User login

Air pollution tied to ventricular arrhythmias in those with ICDs

Ventricular arrhythmias more commonly occur on days when there are higher levels of air pollution, especially with fine particulate matter (PM), a new study suggests.

The investigators studied the relationship between air pollution and ventricular arrhythmias in Piacenza, Italy by examining 5-year data on patients who received an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD).

They found a significant association between PM2.5 levels and ventricular arrhythmias, especially those treated with direct current shock. Moreover, higher levels of PM2.5 and PM10 were associated with increased risk of all ventricular arrhythmias.

“These data confirm that environmental pollution is not only a climate emergency but also a public health problem,” lead author Alessia Zanni, currently at Maggiore Hospital, Bologna, Italy, and previously at Piacenza Hospital, said in an interview.

“The study suggests that the survival of patients with heart disease is affected not only by pharmacological therapies and advances in cardiology, but also by the air that they breathe,” she said.

The results were presented at European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure 2022.

More ED visits

The World Health Organization estimates around 7 million people die every year from exposure to polluted air, “as 91% of the world’s population lives in areas where air contaminants exceed safety levels,” Dr. Zanni said. Furthermore, “air pollution has been defined as the fourth-highest ranking risk factor for mortality – more important than LDL cholesterol, obesity, physical activity, or alcohol use.”

She noted that Piacenza has “historically been very attentive to the issues of early defibrillation and cardiac arrest.” Her group had previously found a correlation between out-of-hospital cardiac arrests and air pollution in the general population.

Moreover, her group recently observed that ED visits for patients with ICDs “tended to cluster; on some special days, many patients with ICDs had cardiac arrhythmias, and during those days, air pollution levels were particularly high.”

Her group therefore decided to compare the concentration of air pollutants on days when patients suffered from an arrhythmia event versus pollution levels on days without an arrhythmia, she said.

Further piece in a complex puzzle

The researchers studied 146 patients with ICDs between January 2013 and December 2017, assigning exposures (short, mid, and long term) to these patients based on their residential addresses.

They extracted day-by-day urban PM10, PM2.5, CO, NO2, and O3 levels from the Environmental Protection Agency monitoring stations and then, using time-stratified case-crossover analysis methodology, they calculated the association of ventricular arrhythmia onset with 0- to 7-day moving averages of the various air pollutants prior to the event.

Patients had received their ICD to control cardiac dysfunction brought on by previous myocardial infarction (n = 93), genetic or inflammatory conditions (n = 53), secondary prevention after a lethal arrhythmia (n = 67), and primary prevention (n = 79).

Of the 440 ventricular arrhythmias recorded, 322 were treated with antitachycardia pacing, while the remaining 118 were treated with direct current shock.

The researchers found a significant association between PM2.5 levels and ventricular arrhythmia treated with shock, corresponding to a 15% increased risk or every additional 10mg/m3 (P < .019).

They also found that, when PM2.5 concentrations were elevated by 1 mg/m3 for an entire week, compared with average levels, there was a 2.4% higher likelihood of ventricular arrhythmias, regardless of the temperature, and when PM10 was 1 mg/m3 above average for a week, there was a 2.1% increased risk for arrhythmias (odds ratio, 1,024; 95% confidence interval, 1,009-1,040] and OR, 1,021; 95% CI, 1,009-1,033, respectively), Dr. Zanni reported.

“Since the majority of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest causes still remain unclear, our data add a further piece to the complex puzzle of cardiac arrest triggers,” Dr. Zanni commented. “We think that particulate matter can cause acute inflammation of the heart muscle and potentially act as a trigger for lethal cardiac arrhythmias.

“As these toxic particles are emitted from power plants, industries, and cars, we think that cardiovascular research should highlight these new findings to promote green projects among the general population, clarifying the risks to the health of the human being, and we think strategies to prevent air pollutant exposure in high-risk patients [with previous cardiac disease] should be developed,” she added.

Further, “we advise patients at risk, during days with high PM2.5 (> 35 mg/m3) and PM10 (> 50 mg/m3) to use a mask of the N95 type outdoors, to reduce time spent outdoors – particularly in traffic – and to improve home air filtration,” Dr. Zanni said.

Entering the mainstream

In a comment, Joel Kaufman, MD, MPH, professor of internal medicine and environmental health, University of Washington, Seattle, said the study “adds to a fairly substantial literature already on this topic of short-term exposure to air pollution.”

The evidence that air pollutants “can be a trigger of worsening of cardiovascular disease is fairly consistent at this time, and although the effect sizes are small, they are consistent,” said Dr. Kaufman, who was the chair of the writing group for the American Heart Association’s 2020 policy statement, “Guidance to Reduce Cardiovascular Burden of Ambient Air Pollutants.”

“The research into this issue has become clearer during the past 10 years but still is not in the mainstream of most cardiologists’ awareness. They tend to focus more on controlling cholesterol and performing procedures, etc., but there are modifiable risk factors like air pollution that are increasingly recognized as being part of the picture,” said Dr. Kaufman, who was not involved with the current study.

Dr. Zanni added: “It is important that politics work hand in hand with the scientific community in order to win the battle against global warming, which will reduce the number of cardiovascular deaths – the leading cause of death worldwide – as well as environmental integrity.”

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Dr. Zanni and coauthors and Dr. Kaufman reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ventricular arrhythmias more commonly occur on days when there are higher levels of air pollution, especially with fine particulate matter (PM), a new study suggests.

The investigators studied the relationship between air pollution and ventricular arrhythmias in Piacenza, Italy by examining 5-year data on patients who received an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD).

They found a significant association between PM2.5 levels and ventricular arrhythmias, especially those treated with direct current shock. Moreover, higher levels of PM2.5 and PM10 were associated with increased risk of all ventricular arrhythmias.

“These data confirm that environmental pollution is not only a climate emergency but also a public health problem,” lead author Alessia Zanni, currently at Maggiore Hospital, Bologna, Italy, and previously at Piacenza Hospital, said in an interview.

“The study suggests that the survival of patients with heart disease is affected not only by pharmacological therapies and advances in cardiology, but also by the air that they breathe,” she said.

The results were presented at European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure 2022.

More ED visits

The World Health Organization estimates around 7 million people die every year from exposure to polluted air, “as 91% of the world’s population lives in areas where air contaminants exceed safety levels,” Dr. Zanni said. Furthermore, “air pollution has been defined as the fourth-highest ranking risk factor for mortality – more important than LDL cholesterol, obesity, physical activity, or alcohol use.”

She noted that Piacenza has “historically been very attentive to the issues of early defibrillation and cardiac arrest.” Her group had previously found a correlation between out-of-hospital cardiac arrests and air pollution in the general population.

Moreover, her group recently observed that ED visits for patients with ICDs “tended to cluster; on some special days, many patients with ICDs had cardiac arrhythmias, and during those days, air pollution levels were particularly high.”

Her group therefore decided to compare the concentration of air pollutants on days when patients suffered from an arrhythmia event versus pollution levels on days without an arrhythmia, she said.

Further piece in a complex puzzle

The researchers studied 146 patients with ICDs between January 2013 and December 2017, assigning exposures (short, mid, and long term) to these patients based on their residential addresses.

They extracted day-by-day urban PM10, PM2.5, CO, NO2, and O3 levels from the Environmental Protection Agency monitoring stations and then, using time-stratified case-crossover analysis methodology, they calculated the association of ventricular arrhythmia onset with 0- to 7-day moving averages of the various air pollutants prior to the event.

Patients had received their ICD to control cardiac dysfunction brought on by previous myocardial infarction (n = 93), genetic or inflammatory conditions (n = 53), secondary prevention after a lethal arrhythmia (n = 67), and primary prevention (n = 79).

Of the 440 ventricular arrhythmias recorded, 322 were treated with antitachycardia pacing, while the remaining 118 were treated with direct current shock.

The researchers found a significant association between PM2.5 levels and ventricular arrhythmia treated with shock, corresponding to a 15% increased risk or every additional 10mg/m3 (P < .019).

They also found that, when PM2.5 concentrations were elevated by 1 mg/m3 for an entire week, compared with average levels, there was a 2.4% higher likelihood of ventricular arrhythmias, regardless of the temperature, and when PM10 was 1 mg/m3 above average for a week, there was a 2.1% increased risk for arrhythmias (odds ratio, 1,024; 95% confidence interval, 1,009-1,040] and OR, 1,021; 95% CI, 1,009-1,033, respectively), Dr. Zanni reported.

“Since the majority of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest causes still remain unclear, our data add a further piece to the complex puzzle of cardiac arrest triggers,” Dr. Zanni commented. “We think that particulate matter can cause acute inflammation of the heart muscle and potentially act as a trigger for lethal cardiac arrhythmias.

“As these toxic particles are emitted from power plants, industries, and cars, we think that cardiovascular research should highlight these new findings to promote green projects among the general population, clarifying the risks to the health of the human being, and we think strategies to prevent air pollutant exposure in high-risk patients [with previous cardiac disease] should be developed,” she added.

Further, “we advise patients at risk, during days with high PM2.5 (> 35 mg/m3) and PM10 (> 50 mg/m3) to use a mask of the N95 type outdoors, to reduce time spent outdoors – particularly in traffic – and to improve home air filtration,” Dr. Zanni said.

Entering the mainstream

In a comment, Joel Kaufman, MD, MPH, professor of internal medicine and environmental health, University of Washington, Seattle, said the study “adds to a fairly substantial literature already on this topic of short-term exposure to air pollution.”

The evidence that air pollutants “can be a trigger of worsening of cardiovascular disease is fairly consistent at this time, and although the effect sizes are small, they are consistent,” said Dr. Kaufman, who was the chair of the writing group for the American Heart Association’s 2020 policy statement, “Guidance to Reduce Cardiovascular Burden of Ambient Air Pollutants.”

“The research into this issue has become clearer during the past 10 years but still is not in the mainstream of most cardiologists’ awareness. They tend to focus more on controlling cholesterol and performing procedures, etc., but there are modifiable risk factors like air pollution that are increasingly recognized as being part of the picture,” said Dr. Kaufman, who was not involved with the current study.

Dr. Zanni added: “It is important that politics work hand in hand with the scientific community in order to win the battle against global warming, which will reduce the number of cardiovascular deaths – the leading cause of death worldwide – as well as environmental integrity.”

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Dr. Zanni and coauthors and Dr. Kaufman reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ventricular arrhythmias more commonly occur on days when there are higher levels of air pollution, especially with fine particulate matter (PM), a new study suggests.

The investigators studied the relationship between air pollution and ventricular arrhythmias in Piacenza, Italy by examining 5-year data on patients who received an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD).

They found a significant association between PM2.5 levels and ventricular arrhythmias, especially those treated with direct current shock. Moreover, higher levels of PM2.5 and PM10 were associated with increased risk of all ventricular arrhythmias.

“These data confirm that environmental pollution is not only a climate emergency but also a public health problem,” lead author Alessia Zanni, currently at Maggiore Hospital, Bologna, Italy, and previously at Piacenza Hospital, said in an interview.

“The study suggests that the survival of patients with heart disease is affected not only by pharmacological therapies and advances in cardiology, but also by the air that they breathe,” she said.

The results were presented at European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure 2022.

More ED visits

The World Health Organization estimates around 7 million people die every year from exposure to polluted air, “as 91% of the world’s population lives in areas where air contaminants exceed safety levels,” Dr. Zanni said. Furthermore, “air pollution has been defined as the fourth-highest ranking risk factor for mortality – more important than LDL cholesterol, obesity, physical activity, or alcohol use.”

She noted that Piacenza has “historically been very attentive to the issues of early defibrillation and cardiac arrest.” Her group had previously found a correlation between out-of-hospital cardiac arrests and air pollution in the general population.

Moreover, her group recently observed that ED visits for patients with ICDs “tended to cluster; on some special days, many patients with ICDs had cardiac arrhythmias, and during those days, air pollution levels were particularly high.”

Her group therefore decided to compare the concentration of air pollutants on days when patients suffered from an arrhythmia event versus pollution levels on days without an arrhythmia, she said.

Further piece in a complex puzzle

The researchers studied 146 patients with ICDs between January 2013 and December 2017, assigning exposures (short, mid, and long term) to these patients based on their residential addresses.

They extracted day-by-day urban PM10, PM2.5, CO, NO2, and O3 levels from the Environmental Protection Agency monitoring stations and then, using time-stratified case-crossover analysis methodology, they calculated the association of ventricular arrhythmia onset with 0- to 7-day moving averages of the various air pollutants prior to the event.

Patients had received their ICD to control cardiac dysfunction brought on by previous myocardial infarction (n = 93), genetic or inflammatory conditions (n = 53), secondary prevention after a lethal arrhythmia (n = 67), and primary prevention (n = 79).

Of the 440 ventricular arrhythmias recorded, 322 were treated with antitachycardia pacing, while the remaining 118 were treated with direct current shock.

The researchers found a significant association between PM2.5 levels and ventricular arrhythmia treated with shock, corresponding to a 15% increased risk or every additional 10mg/m3 (P < .019).

They also found that, when PM2.5 concentrations were elevated by 1 mg/m3 for an entire week, compared with average levels, there was a 2.4% higher likelihood of ventricular arrhythmias, regardless of the temperature, and when PM10 was 1 mg/m3 above average for a week, there was a 2.1% increased risk for arrhythmias (odds ratio, 1,024; 95% confidence interval, 1,009-1,040] and OR, 1,021; 95% CI, 1,009-1,033, respectively), Dr. Zanni reported.

“Since the majority of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest causes still remain unclear, our data add a further piece to the complex puzzle of cardiac arrest triggers,” Dr. Zanni commented. “We think that particulate matter can cause acute inflammation of the heart muscle and potentially act as a trigger for lethal cardiac arrhythmias.

“As these toxic particles are emitted from power plants, industries, and cars, we think that cardiovascular research should highlight these new findings to promote green projects among the general population, clarifying the risks to the health of the human being, and we think strategies to prevent air pollutant exposure in high-risk patients [with previous cardiac disease] should be developed,” she added.

Further, “we advise patients at risk, during days with high PM2.5 (> 35 mg/m3) and PM10 (> 50 mg/m3) to use a mask of the N95 type outdoors, to reduce time spent outdoors – particularly in traffic – and to improve home air filtration,” Dr. Zanni said.

Entering the mainstream

In a comment, Joel Kaufman, MD, MPH, professor of internal medicine and environmental health, University of Washington, Seattle, said the study “adds to a fairly substantial literature already on this topic of short-term exposure to air pollution.”

The evidence that air pollutants “can be a trigger of worsening of cardiovascular disease is fairly consistent at this time, and although the effect sizes are small, they are consistent,” said Dr. Kaufman, who was the chair of the writing group for the American Heart Association’s 2020 policy statement, “Guidance to Reduce Cardiovascular Burden of Ambient Air Pollutants.”

“The research into this issue has become clearer during the past 10 years but still is not in the mainstream of most cardiologists’ awareness. They tend to focus more on controlling cholesterol and performing procedures, etc., but there are modifiable risk factors like air pollution that are increasingly recognized as being part of the picture,” said Dr. Kaufman, who was not involved with the current study.

Dr. Zanni added: “It is important that politics work hand in hand with the scientific community in order to win the battle against global warming, which will reduce the number of cardiovascular deaths – the leading cause of death worldwide – as well as environmental integrity.”

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Dr. Zanni and coauthors and Dr. Kaufman reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESC HEART FAILURE 2022

SGLT2 inhibitors cut AFib risk in real-word analysis

NEW ORLEANS – The case continues to grow for prioritizing a sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor in patients with type 2 diabetes, as real-world evidence of benefit and safety accumulates on top of the data from randomized trials that first established this class as a management pillar.

Another important effect of these agents gaining increasing currency, on top of their well-established benefits in patients with type 2 diabetes for preventing acute heart failure exacerbations and slowing progression of diabetic kidney disease, is that they cut the incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib). That effect was confirmed in an analysis of data from about 300,000 U.S. patients included in recent Medicare records, Elisabetta Patorno, MD, reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

But despite documentation like this, real-world evidence also continues to show limited uptake of SGLT2 inhibitors in U.S. patients with type 2 diabetes. Records from more than 1.3 million patients with type 2 diabetes managed in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System during 2019 or 2022 documented that just 10% of these patients received an agent from this class, even though all were eligible to receive it, according to findings in a separate report at the meeting.

The AFib analysis analyzed two sets of propensity score–matched Medicare patients during 2013-2018 aged 65 years or older with type 2 diabetes and no history of AFib. One analysis focused on 80,475 matched patients who started on treatment with either an SGLT2 inhibitor or a glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, and a second on 74,868 matched patients who began either an SGTL2 inhibitor or a dipeptidyl peptidase–4 (DPP4) inhibitor. In both analyses, matching involved more than 130 variables. In both pair sets, patients at baseline averaged about 72 years old, nearly two-thirds were women, about 8%-9% had heart failure, 77%-80% were on metformin, and 20%-25% were using insulin.

The study’s primary endpoint was the incidence of hospitalization for AFib, which occurred a significant 18% less often in the patients who started on an SGLT2, compared with those who started a DPP4 inhibitor during median follow-up of 6.7 months, and a significant 10% less often, compared with those starting a GLP-1 receptor agonist during a median follow-up of 6.0 months, Elisabetta Patorno, MD, DrPH, reported at the meeting. This worked out to 3.7 fewer hospitalizations for AFib per 1,000 patient-years of follow-up among the people who received an SGLT2 inhibitor, compared with a DPP4 inhibitor, and a decrease of 1.8 hospitalizations/1,000 patient-years when compared against patients in a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

Two secondary outcomes showed significantly fewer episodes of newly diagnosed AFib, and significantly fewer patients initiating AFib treatment among those who received an SGLT2 inhibitor relative to the comparator groups. In addition, these associations were consistent across subgroup analyses that divided patients by their age, sex, history of heart failure, and history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

AFib effects add to benefits

The findings “suggest that initiation of an SGLT2 inhibitor may be beneficial in older adults with type 2 diabetes who are at risk for AFib,” said Dr. Patorno, a researcher in the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. “These new findings on AFib may be helpful when weighing the potential risks and benefits of various glucose-lowering drugs in older patients with type 2 diabetes.”

This new evidence follows several prior reports from other research groups of data supporting an AFib benefit from SGLT2 inhibitors. The earlier reports include a post hoc analysis of more than 17,000 patients enrolled in the DECLARE-TIMI 58 cardiovascular outcome trial of dapagliflozin (Farxiga), which showed a 19% relative decrease in the rate of incident AFib or atrial flutter events during a median 4.2 year follow-up.

Other prior reports that found a reduced incidence of AFib events linked with SGLT2 inhibitor treatment include a 2020 meta-analysis based on data from more than 38,000 patients with type 2 diabetes enrolled in any of 16 randomized, controlled trials, which found a 24% relative risk reduction. And an as-yet unpublished report from researchers at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) and their associates presented in November 2021 at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association that documented a significant 24% relative risk reduction in incident AFib events linked to SGLT2 inhibitor treatment in a prospective study of 13,890 patients at several hospitals in Israel or the United States.

Evidence ‘convincing’ in totality

The accumulated evidence for a reduced incidence of AFib when patients were on treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor are “convincing because it’s real world data that complements what we know from clinical trials,” commented Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, professor of medicine at Yale University and director of the Yale Medicine Diabetes Center in New Haven, Conn., who was not involved with the study.

“If these drugs reduce heart failure, they may also reduce AFib. Heart failure patients easily slip into AFib,” he noted in an interview, but added that “I don’t think this explains all cases” of the reduced AFib incidence.

Dr. Patorno offered a few other possible mechanisms for the observed effect. The class may work by reducing blood pressure, weight, inflammation, and oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, atrial remodeling, and AFib susceptibility. These agents are also known to cause natriuresis and diuresis, which could reduce atrial dilation, a mechanism that again relates the AFib effect to the better documented reduction in acute heart failure exacerbations.

“With the diuretic effect, we’d expect less overload at the atrium and less dilation, and the same mechanism would reduce heart failure,” she said in an interview.

“If you reduce preload and afterload you may reduce stress on the ventricle and reduce atrial stretch, and that might have a significant effect on atrial arrhythmia,” agreed Dr. Inzucchi.

EMPRISE produces more real-world evidence

A pair of additional reports at the meeting that Dr. Patorno coauthored provided real-world evidence supporting the dramatic heart failure benefit of the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin (Jardiance) in U.S. patients with type 2 diabetes, compared with alternative drug classes. The EMPRISE study used data from the Medicare, Optum Clinformatics, and MarketScan databases during the period from August 2014, when empagliflozin became available, to September 2019. The study used more than 140 variables to match patients treated with either empagliflozin or a comparator agent.

The results showed that, in an analysis of more than 130,000 matched pairs, treatment with empagliflozin was linked to a significant 30% reduction in the incidence of hospitalization for heart failure, compared with patients treated with a GLP-1 receptor agonist. Analysis of more than 116,000 matched pairs of patients showed that treatment with empagliflozin linked with a significant 29%-50% reduced rate of hospitalization for heart failure, compared with matched patients treated with a DPP4 inhibitor.

These findings “add to the pool of information” on the efficacy of agents from the SGLT2 inhibitor class, Dr. Patorno said in an interview. “We wanted to look at the full range of patients with type 2 diabetes who we see in practice,” rather than the more selected group of patients enrolled in randomized trials.

SGLT2 inhibitor use lags even when cost isn’t an issue

Despite all the accumulated evidence for efficacy and safety of the class, usage remains low, Julio A. Lamprea-Montealegre, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at the University of California, San Francisco, reported in a separate talk at the meeting. The study he presented examined records for 1,319,500 adults with type 2 diabetes managed in the VA Healthcare System during 2019 and 2020. Despite being in a system that “removes the influence of cost,” just 10% of these patients received treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor, and 7% received treatment with a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

Notably, his analysis further showed that treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor was especially depressed among patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30-44 mL/min per 1.73m2. In this subgroup, usage of a drug from this class was at two-thirds of the rate, compared with patients with an eGFR of at least 90 mL/min per 1.73m2. His findings also documented lower rates of use in patients with higher risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Dr. Lamprea-Montealegre called this a “treatment paradox,” in which patients likely to get the most benefit from an SGLT2 inhibitor were also less likely to actually receive it.

While his findings from the VA System suggest that drug cost is not the only factor driving underuse, the high price set for the SGLT2 inhibitor drugs that all currently remain on U.S. patents is widely considered an important factor.

“There is a big problem of affordability,” said Dr. Patorno.

“SGLT2 inhibitors should probably be first-line therapy” for many patients with type 2 diabetes, said Dr. Inzucchi. “The only thing holding it back is cost,” a situation that he hopes will dramatically shift once agents from this class become generic and have substantially lower price tags.

The EMPRISE study received funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that markets empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Patorno had no relevant commercial disclosures. Dr. Inzucchi is an adviser to Abbott Diagnostics, Esperion Therapeutics, and vTv Therapeutics, a consultant to Merck and Pfizer, and has other relationships with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lexicon, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Lamprea-Montealegre had received research funding from Bayer.

NEW ORLEANS – The case continues to grow for prioritizing a sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor in patients with type 2 diabetes, as real-world evidence of benefit and safety accumulates on top of the data from randomized trials that first established this class as a management pillar.

Another important effect of these agents gaining increasing currency, on top of their well-established benefits in patients with type 2 diabetes for preventing acute heart failure exacerbations and slowing progression of diabetic kidney disease, is that they cut the incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib). That effect was confirmed in an analysis of data from about 300,000 U.S. patients included in recent Medicare records, Elisabetta Patorno, MD, reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

But despite documentation like this, real-world evidence also continues to show limited uptake of SGLT2 inhibitors in U.S. patients with type 2 diabetes. Records from more than 1.3 million patients with type 2 diabetes managed in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System during 2019 or 2022 documented that just 10% of these patients received an agent from this class, even though all were eligible to receive it, according to findings in a separate report at the meeting.

The AFib analysis analyzed two sets of propensity score–matched Medicare patients during 2013-2018 aged 65 years or older with type 2 diabetes and no history of AFib. One analysis focused on 80,475 matched patients who started on treatment with either an SGLT2 inhibitor or a glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, and a second on 74,868 matched patients who began either an SGTL2 inhibitor or a dipeptidyl peptidase–4 (DPP4) inhibitor. In both analyses, matching involved more than 130 variables. In both pair sets, patients at baseline averaged about 72 years old, nearly two-thirds were women, about 8%-9% had heart failure, 77%-80% were on metformin, and 20%-25% were using insulin.

The study’s primary endpoint was the incidence of hospitalization for AFib, which occurred a significant 18% less often in the patients who started on an SGLT2, compared with those who started a DPP4 inhibitor during median follow-up of 6.7 months, and a significant 10% less often, compared with those starting a GLP-1 receptor agonist during a median follow-up of 6.0 months, Elisabetta Patorno, MD, DrPH, reported at the meeting. This worked out to 3.7 fewer hospitalizations for AFib per 1,000 patient-years of follow-up among the people who received an SGLT2 inhibitor, compared with a DPP4 inhibitor, and a decrease of 1.8 hospitalizations/1,000 patient-years when compared against patients in a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

Two secondary outcomes showed significantly fewer episodes of newly diagnosed AFib, and significantly fewer patients initiating AFib treatment among those who received an SGLT2 inhibitor relative to the comparator groups. In addition, these associations were consistent across subgroup analyses that divided patients by their age, sex, history of heart failure, and history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

AFib effects add to benefits

The findings “suggest that initiation of an SGLT2 inhibitor may be beneficial in older adults with type 2 diabetes who are at risk for AFib,” said Dr. Patorno, a researcher in the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. “These new findings on AFib may be helpful when weighing the potential risks and benefits of various glucose-lowering drugs in older patients with type 2 diabetes.”

This new evidence follows several prior reports from other research groups of data supporting an AFib benefit from SGLT2 inhibitors. The earlier reports include a post hoc analysis of more than 17,000 patients enrolled in the DECLARE-TIMI 58 cardiovascular outcome trial of dapagliflozin (Farxiga), which showed a 19% relative decrease in the rate of incident AFib or atrial flutter events during a median 4.2 year follow-up.

Other prior reports that found a reduced incidence of AFib events linked with SGLT2 inhibitor treatment include a 2020 meta-analysis based on data from more than 38,000 patients with type 2 diabetes enrolled in any of 16 randomized, controlled trials, which found a 24% relative risk reduction. And an as-yet unpublished report from researchers at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) and their associates presented in November 2021 at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association that documented a significant 24% relative risk reduction in incident AFib events linked to SGLT2 inhibitor treatment in a prospective study of 13,890 patients at several hospitals in Israel or the United States.

Evidence ‘convincing’ in totality

The accumulated evidence for a reduced incidence of AFib when patients were on treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor are “convincing because it’s real world data that complements what we know from clinical trials,” commented Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, professor of medicine at Yale University and director of the Yale Medicine Diabetes Center in New Haven, Conn., who was not involved with the study.

“If these drugs reduce heart failure, they may also reduce AFib. Heart failure patients easily slip into AFib,” he noted in an interview, but added that “I don’t think this explains all cases” of the reduced AFib incidence.

Dr. Patorno offered a few other possible mechanisms for the observed effect. The class may work by reducing blood pressure, weight, inflammation, and oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, atrial remodeling, and AFib susceptibility. These agents are also known to cause natriuresis and diuresis, which could reduce atrial dilation, a mechanism that again relates the AFib effect to the better documented reduction in acute heart failure exacerbations.

“With the diuretic effect, we’d expect less overload at the atrium and less dilation, and the same mechanism would reduce heart failure,” she said in an interview.

“If you reduce preload and afterload you may reduce stress on the ventricle and reduce atrial stretch, and that might have a significant effect on atrial arrhythmia,” agreed Dr. Inzucchi.

EMPRISE produces more real-world evidence

A pair of additional reports at the meeting that Dr. Patorno coauthored provided real-world evidence supporting the dramatic heart failure benefit of the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin (Jardiance) in U.S. patients with type 2 diabetes, compared with alternative drug classes. The EMPRISE study used data from the Medicare, Optum Clinformatics, and MarketScan databases during the period from August 2014, when empagliflozin became available, to September 2019. The study used more than 140 variables to match patients treated with either empagliflozin or a comparator agent.

The results showed that, in an analysis of more than 130,000 matched pairs, treatment with empagliflozin was linked to a significant 30% reduction in the incidence of hospitalization for heart failure, compared with patients treated with a GLP-1 receptor agonist. Analysis of more than 116,000 matched pairs of patients showed that treatment with empagliflozin linked with a significant 29%-50% reduced rate of hospitalization for heart failure, compared with matched patients treated with a DPP4 inhibitor.

These findings “add to the pool of information” on the efficacy of agents from the SGLT2 inhibitor class, Dr. Patorno said in an interview. “We wanted to look at the full range of patients with type 2 diabetes who we see in practice,” rather than the more selected group of patients enrolled in randomized trials.

SGLT2 inhibitor use lags even when cost isn’t an issue

Despite all the accumulated evidence for efficacy and safety of the class, usage remains low, Julio A. Lamprea-Montealegre, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at the University of California, San Francisco, reported in a separate talk at the meeting. The study he presented examined records for 1,319,500 adults with type 2 diabetes managed in the VA Healthcare System during 2019 and 2020. Despite being in a system that “removes the influence of cost,” just 10% of these patients received treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor, and 7% received treatment with a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

Notably, his analysis further showed that treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor was especially depressed among patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30-44 mL/min per 1.73m2. In this subgroup, usage of a drug from this class was at two-thirds of the rate, compared with patients with an eGFR of at least 90 mL/min per 1.73m2. His findings also documented lower rates of use in patients with higher risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Dr. Lamprea-Montealegre called this a “treatment paradox,” in which patients likely to get the most benefit from an SGLT2 inhibitor were also less likely to actually receive it.

While his findings from the VA System suggest that drug cost is not the only factor driving underuse, the high price set for the SGLT2 inhibitor drugs that all currently remain on U.S. patents is widely considered an important factor.

“There is a big problem of affordability,” said Dr. Patorno.

“SGLT2 inhibitors should probably be first-line therapy” for many patients with type 2 diabetes, said Dr. Inzucchi. “The only thing holding it back is cost,” a situation that he hopes will dramatically shift once agents from this class become generic and have substantially lower price tags.

The EMPRISE study received funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that markets empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Patorno had no relevant commercial disclosures. Dr. Inzucchi is an adviser to Abbott Diagnostics, Esperion Therapeutics, and vTv Therapeutics, a consultant to Merck and Pfizer, and has other relationships with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lexicon, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Lamprea-Montealegre had received research funding from Bayer.

NEW ORLEANS – The case continues to grow for prioritizing a sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor in patients with type 2 diabetes, as real-world evidence of benefit and safety accumulates on top of the data from randomized trials that first established this class as a management pillar.

Another important effect of these agents gaining increasing currency, on top of their well-established benefits in patients with type 2 diabetes for preventing acute heart failure exacerbations and slowing progression of diabetic kidney disease, is that they cut the incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib). That effect was confirmed in an analysis of data from about 300,000 U.S. patients included in recent Medicare records, Elisabetta Patorno, MD, reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

But despite documentation like this, real-world evidence also continues to show limited uptake of SGLT2 inhibitors in U.S. patients with type 2 diabetes. Records from more than 1.3 million patients with type 2 diabetes managed in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System during 2019 or 2022 documented that just 10% of these patients received an agent from this class, even though all were eligible to receive it, according to findings in a separate report at the meeting.

The AFib analysis analyzed two sets of propensity score–matched Medicare patients during 2013-2018 aged 65 years or older with type 2 diabetes and no history of AFib. One analysis focused on 80,475 matched patients who started on treatment with either an SGLT2 inhibitor or a glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, and a second on 74,868 matched patients who began either an SGTL2 inhibitor or a dipeptidyl peptidase–4 (DPP4) inhibitor. In both analyses, matching involved more than 130 variables. In both pair sets, patients at baseline averaged about 72 years old, nearly two-thirds were women, about 8%-9% had heart failure, 77%-80% were on metformin, and 20%-25% were using insulin.

The study’s primary endpoint was the incidence of hospitalization for AFib, which occurred a significant 18% less often in the patients who started on an SGLT2, compared with those who started a DPP4 inhibitor during median follow-up of 6.7 months, and a significant 10% less often, compared with those starting a GLP-1 receptor agonist during a median follow-up of 6.0 months, Elisabetta Patorno, MD, DrPH, reported at the meeting. This worked out to 3.7 fewer hospitalizations for AFib per 1,000 patient-years of follow-up among the people who received an SGLT2 inhibitor, compared with a DPP4 inhibitor, and a decrease of 1.8 hospitalizations/1,000 patient-years when compared against patients in a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

Two secondary outcomes showed significantly fewer episodes of newly diagnosed AFib, and significantly fewer patients initiating AFib treatment among those who received an SGLT2 inhibitor relative to the comparator groups. In addition, these associations were consistent across subgroup analyses that divided patients by their age, sex, history of heart failure, and history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

AFib effects add to benefits

The findings “suggest that initiation of an SGLT2 inhibitor may be beneficial in older adults with type 2 diabetes who are at risk for AFib,” said Dr. Patorno, a researcher in the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. “These new findings on AFib may be helpful when weighing the potential risks and benefits of various glucose-lowering drugs in older patients with type 2 diabetes.”

This new evidence follows several prior reports from other research groups of data supporting an AFib benefit from SGLT2 inhibitors. The earlier reports include a post hoc analysis of more than 17,000 patients enrolled in the DECLARE-TIMI 58 cardiovascular outcome trial of dapagliflozin (Farxiga), which showed a 19% relative decrease in the rate of incident AFib or atrial flutter events during a median 4.2 year follow-up.

Other prior reports that found a reduced incidence of AFib events linked with SGLT2 inhibitor treatment include a 2020 meta-analysis based on data from more than 38,000 patients with type 2 diabetes enrolled in any of 16 randomized, controlled trials, which found a 24% relative risk reduction. And an as-yet unpublished report from researchers at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) and their associates presented in November 2021 at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association that documented a significant 24% relative risk reduction in incident AFib events linked to SGLT2 inhibitor treatment in a prospective study of 13,890 patients at several hospitals in Israel or the United States.

Evidence ‘convincing’ in totality

The accumulated evidence for a reduced incidence of AFib when patients were on treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor are “convincing because it’s real world data that complements what we know from clinical trials,” commented Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, professor of medicine at Yale University and director of the Yale Medicine Diabetes Center in New Haven, Conn., who was not involved with the study.

“If these drugs reduce heart failure, they may also reduce AFib. Heart failure patients easily slip into AFib,” he noted in an interview, but added that “I don’t think this explains all cases” of the reduced AFib incidence.

Dr. Patorno offered a few other possible mechanisms for the observed effect. The class may work by reducing blood pressure, weight, inflammation, and oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, atrial remodeling, and AFib susceptibility. These agents are also known to cause natriuresis and diuresis, which could reduce atrial dilation, a mechanism that again relates the AFib effect to the better documented reduction in acute heart failure exacerbations.

“With the diuretic effect, we’d expect less overload at the atrium and less dilation, and the same mechanism would reduce heart failure,” she said in an interview.

“If you reduce preload and afterload you may reduce stress on the ventricle and reduce atrial stretch, and that might have a significant effect on atrial arrhythmia,” agreed Dr. Inzucchi.

EMPRISE produces more real-world evidence

A pair of additional reports at the meeting that Dr. Patorno coauthored provided real-world evidence supporting the dramatic heart failure benefit of the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin (Jardiance) in U.S. patients with type 2 diabetes, compared with alternative drug classes. The EMPRISE study used data from the Medicare, Optum Clinformatics, and MarketScan databases during the period from August 2014, when empagliflozin became available, to September 2019. The study used more than 140 variables to match patients treated with either empagliflozin or a comparator agent.

The results showed that, in an analysis of more than 130,000 matched pairs, treatment with empagliflozin was linked to a significant 30% reduction in the incidence of hospitalization for heart failure, compared with patients treated with a GLP-1 receptor agonist. Analysis of more than 116,000 matched pairs of patients showed that treatment with empagliflozin linked with a significant 29%-50% reduced rate of hospitalization for heart failure, compared with matched patients treated with a DPP4 inhibitor.

These findings “add to the pool of information” on the efficacy of agents from the SGLT2 inhibitor class, Dr. Patorno said in an interview. “We wanted to look at the full range of patients with type 2 diabetes who we see in practice,” rather than the more selected group of patients enrolled in randomized trials.

SGLT2 inhibitor use lags even when cost isn’t an issue

Despite all the accumulated evidence for efficacy and safety of the class, usage remains low, Julio A. Lamprea-Montealegre, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at the University of California, San Francisco, reported in a separate talk at the meeting. The study he presented examined records for 1,319,500 adults with type 2 diabetes managed in the VA Healthcare System during 2019 and 2020. Despite being in a system that “removes the influence of cost,” just 10% of these patients received treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor, and 7% received treatment with a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

Notably, his analysis further showed that treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor was especially depressed among patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30-44 mL/min per 1.73m2. In this subgroup, usage of a drug from this class was at two-thirds of the rate, compared with patients with an eGFR of at least 90 mL/min per 1.73m2. His findings also documented lower rates of use in patients with higher risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Dr. Lamprea-Montealegre called this a “treatment paradox,” in which patients likely to get the most benefit from an SGLT2 inhibitor were also less likely to actually receive it.

While his findings from the VA System suggest that drug cost is not the only factor driving underuse, the high price set for the SGLT2 inhibitor drugs that all currently remain on U.S. patents is widely considered an important factor.

“There is a big problem of affordability,” said Dr. Patorno.

“SGLT2 inhibitors should probably be first-line therapy” for many patients with type 2 diabetes, said Dr. Inzucchi. “The only thing holding it back is cost,” a situation that he hopes will dramatically shift once agents from this class become generic and have substantially lower price tags.

The EMPRISE study received funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that markets empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Patorno had no relevant commercial disclosures. Dr. Inzucchi is an adviser to Abbott Diagnostics, Esperion Therapeutics, and vTv Therapeutics, a consultant to Merck and Pfizer, and has other relationships with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lexicon, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Lamprea-Montealegre had received research funding from Bayer.

AT ADA 2022

Emergency angiography for cardiac arrest without ST elevation?

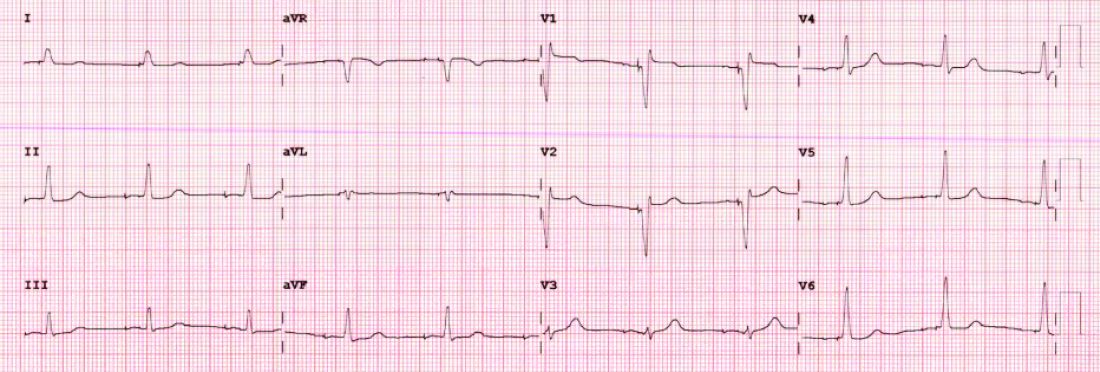

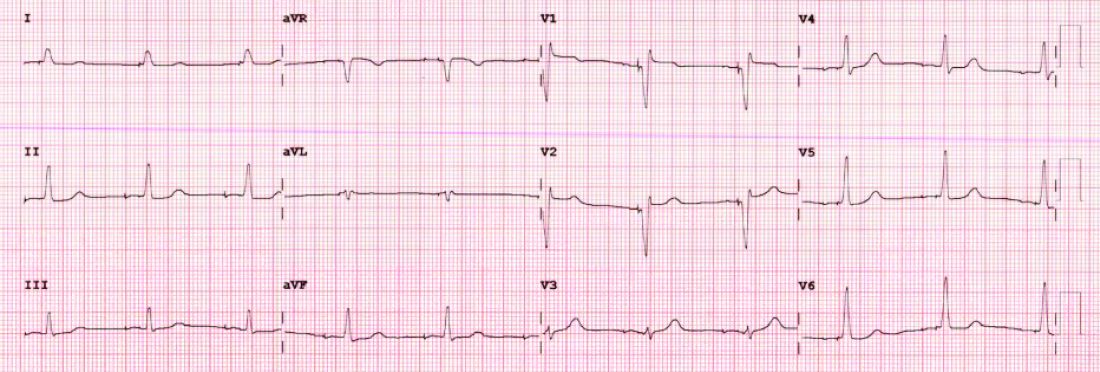

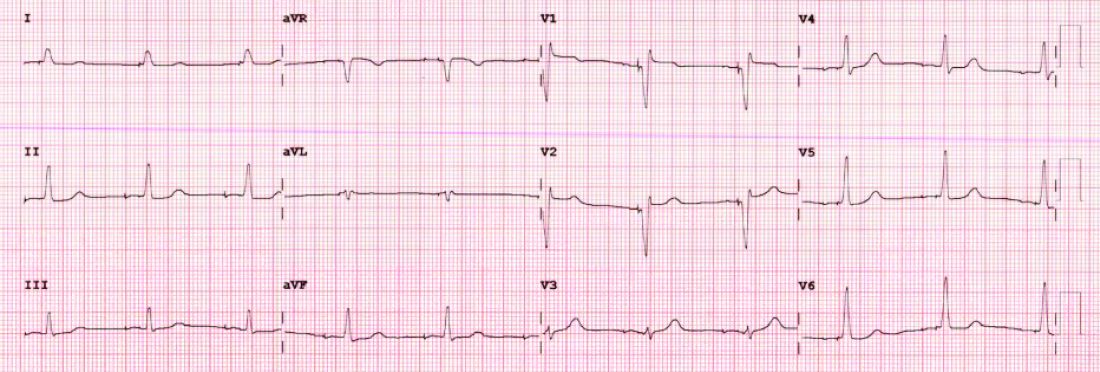

Patients successfully resuscitated after an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest who did not have ST-segment elevation on their electrocardiogram did not benefit from emergency coronary angiography in a new randomized clinical trial.

In the EMERGE trial, a strategy of emergency coronary angiography was not found to be better than a strategy of delayed coronary angiography with respect to the 180-day survival rate with no or minimal neurologic sequelae.

The authors note that, although the study was underpowered, the results are consistent with previously published studies and do not support routine emergency coronary angiography in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest without ST elevation.

But senior author, Christian Spaulding, MD, PhD, European Hospital Georges Pompidou, Paris, believes some such patients may still benefit from emergency angiography.

“Most patients who have been resuscitated after out of hospital cardiac arrest will have neurological damage, which will be the primary cause of death,” Dr. Spaulding told this news organization. “It will not make any difference to these patients if they have a coronary lesion treated. So, going forward, I think we need to look for patients who are likely not to have a high degree of neurological damage and who could still benefit from early angiography.”

The EMERGE study was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

In patients who have suffered an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with no obvious noncardiac cause such as trauma, it is believed that the cardiac arrest is caused by coronary occlusions, and emergency angiography may be able to improve survival in these patients, Dr. Spaulding explained.

In about one-third of such patients, the ECG before hospitalization shows ST elevation, and in this group, there is a high probability (around 70%-80%) that there is going to be a coronary occlusion, so these patients are usually taken directly to emergency angiography.

But, in the other two-thirds of patients, there is no ST elevation on the ECG, and in these patients the chances of finding a coronary occlusion are lower (around 25%-35%).

The EMERGE trial was conducted in this latter group without ST elevation.

For the study, which was conducted in 22 French centers, 279 such patients (mean age, 64 years) were randomized to either emergency or delayed (48-96 hours) coronary angiography. The mean time delay between randomization and coronary angiography was 0.6 hours in the emergency group and 55.1 hours in the delayed group.

The primary outcome was the 180-day survival rate with minimal neurological damage, defined as Cerebral Performance Category of 2 or less. This occurred in 34.1% of the emergency angiography group and 30.7% of the delayed angiography group (hazard ratio, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.65-1.15; P = .32).

There was also no difference in the overall survival rate at 180 days (36.2% vs. 33.3%; HR, 0.86; P = .31) and in secondary outcomes between the two groups.

Dr. Spaulding noted that three other randomized trials in a similar patient population have all shown similar results, with no difference in survival found between patients who have emergency coronary angiography as soon as they are admitted to hospital and those in whom angiography was not performed until a couple of days later.

However, several registry studies in a total of more than 6,000 patients have suggested a benefit of immediate angiography in these patients. “So, there is some disconnect here,” he said.

Dr. Spaulding believes the reason for this disconnect may be that the registry studies may have included patients with less neurological damage so more likely to survive and to benefit from having coronary lesions treated promptly.

“Paramedics sometimes make a judgment on which patients may have minimal neurological damage, and this may affect the choice of hospital a patient is taken to, and then the emergency department doctor may again assess whether a patient should go for immediate angiography or not. So, patients in these registry studies who received emergency angiography were likely already preselected to some extent,” he suggested.

In contrast, the randomized trials have accepted all patients, so there were probably more with neurological damage. “In our trial, almost 70% of patients were in asystole. These are the ones who [are] the most likely to have neurological damage,” he pointed out.

“Because there was such a striking difference in the registry studies, I think there is a group of patients [who] will benefit from immediate emergency coronary angiography, but we have to work out how to select these patients,” he commented.

Dr. Spaulding noted that a recent registry study published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions used a score known as MIRACLE2, (which takes into account various factors including age of patient and type of rhythm on ECG) and the degree of cardiogenic shock on arrival at hospital as measured by the SCAI shock score to define a potential cohort of patients at low risk for neurologic injury who benefit most from immediate coronary angiography.

“In my practice at present, I would advise the emergency team that a young patient who had had resuscitation started quickly, had been defibrillated early, and got to hospital quickly should go for an immediate coronary angiogram. It can’t do any harm, and there may be a benefit in such patients,” Dr. Spaulding added.The EMERGE study was supported in part by Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris and the French Ministry of Health, through the national Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique. Dr. Spaulding reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients successfully resuscitated after an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest who did not have ST-segment elevation on their electrocardiogram did not benefit from emergency coronary angiography in a new randomized clinical trial.

In the EMERGE trial, a strategy of emergency coronary angiography was not found to be better than a strategy of delayed coronary angiography with respect to the 180-day survival rate with no or minimal neurologic sequelae.

The authors note that, although the study was underpowered, the results are consistent with previously published studies and do not support routine emergency coronary angiography in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest without ST elevation.

But senior author, Christian Spaulding, MD, PhD, European Hospital Georges Pompidou, Paris, believes some such patients may still benefit from emergency angiography.

“Most patients who have been resuscitated after out of hospital cardiac arrest will have neurological damage, which will be the primary cause of death,” Dr. Spaulding told this news organization. “It will not make any difference to these patients if they have a coronary lesion treated. So, going forward, I think we need to look for patients who are likely not to have a high degree of neurological damage and who could still benefit from early angiography.”

The EMERGE study was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

In patients who have suffered an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with no obvious noncardiac cause such as trauma, it is believed that the cardiac arrest is caused by coronary occlusions, and emergency angiography may be able to improve survival in these patients, Dr. Spaulding explained.

In about one-third of such patients, the ECG before hospitalization shows ST elevation, and in this group, there is a high probability (around 70%-80%) that there is going to be a coronary occlusion, so these patients are usually taken directly to emergency angiography.

But, in the other two-thirds of patients, there is no ST elevation on the ECG, and in these patients the chances of finding a coronary occlusion are lower (around 25%-35%).

The EMERGE trial was conducted in this latter group without ST elevation.

For the study, which was conducted in 22 French centers, 279 such patients (mean age, 64 years) were randomized to either emergency or delayed (48-96 hours) coronary angiography. The mean time delay between randomization and coronary angiography was 0.6 hours in the emergency group and 55.1 hours in the delayed group.

The primary outcome was the 180-day survival rate with minimal neurological damage, defined as Cerebral Performance Category of 2 or less. This occurred in 34.1% of the emergency angiography group and 30.7% of the delayed angiography group (hazard ratio, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.65-1.15; P = .32).

There was also no difference in the overall survival rate at 180 days (36.2% vs. 33.3%; HR, 0.86; P = .31) and in secondary outcomes between the two groups.

Dr. Spaulding noted that three other randomized trials in a similar patient population have all shown similar results, with no difference in survival found between patients who have emergency coronary angiography as soon as they are admitted to hospital and those in whom angiography was not performed until a couple of days later.

However, several registry studies in a total of more than 6,000 patients have suggested a benefit of immediate angiography in these patients. “So, there is some disconnect here,” he said.

Dr. Spaulding believes the reason for this disconnect may be that the registry studies may have included patients with less neurological damage so more likely to survive and to benefit from having coronary lesions treated promptly.

“Paramedics sometimes make a judgment on which patients may have minimal neurological damage, and this may affect the choice of hospital a patient is taken to, and then the emergency department doctor may again assess whether a patient should go for immediate angiography or not. So, patients in these registry studies who received emergency angiography were likely already preselected to some extent,” he suggested.

In contrast, the randomized trials have accepted all patients, so there were probably more with neurological damage. “In our trial, almost 70% of patients were in asystole. These are the ones who [are] the most likely to have neurological damage,” he pointed out.

“Because there was such a striking difference in the registry studies, I think there is a group of patients [who] will benefit from immediate emergency coronary angiography, but we have to work out how to select these patients,” he commented.

Dr. Spaulding noted that a recent registry study published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions used a score known as MIRACLE2, (which takes into account various factors including age of patient and type of rhythm on ECG) and the degree of cardiogenic shock on arrival at hospital as measured by the SCAI shock score to define a potential cohort of patients at low risk for neurologic injury who benefit most from immediate coronary angiography.

“In my practice at present, I would advise the emergency team that a young patient who had had resuscitation started quickly, had been defibrillated early, and got to hospital quickly should go for an immediate coronary angiogram. It can’t do any harm, and there may be a benefit in such patients,” Dr. Spaulding added.The EMERGE study was supported in part by Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris and the French Ministry of Health, through the national Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique. Dr. Spaulding reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients successfully resuscitated after an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest who did not have ST-segment elevation on their electrocardiogram did not benefit from emergency coronary angiography in a new randomized clinical trial.

In the EMERGE trial, a strategy of emergency coronary angiography was not found to be better than a strategy of delayed coronary angiography with respect to the 180-day survival rate with no or minimal neurologic sequelae.

The authors note that, although the study was underpowered, the results are consistent with previously published studies and do not support routine emergency coronary angiography in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest without ST elevation.

But senior author, Christian Spaulding, MD, PhD, European Hospital Georges Pompidou, Paris, believes some such patients may still benefit from emergency angiography.

“Most patients who have been resuscitated after out of hospital cardiac arrest will have neurological damage, which will be the primary cause of death,” Dr. Spaulding told this news organization. “It will not make any difference to these patients if they have a coronary lesion treated. So, going forward, I think we need to look for patients who are likely not to have a high degree of neurological damage and who could still benefit from early angiography.”

The EMERGE study was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

In patients who have suffered an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with no obvious noncardiac cause such as trauma, it is believed that the cardiac arrest is caused by coronary occlusions, and emergency angiography may be able to improve survival in these patients, Dr. Spaulding explained.

In about one-third of such patients, the ECG before hospitalization shows ST elevation, and in this group, there is a high probability (around 70%-80%) that there is going to be a coronary occlusion, so these patients are usually taken directly to emergency angiography.

But, in the other two-thirds of patients, there is no ST elevation on the ECG, and in these patients the chances of finding a coronary occlusion are lower (around 25%-35%).

The EMERGE trial was conducted in this latter group without ST elevation.

For the study, which was conducted in 22 French centers, 279 such patients (mean age, 64 years) were randomized to either emergency or delayed (48-96 hours) coronary angiography. The mean time delay between randomization and coronary angiography was 0.6 hours in the emergency group and 55.1 hours in the delayed group.

The primary outcome was the 180-day survival rate with minimal neurological damage, defined as Cerebral Performance Category of 2 or less. This occurred in 34.1% of the emergency angiography group and 30.7% of the delayed angiography group (hazard ratio, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.65-1.15; P = .32).

There was also no difference in the overall survival rate at 180 days (36.2% vs. 33.3%; HR, 0.86; P = .31) and in secondary outcomes between the two groups.

Dr. Spaulding noted that three other randomized trials in a similar patient population have all shown similar results, with no difference in survival found between patients who have emergency coronary angiography as soon as they are admitted to hospital and those in whom angiography was not performed until a couple of days later.

However, several registry studies in a total of more than 6,000 patients have suggested a benefit of immediate angiography in these patients. “So, there is some disconnect here,” he said.

Dr. Spaulding believes the reason for this disconnect may be that the registry studies may have included patients with less neurological damage so more likely to survive and to benefit from having coronary lesions treated promptly.

“Paramedics sometimes make a judgment on which patients may have minimal neurological damage, and this may affect the choice of hospital a patient is taken to, and then the emergency department doctor may again assess whether a patient should go for immediate angiography or not. So, patients in these registry studies who received emergency angiography were likely already preselected to some extent,” he suggested.

In contrast, the randomized trials have accepted all patients, so there were probably more with neurological damage. “In our trial, almost 70% of patients were in asystole. These are the ones who [are] the most likely to have neurological damage,” he pointed out.

“Because there was such a striking difference in the registry studies, I think there is a group of patients [who] will benefit from immediate emergency coronary angiography, but we have to work out how to select these patients,” he commented.

Dr. Spaulding noted that a recent registry study published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions used a score known as MIRACLE2, (which takes into account various factors including age of patient and type of rhythm on ECG) and the degree of cardiogenic shock on arrival at hospital as measured by the SCAI shock score to define a potential cohort of patients at low risk for neurologic injury who benefit most from immediate coronary angiography.

“In my practice at present, I would advise the emergency team that a young patient who had had resuscitation started quickly, had been defibrillated early, and got to hospital quickly should go for an immediate coronary angiogram. It can’t do any harm, and there may be a benefit in such patients,” Dr. Spaulding added.The EMERGE study was supported in part by Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris and the French Ministry of Health, through the national Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique. Dr. Spaulding reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Takotsubo syndrome more deadly in men

Takotsubo syndrome occurs much more frequently in women than it does in men, but men are much more likely to die from it, according to the results of a new study.

In an analysis of almost 2,500 patients with Takotsubo syndrome (TSS) who were enrolled in an international registry, men, who made up just 11% of the sample, had significantly higher rates of cardiogenic shock and were more than twice as likely to die in the hospital than their female counterparts.

The authors concluded that TSS in males requires close in-hospital monitoring and long-term follow-up. Their study was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Takotsubo syndrome is a condition characterized by acute heart failure and transient ventricular contractile dysfunction that can be precipitated by acute emotional or physical stress. It affects mostly women, particularly postmenopausal women, although the reasons for this are still not fully clear, Luca Arcari, MD, from the Institute of Cardiology, Madre Giuseppina Vannini Hospital, Rome, and colleagues wrote.

The syndrome also affects men, and recent data have identified that male sex is associated with worse outcomes. But, because it occurs relatively uncommonly in men, information about outcomes in men is limited.

To shed more light on the influence of gender on TTS, the investigators looked at 2,492 TTS patients (286 men, 2,206 women) who were participants in the GEIST (German Italian Spanish Takotsubo) registry and compared the clinical features and short- and long-term outcomes between the two.

Male patients were significantly younger (69 years) than women (71 years; P = .005) and had a higher prevalence of comorbid conditions, including diabetes (25% vs. 19%; P = .01); pulmonary diseases (21% vs. 15%; P = .006); malignancies (25% vs. 13%; P < .001).

In addition, TTS in men was more likely to be caused by physical triggers (55% vs. 32%; P < .01), whereas emotional triggers were more common in females (39% vs. 19%; P < 0.001).

The investigators then performed a propensity score analysis by matching men and women 1:1; this yielded 207 patients from each group.

After propensity matching, male patients had higher rates of cardiogenic shock (16% vs 6%), and in-hospital mortality (8% vs. 3%; both P < .05).

Men also had a higher mortality rate during the acute and long-term follow up. Male sex remained independently associated with both in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 2.26; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-4.40) and long-term mortality (hazard ratio, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.32-2.52).

The study by Dr. Arcari and colleagues “shows convincingly that although men are far less likely to develop TTS than women, they have more serious complications and are more likely to die than women presenting with the syndrome, Ilan S. Wittstein, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

In an interview, Dr. Wittstein said one of the strengths of the study was its size.

“Over the years, there have been a lot of smaller, single center studies. This large registry had over 2,000 patients. So when the researchers say the rate of TTS is 10% in men and 90% in women, this is not necessarily surprising because that’s about the breakdown we’ve had since the very beginning, but it certainly validates that in a cohort that is large,” he said.

“I think what was novel about the paper is that the size of the cohort allowed the researchers to do propensity matching, so they were able not only to compare men versus women, they could do a 1:1 comparison. And they found even when you match men and women for various comorbidities, the men were much sicker

“What makes this a fascinating syndrome and different from most types of heart muscle problems is that, in the majority of patients, the condition is precipitated by an acute stressor,” said Dr. Wittstein.

“It can either be an emotional trigger, so for instance, getting some bad news that a loved one just died. That’s why we nicknamed the syndrome ‘broken heart syndrome’ many years ago. Or it can be a physical trigger, which can be a wide variety of things, such infection, a stroke, bad pneumonia, anything that stresses the body and causes a stress response. Regular heart attacks are not triggered in this way,” he said.

Dr. Arcari and Dr. Wittstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

Takotsubo syndrome occurs much more frequently in women than it does in men, but men are much more likely to die from it, according to the results of a new study.

In an analysis of almost 2,500 patients with Takotsubo syndrome (TSS) who were enrolled in an international registry, men, who made up just 11% of the sample, had significantly higher rates of cardiogenic shock and were more than twice as likely to die in the hospital than their female counterparts.

The authors concluded that TSS in males requires close in-hospital monitoring and long-term follow-up. Their study was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Takotsubo syndrome is a condition characterized by acute heart failure and transient ventricular contractile dysfunction that can be precipitated by acute emotional or physical stress. It affects mostly women, particularly postmenopausal women, although the reasons for this are still not fully clear, Luca Arcari, MD, from the Institute of Cardiology, Madre Giuseppina Vannini Hospital, Rome, and colleagues wrote.

The syndrome also affects men, and recent data have identified that male sex is associated with worse outcomes. But, because it occurs relatively uncommonly in men, information about outcomes in men is limited.

To shed more light on the influence of gender on TTS, the investigators looked at 2,492 TTS patients (286 men, 2,206 women) who were participants in the GEIST (German Italian Spanish Takotsubo) registry and compared the clinical features and short- and long-term outcomes between the two.

Male patients were significantly younger (69 years) than women (71 years; P = .005) and had a higher prevalence of comorbid conditions, including diabetes (25% vs. 19%; P = .01); pulmonary diseases (21% vs. 15%; P = .006); malignancies (25% vs. 13%; P < .001).

In addition, TTS in men was more likely to be caused by physical triggers (55% vs. 32%; P < .01), whereas emotional triggers were more common in females (39% vs. 19%; P < 0.001).

The investigators then performed a propensity score analysis by matching men and women 1:1; this yielded 207 patients from each group.

After propensity matching, male patients had higher rates of cardiogenic shock (16% vs 6%), and in-hospital mortality (8% vs. 3%; both P < .05).

Men also had a higher mortality rate during the acute and long-term follow up. Male sex remained independently associated with both in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 2.26; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-4.40) and long-term mortality (hazard ratio, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.32-2.52).

The study by Dr. Arcari and colleagues “shows convincingly that although men are far less likely to develop TTS than women, they have more serious complications and are more likely to die than women presenting with the syndrome, Ilan S. Wittstein, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

In an interview, Dr. Wittstein said one of the strengths of the study was its size.

“Over the years, there have been a lot of smaller, single center studies. This large registry had over 2,000 patients. So when the researchers say the rate of TTS is 10% in men and 90% in women, this is not necessarily surprising because that’s about the breakdown we’ve had since the very beginning, but it certainly validates that in a cohort that is large,” he said.

“I think what was novel about the paper is that the size of the cohort allowed the researchers to do propensity matching, so they were able not only to compare men versus women, they could do a 1:1 comparison. And they found even when you match men and women for various comorbidities, the men were much sicker

“What makes this a fascinating syndrome and different from most types of heart muscle problems is that, in the majority of patients, the condition is precipitated by an acute stressor,” said Dr. Wittstein.

“It can either be an emotional trigger, so for instance, getting some bad news that a loved one just died. That’s why we nicknamed the syndrome ‘broken heart syndrome’ many years ago. Or it can be a physical trigger, which can be a wide variety of things, such infection, a stroke, bad pneumonia, anything that stresses the body and causes a stress response. Regular heart attacks are not triggered in this way,” he said.

Dr. Arcari and Dr. Wittstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

Takotsubo syndrome occurs much more frequently in women than it does in men, but men are much more likely to die from it, according to the results of a new study.

In an analysis of almost 2,500 patients with Takotsubo syndrome (TSS) who were enrolled in an international registry, men, who made up just 11% of the sample, had significantly higher rates of cardiogenic shock and were more than twice as likely to die in the hospital than their female counterparts.

The authors concluded that TSS in males requires close in-hospital monitoring and long-term follow-up. Their study was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Takotsubo syndrome is a condition characterized by acute heart failure and transient ventricular contractile dysfunction that can be precipitated by acute emotional or physical stress. It affects mostly women, particularly postmenopausal women, although the reasons for this are still not fully clear, Luca Arcari, MD, from the Institute of Cardiology, Madre Giuseppina Vannini Hospital, Rome, and colleagues wrote.

The syndrome also affects men, and recent data have identified that male sex is associated with worse outcomes. But, because it occurs relatively uncommonly in men, information about outcomes in men is limited.

To shed more light on the influence of gender on TTS, the investigators looked at 2,492 TTS patients (286 men, 2,206 women) who were participants in the GEIST (German Italian Spanish Takotsubo) registry and compared the clinical features and short- and long-term outcomes between the two.

Male patients were significantly younger (69 years) than women (71 years; P = .005) and had a higher prevalence of comorbid conditions, including diabetes (25% vs. 19%; P = .01); pulmonary diseases (21% vs. 15%; P = .006); malignancies (25% vs. 13%; P < .001).

In addition, TTS in men was more likely to be caused by physical triggers (55% vs. 32%; P < .01), whereas emotional triggers were more common in females (39% vs. 19%; P < 0.001).

The investigators then performed a propensity score analysis by matching men and women 1:1; this yielded 207 patients from each group.

After propensity matching, male patients had higher rates of cardiogenic shock (16% vs 6%), and in-hospital mortality (8% vs. 3%; both P < .05).

Men also had a higher mortality rate during the acute and long-term follow up. Male sex remained independently associated with both in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 2.26; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-4.40) and long-term mortality (hazard ratio, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.32-2.52).

The study by Dr. Arcari and colleagues “shows convincingly that although men are far less likely to develop TTS than women, they have more serious complications and are more likely to die than women presenting with the syndrome, Ilan S. Wittstein, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in an accompanying editorial.