User login

‘Obesity paradox’ in AFib challenged as mortality climbs with BMI

The relationship between body mass index (BMI) and all-cause mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) is U-shaped, with the risk highest in those who are underweight or severely obese and lowest in patients defined simply as obese, a registry analysis suggests. It also showed a similar relationship between BMI and risk for new or worsening heart failure (HF).

Mortality bottomed out at a BMI of about 30-35 kg/m2, which suggests that mild obesity was protective, compared even with “normal-weight” or “overweight” BMI. Still, mortality went up sharply from there with rising BMI.

But higher BMI, a surrogate for obesity, apparently didn’t worsen outcomes by itself. The risk for death from any cause at higher obesity levels was found to depend a lot on related risk factors and comorbidities when the analysis controlled for conditions such as diabetes and hypertension.

The findings suggest an inverse relationship between BMI and all-cause mortality in AFib only for patients with BMI less than about 30. They therefore argue against any “obesity paradox” in AFib that posits consistently better survival with increasing levels of obesity, say researchers, based on their analysis of patients with new-onset AFib in the GARFIELD-AF registry.

“It’s common practice now for clinicians to discuss weight within a clinic setting when they’re talking to their AFib patients,” observed Christian Fielder Camm, BM, BCh, University of Oxford (England), and Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, Reading, England. So studies suggesting an inverse association between BMI and AFib-related risk can be a concern.

Such studies “seem to suggest that once you’ve got AFib, maintaining a high or very high BMI may in some way be protective – which is contrary to what would seem to make sense and certainly contrary to what our results have shown,” Dr. Camm told this news organization.

“I think that having further evidence now to suggest, actually, that greater BMI is associated with a greater risk of all-cause mortality and heart failure helps reframe that discussion at the physician-patient interaction level more clearly, and ensures that we’re able to talk to our patients appropriately about risks associated with BMI and atrial fibrillation,” said Dr. Camm, who is lead author on the analysis published in Open Heart.

“Obesity is a cause of most cardiovascular diseases, but [these] data would support that being overweight or having mild obesity does not increase the risk,” observed Carl J. Lavie, MD, of the John Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute, New Orleans, La., and the Ochsner Clinical School at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

“At a BMI of 40, it’s very important for them to lose weight for their long-term prognosis,” Dr. Lavie noted, but “at a BMI of 30, the important thing would be to prevent further weight gain. And if they could keep their BMI of 30, they should have a good prognosis. Their prognosis would be particularly good if they didn’t gain weight and put themselves in a more extreme obesity class that is associated with worse risk.”

The current analysis, Dr. Lavie said, “is way better than the AFFIRM study,” which yielded an obesity-paradox report on its patients with AFib about a dozen years ago. “It’s got more data, more numbers, more statistical power,” and breaks BMI into more categories.

That previous analysis based on the influential AFFIRM randomized trial separated its 4,060 patients with AFib into normal (BMI, 18.5-25), overweight (BMI, 25-30), and obese (BMI, > 30) categories, per the convention at the time. It concluded that “obese patients with atrial fibrillation appear to have better long-term outcomes than nonobese patients.”

Bleeding risk on oral anticoagulants

Also noteworthy in the current analysis, variation in BMI didn’t seem to affect mortality or risk for major bleeding or nonhemorrhagic stroke according to choice of oral anticoagulant – whether a new oral anticoagulant (NOAC) or a vitamin K antagonist (VKA).

“We saw that even in the obese and extremely obese group, all-cause mortality was lower in the group taking NOACs, compared with taking warfarin,” Dr. Camm observed, “which goes against the idea that we would need any kind of dose adjustments for increased BMI.”

Indeed, the report notes, use of NOACs, compared with VKA, was associated with a 23% drop in risk for death among patients who were either normal weight or overweight and also in those who were obese or extremely obese.

Those findings “are basically saying that the NOACs look better than warfarin regardless of weight,” agreed Dr. Lavie. “The problem is that the study is not very powered.”

Whereas the benefits of NOACs, compared to VKA, seem similar for patients with a BMI of 30 or 34, compared with a BMI of 23, for example, “none of the studies has many people with 50 BMI.” Many clinicians “feel uncomfortable giving the same dose of NOAC to somebody who has a 60 BMI,” he said. At least with warfarin, “you can check the INR [international normalized ratio].”

The current analysis included 40,482 patients with recently diagnosed AFib and at least one other stroke risk factor from among the registry’s more than 50,000 patients from 35 countries, enrolled from 2010 to 2016. They were followed for 2 years.

The 703 patients with BMI under 18.5 at AFib diagnosis were classified per World Health Organization definitions as underweight; the 13,095 with BMI 18.5-25 as normal weight; the 15,043 with BMI 25-30 as overweight; the 7,560 with BMI 30-35 as obese; and the 4,081 with BMI above 35 as extremely obese. Their ages averaged 71 years, and 55.6% were men.

BMI effects on different outcomes

Relationships between BMI and all-cause mortality and between BMI and new or worsening HF emerged as U-shaped, the risk climbing with both increasing and decreasing BMI. The nadir BMI for risk was about 30 in the case of mortality and about 25 for new or worsening HF.

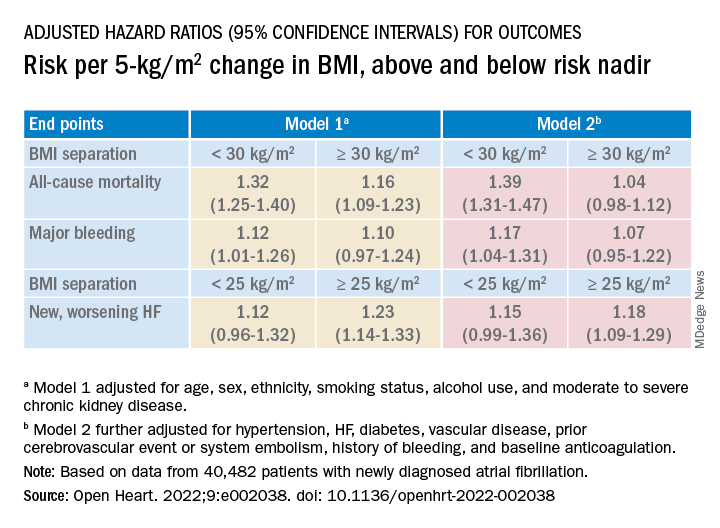

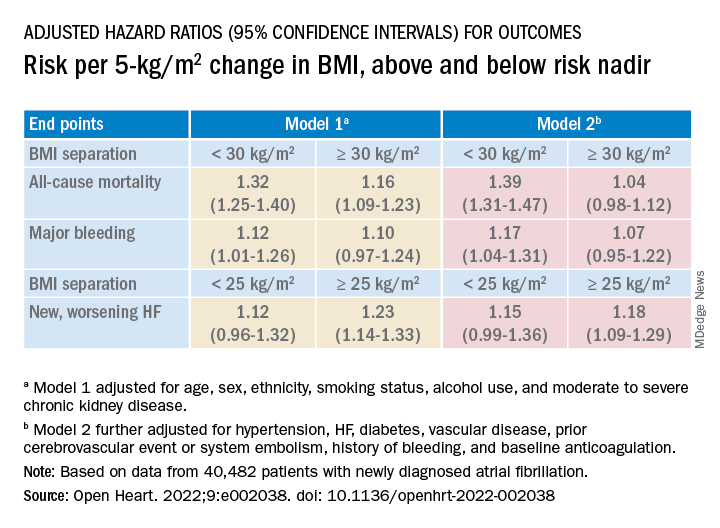

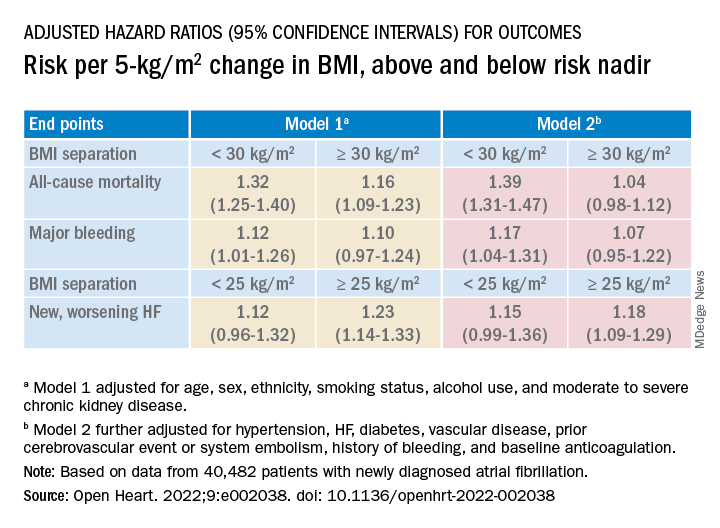

The all-cause mortality risk rose by 32% for every 5 BMI points lower than a BMI of 30, and by 16% for every 5 BMI points higher than 30, in a partially adjusted analysis. The risk for new or worsening HF rose significantly with increasing but not decreasing BMI, and the reverse was observed for the endpoint of major bleeding.

The effect of BMI on all-cause mortality was “substantially attenuated” when the analysis was further adjusted with “likely mediators of any association between BMI and outcomes,” including hypertension, diabetes, HF, cerebrovascular events, and history of bleeding, Dr. Camm said.

That blunted BMI-mortality relationship, he said, “suggests that a lot of the effect is mediated through relatively traditional risk factors like hypertension and diabetes.”

The 2010 AFFIRM analysis by BMI, Dr. Lavie noted, “didn’t even look at the underweight; they actually threw them out.” Yet, such patients with AFib, who tend to be extremely frail or have chronic diseases or conditions other than the arrhythmia, are common. A take-home of the current study is that “the underweight with atrial fibrillation have a really bad prognosis.”

That message isn’t heard as much, he observed, “but is as important as saying that BMI 30 has the best prognosis. The worst prognosis is with the underweight or the really extreme obese.”

Dr. Camm discloses research funding from the British Heart Foundation. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Lavie has previously disclosed serving as a speaker and consultant for PAI Health and DSM Nutritional Products and is the author of “The Obesity Paradox: When Thinner Means Sicker and Heavier Means Healthier” (Avery, 2014).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The relationship between body mass index (BMI) and all-cause mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) is U-shaped, with the risk highest in those who are underweight or severely obese and lowest in patients defined simply as obese, a registry analysis suggests. It also showed a similar relationship between BMI and risk for new or worsening heart failure (HF).

Mortality bottomed out at a BMI of about 30-35 kg/m2, which suggests that mild obesity was protective, compared even with “normal-weight” or “overweight” BMI. Still, mortality went up sharply from there with rising BMI.

But higher BMI, a surrogate for obesity, apparently didn’t worsen outcomes by itself. The risk for death from any cause at higher obesity levels was found to depend a lot on related risk factors and comorbidities when the analysis controlled for conditions such as diabetes and hypertension.

The findings suggest an inverse relationship between BMI and all-cause mortality in AFib only for patients with BMI less than about 30. They therefore argue against any “obesity paradox” in AFib that posits consistently better survival with increasing levels of obesity, say researchers, based on their analysis of patients with new-onset AFib in the GARFIELD-AF registry.

“It’s common practice now for clinicians to discuss weight within a clinic setting when they’re talking to their AFib patients,” observed Christian Fielder Camm, BM, BCh, University of Oxford (England), and Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, Reading, England. So studies suggesting an inverse association between BMI and AFib-related risk can be a concern.

Such studies “seem to suggest that once you’ve got AFib, maintaining a high or very high BMI may in some way be protective – which is contrary to what would seem to make sense and certainly contrary to what our results have shown,” Dr. Camm told this news organization.

“I think that having further evidence now to suggest, actually, that greater BMI is associated with a greater risk of all-cause mortality and heart failure helps reframe that discussion at the physician-patient interaction level more clearly, and ensures that we’re able to talk to our patients appropriately about risks associated with BMI and atrial fibrillation,” said Dr. Camm, who is lead author on the analysis published in Open Heart.

“Obesity is a cause of most cardiovascular diseases, but [these] data would support that being overweight or having mild obesity does not increase the risk,” observed Carl J. Lavie, MD, of the John Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute, New Orleans, La., and the Ochsner Clinical School at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

“At a BMI of 40, it’s very important for them to lose weight for their long-term prognosis,” Dr. Lavie noted, but “at a BMI of 30, the important thing would be to prevent further weight gain. And if they could keep their BMI of 30, they should have a good prognosis. Their prognosis would be particularly good if they didn’t gain weight and put themselves in a more extreme obesity class that is associated with worse risk.”

The current analysis, Dr. Lavie said, “is way better than the AFFIRM study,” which yielded an obesity-paradox report on its patients with AFib about a dozen years ago. “It’s got more data, more numbers, more statistical power,” and breaks BMI into more categories.

That previous analysis based on the influential AFFIRM randomized trial separated its 4,060 patients with AFib into normal (BMI, 18.5-25), overweight (BMI, 25-30), and obese (BMI, > 30) categories, per the convention at the time. It concluded that “obese patients with atrial fibrillation appear to have better long-term outcomes than nonobese patients.”

Bleeding risk on oral anticoagulants

Also noteworthy in the current analysis, variation in BMI didn’t seem to affect mortality or risk for major bleeding or nonhemorrhagic stroke according to choice of oral anticoagulant – whether a new oral anticoagulant (NOAC) or a vitamin K antagonist (VKA).

“We saw that even in the obese and extremely obese group, all-cause mortality was lower in the group taking NOACs, compared with taking warfarin,” Dr. Camm observed, “which goes against the idea that we would need any kind of dose adjustments for increased BMI.”

Indeed, the report notes, use of NOACs, compared with VKA, was associated with a 23% drop in risk for death among patients who were either normal weight or overweight and also in those who were obese or extremely obese.

Those findings “are basically saying that the NOACs look better than warfarin regardless of weight,” agreed Dr. Lavie. “The problem is that the study is not very powered.”

Whereas the benefits of NOACs, compared to VKA, seem similar for patients with a BMI of 30 or 34, compared with a BMI of 23, for example, “none of the studies has many people with 50 BMI.” Many clinicians “feel uncomfortable giving the same dose of NOAC to somebody who has a 60 BMI,” he said. At least with warfarin, “you can check the INR [international normalized ratio].”

The current analysis included 40,482 patients with recently diagnosed AFib and at least one other stroke risk factor from among the registry’s more than 50,000 patients from 35 countries, enrolled from 2010 to 2016. They were followed for 2 years.

The 703 patients with BMI under 18.5 at AFib diagnosis were classified per World Health Organization definitions as underweight; the 13,095 with BMI 18.5-25 as normal weight; the 15,043 with BMI 25-30 as overweight; the 7,560 with BMI 30-35 as obese; and the 4,081 with BMI above 35 as extremely obese. Their ages averaged 71 years, and 55.6% were men.

BMI effects on different outcomes

Relationships between BMI and all-cause mortality and between BMI and new or worsening HF emerged as U-shaped, the risk climbing with both increasing and decreasing BMI. The nadir BMI for risk was about 30 in the case of mortality and about 25 for new or worsening HF.

The all-cause mortality risk rose by 32% for every 5 BMI points lower than a BMI of 30, and by 16% for every 5 BMI points higher than 30, in a partially adjusted analysis. The risk for new or worsening HF rose significantly with increasing but not decreasing BMI, and the reverse was observed for the endpoint of major bleeding.

The effect of BMI on all-cause mortality was “substantially attenuated” when the analysis was further adjusted with “likely mediators of any association between BMI and outcomes,” including hypertension, diabetes, HF, cerebrovascular events, and history of bleeding, Dr. Camm said.

That blunted BMI-mortality relationship, he said, “suggests that a lot of the effect is mediated through relatively traditional risk factors like hypertension and diabetes.”

The 2010 AFFIRM analysis by BMI, Dr. Lavie noted, “didn’t even look at the underweight; they actually threw them out.” Yet, such patients with AFib, who tend to be extremely frail or have chronic diseases or conditions other than the arrhythmia, are common. A take-home of the current study is that “the underweight with atrial fibrillation have a really bad prognosis.”

That message isn’t heard as much, he observed, “but is as important as saying that BMI 30 has the best prognosis. The worst prognosis is with the underweight or the really extreme obese.”

Dr. Camm discloses research funding from the British Heart Foundation. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Lavie has previously disclosed serving as a speaker and consultant for PAI Health and DSM Nutritional Products and is the author of “The Obesity Paradox: When Thinner Means Sicker and Heavier Means Healthier” (Avery, 2014).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The relationship between body mass index (BMI) and all-cause mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) is U-shaped, with the risk highest in those who are underweight or severely obese and lowest in patients defined simply as obese, a registry analysis suggests. It also showed a similar relationship between BMI and risk for new or worsening heart failure (HF).

Mortality bottomed out at a BMI of about 30-35 kg/m2, which suggests that mild obesity was protective, compared even with “normal-weight” or “overweight” BMI. Still, mortality went up sharply from there with rising BMI.

But higher BMI, a surrogate for obesity, apparently didn’t worsen outcomes by itself. The risk for death from any cause at higher obesity levels was found to depend a lot on related risk factors and comorbidities when the analysis controlled for conditions such as diabetes and hypertension.

The findings suggest an inverse relationship between BMI and all-cause mortality in AFib only for patients with BMI less than about 30. They therefore argue against any “obesity paradox” in AFib that posits consistently better survival with increasing levels of obesity, say researchers, based on their analysis of patients with new-onset AFib in the GARFIELD-AF registry.

“It’s common practice now for clinicians to discuss weight within a clinic setting when they’re talking to their AFib patients,” observed Christian Fielder Camm, BM, BCh, University of Oxford (England), and Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, Reading, England. So studies suggesting an inverse association between BMI and AFib-related risk can be a concern.

Such studies “seem to suggest that once you’ve got AFib, maintaining a high or very high BMI may in some way be protective – which is contrary to what would seem to make sense and certainly contrary to what our results have shown,” Dr. Camm told this news organization.

“I think that having further evidence now to suggest, actually, that greater BMI is associated with a greater risk of all-cause mortality and heart failure helps reframe that discussion at the physician-patient interaction level more clearly, and ensures that we’re able to talk to our patients appropriately about risks associated with BMI and atrial fibrillation,” said Dr. Camm, who is lead author on the analysis published in Open Heart.

“Obesity is a cause of most cardiovascular diseases, but [these] data would support that being overweight or having mild obesity does not increase the risk,” observed Carl J. Lavie, MD, of the John Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute, New Orleans, La., and the Ochsner Clinical School at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

“At a BMI of 40, it’s very important for them to lose weight for their long-term prognosis,” Dr. Lavie noted, but “at a BMI of 30, the important thing would be to prevent further weight gain. And if they could keep their BMI of 30, they should have a good prognosis. Their prognosis would be particularly good if they didn’t gain weight and put themselves in a more extreme obesity class that is associated with worse risk.”

The current analysis, Dr. Lavie said, “is way better than the AFFIRM study,” which yielded an obesity-paradox report on its patients with AFib about a dozen years ago. “It’s got more data, more numbers, more statistical power,” and breaks BMI into more categories.

That previous analysis based on the influential AFFIRM randomized trial separated its 4,060 patients with AFib into normal (BMI, 18.5-25), overweight (BMI, 25-30), and obese (BMI, > 30) categories, per the convention at the time. It concluded that “obese patients with atrial fibrillation appear to have better long-term outcomes than nonobese patients.”

Bleeding risk on oral anticoagulants

Also noteworthy in the current analysis, variation in BMI didn’t seem to affect mortality or risk for major bleeding or nonhemorrhagic stroke according to choice of oral anticoagulant – whether a new oral anticoagulant (NOAC) or a vitamin K antagonist (VKA).

“We saw that even in the obese and extremely obese group, all-cause mortality was lower in the group taking NOACs, compared with taking warfarin,” Dr. Camm observed, “which goes against the idea that we would need any kind of dose adjustments for increased BMI.”

Indeed, the report notes, use of NOACs, compared with VKA, was associated with a 23% drop in risk for death among patients who were either normal weight or overweight and also in those who were obese or extremely obese.

Those findings “are basically saying that the NOACs look better than warfarin regardless of weight,” agreed Dr. Lavie. “The problem is that the study is not very powered.”

Whereas the benefits of NOACs, compared to VKA, seem similar for patients with a BMI of 30 or 34, compared with a BMI of 23, for example, “none of the studies has many people with 50 BMI.” Many clinicians “feel uncomfortable giving the same dose of NOAC to somebody who has a 60 BMI,” he said. At least with warfarin, “you can check the INR [international normalized ratio].”

The current analysis included 40,482 patients with recently diagnosed AFib and at least one other stroke risk factor from among the registry’s more than 50,000 patients from 35 countries, enrolled from 2010 to 2016. They were followed for 2 years.

The 703 patients with BMI under 18.5 at AFib diagnosis were classified per World Health Organization definitions as underweight; the 13,095 with BMI 18.5-25 as normal weight; the 15,043 with BMI 25-30 as overweight; the 7,560 with BMI 30-35 as obese; and the 4,081 with BMI above 35 as extremely obese. Their ages averaged 71 years, and 55.6% were men.

BMI effects on different outcomes

Relationships between BMI and all-cause mortality and between BMI and new or worsening HF emerged as U-shaped, the risk climbing with both increasing and decreasing BMI. The nadir BMI for risk was about 30 in the case of mortality and about 25 for new or worsening HF.

The all-cause mortality risk rose by 32% for every 5 BMI points lower than a BMI of 30, and by 16% for every 5 BMI points higher than 30, in a partially adjusted analysis. The risk for new or worsening HF rose significantly with increasing but not decreasing BMI, and the reverse was observed for the endpoint of major bleeding.

The effect of BMI on all-cause mortality was “substantially attenuated” when the analysis was further adjusted with “likely mediators of any association between BMI and outcomes,” including hypertension, diabetes, HF, cerebrovascular events, and history of bleeding, Dr. Camm said.

That blunted BMI-mortality relationship, he said, “suggests that a lot of the effect is mediated through relatively traditional risk factors like hypertension and diabetes.”

The 2010 AFFIRM analysis by BMI, Dr. Lavie noted, “didn’t even look at the underweight; they actually threw them out.” Yet, such patients with AFib, who tend to be extremely frail or have chronic diseases or conditions other than the arrhythmia, are common. A take-home of the current study is that “the underweight with atrial fibrillation have a really bad prognosis.”

That message isn’t heard as much, he observed, “but is as important as saying that BMI 30 has the best prognosis. The worst prognosis is with the underweight or the really extreme obese.”

Dr. Camm discloses research funding from the British Heart Foundation. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Lavie has previously disclosed serving as a speaker and consultant for PAI Health and DSM Nutritional Products and is the author of “The Obesity Paradox: When Thinner Means Sicker and Heavier Means Healthier” (Avery, 2014).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM OPEN HEART

Using wearable devices to detect AFib ‘cost effective’

Screening for atrial fibrillation with wearable devices is cost effective, when compared with either no screening or screening using traditional methods, a new study concludes.

“Undiagnosed atrial fibrillation (AFib) is an important cause of stroke. Screening for AFib using wrist-worn wearable devices may prevent strokes, but their cost effectiveness is unknown,” write Wanyi Chen, PhD, from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues, in JAMA Health Forum.

The investigators used a microsimulation decision-analytic model to evaluate the cost effectiveness of these devices to screen for undiagnosed AFib.

The model comprised 30 million simulated individuals with an age, sex, and comorbidity profile matching the United States population aged 65 years or older.

The model looked at eight AFib screening strategies: six using wrist-worn wearable devices (either watch or band photoplethysmography with or without watch or band electrocardiography) and two using traditional modalities (that is, pulse palpation and 12-lead electrocardiogram) versus no screening.

The primary outcome was the incremental cost effectiveness ratio, defined as U.S. dollars per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). Secondary outcomes included rates of stroke and major bleeding.

In the model, the mean age was 72.5 years and 50% were women.

All 6 screening strategies using wrist-worn wearable devices were estimated to be more cost effective than no screening. The model showed that the range of QALYs gained, compared with no screening, was 226 to 957 per 100,000 individuals.

The wrist-worn devices were also associated with greater relative benefit than screening using traditional modalities, as the range of QALYs gained, compared with no screening, was –116 to 93 per 100,000 individuals.

Compared with no screening, screening with wrist-worn wearable devices was associated with a reduction in stroke incidence by 20 to 23 per 100,000 person-years but an increase in major bleeding by 20 to 44 per 100,000 person years.

Overall, the preferred strategy for screening was wearable photoplethysmography, followed by wearable electrocardiography with patch monitor confirmation. This strategy had an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of $57,894 per QALY, “meeting the acceptability threshold of $100,000 per QALY,” the authors write.

The cost effectiveness of screening was consistent across multiple clinically relevant scenarios, including screening a general population aged 50 years or older with risk factors for stroke, the authors report.

“When deployed within specific AFib screening pathways, wearable devices are likely to be an important component of cost-effective AFib screening,” the investigators conclude.

Study based on modeled data

“This study is the first simulation of various screening strategies for atrial fibrillation using wearable devices and suggests that wearable devices, in particular wrist-worn wearables, in an elderly population, [are] estimated to be cost-effective,” Emma Svennberg, MD, PhD, from the Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, told this news organization.

“I find this study interesting, as the adoption of wearables amongst individuals is high and increasing, hence many wearers will screen themselves for arrhythmias (even if health care recommendations are discordant), and the potential costs for society have been unknown,” said Dr. Svennberg, who was not part of this study.

“Of course, no study is without its flaws, and here one must note that the study is based on modeled data alone and not RCTs of the wearable screening strategies ... hence true clinical outcome data is missing,” Dr. Svennberg added.

The large STROKESTOP study, on which she was the lead investigator, “presented data based on true clinical outcomes at ESC 2021 (European Society of Cardiology) and showed cost effectiveness,” Dr. Svennberg said.

The study authors report financial relationships with Bristol Myers Squibb, Fitbit, Medtronic, Pfizer, UpToDate, American Heart Association, IBM, Bayer AG, Novartis, MyoKardia, Boehringer Ingelheim, Heart Rhythm Society, Avania Consulting, Apple, Premier, the National Institutes of Health, Invitae, Blackstone Life Sciences, Flatiron, and Value Analytics Labs. Dr. Svennberg reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Screening for atrial fibrillation with wearable devices is cost effective, when compared with either no screening or screening using traditional methods, a new study concludes.

“Undiagnosed atrial fibrillation (AFib) is an important cause of stroke. Screening for AFib using wrist-worn wearable devices may prevent strokes, but their cost effectiveness is unknown,” write Wanyi Chen, PhD, from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues, in JAMA Health Forum.

The investigators used a microsimulation decision-analytic model to evaluate the cost effectiveness of these devices to screen for undiagnosed AFib.

The model comprised 30 million simulated individuals with an age, sex, and comorbidity profile matching the United States population aged 65 years or older.

The model looked at eight AFib screening strategies: six using wrist-worn wearable devices (either watch or band photoplethysmography with or without watch or band electrocardiography) and two using traditional modalities (that is, pulse palpation and 12-lead electrocardiogram) versus no screening.

The primary outcome was the incremental cost effectiveness ratio, defined as U.S. dollars per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). Secondary outcomes included rates of stroke and major bleeding.

In the model, the mean age was 72.5 years and 50% were women.

All 6 screening strategies using wrist-worn wearable devices were estimated to be more cost effective than no screening. The model showed that the range of QALYs gained, compared with no screening, was 226 to 957 per 100,000 individuals.

The wrist-worn devices were also associated with greater relative benefit than screening using traditional modalities, as the range of QALYs gained, compared with no screening, was –116 to 93 per 100,000 individuals.

Compared with no screening, screening with wrist-worn wearable devices was associated with a reduction in stroke incidence by 20 to 23 per 100,000 person-years but an increase in major bleeding by 20 to 44 per 100,000 person years.

Overall, the preferred strategy for screening was wearable photoplethysmography, followed by wearable electrocardiography with patch monitor confirmation. This strategy had an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of $57,894 per QALY, “meeting the acceptability threshold of $100,000 per QALY,” the authors write.

The cost effectiveness of screening was consistent across multiple clinically relevant scenarios, including screening a general population aged 50 years or older with risk factors for stroke, the authors report.

“When deployed within specific AFib screening pathways, wearable devices are likely to be an important component of cost-effective AFib screening,” the investigators conclude.

Study based on modeled data

“This study is the first simulation of various screening strategies for atrial fibrillation using wearable devices and suggests that wearable devices, in particular wrist-worn wearables, in an elderly population, [are] estimated to be cost-effective,” Emma Svennberg, MD, PhD, from the Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, told this news organization.

“I find this study interesting, as the adoption of wearables amongst individuals is high and increasing, hence many wearers will screen themselves for arrhythmias (even if health care recommendations are discordant), and the potential costs for society have been unknown,” said Dr. Svennberg, who was not part of this study.

“Of course, no study is without its flaws, and here one must note that the study is based on modeled data alone and not RCTs of the wearable screening strategies ... hence true clinical outcome data is missing,” Dr. Svennberg added.

The large STROKESTOP study, on which she was the lead investigator, “presented data based on true clinical outcomes at ESC 2021 (European Society of Cardiology) and showed cost effectiveness,” Dr. Svennberg said.

The study authors report financial relationships with Bristol Myers Squibb, Fitbit, Medtronic, Pfizer, UpToDate, American Heart Association, IBM, Bayer AG, Novartis, MyoKardia, Boehringer Ingelheim, Heart Rhythm Society, Avania Consulting, Apple, Premier, the National Institutes of Health, Invitae, Blackstone Life Sciences, Flatiron, and Value Analytics Labs. Dr. Svennberg reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Screening for atrial fibrillation with wearable devices is cost effective, when compared with either no screening or screening using traditional methods, a new study concludes.

“Undiagnosed atrial fibrillation (AFib) is an important cause of stroke. Screening for AFib using wrist-worn wearable devices may prevent strokes, but their cost effectiveness is unknown,” write Wanyi Chen, PhD, from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues, in JAMA Health Forum.

The investigators used a microsimulation decision-analytic model to evaluate the cost effectiveness of these devices to screen for undiagnosed AFib.

The model comprised 30 million simulated individuals with an age, sex, and comorbidity profile matching the United States population aged 65 years or older.

The model looked at eight AFib screening strategies: six using wrist-worn wearable devices (either watch or band photoplethysmography with or without watch or band electrocardiography) and two using traditional modalities (that is, pulse palpation and 12-lead electrocardiogram) versus no screening.

The primary outcome was the incremental cost effectiveness ratio, defined as U.S. dollars per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). Secondary outcomes included rates of stroke and major bleeding.

In the model, the mean age was 72.5 years and 50% were women.

All 6 screening strategies using wrist-worn wearable devices were estimated to be more cost effective than no screening. The model showed that the range of QALYs gained, compared with no screening, was 226 to 957 per 100,000 individuals.

The wrist-worn devices were also associated with greater relative benefit than screening using traditional modalities, as the range of QALYs gained, compared with no screening, was –116 to 93 per 100,000 individuals.

Compared with no screening, screening with wrist-worn wearable devices was associated with a reduction in stroke incidence by 20 to 23 per 100,000 person-years but an increase in major bleeding by 20 to 44 per 100,000 person years.

Overall, the preferred strategy for screening was wearable photoplethysmography, followed by wearable electrocardiography with patch monitor confirmation. This strategy had an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of $57,894 per QALY, “meeting the acceptability threshold of $100,000 per QALY,” the authors write.

The cost effectiveness of screening was consistent across multiple clinically relevant scenarios, including screening a general population aged 50 years or older with risk factors for stroke, the authors report.

“When deployed within specific AFib screening pathways, wearable devices are likely to be an important component of cost-effective AFib screening,” the investigators conclude.

Study based on modeled data

“This study is the first simulation of various screening strategies for atrial fibrillation using wearable devices and suggests that wearable devices, in particular wrist-worn wearables, in an elderly population, [are] estimated to be cost-effective,” Emma Svennberg, MD, PhD, from the Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, told this news organization.

“I find this study interesting, as the adoption of wearables amongst individuals is high and increasing, hence many wearers will screen themselves for arrhythmias (even if health care recommendations are discordant), and the potential costs for society have been unknown,” said Dr. Svennberg, who was not part of this study.

“Of course, no study is without its flaws, and here one must note that the study is based on modeled data alone and not RCTs of the wearable screening strategies ... hence true clinical outcome data is missing,” Dr. Svennberg added.

The large STROKESTOP study, on which she was the lead investigator, “presented data based on true clinical outcomes at ESC 2021 (European Society of Cardiology) and showed cost effectiveness,” Dr. Svennberg said.

The study authors report financial relationships with Bristol Myers Squibb, Fitbit, Medtronic, Pfizer, UpToDate, American Heart Association, IBM, Bayer AG, Novartis, MyoKardia, Boehringer Ingelheim, Heart Rhythm Society, Avania Consulting, Apple, Premier, the National Institutes of Health, Invitae, Blackstone Life Sciences, Flatiron, and Value Analytics Labs. Dr. Svennberg reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Staggering’ CVD rise projected in U.S., especially in minorities

A new analysis projects steep increases by 2060 in the prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and disease that will disproportionately affect non-White populations who have limited access to health care.

The study by Reza Mohebi, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, and colleagues was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Even though several assumptions underlie these projections, the importance of this work cannot be overestimated,” Andreas P. Kalogeropoulos, MD, MPH, PhD, and Javed Butler, MD, MPH, MBA, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “The absolute numbers are staggering.”

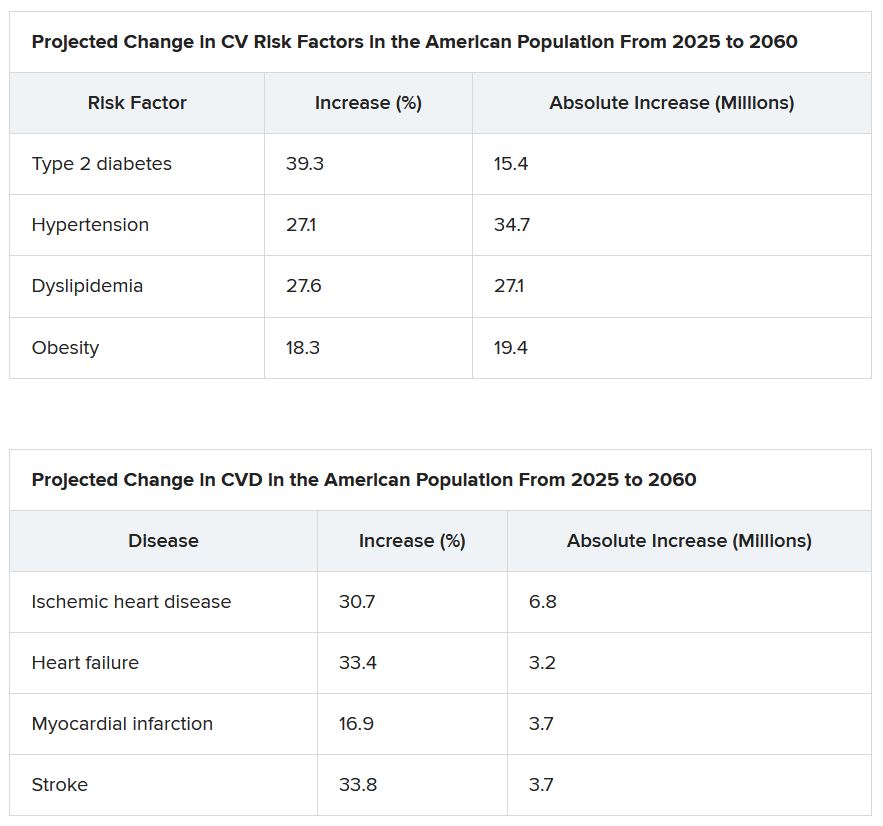

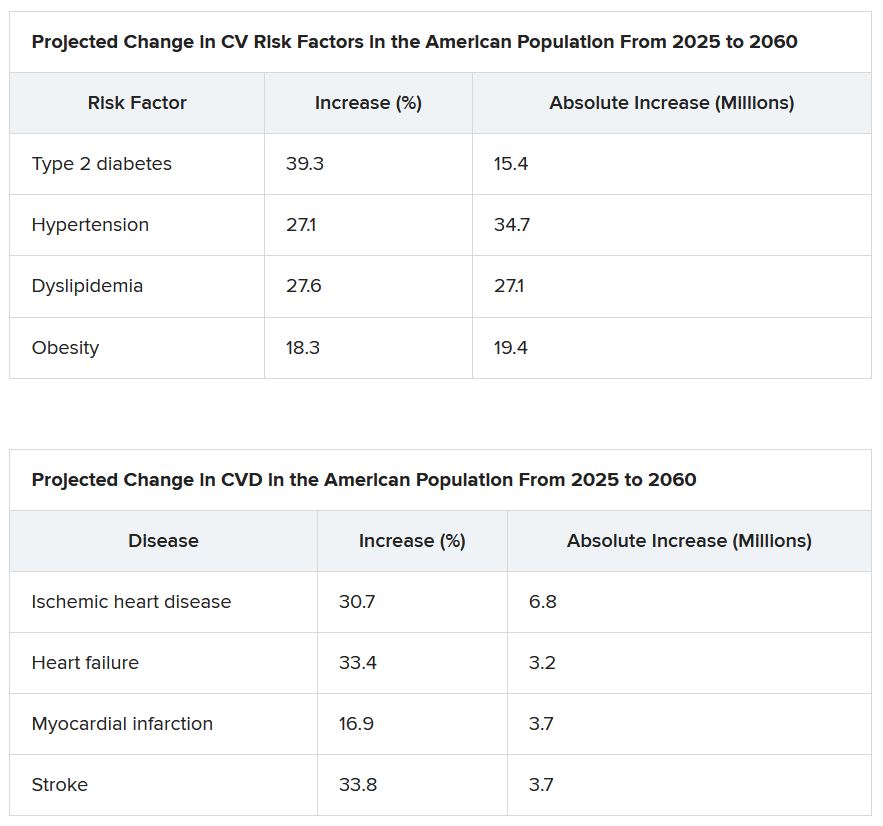

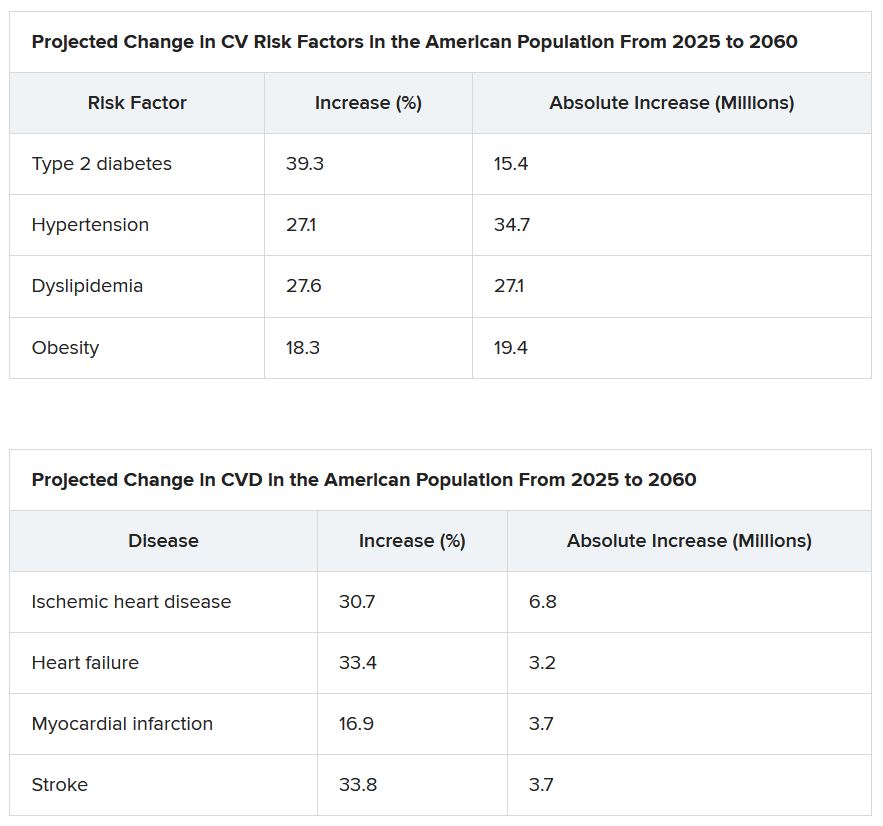

From 2025 to 2060, the number of people with any one of four CV risk factors – type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity – is projected to increase by 15.4 million, to 34.7 million.

And the number of people with of any one of four CV disease types – ischemic heart disease, heart failure, MI, and stroke – is projected to increase by 3.2 million, to 6.8 million.

Although the model predicts that the prevalence of CV risk factors will gradually decrease among White Americans, the highest prevalence of CV risk factors will be among the White population because of its overall size.

Conversely, the projected prevalence of CV risk factors is expected to increase in Black, Hispanic, Asian, and other race/ethnicity populations.

In parallel, the prevalence of CV disease is projected to decrease in the White population and increase among all other race/ethnicities, particularly in the Black and Hispanic populations.

“Our results project a worrisome increase with a particularly ominous increase in risk factors and disease in our most vulnerable patients, including Blacks and Hispanics,” senior author James L. Januzzi Jr., MD, summarized in a video issued by the society.

“The steep rise in CV risk factors and disease reflects the generally higher prevalence in populations projected to increase in the United States, owing to immigration and growth, including Black or Hispanic individuals,” Dr. Januzzi, also from Massachusetts General and Harvard, said in an interview.

“The disproportionate size of the risk is expected in a sense, as minority populations are disproportionately disadvantaged with respect to their health care,” he said. “But whether it is expected or not, the increase in projected prevalence is, nonetheless, concerning and a call to action.”

This study identifies “areas of opportunity for change in the U.S. health care system,” he continued. “Business as usual will result in us encountering a huge number of individuals with CV risk factors and diseases.”

The results from the current analysis assume there will be no modification in health care policies or changes in access to care for at-risk populations, Dr. Mohebi and colleagues noted.

To “stem the rising tide of CV disease in at-risk individuals,” would require strategies such as “emphasis on education regarding CV risk factors, improving access to quality healthcare, and facilitating lower-cost access to effective therapies for treatment of CV risk factors,” according to the researchers.

“Such advances need to be applied in a more equitable way throughout the United States, however,” they cautioned.

Census plus NHANES data

The researchers used 2020 U.S. census data and projected growth and 2013-2018 U.S. National Health and Nutrition Survey data to estimate the number of people with CV risk factors and CV disease from 2025 to 2060.

The estimates are based on a growing population and a fixed frequency.

The projected changes in CV risk factors and disease over time were similar in men and women.

The researchers acknowledge that study limitations include the assumption that the prevalence patterns for CV risk factors and disease will be stable.

“To the extent the frequency of risk factors and disease are not likely to remain static, that assumption may reduce the accuracy of the projections,” Dr. Januzzi said. “However, we would point out that the goals of our analysis were to set general trends, and not to seek to project exact figures.”

Also, they did not take into account the effect of COVID-19. CV diseases were also based on self-report and CV risk factors could have been underestimated in minority populations that do not access health care.

Changing demographic landscape

It is “striking” that the numbers of non-White individuals with CV risk factors is projected to surpass the number of White individuals over time, and the number of non-White individuals with CV disease will be almost as many as White individuals by the year 2060, the editorialists noted.

“From a policy perspective, this means that unless appropriate, targeted action is taken, disparities in the burden of cardiovascular disease are only going to be exacerbated over time,” wrote Dr. Kalogeropoulos, from Stony Brook (N.Y.) University, and Dr. Butler, from Baylor College of Medicine, Dallas.

“On the positive side,” they continued, “the absolute increase in the percent prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and conditions is projected to lie within a manageable range,” assuming that specific prevention policies are implemented.

“This is an opportunity for professional societies, including the cardiovascular care community, to re-evaluate priorities and strategies, for both training and practice, to best match the growing demands of a changing demographic landscape in the United States,” Dr. Kalogeropoulos and Dr. Butler concluded.

Dr. Mohebi is supported by the Barry Fellowship. Dr. Januzzi is supported by the Hutter Family Professorship; is a Trustee of the American College of Cardiology; is a board member of Imbria Pharmaceuticals; has received grant support from Abbott Diagnostics, Applied Therapeutics, Innolife, and Novartis; has received consulting income from Abbott Diagnostics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Novartis, and Roche Diagnostics; and participates in clinical endpoint committees/data safety monitoring boards for AbbVie, Siemens, Takeda, and Vifor. Dr. Kalogeropoulos has received research funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the American Heart Association; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Butler has been a consultant for numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new analysis projects steep increases by 2060 in the prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and disease that will disproportionately affect non-White populations who have limited access to health care.

The study by Reza Mohebi, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, and colleagues was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Even though several assumptions underlie these projections, the importance of this work cannot be overestimated,” Andreas P. Kalogeropoulos, MD, MPH, PhD, and Javed Butler, MD, MPH, MBA, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “The absolute numbers are staggering.”

From 2025 to 2060, the number of people with any one of four CV risk factors – type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity – is projected to increase by 15.4 million, to 34.7 million.

And the number of people with of any one of four CV disease types – ischemic heart disease, heart failure, MI, and stroke – is projected to increase by 3.2 million, to 6.8 million.

Although the model predicts that the prevalence of CV risk factors will gradually decrease among White Americans, the highest prevalence of CV risk factors will be among the White population because of its overall size.

Conversely, the projected prevalence of CV risk factors is expected to increase in Black, Hispanic, Asian, and other race/ethnicity populations.

In parallel, the prevalence of CV disease is projected to decrease in the White population and increase among all other race/ethnicities, particularly in the Black and Hispanic populations.

“Our results project a worrisome increase with a particularly ominous increase in risk factors and disease in our most vulnerable patients, including Blacks and Hispanics,” senior author James L. Januzzi Jr., MD, summarized in a video issued by the society.

“The steep rise in CV risk factors and disease reflects the generally higher prevalence in populations projected to increase in the United States, owing to immigration and growth, including Black or Hispanic individuals,” Dr. Januzzi, also from Massachusetts General and Harvard, said in an interview.

“The disproportionate size of the risk is expected in a sense, as minority populations are disproportionately disadvantaged with respect to their health care,” he said. “But whether it is expected or not, the increase in projected prevalence is, nonetheless, concerning and a call to action.”

This study identifies “areas of opportunity for change in the U.S. health care system,” he continued. “Business as usual will result in us encountering a huge number of individuals with CV risk factors and diseases.”

The results from the current analysis assume there will be no modification in health care policies or changes in access to care for at-risk populations, Dr. Mohebi and colleagues noted.

To “stem the rising tide of CV disease in at-risk individuals,” would require strategies such as “emphasis on education regarding CV risk factors, improving access to quality healthcare, and facilitating lower-cost access to effective therapies for treatment of CV risk factors,” according to the researchers.

“Such advances need to be applied in a more equitable way throughout the United States, however,” they cautioned.

Census plus NHANES data

The researchers used 2020 U.S. census data and projected growth and 2013-2018 U.S. National Health and Nutrition Survey data to estimate the number of people with CV risk factors and CV disease from 2025 to 2060.

The estimates are based on a growing population and a fixed frequency.

The projected changes in CV risk factors and disease over time were similar in men and women.

The researchers acknowledge that study limitations include the assumption that the prevalence patterns for CV risk factors and disease will be stable.

“To the extent the frequency of risk factors and disease are not likely to remain static, that assumption may reduce the accuracy of the projections,” Dr. Januzzi said. “However, we would point out that the goals of our analysis were to set general trends, and not to seek to project exact figures.”

Also, they did not take into account the effect of COVID-19. CV diseases were also based on self-report and CV risk factors could have been underestimated in minority populations that do not access health care.

Changing demographic landscape

It is “striking” that the numbers of non-White individuals with CV risk factors is projected to surpass the number of White individuals over time, and the number of non-White individuals with CV disease will be almost as many as White individuals by the year 2060, the editorialists noted.

“From a policy perspective, this means that unless appropriate, targeted action is taken, disparities in the burden of cardiovascular disease are only going to be exacerbated over time,” wrote Dr. Kalogeropoulos, from Stony Brook (N.Y.) University, and Dr. Butler, from Baylor College of Medicine, Dallas.

“On the positive side,” they continued, “the absolute increase in the percent prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and conditions is projected to lie within a manageable range,” assuming that specific prevention policies are implemented.

“This is an opportunity for professional societies, including the cardiovascular care community, to re-evaluate priorities and strategies, for both training and practice, to best match the growing demands of a changing demographic landscape in the United States,” Dr. Kalogeropoulos and Dr. Butler concluded.

Dr. Mohebi is supported by the Barry Fellowship. Dr. Januzzi is supported by the Hutter Family Professorship; is a Trustee of the American College of Cardiology; is a board member of Imbria Pharmaceuticals; has received grant support from Abbott Diagnostics, Applied Therapeutics, Innolife, and Novartis; has received consulting income from Abbott Diagnostics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Novartis, and Roche Diagnostics; and participates in clinical endpoint committees/data safety monitoring boards for AbbVie, Siemens, Takeda, and Vifor. Dr. Kalogeropoulos has received research funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the American Heart Association; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Butler has been a consultant for numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new analysis projects steep increases by 2060 in the prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and disease that will disproportionately affect non-White populations who have limited access to health care.

The study by Reza Mohebi, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, and colleagues was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Even though several assumptions underlie these projections, the importance of this work cannot be overestimated,” Andreas P. Kalogeropoulos, MD, MPH, PhD, and Javed Butler, MD, MPH, MBA, wrote in an accompanying editorial. “The absolute numbers are staggering.”

From 2025 to 2060, the number of people with any one of four CV risk factors – type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity – is projected to increase by 15.4 million, to 34.7 million.

And the number of people with of any one of four CV disease types – ischemic heart disease, heart failure, MI, and stroke – is projected to increase by 3.2 million, to 6.8 million.

Although the model predicts that the prevalence of CV risk factors will gradually decrease among White Americans, the highest prevalence of CV risk factors will be among the White population because of its overall size.

Conversely, the projected prevalence of CV risk factors is expected to increase in Black, Hispanic, Asian, and other race/ethnicity populations.

In parallel, the prevalence of CV disease is projected to decrease in the White population and increase among all other race/ethnicities, particularly in the Black and Hispanic populations.

“Our results project a worrisome increase with a particularly ominous increase in risk factors and disease in our most vulnerable patients, including Blacks and Hispanics,” senior author James L. Januzzi Jr., MD, summarized in a video issued by the society.

“The steep rise in CV risk factors and disease reflects the generally higher prevalence in populations projected to increase in the United States, owing to immigration and growth, including Black or Hispanic individuals,” Dr. Januzzi, also from Massachusetts General and Harvard, said in an interview.

“The disproportionate size of the risk is expected in a sense, as minority populations are disproportionately disadvantaged with respect to their health care,” he said. “But whether it is expected or not, the increase in projected prevalence is, nonetheless, concerning and a call to action.”

This study identifies “areas of opportunity for change in the U.S. health care system,” he continued. “Business as usual will result in us encountering a huge number of individuals with CV risk factors and diseases.”

The results from the current analysis assume there will be no modification in health care policies or changes in access to care for at-risk populations, Dr. Mohebi and colleagues noted.

To “stem the rising tide of CV disease in at-risk individuals,” would require strategies such as “emphasis on education regarding CV risk factors, improving access to quality healthcare, and facilitating lower-cost access to effective therapies for treatment of CV risk factors,” according to the researchers.

“Such advances need to be applied in a more equitable way throughout the United States, however,” they cautioned.

Census plus NHANES data

The researchers used 2020 U.S. census data and projected growth and 2013-2018 U.S. National Health and Nutrition Survey data to estimate the number of people with CV risk factors and CV disease from 2025 to 2060.

The estimates are based on a growing population and a fixed frequency.

The projected changes in CV risk factors and disease over time were similar in men and women.

The researchers acknowledge that study limitations include the assumption that the prevalence patterns for CV risk factors and disease will be stable.

“To the extent the frequency of risk factors and disease are not likely to remain static, that assumption may reduce the accuracy of the projections,” Dr. Januzzi said. “However, we would point out that the goals of our analysis were to set general trends, and not to seek to project exact figures.”

Also, they did not take into account the effect of COVID-19. CV diseases were also based on self-report and CV risk factors could have been underestimated in minority populations that do not access health care.

Changing demographic landscape

It is “striking” that the numbers of non-White individuals with CV risk factors is projected to surpass the number of White individuals over time, and the number of non-White individuals with CV disease will be almost as many as White individuals by the year 2060, the editorialists noted.

“From a policy perspective, this means that unless appropriate, targeted action is taken, disparities in the burden of cardiovascular disease are only going to be exacerbated over time,” wrote Dr. Kalogeropoulos, from Stony Brook (N.Y.) University, and Dr. Butler, from Baylor College of Medicine, Dallas.

“On the positive side,” they continued, “the absolute increase in the percent prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and conditions is projected to lie within a manageable range,” assuming that specific prevention policies are implemented.

“This is an opportunity for professional societies, including the cardiovascular care community, to re-evaluate priorities and strategies, for both training and practice, to best match the growing demands of a changing demographic landscape in the United States,” Dr. Kalogeropoulos and Dr. Butler concluded.

Dr. Mohebi is supported by the Barry Fellowship. Dr. Januzzi is supported by the Hutter Family Professorship; is a Trustee of the American College of Cardiology; is a board member of Imbria Pharmaceuticals; has received grant support from Abbott Diagnostics, Applied Therapeutics, Innolife, and Novartis; has received consulting income from Abbott Diagnostics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Novartis, and Roche Diagnostics; and participates in clinical endpoint committees/data safety monitoring boards for AbbVie, Siemens, Takeda, and Vifor. Dr. Kalogeropoulos has received research funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the American Heart Association; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Butler has been a consultant for numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Do ICDs still ‘work’ in primary prevention given today’s recommended HF meds?

Contemporary guidelines highly recommend patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) be on all four drug classes that together have shown clinical clout, including improved survival, in major randomized trials.

Although many such patients don’t receive all four drug classes, the more that are prescribed to those with primary-prevention implantable defibrillators (ICD), the better their odds of survival, a new analysis suggests.

The cohort study of almost 5,000 patients with HFrEF and such devices saw their all-cause mortality risk improve stepwise with each additional prescription they were given toward the full quadruple drug combo at the core of modern HFrEF guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT). The four classes are sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), and renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors.

That inverse relation between risk and number of GDMT medications held whether patients had solo-ICD or defibrillating cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT-D) implants, and were independent of device-implantation year and comorbidities, regardless of HFrEF etiology.

“If anybody had doubts about really pushing forward as much of these guideline-directed medical therapies as the patient tolerates, these data confirm that, by doing so, we definitely do better than with two medications or one medication,” Samir Saba, MD, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, said in an interview.

The analysis begs an old and challenging question: Do primary-prevention ICDs confer clinically important survival gains over those provided by increasingly life-preserving recommended HFrEF medical therapy?

Given the study’s incremental survival bumps with each added GDMT med, “one ought to consider whether ICD therapy can still have an impact on overall survival in this population,” proposes a report published online in JACC Clinical Electrophysiology, with Dr. Saba as senior author.

In the adjusted analysis, the 2-year risk for death from any cause in HFrEF patients with primary-prevention devices fell 36% in those with ICDs and 30% in those with CRT-D devices for each added prescribed GDMT drug, from none up to either three or four such agents (P < .001 in both cases).

Only so much can be made of nonrandomized study results, Saba observed in an interview. But they are enough to justify asking whether primary-prevention ICDs are “still valuable” in HFrEF given current GDMT. One interpretation of the study, the published report noted, is that contemporary GDMT improves HFrEF survival so much that it eclipses any such benefit from a primary-prevention ICD.

Both defibrillators and the four core drug therapies boost survival in such cases, “so the fundamental question is, are they additive. Do we save more lives by having a defibrillator on top of the medications, or is it overlapping?” Dr. Saba asked. “We don’t know the answer.”

For now, at least, the findings could reassure clinicians as they consider whether to recommended a primary-prevention ICD when there might be reasons not to, as long there is full GDMT on board, “especially what we today define as quadruple guideline-directed medical therapy.”

Recently announced North American guidelines defining an HFrEF quadruple regimen prefer – beyond a beta-blocker, MRA, and SGLT2 inhibitor – that the selected RAS inhibitor be sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto, Novartis), with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) as a substitute, if needed.

Nearly identical European guidelines on HFrEF quad therapy, unveiled in 2021, include but do not necessarily prefer sacubitril/valsartan over ACE inhibitors as the RAS inhibitor of choice.

GDMT a moving target

Primary-prevention defibrillators entered practice at a time when expected background GDMT consisted of beta-blockers and either ACE inhibitors or ARBs, the current report notes. In practice, many patients receive the devices without both drug classes optimally on board. Moreover, many who otherwise meet guidelines for such ICDs won’t tolerate the kind of maximally tolerated GDMT used in the major primary-prevention device trials.

Yet current guidelines give such devices a class I recommendation, based on the highest level of evidence, in HFrEF patients who remain symptomatic despite quad GDMT, observed Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, University of California Los Angeles Medical Center.

The current analysis “further reinforces the importance of providing all four foundational GDMTs” to all eligible HFrEF patients without contraindications who can tolerate them, he said in an interview. Such quad therapy “is associated with incremental 1-year survival advantages” in patients with primary-prevention devices. And in the major trials, “there were reductions in sudden deaths, as well as progressive heart failure deaths.”

But the current study also suggests that in practice “very few patients can actually get to all four drugs on GDMT,” Roderick Tung, MD, University of Arizona, Phoenix, said in an interview. Optimized GDMT in randomized trials probably represents the best-case scenario. “There is a difference between randomized data and real-world data, which is why we need both.”

And it asserts that “the more GDMT you’re on, the better you do,” he said. “But does that obviate the need for an ICD? I think that’s not clear,” in part because of potential confounding in the analysis. For example, patients who can take all four agents tend to be less sick than those who cannot.

“The ones who can get up to four are preselected, because they’re healthier,” Dr. Tung said. “There are real limitations – such as metabolic disturbances, acute kidney injury and cardiorenal syndrome, and hypotension – that actually make it difficult to initiate and titrate these medications.”

Indeed, the major primary-prevention ICD trials usually excluded the sickest patients with the most comorbidities, Dr. Saba observed, which raises issues about their relevance to clinical practice. But his group’s study controlled for many potential confounders by adjusting for, among other things, Elixhauser comorbidity score, ejection fraction, type of cardiomyopathy, and year of device implantation.

“We tried to level the playing field that way, to see if – despite all of this adjustment – the incremental number of heart failure medicines stills make a difference,” Dr. Saba said. “And our results suggest that yes, they still do.”

GDMT coverage in the real world

The analysis of patients with HFrEF involved 3,210 with ICD-only implants and 1,762 with CRT-D devices for primary prevention at a major medical center from 2010 to 2021. Of the total, 5% had not been prescribed any of the four GDMT agents, 20% had been prescribed only one, 52% were prescribed two, and 23% were prescribed three or four. Only 113 patients had been prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors, which have only recently been indicated for HFrEF.

Adjusted hazard ratios for death from any cause at 2 years for each added GDMT drug (P < .001 in each case), were 0.64 (95% confidence interval, 0.56-0.74) for ICD recipients, 0.70 (95% CI, 0.58-0.86) for those with a CRT-D device, 0.70 (95% CI, 0.60-0.81) for those with ischemic cardiomyopathy, and 0.61 (95% CI, 0.51-0.73) for patients with nonischemic disease.

The results “raise questions rather than answers,” Dr. Saba said. “At some point, someone will need to take patients who are optimized on their heart failure medications and then randomize them to defibrillator versus no defibrillator to see whether there is still an additive impact.”

Current best evidence suggests that primary-prevention ICDs in patients with guideline-based indications confer benefits that far outweigh any risks. But if the major primary-prevention ICD trials were to be repeated in patients on contemporary quad-therapy GDMT, Dr. Tung said, “would the benefit of ICD be attenuated? I think most of us believe it likely would.”

Still, he said, a background of modern GDMT could potentially “optimize” such trials by attenuating mortality from heart failure progression and thereby expanding the proportion of deaths that are arrhythmic, “which the defibrillator can prevent.”

Dr. Saba discloses receiving research support from Boston Scientific and Abbott; and serving on advisory boards for Medtronic and Boston Scientific. The other authors reported no relevant relationships. Dr. Tung has disclosed receiving speaker fees from Abbott and Boston Scientific. Dr. Fonarow has reported receiving personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Cytokinetics, Edwards, Janssen, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Contemporary guidelines highly recommend patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) be on all four drug classes that together have shown clinical clout, including improved survival, in major randomized trials.

Although many such patients don’t receive all four drug classes, the more that are prescribed to those with primary-prevention implantable defibrillators (ICD), the better their odds of survival, a new analysis suggests.

The cohort study of almost 5,000 patients with HFrEF and such devices saw their all-cause mortality risk improve stepwise with each additional prescription they were given toward the full quadruple drug combo at the core of modern HFrEF guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT). The four classes are sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), and renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors.

That inverse relation between risk and number of GDMT medications held whether patients had solo-ICD or defibrillating cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT-D) implants, and were independent of device-implantation year and comorbidities, regardless of HFrEF etiology.

“If anybody had doubts about really pushing forward as much of these guideline-directed medical therapies as the patient tolerates, these data confirm that, by doing so, we definitely do better than with two medications or one medication,” Samir Saba, MD, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, said in an interview.

The analysis begs an old and challenging question: Do primary-prevention ICDs confer clinically important survival gains over those provided by increasingly life-preserving recommended HFrEF medical therapy?

Given the study’s incremental survival bumps with each added GDMT med, “one ought to consider whether ICD therapy can still have an impact on overall survival in this population,” proposes a report published online in JACC Clinical Electrophysiology, with Dr. Saba as senior author.

In the adjusted analysis, the 2-year risk for death from any cause in HFrEF patients with primary-prevention devices fell 36% in those with ICDs and 30% in those with CRT-D devices for each added prescribed GDMT drug, from none up to either three or four such agents (P < .001 in both cases).

Only so much can be made of nonrandomized study results, Saba observed in an interview. But they are enough to justify asking whether primary-prevention ICDs are “still valuable” in HFrEF given current GDMT. One interpretation of the study, the published report noted, is that contemporary GDMT improves HFrEF survival so much that it eclipses any such benefit from a primary-prevention ICD.

Both defibrillators and the four core drug therapies boost survival in such cases, “so the fundamental question is, are they additive. Do we save more lives by having a defibrillator on top of the medications, or is it overlapping?” Dr. Saba asked. “We don’t know the answer.”

For now, at least, the findings could reassure clinicians as they consider whether to recommended a primary-prevention ICD when there might be reasons not to, as long there is full GDMT on board, “especially what we today define as quadruple guideline-directed medical therapy.”

Recently announced North American guidelines defining an HFrEF quadruple regimen prefer – beyond a beta-blocker, MRA, and SGLT2 inhibitor – that the selected RAS inhibitor be sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto, Novartis), with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) as a substitute, if needed.

Nearly identical European guidelines on HFrEF quad therapy, unveiled in 2021, include but do not necessarily prefer sacubitril/valsartan over ACE inhibitors as the RAS inhibitor of choice.

GDMT a moving target

Primary-prevention defibrillators entered practice at a time when expected background GDMT consisted of beta-blockers and either ACE inhibitors or ARBs, the current report notes. In practice, many patients receive the devices without both drug classes optimally on board. Moreover, many who otherwise meet guidelines for such ICDs won’t tolerate the kind of maximally tolerated GDMT used in the major primary-prevention device trials.

Yet current guidelines give such devices a class I recommendation, based on the highest level of evidence, in HFrEF patients who remain symptomatic despite quad GDMT, observed Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, University of California Los Angeles Medical Center.

The current analysis “further reinforces the importance of providing all four foundational GDMTs” to all eligible HFrEF patients without contraindications who can tolerate them, he said in an interview. Such quad therapy “is associated with incremental 1-year survival advantages” in patients with primary-prevention devices. And in the major trials, “there were reductions in sudden deaths, as well as progressive heart failure deaths.”

But the current study also suggests that in practice “very few patients can actually get to all four drugs on GDMT,” Roderick Tung, MD, University of Arizona, Phoenix, said in an interview. Optimized GDMT in randomized trials probably represents the best-case scenario. “There is a difference between randomized data and real-world data, which is why we need both.”

And it asserts that “the more GDMT you’re on, the better you do,” he said. “But does that obviate the need for an ICD? I think that’s not clear,” in part because of potential confounding in the analysis. For example, patients who can take all four agents tend to be less sick than those who cannot.

“The ones who can get up to four are preselected, because they’re healthier,” Dr. Tung said. “There are real limitations – such as metabolic disturbances, acute kidney injury and cardiorenal syndrome, and hypotension – that actually make it difficult to initiate and titrate these medications.”

Indeed, the major primary-prevention ICD trials usually excluded the sickest patients with the most comorbidities, Dr. Saba observed, which raises issues about their relevance to clinical practice. But his group’s study controlled for many potential confounders by adjusting for, among other things, Elixhauser comorbidity score, ejection fraction, type of cardiomyopathy, and year of device implantation.

“We tried to level the playing field that way, to see if – despite all of this adjustment – the incremental number of heart failure medicines stills make a difference,” Dr. Saba said. “And our results suggest that yes, they still do.”

GDMT coverage in the real world

The analysis of patients with HFrEF involved 3,210 with ICD-only implants and 1,762 with CRT-D devices for primary prevention at a major medical center from 2010 to 2021. Of the total, 5% had not been prescribed any of the four GDMT agents, 20% had been prescribed only one, 52% were prescribed two, and 23% were prescribed three or four. Only 113 patients had been prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors, which have only recently been indicated for HFrEF.

Adjusted hazard ratios for death from any cause at 2 years for each added GDMT drug (P < .001 in each case), were 0.64 (95% confidence interval, 0.56-0.74) for ICD recipients, 0.70 (95% CI, 0.58-0.86) for those with a CRT-D device, 0.70 (95% CI, 0.60-0.81) for those with ischemic cardiomyopathy, and 0.61 (95% CI, 0.51-0.73) for patients with nonischemic disease.

The results “raise questions rather than answers,” Dr. Saba said. “At some point, someone will need to take patients who are optimized on their heart failure medications and then randomize them to defibrillator versus no defibrillator to see whether there is still an additive impact.”

Current best evidence suggests that primary-prevention ICDs in patients with guideline-based indications confer benefits that far outweigh any risks. But if the major primary-prevention ICD trials were to be repeated in patients on contemporary quad-therapy GDMT, Dr. Tung said, “would the benefit of ICD be attenuated? I think most of us believe it likely would.”

Still, he said, a background of modern GDMT could potentially “optimize” such trials by attenuating mortality from heart failure progression and thereby expanding the proportion of deaths that are arrhythmic, “which the defibrillator can prevent.”

Dr. Saba discloses receiving research support from Boston Scientific and Abbott; and serving on advisory boards for Medtronic and Boston Scientific. The other authors reported no relevant relationships. Dr. Tung has disclosed receiving speaker fees from Abbott and Boston Scientific. Dr. Fonarow has reported receiving personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Cytokinetics, Edwards, Janssen, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Contemporary guidelines highly recommend patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) be on all four drug classes that together have shown clinical clout, including improved survival, in major randomized trials.

Although many such patients don’t receive all four drug classes, the more that are prescribed to those with primary-prevention implantable defibrillators (ICD), the better their odds of survival, a new analysis suggests.

The cohort study of almost 5,000 patients with HFrEF and such devices saw their all-cause mortality risk improve stepwise with each additional prescription they were given toward the full quadruple drug combo at the core of modern HFrEF guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT). The four classes are sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), and renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors.

That inverse relation between risk and number of GDMT medications held whether patients had solo-ICD or defibrillating cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT-D) implants, and were independent of device-implantation year and comorbidities, regardless of HFrEF etiology.

“If anybody had doubts about really pushing forward as much of these guideline-directed medical therapies as the patient tolerates, these data confirm that, by doing so, we definitely do better than with two medications or one medication,” Samir Saba, MD, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, said in an interview.

The analysis begs an old and challenging question: Do primary-prevention ICDs confer clinically important survival gains over those provided by increasingly life-preserving recommended HFrEF medical therapy?

Given the study’s incremental survival bumps with each added GDMT med, “one ought to consider whether ICD therapy can still have an impact on overall survival in this population,” proposes a report published online in JACC Clinical Electrophysiology, with Dr. Saba as senior author.

In the adjusted analysis, the 2-year risk for death from any cause in HFrEF patients with primary-prevention devices fell 36% in those with ICDs and 30% in those with CRT-D devices for each added prescribed GDMT drug, from none up to either three or four such agents (P < .001 in both cases).

Only so much can be made of nonrandomized study results, Saba observed in an interview. But they are enough to justify asking whether primary-prevention ICDs are “still valuable” in HFrEF given current GDMT. One interpretation of the study, the published report noted, is that contemporary GDMT improves HFrEF survival so much that it eclipses any such benefit from a primary-prevention ICD.

Both defibrillators and the four core drug therapies boost survival in such cases, “so the fundamental question is, are they additive. Do we save more lives by having a defibrillator on top of the medications, or is it overlapping?” Dr. Saba asked. “We don’t know the answer.”

For now, at least, the findings could reassure clinicians as they consider whether to recommended a primary-prevention ICD when there might be reasons not to, as long there is full GDMT on board, “especially what we today define as quadruple guideline-directed medical therapy.”

Recently announced North American guidelines defining an HFrEF quadruple regimen prefer – beyond a beta-blocker, MRA, and SGLT2 inhibitor – that the selected RAS inhibitor be sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto, Novartis), with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) as a substitute, if needed.

Nearly identical European guidelines on HFrEF quad therapy, unveiled in 2021, include but do not necessarily prefer sacubitril/valsartan over ACE inhibitors as the RAS inhibitor of choice.

GDMT a moving target

Primary-prevention defibrillators entered practice at a time when expected background GDMT consisted of beta-blockers and either ACE inhibitors or ARBs, the current report notes. In practice, many patients receive the devices without both drug classes optimally on board. Moreover, many who otherwise meet guidelines for such ICDs won’t tolerate the kind of maximally tolerated GDMT used in the major primary-prevention device trials.

Yet current guidelines give such devices a class I recommendation, based on the highest level of evidence, in HFrEF patients who remain symptomatic despite quad GDMT, observed Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, University of California Los Angeles Medical Center.

The current analysis “further reinforces the importance of providing all four foundational GDMTs” to all eligible HFrEF patients without contraindications who can tolerate them, he said in an interview. Such quad therapy “is associated with incremental 1-year survival advantages” in patients with primary-prevention devices. And in the major trials, “there were reductions in sudden deaths, as well as progressive heart failure deaths.”