User login

Improving Hospital Metrics Through the Implementation of a Comorbidity Capture Tool and Other Quality Initiatives

From the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (Drs. Sosa, Ferreira, Gershengorn, Soto, Parekh, and Suarez), and the Quality Department of the University of Miami Hospital and Clinics (Estin Kelly, Ameena Shrestha, Julianne Burgos, and Sandeep Devabhaktuni), Miami, FL.

Abstract

Background: Case mix index (CMI) and expected mortality are determined based on comorbidities. Improving documentation and coding can impact performance indicators. During and prior to 2018, our patient acuity was under-represented, with low expected mortality and CMI. Those metrics motivated our quality team to develop the quality initiatives reported here.

Objectives: We sought to assess the impact of quality initiatives on number of comorbidities, diagnoses, CMI, and expected mortality at the University of Miami Health System.

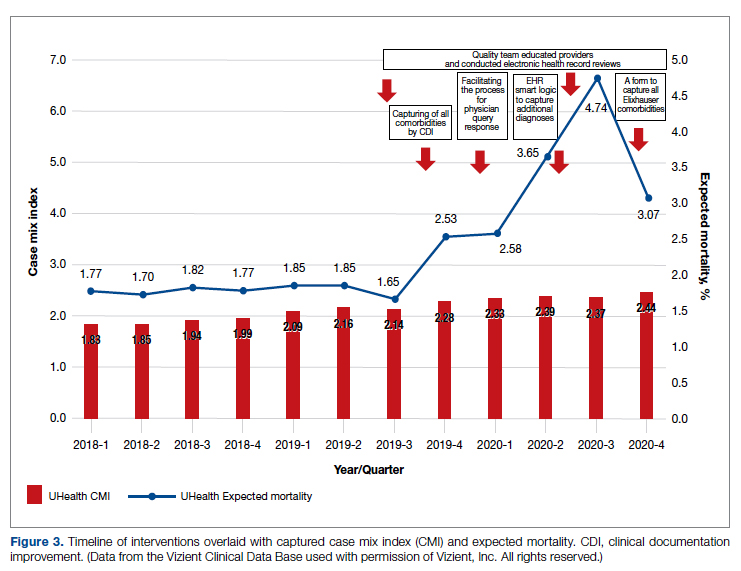

Design: We conducted an observational study of a series of quality initiatives: (1) education of clinical documentation specialists (CDS) to capture comorbidities (10/2019); (2) facilitating the process for physician query response (2/2020); (3) implementation of computer logic to capture electrolyte disturbances and renal dysfunction (8/2020); (4) development of a tool to capture Elixhauser comorbidities (11/2020); and (5) provider education and electronic health record reviews by the quality team.

Setting and participants: All admissions during 2019 and 2020 at University of Miami Health System. The health system includes 2 academic inpatient facilities, a 560-bed tertiary hospital, and a 40-bed cancer facility. Our hospital is 1 of the 11 PPS-Exempt Cancer Hospitals and is the South Florida’s only NCI-Designated Cancer Center.

Conclusion:

Keywords: PS/QI, coding, case mix index, comorbidities, mortality.

Adoption of comprehensive electronic health record (EHR) systems by US hospitals, defined as an EHR capable of meeting all core meaningful-use metrics including evaluation and tracking of quality metrics, has been steadily increasing.3,4 Many institutions have looked to EHR system transitions as an inflection point to expand clinical documentation improvement (CDI) efforts. Over the past several years, our institution, an academic medical center, has endeavored to fully transition to a comprehensive EHR system (Epic from Epic Systems Corporation). Part of the purpose of this transition was to help study and improve outcomes, reduce readmissions, improve quality of care, and meet performance indicators.

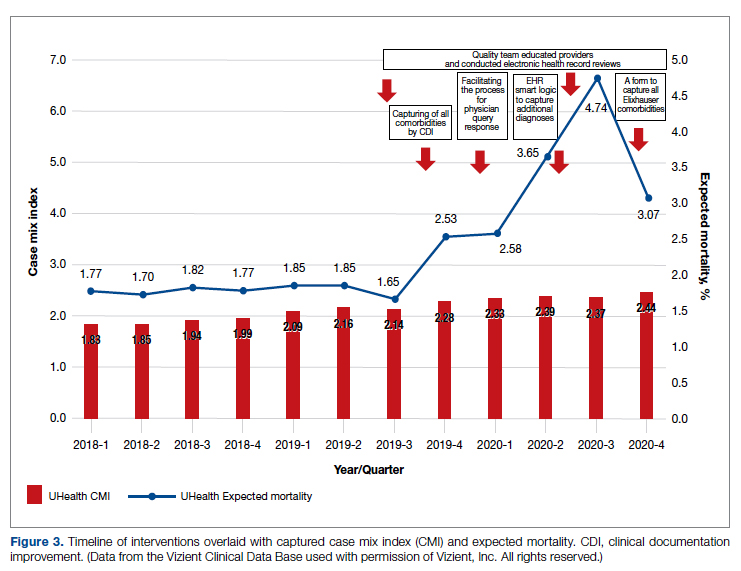

Prior to 2019, our hospital’s patient acuity was low, with a CMI consistently below 2, ranging from 1.81 to 1.99, and an expected mortality consistently below 1.9%, ranging from 1.65% to 1.85%. Our concern that these values underestimated the real severity of illness of our patient population prompted the development of a quality improvement plan. In this report, we describe the processes we undertook to improve documentation and coding of comorbid illness, and report on the impact of these initiatives on performance indicators. We hypothesized that our initiatives would have a significant impact on our ability to capture patient complexity, and thus impact our CMI and expected mortality.

Methods

In the fall of 2019, we embarked on a multifaceted quality improvement project aimed at improving comorbidity capture for patients hospitalized at our institution. The health system includes 2 academic inpatient facilities, a 560-bed tertiary hospital and a 40-bed cancer facility. Since September 2017, we have used Epic as our EHR. In August 2019, we started working with Vizient Clinical Data Base5 to allow benchmarking with peer institutions. We assessed the impact of this initiative with a pre/post study design.

Quality Initiatives

This quality improvement project consisted of a series of 5 targeted interventions coupled with continuous monitoring and education.

1. Comorbidity coding. In October 2019, we met with the clinical documentation specialists (CDS) and the coding team to educate them on the value of coding all comorbidities that have an impact on

2. Physician query. In October 2019, we modified the process for physician query response, allowing physicians to answer queries in the EHR through a reply tool incorporated into the query and accept answers in the body of the Epic message as an active part of the EHR.

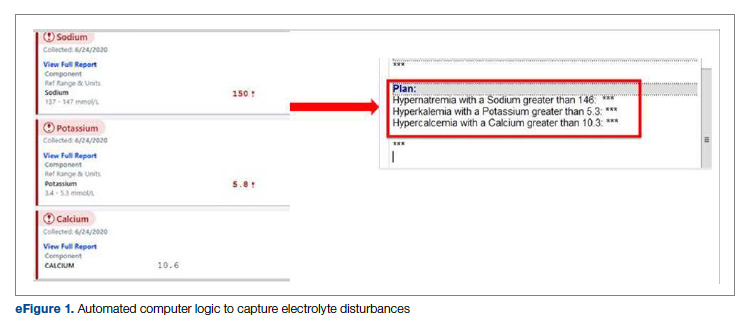

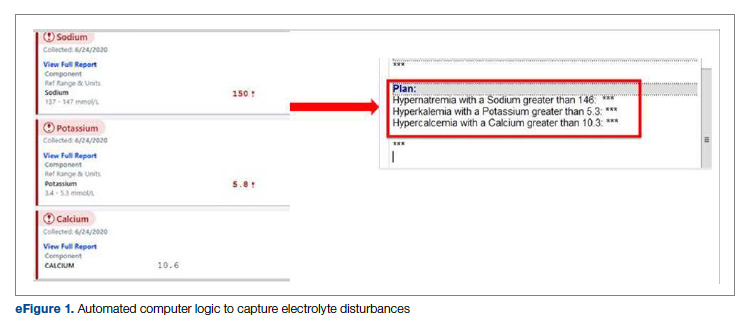

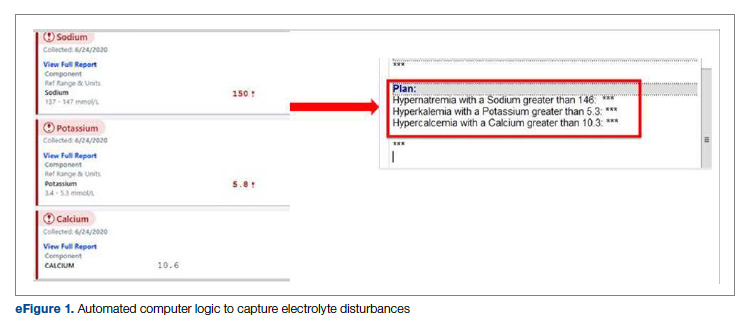

3. EHR logic. In August 2020, we developed an EHR smart logic to automatically capture fluid and electrolyte disturbances and renal dysfunction, based on the most recent laboratory values. The logic automatically populated potentially appropriate diagnoses in the assessment and plan of provider notes, which require provider acknowledgment and which providers are able to modify

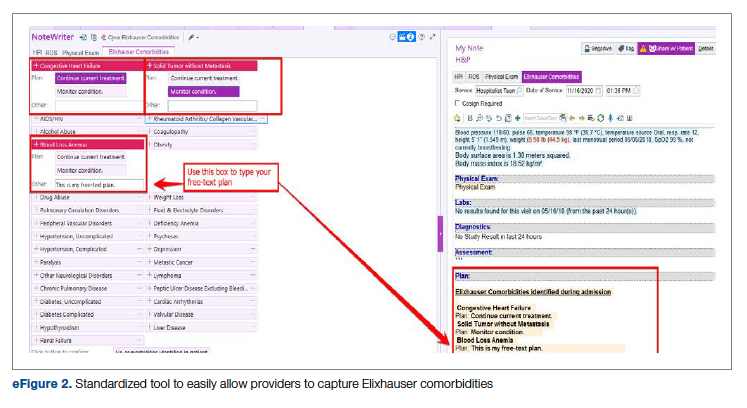

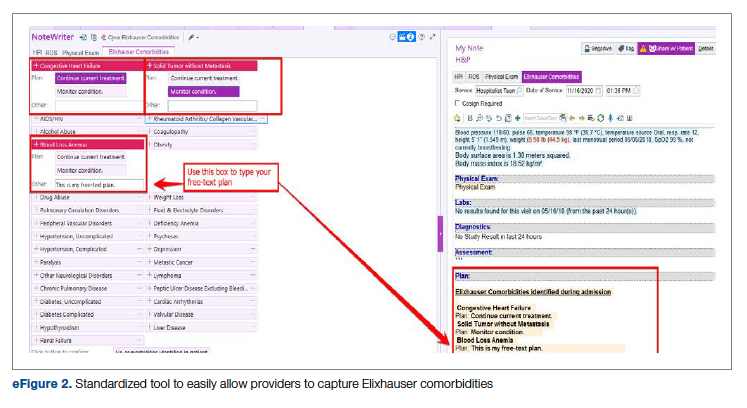

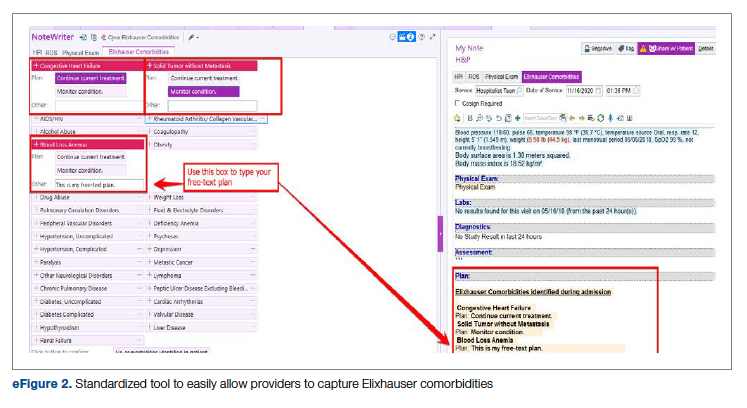

4. Comorbidity capture tool. In November 2020, we developed a standardized tool to allow providers to easily capture Elixhauser comorbidities (eFigure 2). The Elixhauser index is a method for measuring comorbidities based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification and International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision diagnosis codes found in administrative data1-6 and is used by US News & World Report and Vizient to assess comorbidity burden. Our tool automatically captures diagnoses recorded in previous documentation and allows providers to easily provide the management plan for each; this information is automatically pulled into the provider note.

The development of this tool used an existing functionality within the Epic EHR called SmartForms, SmartData Elements, and SmartLinks. The only cost of tool development was the time invested—124 hours inclusive of 4 hours of staff education. Specifically, a panel of experts (including physicians of different specialties, an analyst, and representatives from the quality office) met weekly for 30 minutes per week over 5 weeks to agree on specific clinical criteria and guide the EHR build analyst. Individual panel members confirmed and validated design requirements (in 15 hours over 5 weeks). Our senior clinical analyst II dedicated 80 hours to actual build time, 15 hours to design time, and 25 hours to tailor the function to our institution’s workflow. This tool was introduced in November 2020; completion was optional at the time of hospital admission but mandatory at discharge to ensure compliance.

5. Quality team

Assessment of Quality Initiatives’ Impact

Data on the number of comorbidities and performance indicators were obtained retrospectively. The data included all hospital admissions from 2019 and 2020 divided into 2 periods: pre-intervention from January 1, 2019 through September 30, 2019, and intervention from October 1, 2019 through December 31, 2020. The primary outcome of this observational study was the rate of comorbidity capture during the intervention period. Comorbidity capture was assessed using the Vizient Clinical Data Base (CDB) health care performance tool.5 Vizient CDB uses the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Elixhauser index, which includes 29 of the initial 31 comorbidities described by Elixhauser,6 as it combines hypertension with and without complications into one. We secondarily aimed to examine the impact of the quality improvement initiatives on several institutional-level performance indicators, including total number of diagnoses, comorbidities or complications (CC), major comorbidities or complications (MCC), CMI, and expected mortality.

Case mix index is the average Medicare Severity-DRG (MS-DRG) weighted across all hospital discharges (appropriate to their discharge date). The expected mortality represents the average expected number of deaths based on diagnosed conditions, age, and gender within the same time frame, and it is based on coded diagnosis; we obtained the mortality index by dividing the observed mortality by the expected mortality. The Vizient CDB Mortality Risk Adjustment Model was used to assign an expected mortality (0%-100%) to each case based on factors such as demographics, admission type, diagnoses, and procedures.

Standard statistics were used to measure the outcomes. We used Excel to compare pre-intervention and intervention period characteristics and outcomes, using t-testing for continuous variables and Chi-square testing for categorial outcomes. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The study was reviewed by the institutional review board (IRB) of our institution (IRB ID: 20210070). The IRB determined that the proposed activity was not research involving human subjects, as defined by the Department of Health and Human Services and US Food and Drug Administration regulations, and that IRB review and approval by the organization were not required.

Results

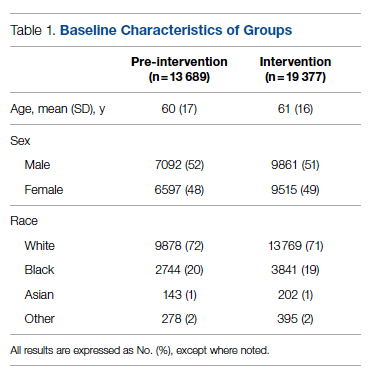

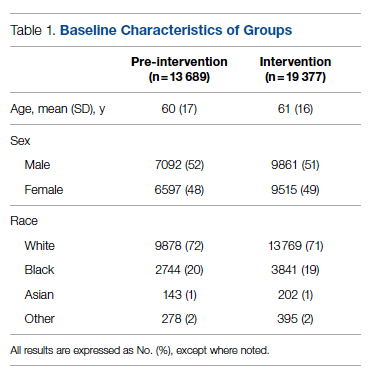

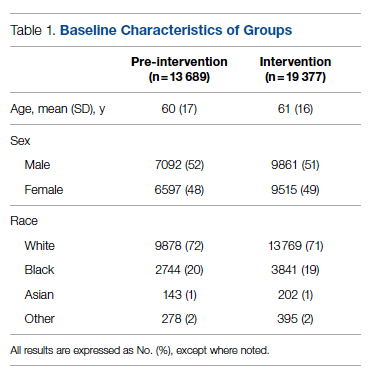

The health system had a total of 33 066 admissions during the study period—13 689 pre-intervention (January 1, 2019 through September 30, 2019) and 19,377 during the intervention period (October 1, 2019 to December 31, 2020). Demographics were similar among the pre-intervention and intervention periods: mean age was 60 years and 61 years, 52% and 51% of patients were male, 72% and 71% were White, and 20% and 19% were Black, respectively (Table 1).

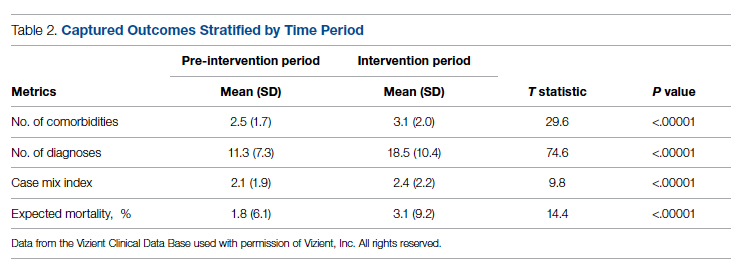

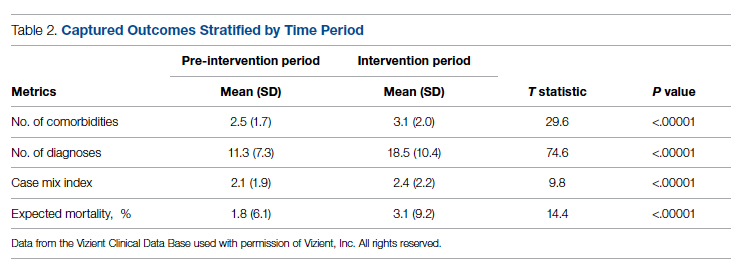

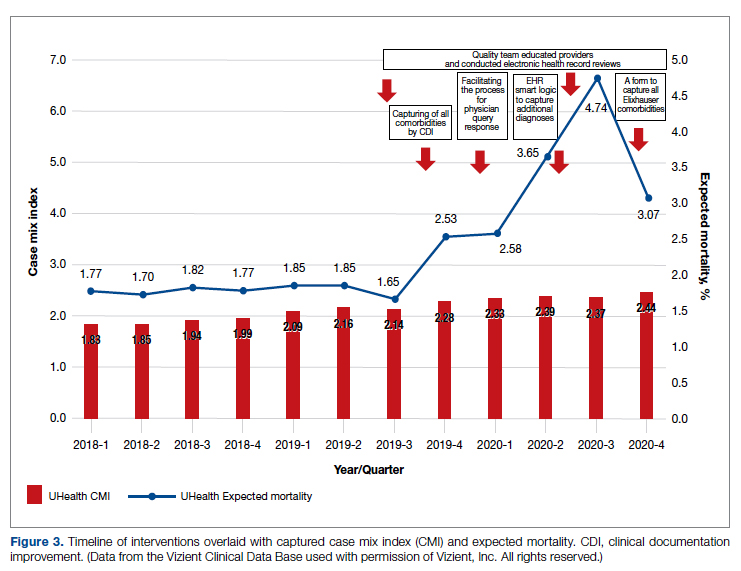

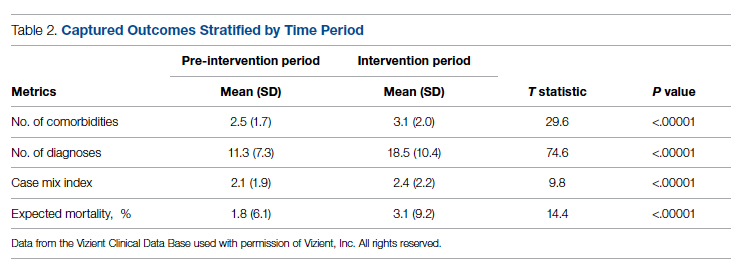

The multifaceted intervention resulted in a significant improvement in the primary outcome: mean comorbidity capture increased from 2.5 (SD, 1.7) before the intervention to 3.1 (SD, 2.0) during the intervention (P < .00001). Secondary outcomes also improved. The mean number of secondary diagnoses for admissions increased from 11.3 (SD, 7.3) prior to the intervention to 18.5 (SD, 10.4) (P < .00001) during the intervention period. The mean CMI increased from 2.1 (SD, 1.9) to 2.4 (SD, 2.2) post intervention (P < .00001), an increase during the intervention period of 14%. The expected mortality increased from 1.8% (SD, 6.1%) to 3.1% (SD, 9.2%) after the intervention (P < .00001) (Table 2).

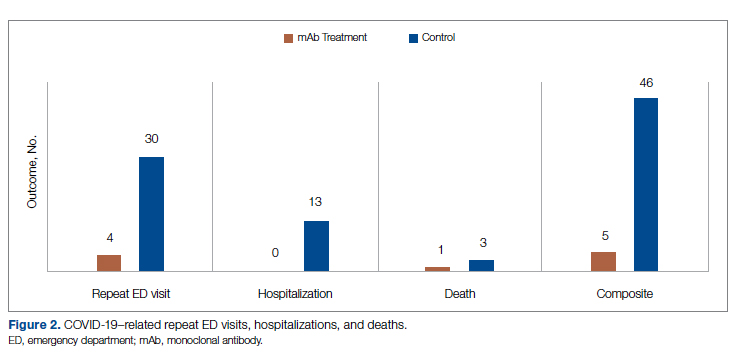

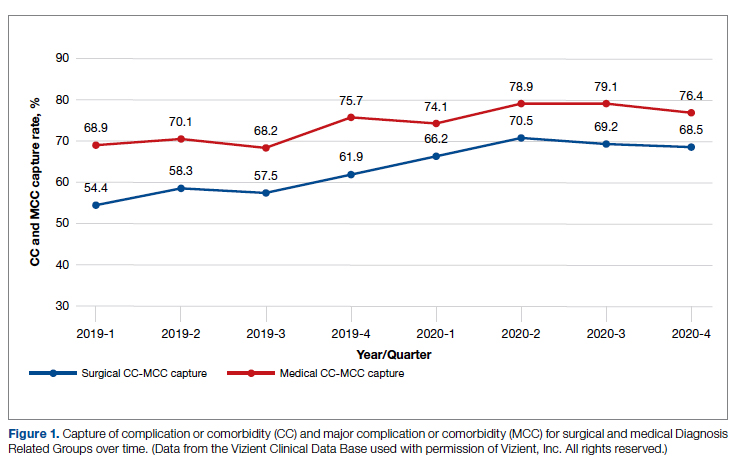

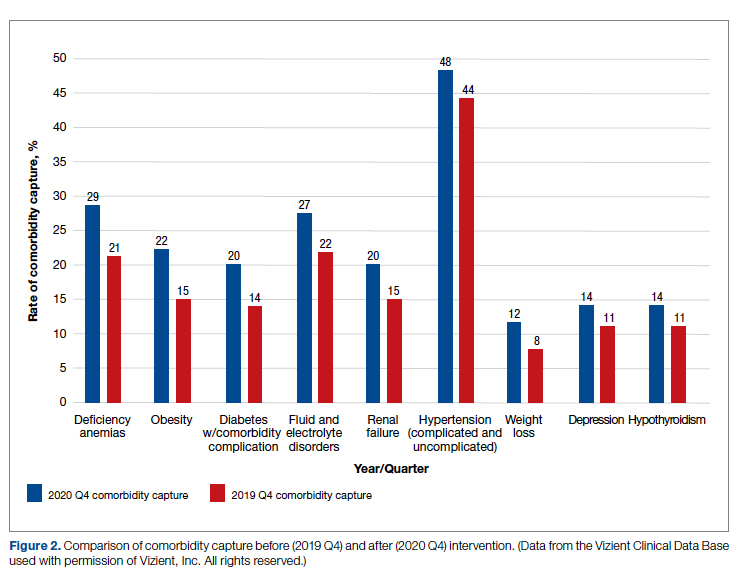

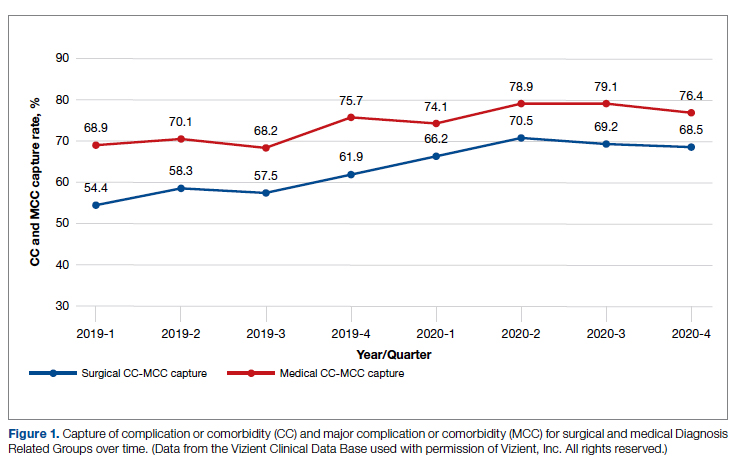

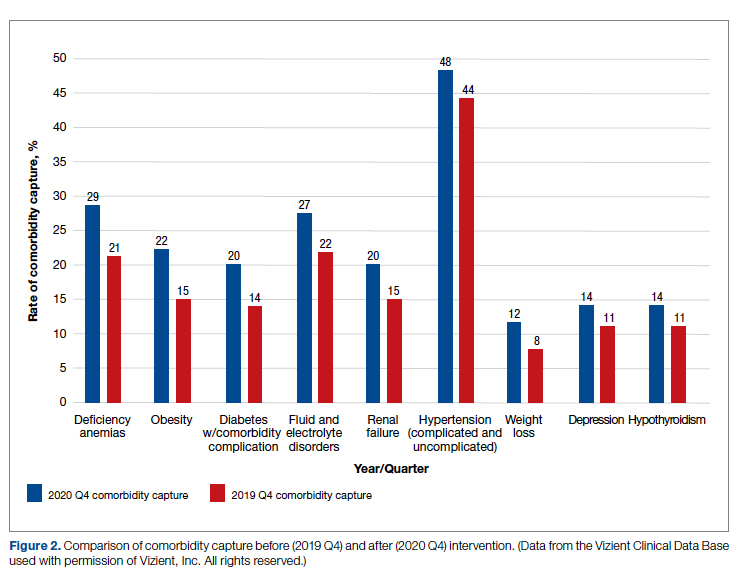

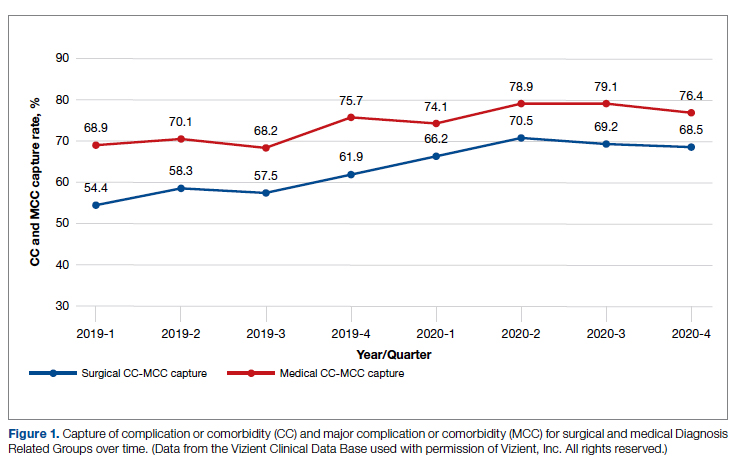

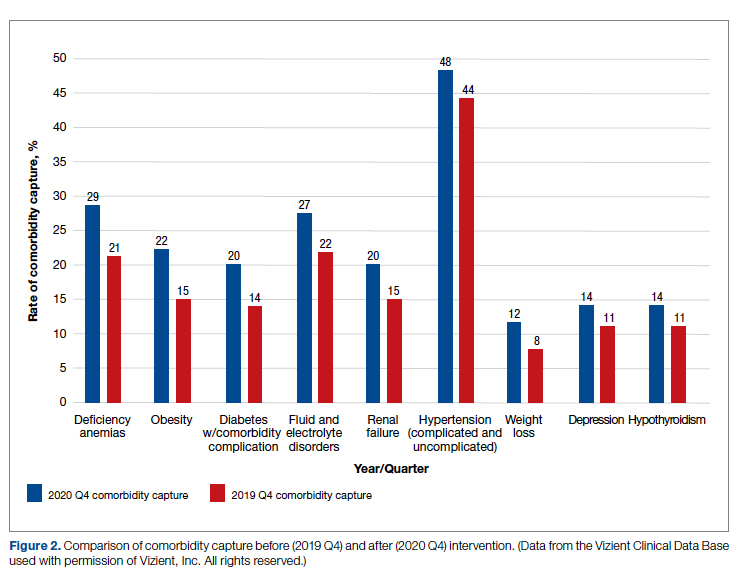

There was an overall observed improvement in percentage of discharges with documented CC and MCC for both surgical and medical specialties. Both CC and MCC increased for surgical specialties, from 54.4% to 68.5%, and for medical specialties, from 68.9% to 76.4%. (Figure 1). The diagnoses that were captured more consistently included deficiency anemia, obesity, diabetes with complications, fluid and electrolyte disorders and renal failure, hypertension, weight loss, depression, and hypothyroidism (Figure 2).

During the 9-month pre-intervention period (January 1 through September 30, 2019), there were 2795 queries, with an agreed volume of 1823; the agreement rate was 65% and the average provider turnaround time was 12.53 days. In the 15-month postintervention period, there were 10 216 queries, with an agreed volume of 6802 at 66%. We created a policy to encourage responses no later than 10 days after the query, and our average turnaround time decreased by more than 50% to 5.86 days. The average number of monthly queries increased by 55%, from an average of 311 monthly queries in the pre-intervention period to an average of 681 per month in the postintervention period. The more common queries that had an impact on CMI included sepsis, antineoplastic chemotherapy–induced pancytopenia, acute posthemorrhagic anemia, malnutrition, hyponatremia, and metabolic encephalopathy.

Discussion

The need for accurate documentation by physicians has been recognized for many years.7

With the growing complexity of the documentation and coding process, it is difficult for clinicians to keep up with the terminology required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Several different methods to improve documentation have been proposed. Prior interventions to standardize documentation templates in the trauma service have shown improvement in CMI.8 An educational program on coding for internal medicine that included a lecture series and creation of a laminated pocket card listing common CMS diagnoses, CC, and MCC has been implemented, with an improvement in the capture rate of CC and MCC from 42% to 48% and an impact on expected mortality.9 This program resulted in a 30% decrease in the median quarterly mortality index and an increase in CMI from 1.27 to 1.36.

Our results show that there was an increase in comorbidities documentation of admitted patients after all interventions were implemented, more accurately reflecting the complexity of our patient population in a tertiary care academic medical center. Our CMI increased by 14% during the intervention period. The estimated CMI dollar impact increased by 75% from the pre-intervention period (adjusted for PPS-exempt hospital). The hospital-expected mortality increased from 1.77 to 3.07 (peak at 4.74 during third quarter of 2020) during the implementation period, which is a key driver of quality rankings for national outcomes reporting services such as US News & World Report.

There was increased physician satisfaction as a result of the change of functionality of the query response system, and no additional monetary provider incentive for complete documentation was allocated, apart from education and 1:1 support that improved physician engagement. Our next steps include the implementation of an advanced program to concurrently and automatically capture and nudge providers to respond and complete their documentation in real time.

Limitations

The limitations of our study include those inherent to a retrospective review and are associative and observational in nature. Although we used expected mortality and CMI as a surrogate for patient acuity for comparison, there was no way to control for actual changes in patient acuity that contributed to the increase in CMI, although we believe that the population we served and the services provided and their structure did not change significantly during the intervention period. Additionally, the observed increase in CMI during the implementation period may be a result of described variabilities in CMI and would be better studied over a longer period. Also, during the year of our interventions, 2020, we were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients with COVID-19 are known to carry a lower-than-expected mortality, and that could have had a negative impact on our results. In fact, we did observe a decrease in our expected mortality during the last quarter of 2020, which correlated with one of our regional peaks for COVID-19, and that could be a confounding factor. While the described intervention process is potentially applicable to multiple EHR systems, the exact form to capture the Elixhauser comorbidities was built into the Epic EHR, limiting external applicability of this tool to other EHR software.

Conclusion

A continuous comprehensive series of interventions substantially increased our patient acuity scores. The increased scores have implications for reimbursement and quality comparisons for hospitals and physicians. Our institution can now be stratified more accurately with our peers and other hospitals. Accurate medical record documentation has become increasingly important, but also increasingly complex. Leveraging the EHR through quality initiatives that facilitate the workflow for providers can have an impact on documentation, coding, and ultimately risk-adjusted outcomes data that influence institutional reputation.

Corresponding author: Marie Anne Sosa, MD; 1120 NW 14th St., Suite 809, Miami, FL, 33134; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

doi:10.12788/jcom.0088

1. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi:10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004.

2. Sehgal AR. The role of reputation in U.S. News & World Report’s rankings of the top 50 American hospitals. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(8):521-525. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-8-201004200-00009

3. Jha AK, DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, et al. Use of electronic health records in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1628-1638. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0900592.

4. Adler-Milstein J, DesRoches CM, Kralovec, et al. Electronic health record adoption in US hospitals: progress continues, but challenges persist. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(12):2174-2180. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0992

5. Vizient Clinical Data Base/Resource ManagerTM. Irving, TX: Vizient, Inc.; 2019. Accessed March 10, 2022. https://www.vizientinc.com

6. Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying increased risk of readmission and in-hospital mortality using hospital administrative data: the AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care. 2017;55(7):698-705. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000735

7. Payne T. Improving clinical documentation in an EMR world. Healthc Financ Manage. 2010;64(2):70-74.

8. Barnes SL, Waterman M, Macintyre D, Coughenour J, Kessel J. Impact of standardized trauma documentation to the hospital’s bottom line. Surgery. 2010;148(4):793-797. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.040

9. Spellberg B, Harrington D, Black S, Sue D, Stringer W, Witt M. Capturing the diagnosis: an internal medicine education program to improve documentation. Am J Med. 2013;126(8):739-743.e1. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.11.035

From the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (Drs. Sosa, Ferreira, Gershengorn, Soto, Parekh, and Suarez), and the Quality Department of the University of Miami Hospital and Clinics (Estin Kelly, Ameena Shrestha, Julianne Burgos, and Sandeep Devabhaktuni), Miami, FL.

Abstract

Background: Case mix index (CMI) and expected mortality are determined based on comorbidities. Improving documentation and coding can impact performance indicators. During and prior to 2018, our patient acuity was under-represented, with low expected mortality and CMI. Those metrics motivated our quality team to develop the quality initiatives reported here.

Objectives: We sought to assess the impact of quality initiatives on number of comorbidities, diagnoses, CMI, and expected mortality at the University of Miami Health System.

Design: We conducted an observational study of a series of quality initiatives: (1) education of clinical documentation specialists (CDS) to capture comorbidities (10/2019); (2) facilitating the process for physician query response (2/2020); (3) implementation of computer logic to capture electrolyte disturbances and renal dysfunction (8/2020); (4) development of a tool to capture Elixhauser comorbidities (11/2020); and (5) provider education and electronic health record reviews by the quality team.

Setting and participants: All admissions during 2019 and 2020 at University of Miami Health System. The health system includes 2 academic inpatient facilities, a 560-bed tertiary hospital, and a 40-bed cancer facility. Our hospital is 1 of the 11 PPS-Exempt Cancer Hospitals and is the South Florida’s only NCI-Designated Cancer Center.

Conclusion:

Keywords: PS/QI, coding, case mix index, comorbidities, mortality.

Adoption of comprehensive electronic health record (EHR) systems by US hospitals, defined as an EHR capable of meeting all core meaningful-use metrics including evaluation and tracking of quality metrics, has been steadily increasing.3,4 Many institutions have looked to EHR system transitions as an inflection point to expand clinical documentation improvement (CDI) efforts. Over the past several years, our institution, an academic medical center, has endeavored to fully transition to a comprehensive EHR system (Epic from Epic Systems Corporation). Part of the purpose of this transition was to help study and improve outcomes, reduce readmissions, improve quality of care, and meet performance indicators.

Prior to 2019, our hospital’s patient acuity was low, with a CMI consistently below 2, ranging from 1.81 to 1.99, and an expected mortality consistently below 1.9%, ranging from 1.65% to 1.85%. Our concern that these values underestimated the real severity of illness of our patient population prompted the development of a quality improvement plan. In this report, we describe the processes we undertook to improve documentation and coding of comorbid illness, and report on the impact of these initiatives on performance indicators. We hypothesized that our initiatives would have a significant impact on our ability to capture patient complexity, and thus impact our CMI and expected mortality.

Methods

In the fall of 2019, we embarked on a multifaceted quality improvement project aimed at improving comorbidity capture for patients hospitalized at our institution. The health system includes 2 academic inpatient facilities, a 560-bed tertiary hospital and a 40-bed cancer facility. Since September 2017, we have used Epic as our EHR. In August 2019, we started working with Vizient Clinical Data Base5 to allow benchmarking with peer institutions. We assessed the impact of this initiative with a pre/post study design.

Quality Initiatives

This quality improvement project consisted of a series of 5 targeted interventions coupled with continuous monitoring and education.

1. Comorbidity coding. In October 2019, we met with the clinical documentation specialists (CDS) and the coding team to educate them on the value of coding all comorbidities that have an impact on

2. Physician query. In October 2019, we modified the process for physician query response, allowing physicians to answer queries in the EHR through a reply tool incorporated into the query and accept answers in the body of the Epic message as an active part of the EHR.

3. EHR logic. In August 2020, we developed an EHR smart logic to automatically capture fluid and electrolyte disturbances and renal dysfunction, based on the most recent laboratory values. The logic automatically populated potentially appropriate diagnoses in the assessment and plan of provider notes, which require provider acknowledgment and which providers are able to modify

4. Comorbidity capture tool. In November 2020, we developed a standardized tool to allow providers to easily capture Elixhauser comorbidities (eFigure 2). The Elixhauser index is a method for measuring comorbidities based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification and International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision diagnosis codes found in administrative data1-6 and is used by US News & World Report and Vizient to assess comorbidity burden. Our tool automatically captures diagnoses recorded in previous documentation and allows providers to easily provide the management plan for each; this information is automatically pulled into the provider note.

The development of this tool used an existing functionality within the Epic EHR called SmartForms, SmartData Elements, and SmartLinks. The only cost of tool development was the time invested—124 hours inclusive of 4 hours of staff education. Specifically, a panel of experts (including physicians of different specialties, an analyst, and representatives from the quality office) met weekly for 30 minutes per week over 5 weeks to agree on specific clinical criteria and guide the EHR build analyst. Individual panel members confirmed and validated design requirements (in 15 hours over 5 weeks). Our senior clinical analyst II dedicated 80 hours to actual build time, 15 hours to design time, and 25 hours to tailor the function to our institution’s workflow. This tool was introduced in November 2020; completion was optional at the time of hospital admission but mandatory at discharge to ensure compliance.

5. Quality team

Assessment of Quality Initiatives’ Impact

Data on the number of comorbidities and performance indicators were obtained retrospectively. The data included all hospital admissions from 2019 and 2020 divided into 2 periods: pre-intervention from January 1, 2019 through September 30, 2019, and intervention from October 1, 2019 through December 31, 2020. The primary outcome of this observational study was the rate of comorbidity capture during the intervention period. Comorbidity capture was assessed using the Vizient Clinical Data Base (CDB) health care performance tool.5 Vizient CDB uses the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Elixhauser index, which includes 29 of the initial 31 comorbidities described by Elixhauser,6 as it combines hypertension with and without complications into one. We secondarily aimed to examine the impact of the quality improvement initiatives on several institutional-level performance indicators, including total number of diagnoses, comorbidities or complications (CC), major comorbidities or complications (MCC), CMI, and expected mortality.

Case mix index is the average Medicare Severity-DRG (MS-DRG) weighted across all hospital discharges (appropriate to their discharge date). The expected mortality represents the average expected number of deaths based on diagnosed conditions, age, and gender within the same time frame, and it is based on coded diagnosis; we obtained the mortality index by dividing the observed mortality by the expected mortality. The Vizient CDB Mortality Risk Adjustment Model was used to assign an expected mortality (0%-100%) to each case based on factors such as demographics, admission type, diagnoses, and procedures.

Standard statistics were used to measure the outcomes. We used Excel to compare pre-intervention and intervention period characteristics and outcomes, using t-testing for continuous variables and Chi-square testing for categorial outcomes. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The study was reviewed by the institutional review board (IRB) of our institution (IRB ID: 20210070). The IRB determined that the proposed activity was not research involving human subjects, as defined by the Department of Health and Human Services and US Food and Drug Administration regulations, and that IRB review and approval by the organization were not required.

Results

The health system had a total of 33 066 admissions during the study period—13 689 pre-intervention (January 1, 2019 through September 30, 2019) and 19,377 during the intervention period (October 1, 2019 to December 31, 2020). Demographics were similar among the pre-intervention and intervention periods: mean age was 60 years and 61 years, 52% and 51% of patients were male, 72% and 71% were White, and 20% and 19% were Black, respectively (Table 1).

The multifaceted intervention resulted in a significant improvement in the primary outcome: mean comorbidity capture increased from 2.5 (SD, 1.7) before the intervention to 3.1 (SD, 2.0) during the intervention (P < .00001). Secondary outcomes also improved. The mean number of secondary diagnoses for admissions increased from 11.3 (SD, 7.3) prior to the intervention to 18.5 (SD, 10.4) (P < .00001) during the intervention period. The mean CMI increased from 2.1 (SD, 1.9) to 2.4 (SD, 2.2) post intervention (P < .00001), an increase during the intervention period of 14%. The expected mortality increased from 1.8% (SD, 6.1%) to 3.1% (SD, 9.2%) after the intervention (P < .00001) (Table 2).

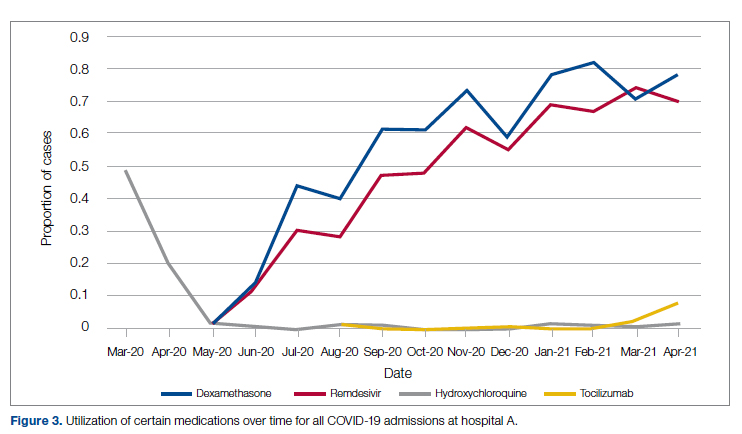

There was an overall observed improvement in percentage of discharges with documented CC and MCC for both surgical and medical specialties. Both CC and MCC increased for surgical specialties, from 54.4% to 68.5%, and for medical specialties, from 68.9% to 76.4%. (Figure 1). The diagnoses that were captured more consistently included deficiency anemia, obesity, diabetes with complications, fluid and electrolyte disorders and renal failure, hypertension, weight loss, depression, and hypothyroidism (Figure 2).

During the 9-month pre-intervention period (January 1 through September 30, 2019), there were 2795 queries, with an agreed volume of 1823; the agreement rate was 65% and the average provider turnaround time was 12.53 days. In the 15-month postintervention period, there were 10 216 queries, with an agreed volume of 6802 at 66%. We created a policy to encourage responses no later than 10 days after the query, and our average turnaround time decreased by more than 50% to 5.86 days. The average number of monthly queries increased by 55%, from an average of 311 monthly queries in the pre-intervention period to an average of 681 per month in the postintervention period. The more common queries that had an impact on CMI included sepsis, antineoplastic chemotherapy–induced pancytopenia, acute posthemorrhagic anemia, malnutrition, hyponatremia, and metabolic encephalopathy.

Discussion

The need for accurate documentation by physicians has been recognized for many years.7

With the growing complexity of the documentation and coding process, it is difficult for clinicians to keep up with the terminology required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Several different methods to improve documentation have been proposed. Prior interventions to standardize documentation templates in the trauma service have shown improvement in CMI.8 An educational program on coding for internal medicine that included a lecture series and creation of a laminated pocket card listing common CMS diagnoses, CC, and MCC has been implemented, with an improvement in the capture rate of CC and MCC from 42% to 48% and an impact on expected mortality.9 This program resulted in a 30% decrease in the median quarterly mortality index and an increase in CMI from 1.27 to 1.36.

Our results show that there was an increase in comorbidities documentation of admitted patients after all interventions were implemented, more accurately reflecting the complexity of our patient population in a tertiary care academic medical center. Our CMI increased by 14% during the intervention period. The estimated CMI dollar impact increased by 75% from the pre-intervention period (adjusted for PPS-exempt hospital). The hospital-expected mortality increased from 1.77 to 3.07 (peak at 4.74 during third quarter of 2020) during the implementation period, which is a key driver of quality rankings for national outcomes reporting services such as US News & World Report.

There was increased physician satisfaction as a result of the change of functionality of the query response system, and no additional monetary provider incentive for complete documentation was allocated, apart from education and 1:1 support that improved physician engagement. Our next steps include the implementation of an advanced program to concurrently and automatically capture and nudge providers to respond and complete their documentation in real time.

Limitations

The limitations of our study include those inherent to a retrospective review and are associative and observational in nature. Although we used expected mortality and CMI as a surrogate for patient acuity for comparison, there was no way to control for actual changes in patient acuity that contributed to the increase in CMI, although we believe that the population we served and the services provided and their structure did not change significantly during the intervention period. Additionally, the observed increase in CMI during the implementation period may be a result of described variabilities in CMI and would be better studied over a longer period. Also, during the year of our interventions, 2020, we were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients with COVID-19 are known to carry a lower-than-expected mortality, and that could have had a negative impact on our results. In fact, we did observe a decrease in our expected mortality during the last quarter of 2020, which correlated with one of our regional peaks for COVID-19, and that could be a confounding factor. While the described intervention process is potentially applicable to multiple EHR systems, the exact form to capture the Elixhauser comorbidities was built into the Epic EHR, limiting external applicability of this tool to other EHR software.

Conclusion

A continuous comprehensive series of interventions substantially increased our patient acuity scores. The increased scores have implications for reimbursement and quality comparisons for hospitals and physicians. Our institution can now be stratified more accurately with our peers and other hospitals. Accurate medical record documentation has become increasingly important, but also increasingly complex. Leveraging the EHR through quality initiatives that facilitate the workflow for providers can have an impact on documentation, coding, and ultimately risk-adjusted outcomes data that influence institutional reputation.

Corresponding author: Marie Anne Sosa, MD; 1120 NW 14th St., Suite 809, Miami, FL, 33134; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

doi:10.12788/jcom.0088

From the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (Drs. Sosa, Ferreira, Gershengorn, Soto, Parekh, and Suarez), and the Quality Department of the University of Miami Hospital and Clinics (Estin Kelly, Ameena Shrestha, Julianne Burgos, and Sandeep Devabhaktuni), Miami, FL.

Abstract

Background: Case mix index (CMI) and expected mortality are determined based on comorbidities. Improving documentation and coding can impact performance indicators. During and prior to 2018, our patient acuity was under-represented, with low expected mortality and CMI. Those metrics motivated our quality team to develop the quality initiatives reported here.

Objectives: We sought to assess the impact of quality initiatives on number of comorbidities, diagnoses, CMI, and expected mortality at the University of Miami Health System.

Design: We conducted an observational study of a series of quality initiatives: (1) education of clinical documentation specialists (CDS) to capture comorbidities (10/2019); (2) facilitating the process for physician query response (2/2020); (3) implementation of computer logic to capture electrolyte disturbances and renal dysfunction (8/2020); (4) development of a tool to capture Elixhauser comorbidities (11/2020); and (5) provider education and electronic health record reviews by the quality team.

Setting and participants: All admissions during 2019 and 2020 at University of Miami Health System. The health system includes 2 academic inpatient facilities, a 560-bed tertiary hospital, and a 40-bed cancer facility. Our hospital is 1 of the 11 PPS-Exempt Cancer Hospitals and is the South Florida’s only NCI-Designated Cancer Center.

Conclusion:

Keywords: PS/QI, coding, case mix index, comorbidities, mortality.

Adoption of comprehensive electronic health record (EHR) systems by US hospitals, defined as an EHR capable of meeting all core meaningful-use metrics including evaluation and tracking of quality metrics, has been steadily increasing.3,4 Many institutions have looked to EHR system transitions as an inflection point to expand clinical documentation improvement (CDI) efforts. Over the past several years, our institution, an academic medical center, has endeavored to fully transition to a comprehensive EHR system (Epic from Epic Systems Corporation). Part of the purpose of this transition was to help study and improve outcomes, reduce readmissions, improve quality of care, and meet performance indicators.

Prior to 2019, our hospital’s patient acuity was low, with a CMI consistently below 2, ranging from 1.81 to 1.99, and an expected mortality consistently below 1.9%, ranging from 1.65% to 1.85%. Our concern that these values underestimated the real severity of illness of our patient population prompted the development of a quality improvement plan. In this report, we describe the processes we undertook to improve documentation and coding of comorbid illness, and report on the impact of these initiatives on performance indicators. We hypothesized that our initiatives would have a significant impact on our ability to capture patient complexity, and thus impact our CMI and expected mortality.

Methods

In the fall of 2019, we embarked on a multifaceted quality improvement project aimed at improving comorbidity capture for patients hospitalized at our institution. The health system includes 2 academic inpatient facilities, a 560-bed tertiary hospital and a 40-bed cancer facility. Since September 2017, we have used Epic as our EHR. In August 2019, we started working with Vizient Clinical Data Base5 to allow benchmarking with peer institutions. We assessed the impact of this initiative with a pre/post study design.

Quality Initiatives

This quality improvement project consisted of a series of 5 targeted interventions coupled with continuous monitoring and education.

1. Comorbidity coding. In October 2019, we met with the clinical documentation specialists (CDS) and the coding team to educate them on the value of coding all comorbidities that have an impact on

2. Physician query. In October 2019, we modified the process for physician query response, allowing physicians to answer queries in the EHR through a reply tool incorporated into the query and accept answers in the body of the Epic message as an active part of the EHR.

3. EHR logic. In August 2020, we developed an EHR smart logic to automatically capture fluid and electrolyte disturbances and renal dysfunction, based on the most recent laboratory values. The logic automatically populated potentially appropriate diagnoses in the assessment and plan of provider notes, which require provider acknowledgment and which providers are able to modify

4. Comorbidity capture tool. In November 2020, we developed a standardized tool to allow providers to easily capture Elixhauser comorbidities (eFigure 2). The Elixhauser index is a method for measuring comorbidities based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification and International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision diagnosis codes found in administrative data1-6 and is used by US News & World Report and Vizient to assess comorbidity burden. Our tool automatically captures diagnoses recorded in previous documentation and allows providers to easily provide the management plan for each; this information is automatically pulled into the provider note.

The development of this tool used an existing functionality within the Epic EHR called SmartForms, SmartData Elements, and SmartLinks. The only cost of tool development was the time invested—124 hours inclusive of 4 hours of staff education. Specifically, a panel of experts (including physicians of different specialties, an analyst, and representatives from the quality office) met weekly for 30 minutes per week over 5 weeks to agree on specific clinical criteria and guide the EHR build analyst. Individual panel members confirmed and validated design requirements (in 15 hours over 5 weeks). Our senior clinical analyst II dedicated 80 hours to actual build time, 15 hours to design time, and 25 hours to tailor the function to our institution’s workflow. This tool was introduced in November 2020; completion was optional at the time of hospital admission but mandatory at discharge to ensure compliance.

5. Quality team

Assessment of Quality Initiatives’ Impact

Data on the number of comorbidities and performance indicators were obtained retrospectively. The data included all hospital admissions from 2019 and 2020 divided into 2 periods: pre-intervention from January 1, 2019 through September 30, 2019, and intervention from October 1, 2019 through December 31, 2020. The primary outcome of this observational study was the rate of comorbidity capture during the intervention period. Comorbidity capture was assessed using the Vizient Clinical Data Base (CDB) health care performance tool.5 Vizient CDB uses the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Elixhauser index, which includes 29 of the initial 31 comorbidities described by Elixhauser,6 as it combines hypertension with and without complications into one. We secondarily aimed to examine the impact of the quality improvement initiatives on several institutional-level performance indicators, including total number of diagnoses, comorbidities or complications (CC), major comorbidities or complications (MCC), CMI, and expected mortality.

Case mix index is the average Medicare Severity-DRG (MS-DRG) weighted across all hospital discharges (appropriate to their discharge date). The expected mortality represents the average expected number of deaths based on diagnosed conditions, age, and gender within the same time frame, and it is based on coded diagnosis; we obtained the mortality index by dividing the observed mortality by the expected mortality. The Vizient CDB Mortality Risk Adjustment Model was used to assign an expected mortality (0%-100%) to each case based on factors such as demographics, admission type, diagnoses, and procedures.

Standard statistics were used to measure the outcomes. We used Excel to compare pre-intervention and intervention period characteristics and outcomes, using t-testing for continuous variables and Chi-square testing for categorial outcomes. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The study was reviewed by the institutional review board (IRB) of our institution (IRB ID: 20210070). The IRB determined that the proposed activity was not research involving human subjects, as defined by the Department of Health and Human Services and US Food and Drug Administration regulations, and that IRB review and approval by the organization were not required.

Results

The health system had a total of 33 066 admissions during the study period—13 689 pre-intervention (January 1, 2019 through September 30, 2019) and 19,377 during the intervention period (October 1, 2019 to December 31, 2020). Demographics were similar among the pre-intervention and intervention periods: mean age was 60 years and 61 years, 52% and 51% of patients were male, 72% and 71% were White, and 20% and 19% were Black, respectively (Table 1).

The multifaceted intervention resulted in a significant improvement in the primary outcome: mean comorbidity capture increased from 2.5 (SD, 1.7) before the intervention to 3.1 (SD, 2.0) during the intervention (P < .00001). Secondary outcomes also improved. The mean number of secondary diagnoses for admissions increased from 11.3 (SD, 7.3) prior to the intervention to 18.5 (SD, 10.4) (P < .00001) during the intervention period. The mean CMI increased from 2.1 (SD, 1.9) to 2.4 (SD, 2.2) post intervention (P < .00001), an increase during the intervention period of 14%. The expected mortality increased from 1.8% (SD, 6.1%) to 3.1% (SD, 9.2%) after the intervention (P < .00001) (Table 2).

There was an overall observed improvement in percentage of discharges with documented CC and MCC for both surgical and medical specialties. Both CC and MCC increased for surgical specialties, from 54.4% to 68.5%, and for medical specialties, from 68.9% to 76.4%. (Figure 1). The diagnoses that were captured more consistently included deficiency anemia, obesity, diabetes with complications, fluid and electrolyte disorders and renal failure, hypertension, weight loss, depression, and hypothyroidism (Figure 2).

During the 9-month pre-intervention period (January 1 through September 30, 2019), there were 2795 queries, with an agreed volume of 1823; the agreement rate was 65% and the average provider turnaround time was 12.53 days. In the 15-month postintervention period, there were 10 216 queries, with an agreed volume of 6802 at 66%. We created a policy to encourage responses no later than 10 days after the query, and our average turnaround time decreased by more than 50% to 5.86 days. The average number of monthly queries increased by 55%, from an average of 311 monthly queries in the pre-intervention period to an average of 681 per month in the postintervention period. The more common queries that had an impact on CMI included sepsis, antineoplastic chemotherapy–induced pancytopenia, acute posthemorrhagic anemia, malnutrition, hyponatremia, and metabolic encephalopathy.

Discussion

The need for accurate documentation by physicians has been recognized for many years.7

With the growing complexity of the documentation and coding process, it is difficult for clinicians to keep up with the terminology required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Several different methods to improve documentation have been proposed. Prior interventions to standardize documentation templates in the trauma service have shown improvement in CMI.8 An educational program on coding for internal medicine that included a lecture series and creation of a laminated pocket card listing common CMS diagnoses, CC, and MCC has been implemented, with an improvement in the capture rate of CC and MCC from 42% to 48% and an impact on expected mortality.9 This program resulted in a 30% decrease in the median quarterly mortality index and an increase in CMI from 1.27 to 1.36.

Our results show that there was an increase in comorbidities documentation of admitted patients after all interventions were implemented, more accurately reflecting the complexity of our patient population in a tertiary care academic medical center. Our CMI increased by 14% during the intervention period. The estimated CMI dollar impact increased by 75% from the pre-intervention period (adjusted for PPS-exempt hospital). The hospital-expected mortality increased from 1.77 to 3.07 (peak at 4.74 during third quarter of 2020) during the implementation period, which is a key driver of quality rankings for national outcomes reporting services such as US News & World Report.

There was increased physician satisfaction as a result of the change of functionality of the query response system, and no additional monetary provider incentive for complete documentation was allocated, apart from education and 1:1 support that improved physician engagement. Our next steps include the implementation of an advanced program to concurrently and automatically capture and nudge providers to respond and complete their documentation in real time.

Limitations

The limitations of our study include those inherent to a retrospective review and are associative and observational in nature. Although we used expected mortality and CMI as a surrogate for patient acuity for comparison, there was no way to control for actual changes in patient acuity that contributed to the increase in CMI, although we believe that the population we served and the services provided and their structure did not change significantly during the intervention period. Additionally, the observed increase in CMI during the implementation period may be a result of described variabilities in CMI and would be better studied over a longer period. Also, during the year of our interventions, 2020, we were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients with COVID-19 are known to carry a lower-than-expected mortality, and that could have had a negative impact on our results. In fact, we did observe a decrease in our expected mortality during the last quarter of 2020, which correlated with one of our regional peaks for COVID-19, and that could be a confounding factor. While the described intervention process is potentially applicable to multiple EHR systems, the exact form to capture the Elixhauser comorbidities was built into the Epic EHR, limiting external applicability of this tool to other EHR software.

Conclusion

A continuous comprehensive series of interventions substantially increased our patient acuity scores. The increased scores have implications for reimbursement and quality comparisons for hospitals and physicians. Our institution can now be stratified more accurately with our peers and other hospitals. Accurate medical record documentation has become increasingly important, but also increasingly complex. Leveraging the EHR through quality initiatives that facilitate the workflow for providers can have an impact on documentation, coding, and ultimately risk-adjusted outcomes data that influence institutional reputation.

Corresponding author: Marie Anne Sosa, MD; 1120 NW 14th St., Suite 809, Miami, FL, 33134; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

doi:10.12788/jcom.0088

1. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi:10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004.

2. Sehgal AR. The role of reputation in U.S. News & World Report’s rankings of the top 50 American hospitals. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(8):521-525. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-8-201004200-00009

3. Jha AK, DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, et al. Use of electronic health records in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1628-1638. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0900592.

4. Adler-Milstein J, DesRoches CM, Kralovec, et al. Electronic health record adoption in US hospitals: progress continues, but challenges persist. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(12):2174-2180. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0992

5. Vizient Clinical Data Base/Resource ManagerTM. Irving, TX: Vizient, Inc.; 2019. Accessed March 10, 2022. https://www.vizientinc.com

6. Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying increased risk of readmission and in-hospital mortality using hospital administrative data: the AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care. 2017;55(7):698-705. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000735

7. Payne T. Improving clinical documentation in an EMR world. Healthc Financ Manage. 2010;64(2):70-74.

8. Barnes SL, Waterman M, Macintyre D, Coughenour J, Kessel J. Impact of standardized trauma documentation to the hospital’s bottom line. Surgery. 2010;148(4):793-797. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.040

9. Spellberg B, Harrington D, Black S, Sue D, Stringer W, Witt M. Capturing the diagnosis: an internal medicine education program to improve documentation. Am J Med. 2013;126(8):739-743.e1. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.11.035

1. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi:10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004.

2. Sehgal AR. The role of reputation in U.S. News & World Report’s rankings of the top 50 American hospitals. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(8):521-525. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-8-201004200-00009

3. Jha AK, DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, et al. Use of electronic health records in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1628-1638. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0900592.

4. Adler-Milstein J, DesRoches CM, Kralovec, et al. Electronic health record adoption in US hospitals: progress continues, but challenges persist. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(12):2174-2180. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0992

5. Vizient Clinical Data Base/Resource ManagerTM. Irving, TX: Vizient, Inc.; 2019. Accessed March 10, 2022. https://www.vizientinc.com

6. Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying increased risk of readmission and in-hospital mortality using hospital administrative data: the AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care. 2017;55(7):698-705. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000735

7. Payne T. Improving clinical documentation in an EMR world. Healthc Financ Manage. 2010;64(2):70-74.

8. Barnes SL, Waterman M, Macintyre D, Coughenour J, Kessel J. Impact of standardized trauma documentation to the hospital’s bottom line. Surgery. 2010;148(4):793-797. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.040

9. Spellberg B, Harrington D, Black S, Sue D, Stringer W, Witt M. Capturing the diagnosis: an internal medicine education program to improve documentation. Am J Med. 2013;126(8):739-743.e1. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.11.035

A Practical and Cost-Effective Approach to the Diagnosis of Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia: A Single-Center Quality Improvement Study

From the Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System Medicine Service (Dr. Cusick), University of Michigan College of Pharmacy, Clinical Pharmacy Service, Michigan Medicine (Dr. Hanigan), Department of Internal Medicine Clinical Experience and Quality, Michigan Medicine (Linda Bashaw), Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI (Dr. Heidemann), and the Operational Excellence Department, Sparrow Health System, Lansing, MI (Matthew Johnson).

Abstract

Background: Diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) requires completion of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)–based heparin-platelet factor 4 (PF4) antibody test. If this test is negative, HIT is excluded. If positive, a serotonin-release assay (SRA) test is indicated. The SRA is expensive and sometimes inappropriately ordered despite negative PF4 results, leading to unnecessary treatment with argatroban while awaiting SRA results.

Objectives: The primary objectives of this project were to reduce unnecessary SRA testing and argatroban utilization in patients with suspected HIT.

Methods: The authors implemented an intervention at a tertiary care academic hospital in November 2017 targeting patients hospitalized with suspected HIT. The intervention was controlled at the level of the laboratory and prevented ordering of SRA tests in the absence of a positive PF4 test. The number of SRA tests performed and argatroban bags administered were identified retrospectively via chart review before the intervention (January 2016 to November 2017) and post intervention (December 2017 to March 2020). Associated costs were calculated based on institutional SRA testing cost as well as the average wholesale price of argatroban.

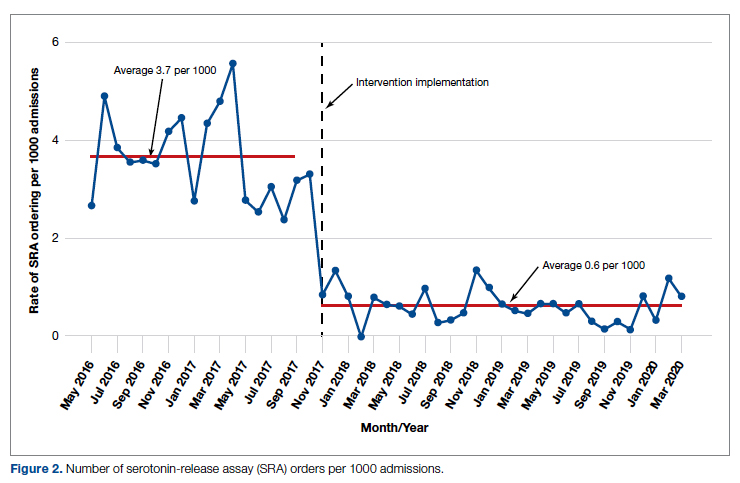

Results: SRA testing decreased from an average of 3.7 SRA results per 1000 admissions before the intervention to an average of 0.6 results per 1000 admissions post intervention. The number of 50-mL argatroban bags used per 1000 admissions decreased from 18.8 prior to the intervention to 14.3 post intervention. Total estimated cost savings per 1000 admissions was $2361.20.

Conclusion: An evidence-based testing strategy for HIT can be effectively implemented at the level of the laboratory. This approach led to reductions in SRA testing and argatroban utilization with resultant cost savings.

Keywords: HIT, argatroban, anticoagulation, serotonin-release assay.

Thrombocytopenia is a common finding in hospitalized patients.1,2 Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is one of the many potential causes of thrombocytopenia in hospitalized patients and occurs when antibodies to the heparin-platelet factor 4 (PF4) complex develop after heparin exposure. This triggers a cascade of events, leading to platelet activation, platelet consumption, and thrombosis. While HIT is relatively rare, occurring in 0.3% to 0.5% of critically ill patients, many patients will be tested to rule out this potentially life-threatening cause of thrombocytopenia.3

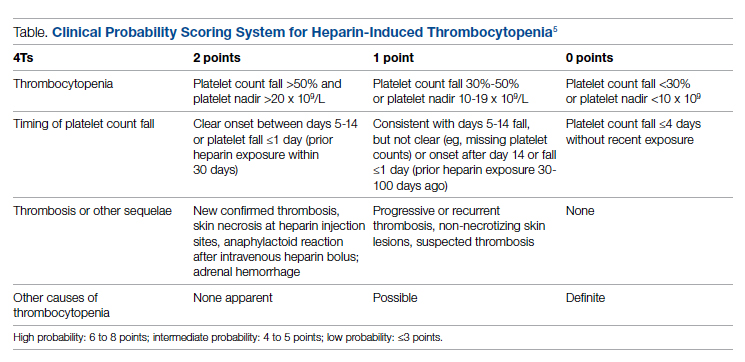

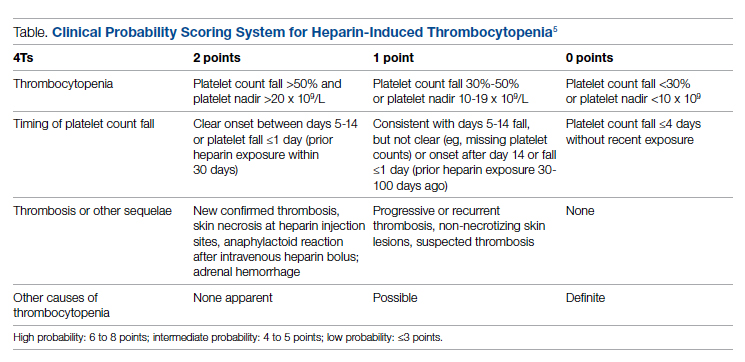

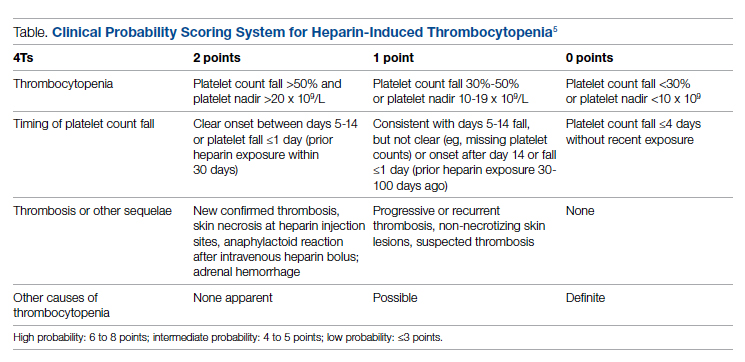

The diagnosis of HIT utilizes a combination of both clinical suspicion and laboratory testing.4 The 4T score (Table) was developed to evaluate the clinical probability of HIT and involves assessing the degree and timing of thrombocytopenia, the presence or absence of thrombosis, and other potential causes of the thrombocytopenia.5 The 4T score is designed to be utilized to identify patients who require laboratory testing for HIT; however, it has low inter-rater agreement in patients undergoing evaluation for HIT,6 and, in our experience, completion of this scoring is time-consuming.

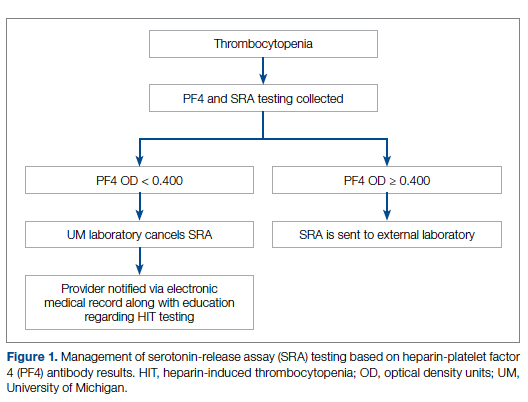

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is a commonly used laboratory test to diagnose HIT that detects antibodies to the heparin-PF4 complex utilizing optical density (OD) units. When using an OD cutoff of 0.400, ELISA PF4 (PF4) tests have a sensitivity of 99.6%, but poor specificity at 69.3%.7 When the PF4 antibody test is positive with an OD ≥0.400, then a functional test is used to determine whether the antibodies detected will activate platelets. The serotonin-release assay (SRA) is a functional test that measures 14C-labeled serotonin release from donor platelets when mixed with patient serum or plasma containing HIT antibodies. In the correct clinical context, a positive ELISA PF4 antibody test along with a positive SRA is diagnostic of HIT.8

The process of diagnosing HIT in a timely and cost-effective manner is dependent on the clinician’s experience in diagnosing HIT as well as access to the laboratory testing necessary to confirm the diagnosis. PF4 antibody tests are time-consuming and not always available daily and/or are not available onsite. The SRA requires access to donor platelets and specialized radioactivity counting equipment, making it available only at particular centers.

The treatment of HIT is more straightforward and involves stopping all heparin products and starting a nonheparin anticoagulant. The direct thrombin inhibitor argatroban is one of the standard nonheparin anticoagulants used in patients with suspected HIT.4 While it is expensive, its short half-life and lack of renal clearance make it ideal for treatment of hospitalized patients with suspected HIT, many of whom need frequent procedures and/or have renal disease.

At our academic tertiary care center, we performed a retrospective analysis that showed inappropriate ordering of diagnostic HIT testing as well as unnecessary use of argatroban even when there was low suspicion for HIT based on laboratory findings. The aim of our project was to reduce unnecessary HIT testing and argatroban utilization without overburdening providers or interfering with established workflows.

Methods

Setting

The University of Michigan (UM) hospital is a 1000-bed tertiary care center in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The UM guidelines reflect evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of HIT.4 In 2016 the UM guidelines for laboratory testing included sending the PF4 antibody test first when there was clinical suspicion of HIT. The SRA was to be sent separately only when the PF4 returned positive (OD ≥ 0.400). Standard guidelines at UM also included switching patients with suspected HIT from heparin to a nonheparin anticoagulant and stopping all heparin products while awaiting the SRA results. The direct thrombin inhibitor argatroban is utilized at UM and monitored with anti-IIa levels. University of Michigan Hospital utilizes the Immucor PF4 IgG ELISA for detecting heparin-associated antibodies.9 In 2016, this PF4 test was performed in the UM onsite laboratory Monday through Friday. At UM the SRA is performed off site, with a turnaround time of 3 to 5 business days.

Baseline Data

We retrospectively reviewed PF4 and SRA testing as well as argatroban usage from December 2016 to May 2017. Despite the institutional guidelines, providers were sending PF4 and SRA simultaneously as soon as HIT was suspected; 62% of PF4 tests were ordered simultaneously with the SRA, but only 8% of these PF4 tests were positive with an OD ≥0.400. Of those patients with negative PF4 testing, argatroban was continued until the SRA returned negative, leading to many days of unnecessary argatroban usage. An informal survey of the anticoagulation pharmacists revealed that many recommended discontinuing argatroban when the PF4 test was negative, but providers routinely did not feel comfortable with this approach. This suggested many providers misunderstood the performance characteristics of the PF4 test.

Intervention

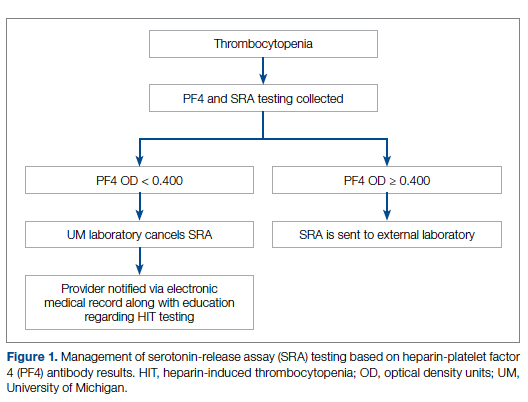

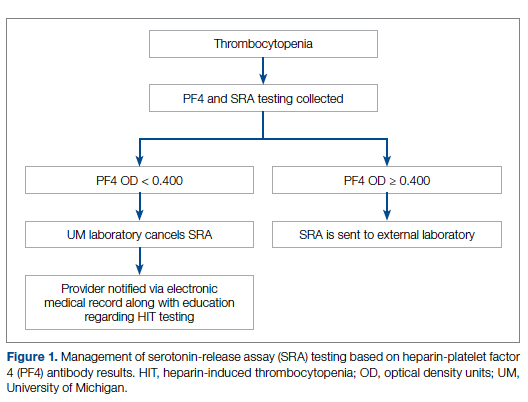

Our team consisted of hematology and internal medicine faculty, pharmacists, coagulation laboratory personnel, and quality improvement specialists. We designed and implemented an intervention in November 2017 focused on controlling the ordering of the SRA test. We chose to focus on this step due to the excellent sensitivity of the PF4 test with a cutoff of OD <0.400 and the significant expense of the SRA test. Under direction of the Coagulation Laboratory Director, a standard operating procedure was developed where the coagulation laboratory personnel did not send out the SRA until a positive PF4 test (OD ≥ 0.400) was reported. If the PF4 was negative, the SRA was canceled and the ordering provider received notification of the cancelled test via the electronic medical record, accompanied by education about HIT testing (Figure 1). In addition, the lab increased the availability of PF4 testing from 5 days to 7 days a week so there were no delays in tests ordered on Fridays or weekends.

Outcomes

Our primary goals were to decrease both SRA testing and argatroban use. Secondarily, we examined the cost-effectiveness of this intervention. We hypothesized that controlling the SRA testing at the laboratory level would decrease both SRA testing and argatroban use.

Data Collection

Pre- and postintervention data were collected retrospectively. Pre-intervention data were from January 2016 through November 2017, and postintervention data were from December 2017 through March 2020. The number of SRA tests performed were identified retrospectively via review of electronic ordering records. All patients who had a hospital admission after January 1, 2016, were included. These patients were filtered to include only those who had a result for an SRA test. In order to calculate cost-savings, we identified both the number of SRA tests ordered retrospectively as well as patients who had both an SRA resulted and had been administered argatroban. Cost-savings were calculated based on our institutional cost of $357 per SRA test.

At our institution, argatroban is supplied in 50-mL bags; therefore, we utilized the number of bags to identify argatroban usage. Savings were calculated using the average wholesale price (AWP) of $292.50 per 50-mL bag. The amounts billed or collected for the SRA testing or argatroban treatment were not collected. Costs were estimated using only direct costs to the institution. Safety data were not collected. As the intent of our project was a quality improvement activity, this project did not require institutional review board regulation per our institutional guidance.

Results

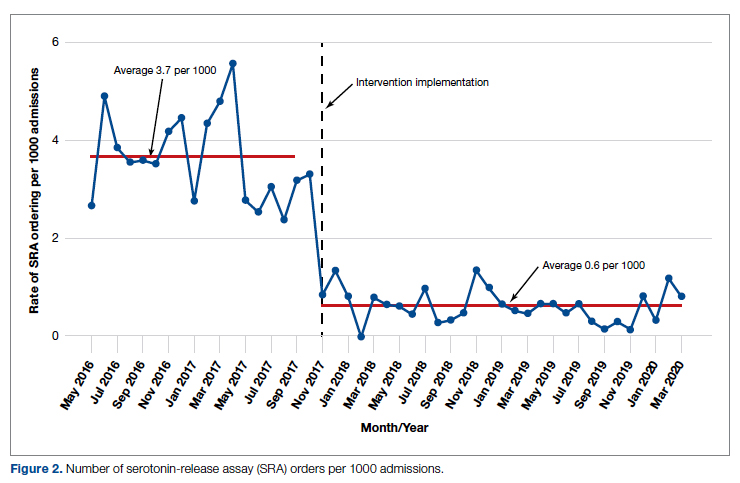

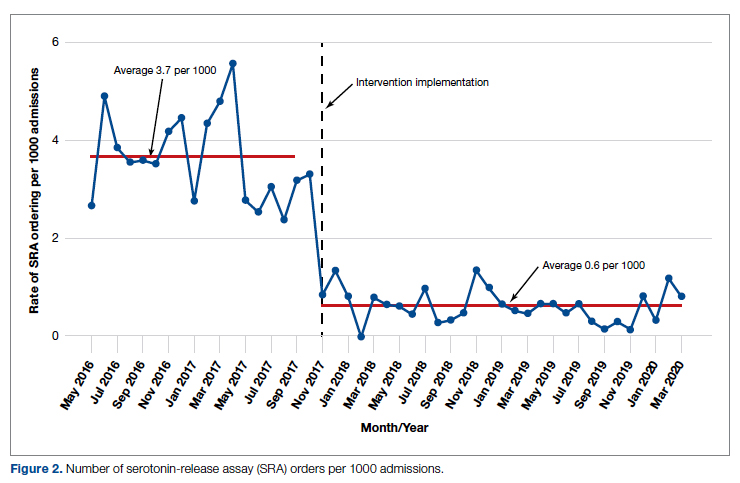

During the pre-intervention period, the average number of admissions (adults and children) at UM was 5863 per month. Post intervention there was an average of 5842 admissions per month. A total of 1192 PF4 tests were ordered before the intervention and 1148 were ordered post intervention. Prior to the intervention, 481 SRA tests were completed, while post intervention 105 were completed. Serotonin-release testing decreased from an average of 3.7 SRA results per 1000 admissions during the pre-intervention period to an average of 0.6 per 1000 admissions post intervention (Figure 2). Cost-savings were $1045 per 1000 admissions.

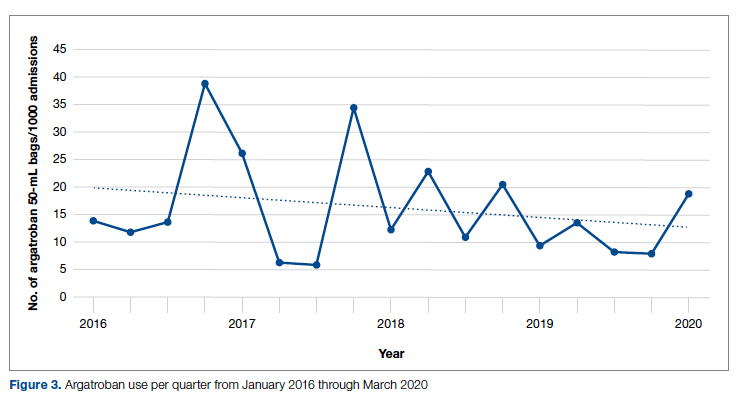

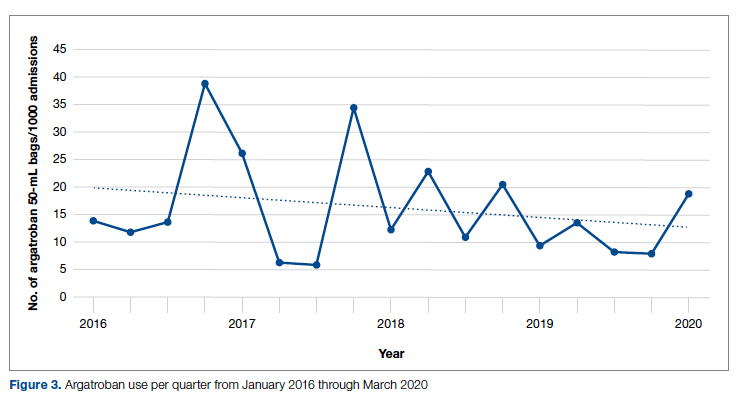

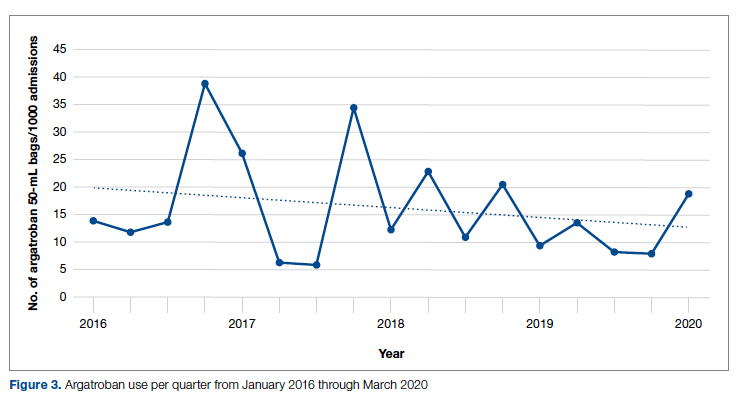

During the pre-intervention period, 2539 bags of argatroban were used, while 2337 bags were used post intervention. The number of 50-mL argatroban bags used per 1000 admissions decreased from 18.8 before the intervention to 14.3 post intervention. Cost-savings were $1316.20 per 1000 admissions. Figure 3 illustrates the monthly argatroban utilization per 1000 admissions during each quarter from January 2016 through March 2020.

Discussion

We designed and implemented an evidence-based strategy for HIT at our academic institution which led to a decrease in unnecessary SRA testing and argatroban utilization, with associated cost savings. By focusing on a single point of intervention at the laboratory level where SRA tests were held and canceled if the PF4 test was negative, we helped offload the decision-making from the provider while simultaneously providing just-in-time education to the provider. This intervention was designed with input from multiple stakeholders, including physicians, quality improvement specialists, pharmacists, and coagulation laboratory personnel.

Serotonin-release testing dramatically decreased post intervention even though a similar number of PF4 tests were performed before and after the intervention. This suggests that the decrease in SRA testing was a direct consequence of our intervention. Post intervention the number of completed SRA tests was 9% of the number of PF4 tests sent. This is consistent with our baseline pre-intervention data showing that only 8% of all PF4 tests sent were positive.

While the absolute number of argatroban bags utilized did not dramatically decrease after the intervention, the quarterly rate did, particularly after 2018. Given that argatroban data were only drawn from patients with a concurrent SRA test, this decrease is clearly from decreased usage in patients with suspected HIT. We suspect the decrease occurred because argatroban was not being continued while awaiting an SRA test in patients with a negative PF4 test. Decreasing the utilization of argatroban not only saved money but also reduced days of exposure to argatroban. While we do not have data regarding adverse events related to argatroban prior to the intervention, it is logical to conclude that reducing unnecessary exposure to argatroban reduces the risk of adverse events related to bleeding. Future studies would ideally address specific safety outcome metrics such as adverse events, bleeding risk, or missed diagnoses of HIT.

Our institutional guidelines for the diagnosis of HIT are evidence-based and helpful but are rarely followed by busy inpatient providers. Controlling the utilization of the SRA at the laboratory level had several advantages. First, removing SRA decision-making from providers who are not experts in the diagnosis of HIT guaranteed adherence to evidence-based guidelines. Second, pharmacists could safely recommend discontinuing argatroban when the PF4 test was negative as there was no SRA pending. Third, with cancellation at the laboratory level there was no need to further burden providers with yet another alert in the electronic health record. Fourth, just-in-time education was provided to the providers with justification for why the SRA test was canceled. Last, ruling out HIT within 24 hours with the PF4 test alone allowed providers to evaluate patients for other causes of thrombocytopenia much earlier than the 3 to 5 business days before the SRA results returned.

A limitation of this study is that it was conducted at a single center. Our approach is also limited by the lack of universal applicability. At our institution we are fortunate to have PF4 testing available in our coagulation laboratory 7 days a week. In addition, the coagulation laboratory controls sending the SRA to the reference laboratory. The specific intervention of controlling the SRA testing is therefore applicable only to institutions similar to ours; however, the concept of removing control of specialized testing from the provider is not unique. Inpatient thrombophilia testing has been a successful target of this approach.11-13 While electronic alerts and education of individual providers can also be effective initially, the effectiveness of these interventions has been repeatedly shown to wane over time.14-16

Conclusion

At our institution we were able to implement practical, evidence-based testing for HIT by implementing control over SRA testing at the level of the laboratory. This approach led to decreased argatroban utilization and cost savings.

Corresponding author: Alice Cusick, MD; LTC Charles S Kettles VA Medical Center, 2215 Fuller Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48105; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

doi: 10.12788/jcom.0087

1. Fountain E, Arepally GM. Thrombocytopenia in hospitalized non-ICU patients. Blood. 2015;126(23):1060. doi:10.1182/blood.v126.23.1060.1060

2. Hui P, Cook DJ, Lim W, Fraser GA, Arnold DM. The frequency and clinical significance of thrombocytopenia complicating critical illness: a systematic review. Chest. 2011;139(2):271-278. doi:10.1378/chest.10-2243

3. Warkentin TE. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2015;21(6):576-585. doi:10.1097/MCC.0000000000000259

4. Cuker A, Arepally GM, Chong BH, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3360-3392. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024489

5. Cuker A, Gimotty PA, Crowther MA, Warkentin TE. Predictive value of the 4Ts scoring system for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2012;120(20):4160-4167. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-07-443051

6. Northam KA, Parker WF, Chen S-L, et al. Evaluation of 4Ts score inter-rater agreement in patients undergoing evaluation for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2021;32(5):328-334. doi:10.1097/MBC.0000000000001042

7. Raschke RA, Curry SC, Warkentin TE, Gerkin RD. Improving clinical interpretation of the anti-platelet factor 4/heparin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia through the use of receiver operating characteristic analysis, stratum-specific likelihood ratios, and Bayes theorem. Chest. 2013;144(4):1269-1275. doi:10.1378/chest.12-2712

8. Warkentin TE, Arnold DM, Nazi I, Kelton JG. The platelet serotonin-release assay. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(6):564-572. doi:10.1002/ajh.24006

9. Use IFOR, Contents TOF. LIFECODES ® PF4 IgG assay:1-9.

10. Ancker JS, Edwards A, Nosal S, Hauser D, Mauer E, Kaushal R. Effects of workload, work complexity, and repeated alerts on alert fatigue in a clinical decision support system. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017;17(1):1-9. doi:10.1186/s12911-017-0430-8

11. O’Connor N, Carter-Johnson R. Effective screening of pathology tests controls costs: thrombophilia testing. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59(5):556. doi:10.1136/jcp.2005.030700

12. Lim MY, Greenberg CS. Inpatient thrombophilia testing: Impact of healthcare system technology and targeted clinician education on changing practice patterns. Vasc Med (United Kingdom). 2018;23(1):78-79. doi:10.1177/1358863X17742509

13. Cox JL, Shunkwiler SM, Koepsell SA. Requirement for a pathologist’s second signature limits inappropriate inpatient thrombophilia testing. Lab Med. 2017;48(4):367-371. doi:10.1093/labmed/lmx040

14. Kwang H, Mou E, Richman I, et al. Thrombophilia testing in the inpatient setting: impact of an educational intervention. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2019;19(1):167. doi:10.1186/s12911-019-0889-6

15. Shah T, Patel-Teague S, Kroupa L, Meyer AND, Singh H. Impact of a national QI programme on reducing electronic health record notifications to clinicians. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(1):10-14. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007447

16. Singh H, Spitzmueller C, Petersen NJ, Sawhney MK, Sittig DF. Information overload and missed test results in electronic health record-based settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):702-704. doi:10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.61

From the Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System Medicine Service (Dr. Cusick), University of Michigan College of Pharmacy, Clinical Pharmacy Service, Michigan Medicine (Dr. Hanigan), Department of Internal Medicine Clinical Experience and Quality, Michigan Medicine (Linda Bashaw), Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI (Dr. Heidemann), and the Operational Excellence Department, Sparrow Health System, Lansing, MI (Matthew Johnson).

Abstract

Background: Diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) requires completion of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)–based heparin-platelet factor 4 (PF4) antibody test. If this test is negative, HIT is excluded. If positive, a serotonin-release assay (SRA) test is indicated. The SRA is expensive and sometimes inappropriately ordered despite negative PF4 results, leading to unnecessary treatment with argatroban while awaiting SRA results.

Objectives: The primary objectives of this project were to reduce unnecessary SRA testing and argatroban utilization in patients with suspected HIT.

Methods: The authors implemented an intervention at a tertiary care academic hospital in November 2017 targeting patients hospitalized with suspected HIT. The intervention was controlled at the level of the laboratory and prevented ordering of SRA tests in the absence of a positive PF4 test. The number of SRA tests performed and argatroban bags administered were identified retrospectively via chart review before the intervention (January 2016 to November 2017) and post intervention (December 2017 to March 2020). Associated costs were calculated based on institutional SRA testing cost as well as the average wholesale price of argatroban.

Results: SRA testing decreased from an average of 3.7 SRA results per 1000 admissions before the intervention to an average of 0.6 results per 1000 admissions post intervention. The number of 50-mL argatroban bags used per 1000 admissions decreased from 18.8 prior to the intervention to 14.3 post intervention. Total estimated cost savings per 1000 admissions was $2361.20.

Conclusion: An evidence-based testing strategy for HIT can be effectively implemented at the level of the laboratory. This approach led to reductions in SRA testing and argatroban utilization with resultant cost savings.

Keywords: HIT, argatroban, anticoagulation, serotonin-release assay.

Thrombocytopenia is a common finding in hospitalized patients.1,2 Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is one of the many potential causes of thrombocytopenia in hospitalized patients and occurs when antibodies to the heparin-platelet factor 4 (PF4) complex develop after heparin exposure. This triggers a cascade of events, leading to platelet activation, platelet consumption, and thrombosis. While HIT is relatively rare, occurring in 0.3% to 0.5% of critically ill patients, many patients will be tested to rule out this potentially life-threatening cause of thrombocytopenia.3

The diagnosis of HIT utilizes a combination of both clinical suspicion and laboratory testing.4 The 4T score (Table) was developed to evaluate the clinical probability of HIT and involves assessing the degree and timing of thrombocytopenia, the presence or absence of thrombosis, and other potential causes of the thrombocytopenia.5 The 4T score is designed to be utilized to identify patients who require laboratory testing for HIT; however, it has low inter-rater agreement in patients undergoing evaluation for HIT,6 and, in our experience, completion of this scoring is time-consuming.

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is a commonly used laboratory test to diagnose HIT that detects antibodies to the heparin-PF4 complex utilizing optical density (OD) units. When using an OD cutoff of 0.400, ELISA PF4 (PF4) tests have a sensitivity of 99.6%, but poor specificity at 69.3%.7 When the PF4 antibody test is positive with an OD ≥0.400, then a functional test is used to determine whether the antibodies detected will activate platelets. The serotonin-release assay (SRA) is a functional test that measures 14C-labeled serotonin release from donor platelets when mixed with patient serum or plasma containing HIT antibodies. In the correct clinical context, a positive ELISA PF4 antibody test along with a positive SRA is diagnostic of HIT.8

The process of diagnosing HIT in a timely and cost-effective manner is dependent on the clinician’s experience in diagnosing HIT as well as access to the laboratory testing necessary to confirm the diagnosis. PF4 antibody tests are time-consuming and not always available daily and/or are not available onsite. The SRA requires access to donor platelets and specialized radioactivity counting equipment, making it available only at particular centers.

The treatment of HIT is more straightforward and involves stopping all heparin products and starting a nonheparin anticoagulant. The direct thrombin inhibitor argatroban is one of the standard nonheparin anticoagulants used in patients with suspected HIT.4 While it is expensive, its short half-life and lack of renal clearance make it ideal for treatment of hospitalized patients with suspected HIT, many of whom need frequent procedures and/or have renal disease.

At our academic tertiary care center, we performed a retrospective analysis that showed inappropriate ordering of diagnostic HIT testing as well as unnecessary use of argatroban even when there was low suspicion for HIT based on laboratory findings. The aim of our project was to reduce unnecessary HIT testing and argatroban utilization without overburdening providers or interfering with established workflows.

Methods

Setting

The University of Michigan (UM) hospital is a 1000-bed tertiary care center in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The UM guidelines reflect evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of HIT.4 In 2016 the UM guidelines for laboratory testing included sending the PF4 antibody test first when there was clinical suspicion of HIT. The SRA was to be sent separately only when the PF4 returned positive (OD ≥ 0.400). Standard guidelines at UM also included switching patients with suspected HIT from heparin to a nonheparin anticoagulant and stopping all heparin products while awaiting the SRA results. The direct thrombin inhibitor argatroban is utilized at UM and monitored with anti-IIa levels. University of Michigan Hospital utilizes the Immucor PF4 IgG ELISA for detecting heparin-associated antibodies.9 In 2016, this PF4 test was performed in the UM onsite laboratory Monday through Friday. At UM the SRA is performed off site, with a turnaround time of 3 to 5 business days.

Baseline Data

We retrospectively reviewed PF4 and SRA testing as well as argatroban usage from December 2016 to May 2017. Despite the institutional guidelines, providers were sending PF4 and SRA simultaneously as soon as HIT was suspected; 62% of PF4 tests were ordered simultaneously with the SRA, but only 8% of these PF4 tests were positive with an OD ≥0.400. Of those patients with negative PF4 testing, argatroban was continued until the SRA returned negative, leading to many days of unnecessary argatroban usage. An informal survey of the anticoagulation pharmacists revealed that many recommended discontinuing argatroban when the PF4 test was negative, but providers routinely did not feel comfortable with this approach. This suggested many providers misunderstood the performance characteristics of the PF4 test.

Intervention