User login

A new papule and “age spots”

An 87-year-old woman came to the office for evaluation of a lesion above her lip (FIGURE 1) that had “been there a while” and had intermittently been bleeding and crusting for the last few months. On examination, there was a distinct, firm (but not hard) papule with some adjacent erythema. No distinct telangiectasias, ulceration, blood, or crusts were visible with handheld magnification or upon dermoscopy. (see “The digital camera: Another stethoscope for the skin,”)

FIGURE 1

Lesion above lip

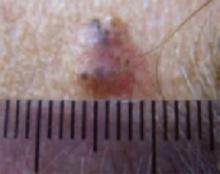

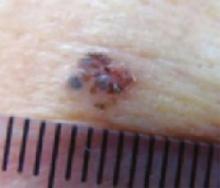

An evaluation of the remainder of the woman’s face revealed 3 more lesions that the patient termed “age spots.” They had been present for quite some time, had not had any notable rapid change, and had not caused her (or a physician in the family) any concern. These “age spots” are depicted in (FIGURE 2A) (left temple), (FIGURE 2B) (forehead), and (FIGURE 2C) (left cheek). Digital photographs were taken through the dermatoscope of the temple, forehead, and cheek lesions (FIGURE 3A, B, AND C).

FIGURE 2A

Digital photos

FIGURE 2B

Digital photos

FIGURE 2C

Digital photos

The 4 lesions are easily identified as worrisome, given that they were pigmented and asymmetric, with a variety of bizarre colors.

The lip. In particular, the lesion above the upper lip (FIGURE 1) clinically presented a wide range of possibilities, including basal cell carcinoma (BCC), milial cyst, nevus, trichoepithelioma, fibrous papule, or any of a variety of adnexal skin neoplasms. Knowing that the lesion was relatively new and had bled and crusted was sufficient to warrant biopsy.

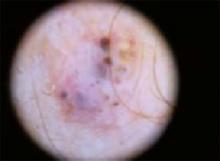

The temple. Dermoscopically, the temple lesion (FIGURE 3A) had blue and brown ovoid structures (also called “blebs” or “blobs”), white areas within the lesion (whiter than normal surrounding skin), a high degree of asymmetry, and distinct telangiectatic vessels. The pink color on dermoscopy was also a cause for concern. The blue ovoid structures plus telangiectasias were highly suggestive of basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 3A

Dermoscopy images

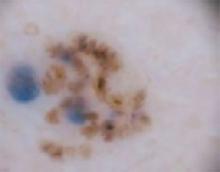

The forehead. Dermoscopy of the forehead lesion (FIGURE 3B) showed leaf-like structures (12 o’clock) and maple-leaf structures (6 o’clock). These alone were highly suggestive of pigmented basal cell carcinoma—but in the absence of distinct telangiectasias, we decided to do a deep incisional biopsy rather than risk potentially “shaving a melanoma.” (If a melanoma is biopsied via a shave technique, the ability to histologically measure its thickness and to stage it according to Clark and Breslow staging is lost.)

FIGURE 3B

Dermoscopy images

The cheek. Dermoscopically, the lesion on the cheek (FIGURE 3C) also had no obvious telangiectasias but had a “spoke-wheel” structure (6 o’clock) highly suggestive of basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 3C

Dermoscopy images

All the lesions—except for the temple lesion, which was biopsied via a shave technique—were biopsied via generous incisional ellipses.

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat?

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

Histology confirmed that all 4 lesions were basal cell carcinomas, the most common type of skin malignancy. The temple lesion in Figures 2A AND 3A and the forehead lesion in Figures 2B AND 3B were histologically both pigmented nodular basal cell carcinomas, clinically characterized as pearly papules with pigment. (FIGURE 3A) also demonstrates telangiectasia.

Differential diagnosis: Innocent papule or carcinoma?

The lip lesion, the presenting “symptom,” did not have evident bleeding and crusting on visual or dermoscopic examination. In the absence of a complete history, it could have been “passed off” as an innocent papule, such as a molluscum (though not common in the elderly) or a milial or epidermoid cyst.

Remember that basal cell carcinoma can be subtle. These lesions were missed by a patient and her family—which included a physician within the household—and grew slowly enough that the patient felt they were simply “age spots.” We have seen basal cell carcinomas that patients have indicated have not changed in years—have not bled, ulcerated, or crusted, while symptomatic lesions have been the least impressive, clinically, at the time of the exam. Always maintain a high index of suspicion.

The clinical types of basal cell carcinoma and their dermoscopic findings are summarized in the (TABLE).

TABLE

Clinical types of basal cell carcinoma and dermoscopic findings

| CLINICAL TYPE | DERMOSCOPIC FINDINGS | NOTES |

|---|---|---|

Nodular (including noduloulcerative and cystic)

“Wart” on a supraclavicular area—note pearly translucency of nodular basal cell carcinoma. | Arborizing (tree-like branching telangiectasias)

Dermoscopy of lesion at left, clearly showing arborized telangiectatic vessels. |

|

| Pigmented |

|

|

| Sclerosing, cicatricial, or morpheaform | Arborizing telangiectasias |

|

| Superficial | Arborizing telangiectasias |

|

| *Sensitivity/specificity. Sensitivity is the percentage of basal cell carcinomas that possess the feature. Specificity listed is the percentage of melanomas that lack the feature.1 All discussion of dermoscopic diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma assumes absence of a melanocytic pigment network, the presence of which suggests a melanocytic lesion such as a nevus, lentigo, or melanoma. | ||

| Note: The primary use of dermoscopy is the evaluation of pigmented lesions. Thus, except to aid in visualization of telangiectasias and ulceration, there are no characteristic dermoscopic findings in other types of basal cell carcinoma. Telangiectasias may not be visualized if the dermatoscope is applied with sufficient pressure to blanch them. Basal cell carcinomas may exhibit no definite or suggestive findings by dermoscopy, as was the case with the lip papule on this patient. | ||

Tips for making an accurate diagnosis

Basal cell carcinoma and melanoma can mimic other lesions, so keep these tips in mind:

- The “company” a lesion keeps sometimes can help in diagnosis. A patient may have a group of small “pearly papules,” only one of which may show the typical umbilication that allows a confident diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum, for example. Here, 3 lesions had similar dermoscopic structures, only one of which exhibited telangiectasia. A fourth lesion lacked diagnostic characteristics. The best guess, based on the sum total appearance of all of these lesions, is that all are basal cell carcinomas because of the “company they are keeping”—but note that this is also potentially a trap: missing the single basal cell carcinoma lesion among a field of sebaceous hyperplasia, for instance.

- Don’t focus exclusively on the symptomatic lesion. Do a survey of the general region. For ultraviolet-associated lesions (including basal cell carcinoma), it’s preferable to perform, at minimum, a survey of “high-radiation” areas (face, exposed scalp, neck, ears, and dorsal hands and forearms) for other ultraviolet “damage” (eg, actinic keratoses).

- Be meticulous when examining patients’ backs. Patients may not spot lesions on their backs—especially if they are older and have poor vision.

- Avoid thinking in terms of absolutes like “never” and “always.” The clinical axiom that basal cell carcinomas “never” have hair growing from them is disproved by (FIGURE 3A), which clinically, dermoscopically, and histologically is a basal cell carcinoma lesion. Some of the hair seen here is overlying, loose scalp hair “caught” in the dermoscopic field because of the location of this lesion on the temple adjacent to the hairline. But there are also very distinct hairs seen coming out from areas (at about 6 and 8 o’clock) that are clearly part of the lesion, especially on its periphery.

When in doubt, biopsy

When in doubt about which technique to perform, do an incisional biopsy—preferably excisional, but at least a good sampling of the most worrisome area(s).

Suspected basal cell carcinoma, when the examiner is confident the lesion is not a melanoma, can be further evaluated by superficial shave biopsy. Potential melanoma generally should not be evaluated by the shave technique.

Options for therapy

Therapy options for basal cell carcinoma vary based on location (high-risk vs low-risk locations), histologic type of basal cell carcinoma, patient preference, and local availability of therapy. The primary therapies for basal cell carcinoma are surgical excision (including Mohs surgery) and curettage, often combined with electrodesiccation. 5-flurouracil (5-FU) should not be used because it can treat the surface tumor while deeper tumor proliferates.3 Imiquimod is not approved for facial lesions or nodular basal cell carcinomas.

While dermatoscopes are the true “skin stethoscopes,” most primary care physicians do not have them. Many, however, do have a digital camera. A digital camera with a macro-focus feature can be viewed as another stethoscope for the skin. Pictures allow great magnification on the computer screen, presenting color and detail that may be missed on routine clinical inspection. They allow an unhurried “self–second opinion”; you can evaluate lesions with no motion, breathing, or other distractions, following the office visit.

Digital images may also be important for:

- the patient, who may not be able to see the lesion, because it’s on his back, buttocks, or behind his ears. Consider, too, the older patient who may not be able to see the seborrhea in his eyebrow with his bifocals, but he can see it on the camera’s monitor.

- the medical record (printed or electronically stored).

- the pathologist—when forwarded with the pathology specimen. The images can be helpful in developing a clinical correlation to include in the pathology report.

- the insurance carrier, as indisputable documentation for the clinical rationale for biopsying 4 lesions on 1 visit in the event of a “Dear Bad Doctor” Medicare letter. In fact, if not for the indisputable photographic record, one author (GNF) would have been extremely hesitant to perform 4 biopsies on a Medicare patient in 1 session.

- light and magnification where the 2 may be in short supply, such as a poorly mobile patient in a hospital bed. A camera with flash, auto-focus, and macro mode may allow access to otherwise inaccessible lesions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Gary N. Fox wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Peggy Elston and Lisa Nichols for their help with portions of this article.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gary N. Fox, MD, 2458 Willesden Green, Toledo, OH. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Marghoob AA, Braun RP, Kopf AW, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2005.

2. Johr R, Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Scalvenzi M. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York: Mosby; 2004.

3. Premalignant and malignant nonmelanoma skin tumors [chapter 21]. In: Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. New York: Mosby; 2004.

An 87-year-old woman came to the office for evaluation of a lesion above her lip (FIGURE 1) that had “been there a while” and had intermittently been bleeding and crusting for the last few months. On examination, there was a distinct, firm (but not hard) papule with some adjacent erythema. No distinct telangiectasias, ulceration, blood, or crusts were visible with handheld magnification or upon dermoscopy. (see “The digital camera: Another stethoscope for the skin,”)

FIGURE 1

Lesion above lip

An evaluation of the remainder of the woman’s face revealed 3 more lesions that the patient termed “age spots.” They had been present for quite some time, had not had any notable rapid change, and had not caused her (or a physician in the family) any concern. These “age spots” are depicted in (FIGURE 2A) (left temple), (FIGURE 2B) (forehead), and (FIGURE 2C) (left cheek). Digital photographs were taken through the dermatoscope of the temple, forehead, and cheek lesions (FIGURE 3A, B, AND C).

FIGURE 2A

Digital photos

FIGURE 2B

Digital photos

FIGURE 2C

Digital photos

The 4 lesions are easily identified as worrisome, given that they were pigmented and asymmetric, with a variety of bizarre colors.

The lip. In particular, the lesion above the upper lip (FIGURE 1) clinically presented a wide range of possibilities, including basal cell carcinoma (BCC), milial cyst, nevus, trichoepithelioma, fibrous papule, or any of a variety of adnexal skin neoplasms. Knowing that the lesion was relatively new and had bled and crusted was sufficient to warrant biopsy.

The temple. Dermoscopically, the temple lesion (FIGURE 3A) had blue and brown ovoid structures (also called “blebs” or “blobs”), white areas within the lesion (whiter than normal surrounding skin), a high degree of asymmetry, and distinct telangiectatic vessels. The pink color on dermoscopy was also a cause for concern. The blue ovoid structures plus telangiectasias were highly suggestive of basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 3A

Dermoscopy images

The forehead. Dermoscopy of the forehead lesion (FIGURE 3B) showed leaf-like structures (12 o’clock) and maple-leaf structures (6 o’clock). These alone were highly suggestive of pigmented basal cell carcinoma—but in the absence of distinct telangiectasias, we decided to do a deep incisional biopsy rather than risk potentially “shaving a melanoma.” (If a melanoma is biopsied via a shave technique, the ability to histologically measure its thickness and to stage it according to Clark and Breslow staging is lost.)

FIGURE 3B

Dermoscopy images

The cheek. Dermoscopically, the lesion on the cheek (FIGURE 3C) also had no obvious telangiectasias but had a “spoke-wheel” structure (6 o’clock) highly suggestive of basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 3C

Dermoscopy images

All the lesions—except for the temple lesion, which was biopsied via a shave technique—were biopsied via generous incisional ellipses.

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat?

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

Histology confirmed that all 4 lesions were basal cell carcinomas, the most common type of skin malignancy. The temple lesion in Figures 2A AND 3A and the forehead lesion in Figures 2B AND 3B were histologically both pigmented nodular basal cell carcinomas, clinically characterized as pearly papules with pigment. (FIGURE 3A) also demonstrates telangiectasia.

Differential diagnosis: Innocent papule or carcinoma?

The lip lesion, the presenting “symptom,” did not have evident bleeding and crusting on visual or dermoscopic examination. In the absence of a complete history, it could have been “passed off” as an innocent papule, such as a molluscum (though not common in the elderly) or a milial or epidermoid cyst.

Remember that basal cell carcinoma can be subtle. These lesions were missed by a patient and her family—which included a physician within the household—and grew slowly enough that the patient felt they were simply “age spots.” We have seen basal cell carcinomas that patients have indicated have not changed in years—have not bled, ulcerated, or crusted, while symptomatic lesions have been the least impressive, clinically, at the time of the exam. Always maintain a high index of suspicion.

The clinical types of basal cell carcinoma and their dermoscopic findings are summarized in the (TABLE).

TABLE

Clinical types of basal cell carcinoma and dermoscopic findings

| CLINICAL TYPE | DERMOSCOPIC FINDINGS | NOTES |

|---|---|---|

Nodular (including noduloulcerative and cystic)

“Wart” on a supraclavicular area—note pearly translucency of nodular basal cell carcinoma. | Arborizing (tree-like branching telangiectasias)

Dermoscopy of lesion at left, clearly showing arborized telangiectatic vessels. |

|

| Pigmented |

|

|

| Sclerosing, cicatricial, or morpheaform | Arborizing telangiectasias |

|

| Superficial | Arborizing telangiectasias |

|

| *Sensitivity/specificity. Sensitivity is the percentage of basal cell carcinomas that possess the feature. Specificity listed is the percentage of melanomas that lack the feature.1 All discussion of dermoscopic diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma assumes absence of a melanocytic pigment network, the presence of which suggests a melanocytic lesion such as a nevus, lentigo, or melanoma. | ||

| Note: The primary use of dermoscopy is the evaluation of pigmented lesions. Thus, except to aid in visualization of telangiectasias and ulceration, there are no characteristic dermoscopic findings in other types of basal cell carcinoma. Telangiectasias may not be visualized if the dermatoscope is applied with sufficient pressure to blanch them. Basal cell carcinomas may exhibit no definite or suggestive findings by dermoscopy, as was the case with the lip papule on this patient. | ||

Tips for making an accurate diagnosis

Basal cell carcinoma and melanoma can mimic other lesions, so keep these tips in mind:

- The “company” a lesion keeps sometimes can help in diagnosis. A patient may have a group of small “pearly papules,” only one of which may show the typical umbilication that allows a confident diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum, for example. Here, 3 lesions had similar dermoscopic structures, only one of which exhibited telangiectasia. A fourth lesion lacked diagnostic characteristics. The best guess, based on the sum total appearance of all of these lesions, is that all are basal cell carcinomas because of the “company they are keeping”—but note that this is also potentially a trap: missing the single basal cell carcinoma lesion among a field of sebaceous hyperplasia, for instance.

- Don’t focus exclusively on the symptomatic lesion. Do a survey of the general region. For ultraviolet-associated lesions (including basal cell carcinoma), it’s preferable to perform, at minimum, a survey of “high-radiation” areas (face, exposed scalp, neck, ears, and dorsal hands and forearms) for other ultraviolet “damage” (eg, actinic keratoses).

- Be meticulous when examining patients’ backs. Patients may not spot lesions on their backs—especially if they are older and have poor vision.

- Avoid thinking in terms of absolutes like “never” and “always.” The clinical axiom that basal cell carcinomas “never” have hair growing from them is disproved by (FIGURE 3A), which clinically, dermoscopically, and histologically is a basal cell carcinoma lesion. Some of the hair seen here is overlying, loose scalp hair “caught” in the dermoscopic field because of the location of this lesion on the temple adjacent to the hairline. But there are also very distinct hairs seen coming out from areas (at about 6 and 8 o’clock) that are clearly part of the lesion, especially on its periphery.

When in doubt, biopsy

When in doubt about which technique to perform, do an incisional biopsy—preferably excisional, but at least a good sampling of the most worrisome area(s).

Suspected basal cell carcinoma, when the examiner is confident the lesion is not a melanoma, can be further evaluated by superficial shave biopsy. Potential melanoma generally should not be evaluated by the shave technique.

Options for therapy

Therapy options for basal cell carcinoma vary based on location (high-risk vs low-risk locations), histologic type of basal cell carcinoma, patient preference, and local availability of therapy. The primary therapies for basal cell carcinoma are surgical excision (including Mohs surgery) and curettage, often combined with electrodesiccation. 5-flurouracil (5-FU) should not be used because it can treat the surface tumor while deeper tumor proliferates.3 Imiquimod is not approved for facial lesions or nodular basal cell carcinomas.

While dermatoscopes are the true “skin stethoscopes,” most primary care physicians do not have them. Many, however, do have a digital camera. A digital camera with a macro-focus feature can be viewed as another stethoscope for the skin. Pictures allow great magnification on the computer screen, presenting color and detail that may be missed on routine clinical inspection. They allow an unhurried “self–second opinion”; you can evaluate lesions with no motion, breathing, or other distractions, following the office visit.

Digital images may also be important for:

- the patient, who may not be able to see the lesion, because it’s on his back, buttocks, or behind his ears. Consider, too, the older patient who may not be able to see the seborrhea in his eyebrow with his bifocals, but he can see it on the camera’s monitor.

- the medical record (printed or electronically stored).

- the pathologist—when forwarded with the pathology specimen. The images can be helpful in developing a clinical correlation to include in the pathology report.

- the insurance carrier, as indisputable documentation for the clinical rationale for biopsying 4 lesions on 1 visit in the event of a “Dear Bad Doctor” Medicare letter. In fact, if not for the indisputable photographic record, one author (GNF) would have been extremely hesitant to perform 4 biopsies on a Medicare patient in 1 session.

- light and magnification where the 2 may be in short supply, such as a poorly mobile patient in a hospital bed. A camera with flash, auto-focus, and macro mode may allow access to otherwise inaccessible lesions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Gary N. Fox wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Peggy Elston and Lisa Nichols for their help with portions of this article.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gary N. Fox, MD, 2458 Willesden Green, Toledo, OH. E-mail: [email protected]

An 87-year-old woman came to the office for evaluation of a lesion above her lip (FIGURE 1) that had “been there a while” and had intermittently been bleeding and crusting for the last few months. On examination, there was a distinct, firm (but not hard) papule with some adjacent erythema. No distinct telangiectasias, ulceration, blood, or crusts were visible with handheld magnification or upon dermoscopy. (see “The digital camera: Another stethoscope for the skin,”)

FIGURE 1

Lesion above lip

An evaluation of the remainder of the woman’s face revealed 3 more lesions that the patient termed “age spots.” They had been present for quite some time, had not had any notable rapid change, and had not caused her (or a physician in the family) any concern. These “age spots” are depicted in (FIGURE 2A) (left temple), (FIGURE 2B) (forehead), and (FIGURE 2C) (left cheek). Digital photographs were taken through the dermatoscope of the temple, forehead, and cheek lesions (FIGURE 3A, B, AND C).

FIGURE 2A

Digital photos

FIGURE 2B

Digital photos

FIGURE 2C

Digital photos

The 4 lesions are easily identified as worrisome, given that they were pigmented and asymmetric, with a variety of bizarre colors.

The lip. In particular, the lesion above the upper lip (FIGURE 1) clinically presented a wide range of possibilities, including basal cell carcinoma (BCC), milial cyst, nevus, trichoepithelioma, fibrous papule, or any of a variety of adnexal skin neoplasms. Knowing that the lesion was relatively new and had bled and crusted was sufficient to warrant biopsy.

The temple. Dermoscopically, the temple lesion (FIGURE 3A) had blue and brown ovoid structures (also called “blebs” or “blobs”), white areas within the lesion (whiter than normal surrounding skin), a high degree of asymmetry, and distinct telangiectatic vessels. The pink color on dermoscopy was also a cause for concern. The blue ovoid structures plus telangiectasias were highly suggestive of basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 3A

Dermoscopy images

The forehead. Dermoscopy of the forehead lesion (FIGURE 3B) showed leaf-like structures (12 o’clock) and maple-leaf structures (6 o’clock). These alone were highly suggestive of pigmented basal cell carcinoma—but in the absence of distinct telangiectasias, we decided to do a deep incisional biopsy rather than risk potentially “shaving a melanoma.” (If a melanoma is biopsied via a shave technique, the ability to histologically measure its thickness and to stage it according to Clark and Breslow staging is lost.)

FIGURE 3B

Dermoscopy images

The cheek. Dermoscopically, the lesion on the cheek (FIGURE 3C) also had no obvious telangiectasias but had a “spoke-wheel” structure (6 o’clock) highly suggestive of basal cell carcinoma.

FIGURE 3C

Dermoscopy images

All the lesions—except for the temple lesion, which was biopsied via a shave technique—were biopsied via generous incisional ellipses.

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat?

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

Histology confirmed that all 4 lesions were basal cell carcinomas, the most common type of skin malignancy. The temple lesion in Figures 2A AND 3A and the forehead lesion in Figures 2B AND 3B were histologically both pigmented nodular basal cell carcinomas, clinically characterized as pearly papules with pigment. (FIGURE 3A) also demonstrates telangiectasia.

Differential diagnosis: Innocent papule or carcinoma?

The lip lesion, the presenting “symptom,” did not have evident bleeding and crusting on visual or dermoscopic examination. In the absence of a complete history, it could have been “passed off” as an innocent papule, such as a molluscum (though not common in the elderly) or a milial or epidermoid cyst.

Remember that basal cell carcinoma can be subtle. These lesions were missed by a patient and her family—which included a physician within the household—and grew slowly enough that the patient felt they were simply “age spots.” We have seen basal cell carcinomas that patients have indicated have not changed in years—have not bled, ulcerated, or crusted, while symptomatic lesions have been the least impressive, clinically, at the time of the exam. Always maintain a high index of suspicion.

The clinical types of basal cell carcinoma and their dermoscopic findings are summarized in the (TABLE).

TABLE

Clinical types of basal cell carcinoma and dermoscopic findings

| CLINICAL TYPE | DERMOSCOPIC FINDINGS | NOTES |

|---|---|---|

Nodular (including noduloulcerative and cystic)

“Wart” on a supraclavicular area—note pearly translucency of nodular basal cell carcinoma. | Arborizing (tree-like branching telangiectasias)

Dermoscopy of lesion at left, clearly showing arborized telangiectatic vessels. |

|

| Pigmented |

|

|

| Sclerosing, cicatricial, or morpheaform | Arborizing telangiectasias |

|

| Superficial | Arborizing telangiectasias |

|

| *Sensitivity/specificity. Sensitivity is the percentage of basal cell carcinomas that possess the feature. Specificity listed is the percentage of melanomas that lack the feature.1 All discussion of dermoscopic diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma assumes absence of a melanocytic pigment network, the presence of which suggests a melanocytic lesion such as a nevus, lentigo, or melanoma. | ||

| Note: The primary use of dermoscopy is the evaluation of pigmented lesions. Thus, except to aid in visualization of telangiectasias and ulceration, there are no characteristic dermoscopic findings in other types of basal cell carcinoma. Telangiectasias may not be visualized if the dermatoscope is applied with sufficient pressure to blanch them. Basal cell carcinomas may exhibit no definite or suggestive findings by dermoscopy, as was the case with the lip papule on this patient. | ||

Tips for making an accurate diagnosis

Basal cell carcinoma and melanoma can mimic other lesions, so keep these tips in mind:

- The “company” a lesion keeps sometimes can help in diagnosis. A patient may have a group of small “pearly papules,” only one of which may show the typical umbilication that allows a confident diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum, for example. Here, 3 lesions had similar dermoscopic structures, only one of which exhibited telangiectasia. A fourth lesion lacked diagnostic characteristics. The best guess, based on the sum total appearance of all of these lesions, is that all are basal cell carcinomas because of the “company they are keeping”—but note that this is also potentially a trap: missing the single basal cell carcinoma lesion among a field of sebaceous hyperplasia, for instance.

- Don’t focus exclusively on the symptomatic lesion. Do a survey of the general region. For ultraviolet-associated lesions (including basal cell carcinoma), it’s preferable to perform, at minimum, a survey of “high-radiation” areas (face, exposed scalp, neck, ears, and dorsal hands and forearms) for other ultraviolet “damage” (eg, actinic keratoses).

- Be meticulous when examining patients’ backs. Patients may not spot lesions on their backs—especially if they are older and have poor vision.

- Avoid thinking in terms of absolutes like “never” and “always.” The clinical axiom that basal cell carcinomas “never” have hair growing from them is disproved by (FIGURE 3A), which clinically, dermoscopically, and histologically is a basal cell carcinoma lesion. Some of the hair seen here is overlying, loose scalp hair “caught” in the dermoscopic field because of the location of this lesion on the temple adjacent to the hairline. But there are also very distinct hairs seen coming out from areas (at about 6 and 8 o’clock) that are clearly part of the lesion, especially on its periphery.

When in doubt, biopsy

When in doubt about which technique to perform, do an incisional biopsy—preferably excisional, but at least a good sampling of the most worrisome area(s).

Suspected basal cell carcinoma, when the examiner is confident the lesion is not a melanoma, can be further evaluated by superficial shave biopsy. Potential melanoma generally should not be evaluated by the shave technique.

Options for therapy

Therapy options for basal cell carcinoma vary based on location (high-risk vs low-risk locations), histologic type of basal cell carcinoma, patient preference, and local availability of therapy. The primary therapies for basal cell carcinoma are surgical excision (including Mohs surgery) and curettage, often combined with electrodesiccation. 5-flurouracil (5-FU) should not be used because it can treat the surface tumor while deeper tumor proliferates.3 Imiquimod is not approved for facial lesions or nodular basal cell carcinomas.

While dermatoscopes are the true “skin stethoscopes,” most primary care physicians do not have them. Many, however, do have a digital camera. A digital camera with a macro-focus feature can be viewed as another stethoscope for the skin. Pictures allow great magnification on the computer screen, presenting color and detail that may be missed on routine clinical inspection. They allow an unhurried “self–second opinion”; you can evaluate lesions with no motion, breathing, or other distractions, following the office visit.

Digital images may also be important for:

- the patient, who may not be able to see the lesion, because it’s on his back, buttocks, or behind his ears. Consider, too, the older patient who may not be able to see the seborrhea in his eyebrow with his bifocals, but he can see it on the camera’s monitor.

- the medical record (printed or electronically stored).

- the pathologist—when forwarded with the pathology specimen. The images can be helpful in developing a clinical correlation to include in the pathology report.

- the insurance carrier, as indisputable documentation for the clinical rationale for biopsying 4 lesions on 1 visit in the event of a “Dear Bad Doctor” Medicare letter. In fact, if not for the indisputable photographic record, one author (GNF) would have been extremely hesitant to perform 4 biopsies on a Medicare patient in 1 session.

- light and magnification where the 2 may be in short supply, such as a poorly mobile patient in a hospital bed. A camera with flash, auto-focus, and macro mode may allow access to otherwise inaccessible lesions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Gary N. Fox wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Peggy Elston and Lisa Nichols for their help with portions of this article.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gary N. Fox, MD, 2458 Willesden Green, Toledo, OH. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Marghoob AA, Braun RP, Kopf AW, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2005.

2. Johr R, Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Scalvenzi M. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York: Mosby; 2004.

3. Premalignant and malignant nonmelanoma skin tumors [chapter 21]. In: Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. New York: Mosby; 2004.

1. Marghoob AA, Braun RP, Kopf AW, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2005.

2. Johr R, Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Scalvenzi M. Dermoscopy: The Essentials. New York: Mosby; 2004.

3. Premalignant and malignant nonmelanoma skin tumors [chapter 21]. In: Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. New York: Mosby; 2004.

Nodulo-cystic eruption with musculoskeletal pain

A healthy 17-year-old white patient with mild acne was treated with isotretinoin (Accutane), 40 mg/day. After a month of treatment, the acne got worse and the patient complained of polymyalgia and arthralgia.

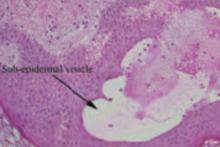

An examination revealed numerous nodules and cysts covered by hemorrhagic crusts on his chest and back (FIGURE). The patient had severe muscular tenderness with gait disability. Leukocytosis and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were found; creatinine phosphokinase was within the normal values.

FIGURE

Nodules and cysts on chest and back

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Acne fulminans

Acne fulminans is an uncommon complication of acne. It was first described by Burns and Colville in 1959;1 Plevig and Kligman coined the term.2

Signs and symptoms. It is characterized by sudden onset ulcerative crusting cystic acne, mostly on the chest and back. Fever, malaise, nausea, arthralgia, myalgia, and weight loss are common.

Leukocytosis and elevated ESR are usually found. There may also be focal osteolytic lesions.

Thomson and Cunliffe suggest that the term acne fulminans may also be used in cases of severe aggravation of acne without systemic features.3

The cause of acne fulminans is not clear. However, alteration of type III and IV hypersensitivity to Propionibacterium acnes,4 circulating immune complexes,5 and increased cellular immunity6 have been found by some investigators.

Isotretinoin has been identified as a potential trigger.5 Some have suggested that isotretinoin increases the fragility of the pilosebaceous ducts, leading to massive contact with the P acnes antigen.

Management: A treatment and a trigger

The treatment of acne fulminans consists of supportive care and systemic steroids that are gradually reduced over weeks or months, according to the patient’s response. Interestingly, isotretinoin—a trigger for acne fulminans—is also very effective in its treatment.5,7

Outcome: Partial, gradual resolution

Isotretinoin stopped, prednisone started. In this patient’s case, we stopped the isotretinoin and treated him with prednisone, with an initial dose of 40 mg/day. His muscle pain improved.

Dosage tapered. Several attempts to reduce his dosage, however, resulted in a recurrence of pain. Gradual tapering of the steroidal treatment was achieved after 3 months.

Gradual improvement. The acne lesions resolved partially, and gradually, during several months of follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Marcelo H. Grunwald, MD Soroka University Medical Center, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel E-mail: [email protected]

1. Burns RE, Colville JM. Acne conglobata with septicaemia. Arch Dermatol 1959;79:361-363.

2. Seukeran DC, Cuniliffe WJ. Treatment of acne fulminans: a review of 25 cases. Br J Dermatol 1999;141:307-309.

3. Thomson KF, Cuniliffe WJ. Acne fulminans ‘sine fulminans’. Clin Exp Dermatol 2000;25:299-301.

4. Karnoven SL, Rasanen L, Cuniliffe WJ, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity to Propionebacterium acnes in patients with severe nodular acne and acne fulminans. Dermatology 1994;189:344-349.

5. Kellet JK, Beck MH, Chalmers RJG. Erythema nodosum and circulating immune complexes in acne fulminans after treatment with isotretinoin. Br Med J 1985;290:820.-

6. Gowland G, Ward RM, Holland KY, Cuniliffe WJ. Cellular immunity to Propionebacterium acnes in normal population and patients with acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 1978;99:43-47.

7. Karvogen SL. Acne fulminans: report of clinical findings and treatment of twenty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;28:572-579.

A healthy 17-year-old white patient with mild acne was treated with isotretinoin (Accutane), 40 mg/day. After a month of treatment, the acne got worse and the patient complained of polymyalgia and arthralgia.

An examination revealed numerous nodules and cysts covered by hemorrhagic crusts on his chest and back (FIGURE). The patient had severe muscular tenderness with gait disability. Leukocytosis and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were found; creatinine phosphokinase was within the normal values.

FIGURE

Nodules and cysts on chest and back

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Acne fulminans

Acne fulminans is an uncommon complication of acne. It was first described by Burns and Colville in 1959;1 Plevig and Kligman coined the term.2

Signs and symptoms. It is characterized by sudden onset ulcerative crusting cystic acne, mostly on the chest and back. Fever, malaise, nausea, arthralgia, myalgia, and weight loss are common.

Leukocytosis and elevated ESR are usually found. There may also be focal osteolytic lesions.

Thomson and Cunliffe suggest that the term acne fulminans may also be used in cases of severe aggravation of acne without systemic features.3

The cause of acne fulminans is not clear. However, alteration of type III and IV hypersensitivity to Propionibacterium acnes,4 circulating immune complexes,5 and increased cellular immunity6 have been found by some investigators.

Isotretinoin has been identified as a potential trigger.5 Some have suggested that isotretinoin increases the fragility of the pilosebaceous ducts, leading to massive contact with the P acnes antigen.

Management: A treatment and a trigger

The treatment of acne fulminans consists of supportive care and systemic steroids that are gradually reduced over weeks or months, according to the patient’s response. Interestingly, isotretinoin—a trigger for acne fulminans—is also very effective in its treatment.5,7

Outcome: Partial, gradual resolution

Isotretinoin stopped, prednisone started. In this patient’s case, we stopped the isotretinoin and treated him with prednisone, with an initial dose of 40 mg/day. His muscle pain improved.

Dosage tapered. Several attempts to reduce his dosage, however, resulted in a recurrence of pain. Gradual tapering of the steroidal treatment was achieved after 3 months.

Gradual improvement. The acne lesions resolved partially, and gradually, during several months of follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Marcelo H. Grunwald, MD Soroka University Medical Center, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel E-mail: [email protected]

A healthy 17-year-old white patient with mild acne was treated with isotretinoin (Accutane), 40 mg/day. After a month of treatment, the acne got worse and the patient complained of polymyalgia and arthralgia.

An examination revealed numerous nodules and cysts covered by hemorrhagic crusts on his chest and back (FIGURE). The patient had severe muscular tenderness with gait disability. Leukocytosis and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were found; creatinine phosphokinase was within the normal values.

FIGURE

Nodules and cysts on chest and back

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage this condition?

Diagnosis: Acne fulminans

Acne fulminans is an uncommon complication of acne. It was first described by Burns and Colville in 1959;1 Plevig and Kligman coined the term.2

Signs and symptoms. It is characterized by sudden onset ulcerative crusting cystic acne, mostly on the chest and back. Fever, malaise, nausea, arthralgia, myalgia, and weight loss are common.

Leukocytosis and elevated ESR are usually found. There may also be focal osteolytic lesions.

Thomson and Cunliffe suggest that the term acne fulminans may also be used in cases of severe aggravation of acne without systemic features.3

The cause of acne fulminans is not clear. However, alteration of type III and IV hypersensitivity to Propionibacterium acnes,4 circulating immune complexes,5 and increased cellular immunity6 have been found by some investigators.

Isotretinoin has been identified as a potential trigger.5 Some have suggested that isotretinoin increases the fragility of the pilosebaceous ducts, leading to massive contact with the P acnes antigen.

Management: A treatment and a trigger

The treatment of acne fulminans consists of supportive care and systemic steroids that are gradually reduced over weeks or months, according to the patient’s response. Interestingly, isotretinoin—a trigger for acne fulminans—is also very effective in its treatment.5,7

Outcome: Partial, gradual resolution

Isotretinoin stopped, prednisone started. In this patient’s case, we stopped the isotretinoin and treated him with prednisone, with an initial dose of 40 mg/day. His muscle pain improved.

Dosage tapered. Several attempts to reduce his dosage, however, resulted in a recurrence of pain. Gradual tapering of the steroidal treatment was achieved after 3 months.

Gradual improvement. The acne lesions resolved partially, and gradually, during several months of follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Marcelo H. Grunwald, MD Soroka University Medical Center, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel E-mail: [email protected]

1. Burns RE, Colville JM. Acne conglobata with septicaemia. Arch Dermatol 1959;79:361-363.

2. Seukeran DC, Cuniliffe WJ. Treatment of acne fulminans: a review of 25 cases. Br J Dermatol 1999;141:307-309.

3. Thomson KF, Cuniliffe WJ. Acne fulminans ‘sine fulminans’. Clin Exp Dermatol 2000;25:299-301.

4. Karnoven SL, Rasanen L, Cuniliffe WJ, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity to Propionebacterium acnes in patients with severe nodular acne and acne fulminans. Dermatology 1994;189:344-349.

5. Kellet JK, Beck MH, Chalmers RJG. Erythema nodosum and circulating immune complexes in acne fulminans after treatment with isotretinoin. Br Med J 1985;290:820.-

6. Gowland G, Ward RM, Holland KY, Cuniliffe WJ. Cellular immunity to Propionebacterium acnes in normal population and patients with acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 1978;99:43-47.

7. Karvogen SL. Acne fulminans: report of clinical findings and treatment of twenty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;28:572-579.

1. Burns RE, Colville JM. Acne conglobata with septicaemia. Arch Dermatol 1959;79:361-363.

2. Seukeran DC, Cuniliffe WJ. Treatment of acne fulminans: a review of 25 cases. Br J Dermatol 1999;141:307-309.

3. Thomson KF, Cuniliffe WJ. Acne fulminans ‘sine fulminans’. Clin Exp Dermatol 2000;25:299-301.

4. Karnoven SL, Rasanen L, Cuniliffe WJ, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity to Propionebacterium acnes in patients with severe nodular acne and acne fulminans. Dermatology 1994;189:344-349.

5. Kellet JK, Beck MH, Chalmers RJG. Erythema nodosum and circulating immune complexes in acne fulminans after treatment with isotretinoin. Br Med J 1985;290:820.-

6. Gowland G, Ward RM, Holland KY, Cuniliffe WJ. Cellular immunity to Propionebacterium acnes in normal population and patients with acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 1978;99:43-47.

7. Karvogen SL. Acne fulminans: report of clinical findings and treatment of twenty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;28:572-579.

A toddler with failure to thrive and impaired vision

A 2½-year-old boy came to the office for a routine check-up. His height and weight were below the fifth percentile and he was developmentally delayed. His parents noted that while he could walk unsupported, he could only say “mama” and “dada,” and had just recently started climbing stairs. His previous physician had diagnosed him with hypothyroidism, but he was not taking any medications.

The child’s birth history revealed that he was born to a 20-year-old G1P0 female via Cesarean section secondary to fetal distress at 42 weeks’ gestation. He subsequently spent 1 week in the neonatal intensive care unit due to hypoglycemia.

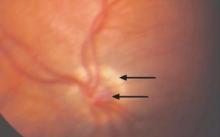

Following the office visit, the patient was admitted to the children’s hospital to investigate his failure to thrive and possible pituitary dysfunction. An ophthalmologic exam in the hospital showed that the patient was unable to follow objects, but did blink to bright light. Intermittent nystagmus was noted. A fundus exam revealed pale, hypoplastic optic nerves, bilaterally. Both nerves were also positive for the “double ring” sign (FIGURE 1).

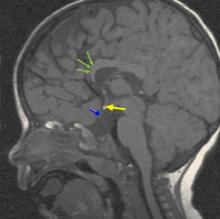

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain (FIGURE 2) revealed hypoplastic genu of the corpus callosum, cavum septum pellucidum, ectopic posterior pituitary, and small anterior pituitary. There was also enhancement of the inferior hypothalamus.

FIGURE 1

Hypoplastic left optic nerve

FIGURE 2

MRI of the brain

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage the patient?

Diagnosis: Septo-optic dysplasia

Septo-optic dysplasia is a form of optic nerve hypoplasia, the most common congenital optic nerve anomaly, which results from a decreased number of ganglion cell axons.1,2 By definition the syndrome also includes the absence or dysplasia of the septum pellucidum. In many cases, there are other central nervous system abnormalities, such as thinning of the corpus callosum, pituitary malformation, and schizencephaly.3 Most cases of septo-optic dysplasia are diagnosed in infancy and childhood, and there is an equal gender distribution. While rare (6.3 cases per 100,000), septo-optic dysplasia is potentially fatal.1,4

The exact cause of septo-optic dysplasia is unknown; however, both genetic and environmental factors appear to play a role. It has been linked with a defect in the HESX1 gene, young maternal age, maternal insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and a variety of toxins.1,5

Poor vision and the “double ring” sign

Most patients present with visual disturbance secondary to optic nerve hypoplasia. Visual acuity may range from 20/20 to no light perception; however, the majority of patients have vision worse than 20/200.1,3 Severe congenital vision loss often leads to sensory nystagmus and strabismus, as well as absent fixation, visual inattentiveness, and an afferent pupillary defect.1,2,6

On examination of the fundus, you may see a “double ring” sign, the appearance of 2 borders around the optic nerve. This outer ring shows a visible sclera at the outer border of a normal-sized nerve and the inner represents the junction between the retinal pigment epithelium and the actual nerve border.1,2,3,7

From CNS abnormalities to pituitary and adrenal problems

While the absence of a septum pellucidum alone has been shown to be clinically insignificant, the presence of other central nervous system abnormalities—such as schizencephaly, cortical heterotopias, or periventricular leukomalacia—can lead to a variety of deficits.8,9 Three-fourths of patients present with seizures, mental retardation, focal neurological deficits, cerebral palsy, or cortical visual loss.1,9

In addition, 15% of patients have some level of pituitary hormone deficiency. Decreased growth hormone is most common, followed by lack of thyroid-stimulating hormone, corticotropic hormone, and vasopressin. Common presentations include failure to thrive, hypoglycemia, prolonged jaundice, thermoregulatory dysfunction, developmental delay, growth retardation, hypotension, recurrent infection, polydipsia, polyuria, and hyper-natremia.1,4,10

Sudden death has been reported in septo-optic dysplasia patients who exhibit hypocortisolism (adrenal insufficiency), diabetes insipidus, and thermo-regulatory dysfunction. Viral illness and other forms of stress are particularly problematic for these patients, as they are unable to mount an appropriate response and are overwhelmed by hypoglycemia, dehydration, shock, and high fevers.4 As a result, clinicians need to be watch for those infants and neonates who are vulnerable to this stress. Extra care should be taken if they require surgery.4,6

Differentiation from a broad swath of possibilities

Due to the variety of presentations, the differential diagnosis for septo-optic dysplasia is very large. It includes all causes of failure to thrive, pituitary dysfunction, neurodevelopmental delay, and congenital vision loss. However, it’s important to maintain a high suspicion for the condition when the combination of the common signs and symptoms are present.

In addition to a full history and physical with dilated fundus exam, one of the most valuable tools in the diagnosis and prognosis of a patient with septo-optic dysplasia is an MRI of the brain with and without contrast, including the pituitary gland. In addition to detecting severely hypoplastic optic nerves, an MRI may also reveal the condition of the septum pellucidum and corpus callosum, cerebral hemispheric abnormalities, and pituitary ectopia. The presence or absence of these findings can help predict the clinical course in relation to pituitary function and neurodevelopmental delay.9,11

Laboratory testing of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis is important, as well. Referrals to both an ophthalmologist and endocrinologist are also necessary.6

Management

In septo-optic dysplasia, the goals of treatment are to preserve the patient’s vision, normalize hormone levels, and assist with neurodevelopmental delays.

Ophthalmology

Patients should be followed closely by an ophthalmologist. That’s because a patient may have a component of delayed maturation of vision, which may improve as he develops. Also, those with unilateral or asymmetric vision loss must be monitored and treated for a resulting amblyopia. Patching of the unaffected eye can aid toward this end.1,7

Endocrinology

Those patients with documented hormonal insufficiency require supplementation. Any patient at risk for developing a deficiency should also be closely monitored so that a change in hormone levels can be quickly recognized and treated. This will help avoid such complications as impaired growth and development—or even death.1,4

Parent education

It’s very important to teach parents about the critical signs and symptoms of dangerous hormone insufficiencies. In patients with cortisol deficiency or diabetes insipidus, febrile illnesses or extreme dehydration require an immediate stress dose of injectable parenteral corticosteroids and hospitalization.3,4 Parents should also be told to monitor their child for the development of other hormone insufficiencies by paying close attention to his growth pattern.1

Outcome

Our patient had deficiencies of growth hormone, thyroid stimulating hormone, and corticotropic hormone. As a result, we started him on supplements, including somatropin, levothyroxine, and hydrocortisone sodium succinate.

Our patient was also diagnosed with oral aversion, so a gastric tube was placed to ensure adequate nutrition. His parents were instructed to follow-up with ophthalmology, neurology, and endocrinology, as well as his primary care physician.

Five months after discharge, the patient had gained 3 kg and adjustments were made to his hormone therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Madhu Agarwal, MD Loma Linda University Department of Ophthalmology, 11370 Anderson, Suite 1800, Loma Linda, CA 92354. [email protected]

1. Smith PM, Rismondo V. Diagnosing septo-optic dysplasia. Eyenet 2006;March:37-39.

2. Zeki SM, Hollman AS, Dutton GN. Neuroradiologic features of patients with optic nerve hypoplasia. J Ped Ophthalmol Strabis 1993;29:107-112.

3. Brodsky MC. Congenital optic disc anomalies. In: Yanoff: Ophthalmogy., 2nd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby, Inc; 2004:1255-1256.

4. Brodsky MC, Conte FA, Taylor D, et al. Sudden death in septo-optic dysplasia. Report of 5 cases. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;155:66-70.

5. Oliver SCN, Bennett JL. Genetic disorders and the optic nerve: a clinical survey. Ophthalmol Clin N Am 2004;17:435-445.

6. Siatkowski RM, Sanchez JC, Andrade R, Alvarez A. The clinical, neuroradiographic, and endocrinologic profile of patients with bilateral optic nerve hypoplasia. Ophthalmology 1997;104:493-496.

7. Levin AV. Congenital eye anomalies. Pediatric Clin N Am 2003;50:55-76.

8. Williams J, Brodsky MC, Griebel M, et al. Septo-optic dysplasia: The clinical insignificance of an absent septum pellucidum. Develop Med Child Neurol 1993;35:490-501.

9. Brodsky MC, Glasier CM. Optic nerve hypoplasia: Clinical significance of associated central nervous system abnormalities of magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Ophthalmol 1993;111:66-74.

10. Donahue SP, Lavina A, Najjar J. Infantile infection and diabetes insipidus in children with optic nerve hypoplasia. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:1275-1277.

11. Brodsky MC, Glasier CM, Pollock SC, et al. Optic nerve hypoplasia: Identification by magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Ophthalmol 1990;108:1562-1568.

A 2½-year-old boy came to the office for a routine check-up. His height and weight were below the fifth percentile and he was developmentally delayed. His parents noted that while he could walk unsupported, he could only say “mama” and “dada,” and had just recently started climbing stairs. His previous physician had diagnosed him with hypothyroidism, but he was not taking any medications.

The child’s birth history revealed that he was born to a 20-year-old G1P0 female via Cesarean section secondary to fetal distress at 42 weeks’ gestation. He subsequently spent 1 week in the neonatal intensive care unit due to hypoglycemia.

Following the office visit, the patient was admitted to the children’s hospital to investigate his failure to thrive and possible pituitary dysfunction. An ophthalmologic exam in the hospital showed that the patient was unable to follow objects, but did blink to bright light. Intermittent nystagmus was noted. A fundus exam revealed pale, hypoplastic optic nerves, bilaterally. Both nerves were also positive for the “double ring” sign (FIGURE 1).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain (FIGURE 2) revealed hypoplastic genu of the corpus callosum, cavum septum pellucidum, ectopic posterior pituitary, and small anterior pituitary. There was also enhancement of the inferior hypothalamus.

FIGURE 1

Hypoplastic left optic nerve

FIGURE 2

MRI of the brain

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage the patient?

Diagnosis: Septo-optic dysplasia

Septo-optic dysplasia is a form of optic nerve hypoplasia, the most common congenital optic nerve anomaly, which results from a decreased number of ganglion cell axons.1,2 By definition the syndrome also includes the absence or dysplasia of the septum pellucidum. In many cases, there are other central nervous system abnormalities, such as thinning of the corpus callosum, pituitary malformation, and schizencephaly.3 Most cases of septo-optic dysplasia are diagnosed in infancy and childhood, and there is an equal gender distribution. While rare (6.3 cases per 100,000), septo-optic dysplasia is potentially fatal.1,4

The exact cause of septo-optic dysplasia is unknown; however, both genetic and environmental factors appear to play a role. It has been linked with a defect in the HESX1 gene, young maternal age, maternal insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and a variety of toxins.1,5

Poor vision and the “double ring” sign

Most patients present with visual disturbance secondary to optic nerve hypoplasia. Visual acuity may range from 20/20 to no light perception; however, the majority of patients have vision worse than 20/200.1,3 Severe congenital vision loss often leads to sensory nystagmus and strabismus, as well as absent fixation, visual inattentiveness, and an afferent pupillary defect.1,2,6

On examination of the fundus, you may see a “double ring” sign, the appearance of 2 borders around the optic nerve. This outer ring shows a visible sclera at the outer border of a normal-sized nerve and the inner represents the junction between the retinal pigment epithelium and the actual nerve border.1,2,3,7

From CNS abnormalities to pituitary and adrenal problems

While the absence of a septum pellucidum alone has been shown to be clinically insignificant, the presence of other central nervous system abnormalities—such as schizencephaly, cortical heterotopias, or periventricular leukomalacia—can lead to a variety of deficits.8,9 Three-fourths of patients present with seizures, mental retardation, focal neurological deficits, cerebral palsy, or cortical visual loss.1,9

In addition, 15% of patients have some level of pituitary hormone deficiency. Decreased growth hormone is most common, followed by lack of thyroid-stimulating hormone, corticotropic hormone, and vasopressin. Common presentations include failure to thrive, hypoglycemia, prolonged jaundice, thermoregulatory dysfunction, developmental delay, growth retardation, hypotension, recurrent infection, polydipsia, polyuria, and hyper-natremia.1,4,10

Sudden death has been reported in septo-optic dysplasia patients who exhibit hypocortisolism (adrenal insufficiency), diabetes insipidus, and thermo-regulatory dysfunction. Viral illness and other forms of stress are particularly problematic for these patients, as they are unable to mount an appropriate response and are overwhelmed by hypoglycemia, dehydration, shock, and high fevers.4 As a result, clinicians need to be watch for those infants and neonates who are vulnerable to this stress. Extra care should be taken if they require surgery.4,6

Differentiation from a broad swath of possibilities

Due to the variety of presentations, the differential diagnosis for septo-optic dysplasia is very large. It includes all causes of failure to thrive, pituitary dysfunction, neurodevelopmental delay, and congenital vision loss. However, it’s important to maintain a high suspicion for the condition when the combination of the common signs and symptoms are present.

In addition to a full history and physical with dilated fundus exam, one of the most valuable tools in the diagnosis and prognosis of a patient with septo-optic dysplasia is an MRI of the brain with and without contrast, including the pituitary gland. In addition to detecting severely hypoplastic optic nerves, an MRI may also reveal the condition of the septum pellucidum and corpus callosum, cerebral hemispheric abnormalities, and pituitary ectopia. The presence or absence of these findings can help predict the clinical course in relation to pituitary function and neurodevelopmental delay.9,11

Laboratory testing of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis is important, as well. Referrals to both an ophthalmologist and endocrinologist are also necessary.6

Management

In septo-optic dysplasia, the goals of treatment are to preserve the patient’s vision, normalize hormone levels, and assist with neurodevelopmental delays.

Ophthalmology

Patients should be followed closely by an ophthalmologist. That’s because a patient may have a component of delayed maturation of vision, which may improve as he develops. Also, those with unilateral or asymmetric vision loss must be monitored and treated for a resulting amblyopia. Patching of the unaffected eye can aid toward this end.1,7

Endocrinology

Those patients with documented hormonal insufficiency require supplementation. Any patient at risk for developing a deficiency should also be closely monitored so that a change in hormone levels can be quickly recognized and treated. This will help avoid such complications as impaired growth and development—or even death.1,4

Parent education

It’s very important to teach parents about the critical signs and symptoms of dangerous hormone insufficiencies. In patients with cortisol deficiency or diabetes insipidus, febrile illnesses or extreme dehydration require an immediate stress dose of injectable parenteral corticosteroids and hospitalization.3,4 Parents should also be told to monitor their child for the development of other hormone insufficiencies by paying close attention to his growth pattern.1

Outcome

Our patient had deficiencies of growth hormone, thyroid stimulating hormone, and corticotropic hormone. As a result, we started him on supplements, including somatropin, levothyroxine, and hydrocortisone sodium succinate.

Our patient was also diagnosed with oral aversion, so a gastric tube was placed to ensure adequate nutrition. His parents were instructed to follow-up with ophthalmology, neurology, and endocrinology, as well as his primary care physician.

Five months after discharge, the patient had gained 3 kg and adjustments were made to his hormone therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Madhu Agarwal, MD Loma Linda University Department of Ophthalmology, 11370 Anderson, Suite 1800, Loma Linda, CA 92354. [email protected]

A 2½-year-old boy came to the office for a routine check-up. His height and weight were below the fifth percentile and he was developmentally delayed. His parents noted that while he could walk unsupported, he could only say “mama” and “dada,” and had just recently started climbing stairs. His previous physician had diagnosed him with hypothyroidism, but he was not taking any medications.

The child’s birth history revealed that he was born to a 20-year-old G1P0 female via Cesarean section secondary to fetal distress at 42 weeks’ gestation. He subsequently spent 1 week in the neonatal intensive care unit due to hypoglycemia.

Following the office visit, the patient was admitted to the children’s hospital to investigate his failure to thrive and possible pituitary dysfunction. An ophthalmologic exam in the hospital showed that the patient was unable to follow objects, but did blink to bright light. Intermittent nystagmus was noted. A fundus exam revealed pale, hypoplastic optic nerves, bilaterally. Both nerves were also positive for the “double ring” sign (FIGURE 1).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain (FIGURE 2) revealed hypoplastic genu of the corpus callosum, cavum septum pellucidum, ectopic posterior pituitary, and small anterior pituitary. There was also enhancement of the inferior hypothalamus.

FIGURE 1

Hypoplastic left optic nerve

FIGURE 2

MRI of the brain

What is your diagnosis?

How would you manage the patient?

Diagnosis: Septo-optic dysplasia

Septo-optic dysplasia is a form of optic nerve hypoplasia, the most common congenital optic nerve anomaly, which results from a decreased number of ganglion cell axons.1,2 By definition the syndrome also includes the absence or dysplasia of the septum pellucidum. In many cases, there are other central nervous system abnormalities, such as thinning of the corpus callosum, pituitary malformation, and schizencephaly.3 Most cases of septo-optic dysplasia are diagnosed in infancy and childhood, and there is an equal gender distribution. While rare (6.3 cases per 100,000), septo-optic dysplasia is potentially fatal.1,4

The exact cause of septo-optic dysplasia is unknown; however, both genetic and environmental factors appear to play a role. It has been linked with a defect in the HESX1 gene, young maternal age, maternal insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and a variety of toxins.1,5

Poor vision and the “double ring” sign

Most patients present with visual disturbance secondary to optic nerve hypoplasia. Visual acuity may range from 20/20 to no light perception; however, the majority of patients have vision worse than 20/200.1,3 Severe congenital vision loss often leads to sensory nystagmus and strabismus, as well as absent fixation, visual inattentiveness, and an afferent pupillary defect.1,2,6

On examination of the fundus, you may see a “double ring” sign, the appearance of 2 borders around the optic nerve. This outer ring shows a visible sclera at the outer border of a normal-sized nerve and the inner represents the junction between the retinal pigment epithelium and the actual nerve border.1,2,3,7

From CNS abnormalities to pituitary and adrenal problems

While the absence of a septum pellucidum alone has been shown to be clinically insignificant, the presence of other central nervous system abnormalities—such as schizencephaly, cortical heterotopias, or periventricular leukomalacia—can lead to a variety of deficits.8,9 Three-fourths of patients present with seizures, mental retardation, focal neurological deficits, cerebral palsy, or cortical visual loss.1,9

In addition, 15% of patients have some level of pituitary hormone deficiency. Decreased growth hormone is most common, followed by lack of thyroid-stimulating hormone, corticotropic hormone, and vasopressin. Common presentations include failure to thrive, hypoglycemia, prolonged jaundice, thermoregulatory dysfunction, developmental delay, growth retardation, hypotension, recurrent infection, polydipsia, polyuria, and hyper-natremia.1,4,10

Sudden death has been reported in septo-optic dysplasia patients who exhibit hypocortisolism (adrenal insufficiency), diabetes insipidus, and thermo-regulatory dysfunction. Viral illness and other forms of stress are particularly problematic for these patients, as they are unable to mount an appropriate response and are overwhelmed by hypoglycemia, dehydration, shock, and high fevers.4 As a result, clinicians need to be watch for those infants and neonates who are vulnerable to this stress. Extra care should be taken if they require surgery.4,6

Differentiation from a broad swath of possibilities

Due to the variety of presentations, the differential diagnosis for septo-optic dysplasia is very large. It includes all causes of failure to thrive, pituitary dysfunction, neurodevelopmental delay, and congenital vision loss. However, it’s important to maintain a high suspicion for the condition when the combination of the common signs and symptoms are present.

In addition to a full history and physical with dilated fundus exam, one of the most valuable tools in the diagnosis and prognosis of a patient with septo-optic dysplasia is an MRI of the brain with and without contrast, including the pituitary gland. In addition to detecting severely hypoplastic optic nerves, an MRI may also reveal the condition of the septum pellucidum and corpus callosum, cerebral hemispheric abnormalities, and pituitary ectopia. The presence or absence of these findings can help predict the clinical course in relation to pituitary function and neurodevelopmental delay.9,11

Laboratory testing of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis is important, as well. Referrals to both an ophthalmologist and endocrinologist are also necessary.6

Management

In septo-optic dysplasia, the goals of treatment are to preserve the patient’s vision, normalize hormone levels, and assist with neurodevelopmental delays.

Ophthalmology

Patients should be followed closely by an ophthalmologist. That’s because a patient may have a component of delayed maturation of vision, which may improve as he develops. Also, those with unilateral or asymmetric vision loss must be monitored and treated for a resulting amblyopia. Patching of the unaffected eye can aid toward this end.1,7

Endocrinology

Those patients with documented hormonal insufficiency require supplementation. Any patient at risk for developing a deficiency should also be closely monitored so that a change in hormone levels can be quickly recognized and treated. This will help avoid such complications as impaired growth and development—or even death.1,4

Parent education

It’s very important to teach parents about the critical signs and symptoms of dangerous hormone insufficiencies. In patients with cortisol deficiency or diabetes insipidus, febrile illnesses or extreme dehydration require an immediate stress dose of injectable parenteral corticosteroids and hospitalization.3,4 Parents should also be told to monitor their child for the development of other hormone insufficiencies by paying close attention to his growth pattern.1

Outcome

Our patient had deficiencies of growth hormone, thyroid stimulating hormone, and corticotropic hormone. As a result, we started him on supplements, including somatropin, levothyroxine, and hydrocortisone sodium succinate.

Our patient was also diagnosed with oral aversion, so a gastric tube was placed to ensure adequate nutrition. His parents were instructed to follow-up with ophthalmology, neurology, and endocrinology, as well as his primary care physician.

Five months after discharge, the patient had gained 3 kg and adjustments were made to his hormone therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Madhu Agarwal, MD Loma Linda University Department of Ophthalmology, 11370 Anderson, Suite 1800, Loma Linda, CA 92354. [email protected]

1. Smith PM, Rismondo V. Diagnosing septo-optic dysplasia. Eyenet 2006;March:37-39.

2. Zeki SM, Hollman AS, Dutton GN. Neuroradiologic features of patients with optic nerve hypoplasia. J Ped Ophthalmol Strabis 1993;29:107-112.

3. Brodsky MC. Congenital optic disc anomalies. In: Yanoff: Ophthalmogy., 2nd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby, Inc; 2004:1255-1256.

4. Brodsky MC, Conte FA, Taylor D, et al. Sudden death in septo-optic dysplasia. Report of 5 cases. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;155:66-70.

5. Oliver SCN, Bennett JL. Genetic disorders and the optic nerve: a clinical survey. Ophthalmol Clin N Am 2004;17:435-445.

6. Siatkowski RM, Sanchez JC, Andrade R, Alvarez A. The clinical, neuroradiographic, and endocrinologic profile of patients with bilateral optic nerve hypoplasia. Ophthalmology 1997;104:493-496.

7. Levin AV. Congenital eye anomalies. Pediatric Clin N Am 2003;50:55-76.

8. Williams J, Brodsky MC, Griebel M, et al. Septo-optic dysplasia: The clinical insignificance of an absent septum pellucidum. Develop Med Child Neurol 1993;35:490-501.

9. Brodsky MC, Glasier CM. Optic nerve hypoplasia: Clinical significance of associated central nervous system abnormalities of magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Ophthalmol 1993;111:66-74.

10. Donahue SP, Lavina A, Najjar J. Infantile infection and diabetes insipidus in children with optic nerve hypoplasia. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:1275-1277.

11. Brodsky MC, Glasier CM, Pollock SC, et al. Optic nerve hypoplasia: Identification by magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Ophthalmol 1990;108:1562-1568.

1. Smith PM, Rismondo V. Diagnosing septo-optic dysplasia. Eyenet 2006;March:37-39.

2. Zeki SM, Hollman AS, Dutton GN. Neuroradiologic features of patients with optic nerve hypoplasia. J Ped Ophthalmol Strabis 1993;29:107-112.

3. Brodsky MC. Congenital optic disc anomalies. In: Yanoff: Ophthalmogy., 2nd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby, Inc; 2004:1255-1256.

4. Brodsky MC, Conte FA, Taylor D, et al. Sudden death in septo-optic dysplasia. Report of 5 cases. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;155:66-70.

5. Oliver SCN, Bennett JL. Genetic disorders and the optic nerve: a clinical survey. Ophthalmol Clin N Am 2004;17:435-445.

6. Siatkowski RM, Sanchez JC, Andrade R, Alvarez A. The clinical, neuroradiographic, and endocrinologic profile of patients with bilateral optic nerve hypoplasia. Ophthalmology 1997;104:493-496.

7. Levin AV. Congenital eye anomalies. Pediatric Clin N Am 2003;50:55-76.

8. Williams J, Brodsky MC, Griebel M, et al. Septo-optic dysplasia: The clinical insignificance of an absent septum pellucidum. Develop Med Child Neurol 1993;35:490-501.

9. Brodsky MC, Glasier CM. Optic nerve hypoplasia: Clinical significance of associated central nervous system abnormalities of magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Ophthalmol 1993;111:66-74.

10. Donahue SP, Lavina A, Najjar J. Infantile infection and diabetes insipidus in children with optic nerve hypoplasia. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:1275-1277.

11. Brodsky MC, Glasier CM, Pollock SC, et al. Optic nerve hypoplasia: Identification by magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Ophthalmol 1990;108:1562-1568.

Itchy rash near the navel

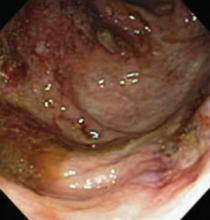

An 8-year-old boy presented with a pruritic periumbilical rash that he’d had for several months. The rash intensified during the day and improved at night. Some days the rash was much worse than others.

The patient’s mother noted he had recently begun tucking the front of his shirt into his pants. Over-the-counter steroid creams had provided intermittent improvement. He had no significant past medical history and took no other medications.

Examination revealed a 4-cm patch of erythema, scaling, and excoriation without a clear border and no central clearing (FIGURES 1 AND 2). The rest of the skin exam was unremarkable.

FIGURE 1

The periumbilical rash

A pruritic rash near the navel, which worsened during the day and improved at night.

FIGURE 2

A closer look

What is your diagnosis?

What therapy would you advise?

Diagnosis: Blue jean button dermatitis

Contact dermatitis secondary to nickel allergy is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction to the nickel contained in many blue jean snaps and buttons (FIGURE 3). The rash is typical of contact dermatitis. Macular erythema, sometimes accompanied by papules or vesicles, is also common.

The border is usually ill-defined, and the lesion may become fissured and excoriated. Long-standing cases may become lichenified and scaly. Occasionally, secondary eruptions on flexor surfaces appear.

FIGURE 3

It all lines up

The child’s nickel allergy rash aligns with the snap and button of his blue jeans.

More common among women

Nickel allergy is relatively common; up to 20% of women and 4% of men are affected.1 This discrepancy is thought to be due to the ways in which individuals become sensitized to nickel.

Many women develop a nickel allergy after getting their ears pierced with nickel-containing studs, whereas men tend to be sensitized by an occupational exposure. Nickel allergy appears to be increasing, which may reflect the more common practice of body piercing in general.

How much nickel is too much?

Sensitized patients will react to a metal if more than 1 part in 10,000 is nickel. Metal objects can be tested for nickel content by using a cotton-tipped applicator to apply a few drops of dimethylglyoxime in ammonium hydroxide to the object. If greater than 1 part per 10,000 is nickel, the cotton will turn pink. Recently, Byer and Morrell found that 10% of blue jeans buttons, and more than 50% of belt buckles, test positive.2

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for a pruritic periumbilical rash in a child would include psoriasis, scabies, tinea corpus and pityriasis rosea.

Psoriatic lesions

The periumbilical area is a common location for psoriatic lesions. More often involved areas include the scalp and areas of trauma such as the knees, elbows, hands and feet. The lesions of psoriasis tend to have a sharp border and characteristically have silvery white scales associated with them. Psoriasis is often associated with nail abnormalities and arthritis.

Scabies

Scabies is a parasitic infestation with the mite Sarcoptes scabiei. Scabies causes an intensely pruritic rash that is classically worse in the finger and toe webs, along the belt line, the groin and axillary regions and, often, periumbilically.

The rash of scabies consists of linearly arranged papules and vesicles due to a hypersensitivity reaction to the mite’s eggs and feces which are left behind as it burrows through the skin. Excoriation often obscures the typical findings and may be extensive. Treatment of scabies with steroid creams often leads to diffuse erythema and crusting.3

Tinea corpus

Tinea corpus is a dermatophyte infection of the body. These lesions are typically oval and pruritic. Tinea corpus lesions tend to enlarge slowly with a clearly demarcated, slightly raised, erythematous border and central clearing. Satellite lesions may be seen. Applying topical steroids to tinea corpus may result in initial improvement with subsequent flare as the body’s immune response is suppressed.

Pityriasis rosea

Pityriasis rosea is a common pruritic exanthem that can begin as a solitary lesion on the trunk (herald patch). The herald patch is typically an erythematous oval lesion several centimeters in size with a collarette of scales along its border. Typically, within a week numerous other salmon-colored lesions appear on the trunk along Langer’s lines.

The age of peak incidence is during the third decade of life but it does develop in children. Therapy is conservative and targets the control of pruritus.4

Treatment: A simple solution

The mainstay of therapy is avoidance of nickel-containing metals. Buttons can be replaced with plastic ones, or covered with cloth. Patients should not coat buttons with nail polish—it doesn’t work very well.

Stainless steel is a good option for piercings because nickel tends to be tightly bound within the alloy. Topical steroids can be used to speed resolution of the rash and antihistamines may help with pruritus.

Outcome

The patient was placed on a topical steroid (triamcinolone 0.1% ointment). His mother sewed a piece of cloth over the inside of all his pants buttons. The ointment was only given because the mother wanted something that would make the rash go away quickly. Within a week, he was no longer itching and his rash was nearly gone.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dean A. Seehusen, MD, MPH Department of Family and Community Medicine, Eisenhower Army Medical Center, Fort Gordon, GA 30509 E-mail: [email protected]

1. Cerveny KA, Brodell RT. Blue jean button dermatitis. Postgrad Med 2002;112:79-80,83.

2. Byer TT, Morrell DS. Periumbilical contact dermatitis: Blue jeans or belt buckles? Pediatr Dermatol 2004;21:223-226.