. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:186-189.

21. Borkowska J, Schwartz RA, Kotulska K, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex: tumors and tumorigenesis. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:13-20.

22. Foster RS, Bint LJ, Halbert AR. Topical 0.1% rapamycin for angiofibromas in paediatric patients with tuberous sclerosis: a pilot study of four patients. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:52-56.

23. Schaffer JV, Gohara MA, McNiff JM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas: a cutaneous manifestation of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:108-111.

A 30-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation and treatment options of a large 4×2-cm, firm, flesh-colored plaque on the superior aspect of the mid forehead. The plaque initially presented at 10 years of age and had grown since then. She reported no prior treatment of this nontender lesion and denied a family history of skin problems. She also had numerous skin tags all over the face, neck, and upper back that had increased in number for most of her adult life. In reviewing her medical history, she reported experiencing her first seizure at 15 months of age. She was evaluated by the neurology department at that time and was diagnosed with epilepsy.

Painful Purpura and Cutaneous Necrosis

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Contaminated Cocaine

Physical examination revealed scattered palpable purpura including the nasal tip and large necrotizing skin lesions with bullae (Figure 1). Retiform purpura was noted on the patient’s trunk and legs. Purpuric plaques in various stages of necrosis were identified on the arms, trunk, breasts, and thighs, with an early lesion involving the left ear (Figure 2). Vitals revealed a blood pressure of 151/79 mm Hg and a temperature of 37.3°C. Although the patient initially denied illicit drug use, she later admitted to smoking crack cocaine prior to the skin eruption.

|

Levamisole, an agent used in the veterinary setting to deworm cattle and pigs, is a common additive found in nearly 77% of the seized cocaine supplies in the United States.1 Because of its immunomodulator effects, the agent was once used in humans to treat conditions such as colon cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and nephritic syndrome. Therapeutic levamisole use has been associated with purpura on the external ears, cheeks, and nasal tip. The predilection for purpura on the ears was first described in children using levam-isole as treatment of nephritic syndrome.2 Antinuclear cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) and antiphospholipid antibodies also were associated with therapeutic use.3 Reported effects of levamisole in cocaine users include fever, agranulocytosis, and infection. The mechanism is currently unknown but is thought to be an immunological process as evidenced by the presence of positive autoantibodies.4 Characteristic purpura in a cocaine abuser should alert the physician to consider levamisole as the culprit.

The diagnosis is largely a clinical one and other serious etiologies must be ruled out. The differential should include purpura fulminans, a rare hemorrhagic condition caused by severe infection, such as meningococcemia or deficiency of the vitamin K–dependent anticoagulants protein C and protein S. Given our patient’s history of hepatitis, purpura fulminans could have been likely. Purpura fulminans is rapidly progressive and is usually accompanied by disseminated intravascular coagulation. Coagulation studies and evidence of a consumptive coagulopathy such as thrombocytopenia, prolonged partial thromboplastin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time would favor this diagnosis. These studies as well as protein C and protein S were normal in our patient. Mixed cryoglobulinemia also should be suspected in a patient with hepatitis C virus who presents with vasculitis and arthralgia. An undetectable viral load in addition to a negative assay for cryoglobulins and normal complement (C3 and C4) levels make this diagnosis unlikely. Further, the purpura in cryoglobulinemia is typically confined to the lower extremities.5 Warfarin-induced skin necrosis also should be considered in patients who are taking warfarin.

Laboratory tests can be used to confirm the presence of infection, agranulocytosis, and coagulopathy. Although urine drug screen can confirm exposure to cocaine, levamisole is not detected in routine toxicology screening. Its half-life is between 5 and 6 hours; therefore, detection in blood or urine should be done within 48 hours of exposure.3,4 Unfortunately, our patient presented 2 weeks after cocaine use, making detection of levamisole unfeasible. Rheumatologic screening also is appropriate in cases of suspected vasculitis. Our patient had a negative antinuclear antibody but tested positive for lupus anticoagulant and perinuclear ANCA. IgA and IgG anticardiolipin were negative with an indeterminate IgM anticardiolipin level. The literature supports these findings, as ANCA antibodies occurred in more than 90% of reported cases.3 Further, IgM anticardiolipin antibodies and lupus anticoagulant were positive in 65% and 51% of cases, respectively.3 Leukocyte and neutrophil count were normal in our patient.

Management of these patients is mainly supportive. Complete avoidance of the offending agent is absolutely essential for resolution and avoidance of recurrence. Provided that the patient abstains from cocaine, the skin findings typically resolve in 2 to 3 weeks.3,6 The antibodies, however, may be present for up to 14 months.2,3,6 Treatment with steroids and other immunosuppressants has been reported, but evidence is lacking on their role in the resolution of the lesions.3 In patients who develop a temporary antiphospholipid syndrome, aspirin may be recommended as a preventative measure.6 Pain management, treatment of secondary infection especially in situations with agranulocytosis, and surgical debridement of wounds are all potential problems that can arise.

Our patient had complete resolution of the purpura involving the nose and ear over the course of 3 weeks. She did, however, have to undergo surgical debridement of the nonhealing full-thickness necrotic lesions on her legs and arms.

The 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health estimates 1.5 million individuals aged 12 years or older were current (within the last month) users of cocaine.7 With levamisole becoming more prevalent in cocaine supplies, clinicians should be aware of this emerging condition. Rapid recognition can spare the patient unnecessary testing and inappropriate treatment regimens. Because testing for levamisole is difficult and not routinely performed, this case highlights the importance of clinical clues and an accurate social history in clinching the diagnosis.

1. National drug threat assessment: 2011. National Drug Intelligence Center Web site. http://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44849/44849p.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed March 9, 2015.

2. Rongioletti F, Gio L, Ginevri F, et al. Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating long-term treatment with levamisole in children. Br J Dermatol. 1999;40:948-951.

3. Gulati S, Donato AA. Lupus anticoagulant and ANCA associated thrombotic vasculopathy due to cocaine contaminated with levamisole: a case report and review of the literature. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2012;34:7-10.

4. de la Hera I, Sanz V, Cullen D, et al. Necrosis of ears after cocaine probably adulterated with levamisole. Dermatology. 2011;223:25-28.

5. Seo P. Immune complex-mediated vasculitis. In: Klippel JH. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases. 13th ed. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; 2008:427-443.

6. Ching JA, Smith DS. Levamisole-induced necrosis of skin, soft tissue, and bone: case report and review of literature. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e1-e5.

7. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Contaminated Cocaine

Physical examination revealed scattered palpable purpura including the nasal tip and large necrotizing skin lesions with bullae (Figure 1). Retiform purpura was noted on the patient’s trunk and legs. Purpuric plaques in various stages of necrosis were identified on the arms, trunk, breasts, and thighs, with an early lesion involving the left ear (Figure 2). Vitals revealed a blood pressure of 151/79 mm Hg and a temperature of 37.3°C. Although the patient initially denied illicit drug use, she later admitted to smoking crack cocaine prior to the skin eruption.

|

Levamisole, an agent used in the veterinary setting to deworm cattle and pigs, is a common additive found in nearly 77% of the seized cocaine supplies in the United States.1 Because of its immunomodulator effects, the agent was once used in humans to treat conditions such as colon cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and nephritic syndrome. Therapeutic levamisole use has been associated with purpura on the external ears, cheeks, and nasal tip. The predilection for purpura on the ears was first described in children using levam-isole as treatment of nephritic syndrome.2 Antinuclear cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) and antiphospholipid antibodies also were associated with therapeutic use.3 Reported effects of levamisole in cocaine users include fever, agranulocytosis, and infection. The mechanism is currently unknown but is thought to be an immunological process as evidenced by the presence of positive autoantibodies.4 Characteristic purpura in a cocaine abuser should alert the physician to consider levamisole as the culprit.

The diagnosis is largely a clinical one and other serious etiologies must be ruled out. The differential should include purpura fulminans, a rare hemorrhagic condition caused by severe infection, such as meningococcemia or deficiency of the vitamin K–dependent anticoagulants protein C and protein S. Given our patient’s history of hepatitis, purpura fulminans could have been likely. Purpura fulminans is rapidly progressive and is usually accompanied by disseminated intravascular coagulation. Coagulation studies and evidence of a consumptive coagulopathy such as thrombocytopenia, prolonged partial thromboplastin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time would favor this diagnosis. These studies as well as protein C and protein S were normal in our patient. Mixed cryoglobulinemia also should be suspected in a patient with hepatitis C virus who presents with vasculitis and arthralgia. An undetectable viral load in addition to a negative assay for cryoglobulins and normal complement (C3 and C4) levels make this diagnosis unlikely. Further, the purpura in cryoglobulinemia is typically confined to the lower extremities.5 Warfarin-induced skin necrosis also should be considered in patients who are taking warfarin.