User login

Transition to Tenecteplase From t-PA for Acute Ischemic Stroke at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center

Tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) has been the standard IV thrombolytic used in acute ischemic stroke treatment since its US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 1995. Trials have established this drug’s efficacy in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke and the appropriate patient population for therapy.1-3 Published guidelines and experiences have made clear that a written protocol with extensive personnel training is important to deliver this care properly.4

Tenecteplase has been available for use in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction (MI) and studied in acute ischemic strokes since 2000. Recent large multicenter trials have suggested tenecteplase may work better than t-PA in the recanalization of large vessel occlusions (LVOs) and have provided guidance on proper dosing in acute ischemic stroke victims.5-8 Compared with t-PA, tenecteplase has a longer half-life, is more fibrin specific (causing less coagulopathy), and is more resistant to endogenous plasminogen activator inhibitor.9,10 Using tenecteplase for acute ischemic stroke is simpler as a single dose bolus rather than a bolus followed by a 1-hour infusion with t-PA. Immediate mechanical thrombectomy for LVO is less complicated without the 1-hour t-PA infusion.5,6 Tenecteplase use also allows for nonthrombectomy hospitals to accelerate transfer times for patients who need thrombectomy following thrombolysis by eliminating the need for critical care nurse–staffed ambulances for interfacility transfer.11 Tenecteplase also is cheaper: Tenecteplase costs $3748 per vial, whereas t-PA costs $5800 per vial equating to roughly a $2000 savings per patient.12,13 Finally, the pharmacy formulary is simplified by using a single thrombolytic agent for both cardiac and neurologic emergencies.

Tenecteplase does have some drawbacks to consider. Currently, tenecteplase is not approved by the FDA for the indication of acute ischemic stroke, though the drug is endorsed by the American Heart Association stroke guidelines of 2019 as an alternative to t-PA.14 There is no stroke-specific preparation of the drug, leading to potential dosing errors. Therefore, a systematic process to safely transition from t-PA to tenecteplase for acute ischemic stroke was undertaken at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC) in Bethesda, Maryland. Here, we report the process required in making a complex switch in thrombolytic medication along with the potential benefits of making this transition.

OBSERVATIONS

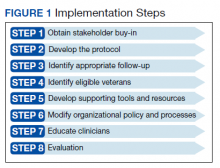

The process to implement tenecteplase required extensive training and education for staff physicians, nurses, pharmacists, radiologists, trainees, and the rapid response team. Our institution administered IV thrombolytic drugs up to 25 times annually to acute ischemic stroke victims, meaning we had to train personnel extensively and repeatedly.

In preparation for the transition to tenecteplase, hospital leadership gathered staff for multidisciplinary administrative meetings that included neurology, emergency medicine, intensive care, pharmacy, radiology, and nursing departments. The purpose of these meetings was to establish a standard operating procedure (SOP) to ensure a safe transition. This process began in May 2020 and involved regular meetings to draft and revise our SOP. Additionally, several leadership and training sessions were held over a 6-month period. Stroke boxes were developed that contained the required evaluation tools, consent forms, medications (tenecteplase and treatments for known complications), dosing cards, and instructions. Final approval of the updated acute ischemic stroke hospital policy was obtained in November 2020 and signed by the above departments.

All inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined to be the same for tenecteplase as they were for t-PA with the notable exception that the WAKE-UP trial protocol would not be supported until further evidence became available.9 The results of the WAKE-UP trial had previously been used at WRNMMC to justify administration of t-PA in patients who awoke with symptoms of acute ischemic stroke, the last known well was unclear or > 4.5 hours, and for whom a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain could be obtained rapidly. Based on the WAKE-UP trial, if the MRI scan of the brain in these patients demonstrated restricted diffusion without fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) signal changes (diffusion-weighted [DWI]-FLAIR mismatch sign), this indicated that the stroke had likely occurred recently, and it was safe to administer t-PA. This allowed for administration of t-PA outside the standard treatment window of 4.5 hours from last known well, especially in the cases of patients who awoke with symptoms.

Since safety data are not yet available for the use of tenecteplase in this fashion, the WAKE-UP trial protocol was not used as an inclusion criterion. The informed consent form was modified, and the following scenarios were outlined: (1) If the patient or surrogate is immediately available to consent, paper consent will be documented with the additional note that tenecteplase is being used off-label; and (2) If the patient cannot consent and a surrogate is not immediately available, the medicine will be used emergently as long as the neurology resident and attending physicians agree.15

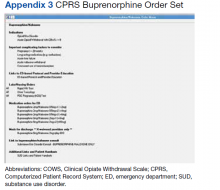

Risk mitigation was considered carefully. The stroke box described above is stocked and maintained by the pharmacy as we have transitioned to using designated pharmacists for the storage and preparation of tenecteplase. We highly recommend the use of designated pharmacists or emergency department pharmacists in this manner to avoid dosing errors.7,16 Since the current pharmacy-provided tenecteplase bottle contains twice the maximum dose indicated for ischemic stroke, only a 5 mL syringe is included in the stroke box to ensure a maximum dose of 25 mg is drawn up after reconstitution. Dosing card charts were made like existing dosing card charts for t-PA to quickly calculate the 0.25 mg/kg dose. In training, the difference in dosing in ischemic stroke was emphasized. Finally, pharmacy has taken responsibility for dosing the medication during stroke codes.

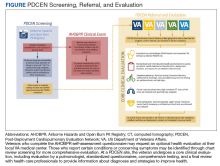

Any medical personnel at WRNMMC can initiate a stroke code by sending a page to the neurology consult service (Figure).

TRANSITION AND RESULTS

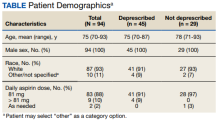

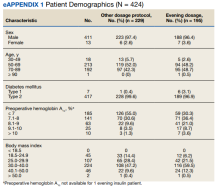

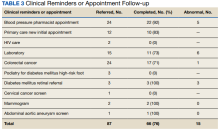

From November 2020 to December 2021, 10 patients have been treated in total at WRNMMC (Table).

CONCLUSIONS

The available evidence supports the transition from t-PA to tenecteplase for acute ischemic stroke. The successful transition required months of preparation involving multidisciplinary meetings between neurology, nursing, pharmacy, radiology, rapid response teams, critical care, and emergency medicine departments. Safeguards must be implemented to avoid a tenecteplase dosing error that can lead to potentially life-threatening adverse effects. The results at WRNMMC thus far are promising for safety and efficacy. Several process improvements are planned: a hospital-wide overhead page will accompany the direct page to neurology; other team members, including radiology and pharmacy, will be included on the acute stroke alert; and a stroke-specific paging application will be implemented to better track real-time stroke metrics and improve flow. These measures mirror processes that are occurring in institutions that treat acute stroke patients.

1. Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. Lancet. 2010;375(9727):1695-1703. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60491-6

2. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(24):1581- 1587. doi:10.1056/NEJM199512143332401

3. Hacke W, Donnan G, Fieschi C, et al. Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet. 2004;363(9411):768-774. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15692-4

4. Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP Jr, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870-947. doi:10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a

5. Campbell B, Mitchell P, Churilov L, et al. Tenecteplase versus alteplase before thrombectomy for ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(17):1573-1582. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1716405

6. Yang P, Zhang Y, Zhang L, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy with or without intravenous alteplase in acute stroke. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1981-1993. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001123

7. Menon BK, Buck BH, Singh N, et al. Intravenous tenecteplase compared with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in Canada (AcT): a pragmatic, multicentre, open-label, registry-linked, randomised, controlled, noninferiority trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10347):161-169. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01054-6

8. Campbell BCV, Mitchell PJ, Churilov L, et al. Effect of intravenous tenecteplase dose on cerebral reperfusion before thrombectomy in patients with large vessel occlusion ischemic stroke: the EXTEND-IA TNK part 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1257- 1265. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1511

9. Warach SJ, Dula AN, Milling TJ Jr. Tenecteplase thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2020;51(11):3440- 3451. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.029749

10. Huang X, Moreton FC, Kalladka D, et al. Coagulation and fibrinolytic activity of tenecteplase and alteplase in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2015;46(12):3543-3546. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011290

11. Burgos AM, Saver JL. Evidence that tenecteplase is noninferior to alteplase for acute ischemic stroke: meta-analysis of 5 randomized trials. Stroke. 2019;50(8):2156-2162. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.025080

12. Potla N, Ganti L. Tenecteplase vs. alteplase for acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review. Int J Emerg Med. 2022;15(1). doi:10.1186/s12245-021-00399-w

13. Warach SJ, Winegar A, Ottenbacher A, Miller C, Gibson D. Abstract WMP52: reduced hospital costs for ischemic stroke treated with tenecteplase. Stroke. 2022;53(suppl 1):AWMP52. doi:10.1161/str.53.suppl_1.WMP52

14. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344-e418. doi:10.1161/str.0000000000000211

15. Faris H, Dewar B, Dowlatshahi D, et al. Ethical justification for deferral of consent in the AcT trial for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2022;53(7):2420-2423. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.122.038760

16. Kvistad CE, Næss H, Helleberg BH, et al. Tenecteplase versus alteplase for the management of acute ischaemic stroke in Norway (NOR-TEST 2, part A): a phase 3, randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(6):511-519. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00124-7

Tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) has been the standard IV thrombolytic used in acute ischemic stroke treatment since its US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 1995. Trials have established this drug’s efficacy in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke and the appropriate patient population for therapy.1-3 Published guidelines and experiences have made clear that a written protocol with extensive personnel training is important to deliver this care properly.4

Tenecteplase has been available for use in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction (MI) and studied in acute ischemic strokes since 2000. Recent large multicenter trials have suggested tenecteplase may work better than t-PA in the recanalization of large vessel occlusions (LVOs) and have provided guidance on proper dosing in acute ischemic stroke victims.5-8 Compared with t-PA, tenecteplase has a longer half-life, is more fibrin specific (causing less coagulopathy), and is more resistant to endogenous plasminogen activator inhibitor.9,10 Using tenecteplase for acute ischemic stroke is simpler as a single dose bolus rather than a bolus followed by a 1-hour infusion with t-PA. Immediate mechanical thrombectomy for LVO is less complicated without the 1-hour t-PA infusion.5,6 Tenecteplase use also allows for nonthrombectomy hospitals to accelerate transfer times for patients who need thrombectomy following thrombolysis by eliminating the need for critical care nurse–staffed ambulances for interfacility transfer.11 Tenecteplase also is cheaper: Tenecteplase costs $3748 per vial, whereas t-PA costs $5800 per vial equating to roughly a $2000 savings per patient.12,13 Finally, the pharmacy formulary is simplified by using a single thrombolytic agent for both cardiac and neurologic emergencies.

Tenecteplase does have some drawbacks to consider. Currently, tenecteplase is not approved by the FDA for the indication of acute ischemic stroke, though the drug is endorsed by the American Heart Association stroke guidelines of 2019 as an alternative to t-PA.14 There is no stroke-specific preparation of the drug, leading to potential dosing errors. Therefore, a systematic process to safely transition from t-PA to tenecteplase for acute ischemic stroke was undertaken at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC) in Bethesda, Maryland. Here, we report the process required in making a complex switch in thrombolytic medication along with the potential benefits of making this transition.

OBSERVATIONS

The process to implement tenecteplase required extensive training and education for staff physicians, nurses, pharmacists, radiologists, trainees, and the rapid response team. Our institution administered IV thrombolytic drugs up to 25 times annually to acute ischemic stroke victims, meaning we had to train personnel extensively and repeatedly.

In preparation for the transition to tenecteplase, hospital leadership gathered staff for multidisciplinary administrative meetings that included neurology, emergency medicine, intensive care, pharmacy, radiology, and nursing departments. The purpose of these meetings was to establish a standard operating procedure (SOP) to ensure a safe transition. This process began in May 2020 and involved regular meetings to draft and revise our SOP. Additionally, several leadership and training sessions were held over a 6-month period. Stroke boxes were developed that contained the required evaluation tools, consent forms, medications (tenecteplase and treatments for known complications), dosing cards, and instructions. Final approval of the updated acute ischemic stroke hospital policy was obtained in November 2020 and signed by the above departments.

All inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined to be the same for tenecteplase as they were for t-PA with the notable exception that the WAKE-UP trial protocol would not be supported until further evidence became available.9 The results of the WAKE-UP trial had previously been used at WRNMMC to justify administration of t-PA in patients who awoke with symptoms of acute ischemic stroke, the last known well was unclear or > 4.5 hours, and for whom a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain could be obtained rapidly. Based on the WAKE-UP trial, if the MRI scan of the brain in these patients demonstrated restricted diffusion without fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) signal changes (diffusion-weighted [DWI]-FLAIR mismatch sign), this indicated that the stroke had likely occurred recently, and it was safe to administer t-PA. This allowed for administration of t-PA outside the standard treatment window of 4.5 hours from last known well, especially in the cases of patients who awoke with symptoms.

Since safety data are not yet available for the use of tenecteplase in this fashion, the WAKE-UP trial protocol was not used as an inclusion criterion. The informed consent form was modified, and the following scenarios were outlined: (1) If the patient or surrogate is immediately available to consent, paper consent will be documented with the additional note that tenecteplase is being used off-label; and (2) If the patient cannot consent and a surrogate is not immediately available, the medicine will be used emergently as long as the neurology resident and attending physicians agree.15

Risk mitigation was considered carefully. The stroke box described above is stocked and maintained by the pharmacy as we have transitioned to using designated pharmacists for the storage and preparation of tenecteplase. We highly recommend the use of designated pharmacists or emergency department pharmacists in this manner to avoid dosing errors.7,16 Since the current pharmacy-provided tenecteplase bottle contains twice the maximum dose indicated for ischemic stroke, only a 5 mL syringe is included in the stroke box to ensure a maximum dose of 25 mg is drawn up after reconstitution. Dosing card charts were made like existing dosing card charts for t-PA to quickly calculate the 0.25 mg/kg dose. In training, the difference in dosing in ischemic stroke was emphasized. Finally, pharmacy has taken responsibility for dosing the medication during stroke codes.

Any medical personnel at WRNMMC can initiate a stroke code by sending a page to the neurology consult service (Figure).

TRANSITION AND RESULTS

From November 2020 to December 2021, 10 patients have been treated in total at WRNMMC (Table).

CONCLUSIONS

The available evidence supports the transition from t-PA to tenecteplase for acute ischemic stroke. The successful transition required months of preparation involving multidisciplinary meetings between neurology, nursing, pharmacy, radiology, rapid response teams, critical care, and emergency medicine departments. Safeguards must be implemented to avoid a tenecteplase dosing error that can lead to potentially life-threatening adverse effects. The results at WRNMMC thus far are promising for safety and efficacy. Several process improvements are planned: a hospital-wide overhead page will accompany the direct page to neurology; other team members, including radiology and pharmacy, will be included on the acute stroke alert; and a stroke-specific paging application will be implemented to better track real-time stroke metrics and improve flow. These measures mirror processes that are occurring in institutions that treat acute stroke patients.

Tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) has been the standard IV thrombolytic used in acute ischemic stroke treatment since its US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 1995. Trials have established this drug’s efficacy in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke and the appropriate patient population for therapy.1-3 Published guidelines and experiences have made clear that a written protocol with extensive personnel training is important to deliver this care properly.4

Tenecteplase has been available for use in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction (MI) and studied in acute ischemic strokes since 2000. Recent large multicenter trials have suggested tenecteplase may work better than t-PA in the recanalization of large vessel occlusions (LVOs) and have provided guidance on proper dosing in acute ischemic stroke victims.5-8 Compared with t-PA, tenecteplase has a longer half-life, is more fibrin specific (causing less coagulopathy), and is more resistant to endogenous plasminogen activator inhibitor.9,10 Using tenecteplase for acute ischemic stroke is simpler as a single dose bolus rather than a bolus followed by a 1-hour infusion with t-PA. Immediate mechanical thrombectomy for LVO is less complicated without the 1-hour t-PA infusion.5,6 Tenecteplase use also allows for nonthrombectomy hospitals to accelerate transfer times for patients who need thrombectomy following thrombolysis by eliminating the need for critical care nurse–staffed ambulances for interfacility transfer.11 Tenecteplase also is cheaper: Tenecteplase costs $3748 per vial, whereas t-PA costs $5800 per vial equating to roughly a $2000 savings per patient.12,13 Finally, the pharmacy formulary is simplified by using a single thrombolytic agent for both cardiac and neurologic emergencies.

Tenecteplase does have some drawbacks to consider. Currently, tenecteplase is not approved by the FDA for the indication of acute ischemic stroke, though the drug is endorsed by the American Heart Association stroke guidelines of 2019 as an alternative to t-PA.14 There is no stroke-specific preparation of the drug, leading to potential dosing errors. Therefore, a systematic process to safely transition from t-PA to tenecteplase for acute ischemic stroke was undertaken at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC) in Bethesda, Maryland. Here, we report the process required in making a complex switch in thrombolytic medication along with the potential benefits of making this transition.

OBSERVATIONS

The process to implement tenecteplase required extensive training and education for staff physicians, nurses, pharmacists, radiologists, trainees, and the rapid response team. Our institution administered IV thrombolytic drugs up to 25 times annually to acute ischemic stroke victims, meaning we had to train personnel extensively and repeatedly.

In preparation for the transition to tenecteplase, hospital leadership gathered staff for multidisciplinary administrative meetings that included neurology, emergency medicine, intensive care, pharmacy, radiology, and nursing departments. The purpose of these meetings was to establish a standard operating procedure (SOP) to ensure a safe transition. This process began in May 2020 and involved regular meetings to draft and revise our SOP. Additionally, several leadership and training sessions were held over a 6-month period. Stroke boxes were developed that contained the required evaluation tools, consent forms, medications (tenecteplase and treatments for known complications), dosing cards, and instructions. Final approval of the updated acute ischemic stroke hospital policy was obtained in November 2020 and signed by the above departments.

All inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined to be the same for tenecteplase as they were for t-PA with the notable exception that the WAKE-UP trial protocol would not be supported until further evidence became available.9 The results of the WAKE-UP trial had previously been used at WRNMMC to justify administration of t-PA in patients who awoke with symptoms of acute ischemic stroke, the last known well was unclear or > 4.5 hours, and for whom a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain could be obtained rapidly. Based on the WAKE-UP trial, if the MRI scan of the brain in these patients demonstrated restricted diffusion without fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) signal changes (diffusion-weighted [DWI]-FLAIR mismatch sign), this indicated that the stroke had likely occurred recently, and it was safe to administer t-PA. This allowed for administration of t-PA outside the standard treatment window of 4.5 hours from last known well, especially in the cases of patients who awoke with symptoms.

Since safety data are not yet available for the use of tenecteplase in this fashion, the WAKE-UP trial protocol was not used as an inclusion criterion. The informed consent form was modified, and the following scenarios were outlined: (1) If the patient or surrogate is immediately available to consent, paper consent will be documented with the additional note that tenecteplase is being used off-label; and (2) If the patient cannot consent and a surrogate is not immediately available, the medicine will be used emergently as long as the neurology resident and attending physicians agree.15

Risk mitigation was considered carefully. The stroke box described above is stocked and maintained by the pharmacy as we have transitioned to using designated pharmacists for the storage and preparation of tenecteplase. We highly recommend the use of designated pharmacists or emergency department pharmacists in this manner to avoid dosing errors.7,16 Since the current pharmacy-provided tenecteplase bottle contains twice the maximum dose indicated for ischemic stroke, only a 5 mL syringe is included in the stroke box to ensure a maximum dose of 25 mg is drawn up after reconstitution. Dosing card charts were made like existing dosing card charts for t-PA to quickly calculate the 0.25 mg/kg dose. In training, the difference in dosing in ischemic stroke was emphasized. Finally, pharmacy has taken responsibility for dosing the medication during stroke codes.

Any medical personnel at WRNMMC can initiate a stroke code by sending a page to the neurology consult service (Figure).

TRANSITION AND RESULTS

From November 2020 to December 2021, 10 patients have been treated in total at WRNMMC (Table).

CONCLUSIONS

The available evidence supports the transition from t-PA to tenecteplase for acute ischemic stroke. The successful transition required months of preparation involving multidisciplinary meetings between neurology, nursing, pharmacy, radiology, rapid response teams, critical care, and emergency medicine departments. Safeguards must be implemented to avoid a tenecteplase dosing error that can lead to potentially life-threatening adverse effects. The results at WRNMMC thus far are promising for safety and efficacy. Several process improvements are planned: a hospital-wide overhead page will accompany the direct page to neurology; other team members, including radiology and pharmacy, will be included on the acute stroke alert; and a stroke-specific paging application will be implemented to better track real-time stroke metrics and improve flow. These measures mirror processes that are occurring in institutions that treat acute stroke patients.

1. Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. Lancet. 2010;375(9727):1695-1703. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60491-6

2. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(24):1581- 1587. doi:10.1056/NEJM199512143332401

3. Hacke W, Donnan G, Fieschi C, et al. Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet. 2004;363(9411):768-774. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15692-4

4. Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP Jr, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870-947. doi:10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a

5. Campbell B, Mitchell P, Churilov L, et al. Tenecteplase versus alteplase before thrombectomy for ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(17):1573-1582. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1716405

6. Yang P, Zhang Y, Zhang L, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy with or without intravenous alteplase in acute stroke. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1981-1993. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001123

7. Menon BK, Buck BH, Singh N, et al. Intravenous tenecteplase compared with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in Canada (AcT): a pragmatic, multicentre, open-label, registry-linked, randomised, controlled, noninferiority trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10347):161-169. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01054-6

8. Campbell BCV, Mitchell PJ, Churilov L, et al. Effect of intravenous tenecteplase dose on cerebral reperfusion before thrombectomy in patients with large vessel occlusion ischemic stroke: the EXTEND-IA TNK part 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1257- 1265. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1511

9. Warach SJ, Dula AN, Milling TJ Jr. Tenecteplase thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2020;51(11):3440- 3451. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.029749

10. Huang X, Moreton FC, Kalladka D, et al. Coagulation and fibrinolytic activity of tenecteplase and alteplase in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2015;46(12):3543-3546. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011290

11. Burgos AM, Saver JL. Evidence that tenecteplase is noninferior to alteplase for acute ischemic stroke: meta-analysis of 5 randomized trials. Stroke. 2019;50(8):2156-2162. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.025080

12. Potla N, Ganti L. Tenecteplase vs. alteplase for acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review. Int J Emerg Med. 2022;15(1). doi:10.1186/s12245-021-00399-w

13. Warach SJ, Winegar A, Ottenbacher A, Miller C, Gibson D. Abstract WMP52: reduced hospital costs for ischemic stroke treated with tenecteplase. Stroke. 2022;53(suppl 1):AWMP52. doi:10.1161/str.53.suppl_1.WMP52

14. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344-e418. doi:10.1161/str.0000000000000211

15. Faris H, Dewar B, Dowlatshahi D, et al. Ethical justification for deferral of consent in the AcT trial for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2022;53(7):2420-2423. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.122.038760

16. Kvistad CE, Næss H, Helleberg BH, et al. Tenecteplase versus alteplase for the management of acute ischaemic stroke in Norway (NOR-TEST 2, part A): a phase 3, randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(6):511-519. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00124-7

1. Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. Lancet. 2010;375(9727):1695-1703. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60491-6

2. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(24):1581- 1587. doi:10.1056/NEJM199512143332401

3. Hacke W, Donnan G, Fieschi C, et al. Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet. 2004;363(9411):768-774. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15692-4

4. Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP Jr, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870-947. doi:10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a

5. Campbell B, Mitchell P, Churilov L, et al. Tenecteplase versus alteplase before thrombectomy for ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(17):1573-1582. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1716405

6. Yang P, Zhang Y, Zhang L, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy with or without intravenous alteplase in acute stroke. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1981-1993. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001123

7. Menon BK, Buck BH, Singh N, et al. Intravenous tenecteplase compared with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in Canada (AcT): a pragmatic, multicentre, open-label, registry-linked, randomised, controlled, noninferiority trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10347):161-169. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01054-6

8. Campbell BCV, Mitchell PJ, Churilov L, et al. Effect of intravenous tenecteplase dose on cerebral reperfusion before thrombectomy in patients with large vessel occlusion ischemic stroke: the EXTEND-IA TNK part 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1257- 1265. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1511

9. Warach SJ, Dula AN, Milling TJ Jr. Tenecteplase thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2020;51(11):3440- 3451. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.029749

10. Huang X, Moreton FC, Kalladka D, et al. Coagulation and fibrinolytic activity of tenecteplase and alteplase in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2015;46(12):3543-3546. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011290

11. Burgos AM, Saver JL. Evidence that tenecteplase is noninferior to alteplase for acute ischemic stroke: meta-analysis of 5 randomized trials. Stroke. 2019;50(8):2156-2162. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.025080

12. Potla N, Ganti L. Tenecteplase vs. alteplase for acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review. Int J Emerg Med. 2022;15(1). doi:10.1186/s12245-021-00399-w

13. Warach SJ, Winegar A, Ottenbacher A, Miller C, Gibson D. Abstract WMP52: reduced hospital costs for ischemic stroke treated with tenecteplase. Stroke. 2022;53(suppl 1):AWMP52. doi:10.1161/str.53.suppl_1.WMP52

14. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344-e418. doi:10.1161/str.0000000000000211

15. Faris H, Dewar B, Dowlatshahi D, et al. Ethical justification for deferral of consent in the AcT trial for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2022;53(7):2420-2423. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.122.038760

16. Kvistad CE, Næss H, Helleberg BH, et al. Tenecteplase versus alteplase for the management of acute ischaemic stroke in Norway (NOR-TEST 2, part A): a phase 3, randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(6):511-519. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00124-7

A Transdisciplinary Program for Care of Veterans With Neurocognitive Disorders

Dementia is a devastating condition resulting in major functional, emotional, and financial impact on patients, their caregivers, and families. Approximately 6.5 million Americans are living with Alzheimer disease (AD), the most common of many causes of dementia.1 The prevalence of AD could increase to 12.7 million Americans by 2050 as the population ages.1 Studies suggest that dementia, also known as major neurocognitive disorder, is common and underdiagnosed among US veterans, a population with a mean age of 65 years.2 During cognitive screening, memory impairment is present in approximately 20% of veterans aged ≥ 75 years who have not been diagnosed with a neurocognitive disorder.3 In addition, veterans might be particularly vulnerable to dementia at an earlier age than the general population because of vascular risk factors and traumatic brain injuries.4 These concerns highlight the need for effective dementia care programs at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities.

The US health care system often does not adequately address the needs of patients with dementia and their caregivers.5 Dementia care requires specialized medical care among collaborating professionals and caregiver and psychosocial interventions and services. However, the US health care system is fragmented with different clinicians and services siloed into separate practices and most dementia care occurring in primary care settings.6 Primary care professionals (PCPs) often are uncomfortable diagnosing and managing dementia because of time constraints, lack of expertise and training, and inability to deal with the range of care needs.7 PCPs do not identify approximately 42% of their patients with dementia and, when recognized, do not adhere to dementia care guidelines and address caregiver needs.8-10 Research indicates that caregiver support improves dementia care by teaching behavioral management skills and caregiver coping strategies, allowing patients to stay at home and delay institutionalization.6,11,12 Clinicians underuse available resources and do not incorporate them in their patient care.10 These community services benefit patients and caregivers and significantly improve the overall quality of care.6

Memory clinics have emerged to address these deficiencies when managing dementia.13 The most effective memory clinics maximize the use of specialists with different expertise in dementia care, particularly integrated programs where disciplines function together rather than independently.1,5,14 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have documented the effectiveness of collaborative care management programs.11,12,15 Integration of dementia care management is associated with earlier diagnosis and interventions, decreased functional and cognitive symptom severity, decreased or delayed institutionalization, improved quality of life for patients and caregivers, enhanced overall quality of care and cost-effectiveness, and better integration of community services.11,12,14-19 In these programs, designating a dementia care manager (DCM) as the patient’s advocate facilitates the integrated structure, increases the quality of care, helps caregivers, facilitates adherence to dementia practice guidelines, and prevents behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD).1,6,11,12,20,21

The best interprofessional model for dementia care might be the transdisciplinary model that includes a DCM. To meet the specific demands of dementia care, there must be a high level of interprofessional collaboration rather than multiple health care professionals (HCPs) delivering care in isolation—an approach that is time consuming and often difficult to implement.22 Whereas multidisciplinary care refers to delivery of parallel services and interdisciplinary care implies a joint formulation, transdisciplinary care aims to maximize integration of HCPs and their specific expertise and contributions through interactions and discussions that deliver focused input to the lead physician. The transdisciplinary model addresses needs that often are missed and can minimize disparities in the quality of dementia care.23 A DCM is an integral part of our program, facilitating understanding and implementation of the final care plan and providing long-term follow-up and care. We outline a conference-centered transdisciplinary dementia care model with a social worker as DCM (SW-DCM) at our VA medical center.

Program Description

In 2020, the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) in California established a multispecialty clinic dedicated to evaluation and treatment of veterans with memory and neurocognitive disorders and to provide support for their caregivers and families. With the agreement of leadership in mental health, neurology, and geriatrics services on the importance of collaboration for dementia care, the psychiatry and neurology services created a joint Memory and Neurobehavior Clinic, which completed its first 2 years of operation as a full-day program. In recent months, the clinic has scheduled 24 veterans per day, approximately 50% new evaluations and 50% follow-up patients, with wait times of < 2 months. There is a mean of 12 intake or lead physicians who could attend sessions in the morning, afternoon, or both. The general clinic flow consists of a 2-hour intake evaluation of new referrals by the lead physician followed by a clinic conference with transdisciplinary discussion. The DCM then follows up with the veteran/caregiver presenting a final care plan individualized to the veterans, caregivers, and families.

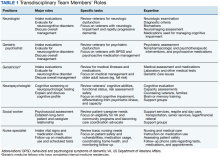

The Memory and Neurobehavior team includes behavioral neurologists, geriatric psychiatrists, neuropsychologists, geriatric fellows, advanced clinical nurses, and social workers who function as the DCM (Table 1).

Procedures

Before the office visit, the coordinating geriatric psychiatrist triages veterans to neurology, psychiatry, or geriatric physicians based on the clinical presentation, history of neurologic signs or symptoms, BPSD or psychiatric history, functional decline, or comorbid medical illnesses. Although veterans often have overlapping concerns, the triage process aims to coordinate the intake evaluations with the most indicated and available specialist with the intention to notify the other specialists during the transdisciplinary conference.

Referrals to the program occur from many sources, notably from primary care (70.8%), mental health (16.7%), and specialty clinics (12.5%). The clinic also receives referrals from the affiliated Veterans Cognitive Assessment and Management Program, which provides dementia evaluation and support via telehealth screening. This VAGLAHS program services a diverse population of veterans: 87% male; 43% aged > 65 years (75% in our clinic); 51% non-Hispanic White; 19% non-Hispanic African American; 16% Hispanic; 4% Asian; and 1% Native American. This population receives care at regional VA medical centers and community-based outpatient clinics over a wide geographic service area.

The initial standardized assessments by intake or lead physicians includes mental status screening with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (with certified clinicians), the Neurobehavioral Status Examination for a more detailed assessment of cognitive domains, the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale, the Patient Health Questionnaire for depression screening, and assessment for impairments in instrumental or basic activities of daily living. This initial evaluation aims to apply clinical guidelines and diagnostic criteria for the differential diagnosis of neurocognitive disorders, determine eligibility for cognitive-enhancing medications and techniques, assess for BPSD and the need for nonpharmacologic or pharmacologic interventions, determine functional status, and evaluate the need for supervision, safety concerns, and evidence of neglect or abuse.

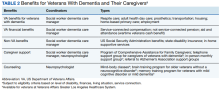

As part of its mission, the clinic is charged with implementing the VA Dementia System of Care (DSOC). The stated goals of the DSOC are to provide individualized person-centered dementia care to help veterans experiencing dementia and their caregivers maintain a positive and optimal quality of life and create an environment where VA medical center staff understand the health care needs of veterans with dementia and their caregivers’ role. As part of this initiative, the clinic includes (1) coordination of care through a SW-DCM; (2)

Transdisciplinary Conference

Clinic conferences are held after the veterans are seen. Staff gather to discuss the patient and review management. All team members are present, as well as the head of the clinical clerical staff who can facilitate appointments, make lobby and wait times more bearable for our patients and caregivers, and help manage emergencies. Although this is an in-person conference, the COVID-19 pandemic has allowed us to include staff who screen at remote sites via videoconferencing, similar to other VA programs.24 The Memory and Neurobehavior Clinic has two ≤ 90-minute conferences daily. The lead physicians and their senior attendings present the new intake evaluations (4-6 at each conference session) with a preliminary formulation and questions for discussion. The moderator solicits contributions from the different disciplines, going from one to the next and recording their responses for each veteran. Further specialists are available for consultation through the conference mechanism if necessary. The final assessment is reviewed, a diagnosis is established, and a tailored, individualized care plan for adjusting or optimizing the veteran’s care is presented to the lead physician who makes the final determination. At the close of the conference, the team’s discussion is recorded along with the lead physician’s original detailed intake evaluation. Currently, the records go into the Computerized Patient Record System, but we are making plans to transition to Cerner as it is implemented.

During the discussion, team members review several areas of consideration. If there is neuroimaging, neurologists review the images projected on a large computer screen. Team members also will assess for the need to obtain biomarker studies, such as blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or positron emission tomography. Psychiatrists could review management of BPSD and use of psychotropic agents, and neuropsychologists might consider the need for more precise cognitive testing and whether a capacity assessment is indicated. Social work might bring up the need for a durable power of attorney as well as applicable caregiver and community resources. Geriatric medicine and nursing could provide input into medical management and care and the ability of veterans and caregivers to follow the prescribed regimen. Further areas of discussion include driving safety and restrictions on driving (as required in California) and the presence of guns in the home. Finally, brief education is provided in short 10-to-15-minute lectures covering pertinent topics so staff remain up-to-date in this changing field.

Postconference Continuity

After the conference, the SW-DCM continues to provide support throughout the disease course, helping veterans and their caregivers understand and follow through on the team’s recommendations. The SW-DCM, who is experienced and trained in case management, forms an ongoing relationship with the veterans and their caregivers and remains an advocate for their care. The SW-DCM communicates the final plan by phone and, when necessary, requests the lead physician to call to clarify any poorly understood or technical aspects of the care plan. About 50% of our veterans—primarily those who do not have a neurocognitive disorder or have mild cognitive impairment—return to their PCPs with our care plan consultation; about 25% are already enrolled in geriatric and other programs with long-term follow-up. The assigned SW-DCM follows up with the remaining veterans and caregivers regularly by phone, facilitates communication with other team members, and endeavors to assure postvisit continuity of care and support during advancing stages of the disease. In addition, the SW-DCM can provide supportive counseling and psychotherapy for stressed caregivers, refer to support groups and cognitive rehabilitation programs, and help develop long-term goals and consideration for supervised living environments. The nurse specialist participates with follow-up calls regarding medications and scheduled tests and appointments, clearing up confusion about instructions, avoiding medication errors, and providing education in dementia care. Both social worker and nurse are present throughout the week, reachable by phone, and, in turn, able to contact the clinic physicians for veterans’ needs.

Discussion

Because of the heterogenous medical and psychosocial needs of veterans with dementia and their caregivers, a transdisciplinary team with a dedicated DCM might offer the most effective and efficient model for dementia care. We present a transdisciplinary program that incorporates dementia specialists in a single evaluation by maximizing their time through a conference-centered program. Our program involves neurologists, psychiatrists, geriatricians, psychologists, nurses, and social workers collaborating and communicating to enact effective dementia care. It further meets the goals of the VA-DSOC in implementing individualized patient and caregiver care.

This transdisciplinary model addresses a number of issues, starting with the differential diagnosis of underlying neurologic conditions. Within the transdisciplinary team, the neurologist can provide specific insights into any neurologic findings and illnesses, such as Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative dementias, vascular dementia syndromes, normal pressure hydrocephalus, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, neurosyphilis, and others. Most veterans with dementia experience BPSD at some point during of their illness. The psychiatrists on the transdisciplinary team can maximize management of BPSD with nonpharmacologic interventions and the fewest and least aversive psychoactive medications. Our program also addresses the need for more precise cognitive evaluation. Neuropsychologists are present and available for administrating neuropsychologic tests and interpreting cognitive performance and any earlier neuropsychologic testing. This model also cares for the caregivers and assesses their needs. The social worker—as well as other members of the team—can provide caregivers with strategies for coping with disruptive and other behaviors related to dementia, counsel them on how to manage the veteran’s functional decline, and aid in establishing a safe living space. Because the social worker serves as a DCM, these coping and adjustment questions occupy significant clinical attention between appointments. This transdisciplinary model places the patient’s illness in the context of their functional status, diagnoses, and medications. The team geriatrician and the nurse specialist are indispensable resources. The clinic conference provides a teaching venue for staff and trainees and a mechanism to discuss new developments in dementia care, such as the increasing need to assess individuals with mild cognitive impairment.25 This model depends on the DCM’s invaluable role in ensuring implementation of the dementia care plan and continuity of care.

Conclusions

We describe effective dementia care with a transdisciplinary team in a conference setting and with the participation of a dedicated DCM.5 To date, this program appears to be an efficient, sustainable application of the limited resources allocated to dementia care. Nevertheless, we are collecting data to compare with performance measures, track use, and assess the programs effects on continuity of care. We look forward to presenting metrics from our program that show improvement in the health care for veterans experiencing a devastating and increasingly common disorder.

1. 2022 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(4):700-789. doi:10.1002/alz.12638

2. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Profile of veterans: 2016. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Veterans_2016.pdf

3. Chodosh J, Sultzer DL, Lee ML, et al. Memory impairment among primary care veterans. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(4):444-450. doi:10.1080/13607860601086272

4. Kennedy E, Panahi S, Stewart IJ, et al. Traumatic brain injury and early onset dementia in post 9-11 veterans. Brain Inj. 2022;36(5):620-627. doi:10.1080/02699052.2022.20338465. Heintz H, Monette P, Epstein-Lubow G, Smith L, Rowlett S, Forester BP. Emerging collaborative care models for dementia care in the primary care setting: a narrative review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(3):320-330. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2019.07.015

6. Reuben DB, Evertson LC, Wenger NS, et al. The University of California at Los Angeles Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care program for comprehensive, coordinated, patient-centered care: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(12):2214-2218. doi:10.1111/jgs.12562

7. Apesoa-Varano EC, Barker JC, Hinton L. Curing and caring: the work of primary care physicians with dementia patients. Qual Health Res. 2011;21(11):1469-1483. doi:10.1177/1049732311412788

8. Creavin ST, Noel-Storr AH, Langdon RJ, et al. Clinical judgement by primary care physicians for the diagnosis of all-cause dementia or cognitive impairment in symptomatic people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;6:CD012558. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012558.pub2

9. Sivananthan SN, Puyat JH, McGrail KM. Variations in self-reported practice of physicians providing clinical care to individuals with dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(8):1277-1285. doi:10.1111/jgs.12368

10. Rosen CS, Chow HC, Greenbaum MA, et al. How well are clinicians following dementia practice guidelines? Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002;16(1):15-23. doi:10.1097/00002093-200201000-00003

11. Reilly S, Miranda-Castillo C, Malouf R, et al. Case management approaches to home support for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD008345. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008345.pub2

12. Tam-Tham H, Cepoiu-Martin M, Ronksley PE, Maxwell CJ, Hemmelgarn BR. Dementia case management and risk of long-term care placement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(9):889-902. doi:10.1002/gps.3906

13. Jolley D, Benbow SM, Grizzell M. Memory clinics. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(965):199-206. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2005.040592

14. Muhlichen F, Michalowsky B, Radke A, et al. Tasks and activities of an effective collaborative dementia care management program in German primary care. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;87(4):1615-1625. doi:10.3233/JAD-215656

15. Somme D, Trouve H, Drame M, Gagnon D, Couturier Y, Saint-Jean O. Analysis of case management programs for patients with dementia: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(5):426-436. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2011.06.004

16. Ramakers IH, Verhey FR. Development of memory clinics in the Netherlands: 1998 to 2009. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(1):34-39. doi:10.1080/13607863.2010.519321

17. LaMantia MA, Alder CA, Callahan CM, et al. The aging brain care medical home: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(6):1209-1213. doi:10.1111/jgs.13447

18. Rubinsztein JS, van Rensburg MJ, Al-Salihy Z, et al. A memory clinic v. traditional community mental health team service: comparison of costs and quality. BJPsych Bull. 2015;39(1):6-11. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.113.044263

19. Lee L, Hillier LM, Harvey D. Integrating community services into primary care: improving the quality of dementia care. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2014;4(1):11-21. doi:10.2217/nmt.13.72

20. Bass DM, Judge KS, Snow AL, et al. Caregiver outcomes of partners in dementia care: effect of a care coordination program for veterans with dementia and their family members and friends. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(8):1377-1386. doi:10.1111/jgs.12362

21. Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(18):2148-2157. doi:10.1001/jama.295.18.2148

22. Leggett A, Connell C, Dubin L, et al. Dementia care across a tertiary care health system: what exists now and what needs to change. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(10):1307-12 e1. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2019.04.006

23. Brown AF, Vassar SD, Connor KI, Vickrey BG. Collaborative care management reduces disparities in dementia care quality for caregivers with less education. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):243-251. doi:10.1111/jgs.12079

24. Powers BB, Homer MC, Morone N, Edmonds N, Rossi MI. Creation of an interprofessional teledementia clinic for rural veterans: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1092-1099. doi:10.1111/jgs.14839

25. Galvin JE, Aisen P, Langbaum JB, et al. Early stages of Alzheimer’s Disease: evolving the care team for optimal patient management. Front Neurol. 2020;11:592302. doi:10.3389/fneur.2020.592302

Dementia is a devastating condition resulting in major functional, emotional, and financial impact on patients, their caregivers, and families. Approximately 6.5 million Americans are living with Alzheimer disease (AD), the most common of many causes of dementia.1 The prevalence of AD could increase to 12.7 million Americans by 2050 as the population ages.1 Studies suggest that dementia, also known as major neurocognitive disorder, is common and underdiagnosed among US veterans, a population with a mean age of 65 years.2 During cognitive screening, memory impairment is present in approximately 20% of veterans aged ≥ 75 years who have not been diagnosed with a neurocognitive disorder.3 In addition, veterans might be particularly vulnerable to dementia at an earlier age than the general population because of vascular risk factors and traumatic brain injuries.4 These concerns highlight the need for effective dementia care programs at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities.

The US health care system often does not adequately address the needs of patients with dementia and their caregivers.5 Dementia care requires specialized medical care among collaborating professionals and caregiver and psychosocial interventions and services. However, the US health care system is fragmented with different clinicians and services siloed into separate practices and most dementia care occurring in primary care settings.6 Primary care professionals (PCPs) often are uncomfortable diagnosing and managing dementia because of time constraints, lack of expertise and training, and inability to deal with the range of care needs.7 PCPs do not identify approximately 42% of their patients with dementia and, when recognized, do not adhere to dementia care guidelines and address caregiver needs.8-10 Research indicates that caregiver support improves dementia care by teaching behavioral management skills and caregiver coping strategies, allowing patients to stay at home and delay institutionalization.6,11,12 Clinicians underuse available resources and do not incorporate them in their patient care.10 These community services benefit patients and caregivers and significantly improve the overall quality of care.6

Memory clinics have emerged to address these deficiencies when managing dementia.13 The most effective memory clinics maximize the use of specialists with different expertise in dementia care, particularly integrated programs where disciplines function together rather than independently.1,5,14 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have documented the effectiveness of collaborative care management programs.11,12,15 Integration of dementia care management is associated with earlier diagnosis and interventions, decreased functional and cognitive symptom severity, decreased or delayed institutionalization, improved quality of life for patients and caregivers, enhanced overall quality of care and cost-effectiveness, and better integration of community services.11,12,14-19 In these programs, designating a dementia care manager (DCM) as the patient’s advocate facilitates the integrated structure, increases the quality of care, helps caregivers, facilitates adherence to dementia practice guidelines, and prevents behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD).1,6,11,12,20,21

The best interprofessional model for dementia care might be the transdisciplinary model that includes a DCM. To meet the specific demands of dementia care, there must be a high level of interprofessional collaboration rather than multiple health care professionals (HCPs) delivering care in isolation—an approach that is time consuming and often difficult to implement.22 Whereas multidisciplinary care refers to delivery of parallel services and interdisciplinary care implies a joint formulation, transdisciplinary care aims to maximize integration of HCPs and their specific expertise and contributions through interactions and discussions that deliver focused input to the lead physician. The transdisciplinary model addresses needs that often are missed and can minimize disparities in the quality of dementia care.23 A DCM is an integral part of our program, facilitating understanding and implementation of the final care plan and providing long-term follow-up and care. We outline a conference-centered transdisciplinary dementia care model with a social worker as DCM (SW-DCM) at our VA medical center.

Program Description

In 2020, the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) in California established a multispecialty clinic dedicated to evaluation and treatment of veterans with memory and neurocognitive disorders and to provide support for their caregivers and families. With the agreement of leadership in mental health, neurology, and geriatrics services on the importance of collaboration for dementia care, the psychiatry and neurology services created a joint Memory and Neurobehavior Clinic, which completed its first 2 years of operation as a full-day program. In recent months, the clinic has scheduled 24 veterans per day, approximately 50% new evaluations and 50% follow-up patients, with wait times of < 2 months. There is a mean of 12 intake or lead physicians who could attend sessions in the morning, afternoon, or both. The general clinic flow consists of a 2-hour intake evaluation of new referrals by the lead physician followed by a clinic conference with transdisciplinary discussion. The DCM then follows up with the veteran/caregiver presenting a final care plan individualized to the veterans, caregivers, and families.

The Memory and Neurobehavior team includes behavioral neurologists, geriatric psychiatrists, neuropsychologists, geriatric fellows, advanced clinical nurses, and social workers who function as the DCM (Table 1).

Procedures

Before the office visit, the coordinating geriatric psychiatrist triages veterans to neurology, psychiatry, or geriatric physicians based on the clinical presentation, history of neurologic signs or symptoms, BPSD or psychiatric history, functional decline, or comorbid medical illnesses. Although veterans often have overlapping concerns, the triage process aims to coordinate the intake evaluations with the most indicated and available specialist with the intention to notify the other specialists during the transdisciplinary conference.

Referrals to the program occur from many sources, notably from primary care (70.8%), mental health (16.7%), and specialty clinics (12.5%). The clinic also receives referrals from the affiliated Veterans Cognitive Assessment and Management Program, which provides dementia evaluation and support via telehealth screening. This VAGLAHS program services a diverse population of veterans: 87% male; 43% aged > 65 years (75% in our clinic); 51% non-Hispanic White; 19% non-Hispanic African American; 16% Hispanic; 4% Asian; and 1% Native American. This population receives care at regional VA medical centers and community-based outpatient clinics over a wide geographic service area.

The initial standardized assessments by intake or lead physicians includes mental status screening with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (with certified clinicians), the Neurobehavioral Status Examination for a more detailed assessment of cognitive domains, the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale, the Patient Health Questionnaire for depression screening, and assessment for impairments in instrumental or basic activities of daily living. This initial evaluation aims to apply clinical guidelines and diagnostic criteria for the differential diagnosis of neurocognitive disorders, determine eligibility for cognitive-enhancing medications and techniques, assess for BPSD and the need for nonpharmacologic or pharmacologic interventions, determine functional status, and evaluate the need for supervision, safety concerns, and evidence of neglect or abuse.

As part of its mission, the clinic is charged with implementing the VA Dementia System of Care (DSOC). The stated goals of the DSOC are to provide individualized person-centered dementia care to help veterans experiencing dementia and their caregivers maintain a positive and optimal quality of life and create an environment where VA medical center staff understand the health care needs of veterans with dementia and their caregivers’ role. As part of this initiative, the clinic includes (1) coordination of care through a SW-DCM; (2)

Transdisciplinary Conference

Clinic conferences are held after the veterans are seen. Staff gather to discuss the patient and review management. All team members are present, as well as the head of the clinical clerical staff who can facilitate appointments, make lobby and wait times more bearable for our patients and caregivers, and help manage emergencies. Although this is an in-person conference, the COVID-19 pandemic has allowed us to include staff who screen at remote sites via videoconferencing, similar to other VA programs.24 The Memory and Neurobehavior Clinic has two ≤ 90-minute conferences daily. The lead physicians and their senior attendings present the new intake evaluations (4-6 at each conference session) with a preliminary formulation and questions for discussion. The moderator solicits contributions from the different disciplines, going from one to the next and recording their responses for each veteran. Further specialists are available for consultation through the conference mechanism if necessary. The final assessment is reviewed, a diagnosis is established, and a tailored, individualized care plan for adjusting or optimizing the veteran’s care is presented to the lead physician who makes the final determination. At the close of the conference, the team’s discussion is recorded along with the lead physician’s original detailed intake evaluation. Currently, the records go into the Computerized Patient Record System, but we are making plans to transition to Cerner as it is implemented.

During the discussion, team members review several areas of consideration. If there is neuroimaging, neurologists review the images projected on a large computer screen. Team members also will assess for the need to obtain biomarker studies, such as blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or positron emission tomography. Psychiatrists could review management of BPSD and use of psychotropic agents, and neuropsychologists might consider the need for more precise cognitive testing and whether a capacity assessment is indicated. Social work might bring up the need for a durable power of attorney as well as applicable caregiver and community resources. Geriatric medicine and nursing could provide input into medical management and care and the ability of veterans and caregivers to follow the prescribed regimen. Further areas of discussion include driving safety and restrictions on driving (as required in California) and the presence of guns in the home. Finally, brief education is provided in short 10-to-15-minute lectures covering pertinent topics so staff remain up-to-date in this changing field.

Postconference Continuity

After the conference, the SW-DCM continues to provide support throughout the disease course, helping veterans and their caregivers understand and follow through on the team’s recommendations. The SW-DCM, who is experienced and trained in case management, forms an ongoing relationship with the veterans and their caregivers and remains an advocate for their care. The SW-DCM communicates the final plan by phone and, when necessary, requests the lead physician to call to clarify any poorly understood or technical aspects of the care plan. About 50% of our veterans—primarily those who do not have a neurocognitive disorder or have mild cognitive impairment—return to their PCPs with our care plan consultation; about 25% are already enrolled in geriatric and other programs with long-term follow-up. The assigned SW-DCM follows up with the remaining veterans and caregivers regularly by phone, facilitates communication with other team members, and endeavors to assure postvisit continuity of care and support during advancing stages of the disease. In addition, the SW-DCM can provide supportive counseling and psychotherapy for stressed caregivers, refer to support groups and cognitive rehabilitation programs, and help develop long-term goals and consideration for supervised living environments. The nurse specialist participates with follow-up calls regarding medications and scheduled tests and appointments, clearing up confusion about instructions, avoiding medication errors, and providing education in dementia care. Both social worker and nurse are present throughout the week, reachable by phone, and, in turn, able to contact the clinic physicians for veterans’ needs.

Discussion

Because of the heterogenous medical and psychosocial needs of veterans with dementia and their caregivers, a transdisciplinary team with a dedicated DCM might offer the most effective and efficient model for dementia care. We present a transdisciplinary program that incorporates dementia specialists in a single evaluation by maximizing their time through a conference-centered program. Our program involves neurologists, psychiatrists, geriatricians, psychologists, nurses, and social workers collaborating and communicating to enact effective dementia care. It further meets the goals of the VA-DSOC in implementing individualized patient and caregiver care.

This transdisciplinary model addresses a number of issues, starting with the differential diagnosis of underlying neurologic conditions. Within the transdisciplinary team, the neurologist can provide specific insights into any neurologic findings and illnesses, such as Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative dementias, vascular dementia syndromes, normal pressure hydrocephalus, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, neurosyphilis, and others. Most veterans with dementia experience BPSD at some point during of their illness. The psychiatrists on the transdisciplinary team can maximize management of BPSD with nonpharmacologic interventions and the fewest and least aversive psychoactive medications. Our program also addresses the need for more precise cognitive evaluation. Neuropsychologists are present and available for administrating neuropsychologic tests and interpreting cognitive performance and any earlier neuropsychologic testing. This model also cares for the caregivers and assesses their needs. The social worker—as well as other members of the team—can provide caregivers with strategies for coping with disruptive and other behaviors related to dementia, counsel them on how to manage the veteran’s functional decline, and aid in establishing a safe living space. Because the social worker serves as a DCM, these coping and adjustment questions occupy significant clinical attention between appointments. This transdisciplinary model places the patient’s illness in the context of their functional status, diagnoses, and medications. The team geriatrician and the nurse specialist are indispensable resources. The clinic conference provides a teaching venue for staff and trainees and a mechanism to discuss new developments in dementia care, such as the increasing need to assess individuals with mild cognitive impairment.25 This model depends on the DCM’s invaluable role in ensuring implementation of the dementia care plan and continuity of care.

Conclusions

We describe effective dementia care with a transdisciplinary team in a conference setting and with the participation of a dedicated DCM.5 To date, this program appears to be an efficient, sustainable application of the limited resources allocated to dementia care. Nevertheless, we are collecting data to compare with performance measures, track use, and assess the programs effects on continuity of care. We look forward to presenting metrics from our program that show improvement in the health care for veterans experiencing a devastating and increasingly common disorder.

Dementia is a devastating condition resulting in major functional, emotional, and financial impact on patients, their caregivers, and families. Approximately 6.5 million Americans are living with Alzheimer disease (AD), the most common of many causes of dementia.1 The prevalence of AD could increase to 12.7 million Americans by 2050 as the population ages.1 Studies suggest that dementia, also known as major neurocognitive disorder, is common and underdiagnosed among US veterans, a population with a mean age of 65 years.2 During cognitive screening, memory impairment is present in approximately 20% of veterans aged ≥ 75 years who have not been diagnosed with a neurocognitive disorder.3 In addition, veterans might be particularly vulnerable to dementia at an earlier age than the general population because of vascular risk factors and traumatic brain injuries.4 These concerns highlight the need for effective dementia care programs at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities.

The US health care system often does not adequately address the needs of patients with dementia and their caregivers.5 Dementia care requires specialized medical care among collaborating professionals and caregiver and psychosocial interventions and services. However, the US health care system is fragmented with different clinicians and services siloed into separate practices and most dementia care occurring in primary care settings.6 Primary care professionals (PCPs) often are uncomfortable diagnosing and managing dementia because of time constraints, lack of expertise and training, and inability to deal with the range of care needs.7 PCPs do not identify approximately 42% of their patients with dementia and, when recognized, do not adhere to dementia care guidelines and address caregiver needs.8-10 Research indicates that caregiver support improves dementia care by teaching behavioral management skills and caregiver coping strategies, allowing patients to stay at home and delay institutionalization.6,11,12 Clinicians underuse available resources and do not incorporate them in their patient care.10 These community services benefit patients and caregivers and significantly improve the overall quality of care.6

Memory clinics have emerged to address these deficiencies when managing dementia.13 The most effective memory clinics maximize the use of specialists with different expertise in dementia care, particularly integrated programs where disciplines function together rather than independently.1,5,14 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have documented the effectiveness of collaborative care management programs.11,12,15 Integration of dementia care management is associated with earlier diagnosis and interventions, decreased functional and cognitive symptom severity, decreased or delayed institutionalization, improved quality of life for patients and caregivers, enhanced overall quality of care and cost-effectiveness, and better integration of community services.11,12,14-19 In these programs, designating a dementia care manager (DCM) as the patient’s advocate facilitates the integrated structure, increases the quality of care, helps caregivers, facilitates adherence to dementia practice guidelines, and prevents behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD).1,6,11,12,20,21

The best interprofessional model for dementia care might be the transdisciplinary model that includes a DCM. To meet the specific demands of dementia care, there must be a high level of interprofessional collaboration rather than multiple health care professionals (HCPs) delivering care in isolation—an approach that is time consuming and often difficult to implement.22 Whereas multidisciplinary care refers to delivery of parallel services and interdisciplinary care implies a joint formulation, transdisciplinary care aims to maximize integration of HCPs and their specific expertise and contributions through interactions and discussions that deliver focused input to the lead physician. The transdisciplinary model addresses needs that often are missed and can minimize disparities in the quality of dementia care.23 A DCM is an integral part of our program, facilitating understanding and implementation of the final care plan and providing long-term follow-up and care. We outline a conference-centered transdisciplinary dementia care model with a social worker as DCM (SW-DCM) at our VA medical center.

Program Description

In 2020, the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) in California established a multispecialty clinic dedicated to evaluation and treatment of veterans with memory and neurocognitive disorders and to provide support for their caregivers and families. With the agreement of leadership in mental health, neurology, and geriatrics services on the importance of collaboration for dementia care, the psychiatry and neurology services created a joint Memory and Neurobehavior Clinic, which completed its first 2 years of operation as a full-day program. In recent months, the clinic has scheduled 24 veterans per day, approximately 50% new evaluations and 50% follow-up patients, with wait times of < 2 months. There is a mean of 12 intake or lead physicians who could attend sessions in the morning, afternoon, or both. The general clinic flow consists of a 2-hour intake evaluation of new referrals by the lead physician followed by a clinic conference with transdisciplinary discussion. The DCM then follows up with the veteran/caregiver presenting a final care plan individualized to the veterans, caregivers, and families.

The Memory and Neurobehavior team includes behavioral neurologists, geriatric psychiatrists, neuropsychologists, geriatric fellows, advanced clinical nurses, and social workers who function as the DCM (Table 1).

Procedures

Before the office visit, the coordinating geriatric psychiatrist triages veterans to neurology, psychiatry, or geriatric physicians based on the clinical presentation, history of neurologic signs or symptoms, BPSD or psychiatric history, functional decline, or comorbid medical illnesses. Although veterans often have overlapping concerns, the triage process aims to coordinate the intake evaluations with the most indicated and available specialist with the intention to notify the other specialists during the transdisciplinary conference.

Referrals to the program occur from many sources, notably from primary care (70.8%), mental health (16.7%), and specialty clinics (12.5%). The clinic also receives referrals from the affiliated Veterans Cognitive Assessment and Management Program, which provides dementia evaluation and support via telehealth screening. This VAGLAHS program services a diverse population of veterans: 87% male; 43% aged > 65 years (75% in our clinic); 51% non-Hispanic White; 19% non-Hispanic African American; 16% Hispanic; 4% Asian; and 1% Native American. This population receives care at regional VA medical centers and community-based outpatient clinics over a wide geographic service area.

The initial standardized assessments by intake or lead physicians includes mental status screening with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (with certified clinicians), the Neurobehavioral Status Examination for a more detailed assessment of cognitive domains, the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale, the Patient Health Questionnaire for depression screening, and assessment for impairments in instrumental or basic activities of daily living. This initial evaluation aims to apply clinical guidelines and diagnostic criteria for the differential diagnosis of neurocognitive disorders, determine eligibility for cognitive-enhancing medications and techniques, assess for BPSD and the need for nonpharmacologic or pharmacologic interventions, determine functional status, and evaluate the need for supervision, safety concerns, and evidence of neglect or abuse.