User login

Tips and tools for safe opioid prescribing

CASE

Marcelo G* is a 46-year-old man who presented to our family medicine clinic with a complex medical history including end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and hemodialysis, chronic anemia, peripheral vascular disease, venous thromboembolism and anticoagulation, major depressive disorder, osteoarthritis, and lumbosacral radiculopathy. His current medications included vitamin B complex, cholecalciferol, atorvastatin, warfarin, acetaminophen, diclofenac gel, and capsaicin cream. Mr. G reported bothersome bilateral knee and back pain despite physical therapy and consistent use of his current medications in addition to occasional intra-articular glucocorticoid injections. He mentioned that he had benefited in the past from intermittent opioid use.

How would you manage this patient’s care?

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

In 2013, an estimated 191 million prescriptions for opioids were written by health care providers, which is the equivalent of all adults living in the United States having their own opioid prescription.1 This large expansion in opioid prescribing and use has also led to a rise in opioid overdose deaths, whether from prescribed or illicit use.1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) points out that each day, approximately 128 Americans die from an opioid overdose.1 Deaths that occur from opioid overdose often involve the prescribed opioids methadone, oxycodone, and hydrocodone, the illicit opioid heroin, and, of particular concern, prescription and illicit fentanyl.1

The extent of this problem has sparked the development of health safety initiatives and research efforts. Through production quotas, the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) reduced the number of opioids produced across all schedule I and schedule II lists in 2017 by as much as 25%.2 The DEA again reduced the amounts produced in 2018.3 For 2020, the DEA has determined that the production quotas and assessment of annual needs are sufficient.4

The CDC has also promoted access to naloxone and prevention initiatives; pharmacies in some states have standing orders for naloxone, and medical personnel and law enforcement now carry it.1,5 Finally, new research has identified risk factors that influence one’s potential for addiction, such as mental illness, history of substance and alcohol abuse, and a low income.6 Interestingly, while numerous initiatives and strategies have been implemented across health systems, there is little evidence that demonstrates how implementation of safe prescribing strategies has affected overall patient safety and avoidance of opioid-related harms.

Nevertheless, concerns related to opioids are especially important for primary care providers, who manage many patients with acute and chronic diseases and disorders that require pain control.7 Family physicians write more opioid prescriptions than any other specialty,8 and they are therefore uniquely positioned to protect patients, improve the quality of their care, and ultimately produce a meaningful public health impact. This article provides a guide to safe opioid prescribing.

Continue to: Use the patient interview to ensure that Tx aligns with patient goals

Use the patient interview to ensure that Tx aligns with patient goals

For patients presenting with chronic pain, conduct a complete general history and physical examination that includes a review of available records; a medical, surgical, social, family, medication, and allergy history; a review of systems; and documentation of any psychiatric comorbidities (ie, depression, anxiety, psychiatric disorders, personality traits). Inquiries about social history and current medications should explore the possibility of previous and current substance use and misuse.

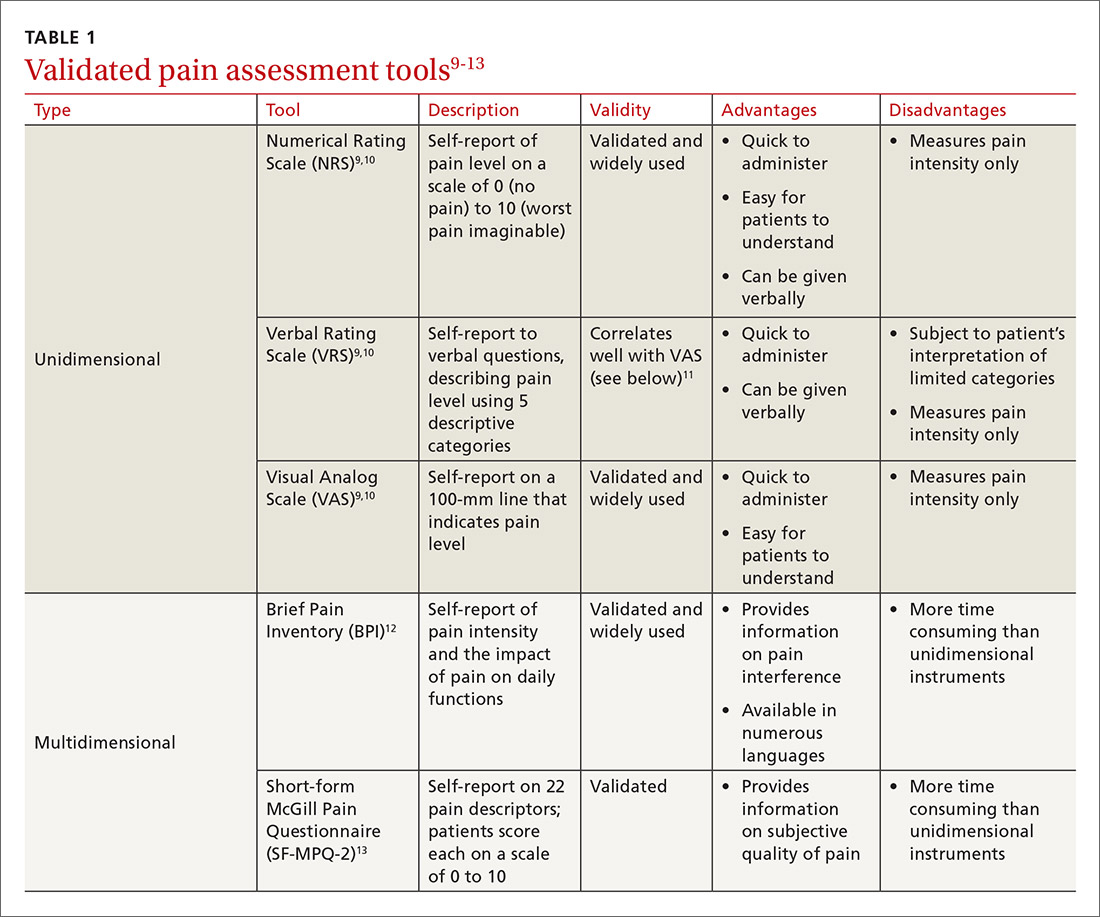

While causes of pain can be assessed through physical examination and diagnostic tests, the patient interview is an invaluable source of information. No single means of assessment has consistently demonstrated superiority over another in measuring pain, and numerous standard assessment tools are available (TABLE 19-13).14 Unidimensional tools are often easy and quick ways to assess pain intensity. Multidimensional tools, although more time intensive, are designed to gather more subjective information about the patient’s pain. Finally, use an instrument such as the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to screen patients for psychological distress.15,16

Provide an environment for patients to openly discuss their experiences, expectations, preferences, fears, and coping efforts, as well as the impact that pain has had on their lives.17,18 Without this foundational understanding, medical treatment may work against the patient’s goals. An empathic approach allows for effective communication, shared decision making, and ultimately, an avenue for individualized therapy.

Balancing treatment with risk mitigation

The challenge of managing chronic pain is to balance treating the patient with the basic principle of nonmaleficence (primum non nocere: “first, do no harm”). The literature has shown that risk factors such as a family history of substance abuse or sexual abuse, younger age, and psychological disease may be linked to greater risk for opioid misuse.19,20 However, despite the many risk-screening tools available, no single instrument has reliably and accurately predicted those at higher propensity for prescription addiction. In fact, risk-screening tools as a whole remain unregulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other authorities.21 Still, screening tools provide useful information as one component of the risk-mitigation process.

Screening tools. The tools most commonly used clinically to stratify risk prior to prescribing opioids are the 5-item Opioid Risk Tool (ORT),22 the revised 24-item Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP-R),23 which are patient self-administered assessments, and the 7-item clinician-administered DIRE (Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk, Efficacy).24 Given the subtle differences in criteria and the time required for each of these risk assessments, we recommend choosing one based on site-specific resources and overall clinician comfort.25 Risk stratification helps to determine the optimal frequency and intensity of monitoring, not necessarily to deny care to “high-risk” patients.

Continue to: In fact, just as the "universal precautions"...

In fact, just as the “universal precautions” approach has been applied to infection control, many have suggested using a similar approach to pain management. Risk screening should never be misunderstood as an attempt to diminish or undermine the patient’s burden of pain. By routinely conducting thorough and respectful inquiries of risk factors for all patients, clinicians can reduce stigma, improve care, and contain overall risk.26,27

Monitoring programs and patient agreements. In addition to risk-screening tools, the CDC recommends using state prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMP) and urine drug testing (UDT) data to confirm the use of prescribed and illicit substances.28 All 50 states have implemented PDMPs.29 Consider incorporating these components into controlled-substance agreements, which ultimately aim to promote safety and trust between patients and providers. Of course, such agreements do not eliminate all risks associated with opioid prescribing, nor do they guarantee the absence of adverse outcomes. However, when used correctly, they can provide safeguards to reduce misuse and abuse. They also have the potential to preserve the patient-provider relationship, as opposed to providers cursorily refusing to prescribe opioids altogether. The term “controlled-substance agreement” is preferable to “pain contract” or “narcotic contract” as the latter 2 terms may feel stigmatizing and threatening.30

Risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS). In an effort to ensure that benefits of opioid analgesics continue to outweigh the risks, the FDA approved the extended-release (ER)/long-acting (LA) opioid analgesics shared system REMS. Under this REMS, a consortium of ER/LA opioid manufacturers is mandated to provide prescriber education in the form of accredited continuing education and patient educational materials, available at https://opioidanalgesicrems.com/RpcUI/home.u.

CASE

After reviewing Mr. G’s chart and conducting a history, we learned that his bilateral knee osteoarthritis was atraumatic and likely due to overuse—although possibly affected by major trauma in a motor vehicle accident 5 years earlier. Imaging also revealed multilevel disc degeneration contributing to his radicular back pain, which seemed to be worse on days after working as a caterer. Poor lifting form at work may have contributed to his pain. Nevertheless, he had been consistent with medical follow-up and denied current or past use of illicit substances. Per the numeric rating scale (NRS), he reported 8 out of 10 pain in his knees and 6 out of 10 in his back. In addition to obtaining a PHQ-9 score of 4, we conducted a DIRE assessment and obtained a score of 19 out of a possible 21, indicating that he may be a good candidate for long-term opioid analgesia.

Criteria for prescribing opioids and for guiding treatment goals

Prescribing an opioid requires establishing a medical necessity based on 3 criteria:31

- pain of moderate-to-severe degree

- a physical diagnosis or suspected organic problem

- documented treatment failure of a noncontrolled substance, adjuvant agents, physician-ordered physical therapy, structured exercise program, and interventional techniques.

Continue to: Treatment goals should be established...

Treatment goals should be established and understood by the prescriber and patient prior to initiation of opioids.28 Overarching treatment goals for all opioids prescribed are pain relief (but not necessarily a focus on pain scores), improvement in functional activity, and minimization of adverse effects, with the latter 2 goals taking precedence.31 To assess outcomes, formally measure progress toward goals from baseline evaluations. This can be achieved through repeated use of validated tools such as those mentioned earlier, or may be more broadly considered as progress toward employment status or increasing participation in activities.31 All pain management plans involving opioids should include continued efforts with nonpharmacologic therapy (eg, exercise therapy, weight loss, behavioral training) and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, anticonvulsants).28

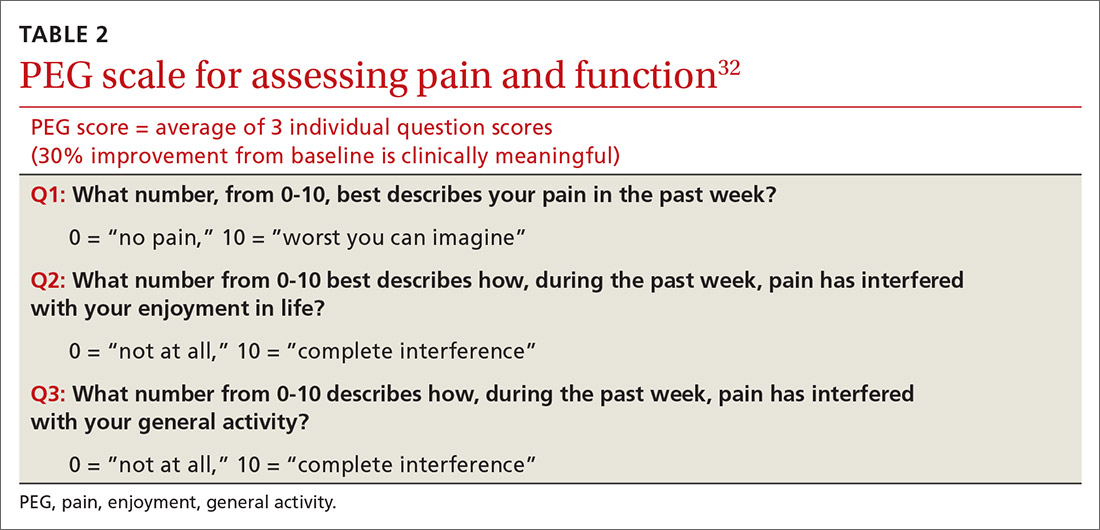

Have an “exit strategy.” As part of goal setting, also consider how therapy will be discontinued if benefits do not outweigh the risks of harm.28 Weigh functional status gains against adverse opioid consequences using the PEG scale (pain, enjoyment of life, and general activity) (TABLE 232).33 Improvements of 30% from baseline have been deemed clinically meaningful by some,32 but not all benefits will be easy to quantify. At the start of treatment dialogue, use the term “therapeutic trial” instead of ”treatment plan” to more effectively convey that opioids will be continued only if safe and effective, and will be prescribed at the lowest effective dose as one component of the multimodal approach to pain.30

Initiation of treatment: Opioid selection and dosing

When initiating opioid therapy, prescribe an immediate-release, short-acting agent instead of an ER/LA formulation.28

For moderate pain, first consider tramadol, codeine, tapentadol, or hydrocodone.31 Second-line agents for moderate pain are hydrocodone or oxycodone.31

For severe pain, first-line agents include hydrocodone, oxycodone, hydromorphone, or morphine.31 Second-line agents for severe pain are fentanyl and, with careful supervision or referral to a pain specialist, methadone or buprenorphine.31

Continue to: Of special note...

Of special note,

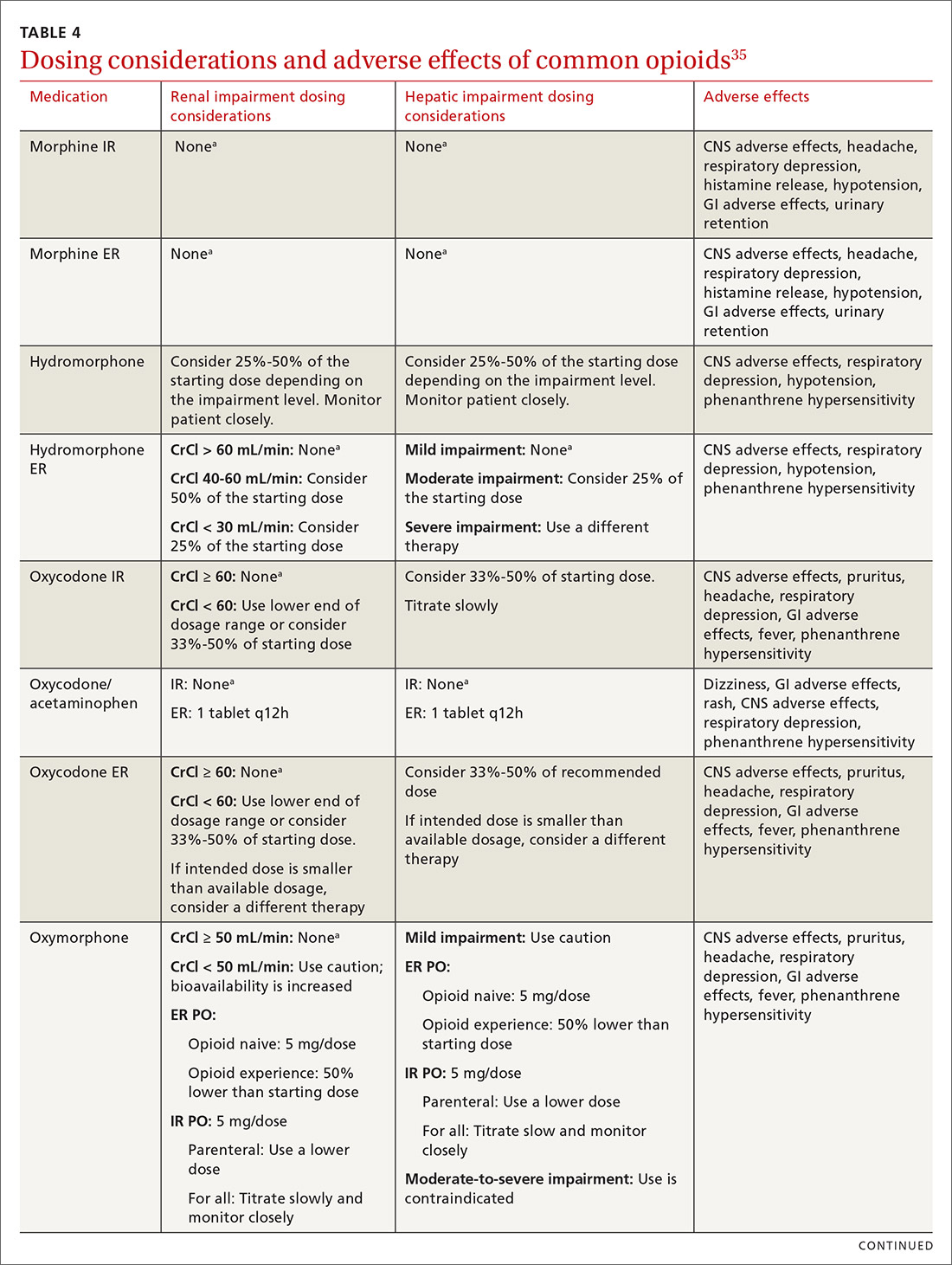

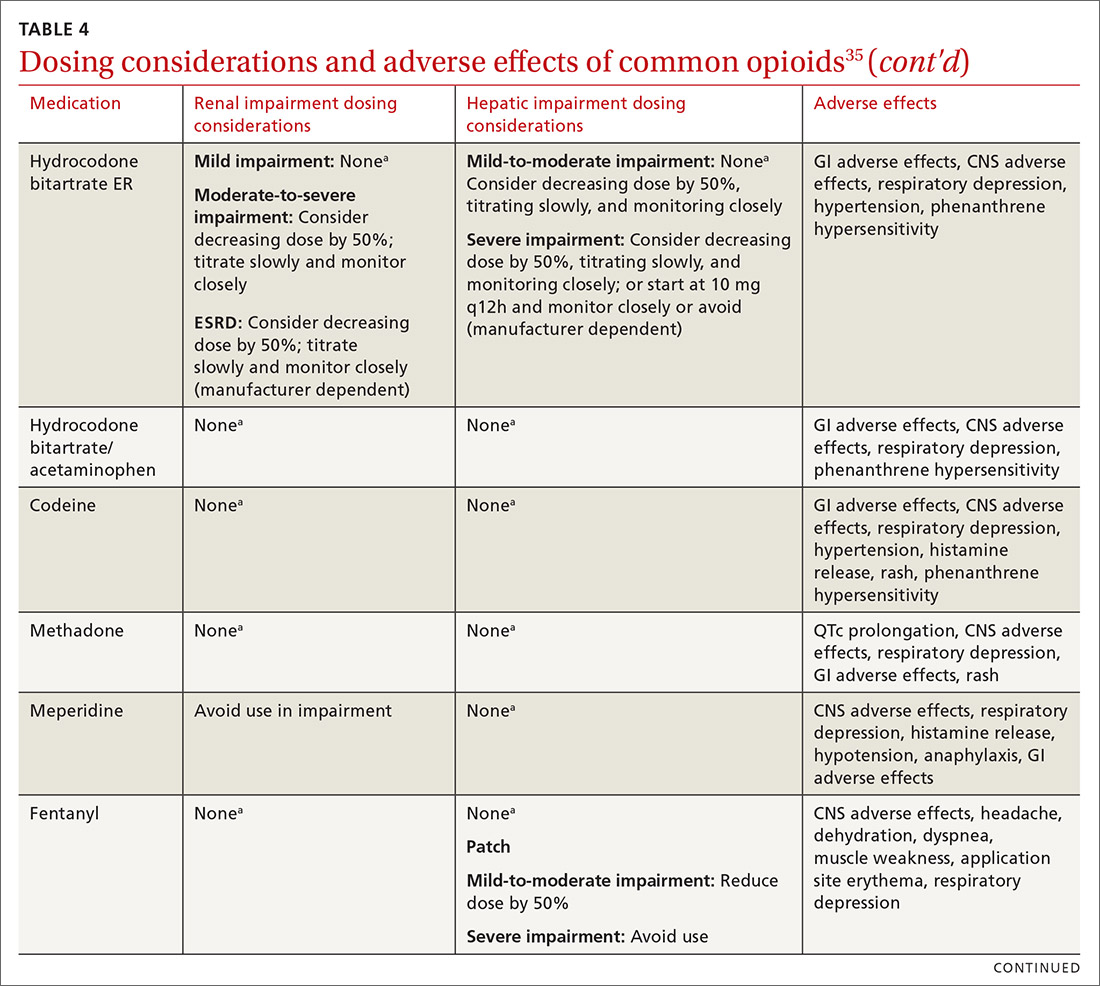

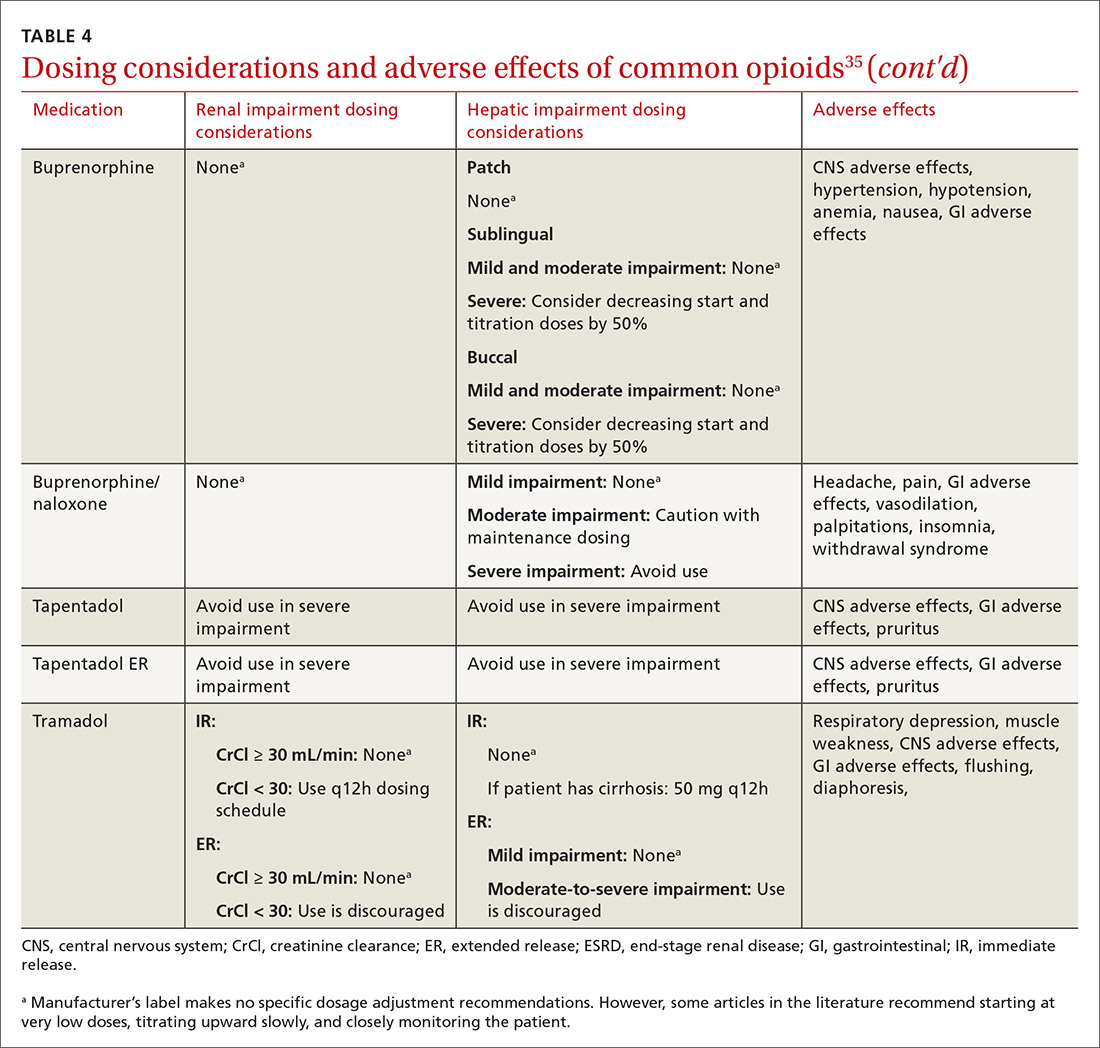

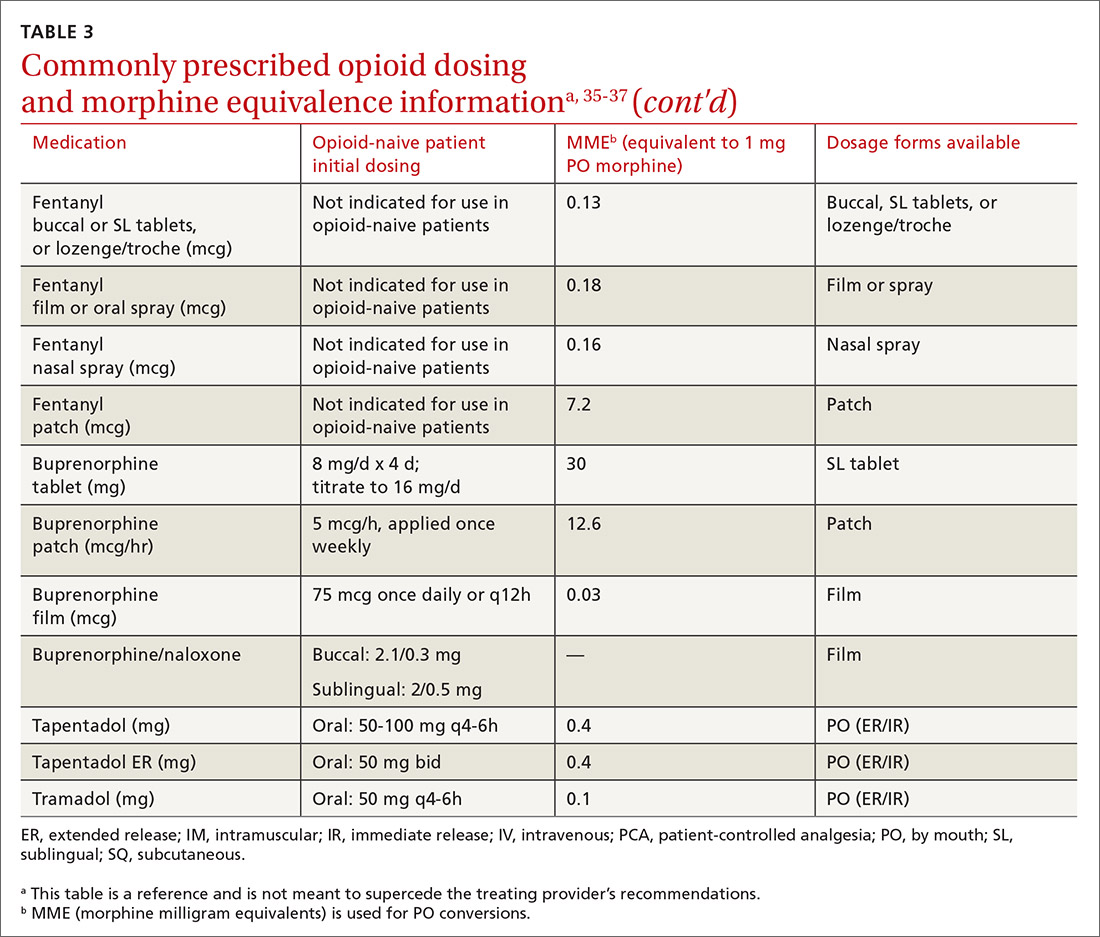

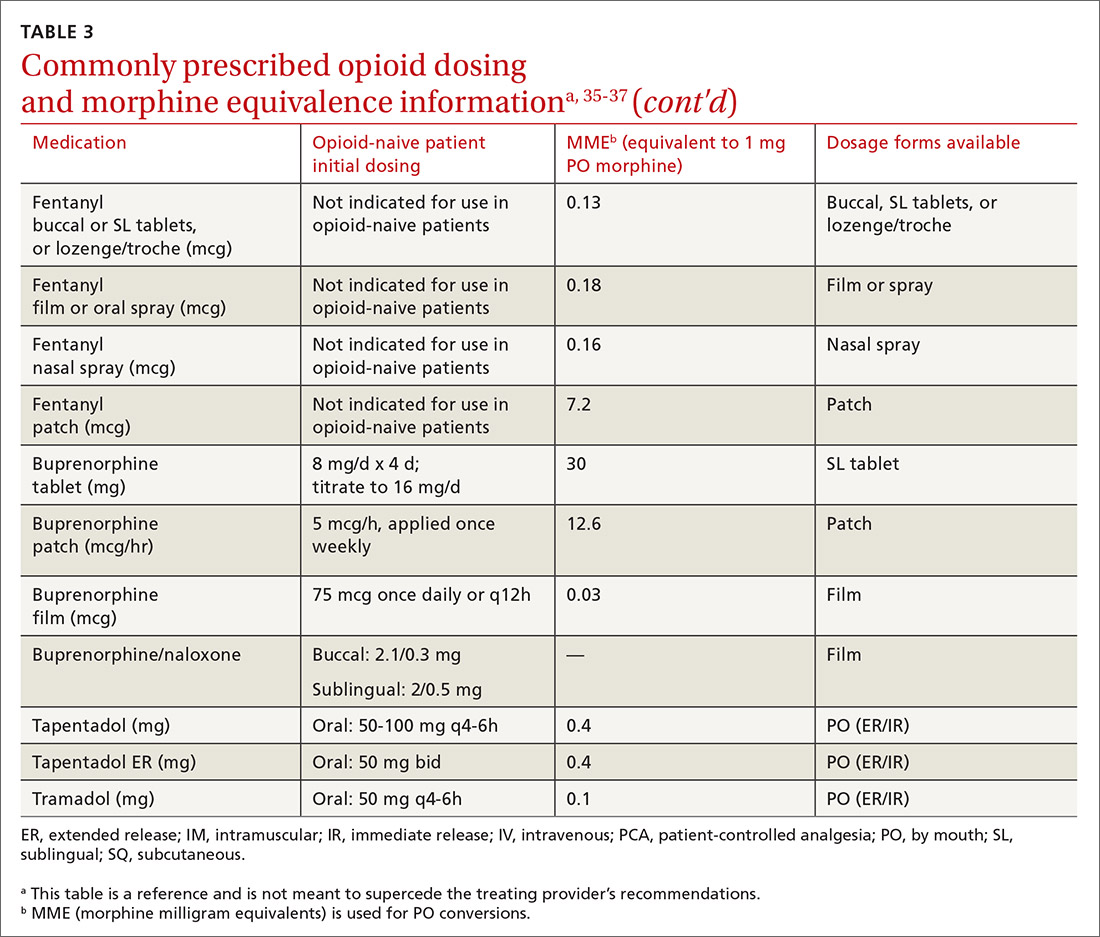

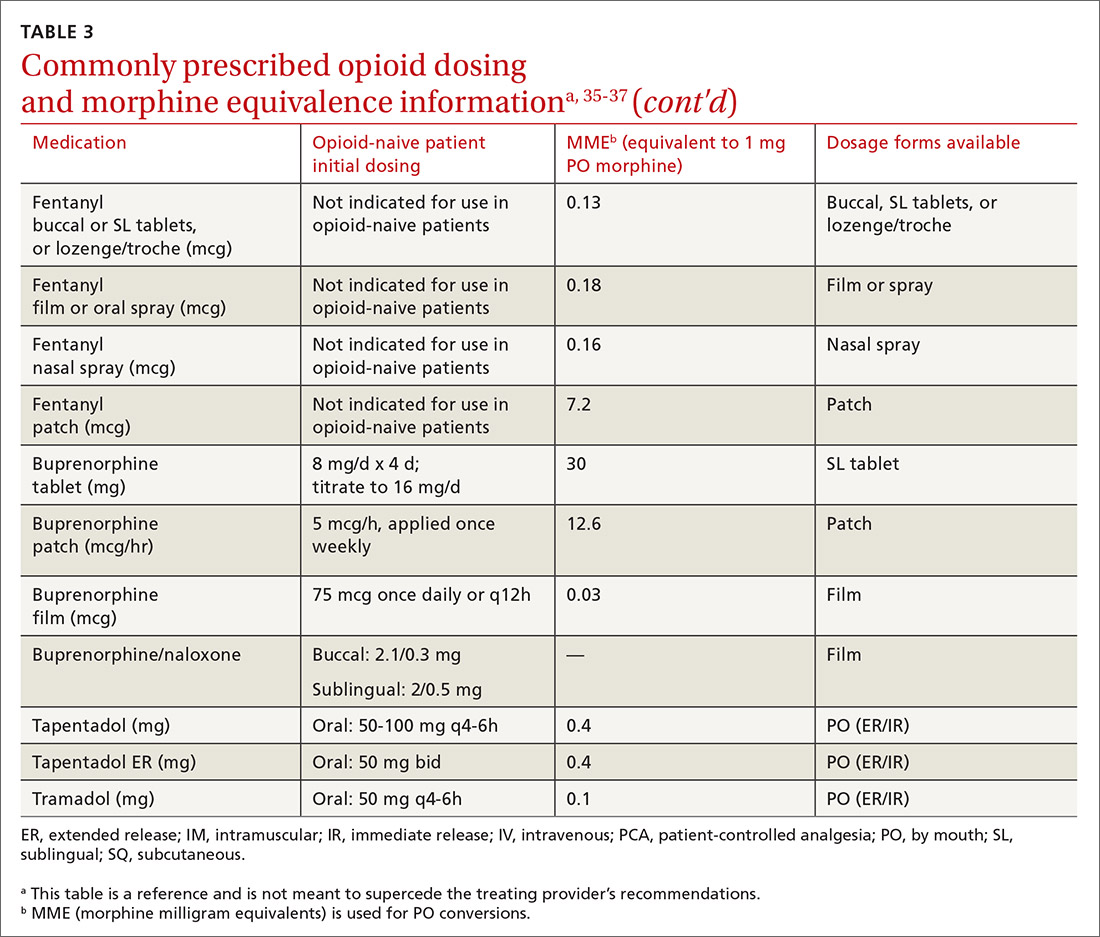

At the start, prescribe the lowest effective dosage (referring to the product labeling for guidance) and calculate total daily dose in terms of morphine milligram equivalents (MME) (TABLE 335-37).28 Exercise caution when considering opioids for patients with respiratory sleep disorders and for patients ≥ 65 years due to altered pharmacokinetics in the elderly population.38 Also make dose adjustments for renal and hepatic insufficiency (TABLE 435).

Doses between 20 to 50 MME/d are considered relatively low dosages.28 Be cautious when prescribing an opioid at any dosage, and reassess evidence of individual benefits and risks before increasing the dosage to ≥ 50 MME/d.28 Regard a dosage of 90 MME/d as maximal.28 While there is no analgesic ceiling, doses greater than 90 MME/d are associated with risk for overdose and should prompt referral to a pain specialist.31 Veterans Administration guidelines cite strong evidence that risk for overdose and death significantly increases at a range of 20 to 50 MME/d.33 Daily doses exceeding 90 MME/d should be documented with rational justification.28

CASE

Noncontrolled medications are preferred in the treatment of chronic pain. However, the utility of adjuvant options such as NSAIDs, duloxetine, or gabapentin were limited in Mr. G’s case due to his ESRD. Calcium channel α2-δ ligands may have been effective in reducing symptoms of neuropathic pain but would have had limited efficacy against osteoarthritis. Based on his low risk for opioid misuse, we decided to start Mr. G on oxycodone 2.5 mg PO, every 6 hours as needed for moderate-to-severe pain, and to follow up in 1 month. We also explained proper lifting form to him and encouraged him to continue with physical therapy.

Deciding to continue therapy with opioids

There is a lack of convincing evidence that opioid use beyond 6 months improves quality of life; patients do not report a significant reduction in pain beyond this time.28 Thus, a repeat evaluation of continued medical necessity is essential before deciding in favor of ongoing, long-term treatment with opioids. Continue prescribing opioids only if there is meaningful pain relief and improved function that outweighs the harms that may be expected for a given patient.31 With all patients, consider prescribing naloxone to accompany dispensed opioid prescriptions.28 This is particularly important for those at risk for misuse (history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, dosages ≥ 50 MME/d, or concurrent benzodiazepine use). Resources for prescribing naloxone in primary care settings can be found through Prescribe to Prevent at http://prescribetoprevent.org. Due to the established risk of overdose, avoid, if possible, concomitant prescriptions of benzodiazepines and opioids.31

Continue to: Follow-up and monitoring

Follow-up and monitoring

Responsiveness to opioids varies greatly among individuals.38,39 An opioid that leads to a therapeutic analgesic effect in one patient may cause adverse events or toxicity in another. Periodically reassess the appropriateness of chronic opioid therapy and modify treatment based on its ability to meet therapeutic goals. While practice behaviors and clinic policies vary across institutions, risk stratification can provide guidance on the frequency and intensity of follow-up and monitoring. Kaye et al21 describe a triage system in which low-risk patients may be managed by a primary care provider with routine follow-up and reassessment every 3 months.21 Moderate-risk patients may warrant additional management by specialists and a monthly follow-up. High-risk patients may need referrals to interdisciplinary pain centers or addiction specialists.21

Along these lines, the CDC recommends conducting a PDMP review and UDT before initiating therapy, followed by a periodic PDMP (every 1-3 months) and a UDT at least annually. Keep in mind, providers should follow their state-specific regulations, as monitoring requirements may vary. In addition, clinicians should always be alert to adverse reactions (TABLE 435) and sudden behavior changes such as respiratory depression, nausea, constipation, pruritus, cognitive impairment, falls, motor vehicle accidents, and aberrant behaviors. Under these circumstances, consider a dose reduction and, in certain cases, discontinuation.

Additionally, in cases of pain unresponsive to escalating opioid doses, include opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) in the differential. Dose reductions, opioid rotations, and office-based detoxifications are all options for the treatment of OIH.40 Assessment of pain and function can be accomplished using the PEG scale (TABLE 2).32

CASE

Two weeks into Mr. G’s initial regimen, he called to report no change in pain or functional status. We increased his dose to 5 mg PO every 6 hours as needed. At his 1-month follow-up appointment, he reported his pain as 6/10 and no adverse effects. We again increased his dose to 10 mg PO every 6 hours as needed, with follow-up in another month.

Discontinuation and tapering of opioids

Indications for discontinuing opioids are patient request, resolution of pain, doses ≥ 90 MME/d (in which case a pain specialist should be consulted), inadequate response, untoward adverse effects, and abuse and misuse.1,31,41 However, providers may also face the challenge of working with patients for whom the benefit of opioid therapy is uncertain but who do not have an absolute contraindication. Guidance on this matter may be found in a 2017 systematic review of studies on reducing or discontinuing long-term opioid therapy.42 Although evidence on the whole was low quality, it showed that tapering or discontinuing opioids may actually reduce pain and improve function and quality of life.

Continue to: When working with a patient to taper treatment

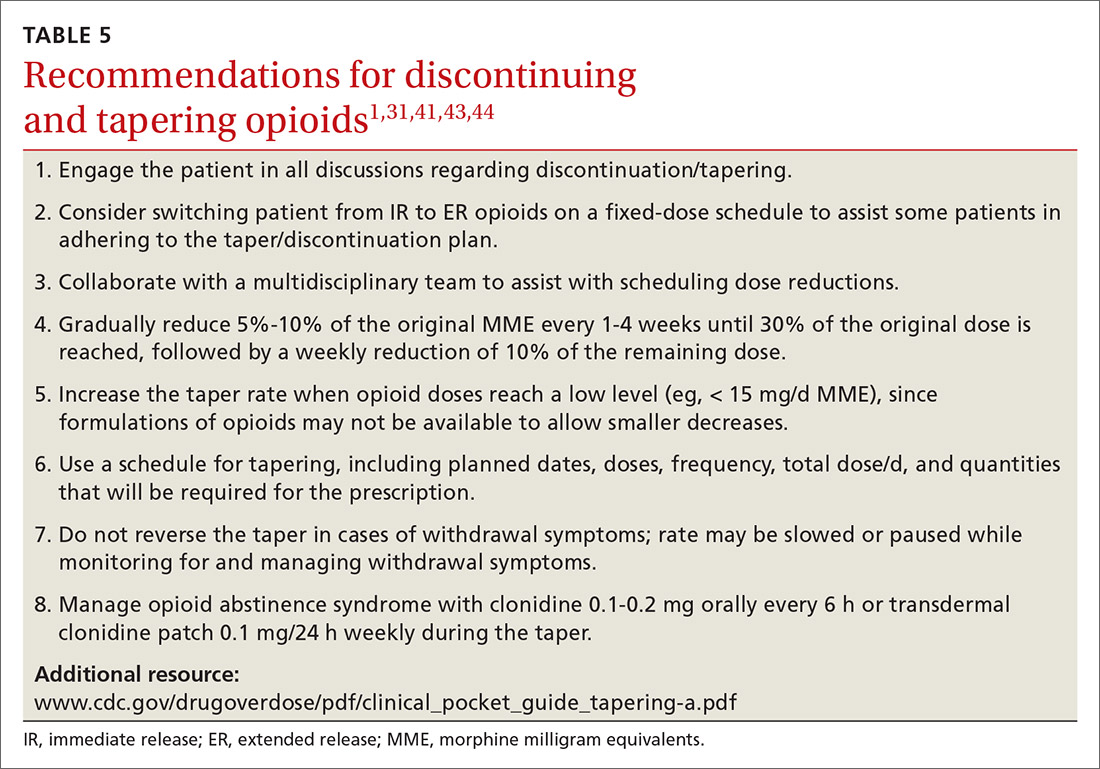

When working with a patient to taper treatment, consider using a multidisciplinary approach. Also, assess the patient’s pain level and perception of needs for opioids, make clear the substantial effort that will be asked of the patient, and agree on coping strategies the patient can use to manage the taper.31,43 While the evidence does not appear to support one tapering regimen over another, we can offer some recommendations on ways to individualize a tapering regimen (TABLE 5).1,31,41,43,44

General recommendations. Gradually reduce the original MME dose by 5% to 10% every week to every 4 weeks, with frequent follow-up and adjustments as needed based on the individual’s response.1,31,41,43 In the event that the patient does not tolerate this dose-reduction schedule, tapering can be slowed further.31 Avoid abrupt discontinuation.33 Opioid abstinence syndrome, a myriad of symptoms caused by deprivation of opioids in physiologically dependent individuals, although rare, can occur during tapering and can be managed with clonidine 0.1 to 0.2 mg orally every 6 hours or transdermal clonidine patch 0.1 mg/24 hours weekly during the taper.31

Tapering of long-term opioid treatment is not without risk. Immediate risks include withdrawal syndrome, hyperalgesia, and dropout, while ongoing issues are potential relapse, problems in increasing and maintaining function, and medicolegal implications.43 Withdrawal symptoms begin 2 to 3 half-lives after the last dose of opioid, and resolution varies depending on the duration of use, the most recent dose, and speed of tapering.43 In general, a patient needs 20% to 25% of the previous day’s dose to prevent withdrawal symptoms.31 Increased pain appears to be a brief, time-limited occurance.43 Dropout and relapse tend to be attributed to patient factors such as depressive symptoms and higher pain scores at initiation of the taper.43 Low pain at the end of tapering has been shown to predict long-term abstinence from opioids.43

CASE

Two months into his oxycodone regimen, Mr. G reported improved functional status at his catering job and overall improved quality of life. He had improved his lifting form and was attending biweekly physical therapy sessions. His pain score was 3/10. He expressed a desire to “not get hooked on opioids,” and mentioned he had “tried stopping the medicine last week” but experienced withdrawal symptoms. We discussed and prescribed the following 5-week taper plan: 2.5 mg reduction of oxycodone per dose, every 2 weeks x 2. Then 2.5 mg PO every 6 hours as needed x 1 week before stopping.

Organizing your approach

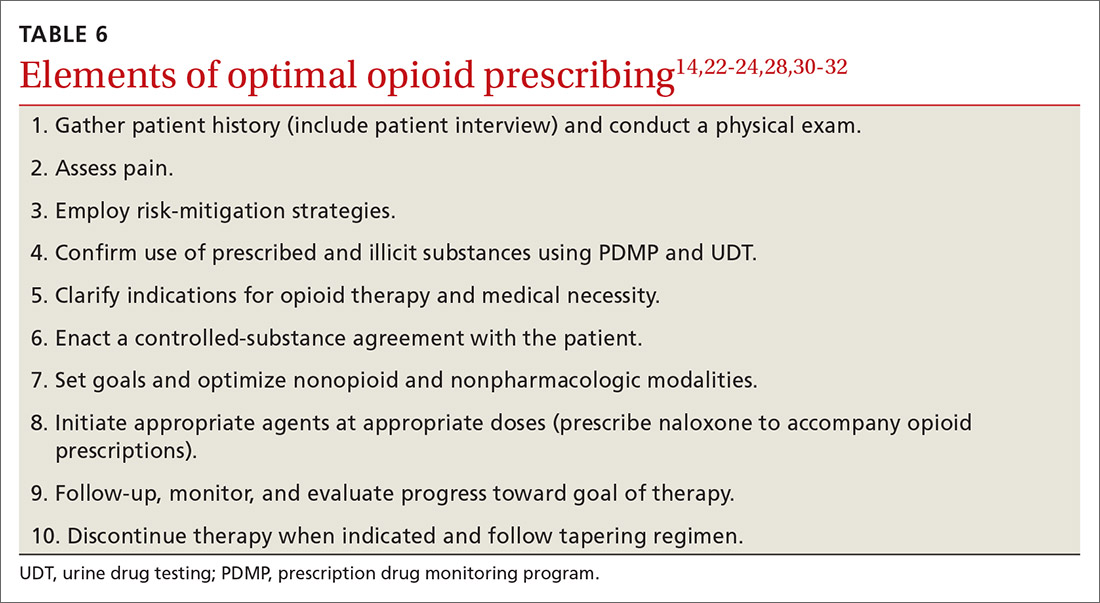

To optimize the chance for success in opioid treatment and to heighten vigilance and minimize harm to patients, we believe an organized approach is key (TABLE 614,22-24,28,30-32), particularly since this class of medication lacks strong evidence to support its long-term use.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tracy Mahvan, PharmD, BCGP, University of Wyoming, School of Pharmacy, 1000 East University Avenue, Laramie, WY 82071; [email protected].

1. CDC. Opioid overdose. www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/opioids/prescribed.html. Accessed June 26, 2020.

2. DEA, Department of Justice. Established aggregate production quotas for schedule I and II controlled substances and assessment of annual needs for the list I chemicals ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine for 2017. www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/quotas/2016/fr1005.htm. Accessed June 26, 2020.

3. DEA, Department of Justice. Established aggregate production quotas for schedule I and II controlled substances and assessment of annual needs for the list I chemicals ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine for 2018. www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/quotas/2017/fr1108.htm. Accessed June 26, 2020.

4. DEA, Department of Justice. Established aggregate production quotas for schedule I and II controlled substances and assessment of annual needs for the list I chemicals ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine for 2020. www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/quotas/2019/fr1202.htm. Accessed June 26, 2020.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy benefits management services: academic detailing service—opioid overdose education & naloxone distribution (OEND). www.pbm.va.gov/AcademicDetailingService/Opioid_Overdose_Education_and_Naloxone_Distribution.asp. Accessed June 26, 2020.

6. McCarberg BH. Pain management in primary care: strategies to mitigate opioid misuse, abuse, and diversion. Postgrad Med. 2011;123:119-130.

7. Dean L. Tramadol therapy and CYP2D6 genotype. In: Pratt V, McLeod H, Rubinstein W, et al (eds). Medical Genetics Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda, Md: National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2015. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK315950/. Accessed June 26, 2020.

8. Chen JH, Humphreys K, Shah NH, et al. Distribution of opioids by different types of Medicare prescribers. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:259-261.

9. Jensen MP, Karoly P. Self-report scales and procedures for assessing pain in adults. In: Turk DC, Melzack R, eds. Handbook of Pain Assessment. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011;19-41.

10. Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs. 2005; 14:798-804.

11. Ohnhaus EE, Adler R. Methodological problems in the measurement of pain: a comparison between the verbal rating scale and the visual analogue scale. Pain. 1975;1:379-384.

12. Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129-138.

13. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Revicki DA, et al. Development and initial validation of an expanded and revised version of the short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ-2). Pain. 2009;144:35-42.

14. Dansie EJ, Turk DC. Assessment of patients with chronic pain. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:19-25.

15. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613.

16. Choi Y, Mayer TG, Williams MJ, Gatchel RJ. What is the best screening test for depression in chronic spinal pain patients? Spine J. 2014;14:1175-1182.

17. Practice guidelines for chronic pain management: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Anesthesiology. 2010;122:810-833.

18. Gallagher RM. Empathy: a timeless skill for the pain medicine toolbox. Pain Med. 2006;7:213-214.

19. Koyyalagunta D, Bruera E, Aigner C, et al. Risk stratification of opioid misuse among patients with cancer pain using the SOAPP-SF. Pain Med. 2013;14:667-675.

20. Trescot AM, Helm S, Hansen H, et al. Opioids in the management of chronic non-cancer pain: an update of American Society of the Interventional Pain Physicians’ (ASIPP) guidelines. Pain Physician. 2008;11:S5-S62.

21. Kaye AD, Jones MR, Kaye AM, et al. Prescription opioid abuse in chronic pain: an updated review of opioid abuse predictors and strategies to curb opioid abuse (part 2). Pain Physician. 2017;20:S111-S133.

22. Webster LR, Webster RM. Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid‐treated patients: preliminary validation of the Opioid Risk Tool. Pain Med. 2005;6:432-442.

23. Butler SF, Fernandez K, Benoit C, et al. Validation of the revised screener and opioid assessment for patients with pain (SOAPP-R). J Pain. 2008;9:360-372.

24. Belgrade MJ, Schamber CD, Lindgren BR. The DIRE score: predicting outcomes of opioid prescribing for chronic pain. J Pain. 2006;7:671-681.

25. Fine PG, Finnegan T, Portenoy RK. Protect your patients, protect your practice: practical risk assessment in the structuring of opioid therapy in chronic pain. J Fam Pract. 2010;59(9 suppl 2):S1-16.

26. Gourlay DL, Heit HA, Almahrezi A. Universal precautions in pain medicine: a rational approach to the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Med. 2005;6:107-112.

27. Manubay JM, Muchow C, Sullivan MA. Prescription drug abuse: epidemiology, regulatory issues, chronic pain management with narcotic analgesics. Prim Care. 2011;38:71-90.

28. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49.

29. Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Training and Technical Assistance Center. State PDMP profiles and contacts. www.pdmpassist.org/State. Accessed June 26, 2020.

30. Tobin DG, Andrews R, Becker WC. Prescribing opioids in primary care: Safely starting, monitoring, and stopping. Cleve Clin J Med. 2016;83:207-215.

31. Manchikanti L, Kaye AM, Knezevis NN, et al. Responsible, safe, and effective prescription of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines. Pain Physician. 2017;20:S3-S92.

32. HHS. Checklist for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/PDO_Checklist-a.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2020.

33. VA/DoD. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for opioid therapy for chronic pain. www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Pain/cot/VADoDOTCPG022717.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2020.

34. Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:38-47.

35. Lexi-Comp Online. Hudson (OH): Wolters Kluwer Clinical Drug Information, Inc; 2018. https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/login. Accessed July 9, 2020.

36. CMS. Opioid oral morphine milligram equivalent (MME) conversion factors. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Opioid-Morphine-EQ-Conversion-Factors-Aug-2017.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2020.

37. Cupp M. Equianalgesic dosing of opioids for pain management. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter. 2018:340406. Stockton (CA): Therapeutic Research Center, LLC; 2018. www.nhms.org/sites/default/files/Pdfs/Opioid-Comparison-Chart-Prescriber-Letter-2012.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2020.

38. Smith HS. Variations in opioid responsiveness. Pain Physician. 2008;11:237-248.

39. Bronstein K, Passik S, Munitz L, et al. Can clinicians accurately predict which patients are misusing their medications? J Pain. 2011;12(suppl):P3.

40. Silverman SM. Opioid induced hyperalgesia: clinical implications for the pain practitioner. Pain Physician. 2009;12:679-684.

41. Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic non-cancer pain. CMAJ. 2017;189:E659-E666.

42. Frank JW, Lovejoy TI, Becker WC, et al. Patient outcomes in dose reduction or discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:181-191.

43. Berna C, Kulich RJ, Rathmell JP. Tapering long-term opioid therapy in chronic non-cancer pain: evidence and recommendations for everyday practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:828-842.

44. Washington State Agency Medical Director’s Group. Interagency guideline on prescribing opioids for pain. June 2015. www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/Files/2015AMDGOpioidGuideline.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2020.

CASE

Marcelo G* is a 46-year-old man who presented to our family medicine clinic with a complex medical history including end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and hemodialysis, chronic anemia, peripheral vascular disease, venous thromboembolism and anticoagulation, major depressive disorder, osteoarthritis, and lumbosacral radiculopathy. His current medications included vitamin B complex, cholecalciferol, atorvastatin, warfarin, acetaminophen, diclofenac gel, and capsaicin cream. Mr. G reported bothersome bilateral knee and back pain despite physical therapy and consistent use of his current medications in addition to occasional intra-articular glucocorticoid injections. He mentioned that he had benefited in the past from intermittent opioid use.

How would you manage this patient’s care?

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

In 2013, an estimated 191 million prescriptions for opioids were written by health care providers, which is the equivalent of all adults living in the United States having their own opioid prescription.1 This large expansion in opioid prescribing and use has also led to a rise in opioid overdose deaths, whether from prescribed or illicit use.1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) points out that each day, approximately 128 Americans die from an opioid overdose.1 Deaths that occur from opioid overdose often involve the prescribed opioids methadone, oxycodone, and hydrocodone, the illicit opioid heroin, and, of particular concern, prescription and illicit fentanyl.1

The extent of this problem has sparked the development of health safety initiatives and research efforts. Through production quotas, the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) reduced the number of opioids produced across all schedule I and schedule II lists in 2017 by as much as 25%.2 The DEA again reduced the amounts produced in 2018.3 For 2020, the DEA has determined that the production quotas and assessment of annual needs are sufficient.4

The CDC has also promoted access to naloxone and prevention initiatives; pharmacies in some states have standing orders for naloxone, and medical personnel and law enforcement now carry it.1,5 Finally, new research has identified risk factors that influence one’s potential for addiction, such as mental illness, history of substance and alcohol abuse, and a low income.6 Interestingly, while numerous initiatives and strategies have been implemented across health systems, there is little evidence that demonstrates how implementation of safe prescribing strategies has affected overall patient safety and avoidance of opioid-related harms.

Nevertheless, concerns related to opioids are especially important for primary care providers, who manage many patients with acute and chronic diseases and disorders that require pain control.7 Family physicians write more opioid prescriptions than any other specialty,8 and they are therefore uniquely positioned to protect patients, improve the quality of their care, and ultimately produce a meaningful public health impact. This article provides a guide to safe opioid prescribing.

Continue to: Use the patient interview to ensure that Tx aligns with patient goals

Use the patient interview to ensure that Tx aligns with patient goals

For patients presenting with chronic pain, conduct a complete general history and physical examination that includes a review of available records; a medical, surgical, social, family, medication, and allergy history; a review of systems; and documentation of any psychiatric comorbidities (ie, depression, anxiety, psychiatric disorders, personality traits). Inquiries about social history and current medications should explore the possibility of previous and current substance use and misuse.

While causes of pain can be assessed through physical examination and diagnostic tests, the patient interview is an invaluable source of information. No single means of assessment has consistently demonstrated superiority over another in measuring pain, and numerous standard assessment tools are available (TABLE 19-13).14 Unidimensional tools are often easy and quick ways to assess pain intensity. Multidimensional tools, although more time intensive, are designed to gather more subjective information about the patient’s pain. Finally, use an instrument such as the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to screen patients for psychological distress.15,16

Provide an environment for patients to openly discuss their experiences, expectations, preferences, fears, and coping efforts, as well as the impact that pain has had on their lives.17,18 Without this foundational understanding, medical treatment may work against the patient’s goals. An empathic approach allows for effective communication, shared decision making, and ultimately, an avenue for individualized therapy.

Balancing treatment with risk mitigation

The challenge of managing chronic pain is to balance treating the patient with the basic principle of nonmaleficence (primum non nocere: “first, do no harm”). The literature has shown that risk factors such as a family history of substance abuse or sexual abuse, younger age, and psychological disease may be linked to greater risk for opioid misuse.19,20 However, despite the many risk-screening tools available, no single instrument has reliably and accurately predicted those at higher propensity for prescription addiction. In fact, risk-screening tools as a whole remain unregulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other authorities.21 Still, screening tools provide useful information as one component of the risk-mitigation process.

Screening tools. The tools most commonly used clinically to stratify risk prior to prescribing opioids are the 5-item Opioid Risk Tool (ORT),22 the revised 24-item Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP-R),23 which are patient self-administered assessments, and the 7-item clinician-administered DIRE (Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk, Efficacy).24 Given the subtle differences in criteria and the time required for each of these risk assessments, we recommend choosing one based on site-specific resources and overall clinician comfort.25 Risk stratification helps to determine the optimal frequency and intensity of monitoring, not necessarily to deny care to “high-risk” patients.

Continue to: In fact, just as the "universal precautions"...

In fact, just as the “universal precautions” approach has been applied to infection control, many have suggested using a similar approach to pain management. Risk screening should never be misunderstood as an attempt to diminish or undermine the patient’s burden of pain. By routinely conducting thorough and respectful inquiries of risk factors for all patients, clinicians can reduce stigma, improve care, and contain overall risk.26,27

Monitoring programs and patient agreements. In addition to risk-screening tools, the CDC recommends using state prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMP) and urine drug testing (UDT) data to confirm the use of prescribed and illicit substances.28 All 50 states have implemented PDMPs.29 Consider incorporating these components into controlled-substance agreements, which ultimately aim to promote safety and trust between patients and providers. Of course, such agreements do not eliminate all risks associated with opioid prescribing, nor do they guarantee the absence of adverse outcomes. However, when used correctly, they can provide safeguards to reduce misuse and abuse. They also have the potential to preserve the patient-provider relationship, as opposed to providers cursorily refusing to prescribe opioids altogether. The term “controlled-substance agreement” is preferable to “pain contract” or “narcotic contract” as the latter 2 terms may feel stigmatizing and threatening.30

Risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS). In an effort to ensure that benefits of opioid analgesics continue to outweigh the risks, the FDA approved the extended-release (ER)/long-acting (LA) opioid analgesics shared system REMS. Under this REMS, a consortium of ER/LA opioid manufacturers is mandated to provide prescriber education in the form of accredited continuing education and patient educational materials, available at https://opioidanalgesicrems.com/RpcUI/home.u.

CASE

After reviewing Mr. G’s chart and conducting a history, we learned that his bilateral knee osteoarthritis was atraumatic and likely due to overuse—although possibly affected by major trauma in a motor vehicle accident 5 years earlier. Imaging also revealed multilevel disc degeneration contributing to his radicular back pain, which seemed to be worse on days after working as a caterer. Poor lifting form at work may have contributed to his pain. Nevertheless, he had been consistent with medical follow-up and denied current or past use of illicit substances. Per the numeric rating scale (NRS), he reported 8 out of 10 pain in his knees and 6 out of 10 in his back. In addition to obtaining a PHQ-9 score of 4, we conducted a DIRE assessment and obtained a score of 19 out of a possible 21, indicating that he may be a good candidate for long-term opioid analgesia.

Criteria for prescribing opioids and for guiding treatment goals

Prescribing an opioid requires establishing a medical necessity based on 3 criteria:31

- pain of moderate-to-severe degree

- a physical diagnosis or suspected organic problem

- documented treatment failure of a noncontrolled substance, adjuvant agents, physician-ordered physical therapy, structured exercise program, and interventional techniques.

Continue to: Treatment goals should be established...

Treatment goals should be established and understood by the prescriber and patient prior to initiation of opioids.28 Overarching treatment goals for all opioids prescribed are pain relief (but not necessarily a focus on pain scores), improvement in functional activity, and minimization of adverse effects, with the latter 2 goals taking precedence.31 To assess outcomes, formally measure progress toward goals from baseline evaluations. This can be achieved through repeated use of validated tools such as those mentioned earlier, or may be more broadly considered as progress toward employment status or increasing participation in activities.31 All pain management plans involving opioids should include continued efforts with nonpharmacologic therapy (eg, exercise therapy, weight loss, behavioral training) and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, anticonvulsants).28

Have an “exit strategy.” As part of goal setting, also consider how therapy will be discontinued if benefits do not outweigh the risks of harm.28 Weigh functional status gains against adverse opioid consequences using the PEG scale (pain, enjoyment of life, and general activity) (TABLE 232).33 Improvements of 30% from baseline have been deemed clinically meaningful by some,32 but not all benefits will be easy to quantify. At the start of treatment dialogue, use the term “therapeutic trial” instead of ”treatment plan” to more effectively convey that opioids will be continued only if safe and effective, and will be prescribed at the lowest effective dose as one component of the multimodal approach to pain.30

Initiation of treatment: Opioid selection and dosing

When initiating opioid therapy, prescribe an immediate-release, short-acting agent instead of an ER/LA formulation.28

For moderate pain, first consider tramadol, codeine, tapentadol, or hydrocodone.31 Second-line agents for moderate pain are hydrocodone or oxycodone.31

For severe pain, first-line agents include hydrocodone, oxycodone, hydromorphone, or morphine.31 Second-line agents for severe pain are fentanyl and, with careful supervision or referral to a pain specialist, methadone or buprenorphine.31

Continue to: Of special note...

Of special note,

At the start, prescribe the lowest effective dosage (referring to the product labeling for guidance) and calculate total daily dose in terms of morphine milligram equivalents (MME) (TABLE 335-37).28 Exercise caution when considering opioids for patients with respiratory sleep disorders and for patients ≥ 65 years due to altered pharmacokinetics in the elderly population.38 Also make dose adjustments for renal and hepatic insufficiency (TABLE 435).

Doses between 20 to 50 MME/d are considered relatively low dosages.28 Be cautious when prescribing an opioid at any dosage, and reassess evidence of individual benefits and risks before increasing the dosage to ≥ 50 MME/d.28 Regard a dosage of 90 MME/d as maximal.28 While there is no analgesic ceiling, doses greater than 90 MME/d are associated with risk for overdose and should prompt referral to a pain specialist.31 Veterans Administration guidelines cite strong evidence that risk for overdose and death significantly increases at a range of 20 to 50 MME/d.33 Daily doses exceeding 90 MME/d should be documented with rational justification.28

CASE

Noncontrolled medications are preferred in the treatment of chronic pain. However, the utility of adjuvant options such as NSAIDs, duloxetine, or gabapentin were limited in Mr. G’s case due to his ESRD. Calcium channel α2-δ ligands may have been effective in reducing symptoms of neuropathic pain but would have had limited efficacy against osteoarthritis. Based on his low risk for opioid misuse, we decided to start Mr. G on oxycodone 2.5 mg PO, every 6 hours as needed for moderate-to-severe pain, and to follow up in 1 month. We also explained proper lifting form to him and encouraged him to continue with physical therapy.

Deciding to continue therapy with opioids

There is a lack of convincing evidence that opioid use beyond 6 months improves quality of life; patients do not report a significant reduction in pain beyond this time.28 Thus, a repeat evaluation of continued medical necessity is essential before deciding in favor of ongoing, long-term treatment with opioids. Continue prescribing opioids only if there is meaningful pain relief and improved function that outweighs the harms that may be expected for a given patient.31 With all patients, consider prescribing naloxone to accompany dispensed opioid prescriptions.28 This is particularly important for those at risk for misuse (history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, dosages ≥ 50 MME/d, or concurrent benzodiazepine use). Resources for prescribing naloxone in primary care settings can be found through Prescribe to Prevent at http://prescribetoprevent.org. Due to the established risk of overdose, avoid, if possible, concomitant prescriptions of benzodiazepines and opioids.31

Continue to: Follow-up and monitoring

Follow-up and monitoring

Responsiveness to opioids varies greatly among individuals.38,39 An opioid that leads to a therapeutic analgesic effect in one patient may cause adverse events or toxicity in another. Periodically reassess the appropriateness of chronic opioid therapy and modify treatment based on its ability to meet therapeutic goals. While practice behaviors and clinic policies vary across institutions, risk stratification can provide guidance on the frequency and intensity of follow-up and monitoring. Kaye et al21 describe a triage system in which low-risk patients may be managed by a primary care provider with routine follow-up and reassessment every 3 months.21 Moderate-risk patients may warrant additional management by specialists and a monthly follow-up. High-risk patients may need referrals to interdisciplinary pain centers or addiction specialists.21

Along these lines, the CDC recommends conducting a PDMP review and UDT before initiating therapy, followed by a periodic PDMP (every 1-3 months) and a UDT at least annually. Keep in mind, providers should follow their state-specific regulations, as monitoring requirements may vary. In addition, clinicians should always be alert to adverse reactions (TABLE 435) and sudden behavior changes such as respiratory depression, nausea, constipation, pruritus, cognitive impairment, falls, motor vehicle accidents, and aberrant behaviors. Under these circumstances, consider a dose reduction and, in certain cases, discontinuation.

Additionally, in cases of pain unresponsive to escalating opioid doses, include opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) in the differential. Dose reductions, opioid rotations, and office-based detoxifications are all options for the treatment of OIH.40 Assessment of pain and function can be accomplished using the PEG scale (TABLE 2).32

CASE

Two weeks into Mr. G’s initial regimen, he called to report no change in pain or functional status. We increased his dose to 5 mg PO every 6 hours as needed. At his 1-month follow-up appointment, he reported his pain as 6/10 and no adverse effects. We again increased his dose to 10 mg PO every 6 hours as needed, with follow-up in another month.

Discontinuation and tapering of opioids

Indications for discontinuing opioids are patient request, resolution of pain, doses ≥ 90 MME/d (in which case a pain specialist should be consulted), inadequate response, untoward adverse effects, and abuse and misuse.1,31,41 However, providers may also face the challenge of working with patients for whom the benefit of opioid therapy is uncertain but who do not have an absolute contraindication. Guidance on this matter may be found in a 2017 systematic review of studies on reducing or discontinuing long-term opioid therapy.42 Although evidence on the whole was low quality, it showed that tapering or discontinuing opioids may actually reduce pain and improve function and quality of life.

Continue to: When working with a patient to taper treatment

When working with a patient to taper treatment, consider using a multidisciplinary approach. Also, assess the patient’s pain level and perception of needs for opioids, make clear the substantial effort that will be asked of the patient, and agree on coping strategies the patient can use to manage the taper.31,43 While the evidence does not appear to support one tapering regimen over another, we can offer some recommendations on ways to individualize a tapering regimen (TABLE 5).1,31,41,43,44

General recommendations. Gradually reduce the original MME dose by 5% to 10% every week to every 4 weeks, with frequent follow-up and adjustments as needed based on the individual’s response.1,31,41,43 In the event that the patient does not tolerate this dose-reduction schedule, tapering can be slowed further.31 Avoid abrupt discontinuation.33 Opioid abstinence syndrome, a myriad of symptoms caused by deprivation of opioids in physiologically dependent individuals, although rare, can occur during tapering and can be managed with clonidine 0.1 to 0.2 mg orally every 6 hours or transdermal clonidine patch 0.1 mg/24 hours weekly during the taper.31

Tapering of long-term opioid treatment is not without risk. Immediate risks include withdrawal syndrome, hyperalgesia, and dropout, while ongoing issues are potential relapse, problems in increasing and maintaining function, and medicolegal implications.43 Withdrawal symptoms begin 2 to 3 half-lives after the last dose of opioid, and resolution varies depending on the duration of use, the most recent dose, and speed of tapering.43 In general, a patient needs 20% to 25% of the previous day’s dose to prevent withdrawal symptoms.31 Increased pain appears to be a brief, time-limited occurance.43 Dropout and relapse tend to be attributed to patient factors such as depressive symptoms and higher pain scores at initiation of the taper.43 Low pain at the end of tapering has been shown to predict long-term abstinence from opioids.43

CASE

Two months into his oxycodone regimen, Mr. G reported improved functional status at his catering job and overall improved quality of life. He had improved his lifting form and was attending biweekly physical therapy sessions. His pain score was 3/10. He expressed a desire to “not get hooked on opioids,” and mentioned he had “tried stopping the medicine last week” but experienced withdrawal symptoms. We discussed and prescribed the following 5-week taper plan: 2.5 mg reduction of oxycodone per dose, every 2 weeks x 2. Then 2.5 mg PO every 6 hours as needed x 1 week before stopping.

Organizing your approach

To optimize the chance for success in opioid treatment and to heighten vigilance and minimize harm to patients, we believe an organized approach is key (TABLE 614,22-24,28,30-32), particularly since this class of medication lacks strong evidence to support its long-term use.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tracy Mahvan, PharmD, BCGP, University of Wyoming, School of Pharmacy, 1000 East University Avenue, Laramie, WY 82071; [email protected].

CASE

Marcelo G* is a 46-year-old man who presented to our family medicine clinic with a complex medical history including end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and hemodialysis, chronic anemia, peripheral vascular disease, venous thromboembolism and anticoagulation, major depressive disorder, osteoarthritis, and lumbosacral radiculopathy. His current medications included vitamin B complex, cholecalciferol, atorvastatin, warfarin, acetaminophen, diclofenac gel, and capsaicin cream. Mr. G reported bothersome bilateral knee and back pain despite physical therapy and consistent use of his current medications in addition to occasional intra-articular glucocorticoid injections. He mentioned that he had benefited in the past from intermittent opioid use.

How would you manage this patient’s care?

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

In 2013, an estimated 191 million prescriptions for opioids were written by health care providers, which is the equivalent of all adults living in the United States having their own opioid prescription.1 This large expansion in opioid prescribing and use has also led to a rise in opioid overdose deaths, whether from prescribed or illicit use.1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) points out that each day, approximately 128 Americans die from an opioid overdose.1 Deaths that occur from opioid overdose often involve the prescribed opioids methadone, oxycodone, and hydrocodone, the illicit opioid heroin, and, of particular concern, prescription and illicit fentanyl.1

The extent of this problem has sparked the development of health safety initiatives and research efforts. Through production quotas, the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) reduced the number of opioids produced across all schedule I and schedule II lists in 2017 by as much as 25%.2 The DEA again reduced the amounts produced in 2018.3 For 2020, the DEA has determined that the production quotas and assessment of annual needs are sufficient.4

The CDC has also promoted access to naloxone and prevention initiatives; pharmacies in some states have standing orders for naloxone, and medical personnel and law enforcement now carry it.1,5 Finally, new research has identified risk factors that influence one’s potential for addiction, such as mental illness, history of substance and alcohol abuse, and a low income.6 Interestingly, while numerous initiatives and strategies have been implemented across health systems, there is little evidence that demonstrates how implementation of safe prescribing strategies has affected overall patient safety and avoidance of opioid-related harms.

Nevertheless, concerns related to opioids are especially important for primary care providers, who manage many patients with acute and chronic diseases and disorders that require pain control.7 Family physicians write more opioid prescriptions than any other specialty,8 and they are therefore uniquely positioned to protect patients, improve the quality of their care, and ultimately produce a meaningful public health impact. This article provides a guide to safe opioid prescribing.

Continue to: Use the patient interview to ensure that Tx aligns with patient goals

Use the patient interview to ensure that Tx aligns with patient goals

For patients presenting with chronic pain, conduct a complete general history and physical examination that includes a review of available records; a medical, surgical, social, family, medication, and allergy history; a review of systems; and documentation of any psychiatric comorbidities (ie, depression, anxiety, psychiatric disorders, personality traits). Inquiries about social history and current medications should explore the possibility of previous and current substance use and misuse.

While causes of pain can be assessed through physical examination and diagnostic tests, the patient interview is an invaluable source of information. No single means of assessment has consistently demonstrated superiority over another in measuring pain, and numerous standard assessment tools are available (TABLE 19-13).14 Unidimensional tools are often easy and quick ways to assess pain intensity. Multidimensional tools, although more time intensive, are designed to gather more subjective information about the patient’s pain. Finally, use an instrument such as the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to screen patients for psychological distress.15,16

Provide an environment for patients to openly discuss their experiences, expectations, preferences, fears, and coping efforts, as well as the impact that pain has had on their lives.17,18 Without this foundational understanding, medical treatment may work against the patient’s goals. An empathic approach allows for effective communication, shared decision making, and ultimately, an avenue for individualized therapy.

Balancing treatment with risk mitigation

The challenge of managing chronic pain is to balance treating the patient with the basic principle of nonmaleficence (primum non nocere: “first, do no harm”). The literature has shown that risk factors such as a family history of substance abuse or sexual abuse, younger age, and psychological disease may be linked to greater risk for opioid misuse.19,20 However, despite the many risk-screening tools available, no single instrument has reliably and accurately predicted those at higher propensity for prescription addiction. In fact, risk-screening tools as a whole remain unregulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other authorities.21 Still, screening tools provide useful information as one component of the risk-mitigation process.

Screening tools. The tools most commonly used clinically to stratify risk prior to prescribing opioids are the 5-item Opioid Risk Tool (ORT),22 the revised 24-item Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP-R),23 which are patient self-administered assessments, and the 7-item clinician-administered DIRE (Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk, Efficacy).24 Given the subtle differences in criteria and the time required for each of these risk assessments, we recommend choosing one based on site-specific resources and overall clinician comfort.25 Risk stratification helps to determine the optimal frequency and intensity of monitoring, not necessarily to deny care to “high-risk” patients.

Continue to: In fact, just as the "universal precautions"...

In fact, just as the “universal precautions” approach has been applied to infection control, many have suggested using a similar approach to pain management. Risk screening should never be misunderstood as an attempt to diminish or undermine the patient’s burden of pain. By routinely conducting thorough and respectful inquiries of risk factors for all patients, clinicians can reduce stigma, improve care, and contain overall risk.26,27

Monitoring programs and patient agreements. In addition to risk-screening tools, the CDC recommends using state prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMP) and urine drug testing (UDT) data to confirm the use of prescribed and illicit substances.28 All 50 states have implemented PDMPs.29 Consider incorporating these components into controlled-substance agreements, which ultimately aim to promote safety and trust between patients and providers. Of course, such agreements do not eliminate all risks associated with opioid prescribing, nor do they guarantee the absence of adverse outcomes. However, when used correctly, they can provide safeguards to reduce misuse and abuse. They also have the potential to preserve the patient-provider relationship, as opposed to providers cursorily refusing to prescribe opioids altogether. The term “controlled-substance agreement” is preferable to “pain contract” or “narcotic contract” as the latter 2 terms may feel stigmatizing and threatening.30

Risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS). In an effort to ensure that benefits of opioid analgesics continue to outweigh the risks, the FDA approved the extended-release (ER)/long-acting (LA) opioid analgesics shared system REMS. Under this REMS, a consortium of ER/LA opioid manufacturers is mandated to provide prescriber education in the form of accredited continuing education and patient educational materials, available at https://opioidanalgesicrems.com/RpcUI/home.u.

CASE

After reviewing Mr. G’s chart and conducting a history, we learned that his bilateral knee osteoarthritis was atraumatic and likely due to overuse—although possibly affected by major trauma in a motor vehicle accident 5 years earlier. Imaging also revealed multilevel disc degeneration contributing to his radicular back pain, which seemed to be worse on days after working as a caterer. Poor lifting form at work may have contributed to his pain. Nevertheless, he had been consistent with medical follow-up and denied current or past use of illicit substances. Per the numeric rating scale (NRS), he reported 8 out of 10 pain in his knees and 6 out of 10 in his back. In addition to obtaining a PHQ-9 score of 4, we conducted a DIRE assessment and obtained a score of 19 out of a possible 21, indicating that he may be a good candidate for long-term opioid analgesia.

Criteria for prescribing opioids and for guiding treatment goals

Prescribing an opioid requires establishing a medical necessity based on 3 criteria:31

- pain of moderate-to-severe degree

- a physical diagnosis or suspected organic problem

- documented treatment failure of a noncontrolled substance, adjuvant agents, physician-ordered physical therapy, structured exercise program, and interventional techniques.

Continue to: Treatment goals should be established...

Treatment goals should be established and understood by the prescriber and patient prior to initiation of opioids.28 Overarching treatment goals for all opioids prescribed are pain relief (but not necessarily a focus on pain scores), improvement in functional activity, and minimization of adverse effects, with the latter 2 goals taking precedence.31 To assess outcomes, formally measure progress toward goals from baseline evaluations. This can be achieved through repeated use of validated tools such as those mentioned earlier, or may be more broadly considered as progress toward employment status or increasing participation in activities.31 All pain management plans involving opioids should include continued efforts with nonpharmacologic therapy (eg, exercise therapy, weight loss, behavioral training) and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, anticonvulsants).28

Have an “exit strategy.” As part of goal setting, also consider how therapy will be discontinued if benefits do not outweigh the risks of harm.28 Weigh functional status gains against adverse opioid consequences using the PEG scale (pain, enjoyment of life, and general activity) (TABLE 232).33 Improvements of 30% from baseline have been deemed clinically meaningful by some,32 but not all benefits will be easy to quantify. At the start of treatment dialogue, use the term “therapeutic trial” instead of ”treatment plan” to more effectively convey that opioids will be continued only if safe and effective, and will be prescribed at the lowest effective dose as one component of the multimodal approach to pain.30

Initiation of treatment: Opioid selection and dosing

When initiating opioid therapy, prescribe an immediate-release, short-acting agent instead of an ER/LA formulation.28

For moderate pain, first consider tramadol, codeine, tapentadol, or hydrocodone.31 Second-line agents for moderate pain are hydrocodone or oxycodone.31

For severe pain, first-line agents include hydrocodone, oxycodone, hydromorphone, or morphine.31 Second-line agents for severe pain are fentanyl and, with careful supervision or referral to a pain specialist, methadone or buprenorphine.31

Continue to: Of special note...

Of special note,

At the start, prescribe the lowest effective dosage (referring to the product labeling for guidance) and calculate total daily dose in terms of morphine milligram equivalents (MME) (TABLE 335-37).28 Exercise caution when considering opioids for patients with respiratory sleep disorders and for patients ≥ 65 years due to altered pharmacokinetics in the elderly population.38 Also make dose adjustments for renal and hepatic insufficiency (TABLE 435).

Doses between 20 to 50 MME/d are considered relatively low dosages.28 Be cautious when prescribing an opioid at any dosage, and reassess evidence of individual benefits and risks before increasing the dosage to ≥ 50 MME/d.28 Regard a dosage of 90 MME/d as maximal.28 While there is no analgesic ceiling, doses greater than 90 MME/d are associated with risk for overdose and should prompt referral to a pain specialist.31 Veterans Administration guidelines cite strong evidence that risk for overdose and death significantly increases at a range of 20 to 50 MME/d.33 Daily doses exceeding 90 MME/d should be documented with rational justification.28

CASE

Noncontrolled medications are preferred in the treatment of chronic pain. However, the utility of adjuvant options such as NSAIDs, duloxetine, or gabapentin were limited in Mr. G’s case due to his ESRD. Calcium channel α2-δ ligands may have been effective in reducing symptoms of neuropathic pain but would have had limited efficacy against osteoarthritis. Based on his low risk for opioid misuse, we decided to start Mr. G on oxycodone 2.5 mg PO, every 6 hours as needed for moderate-to-severe pain, and to follow up in 1 month. We also explained proper lifting form to him and encouraged him to continue with physical therapy.

Deciding to continue therapy with opioids

There is a lack of convincing evidence that opioid use beyond 6 months improves quality of life; patients do not report a significant reduction in pain beyond this time.28 Thus, a repeat evaluation of continued medical necessity is essential before deciding in favor of ongoing, long-term treatment with opioids. Continue prescribing opioids only if there is meaningful pain relief and improved function that outweighs the harms that may be expected for a given patient.31 With all patients, consider prescribing naloxone to accompany dispensed opioid prescriptions.28 This is particularly important for those at risk for misuse (history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, dosages ≥ 50 MME/d, or concurrent benzodiazepine use). Resources for prescribing naloxone in primary care settings can be found through Prescribe to Prevent at http://prescribetoprevent.org. Due to the established risk of overdose, avoid, if possible, concomitant prescriptions of benzodiazepines and opioids.31

Continue to: Follow-up and monitoring

Follow-up and monitoring

Responsiveness to opioids varies greatly among individuals.38,39 An opioid that leads to a therapeutic analgesic effect in one patient may cause adverse events or toxicity in another. Periodically reassess the appropriateness of chronic opioid therapy and modify treatment based on its ability to meet therapeutic goals. While practice behaviors and clinic policies vary across institutions, risk stratification can provide guidance on the frequency and intensity of follow-up and monitoring. Kaye et al21 describe a triage system in which low-risk patients may be managed by a primary care provider with routine follow-up and reassessment every 3 months.21 Moderate-risk patients may warrant additional management by specialists and a monthly follow-up. High-risk patients may need referrals to interdisciplinary pain centers or addiction specialists.21

Along these lines, the CDC recommends conducting a PDMP review and UDT before initiating therapy, followed by a periodic PDMP (every 1-3 months) and a UDT at least annually. Keep in mind, providers should follow their state-specific regulations, as monitoring requirements may vary. In addition, clinicians should always be alert to adverse reactions (TABLE 435) and sudden behavior changes such as respiratory depression, nausea, constipation, pruritus, cognitive impairment, falls, motor vehicle accidents, and aberrant behaviors. Under these circumstances, consider a dose reduction and, in certain cases, discontinuation.

Additionally, in cases of pain unresponsive to escalating opioid doses, include opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) in the differential. Dose reductions, opioid rotations, and office-based detoxifications are all options for the treatment of OIH.40 Assessment of pain and function can be accomplished using the PEG scale (TABLE 2).32

CASE

Two weeks into Mr. G’s initial regimen, he called to report no change in pain or functional status. We increased his dose to 5 mg PO every 6 hours as needed. At his 1-month follow-up appointment, he reported his pain as 6/10 and no adverse effects. We again increased his dose to 10 mg PO every 6 hours as needed, with follow-up in another month.

Discontinuation and tapering of opioids

Indications for discontinuing opioids are patient request, resolution of pain, doses ≥ 90 MME/d (in which case a pain specialist should be consulted), inadequate response, untoward adverse effects, and abuse and misuse.1,31,41 However, providers may also face the challenge of working with patients for whom the benefit of opioid therapy is uncertain but who do not have an absolute contraindication. Guidance on this matter may be found in a 2017 systematic review of studies on reducing or discontinuing long-term opioid therapy.42 Although evidence on the whole was low quality, it showed that tapering or discontinuing opioids may actually reduce pain and improve function and quality of life.

Continue to: When working with a patient to taper treatment

When working with a patient to taper treatment, consider using a multidisciplinary approach. Also, assess the patient’s pain level and perception of needs for opioids, make clear the substantial effort that will be asked of the patient, and agree on coping strategies the patient can use to manage the taper.31,43 While the evidence does not appear to support one tapering regimen over another, we can offer some recommendations on ways to individualize a tapering regimen (TABLE 5).1,31,41,43,44

General recommendations. Gradually reduce the original MME dose by 5% to 10% every week to every 4 weeks, with frequent follow-up and adjustments as needed based on the individual’s response.1,31,41,43 In the event that the patient does not tolerate this dose-reduction schedule, tapering can be slowed further.31 Avoid abrupt discontinuation.33 Opioid abstinence syndrome, a myriad of symptoms caused by deprivation of opioids in physiologically dependent individuals, although rare, can occur during tapering and can be managed with clonidine 0.1 to 0.2 mg orally every 6 hours or transdermal clonidine patch 0.1 mg/24 hours weekly during the taper.31

Tapering of long-term opioid treatment is not without risk. Immediate risks include withdrawal syndrome, hyperalgesia, and dropout, while ongoing issues are potential relapse, problems in increasing and maintaining function, and medicolegal implications.43 Withdrawal symptoms begin 2 to 3 half-lives after the last dose of opioid, and resolution varies depending on the duration of use, the most recent dose, and speed of tapering.43 In general, a patient needs 20% to 25% of the previous day’s dose to prevent withdrawal symptoms.31 Increased pain appears to be a brief, time-limited occurance.43 Dropout and relapse tend to be attributed to patient factors such as depressive symptoms and higher pain scores at initiation of the taper.43 Low pain at the end of tapering has been shown to predict long-term abstinence from opioids.43

CASE

Two months into his oxycodone regimen, Mr. G reported improved functional status at his catering job and overall improved quality of life. He had improved his lifting form and was attending biweekly physical therapy sessions. His pain score was 3/10. He expressed a desire to “not get hooked on opioids,” and mentioned he had “tried stopping the medicine last week” but experienced withdrawal symptoms. We discussed and prescribed the following 5-week taper plan: 2.5 mg reduction of oxycodone per dose, every 2 weeks x 2. Then 2.5 mg PO every 6 hours as needed x 1 week before stopping.

Organizing your approach

To optimize the chance for success in opioid treatment and to heighten vigilance and minimize harm to patients, we believe an organized approach is key (TABLE 614,22-24,28,30-32), particularly since this class of medication lacks strong evidence to support its long-term use.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tracy Mahvan, PharmD, BCGP, University of Wyoming, School of Pharmacy, 1000 East University Avenue, Laramie, WY 82071; [email protected].

1. CDC. Opioid overdose. www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/opioids/prescribed.html. Accessed June 26, 2020.

2. DEA, Department of Justice. Established aggregate production quotas for schedule I and II controlled substances and assessment of annual needs for the list I chemicals ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine for 2017. www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/quotas/2016/fr1005.htm. Accessed June 26, 2020.

3. DEA, Department of Justice. Established aggregate production quotas for schedule I and II controlled substances and assessment of annual needs for the list I chemicals ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine for 2018. www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/quotas/2017/fr1108.htm. Accessed June 26, 2020.

4. DEA, Department of Justice. Established aggregate production quotas for schedule I and II controlled substances and assessment of annual needs for the list I chemicals ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine for 2020. www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/quotas/2019/fr1202.htm. Accessed June 26, 2020.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy benefits management services: academic detailing service—opioid overdose education & naloxone distribution (OEND). www.pbm.va.gov/AcademicDetailingService/Opioid_Overdose_Education_and_Naloxone_Distribution.asp. Accessed June 26, 2020.

6. McCarberg BH. Pain management in primary care: strategies to mitigate opioid misuse, abuse, and diversion. Postgrad Med. 2011;123:119-130.

7. Dean L. Tramadol therapy and CYP2D6 genotype. In: Pratt V, McLeod H, Rubinstein W, et al (eds). Medical Genetics Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda, Md: National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2015. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK315950/. Accessed June 26, 2020.

8. Chen JH, Humphreys K, Shah NH, et al. Distribution of opioids by different types of Medicare prescribers. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:259-261.

9. Jensen MP, Karoly P. Self-report scales and procedures for assessing pain in adults. In: Turk DC, Melzack R, eds. Handbook of Pain Assessment. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011;19-41.

10. Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs. 2005; 14:798-804.

11. Ohnhaus EE, Adler R. Methodological problems in the measurement of pain: a comparison between the verbal rating scale and the visual analogue scale. Pain. 1975;1:379-384.

12. Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129-138.

13. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Revicki DA, et al. Development and initial validation of an expanded and revised version of the short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ-2). Pain. 2009;144:35-42.

14. Dansie EJ, Turk DC. Assessment of patients with chronic pain. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:19-25.

15. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613.

16. Choi Y, Mayer TG, Williams MJ, Gatchel RJ. What is the best screening test for depression in chronic spinal pain patients? Spine J. 2014;14:1175-1182.

17. Practice guidelines for chronic pain management: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Anesthesiology. 2010;122:810-833.

18. Gallagher RM. Empathy: a timeless skill for the pain medicine toolbox. Pain Med. 2006;7:213-214.

19. Koyyalagunta D, Bruera E, Aigner C, et al. Risk stratification of opioid misuse among patients with cancer pain using the SOAPP-SF. Pain Med. 2013;14:667-675.

20. Trescot AM, Helm S, Hansen H, et al. Opioids in the management of chronic non-cancer pain: an update of American Society of the Interventional Pain Physicians’ (ASIPP) guidelines. Pain Physician. 2008;11:S5-S62.

21. Kaye AD, Jones MR, Kaye AM, et al. Prescription opioid abuse in chronic pain: an updated review of opioid abuse predictors and strategies to curb opioid abuse (part 2). Pain Physician. 2017;20:S111-S133.

22. Webster LR, Webster RM. Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid‐treated patients: preliminary validation of the Opioid Risk Tool. Pain Med. 2005;6:432-442.

23. Butler SF, Fernandez K, Benoit C, et al. Validation of the revised screener and opioid assessment for patients with pain (SOAPP-R). J Pain. 2008;9:360-372.

24. Belgrade MJ, Schamber CD, Lindgren BR. The DIRE score: predicting outcomes of opioid prescribing for chronic pain. J Pain. 2006;7:671-681.

25. Fine PG, Finnegan T, Portenoy RK. Protect your patients, protect your practice: practical risk assessment in the structuring of opioid therapy in chronic pain. J Fam Pract. 2010;59(9 suppl 2):S1-16.

26. Gourlay DL, Heit HA, Almahrezi A. Universal precautions in pain medicine: a rational approach to the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Med. 2005;6:107-112.

27. Manubay JM, Muchow C, Sullivan MA. Prescription drug abuse: epidemiology, regulatory issues, chronic pain management with narcotic analgesics. Prim Care. 2011;38:71-90.

28. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49.

29. Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Training and Technical Assistance Center. State PDMP profiles and contacts. www.pdmpassist.org/State. Accessed June 26, 2020.

30. Tobin DG, Andrews R, Becker WC. Prescribing opioids in primary care: Safely starting, monitoring, and stopping. Cleve Clin J Med. 2016;83:207-215.

31. Manchikanti L, Kaye AM, Knezevis NN, et al. Responsible, safe, and effective prescription of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines. Pain Physician. 2017;20:S3-S92.

32. HHS. Checklist for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/PDO_Checklist-a.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2020.

33. VA/DoD. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for opioid therapy for chronic pain. www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Pain/cot/VADoDOTCPG022717.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2020.

34. Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:38-47.

35. Lexi-Comp Online. Hudson (OH): Wolters Kluwer Clinical Drug Information, Inc; 2018. https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/login. Accessed July 9, 2020.

36. CMS. Opioid oral morphine milligram equivalent (MME) conversion factors. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Opioid-Morphine-EQ-Conversion-Factors-Aug-2017.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2020.

37. Cupp M. Equianalgesic dosing of opioids for pain management. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter. 2018:340406. Stockton (CA): Therapeutic Research Center, LLC; 2018. www.nhms.org/sites/default/files/Pdfs/Opioid-Comparison-Chart-Prescriber-Letter-2012.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2020.

38. Smith HS. Variations in opioid responsiveness. Pain Physician. 2008;11:237-248.

39. Bronstein K, Passik S, Munitz L, et al. Can clinicians accurately predict which patients are misusing their medications? J Pain. 2011;12(suppl):P3.

40. Silverman SM. Opioid induced hyperalgesia: clinical implications for the pain practitioner. Pain Physician. 2009;12:679-684.

41. Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic non-cancer pain. CMAJ. 2017;189:E659-E666.

42. Frank JW, Lovejoy TI, Becker WC, et al. Patient outcomes in dose reduction or discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:181-191.

43. Berna C, Kulich RJ, Rathmell JP. Tapering long-term opioid therapy in chronic non-cancer pain: evidence and recommendations for everyday practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:828-842.

44. Washington State Agency Medical Director’s Group. Interagency guideline on prescribing opioids for pain. June 2015. www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/Files/2015AMDGOpioidGuideline.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2020.