User login

Chronic blistering rash on hands

A 60-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with a chronic, recurrent pruritic rash on his hands and neck. He noted that the rash developed into blisters, which he would pick until they scabbed over. The rash only manifested on sun-exposed areas.

The patient did not take any medications. He admitted to drinking alcohol (4 beers/d on average) and had roughly a 50-pack year history of smoking. There was no family history of similar symptoms.

On physical exam, we noted erosions and ulcerations with hemorrhagic crust on the dorsal aspect of his hands, along with milia on the knuckle pads (FIGURE 1A). Further skin examination revealed hypopigmented scars on his shoulders and lower extremities bilaterally, with hypertrichosis of the cheeks (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Porphyria cutanea tarda

Based on the clinical presentation and the patient’s history of smoking and alcohol consumption, we suspected that this was a case of porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT). Laboratory studies, including a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, iron studies, and liver function tests, were ordered. These revealed elevated levels of serum alanine transaminase (116 IU/L; reference range, 20-60 IU/L), aspartate aminotransferase (184 IU/L; reference range, 6-34 IU/L in men), and ferritin (1594 ng/mL; reference range, 12-300 ng/mL in men), consistent with PCT. Total porphyrins were then measured and found to be elevated (128.5 mcg/dL; reference range, 0 to 1 mcg/dL), which confirmed the diagnosis. Further testing revealed that the patient was positive for both hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus infection.

While PCT is the most common porphyria worldwide, it is nonetheless a rare disorder that results from deficient activity (< 20% of normal) of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD), the fifth enzyme in the heme synthetic pathway.1,2 It is typically (~75% cases) an acquired disorder of mid- to late adulthood and more commonly affects males.1 In the remainder of cases, patients have a genetic predisposition—a mutation of the UROD or HFE gene. Patients with a genetic predisposition may present earlier.2,3 Susceptibility factors for both forms of PCT include chronic alcohol use, HCV and/or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, estrogen therapy, and a history of chronic/heavy smoking.1,4

Cutaneous manifestations of PCT are caused by the accumulation of porphyrins, which are photo-oxidized in the skin.1 Findings include photosensitivity, skin fragility, blistering, scarring, hypo- or hyperpigmentation, and milia in sun-exposed areas, such as the dorsum of the hands, forearms, face, ears, neck, and feet.1,2 Hypertrichosis can occur, particularly on the cheeks and forearms.1 Elevated transaminases often accompany cutaneous findings, due to porphyrin accumulation in hepatocytes and the hepatotoxic effects of alcohol, HCV infection, or iron overload.5 Iron overload, in part due to dysregulation of hepcidin, can lead to increased serum ferritin, iron, and transferrin saturation.1

Differential includes autoimmune and autosomal conditions

Diseases that manifest with blistering, elevated porphyrins or porphyrin precursors, and iron overload should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder that occurs when antibodies attack hemidesmosomes in the epidermis. It commonly manifests in the elderly and classically presents with tense bullae, typically on the trunk, abdomen, and proximal extremities. Serologic testing and biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.6

Continue to: Pseudoporphyria...

Pseudoporphyria has a similar presentation to PCT but with no abnormalities in porphyrin metabolism. Risk factors include UV radiation exposure; use of medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, and retinoids; chronic renal failure; and hemodialysis.7

Acute intermittent porphyria is an autosomal dominant disorder due to deficiency of porphobilinogen deaminase, a heme biosynthetic enzyme. Clinical manifestations usually arise in adulthood and include neurovisceral attacks (eg, abdominal pain, vomiting, muscle weakness). Diagnosis during an acute attack can be made by measuring urinary 5-aminolaevulinc acid and porphobilinogen.1

Hereditary hemochromatosis is an autosomal recessive disorder most commonly due to mutations in the HFE gene. Patients typically have iron overload and abnormal liver function test results. The main cutaneous finding is skin hyperpigmentation. Patients also may develop diabetes mellitus, arthropathy, cardiac disease, and hypopituitarism, although most are diagnosed with asymptomatic disease following routine laboratory studies.8

Confirm the diagnosis with total porphyrin measurement

The preferred initial test to confirm the diagnosis of PCT is measurement of plasma or urine total porphyrins, which will be elevated.1 Further testing is then performed to discern PCT from the other, less common cutaneous porphyrias.1 If needed, biopsy can be done to exclude other diagnoses. Testing for HIV and viral hepatitis infection may be performed when clinical suspicion is high.1 Testing for UROD and HFE mutations may also be advised.1

Treatment choice is guided by iron levels

For patients with normal iron levels, low-dose hydroxychloroquine 100 mg or chloroquine 125 mg twice per week can be used until restoration of normal plasma or urine porphyrin levels has been achieved for several months.1 For those with iron excess (serum ferritin > 600 ng/dL), repeat phlebotomy is the preferred treatment; a unit of blood (350-500 mL) is typically removed, as tolerated, until iron stores return to normal.1 In severe cases of PCT, these therapies can be used in combination.1 Clinical remission with these methods can be expected within 6 to 9 months.9

Continue to: In addition...

In addition, it is important to provide patient education regarding proper sun protection and risk factor modification.1 Underlying HIV and viral hepatitis infection should be managed appropriately by the relevant specialists.

Our patient was counseled on proper sun protection and encouraged to cease alcohol consumption and smoking. We subsequently referred him to Hepatology for the treatment of his liver disease. Given that the patient’s ferritin level was so high (1594 ng/mL), serial phlebotomy was initiated twice monthly until levels reached the lower limit of normal. He was also started on direct-acting antiviral therapy with Epclusa (sofosbuvir/velpatasvir) for 12 weeks for treatment of his HCV and is currently in remission.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christopher G. Bazewicz, MD, Department of Dermatology, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

1. Puy H, Gouya L, Deybach JC. Porphyrias. Lancet. 2010;375:924-937.

2. Méndez M, Poblete-Gutiérrez P, García-Bravo M, et al. Molecular heterogeneity of familial porphyria cutanea tarda in Spain: characterization of 10 novel mutations in the UROD gene. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:501-507.

3. Brady JJ, Jackson HA, Roberts AG, et al. Co-inheritance of mutations in the uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase and hemochromatosis genes accelerates the onset of porphyria cutanea tarda. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:868-874.

4. Jalil S, Grady JJ, Lee C, et al. Associations among behavior-related susceptibility factors in porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:297-302, 302.e1.

5. Gisbert JP, García-Buey L, Alonso A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma risk in patients with porphyria cutanea tarda. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:689-692.

6. Di Zenzo G, Della Torre R, Zambruno G, et al. Bullous pemphigoid: from the clinic to the bench. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:3-16.

7. Green JJ, Manders SM. Pseudoporphyria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:100-108.

8. Crownover BK, Covey CJ. Hereditary hemochromatosis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:183-190.

9. Sarkany RP. The management of porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:225-232.

A 60-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with a chronic, recurrent pruritic rash on his hands and neck. He noted that the rash developed into blisters, which he would pick until they scabbed over. The rash only manifested on sun-exposed areas.

The patient did not take any medications. He admitted to drinking alcohol (4 beers/d on average) and had roughly a 50-pack year history of smoking. There was no family history of similar symptoms.

On physical exam, we noted erosions and ulcerations with hemorrhagic crust on the dorsal aspect of his hands, along with milia on the knuckle pads (FIGURE 1A). Further skin examination revealed hypopigmented scars on his shoulders and lower extremities bilaterally, with hypertrichosis of the cheeks (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Porphyria cutanea tarda

Based on the clinical presentation and the patient’s history of smoking and alcohol consumption, we suspected that this was a case of porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT). Laboratory studies, including a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, iron studies, and liver function tests, were ordered. These revealed elevated levels of serum alanine transaminase (116 IU/L; reference range, 20-60 IU/L), aspartate aminotransferase (184 IU/L; reference range, 6-34 IU/L in men), and ferritin (1594 ng/mL; reference range, 12-300 ng/mL in men), consistent with PCT. Total porphyrins were then measured and found to be elevated (128.5 mcg/dL; reference range, 0 to 1 mcg/dL), which confirmed the diagnosis. Further testing revealed that the patient was positive for both hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus infection.

While PCT is the most common porphyria worldwide, it is nonetheless a rare disorder that results from deficient activity (< 20% of normal) of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD), the fifth enzyme in the heme synthetic pathway.1,2 It is typically (~75% cases) an acquired disorder of mid- to late adulthood and more commonly affects males.1 In the remainder of cases, patients have a genetic predisposition—a mutation of the UROD or HFE gene. Patients with a genetic predisposition may present earlier.2,3 Susceptibility factors for both forms of PCT include chronic alcohol use, HCV and/or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, estrogen therapy, and a history of chronic/heavy smoking.1,4

Cutaneous manifestations of PCT are caused by the accumulation of porphyrins, which are photo-oxidized in the skin.1 Findings include photosensitivity, skin fragility, blistering, scarring, hypo- or hyperpigmentation, and milia in sun-exposed areas, such as the dorsum of the hands, forearms, face, ears, neck, and feet.1,2 Hypertrichosis can occur, particularly on the cheeks and forearms.1 Elevated transaminases often accompany cutaneous findings, due to porphyrin accumulation in hepatocytes and the hepatotoxic effects of alcohol, HCV infection, or iron overload.5 Iron overload, in part due to dysregulation of hepcidin, can lead to increased serum ferritin, iron, and transferrin saturation.1

Differential includes autoimmune and autosomal conditions

Diseases that manifest with blistering, elevated porphyrins or porphyrin precursors, and iron overload should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder that occurs when antibodies attack hemidesmosomes in the epidermis. It commonly manifests in the elderly and classically presents with tense bullae, typically on the trunk, abdomen, and proximal extremities. Serologic testing and biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.6

Continue to: Pseudoporphyria...

Pseudoporphyria has a similar presentation to PCT but with no abnormalities in porphyrin metabolism. Risk factors include UV radiation exposure; use of medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, and retinoids; chronic renal failure; and hemodialysis.7

Acute intermittent porphyria is an autosomal dominant disorder due to deficiency of porphobilinogen deaminase, a heme biosynthetic enzyme. Clinical manifestations usually arise in adulthood and include neurovisceral attacks (eg, abdominal pain, vomiting, muscle weakness). Diagnosis during an acute attack can be made by measuring urinary 5-aminolaevulinc acid and porphobilinogen.1

Hereditary hemochromatosis is an autosomal recessive disorder most commonly due to mutations in the HFE gene. Patients typically have iron overload and abnormal liver function test results. The main cutaneous finding is skin hyperpigmentation. Patients also may develop diabetes mellitus, arthropathy, cardiac disease, and hypopituitarism, although most are diagnosed with asymptomatic disease following routine laboratory studies.8

Confirm the diagnosis with total porphyrin measurement

The preferred initial test to confirm the diagnosis of PCT is measurement of plasma or urine total porphyrins, which will be elevated.1 Further testing is then performed to discern PCT from the other, less common cutaneous porphyrias.1 If needed, biopsy can be done to exclude other diagnoses. Testing for HIV and viral hepatitis infection may be performed when clinical suspicion is high.1 Testing for UROD and HFE mutations may also be advised.1

Treatment choice is guided by iron levels

For patients with normal iron levels, low-dose hydroxychloroquine 100 mg or chloroquine 125 mg twice per week can be used until restoration of normal plasma or urine porphyrin levels has been achieved for several months.1 For those with iron excess (serum ferritin > 600 ng/dL), repeat phlebotomy is the preferred treatment; a unit of blood (350-500 mL) is typically removed, as tolerated, until iron stores return to normal.1 In severe cases of PCT, these therapies can be used in combination.1 Clinical remission with these methods can be expected within 6 to 9 months.9

Continue to: In addition...

In addition, it is important to provide patient education regarding proper sun protection and risk factor modification.1 Underlying HIV and viral hepatitis infection should be managed appropriately by the relevant specialists.

Our patient was counseled on proper sun protection and encouraged to cease alcohol consumption and smoking. We subsequently referred him to Hepatology for the treatment of his liver disease. Given that the patient’s ferritin level was so high (1594 ng/mL), serial phlebotomy was initiated twice monthly until levels reached the lower limit of normal. He was also started on direct-acting antiviral therapy with Epclusa (sofosbuvir/velpatasvir) for 12 weeks for treatment of his HCV and is currently in remission.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christopher G. Bazewicz, MD, Department of Dermatology, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

A 60-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic with a chronic, recurrent pruritic rash on his hands and neck. He noted that the rash developed into blisters, which he would pick until they scabbed over. The rash only manifested on sun-exposed areas.

The patient did not take any medications. He admitted to drinking alcohol (4 beers/d on average) and had roughly a 50-pack year history of smoking. There was no family history of similar symptoms.

On physical exam, we noted erosions and ulcerations with hemorrhagic crust on the dorsal aspect of his hands, along with milia on the knuckle pads (FIGURE 1A). Further skin examination revealed hypopigmented scars on his shoulders and lower extremities bilaterally, with hypertrichosis of the cheeks (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Porphyria cutanea tarda

Based on the clinical presentation and the patient’s history of smoking and alcohol consumption, we suspected that this was a case of porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT). Laboratory studies, including a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, iron studies, and liver function tests, were ordered. These revealed elevated levels of serum alanine transaminase (116 IU/L; reference range, 20-60 IU/L), aspartate aminotransferase (184 IU/L; reference range, 6-34 IU/L in men), and ferritin (1594 ng/mL; reference range, 12-300 ng/mL in men), consistent with PCT. Total porphyrins were then measured and found to be elevated (128.5 mcg/dL; reference range, 0 to 1 mcg/dL), which confirmed the diagnosis. Further testing revealed that the patient was positive for both hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus infection.

While PCT is the most common porphyria worldwide, it is nonetheless a rare disorder that results from deficient activity (< 20% of normal) of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD), the fifth enzyme in the heme synthetic pathway.1,2 It is typically (~75% cases) an acquired disorder of mid- to late adulthood and more commonly affects males.1 In the remainder of cases, patients have a genetic predisposition—a mutation of the UROD or HFE gene. Patients with a genetic predisposition may present earlier.2,3 Susceptibility factors for both forms of PCT include chronic alcohol use, HCV and/or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, estrogen therapy, and a history of chronic/heavy smoking.1,4

Cutaneous manifestations of PCT are caused by the accumulation of porphyrins, which are photo-oxidized in the skin.1 Findings include photosensitivity, skin fragility, blistering, scarring, hypo- or hyperpigmentation, and milia in sun-exposed areas, such as the dorsum of the hands, forearms, face, ears, neck, and feet.1,2 Hypertrichosis can occur, particularly on the cheeks and forearms.1 Elevated transaminases often accompany cutaneous findings, due to porphyrin accumulation in hepatocytes and the hepatotoxic effects of alcohol, HCV infection, or iron overload.5 Iron overload, in part due to dysregulation of hepcidin, can lead to increased serum ferritin, iron, and transferrin saturation.1

Differential includes autoimmune and autosomal conditions

Diseases that manifest with blistering, elevated porphyrins or porphyrin precursors, and iron overload should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder that occurs when antibodies attack hemidesmosomes in the epidermis. It commonly manifests in the elderly and classically presents with tense bullae, typically on the trunk, abdomen, and proximal extremities. Serologic testing and biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.6

Continue to: Pseudoporphyria...

Pseudoporphyria has a similar presentation to PCT but with no abnormalities in porphyrin metabolism. Risk factors include UV radiation exposure; use of medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, and retinoids; chronic renal failure; and hemodialysis.7

Acute intermittent porphyria is an autosomal dominant disorder due to deficiency of porphobilinogen deaminase, a heme biosynthetic enzyme. Clinical manifestations usually arise in adulthood and include neurovisceral attacks (eg, abdominal pain, vomiting, muscle weakness). Diagnosis during an acute attack can be made by measuring urinary 5-aminolaevulinc acid and porphobilinogen.1

Hereditary hemochromatosis is an autosomal recessive disorder most commonly due to mutations in the HFE gene. Patients typically have iron overload and abnormal liver function test results. The main cutaneous finding is skin hyperpigmentation. Patients also may develop diabetes mellitus, arthropathy, cardiac disease, and hypopituitarism, although most are diagnosed with asymptomatic disease following routine laboratory studies.8

Confirm the diagnosis with total porphyrin measurement

The preferred initial test to confirm the diagnosis of PCT is measurement of plasma or urine total porphyrins, which will be elevated.1 Further testing is then performed to discern PCT from the other, less common cutaneous porphyrias.1 If needed, biopsy can be done to exclude other diagnoses. Testing for HIV and viral hepatitis infection may be performed when clinical suspicion is high.1 Testing for UROD and HFE mutations may also be advised.1

Treatment choice is guided by iron levels

For patients with normal iron levels, low-dose hydroxychloroquine 100 mg or chloroquine 125 mg twice per week can be used until restoration of normal plasma or urine porphyrin levels has been achieved for several months.1 For those with iron excess (serum ferritin > 600 ng/dL), repeat phlebotomy is the preferred treatment; a unit of blood (350-500 mL) is typically removed, as tolerated, until iron stores return to normal.1 In severe cases of PCT, these therapies can be used in combination.1 Clinical remission with these methods can be expected within 6 to 9 months.9

Continue to: In addition...

In addition, it is important to provide patient education regarding proper sun protection and risk factor modification.1 Underlying HIV and viral hepatitis infection should be managed appropriately by the relevant specialists.

Our patient was counseled on proper sun protection and encouraged to cease alcohol consumption and smoking. We subsequently referred him to Hepatology for the treatment of his liver disease. Given that the patient’s ferritin level was so high (1594 ng/mL), serial phlebotomy was initiated twice monthly until levels reached the lower limit of normal. He was also started on direct-acting antiviral therapy with Epclusa (sofosbuvir/velpatasvir) for 12 weeks for treatment of his HCV and is currently in remission.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christopher G. Bazewicz, MD, Department of Dermatology, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

1. Puy H, Gouya L, Deybach JC. Porphyrias. Lancet. 2010;375:924-937.

2. Méndez M, Poblete-Gutiérrez P, García-Bravo M, et al. Molecular heterogeneity of familial porphyria cutanea tarda in Spain: characterization of 10 novel mutations in the UROD gene. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:501-507.

3. Brady JJ, Jackson HA, Roberts AG, et al. Co-inheritance of mutations in the uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase and hemochromatosis genes accelerates the onset of porphyria cutanea tarda. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:868-874.

4. Jalil S, Grady JJ, Lee C, et al. Associations among behavior-related susceptibility factors in porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:297-302, 302.e1.

5. Gisbert JP, García-Buey L, Alonso A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma risk in patients with porphyria cutanea tarda. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:689-692.

6. Di Zenzo G, Della Torre R, Zambruno G, et al. Bullous pemphigoid: from the clinic to the bench. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:3-16.

7. Green JJ, Manders SM. Pseudoporphyria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:100-108.

8. Crownover BK, Covey CJ. Hereditary hemochromatosis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:183-190.

9. Sarkany RP. The management of porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:225-232.

1. Puy H, Gouya L, Deybach JC. Porphyrias. Lancet. 2010;375:924-937.

2. Méndez M, Poblete-Gutiérrez P, García-Bravo M, et al. Molecular heterogeneity of familial porphyria cutanea tarda in Spain: characterization of 10 novel mutations in the UROD gene. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:501-507.

3. Brady JJ, Jackson HA, Roberts AG, et al. Co-inheritance of mutations in the uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase and hemochromatosis genes accelerates the onset of porphyria cutanea tarda. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:868-874.

4. Jalil S, Grady JJ, Lee C, et al. Associations among behavior-related susceptibility factors in porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:297-302, 302.e1.

5. Gisbert JP, García-Buey L, Alonso A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma risk in patients with porphyria cutanea tarda. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:689-692.

6. Di Zenzo G, Della Torre R, Zambruno G, et al. Bullous pemphigoid: from the clinic to the bench. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:3-16.

7. Green JJ, Manders SM. Pseudoporphyria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:100-108.

8. Crownover BK, Covey CJ. Hereditary hemochromatosis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:183-190.

9. Sarkany RP. The management of porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:225-232.

Atypical Presentation of Acquired Angioedema

To the Editor:

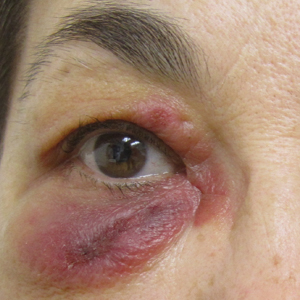

A 65-year-old woman with B-cell marginal zone lymphoma presented with asymptomatic swelling and redness of the upper and lower eyelids of 1 week’s duration that was unresponsive to topical corticosteroids for presumptive allergic contact dermatitis. She denied any lip or tongue swelling, abdominal pain, or difficulty breathing or swallowing. Diagnosis of acquired angioedema (AAE) was confirmed on laboratory analysis, which showed C1q levels less than 3.6 mg/dL (reference range, 5.0–8.6 mg/dL), complement component 4 levels less than 8 mg/dL (reference range, 14–44 mg/dL), and C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) levels of 3 mg/dL (reference range, 12–30 mg/dL).

A review of the patient’s medical record showed chronic thrombocytopenia secondary to previous chemotherapy. It was determined that the patient’s ecchymosis and purpura of the eyelids was secondary to a low platelet count resulting in bleeding into the area of angioedema (Figure). Serum protein electrophoresis did not demonstrate a monoclonal spike, and flow cytometry showed persistent B-cell leukemia without evidence of an aberrant T-cell antigenic profile. The edema and purpura of the eyelids spontaneously resolved over days, and the patient has had no recurrences to date. She was prescribed icatibant for treatment of future acute AAE attacks.

The common pathway of AAE involves the inability of C1-INH to stop activation of the complement, fibrinolytic, and contact systems. Failure to control the contact system leads to increased bradykinin production resulting in vasodilation and edema. Diagnosis of hereditary angioedema (HAE) types 1 and 2 can be confirmed in the setting of low complement component 4 and C1-INH functional levels and normal C1q levels; in AAE, C1q levels also are low.1,2

The malignancies most frequently associated with AAE are non-Hodgkin lymphomas (eg, nodal marginal zone lymphoma, splenic marginal zone lymphoma), such as in our patient, as well as monoclonal gammopathies.2 Triggers of AAE include trauma (eg, surgery, strenuous exercise), infection, and use of certain medications such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and estrogen, but most episodes are spontaneous. Swelling of any cutaneous surface can occur in the setting of AAE. Mucosal involvement appears to be limited to the upper airway and gastrointestinal tract. Edema of the upper airway mucosa can lead to asphyxiation. In these cases, asphyxia can occur rapidly, and therefore all patients with upper airway involvement should present to the emergency room or call 911. Pain from swelling in the gastrointestinal tract can mimic an acute abdomen.3

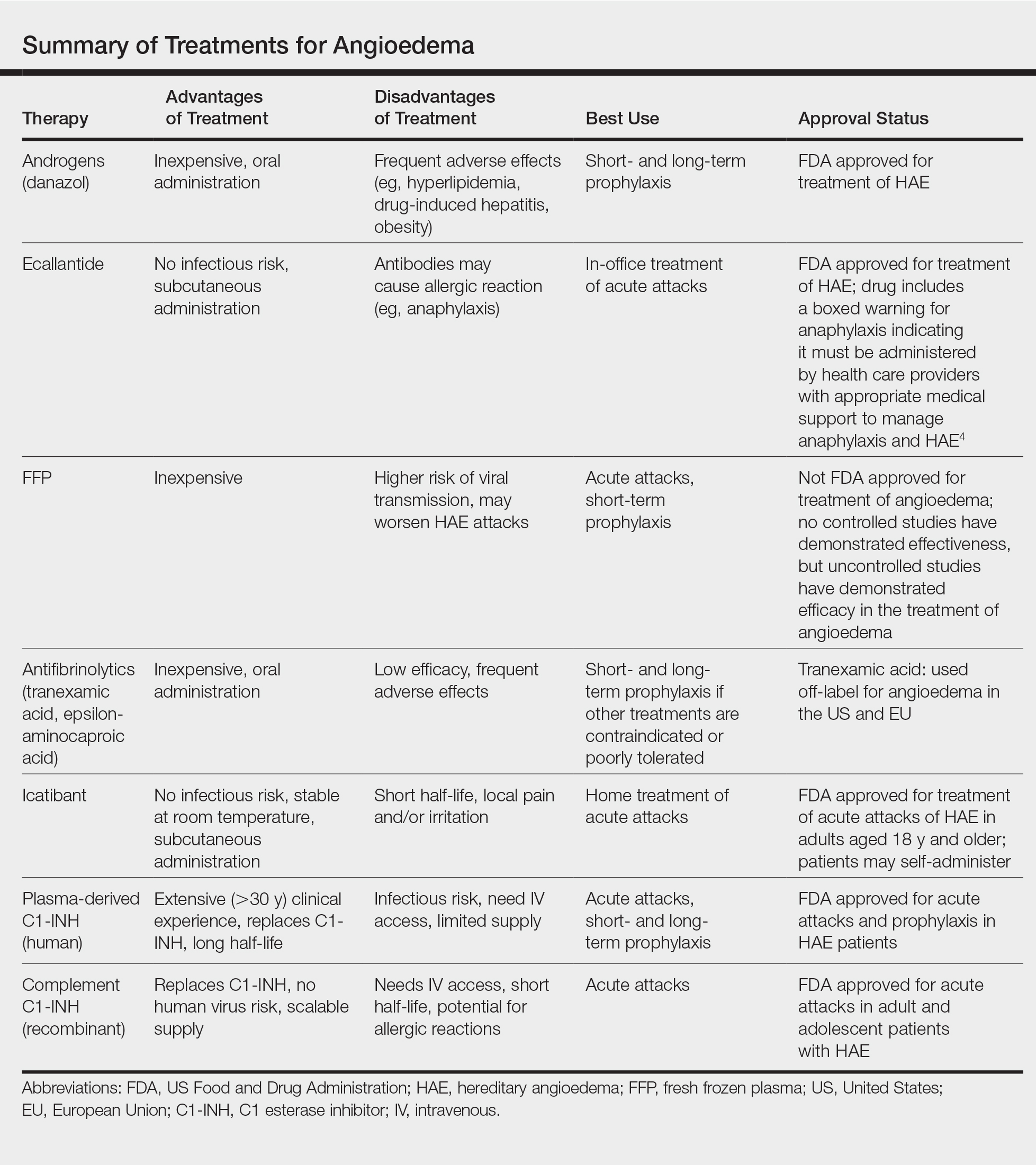

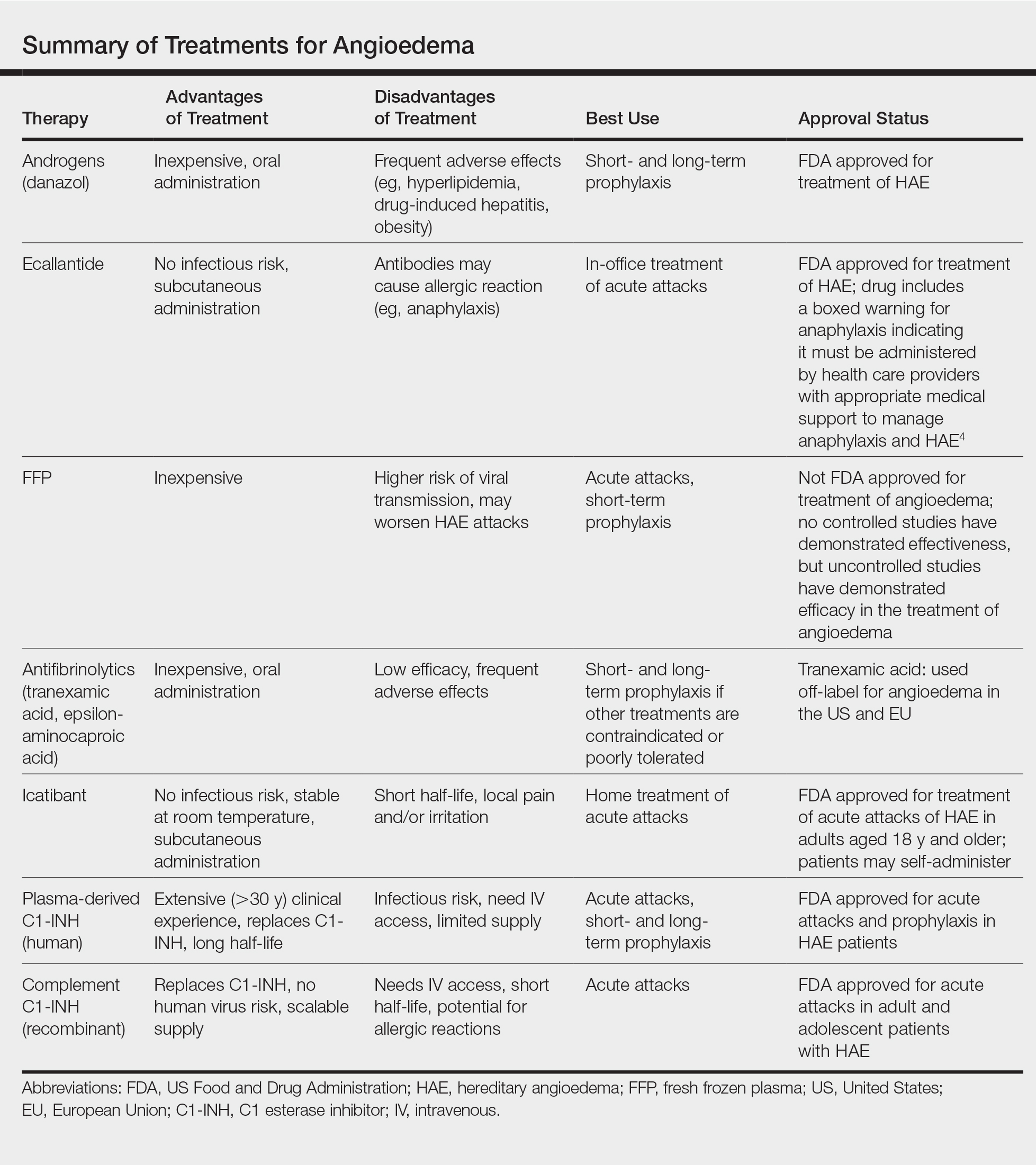

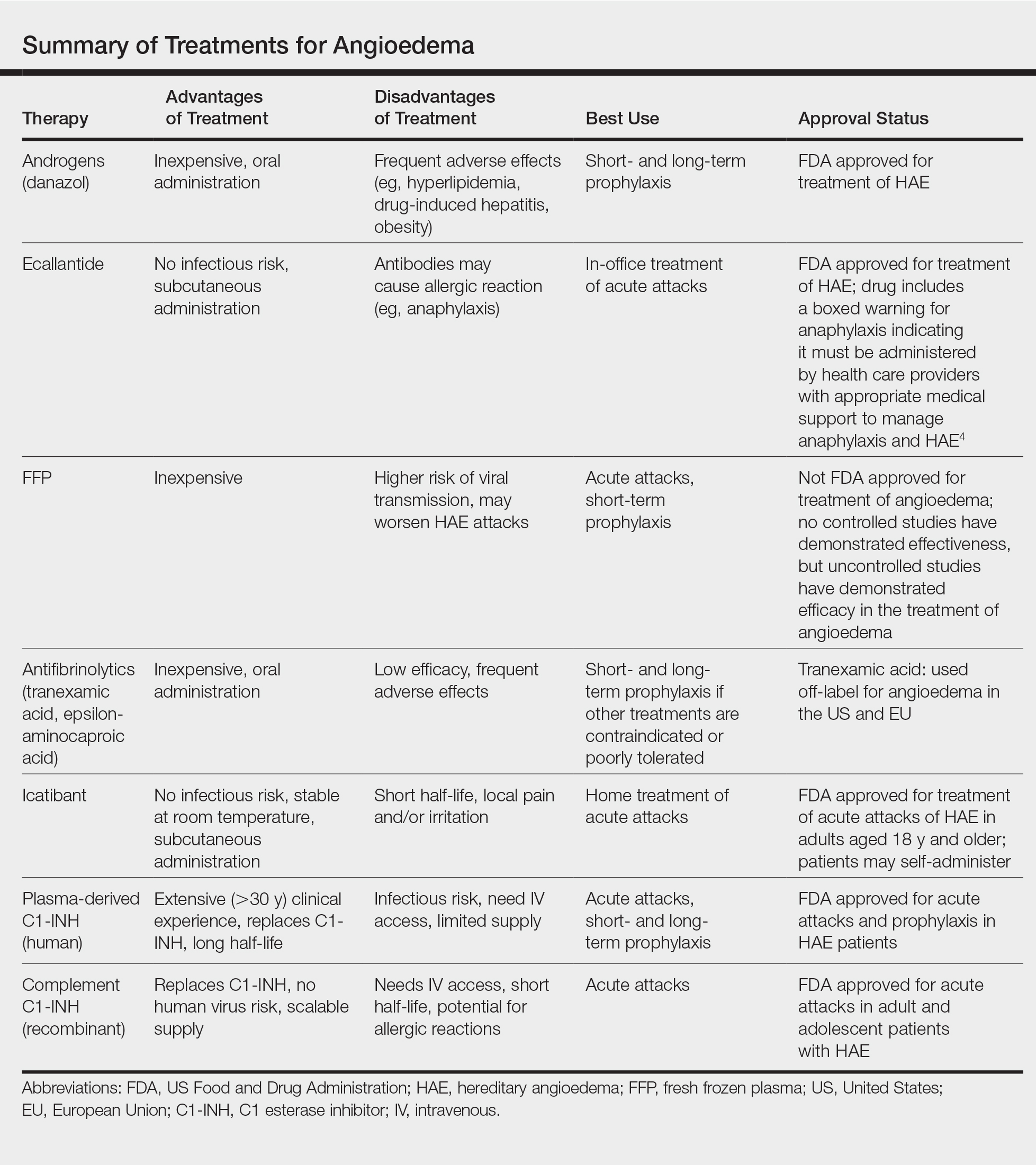

Newly developed targeted therapies for HAE also appear to be effective in treating AAE. A summary of available treatments for angioedema is provided in the Table. Human plasma C1-INH can be used intravenously to treat acute attacks or can be given prophylactically to prevent attacks, but large doses may be necessary due to consumption of the protein.1,3 The risk of bloodborne disease as a result of treatment exists, but screening and processing during production of the plasma makes this unlikely. Ecallantide is a reversible inhibitor of plasma kallikrein.1,3 Rapid onset and subcutaneous dosing make it useful for treatment of acute AAE attacks. Because anaphylaxis has been reported in up to 3% of patients, ecallantide includes a boxed warning indicating that it must be administered by a health care professional with appropriate medical support to manage anaphylaxis and HAE.4 Icatibant is a selective competitive antagonist of bradykinin receptor B2. It can be administered subcutaneously by the patient, making it ideal for rapid treatment of angioedema.1,3 Adverse events include pain and irritation at the injection site.

The most appropriate therapy for AAE is treatment of the underlying malignancy. Recognition and proper treatment of AAE is essential, as bradykinin-induced angioedema (AAE, HAE and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor induced angioedema) does not respond to antihistamines and corticosteroids and instead requires therapy as discussed above.

- Craig T, Riedl M, Dykewicz MS, et al. When is prophylaxis for hereditary angioedema necessary? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102:366-372.

- Cugno M, Castelli R, Cicardi M. Angioedema due to acquired C1-inhibitor deficiency: a bridging connection between autoimmunity and lymphoproliferation. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;8:156-159.

- Buyantseva LV, Sardana N, Craig TJ. Update on treatment of hereditary angioedema. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2012;30:89-98.

- Kalbitor [package insert]. Burlington, MA: Dyax Corp; 2015.

To the Editor:

A 65-year-old woman with B-cell marginal zone lymphoma presented with asymptomatic swelling and redness of the upper and lower eyelids of 1 week’s duration that was unresponsive to topical corticosteroids for presumptive allergic contact dermatitis. She denied any lip or tongue swelling, abdominal pain, or difficulty breathing or swallowing. Diagnosis of acquired angioedema (AAE) was confirmed on laboratory analysis, which showed C1q levels less than 3.6 mg/dL (reference range, 5.0–8.6 mg/dL), complement component 4 levels less than 8 mg/dL (reference range, 14–44 mg/dL), and C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) levels of 3 mg/dL (reference range, 12–30 mg/dL).

A review of the patient’s medical record showed chronic thrombocytopenia secondary to previous chemotherapy. It was determined that the patient’s ecchymosis and purpura of the eyelids was secondary to a low platelet count resulting in bleeding into the area of angioedema (Figure). Serum protein electrophoresis did not demonstrate a monoclonal spike, and flow cytometry showed persistent B-cell leukemia without evidence of an aberrant T-cell antigenic profile. The edema and purpura of the eyelids spontaneously resolved over days, and the patient has had no recurrences to date. She was prescribed icatibant for treatment of future acute AAE attacks.

The common pathway of AAE involves the inability of C1-INH to stop activation of the complement, fibrinolytic, and contact systems. Failure to control the contact system leads to increased bradykinin production resulting in vasodilation and edema. Diagnosis of hereditary angioedema (HAE) types 1 and 2 can be confirmed in the setting of low complement component 4 and C1-INH functional levels and normal C1q levels; in AAE, C1q levels also are low.1,2

The malignancies most frequently associated with AAE are non-Hodgkin lymphomas (eg, nodal marginal zone lymphoma, splenic marginal zone lymphoma), such as in our patient, as well as monoclonal gammopathies.2 Triggers of AAE include trauma (eg, surgery, strenuous exercise), infection, and use of certain medications such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and estrogen, but most episodes are spontaneous. Swelling of any cutaneous surface can occur in the setting of AAE. Mucosal involvement appears to be limited to the upper airway and gastrointestinal tract. Edema of the upper airway mucosa can lead to asphyxiation. In these cases, asphyxia can occur rapidly, and therefore all patients with upper airway involvement should present to the emergency room or call 911. Pain from swelling in the gastrointestinal tract can mimic an acute abdomen.3

Newly developed targeted therapies for HAE also appear to be effective in treating AAE. A summary of available treatments for angioedema is provided in the Table. Human plasma C1-INH can be used intravenously to treat acute attacks or can be given prophylactically to prevent attacks, but large doses may be necessary due to consumption of the protein.1,3 The risk of bloodborne disease as a result of treatment exists, but screening and processing during production of the plasma makes this unlikely. Ecallantide is a reversible inhibitor of plasma kallikrein.1,3 Rapid onset and subcutaneous dosing make it useful for treatment of acute AAE attacks. Because anaphylaxis has been reported in up to 3% of patients, ecallantide includes a boxed warning indicating that it must be administered by a health care professional with appropriate medical support to manage anaphylaxis and HAE.4 Icatibant is a selective competitive antagonist of bradykinin receptor B2. It can be administered subcutaneously by the patient, making it ideal for rapid treatment of angioedema.1,3 Adverse events include pain and irritation at the injection site.

The most appropriate therapy for AAE is treatment of the underlying malignancy. Recognition and proper treatment of AAE is essential, as bradykinin-induced angioedema (AAE, HAE and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor induced angioedema) does not respond to antihistamines and corticosteroids and instead requires therapy as discussed above.

To the Editor:

A 65-year-old woman with B-cell marginal zone lymphoma presented with asymptomatic swelling and redness of the upper and lower eyelids of 1 week’s duration that was unresponsive to topical corticosteroids for presumptive allergic contact dermatitis. She denied any lip or tongue swelling, abdominal pain, or difficulty breathing or swallowing. Diagnosis of acquired angioedema (AAE) was confirmed on laboratory analysis, which showed C1q levels less than 3.6 mg/dL (reference range, 5.0–8.6 mg/dL), complement component 4 levels less than 8 mg/dL (reference range, 14–44 mg/dL), and C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) levels of 3 mg/dL (reference range, 12–30 mg/dL).

A review of the patient’s medical record showed chronic thrombocytopenia secondary to previous chemotherapy. It was determined that the patient’s ecchymosis and purpura of the eyelids was secondary to a low platelet count resulting in bleeding into the area of angioedema (Figure). Serum protein electrophoresis did not demonstrate a monoclonal spike, and flow cytometry showed persistent B-cell leukemia without evidence of an aberrant T-cell antigenic profile. The edema and purpura of the eyelids spontaneously resolved over days, and the patient has had no recurrences to date. She was prescribed icatibant for treatment of future acute AAE attacks.

The common pathway of AAE involves the inability of C1-INH to stop activation of the complement, fibrinolytic, and contact systems. Failure to control the contact system leads to increased bradykinin production resulting in vasodilation and edema. Diagnosis of hereditary angioedema (HAE) types 1 and 2 can be confirmed in the setting of low complement component 4 and C1-INH functional levels and normal C1q levels; in AAE, C1q levels also are low.1,2

The malignancies most frequently associated with AAE are non-Hodgkin lymphomas (eg, nodal marginal zone lymphoma, splenic marginal zone lymphoma), such as in our patient, as well as monoclonal gammopathies.2 Triggers of AAE include trauma (eg, surgery, strenuous exercise), infection, and use of certain medications such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and estrogen, but most episodes are spontaneous. Swelling of any cutaneous surface can occur in the setting of AAE. Mucosal involvement appears to be limited to the upper airway and gastrointestinal tract. Edema of the upper airway mucosa can lead to asphyxiation. In these cases, asphyxia can occur rapidly, and therefore all patients with upper airway involvement should present to the emergency room or call 911. Pain from swelling in the gastrointestinal tract can mimic an acute abdomen.3

Newly developed targeted therapies for HAE also appear to be effective in treating AAE. A summary of available treatments for angioedema is provided in the Table. Human plasma C1-INH can be used intravenously to treat acute attacks or can be given prophylactically to prevent attacks, but large doses may be necessary due to consumption of the protein.1,3 The risk of bloodborne disease as a result of treatment exists, but screening and processing during production of the plasma makes this unlikely. Ecallantide is a reversible inhibitor of plasma kallikrein.1,3 Rapid onset and subcutaneous dosing make it useful for treatment of acute AAE attacks. Because anaphylaxis has been reported in up to 3% of patients, ecallantide includes a boxed warning indicating that it must be administered by a health care professional with appropriate medical support to manage anaphylaxis and HAE.4 Icatibant is a selective competitive antagonist of bradykinin receptor B2. It can be administered subcutaneously by the patient, making it ideal for rapid treatment of angioedema.1,3 Adverse events include pain and irritation at the injection site.

The most appropriate therapy for AAE is treatment of the underlying malignancy. Recognition and proper treatment of AAE is essential, as bradykinin-induced angioedema (AAE, HAE and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor induced angioedema) does not respond to antihistamines and corticosteroids and instead requires therapy as discussed above.

- Craig T, Riedl M, Dykewicz MS, et al. When is prophylaxis for hereditary angioedema necessary? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102:366-372.

- Cugno M, Castelli R, Cicardi M. Angioedema due to acquired C1-inhibitor deficiency: a bridging connection between autoimmunity and lymphoproliferation. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;8:156-159.

- Buyantseva LV, Sardana N, Craig TJ. Update on treatment of hereditary angioedema. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2012;30:89-98.

- Kalbitor [package insert]. Burlington, MA: Dyax Corp; 2015.

- Craig T, Riedl M, Dykewicz MS, et al. When is prophylaxis for hereditary angioedema necessary? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102:366-372.

- Cugno M, Castelli R, Cicardi M. Angioedema due to acquired C1-inhibitor deficiency: a bridging connection between autoimmunity and lymphoproliferation. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;8:156-159.

- Buyantseva LV, Sardana N, Craig TJ. Update on treatment of hereditary angioedema. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2012;30:89-98.

- Kalbitor [package insert]. Burlington, MA: Dyax Corp; 2015.

Practice Points

- Late-onset angioedema without urticaria can be secondary to acquired angioedema with C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency (C1-INH).

- Most patients with angioedema with C1-INH inhibitor deficiency will have either a monoclonal gammopathy or a lymphoma.

Individualizing Patient Education for Greater Patient Satisfaction

Educating patients is critical for good medical care. The need for health care professionals to educate patients is highlighted as a “right” in the Patient’s Charter and a standard by The Joint Commission (formerly the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) that is meant to “enhance [the patient’s] knowledge, skills, and those behaviors necessary to fully benefit from the health-care interventions provided by the organization.”1 Physicians often underestimate how much information patients want, yet studies on patient education demonstrate the importance of information exchange in clinical encounters.2,3

Most research focuses on the benefits of educational intervention on health outcomes4,5 but does not address the most effective educational methods. If education is key to the multidimensional concept of quality health care, physicians must determine patient satisfaction with the educational methods used, how each patient prefers to be taught (ie, verbal instruction [VI], written instruction [WI], demonstration [DM], Internet resources [IR]), and overall patient satisfaction with the education received. The primary aim of this study was to assess preferred modes of education during an outpatient dermatology visit.

Methods

This study was administered at the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center (Hershey, Pennsylvania) outpatient dermatology clinic with approval by the institutional review board. Consenting adult patients (18 years or older) were surveyed over a 3-week period immediately following a clinic appointment. The 12-question survey included questions about patient demographics, the type and reason for the visit, the type of information received during the visit, the level of satisfaction with the educational intervention, patient preference for information delivery, and overall satisfaction with the visit. Patients recorded the educational method(s) used—VI, WI, DM, and/or IR—and rated their level of satisfaction on a 4-point scale (1=not satisfied; 2=somewhat satisfied; 3=satisfied; 4=very satisfied).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were tabulated. The data were summarized by proportions and percentages or median/mean. The t test or χ2 test was performed to determine statistical differences between groups for continuous or binary variables, respectively. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. No power or sample size calculations were performed because the sample was a convenience sample of a defined population.

Results

The survey was completed in person by 157 patients. The majority of respondents were women (55%), non-Hispanic white (87%), and had at least some college education (70%). The mean age was 51 years (age range, 18–89 years) with almost half of respondents older than 55 years (47%). There were approximately equal numbers of new and return patients (45% new patients). Respondents reported receiving education on 1 or more of the following during their visit: diagnosis (70%), prognosis (59%), treatment (79%), and prevention (52%).

Overall Satisfaction With the Visit

The overall mean satisfaction score was 3.7 with 72% of patients reporting being very satisfied, 27% were satisfied, 1% were somewhat satisfied, and 0% were unsatisfied. Demographic variables including new/return status, age, gender, level of education, income, and race did not significantly correlate with the level of satisfaction.

Educational Preference

Respondents indicated their preferred method(s) of learning: VI (92%), WI (63%), DM (43%), and/or IR (24%). Nearly all respondents (97%) who preferred VI received it during their visit. Respondents who had a particularly high preference for WI were older than 55 years (72%), women (71%), college educated (78%), and individuals earning more than $100,000 annually (50%). Of the respondents who reported a preference for WI, DM, or IR, 41%, 31%, and 8%, respectively, were educated during their visit using their preferred method. Demographic variables did not significantly correlate with preference of educational media.

Comment

The aim of this study was to assess patient education preferences during an outpatient dermatology visit. Regardless of demographic variables, the preferred methods of learning were VI, WI, DM, and IR, respectively. Verbal education was consistently preferred by patients and provided to patients during the visit. Of the respondents reporting a preference for WI, DM, or IR, less than 50% received their preference during the visit, suggesting the need to improve patient education. Taking advantage of technology or providing handouts with Internet links for patient education may help satisfy unmet educational needs.

The study limitations include limited variability in our patient demographic and small sample size. Larger, more diversified follow-up studies should take into account language barriers and intellectual disabilities.

Conclusion

This study evaluated patient learning preference(s) in an outpatient dermatology clinic. Although VI is the most preferred method of education, physicians need to give consideration to utilizing alternative educational modalities to meet the educational needs of patients.

1. Hartmann RA, Kochar MS. The provision of patient and family education. Patient Educ Couns. 1994;24:101-108.

2. Ernstene AC. Explaining to the patient; a therapeutic tool and a professional obligation. J Am Med Assoc. 1957;165:1110-1113.

3. Laine C, Davidoff F, Lewis CE, et al. Important elements of outpatient care: a comparison of patients’ and physicians’ opinions. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:640-645.

4. Varma S. Portable video education for informed consent: the shape of things to come? Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:901.

5. Friedman AJ, Cosby R, Boyko S, et al. Effective teaching strategies and methods of delivery for patient education: a systematic review and practice guideline recommendations. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26:12-21.

Educating patients is critical for good medical care. The need for health care professionals to educate patients is highlighted as a “right” in the Patient’s Charter and a standard by The Joint Commission (formerly the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) that is meant to “enhance [the patient’s] knowledge, skills, and those behaviors necessary to fully benefit from the health-care interventions provided by the organization.”1 Physicians often underestimate how much information patients want, yet studies on patient education demonstrate the importance of information exchange in clinical encounters.2,3

Most research focuses on the benefits of educational intervention on health outcomes4,5 but does not address the most effective educational methods. If education is key to the multidimensional concept of quality health care, physicians must determine patient satisfaction with the educational methods used, how each patient prefers to be taught (ie, verbal instruction [VI], written instruction [WI], demonstration [DM], Internet resources [IR]), and overall patient satisfaction with the education received. The primary aim of this study was to assess preferred modes of education during an outpatient dermatology visit.

Methods

This study was administered at the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center (Hershey, Pennsylvania) outpatient dermatology clinic with approval by the institutional review board. Consenting adult patients (18 years or older) were surveyed over a 3-week period immediately following a clinic appointment. The 12-question survey included questions about patient demographics, the type and reason for the visit, the type of information received during the visit, the level of satisfaction with the educational intervention, patient preference for information delivery, and overall satisfaction with the visit. Patients recorded the educational method(s) used—VI, WI, DM, and/or IR—and rated their level of satisfaction on a 4-point scale (1=not satisfied; 2=somewhat satisfied; 3=satisfied; 4=very satisfied).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were tabulated. The data were summarized by proportions and percentages or median/mean. The t test or χ2 test was performed to determine statistical differences between groups for continuous or binary variables, respectively. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. No power or sample size calculations were performed because the sample was a convenience sample of a defined population.

Results

The survey was completed in person by 157 patients. The majority of respondents were women (55%), non-Hispanic white (87%), and had at least some college education (70%). The mean age was 51 years (age range, 18–89 years) with almost half of respondents older than 55 years (47%). There were approximately equal numbers of new and return patients (45% new patients). Respondents reported receiving education on 1 or more of the following during their visit: diagnosis (70%), prognosis (59%), treatment (79%), and prevention (52%).

Overall Satisfaction With the Visit

The overall mean satisfaction score was 3.7 with 72% of patients reporting being very satisfied, 27% were satisfied, 1% were somewhat satisfied, and 0% were unsatisfied. Demographic variables including new/return status, age, gender, level of education, income, and race did not significantly correlate with the level of satisfaction.

Educational Preference

Respondents indicated their preferred method(s) of learning: VI (92%), WI (63%), DM (43%), and/or IR (24%). Nearly all respondents (97%) who preferred VI received it during their visit. Respondents who had a particularly high preference for WI were older than 55 years (72%), women (71%), college educated (78%), and individuals earning more than $100,000 annually (50%). Of the respondents who reported a preference for WI, DM, or IR, 41%, 31%, and 8%, respectively, were educated during their visit using their preferred method. Demographic variables did not significantly correlate with preference of educational media.

Comment

The aim of this study was to assess patient education preferences during an outpatient dermatology visit. Regardless of demographic variables, the preferred methods of learning were VI, WI, DM, and IR, respectively. Verbal education was consistently preferred by patients and provided to patients during the visit. Of the respondents reporting a preference for WI, DM, or IR, less than 50% received their preference during the visit, suggesting the need to improve patient education. Taking advantage of technology or providing handouts with Internet links for patient education may help satisfy unmet educational needs.

The study limitations include limited variability in our patient demographic and small sample size. Larger, more diversified follow-up studies should take into account language barriers and intellectual disabilities.

Conclusion

This study evaluated patient learning preference(s) in an outpatient dermatology clinic. Although VI is the most preferred method of education, physicians need to give consideration to utilizing alternative educational modalities to meet the educational needs of patients.

Educating patients is critical for good medical care. The need for health care professionals to educate patients is highlighted as a “right” in the Patient’s Charter and a standard by The Joint Commission (formerly the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) that is meant to “enhance [the patient’s] knowledge, skills, and those behaviors necessary to fully benefit from the health-care interventions provided by the organization.”1 Physicians often underestimate how much information patients want, yet studies on patient education demonstrate the importance of information exchange in clinical encounters.2,3

Most research focuses on the benefits of educational intervention on health outcomes4,5 but does not address the most effective educational methods. If education is key to the multidimensional concept of quality health care, physicians must determine patient satisfaction with the educational methods used, how each patient prefers to be taught (ie, verbal instruction [VI], written instruction [WI], demonstration [DM], Internet resources [IR]), and overall patient satisfaction with the education received. The primary aim of this study was to assess preferred modes of education during an outpatient dermatology visit.

Methods

This study was administered at the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center (Hershey, Pennsylvania) outpatient dermatology clinic with approval by the institutional review board. Consenting adult patients (18 years or older) were surveyed over a 3-week period immediately following a clinic appointment. The 12-question survey included questions about patient demographics, the type and reason for the visit, the type of information received during the visit, the level of satisfaction with the educational intervention, patient preference for information delivery, and overall satisfaction with the visit. Patients recorded the educational method(s) used—VI, WI, DM, and/or IR—and rated their level of satisfaction on a 4-point scale (1=not satisfied; 2=somewhat satisfied; 3=satisfied; 4=very satisfied).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were tabulated. The data were summarized by proportions and percentages or median/mean. The t test or χ2 test was performed to determine statistical differences between groups for continuous or binary variables, respectively. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. No power or sample size calculations were performed because the sample was a convenience sample of a defined population.

Results

The survey was completed in person by 157 patients. The majority of respondents were women (55%), non-Hispanic white (87%), and had at least some college education (70%). The mean age was 51 years (age range, 18–89 years) with almost half of respondents older than 55 years (47%). There were approximately equal numbers of new and return patients (45% new patients). Respondents reported receiving education on 1 or more of the following during their visit: diagnosis (70%), prognosis (59%), treatment (79%), and prevention (52%).

Overall Satisfaction With the Visit

The overall mean satisfaction score was 3.7 with 72% of patients reporting being very satisfied, 27% were satisfied, 1% were somewhat satisfied, and 0% were unsatisfied. Demographic variables including new/return status, age, gender, level of education, income, and race did not significantly correlate with the level of satisfaction.

Educational Preference

Respondents indicated their preferred method(s) of learning: VI (92%), WI (63%), DM (43%), and/or IR (24%). Nearly all respondents (97%) who preferred VI received it during their visit. Respondents who had a particularly high preference for WI were older than 55 years (72%), women (71%), college educated (78%), and individuals earning more than $100,000 annually (50%). Of the respondents who reported a preference for WI, DM, or IR, 41%, 31%, and 8%, respectively, were educated during their visit using their preferred method. Demographic variables did not significantly correlate with preference of educational media.

Comment

The aim of this study was to assess patient education preferences during an outpatient dermatology visit. Regardless of demographic variables, the preferred methods of learning were VI, WI, DM, and IR, respectively. Verbal education was consistently preferred by patients and provided to patients during the visit. Of the respondents reporting a preference for WI, DM, or IR, less than 50% received their preference during the visit, suggesting the need to improve patient education. Taking advantage of technology or providing handouts with Internet links for patient education may help satisfy unmet educational needs.

The study limitations include limited variability in our patient demographic and small sample size. Larger, more diversified follow-up studies should take into account language barriers and intellectual disabilities.

Conclusion

This study evaluated patient learning preference(s) in an outpatient dermatology clinic. Although VI is the most preferred method of education, physicians need to give consideration to utilizing alternative educational modalities to meet the educational needs of patients.

1. Hartmann RA, Kochar MS. The provision of patient and family education. Patient Educ Couns. 1994;24:101-108.

2. Ernstene AC. Explaining to the patient; a therapeutic tool and a professional obligation. J Am Med Assoc. 1957;165:1110-1113.

3. Laine C, Davidoff F, Lewis CE, et al. Important elements of outpatient care: a comparison of patients’ and physicians’ opinions. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:640-645.

4. Varma S. Portable video education for informed consent: the shape of things to come? Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:901.

5. Friedman AJ, Cosby R, Boyko S, et al. Effective teaching strategies and methods of delivery for patient education: a systematic review and practice guideline recommendations. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26:12-21.

1. Hartmann RA, Kochar MS. The provision of patient and family education. Patient Educ Couns. 1994;24:101-108.

2. Ernstene AC. Explaining to the patient; a therapeutic tool and a professional obligation. J Am Med Assoc. 1957;165:1110-1113.

3. Laine C, Davidoff F, Lewis CE, et al. Important elements of outpatient care: a comparison of patients’ and physicians’ opinions. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:640-645.

4. Varma S. Portable video education for informed consent: the shape of things to come? Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:901.

5. Friedman AJ, Cosby R, Boyko S, et al. Effective teaching strategies and methods of delivery for patient education: a systematic review and practice guideline recommendations. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26:12-21.

Practice Points

- Identify learning techniques for patients about their disease that match their level of understanding.

- Ask patients for their preferred method of education (ie, verbal instruction, written instruction, demonstration, or Internet resources).

- Supplement written instruction with Internet resources for disease education.