User login

Atopic Dermatitis Triggered by Omalizumab and Treated With Dupilumab

To the Editor:

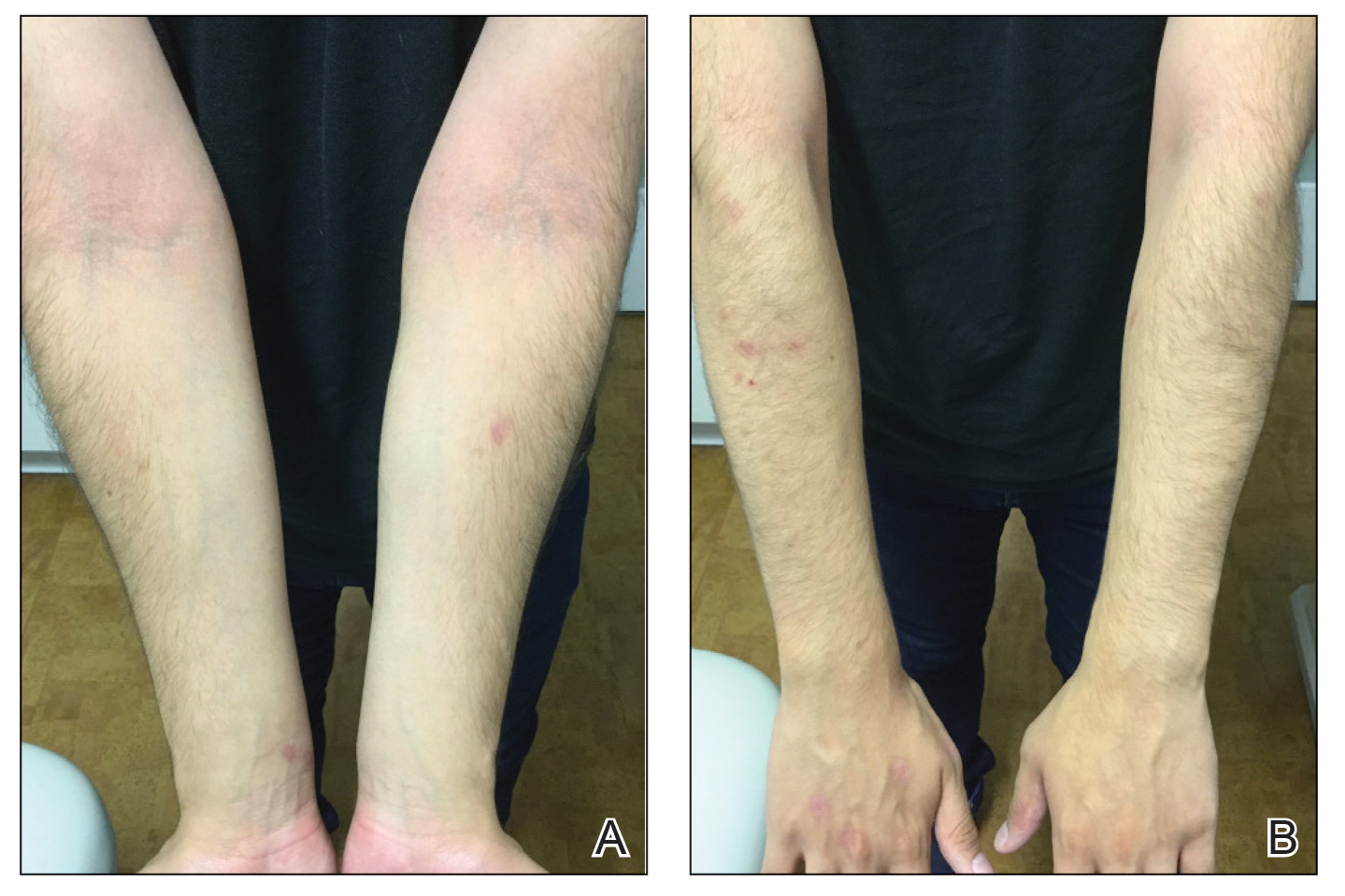

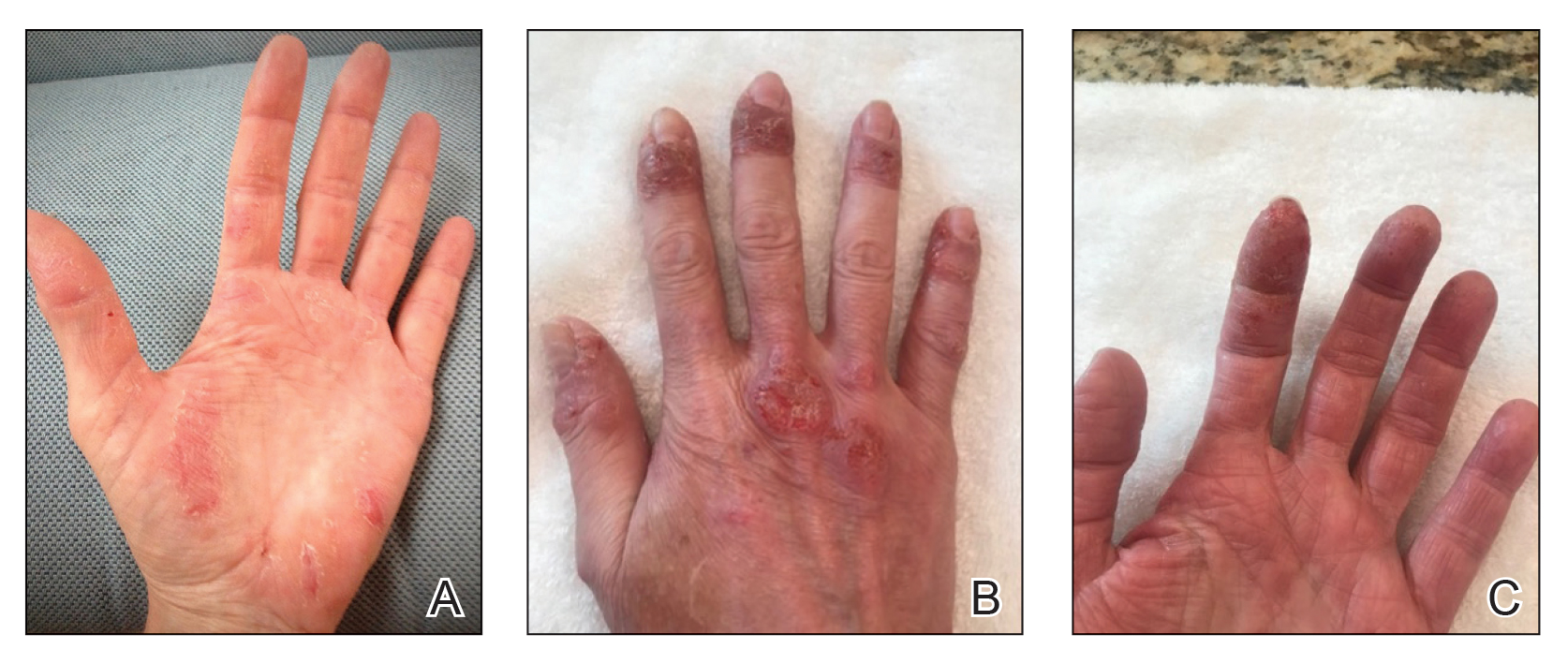

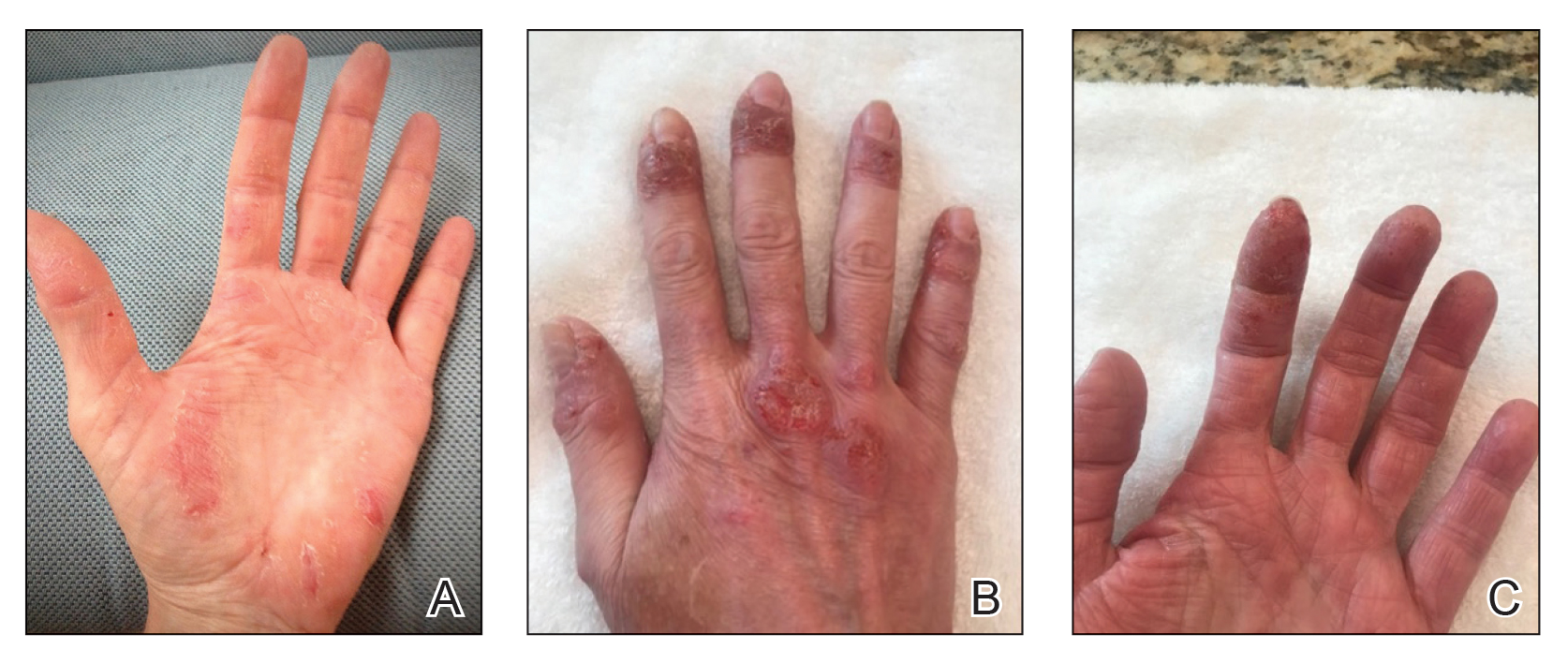

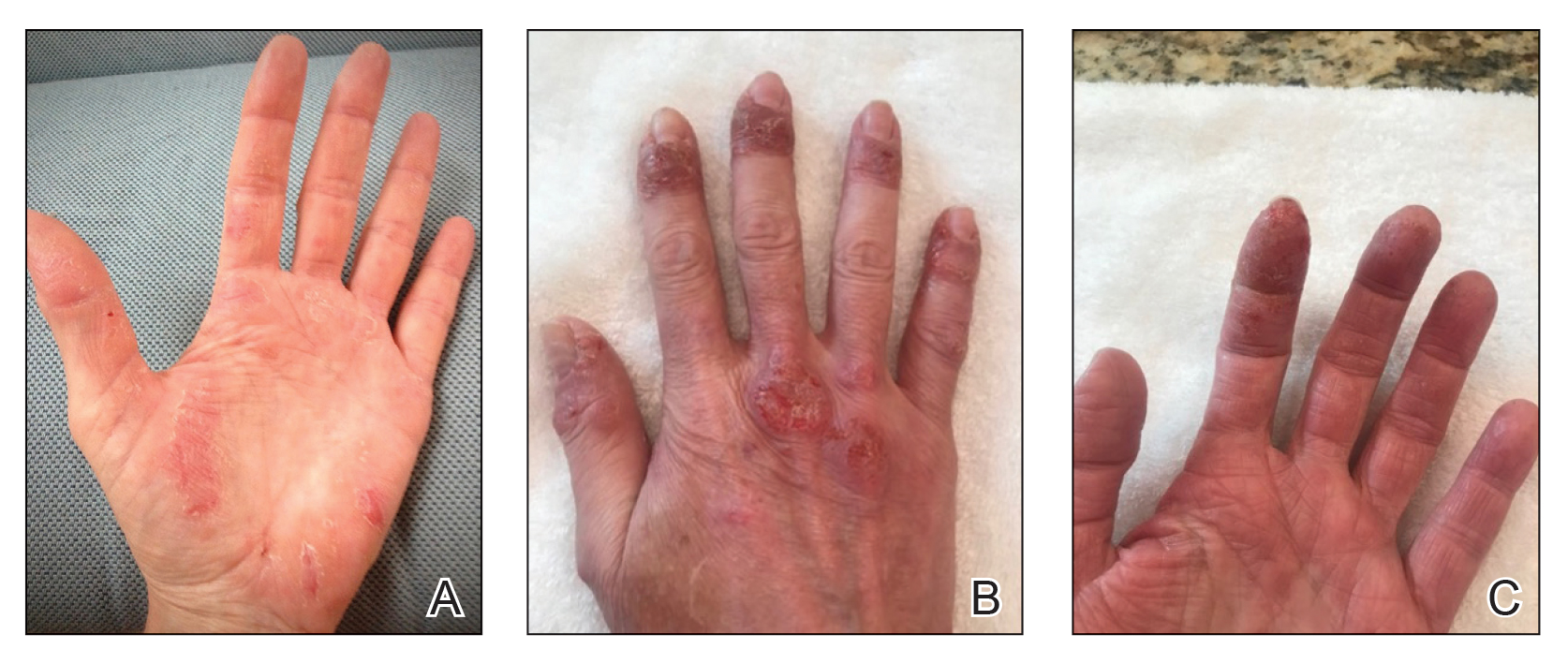

A 16-year-old adolescent boy presented to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of long-standing mild atopic dermatitis (AD) that had become severe over the last year after omalizumab was initiated for severe asthma. The patient had a history of multiple hospitalizations for severe asthma. Despite excellent control of asthma with omalizumab given every 2 weeks, he developed widespread eczematous plaques on the neck, trunk, and extremities over the course of a year. The AD often was complicated by superimposed folliculitis due to scratching from severe pruritus. Treatment with topical corticosteroids including triamcinolone ointment 0.1% to AD on the body, plus clobetasol ointment 0.05% for prurigolike lesions on the legs resulted in modest improvement; however, the AD consistently recurred within a few days after the biweekly omalizumab injection (Figure 1). When the omalizumab injections were delayed, the flares temporarily improved, and when injections were decreased to once monthly, the exacerbations subsided partially but not fully.

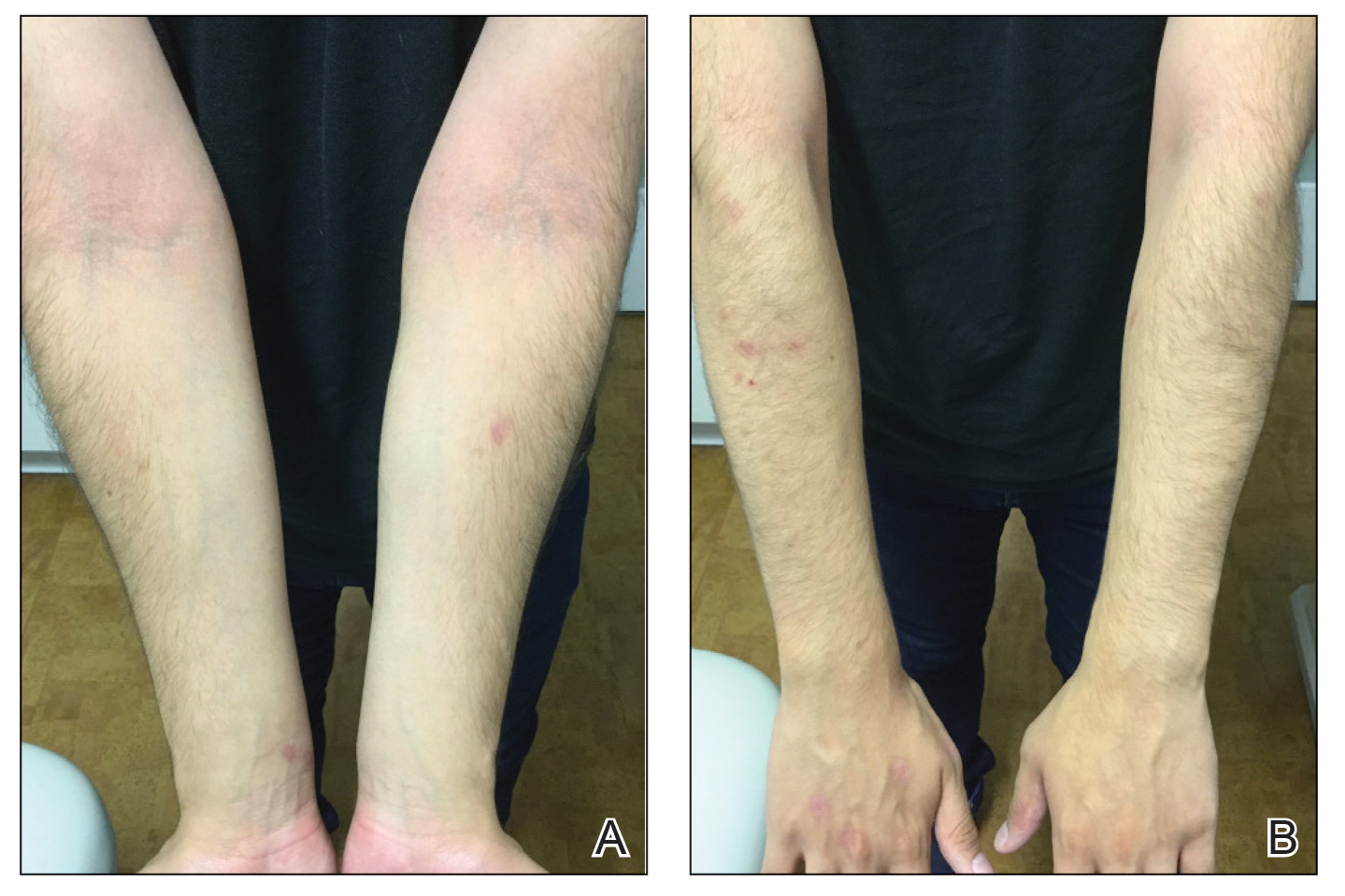

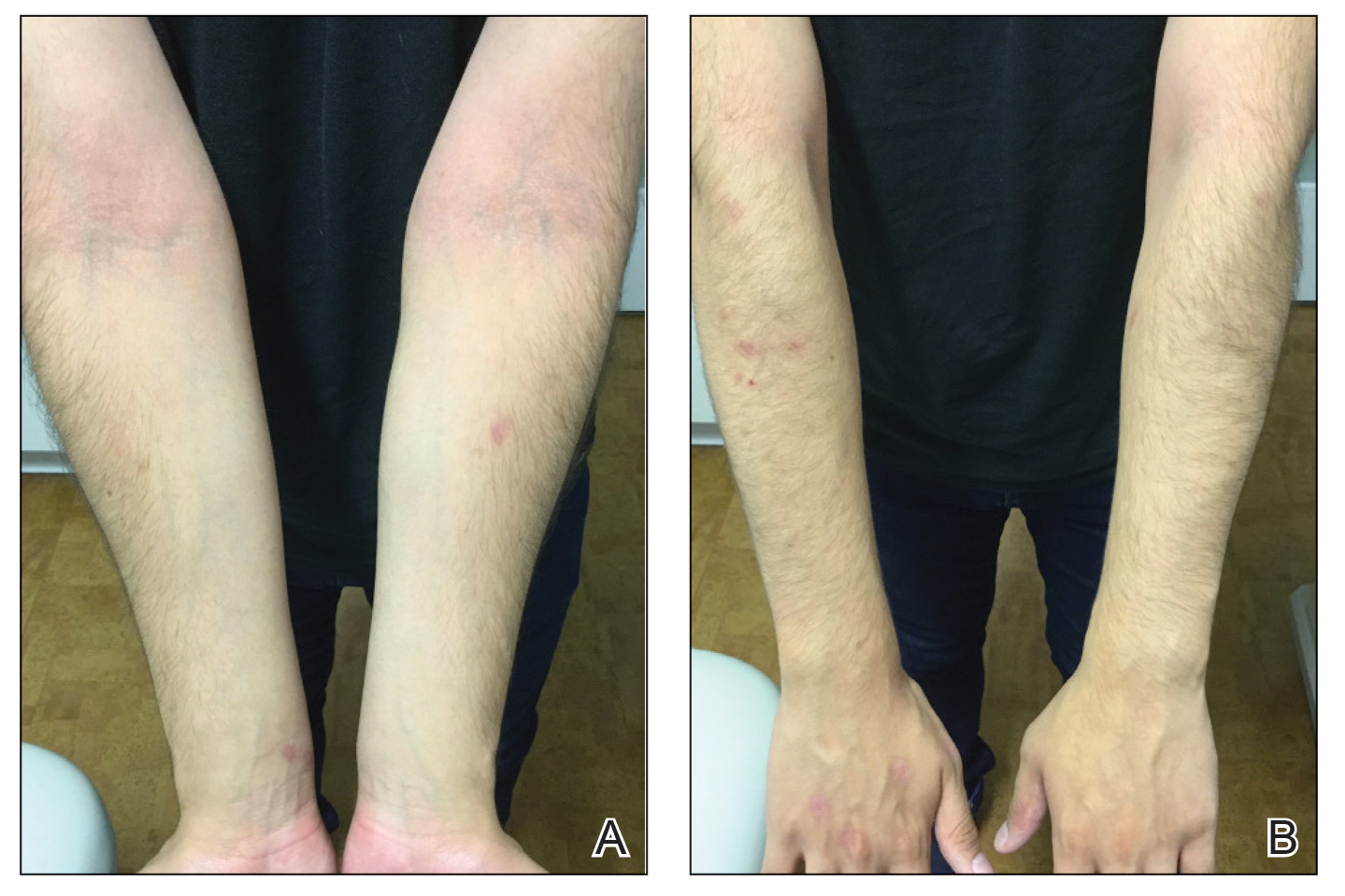

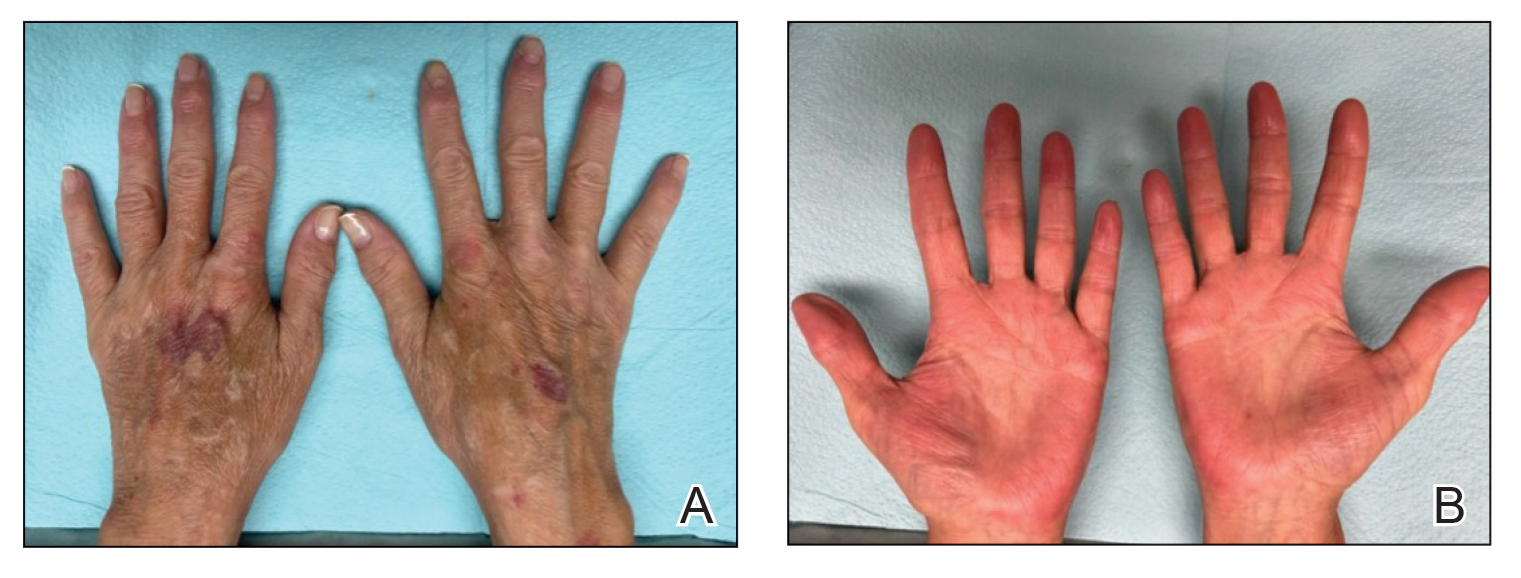

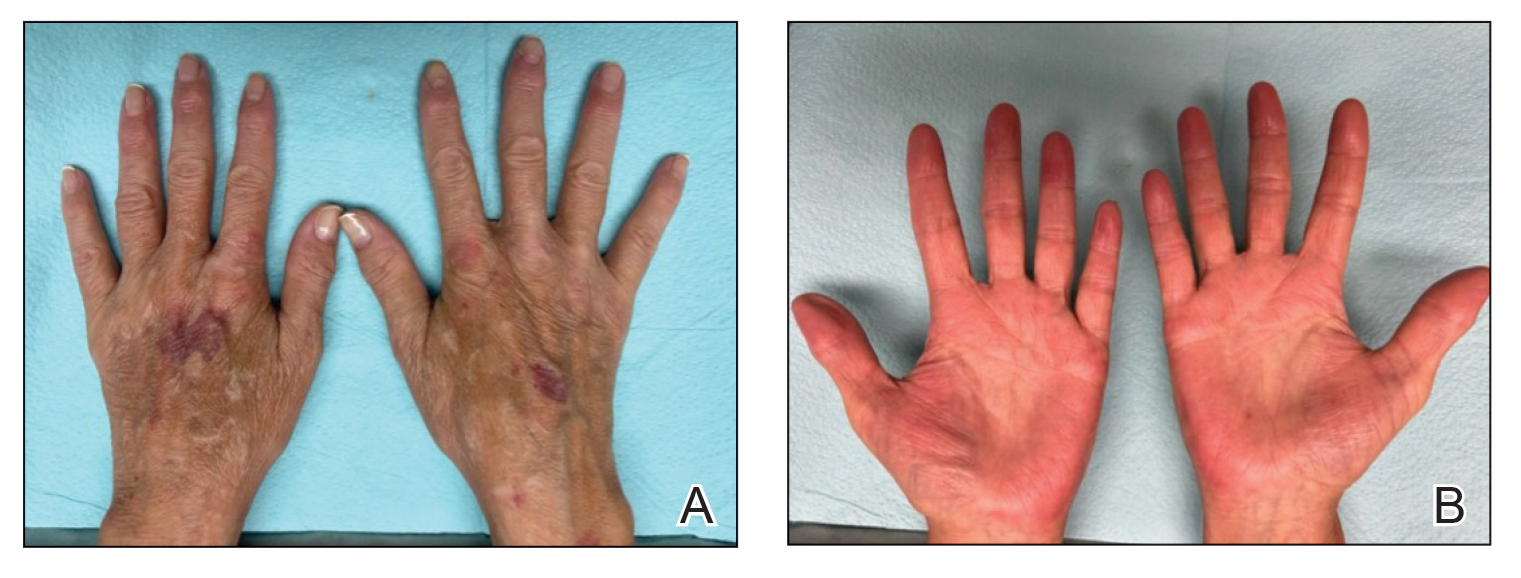

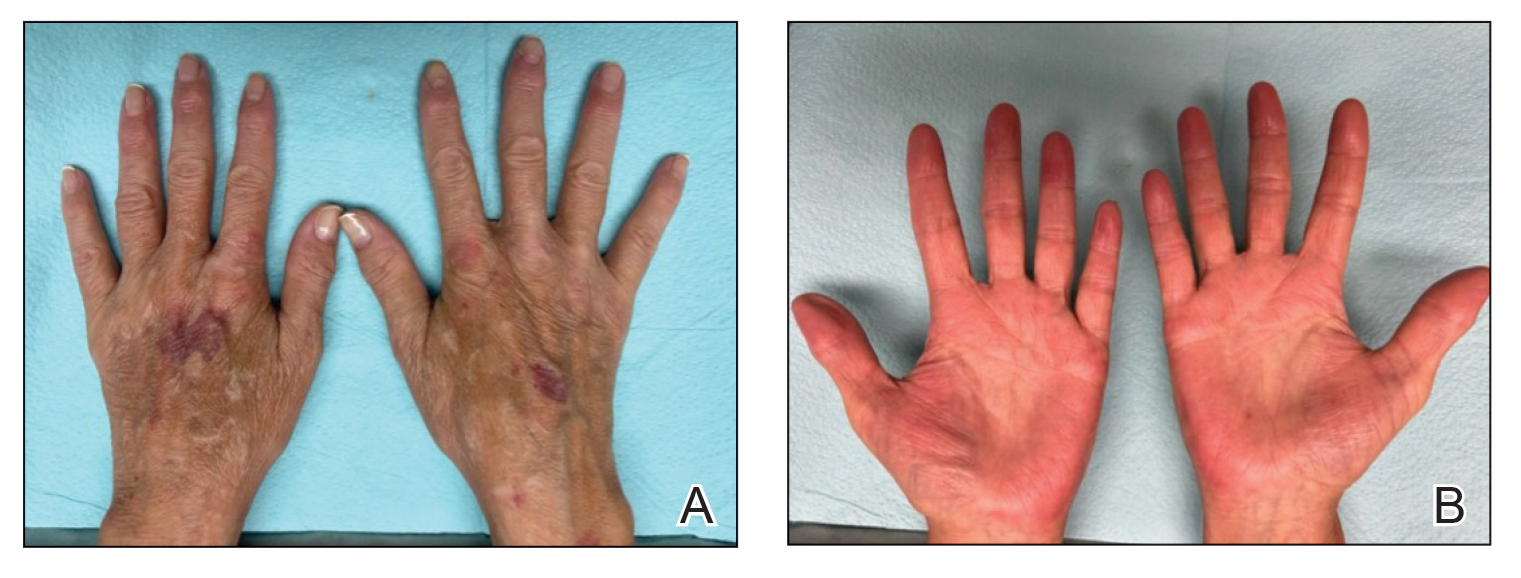

Because omalizumab resulted in dramatic improvement in the patient’s asthma, there was hesitation to discontinue it initially; however, the patient and his parents in conjunction with the dermatology and pulmonary teams decided to transition to dupilumab. The patient reported vast improvement of AD 1 month after initiation of dupilumab (Figure 2), which remained well controlled more than 1 year later. Mid-potency topical corticosteroids for the treatment of occasional mild eczematous flares on the extremities were used. The patient’s asthma has remained well controlled on dupilumab without any exacerbations.

Omalizumab is a recombinant DNA-derived humanized monoclonal antibody that binds both circulating and membrane-bound IgE. It has been proposed as a possible treatment for severe and/or recalcitrant AD, with mixed treatment results.1 A case series and review of 174 patients demonstrated a moderate to complete AD response to treatment with omalizumab in 74.1% of patients.2 The Atopic Dermatitis Anti-IgE Pediatric Trial (ADAPT) showed a statistically significant reduction in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index (P=.01), along with improved quality of life in children treated with omalizumab vs those treated with placebo.3 However, a prior randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study did not show a significant difference in clinical disease parameters in patients treated with omalizumab.4

The humanized monoclonal antibody dupilumab, an anti–IL-4/IL-13 agent, has demonstrated more consistent efficacy for the treatment of AD in children and adults.1 Dupilumab is effective for both intrinsic and extrinsic AD1 because its clinical efficacy is unrelated to circulating levels of IgE in the bloodstream. Although IgE may have a role in childhood AD, our case demonstrated a different pathophysiologic mechanism independent of IgE. Our patient’s AD flares occurred within a few days of omalizumab injection, which may have resulted in a paradoxical increase in basophil sensitivity to other cytokines such as IL-335 and led to an increase in IL-4/IL-13 production within the skin. In our patient, this increase was successfully blocked by dupilumab. Furthermore, omalizumab has been shown to modulate helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin.6 A cytokine imbalance could have exacerbated AD in our case.

Although additional work to clarify the pathogenesis of AD is needed, it is important to recognize the potential for the occurrence of paradoxical AD flares in patients treated with omalizumab, which is analogous to the well-documented entity of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis. It is equally important to recognize the potential benefit for patients treated with dupilumab.

- Nygaard U, Vestergaard C, Deleuran M. Emerging treatment options in atopic dermatitis: systemic therapies. Dermatology. 2017;233:344-357.

- Holm JG, Agner T, Sand C, et al. Omalizumab for atopic dermatitis: case series and a systematic review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:18-26.

- Chan S, Cornelius V, Cro S, et al. Treatment effect of omalizumab on severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: the ADAPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:29-37.

- Heil PM, Maurer D, Klein B, et al. Omalizumab therapy in atopic dermatitis: depletion of IgE does not improve the clinical course – a randomized placebo-controlled and double blind pilot study. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:990-998.

- Imai Y. Interleukin-33 in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 2019;96:2-7.

- Iyengar SR, Hoyte EG, Loza A, et al. Immunologic effects of omalizumab in children with severe refractory atopic dermatitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;162:89-93.

To the Editor:

A 16-year-old adolescent boy presented to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of long-standing mild atopic dermatitis (AD) that had become severe over the last year after omalizumab was initiated for severe asthma. The patient had a history of multiple hospitalizations for severe asthma. Despite excellent control of asthma with omalizumab given every 2 weeks, he developed widespread eczematous plaques on the neck, trunk, and extremities over the course of a year. The AD often was complicated by superimposed folliculitis due to scratching from severe pruritus. Treatment with topical corticosteroids including triamcinolone ointment 0.1% to AD on the body, plus clobetasol ointment 0.05% for prurigolike lesions on the legs resulted in modest improvement; however, the AD consistently recurred within a few days after the biweekly omalizumab injection (Figure 1). When the omalizumab injections were delayed, the flares temporarily improved, and when injections were decreased to once monthly, the exacerbations subsided partially but not fully.

Because omalizumab resulted in dramatic improvement in the patient’s asthma, there was hesitation to discontinue it initially; however, the patient and his parents in conjunction with the dermatology and pulmonary teams decided to transition to dupilumab. The patient reported vast improvement of AD 1 month after initiation of dupilumab (Figure 2), which remained well controlled more than 1 year later. Mid-potency topical corticosteroids for the treatment of occasional mild eczematous flares on the extremities were used. The patient’s asthma has remained well controlled on dupilumab without any exacerbations.

Omalizumab is a recombinant DNA-derived humanized monoclonal antibody that binds both circulating and membrane-bound IgE. It has been proposed as a possible treatment for severe and/or recalcitrant AD, with mixed treatment results.1 A case series and review of 174 patients demonstrated a moderate to complete AD response to treatment with omalizumab in 74.1% of patients.2 The Atopic Dermatitis Anti-IgE Pediatric Trial (ADAPT) showed a statistically significant reduction in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index (P=.01), along with improved quality of life in children treated with omalizumab vs those treated with placebo.3 However, a prior randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study did not show a significant difference in clinical disease parameters in patients treated with omalizumab.4

The humanized monoclonal antibody dupilumab, an anti–IL-4/IL-13 agent, has demonstrated more consistent efficacy for the treatment of AD in children and adults.1 Dupilumab is effective for both intrinsic and extrinsic AD1 because its clinical efficacy is unrelated to circulating levels of IgE in the bloodstream. Although IgE may have a role in childhood AD, our case demonstrated a different pathophysiologic mechanism independent of IgE. Our patient’s AD flares occurred within a few days of omalizumab injection, which may have resulted in a paradoxical increase in basophil sensitivity to other cytokines such as IL-335 and led to an increase in IL-4/IL-13 production within the skin. In our patient, this increase was successfully blocked by dupilumab. Furthermore, omalizumab has been shown to modulate helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin.6 A cytokine imbalance could have exacerbated AD in our case.

Although additional work to clarify the pathogenesis of AD is needed, it is important to recognize the potential for the occurrence of paradoxical AD flares in patients treated with omalizumab, which is analogous to the well-documented entity of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis. It is equally important to recognize the potential benefit for patients treated with dupilumab.

To the Editor:

A 16-year-old adolescent boy presented to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of long-standing mild atopic dermatitis (AD) that had become severe over the last year after omalizumab was initiated for severe asthma. The patient had a history of multiple hospitalizations for severe asthma. Despite excellent control of asthma with omalizumab given every 2 weeks, he developed widespread eczematous plaques on the neck, trunk, and extremities over the course of a year. The AD often was complicated by superimposed folliculitis due to scratching from severe pruritus. Treatment with topical corticosteroids including triamcinolone ointment 0.1% to AD on the body, plus clobetasol ointment 0.05% for prurigolike lesions on the legs resulted in modest improvement; however, the AD consistently recurred within a few days after the biweekly omalizumab injection (Figure 1). When the omalizumab injections were delayed, the flares temporarily improved, and when injections were decreased to once monthly, the exacerbations subsided partially but not fully.

Because omalizumab resulted in dramatic improvement in the patient’s asthma, there was hesitation to discontinue it initially; however, the patient and his parents in conjunction with the dermatology and pulmonary teams decided to transition to dupilumab. The patient reported vast improvement of AD 1 month after initiation of dupilumab (Figure 2), which remained well controlled more than 1 year later. Mid-potency topical corticosteroids for the treatment of occasional mild eczematous flares on the extremities were used. The patient’s asthma has remained well controlled on dupilumab without any exacerbations.

Omalizumab is a recombinant DNA-derived humanized monoclonal antibody that binds both circulating and membrane-bound IgE. It has been proposed as a possible treatment for severe and/or recalcitrant AD, with mixed treatment results.1 A case series and review of 174 patients demonstrated a moderate to complete AD response to treatment with omalizumab in 74.1% of patients.2 The Atopic Dermatitis Anti-IgE Pediatric Trial (ADAPT) showed a statistically significant reduction in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index (P=.01), along with improved quality of life in children treated with omalizumab vs those treated with placebo.3 However, a prior randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study did not show a significant difference in clinical disease parameters in patients treated with omalizumab.4

The humanized monoclonal antibody dupilumab, an anti–IL-4/IL-13 agent, has demonstrated more consistent efficacy for the treatment of AD in children and adults.1 Dupilumab is effective for both intrinsic and extrinsic AD1 because its clinical efficacy is unrelated to circulating levels of IgE in the bloodstream. Although IgE may have a role in childhood AD, our case demonstrated a different pathophysiologic mechanism independent of IgE. Our patient’s AD flares occurred within a few days of omalizumab injection, which may have resulted in a paradoxical increase in basophil sensitivity to other cytokines such as IL-335 and led to an increase in IL-4/IL-13 production within the skin. In our patient, this increase was successfully blocked by dupilumab. Furthermore, omalizumab has been shown to modulate helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin.6 A cytokine imbalance could have exacerbated AD in our case.

Although additional work to clarify the pathogenesis of AD is needed, it is important to recognize the potential for the occurrence of paradoxical AD flares in patients treated with omalizumab, which is analogous to the well-documented entity of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis. It is equally important to recognize the potential benefit for patients treated with dupilumab.

- Nygaard U, Vestergaard C, Deleuran M. Emerging treatment options in atopic dermatitis: systemic therapies. Dermatology. 2017;233:344-357.

- Holm JG, Agner T, Sand C, et al. Omalizumab for atopic dermatitis: case series and a systematic review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:18-26.

- Chan S, Cornelius V, Cro S, et al. Treatment effect of omalizumab on severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: the ADAPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:29-37.

- Heil PM, Maurer D, Klein B, et al. Omalizumab therapy in atopic dermatitis: depletion of IgE does not improve the clinical course – a randomized placebo-controlled and double blind pilot study. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:990-998.

- Imai Y. Interleukin-33 in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 2019;96:2-7.

- Iyengar SR, Hoyte EG, Loza A, et al. Immunologic effects of omalizumab in children with severe refractory atopic dermatitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;162:89-93.

- Nygaard U, Vestergaard C, Deleuran M. Emerging treatment options in atopic dermatitis: systemic therapies. Dermatology. 2017;233:344-357.

- Holm JG, Agner T, Sand C, et al. Omalizumab for atopic dermatitis: case series and a systematic review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:18-26.

- Chan S, Cornelius V, Cro S, et al. Treatment effect of omalizumab on severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: the ADAPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:29-37.

- Heil PM, Maurer D, Klein B, et al. Omalizumab therapy in atopic dermatitis: depletion of IgE does not improve the clinical course – a randomized placebo-controlled and double blind pilot study. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:990-998.

- Imai Y. Interleukin-33 in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 2019;96:2-7.

- Iyengar SR, Hoyte EG, Loza A, et al. Immunologic effects of omalizumab in children with severe refractory atopic dermatitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;162:89-93.

Practice Points

- Monoclonal antibodies are promising therapies for atopic conditions, although its efficacy for atopic dermatitis (AD) is debated and the side-effect profile is not entirely known.

- Omalizumab may cause a paradoxical exacerbation of AD in select patients analogous to tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis.

Topical botanical drug coacillium curbs childhood alopecia

Considerable hair regrowth can be achieved in children with alopecia areata with the use of a novel plant-based drug, according to research presented during the first late-breaking news session at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

(–8.0%), with a significant 31% overall difference (P < .0001).

“Coacillium cutaneous solution was used for the first time for treatment of alopecia areata and also for the first time used in a pediatric population,” the presenting investigator Ulrike Blume-Peytavi, MD, said at the meeting.

“It’s well tolerated, and in fact what is interesting is, it has a durable response, even after treatment discontinuation,” added Dr. Blume-Peytavi, who is the deputy head of the department of dermatology, venereology and allergology at Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Backing the botanical?

Paola Pasquali, MD, a dermatologist at Pius Hospital de Valls in Spain, who cochaired the session where the findings were presented, commented, “Thank you for showing that chocolate is great! I knew it. It is fantastic to see how chocolate is used.”

Dr. Pasquali was referring to the coacillium ingredient Theobroma cacao extract. The seeds of T. cacao, or the cocoa tree, are used to make various types of chocolate products. Theobroma cacao is one of four plant extracts that make up coacillium, the others being Allium cepa (onion), Citrus limon (lemon), and Paullinia cupana (guaraná, a source of caffeine).

The four plant extracts are classified as “generally regarded as safe” (GRAS), Dr. Blume-Peytavi observed, noting that the development of coacillium fell under the category of a prescription botanical drug as set out by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or a herbal medicinal product as set out by the European Medicines Agency.

But how does it work?

The botanical’s mode of action of acting positively on hair follicle cycling and endothelial cell activation was called into question, however, by Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, who was in the audience.

She asked, “So how do you explain that, after three large studies with topical JAK inhibitors that did not work actually in alopecia areata because it’s very hard to penetrate the scalp for a topical [drug], this one works?”

Dr. Guttman-Yassky, professor of dermatology and immunology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, added: “Looking at the ingredients, to me, it seems that it’s more like a DPCP [diphenylcyclopropenone]-like reaction.”

DPCP, which has been used to treat alopecia, purportedly works by stimulating the immune response to target the skin surface – causing an allergic reaction – rather than the hair follicle.

It’s an interesting question as to how a molecule penetrates the hair follicle, and it depends on the size of the molecule, Dr. Blume-Peytavi responded.

“We have done a lot of studies on follicular penetration, and we are quite aware that you need a certain size of the molecule,” she said. Between 14 and 200 nanometers appears to produce “the best penetrators,” she observed.

Dr. Blume-Peytavi commented that even after topical JAK inhibitors are applied, the molecules that penetrate do not remain in the local area for very long, yet still produce an inhibitory signaling effect.

No scalp irritation was seen in the trial, which suggests that coacillium is not working in the same way as DPCP, Dr. Blume-Peytavi countered.

Evaluating efficacy and safety: The RAAINBOW study

Dr. Blume-Peytavi acknowledged that JAK inhibitors were “a tremendous advance in treating severe and very severe alopecia areata,” but because of their benefit-to-risk ratio, there was still an unmet need for new treatments, particularly in children, in whom drug safety is of critical importance.

Having a drug that could be given safely and also have an effect early on in the disease, while it is still at a mild to moderate stage, would be of considerable value, Dr. Blume-Peytavi maintained.

The RAAINBOW study was a randomized, double-blind, phase 2/3 trial conducted at 12 sites in Germany and three other countries between March 2018 and March 2022 to evaluate the efficacy and safety of coacillium in the treatment of children and adolescents with moderate to severe alopecia areata.

In all, 62 children aged 2-18 years (mean age, 11 years) participated; 42 were treated twice daily with coacillium cutaneous solution 22.5% and 20 received placebo for 24 weeks. Treatment was then stopped, and participants followed for another 24 weeks off treatment to check for disease relapse, bringing the total study duration up to 48 weeks.

Baseline characteristics were “relatively comparable for severity,” Dr. Blume-Peytavi said. Most of the children had severe alopecia areata (57% for coacillium and 65% for placebo); the remainder had moderate disease (43% vs. 35%, respectively).

The average SALT scores at the start of treatment were 56 in the coacillium group and 62 in the placebo group, and a respective 44 and 61 at the end of 24 weeks’ treatment.

Perhaps the most important results, Dr. Blume-Peytavi said, was that at 48 weeks of follow-up, which was 24 weeks after treatment had been discontinued, the mean SALT scores were 29 for coacillium and 56 for placebo (P < .0001).

“You can see the improvement in the treated group is continuing even without treatment. However, the placebo group stays relatively about the same range,” she said.

Overall, 82% of patients treated with coacillium and 37% of those who received placebo experienced hair growth after treatment had stopped, and by week 48, a respective 46.7% vs. 9.1% had a SALT score of 20 or less, and 30.0% vs. 0% had a SALT score of 10 or less.

No safety concerns were raised, with no serious treatment-related reactions, no immunosuppressant-like reactions, and no steroidlike side effects.

Beyond the RAAINBOW

Larger studies are needed, Dr. Blume-Peytavi said. According to developer Legacy Healthcare’s website, coacillium cutaneous solution is not being developed just for childhood alopecia areata. It is also under investigation as a treatment for persistent chemotherapy-induced alopecia, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis. In addition, an oral solution is being tested for cancer-related fatigue.

The study was funded by Legacy Healthcare. Dr. Blume-Peytavi has received research funding and acts as an advisor to the company, among others; four of the study’s coauthors are employees of the company. Dr. Pasquali and Dr. Guttman-Yassky were not involved in the study and had no relevant financial ties to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Considerable hair regrowth can be achieved in children with alopecia areata with the use of a novel plant-based drug, according to research presented during the first late-breaking news session at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

(–8.0%), with a significant 31% overall difference (P < .0001).

“Coacillium cutaneous solution was used for the first time for treatment of alopecia areata and also for the first time used in a pediatric population,” the presenting investigator Ulrike Blume-Peytavi, MD, said at the meeting.

“It’s well tolerated, and in fact what is interesting is, it has a durable response, even after treatment discontinuation,” added Dr. Blume-Peytavi, who is the deputy head of the department of dermatology, venereology and allergology at Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Backing the botanical?

Paola Pasquali, MD, a dermatologist at Pius Hospital de Valls in Spain, who cochaired the session where the findings were presented, commented, “Thank you for showing that chocolate is great! I knew it. It is fantastic to see how chocolate is used.”

Dr. Pasquali was referring to the coacillium ingredient Theobroma cacao extract. The seeds of T. cacao, or the cocoa tree, are used to make various types of chocolate products. Theobroma cacao is one of four plant extracts that make up coacillium, the others being Allium cepa (onion), Citrus limon (lemon), and Paullinia cupana (guaraná, a source of caffeine).

The four plant extracts are classified as “generally regarded as safe” (GRAS), Dr. Blume-Peytavi observed, noting that the development of coacillium fell under the category of a prescription botanical drug as set out by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or a herbal medicinal product as set out by the European Medicines Agency.

But how does it work?

The botanical’s mode of action of acting positively on hair follicle cycling and endothelial cell activation was called into question, however, by Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, who was in the audience.

She asked, “So how do you explain that, after three large studies with topical JAK inhibitors that did not work actually in alopecia areata because it’s very hard to penetrate the scalp for a topical [drug], this one works?”

Dr. Guttman-Yassky, professor of dermatology and immunology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, added: “Looking at the ingredients, to me, it seems that it’s more like a DPCP [diphenylcyclopropenone]-like reaction.”

DPCP, which has been used to treat alopecia, purportedly works by stimulating the immune response to target the skin surface – causing an allergic reaction – rather than the hair follicle.

It’s an interesting question as to how a molecule penetrates the hair follicle, and it depends on the size of the molecule, Dr. Blume-Peytavi responded.

“We have done a lot of studies on follicular penetration, and we are quite aware that you need a certain size of the molecule,” she said. Between 14 and 200 nanometers appears to produce “the best penetrators,” she observed.

Dr. Blume-Peytavi commented that even after topical JAK inhibitors are applied, the molecules that penetrate do not remain in the local area for very long, yet still produce an inhibitory signaling effect.

No scalp irritation was seen in the trial, which suggests that coacillium is not working in the same way as DPCP, Dr. Blume-Peytavi countered.

Evaluating efficacy and safety: The RAAINBOW study

Dr. Blume-Peytavi acknowledged that JAK inhibitors were “a tremendous advance in treating severe and very severe alopecia areata,” but because of their benefit-to-risk ratio, there was still an unmet need for new treatments, particularly in children, in whom drug safety is of critical importance.

Having a drug that could be given safely and also have an effect early on in the disease, while it is still at a mild to moderate stage, would be of considerable value, Dr. Blume-Peytavi maintained.

The RAAINBOW study was a randomized, double-blind, phase 2/3 trial conducted at 12 sites in Germany and three other countries between March 2018 and March 2022 to evaluate the efficacy and safety of coacillium in the treatment of children and adolescents with moderate to severe alopecia areata.

In all, 62 children aged 2-18 years (mean age, 11 years) participated; 42 were treated twice daily with coacillium cutaneous solution 22.5% and 20 received placebo for 24 weeks. Treatment was then stopped, and participants followed for another 24 weeks off treatment to check for disease relapse, bringing the total study duration up to 48 weeks.

Baseline characteristics were “relatively comparable for severity,” Dr. Blume-Peytavi said. Most of the children had severe alopecia areata (57% for coacillium and 65% for placebo); the remainder had moderate disease (43% vs. 35%, respectively).

The average SALT scores at the start of treatment were 56 in the coacillium group and 62 in the placebo group, and a respective 44 and 61 at the end of 24 weeks’ treatment.

Perhaps the most important results, Dr. Blume-Peytavi said, was that at 48 weeks of follow-up, which was 24 weeks after treatment had been discontinued, the mean SALT scores were 29 for coacillium and 56 for placebo (P < .0001).

“You can see the improvement in the treated group is continuing even without treatment. However, the placebo group stays relatively about the same range,” she said.

Overall, 82% of patients treated with coacillium and 37% of those who received placebo experienced hair growth after treatment had stopped, and by week 48, a respective 46.7% vs. 9.1% had a SALT score of 20 or less, and 30.0% vs. 0% had a SALT score of 10 or less.

No safety concerns were raised, with no serious treatment-related reactions, no immunosuppressant-like reactions, and no steroidlike side effects.

Beyond the RAAINBOW

Larger studies are needed, Dr. Blume-Peytavi said. According to developer Legacy Healthcare’s website, coacillium cutaneous solution is not being developed just for childhood alopecia areata. It is also under investigation as a treatment for persistent chemotherapy-induced alopecia, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis. In addition, an oral solution is being tested for cancer-related fatigue.

The study was funded by Legacy Healthcare. Dr. Blume-Peytavi has received research funding and acts as an advisor to the company, among others; four of the study’s coauthors are employees of the company. Dr. Pasquali and Dr. Guttman-Yassky were not involved in the study and had no relevant financial ties to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Considerable hair regrowth can be achieved in children with alopecia areata with the use of a novel plant-based drug, according to research presented during the first late-breaking news session at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

(–8.0%), with a significant 31% overall difference (P < .0001).

“Coacillium cutaneous solution was used for the first time for treatment of alopecia areata and also for the first time used in a pediatric population,” the presenting investigator Ulrike Blume-Peytavi, MD, said at the meeting.

“It’s well tolerated, and in fact what is interesting is, it has a durable response, even after treatment discontinuation,” added Dr. Blume-Peytavi, who is the deputy head of the department of dermatology, venereology and allergology at Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Backing the botanical?

Paola Pasquali, MD, a dermatologist at Pius Hospital de Valls in Spain, who cochaired the session where the findings were presented, commented, “Thank you for showing that chocolate is great! I knew it. It is fantastic to see how chocolate is used.”

Dr. Pasquali was referring to the coacillium ingredient Theobroma cacao extract. The seeds of T. cacao, or the cocoa tree, are used to make various types of chocolate products. Theobroma cacao is one of four plant extracts that make up coacillium, the others being Allium cepa (onion), Citrus limon (lemon), and Paullinia cupana (guaraná, a source of caffeine).

The four plant extracts are classified as “generally regarded as safe” (GRAS), Dr. Blume-Peytavi observed, noting that the development of coacillium fell under the category of a prescription botanical drug as set out by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or a herbal medicinal product as set out by the European Medicines Agency.

But how does it work?

The botanical’s mode of action of acting positively on hair follicle cycling and endothelial cell activation was called into question, however, by Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, who was in the audience.

She asked, “So how do you explain that, after three large studies with topical JAK inhibitors that did not work actually in alopecia areata because it’s very hard to penetrate the scalp for a topical [drug], this one works?”

Dr. Guttman-Yassky, professor of dermatology and immunology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, added: “Looking at the ingredients, to me, it seems that it’s more like a DPCP [diphenylcyclopropenone]-like reaction.”

DPCP, which has been used to treat alopecia, purportedly works by stimulating the immune response to target the skin surface – causing an allergic reaction – rather than the hair follicle.

It’s an interesting question as to how a molecule penetrates the hair follicle, and it depends on the size of the molecule, Dr. Blume-Peytavi responded.

“We have done a lot of studies on follicular penetration, and we are quite aware that you need a certain size of the molecule,” she said. Between 14 and 200 nanometers appears to produce “the best penetrators,” she observed.

Dr. Blume-Peytavi commented that even after topical JAK inhibitors are applied, the molecules that penetrate do not remain in the local area for very long, yet still produce an inhibitory signaling effect.

No scalp irritation was seen in the trial, which suggests that coacillium is not working in the same way as DPCP, Dr. Blume-Peytavi countered.

Evaluating efficacy and safety: The RAAINBOW study

Dr. Blume-Peytavi acknowledged that JAK inhibitors were “a tremendous advance in treating severe and very severe alopecia areata,” but because of their benefit-to-risk ratio, there was still an unmet need for new treatments, particularly in children, in whom drug safety is of critical importance.

Having a drug that could be given safely and also have an effect early on in the disease, while it is still at a mild to moderate stage, would be of considerable value, Dr. Blume-Peytavi maintained.

The RAAINBOW study was a randomized, double-blind, phase 2/3 trial conducted at 12 sites in Germany and three other countries between March 2018 and March 2022 to evaluate the efficacy and safety of coacillium in the treatment of children and adolescents with moderate to severe alopecia areata.

In all, 62 children aged 2-18 years (mean age, 11 years) participated; 42 were treated twice daily with coacillium cutaneous solution 22.5% and 20 received placebo for 24 weeks. Treatment was then stopped, and participants followed for another 24 weeks off treatment to check for disease relapse, bringing the total study duration up to 48 weeks.

Baseline characteristics were “relatively comparable for severity,” Dr. Blume-Peytavi said. Most of the children had severe alopecia areata (57% for coacillium and 65% for placebo); the remainder had moderate disease (43% vs. 35%, respectively).

The average SALT scores at the start of treatment were 56 in the coacillium group and 62 in the placebo group, and a respective 44 and 61 at the end of 24 weeks’ treatment.

Perhaps the most important results, Dr. Blume-Peytavi said, was that at 48 weeks of follow-up, which was 24 weeks after treatment had been discontinued, the mean SALT scores were 29 for coacillium and 56 for placebo (P < .0001).

“You can see the improvement in the treated group is continuing even without treatment. However, the placebo group stays relatively about the same range,” she said.

Overall, 82% of patients treated with coacillium and 37% of those who received placebo experienced hair growth after treatment had stopped, and by week 48, a respective 46.7% vs. 9.1% had a SALT score of 20 or less, and 30.0% vs. 0% had a SALT score of 10 or less.

No safety concerns were raised, with no serious treatment-related reactions, no immunosuppressant-like reactions, and no steroidlike side effects.

Beyond the RAAINBOW

Larger studies are needed, Dr. Blume-Peytavi said. According to developer Legacy Healthcare’s website, coacillium cutaneous solution is not being developed just for childhood alopecia areata. It is also under investigation as a treatment for persistent chemotherapy-induced alopecia, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis. In addition, an oral solution is being tested for cancer-related fatigue.

The study was funded by Legacy Healthcare. Dr. Blume-Peytavi has received research funding and acts as an advisor to the company, among others; four of the study’s coauthors are employees of the company. Dr. Pasquali and Dr. Guttman-Yassky were not involved in the study and had no relevant financial ties to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

Patch testing finds higher prevalence of ACD among children with AD

, a finding that investigators say underscores the value of considering ACD in patients with AD and referring more children for testing.

ACD is underdetected in children with AD. In some cases, it may be misconstrued to be AD, and patch testing, the gold standard for diagnosing ACD, is often not performed, said senior author JiaDe Yu, MD, MS, a pediatric dermatologist and director of contact and occupational dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his co-authors, in the study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Dr. Yu and his colleagues utilized a database in which dermatologists and some allergists, all of whom had substantive experience in patch testing and in diagnosing and managing ACD in children, entered information about children who were referred to them for testing.

Of 912 children referred for patch testing between 2018 and 2022 from 14 geographically diverse centers in the United States (615 with AD and 297 without AD), those with AD were more likely to have more than one positive reaction (odds radio, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-2.14; P = .005) and had a greater number of positive results overall (2.3 vs. 1.9; P = .012).

AD and ACD both present with red, itchy, eczema-like patches and plaques and can be “really hard to differentiate,” Dr. Yu said in an interview.

“Not everybody with AD needs patch testing,” he said, “but I do think some [patients] who have rashes in unusual locations or rashes that don’t seem to improve within an appropriate amount of time to topical medications ... are the children who probably should have patch testing.”

Candidates for patch testing include children with AD who present with isolated head or neck, hand or foot, or anal or genital dermatitis, Dr. Yu and his colleagues write in the study. In addition, Dr. Yu said in the interview, “if you have a child who has AD that involves the elbow and back of the knees but then they get new-onset facial dermatitis, say, or new-onset eyelid dermatitis ... there’s [significant] value in patch testing.”

Children with AD in the study had a more generalized distribution of dermatitis and were significantly less likely to have dermatitis affecting the anal or genital region, the authors note in the study.

Asked to comment on the results, Jennifer Perryman, MD, a dermatologist at UCHealth, Greeley, Colo., who performs patch testing in children and adults, said that ACD is indeed “often underdiagnosed” in children with AD, and the study “solidifies” the importance of considering ACD in this population.

“Clinicians should think about testing children when AD is [not well controlled or] is getting worse, is in an atypical distribution, or if they are considering systemic treatment,” she said in an e-mail.

“I tell my patients, ‘I know you have AD, but you could also have comorbid ACD, and if we can find and control that, we can make you better without adding more to your routine, medications, etc.’ ” said Dr. Perryman, who was not involved in the research.

Top allergens

The top 10 allergens between children with and without AD were largely similar, the authors of the study report. Nickel was the most common allergen identified in both groups, and cobalt was in the top five for both groups. Fragrances (including hydroperoxides of linalool), preservatives (including methylisothiazolinone [MI]), and neomycin ranked in the top 10 in both groups, though prevalence differed.

MI, a preservative frequently used in personal care products and in other products like school glue and paint, was the second most common allergen identified in children with AD. Allergy to MI has “recently become an epidemic in the United States, with rapidly increasing prevalence and importance as a source of ACD among both children and adults,” the authors note.

Children with AD were significantly more likely, however, to have ACD to bacitracin (OR, 3.23; P = .030) and to cocamidopropyl betaine (OR, 3.69; P = .0007), the latter of which is a popular surfactant used in “baby” and “gentle” skincare products. This is unsurprising, given that children with AD are “more often exposed to a myriad of topical treatments,” Dr. Yu and his colleagues write.

Although not a top 10 allergen for either group, ACD to “carba mix,” a combination of three chemicals used to make medical adhesives and other rubber products (such as pacifiers, toys, school supplies, and rubber gloves) was significantly more common in children with AD than in those without (OR, 3.36; P = .025).

Among other findings from the study: Children with AD were more likely to have a longer history of dermatitis (4.1 vs. 1.6 years, P < .0001) prior to patch testing. Testing occurred at a mean age of 11 and 12.3 years for children with and without AD, respectively.

The number of allergens tested and the patch testing series chosen per patient were “not statistically different” between the children with and without AD, the researchers report.

Patch testing availability

Clinicians may be hesitant to subject a child to patch testing, but the process is well tolerated in most children, Dr. Perryman said. She uses a modified panel for children that omits less relevant allergens and usually limits patch testing to age 2 years or older due to a young child’s smaller surface area.

Dr. Yu, who developed an interest in patch testing during his residency at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, where he worked with a patch-testing expert, will test children as young as 3-4 months with a “small selection of patches.”

The challenge with a call for more patch testing is a shortage of trained physicians. “In all of Boston, where we have hundreds of dermatologists, there are only about four of us who really do patch testing. My wait time is about 6 months,” said Dr. Yu, who is also an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Allergists at Massachusetts General Hospital do “some patch testing ... but they refer a lot of the most complicated cases to me,” he said, noting that patch testing and management of ACD involves detailed counseling for patients about avoidance of allergens. “Overall dermatologists represent the largest group of doctors who have proficiency in patch testing, and there just aren’t many of us.”

Dr. Perryman also said that patch testing is often performed by dermatologists who specialize in treating ACD and AD, though there seems to be “regional variance” in the level of involvement of dermatologists and allergists in patch testing.

Not all residency programs have hands-on patch testing opportunities, Dr. Yu said. A study published in Dermatitis, which he co-authored, showed that in 2020, 47.5% of dermatology residency programs had formal patch testing rotations. This represented improvement but is still not enough, he said.

The American Contact Dermatitis Society offers patch-testing mentorship programs, and the American Academy of Dermatology has recently begun offered a patch testing workshop at its annual meetings, said Dr. Yu, who received 4 weeks of training in the Society’s mentorship program and is now involved in the American Academy of Dermatology’s workshops and as a trainer/lecturer at the Contact Dermatitis Institute.

The study was supported by the Dermatology Foundation. Dr. Yu and his co-investigators reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Perryman had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a finding that investigators say underscores the value of considering ACD in patients with AD and referring more children for testing.

ACD is underdetected in children with AD. In some cases, it may be misconstrued to be AD, and patch testing, the gold standard for diagnosing ACD, is often not performed, said senior author JiaDe Yu, MD, MS, a pediatric dermatologist and director of contact and occupational dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his co-authors, in the study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Dr. Yu and his colleagues utilized a database in which dermatologists and some allergists, all of whom had substantive experience in patch testing and in diagnosing and managing ACD in children, entered information about children who were referred to them for testing.

Of 912 children referred for patch testing between 2018 and 2022 from 14 geographically diverse centers in the United States (615 with AD and 297 without AD), those with AD were more likely to have more than one positive reaction (odds radio, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-2.14; P = .005) and had a greater number of positive results overall (2.3 vs. 1.9; P = .012).

AD and ACD both present with red, itchy, eczema-like patches and plaques and can be “really hard to differentiate,” Dr. Yu said in an interview.

“Not everybody with AD needs patch testing,” he said, “but I do think some [patients] who have rashes in unusual locations or rashes that don’t seem to improve within an appropriate amount of time to topical medications ... are the children who probably should have patch testing.”

Candidates for patch testing include children with AD who present with isolated head or neck, hand or foot, or anal or genital dermatitis, Dr. Yu and his colleagues write in the study. In addition, Dr. Yu said in the interview, “if you have a child who has AD that involves the elbow and back of the knees but then they get new-onset facial dermatitis, say, or new-onset eyelid dermatitis ... there’s [significant] value in patch testing.”

Children with AD in the study had a more generalized distribution of dermatitis and were significantly less likely to have dermatitis affecting the anal or genital region, the authors note in the study.

Asked to comment on the results, Jennifer Perryman, MD, a dermatologist at UCHealth, Greeley, Colo., who performs patch testing in children and adults, said that ACD is indeed “often underdiagnosed” in children with AD, and the study “solidifies” the importance of considering ACD in this population.

“Clinicians should think about testing children when AD is [not well controlled or] is getting worse, is in an atypical distribution, or if they are considering systemic treatment,” she said in an e-mail.

“I tell my patients, ‘I know you have AD, but you could also have comorbid ACD, and if we can find and control that, we can make you better without adding more to your routine, medications, etc.’ ” said Dr. Perryman, who was not involved in the research.

Top allergens

The top 10 allergens between children with and without AD were largely similar, the authors of the study report. Nickel was the most common allergen identified in both groups, and cobalt was in the top five for both groups. Fragrances (including hydroperoxides of linalool), preservatives (including methylisothiazolinone [MI]), and neomycin ranked in the top 10 in both groups, though prevalence differed.

MI, a preservative frequently used in personal care products and in other products like school glue and paint, was the second most common allergen identified in children with AD. Allergy to MI has “recently become an epidemic in the United States, with rapidly increasing prevalence and importance as a source of ACD among both children and adults,” the authors note.

Children with AD were significantly more likely, however, to have ACD to bacitracin (OR, 3.23; P = .030) and to cocamidopropyl betaine (OR, 3.69; P = .0007), the latter of which is a popular surfactant used in “baby” and “gentle” skincare products. This is unsurprising, given that children with AD are “more often exposed to a myriad of topical treatments,” Dr. Yu and his colleagues write.

Although not a top 10 allergen for either group, ACD to “carba mix,” a combination of three chemicals used to make medical adhesives and other rubber products (such as pacifiers, toys, school supplies, and rubber gloves) was significantly more common in children with AD than in those without (OR, 3.36; P = .025).

Among other findings from the study: Children with AD were more likely to have a longer history of dermatitis (4.1 vs. 1.6 years, P < .0001) prior to patch testing. Testing occurred at a mean age of 11 and 12.3 years for children with and without AD, respectively.

The number of allergens tested and the patch testing series chosen per patient were “not statistically different” between the children with and without AD, the researchers report.

Patch testing availability

Clinicians may be hesitant to subject a child to patch testing, but the process is well tolerated in most children, Dr. Perryman said. She uses a modified panel for children that omits less relevant allergens and usually limits patch testing to age 2 years or older due to a young child’s smaller surface area.

Dr. Yu, who developed an interest in patch testing during his residency at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, where he worked with a patch-testing expert, will test children as young as 3-4 months with a “small selection of patches.”

The challenge with a call for more patch testing is a shortage of trained physicians. “In all of Boston, where we have hundreds of dermatologists, there are only about four of us who really do patch testing. My wait time is about 6 months,” said Dr. Yu, who is also an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Allergists at Massachusetts General Hospital do “some patch testing ... but they refer a lot of the most complicated cases to me,” he said, noting that patch testing and management of ACD involves detailed counseling for patients about avoidance of allergens. “Overall dermatologists represent the largest group of doctors who have proficiency in patch testing, and there just aren’t many of us.”

Dr. Perryman also said that patch testing is often performed by dermatologists who specialize in treating ACD and AD, though there seems to be “regional variance” in the level of involvement of dermatologists and allergists in patch testing.

Not all residency programs have hands-on patch testing opportunities, Dr. Yu said. A study published in Dermatitis, which he co-authored, showed that in 2020, 47.5% of dermatology residency programs had formal patch testing rotations. This represented improvement but is still not enough, he said.

The American Contact Dermatitis Society offers patch-testing mentorship programs, and the American Academy of Dermatology has recently begun offered a patch testing workshop at its annual meetings, said Dr. Yu, who received 4 weeks of training in the Society’s mentorship program and is now involved in the American Academy of Dermatology’s workshops and as a trainer/lecturer at the Contact Dermatitis Institute.

The study was supported by the Dermatology Foundation. Dr. Yu and his co-investigators reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Perryman had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a finding that investigators say underscores the value of considering ACD in patients with AD and referring more children for testing.

ACD is underdetected in children with AD. In some cases, it may be misconstrued to be AD, and patch testing, the gold standard for diagnosing ACD, is often not performed, said senior author JiaDe Yu, MD, MS, a pediatric dermatologist and director of contact and occupational dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his co-authors, in the study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Dr. Yu and his colleagues utilized a database in which dermatologists and some allergists, all of whom had substantive experience in patch testing and in diagnosing and managing ACD in children, entered information about children who were referred to them for testing.

Of 912 children referred for patch testing between 2018 and 2022 from 14 geographically diverse centers in the United States (615 with AD and 297 without AD), those with AD were more likely to have more than one positive reaction (odds radio, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-2.14; P = .005) and had a greater number of positive results overall (2.3 vs. 1.9; P = .012).

AD and ACD both present with red, itchy, eczema-like patches and plaques and can be “really hard to differentiate,” Dr. Yu said in an interview.

“Not everybody with AD needs patch testing,” he said, “but I do think some [patients] who have rashes in unusual locations or rashes that don’t seem to improve within an appropriate amount of time to topical medications ... are the children who probably should have patch testing.”

Candidates for patch testing include children with AD who present with isolated head or neck, hand or foot, or anal or genital dermatitis, Dr. Yu and his colleagues write in the study. In addition, Dr. Yu said in the interview, “if you have a child who has AD that involves the elbow and back of the knees but then they get new-onset facial dermatitis, say, or new-onset eyelid dermatitis ... there’s [significant] value in patch testing.”

Children with AD in the study had a more generalized distribution of dermatitis and were significantly less likely to have dermatitis affecting the anal or genital region, the authors note in the study.

Asked to comment on the results, Jennifer Perryman, MD, a dermatologist at UCHealth, Greeley, Colo., who performs patch testing in children and adults, said that ACD is indeed “often underdiagnosed” in children with AD, and the study “solidifies” the importance of considering ACD in this population.

“Clinicians should think about testing children when AD is [not well controlled or] is getting worse, is in an atypical distribution, or if they are considering systemic treatment,” she said in an e-mail.

“I tell my patients, ‘I know you have AD, but you could also have comorbid ACD, and if we can find and control that, we can make you better without adding more to your routine, medications, etc.’ ” said Dr. Perryman, who was not involved in the research.

Top allergens

The top 10 allergens between children with and without AD were largely similar, the authors of the study report. Nickel was the most common allergen identified in both groups, and cobalt was in the top five for both groups. Fragrances (including hydroperoxides of linalool), preservatives (including methylisothiazolinone [MI]), and neomycin ranked in the top 10 in both groups, though prevalence differed.

MI, a preservative frequently used in personal care products and in other products like school glue and paint, was the second most common allergen identified in children with AD. Allergy to MI has “recently become an epidemic in the United States, with rapidly increasing prevalence and importance as a source of ACD among both children and adults,” the authors note.

Children with AD were significantly more likely, however, to have ACD to bacitracin (OR, 3.23; P = .030) and to cocamidopropyl betaine (OR, 3.69; P = .0007), the latter of which is a popular surfactant used in “baby” and “gentle” skincare products. This is unsurprising, given that children with AD are “more often exposed to a myriad of topical treatments,” Dr. Yu and his colleagues write.

Although not a top 10 allergen for either group, ACD to “carba mix,” a combination of three chemicals used to make medical adhesives and other rubber products (such as pacifiers, toys, school supplies, and rubber gloves) was significantly more common in children with AD than in those without (OR, 3.36; P = .025).

Among other findings from the study: Children with AD were more likely to have a longer history of dermatitis (4.1 vs. 1.6 years, P < .0001) prior to patch testing. Testing occurred at a mean age of 11 and 12.3 years for children with and without AD, respectively.

The number of allergens tested and the patch testing series chosen per patient were “not statistically different” between the children with and without AD, the researchers report.

Patch testing availability

Clinicians may be hesitant to subject a child to patch testing, but the process is well tolerated in most children, Dr. Perryman said. She uses a modified panel for children that omits less relevant allergens and usually limits patch testing to age 2 years or older due to a young child’s smaller surface area.

Dr. Yu, who developed an interest in patch testing during his residency at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, where he worked with a patch-testing expert, will test children as young as 3-4 months with a “small selection of patches.”

The challenge with a call for more patch testing is a shortage of trained physicians. “In all of Boston, where we have hundreds of dermatologists, there are only about four of us who really do patch testing. My wait time is about 6 months,” said Dr. Yu, who is also an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Allergists at Massachusetts General Hospital do “some patch testing ... but they refer a lot of the most complicated cases to me,” he said, noting that patch testing and management of ACD involves detailed counseling for patients about avoidance of allergens. “Overall dermatologists represent the largest group of doctors who have proficiency in patch testing, and there just aren’t many of us.”

Dr. Perryman also said that patch testing is often performed by dermatologists who specialize in treating ACD and AD, though there seems to be “regional variance” in the level of involvement of dermatologists and allergists in patch testing.

Not all residency programs have hands-on patch testing opportunities, Dr. Yu said. A study published in Dermatitis, which he co-authored, showed that in 2020, 47.5% of dermatology residency programs had formal patch testing rotations. This represented improvement but is still not enough, he said.

The American Contact Dermatitis Society offers patch-testing mentorship programs, and the American Academy of Dermatology has recently begun offered a patch testing workshop at its annual meetings, said Dr. Yu, who received 4 weeks of training in the Society’s mentorship program and is now involved in the American Academy of Dermatology’s workshops and as a trainer/lecturer at the Contact Dermatitis Institute.

The study was supported by the Dermatology Foundation. Dr. Yu and his co-investigators reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Perryman had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

What’s Eating You? Noble False Widow Spider (Steatoda nobilis)

Incidence and Characteristics

The noble false widow spider (Steatoda nobilis) is one of the world’s most invasive spider species, having spread across the globe from Madeira and the Canary Islands into the North Atlantic.1,2 Steatoda comprise multiple species of false widow spiders, named for their resemblance to black widow spiders (Latrodectus). The noble false widow spider is the dominant species in buildings in southern Ireland and Great Britain, with a population surge in 2018 that caused multiple temporary school closures in London, England, for fumigation.3 The noble false widow spider was first documented in the United States in Ventura County, California, in 2011, with numerous specimens found in urban areas (eg, in parks, underneath garbage cans) closer to the coastline as well as farther inland. The species may have been introduced to this area by way of Port Hueneme, a city in California with a US naval base with routes to various other military bases in Western Europe.4 Given its already rapid expansion outside of the United States with a concurrent rise in bite reports, dermatologists should be familiar with these invasive and potentially dangerous arachnids.

The spread of noble false widow spiders is assisted by their wide range of temperature tolerance and ability to survive for months with little food and no water. They can live for several years, with one report of a noble false widow spider living up to 7 years.5 These spiders are found inside homes and buildings year-round, and they prefer to build their webs in an elevated position such as the top corner of a room. Steatoda weave tangle webs with crisscrossing threads that often have a denser middle section.5

Noble false widow spiders are sexually dimorphic, with males typically no larger than 1-cm long and females up to 1.4-cm long. They have a dark brown to black thorax and brown abdomen with red-brown legs. Males have brighter cream-colored abdominal markings than females, who lack markings altogether on their distinctive globular abdomen (Figure). The abdominal markings are known to resemble a skull or house.

Although noble false widow spiders are not exclusively synanthropic, they can be found in any crevice in homes or other structures where there are humans such as office buildings.5-7 Up until the last 20 years, reports of bites from noble false widow spiders worldwide were few and far between. In Great Britain, the spiders were first considered to be common in the 1980s, with recent evidence of an urban population boom in the last 5 to 10 years that has coincided with an increase in bite reports.5,8,9

Clinical Significance

Most bites occur in a defensive manner, such as when humans perform activities that disturb the hiding space, cause vibrations in the web, or compress the body of the arachnid. Most envenomations in Great Britain occur while the individual is in bed, though they also may occur during other activities that disturb the spider, such as moving boxes or putting on a pair of pants.5 Occupational exposure to noble false widow spiders may soon be a concern for those involved in construction, carpentry, cleaning, and decorating given their recent invasive spread into the United States.

The venom from these spiders is neurotoxic and cytotoxic, causing moderate to intense pain that may resemble a wasp sting. The incidence of steatodism—which can include symptoms of pain in addition to fever, hypotension, headache, lethargy, nausea, localized diaphoresis, abdominal pain, paresthesias, and malaise—is unknown but reportedly rare.5,10 There are considerable similarities between Steatoda and true black widow spider venom, which explains the symptom overlap with latrodectism. There are reports of severe debilitation lasting weeks due to pain and decreased affected limb movement after bites from noble false widow spiders.10-12

Nearly all noble false widow spider bite reports describe immediate pain upon bite/envenomation, which is unlike the delayed pain from a black widow spider bite (after 10 minutes or more).6,13,14 Erythema and swelling occur around a pale raised site of envenomation lasting up to 72 hours. The bite site may be highly tender and blister or ulcerate, with reports of cellulitis and local skin necrosis.7,15 Pruritus during this period can be intense, and excoriation increases the risk for complications such as infection. Reports of anaphylaxis following a noble false widow spider bite are rare.5,16 The incidence of bites may be underreported due to the lack of proper identification of the responsible arachnid for those who do not seek care or require hospitalization, though this is not unique to Steatoda.

There are reports of secondary infection after bites and even cases of limb amputation, septicemia, and death.14,17 However, it is unknown if noble false widow spiders are vectors for bacteria transmitted during envenomation, and infection likely is secondary to scratching or inadequate wound care.18,19 Potentially pathogenic bacteria have been isolated from the body surfaces of the noble false widow spider, including Pseudomonas putida, Staphylococcus capitis, and Staphylococcus epidermidis.20 Fortunately, most captured cases (ie, events in which the biting arachnid was properly identified) report symptoms ranging from mild to moderate in severity without the need for hospitalization. A series of 24 reports revealed that all individuals experienced sharp pain upon the initial bite followed by erythema, and 18 of them experienced considerable swelling of the area soon thereafter. One individual experienced temporary paralysis of the affected limb, and 3 individuals experienced hypotension or hypertension in addition to fever, skin necrosis, or cellulitis.14

Treatment

The envenomation site should be washed with antibacterial soap and warm water and should be kept clean to prevent infection. There is no evidence that tight pressure bandaging of these bite sites will restrict venom flow; because it may worsen pain in the area, pressure bandaging is not recommended. When possible, the arachnid should be collected for identification. Supportive care is warranted for symptoms of pain, erythema, and swelling, with the use of cool compresses, oral pain relievers (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen), topical anesthetic (eg, lidocaine), or antihistamines as needed.

Urgent care is warranted for patients who experience severe symptoms of steatodism such as hypertension, lymphadenopathy, paresthesia, or limb paralysis. Limited reports show onset of this distress typically within an hour of envenomation. Treatments analogous to those for latrodectism including muscle relaxers and pain medications have demonstrated rapid attenuation of symptoms upon intramuscular administration of antivenom made from Latrodectus species.21-23

Signs of infection warrant bacterial culture with antibiotic susceptibilities to ensure adequate treatment.20 Infections from spider bites can present a few days to a week following envenomation. Symptoms may include spreading redness or an enlarging wound site, pus formation, worsening or unrelenting pain after 24 hours, fevers, flulike symptoms, and muscle cramps.

Final Thoughts

- Kulczycki A, Legittimo C, Simeon E, et al. New records of Steatoda nobilis (Thorell, 1875) (Araneae, Theridiidae), an introduced species on the Italian mainland and in Sardinia. Bull Br Arachnological Soc. 2012;15:269-272.

- Bauer T, Feldmeier S, Krehenwinkel H, et al. Steatoda nobilis, a false widow on the rise: a synthesis of past and current distribution trends. NeoBiota. 2019; 42:19. doi:10.3897/neobiota.42.31582

- Murphy A. Web of cries: false widow spider infestation fears forceeleventh school in London to close as outbreak spreads. The Sun.October 19, 2018. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/7534016/false-widow-spider-infestation-fears-force-eleventh-londonschool-closing

- Vetter R, Rust M. A large European combfoot spider, Steatoda nobilis (Thorell 1875)(Araneae: Theridiidae), newly established in Ventura County, California. The Pan-Pacific Entomologist. 2012;88:92-97.

- Hambler C. The ‘noble false widow’ spider Steatoda nobilis is an emerging public health and ecological threat. OSF Preprints. Preprint posted online October 15, 2019. doi:10.31219/osf.io/axbd4

- Dunbar J, Schulte J, Lyons K, et al. New Irish record for Steatoda triangulosa (Walckenaer, 1802), and new county records for Steatoda nobilis (Thorell, 1875), Steatoda bipunctata (Linnaeus, 1758) and Steatoda grossa (C.L. Koch, 1838). Ir Naturalists J. 2018;36:39-43.

- Duon M, Dunbar J, Afoullouss S, et al. Occurrence, reproductive rate and identification of the non-native noble false widow spider Steatoda nobilis (Thorell, 1875) in Ireland. Biol Environment: Proc Royal Ir Acad. 2017;117B:77-89. doi:10.3318/bioe.2017.11

- Burrows T. Great bitten: Britain’s spider bite capital revealed as Essex with 450 attacks—find out where your town ranks. The Sun. Published April 3, 2019. Accessed September 14, 2023. https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/8782355/britains-spider-bite-capital-revealed-as-essex-with-450- attacks-find-out-where-your-town-ranks/

- Wathen T. Essex is the UK capital for spider bites—and the amount is terrifying. Essex News. April 4, 2019. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.essexlive.news/news/essex-news/essex-uk-capital-spider-bites- 2720935

- Dunbar J, Afoullouss S, Sulpice R, et al. Envenomation by the noble false widow spider Steatoda nobilis (Thorell, 1875)—five new cases of steatodism from Ireland and Great Britain. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56:433-435. doi:10.1080/15563650.2017.1393084

- Dunbar J, Fort A, Redureau D, et al. Venomics approach reveals a high proportion of Latrodectus-like toxins in the venom of the noble false widow spider Steatoda nobilis. Toxins. 2020;12:402.

- Warrell D, Shaheen J, Hillyard P, et al. Neurotoxic envenoming by an immigrant spider (Steatoda nobilis) in southern England. Toxicon. 1991;29:1263-1265.

- Zhou H, Xu K, Zheng PY, et. al. Clinical characteristics of patients with black widow spider bites: a report of 59 patients and single-center experience. World J Emerg Med. 2021;12:317-320. doi:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2021.04.011

- Dunbar J, Vitkauskaite A, O’Keeffe D, et. al. Bites by the noble false widow spider Steatoda nobilis can induce Latrodectus-like symptoms and vector-borne bacterial infections with implications for public health: a case series. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2022;60:59-70. doi:10.1080/15563650.2021.1928165

- Dunbar J, Sulpice R, Dugon M. The kiss of (cell) death: can venom-induced immune response contribute to dermal necrosis following arthropod envenomations? Clin Toxicol. 2019;57:677-685. doi:10.1080/15563650.2019.1578367

- Magee J. Bite ‘nightmare’: close encounter with a false widow. The Bournemouth Echo. September 7, 2009. Accessed September 21, 2023. http://www.bournemouthecho.co.uk/news/4582887.Bite____nightmare_____close_encounter_with_a_false_widow_spider/

- Marsh H. Woman nearly loses hand after bite from false widow. Daily Echo. April 17, 2012. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.bournemouthecho.co.uk/news/9652335.woman-nearly-loses-hand-after-bite-from-false-widow-spider/

- Stuber N, Nentwig W. How informative are case studies of spider bites in the medical literature? Toxicon. 2016;114:40-44. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.02.023

- Vetter R, Swanson D, Weinstein S, et. al. Do spiders vector bacteria during bites? the evidence indicates otherwise. Toxicon. 2015;93:171-174. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.11.229

- Dunbar J, Khan N, Abberton C, et al. Synanthropic spiders, including the global invasive noble false widow Steatoda nobilis, are reservoirs for medically important and antibiotic resistant bacteria. Sci Rep. 2020;10:20916. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-77839-9

- Atakuziev BU, Wright CE, Graudins A, et al. Efficacy of Australian red-back spider (Latrodectus hasselti) antivenom in the treatment of clinical envenomation by the cupboard spider Steatoda capensis (Theridiidae). Toxicon. 2014;86:68-78. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.04.011

- Graudins A, Gunja N, Broady KW, et al. Clinical and in vitro evidence for the efficacy of Australian red-back spider (Latrodectus hasselti) antivenom in the treatment of envenomation by a cupboard spider (Steatoda grossa). Toxicon. 2002;40:767-775. doi:10.1016/S0041-0101(01)00280-X.

- South M, Wirth P, Winkel KD. Redback spider antivenom used to treat envenomation by a juvenile Steatoda spider. Med J Aust. 1998;169:642-642. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb123445.x

Incidence and Characteristics

The noble false widow spider (Steatoda nobilis) is one of the world’s most invasive spider species, having spread across the globe from Madeira and the Canary Islands into the North Atlantic.1,2 Steatoda comprise multiple species of false widow spiders, named for their resemblance to black widow spiders (Latrodectus). The noble false widow spider is the dominant species in buildings in southern Ireland and Great Britain, with a population surge in 2018 that caused multiple temporary school closures in London, England, for fumigation.3 The noble false widow spider was first documented in the United States in Ventura County, California, in 2011, with numerous specimens found in urban areas (eg, in parks, underneath garbage cans) closer to the coastline as well as farther inland. The species may have been introduced to this area by way of Port Hueneme, a city in California with a US naval base with routes to various other military bases in Western Europe.4 Given its already rapid expansion outside of the United States with a concurrent rise in bite reports, dermatologists should be familiar with these invasive and potentially dangerous arachnids.

The spread of noble false widow spiders is assisted by their wide range of temperature tolerance and ability to survive for months with little food and no water. They can live for several years, with one report of a noble false widow spider living up to 7 years.5 These spiders are found inside homes and buildings year-round, and they prefer to build their webs in an elevated position such as the top corner of a room. Steatoda weave tangle webs with crisscrossing threads that often have a denser middle section.5

Noble false widow spiders are sexually dimorphic, with males typically no larger than 1-cm long and females up to 1.4-cm long. They have a dark brown to black thorax and brown abdomen with red-brown legs. Males have brighter cream-colored abdominal markings than females, who lack markings altogether on their distinctive globular abdomen (Figure). The abdominal markings are known to resemble a skull or house.

Although noble false widow spiders are not exclusively synanthropic, they can be found in any crevice in homes or other structures where there are humans such as office buildings.5-7 Up until the last 20 years, reports of bites from noble false widow spiders worldwide were few and far between. In Great Britain, the spiders were first considered to be common in the 1980s, with recent evidence of an urban population boom in the last 5 to 10 years that has coincided with an increase in bite reports.5,8,9

Clinical Significance

Most bites occur in a defensive manner, such as when humans perform activities that disturb the hiding space, cause vibrations in the web, or compress the body of the arachnid. Most envenomations in Great Britain occur while the individual is in bed, though they also may occur during other activities that disturb the spider, such as moving boxes or putting on a pair of pants.5 Occupational exposure to noble false widow spiders may soon be a concern for those involved in construction, carpentry, cleaning, and decorating given their recent invasive spread into the United States.

The venom from these spiders is neurotoxic and cytotoxic, causing moderate to intense pain that may resemble a wasp sting. The incidence of steatodism—which can include symptoms of pain in addition to fever, hypotension, headache, lethargy, nausea, localized diaphoresis, abdominal pain, paresthesias, and malaise—is unknown but reportedly rare.5,10 There are considerable similarities between Steatoda and true black widow spider venom, which explains the symptom overlap with latrodectism. There are reports of severe debilitation lasting weeks due to pain and decreased affected limb movement after bites from noble false widow spiders.10-12

Nearly all noble false widow spider bite reports describe immediate pain upon bite/envenomation, which is unlike the delayed pain from a black widow spider bite (after 10 minutes or more).6,13,14 Erythema and swelling occur around a pale raised site of envenomation lasting up to 72 hours. The bite site may be highly tender and blister or ulcerate, with reports of cellulitis and local skin necrosis.7,15 Pruritus during this period can be intense, and excoriation increases the risk for complications such as infection. Reports of anaphylaxis following a noble false widow spider bite are rare.5,16 The incidence of bites may be underreported due to the lack of proper identification of the responsible arachnid for those who do not seek care or require hospitalization, though this is not unique to Steatoda.

There are reports of secondary infection after bites and even cases of limb amputation, septicemia, and death.14,17 However, it is unknown if noble false widow spiders are vectors for bacteria transmitted during envenomation, and infection likely is secondary to scratching or inadequate wound care.18,19 Potentially pathogenic bacteria have been isolated from the body surfaces of the noble false widow spider, including Pseudomonas putida, Staphylococcus capitis, and Staphylococcus epidermidis.20 Fortunately, most captured cases (ie, events in which the biting arachnid was properly identified) report symptoms ranging from mild to moderate in severity without the need for hospitalization. A series of 24 reports revealed that all individuals experienced sharp pain upon the initial bite followed by erythema, and 18 of them experienced considerable swelling of the area soon thereafter. One individual experienced temporary paralysis of the affected limb, and 3 individuals experienced hypotension or hypertension in addition to fever, skin necrosis, or cellulitis.14

Treatment

The envenomation site should be washed with antibacterial soap and warm water and should be kept clean to prevent infection. There is no evidence that tight pressure bandaging of these bite sites will restrict venom flow; because it may worsen pain in the area, pressure bandaging is not recommended. When possible, the arachnid should be collected for identification. Supportive care is warranted for symptoms of pain, erythema, and swelling, with the use of cool compresses, oral pain relievers (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen), topical anesthetic (eg, lidocaine), or antihistamines as needed.

Urgent care is warranted for patients who experience severe symptoms of steatodism such as hypertension, lymphadenopathy, paresthesia, or limb paralysis. Limited reports show onset of this distress typically within an hour of envenomation. Treatments analogous to those for latrodectism including muscle relaxers and pain medications have demonstrated rapid attenuation of symptoms upon intramuscular administration of antivenom made from Latrodectus species.21-23

Signs of infection warrant bacterial culture with antibiotic susceptibilities to ensure adequate treatment.20 Infections from spider bites can present a few days to a week following envenomation. Symptoms may include spreading redness or an enlarging wound site, pus formation, worsening or unrelenting pain after 24 hours, fevers, flulike symptoms, and muscle cramps.

Final Thoughts

Incidence and Characteristics