User login

Use of the Retroauricular Pull-Through Sandwich Flap for Repair of an Extensive Conchal Bowl Defect With Complete Cartilage Loss

Practice Gap

Repair of a conchal defect requires careful consideration to achieve an optimal outcome. Reconstruction should resurface exposed cartilage, restore the natural projection of the auricle, and direct sound into the external auditory meatus. Patients also should be able to wear glasses and a hearing aid.

The reconstructive ladder for most conchal bowl defects includes secondary intention healing, full-thickness skin grafting (FTSG), and either a revolving-door flap or a flip-flop flap. Secondary intention and FTSG are appropriate for superficial defects, in which the loss of cartilage is not substantial.1,2 Revolving-door and flip-flop flaps are single-stage retroauricular approaches used to repair relatively small defects of the conchal bowl.3 However, reconstructive options are limited for a large defect in which there is extensive loss of cartilage; 3-stage retroauricular approaches have been utilized. The anterior pedicled retroauricular flap is a 3-stage repair that can be utilized to reconstruct a through-and-through defect of the central ear:

- Stage 1: an anteriorly based retroauricular pedicle is incised, hinged over, and sutured to the medial aspect of the defect, resurfacing the posterior ear.

- Stage 2: the pedicle is severed and the flap is folded on itself to resurface the anterior ear.

- Stage 3: the folded edge is de-epithelialized and set into the lateral defect.4

The revolving-door flap also uses a 3-stage approach and is utilized for a full-thickness central auricular defect:

- Stage 1: a revolving-door flap is used to resurface the anterior ear.

- Stage 2: a cartilage graft provides structural support.

- Stage 3: division and inset with an FTSG is used to resurface the posterior ear.

The anterior pedicled retroauricular flap and revolving-door flap techniques are useful for defects when there is intact posterior auricular skin but not when there is extensive loss of cartilage. Other downsides to these 3-stage approaches are the time and multiple procedures required.5

We describe the technique of a retroauricular pull-through sandwich flap for repair of a large conchal bowl defect with extensive cartilage loss and intact posterior auricular skin.

Technique

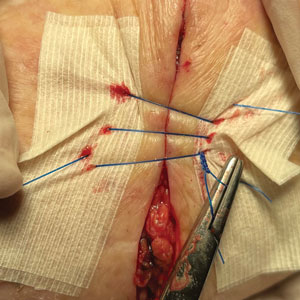

A 62-year-old man presented for treatment of a 2.6×2.4-cm nodular and infiltrative basal cell carcinoma of the right conchal bowl. The tumor was cleared with 3 stages of Mohs micrographic surgery, resulting in a 5.5×4.2-cm defect with complete loss of cartilage throughout the concha, helical crus, and inner rim of the antihelix (Figure 1). A 2-stage repair was performed utilizing a cartilage graft and a pull-through retroauricular interpolation flap.

Stage 1—A cartilage graft was harvested from the left concha and sutured into the central defect for structural support (Figure 2). An incision was then made through the posterior auricular skin, just medial to the residual antihelical cartilage, and a retroauricular interpolation flap was pulled through this incision to resurface the lateral two-thirds of the conchal bowl defect. This created a “sandwich” of tissue, with the following layers (ordered from anterior to posterior): retroauricular interpolation flap, cartilage graft, and intact posterior auricular skin.

A preauricular banner transposition flap was used to repair the medial one-third of the conchal defect. A small area was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 3).

Stage 2—The patient returned 3 weeks later for division and inset of the retroauricular interpolation flap. The pedicle of the flap was severed and its free edge was sutured into the lateral aspect of the defect. The posterior auricular incision that the flap had been pulled through in stage 1 of the repair was closed in a layered fashion, and the secondary defect of the postauricular scalp was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 4).

Final Results—At follow-up 1 month later, the patient was noted to have good aesthetic and functional outcomes (Figure 5).

Practice Implications

The retroauricular pull-through sandwich flap combines a cartilage graft and a retroauricular interpolation flap pulled through an incision in the posterior auricular skin to resurface the anterior ear. This repair is most useful for a large conchal bowl defect in which there is extensive missing cartilage but intact posterior auricular skin.

The retroauricular scalp is a substantial tissue reservoir with robust vasculature; an interpolation flap from this area frequently is used to repair an extensive ear defect. The most common use of an interpolation flap is for a large helical defect; however, the flap also can be pulled through an incision in the posterior auricular skin to the front of the ear in a manner similar to revolving-door and flip-flop flaps, thus allowing for increased flap reach.

A cartilage graft provides structural support, helping to maintain auricular projection. The helical arcades provide a robust vascular supply and maintain viability of the helical rim tissue, despite the large aperture created for the pull-through flap.

We recommend this 2-stage repair for large conchal bowl defects with extensive cartilage loss and intact posterior auricular skin.

- Clark DP, Hanke CW. Neoplasms of the conchal bowl: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:1223-1228. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1988.tb03479.x

- Dessy LA, Figus A, Fioramonti P, et al. Reconstruction of anterior auricular conchal defect after malignancy excision: revolving-door flap versus full-thickness skin graft. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2009.01.073

- Golash A, Bera S, Kanoi AV, et al. The revolving door flap: revisiting an elegant but forgotten flap for ear defect reconstruction. Indian J Plast Surg. 2020;53:64-70. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709531

- Heinz MB, Hölzle F, Ghassemi A. Repairing a non-marginal full-thickness auricular defect using a reversed flap from the postauricular area. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:764-768. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2014.11.005

- Leitenberger JJ, Golden SK. Reconstruction after full-thickness loss of the antihelix, scapha, and triangular fossa. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:893-896. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000664

Practice Gap

Repair of a conchal defect requires careful consideration to achieve an optimal outcome. Reconstruction should resurface exposed cartilage, restore the natural projection of the auricle, and direct sound into the external auditory meatus. Patients also should be able to wear glasses and a hearing aid.

The reconstructive ladder for most conchal bowl defects includes secondary intention healing, full-thickness skin grafting (FTSG), and either a revolving-door flap or a flip-flop flap. Secondary intention and FTSG are appropriate for superficial defects, in which the loss of cartilage is not substantial.1,2 Revolving-door and flip-flop flaps are single-stage retroauricular approaches used to repair relatively small defects of the conchal bowl.3 However, reconstructive options are limited for a large defect in which there is extensive loss of cartilage; 3-stage retroauricular approaches have been utilized. The anterior pedicled retroauricular flap is a 3-stage repair that can be utilized to reconstruct a through-and-through defect of the central ear:

- Stage 1: an anteriorly based retroauricular pedicle is incised, hinged over, and sutured to the medial aspect of the defect, resurfacing the posterior ear.

- Stage 2: the pedicle is severed and the flap is folded on itself to resurface the anterior ear.

- Stage 3: the folded edge is de-epithelialized and set into the lateral defect.4

The revolving-door flap also uses a 3-stage approach and is utilized for a full-thickness central auricular defect:

- Stage 1: a revolving-door flap is used to resurface the anterior ear.

- Stage 2: a cartilage graft provides structural support.

- Stage 3: division and inset with an FTSG is used to resurface the posterior ear.

The anterior pedicled retroauricular flap and revolving-door flap techniques are useful for defects when there is intact posterior auricular skin but not when there is extensive loss of cartilage. Other downsides to these 3-stage approaches are the time and multiple procedures required.5

We describe the technique of a retroauricular pull-through sandwich flap for repair of a large conchal bowl defect with extensive cartilage loss and intact posterior auricular skin.

Technique

A 62-year-old man presented for treatment of a 2.6×2.4-cm nodular and infiltrative basal cell carcinoma of the right conchal bowl. The tumor was cleared with 3 stages of Mohs micrographic surgery, resulting in a 5.5×4.2-cm defect with complete loss of cartilage throughout the concha, helical crus, and inner rim of the antihelix (Figure 1). A 2-stage repair was performed utilizing a cartilage graft and a pull-through retroauricular interpolation flap.

Stage 1—A cartilage graft was harvested from the left concha and sutured into the central defect for structural support (Figure 2). An incision was then made through the posterior auricular skin, just medial to the residual antihelical cartilage, and a retroauricular interpolation flap was pulled through this incision to resurface the lateral two-thirds of the conchal bowl defect. This created a “sandwich” of tissue, with the following layers (ordered from anterior to posterior): retroauricular interpolation flap, cartilage graft, and intact posterior auricular skin.

A preauricular banner transposition flap was used to repair the medial one-third of the conchal defect. A small area was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 3).

Stage 2—The patient returned 3 weeks later for division and inset of the retroauricular interpolation flap. The pedicle of the flap was severed and its free edge was sutured into the lateral aspect of the defect. The posterior auricular incision that the flap had been pulled through in stage 1 of the repair was closed in a layered fashion, and the secondary defect of the postauricular scalp was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 4).

Final Results—At follow-up 1 month later, the patient was noted to have good aesthetic and functional outcomes (Figure 5).

Practice Implications

The retroauricular pull-through sandwich flap combines a cartilage graft and a retroauricular interpolation flap pulled through an incision in the posterior auricular skin to resurface the anterior ear. This repair is most useful for a large conchal bowl defect in which there is extensive missing cartilage but intact posterior auricular skin.

The retroauricular scalp is a substantial tissue reservoir with robust vasculature; an interpolation flap from this area frequently is used to repair an extensive ear defect. The most common use of an interpolation flap is for a large helical defect; however, the flap also can be pulled through an incision in the posterior auricular skin to the front of the ear in a manner similar to revolving-door and flip-flop flaps, thus allowing for increased flap reach.

A cartilage graft provides structural support, helping to maintain auricular projection. The helical arcades provide a robust vascular supply and maintain viability of the helical rim tissue, despite the large aperture created for the pull-through flap.

We recommend this 2-stage repair for large conchal bowl defects with extensive cartilage loss and intact posterior auricular skin.

Practice Gap

Repair of a conchal defect requires careful consideration to achieve an optimal outcome. Reconstruction should resurface exposed cartilage, restore the natural projection of the auricle, and direct sound into the external auditory meatus. Patients also should be able to wear glasses and a hearing aid.

The reconstructive ladder for most conchal bowl defects includes secondary intention healing, full-thickness skin grafting (FTSG), and either a revolving-door flap or a flip-flop flap. Secondary intention and FTSG are appropriate for superficial defects, in which the loss of cartilage is not substantial.1,2 Revolving-door and flip-flop flaps are single-stage retroauricular approaches used to repair relatively small defects of the conchal bowl.3 However, reconstructive options are limited for a large defect in which there is extensive loss of cartilage; 3-stage retroauricular approaches have been utilized. The anterior pedicled retroauricular flap is a 3-stage repair that can be utilized to reconstruct a through-and-through defect of the central ear:

- Stage 1: an anteriorly based retroauricular pedicle is incised, hinged over, and sutured to the medial aspect of the defect, resurfacing the posterior ear.

- Stage 2: the pedicle is severed and the flap is folded on itself to resurface the anterior ear.

- Stage 3: the folded edge is de-epithelialized and set into the lateral defect.4

The revolving-door flap also uses a 3-stage approach and is utilized for a full-thickness central auricular defect:

- Stage 1: a revolving-door flap is used to resurface the anterior ear.

- Stage 2: a cartilage graft provides structural support.

- Stage 3: division and inset with an FTSG is used to resurface the posterior ear.

The anterior pedicled retroauricular flap and revolving-door flap techniques are useful for defects when there is intact posterior auricular skin but not when there is extensive loss of cartilage. Other downsides to these 3-stage approaches are the time and multiple procedures required.5

We describe the technique of a retroauricular pull-through sandwich flap for repair of a large conchal bowl defect with extensive cartilage loss and intact posterior auricular skin.

Technique

A 62-year-old man presented for treatment of a 2.6×2.4-cm nodular and infiltrative basal cell carcinoma of the right conchal bowl. The tumor was cleared with 3 stages of Mohs micrographic surgery, resulting in a 5.5×4.2-cm defect with complete loss of cartilage throughout the concha, helical crus, and inner rim of the antihelix (Figure 1). A 2-stage repair was performed utilizing a cartilage graft and a pull-through retroauricular interpolation flap.

Stage 1—A cartilage graft was harvested from the left concha and sutured into the central defect for structural support (Figure 2). An incision was then made through the posterior auricular skin, just medial to the residual antihelical cartilage, and a retroauricular interpolation flap was pulled through this incision to resurface the lateral two-thirds of the conchal bowl defect. This created a “sandwich” of tissue, with the following layers (ordered from anterior to posterior): retroauricular interpolation flap, cartilage graft, and intact posterior auricular skin.

A preauricular banner transposition flap was used to repair the medial one-third of the conchal defect. A small area was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 3).

Stage 2—The patient returned 3 weeks later for division and inset of the retroauricular interpolation flap. The pedicle of the flap was severed and its free edge was sutured into the lateral aspect of the defect. The posterior auricular incision that the flap had been pulled through in stage 1 of the repair was closed in a layered fashion, and the secondary defect of the postauricular scalp was left to heal by secondary intention (Figure 4).

Final Results—At follow-up 1 month later, the patient was noted to have good aesthetic and functional outcomes (Figure 5).

Practice Implications

The retroauricular pull-through sandwich flap combines a cartilage graft and a retroauricular interpolation flap pulled through an incision in the posterior auricular skin to resurface the anterior ear. This repair is most useful for a large conchal bowl defect in which there is extensive missing cartilage but intact posterior auricular skin.

The retroauricular scalp is a substantial tissue reservoir with robust vasculature; an interpolation flap from this area frequently is used to repair an extensive ear defect. The most common use of an interpolation flap is for a large helical defect; however, the flap also can be pulled through an incision in the posterior auricular skin to the front of the ear in a manner similar to revolving-door and flip-flop flaps, thus allowing for increased flap reach.

A cartilage graft provides structural support, helping to maintain auricular projection. The helical arcades provide a robust vascular supply and maintain viability of the helical rim tissue, despite the large aperture created for the pull-through flap.

We recommend this 2-stage repair for large conchal bowl defects with extensive cartilage loss and intact posterior auricular skin.

- Clark DP, Hanke CW. Neoplasms of the conchal bowl: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:1223-1228. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1988.tb03479.x

- Dessy LA, Figus A, Fioramonti P, et al. Reconstruction of anterior auricular conchal defect after malignancy excision: revolving-door flap versus full-thickness skin graft. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2009.01.073

- Golash A, Bera S, Kanoi AV, et al. The revolving door flap: revisiting an elegant but forgotten flap for ear defect reconstruction. Indian J Plast Surg. 2020;53:64-70. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709531

- Heinz MB, Hölzle F, Ghassemi A. Repairing a non-marginal full-thickness auricular defect using a reversed flap from the postauricular area. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:764-768. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2014.11.005

- Leitenberger JJ, Golden SK. Reconstruction after full-thickness loss of the antihelix, scapha, and triangular fossa. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:893-896. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000664

- Clark DP, Hanke CW. Neoplasms of the conchal bowl: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:1223-1228. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1988.tb03479.x

- Dessy LA, Figus A, Fioramonti P, et al. Reconstruction of anterior auricular conchal defect after malignancy excision: revolving-door flap versus full-thickness skin graft. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2009.01.073

- Golash A, Bera S, Kanoi AV, et al. The revolving door flap: revisiting an elegant but forgotten flap for ear defect reconstruction. Indian J Plast Surg. 2020;53:64-70. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709531

- Heinz MB, Hölzle F, Ghassemi A. Repairing a non-marginal full-thickness auricular defect using a reversed flap from the postauricular area. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:764-768. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2014.11.005

- Leitenberger JJ, Golden SK. Reconstruction after full-thickness loss of the antihelix, scapha, and triangular fossa. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:893-896. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000664

Glitter Effects of Nail Art on Optical Coherence Tomography

Practice Gap

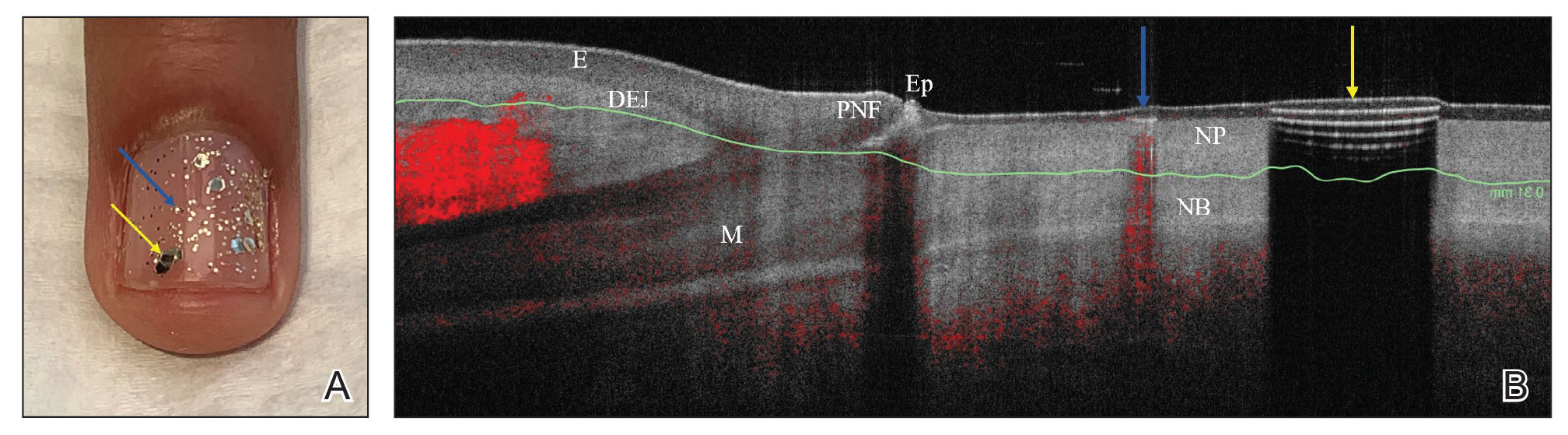

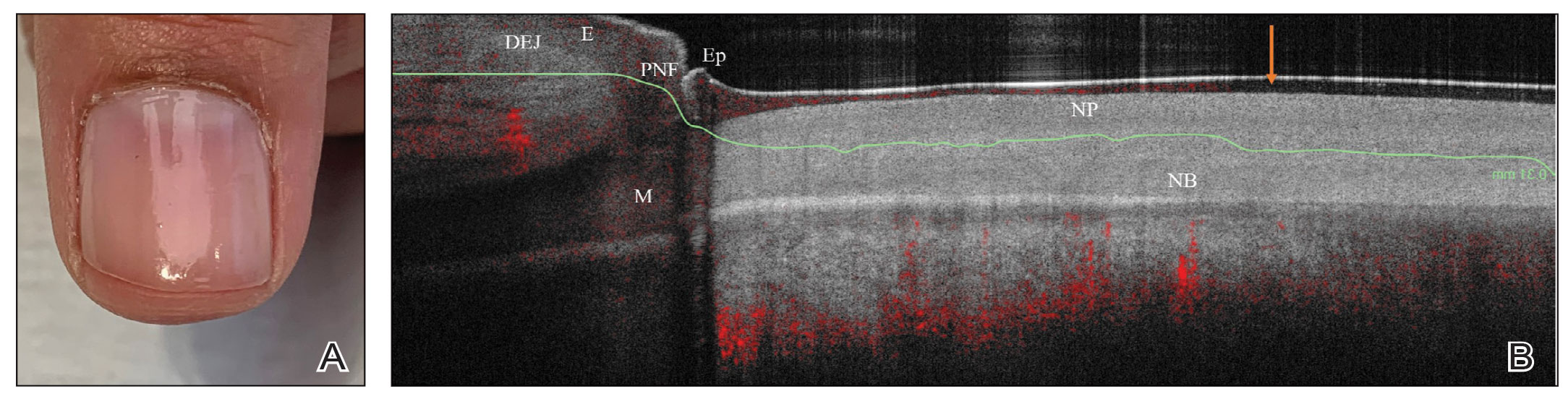

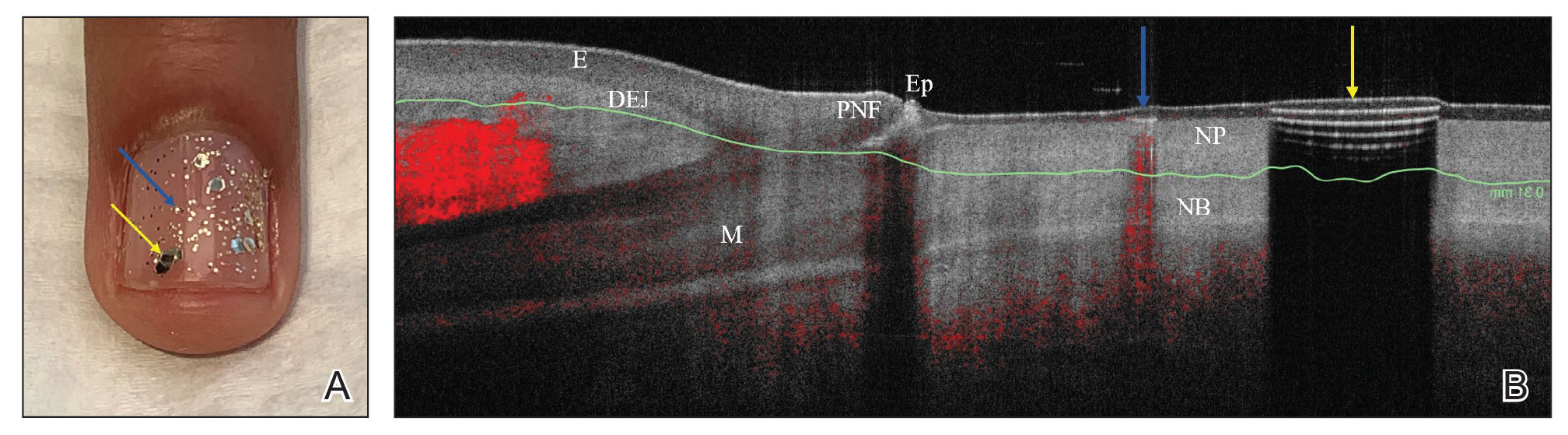

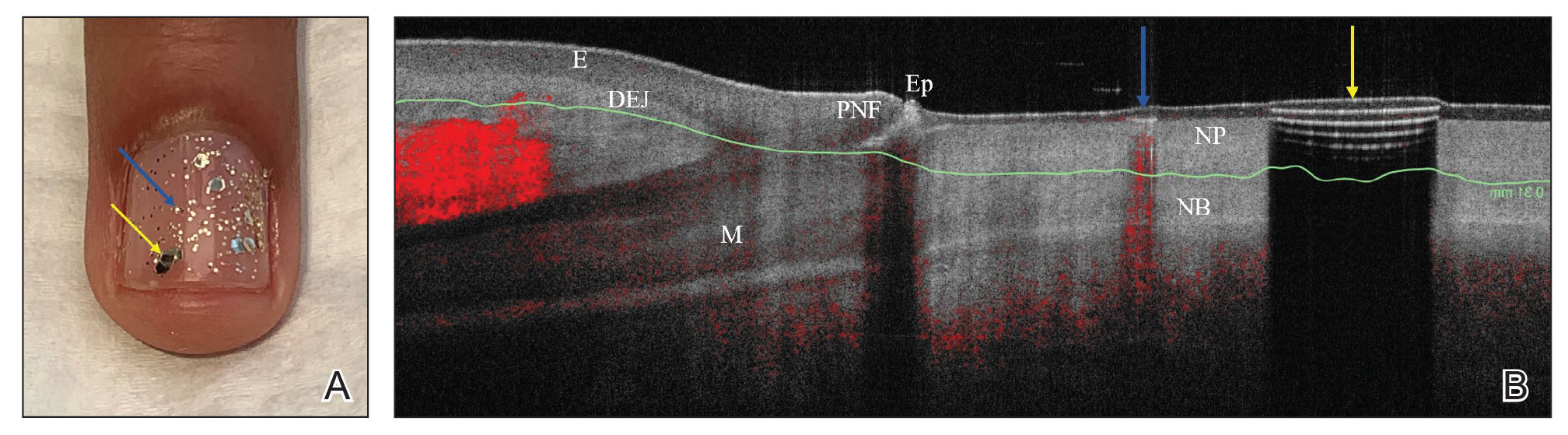

Nail art can skew the results of optical coherence tomography (OCT), a noninvasive imaging technology that is used to visualize nail morphology in diseases such as psoriatic arthritis and onychomycosis, with a penetration depth of 2 mm and high-resolution images.1 Few studies have evaluated the effects of nail art on OCT. Saleah and colleagues1 found that clear, semitransparent, and red nail polishes do not interfere with visualization of the nail plate, whereas nontransparent gel polish and art stones obscure the image. They did not comment on the effect of glitter nail art in their study, though they did test 1 nail that contained glitter.1 Monpeurt et al2 compared matte and glossy nail polishes. They found that matte polish was readily identifiable from the nail plate, whereas glossy polish presented a greater number of artifacts.2

The Solution

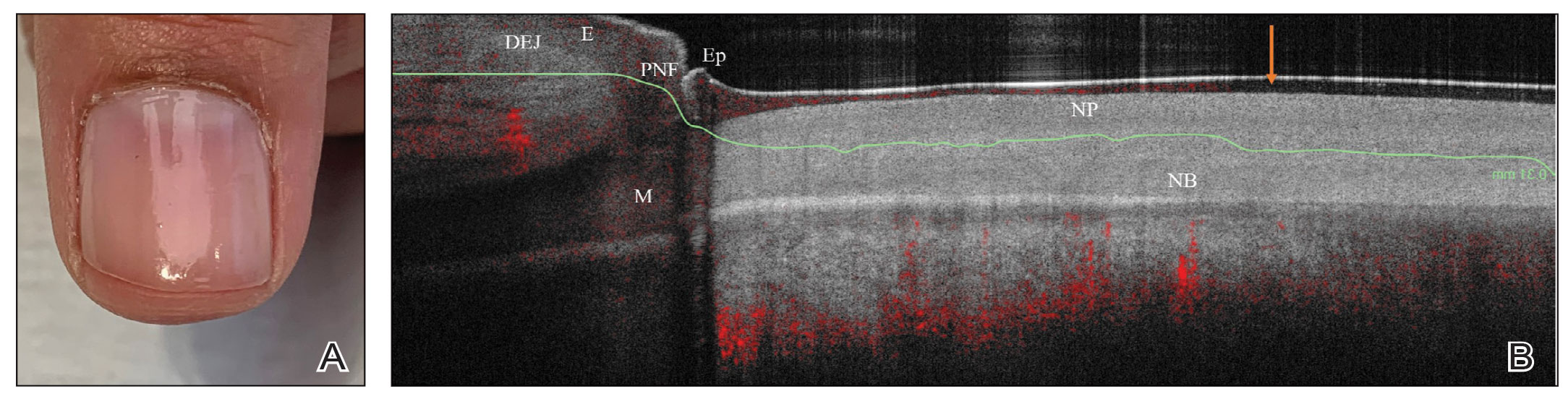

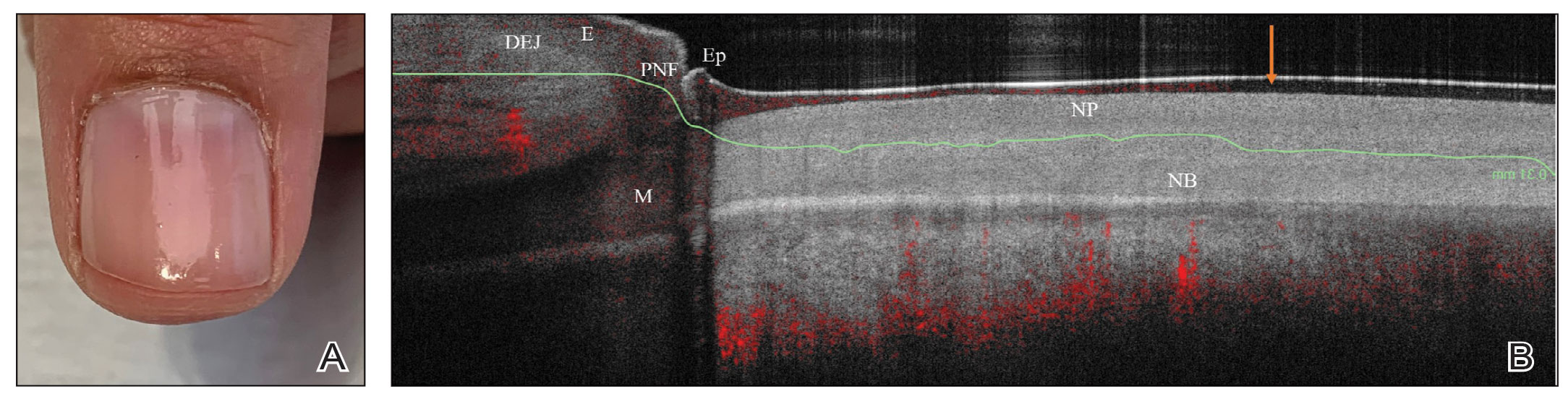

We looked at 3 glitter nail polishes—gold, pink, and silver—that were scanned by OCT to assess the effect of the polish on the resulting image. We determined that glitter particles completely obscured the nail bed and nail plate, regardless of color (Figure 1). Glossy clear polish imparted a distinct film on the top of the nail plate that did not obscure the nail plate or the nail bed (Figure 2).

We conclude that glitter nail polish contains numerous reflective solid particles that interfere with OCT imaging of the nail plate and nail bed. As a result, we recommend removal of nail art to properly assess nail pathology. Because removal may need to be conducted by a nail technician, the treating clinician should inform the patient ahead of time to come to the appointment with bare (ie, unpolished) nails.

Practice Implications

Bringing awareness to the necessity of removing nail art prior to OCT imaging is crucial because many patients partake in its application, and removal may require the involvement of a professional nail technician. If a patient can be made aware that they should remove all nail art in advance, they will be better prepared for an OCT imaging session. Such a protocol increases efficiency, decreases diagnostic delay, and reduces cost associated with multiple office visits.

- Saleah S, Kim P, Seong D, et al. A preliminary study of post-progressive nail-art effects on in vivo nail plate using optical coherence tomography-based intensity profiling assessment. Sci Rep. 2021;11:666. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79497-3

- Monpeurt C, Cinotti E, Hebert M, et al. Thickness and morphology assessment of nail polishes applied on nails by high-definition optical coherence tomography. Skin Res Technol. 2018;24:156-157. doi:10.1111/srt.12406

Practice Gap

Nail art can skew the results of optical coherence tomography (OCT), a noninvasive imaging technology that is used to visualize nail morphology in diseases such as psoriatic arthritis and onychomycosis, with a penetration depth of 2 mm and high-resolution images.1 Few studies have evaluated the effects of nail art on OCT. Saleah and colleagues1 found that clear, semitransparent, and red nail polishes do not interfere with visualization of the nail plate, whereas nontransparent gel polish and art stones obscure the image. They did not comment on the effect of glitter nail art in their study, though they did test 1 nail that contained glitter.1 Monpeurt et al2 compared matte and glossy nail polishes. They found that matte polish was readily identifiable from the nail plate, whereas glossy polish presented a greater number of artifacts.2

The Solution

We looked at 3 glitter nail polishes—gold, pink, and silver—that were scanned by OCT to assess the effect of the polish on the resulting image. We determined that glitter particles completely obscured the nail bed and nail plate, regardless of color (Figure 1). Glossy clear polish imparted a distinct film on the top of the nail plate that did not obscure the nail plate or the nail bed (Figure 2).

We conclude that glitter nail polish contains numerous reflective solid particles that interfere with OCT imaging of the nail plate and nail bed. As a result, we recommend removal of nail art to properly assess nail pathology. Because removal may need to be conducted by a nail technician, the treating clinician should inform the patient ahead of time to come to the appointment with bare (ie, unpolished) nails.

Practice Implications

Bringing awareness to the necessity of removing nail art prior to OCT imaging is crucial because many patients partake in its application, and removal may require the involvement of a professional nail technician. If a patient can be made aware that they should remove all nail art in advance, they will be better prepared for an OCT imaging session. Such a protocol increases efficiency, decreases diagnostic delay, and reduces cost associated with multiple office visits.

Practice Gap

Nail art can skew the results of optical coherence tomography (OCT), a noninvasive imaging technology that is used to visualize nail morphology in diseases such as psoriatic arthritis and onychomycosis, with a penetration depth of 2 mm and high-resolution images.1 Few studies have evaluated the effects of nail art on OCT. Saleah and colleagues1 found that clear, semitransparent, and red nail polishes do not interfere with visualization of the nail plate, whereas nontransparent gel polish and art stones obscure the image. They did not comment on the effect of glitter nail art in their study, though they did test 1 nail that contained glitter.1 Monpeurt et al2 compared matte and glossy nail polishes. They found that matte polish was readily identifiable from the nail plate, whereas glossy polish presented a greater number of artifacts.2

The Solution

We looked at 3 glitter nail polishes—gold, pink, and silver—that were scanned by OCT to assess the effect of the polish on the resulting image. We determined that glitter particles completely obscured the nail bed and nail plate, regardless of color (Figure 1). Glossy clear polish imparted a distinct film on the top of the nail plate that did not obscure the nail plate or the nail bed (Figure 2).

We conclude that glitter nail polish contains numerous reflective solid particles that interfere with OCT imaging of the nail plate and nail bed. As a result, we recommend removal of nail art to properly assess nail pathology. Because removal may need to be conducted by a nail technician, the treating clinician should inform the patient ahead of time to come to the appointment with bare (ie, unpolished) nails.

Practice Implications

Bringing awareness to the necessity of removing nail art prior to OCT imaging is crucial because many patients partake in its application, and removal may require the involvement of a professional nail technician. If a patient can be made aware that they should remove all nail art in advance, they will be better prepared for an OCT imaging session. Such a protocol increases efficiency, decreases diagnostic delay, and reduces cost associated with multiple office visits.

- Saleah S, Kim P, Seong D, et al. A preliminary study of post-progressive nail-art effects on in vivo nail plate using optical coherence tomography-based intensity profiling assessment. Sci Rep. 2021;11:666. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79497-3

- Monpeurt C, Cinotti E, Hebert M, et al. Thickness and morphology assessment of nail polishes applied on nails by high-definition optical coherence tomography. Skin Res Technol. 2018;24:156-157. doi:10.1111/srt.12406

- Saleah S, Kim P, Seong D, et al. A preliminary study of post-progressive nail-art effects on in vivo nail plate using optical coherence tomography-based intensity profiling assessment. Sci Rep. 2021;11:666. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79497-3

- Monpeurt C, Cinotti E, Hebert M, et al. Thickness and morphology assessment of nail polishes applied on nails by high-definition optical coherence tomography. Skin Res Technol. 2018;24:156-157. doi:10.1111/srt.12406

Polyurethane Tubing to Minimize Pain During Nail Injections

Practice Gap

Nail matrix and nail bed injections with triamcinolone acetonide are used to treat trachyonychia and inflammatory nail conditions, including nail psoriasis and nail lichen planus. The procedure should be quick in well-trained hands, with each nail injection taking only seconds to perform. Typically, patients have multiple nails involved, requiring at least 1 injection into the nail matrix or the nail bed (or both) in each nail at each visit. Patients often are anxious when undergoing nail injections; the nail unit is highly innervated and vascular, which can cause notable transient discomfort during the procedure1,2 as well as postoperative pain.3

Nail injections must be repeated every 4 to 6 weeks to sustain clinical benefit and maximize outcomes, which can lead to heightened anxiety and apprehension before and during the visit. Furthermore, pain and anxiety associated with the procedure may deter patients from returning for follow-up injections, which can impact treatment adherence and clinical outcomes.

Dermatologists should implement strategies to decrease periprocedural anxiety to improve the nail injection experience. In our practice, we routinely incorporate stress-reducing techniques—music, talkesthesia, a sleep mask, cool air, ethyl chloride, and squeezing a stress ball—into the clinical workflow of the procedure. The goal of these techniques is to divert attention away from painful stimuli. Most patients, however, receive injections in both hands, making it impractical to employ some of these techniques, particularly squeezing a stress ball. We employed a unique method involving polyurethane tubing to reduce stress and anxiety during nail procedures.

The Technique

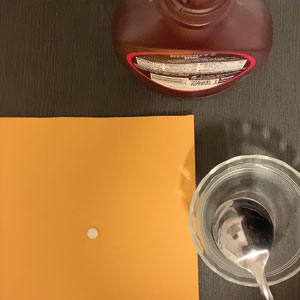

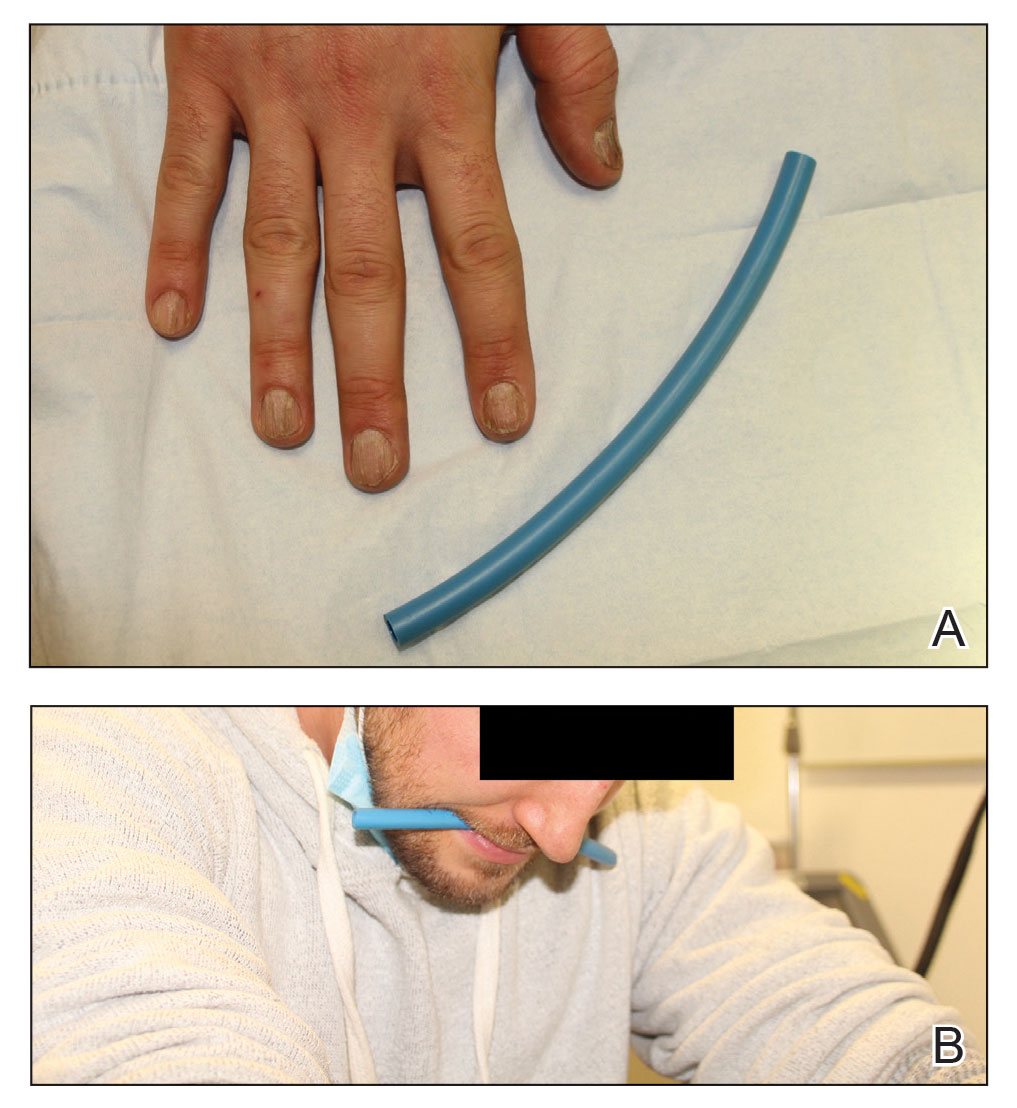

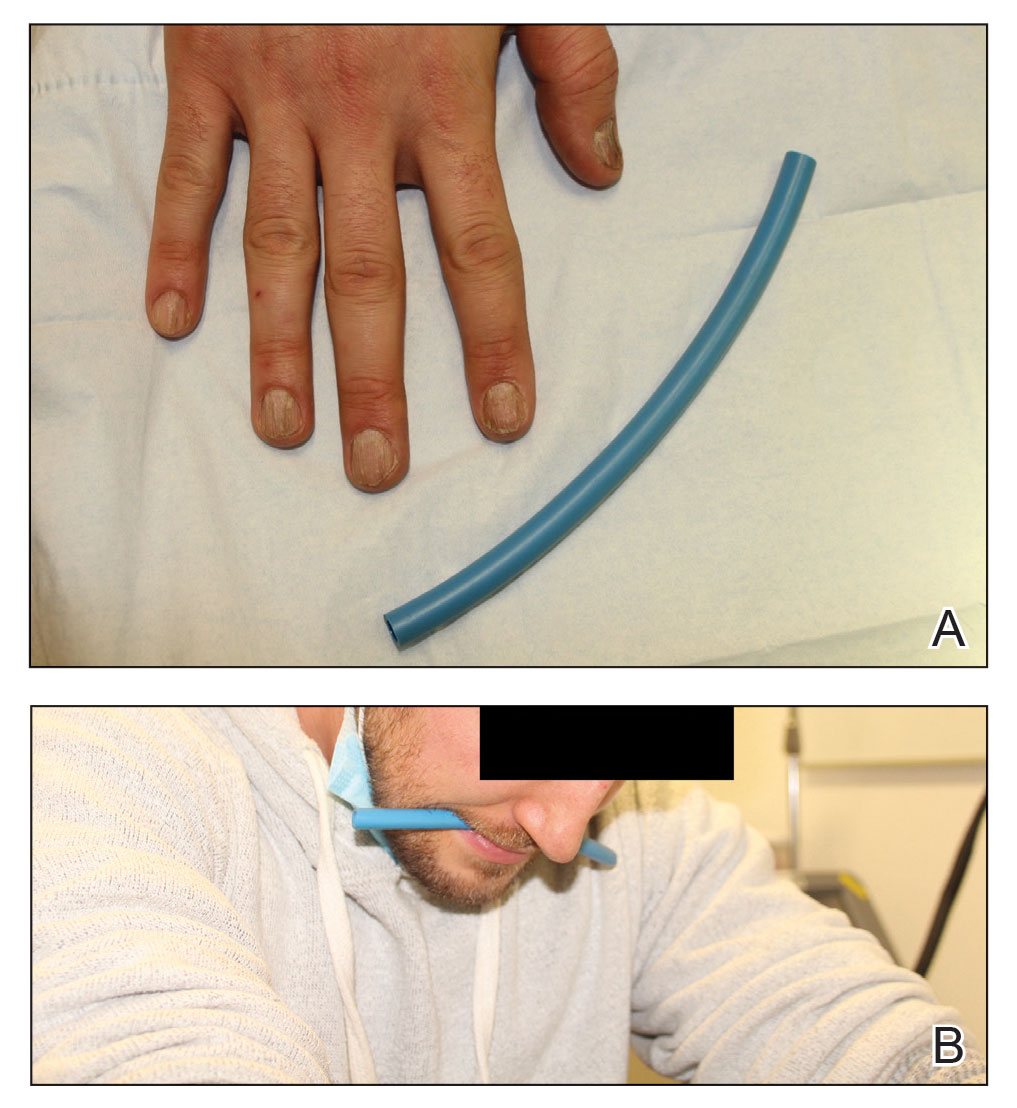

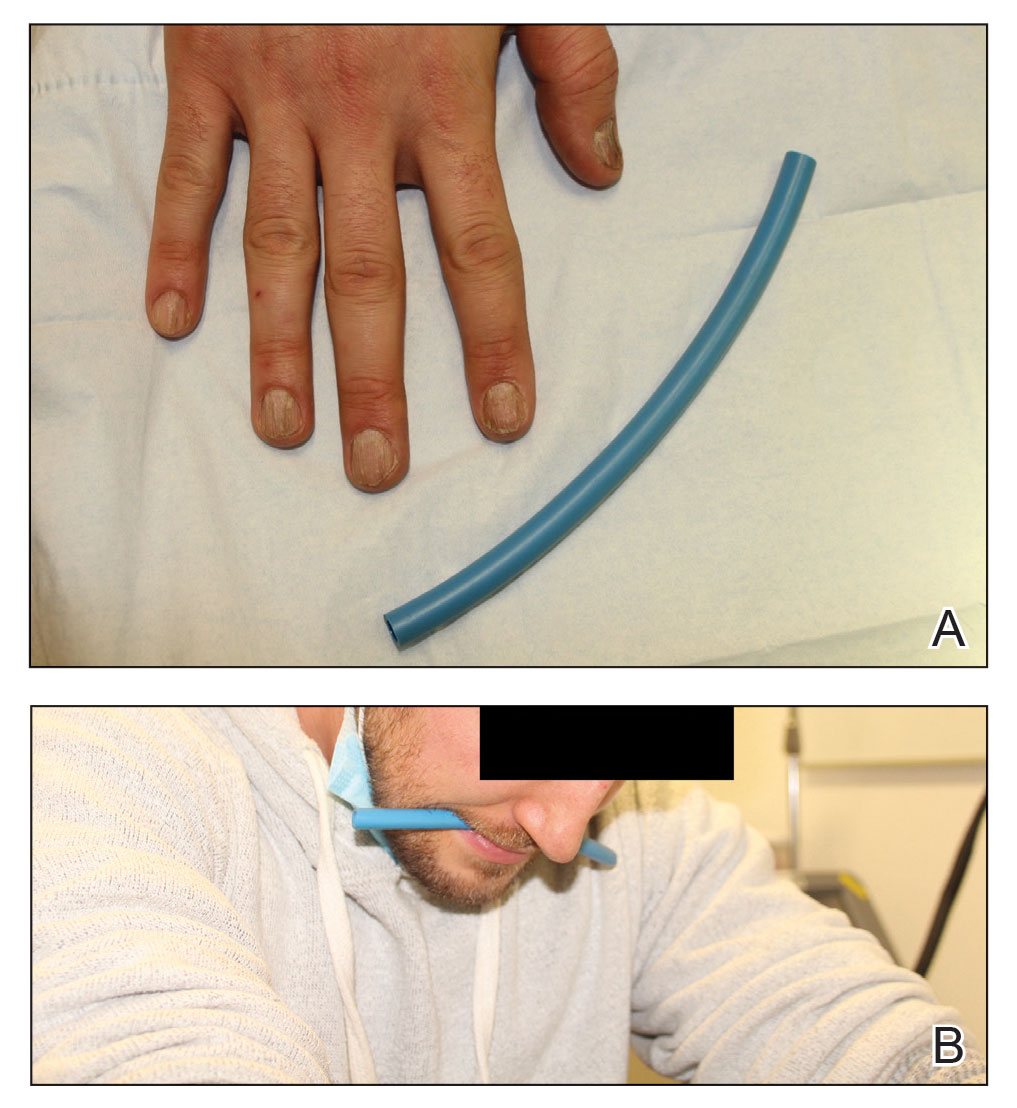

A patient was receiving treatment with intralesional triamcinolone injections to the nail matrix for trachyonychia involving all of the fingernails. He worked as an equipment and facilities manager, giving him access to polyurethane tubing, which is routinely used in the manufacture of some medical devices that require gas or liquid to operate. He found the nail injections to be painful but was motivated to proceed with treatment. He brought in a piece of polyurethane tubing to a subsequent visit to bite on during the injections (Figure) and reported considerable relief of pain.

What you were not taught in United States history class was that this method—clenching an object orally—dates to the era before the Civil War, before appropriate anesthetics and analgesics were developed, when patients and soldiers bit on a bullet or leather strap during surgical procedures.4 Clenching and chewing have been shown to promote relaxation and reduce acute pain and stress.5

Practical Implications

Polyurethane tubing can be purchased in bulk, is inexpensive ($0.30/foot on Amazon), and unlikely to damage teeth due to its flexibility. It can be cut into 6-inch pieces and given to the patient at their first nail injection appointment. The patient can then bring the tubing to subsequent appointments to use as a mastication tool during nail injections.

We instruct the patient to disinfect the dedicated piece of tubing after the initial visit and each subsequent visit by soaking it for 15 minutes in either a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution, antibacterial mouthwash, a solution of baking soda (bicarbonate of soda) and water (1 cup of water to 2 teaspoons of baking soda), or white vinegar. We instruct them to thoroughly dry the disinfected polyurethane tube and store it in a clean, reusable, resealable zipper storage bag between appointments.

In addition to reducing anxiety and pain, this method also distracts the patient and therefore promotes patient and physician safety. Patients are less likely to jump or startle during the injection, thereby reducing the risk of physically interfering with the nail surgeon or making an unanticipated advance into the surgical field.

Although frustrated patients with nail disease may need to “bite the bullet” when they accept treatment with nail injections, lessons from our patient and from United States history offer a safe and cost-effective pain management strategy. Minimizing discomfort and anxiety during the first nail injection is crucial because doing so is likely to promote adherence with follow-up injections and therefore improve clinical outcomes.

Future clinical studies should validate the clinical utility of oral mastication and clenching during nail procedures compared to other perioperative stress- and anxiety-reducing techniques.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilization of a stress ball to diminish anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2020;105:294. doi:10.12788/cutis.0013

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilizing a sleep mask to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2021;108:36. doi:10.12788/cutis.0285

- Ip HYV, Abrishami A, Peng PW, et al. Predictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:657-677. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181aae87a

- Albin MS. The use of anesthetics during the Civil War, 1861-1865. Pharm Hist. 2000;42:99-114.

- Tahara Y, Sakurai K, Ando T. Influence of chewing and clenching on salivary cortisol levels as an indicator of stress. J Prosthodont. 2007;16:129-135. doi:10.1111/j.1532-849X.2007.00178.x

Practice Gap

Nail matrix and nail bed injections with triamcinolone acetonide are used to treat trachyonychia and inflammatory nail conditions, including nail psoriasis and nail lichen planus. The procedure should be quick in well-trained hands, with each nail injection taking only seconds to perform. Typically, patients have multiple nails involved, requiring at least 1 injection into the nail matrix or the nail bed (or both) in each nail at each visit. Patients often are anxious when undergoing nail injections; the nail unit is highly innervated and vascular, which can cause notable transient discomfort during the procedure1,2 as well as postoperative pain.3

Nail injections must be repeated every 4 to 6 weeks to sustain clinical benefit and maximize outcomes, which can lead to heightened anxiety and apprehension before and during the visit. Furthermore, pain and anxiety associated with the procedure may deter patients from returning for follow-up injections, which can impact treatment adherence and clinical outcomes.

Dermatologists should implement strategies to decrease periprocedural anxiety to improve the nail injection experience. In our practice, we routinely incorporate stress-reducing techniques—music, talkesthesia, a sleep mask, cool air, ethyl chloride, and squeezing a stress ball—into the clinical workflow of the procedure. The goal of these techniques is to divert attention away from painful stimuli. Most patients, however, receive injections in both hands, making it impractical to employ some of these techniques, particularly squeezing a stress ball. We employed a unique method involving polyurethane tubing to reduce stress and anxiety during nail procedures.

The Technique

A patient was receiving treatment with intralesional triamcinolone injections to the nail matrix for trachyonychia involving all of the fingernails. He worked as an equipment and facilities manager, giving him access to polyurethane tubing, which is routinely used in the manufacture of some medical devices that require gas or liquid to operate. He found the nail injections to be painful but was motivated to proceed with treatment. He brought in a piece of polyurethane tubing to a subsequent visit to bite on during the injections (Figure) and reported considerable relief of pain.

What you were not taught in United States history class was that this method—clenching an object orally—dates to the era before the Civil War, before appropriate anesthetics and analgesics were developed, when patients and soldiers bit on a bullet or leather strap during surgical procedures.4 Clenching and chewing have been shown to promote relaxation and reduce acute pain and stress.5

Practical Implications

Polyurethane tubing can be purchased in bulk, is inexpensive ($0.30/foot on Amazon), and unlikely to damage teeth due to its flexibility. It can be cut into 6-inch pieces and given to the patient at their first nail injection appointment. The patient can then bring the tubing to subsequent appointments to use as a mastication tool during nail injections.

We instruct the patient to disinfect the dedicated piece of tubing after the initial visit and each subsequent visit by soaking it for 15 minutes in either a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution, antibacterial mouthwash, a solution of baking soda (bicarbonate of soda) and water (1 cup of water to 2 teaspoons of baking soda), or white vinegar. We instruct them to thoroughly dry the disinfected polyurethane tube and store it in a clean, reusable, resealable zipper storage bag between appointments.

In addition to reducing anxiety and pain, this method also distracts the patient and therefore promotes patient and physician safety. Patients are less likely to jump or startle during the injection, thereby reducing the risk of physically interfering with the nail surgeon or making an unanticipated advance into the surgical field.

Although frustrated patients with nail disease may need to “bite the bullet” when they accept treatment with nail injections, lessons from our patient and from United States history offer a safe and cost-effective pain management strategy. Minimizing discomfort and anxiety during the first nail injection is crucial because doing so is likely to promote adherence with follow-up injections and therefore improve clinical outcomes.

Future clinical studies should validate the clinical utility of oral mastication and clenching during nail procedures compared to other perioperative stress- and anxiety-reducing techniques.

Practice Gap

Nail matrix and nail bed injections with triamcinolone acetonide are used to treat trachyonychia and inflammatory nail conditions, including nail psoriasis and nail lichen planus. The procedure should be quick in well-trained hands, with each nail injection taking only seconds to perform. Typically, patients have multiple nails involved, requiring at least 1 injection into the nail matrix or the nail bed (or both) in each nail at each visit. Patients often are anxious when undergoing nail injections; the nail unit is highly innervated and vascular, which can cause notable transient discomfort during the procedure1,2 as well as postoperative pain.3

Nail injections must be repeated every 4 to 6 weeks to sustain clinical benefit and maximize outcomes, which can lead to heightened anxiety and apprehension before and during the visit. Furthermore, pain and anxiety associated with the procedure may deter patients from returning for follow-up injections, which can impact treatment adherence and clinical outcomes.

Dermatologists should implement strategies to decrease periprocedural anxiety to improve the nail injection experience. In our practice, we routinely incorporate stress-reducing techniques—music, talkesthesia, a sleep mask, cool air, ethyl chloride, and squeezing a stress ball—into the clinical workflow of the procedure. The goal of these techniques is to divert attention away from painful stimuli. Most patients, however, receive injections in both hands, making it impractical to employ some of these techniques, particularly squeezing a stress ball. We employed a unique method involving polyurethane tubing to reduce stress and anxiety during nail procedures.

The Technique

A patient was receiving treatment with intralesional triamcinolone injections to the nail matrix for trachyonychia involving all of the fingernails. He worked as an equipment and facilities manager, giving him access to polyurethane tubing, which is routinely used in the manufacture of some medical devices that require gas or liquid to operate. He found the nail injections to be painful but was motivated to proceed with treatment. He brought in a piece of polyurethane tubing to a subsequent visit to bite on during the injections (Figure) and reported considerable relief of pain.

What you were not taught in United States history class was that this method—clenching an object orally—dates to the era before the Civil War, before appropriate anesthetics and analgesics were developed, when patients and soldiers bit on a bullet or leather strap during surgical procedures.4 Clenching and chewing have been shown to promote relaxation and reduce acute pain and stress.5

Practical Implications

Polyurethane tubing can be purchased in bulk, is inexpensive ($0.30/foot on Amazon), and unlikely to damage teeth due to its flexibility. It can be cut into 6-inch pieces and given to the patient at their first nail injection appointment. The patient can then bring the tubing to subsequent appointments to use as a mastication tool during nail injections.

We instruct the patient to disinfect the dedicated piece of tubing after the initial visit and each subsequent visit by soaking it for 15 minutes in either a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution, antibacterial mouthwash, a solution of baking soda (bicarbonate of soda) and water (1 cup of water to 2 teaspoons of baking soda), or white vinegar. We instruct them to thoroughly dry the disinfected polyurethane tube and store it in a clean, reusable, resealable zipper storage bag between appointments.

In addition to reducing anxiety and pain, this method also distracts the patient and therefore promotes patient and physician safety. Patients are less likely to jump or startle during the injection, thereby reducing the risk of physically interfering with the nail surgeon or making an unanticipated advance into the surgical field.

Although frustrated patients with nail disease may need to “bite the bullet” when they accept treatment with nail injections, lessons from our patient and from United States history offer a safe and cost-effective pain management strategy. Minimizing discomfort and anxiety during the first nail injection is crucial because doing so is likely to promote adherence with follow-up injections and therefore improve clinical outcomes.

Future clinical studies should validate the clinical utility of oral mastication and clenching during nail procedures compared to other perioperative stress- and anxiety-reducing techniques.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilization of a stress ball to diminish anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2020;105:294. doi:10.12788/cutis.0013

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilizing a sleep mask to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2021;108:36. doi:10.12788/cutis.0285

- Ip HYV, Abrishami A, Peng PW, et al. Predictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:657-677. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181aae87a

- Albin MS. The use of anesthetics during the Civil War, 1861-1865. Pharm Hist. 2000;42:99-114.

- Tahara Y, Sakurai K, Ando T. Influence of chewing and clenching on salivary cortisol levels as an indicator of stress. J Prosthodont. 2007;16:129-135. doi:10.1111/j.1532-849X.2007.00178.x

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilization of a stress ball to diminish anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2020;105:294. doi:10.12788/cutis.0013

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilizing a sleep mask to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2021;108:36. doi:10.12788/cutis.0285

- Ip HYV, Abrishami A, Peng PW, et al. Predictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:657-677. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181aae87a

- Albin MS. The use of anesthetics during the Civil War, 1861-1865. Pharm Hist. 2000;42:99-114.

- Tahara Y, Sakurai K, Ando T. Influence of chewing and clenching on salivary cortisol levels as an indicator of stress. J Prosthodont. 2007;16:129-135. doi:10.1111/j.1532-849X.2007.00178.x

Habit Reversal Therapy for Skin Picking Disorder

Practice Gap

Skin picking disorder is characterized by repetitive deliberate manipulation of the skin that causes noticeable tissue damage. It affects approximately 1.6% of adults in the United States and is associated with marked distress as well as a psychosocial impact.1 Complications of skin picking disorder can include ulceration, infection, scarring, and disfigurement.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques have been established to be effective in treating skin picking disorder.2 Although referral to a mental health professional is appropriate for patients with skin picking disorder, many of them may not be interested. Cognitive behavioral therapy for diseases at the intersection of psychiatry and dermatology typically is not included in dermatology curricula. Therefore, dermatologists should be aware of CBT techniques that can mitigate the impact of skin picking disorder for patients who decline referral to a mental health professional.

The Technique

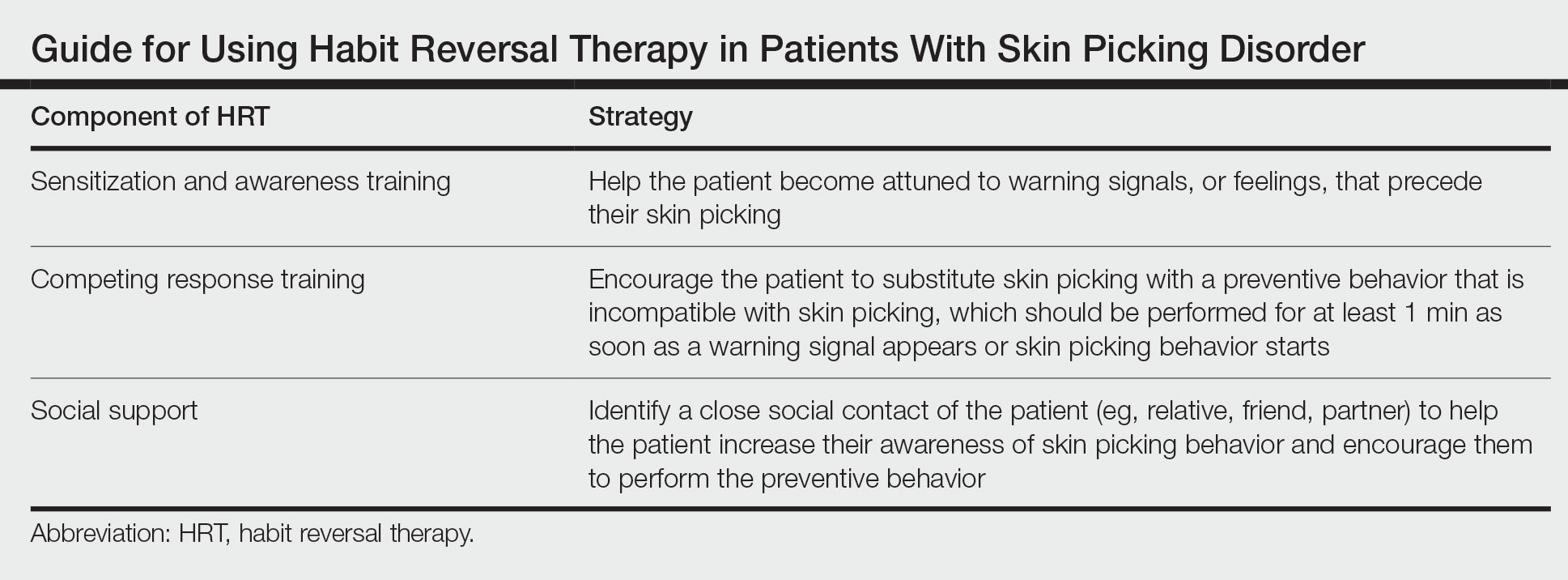

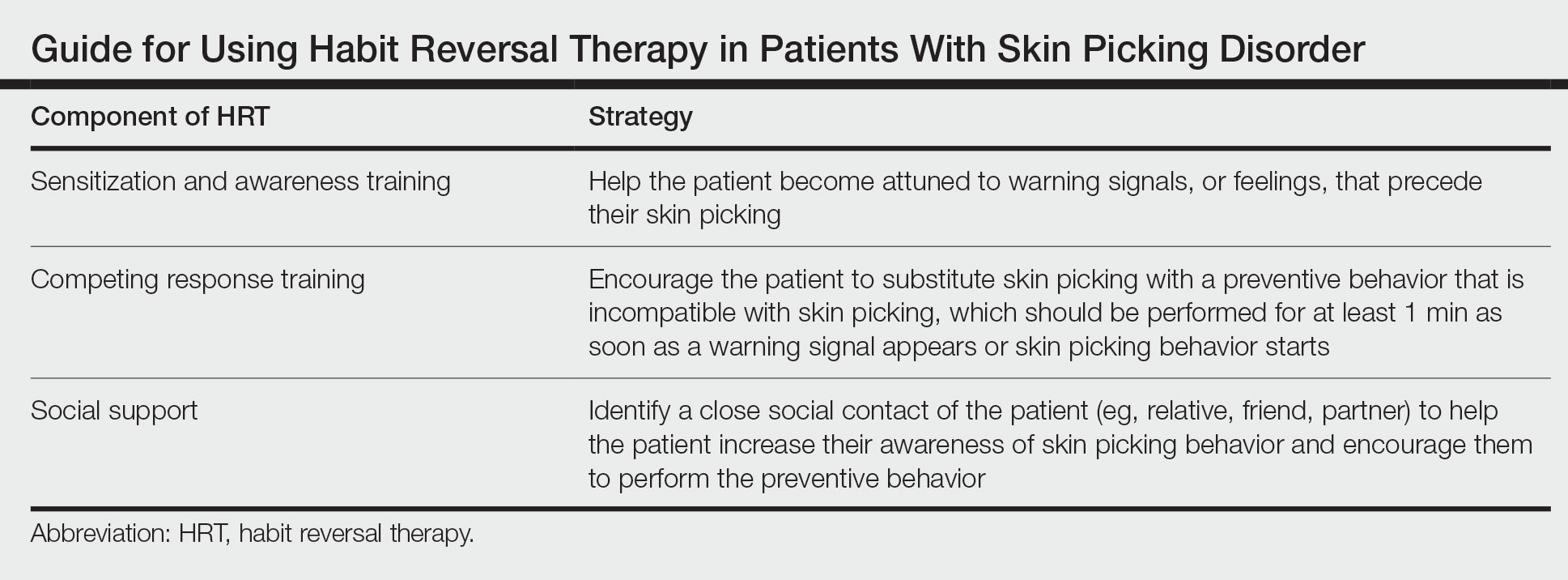

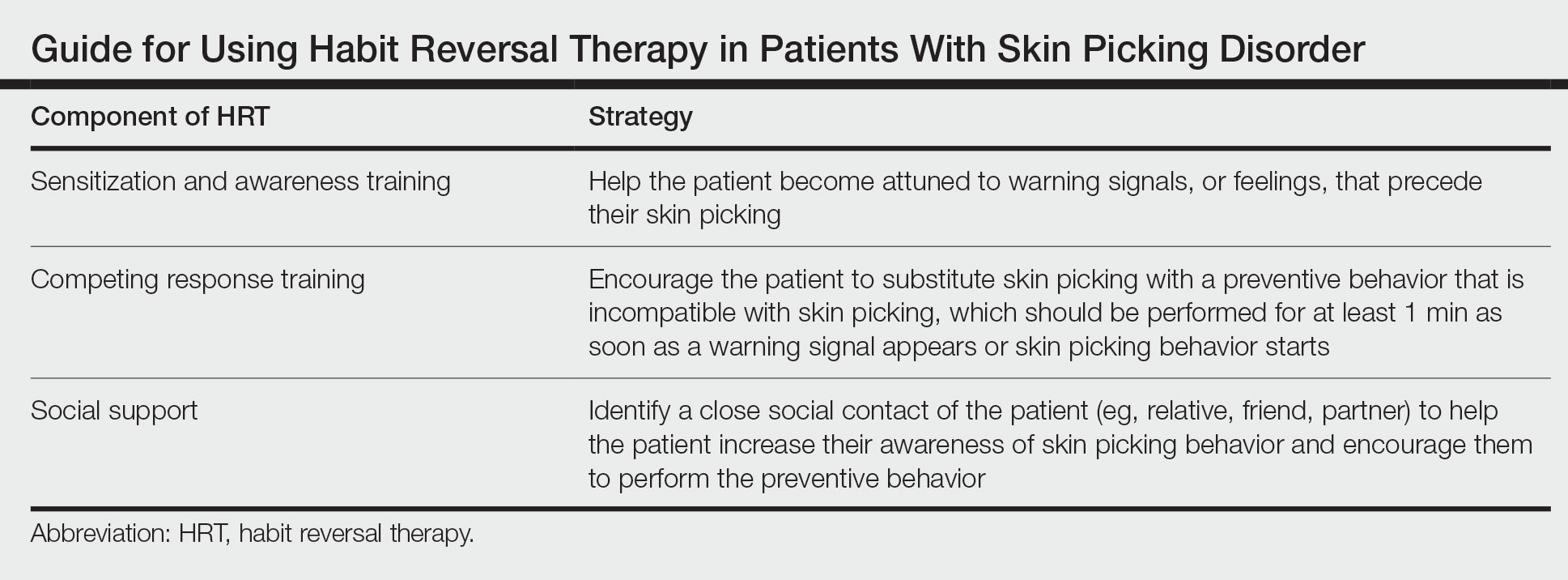

Cognitive behavioral therapy is one of the more effective forms of psychotherapy for the treatment of skin picking disorder. Consistent utilization of CBT techniques can achieve relatively permanent change in brain function and contribute to long-term treatment outcomes. A particularly useful CBT technique for skin picking disorder is habit reversal therapy (HRT)(Table). Studies have shown that HRT techniques have demonstrated efficacy in skin picking disorder with sustained impact.3 Patients treated with HRT have reported a greater decrease in skin picking compared with controls after only 3 sessions (P<.01).4 There are 3 elements to HRT:

1. Sensitization and awareness training: This facet of HRT involves helping the patient become attuned to warning signals, or feelings, that precede their skin picking, as skin picking often occurs automatically without the patient noticing. Such feelings can include tingling of the skin, tension, and a feeling of being overwhelmed.5 Ideally, the physician works with the patient to identify 2 or 3 warning signals that precede skin picking behavior.

2. Competing response training: The patient is encouraged to substitute skin picking with a preventive behavior—for example, crossing the arms and gently squeezing the fists—that is incompatible with skin picking. The preventive behavior should be performed for at least 1 minute as soon as a warning signal appears or skin picking behavior starts. After 1 minute, if the urge for skin picking recurs, then the patient should repeat the preventive behavior.5 It can be helpful to practice the preventive behavior with the patient once in the clinic.

3. Social support: This technique involves identifying a close social contact of the patient (eg, relative, friend, partner) to help the patient increase their awareness of skin picking behavior and encourage them to perform the preventive behavior.5 The purpose of identifying a close social contact is to ensure accountability for the patient in their day-to-day life, given the limited scope of the relationship between the patient and the dermatologist.

Other practical solutions to skin picking include advising patients to cut their nails short; using finger cots to cover the nails and thus lessen the potential for skin injury; and using a sensory toy, such as a fidget spinner, to distract or occupy the patient when they feel the urge for skin picking.

Practice Implications

Although skin picking disorder is a challenging condition to manage, there are proven techniques for treatment. Techniques drawn from HRT are quite practical and can be implemented by dermatologists for patients with skin picking disorder to reduce the burden of their disease.

- Keuthen NJ, Koran LM, Aboujaoude E, et al. The prevalence of pathologic skin picking in US adults. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51:183-186. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.04.003

- Jafferany M, Mkhoyan R, Arora G, et al. Treatment of skin picking disorder: interdisciplinary role of dermatologist and psychiatrist. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13837. doi:10.1111/dth.13837

- Schuck K, Keijsers GP, Rinck M. The effects of brief cognitive-behaviour therapy for pathological skin picking: a randomized comparison to wait-list control. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:11-17. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.09.005

- Teng EJ, Woods DW, Twohig MP. Habit reversal as a treatment for chronic skin picking: a pilot investigation. Behav Modif. 2006;30:411-422. doi:10.1177/0145445504265707

- Torales J, Páez L, O’Higgins M, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for excoriation (skin picking) disorder. Telangana J Psych. 2016;2:27-30.

Practice Gap

Skin picking disorder is characterized by repetitive deliberate manipulation of the skin that causes noticeable tissue damage. It affects approximately 1.6% of adults in the United States and is associated with marked distress as well as a psychosocial impact.1 Complications of skin picking disorder can include ulceration, infection, scarring, and disfigurement.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques have been established to be effective in treating skin picking disorder.2 Although referral to a mental health professional is appropriate for patients with skin picking disorder, many of them may not be interested. Cognitive behavioral therapy for diseases at the intersection of psychiatry and dermatology typically is not included in dermatology curricula. Therefore, dermatologists should be aware of CBT techniques that can mitigate the impact of skin picking disorder for patients who decline referral to a mental health professional.

The Technique

Cognitive behavioral therapy is one of the more effective forms of psychotherapy for the treatment of skin picking disorder. Consistent utilization of CBT techniques can achieve relatively permanent change in brain function and contribute to long-term treatment outcomes. A particularly useful CBT technique for skin picking disorder is habit reversal therapy (HRT)(Table). Studies have shown that HRT techniques have demonstrated efficacy in skin picking disorder with sustained impact.3 Patients treated with HRT have reported a greater decrease in skin picking compared with controls after only 3 sessions (P<.01).4 There are 3 elements to HRT:

1. Sensitization and awareness training: This facet of HRT involves helping the patient become attuned to warning signals, or feelings, that precede their skin picking, as skin picking often occurs automatically without the patient noticing. Such feelings can include tingling of the skin, tension, and a feeling of being overwhelmed.5 Ideally, the physician works with the patient to identify 2 or 3 warning signals that precede skin picking behavior.

2. Competing response training: The patient is encouraged to substitute skin picking with a preventive behavior—for example, crossing the arms and gently squeezing the fists—that is incompatible with skin picking. The preventive behavior should be performed for at least 1 minute as soon as a warning signal appears or skin picking behavior starts. After 1 minute, if the urge for skin picking recurs, then the patient should repeat the preventive behavior.5 It can be helpful to practice the preventive behavior with the patient once in the clinic.

3. Social support: This technique involves identifying a close social contact of the patient (eg, relative, friend, partner) to help the patient increase their awareness of skin picking behavior and encourage them to perform the preventive behavior.5 The purpose of identifying a close social contact is to ensure accountability for the patient in their day-to-day life, given the limited scope of the relationship between the patient and the dermatologist.

Other practical solutions to skin picking include advising patients to cut their nails short; using finger cots to cover the nails and thus lessen the potential for skin injury; and using a sensory toy, such as a fidget spinner, to distract or occupy the patient when they feel the urge for skin picking.

Practice Implications

Although skin picking disorder is a challenging condition to manage, there are proven techniques for treatment. Techniques drawn from HRT are quite practical and can be implemented by dermatologists for patients with skin picking disorder to reduce the burden of their disease.

Practice Gap

Skin picking disorder is characterized by repetitive deliberate manipulation of the skin that causes noticeable tissue damage. It affects approximately 1.6% of adults in the United States and is associated with marked distress as well as a psychosocial impact.1 Complications of skin picking disorder can include ulceration, infection, scarring, and disfigurement.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques have been established to be effective in treating skin picking disorder.2 Although referral to a mental health professional is appropriate for patients with skin picking disorder, many of them may not be interested. Cognitive behavioral therapy for diseases at the intersection of psychiatry and dermatology typically is not included in dermatology curricula. Therefore, dermatologists should be aware of CBT techniques that can mitigate the impact of skin picking disorder for patients who decline referral to a mental health professional.

The Technique

Cognitive behavioral therapy is one of the more effective forms of psychotherapy for the treatment of skin picking disorder. Consistent utilization of CBT techniques can achieve relatively permanent change in brain function and contribute to long-term treatment outcomes. A particularly useful CBT technique for skin picking disorder is habit reversal therapy (HRT)(Table). Studies have shown that HRT techniques have demonstrated efficacy in skin picking disorder with sustained impact.3 Patients treated with HRT have reported a greater decrease in skin picking compared with controls after only 3 sessions (P<.01).4 There are 3 elements to HRT:

1. Sensitization and awareness training: This facet of HRT involves helping the patient become attuned to warning signals, or feelings, that precede their skin picking, as skin picking often occurs automatically without the patient noticing. Such feelings can include tingling of the skin, tension, and a feeling of being overwhelmed.5 Ideally, the physician works with the patient to identify 2 or 3 warning signals that precede skin picking behavior.

2. Competing response training: The patient is encouraged to substitute skin picking with a preventive behavior—for example, crossing the arms and gently squeezing the fists—that is incompatible with skin picking. The preventive behavior should be performed for at least 1 minute as soon as a warning signal appears or skin picking behavior starts. After 1 minute, if the urge for skin picking recurs, then the patient should repeat the preventive behavior.5 It can be helpful to practice the preventive behavior with the patient once in the clinic.

3. Social support: This technique involves identifying a close social contact of the patient (eg, relative, friend, partner) to help the patient increase their awareness of skin picking behavior and encourage them to perform the preventive behavior.5 The purpose of identifying a close social contact is to ensure accountability for the patient in their day-to-day life, given the limited scope of the relationship between the patient and the dermatologist.

Other practical solutions to skin picking include advising patients to cut their nails short; using finger cots to cover the nails and thus lessen the potential for skin injury; and using a sensory toy, such as a fidget spinner, to distract or occupy the patient when they feel the urge for skin picking.

Practice Implications

Although skin picking disorder is a challenging condition to manage, there are proven techniques for treatment. Techniques drawn from HRT are quite practical and can be implemented by dermatologists for patients with skin picking disorder to reduce the burden of their disease.

- Keuthen NJ, Koran LM, Aboujaoude E, et al. The prevalence of pathologic skin picking in US adults. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51:183-186. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.04.003

- Jafferany M, Mkhoyan R, Arora G, et al. Treatment of skin picking disorder: interdisciplinary role of dermatologist and psychiatrist. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13837. doi:10.1111/dth.13837

- Schuck K, Keijsers GP, Rinck M. The effects of brief cognitive-behaviour therapy for pathological skin picking: a randomized comparison to wait-list control. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:11-17. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.09.005

- Teng EJ, Woods DW, Twohig MP. Habit reversal as a treatment for chronic skin picking: a pilot investigation. Behav Modif. 2006;30:411-422. doi:10.1177/0145445504265707

- Torales J, Páez L, O’Higgins M, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for excoriation (skin picking) disorder. Telangana J Psych. 2016;2:27-30.

- Keuthen NJ, Koran LM, Aboujaoude E, et al. The prevalence of pathologic skin picking in US adults. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51:183-186. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.04.003

- Jafferany M, Mkhoyan R, Arora G, et al. Treatment of skin picking disorder: interdisciplinary role of dermatologist and psychiatrist. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13837. doi:10.1111/dth.13837

- Schuck K, Keijsers GP, Rinck M. The effects of brief cognitive-behaviour therapy for pathological skin picking: a randomized comparison to wait-list control. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:11-17. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.09.005

- Teng EJ, Woods DW, Twohig MP. Habit reversal as a treatment for chronic skin picking: a pilot investigation. Behav Modif. 2006;30:411-422. doi:10.1177/0145445504265707

- Torales J, Páez L, O’Higgins M, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for excoriation (skin picking) disorder. Telangana J Psych. 2016;2:27-30.

A “Solution” for Patients Unable to Swallow a Pill: Crushed Terbinafine Mixed With Syrup

Practice Gap

Terbinafine can be used safely and effectively in adult and pediatric patients to treat superficial fungal infections, including onychomycosis.1 These superficial fungal infections have become increasingly prevalent in children and often require oral therapy2; however, children are frequently unable to swallow a pill.

Until 2016, terbinafine was available as oral granules that could be sprinkled on food, but this formulation has been discontinued.3 In addition, terbinafine tablets have a bitter taste. Therefore, the inability to swallow a pill—typical of young children and other patients with pill dysphagia—is a barrier to prescribing terbinafine.

The Technique

For patients who cannot swallow a pill, a terbinafine tablet can be crushed and mixed with food or a syrup without loss of efficacy. Terbinafine in tablet form has been shown to have relatively unchanged properties after being crushed and mixed in solution, even several weeks after preparation.4 Crushing and mixing a terbinafine tablet with food or a syrup therefore is an effective option for patients who cannot swallow a pill but can safely swallow food.

The food or syrup used for this purpose should have a pH of at least 5 because greater acidity reduces absorption of terbinafine. Therefore, avoid mixing it with fruit juices, applesauce, or soda. Given the bitter taste of the terbinafine tablet, mixing it with a sweet food or syrup improves taste and compliance, which makes pudding a particularly good food option for this purpose.

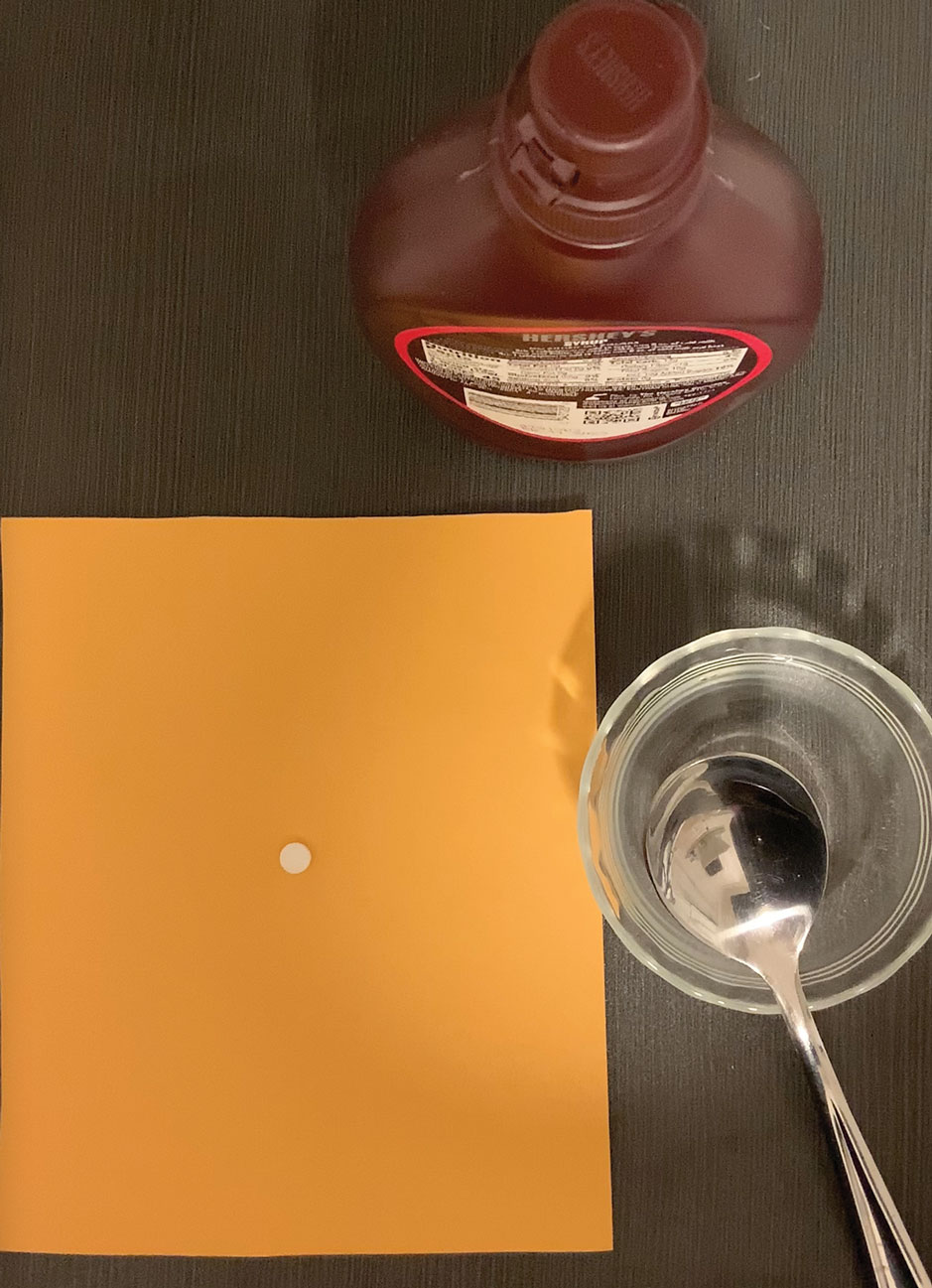

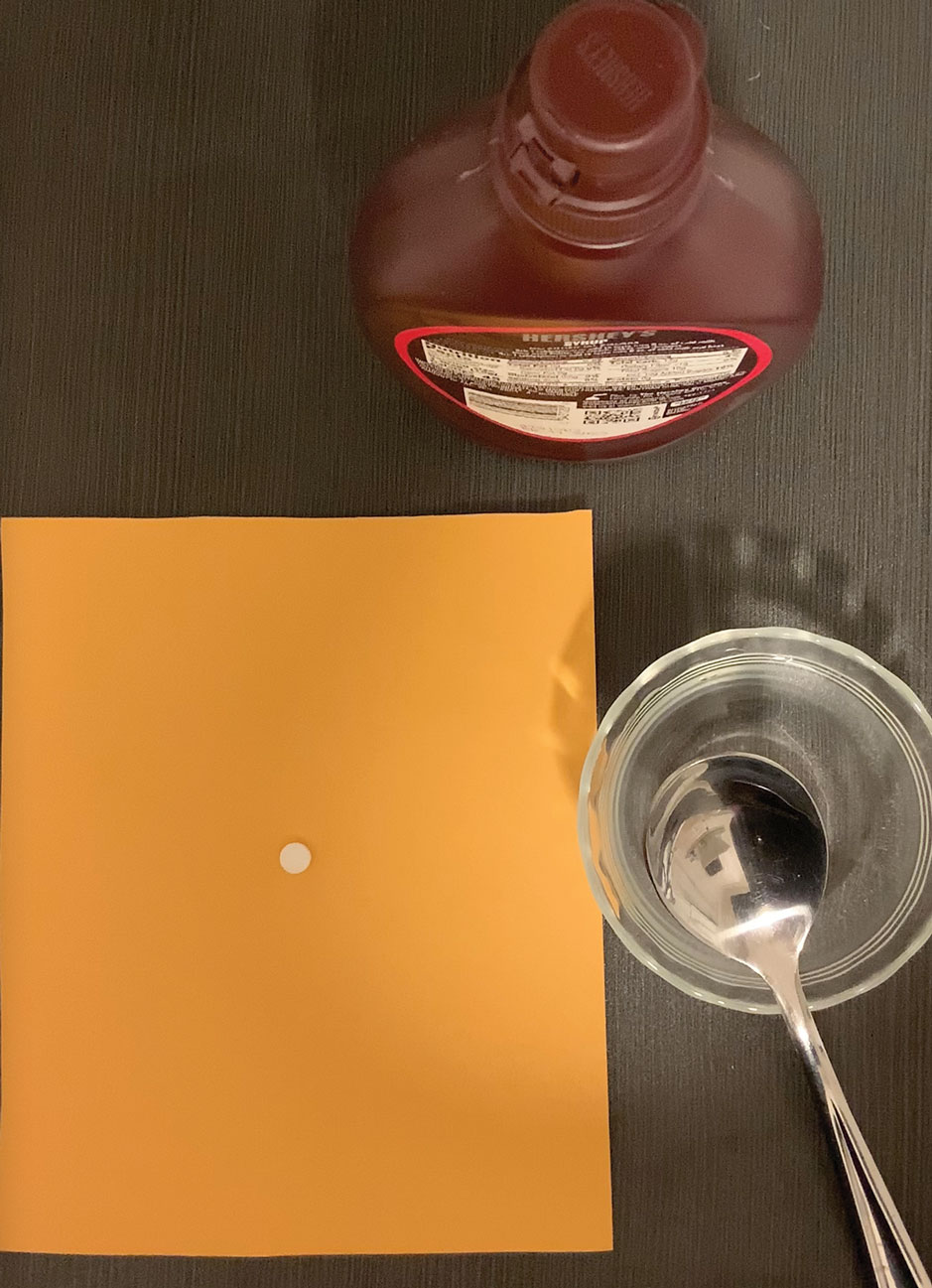

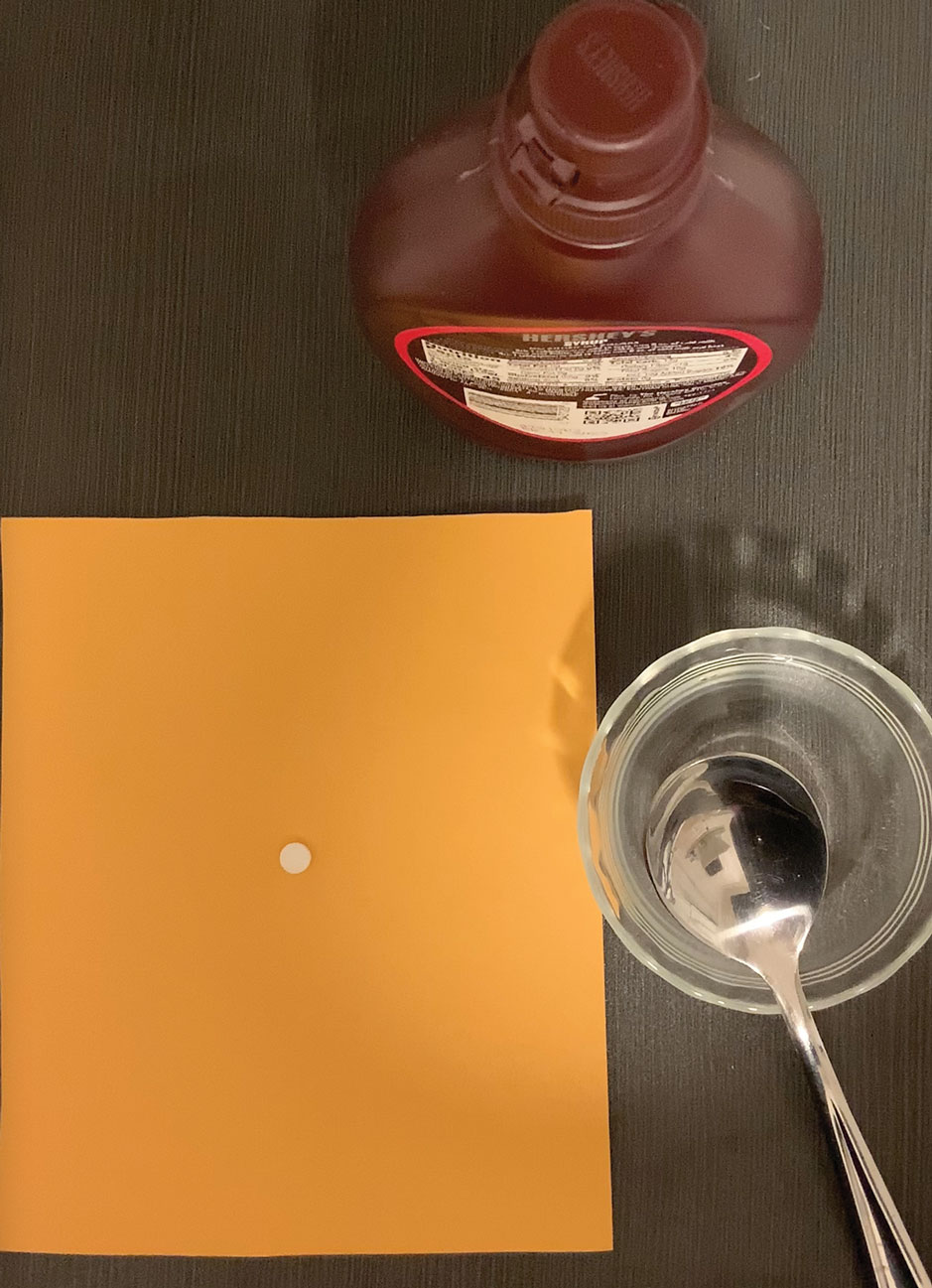

However, because younger patients might not finish an entire serving of pudding or other food into which the tablet has been crushed and mixed, inconsistent dosing might result. Therefore, we recommend mixing the crushed terbinafine tablet with 1 oz (30 mL) of chocolate syrup or corn syrup (Figure). This solution is sweet, easy to prepare and consume, widely available, and affordable (as low as $0.28/oz for corn syrup and as low as $0.10/oz for chocolate syrup, as priced on Amazon).

The tablet can be crushed using a pill crusher ($5–$10 at pharmacies or on Amazon) or by placing it on a piece of paper and crushing it with the back of a metal spoon. For children, the recommended dosing of terbinafine with a 250-mg tablet is based on weight: one-quarter of a tablet for a child weighing 10 to 20 kg; one-half of a tablet for a child weighing 20 to 40 kg; and a full tablet for a child weighing more than 40 kg.5 Because terbinafine tablets are not scored, a combined pill splitter–crusher can be used (also available at pharmacies or on Amazon; the price of this device is within the same price range as a pill crusher).

Practical Implication

Use of this method for crushing and mixing the terbinafine tablet allows patients who are unable to swallow a pill to safely and effectively use oral terbinafine.

- Solís-Arias MP, García-Romero MT. Onychomycosis in children. a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:123-130. doi:10.1111/ijd.13392

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of abnormal laboratory test results in pediatric patients prescribed terbinafine for superficial fungal infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1042-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.073

- Lamisil (terbinafine hydrochloride) oral granules. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation; 2013. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/022071s009lbl.pdf

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Nahata MC. Stability of terbinafine hydrochloride in an extemporaneously prepared oral suspension at 25 and 4 degrees C. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:243-245. doi:10.1093/ajhp/56.3.243

- Gupta AK, Adamiak A, Cooper EA. The efficacy and safety of terbinafine in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:627-640. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00691.x

Practice Gap

Terbinafine can be used safely and effectively in adult and pediatric patients to treat superficial fungal infections, including onychomycosis.1 These superficial fungal infections have become increasingly prevalent in children and often require oral therapy2; however, children are frequently unable to swallow a pill.

Until 2016, terbinafine was available as oral granules that could be sprinkled on food, but this formulation has been discontinued.3 In addition, terbinafine tablets have a bitter taste. Therefore, the inability to swallow a pill—typical of young children and other patients with pill dysphagia—is a barrier to prescribing terbinafine.

The Technique

For patients who cannot swallow a pill, a terbinafine tablet can be crushed and mixed with food or a syrup without loss of efficacy. Terbinafine in tablet form has been shown to have relatively unchanged properties after being crushed and mixed in solution, even several weeks after preparation.4 Crushing and mixing a terbinafine tablet with food or a syrup therefore is an effective option for patients who cannot swallow a pill but can safely swallow food.

The food or syrup used for this purpose should have a pH of at least 5 because greater acidity reduces absorption of terbinafine. Therefore, avoid mixing it with fruit juices, applesauce, or soda. Given the bitter taste of the terbinafine tablet, mixing it with a sweet food or syrup improves taste and compliance, which makes pudding a particularly good food option for this purpose.

However, because younger patients might not finish an entire serving of pudding or other food into which the tablet has been crushed and mixed, inconsistent dosing might result. Therefore, we recommend mixing the crushed terbinafine tablet with 1 oz (30 mL) of chocolate syrup or corn syrup (Figure). This solution is sweet, easy to prepare and consume, widely available, and affordable (as low as $0.28/oz for corn syrup and as low as $0.10/oz for chocolate syrup, as priced on Amazon).

The tablet can be crushed using a pill crusher ($5–$10 at pharmacies or on Amazon) or by placing it on a piece of paper and crushing it with the back of a metal spoon. For children, the recommended dosing of terbinafine with a 250-mg tablet is based on weight: one-quarter of a tablet for a child weighing 10 to 20 kg; one-half of a tablet for a child weighing 20 to 40 kg; and a full tablet for a child weighing more than 40 kg.5 Because terbinafine tablets are not scored, a combined pill splitter–crusher can be used (also available at pharmacies or on Amazon; the price of this device is within the same price range as a pill crusher).

Practical Implication

Use of this method for crushing and mixing the terbinafine tablet allows patients who are unable to swallow a pill to safely and effectively use oral terbinafine.

Practice Gap

Terbinafine can be used safely and effectively in adult and pediatric patients to treat superficial fungal infections, including onychomycosis.1 These superficial fungal infections have become increasingly prevalent in children and often require oral therapy2; however, children are frequently unable to swallow a pill.

Until 2016, terbinafine was available as oral granules that could be sprinkled on food, but this formulation has been discontinued.3 In addition, terbinafine tablets have a bitter taste. Therefore, the inability to swallow a pill—typical of young children and other patients with pill dysphagia—is a barrier to prescribing terbinafine.

The Technique

For patients who cannot swallow a pill, a terbinafine tablet can be crushed and mixed with food or a syrup without loss of efficacy. Terbinafine in tablet form has been shown to have relatively unchanged properties after being crushed and mixed in solution, even several weeks after preparation.4 Crushing and mixing a terbinafine tablet with food or a syrup therefore is an effective option for patients who cannot swallow a pill but can safely swallow food.

The food or syrup used for this purpose should have a pH of at least 5 because greater acidity reduces absorption of terbinafine. Therefore, avoid mixing it with fruit juices, applesauce, or soda. Given the bitter taste of the terbinafine tablet, mixing it with a sweet food or syrup improves taste and compliance, which makes pudding a particularly good food option for this purpose.

However, because younger patients might not finish an entire serving of pudding or other food into which the tablet has been crushed and mixed, inconsistent dosing might result. Therefore, we recommend mixing the crushed terbinafine tablet with 1 oz (30 mL) of chocolate syrup or corn syrup (Figure). This solution is sweet, easy to prepare and consume, widely available, and affordable (as low as $0.28/oz for corn syrup and as low as $0.10/oz for chocolate syrup, as priced on Amazon).

The tablet can be crushed using a pill crusher ($5–$10 at pharmacies or on Amazon) or by placing it on a piece of paper and crushing it with the back of a metal spoon. For children, the recommended dosing of terbinafine with a 250-mg tablet is based on weight: one-quarter of a tablet for a child weighing 10 to 20 kg; one-half of a tablet for a child weighing 20 to 40 kg; and a full tablet for a child weighing more than 40 kg.5 Because terbinafine tablets are not scored, a combined pill splitter–crusher can be used (also available at pharmacies or on Amazon; the price of this device is within the same price range as a pill crusher).

Practical Implication

Use of this method for crushing and mixing the terbinafine tablet allows patients who are unable to swallow a pill to safely and effectively use oral terbinafine.

- Solís-Arias MP, García-Romero MT. Onychomycosis in children. a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:123-130. doi:10.1111/ijd.13392

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of abnormal laboratory test results in pediatric patients prescribed terbinafine for superficial fungal infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1042-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.073

- Lamisil (terbinafine hydrochloride) oral granules. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation; 2013. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/022071s009lbl.pdf

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Nahata MC. Stability of terbinafine hydrochloride in an extemporaneously prepared oral suspension at 25 and 4 degrees C. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:243-245. doi:10.1093/ajhp/56.3.243

- Gupta AK, Adamiak A, Cooper EA. The efficacy and safety of terbinafine in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:627-640. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00691.x

- Solís-Arias MP, García-Romero MT. Onychomycosis in children. a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:123-130. doi:10.1111/ijd.13392

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of abnormal laboratory test results in pediatric patients prescribed terbinafine for superficial fungal infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1042-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.073

- Lamisil (terbinafine hydrochloride) oral granules. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation; 2013. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/022071s009lbl.pdf

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Nahata MC. Stability of terbinafine hydrochloride in an extemporaneously prepared oral suspension at 25 and 4 degrees C. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:243-245. doi:10.1093/ajhp/56.3.243

- Gupta AK, Adamiak A, Cooper EA. The efficacy and safety of terbinafine in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:627-640. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00691.x

Bone Wax as a Physical Hemostatic Agent

Practice Gap

Hemostasis after cutaneous surgery typically can be aided by mechanical occlusion with petrolatum and gauze known as a pressure bandage. However, in certain scenarios such as bone bleeding or irregularly shaped areas (eg, conchal bowl), difficulty applying a pressure bandage necessitates alternative hemostatic measures.1 In those instances, physical hemostatic agents, such as gelatin, oxidized cellulose, microporous polysaccharide spheres, hydrophilic polymers with potassium salts, microfibrillar collagen, and chitin, also can be used.2 However, those agents are expensive and often adhere to wound edges, inducing repeat trauma with removal. To avoid such concerns, we propose the use of bone wax as an effective hemostatic technique.

The Technique

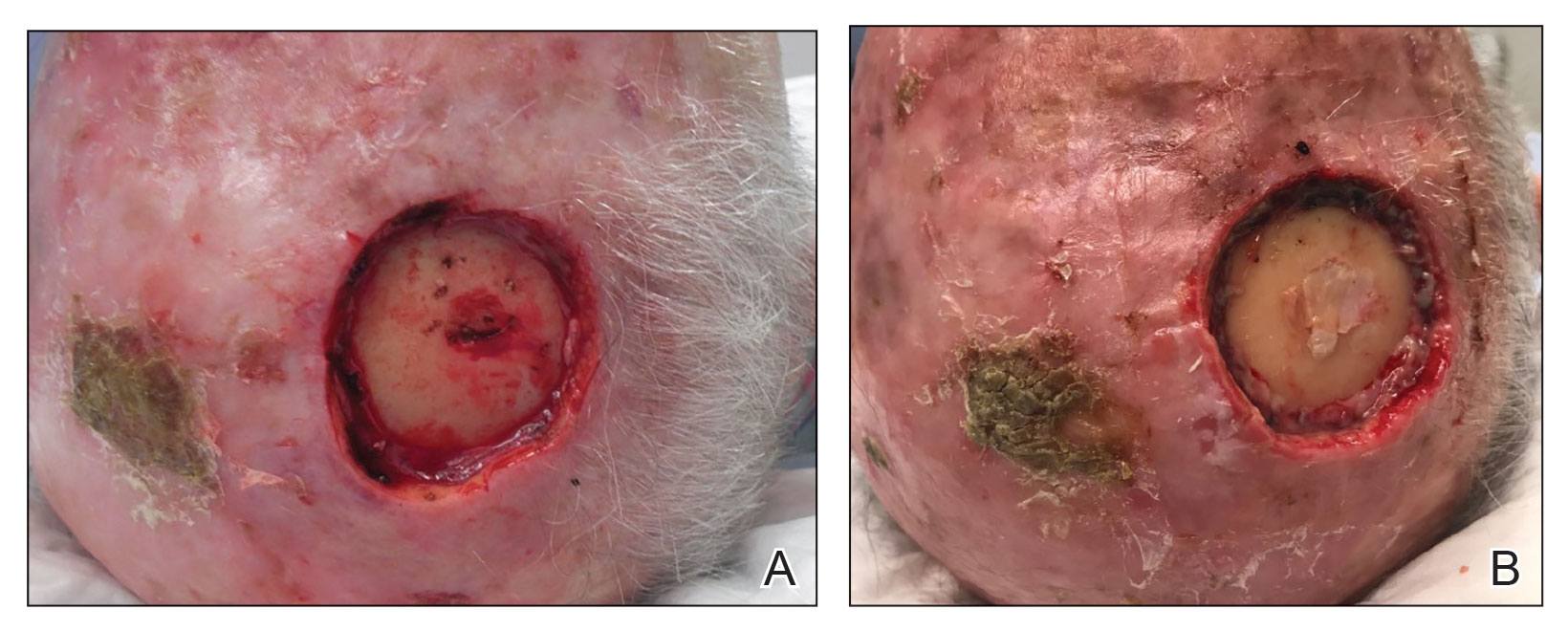

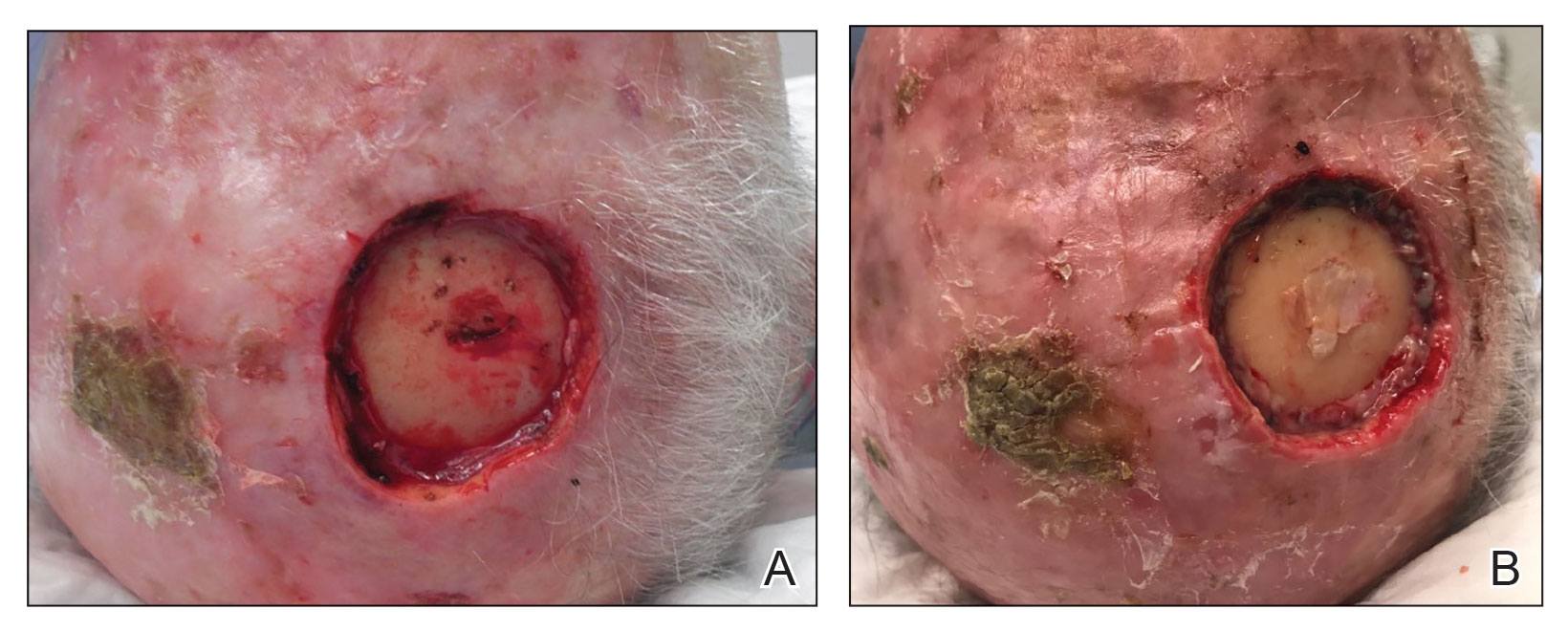

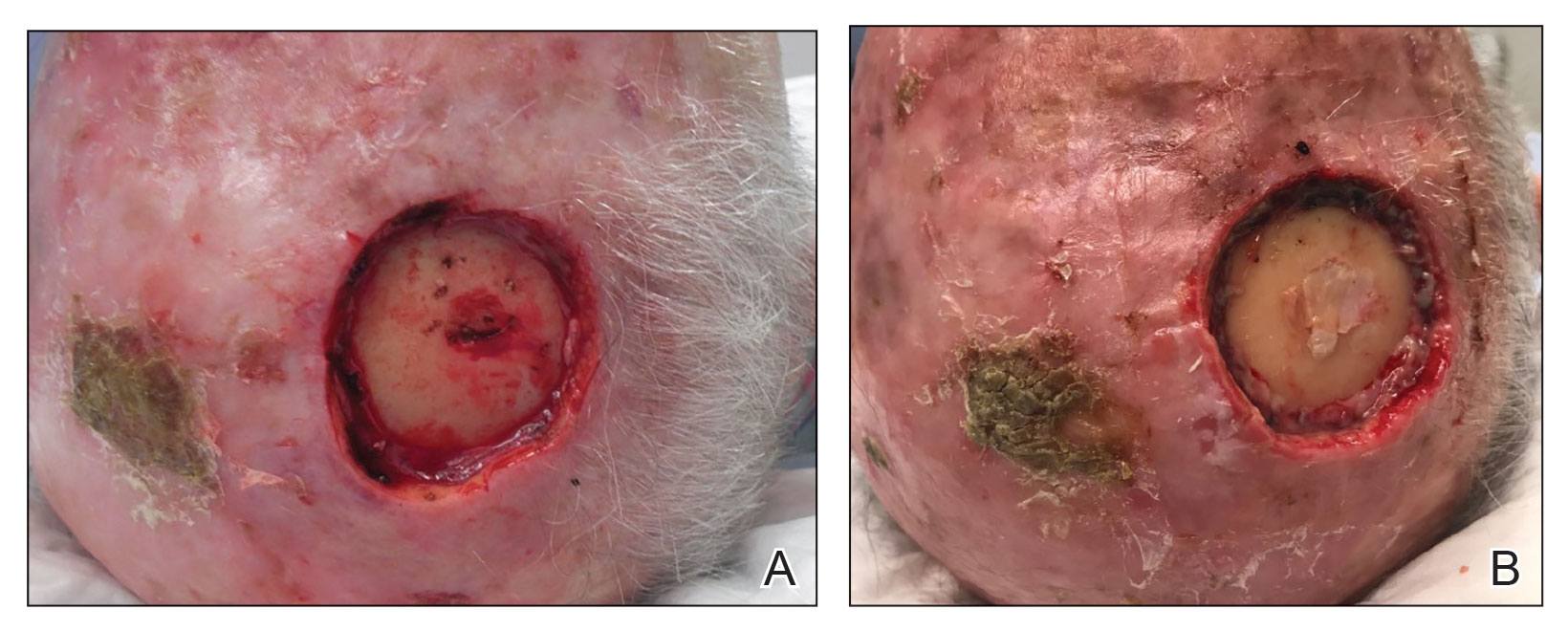

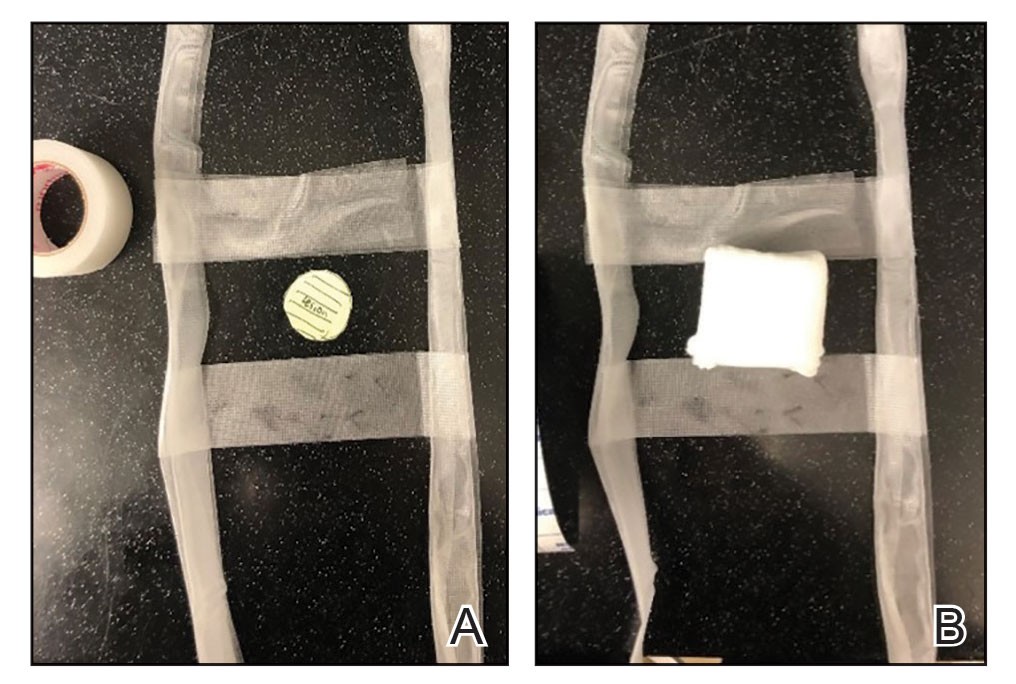

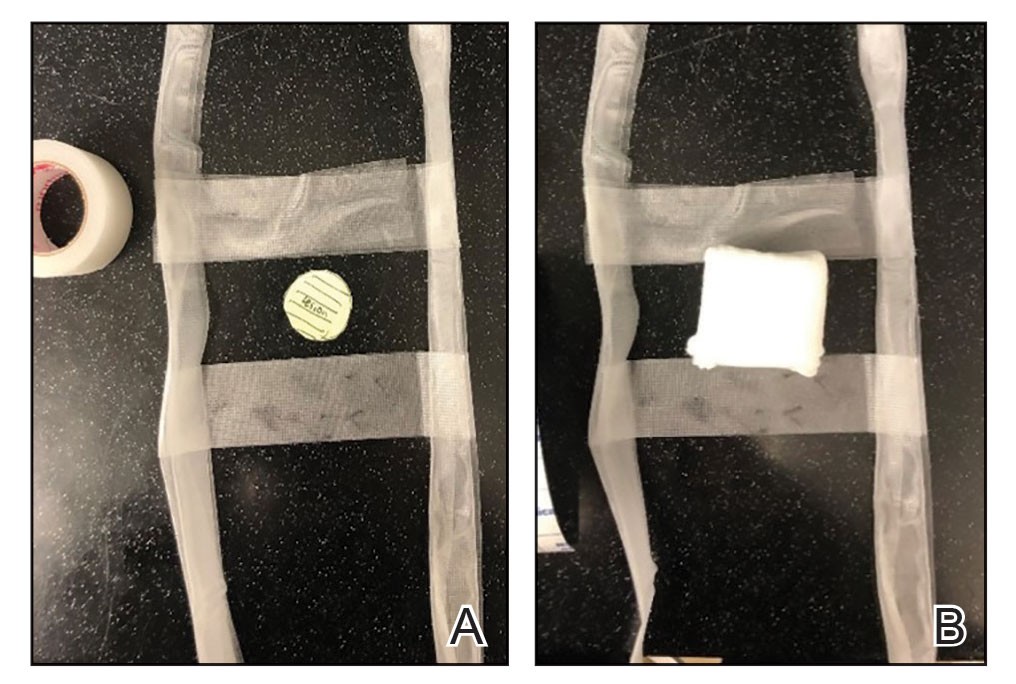

When secondary intention healing is chosen or a temporary bandage needs to be placed, we offer the use of bone wax as an alternative to help achieve hemostasis. Bone wax—a combination of beeswax, isopropyl palmitate, and a stabilizing agent such as almond oils or sterilized salicylic acid3—helps achieve hemostasis by purely mechanical means. It is malleable and can be easily adapted to the architecture of the surgical site (Figure 1). The bone wax can be applied immediately following surgery and removed during bandage change.

Practice Implications

Use of bone wax as a physical hemostatic agent provides a practical alternative to other options commonly used in dermatologic surgery for deep wounds or irregular surfaces. It offers several advantages.

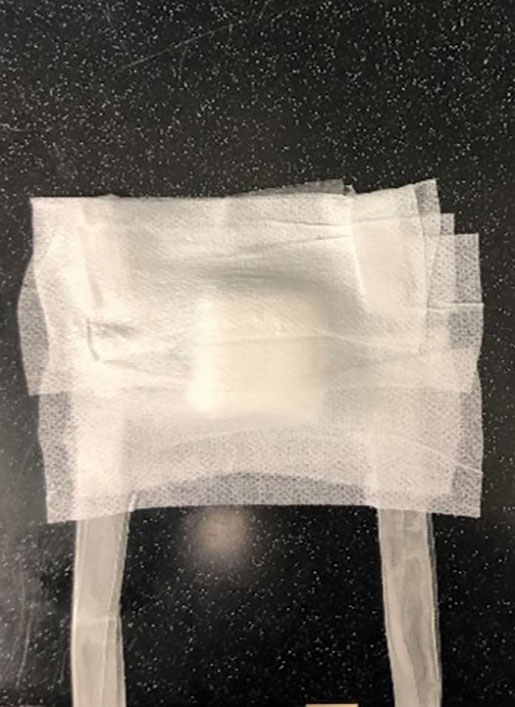

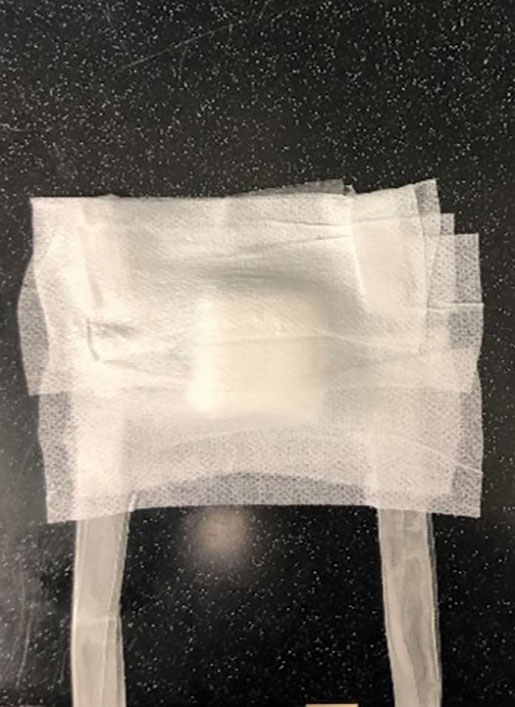

Bone wax is not absorbed and does not adhere to wound surfaces, which makes removal easy and painless. Furthermore, bone wax allows for excellent growth of granulation tissue2 (Figure 2), most likely due to the healing and emollient properties of the beeswax and the moist occlusive environment created by the bone wax.

Additional advantages are its low cost, especially compared to other hemostatic agents, and long shelf-life (approximately 5 years).2 Furthermore, in scenarios when cutaneous tumors extend into the calvarium, bone wax can prevent air emboli from entering noncollapsible emissary veins.4

When bone wax is used as a temporary measure in a dermatologic setting, complications inherent to its use in bone healing (eg, granulomatous reaction, infection)—for which it is left in place indefinitely—are avoided.

- Perandones-González H, Fernández-Canga P, Rodríguez-Prieto MA. Bone wax as an ideal dressing for auricle concha. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:e75-e76. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.002

- Palm MD, Altman JS. Topical hemostatic agents: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:431-445. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34090.x

- Alegre M, Garcés JR, Puig L. Bone wax in dermatologic surgery. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:299-303. doi:10.1016/j.adengl.2013.03.001

- Goldman G, Altmayer S, Sambandan P, et al. Development of cerebral air emboli during Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1414-1421. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01250.x

Practice Gap

Hemostasis after cutaneous surgery typically can be aided by mechanical occlusion with petrolatum and gauze known as a pressure bandage. However, in certain scenarios such as bone bleeding or irregularly shaped areas (eg, conchal bowl), difficulty applying a pressure bandage necessitates alternative hemostatic measures.1 In those instances, physical hemostatic agents, such as gelatin, oxidized cellulose, microporous polysaccharide spheres, hydrophilic polymers with potassium salts, microfibrillar collagen, and chitin, also can be used.2 However, those agents are expensive and often adhere to wound edges, inducing repeat trauma with removal. To avoid such concerns, we propose the use of bone wax as an effective hemostatic technique.

The Technique

When secondary intention healing is chosen or a temporary bandage needs to be placed, we offer the use of bone wax as an alternative to help achieve hemostasis. Bone wax—a combination of beeswax, isopropyl palmitate, and a stabilizing agent such as almond oils or sterilized salicylic acid3—helps achieve hemostasis by purely mechanical means. It is malleable and can be easily adapted to the architecture of the surgical site (Figure 1). The bone wax can be applied immediately following surgery and removed during bandage change.

Practice Implications

Use of bone wax as a physical hemostatic agent provides a practical alternative to other options commonly used in dermatologic surgery for deep wounds or irregular surfaces. It offers several advantages.

Bone wax is not absorbed and does not adhere to wound surfaces, which makes removal easy and painless. Furthermore, bone wax allows for excellent growth of granulation tissue2 (Figure 2), most likely due to the healing and emollient properties of the beeswax and the moist occlusive environment created by the bone wax.

Additional advantages are its low cost, especially compared to other hemostatic agents, and long shelf-life (approximately 5 years).2 Furthermore, in scenarios when cutaneous tumors extend into the calvarium, bone wax can prevent air emboli from entering noncollapsible emissary veins.4

When bone wax is used as a temporary measure in a dermatologic setting, complications inherent to its use in bone healing (eg, granulomatous reaction, infection)—for which it is left in place indefinitely—are avoided.

Practice Gap

Hemostasis after cutaneous surgery typically can be aided by mechanical occlusion with petrolatum and gauze known as a pressure bandage. However, in certain scenarios such as bone bleeding or irregularly shaped areas (eg, conchal bowl), difficulty applying a pressure bandage necessitates alternative hemostatic measures.1 In those instances, physical hemostatic agents, such as gelatin, oxidized cellulose, microporous polysaccharide spheres, hydrophilic polymers with potassium salts, microfibrillar collagen, and chitin, also can be used.2 However, those agents are expensive and often adhere to wound edges, inducing repeat trauma with removal. To avoid such concerns, we propose the use of bone wax as an effective hemostatic technique.

The Technique

When secondary intention healing is chosen or a temporary bandage needs to be placed, we offer the use of bone wax as an alternative to help achieve hemostasis. Bone wax—a combination of beeswax, isopropyl palmitate, and a stabilizing agent such as almond oils or sterilized salicylic acid3—helps achieve hemostasis by purely mechanical means. It is malleable and can be easily adapted to the architecture of the surgical site (Figure 1). The bone wax can be applied immediately following surgery and removed during bandage change.

Practice Implications

Use of bone wax as a physical hemostatic agent provides a practical alternative to other options commonly used in dermatologic surgery for deep wounds or irregular surfaces. It offers several advantages.

Bone wax is not absorbed and does not adhere to wound surfaces, which makes removal easy and painless. Furthermore, bone wax allows for excellent growth of granulation tissue2 (Figure 2), most likely due to the healing and emollient properties of the beeswax and the moist occlusive environment created by the bone wax.

Additional advantages are its low cost, especially compared to other hemostatic agents, and long shelf-life (approximately 5 years).2 Furthermore, in scenarios when cutaneous tumors extend into the calvarium, bone wax can prevent air emboli from entering noncollapsible emissary veins.4

When bone wax is used as a temporary measure in a dermatologic setting, complications inherent to its use in bone healing (eg, granulomatous reaction, infection)—for which it is left in place indefinitely—are avoided.

- Perandones-González H, Fernández-Canga P, Rodríguez-Prieto MA. Bone wax as an ideal dressing for auricle concha. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:e75-e76. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.002

- Palm MD, Altman JS. Topical hemostatic agents: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:431-445. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34090.x

- Alegre M, Garcés JR, Puig L. Bone wax in dermatologic surgery. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:299-303. doi:10.1016/j.adengl.2013.03.001

- Goldman G, Altmayer S, Sambandan P, et al. Development of cerebral air emboli during Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1414-1421. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01250.x

- Perandones-González H, Fernández-Canga P, Rodríguez-Prieto MA. Bone wax as an ideal dressing for auricle concha. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:e75-e76. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.002

- Palm MD, Altman JS. Topical hemostatic agents: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:431-445. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34090.x

- Alegre M, Garcés JR, Puig L. Bone wax in dermatologic surgery. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:299-303. doi:10.1016/j.adengl.2013.03.001

- Goldman G, Altmayer S, Sambandan P, et al. Development of cerebral air emboli during Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1414-1421. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01250.x

How to Optimize Wound Closure in Thin Skin

Practice Gap

Cutaneous surgery involves many areas where skin is quite thin and fragile, which often is encountered in elderly patients; the forearms and lower legs are the most frequent locations for thin skin.1 Dermatologic surgeons frequently encounter these situations, making this a highly practical arena for technical improvements.

For many of these patients, there is little meaningful dermis for placement of subcutaneous sutures. Therefore, a common approach following surgery, particularly following Mohs micrographic surgery in which tumors and defects typically are larger, is healing by secondary intention.2 Although healing by secondary intention often is a reasonable option, we have found that maximizing the use of epidermal skin for primary closure can be an effective means of closing many such defects. Antimicrobial reinforced skin closure strips have been incorporated in wound closure for thin skin. However, earlier efforts involving reinforcement perpendicular to the wound lacked critical details or used a different technique.3

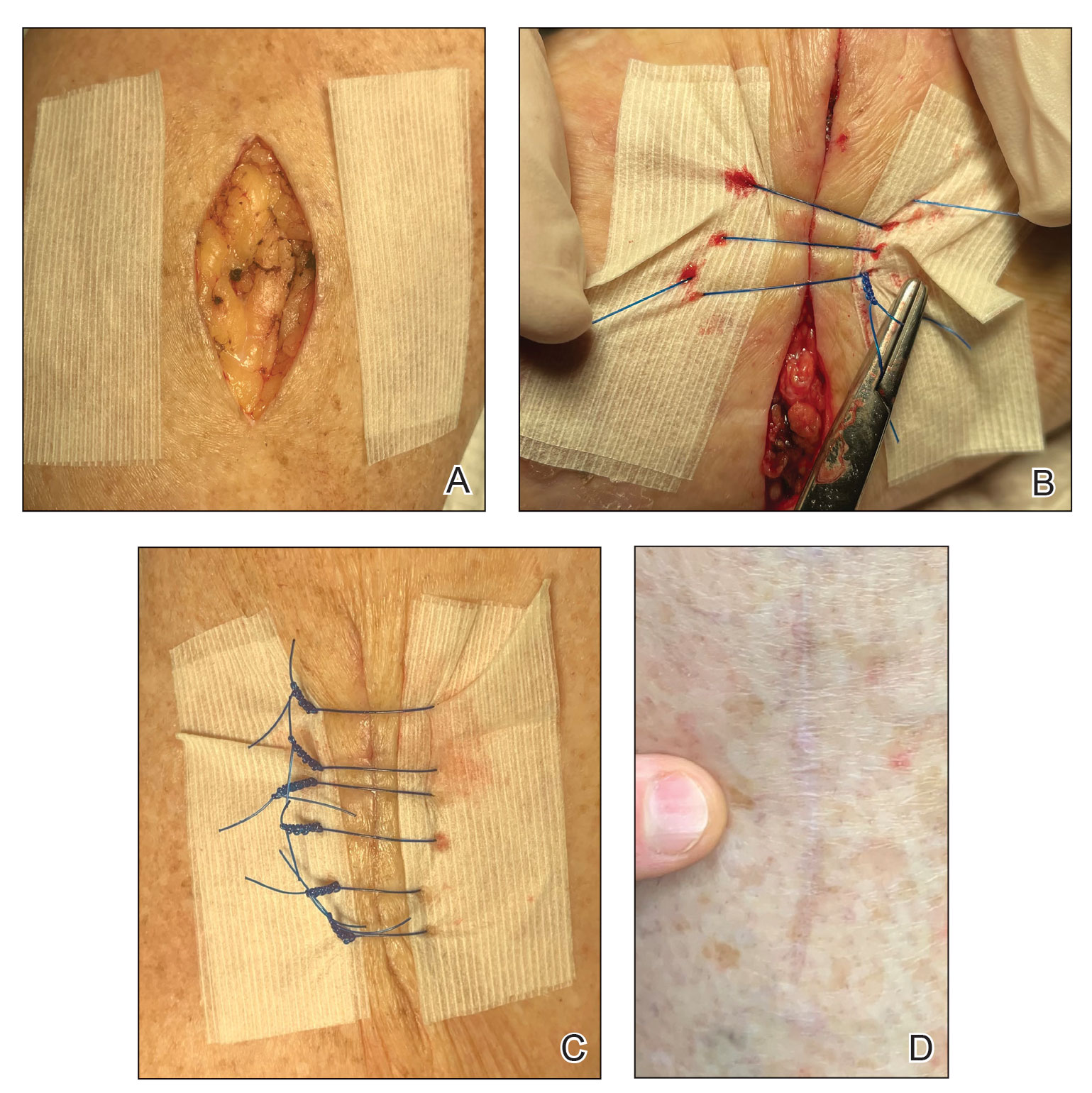

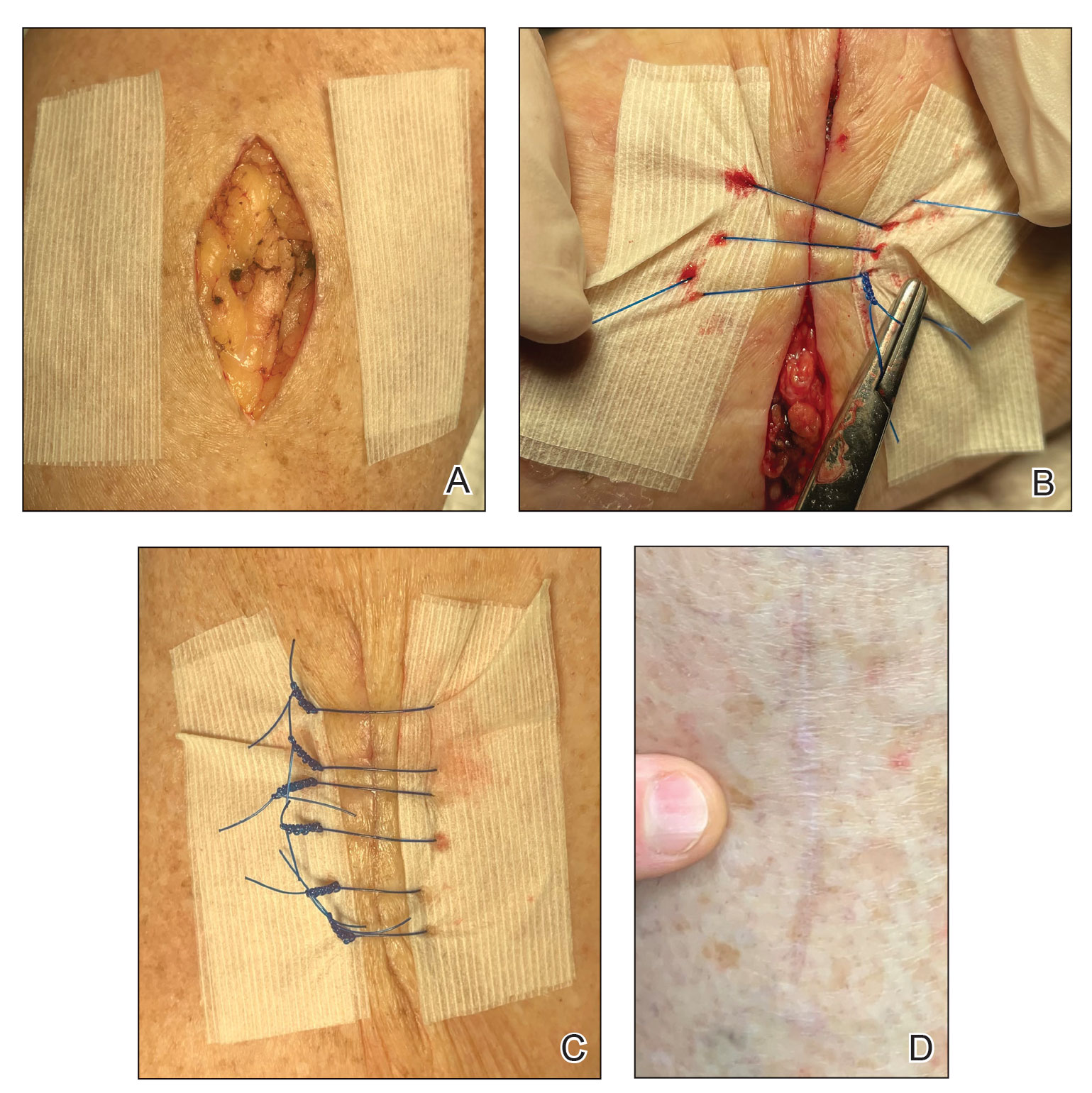

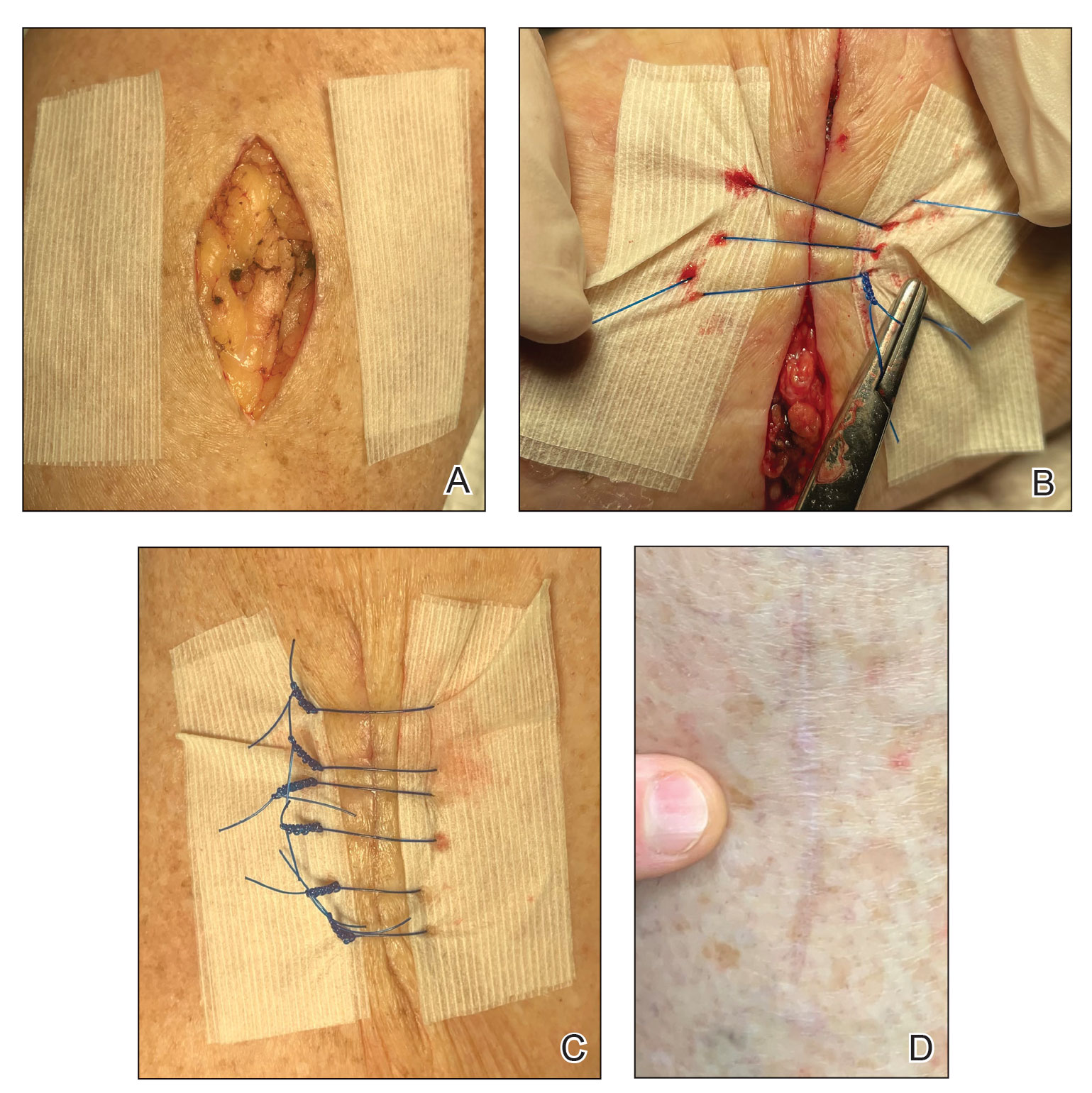

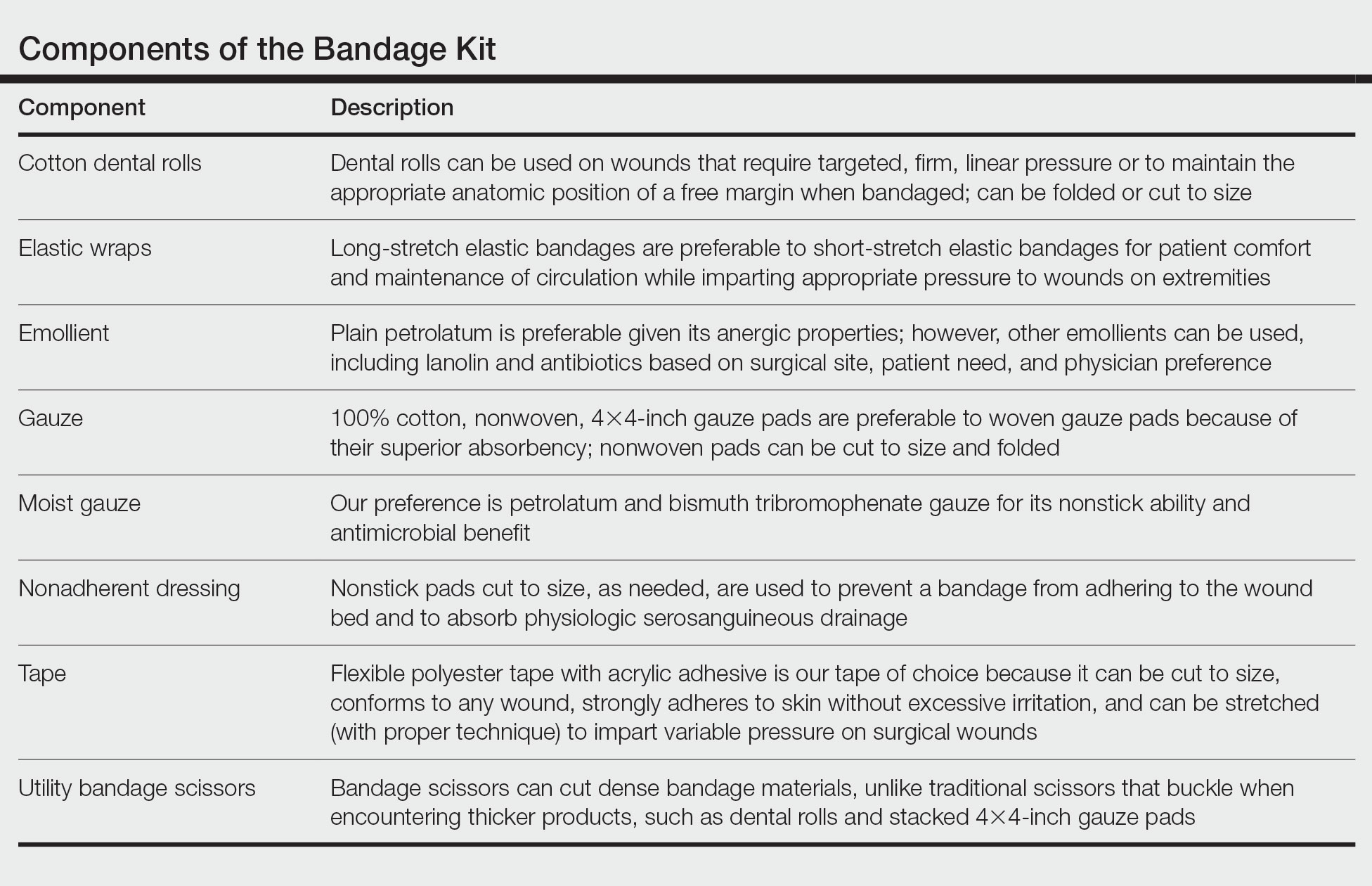

The Technique