User login

Resilience: Our only remedy?

Resilience is like patience; we all wish we had more of it, but we hope to avoid getting it the hard way. This wasn’t really an area of interest for me, until it needed to be. When one academic year brings the suicide of one colleague and the murder of another, resilience becomes the only alternative to despair.

I realize that even though the particular pain or trauma we endured may be unique, it’s becoming increasingly common. The alarming studies of resident depression and suicide are too difficult for us to ignore. Now we must look in that evidence-based mirror and decide where we will go from here, as a profession and as trainees. The 2018 American Psychiatric Association annual meeting gave us a rude awakening that we may not have it figured out. Even during a year-long theme on wellness, and several sessions at the meeting focusing on the same, we all found ourselves mourning the loss of 2 colleagues to suicide that very weekend only a few miles away from the gathering of the world’s experts.

It brought an eerie element to the conversation.

The wellness “window dressing” will not get the job done. I recently had a candid discussion with a mentor in administrative leadership, and his words surprised as well as challenged me. He told me that the “system” will not save you. You must save yourself. I have decided to respectfully reject that. I think everyone should be involved, including the “system” that is entrusted with my training, and the least that it ought to ensure is that I get out alive.

Has that really become too much to ask of our profession?

We must hold our system to a higher standard. More mindfulness and better breathing will surely be helpful—but I hope we can begin to admit that this is not the answer. Unfortunately, the culture of “pay your dues” and “you know how much harder it was when I was a resident?” is still the norm. We now receive our training in an environment where the pressure is extraordinarily high, the margin for error very low, and the possibility of support is almost a fantasy. “Sure, you can get the help you need ... but don’t take time off or you will be off cycle and create extra work for all your colleagues, who are also equally stressed and will hate you. In the meantime … enjoy this free ice cream and breathing exercise to mindfully cope with the madness around you.”

The perfectly resilient resident may very well be a mythical figure, a clinical unicorn, that we continue chasing. This is the resident who remarkably discovers posttraumatic growth in every stressor. The vicarious trauma they experience from their patients only bolsters their deep compassion, and they thrive under pressure, so we can continue to pile it on. In our search for this “super resident,” we seem to continue to lose a few ordinary residents along the way.

Are we brave enough as a health care culture to take a closer look at the way we are training the next generation of healers? As I get to the end of this article, I wish I had more answers. I’m just a trainee. What do I know? My fear is that we’ve been avoiding this question altogether and have had our eyes closed to the real problem while pacifying ourselves with one “wellness” activity after another. My sincere hope is that this article will make you angry enough to be driven by a conviction that this is not

Resilience is like patience; we all wish we had more of it, but we hope to avoid getting it the hard way. This wasn’t really an area of interest for me, until it needed to be. When one academic year brings the suicide of one colleague and the murder of another, resilience becomes the only alternative to despair.

I realize that even though the particular pain or trauma we endured may be unique, it’s becoming increasingly common. The alarming studies of resident depression and suicide are too difficult for us to ignore. Now we must look in that evidence-based mirror and decide where we will go from here, as a profession and as trainees. The 2018 American Psychiatric Association annual meeting gave us a rude awakening that we may not have it figured out. Even during a year-long theme on wellness, and several sessions at the meeting focusing on the same, we all found ourselves mourning the loss of 2 colleagues to suicide that very weekend only a few miles away from the gathering of the world’s experts.

It brought an eerie element to the conversation.

The wellness “window dressing” will not get the job done. I recently had a candid discussion with a mentor in administrative leadership, and his words surprised as well as challenged me. He told me that the “system” will not save you. You must save yourself. I have decided to respectfully reject that. I think everyone should be involved, including the “system” that is entrusted with my training, and the least that it ought to ensure is that I get out alive.

Has that really become too much to ask of our profession?

We must hold our system to a higher standard. More mindfulness and better breathing will surely be helpful—but I hope we can begin to admit that this is not the answer. Unfortunately, the culture of “pay your dues” and “you know how much harder it was when I was a resident?” is still the norm. We now receive our training in an environment where the pressure is extraordinarily high, the margin for error very low, and the possibility of support is almost a fantasy. “Sure, you can get the help you need ... but don’t take time off or you will be off cycle and create extra work for all your colleagues, who are also equally stressed and will hate you. In the meantime … enjoy this free ice cream and breathing exercise to mindfully cope with the madness around you.”

The perfectly resilient resident may very well be a mythical figure, a clinical unicorn, that we continue chasing. This is the resident who remarkably discovers posttraumatic growth in every stressor. The vicarious trauma they experience from their patients only bolsters their deep compassion, and they thrive under pressure, so we can continue to pile it on. In our search for this “super resident,” we seem to continue to lose a few ordinary residents along the way.

Are we brave enough as a health care culture to take a closer look at the way we are training the next generation of healers? As I get to the end of this article, I wish I had more answers. I’m just a trainee. What do I know? My fear is that we’ve been avoiding this question altogether and have had our eyes closed to the real problem while pacifying ourselves with one “wellness” activity after another. My sincere hope is that this article will make you angry enough to be driven by a conviction that this is not

Resilience is like patience; we all wish we had more of it, but we hope to avoid getting it the hard way. This wasn’t really an area of interest for me, until it needed to be. When one academic year brings the suicide of one colleague and the murder of another, resilience becomes the only alternative to despair.

I realize that even though the particular pain or trauma we endured may be unique, it’s becoming increasingly common. The alarming studies of resident depression and suicide are too difficult for us to ignore. Now we must look in that evidence-based mirror and decide where we will go from here, as a profession and as trainees. The 2018 American Psychiatric Association annual meeting gave us a rude awakening that we may not have it figured out. Even during a year-long theme on wellness, and several sessions at the meeting focusing on the same, we all found ourselves mourning the loss of 2 colleagues to suicide that very weekend only a few miles away from the gathering of the world’s experts.

It brought an eerie element to the conversation.

The wellness “window dressing” will not get the job done. I recently had a candid discussion with a mentor in administrative leadership, and his words surprised as well as challenged me. He told me that the “system” will not save you. You must save yourself. I have decided to respectfully reject that. I think everyone should be involved, including the “system” that is entrusted with my training, and the least that it ought to ensure is that I get out alive.

Has that really become too much to ask of our profession?

We must hold our system to a higher standard. More mindfulness and better breathing will surely be helpful—but I hope we can begin to admit that this is not the answer. Unfortunately, the culture of “pay your dues” and “you know how much harder it was when I was a resident?” is still the norm. We now receive our training in an environment where the pressure is extraordinarily high, the margin for error very low, and the possibility of support is almost a fantasy. “Sure, you can get the help you need ... but don’t take time off or you will be off cycle and create extra work for all your colleagues, who are also equally stressed and will hate you. In the meantime … enjoy this free ice cream and breathing exercise to mindfully cope with the madness around you.”

The perfectly resilient resident may very well be a mythical figure, a clinical unicorn, that we continue chasing. This is the resident who remarkably discovers posttraumatic growth in every stressor. The vicarious trauma they experience from their patients only bolsters their deep compassion, and they thrive under pressure, so we can continue to pile it on. In our search for this “super resident,” we seem to continue to lose a few ordinary residents along the way.

Are we brave enough as a health care culture to take a closer look at the way we are training the next generation of healers? As I get to the end of this article, I wish I had more answers. I’m just a trainee. What do I know? My fear is that we’ve been avoiding this question altogether and have had our eyes closed to the real problem while pacifying ourselves with one “wellness” activity after another. My sincere hope is that this article will make you angry enough to be driven by a conviction that this is not

Promoting wellness during residency

The rate of burnout among physicians is disturbingly high, and wellness promotion is needed at all levels of training. While rigorous clinical training is necessary to build competence for making life-or-death decisions, training should not cause an indifference toward life or death. Because many physicians experience burnout during residency, we all must commit to wellness, which directly leads to healthier professionals and improved patient care.

Ey et al1 evaluated the feasibility and application of a wellness program for residents/fellows and faculty in an academic health center over 10 years. They concluded that a comprehensive model of care was viable and well-valued, based on high levels of physician satisfaction with the program. This model, which involves educational outreach, direct care, and consultation, inspired me to reflect on the resident burnout prevention strategies employed by the residency program in which I am currently training.

Even in situations where a formal wellness program does not exist, measures that promote resident well-being can be embedded and easily adapted:

- Education on recognizing the early signs of burnout or establishing a “buddy system” can promote a help-seeking culture and ease the transition into residency.

- Faculty who provide feedback in the “sandwich method” (praise followed by corrective feedback followed by more praise) can help promote self-confidence among residents.

- Process groups and monthly meetings with chief residents present opportunities for professional development and for residents to express concerns.

- Social gatherings that encourage team building and regular interaction among residents, attendings, and family members help build a comforting sense of community.

- A residency program director and faculty who adopt open-door policies and foster personal attention and guidance are also essential.

A recent cross-sectional analysis found that building competence, autonomy, coping mechanisms, adequate sleep, and social relatedness were associated with resident well-being.2 Hence, these factors should be integrated within residency training programs.

Residency should be approached as an engagement between colleagues where autonomy and confidence are promoted while residents acquire clinical skills within a wellness-promoting, learning environment. Demanding schedules may limit access to a dedicated wellness program; however, it is essential that a system be established to quickly identify and mitigate burnout. We all strive to be the best in our respective fields, and we must re-evaluate how we achieve excellent training while developing proper skills for future success. As physicians, we are not machines; our humanity connects us with our patients, explains life-changing news, or consoles the bereaved when there is loss of life. We must embrace our humanity and be mindful that physicians experiencing burnout cannot deliver high-quality care. Early detection and prevention strategies during residency training are key.

1. Ey S, Moffit M, Kinzie JM, et al. Feasibility of a comprehensive wellness and suicide prevention program: a decade of caring for physicians in training and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):747-753.

2. Raj KS. Well-being in residency: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):674-684.

The rate of burnout among physicians is disturbingly high, and wellness promotion is needed at all levels of training. While rigorous clinical training is necessary to build competence for making life-or-death decisions, training should not cause an indifference toward life or death. Because many physicians experience burnout during residency, we all must commit to wellness, which directly leads to healthier professionals and improved patient care.

Ey et al1 evaluated the feasibility and application of a wellness program for residents/fellows and faculty in an academic health center over 10 years. They concluded that a comprehensive model of care was viable and well-valued, based on high levels of physician satisfaction with the program. This model, which involves educational outreach, direct care, and consultation, inspired me to reflect on the resident burnout prevention strategies employed by the residency program in which I am currently training.

Even in situations where a formal wellness program does not exist, measures that promote resident well-being can be embedded and easily adapted:

- Education on recognizing the early signs of burnout or establishing a “buddy system” can promote a help-seeking culture and ease the transition into residency.

- Faculty who provide feedback in the “sandwich method” (praise followed by corrective feedback followed by more praise) can help promote self-confidence among residents.

- Process groups and monthly meetings with chief residents present opportunities for professional development and for residents to express concerns.

- Social gatherings that encourage team building and regular interaction among residents, attendings, and family members help build a comforting sense of community.

- A residency program director and faculty who adopt open-door policies and foster personal attention and guidance are also essential.

A recent cross-sectional analysis found that building competence, autonomy, coping mechanisms, adequate sleep, and social relatedness were associated with resident well-being.2 Hence, these factors should be integrated within residency training programs.

Residency should be approached as an engagement between colleagues where autonomy and confidence are promoted while residents acquire clinical skills within a wellness-promoting, learning environment. Demanding schedules may limit access to a dedicated wellness program; however, it is essential that a system be established to quickly identify and mitigate burnout. We all strive to be the best in our respective fields, and we must re-evaluate how we achieve excellent training while developing proper skills for future success. As physicians, we are not machines; our humanity connects us with our patients, explains life-changing news, or consoles the bereaved when there is loss of life. We must embrace our humanity and be mindful that physicians experiencing burnout cannot deliver high-quality care. Early detection and prevention strategies during residency training are key.

The rate of burnout among physicians is disturbingly high, and wellness promotion is needed at all levels of training. While rigorous clinical training is necessary to build competence for making life-or-death decisions, training should not cause an indifference toward life or death. Because many physicians experience burnout during residency, we all must commit to wellness, which directly leads to healthier professionals and improved patient care.

Ey et al1 evaluated the feasibility and application of a wellness program for residents/fellows and faculty in an academic health center over 10 years. They concluded that a comprehensive model of care was viable and well-valued, based on high levels of physician satisfaction with the program. This model, which involves educational outreach, direct care, and consultation, inspired me to reflect on the resident burnout prevention strategies employed by the residency program in which I am currently training.

Even in situations where a formal wellness program does not exist, measures that promote resident well-being can be embedded and easily adapted:

- Education on recognizing the early signs of burnout or establishing a “buddy system” can promote a help-seeking culture and ease the transition into residency.

- Faculty who provide feedback in the “sandwich method” (praise followed by corrective feedback followed by more praise) can help promote self-confidence among residents.

- Process groups and monthly meetings with chief residents present opportunities for professional development and for residents to express concerns.

- Social gatherings that encourage team building and regular interaction among residents, attendings, and family members help build a comforting sense of community.

- A residency program director and faculty who adopt open-door policies and foster personal attention and guidance are also essential.

A recent cross-sectional analysis found that building competence, autonomy, coping mechanisms, adequate sleep, and social relatedness were associated with resident well-being.2 Hence, these factors should be integrated within residency training programs.

Residency should be approached as an engagement between colleagues where autonomy and confidence are promoted while residents acquire clinical skills within a wellness-promoting, learning environment. Demanding schedules may limit access to a dedicated wellness program; however, it is essential that a system be established to quickly identify and mitigate burnout. We all strive to be the best in our respective fields, and we must re-evaluate how we achieve excellent training while developing proper skills for future success. As physicians, we are not machines; our humanity connects us with our patients, explains life-changing news, or consoles the bereaved when there is loss of life. We must embrace our humanity and be mindful that physicians experiencing burnout cannot deliver high-quality care. Early detection and prevention strategies during residency training are key.

1. Ey S, Moffit M, Kinzie JM, et al. Feasibility of a comprehensive wellness and suicide prevention program: a decade of caring for physicians in training and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):747-753.

2. Raj KS. Well-being in residency: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):674-684.

1. Ey S, Moffit M, Kinzie JM, et al. Feasibility of a comprehensive wellness and suicide prevention program: a decade of caring for physicians in training and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):747-753.

2. Raj KS. Well-being in residency: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):674-684.

Family therapy and cultural conflicts

I recently had the privilege of treating a family who spoke my first language, Hindi. My patient, Ms. M, was 16 years old and struggling to adjust to her new life in the United States, having recently come from India. America’s schooling, culture, and “open society” was a contrast to her life in a semi-rural town, especially her close-knit family structure in which her parents and siblings are everything. Due to their cultural beliefs and religious faith in Islam, both Ms. M and her father were initially resistant to begin treatment for her depression and anxiety. “Let’s give it a trial” was the attitude I finally got from the father. But to me, there was a clear discordance in the communication among the family members in addition to the primary mental illness that led them to come for treatment. I was attracted to work with this family because I had a reasonable understanding of their faith, their culture, and their family system, and I have an inclination toward spirituality. Even though I recognized this family’s social isolation, I wondered why they were still in a state of unrest, given their deep commitment to their faith.

Ms. M was isolating herself at home, in an environment that wasn’t supportive of talking about her concerns. These included being bullied for being “different,” for how she dressed, and for having home-cooked traditional meals for lunch, and being unable to socialize with most of her male peers, except for those from her same community. This led her to dream of returning to India.

The family did not have a social life. Ms. M told me, “I wanted to socialize, but I cannot because of my faith and religion.” So she chose to wear attire to identify with her mother and her culture of origin. She also did this to hide her emotional pain from enduring trauma related to bullying at her school. It was a challenge to understand how faith, resilience, and trauma were intermingled in Ms. M and her family.

I saw Ms. M and her family for 12 one-hour family psychotherapy sessions. The initial session unfolded uneasily. It was a challenge to build rapport and help them understand how family therapy works. Circular inquiries to each family member, specifically to get the mother’s point of view, brought mourning, shame, and guilt to this family. The importance of marriage, education, and immigration were processed in reference to their culture and their incomplete acculturation to life in the United States.

I wondered if there were other families with different cultural backgrounds who struggled with similar conflicts. I also wondered if those families understood the value of family therapy or had ever experienced this therapeutic process.

The 3 key signs that made me believe that this family was making progress through our work together included:

- They complied with treatment; the family never missed a session.

- The parents acknowledged that their daughter was doing better.

- The mother brought me a dinner as a gesture of gratitude in our last session. This is a particularly meaningful gesture on the part of people with their cultural background.

I clearly remember our first meeting, when Ms. M asked

I recently had the privilege of treating a family who spoke my first language, Hindi. My patient, Ms. M, was 16 years old and struggling to adjust to her new life in the United States, having recently come from India. America’s schooling, culture, and “open society” was a contrast to her life in a semi-rural town, especially her close-knit family structure in which her parents and siblings are everything. Due to their cultural beliefs and religious faith in Islam, both Ms. M and her father were initially resistant to begin treatment for her depression and anxiety. “Let’s give it a trial” was the attitude I finally got from the father. But to me, there was a clear discordance in the communication among the family members in addition to the primary mental illness that led them to come for treatment. I was attracted to work with this family because I had a reasonable understanding of their faith, their culture, and their family system, and I have an inclination toward spirituality. Even though I recognized this family’s social isolation, I wondered why they were still in a state of unrest, given their deep commitment to their faith.

Ms. M was isolating herself at home, in an environment that wasn’t supportive of talking about her concerns. These included being bullied for being “different,” for how she dressed, and for having home-cooked traditional meals for lunch, and being unable to socialize with most of her male peers, except for those from her same community. This led her to dream of returning to India.

The family did not have a social life. Ms. M told me, “I wanted to socialize, but I cannot because of my faith and religion.” So she chose to wear attire to identify with her mother and her culture of origin. She also did this to hide her emotional pain from enduring trauma related to bullying at her school. It was a challenge to understand how faith, resilience, and trauma were intermingled in Ms. M and her family.

I saw Ms. M and her family for 12 one-hour family psychotherapy sessions. The initial session unfolded uneasily. It was a challenge to build rapport and help them understand how family therapy works. Circular inquiries to each family member, specifically to get the mother’s point of view, brought mourning, shame, and guilt to this family. The importance of marriage, education, and immigration were processed in reference to their culture and their incomplete acculturation to life in the United States.

I wondered if there were other families with different cultural backgrounds who struggled with similar conflicts. I also wondered if those families understood the value of family therapy or had ever experienced this therapeutic process.

The 3 key signs that made me believe that this family was making progress through our work together included:

- They complied with treatment; the family never missed a session.

- The parents acknowledged that their daughter was doing better.

- The mother brought me a dinner as a gesture of gratitude in our last session. This is a particularly meaningful gesture on the part of people with their cultural background.

I clearly remember our first meeting, when Ms. M asked

I recently had the privilege of treating a family who spoke my first language, Hindi. My patient, Ms. M, was 16 years old and struggling to adjust to her new life in the United States, having recently come from India. America’s schooling, culture, and “open society” was a contrast to her life in a semi-rural town, especially her close-knit family structure in which her parents and siblings are everything. Due to their cultural beliefs and religious faith in Islam, both Ms. M and her father were initially resistant to begin treatment for her depression and anxiety. “Let’s give it a trial” was the attitude I finally got from the father. But to me, there was a clear discordance in the communication among the family members in addition to the primary mental illness that led them to come for treatment. I was attracted to work with this family because I had a reasonable understanding of their faith, their culture, and their family system, and I have an inclination toward spirituality. Even though I recognized this family’s social isolation, I wondered why they were still in a state of unrest, given their deep commitment to their faith.

Ms. M was isolating herself at home, in an environment that wasn’t supportive of talking about her concerns. These included being bullied for being “different,” for how she dressed, and for having home-cooked traditional meals for lunch, and being unable to socialize with most of her male peers, except for those from her same community. This led her to dream of returning to India.

The family did not have a social life. Ms. M told me, “I wanted to socialize, but I cannot because of my faith and religion.” So she chose to wear attire to identify with her mother and her culture of origin. She also did this to hide her emotional pain from enduring trauma related to bullying at her school. It was a challenge to understand how faith, resilience, and trauma were intermingled in Ms. M and her family.

I saw Ms. M and her family for 12 one-hour family psychotherapy sessions. The initial session unfolded uneasily. It was a challenge to build rapport and help them understand how family therapy works. Circular inquiries to each family member, specifically to get the mother’s point of view, brought mourning, shame, and guilt to this family. The importance of marriage, education, and immigration were processed in reference to their culture and their incomplete acculturation to life in the United States.

I wondered if there were other families with different cultural backgrounds who struggled with similar conflicts. I also wondered if those families understood the value of family therapy or had ever experienced this therapeutic process.

The 3 key signs that made me believe that this family was making progress through our work together included:

- They complied with treatment; the family never missed a session.

- The parents acknowledged that their daughter was doing better.

- The mother brought me a dinner as a gesture of gratitude in our last session. This is a particularly meaningful gesture on the part of people with their cultural background.

I clearly remember our first meeting, when Ms. M asked

Proactive consultation: A new model of care in consultation-liaison psychiatry

During my residency training, I was trained in the standard “reactive” psychiatric consultation model. In this system, I would see consults placed by the primary team after they identified a behavioral issue in a patient. As a trainee, I experienced frequent frustrations working in this model: Consults that are discharge-dependent (“Can you see the patient before he is discharged this morning?”), consults for acute behavioral dysregulation (“The patient is near the elevator, can you come see him ASAP?”), or consults for consequences of poor management of alcohol/benzodiazepine withdrawal (“The patient is confused and trying to leave”).

As a fellow in consultation-liaison (C-L) psychiatry, I was introduced to the “proactive” consultation model, which avoids some of these issues. In this article, which is intended for residents who have not been exposed to this new approach, I explain how the proactive model changes our experience as C-L clinicians.

The Behavioral Intervention Team

At Yale New Haven Hospital, the Behavioral Intervention Team (BIT) is a proactive, multidisciplinary psychiatric consultation service that serves the internal medicine units at the hospital. The team consists of nurse practitioners, nurse liaison specialists, social workers, and psychiatrists. The team identifies and removes behavioral barriers in the care of hospitalized mentally ill patients.

The BIT collaborates closely with the medical team through formal and informal consultation; co-management of behavioral issues; education of medical, nursing, and social work staff; and direct care of complex patients with behavioral disorders. The BIT assists the medical team with transitions to appropriate outpatient and inpatient psychiatric care. The team also manages the relationship with the insurer when a patient requires a stay in a psychiatric unit.

This model has a critical financial benefit in reducing the length of stay, but it also has many other benefits. It focuses on early recognition and treatment, and helps mitigate the effects of mental or substance use disorders on patients’ recovery. BIT members educate their peers regarding management of a multitude of behavioral issues. This fosters extensive informal collaboration (“curbside consultation”), which helps patients who did not receive a formal consult. The model distributes work more rationally among different professional specialists. It yields a relationship with medical teams that is not only more effective, but also more enjoyable. In the BIT model, psychiatrists pick the cases where they feel they can have the most impact, and avoid the cases they feel they cannot have any.1-3

CASE A better approach to alcohol withdrawal

Mr. X, age 56, has a history of alcohol use disorder, hypertension, and coronary artery disease. He’s had multiple past admissions for complicated alcohol withdrawal. He is transferred from a local community hospital, where he had presented with chest pain. His last drink was 2 days prior to admission, and his blood alcohol level is <10 mg/dL.

During Mr. X’s previous hospitalizations, psychiatric consults were performed in the standard reactive model. The primary team initially prescribed an ineffective dosage of benzodiazepines for his alcohol withdrawal. This escalated his withdrawal into delirium tremens, after which psychiatry was involved. Due to this early ineffective management, the patient had a prolonged medical ICU stay and overall stay, experienced increased medical complications, and required increased staff resources because he was extremely agitated.

Continued to: During this hospitalization...

During this hospitalization, Mr. X arrives with similar medical complaints. The nurse practitioner on the BIT service, who screened all admissions each day, examines the prior notes (she finds the team sign-outs to be particularly useful). She suggests a psychiatric consult on Day 1 of the admission, which the primary medical team orders. The BIT nurse practitioner gives apt recommendations of evidence-based management, including a benzodiazepine taper, high-dose thiamine, and psychopharmacologic approaches to severe agitation. The nurse liaison specialist on the service makes behavioral plans for managing agitation, which she communicates to the nurses caring for Mr. X.

Because his withdrawal is managed more promptly, Mr. X’s length of stay is shorter and he does not experience any medical complications. The BIT social worker helps find appropriate aftercare options, including residential treatment and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, to which the patient agrees.

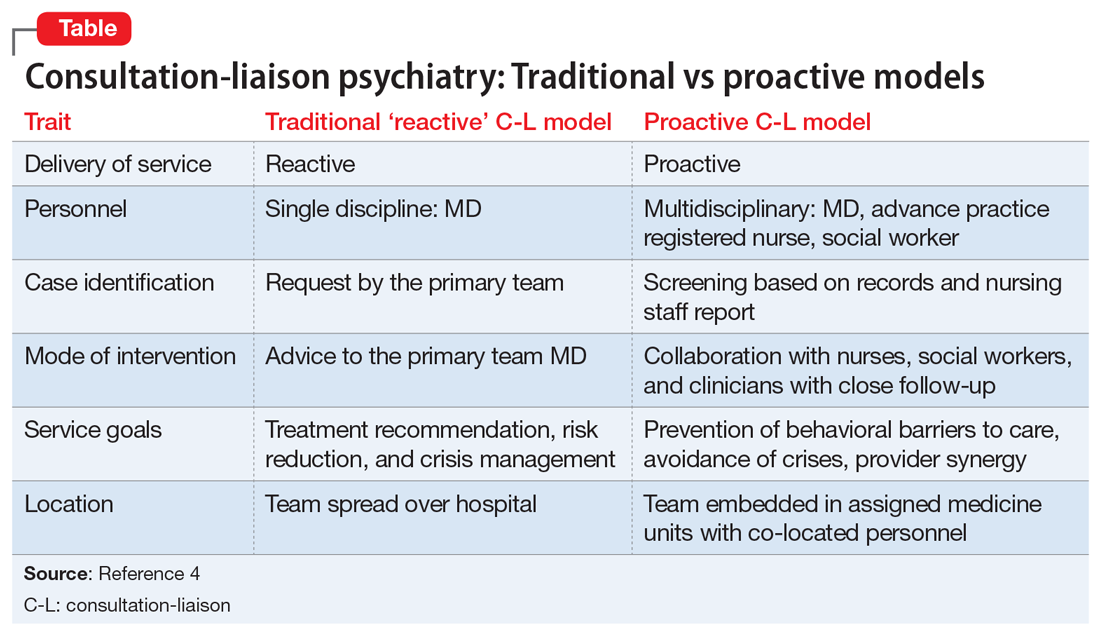

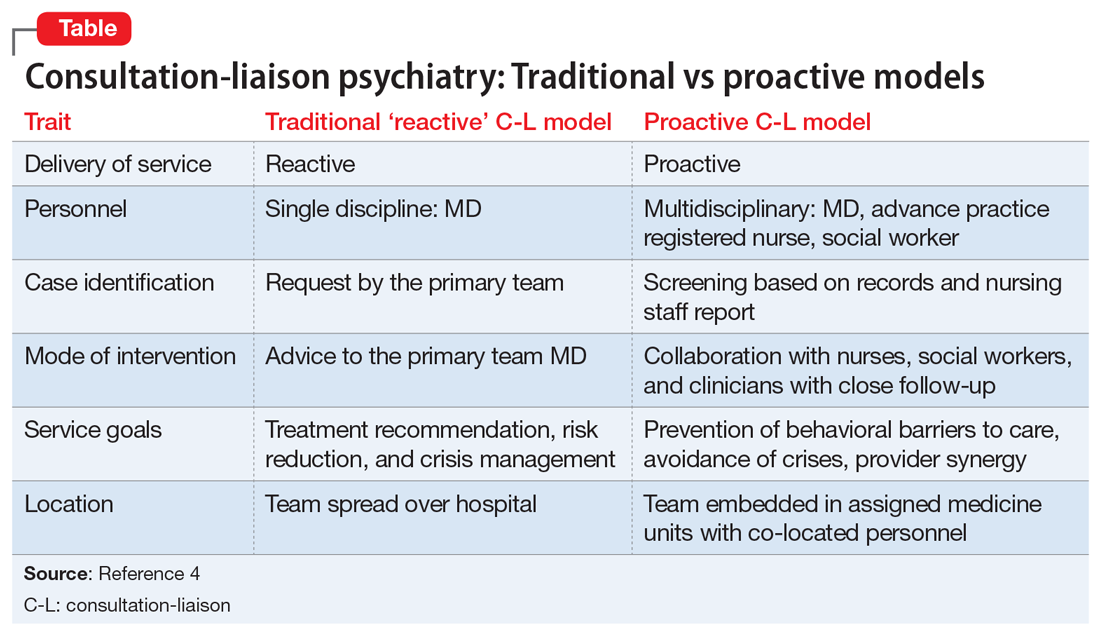

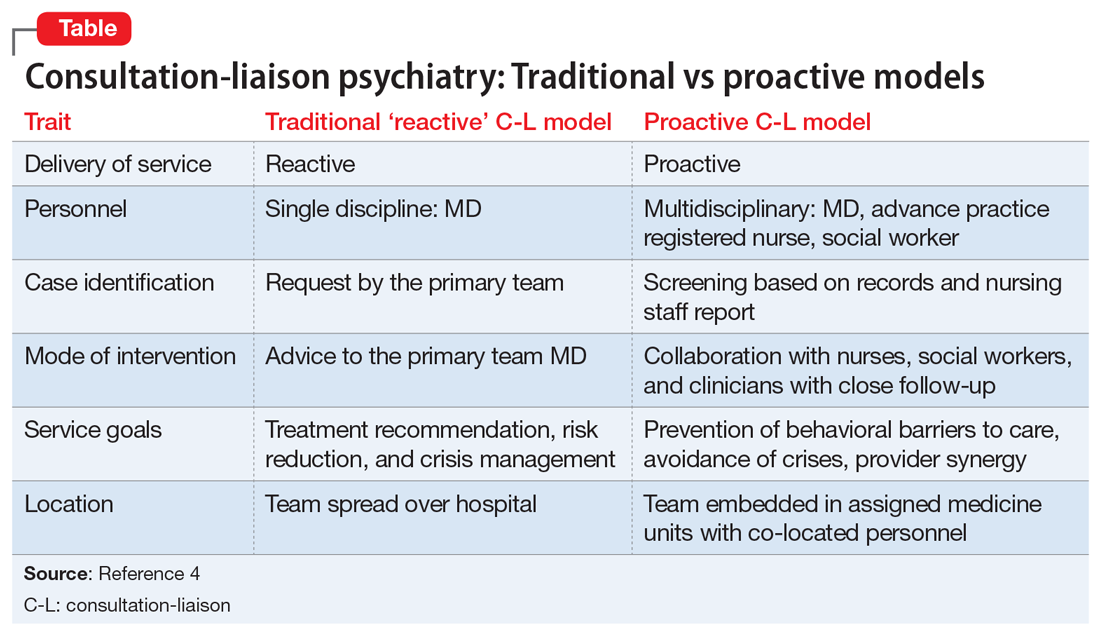

Participating in this case was highly educational for me as a trainee. This case is but one example among many where proactive consultation provided prompt care, lowered the rate of complications, reduced length of stay, and resulted in greater provider satisfaction. The Table4 contrasts the proactive and reactive consultation models. The following 5 factors are critical in the proactive consultation model4,5:

1. Standardized and reliable procedure screening of all admissions, involving a mental health professional, through record review and staff contact. This screening should identify patients with issues who will benefit specifically from in-hospital services, rather than just patients with any psychiatric issue. An electronic medical record is essential to efficient screening, team communication, and progress monitoring. Truly integrated consultation would be impossible with a paper chart.

Continued to: 2. Rapid intervention...

2. Rapid intervention that anticipates impending problems before a cascade of complications starts.

3. Collaborative engagement with the primary medical team, sharing the burden of caring for the complex inpatient, and transmitting critical behavioral management skills to all caregivers, including the skill of recognizing patients who can benefit from a psychiatric consultation.

4. Daily and close contact between behavioral and medical teams, ensuring that treatment recommendations are understood, enacted, and reinforced, ineffective treatments are discontinued, and new problems are addressed before complicating consequences arise. Dedicating specific personnel to specific hospital units and placing them in rounds simplifies communication and speeds intervention implementation.

5. A multidisciplinary consultation team, offering a range of responses, including informal curbside consultation, consultation with an advanced practice registered nurse, social work interventions, advice to discharge planning teams, psychological services, and access to specialized providers, such as addiction teams, as well as traditional consultation with an experienced psychiatrist.

Research has shown the effectiveness of proactive, embedded, multidisciplinary approaches.1-3,5 It was a gratifying experience to work in this model. I worked intimately with medical clinicians, and shared the burden of responsibilities leading to optimal patient outcomes. The proactive consultation model truly re-emphasizes the “liaison” component of C-L psychiatry, as it was originally envisioned.

1. Sledge WH, Gueorguieva R, Desan P, et al. Multidisciplinary proactive psychiatric consultation service: impact on length of stay for medical inpatients. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(4):208-216.

2. Desan PH, Zimbrean PC, Weinstein AJ, et al. Proactive psychiatric consultation services reduce length of stay for admissions to an inpatient medical team. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):513-520.

3. Sledge WH, Bozzo J, White-McCullum BA, et al. The cost-benefit from the perspective of the hospital of a proactive psychiatric consultation service on inpatient general medicine services. Health Econ Outcome Res Open Access. 2016;2(4):122.

4. Sledge WH, Lee HB. Proactive psychiatric consultation for hospitalized patients, a plan for the future. Health Affairs. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20150528.048026/full/. Published May 28, 2015. Accessed September 12, 2018.

5. Desan P, Lee H, Zimbrean P, et al. New models of psychiatric consultation in the general medical hospital: liaison psychiatry is back. Psychiatr Ann. 2017;47:355-361.

During my residency training, I was trained in the standard “reactive” psychiatric consultation model. In this system, I would see consults placed by the primary team after they identified a behavioral issue in a patient. As a trainee, I experienced frequent frustrations working in this model: Consults that are discharge-dependent (“Can you see the patient before he is discharged this morning?”), consults for acute behavioral dysregulation (“The patient is near the elevator, can you come see him ASAP?”), or consults for consequences of poor management of alcohol/benzodiazepine withdrawal (“The patient is confused and trying to leave”).

As a fellow in consultation-liaison (C-L) psychiatry, I was introduced to the “proactive” consultation model, which avoids some of these issues. In this article, which is intended for residents who have not been exposed to this new approach, I explain how the proactive model changes our experience as C-L clinicians.

The Behavioral Intervention Team

At Yale New Haven Hospital, the Behavioral Intervention Team (BIT) is a proactive, multidisciplinary psychiatric consultation service that serves the internal medicine units at the hospital. The team consists of nurse practitioners, nurse liaison specialists, social workers, and psychiatrists. The team identifies and removes behavioral barriers in the care of hospitalized mentally ill patients.

The BIT collaborates closely with the medical team through formal and informal consultation; co-management of behavioral issues; education of medical, nursing, and social work staff; and direct care of complex patients with behavioral disorders. The BIT assists the medical team with transitions to appropriate outpatient and inpatient psychiatric care. The team also manages the relationship with the insurer when a patient requires a stay in a psychiatric unit.

This model has a critical financial benefit in reducing the length of stay, but it also has many other benefits. It focuses on early recognition and treatment, and helps mitigate the effects of mental or substance use disorders on patients’ recovery. BIT members educate their peers regarding management of a multitude of behavioral issues. This fosters extensive informal collaboration (“curbside consultation”), which helps patients who did not receive a formal consult. The model distributes work more rationally among different professional specialists. It yields a relationship with medical teams that is not only more effective, but also more enjoyable. In the BIT model, psychiatrists pick the cases where they feel they can have the most impact, and avoid the cases they feel they cannot have any.1-3

CASE A better approach to alcohol withdrawal

Mr. X, age 56, has a history of alcohol use disorder, hypertension, and coronary artery disease. He’s had multiple past admissions for complicated alcohol withdrawal. He is transferred from a local community hospital, where he had presented with chest pain. His last drink was 2 days prior to admission, and his blood alcohol level is <10 mg/dL.

During Mr. X’s previous hospitalizations, psychiatric consults were performed in the standard reactive model. The primary team initially prescribed an ineffective dosage of benzodiazepines for his alcohol withdrawal. This escalated his withdrawal into delirium tremens, after which psychiatry was involved. Due to this early ineffective management, the patient had a prolonged medical ICU stay and overall stay, experienced increased medical complications, and required increased staff resources because he was extremely agitated.

Continued to: During this hospitalization...

During this hospitalization, Mr. X arrives with similar medical complaints. The nurse practitioner on the BIT service, who screened all admissions each day, examines the prior notes (she finds the team sign-outs to be particularly useful). She suggests a psychiatric consult on Day 1 of the admission, which the primary medical team orders. The BIT nurse practitioner gives apt recommendations of evidence-based management, including a benzodiazepine taper, high-dose thiamine, and psychopharmacologic approaches to severe agitation. The nurse liaison specialist on the service makes behavioral plans for managing agitation, which she communicates to the nurses caring for Mr. X.

Because his withdrawal is managed more promptly, Mr. X’s length of stay is shorter and he does not experience any medical complications. The BIT social worker helps find appropriate aftercare options, including residential treatment and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, to which the patient agrees.

Participating in this case was highly educational for me as a trainee. This case is but one example among many where proactive consultation provided prompt care, lowered the rate of complications, reduced length of stay, and resulted in greater provider satisfaction. The Table4 contrasts the proactive and reactive consultation models. The following 5 factors are critical in the proactive consultation model4,5:

1. Standardized and reliable procedure screening of all admissions, involving a mental health professional, through record review and staff contact. This screening should identify patients with issues who will benefit specifically from in-hospital services, rather than just patients with any psychiatric issue. An electronic medical record is essential to efficient screening, team communication, and progress monitoring. Truly integrated consultation would be impossible with a paper chart.

Continued to: 2. Rapid intervention...

2. Rapid intervention that anticipates impending problems before a cascade of complications starts.

3. Collaborative engagement with the primary medical team, sharing the burden of caring for the complex inpatient, and transmitting critical behavioral management skills to all caregivers, including the skill of recognizing patients who can benefit from a psychiatric consultation.

4. Daily and close contact between behavioral and medical teams, ensuring that treatment recommendations are understood, enacted, and reinforced, ineffective treatments are discontinued, and new problems are addressed before complicating consequences arise. Dedicating specific personnel to specific hospital units and placing them in rounds simplifies communication and speeds intervention implementation.

5. A multidisciplinary consultation team, offering a range of responses, including informal curbside consultation, consultation with an advanced practice registered nurse, social work interventions, advice to discharge planning teams, psychological services, and access to specialized providers, such as addiction teams, as well as traditional consultation with an experienced psychiatrist.

Research has shown the effectiveness of proactive, embedded, multidisciplinary approaches.1-3,5 It was a gratifying experience to work in this model. I worked intimately with medical clinicians, and shared the burden of responsibilities leading to optimal patient outcomes. The proactive consultation model truly re-emphasizes the “liaison” component of C-L psychiatry, as it was originally envisioned.

During my residency training, I was trained in the standard “reactive” psychiatric consultation model. In this system, I would see consults placed by the primary team after they identified a behavioral issue in a patient. As a trainee, I experienced frequent frustrations working in this model: Consults that are discharge-dependent (“Can you see the patient before he is discharged this morning?”), consults for acute behavioral dysregulation (“The patient is near the elevator, can you come see him ASAP?”), or consults for consequences of poor management of alcohol/benzodiazepine withdrawal (“The patient is confused and trying to leave”).

As a fellow in consultation-liaison (C-L) psychiatry, I was introduced to the “proactive” consultation model, which avoids some of these issues. In this article, which is intended for residents who have not been exposed to this new approach, I explain how the proactive model changes our experience as C-L clinicians.

The Behavioral Intervention Team

At Yale New Haven Hospital, the Behavioral Intervention Team (BIT) is a proactive, multidisciplinary psychiatric consultation service that serves the internal medicine units at the hospital. The team consists of nurse practitioners, nurse liaison specialists, social workers, and psychiatrists. The team identifies and removes behavioral barriers in the care of hospitalized mentally ill patients.

The BIT collaborates closely with the medical team through formal and informal consultation; co-management of behavioral issues; education of medical, nursing, and social work staff; and direct care of complex patients with behavioral disorders. The BIT assists the medical team with transitions to appropriate outpatient and inpatient psychiatric care. The team also manages the relationship with the insurer when a patient requires a stay in a psychiatric unit.

This model has a critical financial benefit in reducing the length of stay, but it also has many other benefits. It focuses on early recognition and treatment, and helps mitigate the effects of mental or substance use disorders on patients’ recovery. BIT members educate their peers regarding management of a multitude of behavioral issues. This fosters extensive informal collaboration (“curbside consultation”), which helps patients who did not receive a formal consult. The model distributes work more rationally among different professional specialists. It yields a relationship with medical teams that is not only more effective, but also more enjoyable. In the BIT model, psychiatrists pick the cases where they feel they can have the most impact, and avoid the cases they feel they cannot have any.1-3

CASE A better approach to alcohol withdrawal

Mr. X, age 56, has a history of alcohol use disorder, hypertension, and coronary artery disease. He’s had multiple past admissions for complicated alcohol withdrawal. He is transferred from a local community hospital, where he had presented with chest pain. His last drink was 2 days prior to admission, and his blood alcohol level is <10 mg/dL.

During Mr. X’s previous hospitalizations, psychiatric consults were performed in the standard reactive model. The primary team initially prescribed an ineffective dosage of benzodiazepines for his alcohol withdrawal. This escalated his withdrawal into delirium tremens, after which psychiatry was involved. Due to this early ineffective management, the patient had a prolonged medical ICU stay and overall stay, experienced increased medical complications, and required increased staff resources because he was extremely agitated.

Continued to: During this hospitalization...

During this hospitalization, Mr. X arrives with similar medical complaints. The nurse practitioner on the BIT service, who screened all admissions each day, examines the prior notes (she finds the team sign-outs to be particularly useful). She suggests a psychiatric consult on Day 1 of the admission, which the primary medical team orders. The BIT nurse practitioner gives apt recommendations of evidence-based management, including a benzodiazepine taper, high-dose thiamine, and psychopharmacologic approaches to severe agitation. The nurse liaison specialist on the service makes behavioral plans for managing agitation, which she communicates to the nurses caring for Mr. X.

Because his withdrawal is managed more promptly, Mr. X’s length of stay is shorter and he does not experience any medical complications. The BIT social worker helps find appropriate aftercare options, including residential treatment and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, to which the patient agrees.

Participating in this case was highly educational for me as a trainee. This case is but one example among many where proactive consultation provided prompt care, lowered the rate of complications, reduced length of stay, and resulted in greater provider satisfaction. The Table4 contrasts the proactive and reactive consultation models. The following 5 factors are critical in the proactive consultation model4,5:

1. Standardized and reliable procedure screening of all admissions, involving a mental health professional, through record review and staff contact. This screening should identify patients with issues who will benefit specifically from in-hospital services, rather than just patients with any psychiatric issue. An electronic medical record is essential to efficient screening, team communication, and progress monitoring. Truly integrated consultation would be impossible with a paper chart.

Continued to: 2. Rapid intervention...

2. Rapid intervention that anticipates impending problems before a cascade of complications starts.

3. Collaborative engagement with the primary medical team, sharing the burden of caring for the complex inpatient, and transmitting critical behavioral management skills to all caregivers, including the skill of recognizing patients who can benefit from a psychiatric consultation.

4. Daily and close contact between behavioral and medical teams, ensuring that treatment recommendations are understood, enacted, and reinforced, ineffective treatments are discontinued, and new problems are addressed before complicating consequences arise. Dedicating specific personnel to specific hospital units and placing them in rounds simplifies communication and speeds intervention implementation.

5. A multidisciplinary consultation team, offering a range of responses, including informal curbside consultation, consultation with an advanced practice registered nurse, social work interventions, advice to discharge planning teams, psychological services, and access to specialized providers, such as addiction teams, as well as traditional consultation with an experienced psychiatrist.

Research has shown the effectiveness of proactive, embedded, multidisciplinary approaches.1-3,5 It was a gratifying experience to work in this model. I worked intimately with medical clinicians, and shared the burden of responsibilities leading to optimal patient outcomes. The proactive consultation model truly re-emphasizes the “liaison” component of C-L psychiatry, as it was originally envisioned.

1. Sledge WH, Gueorguieva R, Desan P, et al. Multidisciplinary proactive psychiatric consultation service: impact on length of stay for medical inpatients. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(4):208-216.

2. Desan PH, Zimbrean PC, Weinstein AJ, et al. Proactive psychiatric consultation services reduce length of stay for admissions to an inpatient medical team. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):513-520.

3. Sledge WH, Bozzo J, White-McCullum BA, et al. The cost-benefit from the perspective of the hospital of a proactive psychiatric consultation service on inpatient general medicine services. Health Econ Outcome Res Open Access. 2016;2(4):122.

4. Sledge WH, Lee HB. Proactive psychiatric consultation for hospitalized patients, a plan for the future. Health Affairs. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20150528.048026/full/. Published May 28, 2015. Accessed September 12, 2018.

5. Desan P, Lee H, Zimbrean P, et al. New models of psychiatric consultation in the general medical hospital: liaison psychiatry is back. Psychiatr Ann. 2017;47:355-361.

1. Sledge WH, Gueorguieva R, Desan P, et al. Multidisciplinary proactive psychiatric consultation service: impact on length of stay for medical inpatients. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(4):208-216.

2. Desan PH, Zimbrean PC, Weinstein AJ, et al. Proactive psychiatric consultation services reduce length of stay for admissions to an inpatient medical team. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):513-520.

3. Sledge WH, Bozzo J, White-McCullum BA, et al. The cost-benefit from the perspective of the hospital of a proactive psychiatric consultation service on inpatient general medicine services. Health Econ Outcome Res Open Access. 2016;2(4):122.

4. Sledge WH, Lee HB. Proactive psychiatric consultation for hospitalized patients, a plan for the future. Health Affairs. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20150528.048026/full/. Published May 28, 2015. Accessed September 12, 2018.

5. Desan P, Lee H, Zimbrean P, et al. New models of psychiatric consultation in the general medical hospital: liaison psychiatry is back. Psychiatr Ann. 2017;47:355-361.

How to make psychiatry residency more rewarding

During my residency, I have taken advantage of several opportunities that helped me develop and become more confident as I assumed the role of Academic Chief Resident in my final year of residency. In this article, I describe some of these opportunities, including seeking extra supervision while providing psychotherapy, engaging in psychotherapy for oneself, becoming part of leadership, and participating in quality improvement (QI) projects.

Obtain extra supervision while providing psychotherapy. I feel it is important to become comfortable with different types of therapy during residency. There are various opportunities to receive additional education via 1- and 2-year courses. I attended the Prelude t

Consider seeking out psychotherapy. When I started providing therapy to my patients, I became aware of how important it is to invest in your own personal therapy to understand your mind. I researched the importance of personal therapy for psychiatric clinicians, and to my surprise there have been lengthy debates on both its positive and negative impacts. However, I have come to believe that personal therapy is an important part of training for mental health professionals because it helps us better understand ourselves, since it is impossible to take the therapist’s mind out of the session. Although personal psychotherapy is not required, residency is an opportune time to pursue it.

Get involved and become part of leadership. I always believed that when united, we are stronger. It is a great privilege that as residents, we can become an integral part of advocacy and leadership in different organizations at both the state and national level. Here are 2 examples of how I got involved:

- The American Psychiatric Association (APA). When I attended the APA to present my posters for the first time, I wanted to become more actively involved. So I contacted my district branch representatives for guidance. I attended meetings and became involved in the Brooklyn District Branch as a resident representative. I was elected APA Area 2 Resident Fellow Member Deputy representative (a 2-year position). In this position, I represent residents and fellows from New York in the APA assembly. This has been a gratifying experience, and I have come to appreciate the proceedings of the Assembly and the amount of work that goes into creating Action Papers and Policy Statements.

- The Committee of Interns and Residents (CIR). Representation in CIR is extremely important in this political climate. The resident CIR Delegates are selected via elections. Delegates have an excellent opportunity to attend the Delegate Conference to learn how CIR operates and represent the department in CIR meetings. CIR is extremely supportive of resident involvement in QI projects and provides opportunities to chair a quality council for residents.

Participate in QI projects. Involvement in QI projects provided me with the opportunity to learn unique skills, including how to think creatively, design a study, and work with statisticians to extract and analyze data. The main focus of my research has been resident well-being and burnout.

These are a few of the wonderful opportunities I have been able to experience during my residency. I would love to hear from other residents about their similar experiences.

During my residency, I have taken advantage of several opportunities that helped me develop and become more confident as I assumed the role of Academic Chief Resident in my final year of residency. In this article, I describe some of these opportunities, including seeking extra supervision while providing psychotherapy, engaging in psychotherapy for oneself, becoming part of leadership, and participating in quality improvement (QI) projects.

Obtain extra supervision while providing psychotherapy. I feel it is important to become comfortable with different types of therapy during residency. There are various opportunities to receive additional education via 1- and 2-year courses. I attended the Prelude t

Consider seeking out psychotherapy. When I started providing therapy to my patients, I became aware of how important it is to invest in your own personal therapy to understand your mind. I researched the importance of personal therapy for psychiatric clinicians, and to my surprise there have been lengthy debates on both its positive and negative impacts. However, I have come to believe that personal therapy is an important part of training for mental health professionals because it helps us better understand ourselves, since it is impossible to take the therapist’s mind out of the session. Although personal psychotherapy is not required, residency is an opportune time to pursue it.

Get involved and become part of leadership. I always believed that when united, we are stronger. It is a great privilege that as residents, we can become an integral part of advocacy and leadership in different organizations at both the state and national level. Here are 2 examples of how I got involved:

- The American Psychiatric Association (APA). When I attended the APA to present my posters for the first time, I wanted to become more actively involved. So I contacted my district branch representatives for guidance. I attended meetings and became involved in the Brooklyn District Branch as a resident representative. I was elected APA Area 2 Resident Fellow Member Deputy representative (a 2-year position). In this position, I represent residents and fellows from New York in the APA assembly. This has been a gratifying experience, and I have come to appreciate the proceedings of the Assembly and the amount of work that goes into creating Action Papers and Policy Statements.

- The Committee of Interns and Residents (CIR). Representation in CIR is extremely important in this political climate. The resident CIR Delegates are selected via elections. Delegates have an excellent opportunity to attend the Delegate Conference to learn how CIR operates and represent the department in CIR meetings. CIR is extremely supportive of resident involvement in QI projects and provides opportunities to chair a quality council for residents.

Participate in QI projects. Involvement in QI projects provided me with the opportunity to learn unique skills, including how to think creatively, design a study, and work with statisticians to extract and analyze data. The main focus of my research has been resident well-being and burnout.

These are a few of the wonderful opportunities I have been able to experience during my residency. I would love to hear from other residents about their similar experiences.

During my residency, I have taken advantage of several opportunities that helped me develop and become more confident as I assumed the role of Academic Chief Resident in my final year of residency. In this article, I describe some of these opportunities, including seeking extra supervision while providing psychotherapy, engaging in psychotherapy for oneself, becoming part of leadership, and participating in quality improvement (QI) projects.

Obtain extra supervision while providing psychotherapy. I feel it is important to become comfortable with different types of therapy during residency. There are various opportunities to receive additional education via 1- and 2-year courses. I attended the Prelude t

Consider seeking out psychotherapy. When I started providing therapy to my patients, I became aware of how important it is to invest in your own personal therapy to understand your mind. I researched the importance of personal therapy for psychiatric clinicians, and to my surprise there have been lengthy debates on both its positive and negative impacts. However, I have come to believe that personal therapy is an important part of training for mental health professionals because it helps us better understand ourselves, since it is impossible to take the therapist’s mind out of the session. Although personal psychotherapy is not required, residency is an opportune time to pursue it.

Get involved and become part of leadership. I always believed that when united, we are stronger. It is a great privilege that as residents, we can become an integral part of advocacy and leadership in different organizations at both the state and national level. Here are 2 examples of how I got involved:

- The American Psychiatric Association (APA). When I attended the APA to present my posters for the first time, I wanted to become more actively involved. So I contacted my district branch representatives for guidance. I attended meetings and became involved in the Brooklyn District Branch as a resident representative. I was elected APA Area 2 Resident Fellow Member Deputy representative (a 2-year position). In this position, I represent residents and fellows from New York in the APA assembly. This has been a gratifying experience, and I have come to appreciate the proceedings of the Assembly and the amount of work that goes into creating Action Papers and Policy Statements.

- The Committee of Interns and Residents (CIR). Representation in CIR is extremely important in this political climate. The resident CIR Delegates are selected via elections. Delegates have an excellent opportunity to attend the Delegate Conference to learn how CIR operates and represent the department in CIR meetings. CIR is extremely supportive of resident involvement in QI projects and provides opportunities to chair a quality council for residents.

Participate in QI projects. Involvement in QI projects provided me with the opportunity to learn unique skills, including how to think creatively, design a study, and work with statisticians to extract and analyze data. The main focus of my research has been resident well-being and burnout.

These are a few of the wonderful opportunities I have been able to experience during my residency. I would love to hear from other residents about their similar experiences.

Embracing therapeutic silence: A resident’s perspective on learning psychotherapy

There is a tendency among young psychiatric residents, including me, to experience significant anxiety when providing outpatient psychotherapy for the first time. This anxiety often leads to rigid adherence to structured sessions aimed at a specific therapeutic target. Unfortunately, as patients begin to stray from the mold, this model breaks down and leaves the resident with little direction.

As a resident with an engineering background, I felt a strong affinity for this targeted approach, and have struggled for direction with patients whose symptoms or willingness to engage therapeutically did not match this method. I have slowly come to appreciate a more nimble approach that balances elements of both a structured method (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) with more free-flowing psychoanalytic techniques. This approach is based on several principles, including relinquishing a desire for a grand therapeutic arc, gaining comfort with silence, and, finally, allowing the patient to do the work.

Perhaps the most difficult part of this evolving realization is learning to resist the desire for an overarching path from session to session. As a novice therapist, I struggled with the apparent disconnect from session to session, and attempted to force this need for a therapeutic arc on each subsequent visit. This meant that rather than meeting the patient in his or her current state, I was forever reaching to the past, attempting to create a link between what was discussed previously to the topic of today’s session. While some patients readily identified with the concepts of CBT—where maladaptive cognitions are identified and challenged via reflection on past progress—there was another subset of patients who seemed unwilling to do so.

In his Notes On Memory and Desire,1 psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion proclaimed, “Do not remember past sessions.” As I discussed this concept in psychotherapy supervision, I began to understand the value of a less directed approach, and to try it with patients. I soon discovered interactions were more rewarding, and I gained a deeper understanding than I had before. Without a formulaic approach, patients were free to give voice to any issue, whether or not it conformed to their perceived “chief complaint.” It was refreshing to see the work progress over time as we began to slowly integrate the seemingly disparate themes of each session.

In addition to the naive idea of forcing a formulaic arc on the therapeutic process, I felt a strong desire for tangible results. Perhaps it was my engineering side yearning for the quantifiable, but nonetheless, I fell into the trap of trying to push patients to gain insights they may have not been ready to make. This led to dissatisfaction on both sides. I was reminded of another directive from Bion: “Desires for results, cure, or even understanding must not be allowed to proliferate.”1 It was interesting: the less I focused on results, the more patients began to open up and explore. By using their present experiences to examine patterns of behavior, we were able to slowly reach new levels of understanding.

The corollary to gaining comfort with relinquishing my desire for results was gaining comfort with silence and learning to meet patients where they are. The concept of using nonverbal cues to communicate is not a novel one. However, the idea that one might communicate by doing nothing at all is somewhat profound. I began to explore the use of silence with my patients, and have found an unknown richness that was previously hidden by my own tendency to interject. Psychotherapist Mark Epstein wrote, “When a therapist can sit with a patient without an agenda, without trying to force an experience, without thinking that she knows what is going to happen or who this person is…when he falls silent…the possibility of some real, spontaneous, unscripted communication exists.”2 Sitting in silence and allowing my patients to grow in their own insight has given them a sense of empowerment and mastery, and has greatly enriched our sessions.

Psychotherapy is not an easy thing for most embryonic psychiatrists or therapists, and many cling to formulaic methods because such methods are an easy approach. Initially, I, too, clung to this rigid approach, but it ultimately left me unfulfilled. I have learned to be more nimble, embrace silence, and relinquish my desire for results. I was initially uncomfortable with this unstructured model of psychotherapeutic interaction, preferring the more concrete thinking I had come to expect from engineering. It is likely that few residents will share this unique background, and thus may not struggle as I have, but I believe that the process of adaptation and change is relevant to all. As a young psychiatrist, I have gained much joy from being able to work with patients in psychotherapy. It is my hope that other young trainees, regardless of background, will learn to let go of their preconceived ideas and embrace change, for it is only through change that we grow.

1. Bion WR. Wilfred R. Bion: notes on memory and desire. In: Aguayo J, Malin B, eds. Wilfred Bion: Los Angeles seminars and supervision. London, UK: Karnac; 2013:136-138.

2. Epstein M. Remembering. In: Thoughts without a thinker. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1995:187-189.

There is a tendency among young psychiatric residents, including me, to experience significant anxiety when providing outpatient psychotherapy for the first time. This anxiety often leads to rigid adherence to structured sessions aimed at a specific therapeutic target. Unfortunately, as patients begin to stray from the mold, this model breaks down and leaves the resident with little direction.

As a resident with an engineering background, I felt a strong affinity for this targeted approach, and have struggled for direction with patients whose symptoms or willingness to engage therapeutically did not match this method. I have slowly come to appreciate a more nimble approach that balances elements of both a structured method (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) with more free-flowing psychoanalytic techniques. This approach is based on several principles, including relinquishing a desire for a grand therapeutic arc, gaining comfort with silence, and, finally, allowing the patient to do the work.

Perhaps the most difficult part of this evolving realization is learning to resist the desire for an overarching path from session to session. As a novice therapist, I struggled with the apparent disconnect from session to session, and attempted to force this need for a therapeutic arc on each subsequent visit. This meant that rather than meeting the patient in his or her current state, I was forever reaching to the past, attempting to create a link between what was discussed previously to the topic of today’s session. While some patients readily identified with the concepts of CBT—where maladaptive cognitions are identified and challenged via reflection on past progress—there was another subset of patients who seemed unwilling to do so.

In his Notes On Memory and Desire,1 psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion proclaimed, “Do not remember past sessions.” As I discussed this concept in psychotherapy supervision, I began to understand the value of a less directed approach, and to try it with patients. I soon discovered interactions were more rewarding, and I gained a deeper understanding than I had before. Without a formulaic approach, patients were free to give voice to any issue, whether or not it conformed to their perceived “chief complaint.” It was refreshing to see the work progress over time as we began to slowly integrate the seemingly disparate themes of each session.

In addition to the naive idea of forcing a formulaic arc on the therapeutic process, I felt a strong desire for tangible results. Perhaps it was my engineering side yearning for the quantifiable, but nonetheless, I fell into the trap of trying to push patients to gain insights they may have not been ready to make. This led to dissatisfaction on both sides. I was reminded of another directive from Bion: “Desires for results, cure, or even understanding must not be allowed to proliferate.”1 It was interesting: the less I focused on results, the more patients began to open up and explore. By using their present experiences to examine patterns of behavior, we were able to slowly reach new levels of understanding.

The corollary to gaining comfort with relinquishing my desire for results was gaining comfort with silence and learning to meet patients where they are. The concept of using nonverbal cues to communicate is not a novel one. However, the idea that one might communicate by doing nothing at all is somewhat profound. I began to explore the use of silence with my patients, and have found an unknown richness that was previously hidden by my own tendency to interject. Psychotherapist Mark Epstein wrote, “When a therapist can sit with a patient without an agenda, without trying to force an experience, without thinking that she knows what is going to happen or who this person is…when he falls silent…the possibility of some real, spontaneous, unscripted communication exists.”2 Sitting in silence and allowing my patients to grow in their own insight has given them a sense of empowerment and mastery, and has greatly enriched our sessions.

Psychotherapy is not an easy thing for most embryonic psychiatrists or therapists, and many cling to formulaic methods because such methods are an easy approach. Initially, I, too, clung to this rigid approach, but it ultimately left me unfulfilled. I have learned to be more nimble, embrace silence, and relinquish my desire for results. I was initially uncomfortable with this unstructured model of psychotherapeutic interaction, preferring the more concrete thinking I had come to expect from engineering. It is likely that few residents will share this unique background, and thus may not struggle as I have, but I believe that the process of adaptation and change is relevant to all. As a young psychiatrist, I have gained much joy from being able to work with patients in psychotherapy. It is my hope that other young trainees, regardless of background, will learn to let go of their preconceived ideas and embrace change, for it is only through change that we grow.

There is a tendency among young psychiatric residents, including me, to experience significant anxiety when providing outpatient psychotherapy for the first time. This anxiety often leads to rigid adherence to structured sessions aimed at a specific therapeutic target. Unfortunately, as patients begin to stray from the mold, this model breaks down and leaves the resident with little direction.

As a resident with an engineering background, I felt a strong affinity for this targeted approach, and have struggled for direction with patients whose symptoms or willingness to engage therapeutically did not match this method. I have slowly come to appreciate a more nimble approach that balances elements of both a structured method (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) with more free-flowing psychoanalytic techniques. This approach is based on several principles, including relinquishing a desire for a grand therapeutic arc, gaining comfort with silence, and, finally, allowing the patient to do the work.

Perhaps the most difficult part of this evolving realization is learning to resist the desire for an overarching path from session to session. As a novice therapist, I struggled with the apparent disconnect from session to session, and attempted to force this need for a therapeutic arc on each subsequent visit. This meant that rather than meeting the patient in his or her current state, I was forever reaching to the past, attempting to create a link between what was discussed previously to the topic of today’s session. While some patients readily identified with the concepts of CBT—where maladaptive cognitions are identified and challenged via reflection on past progress—there was another subset of patients who seemed unwilling to do so.

In his Notes On Memory and Desire,1 psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion proclaimed, “Do not remember past sessions.” As I discussed this concept in psychotherapy supervision, I began to understand the value of a less directed approach, and to try it with patients. I soon discovered interactions were more rewarding, and I gained a deeper understanding than I had before. Without a formulaic approach, patients were free to give voice to any issue, whether or not it conformed to their perceived “chief complaint.” It was refreshing to see the work progress over time as we began to slowly integrate the seemingly disparate themes of each session.

In addition to the naive idea of forcing a formulaic arc on the therapeutic process, I felt a strong desire for tangible results. Perhaps it was my engineering side yearning for the quantifiable, but nonetheless, I fell into the trap of trying to push patients to gain insights they may have not been ready to make. This led to dissatisfaction on both sides. I was reminded of another directive from Bion: “Desires for results, cure, or even understanding must not be allowed to proliferate.”1 It was interesting: the less I focused on results, the more patients began to open up and explore. By using their present experiences to examine patterns of behavior, we were able to slowly reach new levels of understanding.

The corollary to gaining comfort with relinquishing my desire for results was gaining comfort with silence and learning to meet patients where they are. The concept of using nonverbal cues to communicate is not a novel one. However, the idea that one might communicate by doing nothing at all is somewhat profound. I began to explore the use of silence with my patients, and have found an unknown richness that was previously hidden by my own tendency to interject. Psychotherapist Mark Epstein wrote, “When a therapist can sit with a patient without an agenda, without trying to force an experience, without thinking that she knows what is going to happen or who this person is…when he falls silent…the possibility of some real, spontaneous, unscripted communication exists.”2 Sitting in silence and allowing my patients to grow in their own insight has given them a sense of empowerment and mastery, and has greatly enriched our sessions.