User login

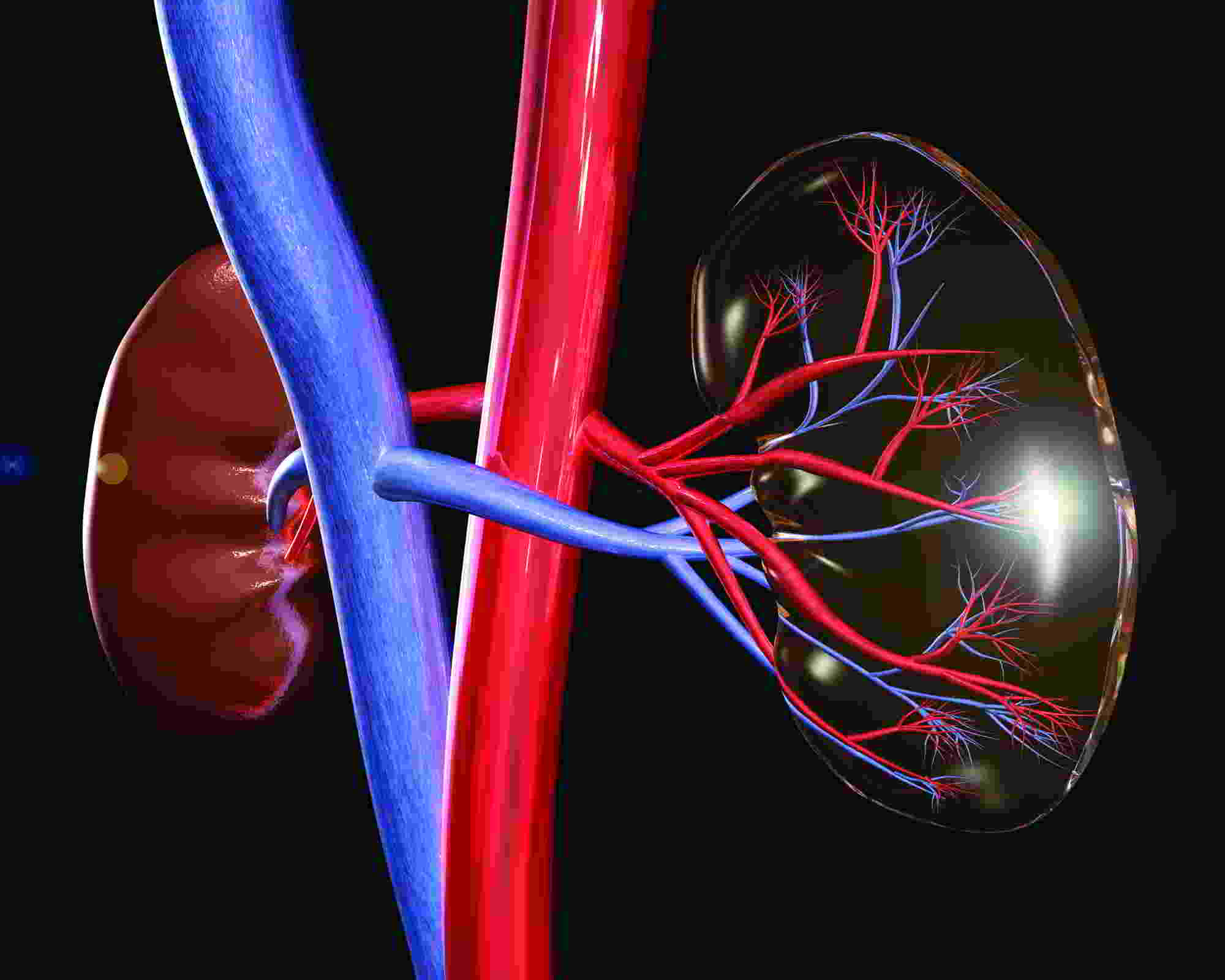

In angiography, intracoronary contrast damaged kidneys more than IV contrast

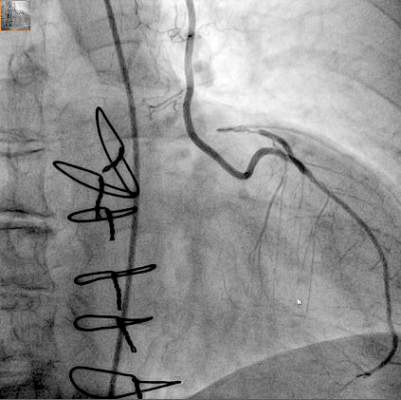

SAN DIEGO – Contrast agents administered through the coronary vessels for invasive angiography led to significantly more kidney damage than contrast agents administered intravenously for coronary computed tomography angiography, according to a randomized study.

In the Coronary Artery Disease-Management (CAD-Man) study, contrast-induced kidney injury was two to three times more likely after intracoronary than after intravenous contrast administration, explained study investigators Dr. Eva Schönenberger and Dr. Marc Dewey of Charité Medical University, Berlin.

Contrast agents used to detect and treat blockages in coronary arteries are known to damage the kidneys in 2%-20% of patients. In the United States, about 4 million doses of contrast are administered directly into the coronary vessels during invasive catheterization, and 40 million into superficial veins, said Dr. Dewey, Heisenberg Professor of Radiology at the German Research Foundation and vice chair of the department of radiology at Charité.

That makes contrast administration a significant clinical decision for physicians, he added, not just because of potential for harm, but also the potential for added costs.

CAD-Man included 326 patients with suspected coronary disease. Researchers randomized 161 patients to intracoronary contrast agent (ICA) for invasive coronary angiography and 165 patients to IV contrast agent for coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA). All patients received the same contrast agent.

Blood samples were taken at baseline before the procedure, and at two time points after: between 18 and 24 hours, and between 46 and 50 hours. Baseline creatinine levels were similar in the two groups. The researchers defined contrast-associated nephrotoxicity as an increase in creatinine of at least 0.5 mg/dL, or 25%.

At follow-up, 21 of 158 ICA patients (13%) and 9 of 160 CTA patients (6%) had contrast-associated nephropathy, a significant difference (P less than .05). In patients without coronary disease, 13% of ICA patients and 4% of CTA patients developed contrast-associated nephropathy, also a significant difference (P less than .05).

Catheter administration concentrates more contrast in the heart and above the kidneys than intravenous administration, Dr. Schönenberger explained at the meeting sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology. Thus, the increased kidney damage in invasive-angiography patients may be due to higher dosages of contrast in their kidneys.

Physicians “have to keep in mind that putting contrast agents directly into the coronaries might produce more of an increase of creatinine, and more acute kidney injury, than just giving it through an IV,” explained Dr. Schönenberger, a nephrologist in the department of anesthesiology and operative intensive care medicine at Charité.

Physicians should take this information into consideration when deciding how to administer contrast for patients suspected of having coronary artery disease, Dr. Dewey noted. “In addition to being noninvasive, cardiac CT may thus also have the advantage of reducing kidney risk.”

Cost should be a big concern as well. Dr. Dewey referred to published literature indicating that contrast-induced kidney injury can lead to “longer hospital and intensive care unit stays, [increased] dialysis, cost of adverse events, and higher mortality rates. The in-hospital cost was $10,000 per contrast-induced acute kidney injury, and the 1-year cost of treatment was more than $11,000.”

Because CAD-Man’s last patient was enrolled in mid-September, the data are still being analyzed, Dr. Schönenberger noted. Therefore, some confounders may be discovered that influenced the results.

For example, cardiologists may select their sicker patients for invasive procedures in order to be ready to insert stents, so there may not be as much flexibility in which approach to use.

Also unclear is the amount of contrast used for each patient in each arm of this study. Some physicians may have used more contrast for patients suspected of having disease that was harder to detect, although that part of the analysis remains under review, Dr. Dewey and Dr. Schönenberger said.

It remains unclear whether the nephrotoxicity found in the invasive angiography group was all due to the contrast, Dr. Schönenberger noted, or whether some of it might have been caused by small particles of hardened cholesterol spreading to blood vessels in the kidneys – a process known as atheroembolic renal disease. That, too, is under review.

The contrast agent used in the study, low-osmolar nonionic Xenetix 350, is used in 96 countries but is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Schönenberger said. However, it is very similar to those agents that are in use in the United States, she added.

The study was funded by the German Research Foundation through the Heisenberg Professorship Program. The researchers reported no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Contrast agents administered through the coronary vessels for invasive angiography led to significantly more kidney damage than contrast agents administered intravenously for coronary computed tomography angiography, according to a randomized study.

In the Coronary Artery Disease-Management (CAD-Man) study, contrast-induced kidney injury was two to three times more likely after intracoronary than after intravenous contrast administration, explained study investigators Dr. Eva Schönenberger and Dr. Marc Dewey of Charité Medical University, Berlin.

Contrast agents used to detect and treat blockages in coronary arteries are known to damage the kidneys in 2%-20% of patients. In the United States, about 4 million doses of contrast are administered directly into the coronary vessels during invasive catheterization, and 40 million into superficial veins, said Dr. Dewey, Heisenberg Professor of Radiology at the German Research Foundation and vice chair of the department of radiology at Charité.

That makes contrast administration a significant clinical decision for physicians, he added, not just because of potential for harm, but also the potential for added costs.

CAD-Man included 326 patients with suspected coronary disease. Researchers randomized 161 patients to intracoronary contrast agent (ICA) for invasive coronary angiography and 165 patients to IV contrast agent for coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA). All patients received the same contrast agent.

Blood samples were taken at baseline before the procedure, and at two time points after: between 18 and 24 hours, and between 46 and 50 hours. Baseline creatinine levels were similar in the two groups. The researchers defined contrast-associated nephrotoxicity as an increase in creatinine of at least 0.5 mg/dL, or 25%.

At follow-up, 21 of 158 ICA patients (13%) and 9 of 160 CTA patients (6%) had contrast-associated nephropathy, a significant difference (P less than .05). In patients without coronary disease, 13% of ICA patients and 4% of CTA patients developed contrast-associated nephropathy, also a significant difference (P less than .05).

Catheter administration concentrates more contrast in the heart and above the kidneys than intravenous administration, Dr. Schönenberger explained at the meeting sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology. Thus, the increased kidney damage in invasive-angiography patients may be due to higher dosages of contrast in their kidneys.

Physicians “have to keep in mind that putting contrast agents directly into the coronaries might produce more of an increase of creatinine, and more acute kidney injury, than just giving it through an IV,” explained Dr. Schönenberger, a nephrologist in the department of anesthesiology and operative intensive care medicine at Charité.

Physicians should take this information into consideration when deciding how to administer contrast for patients suspected of having coronary artery disease, Dr. Dewey noted. “In addition to being noninvasive, cardiac CT may thus also have the advantage of reducing kidney risk.”

Cost should be a big concern as well. Dr. Dewey referred to published literature indicating that contrast-induced kidney injury can lead to “longer hospital and intensive care unit stays, [increased] dialysis, cost of adverse events, and higher mortality rates. The in-hospital cost was $10,000 per contrast-induced acute kidney injury, and the 1-year cost of treatment was more than $11,000.”

Because CAD-Man’s last patient was enrolled in mid-September, the data are still being analyzed, Dr. Schönenberger noted. Therefore, some confounders may be discovered that influenced the results.

For example, cardiologists may select their sicker patients for invasive procedures in order to be ready to insert stents, so there may not be as much flexibility in which approach to use.

Also unclear is the amount of contrast used for each patient in each arm of this study. Some physicians may have used more contrast for patients suspected of having disease that was harder to detect, although that part of the analysis remains under review, Dr. Dewey and Dr. Schönenberger said.

It remains unclear whether the nephrotoxicity found in the invasive angiography group was all due to the contrast, Dr. Schönenberger noted, or whether some of it might have been caused by small particles of hardened cholesterol spreading to blood vessels in the kidneys – a process known as atheroembolic renal disease. That, too, is under review.

The contrast agent used in the study, low-osmolar nonionic Xenetix 350, is used in 96 countries but is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Schönenberger said. However, it is very similar to those agents that are in use in the United States, she added.

The study was funded by the German Research Foundation through the Heisenberg Professorship Program. The researchers reported no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Contrast agents administered through the coronary vessels for invasive angiography led to significantly more kidney damage than contrast agents administered intravenously for coronary computed tomography angiography, according to a randomized study.

In the Coronary Artery Disease-Management (CAD-Man) study, contrast-induced kidney injury was two to three times more likely after intracoronary than after intravenous contrast administration, explained study investigators Dr. Eva Schönenberger and Dr. Marc Dewey of Charité Medical University, Berlin.

Contrast agents used to detect and treat blockages in coronary arteries are known to damage the kidneys in 2%-20% of patients. In the United States, about 4 million doses of contrast are administered directly into the coronary vessels during invasive catheterization, and 40 million into superficial veins, said Dr. Dewey, Heisenberg Professor of Radiology at the German Research Foundation and vice chair of the department of radiology at Charité.

That makes contrast administration a significant clinical decision for physicians, he added, not just because of potential for harm, but also the potential for added costs.

CAD-Man included 326 patients with suspected coronary disease. Researchers randomized 161 patients to intracoronary contrast agent (ICA) for invasive coronary angiography and 165 patients to IV contrast agent for coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA). All patients received the same contrast agent.

Blood samples were taken at baseline before the procedure, and at two time points after: between 18 and 24 hours, and between 46 and 50 hours. Baseline creatinine levels were similar in the two groups. The researchers defined contrast-associated nephrotoxicity as an increase in creatinine of at least 0.5 mg/dL, or 25%.

At follow-up, 21 of 158 ICA patients (13%) and 9 of 160 CTA patients (6%) had contrast-associated nephropathy, a significant difference (P less than .05). In patients without coronary disease, 13% of ICA patients and 4% of CTA patients developed contrast-associated nephropathy, also a significant difference (P less than .05).

Catheter administration concentrates more contrast in the heart and above the kidneys than intravenous administration, Dr. Schönenberger explained at the meeting sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology. Thus, the increased kidney damage in invasive-angiography patients may be due to higher dosages of contrast in their kidneys.

Physicians “have to keep in mind that putting contrast agents directly into the coronaries might produce more of an increase of creatinine, and more acute kidney injury, than just giving it through an IV,” explained Dr. Schönenberger, a nephrologist in the department of anesthesiology and operative intensive care medicine at Charité.

Physicians should take this information into consideration when deciding how to administer contrast for patients suspected of having coronary artery disease, Dr. Dewey noted. “In addition to being noninvasive, cardiac CT may thus also have the advantage of reducing kidney risk.”

Cost should be a big concern as well. Dr. Dewey referred to published literature indicating that contrast-induced kidney injury can lead to “longer hospital and intensive care unit stays, [increased] dialysis, cost of adverse events, and higher mortality rates. The in-hospital cost was $10,000 per contrast-induced acute kidney injury, and the 1-year cost of treatment was more than $11,000.”

Because CAD-Man’s last patient was enrolled in mid-September, the data are still being analyzed, Dr. Schönenberger noted. Therefore, some confounders may be discovered that influenced the results.

For example, cardiologists may select their sicker patients for invasive procedures in order to be ready to insert stents, so there may not be as much flexibility in which approach to use.

Also unclear is the amount of contrast used for each patient in each arm of this study. Some physicians may have used more contrast for patients suspected of having disease that was harder to detect, although that part of the analysis remains under review, Dr. Dewey and Dr. Schönenberger said.

It remains unclear whether the nephrotoxicity found in the invasive angiography group was all due to the contrast, Dr. Schönenberger noted, or whether some of it might have been caused by small particles of hardened cholesterol spreading to blood vessels in the kidneys – a process known as atheroembolic renal disease. That, too, is under review.

The contrast agent used in the study, low-osmolar nonionic Xenetix 350, is used in 96 countries but is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Schönenberger said. However, it is very similar to those agents that are in use in the United States, she added.

The study was funded by the German Research Foundation through the Heisenberg Professorship Program. The researchers reported no financial disclosures.

AT KIDNEY WEEK 2015

Key clinical point: Patients undergoing angiography with intracoronary contrast agent instead of IV contrast agent may be at greater risk of kidney injury.

Major finding: Kidney injury was two to three times more likely after intracoronary than after intravenous contrast administration in patients undergoing angiography for suspected heart disease.

Data source: A randomized study of 326 patients with atypical angina pectoris who were scheduled for angiography.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the German Research Foundation through the Heisenberg Professorship Program. The researchers reported no financial disclosures.

AHA: SPRINT’s results upend hypertension targets

ORLANDO – Results from the SPRINT hypertension trial had been highly anticipated ever since the study stopped early in August and the sponsoring National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute released the top-line positive result in September that treating systolic blood pressure to a target of less than 120 mm Hg led to statistically significant drops in a composite of cardiovascular endpoints as well as in all-cause death, compared with the standard target of less than 140 mm Hg.

When the much fuller report on the results finally came out in a special session at the American Heart Association scientific sessions as well as in a simultaneous publication (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939), the data left attendees buzzing and debating what the results will mean for revised hypertension guidelines and for clinical practice.

The most prominent reactions were accolades for the trial, starting with the independent discussants that the AHA invited to comment at the session, an outpouring of praise reminiscent of that showered on a hit movie:

“A major coup. Thank you, NHLBI,” declared Dr. Marc A. Pfeffer, professor of medicine at Harvard and a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Thank you for this groundbreaking study,” said Dr. Clive Rosendorff, professor and cardiologist at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

“A remarkable trial. The most important blood pressure study in the last 40 years,” gushed Dr. Daniel W. Jones, professor of medicine at the University of Mississippi, Oxford, and director of clinical and population sciences at the Mississippi Center for Obesity Research, Jackson.

Following the huzzahs came a more substantive discussion among meeting attendees of what results from the 9,361-patient Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial will mean for revised blood pressure goals in U.S. guidelines, what it might mean for defining who has hypertension, and how it might influence practice. Perhaps the most pressing issue for the AHA and American College of Cardiology panel that began work on a new revision of hypertension treatment guidelines earlier this year is how to reconcile the SPRINT results with finding from prior studies, especially the 2010 report of results from the ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) trial (N Engl J Med. 2010;362[17]:1575-85.).

ACCORD, at half the size of SPRINT with 4,733 patients, had a very similar design as SPRINT but included only patients with diabetes while SPRINT excluded patients with diabetes. ACCORD failed to show a significant difference in its primary composite outcome after an average of 4.7 years between patients randomized to a hypertension treatment target of less than 140 mm Hg or less than 120 mm Hg, the same goals as in SPRINT. ACCORD did show a statistically significant 41% relative risk reduction for stroke, also in contrast to SPRINT, which showed a much less robust and nonsignificant 11% relative risk reduction in stroke.

In his commentary on SPRINT, Dr. Jones offered several possible explanations for the divergent results, including a possible inherent difference in vascular physiology between patients with diabetes and those with normal glycemic control; the younger patients enrolled in ACCORD (patients averaged 62 years old in ACCORD and 68 years old in SPRINT, and 28% of patients in SPRINT were at least 75 years old); the use of hydrochlorothiazide as the predominant diuretic in ACCORD versus predominant use of chlorthalidone in SPRINT; and the multiple interventions simultaneously tested in ACCORD, which also randomized patients into two arms with respect to glycemic control and into two arms of different lipid-controlling treatment.

SPRINT’s results “need to be assessed in the context of ACCORD,” commented Dr. Salim Yusuf in an interview. “I think the real result is somewhere in between the results of SPRINT and ACCORD” in terms of the appropriate systolic blood pressure target. What we need is a balanced perspective that takes all the trials. SPRINT was a very good trial, but like all studies it should be interpreted in the context of all the other related studies, not in isolation,” said Dr. Yusuf, professor and director of the Population Health Research Institute of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

“Understandably, when something like SPRINT comes out there is a lot of enthusiasm. The first reaction is always ‘Wow!’ For patients who meet SPRINT’s enrollment criteria I think we will treat to a target of less than 120 mm Hg. But the guideline writers need to discuss SPRINT and balance it,” he said.

Despite his regard for SPRINT, Dr. Yusuf cited several additional concerns he has about the trial:

• Its early stoppage (SPRINT had originally been designed to run 5-6 years, but it was halted after an average treatment duration of just over 3 years). “When you stop a trial early there is always an upward bias. The apparent treatment effect gets inflated,” he said.

• The increased rate of acute kidney injury among patients randomized to the more aggressive treatment arm, a 4.1% rate, compared with a 2.5% rate in the control patients randomized to treatment to a goal of systolic pressure less than 140 mm Hg, a statistically significant difference.

• The “highly selected, high-risk” patients enrolled into SPRINT. “You can’t extrapolate the results to the average patient,” Dr. Yusuf said.

Some of these concerns and cautions were shared by Dr. Prakash Deedwania, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, although overall he called the SPRINT results “very exciting.”

“Superficially, SPRINT seems to say treat everyone to a blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg, but that’s not the case. The patients in SPRINT were primarily very well established patients with hypertension. I’d be concerned about an elderly patient with cardiovascular disease and a blood pressure of 130 mm Hg. If you reduce that to less than 120 mm Hg the diastolic pressure may also fall and that’s important for coronary perfusion.” He also cited the absence so far of a subanalysis of what happened to patients with preexisting renal disease and the lack of data on the outcomes of patients whose systolic pressure fell to levels well below 120 mm Hg.

For others, however, the overall, statistically significant 27% reduction in overall mortality was a reassuring indicator of the safety of the aggressive treatment regimen used in SPRINT. “If there was a meaningful worsening of renal function that harmed patients, you would not see a reduction in all-cause mortality,” commented Dr. Gregg C. Fonarow, professor and associate chief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“We have had so many trials that couldn’t dream of producing a reduction in all-cause mortality. Here we have a trial with a robust, clinically meaningful reduction in all-cause mortality that ultimately demonstrates the benefits outweigh the risks,” he said in an interview.

SPRINT “is a phenomenal breakthrough. It’s data we’ve been awaiting for 20-plus years, to now know that a lower blood pressure target is safe and absolutely essential, and where the benefits outweigh the risks,” Dr. Fonarow said. “Now implementation becomes critical. The SPRINT results are truly practice changing.”

SPRINT received no commercial support. The study received antihypertensive drugs from Arbor and Takeda at no charge for a small percentage of enrolled patients. Dr. Pfeffer has been a consultant to more than 20 companies. Dr. Rosendorff has been a consultant to McNeil and received research funding from Eisai. Dr. Yusuf has received honoraria and research grants from Sanofi-Aventis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bayer, and Astra Zeneca. Dr. Jones, Dr. Deedwania, and Dr. Fonarow had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Results from the SPRINT hypertension trial had been highly anticipated ever since the study stopped early in August and the sponsoring National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute released the top-line positive result in September that treating systolic blood pressure to a target of less than 120 mm Hg led to statistically significant drops in a composite of cardiovascular endpoints as well as in all-cause death, compared with the standard target of less than 140 mm Hg.

When the much fuller report on the results finally came out in a special session at the American Heart Association scientific sessions as well as in a simultaneous publication (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939), the data left attendees buzzing and debating what the results will mean for revised hypertension guidelines and for clinical practice.

The most prominent reactions were accolades for the trial, starting with the independent discussants that the AHA invited to comment at the session, an outpouring of praise reminiscent of that showered on a hit movie:

“A major coup. Thank you, NHLBI,” declared Dr. Marc A. Pfeffer, professor of medicine at Harvard and a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Thank you for this groundbreaking study,” said Dr. Clive Rosendorff, professor and cardiologist at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

“A remarkable trial. The most important blood pressure study in the last 40 years,” gushed Dr. Daniel W. Jones, professor of medicine at the University of Mississippi, Oxford, and director of clinical and population sciences at the Mississippi Center for Obesity Research, Jackson.

Following the huzzahs came a more substantive discussion among meeting attendees of what results from the 9,361-patient Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial will mean for revised blood pressure goals in U.S. guidelines, what it might mean for defining who has hypertension, and how it might influence practice. Perhaps the most pressing issue for the AHA and American College of Cardiology panel that began work on a new revision of hypertension treatment guidelines earlier this year is how to reconcile the SPRINT results with finding from prior studies, especially the 2010 report of results from the ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) trial (N Engl J Med. 2010;362[17]:1575-85.).

ACCORD, at half the size of SPRINT with 4,733 patients, had a very similar design as SPRINT but included only patients with diabetes while SPRINT excluded patients with diabetes. ACCORD failed to show a significant difference in its primary composite outcome after an average of 4.7 years between patients randomized to a hypertension treatment target of less than 140 mm Hg or less than 120 mm Hg, the same goals as in SPRINT. ACCORD did show a statistically significant 41% relative risk reduction for stroke, also in contrast to SPRINT, which showed a much less robust and nonsignificant 11% relative risk reduction in stroke.

In his commentary on SPRINT, Dr. Jones offered several possible explanations for the divergent results, including a possible inherent difference in vascular physiology between patients with diabetes and those with normal glycemic control; the younger patients enrolled in ACCORD (patients averaged 62 years old in ACCORD and 68 years old in SPRINT, and 28% of patients in SPRINT were at least 75 years old); the use of hydrochlorothiazide as the predominant diuretic in ACCORD versus predominant use of chlorthalidone in SPRINT; and the multiple interventions simultaneously tested in ACCORD, which also randomized patients into two arms with respect to glycemic control and into two arms of different lipid-controlling treatment.

SPRINT’s results “need to be assessed in the context of ACCORD,” commented Dr. Salim Yusuf in an interview. “I think the real result is somewhere in between the results of SPRINT and ACCORD” in terms of the appropriate systolic blood pressure target. What we need is a balanced perspective that takes all the trials. SPRINT was a very good trial, but like all studies it should be interpreted in the context of all the other related studies, not in isolation,” said Dr. Yusuf, professor and director of the Population Health Research Institute of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

“Understandably, when something like SPRINT comes out there is a lot of enthusiasm. The first reaction is always ‘Wow!’ For patients who meet SPRINT’s enrollment criteria I think we will treat to a target of less than 120 mm Hg. But the guideline writers need to discuss SPRINT and balance it,” he said.

Despite his regard for SPRINT, Dr. Yusuf cited several additional concerns he has about the trial:

• Its early stoppage (SPRINT had originally been designed to run 5-6 years, but it was halted after an average treatment duration of just over 3 years). “When you stop a trial early there is always an upward bias. The apparent treatment effect gets inflated,” he said.

• The increased rate of acute kidney injury among patients randomized to the more aggressive treatment arm, a 4.1% rate, compared with a 2.5% rate in the control patients randomized to treatment to a goal of systolic pressure less than 140 mm Hg, a statistically significant difference.

• The “highly selected, high-risk” patients enrolled into SPRINT. “You can’t extrapolate the results to the average patient,” Dr. Yusuf said.

Some of these concerns and cautions were shared by Dr. Prakash Deedwania, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, although overall he called the SPRINT results “very exciting.”

“Superficially, SPRINT seems to say treat everyone to a blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg, but that’s not the case. The patients in SPRINT were primarily very well established patients with hypertension. I’d be concerned about an elderly patient with cardiovascular disease and a blood pressure of 130 mm Hg. If you reduce that to less than 120 mm Hg the diastolic pressure may also fall and that’s important for coronary perfusion.” He also cited the absence so far of a subanalysis of what happened to patients with preexisting renal disease and the lack of data on the outcomes of patients whose systolic pressure fell to levels well below 120 mm Hg.

For others, however, the overall, statistically significant 27% reduction in overall mortality was a reassuring indicator of the safety of the aggressive treatment regimen used in SPRINT. “If there was a meaningful worsening of renal function that harmed patients, you would not see a reduction in all-cause mortality,” commented Dr. Gregg C. Fonarow, professor and associate chief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“We have had so many trials that couldn’t dream of producing a reduction in all-cause mortality. Here we have a trial with a robust, clinically meaningful reduction in all-cause mortality that ultimately demonstrates the benefits outweigh the risks,” he said in an interview.

SPRINT “is a phenomenal breakthrough. It’s data we’ve been awaiting for 20-plus years, to now know that a lower blood pressure target is safe and absolutely essential, and where the benefits outweigh the risks,” Dr. Fonarow said. “Now implementation becomes critical. The SPRINT results are truly practice changing.”

SPRINT received no commercial support. The study received antihypertensive drugs from Arbor and Takeda at no charge for a small percentage of enrolled patients. Dr. Pfeffer has been a consultant to more than 20 companies. Dr. Rosendorff has been a consultant to McNeil and received research funding from Eisai. Dr. Yusuf has received honoraria and research grants from Sanofi-Aventis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bayer, and Astra Zeneca. Dr. Jones, Dr. Deedwania, and Dr. Fonarow had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Results from the SPRINT hypertension trial had been highly anticipated ever since the study stopped early in August and the sponsoring National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute released the top-line positive result in September that treating systolic blood pressure to a target of less than 120 mm Hg led to statistically significant drops in a composite of cardiovascular endpoints as well as in all-cause death, compared with the standard target of less than 140 mm Hg.

When the much fuller report on the results finally came out in a special session at the American Heart Association scientific sessions as well as in a simultaneous publication (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939), the data left attendees buzzing and debating what the results will mean for revised hypertension guidelines and for clinical practice.

The most prominent reactions were accolades for the trial, starting with the independent discussants that the AHA invited to comment at the session, an outpouring of praise reminiscent of that showered on a hit movie:

“A major coup. Thank you, NHLBI,” declared Dr. Marc A. Pfeffer, professor of medicine at Harvard and a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Thank you for this groundbreaking study,” said Dr. Clive Rosendorff, professor and cardiologist at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

“A remarkable trial. The most important blood pressure study in the last 40 years,” gushed Dr. Daniel W. Jones, professor of medicine at the University of Mississippi, Oxford, and director of clinical and population sciences at the Mississippi Center for Obesity Research, Jackson.

Following the huzzahs came a more substantive discussion among meeting attendees of what results from the 9,361-patient Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial will mean for revised blood pressure goals in U.S. guidelines, what it might mean for defining who has hypertension, and how it might influence practice. Perhaps the most pressing issue for the AHA and American College of Cardiology panel that began work on a new revision of hypertension treatment guidelines earlier this year is how to reconcile the SPRINT results with finding from prior studies, especially the 2010 report of results from the ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) trial (N Engl J Med. 2010;362[17]:1575-85.).

ACCORD, at half the size of SPRINT with 4,733 patients, had a very similar design as SPRINT but included only patients with diabetes while SPRINT excluded patients with diabetes. ACCORD failed to show a significant difference in its primary composite outcome after an average of 4.7 years between patients randomized to a hypertension treatment target of less than 140 mm Hg or less than 120 mm Hg, the same goals as in SPRINT. ACCORD did show a statistically significant 41% relative risk reduction for stroke, also in contrast to SPRINT, which showed a much less robust and nonsignificant 11% relative risk reduction in stroke.

In his commentary on SPRINT, Dr. Jones offered several possible explanations for the divergent results, including a possible inherent difference in vascular physiology between patients with diabetes and those with normal glycemic control; the younger patients enrolled in ACCORD (patients averaged 62 years old in ACCORD and 68 years old in SPRINT, and 28% of patients in SPRINT were at least 75 years old); the use of hydrochlorothiazide as the predominant diuretic in ACCORD versus predominant use of chlorthalidone in SPRINT; and the multiple interventions simultaneously tested in ACCORD, which also randomized patients into two arms with respect to glycemic control and into two arms of different lipid-controlling treatment.

SPRINT’s results “need to be assessed in the context of ACCORD,” commented Dr. Salim Yusuf in an interview. “I think the real result is somewhere in between the results of SPRINT and ACCORD” in terms of the appropriate systolic blood pressure target. What we need is a balanced perspective that takes all the trials. SPRINT was a very good trial, but like all studies it should be interpreted in the context of all the other related studies, not in isolation,” said Dr. Yusuf, professor and director of the Population Health Research Institute of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

“Understandably, when something like SPRINT comes out there is a lot of enthusiasm. The first reaction is always ‘Wow!’ For patients who meet SPRINT’s enrollment criteria I think we will treat to a target of less than 120 mm Hg. But the guideline writers need to discuss SPRINT and balance it,” he said.

Despite his regard for SPRINT, Dr. Yusuf cited several additional concerns he has about the trial:

• Its early stoppage (SPRINT had originally been designed to run 5-6 years, but it was halted after an average treatment duration of just over 3 years). “When you stop a trial early there is always an upward bias. The apparent treatment effect gets inflated,” he said.

• The increased rate of acute kidney injury among patients randomized to the more aggressive treatment arm, a 4.1% rate, compared with a 2.5% rate in the control patients randomized to treatment to a goal of systolic pressure less than 140 mm Hg, a statistically significant difference.

• The “highly selected, high-risk” patients enrolled into SPRINT. “You can’t extrapolate the results to the average patient,” Dr. Yusuf said.

Some of these concerns and cautions were shared by Dr. Prakash Deedwania, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, although overall he called the SPRINT results “very exciting.”

“Superficially, SPRINT seems to say treat everyone to a blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg, but that’s not the case. The patients in SPRINT were primarily very well established patients with hypertension. I’d be concerned about an elderly patient with cardiovascular disease and a blood pressure of 130 mm Hg. If you reduce that to less than 120 mm Hg the diastolic pressure may also fall and that’s important for coronary perfusion.” He also cited the absence so far of a subanalysis of what happened to patients with preexisting renal disease and the lack of data on the outcomes of patients whose systolic pressure fell to levels well below 120 mm Hg.

For others, however, the overall, statistically significant 27% reduction in overall mortality was a reassuring indicator of the safety of the aggressive treatment regimen used in SPRINT. “If there was a meaningful worsening of renal function that harmed patients, you would not see a reduction in all-cause mortality,” commented Dr. Gregg C. Fonarow, professor and associate chief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“We have had so many trials that couldn’t dream of producing a reduction in all-cause mortality. Here we have a trial with a robust, clinically meaningful reduction in all-cause mortality that ultimately demonstrates the benefits outweigh the risks,” he said in an interview.

SPRINT “is a phenomenal breakthrough. It’s data we’ve been awaiting for 20-plus years, to now know that a lower blood pressure target is safe and absolutely essential, and where the benefits outweigh the risks,” Dr. Fonarow said. “Now implementation becomes critical. The SPRINT results are truly practice changing.”

SPRINT received no commercial support. The study received antihypertensive drugs from Arbor and Takeda at no charge for a small percentage of enrolled patients. Dr. Pfeffer has been a consultant to more than 20 companies. Dr. Rosendorff has been a consultant to McNeil and received research funding from Eisai. Dr. Yusuf has received honoraria and research grants from Sanofi-Aventis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bayer, and Astra Zeneca. Dr. Jones, Dr. Deedwania, and Dr. Fonarow had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: The first full report of results from the SPRINT trial of hypertension treatment targets generated lots of opinions on their implications.

Major finding: Combined cardiovascular events occurred in 5.2% of patients treated to a target systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg and 6.8% of patients treated to a target of less than 140 mm Hg.

Data source: The multicenter, randomized trial involved 9,361 patients.

Disclosures: SPRINT received no commercial support. The study received antihypertensive drugs from Arbor and Takeda at no charge for a small percentage of enrolled patients. Dr. Pfeffer has been a consultant to more than 20 companies. Dr. Rosendorff has been a consultant to McNeil and received research funding from Eisai. Dr. Yusuf has received honoraria and research grants from Sanofi-Aventis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bayer, and Astra Zeneca. Dr. Jones, Dr. Deedwania, and Dr. Fonarow had no disclosures.

Conservative management for AR safe at 10 years

Whether to operate on patients with severe aortic regurgitation (AR) before or after symptoms appear has been a point of controversy among cardiothoracic surgeons, but a recent study has found that patients who have early surgery may not fare any better for up to 10 years than those who opt for a more conservative “watchful waiting” course of care.

Investigators from Belgium reported results from an analysis of 160 patients in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015;150:1100-08). “In asymptomatic severe AR, delaying surgery until the onset of class I/IIa operative triggers is safe, supporting current guidelines,” said Dr. Christophe de Meester and colleagues at the Catholic University of Louvain and St. Luc University Clinic in Brussels.

The goal of the study was to evaluate long-term outcomes and incidence of cardiac complications in patients with severe AR who did not have any signs and symptoms that called for surgery, and who either had surgery early on or entered conservative management and eventually had an operation when signs and symptoms did appear.

The study found that close follow-up and monitoring of patients with severe AR was a cornerstone of successful conservative management. “We found that survival was similar between the two groups,” Dr. De Meester and coauthors said. “Better survival was nonetheless observed in conservatively managed patients with regular as opposed to no or a looser follow-up.”

The most recent European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines and American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines state that symptomatic severe AR is a class I indication for surgery regardless of left ventricular (LV) systolic function.

However, Dr. De Meester and colleagues said, the timing of that surgery is not so clear-cut. Earlier studies have shown that surgery could be delayed for patients with minimal symptoms, but more recent evidence has suggested the opposite, according to the study. Two factors favor surgery before symptoms arise – poor aortic valve repair outcomes in patients with symptoms of heart failure and long-standing severe AR, which eventually leads to LV dysfunction.

Yet, the latest ESC guidelines have been “reluctant” to make a strong case for early surgery before symptoms of LV dysfunction appear, and the AHA/ACC guidelines call for surgery only when symptoms of LV dysfunction or LV dilatation develop, Dr. de Meester and his coauthors said.

In the past, the risks of aortic valve replacement were too high to consider early surgery, the study authors said. “However, with the advent of aortic valve repair, operative mortality and long-term outcomes have improved to such an extent that early surgery has become a plausible option for patients.”

But the risk of these patients developing symptoms for surgery was nonetheless low over 10 years, the study found: 7.4% for developing severe LV dilatation; 0.6% for becoming symptomatic; and 0.9% for developing LV dysfunction. Overall, the rate of adverse events in the study population was 9.9% at 10 years.

In the study, 69 patients were initially managed conservatively, 49 of whom were in the watchful waiting group that visited a cardiologist at least annually and another 20 considered an “irregular follow-up subgroup.” Among the watchful waiting group, 31 developed symptoms for surgery (only two declined surgery). Watchful waiting patients had five- and 10-year survival of 100% and 95%, respectively, compared with 90% and 79% among those who had irregular follow-up.

Overall, the conservatively managed group had outcomes better than or equal to the early surgery group. Ten-year cardiovascular survival was 96% in both groups, whereas event-free survival was 92% at 10 years in the conservatively managed group vs. 81% in the early surgery group.

The study was supported by the Belgium National Fund for Scientific Research. The authors had no conflicts to disclose.

The design of the Belgium study “challenges” existing treatment guidelines for asymptomatic chronic aortic insufficiency in two ways, Dr. Leora Balsam and Dr. Abe deAndra Jr., both of the New York University-Langone Medical Center, write in their commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1108-10): first, by making aortic valve repair the preferred surgical treatment in the study and, secondly, by offering surgery to both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

“In the era of evidence-based medicine,” Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra wrote, “there remains a need for research and innovation even in areas where guidelines exist.”

While many authors have described aortic valve repair as an alternative to aortic valve replacement for chronic severe aortic insufficiency, Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra explained that the term aortic valve repair “encompasses a wide array of techniques,” among them valve-sparing aortic root replacement, subcommissural annuloplasty and “myriad” leaf resection, plication, and reconstruction techniques. Because of mounting reports of excellent results with aortic valve repair techniques, growing ranks of cardiothoracic surgeons have advocated for repair as an early intervention for aortic valve problems. But the question remains: “Have we identified the optimal triggers for intervention for aortic insufficiency?” they asked. “The answer is probably no, and that newer technology and diagnostic studies will better discriminate between patients that can benefit from intervention and those that will not.”

Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra had no disclosures.

The design of the Belgium study “challenges” existing treatment guidelines for asymptomatic chronic aortic insufficiency in two ways, Dr. Leora Balsam and Dr. Abe deAndra Jr., both of the New York University-Langone Medical Center, write in their commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1108-10): first, by making aortic valve repair the preferred surgical treatment in the study and, secondly, by offering surgery to both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

“In the era of evidence-based medicine,” Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra wrote, “there remains a need for research and innovation even in areas where guidelines exist.”

While many authors have described aortic valve repair as an alternative to aortic valve replacement for chronic severe aortic insufficiency, Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra explained that the term aortic valve repair “encompasses a wide array of techniques,” among them valve-sparing aortic root replacement, subcommissural annuloplasty and “myriad” leaf resection, plication, and reconstruction techniques. Because of mounting reports of excellent results with aortic valve repair techniques, growing ranks of cardiothoracic surgeons have advocated for repair as an early intervention for aortic valve problems. But the question remains: “Have we identified the optimal triggers for intervention for aortic insufficiency?” they asked. “The answer is probably no, and that newer technology and diagnostic studies will better discriminate between patients that can benefit from intervention and those that will not.”

Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra had no disclosures.

The design of the Belgium study “challenges” existing treatment guidelines for asymptomatic chronic aortic insufficiency in two ways, Dr. Leora Balsam and Dr. Abe deAndra Jr., both of the New York University-Langone Medical Center, write in their commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1108-10): first, by making aortic valve repair the preferred surgical treatment in the study and, secondly, by offering surgery to both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

“In the era of evidence-based medicine,” Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra wrote, “there remains a need for research and innovation even in areas where guidelines exist.”

While many authors have described aortic valve repair as an alternative to aortic valve replacement for chronic severe aortic insufficiency, Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra explained that the term aortic valve repair “encompasses a wide array of techniques,” among them valve-sparing aortic root replacement, subcommissural annuloplasty and “myriad” leaf resection, plication, and reconstruction techniques. Because of mounting reports of excellent results with aortic valve repair techniques, growing ranks of cardiothoracic surgeons have advocated for repair as an early intervention for aortic valve problems. But the question remains: “Have we identified the optimal triggers for intervention for aortic insufficiency?” they asked. “The answer is probably no, and that newer technology and diagnostic studies will better discriminate between patients that can benefit from intervention and those that will not.”

Dr. Balsam and Dr. deAndra had no disclosures.

Whether to operate on patients with severe aortic regurgitation (AR) before or after symptoms appear has been a point of controversy among cardiothoracic surgeons, but a recent study has found that patients who have early surgery may not fare any better for up to 10 years than those who opt for a more conservative “watchful waiting” course of care.

Investigators from Belgium reported results from an analysis of 160 patients in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015;150:1100-08). “In asymptomatic severe AR, delaying surgery until the onset of class I/IIa operative triggers is safe, supporting current guidelines,” said Dr. Christophe de Meester and colleagues at the Catholic University of Louvain and St. Luc University Clinic in Brussels.

The goal of the study was to evaluate long-term outcomes and incidence of cardiac complications in patients with severe AR who did not have any signs and symptoms that called for surgery, and who either had surgery early on or entered conservative management and eventually had an operation when signs and symptoms did appear.

The study found that close follow-up and monitoring of patients with severe AR was a cornerstone of successful conservative management. “We found that survival was similar between the two groups,” Dr. De Meester and coauthors said. “Better survival was nonetheless observed in conservatively managed patients with regular as opposed to no or a looser follow-up.”

The most recent European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines and American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines state that symptomatic severe AR is a class I indication for surgery regardless of left ventricular (LV) systolic function.

However, Dr. De Meester and colleagues said, the timing of that surgery is not so clear-cut. Earlier studies have shown that surgery could be delayed for patients with minimal symptoms, but more recent evidence has suggested the opposite, according to the study. Two factors favor surgery before symptoms arise – poor aortic valve repair outcomes in patients with symptoms of heart failure and long-standing severe AR, which eventually leads to LV dysfunction.

Yet, the latest ESC guidelines have been “reluctant” to make a strong case for early surgery before symptoms of LV dysfunction appear, and the AHA/ACC guidelines call for surgery only when symptoms of LV dysfunction or LV dilatation develop, Dr. de Meester and his coauthors said.

In the past, the risks of aortic valve replacement were too high to consider early surgery, the study authors said. “However, with the advent of aortic valve repair, operative mortality and long-term outcomes have improved to such an extent that early surgery has become a plausible option for patients.”

But the risk of these patients developing symptoms for surgery was nonetheless low over 10 years, the study found: 7.4% for developing severe LV dilatation; 0.6% for becoming symptomatic; and 0.9% for developing LV dysfunction. Overall, the rate of adverse events in the study population was 9.9% at 10 years.

In the study, 69 patients were initially managed conservatively, 49 of whom were in the watchful waiting group that visited a cardiologist at least annually and another 20 considered an “irregular follow-up subgroup.” Among the watchful waiting group, 31 developed symptoms for surgery (only two declined surgery). Watchful waiting patients had five- and 10-year survival of 100% and 95%, respectively, compared with 90% and 79% among those who had irregular follow-up.

Overall, the conservatively managed group had outcomes better than or equal to the early surgery group. Ten-year cardiovascular survival was 96% in both groups, whereas event-free survival was 92% at 10 years in the conservatively managed group vs. 81% in the early surgery group.

The study was supported by the Belgium National Fund for Scientific Research. The authors had no conflicts to disclose.

Whether to operate on patients with severe aortic regurgitation (AR) before or after symptoms appear has been a point of controversy among cardiothoracic surgeons, but a recent study has found that patients who have early surgery may not fare any better for up to 10 years than those who opt for a more conservative “watchful waiting” course of care.

Investigators from Belgium reported results from an analysis of 160 patients in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015;150:1100-08). “In asymptomatic severe AR, delaying surgery until the onset of class I/IIa operative triggers is safe, supporting current guidelines,” said Dr. Christophe de Meester and colleagues at the Catholic University of Louvain and St. Luc University Clinic in Brussels.

The goal of the study was to evaluate long-term outcomes and incidence of cardiac complications in patients with severe AR who did not have any signs and symptoms that called for surgery, and who either had surgery early on or entered conservative management and eventually had an operation when signs and symptoms did appear.

The study found that close follow-up and monitoring of patients with severe AR was a cornerstone of successful conservative management. “We found that survival was similar between the two groups,” Dr. De Meester and coauthors said. “Better survival was nonetheless observed in conservatively managed patients with regular as opposed to no or a looser follow-up.”

The most recent European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines and American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines state that symptomatic severe AR is a class I indication for surgery regardless of left ventricular (LV) systolic function.

However, Dr. De Meester and colleagues said, the timing of that surgery is not so clear-cut. Earlier studies have shown that surgery could be delayed for patients with minimal symptoms, but more recent evidence has suggested the opposite, according to the study. Two factors favor surgery before symptoms arise – poor aortic valve repair outcomes in patients with symptoms of heart failure and long-standing severe AR, which eventually leads to LV dysfunction.

Yet, the latest ESC guidelines have been “reluctant” to make a strong case for early surgery before symptoms of LV dysfunction appear, and the AHA/ACC guidelines call for surgery only when symptoms of LV dysfunction or LV dilatation develop, Dr. de Meester and his coauthors said.

In the past, the risks of aortic valve replacement were too high to consider early surgery, the study authors said. “However, with the advent of aortic valve repair, operative mortality and long-term outcomes have improved to such an extent that early surgery has become a plausible option for patients.”

But the risk of these patients developing symptoms for surgery was nonetheless low over 10 years, the study found: 7.4% for developing severe LV dilatation; 0.6% for becoming symptomatic; and 0.9% for developing LV dysfunction. Overall, the rate of adverse events in the study population was 9.9% at 10 years.

In the study, 69 patients were initially managed conservatively, 49 of whom were in the watchful waiting group that visited a cardiologist at least annually and another 20 considered an “irregular follow-up subgroup.” Among the watchful waiting group, 31 developed symptoms for surgery (only two declined surgery). Watchful waiting patients had five- and 10-year survival of 100% and 95%, respectively, compared with 90% and 79% among those who had irregular follow-up.

Overall, the conservatively managed group had outcomes better than or equal to the early surgery group. Ten-year cardiovascular survival was 96% in both groups, whereas event-free survival was 92% at 10 years in the conservatively managed group vs. 81% in the early surgery group.

The study was supported by the Belgium National Fund for Scientific Research. The authors had no conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Delaying surgery until the onset of symptoms of aortic insufficiency is safe, in support of current clinical guidelines.

Major finding: Ten-year cardiovascular survival was equal among conservatively managed and early-surgery groups, but event free survival was 92% at 10 years in the conservatively managed group vs. 81% in the early surgery group.

Data source: Analysis of 160 consecutive asymptomatic patients with severe aortic regurgitation who were assigned to either conservative management or early surgery and followed up for a median of 7.2 years.

Disclosures: The Belgium National Fund of Scientific Research supported the study. The authors had no disclosures.

Does LVAD inhibit cardio protection?

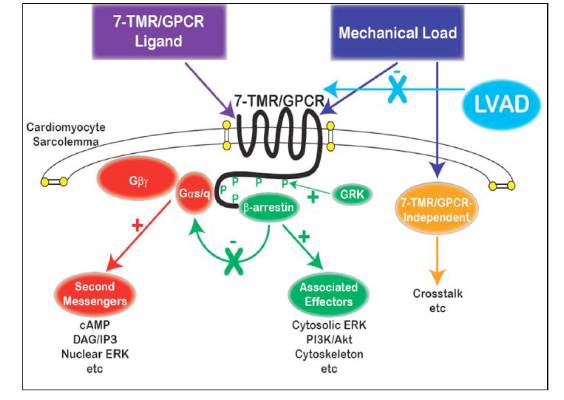

Placement of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) after a heart attack has been found to suppress certain cellular signaling pathways that protect coronary tissue, but at the same time LVAD placement seemed to help normalize other protective properties in areas of the heart closest to the infarcted region, investigators reported in a recent study.

The findings could have implications in determining the best method for unloading and other medical therapies in the aftermath of a heart attack, Dr. Keshava Rajagopal of the University of Texas, Houston, and associates reported in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015;150:1332-41).

To study the effect of LVAD on cardiac tissue, the investigators induced myocardial infarction in sheep and then placed the animals on LVAD support for 2 weeks. After 10 more weeks of observation, the investigators harvested and analyzed the myocardial specimens. The principal goal of the study was to investigate how heart attack and subsequent short-term mechanical support of the left ventricle can influence signaling controlled by the protein beta-arrestin.

They found that an infarction of myocardial tissue caused activation of the beta-arrestin protein that regulates cellular pathways that can benefit cardiac cells. At the same time, LVAD support inhibited beta-arrestin activation, specifically in regulating pathways of two cardioprotective proteins: Akt, also called protein kinase B (PKB), and, to a lesser extent, ERK-1 and -2.

They also found that MI resulted in regional activation of load-induced signaling of cardiac G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) via G proteins.

“These studies demonstrate that small platform catheter-based LVAD support exerts suppressive effects on cardioprotective beta-arrestin–mediated signal transduction, while normalizing the signaling networks of G-alpha-q–coupled cardiac GPCRS in the MI-adjacent zone,” Dr. Rajagopal and colleagues said.

They acknowledged that further studies are needed to better understand the roles that specific GPCRs in beta-arrestin–regulated signaling play in left ventricle dysfunction after a heart attack and to help define the optimal timing for LVAD based on signaling and genetic markers along with standard LV functional endpoints.

The authors had no disclosures.

The University of Maryland investigators in this study have joined the ranks of other investigators who have begun to unravel the consequences of mechanical unloading at the cellular level as well as its effect on the heart’s ability to handle calcium after infarction, Dr. William Hiesinger and Dr. Pavan Atluri of the University of Pennsylvania wrote in their invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1342-3).

“More broadly, these investigations are building the foundation of what will likely be the best platform for an efficacious bridge to recovery: multimodal therapy utilizing the titration of mechanical myocardial unloading,” they said. Dr. Hiesinger and Dr. Atluri commented on the limitations of the University of Maryland study, namely its small sample size and narrow scope. “This is, however, reflective more of the amazing complexity of the biologic and mechanical interactions between the heart and VAD and the need for further investigations of this kind than the quality of the research,” they said.

Understanding the molecular basis and metabolic function cardiac dysfunction after a heart attack is in the “nascent stages,” and even less is known about the effect ventricular loading has on these pathways, Dr. Hiesinger and Dr. Atluri said. “This study offers a concrete platform for both specific treatment and further study,” they wrote.

The University of Maryland investigators in this study have joined the ranks of other investigators who have begun to unravel the consequences of mechanical unloading at the cellular level as well as its effect on the heart’s ability to handle calcium after infarction, Dr. William Hiesinger and Dr. Pavan Atluri of the University of Pennsylvania wrote in their invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1342-3).

“More broadly, these investigations are building the foundation of what will likely be the best platform for an efficacious bridge to recovery: multimodal therapy utilizing the titration of mechanical myocardial unloading,” they said. Dr. Hiesinger and Dr. Atluri commented on the limitations of the University of Maryland study, namely its small sample size and narrow scope. “This is, however, reflective more of the amazing complexity of the biologic and mechanical interactions between the heart and VAD and the need for further investigations of this kind than the quality of the research,” they said.

Understanding the molecular basis and metabolic function cardiac dysfunction after a heart attack is in the “nascent stages,” and even less is known about the effect ventricular loading has on these pathways, Dr. Hiesinger and Dr. Atluri said. “This study offers a concrete platform for both specific treatment and further study,” they wrote.

The University of Maryland investigators in this study have joined the ranks of other investigators who have begun to unravel the consequences of mechanical unloading at the cellular level as well as its effect on the heart’s ability to handle calcium after infarction, Dr. William Hiesinger and Dr. Pavan Atluri of the University of Pennsylvania wrote in their invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1342-3).

“More broadly, these investigations are building the foundation of what will likely be the best platform for an efficacious bridge to recovery: multimodal therapy utilizing the titration of mechanical myocardial unloading,” they said. Dr. Hiesinger and Dr. Atluri commented on the limitations of the University of Maryland study, namely its small sample size and narrow scope. “This is, however, reflective more of the amazing complexity of the biologic and mechanical interactions between the heart and VAD and the need for further investigations of this kind than the quality of the research,” they said.

Understanding the molecular basis and metabolic function cardiac dysfunction after a heart attack is in the “nascent stages,” and even less is known about the effect ventricular loading has on these pathways, Dr. Hiesinger and Dr. Atluri said. “This study offers a concrete platform for both specific treatment and further study,” they wrote.

Placement of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) after a heart attack has been found to suppress certain cellular signaling pathways that protect coronary tissue, but at the same time LVAD placement seemed to help normalize other protective properties in areas of the heart closest to the infarcted region, investigators reported in a recent study.

The findings could have implications in determining the best method for unloading and other medical therapies in the aftermath of a heart attack, Dr. Keshava Rajagopal of the University of Texas, Houston, and associates reported in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015;150:1332-41).

To study the effect of LVAD on cardiac tissue, the investigators induced myocardial infarction in sheep and then placed the animals on LVAD support for 2 weeks. After 10 more weeks of observation, the investigators harvested and analyzed the myocardial specimens. The principal goal of the study was to investigate how heart attack and subsequent short-term mechanical support of the left ventricle can influence signaling controlled by the protein beta-arrestin.

They found that an infarction of myocardial tissue caused activation of the beta-arrestin protein that regulates cellular pathways that can benefit cardiac cells. At the same time, LVAD support inhibited beta-arrestin activation, specifically in regulating pathways of two cardioprotective proteins: Akt, also called protein kinase B (PKB), and, to a lesser extent, ERK-1 and -2.

They also found that MI resulted in regional activation of load-induced signaling of cardiac G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) via G proteins.

“These studies demonstrate that small platform catheter-based LVAD support exerts suppressive effects on cardioprotective beta-arrestin–mediated signal transduction, while normalizing the signaling networks of G-alpha-q–coupled cardiac GPCRS in the MI-adjacent zone,” Dr. Rajagopal and colleagues said.

They acknowledged that further studies are needed to better understand the roles that specific GPCRs in beta-arrestin–regulated signaling play in left ventricle dysfunction after a heart attack and to help define the optimal timing for LVAD based on signaling and genetic markers along with standard LV functional endpoints.

The authors had no disclosures.

Placement of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) after a heart attack has been found to suppress certain cellular signaling pathways that protect coronary tissue, but at the same time LVAD placement seemed to help normalize other protective properties in areas of the heart closest to the infarcted region, investigators reported in a recent study.

The findings could have implications in determining the best method for unloading and other medical therapies in the aftermath of a heart attack, Dr. Keshava Rajagopal of the University of Texas, Houston, and associates reported in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2015;150:1332-41).

To study the effect of LVAD on cardiac tissue, the investigators induced myocardial infarction in sheep and then placed the animals on LVAD support for 2 weeks. After 10 more weeks of observation, the investigators harvested and analyzed the myocardial specimens. The principal goal of the study was to investigate how heart attack and subsequent short-term mechanical support of the left ventricle can influence signaling controlled by the protein beta-arrestin.

They found that an infarction of myocardial tissue caused activation of the beta-arrestin protein that regulates cellular pathways that can benefit cardiac cells. At the same time, LVAD support inhibited beta-arrestin activation, specifically in regulating pathways of two cardioprotective proteins: Akt, also called protein kinase B (PKB), and, to a lesser extent, ERK-1 and -2.

They also found that MI resulted in regional activation of load-induced signaling of cardiac G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) via G proteins.

“These studies demonstrate that small platform catheter-based LVAD support exerts suppressive effects on cardioprotective beta-arrestin–mediated signal transduction, while normalizing the signaling networks of G-alpha-q–coupled cardiac GPCRS in the MI-adjacent zone,” Dr. Rajagopal and colleagues said.

They acknowledged that further studies are needed to better understand the roles that specific GPCRs in beta-arrestin–regulated signaling play in left ventricle dysfunction after a heart attack and to help define the optimal timing for LVAD based on signaling and genetic markers along with standard LV functional endpoints.

The authors had no disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Left ventricular assist device (LVAD) support inhibits pathologic responses to mechanical loading but also can inhibit adaptive responses after myocardial infarction.

Major finding: LVAD support inhibited cardioprotective beta-arrestin–mediated signaling, but net benefits of normalization of load-induced G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling were observed in the MI-adjacent zone.

Data source: Sheep were induced with myocardial infarction and then placed on LVAD support for 2 weeks and observed for a total of 12 weeks. Then myocardial specimens were harvested and analyzed.

Disclosures: The study authors had no relationships to disclose.

Hybrid revascularization shows promise, but there are concerns

A hybrid coronary revascularization procedure that combines off-pump left internal mammary artery (LIMA) grafting with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) showed good results at 1 year after surgery, but nonetheless showed a rate of adverse events that may raise questions about the procedure.

In a study published in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, a team of investigators from Aarhus University Hospital in Denmark reported high rates of graft patency and low rates of death and stroke with the procedure 1 year after a series of 100 operations (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1181-6).

“The high left internal mammary artery graft patency rate and low risk of death and stroke at 1 year seem promising for the long-term outcome of this revascularization strategy,” said Dr. Ivy Susanne Modrau and colleagues.

The single-center study evaluated 1-year clinical and angiographic results of 100 consecutive trial patients with multivessel disease who had the hybrid procedure between October 2010 and February 2012. “The rationale of hybrid coronary revascularization is to achieve the survival benefits of the LIMA to LAD (left anterior descending artery) graft with reduced invasiveness to minimize postprocedural discomfort and morbidity, in particular the risk of stroke,” Dr. Modrau and colleagues said.

The study used the LIMA to LAD graft performed off-pump through a reversed J-hemisternotomy “We chose this technique because of its excellent exposure of the heart, technical ease, low risk of complicating chronic pain, and applicability in virtually all patients,” Dr. Modrau said. Eighty-nine patients had surgery prior to PCI and 11 had PCI prior to surgery.

The primary endpoint was rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE), the composite of all-cause death, stroke, myocardial infarction, and repeat revascularization by PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting at 1 year. Secondary endpoints included individual components and status of stent and graft patency on angiography.

Overall, 20 patients met the 1-year primary endpoint of MACCE. One patient died, one other had a stroke, and three had heart attacks. Sixteen patients had repeat revascularization procedures, eight performed during the index hospitalization. Graft patency was 98% after 1 year.

Dr. Modrau and coauthors noted the MACCE rate of 20% “was higher than expected,” and certainly higher than results in the SYNTAX study (17.8% in the PCI group and 12.4% in the coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG] group) (Euro. Intervention. 2015;10:e1-e6). One possible reason the Danish investigators cited for higher than expected MACCE rates was that they may be attributed to the learning curve involved with LIMA grafting and the use of early angiography possibly revealing “clinically silent LIMA graft dysfunction due to technical errors.”

The number of repeat revascularizations in the study was more in line with the SYNTAX study: 7% in the Aarhus University study and 6% in the SYNTAX CABG group. However, a meta-analysis of six studies with 1,190 patients reported 1-year repeat revascularization rates of 3.8% after a hybrid procedure and 1.4% after CABG (Am Heart J. 2014;167:585-92).

Ultimately, the safety and efficacy of the hybrid revascularization approach will require long-term follow-up data and head-to-head comparison with conventional CABG and PCI in clinical trials. “Meanwhile, LIMA patency, the cornerstone of surgical revascularization, may be used as a surrogate endpoint for long-term survival after HCR,” Dr. Modrau and coauthors said.

They reported having no disclosures.

Hybrid revascularization procedures are “still not ready for prime time,” Dr. Carlos Mestres of Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1028-9).

The study illuminates two key points of concern, Dr. Mestres said: the “unexpectedly high” 20% rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE); and the in-hospital revascularization rate that was significantly higher than the 1% after CABG that the authors reported in their own institution. That calls into question the reason the investigators would change their own department strategy away from conventional CABG, where they had optimal results, he said.

Dr. Mestres also said the Danish investigators’ conclusion that the study results seemed promising for long-term outcomes of the hybrid procedure “are to be carefully dissected.”

He commended the investigators for collecting angiographic data at 1 year, but said that 1 year of follow-up “is simply not enough” to credibly compare staged procedures with CABG.

Dr. Mestres had no disclosures.

Hybrid revascularization procedures are “still not ready for prime time,” Dr. Carlos Mestres of Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1028-9).

The study illuminates two key points of concern, Dr. Mestres said: the “unexpectedly high” 20% rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE); and the in-hospital revascularization rate that was significantly higher than the 1% after CABG that the authors reported in their own institution. That calls into question the reason the investigators would change their own department strategy away from conventional CABG, where they had optimal results, he said.

Dr. Mestres also said the Danish investigators’ conclusion that the study results seemed promising for long-term outcomes of the hybrid procedure “are to be carefully dissected.”

He commended the investigators for collecting angiographic data at 1 year, but said that 1 year of follow-up “is simply not enough” to credibly compare staged procedures with CABG.

Dr. Mestres had no disclosures.

Hybrid revascularization procedures are “still not ready for prime time,” Dr. Carlos Mestres of Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1028-9).

The study illuminates two key points of concern, Dr. Mestres said: the “unexpectedly high” 20% rate of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE); and the in-hospital revascularization rate that was significantly higher than the 1% after CABG that the authors reported in their own institution. That calls into question the reason the investigators would change their own department strategy away from conventional CABG, where they had optimal results, he said.

Dr. Mestres also said the Danish investigators’ conclusion that the study results seemed promising for long-term outcomes of the hybrid procedure “are to be carefully dissected.”

He commended the investigators for collecting angiographic data at 1 year, but said that 1 year of follow-up “is simply not enough” to credibly compare staged procedures with CABG.

Dr. Mestres had no disclosures.

A hybrid coronary revascularization procedure that combines off-pump left internal mammary artery (LIMA) grafting with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) showed good results at 1 year after surgery, but nonetheless showed a rate of adverse events that may raise questions about the procedure.

In a study published in the November issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, a team of investigators from Aarhus University Hospital in Denmark reported high rates of graft patency and low rates of death and stroke with the procedure 1 year after a series of 100 operations (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1181-6).

“The high left internal mammary artery graft patency rate and low risk of death and stroke at 1 year seem promising for the long-term outcome of this revascularization strategy,” said Dr. Ivy Susanne Modrau and colleagues.

The single-center study evaluated 1-year clinical and angiographic results of 100 consecutive trial patients with multivessel disease who had the hybrid procedure between October 2010 and February 2012. “The rationale of hybrid coronary revascularization is to achieve the survival benefits of the LIMA to LAD (left anterior descending artery) graft with reduced invasiveness to minimize postprocedural discomfort and morbidity, in particular the risk of stroke,” Dr. Modrau and colleagues said.

The study used the LIMA to LAD graft performed off-pump through a reversed J-hemisternotomy “We chose this technique because of its excellent exposure of the heart, technical ease, low risk of complicating chronic pain, and applicability in virtually all patients,” Dr. Modrau said. Eighty-nine patients had surgery prior to PCI and 11 had PCI prior to surgery.