User login

Reducing COVID-19 opioid deaths

Editor's Note: Due to updated statistics from the CDC, the online version of this article has been modified from the version that appears in the printed edition of the January 2021 issue of Current Psychiatry.

Individuals with mental health and substance use disorders (SUDs) are particularly susceptible to negative effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The collision of the COVID-19 pandemic and the drug overdose epidemic has highlighted the urgent need for physicians, policymakers, and health care professionals to optimize care for individuals with SUDs because they may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of the virus due to compromised respiratory and immune function, and poor social support.1 In this commentary, we highlight the challenges of the drug overdose epidemic, and recommend strategies to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among patients with SUDs.

A crisis exacerbated by COVID-19

The current drug overdose epidemic has become an American public health nightmare. According to preliminary data released by the CDC on December 17, 2020, there were more than 81,000 drug overdose deaths in the United States in the 12 months ending May 2020.2,3 This is the highest number of overdose deaths ever recorded in a 12-month period. The CDC also noted that while overdose deaths were already increasing in the months preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, the latest numbers suggest an acceleration of overdose deaths during the pandemic.

What is causing this significant loss of life? Prescription opioids and illegal opioids such as heroin and illicitly manufactured fentanyl are the main agents associated with overdose deaths. These opioids were responsible for 61% (28,647) of drug overdose deaths in the United States in 2014.4 In 2015, the opioid overdose death rate increased by 15.6%.5

The increase in the number of opioid overdose deaths in part coincides with a sharp increase in the availability and use of heroin. Heroin overdose deaths have more than tripled since 2010, but heroin is not the only opiate involved. Fentanyl, a synthetic, short-acting opioid that is approved for managing pain in patients with advanced cancers, is 50 times more potent than heroin. The abuse of prescribed fentanyl has been accelerating over the past decade, as is the use of illicitly produced fentanyl. Evidence from US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) seizure records shows heroin is being adulterated with illicit fentanyl to enhance the potency of the heroin.6,7 Mixing illicit fentanyl with heroin may be contributing to the recent increase in heroin overdose fatalities. According to the CDC, overdose deaths related to synthetic opioids increased 38.4% from the 12-month period leading up to June 2019 compared with the 12-month period leading up to May 2020.2,3 Postmortem studies of individuals who died from a heroin overdose have frequently found the presence of fentanyl along with heroin.8 Overdose deaths involving heroin may be occurring because individuals may be unknowingly using heroin adulterated with fentanyl.9 In addition, carfentanil, a powerful new synthetic fentanyl, has been recently identified in heroin mixtures. Carfentanil is 10,000 times stronger than morphine. Even in miniscule amounts, carfentanil can suppress breathing to the degree that multiple doses of naloxone are needed to restore respirations.

Initial studies indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has been exacerbating this situation. Wainwright et al10 conducted an analysis of urine drug test results of patients with SUDs from 4 months before and 4 months after COVID-19 was declared a national emergency on March 13, 2020. Compared with before COVID-19, the proportion of specimens testing positive since COVID-19 increased from 3.80% to 7.32% for fentanyl and from 1.29% to 2.09% for heroin.10

A similar drug testing study found that during the pandemic, the proportion of positive results (positivity) increased by 35% for non-prescribed fentanyl and 44% for heroin.11 Positivity for non-prescribed fentanyl increased significantly among patients who tested positive for other drugs, including by 89% for amphetamines; 48% for benzodiazepines; 34% for cocaine; and 39% for opiates (P < .1 for all).11

In a review of electronic medical records, Ochalek et al12 found that the number of nonfatal opioid overdoses in an emergency department in Virginia increased from 102 in March-June 2019 to 227 in March-June 2020. In an issue brief published on October 31, 2020, the American Medical Association reported increase in opioid and other drug-related overdoses in more than 40 states during the COVID-19 pandemic.13

Continue to: Strategies for intervention...

Strategies for intervention

A multi-dimensional approach is needed to protect the public from this growing opioid overdose epidemic. To address this challenging task, we recommend several strategies:

Enhance access to virtual treatment

Even when in-person treatment cannot take place due to COVID-19-related restrictions, it is vital that services are accessible to patients with SUDs during this pandemic. Examples of virtual treatment include:

- Telehealth for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) using buprenorphine (recently updated guidance from the US DEA and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] allows this method of prescribing)

- Teletherapy to prevent relapse

- Remote drug screens by sending saliva or urine kits to patients' homes, visiting patients to collect fluid samples, or asking patients to come to a "drive-through" facility to provide samples

- Virtual (online) Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, SMART Recovery, and similar meetings to provide support in the absence of in-person meetings.

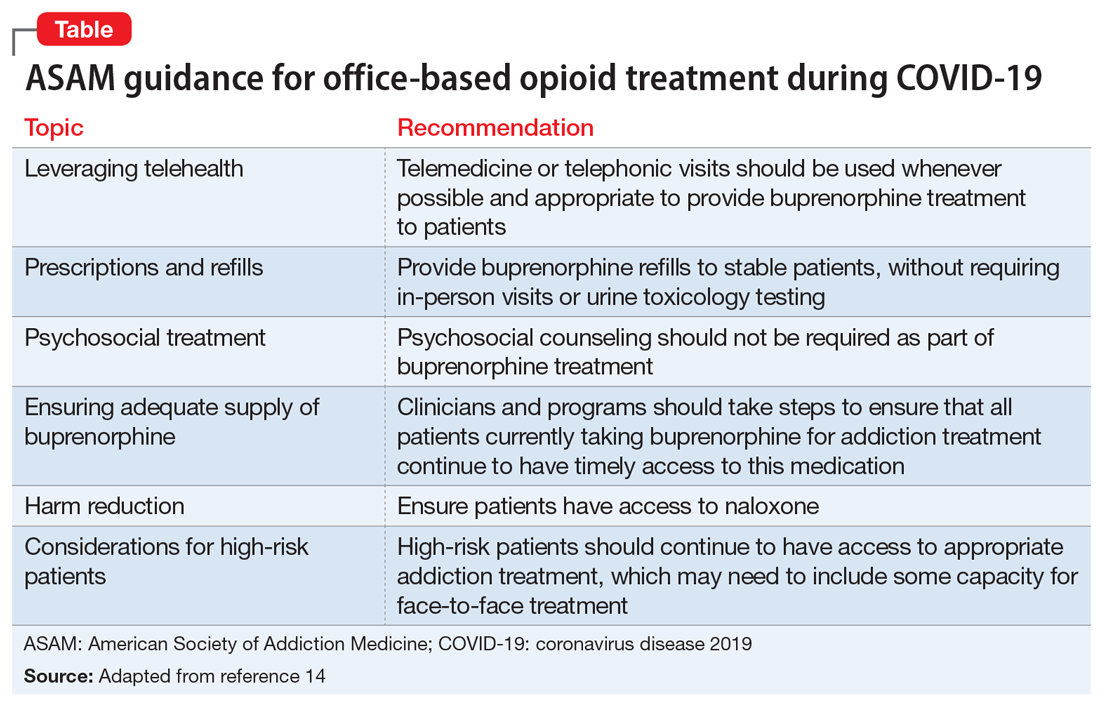

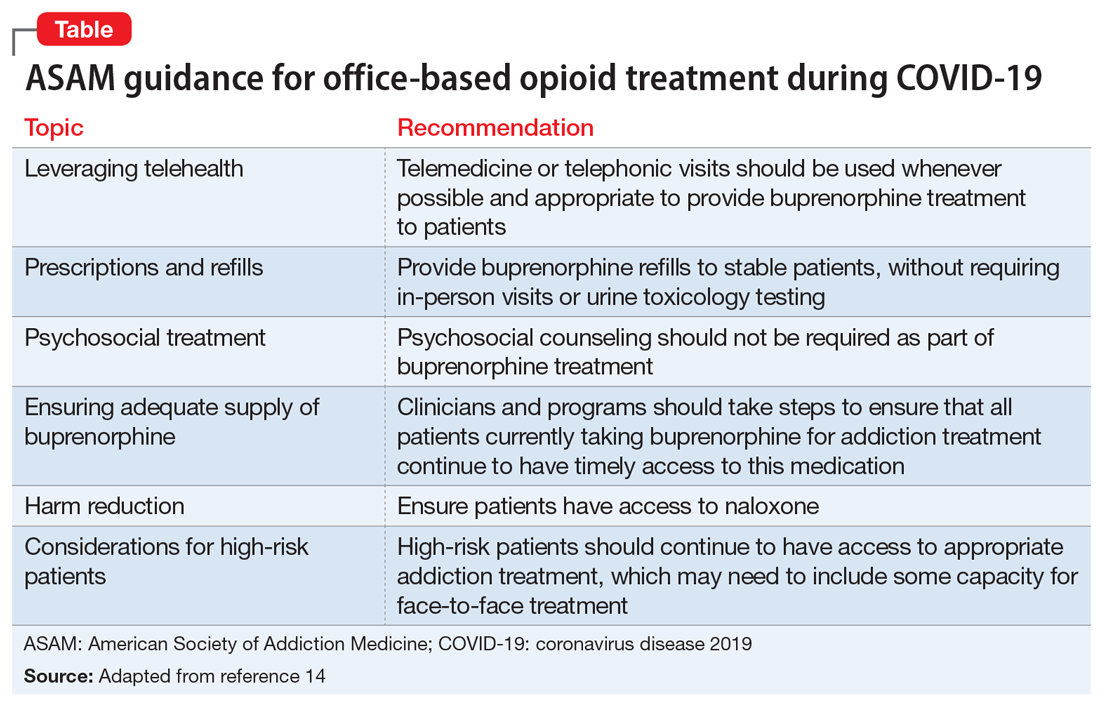

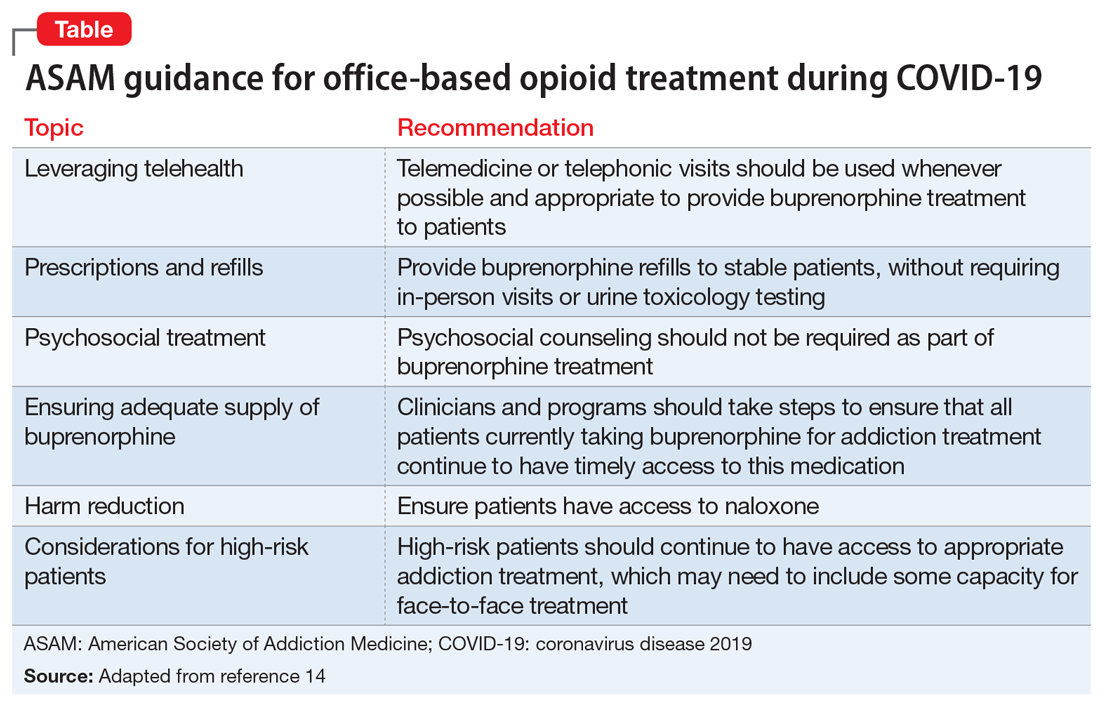

The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) offers guidance to treatment programs to focus on infection control and mitigation. The Table14 summarizes the ASAM recommendations for office-based opioid treatment during COVID-19.

Expand access to treatment

This includes access to MAT (such as buprenorphine/naloxone, methadone, naltrexone, and depot naltrexone) and, equally important, to psychosocial treatment, counseling, and/or recovery services. Recent legislative changes have increased the number of patients that a qualified physician can treat with buprenorphine/naloxone from 100 to 275, and allowed physician extenders to prescribe buprenorphine/naloxone in office-based settings. A recent population-based, retrospective Canadian study showed that opioid agonist treatment decreased the risk of mortality among opioid users, and the protective effects of this treatment increased as fentanyl and other synthetic opioids became common in the illicit drug supply.15 However, because of the shortage of psychiatrists and addiction medicine specialists in several regions of the United States, access to treatment is extremely limited and often inadequate. This constitutes a major public health crisis and contributes to our inability to intervene effectively in the opioid epidemic. Telepsychiatry programs can bring needed services to underserved areas, but they need additional support and development. Further, involving other specialties is paramount for treating this epidemic. Integrating MAT in primary care settings can improve access to treatment. Harm-reduction approaches, such as syringe exchange programs, can play an important role in reducing the adverse consequences associated with heroin use and establish health care relationships with at-risk individuals. Syringe exchange programs can also reduce the rate of infections associated with IV drug use, such as human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus.

Continue to: Increase education on naloxone...

Increase education on naloxone

Naloxone is a safe and effective opioid antagonist used to treat opioid overdoses. Timely access to naloxone is of the essence when treating opioid-related overdoses. Many states have enacted laws allowing health care professionals, law enforcement officers, and patients and relatives to obtain naloxone without a physician's prescription. It appears this approach may be yielding results. For example, the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition distributed >101,000 free overdose rescue kits that included naloxone and recorded 13,392 confirmed cases of overdose rescue with naloxone from 2013 to 2019.16

Divert patients with SUDs from the criminal justice system to treatment

We need to develop programs to divert patients with SUDs from the criminal justice system, which is focused on punishment, to interventions that focus on treatment. Data indicates high recidivism rates for incarcerated individuals with SUDs who do not have access to treatment after they are released. Recognizing this, communities are developing programs that divert low-level offenders from the criminal justice system into treatment. For instance, in Seattle, the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion is a pilot program developed to divert low-level drug and prostitution offenders into community-based treatment and support services. This helps provide housing, health care, job training, treatment, and mental health support. Innovative programs are needed to provide SUD treatment in the rehabilitation programs of correctional facilities and ensure case managers and discharge planners can transition participants to community treatment programs upon their release.

Develop early identification and prevention programs

These programs should focus on individuals at high risk, such as patients with comorbid SUDs and psychiatric disorders, those with chronic pain, and at-risk children whose parents abuse opiates. Traditional addiction treatment programs typically do not address patients with complex conditions or special populations, such as adolescents or pregnant women with substance use issues. Evidence-based approaches such as Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment (IDDT), and prevention approaches that target students in middle schools and high schools need to be more widely available.

Improve education on opioid prescribing

Responsible opioid prescribing for clinicians should include education about the regular use of prescription drug monitoring programs, urine drug screening, avoiding co-prescription of opioids with sedative-hypnotic medications, and better linkage with addiction treatment.

Treat comorbid psychiatric conditions

It is critical to both identify and effectively treat underlying affective, anxiety, and psychotic disorders in patients with SUDs. Anxiety, depression, and emotional dysregulation often contribute to worsening substance abuse, abuse of prescription drugs, diversion of prescribed drugs, and an increased risk of overdoses and suicides. Effective treatment of comorbid psychiatric conditions also may reduce relapses.

Increase research on causes and treatments

Through research, we must expand our knowledge to better understand the factors that contribute to this epidemic and develop better treatments. These efforts may allow for the development of prevention mechanisms. For example, a recent study found that the continued use of opioid medications after an overdose was associated with a high risk of a repeated overdosecall out material?.17 At the end of a 2-year observation, 17% (confidence interval [CI]: 14% to 20%) of patients receiving a high daily dosage of a prescribed opioid had a repeat overdose compared with 15% (CI: 10% to 21%) of those receiving a moderate dosage, 9% (CI: 6% to 14%) of those receiving a low dosage, and 8% (CI: 6% to 11%) of those receiving no opioids.17 Of the patients who overdosed on prescribed opiates, 30% switched to a new prescriber after their overdose, many of whom may not have been aware of the previous overdose. From a public health perspective, it would make sense for prescribers to know of prior opioid and/or benzodiazepine overdoses. This could be reported by emergency department clinicians, law enforcement, and hospitals into a prescription drug monitoring program, which is readily available to prescribers in most states.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Scott Proescholdbell, MPH, Injury and Violence Prevention Branch, Chronic Disease and Injury Section, Division of Public Health, North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, for his assistance.

Bottom Line

The collision of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and the drug overdose epidemic has highlighted the urgent need for health care professionals to optimize care for individuals with substance use disorders. Suggested interventions include enhancing access to medication-assisted treatment and virtual treatment, improving education about naloxone and safe opioid prescribing practices, and diverting at-risk patients from the criminal justice system to interventions that focus on treatment.

1. Volkow ND. Collision of the COVID-19 and addiction epidemics. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(1):61-62.

2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose deaths accelerating during COVID-19. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p1218-overdose-deaths-covid-19.html

3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics Vital Statistics Rapid Release. Provisional drug overdose death counts. Accessed December 30, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

4.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, et al. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths -- United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(50-51):1378-1382.

5.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, et al. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths -- United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50-51):1445-1452.

6.US Drug Enforcement Administration. DEA issues nationwide alert on fentanyl as threat to health and public safety. Published March 19, 2015. Accessed October 28, 2020. http://www.dea.gov/divisions/hq/2015/hq031815.shtml

7.Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths - 27 states, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(33):837-843.

8.Algren DA, Monteilh CP, Punja M, et al. Fentanyl-associated fatalities among illicit drug users in Wayne County, Michigan (July 2005-May 2006). J Med Toxicol. 2013;9(1):106-115.

9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increases in fentanyl drug confiscations and fentanyl-related overdose fatalities. HAN Health Advisory. Published October 26, 2015. Accessed October 28, 2020. http://emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00384.asp

10.Wainwright JJ, Mikre M, Whitley P, et al. Analysis of drug test results before and after the us declaration of a national emergency concerning the COVID-19 outbreak. JAMA. 2020;324(16):1674-1677.

11.Niles JK, Gudin J, Radliff J, et al. The opioid epidemic within the COVID-19 pandemic: drug testing in 2020 [published online October 8, 2020]. Population Health Management. doi: 10.1089/pop.2020.0230

12.Ochalek TA, Cumpston KL, Wills BK, et al. Nonfatal opioid overdoses at an urban emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(16):1673-1674.

13.American Medical Association. Issue brief: reports of increases in opioid- and other drug-related overdose and other concerns during COVID pandemic. Published October 31, 2020. Accessed November 9, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-11/issue-brief-increases-in-opioid-related-overdose.pdf

14.American Society of Addiction Medicine. Caring for patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: ASAM COVID-19 Task Force recommendations. Accessed October 30, 2020. https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/covid-19/medication-formulation-and-dosage-guidance-(1).pdf

15.Pearce LA, Min JE, Piske M, et al. Opioid agonist treatment and risk of mortality during opioid overdose public health emergency: population based retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;368:m772. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m772

16.North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition. NCHRC'S community-based overdose prevention project. Accessed March 29, 2020. http://www.nchrc.org/programs-and-services

17.Larochelle MR, Liebschutz JM, Zhang F, et al. Opioid prescribing after nonfatal overdose and association with repeated overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(1):1-9.

Editor's Note: Due to updated statistics from the CDC, the online version of this article has been modified from the version that appears in the printed edition of the January 2021 issue of Current Psychiatry.

Individuals with mental health and substance use disorders (SUDs) are particularly susceptible to negative effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The collision of the COVID-19 pandemic and the drug overdose epidemic has highlighted the urgent need for physicians, policymakers, and health care professionals to optimize care for individuals with SUDs because they may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of the virus due to compromised respiratory and immune function, and poor social support.1 In this commentary, we highlight the challenges of the drug overdose epidemic, and recommend strategies to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among patients with SUDs.

A crisis exacerbated by COVID-19

The current drug overdose epidemic has become an American public health nightmare. According to preliminary data released by the CDC on December 17, 2020, there were more than 81,000 drug overdose deaths in the United States in the 12 months ending May 2020.2,3 This is the highest number of overdose deaths ever recorded in a 12-month period. The CDC also noted that while overdose deaths were already increasing in the months preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, the latest numbers suggest an acceleration of overdose deaths during the pandemic.

What is causing this significant loss of life? Prescription opioids and illegal opioids such as heroin and illicitly manufactured fentanyl are the main agents associated with overdose deaths. These opioids were responsible for 61% (28,647) of drug overdose deaths in the United States in 2014.4 In 2015, the opioid overdose death rate increased by 15.6%.5

The increase in the number of opioid overdose deaths in part coincides with a sharp increase in the availability and use of heroin. Heroin overdose deaths have more than tripled since 2010, but heroin is not the only opiate involved. Fentanyl, a synthetic, short-acting opioid that is approved for managing pain in patients with advanced cancers, is 50 times more potent than heroin. The abuse of prescribed fentanyl has been accelerating over the past decade, as is the use of illicitly produced fentanyl. Evidence from US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) seizure records shows heroin is being adulterated with illicit fentanyl to enhance the potency of the heroin.6,7 Mixing illicit fentanyl with heroin may be contributing to the recent increase in heroin overdose fatalities. According to the CDC, overdose deaths related to synthetic opioids increased 38.4% from the 12-month period leading up to June 2019 compared with the 12-month period leading up to May 2020.2,3 Postmortem studies of individuals who died from a heroin overdose have frequently found the presence of fentanyl along with heroin.8 Overdose deaths involving heroin may be occurring because individuals may be unknowingly using heroin adulterated with fentanyl.9 In addition, carfentanil, a powerful new synthetic fentanyl, has been recently identified in heroin mixtures. Carfentanil is 10,000 times stronger than morphine. Even in miniscule amounts, carfentanil can suppress breathing to the degree that multiple doses of naloxone are needed to restore respirations.

Initial studies indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has been exacerbating this situation. Wainwright et al10 conducted an analysis of urine drug test results of patients with SUDs from 4 months before and 4 months after COVID-19 was declared a national emergency on March 13, 2020. Compared with before COVID-19, the proportion of specimens testing positive since COVID-19 increased from 3.80% to 7.32% for fentanyl and from 1.29% to 2.09% for heroin.10

A similar drug testing study found that during the pandemic, the proportion of positive results (positivity) increased by 35% for non-prescribed fentanyl and 44% for heroin.11 Positivity for non-prescribed fentanyl increased significantly among patients who tested positive for other drugs, including by 89% for amphetamines; 48% for benzodiazepines; 34% for cocaine; and 39% for opiates (P < .1 for all).11

In a review of electronic medical records, Ochalek et al12 found that the number of nonfatal opioid overdoses in an emergency department in Virginia increased from 102 in March-June 2019 to 227 in March-June 2020. In an issue brief published on October 31, 2020, the American Medical Association reported increase in opioid and other drug-related overdoses in more than 40 states during the COVID-19 pandemic.13

Continue to: Strategies for intervention...

Strategies for intervention

A multi-dimensional approach is needed to protect the public from this growing opioid overdose epidemic. To address this challenging task, we recommend several strategies:

Enhance access to virtual treatment

Even when in-person treatment cannot take place due to COVID-19-related restrictions, it is vital that services are accessible to patients with SUDs during this pandemic. Examples of virtual treatment include:

- Telehealth for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) using buprenorphine (recently updated guidance from the US DEA and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] allows this method of prescribing)

- Teletherapy to prevent relapse

- Remote drug screens by sending saliva or urine kits to patients' homes, visiting patients to collect fluid samples, or asking patients to come to a "drive-through" facility to provide samples

- Virtual (online) Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, SMART Recovery, and similar meetings to provide support in the absence of in-person meetings.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) offers guidance to treatment programs to focus on infection control and mitigation. The Table14 summarizes the ASAM recommendations for office-based opioid treatment during COVID-19.

Expand access to treatment

This includes access to MAT (such as buprenorphine/naloxone, methadone, naltrexone, and depot naltrexone) and, equally important, to psychosocial treatment, counseling, and/or recovery services. Recent legislative changes have increased the number of patients that a qualified physician can treat with buprenorphine/naloxone from 100 to 275, and allowed physician extenders to prescribe buprenorphine/naloxone in office-based settings. A recent population-based, retrospective Canadian study showed that opioid agonist treatment decreased the risk of mortality among opioid users, and the protective effects of this treatment increased as fentanyl and other synthetic opioids became common in the illicit drug supply.15 However, because of the shortage of psychiatrists and addiction medicine specialists in several regions of the United States, access to treatment is extremely limited and often inadequate. This constitutes a major public health crisis and contributes to our inability to intervene effectively in the opioid epidemic. Telepsychiatry programs can bring needed services to underserved areas, but they need additional support and development. Further, involving other specialties is paramount for treating this epidemic. Integrating MAT in primary care settings can improve access to treatment. Harm-reduction approaches, such as syringe exchange programs, can play an important role in reducing the adverse consequences associated with heroin use and establish health care relationships with at-risk individuals. Syringe exchange programs can also reduce the rate of infections associated with IV drug use, such as human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus.

Continue to: Increase education on naloxone...

Increase education on naloxone

Naloxone is a safe and effective opioid antagonist used to treat opioid overdoses. Timely access to naloxone is of the essence when treating opioid-related overdoses. Many states have enacted laws allowing health care professionals, law enforcement officers, and patients and relatives to obtain naloxone without a physician's prescription. It appears this approach may be yielding results. For example, the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition distributed >101,000 free overdose rescue kits that included naloxone and recorded 13,392 confirmed cases of overdose rescue with naloxone from 2013 to 2019.16

Divert patients with SUDs from the criminal justice system to treatment

We need to develop programs to divert patients with SUDs from the criminal justice system, which is focused on punishment, to interventions that focus on treatment. Data indicates high recidivism rates for incarcerated individuals with SUDs who do not have access to treatment after they are released. Recognizing this, communities are developing programs that divert low-level offenders from the criminal justice system into treatment. For instance, in Seattle, the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion is a pilot program developed to divert low-level drug and prostitution offenders into community-based treatment and support services. This helps provide housing, health care, job training, treatment, and mental health support. Innovative programs are needed to provide SUD treatment in the rehabilitation programs of correctional facilities and ensure case managers and discharge planners can transition participants to community treatment programs upon their release.

Develop early identification and prevention programs

These programs should focus on individuals at high risk, such as patients with comorbid SUDs and psychiatric disorders, those with chronic pain, and at-risk children whose parents abuse opiates. Traditional addiction treatment programs typically do not address patients with complex conditions or special populations, such as adolescents or pregnant women with substance use issues. Evidence-based approaches such as Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment (IDDT), and prevention approaches that target students in middle schools and high schools need to be more widely available.

Improve education on opioid prescribing

Responsible opioid prescribing for clinicians should include education about the regular use of prescription drug monitoring programs, urine drug screening, avoiding co-prescription of opioids with sedative-hypnotic medications, and better linkage with addiction treatment.

Treat comorbid psychiatric conditions

It is critical to both identify and effectively treat underlying affective, anxiety, and psychotic disorders in patients with SUDs. Anxiety, depression, and emotional dysregulation often contribute to worsening substance abuse, abuse of prescription drugs, diversion of prescribed drugs, and an increased risk of overdoses and suicides. Effective treatment of comorbid psychiatric conditions also may reduce relapses.

Increase research on causes and treatments

Through research, we must expand our knowledge to better understand the factors that contribute to this epidemic and develop better treatments. These efforts may allow for the development of prevention mechanisms. For example, a recent study found that the continued use of opioid medications after an overdose was associated with a high risk of a repeated overdosecall out material?.17 At the end of a 2-year observation, 17% (confidence interval [CI]: 14% to 20%) of patients receiving a high daily dosage of a prescribed opioid had a repeat overdose compared with 15% (CI: 10% to 21%) of those receiving a moderate dosage, 9% (CI: 6% to 14%) of those receiving a low dosage, and 8% (CI: 6% to 11%) of those receiving no opioids.17 Of the patients who overdosed on prescribed opiates, 30% switched to a new prescriber after their overdose, many of whom may not have been aware of the previous overdose. From a public health perspective, it would make sense for prescribers to know of prior opioid and/or benzodiazepine overdoses. This could be reported by emergency department clinicians, law enforcement, and hospitals into a prescription drug monitoring program, which is readily available to prescribers in most states.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Scott Proescholdbell, MPH, Injury and Violence Prevention Branch, Chronic Disease and Injury Section, Division of Public Health, North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, for his assistance.

Bottom Line

The collision of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and the drug overdose epidemic has highlighted the urgent need for health care professionals to optimize care for individuals with substance use disorders. Suggested interventions include enhancing access to medication-assisted treatment and virtual treatment, improving education about naloxone and safe opioid prescribing practices, and diverting at-risk patients from the criminal justice system to interventions that focus on treatment.

Editor's Note: Due to updated statistics from the CDC, the online version of this article has been modified from the version that appears in the printed edition of the January 2021 issue of Current Psychiatry.

Individuals with mental health and substance use disorders (SUDs) are particularly susceptible to negative effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The collision of the COVID-19 pandemic and the drug overdose epidemic has highlighted the urgent need for physicians, policymakers, and health care professionals to optimize care for individuals with SUDs because they may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of the virus due to compromised respiratory and immune function, and poor social support.1 In this commentary, we highlight the challenges of the drug overdose epidemic, and recommend strategies to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among patients with SUDs.

A crisis exacerbated by COVID-19

The current drug overdose epidemic has become an American public health nightmare. According to preliminary data released by the CDC on December 17, 2020, there were more than 81,000 drug overdose deaths in the United States in the 12 months ending May 2020.2,3 This is the highest number of overdose deaths ever recorded in a 12-month period. The CDC also noted that while overdose deaths were already increasing in the months preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, the latest numbers suggest an acceleration of overdose deaths during the pandemic.

What is causing this significant loss of life? Prescription opioids and illegal opioids such as heroin and illicitly manufactured fentanyl are the main agents associated with overdose deaths. These opioids were responsible for 61% (28,647) of drug overdose deaths in the United States in 2014.4 In 2015, the opioid overdose death rate increased by 15.6%.5

The increase in the number of opioid overdose deaths in part coincides with a sharp increase in the availability and use of heroin. Heroin overdose deaths have more than tripled since 2010, but heroin is not the only opiate involved. Fentanyl, a synthetic, short-acting opioid that is approved for managing pain in patients with advanced cancers, is 50 times more potent than heroin. The abuse of prescribed fentanyl has been accelerating over the past decade, as is the use of illicitly produced fentanyl. Evidence from US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) seizure records shows heroin is being adulterated with illicit fentanyl to enhance the potency of the heroin.6,7 Mixing illicit fentanyl with heroin may be contributing to the recent increase in heroin overdose fatalities. According to the CDC, overdose deaths related to synthetic opioids increased 38.4% from the 12-month period leading up to June 2019 compared with the 12-month period leading up to May 2020.2,3 Postmortem studies of individuals who died from a heroin overdose have frequently found the presence of fentanyl along with heroin.8 Overdose deaths involving heroin may be occurring because individuals may be unknowingly using heroin adulterated with fentanyl.9 In addition, carfentanil, a powerful new synthetic fentanyl, has been recently identified in heroin mixtures. Carfentanil is 10,000 times stronger than morphine. Even in miniscule amounts, carfentanil can suppress breathing to the degree that multiple doses of naloxone are needed to restore respirations.

Initial studies indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has been exacerbating this situation. Wainwright et al10 conducted an analysis of urine drug test results of patients with SUDs from 4 months before and 4 months after COVID-19 was declared a national emergency on March 13, 2020. Compared with before COVID-19, the proportion of specimens testing positive since COVID-19 increased from 3.80% to 7.32% for fentanyl and from 1.29% to 2.09% for heroin.10

A similar drug testing study found that during the pandemic, the proportion of positive results (positivity) increased by 35% for non-prescribed fentanyl and 44% for heroin.11 Positivity for non-prescribed fentanyl increased significantly among patients who tested positive for other drugs, including by 89% for amphetamines; 48% for benzodiazepines; 34% for cocaine; and 39% for opiates (P < .1 for all).11

In a review of electronic medical records, Ochalek et al12 found that the number of nonfatal opioid overdoses in an emergency department in Virginia increased from 102 in March-June 2019 to 227 in March-June 2020. In an issue brief published on October 31, 2020, the American Medical Association reported increase in opioid and other drug-related overdoses in more than 40 states during the COVID-19 pandemic.13

Continue to: Strategies for intervention...

Strategies for intervention

A multi-dimensional approach is needed to protect the public from this growing opioid overdose epidemic. To address this challenging task, we recommend several strategies:

Enhance access to virtual treatment

Even when in-person treatment cannot take place due to COVID-19-related restrictions, it is vital that services are accessible to patients with SUDs during this pandemic. Examples of virtual treatment include:

- Telehealth for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) using buprenorphine (recently updated guidance from the US DEA and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] allows this method of prescribing)

- Teletherapy to prevent relapse

- Remote drug screens by sending saliva or urine kits to patients' homes, visiting patients to collect fluid samples, or asking patients to come to a "drive-through" facility to provide samples

- Virtual (online) Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, SMART Recovery, and similar meetings to provide support in the absence of in-person meetings.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) offers guidance to treatment programs to focus on infection control and mitigation. The Table14 summarizes the ASAM recommendations for office-based opioid treatment during COVID-19.

Expand access to treatment

This includes access to MAT (such as buprenorphine/naloxone, methadone, naltrexone, and depot naltrexone) and, equally important, to psychosocial treatment, counseling, and/or recovery services. Recent legislative changes have increased the number of patients that a qualified physician can treat with buprenorphine/naloxone from 100 to 275, and allowed physician extenders to prescribe buprenorphine/naloxone in office-based settings. A recent population-based, retrospective Canadian study showed that opioid agonist treatment decreased the risk of mortality among opioid users, and the protective effects of this treatment increased as fentanyl and other synthetic opioids became common in the illicit drug supply.15 However, because of the shortage of psychiatrists and addiction medicine specialists in several regions of the United States, access to treatment is extremely limited and often inadequate. This constitutes a major public health crisis and contributes to our inability to intervene effectively in the opioid epidemic. Telepsychiatry programs can bring needed services to underserved areas, but they need additional support and development. Further, involving other specialties is paramount for treating this epidemic. Integrating MAT in primary care settings can improve access to treatment. Harm-reduction approaches, such as syringe exchange programs, can play an important role in reducing the adverse consequences associated with heroin use and establish health care relationships with at-risk individuals. Syringe exchange programs can also reduce the rate of infections associated with IV drug use, such as human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus.

Continue to: Increase education on naloxone...

Increase education on naloxone

Naloxone is a safe and effective opioid antagonist used to treat opioid overdoses. Timely access to naloxone is of the essence when treating opioid-related overdoses. Many states have enacted laws allowing health care professionals, law enforcement officers, and patients and relatives to obtain naloxone without a physician's prescription. It appears this approach may be yielding results. For example, the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition distributed >101,000 free overdose rescue kits that included naloxone and recorded 13,392 confirmed cases of overdose rescue with naloxone from 2013 to 2019.16

Divert patients with SUDs from the criminal justice system to treatment

We need to develop programs to divert patients with SUDs from the criminal justice system, which is focused on punishment, to interventions that focus on treatment. Data indicates high recidivism rates for incarcerated individuals with SUDs who do not have access to treatment after they are released. Recognizing this, communities are developing programs that divert low-level offenders from the criminal justice system into treatment. For instance, in Seattle, the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion is a pilot program developed to divert low-level drug and prostitution offenders into community-based treatment and support services. This helps provide housing, health care, job training, treatment, and mental health support. Innovative programs are needed to provide SUD treatment in the rehabilitation programs of correctional facilities and ensure case managers and discharge planners can transition participants to community treatment programs upon their release.

Develop early identification and prevention programs

These programs should focus on individuals at high risk, such as patients with comorbid SUDs and psychiatric disorders, those with chronic pain, and at-risk children whose parents abuse opiates. Traditional addiction treatment programs typically do not address patients with complex conditions or special populations, such as adolescents or pregnant women with substance use issues. Evidence-based approaches such as Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment (IDDT), and prevention approaches that target students in middle schools and high schools need to be more widely available.

Improve education on opioid prescribing

Responsible opioid prescribing for clinicians should include education about the regular use of prescription drug monitoring programs, urine drug screening, avoiding co-prescription of opioids with sedative-hypnotic medications, and better linkage with addiction treatment.

Treat comorbid psychiatric conditions

It is critical to both identify and effectively treat underlying affective, anxiety, and psychotic disorders in patients with SUDs. Anxiety, depression, and emotional dysregulation often contribute to worsening substance abuse, abuse of prescription drugs, diversion of prescribed drugs, and an increased risk of overdoses and suicides. Effective treatment of comorbid psychiatric conditions also may reduce relapses.

Increase research on causes and treatments

Through research, we must expand our knowledge to better understand the factors that contribute to this epidemic and develop better treatments. These efforts may allow for the development of prevention mechanisms. For example, a recent study found that the continued use of opioid medications after an overdose was associated with a high risk of a repeated overdosecall out material?.17 At the end of a 2-year observation, 17% (confidence interval [CI]: 14% to 20%) of patients receiving a high daily dosage of a prescribed opioid had a repeat overdose compared with 15% (CI: 10% to 21%) of those receiving a moderate dosage, 9% (CI: 6% to 14%) of those receiving a low dosage, and 8% (CI: 6% to 11%) of those receiving no opioids.17 Of the patients who overdosed on prescribed opiates, 30% switched to a new prescriber after their overdose, many of whom may not have been aware of the previous overdose. From a public health perspective, it would make sense for prescribers to know of prior opioid and/or benzodiazepine overdoses. This could be reported by emergency department clinicians, law enforcement, and hospitals into a prescription drug monitoring program, which is readily available to prescribers in most states.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Scott Proescholdbell, MPH, Injury and Violence Prevention Branch, Chronic Disease and Injury Section, Division of Public Health, North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, for his assistance.

Bottom Line

The collision of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and the drug overdose epidemic has highlighted the urgent need for health care professionals to optimize care for individuals with substance use disorders. Suggested interventions include enhancing access to medication-assisted treatment and virtual treatment, improving education about naloxone and safe opioid prescribing practices, and diverting at-risk patients from the criminal justice system to interventions that focus on treatment.

1. Volkow ND. Collision of the COVID-19 and addiction epidemics. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(1):61-62.

2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose deaths accelerating during COVID-19. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p1218-overdose-deaths-covid-19.html

3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics Vital Statistics Rapid Release. Provisional drug overdose death counts. Accessed December 30, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

4.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, et al. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths -- United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(50-51):1378-1382.

5.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, et al. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths -- United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50-51):1445-1452.

6.US Drug Enforcement Administration. DEA issues nationwide alert on fentanyl as threat to health and public safety. Published March 19, 2015. Accessed October 28, 2020. http://www.dea.gov/divisions/hq/2015/hq031815.shtml

7.Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths - 27 states, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(33):837-843.

8.Algren DA, Monteilh CP, Punja M, et al. Fentanyl-associated fatalities among illicit drug users in Wayne County, Michigan (July 2005-May 2006). J Med Toxicol. 2013;9(1):106-115.

9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increases in fentanyl drug confiscations and fentanyl-related overdose fatalities. HAN Health Advisory. Published October 26, 2015. Accessed October 28, 2020. http://emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00384.asp

10.Wainwright JJ, Mikre M, Whitley P, et al. Analysis of drug test results before and after the us declaration of a national emergency concerning the COVID-19 outbreak. JAMA. 2020;324(16):1674-1677.

11.Niles JK, Gudin J, Radliff J, et al. The opioid epidemic within the COVID-19 pandemic: drug testing in 2020 [published online October 8, 2020]. Population Health Management. doi: 10.1089/pop.2020.0230

12.Ochalek TA, Cumpston KL, Wills BK, et al. Nonfatal opioid overdoses at an urban emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(16):1673-1674.

13.American Medical Association. Issue brief: reports of increases in opioid- and other drug-related overdose and other concerns during COVID pandemic. Published October 31, 2020. Accessed November 9, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-11/issue-brief-increases-in-opioid-related-overdose.pdf

14.American Society of Addiction Medicine. Caring for patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: ASAM COVID-19 Task Force recommendations. Accessed October 30, 2020. https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/covid-19/medication-formulation-and-dosage-guidance-(1).pdf

15.Pearce LA, Min JE, Piske M, et al. Opioid agonist treatment and risk of mortality during opioid overdose public health emergency: population based retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;368:m772. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m772

16.North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition. NCHRC'S community-based overdose prevention project. Accessed March 29, 2020. http://www.nchrc.org/programs-and-services

17.Larochelle MR, Liebschutz JM, Zhang F, et al. Opioid prescribing after nonfatal overdose and association with repeated overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(1):1-9.

1. Volkow ND. Collision of the COVID-19 and addiction epidemics. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(1):61-62.

2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose deaths accelerating during COVID-19. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p1218-overdose-deaths-covid-19.html

3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics Vital Statistics Rapid Release. Provisional drug overdose death counts. Accessed December 30, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

4.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, et al. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths -- United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(50-51):1378-1382.

5.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, et al. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths -- United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50-51):1445-1452.

6.US Drug Enforcement Administration. DEA issues nationwide alert on fentanyl as threat to health and public safety. Published March 19, 2015. Accessed October 28, 2020. http://www.dea.gov/divisions/hq/2015/hq031815.shtml

7.Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths - 27 states, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(33):837-843.

8.Algren DA, Monteilh CP, Punja M, et al. Fentanyl-associated fatalities among illicit drug users in Wayne County, Michigan (July 2005-May 2006). J Med Toxicol. 2013;9(1):106-115.

9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increases in fentanyl drug confiscations and fentanyl-related overdose fatalities. HAN Health Advisory. Published October 26, 2015. Accessed October 28, 2020. http://emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00384.asp

10.Wainwright JJ, Mikre M, Whitley P, et al. Analysis of drug test results before and after the us declaration of a national emergency concerning the COVID-19 outbreak. JAMA. 2020;324(16):1674-1677.

11.Niles JK, Gudin J, Radliff J, et al. The opioid epidemic within the COVID-19 pandemic: drug testing in 2020 [published online October 8, 2020]. Population Health Management. doi: 10.1089/pop.2020.0230

12.Ochalek TA, Cumpston KL, Wills BK, et al. Nonfatal opioid overdoses at an urban emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(16):1673-1674.

13.American Medical Association. Issue brief: reports of increases in opioid- and other drug-related overdose and other concerns during COVID pandemic. Published October 31, 2020. Accessed November 9, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-11/issue-brief-increases-in-opioid-related-overdose.pdf

14.American Society of Addiction Medicine. Caring for patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: ASAM COVID-19 Task Force recommendations. Accessed October 30, 2020. https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/covid-19/medication-formulation-and-dosage-guidance-(1).pdf

15.Pearce LA, Min JE, Piske M, et al. Opioid agonist treatment and risk of mortality during opioid overdose public health emergency: population based retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;368:m772. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m772

16.North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition. NCHRC'S community-based overdose prevention project. Accessed March 29, 2020. http://www.nchrc.org/programs-and-services

17.Larochelle MR, Liebschutz JM, Zhang F, et al. Opioid prescribing after nonfatal overdose and association with repeated overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(1):1-9.

Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder in patients with hepatic impairment

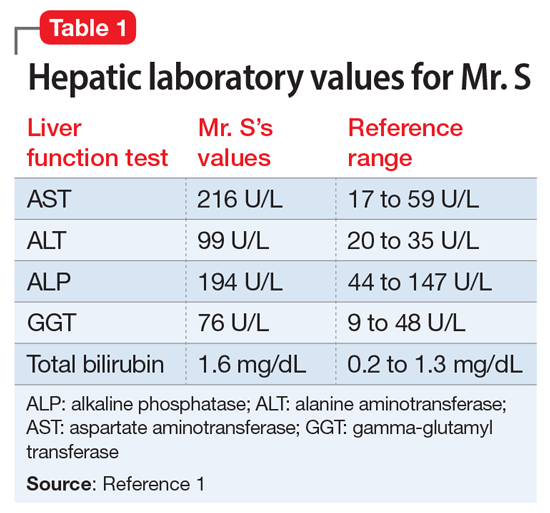

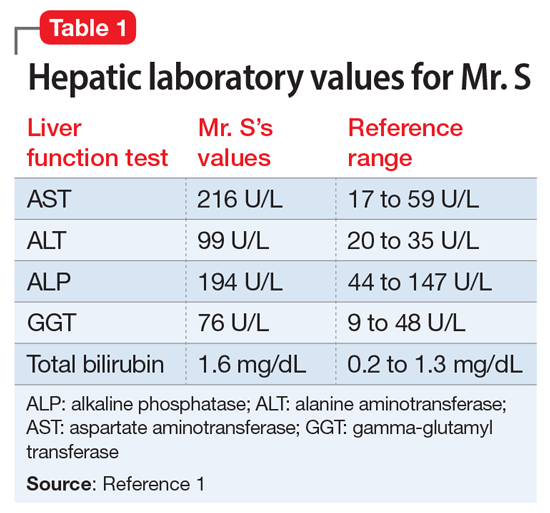

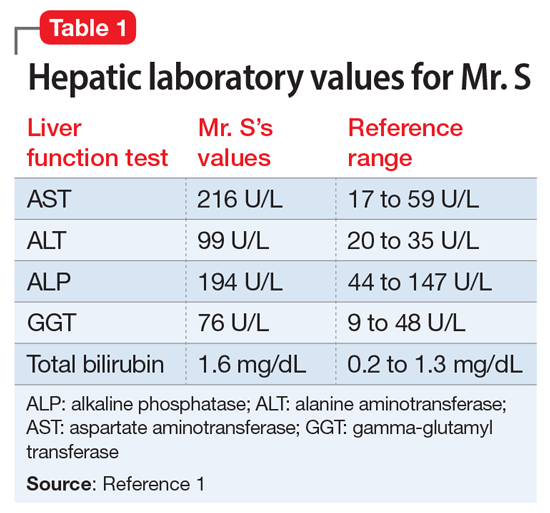

Mr. S, age 64, presents for an outpatient follow-up after a recent hospital discharge for alcohol detoxification. He reports a long history of alcohol use, which has resulted in numerous hospital admissions. He has recently been receiving care from a gastroenterologist because the results of laboratory testing suggested hepatic impairment (Table 1). Mr. S says that a friend of his was able to stop drinking by taking a medication, and he wonders if he can be prescribed a medication to help him as well.

A chart review shows that Mr. S recently underwent paracentesis, during which 6 liters of fluid were removed. Additionally, an abdominal ultrasound confirmed hepatic cirrhosis.

According to the World Health Organization, alcohol consumption contributes to 3 million deaths annually.2 The highest proportion of these deaths (21.3%) is due to alcohol-associated gastrointestinal complications, including alcoholic and infectious hepatitis, pancreatitis, and cirrhosis. Because the liver is the primary site of ethanol metabolism, it sustains the greatest degree of tissue injury with heavy alcohol consumption. Additionally, the association of harmful use of alcohol with risky sexual behavior may partially explain the higher prevalence of viral hepatitis among persons with alcohol use disorder (AUD) compared with the general population. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) progresses through several stages, beginning with hepatic steatosis and progressing through alcohol-related hepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and potentially hepatocellular carcinoma.3

Liver markers of alcohol use

Although biological markers can be used in clinical practice to screen and monitor for alcohol abuse, making a diagnosis of ALD can be challenging. Typically, a history of heavy alcohol consumption in addition to certain physical signs and laboratory tests for liver disease are the best indicators of ALD. However, the clinical assessment can be confounded by patients who deny or minimize how much alcohol they have consumed. Furthermore, physical and laboratory findings may not be specific to ALD.

Liver enzymes, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), have historically been used as the basis of diagnosing ALD. In addition to elevated bilirubin and evidence of macrocytic anemia, elevations in these enzymes may suggest heavy alcohol use, but these values alone are inadequate to establish ALD. Gamma-glutamyltransferase is found in cell membranes of several body tissues, including the liver and spleen, and therefore is not specific to liver damage. However, elevated GGT is the best indicator of excessive alcohol consumption because it has greater sensitivity than AST and ALT.1,3,4

Although these biomarkers are helpful in diagnosing ALD, they lose some of their utility in patients with advanced liver disease. Patients with severe liver dysfunction may not have elevated serum aminotransferase levels because the degree of liver enzyme elevation does not correlate well with the severity of ALD. For example, patients with advanced cirrhosis may have liver enzyme levels that appear normal. However, the pattern of elevation in transaminases can be helpful in making a diagnosis of liver dysfunction; using the ratio of AST to ALT may aid in diagnosing ALD, because AST is elevated more than twice that of ALT in >80% of patients with ALD.1,3,4

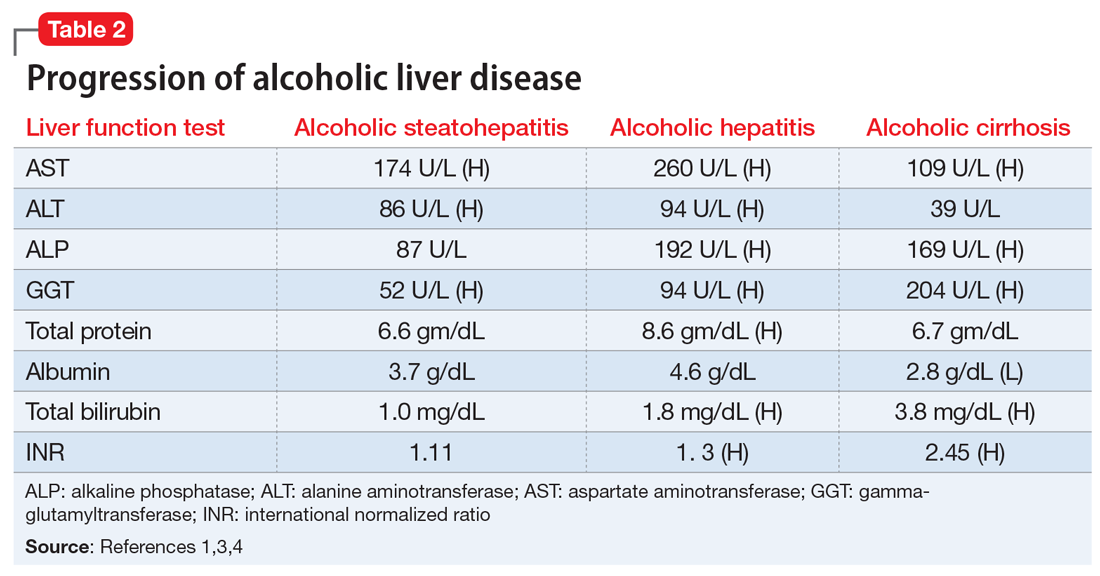

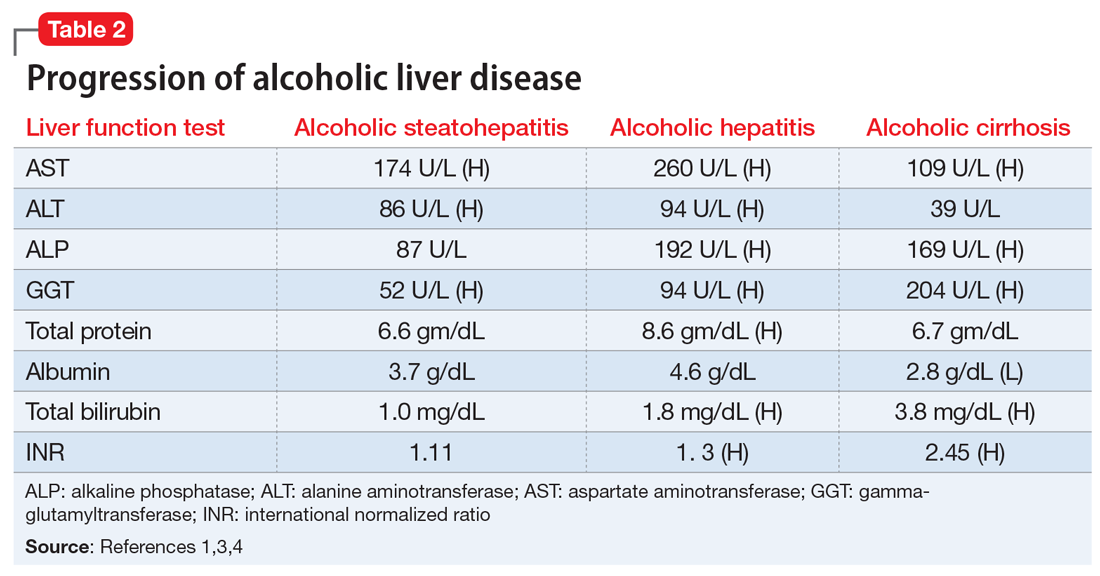

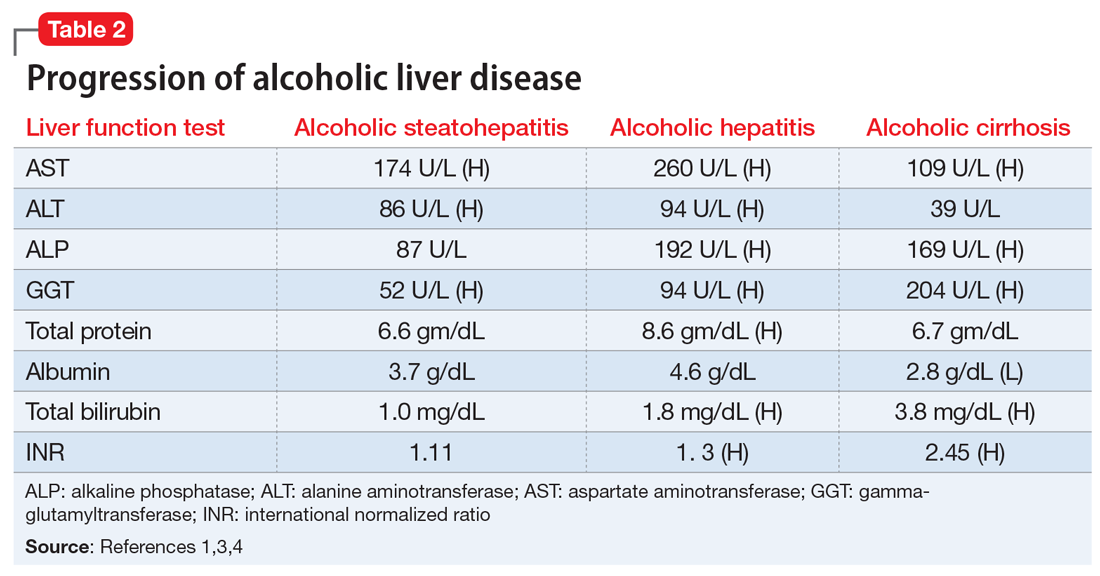

Table 21,3,4 shows the progression of ALD from steatohepatitis to alcoholic hepatitis to cirrhosis. In steatohepatitis, transaminitis is present but all other biomarkers normal. In alcoholic hepatitis, transaminitis is present along with elevated alkaline phosphatase, elevated bilirubin, and elevated international normalized ratio (INR). In alcoholic cirrhosis, the AST-to-ALT ratio is >2, and hypoalbuminemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and coagulopathy (evidenced by elevated INR) are present, consistent with long-term liver damage.1,3,4

Continue to: FDA-approved medications

FDA-approved medications

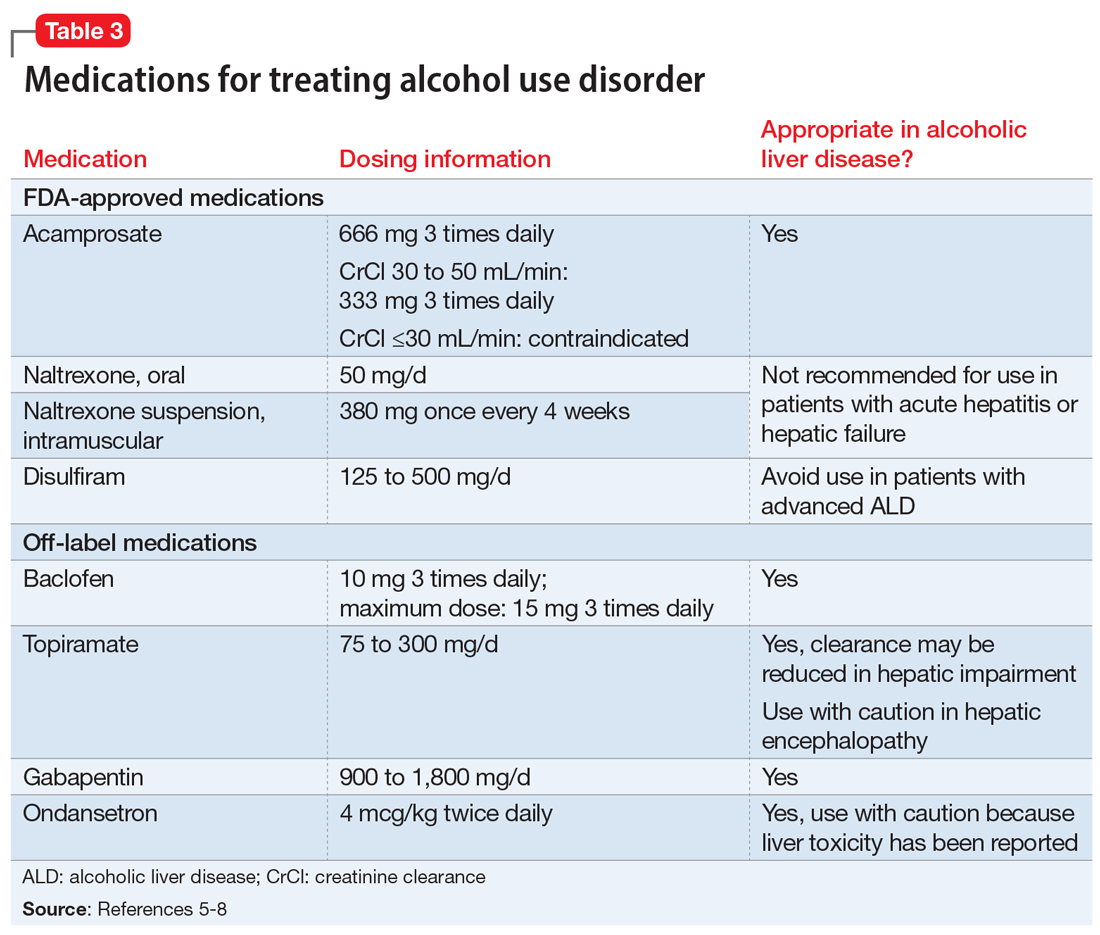

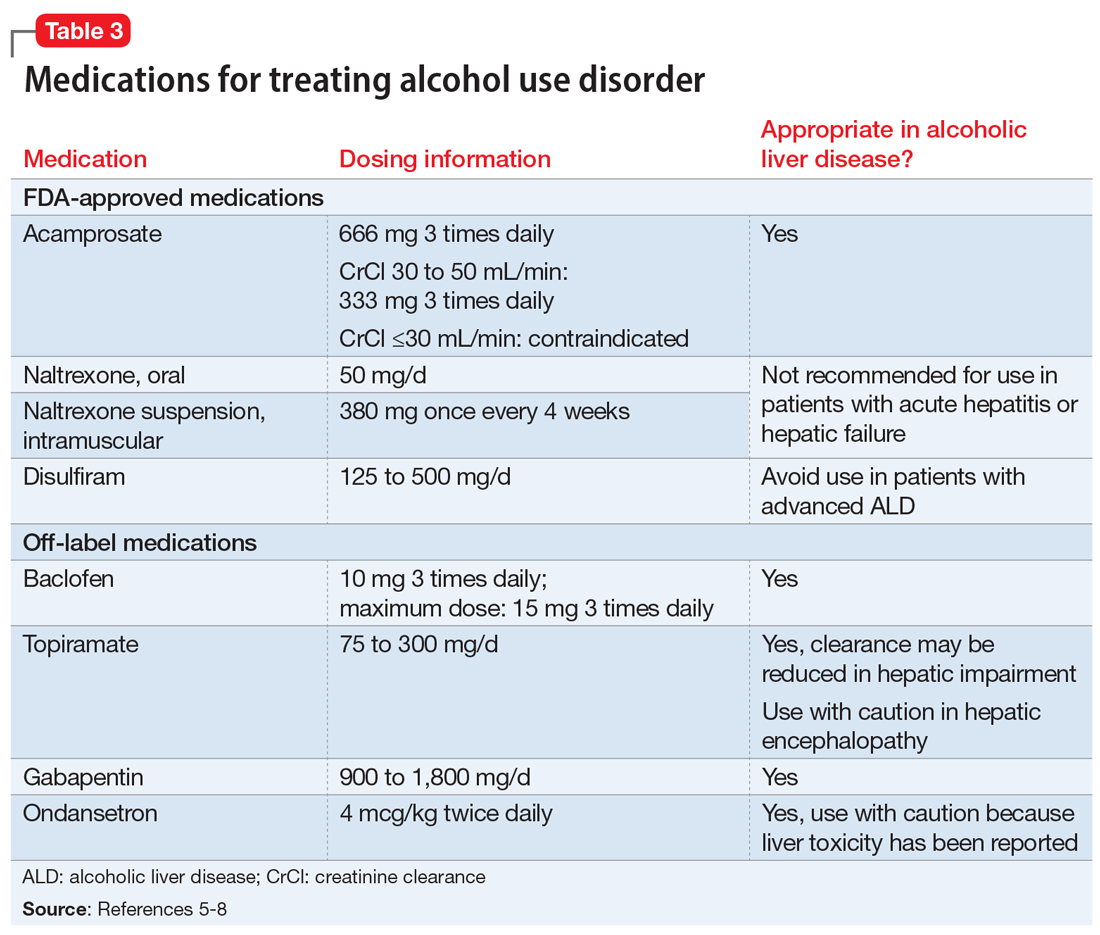

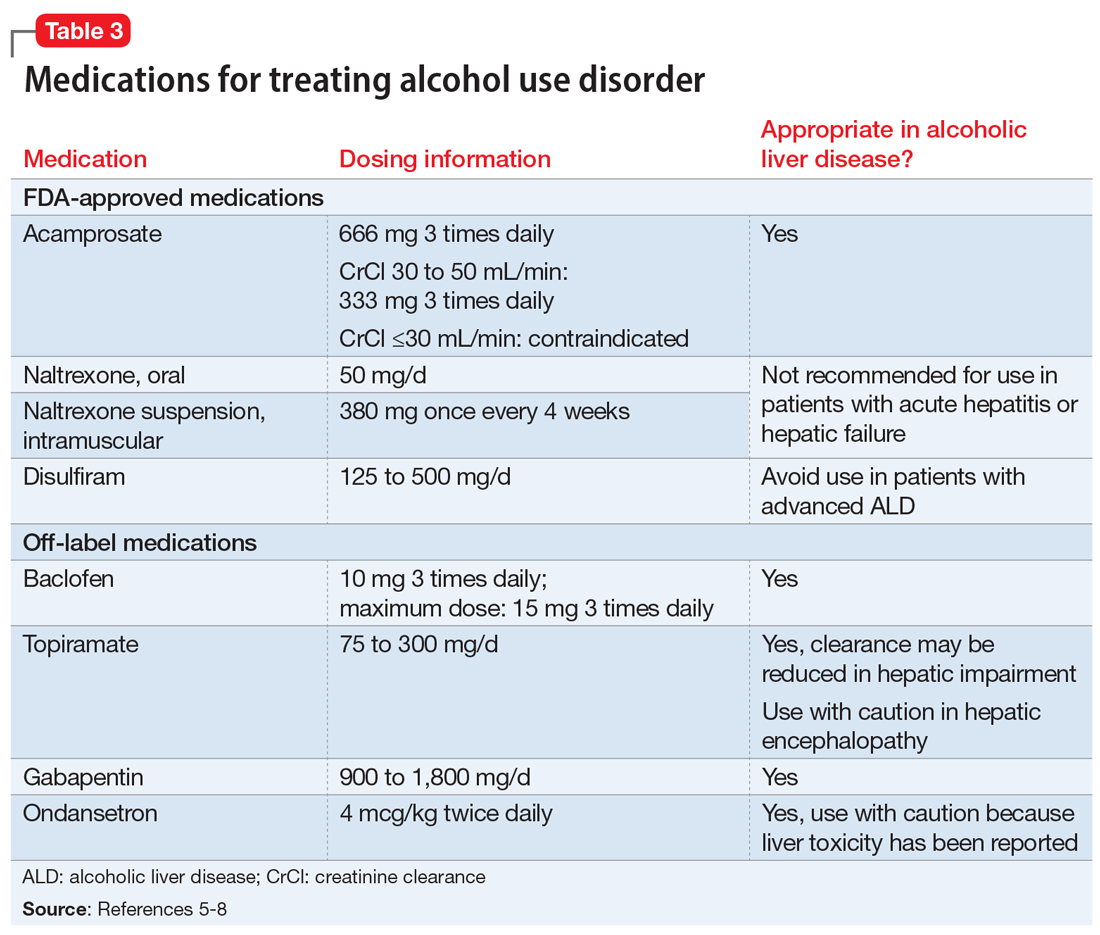

Three medications—acamprosate, naltrexone, and disulfiram—currently are FDA-approved for treating AUD.5,6 Additionally, several other medications have shown varying levels of efficacy in treating patients with AUD but are not FDA-approved for this indication (Table 3).5-8

Acamprosate is thought to create a balance of inhibitor and excitatory neurotransmitters by functioning as a glutamate antagonist and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonist. This is speculated to aid in abstinence from alcohol. Data suggests that acamprosate may be more effective for maintaining abstinence than for inducing remission in individuals who have not yet detoxified from alcohol. Because of its renal excretion, acamprosate is the only FDA-approved medication for AUD that is not associated with liver toxicity. The most commonly reported adverse effect with acamprosate use is diarrhea.

Naltrexone, a mu-opioid receptor antagonist, is available in both tablet and long-acting IM injection formulations. Naltrexone blocks the binding of endorphins created by alcohol consumption to opioid receptors. This results in diminished dopamine release and is speculated to decrease reward and positive reinforcement with alcohol consumption, leading to fewer heavy drinking days. Due to hepatic metabolism, naltrexone use carries a risk of liver injury. Cases of hepatitis and clinically significant liver dysfunction as well as transient, asymptomatic, hepatic transaminase elevations have been observed in patients who receive naltrexone. Because of the absence of first-pass metabolism, long-acting IM naltrexone may produce less hepatotoxicity than the oral formulation. When the FDA approved both formulations of naltrexone, a “black-box” warning was issued concerning the risk of liver damage; however, these warnings have since been removed from their respective prescribing information.

Disulfiram inhibits acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, resulting in elevated acetaldehyde concentrations after consuming alcohol. In theory, this medication reduces a person’s desire to drink due to the negative physiological and physical effects associated with increased acetaldehyde, including hypotension, flushing, nausea, and vomiting. Although most of these reactions are short-lived, disulfiram can induce hepatotoxicity and liver failure that may prove fatal. Disulfiram should be avoided in patients with advanced ALD.

Off-label medications for AUD

Additional pharmacotherapeutic agents have been evaluated in patients with AUD. Baclofen, topiramate, gabapentin, and ondansetron have shown varying levels of efficacy and pose minimal concern in patients with ALD.

Continue to: Baclofen

Baclofen. Although findings are conflicting, baclofen is the only agent that has been specifically studied for treating AUD in patients with ALD. A GABA B receptor antagonist, baclofen is currently FDA-approved for treating spasticity. In a series of open-label and double-blind studies, baclofen has been shown to effectively reduce alcohol intake, promote abstinence, and prevent relapse.5,6 Further studies identified a possible dose-related response, noting that 20 mg taken 3 times daily may confer additional response over 10 mg taken 3 times daily.5,6 Conversely, the ALPADIR study failed to demonstrate superiority of baclofen vs placebo in the maintenance of abstinence from alcohol despite dosing at 180 mg/d.9 This study did, however, find a significant reduction in alcohol craving in favor of baclofen.9 Further, in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted in veterans with chronic hepatitis C, baclofen 30 mg/d failed to show superiority over placebo with regard to increasing abstinence or reducing alcohol use

Topiramate. A recent meta-analysis found that topiramate use may result in fewer drinking days, heavy drinking days, and number of drinks per drinking day.7 Additionally, topiramate has demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in alcohol craving as well as the ability to decrease all liver function test values.5 This agent should be used with caution in patients with hepatic encephalopathy because the adverse cognitive effects associated with topiramate may confound the clinical course and treatment of such.

Gabapentin. The use of gabapentin to treat patients with AUD is supported by multiple RCTs. In studies that evaluated dose-related response, higher doses of gabapentin (up to 1,800 mg/d) showed greater efficacy than lower doses (ie, 900 mg/d).8 Because gabapentin does not undergo hepatic metabolism, its use in patients with ALD is considered safe. Although the abuse potential of gabapentin is less defined in patients with AUD, there have been reports of abuse in other high-risk populations (ie, those with opioid use disorder, incarcerated persons, and those who misuse prescriptions recreationally).8

Ondansetron is speculated to decrease the reward from alcohol via the down-regulation of dopaminergic neurons. Studies examining ondansetron for patients with AUD have found that it decreases alcohol cravings in those with early-onset alcoholism (initial onset at age ≤25), but not in late-onset alcoholism (initial onset at age >25).5 However, the ondansetron doses used in these trials were very low (4 mcg/kg), and those doses are not available commercially.5

CASE CONTINUED

Following a discussion of available pharmacotherapeutic options for AUD, Mr. S is started on baclofen, 10 mg 3 times daily, with plans for dose titration. At a 2-week follow-up appointment, Mr. S reports that he had not been taking baclofen as often as instructed; however, he denies further alcohol consumption and re-commits to baclofen treatment. Unfortunately, Mr. S is soon admitted to hospice care due to continued decompensation and is unable to attend any additional outpatient follow-up appointments. Three months after his initial outpatient contact, Mr. S dies due to alcoholic cirrhosis.

Related Resources

• Crabb DW, Im GY, Szabo G, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of alcohol-related liver diseases: 2019 practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2020;71(1):306-333.

• Murail AR, Carey WD. Disease management. Liver test interpretation - approach to the patient with liver disease: a guide to commonly used liver tests. Cleveland Clinic Center for Continuing Education. Updated August 2017. www.clevelandclinicmeded. com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/hepatology/ guide-to-common-liver-tests/

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Baclofen • Lioresal

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Naltrexone • Revia, Vivitrol

Ondansetron • Zofran

Topiramate • Topamax

1. Agrawal S, Dhiman RK, Limdi JK. Evaluation of abnormal liver function tests. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92(1086):223-234.

2. World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Published 2018. Accessed November 5, 2020. https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/gsr_2018/en/

3. Osna NA, Donohue TM, Kharbanda KK. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and current management. Alcohol Res. 2017;38(2):147-161.

4. Leggio L, Lee MR. Treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Am J Med. 2017;130(2):124-134.

5. Addolorato G, Mirijello A, Leggio L, et al. Management of alcohol dependence in patients with liver disease. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(4):287-299.

6. Vuittonet CL, Halse M, Leggio L, et al. Pharmacotherapy for alcoholic patients with alcoholic liver disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(15):1265-1276.

7. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889-1900.

8. Mason BJ, Quello S, Shadan F. Gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2018;27(1):113-124.

9. Reynaud M, Aubin HJ, Trinquet F, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of high-dose baclofen in alcohol-dependent patients-the ALPADIR study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2017;52(4):439-446.

10. Hauser P, Fuller B, Ho S, et al. The safety and efficacy of baclofen to reduce alcohol use in veterans with chronic hepatitis C: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2017;112(7):1173-1183.

Mr. S, age 64, presents for an outpatient follow-up after a recent hospital discharge for alcohol detoxification. He reports a long history of alcohol use, which has resulted in numerous hospital admissions. He has recently been receiving care from a gastroenterologist because the results of laboratory testing suggested hepatic impairment (Table 1). Mr. S says that a friend of his was able to stop drinking by taking a medication, and he wonders if he can be prescribed a medication to help him as well.

A chart review shows that Mr. S recently underwent paracentesis, during which 6 liters of fluid were removed. Additionally, an abdominal ultrasound confirmed hepatic cirrhosis.

According to the World Health Organization, alcohol consumption contributes to 3 million deaths annually.2 The highest proportion of these deaths (21.3%) is due to alcohol-associated gastrointestinal complications, including alcoholic and infectious hepatitis, pancreatitis, and cirrhosis. Because the liver is the primary site of ethanol metabolism, it sustains the greatest degree of tissue injury with heavy alcohol consumption. Additionally, the association of harmful use of alcohol with risky sexual behavior may partially explain the higher prevalence of viral hepatitis among persons with alcohol use disorder (AUD) compared with the general population. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) progresses through several stages, beginning with hepatic steatosis and progressing through alcohol-related hepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and potentially hepatocellular carcinoma.3

Liver markers of alcohol use

Although biological markers can be used in clinical practice to screen and monitor for alcohol abuse, making a diagnosis of ALD can be challenging. Typically, a history of heavy alcohol consumption in addition to certain physical signs and laboratory tests for liver disease are the best indicators of ALD. However, the clinical assessment can be confounded by patients who deny or minimize how much alcohol they have consumed. Furthermore, physical and laboratory findings may not be specific to ALD.

Liver enzymes, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), have historically been used as the basis of diagnosing ALD. In addition to elevated bilirubin and evidence of macrocytic anemia, elevations in these enzymes may suggest heavy alcohol use, but these values alone are inadequate to establish ALD. Gamma-glutamyltransferase is found in cell membranes of several body tissues, including the liver and spleen, and therefore is not specific to liver damage. However, elevated GGT is the best indicator of excessive alcohol consumption because it has greater sensitivity than AST and ALT.1,3,4

Although these biomarkers are helpful in diagnosing ALD, they lose some of their utility in patients with advanced liver disease. Patients with severe liver dysfunction may not have elevated serum aminotransferase levels because the degree of liver enzyme elevation does not correlate well with the severity of ALD. For example, patients with advanced cirrhosis may have liver enzyme levels that appear normal. However, the pattern of elevation in transaminases can be helpful in making a diagnosis of liver dysfunction; using the ratio of AST to ALT may aid in diagnosing ALD, because AST is elevated more than twice that of ALT in >80% of patients with ALD.1,3,4

Table 21,3,4 shows the progression of ALD from steatohepatitis to alcoholic hepatitis to cirrhosis. In steatohepatitis, transaminitis is present but all other biomarkers normal. In alcoholic hepatitis, transaminitis is present along with elevated alkaline phosphatase, elevated bilirubin, and elevated international normalized ratio (INR). In alcoholic cirrhosis, the AST-to-ALT ratio is >2, and hypoalbuminemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and coagulopathy (evidenced by elevated INR) are present, consistent with long-term liver damage.1,3,4

Continue to: FDA-approved medications

FDA-approved medications

Three medications—acamprosate, naltrexone, and disulfiram—currently are FDA-approved for treating AUD.5,6 Additionally, several other medications have shown varying levels of efficacy in treating patients with AUD but are not FDA-approved for this indication (Table 3).5-8

Acamprosate is thought to create a balance of inhibitor and excitatory neurotransmitters by functioning as a glutamate antagonist and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonist. This is speculated to aid in abstinence from alcohol. Data suggests that acamprosate may be more effective for maintaining abstinence than for inducing remission in individuals who have not yet detoxified from alcohol. Because of its renal excretion, acamprosate is the only FDA-approved medication for AUD that is not associated with liver toxicity. The most commonly reported adverse effect with acamprosate use is diarrhea.

Naltrexone, a mu-opioid receptor antagonist, is available in both tablet and long-acting IM injection formulations. Naltrexone blocks the binding of endorphins created by alcohol consumption to opioid receptors. This results in diminished dopamine release and is speculated to decrease reward and positive reinforcement with alcohol consumption, leading to fewer heavy drinking days. Due to hepatic metabolism, naltrexone use carries a risk of liver injury. Cases of hepatitis and clinically significant liver dysfunction as well as transient, asymptomatic, hepatic transaminase elevations have been observed in patients who receive naltrexone. Because of the absence of first-pass metabolism, long-acting IM naltrexone may produce less hepatotoxicity than the oral formulation. When the FDA approved both formulations of naltrexone, a “black-box” warning was issued concerning the risk of liver damage; however, these warnings have since been removed from their respective prescribing information.

Disulfiram inhibits acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, resulting in elevated acetaldehyde concentrations after consuming alcohol. In theory, this medication reduces a person’s desire to drink due to the negative physiological and physical effects associated with increased acetaldehyde, including hypotension, flushing, nausea, and vomiting. Although most of these reactions are short-lived, disulfiram can induce hepatotoxicity and liver failure that may prove fatal. Disulfiram should be avoided in patients with advanced ALD.

Off-label medications for AUD

Additional pharmacotherapeutic agents have been evaluated in patients with AUD. Baclofen, topiramate, gabapentin, and ondansetron have shown varying levels of efficacy and pose minimal concern in patients with ALD.

Continue to: Baclofen

Baclofen. Although findings are conflicting, baclofen is the only agent that has been specifically studied for treating AUD in patients with ALD. A GABA B receptor antagonist, baclofen is currently FDA-approved for treating spasticity. In a series of open-label and double-blind studies, baclofen has been shown to effectively reduce alcohol intake, promote abstinence, and prevent relapse.5,6 Further studies identified a possible dose-related response, noting that 20 mg taken 3 times daily may confer additional response over 10 mg taken 3 times daily.5,6 Conversely, the ALPADIR study failed to demonstrate superiority of baclofen vs placebo in the maintenance of abstinence from alcohol despite dosing at 180 mg/d.9 This study did, however, find a significant reduction in alcohol craving in favor of baclofen.9 Further, in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted in veterans with chronic hepatitis C, baclofen 30 mg/d failed to show superiority over placebo with regard to increasing abstinence or reducing alcohol use

Topiramate. A recent meta-analysis found that topiramate use may result in fewer drinking days, heavy drinking days, and number of drinks per drinking day.7 Additionally, topiramate has demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in alcohol craving as well as the ability to decrease all liver function test values.5 This agent should be used with caution in patients with hepatic encephalopathy because the adverse cognitive effects associated with topiramate may confound the clinical course and treatment of such.

Gabapentin. The use of gabapentin to treat patients with AUD is supported by multiple RCTs. In studies that evaluated dose-related response, higher doses of gabapentin (up to 1,800 mg/d) showed greater efficacy than lower doses (ie, 900 mg/d).8 Because gabapentin does not undergo hepatic metabolism, its use in patients with ALD is considered safe. Although the abuse potential of gabapentin is less defined in patients with AUD, there have been reports of abuse in other high-risk populations (ie, those with opioid use disorder, incarcerated persons, and those who misuse prescriptions recreationally).8

Ondansetron is speculated to decrease the reward from alcohol via the down-regulation of dopaminergic neurons. Studies examining ondansetron for patients with AUD have found that it decreases alcohol cravings in those with early-onset alcoholism (initial onset at age ≤25), but not in late-onset alcoholism (initial onset at age >25).5 However, the ondansetron doses used in these trials were very low (4 mcg/kg), and those doses are not available commercially.5

CASE CONTINUED

Following a discussion of available pharmacotherapeutic options for AUD, Mr. S is started on baclofen, 10 mg 3 times daily, with plans for dose titration. At a 2-week follow-up appointment, Mr. S reports that he had not been taking baclofen as often as instructed; however, he denies further alcohol consumption and re-commits to baclofen treatment. Unfortunately, Mr. S is soon admitted to hospice care due to continued decompensation and is unable to attend any additional outpatient follow-up appointments. Three months after his initial outpatient contact, Mr. S dies due to alcoholic cirrhosis.

Related Resources

• Crabb DW, Im GY, Szabo G, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of alcohol-related liver diseases: 2019 practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2020;71(1):306-333.

• Murail AR, Carey WD. Disease management. Liver test interpretation - approach to the patient with liver disease: a guide to commonly used liver tests. Cleveland Clinic Center for Continuing Education. Updated August 2017. www.clevelandclinicmeded. com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/hepatology/ guide-to-common-liver-tests/

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Baclofen • Lioresal

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Naltrexone • Revia, Vivitrol

Ondansetron • Zofran

Topiramate • Topamax

Mr. S, age 64, presents for an outpatient follow-up after a recent hospital discharge for alcohol detoxification. He reports a long history of alcohol use, which has resulted in numerous hospital admissions. He has recently been receiving care from a gastroenterologist because the results of laboratory testing suggested hepatic impairment (Table 1). Mr. S says that a friend of his was able to stop drinking by taking a medication, and he wonders if he can be prescribed a medication to help him as well.

A chart review shows that Mr. S recently underwent paracentesis, during which 6 liters of fluid were removed. Additionally, an abdominal ultrasound confirmed hepatic cirrhosis.

According to the World Health Organization, alcohol consumption contributes to 3 million deaths annually.2 The highest proportion of these deaths (21.3%) is due to alcohol-associated gastrointestinal complications, including alcoholic and infectious hepatitis, pancreatitis, and cirrhosis. Because the liver is the primary site of ethanol metabolism, it sustains the greatest degree of tissue injury with heavy alcohol consumption. Additionally, the association of harmful use of alcohol with risky sexual behavior may partially explain the higher prevalence of viral hepatitis among persons with alcohol use disorder (AUD) compared with the general population. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) progresses through several stages, beginning with hepatic steatosis and progressing through alcohol-related hepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and potentially hepatocellular carcinoma.3

Liver markers of alcohol use

Although biological markers can be used in clinical practice to screen and monitor for alcohol abuse, making a diagnosis of ALD can be challenging. Typically, a history of heavy alcohol consumption in addition to certain physical signs and laboratory tests for liver disease are the best indicators of ALD. However, the clinical assessment can be confounded by patients who deny or minimize how much alcohol they have consumed. Furthermore, physical and laboratory findings may not be specific to ALD.

Liver enzymes, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), have historically been used as the basis of diagnosing ALD. In addition to elevated bilirubin and evidence of macrocytic anemia, elevations in these enzymes may suggest heavy alcohol use, but these values alone are inadequate to establish ALD. Gamma-glutamyltransferase is found in cell membranes of several body tissues, including the liver and spleen, and therefore is not specific to liver damage. However, elevated GGT is the best indicator of excessive alcohol consumption because it has greater sensitivity than AST and ALT.1,3,4

Although these biomarkers are helpful in diagnosing ALD, they lose some of their utility in patients with advanced liver disease. Patients with severe liver dysfunction may not have elevated serum aminotransferase levels because the degree of liver enzyme elevation does not correlate well with the severity of ALD. For example, patients with advanced cirrhosis may have liver enzyme levels that appear normal. However, the pattern of elevation in transaminases can be helpful in making a diagnosis of liver dysfunction; using the ratio of AST to ALT may aid in diagnosing ALD, because AST is elevated more than twice that of ALT in >80% of patients with ALD.1,3,4

Table 21,3,4 shows the progression of ALD from steatohepatitis to alcoholic hepatitis to cirrhosis. In steatohepatitis, transaminitis is present but all other biomarkers normal. In alcoholic hepatitis, transaminitis is present along with elevated alkaline phosphatase, elevated bilirubin, and elevated international normalized ratio (INR). In alcoholic cirrhosis, the AST-to-ALT ratio is >2, and hypoalbuminemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and coagulopathy (evidenced by elevated INR) are present, consistent with long-term liver damage.1,3,4

Continue to: FDA-approved medications

FDA-approved medications

Three medications—acamprosate, naltrexone, and disulfiram—currently are FDA-approved for treating AUD.5,6 Additionally, several other medications have shown varying levels of efficacy in treating patients with AUD but are not FDA-approved for this indication (Table 3).5-8

Acamprosate is thought to create a balance of inhibitor and excitatory neurotransmitters by functioning as a glutamate antagonist and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonist. This is speculated to aid in abstinence from alcohol. Data suggests that acamprosate may be more effective for maintaining abstinence than for inducing remission in individuals who have not yet detoxified from alcohol. Because of its renal excretion, acamprosate is the only FDA-approved medication for AUD that is not associated with liver toxicity. The most commonly reported adverse effect with acamprosate use is diarrhea.

Naltrexone, a mu-opioid receptor antagonist, is available in both tablet and long-acting IM injection formulations. Naltrexone blocks the binding of endorphins created by alcohol consumption to opioid receptors. This results in diminished dopamine release and is speculated to decrease reward and positive reinforcement with alcohol consumption, leading to fewer heavy drinking days. Due to hepatic metabolism, naltrexone use carries a risk of liver injury. Cases of hepatitis and clinically significant liver dysfunction as well as transient, asymptomatic, hepatic transaminase elevations have been observed in patients who receive naltrexone. Because of the absence of first-pass metabolism, long-acting IM naltrexone may produce less hepatotoxicity than the oral formulation. When the FDA approved both formulations of naltrexone, a “black-box” warning was issued concerning the risk of liver damage; however, these warnings have since been removed from their respective prescribing information.

Disulfiram inhibits acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, resulting in elevated acetaldehyde concentrations after consuming alcohol. In theory, this medication reduces a person’s desire to drink due to the negative physiological and physical effects associated with increased acetaldehyde, including hypotension, flushing, nausea, and vomiting. Although most of these reactions are short-lived, disulfiram can induce hepatotoxicity and liver failure that may prove fatal. Disulfiram should be avoided in patients with advanced ALD.

Off-label medications for AUD