User login

Nonblanchable Violaceous Macules of the Periorbital Skin

The Diagnosis: Primary AL Amyloidosis

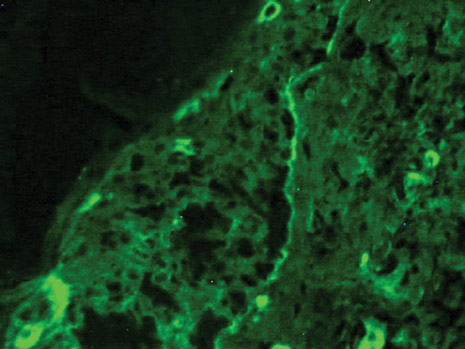

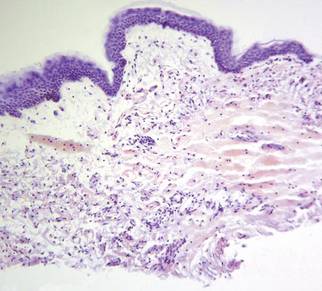

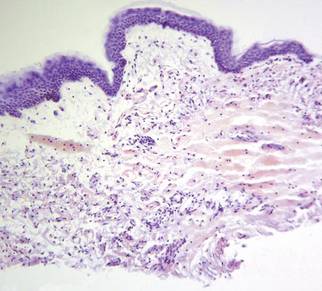

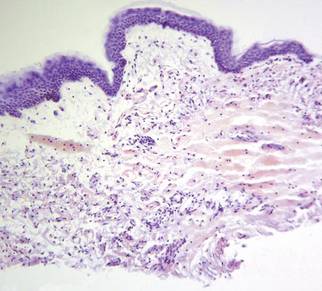

The patient initially presented with bruising around the eyes. She noted characteristic “easy bruising” after minor trauma. Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated an elevated IgG κ level of 1.4 g/dL (reference range, 0.61–1.04 g/dL) with normal IgA and IgM. Skin biopsy revealed focal amyloid deposition in the dermis (Figures 1 and 2). Liquid chromatography tandem-mass spectrometry performed on peptides extracted from Congo red–positive areas of paraffin-embedded specimen identified peptides representing immunoglobulin κ light chain variable region 1, favoring AL κ-type amyloid deposition.

|

|

A bone marrow biopsy revealed plasma cell dyscrasia with 15% plasma cells but was negative for amyloid. A fine-needle fat-pad biopsy also was negative for amyloid. Systemic amyloid involvement was evaluated with a 24-hour urine collection but was negative for light chain proteinuria and albuminuria. A complete osseous survey was negative for focal lytic or sclerotic lesions, ruling out multiple myeloma. Echocardiogram and liver function tests were normal. We concluded that this patient exhibited a rare case of primary AL amyloidosis due to plasma cell dyscrasia with only cutaneous involvement. The patient was not a candidate for stem cell therapy because she was older than 70 years. She was initiated on several cycles of melphalan with dexamethasone by a collaborating oncology team.

The amyloidoses are a group of diseases that result from the extracellular deposition of insoluble fibrils in various organs. Amyloidosis can occur primarily from a plasma cell proliferative process or secondarily from a chronic inflammatory process. Light chain (AL) amyloidosis is the most commonform of primary systemic amyloidosis. In AL amyloidosis, an immunoglobulin light chain or a fragment of a light chain is produced by a clonal proliferation of plasma cells, with plasma cell dyscrasia typically ranging from 5% to 10%.1 Rarely, amyloidoses may present primarily as cutaneous lesions, as in this patient, which would warrant an evaluation for systemic involvement.

Skin biopsy was the key to diagnosis, as prior biopsy of bone marrow and fat-pad failed to demonstrate amyloid protein. Further analysis with mass spectrometry was used in conjunction with Congo red staining to increase the sensitivity and specificity of detecting overexpressed light chains. Recognition of the limited differential diagnosis of pinch purpura and appropriate processing of the biopsy specimen allowed diagnosis. The patient improved with cycles of combination melphalan and dexamethasone, which was shown to have similar outcome to those treated with melphalan and autologous stem cell rescue.2 Overall, this case highlights the extensive search for systemic involvement that should be undertaken with cutaneous presentations of amyloidosis and the importance of an interdisciplinary approach to treatment.

1. Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Primary systemic amyloidosis: clinical and laboratory features in 474 cases. Semin Hematol. 1995;32:45-49.

2. Jaccard A, Moreau P, Leblond V, et al. High-dose melphalan versus melphalan plus dexamethasone for AL amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:11.

The Diagnosis: Primary AL Amyloidosis

The patient initially presented with bruising around the eyes. She noted characteristic “easy bruising” after minor trauma. Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated an elevated IgG κ level of 1.4 g/dL (reference range, 0.61–1.04 g/dL) with normal IgA and IgM. Skin biopsy revealed focal amyloid deposition in the dermis (Figures 1 and 2). Liquid chromatography tandem-mass spectrometry performed on peptides extracted from Congo red–positive areas of paraffin-embedded specimen identified peptides representing immunoglobulin κ light chain variable region 1, favoring AL κ-type amyloid deposition.

|

|

A bone marrow biopsy revealed plasma cell dyscrasia with 15% plasma cells but was negative for amyloid. A fine-needle fat-pad biopsy also was negative for amyloid. Systemic amyloid involvement was evaluated with a 24-hour urine collection but was negative for light chain proteinuria and albuminuria. A complete osseous survey was negative for focal lytic or sclerotic lesions, ruling out multiple myeloma. Echocardiogram and liver function tests were normal. We concluded that this patient exhibited a rare case of primary AL amyloidosis due to plasma cell dyscrasia with only cutaneous involvement. The patient was not a candidate for stem cell therapy because she was older than 70 years. She was initiated on several cycles of melphalan with dexamethasone by a collaborating oncology team.

The amyloidoses are a group of diseases that result from the extracellular deposition of insoluble fibrils in various organs. Amyloidosis can occur primarily from a plasma cell proliferative process or secondarily from a chronic inflammatory process. Light chain (AL) amyloidosis is the most commonform of primary systemic amyloidosis. In AL amyloidosis, an immunoglobulin light chain or a fragment of a light chain is produced by a clonal proliferation of plasma cells, with plasma cell dyscrasia typically ranging from 5% to 10%.1 Rarely, amyloidoses may present primarily as cutaneous lesions, as in this patient, which would warrant an evaluation for systemic involvement.

Skin biopsy was the key to diagnosis, as prior biopsy of bone marrow and fat-pad failed to demonstrate amyloid protein. Further analysis with mass spectrometry was used in conjunction with Congo red staining to increase the sensitivity and specificity of detecting overexpressed light chains. Recognition of the limited differential diagnosis of pinch purpura and appropriate processing of the biopsy specimen allowed diagnosis. The patient improved with cycles of combination melphalan and dexamethasone, which was shown to have similar outcome to those treated with melphalan and autologous stem cell rescue.2 Overall, this case highlights the extensive search for systemic involvement that should be undertaken with cutaneous presentations of amyloidosis and the importance of an interdisciplinary approach to treatment.

The Diagnosis: Primary AL Amyloidosis

The patient initially presented with bruising around the eyes. She noted characteristic “easy bruising” after minor trauma. Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated an elevated IgG κ level of 1.4 g/dL (reference range, 0.61–1.04 g/dL) with normal IgA and IgM. Skin biopsy revealed focal amyloid deposition in the dermis (Figures 1 and 2). Liquid chromatography tandem-mass spectrometry performed on peptides extracted from Congo red–positive areas of paraffin-embedded specimen identified peptides representing immunoglobulin κ light chain variable region 1, favoring AL κ-type amyloid deposition.

|

|

A bone marrow biopsy revealed plasma cell dyscrasia with 15% plasma cells but was negative for amyloid. A fine-needle fat-pad biopsy also was negative for amyloid. Systemic amyloid involvement was evaluated with a 24-hour urine collection but was negative for light chain proteinuria and albuminuria. A complete osseous survey was negative for focal lytic or sclerotic lesions, ruling out multiple myeloma. Echocardiogram and liver function tests were normal. We concluded that this patient exhibited a rare case of primary AL amyloidosis due to plasma cell dyscrasia with only cutaneous involvement. The patient was not a candidate for stem cell therapy because she was older than 70 years. She was initiated on several cycles of melphalan with dexamethasone by a collaborating oncology team.

The amyloidoses are a group of diseases that result from the extracellular deposition of insoluble fibrils in various organs. Amyloidosis can occur primarily from a plasma cell proliferative process or secondarily from a chronic inflammatory process. Light chain (AL) amyloidosis is the most commonform of primary systemic amyloidosis. In AL amyloidosis, an immunoglobulin light chain or a fragment of a light chain is produced by a clonal proliferation of plasma cells, with plasma cell dyscrasia typically ranging from 5% to 10%.1 Rarely, amyloidoses may present primarily as cutaneous lesions, as in this patient, which would warrant an evaluation for systemic involvement.

Skin biopsy was the key to diagnosis, as prior biopsy of bone marrow and fat-pad failed to demonstrate amyloid protein. Further analysis with mass spectrometry was used in conjunction with Congo red staining to increase the sensitivity and specificity of detecting overexpressed light chains. Recognition of the limited differential diagnosis of pinch purpura and appropriate processing of the biopsy specimen allowed diagnosis. The patient improved with cycles of combination melphalan and dexamethasone, which was shown to have similar outcome to those treated with melphalan and autologous stem cell rescue.2 Overall, this case highlights the extensive search for systemic involvement that should be undertaken with cutaneous presentations of amyloidosis and the importance of an interdisciplinary approach to treatment.

1. Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Primary systemic amyloidosis: clinical and laboratory features in 474 cases. Semin Hematol. 1995;32:45-49.

2. Jaccard A, Moreau P, Leblond V, et al. High-dose melphalan versus melphalan plus dexamethasone for AL amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:11.

1. Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Primary systemic amyloidosis: clinical and laboratory features in 474 cases. Semin Hematol. 1995;32:45-49.

2. Jaccard A, Moreau P, Leblond V, et al. High-dose melphalan versus melphalan plus dexamethasone for AL amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:11.

A 71-year-old white woman presented with nonblanchable, violaceous, monomorphic macules involving the bilateral periorbital skin, upper chest, upper arms, and dorsal forearms of 1 year’s duration. Skin and bone marrow biopsies were performed.

Cystic Nodule on the Palm

The Diagnosis: Nodular Hidradenoma

Nodular hidradenomas (NHs) are rare benign cutaneous adnexal neoplasms first described in 1949 as clear cell papillary carcinomas.1 Since then, various terms have been used to describe this entity, such as eccrine acrospiroma, solid-cystic hidradenoma, and clear cell hidradenoma.2 Review of the literature revealed a female predominance (2:1 ratio) and a mean age at presentation of 37.2 years.3,4 Nodular hidradenoma presents as an asymptomatic, solitary, mobile, firm nodule with intact overlying skin. Rarely, multiple nodules may occur.3 Some tumors display ulceration and serous fluid leakage.5 They occur most commonly on the scalp, face, and upper extremities with an average size of 2 cm.3 Rapid growth of the tumor may signal a malignant change.6

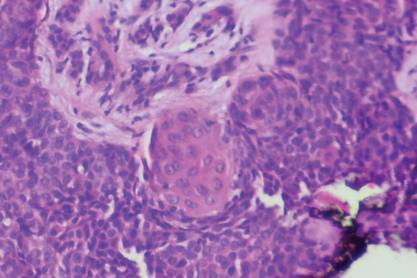

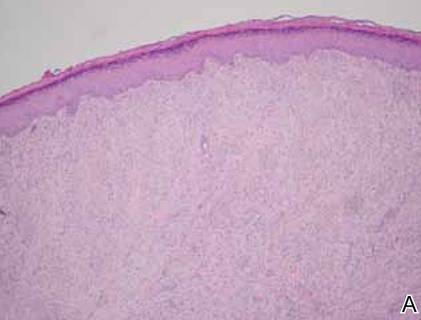

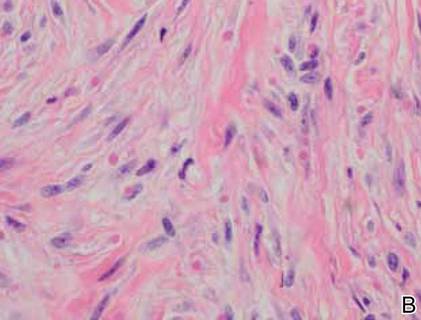

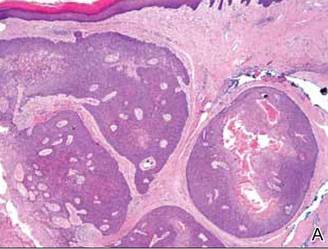

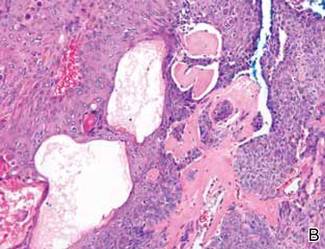

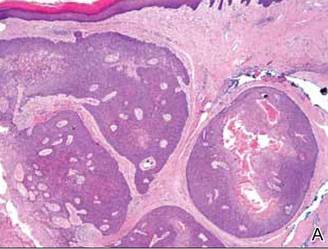

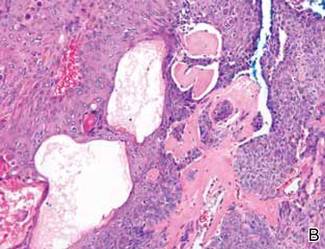

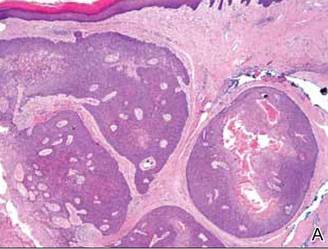

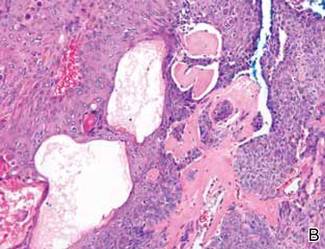

Histopathology reveals a lobulated, circumscribed, symmetrical tumor with dermal nests of epithelial cells that are polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm forming ductlike spaces (Figure). However, clear cell changes and squamous differentiation may be prominent features. Cystic spaces may result from tumor cell degeneration. Most tumors are encased by collagenous fibrous tissue and rarely have epidermal attachments.3

Anastomosing aggregates of squamous cells forming ductlike spaces were viewed on low-power magnification (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). On higher power there were ductlike spaces and eosinophilic hyalinized stroma entrapped by the bland-appearing squamous proliferation (B)(H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Nodular hidradenoma traditionally has been considered to be of eccrine origin, but more recent literature indicates that the majority of NHs are of apocrine origin. Histologically, apocrine tumors display eosinophilic secretion, mucinous epithelium, squamous or sebaceous differentiation, and decapitation secretion, whereas eccrine tumors are identified by their lack of specific features.3

Nodular hidradenoma may recur after excision. Malignant transformation is rare. In one review, 6.7% (6/89) of NHs were malignant, characterized by abnormal mitoses, nuclear atypia, and necrosis.4 Malignant NH or nodular hidradenocarcinoma behaves aggressively with up to an 86% local recurrence and 60% rate of metastasis within 2 years.6 Survival time is inversely proportional to the size of the tumor and is generally poor, with a 5-year disease-free survival of less than 30%.6,7

Treatment of NH is achieved through primary excision or Mohs micrographic surgery; however, treatment of nodular hidradenocarcinoma is controversial and typically begins with wide local excision but may involve lymph node dissection if necessary. Use of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for metastases warrants more clinical studies, as it is a rare occurrence.6 Our patient planned to undergo a total excision of the benign nodule once she healed from the biopsy; however, she was lost to follow-up, as she moved out of state.

1. Lui Y. The histogenesis of clear cell papillary carcinoma of the skin. Am J Pathol. 1949;25:93-103.

2. Obaidat NA, Khaled OA, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms–part 2: an approach to tumours of cutaneous sweat glands. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:145-159.

3. Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T. A study of histopathologic spectrum of nodular hidradenoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:461-470.

4. Hernández-Pérez E, Cestoni-Parducci R. Nodular hidradenoma and hidradenocarcinoma: a 10-year review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:15-20.

5. Sirinoglu H, Celebiler O. Benign nodular hidradenoma of the face. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:750-751.

6. Souvatzidis P, Sbano P, Mandato F, et al. Malignant nodular hidradenoma of the skin: report of seven cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:549-554.

7. Ko CJ, Cochran AJ, Eng W, et al. Hidradenocarcinoma: a histological and immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:726-730.

The Diagnosis: Nodular Hidradenoma

Nodular hidradenomas (NHs) are rare benign cutaneous adnexal neoplasms first described in 1949 as clear cell papillary carcinomas.1 Since then, various terms have been used to describe this entity, such as eccrine acrospiroma, solid-cystic hidradenoma, and clear cell hidradenoma.2 Review of the literature revealed a female predominance (2:1 ratio) and a mean age at presentation of 37.2 years.3,4 Nodular hidradenoma presents as an asymptomatic, solitary, mobile, firm nodule with intact overlying skin. Rarely, multiple nodules may occur.3 Some tumors display ulceration and serous fluid leakage.5 They occur most commonly on the scalp, face, and upper extremities with an average size of 2 cm.3 Rapid growth of the tumor may signal a malignant change.6

Histopathology reveals a lobulated, circumscribed, symmetrical tumor with dermal nests of epithelial cells that are polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm forming ductlike spaces (Figure). However, clear cell changes and squamous differentiation may be prominent features. Cystic spaces may result from tumor cell degeneration. Most tumors are encased by collagenous fibrous tissue and rarely have epidermal attachments.3

Anastomosing aggregates of squamous cells forming ductlike spaces were viewed on low-power magnification (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). On higher power there were ductlike spaces and eosinophilic hyalinized stroma entrapped by the bland-appearing squamous proliferation (B)(H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Nodular hidradenoma traditionally has been considered to be of eccrine origin, but more recent literature indicates that the majority of NHs are of apocrine origin. Histologically, apocrine tumors display eosinophilic secretion, mucinous epithelium, squamous or sebaceous differentiation, and decapitation secretion, whereas eccrine tumors are identified by their lack of specific features.3

Nodular hidradenoma may recur after excision. Malignant transformation is rare. In one review, 6.7% (6/89) of NHs were malignant, characterized by abnormal mitoses, nuclear atypia, and necrosis.4 Malignant NH or nodular hidradenocarcinoma behaves aggressively with up to an 86% local recurrence and 60% rate of metastasis within 2 years.6 Survival time is inversely proportional to the size of the tumor and is generally poor, with a 5-year disease-free survival of less than 30%.6,7

Treatment of NH is achieved through primary excision or Mohs micrographic surgery; however, treatment of nodular hidradenocarcinoma is controversial and typically begins with wide local excision but may involve lymph node dissection if necessary. Use of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for metastases warrants more clinical studies, as it is a rare occurrence.6 Our patient planned to undergo a total excision of the benign nodule once she healed from the biopsy; however, she was lost to follow-up, as she moved out of state.

The Diagnosis: Nodular Hidradenoma

Nodular hidradenomas (NHs) are rare benign cutaneous adnexal neoplasms first described in 1949 as clear cell papillary carcinomas.1 Since then, various terms have been used to describe this entity, such as eccrine acrospiroma, solid-cystic hidradenoma, and clear cell hidradenoma.2 Review of the literature revealed a female predominance (2:1 ratio) and a mean age at presentation of 37.2 years.3,4 Nodular hidradenoma presents as an asymptomatic, solitary, mobile, firm nodule with intact overlying skin. Rarely, multiple nodules may occur.3 Some tumors display ulceration and serous fluid leakage.5 They occur most commonly on the scalp, face, and upper extremities with an average size of 2 cm.3 Rapid growth of the tumor may signal a malignant change.6

Histopathology reveals a lobulated, circumscribed, symmetrical tumor with dermal nests of epithelial cells that are polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm forming ductlike spaces (Figure). However, clear cell changes and squamous differentiation may be prominent features. Cystic spaces may result from tumor cell degeneration. Most tumors are encased by collagenous fibrous tissue and rarely have epidermal attachments.3

Anastomosing aggregates of squamous cells forming ductlike spaces were viewed on low-power magnification (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). On higher power there were ductlike spaces and eosinophilic hyalinized stroma entrapped by the bland-appearing squamous proliferation (B)(H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Nodular hidradenoma traditionally has been considered to be of eccrine origin, but more recent literature indicates that the majority of NHs are of apocrine origin. Histologically, apocrine tumors display eosinophilic secretion, mucinous epithelium, squamous or sebaceous differentiation, and decapitation secretion, whereas eccrine tumors are identified by their lack of specific features.3

Nodular hidradenoma may recur after excision. Malignant transformation is rare. In one review, 6.7% (6/89) of NHs were malignant, characterized by abnormal mitoses, nuclear atypia, and necrosis.4 Malignant NH or nodular hidradenocarcinoma behaves aggressively with up to an 86% local recurrence and 60% rate of metastasis within 2 years.6 Survival time is inversely proportional to the size of the tumor and is generally poor, with a 5-year disease-free survival of less than 30%.6,7

Treatment of NH is achieved through primary excision or Mohs micrographic surgery; however, treatment of nodular hidradenocarcinoma is controversial and typically begins with wide local excision but may involve lymph node dissection if necessary. Use of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for metastases warrants more clinical studies, as it is a rare occurrence.6 Our patient planned to undergo a total excision of the benign nodule once she healed from the biopsy; however, she was lost to follow-up, as she moved out of state.

1. Lui Y. The histogenesis of clear cell papillary carcinoma of the skin. Am J Pathol. 1949;25:93-103.

2. Obaidat NA, Khaled OA, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms–part 2: an approach to tumours of cutaneous sweat glands. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:145-159.

3. Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T. A study of histopathologic spectrum of nodular hidradenoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:461-470.

4. Hernández-Pérez E, Cestoni-Parducci R. Nodular hidradenoma and hidradenocarcinoma: a 10-year review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:15-20.

5. Sirinoglu H, Celebiler O. Benign nodular hidradenoma of the face. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:750-751.

6. Souvatzidis P, Sbano P, Mandato F, et al. Malignant nodular hidradenoma of the skin: report of seven cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:549-554.

7. Ko CJ, Cochran AJ, Eng W, et al. Hidradenocarcinoma: a histological and immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:726-730.

1. Lui Y. The histogenesis of clear cell papillary carcinoma of the skin. Am J Pathol. 1949;25:93-103.

2. Obaidat NA, Khaled OA, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms–part 2: an approach to tumours of cutaneous sweat glands. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:145-159.

3. Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T. A study of histopathologic spectrum of nodular hidradenoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:461-470.

4. Hernández-Pérez E, Cestoni-Parducci R. Nodular hidradenoma and hidradenocarcinoma: a 10-year review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:15-20.

5. Sirinoglu H, Celebiler O. Benign nodular hidradenoma of the face. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:750-751.

6. Souvatzidis P, Sbano P, Mandato F, et al. Malignant nodular hidradenoma of the skin: report of seven cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:549-554.

7. Ko CJ, Cochran AJ, Eng W, et al. Hidradenocarcinoma: a histological and immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:726-730.

A 73-year-old woman with a history of multiple strokes with residual left-sided motor deficits and resultant left-hand contracture, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and a remote history of treated colon cancer and breast cancer presented with hypertensive urgency and neck pain. Upon admission, the nursing staff found an “unusual growth” on the patient’s left hand. Dermatology was consulted and a 2×1.5×1.5-cm multilobulated, malodorous, slightly tender, nonfluctuant, gelatinous, mobile, cystic nodule overlying the fourth metacarpal palmar head was examined. The patient reported the lesion was present for more than a year. Imaging was pursued, but radiography, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging could not be performed adequately due to the patient’s severe contracture. Given the extensive differential diagnoses, an orthopedic hand surgeon performed a large incisional biopsy to obtain tissue diagnosis.

Firm Plaques and Nodules Over the Body

The Diagnosis: Pancreatic Panniculitis

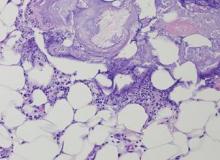

The biopsy specimen revealed necrosis of the panniculus with “ghost” cells (Figure). Calcification was encountered. Changes of vasculitis were not identified and fungal organisms were not noted. The histopathologic findings supported a diagnosis of pancreatic panniculitis.

Pancreatic panniculitis has been associated with pancreatitis, pancreatic carcinoma, pancreatic pseudocysts, congenital abnormalities of the pancreas, and drug-induced pancreatitis.1 Skin lesions may herald a diagnosis of pancreatic disease in an outpatient and should prompt thorough clinical evaluation when encountered in an outpatient setting. Our patient first developed tender nodules on the left shin 2 to 3 weeks prior to presentation. She reported that her initial nodules were flesh colored but then became erythematous and tender over 1 week’s time. The patient’s history was remarkable for ovarian cancer. She had been hospitalized 2 weeks prior to presentation for abdominal pain and ascites. Imaging studies revealed a cystic lesion in the head of the pancreas. The pancreas was traumatized during a peritoneal tap. Her nodules developed shortly thereafter and were distributed on the arms, legs, back, and abdomen.

Pancreatic tumors or inflammation are thought to trigger pancreatic panniculitis by releasing enzymes. Pancreatic enzymes such as lipase are thought to play a role in the development of pancreatic panniculitis by entering the vascular system and leading to fat necrosis.2,3 Biopsy reveals necrosis of adipocytes in the center of fat lobules.4 Ghost cells result from hydrolytic activity of enzymes on the fat cells followed by calcium deposition. A report indicates that fungal infection or gout also can cause changes that mimic pancreatic panniculitis.5

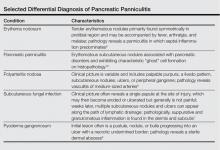

Other entities in the differential diagnosis can be excluded by biopsy. Polyarteritis nodosa is a vasculitis. Although panniculitis may be seen in polyarteritis as a secondary phenomenon, lesions are centered around blood vessels and often eventuate in ulceration.6 Subcutaneous fungal infection typically reveals organisms on periodic acid–Schiff stain.7 Pyoderma gangrenosum is associated with ulceration and a neutrophilic infiltrate that is often centered around a central pilosebaceous unit in developing lesions.8 Erythema nodosum is a panniculitis in which septal inflammation predominates.9 These differential diagnoses of pancreatic panniculitis are summarized in the Table.

Pancreatic panniculitis can be associated with acute arthritis and inflammation of periarticular fat.10 Treatment of pancreatic panniculitis is usually focused on the underlying pancreatic disease.11,12 Our patient benefited from analgesic therapy and her lesions improved on follow-up. Clinicians encountering a patient with new tender nodules should be prompted to perform a biopsy. When histopathologic evaluation reveals ghosted adipocytes, pancreatic panniculitis should be suspected and clinical evaluation undertaken.

1. Garcia-Romero D, Vanaclocha F. Pancreatic panniculitis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:465-470.

2. Berman B, Conteas C, Smith B, et al. Fatal pancreatitis presenting with subcutaneous fat necrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:359-364.

3. Dhawan SS, Jimenez-Acosta F, Poppiti RJ Jr, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatitis: histochemical and electron microscopic findings. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1025-1028.

4. Cannon JR, Pitha JV, Everett MA. Subcutaneous fat necrosis in pancreatitis. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:501-506.

5. Requena L, Sitthinamsuwan P, Santonja C, et al. Cutaneous and mucosal mucormycosis mimicking pancreatic panniculitis and gouty panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:975-984.

6. Grattan CEH. Polyarteritis nodosa. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:405-407.

7. Millett CR, Halpern AV, Heymann WR. Subcutaneous mycoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1266-1273.

8. Moschella SL, Davis MDP. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:427-431.

9. Patterson JW. Erythema nodosum. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1641-1645.

10. Patterson JW. Pancreatic panniculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1649-1650.

11. Requena L, Sanchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

12. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

The Diagnosis: Pancreatic Panniculitis

The biopsy specimen revealed necrosis of the panniculus with “ghost” cells (Figure). Calcification was encountered. Changes of vasculitis were not identified and fungal organisms were not noted. The histopathologic findings supported a diagnosis of pancreatic panniculitis.

Pancreatic panniculitis has been associated with pancreatitis, pancreatic carcinoma, pancreatic pseudocysts, congenital abnormalities of the pancreas, and drug-induced pancreatitis.1 Skin lesions may herald a diagnosis of pancreatic disease in an outpatient and should prompt thorough clinical evaluation when encountered in an outpatient setting. Our patient first developed tender nodules on the left shin 2 to 3 weeks prior to presentation. She reported that her initial nodules were flesh colored but then became erythematous and tender over 1 week’s time. The patient’s history was remarkable for ovarian cancer. She had been hospitalized 2 weeks prior to presentation for abdominal pain and ascites. Imaging studies revealed a cystic lesion in the head of the pancreas. The pancreas was traumatized during a peritoneal tap. Her nodules developed shortly thereafter and were distributed on the arms, legs, back, and abdomen.

Pancreatic tumors or inflammation are thought to trigger pancreatic panniculitis by releasing enzymes. Pancreatic enzymes such as lipase are thought to play a role in the development of pancreatic panniculitis by entering the vascular system and leading to fat necrosis.2,3 Biopsy reveals necrosis of adipocytes in the center of fat lobules.4 Ghost cells result from hydrolytic activity of enzymes on the fat cells followed by calcium deposition. A report indicates that fungal infection or gout also can cause changes that mimic pancreatic panniculitis.5

Other entities in the differential diagnosis can be excluded by biopsy. Polyarteritis nodosa is a vasculitis. Although panniculitis may be seen in polyarteritis as a secondary phenomenon, lesions are centered around blood vessels and often eventuate in ulceration.6 Subcutaneous fungal infection typically reveals organisms on periodic acid–Schiff stain.7 Pyoderma gangrenosum is associated with ulceration and a neutrophilic infiltrate that is often centered around a central pilosebaceous unit in developing lesions.8 Erythema nodosum is a panniculitis in which septal inflammation predominates.9 These differential diagnoses of pancreatic panniculitis are summarized in the Table.

Pancreatic panniculitis can be associated with acute arthritis and inflammation of periarticular fat.10 Treatment of pancreatic panniculitis is usually focused on the underlying pancreatic disease.11,12 Our patient benefited from analgesic therapy and her lesions improved on follow-up. Clinicians encountering a patient with new tender nodules should be prompted to perform a biopsy. When histopathologic evaluation reveals ghosted adipocytes, pancreatic panniculitis should be suspected and clinical evaluation undertaken.

The Diagnosis: Pancreatic Panniculitis

The biopsy specimen revealed necrosis of the panniculus with “ghost” cells (Figure). Calcification was encountered. Changes of vasculitis were not identified and fungal organisms were not noted. The histopathologic findings supported a diagnosis of pancreatic panniculitis.

Pancreatic panniculitis has been associated with pancreatitis, pancreatic carcinoma, pancreatic pseudocysts, congenital abnormalities of the pancreas, and drug-induced pancreatitis.1 Skin lesions may herald a diagnosis of pancreatic disease in an outpatient and should prompt thorough clinical evaluation when encountered in an outpatient setting. Our patient first developed tender nodules on the left shin 2 to 3 weeks prior to presentation. She reported that her initial nodules were flesh colored but then became erythematous and tender over 1 week’s time. The patient’s history was remarkable for ovarian cancer. She had been hospitalized 2 weeks prior to presentation for abdominal pain and ascites. Imaging studies revealed a cystic lesion in the head of the pancreas. The pancreas was traumatized during a peritoneal tap. Her nodules developed shortly thereafter and were distributed on the arms, legs, back, and abdomen.

Pancreatic tumors or inflammation are thought to trigger pancreatic panniculitis by releasing enzymes. Pancreatic enzymes such as lipase are thought to play a role in the development of pancreatic panniculitis by entering the vascular system and leading to fat necrosis.2,3 Biopsy reveals necrosis of adipocytes in the center of fat lobules.4 Ghost cells result from hydrolytic activity of enzymes on the fat cells followed by calcium deposition. A report indicates that fungal infection or gout also can cause changes that mimic pancreatic panniculitis.5

Other entities in the differential diagnosis can be excluded by biopsy. Polyarteritis nodosa is a vasculitis. Although panniculitis may be seen in polyarteritis as a secondary phenomenon, lesions are centered around blood vessels and often eventuate in ulceration.6 Subcutaneous fungal infection typically reveals organisms on periodic acid–Schiff stain.7 Pyoderma gangrenosum is associated with ulceration and a neutrophilic infiltrate that is often centered around a central pilosebaceous unit in developing lesions.8 Erythema nodosum is a panniculitis in which septal inflammation predominates.9 These differential diagnoses of pancreatic panniculitis are summarized in the Table.

Pancreatic panniculitis can be associated with acute arthritis and inflammation of periarticular fat.10 Treatment of pancreatic panniculitis is usually focused on the underlying pancreatic disease.11,12 Our patient benefited from analgesic therapy and her lesions improved on follow-up. Clinicians encountering a patient with new tender nodules should be prompted to perform a biopsy. When histopathologic evaluation reveals ghosted adipocytes, pancreatic panniculitis should be suspected and clinical evaluation undertaken.

1. Garcia-Romero D, Vanaclocha F. Pancreatic panniculitis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:465-470.

2. Berman B, Conteas C, Smith B, et al. Fatal pancreatitis presenting with subcutaneous fat necrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:359-364.

3. Dhawan SS, Jimenez-Acosta F, Poppiti RJ Jr, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatitis: histochemical and electron microscopic findings. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1025-1028.

4. Cannon JR, Pitha JV, Everett MA. Subcutaneous fat necrosis in pancreatitis. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:501-506.

5. Requena L, Sitthinamsuwan P, Santonja C, et al. Cutaneous and mucosal mucormycosis mimicking pancreatic panniculitis and gouty panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:975-984.

6. Grattan CEH. Polyarteritis nodosa. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:405-407.

7. Millett CR, Halpern AV, Heymann WR. Subcutaneous mycoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1266-1273.

8. Moschella SL, Davis MDP. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:427-431.

9. Patterson JW. Erythema nodosum. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1641-1645.

10. Patterson JW. Pancreatic panniculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1649-1650.

11. Requena L, Sanchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

12. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

1. Garcia-Romero D, Vanaclocha F. Pancreatic panniculitis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:465-470.

2. Berman B, Conteas C, Smith B, et al. Fatal pancreatitis presenting with subcutaneous fat necrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:359-364.

3. Dhawan SS, Jimenez-Acosta F, Poppiti RJ Jr, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatitis: histochemical and electron microscopic findings. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1025-1028.

4. Cannon JR, Pitha JV, Everett MA. Subcutaneous fat necrosis in pancreatitis. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:501-506.

5. Requena L, Sitthinamsuwan P, Santonja C, et al. Cutaneous and mucosal mucormycosis mimicking pancreatic panniculitis and gouty panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:975-984.

6. Grattan CEH. Polyarteritis nodosa. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:405-407.

7. Millett CR, Halpern AV, Heymann WR. Subcutaneous mycoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1266-1273.

8. Moschella SL, Davis MDP. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:427-431.

9. Patterson JW. Erythema nodosum. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1641-1645.

10. Patterson JW. Pancreatic panniculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1649-1650.

11. Requena L, Sanchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

12. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

A 52-year-old woman presented with painful erythematous nodules of 2 weeks’ duration that began as a single lesion on the left shin and spread rapidly to involve the trunk, arms, and legs. A punch biopsy was performed. Pertinent history included a recent hospitalization for drainage of malignant ascites secondary to metastatic ovarian cancer. The lesions did not drain and were not pruritic. The patient did not have a history of fever, night sweats, nausea, headache, neurologic change, muscle aching, or recent weight loss.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Onychomadesis Following Hand-foot-and-mouth Disease

The Diagnosis: Onychomadesis Following Hand-foot-and-mouth Disease

In 1846, Joseph Honoré Simon Beau described specific diagnostic signs manifested in the nails during various disease states.1 He suggested that the width of the nail plate depression correlated with the duration of illness. Since then, the correlation of nail changes during times of illness has been confirmed. The term Beau lines currently is used to describe transverse ridging of the nail plate due to transient arrest in nail plate formation.1 Onychomadesis is believed to be an extreme form of Beau lines in which the whole thickness of the nail plate is affected, resulting in its separation from the proximal nail fold and shedding of the nail plate.

Nail plate detachment in onychomadesis is due to a severe insult that results in complete arrest of the nail matrix activity. Onychomadesis has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations, ranging from mild transverse ridges of the nail plate (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding.2 Trauma is the leading cause of single-digit onychomadesis, while multiple-digit onychomadesis usually is caused by a systemic disease (eg, blistering illnesses). Cases of multiple-nail onychomadesis have been reported following hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD), though the majority of cases of HFMD do not present with onychomadesis.

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is most commonly caused by 2 types of intestinal strains of Human enterovirus A: (1) coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6) or A16 (CVA16) and (2) enterovirus 71.3,4 Symptoms of HFMD include fever and sore throat followed by the development of oral ulcerations 1 to 2 days later. A vesicular or maculopapular rash can then develop on the hands, feet, and mouth. Complications following HFMD are rare but can include encephalitis, meningitis, and pneumonia. Symptoms typically resolve after 6 days without any treatment.3

A cluster of onychomadesis cases following HFMD outbreaks have been reported in Europe, Asia, and the United States. In some reports, causative viral strains have been identified. After a national HFMD outbreak in Finland in fall 2008, investigators isolated strains of CVA6 in the shedded nails of sibling patients.4 The CVA6 strain was found to be the primary pathogen causing that particular HFMD outbreak and onychomadesis was a hallmark presentation of this viral epidemic. Previously, HFMD outbreaks were known to be caused by CVA16 or enterovirus 71, with enterovirus 71 strains occurring mostly in Southeast Asia and Australia.4 In a report from Taiwan, the incidence of onychomadesis after CVA6 infection was 37% (48/130) as compared to 5% (7/145) in cases with non-CVA6 causative strains. Among patients with onychomadesis, 69% (33/48) were reported to experience concurrent palmoplantar desquamation before or during presentation of nail changes.5

Another Finnish study investigated an atypical outbreak of HFMD that occurred primarily in adult patients.6 Many of these patients also had onychomadesis several weeks following HFMD. Of 317 cases, human enteroviruses were detected in specimens from 212 cases (67%), including both children and adults. Two human enterovirus types—CVA6 (71% [83/117]) and coxsackievirus A10 (28% [33/117])—were identified as the causative agents of the outbreak. One genetic variant of CVA6 predominated, but 3 other genetically distinct CVA6 strains also were found.6 The 2008 HFMD outbreak in Finland was found to be caused by 2 concomitantly circulating human enteroviruses, which up until now have been infrequently detected together as causative agents of HFMD. Onychomadesis was a common occurrence in the Finnish HFMD outbreak, which has been previously linked to CVA6. The co-circulation of CVA6 and coxsackievirus A10 suggests an endemic emergence of new genetic variants of these enteroviruses.6

There also have been several reports of onychomadesis outbreaks in Spain, 2 of which occurred in nursery settings. One report noted that patients with a history of HFMD were 14 times more likely to develop onychomadesis (relative risk, 14; 95% confidence interval, 4.57-42.86).3 There also was a noted difference in prevalence of onychomadesis regarding age: a 55% (18/33) occurrence rate was noted in the youngest age group (9–23 months), 30% (8/27) in the middle age group (24–32 months), and 4% (1/28) in the oldest age group (33–42 months). Occurrence of onychomadesis and nail plate changes was observed on average 40 days after HFMD, and an average of 4 nails were shed per case.3 A report investigating a separate HFMD outbreak in Spain found a high percentage of onychomadesis (96% [298/311]) occurring in children younger than 6 years. This outbreak, which occurred in the metropolitan area of Valencia, was associated with an outbreak of HFMD primarily caused by coxsackievirus A10.7 A third Spanish study uncovered a high occurrence of onychomadesis in a nursery setting as a consequence of HFMD, where 92% (11/12) of onychomadesis cases were preceded by HFMD 2 months prior.8

A case series reported in Chicago, Illinois, in the late 1990s identified 5 pediatric patients with HFMD associated with Beau lines and onychomadesis.1 Only 3 of 5 (60%) patients had a fever; therefore, fever-induced nail matrix arrest was ruled out as the inciting factor of the nail changes seen. All patients were given over-the-counter analgesics and 2 received antibiotics (amoxicillin for the first 48 hours). None of these medications have been implicated as plausible causes of nail matrix arrest. Two patients were siblings and the rest were not related. None of the patients had a history of close physical proximity (eg, attendance at the same day care or school). All 5 patients developed HFMD within 4 weeks of one another, and all were from the suburbs of Chicago (with 4 of 5 [80%] patients living within a 60-mile radius of each other). Although the causative viral strain was not isolated, the authors concluded that all the patients were likely to have been infected by the same virus due to the general vicinity of the patients to each other. Furthermore, the collective case reports likely represented an HFMD epidemic caused by a particular strain that can induce onychomadesis.1

Supportive care for the viral illness paired with protection of the nail bed until new nail growth occurs is ideal, which requires maintaining short nails and using adhesive bandages over the affected nails to avoid snagging the nail or ripping off the partially attached nails.

Onychomadesis can follow HFMD, especially in cases caused by CVA6. Cases of onychomadesis are mild and self-limited. When onychomadesis is noted, historical review of viral illnesses within 1 to 2 months prior to nail changes often will identify the causative disease.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM. Nail disorders. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. China: Elsevier; 2012:1130-1131.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346.

- Blomqvist S, Klemola P, Kaijalainen S, et al. Co-circulation of coxsackieviruses A6 and A10 in hand, foot and mouth disease outbreak in Finland. J Clin Virol. 2010;48:49-54.

- Davia JL, Bel PH, Ninet VZ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak in Valencia, Spain, associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by enteroviruses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:1-5.

- Cabrerizo M, De Miguel T, Armada A, et al. Onychomadesis after a hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreak in Spain, 2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1775-1778.

The Diagnosis: Onychomadesis Following Hand-foot-and-mouth Disease

In 1846, Joseph Honoré Simon Beau described specific diagnostic signs manifested in the nails during various disease states.1 He suggested that the width of the nail plate depression correlated with the duration of illness. Since then, the correlation of nail changes during times of illness has been confirmed. The term Beau lines currently is used to describe transverse ridging of the nail plate due to transient arrest in nail plate formation.1 Onychomadesis is believed to be an extreme form of Beau lines in which the whole thickness of the nail plate is affected, resulting in its separation from the proximal nail fold and shedding of the nail plate.

Nail plate detachment in onychomadesis is due to a severe insult that results in complete arrest of the nail matrix activity. Onychomadesis has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations, ranging from mild transverse ridges of the nail plate (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding.2 Trauma is the leading cause of single-digit onychomadesis, while multiple-digit onychomadesis usually is caused by a systemic disease (eg, blistering illnesses). Cases of multiple-nail onychomadesis have been reported following hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD), though the majority of cases of HFMD do not present with onychomadesis.

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is most commonly caused by 2 types of intestinal strains of Human enterovirus A: (1) coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6) or A16 (CVA16) and (2) enterovirus 71.3,4 Symptoms of HFMD include fever and sore throat followed by the development of oral ulcerations 1 to 2 days later. A vesicular or maculopapular rash can then develop on the hands, feet, and mouth. Complications following HFMD are rare but can include encephalitis, meningitis, and pneumonia. Symptoms typically resolve after 6 days without any treatment.3

A cluster of onychomadesis cases following HFMD outbreaks have been reported in Europe, Asia, and the United States. In some reports, causative viral strains have been identified. After a national HFMD outbreak in Finland in fall 2008, investigators isolated strains of CVA6 in the shedded nails of sibling patients.4 The CVA6 strain was found to be the primary pathogen causing that particular HFMD outbreak and onychomadesis was a hallmark presentation of this viral epidemic. Previously, HFMD outbreaks were known to be caused by CVA16 or enterovirus 71, with enterovirus 71 strains occurring mostly in Southeast Asia and Australia.4 In a report from Taiwan, the incidence of onychomadesis after CVA6 infection was 37% (48/130) as compared to 5% (7/145) in cases with non-CVA6 causative strains. Among patients with onychomadesis, 69% (33/48) were reported to experience concurrent palmoplantar desquamation before or during presentation of nail changes.5

Another Finnish study investigated an atypical outbreak of HFMD that occurred primarily in adult patients.6 Many of these patients also had onychomadesis several weeks following HFMD. Of 317 cases, human enteroviruses were detected in specimens from 212 cases (67%), including both children and adults. Two human enterovirus types—CVA6 (71% [83/117]) and coxsackievirus A10 (28% [33/117])—were identified as the causative agents of the outbreak. One genetic variant of CVA6 predominated, but 3 other genetically distinct CVA6 strains also were found.6 The 2008 HFMD outbreak in Finland was found to be caused by 2 concomitantly circulating human enteroviruses, which up until now have been infrequently detected together as causative agents of HFMD. Onychomadesis was a common occurrence in the Finnish HFMD outbreak, which has been previously linked to CVA6. The co-circulation of CVA6 and coxsackievirus A10 suggests an endemic emergence of new genetic variants of these enteroviruses.6

There also have been several reports of onychomadesis outbreaks in Spain, 2 of which occurred in nursery settings. One report noted that patients with a history of HFMD were 14 times more likely to develop onychomadesis (relative risk, 14; 95% confidence interval, 4.57-42.86).3 There also was a noted difference in prevalence of onychomadesis regarding age: a 55% (18/33) occurrence rate was noted in the youngest age group (9–23 months), 30% (8/27) in the middle age group (24–32 months), and 4% (1/28) in the oldest age group (33–42 months). Occurrence of onychomadesis and nail plate changes was observed on average 40 days after HFMD, and an average of 4 nails were shed per case.3 A report investigating a separate HFMD outbreak in Spain found a high percentage of onychomadesis (96% [298/311]) occurring in children younger than 6 years. This outbreak, which occurred in the metropolitan area of Valencia, was associated with an outbreak of HFMD primarily caused by coxsackievirus A10.7 A third Spanish study uncovered a high occurrence of onychomadesis in a nursery setting as a consequence of HFMD, where 92% (11/12) of onychomadesis cases were preceded by HFMD 2 months prior.8

A case series reported in Chicago, Illinois, in the late 1990s identified 5 pediatric patients with HFMD associated with Beau lines and onychomadesis.1 Only 3 of 5 (60%) patients had a fever; therefore, fever-induced nail matrix arrest was ruled out as the inciting factor of the nail changes seen. All patients were given over-the-counter analgesics and 2 received antibiotics (amoxicillin for the first 48 hours). None of these medications have been implicated as plausible causes of nail matrix arrest. Two patients were siblings and the rest were not related. None of the patients had a history of close physical proximity (eg, attendance at the same day care or school). All 5 patients developed HFMD within 4 weeks of one another, and all were from the suburbs of Chicago (with 4 of 5 [80%] patients living within a 60-mile radius of each other). Although the causative viral strain was not isolated, the authors concluded that all the patients were likely to have been infected by the same virus due to the general vicinity of the patients to each other. Furthermore, the collective case reports likely represented an HFMD epidemic caused by a particular strain that can induce onychomadesis.1

Supportive care for the viral illness paired with protection of the nail bed until new nail growth occurs is ideal, which requires maintaining short nails and using adhesive bandages over the affected nails to avoid snagging the nail or ripping off the partially attached nails.

Onychomadesis can follow HFMD, especially in cases caused by CVA6. Cases of onychomadesis are mild and self-limited. When onychomadesis is noted, historical review of viral illnesses within 1 to 2 months prior to nail changes often will identify the causative disease.

The Diagnosis: Onychomadesis Following Hand-foot-and-mouth Disease

In 1846, Joseph Honoré Simon Beau described specific diagnostic signs manifested in the nails during various disease states.1 He suggested that the width of the nail plate depression correlated with the duration of illness. Since then, the correlation of nail changes during times of illness has been confirmed. The term Beau lines currently is used to describe transverse ridging of the nail plate due to transient arrest in nail plate formation.1 Onychomadesis is believed to be an extreme form of Beau lines in which the whole thickness of the nail plate is affected, resulting in its separation from the proximal nail fold and shedding of the nail plate.

Nail plate detachment in onychomadesis is due to a severe insult that results in complete arrest of the nail matrix activity. Onychomadesis has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations, ranging from mild transverse ridges of the nail plate (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding.2 Trauma is the leading cause of single-digit onychomadesis, while multiple-digit onychomadesis usually is caused by a systemic disease (eg, blistering illnesses). Cases of multiple-nail onychomadesis have been reported following hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD), though the majority of cases of HFMD do not present with onychomadesis.

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is most commonly caused by 2 types of intestinal strains of Human enterovirus A: (1) coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6) or A16 (CVA16) and (2) enterovirus 71.3,4 Symptoms of HFMD include fever and sore throat followed by the development of oral ulcerations 1 to 2 days later. A vesicular or maculopapular rash can then develop on the hands, feet, and mouth. Complications following HFMD are rare but can include encephalitis, meningitis, and pneumonia. Symptoms typically resolve after 6 days without any treatment.3

A cluster of onychomadesis cases following HFMD outbreaks have been reported in Europe, Asia, and the United States. In some reports, causative viral strains have been identified. After a national HFMD outbreak in Finland in fall 2008, investigators isolated strains of CVA6 in the shedded nails of sibling patients.4 The CVA6 strain was found to be the primary pathogen causing that particular HFMD outbreak and onychomadesis was a hallmark presentation of this viral epidemic. Previously, HFMD outbreaks were known to be caused by CVA16 or enterovirus 71, with enterovirus 71 strains occurring mostly in Southeast Asia and Australia.4 In a report from Taiwan, the incidence of onychomadesis after CVA6 infection was 37% (48/130) as compared to 5% (7/145) in cases with non-CVA6 causative strains. Among patients with onychomadesis, 69% (33/48) were reported to experience concurrent palmoplantar desquamation before or during presentation of nail changes.5

Another Finnish study investigated an atypical outbreak of HFMD that occurred primarily in adult patients.6 Many of these patients also had onychomadesis several weeks following HFMD. Of 317 cases, human enteroviruses were detected in specimens from 212 cases (67%), including both children and adults. Two human enterovirus types—CVA6 (71% [83/117]) and coxsackievirus A10 (28% [33/117])—were identified as the causative agents of the outbreak. One genetic variant of CVA6 predominated, but 3 other genetically distinct CVA6 strains also were found.6 The 2008 HFMD outbreak in Finland was found to be caused by 2 concomitantly circulating human enteroviruses, which up until now have been infrequently detected together as causative agents of HFMD. Onychomadesis was a common occurrence in the Finnish HFMD outbreak, which has been previously linked to CVA6. The co-circulation of CVA6 and coxsackievirus A10 suggests an endemic emergence of new genetic variants of these enteroviruses.6

There also have been several reports of onychomadesis outbreaks in Spain, 2 of which occurred in nursery settings. One report noted that patients with a history of HFMD were 14 times more likely to develop onychomadesis (relative risk, 14; 95% confidence interval, 4.57-42.86).3 There also was a noted difference in prevalence of onychomadesis regarding age: a 55% (18/33) occurrence rate was noted in the youngest age group (9–23 months), 30% (8/27) in the middle age group (24–32 months), and 4% (1/28) in the oldest age group (33–42 months). Occurrence of onychomadesis and nail plate changes was observed on average 40 days after HFMD, and an average of 4 nails were shed per case.3 A report investigating a separate HFMD outbreak in Spain found a high percentage of onychomadesis (96% [298/311]) occurring in children younger than 6 years. This outbreak, which occurred in the metropolitan area of Valencia, was associated with an outbreak of HFMD primarily caused by coxsackievirus A10.7 A third Spanish study uncovered a high occurrence of onychomadesis in a nursery setting as a consequence of HFMD, where 92% (11/12) of onychomadesis cases were preceded by HFMD 2 months prior.8

A case series reported in Chicago, Illinois, in the late 1990s identified 5 pediatric patients with HFMD associated with Beau lines and onychomadesis.1 Only 3 of 5 (60%) patients had a fever; therefore, fever-induced nail matrix arrest was ruled out as the inciting factor of the nail changes seen. All patients were given over-the-counter analgesics and 2 received antibiotics (amoxicillin for the first 48 hours). None of these medications have been implicated as plausible causes of nail matrix arrest. Two patients were siblings and the rest were not related. None of the patients had a history of close physical proximity (eg, attendance at the same day care or school). All 5 patients developed HFMD within 4 weeks of one another, and all were from the suburbs of Chicago (with 4 of 5 [80%] patients living within a 60-mile radius of each other). Although the causative viral strain was not isolated, the authors concluded that all the patients were likely to have been infected by the same virus due to the general vicinity of the patients to each other. Furthermore, the collective case reports likely represented an HFMD epidemic caused by a particular strain that can induce onychomadesis.1

Supportive care for the viral illness paired with protection of the nail bed until new nail growth occurs is ideal, which requires maintaining short nails and using adhesive bandages over the affected nails to avoid snagging the nail or ripping off the partially attached nails.

Onychomadesis can follow HFMD, especially in cases caused by CVA6. Cases of onychomadesis are mild and self-limited. When onychomadesis is noted, historical review of viral illnesses within 1 to 2 months prior to nail changes often will identify the causative disease.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM. Nail disorders. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. China: Elsevier; 2012:1130-1131.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346.

- Blomqvist S, Klemola P, Kaijalainen S, et al. Co-circulation of coxsackieviruses A6 and A10 in hand, foot and mouth disease outbreak in Finland. J Clin Virol. 2010;48:49-54.

- Davia JL, Bel PH, Ninet VZ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak in Valencia, Spain, associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by enteroviruses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:1-5.

- Cabrerizo M, De Miguel T, Armada A, et al. Onychomadesis after a hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreak in Spain, 2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1775-1778.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM. Nail disorders. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. China: Elsevier; 2012:1130-1131.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346.

- Blomqvist S, Klemola P, Kaijalainen S, et al. Co-circulation of coxsackieviruses A6 and A10 in hand, foot and mouth disease outbreak in Finland. J Clin Virol. 2010;48:49-54.

- Davia JL, Bel PH, Ninet VZ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak in Valencia, Spain, associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by enteroviruses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:1-5.

- Cabrerizo M, De Miguel T, Armada A, et al. Onychomadesis after a hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreak in Spain, 2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1775-1778.

Indurated Erythematous Papules and Plaques on the Forearm

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium chelonae Arising Within a Tattoo

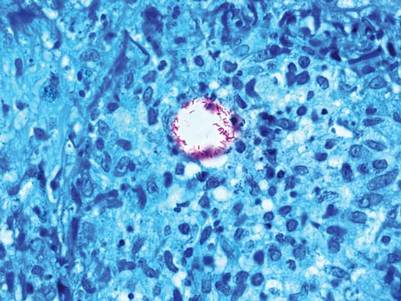

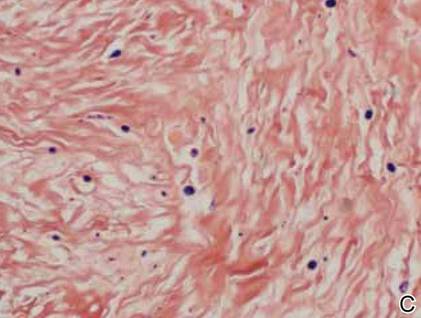

A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from one of the plaques. Histopathology revealed an unremarkable epidermis with granulomatous collections of epithelioid histiocytes in association with neutrophils and lymphocytes in the dermis (Figure 1). Periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms. Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacilli (Figure 2). Clinical and histopathologic findings led to the initial diagnosis of a mycobacterial infection within the tattoo. The patient was empirically started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and oral clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily with mild improvement of the lesions over the next month. After 6 weeks the mycobacterial cultures were persistently negative and high-performance liquid chromatography was performed verifying the presence of Mycobacterium chelonae. Clarithromycin was continued and the doxycycline was replaced with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (double strength) twice daily due to resistance. The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who concurred with the treatment regimen for a duration of 6 months to a year. A chest radiograph also was performed to rule out disseminated disease. Several months later the patient’s close friend presented with a similar infection that was acquired on the same day as our patient at the same tattoo parlor. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene was notified about these cases and informed us of other cases in New York State linked to contaminated tattoo ink.

|

Mycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacteria (Runyon group IV) that is found in nature and contaminated sources such as soil, lakes, sewage, and tap water.1 Inoculation ofM chelonae through contaminated instruments leads to the formation of painful lesions, abscesses, fistulas, and granulomas that are extremely difficult to treat.2 In our patient, M chelonae was most likely transmitted via contaminated tap water that was used to dilute the black tattoo ink to yield a gray color. Alternative sources are the ink itself or the container used to mix the ink.3Mycobacterium chelonae can cause infections in the skin, lungs, joints, bones, and eyes.4 With the exception of lung disease, trauma is the usual inciting factor. Disseminated infections are almost exclusively found in immunosuppressed individuals. Mycobacterium chelonae is typically found to grow on culture within 7 days. However, in our case there was no growth after 6 weeks of incubation. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of mycolic acid is an alternative method of identifying mycobacteria. This technique verified the presence of M chelonae in our case when cultures were persistently negative.5

Mycobacterium chelonae is difficult to treat. The most common antibiotics used for treatment are clarithromycin, azithromycin, doxycycline, and linezolid.6 Studies of various antibiotics have shown that clarithromycin is the most effective macrolide against M chelonae.7 Tetracyclines also were studied in their effectiveness at treating nontuberculous mycobacteria infections but were found to have increased resistance to M chelonae.8 Although treatment regimens vary, the highest success rates are achieved with a minimum of 6 months of therapy using at least 2 drugs. Longer treatment is recommended for immunocompromised individuals.9

The case we present is important from a public health perspective. The tattoo industry and ink manufacturers should bemade aware of the risks of various infections from nonsterile techniques. Tattoo parlor employees should be advised of the risks of using nonsterile water for ink dilution and cleaning tattoo equipment. They also should be continuously educated on aseptic techniques.

1. Lee RP, Cheung KW, Chiu KH, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection after total knee arthroplasty: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2012;20:134-136.

2. Camargo D, Saad C, Ruiz F, et al. latrogenic outbreak of M. chelonae skin abscesses. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;117:113-119.

3. Rodríguez-Blanco I, Fernández LC, Suárez-Peñaranda JM, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection associated with tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:61-62.

4. Karak K, Bhattacharyya S, Majumdar S, et al. Pulmonary infections caused by mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis in and around Calcutta. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1996;39:131-134.

5. Butler WR, Floyd MM, Silcox V, et al. Standardized Method for HPLC Identification of Mycobacteria. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1996.

6. Brown-Elliot BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Blinkhorn R, et al. Successful treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium chelonae infection with linezolid. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1433-1434.

7. Brown BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Onyi GO, et al. Activities of four macrolides, including clarithromycin, against Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonae, and Mycobacterium chelonae-like organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:180-184.

8. Swenson JM, Wallace RJ Jr, Silcox VA, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of five subgroups of Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:807-811.

9. Leung YY, Choi KW, Ho KM, et al. Disseminated cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium chelonae mimicking panniculitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. Hong Kong Med J. 2005;11:515-519.

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium chelonae Arising Within a Tattoo

A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from one of the plaques. Histopathology revealed an unremarkable epidermis with granulomatous collections of epithelioid histiocytes in association with neutrophils and lymphocytes in the dermis (Figure 1). Periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms. Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacilli (Figure 2). Clinical and histopathologic findings led to the initial diagnosis of a mycobacterial infection within the tattoo. The patient was empirically started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and oral clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily with mild improvement of the lesions over the next month. After 6 weeks the mycobacterial cultures were persistently negative and high-performance liquid chromatography was performed verifying the presence of Mycobacterium chelonae. Clarithromycin was continued and the doxycycline was replaced with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (double strength) twice daily due to resistance. The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who concurred with the treatment regimen for a duration of 6 months to a year. A chest radiograph also was performed to rule out disseminated disease. Several months later the patient’s close friend presented with a similar infection that was acquired on the same day as our patient at the same tattoo parlor. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene was notified about these cases and informed us of other cases in New York State linked to contaminated tattoo ink.

|

Mycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacteria (Runyon group IV) that is found in nature and contaminated sources such as soil, lakes, sewage, and tap water.1 Inoculation ofM chelonae through contaminated instruments leads to the formation of painful lesions, abscesses, fistulas, and granulomas that are extremely difficult to treat.2 In our patient, M chelonae was most likely transmitted via contaminated tap water that was used to dilute the black tattoo ink to yield a gray color. Alternative sources are the ink itself or the container used to mix the ink.3Mycobacterium chelonae can cause infections in the skin, lungs, joints, bones, and eyes.4 With the exception of lung disease, trauma is the usual inciting factor. Disseminated infections are almost exclusively found in immunosuppressed individuals. Mycobacterium chelonae is typically found to grow on culture within 7 days. However, in our case there was no growth after 6 weeks of incubation. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of mycolic acid is an alternative method of identifying mycobacteria. This technique verified the presence of M chelonae in our case when cultures were persistently negative.5

Mycobacterium chelonae is difficult to treat. The most common antibiotics used for treatment are clarithromycin, azithromycin, doxycycline, and linezolid.6 Studies of various antibiotics have shown that clarithromycin is the most effective macrolide against M chelonae.7 Tetracyclines also were studied in their effectiveness at treating nontuberculous mycobacteria infections but were found to have increased resistance to M chelonae.8 Although treatment regimens vary, the highest success rates are achieved with a minimum of 6 months of therapy using at least 2 drugs. Longer treatment is recommended for immunocompromised individuals.9

The case we present is important from a public health perspective. The tattoo industry and ink manufacturers should bemade aware of the risks of various infections from nonsterile techniques. Tattoo parlor employees should be advised of the risks of using nonsterile water for ink dilution and cleaning tattoo equipment. They also should be continuously educated on aseptic techniques.

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium chelonae Arising Within a Tattoo

A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from one of the plaques. Histopathology revealed an unremarkable epidermis with granulomatous collections of epithelioid histiocytes in association with neutrophils and lymphocytes in the dermis (Figure 1). Periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms. Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacilli (Figure 2). Clinical and histopathologic findings led to the initial diagnosis of a mycobacterial infection within the tattoo. The patient was empirically started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and oral clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily with mild improvement of the lesions over the next month. After 6 weeks the mycobacterial cultures were persistently negative and high-performance liquid chromatography was performed verifying the presence of Mycobacterium chelonae. Clarithromycin was continued and the doxycycline was replaced with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (double strength) twice daily due to resistance. The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who concurred with the treatment regimen for a duration of 6 months to a year. A chest radiograph also was performed to rule out disseminated disease. Several months later the patient’s close friend presented with a similar infection that was acquired on the same day as our patient at the same tattoo parlor. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene was notified about these cases and informed us of other cases in New York State linked to contaminated tattoo ink.

|

Mycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacteria (Runyon group IV) that is found in nature and contaminated sources such as soil, lakes, sewage, and tap water.1 Inoculation ofM chelonae through contaminated instruments leads to the formation of painful lesions, abscesses, fistulas, and granulomas that are extremely difficult to treat.2 In our patient, M chelonae was most likely transmitted via contaminated tap water that was used to dilute the black tattoo ink to yield a gray color. Alternative sources are the ink itself or the container used to mix the ink.3Mycobacterium chelonae can cause infections in the skin, lungs, joints, bones, and eyes.4 With the exception of lung disease, trauma is the usual inciting factor. Disseminated infections are almost exclusively found in immunosuppressed individuals. Mycobacterium chelonae is typically found to grow on culture within 7 days. However, in our case there was no growth after 6 weeks of incubation. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of mycolic acid is an alternative method of identifying mycobacteria. This technique verified the presence of M chelonae in our case when cultures were persistently negative.5

Mycobacterium chelonae is difficult to treat. The most common antibiotics used for treatment are clarithromycin, azithromycin, doxycycline, and linezolid.6 Studies of various antibiotics have shown that clarithromycin is the most effective macrolide against M chelonae.7 Tetracyclines also were studied in their effectiveness at treating nontuberculous mycobacteria infections but were found to have increased resistance to M chelonae.8 Although treatment regimens vary, the highest success rates are achieved with a minimum of 6 months of therapy using at least 2 drugs. Longer treatment is recommended for immunocompromised individuals.9

The case we present is important from a public health perspective. The tattoo industry and ink manufacturers should bemade aware of the risks of various infections from nonsterile techniques. Tattoo parlor employees should be advised of the risks of using nonsterile water for ink dilution and cleaning tattoo equipment. They also should be continuously educated on aseptic techniques.

1. Lee RP, Cheung KW, Chiu KH, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection after total knee arthroplasty: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2012;20:134-136.

2. Camargo D, Saad C, Ruiz F, et al. latrogenic outbreak of M. chelonae skin abscesses. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;117:113-119.

3. Rodríguez-Blanco I, Fernández LC, Suárez-Peñaranda JM, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection associated with tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:61-62.

4. Karak K, Bhattacharyya S, Majumdar S, et al. Pulmonary infections caused by mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis in and around Calcutta. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1996;39:131-134.

5. Butler WR, Floyd MM, Silcox V, et al. Standardized Method for HPLC Identification of Mycobacteria. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1996.

6. Brown-Elliot BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Blinkhorn R, et al. Successful treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium chelonae infection with linezolid. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1433-1434.

7. Brown BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Onyi GO, et al. Activities of four macrolides, including clarithromycin, against Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonae, and Mycobacterium chelonae-like organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:180-184.

8. Swenson JM, Wallace RJ Jr, Silcox VA, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of five subgroups of Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:807-811.

9. Leung YY, Choi KW, Ho KM, et al. Disseminated cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium chelonae mimicking panniculitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. Hong Kong Med J. 2005;11:515-519.

1. Lee RP, Cheung KW, Chiu KH, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection after total knee arthroplasty: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2012;20:134-136.

2. Camargo D, Saad C, Ruiz F, et al. latrogenic outbreak of M. chelonae skin abscesses. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;117:113-119.

3. Rodríguez-Blanco I, Fernández LC, Suárez-Peñaranda JM, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection associated with tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:61-62.

4. Karak K, Bhattacharyya S, Majumdar S, et al. Pulmonary infections caused by mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis in and around Calcutta. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1996;39:131-134.

5. Butler WR, Floyd MM, Silcox V, et al. Standardized Method for HPLC Identification of Mycobacteria. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1996.

6. Brown-Elliot BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Blinkhorn R, et al. Successful treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium chelonae infection with linezolid. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1433-1434.

7. Brown BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Onyi GO, et al. Activities of four macrolides, including clarithromycin, against Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonae, and Mycobacterium chelonae-like organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:180-184.

8. Swenson JM, Wallace RJ Jr, Silcox VA, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of five subgroups of Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:807-811.

9. Leung YY, Choi KW, Ho KM, et al. Disseminated cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium chelonae mimicking panniculitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. Hong Kong Med J. 2005;11:515-519.

A 21-year-old man presented with growing, mildly pruritic, cutaneous papules and plaques on the right extensor forearm of 3 weeks’ duration. The lesions appeared 1 week after receiving a tattoo on the arm. One year prior the patient had a similar tattoo placed on another section of the right arm without any complications. The patient was afebrile and denied a history of sarcoidosis. Physical examination revealed indurated erythematous papules and plaques on the right extensor forearm that were most prominent in the gray-colored areas of the tattoo.

Papules on the Face and Body

The Diagnosis: Lichen Spinulosus