User login

Tense Bullae With Widespread Erosions

The Diagnosis: Linear IgA Bullous Dermatosis

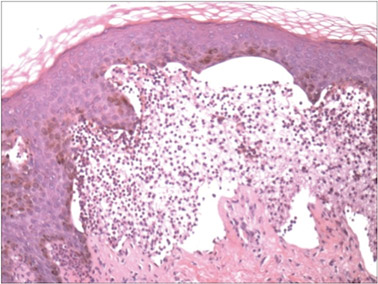

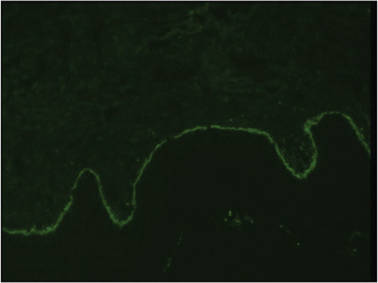

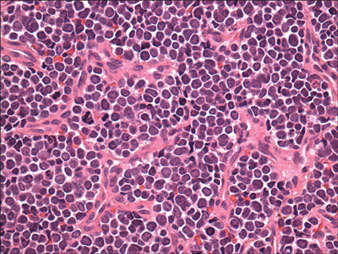

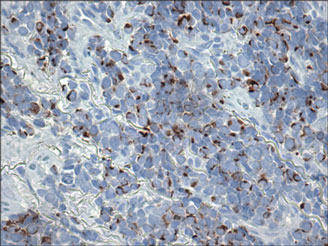

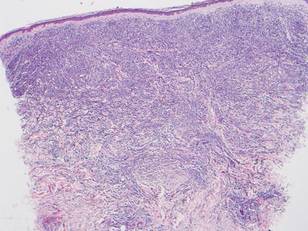

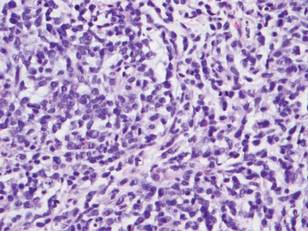

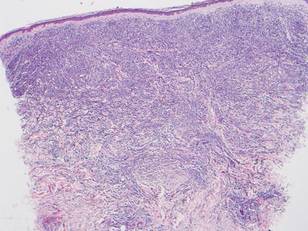

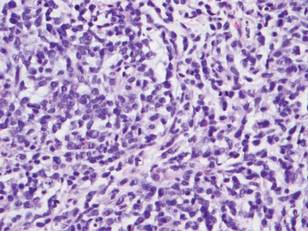

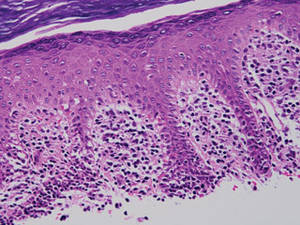

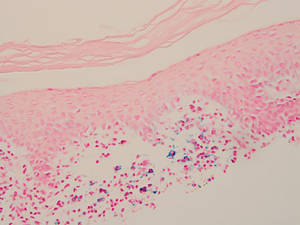

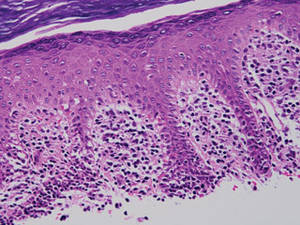

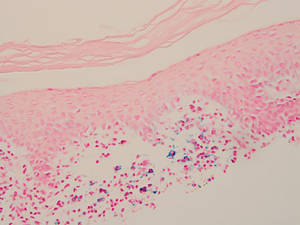

A biopsy specimen from an intact vesicle was obtained. Histologic findings showed a basket weave stratum corneum suggestive of an acute process. There was subepidermal separation with an inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence yielded a pattern of IgA deposition along the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD) was made. The patient was started on 100 mg daily of dapsone. The dose was subsequently increased to 175 mg twice daily, resulting in complete clearance. He became dermatologically disease free after 10 months and the dapsone was successfully tapered.

|

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease with linear IgA deposits found along the basement membrane of the skin. There are 3 major categories of LABD: drug induced, systemic disorder related, and idiopathic.1 Patients with LABD present with a pruritic vesicobullous eruption that tends to favor the trunk, proximal extremities, and acral regions of the body. Mucous membrane lesions are present in less than 50% of patients.2 Linear IgA bullous dermatosis may resemble bullous pemphigoid, erythema multiforme, dermatitis herpetiformis, or toxic epidermal necrolysis. The gold standard for diagnosis is immunofluorescence staining that shows linear IgA deposition along the skin’s basement membrane.1 Prognosis for LABD is variable; there is risk for persistence and scarring.2 The drug-induced form of LABD is associated with clearance with the removal of the inciting agent.1

There are several autoimmune disorders that have been described in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).3 Autoimmune bullous dermatoses, while described, are very uncommon in the setting of HIV infection. Previously reported cases include bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, pemphigus herpetiformis, pemphigus vegetans, pemphigus vulgaris, and cicatricial pemphigoid.4-12 The presentation of LABD in an HIV-positive patient is extremely rare.

There are 3 proposed mechanisms by which HIV and autoimmune bullous dermatoses coexist: unregulated B-cell activation, loss of T-suppressor cell regulation, and molecular mimicry. In patients with HIV, infected macrophages increase production of IL-1 and IL-6, causing nonspecific stimulation of B cells. Further production of tumor necrosis factor and other lymphotoxins may kill CD8+ T-suppressor cells, which further reduces B-cell regulation and production of nonspecific antibodies. Unregulated B-cell activation could lead to proliferation of antiself-specific B cells and autoantibodies. Additionally, various autoantibodies may arise due to mimicry between HIV antigens and human proteins. Some of the antibodies produced may be cytotoxic antilymphocyte antibodies that further disrupt B-cell regulation.13,14

Zandman-Goddard and Shoenfeld14 proposed a staging system of autoimmune disease and HIV with respect to CD4 count and viral load. Stage I is clinical latency of HIV, with a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and high viral load, which correlates with an acute infection of HIV and an intact immune system. Autoimmune disease can be seen in this stage. Stage II is cellular response, a quiescent period without overt manifestations of AIDS. The CD4 count is declining (200–499 cells/mm3), indicating immunosuppression, and the viral count is high. Autoimmune disease can occur and typically includes immune complex–mediated disease and vasculitis. Stage III is immune deficiency. The CD4 count is low (<200 cells/mm3), viral load is high, and AIDS develops. Autoimmune disease is not seen during this stage. Stage IV is the period of immune restoration following the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy. There is a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and low viral load. There is a resurgence of autoimmune disease in this stage. Autoimmune disease can occur with an immune system capable of B- and T-cell interactions and a normal CD4 count. Autoimmunity is possible in stages I, II, and IV.14 Our patient developed bullous disease in stage II.

Although uncommon, autoimmune disease is possible in the setting of immune deficiency. The presence of autoimmune disease in a patient with HIV can only be seen during certain stages of infection. Knowledge of the possible scenarios of autoimmune disease can assist the clinician with monitoring status of the HIV infection or immune reconstitution.

1. Bouldin MB, Clowers-Webb HE, Davis JL, et al. Naproxen-associated linear IgA bullous dermatosis: case report and review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:967-970.

2. Nousari HC, Kimyai-Asadi A, Caeiro JP, et al. Clinical, demographic, and immunohistologic features of vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous disease of the skin: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 1999;78:1-8.

3. Gala S, Fulcher DA. How HIV leads to autoimmune disorders. Med J Aust. 1996;164:224-226.

4. Lateef A, Packles MR, White SM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in association with human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:778-781.

5. Levy PM, Balavoine JF, Salomon D, et al. Ritodrine-responsive bullous pemphigoing in a patient with AIDS-related complex. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:635-636.

6. Bull RH, Fallowfield ME, Marsden RA. Autoimmune blistering diseases associated with HIV infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:47-50.

7. Chou K, Kauh YC, Jacoby RA, et al. Autoimmune bullous disease in a patient with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:1022-1023.

8. Mahé A, Flageul B, Prost C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in an HIV-1-infected man. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:447.

9. Capizzi R, Marasca G, De Luca A, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in a human-immunodeficiency-virus-infected patient. Dermatology. 1998;197:97-98.

10. Splaver A, Silos S, Lowell B, et al. Case report: pemphigus vulgaris in a patient infected with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:295-296.

11. Hodgson TA, Fidler SJ, Speight PM, et al. Oral pemphigus vulgaris associated with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:313-315.

12. Demathé A, Arede LT, Miyahara GI. Mucous membrane pemphigoid in HIV patient: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:345.

13. Etzioni A. Immune deficiency and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2003;2:364-369.

14. Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y. HIV and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2002;1:329-337.

The Diagnosis: Linear IgA Bullous Dermatosis

A biopsy specimen from an intact vesicle was obtained. Histologic findings showed a basket weave stratum corneum suggestive of an acute process. There was subepidermal separation with an inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence yielded a pattern of IgA deposition along the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD) was made. The patient was started on 100 mg daily of dapsone. The dose was subsequently increased to 175 mg twice daily, resulting in complete clearance. He became dermatologically disease free after 10 months and the dapsone was successfully tapered.

|

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease with linear IgA deposits found along the basement membrane of the skin. There are 3 major categories of LABD: drug induced, systemic disorder related, and idiopathic.1 Patients with LABD present with a pruritic vesicobullous eruption that tends to favor the trunk, proximal extremities, and acral regions of the body. Mucous membrane lesions are present in less than 50% of patients.2 Linear IgA bullous dermatosis may resemble bullous pemphigoid, erythema multiforme, dermatitis herpetiformis, or toxic epidermal necrolysis. The gold standard for diagnosis is immunofluorescence staining that shows linear IgA deposition along the skin’s basement membrane.1 Prognosis for LABD is variable; there is risk for persistence and scarring.2 The drug-induced form of LABD is associated with clearance with the removal of the inciting agent.1

There are several autoimmune disorders that have been described in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).3 Autoimmune bullous dermatoses, while described, are very uncommon in the setting of HIV infection. Previously reported cases include bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, pemphigus herpetiformis, pemphigus vegetans, pemphigus vulgaris, and cicatricial pemphigoid.4-12 The presentation of LABD in an HIV-positive patient is extremely rare.

There are 3 proposed mechanisms by which HIV and autoimmune bullous dermatoses coexist: unregulated B-cell activation, loss of T-suppressor cell regulation, and molecular mimicry. In patients with HIV, infected macrophages increase production of IL-1 and IL-6, causing nonspecific stimulation of B cells. Further production of tumor necrosis factor and other lymphotoxins may kill CD8+ T-suppressor cells, which further reduces B-cell regulation and production of nonspecific antibodies. Unregulated B-cell activation could lead to proliferation of antiself-specific B cells and autoantibodies. Additionally, various autoantibodies may arise due to mimicry between HIV antigens and human proteins. Some of the antibodies produced may be cytotoxic antilymphocyte antibodies that further disrupt B-cell regulation.13,14

Zandman-Goddard and Shoenfeld14 proposed a staging system of autoimmune disease and HIV with respect to CD4 count and viral load. Stage I is clinical latency of HIV, with a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and high viral load, which correlates with an acute infection of HIV and an intact immune system. Autoimmune disease can be seen in this stage. Stage II is cellular response, a quiescent period without overt manifestations of AIDS. The CD4 count is declining (200–499 cells/mm3), indicating immunosuppression, and the viral count is high. Autoimmune disease can occur and typically includes immune complex–mediated disease and vasculitis. Stage III is immune deficiency. The CD4 count is low (<200 cells/mm3), viral load is high, and AIDS develops. Autoimmune disease is not seen during this stage. Stage IV is the period of immune restoration following the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy. There is a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and low viral load. There is a resurgence of autoimmune disease in this stage. Autoimmune disease can occur with an immune system capable of B- and T-cell interactions and a normal CD4 count. Autoimmunity is possible in stages I, II, and IV.14 Our patient developed bullous disease in stage II.

Although uncommon, autoimmune disease is possible in the setting of immune deficiency. The presence of autoimmune disease in a patient with HIV can only be seen during certain stages of infection. Knowledge of the possible scenarios of autoimmune disease can assist the clinician with monitoring status of the HIV infection or immune reconstitution.

The Diagnosis: Linear IgA Bullous Dermatosis

A biopsy specimen from an intact vesicle was obtained. Histologic findings showed a basket weave stratum corneum suggestive of an acute process. There was subepidermal separation with an inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence yielded a pattern of IgA deposition along the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD) was made. The patient was started on 100 mg daily of dapsone. The dose was subsequently increased to 175 mg twice daily, resulting in complete clearance. He became dermatologically disease free after 10 months and the dapsone was successfully tapered.

|

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease with linear IgA deposits found along the basement membrane of the skin. There are 3 major categories of LABD: drug induced, systemic disorder related, and idiopathic.1 Patients with LABD present with a pruritic vesicobullous eruption that tends to favor the trunk, proximal extremities, and acral regions of the body. Mucous membrane lesions are present in less than 50% of patients.2 Linear IgA bullous dermatosis may resemble bullous pemphigoid, erythema multiforme, dermatitis herpetiformis, or toxic epidermal necrolysis. The gold standard for diagnosis is immunofluorescence staining that shows linear IgA deposition along the skin’s basement membrane.1 Prognosis for LABD is variable; there is risk for persistence and scarring.2 The drug-induced form of LABD is associated with clearance with the removal of the inciting agent.1

There are several autoimmune disorders that have been described in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).3 Autoimmune bullous dermatoses, while described, are very uncommon in the setting of HIV infection. Previously reported cases include bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, pemphigus herpetiformis, pemphigus vegetans, pemphigus vulgaris, and cicatricial pemphigoid.4-12 The presentation of LABD in an HIV-positive patient is extremely rare.

There are 3 proposed mechanisms by which HIV and autoimmune bullous dermatoses coexist: unregulated B-cell activation, loss of T-suppressor cell regulation, and molecular mimicry. In patients with HIV, infected macrophages increase production of IL-1 and IL-6, causing nonspecific stimulation of B cells. Further production of tumor necrosis factor and other lymphotoxins may kill CD8+ T-suppressor cells, which further reduces B-cell regulation and production of nonspecific antibodies. Unregulated B-cell activation could lead to proliferation of antiself-specific B cells and autoantibodies. Additionally, various autoantibodies may arise due to mimicry between HIV antigens and human proteins. Some of the antibodies produced may be cytotoxic antilymphocyte antibodies that further disrupt B-cell regulation.13,14

Zandman-Goddard and Shoenfeld14 proposed a staging system of autoimmune disease and HIV with respect to CD4 count and viral load. Stage I is clinical latency of HIV, with a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and high viral load, which correlates with an acute infection of HIV and an intact immune system. Autoimmune disease can be seen in this stage. Stage II is cellular response, a quiescent period without overt manifestations of AIDS. The CD4 count is declining (200–499 cells/mm3), indicating immunosuppression, and the viral count is high. Autoimmune disease can occur and typically includes immune complex–mediated disease and vasculitis. Stage III is immune deficiency. The CD4 count is low (<200 cells/mm3), viral load is high, and AIDS develops. Autoimmune disease is not seen during this stage. Stage IV is the period of immune restoration following the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy. There is a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and low viral load. There is a resurgence of autoimmune disease in this stage. Autoimmune disease can occur with an immune system capable of B- and T-cell interactions and a normal CD4 count. Autoimmunity is possible in stages I, II, and IV.14 Our patient developed bullous disease in stage II.

Although uncommon, autoimmune disease is possible in the setting of immune deficiency. The presence of autoimmune disease in a patient with HIV can only be seen during certain stages of infection. Knowledge of the possible scenarios of autoimmune disease can assist the clinician with monitoring status of the HIV infection or immune reconstitution.

1. Bouldin MB, Clowers-Webb HE, Davis JL, et al. Naproxen-associated linear IgA bullous dermatosis: case report and review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:967-970.

2. Nousari HC, Kimyai-Asadi A, Caeiro JP, et al. Clinical, demographic, and immunohistologic features of vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous disease of the skin: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 1999;78:1-8.

3. Gala S, Fulcher DA. How HIV leads to autoimmune disorders. Med J Aust. 1996;164:224-226.

4. Lateef A, Packles MR, White SM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in association with human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:778-781.

5. Levy PM, Balavoine JF, Salomon D, et al. Ritodrine-responsive bullous pemphigoing in a patient with AIDS-related complex. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:635-636.

6. Bull RH, Fallowfield ME, Marsden RA. Autoimmune blistering diseases associated with HIV infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:47-50.

7. Chou K, Kauh YC, Jacoby RA, et al. Autoimmune bullous disease in a patient with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:1022-1023.

8. Mahé A, Flageul B, Prost C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in an HIV-1-infected man. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:447.

9. Capizzi R, Marasca G, De Luca A, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in a human-immunodeficiency-virus-infected patient. Dermatology. 1998;197:97-98.

10. Splaver A, Silos S, Lowell B, et al. Case report: pemphigus vulgaris in a patient infected with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:295-296.

11. Hodgson TA, Fidler SJ, Speight PM, et al. Oral pemphigus vulgaris associated with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:313-315.

12. Demathé A, Arede LT, Miyahara GI. Mucous membrane pemphigoid in HIV patient: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:345.

13. Etzioni A. Immune deficiency and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2003;2:364-369.

14. Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y. HIV and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2002;1:329-337.

1. Bouldin MB, Clowers-Webb HE, Davis JL, et al. Naproxen-associated linear IgA bullous dermatosis: case report and review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:967-970.

2. Nousari HC, Kimyai-Asadi A, Caeiro JP, et al. Clinical, demographic, and immunohistologic features of vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous disease of the skin: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 1999;78:1-8.

3. Gala S, Fulcher DA. How HIV leads to autoimmune disorders. Med J Aust. 1996;164:224-226.

4. Lateef A, Packles MR, White SM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in association with human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:778-781.

5. Levy PM, Balavoine JF, Salomon D, et al. Ritodrine-responsive bullous pemphigoing in a patient with AIDS-related complex. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:635-636.

6. Bull RH, Fallowfield ME, Marsden RA. Autoimmune blistering diseases associated with HIV infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:47-50.

7. Chou K, Kauh YC, Jacoby RA, et al. Autoimmune bullous disease in a patient with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:1022-1023.

8. Mahé A, Flageul B, Prost C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in an HIV-1-infected man. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:447.

9. Capizzi R, Marasca G, De Luca A, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in a human-immunodeficiency-virus-infected patient. Dermatology. 1998;197:97-98.

10. Splaver A, Silos S, Lowell B, et al. Case report: pemphigus vulgaris in a patient infected with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:295-296.

11. Hodgson TA, Fidler SJ, Speight PM, et al. Oral pemphigus vulgaris associated with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:313-315.

12. Demathé A, Arede LT, Miyahara GI. Mucous membrane pemphigoid in HIV patient: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:345.

13. Etzioni A. Immune deficiency and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2003;2:364-369.

14. Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y. HIV and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2002;1:329-337.

A 50-year-old black man presented with a new-onset widespread pruritic bullous eruption 7 months after being diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus. The CD4 lymphocyte count was 421 cells/mm3 and viral load was 7818 copies/mL. Results of a viral culture were negative for herpes simplex virus. Dermatologic examination revealed numerous intact tense bullae as well as scattered erosions on the trunk and extremities. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was prominent, with some areas of hypopigmentation and depigmentation.

Lobular-Appearing Nodule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Dermal Cylindroma

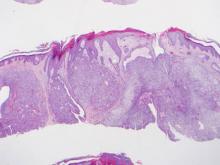

Microsopic evaluation of a tangential biopsy revealed findings of a dermal process consisting of well-circumscribed islands of pale and darker blue cells with little cytoplasm outlined by a hyaline basement membrane (Figure). These cellular islands were arranged in a jigsawlike configuration. These findings were thought to be consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma.

|

Cylindromas are benign appendageal neoplasms with a somewhat controversial histogenesis. Munger and colleagues1 investigated the pattern of acid mucopolysaccharide secretion by these tumors in association with prosecretory vacuoles in proximity to the Golgi apparatus, which led to their impression that cylindromas most resemble eccrine rather than apocrine sweat glands. Other researchers, however, have concluded that cylindromas are of apocrine derivation.2

Clinically, cylindromas appear most often in 2 settings: isolated or as a manifestation of one of several inherited familial syndromes. One such syndrome is familial cylindromatosis, a rare autosomal-dominant disorder in which affected individuals develop multiple cylindromas, usually on the head and neck. The merging of multiple lesions gives rise to the often-employed term turban tumor.3 This syndrome has been linked to mutations in the cylindromatosis gene, CYLD.4 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome also has been associated with the development of multiple cylindromas. Similar to familial cylindromatosis, it is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is typified by the appearance of multiple cylindromas, trichoepitheliomas, and less commonly spiradenomas. Mutations in the CYLD gene also have been linked to Brooke-Spiegler syndrome in some cases.5

Although considered a benign entity, in rare cases cylindromas have shown evidence of malignant transformation to cylindrocarcinoma. This more aggressive tumor may occur in the setting of isolated cylindromas or more commonly in individuals with numerous lesions, as with both familial cylindromatosis and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. These lesions may appear to grow rapidly, ulcerate, or bleed, traits that are not associated with their benign counterparts.

Diagnosis of cylindromas rests on histopathologic confirmation, which demonstrates well-defined dermal islands of epithelial cells comprised of dark- and pale-staining nuclei. These tumor islands are surrounded by a hyaline basement membrane and often take on the appearance of a jigsaw puzzle. Cylindrocarcinomas exhibit greater cellular pleomorphism and higher mitotic rates.

Dermal cylindromas require no further treatment but can be electively excised, while treatment of cylindrocarcinoma with excision is curative.6 Definitive excision was offered to our patient, but she declined treatment.

1. Munger BL, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Ultrastructure and histochemical characteristics of dermal eccrine cylindroma (turban tumor). J Invest Dermatol. 1962;39:577-595.

2. Tellechea O, Reis JP, Ilheu O, et al. Dermal cylindroma. an immunohistochemical study of thirteen cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:260-265.

3. Biggs PJ, Wooster R, Ford D, et al. Familial cylindromatosis (turban tumour syndrome) gene localised to chromosome 16q12-q13: evidence for its role as a tumour suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 1995;11:441-443.

4. Bignell GR, Warren W, Seal S, et al. Identification of the familial cylindromatosis tumour-suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 2000;25:160-165.

5. Bowen S, Gill M, Lee DA, et al. Mutations in the CYLD gene in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, familial cylindromatosis, and multiple familial trichoepithelioma: lack of genotype-phenotype correlation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:919-920.

6. Gerretsen AL, van der Putte SC, Deenstra W, et al. Cutaneous cylindroma with malignant transformation. Cancer. 1993;72:1618-1623.

The Diagnosis: Dermal Cylindroma

Microsopic evaluation of a tangential biopsy revealed findings of a dermal process consisting of well-circumscribed islands of pale and darker blue cells with little cytoplasm outlined by a hyaline basement membrane (Figure). These cellular islands were arranged in a jigsawlike configuration. These findings were thought to be consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma.

|

Cylindromas are benign appendageal neoplasms with a somewhat controversial histogenesis. Munger and colleagues1 investigated the pattern of acid mucopolysaccharide secretion by these tumors in association with prosecretory vacuoles in proximity to the Golgi apparatus, which led to their impression that cylindromas most resemble eccrine rather than apocrine sweat glands. Other researchers, however, have concluded that cylindromas are of apocrine derivation.2

Clinically, cylindromas appear most often in 2 settings: isolated or as a manifestation of one of several inherited familial syndromes. One such syndrome is familial cylindromatosis, a rare autosomal-dominant disorder in which affected individuals develop multiple cylindromas, usually on the head and neck. The merging of multiple lesions gives rise to the often-employed term turban tumor.3 This syndrome has been linked to mutations in the cylindromatosis gene, CYLD.4 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome also has been associated with the development of multiple cylindromas. Similar to familial cylindromatosis, it is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is typified by the appearance of multiple cylindromas, trichoepitheliomas, and less commonly spiradenomas. Mutations in the CYLD gene also have been linked to Brooke-Spiegler syndrome in some cases.5

Although considered a benign entity, in rare cases cylindromas have shown evidence of malignant transformation to cylindrocarcinoma. This more aggressive tumor may occur in the setting of isolated cylindromas or more commonly in individuals with numerous lesions, as with both familial cylindromatosis and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. These lesions may appear to grow rapidly, ulcerate, or bleed, traits that are not associated with their benign counterparts.

Diagnosis of cylindromas rests on histopathologic confirmation, which demonstrates well-defined dermal islands of epithelial cells comprised of dark- and pale-staining nuclei. These tumor islands are surrounded by a hyaline basement membrane and often take on the appearance of a jigsaw puzzle. Cylindrocarcinomas exhibit greater cellular pleomorphism and higher mitotic rates.

Dermal cylindromas require no further treatment but can be electively excised, while treatment of cylindrocarcinoma with excision is curative.6 Definitive excision was offered to our patient, but she declined treatment.

The Diagnosis: Dermal Cylindroma

Microsopic evaluation of a tangential biopsy revealed findings of a dermal process consisting of well-circumscribed islands of pale and darker blue cells with little cytoplasm outlined by a hyaline basement membrane (Figure). These cellular islands were arranged in a jigsawlike configuration. These findings were thought to be consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma.

|

Cylindromas are benign appendageal neoplasms with a somewhat controversial histogenesis. Munger and colleagues1 investigated the pattern of acid mucopolysaccharide secretion by these tumors in association with prosecretory vacuoles in proximity to the Golgi apparatus, which led to their impression that cylindromas most resemble eccrine rather than apocrine sweat glands. Other researchers, however, have concluded that cylindromas are of apocrine derivation.2

Clinically, cylindromas appear most often in 2 settings: isolated or as a manifestation of one of several inherited familial syndromes. One such syndrome is familial cylindromatosis, a rare autosomal-dominant disorder in which affected individuals develop multiple cylindromas, usually on the head and neck. The merging of multiple lesions gives rise to the often-employed term turban tumor.3 This syndrome has been linked to mutations in the cylindromatosis gene, CYLD.4 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome also has been associated with the development of multiple cylindromas. Similar to familial cylindromatosis, it is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is typified by the appearance of multiple cylindromas, trichoepitheliomas, and less commonly spiradenomas. Mutations in the CYLD gene also have been linked to Brooke-Spiegler syndrome in some cases.5

Although considered a benign entity, in rare cases cylindromas have shown evidence of malignant transformation to cylindrocarcinoma. This more aggressive tumor may occur in the setting of isolated cylindromas or more commonly in individuals with numerous lesions, as with both familial cylindromatosis and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. These lesions may appear to grow rapidly, ulcerate, or bleed, traits that are not associated with their benign counterparts.

Diagnosis of cylindromas rests on histopathologic confirmation, which demonstrates well-defined dermal islands of epithelial cells comprised of dark- and pale-staining nuclei. These tumor islands are surrounded by a hyaline basement membrane and often take on the appearance of a jigsaw puzzle. Cylindrocarcinomas exhibit greater cellular pleomorphism and higher mitotic rates.

Dermal cylindromas require no further treatment but can be electively excised, while treatment of cylindrocarcinoma with excision is curative.6 Definitive excision was offered to our patient, but she declined treatment.

1. Munger BL, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Ultrastructure and histochemical characteristics of dermal eccrine cylindroma (turban tumor). J Invest Dermatol. 1962;39:577-595.

2. Tellechea O, Reis JP, Ilheu O, et al. Dermal cylindroma. an immunohistochemical study of thirteen cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:260-265.

3. Biggs PJ, Wooster R, Ford D, et al. Familial cylindromatosis (turban tumour syndrome) gene localised to chromosome 16q12-q13: evidence for its role as a tumour suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 1995;11:441-443.

4. Bignell GR, Warren W, Seal S, et al. Identification of the familial cylindromatosis tumour-suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 2000;25:160-165.

5. Bowen S, Gill M, Lee DA, et al. Mutations in the CYLD gene in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, familial cylindromatosis, and multiple familial trichoepithelioma: lack of genotype-phenotype correlation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:919-920.

6. Gerretsen AL, van der Putte SC, Deenstra W, et al. Cutaneous cylindroma with malignant transformation. Cancer. 1993;72:1618-1623.

1. Munger BL, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Ultrastructure and histochemical characteristics of dermal eccrine cylindroma (turban tumor). J Invest Dermatol. 1962;39:577-595.

2. Tellechea O, Reis JP, Ilheu O, et al. Dermal cylindroma. an immunohistochemical study of thirteen cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:260-265.

3. Biggs PJ, Wooster R, Ford D, et al. Familial cylindromatosis (turban tumour syndrome) gene localised to chromosome 16q12-q13: evidence for its role as a tumour suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 1995;11:441-443.

4. Bignell GR, Warren W, Seal S, et al. Identification of the familial cylindromatosis tumour-suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 2000;25:160-165.

5. Bowen S, Gill M, Lee DA, et al. Mutations in the CYLD gene in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, familial cylindromatosis, and multiple familial trichoepithelioma: lack of genotype-phenotype correlation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:919-920.

6. Gerretsen AL, van der Putte SC, Deenstra W, et al. Cutaneous cylindroma with malignant transformation. Cancer. 1993;72:1618-1623.

A 79-year-old woman presented with a lesion on the left side of the scalp of several years’ duration that had slowly increased in size. Despite its growth, the lesion remained asymptomatic. Physical examination revealed an exophytic, lobular-appearing nodule on the left side of the temporoparietal scalp, measuring 1.5 cm in size.

Lesions With a Distinct Fingerprint Presentation

The Diagnosis: Phytophotodermatitis

Phytophotodermatitis (PPD) is a nonimmunologic cutaneous phototoxic inflammatory reaction resulting from the activation of photosensitizing botanical agents such as furanocoumarins in contact with the skin by exposure to UVA light.1,2 Furanocoumarins, including psoralens and angelicins, become photoexcited and covalently bind to pyrimidine bases on DNA strands, resulting in acute damage to epidermal, dermal, and endothelial cells.1,3

Vegetation most commonly implicated in this plant solar dermatitis are celery, fennel, parsnip, parsley, and hogweed (Apiaceae [formerly known as the Umbelliferae family]), as well as oranges, lemons, limes, and grapefruits (Rutaceae or citrus family).1,3 Psoralens found in the Persian lime have been noted to cause phototoxic eruptions in the United States, with the rind containing higher concentrations than the pulp.4

Clinical features of PPD include erythema, edema, and vesicle or bullae formation 12 to 36 hours after psoralen and UV light exposure. Burning and pain may be present, but pruritus is not a common characteristic of the eruptions, distinguishing PPD from allergic phytodermatitis.

Hyperpigmentation appears on resolution of the lesions and slowly fades over months to years.1,3,5 Mild exposure may lead to hyperpigmentation without a vesicular or erythematous eruption.1 Phytophotodermatitis follows a benign course and often spontaneously resolves; however, prolonged hyperpigmentation may cause concern for these patients.

Phytophotodermatitis is common among patients preparing drinks and foods with citrus juices or after gardening. Our patient had prepared limeade 3 weeks prior to presentation. The distribution of cutaneous exposure to furanocoumarins influences clinical presentation and may range from blotches and streaks to distinct fingerprint smudges and handprints, as seen in our patient. The distinct full handprint on the right arm was striking. The bullous lesions and resulting hyperpigmentation may mimic burns and healing bruises. In children, PPD often is mistaken for child abuse.1,6,7 In adults, it often is misdiagnosed as poison oak dermatitis, erythema multiforme, and thrombocytopenic purpura.1,3 It is important to recognize PPD to avoid delay in or misdiagnosis and to better counsel patients on how to avoid recurrent episodes of PPD.

1. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby; 2008.

2. Pomeranz MK, Karen JK. Phytophotodermatitis and limes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:e1.

3. Sassiville D. Clinical patterns of phytophotodermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:299-308.

4. Wagner AM, Wu JJ, Hansen RC, et al. Bullous phytophotodermatitis associated with high natural concentrations of furanocoumarins in limes. Am J Contact Dermat. 2002;13:10-14.

5. Flugman SL. Mexican beer dermatitis: a unique variant of lime phytophotodermatitis attributable to contemporary beer-drinking practices. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1194-1195.

6. Mill J, Wallis B, Cuttle L, et al. Phytophotodermatitis: case reports of children presenting with blistering after preparing lime juice. Burns. 2008;34:731-733.

7. Carlsen K, Weismann K. Phytophotodermatitis in 19 children admitted to hospital and their differential diagnoses: child abuse and herpes simplex virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(suppl):S88-S91.

The Diagnosis: Phytophotodermatitis

Phytophotodermatitis (PPD) is a nonimmunologic cutaneous phototoxic inflammatory reaction resulting from the activation of photosensitizing botanical agents such as furanocoumarins in contact with the skin by exposure to UVA light.1,2 Furanocoumarins, including psoralens and angelicins, become photoexcited and covalently bind to pyrimidine bases on DNA strands, resulting in acute damage to epidermal, dermal, and endothelial cells.1,3

Vegetation most commonly implicated in this plant solar dermatitis are celery, fennel, parsnip, parsley, and hogweed (Apiaceae [formerly known as the Umbelliferae family]), as well as oranges, lemons, limes, and grapefruits (Rutaceae or citrus family).1,3 Psoralens found in the Persian lime have been noted to cause phototoxic eruptions in the United States, with the rind containing higher concentrations than the pulp.4

Clinical features of PPD include erythema, edema, and vesicle or bullae formation 12 to 36 hours after psoralen and UV light exposure. Burning and pain may be present, but pruritus is not a common characteristic of the eruptions, distinguishing PPD from allergic phytodermatitis.

Hyperpigmentation appears on resolution of the lesions and slowly fades over months to years.1,3,5 Mild exposure may lead to hyperpigmentation without a vesicular or erythematous eruption.1 Phytophotodermatitis follows a benign course and often spontaneously resolves; however, prolonged hyperpigmentation may cause concern for these patients.

Phytophotodermatitis is common among patients preparing drinks and foods with citrus juices or after gardening. Our patient had prepared limeade 3 weeks prior to presentation. The distribution of cutaneous exposure to furanocoumarins influences clinical presentation and may range from blotches and streaks to distinct fingerprint smudges and handprints, as seen in our patient. The distinct full handprint on the right arm was striking. The bullous lesions and resulting hyperpigmentation may mimic burns and healing bruises. In children, PPD often is mistaken for child abuse.1,6,7 In adults, it often is misdiagnosed as poison oak dermatitis, erythema multiforme, and thrombocytopenic purpura.1,3 It is important to recognize PPD to avoid delay in or misdiagnosis and to better counsel patients on how to avoid recurrent episodes of PPD.

The Diagnosis: Phytophotodermatitis

Phytophotodermatitis (PPD) is a nonimmunologic cutaneous phototoxic inflammatory reaction resulting from the activation of photosensitizing botanical agents such as furanocoumarins in contact with the skin by exposure to UVA light.1,2 Furanocoumarins, including psoralens and angelicins, become photoexcited and covalently bind to pyrimidine bases on DNA strands, resulting in acute damage to epidermal, dermal, and endothelial cells.1,3

Vegetation most commonly implicated in this plant solar dermatitis are celery, fennel, parsnip, parsley, and hogweed (Apiaceae [formerly known as the Umbelliferae family]), as well as oranges, lemons, limes, and grapefruits (Rutaceae or citrus family).1,3 Psoralens found in the Persian lime have been noted to cause phototoxic eruptions in the United States, with the rind containing higher concentrations than the pulp.4

Clinical features of PPD include erythema, edema, and vesicle or bullae formation 12 to 36 hours after psoralen and UV light exposure. Burning and pain may be present, but pruritus is not a common characteristic of the eruptions, distinguishing PPD from allergic phytodermatitis.

Hyperpigmentation appears on resolution of the lesions and slowly fades over months to years.1,3,5 Mild exposure may lead to hyperpigmentation without a vesicular or erythematous eruption.1 Phytophotodermatitis follows a benign course and often spontaneously resolves; however, prolonged hyperpigmentation may cause concern for these patients.

Phytophotodermatitis is common among patients preparing drinks and foods with citrus juices or after gardening. Our patient had prepared limeade 3 weeks prior to presentation. The distribution of cutaneous exposure to furanocoumarins influences clinical presentation and may range from blotches and streaks to distinct fingerprint smudges and handprints, as seen in our patient. The distinct full handprint on the right arm was striking. The bullous lesions and resulting hyperpigmentation may mimic burns and healing bruises. In children, PPD often is mistaken for child abuse.1,6,7 In adults, it often is misdiagnosed as poison oak dermatitis, erythema multiforme, and thrombocytopenic purpura.1,3 It is important to recognize PPD to avoid delay in or misdiagnosis and to better counsel patients on how to avoid recurrent episodes of PPD.

1. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby; 2008.

2. Pomeranz MK, Karen JK. Phytophotodermatitis and limes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:e1.

3. Sassiville D. Clinical patterns of phytophotodermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:299-308.

4. Wagner AM, Wu JJ, Hansen RC, et al. Bullous phytophotodermatitis associated with high natural concentrations of furanocoumarins in limes. Am J Contact Dermat. 2002;13:10-14.

5. Flugman SL. Mexican beer dermatitis: a unique variant of lime phytophotodermatitis attributable to contemporary beer-drinking practices. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1194-1195.

6. Mill J, Wallis B, Cuttle L, et al. Phytophotodermatitis: case reports of children presenting with blistering after preparing lime juice. Burns. 2008;34:731-733.

7. Carlsen K, Weismann K. Phytophotodermatitis in 19 children admitted to hospital and their differential diagnoses: child abuse and herpes simplex virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(suppl):S88-S91.

1. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby; 2008.

2. Pomeranz MK, Karen JK. Phytophotodermatitis and limes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:e1.

3. Sassiville D. Clinical patterns of phytophotodermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:299-308.

4. Wagner AM, Wu JJ, Hansen RC, et al. Bullous phytophotodermatitis associated with high natural concentrations of furanocoumarins in limes. Am J Contact Dermat. 2002;13:10-14.

5. Flugman SL. Mexican beer dermatitis: a unique variant of lime phytophotodermatitis attributable to contemporary beer-drinking practices. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1194-1195.

6. Mill J, Wallis B, Cuttle L, et al. Phytophotodermatitis: case reports of children presenting with blistering after preparing lime juice. Burns. 2008;34:731-733.

7. Carlsen K, Weismann K. Phytophotodermatitis in 19 children admitted to hospital and their differential diagnoses: child abuse and herpes simplex virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(suppl):S88-S91.

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented with scattered brown macules over the dorsal aspect of the hands bilaterally and a brown patch in the shape of a hand on the right upper arm of 3 weeks’ duration.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Lepromatous Leprosy

The Diagnosis: Lepromatous Leprosy

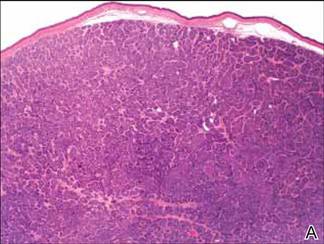

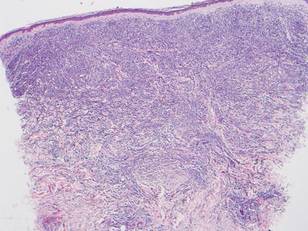

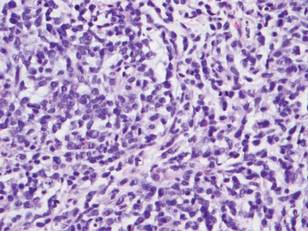

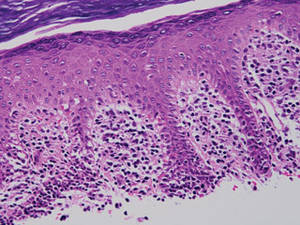

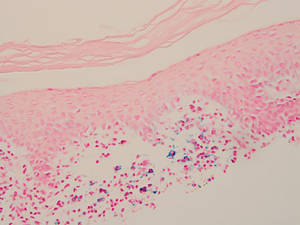

Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy specimen (Figures 1 and 2) disclosed a grenz zone and a diffuse infiltrative process beneath a normal-appearing epidermis. Higher-power examination revealed areas containing macrophages (Virchow cells) with cloudy regions devoid of nuclei (globi). Fite stain demonstrated numerous intracytoplasmic acid-fast bacilli (Figure 3). Laboratory test results for rapid plasma reagin and human immunodeficiency virus were negative, and a complete blood cell count was normal.

On further questioning the patient revealed he was an immigrant from Micronesia, and he described decreased sensation and numbness in the lesions that had been present from onset. Physical examination was consistent with this history and revealed hypoesthesia of the lesions, particularly over the central aspect of the depigmented macules. Based on the clinical examination and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy was made.

Therapy with rifampin, clofazimine, and dapsone was initiated. Unfortunately, compliance was poor, and at clinic follow-up 10 months later the patient demonstrated formation of new indurated lesions as well as mild eyelid swelling and edema of the hands thought to be consistent with erythema nodosum leprosum. Prednisone was then initiated and the dose of clofazimine was increased from 50 mg daily to 100 mg daily with excellent clinical response.

Mycobacterium leprae is a small, slightly curved rod that is an acid-fast, obligate, intracellular organism. It remains endemic in Brazil and Southeast Asia but may present outside of these areas secondary to immigration.1

Hallmarks of the disease are anesthetic skin or mucous membrane lesions with thickened peripheral nerves.2 It grows best at 27°C to 33°C, thereby affecting cooler areas of the human body such as earlobes, knees, and distal extremities.3 It is most likely spread by aerosolized respiratory droplets and less commonly by direct contact. There have been reports suggesting transmission via armadillos.4

Genetic susceptibility influences the development of leprosy, while HLA type influences the immune response and hence the type of leprosy.5 Ridley and Jopling6 devised a classification system based on the immunologic response to M leprae. Highly reactive hosts with a vigorous cell-mediated response to M leprae develop tuberculoid leprosy and exhibit few skin lesions containing rare organisms. In contrast, anergic hosts develop lepromatous leprosy, characterized by multiple skin lesions, abundant organisms, and diffuse disease. Borderline tuberculoid, borderline, and borderline lepromatous make up the middle of the spectrum.6-9 Skin lesions can present with poorly defined, hypopigmented macules of indeterminate leprosy on one end and diffuse skin involvement of lepromatous leprosy on the opposite end. Diffuse involvement includes facial skin thickening, classic leonine facies, loss of eyebrows and eyelashes, anesthetic lesions, and anhidrosis.

Erythema nodosum leprosum occurs with chronic infection from M leprae, most commonly lepromatous leprosy. Immune complex deposition results in vasculitis and inflammatory foci. This phenomenon is thought to be secondary to high antigen load released by dying mycobacteria, causing secretion of tumor necrosis factor a from macrophages.1 Erythema nodosum leprosum demonstrates rapid onset of tender erythematous plaques or nodules, most commonly on the face and extensor surfaces of the extremities, with fever, malaise, iritis, arthralgia, and orchitis. Clofazimine therapy probably decreases the occurence.1 Treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and/or thalidomide.

- Moschella S, Ooi W. Update on leprosy in immigrants in the United States: status in the year 2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:930-937.

- Abraham S, Job C, Joseph G, et al. Epidemiological significance of first skin lesion in leprosy. Int J Lep Other Mycobact Dis. 1998;66:131-139.

- Shepard C. The experimental disease that follows the injection of human bacilli into footpads of mice. J Exp Med. 1960;112:445-454.

- Leprosy: global target attained. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2001;20:155-156.

- World Health Organization. Global leprosy situation, 2005. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2005;80:289-295.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. A classification of leprosy for research purposes. Lepr Rev. 1962;33:119-128.

- Lane J. Borderline tuberculoid leprosy in a woman from the state of Georgia with armadillo exposure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:714-716.

- Fitness J, Tosh K, Hill AV. Genetics of susceptibility to leprosy. Genes Immun. 2002;3:441-453.

- Moschella SL. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of leprosy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:417-426.

The Diagnosis: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy specimen (Figures 1 and 2) disclosed a grenz zone and a diffuse infiltrative process beneath a normal-appearing epidermis. Higher-power examination revealed areas containing macrophages (Virchow cells) with cloudy regions devoid of nuclei (globi). Fite stain demonstrated numerous intracytoplasmic acid-fast bacilli (Figure 3). Laboratory test results for rapid plasma reagin and human immunodeficiency virus were negative, and a complete blood cell count was normal.

On further questioning the patient revealed he was an immigrant from Micronesia, and he described decreased sensation and numbness in the lesions that had been present from onset. Physical examination was consistent with this history and revealed hypoesthesia of the lesions, particularly over the central aspect of the depigmented macules. Based on the clinical examination and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy was made.

Therapy with rifampin, clofazimine, and dapsone was initiated. Unfortunately, compliance was poor, and at clinic follow-up 10 months later the patient demonstrated formation of new indurated lesions as well as mild eyelid swelling and edema of the hands thought to be consistent with erythema nodosum leprosum. Prednisone was then initiated and the dose of clofazimine was increased from 50 mg daily to 100 mg daily with excellent clinical response.

Mycobacterium leprae is a small, slightly curved rod that is an acid-fast, obligate, intracellular organism. It remains endemic in Brazil and Southeast Asia but may present outside of these areas secondary to immigration.1

Hallmarks of the disease are anesthetic skin or mucous membrane lesions with thickened peripheral nerves.2 It grows best at 27°C to 33°C, thereby affecting cooler areas of the human body such as earlobes, knees, and distal extremities.3 It is most likely spread by aerosolized respiratory droplets and less commonly by direct contact. There have been reports suggesting transmission via armadillos.4

Genetic susceptibility influences the development of leprosy, while HLA type influences the immune response and hence the type of leprosy.5 Ridley and Jopling6 devised a classification system based on the immunologic response to M leprae. Highly reactive hosts with a vigorous cell-mediated response to M leprae develop tuberculoid leprosy and exhibit few skin lesions containing rare organisms. In contrast, anergic hosts develop lepromatous leprosy, characterized by multiple skin lesions, abundant organisms, and diffuse disease. Borderline tuberculoid, borderline, and borderline lepromatous make up the middle of the spectrum.6-9 Skin lesions can present with poorly defined, hypopigmented macules of indeterminate leprosy on one end and diffuse skin involvement of lepromatous leprosy on the opposite end. Diffuse involvement includes facial skin thickening, classic leonine facies, loss of eyebrows and eyelashes, anesthetic lesions, and anhidrosis.

Erythema nodosum leprosum occurs with chronic infection from M leprae, most commonly lepromatous leprosy. Immune complex deposition results in vasculitis and inflammatory foci. This phenomenon is thought to be secondary to high antigen load released by dying mycobacteria, causing secretion of tumor necrosis factor a from macrophages.1 Erythema nodosum leprosum demonstrates rapid onset of tender erythematous plaques or nodules, most commonly on the face and extensor surfaces of the extremities, with fever, malaise, iritis, arthralgia, and orchitis. Clofazimine therapy probably decreases the occurence.1 Treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and/or thalidomide.

The Diagnosis: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy specimen (Figures 1 and 2) disclosed a grenz zone and a diffuse infiltrative process beneath a normal-appearing epidermis. Higher-power examination revealed areas containing macrophages (Virchow cells) with cloudy regions devoid of nuclei (globi). Fite stain demonstrated numerous intracytoplasmic acid-fast bacilli (Figure 3). Laboratory test results for rapid plasma reagin and human immunodeficiency virus were negative, and a complete blood cell count was normal.

On further questioning the patient revealed he was an immigrant from Micronesia, and he described decreased sensation and numbness in the lesions that had been present from onset. Physical examination was consistent with this history and revealed hypoesthesia of the lesions, particularly over the central aspect of the depigmented macules. Based on the clinical examination and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy was made.

Therapy with rifampin, clofazimine, and dapsone was initiated. Unfortunately, compliance was poor, and at clinic follow-up 10 months later the patient demonstrated formation of new indurated lesions as well as mild eyelid swelling and edema of the hands thought to be consistent with erythema nodosum leprosum. Prednisone was then initiated and the dose of clofazimine was increased from 50 mg daily to 100 mg daily with excellent clinical response.

Mycobacterium leprae is a small, slightly curved rod that is an acid-fast, obligate, intracellular organism. It remains endemic in Brazil and Southeast Asia but may present outside of these areas secondary to immigration.1

Hallmarks of the disease are anesthetic skin or mucous membrane lesions with thickened peripheral nerves.2 It grows best at 27°C to 33°C, thereby affecting cooler areas of the human body such as earlobes, knees, and distal extremities.3 It is most likely spread by aerosolized respiratory droplets and less commonly by direct contact. There have been reports suggesting transmission via armadillos.4

Genetic susceptibility influences the development of leprosy, while HLA type influences the immune response and hence the type of leprosy.5 Ridley and Jopling6 devised a classification system based on the immunologic response to M leprae. Highly reactive hosts with a vigorous cell-mediated response to M leprae develop tuberculoid leprosy and exhibit few skin lesions containing rare organisms. In contrast, anergic hosts develop lepromatous leprosy, characterized by multiple skin lesions, abundant organisms, and diffuse disease. Borderline tuberculoid, borderline, and borderline lepromatous make up the middle of the spectrum.6-9 Skin lesions can present with poorly defined, hypopigmented macules of indeterminate leprosy on one end and diffuse skin involvement of lepromatous leprosy on the opposite end. Diffuse involvement includes facial skin thickening, classic leonine facies, loss of eyebrows and eyelashes, anesthetic lesions, and anhidrosis.

Erythema nodosum leprosum occurs with chronic infection from M leprae, most commonly lepromatous leprosy. Immune complex deposition results in vasculitis and inflammatory foci. This phenomenon is thought to be secondary to high antigen load released by dying mycobacteria, causing secretion of tumor necrosis factor a from macrophages.1 Erythema nodosum leprosum demonstrates rapid onset of tender erythematous plaques or nodules, most commonly on the face and extensor surfaces of the extremities, with fever, malaise, iritis, arthralgia, and orchitis. Clofazimine therapy probably decreases the occurence.1 Treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and/or thalidomide.

- Moschella S, Ooi W. Update on leprosy in immigrants in the United States: status in the year 2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:930-937.

- Abraham S, Job C, Joseph G, et al. Epidemiological significance of first skin lesion in leprosy. Int J Lep Other Mycobact Dis. 1998;66:131-139.

- Shepard C. The experimental disease that follows the injection of human bacilli into footpads of mice. J Exp Med. 1960;112:445-454.

- Leprosy: global target attained. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2001;20:155-156.

- World Health Organization. Global leprosy situation, 2005. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2005;80:289-295.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. A classification of leprosy for research purposes. Lepr Rev. 1962;33:119-128.

- Lane J. Borderline tuberculoid leprosy in a woman from the state of Georgia with armadillo exposure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:714-716.

- Fitness J, Tosh K, Hill AV. Genetics of susceptibility to leprosy. Genes Immun. 2002;3:441-453.

- Moschella SL. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of leprosy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:417-426.

- Moschella S, Ooi W. Update on leprosy in immigrants in the United States: status in the year 2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:930-937.

- Abraham S, Job C, Joseph G, et al. Epidemiological significance of first skin lesion in leprosy. Int J Lep Other Mycobact Dis. 1998;66:131-139.

- Shepard C. The experimental disease that follows the injection of human bacilli into footpads of mice. J Exp Med. 1960;112:445-454.

- Leprosy: global target attained. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2001;20:155-156.

- World Health Organization. Global leprosy situation, 2005. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2005;80:289-295.

- Ridley DS, Jopling WH. A classification of leprosy for research purposes. Lepr Rev. 1962;33:119-128.

- Lane J. Borderline tuberculoid leprosy in a woman from the state of Georgia with armadillo exposure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:714-716.

- Fitness J, Tosh K, Hill AV. Genetics of susceptibility to leprosy. Genes Immun. 2002;3:441-453.

- Moschella SL. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of leprosy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:417-426.

A 37-year-old man presented with pruritic lesions over the arms, legs, face, and back of 4 months’ duration that had been refractory to topical steroid treatment. He reported a 15-lb weight loss that he attributed to recent intranasal cocaine use. His medical history revealed obesity. There was no known history of sexually transmitted diseases, human immunodeficiency virus infection, tuberculosis, diabetes mellitus, or intravenous drug use. Physical examination revealed small nodules over the pinnae, plaques on the forehead, and large plaques with depigmented macules of variable sizes over the extremities and back. Some lesions on the extremities were violaceous in appearance, while others on the upper extremities had raised borders.

Multiple Firm Pink Papules and Nodules

The Diagnosis: Myeloid Leukemia Cutis

Leukemia cutis represents the infiltration of leukemic cells into the skin. It has been described in the setting of both myeloid and lymphoid leukemia. In the setting of acute myeloid leukemia, it has been reported to occur in 2% to 13% of patients overall,1,2 but it may occur in 31% of patients with the acute myelomonocytic or acute monocytic leukemia subtypes.3 Leukemia cutis is less common, with chronic myeloid leukemia occurring in 2.7% of patients in one study.4 In another study, 65% of patients with myeloid leukemia cutis had an acute myeloid leukemia.5

Myeloid leukemia cutis has been reported in patients aged 22 days to 90 years, with a median age of 62 years. There is a male predominance (1.4:1 ratio).5,6 The diagnosis of leukemia cutis is made concurrently with the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 30% of cases, subsequent to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 60% of cases, and prior to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 10% of cases.5

Clinically, myeloid leukemia cutis presents as an asymptomatic solitary lesion in 23% of cases or as multiple lesions in 77% of cases. Lesions consist of pink to red to violaceous papules, nodules, and macules that are occasionally purpuric and involve any cutaneous surface.5

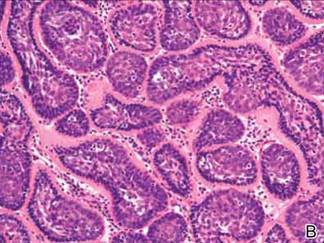

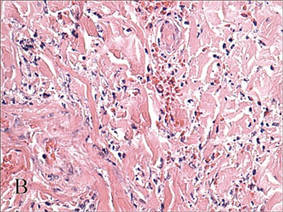

Histologically, the epidermis is unremarkable. Beneath a grenz zone within the dermis and usually extending into the subcutis there is a diffuse or nodular proliferation of neoplastic cells, often with perivascular and periadnexal accentuation and sometimes single filing of cells between collagen bundles (Figure 1). The cells are immature myeloid cells with irregular nuclear contours that may be indented or reniform (Figure 2). Nuclei contain finely dispersed chromatin with variably prominent nucleoli.5,6 Immunohistochemically, CD68 is positive in approximately 97% of cases, myeloperoxidase in 62%, and lysozyme in 85%. CD168, CD14, CD4, CD33, CD117, CD34, CD56, CD123, and CD303 are variably positive. CD3 and CD20, markers of lymphoid leukemia, are negative.5-8

Leukemia cutis in the setting of a myeloid leukemia portends a grave prognosis. In a series of 18 patients, 16 had additional extramedullary leukemia, including meningeal leukemia in 6 patients.2 Most patients with myeloid leukemia cutis die within an average of 1 to 8 months of diagnosis.9

- Boggs DR, Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE. The acute leukemias. analysis of 322 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1962;41:163-225.

- Baer MR, Barcos M, Farrell H, et al. Acute myelogenous leukemia with leukemia cutis. eighteen cases seen between 1969 and 1986. Cancer. 1989;63:2192-2200.

- Straus DJ, Mertelsmann R, Koziner B, et al. The acute monocytic leukemias: multidisciplinary studies in 45 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:409-425.

- Rosenthal S, Canellos GP, DeVita VT Jr, et al. Characteristics of blast crisis in chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1977;49:705-714.

- Bénet C, Gomez A, Aguilar C, et al. Histologic and immunohistologic characterization of skin localization of myeloid disorders: a study of 173 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:278-290.

- Cronin DM, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:101-110.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:966-978.

- Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:121-128.

The Diagnosis: Myeloid Leukemia Cutis

Leukemia cutis represents the infiltration of leukemic cells into the skin. It has been described in the setting of both myeloid and lymphoid leukemia. In the setting of acute myeloid leukemia, it has been reported to occur in 2% to 13% of patients overall,1,2 but it may occur in 31% of patients with the acute myelomonocytic or acute monocytic leukemia subtypes.3 Leukemia cutis is less common, with chronic myeloid leukemia occurring in 2.7% of patients in one study.4 In another study, 65% of patients with myeloid leukemia cutis had an acute myeloid leukemia.5

Myeloid leukemia cutis has been reported in patients aged 22 days to 90 years, with a median age of 62 years. There is a male predominance (1.4:1 ratio).5,6 The diagnosis of leukemia cutis is made concurrently with the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 30% of cases, subsequent to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 60% of cases, and prior to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 10% of cases.5

Clinically, myeloid leukemia cutis presents as an asymptomatic solitary lesion in 23% of cases or as multiple lesions in 77% of cases. Lesions consist of pink to red to violaceous papules, nodules, and macules that are occasionally purpuric and involve any cutaneous surface.5

Histologically, the epidermis is unremarkable. Beneath a grenz zone within the dermis and usually extending into the subcutis there is a diffuse or nodular proliferation of neoplastic cells, often with perivascular and periadnexal accentuation and sometimes single filing of cells between collagen bundles (Figure 1). The cells are immature myeloid cells with irregular nuclear contours that may be indented or reniform (Figure 2). Nuclei contain finely dispersed chromatin with variably prominent nucleoli.5,6 Immunohistochemically, CD68 is positive in approximately 97% of cases, myeloperoxidase in 62%, and lysozyme in 85%. CD168, CD14, CD4, CD33, CD117, CD34, CD56, CD123, and CD303 are variably positive. CD3 and CD20, markers of lymphoid leukemia, are negative.5-8

Leukemia cutis in the setting of a myeloid leukemia portends a grave prognosis. In a series of 18 patients, 16 had additional extramedullary leukemia, including meningeal leukemia in 6 patients.2 Most patients with myeloid leukemia cutis die within an average of 1 to 8 months of diagnosis.9

The Diagnosis: Myeloid Leukemia Cutis

Leukemia cutis represents the infiltration of leukemic cells into the skin. It has been described in the setting of both myeloid and lymphoid leukemia. In the setting of acute myeloid leukemia, it has been reported to occur in 2% to 13% of patients overall,1,2 but it may occur in 31% of patients with the acute myelomonocytic or acute monocytic leukemia subtypes.3 Leukemia cutis is less common, with chronic myeloid leukemia occurring in 2.7% of patients in one study.4 In another study, 65% of patients with myeloid leukemia cutis had an acute myeloid leukemia.5

Myeloid leukemia cutis has been reported in patients aged 22 days to 90 years, with a median age of 62 years. There is a male predominance (1.4:1 ratio).5,6 The diagnosis of leukemia cutis is made concurrently with the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 30% of cases, subsequent to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 60% of cases, and prior to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 10% of cases.5

Clinically, myeloid leukemia cutis presents as an asymptomatic solitary lesion in 23% of cases or as multiple lesions in 77% of cases. Lesions consist of pink to red to violaceous papules, nodules, and macules that are occasionally purpuric and involve any cutaneous surface.5

Histologically, the epidermis is unremarkable. Beneath a grenz zone within the dermis and usually extending into the subcutis there is a diffuse or nodular proliferation of neoplastic cells, often with perivascular and periadnexal accentuation and sometimes single filing of cells between collagen bundles (Figure 1). The cells are immature myeloid cells with irregular nuclear contours that may be indented or reniform (Figure 2). Nuclei contain finely dispersed chromatin with variably prominent nucleoli.5,6 Immunohistochemically, CD68 is positive in approximately 97% of cases, myeloperoxidase in 62%, and lysozyme in 85%. CD168, CD14, CD4, CD33, CD117, CD34, CD56, CD123, and CD303 are variably positive. CD3 and CD20, markers of lymphoid leukemia, are negative.5-8

Leukemia cutis in the setting of a myeloid leukemia portends a grave prognosis. In a series of 18 patients, 16 had additional extramedullary leukemia, including meningeal leukemia in 6 patients.2 Most patients with myeloid leukemia cutis die within an average of 1 to 8 months of diagnosis.9

- Boggs DR, Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE. The acute leukemias. analysis of 322 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1962;41:163-225.

- Baer MR, Barcos M, Farrell H, et al. Acute myelogenous leukemia with leukemia cutis. eighteen cases seen between 1969 and 1986. Cancer. 1989;63:2192-2200.

- Straus DJ, Mertelsmann R, Koziner B, et al. The acute monocytic leukemias: multidisciplinary studies in 45 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:409-425.

- Rosenthal S, Canellos GP, DeVita VT Jr, et al. Characteristics of blast crisis in chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1977;49:705-714.

- Bénet C, Gomez A, Aguilar C, et al. Histologic and immunohistologic characterization of skin localization of myeloid disorders: a study of 173 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:278-290.

- Cronin DM, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:101-110.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:966-978.

- Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:121-128.

- Boggs DR, Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE. The acute leukemias. analysis of 322 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1962;41:163-225.

- Baer MR, Barcos M, Farrell H, et al. Acute myelogenous leukemia with leukemia cutis. eighteen cases seen between 1969 and 1986. Cancer. 1989;63:2192-2200.

- Straus DJ, Mertelsmann R, Koziner B, et al. The acute monocytic leukemias: multidisciplinary studies in 45 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:409-425.

- Rosenthal S, Canellos GP, DeVita VT Jr, et al. Characteristics of blast crisis in chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1977;49:705-714.

- Bénet C, Gomez A, Aguilar C, et al. Histologic and immunohistologic characterization of skin localization of myeloid disorders: a study of 173 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:278-290.

- Cronin DM, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:101-110.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:966-978.

- Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:121-128.

A 91-year-old man presented with numerous, scattered, asymptomatic, 3- to 9-mm, smooth, firm, pink papules and nodules involving the neck, trunk, and arms and legs of 1 week’s duration.

Erythematous Nodular Plaque Encircling the Lower Leg

The Diagnosis: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Histopathology showed small round cells (Figure 1) that stained positive for cytokeratin 20 in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (Figure 2). The tumor stained negative for lymphoma (CD45) marker. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed focally increased activity at cutaneous sites corresponding to the nodules, but lymph nodes and visceral sites did not show areas of increased metabolic activity. She underwent an above-knee amputation. She was started on a chemotherapy regimen of etoposide and carboplatin given that the pathology of the excised limb demonstrated vascular and lymphatic invasion by the tumor cells in the proximal skin margin. After 4 months she presented with gangrenous changes of the amputated limb and evidence of metastasis to the region of the skin flap. Similar tumors presented on the ipsilateral hip. Given her general poor condition and aggressive nature of the tumor, the patient decided to pursue hospice care 6 months after her diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

Figure 1. The tumor was composed of sheets of cells with a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio and fine chromatin without nucleoli (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokera-tin 20 showed positivity in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (original magnification ×40). |

Merkel cell carcinoma usually presents as firm, red to purple papules on sun-exposed skin in older patients with light skin. Factors strongly associated with the development of MCC are age (>65 years), lighter skin types, history of extensive sun exposure, and chronic immune suppression (eg, kidney or heart transplantation, human immunodeficiency virus).1 The rate of MCC has increased 3-fold between 1986 and 2001; the rate of MCC was 0.15 cases per 100,000 individuals in 1986, climbing up to 0.44 cases per 100,000 individuals in 2001.2 Our patient had been on immunosuppressants—prednisone, cyclosporine, and sirolimus—for nearly a decade following kidney transplants, which had been discontinued 2 years prior to presentation.

Heath et al3 defined an acronym AEIOU (asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, expanding rapidly, immune suppression, older than 50 years, UV-exposed site on a person with fair skin) for MCC features derived from 195 patients. They advised that a biopsy is warranted if the patient presents with more than 3 of these features.3

The 1991 MCC staging system was revised in 1999 and 2005 based on experience at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, New York).4 In 2010 the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging was introduced for MCC, which follows other skin malignancies.5 Using this TNM staging system for primary tumors, regional lymph nodes, and distant metastasis, our patient at the time of presentation was stage IIB (T3N0M0), with tumor size greater than 5 cm, nodes negative by clinical examination, and no distant metastasis. In a span of 3 months, she had metastasis to the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and distant lymph nodes, which resulted in classification as stage IV, proving the aggressive nature of the tumor.

The newly discovered Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) is found integrating into the Merkel cell genome. Merkel cell polyomavirus is present in 80% of cancers and is expressed in a clonal pattern, while 90% of MCC patients are seropositive for the same. Unlike antibodies to MCPyV VP1 protein, antibodies to the T antigen for MCPyV track disease burden and may be a useful biomarker for MCC in the future.6

A study of 251 patients in 1970-2002 showed that pathologic nodal staging identifies a group of patients with excellent long-term survival.1 Our patient preferred to undergo positron emission tomography rather than a sentinel lymph node biopsy prior to surgery. Also, after margin-negative excision and pathologic nodal staging, local and nodal recurrence rates were low. Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III patients showed a trend (P=.08) to decreased survival compared with stage II patients who did not receive chemotherapy.7 A multidisciplinary approach to treatment including surgery, radiation,8 and chemotherapy needs to be created for each individual patient. Merkel cell carcinoma is the cause of death in 35% of patients within 3 years of diagnosis.9

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare orphan tumor with rapidly increasing incidence in an era of immunosuppression. It has a grave prognosis, as demonstrated in our case, if not detected early. People at increased risk for MCC must have regular skin checks. Unfortunately, our patient was a nursing home resident and had not had a skin check for 2 years prior to presentation.

1. Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309.

2. Hodgson NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:1-4.

3. Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

4. Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York, NY: Springer; 2010.

5. Assouline A, Tai P, Joseph K, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of skin-current controversies and recommendations.Rare Tumors. 2011;4:e23.

6. Paulson KG, Carter JJ, Johnson LG, et al. Antibodies to Merkel cell polyomavirus T-antigen oncoproteins reflect tumor burden in Merkel cell carcinoma patients. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8388-8397.

7. Poulsen M, Rischin D, Walpole E, et al; Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group. High-risk Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin treated with synchronous carboplatin/etoposide and radiation: a Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group Study—TROG 96:07. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4371-4376.

8. Lewis KG, Weinstock MA, Weaver AL, et al. Adjuvant local irradiation for Merkel cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:693-700.

9. Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:832-841.

The Diagnosis: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Histopathology showed small round cells (Figure 1) that stained positive for cytokeratin 20 in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (Figure 2). The tumor stained negative for lymphoma (CD45) marker. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed focally increased activity at cutaneous sites corresponding to the nodules, but lymph nodes and visceral sites did not show areas of increased metabolic activity. She underwent an above-knee amputation. She was started on a chemotherapy regimen of etoposide and carboplatin given that the pathology of the excised limb demonstrated vascular and lymphatic invasion by the tumor cells in the proximal skin margin. After 4 months she presented with gangrenous changes of the amputated limb and evidence of metastasis to the region of the skin flap. Similar tumors presented on the ipsilateral hip. Given her general poor condition and aggressive nature of the tumor, the patient decided to pursue hospice care 6 months after her diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

Figure 1. The tumor was composed of sheets of cells with a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio and fine chromatin without nucleoli (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokera-tin 20 showed positivity in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (original magnification ×40). |

Merkel cell carcinoma usually presents as firm, red to purple papules on sun-exposed skin in older patients with light skin. Factors strongly associated with the development of MCC are age (>65 years), lighter skin types, history of extensive sun exposure, and chronic immune suppression (eg, kidney or heart transplantation, human immunodeficiency virus).1 The rate of MCC has increased 3-fold between 1986 and 2001; the rate of MCC was 0.15 cases per 100,000 individuals in 1986, climbing up to 0.44 cases per 100,000 individuals in 2001.2 Our patient had been on immunosuppressants—prednisone, cyclosporine, and sirolimus—for nearly a decade following kidney transplants, which had been discontinued 2 years prior to presentation.

Heath et al3 defined an acronym AEIOU (asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, expanding rapidly, immune suppression, older than 50 years, UV-exposed site on a person with fair skin) for MCC features derived from 195 patients. They advised that a biopsy is warranted if the patient presents with more than 3 of these features.3

The 1991 MCC staging system was revised in 1999 and 2005 based on experience at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, New York).4 In 2010 the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging was introduced for MCC, which follows other skin malignancies.5 Using this TNM staging system for primary tumors, regional lymph nodes, and distant metastasis, our patient at the time of presentation was stage IIB (T3N0M0), with tumor size greater than 5 cm, nodes negative by clinical examination, and no distant metastasis. In a span of 3 months, she had metastasis to the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and distant lymph nodes, which resulted in classification as stage IV, proving the aggressive nature of the tumor.

The newly discovered Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) is found integrating into the Merkel cell genome. Merkel cell polyomavirus is present in 80% of cancers and is expressed in a clonal pattern, while 90% of MCC patients are seropositive for the same. Unlike antibodies to MCPyV VP1 protein, antibodies to the T antigen for MCPyV track disease burden and may be a useful biomarker for MCC in the future.6