User login

AHA: COPD doubles sudden cardiac death risk in hypertensives

ORLANDO – A second, confirmatory major study has shown that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease independently increases the risk of sudden cardiac death severalfold.

COPD was associated with a roughly twofold increased risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in hypertensive patients with COPD, compared with those without the pulmonary disease, in the Scandinavian Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) trial, Dr. Peter M. Okin reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Moreover, aggressive blood pressure lowering in the hypertensive COPD patients didn’t negate this risk, added Dr. Okin of Cornell University in New York.

The impetus for his secondary analysis of LIFE data was an earlier report from the landmark, population-based Rotterdam Heart Study. Among 1,615 participants with COPD, the age- and sex-adjusted risk of SCD was 1.34-fold greater than in nearly 12,000 controls. This increased SCD risk climbed to 2.12-fold during the first 2,000 days following diagnosis of COPD and reached 3.58-fold among those with frequent COPD exacerbations during this period (Eur Heart J. 2015 Jul 14;36[27]:1754-61).

Dr. Okin’s secondary analysis of LIFE data included 9,193 hypertensive subjects with ECG evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy who were randomized to lisinopril- or atenolol-based blood pressure lowering to a target of 140/90 mm Hg or less. A history of COPD was present in 385 patients (4.2%) at enrollment.

During a mean 4.8 years of prospective follow-up, 178 patients experienced SCD, a prespecified secondary endpoint in the LIFE trial. The incidence rate was 9 cases per 1,000 patient-years in those with COPD and 3.8 per 1,000 person-years in those without the pulmonary disease.

In a univariate analysis, a history of COPD was associated with a 2.36-fold increased risk of SCD during follow-up. In a multivariate analysis extensively adjusted for potential confounders – treatment arm, age, race, gender, history of atrial fibrillation, baseline serum creatinine and serum glucose, stroke or TIA, as well as on-treatment blood pressure, heart rate, QRS duration, HDL cholesterol level, use of a statin or hydrochlorothiazide, and incident MI or heart failure – COPD remained associated with a 1.82-fold increased risk of SCD, the cardiologist reported.

“These results suggest the need for additional studies to assess whether there are targeted therapies that can reduce the risk of SCD in patients with COPD,” he concluded.

As previously reported, the main finding in LIFE was that losartan conferred benefits beyond blood pressure control (Lancet. 2002 Mar 23;359[9311]:995-1003).

Dr. Okin reported serving as a consultant to Novartis.

ORLANDO – A second, confirmatory major study has shown that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease independently increases the risk of sudden cardiac death severalfold.

COPD was associated with a roughly twofold increased risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in hypertensive patients with COPD, compared with those without the pulmonary disease, in the Scandinavian Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) trial, Dr. Peter M. Okin reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Moreover, aggressive blood pressure lowering in the hypertensive COPD patients didn’t negate this risk, added Dr. Okin of Cornell University in New York.

The impetus for his secondary analysis of LIFE data was an earlier report from the landmark, population-based Rotterdam Heart Study. Among 1,615 participants with COPD, the age- and sex-adjusted risk of SCD was 1.34-fold greater than in nearly 12,000 controls. This increased SCD risk climbed to 2.12-fold during the first 2,000 days following diagnosis of COPD and reached 3.58-fold among those with frequent COPD exacerbations during this period (Eur Heart J. 2015 Jul 14;36[27]:1754-61).

Dr. Okin’s secondary analysis of LIFE data included 9,193 hypertensive subjects with ECG evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy who were randomized to lisinopril- or atenolol-based blood pressure lowering to a target of 140/90 mm Hg or less. A history of COPD was present in 385 patients (4.2%) at enrollment.

During a mean 4.8 years of prospective follow-up, 178 patients experienced SCD, a prespecified secondary endpoint in the LIFE trial. The incidence rate was 9 cases per 1,000 patient-years in those with COPD and 3.8 per 1,000 person-years in those without the pulmonary disease.

In a univariate analysis, a history of COPD was associated with a 2.36-fold increased risk of SCD during follow-up. In a multivariate analysis extensively adjusted for potential confounders – treatment arm, age, race, gender, history of atrial fibrillation, baseline serum creatinine and serum glucose, stroke or TIA, as well as on-treatment blood pressure, heart rate, QRS duration, HDL cholesterol level, use of a statin or hydrochlorothiazide, and incident MI or heart failure – COPD remained associated with a 1.82-fold increased risk of SCD, the cardiologist reported.

“These results suggest the need for additional studies to assess whether there are targeted therapies that can reduce the risk of SCD in patients with COPD,” he concluded.

As previously reported, the main finding in LIFE was that losartan conferred benefits beyond blood pressure control (Lancet. 2002 Mar 23;359[9311]:995-1003).

Dr. Okin reported serving as a consultant to Novartis.

ORLANDO – A second, confirmatory major study has shown that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease independently increases the risk of sudden cardiac death severalfold.

COPD was associated with a roughly twofold increased risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in hypertensive patients with COPD, compared with those without the pulmonary disease, in the Scandinavian Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) trial, Dr. Peter M. Okin reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Moreover, aggressive blood pressure lowering in the hypertensive COPD patients didn’t negate this risk, added Dr. Okin of Cornell University in New York.

The impetus for his secondary analysis of LIFE data was an earlier report from the landmark, population-based Rotterdam Heart Study. Among 1,615 participants with COPD, the age- and sex-adjusted risk of SCD was 1.34-fold greater than in nearly 12,000 controls. This increased SCD risk climbed to 2.12-fold during the first 2,000 days following diagnosis of COPD and reached 3.58-fold among those with frequent COPD exacerbations during this period (Eur Heart J. 2015 Jul 14;36[27]:1754-61).

Dr. Okin’s secondary analysis of LIFE data included 9,193 hypertensive subjects with ECG evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy who were randomized to lisinopril- or atenolol-based blood pressure lowering to a target of 140/90 mm Hg or less. A history of COPD was present in 385 patients (4.2%) at enrollment.

During a mean 4.8 years of prospective follow-up, 178 patients experienced SCD, a prespecified secondary endpoint in the LIFE trial. The incidence rate was 9 cases per 1,000 patient-years in those with COPD and 3.8 per 1,000 person-years in those without the pulmonary disease.

In a univariate analysis, a history of COPD was associated with a 2.36-fold increased risk of SCD during follow-up. In a multivariate analysis extensively adjusted for potential confounders – treatment arm, age, race, gender, history of atrial fibrillation, baseline serum creatinine and serum glucose, stroke or TIA, as well as on-treatment blood pressure, heart rate, QRS duration, HDL cholesterol level, use of a statin or hydrochlorothiazide, and incident MI or heart failure – COPD remained associated with a 1.82-fold increased risk of SCD, the cardiologist reported.

“These results suggest the need for additional studies to assess whether there are targeted therapies that can reduce the risk of SCD in patients with COPD,” he concluded.

As previously reported, the main finding in LIFE was that losartan conferred benefits beyond blood pressure control (Lancet. 2002 Mar 23;359[9311]:995-1003).

Dr. Okin reported serving as a consultant to Novartis.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Two large studies link chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with increased risk of sudden cardiac death.

Major finding: Patients with COPD and hypertension had nearly a twofold increased risk of sudden cardiac death, compared with hypertensives without the pulmonary disease.

Data source: This was a secondary analysis comparing sudden cardiac death rates in 385 hypertensive patients with and nearly 12,000 without COPD, all participants in the LIFE trial.

Disclosures: The presenter reported serving as a consultant to Novartis.

Diabetes raises the cardiovascular risk higher in women than men

Women with type 2 diabetes mellitus have a twofold greater risk of developing coronary heart disease, compared with men with type 2 diabetes, according to a scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

In outlining the many sex differences in the impact of diabetes on cardiovascular disease risk, the authors of the statement have also called for more research into why there are these sex differences and how to treat them.

Around 1 in 10 adult Americans are estimated to have diabetes, and among those individuals, cardiovascular disease alone accounts for more than three-quarters of hospitalizations and half of all deaths.

“Although nondiabetic women have fewer cardiovascular events than nondiabetic men of the same age, this advantage appears to be lost in the context of [type 2 diabetes],” wrote American Heart Association Diabetes Committee Cochair Dr. Judith G. Regensteiner, director of the Center for Women’s Health Research at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and her coauthors.

Women with type 2 diabetes experience myocardial infarctions earlier in life than do men and are more likely to die from them, yet the rates of revascularization are lower in women with diabetes, compared with men, according to a statement published in the December 7 online issue of Circulation.

Women with diabetes also have more impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation, worse atherogenic dyslipidemia, prothrombotic coagulation profile and higher metabolic syndrome prevalence than men with diabetes (Circulation. 2015 Dec 7. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000343).

Diabetes is also associated with a greater risk of incident heart failure and is a stronger risk factor for stroke in women than in men, although men with stroke are more likely to have diabetes.

Black and Hispanic women with type 2 diabetes also experience a disproportionately larger impact of the disease on their coronary artery disease and stroke risk, compared with men.

The authors of the statement also observed that, compared with men with diabetes, women are less likely to be taking statins, aspirin, ACE inhibitors, or beta-blockers, with the suggestion of lower medication adherence in women.

While the overall prevalence of diabetes is similar in men and women, there are sex-specific conditions such as gestational diabetes and polycystic ovary syndrome that contribute to women’s risk of the disease.

Research is needed to explore the full extent of sex differences between men and women, as this may have therapeutic implications, Dr. Regensteiner said in an interview.

“There really isn’t too much a clinician can do differently at this point because we don’t have information to guide changes in therapy,” she said, noting that any potential heart problems should be subject to the same level of scrutiny in women as in men.

The authors of the statement pointed out that observational evidence suggested women with diabetes may benefit from a higher frequency and intensity of physical activity than men with diabetes, and women with type 1 diabetes may experience greater improvements in hemoglobin A1c with exercise, compared with men.

The American Heart Association issued the statement. Several authors declared research grants or consultancies from the pharmaceutical industry or ownership interests in private companies.

Women with type 2 diabetes mellitus have a twofold greater risk of developing coronary heart disease, compared with men with type 2 diabetes, according to a scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

In outlining the many sex differences in the impact of diabetes on cardiovascular disease risk, the authors of the statement have also called for more research into why there are these sex differences and how to treat them.

Around 1 in 10 adult Americans are estimated to have diabetes, and among those individuals, cardiovascular disease alone accounts for more than three-quarters of hospitalizations and half of all deaths.

“Although nondiabetic women have fewer cardiovascular events than nondiabetic men of the same age, this advantage appears to be lost in the context of [type 2 diabetes],” wrote American Heart Association Diabetes Committee Cochair Dr. Judith G. Regensteiner, director of the Center for Women’s Health Research at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and her coauthors.

Women with type 2 diabetes experience myocardial infarctions earlier in life than do men and are more likely to die from them, yet the rates of revascularization are lower in women with diabetes, compared with men, according to a statement published in the December 7 online issue of Circulation.

Women with diabetes also have more impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation, worse atherogenic dyslipidemia, prothrombotic coagulation profile and higher metabolic syndrome prevalence than men with diabetes (Circulation. 2015 Dec 7. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000343).

Diabetes is also associated with a greater risk of incident heart failure and is a stronger risk factor for stroke in women than in men, although men with stroke are more likely to have diabetes.

Black and Hispanic women with type 2 diabetes also experience a disproportionately larger impact of the disease on their coronary artery disease and stroke risk, compared with men.

The authors of the statement also observed that, compared with men with diabetes, women are less likely to be taking statins, aspirin, ACE inhibitors, or beta-blockers, with the suggestion of lower medication adherence in women.

While the overall prevalence of diabetes is similar in men and women, there are sex-specific conditions such as gestational diabetes and polycystic ovary syndrome that contribute to women’s risk of the disease.

Research is needed to explore the full extent of sex differences between men and women, as this may have therapeutic implications, Dr. Regensteiner said in an interview.

“There really isn’t too much a clinician can do differently at this point because we don’t have information to guide changes in therapy,” she said, noting that any potential heart problems should be subject to the same level of scrutiny in women as in men.

The authors of the statement pointed out that observational evidence suggested women with diabetes may benefit from a higher frequency and intensity of physical activity than men with diabetes, and women with type 1 diabetes may experience greater improvements in hemoglobin A1c with exercise, compared with men.

The American Heart Association issued the statement. Several authors declared research grants or consultancies from the pharmaceutical industry or ownership interests in private companies.

Women with type 2 diabetes mellitus have a twofold greater risk of developing coronary heart disease, compared with men with type 2 diabetes, according to a scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

In outlining the many sex differences in the impact of diabetes on cardiovascular disease risk, the authors of the statement have also called for more research into why there are these sex differences and how to treat them.

Around 1 in 10 adult Americans are estimated to have diabetes, and among those individuals, cardiovascular disease alone accounts for more than three-quarters of hospitalizations and half of all deaths.

“Although nondiabetic women have fewer cardiovascular events than nondiabetic men of the same age, this advantage appears to be lost in the context of [type 2 diabetes],” wrote American Heart Association Diabetes Committee Cochair Dr. Judith G. Regensteiner, director of the Center for Women’s Health Research at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and her coauthors.

Women with type 2 diabetes experience myocardial infarctions earlier in life than do men and are more likely to die from them, yet the rates of revascularization are lower in women with diabetes, compared with men, according to a statement published in the December 7 online issue of Circulation.

Women with diabetes also have more impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation, worse atherogenic dyslipidemia, prothrombotic coagulation profile and higher metabolic syndrome prevalence than men with diabetes (Circulation. 2015 Dec 7. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000343).

Diabetes is also associated with a greater risk of incident heart failure and is a stronger risk factor for stroke in women than in men, although men with stroke are more likely to have diabetes.

Black and Hispanic women with type 2 diabetes also experience a disproportionately larger impact of the disease on their coronary artery disease and stroke risk, compared with men.

The authors of the statement also observed that, compared with men with diabetes, women are less likely to be taking statins, aspirin, ACE inhibitors, or beta-blockers, with the suggestion of lower medication adherence in women.

While the overall prevalence of diabetes is similar in men and women, there are sex-specific conditions such as gestational diabetes and polycystic ovary syndrome that contribute to women’s risk of the disease.

Research is needed to explore the full extent of sex differences between men and women, as this may have therapeutic implications, Dr. Regensteiner said in an interview.

“There really isn’t too much a clinician can do differently at this point because we don’t have information to guide changes in therapy,” she said, noting that any potential heart problems should be subject to the same level of scrutiny in women as in men.

The authors of the statement pointed out that observational evidence suggested women with diabetes may benefit from a higher frequency and intensity of physical activity than men with diabetes, and women with type 1 diabetes may experience greater improvements in hemoglobin A1c with exercise, compared with men.

The American Heart Association issued the statement. Several authors declared research grants or consultancies from the pharmaceutical industry or ownership interests in private companies.

FROM CIRCULATION

Key clinical point: There are significant sex differences in the impact of diabetes on cardiovascular risk.

Major finding: Women with diabetes have a greater than twofold risk of coronary artery disease, compared with men with diabetes.

Data source: Scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

Disclosures: The statement is produced by the American Heart Association. Several authors declared research grants or consultancies from the pharmaceutical industry or ownership interests in private companies.

Does position matter in ViV implantation?

With transcatheter valve-in-valve implantation emerging as a novel treatment for high-risk patients whose existing bioprostheses have deteriorated, a team of investigators at University Heart Center in Hamburg, Germany, has found that the procedure can be done successfully in four different anatomic positions with a variety of bioprostheses.

The findings from the single-center study were published in the December issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1557-67). They retrospectively analyzed results of 75 patients who had transcatheter valve-in-valve (ViV) replacement at their institution from 2008 to 2014.

“ViV can be performed in all anatomic positions with acceptable hemodynamic and clinical outcome in high-risk patients,” wrote Dr. Lenard Conradi and coauthors. “Increasing importance of ViV can be anticipated considering growing use of surgical bioprostheses.”

Replacement of biological valves is becoming more common. For surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), biological procedures have largely replaced mechanical valve implantation, comprising 87% of all such procedures by 2014, according to data from the German Society for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;62:380-92). “Therefore, increasing caseload of patients with deteriorated bioprostheses can be expected,” wrote Dr. Conradi and coauthors.

The four anatomic positions in which the investigators performed the procedures and their share of cases are: aortic (54 patients/72%), mitral (17/22.7%), and tricuspid and pulmonary positions (2/2.7% each). The average interval between the index procedure and ViV was 9 years, with a deviation of nearly 5 years among all procedures. Dr. Conradi and coinvestigators said their study focused on technical aspects of ViV procedures from each position to provide guidance for surgeons.

Overall, the study authors performed ViV successfully in 97.3% of patients, with two patients requiring sequential transcatheter heart valve implantation for initial malpositioning. Thirty-day mortality was 8%, which “ranged lower” than expected when compared to standard preoperative risk stratification, they wrote. Mortality was at 5.6% in the aortic group and 17.6% in the mitral group.

That none of the currently available surgical bioprostheses or transcatheter heart valves (THV) were designed for later ViV procedures in deteriorated bioprostheses – although the CoreValve and Sapein THV have approvals for the indication – “may explain some of the apparent shortcomings of ViV therapy,” the researchers wrote.

The most significant challenge of ViV therapy is dealing with elevated residual gradients, which positioning can influence, according to the study findings. “This is not so much an issue for mitral, tricuspid, or pulmonary positions since surgical bioprostheses implanted in these positions are usually of sufficient size to accommodate the THV,” the researchers noted. “However, in the aortic position, more severe spatial restrictions may apply.”

They cited other reports that described a reverse relationship between size of the bioprosthetic and resulting transvalvular gradient after ViV (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:1218-27; JAMA 2014;312:162-70).

To reduce gradients, the investigators used post-ballooning after aortic ViV with a self-expandable THV in 16 cases, succeeding in 12. “Likely, further THV expansion with active compression of soft leaflet and/or pannus tissue and tighter apposition of THV against the frames of surgical bioprostheses contributed to this desired effect,” wrote the researchers. Patient-prosthesis mismatch probably explained the four cases in which gradients could not be further reduced, they noted.

They issued one “word of caution” regarding aortic ViV in small-sized surgical bioprostheses: “Elevated postprocedural gradients have to be expected and must be weighed against expected benefits and against risk of repeat open heart surgery.”

The six transcatheter heart valves the investigators used were Edwards Sapien (XT)/Sapien3 (52%, 39/75); Medtronic CoreValve/CoreValveEvolut (34.7%, 26); St. Jude Portico and Boston Scientific Lotus (4%, three each); and JenaValve and Medtronic Engager (2.7%, two each). The study also looked at different access routes: transapical in 53.3% (40), transfemoral (transarterial or transvenous) in 42.7% (32), transaortic in 2.7% (2), and transjugular in 1.3% (1).

Dr. Conradi and coauthors Dr. Moritz Seiffert, Dr. Ulrich Schaefer, and Dr. Hendrik Treede disclosed ties with Edwards Lifesciences, JenaValve Technology, Medtronic, Symetis, and St. Jude Medical. Four other coauthors reported no disclosures.

As the population ages and younger patients choose bioprosthetic valves to avoid lifelong warfarin, surgeons are going to face more situations where they will have to decide whether to perform surgical or transcatheter reoperative valve surgery, Dr. Jessica Forcillo of Emory University, Atlanta, and coauthors wrote in an invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1568-9).

They called the 8% 30-day mortality rate in the Hamburg study “high” even though the average age of the study population was a “relatively young” 74 years. The Hamburg authors may have learned more had they evaluated fewer prostheses. “With a small number of patients and at the beginning of an experience, focusing on one or two available prostheses may have resulted in more accurate and reliable results,” noted Dr. Forcillo and her colleagues. That 53% of the procedures were done via the transapical approach may also explain the mortality rate, they said.

The overall 30-day mortality rate along with a 17.6% mortality in the mitral ViV group are causes for “some caution against overzealous performance of this procedure and continued monitoring of outcomes in other series,” wrote Dr. Forcillo and her colleagues.

But ViV implantation is a “transformative” technology, they said. “For the elderly, high-risk patients with [structural valve degeneration], transcatheter options may provide improved short-term outcomes,” they added. “The valve community eagerly awaits larger series with adjudicated outcomes of the transcatheter valve-in-valve procedure.”

Dr. Forcillo and coauthor Lillian Tsai had no disclosures. Dr. Vinod Thourani disclosed ties with St. Jude Medical, Edwards Lifesciences, Boston Scientific, Abbott Medical, Medtronic, Directflow, and Sorin Medical.

As the population ages and younger patients choose bioprosthetic valves to avoid lifelong warfarin, surgeons are going to face more situations where they will have to decide whether to perform surgical or transcatheter reoperative valve surgery, Dr. Jessica Forcillo of Emory University, Atlanta, and coauthors wrote in an invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1568-9).

They called the 8% 30-day mortality rate in the Hamburg study “high” even though the average age of the study population was a “relatively young” 74 years. The Hamburg authors may have learned more had they evaluated fewer prostheses. “With a small number of patients and at the beginning of an experience, focusing on one or two available prostheses may have resulted in more accurate and reliable results,” noted Dr. Forcillo and her colleagues. That 53% of the procedures were done via the transapical approach may also explain the mortality rate, they said.

The overall 30-day mortality rate along with a 17.6% mortality in the mitral ViV group are causes for “some caution against overzealous performance of this procedure and continued monitoring of outcomes in other series,” wrote Dr. Forcillo and her colleagues.

But ViV implantation is a “transformative” technology, they said. “For the elderly, high-risk patients with [structural valve degeneration], transcatheter options may provide improved short-term outcomes,” they added. “The valve community eagerly awaits larger series with adjudicated outcomes of the transcatheter valve-in-valve procedure.”

Dr. Forcillo and coauthor Lillian Tsai had no disclosures. Dr. Vinod Thourani disclosed ties with St. Jude Medical, Edwards Lifesciences, Boston Scientific, Abbott Medical, Medtronic, Directflow, and Sorin Medical.

As the population ages and younger patients choose bioprosthetic valves to avoid lifelong warfarin, surgeons are going to face more situations where they will have to decide whether to perform surgical or transcatheter reoperative valve surgery, Dr. Jessica Forcillo of Emory University, Atlanta, and coauthors wrote in an invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1568-9).

They called the 8% 30-day mortality rate in the Hamburg study “high” even though the average age of the study population was a “relatively young” 74 years. The Hamburg authors may have learned more had they evaluated fewer prostheses. “With a small number of patients and at the beginning of an experience, focusing on one or two available prostheses may have resulted in more accurate and reliable results,” noted Dr. Forcillo and her colleagues. That 53% of the procedures were done via the transapical approach may also explain the mortality rate, they said.

The overall 30-day mortality rate along with a 17.6% mortality in the mitral ViV group are causes for “some caution against overzealous performance of this procedure and continued monitoring of outcomes in other series,” wrote Dr. Forcillo and her colleagues.

But ViV implantation is a “transformative” technology, they said. “For the elderly, high-risk patients with [structural valve degeneration], transcatheter options may provide improved short-term outcomes,” they added. “The valve community eagerly awaits larger series with adjudicated outcomes of the transcatheter valve-in-valve procedure.”

Dr. Forcillo and coauthor Lillian Tsai had no disclosures. Dr. Vinod Thourani disclosed ties with St. Jude Medical, Edwards Lifesciences, Boston Scientific, Abbott Medical, Medtronic, Directflow, and Sorin Medical.

With transcatheter valve-in-valve implantation emerging as a novel treatment for high-risk patients whose existing bioprostheses have deteriorated, a team of investigators at University Heart Center in Hamburg, Germany, has found that the procedure can be done successfully in four different anatomic positions with a variety of bioprostheses.

The findings from the single-center study were published in the December issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1557-67). They retrospectively analyzed results of 75 patients who had transcatheter valve-in-valve (ViV) replacement at their institution from 2008 to 2014.

“ViV can be performed in all anatomic positions with acceptable hemodynamic and clinical outcome in high-risk patients,” wrote Dr. Lenard Conradi and coauthors. “Increasing importance of ViV can be anticipated considering growing use of surgical bioprostheses.”

Replacement of biological valves is becoming more common. For surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), biological procedures have largely replaced mechanical valve implantation, comprising 87% of all such procedures by 2014, according to data from the German Society for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;62:380-92). “Therefore, increasing caseload of patients with deteriorated bioprostheses can be expected,” wrote Dr. Conradi and coauthors.

The four anatomic positions in which the investigators performed the procedures and their share of cases are: aortic (54 patients/72%), mitral (17/22.7%), and tricuspid and pulmonary positions (2/2.7% each). The average interval between the index procedure and ViV was 9 years, with a deviation of nearly 5 years among all procedures. Dr. Conradi and coinvestigators said their study focused on technical aspects of ViV procedures from each position to provide guidance for surgeons.

Overall, the study authors performed ViV successfully in 97.3% of patients, with two patients requiring sequential transcatheter heart valve implantation for initial malpositioning. Thirty-day mortality was 8%, which “ranged lower” than expected when compared to standard preoperative risk stratification, they wrote. Mortality was at 5.6% in the aortic group and 17.6% in the mitral group.

That none of the currently available surgical bioprostheses or transcatheter heart valves (THV) were designed for later ViV procedures in deteriorated bioprostheses – although the CoreValve and Sapein THV have approvals for the indication – “may explain some of the apparent shortcomings of ViV therapy,” the researchers wrote.

The most significant challenge of ViV therapy is dealing with elevated residual gradients, which positioning can influence, according to the study findings. “This is not so much an issue for mitral, tricuspid, or pulmonary positions since surgical bioprostheses implanted in these positions are usually of sufficient size to accommodate the THV,” the researchers noted. “However, in the aortic position, more severe spatial restrictions may apply.”

They cited other reports that described a reverse relationship between size of the bioprosthetic and resulting transvalvular gradient after ViV (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:1218-27; JAMA 2014;312:162-70).

To reduce gradients, the investigators used post-ballooning after aortic ViV with a self-expandable THV in 16 cases, succeeding in 12. “Likely, further THV expansion with active compression of soft leaflet and/or pannus tissue and tighter apposition of THV against the frames of surgical bioprostheses contributed to this desired effect,” wrote the researchers. Patient-prosthesis mismatch probably explained the four cases in which gradients could not be further reduced, they noted.

They issued one “word of caution” regarding aortic ViV in small-sized surgical bioprostheses: “Elevated postprocedural gradients have to be expected and must be weighed against expected benefits and against risk of repeat open heart surgery.”

The six transcatheter heart valves the investigators used were Edwards Sapien (XT)/Sapien3 (52%, 39/75); Medtronic CoreValve/CoreValveEvolut (34.7%, 26); St. Jude Portico and Boston Scientific Lotus (4%, three each); and JenaValve and Medtronic Engager (2.7%, two each). The study also looked at different access routes: transapical in 53.3% (40), transfemoral (transarterial or transvenous) in 42.7% (32), transaortic in 2.7% (2), and transjugular in 1.3% (1).

Dr. Conradi and coauthors Dr. Moritz Seiffert, Dr. Ulrich Schaefer, and Dr. Hendrik Treede disclosed ties with Edwards Lifesciences, JenaValve Technology, Medtronic, Symetis, and St. Jude Medical. Four other coauthors reported no disclosures.

With transcatheter valve-in-valve implantation emerging as a novel treatment for high-risk patients whose existing bioprostheses have deteriorated, a team of investigators at University Heart Center in Hamburg, Germany, has found that the procedure can be done successfully in four different anatomic positions with a variety of bioprostheses.

The findings from the single-center study were published in the December issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1557-67). They retrospectively analyzed results of 75 patients who had transcatheter valve-in-valve (ViV) replacement at their institution from 2008 to 2014.

“ViV can be performed in all anatomic positions with acceptable hemodynamic and clinical outcome in high-risk patients,” wrote Dr. Lenard Conradi and coauthors. “Increasing importance of ViV can be anticipated considering growing use of surgical bioprostheses.”

Replacement of biological valves is becoming more common. For surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), biological procedures have largely replaced mechanical valve implantation, comprising 87% of all such procedures by 2014, according to data from the German Society for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;62:380-92). “Therefore, increasing caseload of patients with deteriorated bioprostheses can be expected,” wrote Dr. Conradi and coauthors.

The four anatomic positions in which the investigators performed the procedures and their share of cases are: aortic (54 patients/72%), mitral (17/22.7%), and tricuspid and pulmonary positions (2/2.7% each). The average interval between the index procedure and ViV was 9 years, with a deviation of nearly 5 years among all procedures. Dr. Conradi and coinvestigators said their study focused on technical aspects of ViV procedures from each position to provide guidance for surgeons.

Overall, the study authors performed ViV successfully in 97.3% of patients, with two patients requiring sequential transcatheter heart valve implantation for initial malpositioning. Thirty-day mortality was 8%, which “ranged lower” than expected when compared to standard preoperative risk stratification, they wrote. Mortality was at 5.6% in the aortic group and 17.6% in the mitral group.

That none of the currently available surgical bioprostheses or transcatheter heart valves (THV) were designed for later ViV procedures in deteriorated bioprostheses – although the CoreValve and Sapein THV have approvals for the indication – “may explain some of the apparent shortcomings of ViV therapy,” the researchers wrote.

The most significant challenge of ViV therapy is dealing with elevated residual gradients, which positioning can influence, according to the study findings. “This is not so much an issue for mitral, tricuspid, or pulmonary positions since surgical bioprostheses implanted in these positions are usually of sufficient size to accommodate the THV,” the researchers noted. “However, in the aortic position, more severe spatial restrictions may apply.”

They cited other reports that described a reverse relationship between size of the bioprosthetic and resulting transvalvular gradient after ViV (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:1218-27; JAMA 2014;312:162-70).

To reduce gradients, the investigators used post-ballooning after aortic ViV with a self-expandable THV in 16 cases, succeeding in 12. “Likely, further THV expansion with active compression of soft leaflet and/or pannus tissue and tighter apposition of THV against the frames of surgical bioprostheses contributed to this desired effect,” wrote the researchers. Patient-prosthesis mismatch probably explained the four cases in which gradients could not be further reduced, they noted.

They issued one “word of caution” regarding aortic ViV in small-sized surgical bioprostheses: “Elevated postprocedural gradients have to be expected and must be weighed against expected benefits and against risk of repeat open heart surgery.”

The six transcatheter heart valves the investigators used were Edwards Sapien (XT)/Sapien3 (52%, 39/75); Medtronic CoreValve/CoreValveEvolut (34.7%, 26); St. Jude Portico and Boston Scientific Lotus (4%, three each); and JenaValve and Medtronic Engager (2.7%, two each). The study also looked at different access routes: transapical in 53.3% (40), transfemoral (transarterial or transvenous) in 42.7% (32), transaortic in 2.7% (2), and transjugular in 1.3% (1).

Dr. Conradi and coauthors Dr. Moritz Seiffert, Dr. Ulrich Schaefer, and Dr. Hendrik Treede disclosed ties with Edwards Lifesciences, JenaValve Technology, Medtronic, Symetis, and St. Jude Medical. Four other coauthors reported no disclosures.

Key clinical point: Transcatheter valve-in-valve (ViV) implantation is a relatively safe treatment for patients with a deteriorated bioprostheses.

Major finding: A ViV implantation when performed in four different positions with six different transcatheter heart valves had a 30-day mortality of 8%.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 75 consecutive patients receiving ViV procedures from 2008 to 2014 at a single institution.

Disclosures: Dr. Conradi and coauthors Dr. Moritz Seiffert, Dr. Ulrich Schaefer, and Dr. Hendrik Treede disclosed relationships with Edwards Lifesciences, JenaValve Technology, Medtronic, Symetis, and St. Jude Medical. Four other coauthors reported no disclosures.

Surgical ablation endures at 5 years

The Cox-Maze IV procedure (CMPIV) has become the standard for surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation (AF), yet little information has been available on how late outcomes compare with catheter-based ablation. A recent analysis of 576 procedures found that after 5 years, most people who had the procedure remained free of atrial tachyarrhythmias and anticoagulation.

The study, by investigators from Washington University, Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, was published in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1168-78). The researchers first presented the study in April at the American Association for Thoracic Surgery meeting in Seattle.

“The results of the CMPIV remain superior to those reported for catheter ablation and other forms of surgical AF ablation, especially for patients with persistent or long-standing AF,” wrote Dr. Matthew C. Henn and his colleagues.

They set out to evaluate late outcomes after CMPIV using current consensus definitions of treatment failure, noting that such outcomes had yet to be reported. They followed 576 patients with atrial fibrillation who had a CMPIV from 2002 to 2014 and compared long-term freedom from atrial fibrillation on and off antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) across various subgroups. They included the left-sided CMPIV lesion in the analysis because, they said, it had success rates similar to those of biatrial CMPIV.

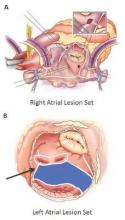

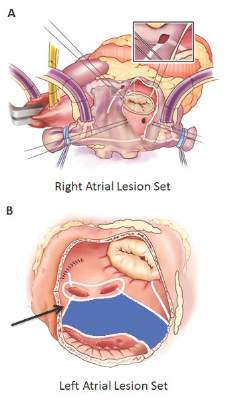

The Cox-Maze procedure was first introduced by Dr. James Cox in 1987 and updated from the original “cut-and-sew” technique in 2002 to combine bipolar radiofrequency and cryothermal ablation lines in place of most surgical incisions. This iteration was called the Cox-Maze IV procedure. In 2005, CMPIV was modified to include a superior connecting lesion, which formed a “box lesion” by completely isolating the entire posterior left atrium. The study included 512 people who underwent the “box lesion” set procedure.

“The modifications of the CMPIV have allowed it to be performed through a right minithoracotomy (RMT) approach, which has further reduced major morbidity, mortality, and hospital stay compared to those who underwent sternotomy while enjoying equivalent outcomes with regards to freedom from AF,” wrote Dr. Henn and his coauthors.

In the entire cohort, the overall freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias (ATAs) and anticoagulation were 92% at 1 year, 88% at 2 years, 87% at 3 years, 81% at 4 years, and 73% at 5 years. Overall freedom from ATAs off antiarrhythmic drugs for the entire cohort ranged from 81% at 1 year to 61% at 5 years, and freedom from anticoagulation ranged from 65% at 1 year to 55% at 5 years.

“Freedoms from ATAs on or off AADs were significantly higher in those who underwent box lesion sets when compared to those who did not at 5 years,” noted Dr. Henn and his coauthors. Among the box lesion set group, 78% of those on AADs remained free of ATAs vs. 45% in the non–box lesion set group, and for those off AADs, 66% had no ATAs at 5 years while 33% of the non–box lesion set group did.

Of the overall study population, 41% had paroxysmal AF and 58% had nonparoxysmal AF. Among the latter group, 20% had persistent and 80% had long-standing persistent AF. The nonparoxysmal AF group had a longer duration of preoperative AF, larger left atria and more failed catheter ablations, Dr. Henn and coauthors reported. But, the study showed no differences in freedom from atrial fibrillation on or off AADs at 5 years between patients with paroxysmal AF or persistent/long-standing persistent AF, or between those who underwent stand-alone procedure and those who received a concomitant Cox-Maze procedure. Among those who had a concomitant procedure, 50% had a concomitant mitral valve procedure and 23% had coronary artery bypass grafting.

“The CMPIV results in our series were better than what has been achieved with catheter ablation,” the researchers wrote. They cited studies that showed arrhythmia-free survival after a single ablation procedure ranging from 17% to 29% and “equally poor results.” (Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:18-24; J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:160-166; J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e004549.)

“The CMPIV remains the most successful surgical treatment for AF, even in patients with non-paroxysmal AF and regardless of the complexity of the concomitant procedures,” Dr. Henn and his coauthors concluded.

Inconsistencies in this study of the Cox-Maze IV procedure include differing types of atrial fibrillation, heterogeneous concomitant operations, multiple lesion sets and energy sources and inconsistent postablation monitoring, all of which make direct comparisons of surgical ablation strategies or even catheter ablation difficult, Dr. Robert Hawkins and Dr. Gorav Ailawadi of the University of Virginia noted in their invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1179-80). “Moreover, without controls or selection criteria, it is difficult to account for selection bias,” they wrote.

Yet, this study has “some important findings” despite its shortcomings, namely the “respectable” rates of atrial tachyarrhythmias off antiarrhythmic drugs. These results are superior to other clinical trials, “in part due to the expertise at Washington University,” noted Dr. Hawkins and Dr. Ailawadi.

Adding patients who had the box lesion set approach also improved 5-year outcomes in the study substantially, and left atrium (LA) ablation alone has good results in patients with paroxysmal AF, left atria less than 5.0 cm, and no right atrial enlargement. “Yet, a direct comparison between biatrial and LA lesion sets cannot be made due to the above listed limitations,” they wrote.

The study makes a case for surgical ablation when the preoperative duration of AF is less than 5-10 years and left atrium size is not a problem, and the lesion-set requires further investigation, they said. “Finally, this study highlights the continued need for rigorous monitoring and comparisons of homogeneous patient populations to make stronger conclusions.”

Dr. Ailawadi disclosed relationships with Abbot Vascular, Mitralign, Edwards Lifesciences and St. Jude Medical. Dr. Hawkins had no relationships to disclose.

Inconsistencies in this study of the Cox-Maze IV procedure include differing types of atrial fibrillation, heterogeneous concomitant operations, multiple lesion sets and energy sources and inconsistent postablation monitoring, all of which make direct comparisons of surgical ablation strategies or even catheter ablation difficult, Dr. Robert Hawkins and Dr. Gorav Ailawadi of the University of Virginia noted in their invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1179-80). “Moreover, without controls or selection criteria, it is difficult to account for selection bias,” they wrote.

Yet, this study has “some important findings” despite its shortcomings, namely the “respectable” rates of atrial tachyarrhythmias off antiarrhythmic drugs. These results are superior to other clinical trials, “in part due to the expertise at Washington University,” noted Dr. Hawkins and Dr. Ailawadi.

Adding patients who had the box lesion set approach also improved 5-year outcomes in the study substantially, and left atrium (LA) ablation alone has good results in patients with paroxysmal AF, left atria less than 5.0 cm, and no right atrial enlargement. “Yet, a direct comparison between biatrial and LA lesion sets cannot be made due to the above listed limitations,” they wrote.

The study makes a case for surgical ablation when the preoperative duration of AF is less than 5-10 years and left atrium size is not a problem, and the lesion-set requires further investigation, they said. “Finally, this study highlights the continued need for rigorous monitoring and comparisons of homogeneous patient populations to make stronger conclusions.”

Dr. Ailawadi disclosed relationships with Abbot Vascular, Mitralign, Edwards Lifesciences and St. Jude Medical. Dr. Hawkins had no relationships to disclose.

Inconsistencies in this study of the Cox-Maze IV procedure include differing types of atrial fibrillation, heterogeneous concomitant operations, multiple lesion sets and energy sources and inconsistent postablation monitoring, all of which make direct comparisons of surgical ablation strategies or even catheter ablation difficult, Dr. Robert Hawkins and Dr. Gorav Ailawadi of the University of Virginia noted in their invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1179-80). “Moreover, without controls or selection criteria, it is difficult to account for selection bias,” they wrote.

Yet, this study has “some important findings” despite its shortcomings, namely the “respectable” rates of atrial tachyarrhythmias off antiarrhythmic drugs. These results are superior to other clinical trials, “in part due to the expertise at Washington University,” noted Dr. Hawkins and Dr. Ailawadi.

Adding patients who had the box lesion set approach also improved 5-year outcomes in the study substantially, and left atrium (LA) ablation alone has good results in patients with paroxysmal AF, left atria less than 5.0 cm, and no right atrial enlargement. “Yet, a direct comparison between biatrial and LA lesion sets cannot be made due to the above listed limitations,” they wrote.

The study makes a case for surgical ablation when the preoperative duration of AF is less than 5-10 years and left atrium size is not a problem, and the lesion-set requires further investigation, they said. “Finally, this study highlights the continued need for rigorous monitoring and comparisons of homogeneous patient populations to make stronger conclusions.”

Dr. Ailawadi disclosed relationships with Abbot Vascular, Mitralign, Edwards Lifesciences and St. Jude Medical. Dr. Hawkins had no relationships to disclose.

The Cox-Maze IV procedure (CMPIV) has become the standard for surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation (AF), yet little information has been available on how late outcomes compare with catheter-based ablation. A recent analysis of 576 procedures found that after 5 years, most people who had the procedure remained free of atrial tachyarrhythmias and anticoagulation.

The study, by investigators from Washington University, Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, was published in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1168-78). The researchers first presented the study in April at the American Association for Thoracic Surgery meeting in Seattle.

“The results of the CMPIV remain superior to those reported for catheter ablation and other forms of surgical AF ablation, especially for patients with persistent or long-standing AF,” wrote Dr. Matthew C. Henn and his colleagues.

They set out to evaluate late outcomes after CMPIV using current consensus definitions of treatment failure, noting that such outcomes had yet to be reported. They followed 576 patients with atrial fibrillation who had a CMPIV from 2002 to 2014 and compared long-term freedom from atrial fibrillation on and off antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) across various subgroups. They included the left-sided CMPIV lesion in the analysis because, they said, it had success rates similar to those of biatrial CMPIV.

The Cox-Maze procedure was first introduced by Dr. James Cox in 1987 and updated from the original “cut-and-sew” technique in 2002 to combine bipolar radiofrequency and cryothermal ablation lines in place of most surgical incisions. This iteration was called the Cox-Maze IV procedure. In 2005, CMPIV was modified to include a superior connecting lesion, which formed a “box lesion” by completely isolating the entire posterior left atrium. The study included 512 people who underwent the “box lesion” set procedure.

“The modifications of the CMPIV have allowed it to be performed through a right minithoracotomy (RMT) approach, which has further reduced major morbidity, mortality, and hospital stay compared to those who underwent sternotomy while enjoying equivalent outcomes with regards to freedom from AF,” wrote Dr. Henn and his coauthors.

In the entire cohort, the overall freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias (ATAs) and anticoagulation were 92% at 1 year, 88% at 2 years, 87% at 3 years, 81% at 4 years, and 73% at 5 years. Overall freedom from ATAs off antiarrhythmic drugs for the entire cohort ranged from 81% at 1 year to 61% at 5 years, and freedom from anticoagulation ranged from 65% at 1 year to 55% at 5 years.

“Freedoms from ATAs on or off AADs were significantly higher in those who underwent box lesion sets when compared to those who did not at 5 years,” noted Dr. Henn and his coauthors. Among the box lesion set group, 78% of those on AADs remained free of ATAs vs. 45% in the non–box lesion set group, and for those off AADs, 66% had no ATAs at 5 years while 33% of the non–box lesion set group did.

Of the overall study population, 41% had paroxysmal AF and 58% had nonparoxysmal AF. Among the latter group, 20% had persistent and 80% had long-standing persistent AF. The nonparoxysmal AF group had a longer duration of preoperative AF, larger left atria and more failed catheter ablations, Dr. Henn and coauthors reported. But, the study showed no differences in freedom from atrial fibrillation on or off AADs at 5 years between patients with paroxysmal AF or persistent/long-standing persistent AF, or between those who underwent stand-alone procedure and those who received a concomitant Cox-Maze procedure. Among those who had a concomitant procedure, 50% had a concomitant mitral valve procedure and 23% had coronary artery bypass grafting.

“The CMPIV results in our series were better than what has been achieved with catheter ablation,” the researchers wrote. They cited studies that showed arrhythmia-free survival after a single ablation procedure ranging from 17% to 29% and “equally poor results.” (Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:18-24; J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:160-166; J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e004549.)

“The CMPIV remains the most successful surgical treatment for AF, even in patients with non-paroxysmal AF and regardless of the complexity of the concomitant procedures,” Dr. Henn and his coauthors concluded.

The Cox-Maze IV procedure (CMPIV) has become the standard for surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation (AF), yet little information has been available on how late outcomes compare with catheter-based ablation. A recent analysis of 576 procedures found that after 5 years, most people who had the procedure remained free of atrial tachyarrhythmias and anticoagulation.

The study, by investigators from Washington University, Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, was published in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1168-78). The researchers first presented the study in April at the American Association for Thoracic Surgery meeting in Seattle.

“The results of the CMPIV remain superior to those reported for catheter ablation and other forms of surgical AF ablation, especially for patients with persistent or long-standing AF,” wrote Dr. Matthew C. Henn and his colleagues.

They set out to evaluate late outcomes after CMPIV using current consensus definitions of treatment failure, noting that such outcomes had yet to be reported. They followed 576 patients with atrial fibrillation who had a CMPIV from 2002 to 2014 and compared long-term freedom from atrial fibrillation on and off antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) across various subgroups. They included the left-sided CMPIV lesion in the analysis because, they said, it had success rates similar to those of biatrial CMPIV.

The Cox-Maze procedure was first introduced by Dr. James Cox in 1987 and updated from the original “cut-and-sew” technique in 2002 to combine bipolar radiofrequency and cryothermal ablation lines in place of most surgical incisions. This iteration was called the Cox-Maze IV procedure. In 2005, CMPIV was modified to include a superior connecting lesion, which formed a “box lesion” by completely isolating the entire posterior left atrium. The study included 512 people who underwent the “box lesion” set procedure.

“The modifications of the CMPIV have allowed it to be performed through a right minithoracotomy (RMT) approach, which has further reduced major morbidity, mortality, and hospital stay compared to those who underwent sternotomy while enjoying equivalent outcomes with regards to freedom from AF,” wrote Dr. Henn and his coauthors.

In the entire cohort, the overall freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias (ATAs) and anticoagulation were 92% at 1 year, 88% at 2 years, 87% at 3 years, 81% at 4 years, and 73% at 5 years. Overall freedom from ATAs off antiarrhythmic drugs for the entire cohort ranged from 81% at 1 year to 61% at 5 years, and freedom from anticoagulation ranged from 65% at 1 year to 55% at 5 years.

“Freedoms from ATAs on or off AADs were significantly higher in those who underwent box lesion sets when compared to those who did not at 5 years,” noted Dr. Henn and his coauthors. Among the box lesion set group, 78% of those on AADs remained free of ATAs vs. 45% in the non–box lesion set group, and for those off AADs, 66% had no ATAs at 5 years while 33% of the non–box lesion set group did.

Of the overall study population, 41% had paroxysmal AF and 58% had nonparoxysmal AF. Among the latter group, 20% had persistent and 80% had long-standing persistent AF. The nonparoxysmal AF group had a longer duration of preoperative AF, larger left atria and more failed catheter ablations, Dr. Henn and coauthors reported. But, the study showed no differences in freedom from atrial fibrillation on or off AADs at 5 years between patients with paroxysmal AF or persistent/long-standing persistent AF, or between those who underwent stand-alone procedure and those who received a concomitant Cox-Maze procedure. Among those who had a concomitant procedure, 50% had a concomitant mitral valve procedure and 23% had coronary artery bypass grafting.

“The CMPIV results in our series were better than what has been achieved with catheter ablation,” the researchers wrote. They cited studies that showed arrhythmia-free survival after a single ablation procedure ranging from 17% to 29% and “equally poor results.” (Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:18-24; J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:160-166; J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e004549.)

“The CMPIV remains the most successful surgical treatment for AF, even in patients with non-paroxysmal AF and regardless of the complexity of the concomitant procedures,” Dr. Henn and his coauthors concluded.

Key clinical point: Outcomes with the Cox-Maze IV procedure for surgical ablation are superior to catheter ablation and other forms of surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation for up to 5 years duration.

Major finding: Seventy-three percent of the study population was free from atrial tachyarrhythmias and 55% were free from anticoagulation at 5 years.

Data source: Prospective analysis of 576 consecutive patients with atrial fibrillation who had Cox-Maze IV procedure or a left-sized Cox-Maze IV procedure from 2002 to 2014 at a single institution

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health provided grants for the study. Coauthor Dr. Ralph J. Damiano Jr. disclosed research grants and educational funding from AtriCure and Edwards LifeSciences. The other authors had no disclosures.

Pediatric heart transplant results not improving

A 25-year study of heart transplants in children with congenital heart disease (CHD) at one institution has found that results haven’t improved over time despite advances in technology and techniques. To improve outcomes, transplant surgeons may need to do a better job of selecting patients and matching patients and donors, according to study in the December issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1455-62).

“Strategies to improve outcomes in CHD patients might need to address selection criteria, transplantation timing, pretransplant and posttransplant care,” noted Dr. Bahaaldin Alsoufi, of the division of cardiothoracic surgery, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Emory University. “The effect of donor/recipient race mismatch warrants further investigation and might impact organ allocation algorithms or immunosuppression management,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

The researchers analyzed results of 124 children with CHD who had heart transplants from 1988 to 2013 at Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. Median age was 3.8 years; 61% were boys. Ten years after heart transplantation, 44% (54) of patients were alive without a second transplant, 13% (17) had a second transplant and 43% (53) died without a second transplant. After the second transplant, 9 of the 17 patients were alive, but 3 of them had gone onto a third transplant. Overall 15-year survival following the first transplant was 41% (51).

The study cited data from the Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation that reported more than 11,000 pediatric heart transplants worldwide in 2013, and CHD represents about 54% of all heart transplants in infants.

A multivariate analysis identified the following risk factors for early mortality after transplant: age younger than 12 months (hazard ration [HR] 7.2) and prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass (HR 5). Late-phase mortality risk factors were age younger than 12 months (HR 3) and donor/recipient race mismatch (HR 2.2).

“Survival was not affected by era, underlying anomaly, prior Fontan, sensitization or pulmonary artery augmentation,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

Among the risk factors, longer bypass times may be a surrogate for a more complicated operation, the authors said. But where prior sternotomy is a risk factor following a heart transplant in adults, the study found no such risk in children. Another risk factor previous reports identified is pulmonary artery augmentation, but, again, this study found no risk in the pediatric group.

The researchers looked at days on the waiting list, with a median wait of 39 days in the study group. In all, 175 children were listed for transplants, but 51 did not go through for various reasons. Most of the children with CHD who had a heart transplant had previous surgery; only 13% had a primary heart transplant, mostly in the earlier phase of the study.

Dr. Alsoufi and coauthors also identified African American race as a risk factor for lower survival, which is consistent with other reports. But this study agreed with a previous report that donor/recipient race mismatch was a significant risk factor in white and African American patients (Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:204-9). “While our finding might be anecdotal and specific to our geographic population, this warrants some investigation and might have some impact on future organ allocation algorithms and immunosuppression management,” the researchers wrote.

The authors had no relevant disclosures. Emory University School of Medicine, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta provided study funding.

In his invited commentary, Dr. Robert D.B. Jaquiss of Duke University, Durham, N.C., took issue with the study authors’ “distress” at the lack of improvement in survival over the 25-year term of the study (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1463-4) . Using the year 2000 as a demarcation line for early and late-phase results, Dr. Jaquiss said, “It must be pointed out that in the latter period recipients were much more ill.” He noted that 89% of post-2000 heart transplant patients had UNOS status 1 vs. 49% in the pre-2000 period.

|

Dr. Robert Jaquiss |

“Considering these between-era differences, an alternative, less ‘discouraging’ interpretation is that excellent outcomes were maintained despite the trend toward transplantation in sicker patients, undergoing more complex transplants, with longer ischemic times,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss also cited “remarkably outstanding outcomes” in Fontan patients, reporting only one operative death in 33 patients. He found the lower survival for African-American patients in the study group “more sobering,” but also controversial because, among other reasons, “a complete mechanistic explanation remains elusive.” How these findings influence pediatric heart transplant practice “requires thoughtful and extensive investigation and discussion,” he said.

Wait-list mortality and mechanical bridge to transplant also deserve mention, he noted. “Though they are only briefly mentioned, the patients who died prior to transplant provide mute testimony to the lack of timely access to suitable donors,” Dr. Jaquiss said. Durable mechanical circulatory support can provide a bridge for these patients, but was not available through the majority of the study period.

“It is striking that no patient in this report was supported by a ventricular assist device (VAD), and only a small number (5%) had been on [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] support,” Dr. Jaquiss said. “This is an unfortunate and unavoidable weakness of this report, given the recent introduction of VADs for pediatric heart transplant candidates.” The use of VAD in patients with CHD is “increasing rapidly,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss had no disclosures.

In his invited commentary, Dr. Robert D.B. Jaquiss of Duke University, Durham, N.C., took issue with the study authors’ “distress” at the lack of improvement in survival over the 25-year term of the study (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1463-4) . Using the year 2000 as a demarcation line for early and late-phase results, Dr. Jaquiss said, “It must be pointed out that in the latter period recipients were much more ill.” He noted that 89% of post-2000 heart transplant patients had UNOS status 1 vs. 49% in the pre-2000 period.

|

Dr. Robert Jaquiss |

“Considering these between-era differences, an alternative, less ‘discouraging’ interpretation is that excellent outcomes were maintained despite the trend toward transplantation in sicker patients, undergoing more complex transplants, with longer ischemic times,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss also cited “remarkably outstanding outcomes” in Fontan patients, reporting only one operative death in 33 patients. He found the lower survival for African-American patients in the study group “more sobering,” but also controversial because, among other reasons, “a complete mechanistic explanation remains elusive.” How these findings influence pediatric heart transplant practice “requires thoughtful and extensive investigation and discussion,” he said.

Wait-list mortality and mechanical bridge to transplant also deserve mention, he noted. “Though they are only briefly mentioned, the patients who died prior to transplant provide mute testimony to the lack of timely access to suitable donors,” Dr. Jaquiss said. Durable mechanical circulatory support can provide a bridge for these patients, but was not available through the majority of the study period.

“It is striking that no patient in this report was supported by a ventricular assist device (VAD), and only a small number (5%) had been on [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] support,” Dr. Jaquiss said. “This is an unfortunate and unavoidable weakness of this report, given the recent introduction of VADs for pediatric heart transplant candidates.” The use of VAD in patients with CHD is “increasing rapidly,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss had no disclosures.

In his invited commentary, Dr. Robert D.B. Jaquiss of Duke University, Durham, N.C., took issue with the study authors’ “distress” at the lack of improvement in survival over the 25-year term of the study (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1463-4) . Using the year 2000 as a demarcation line for early and late-phase results, Dr. Jaquiss said, “It must be pointed out that in the latter period recipients were much more ill.” He noted that 89% of post-2000 heart transplant patients had UNOS status 1 vs. 49% in the pre-2000 period.

|

Dr. Robert Jaquiss |

“Considering these between-era differences, an alternative, less ‘discouraging’ interpretation is that excellent outcomes were maintained despite the trend toward transplantation in sicker patients, undergoing more complex transplants, with longer ischemic times,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss also cited “remarkably outstanding outcomes” in Fontan patients, reporting only one operative death in 33 patients. He found the lower survival for African-American patients in the study group “more sobering,” but also controversial because, among other reasons, “a complete mechanistic explanation remains elusive.” How these findings influence pediatric heart transplant practice “requires thoughtful and extensive investigation and discussion,” he said.

Wait-list mortality and mechanical bridge to transplant also deserve mention, he noted. “Though they are only briefly mentioned, the patients who died prior to transplant provide mute testimony to the lack of timely access to suitable donors,” Dr. Jaquiss said. Durable mechanical circulatory support can provide a bridge for these patients, but was not available through the majority of the study period.

“It is striking that no patient in this report was supported by a ventricular assist device (VAD), and only a small number (5%) had been on [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] support,” Dr. Jaquiss said. “This is an unfortunate and unavoidable weakness of this report, given the recent introduction of VADs for pediatric heart transplant candidates.” The use of VAD in patients with CHD is “increasing rapidly,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss had no disclosures.

A 25-year study of heart transplants in children with congenital heart disease (CHD) at one institution has found that results haven’t improved over time despite advances in technology and techniques. To improve outcomes, transplant surgeons may need to do a better job of selecting patients and matching patients and donors, according to study in the December issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1455-62).

“Strategies to improve outcomes in CHD patients might need to address selection criteria, transplantation timing, pretransplant and posttransplant care,” noted Dr. Bahaaldin Alsoufi, of the division of cardiothoracic surgery, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Emory University. “The effect of donor/recipient race mismatch warrants further investigation and might impact organ allocation algorithms or immunosuppression management,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

The researchers analyzed results of 124 children with CHD who had heart transplants from 1988 to 2013 at Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. Median age was 3.8 years; 61% were boys. Ten years after heart transplantation, 44% (54) of patients were alive without a second transplant, 13% (17) had a second transplant and 43% (53) died without a second transplant. After the second transplant, 9 of the 17 patients were alive, but 3 of them had gone onto a third transplant. Overall 15-year survival following the first transplant was 41% (51).

The study cited data from the Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation that reported more than 11,000 pediatric heart transplants worldwide in 2013, and CHD represents about 54% of all heart transplants in infants.

A multivariate analysis identified the following risk factors for early mortality after transplant: age younger than 12 months (hazard ration [HR] 7.2) and prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass (HR 5). Late-phase mortality risk factors were age younger than 12 months (HR 3) and donor/recipient race mismatch (HR 2.2).

“Survival was not affected by era, underlying anomaly, prior Fontan, sensitization or pulmonary artery augmentation,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

Among the risk factors, longer bypass times may be a surrogate for a more complicated operation, the authors said. But where prior sternotomy is a risk factor following a heart transplant in adults, the study found no such risk in children. Another risk factor previous reports identified is pulmonary artery augmentation, but, again, this study found no risk in the pediatric group.

The researchers looked at days on the waiting list, with a median wait of 39 days in the study group. In all, 175 children were listed for transplants, but 51 did not go through for various reasons. Most of the children with CHD who had a heart transplant had previous surgery; only 13% had a primary heart transplant, mostly in the earlier phase of the study.

Dr. Alsoufi and coauthors also identified African American race as a risk factor for lower survival, which is consistent with other reports. But this study agreed with a previous report that donor/recipient race mismatch was a significant risk factor in white and African American patients (Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:204-9). “While our finding might be anecdotal and specific to our geographic population, this warrants some investigation and might have some impact on future organ allocation algorithms and immunosuppression management,” the researchers wrote.

The authors had no relevant disclosures. Emory University School of Medicine, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta provided study funding.

A 25-year study of heart transplants in children with congenital heart disease (CHD) at one institution has found that results haven’t improved over time despite advances in technology and techniques. To improve outcomes, transplant surgeons may need to do a better job of selecting patients and matching patients and donors, according to study in the December issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1455-62).

“Strategies to improve outcomes in CHD patients might need to address selection criteria, transplantation timing, pretransplant and posttransplant care,” noted Dr. Bahaaldin Alsoufi, of the division of cardiothoracic surgery, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Emory University. “The effect of donor/recipient race mismatch warrants further investigation and might impact organ allocation algorithms or immunosuppression management,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

The researchers analyzed results of 124 children with CHD who had heart transplants from 1988 to 2013 at Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. Median age was 3.8 years; 61% were boys. Ten years after heart transplantation, 44% (54) of patients were alive without a second transplant, 13% (17) had a second transplant and 43% (53) died without a second transplant. After the second transplant, 9 of the 17 patients were alive, but 3 of them had gone onto a third transplant. Overall 15-year survival following the first transplant was 41% (51).

The study cited data from the Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation that reported more than 11,000 pediatric heart transplants worldwide in 2013, and CHD represents about 54% of all heart transplants in infants.

A multivariate analysis identified the following risk factors for early mortality after transplant: age younger than 12 months (hazard ration [HR] 7.2) and prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass (HR 5). Late-phase mortality risk factors were age younger than 12 months (HR 3) and donor/recipient race mismatch (HR 2.2).

“Survival was not affected by era, underlying anomaly, prior Fontan, sensitization or pulmonary artery augmentation,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

Among the risk factors, longer bypass times may be a surrogate for a more complicated operation, the authors said. But where prior sternotomy is a risk factor following a heart transplant in adults, the study found no such risk in children. Another risk factor previous reports identified is pulmonary artery augmentation, but, again, this study found no risk in the pediatric group.

The researchers looked at days on the waiting list, with a median wait of 39 days in the study group. In all, 175 children were listed for transplants, but 51 did not go through for various reasons. Most of the children with CHD who had a heart transplant had previous surgery; only 13% had a primary heart transplant, mostly in the earlier phase of the study.

Dr. Alsoufi and coauthors also identified African American race as a risk factor for lower survival, which is consistent with other reports. But this study agreed with a previous report that donor/recipient race mismatch was a significant risk factor in white and African American patients (Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:204-9). “While our finding might be anecdotal and specific to our geographic population, this warrants some investigation and might have some impact on future organ allocation algorithms and immunosuppression management,” the researchers wrote.

The authors had no relevant disclosures. Emory University School of Medicine, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta provided study funding.

Key clinical point: Pediatric heart transplantation outcomes for congenital heart disease haven’t improved in the current era, indicating ongoing challenges.

Major finding: Ten years following heart transplantation, 13% of patients had undergone retransplantation, 43% had died without retransplantation, and 44% were alive without retransplantation.

Data source: A review of 124 children with congenital heart disease who had heart transplantation at a single center.

Disclosures: The study authors had no relationships to disclose.

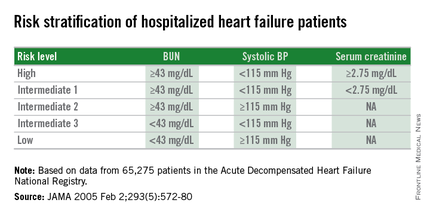

AHA: Three measures risk stratify acute heart failure

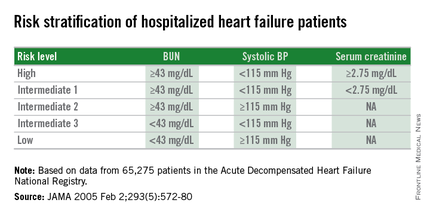

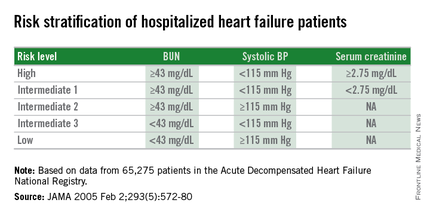

ORLANDO – Three simple, routinely collected measurements together provide a lot of insight into the risk faced by community-dwelling patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure, according to data collected from 3,628 patients at one U.S. center.

The three measures are blood urea nitrogen (BUN), systolic blood pressure, and serum creatinine. Using dichotomous cutoffs first calculated a decade ago, these three parameters distinguish up to an eightfold range of postdischarge mortality during the 30 or 90 days following an index hospitalization, and up to a fourfold range of risk for rehospitalization for heart failure during the ensuing 30 or 90 days, Dr. Sithu Win said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Applying this three-measure assessment to patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure “may guide care-transition planning and promote efficient allocation of limited resources,” said Dr. Win, a cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. The next step is to try to figure out the best way to use this risk prognostication in routine practice, he added.